FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Latitude Finance Australia (No 2) [2024] FCA 1205

ORDERS

AUSTRALIAN SECURITIES AND INVESTMENTS COMMISSION Plaintiff | ||

AND: | LATITUDE FINANCE AUSTRALIA ACN 008 583 588 First Defendant HARVEY NORMAN HOLDINGS LTD ACN 003 237 545 Second Defendant | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties bring in agreed draft orders or, if agreement cannot be reached, competing draft orders, giving effect to these reasons, by 4.00 pm on 28 October 2024.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

[1] | |

[6] | |

[6] | |

[14] | |

[36] | |

[41] | |

The involvement of officers/employees of Latitude and Harvey Norman in the conduct | [57] |

[84] | |

[101] | |

[108] | |

[108] | |

[114] | |

[114] | |

[128] | |

[148] | |

[166] | |

[180] | |

[206] | |

[223] | |

[230] | |

[230] | |

[231] | |

[239] | |

[243] | |

[254] | |

[257] | |

[266] | |

[269] | |

[270] | |

[276] | |

[278] | |

[287] | |

[295] | |

[308] | |

[322] | |

[328] | |

[330] | |

[335] | |

[337] | |

[342] | |

[345] | |

[348] | |

[348] | |

[352] | |

[367] | |

[367] | |

[374] | |

[374] | |

[374] | |

[409] | |

[422] | |

[422] | |

Other radio representative advertisements | [436] |

[439] | |

[439] | |

[459] | |

[466] | |

[467] | |

[482] | |

[488] | |

[491] | |

[495] | |

[507] | |

YATES J:

1 The Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) claims relief under the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth) (the ASIC Act) and the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (the Federal Court Act) against Latitude Finance Australia (Latitude) and Harvey Norman Holdings Ltd (Harvey Norman) in relation to the publication of certain advertisements.

2 Specifically, ASIC claims (amongst other relief): (a) declarations under s 21 of the Federal Court Act and s 12GBA(1) of the ASIC Act; (b) injunctions under s 23 of the Federal Court Act and s 12GD(1) of the ASIC Act; (c) pecuniary penalties under s 12GBB of the ASIC Act; and (d) punitive orders requiring adverse publicity under s 12GLB(1) of the ASIC Act or, alternatively, non-punitive orders requiring adverse publicity under ss 12GLA(1) and (2)(d) of the ASIC Act.

3 ASIC’s originating process (which was amended pursuant to leave granted on 30 June 2023) is now supported by an amended concise statement (the concise statement).

4 On 10 November 2022, prior to the first case management hearing, and at the request of the parties, I made an order that there be separate hearings on the questions of liability and relief. On 17 April 2023, I made a further order providing for the listing of the proceeding for a hearing on liability. The date of the hearing was fixed by an order made on 5 May 2023.

5 The proceeding is presently before me to determine the question of liability only, based on the allegations in the concise statement with reference to 11 representative advertisements.

Introduction

6 During the period 1 January 2020 to 11 August 2021 (the relevant period), the defendants prepared and published (including by broadcasting), or caused to be prepared and published, a large number of advertisements across Australia in newspapers and on television and radio, which promoted the purchase of home and electrical goods from Harvey Norman stores by equal monthly payments of the purchase price for the goods over 60 months on “no deposit” and “no interest” terms (the promotion).

7 According to ASIC, the payment method involved in the promotion, as advertised:

… looked like a one-off loan. It was not. In fact, it was a rolling credit facility with an associated credit card. The reality was that consumers could not avail themselves of the payment method unless they already had, or applied and were approved for, an eligible credit card issued by Latitude. The Advertisements did not disclose, or adequately disclose, the true scope of this financial arrangement. Further, the Advertisements did not disclose, or adequately disclose, the substantial establishment and monthly account service fees associated with the financial arrangement.

8 In opening its case, ASIC stressed that, although it was not necessary to quantify, at the present stage of the proceeding, the number of advertisements that were published or broadcast (and, hence, on its case, the number of separate contraventions of the ASIC Act), the defendants had admitted that, in the relevant period:

(a) the television advertisements were broadcast on at least 900,000 occasions on 367 specified stations;

(b) the radio advertisements were broadcast on 143 radio stations; and

(c) the newspaper advertisements were published in 168 newspapers.

9 ASIC described this as an “advertising blitz” that “one may readily anticipate most adults in Australia saw, watched or heard”. It submits that this reinforced the “dominant message” of the advertisements (as to which, see [84] – [100] below). According to ASIC, this:

… had the impact that consumers would consider they already knew “the deal” and therefore did not take any particular care in seeking to understand the “fine print” of subsequent Advertisements. Thus, an important contextual matter is that consumers likely “saw the advertisements in more than one form and on more than one occasion”, such that impressions conveyed by one Advertisement likely had a continuing effect on that consumer viewing another Advertisement.

(Footnotes omitted.)

10 As ASIC puts it in closing submissions:

It was such that the Advertisements would have been seen by millions of people in Australia, and likely on multiple occasions and across multiple media. The Advertisements’ dominant message would have been reinforced by repetition and reasonable consumers would “tune out” to the remainder of it.

11 To demonstrate the scale of the advertising campaign, ASIC tendered a sample of media bookings, invoices, and advertising calendars. The evidence included invoices rendered by Harvey Norman on Latitude for marketing support.

12 The defendants admitted the summary description of the national advertising campaign in the concise statement (i.e., that, during the relevant period, a number of advertisements were prepared and published in newspapers and broadcast on television and radio across Australia), while taking exception as to what was conveyed in the advertisements. In its concise statement in response, Harvey Norman initially denied involvement in the advertising campaign, claiming that Generic Publications Pty Limited (Generic Publications), a wholly owned subsidiary of Harvey Norman, arranged the campaign.

13 In its opening submissions, however, Harvey Norman acknowledged that, for the purposes of this proceeding, “the conduct of Generic Publications Pty Ltd in arranging the advertising campaign … can be taken to be the conduct of” Harvey Norman.

14 The parties conducted the case with reference to five agreed representative newspaper advertisements, which took a variety of forms. Some advertisements were on one page, some were on two or more pages. Some were spread throughout the newspaper. Some were in the form of a wraparound (so that the advertisement appeared on the first and last pages of the newspaper).

15 The advertisements were published in: (a) The Advertiser on 23 April 2020 (published as a wraparound, totalling four pages) (Representative Advertisement 1); (b) The Sydney Morning Herald on 23 – 24 January 2021 (published on one page) (Representative Advertisement 2); (c) The Herald Sun on 24 February 2021 (published over three pages) (Representative Advertisement 3); (d) The Age on 23 March 2021 (published over two pages) (Representative Advertisement 4); and (e) The Weekend Australian on 13 – 14 March 2021 (published on one broadsheet page) (Representative Advertisement 5).

16 The newspapers referred to in (b) and (c) above contained additional advertisements for Harvey Norman that referenced the promotion. The additional advertisements are not part of the representative advertisements. In oral closing submissions, I was told that, even though these advertisements were not part of the representative advertisements, it had been agreed that “the context of the newspaper would be relevant” and these advertisements should be taken into account to the extent that they had “any significance”. This cryptic observation was never explained, and the parties did not advance any submission with respect to these particular advertisements.

