FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Securities and Investments Commission v H C F Life Insurance Company Pty Limited [2024] FCA 1240

ORDERS

AUSTRALIAN SECURITIES AND INVESTMENTS COMMISSION Plaintiff | ||

AND: | H C F LIFE INSURANCE COMPANY PTY LIMITED ACN 001 831 250 Defendant | |

DATE OF ORDER: | 28 October 2024 |

THE COURT:

1. Adopts the following defined terms in the paragraphs which follow:

Term | Definition |

ASIC Act | Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth) |

First Cash Back Class Contracts | Each contract: (a) entered into from 5 April 2021; (b) between the defendant and any Non-Party Consumer; (c) which meets the definition of a consumer contract within the meaning of s 12BF(3) of the ASIC Act; and (d) which incorporates one of:

|

First Cash Back PDS | The combined Product Disclosure Statement, Policy Document and Financial Services Guide entitled “Cash Back Cover” and dated 1 April 2021. |

First Income Protect Class Contracts | Each contract: (a) entered into from 1 October 2021; (b) between the defendant and any Non-Party Consumer; (c) which meets the definition of a consumer contract within the meaning of s 12BF(3) of the ASIC Act; and (d) which incorporates the First Income Protect PDS. |

First Income Protect PDS | The combined Product Disclosure Statement, Policy Document and Financial Services Guide entitled “Income Protect Insurance” and dated 1 October 2021. |

First Smart Term PDS | The combined Product Disclosure Statement, Policy Document and Financial Services Guide entitled “Smart Term Insurance” and dated 1 April 2021. |

Fourth Cash Back PDS | The combined Product Disclosure Statement, Policy Document and Financial Services Guide entitled “Cash Back Cover” and dated 25 March 2023. |

Income Assist Class Contracts | Each contract: (a) entered into from 5 April 2021; (b) between the defendant and any Non-Party Consumer; and (c) which meets the definition of a consumer contract within the meaning of s 12BF(3) of the ASIC Act; and (d) which incorporates the Income Assist PDS; |

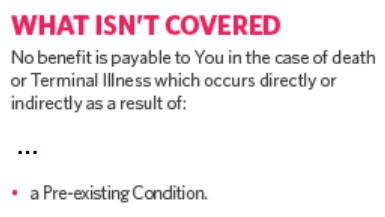

Income Assist PDS | The combined Product Disclosure Statement, Policy Document and Financial Services Guide entitled “Income Assist” and dated 1 April 2021. |

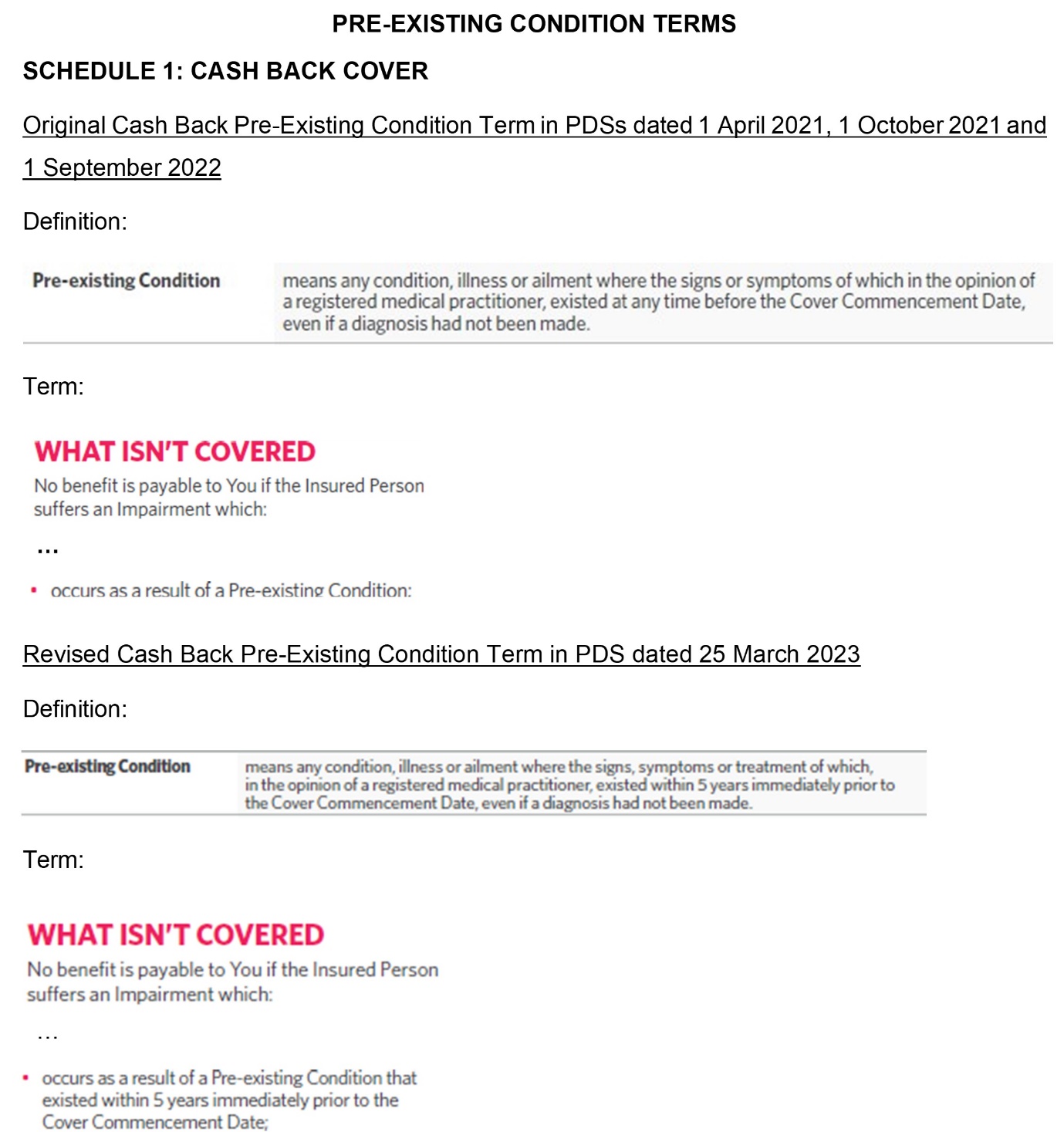

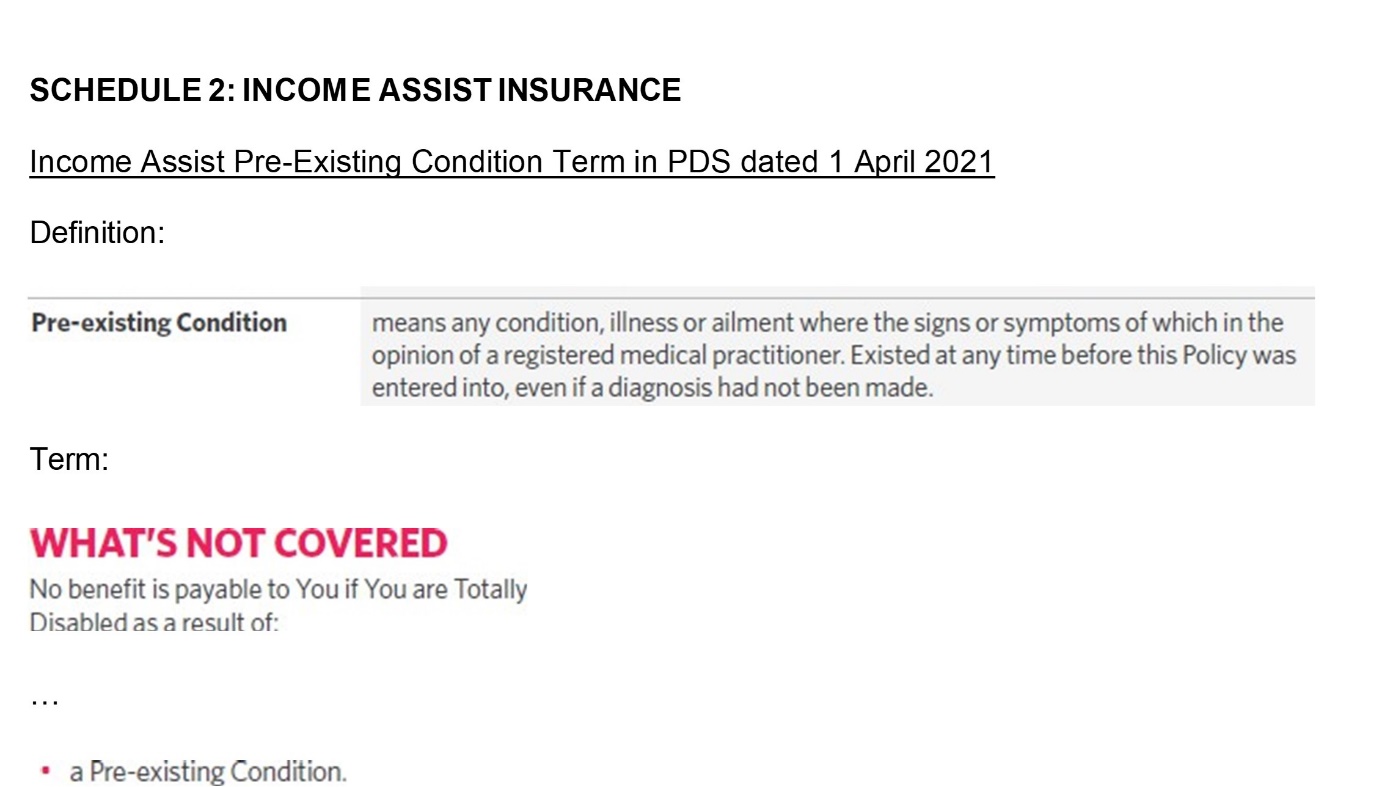

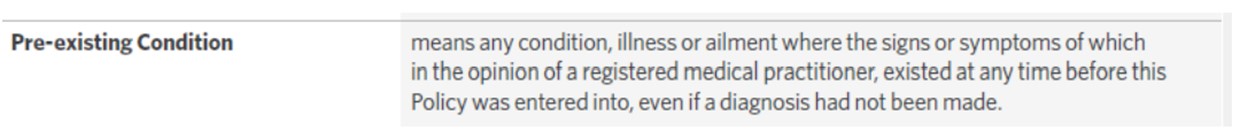

Income Assist Pre-Existing Condition Term | The term identified as such in Annexure “A”. |

Non-Party Consumer | The meaning given in s 12BA of the ASIC Act. |

Original Cash Back Pre-Existing Condition Term | The term identified as such in Annexure “A”. |

