FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Fortescue Limited v Element Zero Pty Limited (No 2) [2024] FCA 1157

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The interlocutory application filed by the first, second and fourth respondents on 21 June 2024 is dismissed.

2. The first, second and fourth respondents are to pay the applicants’ costs of the interlocutory application.

3. Order 22(b) and Order 23 of the Orders made on 14 May 2024 be vacated.

4. The text of the reasons for judgment published today is to be published and disclosed only to the parties and their legal advisors.

5. By midday AEDT on 9 October 2024 the parties are to confer and to inform the Associate to Markovic J of any redactions that they propose are to be made to the reasons as a result of and in accordance with orders made to date in this proceeding pursuant to s 37AF of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth).

6. The proceeding be listed for case management hearing on 23 October 2024 at 9.30 am AEDT.

THE COURT NOTES THAT:

7. The reasons for judgment will be published on 11 October 2024 at midday AEDT and any redactions made in the reasons are made in accordance with the orders made to date in this proceeding pursuant to s 37AF of the Act.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

MARKOVIC J:

1 On 30 April 2024 the applicants, Fortescue Limited, Fortescue Future Industries Pty Ltd (FFI) and FMG Personnel Services Pty Ltd (together, Fortescue), commenced this proceeding against Element Zero Pty Limited, Bartlomiej Piotr Kolodziejczyk, Bjorn Winther-Jensen and Michael George Masterman as respondents. At the time, Fortescue filed an originating application and statement of claim (SoC).

2 Element Zero was registered on 7 December 2022. Element Zero is a start-up that has technology to convert metal ores such as iron and nickel into pure metal using intermittent renewable energy. Mr Masterman is a director and shareholder of Element Zero and its chief executive officer (CEO), Dr Kolodziejczyk is the chief technology officer and a shareholder and director of Element Zero, and Dr Winther-Jensen is a shareholder of Element Zero and was its research and development manager and from 7 December 2022 to 11 January 2024 a director. Dr Winther-Jensen ended his employment with Element Zero in December 2023.

FORTESCUE’S EX PARTE APPLICATION

3 The proceeding first came before Perry J in her Honour’s capacity as general duty judge on 9 May 2024 on an ex parte application made by Fortescue for search orders. The transcript of the hearing on 9 May 2024 discloses that her Honour was provided with affidavits and submissions dated 8 May 2024 prior to the hearing, and that some additional affidavits were provided at the hearing. The hearing lasted for approximately 2 hours and 20 minutes. Towards its conclusion, her Honour said:

The last thing – this is the – to my mind at the moment, I can indicate that I do agree that there is a strong prima facie case that’s really established by a very substantial body of evidence. And there’s also, one would have thought in light of the matters that have been covered in the written submissions, a real risk that if information were provided in advance and it weren’t inter partes application, there is a real risk that information might be destroyed or hidden, squirrelled away. And obviously, the prejudice – you’ve clearly established prejudice of a very substantial nature to the applicants in the event that the orders are not made, so that I do consider it’s appropriate to make the orders, but subject to that concern.

And after reviewing Fortescue’s proposed orders added:

I mean, as I said, I’ve been very carefully through the written submissions. And then having those, having the benefit of being taken through the evidence in a closely and in the structured way that you have, has led me to the view that it is appropriate, subject to addressing the particular issues I’ve raised, to make orders in the nature that are sought.

4 On 9 May 2024 the Court made interim suppression orders pursuant to s 37AI of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) and otherwise adjourned the proceeding to 14 May 2024 to allow Fortescue to deal with a number of matters raised by her Honour principally in relation to practical issues that might arise on execution of the proposed orders.

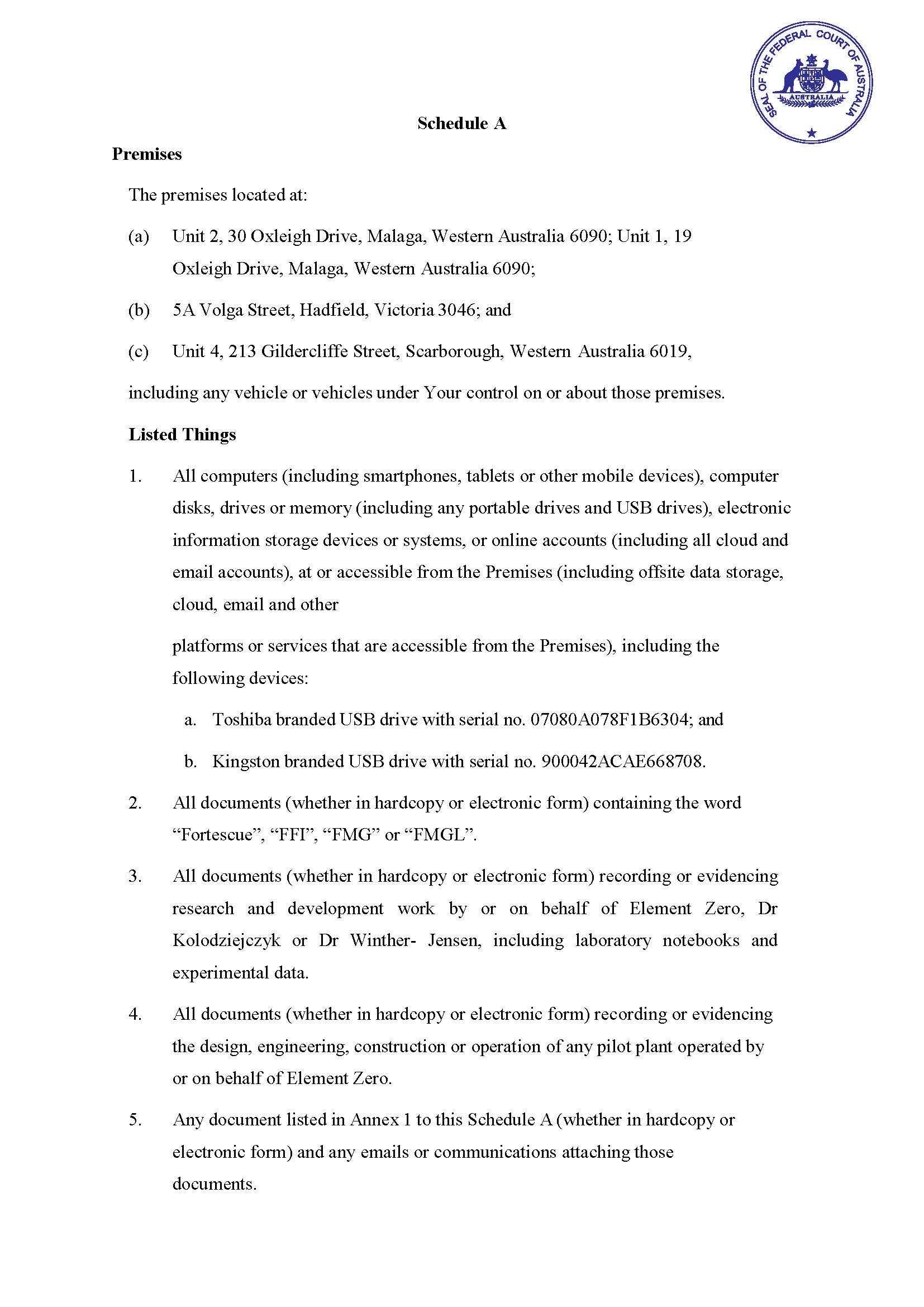

5 On 14 May 2024, when the proceeding was next listed before Perry J, the search orders were made. Those orders are directed to Element Zero, Dr Kolodziejczyk, Dr Winther-Jensen and the occupants of three identified premises. Relevantly, the search orders permit searches to be undertaken in accordance with their terms at the premises and require the recipients or targets of the search orders, referred to as “You”, among other things:

(1) to permit members of the “Search Party”, as defined, to enter the premises so that they can carry out the search and other activities referred to in the search orders;

(2) having permitted members of the Search Party to enter the premises, to:

(a) permit them to search for and inspect the “Listed Things” as defined in Sch A to the search orders, and to make or obtain a copy, photograph, film, sample, test or other record of the Listed Things;

(b) disclose to them the whereabouts of all the Listed Things in their possession, custody or power, whether at the premises or otherwise;

(c) disclose the whereabouts of all computers (including smartphones, tablets and other mobile devices), computer disks, drives or memory (including portable drives and USB drives), electronic information storage devices or systems, and online accounts (including all cloud and email accounts) at or accessible from the premises in which any documents among the Listed Things are or may be stored, located or recorded and cause and permit those documents to be copied or printed out;

(d) do all things necessary to enable the Search Party to access the Listed Things including by opening or providing keys to physical or digital locks and enabling them to access and operate computers and online accounts and providing them with all necessary passwords, access credentials and other means of access;

(e) permit any “Independent Lawyer”, as defined, to remove certain specified things into their custody; and

(f) permit any “Independent Computer Expert”, as defined, to search any computer (including any smartphone, tablet and other mobile device), computer disk, drive or memory (including any portable drive and USB drive), any electronic information storage device or system, and online accounts (including all cloud and email accounts) at or accessible from the premises, and make a copy or digital copy of any of the foregoing and permit any Independent Computer Expert to remove any of the foregoing from the premises in accordance with the terms of the search orders.

