Federal Court of Australia

Credit Suisse Virtuoso SICAV-SIF v Insurance Australia Limited (No 2) [2024] FCA 1308

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT NOTES THAT:

A. The following ten proceedings (together, the Greensill Proceedings) are being case managed together:

(i) White Oak Commercial Finance Europe (Non-Levered) Limited v Insurance Australia Limited (NSD 1039 of 2021) (White Oak Matter);

(ii) Credit Suisse Virtuoso SICAV-SIF in respect of the sub-fund Credit Suisse (Lux) Supply Chain Finance Fund v Insurance Australia Limited (NSD 106 of 2022) (Catfoss Matter);

(iii) Credit Suisse Virtuoso SICAV-SIF in respect of the sub-fund Credit Suisse (Lux) Supply Chain Finance Fund v Insurance Australia Limited (NSD 110 of 2022) (NMC Matter);

(iv) Credit Suisse Virtuoso SICAV-SIF in respect of the sub-fund Credit Suisse (Lux) Supply Chain Finance Fund v Insurance Australia Limited (NSD 169 of 2023) (Credit Suisse Global Matter);

(v) Greensill Bank AG v Insurance Australia Limited (NSD 1216 of 2021) (EHG Matter);

(vi) Greensill Bank AG v Insurance Australia Limited (NSD 173 of 2023) (Atlantic 57 Matter);

(vii) Greensill Bank AG v Insurance Australia Limited (NSD 174 of 2023) (Bluestone Matter);

(viii) Greensill Bank AG v Insurance Australia Limited (NSD 175 of 2023) (Liberty Commodities Matter);

(ix) Greensill Bank AG v Insurance Australia Limited (NSD 177 of 2023) (SIMEC Matter); and

(x) Greensill Bank AG v Insurance Australia Limited (NSD 602 of 2023) (Liberty Delta Matter).

THE COURT DECLARES THAT:

1. Marsh Ltd and Marsh Pty Ltd relied upon documents, and information contained in documents, discovered in the Greensill Proceedings in support of the Anti-suit Application (as defined in the reasons for judgment dated 12 November 2024) (the Anti-suit Application), in breach of their obligation to this Court not to use discovered documents or discovered information for any purpose other than that for which it was given unless it is received into evidence, without leave of this Court.

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

2. If and to the extent necessary, the requirements of r 42.12 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 be dispensed with.

3. From the date of this order, Marsh Ltd and Marsh Pty Ltd be released from the obligation described in paragraph 1 above, in relation to the documents discovered by Greensill Bank AG (in administration) (GBAG) and Dr Michael Frege (in his capacity as Insolvency Administrator of GBAG) to Marsh Ltd in the Greensill Proceedings, such that those documents may be used for the purpose of the Anti-suit Application.

4. The informal application by Marsh Ltd and Marsh Pty Ltd for release from the obligation described in paragraph 1 above otherwise be dismissed.

5. Within 14 days, the parties provide to the Court any agreed proposed order in relation to costs.

6. If the parties cannot agree, then within a further seven days, each party file and serve an outline of submissions (of no more than three pages) in relation to costs. The issue of costs will then be determined on the papers.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

MOSHINSKY J:

Introduction

1 These reasons for judgment deal with the issue whether Marsh Ltd (one of the respondents to the present proceeding) and Marsh Pty Ltd (a non-party) (together, Marsh) have breached the obligation to the Court that is commonly referred to as the “implied undertaking”, which I will refer to as the Hearne v Street obligation (see Hearne v Street [2008] HCA 36; 235 CLR 125), as alleged by Greensill Bank AG (in administration) (GBAG) and Dr Michael Frege (in his capacity as Insolvency Administrator of GBAG) (Dr Frege), who are respondents to the proceeding and made discovery of documents to Marsh Ltd.

2 The present proceeding (NSD 106 of 2022) is one of ten proceedings in this Court relating to the collapse of the Greensill group, in which claims are made against Insurance Australia Ltd (IAL) and others (the Greensill Proceedings). The Greensill Proceedings are described below.

3 The issue relates to a proceeding (the Anti-suit Application) commenced by Marsh against GBAG and Dr Frege in the High Court of Justice of England and Wales (the English Court) (proceeding CL-2024-000433) on 29 July 2024. The Anti-suit Application sought to restrain GBAG and Dr Frege from joining Marsh to certain of the Greensill Proceedings. The application relied on an English exclusive jurisdiction clause. On 30 July 2024, an ex parte (or without notice) hearing took place before the English Court. (I note that the usual English terminology is “without notice” and I will adopt that expression in these reasons in relation to English proceedings.) The application was partially successful, in that the English Court granted an interim anti-suit injunction to restrain GBAG and Dr Frege from joining Marsh Ltd to the relevant Greensill Proceedings. However, the English Court did not grant an anti-suit injunction restraining GBAG and Dr Frege from joining Marsh Pty Ltd to the relevant Greensill Proceedings.

4 In broad terms, GBAG and Dr Frege allege that, in preparing for and making the Anti-suit Application, Marsh relied on documents, and information contained in documents, that had been discovered by GBAG and Dr Frege in the Greensill Proceedings, and that Marsh thereby breached the Hearne v Street obligation owed to this Court.

5 The issue is raised by paragraph 13 of GBAG and Dr Frege’s amended interlocutory application dated 18 October 2024 (the Amended Interlocutory Application). By that paragraph, GBAG and Dr Frege seek the following relief:

Final Orders Sought

THE COURT:

13. Declares that Marsh Limited and Marsh Pty Ltd have relied upon documents and information discovered in the Greensill Proceedings in support of the Anti-Suit Application, in breach of their implied undertaking to this Court not to use discovered documents or discovered information for any purpose other than that for which it was given unless it is received into evidence, without leave of this Court.

6 On 18 October 2024, I made an order that the question raised by paragraph 13 of the Amended Interlocutory Application (the Paragraph 13 Issue) be determined separately and in advance of the issues raised by paragraphs 14 to 16 of the Amended Interlocutory Application, and listed the issue for hearing on 11 November 2024.

7 Although paragraph 13 of the Amended Interlocutory Application is not expressed in terms of “contempt of court”, the authorities make clear that a breach of the Hearne v Street obligation constitutes a contempt of court. Accordingly, to reflect the substance of r 42.12 of the Federal Court Rules 2011, which requires an application alleging that a contempt has been committed to be accompanied by a “statement of charge”, GBAG and Dr Frege were ordered to file and serve a statement of particulars that provides full particulars of the alleged breach or breaches of the implied undertaking by Marsh Ltd and Marsh Pty Ltd that is or are the subject of the Paragraph 13 Issue. Pursuant to that order, GBAG and Dr Frege filed a Statement of Particulars dated 22 October 2024 (the Statement of Particulars). A copy of the Statement of Particulars is annexed to these reasons. I will approach the question whether GBAG and Dr Frege are entitled to the relief sought in paragraph 13 by reference to the Statement of Particulars. In the circumstances, it is appropriate to make an order, if and to the extent necessary, dispensing with the requirements of r 42.12.

8 At the outset of the hearing on 11 November 2024, I raised with the parties whether the applicable standard of proof for the determination of the Paragraph 13 Issue was the “beyond reasonable doubt” standard, given that this is the standard for civil contempt. Both parties agreed that it was appropriate for me to apply that standard. I will therefore do so.

9 Further, at the outset of the hearing on 11 November 2024, I raised with the parties whether the hearing was final or interlocutory (noting that this could affect whether the Court has power to make a declaration – see Graham Barclay Oysters Pty Ltd v Ryan [2022] HCA 54; 211 CLR 540 at [128] per Gummow and Hayne JJ). It was common ground between the parties that the Paragraph 13 Issue was being dealt with on a final basis. I will proceed on this basis.

10 The parties filed and served outlines of submissions in advance of the hearing on 11 November 2024. In paragraph 54 of Marsh’s outline of submissions, Marsh stated that if, contrary to its earlier submissions, the Court were to find that Marsh’s use of discovered documents was in breach of its implied undertaking to this Court, it would nevertheless be appropriate to exercise its discretion to grant Marsh, nunc pro tunc, leave to use the discovered documents for the purpose of the Anti-suit Application (the Release Application). At the outset of the hearing on 11 November 2024, I sought clarification from the parties as to whether the Release Application was before the Court for hearing that day (indicating that I was content to deal with it). After a short adjournment, it was agreed between the parties that the Release Application was before the Court for hearing that day. Accordingly, these reasons will also deal with the Release Application.

11 GBAG and Dr Frege rely on the following evidence:

(a) three affidavits of Michelle Fox, a partner of Quinn Emanuel Urquhart & Sullivan (in Australia) (QE Australia), the solicitors acting for GBAG and Dr Frege in the Greensill Proceedings, dated 3 October 2024 (First Fox Affidavit), 9 October 2024 and 17 October 2024;

(b) two affidavits of the Right Honourable Lord Hoffmann, dated 5 November 2024 and 8 November 2024, annexing an expert report and a supplementary expert report on English Law in relation to (broadly) the duty of disclosure on a without notice application; and

(c) the documents at tabs 22, 23 and 24 of the electronic Court Book.

12 Marsh relies on the following evidence:

(a) two affidavits of Christopher David Foster, a partner in the firm Holman Fenwick Willan LLP (in England) (HFW England), the solicitors acting for Marsh, dated 1 November 2024 (the First Foster Affidavit) and 5 November 2024;

(b) an affidavit of the Right Honourable Lord Mance dated 31 October 2024, annexing an expert report on English Law relating to (broadly) the duty of full and frank disclosure on a without notice application; and

(c) a letter from QE Australia to HFW England dated 10 October 2024.

13 There were no objections to any of the affidavits referred to above. No deponent was required to attend for cross-examination.

14 At the end of the hearing on 11 October 2024, senior counsel for GBAG and Dr Frege stated that, if the Court formed the view that it was in the interests of justice that going forward there was a release, GBAG and Dr Frege would not oppose this. Senior counsel stated that, in this way, both parties would have access to the documents to put the facts before the English Court (T88). Senior counsel for Marsh indicated that he sought such a release (in the alternative).

15 For the reasons that follow I have concluded, in summary, that:

(a) Marsh did rely on documents, and information contained in documents, discovered in the Greensill Proceedings in support of the Anti-suit Application in breach of the Hearne v Street obligation;

(b) I am not satisfied that it is appropriate to grant Marsh a retrospective release from the Hearne v Street obligation; and

(c) I consider it appropriate to grant Marsh a prospective release from the Hearne v Street obligation, in relation to the documents discovered by GBAG and Dr Frege to Marsh Ltd in the Greensill Proceedings, for the purpose of the Anti-suit Application.