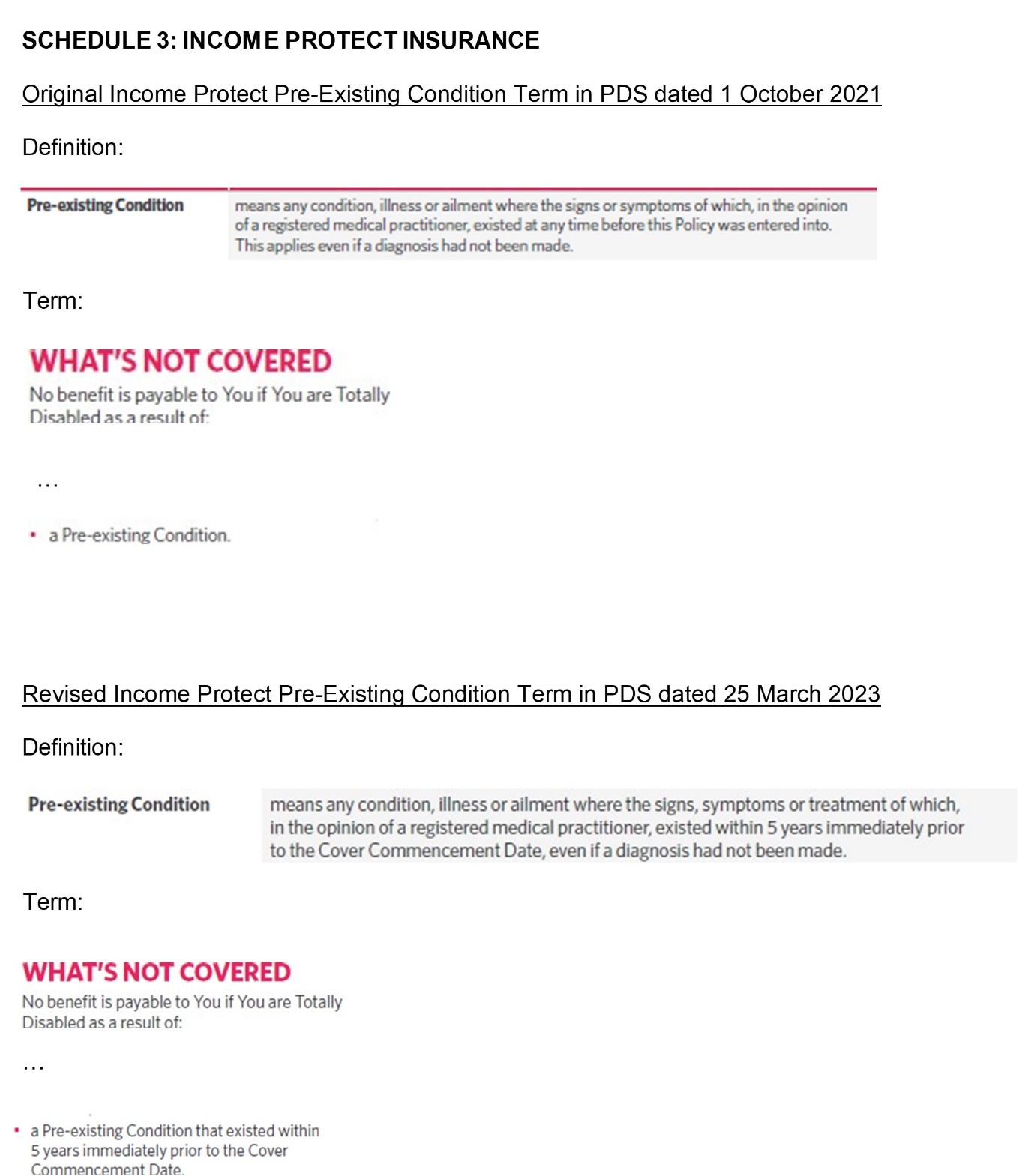

Original Income Protect Pre-Existing Condition Term | The term identified as such in Annexure “A”. |

Revised Cash Back Pre-Existing Condition Term | The term identified as such in Annexure “A”. |

Revised Income Protect Pre-Existing Condition Term | The term identified as such in Annexure “A” |

Second Cash Back Class Contracts | Each contract: (a) entered into from 25 March 2023; (b) between the defendant and any Non-Party Consumer; (c) which meets the definition of a consumer contract within the meaning of s 12BF(3) of the ASIC Act; and (d) which incorporates the Fourth Cash Back PDS. |

Second Cash Back PDS | The combined Product Disclosure Statement, Policy Document and Financial Services Guide entitled “Cash Back Cover” and dated 1 October 2021. |

Second Income Protect Class Contracts | Each contract: (a) entered into from 25 March 2023; (b) between the defendant and any Non-Party Consumer; (c) which meets the definition of a consumer contract within the meaning of s 12BF(3) of the ASIC Act; and (d) which incorporates the Second Income Protect PDS. |

Second Income Protect PDS | The combined Product Disclosure Statement, Policy Document and Financial Services Guide entitled “Income Protect Insurance” and dated 25 March 2023. |

Second Smart Term PDS | The combined Product Disclosure Statement, Policy Document and Financial Services Guide entitled “Smart Term Insurance” and dated 1 October 2021. |

Smart Term Class Contracts | Each contract: (a) entered into from 5 April 2021; (b) between the defendant and any Non-Party Consumer; and (c) which meets the definition of a consumer contract within the meaning of s 12BF(3) of the ASIC Act; and (d) which incorporates one of:

|

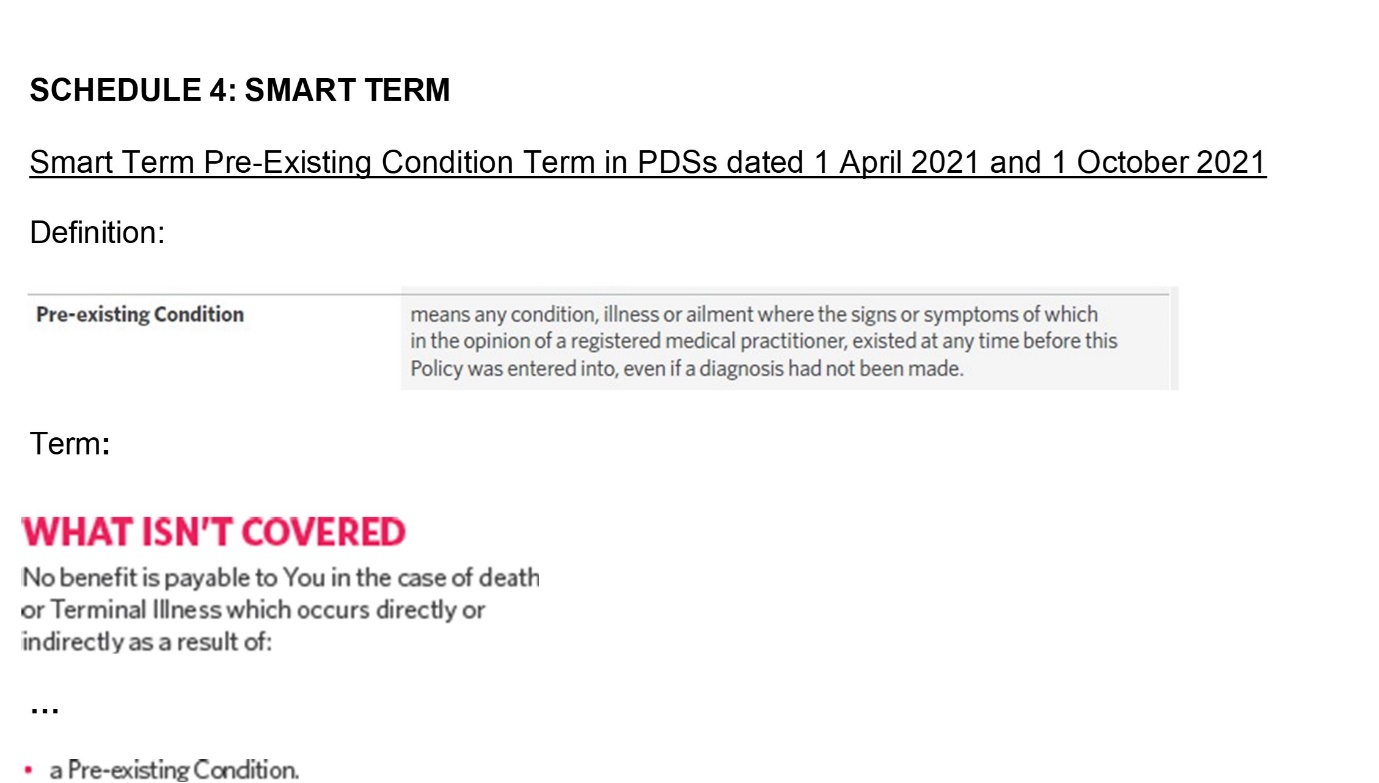

Smart Term Pre-Existing Condition Term | The term identified as such in Annexure “A”. |

Third Cash Back PDS | The combined Product Disclosure Statement, Policy Document and Financial Services Guide entitled “Cash Back Cover” and dated 1 September 2022. |

2. Declares that by publishing the First and Second Smart Term PDS, giving the First and Second Smart Term PDS to members of the public and entering into the Smart Term Class Contracts with members of the public, in circumstances where the First and Second Smart Term PDS:

(a) contained the Smart Term Pre-Existing Condition Term; and

(b) did not advert to, or explain, the existence or effect of s 47 of the Insurance Contracts Act 1984 (Cth) (ICA) or that the Smart Term Pre-Existing Condition Term is partially unenforceable,

the defendant contravened s 12DF(1) of the ASIC Act.

3. Declares that by publishing the First, Second and Third Cash Back PDS, giving the First, Second and Third Cash Back PDS to members of the public and entering into the First Cash Back Class Contracts with members of the public, in circumstances where the First, Second and Third Cash Back PDS:

(a) contained the Original Cash Back Pre-Existing Condition Term; and

(b) did not advert to, or explain, the existence or effect of s 47 of the ICA or that the Original Cash Back Pre-Existing Condition Term is partially unenforceable,

the defendant contravened s 12DF(1) of the ASIC Act.

4. Declares that by publishing the Fourth Cash Back PDS, giving the Fourth Cash Back PDS to members of the public and entering into the Second Cash Back Class Contracts with members of the public, in circumstances where the Fourth Cash Back PDS:

(a) contained the Revised Cash Back Pre-Existing Condition Term; and

(b) did not advert to, or explain, the existence or effect of s 47 of the ICA or that the Revised Cash Back Pre-Existing Condition Term is partially unenforceable,

the defendant contravened s 12DF(1) of the ASIC Act.

5. Declares that by publishing the Income Assist PDS, giving the Income Assist PDS to members of the public and entering into the Income Assist Class Contracts with members of the public, in circumstances where the Income Assist PDS:

(a) contained the Income Assist Pre-Existing Condition Term; and

(b) did not advert to, or explain, the existence or effect of s 47 of the ICA or that the Income Assist Pre-Existing Condition Term is partially unenforceable,

the defendant contravened s 12DF(1) of the ASIC Act.

