FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v EnergyAustralia Pty Ltd [2024] FCA 1126

ORDERS

VID 805 of 2023 | ||

AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION Applicant | ||

AND: | ENERGYAUSTRALIA PTY LTD (ACN 086 014 968) Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: | 26 September 2024 |

THE COURT DECLARES THAT:

1. During the period 20 June 2022 to 28 September 2022, EnergyAustralia Pty Ltd (EnergyAustralia) contravened section 12(2) of the Competition and Consumer (Industry Code—Electricity Retail) Regulations 2019 (Code), and therefore section 51ACB of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (CCA):

(a) on 591,924 occasions during the period 20 June 2022 to 28 September 2022, by notifying 566,827 small customers of changes to EnergyAustralia’s electricity prices in writing, without stating the lowest possible price for a representative customer, clearly and conspicuously or at all; and

(b) on 223,591 occasions during the period 1 July 2022 to 27 September 2022, by communicating offered prices in respect of 27 electricity offers published on EnergyAustralia’s website (energyaustralia.com.au), without stating clearly and conspicuously, or at all:

(i) the difference between the reference price and the unconditional price, expressed as a percentage of the reference price; and

(ii) the lowest possible price.

2. During the period 20 June 2022 to 28 September 2022, EnergyAustralia contravened sections 18 and 29(1)(i) of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL) on 591,924 occasions, by representing to consumers in written communications that the estimated annual price of its electricity offer for an average customer of a specified type, using a specified amount of electricity, on a specific tariff, and in a specified area, was a dollar amount that was not the estimated annual price of electricity for an average customer with those characteristics.

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

Pecuniary Penalties

3. Pursuant to section 76(1)(a)(iv) of the CCA, EnergyAustralia pay to the Commonwealth of Australia a pecuniary penalty in the sum of $4,000,000 in respect of the contraventions referred to in paragraph 1(b) of this order, to be paid within 30 days of this order.

4. Pursuant to section 224(1)(a)(ii) of the ACL, EnergyAustralia pay to the Commonwealth of Australia a pecuniary penalty in the sum of $10,000,000 in respect of the contraventions of section 29(1)(i) of the ACL referred to in paragraph 2 of this order, to be paid within 30 days of this order.

Compliance

5. Pursuant to section 86C(2)(b) of the CCA and section 246(2)(b) of the ACL, EnergyAustralia, at its own expense:

(a) appoint a suitably qualified independent compliance professional (the Reviewer), whose appointment has been approved by the Applicant (ACCC) or failing agreement, as proposed by each of them and determined by the Court, to:

(i) conduct a review of the implementation and effectiveness of EnergyAustralia’s compliance and training program (insofar as it relates to compliance with sections 18 and 29 of the ACL, section 12 of the Code, and section 51ACB of the CCA) annually for three years, commencing 90 days after the date of this order; and

(ii) prepare a written report to be provided to EnergyAustralia within 90 days of the commencement of each review.

The appointed Reviewer may be replaced by EnergyAustralia if necessary, with the prior approval of the ACCC;

(b) ensure that the Reviewer will be independent for the purposes of paragraph (a) by appointing only a Reviewer who did not design or implement the compliance and training program referred to in paragraph (a);

(c) use its best endeavours to provide the Reviewer with access to all sources of information within the possession, power or control of EnergyAustralia or any related body corporate that is relevant to the review;

(d) within 30 days after receiving the Reviewer’s written report, provide a copy of that report to the ACCC and the board of directors of EnergyAustralia Holdings Limited (ACN 101 876 135); and

(e) implement promptly and with due diligence any recommendations made by the Reviewer (unless the ACCC consents to a request by EnergyAustralia, acting reasonably, not to do so) and advise the ACCC in writing of each of the steps it has taken and/or will take to implement the recommendations and the date on or by which each of those steps was or will be taken.

6. Pursuant to section 86C(2)(b) of the CCA and section 246(2)(b) of the ACL, EnergyAustralia, at its own expense, for a period of three years commencing 90 days after the date of this order:

(a) maintain its existing executive regulatory steering committee, including at least one member of its Executive Leadership Team, to monitor the implementation of any recommendations made by the Reviewer pursuant to paragraph 5(e);

(b) maintain a record of and keep all documents relating to the implementation of any recommendations made by the Reviewer pursuant to paragraph 5(e) and the performance by the executive regulatory steering committee of its monitoring functions described in paragraph 5(a); and

(c) if requested to do so by the ACCC, provide to the ACCC copies of all documents kept pursuant to paragraph 6(b).

Other

7. The Applicant’s claims against the Respondent be otherwise dismissed.

8. The Respondent pay a contribution to the Applicant’s costs in the sum of $50,000, pursuant to s 43 of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) within 30 days of this order.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

O’CALLAGHAN J

INTRODUCTION

1 The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) brings this proceeding against EnergyAustralia Pty Ltd (EnergyAustralia), an electricity retailer within the meaning of s 5 of the Competition and Consumer (Industry Code—Electricity Retail) Regulations 2019 (the Code).

2 EnergyAustralia admitted that it has contravened:

(a) section 12(2) of the Code and section 51ACB of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (CCA) by: (a) failing in its communications with approximately 560,000 “small customers” to state the “lowest possible price”; and (b) failing in communications on its website, which were viewed approximately 220,000 times, to state the “lowest possible price” and the difference between the “reference price” and the “unconditional price”, expressed as a percentage of the reference price; and

(b) sections 18 and 29(1)(i) of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL), being Schedule 2 to the CCA, in its communications to approximately 560,000 small customers, by stating an “estimated annual price” for its electricity offers based on an “average” customer with certain stated characteristics, when the dollar figure stated was not the estimated annual price for such a customer.

3 The facts agreed between the parties, and the formal admissions of contravention by EnergyAustralia, are set out in the Statement of Agreed Facts and Admissions dated 30 August 2024, which is attached to these reasons and marked Annexure A.

4 The parties also relied on a document titled “Joint Submissions on Contraventions and Relief” dated 30 August 2024, signed by Mr S Parmenter KC and Ms C Cunliffe of counsel for the ACCC and Mr N De Young KC and Ms H A Tiplady of counsel for EnergyAustralia.

5 At the hearing on 4 September 2024, Mr Parmenter appeared on behalf of the ACCC. Ms Tiplady appeared on behalf of EnergyAustralia.

6 The parties sought the declarations and orders set out above by consent.

7 For the reasons set out below, I am satisfied that the making of the declarations and orders sought is appropriate.

BACKGROUND

8 The Code, which commenced on 1 July 2019, is a mandatory industry code for the purposes of Part IVB of the CCA.

9 I was told that this is the first enforcement proceeding brought by the ACCC under the Code.

10 The Code was introduced because the ACCC found in its Retail Electricity Pricing Inquiry that the national electricity market (or “NEM”) was not working in the interests of retail consumers. The Inquiry found that “standing offers” were used by retailers as a high benchmark from which to advertise discounts, subjecting unengaged consumers to unreasonably high prices. The Inquiry also found that the use of advertising using headline discounts off a standing offer price did not give consumers the ability to easily compare offers, or estimate how much they are likely to pay, because standing offer prices varied between retailers.

11 The Code was introduced, among other reasons, to increase transparency in the retail electricity market to allow consumers to easily compare offers and remove the confusion arising from pricing practices including discounts.

12 The reference price was identified as a means of providing consumers with a clear benchmark against which to compare offers available in the market and identify which offers represent the best deal for them. The Code requires retailers, in their communications with small customers (including advertising and publishing price offers) to compare their prices with the reference price.

13 Between 20 June 2022 and 28 September 2022 (the Relevant Period), the retail electricity market in the eastern states of Australia and South Australia was particularly volatile. The NEM was suspended between 15 and 23 June 2022, various smaller energy retailers failed and exited the market, and retail prices were increased.

14 At all material times, EnergyAustralia supplied electricity to small customers within a distribution region to which s 8 of the Code applies.

15 EnergyAustralia is one of the largest retailers in the NEM. In the 2023/2024 financial year, it had over one million residential customers, 14.8% electricity residential market share, and 13.8% of the small business market. Its group revenue in the 2021/2022 financial year was $6.449 billion.

16 EnergyAustralia reviews its electricity prices for its existing customers annually (other than for customers who have a fixed price). The annual price review that preceded the sending of the “Price Change Communications” which are relevant for this proceeding occurred with effect from 1 July 2022, taking into account various factors including the Australian Energy Regulator’s (AER) determination of the reference price.

17 The AER’s determination of the reference price for New South Wales, South East Queensland and South Australia for 2022–2023 provided for an increase in electricity prices compared to the previous year of between 5.7% and 19.7% for small business customers, 7.2% and 14.1% for some residential customers and 9.5% to 18.3% for other residential customers. The AER stated that the reason for the increase was “mainly due to higher expected wholesale costs in all regions, especially NSW and South East Queensland. Factors contributing to this include unplanned generator outages, higher coal and gas costs, and increasingly ‘peaky’ demand driving up the cost of energy contracts for retailers”.

18 The Code had been in place for approximately three years at the time of the conduct occurring. EnergyAustralia admits that it was aware of its obligations under the Code, and that the ACCC and AER sent EnergyAustralia a reminder letter in relation to its obligations under the Code on 10 June 2022.

LIABILITY

The relevant provisions of the Code

19 Part IVB of the CCA provides for the creation and enforcement of industry codes. The purpose of an industry code is to regulate the conduct of participants in an industry toward other participants or consumers in the industry. An industry code may be a mandatory industry code, if it is declared to be mandatory by regulation: ss 51ACA(1), 51AE. The Code is a mandatory industry code. By reason of s 51ACB, a corporation must not, in trade or commerce, contravene the Code.

20 The Code defines the reference price for a financial year, in relation to supplying electricity in a distribution region to a small customer of a particular type, as the per-customer annual price determined by the AER for the year in relation to the supply.

21 The reference price operates to set a cap on “standing offer prices”, in that standing offer prices must be set such that, were a small customer to be supplied in a financial year at those prices with the “model annual usage”, the total amount the customer would have to pay for the supply would not exceed the reference price. It also operates as a benchmark against which the Code requires retailers to compare their offered prices.

