FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Koninklijke Douwe Egberts BV v Cantarella Bros Pty Ltd [2024] FCA 1277

ORDERS

First Applicant JACOBS DOUWE EGBERTS AU PTY LTD (ACN 051 278 409) Second Applicant | ||

AND: | CANTARELLA BROS PTY LTD (ACN 000 095 607) Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The applicants’ claims be dismissed.

2. The cross-claimant’s claims for relief specified in paragraphs 1 to 7 of its amended notice of cross-claim be dismissed.

3. The question of the parties’ costs of the claim and the cross-claim be reserved until after the hearing and determination of the cross-claimant’s claims for damages and additional damages pursuant to s 129 of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth).

4. Pursuant to ss 37AF and 37AG(1)(a) of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth), until further order, access to and disclosure (by publication or otherwise) of Confidential Annexure A to the reasons of the Court delivered on 7 November 2024, comprising paragraphs [564]–[603], be restricted to the persons identified below –

(a) the respondent;

(b) the legal representatives of the respondent; and

(c) those persons to whom access is allowed

(i) under the terms of the confidentiality regime agreed between the parties relating to information claimed to be confidential by the respondent; or

(ii) by express written permission from the respondent.

5. If any party wishes to apply for a further non-publication order under s 37AF of the Federal Court of Australia Act in relation to any part of the balance of the reasons for judgment, then that party may do so by emailing the Chambers of the Hon Justice Wheelahan by 12 noon on 8 November 2024 identifying with precision the part or parts of the reasons in respect of which a non-publication order is sought.

6. Upon receipt of any application in accordance with order 5 above, the Court will consider making an interim order in Chambers under s 37AI of the Act.

7. The hearing of any application for a further non-publication order is fixed for 15 November 2024 at 9.30 am.

8. By 4.00 pm on 14 November 2024, the legal practitioners for the parties are to confer in relation to procedural orders for the hearing and determination of the cross-claimant’s claims for damages and the hearing of any further applications for non-publication orders, including the final determination of applications that are the subject of existing interim orders.

9. The proceeding is listed for further case management on 15 November 2024 at 9.30 am.

10. Any proposed consent orders are to be emailed to the Chambers of the Hon Justice Wheelahan by 4.00 pm 14 November 2024.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

WHEELAHAN J:

1 This case concerns the shape of a glass jar in which the respondent, Cantarella Bros Pty Ltd (Cantarella), has marketed and sold freeze-dried instant coffee under its “Vittoria” brand. The applicants are associated with a brand of freeze-dried instant coffee, styled “MOCCONA”. The applicants claim that by the use of its glass jar Cantarella has infringed a registered trade mark, engaged in misleading and deceptive conduct, and committed the tort of passing off. Cantarella denies these claims and has cross-claimed seeking orders that the registered trade mark be cancelled and that the Register be rectified accordingly.

Background

Overview of the claims

2 The first applicant, Koninklijke Douwe Egberts BV (KDE), is the registered owner of Australian Trade Mark Registration No 1599824 (KDE shape mark), which is a mark constituted by the shape of a container. The applicants claim that the second applicant, Jacobs Douwe Egberts AU Pty Ltd (JDE AU) is an authorised user of the KDE shape mark in Australia, although this is contentious, and is one of the questions in this proceeding that require resolution.

3 JDE AU sells coffee — predominantly instant coffee — which is available for purchase from retailers throughout Australia under the Moccona name. Moccona-branded coffee products are sold in jars, capsules, soft packs, sticks, sachets, and tins. Below is an example of a Moccona-branded instant coffee product, namely a jar of “Moccona Classic Medium Roast” –

4 The following graphical representation of the KDE shape mark is entered on the Register –

5 The image description entered on the Register for the graphical representation is “CONTAINER, 5 VIEWS”. The Register also records that the kind of mark in question is a shape. KDE obtained registration of its shape mark with effect from 7 January 2014 in relation to “Class 30: Coffee; instant coffee”, with the following endorsements –

Evidence provided under subsection 41(3).

Shape - The trade mark consists of the three-dimensional shape of a container as shown in the representations attached to the application form.

6 The dimensions of the KDE shape mark form no part of the registered mark. Nor does colour or material. For those reasons, while some of the evidence and submissions in this proceeding concerned 400-gram products contained in transparent glass jars with plastic stoppers bearing labels with gold detailing, it is important to appreciate from the outset that the KDE shape mark comprises only the “three-dimensional shape of a container as shown in the representations” entered on the Register.

7 Cantarella also sells coffee products which are available for purchase in retail stores throughout Australia. One of Cantarella’s major brands is Vittoria. As at May 2023, Vittoria was the highest-selling brand by value in Australia in the bean and ground coffee market, which was recognised in the evidence as being a different market from the instant coffee market.

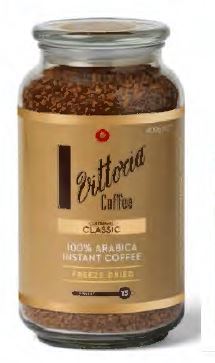

8 In May 2021, Cantarella launched a 100-gram freeze-dried instant coffee product under the Vittoria brand, in four flavour variants. After being sold initially in Woolworths stores, the Vittoria 100-gram product began to be stocked and sold also in Coles stores from around November 2021. The Vittoria 100-gram product has been sold in a cylindrical glass jar with a gold-coloured plastic lid. Below is an image of the “classic” variant in the 100-gram jar –

9 In August 2022, Cantarella launched a new freeze-dried instant coffee product under the Vittoria brand: a 400-gram product, sold in a cylindrical glass jar with a glass stopper lid. From launch, the Vittoria 400-gram product also came in four flavour variants. A representative image of the “Classic” flavour is below, noting that the applicants’ claims extend also to each of the other three variants about which there was evidence, namely “Italian”, “Mountain Grown”, and “Latte” –

10 By their originating application, the applicants seek relief against Cantarella on three main grounds –

(1) First, the applicants contend that Cantarella has, within the meaning of s 120 of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth), infringed the registered KDE shape mark.

(2) Secondly, the applicants allege that Cantarella has contravened ss 18, 29, and 33 of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL), which is sch 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth).

(3) Thirdly, the applicants allege that Cantarella has, by various forms of conduct, passed off its coffee products as coffee products that emanate from, or are associated with, the applicants and their coffee products.

11 Cantarella denies that the applicants are entitled to relief. Further, by its cross-claim, Cantarella seeks the cancellation of the KDE shape mark under s 88 of the Trade Marks Act with effect from the priority date of 7 January 2014, on the grounds that –

(1) at that time, the shape mark was not inherently adapted to distinguish, or did not in fact distinguish, KDE’s goods from the goods of other traders, as required by s 41 of the Trade Marks Act;

(2) the Registrar of Trade Marks accepted the application for registration of the shape mark on the basis of evidence or representations that were false in material particulars, thereby engaging the ground of opposition in s 62(b) of the Act;

(3) the shape mark was entered on the Register as a result of false suggestion or misrepresentation, thereby engaging the ground of cancellation in s 88(2)(e) of the Act;

(4) the application for registration of the shape mark was made in bad faith, thereby engaging the ground of opposition in s 62A of the Act; and

(5) as at the priority date, KDE did not intend to use the shape mark in Australia as a trade mark, to authorise its use in Australia as a trade mark, or to assign the shape mark to a body corporate for use as a trade mark by that body corporate in Australia, thereby engaging the ground of opposition in s 59 of the Act.

12 Alternatively, by its cross-claim Cantarella seeks to have the Register amended pursuant to s 92 of the Act by the removal of the KDE shape mark, with effect from the priority date, on the grounds set out in ss 92(4)(a)–(b) of the Trade Marks Act. In brief terms, this claim was put at trial on the footing that the KDE shape mark should be removed from the Register because –

(1) KDE has not used the shape mark as a trade mark since the priority date;

(2) KDE had no bona fide intention as at the priority date to use the shape mark, to authorise its use, or to assign it for use as a trade mark in the relevant way, and because KDE has not used the shape mark, or not used it in good faith, at any time before the period of one month ending on 24 March 2023; and

(3) the shape mark remained registered for a continuous period of three years ending one month before 24 March 2023, and at no time during that period did KDE use the shape mark, or use the shape mark in good faith, as a trade mark, in Australia.

13 By its cross-claim, Cantarella also seeks a declaration pursuant to s 129(2)(a) of the Trade Marks Act that the applicants have made unjustified threats of trade mark infringement proceedings, together with claims for an injunction, damages, and additional damages in relation to those unjustified threats.

The parties

14 The corporate structure within which the applicants sit is fairly complex. Since some issues turn upon that corporate structure, it is necessary to be precise about the relationships between various entities within the structure.

15 The first applicant, KDE, was incorporated in the Netherlands in 1970. It remains incorporated there at the present day. KDE is an immediate, wholly owned subsidiary of JDE International BV, another company incorporated in the Netherlands.