6. Declares that by publishing the First Income Protect PDS, giving the First Income Protect PDS to members of the public and entering into the First Income Protect Class Contracts with members of the public, in circumstances where the First Income Protect PDS:

(a) contained the Original Income Protect Pre-Existing Condition Term; and

(b) did not advert to, or explain, the existence or effect of s 47 of the ICA or that the Original Income Protect Pre-Existing Condition Term is partially unenforceable,

the defendant contravened s 12DF(1) of the ASIC Act.

7. Declares that by publishing the Second Income Protect PDS, giving the Second Income Protect PDS to members of the public and entering into the Second Income Protect Class Contracts with members of the public, in circumstances where the Second Income Protect PDS:

(a) contained a Revised Income Protect Pre-Existing Condition Term; and

(b) did not advert to, or explain, the existence or effect of s 47 of the ICA or that the Revised Income Protect Pre-Existing Condition Term is partially unenforceable,

the defendant contravened s 12DF(1) of the ASIC Act.

8. Orders that the costs of the proceedings to date be reserved.

9. Orders that the proceedings be listed for case management at 9.30 am on 8 November 2024.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ANNEXURE A

JACKMAN J:

Introduction

1 The defendant (HCF Life) is a life insurer that offers products which contain exclusions in respect of pre-existing conditions. HCF Life historically adopted definitions of pre-existing condition that broadly mirrored the language of s 47 of the Insurance Contracts Act 1984 (Cth) (ICA), which provides that an insurer may not rely upon an exclusion in respect of a pre-existing condition where, at the time when the contract was entered into, the insured was not aware of, and a reasonable person in the circumstances could not be expected to have been aware of, the sickness or disability. But in August 2019, HCF Life adopted a definition of pre-existing condition that excludes cover where a medical practitioner is of the opinion that signs or symptoms of the relevant condition existed before policy inception. HCF Life did not advert to or explain the existence or effect of s 47 of the ICA.

2 The plaintiff (ASIC) claims that by distributing product disclosure statements and entering into policies on such terms, which ASIC says are rendered partially unenforceable by virtue of ICA s 47, HCF Life engaged in conduct that was liable to mislead the public as to the nature, characteristics and suitability of financial services in contravention of s 12DF of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth) (ASIC Act). ASIC also claims that the terms are unfair within the meaning of s 12BF of the ASIC Act.

Factual Background

3 Facts agreed by the parties are set out in a Statement of Agreed Facts signed on 25 August 2023 (SAF). Other background facts are contained in the affidavits of Kevin Keane (HCF Life’s former General Manager) (Keane Affidavit) and Scott Niven (HCF Life’s Claims Manager) (Niven Affidavit), both sworn 19 December 2023.

HCF and HCF Life

4 HCF Life is a wholly owned subsidiary of The Hospitals Contribution Fund of Australia Limited (HCF), a not-for-profit private health insurer. The HCF group of companies conducts two primary lines of business: a private health insurance business (which is HCF’s main business), and a life insurance business (which sells life insurance products issued by HCF Life). HCF Life outsources its front-line operations to HCF: Keane Affidavit at [26].

The Recover Cover Products

5 The product disclosure statements to which ASIC’s claims relate are set out at [5] of the SAF and are defined compendiously as the Recover Cover PDSs. In addition to being product disclosure statements, each Recover Cover PDS is also a policy document and financial services guide. The exclusions for pre-existing condition contained in the Recover Cover PDSs are referred to as the Pre-Existing Condition Terms.

6 The Recover Cover PDSs concern products known as “Smart Term Insurance”, “Cash Back Cover”, “Income Assist Insurance” and “Income Protect Insurance” (the Recover Cover Products).

7 Smart Term Insurance provided fixed benefits of up to $500,000 upon the death of the insured person or their diagnosis with a terminal illness, and fixed benefits of up to $1,000,000 upon accidental death. ASIC’s claims concern Smart Term PDSs published on 1 April 2021 and 1 October 2021.

8 Cash Back Cover provided fixed benefits of $5,000 if an insured person suffered from a specified impairment, up to a total benefit amount of $20,000 or $40,000 depending on the level of cover. ASIC’s claims concern Cash Back PDSs published on 1 April 2021, 1 October 2021, 1 September 2022 and 25 March 2023.

9 Income Assist and Income Protect Insurance provided benefits calculated as a percentage of the insured person’s monthly pre-tax income (up to specified maximums) if the insured was totally disabled as a result of sickness or injury. ASIC’s claims concern the Income Assist PDS published on 1 April 2021, and the Income Protect PDSs published on 1 October 2021 and 25 March 2023.

10 HCF Life published each Recover Cover PDS on its website while the policies to which each Recover Cover PDS was applicable were available for purchase. Each of the Recover Cover Products was available for purchase by members of the public and was sold on a “guaranteed acceptance” basis. This means that the products were not underwritten, with the result that HCF Life did not require prospective policyholders to: complete a long application; answer individual medical underwriting questions (other than disclosing smoking status and their height to weight ratio in some products); undergo medical testing; or disclose their medical history, their family medical history, or their exposure to high risk recreational activities, sporting activities or lifestyle factors.

11 From 1 April 2021, HCF Life entered into contracts with non-party consumers (within the meaning of s 12BA of the ASIC Act), the terms of which were recorded in a Recover Cover PDS and each consumer’s policy schedule (together Recover Cover Contracts): SAF [11]. There is no dispute that each of the Recover Cover Contracts is: a financial product within the meaning of s 12BAA of the ASIC Act; a financial service within the meaning of s 12BAB of the ASIC Act; a standard form contract for the purposes of s 12BF(1)(b) of the ASIC Act; a contract for the supply, or possible supply, of services that are financial services within the meaning of s 12BF(1)(c)(ii) of the ASIC Act; and a consumer contract within the meaning of s 12BF(3) of the ASIC Act.

12 From 5 April 2021 to 27 April 2023, HCF Life entered into approximately 12,265 Recover Cover Contracts, of which 9,370 remained on foot as at 27 April 2023: SAF [15]–[16].

13 Upon entering into a Recover Cover Contract, HCF Life provided to each consumer a copy of the applicable Recover Cover PDS by email or post: SAF [12].

14 Each Recover Cover PDS sets out the principal terms of the relevant product. Individual policy schedules list additional details, such as policy number, policy owner, insured persons, levels of cover, weekly premiums, cover commencement dates and policy issue dates. In the case of the Income Protect and Income Assist products, policy schedules also list details such as occupation, height, weight and smoking status. Together, the policy schedule and the applicable Recover Cover PDS form the contract of insurance between HCF Life and a given consumer.

15 Each Recover Cover PDS contains an introductory section under a heading “About This Document”. That section contains text to the following effect (the below being taken from the Smart Term Insurance Product as at 1 April 2021):

This document contains important information that You should know about Smart Term Insurance. This information is designed to help You decide whether this product is right for You.

If we issue You with a Smart Term Insurance policy, You will receive a copy of this Combined Product Disclosure Statement and Policy Document, along with Your Policy Schedule. Together, these documents form Your Policy and should be kept in a safe place.

Throughout this document, some words and expressions have a special meaning. These words begin with capital letters, and their meanings can be found in the Glossary section of this document.

16 Another section entitled “Risks” states that:

It is important to understand the associated risks of purchasing a life insurance policy. Things You may wish to consider include:

determining whether this Policy suits Your needs;

if You are replacing an existing policy, consider the terms and conditions of this Policy and your existing policy before making a decision;

this Policy does not have a surrender value, which means no money is payable to You unless We have approved a claim under this Policy.

17 There is also a section headed “Other Things You Need to Know”. This includes a section on the insured’s duty of disclosure and the consequences of non-disclosure, including that HCF Life “may refuse to pay a claim and treat all or part of the contract as if it never existed”.

18 Each of the Recover Cover PDSs contains a section entitled “What’s Covered”, which sets out the main benefits of each product. That section is followed by a section entitled “What Isn’t Covered” or “What’s Not Covered”, which lists exclusions to cover. In that section, each Recover Cover PDS contains an exclusion providing that no benefits are payable if the impairment, total disability, terminal illness or death (as the case may be) occurs “as a result of” a “Pre-Existing Condition”.

19 In the Recover Cover Contracts entered into between 1 April 2021 and 24 March 2023, “Pre-Existing Condition” is defined in the Glossary to mean (or in substantially similar terms to):

any condition, illness or ailment where the signs or symptoms of which in the opinion of a registered medical practitioner, existed at any time before the Cover Commencement Date, even if a diagnosis had not been made.

20 In the Recover Cover Contracts entered into on or after 25 March 2023, Pre-Existing Condition is defined in the Glossary to mean:

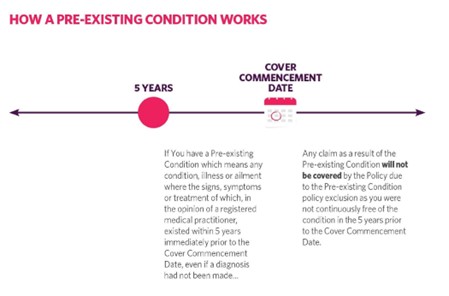

any condition, illness or ailment where the signs, symptoms or treatment of which, in the opinion of a registered medical practitioner, existed within 5 years immediately prior to the Cover Commencement Date, even if a diagnosis had not been made.

