Federal Court of Australia

PricewaterhouseCoopers Inc in its Capacity as Foreign Representative of IE CA 3 Holdings Ltd v IE CA Holdings Ltd [2024] FCA 1208

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Pursuant to Art 17(1) of the UNCITRAL Model Law on Cross-Border Insolvency, being Sch 1 to the Cross-Border Insolvency Act 2008 (Cth), the bankruptcies that commenced in respect of the defendants in British Columbia, Canada on 28 June 2023 (Vancouver Registry Action No. S230488) (Proceeding) be recognised as a foreign proceeding within the meaning of Art 2(a) of the Model Law.

2. Pursuant to Art 17(2)(a) of the Model Law, the Proceeding be recognised as a foreign main proceeding within the meaning of Art 2(b) of the Model Law.

3. Pursuant to Art 17(1)(b) of the Model Law, the plaintiff be recognised as the foreign representative of the Proceeding within the meaning of Art 2(d) of the Model Law.

4. Pursuant to Art 20(1) of the Model Law, except with the consent of the plaintiff or with leave of the Court:

(a) the commencement or continuation of individual actions or individual proceedings concerning either defendant’s property rights, obligations or liabilities is stayed;

(b) any execution against either defendant’s property is stayed; and

(c) the right to transfer, encumber or otherwise dispose of any property of the defendants is suspended.

5. Pursuant to Art 21(1)(e) of the Model Law, the administration and realisation of each defendant’s assets located in Australia be entrusted to Christopher Hill and David McGrath of FTI Consulting (Local Representatives).

6. Pursuant to Art 21(1)(g) of the Model Law, the Local Representatives be invested with all powers available to a liquidator of a corporation appointed under the provisions of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth).

7. Pursuant to Art 21(1)(d) and 21(1)(g) of the Model Law, the Local Representatives may, as they deem appropriate, examine witnesses, take evidence or require the delivery of information concerning each of the defendants’ affairs, rights, obligations or liabilities as if the Local Representatives were liquidators appointed to the relevant defendant under Pt 5.4B of the Corporations Act.

8. Pursuant to Art 21(2) of the Model Law, the distribution of all of the debtors’ assets located in Australia is entrusted to the plaintiff.

9. The requirement for notice under r 15A.7 of the Federal Court (Corporations) Rules 2000 (Cth) is dispensed with.

10. Any party affected by these Orders has liberty to apply upon five business days’ notice.

11. The interlocutory application filed by Iris Energy Ltd (Intervenor) be dismissed.

12. Subject to Order 13 below, the costs of this proceeding be costs of the liquidation of the defendants and accorded the same priority as costs of proceedings incurred by a liquidator under the Corporations Act.

13. The Intervenor is to pay the plaintiff’s costs of the interlocutory application.

14. Leave is granted to any party seeking a variation of Orders 12 and/or 13 above to file submissions not exceeding two pages in length setting out the proposed variation and the reasons why such a variation should be made within seven days of the date of publication of these reasons.

15. If any application is made pursuant to Order 14 above, it will be dealt with on the papers.

THE COURT DECLARES THAT:

16. Pursuant to s 16 of the Act and Art 20(2) of the Model Law, the stay and suspension described in Order 4 above be:

(a) the same in scope and effect as if the defendants had been made the subject of a winding up under Pt 5.4B of the Corporations Act; and

(b) subject to the same powers of the Court and the same prohibitions, limitations, exceptions and conditions as would apply under the law of Australia in such a case.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

MARKOVIC J:

1 IE CA 3 Holdings Ltd and IE CA 4 Holdings Ltd (together, IE CA Companies), the defendants in this proceeding, are companies registered in Canada. On 28 June 2023 the Office of the Superintendent of Bankruptcy appointed PricewaterhouseCoopers Inc (PwC) as the trustee of the bankrupt estates of the IE CA Companies in Vancouver Registry Action No S230488 (Bankruptcy Proceeding) commenced under the Bankruptcy and Insolvency Act R.S.C 1985, c.B-3 (BI Act).

2 PwC in its capacity as foreign representative of the IE CA Companies, the plaintiff in this proceeding (also referred to as the trustee), seeks recognition of the Bankruptcy Proceeding as a foreign proceeding pursuant to Art 17 of the UNCITRAL Model Law on Cross-Border Insolvency being Sch 1 to the Cross-Border Insolvency Act 2008 (Cth) (CBI Act) and related relief.

3 Iris Energy Ltd is the ultimate holding company of the IE CA Companies. On 26 September 2024 Iris was granted leave to file an interlocutory application (Iris IA) by which it seeks leave to intervene in the proceeding and orders that PwC’s originating process be set aside or, in the alternative, dismissed or permanently stayed. On 9 October 2024, I granted leave to Iris pursuant to r 9.12 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) to intervene in the proceeding.

4 PwC’s application for recognition and the Iris IA were heard together.

Background

5 On 13 June 2023, the Supreme Court of British Columbia (BC Supreme Court) granted, among others, an order authorising PwC, in its capacity as receiver and manager of the IE CA Companies, to assign the IE CA Companies into bankruptcy. The circumstances in which PwC was appointed as receiver of the IE CA Companies are described below.

6 On 27 June 2023 bankruptcy assignment documents were filed in accordance with the BI Act. On 28 June 2023 those documents were accepted by the Office of the Superintendent and PwC was appointed as trustee of the bankrupt estates of each of the IE CA Companies in the Bankruptcy Proceeding. In accordance with the BC Supreme Court’s order, on 28 June 2023 the IE CA Companies were assigned into bankruptcy by PwC acting in its capacity as receiver.

7 Michelle Anne Grant, senior vice president, corporate advisory and restructuring, PwC, chartered insolvency and restructuring professional and licensed insolvency trustee, and her colleague Georgina Foster, manager, corporate advisory and restructuring, PwC, together have the day-to-day carriage of the insolvency proceeding relating to the IE CA Companies. Ms Grant explains that this includes the protection and realisation of the assets and undertakings of the IE CA Companies.

Iris and the Iris Group

8 As set out above, the IE CA Companies are wholly owned subsidiaries of Iris, a public company registered in Australia and listed on the NASDAQ. According to a search undertaken on 13 September 2024 of the register maintained by the Australian Securities and Investments Commission in relation to Iris, its registered office is in Melbourne, Victoria, its principal place of business is in Sydney, New South Wales and three of its six current directors are located in New South Wales.

9 The IE CA Companies are part of a larger group of companies, known as the Iris Energy Group, of which Iris is the parent company. Iris has approximately 27 subsidiaries in Canada, the United States of America (USA) and Australia. To the best of Ms Grant’s knowledge, the IE CA Companies are the only members of the Iris Group that are subject to any form of insolvency process.

10 The Iris Group is primarily in the business of owning and operating Bitcoin mining data centres and undertaking Bitcoin mining. Ms Grant explains that Bitcoin mining involves the application of computational power to generate multiple guesses aimed at solving mathematical problems. When the guess is successful, the winner receives an “award” in the form of Bitcoin.

11 The Iris Group maintains corporate offices in Vancouver, British Colombia, Canada and, as at the date that PwC was appointed as receiver to the IE CA Companies, nearly all the mining facilities owned or leased by Iris Group companies and all Bitcoin operations conducted by it or on its behalf were based in British Colombia, Canada. More particularly, Iris Group companies own and lease special purpose mining facilities in Mackenzie, Canal Flats and Prince George, British Colombia, Canada (together, Iris BC Sites).

The IE CA Companies

12 Each of the IE CA Companies was incorporated under the laws of the province of British Columbia, Canada in 2021 and has its registered office at the same address in Kimberley, British Columbia.

13 To the best of Ms Grant’s knowledge, as at the date of the appointment of PwC as receiver, the IE CA Companies:

(1) did not have any subsidiaries;

(2) maintained bank accounts with the Royal Bank of Canada;

(3) did not have any employees;

(4) did not have offices outside Canada; and

(5) owned equipment for cryptocurrency mining, which was their predominant business, which then operated from facilities in British Columbia and leased from related parties in the Iris Group at the Iris BC Sites.

14 Ms Grant is not aware of any other real property assets owned or leased by the IE CA Companies in or outside Canada.

15 The IE CA Companies are not registered under the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) and are not authorised deposit taking institutions within the meaning of the Banking Act 1959 (Cth), general insurers within the meaning of the Insurance Act 1973 (Cth) or life companies within the meaning the Life Insurance Act 1995 (Cth).