16 JDE International BV is a wholly owned subsidiary of JDE Holdings BV, another company incorporated in the Netherlands. In turn, JDE Holdings BV is a wholly owned subsidiary of Jacobs Douwe Egberts BV, which is also incorporated in the Netherlands.

17 Jacobs Douwe Egberts BV is itself a wholly owned subsidiary of JDE Peet’s NV, a public limited liability company incorporated under the laws of the Netherlands, which is listed on the Euronext Amsterdam stock exchange. While roughly 55% of its share capital is owned by another company, JDE Peet’s NV may fairly be regarded as the parent company of a corporate group.

18 The second applicant, JDE AU, is a company incorporated in Australia. JDE AU is also owned by JDE International BV, via two interposed Australian companies, being DE Investments Australia Pty Ltd and DE Holdings Australia Pty Ltd. While one organisational chart showed the parent company of JDE AU as “DE Investments Pty Ltd”, I infer from other evidence that this should have read “DE Investments Australia Pty Ltd”. Accordingly, JDE AU also forms part of the corporate group that sits under JDE Peet’s NV.

19 There were two principal business divisions within that corporate group: the “Jacobs Douwe Egberts” business, and the “Peet’s Coffee” business. KDE and JDE AU are a part of the “Jacobs Douwe Egberts” business division. The origins of the Jacobs Douwe Egberts business can be traced back to 1753, when Egbert Douwes and Akke Thijsses opened a grocery store called, in English, “The White Ox” in Joure, in what is now the Kingdom of the Netherlands. That store sold various products, including coffee and tea. In the present day, the Jacobs Douwe Egberts business, and indeed the JDE Peet’s NV corporate group in general, carry on a “pure-play” coffee and tea business: that is, one that is focused primarily on sourcing, manufacturing, packaging, distributing, and selling coffee and tea products.

20 The respondent, Cantarella, was incorporated in Australia in 1951. The origins of its business lie in a business established in Australia in 1947 by brothers Orazio and Carmelo Cantarella. That business involved the importation into Australia of various European products, such as mineral water, parmesan cheese, preserved tomato products, wine, olive oil, and pasta. Since 1958, Cantarella has carried on a business distributing beans and ground coffee products under the trade mark “Vittoria” to delicatessens, cafes, and restaurants. In the early 1980s, Cantarella began supplying Vittoria coffee beans and ground coffee to supermarkets.

The evidence

21 Evidence in chief was given by affidavit, and most but not all of the documentary evidence, although organised in the court book, comprised annexures to the affidavit evidence. The lay witnesses whose affidavit evidence was read by the applicants were –

(a) Ross Norman Tillman, the “Head of Category Development and Shopper Insights” of JDE AU, who made three affidavits and was cross-examined;

(b) Louise Marie Smith, the “Director of Global Intellectual Property” of the JDE Peet’s group of companies, who addressed and was cross-examined on the group corporate structure and licensing arrangements between the applicants;

(c) Linda Margaret Armstrong, the Finance Director of JDE AU, who produced documents and was cross-examined on issues relating to the applicants’ claim that JDE AU was an authorised user of the KDE shape mark; and

(d) Georgia Rosemary Mae Christie, a lawyer employed by the applicants’ solicitors, who produced documents and who was not required for cross-examination.

22 Of the applicants’ witnesses who were cross-examined, only Mr Tillman’s evidence calls for any comment. Mr Tillman’s position with JDE AU placed him in a position of some expertise, as he demonstrated a high degree of familiarity and experience with the consumer coffee market in Australia. Mr Tillman was challenged in cross-examination in relation to a number of contentious opinions that he expressed. I formed the view that Mr Tillman was an honest witness, and no questions going to his credit arise. However, he was cautious about making concessions, and the evidence of his opinions on contentious issues concerning the claimed similarities and differences between the Moccona jars, the Vittoria jars, and other jars containing products such as scented candles, was coloured. This was demonstrated most clearly when Mr Tillman was taken to two jars containing scented candles with clear similarities to the Moccona jar, yet did not accept that they were similar. In relation to a third jar containing a lemongrass and ginger scented candle, Mr Tillman did not accept that it was different from the Moccona jar, or that it was similar to the Vittoria jar. These are opinions that I do not share. These are not criticisms of Mr Tillman, because he was not put forward as an independent witness, and his position with JDE AU precludes any conclusion that he came to his evidence with objectivity. Moreover, Mr Tillman’s opinions on these issues were never going to carry much weight, and it is evident that the forensic purpose of much of the cross-examination of Mr Tillman was to provoke responses to expose more completely some of the questions that the Court must decide for itself.

23 Otherwise, no issues of presentation or credit arise in relation to the lay witnesses of the applicants who were cross-examined. Both Ms Armstrong and Ms Smith answered questions in cross-examination clearly and directly.

24 The lay witnesses whose affidavit evidence was read by Cantarella were –

(a) Matthew William Hill, the Chief Operating Officer of Cantarella, who gave evidence about Cantarella’s business and its decision to use the impugned jar for its 400-gram instant coffee product, and who was cross-examined;

(b) Leigh Alfred Harrison, a director of Abel Lemon Trading Pty Ltd, who gave evidence about the importation and sale of “Park Avenue”-branded instant coffee in around 1993 in a jar similar to the KDE shape mark, and who was not required for cross-examination;

(c) Sue Maree Gilchrist, a partner with Cantarella’s solicitors, who produced documents and who was not required for cross-examination.

25 When cross-examined, Mr Hill gave evidence in a direct, straightforward manner. I formed a favourable view of his presentation as a witness and considered that he gave honest, reliable evidence to the Court. Mr Hill stood up well to cross-examination on disputed factual issues and readily made concessions.

26 Expert evidence was given in two areas of expertise: (a) marketing; and (b) industrial design. For each area of expertise, a joint report was prepared and the evidence of the experts was given concurrently. The marketing experts were –

(a) Richard Don O’Sullivan, Professor of Marketing at Melbourne Business School, who was engaged by the applicants; and

(b) Paul Lindsay Blanket, Founder and Principal of First Impressions Pty Ltd, a marketing and communications consulting firm, who was engaged by Cantarella.

27 The expert marketing evidence presented difficulties. The difficulties had several dimensions. The first is that there were opinions given by both Professor O’Sullivan and Mr Blanket which I do not find persuasive. The second is that there are questions as to whether the marketing evidence addressed the same issues that the Court must decide, and whether the marketing evidence veered off into collateral issues, such as branding, and “brand elements”. The third is that ultimately the key questions, such as use of a sign as a mark of origin, deceptive similarity, and misleading and deceptive conduct, are questions of fact for the Court itself to determine by reference to legal standards, which brings into question the utility of the expert marketing evidence. I will address the marketing evidence in more detail later after setting out more background facts.

28 The industrial design experts were –

(a) Andrew Charles Simpson, an industrial designer and principal of Vert Design Pty Ltd, who was engaged by the applicants; and

(b) David Fulton Francis, a director at D3 Design, a specialist packaging and product design consultancy, who was engaged by Cantarella.

29 Both Mr Simpson and Mr Francis were impressive witnesses and presented as being clearly independent. These impressions may have been strengthened by the fact that there were large areas of agreement between them in relation to the matters that were the subject of their experience and expertise.

Factual setting

30 In light of how the parties joined issue at trial, it is necessary for me to make some more particular findings about various aspects of the parties’ businesses and the coffee industry over time. To resolve some of the questions raised at trial, attention must be given to how Moccona and Vittoria-branded products have been produced, distributed, marketed, and sold over the years. Understandably, the evidence about how particular products were packaged and marketed decades ago was not always clear. Nevertheless, much of the evidence that went towards establishing several of the key events in this period was uncontradicted. I will therefore make factual findings in the paragraphs that follow on the basis of that evidence. Where necessary, I will set out any points of contention between the parties and make explicit the findings I make.

History of the Moccona brand in Australia

31 Moccona-branded instant coffee was launched in Australia in 1960. The word “Moccona” was registered as a trade mark in Australia in respect of “Coffee, inclusive of coffee in powder form” from 5 April 1960.

32 There was an issue at trial as to when Moccona-branded instant coffee began to be sold in a glass jar with a glass stopper lid, substantially in the form of the KDE shape mark. While the applicants’ original position was that Moccona instant coffee was sold in “its cylindrical glass jar with flat-topped stopper” from the very beginning in 1960, there was no evidence beyond some hearsay representations in the 2020 annual report for JDE Peet’s NV, and a statement on a web site, to support that position. Since Cantarella disputed this claim, it is necessary to step through the evidence on this question.