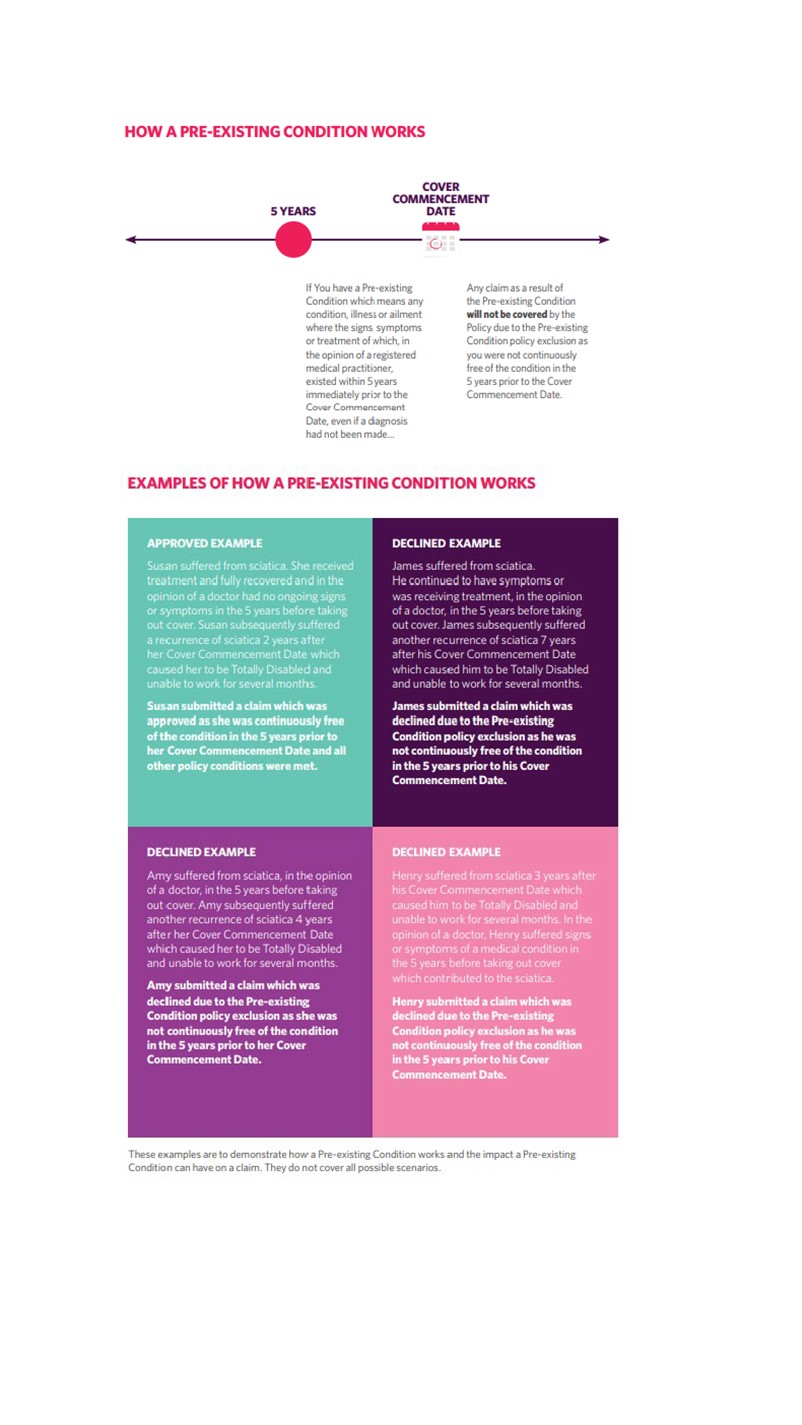

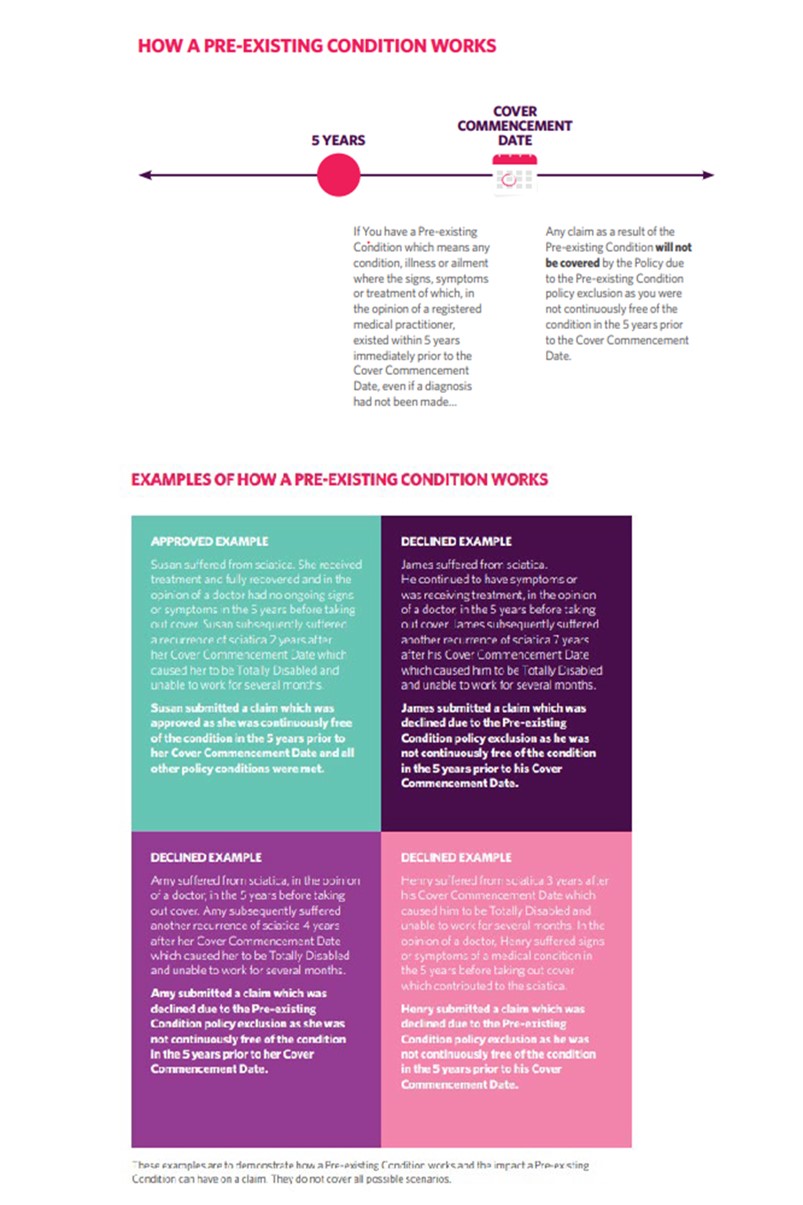

21 The Recover Cover Contracts entered into on or after 25 March 2023 also include statements purporting to describe “How a Pre-Existing Condition Works” and “Examples of How a Pre-Existing Condition Works” to demonstrate “the impact a Pre-Existing Condition can have on a claim”. For example, the 25 March 2023 Income Protect PDS contained the following:

22 None of the Recover Cover PDSs which are the subject of ASIC’s claims make any mention of the existence or effect of s 47 of the ICA, or the possibility that the exclusion in respect of Pre-Existing Conditions may not take effect in accordance with its terms. Nor were those matters mentioned in the standard-form welcome emails and letters sent to consumers upon entry into a policy.

23 The Recover Cover PDSs are not silent about the implications of statutory provisions for consumers. Under the heading “Changing Premiums and Benefits”, it is explained that:

Generally, insurance premiums are not tax deductible and benefits are paid free of personal tax. This is a general statement based on present laws and their interpretation.

History of the Pre-Existing Condition Terms

24 Over the years that HCF Life has offered the Recover Cover products, there have been five different definitions of Pre-Existing Condition that have been deployed.

Pre-2019 PEC Clause

25 Prior to 9 August 2019, HCF Life employed a materially different form of pre-existing condition definition which broadly mirrored the language of s 47 of the ICA. For example, the definition in Cash Back products provided that Pre-Existing Condition means (Pre-2019 PEC Clause):

any Disablement which is directly or indirectly attributable to or consequential wholly or in part upon any sickness, disability, bodily injury or other condition to which the Insured Person was subject at the time or at any time before the Policy was entered into. This is provided the Insured Person was aware of whether by their own observation or experience or through a medical test or report, such sickness, disability, bodily injury or condition at the time the Policy was entered into or a reasonable person in their circumstances would have been aware of such sickness, disability, bodily injury or condition (whether or not diagnosed).

2019 PEC Clause

26 In policies issued from between 9 August 2019 and 1 April 2021, Pre-Existing Condition was defined as (2019 PEC Clause):

any condition, illness or ailment where the signs or symptoms of which in the opinion of a medical practitioner appointed by HCF Life, existed at any time before this Policy was entered into, even if a diagnosis had not been made.

27 The change from the Pre-2019 PEC Clause to the 2019 PEC Clause arose from internal research conducted in early 2017 at HCF Life into, inter alia, pre-existing condition clauses in HCF Life policies, the claims experiences concerning those clauses, and the possibility of consistent wording with the private health definitions.

28 That research culminated in a submission to the Board of HCF Life contained in the “General Manager’s Report” and dated 20 February 2017. Annexure 6 to that report was a “Product Roadmap Update” (Product Update). The Board considered the Product Update on 20 February 2017. The Product Update relevantly provided that it had been eight years since the total HCF Life product range was reviewed and that the Pre-2019 PEC Clause was “broader and more restrictive than most competitors”. To alleviate this concern, it was proposed to:

Analyse claims experience over the past five years and ascertain the number of claims denied due to PEC (where possible when PEC was first diagnosed) and the length of time claimants have held policy prior to claiming

Seek pricing advice for the lifetime PEC for heart attack and stroke events with a PEC expiry of 12 months for other condition (new and existing policies, legacy products excluded) OR PEC expiry of 3 years for all claim events (new and existing polices, legacy products excluded)

Develop a “plain English” version of the definition

29 Those action items were progressed over the course of 2017 and into 2018.

30 On 30 August 2018, ASIC published Report 587 on “The Sale of Direct Life Insurance” (Report 587). Under Finding 5, the report stated that “[s]ome products or product features provided little value to consumers, while others were difficult to understand and therefore may not perform as expected”, before proceeding in paragraph 34 to observe that “[g]uaranteed acceptance products, such as … products with pre-existing condition exclusions, have a lower likelihood of consumers being eligible to claim due to the substantial limitations and exclusions applied to these products.” Under the heading “Expectation 1”, ASIC explained that it expected the revised Life Insurance Code of Practice to set rigorous standards to address ASIC’s findings, including requiring insurers to:

Provide adequate explanations of key exclusions and future cost — Firms should clearly explain these features and limitations as part of their sales calls. Firms should not rely on including this information in lengthy pre-recorded or verbatim disclosures. Pre-existing condition exclusions in particular should be clearly explained to the consumer, with practical examples to highlight the breadth of this exclusion.

31 ASIC went on to explain that its research indicated that the limitations of pre-existing condition exclusions could be difficult for consumers to understand and noted in particular that:

The definition of a pre-existing condition can extend to more than just conditions that have been diagnosed, for example where a consumer has experienced symptoms of a condition prior to buying their policy. A failure to explain such exclusions can have a significant financial effect on the consumer or their family if a claim is declined.

32 In the year that followed, further internal developments were made to the pre-existing condition clauses in HCF Life’s products, and by 9 August 2019 versions of the Recover Cover PDSs that contained the 2019 PEC Clause had been released by HCF Life. At that time, it was explained that:

The key changes here were to update some medical definitions in Bounceback and Critical Illness to be [in] line with that of the Life Code of Practice, as well as some minor wording changes to make the policies simpler and easier to understand however no changes have been made to the product terms and conditions.

33 On 28 August 2019, the Board of HCF Life was updated about the policy changes, which included the 2019 PEC Clause. The General Manager’s Report to the Board meeting held on that day recorded that:

Management have released updated Policy Documents for six of seven on sale products, Personal Accident was updated in November 2018. While the terms and conditions have not changed, with the exception of updated medical definitions, a significant rewrite has been undertaken to improve transparency and member centricity.

34 The evidence before me is that, at least internally within HCF Life, it was not intended that these changes to the policy would change how claims were to be assessed. Instead, the intent of the change was to make the pre-existing condition definition clearer for policyholders to understand: Niven Affidavit at [59]–[63].