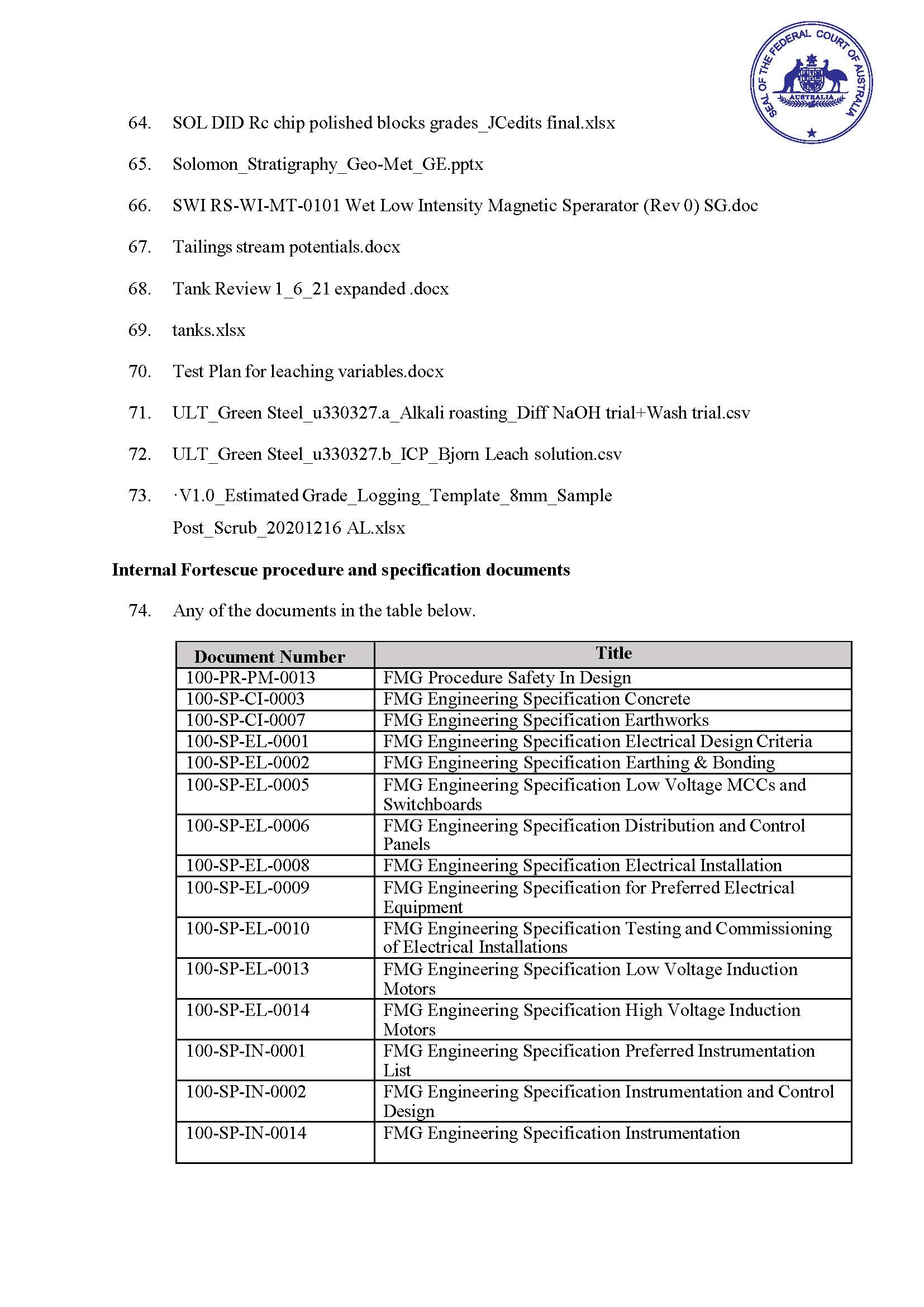

The “Listed Things” as set out in Annexure A to the search orders are reproduced at Annexure A to these reasons.

6 The search orders have been executed. Hard copy material was seized and devices imaged. That material is in the possession of the Court and the Independent Computer Experts, and a copy has been provided to the respondents.

7 On 30 May 2024 the search orders were returnable before the Court. On that occasion the proceeding was listed before Logan J in his Honour’s capacity as general duty judge. Orders were made varying parts of the search orders (in particular orders 19, 20, 22, 23 and 26 of those orders), for: Element Zero, Dr Kolodziejczyk and Mr Masterman (who I will refer to collectively as the EZ respondents) to file their defences; for Dr Winther-Jensen to file his defence; for Fortescue to file any interlocutory application for discovery by the respondents; and for the EZ respondents to file an interlocutory application seeking orders to discharge the search orders (Discharge Application). Justice Logan published reasons for making those orders: see Fortescue Ltd v Element Zero Pty Ltd [2024] FCA 590.

8 On 17 June 2024 Fortescue filed an amended statement of claim (ASoC).

9 On 21 June 2024 the EZ respondents filed the Discharge Application seeking orders pursuant to r 39.05 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) or the inherent jurisdiction of the Court that the search orders be set aside ab initio or, in the alternative, that they be set aside, or varied in so far as they operate in futuro and related orders for delivery up and return of all material seized and records created in executing the search orders.

10 It is the Discharge Application that is now before the Court for resolution. I note that, although he was represented at the hearing of the Discharge Application, the third respondent, Dr Winther-Jensen, did not file an application for discharge of the search orders. The EZ respondents relied on an affidavit affirmed by Dr Winther-Jensen in support of the Discharge Application and counsel appearing for Dr Winther-Jensen was given leave to make brief submissions going only to questions of Dr Winther-Jensen’s credit.

FORTESCUE’S CLAIM

11 Before proceeding further, it is convenient to set out a summary of Fortescue’s claim. In short, Fortescue alleges that the respondents engaged in misuse of confidential information, breaches of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth), copyright infringement, breach of contract and misleading or deceptive conduct.

12 More particularly in the SoC, which was the form of the pleading before the Court at the time the search orders were made, Fortescue alleges in summary that:

(1) while employed by Fortescue as chief scientist and technology development lead respectively, Drs Kolodziejczyk and Winther-Jensen undertook confidential research and development work into a particular direct electrochemical reduction process utilising, among other things, an ionic liquid electrolyte (Ionic Liquid R&D). While undertaking this work, they created the Fortescue Process CI, also referred to as Ionic Liquid R&D Information;

(2) before their employment with Fortescue ended in November 2021 and without Fortescue’s knowledge or permission, Drs Kolodziejczyk and Winther-Jensen took the Fortescue Process CI and took steps to ensure that the Fortescue Process CI was not available to Fortescue;

(3) further, before leaving Fortescue and without its knowledge or permission, Drs Kolodziejczyk and Winther-Jensen took documents containing confidential information useful in the design, engineering, construction, operation and/or feasibility of a green iron pilot plant (Fortescue Plant CI);

(4) the Fortescue Process CI and Fortescue Plant CI is confidential information belonging to Fortescue;

(5) Element Zero was incorporated in December 2022. Its founding directors, each owning either directly or indirectly a third of Element Zero’s ordinary shares, are Dr Kolodziejczyk, who is also its chief technical officer, Dr Winther-Jensen, who was a director until January 2024, and Mr Masterman who is also its CEO. Dr Winther-Jensen reported to Mr Masterman at Fortescue for part of 2021 and Mr Masterman was a Fortescue director for part of 2022;

(6) the respondents have commercialised and used an electrochemical reduction process which includes utilising an ionic liquid electrolyte (EZ Process) and designed, engineered, constructed, and operated a green iron pilot plant (EZ Plant) which implements the EZ Process; and

(7) the respondents misused:

(a) the Fortescue Process CI in commercialising and using the EZ Process;

(b) the Fortescue Process CI and Fortescue Plant CI in designing, engineering, constructing and operating the EZ Plant; and

(c) the Fortescue Process CI and Fortescue Plant CI in inventing, preparing and filing patent applications in Element Zero’s name (EZ Patent Applications).

13 The amendments made to the SoC, and reflected in the ASoC, do not materially change Fortescue’s case as summarised above.

THE DISCHARGE APPLICATION

14 The EZ respondents contend that the orders sought in the Discharge Application should be made and the search orders set aside or varied for the following reasons:

(1) Fortescue’s prima facie case was overstated and misrepresented to the duty judge who granted the search orders;

(2) on the evidence, there was no real risk of destruction of documents;

(3) there was material non-disclosure by Fortescue when seeking the search orders;

(4) Fortescue undertook excessive and unnecessarily intrusive surveillance of the respondents, which it deployed in evidence on the ex parte application; and

(5) the form and scope of the search orders was inappropriately broad and resulted in excessive capture of the EZ respondents’ information.

15 In support of the Discharge Application, the EZ respondents rely on evidence given by each of Dr Kolodziejczyk, Dr Winther-Jensen and Mr Masterman, and evidence given by the EZ respondents’ solicitor, Michael John Williams, a partner of Gilbert + Tobin, Melissa Gravina, Element Zero’s corporate and finance operations manager, and Michael Geoffrey Hales, a partner of Minter Ellison and Dr Winther-Jensen’s solicitor.

16 In response to the Discharge Application, Fortescue relies on evidence given by its solicitor, Paul Alexander Dewar, a principal of Davies Collison Cave Law, Matthew Fitzgerald Roper, an employee of FMG Personnel who holds the position of intellectual property manager for FFI, and Dr Anand Indravadan Bhatt, also an employee of FMG Personnel who holds the position of manager of minerals, research and development. In addition, Fortescue tendered the evidence that it relied on before the duty judge on 9 May 2024 when it made the ex parte application.

17 Both parties provided written submissions. However, in the course of oral argument the EZ respondents raised a number of matters not referred to in their evidence or submissions which they contended amounted either to “misstatements or omissions” on the part of Fortescue when it was before the duty judge on its ex parte application and is relevant to the Discharge Application insofar as they contend that the search orders should be set aside because there was a weak prima facie case, no real risk of destruction of material or there was a material non-disclosure.