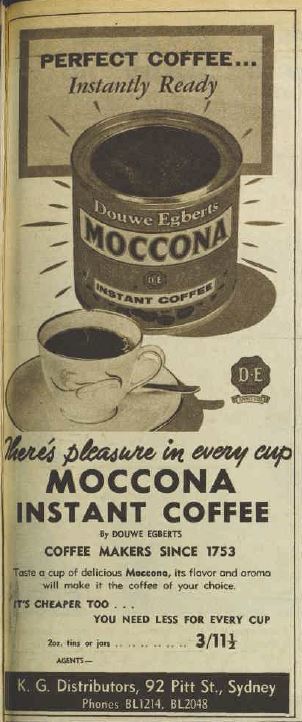

33 The starting point is an advertisement for Moccona instant coffee that appeared in the 7 December 1960 issue of “The Australian Women’s Weekly” –

34 This advertisement depicts a tin, rather than a jar, of Moccona instant coffee. The text of the advertisement states a price of “3/11½” in respect of “2oz. tins or jars”. From the advertisement as a whole, I find that Moccona instant coffee was marketed at the time of the advertisement in both tins and jars, although I cannot conclude that the jar used at that time was in any way similar to the KDE shape mark.

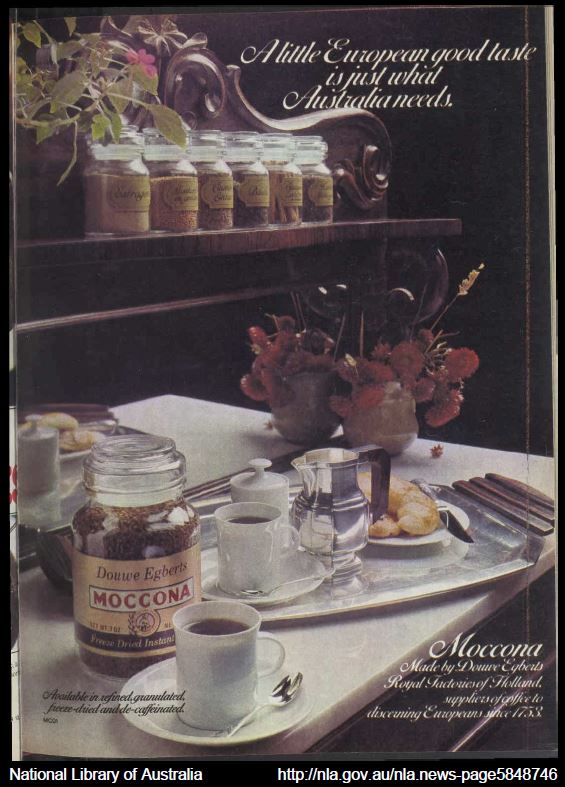

35 The following advertisement, from the 2 December 1966 issue of “Dutch-Australian Weekly”, was also in evidence –

36 This advertisement appears to show Moccona-branded coffee being offered for sale in Australia in a cylindrical glass jar not entirely unlike the body of the KDE shape mark. The jar, however, seems to have a screw-top lid, not a stopper lid. Since a stopper lid is an inherent element of the KDE shape mark, this advertisement would not support a finding that Moccona-branded instant coffee was sold in a jar resembling the KDE shape mark from 1966.

37 Also in evidence was a photograph, dated September 1972, which was said to depict a factory in Joure, the Netherlands, where Moccona instant coffee was then produced –

38 This photograph appears to depict a conveyor belt carrying coffee in unlabelled glass jars of a shape similar to the KDE shape mark. The evidence did not establish, however, that in 1972 the Joure factory produced coffee in only one container. Indeed, as will appear below, Moccona-branded instant coffee was sold in a variety of containers in the 1970s, suggesting that the Joure factory may have used more than one shape of container during this period. Given that no Moccona labels appear on the jars in the photograph, and that there is no other indication that any of the depicted jars was ever shipped to Australia, I cannot find based on this photograph alone that Moccona-branded instant coffee was sold in a jar similar to the KDE shape mark in Australia by 1972.

39 Also in evidence was a photograph sourced from the National Archives of Australia, which was taken in a supermarket in 1977 –

40 This photograph shows, amongst other things, various coffee products for sale on shelves, including Moccona-branded instant coffee in a cylindrical glass jar with a glass stopper lid, as well as Moccona-branded instant coffee in at least one other form of packaging, being a transparent cylindrical jar bearing a red label with a gold lid. The shape of the jars with the glass stopper lids in the photograph appears to resemble the KDE shape mark.

41 More specifically, an advertisement in the 12 October 1977 edition of “The Australian Women’s Weekly” depicts a Moccona-branded cylindrical glass jar with a glass stopper lid containing instant coffee –

42 On the basis of the last two photographs, I find that by October 1977 Moccona-branded instant coffee was sold in Australia in a jar with a shape that was substantially similar to the KDE shape mark. However, based upon my own examination of the photographs and the applicants’ current products, I cannot exclude the possibility that the 1977 jars may have had some slight differences in shape, particularly of the angle of the shoulders of the jars and the height of the glass stopper lid.

43 To support their claim that Moccona instant coffee was sold in a jar similar to the KDE shape mark from earlier than 1977, the applicants drew attention to the reasons for judgment of Lockhart J in Stuart Alexander & Co (Interstate) Pty Ltd v Blenders Pty Ltd (1981) 53 FLR 307 (Stuart Alexander). The Court received those reasons into evidence without objection, and the parties proceeded on the basis that the Court could rely on Lockhart J’s reasons as evidence of the truth of matters asserted in that judgment. No objection was taken under s 91 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) or by reference to any corresponding common law principle.

44 The applicants relied upon Lockhart J’s reference at 308 to a jar which was, in October 1981, “substantially the same as the jar in which Moccona ha[d] been sold for at least fifteen years”. It is clear that the jar in question had substantially the same shape as the KDE shape mark. From this, the applicants asked the Court to infer that Moccona has been sold in a jar like the KDE shape mark since 1966. Cantarella submitted that the evidentiary basis for Lockhart J’s finding was not apparent, and that his Honour did not need, in that case, to address the precise date on which the Moccona jar was first used. I accept Cantarella’s submission. I also note that the advertisement in the 2 December 1966 edition of the “Dutch-Australian Weekly”, reproduced at [35] above, shows a Moccona jar with a screw-top lid. Unless there were two Moccona jars available for purchase in 1966 that differed only in terms of their lids, this advertisement is inconsistent with the statement in Lockhart J’s reasons of 8 October 1981 that the same jar had been used for “at least fifteen years”. The more fundamental point, however, is that I am unable to identify the evidentiary foundation for his Honour’s finding. I therefore attribute it little weight, and conclude that I am not affirmatively persuaded on the evidence before me that Moccona instant coffee was sold in Australia in a jar with a shape like that of the KDE shape mark before October 1977.

Advertisements for the Moccona brand in Australia

45 As this discussion shows, there is a long history of Moccona instant coffee advertisements in Australia. In what follows, I will describe a series of Moccona instant coffee advertisements, which were relied upon by the parties for various purposes. It was not in dispute that these advertisements had been published in Australia.

46 The applicants relied upon a campaign in 2008, centred around a television advertisement entitled “Cinderella”. The advertisement is obviously a play on the “Cinderella” fairy tale, in which a prince tries to find the woman whose foot fits a glass slipper. In the advertisement, a man is shown sitting on a wall next to a beach, holding a glass stopper lid that resembles the Moccona lid, as appears below –

47 The man goes from door to door with his glass stopper lid in hand. Each of the doors is opened by a woman who has a coffee jar, but no lid. The jars have a range of different shapes. The man and each woman test whether the lid fits the jar. At each door before the last one, the lid fails to fit the jar. At the final door, the woman’s jar is a Moccona Classic Medium Roast jar, with which the man’s lid fits perfectly. The advertisement features a close-up depiction of the Moccona jar and lid in the hands of the man and woman, as appears below –

48 The advertisement ends on the following frame, which shows a dramatically lit Moccona jar against a black background, above the gold cursive motto “Never settle for less than Special” and a gold URL for “www.moccona.com.au” –

49 The next advertisement relied upon by the applicants was entitled “Candles”. It was screened on free-to-air and pay television channels from at least 2010. This advertisement depicts a woman purchasing Moccona jars from a man behind the counter of a store. Behind the man, Moccona jars are stacked in a row, two jars high –

50 A close-up shot of the Moccona jar, with label, follows. The advertisement then depicts the woman purchasing more jars from the man on further occasions. The culmination of the advertisement comes when the man leaves the store at night to find that the woman has placed a candle in an empty Moccona jar (without its lid) on the setts of the street –

51 In fact, there are several of these Moccona jar candles, which lead in a line to the woman’s apartment building. The man follows the path they create and encounters the woman drinking something — presumably coffee — from a mug. At the bottom of the shot appears the Moccona logo, as part of the tagline “New Moccona Inspirations Range” –