2021 PEC Clause

35 Next there was the definition that appeared in policies between 1 April 2021 and 25 March 2023, the text of which is set out at para 19 above and is the subject of these proceedings (2021 PEC Clause). The difference between this clause and the 2019 PEC Clause is that the words “medical practitioner appointed by HCF Life” were removed and replaced with “registered medical practitioner”.

36 Mr Keane gives evidence that this change was made in the context of HCF Life undertaking an internal review of its contract terms to prepare for the commencement of the unfair contract regime: Keane Affidavit at [107]. This review commenced in around October or November 2020 and ran for 6 months. The trigger for the review was a letter that HCF Life received from ASIC dated 20 October 2020 in respect of ASIC’s thematic review of unfair contract terms in life insurance contracts. Appendix 1 to the 20 October 2020 letter set out terms identified by ASIC as being potentially unfair contract terms, including the pre-existing condition clause in HCF Life’s “Bounceback” Policy. The change from the 2019 PEC Clause to the 2021 PEC Clause was made in the context of this review.

37 Another definition appeared in policies between 25 March 2023 and 9 November 2023, the text of which is set out in para 20 above and is the subject of these proceedings (2023 PEC Clause).The primary difference between the 2021 PEC Clause and the 2023 PEC Clause was the addition of a five-year “look back” limitation.

38 The look back limitation was introduced after Mr Keane discussed pre-existing condition clauses with Lorraine Thomas, the Chief Officer of Product and Diversified Business of HCF (to whom Mr Keane reported). During that conversation, it was agreed that a pre-existing condition term was a reasonable protection for HCF Life in supporting its offering of general acceptance products. Mr Keane and Ms Thomas considered that if a pre-existing condition term was removed altogether, the only alternative was to move away from guaranteed acceptance to fully underwritten products: Keane Affidavit at [132]–[133].

39 At the time, Mr Keane formed the view that HCF Life would not have adequate time to have the technology systems in place to replace the pre-existing condition terms with an underwriting system. And in any event, Mr Keane’s view was that short form or full underwriting was not generally appropriate for Recover Cover Products. He considered that HCF Life could seek to ameliorate the concerns with the 2021 PEC Clause by inserting a time-based limitation on the period in which HCF Life could rely on the clause: Keane Affidavit at [137].

40 After discussions about the scope of the “look back” period that could be included in the pre-existing condition clause between Mr Keane, the Head of Product (Diversified Business) and the Head of Actuarial (Diversified Business), a paper was prepared for HCF Life’s Product & Pricing Committee dated 6 September 2022. That paper noted that a “review of the lifetime PEC exclusion is being undertaken” including in relation to the Cash Back and Income Protect products. At that time, it was proposed that the meaning of Pre-Existing Condition be:

any condition, illness or ailment where the signs or symptoms of which in the opinion of a registered medical practitioner, existed within (3 or 5) years immediately prior to the Cover Commencement Date, even if a diagnosis had not been made.

41 That paper was presented by Rebecca Thomsen (Senior Product Manager, Diversified Business) at a meeting of the HCF Life Product & Pricing Committee on 6 September 2022 and it was advised that the proposal was being finalised and approval would be sought at the November Product & Pricing Committee meeting, followed by approval at the December 2022 HCF Life Board meeting.

42 As part of the process of considering that proposal, including whether HCF Life should adopt a five-year limitation in its pre-existing condition terms, HCF Life sought advice from Martin Paino of KPMG, the Appointed Actuary for HCF Life. In his written advice of 18 November 2022, Mr Paino concluded that the proposed change (from the 2021 PEC Clause to the 2023 PEC Clause) was not expected to have a material impact on the capital position of HCF Life. He also agreed with management’s assessment that the proposed changes would improve the customer experience by providing more generous terms and maintaining simplicity of the definition for customer and front-line distribution staff’s understanding. He further agreed with management’s plans to further mitigate the risks associated with the proposed definitional change, and accordingly was supportive of the HCF Life Board approving the definitional change.

43 On 14 November 2022, there was a further meeting of the Product & Pricing Committee where the Committee approved a proposal to change HCF Life’s lifetime pre-existing condition exclusion for on-sale life products as set out in a paper dated 14 November 2022 that was prepared by Ms Thomsen entitled “HCF Life (HFCL) PEC Exclusion Proposal – Onsale Products”. That definition was in the terms of the 2023 PEC Clause. The paper noted:

The new proposed PEC exclusion definition is intended to be more in line with current consumer expectations by only considering conditions, signs and symptoms within the 5 years period prior to policy inception, compared to the current definition, which takes into account any condition or signs and symptoms that has ever existed for the member in their lifetime prior to policy inception.

44 The paper also went on to note that HCF Life had considered whether the exclusion could also have included an expiry or “waiting” period, either at a set point after policy commencement or after a symptom-free period following policy commencement; however, HCF Life determined that this was not feasible to include as it increased the risk of anti-selection (also known as “adverse selection”).

45 On 9 December 2022, the Board of HCF Life resolved to approve the recommendation to change the definition to the form that is the 2023 PEC Clause.

Current PEC Clause

46 Most recently, the Cash Back and Income Protect policies issued from 9 November 2023 have defined Pre-Existing Condition to mean:

a sickness of disability which You:

were subject on the Cover Commencement Date; or

had been subject at any time within 5 years immediately prior to the Cover Commencement Date,

and which sickness or disability, at the time when this Policy was entered into (i.e. the Cover Commencement Date) You were aware of, or a reasonable person in the circumstances could be expected to have been aware of.

47 Those PDSs contained revised “Examples of How a Pre-Existing Condition Works” which addressed whether the example insureds were aware of the sickness or disability (or could reasonably be expected to have been aware). They also included a new section entitled “How We Assess Pre-Existing Conditions”, which included the following text:

We will decline to pay a benefit to You on the basis of a Pre-Existing Condition if, at the time when this Policy was entered into (i.e. the Cover Commencement Date), You were aware of, or a reasonable person in the circumstances could be expected to have been aware of, the sickness or disability to which you were subject on the Cover Commencement Date or had been subject at any time within 5 years immediately prior to the Cover Commencement Date.

We will take into account information that includes but is not limited to:

The information that You supply to Us; and

The information that Your treating registered medical practitioner supplies to Us, such as their opinion of whether the signs, symptoms or treatment of the sickness of disability existed prior to the time when the Policy was entered into, even if a diagnosis had not been made.

48 Thus, the new clause combines the terms of s 47 of the ICA with the plain English aspects of the previous clauses.

Product distribution

49 HCF Life has four distribution channels through which policyholders can sign up to its policies, including the Recover Cover Contracts: HCF branch attendance; telephone call centres; HCF’s website and other digital marketing; and through corporate channels.

50 The steps involved in the application process for issuing new cover by HCF Life pursuant to the Recover Cover Contracts are broadly similar across the four distribution channels. In particular (Keane Affidavit at [65]):

(a) A prospective policyholder contacts HCF to discuss HCF Life products over the telephone or by visiting a branch office.

(b) An HCF consultant or agent takes the call from the prospective policyholder and discusses the relevant product and features, confirming that the product is what the prospective policyholder is looking for and that the prospective policyholder is eligible and suitable for the product. For Smart Term, Income Assist and Income Protect products, the HCF consultant or agent asks some additional questions (as relevant to the product) surrounding age, gender, occupation, height and weight, smoking status and income to generate a quote. If the prospective policyholder chooses to proceed based on the quote, the HCF consultant or agent notifies the prospective policyholder of any relevant disclosures, exclusions, key product terms and disclaimers. If the prospective policyholder accepts these, the HCF consultant or agent takes payment, and the policy is added to the member’s account.

(c) For purchases made in branches, the HCF consultant or agent prints a hard copy application form that the member signs. The policyholder then takes the relevant policy documents and applicable PDS.

(d) Irrespective of whether a policyholder signs up by telephone or in branch, within 5 business days HCF Life sends a “welcome pack” to the member that includes a welcome letter or email, the policyholder’s policy schedule, and the applicable Recover Cover PDS. HCF Life sends these documents either by email or in hard copy depending on the policyholder’s preference.

51 The HCF website channel follows a similar process, but initiates with the prospective policyholder entering some basic information on the HCF website. However, HCF does not sell any products, including the Recover Cover Products, through its website. To purchase a policy, a policyholder must request a call back and an HCF consultant or agent will contact them, step through the steps above, and read any required disclaimers and exclusions before finalising purchase. The Recover Cover PDSs were published by HCF Life on HCF’s website at all material times.

52 The Recover Cover Contracts automatically renew every year. HCF Life issues policyholders with a significant event notice if there is a material change to their policy. A policyholder is provided with an annual notice advising that the policy is due for renewal and can contact HCF Life if they wish to cancel their cover. No disclosures of a medical nature or otherwise are sought from the policyholder on renewal.

Customer base

53 Although the Recover Cover Products are offered to the public at large via the distribution channels outlined above, more than 90% of the Recover Cover Contract customers were HCF private health insurance fund members at any given point in time. Mr Keane gives evidence of a summary analysis provided to him for the purpose of this proceeding which shows that, as at 28 November 2023, there were 204,237 active HCF Life insurance policies in existence of which:

(a) 93.1% were associated with an active HCF private health insurance policy;

(b) a further 5.8% were, at one point in time, associated with an HCF private health insurance policy; and

(c) only 1.1% were not associated with any active (or cancelled/lapsed) HCF private health insurance.

Claims under the Recover Cover Contracts

54 While the impugned conduct here is alleged to have occurred at the time HCF Life published and provided the Recover Cover PDSs to the public (including prospective insured persons), HCF Life submits that it is relevant to both aspects of ASIC’s case for the Court to have regard to HCF Life’s practice at the later time claims are made. HCF Life makes that submission on the basis that:

(a) the foundational allegation of ASIC’s case in respect of misleading conduct and unfair contract terms is that the Pre-Existing Condition Terms are “partially unenforceable” by reason of s 47 of the ICA. HCF Life submits that ASIC’s foundational allegation is incorrect because, inter alia, it has always been HCF Life’s practice to apply the Pre-Existing Condition Terms having regard to s 47 of the ICA; and

(b) one aspect of the relief that ASIC seeks in these proceedings is an order directing that HCF Life, at its own expense, reassess any claim made by a non-party consumer which the defendant has refused to pay in reliance upon the Pre-Existing Condition Terms.

55 HCF Life has a team of Claims Assessors (Claims Team) which is led by Mr Niven, the Claims Manager of HCF Life. Mr Niven commenced in this role in February 2019 and reports to the General Manager of HCF Life. The Claims Team is responsible for assessing all claims that are made under insurance policies issued by HCF Life, including the Recover Cover Contracts.

56 Mr Niven’s evidence is that he became aware of s 47 of the ICA in or around July 2019 to early 2020. He became aware of the statutory provision in the context of his dealing with complaints made by insured persons to the Australian Financial Complaints Authority (AFCA). At around that same time, Mr Niven became aware of the document published by AFCA entitled “The AFCA Approach to section 47 of the Insurance Contracts Act” (AFCA Guidance). The AFCA Guidance sets out how AFCA applies s 47 and the key issues in its application.