18 A document titled “Fortescue’s aide memoire regarding Element Zero respondents’ allegations in oral submissions of material inaccurate and misleading information before duty judge” was prepared for the assistance of the Court. The aide memoire records the submissions made by the EZ respondents described in the preceding paragraph, Fortescue’s response to those submissions and the EZ respondents’ reply. To the extent possible, and where they overlap, the issues recorded in the aide memoire are considered in the course of my consideration of grounds 1, 2 and 3 raised by the EZ respondents in support of the Discharge Application and otherwise as discrete matters.

Some legal principles

19 Orders in the nature of the search orders are sometimes referred to as “Anton Piller” orders having taken that name from the decision in Anton Piller KG v Manufacturing Processes Limited [1976] 1 All ER 779. In Anton Piller at 784 Ormrod LJ, after observing that such an order “will rarely be made” and only when “there is no alternative way of ensuring that justice is done to the plaintiff”, set out the “three essential pre-conditions” for making such an order:

… First, there must be an extremely strong prima facie case. Secondly, the damage, potential or actual, must be very serious for the plaintiff. Thirdly, there must be clear evidence that the defendants have in their possession incriminating documents or things, and that there is a real possibility that they may destroy such material before any application inter partes can be made.

20 In Long v Specifier Publications Pty Ltd (1998) 44 NSWLR 545 Powell JA (with whom Meagher and Handley JJA agreed) observed at 547:

Reduced to its essentials, an Anton Piller order is an order that the defendant to whom, or to which, it is directed, should permit the persons specified in the order to enter upon his, or its, premises, and to inspect, take copies of, and to remove, specified material, or classes of material, indicating, where appropriate, documents, articles or other forms of property. It is an extraordinary remedy, designed to obtain, and to preserve, vital evidence pending the final determination of the plaintiff’s claim in the proceedings, in a case in which it can be shown that there is a high risk that, if forewarned, the defendant, would destroy, or hide, the evidence, or cause it to be removed from the jurisdiction of the court. For this reason, such orders are invariably made ex parte.

21 There is no question that the Court has power to make an Anton Piller order and, accordingly, in this case had power to make the search orders: see s 23 of the Federal Court Act and r 7.42 of the Rules.

22 Rule 7.43 of the Rules sets out the requirements for the grant of a search order and provides:

The Court may make a search order if the Court is satisfied that:

(a) an applicant seeking the order has a strong prima facie case on an accrued cause of action; and

(b) the potential or actual loss or damage to the applicant will be serious if the search order is not made; and

(c) there is sufficient evidence in relation to a respondent that:

(i) the respondent possesses important evidentiary material; and

(ii) there is a real possibility that the respondent might destroy such material or cause it to be unavailable for use in evidence in a proceeding or anticipated proceeding before the Court.

23 On an application to set aside a search order, the party moving for that relief bears the onus. In Austress Freyssinet Pty Ltd v Joseph [2006] NSWSC 77 at [25]-[26], Campbell J relevantly said:

25 … It is not as though there is a right to automatically have such an order set aside simply by asking. Nor is it correct that, on such an application, the person seeking to have the order set aside can require the person who has obtained the order to prove again the case in favour of making the order.

26 It is also most important that, when one judge of first instance hears an application to set aside or vary an interlocutory order made by another judge in the first instance, the proceedings are not in the nature of an appeal. The application to set aside or vary is one which must demonstrate that there is reason why the order which was made ought be set aside. …

24 In Brags Electrics Pty Ltd trading as Inscope Building Technologies v Gregory [2010] NSWSC 1205, Brereton J considered an application for discharge of a search order. His Honour summarised the position of an applicant to set aside a search order at [17] as follows (emphasis in original):

First, where an Anton Pill[e]r order is made ex parte (as it ordinarily will be), an applicant to set the order aside bears an onus of showing some reason why it should be set aside. However, it may be a sufficient reason to set aside the order that the grounds for such an order were not satisfied. Secondly, where such an application is made on the ground that there has been bad faith or material non-disclosure, then the court may set aside the order ab initio, but otherwise a discharge will operate in futuro only. Thus, where an application is made to set aside or discharge the order on the basis that the grounds for making such an order were not established, that will be of little utility if made after the order has been executed. At least in the absence of bad faith or non-disclosure, the remedy for a defendant where it is shown ultimately that an Anton Pill[e]r order ought not have been made, is not to have the order set aside, but pursuant to the undertaking as to damages. Thirdly, on an application to set aside an Anton Pil[le]r order, the court may take into account on the hearing of the application the “fruits of the order” – that is to say, any evidence or admission procured as a result of the order – and any further evidence adduced in the meantime.

25 I pause to observe that an issue arose between the parties as to the effect of an aspect of this statement in Brags. The EZ respondents submit, contrary to the position taken by Fortescue, that it is not the case that a search order can only be set aside ab initio where it is set aside on the basis that there was bad faith or a material non-disclosure at the time of making an application. They submit that to the extent that Brags is said to stand as authority for that proposition it is plainly wrong. However, given that the EZ respondents rely principally on alleged material non-disclosure to ground the Discharge Application and in light of the findings I have made, whether that is so does not arise for determination on this application.

Duty of candour

26 As is apparent, an application for an Anton Piller order is ordinarily made ex parte without notice to the parties affected by the proposed order. The seminal statement of the significant obligations imposed on a party approaching a court for ex parte orders is set out in Thomas A Edison Ltd v Bullock (1912) 15 CLR 679 at 681-682 where Isaacs J, on hearing an application to dissolve an interlocutory injunction, said:

… There is a primary precept governing the administration of justice, that no man is to be condemned unheard; and therefore, as a general rule, no order should be made to the prejudice of a party unless he has the opportunity of being heard in defence. But instances occur where justice could not be done unless the subject matter of the suit were preserved, and, if that is in danger of destruction by one party, or if irremediable or serious damage be imminent, the other may come to the Court, and ask for its interposition even in the absence of his opponent, on the ground that delay would involve greater injustice than instant action. But, when he does so, and the Court is asked to disregard the usual requirement of hearing the other side, the party moving incurs a most serious responsibility.

Dalglish v. Jarvie, a case of high authority, establishes that it is the duty of a party asking for an injunction ex parte to bring under the notice of the Court all facts material to the determination of his right to that injunction, and it is no excuse for him to say he was not aware of their importance. Uberrima fides is required, and the party inducing the Court to act in the absence of the other party, fails in his obligation unless he supplies the place of the absent party to the extent of bringing forward all the material facts which that party would presumably have brought forward in his defence to that application. Unless that is done, the implied condition upon which the Court acts in forming its judgment is unfulfilled and the order so obtained must almost invariably fall. …

(Footnote omitted.)

His Honour’s observations were approved in International Finance Trust Company Ltd v New South Wales Crime Commission (2009) 240 CLR 319 at [131] (Hayne, Crennan and Kiefel JJ).

27 In Walter Rau Neusser Oel Und Fett AG v Cross Pacific Trading Ltd [2005] FCA 955 Allsop J (as his Honour then was) said at [38]:

In an ex parte hearing, it is the obligation of the party seeking orders, through its representatives, to take the place of the absent party to the extent of bringing forward all the material facts which that party would have brought forward in defence of the application: Thomas A Edison Ltd v Bullock (1912) 15 CLR 678 at 681-82 per Isaacs J. That does not mean stating matters obliquely, including documents in voluminous exhibits, and merely not mis-stating the position. It means squarely putting the other side’s case, if there is one, by coherently expressing the known facts in a way such that the Court can understand, in the urgent context in which the application is brought forward, what might be said against the making of the orders. It is not for the Court to search out, organise and bring together what can be said on the respondents’ behalf. That is the responsibility of the applicant, through its representatives.

Material non-disclosure

28 Savcor Pty Ltd v Cathodic Protection International Aps (2005) 12 VR 639 concerned an appeal from an order made discharging an earlier order to extend the period of validity of a writ. The application for discharge before the primary judge was made on the basis that Savcor Pty Ltd had failed to place all relevant material before the court at the time the order extending the writ was made and therefore breached its obligation of good faith to the court. At [22], Gillard AJA (with whom Ormiston and Buchanan JJA agreed) said the following about the exercise of the jurisdiction to set aside an ex parte order because of a material non-disclosure:

… The order is set aside because of some irregularity and not on the merits. When this jurisdiction is enlivened, the court’s function is to determine on the material that was placed before the judicial officer at first instance, whether a party has failed to discharge the obligation which rests upon any party seeking an order ex parte, namely, making a full and fair disclosure of all matters within its knowledge and which are material, to the court. The court is not concerned whether the order should have been made on the material before the court. Whether or not the court will set aside the order upon proof of the failure to discharge the obligation depends upon the particular circumstances.

29 At [35], Gillard AJA observed that the obligation “is to disclose all material facts”. His Honour continued at [35]-[36]:

35 … What is a material fact is a matter which is relevant to the court’s determination. To be material, it would have to be a matter of substance in the decision making process.

36 In Brink’s Mat Ltd v Elcombe, Ralph Gibson LJ conveniently summarised the principles. His Lordship noted that “the material facts are those which it is material for the judge to know in dealing with the application as made: materiality is to be decided by the court and not by the assessment of the applicant or his legal advisers.” His Lordship observed that the applicant must make proper enquiries before making an application. If a material non-disclosure is established the court would be astute to ensure that the plaintiff obtaining an ex parte order without full disclosure is deprived of any advantage he may have derived, and further that whether a fact not disclosed “is of sufficient materiality to justify or require immediate discharge of the order without examination of the merits depends on the importance of the facts to the issues which were to be decided by the judge on the application.” His Lordship pointed out that the innocence or otherwise of the non-disclosure and the failure to understand its relevance are important factors to take into account.