52 The next advertisement was titled “Keepsakes”. This advertisement was broadcast in 2011. Ancillary advertisements were published in other media as part of the same campaign. The “Keepsakes” advertisement opens with a series of shots depicting a woman’s romantic stay in a luxury hotel. Several shots prominently feature her room key and a tag emblazoned with the number “18”. In one such shot, the woman drops the key. The next shot in the advertisement depicts the key dropping into a glass Moccona jar –

53 As this picture demonstrates, only the cylindrical body of the Moccona jar is visible. The woman is then shown drinking coffee and wistfully remembering her hotel stay. She places a glass stopper lid on the jar containing the key, and in this shot the entire Moccona jar with lid is visible in profile, without any label or the word “Moccona” –

54 A glass jar containing coffee, with a Moccona label, is depicted on the woman’s kitchen bench in the same shot as the unlabelled jar. The unlabelled jar is then placed on a shelf alongside a series of other unlabelled glass jars containing keepsakes –

55 The final shot of the “Keepsakes” advertisement is a close-up of a labelled Moccona jar with the taglines “INDULGE IN THE MOMENT”, “Specialty Blends” and “For Lovers of Coffee” –

56 A subsequent version of the “Keepsakes” advertisement was broadcast in 2012. That version depicts the same woman placing a glass jar on a shelf with other jars that contain keepsakes. This time, however, the jars on the shelf have decorative patterns, though still no labels –

57 The advertisement ends on a shot of three limited-edition jars of Moccona, in “EXOTIC”, “INDULGENCE” and “RICH” flavour varieties, above the Moccona logo and the tagline “For Lovers of Coffee” –

58 One video played during Mr Tillman’s cross-examination was titled “Moccona Me-Time Moments: Emma (60”)”. This video was downloaded from YouTube, having been posted on the Moccona YouTube page on 14 July 2021. The video, which had garnered more than 32,000 views, depicts the eponymous Emma engaging in various forms of community volunteering, as well as making and drinking a cup of Moccona instant coffee. This footage was accompanied by an audio voiceover of Emma describing her activities. A partially obscured Moccona-branded jar appears in the background of the video while Emma is cooking –

59 A partially obscured Moccona-branded jar, with a detached but visible lid, is also shown more prominently when Emma spoons out some instant coffee –

60 Also played during the cross-examination of Mr Tillman was a YouTube video titled “The Quest – Moccona (15”)”, which was posted on the Moccona YouTube channel on 1 March 2021 and which had recorded over 460,000 views. This video depicted a woman making a cup of Moccona instant coffee and choosing to drink her coffee rather than socialise with her friends. One image in the video shows the woman smelling an open jar of Moccona instant coffee, with the jar’s lid held in her right hand –

61 Another relevant image from the video is the final image of a mug and three Moccona-branded products, being a box of sachets, a jar of instant coffee, and a box of capsules. Each of these products bears the Moccona logo –

62 Another video played during the cross-examination of Mr Tillman was titled “Moccona Me-Time Moments: Katie (60”)”. This video was posted to the Moccona YouTube channel on 14 July 2021 and had recorded over 160,000 views. The video follows a similar format to the video featuring Emma, which I have already described. Relevantly, the video opens with an image of the Moccona logo and the tagline “Giving a little me-time to deserving Aussies” in front of a blurred image of Katie and her family –

63 Later in the video, Katie’s husband is shown spooning instant coffee out of a Moccona-branded jar, which is partially obscured –

64 The video also contains images of Katie at a beach, drinking from a Moccona-branded cup –

65 The video’s concluding image is of a Moccona logo superimposed over Katie drinking from the same Moccona-branded cup –

66 Counsel for Cantarella also played a video entitled “Dec Jar 2022”, which was posted to the Moccona YouTube channel on 8 July 2022 and has attracted over one million views. The evidence established that this video related to the “Be Inspired” range of limited-edition Moccona glass jars. A campaign involving these jars, which ran between at least June 2022 and December 2022, was run on several social media platforms. The video depicts a range of six limited-edition Moccona jars. Initially, the six jars are presented together above the Moccona logo –

67 Each jar is also presented individually, as in the case of the following jar –

68 At the conclusion of the video, the six jars are again presented together above the Moccona logo –

69 Throughout the video, each of the jars depicted is filled with freeze-dried instant coffee, and bears a decorative design. Nowhere in the video is a jar shown with a Moccona label affixed.

70 Another video played by counsel for Cantarella was titled “Moccona Sleeping Beauty”. This video was posted to the Moccona YouTube channel on 12 April 2014, and has been viewed more than 19,000 times. This video opens with various suitors attempting to wake a sleeping woman, using loud noises such as a cockerel, an accordion and a band. None of these methods succeeds. As these failed attempts unfold, there are brief images of a man with a jar of Moccona instant coffee –

71 Eventually, the man is shown opening the Moccona jar and making a cup of coffee –

72 This causes the sleeping woman to stir, and she eventually awakes when the man brings the coffee to her chamber. The video ends on an image of a labelled jar of Moccona “Awaken” instant coffee, next to the taglines “WAKE UP TO SOMETHING SPECIAL” and “For Lovers of Coffee” –

73 Another video shown by counsel for Cantarella was titled “Moccona Chase (15”)”, which was posted to the Moccona YouTube channel on 7 March 2018 and had more than 440,000 recorded views. This video shows a man running after a woman on a tram, with a labelled jar of Moccona instant coffee in hand –

74 The video then shows the man reaching the woman inside a building and handing her the labelled jar of Moccona instant coffee –

75 The video finishes on an image of a labelled Moccona jar next to the tagline “FOR LOVERS OF COFFEE” –

76 Another video shown by counsel for Cantarella was titled “Moccona by Peter Alexander”, which was posted on 23 March 2018 and has recorded over 500 views. This video forms part of a campaign run by JDE AU in collaboration with the Australian sleepwear company Peter Alexander. The campaign involved limited-edition “Wake Up In Style” glass jars, and ran between at least February 2018 and October 2018. Around 950,000 of these jars were sold during that period. The advertising campaign involved billboards, social media, and other online advertising, an event in Sydney at which Peter Alexander himself appeared, and various other forms of promotion. This particular video opens on a cascading shot of four decorative glass Moccona jars containing freeze-dried instant coffee. The word “Moccona” does not appear on the jars, or anywhere else in the opening sequence –

77 The video then finishes on an image of a decorative glass Moccona jar, without a label, next to the Moccona logo and the tagline “WAKE UP IN STYLE” –

78 The next video played by counsel for Cantarella was titled “Fall in love with coffee at home with Moccona”. This video was posted to the Moccona YouTube channel on 13 May 2020, and had recorded more than 2,500 views. The video opens with a coffee bean turning into a love heart, before a jar of Moccona instant coffee, along with its label, is featured –

79 The video then features two other Moccona products, being a box of “Cappuccino” sachets, and a tin of “Barista Reserve” –

80 The video concludes with an image of four Moccona products, being a tin of “Barista Reserve”, a box of “Cappuccino” sachets, a 100-gram jar of Moccona Classic freeze-dried instant coffee, and a box of “Ristretto” capsules. The jar of Moccona instant coffee is placed at the front of the range –

81 Counsel for Cantarella also played a video titled “Moccona Upcycling #InspiredByMoccona”, which was posted to the Moccona YouTube channel on 21 July 2020 and which had more than 1,500 recorded views. The video is an advertisement for Moccona that illustrates how, once the coffee inside has been used, Moccona jars can be used for purposes other than storing coffee. The video opens on an image of the Moccona logo above the tagline “Be inspired” –

82 The video then shows some unlabelled Moccona jars before showing an image of a labelled jar of Moccona instant coffee –

83 The next shot in the video shows, from above, coffee being spooned out of a jar of Moccona instant coffee, without its lid. The word “Moccona” does not appear in this shot, and it is not clear whether the jar has any label attached to it –

84 Following these images comes a series of images that illustrate the uses to which empty Moccona jars can be put. The jars are variously used as water vessels, candle holders, and vases. In each case, the body of the Moccona jar is visible, though the lid is not always present –

85 The next video played by counsel for Cantarella was titled “Inspire your moment with Moccona (15”)”, which was posted to the Moccona YouTube channel on 17 August 2020 and which had more than 2.4 million recorded views. This video centres on a woman painting a watercolour bird, which comes to life and imparts a design onto a plain and unlabelled jar of Moccona instant coffee. The video opens on a shot of a woman drinking coffee from a mug, with an unlabelled jar of Moccona instant coffee next to a small easel on the table in front of her –

86 In the next shot, the woman puts the finishing touches on the watercolour of a bird carrying a garland of flowers. The bird magically flies off the page and floats above the unlabelled Moccona jar –

87 The bird then flies around the jar and wreathes it with the garland of flowers, which is imparted on the jar as a decorative design –

88 In the final shot, the jar with the decorative design expands into six jars, each with its own design. The jars, which do not bear a Moccona label, are placed above a glinting Moccona logo and the tagline “INSPIRE YOUR moment” in the final frames –

History of the Vittoria brand in Australia

89 As I have noted, Cantarella’s Vittoria business focused, for most of its existence, on beans and ground coffee. For at least some time between the late 1950s and the late 1970s, however, Cantarella also sold a Vittoria-branded instant coffee product, in a jar that appears below –

90 At other times, Cantarella has sold instant coffee products under different brands. There was no suggestion that any Vittoria-branded instant coffee product had been sold in Australia between the late 1970s until the launch of the Vittoria 100-gram instant coffee product in 2021.

