Federal Court of Australia

Cytec Industries Inc. v Nalco Company (No 4) [2024] FCA 1318

ORDERS

Appellant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

AND BETWEEN: | Cross-Appellant | |

AND: | Cross-Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties confer and supply to the chambers of Justice Burley, within 14 days, short minutes of order giving effect to these reasons.

2. Insofar as the parties are unable to agree to the terms of the short minutes of order referred to in order 1, the areas of disagreement should be set out in mark-up.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

[1] | |

[6] | |

[14] | |

[29] | |

[29] | |

[32] | |

[39] | |

[40] | |

[47] | |

[47] | |

[55] | |

[55] | |

[60] | |

[76] | |

[76] | |

[80] | |

[89] | |

5.1 Lack of support and lack of clear and complete description | [94] |

[98] | |

[111] |

BURLEY J:

1 By amended interlocutory application dated 23 December 2022, Nalco Company seeks an order for the amendment pursuant to s 105(1A) of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) of patent application No 2012220990 entitled “Reducing aluminosilicate scale in the Bayer Process” (amendment application or sixth proposed amendment). Cytec Industries Inc opposes the application. The application arises from the decision in Cytec Industries Inc. v Nalco Company [2021] FCA 970 (Burley J) (judgment or J) where I found that the present claims to the patent application lacked support within s 40(3) and lacked sufficient disclosure within s 40(2)(a) of the Patents Act.

2 Cytec raises multiple grounds of opposition to the amendment. In short, they are that the proposed amendment is not allowable under s105(4) and s 102 of the Patents Act because the specification would lack support, lack clarity, claim matter that extends beyond that disclosed in the specification and fail to disclose the best method known to Nalco of performing the invention (grounds 4, 5, 6, 6A). In addition, Cytec contends that the sixth proposed amendment should be refused on discretionary grounds under s 105(1A) because the amendment does not overcome the deficiencies identified in the judgment and also for reasons related to alleged delay and misconduct in seeking the amendment (grounds 7 and 8).

3 Broadly, the dispute may be corralled into three issues. First, the proper construction of the claims as amended. Secondly, the consequence of that construction under ss 105(4) and 102(2) of the Patents Act. Thirdly, the exercise of discretion under s 105(1A) of the Patents Act.

4 These reasons assume familiarity with the judgment and do not repeat the primer set out in section 3 or the summary of the patent application set out in section 4.

5 For the reasons set out below, I have concluded that Nalco’s amendment application does not overcome the deficiencies identified in the judgment, namely that: (a) the specification does not disclose the invention in a manner which is clear enough and complete enough for the invention to be performed by a person skilled in the art pursuant to s 40(2)(a); and (b) the invention claimed in each of the claims was not supported by the matter disclosed in the specification within s 40(3). As a result, the requirements of s 102(2) of the Patents Act have not been met. I am satisfied that I should decline to exercise the discretion under s 105(1A) to grant the amendment application.

6 Pursuant to ss 105(1A) and 112A of the Patents Act, the Court has the exclusive power to consider and allow amendments requested by a patent applicant during an appeal to the Federal Court against a decision or direction of the Commissioner in relation to a patent application. This includes the power to order amendments to address deficiencies identified by the Court after the Court has delivered its reasons on the grounds of opposition: Meat & Livestock Australia Limited v Cargill, Inc (No 2) (2019) 139 IPR 147; [2019] FCA 33 at [103]-[105] (Beach J).

7 Section 105 of the Patents Act relevantly provides:

Order for amendment during an appeal

(1A) If an appeal is made to the Federal Court against a decision or direction of the Commissioner in relation to a patent application, the Federal Court may, on the application of the applicant for the patent, by order direct the amendment of the patent request or the complete specification in the manner specified in the order.

8 Pursuant to s 105(4), in order to be allowable, the amendments sought must comply with s 102 of the Patents Act.

9 Section 102 relevantly provides:

Certain amendments of complete specification are not allowable after relevant time

(2) An amendment of a complete specification is not allowable after the relevant time if, as a result of the amendment:

(a) a claim of the specification would not in substance fall within the scope of the claims of the specification before amendment; or

(b) the specification would not comply with subsection 40(2), (3) or (3A).

10 Sections 40(2) and (3) of the Patents Act provide:

Requirements relating to complete specifications

(2) A complete specification must:

(a) disclose the invention in a manner which is clear enough and complete enough for the invention to be performed by a person skilled in the relevant art; and

(aa) disclose the best method known to the applicant of performing the invention; and

(b) where it relates to an application for a standard patent—end with a claim or claims defining the invention; and

(c) where it relates to an application for an innovation patent—end with at least one and no more than 5 claims defining the invention.

(3) The claim or claims must be clear and succinct and supported by matter disclosed in the specification.

11 If the proposed amendments are allowable under s 102, then the Court has a discretion as to whether to grant the amendments under s 105(1A): Meat & Livestock at [342]; ToolGen Incorporated v Fisher (No 3) [2024] FCA 539 at [22] (Nicholas J). Nalco as the applicant for amendment bears the onus of establishing that the amendment should be allowed in the circumstances: Les Laboratoires Servier v Apotex Pty Ltd (2016) 247 FCR 61; [2016] FCAFC 27 at [242]-[245]; cited with approval in the context of s 105(1A) in Meat & Livestock at [344].

12 The discretion is exercised by reference to guiding principles that seek to balance the right of the patent applicant to apply to amend claims and the public interest in ensuring that an amendment application is made promptly and for proper purposes, and that any amendment made does not confer on the patentee an unfair advantage: see in the context of the discretion under s 105(1) of the Patents Act, Neurim Pharmaceuticals (1991) Ltd v Generic Partners Pty Ltd (No 2) (2019) 139 IPR 424; [2019] FCA 154 at [107].

13 The manner in which the discretion should be exercised is addressed further in section 5 below.

14 For convenience, I set out below a brief history of the patent application and the various amendments sought to it by Nalco.

15 On 7 February 2012, Nalco filed its patent application with the Australian Patent Office (APO). On 24 February 2015, the first examination report was issued, raising a novelty and inventive step objection in light of an identified prior art document.

16 On 1 May 2015, Nalco filed its first amendment application to address the cited prior art. On 21 May 2015, the application was accepted.

17 On 21 August 2015, Cytec filed a notice of opposition pursuant to s 59 of the Patents Act contending that the patent application should not proceed to grant on the basis that the claims were not novel, lacked an inventive step and the application did not comply with the requirements of ss 40(2) and (3) of the Patents Act.

18 On 25 May 2016, Nalco filed its second amendment application (proposed second amendment) seeking to remove the Markush format of the claims and define the claims in the form of small molecules. On 14 September 2016, Cytec filed a notice of opposition to the proposed second amendment.

19 On 16 January 2018, a delegate of the Commissioner refused the proposed second amendment on the basis that there was not clear enough and complete enough disclosure of various claimed small molecules and that those small molecules in isolated form were not supported by the technical contribution to the art, such that the amendment did not comply with s 102(2)(a) of the Patents Act: Cytec Industries Inc. v Nalco Company [2018] APO 4.