(Footnote omitted.)

30 In Naidenov, in the matter of 30 Denham Pty Ltd (in liq) [2023] FCA 134, on an application to discharge freezing orders made under s 1323(3) of the Corporations Act for material non-disclosure, Stewart J said at [10]-[11] (emphasis in original):

10 Dealing first with the alleged non-disclosures, it is uncontroversial that on an ex parte application the plaintiff has a duty of candour to bring to the attention of the court “all the material facts which [the absent] party would presumably have brought forward in his defence to that application”: Thomas A Edison Ltd v Bullock [1912] HCA 72; 15 CLR 679 at 682; International Finance Trust Company Ltd v New South Wales Crime Commission [2009] HCA 49; 240 CLR 319 at [131]. Just what is material in this context has been put in different ways in the authorities, but I do not consider that there is anything of substance in the differences.

11 I adopt what was said in Savcor Pty Ltd v Cathodic Protection International APS [2005] VSCA 213; 12 VR 639 at [35] by Gillard AJA (with whom Ormiston and Buchanan JJA agreed), namely that what is a material factor is a matter which is relevant to the court’s determination – it would have to be a matter of substance in the decision-making process. I take that to mean that the matter must be material in the sense of being capable of having affected the court’s decision, and not that it would have affected the decision.

31 In Tugushev v Orlov [2019] EWHC 2031, among other things, Carr J considered an application to challenge a worldwide freezing order and an order permitting service outside the jurisdiction on the basis of alleged breaches of the duty of full and frank disclosure on the ex parte application in which those orders were made. At [7], her Honour set out the applicable principles including relevantly:

iv) An applicant must make proper enquiries before making the application. He must investigate the cause of action asserted and the facts relied on before identifying and addressing any likely defences. The duty to disclose extends to matters of which the applicant would have been aware had reasonable enquiries been made. The urgency of a particular case may make it necessary for evidence to be in a less tidy or complete form than is desirable. But no amount of urgency or practical difficulty can justify a failure to identify the relevant cause of action and principal facts to be relied on;

v) Material facts are those which it is material for the judge to know in dealing with the application as made. The duty requires an applicant to make the court aware of the issues likely to arise and the possible difficulties in the claim, but need not extend to a detailed analysis of every possible point which may arise. It extends to matters of intention and for example to disclosure of related proceedings in another jurisdiction;

vi) Where facts are material in the broad sense, there will be degrees of relevance and a due sense of proportion must be kept. Sensible limits have to be drawn, particularly in more complex and heavy commercial cases where the opportunity to raise arguments about non-disclosure will be all the greater. The question is not whether the evidence in support could have been improved (or one to be approached with the benefit of hindsight). The primary question is whether in all the circumstances its effect was such as to mislead the court in any material respect;

32 In Liberty Financial Pty Ltd v Scott [2002] FCA 345, Weinberg J considered an application to set aside Anton Piller orders. In summarising the applicable principles, his Honour referred to the decision in Brink’s-MAT Ltd v Elcombe [1988] 3 All ER 188 (see [29] above) noting in doing so the following additional principles at [46]-[47] (emphasis in original):

46 Balcombe LJ agreed with Ralph Gibson LJ that notwithstanding that an ex parte injunction had been obtained without full disclosure, the court had a discretion to continue it, or to grant a fresh injunction in its place.

47 Slade J said, at 194:

“Particularly in heavy commercial cases, the borderline between material facts and non-material facts may be a somewhat uncertain one. While in no way discounting the heavy duty of candour and care which falls on persons making ex parte applications, I do not think the application of the principle should be taken to extreme lengths.”

Discretion

33 Whether or not to set aside an order where there was a failure to disclose material facts is a matter of discretion: Savcor at [27]-[28]. In Savcor, Gillard AJA relevantly said at [29]-[33]:

29 … In my view it is not an inflexible rule that a non-disclosure of a material fact in an ex parte application invariably leads to the order being set aside. Of course if there is a high degree of culpability in the sense that a party has set out to mislead a court, a court in most if not all cases would be reluctant to excuse the intentional misconduct. Each case will depend upon its own circumstances. Justice is the determinant. I respectfully agree with Balcombe LJ in Brink’s Mat Ltd v Elcombe where his Lordship said in relation to an ex parte injunction:

… But it also serves as a deterrent to ensure that persons who make ex parte applications realise that they have this duty of disclosure and of the consequences (which may include a liability in costs) if they fail in that duty. Nevertheless, this judge-made rule cannot be allowed itself to become an instrument of injustice. It is for this reason that there must be a discretion in the court to continue the injunction, or to grant a fresh injunction in its place, notwithstanding that there may have been non-disclosure when the original ex parte injunction was obtained. [Emphasis added.]

30 In the same case, Ralph-Gibson LJ said:

Finally, it “is not for every omission that the injunction will be automatically discharged. A locus poenitentiae may sometimes be afforded” per Lord Denning MR in Bank Mellat v Nikpour. The court has a discretion, notwithstanding proof of material non-disclosure which justifies or requires immediate discharge of the ex parte order, nevertheless to continue the order, or to make a new order on terms.

31 Whether a court will set aside an order will depend upon many factors. The court should not overlook the practical effect of such a step. What would be achieved by setting aside the order? Absent deliberate and intentional non-disclosure or misleading information (which usually leads to a discharge), the court must weigh all relevant material. An important matter is that the setting aside of the order will not necessarily preclude another application being made. See Fitch v Rochfort and The Hagen. The practical effect would be a waste of time and costs. The point was made by Morton J in Ellinger v Guinness Mahon & Co. His Lordship said:

… Counsel for the applicants … argues that, if there has been non-disclosure of any material fact on the ex parte application, the ex parte order ought to be set aside, even if the judge, on being fully informed of the facts, thinks that the case is a proper one for allowing service of the notice of the writ out of the jurisdiction. In my judgment that argument cannot succeed. In the absence of any attempt to deceive the court I do not think it would be right for a judge to take this course. The only result would be to put the applicant to the expense of making a further application under RSC Ord 11, r 1 which would be bound to succeed.

32 It cannot be overlooked as was stated in Wiseman v Wiseman that an order made where the material facts have not been fully disclosed is not void but is irregular and therefore voidable. It stands until it is set aside.

33 In my opinion a court does have a discretion to not set aside an order despite a material non-disclosure or misrepresentation of law or fact. Setting aside does not follow as a matter of course. Relevant to the discretion is whether the material non-disclosure was serious or otherwise the importance or weight that should be attached to the omitted fact in the decision making process and also any hardship if the order was set aside. The approach is different if the plaintiff has acted culpably in the sense that the omission to disclose relevant matters was done deliberately to mislead the court. The most likely result in those circumstances would be that the order would be vacated.

(Footnotes omitted.)

Ground 1: Weak prima facie case

34 The first ground on which the EZ respondents contend that the search orders should be set aside is because Fortescue has a weak prima facie case in relation to the causes of action relied upon to obtain those orders.

35 Relevantly, Fortescue relied on two of the six causes of action pleaded in its SoC when seeking the search orders: breach of the equitable obligation of confidence; and contravention of s 183 of the Corporations Act. In each case the alleged breaches concern two categories of confidential information: the Fortescue Process CI; and the Fortescue Plant CI. It was not in dispute that, before the duty judge, Fortescue submitted that it had a strong prima facie case in relation to both causes of action. However, the EZ respondents submit that in doing so Fortescue overstated and incorrectly presented the strength of its prima facie case to the Court.

The EZ respondents’ submissions

36 The EZ respondents submit that critically absent from the case for breach of confidence were two key elements: the specific identification of the confidential information; and the need for there to have been an actual or threatened misuse of the information without Fortescue’s consent.

37 The EZ respondents note, by reference to Fortescue’s submissions dated 8 May 2024 relied on before the duty judge on its application for the search orders (Search Order Submissions), that central to Fortescue’s claim in relation to the Fortescue Process CI on the ex parte application were the following propositions:

(1) Dr Kolodziejczyk undertook and led research and development work at Fortescue on Ionic Liquid R&D ([3] Search Order Submissions);

(2) Fortescue cannot locate documents recording the Ionic Liquid R&D Information but “these documents must have existed because Dr Kolodziejczyk referred to Ionic Liquid R&D in multiple internal and external communications, in the period at least from Sep[tember] 2020 to Jan[uary] 2021” ([51(b)] Search Order Submissions; emphasis in original); and

(3) because Fortescue cannot locate documents recording the Ionic Liquid R&D Information, it may be inferred that Dr Kolodziejczyk “took the documents” ([56(c)] Search Order Submissions).

38 The EZ respondents submit that the case in relation to the Fortescue Process CI is circular and weak. They say that Fortescue’s case is that Dr Kolodziejczyk undertook and led an entire body of work concerning Ionic Liquid R&D but there is no evidence of the type that would be expected in relation to such an allegedly important project for a major organisation like Fortescue, e.g. no Fortescue employee gives evidence about the nature and scope of the alleged work and there are no significant internal documents of the type that would be expected, including board papers. They submit that the claim is “patched together” by a retrospective analysis undertaken by Dr Bhatt, who was not employed by Fortescue until January 2022, of a “minute number” of Dr Kolodziejczyk’s emails.