22 Section 12 of the Code provides that an electricity retailer must not communicate offered prices to small customers of a particular type unless the communication meets certain requirements. In particular, communications must clearly and conspicuously state:

(a) the difference between the reference price and the “unconditional price”, expressed as a percentage of the reference price; and

(b) “the lowest possible price”;

making it clear that those matters relate to a representative customer.

23 The Code defines the lowest possible price as the total amount a “representative customer” (as defined under the Code) would be charged for the supply of electricity in the financial year at the offered prices, assuming that the conditions on all “conditional discounts” (if any) mentioned in the communication were met.

24 The Code defines the unconditional price as the total amount a representative customer would be charged for the supply of electricity in the financial year at the offered prices, disregarding any conditional discounts.

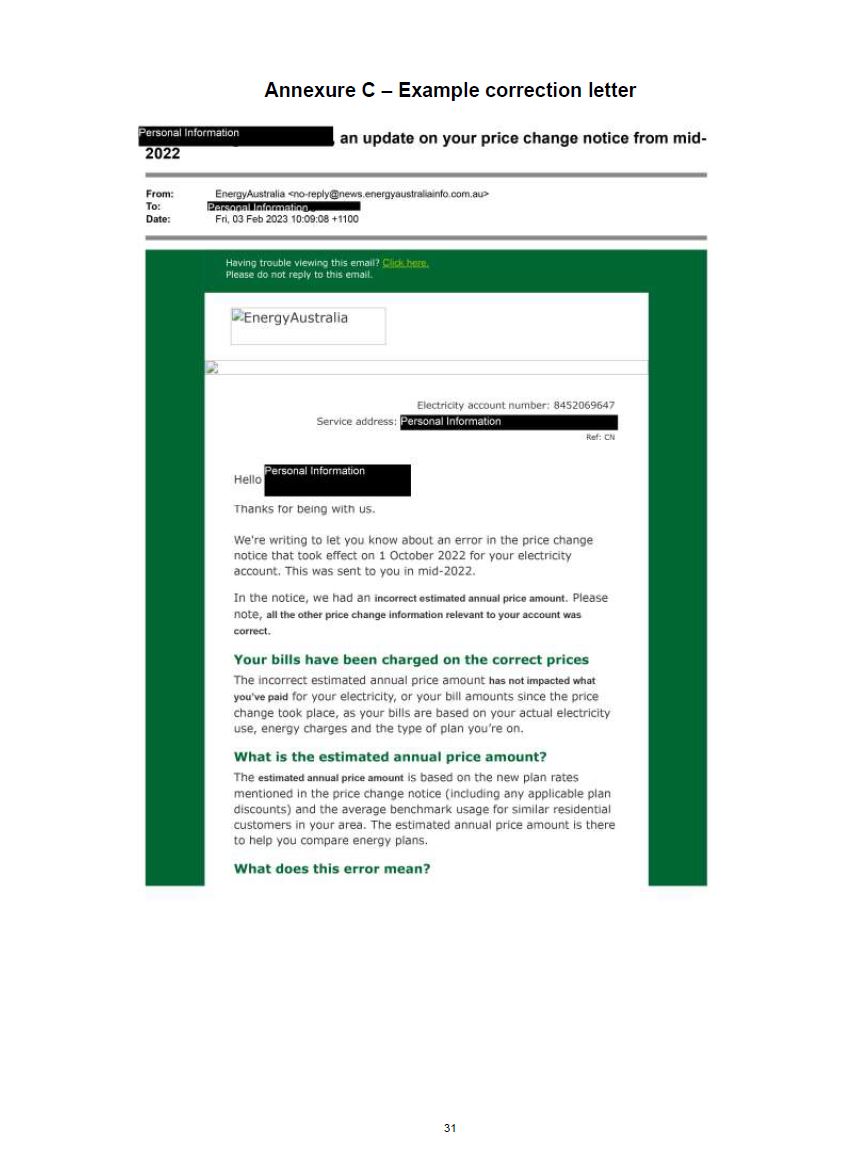

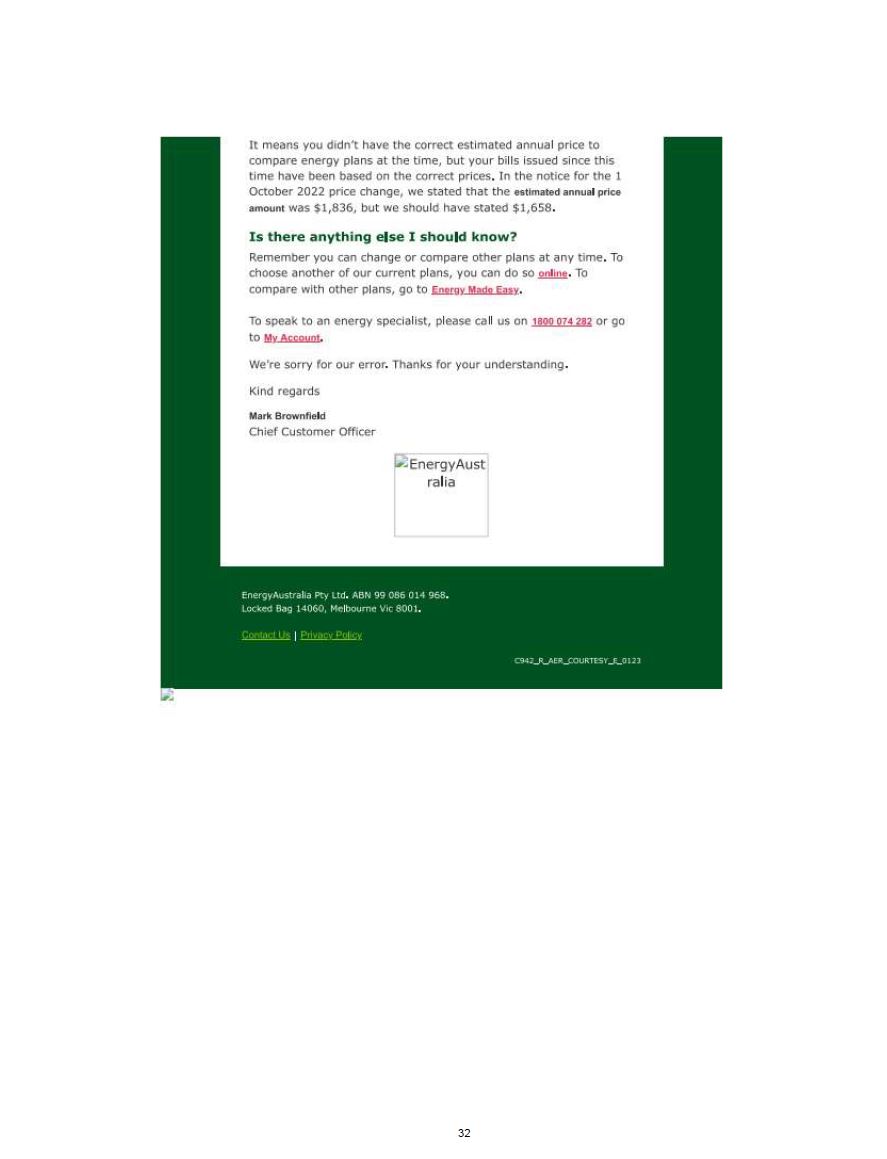

The relevant provisions of the ACL

25 A corporation will breach s 18 of the ACL if its conduct is “misleading or deceptive” or “likely to mislead or deceive”. Whether conduct is misleading or deceptive, or is likely to mislead or deceive, is a question of fact. Whether a contravention of s 18 has occurred is determined by reference to the alleged conduct in light of the relevant surrounding facts and circumstances. Whether conduct is, or is likely to be, misleading or deceptive is determined objectively. Conduct will be misleading or deceptive if it induces, or is capable of inducing, error.

26 Where the conduct concerns statements made to the public at large, as in this case, the court enquires into whether an ordinary or reasonable person within the relevant target audience would have been likely to have been misled or deceived. In determining the qualities of the reasonable person, it is necessary to consider who comes within that section of the public, including the astute and the gullible, the intelligent and the not so intelligent, the well-educated as well as the poorly educated.

27 Section 29(1)(i) of the ACL relevantly provides that a person must not, in trade or commerce, in connection with the supply or possible supply of goods or in connection with the promotion by any means of the supply or use of goods, make a false or misleading representation with respect to the price of goods.

