Federal Court of Australia

Faruqi v Hanson [2024] FCA 1264

ORDERS

Applicant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

ATTORNEY-GENERAL OF THE COMMONWEALTH Intervener | ||

DATE OF ORDER: |

The Court declares that:

1. The conduct of the respondent in publishing a tweet on the messaging platform then known as Twitter under the handle @PaulineHansonOz at 4.05pm on 9 September 2022 in terms that included telling the applicant to “piss off back to Pakistan”:

(a) is unlawful under s 18C of the Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth) in that it:

(i) was reasonably likely in all the circumstances to offend, insult, humiliate and intimidate the applicant and groups of people, namely people of colour who are migrants to Australia or are Australians of relatively recent migrant heritage and Muslims who are people of colour in Australia;

(ii) was done by the respondent because of the race, colour or national or ethnic origin of the applicant; and

(b) is not exempted under s 18D(c)(ii) as it was not done reasonably and in good faith as a fair comment on a matter of public interest.

The Court orders that:

1. Within seven days of these orders, the respondent cause the tweet identified in the declaration in paragraph 1 above to be deleted from her Twitter (now X) profile under the handle @PaulineHansonOz.

2. The respondent pay the applicant’s costs of the proceeding.

3. The parties, including the intervener, have liberty to apply for a variation of order 2 within 14 days of these orders by serving and filing brief submissions (of no more than three pages) and any supporting evidence failing which order 2 shall be final.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

STEWART J:

TABLE OF CONTENTS

[1] | |

[11] | |

[15] | |

[27] | |

[30] | |

[31] | |

[60] | |

[62] | |

[70] | |

[79] | |

[84] | |

[90] | |

[98] | |

[104] | |

[108] | |

[114] | |

[119] | |

[120] | |

[140] | |

[150] | |

[156] | |

[158] | |

[162] | |

[162] | |

[179] | |

[188] | |

Senator Hanson’s tendency to make racist, nativist and Islamophobic statements | [189] |

[200] | |

[218] | |

[219] | |

[224] | |

[235] | |

[242] | |

[259] | |

[259] | |

[259] | |

[263] | |

[281] | |

[292] | |

[292] | |

[302] | |

[308] | |

[308] | |

[314] | |

Question 1: does Pt IIA effectively burden the implied freedom? | [318] |

[339] | |

Question 3: is Pt IIA reasonably appropriate and adapted to advance that legitimate object? | [347] |

[349] | |

[351] | |

[361] | |

[378] | |

[379] |

1 The principal parties to this case are both members of the Senate of the Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia. At all relevant times they both held accounts on the social media messaging platform that was then called Twitter (now X) on which they regularly published messages under their own names.

2 The applicant is Mehreen Saeed Faruqi, a Senator for New South Wales since 2018 as a member of the Australian Greens party.

3 The respondent is Pauline Lee Hanson, a Senator for Queensland since 2016. She is a member of Pauline Hanson’s One Nation party.

4 The Attorney-General of the Commonwealth has intervened for the purpose of defending the constitutionality of certain legislation, to which I will come, but has not otherwise joined in the dispute between the principal parties.

5 Early in the morning of 9 September 2022 in Australia, it was announced that Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II had died at Balmoral Castle after a reign of more than 70 years.

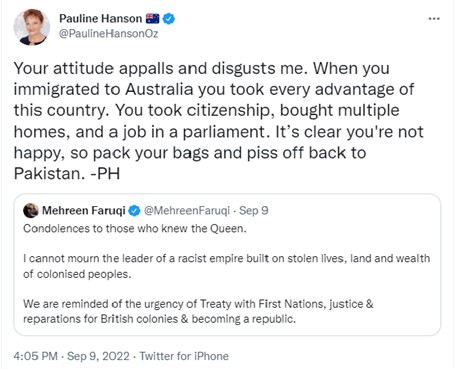

6 Less than 12 hours later, shortly before midday, Senator Faruqi published the following tweet:

Condolences to those who knew the Queen.

I cannot mourn the leader of a racist empire built on stolen lives, land and wealth of colonised peoples.

We are reminded of the urgency of Treaty with First Nations, justice & reparations for British colonies & becoming a republic.

7 In reply to that tweet, more than four hours later Senator Hanson published the following tweet as a quote tweet thereby incorporating Senator Faruqi’s tweet (as written):

Your attitude appalls and disgusts me. When you immigrated to Australia you took every advantage of this country. You took citizenship, bought multiple homes, and a job in a parliament. It’s clear you’re not happy, so pack your bags and piss off back to Pakistan. – PH

8 The tweets appear as follows:

9 It is common ground that by the manner in which Senator Hanson published her tweet, at least the first two sentences of Senator Faruqi’s tweet would have been visible to anyone reading Senator Hanson’s tweet. That is relevant to the way in which a reader of Senator Hanson’s tweet would have understood it, most notably as a direct response or reply to Senator Faruqi’s tweet.

10 Senator Faruqi made a complaint about Senator Hanson’s tweet to the Australian Human Rights Commission. Senator Hanson declined to participate in that process, whereafter the complaint was terminated under s 46PH(1B)(b) of the Australian Human Rights Commission Act 1986 (Cth) (AHRC Act) enabling Senator Faruqi to pursue her claim in this Court.

The claim and the defences to it

11 Senator Faruqi claims that Senator Hanson, by posting her tweet, engaged in offensive conduct because of Senator Faruqi’s race, colour or national or ethnic origin that is unlawful under s 18C of the Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth) (RDA). Section 18C makes it unlawful for a person to do an act, otherwise than in private, if the act is reasonably likely, in all the circumstances, to offend, insult, humiliate or intimidate another person or a group of people and the act is done because of the race, colour or national or ethnic origin of the other person or of some or all of the people in the group.

12 Senator Faruqi’s concise statement, in summary, asserts the following:

(1) The relevant act was Senator Hanson’s tweet which occurred in public; it was reasonably likely that Senator Faruqi and members of the “group”, or some of them, would be offended, insulted, humiliated or intimidated; and the act was done by Senator Hanson including because of the race, colour or national or ethnic origin of Senator Faruqi.

(2) The relevant group includes people with the following attributes:

(a) Persons of colour;

(b) Migrants to Australia;

(c) Persons with migrant heritage, born in Australia;

(d) Persons who by virtue of their appearance have been incorrectly identified as migrants;

(e) Muslim people;

(f) Persons with visible signs or expressions of religion;

(g) Persons who have been told to “go back to where they came from” or variations of that phrase due to their race, colour or national or ethnic origin; and/or

(h) Persons who have experienced racism.

(3) Senator Faruqi was herself offended, insulted, humiliated and intimidated by the tweet, including by the insinuation that as a Muslim, migrant, woman of colour she is less entitled than other Australian citizens to live in Australia and enjoy the benefits and opportunities afforded by that citizenship; the suggestion that she does not belong in Australia and should remove herself; and because of the incitement to racial hatred by, and manifest racial hatred that is expressed in, the phrase “go back to where you came from” and variations of that phrase.

(4) Senator Hanson published the tweet because of Senator Faruqi’s race, colour or national or ethnic origin.

(5) The term “race” in s 18C extends to groups of people including Muslims as a term of “ethno-religious” origin, and the tweet was published by Senator Hanson including because of Senator Faruqi’s race and ethnic origin, “including because she is Pakistani-born and Muslim.”

(6) Senator Hanson directed the tweet towards Senator Faruqi as a woman of colour and a person from a migrant background as a means to invalidate and delegitimise her entitlement to Australian citizenship, her participation in public debate and her enjoyment of the many benefits of life in Australia which is evident from Senator Hanson’s long and well-documented history of commentary implying that she holds white supremacist views, including having made countless hateful remarks over many years about Asian and Muslim people.

(7) The phrase in the tweet “pack your bags and piss off back to Pakistan” is directed at Senator Faruqi’s origins as a citizen of Pakistan, and her identity as a Pakistani-born Australian and an immigrant.