20 On 10 August 2018, Nalco filed its third amendment application (third proposed amendment) addressing the s 102(2)(a) concern raised by the delegate in respect of the proposed second amendment by seeking to delete the specific identified small molecules from the claims. The third proposed amendment also sought to insert the phrase “within a product mixture”. The proposed amendment was not considered by the delegate during the s 59 opposition hearing, which proceeded on the basis of the unamended claims.

21 On 8 January 2019, a delegate handed down their opposition decision in the s 59 opposition, finding that the specification did not provide a clear enough and complete enough disclosure of the invention and that the claims were not supported. The delegate also found that several of the claims lacked clarity and novelty. Other grounds advanced, including lack of inventive step, were rejected: Cytec Industries Inc. v Nalco Company [2019] APO 2.

22 On 17 January 2019, Nalco filed in the APO its fourth amendment application, which was substantially in the form of the third proposed amendment, updated to also address the lack of novelty ground identified by the delegate’s decision on the s 59 opposition.

23 On 29 January 2019, Cytec filed a notice of appeal pursuant to s 60(4) in this Court appealing from parts of the delegate’s s 59 opposition decision upon which it did not succeed. On 25 February 2019, Nalco filed a cross-appeal.

24 On 29 March 2019, Nalco filed an amendment application in the appeal proceedings seeking an amendment pursuant to s 105(1A) of the Patents Act (fourth proposed amendment). The amendment sought was the same as that filed before the APO on 17 January 2019.

25 On 4 November 2019, Nalco obtained the leave of the Court pursuant to s 105(1A) to amend the claims of the patent application in accordance with the fourth proposed amendment: Cytec Industries Inc. v Nalco Company [2019] FCA 1800.

26 On 29 August 2021, I handed down judgment in respect of the substantive appeal and cross-appeal proceedings, in which I rejected Nalco’s construction of the claims in their current form, finding that:

(a) the invention claimed in each of the claims was not supported by the matter disclosed in the specification within s 40(3) of the Patents Act;

(b) in light of the breadth of the invention claimed, the specification did not disclose the invention in a manner which is clear enough and complete enough for it to be performed by a person skilled in the relevant art within s 40(2)(a) of the Patents Act; and

(c) Cytec had not established its grounds of opposition based on lack of novelty or lack of best method known to Nalco within the requirements of s 40(2)(aa) of the Patents Act.

27 On 20 September 2021, Nalco filed its fifth amendment application (fifth proposed amendment) which it submits addresses the Court’s findings in the judgment with respect to deficiencies identified in the support and disclosure requirements.

28 On 23 December 2022, Nalco filed (following the grant of leave by consent) its sixth proposed amendment, being an amended version of its fifth amendment application. Nalco contends the amendment arises from Cytec’s amended particulars of grounds of opposition to the fifth proposed amendment served on 24 October 2022.

29 I refer to qualifications and experience of John Belwood at J[20] and [21]. He affirmed three affidavits in relation to the amendment application. He is retained by Nalco and gives evidence about: the nature of the amendments proposed in the fifth and sixth proposed amendment, including the significance of claims including both hydrolysed and unhydrolysed forms of the identified small molecules; the disclosure in the specifications (as filed and most recently) with respect to those versions of the claims; and his response to the affidavits of Professor Easton.

30 I refer to the qualifications and experience Christopher Easton at J[15] and [16]. He affirmed three affidavits in relation to the amendment application. He is retained by Cytec and gives evidence about: what he understands is claimed by and within the scope of the claims as proposed by the fifth and sixth proposed amendment; the disclosure in the specifications (as filed and most recently) with respect to those versions of the claims; and his response to the affidavits of Mr Bellwood.

31 Mr Bellwood and Professor Eastern joined in the preparation of a joint expert report for the purpose of the amendment application. They both gave oral evidence in concurrent session and were cross-examined on their evidence.

32 Gareth Michael Dixon is a registered patent attorney and a Principal of Spruson & Ferguson Pty Ltd, the patent and trade mark attorneys associated with Spruson & Ferguson Lawyers Pty Ltd, the solicitors for Nalco. As of November 2021, Shelston IP Pty Ltd and Shelston IP Lawyers Pty Ltd, previously the solicitors for Nalco were acquired by Spruson & Ferguson.

33 Mr Dixon affirmed two affidavits in relation to the amendment application. Mr Dixon was cross-examined about his evidence. He gives evidence about: what he understood, as Nalco’s patent attorney (and the advice actually given), to be the invalidity risk to the patent application in respect of the disclosure and support requirements before the commencement of the appeal proceedings; the history of and basis for the associated amendment applications before the APO.

34 Duncan Roland Longstaff is a legal practitioner and Principal of Spruson & Ferguson Lawyers Pty Ltd, and prior to that was a Principal of Shelston IP Lawyers Pty Ltd. Since November 2019, Mr Longstaff has had the care and conduct of these proceedings on behalf of Nalco.

35 Mr Longstaff affirmed four affidavits in relation to the amendment application. Mr Longstaff was cross-examined about his evidence. He gives evidence about: the nature and effect of the proposed amendments sought by the fifth proposed amendment; the history of amendments to and Cytec’s opposition of the patent application; the consideration given by Nalco or Shelston IP to the sufficiency and support issues the subject of the judgment prior to the filing of the fifth proposed amendment; and the basis for and effect of the sixth proposed amendment.

36 Corey Ricardo Anthony is a Senior Intellectual Property Counsel of Ecolab Inc., the parent company of Nalco. Since May 2017, Dr Anthony has been responsible for prosecuting the patent application, instructing Spruson & Ferguson (previously Shelston IP) during the opposition before the APO and in the appeal proceeding before this Court. Dr Anthony affirmed one affidavit in relation to the amendment application and an earlier affidavit in the proceedings in relation to discovery. Nalco sought to read and rely on both affidavits. He was cross-examined about his evidence. In his second affidavit, Dr Anthony gives evidence about: the history of the proceedings before the APO and this Court, including correspondence between Nalco’s legal team as to the form and rationale of proposed amendments; and the consideration given by Nalco to the sufficiency and support issues the subject of the judgment.

37 Eric Eugene DeMaster is the Assistant Chief Intellectual Property Counsel of Ecolab Inc. From August 2015 to May 2017, Mr DeMaster had responsibility for the prosecution of the patent application, including instructing Shelston IP. Mr DeMaster affirmed one affidavit in relation to the amendment application. He gave evidence about the history of the proceedings during that time, including the basis for the second proposed amendment. He was not cross-examined.

38 Katrina May Crooks is a legal practitioner and Principal of Spruson & Ferguson Lawyers Pty Ltd and previously a Principal of Shelston IP Lawyers Pty Ltd. She had carriage of and otherwise assisted on the matter from January 2019 to April 2021. Ms Crooks affirmed one affidavit in relation to the amendment application. Ms Crooks gave evidence as to the history of the proceedings before this Court in respect of the fourth proposed amendment. Ms Crooks was not cross-examined.