91 The Vittoria 100-gram instant coffee product began to be sold by Woolworths in May 2021. As I have mentioned, the Vittoria 100-gram product has been sold in a tall, cylindrical glass jar with a gold-coloured plastic lid, with Vittoria branding involving the use of registered trade marks owned by Cantarella. The 100-gram product is available in four varieties –

(1) Original Classic, with a predominantly gold label;

(2) Mountain Grown, with a predominantly black label;

(3) Latte, with a predominantly white label; and

(4) Italian, with a predominantly brown label.

92 The evidence was that these four varieties mirror varieties of coffee beans and ground coffee sold under the Vittoria brand.

93 From around November 2021, Coles also began to stock the Vittoria 100-gram product. The Vittoria 100-gram product was initially priced at $10.00 per jar, and subsequently at $11.00 per jar. Since its launch, it has often been discounted and sold for prices between $6.00 and $7.60.

94 In July 2023, Cantarella launched a 300-gram, Vittoria-branded instant coffee product range that is sold in a resealable pouch. The evidence suggested that this product range is sold in independent supermarkets and grocers, rather than Coles and Woolworths stores. A stock image of an “Original Classic” variety resealable pouch of Vittoria instant coffee was in evidence –

95 Also in evidence were photographs of “Original Classic” and “Mountain Grown” variety resealable pouches of Vittoria instant coffee, as they appeared on the shelves of independent supermarkets and grocers –

Development of the Vittoria 400-gram product

96 The parties adduced evidence relating to the development of the Vittoria instant coffee range, including the 400-gram product and its packaging. Much of the evidence was confidential, and was heard in closed court. In general terms, the evidence related to precisely how, why, and with what knowledge and motivation Cantarella settled on the packaging it ultimately adopted for the Vittoria 400-gram product. Because of its confidentiality, I will deal with aspects of the evidence concerning the development of the Vittoria instant coffee range in a confidential annexure to these reasons. I will, however, explain in these open reasons the outline of my reasoning in relation to this topic.

97 The evidence on this topic was said to be relevant to the applicants’ infringement case, and the misleading or deceptive conduct and passing off cases. Now, it is not an element of any of those causes of action that the respondent intended to deceive. It was common ground that, for example, deceptive similarity or a likelihood of misleading or deceiving can be established whether or not Cantarella intended to achieve those results. In their statement of claim, the applicants pleaded as part of their infringement case that the –

[r]espondent’s Infringing Shape Mark is deceptively similar to the [a]pplicants’ Shape Mark … in that a number of Australian consumers … are at a real risk … of being confused … particularly given that … there is no requirement to prove an actual subjective intention to cause confusion, but in any event … the [r]espondent chose to adopt packaging “sailing close to the wind” of the [a]pplicants’ Shape Get-Up …

98 Similar allegations were made in relation to the applicants’ ACL claim.

99 The evidence about the development of the Vittoria 400-gram product’s packaging has to be understood in this context. The applicants submitted that the process by which the packaging for the Vittoria 400-gram product was developed reinforced the conclusions that Cantarella had used the shape of the 400-gram product as a trade mark, and that the shape of the 400-gram product was likely to be confused by some notional consumers with the shape registered by the KDE shape mark. The applicants sought to engage the principle that, where a trader consciously emulates aspects of a competitor’s get-up, it is a reasonable inference that the trader believes there will be a market benefit in doing so, in the form of attracting custom that would otherwise have gone to the competitor. From those propositions, it was said, it is an available inference that the trader considered that such emulation was “fitted for the purpose and therefore likely to deceive or confuse”: see Australian Woollen Mills Ltd v F S Walton & Co Ltd (1937) 58 CLR 641 (Australian Woollen Mills) at 657 (Dixon and McTiernan JJ). The applicants cited Sydneywide Distributors Pty Ltd v Red Bull Australia Pty Ltd [2002] FCAFC 157; 234 FCR 549 (Sydneywide) at [117] (Weinberg and Dowsett JJ) in support of these propositions.

100 Of course, whether the respondent believed that the Vittoria 400-gram product’s jar was fitted for the purpose of attracting custom that would otherwise have gone to the applicants is not, without more, relevant to any cause of action. I understood the applicants’ case to be that, where these facts arise, the Court may infer more readily that Cantarella’s jar was (a) used as a trade mark; and (b) deceptively similar to the KDE shape mark, or likely to mislead or deceive consumers on the ground that these facts at least provide “a reliable and expert opinion” on the question whether what was done was in fact likely to deceive: see Australian Woollen Mills at 657.

101 Without disclosing the contents of confidential evidence, I will summarise the salient features of the development process.

102 In May 2020, Cantarella conducted a market review dealing with the pre-mixed sachet and instant coffee segments of the coffee market. The review identified the instant coffee segment as a large segment of the coffee market. By August 2020, Cantarella had decided to launch a Vittoria-branded instant coffee product. Various formats and packaging options were considered. For various reasons, Cantarella decided to launch a 100-gram product. Once that product was launched in May 2021, Cantarella resumed its consideration of other formats for Vittoria instant coffee products, including a 400-gram product. Again, various packaging options were considered. Among these options were a glass jar with a plastic screw-top lid, and a glass jar with a metal clamp lid. In mid-2021, a potential supplier sent to representatives of Cantarella two proposed packaging options, both of which were glass jars with glass stopper lids. Cantarella selected the second jar as the preferred option. Some time later, Cantarella received a physical version of that glass jar as a sample. That sample jar was in evidence, and a photograph of it appears below –

103 It became apparent that this jar was not large enough to hold 400 grams of freeze-dried instant coffee. Further, concerns were raised as to whether it was too tall for the standard-sized height of supermarket shelves such as those on which 400-gram Moccona jars were displayed. The dimensions of the jar were therefore adjusted: the height was reduced, so as to better fit the supermarket shelves; and the diameter of the cylindrical body was increased, so that the jar could hold 400 grams of coffee. The result was a jar in the shape that Cantarella ultimately used for the Vittoria 400-gram product.

104 Ultimately, I am not persuaded that the evidence about the development of the Vittoria 400-gram jar bears on the issues in this case. The evidence reveals that Cantarella wished to enter the instant coffee market using its Vittoria brand, believing that the market for Vittoria might be profitable, and knowing that Moccona was a major brand in that market. It also reveals that Cantarella considered a range of packaging formats. Cantarella assessed those formats against various criteria, including the degree to which they were perceived as “premium”. Cantarella wished to compete with the Moccona brand, and to launch a product that was capable of being sold in supermarkets just as widely as Moccona instant coffee was sold. Cantarella also wished to occupy a similarly premium position in the instant coffee market to Moccona. However, Cantarella selected as a starting point a jar that was put forward by a supplier. As events transpired, that jar had to be modified to suit Cantarella’s requirements. One requirement was that it was actually large enough to hold 400 grams of coffee. Another was shelf height. In combination, these requirements led to an increase in diameter and a reduction in height.

105 I find that for the purposes of sale of instant coffee products in supermarkets where a share of the instant coffee market could be expected to be gained at the expense of other suppliers, it is unremarkable that Cantarella should decide that its 400-gram jar should have a similar height to that of the Moccona 400 gram jar, which at the time of launch was the only competing 400-gram freeze-dried coffee in a jar. Nescafé Gold was introduced in 400-gram jars a month or two after the Vittoria 400-gram product was introduced. The Nescafé Gold 400-gram jar is slightly taller than the Moccona and Vittoria 400-gram jars. Mr Tillman accepted that, generally speaking, supermarkets prefer not to have significant headspace in their shelving because it would be a waste of space, and that generally supermarkets want products to conform. Some of the contemporary photographs of consumer items displayed on supermarket shelves that were in evidence showed competing products on the same shelf. In the case of instant coffee, a photograph on p 71 of Professor O’Sullivan’s first report showed a number of shelves displaying competing products. Taller products, such as large tins of International Roast and Nescafé Blend 43, and 400-gram jars of Moccona, Vittoria, and Nescafé Gold were on the two lowest shelves. The tallest product by a margin appeared to be the 400-gram jars of Nescafé Gold –

106 The statements of Dixon and McTiernan JJ in Australian Woollen Mills and of Weinberg and Dowsett JJ in Sydneywide should not be understood as erecting a rule of law. They constitute appellate guidance in relation to fact-finding, which is plain from the statement of Dixon and McTiernan JJ in Australian Woolen Mills at 658 that “in the end, it becomes a question of fact for the court to decide whether in fact there is such a reasonable probability of deception or confusion that the use of the new mark and title should be restrained”. Intention is but one factor that the court may take into account in its factual evaluation, perhaps in a borderline case: Hashtag Burgers Pty Ltd v In-N-Out Burgers, Inc [2020] FCAFC 235; 385 ALR 514 at [68] (Nicholas, Yates and Burley JJ). I do not conclude from the entire series of events, only aspects of which I have canvassed in these open reasons, that Cantarella was deliberately attempting to mislead consumers, or that it considered that its jar shape was likely to deceive or confuse. I do not accept the applicants’ claim that Cantarella was attempting to “sail close to the wind” in any relevant sense. The process by which Cantarella developed its jar is, therefore, irrelevant to the pleaded causes of action. The questions of trade mark use, deceptive similarity, and likelihood of misleading or deceiving are to be considered in this case by reference to the objective facts alone.

107 In arriving at the above conclusions, and the supporting findings set out in the confidential annexure, I have had regard to the applicants’ submission about the significance of Cantarella’s failure to call as witnesses three persons involved in the process of selecting the Cantarella jar shape: Les Schirato, Roland Schirato, and Mathias Stamm. The applicants submitted that I should more comfortably draw inferences adverse to Cantarella by reason of their absence from the witness box. However, for the reasons that I give, the evidence does not get to the point where I would contemplate drawing the inferences for which the applicants contended. What Cantarella did is well documented, as detailed in the confidential annexure. And Cantarella did call Mr Hill, to whom Mr Stamm reported, and who in turn reported to Mr Les Schirato. Mr Hill was cross-examined. It was put to Mr Hill that in developing and finalising the design of its 400-gram jar, Cantarella was consciously trying to align the shape and size of its jar as close to the Moccona shape as it could, which Mr Hill denied. As I stated at [25] above, I formed a favourable view of Mr Hill as a witness. I accept Mr Hill’s evidence. The evidence shows that Cantarella was well aware of Moccona’s presence in the market for freeze-dried coffee, and that it sought to enter that market with its own product. But for the reasons explained in the confidential annexure, the final shape of the Cantarella jar was not developed for the purpose of emulating the shape of the Moccona jar, or to mislead consumers, but was largely the result of the functional considerations that are referred to in the annexure.

Advertisements for the Vittoria brand in Australia

108 Over various periods from 30 October 2022 to 22 July 2023, television advertisements for the Vittoria 100-gram product were broadcast on various Channel 9 channels. One of the advertisements in question was a 30-second advertisement that focused on the process of coffee growing and processing. Relevantly, it includes a shot of a man holding up a cylindrical glass jar full of coffee beans. The jar in question is unlabelled, but it appears to be similar in shape to the Vittoria 100-gram product –

109 The advertisement ends on a shot of all four varieties of the labelled Vittoria 100-gram product, next to the tagline “Now in Instant”, as a ray of light passes over and illuminates the four jars –

110 In a 15-second version of the advertisement broadcast on the Channel 9 channels (which does not feature the empty jar), the final image appears as follows –

111 Advertising of the Vittoria 100-gram product has taken a range of other forms. As well as television advertisements, Cantarella has employed sponsorships, radio advertisements, print advertisements, posters, and billboards to advertise its Vittoria 100-gram product. Now, there was no issue in the case concerning whether Cantarella has used the shape of the Vittoria 100-gram product as a trade mark. Some of the following advertisements, however, provide context in which to place Cantarella’s advertisements for the Vittoria 400-gram product.

112 Cantarella placed a full-page advertisement for the Vittoria 100-gram product in the 4 August 2021 edition of the “Sunday Mail”. That advertisement prominently features an image of the 100-gram product, beneath the word “Instantaneous.” and above the phrase “Now in instant.” –

113 This advertisement and variations of it in relation to other flavour varieties were placed in several newspapers and magazines in 2021, along with half-page versions.

114 In two phases between 4 October 2022 and 1 January 2023, Cantarella also ran an outdoor campaign for the Vittoria 100-gram product that involved placing advertisements on over 100 “panels”. A photograph of an example bus-stop panel featured the Vittoria 100-gram product beneath the tagline “Instant classic” –

115 The same advertisement was featured on bills posted on streets in Sydney, Melbourne, and Brisbane in January, April, and May 2023 –

116 In late 2022 and mid-2023, Cantarella also caused the following billboard to be displayed near Melbourne’s Tullamarine Airport –

117 Across various periods from June 2021 to May 2023, Woolworths displayed aisle fins for the Vittoria 100-gram product, which featured a picture of that product as well as a separate Vittoria logo. The aisle fins were displayed in all Woolworths stores in Australia, and in Coles stores nationally. An aisle fin is essentially an advertising placard hung perpendicular to the shelves in a supermarket aisle. An example of one of the Woolworths aisle fins appears below –

118 Cantarella has also engaged in several marketing campaigns for the Vittoria 400-gram product. The applicants relied on these marketing campaigns to support the submission, within their infringement case, that the respondent had used its Vittoria 400-gram jar as a trade mark. I will therefore set out the advertisements that I consider to be salient to that question.

119 Between September 2022 and June 2023, Cantarella commissioned 10 full-page colour advertisements and two half-page colour advertisements for the Vittoria 400-gram product in major metropolitan newspapers. The Court received into evidence an A3 copy of parts of the 25 September 2022 edition of the “Sunday Age”, which was as close as possible to the actual size of that newspaper. The mock-up included a full-page colour advertisement for the “Original Classic” Vittoria 400-gram product. An electronic version of the double-page spread on which this advertisement appeared is below –

120 The advertisement prominently features an image of the 400-gram product, beneath the tagline “Instant classic” and above the phrase “Now in 400g”. As I noted at [114] above, the tagline “Instant classic” was also used in connection with the Vittoria 100-gram product. The applicants stressed that full-page advertisements cost more because they have a greater effect. I understand this to mean that advertisers are willing to secure full-page advertisements, despite their greater cost, because those advertisements are more effective. While the image I have reproduced here is small, I have taken into account the impression created by the size it would have had in the newspaper. The applicants also stressed that this advertisement contains minimal text or branding beyond the jar itself.

121 The Vittoria 400-gram product was also advertised on billboards. A photograph of one such billboard, which was posted between 21 November 2022 and 18 December 2022 near Tooronga railway station in Malvern, Victoria, is below –

122 The applicants again emphasised that this billboard featured the jar with minimal text or additional branding, though I note that there is an additional Vittoria logo.

123 Cantarella also used social media to advertise its Vittoria 400-gram product at various periods in 2022 and 2023. The applicants drew attention to one such advertisement, which fairly represents the overall nature of the advertisements, and pointed out that it featured the jar prominently with minimal text or additional branding –

124 Another way in which the Vittoria 400-gram product was advertised was through the use of aisle fins in more than 800 Coles supermarkets. These aisle fins were displayed from November 2022 to December 2022, and again from May 2023 to June 2023. Some of the aisle fins featured the Vittoria 400-gram product alone –

125 Other aisle fins featured the Vittoria 400-gram product alongside the 100-gram product –

126 The applicants pointed out that the aisle fins prominently feature the Vittoria 400-gram jar, again with minimal text or additional branding.

Other coffee brands sold or marketed in Australia using a jar similar to the KDE shape mark

127 In support of its cross-claim, Cantarella drew attention to the existence of other brands of coffee that have sold, or proposed to sell, instant coffee in a cylindrical glass jar substantially in the form of the KDE shape mark.

128 The first of these brands in time was the “Andronicus” brand. The dispute that provided the occasion for Lockhart J’s judgment in Stuart Alexander concerned instant coffee, and in particular the Moccona and Andronicus brands. As I have noted, Lockhart J’s reasons were received into evidence for all purposes.

129 The Court received into evidence the originating application that commenced the proceeding which culminated in Lockhart J’s reasons reported as Stuart Alexander. That originating application records that the applicants in the proceeding were “Stuart Alexander & Co (Interstate) Pty Limited” and “Douwe Egberts Koninklijke Tabaksfabriek-Koffiebranderijen-Theehandel NV”, and the respondent was “Blenders Pty Limited”. Relatedly, the evidence was that, in around 1975 or 1976, an Australian company trading as Stuart Alexander was appointed as the Australian distributor of Moccona-branded instant coffee. The distribution arrangement involving Stuart Alexander ended on 1 July 1992. From that date onwards, JDE AU took over the importation and distribution of Moccona-branded instant coffee in Australia. The reasons of Lockhart J at 308 state that the second applicant to that proceeding, Douwe Egberts Koninklijke Tabaksfabriek-Koffiebranderijen-Theehandel NV, was the manufacturer of Moccona-branded coffee.

130 Lockhart J’s reasons also state at 308 that Andronicus was a well-known brand name in Australia, which was associated with premium quality instant coffee. Lockhart J stated at 308 that, in the middle of 1981, Andronicus coffee began to be sold “in a jar substantially the same as the jar in which Moccona ha[d] been sold for at least fifteen years”. I have already dealt with the evidentiary weight of Lockhart J’s statement as to the length of time for which Moccona had been using a jar in the shape of the KDE shape mark. Nevertheless, given the immediacy of the event in question, I consider his Honour’s statement that Andronicus coffee began to be sold in a jar similar to the KDE shape mark to be probative.

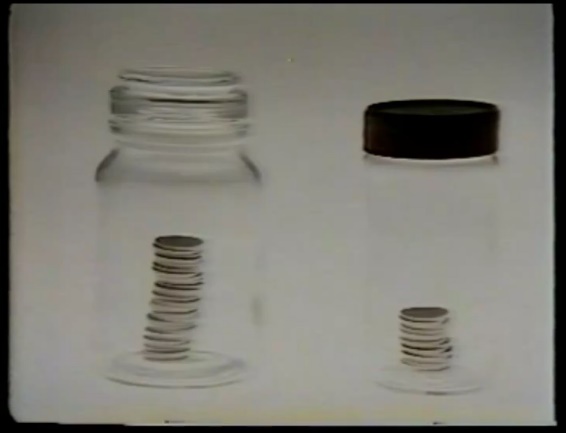

131 More specifically, Stuart Alexander focused on a particular television advertisement for Andronicus coffee. That advertisement, which Lockhart J noted at 309 was screened in August 1981, was in evidence in this case. The advertisement opens on an image of an unlabelled, cylindrical glass jar with a glass stopper lid, which is similar in form to the KDE shape mark –

132 That glass jar gradually fills up with coins while a voiceover can be heard to say: “Some imported coffees come in a beautiful jar, but they cost the earth” –

133 Next, a plain cylindrical glass jar with a plastic screw-top lid appears next to the previous jar. The new jar itself begins to fill with a smaller pile of coins, as the voiceover says: “Other coffees come in a plain jar, at a much lower price” –

134 The frame then grows to include a third jar within its compass. The third jar, which is the same shape as the first jar, fills with a pile of coins roughly the same size as the pile in the second jar.

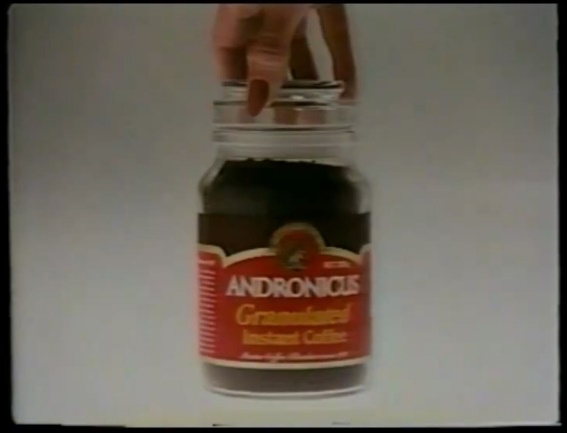

135 In the next shot, a hand rotates the third jar as an Andronicus label appears on it. At the same time, the voiceover states: “Only one offers you the right combination of quality and value: Andronicus, the taste of coffee from the heart of the bean” –

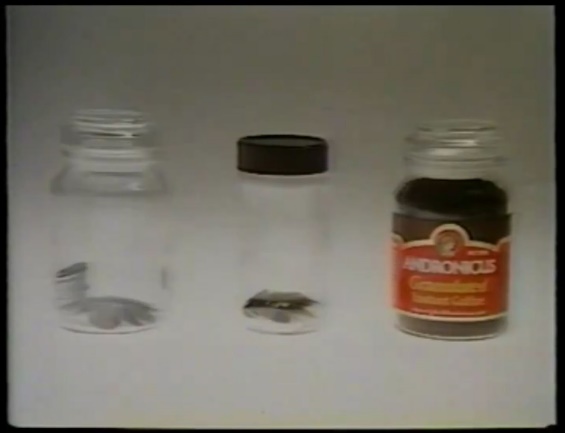

136 The advertisement concludes with a sequence showing the three jars back in the same frame. This time, the jar on the right is full of coffee, and is labelled as an Andronicus product. The piles of coins in the first and second jars collapse, as the voiceover states: “Andronicus: premium instant coffee, at a sensible price” –

137 The Andronicus advertisement was relevant in Stuart Alexander because the applicants in that case alleged that the respondent had engaged in misleading or deceptive conduct, and made certain false or misleading statements, by procuring the broadcast of the advertisement. In particular, the applicants in Stuart Alexander attacked the advertisement on the grounds that it suggested that while Moccona coffee was imported, Andronicus coffee was not imported, whereas in fact Andronicus coffee was also imported. The second aspect of the applicants’ case was that the labelling and general appearance of the jars containing Andronicus instant coffee would mislead consumers.

138 As Lockhart J noted at 309, both of these attacks assumed that the viewer of the advertisement would associate the first jar with Moccona coffee. His Honour found as a fact at 310 that “people who look at the television commercial would associate the first jar with Moccona instant coffee”, based on the evidence of witnesses along with the fact that only three brands of instant coffee used the “apothecary”-style jar, of which only Moccona and Andronicus were sold widely in supermarkets.

139 Also in evidence was a full-page advertisement for Andronicus coffee from the 12 May 1982 edition of “The Australian Women’s Weekly” –

140 There were further advertisements for Andronicus coffee in evidence, which spanned the years between 1982 and 1985. The advertisement from 1985 was a small, black-and-white drawing in a catalogue within the 13 March 1985 edition of “The Canberra Times”. It appears to show Andronicus being offered for sale in a jar substantially similar to the KDE shape mark, as do all the intervening advertisements –

141 The Court also received into evidence a cylindrical glass jar with a glass stopper lid, which was identified as an Andronicus jar with its label removed. This jar was substantially in the form of the KDE shape mark –

142 On the basis of the evidence I have identified, I am satisfied that instant coffee was sold in Australia under the Andronicus brand in a jar substantially resembling the KDE shape mark from the middle of 1981 to at least 13 March 1985.

143 The second of the brands to which Cantarella drew attention on its cross-claim was the “Park Avenue” brand. As noted above, Cantarella read to the Court an affidavit of Leigh Alfred Harrison, who has been a director of Abel Lemon Trading Pty Ltd since 1992. Mr Harrison was not required for cross-examination, and his evidence was therefore unchallenged. In his affidavit, Mr Harrison referred to his inability to remember certain details. I accept, however, that Mr Harrison’s evidence about the “Park Avenue” brand can be relied upon in relation to the matters it positively addresses.

144 Mr Harrison became the Sales Director for Abel Lemon Food Services (a predecessor of Abel Lemon Trading Pty Ltd) in 1993. Mr Harrison deposed that, in around 1993, Abel Lemon Food Services imported approximately four to six shipping containers (each 20 feet in length) of a coffee product known as “Park Avenue” from Brazil. Annexed to Mr Harrison’s affidavit was an excerpt from the 21 April 1993 edition of the “Australian Supermarket News”, which contained an article about Park Avenue instant coffee, accompanied by the following photograph –

145 Mr Harrison stated that Park Avenue coffee was not sold in any packaging format other than the one depicted in this photograph. Park Avenue coffee was sold only in the two sizes shown in the photograph, being a 100-gram size and a 200-gram size. Mr Harrison stated that Park Avenue coffee was sold in supermarkets nationally, though he could not recall which particular supermarkets stocked it. He also deposed that Park Avenue coffee was advertised using in-store promotions in addition to the article in the “Australian Supermarket News”.

146 Mr Harrison stated that Abel Lemon Food Services did not continue to import the Park Avenue coffee product, or place any further orders, after the initial order. Based on his experience, Mr Harrison stated that he believed it would have taken supermarkets around six to 12 months to sell through the supplied stock of Park Avenue instant coffee.