The Greensill Proceedings

16 To provide background and context, in this section of these reasons I provide a brief outline of the Greensill Proceedings. The Greensill Proceedings can be grouped as follows:

(a) one proceeding that has been commenced by White Oak Commercial Finance Europe (Non-Levered) Limited (the White Oak Matter);

(b) three proceedings that have been commenced by Credit Suisse entities (the Credit Suisse Proceedings); these are referred to as the Catfoss, NMC and Credit Suisse Global Matters; the present proceeding is the Catfoss Matter; GBAG and Dr Frege are the second and third respondents, cross-claimants and cross-respondents in each of the Credit Suisse Proceedings;

(c) six proceedings that have been commenced by GBAG and Dr Frege (the GBAG Proceedings).

17 By the Greensill Proceedings, the applicants (the Applicants) each seek judgment against IAL in respect of amounts alleged to be payable under insurance policies (Policies) purportedly issued by BCC Trade Credit Pty Ltd (BCC) as authorised representative of IAL to GBAG and Greensill Capital Pty Limited (in liquidation) (GCPL). The claimed insured losses total approximately AUD 7 billion. Those claimed losses relate to debts owed to Greensill Capital (UK) Limited (in administration) (GCUK) by its customers under various purported supply chain or accounts receivable finance facilities. The Applicants invested in the finance programs set up by GCUK.

18 The Applicants also:

(a) bring alternative claims against BCC and its former Head of Trade Credit, Greg Brereton, seeking damages and compensation for misleading or deceptive conduct, false or misleading representations and breach of warranties of authority under the general law with respect to the authority to enter into the Policies;

(b) claim that IAL and/or Tokio Marine & Nichido Fire Insurance Co Ltd (TMNF) are responsible for BCC and Mr Brereton’s conduct as Australian financial services licensees under the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth);

(c) in the Catfoss, NMC, Credit Suisse Global and White Oak Matters (Loss Payee Proceedings), bring claims against IAL, BCC, TMNF and its Australian managing agent, Tokio Marine Management (Australasia) Pty Ltd (TMMA) (collectively, Tokio Marine) seeking damages and compensation for misleading or deceptive conduct and in negligence (among other claims) with respect to the alleged “post-July 2020 conduct”; and

(d) in the Credit Suisse Proceedings, bring a claim against Marsh Ltd (a company registered in England), seeking damages and compensation for misleading or deceptive conduct and in negligence. Marsh Ltd was joined to the Credit Suisse proceedings on 7 November 2023.

19 IAL, BCC, Mr Brereton and Tokio Marine bring various defences and cross-claims, including allegations of misrepresentation, misleading or deceptive conduct, and deceit, against GCUK, GCPL and GBAG. In its defences, IAL brings alternative allegations that certain entities including Marsh Ltd and Marsh Pty Ltd (a company registered in Australia) are “concurrent wrongdoers” under the proportionate liability provisions of Australian legislation. IAL has not joined Marsh Ltd or Marsh Pty Ltd as parties to the proceedings.

20 During the period 1 March to 1 July 2024 (being the period during which GBAG relevantly made discovery in the Greensill Proceedings) and as at 29 July 2024 (when Marsh filed the Anti-suit Application):

(a) Marsh Ltd was a respondent to the Credit Suisse Proceedings, but not to any of the other Greensill Proceedings; and

(b) Marsh Pty Ltd was not a party to any of the Greensill Proceedings.

21 On 4 November 2024, GBAG and Dr Frege were given leave to join Marsh Pty Ltd as a respondent to the GBAG Proceedings.

Factual findings

22 On 30 March 2023 and 26 July 2023, orders were made by Justice Lee of this Court, who was case managing the Greensill Proceedings, that the Greensill Proceedings be case managed together.

23 The Greensill Proceedings have been subject to numerous Case Management Hearings. The scope of discovery has been a central issue at the hearings.

24 On 30 March 2023, Justice Lee made the following orders in the Greensill Proceedings (excluding the Delta Proceeding which was filed at a later date) which relate to the sharing, production and use of documents disclosed in those proceedings.

Sharing of documents

14. All parties provide copies of any pleadings, requests for further and better particulars (including requests for documents referred to in pleadings) and responses to such requests to the parties to each of the Proceedings at the time that the other parties to the proceeding are served.

15. Documents produced in any Proceeding, whether by any party or by any third party under compulsion, may also be:

(a) used by any party in this proceeding in any of the other Proceedings; and/or

(b) produced, or provided, by any party to the Proceeding, to any party to any of the other Proceedings who is not a party to the Proceeding, for their use in any Proceeding.

16. Each party produce to the parties in each Proceeding all documents produced by that party in a Proceeding:

(a) in the case of documents so produced prior to the making of these Orders but not provided to a party, within 10 business days after the making of these Orders; and

(b) for any documents so produced after the making of these Orders, concurrently with production by that party of those documents in a Proceeding.

25 On 5 September 2023, GBAG, Dr Frege, Marsh Ltd and Marsh Pty Ltd entered into a confidential Standstill Deed to toll limitation periods in respect of certain claims that GBAG and Dr Frege may have against Marsh, including claims relating to the GBAG Proceedings (the Standstill Deed).

26 On 30 October 2023, Justice Lee ordered that the parties to the Greensill Proceedings (excluding GCUK and GCPL) provide standard discovery in the Greensill Proceedings in tranches on dates to be fixed at the “Discovery Conference”.

27 On 7 November 2023, Credit Suisse filed Amended Statements of Claim, joining Marsh Ltd to each of the Credit Suisse Proceedings.

28 On 21 December 2023, at the Discovery Conference, Justice Lee ordered that the 30 October orders be amended so that certain parties to the Greensill Proceedings (including GBAG and Marsh Ltd) would be required to provide standard discovery by way of tranches on specific dates.

29 At the same Discovery Conference, Justice Lee directed the parties as follows:

... people just discover documents in accordance with the usual course. If they want a suppression or confidentiality order when the documents are admitted into evidence, they can seek it. And, prior to that, to the extent documents are given to people, it’s subject to the Hearne v Street undertaking.

(Emphasis added.)

30 At the same Discovery Conference, Mr Braham SC, appearing on behalf of BCC and Tokio Marine, drew the Court’s attention to orders 14 to 16 made on 30 March 2023 (set out above). Mr Braham SC submitted that it was necessary for the 30 March 2023 orders to be varied to include the Delta Proceeding (which was filed after 30 March 2023). Mr Braham SC reminded the Court that the purpose of these orders was “Just to deal with a Harman – release from a Harman undertaking” (see Harman v Secretary of State for the Home Department [1983] 1 AC 280). Justice Lee then made orders to bring the Delta Proceeding under the same regime as set out in orders 14 to 16 made on 30 March 2023.

31 Paragraph 6 of the Orders made by Justice Lee on 21 December 2023 required discovery to be provided in an electronic format in accordance with the electronic discovery protocol appended to the Orders at Annexure A. Clause 7.1 of the electronic discovery protocol (at Annexure A to the 21 December Orders) provided:

every page of every Hard Copy and Standard File electronic document is to be visibly numbered on the top right-hand corner of the page in one of the following number formats: PPP.BBB.FFF.DDD or PPP.BBBB.FFFF.DDDD_NNNN Where: PPP is a Party code which identifies the Party which has produced the document to the Court. See Schedule 1 for a list of Valid Party codes.

32 Schedule 1 to the electronic discovery protocol listed “GBA” as a party source code for GBAG.

33 Prior to Marsh filing the Anti-suit Application, GBAG provided discovery of documents to each of the parties in the Greensill Proceedings, including to Marsh Ltd, in the following tranches:

(a) Tranche 1 on 1 March 2024;

(b) Tranche 2 on 28 March 2024;

(c) Tranche 3 on 2 May 2024;

(d) Tranche 4 on 3 June 2024; and

(e) Tranche 5 on 1 July 2024.

34 Between 1 March and 1 July 2024, GBAG produced a total of 221,027 documents to all the parties, including Marsh Ltd.

35 On 2 July 2024, Ms Fox (of QE Australia) wrote to Mr Foster (of HFW England) communicating GBAG and Dr Frege’s intention to join Marsh Ltd to the GBAG Proceedings. The letter included:

For Marsh’s awareness, it is not the intention of GBAG and Dr Frege to bring claims against Marsh Ltd which contradict their primary claim against Insurers. It is intended that the claims against Marsh Ltd will be brought strictly in the alternative and will be based on IAL’s pleadings (against Marsh Ltd) in the GBAG Proceedings.

36 The letter enclosed a termination notice dated 2 July 2024 issued under the Standstill Deed, terminating the Standstill Period in respect of claims against Marsh Ltd arising in connection with the GBAG Proceedings. Under the Standstill Deed and the termination notice, the final day of the Standstill Period in respect of the relevant claims would be 30 days later, namely 1 August 2024. It is now common ground between the parties that the termination notice should be treated as also terminating the Standstill Deed against Marsh Pty Ltd in respect of relevant claims.

37 Mr Foster gives evidence in the First Foster Affidavit that an issue that immediately arose in relation to any attempt to join Marsh to the GBAG Proceedings was whether such an attempt would be inconsistent with the English exclusive jurisdiction clause in Marsh Ltd’s standard terms of engagement. Mr Foster states that he was well aware of that clause. He also states that he was aware that Marsh Ltd had a direct letter of engagement with GBAG for the 2018-2019 year, which incorporated the terms of engagement; he was also aware that Marsh Ltd had other letters of engagements directly with GCUK, which incorporated the terms of engagement; the terms of engagement contained an “affiliates” clause that he considered extended to GBAG. Mr Foster gives the following evidence in the First Foster Affidavit:

20 In light of the matters referred to in the previous two paragraphs, following receipt of the Standstill Notice and covering letter from QE on 2 July 2024 as described above, I formed the view on the same day that Marsh would need to apply for an anti-suit injunction from the English Court.

21 By the next day (3 July 2024), I had determined, and had sought and obtained instructions, to proceed with an ex parte application (commonly referred to in England as a “without notice” application) for an anti-suit injunction, to be filed with the English Court, to restrain GBAG and Dr Frege from taking steps to join Marsh to the GBAG Proceedings in Australia (as GBAG and Dr Frege had threatened to do in the Standstill Notice and accompanying letter, as set out above). Those instructions were obtained without the review of any documents discovered by GBAG in the Greensill Proceedings. At the time of my determination, and of seeking and obtaining instructions, to bring an ex parte application, I had not reviewed any documents discovered by GBAG in the Greensill Proceedings for the purposes of the application and nor had anyone else, to my knowledge.

22 I understood from my experience as an English legal practitioner that Marsh, as a party bringing an ex parte application, owed a duty of full and frank disclosure to the English court in connection with the application. I further understood from my experience as a legal practitioner that, in order to comply with that duty, Marsh was required to disclose all material facts, whether adverse or favourable, in respect of that application to the Court, and to make enquiries before making the application in order to identify material facts that would need to be disclosed.