39 Andrew James Wiseman is a legal practitioner and Partner of Allens, the solicitors for Cytec, with day-to-day carriage of the matter. He gives evidence about Nalco’s delay in bringing the fifth proposed amendment. He was not cross-examined.

40 In section 4 of the judgment, the complete specification is summarised and the claims in their present form are recited.

41 Claim 1, in its current form is (with integer numbers added) as follows:

(1) A method for the reduction of aluminosilicate containing scale in a Bayer process comprising the step of:

(2) adding to the Bayer process stream an aluminosilicate scale inhibiting amount of a composition comprising at least one small molecule

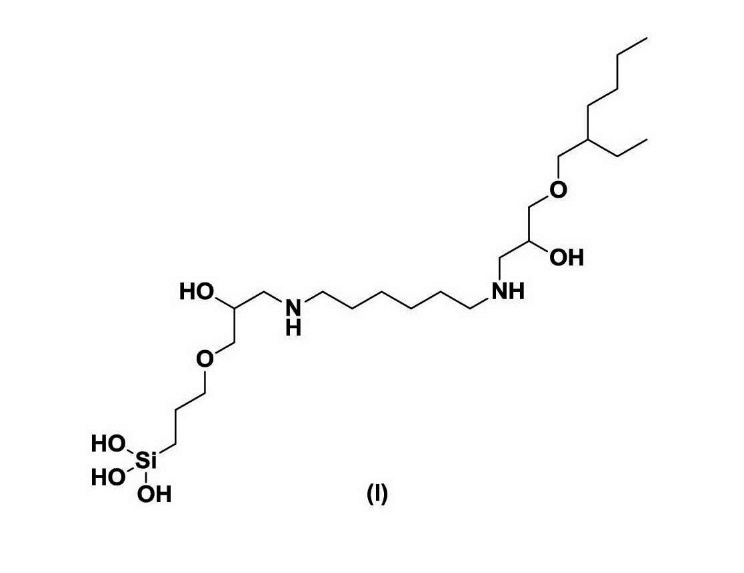

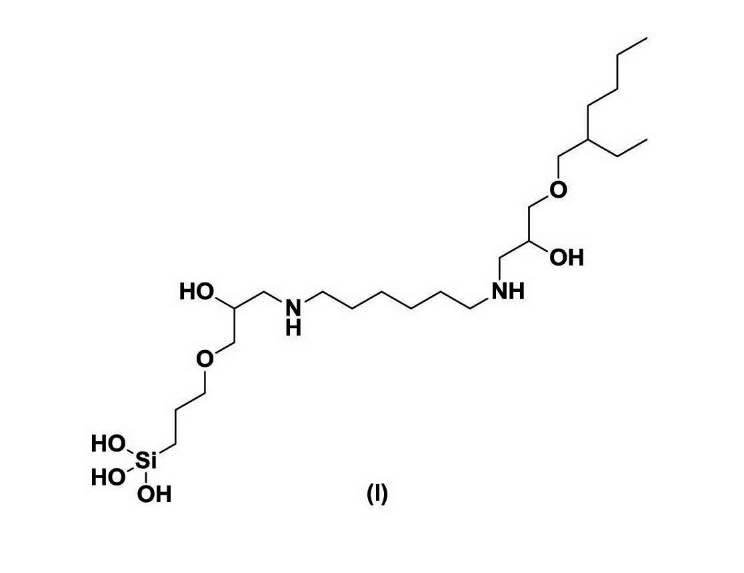

(3) selected from the group consisting of compounds (I) through (XIII), (XV) through (XXX), (XXXII) through (XLVII), (LIII) through (LVIII) and (LX)

(4) within a product mixture formed from the reaction of a) hexane diamine, ethylene diamine or 1-amino-2-propanol; b) 3-glycidoxypropyltrimethoxysilane; and c) 2-ethylhexyl glycidyl ether:

[drawn thereafter are the 46 further compounds referred to in integer (3)]

42 Claim 1 in the form sought to by the amendment application, is as follows (with integer numbers added and marked-up against claim 1 in its current form) (amended claim 1):

(1) A method for the reduction or aluminosilicate containing scale in a Bayer process comprising the steps of:

(2) adding to the Bayer process stream an aluminosilicate scale inhibiting amount of a composition comprising at least one small molecules is selected from the group consisting of compounds:

(3) (I) through (IX), (XXVIII) (XIII), (XV) through (XXX) and (XXXII) through (XLVII), (LIII) through (LVIII) and (LX)

(4) within a product mixture formed from the reaction of a) hexane diamine, ethylene diamine or 1-amino-2-propanol; b) 3-glycdixoypropyltrimethoxysilane; and c) 2-ethylhexyl glycidyl ether:

[drawn thereafter are the 12 further compounds referred to in integer (3)]

43 The amendment application also seeks to remove dependent claims 216 and replace them with independent claims 25, in the form as follows:

2. A method for the reduction of aluminosilicate containing scale in a Bayer process comprising the step of adding to the Bayer process stream an aluminosilicate scale inhibiting amount of a composition comprising small molecules (X) through (XIII), (XV) through (XIX), (XXIII) through (XXVII) within a product mixture formed from the reaction of ethylene diamine, 3-glycidoxypropyltrimethoxysilane and 2-ethylhexyl glycidyl ether.

[drawn thereafter are the 14 compounds referred to in integer (3)]

3. A method for the reduction of aluminosilicate containing scale in a Bayer process comprising the step of adding to the Bayer process stream an aluminosilicate scale inhibiting amount of a composition comprising small molecules (XXXIII) through (XLII), (LVI) through (LVIII) and (LX) within a product mixture formed from the reaction of ethylene diamine, 3-glycidoxypropyltrimethoxysilane and 2-ethylhexyl glycidyl ether.

[drawn thereafter are the 14 compounds referred to in integer (3)]

4. A method for the reduction of aluminosilicate containing scale in a Bayer process comprising the step of adding to the Bayer process stream an aluminosilicate scale inhibiting amount of a composition comprising small molecules (XX) through (XXII) within a product mixture formed from the reaction of 1-amino-2-propanol, 3- glycidoxypropyltrimethoxysilane and 2-ethylhexyl glycidyl ether.

[drawn thereafter are the 3 compounds referred to in integer (3)]

5. A method for the reduction of aluminosilicate containing scale in a Bayer process comprising the step of adding to the Bayer process stream an aluminosilicate scale inhibiting amount of a composition comprising small molecules (LIII) through (LV) within a product mixture formed from the reaction of 1-amino-2-propanol, 3- glycidoxypropyltrimethoxysilane and 2-ethylhexyl glycidyl ether.

[drawn thereafter are the 3 compounds referred to in integer (3)]

44 I refer to these proposed amended claims below as the amended claims.

45 In summary, Nalco’s amendment application proposes to:

(a) narrow the language of claim 1 by removing the phrase “at least one” as follows (with the changes in mark-up): “…adding to the Bayer process stream an aluminosilicate scale inhibiting amount of a composition comprising at least one small molecules is selected from the group consisting of compounds…” (narrowing amendment); and

(a) separate claim 1 into five independent claims, which specify: (i) a choice of amine: hexanediamine in the case of claim 1; ethylenediamine in the case of claims 2 and 3; and 1-amino-2-propanol in the case of claims 4 and 5; and (ii) whether the product mixture has undergone a hydrolysis step prior to being added to the Bayer Process Stream, in the case of claims 1, 2 and 4; or not, in the case of claims 3 and 5 (separation amendment).