(8) Senator Faruqi and members of the group have suffered various forms of harm in consequence of the tweet, including that Senator Faruqi has been the subject of a torrent of abusive phone calls, social media posts and hate mail (including death threats and misogynistic, racist and sexually violent content).

13 Senator Hanson’s concise response admits various formal matters including that she published the tweet and that the publication of the tweet is an act that was done in public but otherwise denies nearly every aspect of Senator Faruqi’s claim. The concise response, in summary, asserts the following:

(1) Of the many attributes of people in the group pleaded by Senator Faruqi, only “persons of colour” is a group protected by s 18C.

(2) Even if Senator Faruqi’s claim is otherwise made out, the publication of the tweet was done reasonably and in good faith in making a fair comment on an event and/or matter of public interest that was an expression of a genuine belief held by Senator Hanson within the meaning of s 18D of the RDA.

(3) In the further alternative, ss 18C and 18D of the RDA infringe the implied freedom of political communication in the Constitution and are therefore invalid in whole or in part to the extent of the use of the words “offend” and/or “insult” and/or “humiliate” in s 18C(1)(a).

14 At the end of the hearing, Senator Faruqi sought the following amended relief:

Remedy sought

The Applicant asks the Court for orders:

1. declaring:

a. that the Respondent engaged in conduct by causing to be posted at 4.05pm on 9 September 2022 a tweet under the Twitter handle @PaulineHansonOz (the Conduct);

b. that the conduct contravened s18C(1) of the Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth) and was unlawful in that:

i. it was reasonably likely to offend, insult, humiliate or intimidate the Applicant or a group of people, namely people who have one or more of the following characteristics: migrants (particularly from Pakistan or other Asian Countries), people of colour and Muslims;

ii. the conduct was done because of the race, colour or national or ethnic origin of the Applicant or some of or all of the people in the group;

c. that conduct was not exempted from being unlawful by s 18D of the Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth).

2. restraining the Respondent from using the phrases ‘piss off back to Pakistan’, ‘go back where you came from’ or any variation thereof in public;

3. requiring the Respondent to take down her tweet of 4.05pm on 9 September 2022 posted under the Twitter handle @PaulineHansonOz;

4. requiring the Respondent to ‘pin’ a tweet to her Twitter account with the Twitter handle @PaulineHansonOz for a period of 3 months, stating that she has been found by the Court to have engaged in an act that contravened s18C of the Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth) in that:

a. it was reasonably likely to offend, insult, humiliate or intimidate the a group of people, namely people who have one or more of the following characteristics: migrants (particularly from Pakistan or other Asian Countries), people of colour and Muslims; and

b. the conduct was done because of the race, colour or national or ethnic origin of the Applicant or some of or all of the people in the group; and

c. the conduct was not exempted from being unlawful by s 18D of the Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth).

5. requiring the Respondent to pay a donation in the amount of $150,000 to the Sweatshop Literacy Movement in Western Sydney;

6. requiring the Respondent to undertake anti-racism training at her own expense;

7. costs.

The statutory scheme: overview

15 The preamble to the RDA references the International Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Racial Discrimination (1965) (CERD), which is a Schedule to the RDA, and states:

AND WHEREAS it is desirable, in pursuance of all relevant powers of the Parliament, including, but not limited to, its power to make laws with respect to external affairs, with respect to the people of any race for whom it is deemed necessary to make special laws and with respect to immigration, to make the provisions contained in this Act for the prohibition of racial discrimination and certain other forms of discrimination and, in particular, to make provision for giving effect to the Convention:

16 One sees in the preamble references to the making of special laws with respect to race and immigration, and the prohibition of racial and certain other forms of discrimination. CERD entered into force in 1969 and was ratified by Australia in 1975.

17 Part I of the RDA deals with various preliminary matters. Part II provides for the prohibition of racial discrimination, including by making it unlawful (subject to various qualifications) for a person to do any act involving a distinction, exclusion, restriction or preference based on race, colour, descent or national or ethnic origin (s 9) and by providing for rights to equality before the law (s 10). There are also provisions dealing with discrimination in relation to access to places and facilities (s 11), land, housing and other accommodation (s 12), the provision of goods and services (s 13), the right to join trade unions (s 14), employment (s 15) and advertisements (s 16).

18 Part IIA was introduced into the RDA by the Racial Hatred Act 1995 (Cth). Justice Allsop in Toben v Jones [2003] FCAFC 137; 129 FCR 515 at [92]-[132] comprehensively described what led to those amendments, from “an ‘epidemic’ of swastika-painting and other manifestations of anti-Semitic hatred and prejudice in the northern hemisphere winter of 1959-60” to the adoption of the Racial Hatred Act in 1995.

19 The Explanatory Memorandum to the Racial Hatred Bill 1994 (Cth) (EM) which preceded the Act explains that the Bill was intended to address concerns highlighted by the findings of the National Inquiry into Racist Violence and the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody. The Bill was intended to strengthen and support the significant degree of social cohesion demonstrated by the Australian community at large. It was based on the principle that no person in Australia needs to live in fear because of their race, colour, or national or ethnic origin. The EM also addressed the intended relationship between the Bill and the implied freedom of political communication inherent in the democratic process enshrined in the Constitution and the meanings to be given to the terms “ethnic origin” and “race.” I will return to those matters in due course.

20 As identified in Toben v Jones (at [131]), and with Allsop J’s emphasis, the Attorney-General said the following about the Bill in the House on 15 November 1994:

The Racial Discrimination Act does not eliminate racist attitudes. It does not try to, for a law cannot change what people think. But it does target behaviour — behaviour that causes an individual to suffer discrimination. The parliament is now being asked to pass a new law dealing with racism in Australia. It too targets behaviour — behaviour which affects not only the individual but the community as a whole.

21 Section 18C(1) contains the proscription of certain conduct that is at the heart of this case. Subsections (2) and (3), dealing with the meaning of the requirement that the relevant act was done in public, are not relevant to the resolution of this case. Section 18C(1) is in the following terms:

18C Offensive behaviour because of race, colour or national or ethnic origin

(1) It is unlawful for a person to do an act, otherwise than in private, if:

(a) the act is reasonably likely, in all the circumstances, to offend, insult, humiliate or intimidate another person or a group of people; and

(b) the act is done because of the race, colour or national or ethnic origin of the other person or of some or all of the people in the group.

Note: [omitted]

22 Section 18B provides that if an act is done for two or more reasons and one of those reasons is the race, colour or national or ethnic origin of a person, whether or not it is the dominant reason or a substantial reason for doing the act, then the act is taken to be done because of the person’s race, colour or national or ethnic origin. It follows that in order to establish that a particular act is unlawful, the requirement in s 18C(1)(b) will be satisfied if it is established that the act was done at least in part because of the race, colour or national or ethnic origin of the relevant person or group of people.

23 Section 18D sets out exemptions from the proscription in s 18C, including the “fair comment” exemption in subs (c)(ii) on which Senator Hanson relies. The section as a whole is in the following terms:

18D Exemptions

Section 18C does not render unlawful anything said or done reasonably and in good faith:

(a) in the performance, exhibition or distribution of an artistic work; or

(b) in the course of any statement, publication, discussion or debate made or held for any genuine academic, artistic or scientific purpose or any other genuine purpose in the public interest; or

(c) in making or publishing:

(i) a fair and accurate report of any event or matter of public interest; or

(ii) a fair comment on any event or matter of public interest if the comment is an expression of a genuine belief held by the person making the comment.

24 The remaining sections in Pt IIA, ss 18E and 18F, deal with vicarious liability and State and Territory laws being unaffected. Those sections do not call for consideration in this case.

25 A contravention of s 18C(1) has three elements: (1) the relevant act must be done “otherwise than in private”, (2) the act must be “reasonably likely” to “offend, insult, humiliate or intimidate” and (3) the act must be done “because of” the race, colour or national or ethnic origin of a person or group of people. See Jones v Scully [2002] FCA 1080; 120 FCR 243 at [95] per Hely J; Bropho v Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission [2004] FCAFC 16; 135 FCR 105 at [63] per French J; Bharatiya v Antonio [2022] FCA 428 at [16]-[18] per Colvin J.