23 In order to satisfy that duty to the English Court, I had to consider what issues might be raised by GBAG in response to the application. It seemed to me that one potential issue was whether or not GCUK had actual (or another species of) authority to bind GBAG to the Letters of Engagement with Marsh – although, at that stage, GBAG had not denied that such authority existed. That view proved correct, as GBAG did indeed subsequently deny the existence of GCUK authority.

24 Having formed such view, and in order to comply with the duty of full and frank disclosure to the English court, I then considered (and coordinated others acting for Marsh Limited to consider) whether documents that Marsh Limited had received from GBAG through discovery given in the Greensill Proceedings were material to this issue. In this regard, and before any steps were taken to review such documents, I read the observations of Mason CJ in Esso Australia Resources Limited v Plowman (1995) 183 CLR 10. I had also read other Australian cases, being:

(a) Patrick v Capital Finance Pty Ltd (No 4) [2004] FCA 436;

(b) Hearne v Street (2008) 235 CLR 125;

(c) Cadbury Schweppes Pty Ltd v Amcor Ltd [2008] FCA 398;

(d) Deputy Commissioner of Taxation v Rennie Produce (Aust) Pty Ltd (In Liq) (2018) 260 FCR 272; and

(e) Hancock Prospecting Pty Ltd v DFD Rhodes Pty Ltd (No 2) [2023] WASCA 108.

I understood that the Harman obligation did not extend to prevent the use or disclosure of documents where that was required by the process of another court.

(Emphasis added.)

38 I accept the evidence of Mr Foster in the First Foster Affidavit as set out above. Mr Foster was not required to attend for cross-examination and there does not appear to be any contrary evidence.

39 It appears from a later document that Marsh conducted searches of thousands of documents that had been discovered by GBAG and Dr Frege to Marsh Ltd in the Greensill Proceedings before commencing the Anti-suit Application. In a letter to the English Court dated 27 August 2024 (First Fox Affidavit, Exhibit MXW-1, p 3165), HFW England referred to the duty to make full and frank disclosure on a without notice application, and stated at paragraph 18:

As noted above, in accordance with that duty, searches were conducted of thousands of documents produced on disclosure in the Australian proceedings. Of those thousands, a small number of documents were assessed as requiring to be disclosed in accordance with Marsh's obligation to make full and frank disclosure. These consisted of a number of service level agreements which might be considered adverse to Marsh's position that GCUK had actual authority to bind GBAG to broking agreements and other documents which might be considered by the Court to indicate that GBAG was so bound.

(Emphasis added.)

40 Marsh did not seek or obtain a release from the Hearne v Street obligation before reviewing the discovered documents in the way described above.

41 On 29 July 2024, Marsh commenced the Anti-suit Application in the English Court. The evidence before this Court on the present application includes a copy of the First Witness Statement of Mr Foster dated 26 July 2024 (filed in support of the Anti-suit Application) (Foster Witness Statement) and Marsh’s Skeleton Argument (provided to the English Court on 29 July 2024) (the Skeleton Argument).

42 On 30 July 2024, the Anti-suit Application was heard by the Honourable Mrs Justice Cockerill DBE of the English Court. The hearing commenced at 10.30 am. Approximately two hours before the commencement (i.e. at about 8.30 am London time), Mr Foster contacted Ms Fox (of QE Australia) by telephone and email to give informal notice of the application. GBAG and Dr Frege did not appear at the hearing and the application proceeded on a without notice basis. The transcript of the hearing on 30 July 2024 is in evidence before this Court on the present application.

43 The essential basis of the application was an English exclusive jurisdiction clause contained in Marsh’s terms of engagement. As indicated above, for one relevant year (the 2018-2019 year), there was a letter of engagement (apparently incorporating the terms of engagement) between Marsh Ltd and GBAG itself. However, for the other relevant years, the letters of engagement (apparently incorporating the terms of engagement) were between Marsh Ltd and GCUK. In respect of those years, Marsh contended, in summary, that GBAG was bound by the terms of engagement as an “affiliate” of GCUK.

44 In the course of seeking anti-suit relief on 30 July 2024, Marsh relied on the Foster Witness Statement and the Skeleton Argument. The Foster Witness Statement and the Skeleton Argument, and the oral submissions themselves, referred to and relied on documents that had been discovered by GBAG and Dr Frege to Marsh Ltd in the Greensill Proceedings. There is no evidence to suggest that these documents were otherwise in the possession of Marsh, and I find that they were not. Marsh did not seek or obtain a release from the Hearne v Street obligation before relying on the documents in this way. Marsh did not disclose to the English Court that the source of these documents was discovery in the Greensill Proceedings.

45 It should be noted that Marsh contends that its reliance on the discovered documents was (a) to satisfy its obligation of full and frank disclosure to the English Court on a without notice application; and (b) accordingly, not subject to the Hearne v Street obligation. I will discuss these contentions later in these reasons.