46 The separation amendment is not in contest. The construction dispute substantially concerns the scope and effect of the narrowing amendment.

47 The parties agree that the principles of construction to be applied are well settled. These are summarised at J[91].

48 In section 5 of the judgment, I consider the construction to be given to claim 1 and in particular, whether the claim encompasses an embodiment wherein the composition added to the Bayer process stream comprises only one type of small molecule selected from the group of compounds identified in claim 1.

49 There was little disagreement between the experts as to the practical question of the complexity of the product mixtures produced. They agreed that: (a) when one of the three different forms of amine is reacted with GPS and E, the consequent reaction mixture will contain an extremely large variety of small molecules and will include all the small molecules listed in claim 1, subject only to being limited by those molecules containing the same form of amine backbone that was added to the mixture (J[87]); and (b) there is no known way to avoid the production of a complex product mixture including within it all of the other compounds specified in the claim (J[88]).

50 Turning to the specific language of the claim 1, I found at J[106] that:

The claim refers to adding to the Bayer process stream an “aluminosilicate scale inhibiting amount of a composition comprising at least one small molecule selected from the group” consisting of 47 identified compounds. The word “comprising” is defined to mean “including, but not limited to” and the words “at least one small molecule” includes the selection of one molecule only. It is apparent from the breadth of the meaning of “including” that the entirety of the composition may be one type of small molecule or more than one such type. It is difficult to read the claim in a different way. The type of small molecule may be one or more selected from the group of nominated compounds that are “within a product mixture” that is “formed from the reaction of a) hexane diamine, ethylene diamine or 1-amino-2-propanol; b) 3-glycidoxypropyltrimethoxysilane; and c) 2-ethylhexyl glycidyl ether”.

51 Having regard to the above, I concluded at J[108] that the language of claim 1 must encompass:

(a) a complex reaction mixture, formed from the reaction of A + GPS + E that includes within it many of the identified small molecules, as well as many other compounds; and

(b) a reaction mixture, formed from the reaction of A + GPS + E, that is made up of a single type of small molecule identified in the claim; and

(c) the spectrum between those two possibilities.

52 In the present circumstances, Nalco submits that there are two issues of claim construction arising for present determination:

(a) Whether the proposed amended claims include within their scope product mixtures made up of all of the particular small molecules identified in the claims (being 13 identified small molecules for claim 1, 14 small molecules for claims 2 and 3 and 3 small molecules for claims 4 and 5) but no others (small molecule construction issue); and

(b) Whether claims 1, 2 and 4 are directed to a product mixture that has undergone a hydrolysis step and claims 3 and 5 directed to a product mixture that has not undergone a hydrolysis step prior to being added to the Bayer Process stream (hydrolysis construction issue).

53 The parties agree that the small molecule construction issue may be determined by reference to claim 1.

54 The following matters are accepted between the parties in respect of the amended claims. These are set out below to contextualise the scope of the dispute:

(a) the amended claims are not directed to a product mixture that contains only some of the identified small molecules. It is accepted that the product mixture includes all of the identified small molecules in each claim, as well as others; and

(b) the claims do not require the scale-inhibiting action of a product mixture to be attributable to any specific individual small molecule or only to the small molecules identified in the claims. Rather, it is the aggregate influences of all of the silane compounds present in the product mixture formed from the reaction of A + GPS + E.

4.2 Small molecule construction issue

55 Nalco contends that the amended claims are directed to a complex product mixture formed from the reaction of A + GPS + E, which must include, but must not be limited to, all of the identified small molecules in each of the particular claims. That is, depending upon the amine molecule used in the reaction, the product mixture will include many other small molecules and polymers in addition to each of the listed small molecules in the particular claim.

56 Nalco puts forward a number of matters in support of its construction. However, central to its argument is that:

(a) having regard to the findings at J[87], it is not practically possible to react A, GPS and E in a way that results in only the specified small molecules in the claim being present to the exclusion of other small molecules and polymers;

(b) the claims require all of the identified small molecules to be within a product mixture formed from the reaction of A, GPS and E. The words “within” and “formed” are ordinary English words which, in context, mean “inside; in” and “produced”, respectively. Thus, a person skilled in the art would understand from the above and having regard to the term “product mixture” as a term of art that the claims require these small molecules to be in a product mixture that has been produced by the reaction of the three reactants, and the claims do not include within their scope a product mixture that contains only the small molecules listed; and

(c) the words “at least one” and “selected from” have been removed, and work should be given to those deletions such that the composition now comprises the identified small molecules (along with many others and polymers) within a product mixture formed from the reaction of A, GPS and E. As a matter of ordinary English, the fact that the identified small molecules are “within” a product mixture means that the identified small molecules are not coterminous with the product mixture.

57 Nalco further contends that its construction fits within the definition of “comprising” provided at page 4 lines 7–10 in the specification, which states:

Unless the context clearly requires otherwise, throughout the description and the claims, the words "comprise", "comprising", and the like are to be construed in an inclusive sense as opposed to an exclusive or exhaustive sense; that is to say, in the sense of "including, but not limited to”.

Having regard to the fact that the identified small molecules are within a product mixture, which will contain those molecules, along with many others, a skilled addressee would understand “comprises” in the context of the amended claims to include product mixtures not limited to only those identified small molecules.

58 Cytec contends that the amended claims define an invention which includes within its scope compositions comprising only the particular small molecules identified. Cytec notes that in the judgment the Court found that the complete specification does not identify or describe beneficial effects of any particular small molecules, or how to produce a reaction product mixture that contains only those small molecules.

59 Cytec thus contends that its construction must follow as a result of, or alternatively by applying the same logic underpinning the findings at J[108] that claim 1 included within its scope a reaction mixture that is made up of a single type of small molecule identified in the claim. Cytec submits that there can be no other way to read the amended claims and that the deletion of “at least one” does not alter that conclusion because: (a) the small molecule integer must be given meaning independent of the product mixture integer; and (b) “comprising” remains an inclusive term. That is, a composition within the method must comprise each of the specified small molecules and may, but need not, comprise other small molecules. The probability of obtaining a composition comprising only the listed types of small molecules is not to the point.

60 I accept the construction advanced by Cytec. In my view, each of the amended claims includes within its scope a product mixture consisting of only the listed small molecules.

61 Looking first at the language of amended claim 1, the method there involves adding to the Bayer process stream an aluminosilicate scale inhibiting amount of a composition “comprising” the small molecules identified in integer (3) within a product mixture formed from the reaction of A, GPS and E. The requirement of integers (2) and (3) is that all of the small molecules identified must be present in the product mixture, although given the inclusive definition of “comprising” in the specification, other components may also (optionally) be present.