The Iris Group business

16 The Iris Group which, as set out above, is primarily in the business of owning and operating Bitcoin mining data centres and undertaking the process of Bitcoin mining, has divided its operations into three components:

(1) owning, through Iris subsidiaries, mining servers which are specialised computers called “application-specific integrated circuit miners”;

(2) hosting the mining servers. This is a process by which different subsidiaries acquire or lease the premises where the mining servers are operated and provide the associated infrastructure; and

(3) selling the Bitcoin from “mining pools” generated by the mining servers.

17 The Iris Group’s operations in British Columbia included approximately 36,400 mining servers owned by the IE CA Companies and distributed across the Iris BC Sites (Mining Equipment). The IE CA Companies, which were special purpose vehicles incorporated for the purposes of owning the Mining Equipment, purchased that equipment from Bitmain Technologies Limited. They obtained secured funding to finance that purchase from NYDIG ABL LLC pursuant to two master equipment financing agreements.

18 Ms Grant summarises the structure of the Iris Group’s business as it relates to the IE CA Companies and Iris as follows:

(1) the IE CA Companies purchased and operated the Mining Equipment which produced hashpower which was ultimately used to generate Bitcoin;

(2) the IE CA Companies entered into hosting agreements with hosts, all of which were subsidiaries within the Iris Group. The hosts acquired or leased the premises where the Mining Equipment was operated and provided the associated infrastructure in exchange for a fixed fee based on cost per kilowatt hour of electricity usage of CAD$0.08/kWh;

(3) Iris purchased the hashpower from the IE CA Companies at a fixed rate of CAD$0.096/kWh under hashpower agreements and submitted the hashpower to a mining pool where it earned Bitcoin. Iris then sold the Bitcoin for dollars on a daily basis; and

(4) the IE CA Companies’ net income was the revenue generated by selling the hashpower to Iris pursuant to the hashpower agreements less their expenses paid to the hosts pursuant to the hosting agreements and other expenses including interest payments.

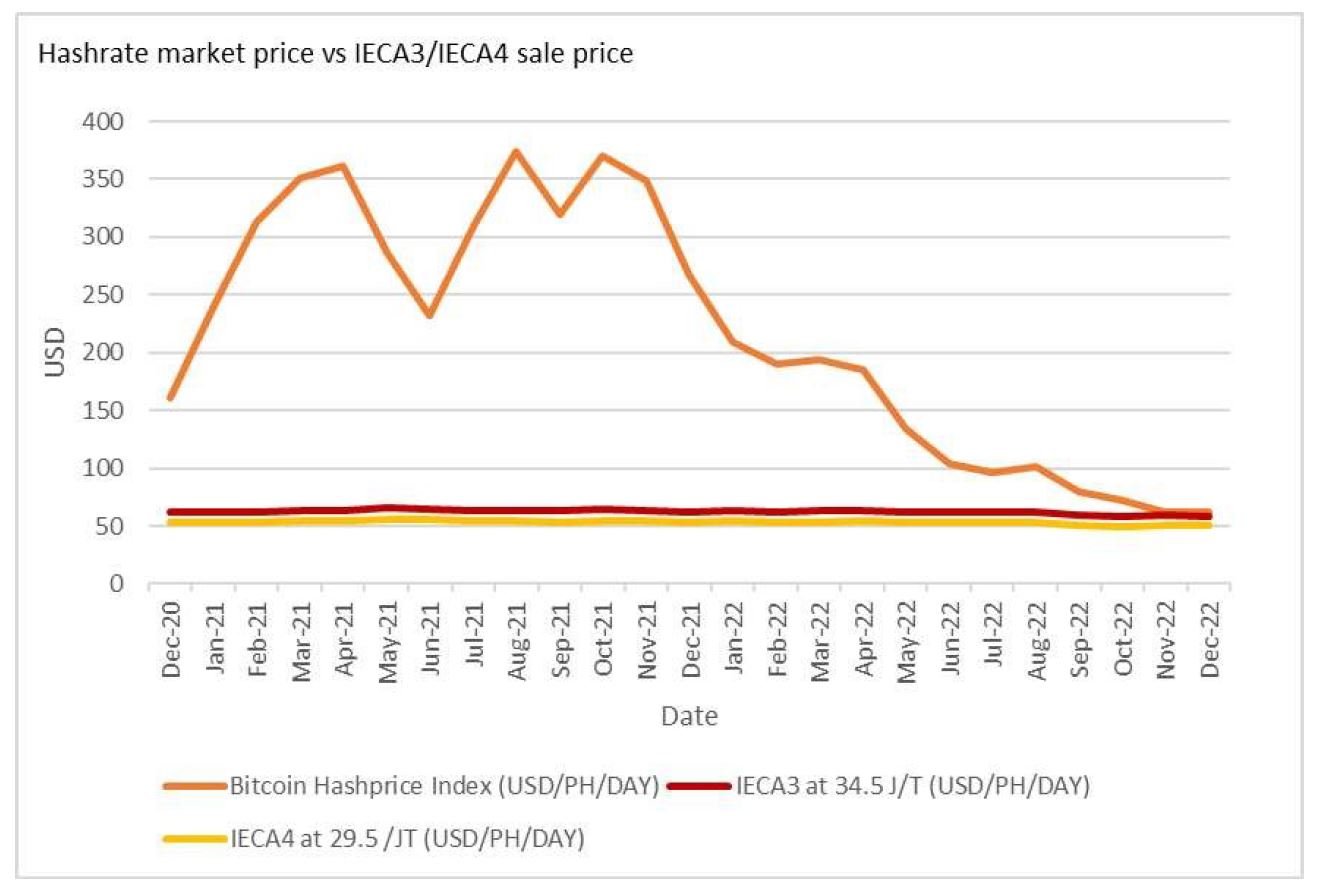

19 Ms Grant opines that, based on the average market daily rate of hashrate, the compensation structure under the hashpower agreements between Iris and the IE CA Companies was substantially below market price before December 2022 and the difference between income received by the IE CA Companies compared to the Bitcoin attributed to the same hashpower was significant. That is illustrated in the following chart which shows the average daily market price of hashrate to that of the sale price Iris had in place with the IE CA Companies for their hashpower contribution under the hashpower agreements:

20 Based on the investigations undertaken by the receiver, Ms Grant understands that the IE CA Companies were not financially viable on their own from the beginning of the arrangements described at [19] above and were dependent on Iris supplementing their income so they could make the payments required of them to NYDIG under the financing agreements. In particular the receiver formed the following view in relation to the solvency of the IE CA Companies:

(1) Iris maintained that the IE CA Companies were only entitled to revenue pursuant to the hashpower agreements and were required to pay the expenses under the hosting agreements;

(2) in addition to the hosting fees, the IE CA Companies were responsible for repayment under the financing agreements which initially required payments of interest and subsequently monthly principal and interest payments; and

(3) based on Iris’ position that the only income to which the IE CA Companies were entitled was the small profit margin realised under the hashpower agreements, the IE CA Companies were not, and never would be, generating sufficient profits to fund the monthly loan payments under the financing agreements. They were reliant on support from Iris or other Iris Group companies to make ordinary course payments and provide top up funding for the payments that were made under the financing agreements.

Directors and officers of the IE CA Companies and Iris

21 Until 29 June 2023, when the receiver filed an application for their removal because on its understanding they had resigned just prior to commencement of the receivership, the following persons were directors of each of the IE CA Companies:

(1) William Roberts, who resides in Sydney and who is the co-founder, co-CEO and a current director and officer of Iris;

(2) Michael Alfred, who resides in Las Vegas, Nevada, USA and who is a current independent, non-executive director of Iris; and

(3) Christopher Guzowski, who resides in London, United Kingdom and who is a current independent, non-executive director of Iris.

22 Together with Messrs William Roberts, Alfred and Guzowski, the following persons are also directors of Iris:

(1) Daniel Roberts, who resides in Sydney and is a co-founder, co-CEO and a director of Iris;

(2) David Bartholomew, who resides in Sydney and is an independent director of Iris; and

(3) Sunita Parasuraman, who resides in the USA and is an independent director of Iris.

23 Based on investigations undertaken first by the receiver and then the trustee in relation to the conduct of the Iris Group business Ms Grant is of the opinion that Iris, as the parent corporation of the IE CA Companies, conducted the IE CA Companies’ business with very little regard to their separate corporate identities. She understands that Iris:

(1) completed all business with Bitmain through one account on behalf of the entire Iris Group;

(2) applied coupons and other credits belonging to the IE CA Companies in the Bitmain account to other entities within the Iris Group;

(3) paid third party invoices from one entity on behalf of other entities within the Iris Group;

(4) conducted the majority of cash transactions in the IE CA Companies’ bank accounts with other Iris Group members; and

(5) completed various adjustments in the IE CA Companies’ accounts without any corresponding intercompany cash receipts.