17 Despite their various forms, the representative newspaper advertisements were presented with common elements.

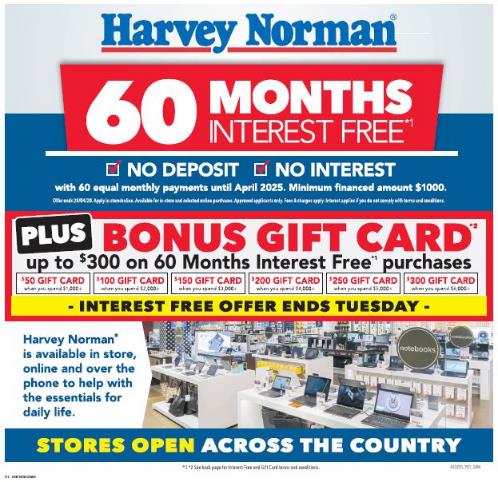

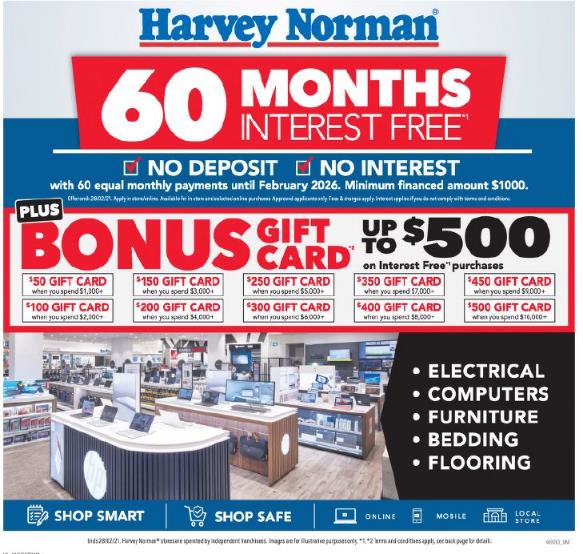

18 All the advertisements had a large red banner with the words appearing thereon in large white letters (Statement A):

60 MONTHS INTEREST FREE*1

19 In each case Statement A was accompanied by the following statement in similar but smaller lettering (Statement B):

NO DEPOSIT

NO DEPOSIT  NO INTEREST

NO INTEREST

20 As is apparent, the words NO DEPOSIT and the words NO INTEREST were preceded by a ticked-box device. In some cases, Statement B was in white letters against a blue background with red ticks. In other cases, it was in black letters against a white background with red ticks.

21 Under Statement B the following statement was made in similar but smaller lettering (Statement C):

with 60 equal monthly payments until [month/year inserted]. Minimum financed amount $1000.

22 In some cases, Statement C was in white letters against a blue background. In other cases, it was in black letters against a white background.

23 I will refer to Statement A, Statement B, and Statement C, as depicted in the representative advertisements, as the banner statements.

24 Under Statement C, the following further statements were made in much smaller lettering (Statement D):

Offer ends [date]. Apply in store/online. Available for in-store and selected online purchases. Approved applicants only. Fees & charges apply. Interest applies if you do not comply with terms and conditions.

25 In some cases, Statement D was in white letters against a blue background. In other cases, it was in black letters against a white background.

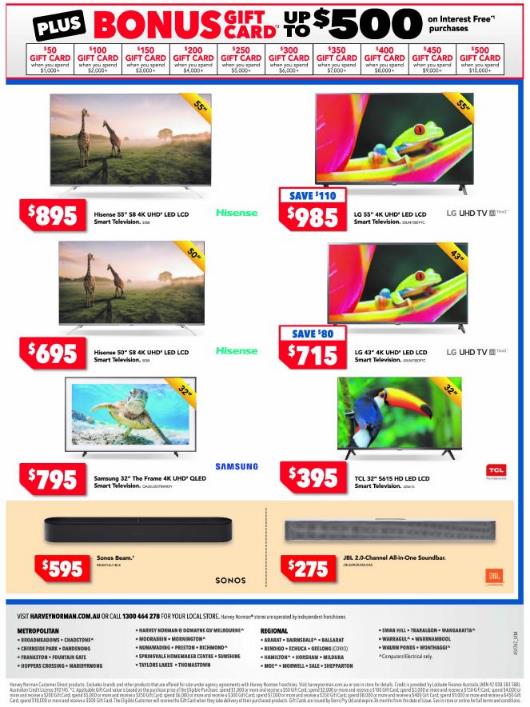

26 A separate box under (or, in Representative Advertisement 4, beside) these statements promoted a Bonus Gift Card (of a certain value or certain values) on interest-free purchases (the Bonus Gift Card statement). The Bonus Gift Card statement was represented no less prominently than the banner statements.

27 Representative Advertisements 1 to 5 are reproduced in Schedule A to these reasons (albeit not true to size).

28 Other than Representative Advertisement 2, the graphical elements to which I have referred were accompanied by images of Harvey Norman goods.

29 In some of the advertisements, Statements A, B, C, D, and the Bonus Gift Card statement, were made more than once. In Representative Advertisement 1, the statements were made three times (each time in a different presentation). In Representative Advertisement 3, the statements were made two times (in different presentations).

30 Each of the representative newspaper advertisements included statements in tightly-packed text in very small lettering over several lines (i.e., “fine print”). In its submissions, ASIC described these statements as being in one of three broad forms: (a) shortened terms; (b) varied shortened terms; or (c) extended terms. I say “broad forms” because within each form there were textual variations, mainly concerning the goods that were eligible for the promotion.

31 These statements appeared in different parts of the advertisements:

(a) in Representative Advertisement 1, the shortened terms appeared at the bottom of the last page of the advertisement;

(b) in Representative Advertisement 2, the shortened terms appeared under the Bonus Gift Card statement at the bottom of the page;

(c) in Representative Advertisement 3, the shortened terms appeared at the bottom of the second page and also at the bottom of the third page of the advertisement;

(d) in Representative Advertisement 4, the varied shortened terms appeared at the bottom of, and across, the two pages of the advertisement; and

(e) in Representative Advertisement 5, the extended terms appeared at the bottom of the page.

32 The shortened terms in Representative Advertisement 1 were:

Ends 28/04/20. Harvey Norman® stores are operated by independent franchisees. The products in this advertisement may not be on display or available at all Harvey Norman complexes. If you wish to view these products in person, you should ring 1300 GO HARVEY (1300 464 278) before attending any complex to check to see if a franchisee at that complex has these products in store. Accessories shown are not included. ˄Available online and in selected stores. ⴕColours may vary between stores. *1. 60 Months Interest Free - No Deposit, No Interest with 60 Equal Monthly Payments until April 2025: Approved applicants only. Conditions, fees and charges apply. Minimum amount financed $1000 on transactions made between 23/04/20 and 28/04/20. Interest applies if you do not comply with terms and conditions. Excludes mobile phones, gaming consoles, gift cards, digital cameras and lenses, hot water system supply & installation, Octopuss installation services, Microsoft Surface Studio, Apple, Miele and Harvey Norman Customer Direct products. Excludes brands and other products that are offered for sale under agency agreements with Harvey Norman franchises. Refer to product websites for conditions, fees and charges. Credit is provided by Latitude Finance Australia (ABN 42 008 583 588). Australian Credit Licence 392145. *2. Applicable Gift Card value is based on the purchase price of the Eligible Purchase: spend $1,000 or more and receive a $50 Gift Card; spend $2,000 or more and receive a $100 Gift Card; spend $3,000 or more and receive a $150 Gift Card; spend $4,000 or more and receive a $200 Gift Card; spend $5,000 or more and receive a $250 Gift Card; spend $6,000 or more and receive a $300 Gift Card. The Eligible Customer will receive the Gift Card when they take delivery of their purchased products. Gift Cards are issued by Derni Pty Ltd and expire 36 months from the date of issue. See in store or online for full terms and conditions. *3. Discounts are off the normal ticketed prices. Terms and conditions apply, see in store for details. *4. Bonus is by redemption from the supplier. Various postage and handling fees may be applicable in order to receive the bonus and are dependent on the supplier’s offer. Terms and conditions apply, see in store for full details.

33 The varied shortened terms in Representative Advertisement 4 were:

Ends 31/03/21. Harvey Norman® stores are operated by independent franchisees. The products in this advertisement may not be on display or available at all Harvey Norman complexes. If you wish to view these products in person, you should ring 1300 GO HARVEY (1300 464 278) before attending any complex to check to see if a franchisee at that complex has these products in store. Accessories shown are not included. #Ultra High Definition not broadcast on free-to-air TV in Australia. ⴕColours may vary between stores. *1. 60 Months Interest Free - No Deposit, No Interest with 60 Equal Monthly Payments until March 2026: Approved applicants only. Conditions, fees and charges apply. Minimum amount financed $1000 on transactions made between 16/03/21 and 31/03/21. Interest applies if you do not comply with terms and conditions. If there is an outstanding balance after the interest free period ends in March 2026, interest will be charged at 25.90%. Excludes mobile phones, gaming consoles, gift cards, digital cameras and lenses, hot water system supply & installation, Octopuss installation services, Microsoft Surface Studio, Apple, Miele and

[continued on the following page of the advertisement:]

Harvey Norman Customer Direct products. Excludes brands and other products that are offered for sale under agency agreements with Harvey Norman franchises. Visit harveynorman.com.au or see in store for details. Credit is provided by Latitude Finance Australia (ABN 42 008 583 588). Australian Credit Licence 392145. *2. Applicable Gift Card value is based on the purchase price of the Eligible Purchase: spend $1,000 or more and receive a $50 Gift Card; spend $2,000 or more and receive a $100 Gift Card; spend $3,000 or more and receive a $150 Gift Card; spend $4,000 or more and receive a $200 Gift Card; spend $5,000 or more and receive a $250 Gift Card; spend $6,000 or more and receive a $300 Gift Card; spend $7,000 or more and receive a $350 Gift Card; spend $8,000 or more and receive a $400 Gift Card; spend $9,000 or more and receive a $450 Gift Card; spend $10,000 or more and receive a $500 Gift Card. The Eligible Customer will receive the Gift Card when they take delivery of their purchased products. Gift Cards are issued by Demi Pty Ltd and expire 36 months from the date of issue. See in store or online for full terms and conditions.