46 Marsh relied on the discovered documents both specifically and generally. I will address each in turn.

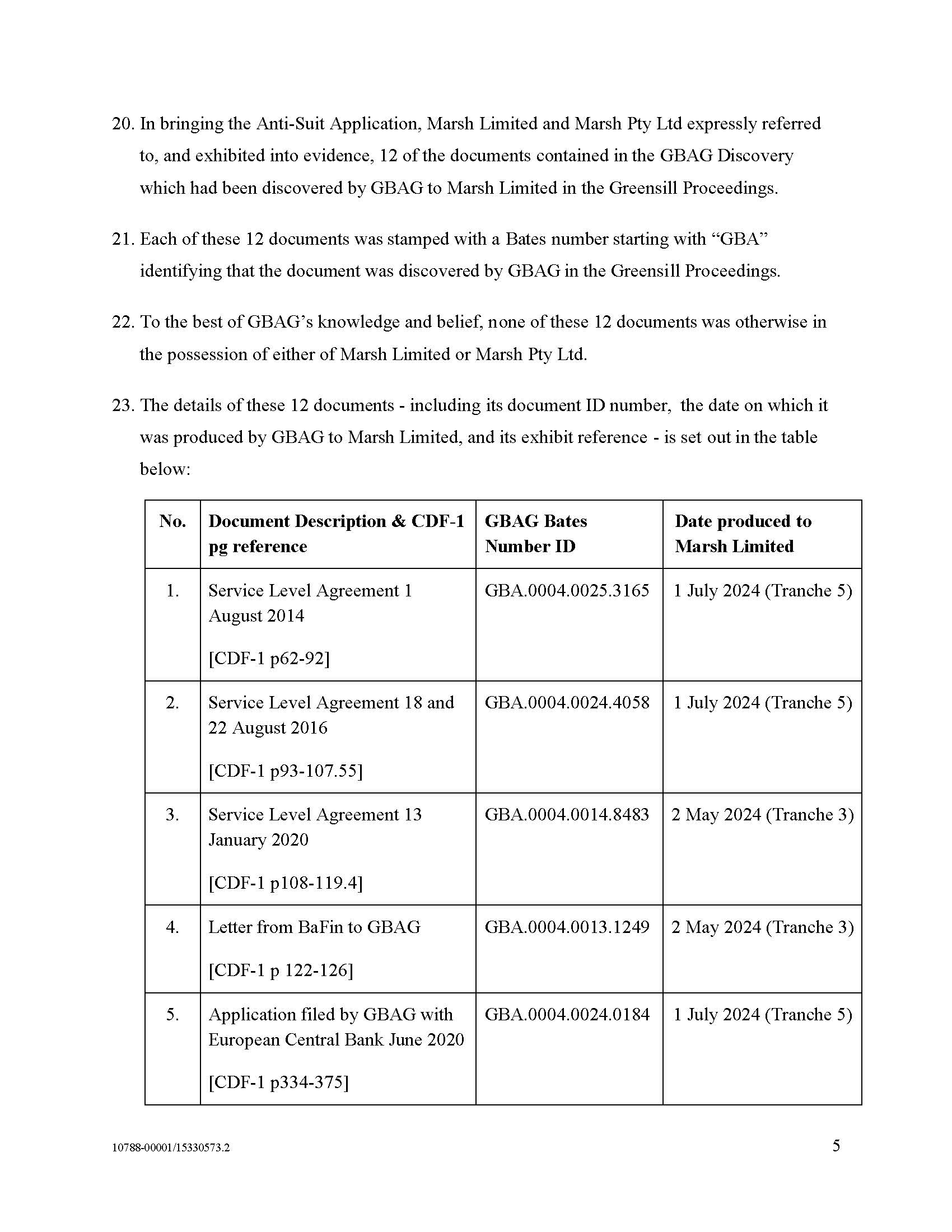

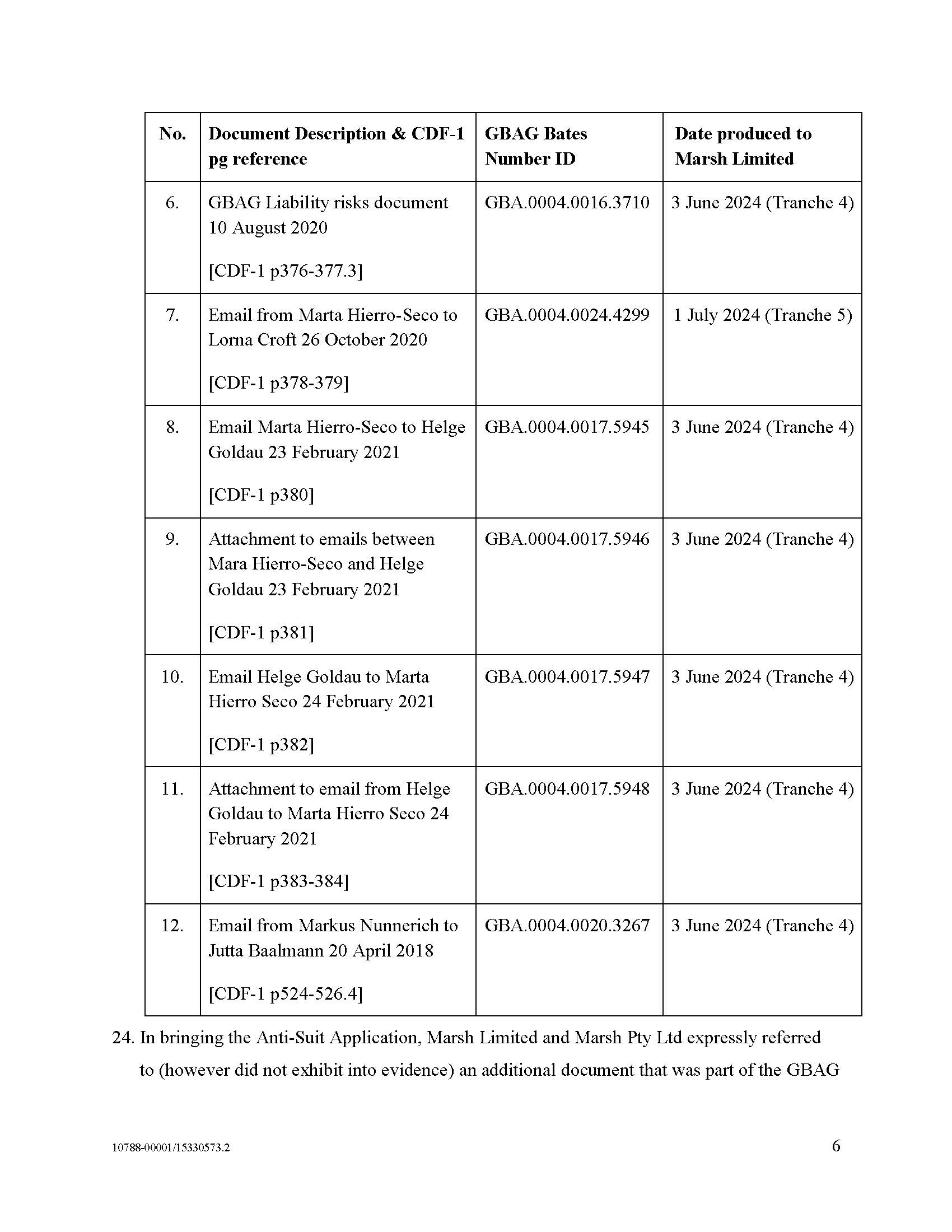

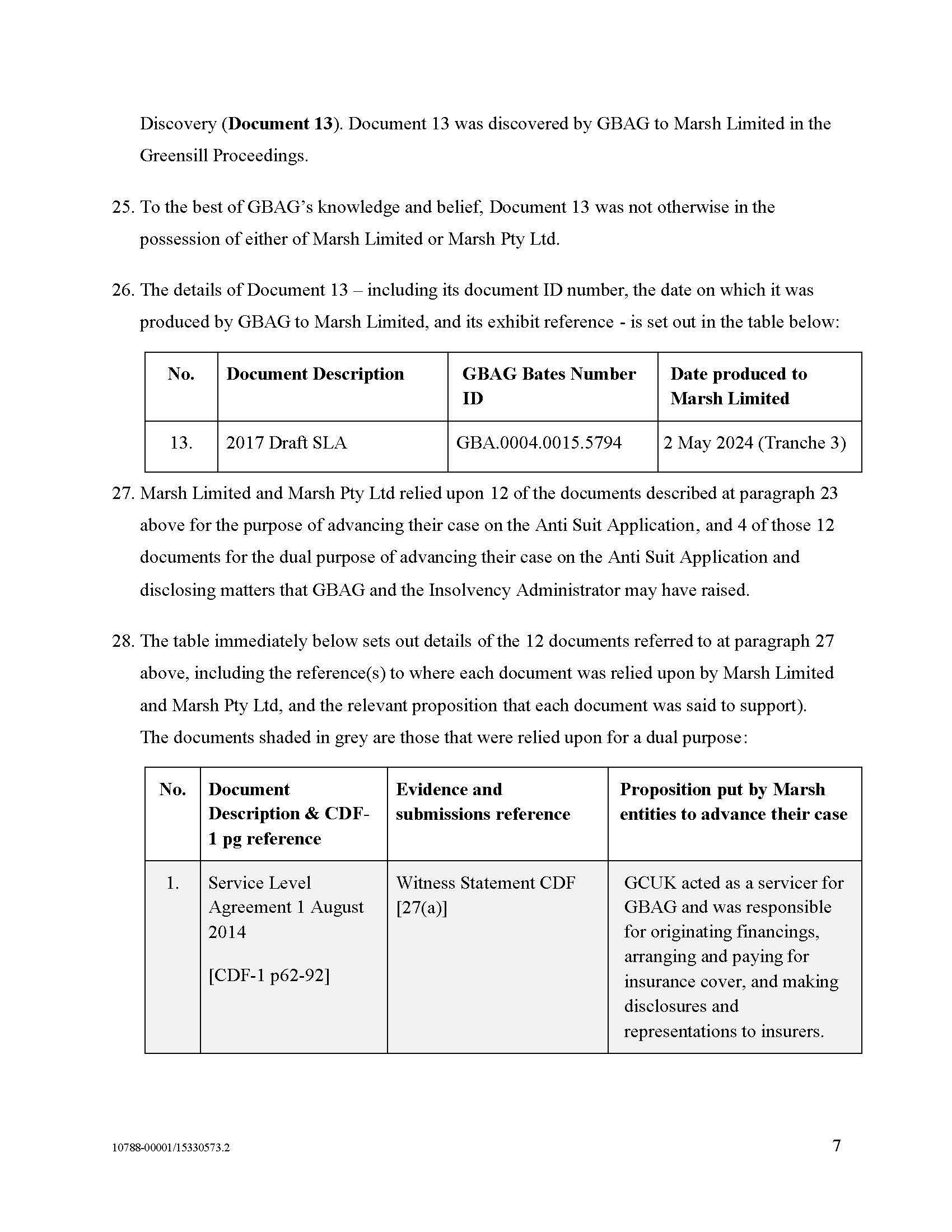

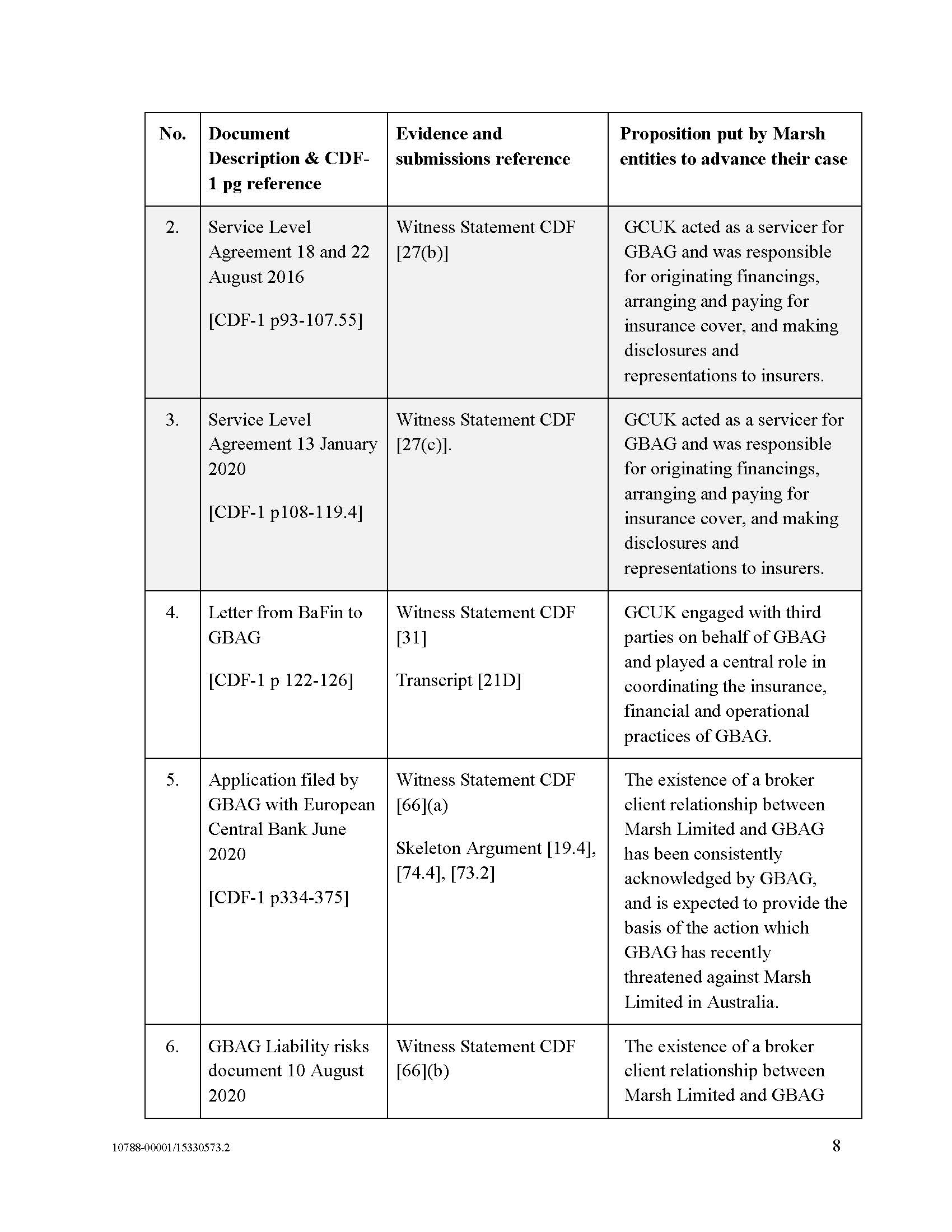

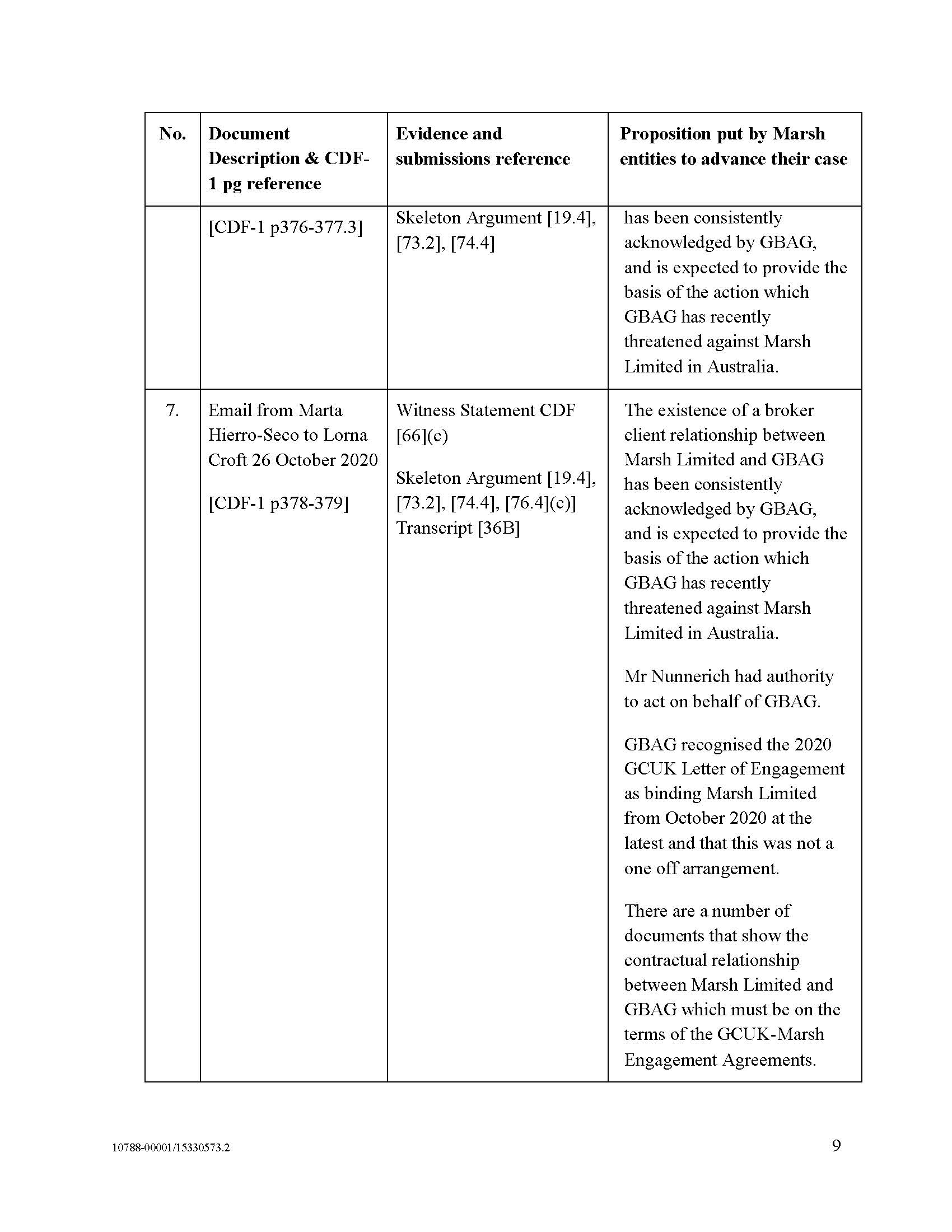

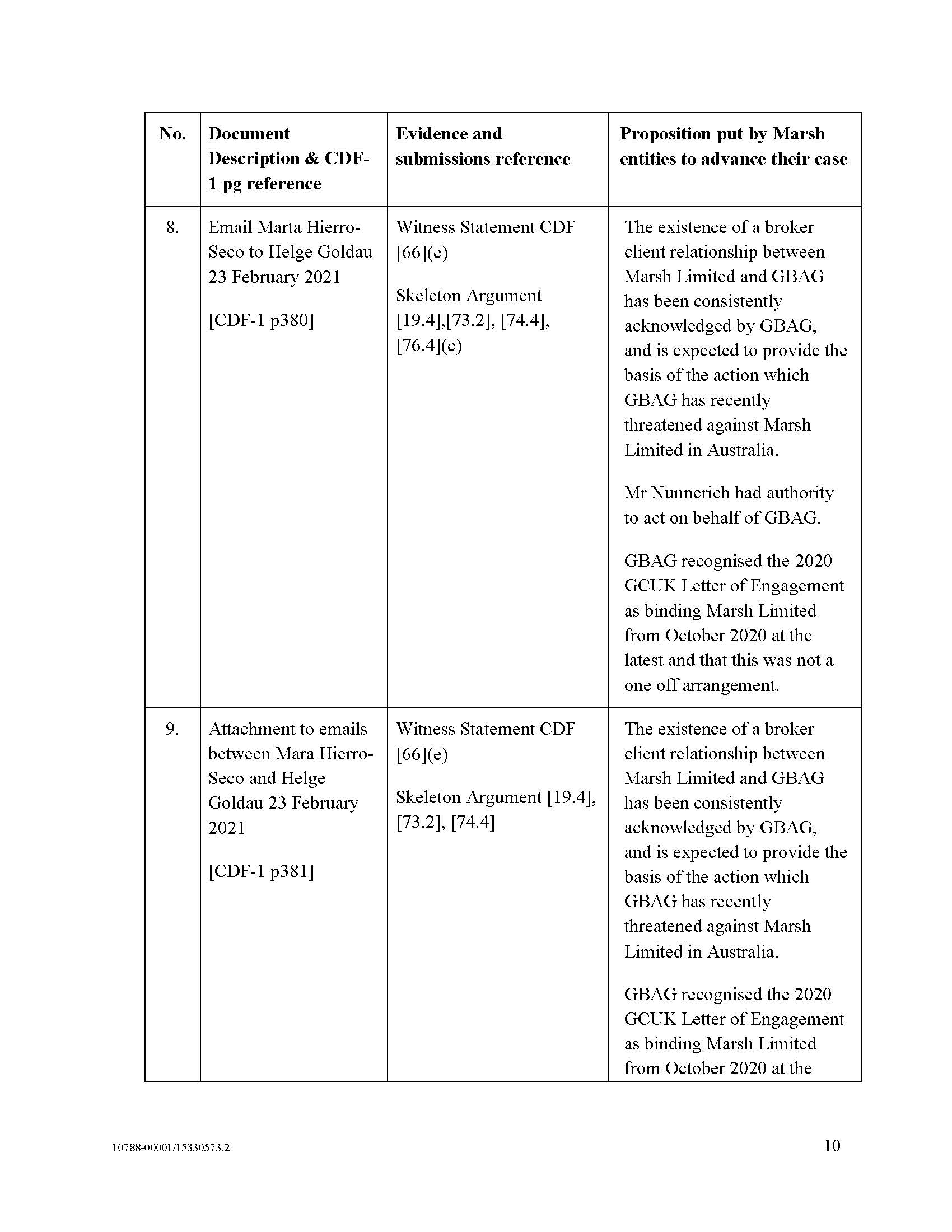

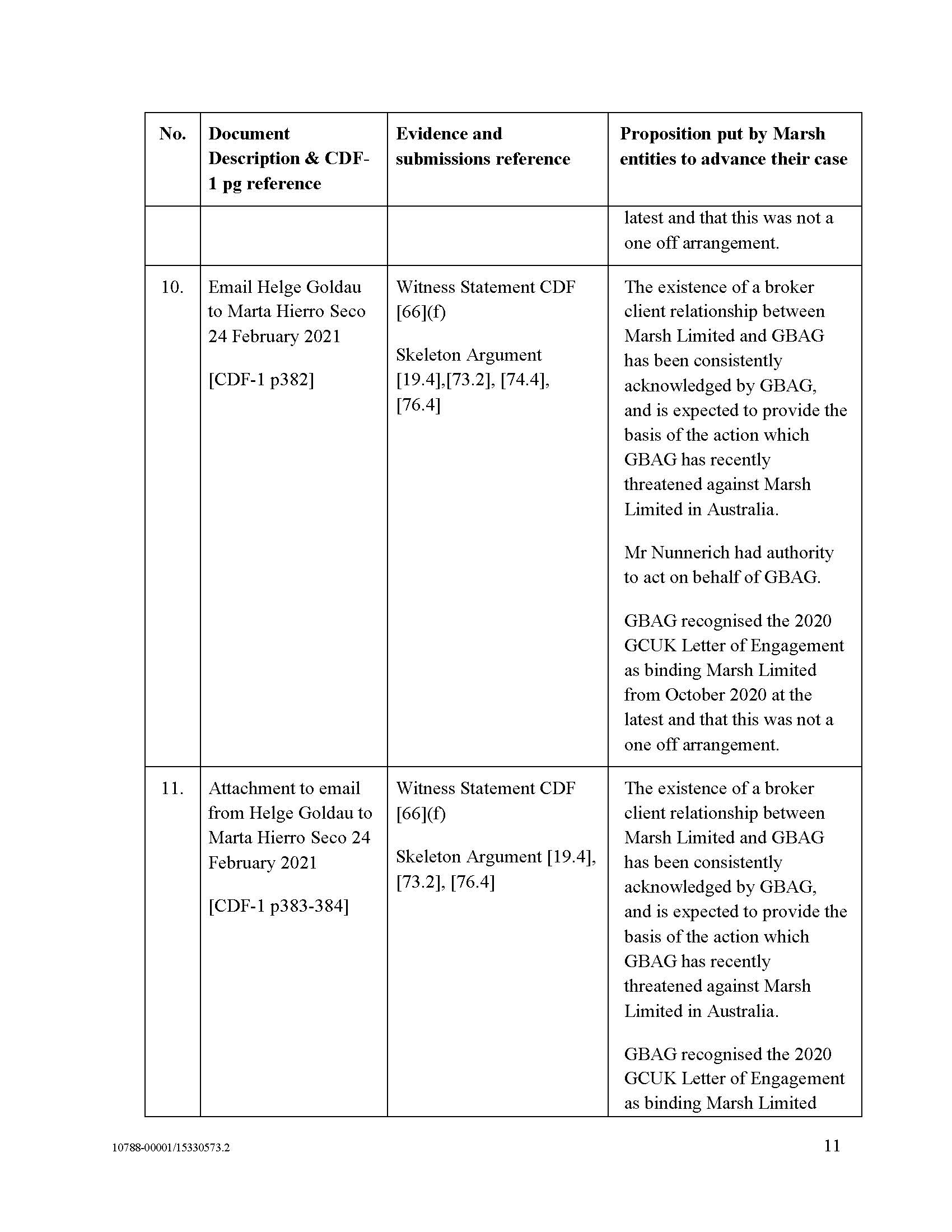

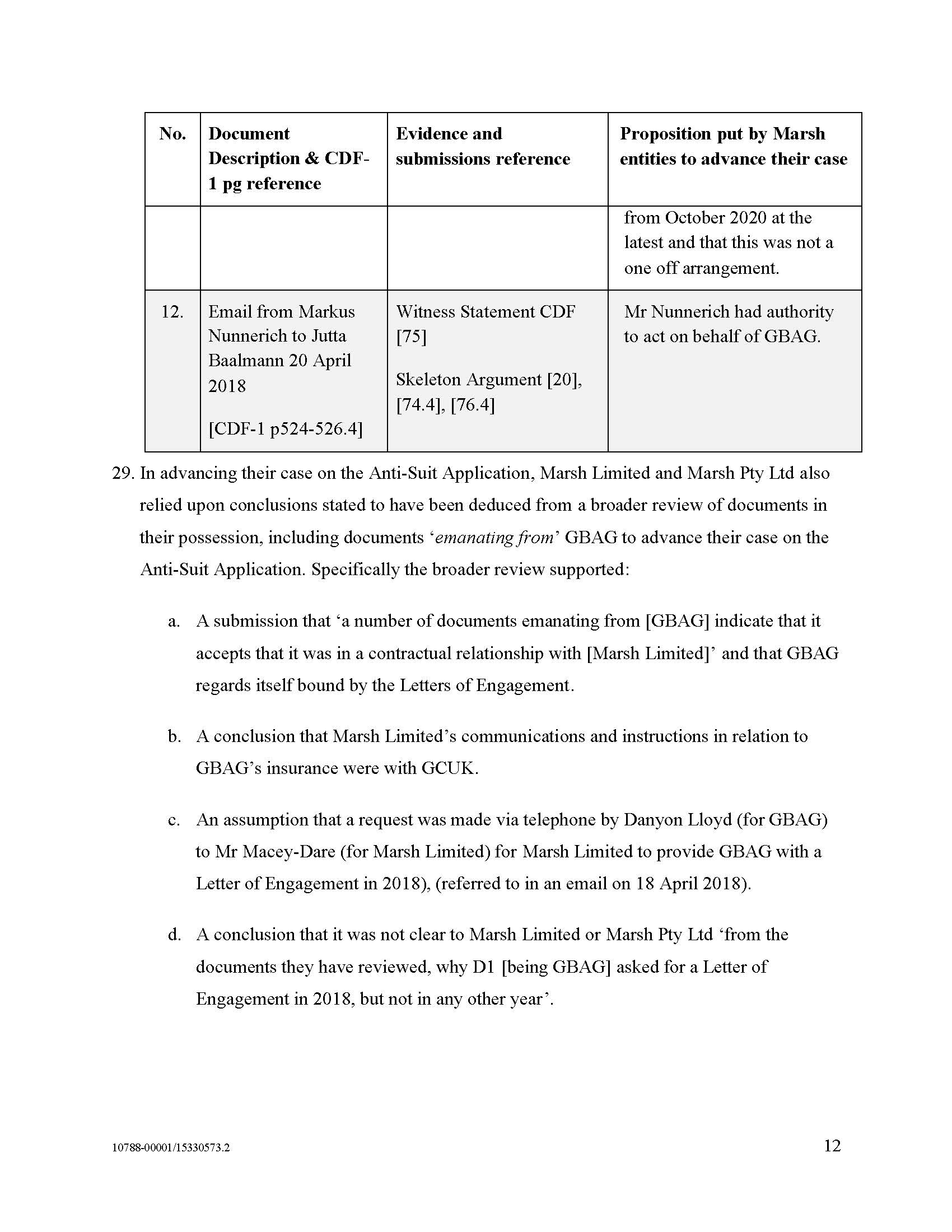

47 Marsh relied on 12 specific discovered documents. These are itemised in the table in paragraph 23 of the Statement of Particulars. I find that these documents were specifically relied on by Marsh in the course of making the application for anti-suit relief on 30 July 2024. The places where these documents appear in the Foster Witness Statement and/or the Skeleton Argument are identified in the table in paragraph 28 of the Statement of Particulars. The documents were relied on in two ways. In some cases (the documents numbered 1, 2, 3 and 12 in the table), the documents were referred to on the basis that they could be considered to be adverse to Marsh’s application for anti-suit relief. In other cases (the balance of the 12 documents), the documents were relied on in response to arguments that may have been raised by GBAG and Dr Frege had they had notice of the application; in particular, the documents were relied on to rebut a potential contention by GBAG and Dr Frege that GCUK lacked authority to bind GBAG to the terms of engagement.

48 For example, paragraphs 65 and 66 of the Foster Witness Statement stated in part:

65. It follows that, on each occasion when GCUK entered into an “Engagement” with [Marsh Ltd] for brokerage services, it also entered into that Engagement as agent for [GBAG], with the actual and/or apparent authority of [GBAG], and [GBAG] was bound by the relevant Terms of Engagement, including their Exclusive Jurisdiction Clause. The legal analysis in terms of actual/apparent authority, and ratification if necessary, will be further explained in [Marsh’s] skeleton argument.

66. The existence of a broker-client relationship between [Marsh Ltd] and [GBAG] has been consistently acknowledged by [GBAG], and is expected to provide the basis of the action which [GBAG] has recently threatened against [Marsh Ltd] in Australia. For example:

a. In June 2020, [GBAG] filed with the ECB an “Application for eligibility of Supply Chain Finance Assets under ECB Programmes”, which stated in a section entitled “4. Credit Risk & Rating” [CDF1/334-375, 347]:

“In order to obtain insurance, GB’s insurance broker, Marsh Ltd., arranges credit enhancement on the payment obligation of the obligor in the form of comprehensive nonpayment insurance from insurers (rated single-A or better) which covers 100% of any shortfall in all non-payment scenarios (other than shortfalls arising expressly from nuclear disaster or war).”

(Emphasis added)

b. Following receipt of a letter from insurer BCC dated 4 August 2020, it appears that [GBAG] started preparing an internal Memorandum, the first iteration of which is dated 10 August 2020 (but unsigned), and contains the statement (translated from the German) [CDF1/376-377.3, 377.1]:

“Due to its brokerage activities, Marsh is liable to GCUK up to a maximum of GBP 10 million (Terms of Engagement, clause 7.1).”

c. On 26 October 2020, Marta Hierro Seco (Head of Credit Insurance / Collaterals, [GBAG]), emailed Lorna Croft (GCUK) in terms which acknowledged both (i) GCUK’s central role in liaising with [Marsh Ltd], and (ii) GBAG's contractual relationship with [Marsh Ltd] [CDF1/378-379]: …