62 That construction is consistent with the findings at J[108] in respect of the current version of claim 1:

The result is that, properly construed, the claim includes within its scope both: (a) a complex reaction mixture, formed from the reaction of A + GPS + E, that includes within it many of the identified small molecules as well as many more compounds; and (b) a reaction mixture, formed from the reaction of A + GPS + E, that is made up of a single type of small molecule identified in the claim. The language of “comprising at least one small molecule” indicates that the claim covers the spectrum between these two possibilities.

63 I see no reason why a different construction of the word “comprising” in the context of the claim would arise from the language of amended claim 1. Although the amended claims refer to a number of specified small molecules (varying in amount from 3 to 13 or 14) rather than a single small molecule, the logic of J[108] still applies. The amended claims require at a minimum that the specified small molecules be present. Many more may be included, but that is not essential.

64 I do not accept Nalco’s submission that the words “within a product mixture formed from the reaction of A, GPS and E”, which appear in the current version of claim 1, would now be understood by the person skilled in the art to mean that the amended claims do not include within their scope a product mixture that only contains the small molecules listed. Read as a whole, the language of amended claim 1 more sensibly has the meaning that the product mixture may be made up of those specified molecules only or made up of those specified molecules as well as others. I am fortified in that conclusion by the evidence of the experts in the Joint Expert Report, who agreed, in relation to the proposed amended claims:

All the small molecules illustrated and referred to by Roman numerals in each claim must be present in the product mixture of that Claim. No other small molecule is either excluded or required. That is, other small molecules may also be present in the product mixture, but the Claim does not require or exclude the presence of any other material in the product mixture.

65 In support of its submission, Nalco draws attention to the evidence of the experts that it is, in effect, impossible to create a reaction mixture from A, GPS and E that results only in the specified small molecules. It submits that whilst the words “within” and “formed” are ordinary English words, the term “product mixture” is a term of art such that the skilled addressee would understand those terms together to mean that the claims do not include within their scope a product mixture that only contains the small molecules listed.

66 However, the expression “term of art”, and the role of the expert evidence should be correctly understood. The words “product mixture” are part of a phrase, being “product mixture formed from the reaction of [A + GPS + E]”, that describes, as the expert evidence explains, how a product mixture is created and the end result of that product mixture. The words “product mixture” themselves are ordinary English words that are to be understood in that technical context. Explaining the technical context falls within the realm of expert evidence but determining the meaning of the words “product mixture” is a matter for the Court. To the extent that Nalco’s submission suggests that the Court is bound by an expert’s construction of “product mixture”, I reject that proposition. As the Full Court said in Commissioner of Patents v Rokt Pte Ltd [2020] FCAFC 86; (2020) 277 FCR 267 at [73] (Rares, Nicholas and Burley JJ):

The role of expert evidence in construing the patent specification and the claims is limited. It is to place the Court in the position of the person acquainted with the surrounding circumstances as to the state of the art and manufacture as at the priority date: Kimberly-Clark Australia Pty Ltd v Arico Trading International Pty Ltd (2001) 207 CLR 1 at [24]; Myriad Genetics at [12]. Typically, the Court will read the specification with the benefit of expert evidence as to the meaning of words that are terms of art, or with an explanation of technical concepts relevant to the understanding of the invention as described and claimed. The question of construction remains with the Court.

67 Nalco also submits that the word “comprising” supports its position, because the words “including, but not limited to” would be understood in the context of the reaction mixture to mean that the small molecules are to be within the product mixture so formed, which will invariably contain the identified small molecules as well as many others.

68 In my view the principles of construction set out at J[91] do not support that approach. The plain meaning of “comprising” is that the composition of the amended claims will include at least the specified compounds within the reaction mixture but may contain more than those compounds. One may not distort the clear language of the claim by reference to glosses drawn from the specification or elsewhere. The tortured history of amendments of the claims identified in section 1.2 above demonstrates, even if it were not a given in patent law, that the language of the claim is of the patentee’s own choosing. If the patentee wished to signify that only product mixtures containing more than the specified molecules were present in the product mixtures, then it could have done so.

69 In contesting this construction, Nalco accepts that it is practically not possible to specify the outcome of the reaction of A, GPS and E such that any individual small molecule, or group of small molecules is produced. It submits that this aids its construction, noting that when one of the three different forms of amine is reacted with GPS and E, the consequent product mixture will always contain an extremely large variety of small molecules and will include all the small molecules listed in the current and amended claims, as well as many others, and polymers. It contends that because it is not practically possible to react A, GPS and E in a way that results only in those small molecules being present to the exclusion of other small molecules or polymers it is not practical or within common sense to construe the claims in the manner set out above. As I have noted, that is not the approach taken by the experts, who were well familiar with the practical difficulties to which Nalco refers but still read the plain words of the claims for the meaning to which I have referred at [64] above.

70 Nalco submits that the evidence of Mr Bellwood, in agreeing to the passage from the Joint Expert Report quoted above, should not be determinative of the small molecule construction issue. It submits that the substance of Mr Bellwood’s evidence elsewhere was such that he would never have agreed to that construction of the claim if it had been pointed out to him that the consequence was that the amended claims included within their scope a product mixture containing only the specified small molecules, because he considered that this was impossible to achieve. Nalco complains that it was not permitted to “explore this during the oral expert evidence” on the basis that construction was a matter for the court.

71 The proposition advanced by Nalco is, in effect, that it ought to have had an opportunity to cross examine its own witness in order to enable it or him to retreat from a clear concession that he made in joint session and produced in a joint expert report. Mr Bellwood was a careful and well qualified witness whose evidence reflected a clear understanding of the issues in the case. He joined in the answer given above in a manner that was consistent with the construction that I have (separately) adopted.

72 There are three reasons why Nalco was not permitted to cross examine its own witness.

73 First, to do so would undermine the process of the preparation and presentation of joint expert reports and evidence. Unless an expert witness wishes to retract evidence given because it contains a mistake or that witness wishes to change the opinion expressed, a view expressed in a joint expert report should generally be accepted on its face.

74 Secondly, as I have noted, questions of construction are for the Court. In the present case, the proposition that Nalco advances is that Mr Bellwood would not have agreed to the construction I now adopt is because his evidence was that he knew that a product mixture containing only the identified small molecules could not be achieved. Mr Bellwood gave evidence of the technical consequences of a mixture of A + GPS + E at the initial hearing of the case and repeated several times in his evidence on the amendment application, including in the Joint Expert Report. Perhaps more importantly, it is a point that has been made to the Court and has been taken into consideration in construing the claims. However, as I have found, and as Mr Bellwood agreed, the terms of the claim nonetheless include the very construction that Nalco seeks to avoid.

75 Thirdly, the substantive submission advanced by Nalco is that because it is impossible to make a composition consisting only of the small molecules identified in integer (3) of amended claim 1, no person would construe the language of the claim to include such a composition. That proposition assumes that the construction of the claims is to be entirely driven by the technical contribution to the art described in the specification. Such a circular proposition is repugnant to the authorities that require the claims to be understood according to their terms, albeit in the context of the specification as a whole. To distort the plain language of the claim by reference to the technical contribution is to place a gloss on the language of the claim of the type that has long been forbidden; Welch Perrin & Co Pty Ltd v Worrel [1961] HCA 91; (1961) 106 CLR 588 at 610. Furthermore, that submission, and many of the other submissions concerning the construction of the amended claims were substantively advanced before me at the trial of the opposition to the current claims and rejected. I return to this in section 5 below.