147 The third brand relied upon by Cantarella in support of its cross-claim was the “Bomcafé” brand. Unlike Andronicus and Park Avenue, there is no evidence that any instant coffee has ever been sold in Australia under the Bomcafé brand. In evidence, however, was a copy of a web page for Bomcafé, part of which showed three clear jars of instant coffee substantially in the form of the KDE shape mark –

148 I have said that there is no evidence Bomcafé was ever sold in Australia. The web page that is in evidence contains several indications that support a finding that no Bomcafé products had been sold in the jar depicted, at least by the date the copy of the web page was made. For example, the web page states –

(a) “We aim to offer masterly crafted coffee-based products”;

(b) “Bomcafé will offer a truly exceptional specialty coffee”;

(c) “Our unique range … will include” various products;

(d) “Here are a few samples of our 60+ products and an overview of proposed design concepts for a new line to be developed”; and

(e) “Artwork designs, illustrations and photographs/images on this website and in our brochures depict finishes and features of the proposed packaging for the brand. Artwork designs and all rendered packaging concepts displayed herein are for presentation only and may be subject to changes before packaging manufacturing process and/or a product launch”.

149 Indeed, while nothing particularly turns on this, I am not satisfied that any Bomcafé product has ever been sold in Australia, or that Bomcafé has any reputation in Australia.

The marketing experts

150 As I mentioned earlier, the parties called two witnesses with expertise in marketing, namely Professor Richard Don O’Sullivan, who was called on behalf of the applicants, and Mr Paul Lindsay Blanket, who was called on behalf of Cantarella.

The applicants’ marketing expert — Professor O’Sullivan

151 Professor O’Sullivan is a Professor of Marketing at Melbourne Business School within The University of Melbourne. Professor O’Sullivan has held various positions at Melbourne Business School since 2008. Before this, he was a Lecturer in Marketing at University College Cork (in Ireland) from 1992 to 2007, except for a period between 2000 and 2003, when he worked as the Director of Strategic Marketing at a marketing services company called TecBrand. At TecBrand, Professor O’Sullivan’s duties involved advising clients on marketing strategy and brand management. Professor O’Sullivan has attained the degrees of Bachelor of Commerce, Masters in Business Studies, and Doctor of Philosophy within University College Cork. Alongside his research and teaching in marketing at Melbourne Business School, he spends about a quarter of his time working as a marketing consultant to businesses.

152 Professor O’Sullivan produced two reports of his own, as well as contributing to a joint report with Mr Blanket.

Professor O’Sullivan’s first report

153 Professor O’Sullivan’s first report was dated 26 May 2023. This report addressed eight questions put to Professor O’Sullivan by the applicants’ solicitors in a letter of instructions dated 24 March 2023. In his first report, Professor O’Sullivan proceeded on the basis of assumptions and material provided to him in that letter, as well as further assumptions provided in a supplementary letter from the applicants’ solicitors dated 3 May 2023.

154 Professor O’Sullivan commenced his first report by explaining some key concepts he deployed to ground his opinions. He explained that, in a marketing context, the term “brand” refers to a “name, term, design, symbol, or any other feature that identifies one seller’s good or service as distinct from those of other sellers”. Professor O’Sullivan explained that, in accordance with the usage of marketing academics and practitioners, he treated the terms “brand” and “trade mark” as having the same meaning. He also explained that he used the term “brand element” when referring to any feature that identifies one seller’s good or service as being distinct from those of other sellers. He stated that the expression “line extension” refers to the use of an established brand to market products in a new market segment, while the expression “brand extension” refers to the use of an established brand to promote a completely different type of product, in a new category.

155 He further stated that, in a marketing context, “involvement” refers to the perceived relevance of an object to a consumer and is based on their inherent needs, values, and interests. He opined that consumers tend to engage in a more considered assessment of available information when they are more highly involved.

156 Professor O’Sullivan stated that a “diagnostic cue” is any stimulus that people rely on in order to categorise objects, and that “brand elements” operate as diagnostic cues when they are relied upon by consumers engaged in brand search and identification. Professor O’Sullivan opined that consumers, when faced with multiple diagnostic cues, tend to place greater weight on cues that are perceived to be more useful in identifying the brand or differentiating between products from different brands in the same category. In Professor O’Sullivan’s view, for consumers to rely on a brand element as a diagnostic cue, it must be an element that consumers both notice and link uniquely to the brand. He stated that, while consumers may rely on a logo as a diagnostic cue, they may also rely on cues like colour and other elements of packaging to identify and notice specific brands. Professor O’Sullivan gave his opinion that packaging is an important aspect of the way brands are identified, particularly for brands sold in supermarkets.

157 Professor O’Sullivan was asked to comment on how the principles explained in the first section of his report applied in the context of instant coffee products for sale in Australia. Professor O’Sullivan relied upon prior studies, which in his view “point[ed] to instant coffee being a low-involvement product category for consumers”. Professor O’Sullivan also stated that, in a supermarket context, consumers will select from a wide array of products and brands in a matter of one or two seconds. He stated that it was his opinion that, in line with the “principle” of diagnostic cues, consumers will tend to seek out distinctive brand elements and screen out stimuli that are not diagnostic. Consumers looking for their usual brands, Professor O’Sullivan opined, are likely to search for the brands’ key elements, including logo, package shape, and other distinctive elements. Professor O’Sullivan opined that package shape is used as a brand element by several instant coffee brands available in Australian supermarkets, most notably Moccona, Robert Timms, and Nescafé Blend 43.

158 Professor O’Sullivan was also asked to give his opinion as to what consumers would recognise as the key branding elements in relation to Moccona instant coffee products. As part of his response to this question, Professor O’Sullivan identified the Moccona logo, sub-brands, the colour scheme, imagery, numbering on labels, descriptors, and packaging shape and material as elements that appear in relation to Moccona instant coffee products. With respect to their weighting, Professor O’Sullivan stated that, as well as appearing on jars of Moccona coffee, the Moccona logo appears on products such as packets of ground or bean coffee, coffee capsules, and sachets. He opined that, as the Moccona logo is common to a range of products, consumers searching for Moccona instant coffee products may not rely upon the Moccona logo as the most diagnostic cue. By contrast, he opined that the cylindrical glass jar with a flat-topped glass stopper is likely to be perceived by consumers as being highly diagnostic, and thus relied on heavily when searching for Moccona instant coffee products. The basis for this opinion was that Moccona is offered for sale in a form of packaging that is unique within the category and uniform across the jars in the range, and which has remained consistent since the brand’s introduction to the market.

159 Professor O’Sullivan was asked whether consumers were likely to perceive the shape of the Moccona jar as indicating a connection in the course of trade between the product and Moccona. He stated that, in his opinion, many consumers are likely to perceive the shape of the Moccona jar as indicating such a connection. In brief terms, the considerations that formed the basis for this opinion were identified as the following –

(a) the brand has been present and prominently displayed in supermarkets in Australia for many years;

(b) awareness of the cylindrical glass jar with a flat-topped glass stopper, and association of it with the Moccona brand, is likely to be high due to the uniqueness of this packaging in the instant coffee category;

(c) the Moccona jar is unique to Moccona instant coffee products, and so consumers are likely to have relied upon this feature when searching for products in store;

(d) the Moccona jar will be familiar through actual regular usage of the jar to consumers who have purchased it;

(e) efforts have been made over many years to associate in the minds of consumers the cylindrical glass jar with a flat-topped glass stopper with the Moccona brand; and

(f) advertising of Moccona instant coffee products has, at times, presented the jar as an item of value in itself, not simply as a container, and these advertising initiatives would only have been repeated if they “generated meaningful participation from consumers”.

160 Professor O’Sullivan was also asked to consider what consumers would recognise as the key branding elements of the Vittoria 400-gram product. He identified the Vittoria logo, the label on the jar, the package shape, and the branded packing trays in which the products were displayed as the key branding elements of the Vittoria 400-gram product.

161 Professor O’Sullivan was asked to consider whether consumers were likely to perceive the shape of the Vittoria 400-gram jar as indicating a connection in the course of trade between the product and Vittoria. In response, he opined that consumers were likely to perceive the shape of the Vittoria 400-gram jar as indicating such a connection. He gave his opinion that package shape is used as a brand element for the Vittoria 400-gram product, and reiterated that a brand element identifies one seller’s good or service as distinct from those of other sellers. Professor O’Sullivan further opined that it was a highly noticeable feature of the Vittoria 400-gram product that it was packaged in a cylindrical glass jar with a flat-topped glass stopper. Because it was a highly noticeable feature, Professor O’Sullivan opined that consumers were likely to view package shape as a brand element. He also expressed the opinion that consumers were likely to rely on the package shape when identifying the Vittoria 400-gram product. To adopt Professor O’Sullivan’s terminology, that would appear to mean that package shape also constitutes a “diagnostic cue” in relation to the Vittoria 400-gram product.

162 Professor O’Sullivan was asked whether there is a “real risk” that consumers who know, but have an imperfect recollection of, the shape of the Moccona jar will see the shape of the Vittoria jar and be caused to wonder whether it might not be the case that the products come from the same source or are otherwise related. Professor O’Sullivan stated that, in his opinion, there is such a risk. The gist of the reasoning underpinning his opinion was that –

(a) consumers are likely strongly to associate Moccona instant coffee products with a cylindrical glass jar with a flat-topped glass stopper;