26 As mentioned above, there is no dispute in this case that the relevant act was done in public, so that aspect need not be considered any further. Senator Hanson submits, however, that neither the requirements of s 18C(1)(a) (para (a)) nor s 18C(1)(b) (para (b)) are met. She also submits that in any event the requirements for the operation of the exemption in s 18D(c)(ii) are met.

27 Arising from the statutory provisions and the ways in which the case has been put on both sides, the following issues have to be decided:

(1) Was Senator Hanson’s tweet reasonably likely, in all the circumstances, to offend, insult, humiliate or intimidate another person (relevantly, Senator Faruqi) or a group of people (which group needs to be identified)? These are the para (a) requirements.

(2) Did Senator Hanson publish the tweet in the terms that she did because of the race, colour or national or ethnic origin of the other person (again, Senator Faruqi) or of some or all of the people in the group (again, to be identified)? These are the para (b) requirements.

(3) If the para (a) and para (b) requirements are satisfied, was the tweet published, in the terms that it was:

(a) reasonably and in good faith;

(b) as an expression of a genuine belief held by Senator Hanson; and

(c) as a fair comment on an event or matter of public interest?

These are the elements of the s 18D(c)(ii) defence relied on by Senator Hanson.

28 If the answers to those inquiries lead to the conclusion that the publication of the tweet by Senator Hanson was unlawful under s 18C, then it will be necessary to decide whether the prohibition of a certain type of speech by s 18C as subject to the exemption in s 18D infringes the implied freedom of political communication in the Constitution rendering those sections invalid in full, or in part in setting the requirement for unlawfulness at too low a level by using the words “offend” and/or “insult” and/or “humiliate” in s 18C(1)(a).

29 If the prohibition is not constitutionally invalid, or if it is only partly invalid, it will be necessary to decide what remedy or remedies should be ordered.

Senator Faruqi’s witnesses and their evidence

30 In this section I summarise the evidence of Senator Faruqi and the witnesses called by her, mostly using the language used by them. I also consider the reliability of that evidence where that is relevant.

31 Senator Faruqi was born in Lahore, Pakistan in 1963. She is Muslim. I infer that she was born into a Muslim family although she was educated at a private Catholic school in Lahore. Senator Faruqi’s father studied at the University of New South Wales (UNSW) in the 1950s.

32 In 1988, Senator Faruqi graduated with a Bachelor of Engineering (Civil) degree at the University of Engineering and Technology in Lahore. She commenced work as a structural engineer with a firm of consulting engineers in Pakistan, holding that position until 1992. In the meanwhile, in 1989 she married Omar Faruqi. The couple have two children, a son who was born in Pakistan and a younger daughter who was born in Australia.

33 In 1992, the family emigrated from Pakistan and settled in Sydney, initially with permanent residency. Senator Faruqi has resided in Australia since then. She became an Australian citizen in 1994.

34 In 1994, Senator Faruqi completed a Master of Engineering Science, Environmental Management, Solid and Hazardous Water Management at UNSW. In 2000, she completed a Doctorate in Environmental Engineering, Wastewater Management and Energy Recovery at UNSW.

35 Between 1999 and 2013, Senator Faruqi worked in various positions consistent with her qualifications in engineering, including as a consulting engineer, for local councils and in academia.

36 In 2004, Senator Faruqi became a member of the political party, The Greens NSW. She ran unsuccessfully as a candidate for the Legislative Assembly seat of Heffron in 2011 and in a by-election in 2012. In 2013, Senator Faruqi was elected to the NSW Legislative Council, becoming the first Muslim woman to be a member of any Australian Parliament. She held that position until August 2018 when she resigned to enter federal politics.

37 On 20 August 2018, Senator Faruqi was sworn in as a Senator for NSW in the Federal Parliament. In doing so, she became the first female Muslim Senator. In order to be eligible for the Senate, Senator Faruqi had to, and did, renounce her Pakistani citizenship. Senator Faruqi holds the “Republic” portfolio for the Greens.

38 Senator Faruqi gave evidence of her experience of racism in Australia before the events at the centre of this case. She spoke of a number of incidents over the years in which she was made to feel that she was being treated differently or being mistrusted because she is a woman of colour, and when she was identifiable as being an immigrant and Muslim. She gave evidence of how, in various ways, she or her family were made to feel unwelcome or different, ie they were “othered” in the sense of being conceptualised as intrinsically different from and inferior to the prevailing social group and thereby excluded from it.

39 Senator Faruqi explained that when she entered politics, her experience of racism intensified. Often that was reflected in people responding to things that she said by attacking her as a person, rather than criticising her message or stance. They have included telling her that she is “not from Australia” or that she “doesn’t belong here.” Her Muslim identity has often been the focus or subject of the attacks.

40 Senator Faruqi explained that she feels that some people do not want her in Australia because she is Muslim. She feels that they consider Muslims to have an outlook and a way of life that is incompatible with modern Australia. Senator Faruqi’s experience is that anti-Muslim sentiment, or Islamophobia, is based on a racialized stereotype and that hateful comments about her religion are also tied to where she comes from and her ethnicity.

41 Senator Faruqi and her staff maintain several social media accounts in her name – Facebook, Twitter and Instagram. At the relevant time, Senator Faruqi had about 40,000 followers on Twitter, and Senator Hanson had “a lot more”, “thousands and thousands of people.”

42 In cross-examination, Senator Faruqi explained that she and her staff drafted the tweet about the Queen having died. She said that she chose the words carefully, intending to put some issues on the political agenda which she felt should be discussed and debated. She wished to put her views on the record and for people to debate them.

43 Senator Faruqi explained that in the tweet she was stating a fact of how she felt about the Queen dying and about the British Empire and its legacy of colonialism. She was raising the issues of Australia becoming a republic and the conclusion of a treaty with First Nations people. She felt that that was a time when people would be more attuned to those issues. It was a time when people would be talking about those issues.

44 Senator Faruqi denied that the tweet incorporated false words of condolence, or that her condolences were disingenuous. She said that the tweet was a genuine and honest statement of her feelings and beliefs at the time.

45 Senator Faruqi said that she found Senator Hanson’s tweet to challenge her sense of belonging and her sense of self; it had a triggering effect. She found it to be insulting and humiliating. She said that it made her feel like she was not accepted and that she did not belong in Australia. It caused her to cry. She was scared of the response that Senator Hanson’s tweet would encourage in others – that it would “encourage others to join the chorus of hate.” Senator Faruqi said that, over a long period of time, she has suffered sleepless nights and on occasion woken up in great distress because of the trauma induced by the tweet (T82:1-6).

46 The responses on Twitter to Senator Faruqi’s tweet in the period between it being published and Senator Hanson’s tweet being published were tendered. Many of the tweets are personally abusive, including in racist and Islamophobic ways, although some are supportive of her and the views expressed in her tweet. Only a few express the sentiment “go back to where you come from”, or variations of it. The overwhelming majority are disapproving, in one way or another.

47 Following the publishing of Senator Hanson’s tweet at 4.05pm on 9 September 2022, Senator Faruqi was the target of intense abuse across her social media accounts as well as by phone calls to her parliamentary office and emails to her parliamentary email address. It is a common theme of a substantial proportion of the abusive messages that Senator Faruqi should “piss off back to Pakistan” or “piss off back to where she came from.” Another common theme of a substantial proportion of the abusive messages is that Senator Faruqi is in some way less entitled, or not entitled at all, to make critical comments about Australian colonial history because she is not “from” Australia. Yet another theme is that Senator Faruqi is in some way hypocritical for having “taken” the benefits of Australia and now has the audacity to make criticisms, without any acknowledgement in those messages of Senator Faruqi’s contribution to Australia over 31 years including some 10 years of public service.