28 Electricity is a “good” within the meaning of the ACL.

The contraventions

The Price Change Communications

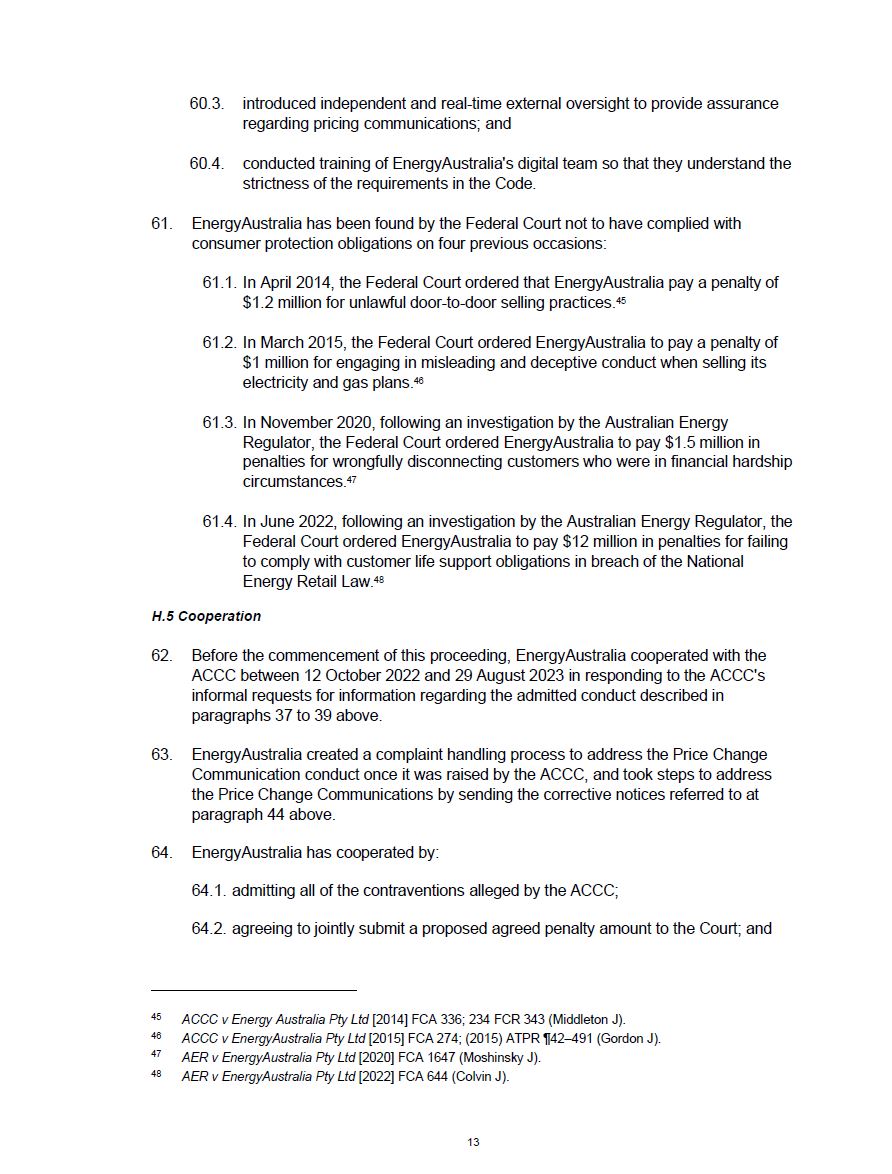

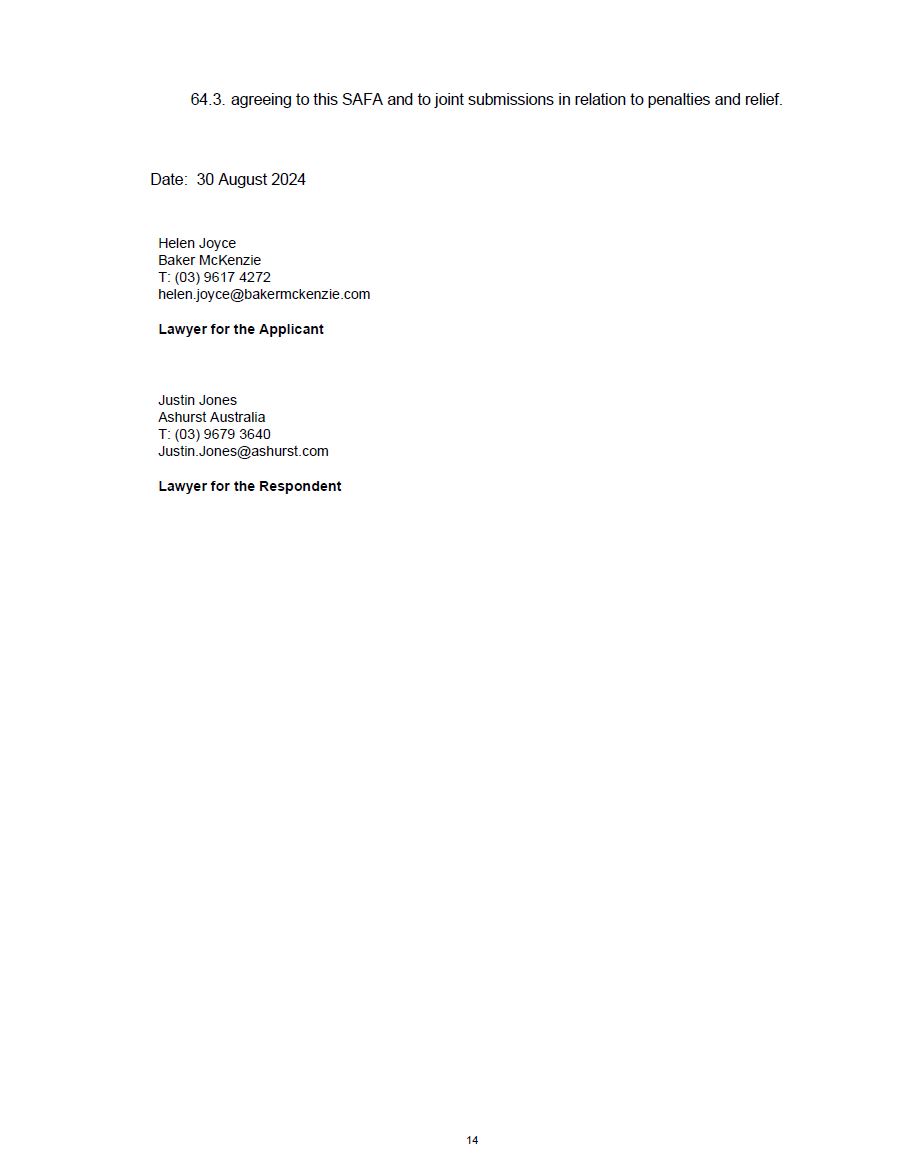

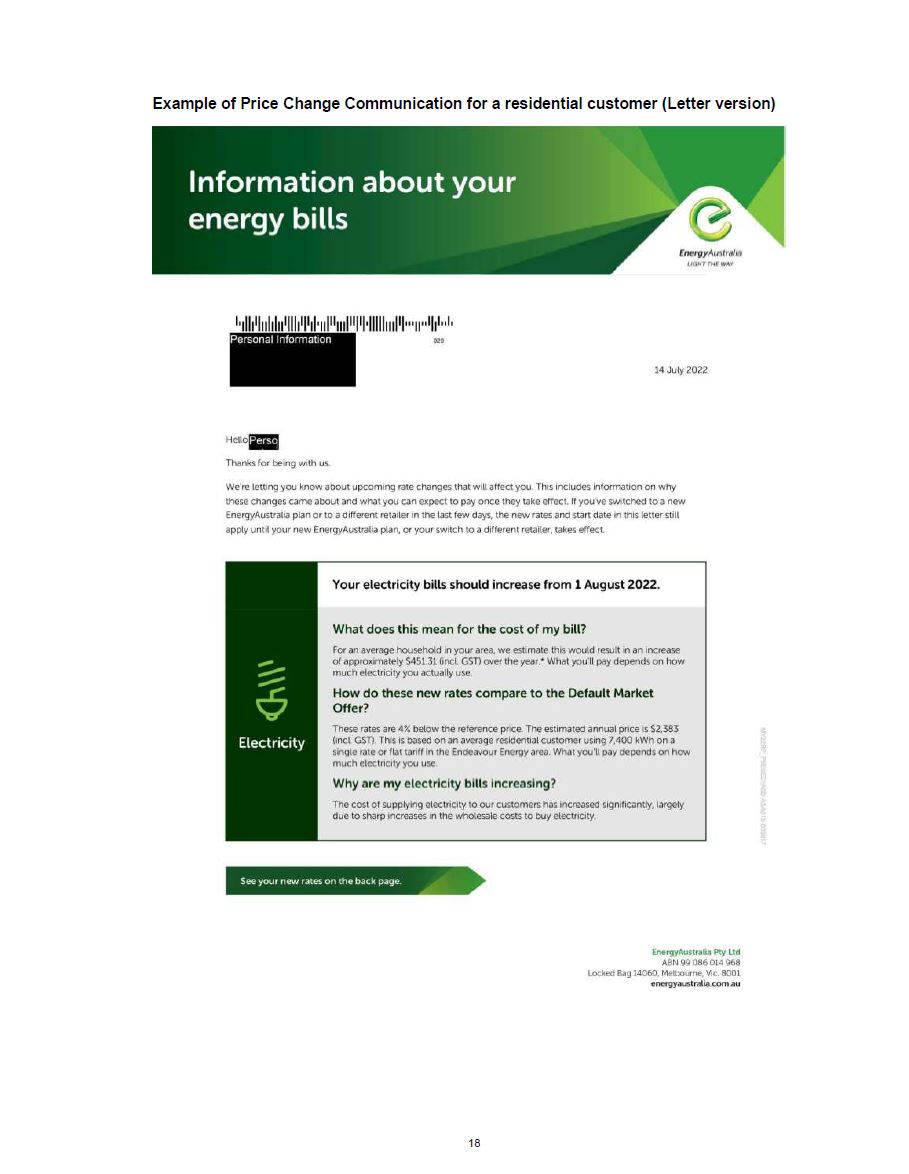

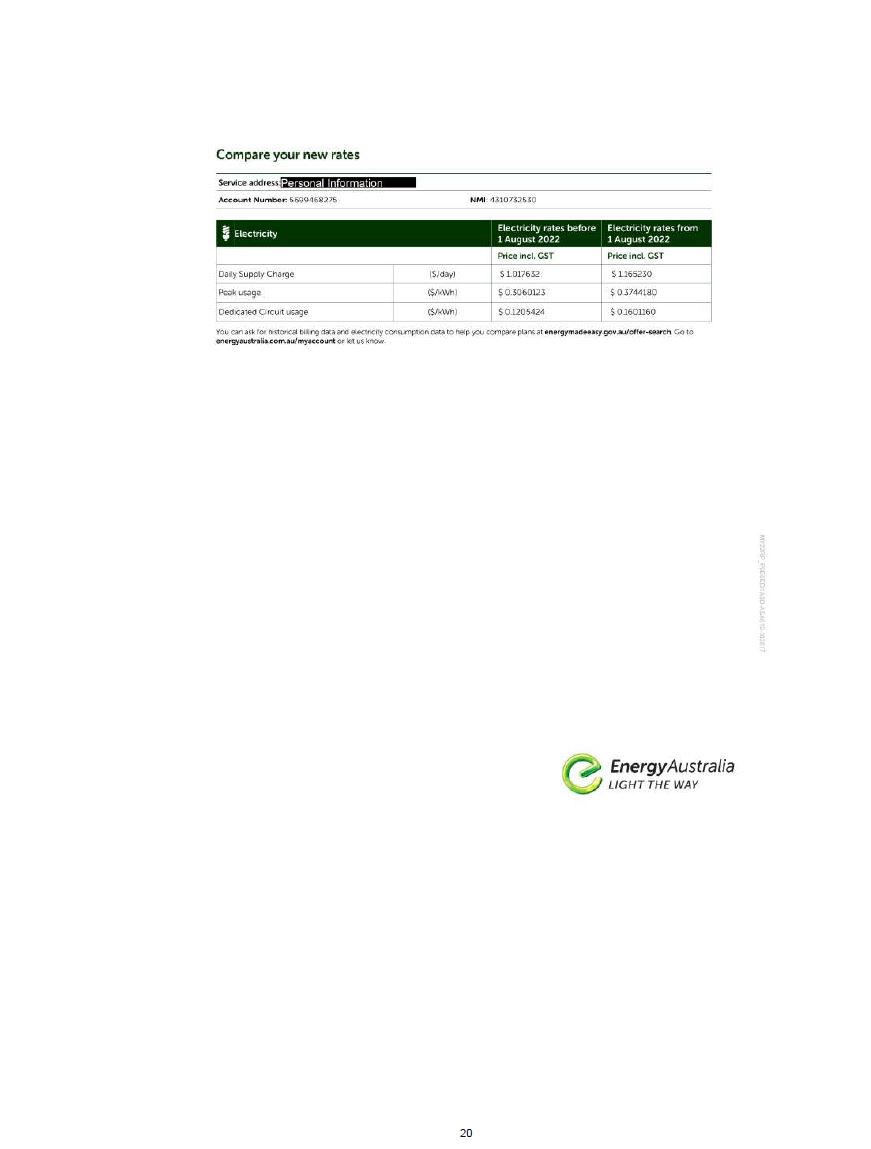

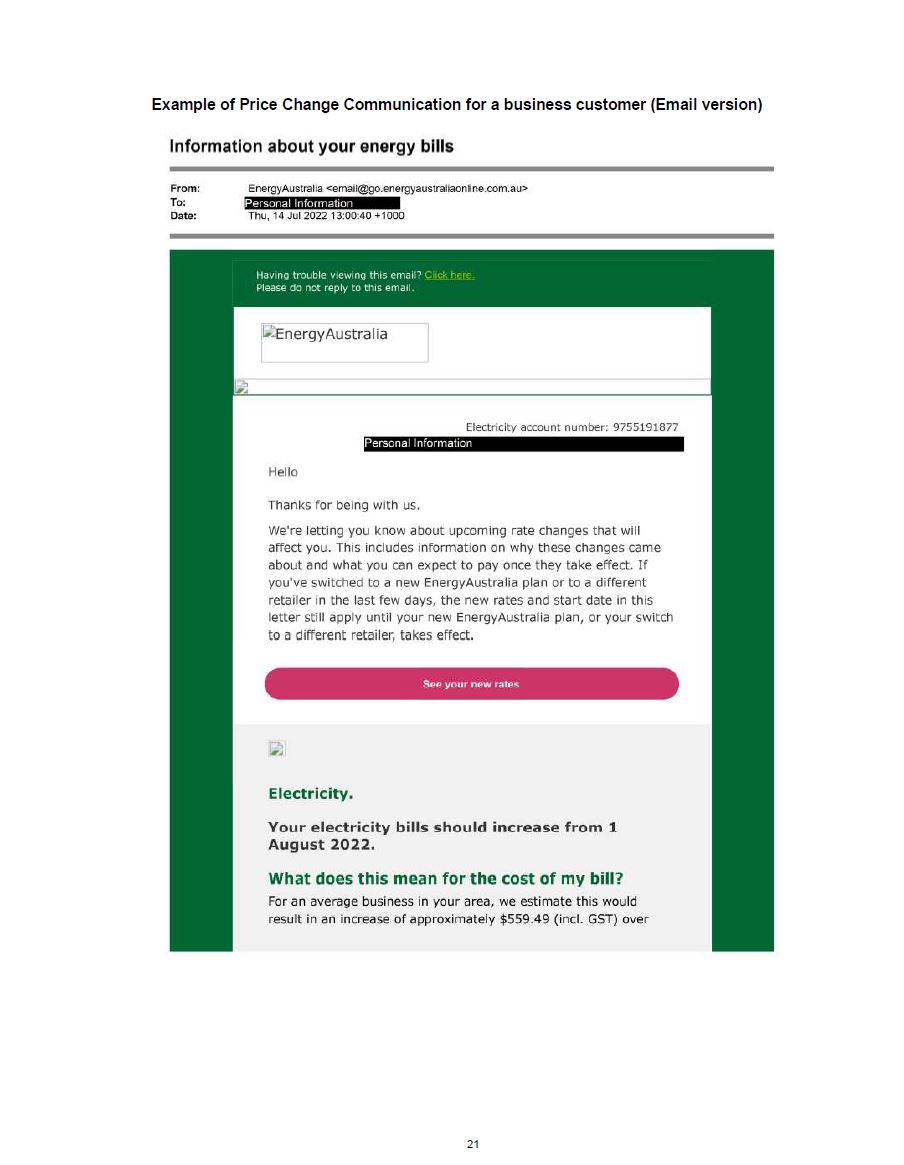

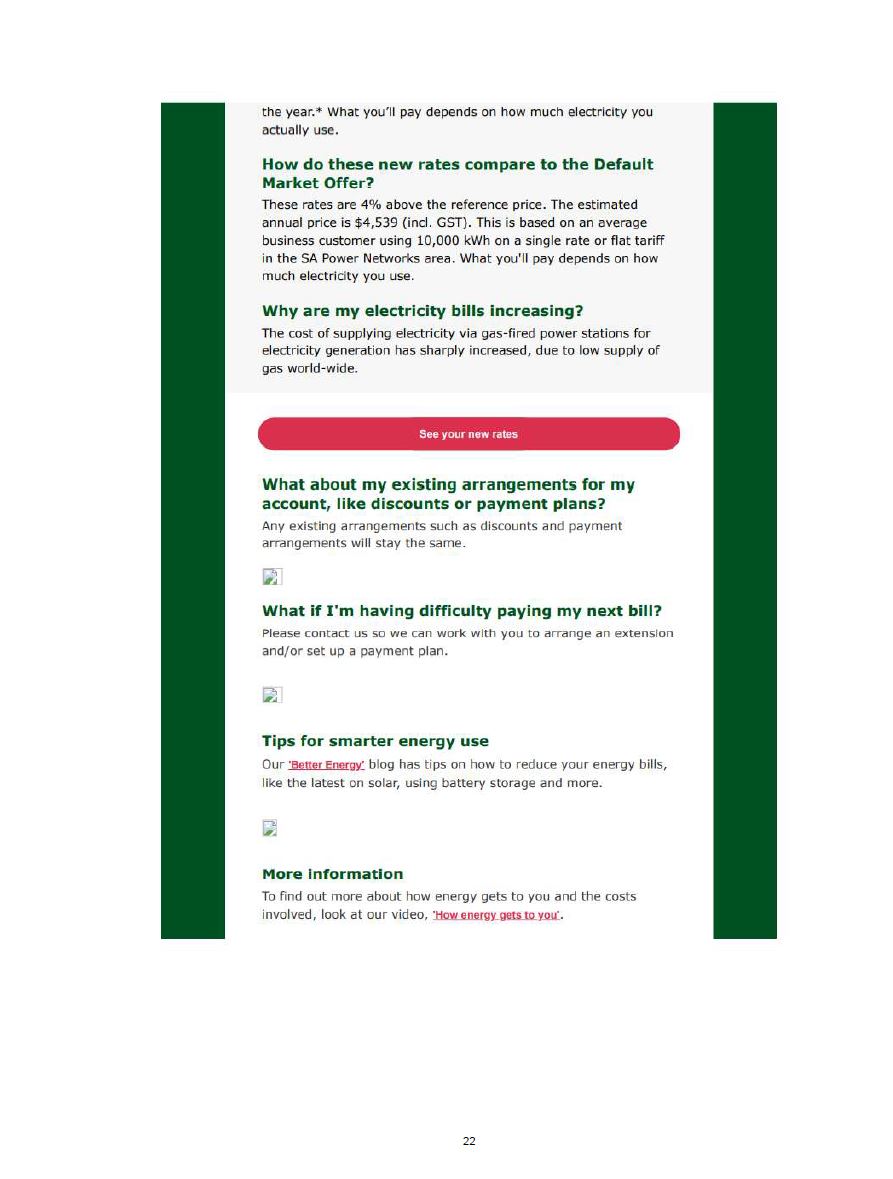

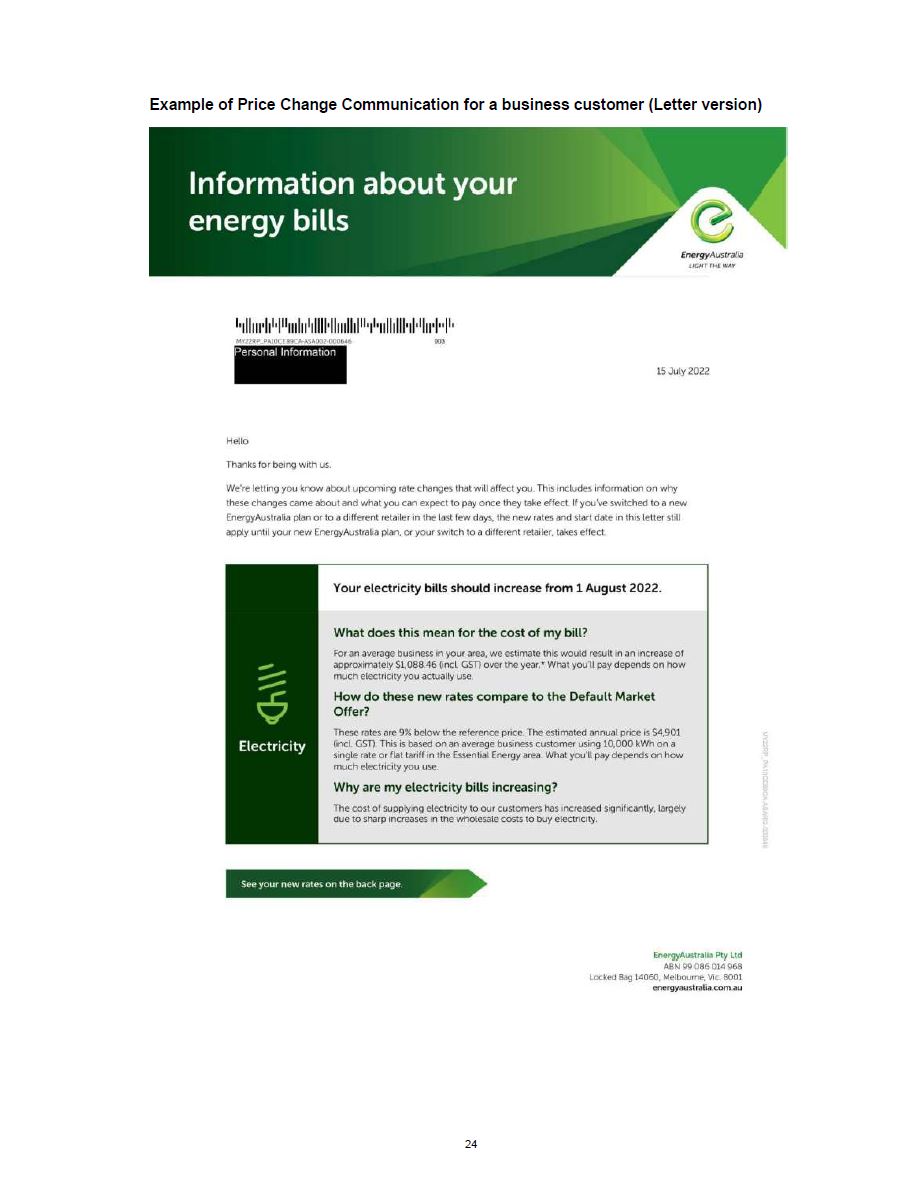

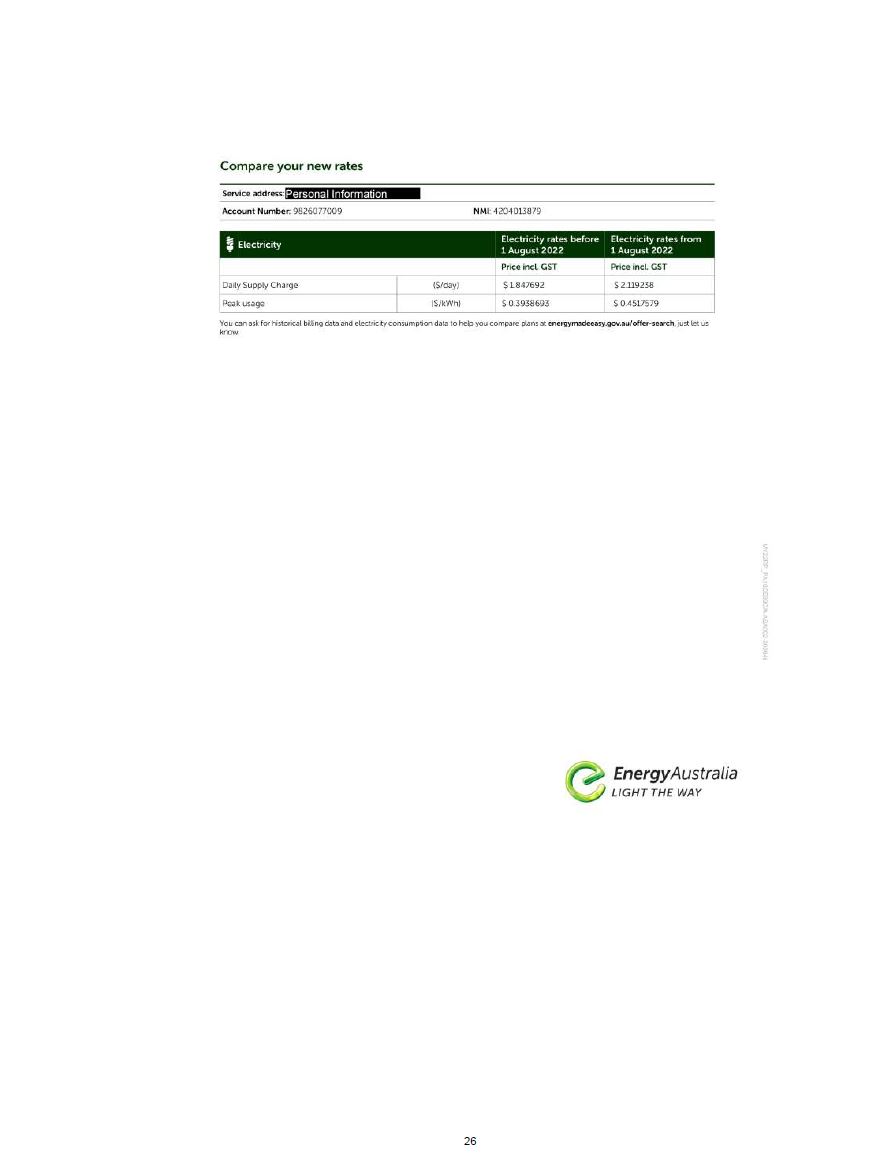

29 In the Relevant Period, EnergyAustralia sent 591,924 Price Change Communications to 566,827 of its small customers to notify them of changes to its electricity prices. The Price Change Communications were sent in batches between 20 June 2022 to 21 June 2022, 11 July 2022 to 21 July 2022, 11 August 2022 to 19 August 2022 and on 12 September 2022 to customers in all relevant distribution regions in the three states (South