4.3 Hydrolysis construction issue

76 Nalco contends that properly construed, the amended claims are directed to product mixtures that have either undergone a hydrolysis step (amended claims 1, 2 and 4) or have not undergone a hydrolysis step (amended claims 3 and 5), prior to being introduced to the Bayer process stream. The basis being that a person skilled in the art would understand there to be a distinction between those two groups of claims, and that distinction must be given work to do.

77 Cytec submits that none of the amended claims includes any hydrolysis step of the product mixture as an integer and such an integer should not be read into any claim. It submits that to do so would be to add an impermissible gloss to the claims from the specification. Similarly, Cytec notes that there is no basis for limiting any of the amended claims by reference to the water content of the reactants.

78 Nalco suggests that Cytec’s construction would mean that two of the amended claims would have no work to do and would be redundant, citing Davies v Lazer Safe Pty Ltd [2019] FCAFC 65 at [65]; Nichia Corporation v Arrow Electronics Australia Pty Ltd [2019] FCAFC 2; (2019) 175 IPR 187 at [41], and the Court should endeavour to construe claims in a manner that avoids such redundancy. That is, the Court should give effect to the difference between amended claims 2 and 3 on the one hand and amended claims 4 and 5 on the other by finding that the claims are directed to product mixtures that have or have not undergone a hydrolysis step.

79 Further in support of its construction, Nalco relies on a number of matters, including that:

(a) the skilled addressee would understand that the reaction of A, GPS and E required by the claims should be done in the absence of water, such that the presence of hydrolysed small molecules in amended claims 1, 2 and 4 must be the result of a hydrolysis step performed on the product mixture. Nalco supports this view by noting that the amended claims and common general knowledge support the use of anhydrous reactants, and there is otherwise no basis to suggest water should be added to the reaction; and

(b) it is not to the point that there may inevitably be hydrolysed molecules in the product mixture the subject of amended claims 3 and 5, or unhydrolyzed molecules in the product mixture the subject of amended claims 1, 2 and 4, and that according to Professor Easton such occurrences were likely to occur. The distinction between these two classes of claims is simply the performance/requirement of a hydrolysis step.

80 I prefer the argument advanced by Cytec.

81 In section 4 of the judgment the patent application is described. The specification points out that the invention resides in the use of small molecules as opposed to the higher molecular weight polymers of the prior art as the means by which aluminosilicate scale could be minimized or prevented; see J[60]–[64]. Examples are given in the specification so that the invention so described “may be better understood” but “are not intended to limit the scope of the invention” (page 34 lines 3–5). Example 1 is entitled “Example of a synthesis reaction A, E and G”.

82 The specification provides, in relation to Example 1 (page 34 lines 8–19):

In a typical synthesis reaction the three constituents: A (e.g. hexane diamine), G (e.g. 3-glycidoxypropyltrimethoxysilane) and E (e.g. ethyl hexyl glycidl ether) are added to a suitable reaction vessel at a temperature between 23-40°C and allowed to mix. The reaction vessel is then warmed to 65-70°C during which time the reaction begins and a large exotherm is generated. The reaction becomes self-sustaining and depending on the scale of the reaction, can reach temperatures as high as 125 to 180°C. (see FIG. 1). Typically the reaction is complete after 1 to 2 hours and then the mixture is allowed to cool down. As an aspect of this invention this un-hydrolyzed product mixture can be isolated as a liquid or gel or a solid in a suitable manner. Alternatively, the reaction product mixture can be hydrolyzed, via a number of methods, to prepare a solution of the hydrolyzed product mixture in water. The hydrolysis of the alkoxysilane groups in the component G results in the formation of the corresponding alcohol (e.g. methanol, ethanol etc,. depending on the akloxysilane used in the synthesis).

(Emphasis added)

83 The agreed primer explains the meaning of hydrolysed:

When reference is made to compounds as being hydrolysed or not hydrolysed, this refers to the GPS component of the molecules, which in some of the structures appears as a trimethoxysilane (Si(OCH3)3) and in others appears hydrolysed as a trihydroxysilane (Si(OH)3). Hydrolysis involves water reacting with the trimethoxysilane to replace the methoxy (OCH3) groups with hydroxyl (OH) groups, forming methanol as a by-product which can be removed by evaporation. Hydrolysis can be performed before the molecules are added to the Bayer process stream. Hydrolysis will occur if there is water present anywhere in the composition or in contact with that composition. However, if the molecules are not hydrolysed beforehand and they are added to the caustic Bayer process liquor, they will then hydrolyse in the liquor and the methanol produced could be dealt with and evaporated – although this is unlikely to be necessary given the small amount produced and it would simply end up being burned off as waste. The silane group will be hydrolysed when the composition is added to the Bayer process, if it is not hydrolysed already. As such, within the Bayer process stream the product will always contain the hydrolysed manifestation of the silane because it will always be in an aqueous solution. Hydrolysis is a fairly straightforward and well-known chemical process.

84 The argument advanced by Nalco is that amended claim 1 should be understood to be “directed to” a product mixture that has undergone a hydrolysis step. The language of the claim does not support that construction. The claim is expressed to be a method comprising the single step of adding to the Bayer process stream an aluminosilicate scale inhibiting amount of “a composition”, being the composition described in integers (2)–(4). The judgment at [111], in respect of the current version of the claims records, that:

…claim 1 is not to be understood as claiming only the infinitesimally small happenstance to which the evidence refers. The claim is not limited in scope as to how the single type of molecule becomes the result of the reaction product mixture. Claim 1 simply encompasses a circumstance where 100% of the reaction mixture formed from the reaction of A + GPS + E is composed of a single type of one of the identified small molecules. Put another way, the claim includes within its scope any circumstance where a single type of the small molecules identified in integer (3) emerges as the outcome of the product mixture, regardless of the conditions in which the reaction is conducted.

(Emphasis added)

See also J[118] which finds that no language in the current claims identifies that the product mixture formed from the reaction of A, GPS and E must be undertaken under any particular conditions, or that there be any limitation on the way the synthesis reaction is brought into effect.

85 The same applies to amended claim 1. It is not limited in scope as to how the 13 small molecules specified in amended claim 1 are to be made. Put another way, any composition comprising the small molecules identified within a product mixture as described will fall within the scope of the claims, regardless of how the composition is formed.

86 Nalco’s argument based on Nichia at [41] and Lazer Safe at [65] tends to overstate the role of other claims in the construction of one claim in issue. The preference of the Court to construe claims in a manner that avoids redundancy cannot here serve as the basis to incorporate into the language of a claim words that are not present. The effect of Nalco’s argument would be to include words to the effect that the “composition is hydrolysed before being added to the Bayer process stream”.