The Canadian Insolvency Proceedings

24 As set out above, from May 2021 to October 2022 the IE CA Companies obtained secured funding from NYDIG pursuant to, amongst others, the financing agreements to finance the acquisition of the Mining Equipment. In November 2022, following a drop in the Bitcoin market, the IE CA Companies defaulted on their payment obligations under the financing agreements.

25 Following attempts by NYDIG to facilitate a consensual restructuring, NYDIG’s relationship with the IE CA Companies broke down and it issued demands for payment and notices of intention to enforce security in respect of the Mining Equipment.

26 Iris announced in a release to the market issued in November 2022 (November 2022 Release) that certain of its subsidiaries had terminated their respective hosting agreements with the IE CA Companies. Thus, the IE CA Companies have not generated any revenue since early November 2022.

27 The November 2022 Release, which refers to the IE CA Companies as SPV 2 and SPV 3, included under the heading “Limited Recourse Equipment Financing”:

The Group has no debt other than the limited recourse equipment financing arrangements described below.

The Company has three wholly-owned special purpose vehicles (referred to as “Non-Recourse SPV 1”, “Non-Recourse SPV 2”, “Non-Recourse SPV 3” and together, “Non-Recourse SPVs”), which were each incorporated for the specific purpose of financing certain miners. As at September 30, 2022, the Non-Recourse SPVs had the following principal amounts outstanding under their respective limited recourse equipment financing facilities:

• Non-Recourse SPV 1 – $1 million, secured against 0.2 EH/s of miners.

• Non-Recourse SPV 2 – $32 million, secured against 1.6 EH/s of miners.

• Non-Recourse SPV 3 – $71 million, secured against 2.0 EH/s of miners.

The lender to each Non-Recourse SPV has no recourse to, and no cross collateralization with respect to, assets of the Company or any other Group entity, including other Non-Recourse SPVs.

Non-Recourse SPVs and their limited recourse equipment financing arrangements were intentionally structured for prudent risk management to protect the underlying business and data center infrastructure the Group has built.

The secured miners owned by each of Non-Recourse SPV 2 and Non-Recourse SPV 3 currently produce insufficient cash flow to service their respective debt financing obligations and, in aggregate:

• Are currently capable of generating an indicative $2 million of Bitcoin mining monthly gross profit, compared to aggregate required monthly principal and interest payment obligations of $7 million.

• Have a market value which the Company currently estimates to be approximately $65 to $70 million, relative to an aggregate $103 million principal amount of loans outstanding as at September 30, 2022.

Non-Recourse SPV 2 and Non-Recourse SPV 3 are engaged in discussions with their lender and reached an agreement for a two-week deferral of scheduled principal payments originally due under both equipment financing arrangements on October 25, 2022, to November 8, 2022.

Unless a suitable agreement is reached with the lender on modified terms for both equipment financing arrangements, the Group does not intend to provide further financial support to Non-Recourse SPV 2 and Non-Recourse SPV 3.

In this case, the Company expects that neither of those Non-Recourse SPVs will be able to make the scheduled principal payment on November 8, 2022, which would result in a default for those Non-Recourse SPVs under their respective limited recourse equipment financing arrangements.

…

(Footnotes omitted.)

28 In a later part of the November 2022 Release a quote attributed to Mr Daniel Roberts, co-founder and co-CEO of Iris, includes:

The limited recourse equipment financing arrangements have been a recent focus for us. We remain committed to exploring a way in which we may be able to allow the lender to recover its capital investment, however, we are also mindful of the current market and that these arrangements were deliberately structured to minimize any potential impact on the broader Group during a protracted market downturn.

29 In November 2022 NYDIG representatives attended the Iris BC Sites to inspect NYDIG’s collateral and found that the Mining Equipment remained on the racking at the sites but that it was unplugged and not operating.

Receivership of the IE CA Companies

30 On 3 February 2023, on the application of NYDIG, the BC Supreme Court appointed PwC as receiver of the assets, undertakings and property of the IE CA Companies. As at that date IE CA 3 owed NYDIG approximately US$36 million and IE CA 4 owed NYDIG approximately US$79 million (in each case excluding interest, fees and costs).

31 Ms Grant explains that the receivership process in relation to the IE CA Companies included the following activities:

(1) requesting and reviewing the books and records of the IE CA Companies and participating in numerous discussions with representatives of the Iris Group in respect of requests for information;

(2) establishing a website on which all prescribed materials filed by the receiver in relation to the insolvency proceeding were made available to creditors and other interested parties and where regular updates were provided on the status of the proceeding;

(3) undertaking steps to identify, take possession of, secure and insure the Mining Equipment;

(4) undertaking analysis of the intercompany relationships between Iris and certain of its subsidiaries, including the IE CA Companies;

(5) completing all statutory requirements including distribution of a notice to creditors, advertisements in local newspapers and the filing of all relevant documents with the Office of the Superintendent; and

(6) undertaking an extensive sale and solicitation process (SSP) in relation to the IE CA Companies’ secured assets and obtaining orders from the BC Supreme Court in relation to that process. The SSP ultimately resulted in a Court approved acquisition by NYDIG of all the Mining Equipment on an “as is, where is” basis. The purchase price comprised (in part) a credit bid against NYDIG’s secured claim in the amount of US$21 million. As a result the IE CA Companies remain indebted to NYDIG in an amount exceeding US$94 million.

Bankruptcies of the IE CA Companies

32 As set out above, on 28 June 2023 the IE CA Companies were assigned into bankruptcy by PwC, acting in its capacity as receiver, and PwC was appointed trustee of the bankrupt estates. The trustee’s appointment was confirmed at the first meeting of creditors for each of the IE CA Companies held on 18 July 2023.

33 Based on an analysis undertaken by the receiver of the intercompany transactions between the IE CA Companies and Iris and various other subsidiaries in the Iris Group, the receiver confirmed that there were a substantial number of intercompany transactions. As a result the receiver sought the order for assignment of the IE CA Companies into bankruptcy to access the enhanced powers available to a trustee in bankruptcy, including the powers to conduct examinations and to better investigate the pre-receivership transactions and dealings between the IE CA Companies and Iris and, if necessary, the ability to avail itself of the remedies provided under the BI Act.

34 Ms Grant explains, by way of overview, that an assignment into bankruptcy is a proceeding under s 49 of the BI Act in which a licensed insolvency trustee is appointed to manage the bankruptcy process and take assignment of the debtor’s assets for the general benefit of creditors. This typically involves investigating the affairs of the debtor, attending the debtor’s premises, communicating with principals and staff, changing locks, completing an inventory of assets, ensuring there is sufficient insurance in place and generally securing and protecting the debtor’s assets. Within 21 days of the date of bankruptcy, there is a first meeting of creditors where an inspector may be appointed (usually from the creditors in attendance). Inspectors are similar to a board of directors and provide direction to the trustee throughout the bankruptcy process. The trustee runs a sales process to liquidate the debtor’s assets and, once all assets are liquidated, distributes proceeds to creditors in accordance with their ranking in the BI Act.

35 More specifically, Ms Grant explains that a trustee in bankruptcy is given broad powers under s 163(1) of the BI Act to examine, on an ordinary resolution passed by the creditors of the bankrupt or a resolution passed by the majority of inspectors, the bankrupt, any person who would reasonably be thought to know the affairs of the bankrupt, or any person who is or has been an agent, clerk, officer, director or employee with respect to the bankrupt or the bankrupt’s dealings. A trustee does not require an order of the court to conduct an examination pursuant to s 163 of the BI Act and is entitled to examine as many persons as it considers necessary and for whom it can obtain the requisite creditor or inspector approvals. However, a court may set a limitation on the number and length of examinations to be undertaken pursuant to s 163 of the BI Act.

36 On 18 July 2023 and 21 August 2023 NYDIG (as the only third party creditor of the IE CA Companies) passed resolutions at the creditors’ meetings of IE CA 3 and IE CA 4 respectively authorising the trustee to examine Ms Belinda Nucifora, the chief financial officer of Iris, and Messrs Daniel Roberts, William Roberts, Alfred, Guzowski and Bartholomew (Proposed Examinees) in respect of a variety of matters, including in relation to transactions that took place between the IE CA Companies and their affiliates including Iris (Examinable Affairs).

37 On 3 August 2023 the trustee wrote to each of the Proposed Examinees requesting that they attend court in Vancouver, Canada to be examined.

38 On 14 August 2023 Norton Rose Fulbright Canada LLP (NRFC), the solicitors for Iris, responded to the examination requests. They objected to them but offered to make Mr William Roberts, one of the Proposed Examinees, available to be examined in Sydney, either in person or remotely by video conference.