39 The EZ respondents submit that a proper analysis of the documents relied on by Fortescue shows that Dr Kolodziejczyk (and later Dr Winther-Jensen) was considering various avenues for further research, one of which involved ionic liquid, but that avenue was not pursued given the urgency of the project. They submit that the documents relied on by Fortescue rise no higher than to show preliminary investigation and funding approval for research into ionic liquid reduction in the context of a “stretch target” imposed by Dr Andrew Forrest, Fortescue’s chairman, which is not evidence of what was done.

40 The EZ respondents rely on Dr Kolodziejczyk’s evidence on the Discharge Application to the effect that he did not work on an “ionic process” at Fortescue and that several current Fortescue employees, none of whom gave evidence, would have been aware of the work he was undertaking in 2020 and 2021. The EZ respondents submit that Fortescue relies on the absence of any documents about Ionic Liquid R&D to substantiate the claim that such documents not only existed but were taken by Dr Kolodziejczyk upon his departure. They say that such a construction of the available facts is, at best, speculative and does not rise to the level of a strong case, let alone one justifying search orders.

41 The EZ respondents submit that, in terms of the actual components of the cause of action, no documents were identified by Fortescue as being confidential (within the broad category of Ionic Liquid R&D Information). They contend that to establish a claim, information must be identified with specificity and precision, and that the lack of any precision in identifying the documents in the Ionic Liquid R&D category highlights the unreality of this part of Fortescue’s claim. Further, the information cannot be shown to meet the threshold justifying protection in equity, let alone in support of a search order.

42 The EZ respondents submit that there is also no evidence of real or threatened misuse and that Fortescue’s submission rises no higher than to say that because Fortescue cannot locate the documents it may be inferred that they existed and that Drs Kolodziejczyk and Winther-Jensen took them, referring to [56(c)] of the Search Order Submissions.

43 In relation to the Fortescue Plant CI, the EZ respondents observe that Fortescue relies on conduct pleaded at [19] and [20] of the SoC in which Fortescue alleged that Drs Kolodziejczyk and Winther-Jensen “took” the material identified there in their final days at Fortescue ([52] Search Order Submissions). The EZ respondents also note that, during the ex parte hearing before the duty judge, Fortescue referred the Court to the summary of Rodney McKemmish’s forensic analysis (explained below at [50(22)(e)]) at [77] of Mr Huber’s affidavit in support of a submission that “we have evidence that [Dr Kolodziejczyk] took these documents before he left Fortescue”, rather than Mr McKemmish’s report which, in the EZ respondents’ submission, expressed findings in a much more qualified form.

44 The EZ respondents submit that Fortescue’s submissions to the duty judge about the “exfiltration” of documents by Dr Kolodziejczyk incorrectly represented Mr McKemmish’s and Deloitte Financial Advisory Pty Ltd’s respective reports and, contrary to the Search Order Submissions, the emails annexed to the affidavit of Nicholas Marrast do not support a submission that there was any lack of co-operation, let alone secrecy, on the part of Drs Kolodziejczyk and Winther-Jensen.

45 The EZ respondents submit that the weakness of the claim, to the extent it relies on Dr Kolodziejczyk’s conduct as pleaded in [19] of the SoC, is exemplified by the amendments to the ASoC. Despite SoC [19] being central to the application for the search orders, Fortescue no longer pleads that Dr Kolodziejczyk obtained “a copy” of the specific documents, but instead pleads that he obtained “information”. The EZ respondents contend that this is an entirely different allegation, resting on a distinction between taking documents and information, and that this is material to whether there was conduct from which a risk of destruction could be inferred.

46 The EZ respondents submit that the amendments to SoC [19] also confirm that the original pleading and associated submissions relied on before the duty judge could not be sustained. They contend that, in effect, and only after executing the search orders, Fortescue has, without explanation, withdrawn one of the fundamental planks on which it obtained the orders.

47 The EZ respondents submit that for the same reasons as outlined in relation to the breach of confidence claim, the claim for breach of the Corporations Act which relies on the same allegations is, at best, weak and takes the assessment of the strength of the case no further.

48 In oral submissions, the EZ respondents also raised a number of additional matters, being evidence relied on or submissions made by Fortescue before the duty judge, which they contend were either misleading or inaccurate and which they rely on in support of their overarching contention that Fortescue has (and when before the duty judge had) a weak prima facie case. Those matters are identified and addressed below.

Before the duty judge

49 It is convenient to commence with a summary of the evidence and submissions relied on by Fortescue before the duty judge. At the time of making its application for the search orders, Fortescue relied on a significant volume of evidence, comprising 12 affidavits, and the Search Order Submissions. What follows is no more than a summary of that material relying principally on the Search Order Submissions.

50 The evidence relied on by Fortescue, combined with its submissions, was that:

(1) in 2021, Dr Kolodziejczyk and Dr Winther-Jensen were employed by Fortescue as chief scientist and technology development lead respectively;

(2) from October 2020 to July 2022, Mr Masterman was employed as FFI’s chief financial officer (CFO);

(3) green iron technology is technology for processing iron ore into metallic iron without burning fossil fuels which produce carbon dioxide. There are different technologies for producing “green” iron. This proceeding is concerned with a subset of the technology which involves the electrochemical reduction of the iron oxides found in iron ore to produce metallic iron. That process is “electrochemical” because the iron ore is placed into a solution, an electrolyte, to which an external voltage is applied which causes a reduction of the iron ore compound (the removal of oxygen atoms) to produce iron;

(4) at a high level, participants in the global iron-making industry are involved in developing proprietary processes that come within the two approaches to electrochemical reduction either dissolving iron ore into an electrolyte solution (for example, an ionic liquid) or suspending solid iron ore particles in the electrolyte;

(5) Fortescue currently operates a pilot plant implementing the second approach referred to above, the reduction of solid ore particles, which it implements at pilot scale. Element Zero has announced that it has commercialised and used a process implementing the first approach referred to above, the EZ Process, which it also implements at pilot plant scale, i.e. the EZ Plant;

(6) Dr Kolodziejczyk was involved in the development of green iron technology for Fortescue since the commencement of his employment in March 2019;

(7) by mid-2020, Dr Kolodziejczyk was investigating opportunities for Fortescue to develop green iron technology that used electrochemical reduction with an ionic liquid;

(8) Dr Bhatt analysed information from Dr Kolodziejczyk’s Fortescue email inbox and provided a summary of those emails which showed that:

(a) between August and October 2020 Dr Kolodziejczyk was exchanging emails and having discussions, which were subject to a non-disclosure regime, with a third party about developing certain technologies including “low-temperature oxide (predominantly iron ore) reduction technology”. An email sent by Dr Kolodziejczyk in October 2020 to that third party referred to the provision of an overview of the “preliminary work” Fortescue had undertaken in ionic liquids and low temperature iron ore reduction, although a subsequent email providing that overview could not be located;

(b) in early to mid-December 2020, Dr Kolodziejczyk sent emails to senior Fortescue management which indicated that he was working on setting up a testing facility for low temperature processing from ionic liquids;

(c) in an email sent on 22 December 2020 attaching a “patent assessment form for the intended patent application covering low-temperature electrochemical ores reduction in ionic liquids”, Dr Kolodziejczyk said that “[t]he technology [was] proven” because he had “developed this method” and tested it “in a small scale laboratory setting before”. The invention was described in the attached patent assessment form as revolving around “the use of ionic solvents and electrochemical devices for the low-temperature reduction of ores and oxides”; and

(d) in late December 2020 to January 2021, Dr Kolodziejczyk was progressing two technologies, low temperature ionic process and a molten carbide route;

(9) according to Dr Bhatt, Dr Kolodziejczyk must have commenced preliminary work on ionic liquids and low temperature iron ore reduction in June 2020;

(10) in December 2020, Dr Kolodziejczyk recruited Dr Winther-Jensen, his former PhD supervisor, to work as an electrochemist on the development of low temperature processing from ionic liquids. By email sent on 27 January 2021, Dr Kolodziejczyk informed Dr Winther-Jensen of his visit to another third party and that he had “looked at water, ionic liquids, and molten carbonate”;

(11) on 23 February 2021, Dr Winther-Jensen provided a draft research plan to Dr Kolodziejczyk. Dr Bhatt explained that, among other things, the draft research plan suggested that the preferred “priority” scenario from a research and development perspective was the pursuit of solid-state reduction of magnetite concentrate to steel and that the ionic process should be considered as “parallel research with [a] longer lead-time”;

(12) other than some further emails exchanged between Dr Kolodziejczyk and Dr Winther-Jensen on 24 February 2021 about the “particle size of the available and ‘possible’ ore qualities” and the possibility of using magnetite, there are no further records that could be located in Dr Kolodziejczyk’s Fortescue email account about electrochemical reduction using an ionic liquid. In the last email in evidence between Dr Kolodziejczyk and Dr Winther-Jensen sent on 24 February 2021, Dr Winther-Jensen wrote, among other things, that:

I guess the fastest way to “something” is by reduction of hematite with hydrogen at high temperature (700 – 900 degC) followed by removal of oxides in the molten state (1500 degC). These processes are well outside my expertize and a more appropriate person should be appointed for pursuing such path.