49 Each of the documents referred to in the above extract was discovered by GBAG in the Greensill Proceedings. Paragraph 66 of the Foster Witness Statement is lengthy and continues for several pages. In the balance of para 66, several other discovered documents are specifically relied on.

50 I now turn to how Marsh relied on the discovered documents generally. In some instances, Marsh advanced general propositions about the effect of the body of documents that were in its possession or emanated from GBAG. These included the discovered documents (although the fact that they had been discovered by GBAG in the Greensill Proceedings was not disclosed). For example, at para 19.4 of the Skeleton Argument, Marsh submitted:

The documents in [Marsh’s] possession mostly suggest that [GBAG] acknowledges that it had a broker-client relationship with [Marsh Ltd] and/or that it is bound by the GCUK Letters of Engagement. …

(Emphasis added.)

51 Further, at para 73.2 of the Skeleton Argument, Marsh submitted:

Secondly, while [Marsh Ltd and Marsh Pty Ltd] have sought to anticipate the way in which a “no authority” argument could be run, as part of their duty of full and frank disclosure, the reality is that [GBAG and Dr Frege] have never actually articulated any such argument. On the contrary, the preponderance of the documents emanating from [GBAG and Dr Frege], whether internal or external, suggests that [GBAG and Dr Frege] do regard themselves as bound by the GCUK Letters of Engagement. Mr. Foster quotes a number of documents to this effect at Foster, [66].

(Emphasis added.)

52 At the conclusion of the hearing on 30 July 2024, the English Court made an interim anti-suit injunction restraining GBAG and Dr Frege from joining Marsh Ltd to the GBAG Proceedings. However, the English Court did not make an anti-suit injunction restraining GBAG and Dr Frege from joining Marsh Pty Ltd to the GBAG Proceedings.

53 Insofar as the Anti-suit Application was brought by Marsh Pty Ltd, which was not a party to any of the Greensill Proceedings at that time, Mr Foster gives the following evidence in para 28 of the First Foster Affidavit:

I understand that GBAG and Dr Frege allege that Marsh Limited allowed Marsh Pty Ltd to “access” documents from GBAG’s discovery in the Greensill Proceedings for the purposes of the application. While Marsh Pty Ltd was included as a claimant in the application for the [Anti-suit Application], at no stage in the application were any employees of Marsh Pty Ltd given access to documents (or information derived) from GBAG’s discovery in the Greensill Proceedings, nor have any such employees been provided with documents which refer to those discovery documents. My instructions as regards Marsh Pty Ltd were provided by Katherine Brennan, the General Counsel of the entire Marsh McLennan Group.

I accept the evidence of Mr Foster in the First Foster Affidavit as set out above.

54 On 1 August 2024, Quinn Emanuel Urquhart & Sullivan (in London), on behalf of GBAG and Dr Frege, wrote to HFW England communicating their concerns with the Anti-suit Application and the basis on which interim relief was granted to Marsh Ltd, including the apparent breach of the implied undertaking and non-compliance with Marsh’s duty of full and frank disclosure. The letter also asked that HFW England take immediate steps to inform the English Court that the Anti-suit Application contained documents subject to the implied undertaking, and that the documents should be marked as confidential on the Court file.