39 On 24 October 2023 the trustee filed an application (Examination Application) in the BC Supreme Court seeking to examine the Proposed Examinees about their knowledge of the affairs of the IE CA Companies. As well as the trustee, the IE CA Companies, Iris, the Proposed Examinees and NYDIG were each party to the Examination Application. NRFC acted for Iris and the IE CA Companies and Lenczner Slaght LLP acted for the Proposed Examinees.

40 The trustee’s report to the BC Supreme Court dated 28 September 2023 in support of the Examination Application (September 2023 Report), among other things, set out the areas which the trustee sought to explore in the examinations including:

4.5 In addition to the outstanding financial issues identified by the Receiver in the foregoing Receiver’s Reports, the Trustee has questions concerning numerous operational and structural issues involving the Debtors which require further information. These operational and structural issues have also been identified in the Receiver’s Reports. Such issues and questions include, inter alia:

4.5.1 the Debtors’ and/or Iris Energy’s decision to delay plugging in the Mining Equipment, notwithstanding the capacity in the Iris BC Sites to bring them online;

4.5.2 the decision to unplug and package up the Mining Equipment in early November 2022;

4.5.3 questions with respect to the corporate structure of the Iris Energy Group, including the rationale for 27 separate entities;

4.5.4 questions with respect to each of the Iris BC Sites, including questions relating to capacity, storage and other matters;

4.5.5 questions with respect to Bitmain, including the account, the relationship with Bitmain, the contracts with Bitmain and various other matters relevant to the selection of Bitmain as the supplier of the Mining Equipment;

4.5.6 questions relating to the operational reporting available for each of the machines NYDIG financed and other machines, including information available from the Foreman reports;

4.5.7 questions about the Hashpower Agreement and the Hosting Agreement;

4.5.8 questions about the relationship with NYDIG and its predecessor firm, including questions about the [financing agreements] and other documentation in respect of the loans; and,

4.5.9 various other matters that have been described in the reports filed by the Receiver in the receivership proceedings.

4.6 As the Debtors have now been assigned into bankruptcy, the Trustee intends to complete its investigation regarding the affairs, property and dealings of the Debtors. The next step in such investigation is the examination of the First Set of Individuals.

41 After setting out the correspondence exchanged between the trustee and the Proposed Examinees (who are referred to in the report as the “First Set of Individuals”), the September 2023 Report provided:

5.5 In addition to the First Set of Individuals, already identified by the Trustee for examination, the Trustee has identified certain other individuals that it may need to examine, in the event that the First Set of Individuals is unable to answer some of the Trustee’s questions that are relevant to its investigation. These individuals include, inter alia:

5.5.1 Mr. Kent Draper, Chief Commercial Officer of Iris Energy. Mr. Draper has been the main point of contact for the Receiver and has sworn one affidavit in the Receivership proceedings;

5.5.2 Ms. Anne Hayes, the Vice President – Finance for the Iris Energy Group from January 2022 through September 2022. Some of the transactions subject to the Trustee’s investigation took place during this period and, as a result, Ms. Nucifora the current Chief Financial Officer of Iris Energy may be unable to answer these questions; and,

5.5.3 Mr. Gregoire Mauve, Senior Manager – Operations for Iris Energy, may be integral to the Trustee’s investigation into the relationship with Bitmain, the capacity questions, the Foreman reports and other matters relating to the Mining Equipment. Mr. Mauve was the individual that provided on screen viewing of the Bitmain account to the Receiver.

5.6 At this juncture, the Trustee is unable to produce an exhaustive list of individuals that may need to be examined as the necessity of such examinations will be dictated in large part by whether the First Set of Individuals are able to answer all of the Trustee’s questions and whether any issues require further investigation following completion of the examinations of the First Set of Individuals. The Trustee only intends to examine individuals that are deemed relevant to its ongoing investigation into the Debtors financial and business affairs (and which comply with the requirements of section 163(1) of the BIA). The basis for the requirement to examination various former and current employees and/or directors of the Debtors and Iris Energy is well documented in the reports filed by the Receiver.

42 On 1 December 2023 the BC Supreme Court allowed the Examination Application in part and made orders (Examination Orders) that:

(1) Iris make each of Messrs William Roberts, Alfred and Guzowski and Ms Nucifora, (Examinees) available for examination by the trustee;

(2) permitted the trustee to choose the sequence in which such examinations would occur; and

(3) limited the trustee such that it was permitted to select two of the Examinees to examine for up to one full day with the balance to be examined for no longer than half a day each,

see IE CA 3 Holdings Ltd. (Re), 2023 BCSC 2120.

43 In IE CA 3 Holdings Milman J noted at [3] that Iris, the IE CA Companies and the Proposed Examinees opposed the Examination Application on the following bases:

a) this court lacks the jurisdiction to compel the proposed examinees, as foreign residents, to submit to the proposed examinations; and

b) the proposed examinations, except for that of William Roberts, would be unnecessary and abusive, particularly because he can answer whatever questions the Trustee may have.

44 Commencing at [29] Milman J considered the question of jurisdiction to make the orders sought by the trustee. His Honour relevantly found at [33]-[34]:

33 First, the court will acquire the requisite in personam jurisdiction over non-resident examinees who have attorned to the court’s jurisdiction, such as by advancing substantive arguments on the merits of the dispute before the court: Barer. I agree with the Trustee that that is what has occurred here. By seeking to have the application resolved, even if only in part, on the basis that the Trustee has acted unreasonably in refusing to examine only William Roberts in the first instance, the proposed examinees have, albeit “begrudgingly”, attorned to this court’s jurisdiction.

34 Second, the proposed examinees are directors and officers of IEL, a foreign corporation that has, without question, already attorned to this court’s jurisdiction. This bankruptcy action is closely related to, and indeed, arises directly out of the receivership proceeding. IEL cannot properly seek to advance its interests in this litigation before this court and the Court of Appeal, while refusing to make its directors and officers available for examination as the law requires. I therefore agree with the Trustee that this court can, to the extent required, also invoke its in personam jurisdiction over IEL by ordering it to make the proposed examinees available for the proposed examinations.

45 The next question was whether limits should be placed on the number of examinations and the use of the information obtained through them. After referring to the evidence before the court his Honour concluded at [47]-[48]:

47 Having considered the evidence adduced on this application in light of the parties’ submissions, I am satisfied that the matters canvassed in the preceding paragraphs are worthy of further investigation by the Trustee, including by way of one or more examinations under s. 163.

48 However, the Trustee has not demonstrated that all six of the proposed examinees fall within at least one of the categories of examinable persons listed in s. 163. I accept that Michael Alfred, William Roberts and Christopher Guzowski, as former directors of the Debtors, as well as Belinda Nucifora, as CFO of IEL (and, as such, a person “reasonably thought to have knowledge of the affairs of the bankrupt”) meet that description. On other hand, the Trustee has not presented a sufficient evidentiary basis to justify including Daniel Roberts and David Bartholomew on that list. Accordingly, my order will, for now, be restricted to the other four.

46 At [49] Milman J concluded that it was not necessary or appropriate to place any restriction on the use of information that may be provided to the trustee through the examinations.

47 Between 23 January 2024 and 15 March 2024 the trustee examined each of the Examinees. According to Mr Siddall, managing partner at NRFC, on 24 May 2024 NRFC provided responses to the requests left at the examinations of the Examinees.

48 Ms Grant says that the examinations of the Examinees did not produce the level of information that the trustee requires to finalise investigations in respect of the affairs, property and dealings of the IE CA Companies. As explained by Ms Grant a variety of factors resulted in the examinations not being satisfactory from the trustee’s perspective including:

(1) the trustee was not able to examine Messrs Daniel Roberts and Bartholomew;

(2) the limited time made available under the Examination Orders for the trustee to conduct the examinations; and

(3) the number of questions submitted by the trustee in the examinations that were not answered by the Examinees (because of objection or otherwise). By way of example Ms Grant notes that the trustee did not obtain sufficient information during the examinations in relation to the following matters which it considers would assist its investigations:

(a) the corporate structure of the Iris Group, including the rationale for incorporating 27 entities within the group;

(b) the commercial rationale for causing the IE CA Companies to enter into the hashpower and hosting arrangements with Iris and other entities within the Iris Group, including the justification relied upon by the IE CA Companies and their directors for entering into the compensation structure within these arrangements;

(c) the corporate governance protocols for the Iris Group; and

(d) the various intercompany transactions between the IE CA Companies and certain entities within the Iris Group.