87 Furthermore, the effect of the construction that I have favoured does not serve to make any of the amended claims redundant. Each claim is for a separate composition which requires the inclusion of different small molecules. No claim is redundant upon the other for the simple fact that there is no overlap between the claims.

88 Nor do I consider that the passage on page 34 of the specification (quoted at [82] above) provides a basis for reading down the language of amended claim 1. The examples are expressed to be given without limitation to the scope of the invention. Whilst the specification does make a distinction between hydrolysed and non-hydrolysed product mixtures, the language of the claims does not. That this was a clear choice on the part of the drafter is further apparent from the language of the current claim set, which in claim 16 provides for a “method according to claim 1, wherein the composition is hydrolyzed prior to being added to the Bayer process”.

5. CONSIDERATION OF THE GROUNDS OF OPPOSITION

89 I have found above that the small molecule construction issue be determined in favour of Cytec such that the amended claims include within their scope a composition that includes only the identified small molecules within a product mixture, although a large number of other small molecules and polymers may also be included. I have also found that Nalco’s arguments in relation to the hydrolysis construction issue must be rejected.

90 The finding in relation to the small molecule construction issue has the consequence that Cytec’s ground 4 does not arise, because its lack of clarity point is pleaded on the basis that Nalco’s construction is accepted, which it is not. The finding in relation to the hydrolysis construction issue has the consequence that ground 6A also does not arise, because the lack of best method ground pleaded is based on Nalco’s construction, which I have rejected.

91 The remaining grounds concern the consequences of my findings in relation to the small molecule construction issue.

92 Cytec submits that in light of this construction the amendment application must be determined adversely to Nalco on three separate alternative bases. First, that as a matter of discretion the amendment is futile and ought to be refused (ground 7), second, that the amendment is not allowable because as a result of the amendment the specification would claim matter that extends beyond that disclosed in the complete specification in breach of s 105(4) and s 102(1) (ground 5) and thirdly because as a result of the amendment the specification would not comply with the requirement of s 40(2)(a) that the specification disclose the invention clearly and be supported within the requirements of s 40(3) in breach of s105(4) and s 102(2)(b) (ground 6).

93 For the reasons given below, I accept that each of these grounds applies to defeat the application to amend.

5.1 Lack of support and lack of clear and complete description

94 The construction that I have determined in relation to the small molecule construction issue is one that is materially the same as that which I adopted in the judgment in section 5.2. In short, I concluded that the word “comprising” in current claim 1 is to be given the inclusive meaning defined in the body of the specification, with the consequence that claim 1 includes within its scope a product mixture formed from the reaction of A + GPS + E that consisted entirely of a single type of small molecule. I have reached the same conclusion in section 4.2 above albeit that instead of a single type of small molecule for amended claim 1 there are 13 specified small molecules, for amended claims 2 and 3 there are 14 specified small molecules and for amended claims 4 and 5 there are three such specified small molecules. Indeed, it seems to me that the ineluctable outcome of the reasoning set out in the judgment is that I should reach the same conclusion in relation to the amended claims. The amendments proposed by Nalco do not serve to afford any different meaning to the word “comprising” or the words “within a product mixture” in the context of the amended claims. Nor was there any material difference in the evidence concerning the fact that the technical contribution of the specification was not directed to the ability to isolate given small molecules – whether it be a single small molecule or a group of small molecules.

95 The consequence is that, as for the current claim set considered in the judgment, so too for the amended claims, the amended claims ought not to be allowed because they do not satisfy the requirement in s 40(3) of the Patents Act that the claims be supported by matter disclosed in the specification. The reasons provided in the judgment in section 6 apply. In short, in the absence of any technical contribution sufficient to encompass the full scope of the monopoly claimed, the amended claims lack support.

96 The same outcome applies in relation to the application of s 40(2)(a) which requires that the complete specification disclose the invention in a manner which is clear enough and complete enough for the invention to be performed by a person skilled in the relevant art. For substantially the same reasons as set out in section 7 of the judgment, I consider that the disclosure of the specification, including the amended claims, is not sufficient to enable the invention to be performed without undue experimentation insofar as those claims include a product mixture made up of only the identified small molecules.

97 Nalco continues to seek to claim something despite not disclosing how it is to be done.

98 The failure on the part of Nalco to satisfy the requirements of s 40(2)(a) and s 40(3) of the Patents Act has the consequence that the amendments are not allowable pursuant to s 102(2).

99 Nevertheless, I address below the argument that Cytec additionally raises, namely that the amendments should be refused on the basis that they do not overcome the deficiencies in the patent application identified in the judgment and that they ought not be allowed as a matter of the exercise of discretion pursuant to s 105(1A) because granting such amendments would be futile.

100 The discretion to consider and allow an amendment must be understood in the context of the policy and purpose of the opposition procedure under s 59 of the Patents Act.

101 In Genetics Institute Inc v Kirin-Amgen Inc [1999] FCA 742; (1999) 92 FCR 106 at [19], the Full Court said the following:

As the parties in the present case accepted, the purpose of pre-grant opposition proceedings is to provide a swift and economical means of settling disputes that would otherwise need to be dealt with by the courts in more expensive and time consuming post-grant litigation; that is, to decrease the occasion for costly revocation proceedings by ensuring that bad patents do not proceed to grant. This purpose is reflected in the explanation by the Minister for Science for the Federal Government’s policy decision to retain pre-grant opposition proceedings in Australia, despite the recommendation of the 1984 Industrial Property Advisory Committee Report Patents, Innovation and Competition in Australia (“IPAC Report”) that they be abolished (recommendation 29).

“Pre-grant opposition provides a relatively inexpensive mechanism for resolving third party disputes as to validity. Opposition procedures will be made more stringent in order to expedite the determination of oppositions.” [(1986) 56 No 47 Official Journal of Patents, Trade Marks and Designs 1475.]

(Emphasis added)

102 The amendments pursuant to the Intellectual Property Laws Amendment (Raising the Bar) Act 2012 (Cth) (Raising the Bar Act) introducing s 105(1A) of the Patents Act tend to reinforce the importance that pre-grant opposition is intended to provide a relatively inexpensive mechanism. The explanatory memorandum to the Raising the Bar Act in respect of s 105 observes that:

Currently, during an appeal from a decision of the Commissioner the Court must confine itself to the same subject matter as considered by the Commissioner. This means that where an applicant has amended their specification subsequent to the Commissioner’s decision, the Court cannot consider the amended specification, even where the amendments may overcome the grounds on which the decision is being appealed.

This adds complexity to the appeals process and to resolution of opposed patent applications.

The item addresses this problem by giving a court power to consider and decide upon any amendments proposed by the applicant while an appeal is on foot. These amendments would be considered under the existing provisions under which courts may direct amendments.

The provision applies only to amendment of patent applications, not to amendment of granted patents.

(Footnotes omitted)

103 In the present case, it cannot be said that the opposition process has been the sort of swift and economical skirmish contemplated in the legislation. To the contrary, by means of multiple proposed amendments and oppositions, the process resembles a decade-long war of attrition where, even after a contested hearing on appeal from the APO, the patent applicant seeks to battle on.