48 Senator Faruqi said that the impact of Senator Hanson’s tweet made her think like never before of the consequences and impacts of “telling it like it is” for someone like her in Australian politics. It had a silencing effect on her. She said that she found that after the tweet she moderated herself when speaking about colonialism or racism because those topics generate such hate. She said that she finds that she is constantly monitoring and being selective about what she feels she can or should respond to out of fear of the backlash. Senator Hanson’s tweet, and the responses that it generated, have made Senator Faruqi feel “small, ‘othered’ and isolated.”

49 Senator Faruqi explained that there are already many barriers for political outsiders like her, and that every time she rises above the barriers – like becoming a Senator – she has to consider the repercussions and toll of that. She has to make decisions about whether she responds to racist vitriol, or whether she remains quiet and merely absorbs the hatred. She said that choosing to stay silent means that the racist vitriol continues, but standing up and calling it out means that it is directed more intensely at her. Being a public figure does not inure her from the harm and psychological damage that comes from experiencing racism.

50 The emotional toll is an everyday experience, which felt so much worse when the attack came from a workplace colleague, Senator Hanson. Senator Faruqi experienced Senator Hanson’s tweet as “a direct attack from a colleague” in her workplace; “a very direct attack from a colleague with a big platform.” Senator Faruqi finds it extremely stressful being in a workplace with someone who has attacked her in that way. She said that she has a physiological reaction to going into the Senate chamber to sit in close proximity to someone who has caused so much distress for her.

51 Senator Faruqi accepts that it is perfectly acceptable for Senator Hanson to object and respond to her comments about the Queen and to engage in a debate about the Queen’s legacy. However, she found being told to “piss off back” to where she came from as insulting, offensive and humiliating.

52 It is not just the final sentiment of “piss off back to Pakistan” that Senator Faruqi found offensive and insulting. The first part of Senator Hanson’s tweet about Senator Faruqi being an immigrant and not having the right to the same things or opportunities that other people have in Australia including the same right or opportunity to express herself was experienced by her as being insulting and humiliating. Senator Faruqi also felt intimidated by the tweet because her workplace was made to feel hostile and unsafe. She felt that it could happen again, and that there is a threat of physical violence from people who might feel emboldened or encouraged by Senator Hanson’s tweet.

53 On the day that Senator Faruqi announced to the media that she was commencing this proceeding, she received a threat on social media that included the street address of her electoral office and the words “See you real soon you fucking dead cunt.”

54 Senator Faruqi was an impressive witness. She was thoughtful and careful in her evidence, and despite significant provocation in cross-examination retained her composure and grace. I gained the clear impression that she was doing her best to recollect matters correctly and give true and accurate evidence.

55 The provocations include it being put to her that she is a hypocrite because she is an immigrant to Australia and yet she is critical of Australia. That is provocative because it suggests that Australian citizens who are immigrants are less worthy citizens than those who are not immigrants and that one cannot be loyal to one’s country and be critical of it at the same time. It was put to her that her denial that she had understood Senator Hanson’s tweet as telling her that she had “lived a good and fulfilled life in Australia” was disingenuous (T67:39-68:14), when plainly that was not the message of the tweet. It was also put to her that by her tweet she was accusing all non-Indigenous Australians of having engaged in a joint act of stealing land (she was not) (T60:1-5). It was said to her that she had “denigrated Jews” and that the only reason she was interested in what was referred to as the genocide in Gaza was “because it is being engaged in by Jews” as demonstrated by her not having “said anything … politically or publicly about the genocide of the Armenians by the Turks” (a reference to events that took place more than 100 years ago) (T84:40-85:2). In the face of all that, Senator Faruqi maintained her equanimity.

56 It is submitted on behalf of Senator Hanson that Senator Faruqi’s evidence should be approached with caution. Three criticisms are raised in that regard. The first is that she was unwilling to accept what was said to be the obvious basis for Senator Hanson saying in her tweet that Senator Faruqi was “not happy”, namely the content of Senator Faruqi’s tweet. Senator Faruqi was asked whether she understood the words “it’s clear you’re not happy” to be a reference to her tweet earlier that day, to which Senator Faruqi answered, “I did not” (T68:16-17). Senator Faruqi went on to say that she has no idea why that was said of her because she is very happy in Australia (T68:19-21), and that she did not see her tweet inferring anything about her happiness or unhappiness in Australia (T68:26-29). Those are perfectly legitimate and understandable answers. There is nothing in them that constitutes evasion from accepting the obvious.

57 The second criticism of Senator Faruqi is said to be her claim that “colour” was implicit in Senator Hanson’s tweet which, it is said, self-evidently involved no such notion (T68:45-47). It is true the words in Senator Hanson’s tweet did not refer to skin colour. Beyond that, there is nothing self-evident about it. The tweet was directed to a Muslim woman of colour who immigrated from Pakistan and instructed her, in particularly rude and emphatic terms, to “piss off back to Pakistan.” As I will come to in more detail, that statement is a variation of an age-old racist trope. As Senator Faruqi said in the next exchange, the reference to her national origin was a reference to Pakistan “where almost 100 percent of the people look like me” (T69:1-2). There is nothing unreasonable in Senator Faruqi seeing “colour” being implicit in Senator Hanson’s tweet.

58 The third criticism is that Senator Faruqi claimed to hold the view that there is no place for offensive conduct or comments in day-to-day political discourse despite her own political comments including in relation to Prime Minister Scott Morrison in 2019 (T82:43-46). Senator Faruqi had said the following in her affidavit in the context of explaining why she felt insulted by Senator Hanson’s tweet:

I don’t think there is a place for offensive conduct or comments in day-to-day political discourse. I feel offending and insulting comments are often couched as robust debate, but I think there is a clear line between being insulting and offensive to someone and robust debate. You can have really good, robust debate without being offensive or insulting.

It was put to Senator Faruqi that she was not being honest when she said that, which she denied (T82:47). The asserted basis for dishonesty, which was not put to Senator Faruqi, is that on 10 December 2019 during the severe New South Wales bushfires at that time, Senator Faruqi had posted a tweet saying “just fuck off” in response to it being said that the Prime Minister had rejected calls for more assistance to fire fighters (T52:12-35; Exh R5/3). In that earlier exchange, Senator Faruqi had accepted that her tweet used very strong language but she defended it on the basis that it did not attack anyone personally and it was not racist. Although the tweet might be regarded as attacking the Prime Minister personally, that is not really the point. The point is that one can simultaneously hold a belief that there is no place for offensive and insulting conduct and comments in day-to-day political discourse, yet on one occasion more than four years earlier have publicly made an offensive or insulting comment about a political opponent. There is no basis on which the reliability of Senator Faruqi’s evidence can be criticised on that inconsistency or tension, if indeed it is that.

59 In the circumstances, I consider Senator Faruqi’s evidence to have been unshaken in cross-examination and I accept it.

60 Senator Faruqi relies on the evidence of nine witnesses who were referred to at trial as the autobiographical witnesses. Each is a person who responded to a public invitation published by Senator Faruqi to document the effect that Senator Hanson’s tweet had on them. Each deponent states their demographic characteristics by which they identify including, by way of example, “person of colour”, “person of migrant heritage”, “Muslim”, “culturally Jewish”, and so on, and cites their experiences of discrimination on the basis of one or more of those characteristics. Their evidence is potentially relevant to the para (a) inquiry, ie the likelihood of Senator Hanson’s tweet causing one of the identified results. See Faruqi v Hanson (evidence rulings) [2024] FCA 225 at [39]-[49].

61 None of the autobiographical witnesses was required for cross-examination. I accept their evidence.

62 Anna Ellen Sri was born in Australia in 1989 and is an Australian citizen. She identifies as a person of colour because her father is Tamil. She also identifies as a person of migrant heritage because her father is an immigrant from Sri Lanka in the 1980s. Dr Sri is a veterinarian.