57 Mr Niven formed the view that the Pre-2019 PEC Clause (which was the relevant clause in place at the time), the AFCA Guidance and s 47 of the ICA were all directed to essentially the same question of whether the insured person was actually aware, or based on signs and symptoms experienced by the insured person at the time the policy was entered into, would have been aware, of their pre-existing condition at the time they entered into the policy of insurance: Niven Affidavit at [45]. Accordingly, his and the Claims Team’s approach to assessing claims is as follows:

In handling claims, I assess the information provided by the member and by the member’s treating doctor. My view is that a member has a pre-existing condition if, by reference to that information, the member was aware or would have been aware of the pre-existing condition at the time the policy was entered into. By “would have been aware”, I mean that the member’s signs or symptoms were significant or substantial enough for me to conclude that they knew that they had the condition prior to taking out the policy, even if a formal diagnosis has not been made. This is a conclusion that I draw from all the evidence that is presented to HCF Life as part of the claims assessment process. Based on my supervision of them, it is also the approach adopted by other members of the Claims Team.

58 This is the approach that Mr Niven and the Claims Team have taken in assessing claims made under policies that included the Pre-2019 PEC Clause, the 2019 PEC Clause and the 2021 PEC Clause. In particular:

(a) The approach of Mr Niven and the Claims Team to assessing pre-existing conditions once the 2019 PEC Clause was adopted remained the same as it did to assessing claims made under the Pre-2019 PEC Clause (despite the wording of the Pre-2019 PEC Clause being closer to the text of s 47 of the ICA).

(b) As to the change from the 2019 PEC Clause to the 2021 PEC Clause (which removed the reference to the opinion of a doctor being the opinion of a doctor “appointed by HCF Life”), although Mr Niven was aware of this change, he did not consider that it had any impact on how the Claims Team and he would assess the claims. The reason for this was that prior to the 2021 PEC Clause being implemented, the Claims Team had in practice assessed claims by reference to the opinion and records of the treating doctor of the claimant, as opposed to HCF Life engaging its own medical specialist as contemplated by the terms of the 2019 PEC Clause. Although there were occasions where HCF Life sought an external opinion, in Mr Niven’s experience this was rare.

(c) As to the change between the 2021 PEC Clause and the 2023 PEC Clause, in the lead up to this change Mr Niven was asked to look at the historical claims denials that were based on the existence of a pre-existing condition, then determine whether there would be a different result if a time-limited pre-existing condition clause had been in place.

59 As to how claims assessment is undertaken, particularly in respect of claims made under the relevant products that may involve a pre-existing condition, the Claims Assessor reviews the documentation provided by the policyholder in support of their claim, which is contained in a document called a “Claim Form” and reports from their treating medical practitioners. For Income Assist and Income Protect, the documents also include an “Employer’s Form” and a “Self Employed Form”. For all relevant products, the Claim Form includes a “Doctor’s Form” for the policyholder’s treating doctor to fill out. The Claim Form seeks information from the policyholder and their treating doctor about the commencement date of the condition (or associated signs or symptoms) for which a claim is being made and any other related conditions.

60 If the claimant’s treating doctor advises that the relevant condition was pre-existing, or the policyholder self-reports that the relevant condition commenced prior to the policy commencement date, the HCF Life Claims Assessor will make a decision based on this information that the pre-existing condition exclusion applies and decline the claim. If there is an indication in the Claim Form of a potential pre-existing condition and the information from the policyholder and their treating doctor is unclear, HCF Life, with appropriate authority from the policyholder, will seek additional information from the treating doctor to clarify the question of a pre-existing condition. Based on the additional information, the HCF Life Claims Assessor will make a decision whether the pre-existing condition exclusion clause is applicable or not. All decisions to decline a claim are reviewed by Mr Niven or an HCF Life Senior Claims Assessor: Niven Affidavit at [96].

61 Mr Niven explains that there are some cases where a Claims Assessor may require guidance from a medical practitioner about whether the information provided with the claim demonstrates that the policyholder knew about the condition claimed or would have been aware of the condition given the signs and symptoms experienced by the policyholder. In these cases, the practice of the Claims Team is to bring the case to Mr Niven’s attention so that he can seek an opinion from the Chief Medical Officer of HCF as to whether the sickness or illness that is subject to the claim is pre-existing: Niven Affidavit at [107]–[111].

62 In assessing claims, HCF Life Claims Assessors are guided by several guideline documents. They include the Claims Assessment Guideline which includes guidance for the following “Situation”: “Application of PEC to a claim for ICU for other than Policy Holder under Medical Trauma Insurance”. The “Policy” column for this entry provides:

In all products except Kids Accident, Personal Accident and Critical Illness Cover the Pre-Existing Condition means “any disablement which is directly or indirectly attributable to or consequential wholly or in part upon any sickness, disability, bodily injury or other condition to which the Insured Person was subject at the time or at any time before the Policy was entered into. This is provided the Insured Person was aware of whether by their own observation or experience or through a medical test or report, such sickness, disability, bodily injury or condition at the time the Policy was entered into or a reasonable person in their circumstances would have been aware of such sickness, disability, bodily injury or condition (whether or not diagnosed).”

63 The “Guidelines” column for this entry provides:

To successfully apply the PEC we have to be satisfied and prove that the Life Insured had the knowledge.

64 The “Comment” column for this entry provides:

The PEC requires the Insured Person to possess this knowledge, not the Policy Holder. Where the Insured Person is a baby, child or a minor (under age 18) they cannot be considered to have this knowledge. A claim for a PEC admission to ICU for a baby, child or minor cannot be declined.

65 Although this particular entry is in the context of Medical Trauma Insurance, Mr Niven gives evidence that this guidance is reflective of the approach taken to claims made under the Recover Cover Contracts: Niven Affidavit at [122]–[123].

66 There is also a complaints procedure in place whereby if a complaint is made in respect of a decision to refuse a claim, HCF Life’s Claims Review Committee reviews the decision and considers any further information provided by the claimant. If the decision remains to decline the claim and the claimant disagrees, then the claim is referred to HCF Life’s Internal Dispute Resolution Committee (comprising four persons not involved in the original handling of the claim). A policyholder can also seek external dispute resolution by making a complaint to AFCA.

67 Mr Keane also gives unchallenged evidence that HCF Life approaches its claims handling of pre-existing conditions in a manner that is aligned with the AFCA Guidance: Keane Affidavit at [109]–[110], [114].

68 Accordingly, HCF Life submits, and I accept, that the Pre-Existing Condition Terms were at all times administered consistently with s 47 of the ICA.

The Expert Report of David Goodsall

69 Mr Goodsall is a consulting actuary and a Fellow of the Institute of Actuaries of Australia. He has worked as a consulting actuary in the life insurance industry in Australia since 1988.

70 Mr Goodsall’s report was primarily directed to whether the pre-existing condition clauses (or “PECs”) were necessary to protect HCF Life’s legitimate interests. For present purposes, it suffices to note that at [5.25] of his report, Mr Goodsall stated that “I have frequently observed that policyholders are not put off by policy conditions and tend to claim even when the policy conditions clearly say they are not eligible”. At [5.26] (as amended by [3.6] of Mr Goodsall’s Supplementary Report), Mr Goodsall opined that a genuine policy holder is either:

(a) likely to be aware of the terms of a PEC, in which case if they are concerned at the potential application of the PEC they may:

(i) take positive action to address those concerns such as seeking medical advice prior to purchasing the policy; or

(ii) make a claim despite the PEC in case they are covered; or

(b) not aware of the terms of the PEC, regardless of its form, and make a claim decision in ignorance of the policy conditions anyway.

71 At the hearing, the parties agreed (and I accepted) that [5.25] and [5.26] of Mr Goodsall’s report should be admitted:

solely as evidence of his experience that:

a. policyholders tend to claim on policies even when they are aware of policy conditions which say they are not eligible to benefits; and

b. policyholders tend to claim on policies when they are unaware of their eligibility to benefits because they are ignorant of the policy conditions,

and not as evidence of invariable policyholder behaviour.

Principles of Interpretation

Contract

72 The principles of construction of commercial contracts were summarised by French CJ, Nettle and Gordon JJ in Mount Bruce Mining Pty Ltd v Wright Prospecting Pty Ltd [2015] HCA 37; (2015) 256 CLR 104 relevantly as follows:

(a) the rights and liabilities of parties under a provision of a contract are determined objectively, by reference to its text, context (the entire text of the contract as well as any contract, document or statutory provision referred to in the text of the contract) and purpose: at [46];

(b) in determining the meaning of the terms of a commercial contract, it is necessary to ask what a reasonable businessperson would have understood those terms to mean, and that inquiry will require consideration of the language used by the parties in the contract, the circumstances addressed by the contract and the commercial purpose or objects to be secured by the contract: at [47]; and

(c) unless a contrary intention is indicated in the contract, a court is entitled to approach the task of giving a commercial contract an interpretation on the assumption that the parties intended to produce a commercial result, or put another way, a commercial contract should be construed so as to avoid it making commercial nonsense or working commercial inconvenience: at [51].

73 The principles concerning the construction of commercial contracts apply to contracts of insurance: Todd v Alterra at Lloyd’s Limited [2016] FCAFC 15; (2016) 239 FCR 12 at [42] (Allsop CJ and Gleeson J). As Allsop CJ and Gleeson J said in that case at [38], a contract of insurance has the object or purpose of sharing the risk of, or spreading loss from, a contingency. That object or purpose necessarily involves identifying the risks that the insurer has agreed to cover, and those which it has declined: Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Auto & General Insurance Company Limited [2024] FCA 272, [39] (Jackman J). Further, in construing an insurance policy, preference is to be given to a construction supplying a congruent operation to the various components of the whole: Wilkie v Gordian Runoff Ltd [2005] HCA 17; (2005) 221 CLR 522 at [16] (Gleeson CJ, McHugh, Gummow and Kirby JJ).

Statute

74 In Alcan (NT) Alumina Pty Ltd v Commissioner of Territory Revenue [2009] HCA 41; (2009) 239 CLR 27, Hayne, Heydon, Crennan and Kiefel JJ said at [41]:

This Court has stated on many occasions that the task of statutory construction must begin with a consideration of the text itself. Historical considerations and extrinsic materials cannot be relied on to displace the clear meaning of the text. The language which has actually been employed in the text of legislation is the surest guide to legislative intention. The meaning of the text may require consideration of the context, which includes the general purpose and policy of a provision, in particular the mischief it is seeking to remedy.