104 In my view the observations in Meat & Livestock at [103] and [104] to the effect that s 105(1A) contains no limitation as to the point in time during an appeal which an amendment application can be made or determined and no limitation confining the exercise of discretion to addressing adverse findings, must be understood in the context of the policy and purpose to which I have referred. It should not be understood to provide a magic pudding of opportunity for the creative endeavours of a patentee to craft ways of avoiding the consequences of adverse findings. Nor should the existence of the power under s 105(1A) enabling the Court to allow an amendment to a patent application be regarded as a mechanism to provide a patent applicant with a basis for attempting to relitigate an issue that has already been before the Court.

105 As a general proposition, a patent applicant should, on appeal from an opposition, advance its best and final version of the specification and claims that it desires to litigate and the decision on appeal should be regarded as resolving any controversy regarding the scope and construction of the specification. Any other approach is, in my view, contrary to basic principles of the finality of litigation, as noted by McKerracher J in Repipe Pty Ltd v Commissioner of Patents (No 3) [2021] FCA 31 in the context of an application to amend a patent that had been found to be invalid for want of manner of manufacture. There, his Honour considered (at [60]) the principles of finality of litigation as articulated in Autodesk Inc v Dyason (No 2) [1993] HCA 6; (1993) 176 CLR 300 at 303 (Mason CJ – in dissent on the outcome but not on the general principles), before endorsing as relevant the following observation of Finkelstein J in Nutrasweet Australia Pty Ltd v Ajinomoto Co Inc (No 3) [2007] FCA 966; (2007) 73 IPR 282 at [20]–[25]:

…. According to the cases, a patentee is not entitled, following a trial on validity, to bring an application to amend the invalid claims, except in very limited circumstances and this is not one of them.

Windsurfing International Inc. v Tabur Marine (Great Britain) Ltd [1985] RPC 59 was an infringed action. The defendant successfully contested the validity of the patent in suit on several grounds, including obviousness. After judgment against the plaintiff was given, counsel asked for the order revoking the patent to be suspended pending consideration of an amendment to the specification. The application was refused. Oliver J said (at 81):

“[I]t was for the plaintiffs, if they wished to support their claim to monopoly on some alternative basis, to raise the point and adduce the appropriate evidence for that purpose at the trial. In fact, however, no-one, from first to last, advanced or considered the specialised qualities of a surfboard as an inventive concept and the suggestion that there should be an adjournment for this now to be raised and investigated as a basis for the claim to monopoly involves, in effect, a fresh trial, the recalling of most, if not all, of the most important witnesses, and a considerable degree of recapitulation of the evidence as well as the calling of fresh evidence on an issue never previously suggested either in the specification or in the pleadings. We would require considerable persuasion that the imposition upon a successful defendant of such a manifestly inconvenient and oppressive course would be a proper exercise of discretion even in an otherwise strong case.”

A similar situation arose in Lubrizol Corp. and Another v Esso Petroleum Co. Limited and Others [1998] RPC 727. In that case Aldous LJ (with whom Brooke and Roch LJJ agreed) refused an application for leave to amend a patent after trial. He said “(at 790) “[I]t is a fundamental principle of patent litigation that a party must bring before the court the issues that he seeks to have resolved, so as to enable the court to conclude the litigation between the parties.”

So also in Sara Lee Household & Body Care U.K. Ltd v Johnson Wax Ltd (2001) 17 FSR 261. There David Young QC, sitting as a Deputy Judge of the High Court, refused an application to add new claims to a patent found to be invalid. He said that what the patentees wanted was “to have their cake and eat it”. He referred to Raleigh Cycle Co. Ltd v Miller H. & Co. Ltd (1950) 67 RPC 226, 230 where Lord Normand said that having been put on notice that there was an attack on the validity of their patent, the patentees were “put to an election between amending these claims and continuing their action without amending while maintaining that the claims were valid” and having chosen the second alternative, they were disentitled from pursuing the first except in “very special circumstances”. Mr Young QC also referred to Lubrizol Corp. v Esso Petroleum Co. Ltd.

In Ancare New Zealand Ltd’s Patent [2001] 20 RPC 335, Gault J (with whom Henry and Thomas JJ agreed) suggested there may be “special circumstances” in which an amendment could be entertained after judgment. He instanced by way of example a patent held to be invalid in part where the amendment is required to excise the invalid part. For example in Nikken Kosakusho Works v Pioneer Trading Co. [2006] FSR 4 the English Court of Appeal (per Jacob LJ) said that it might also be possible to permit an amendment the effect of which would be to rewrite claims so as to exclude invalid claims (or dependencies). Reference was made to Hallen Co v Brabantia (UK) Ltd [1990] FSR 134 where it was said that “a proposed claim which was not under attack and could not have been under attack prior to trial” would not be allowed after trial.

These cases (most of which were followed by the Full Court in Woolworths Limited v BP plc (No 3) [2006] FCAFC 160) show that the course Ajinomoto was attempting to take was simply not available to it.

106 Whilst recognising the different position of a patent application compared to a granted patent, the principles relevant to finality articulated in the above passages, to which may be added the requirements of ss 37M and 37N of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth), indicate that particular care must be taken in exercising the discretion in favour of amendment after a full hearing on appeal from an opposition.

107 In the present case, for the reasons set out in section 5.1 above, the issues between the parties regarding the specification were substantively determined in the judgment. The proposed amendments do not overcome the difficulties consequent upon the finding at J[131] that the technical contribution disclosed in the specification rises no higher than the general discovery that small molecule-based inhibitors are effective in reducing aluminosilicate scale in Bayer refineries. For that reason, had the requirements of s 102(2) been met by Nalco’s sixth proposed amendment, I would not have exercised the discretion under s 105(1A) in favour of Nalco.

108 A separate basis upon which I would have refused the amendment as a matter of discretion lies in the application of the principles to which I have referred in [105] above.

109 Finally, in ground 8 of its amended particulars of grounds of opposition, Cytec contends that the Court should not otherwise exercise its discretion under s 105(1A) of the Patents Act to allow the amendments on eight separately particularised bases which may collectively be described as relating to unreasonable delay on the part of Nalco in proposing the amendments at different points in time during the opposition proceedings before the APO and on appeal before this Court. Nalco disputes that any of these bases is well founded.

110 I do not consider it necessary or appropriate to reach any conclusion regarding ground 8. If I am correct in relation to one of the other grounds to which I have referred above, then the occasion for the exercise of that discretion does not arise and Cytec succeeds in its opposition to the amendment application. However, posing a hypothetical exercise of discretion based on an assumption that Nalco succeeds on one or the other, and then considering the exercise of that discretion taking into account the various other discretionary considerations involves too many assumptions to be of assistance; Prince Alfred College Inc v ADC [2016] HCA 37; (2016) 258 CLR 134 at [113] (French CJ, Kiefel, Bell, Keane and Nettle JJ).

111 For the reasons set out above I have concluded that Nalco’s amendment application must be refused. The parties should confer and provide draft short minutes of order for the disposition of the proceedings, reflecting these reasons.

I certify that the preceding one hundred and eleven (111) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice Burley. |

Associate: