Federal Court of Australia

Novartis AG v Pharmacor Pty Limited (No 3) [2024] FCA 1307

ORDERS

First Applicant NOVARTIS PHARMACEUTICALS AUSTRALIA PTY LIMITED Second Applicant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties bring in agreed or, if not agreed competing, draft orders giving effect to these reasons by no later than 4.00pm on 20 November 2024.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

YATES J:

1 Novartis AG as patentee, and Novartis Pharmaceuticals Australia Pty Limited (Novartis Australia) as Novartis AG’s exclusive licensee (together, Novartis), sue Pharmacor Pty Limited (Pharmacor) for threatened infringement of claim 1 of Patent No. 2003206738 (the patent) based on Pharmacor’s intended supply in Australia of pharmaceutical products entered on the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods (ARTG), referred to in these reasons as Valtresto.

2 The application for the patent was filed on 16 January 2003. The patent was granted on 5 April 2007 for a term of 20 years expiring on 16 January 2023. The complete specification filed with the patent application is titled “Pharmaceutical compositions comprising valsartan and NEP inhibitors” (the specification).

3 The specification is directed to pharmaceutical compositions containing certain active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs); a method of treating or preventing hypertension, heart failure (such as congestive heart failure), or myocardial infarction and its sequelae, by administering a therapeutically effective amount of a combination of certain APIs; and the use of certain APIs in the manufacture of a medicament for treating or preventing one or more of these diseases or conditions. The treatment of hypertension and heart failure is particularly relevant to the issues raised in this case.

4 On 10 June 2016, Novartis AG applied for an extension of the term of the patent under s 70 of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) (the Patents Act). The application was granted on 5 December 2016. The term was extended to 16 January 2028.

5 The priority date of claim 1 of the patent is 17 January 2002 (the priority date) based on the filing of US Provisional Patent Application No. 60/349,660.

6 Pharmacor denies that it threatens to infringe claim 1. Further, by a notice of cross-claim, it seeks a declaration that claim 1 of the patent is invalid and an order that it be revoked under s 138(3) of the Patents Act.

7 Pharmacor relies on three grounds of revocation, which are pleaded in its further amended statement of cross-claim: (a) the specification of the patent does not comply with s 40(2)(a) of the Patents Act (in its relevant form) in that it does not describe the best method of performing the alleged invention known to Novartis AG at the relevant time; (b) claim 1 of the patent does not comply with s 40(3) of the Patents Act (in its relevant form) in that it is not fairly based on the matter described in the specification; and (c) the invention claimed in claim 1 is not a patentable invention within the meaning of s 18(1)(b)(ii) of the Patents Act (in its relevant form) in that it does not involve an inventive step when compared with the prior art base as it existed before the priority date. Pharmacor has not pursued another pleaded ground of revocation.

8 The relevant form of the Patents Act is the form it took after the Patents Amendment Act 2001 (Cth) and before the Intellectual Property Laws Amendment (Raising the Bar) Act 2012 (Cth) (the RTB Act).

9 Pharmacor also alleges that the term of the patent was wrongly extended because the requirements of ss 70(2)(a) and 70(3)(a) were not satisfied at the time of the application. In its notice of cross-claim, it seeks an order under s 192 of the Patents Act that the Register of Patents (the Register) be rectified by: (a) removing reference to the patent term having been extended to 16 January 2028; and (b) recording that the term of the patent expired on 16 January 2023.

10 If Pharmacor establishes its case on rectification, or its case on revocation on any one of its grounds of invalidity, then Novartis’s case on infringement necessarily fails.

11 For the reasons given below, I have concluded that Novartis has not established that Pharmacor threatens to infringe claim 1 of the patent, having regard to the proper construction of that claim. I have also concluded that the term of the patent was not validly extended. Therefore, Novartis cannot assert the patent rights it claims.

12 It follows from this that Pharmacor’s challenge to the validity of claim 1 does not arise for determination. In any event, its challenge based on the grounds that claim 1 is not fairly based on the matter described in the specification, or because the specification does not describe the best method known to Novartis AG of performing the invention, depends on a construction of claim 1 that I do not accept. Further, even if, contrary to my finding, the patent subsists, Pharmacor has not established that claim 1 is invalid for lack of an inventive step.

13 The cardiovascular system, which includes the heart and blood vessels, is the continuous circulation of blood which returns through the heart twice. Blood is pumped from the right side of the heart to the lungs where it becomes oxygenated. The oxygenated blood then flows to the left side of the heart where it is pumped around the body through blood vessels to deliver oxygenated blood to organs such as the liver and kidneys. Deoxygenated blood is collected by the veins and returned to the right side of the heart to be pumped back to the lungs.

14 The cardiac cycle refers to the steps that occur in a single heartbeat. Around once a second, the cycle commences with an initial “kick” (a rapid increase in pressure as the blood is ejected from the contraction of the left ventricle of the heart into the aorta) occupying about one-tenth of the cycle, followed by a longer period of relaxation as the heart refills with blood, occupying approximately nine-tenths of the cycle. Because of this, blood circulation is pulsatile.

15 In a healthy person, the common measurement of blood pressure is expressed as 120/80—meaning, 120 mmHg (the maximum pressure reached in the aorta during maximal ejection from the left ventricle, which is called the systolic blood pressure) and 80 mmHg (the pressure at which the aortic valve opens, which is called the diastolic blood pressure).

16 The performance of the heart and blood vessels can be assessed by reference to “contractility” (the ability of the heart to contract) and the “ejection fraction” (the percentage of blood pumped out of a ventricle during each cardiac cycle). Assessing contractility involves measuring the rate at which pressure develops in the left ventricle and the speed at which blood is ejected from the left ventricle. The ejection fraction is typically measured from the left ventricle. A normal left ventricle ejection fraction in a healthy adult is around >55% (i.e., in each cardiac cycle more than 55% of the blood in the left ventricle is ejected into the aorta and arteries). The ejection fraction is an indirect measure of contractility.

17 The cardiovascular system is regulated by a number of systems. Two important systems that are particularly relevant to understanding the specification are: (a) the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS); and (b) the natriuretic peptide (NP) system.

18 The RAAS is a neurohormonal system that is responsible for longer term regulation of blood pressure by the release of hormones and blood factors. It is a cascade which is triggered by insufficient blood volume reaching the kidney and results in increased blood pressure.

19 The process begins with cells in the kidneys called juxtaglomerular cells. These cells act as a chemical monitor of matter filtered out of the blood by capillaries in the kidneys. Amongst other things, they detect the rate at which sodium is delivered to the kidneys. If blood pressure is low, less blood will reach the kidneys, and the juxtaglomerular cells will detect less sodium. This activates the RAAS.

20 Once the RAAS is activated, the juxtaglomerular cells cause an enzyme—renin—to be released into the blood. Renin then triggers the production of a hormone—angiotensin I. Angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE), which is diffused throughout the circulatory system, converts angiotensin I into a more active form—angiotensin II.

21 Angiotensin II binds to receptors that cause effects that include: (a) stimulating vasoconstriction; (b) promoting sodium reabsorption (causing sodium retention); (c) inducing the synthesis and release of aldosterone (which promotes sodium and fluid retention); (d) stimulating thirst to encourage fluid intake; and (e) reducing the sensitivity of the baroreceptor reflex—an autonomic nervous system response for maintaining short term stable blood pressure (homeostasis) through triggering a short term increase or decrease in blood pressure by modifying the contractility (power) or rate (speed) of the heart and by changing the vascular tone (the resistance of peripheral arteries).

22 There are two main types of angiotensin II receptors, conveniently referred to as type-1 (AT 1-receptors) and type-2 (AT 2-receptors). Activation of the AT 1-receptors typically causes vasoconstriction and has effects on the heart similar to the baroreceptor reflex to elevate blood pressure. Activation of the AT 2-receptors has almost the opposite effect, reducing blood pressure. However, the effects of activating the AT 2-receptors are less powerful than the effects of activating the AT 1-receptors.

23 The release of aldosterone causes fluid retention, potassium loss, sodium retention, and increases thirst. It does so by blocking the exchange of sodium, potassium and water in the kidneys.

24 As noted, angiotensin II and aldosterone both promote sodium retention. Sodium levels are important because sodium is a substance through which the body controls fluid retention. Increasing sodium concentration in the kidneys means that more water is reabsorbed into the body rather than leaving the body in the form of urine. Fluid content, and hence blood volume, is increased, thereby increasing blood pressure. Decreasing sodium concentration has the opposite effect.

25 In addition to converting angiotensin I to angiotensin II, ACE also interacts with other vasoactive peptides. For example, it inactivates bradykinin, which is a vasodilator that relaxes blood vessels and reduces blood pressure.

26 Heart failure can inappropriately trigger the RAAS into a permanent “on” state leading, ultimately, to damage to the heart and blood vessels.

27 Inhibiting the RAAS is a powerful mechanism for reducing blood pressure.

28 Natriuretic peptides (NPs) promote natriuresis, which is the excretion of sodium via urine.

29 Different parts of the heart produce different NPs: (a) A-type NPs (ANP) (also called atrial natriuretic peptides or atrial natriuretic factor (ANF)) are released by the heart atria when the heart wall muscles are under increased stress by blood volume overload; (b) B-type NPs (BNP) (also called brain natriuretic peptides) are released by the heart ventricles when the heart wall muscles are subject to increased stress by blood volume overload or ventricular hypertrophy (increased muscle mass in the ventricle walls); (c) C-type NPs (CNP) are primarily released by the blood vessel in and around the heart in response to increased blood volume load; and (d) D-type NPs (DNP).

30 At the priority date, CNP and DNP were rarely discussed.

31 ANP and BNP both have effects that act to reduce blood volume. They:

(a) trigger a decrease in sodium reabsorption in the kidneys, causing more sodium to exit the body, and more water to follow;

(b) promote vasodilation, including through the inhibition of vasopressin, primarily on the venous side of the circulatory system, which increases the volume of blood reaching the heart;

(c) promote vasodilation of the blood vessels in the kidney’s filtration system, which increases filtration, causing more sodium (and therefore water) to be excreted as urine;

(d) slightly inhibit the RAAS and sympathetic nervous system; and

(e) reduce aldosterone secretion.

32 Even though ANP and BNP both have these effects, BNP is considered more important because it is released in greater amounts (because of the increased muscle mass of the heart ventricles compared to the heart atria) and has greater effect.

33 ANP and BNP concentration in the blood is a biomarker for the heart and indicates the occurrence and magnitude of heart stressors. Therefore, the measurement of ANP and BNP is a diagnostic tool.

34 NPs are broken down by an enzyme—neutral endopeptidase (NEP). NEP is an important part of the deactivation of NP system. NEP also breaks down bradykinin into inactive fragments.

35 Hypertension (high blood pressure) is largely a disease of the blood vessels. It occurs when the heart is pumping blood under pressure into a vascular system that is restricted. Treatment is directed to stopping the heart creating so much pressure (e.g., by using beta blockers) or reducing the restrictions on the vascular system (e.g., by inhibiting the RAAS to reduce blood volume).

36 Hypertension is more prevalent with age, in part because the blood vessels lose elasticity. During the maximal ejection phase of the cardiac cycle—the “kick”—the blood pressure curve, for a healthy adult, is smoothed out by the elasticity of the aorta and surrounding blood vessels, which expand in response to the spiking blood pressure, increasing the volume of the blood vessels, and thereby reducing the maximum pressure that is reached. As blood vessels become less elastic with age, they do not expand to the same extent. Consequently, blood pressure spikes at a higher level. Approximately two-thirds of the population will develop hypertension over their lifetime.

37 High blood pressure is recognised as a risk factor that is diagnosed as hypertension when it exceeds a “number” at which it is recognised that treatment will provide a meaningful clinical improvement. At the priority date, systolic blood pressure above 140 mmHg (when measured robustly over a 24-hour period) would have been diagnosed as hypertension.

38 Hypertension is largely asymptomatic. However, over time, it can cause significant damage to other organs, including the eyes, brain, kidneys, and heart. For example, persistent high blood pressure can cause blood vessels to burst and bleed, or cause the lining of the blood vessels to thicken and occlude, or make blood plaques worse, which, in turn, can lead to heart attacks, stroke, kidney failure, heart failure, and dementia.

39 Heart failure is a syndrome where the heart ceases to work as expected because of an abnormality in the heart. It is generally a chronic disorder.

40 The diagnosis of heart failure is based on: (a) the presence of one or more classical symptoms (including, shortness of breath, fluid retention, fatigue, and an inability to exercise); (b) the establishment of a causal link between these symptoms and a change in the heart that can be detected through measurement and clinical judgment; and (c) external confirmation that heart failure is occurring, such as by chest X-ray (which may show pulmonary congestion), the measure of NPs, or haemodynamic measurement of the pressure within the heart.

41 There are two types of heart failure, broadly speaking: (a) heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF); and (b) heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF).

42 As I have noted, a typical left ventricle ejection fraction for a healthy adult is >55%. A patient with a lower ejection fraction is said to have a “reduced” ejection fraction. A patient who has heart failure, but a normal ejection fraction (>55%) is said to have a “preserved” ejection fraction. At the priority date, HFrEF dominated attention and practice, and pharmacotherapies were largely directed to this condition.

43 There are a wide range of causes of heart failure. The most common causes of HFrEF are: (a) ischaemic heart disease (or coronary heart disease), which refers to narrowed arteries (which may be contributed to by hypertension); (b) hypertension; and (c) myocardial infarction (heart attack), which may damage or destroy the heart muscle.

44 Hypertension is significantly more common than heart failure, affecting (as I have said) around two-thirds of the population over their lifetime. Two-thirds of heart failure patients will first have hypertension, which is an underlying risk factor or cause of heart failure, either directly or through ischaemic heart disease. Once a patient with hypertension develops heart failure, in particular HFrEF, their hypertension will remain present. However, in some cases, the patient’s blood pressure will reduce (but still be relatively high) because the heart is not producing as much pressure as it did.

45 All the first line therapies for heart failure reduce blood pressure. For around half the patients with heart failure and hypertension, who are receiving treatment for heart failure, there is no need to separately manage their hypertension. For example, they do not need to take additional pharmacotherapies to reduce their blood pressure.

46 Heart attack is the next most common cause of heart failure. A large heart attack may cause sufficient damage to immediately trigger heart failure. A smaller heart attack may lead to heart failure over time because of deteriorated heart function. For example, the increased stress on the heart wall following a heart attack may result in an enlarged heart through neurohormonal activation. As the heart enlarges, the left ventricle generally becomes more globular and less efficient at pumping than an ordinarily conically-shaped ventricle with smaller muscles.

47 There are other indirect causes of heart failure, as well as contributory risk factors, that need not be detailed for the purposes of these reasons.

48 In Australia, it is common for cardiologists to treat both hypertension and heart failure, although much of the clinical treatment of hypertension is performed by generalists in internal medicine or clinical pharmacology.

49 At the priority date, the development of pharmacotherapies for the treatment of hypertension and heart failure generally involved modifying the various regulatory systems of the cardiovascular system. There were a range of pharmacotherapies and, typically, a patient with hypertension or heart failure would receive more than one type of drug with different modes of action. This was required for heart failure to target different systems to reduce mortality and improve patient outcomes in an additive way. For hypertension, it was possible to use one drug with one mode of action. However, it was common to use multiple drugs with different modes of action to reduce blood pressure without creating unacceptable levels of side effects.

50 In the following paragraphs, I refer to some of the therapies that are of particular relevance to the present case.

51 These drugs inhibit the RAAS by reducing the activity of angiotensin II. They are useful in the treatment of hypertension (they reduce blood pressure by vasodilation) and heart failure.

52 At the priority date, the following ACE inhibitors were available: (a) captopril; (b) enalapril; (c) lisinopril; (d) ramipril; and (e) perindopril. Captopril was one of the first ACE inhibitors with widespread approval and use. It needed to be dosed more frequently and at higher doses than later agents. Enalapril was the next ACE inhibitor to reach widespread approval and use. It was the agent that first demonstrated the benefits of ACE inhibition for heart failure.

53 ACE inhibitors have notable side effects—dry cough and angioedema. Angioedema is a dangerous side effect that involves a dramatic swelling of the tissues of the head and neck. It affects <1% of patients. This, however, is a matter of concern because of the severity of the condition. ACE inhibition leads to a build up of bradykinin, which is associated with both conditions. ACE inhibitors are also contraindicated for patients with renal artery stenosis (blockage of the renal artery).

54 However, when tolerated, ACE inhibitors were considered to be mandatory treatment for chronic heart failure.

55 Angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) (also known as angiotensin II antagonists) were the next major development in inhibiting the RAAS. They block the activity of angiotensin II one further step along the RAAS cascade from ACE inhibitors. They do not, therefore, reduce ACE activity as such.

56 ARBs target and predominantly block AT 1-receptors. As I have noted, activation of the AT 1-receptors typically causes vasoconstriction and has effects on the heart similar to the baroreceptor reflex to elevate blood pressure.

57 At the priority date, ACE inhibitors and ARBs were viewed as substitutes, although there was uncertainty as to which was more efficacious in the treatment of heart failure. The ELITE clinical trial—a safety and tolerability study of losartan (an ARB) versus captopril—reported in 1997 that losartan was significantly superior to captopril in reducing mortality. However, ELITE-II—a larger, follow-on trial conducted from 1997—concluded that mortality did not differ significantly between losartan and captopril. The study also confirmed that ARBs had superior tolerability to ACE inhibitors.

58 Notwithstanding the findings of ELITE-II, there continued to be uncertainty as to whether ARBs or ACE inhibitors were superior in the treatment of heart failure. At the priority date, ACE inhibitors remained the first line therapy for heart failure because there had been more studies of their effect in treating heart failure in major clinical trials.

59 ARBs have low rates of side effects (including angioedema) similar to a placebo. As a result, by the priority date, ARBs started to replace ACE inhibitors as first line therapy for hypertension. ARBs also have a wide therapeutic window (the therapeutic window is the range between the concentration of the agent necessary to produce therapeutic effects and the concentration at which there is an unacceptable risk of side effects).

60 At the priority date, a number of ARBs were in use or in development. Their effects were largely thought to be class effects. There were, however, differences in the extent to which each ARB had been proven in large-scale clinical trials.

61 Losartan was the first ARB to receive regulatory approval, globally. As I have noted, it was shown in ELITE-II to be effective in treating heart failure. It was, however, short-acting and generally needed to be administered twice daily.

62 Valsartan is another ARB that has been shown to be effective in treating heart failure. It was the subject of the Val-HeFT clinical trial—a Phase III trial against placebo involving over 5,000 participants, who were also taking the standard heart failure treatments (ACE inhibitors, beta blockers, diuretics and/or digoxin).

63 The results of the Val-HeFT trial were reported in November 2000 at the American Heart Association Meeting and published in Thackray SDR et al, “Clinical trials update: highlights of the scientific sessions of the American Heart Association year 2000: Val HeFT, COPERNICUS, MERIT, CIBIS-II, BEST, AMIOVIRT, V-MAC, BREATHE, HEAT, MIRACL, FLORIDA, VIVA and the first human cardiac skeletal muscle myoblat transfer for heart failure” (2001) 3 European Journal of Heart Failure 117–124 (Thackray). Two relevant conclusions were:

Valsartan significantly reduces the combined end point of mortality and morbidity and improves clinical signs and symptoms in patients with heart failure, when added to prescribed therapy.

and

However, the post hoc observation of an adverse effect on mortality and morbidity in the subgroup receiving valsartan, an ACE inhibitor, and a beta-blocker raises concern about the potential safety of this specific combination.

64 The final results of the Val-HeFT clinical trial were published in December 2001 in Cohn JN and Tognoni G, “A Randomized Trial of The Angiotensin-Receptor Blocker Valsartan in Chronic Heart Failure” (2001) 345(23) The New England Journal of Medicine 167-175 (Cohn).

65 Other ARBs known at the priority date were: (a) candesartan; (b) irbesartan; (c) telmisartan; and (d) eprosartan. Candesartan was the subject of a large-scale clinical trial called the CHARM Program. The CHARM Program was still underway at the priority date. At that time, its results were not expected until 2003.

Aldosterone receptor antagonists

66 Aldosterone receptor antagonists block the effects of aldosterone. As discussed, one function of angiotensin II in the RAAS is to release aldosterone. However, angiotensin II is not the only trigger. Potassium levels can also trigger its release. For this reason, it is useful to inhibit both angiotensin II (by an ACE inhibitor or an ARB) and aldosterone (by an aldosterone receptor antagonist).

67 Spironolactone was the first aldosterone receptor antagonist. It was first used for the treatment of hypertension but was later found to be useful in the treatment of severe heart failure. Its activity is complementary to the activity of ACE inhibitors, ARBs, and beta blockers. Because of this, it was included in various heart failure guidelines, and its use increased significantly. However, its use as an additional drug therapy in mild heart failure was not demonstrated until after the priority date.

68 Spironolactone also reduces blood pressure and was used to treat hypertension (although not commonly prescribed solely for that effect).

69 The main side effects associated with spironolactone were hyperkalaemia (high potassium levels) and gynecomastia (swelling of the breast tissue) in men.

70 Eplerenone was another aldosterone receptor antagonist in development at the priority date.

71 Beta blockers are a broad class of drugs that block beta receptors and inhibit the effects of epinephrine (or adrenaline) and norepinephrine (or noradrenalin). This slows and reduces the power of the heart, thereby reducing blood pressure generated by the heart.

72 Beta receptors, and the mechanisms for blocking them, are diverse and varied. As a result, there can be significant differences in how beta blockers act.

73 Only certain beta blockers are indicated for heart failure, the most commonly used being carvedilol, bisoprolol, metoprolol, and nebivolol. A much wider range can be used for hypertension.

74 Beta blockers have a range of side effects, including depression, sleep impairment, bronchospasm, and erectile dysfunction. Although beta blockers were initially used as primary treatment for hypertension, by the priority date other treatments were being prioritised with fewer side effects.

75 Before the priority date, there was interest in seeking to influence the NP system to treat heart failure and to treat hypertension. As I have noted, NPs are broken down by NEP, which is an important part of the deactivation of the NP system. The action of NPs, which reduces blood pressure, can be prolonged by inhibiting NEPs.

76 The potential role of NEP inhibitors for the treatment of heart failure had been investigated, but none had been approved or were in use. In limited clinical trials, NEP inhibitors had relatively little efficacy.

77 However, before the priority date, there had been development, and widely reported clinical trials, of dual vasopeptidase inhibitors, which are naturally occurring single chemical entities possessing both ACE and NEP inhibitory action—in other words, the complementary action of inhibiting the RAAS and promoting the positive action of NPs. Two such drugs were omapatrilat and sampatrilat.

78 Early clinical trials of omapatrilat were very promising in terms of its efficacy in treating hypertension and heart failure. It was widely reported at leading conferences and in major journals in cardiology. It had also been referred to in at least one teaching text in Australia which reported that it seemed likely that it would prove useful in the treatment of chronic heart failure:

The combination of an NEP antagonist with an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor has been shown to result in a more sustained natriuretic effects than has an NEP antagonist alone in experimental animal models of HF, in part because of the inhibition of angiotensin II-mediated effects but also because of the fact that both NEP and ACE degrade bradykinin, a vasodilatory and natriuretic peptide.

79 Other pharmacotherapies (relevant to the consideration of this case) include vasopressin receptor antagonists, endothelin receptor antagonists, and positive inotropic agents.

80 Vasopressin is a vasoconstrictor hormone that also effects the kidneys. At the priority date, vasopressin receptor antagonists were theoretically promising. However, work on them had not resulted in any drug products approved for hypertension or heart failure.

81 Endothelin is also a vasoconstrictor. Endothelin receptor antagonists inhibit the binding of endothelin to receptors in smooth muscle cells. At the priority date, such drugs were also theoretically promising, but work on them had not led to any approved drug products.

82 Positive inotropic agents are drugs which increase the strength of the heartbeat. They are only used for heart failure. They are not used for hypertension because they increase blood pressure. At the priority date, positive inotropic agents were a relatively minor part of the range of pharmacotherapies in use and in development. Their use at the priority date was limited to symptomatic relief where longer term mortality was a less relevant consideration (such as in the case of palliative care or where the patient was in acute heart failure requiring emergency treatment).

83 A prodrug is a compound with little or no pharmacological activity that converts into a pharmacologically active compound by the body’s metabolic processes. Prodrugs are typically used to assist the absorption of a compound that would otherwise be poorly absorbed. If an API has any chemical groups that will affect its absorption when administered, and hence its bioavailability, then a prodrug might be suitable as a strategy for improving its oral bioavailability so that the API can have its intended therapeutic effect in the body.

84 If the API has an appropriate chemical functional group, such as an alcohol group or an acidic group, a non-toxic “prodrug group” can be attached to the compound by an “ester” linkage to form an ester prodrug.

85 Esters are organic compounds formed by a reaction between an alcohol group (OH, which is also referred to as a hydroxy or hydroxyl group) and an acid group (commonly a carboxylic acid group, COOH, which is also referred to as a carboxy or carboxyl group). Esters are a common form of prodrug.

86 More than one API can be combined in a single dosage form. A “fixed dose combination” is a tablet or other dosage form that incorporates two or more APIs in a fixed dosage, or amount. Such a combination, which reduces the number of dosage forms a patient might otherwise be required to take, is a strategy for facilitating patient compliance.

87 Well before the priority date, various fixed dose combination products were available in Australia, including: (a) antihypertensive drugs combined with diuretics in a single tablet; (b) certain antibiotics, including amoxycillin plus clavulanic acid and trimethoprim plus sulphamethoxazole in a single unit dosage form; (c) paracetamol plus doxylamine in a single tablet or capsule; and (d) various analgesic combinations, including paracetamol plus codeine in a single tablet.

88 A complex is a unique single entity consisting of two or more molecules (or charged molecules, i.e., ions) bound together by non-covalent bonds. As a solid, a complex exists as a single, distinct physical material in which all the solid particles have the same chemical composition. This material has a different identity and different properties to the physical materials of its component parts.

89 A solid complex is distinct from a physical mixture of particles. A complex is typically formed by combining its constituent molecules in solution. This process is not equivalent to simply physically mixing the solid components together. It may require specific reaction conditions (e.g., specific temperature, pH, pressure, solvents, catalysts, and, potentially, the use of a complexing agent). The process may be driven by separating the solid complex from solution (e.g., by crystallisation).

90 A complex in a solid state has its own unique set of physical properties, such as solubility, stability, hygroscopicity, melting point (or glass transition for amorphous materials), density, bulk density, powder flowability, adhesion, and physical appearance. Solid complexes also have their own set of analytical properties, such as infrared spectrum, Raman spectrum, solid state NMR spectrum, fluorescence behaviour and, for crystalline materials, X-ray powder diffraction pattern. These properties will be different from those of the separate components of the complex, even when those separate components are physically mixed.

91 Therefore, a solid complex is not the mere sum of its constituent parts. In complexes that involve ions, the ions of opposite charge cannot be physically separated because of the great strength of ionic bonds.

92 A complex can also exist in liquid and semi-solid pharmaceutical dosage forms.

93 A complex can be used in pharmaceutical products to meet a range of product needs, including: (a) taste masking an API; (b) improving the solubility and absorption of an API; (c) retarding the release and absorption of an API; (d) enabling a product to have an adequate storage shelf life; and (e) minimising toxicity.

94 The most important characteristic of complexes in solution, if they do not dissociate completely, is their stability, which can be measured by various, known means.

95 A salt complex can be a so-called “double salt” that comprises one kind of cation and two kinds of anion, or one kind of anion and two kinds of cation, held together by ionic interaction. This does not mean that there are two salts present in the complex. It only means that there are two different ions of one particular charge, and one ion of the opposite charge, reacting to produce a new, single salt—the “double salt”. It is as if the salt-forming reaction has occurred twice to form the one, new salt.

96 Entresto is a film-coated tablet drug product that contains an active ingredient which is a salt complex of the anionic forms of sacubitril and valsartan, sodium cations, and water molecules in the ratio of 1:1:3:2.5, termed TSVH, and excipients. TSVH is a single crystalline complex material that comprises a repeating unit of 18 sodium cations, 6 sacubitril anions, 6 valsartan anions, and 15 water molecules in a coordinated complex arrangement involving ionic bonding, hydrogen bonding and a range of other non-covalent interactions. The overall complex is a single physical material with a unique set of physicochemical properties.

97 The relevant experts agree that TSVH is a single salt. It is also a “double salt” but, as I have already said, this does not mean it is two salts. The anionic sacubitril, anionic valsartan, and sodium cations do not, and cannot, exist independently as distinct materials in the solid state.

98 Following oral administration of the tablet, Entresto disintegrates. The salt complex, TSVH, is released and then dissolved in the gastrointestinal tract fluids. The pharmaceutical composition no longer exists. The salt complex dissociates into solvated anionic sacubitril and anionic valsartan. The anions are then protonated (i.e., they gain a hydrogen atom) into their free acid forms.

99 TSVH was first synthesised in January 2006 following experimental work between March 2005 and January 2006.

100 The relevant experts agree that the specification (discussed below) does not envisage or mention TSVH. However, TSVH is disclosed in an International Patent Application (PCT/US2006/043710) by Novartis AG, published as WO 2007/056546 A1, titled “Pharmaceutical combinations of an angiotensin receptor antagonist and an NEP inhibitor”.

101 Valtresto is a film-coated tablet drug product for the treatment of chronic heart failure in patients with a reduced ejection fraction. It comes in three dosage strengths and comprises an amorphous complex, termed SVT1, and excipients, in which valsartan anions, sacubitril anions, and sodium cations are present in a 1:1:3 ratio.

102 SVT1 is a single chemical entity with a single glass transition. Following oral administration, Valtresto, like Entresto, disintegrates and SVT1 dissociates.

103 The specification commences by referring to ARBs, ACE inhibitors, and NEPs. It refers to ARBs by their alternative name “angiotensin II antagonists” and notes their inhibition of AT 1-receptors and, hence, their use as antihypertensives and in the treatment of congestive heart failure, among other indications.

104 The specification says that inhibitors of the renin angiotensin system “are well known drugs that lower blood pressure and exert beneficial actions in hypertension and in congestive heart failure”. It singles out ACE inhibitors as the most widely studied inhibitors and specifically mentions captopril, enalapril, lisinopril, benazepril, and spirapril.

105 The specification notes that ACE cleaves a variety of substrates, including bradykinin. It says that the prevention of the degradation of bradykinin by ACE inhibitors has been demonstrated, and that:

.. the activity of the ACE inhibitors in some conditions has been reported … to be mediated by elevation of the bradykinin levels rather than the inhibition of Ang II formation. Consequently, it cannot be presumed that the effect of an ACE inhibitors is due solely to prevention of angiotensin formation and subsequent inhibition of the renin angiotensin system.

106 The specification notes that NEP cleaves a variety of peptide substrates including ANP (which it alternately calls ANF), BNP, and bradykinin. It refers to ANPs as “a family of vasodilator, diuretic and antihypertensive peptides which have been the subject of many recent reports in the literature”.

107 After referring to the function of ANPs to maintain salt and water homeostasis, and to regulate blood pressure, the specification says that ANP is rapidly inactivated in the circulation by at least two processes. One process is “enzymatic inactivation via NEP”.

108 The specification says that it has been demonstrated in animal experiments that inhibitors of NEP potentiate the hypotensive, diuretic, natriuretic, and plasma ANP responses. It refers to literature reporting on the potentiation of ANP by specific NEP inhibitors and NEP inhibitors in general.

109 The specification discusses combination therapy:

Prolonged and uncontrolled hypertensive vascular disease ultimately leads to a variety of pathological changes in target organs such as the heart and kidney. Sustained hypertension can lead as well to an increased occurrence of stroke. Therefore, there is a strong need to evaluate the efficacy of antihypertensive therapy, an examination of additional cardiovascular endpoints, beyond those of blood pressure lowering, to get further insight into the benefits of combined treatment.

The nature of hypertensive vascular diseases is multifactorial. Under certain circumstances, drugs with different mechanisms of action have been combined. However, just considering any combination of drugs having different mode (sic) of action does not necessarily lead to combinations with advantageous effects. Accordingly, there is a need for more efficacious combination therapy which has less deleterious side effects.

110 Although this part of the specification addresses a need for new efficacious combination therapy in the context of treating hypertension, later passages speak of the utility of the invention in treating or preventing heart failure, and myocardial infraction and its sequelae.

111 After this introduction, the specification turns to the alleged invention:

In one aspect the present invention relates to pharmaceutical combinations comprising valsartan or pharmaceutically acceptable salts thereof and the neutral endopeptidase (NEP) inhibitor N-(3-carboxy-1-oxopropyl)-(4S)-p-phenylphenylmethyl)-4-amino-2R-methylbutanoic acid ethyl ester or (2R,4S)-5-Biphenyl-4-yl-4-(3-carboxy propionylamino)-2-methyl-pentanoic acid or pharmaceutically effective salts thereof, optionally in the presence of a pharmaceutically acceptable carrier and pharmaceutical compositions comprising them.

112 The pharmaceutical combination is: (a) valsartan (an ARB), which the specification says is disclosed in a European patent (EP 0443983 A) and also in US patent (5,399,578), or its pharmaceutically acceptable salts; and (b) a particular NEP inhibitor as an ethyl ester or as a free acid, or as pharmaceutically acceptable salt of the ethyl ester or the pharmaceutically acceptable salt of the free acid. The ethyl ester is the substance called sacubitril. The free acid is the substance called sacubitrilat. Although not referred to as such in the specification, I will use the name sacubitril to refer to the ethyl ester and the name sacubitrilat to refer to the free acid.

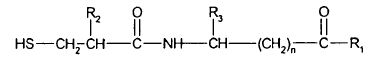

113 The specification discusses, more generally, NEP inhibitors that are useful in combination with valsartan. Page 3 of the specification discloses one such inhibitor:

A NEP inhibitor useful in said combination is a compound of the formula (II)

(II)

and pharmaceutically acceptable salts thereof wherein:

R2 is alkyl of 1 to 7 carbons, trifluoromethyl, phenyl, substituted phenyl, -(CH2)1 to 4- phenyl, or -(CH2)1 to 4-substituted phenyl;

R3 is hydrogen, alkyl of 1 to 7 carbons, phenyl, substituted phenyl, -(CH2)1 to 4-phenyl, or -(CH2)1 to 4-substituted phenyl;

R1 is hydroxy, alkoxy of 1 to 7 carbons, or NH2;

n is an integer from 1 to 15; and

the term substituted phenyl refers to a substituent selected from lower alkyl of 1 to 4 carbons, lower alkoxy of 1 to 4 carbons, lower alkylthio of 1 to 4 carbons, hydroxy, Cl, Br, or F.

114 Pages 4 to 6 of the specification disclose NEP inhibitors that are said to be “within the scope of the present invention”. The list includes (by chemical name) sacubitril and sacubitrilat. Not all compounds listed on pages 4 to 6, including sacubitril and sacubitrilat, fall within formula (II).

115 Page 6 of the specification reinforces that:

The compounds to be combined can be present as pharmaceutically acceptable salts.

116 On page 6, the specification says that the preferred salts of sacubitril “include the sodium salt disclosed in U.S. Patent No. 5,217,996, the triethanolamine salt and the tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane salt”.

117 The specification teaches that the two last-mentioned salts are novel. They are said to be another embodiment of the invention, which includes: (a) their use as NEP inhibitors, especially for preventing and treating conditions and diseases “associated with the inhibition on NEP”; and (b) their combination with valsartan in a pharmaceutical composition, especially for the treatment of conditions and diseases “as disclosed for the combinations of the present invention hereinbefore or hereinafter”. A pharmaceutical composition with either one of these salts is claimed in claim 2.

118 The specification then addresses the effect of combining valsartan with NEP inhibitors:

It has surprisingly been found that, a combination of valsartan and a NEP inhibitor achieves greater therapeutic effect than the administration of valsartan, ACE inhibitors or NEP inhibitors alone and promotes less angioedema than is seen with the administration of a vasopeptidase inhibitor alone. Greater efficacy can also be documented as a prolonged duration of action. The duration of action can be monitored as either the time to return to baseline prior to the next dose or as the area under the curve (AUC) and is expressed as the product of the change in blood pressure in millimeters of mercury (change in mmHg) and the duration of the effect (minutes, hours or days).

Further benefits are that lower doses of the individual drugs to be combined according to the present invention can be used to reduce the dosage, for example, that the dosages need not only often be smaller but are also applied less frequently, or can be used to diminish the incidence of side effects. The combined administration of valsartan or a pharmaceutically acceptable salt thereof and a NEP inhibitor or a pharmaceutically acceptable salt thereof results in a significant response in a greater percentage of treated patients, that is, a greater responder rate results, regardless of the underlying etiology of the condition. This is in accordance with the desires and requirements of the patients to be treated.

It can be shown that combination therapy with valsartan and a NEP inhibitor results in a more effective antihypertensive therapy (whether for malignant, essential, reno-vascular, diabetic, isolated systolic, or other secondary type of hypertension) through improved efficacy as well as a greater responder rate. The combination is also useful in the treatment or prevention of heart failure such as (acute and chronic) congestive heart failure. It can further be shown that a valsartan and NEP inhibitor therapy proves to be beneficial in the treatment and prevention of myocardial infarction and its sequelae.

119 Pages 9 to 12 of the specification summarise the methodology of certain representative studies carried out with the combination of valsartan and sacubitril.

120 At pages 12 – 13, the specification says:

In one aspect … the object of this invention [is] to provide a pharmaceutical combination composition, e.g. for the treatment or prevention of a condition or disease selected from the group consisting of hypertension, heart failure such as (acute and chronic) congestive heart failure, and myocardial infarction and its sequelae, which composition comprises (i) the AT 1-antagonists valsartan or a pharmaceutically acceptable salt thereof and (ii) a NEP inhibitor or a pharmaceutically acceptable salt thereof and a pharmaceutically acceptable carrier. A further active ingredient may be a diuretic, especially hydrochlorothiazide.

121 These passages of the specification are followed by the statement:

In this composition, components (i) and (ii) can be obtained and administered together, one after the other or separately in one combined unit dose form or in two separate unit dose forms. The unit dose form may also be a fixed combination.

122 The interpretation of this statement is controversial. I shall return to it when discussing the proper construction of claim 1.

123 Page 14 includes the following statement on which the parties also relied in respect of the proper construction of claim 1:

A therapeutically effective amount of each of the component of the combination of the present invention may be administered simultaneously or sequentially and in any order.

124 Over the following pages, the specification discusses: (a) how pharmaceutical compositions according to the invention can be prepared; (b) typical pharmaceutically acceptable carriers for use in the formulations that are described; (c) combining separate pharmaceutical compositions (a valsartan pharmaceutical composition and a NEP inhibitor pharmaceutical composition) as two separate units in kit form; (d) methods of administering the pharmaceutical compositions; (e) the dosages of valsartan; and (f) the dosages of NEP inhibitors.

125 Pages 16 to 21 of the specification provide example formulations (Examples 1 to 7). Examples 1 to 3 are film-coated tablets. Examples 4 to 7 are capsules. Each formulation contains valsartan but not sacubitril or sacubitrilat.

126 Pages 21A to 21D of the specification report on experiments using two animal models of hypertension (Example 8). The first model used Dahl salt-sensitive rats, where a high salt diet causes suppression of the renin-angiotensin system resulting in hypertension. The second model used SHR rats, which did not require a particular diet to exhibit symptoms of hypertension.

127 It is not necessary to discuss Example 8 other than to note that the substance administered to the rats involved valsartan and a chemical which the relevant experts presumed was sacubitril (it appears that the systematic chemical name used in the title of Example 8 contains a typographical error). The substance was administered as an aqueous solution (in drinking water) by oral gavage. However, the vehicle included polyethylene glycol 400 (a polymeric organic solvent) (PEG 400) and Tween 80 (a surfactant). I will return to the significance of organic solvents when discussing the correct construction of claim 1.

128 After the discussion of Example 8, the specification records three matters.

129 First, the publications and patents mentioned in the specification are incorporated, by reference, in their entirety, as if those documents were set out, in full, in the specification.

130 Secondly, the word “comprise” (and its variations) in the body of the specification and in the claims is to be understood as implying inclusion, not exclusion.

131 Thirdly, references in the specification to any prior publication, or the information derived from any prior publication, or to any matter that is known, are not to be taken as an acknowledgement or admission or suggestion that the prior publication, information, or known matter form part of the common general knowledge.

132 Claim 1, which is central to this case, is:

1. A pharmaceutical composition comprising:

(i) the AT 1-antagonist valsartan or a pharmaceutically acceptable salt thereof;

and

(ii) the NEP inhibitor N-(3-carboxy-1-oxopropyl)-(4S)-p-phenylphenylmethyl)-4-amino-2R-methylbutanoic acid ethyl ester or (2R,4S)-5-Biphenyl-4-yl-4-(3-carboxypropionylamino)-2-methyl-pentanoic acid or pharmaceutically acceptable salts thereof and a pharmaceutically acceptable carrier.

133 The parties accept that the inclusion in integer (ii) of the pharmaceutically acceptable carrier is inapposite, and that integer (ii) should be understood as referring only to the two NEP inhibitors (or the pharmaceutically acceptable salts thereof), with the pharmaceutically acceptable carrier standing apart, as a separate integer of the claim, notionally considered as integer (iii). I will read, and treat, claim 1 accordingly.

134 As I have said, the two NEP inhibitors are, respectively, sacubitril and sacubitrilat (conveniently referred to as sacubitril/at). In integer (ii), sacubitril and sacubitrilat are free acids (meaning that their acidic functional groups are fully protonated). Sacubitril is an ethyl ester and a prodrug of sacubitrilat.

135 Claim 1 is notable for its simplicity. It does not specify the form that the composition should take or its suitability for any particular mode of administration. It does not specify the salts of each component that can be present in the composition (if salts are used), beyond requiring that they be pharmaceutically acceptable. It does not specify the amount (dose) of each component in the composition or the suitability of the composition for any particular dosing regimen. It does not identify the disease or condition for which the pharmaceutical composition is to be used, beyond stating that its identified components are, respectively, an AT 1-antagonist and an NEP inhibitor.

136 Claim 2 claims the pharmaceutical composition of claim 1, where sacubitril is a triethanolamine or tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane salt. Claim 3 is also a pharmaceutical composition whose features are dependent on claim 1, and also includes a diuretic.

137 Claim 4 is method of treatment claim, involving the administration of the APIs identified in claim 1 with a pharmaceutically acceptable carrier. Claim 5 is a method of treatment claim, involving the administration of the APIs identified in claim 2 with a pharmaceutically acceptable carrier. Claims 4 and 5 are not limited to the APIs being components of the one pharmaceutical composition.

138 Claims 6 to 8 claim the use of, respectively: (a) valsartan or a pharmaceutically acceptable salt thereof in the manufacture of a medicament to be used in combination with sacubitril/at or their pharmaceutically acceptable salts, to treat or prevent selected conditions or diseases; (b) sacubitril/at or their pharmaceutically acceptable salts in the manufacture of a medicament to be used in combination with valsartan or a pharmaceutically acceptable salt thereof, to treat or prevent selected conditions or diseases; and (c) valsartan or a pharmaceutically acceptable salt thereof and sacubitril/at and their pharmaceutically acceptable salts in the manufacture of a medicament to treat or prevent selected conditions or diseases.

139 Claim 9 claims the use according to any one of claims 6 to 8, wherein sacubitril is in the form of one of the salts identified in claim 2.

140 Claims 6 to 9 are in the form of Swiss type claims (as to which, see Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co Ltd v Generic Health Pty Ltd (No 4) [2015] FCA 634; 113 IPR 191 (Otsuka) at [100] – [121]).

141 I mention these matters because the specification is not directed simply to the invention as defined in claim 1. It contains other teachings directed to supporting the invention as defined by each of the claims.

142 Novartis called expert evidence from:

(a) Professor David Linley Hare OAM. Professor Hare is a Professorial Fellow and cardiologist. He holds Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery degrees and a Diploma in Psychological Medicine from the University of Melbourne. Professor Hare has extensive experience in treating patients with heart failure and hypertension. He has also been involved in cardiovascular research. Professor Hare made two affidavits and provided a joint expert report with Professor Coats (see below).

(b) Professor Jonathan Michael White. Professor White is an organic chemist with over 30 years’ experience in synthetic organic chemistry and physical organic chemistry. Professor White holds a Bachelor of Science (Honours, First Class) degree majoring in chemistry and a PhD in chemistry from the University of Canterbury. He has an extensive understanding of the principles of organic synthesis and the analysis of compounds, including the nature and characteristics of different types of bonds that exist between atoms, ions and molecules. Professor White made three affidavits and provided a joint expert report with Professor Roberts and Professor Steed (see below).

143 Novartis also read affidavits from John Fredrick Howards Collins, a partner in Clayton Utz, the solicitors for Novartis.

144 Pharmacor called expert evidence from:

(a) Professor Andrew Justin Stewart Coats AO. Professor Coats is a cardiologist. Professor Coats holds Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery degrees from the University of Cambridge and a Master of Arts (Physiological Sciences) degree from the University of Oxford. He also holds a Doctorate of Medicine from the University of Oxford and a Doctorate of Science from Imperial College London. He holds specialist accreditations in Australia and the United Kingdom in general internal medicine and cardiology. He has extensive experience in treating patients with heart failure and hypertension. He has been involved in cardiovascular research. Professor Coats made two affidavits and provided a joint expert report with Professor Hare.

(b) Professor Jonathan William Steed. Professor Steed is Professor of Inorganic Chemistry at Durham University. He has over 30 years’ experience in the fields of organic, inorganic and solid-state chemistry. He holds a Bachelor of Science degree majoring in Chemistry (Honours, First Class) and a PhD in Chemistry University College London. His research career has focused on, amongst other things, solid-state chemistry. Professor Steed made two affidavits and provided a joint expert report with Professor Roberts and Professor White.

(c) Professor Michael Stephen Roberts: Professor Roberts is a pharmaceutical scientist with over 50 years’ experience working in the fields of drug formulation, drug absorption, pharmacology, toxicology, and pharmacokinetics. He holds Bachelor of Pharmacy degree from the University of Adelaide. He also holds a Master of Science degree in pharmacy, a PhD in pharmaceutical science, and a DSc degree from the University of Sydney. Professor Roberts made two affidavits and provided a joint expert report with Professor Steed and Professor White.

(d) Dr George Mokdsi: Dr Mokdsi is an intellectual property analyst and searcher, and a director of The Patent Searcher. Dr Mokdsi has a PhD in chemistry from the University of Sydney. He has expertise in the searching of pharmaceutical patents and scientific literature. Dr Mokdsi made one affidavit.

145 Pharmacor also read affidavits from Nina Jacqueline Fitzgerald, a partner in Ashurst Australia, the solicitors for Pharmacor. A redacted version of an affidavit from Ray Cheng, a solicitor at Ashurst Australia, was admitted into evidence as Exhibit I.

146 In closing submissions, the parties advanced criticisms of each other expert witnesses. I do not propose to address those criticisms in specific terms. I am satisfied that all witnesses, whose expertise is unquestioned, gave evidence consistent with their obligations as independent experts. Each provided considerable assistance in resolving the complex issues advanced by the parties.

147 It was a feature of the present case that all the experts were provided with standard instructions in relation to the giving of evidence on the question of inventive step. The background to this happening was that, on 8 June 2023, the Federal Court of Australia IP Practice Area User Group presented a draft of such instructions for discussion at a meeting with Judges in the Court’s Intellectual Property NPA Patents and associated Statutes sub-area. I considered it appropriate that those instructions be used for the assistance of the experts in this case. The instructions are reproduced in the Schedule to these reasons.

148 The “person skilled in the art” is a construct that is used to analyse questions that arise in patent law.

149 It is well-recognised that this construct can be understood as a “team”, particularly if the art is one having a highly developed technology: General Tire & Rubber Co v Firestone Tyre & Rubber Co Ltd [1972] RPC 457 at 485. As such, the construct combines and deploys the knowledge and skills of the members of the “team”. This means that, in real life, the knowledge and skills of some members of the “team” may not be known or shared by others in the “team”. There is, however, but one construct. The person skilled in the art thinks with one mind, speaks with one voice, and draws, when and to the extent necessary, on the disparate knowledge and skills of all the members of the “team”. The person skilled in the art is indivisible: see Otsuka at [127].

150 Depending on the relevant art, the members of the “team” may be highly skilled with research capabilities. In the context of chemical and pharmaceutical patents in particular, it is common to equate the person skilled in the art with a “notional research group” which is confronted with a particular task: Aktiebolaget Hassle v Alphapharm Pty Limited [2002] HCA 59; 212 CLR 411 (AB Hassle) at [53].

151 This does not mean, however, that the person skilled in the art, understood as a highly skilled team or a notional research group, exhibits the capacity for invention. The person skilled in the art, even when understood as a highly skilled team or a notional research group, is taken to have no inventive capacity whatsoever, and is constrained to act only with knowledge that is publicly known, and commonly accepted, by those within the calling of the art in question.

152 The knowledge and skills of the person skilled in the art can be informed by the evidence of expert witnesses. It is important to bear in mind, however, that the person skilled in the art is not a mere avatar of those witnesses: AstraZeneca AB v Apotex Pty Ltd [2015] HCA 30; 257 CLR 356 at [23].

153 The parties accept that, in the present case, the person skilled in the art should be understood as a “team”. However, they disagree on who is in the “team”.

154 They accept that the “team” should include a cardiologist. Pharmacor submits that the cardiologist should have expertise, and a research interest, in the treatment of hypertension and heart failure. Both Professor Coats and Professor Hare are representative of such a cardiologist.

155 Novartis submits that the cardiologist should be one who does not have Professor Coats’s and Professor Hare’s skills and interests, which Novartis describes as “an extreme subset of cardiologists” in Australia. It submits that, at the priority date, cardiologists in Australia were mainly engaged in imaging, interventional or electrophysiological subspecialties. There was no requirement in Australia for a cardiologist to have specialist training in hypertension, and other medical specialists (non-cardiologists) also treated hypertension (e.g., in hypertension clinics), as did general practitioners.

156 Further, Novartis says that, at the priority date, there was no formal training scheme for cardiologists in Australia in relation to heart failure. Novartis accepts that some cardiologists in Australia had an interest in heart failure. It says, however, that, while all heart failure was treated by cardiologists, not all cardiologists who treated heart failure had a special or exclusive interest in that area.

157 The patent specification is directed to those with a real, not a peripheral, interest in its subject matter, which is the development of effective therapy for the treatment of hypertension, the treatment or prevention of heart failure, and the treatment and prevention of myocardial infarction and its sequelae: p 8 of the specification.

158 I am satisfied that the “team” would include a cardiologist who has specialised knowledge and a specialised interest in the development of effective therapy for the treatment of hypertension. The “team” would also include a cardiologist who has specialised knowledge and a specialised interest in the development of effective therapy for the treatment or prevention of heart failure (I need say nothing about the treatment and prevention of myocardial infarction and its sequelae because it does not feature in this case). Given the “pooling” of knowledge within the “team”, it does not matter whether, in real life, there is a cardiologist who has specialised knowledge and a specialised interest in the development of effective treatment for both hypertension and heart failure. That, in my view, is a non-issue. Nor does it matter that, in real life, the pool from which such cardiologists can be drawn is small.

159 I accept that Professor Coats and Professor Hare are representative of the cardiologist on the “team”. For the purpose of defining the attributes of the person skilled in the art, it is their knowledge and skills that are relevant, not those of cardiologists (or other specialists) in the main, or of general practitioners, who just happen to treat hypertension or heart failure.

160 The parties also disagree about whether the “team” also includes a pharmaceutical scientist, a solid-state chemist, an organic chemist, a medicinal chemist, and a formulator.

161 I have little doubt that, as the specification is directed, in part, to pharmaceutical compositions—with claim 1 directed, specifically, to a pharmaceutical composition—a pharmaceutical scientist would be a member of the “team”. I accept that Professor Roberts is representative of such a scientist.

162 I am not persuaded that the specification is addressed, specifically, to a specialist solid-state chemist or specialist organic chemist, and that such persons are part of the “team”. However, I accept that aspects of the knowledge of such persons are relevant to informing the proper construction of claim 1. The evidence of Professor Steed, a solid-state chemist, and Professor White, an organic chemist, was relevant and admissible for that purpose, but not because they were members of the “team”. Their knowledge of chemistry, as relevant to the present case, was shared, substantially, by Professor Roberts, the pharmaceutical scientist.

163 I am not persuaded that a medicinal chemist is part of the “team”. The specification is not concerned with the synthesis of new molecules or variations to known molecules. In any event, no medicinal chemist gave evidence.

164 It is possible that a formulator would be part of the “team” for the purposes of other claims of the patent. However, claim 1 is not an invention for a formulation as such (beyond specifying the need for the pharmaceutical composition to include a pharmaceutically acceptable carrier). To the extent that evidence about formulations arose, it was given by Professor Roberts in his capacity as a pharmaceutical scientist.

The principles of construction

165 Despite the principles of construction applicable to patent specifications and patent claims being settled, the parties nevertheless advanced various statements of these principles in their submissions.

166 Novartis referred to a recent summary of some of the principles in MMD Australia Pty Ltd v Camco Engineering Pty Ltd [2024] FCAFC 38, particularly the following (at [18]):

…

(c) a patent specification should be given a purposive, not a purely literal, construction;

(d) a patent specification is not to be read in the abstract but is to be construed through the eyes of the person skilled in the art in the light of the common general knowledge and the art before the priority date: Jupiters at [67(ii)];

(e) the claims are to be construed in light of the specification as a whole, but the plain and unambiguous meaning of a claim cannot be varied or qualified by reference to the body of the specification: Welch Perrin & Co Pty Ltd v Worrel (1961) 106 CLR 588 at 610 (Dixon CJ, Kitto and Windeyer JJ);

(f) claims in a patent are not to be narrowed by reference to the preferred embodiment: Rehm Pty Ltd v Websters Security Systems (International) Pty Ltd (1988) 11 IPR 289 at 299 (Gummow J); and

(g) the preferred embodiment cannot be used to introduce into the definite words of a claim an additional definition or qualification of the patentee’s invention: Erickson’s Patent (1923) 40 RPC 477 at 491; Globaltech Corporation Pty Ltd v Australian Mud Company Pty Ltd [2019] FCAFC 162; (2019) 145 IPR 39 at [111] (Kenny, Robertson and Moshinsky JJ); Welch Perrin at 612.

167 Novartis also referred the following passage from AstraZeneca AB v Apotex Pty Ltd [2014] FCAFC 99; 226 FCR 324 (Apotex) at [100]:

100 The primary judge set out the principles relevant to the construction of claims of a patent in a manner which was not the subject of criticism by any of the parties to the appeals. Of particular significance was her Honour’s reference to Welch Perrin and Company Proprietary Limited v Worrel and Another (1961) 106 CLR 588 at 610 per Dixon CJ, Kitto and Windeyer JJ and the following passage from the decision of the Full Court of this Court in Kinabalu Investments Pty Ltd v Barron & Rawson Pty Ltd [2008] FCAFC 178 at [44]:

When determining the nature and extent of the monopoly claimed, the specification must be read as a whole. But as a whole it is made up of several parts which have different functions. The claims mark out the legal limits of the monopoly granted. The specification describes how to carry out the process claimed and the best method known to the patentee of doing that. Although the claims are construed in the context of the specification as a whole, it is not legitimate to narrow or expand the boundaries of monopoly as fixed by the words of a claim, by adding to those words glosses drawn from other parts of the specification. If a claim is clear and unambiguous, it is not to be varied, qualified or made obscure by statements found in other parts of the document. It is legitimate, however, to refer to the rest of the specification to explain the background of the claims, to ascertain the meaning of technical terms and resolve ambiguities in the construction of the claims.

168 Novartis emphasised the well-understood passage from Lord Diplock’s speech in Catnic Components v Hill & Smith Ltd [1982] RPC 183 at 243 that:

A patent specification should be given a purposive construction rather than a purely literal one derived from applying to it the kind of meticulous verbal analysis in which lawyers are too often tempted by their training to indulge. The question in each case is: whether persons with practical knowledge and experience of the kind of work in which the invention was intended to be used, would understand that strict compliance with a particular descriptive word or phrase appearing in a claim was intended by the patentee to be an essential requirement of the invention so that any variant would fall outside the monopoly claimed, even though it could have no material effect upon the way the invention worked.

169 Novartis accepted, nevertheless, Lord Hoffmann’s cautionary observation in Kirin-Amgen Inc v Hoechst Marion Roussel Ltd [2005] RPC 9 at [34] (accepted in, for example, GlaxoSmithKline Consumer Healthcare Investments (Ireland) (No 2) Ltd v Generic Partners Pty Ltd [2018] FCAFC 71; 264 FCR 474 at [108]):

“Purposive construction” does not mean that one is extending or going beyond the definition of the technical matter for which the patentee seeks protection in the claims. The question is always what the person skilled in the art would have understood the patentee to be using the language of the claim to mean. And for this purpose, the language he has chosen is usually of critical importance. The conventions of word meaning and syntax enable us to express our meanings with great accuracy and subtlety and the skilled man will ordinarily assume that the patentee has chosen his language accordingly. As a number of judges have pointed out, the specification is a unilateral document in words of the patentee’s own choosing. Furthermore, the words will usually have been chosen upon skilled advice. The specification is not a document inter rusticos for which broad allowances must be made. On the other hand, it must be recognised that the patentee is trying to describe something which, at any rate in his opinion, is new; which has not existed before and of which there may be no generally accepted definition. There will be occasions upon which it will be obvious to the skilled man that the patentee must in some respect have departed from conventional use of language or included in his description of the invention some element which he did not mean to be essential. But one would not expect that to happen very often.

170 Pharmacor drew attention to four principles. First, claims are to be construed in the context of the specification as a whole. Secondly, a claim’s function is to define a monopoly with precision with the object of limiting, not extending, the monopoly. Thirdly, the specification is a unilateral document in words of the patentee’s choosing. Fourthly, there is no warrant for adopting a method of construction that gives a patentee what it might wished to have claimed rather than what the words of the claim actually say.

A consequential question of construction

171 The construction of claim 1 is in dispute on one matter only—whether integers (i) and (ii) of the pharmaceutical composition are satisfied by a complex containing anionic valsartan, anionic sacubitril and pharmaceutically acceptable cations (such as sodium cations).

172 The resolution of this question is particularly important because the answer has consequences for several contested issues.

173 Each party advances a “simple” position on this question of construction, but has done so through lengthy submissions, even though they accept that, in this case, the question turns on the meaning of ordinary English words. Those words must, of course, be considered in the context of the specification as a whole as read through the eyes of the person skilled in the art possessing the common general knowledge at the priority date.

174 In this case, the differing positions of the parties was advanced through the competing views of Professor White on the one hand, and Professor Roberts and Professor Steed on the other, as to how the specification should be understood.

175 Novartis contends that claim 1 is to a pharmaceutical composition comprising:

(a) valsartan, or a pharmaceutically acceptable salt thereof;

(b) sacubitril or sacubitrilat, or pharmaceutically acceptable salts thereof; and

(c) a pharmaceutically acceptable carrier.

176 Novartis submits:

… Any pharmaceutical composition that comprises integers (a) to (c) above is within the claim, irrespective of whether it includes any other integers, and irrespective of the form of, or non-covalent association between, the sacubitril/at (or salt), valsartan (or salt), and carrier. … [A] “complex” (whether crystalline or amorphous) is one form of combination of integers (a) and (b).

177 Novartis submits that this construction is consistent with what I said when giving an interlocutory judgment in this proceeding: Novartis AG v Pharmacor Pty Limited [2023] FCA 804 (Novartis 1) at [13] – [19], especially at [17].

178 It is appropriate that I deal with that submission immediately. The relevant paragraphs of the reasons in Novartis 1 are:

13 Claim 1 is:

1. A pharmaceutical composition comprising:

(i) the AT 1-antagonist valsartan or a pharmaceutically acceptable salt thereof;

and

(ii) the NEP inhibitor N-(3-carboxy-1-oxopropyl)-(4S)-p-phenylphenylmethyl)-4-amino-2R-methylbutanoic acid ethyl ester or (2R,4S)-5-Biphenyl-4-yl-4-(3-carboxypropionylamino)-2-methyl-pentanoic acid or pharmaceutically acceptable salts thereof and a pharmaceutically acceptable carrier.

14 Plainly, claim 1 claims a composition which includes valsartan (or a pharmaceutically acceptable salt of valsartan) in combination with one of two identified NEP inhibitors (or a pharmaceutically acceptable salt of the chosen NEP inhibitor). The evidence before me is that the first identified NEP inhibitor—the ethyl ester—is known as sacubitril. The second identified NEP inhibitor is known as sacubitrilat.

15 Claim 1 does not specify, in terms, the particular dose of valsartan or of the NEP inhibitor in the composition. Further, it does not specify the molar or weight ratio between the two active ingredients or their ratio relative to the pharmaceutically acceptable carrier or any other component of the composition (it being noted that the complete specification makes clear that the word “comprising” is to be understood to imply inclusion, not exclusion).

16 Claim 1 does not limit, in terms, the salts that can be used in the composition (other than that they be pharmaceutically acceptable salts) or require that the same salt be used (if the two active ingredients are present as salts).

17 Claim 1 does not limit, in terms, the form of the two active ingredients (such as whether they must be in crystalline form, amorphous form or polymorphic form, or be present as hydrates, or have a supramolecular structure) or limit the way in which the two active ingredients are to be combined.

18 Claim 1 does not limit, in terms, the particular form of the pharmaceutical composition itself.

19 It is clear, however, that claim 1 is more limited in scope than the disclosures made in the complete specification by reference to the “invention”. Its limitation is to compositions that include valsartan (or a pharmaceutically acceptable salt thereof), one or other of the two identified NEP inhibitors (or their pharmaceutically acceptable salts), and a pharmaceutically acceptable carrier.

179 It is important to understand that, in Novartis 1, I was considering the interlocutory question whether discovery should be permitted in aid of Pharmacor’s challenge to the validity of the patent on the ground that, contrary to s 40(2)(a) of the Patents Act, the specification does not describe the best method of performing the invention. The proper construction of claim 1 was not directly before me, as it is now with the benefit of the expert evidence that has been adduced.

180 Moreover, the observation that I made at [17] of Novartis 1 was directed only to the structure of claim 1 and the absence of express words of limitation, as exemplified by Novartis in its submissions, in particular an express limitation such as “wherein the valsartan and sacubitril are combined in the form of a complex”. To note, as I did, that claim 1 does not limit, in terms, the form of the two active ingredients to a supramolecular structure does not mean that claim 1, properly construed, includes the two active ingredients synthesised in a supramolecular structure. I made no such finding and nothing that I said in Novartis 1 constrains my consideration of the proper construction of claim 1 now.

181 Novartis submits that the correct approach to construing claim 1 is to look at each integer (within the patent, integers (i) and (ii) (with integer (ii) read as I have indicated) and notional integer (iii)) and simply ask whether each integer is present in the pharmaceutical composition being considered. It contends that this approach is informed by the following considerations.

182 First, Novartis points to the fact that integer (i) refers to valsartan (or a pharmaceutically acceptable salt) as “the AT 1-antagonist” and that integer (ii) refers to sacubitril/at (and their pharmaceutically acceptable salts) as “the NEP inhibitor”. It submits that the significance of these descriptions is to make clear that the claim is concerned with the pharmacological activity of valsartan and sacubitril/at rather than: (a) the physical form in which each is present in the composition; or (b) the physicochemical properties of that form.