63 Dr Sri saw and read Senator Hanson’s tweet on or about the day it was published, her attention possibly having first been drawn to it through media coverage about it. Dr Sri said that she understood the tweet to be telling Senator Faruqi to go back to where she was born, ie Pakistan. She felt that the use of the language “piss off” rather than merely “go” conveyed a higher degree of intolerance.

64 Dr Sri said that she also understood the tweet to convey the message that Senator Faruqi is not welcome in Australia and is not permitted to contribute to public discourse about matters which impact Australia because she was born in Pakistan. That is, Senator Faruqi and other people of colour, such as Dr Sri, should know their place in Australia, which is to be grateful and not provide any critique or even basic suggestions for improvement to Australia.

65 Dr Sri said that she felt humiliated and intimidated by the tweet. She felt humiliated because it reminded her of experiences that she had during her childhood growing up in Australia as a person of colour. She was intimidated because both Senator Hanson and Senator Faruqi are public officials – if someone like Senator Faruqi can be victimised by that kind of racism, then other immigrants and people of colour in Australia are even more vulnerable.

66 Dr Sri gave some examples of her personal experiences of racism. She said that she clearly remembers as a child seeing coverage of Senator Hanson saying that Australia was in danger of being “swamped by Asians”. Because she had been told that she “looked Chinese”, she felt that Senator Hanson’s comments applied to her. She also recalls Senator Hanson saying words to the effect of “I’m just saying what everyone is thinking.” Dr Sri felt that that normalised and legitimised the anti-Asian sentiment. Dr Sri was thereby made to feel paranoid that the majority of people, including her classmates, did not accept her or had negative thoughts about her because she “looked Chinese.”

67 Dr Sri remembers that Senator Hanson’s comments undermined her sense of self-confidence and caused her to internalise feelings of inadequacy and a lack of acceptance and appreciation by the wider Australian society. She recalls feeling as though she had to consistently demonstrate good behaviour and perform at a high level to maintain acceptance in society and in her school community.

68 Dr Sri recalls, in the early 2000’s, seeing bumper stickers with words to the effect of “if you don’t love it, leave” and “fuck off, we’re full.” She interpreted the bumper stickers to mean that if you are a migrant or a person of colour, then you are not allowed to offer critiques or suggestions about how to improve Australian life but instead had to be grateful.

69 Dr Sri said that as a result of her experiences of racism, she has felt scared, paranoid and intimidated, particularly when meeting new people and going into new situations with an unknown group of people, she has suffered depression and her sense of self and self-confidence has been negatively impacted. She said that she has felt unwelcome in Australia, even though she was born in Australia and it is the only place where she has ever lived. She has felt silenced and dismissed, and that she does not have the right to voice her thoughts and feelings particularly around subjects such as political issues including issues of racism, migration and refugees.

70 Ayan Abdirashid Ali is a student who identifies as being of Somali origin which is where her parents are from, although she was born in Italy in 2000. She is Muslim and wears a hijab. She has lived in Australia since 2001 except for a period of four years when she was in high school and lived in the United Arab Emirates (UAE).

71 Ms Ali saw Senator Hanson’s tweet on Twitter on 9 September 2022. Ms Ali interpreted the phrase “piss off back to Pakistan” in the tweet as a variation of the phrase “go back to where you came from”, which to her is a hateful, inflammatory and xenophobic phrase that she knows very well. As a person of colour from a culturally and linguistically diverse background, and an immigrant and a Muslim, Ms Ali has previously been told words to the effect of “go back to where you came from.” Senator Hanson’s tweet thus reminded her of her experience of those words. She felt personally offended by the tweet even though it was not directed to her personally.

72 Ms Ali said that she felt insulted and humiliated by the tweet, including because it came from a Senator, being an important position in Australian society, with a significant platform. Also, if Senator Faruqi could be the subject of such abuse, then ordinary people like Ms Ali could never be safe from such discriminatory words and sentiment.

73 Ms Ali said that she felt intimidated by Senator Hanson’s tweet because it gave a platform and a voice to people who share similar thoughts and feelings. She saw that the tweet generated a significant volume of hatred and discrimination directed towards Senator Faruqi, including threats of violence. Knowing that people with those views could be anywhere around her made Ms Ali feel intimidated, hopeless, scared and unwelcome in the country that she calls home. On many occasions she has felt unsafe in public spaces.

74 Ms Ali recounted various instances of racism or other abuse based on her colour, ethnic origin or religion experienced by her. These included, for example, people yelling words to the effect of “fucking Muzzos” and “black bastards.”

75 One of the earliest experiences of racism recalled by Ms Ali occurred when she was about eight years old. She and her older sister, who at the time was about 10 years old, were in a local shopping centre when an older white man approached them and angrily yelled in their faces words to the effect of “go back to where you came from.” Ms Ali felt terrified, confused and upset. She and her sister began crying. She said that she was made to feel like she did not belong in Australia and that she was unwelcome in her own home. She recalls thinking that she did not know where else she was supposed to go.

76 In another incident, she and her four sisters had the day off from their Islamic school to celebrate Eid. They were in a park with their father playing football when a white man approached their father and yelled at him words to the following effect: “why aren’t your kids in school?” The man also said words to the effect of “you are illiterate” and “you will need to integrate into the Australian way of life.” The man later unleashed his dog which chased Ms Ali’s family.

77 Ms Ali recalls that since living in Australia, and at least up until 2015, people regularly said words to the effect of “go back to where you came from” to her. Since 2019, after she returned from the UAE, she feels that she has fortunately experienced overt racism less frequently. She nevertheless recounted some incidents of such racism, in particular instances where people seemed surprised to find her, a person of colour wearing a hijab, in a professional setting.

78 Ms Ali said that she has suffered various impacts in her day-to-day life from her experiences of racism. She has felt scared and intimidated and has on occasion even felt scared to wear her hijab in public. She said that she has learned to hide from people in public. By “hide”, she means different things depending on the situation. For example, she might not go to certain public spaces at certain times, or when it is difficult to avoid public spaces she has kept to herself, keeping her head down and walking quickly in situations that make her feel uncomfortable. Hiding has also taken the form of running away and hiding from people that have made her feel unsafe, or who have shouted or said aggressive things to her. She said that she is constantly hypervigilant.

79 Coco-Jacinta Cherian was born in Western Australia in 1997. She is a person of colour and a person of migrant heritage. Her father, and his parents before him, were born in India. She works as a program support officer.

80 Ms Cherian cannot remember when she first saw Senator Hanson’s tweet, although she believes that it was on Instagram in the week following the Queen’s death.

81 When she first read the tweet, Ms Cherian felt that Senator Hanson was telling Senator Faruqi to “go back to where she comes from” which is a hurtful phrase for her that has often been directed to her. She also understood the tweet to be saying that Senator Faruqi is not deserving of the same rights and entitlements as people who are born in Australia and that if Senator Faruqi wishes to live in Australia, she needs to act in a certain way. That would include not criticising Australia’s history and its ties to the monarchy and colonialism.

82 Ms Cherian said that she was offended by Senator Hanson’s tweet, understanding it to express the sentiment that there is a hierarchy of races and that “whiteness” is to be preferred over “colouredness.” She felt humiliated by the tweet by being made to feel embarrassed to be a person of colour. She felt insulted by the idea that she will not be accepted fully as part of Australian society unless she behaves in a certain way.

83 Ms Cherian also gave evidence of her experiences of racism in Australia. Those include experiences as a young member of the cast of the iconic Australian television series Neighbours – there was racist backlash to the idea of people of Indian background living on the show’s “Ramsay Street.” That included being told that she and her fellow cast members of Indian heritage should go back to where they came from and that the show should only feature “real Australians.” Such sentiments caused Ms Cherian to question whether she did in fact belong in Australia or had a right to be cast in Neighbours. She also started to hate her race and hate that part of her that is Indian. She recalls not liking her skin and not feeling comfortable in it.