Australia, New South Wales and South East Queensland) subject to the Code. More than 95% of the customers who received the Price Change Communications were residential customers.

30 The Price Change Communications did not state the lowest possible price as required by the Code.

31 Each Price Change Communication referred to a price described by EnergyAustralia as the “estimated annual price” for an “average” customer of the type specified. The dollar amount referred to in each Price Change Communication as the “estimated annual price” was in fact the reference price for the 2022/2023 financial year in relation to supplying electricity to a small customer of the type specified, in the distribution region specified, not the lowest possible price.

32 EnergyAustralia has admitted that the Price Change Communications failed to state the lowest possible price, with the effect that EnergyAustralia contravened s 12(2) of the Code and also contravened s 51ACB of the CCA.

33 Further, in each Price Change Communication, EnergyAustralia represented to the recipient of the communication that the estimated annual price of its offer for an average customer of the type specified, using the amount of electricity specified, on the tariff specified, in the area specified, was the dollar amount referred to as the “estimated annual price” (the Estimated Annual Price Representations).

34 As explained above, the Estimated Annual Price Representations misrepresented the estimated annual price of electricity for an average customer with the characteristics identified in each Price Change Communication, because the dollar amount referred to was the reference price, not the estimated annual price of electricity for an average customer with those characteristics.