49 The trustee presently considers that there is limited utility in seeking to undertake further examinations in Canada pursuant to its powers under s 163(1) of the BI Act, particularly in circumstances where the IE CA Companies do not presently hold any assets in that jurisdiction. However, the trustee is presently of the view that certain current and former officers of the IE CA Companies may need to be examined, or re-examined, in order to progress and complete its investigations into the affairs, property and dealings of the IE CA Companies. Certain of those potential examinees are located in Australia or otherwise outside of Canada.

The IE CA Companies’ assets

50 To the best of Ms Grant’s knowledge, the IE CA Companies do not hold any tangible assets in Australia or otherwise. The trustee intends to continue investigations, including to understand whether any claims or contingent claims may arise from the Examinable Affairs.

51 Ms Grant understands, based on the receiver’s and trustee’s respective investigations up to mid-September 2024 and communications with, and information obtained from, Iris and from NYDIG, that Iris holds assets in Australia including cash at bank in an account held with the National Australia Bank.

Creditors

52 NYDIG is the only material third party creditor of the IE CA Companies with estimated claims, including contingent claims, as at the date of the IE CA Companies’ respective bankruptcies, of more than US$115 million, excluding interest, fees and costs. Based on the information presently available to Ms Grant, she has not identified any Australian third party creditors of the IE CA Companies but notes that Iris is a related party creditor.

Proceedings involving the IE CA Companies

53 Ms Grant’s evidence is that as at 16 September 2024:

(1) there were no insolvency proceedings other than the Bankruptcy Proceeding which had been commenced against the IE CA Companies anywhere in the world;

(2) she was not aware of any proceedings under Ch 5, s 601CL of, or Sch 2 to, the Corporations Act against the IE CA Companies; and

(3) there were no other ongoing legal proceedings commenced against the IE CA Companies anywhere in the world.

54 During the course of the IE CA Companies’ receivership, NYDIG brought an application in the BC Supreme Court (NYDIG Application) seeking relief related to the Bitcoin mined by Iris using the hashpower produced by the IE CA Companies. Amongst others, it sought declarations that:

(1) the Bitcoin mined by Iris, and the proceeds thereof, was collateral for the debt owed by the IE CA Companies to NYDIG under the financing agreements;

(2) the transactions carried out pursuant to the hashpower agreements were fraudulent conveyances and void as against NYDIG; and

(3) the affairs of the IE CA Companies and Iris had been conducted in a manner oppressive to NYDIG (Oppression Claim).

55 On 10 August 2023 the BC Supreme Court delivered judgment in respect of the NYDIG Application. In summary that court:

(1) held that the Bitcoin was not collateral for the NYDIG debt;

(2) found that the transactions referred to at [54(2)] above were voidable conveyances; and

(3) dismissed the Oppression Claim.

According to Ms Grant the receiver took no position in respect of the NYDIG Application, save for filing evidence in relation to the Iris Group’s business model.

56 The IE CA Companies appealed and NYDIG cross-appealed from the BC Supreme Court’s judgment and orders referred to in the preceding paragraph. The British Columbia Court of Appeal allowed the IE CA Companies’ appeal and set aside the declaration of fraudulent conveyances and allowed NYDIG’s cross appeal and made an order remitting the Oppression Claim to the trial court. As at 16 September 2024 Ms Grant was not aware of any further steps having been taken in respect of the NYDIG Application consequent on the order for remittal of the Oppression Claim.

The relief sought

57 Ms Grant explains that that PwC seeks the relief in its originating application because:

(1) the trustee has a legal duty under Canadian law to safeguard all assets of the IE CA Companies by getting in, managing and controlling them, as best and quickly as possible;

(2) given that investigations are still ongoing, the trustee cannot yet be sure that it is aware of all claims that the IE CA Companies may have in Australia (or elsewhere) and seeks assistance where necessary to enable it to understand this;

(3) due to the complexities of the matter, the trustee requires further time and assistance to ascertain and understand certain matters identified by it to date, including questions that it has concerning numerous operational and structural issues involving the IE CA Companies. The trustee is of the view that its investigations may be more appropriately progressed in Australia and may result in bringing claims against, among others, directors and officers of the IE CA Companies and their related entities. At present, the trustee does not know whether such claims exist. However, Ms Grant notes:

(a) based on the information available to the trustee, the compensation structure under the hashpower agreements and hosting agreements was not commercially reasonable;

(b) the IE CA Companies were not (and never were) generating sufficient profit to fund their financial obligations under the funding agreements and were entirely reliant on support from Iris to provide funding; and

(c) the trustee has duties pursuant to the BI Act to provide full and frank disclosure to the court, maximise realisations on the debtors’ estates, and not permit any conduct that is illegal or dishonest in respect of the bankruptcy process. As such, the trustee must further investigate the circumstances surrounding the entry into these arrangements by the IE CA Companies, including investigating the role of Iris in them, and requires the relief being sought to progress the investigations;

(4) for those purposes, among other things, the trustee wishes to use the broader examination powers available under Australian law;

(5) the trustee is not presently aware of the IE CA Companies being subject to any third party claims or actions; and

(6) the trustee understands that Bragar Eagel & Squire, P.C. a law firm based in the USA, issued a public alert on 29 July 2024 stating that it is investigating potential claims against Iris on behalf of Iris stockholders concerning “whether [Iris] has violated the federal securities laws and/or engaged in other unlawful business practices”.

Expert evidence

58 Both PwC and Iris relied on expert evidence. Iris relied on a report prepared by John Grieve, a legal consultant at John Grieve Law Corporation who has practised in bankruptcy and insolvency law since 1985. PwC relied on a report prepared by Francis Lamer, a partner of Kornfeld LLP and a solicitor and barrister admitted to practice in Canada who has practised law in British Columbia since 1990 in the area of general commercial litigation including insolvency.

59 Each of Messrs Grieve and Lamer gave evidence about Canadian law including, among other things, the effect of the Examination Orders and s 163 of the BI Act. It is fair to say that their respective opinions, to the extent they considered the same or similar questions, did not differ in any significant way. I do not intend to set out their evidence in any detail. It is referred to below as necessary.

Legislative Framework

60 Section 6 of the CBI Act provides that the Model Law, with the modifications set out in the CBI Act, is to have the force of law in Australia.

61 Article 17 of the Model Law relevantly provides:

1. Subject to article 6, a foreign proceeding shall be recognized if:

(a) The foreign proceeding is a proceeding within the meaning of subparagraph (a) of article 2;

(b) The foreign representative applying for recognition is a person or body within the meaning of subparagraph (d) of article 2;

(c) The application meets the requirements of paragraph 2 of article 15;

(d) The application has been submitted to the court referred to in article 4.

2. The foreign proceeding shall be recognized:

(a) As a foreign main proceeding if it is taking place in the State where the debtor has the centre of its main interests; or

(b) As a foreign non‑main proceeding if the debtor has an establishment within the meaning of subparagraph (f) of article 2 in the foreign State.

3. An application for recognition of a foreign proceeding shall be decided upon at the earliest possible time.

…

62 Article 6 is the public policy exception. It provides that the Court may refuse to take an action governed by the Model Law if “the action would be manifestly contrary to the public policy of” relevantly, Australia.

63 Article 2 sets out definitions and relevantly provides:

(a) “Foreign proceeding” means a collective judicial or administrative proceeding in a foreign State, including an interim proceeding, pursuant to a law relating to insolvency in which proceeding the assets and affairs of the debtor are subject to control or supervision by a foreign court, for the purpose of reorganization or liquidation;

(b) “Foreign main proceeding” means a foreign proceeding taking place in the State where the debtor has the centre of its main interests;

…

(d) “Foreign representative” means a person or body, including one appointed on an interim basis, authorized in a foreign proceeding to administer the reorganization or the liquidation of the debtor’s assets or affairs or to act as a representative of the foreign proceeding;

…

64 Article 15 sets out the requirements for an application for recognition of a foreign proceeding and, among other things, provides:

2. An application for recognition shall be accompanied by:

(a) A certified copy of the decision commencing the foreign proceeding and appointing the foreign representative; or

(b) A certificate from the foreign court affirming the existence of the foreign proceeding and of the appointment of the foreign representative; or

(c) In the absence of evidence referred to in subparagraphs (a) and (b), any other evidence acceptable to the court of the existence of the foreign proceeding and of the appointment of the foreign representative.

3. An application for recognition shall also be accompanied by a statement identifying all foreign proceedings in respect of the debtor that are known to the foreign representative.