84 Daniel Jacob Levy is a student. He was born in Australia in 1989. He identifies as being culturally Jewish, although he does not practice the Jewish faith. Mr Levy also identifies as a person with migrant heritage because his four grandparents were born in Lithuania, Poland, Germany and Latvia before migrating to Australia. They fled Europe before and after World War II as Holocaust survivors.

85 Mr Levy saw Senator Hanson’s tweet on 9 September 2022 on his personal Twitter account. Mr Levy understood the tweet to be telling Senator Faruqi to go back to where she came from, and that it conveyed the notion that if someone from a migrant background does not like living in Australia (because, for example, they have criticised certain aspects of Australian life, politics or history) then they should leave Australia. He understood the phrase “piss off back to Pakistan” to convey the same message as, to him, the common racist phrase “fuck off, we’re full.”

86 Mr Levy said that he felt offended, insulted, humiliated and intimidated by Senator Hanson’s tweet. He felt that the words used by Senator Hanson were xenophobic, and he is deeply offended by xenophobia. He believes that the sentiments conveyed by Senator Hanson in her tweet are the same as have previously been used against Jewish people. Because of that, even though the tweet was not directed at him, he felt personally insulted by it because he is Jewish.

87 Mr Levy said that his strongest reaction to the tweet was that he felt intimidated. That is because the tweet evoked a deep sense of intergenerational trauma that he believes that he suffers from as a result of being a descendant of Holocaust survivors. The intimidation was heightened because of Senator Hanson’s position of political leadership and because Senator Faruqi is part of a racial minority in Australia.

88 Mr Levy gave evidence of his experience of anti-Semitism and other discrimination or hatred directed at him for being Jewish. For example, when he was about eight years old he was playing community sport with his Jewish football club. He recalls some opposing players walking past his team and saying words to the effect of “bloody Jews” to them.

89 Mr Levy said that, because of his family history, he is constantly anxious about fascism taking root again, and what it would mean for him and everyone he cares about. That is especially aggravated for him when political leaders campaign on xenophobia and bigotry in general, which he sees to be hallmarks of fascism. He gave evidence of the negative effects of anti-Semitism on his mental health.

90 Fatima Hasan was born in 1991 in Lahore, Pakistan. She identifies as being of Pakistani origin and is Muslim. She immigrated to Australia in 2016. She works as a nurse.

91 Ms Hasan believes that it is likely that she saw Senator Hanson’s tweet on Twitter on or about 9 September 2022. She understood the tweet as an attack on her personal identity as an immigrant to Australia because, like Senator Faruqi, she was born in Pakistan. She interpreted Senator Hanson’s tweet as racist and xenophobic. She felt offended, insulted, humiliated and intimidated by the tweet.

92 She said that she was offended because she understood that the words “piss off back to Pakistan” and the sentiment conveyed by them were directed towards everyone originally from Pakistan, including her. She took those words personally. They made her feel like all the hard work that she had done in her life and particularly during the time that she has lived in Australia meant nothing because she was made to feel like she does not belong in Australia.

93 She said that reading the tweet reminded her of her previous experiences of racism which reactivated trauma and insult. It made her realise that attitudes she had experienced in the past had not changed. She felt humiliated because she understood the tweet to be a direct threat that challenged her right to continue to live in Australia.

94 Ms Hasan said that she felt intimidated by the tweet because she believed that the thoughts and views expressed in the tweet by an elected politician with a large public profile must represent the thoughts and views of people who had voted for Senator Hanson or who follow her on Twitter. She fears being subjected to racist comments or attacks, verbal or physical. After seeing Senator Hanson’s tweet, she saw numerous racist comments directed at Senator Faruqi from other people on Twitter which reiterated the thoughts and views of Senator Hanson conveyed in the latter’s tweet. Ms Hasan remembers thinking that by publishing the tweet, Senator Hanson had given a voice to many other people in Australia that share her views; it was as if Senator Hanson had magnified those racist views.

95 Ms Hasan said that she cried after reading Senator Hanson’s tweet. The sadness subsequently turned into desperation and anger. She recalls thinking that if someone like Senator Faruqi, an elected politician, is unable to escape racism and discrimination in Australia, then there is nothing that Ms Hasan will ever be able to do to reduce or stop racist incidents against herself.

96 Ms Hasan gave evidence about her experiences of racism in Australia during her work in a rural nursing placement and in hospitality. Those experiences include being told words to the effect of “go back to where you came from”, “where are you really from?” and “did you come here by boat?” He also recounted experiences of a patient not wanting to be treated by her, asking for “an Australian nurse”, and being asked by a patient whether she was qualified because she was “not from Australia.”

97 Ms Hasan’s experiences of racism have caused her to feel like she does not belong in Australia, and to feel as though she cannot continue to be a nurse in Australia because people do not accept her, or refuse care from her, because she was not born in Australia. She has been caused to feel suicidal, to feel like a failure, and to have suffered hypervigilance at work.

98 Muhammud Yunus Moolla was born in 1984 in Cape Town, South Africa. He identifies as being of African origin and Indian because he is a fourth-generation South African whose relatives immigrated to South Africa from India. He is Muslim, although he considers himself to be non-religious and is not a practising Muslim. He immigrated to Australia with his wife in 2017 and is an Australian citizen. He works as a manager.

99 Mr Moolla believes that he saw Senator Hanson’s tweet on or about 9 September 2022 on his Twitter account. He understood the tweet to mean that non-white immigrants to Australia, including Senator Faruqi, are inferior to and should be fearful of “white” Australians; that they are less deserving of occupying space within Australia because they were not born here.

100 Mr Moolla said that the tweet made him feel that as a non-white immigrant to Australia, his identity as an Australian will always be under threat even though he is an Australian citizen. He felt that his “Australian-ness” and his place within Australia will never be whole and could be taken away by Senator Hanson, or any white Australian, at any time if he does not behave in a way that other white Australians expect him to behave. He felt that the tweet conveyed that non-white migrants to Australia will never be entirely welcome in Australia because Senator Hanson was telling Senator Faruqi and other non-white immigrants to Australia to go back to where they came from.

101 Senator Hanson’s tweet reminded Mr Moolla of having been told words to the effect of “go back to where you came from” and other incidents of overt racism experienced by him on many occasions. The tweet brought up trauma and the feelings of fear, humiliation and anger that he associates with being the subject of racist abuse in Australia.

102 Mr Moolla said that he felt intimidated by Senator Hanson’s tweet because it scares him that Senator Hanson, an Australian Senator with a significant public profile, would say those words publicly to another Australian, let alone another Senator. He believes that if someone like Senator Hanson can hold those views and engage in that kind of conduct, it amplifies and legitimises similar views held by other individuals living in Australia. That makes him scared for his own safety and also for the safety of other migrant people living in Australia. He also feels unable to fight back against that kind of conduct out of fear that the situation could escalate and that he would be at risk of being subjected to physical violence.

103 Mr Moolla gave evidence of racist experiences suffered by him. They included being told by a man on a bus “you are not Aussie”, and being told “oh she’s like you, just go marry her” in relation to a woman who appeared to be of Middle Eastern descent who boarded the bus. Such incidents have caused him to feel angry and fearful, that he was doing something wrong, and that his identity as an Australian, and his right to exist in Australia as a human being, had been taken from him.

104 Sana Ashraf was born in Pakistan in 1990. She migrated to Australia in 2015 to do a PhD at the Australian National University (ANU) which she completed in 2019. She married an Australian man and became an Australian citizen in June 2023. She works as a public servant.

105 Ms Ashraf believes that she saw Senator Hanson’s tweet on social media in the week following the Queen’s death. She understood the tweet to be telling Senator Faruqi to go back to Pakistan, or to go back to where she comes from. She understood the strength of the language in “piss off back to Pakistan” to express hatred and intolerance and to be telling Senator Faruqi that Senator Hanson was not willing to tolerate her continued presence in Australia.

106 Ms Ashraf said that she was offended, humiliated, insulted and intimidated by Senator Hanson’s tweet. She felt that it is dismissive of Senator Faruqi’s existence as an Australian citizen. She finds it offensive as an immigrant to Australia. She felt that the tweet expressed what she has experienced to be a popular sentiment amongst some Australians, which is that she is not truly accepted because of her migrant heritage and that it is not acceptable for her to share an opinion about life in Australia which is not positive. She feels as though she can only be accepted as an Australian citizen on a conditional basis – as long as she is grateful for the fact that she lives in Australia, she will be liked and accepted.

107 Ms Ashraf said that she felt intimidated by the tweet because it made her feel unable to participate fully and freely in political and societal discussions, as though she does not have the right to share her opinions in her own country.

108 Stephen Mandivengerei, who works as a support worker, was born in 1975 in Chiredzi, Zimbabwe (then Rhodesia). He identifies as being of African origin, of Mbire ethnicity and a person of colour. Mr Mandivengerei immigrated to Australia in 2008 with his wife and two children. They now have a third child. All three children are Australian citizens.

109 Mr Mandivengerei does not recall seeing Senator Hanson’s tweet until he saw a Facebook post by Senator Faruqi in June 2023 in which she invited people to fill in an online survey about their responses to the tweet. That caused him to conduct some internet searches which turned up Senator Hanson’s tweet.

110 Mr Mandivengerei understood Senator Hanson’s tweet to be telling Senator Faruqi to go back to Pakistan. However, in his view the words “piss off back to Pakistan” are a stronger, more vulgar and unkind way of saying “go back” and they convey a higher degree of anger, exasperation or disgust. He felt offended, insulted and intimidated by the tweet.

111 Mr Mandivengerei said that he felt offended and insulted because he was reminded of previous incidents when he had been told to “go back to where you came from” by people in Australia. Further, he said that the fact that the views expressed in the tweet were expressed by one Australian Senator to another added to the overall offence and insult he experienced as a result of the tweet. He felt that those views must also be held by a broader section of Australian society, as represented by Senator Hanson.

112 Mr Mandivengerei said that he felt intimidated by the tweet because it caused him to realise that the racism and discrimination that he previously experienced can happen at all levels within Australia and can happen to people who hold high positions. He felt silenced by the tweet, and that Senator Hanson had normalised the views expressed in the tweet.

113 Mr Mandivengerei gave evidence of his experiences of racism, particularly in the workplace. They included his work colleagues giving him a nickname based on a character from a 1975 movie who was black and had abnormally large genitals. His complaint about his colleagues using that nickname for him was dismissed by his manager on the basis that “giving a nickname to a person is part of Australian culture and is a sign of mateship.” Racist incidents suffered by him have caused him to feel scared and intimidated, including at times feeling physically unsafe and fearful that he would be subjected to racial violence. He has felt hopeless and powerless because when he has tried to raise complaints they were not taken seriously and nothing was done.

114 Swikriti Kattel was born in Nepal in 1997 and identifies as a person of colour. She immigrated to Australia in 2015 and currently works as a management consultant.

115 Ms Kattel saw Senator Hanson’s tweet on the day that it was published on Twitter. She understood the words “piss off back to Pakistan” as a variation of the “go back to where you came from” rhetoric. She was reminded by the tweet that such harmful rhetoric is still prevalent in Australia. She interpreted the choice of words as being more hateful and more disrespectful than saying “go back to where you came from” because of the harshness of the language in the phrase “piss off.”

116 Ms Kattel said that she felt offended by the tweet, in particular because someone in the position of a Senator had expressed such views publicly and garnered support from other Australians without appearing to be concerned about the consequences. She felt that the tweet expressed the view that Senator Faruqi was unable to express her opinion about controversial issues because of her ethnicity despite the contributions that she has made to Australia and the fact that she is an elected official.

117 The tweet caused Ms Kattel to feel that no matter what she did for the Australian community or how much she contributed, her contributions would have a reduced impact and would always be less respected; she would be likely to be treated as a second-class citizen because she is an immigrant. The tweet made her feel angry and defeated because it brought back memories of previous experiences of racism since moving to Australia.

118 Ms Kattel gave evidence of her experiences of racism. They include incidents when she was working in a McDonald’s in Perth as a student and she was told things by customers such as “hop on a camel and go back to where you come from” and “you’re stealing jobs from Australians.” Ms Kattel’s experiences of racism have made her conscious about how she appeared and dressed and what she said and how she said it in order to avoid it being thought that she did not belong or fit in Australia. She has been made to feel self-conscious and anxious, as well as alone and depressed.

119 Senator Faruqi relies on the evidence of three expert witnesses.

120 Professor Paradies holds the Chair in Race Relations in the Faculty of Arts and Education at Deakin University. He has held that position since March 2014. Before that he worked in various positions, including as a Research Officer at the Australian Bureau of Statistics, a Research Fellow at the Menzies School of Health Research and a Senior Research Fellow at the University of Melbourne. He has a PhD in social epidemiology from the University of Melbourne. Professor Paradies conducts research on the health, social and economic effects of racism as well as anti-racism theory, policy and practice across diverse settings, including online, in workplaces, schools, universities, housing, the arts, sports and health.

121 Professor Paradies says that based on a large and consistent body of existing literature, it is clear that racism can result in both acute and chronic emotional and physiological impacts. In particular, racist conduct is a pernicious form of stress that can have significant consequences for immediate emotional and psychological health and can also result in long-term pathophysiological changes that affect both mental and physical health.

122 At the individual level, racism can cause immediate sequelae such as shock, denial, anger, rage, frustration, fear, anxiety, guilt, shame, sadness, suppression, distress, and so on.

123 In the medium to long-term at a population level, racism has been linked to a range of mental and physical health outcomes, including anxiety, depression, suicidality, high blood pressure, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, genetic damage, inflammation, poor immune functioning, and so on.

124 Racism is also a social determinant of health that shapes people’s environments, resources and opportunities, driving diverse pathways leading to ill-health. Racism impacts jobs and careers, education, formal and informal networks, transport, recreation, housing and access to healthcare.

125 Racism can directly affect the body through activating the stress response, resulting in short, medium and long-term biological changes. Through mechanisms such as epigenetic changes, exposure to racism in one generation might propagate adverse health effects to subsequent generations. For example, a recent study found that in models adjusting for covariates, including socio-economic status and health status, Māori mothers who experienced a racist physical attack during pregnancy had children who, at 4.5 years of age, had significantly shorter telomere length than children of Māori mothers who did not report a racist physical attack during pregnancy. Telomeres are structures made from DNA sequences and proteins found at the ends of chromosomes required for cell division. They cap and protect the end of chromosomes.

126 Racism is perceived as, and often is, a threat which activates stress response pathways. Being exposed to racism regularly over the course of one’s life can lead to chronic activation of an energy-consuming emergency response that results in physiological wear and tear as well as dysregulation at the cellular level. It can lead to poor self-worth, self-efficacy and self-esteem.

127 Professor Paradies gave evidence that Senator Hanson’s tweet is a common form of racism which can be described as “go back to where you came from.” A 2011 study surveyed 580 culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) Victorian women from four local areas in Victoria, including both rural and urban communities. They were asked, amongst other questions, whether someone had suggested to them that “you do not belong in Australia, that you should ‘go home’ or ‘get out’ and so on.” Among the 35.2% (n=204) of Muslim women participants, 50% (compared to 36.4% of non-Muslim women) reported being told that they do not belong, and that they should “go home” or “get out.” Adjusting for local government area, education, age, country of birth and duration of residence in Australia, Muslim women had 1.61 times the odds of being told that they do not belong in Australia and should go back to their country, compared to non-Muslim women. After experiencing this form of racism, 33.8% of Muslim women who were surveyed (compared to 24.2% of non-Muslim women) were above the threshold for high or very high psychological distress.

128 The survey showed that even Indigenous Australians are often subject to that form of racism. In a survey among 755 Aboriginal Australians in communities across Victoria in 2011, two thirds of participants reported being told that they do not belong or that they should “go home” or “get out.”

129 Professor Paradies explained that vicarious racism, also known as secondary racism or second-hand racism, refers to a form of racism experienced by individuals who are not directly targeted but, instead, witness, learn of after-the-fact, or indirectly encounter racism directed at others. Vicarious racism has been associated with anxiety, depression, stress, trauma symptoms and other socioemotional and mental health outcomes.

130 Professor Paradies was instructed that the relevant “Group Attributes” were: persons of colour, migrants to Australia, persons with migrant heritage born in Australia, persons who by virtue of their appearance have been incorrectly identified as migrants, Muslim people, persons with visible signs or expressions of religion, persons who have been told to “go back to where you came from” or variations of that phrase due to their race, colour national or ethnic origin, and persons who have experienced racism. He said that a person who shared one or some of the Group Attributes and read Senator Hanson’s tweet is likely to be negatively impacted via vicarious racism, with one or more of the immediate sequelae of racism likely to ensue, viz. shock, denial, anger, rage, frustration, fear, anxiety, guilt, shame, sadness, suppression, distress, and so on.

131 That opinion of Professor Paradies was challenged in cross-examination. Professor Paradies explained that Senator Hanson’s tweet is an example of “a fairly strong form of racism – it’s exclusionary, and it’s very much about who belongs and who doesn’t belong.” For that reason, he said that the tweet would be likely to have a negative impact on people who had experienced a similar thing themselves.

132 He explained that the extent to which they would be negatively impacted would depend on a number of factors such as their previous experiences of racism, especially this form of “go back to where you came from” racism, the potential for and history of exclusion from public life to racism of this kind, and other aspects of their life situation including their overall and racism-related resilience.

133 Professor Paradies was asked whether the impact experienced by the person would likely be exacerbated when the publisher of the phrase “go back to where you came from” is a colleague, a person with a significant public profile or an elected public official. Professor Paradies cited a study which found that interpersonal discrimination (ie negative behaviours that occur in everyday workplace social interactions) was at least equally harmful, and in many cases more harmful, than formal discrimination (ie decisions such as hiring, promotion or compensation).

134 Professor Paradies explained that racism is a function of power plus prejudice – people with significant public profiles have considerable power through the importance attached to fame in modern societies. Similarly, elected public officials also occupy positions of considerable power in representative democracies. Racism from those in positions of power is likely to have a heightened impact due to the increased threat (perceived or real) of abuse, harm, oppression, marginalisation, restriction, exclusion, ostracisation, disadvantage, deprivation, etc, both directly from the powerful perpetrator themselves and, more importantly, from the authorising effect of such racism through its influence on the general public. Among the general public there will be those who feel empowered to emulate, model and imitate such racism.

135 In cross-examination, Professor Paradies accepted that it is possible for there to be racism to or against white people, or on the basis of being of British descent (T96:35). He did not accept that criticising British colonialism could amount to racism against people of British descent (T97:13) and explained that there is a difference between criticising or critiquing societal institutions or societal processes, particularly those also engaged in by other nations, and making a critique of the people within the society (T120:5-14). In re-examination he explained that power within society is a significant moderator in relation to racism and its effects. Studies have shown that where there is discrimination directed against people on account of being white, the negative effects of such discrimination are significantly less than the effects of discrimination felt by other ethnic groups. Essentially, racism experienced by people who are white has a weaker or “qualitatively different” association with negative health outcomes than for people who are not white (T119:16-24).

136 Professor Paradies explained that, perhaps paradoxically, what is referred to as “white fragility” has been observed. There are cases where white people who experience discrimination can be particularly perturbed by the experience because they do not have much history or experience of being subject to such treatment (T119:34-42).

137 Professor Paradies concluded that the impact experienced, upon reading Senator Hanson’s tweet, by a person who shared any or some of the Group Attributes would likely be exacerbated when the publisher is a colleague, a person with a significant public profile or an elected public official. He said that the harms outlined at [36] of the concise statement are consistent with what he would expect a person who shares any or some of the Group Attributes to suffer after becoming aware of Senator Hanson’s tweet. That harm is described as:

(1) suffering offence, insult, humiliation and intimidation;

(2) psychological distress, mental ill-health, fear including fear of imminent physical attack and hypervigilance including to the extent of insomnia and lack of enjoyment of home and private life; and

(3) experiencing inhibition and self-censorship in personal and professional life, having feelings of being silent, having feelings of illegitimacy or invalidity of their views, opinions, experiences and expertise, being caused to second guess and “tone police” their responses and reactions to situations, having feelings of isolation and being stripped of a sense of belonging, having feelings of displacement, marginalisation and ostracization, and suffering a reduction in the enjoyment of their human rights.

138 In closing submissions, the only challenge to Professor Paradies evidence was to his conclusions, as probed in cross-examination, that Senator’s Hanson’s tweet would be likely to cause the results that he identified. That was on the basis that the assessment of any likely response is context and fact specific, and that it cannot therefore be said that a particular response was likely for a group of people as a group. Professor Paradies’ evidence cited on behalf of Senator Hanson in support of that submission is this (T100:24-30):

MS CHRYSANTHOU: And you agree, don’t you, that, depending on the context and the severity of the racism in question and perhaps other moderating factors, there is not some generalised study that finds that racism as a whole, in all forms, will give rise to each of these adverse health reactions? --- No. No. The impacts of racism are contextual to the setting, to expectations, to previous experiences, to aspects and characteristics of the person who experiences racism and also characteristics of perpetrators and even witnesses and bystanders in the setting where racism has occurred.

139 That answer does not detract from the force of Professor Paradies’ evidence. The individualised characteristics of persons exposed to racism will have a bearing on whether they are more or less susceptible to the indicated harms. That is not to say, however, that Professor Paradies’ evidence specific to the susceptibility of persons who possess one or more of the Group Attributes to harm from exposure to the content of Senator Hanson’s tweet should be discounted. Such Group Attributes form an indelible part of the context to which persons respond to racism. Overall, I consider that he was unshaken in cross-examination. I accept his evidence.

Professor Katherine Jane Reynolds

140 Professor Reynolds has been Professor of Psychology and Learning at the Faculty of Education, University of Melbourne, since 2022. Prior to that, she was an Associate Professor and then Professor of Psychology at the ANU Department of Psychology where she served as Associate Director (2014-2017). She is a leading expert in the areas of group processes (leadership, influence, norms) and intergroup relations (stereotyping, prejudice, conflict, cohesion) from a social identity perspective. She was awarded a PhD in social psychology by ANU in 1997.

141 Professor Reynolds’ evidence includes an overview of social psychology as a sub-discipline of psychology. Much of that is not immediately relevant for present purposes. However, she explained that prejudice, discrimination and racism are topics that have been central to social psychology over the last 80 years. Typically, prejudice is defined as a negative attitude or emotional response towards members of a particular social group based solely on their membership in that group. Prejudice involves making generalised judgments about individuals or groups. It often involves negative stereotypes and feelings directed towards a particular group.

142 Professor Reynolds said that racism occurs when negative prejudice is directed towards an individual or group on the basis of their ethnic, cultural (and often religious) or racial heritage and can be institutional where racism is embedded in the culture, ethos, laws and societal norms. Discrimination concerns behaviour where an individual or group’s actions harm others through exclusion, negative treatment, violence, or inequity in opportunities.

143 Professor Reynolds summarised the opinions presented in her report as follows. A person who attributes their own personal negative treatment or that of their group to prejudice (racism) is likely to experience significantly poor physical and mental health. Those who experience prejudice (racism) will likely feel devalued, excluded and rejected from the majority group which reduces belonging to the larger group (eg nation) in which they live. Even when not the direct target of the negative treatment, the impacts of such treatment such as poor physical and mental health and reduced belonging can generalise to members of the group as a whole (those who share a social identity).