35 EnergyAustralia has admitted such conduct contravened ss 18 and 29(1)(i) of the ACL.

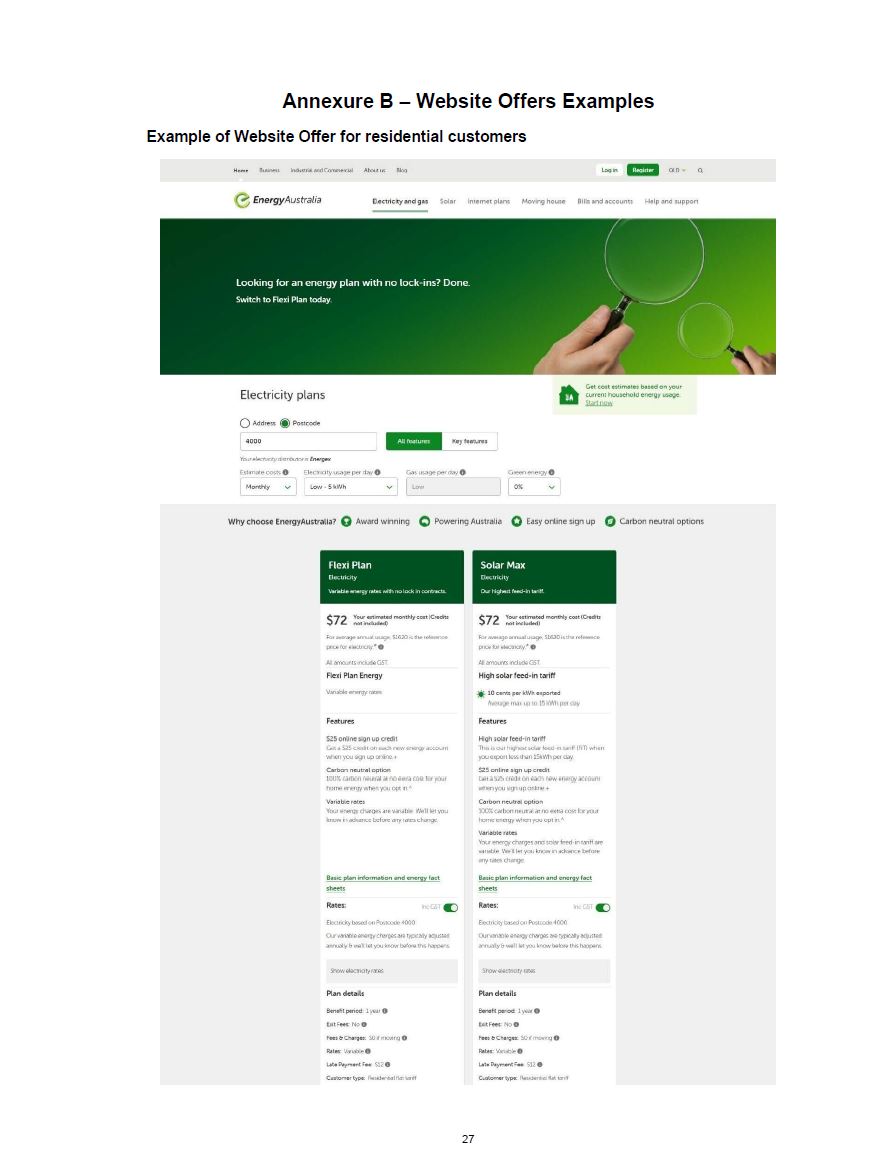

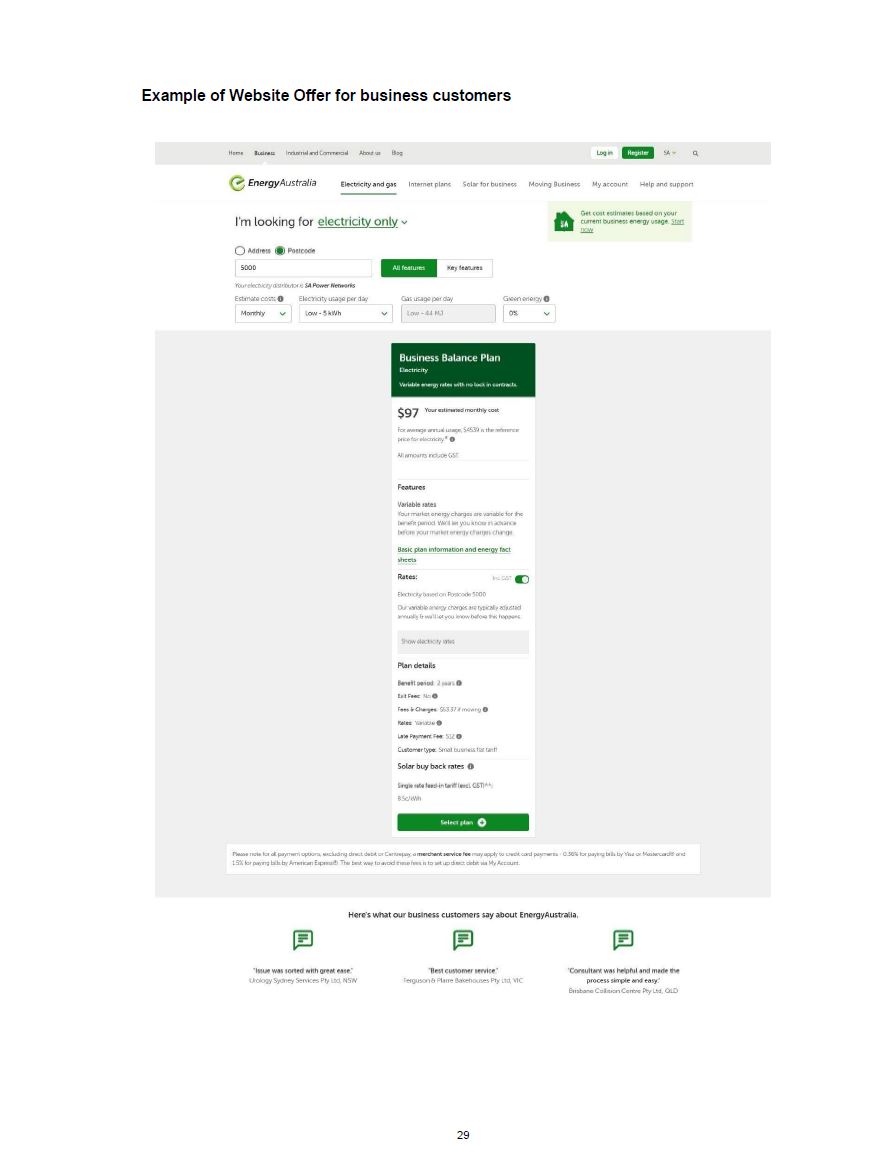

The Website Offers

36 Between 1 July 2022 and 27 September 2022, EnergyAustralia published 27 electricity price offers on its website (Website Offers). There were 223,591 unique visits to the webpages on which the Website Offers were displayed, and approximately 2,157 customers subscribed through EnergyAustralia’s website to the Website Offers.

37 The Website Offers each comprised offers for which the lowest possible price was the same as the reference price. The reference price was stated in each of the Website Offers. The Website Offers were displayed on an interactive part of EnergyAustralia’s website.

38 EnergyAustralia has admitted that the Website Offers did not state the lowest possible price.

39 Further, EnergyAustralia has admitted that the Website Offers did not state the difference between the reference price and the unconditional price, expressed as a percentage of the reference price. As there was no difference between the reference price and the unconditional price, the percentage would have been zero.

40 EnergyAustralia has admitted that it contravened s 12(2) of the Code and s 51ACB of the CCA by failing to state in the Website Offers: (a) the lowest possible price; and (b) the difference between the reference price and the unconditional price, expressed as a percentage of the reference price.

ORDERS MADE BY AGREEMENT – PRINCIPLES APPLICABLE

41 As French CJ, Kiefel, Bell, Nettle and Gordon JJ explained in Commonwealth v Director, Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate (2015) 258 CLR 482 at 507–8 [58]–[59]:

There is, however, no reason in principle or practice why civil penalty proceedings should be treated as an exception. Subject to the court being sufficiently persuaded of the accuracy of the parties’ agreement as to facts and consequences, and that the penalty which the parties propose is an appropriate remedy in the circumstances thus revealed, it is consistent with principle and, for the reasons identified in Allied Mills, highly desirable in practice for the court to accept the parties’ proposal and therefore impose the proposed penalty. To do so is no different in principle or practice from approving an infant’s compromise, a custody or property compromise, a group proceeding settlement or a scheme of arrangement.

It is true that there is a public interest in the imposition of civil penalties as opposed to the purely private interests which are in issue in many civil proceedings. But civil penalty proceedings are by no means the only civil proceedings in which the public interest is involved. Custody disputes involve the public interest. So do group proceedings and schemes of arrangement. So also do taxation, customs and social security appeals, and detention orders; and examples can be multiplied. Yet in each of those cases, it is wholly unexceptionable for a court to accept an agreed submission as to the nature and quantum of relief, provided the court is persuaded that it is an appropriate remedy. Once it is understood that civil penalties are not retributive, but like most other civil remedies essentially deterrent or compensatory and therefore protective, there is nothing odd or exceptionable about a court approving an agreed settlement of a civil proceeding which involves the public interest; provided of course that the court is persuaded that the settlement is appropriate.

(Emphasis added).

42 In a case such as this, it is also of some comfort that the parties are sophisticated, legally represented, and well able to understand and evaluate the desirability of settlement. Compare Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Colgate-Palmolive Pty Ltd (No 3) [2016] FCA 676 at [27] (Jagot J).

PENALTIES

43 As I have already said, EnergyAustralia has admitted that, by making the Price Change Communications, it has contravened s 12(2) of the Code and s 29(1)(i) of the ACL. EnergyAustralia has also admitted that by making the Website Offers, it has contravened s 12(2) of the Code.

44 Section 12(2) of the Code is a civil penalty provision of an industry code. Pursuant to s 76(1)(a)(iv) of the CCA, if the court is satisfied that a person has contravened a civil penalty provision of an industry code, the court may order the person to pay such pecuniary penalty, in respect of each act or omission by the person to which the section applies, as the court determines to be “appropriate” in the particular circumstances of the case.

45 EnergyAustralia is also liable to have penalties imposed under s 224(1)(a)(ii) of the ACL in respect of its admitted contraventions of s 29(1)(i) of the ACL.

Principles governing the imposition of pecuniary penalties

The central purpose – ensuring deterrence

46 The applicable legal principles are nowadays well settled. See, by way of example only, Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Dell Australia Pty Ltd (No 2) [2023] FCA 983 at [4]–[18]; and Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Mazda Australia Pty Ltd (No 3) [2024] FCA 83 at [35]–[46].

47 Deterrence, both specific and general, is the primary, if not sole, objective for imposing pecuniary penalties of the type sought here. The penalty must be fixed at a level that ensures that neither the contravener, nor would-be contraveners, would regard it as an acceptable cost of doing business. That said, a penalty is appropriate if it is no more than is reasonably necessary to deter further contraventions by the respondent and others.

48 In determining the appropriate penalty, the court must have regard to all relevant matters, including the nature and extent of the act or omission and of any loss or damage suffered as a result of the act or omission; the circumstances in which the act or omission took place; and whether the contravener has previously been found by a court in proceedings to have engaged in any similar conduct.

49 The loss or damage to be considered by the court is not limited to financial harm. It could be non-pecuniary, such as a lost opportunity to make a different purchasing choice with accurate information.

50 The court must assess the nature and extent of the harm even if quantifying the harm is difficult and requires broad or rough estimation.

51 The prescribed maximum penalty is one yardstick that ordinarily must be applied and must be treated as one of a number of relevant factors. What is required is a reasonable relationship between the theoretical maximum and the final penalty imposed. That relationship is established where the maximum penalty does not exceed what is reasonably necessary to achieve the purpose of specific and general deterrence of future contraventions of a like kind by the contravener and by others. This may be established by reference to the circumstances of the contravener and the contravening conduct.

52 Two principles or tools of analysis that can assist the court in determining an appropriate penalty for multiple contraventions are the course of conduct principle and the totality principle. These concepts may assist in the assessment of what may be considered reasonably necessary to deter further contraventions.

53 The course of conduct principle is commonly referred to as recognising that where there is an interrelationship of legal and factual elements of multiple contraventions, the court may penalise the acts or omissions as a single course of conduct.

54 The totality principle is that the total penalty for related contraventions should not exceed what is proper for the entire contravening conduct involved. This can be used by the court as a tool of analysis to ensure that the penalty is no more than reasonably necessary for deterrence. The exercise of the totality adjustment is directed to the overall impact of the accumulated effect of otherwise acceptable penalties to ensure that the whole is not greater than the sum of the parts. It is typically used as a “final check”.

55 Other commonly relevant factors to consider in determining a penalty in cases such as this were described by Edelman J in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Woolworths Ltd [2016] FCA 44; [2016] ATPR 42-521 at [123]–[126], as follows:

(a) the deliberateness of the contravention and the period over which it extended;

(b) whether the contravention arose out of the conduct of senior management of the contravener or at some lower level;

(c) whether the contravener has a corporate culture conducive to compliance as evidenced by educational programs and disciplinary or other corrective measures in response to an acknowledged contravention;

(d) whether the contravener has shown a disposition to cooperate with the authorities responsible for enforcement in relation to the contravention;

(e) the financial position of the contravener;

(f) whether the contravening conduct was systematic, deliberate or covert;

(g) the extent of contrition;

(h) whether the contravening company made a profit from the contraventions;

(i) the extent of the profit made by the contravening company; and

(j) whether the contravening company engaged in the conduct with an intention to profit from it.

56 But as the cases repeatedly say, that is not a shopping list of factors that must be taken into account. On the other hand, nor is it an exhaustive list.

57 The size of a contravener is relevant because, all other things being equal, a greater financial incentive will be necessary to persuade a well-resourced contravener to abide by the law than a poorly resourced contravener.

58 The extent to which the contravener has conceded liability and cooperated with the investigating authority is relevant to determining penalties and typically results in a discount off the penalty that otherwise would have been imposed. This reflects the fact that such discounts increase the likelihood of cooperation in the future by contraveners and free up the ACCC’s resources.