55 On 2 August 2024, HFW England responded to the above letter.

56 During August and September 2024, there was correspondence between the parties, and between the parties and the English Court. The Return Date for the Anti-suit Application was initially 13 September 2024. Following submissions made by the parties, the English Court determined that that date should be vacated and the matter re-fixed for hearing. The hearing has now been re-listed on 20 and 21 November 2024 (with 18 and 19 November 2024 allocated for judicial pre-reading).

57 On 10 October 2024, this Court heard an ex parte application by GBAG and Dr Frege for interim anti-anti-suit relief against Marsh. The application was made by interlocutory application dated 3 October 2024 (the original form of the Amended Interlocutory Application). The Court determined that an interim anti-anti-suit injunction should be made in respect of Marsh Pty Ltd but not Marsh Ltd: Credit Suisse Virtuoso SICAV-SIF v Insurance Australia Limited [2024] FCA 1193.

58 On 18 October 2024, GBAG and Dr Frege’s interlocutory application dated 3 October 2024 returned to the Court on an inter partes basis. On that occasion, Marsh Pty Ltd did not oppose the continuation of the anti-anti-suit injunction until the determination of the final orders sought by GBAG and Dr Frege in the interlocutory application. Accordingly, the anti-anti-suit injunction in respect of Marsh Pty Ltd was continued.

59 As indicated above, on 4 November 2024, this Court granted GBAG and Dr Frege leave to join Marsh Pty Ltd as a respondent to the GBAG Proceedings. Subsequently, GBAG and Dr Frege filed and served amended documents joining Marsh Pty Ltd to the GBAG Proceedings.

60 At the end of the First Foster Affidavit, Mr Foster states:

E. Apology to Federal Court of Australia

39 If this Court were to find that Marsh or I have breached the Harman undertaking, then I would wish to extend a sincere apology to the Court. At all times, I considered that Marsh’s obligations under the Harman undertaking yielded to Marsh’s obligations to comply with the duty of full and frank disclosure that Marsh owed to the English Court in making an ex parte application for the anti-suit injunction. Accordingly, any breach of the Harman undertaking to this Court was not a deliberate breach. If I was wrong about the legal position, then I sincerely apologise to the Court on my own behalf and on behalf of Marsh.

61 I accept that this apology is genuinely given. Insofar as the above paragraph contains evidence about Mr Foster’s state of mind, I accept that evidence.

Expert evidence about English law

62 As indicated above, the parties have filed expert evidence about the English law relating to the duty of full and frank disclosure on a without notice application. The eminence of both experts is understood by this Court. The first report in time is that of Lord Mance. Lord Hoffmann’s first report is largely responsive to Lord Mance’s report. (Lord Hoffmann’s second report deals with one additional matter for completeness.) There is broad agreement between the experts. I accept the opinions expressed in the reports of Lord Mance and Lord Hoffmann, save to the extent that there is disagreement between them. To the extent that there is disagreement, I do not consider it necessary to resolve that issue.