65 Article 15(3) has been modified by s 13 of the CBI Act to require additionally that an application for recognition is accompanied by a statement identifying, relevantly, any appointment of a receiver within the meaning of s 416 of the Corporations Act in relation to the property of the debtor and all proceedings under Ch 5 and s 601CL of, and Sch 2 to, the Corporations Act in respect of the debtor that are known to the foreign representative.

66 Article 16 sets out certain presumptions concerning recognition including, relevantly, that, in the absence of proof to the contrary, the debtor’s registered office is presumed to be the centre of the debtor’s main interests (COMI): Art 16(3).

67 Article 20 concerns the effects of recognition of a foreign main proceeding. Pursuant to Art 20(1)(a), upon the grant of recognition of a foreign proceeding as a foreign main proceeding, commencement or continuation of individual actions or proceedings concerning the debtor’s assets, right, obligations or liabilities is stayed. Section 16 of the CBI Act provides that the scope and modification or termination of, relevantly, the stay referred to in Art 20(1) is the same as if the stay arose under Ch 5 of the Corporations Act (other than Pt 5.2 and Pt 5.4A).

68 Article 21 provides for additional relief which a court may grant upon recognition of a foreign proceeding. It relevantly provides:

1. Upon recognition of a foreign proceeding, whether main or non‑main, where necessary to protect the assets of the debtor or the interests of the creditors, the court may, at the request of the foreign representative, grant any appropriate relief, including:

…

(d) Providing for the examination of witnesses, the taking of evidence or the delivery of information concerning the debtor’s assets, affairs, rights, obligations or liabilities;

(e) Entrusting the administration or realization of all or part of the debtor’s assets located in this State to the foreign representative or another person designated by the court;

…

(g) Granting any additional relief that may be available to [insert the title of a person or body administering a reorganization or liquidation under the law of the enacting State] under the laws of this State.

2. Upon recognition of a foreign proceeding, whether main or non‑main, the court may, at the request of the foreign representative, entrust the distribution of all or part of the debtor’s assets located in this State to the foreign representative or another person designated by the court, provided that the court is satisfied that the interests of creditors in this State are adequately protected.

3. In granting relief under the present article to a representative of a foreign non‑main proceeding, the court must be satisfied that the relief relates to assets that, under the law of this State, should be administered in the foreign non‑main proceeding or concerns information required in that proceeding.

69 Lastly, Art 8 concerns interpretation and provides:

In the interpretation of the present Law, regard is to be had to its international origin and to the need to promote uniformity in its application and the observance of good faith.

Questions for consideration

70 PwC’s application for recognition and the Iris IA essentially raise two questions for consideration and determination:

(1) should the Bankruptcy Proceeding should be recognised as a foreign main proceeding; and

(2) if so, what additional discretionary relief ought to be granted.

Should the Bankruptcy Proceeding be recognised?

71 As set out above, the requirements for recognition of a foreign proceeding are found in the Model Law which has force of law in Australia by reason of, and subject to the modifications in, the CBI Act.

Have the requirements of Art 17 been met?

72 Putting to one side the exception introduced by Art 6 of the Model Law (which I consider below), for the reasons set out below I am satisfied that PwC has met the requirements of Art 17 for the purposes of recognition of the Bankruptcy Proceeding. My reasons follow.

73 First, the Bankruptcy Proceeding is a “foreign proceeding” within the meaning of Art 2(a) of the Model Law:

(1) the Bankruptcy Proceeding is a collective judicial or administrative proceeding in a foreign State. The Bankruptcy Proceeding was opened by a Canadian Government Authority at the instigation of PwC which was authorised to do so by an order of the BC Supreme Court. The collective nature of the proceeding is apparent from Ms Grant’s evidence as to the effect of an assignment into bankruptcy under s 49 of the BI Act (see [33] above);

(2) the Bankruptcy Proceeding is conducted pursuant to a law relating to insolvency, namely the BI Act;

(3) the assets and affairs of the IE CA Companies during the proceeding are subject to control or supervision of a foreign court. In particular, s 183(1)(c) of the BI Act provides that the BC Supreme Court is invested with such jurisdiction at law and in equity as will enable it to exercise original, auxiliary and ancillary jurisdiction in bankruptcy proceedings authorised under the BI Act; and

(4) the proceeding is for the purpose of reorganisation or liquidation. As Ms Grant explains (see [33] above) the purpose of the proceeding is to liquidate the assets of, and wind up, each of the IE CA Companies.

74 Secondly, PwC is a “foreign representative” within the meaning of Art 2(d) of the Model Law. It is a person or body authorised in a foreign proceeding to administer the liquidation of the IE CA Companies’ assets.

75 Thirdly, the requirements of Art 17(1)(c) of the Model Law have been met. As required by Art 15(2) the application for recognition was accompanied by certificates from the Office of the Superintendent confirming the existence of the Bankruptcy Proceeding and the appointment of PwC as trustee of the IE CA Companies. Pursuant to Art 16(2) the Court is entitled to presume that documents submitted in support of an application for recognition are authentic, whether or not they have been legalised.

76 Fourthly, Art 17(1)(d) of the Model Law has been satisfied. This Court is a court referred to in Art 4 of the Model Law by operation of s 10(b)(i) of the CBI Act.

77 Finally, the requirements of Art 15(3) of the Model Law have been satisfied. Ms Grant has given evidence that there are no other proceedings commenced against the IE CA Companies of which she is aware anywhere in the world or any proceedings pursuant to Ch 5 or s 601CL of, or Sch 2 to, the Corporations Act (see [53] above).

78 I am also satisfied that the Bankruptcy Proceeding should be recognised as a foreign main proceeding pursuant to Art 17(2)(a).

79 The evidence discloses that the registered office of each of the IE CA Companies is at an address in Kimberley, British Columbia, Canada (see [12] above). In the absence of proof to the contrary, a debtor’s registered office is presumed to be the COMI: see Art 16(3). The rebuttal of that presumption requires regard to be had to factors which are both objective and ascertainable by third parties, including creditors: see Kapila, Re Edelsten [2014] FCA 1112; (2014) 320 ALR 506 at [53]-[54].

80 There was no evidence before me to rebut the presumption. Rather, the evidence discloses that: the Iris Group, which includes the IE CA Companies, maintains corporate offices in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada; nearly all of the mining facilities owned or leased by the Iris Group were based in British Columbia, Canada at the time of PwC’s appointment; neither of the IE CA Companies had a presence outside of Canada; each of the IE CA Companies maintained bank accounts in Canada; and the IE CA Companies owned the Mining Equipment which was situated in facilities in British Columbia, Canada.

81 On 26 September 2024 I made orders (September Orders) for the notification of PwC’s application for recognition requiring it to publish a notice in The Australian and The Australian Financial Review newspapers and on its website and to give notice of the making of the September Orders by email to each person who, to PwC’s knowledge, is a creditor or claims to be a creditor of the IE CA Companies. I am satisfied that PwC has complied with the September Orders:

(1) on 2 and 5 October 2024 PwC published a notice in the form required by the September Orders on its website and caused a copy of that notice together with a copy of the September Orders to be sent to all known third party creditors of the IE CA Companies; and

(2) on 3 and 4 October 2024 respectively a notice in the form required by the September Orders was published in The Australian and The Australian Financial Review newspapers.

82 It follows from the above and from the requirements of Art 17(1) of the Model Law that, subject to the applicability of Art 6 of the Model Law, the Bankruptcy Proceeding should be recognised as a foreign main proceeding.

83 Upon the grant of recognition of a foreign proceeding as a foreign main proceeding, commencement or continuation of individual actions or individual proceedings concerning the debtor’s assets, rights, obligations or liabilities is stayed pursuant to Art 20(1)(a) of the Model Law. Ms Grant’s evidence is that the Bankruptcy Proceeding is similar to a liquidation. As the trustee submits, the closest analogy in the Australian context is a winding up under Pt 5.4B of the Corporations Act which concerns winding up in insolvency or by the court. Accordingly, the stay to be applied under Art 20 of the Model Law should be the same as that under Pt 5.4B of the Corporations Act.

Article 6 – the public policy exception

84 As set out above, recognition under Art 17 is subject to Art 6 which provides that the Court may refuse to take an action governed by the Model Law if it “would be manifestly contrary” to public policy of the enacting State.

The parties’ submissions

85 Iris submits that PwC’s stated purpose of recognition is to conduct examinations of company officers which is an abuse of process and “manifestly contrary” to public policy in Australia. It submits that the Court, in its inherent jurisdiction to control its own processes and refuse to let them be turned into an abusive process, may refuse to grant the relief sought by PwC. Iris says that is informed by what is required by, but not dependent on, the Model Law for jurisdiction to refuse.