59 I turn now to consider the factors which the parties correctly agreed were relevant here.

Price Change Communications

60 At the time of the relevant conduct (June–September 2022), the maximum penalty for a contravention of section 29(1)(i) of the ACL was the greater of:

(a) $10 million;

(b) if the court can determine the value of the benefit that the body corporate has obtained and that is reasonably attributable to the contravention, three times that value; or

(c) if the court cannot determine the value of that benefit, 10% of the annual turnover of the body corporate during the period of 12 months ending at the end of the month in which the contravention occurred.

61 The value of the benefit reasonably attributable to each contravention in respect of the Estimated Annual Price Representations cannot be determined. The maximum penalty for each contravention arising from the Estimated Annual Price Representations made by the Price Change Communications is therefore the higher of:

(a) $10 million; or

(b) approximately $645 million, which is 10% of EnergyAustralia’s annual turnover of approximately $6.45 billion in the 12 months ending in the month the relevant conduct commenced.

62 The total theoretical maximum penalty for the 591,924 contraventions arising from the Estimated Annual Price Representations is therefore so large, and so far exceeds the amount which would be necessary for deterrence, that it does not provide a useful numerical guide.

Website Offers

63 The maximum penalty for a contravention of s 12(2) of the Code is 300 penalty units. At the time of the relevant conduct, a penalty unit was set at $222, and therefore the maximum penalty per contravention is $66,600.

64 Multiplying $66,600 by the 223,591 Code contraventions arising from the Website Offers again results in a figure that is so large, and that so far exceeds the amount which would be necessary for deterrence, that it also does not provide a useful numerical guide.

Penalties proposed

65 The parties submitted that a penalty of $10,000,000 should be imposed in respect of the contraventions arising from the Price Change Communications, and a further penalty of $4,000,000 should be imposed in respect of the contraventions arising from the Website Offers.

66 A higher penalty was agreed in respect of the Price Change Communications to reflect the higher number of contraventions (566,827 compared to 223,591) and the fact that the maximum penalty under the ACL for each contravention in respect of a Price Change Communication is much higher than the maximum penalty for each contravention in respect of a Website Offer under the Code ($645 million rather than $66,600).

67 The parties submitted, and I agree, that the proposed penalties will have the appropriate specific and general deterrence effect, and strike the right balance between achieving deterrence and avoiding oppressive severity, for the reasons that follow.

Nature, extent and duration of the conduct

68 It was submitted, and I agree, that the penalties should reflect that:

(a) there was a contravention each time a Price Change Communication or a Website Offer was viewed by a customer or potential customer;

(b) the Website Offers were published for a period of almost three months and applied to all relevant distribution regions and states subject to the Code (South Australia, New South Wales and South East Queensland);

(c) approximately 590,000 Price Change Communications were sent to approximately 566,000 small customers over a period of more than three months in all distribution regions and states subject to the Code; and

(d) there were approximately 220,000 views of the Website Offers, and approximately 2,100 customers signed up to those offers.

Loss and damage suffered as a result of acts and omissions

69 The parties agreed that EnergyAustralia’s contravening conduct in making the Estimated Annual Price Representation in the Price Change Communications may have caused harm to consumers as follows:

(a) Consumers were denied the opportunity to make an informed purchasing decision based on accurate information.

(b) Some consumers may have suffered direct financial loss, in that they may have chosen to continue to use EnergyAustralia as a provider (or may have chosen a provider other than EnergyAustralia) on the basis of an inaccurate understanding of the costs of electricity. In this respect:

(i) the parties noted that approximately 38% of the Price Change Communications contained an understated estimated annual price, which may have misled consumers into thinking the price change was more competitive than it actually was, when in fact a different plan offered by EnergyAustralia or by another retailer may have represented a better deal;

(ii) approximately 62% of the Price Change Communications contained an overstated estimated annual price, which may have misled consumers into thinking that the price change was higher than it actually was, which may have caused consumers to seek out a different plan offered by EnergyAustralia or by another retailer when in fact the consumer’s current plan was better value.

(c) Consumers were denied the opportunity to make decisions to change their electricity usage based on accurate information. Consumers who received an understated estimated annual price may have chosen to reduce their usage to reduce their bill had they known the actual price was higher than quoted. Consumers who received an overstated estimated annual price may have reduced their usage as a consequence of the overstated price (e.g. by not using, or reducing their usage of, heating in winter), where they may not have done so had the correct price been stated. Although there was other accurate pricing information contained in the Price Change Communications, including:

(i) how the new rates compared to the reference price (in percentage terms) (which is information that is required by the Code); and

(ii) what the new rates would mean for the cost of the customer’s bill (which is information that is not required by the Code).

(d) Consumers had no way to identify what information in the Price Change Communication was correct or incorrect (and were likely to assume all information was accurate).

70 After the ACCC contacted EnergyAustralia on 28 September 2022 raising concerns that the Price Change Communications did not state the lowest possible price, between 24 January 2023 to 21 February 2023, EnergyAustralia contacted all of the customers who had received a Price Change Communication (using that customer’s preferred method of contact) to give notice of the error in those communications and to provide the customer with the correct lowest possible price (the correction letter).

71 The correction letter included a dedicated telephone number for residential customers to call in order to speak to an energy specialist. It did not offer any remedy or compensation for any harm suffered as a result of the error.

72 In total:

(a) EnergyAustralia sent 592,639 correction letters to 566,827 customers who had received Price Change Communications.

(b) EnergyAustralia received 3,931 calls to the dedicated telephone number in the 4 weeks after the letter was sent. 235 of these calls concerned the correction letter. For these callers, the notes left by customer service agents record the following outcomes of those calls:

(i) 143 customers (61%) were given an explanation of the correction letter;

(ii) 34 (14%) completed a plan comparison and did not change their plan;

(iii) 22 (9%) completed a plan comparison and changed their plan to a different EnergyAustralia plan;

(iv) 22 (9%) were provided a credit;

(v) 5 (2%) had updates made to their account details;

(vi) 5 (2%) were sent additional information requested by them; and

(vii) 4 (2%) were offered a call back.

73 The parties agreed that EnergyAustralia’s contravening conduct comprised by the Website Offers may have resulted in harm to consumers, by denying consumers the opportunity to make a fully informed purchasing decision based on the information which EnergyAustralia was required to provide.

74 They also agreed that the harm that may have been caused by EnergyAustralia’s conduct is the very kind of harm the Code seeks to avoid, but that it is not possible to determine the extent to which consumers actually suffered harm, because the extent to which they may have relied on the incorrect information, and the choices they made in reliance on it, is not known and cannot realistically be known.

How the conduct arose

75 During the Relevant Period, it was admitted that price change communications which were sent by EnergyAustralia (including the Price Change Communications) required the approval of senior management from various departments of EnergyAustralia, including the marketing and products and pricing departments, and also the approval of EnergyAustralia’s legal counsel and compliance personnel. However, the calculations behind the numerical variables in the Price Change Communications were not included in the draft Price Change Communications and were therefore not reviewed by senior management.

76 The parties agreed in their joint submissions that the contraventions in relation to the Price Change Communications arose from, what they initially described as a “technical error”, as follows:

(a) EnergyAustralia’s process to create the information required to prepare and send the Price Change Communications had four data processing steps which all required manual intervention. The process and the data files used were as follows:

(i) An extract of customer information, usage, and current rates is taken from the system. This forms the Input File.

(ii) The Input File is taken and, for each row, values to be included in the Price Change Communications are calculated and appended to the Input File. This file becomes known as the Calculation File.

(iii) Once the calculations are validated, fields are removed from the Calculation File to create a new file that contains only the information required to produce the Price Change Communications. This is the Data Automation File.

(iv) The Data Automation File is then processed via a campaign management tool to create the final file (Mail house File) that is sent to the mail house to prepare customer letters.

(b) The Calculation File included the correct dollar value for the lowest possible price, as required by section 12(3)(c) of the Code. This value was tested and was the value used to calculate the percentage difference between the lowest possible price and the reference price.

(c) During the process for transferring this data and building the Data Automation File, the reference price value, rather than the value for the lowest possible price, was transferred to the relevant part of the Data Automation File. The other values were transferred correctly to the Data Automation File. The data in the Data Automation File, including the erroneously included reference price, was then included in the Mail house File that was sent to the mail house.

77 During oral submissions, however, the parties agreed with my suggestion that the term “inadvertent” better described the nature of the errors.

78 The process of publishing the Website Offers also required the approval of senior management from various departments, including marketing and products and pricing departments, and the approval of EnergyAustralia’s legal counsel and compliance personnel.

79 It was also agreed that the contraventions in relation to the Website Offers arose from actions by EnergyAustralia personnel to amend text to remove the lowest possible price, and state the reference price, omitting the difference between the reference price and the unconditional price, expressed as a percentage of the reference price.

80 The Website Offers ceased, and corrective letters were sent in relation to the Price Change Communications, after the ACCC alerted EnergyAustralia to its concerns. EnergyAustralia should have had effective and appropriate compliance systems in place to prevent widespread non-compliance from occurring and to detect such occurrences once they had occurred.

Prior similar conduct

81 EnergyAustralia has a history of failures of regulatory compliance. Therefore, it is necessary and again, this was agreed, to set an adequate penalty to act as a strong deterrent to EnergyAustralia (and its competitors) engaging in this form of conduct again.

82 EnergyAustralia has been found to have engaged in similar conduct in March 2015, when the Federal Court ordered EnergyAustralia to pay a penalty of $1 million for engaging in misleading and deceptive conduct when selling its electricity and gas plans: see Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v EnergyAustralia Pty Ltd [2015] FCA 274; (2015) ATPR 42–491 (Gordon J).

83 It has also been found by the Federal Court not to have complied with other consumer protection obligations on three other occasions:

(a) In April 2014, the Federal Court ordered by consent that EnergyAustralia pay a penalty of $1.2 million for unlawful door-to-door selling practices: see Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v EnergyAustralia Pty Ltd (2014) 234 FCR 343 (Middleton J).

(b) In November 2020, following an investigation by the Australian Energy Regulator, the Federal Court ordered EnergyAustralia to pay $1.5 million in penalties for wrongfully disconnecting customers who were in financial hardship circumstances: see Australian Energy Regulator v EnergyAustralia Pty Ltd [2020] FCA 1647 (Moshinksy J).