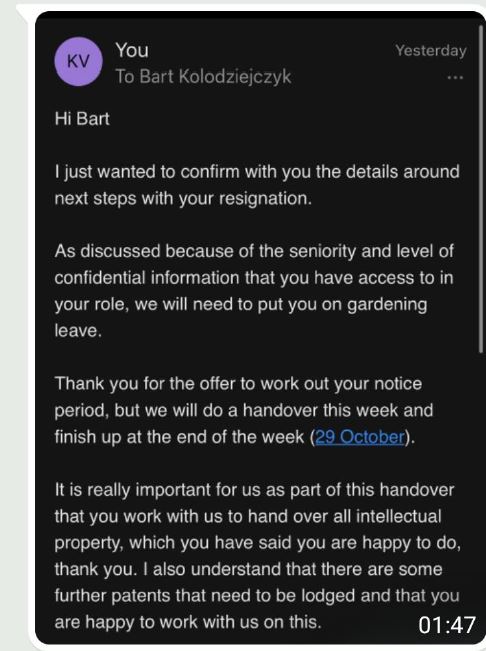

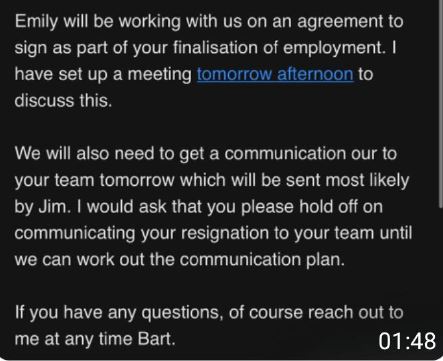

(13) Dr Kolodziejczyk first tendered his resignation on 14 June 2021 but retracted it the following day on 15 June 2021. Dr Kolodziejczyk then resigned from Fortescue on 22 October 2021. His last day was 5 November 2021 and his access to the Fortescue network and emails was cut off on that date;

(14) Dr Winther-Jensen resigned from Fortescue on 4 November 2021 and his last day was 12 November 2021;

(15) between his resignation and his last day at Fortescue, FFI conducted an internal investigation into Dr Kolodziejczyk in response to a complaint filed against him. No such investigation was carried out in relation to Dr Winther-Jensen for the same period i.e. between his date of resignation and his last day at Fortescue;

(16) for the investigation, Control Risks Group Pty Ltd was retained to prepare a business intelligence report to verify Dr Kolodziejczyk’s CV and Deloitte was retained to forensically analyse Dr Kolodziejczyk’s work-issued laptop for signs of IP theft or other misconduct for which purpose Deloitte took a forensic image of Dr Kolodziejczyk’s laptop. The findings of the investigation included that Dr Kolodziejczyk had: made material misrepresentations in his CV; deleted a folder named “TempSD” (including its subfolder ‘To Save\ Fortescue IP’) from his work-issued computer on the day of his resignation; and accessed the same files on a USB connected to his work-issued laptop on 5, 18 and 22 October 2021. However, at the time, Deloitte did not identify “information that may suggest [Dr Kolodziejczyk] had removed or attempted to remove commercially sensitive intellectual property from the FFI network”;

(17) on 31 July 2022 Mr Masterman ceased in his role as CFO of FFI. However, Mr Masterman maintained contact with Fortescue’s metals technology department which provided him with iron ore samples in May 2023;

(18) on about 15 August 2023 Andrew Hamilton, technical director of the metals technology department, informed Phil McKeiver, Fortescue’s chief general counsel, of “concerns” regarding Mr Masterman and his team that may cause the metals technology department to reassess providing support in the form of supplying iron ore samples to those persons;

(19) Mr McKeiver telephoned Mr Masterman to raise concerns about potential intellectual property infringement and Element Zero’s activities. Adrian Huber, FFI’s senior legal counsel, was present on the call but did not speak. He gave evidence that he heard Mr Masterman tell Mr McKeiver that “there was nothing to worry about”. I note that the evidence before the duty judge was that Mr Huber considered this call took place in about August 2023 but, having reviewed an affidavit sworn by Mr Masterman on 20 June 2024 for the purpose of the Discharge Application (see [175] and [179] below), he considers that the call may have occurred in November 2023;

(20) on 11 September 2023 Mr Huber sent an email to Dr Kolodziejczyk in which he said that he had “recently discovered that [Dr Kolodziejczyk was] a co-director and shareholder of two recently incorporated companies together with some ex-employees of Fortescue, Michael Masterman (FFl’s former CFO) and Bjorn Winther-Jensen (FFl’s former Technology Development Lead)”, one of which was Element Zero. He understood that one or both of those companies was “potentially developing technology that is similar to technology [they] developed for Fortescue” and that Dr Kolodziejczyk’s colleagues had sought iron ore samples from Fortescue to help test their technology. He noted that “[r]ecent searches of IP Australia’s patent records also identify two patent applications for ‘ore processing’ methods for which [Element Zero] is the applicant”. In light of those matters Mr Huber invited Dr Kolodziejczyk and his co-directors to meet “on a confidential, without prejudice basis, to discuss [Fortescue’s] concerns, and in particular, whether [their] patent applications are based on, or otherwise incorporate, Fortescue’s intellectual property or confidential information”;

(21) on 17 January 2024, the Australian Financial Review published an article with the title “Former Fortescue duo breakaway green iron dream” which reported that:

One of Fortescue chairman Andrew Forrest’s most senior lieutenants of the past 25 years, Michael Masterman, has joined forces with former Fortescue chief scientist Bart Kolodziejczyk to create a metals processing start-up that is already turning iron ore into pure iron at laboratory scale.

Dubbed Element Zero, the new company has a patented method of “electro-reduction” that uses an alkaline solution and electric current to separate pure iron from the waste products in iron ore such as silica, alumina and oxygen.

Mr Masterman and Mr Kolodziejczyk say Element Zero’s patented process can work for the hematite ores that dominate the Australian iron ore industry, plus other metals like nickel.

“Everything we do was developed after Fortescue and doesn’t bring anything from Fortescue,” said Mr Kolodziejczyk.

…

Under Element Zero’s process, iron ore is dissolved into a clear, alkaline solution that does not include water. When renewable electricity is passed through the solution, the pure iron plates onto a cathode, from where it can be collected for sale.

Element Zero is commissioning a green iron pilot plant in the Perth suburb of Malaga, where 100 kilograms of iron ore will be fed into the process each day.

Mr Kolodziejczyk received an Order of Australia in 2022 for services to hydrogen energy science. But he said the lack of hydrogen in Element Zero’s process was an advantage because it lowered capital costs and allowed for a more direct and efficient use of renewable power.

…

Mr Masterman said exiting Fortescue better enabled him to focus on a smaller number of projects.

“There became a point in time where, for me, [there were] too many time zones; let’s come back and focus. So I stepped back in 2022 and focused on where there are opportunities for very, very large-scale decarbonisation,” he said.

Some of the green iron technologies being pursued by Fortescue were developed by Mr Kolodziejczyk during his time at the company, and his name is still on some Fortescue patents.

Asked why he did not pursue Element Zero’s electro-reduction method while working at Fortescue, Mr Kolodziejczyk said the idea had not dawned on him until later.

“You actually had to step out of Fortescue to brainstorm, ideate and develop a pathway,” he said. “We tested it in our garage initially to make sure it works.

…

(22) following publication of the article referred to above, Mr Huber took the following steps:

(a) on 17 January 2024 he requested Fortescue’s IT department to provide access to the Fortescue email inboxes of Robert Kerr, a green iron team member who was supervised by Dr Winther-Jensen in the University of Western Australia (UWA) laboratory, Dr Kolodziejczyk, Dr Winther-Jensen and Mr Masterman;

(b) from about 18 January 2024 he requested Dr Bhatt to review Dr Kolodziejczyk’s, Dr Winther-Jensen’s and Mr Masterman’s emails and relevant documents. On about 22 January 2024 Dr Bhatt informed Mr Huber that he had identified that Dr Winther-Jensen had sent confidential Fortescue documents to his personal email address in the days prior to his departure from Fortescue;

(c) on 10 February 2024 he made enquiries of Fortescue’s data protection team in relation to Dr Winther-Jensen’s Fortescue laptop as a result of which he understood that it was likely that Dr Winther-Jensen was using a Fortescue issued laptop;

(d) between 1 and 17 April 2024 Fortescue conducted further investigations to identify documents taken by Drs Kolodziejczyk and Winther-Jensen prior to their departure from Fortescue; and

(e) between 17 and 22 April 2024 he retained Mr McKemmish, a forensic and technology expert and a principal of CYTER, a specialist technology business specialising in digital and cyber forensic services, to examine a laptop used by Dr Winther-Jensen in the UWA laboratory;

(23) in undertaking his review, on 19 January 2024 Dr Bhatt identified five emails that contained documents of concern that Dr Winther-Jensen sent from his Fortescue email address to his personal email address between the date of his resignation and his final day at Fortescue i.e. between 3 and 12 November 2021. They contain the confidential information referred to at SoC [19(b)] and [20] which is described as (i) the Leaching Report (SoC [20(a)]), (ii) Leaching Data (SoC [20(b)-(c)]), (iii) documents filed in support of Fortescue’s provisional applications no 2021901547 (SoC [19(b)], [20(d)]), (iv) Technical Evaluation Email and Technical Evaluation Sheet (SoC [20(e)-(f)]) and (v) the Green Iron Update (SoC [20(g)]);

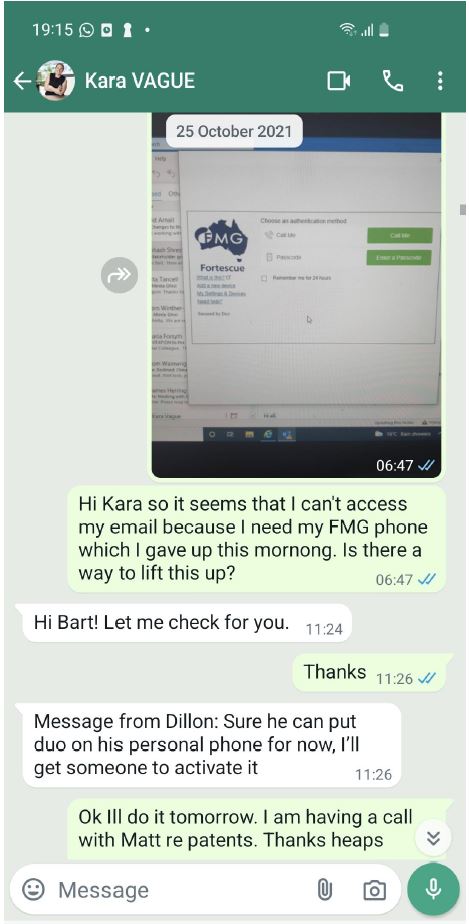

(24) the forensic image of Dr Kolodziejczyk’s laptop taken by Deloitte at the time it prepared its report was also re-examined in April 2024 by Mr McKemmish. Mr Huber gave the following evidence by way of summary of Mr McKemmish’s report:

(a) it confirms that at least two external USB devices were connected to the laptop between September 2021 and November 2021;

(b) Dr Kolodziejczyk accessed a number of files stored on external USB devices connected to the laptop, including those relevant to Fortescue’s “green iron” technologies work that he had been undertaking before leaving Fortescue and patent applications for which FFI is the applicant and which were filed while Dr Kolodziejczyk was at Fortescue;

(c) it confirms the finding in the Deloitte report that a folder called “TempSD” (TempSD folder) was deleted on 22 October 2021 and that the structure of this folder is very similar to the files and folders on one of the USB devices, suggesting that the USB device may contain copies of the files found in the TempSD folder;

(d) Dr Kolodziejczyk’s Fortescue laptop was used to access the file “FFI0302-1 0000-00-EG-BOD-0001_A (002) (BK).docx” (referred to at SoC [19(c)]) while a USB device was connected to the laptop. Mr Huber has been informed that this file was the Basis of Design document for the “Chameleon Pilot Plant”. This file was accessed from the USB device in mid-late October 2021, including on 25 October 2021 after Dr Kolodziejczyk had resigned;

(e) Dr Kolodziejczyk’s Fortescue laptop was used to access the file “Bumblebee PIO markups 26_ 10_21.pdf” (referred to at SoC [19(d)]) on 26 October 2021 and 1 November 2021 (after Dr Kolodziejczyk’s resignation) while a USB device was connected to the laptop. A copy of this file is no longer on Dr Kolodziejczyk’s laptop and Mr Huber understands that this means the file was deleted and/or transferred onto a USB drive;

(f) Dr Kolodziejczyk’s Fortescue laptop was used to access the file “Green Iron Update (02.08.2021 ).pdf” (referred to at SoC [19(a)]) on 22 October 2021, the date of Dr Kolodziejczyk’s resignation. This file was also accessed from a USB device connected to Dr Kolodziejczyk’s laptop; and

(g) Dr Kolodziejczyk’s Fortescue laptop was used to access the files “35557986AU -Drawings as filed (35557986).pdf” and “35557986AU-Specification as filed (35557986).pdf” (referred to at SoC [19(b)]) on 22 October 2021, the date of Dr Kolodziejczyk’s resignation. These files are identified as once being stored on Dr Kolodziejczyk’s Fortescue laptop hard drive with the following file pathway: /TempSD/To save/Fortescue IP/Patent #5 (Electrochemical ore reduction)/. This file structure is similar to that of a USB drive connected to the laptop. The entire TempSD folder was deleted from the laptop on 22 October 2021;

(25) Dr Bhatt reviewed the SharePoint Folder, which is the folder in which Dr Winther-Jensen and Dr Kolodziejczyk as members of the green iron project team were expected to store their work output, and Fortescue raw data files, such as experiment/test results, in which Dr Winther-Jensen is identified as the author. He notes that from February to November 2021 Dr Winther-Jensen was supervising a team of around four scientists. However, his review of the SharePoint Folder identified only five documents in which Dr Winther-Jensen is named as an author. Having regard to Dr Winther-Jensen’s expertise, Dr Bhatt would have expected him to have produced and saved a significantly greater amount of work output on the SharePoint Folder for the green output team. Given the limited material available Dr Bhatt is concerned that Dr Winther-Jensen took work output, including Fortescue’s confidential information, with him when he left Fortescue;

(26) on 25 April 2024 an Element Zero patent application titled ‘‘WO2024082020 – METHOD OF ORE PROCESSING” became public as a PCT application (EZ PCT Application). Dr Bhatt considers that the EZ PCT Application is consistent with the previous information published by Element Zero about the EZ Process and the EZ Plant and that the temperature window described falls within the window of temperatures tested and analysed in the Leaching Report; and

(27) Wayne McFaull, chartered engineer who is the manager of energy technology scale-up at Fortescue, has reviewed Fortescue’s expenditure on its pilot plant and the documents which Fortescue alleges were taken by, and the documents available to, Drs Kolodziejczyk and Winther-Jensen. Having done so he is of the view that the EZ Process and the EZ Plant could only have been achieved with the modest resources available to Element Zero if Dr Kolodziejczyk, Dr Winther-Jensen and Element Zero had used a substantial amount of the information from the documents set out at [19] and [20] of the SoC, together with other Fortescue confidential information.

Consideration

51 The first matter relied on by the EZ respondents in support of their contention that there was a weak prima facie case insofar as the claim for breach of confidence is concerned is an alleged failure by Fortescue to identify the confidential information with the necessary specificity.

52 Fortescue was aware of and set out the elements required to establish a breach of the equitable obligation of confidence at [46] of the Search Order Submissions noting relevantly that:

The Full Court (Finn, Sundberg and Jacobson JJ) identified the elements for a breach of equitable obligations of confidence in Optus Networks v Telstra Corporation Ltd [2010] FCAFC 21; 265 ALR 281 at [39]:

(a) the information in question must be identified with specificity;

(b) it must have the necessary quality of confidence;

(c) it must have been received by the defendant in circumstances importing an obligation of confidence; and

(d) there must be an actual or threatened misuse of the information without the plaintiff’s consent.

53 The confidential information the subject of the claim was identified at [12]-[14] of the SoC in relation to the Fortescue Process CI (or the Ionic Liquid R&D Information) and [19]-[20] of the SoC in relation to the Fortescue Plant CI. Fortescue was, and based on the ASoC remains, unable to identify specific documents in relation to the Fortescue Process CI because, as pleaded, it can be inferred that before they ceased their employment with Fortescue, Dr Kolodziejczyk and/or Dr Winther-Jensen took the documents, or otherwise caused the documents to be unavailable to Fortescue. That is, Fortescue contends that it cannot specify the documents or material with more precision as they are not in its possession inferentially because of Dr Kolodziejczyk’s and Dr Winther-Jensen’s conduct.

54 No further specificity of the information in question was or is required for the purpose of obtaining the search orders. As Henry J observed in Macquarie Holdings (NSW) Pty Ltd v Maharaj [2019] NSWSC 811 at [44]-[45], where it was similarly contended that the nature of the confidential information the subject of the alleged breach of confidence claim lacked specificity:

44 The realities of interlocutory applications must also be borne in mind. A plaintiff’s pleading may not always be comprehensive in such applications, having been prepared in more urgent circumstances than usual, and while further factual inquiries are ongoing. An injunction may nevertheless be appropriate where the pleading does sufficiently (albeit imprecisely) identify a serious question to be tried: see Australian Broadcasting Corporation v Lenah Game Meats Pty Ltd (2001) 208 CLR 199; [2001] HCA 63 at [159] per Kirby J.

45 In that context, I accepted there was a sufficient basis to proceed in respect of the misuse of confidential information claim as against the first defendant but on the basis that the plaintiff would be amending the statement of claim to clarify matters in the pleading regarding the nature of the confidential information alleged to have been accessed and used.

55 Similarly, here Fortescue states in the SoC (and the ASoC) that it will provide further particulars, i.e. specificity, after discovery.

56 Secondly, the EZ respondents contend insofar as the alleged breach of confidence is concerned that there was no actual or threatened misuse of the alleged confidential information without the consent of Fortescue.

57 Fortescue pleaded alleged misuse of the Fortescue Process CI and the Fortescue Plant CI (referred to collectively as Fortescue CI) at [31] and [33]-[35] of the SoC as follows:

31 Each of Dr Kolodziejczyk and Dr Winther-Jensen has:

(a) disclosed Fortescue Cl to each of Element Zero and Mr Masterman; and

(b) used Fortescue Cl as follows:

(i) used Fortescue Process Cl in commercialising and using the EZ Process;

(ii) used Fortescue Process Cl and Fortescue Plant Cl in designing, engineering, constructing and operating the EZ Plant or causing those things to be done;

(iii) to the extent either is an inventor of any invention described or claimed in each Patent Application— used Fortescue Process Cl and/or Fortescue Plant Cl in inventing the invention so described or claimed; and

(iv) used Fortescue Process Cl and/or Fortescue Plant Cl in preparing and filing each Patent Application.

Particulars

(i) Inferences available from the commonality of the features of the Ionic Liquid R&D pleaded in subparagraphs 12(a) to 12(f) above and the features of the EZ Process pleaded in subparagraphs 29(a) to 29(f) above.

(ii) Inferences available from Dr Kolodziejczyk’s and Dr Winther-Jensen’s exfiltration of the documents at pleaded in paragraphs 19 and 20 above.

(iii) The facts, matters and circumstances in the affidavit of Dr Anand lndravadan Bhatt.

(iv) The facts, matters and circumstances in the affidavit of Mr Wayne McFaull.

(v) The facts, matters and circumstances in the affidavit of Ms Susanne Monica Hantos.

(vi) Further particulars may be provided.

…

33 Each of Element Zero and Mr Masterman has:

(a) used Fortescue Process Cl in Element Zero’s commercialising and using the EZ Process; and

(b) used Fortescue Process Cl and Fortescue Plant Cl in designing, engineering, constructing and operating the EZ Plant or causing those things to be done.

Particulars

(i) Particulars to paragraph 31 above are repeated.

(ii) Further particulars may be provided.

34 Each Respondent disclosed Fortescue Cl by causing the PCT Application to be published on and from 25 April 2024.

35 Each Respondent’s uses of Fortescue Cl pleaded in paragraphs 31, 33 and 34 above was done without Fortescue’s authorisation.

58 The alleged misuse is for the most part alleged to arise inferentially from the surrounding facts and circumstances. There is no difficulty with proceeding in that way: see Thales Australia Limited v Madritsch KG [2022] QCA 205 at [41], [42] and [44].

59 Thirdly, more specifically, in relation to the claim about the Fortescue Process CI, the EZ respondents contend that no Fortescue employee gave evidence as to the nature and scope of the alleged work undertaken by Dr Kolodziejczyk in relation to the Ionic Liquid R&D and that there are no significant internal documents or the type of documents that would be expected e.g. board papers or reports.

60 As to the former, Dr Kolodziejczyk gives evidence that there are a number of current Fortescue employees who were working at Fortescue at the same time as him and who knew about the work he was doing. Those people included Mr Roper and Sienna Mohammadzadehmoghadam, a materials scientist with whom he worked in the laboratory on the development of technology using electrochemical reduction of solid iron ore particles suspended in an electrolyte slurry (Fortescue technology). Dr Kolodziejczyk recalls corresponding with Mr Roper during his final weeks of employment, including about the Fortescue technology and development of a process to produce zero carbon or “green” cement (Green Cement).

61 Mr Roper is a registered patent and trade marks attorney. He has been employed as FFI’s intellectual property manager since May 2021. He gives evidence that Dr Kolodziejczyk neither reported, nor handed over his role on resignation, to him. Dr Kolodziejczyk’s work did not overlap with that of Mr Roper except to the extent it concerned FFI’s intellectual property.

62 The only email correspondence between Dr Kolodziejczyk and Mr Roper in October 2021 was:

(1) an email from Dr Kolodziejczyk sent on 5 October 2021 with the subject “Iron donor electrodes” attaching a completed invention disclosure form dated 3 October 2021 with the title “Iron acceptor and donor electrode for all-iron-flow battery”; and

(2) emails concerning the provision of completed invention disclosure forms after Dr Kolodziejczyk’s resignation and as part of finishing up his employment with Fortescue (see [155] below).

63 Mr Roper checked his emails and confirmed that he did not receive any correspondence from Dr Kolodziejczyk about Green Cement. However, he did receive an email from Dr Aabhash Shrestha, an FFI electrochemist, on 21 September 2021, copying Dr Kolodziejczyk and others, which attached an invention disclosure form of the same date titled [REDACTED] [REDACTED] [REDACTED] which identifies Dr Kolodziejczyk and others as co-inventors.

64 Dr Mohammadzadehmoghadam commenced working at FFI in April 2021 as a junior engineer and was based at FFI’s laboratory at UWA. Dr Bhatt notes that this was after the last date of the emails he reviewed which referred to Ionic Liquid R&D (see [50(12)] above) and, while Dr Kolodziejczyk had access to the laboratory at UWA, he was not based there exclusively.

65 The evidence suggests that any interaction by Dr Kolodziejczyk with either Mr Roper or Dr Mohammadzadehmoghadam was at best limited and in the case of Mr Roper did not concern the actual research he undertook except to the extent that it had to be described in order to capture its nature and to determine whether intellectual property protection should be obtained for it. On the other hand, it can be inferred that Dr Kolodziejczyk largely worked alone (see for example [50(8)(c)] above) until Dr Winther-Jensen joined Fortescue after which time he worked with him.

66 As to the latter, while there were no board reports or papers relied on by Fortescue before the duty judge, there were a number of internal documents in evidence in relation to the nature and scope of the work including:

(1) email dated 21 October 2020 from Dr Kolodziejczyk to a third party collaborator in which Dr Kolodziejczyk wrote that he would “draft a quick overview of preliminary work that we have done in ionic liquids and low temperature iron ore reduction and share it with you shortly”;

(2) emails from Dr Kolodziejczyk to Dr Forrest, in which, among other things, Dr Kolodziejczyk suggested that he was setting up a testing facility in Perth which would involve “low temperature processing from ionic liquids”, that he was getting the manufacturing and R&D facilities set up and that “this work”, being the construction of a mini plant and later a commercial scale pilot plant, would proceed shortly;

(3) the patent assessment form completed and sent by Dr Kolodziejczyk on 22 December 2020 referred to at [50(8)(c)] above;

(4) an email from Dr Kolodziejczyk to Julie Shuttleworth, FFI’s then CEO, in which Dr Kolodziejczyk stated that “[w]e are proposing the development of two green steel technologies. One will be low-temperature electrochemical ore reduction in ionic liquids. The second one will be the electrolysis of iron ore in molten carbides” and that he was “drafting R&D roadmaps” for both technologies which would subsequently be used for patent applications;

(5) a draft board paper shared on 22 January 2021 titled [REDACTED] [REDACTED] [REDACTED] [REDACTED] [REDACTED] [REDACTED] [REDACTED] [REDACTED] [REDACTED] [REDACTED] [REDACTED] and stated that the Fortescue team had undertaken “an initial evaluation of various suitable electrolytes”; and

(6) Dr Kolodziejczyk’s email dated 27 January 2021 to Dr Winther-Jensen referred to at [50(10)] above.

67 Contrary to the EZ respondents’ submissions, a number of these documents could be described as “significant” and, in any event, demonstrate that work had been undertaken including by laboratory testing and that there was an intention to scale up to a commercial system (see [50(8)(c) and (d)] above).

68 In oral address, the EZ respondents submitted that Fortescue should have taken the duty judge to the emails sent by Dr Kolodziejczyk (some of which are referred to above) instead of relying on Dr Bhatt’s summary of them and to suggest a different complexion as to what they showed. Dr Bhatt’s summary of the emails was detailed and the emails were available to the Court if the duty judge wished to review them. The obligations imposed on Fortescue on the ex parte application did not require a counsel of perfection, nor did it require Fortescue to identify every submission about the weight of the available evidence or that the respondents might have put had they been present: see Geneva Laboratories Ltd v Nguyen (2014) 110 IPR 195 at [73], [93] (Gleeson J).

69 Lastly, a central plank of the EZ respondents’ contention that Fortescue has a weak prima facie case in relation to the Fortescue Process CI is Dr Kolodziejczyk’s evidence on the Discharge Application that he “did not work on an ‘Ionic Process’ while [he] was at Fortescue”. Dr Kolodziejczyk gave evidence that Dr Bhatt’s analysis and proposed timeline is not correct and does not reflect the work he undertook at Fortescue for the following reasons:

(1) between August 2020 and mid-January 2021, he was travelling extensively as part of the “Fortescue Travelling Team”. He was responsible for scoping renewable energy projects globally, and for evaluation of investments and technologies. Between extensive travels and manufacturing responsibilities, he did not have time to pursue other projects;

(2) the scientific work he undertook at Fortescue focused on the development of technology using electrochemical reduction of solid iron ore particles suspended in an electrolyte slurry (as described in Part C.3 of Dr Bhatt’s affidavit affirmed on 1 May 2024), i.e. the Fortescue technology. This work led to the filing of a patent application by Fortescue. Dr Kolodziejczyk worked on the Fortescue technology intensively in 2021 with the “stretch target” of producing products by the end of financial year 2021, which was met. Dr Kolodziejczyk says that the Fortescue technology is very different to the Element Zero technology;

(3) between February or March and October 2021, he was also researching and developing a process to produce Green Cement. This involved using gangue (which is the commercially valueless material in Fortescue’s iron ore) to produce geopolymers based on sodium silicate and sodium aluminate. In his role at Fortescue, he was responsible for designing that process and leading the work. Dr Kolodziejczyk worked on that process throughout 2021 and produced small scale samples of Green Cement from iron ore waste in late August 2021; and

(4) he was involved in a number of other projects in 2020 and 2021 including the development of “green” hydrogen technologies, hydrogen buses and a hydrogen refuelling station, a flow battery, optimisation tool and electrolyser design.

70 Dr Kolodziejczyk’s assertion that he did not undertake any work on an ionic process is of limited utility in the context of this application.

71 As set out at [23] above, it is not the case that on the Discharge Application the EZ respondents can require Fortescue to prove again the case in favour of making the order: Austress at [25]. Fortescue’s evidence was accepted by the duty judge. As Moshinsky J explained in Fine China Capital Investment Limited v Qi (No 2) [2023] FCA 1059, in the context of a contested application to extend a freezing order, at [23]:

It is common ground that, in circumstances where the Court is confronted with conflicting bodies of evidence, the following principles apply (based on Parbery v QNI Metals Pty Ltd [2018] QSC 107; 358 ALR 88 at [71]-[75] per Bond J):

(a) in assessing whether the applicant has discharged its burden, the Court must exercise a degree of caution;

(b) in general, this is not an occasion to determine contested questions of fact and conflicts in affidavit evidence;