86 Iris submits that its position is supported by Art 6 of the Model Law. It contends that the emphasis of “manifestly” directs attention to the fundamental public policy of Australia and that the word “manifestly” is understood in the context of the breadth of what constitutes “public policy” in the Model Law, noting that there is a distinction drawn between “procedural” (which is not of the requisite type for the purposes of Art 6) as opposed to “fundamental” public policy.

87 Iris submits that it ought not to be doubted that the public policy manifested by the refusal of the court to allow an abuse of its processes, whether by re-litigation or vexing a litigant with concurrent proceedings, is a central, indeed constitutionally significant public policy. It contends that if proceedings are an abuse of process an Australian court “must not permit the trial to be held”, citing GLJ v Trustees of Roman Catholic Church for the Diocese of Lismore [2023] HCA 32; 97 ALJR 857 at [23], [26].

88 After referring to a number of the cases which concern abuse of process (see below), Iris submits that the varied circumstances in which the use of the court’s processes will amount to an abuse, notwithstanding that the use is consistent with the literal application of its rules, do not lend themselves to exhaustive statement, citing UBS AG v Tyne (2018) 265 CLR 77 at [1]. It contends however, that they are manifest in the principles concerning a stay of local proceedings in favour of foreign proceedings because it “is prima facie vexatious and oppressive, in the strict sense of those terms, to commence a second or subsequent action in the courts of this country if an action is already pending with respect to the matter in issue”, quoting from Henry v Henry (1996) 185 CLR 571 at 591.

89 Iris submits that, following those principles, it has been held that recognition should be refused where it is sought in an abuse of process. Iris relies on Nordic Trustee ASA and another v OGX Petróleo e Gás SA (Em Recuperacao Judicial) and another [2016] EWHC 25 (Ch); [2016] Bus LR 121 where Snowden J (as his Honour then was) held that recognition would be an abuse of process where it was for the ulterior purpose of stymying an arbitration. Iris also contends that its submissions are consistent with the Model Law’s purpose which includes cooperation between the courts of different jurisdictions.

90 Iris submits that the Model Law should thus be understood to support a policy of cooperation, not competition, between courts which reflects in its use of the COMI concept, and its purpose of facilitating efficient enforcement of existing substantive rights from the insolvent company’s COMI, not creating new ones in the jurisdiction in which recognition is to occur. Iris submits that the forum shopping nature of this application is accepted all but expressly by Ms Grant where she frankly accepts that she regards further examinations in British Columbia as lacking utility but wishes to invoke the Australian examination powers. Iris contends that this is both an abuse of process and inimical to at least paras (a)-(c) of the Model Law and likely para (d) and is an attempt to restart investigations and litigation outside of the IE CA Companies’ COMI.

91 Iris submits that this proceeding is an abuse of process because recognition is sought for an improper purpose: first, to seek recognition to conduct examinations which have already been performed or sought and rejected; and/or secondly, to conduct litigation which is unavailable.

92 In summary, the trustee submits that Iris’ abuse of process argument must fail for the following reasons:

(1) the trustee does not by this proceeding seek any specific examination orders – it seeks recognition of the Bankruptcy Proceeding for the purpose of pursuing the Canadian bankruptcies in Australia, including via investigations, recovery action and any legal action that the trustee may be advised to take, and orders empowering local representatives to assist it in that purpose (including by applying to conduct examinations);

(2) any specific examinations would only occur following a further application to a court, and under supervision of the court. Any alleged abuse of process is properly tested at one of those stages, not upon recognition;

(3) the alleged abuse of process would not satisfy the public policy exception in Art 6 of the Model Law;

(4) in any event, further or additional examinations are consistent with the foreign proceeding and the processes of Australian law and are not abusive of process; and

(5) Iris’ submissions that by its recognition application the trustee seeks to pursue litigation that is unavailable to it because it has already been determined (because of the NYDIG Application) and therefore the application is an abuse of process is speculative. At present the trustee does not know what causes of action are available to it.

Some legal principles

93 The purpose and approach of the Model Law were discussed in Akers v Deputy Commissioner of Taxation (2014) 223 FCR 8. Chief Justice Allsop (with whom Robertson and Griffiths JJ agreed) relevantly said at [111]-[114]:

111 That the Model Law reflects a universalist approach (reflected in the pre-existing common law framework discussed in Re HIH) can be accepted: see the 2002 discussion paper entitled CLERP 8 at 17 and 21. CLERP 8 explained the universal approach as:

[O]ne insolvency proceeding will be universally recognised by the jurisdictions in which the entity has assets or carries on business. All the assets of the insolvent company will be administered by the court or the administrator in, and possibly also according to, the law of the place of incorporation. All creditors seeking to claim in the winding up submit claims to that court or administrator. When assets of the insolvent company are located in foreign countries, the court has the power to apply for assistance from the courts of those countries.

112 A similar statement of general approach and underlying informing concept is to be found in Re ABC Learning Ctrs Ltd 3rd Circuit 27 August 2013 at 9:

The Model Law reflects a universalism approach to transnational insolvency. It treats the multinational bankruptcy as a single process in the foreign main proceeding, with other courts assisting in that single proceeding. In contrast, under a territorialism approach a debtor must initiate insolvency actions in each country where its property is found. This approach is the so-called “grab rule” where each country seizes assets and distributes them according to each country’s insolvency proceedings.

113 This, the court said, at 10, involved a rejection of:

the territorialism approach … in favour of aiding one main proceeding. “The purpose is to maximise assistance to the foreign court conducting the main proceeding.” Thus, a Chapter 15 court in the United States acts as an adjunct or arm of a foreign bankruptcy court where the main proceedings are conducted.

114 These statements can be accepted; …

94 As the Full Court observed, the purpose of seeking recognition of a foreign insolvency proceeding is to enable use of the powers in the recognising jurisdiction to assist the foreign insolvency proceeding. To adopt the words of Allsop CJ, the recognising court acts as an adjunct of the foreign insolvency court where the main proceeding is conducted.

95 In Akers, in addressing generally the provisions of the Model Law and CBI Act, Allsop CJ observed in relation to Art 6 of the Model Law at [40]-[41]:

40 The explanatory memorandum to the Cross-Border Insolvency Bill 2008 noted the use of the word “manifestly” in Art 6 and stated:

The purpose of the expression “manifestly”, used also in many other international legal texts as a qualifier of the expression “public policy”, is to emphasise that public policy exceptions should be interpreted restrictively and that article 6 is only intended to be invoked under exceptional circumstances concerning matters of fundamental importance for the enacting State.

41 The above remarks in the explanatory memorandum broadly reflect the comments on Art 6 in the Guide to Enactment and Interpretation of the UNCITRAL Model Law on Cross-Border Insolvency (the Guide to Enactment) and in another UNCITRAL publication UNCITRAL Model Law on Cross-Border Insolvency: the Judicial Perspective (the Judicial Perspective) drafted by judges after the passing of the Model Law and presented to the UNCITRAL Working Group V (Insolvency Law) in 2010, circulated to Governments in 2011 and presented to the Ninth UNCITRAL/INSOL International/World Bank Multinational Judicial Colloquium in Singapore in 2011.

96 Commencing at [144] of Akers Allsop CJ referred, in obiter, to an alternative argument put by the respondent, the Deputy Commissioner of Taxation, and considered by the primary judge that it would be manifestly contrary to Australian public policy to permit the orders for recognition in that case to operate without amendment. Reflecting on the high bar posed by Art 6 his Honour said at [144]-[148]:

144 … The primary judge observed that there was considerable force in the argument. At [45], his Honour said:

[45] It is fundamental to any society that its government be able to require its citizens and others who operate a business or reside within that society, to pay taxation so as to maintain the State.

145 The same ideas were expressed by Holmes J in Compania General De Tabacos De Filipinas v Collector of Internal Revenue (1927) 272 US 87 at 100:

Taxes are what we pay for civilized society.

146 These entirely acceptable (and one would think in the twenty-first century, unremarkable) civic notions must, however, be seen in the context of Australian domestic law and the meaning of public policy in Art 6, as part of an international instrument. No priority is given to taxation debts under Australian law. Infractions of laws concerning taxation may be attended by civil (including civil penalty) and criminal consequences. The refusal to recognise or enforce foreign revenue debts is a commonly accepted principle — one which Australia itself adopts.

147 In this context, if the operation of the Model Law and the CBI Act (as laws of the parliament) otherwise would see the funds remitted to the Cayman Islands, I see no basis to conclude that such would be contrary to a matter of fundamental importance to Australia.