(c) In June 2022, following an investigation by the Australian Energy Regulator, the Federal Court ordered EnergyAustralia to pay $12 million in penalties for failing to comply with customer life support obligations in breach of the National Energy Retail Law: see Australian Energy Regulator v EnergyAustralia Pty Ltd [2022] FCA 644 (Colvin J).

84 Given this history, as was agreed, it is particularly important that the penalty be sufficiently large to have a persuasive impact on EnergyAustralia to ensure compliance, including by sufficient investment in adequate and effective compliance systems and processes.

Size of contravener and financial position

85 A larger penalty will be necessary to persuade a well‑resourced contravener to abide by the law. EnergyAustralia’s financial size means that a very substantial penalty is necessary to ensure that the costs of contravening the Code and ACL mean it is an economically irrational choice even for a well-resourced party. That, in turn, will ensure that the pecuniary penalty serves the objective of general and specific deterrence.

86 As set out above, EnergyAustralia is one of the largest retailers in the market, with over 1 million residential customers, and 14.8% electricity residential market share, and 13.8% of the small business market. EnergyAustralia’s revenue in the 2021/2022 financial year was $6.449 billion.

87 To achieve specific deterrence, the size of the proposed penalty must take those facts into account.

A lack of a culture of compliance

88 The following was also agreed.

89 During the Relevant Period, EnergyAustralia relied on two key enterprise-wide documents to support compliance with obligations applicable to EnergyAustralia, the Regulatory Compliance Assurance Program (RCAP) document and the Regulatory Compliance Policy. The RCAP and Policy were first implemented in 2013 and were, and remain to be, reviewed every two years, or when business strategy, structure, practices or legislation changes, whichever occurs first. The RCAP and Policy did not describe EnergyAustralia’s obligations under the Code and the CCA or how staff should adhere to those obligations. EnergyAustralia’s obligations under the Code and the CCA were included in ARCHER, a tool implemented by EnergyAustralia to manage its regulatory obligations and controls, but they were not described clearly so as to facilitate compliance by staff.

90 These compliance policies did not prevent the contraventions from occurring, despite EnergyAustralia having the resources and capacity to invest in robust and effective compliance measures to ensure compliance with key regulatory requirements like the Code and ACL.

91 Before the Relevant Period, EnergyAustralia had:

(a) A “three lines of defence” framework for regulatory compliance, which comprised:

(i) the staff who conducted the activities that are subject to regulatory obligations such as those contained in the Code (the first line);

(ii) compliance personnel who advised first line staff to comply with regulatory obligations, and who also independently identified compliance risks for management action (the second line); and

(iii) internal auditors who reviewed the effectiveness of the first and second lines (the third line).

(b) Implemented ARCHER, a tool to help EnergyAustralia improve its management of regulatory obligations and controls, and to reveal insights into opportunities for improvement.

92 To improve its compliance with the Code, after the Relevant Period, (and after the ACCC raised its concerns) by 23 July 2023, EnergyAustralia:

(a) conducted a review and implemented an additional business verification step to check the content of Price Change Communications before they are issued, to ensure they state the difference between the reference price and unconditional price, and the lowest possible price, as required by the Code;

(b) conducted a review and improved the way in which Website Offers are presented on EnergyAustralia’s website;

(c) introduced independent and real-time external oversight to provide assurance regarding pricing communications; and

(d) conducted training of EnergyAustralia’s digital team so that they understand the strictness of the requirements in the Code.

Senior management

93 The process of sending the Price Change Communications and publishing the Website Offers required the approval of senior management from various departments, including marketing and products and pricing departments, and the approval of EnergyAustralia’s legal counsel and compliance personnel. However, the parties agreed that the calculations behind the numerical variables in the Price Change Communications were not included in the draft Price Change Communications and were therefore not reviewed by senior management.

Cooperation

94 The following was also agreed.

95 EnergyAustralia created a complaint handling process to address the Price Change Communications conduct once it was raised by the ACCC, and took steps to address the Price Change Communications by sending corrective notices informing customers of pricing errors contained in the Price Change Communications.

96 EnergyAustralia has cooperated with the ACCC during the course of the proceeding. EnergyAustralia accepted that these contraventions should attract the imposition of the significant penalties to which it agreed. Prior to the parties filing evidence in the proceeding, EnergyAustralia made full admissions, agreed to the making of all appropriate orders, agreed to proposed penalty amounts, and joined in the making of the Joint Submissions which acknowledge the seriousness of its wrongdoing. The agreed penalty which the parties have proposed factors in an appropriate reduction to reflect EnergyAustralia’s cooperation. If not for that cooperation, the parties agreed that the ACCC would have sought a penalty of $20 million.

The proposed pecuniary penalties are appropriate

97 Having regard to all of the matters above, it was submitted, and I agree, that the proposed penalties are appropriate, for the following reasons.

98 A strong deterrent penalty is required to ensure that businesses comply with the Code and ACL, and that consumers are not misled and are provided with accurate information to enable them to make an informed choice.

99 EnergyAustralia’s contravening conduct meant that consumers may have been unable to accurately assess the costs of their electricity, in disregard of the purpose of the Code, and were unable to make informed choices.

100 A recognition of that fact should be marked with an appropriate penalty, which is sufficient to ensure other market participants comply with their obligations.

101 To achieve general deterrence, the penalty must be sufficiently large to convey to all market participants the importance of ensuring that their systems and processes are adequate to prevent non-compliance with the Code and ACL. Electricity retailers should be left in no doubt as to the costs of non-compliance with the Code and the ACL. And it is necessary to set the penalty at a sufficiently high level that penalties are not regarded by EnergyAustralia or others in the industry as the cost of doing business.

102 Accordingly, the proposed penalties are necessary and sufficient to remind other retailers of the importance of ensuring that advertising and communications with consumers comply with the Code and the ACL and do not contain misleading or false information.

103 There are also a number of specific deterrence considerations which support the imposition of a significant penalty in respect of the contraventions in the present case.

104 First, EnergyAustralia is one of Australia’s largest energy retailers, and its revenue from supply of electricity is very significant. The penalty must be sufficiently large to have a persuasive impact on EnergyAustralia to continue to invest in systems and processes to ensure compliance with the Code and ACL. The penalty must also be sufficiently large to specifically deter EnergyAustralia from engaging in this conduct in the future and to ensure it does not see non-compliance as a cost of doing business. Given the very high revenue generated by EnergyAustralia, this calls for a very significant penalty. The penalties proposed are of a sufficient quantum having regard to EnergyAustralia’s revenue in the Relevant Period not to be regarded as an acceptable cost of doing business.

105 Secondly, EnergyAustralia has a history of non-compliance with consumer protection obligations. Further, it failed to make sufficient investment in compliance systems and policies which may have prevented this conduct or detected it at an early stage.

106 Thirdly, the Code had been in place for approximately three years at the time of the conduct occurring. EnergyAustralia was aware of its obligations under the Code, and the ACCC and the AER sent EnergyAustralia a reminder letter in relation to its obligations under the Code on 10 June 2022. Although the Price Change Communications arose from inadvertent error, EnergyAustralia should have had systems in place to prevent widespread errors from occurring.

107 Fourthly, the Website Offers only ceased and corrective letters were only sent in relation to the Price Change Communications once the ACCC alerted EnergyAustralia to its concerns. EnergyAustralia should have had systems in place to prevent conduct of that kind from occurring and to identify such occurrences once they had occurred.

108 The parties noted in EnergyAustralia’s favour that EnergyAustralia created a complaint handling process to address the Price Change Communications conduct once it was raised by the ACCC and took steps to address the Price Change Communications by sending the corrective notices.

109 Further, the fact that EnergyAustralia has made admissions and agreed to the relief set out in the Joint Submissions should be reflected in any penalty as a mitigating factor.

110 It was submitted, and again I agree, the penalties make proper allowance for the considerations that EnergyAustralia has cooperated in the proceedings and agreed to non-punitive orders to improve its compliance.

111 The penalties do not need adjustment by reference to the totality principle.

DECLARATIONS OF CONTRAVENTIONS

112 The contraventions are established by the facts and admissions set out in the Statement of Agreed Facts and Admissions. I agree that it is appropriate to make declarations as to those contraventions as set out in the proposed orders, so the declarations will be made.

COMPLIANCE PROGRAM

113 The proposed orders also seek an order requiring EnergyAustralia to review its ACL Compliance Program.

114 Having regard to the nature of the conduct and declarations sought in this proceeding, it is appropriate to require EnergyAustralia to review its compliance program annually for three years to ensure its ongoing compliance with the ACL. To improve compliance in such a way is a fundamental purpose of the statutory regime.

115 Section 246(2)(b) of the ACL empowers the court to make such orders and the preconditions enlivening that power are met in the present case. First, it is sought by the regulator in relation to a person who has contravened provisions of Chapters 2 and 3 of the ACL. Secondly, it has the purpose of ensuring that EnergyAustralia does not engage in the same conduct, or similar or related conduct, for a period not exceeding 3 years.

116 The proposed orders should be made in this case for these reasons:

(a) First, the proposed order has a clear nexus to the contravening conduct. It requires EnergyAustralia to review its compliance program, with particular focus on compliance with ss 18 and 29 of the ACL, s 12 of the Code and s 51ACB of the CCA, the subject of the wrongdoing in the present case.

(b) Secondly, the proposed order will enhance senior management’s awareness and oversight of responsibilities and obligations in relation to the contravening conduct or similar or related conduct, by requiring a member of EnergyAustralia’s executive leadership to monitor the implementation of any recommendations, and by requiring documents to be kept relating to the implementation of any recommendations, with a view to minimising the risk of similar conduct occurring in the future.

(c) Thirdly, it is in the public interest that EnergyAustralia be required to review its compliance program, having regard to the wrongdoing in the present case and, in particular, the fact that EnergyAustralia has repeatedly contravened its consumer protection obligations in the past.

COSTS

117 EnergyAustralia has agreed to make a contribution of $50,000 towards the ACCC’s costs of the proceeding, to be paid within 30 days. This amount does not reflect the ACCC’s actual costs in the matter, but the ACCC is prepared not to fully pursue its costs given the agreed nature of the resolution. I will therefore make the agreed costs order.

I certify that the preceding one hundred and seventeen (117) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice O’Callaghan. |

Associate:

ANNEXURE A