63 Lord Mance expresses the following opinions in his report:

22. The duty of full and frank disclosure entails a requirement to make proper enquiries before making the application: …

23. The duty of disclosure thus “applies not only to material facts known to the applicant but also to any additional facts which he would have known if he had made such enquiries”: …

(Cases omitted.)

64 In response to a question about the content of any obligations earlier identified, Lord Mance sets out at para 46 of his report an extract from the judgment of Carr J in Tugushev v Orlov [2019] EWHC 2031 (Comm) at [7], noting that the judgment has received subsequent appellate approval. The extract from that case includes the proposition that “[a]n applicant must make proper enquiries before making the application”.

65 Lord Mance expresses the following opinions at para 53 of his report:

The duty of full and frank disclosure may be described as coming into effect when a party files a without notice application. Without an application, there is no context for any disclosure and no judge to whom to make it and it will be irrelevant what enquiries may or may not have been made. But any application made to a court goes through a prior phase (long or short) of consideration and preparation. The concomitant of the duty of full and frank disclosure once an application is made is that the applicant will have previously been considering and preparing for the application with the forthcoming duty to make full and frank disclosure after proper enquiries well in mind, and that, throughout this preparatory phase, the (during this phase, potential) applicant and its advisers will have actually been making such enquiries. As Carr J said in Tugushev at [7(iv] and Ralph Gibson LJ said in Brink’s Mat Ltd v Elcombe [1988] 1 WLR 1350 at 1356H (point (3)), the duty of full and frank disclosure requires the applicant to make proper enquiries “before” filing the without notice application.

66 The difference between the opinions of Lord Mance and Lord Hoffmann is summarised in para 9 of Lord Hoffmann’s first report:

I have read the comprehensive opinion of Lord Mance on the duty of full and frank disclosure in ex parte applications, as well as the authorities and materials to which Lord Mance refers. The only part of Lord Mance’s report with which I would disagree is the apparent suggestion in paragraphs 54 to 59 that, because the application is made ex parte, the applicant’s duty of disclosure is so uncompromising that it applies to facts in its favour. In my opinion, none of the authorities referred to by Lord Mance refer to a specific duty to disclose material which is supportive of the applicants’ case.

67 It is important to note that Lord Mance was not asked to express an opinion (and does not express an opinion) as to the scope or content of the duty of full and frank disclosure in circumstances where the applicant (or potential applicant) is subject to a Harman undertaking. In paragraph 12 of his first report, Lord Hoffmann expresses the following opinion (which I accept):

Furthermore, none of the authorities cited by Lord Mance (or any other cases of which I am aware) deal with a situation in which an applicant for an ex parte order is under a positive duty (such as the Harman undertaking creates) not to disclose the information in question.

Applicable principles

68 In Hearne v Street, Hayne, Heydon and Crennan JJ (comprising a majority of the High Court of Australia in that case) expressed the relevant obligation in the following terms at [96]:

Where one party to litigation is compelled, either by reason of a rule of court, or by reason of a specific order of the court, or otherwise, to disclose documents or information, the party obtaining the disclosure cannot, without the leave of the court, use it for any purpose other than that for which it was given unless it is received into evidence. The types of material disclosed to which this principle applies include documents inspected after discovery, answers to interrogatories, documents produced on subpoena, documents produced for the purposes of taxation of costs, documents produced pursuant to a direction from an arbitrator, documents seized pursuant to an Anton Piller order, witness statements served pursuant to a judicial direction and affidavits.

(Footnotes omitted; emphasis added.)

69 Further, Hayne, Heydon and Crennan JJ stated at [102] (Gleeson CJ agreeing at [3]):

… to call the obligation of the litigant who has received material generated by litigious processes one which arises from an “implied undertaking” is misleading unless it is understood that in truth it is an obligation of law arising from circumstances in which the material was generated and received.

(Emphasis added.)

See also at [105]-[108].

70 In the same case, Hayne, Heydon and Crennan JJ discussed the extension of the principle to third parties in certain circumstances. Their Honours stated at [109]:

The primary person bound by the relevant obligation is the litigant who receives documents or information from the other side pursuant to litigious processes. The implied undertaking also binds others to whom documents and information are given. … Thus Hobhouse J said: “[A]ny person who knowingly … does acts which are inconsistent with the undertaking is himself in contempt and liable to sanctions”.

(Footnote omitted.)

See also at [110]-[112].

71 It may be accepted that the relevant obligation has been differently expressed in different cases. In some cases, the obligation has been expressed more restrictively, in terms of not using discovered documents other than for the purposes of the action in which they were disclosed. In other cases, the obligation has been expressed less restrictively. The judgment of Chesterman JA in Northbuild Construction Pty Ltd v Discovery Beach Project Pty Ltd (No 4) [2009] QCA 345; 1 Qd R 145 (Northbuild) contains a helpful collection of cases on this point. I will discuss this further below.

72 In the course of submissions in the present case, considerable attention was given to the following passage from the judgment of Mason CJ (with whom Dawson and McHugh JJ agreed) in Esso Australia Resources Ltd v Plowman [1995] HCA 19; 183 CLR 10 (Esso v Plowman) at 33:

It would be inequitable if a party were compelled by court process to produce private documents for the purposes of the litigation yet be exposed to publication of them for other purposes. No doubt the implied obligation must yield to inconsistent statutory provisions and to the requirements of curial process in other litigation, eg discovery and inspection, but that circumstance is not a reason for denying the existence of the implied obligation.

(Emphasis added.)

73 The principle set out in that passage was considered by the Court of Appeal of the Supreme Court of Western Australia (Quinlan CJ, Beech and Vaughan JJA) in Hancock Prospecting Pty Ltd v DFD Rhodes Pty Ltd (No 2) [2023] WASCA 108 (Hancock) at [71]-[97].

74 One of the issues to be considered in the present case is the scope of the principle that the relevant obligation will “yield” to the requirements of “curial process” in other litigation. This is discussed further below.

75 It is well established that the Court may release a party from the Hearne v Street obligation. The applicable principles were stated by the Full Court of this Court (Branson, Sundberg and Allsop JJ) in Liberty Funding Pty Ltd v Phoenix Capital Ltd [2005] FCAFC 3; 218 ALR 283 (Liberty Funding) at [31]:

In order to be released from the implied undertaking it has been said that a party in the position of the appellants must show “special circumstances”: see, for example, Springfield Nominees Pty Ltd v Bridgelands Securities Ltd (1992) 38 FCR 217; 110 ALR 685. It is unnecessary to examine the authorities in this area in any detail. The parties were not in disagreement as to the legal principles. The notion of “special circumstances” does not require that some extraordinary factors must bear on the question before the discretion will be exercised. It is sufficient to say that, in all the circumstances, good reason must be shown why, contrary to the usual position, documents produced or information obtained in one piece of litigation should be used for the advantage of a party in another piece of litigation or for other non-litigious purposes. The discretion is a broad one and all the circumstances of the case must be examined. In Springfield Nominees, Wilcox J identified a number of considerations which may, depending upon the circumstances, be relevant to the exercise of the discretion. These were:

• the nature of the document;

• the circumstances under which the document came into existence;

• the attitude of the author of the document and any prejudice the author may sustain;

• whether the document pre-existed litigation or was created for that purpose and therefore expected to enter the public domain;

• the nature of the information in the document (in particular whether it contains personal data or commercially sensitive information);

• the circumstances in which the document came in to the hands of the applicant; and

• most importantly of all, the likely contribution of the document to achieving justice in the other proceeding.

(Emphasis added.)

76 In Liberty Funding at [32], the Full Court referred to the above matters as a “helpful guide”.

Consideration

Whether Marsh breached the Hearne v Street obligation

77 In summary, GBAG and Dr Frege contend that, in preparing for and bringing the Anti-suit Application, Marsh Ltd relied on documents that had been discovered by GBAG and Dr Frege to Marsh Ltd in the Greensill Proceedings, and that Marsh Ltd thereby breached the Hearne v Street obligation. GBAG and Dr Frege note that Marsh Pty Ltd was not a party to the Greensill Proceedings at the relevant times and therefore did not itself receive the documents through discovery in those proceedings. GBAG and Dr Frege contend that: Marsh Ltd gave Marsh Pty Ltd access to the discovered documents, and that Marsh Pty Ltd (having received the documents with knowledge) was also subject to the Hearne v Street obligation. GBAG and Dr Frege contend that, in preparing for and bringing the Anti-suit Application, Marsh Pty Ltd also breached the Hearne v Street obligation.

78 The detailed allegations of breach by Marsh Ltd are set out in paragraphs 36-39 of the Statement of Particulars.

79 The detailed allegations of breach by Marsh Pty Ltd are set out in paragraphs 41-44 of the Statement of Particulars.

80 In response to these allegations, Marsh contends that two issues arise:

(a) The first is whether any use of documents in connection with the Anti-suit Application was for a purpose that was collateral to the Greensill Proceedings (i.e. “disconnected”).

(b) The second is whether, in any event, there was a requirement to disclose the documents such that the Hearne v Street obligation did not operate to prevent such disclosure.

81 In relation to the first issue, Marsh submits, in summary, that: GBAG and Dr Frege’s submissions adopt the wrong starting point and involve mischaracterisation; the Anti-suit Application is centrally concerned with the subject-matter of the Greensill Proceedings; a matter bound up in any claim in litigation is the appropriate forum in which to determine that claim; the resolution of the forum in which to determine a claim (and the effect of an exclusive jurisdiction clause voluntarily agreed by the claiming party) is not a matter that is unconnected in the relevant sense from the claim itself; Marsh’s purpose was not collateral to the matters on which discovery had been given; indeed, given that the litigation in Australia and England arises directly out of the same controversy, it would be artificial to treat the forum dispute as “extraneous” or “alien” to the Greensill Proceedings; the bringing of the Anti-suit Application was a reasonable step in the proper conduct of Marsh’s defence to the claims; such use, therefore, did not constitute a breach of the Hearne v Street obligation.

82 In relation to the second issue, Marsh submits, in summary, that: the Hearne v Street obligation does not operate to prevent use for the purpose of complying with a legal obligation; Marsh’s use of discovered documents was necessitated by Marsh’s obligation to the English Court, as the moving party on a without notice application, to give full and frank disclosure in respect of all material facts; that obligation differs from the equivalent obligation under Australian law, and is more extensive; in particular, it requires a party to make reasonable enquiries, and to inform the Court of all relevant matters (i.e. to place the Court in an informed position as to the strengths and weaknesses of the case). Marsh submits that, in order to comply with its legal obligation to the English Court, Marsh was required to: consider and review the discovery given by GBAG in the Greensill Proceedings; disclose to the Court documents bearing upon material facts, whether favourable or unfavourable to its position on the application; and to draw the Court’s attention to those documents (and their materiality) to ensure the fair presentation of the application. Marsh submits that its use of discovered documents in this manner did not breach the Hearne v Street obligation, because the implied obligation did not extend to prohibit such use.

83 Given the factual findings set out earlier in these reasons, GBAG and Dr Frege’s factual case (of use of the discovered documents) is substantially made out. Further, I consider that, by reason of Marsh Pty Ltd (through its lawyers) having access to the discovered documents, Marsh Pty Ltd came under a like obligation in relation to the documents. In other words, it too was subject to the Hearne v Street obligation.

84 I will now consider each of Marsh’s two main contentions.

85 Marsh’s first contention is (in summary) that its use of the documents was not for a collateral purpose, because the issue of forum formed part of the dispute between the parties, or, at least, the issue was not “unconnected” or “unrelated” to the claims in the Greensill Proceedings. I do not accept this contention.

86 First, I consider that this contention takes too broad a view of what may constitute a permissible use. I consider that the test is as articulated by Hayne, Heydon and Crennan JJ in Hearne v Street at [96] (set out above). Accordingly, the party obtaining disclosure cannot, without the leave of the court, use it “for any purpose other than that for which it was given” (unless it is received into evidence). While the judgment of Chesterman JA in Northbuild at [44]-[46] may at first blush suggest a wider notion of permissible use, the factual context in which those observations were made was very different from the present case. The observations need to be understood in the context in which they were made. It was in that particular context that Chesterman JA concluded that documents produced in the course of a freezing order application were produced for purposes extending beyond the conduct of that application to the wider dispute between the parties.

87 Secondly, on the facts of this case, I do not accept that Marsh’s use of the discovered documents was for the purpose for which they were given. The purpose for which the documents were given may be described as: the purpose of the conduct of the Greensill Proceedings (including defending claims brought against a party in the proceedings). I do not accept Marsh’s characterisation of the purpose of production, which referred in general terms to the dispute between the parties, and was unmoored from any particular proceeding or process. In my opinion, the purpose for which the documents were used by Marsh (preparing for and bringing the Anti-suit Application) falls well outside the purpose for which the documents were given. The Anti-suit Application sought an order that GBAG and Dr Frege be restrained from joining Marsh as a respondent to the GBAG Proceedings. In other words, the application sought to prevent a claim even being made in the Greensill Proceedings. In practical terms, the application sought to prevent this Court exercising jurisdiction in relation to a claim (because the claimant was personally enjoined from commencing the claim). This is the antithesis of the purpose of the conduct of the Greensill Proceedings.

88 It may be accepted that, if the Anti-suit Application had not been made, and if GBAG had joined Marsh Ltd to the GBAG Proceedings, it would have been open to Marsh Ltd to bring an application for a stay of the proceedings on the basis of the English exclusive jurisdiction clause, and to have relied on discovered documents in bringing such an application. Marsh submitted that the Anti-suit Application was analogous to, and sought to achieve the same thing as, a stay. However, a stay application in that scenario would have had an entirely different character from the Anti-suit Application. A stay application would have been brought after a claim had already been made in the Greensill Proceedings; it would not have precluded the claim from being made. Further, a stay application would not prevent this Court from exercising its jurisdiction in relation to the claim; rather, it would seek to have this Court exercise jurisdiction in relation to the claim, by considering whether or not there should be a stay.

89 For these reasons, I do not accept the contention that Marsh’s use of the documents was not for a collateral purpose.

90 Marsh’s second contention is (in summary) that the Hearne v Street obligation yielded to the obligation to make full and frank disclosure on a without notice application. I do not accept this contention.

91 First, there is a temporal difficulty with this contention. The relevant passage from the judgment of Mason CJ in Esso v Plowman (set out above) refers to the requirements of “curial process in other litigation”. At the time that Marsh conducted its review of thousands of discovered documents, it had not yet commenced the Anti-suit Application. While instructions had been given to commence a without notice application for anti-suit relief, the proceeding had not been commenced. While the obligation of full and frank disclosure in England requires enquiries to be made before the commencement of proceedings, the obligation nonetheless does not come into effect until proceedings are commenced, as Lord Mance explained at para 53 of his report (quoted above). As a matter of principle, I do not consider that the Hearne v Street obligation yields to requirements in relation to yet-to-be-commenced litigation.

92 Secondly, on the facts of this case, I do not consider that the Hearne v Street obligation yielded to the obligation to make full and frank disclosure on the without notice application. For present purposes, I will assume that, as a matter of English law, the obligation to make full and frank disclosure on a without notice application extends to facts in the applicant’s favour. Whether the application for anti-suit relief was brought on a without notice basis (rather than with notice) was a matter of choice for Marsh. True it is that there were good practical reasons for bringing the application on a without notice basis. However, the application did not need to be brought on a without notice basis. In these circumstances, the obligation of full and frank disclosure was self-imposed. If the Hearne v Street obligation were to yield to the obligation to make full and frank disclosure in such circumstances it would produce the bizarre result that the obligation would yield if the application for anti-suit relief were brought on a without notice basis but not if the application for anti-suit relief were brought on notice (a point made by Lord Hoffmann in para 12 of his first report). Having regard to these matters, in my view, the Hearne v Street obligation did not yield to the obligation to make full and frank disclosure.

93 In the circumstances of this case, once a decision had been made to bring a without notice application for an anti-suit injunction, and Marsh was faced with two potentially conflicting obligations, the appropriate course to have adopted was to seek a release from the Hearne v Street obligation. Thus, a practical mechanism was available to seek to avoid being faced with two potentially inconsistent obligations.

94 For these reasons, I do not accept Marsh’s second contention.

95 Having rejected Marsh’s two contentions, I am satisfied (to the requisite standard) that Marsh Ltd breached the Hearne v Street obligation as alleged in paragraph 36 of the Statement of Particulars, and that Marsh Pty Ltd breached that obligation as alleged in paragraph 41 of the Statement of Particulars.

The Release Application

96 Given the above conclusions, it is necessary to consider the Release Application.

97 In its outline of submissions, Marsh submits: if, contrary to its earlier submissions, the Court were to find that Marsh’s use of discovered documents was in breach of its implied obligation to this Court, it would nevertheless be appropriate for the Court to exercise its discretion to grant to Marsh, nunc pro tunc, leave to use the discovered documents for the purpose of the Anti-suit Application, having regard to the close connection between the Anti-suit Application and the Greensill Proceedings in which the documents were produced, and the important contribution of such documents to achieving justice on the Anti-suit Application (namely, ensuring that all relevant material was before the English Court). Marsh refers to Hancock at [77]; Treasury Wine Estates Limited v Maurice Blackburn Pty Ltd [2020] FCAFC 226 at [83]-[89]; Liberty Funding at [31]; Springfield Nominees Pty Ltd v Bridgelands Securities Ltd (1992) 38 FCR 217 at 225.

98 The applicable principles as stated by the Full Court in Liberty Funding have been set out above. The other cases referred to by Marsh in its submissions are to similar effect.

99 Insofar as Marsh seeks a release on a nunc pro tunc basis, I am not satisfied that it is appropriate to make such an order. The parties that discovered the documents (GBAG and Dr Frege) strongly oppose a release being given on a nunc pro tunc basis. The position of those parties is a relevant, albeit not determinative factor. For the reasons discussed above, I consider that a release should have been sought by Marsh once it had made a decision to seek anti-suit relief on a without notice basis and before it began reviewing any of the discovered documents for the purpose of bringing an application for anti-suit relief. As the factual findings set out earlier in these reasons demonstrate, the use made of the discovered documents was extensive (including reviewing thousands of discovered documents). The breaches of the Hearne v Street obligation were serious. In the circumstances, I do not consider it appropriate to effectively regularise the situation by granting a release on a nunc pro tunc basis.

100 Insofar as Marsh seeks a release on a prospective basis, however, the position is different. Critically, such an order will facilitate the parties being able to make submissions to the English Court at the forthcoming hearing before that Court. Further, a release on a prospective basis is not opposed by GBAG and Dr Frege. In these circumstances, I consider it appropriate to grant a release on a prospective basis.

Conclusion

101 For the reasons set out above, I have concluded that Marsh Ltd and Marsh Pty Ltd breached the Hearne v Street obligation. I consider it appropriate to make a declaration substantially in the terms sought by GBAG and Dr Frege (with some minor stylistic changes). The requirements for the making of a declaration are satisfied: see Forster v Jododex Australia Pty Ltd [1972] HCA 61; 127 CLR 421 at 437-438. It was not suggested that, should I conclude that there had been a breach, there was any reason not to reflect that conclusion in a declaration. I propose to make a declaration to the effect that:

Marsh Ltd and Marsh Pty Ltd relied upon documents, and information contained in documents, discovered in the Greensill Proceedings in support of the Anti-suit Application, in breach of their obligation to this Court not to use discovered documents or discovered information for any purpose other than that for which it was given unless it is received into evidence, without leave of this Court.

102 In relation to the Release Application, I will make an order to the effect that, from the date of the order, Marsh Ltd and Marsh Pty Ltd be released from the Hearne v Street obligation in relation to the documents discovered by GBAG and Dr Frege to Marsh Ltd in the Greensill Proceedings, such that those documents may be used for the purpose of the Anti-suit Application. The Release Application will otherwise be dismissed.

103 In relation to costs, I will provide an opportunity for the parties to seek to agree an order on costs. In the event that they cannot agree, then I will give the parties the opportunity to file short submissions, and the issue of costs will be determined on the papers.

I certify that the preceding one hundred and three (103) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice Moshinsky. |

Associate:

ANNEXURE

NSD 106 of 2022 | |

BCC TRADE CREDIT PTY LTD | |

Fifth Respondent: | GREG BRERETON |

Sixth Respondent: | TOKIO MARINE MANAGEMENT (AUSTRALASIA) PTY LTD |

Seventh Respondent: | TOKIO MARINE & NICHIDO FIRE INSURANCE CO LTD |

Eighth Respondent: | MARSH LIMITED |

GREENSILL BANK AG | |

Second Cross-Claimant | MICHAEL FREGE IN HIS CAPACITY AS INSOLVENCY ADMINISTRATOR FOR GREENSILL BANK AG |

Cross Respondent | INSURANCE AUSTRALIA LIMITED |

Cross-Claim | |

Cross-Claimant | BCC TRADE CREDIT PTY LTD |

Cross Respondent | GREENSILL CAPITAL (UK) LTD |

Second Cross Respondent | GREENSILL BANK AG |

Third Cross Respondent | GREENSILL CAPITAL PTY LTD (IN LIQUIDATION) |