34 The extended terms in Representative Advertisement 5 were:

Ends 14/03/21. Harvey Norman® stores are operated by independent franchisees. Accessories shown are not included. The products in this advertisement may not be on display or available at all Harvey Norman complexes. If you wish to view these products in person, you should ring 1300 GO HARVEY (1300 464 278) before attending any complex to check to see if a franchisee at that complex has these products in store. ^Available online and in selected stores. ⴕColours may vary between stores. Ultrabook, Celeron, Celeron Inside, Core Inside, Intel, Intel Logo, Intel Atom, Intel Atom Inside, Intel Core, Intel Inside, Intel Inside Logo, Intel vPro, Intel Evo, Itanium, Itanium Inside, Pentium, Pentium Inside, vPro Inside, Xeon, Xeon Phi, Xeon Inside, Intel Agilex, Arria, Cyclone, Movidius, eASIC, Iris, MAX, Intel RealSense, Stratix, and Intel Optaneare are trademarks of Intel Corporation or its subsidiaries. *1. Conditions of 60 Months Interest Free until March 2026: Available to approved Latitude Go Mastercard customers on transactions made between 01/03/21 and 15/03/21 where the amount financed is $1000 or more. Offer available on purchases from Harvey Norman franchises. Excludes mobile phones, gaming consoles, gift cards, digital cameras and lenses, hot water system supply & installation, Octopuss installation services, Microsoft Surface Studio, Apple, Miele and Harvey Norman Customer Direct products. Excludes brands and other products that are offered for sale under agency agreements with Harvey Norman franchises. Offer available on advertised or ticketed price. Total amount is payable by 60 approximate equal monthly instalments (exact amounts specified in your statement). If there is an outstanding balance after the interest free period ends in March 2026, interest will be charged at 25.90%. This notice is given under the Latitude GO Mastercard Conditions of Use, which specify all other conditions for this offer. A $25.00 Establishment Fee applies to new approved applicants. Account Service fee of $5.95 per month applies. Also available to existing CreditLine, Latitude Gem Visa and Buyer's Edge customers. Refer to product websites for conditions, fees and charges. Credit is provided by Latitude Finance Australia (ABN 42 008 583 588). Australian Credit Licence 392145. *2. Applicable Gift Card value is based on the purchase price of the Eligible Purchase: spend $1,000 or more and receive a $50 Gift Card; spend $2,000 or more and receive a $100 Gift Card; spend $3,000 or more and receive a $150 Gift Card; spend $4,000 or more and receive a $200 Gift Card; spend $5,000 or more and receive a $250 Gift Card; spend $6,000 or more and receive a $300 Gift Card; spend $7,000 or more and receive a $350 Gift Card; spend $8,000 or more and receive a $400 Gift Card; spend $9,000 or more and receive a $450 Gift Card; spend $10,000 or more and receive a $500 Gift Card. The Eligible Customer will receive the Gift Card when they take delivery of their purchased products. Gift Cards are issued by Derni Pty Ltd and expire 36 months from the date of issue. See instore or online for full terms and conditions. *3. Savings are off the normal online displayed prices.

35 The margins used for the shortened terms, the varied shortened terms, and the extended terms, as quoted in these reasons, assists in reading, and hence, comprehending them. In the newspaper advertisements themselves, the text extended to the margins used for the newspaper—a much wider field of vision. This makes for challenging reading. To add to that challenge, the text was on newsprint.

36 The parties conducted the case with reference to three agreed representative radio advertisements.

37 Representative Advertisement 6 was broadcast between 26 March 2020 and 8 April 2020:

MALE SPEAKER: 60 months interest-free at Harvey Norman and receive a bonus gift card. The more you spend, the greater the value of the gift card, up to $300 when you purchase using 60 months interest free. Furniture, bedding, computers, electrical, bathrooms and flooring, 60 months interest free. No deposit, no interest with 60 equal monthly payments until March 2025. Minimum finance amount $1,000, approved applicants only. Interest applies if you do not comply with terms and conditions. Fees and exclusions apply. Buy with 60 months interest free and receive a bonus gift card now at Harvey Norman.

FEMALE SPEAKER: Go.

38 Representative Advertisement 7 was broadcast between 23 and 28 April 2020:

MALE SPEAKER: At Harvey Norman our spacious stores are open, with teams practising social distancing to keep our community safe. Until Tuesday, buy with 60 months interest-free and receive a bonus gift card. No deposit, no interest, with 60 equal monthly payments until April 2025. Fridges, washing machines, air purifiers, laptops, home wi-fi, mattresses and sofa beds. Shop in store or online, with Click & Collect and delivery available. Minimum financed amount $1000. Approved applicants only. Interest applies if you do not comply with terms and conditions. Fees and exclusions apply. Harvey Norman. We have your essentials covered.

FEMALE SPEAKER: Go.

39 Representative Advertisement 8 was broadcast between 14 and 31 January 2021:

MALE SPEAKER: Harvey Norman summer sizzlers. Lenovo IdeaPad Slim 1 laptop, just $333. Dyson V7 cord-free vacuum, $399. Hisense 512 litre French door fridge, $999. Purchase with 60 months interest-free and receive a bonus gift card up to the value of $500. Minimum financed amount $1000. Approved applicants only. 60 equal monthly payments. Interest applies if you do not comply with terms and conditions. Fees and exclusions apply. Savings off normal ticketed prices. Summer sizzlers at Harvey Norman.

FEMALE SPEAKER: Go.

40 Each advertisement was 30 seconds in duration. Except for the word “go”, each advertisement was delivered in (what appears to have been) the same male voice, over the same musical background (a jingle in the form of a repeated musical motif). The words of the script were spoken at a moderate pace in (what ASIC describes as) “an upbeat tone”, except for the italicised words in the above quotations which were spoken more softly and delivered at a rapid pace, as an aside.

41 The parties conducted the case with reference to three agreed representative television advertisements.

42 Representative Advertisement 9 was televised between 27 March 2020 and 11 April 2020. The spoken part of the advertisement was:

MALE SPEAKER: Get 60 months interest free now at Harvey Norman and receive a bonus gift card. The more you spend using interest-free, the greater the value of the bonus gift card, up to $300. Get what you need now with great deals across a huge range of furniture and bedding. Get 60 months interest free and receive a bonus gift card. The more you spend using interest free, the greater the value of the bonus gift card, up to $300. Limited time only, now at Harvey Norman.

FEMALE SPEAKER: Go.

43 In the course of the advertisement, the following images were shown ephemerally, and in moving form, on the screen to coincide with the spoken words:

44 In the above image, the small rectangle to the right of screen containing the words “$300 GIFT CARD when you spend $6,000 +” flashed red to coincide with the spoken words: “The more you spend using interest-free, the greater the value of the bonus gift card, up to $300”.

45 In the above image, the textual graphics were shown on screen for approximately five seconds, accompanied by footage of various goods within a Harvey Norman store.

46 In the same manner as the earlier image, the small rectangle to the right of screen containing the words “$300 GIFT CARD when you spend $6,000 +” flashed red to coincide with the repeated spoken words: “The more you spend using interest-free, the greater the value of the bonus gift card, up to $300”.

47 The advertisement ended with the following image displayed for less than one second:

48 Representative Advertisement 10 was televised between 14 and 19 May 2020. The spoken part of the advertisement was:

MALE SPEAKER: At Harvey Norman get 60 months interest-free and receive a bonus gift card up to the value of $500. The more you spend on 60 months interest-free, the greater the value of the bonus gift card. Shop for laptops, TVs, fridges, ovens, lounges, beds, flooring, bath vanities and so much more. Shop in our spacious stores or online. We’re practising social distancing to keep our community safe. Get 60 months interest-free and receive a bonus gift card valued at up to $500 now at Harvey Norman. Hurry, offer ends Tuesday.

FEMALE SPEAKER: Go.

49 In the course of the advertisement, the following images were shown ephemerally, and in moving form, on the screen to coincide with the spoken words:

50 In the above image, the textual graphics were shown on screen for approximately nine seconds, accompanied by footage of various goods within a Harvey Norman store.

51 The advertisement ended with a similar image used at the end of Representative Advertisement 9:

52 Representative Advertisement 11 was televised between 1 and 17 April 2021. The spoken part of the advertisement was:

MALE SPEAKER: Australian made for Australian homes, now at Harvey Norman. Snuggle into the L’Avenue 80 per cent duck down and feather queen quilt, just $279. Style it up with the Australian made Jia upholstered queen bed, only $1399, available in a selection of size and fabric options. Enjoy five-zone micro-pocket coil support with the Sleepmaker Alaska queen mattress. Two feels, one great price: $1699. Buy on 60 months interest-free and receive a bonus gift card. Now at Harvey Norman.

FEMALE SPEAKER: Go.

53 The first 24 seconds of the advertisement contained still images of various Harvey Norman bedding products to coincide with the spoken words.

54 Towards the end of the advertisement, the following images appeared:

55 Once again, the advertisement ended with a similar image used at the end of Representative Advertisement 9:

56 Each advertisement was 30 seconds in duration. Except for the word “go”, the spoken words in each advertisement were delivered in (what appears to have been) the same male voice used in the radio advertisements over the same musical background. The words were spoken at a moderate pace in the same “upbeat tone”.

The involvement of officers/employees of Latitude and Harvey Norman in the conduct

57 In the relevant period, Bradley Symmons held the position within Latitude of General Manager Retail Australia, Harvey Norman. He reported to Paul Varro who was a director of Latitude and Latitude Financial Services Australia Holding Pty Ltd. In the relevant period before June 2020, Mr Varro held the position of Executive General Manager, Latitude Pay and Insurance. In the relevant period after June 2020, he held the position of Chief Commercial Officer. Mr Varro reported to Ahmed Fahour, Latitude’s Chief Executive Officer and also a director of Latitude Financial Services Australia Holdings Pty Ltd.

58 In the relevant period, James Monahan held the position within Latitude of Program Leader Commercial, Harvey Norman. He reported to Mr Symmons.

59 The evidence establishes that Latitude was involved in developing and approving the content of advertisements placed by Harvey Norman for the promotions involving Latitude and the GO Mastercard. This included signing off on the disclaimers and disclosures made in the advertisements to which I have referred, based on Latitude’s advertising and brand guidelines. Mr Symmons was the person carrying out this task, although from time to time Mr Monahan undertook this role (e.g., when Mr Symmons was absent). Mr Monahan also carried out six-monthly audits of the advertising campaigns to check that they had been signed-off in accordance with Latitude’s guidelines.

60 Although there was no formal process to do so, Mr Symmons kept an eye out (and ear out) for Harvey Norman advertisements in respect of promotions involving Latitude. He would, for example, make copies of newspaper advertisements and share these with others within Latitude, including Mr Varro.

61 Mr Symmons was the “main interface” with Harvey Norman. He would make recommendations to Harvey Norman about the interest-free promotions it should run, based on Harvey Norman’s previous advertising campaigns and what Harvey Norman’s competitors were currently doing in the market. He would provide the pricing for these recommendations.

62 The key elements of these recommendations were the length of the interest-free period; the type of promotion (e.g., interest-free with equal instalment repayments, interest-free with minimum repayments, or interest-free with deferred repayments); the customer’s minimum spend associated with the promotion; and the cost of the promotion (i.e., the merchant service fee and what Latitude was going to charge the Harvey Norman franchisees).

63 The evidence includes recommendations made by Mr Symmons on 17 March 2020 (for April and May 2020) and on 30 April 2020 (for May and June 2020). The recommendations were sent to Chris Mentis. Mr Mentis was the Chief Financial Officer, the Company Secretary, and an Executive Director of Harvey Norman. Mr Mentis reported to Kay (known as Katie) Page, the Chief Executive Officer of Harvey Norman.

64 The recommendations made on 17 March 2020 covered the promotion advertised in Representative Advertisement 1 and Representative Advertisement 7. The recommendations made on 30 April 2020 covered the promotion advertised in Representative Advertisement 10.

65 Typically, Mr Mentis and Ms Page would meet to discuss Latitude’s recommendations with a view to putting those recommendations to Harvey Norman franchisees for adoption. Mr Mentis was one of the people within Harvey Norman who approved whether a particular advertisement offering an interest-free promotion was published. On occasion, Ms Page was involved in giving that approval.

66 From time to time, and without the intervention of Latitude, Mr Mentis and Ms Page would meet and decide on interest-free promotions to be recommended to Harvey Norman franchisees, including the particulars of the promotion. The factors informing those decisions included the current market conditions; the interest-free offerings of competitors; the costs of the promotion to franchisees; and the impact of any existing restrictions placed on Harvey Norman stores due to the Covid-19 pandemic (different jurisdictions had different lockdown laws affecting store openings, the engagement with customers, and the ability to effect product deliveries).

67 Once a decision was made, Mr Mentis or Ms Page (or both) advised representatives of Generic Publications (which functioned as Harvey Norman’s inhouse advertising agency with a focus on advertising production) of the upcoming interest-free promotion and provided them with details that generally consisted of the promotional period; the number of applicable interest-free months (e.g., 60 months interest-free); whether the promotion would or would not require a deposit or instalment payments (and, if so, the amount of the deposit and instalment payments); the minimum purchase price for the promotion; the goods to which the promotion applied; the goods that were excluded from the promotion; the dollar amount of any gift card; and whether the promotion would be advertised.

68 Generic Publications would then prepare the advertising materials, which typically included terms and conditions, posters for stores, print advertisements (including catalogues and newspaper advertisements), scripts and graphics for television and radio advertisements, and memoranda to franchisees containing details of the recommended promotion.

69 Templates were used to create these materials. The range of materials produced were substantially similar for every interest-free promotion. The materials generally did not change from promotion to promotion, other than in respect of the particulars of the interest-free promotion.

70 Once the materials were prepared, they were given to Daniel Child (the Chief Operating Officer of Generic Publications prior to 1 March 2021) for review, and then to Mr Mentis for approval.

71 Once approved, materials pertaining to the print advertisements (other than the memoranda to franchisees) were sent to Mr Symmons for review and comment. Latitude typically provided its approval for the print advertisements subject to the correction of minor typographical errors. After this review and certain other administrative steps, the print advertisements were published. Publication was on Ms Page’s direction.

72 Generic Publications liaised with DMC Digital Pty Limited (DMC), a production house, for the creation of television advertisements.

73 After DMC created the advertisements, they would be submitted to Generic Publications for approval. Kristie Gee (the Head of Television and Radio at Generic Publications, who reported to Ms Page) would give the advertisements to Mr Mentis for review and approval. The terms of the offer in the advertisements were, like the newspaper advertisements, based on templates approved by Latitude. Mr Symmons was involved in this process from time to time.

74 Sometimes, Ms Page was also involved in approving television advertisements. An email from Ms Gee to Mr Mentis and Mr Symmons on 25 March 2020 states:

Hi Chris and Brad

Katie has approved the attached radio & TV scripts to start on air tomorrow with the IF & Bonus gift card offer.

Can you please approve from a compliant POV

Thanks

75 On 12 May 2020, Ms Gee sent an email to Mr Mentis, stating:

Hi Chris

Please find attached script for approval for the Corporate campaign this weekend.

I also wanted to run past you the graphics promoting the offer. I have attached 3 examples of how we can show it on TV.

Having the full suite as per the press ad below will look very confusing on TV so I just wanted to advertise the key elements. Happy to email to Katie for her approval if you think that is best.

Looking forward to hearing from you.

If possible I would love approval prior to 11am today so we can produce the commercial in time for on air date

Thank you

76 Another email on the same day from Ms Gee to Mr Mentis’s personal assistant, Valerie Salame, refers to the fact that Ms Gee had spoken to Ms Page and that Ms Page had “approved the graphics”.

77 Ms Page gave instructions to Ms Gee about booking television campaigns involving the promotions. This was usually done by telephone or via WhatsApp.

78 Scripts for radio advertisements were prepared by Generic Publications once television advertisements had been finalised. Those Voice Over Guys (a firm) recorded and mixed the advertisements.

79 As with the television campaigns, Ms Page issued instructions to Ms Gee regarding the booking of radio campaigns.

80 ASIC submits that the Court should find that Ms Page and Mr Mentis were “intimately involved in all aspects of the advertising” and that the process was “micro-managed” by Ms Page. It is not clear to me what the word “intimately” adds to the findings I have made. Further, I am not satisfied that Ms Page “micro-managed” the process by which the newspaper, television, and radio advertisements were devised, created, and published or broadcast. On Harvey Norman’s part, these campaigns were undertaken under the overall direction and control of Ms Page with significant management involvement from Mr Mentis, Mr Anderson, Mr Childs, and Ms Gee, as I have described, along with Martin Anderson (General Manger of Generic Publication until June 2021).

81 Before departing from these findings, it is necessary to address a submission made by ASIC in closing that there is evidence that the defendants deliberately sought to minimise the “credit card aspect” of the GO Mastercard in material promoting it.

82 It is important to appreciate that this submission was advanced in circumstances where ASIC has not alleged in its concise statement that Latitude or Harvey Norman deliberately engaged in misleading or deceptive conduct or deliberately made false representations, or acted with any other particular state of mind. It is also important to appreciate that this submission was advanced in respect of activities that went beyond the publication or broadcasting of the newspaper, radio, and television advertisements that advertised the promotion.

83 In the course of the hearing, there was significant debate about the admissibility of many documents that ASIC wished to tender. I was prepared to admit some documents on the limited basis that they showed the involvement of Ms Page in the advertising campaign of which the representative advertisements formed part. They were not admitted for any wider purpose, and certainly not for the purpose of attempting to establish that the defendants deliberately sought to minimise the credit card aspect of the GO Mastercard in material promoting it. What is more, conduct outside the publication or broadcast of the advertisements advertising the promotion is outside the case that ASIC has brought. I therefore make no findings on such matters.

84 ASIC’s case is structured around what it contends was the “dominant message” or “general thrust” of all the newspaper, radio, and television advertisements advertising the promotion—namely, that a payment method was available for purchasing selected goods at Harvey Norman stores that comprised 60 equal monthly repayments on no deposit and interest-free terms.

85 There are two main branches to ASIC’s case, and a number of subsidiary branches. The two main branches are the payment method case (or, as ASIC also called it, the Advertised Payment Method case) and the fees and charges case.

86 As to the payment method case, ASIC alleges that the dominant message conveyed the impression, to reasonable consumers, that the material terms of the payment method were only those to which I have referred at [84] above. ASIC alleges that this was misleading because an essential precondition to acquiring the goods pursuant to the payment method was that the consumer: (a) have, or apply for and be approved for, an eligible credit card issued by Latitude; and (b) use that credit card, or the account linked to that credit card, to purchase the goods from Harvey Norman stores.

87 ASIC alleges that this was misleading because the “essential nature” of the offered arrangement was “masked”. As ASIC puts it in the concise statement:

16. … The GO Mastercard brings into existence a continuing credit contract, which contemplates multiple advances of credit (including through cash advances) and permits Latitude to change contractual terms over time. Fees and charges apply for the right to hold and use the GO Mastercard, including an establishment fee and/or a monthly account service fee, and (in certain circumstances) late payment fees, payment handling fees, fees on international transactions, paper statement fees, cash advance fees and interest. Latitude also discloses information about a GO Mastercard cardholder to credit reporting bodies, including repayment history and any repayment defaults, such that late payments or non-payments may affect a consumer’s capacity to secure finance in future.

88 In its closing submissions, ASIC referred to this part of its case as the Advertised Payment Method – Complete Offer Case. It based this aspect of its case on the theory that, absent disclosure of the essential precondition, referred to in [86] above, consumers reading, seeing, or hearing the advertisements (depending on the medium in question) were led into the mistaken belief that the “dominant message” was a complete statement of the advertised payment method for purchasing Harvey Norman Goods (a defined term): Miller & Associates Insurance Broking Pty Ltd v BMW Australia Finance Limited [2010] HCA 31; 241 CLR 357 (Miller) at [23].

89 ASIC alleges, alternatively, that the dominant message did not disclose the essential precondition to which I have referred, which was, in all the circumstances, an important qualifying fact. In closing submissions, ASIC referred to this part of its case as the Advertised Payment Method – Non-Disclosure Case. It based this aspect of its case on the theory that conduct involving the non-disclosure of an important qualifying fact—which consumers would reasonably expect to have been disclosed by the person engaging in the conduct—renders the conduct misleading or deceptive: Miller at [19].

90 ASIC alleges, further, that the advertisements represented that the material terms of the arrangement were only those stated by the “dominant message”. According to ASIC, this representation was false or misleading for the reasons stated above. In closing submissions, ASIC referred to this as the Advertised Payment Method – Complete Offer Representation.

91 ASIC contends that the Advertised Payment Method – Complete Offer Case, and the Advertised Payment Method – Non-Disclosure case, each lead to contraventions of ss 12DA(1) and 12DF(1) of the ASIC Act and that the Advertised Payment Method – Complete Offer Representation leads to contraventions of ss 12DB(1)(a) and (i) of the ASIC Act.

92 As to the fees and charges case, ASIC alleges that the “dominant message” conveyed, to reasonable consumers, the impression that a consumer taking up the payment method to buy Harvey Norman Goods would only be liable to pay the price of those goods by way of 60 equal monthly payments or, alternatively, that any fees or charges would be relatively insubstantial.

93 ASIC alleges that this was misleading because, in addition to the payments referred to in the “dominant message”, the consumer was also required to pay (in respect of cards issued before 16 March 2021) an establishment fee of $25.00 and a monthly account service fee of $5.95 and (since 16 March 2021) a monthly account service fee of $8.95.

94 In closing submissions, ASIC referred to this as the Fees and Charges Case. It appears to be based on the same theory as the Advertised Payment Method – Complete Offer Case.

95 ASIC alleges, alternatively, that the dominant message did not disclose, or adequately disclose the important qualifying fact that “the consumer would be required to pay at least the establishment fee and/or the monthly account service fees in addition to the 60 equal monthly payments”.

96 In closing submissions, ASIC referred to this as the Fees and Charges – Non-Disclosure Case. It appears to be based on the same theory as the Advertised Payment Method – Non-Disclosure Case.

97 ASIC alleges, further, that the advertisements represented that a consumer taking up the payment method to buy Harvey Norman Goods would only be liable to pay the retail price of those goods by way of 60 equal monthly payments, or alternatively that any fees or charges in connection with the payment method would be relatively insubstantial. ASIC alleges that this was false or misleading because the consumer would also be required to pay the establishment fee and/or the monthly account service fees to which I have referred. In closing submissions, ASIC referred to this as the Fees and Charges Representation.

98 ASIC contends that the Fees and Charges Case, and the Fees and Charges – Non-Disclosure Case, each lead to contraventions of s 12DA(1) of the ASIC Act and that the Fees and Charges Representation leads to contraventions of ss 12DB(1)(a), (g), and (i) of the ASIC Act.

99 The structure of ASIC’s case is complicated—perhaps unnecessarily so. This is probably because the pleader has endeavoured to be as thorough and as comprehensive as possible in describing the legal attributes of the impugned conduct. But, whatever the intent, the case suffers from over-analysis. Despite their distinct doctrinal underpinnings, the six cases described by ASIC are no more than different ways at looking at the same representational conduct with the same question in mind: what did the advertisements convey about paying for the goods?

100 If the advertisements conveyed to ordinary and reasonable consumers, even if not to all ordinary and reasonable consumers, that they could buy eligible goods from Harvey Norman stores on the payment terms stated in the “dominant message”, and that these were the material terms of the financial arrangement in contemplation, then the alleged contraventions will have been made out because, in fact, to take advantage of the promotion, consumers were required to enter into a substantially different financial arrangement—namely, a continuing credit contract with Latitude that was linked to a credit card (the GO Mastercard), whether or not they wanted a credit card (let alone a GO Mastercard), which required them to pay an establishment fee and monthly account service fees for amounts determined by Latitude from time to time in respect of that linked account. ASIC’s overall case is no more complicated than that.

LATITUDE’S PROVISION OF FINANCE

101 In the relevant period, holders of a GO Mastercard, issued by Latitude, had ongoing access to a range of 0% interest payment plans at Harvey Norman stores and other retailers in Australia. One of these plans required equal monthly payments to be made on time and in full. This was the plan promoted in the representative advertisements.

102 In order to obtain a GO Mastercard, consumers were required to establish a GO Mastercard account with Latitude under the terms of a credit contract. The terms of the contract were contained in the GO Mastercard Conditions of Use, and Financial Tables issued by Latitude from time to time.

103 The account could be established at a supplier’s premises (such as at a Harvey Norman store). Before 16 March 2021, consumers were required to pay an establishment fee of $25.00. Once the account was established, Latitude issued the account holder with a “traditional” plastic credit card and PIN for use on that account. Provision existed for the issue of additional cards and for additional cardholders to operate on the account.

104 Under the GO Mastercard Conditions of Use, the account holder became bound by the credit contract when that person (or any additional cardholder) used the account (in described ways) or activated the card. In other words, even though account holders were required to have a GO Mastercard (and could not opt-out from receiving the credit card), they could operate their account without activating, and therefore without using, the card itself.

105 This meant that the account holder only needed to use the account, not the credit card, to take advantage of the plan promoted in the advertisements. However, using the account (including for a 0% interest payment plan) meant that monthly account service fees were incurred. These were fees referable to the servicing of the linked credit card account that had been established. Before 16 March 2021, account holders were charged a monthly account service fee of $5.95 when the account closing balance one day before the statement date was $10.00 or more. On and from 16 March 2021, the monthly account service fee was $8.95 per month. Since early 2023, the fee has been $9.95 per month.

106 If the account holder chose to activate the card, it could be used to obtain credit from Latitude for a variety of purposes: to pay for all or part of the price of goods and services; for cash advances; for balance transfers; and for BPAY payments. Other fees and charges were payable when the GO Mastercard was used in these ways.

107 In the present case, the finance provided by Latitude in respect of the Harvey Norman promotion was not a one-off loan but a continuing credit facility.

108 Apart from a large number of documentary tenders, ASIC relies on the following affidavit evidence:

(a) Alicia Lam made 20 July 2023;

(b) Anaise Rose Cottrell made 28 November 2023 (parts only admitted into evidence); and

(c) various affidavits by consumers (Brian Rodney Harris made 5 July 2023; David John Hill made 5 July 2023; David George North made 6 July 2023; and Simone Jane Jenkins made 6 July 2023), which are summarised in the next section of these reasons (the consumer affidavits).

109 Ms Lam is an analyst in ASIC’s Enforcement Data and Analytics Team. Ms Lam’s affidavit and accompanying exhibit includes analysis she conducted of data provided by Latitude pursuant to a notice given under s 19 of the ASIC Act and through discovery.

110 Ms Cottrell is a lawyer at ASIC. Only paragraphs 16 to 18 of Ms Cottrell’s affidavit were read, in which she provided evidence as to ASIC’s storage and identification of documents obtained from Latitude and Harvey Norman.

111 Latitude relies on the following affidavit evidence: (a) Blake Anthony Smith made 24 October 2023; and (b) Andrew John Whitley made 25 October 2023.

112 Mr Smith is a Program Leader at Latitude Financial Services. Mr Smith has previously worked as an account manager responsible for the training, monitoring and supervising of a range of Harvey Norman stores. Mr Smith provided evidence as to the training conducted with Harvey Norman franchisees and salespeople regarding Latitude’s Sales Merchant Portal (an online portal which allowed merchants to process new applications for Latitude products, including the Go Mastercard).

113 Mr Whitley is Latitude’s Senior Manager of Remediation and Regulation Analytics. Mr Whitley’s affidavit and accompanying exhibit included an analysis spreadsheet derived from data concerning the GO Mastercard.

114 Mr Harris gave evidence of purchasing a television set and PlayStation4 (PS4) in July 2020 from a Harvey Norman store at Noarlunga in South Australia after seeing the promotion advertised in a Harvey Norman catalogue and in multiple radio advertisements. (It should be stressed that ASIC’s case does not include advertisements in catalogues.)

115 The promotion was attractive to Mr Harris because he wanted to purchase the television set and PS4 interest-free; he did not want to make any upfront payments; and he wanted the advertised gift card. He said:

18. My understanding of the Harvey Norman 60 months interest free offer was that there was a minimum amount due each month, which would be the price of the product I purchased divided by 60 months and as long as I made the payment due each month, I wouldn’t incur interest. I thought the repayments towards the purchase price of the product would be the only amounts I would pay in connection with the interest free arrangement. I also understood the words “no deposit” in the catalogue advertisement or radio advertisements to mean that I could purchase the PS4 and TV using the 60 months interest free offer with Harvey Norman and get the bonus gift card without paying a deposit or any payment at the time I made the purchases.

116 At this time, Mr Harris thought he would be borrowing money from Harvey Norman. He did not recall seeing or hearing anything about a finance company, GO Mastercard, a credit card, or any fees. He assumed that the financing was provided by Harvey Norman itself, not a finance company. He was not aware that he needed to sign up, and be approved, for a credit card to take advantage of the offer. He said that, at that time, he did not need a new credit card and was not intending to sign up for a new credit card.

117 Mr Harris attended the Noarlunga store on 19 July 2020. His first purchase was the television set (the PS4 was only available in a different sales department). He gave evidence of the following exchange:

22. … I said, “I would like to do 60 months interest free”. The TV salesperson asked, “Have you signed up with Latitude Finance?”. I said in response, “No I don’t know anything about that”. At that time, I didn’t know what “Latitude Finance” was. The TV salesperson responded and said words to the effect of “Latitude Finance is a credit card company”. I assumed that “Latitude Finance” was the company that provided the finance. At the end of our conversation, the TV Salesperson told me I could sign-up for the 60 month interest free offer in-store right then.

118 Mr Harris said that the salesperson completed the application for him by typing details into a computer. Mr Harris said that he was not given any paperwork at the time, and did not sign anything. He was told that the application would take about one hour to approve.

119 Mr Harris said that, at this time, he still thought that he was applying for an interest-free loan that required him to make equal monthly repayments, and that no deposit was required. He was not told about the repayments he would need to make, although he assumed that they would be “the purchase price divided by 60”. He was not told that there was a $25 establishment fee or any other fees associated with the offer.

120 Mr Harris said that, about one hour later (after he had left the store to have lunch with his son), he received a text message from Latitude to the effect that his application had been approved and that he could pick up the items he had selected from the Harvey Norman store.

121 Mr Harris returned to the Noarlunga store that day to collect the television and purchase the PS4. He wanted to bundle the PS4 purchase with his television set purchase on the 60 months interest-free offer. He saw a different salesperson. This salesperson told Mr Harris that he could not bundle his purchase of the PS4 with his purchase of the television set under the 60 months interest-free offer. He could, however, purchase the PS4 for a 33 month interest-free period. He accepted that offer. He then asked the PS4 salesperson about the gift card. He was told that he was not eligible for the gift card because he had purchased the television set and the PS4 separately from two different franchisees in the store.

122 Mr Harris said:

31. … When I left the store, my understanding was that I had signed up to a contract for 60 months interest free to pay off the price of the TV and a contract for 33 months interest free to pay off the PS4. I assumed that if I paid off the price of those items within those interest free periods, that those prices were all that I owed.

123 Sometime after, Mr Harris received a letter from Latitude that included a “Financial Table”. The letter stated that Mr Harris would be charged fees in relation to his account, including a $25 establishment fee and a $5.95 monthly account fee. Mr Harris said that he was surprised. He said that he sent an email to Latitude complaining about the monthly service fee because this had not been explained to him upfront.

124 On receiving this correspondence, Mr Harris realised that, when he had purchased the television set and the PS4, he had been approved for a credit card with a $10,000 credit limit.

125 Mr Harris received a GO Mastercard credit card in another letter. He said that, at the time he received the credit card, he did not know that it could be used for everyday purchases. He subsequently activated the card.

126 Approximately one month later, Mr Harris received, by email, a GO Mastercard statement. The statement said that a minimum monthly repayment of $36.59 was required. It also said that he might like to pay $66.54 to reduce further interest.

127 Subsequently, Mr Harris purchased a washing machine from Harvey Norman using the GO Mastercard.

128 Mr Hill gave evidence of purchasing a laptop computer from a Harvey Norman store at Goulburn in June 2021 after seeing multiple advertisements for the 60 months interest-free promotion on television. Mr Hill said that between May and June 2021 he saw approximately five such advertisements each week.

129 Mr Hill’s recollection of the advertisements was (in his words):

(a) The 60-month interest free offer was displayed in large font. The font was large enough for me to read it clearly. I noticed that there was fine print displayed, but I could not make out the small font displayed on the TV screen. It was also not displayed on the screen long enough for me to make adjustments (such as moving closer to the screen) to allow me to read it, so I did not read it.

(b) The 60-month interest free offer appeared fairly early during the advertisement and I noticed that it was displayed for quite a while during the advertisement.

(c) There was a $1,000 minimum purchase requirement in order to qualify for the interest free offer.

(d) That if you spent $1,000 you would receive a $100 Harvey Norman gift card, with increased amounts up to a $1,000 Harvey Norman gift card for spending $10,000.

(e) There was a male voiceover speaking during the advertisement. I recall that the voiceover said words to the effect of, “60 months interest free”, “every $1,000, $100 in store credit”, “rush in now”, “spend the minimum and then you can get 60 months interest free” and “60 months equal repayments”.

130 Mr Hill said that he recalled seeing the word “Latitude” in the advertisements which, he said, was “displayed in the bottom corner of the advertisement in small font”. From this he understood that the money to purchase the goods at Harvey Norman would be borrowed from Latitude, instead of Harvey Norman. However, at that time, he did not think that Latitude was providing a credit card. He said that he did not recall the advertisements mentioning the requirement to obtain a credit card to access the interest-free offer.

131 Mr Hill said:

15. I understood from the Harvey Norman advertisements that I would be able to pay my purchase of the laptop off over a 60-month period without being charged any interest as long as I was approved to borrow the funds, and that no fees would be charged. I did not know that I would need to sign up for a GO Mastercard credit card offered through Latitude to access the interest free offer. At that time, I was not expecting to be charged any fees to access the interest free offer because I did not see any reference to Latitude or Harvey Norman charging any fees to access the offer in the Harvey Norman advertisements.

132 Mr Hill also said:

17. … I understood from the Harvey Norman advertisements that I had five years to pay off the purchase price of any products I was to buy, and that no interest would be charged. This arrangement was better for me than taking out a loan directly from a bank or getting another credit card. My existing credit card with St George was maxed out at the time. I needed a laptop for work and saw the advertisements and thought that the 60 month interest free offer was an easy way to purchase the laptop without having to pay any money upfront.

133 Mr Hill attended the Goulburn store on about 5 June 2021. After choosing the computer he wanted to buy, he told the salesperson that he wanted to make the purchase “on the 60-months interest-free loan”. The purchase price of the computer was $2,381 less a small discount which Mr Hill was able to negotiate.

134 Mr Hill said:

24. After telling the Salesperson that I wanted to purchase the laptop on the 60-month interest free offer, the Salesperson completed an application in relation to the interest free offer. At no stage during the application process did the Salesperson tell me that I was applying for a credit card, and at no stage did I believe I was applying for a credit card. I was not given any details about the application or any written information about the interest free offer. At that time, I understood from the Harvey Norman advertising that I was completing an application for a one off interest free loan to allow me to purchase the laptop. The application was completed by the Salesperson at a desk near the laptop section. I remember the Salesperson told me that he was undertaking a reference and financial check, and he asked me questions about my income and expenses. I answered the questions he asked me to the best of my abilities and he appeared to include that information in the application. To the best of my recollection, I did not give the Salesperson any documents or show him any information on my phone to verify the answers I provided to him.

135 Mr Hill said that although he could not remember what the salesperson said about the loan amount he could apply for, he (Mr Hill) remembered asking for a limit of $2,500 and being told by the salesperson at the end of the application process that this limit had been approved.

136 Mr Hill then said:

27. At no stage during the application process did the Salesperson tell me that he would do a credit card assessment or a credit check for the purpose of making a credit card application on my behalf. I was not told by the Salesperson that I was required to apply for, and be approved for, a GO Mastercard in order to take advantage of the interest free offer, or that I was applying for a GO Mastercard credit card that could be used in stores other than Harvey Norman that had a maximum credit limit of $2,500. At no stage did the Salesperson tell me that I would be charged a monthly account service fee or any other fees.

137 Mr Hill said that he remembered signing a document while at the store, but he did not remember what it was. He said he only glanced at it and did not read it. He said that “it just seemed like general contract paperwork that I did not understand because of its legal jargon”. He said that he did not appreciate that it was a contract for a credit card. He thought he had signed up for an interest-free loan. He did not intend to sign up for a credit card and had no need for one.

138 On 10 June 2021, Mr Hill received an email from “Latitude GO Mastercard” informing him that his “Latitude GO Mastercard is on the way”. He later received a letter from Latitude enclosing the plastic card. Mr Hill said that he was surprised because he “did not know what it was for”, although he thought it was connected with the purchase of his computer at the Harvey Norman store.

139 When Mr Hill received his first statement, he saw that he was being charged an $8.95 monthly account fee, which he was not expecting because he had not been told about it. Mr Hill thought that Latitude was “sneaky” for charging fees attached to the interest-free offer and that, as a recurring amount, the $8.95 monthly account-keeping fee was “a bit steep” because over the 60 months interest-free period, he would be charged $550 in monthly fees. Mr Hill said:

34. … I then realised that the laptop, including the additional fees charged by Latitude, would cost me almost $3,000 if I repaid the minimum amount over the 60-month interest free period. I thought that was a bit rich.

140 The first statement that Mr Hill received from Latitude confirmed that the purchase price for his computer was $2,381. It listed the purchase as:

Harvey Nrm Goulburn Compu

60 instalments & 0%

Monthly instalment required of $39.69

(Emphasis in original.)

141 Although the statement said that Mr Hill’s monthly instalment was $39.69, it also said that the minimum monthly payment he was required to make “to reduce future interest” was $48.64. It is apparent that the sum of $48.64 included the amount of the monthly account service fee.

142 Mr Hill activated the credit card and made subsequent purchases with it.

143 In December 2021, Mr Hill decided to purchase a tablet computer at the Goulburn Harvey Norman store using the 60 months interest-free offer. He thought that he could use his GO Mastercard for that purpose and increased his credit limit to $3,200 after contacting Latitude.

144 The tablet computer that Mr Hill wanted could be purchased at a discounted price. However, when Mr Hill told the salesperson that he wanted to use the 60 months interest-free offer, he was informed that the discounted price could only be obtained if he paid cash or used a credit card. As it was important to Mr Hill to have the discounted price, he decided to use his GO Mastercard, and the sale was processed accordingly.

145 Mr Hill’s evidence as to his reason for using the GO Mastercard for this purchase was that: (a) he did not understand that the GO Mastercard was a credit card; (b) he did not know that the GO Mastercard could be used for purchasing items from Harvey Norman otherwise than on interest-free terms; and (c) he did not understand that he would be charged interest if he used the GO Mastercard to purchase the tablet computer, “in the way that the [salesperson] processed it”.

146 When Mr Hill received his monthly account statement from Latitude in March 2022, he saw that he had been charged interest on the tablet computer purchase as well as the monthly account fee. He said:

42. … It was at this point that it clicked that I had signed up for a “real” Mastercard, by which I mean a general use credit card. Before this, I thought Latitude gave me a token Mastercard for the interest free loan only. I didn’t feel that best about having another general use credit card where I would be charged interest, so I increased the monthly repayments I was making. I wanted to pay the balance of the amount owing to Latitude as quickly as possible and get the whole episode out of the way. I did not know what the applicable interest rate was for purchases made not on interest free terms.

147 Mr Hill also used his GO Mastercard on 5 April 2023 to pay for car repairs. He said that he knew that he would be charged interest on this purchase.

148 Mr North gave evidence of purchasing a television set from a Harvey Norman store at Campbelltown in December 2020 after seeing a number of different Harvey Norman advertisements on television advertising the 60 months interest-free promotion.

149 Mr North’s recollection of the advertisements was (in his words):

(a) The offer was for 60 months interest free.

(b) The words “60 months interest free” appeared in large font towards the end of the advertisement in white font in a red box. From seeing this, my impression was that this was the “key sell” of the promotion. To the best of my recollection, the 60 months interest free offer was displayed at the end of the advertisement, after the images of the products being advertised.

(c) There was writing that said words to the effect that you had to spend a minimum of $1,000 to access the interest free offer. This writing was smaller than the “60 months interest free”. I considered that this was not as prominent, but it was not in fine print.

(d) There were images of certain products that Harvey Norman was advertising, similar to the images of products that are advertised in Harvey Norman catalogues that I have received in the mail ...

(e) At the bottom of the advertisement, there were words to the effect of “terms and conditions apply” and fine print in small writing, but I was unable to read it in the time it was shown on the screen. I typically did not pay much attention to the fine print in TV advertisements.

(f) There was a male voiceover speaking during the advertisement. The voiceover was talking about the 60-month interest free offer. I do not recall the specific details of what the man said in the voiceover.

(g) I did not see any reference to fees in the advertisements.

(h) I do not remember there being any reference to a credit card or GO Mastercard.

150 At this time, Mr North had also heard radio advertisements and seen catalogues advertising the same promotion.

151 Mr North said:

14. My understanding from seeing the Harvey Norman advertisements, was that if I spent a minimum of $1,000 at Harvey Norman, I would be able to pay off my purchase over a 60 month period without being charged interest. My understanding of the interest free promotion was that there would be no interest or fees charged in connection with the repayments. From seeing the Harvey Norman advertisements, I did not think that you would need to sign up for a credit card in order to take advantage of the 60 months interest free offer. I understood that each specific 60 months interest free offer was available for a limited time.

152 Mr North assumed that the offer was being financed by a third party, not Harvey Norman. He made this assumption based on his work in the financial services industry (Mr North is the managing director of his own insurance broking business which has 15 employees) and his understanding that retail businesses can outsource financing to a credit provider. He understood that if he failed to make a required payment under the offer, he would be charged interest on the amount of the purchase.

153 Mr North attended the Harvey Norman store at Campbelltown on 13 December 2020 with his wife. His reason for going there on that occasion was to purchase a television set on interest-free terms without an upfront payment. While at the store, he saw signage promoting the 60 months interest-free offer.

154 Mr North negotiated the purchase of a television set at a discounted price (it was floor stock), and then told the salesperson that he wanted to take advantage of the 60 months interest-free offer. Further negotiations ensued because Mr North was told that the store could not do that price “with the interest-free scenario”. Mr North then negotiated a smaller discount, with which he was happy at the time.

155 Mr North’s evidence was that he was unsure of the actual interest-free period he had negotiated. As to this, he said:

25. … At the time, I understood that I was purchasing the TV on 60 month interest free terms, but the length of the promotion for the TV that I purchased may have been less. The precise length of the interest free promotion did not concern me, as I intended to pay off the purchase price of the TV within 12 months.

156 Mr North explained the application process that then ensued while he was at the store. He said that he had understood from the advertisements that he was applying for an interest-free loan that required him to make equal monthly repayments, that no deposit was required, and no fees would be charged. He said that he did not know that he was, in fact, applying for a credit card, and he did not know that he needed to apply, and be approved, for a credit card in order to take advantage of the interest-free offer.

157 Mr North gave evidence of the salesperson completing the application on a computer in the store and asking Mr North questions about his financial circumstances. It appears that the approval was given promptly. The salesperson informed Mr North that there were “some contracts” to sign, which Mr North did. After this, the salesperson gave him “a lot of paperwork”, including receipts and a booklet. Mr North said:

32. … There was a tonne of pages of fine print. I did not read the paperwork, but I understood that I was entering into a contract in relation to the purchase of the TV on interest free terms. I did not read the documents in the store or at home. My circumstances allowed my wife and I to pay off the purchase price of the TV within 12 months. My plan was to pay it off quickly so I wouldn’t get caught out by interest charges on the purchase price of the TV.

33. The entire application process took around 45 minutes and by the end of the application process, I understood that I had signed up for an interest free loan, but I did not understand I had signed up for a credit card.

34. …The Salesperson did not mention a monthly account keeping fee, payment processing fee or any other fees associated with the interest free purchase. I do not recall talking to the Salesperson about a credit limit.

…

36. When I left the Campbelltown store, my understanding was that I had signed up for an interest free loan and I had to make regular repayments to pay the purchase price of the TV off within the designated timeframe, otherwise I would get charged interest. It was based on this understanding that I purchased the TV from Harvey Norman and I would not have purchased it from Harvey Norman if [it] was not for the interest free offer.

158 On 17 December 2020, Mr North received an email from Latitude informing him that his GO Mastercard was “on its way”. Mr North said that it was when he saw the word “Mastercard” that he realised that he had signed up for a credit card when purchasing the television set from Harvey Norman, even though he had no need for a further credit card and had not intended to sign up for one.

159 Mr North said:

38. … I was not happy about having signed up for a credit card because at that time I was not interested in owning another credit card. I was more interested in reducing debt instead of applying for credit. I remember being confused about the difference between GO Latitude and a GO Mastercard, and I did not understand that a credit card was involved until around this time. I later received a letter from Latitude enclosing a GO Mastercard credit card.

160 After Mr North received his GO Mastercard in the mail, he understood it could be used where Mastercard was accepted. However, he did not activate the card, despite receiving an email from Latitude inviting him to do so.

161 On 5 January 2021, Mr North registered with the GO Mastercard Online Service Centre. Shortly after that, he received his first statement. On receiving the statement, he realised that he had purchased the television set using a 33 months interest-free promotion, not a 60 months interest-free promotion. This was not of particular concern to him.

162 However, when Mr North received his second statement in February 2021, he was surprised to discover that he was being charged a monthly account fee and a $0.95 handling fee for every repayment he made using BPAY. Mr North said:

45. …That was a surprise to me as these fees were not explained to me by the Salesperson at the Campbelltown Harvey Norman store. I couldn’t believe I was being charged to make repayments. My wife and I had already both been making weekly repayments toward the outstanding amount on the GO Mastercard credit card via BPAY. By that time, I had been charged about $20 in fees. The processing fee was high and unexpected. My reaction was along the lines of “what? That’s a rip off”. I thought the fees, and in particular the handling fee, were outrageous. Upon discovering these charges, I sent an email to my wife on 16 February 2021 outlining the additional payments I calculated that we would have to make as a result of these charges. …

163 Mr North said that he also thought the monthly fee was substantial because monthly fees were not charged on his other credit cards. He said that, had he known about the fees charged in connection with the interest-free purchase beforehand, he would have taken more time to consider whether to take up the offer.

164 After repaying the amount of the loan, Mr North cancelled the credit card. He said:

51. Based on my experience in purchasing my TV from Harvey Norman on interest free terms, in my opinion, the process of taking up the “interest free offer” was not transparent because I did not know that I had to apply, and be approved, for a credit card and had in fact applied for a credit card until around the time I received the email from Latitude on 17 December 2022.

52. I definitely will not take up another interest free offer if a credit card process is involved.

165 Mr North also gave evidence about the promotional material he received from Latitude in 2022.

166 Ms Jenkins gave evidence of purchasing kitchen appliances from a Harvey Norman store at Bundall in February 2020 after seeing a Harvey Norman advertisement in the Sunday Telegraph advertising the 60 months interest-free promotion.

167 Ms Jenkins’s recollection of the advertisement was (in her words):

(a) It was a full page of advertising;

(b) The phrase “60 Months Interest Free” was in large font across the top of the page with an asterisk, and was in a larger font than any other wording in the advertisement. I recall that this statement grabbed my attention and was the first thing I saw when I looked at the advertisement;

(c) It included statements in speech bubbles at the top of the advertisement, which said words to the effect of “buy now pay later”;

(d) It contained information in fine print across the bottom of the advertisement. While I cannot remember exactly what the fine print said, I recall that this information included statements to the effect of, “not Apple products”, “see in store” or “conditions apply” and I also can recall a reference to the interest percentage if payment was not made;

(e) It included various specials that were on offer, for example, I recall seeing 9 or 10 washing machines for sale.