75 That passage was recently cited by Kennett J in Blinqld Finances Pty Ltd (in liq) v Binetter [2024] FCA 361 at [46], where after framing the relevant issue of statutory construction his Honour said:

The legislative intention for these purposes resides in the text, with which the task of statutory interpretation must begin and end (Alcan …). It is not a function of the subjective intentions of people involved in the legislative process and is not to be inferred from other sources. The consequences of competing interpretations may provide significant guidance as to what the legislative intention is taken to be, to the extent that such consequences are obviously unlikely to have been intended. However, that form of reasoning should generally be confined to cases where a particular construction renders the statute incoherent or runs against one of the accepted presumptions of legislative intention found in the cases. There is a danger in the Court identifying its own view of what constitutes a sensible policy and assuming this to have been the legislative intention (Certain Lloyd’s Underwriters v Cross [2012] HCA 56; 248 CLR 378 at [25]-[26] (French CJ and Hayne J)).

76 I respectfully agree with these observations.

Section 47 of the ICA

77 As Perram J noted in Edser v QSuper Board [2021] FCA 1437 at [74], s 47 of the ICA “harks from the lost golden era in which Commonwealth statutes were still written in English”. The section provides that:

(1) This section applies where a claim under a contract of insurance is made in respect of a loss that occurred as a result, in whole or in part, of a sickness or disability to which a person was subject or had at any time been subject.

(2) Where, at the time when the contract was entered into, the insured was not aware of, and a reasonable person in the circumstances could not be expected to have been aware of, the sickness or disability, the insurer may not rely on a provision included in the contract that has the effect of limiting or excluding the insurer’s liability under the contract by reference to a sickness or disability to which the insured was subject at a time before the contract was entered into.

78 Save for an immaterial amendment in 1997 (“his” became “the insurer’s”), s 47 has remained unchanged since the Insurance Contracts Act was enacted. It reflects the recommendation of the Law Reform Commission, which stated in its report on Insurance Contracts (Report No 20, 1982) at [184] that:

Some absolute warranties of existing fact might be rephrased as exclusions from cover. An example is the common exclusion of pre-existing illness contained in a personal accident policy. This applied to any pre-existing illness, even if the insured was not, and could not reasonably have been aware of it. Exclusions of that type are as objectionable as analogous warranties. Where an exclusion is based on the state or condition of the subject matter of the insurance, the insurer should not be able to rely on that exclusion if the insured proves that, at the time the contract was entered into, he did not know, and a reasonable man in his circumstances would not have known, of the existence of the relevant state or condition.

79 Section 47 does not vary the terms of the contract of insurance per se. Instead, the provision creates a conditional statutory prohibition that precludes the insurer from relying upon exclusions for pre-existing conditions in specified circumstances.

80 The application of s 47(2) requires an objective assessment of: (a) whether the insured was not in fact aware of the sickness or disability at the time of contracting; and, if so, (b) whether a reasonable person in the circumstances could not be expected to have been so aware. The first limb is directed at the subjective awareness of the insured. The second limb is an objective inquiry as to what a reasonable person in the circumstances could be expected to have been aware.

81 With respect to the second limb, cognate language in the ICA has been interpreted as meaning that one should take into account only factors which are “extrinsic” to the insured, such as the circumstances in which the policy was entered into, rather than “intrinsic” factors such as the individual idiosyncrasies of the insured: CGU Insurance Ltd v Porthouse [2008] HCA 30; (2008) 235 CLR 103 at [52] (Gummow, Kirby, Heydon, Crennan and Kiefel JJ). However, I accept ASIC’s submission that the “circumstances” to which regard can be had include the state of knowledge of the insured. In Stealth Enterprises Pty Ltd t/as Gentlemen’s Club v Calliden Insurance Ltd [2017] NSWCA 71 at [39]–[41], after referring to Porthouse, Meagher JA said the following of ICA s 21(1)(b):

The test for disclosure in s 21(1)(b) takes an objective standard — that of a hypothetical reasonable person — and requires a determination as to whether “in the circumstances” it “could be expected” that person would “know” the matter not disclosed to have been relevant. Thus it poses the question whether a reasonable person in the circumstances could be expected to know that the matter was relevant to the insurer’s decision to accept the risk. In answering that question:

it is necessary … to take into account the circumstances affecting the actual insured, but the ultimate question turns on what could be expected of a reasonable person’s state of mind, not on the insured’s state of mind.

GIO General Ltd v Wallace [2001] NSWCA 299; 11 ANZ Ins Cas 61-506 at [23] (Heydon JA), cited with approval in Porthouse at [52 n 37].

In this case that determination requires an evaluation of what that person “could be expected to know” in circumstances which are not disputed. For that reason, as was also held to be the position in Porthouse at [69], this Court is in as good a position as the primary judge was to make that determination; and having done so this Court must not “shrink from giving effect to it”: Warren v Coombes (1979) 142 CLR 531 at 551 (Gibbs ACJ, Jacobs and Murphy JJ).

As is noted above, the imputing of knowledge of the insured’s “circumstances” to the hypothetical reasonable person is directed to putting them in the same position as the insured without taking into account the insured’s subjective state of mind (for example, that the insured thought information was irrelevant to an insurer). The Court does however take into account that the insured knows the facts relied on as not having been disclosed (in this case, the Tukel brothers’ association with the Comancheros): see Porthouse at [53], [57].

82 The second limb of s 47(2) requires that a reasonable person in the circumstances “could not be expected” to have been aware of the sickness or disability, as opposed to “would not be expected” or “should have expected” (emphasis added). The phrase actually adopted is the least onerous of the three, but there is also present in the formula an element of expectation. Writing extra-judicially with Ronald Ashton, Desmond Derrington J has argued that the application of the formula could be encapsulated in the question: is it reasonably possible that a reasonable person would probably (or most probably) know of the relevance of the fact? (“What Have They Done to the Common Law? Disclosure and Misrepresentation” (1988) 1 Insurance Law Journal 1 at 3).

83 The short point is that attention must focus on what the reasonable person could be expected to have been aware. Thus, as ASIC submits, the fact that medical tests could have been taken and would have disclosed the insured’s condition will not be to the point if a reasonable person in the circumstances could not be expected to have taken such tests (eg where the insured actually consulted a doctor who did not advise that such tests be taken; or where a reasonable person could not be expected to have consulted a doctor at all). Accordingly, I reject HCF Life’s submission that the statement of constructive knowledge in the second limb of s 47(2) necessarily includes the awareness that would have been obtained had the insured consulted their doctor prior to entry into the insurance conduct.

84 HCF Life submits that there is no temporal limit on the point of time at which the relevant subjective or objective awareness must have existed prior to contracting. I reject that submission. Section 47(2) requires that the subjective or objective awareness of the insured be assessed “at the time when the contract was entered into”. HCF Life relied upon P Mann and S Drummond, Mann’s Annotated Insurance Contracts Act (8th ed, Lawbook Co, 2022) at [47.20] and Asteron Life Ltd v Zeiderman [2004] NSWCA 47; (2004) 59 NSWLR 585 at [16] (Spigelman CJ, with whom Meagher JA and Bergin J agreed on this point), but neither supports its submission. The point made at [47.20] of Mann’s Annotated Insurance Contracts Act is simply that the condition itself need not subsist at the time of contracting, and the point made at [16] of Asteron Life is that s 47 does not apply where the time of entry into the contract of insurance is irrelevant to the exclusion (eg because the exclusion takes effect by reference to sickness or disability arising after the contract of insurance was entered into).

85 HCF Life also argues that the meaning of “aware” in the first and second limbs of s 47(2) is different from, and of a lesser state of cognisance than, “know”. HCF Life relies upon the definitions of those terms in the Macquarie Dictionary, where “aware” is defined as “cognisant or conscious”, and “know” is defined as “to perceive or understand as fact or truth, or apprehend with clearness and certainty”. This purported distinction is rather too subtle for my mind. But it is unnecessary to take the matter any further. In the present case, nothing turns upon whether the verbs “aware” and “know” might bear subtly different shades of epistemological meaning. Awareness must mean at least an actual state of consciousness of a matter. It does not include suspicion. Nor does it include awareness of inferences that were not in fact made by the insured, and of which they were not told. It is the additional phrase — “and a reasonable person in the circumstances could not be expected to have been aware of” — that provides for a form of constructive awareness.

Construction of the Pre-Existing Condition Terms

86 It suffices to repeat the 2021 PEC Clause, noting that the only material amendment in the 2023 PEC Clause was the addition of the five-year look back limitation. As set out above, the 2021 PEC Clause defined “Pre-Existing Condition” as:

any condition, illness or ailment where the signs or symptoms of which in the opinion of a registered medical practitioner, existed at any time before the Cover Commencement Date, even if a diagnosis had not been made.

87 Four points can be made about the Pre-Existing Condition Terms at this stage. First, the definitions give determinative effect to the subjective opinion of a registered medical practitioner. That is, they are not directed to an objective ascertainment of whether the signs or symptoms existed at any time before the Cover Commencement Date. It is the registered medical practitioner’s formation of an opinion that that was the case which has operative and conclusive effect.

88 In this regard, the term is somewhat akin to definitions of disablement which turn on the subjective opinion of the insurer, trustee or some other person as to whether the claimant is totally disabled: see, eg, Edwards v Hunter Valley Co-op Dairy Co Ltd (1992) 7 ANZ Ins Cas 61-113. The opinion of the nominated arbiter is not subject to “merits review” — it cannot be challenged on the grounds that it is objectively wrong: Hannover Life Re of Australasia Ltd v Jones [2017] NSWCA 233 at [89]–[99] (Gleeson JA, with whom Macfarlan JA and Meagher JA agreed). At most, there may be an implicit condition that the opinion of the registered medical practitioner be addressed to the correct question and formed fairly and reasonably. Whether signs or symptoms of an illness existed at a given point in time in the past is a matter about which reasonable medical minds may differ. Similarly, reasonable medical minds may differ as to whether a given symptom was caused by one condition or another condition, both of which the insured may ultimately suffer from.

89 Second, the opinion to be formed by the registered medical practitioner is only as to the existence of signs or symptoms before the Cover Commencement Date. The registered medical practitioner is not required to form any opinion as to: (a) whether the insured was actually aware of the underlying condition, illness or ailment to which the signs or symptoms related; (b) whether the signs or symptoms were such that a reasonable person in the circumstances of the insured could be expected to have been aware of the condition, illness or ailment before the Cover Commencement Date; or (c) whether the signs or symptoms could or should have permitted diagnosis of the underlying condition, illness or ailment before the Cover Commencement Date.

90 Third, although the phrase “signs or symptoms” is not separately defined in the Recover Cover PDSs, the meaning of those terms has been considered in a number of veterans’ entitlements cases. For example, in Harris v Repatriation Commission (2000) 62 ALD 161; (2000) 32 AAR 84; [2000] FCA 1687 at [52]–[53], the Full Court had regard to the following “uncontroversial medical usages” contained in Butterworths Medical Dictionary (2nd ed, 1978):

Symptom The consciousness of a disturbance in a bodily function; the subjective feeling that there is something wrong in the working of the body and of which the patient complains, eg shortness of breath, pain, fatigue, palpitation, etc. The symptom may or may not be accompanied by observable signs.