148 The DCT referred to what was said by Judge Trust in Re Gold & Honey Ltd 410 BR 357 (EDNY 2009) that an action would be contrary to United States public policy if it would place at risk fundamental policies of the United States. That is one way of expressing the matter. It does not advance the argument. If the terms of the Model Law and the CBI Act require remitter of the funds to the Cayman Islands, there are no additional circumstances here to engage Art 6.

97 Having regard to the requirements of Art 8 of the Model Law (as to interpretation), I accept the trustee’s submission that the international context underscores the narrow scope of Art 6. To that end, the tenor of the remarks found in the Explanatory Memorandum in relation to Art 6 at the time of enactment of the CBI Act in this jurisdiction are not unique. For example, in adapting the Model Law for inclusion in the United States Bankruptcy Code, the United States Congress stated that “the word ‘manifestly’ in international usage restricts the public policy exception to the most fundamental policies of the United States”: HR Rep No 109-31(1), 109th Cong, 1st Sess (2005). In Canada the adoption of the Model Law did not include the word “manifestly” in the Art 6 public policy exception. Notwithstanding that, Canadian courts have universally held that the public policy exception is to be interpreted narrowly: see J Sarra, S Madaus and I Mevorach, “Chasing assets abroad: Ideas for more effective asset tracing and recovery in cross-border insolvency” (2023) 32(2) International Insolvency Review 253 at 271 and fn 154.

98 Australian authority on the public policy exception is, as observed by McDougall J writing extra-curially, “relatively light”. His Honour said (footnotes omitted):

… This is likely because of the difficulty that parties seeking to resist recognition perceive in running such an argument. Indeed, it appears that no Australian court has ever declined to recognise a foreign insolvency proceeding on this basis. This judicial caution is one imbued in Australian law, and it aligns with the Australian treatment of foreign arbitral awards under the New York Convention, and of judgments of foreign courts. What the jurisprudence in those areas shows (and I suggest that it is applicable by analogy to our present discussion) is that essential principles of justice or morality generally need to be at stake before an Australian court will refuse recognition on public policy grounds.

See Recognition of Foreign Insolvency Proceedings – An Australian Perspective, Paper prepared for the 31st LAWASIA Conference, 3 November 2018 at [36].

99 The analogous regimes referred to by McDougall J include the recognition and enforcement of foreign judgments. In LFDB v SM (2017) 256 FCR 218 a Full Court of this Court (Besanko, Jagot and Lee JJ) in considering an argument that enforcement of a New Zealand judgment which was the result of an allegedly flawed process was contrary to public policy in Australia said at [43]:

In any event, at the very least, the primary judge was correct to reject the notion that merely because a different approach is taken to a common problem in an overseas jurisdiction, that difference renders such an approach contrary to public policy in Australia. The primary judge recognised at [102] that the authorities demonstrate the need to go further. As Tamberlin J noted in Stern v National Australia Bank [1999] FCA 1421 at [143]:

“The thread running through the authorities is that the extent to which the enforcement of the foreign judgment is contrary to public policy must be of a high order to establish a defence. A number of the cases involve questions of moral and ethical policy; fairness of procedure, and illegality, of a fundamental nature.”

100 There has been only limited consideration of Art 6 of the Model Law in Australia. However, it has been considered in other jurisdictions.

101 In Re PT Garuda Indonesia (Persero) Tbk [2024] SGHC(I) 1 the Singapore International Commercial Court (SICC) considered the effect of the omission of the word “manifestly” in the adoption of the public policy exception in Art 6 in the Third Schedule of the Insolvency, Restructuring and Dissolution Act 2018 (2020 Rev Ed). The question that arose for the court was the standard to adopt in examining an objection against recognition and relief premised on Art 6 of the Third Schedule. At [83] Sontchi IJ writing for the SICC (Ramesh JAD, Reyes IJ and Sontchi IJ) observed that:

In this regard, the Greylag Entities refer to Re Zetta Jet Pte Ltd and others [2018] 4 SLR 801 (“Zetta Jet”), a decision in which the General Division of the High Court had the occasion to consider the effect of Article 6 of the Third Schedule. The court observed that there was no indication in the Parliamentary debates or any preparatory material to explain the omission of the word “manifestly”, and that the omission “had to be deliberate and conscious” in light of the drafter’s emphasis on the importance of the word “manifestly”: see Zetta Jet at [22]. The omission therefore suggests, in the view of the court in Zetta Jet (at [23]):

… the standard of exclusion on public policy grounds in Singapore is lower than that in jurisdictions where the Model Law has been enacted unmodified. That is, in Singapore, recognition may be denied on public policy grounds though such recognition may not be manifestly contrary to public policy.

Accordingly, the Greylag Entities submit a lower threshold applies and a mere breach of public policy is sufficient to deny recognition.

102 At [84] his Honour expressed the view that the omission of the word “manifestly” did not necessarily mean that the threshold for denying recognition on public policy grounds under Art 6 of the Third Schedule ought to be lower than under Art 6 of the Model Law. At [87]-[88] Sontchi IJ said:

87 Both the 1997 Guide and the 2013 Guide state that where matters of international cooperation and the recognition of the effects of foreign laws are concerned, it is fundamental public policy that is pertinent. This is because “international cooperation would be unduly hampered if public policy would be understood in an extensive manner [ie, in the sense of domestic public policy]”: see 1997 Guide at para 88 and the 2013 Guide at para 103. With this in mind, both documents state that the inclusion of the term “manifestly” as a qualifier to the expression of “public policy” was to “emphasize that public policy exceptions should be interpreted restrictively and that Article 6 is only intended to be invoked under exceptional circumstances concerning matters of fundamental importance for the enacting State” [emphasis added]: see 1997 Guide at para 89 and the 2013 Guide at para 104.

88 It is therefore clear that the inclusion of the term “manifestly” is not meant to affect in any way the standard of “public policy” as contemplated and applied in Article 6 of the Model Law. Rather, its inclusion is to make explicit what was always implicitly understood to be the test when a public policy objection is raised as a challenge to the recognition, namely that a high threshold has to be met before recognition is refused. Put another way, the word “manifestly” does not add any further depth to the requirement but is simply included for the purposes of erasing doubt and giving clarity: see Re Agrokor DD [2018] 2 BCLC 75 at [109]. We therefore respectfully disagree with the decision in Zetta Jet that Parliament intended a lower threshold by removing “manifestly” in Article 6 of the Third Schedule.

103 In In re Black Gold S.A.R.L. 635 BR 517 (9th Cir. BAP 2022) Jean-Paul Samba, the Foreign Representative of Black Gold S.A.R.L., appealed from an order refusing recognition of a foreign proceeding under Chapter 15 of the Bankruptcy Code, 11 U.S.C. Black Gold had filed an insolvency proceeding in Monaco and Mr Samba was the appointed trustee. Black Gold’s primary creditor, International Petroleum Products and Additives Company, Inc. (IPAC), contended that the Monegasque proceeding was a sham and that the Chapter 15 filing was an act in furtherance of the sham.

104 In reversing the decision of the primary judge, the Bankruptcy Appeals Panel held that § 1501 (which sets out the purpose of Chapter 15) did not provide the court with the discretion to deny recognition of a foreign proceeding, that determination had to be made under § 1517(a) (which sets out the requirements for recognition subject to § 1506) and, if the requirements under that section were satisfied, the court could only deny recognition if it found that not doing so would be manifestly contrary to US public policy (§ 1506). At first instance, the court did not make any findings under § 1517(a), and it declined to find that the Monegasque proceeding violated the public policy provision of § 1506. The Appeals Panel concluded that the requirements for recognition under § 1517(a) were satisfied and that recognition of the Monegasque proceeding would not be manifestly contrary to US public policy.

105 In relation to the application of the public policy exception the Appeals Panel said at [14]:

While courts agree that the public policy exception in § 1506 should be invoked only under exceptional circumstances concerning matters of fundamental importance for the United States, …, few have addressed the question of when U.S. policy is indeed “fundamental,” thus warranting § 1506 protection. Some courts have held that even the absence of certain procedural or constitutional rights will not itself be a bar under § 1506. … Some courts have held that a difference in foreign law and U.S. law does not mean that recognition would be manifestly contrary to U.S. public policy. …

Only a handful of courts have addressed whether a foreign debtor’s misconduct or “bad faith” is a proper basis for invoking § 1506 to deny recognition. Those that have done so have concluded that misconduct or bad faith, standing alone, is insufficient. …

In Creative Finance, the bankruptcy court declined to invoke § 1506 to deny recognition even though the case was “the most blatant effort to hinder, delay and defraud a creditor this Court has ever seen.” 543 B.R. at 502. …

(Citations omitted.)