Sign Objective evidence of disease or deformity.

Objective symptom A symptom accompanied by signs from which the existence of the symptom can be deduced.

Subjective symptom One appreciated by the patient only; all symptoms are, strictly speaking, subjective.

Objective sign A sign that is appreciable to the examiner’s senses.

Subjective sign A symptom appreciable only by the patient.

91 The words “signs” or “symptoms” where used in the Pre-Existing Condition definitions bear their medical meanings, given that they are directed to a state of opinion to be formed by a medical practitioner. That is, a “sign” is some objectively discernible indication of disease, whereas a “symptom” is a subjective consciousness of disturbance in bodily function experienced by the insured person.

92 Fourth, both parties agreed that there is no relevant difference between the phrases “sickness or disability” in s 47 and “condition, illness or ailment” in the Pre-Existing Condition Terms: HCF Life’s Submissions at [99]; ASIC’s Submissions in Reply at [19].

Does ICA s 47 render the Pre-Existing Condition Terms partially unenforceable?

93 ASIC’s complaints in the present case both rest upon an allegation that the Pre-Existing Condition Terms are rendered partially unenforceable by s 47 of the ICA. In my view, that foundational allegation is made out for the reasons below.

94 The inquiries under the Pre-Existing Condition Terms and s 47 of the ICA are fundamentally different. On the one hand, the Pre-Existing Condition Terms turn upon whether a registered medical practitioner holds a subjective opinion that the signs or symptoms of a condition, illness or ailment existed before the policy was entered into. On the other, s 47 of the ICA asks whether the insured was aware (or a reasonable person in the circumstances could be expected to have been aware) of the underlying sickness at the time of contracting. Unsurprisingly, those different inquiries will, in some circumstances, yield different outcomes.

95 Consider the following example provided by Fletcher Moulton LJ in Joel v Law Union and Crown Insurance Company [1980] 2 KB 863 at 884:

Let me take an example. I will suppose that a man has, as is the case with most of us, occasionally had a headache. It may be that a particular one of those headaches would have told a brain specialist of hidden mischief. But to the man it was an ordinary headache undistinguishable from the rest.

96 Suppose that a registered medical practitioner reasonably forms and states an opinion that headaches experienced by an insured in March were symptoms of a cancer subsequently diagnosed in May. If the insured purchased a Recover Cover Product in April, the cancer would be a Pre-Existing Condition as defined — a registered medical practitioner is of the opinion that symptoms of the illness existed before the Cover Commencement Date. But unless the insured was aware (or a reasonable person in his or her circumstances could be expected to have been aware) of the cancer at the time of contracting in April, s 47 would preclude HCF Life from relying upon the Pre-Existing Condition Term to deny a claim. The term is partially unenforceable.

97 There are two fundamental reasons that the inquiry under the Pre-Existing Condition Terms materially differs from that under s 47 of the ICA. First, there is a distinction between the existence of signs and symptoms, on the one hand, and awareness of the underlying condition, illness or ailment to which they relate, on the other hand. As Shepherdson J (with whom McMurdo P and Thomas JA agreed) observed in Australian Casualty and Life Ltd v Hall (1999) 151 FLR 360 at [73]: “a symptom is not a condition”. That observation was picked up by the Hon J C Campbell KC in “Unenforceable Exclusions in Travel Insurance” (2018) 29 Insurance Law Journal 71 at 83 (Unenforceable Exclusions), in saying that “even if an insured knows that he or she has something that is in fact a symptom of a medical condition, that is not the same as knowing that he or she has the condition”. I respectfully agree, and also go one step further in saying not only that a symptom of a sickness is not a condition, but also that the symptoms of that sickness are not a condition. Not all signs or symptoms will, upon first manifestation, cause a reasonable person to become aware of the underlying sickness to which they relate, even if arising in combination. The signs or symptoms may not, at that time, warrant medical attention. And even if medical attention is (or would, by a reasonable person, be) sought, the signs or symptoms may not (at that point in time) permit diagnosis, such that a reasonable person would not become aware of the illness to which they relate. Notwithstanding this distinction, the Pre-Existing Condition Terms focus upon the existence of signs and symptoms, while s 47 of the ICA focuses upon knowledge of the condition, illness or ailment to which they relate.

98 Second, even if the inquiries under s 47 of the ICA and the Pre-Existing Condition Terms were otherwise identical, it is only the latter which gives determinative effect to the subjective opinion of a registered medical practitioner. A provision that is engaged upon one individual’s satisfaction of an objective fact will inevitably be broader than a provision that is engaged only upon the actual existence of that same fact. Consider again the case where a registered medical practitioner forms and states the opinion that headaches experienced in March were symptoms of a cancer subsequently diagnosed in May. Suppose the opinion is reasonably formed, but in ensuing litigation the Court concludes that it is incorrect because the headache was entirely unrelated to the subsequent cancer. The Pre-Existing Condition Terms would bar the insured’s claim, but s 47 of the ICA would intervene. The possibility of conflict between the reasonable opinion of a medical practitioner and the opinion of the Court is not speculative, because the inquiries mandated by the Pre-Existing Condition Terms and s 47 of the ICA pose questions upon which reasonable minds may differ. As Senior Counsel for HCF Life himself submitted: “to take your Honour’s example, that headache, or that mild temperature raise, or whatever it might be — shivering — is equally consistent with the absence of an identifiable condition, illness or ailment, as it is with one”: T69.31–33.

99 The upshot is that s 47 of the ICA renders the Pre-Existing Condition Terms partially unenforceable. That foundational allegation having been made out, I turn now to consider whether HCF Life has contravened ss 12DF and/or 12BF or of the ASIC Act.

Misleading Conduct

100 Section 12DF(1) of the ASIC Act provides that:

A person must not, in trade or commerce, engage in conduct that is liable to mislead the public as to the nature, the characteristics, the suitability for their purpose or the quantity of any financial services.

101 The applicable principles are not in dispute. There is first instance authority stemming from O’Loughlin J’s decision in Trade Practices Commission v J & R Enterprises Pty Ltd (1991) 99 ALR 325 at 338–9 that the phrase “liable to mislead” creates a higher standard than the similar phrase “likely to mislead or deceive” used in the progeny of s 52 of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth): see Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Master Wealth Control Pty Ltd [2024] FCA 344 at [38] (Jackman J). It is common ground that s 12DF(1) is only contravened if there is “an actual probability” that the public will be misled by the impugned conduct.

102 The error into which the public must be led is not at large, but must be as to “the nature, the characteristics, the suitability for their purpose or the quantity” of any financial services. In Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Westpac Banking Corporation (No 2) [2018] FCA 751; (2018) 266 FCR 147 at [2311], Beach J noted that cognate terms appear in s 55 of the Trade Practices Act (now s 33 of the Australian Consumer Law) and accepted “that no narrow or technical meaning should be attributed to those terms”. Similarly, in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Meriton Property Services Pty Ltd [2017] FCA 1305; (2017) 350 ALR 494 at [195], Moshinsky J observed that:

The expressions “nature”, “characteristics” and “suitability for their purpose” are not defined in the Australian Consumer Law. In my opinion, they are to be given their ordinary meaning, in the context of the consumer protection purpose of the provisions. The word “nature” is defined in the Macquarie Dictionary (6th ed, 2013) as meaning (among other things) “the particular combination of qualities belonging to a person or thing by birth or constitution; native or inherent character” and “character, kind, or sort”. See also Spunwill Pty Ltd v BAB Pty Ltd (1994) 36 NSWLR 290 at 302. The word “characteristic” is defined as meaning (as a noun) “a distinguishing feature or quality”. Different views have been expressed as to whether the word “characteristics” in s 33 (or its predecessor, s 55 of the Trade Practices Act) is limited to the internal constitution or utility of goods, or also extends to the manner of their creation: see [Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Snowdale Holdings Pty Ltd (2016) 339 ALR 455; [2016] FCA 541] at [528]-[535]; cf Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Turi Foods Pty Ltd (No 4) [2013] FCA 665 at [124]-[129]. However, this issue does not arise in the present case. The word “suitability” is defined by reference to the adjective “suitable”, which is defined as meaning “such as to suit; appropriate; fitting; becoming”.

103 The words “the public” do not mean the world at large or the whole community; there will be a sufficient approach to the public if the approach is general and random, and if the number of people approached is sufficiently large: Master Wealth Control at [38]. In Shahid v Australian College of Dermatologists (2008) 168 FCR 46 at [206], Jessup J (with whom Branson and Stone JJ relevantly agreed) stated that:

I would accept that a representation might be regarded as being addressed to the public in the relevant sense notwithstanding that the potential users of the services in question were, in the nature of things, few in number. I have in mind, for example, a representation made in an advertisement for services of a very specialised kind. It would be the generality of the range of persons to whom the representation was addressed, rather than the practical likelihood of many of them being interested in acting upon the representation, that would justify the conclusion that it was addressed to the public.

104 The publication of product disclosure statements in respect of financial products available, on application, to members of the public have this quality. HCF Life accepts that its conduct was directed to the public.

105 Subject to those matters, the propositions concerning the more general prohibition of misleading or deceptive conduct in trade or commerce in s 18 of the Australian Consumer Law summarised by the High Court in Self Care IP Holdings Pty Ltd v Allergan Australia Pty Ltd [2023] HCA 8; (2023) 408 ALR 195 at [80]–[84] are apposite: ASIC v Vanguard Investments Australia Ltd [2024] FCA 308 at [21] (O’Bryan J). Determination of contravention there involves four steps (Self Care at [80]):

first, identifying with precision the “conduct” said to contravene s 18; second, considering whether the identified conduct was conduct “in trade or commerce”; third, considering what meaning that conduct conveyed; and fourth, determining whether that conduct in light of that meaning was “misleading or deceptive or … likely to mislead or deceive”.

106 Where, as here, “the conduct was directed to the public or part of the public, the third and fourth steps must be undertaken by reference to the effect or likely effect of the conduct on the ordinary and reasonable members of the relevant class of persons”: Self Care at [83]. In order to undertake that analysis, it is not necessary to adduce evidence from members of the public themselves. The question is one for the court: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Coles Supermarkets Australia Pty Ltd [2014] FCA 634; (2014) 317 ALR 73 at [45] (Allsop CJ).

107 In accordance with the parties’ submissions, I will structure my reasoning with reference to the four steps identified in Self Care before turning to an additional aspect of s 12DF.

The first and second steps — impugned conduct in trade or commerce

108 The impugned conduct is HCF Life’s publishing of each Recover Cover PDS, giving the Recover Cover PDSs to members of the public, and entering into the Recover Cover Contracts with members of the public, in circumstances where the Recover Cover PDSs:

(a) contained the Pre-Existing Condition Terms; and

(b) did not advert to, or explain, the existence or effect of s 47 of the ICA or that the Pre-Existing Condition Terms were partially unenforceable.

109 HCF Life does not dispute that it engaged in that conduct, nor that it did so in trade or commerce.

The third step — meaning conveyed