Federal Court of Australia

Secretary, Department of Health v Medtronic Australasia Pty Ltd [2024] FCA 1096

ORDERS

SECRETARY OF THE DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH Applicant | ||

AND: | MEDTRONIC AUSTRALIASIA PTY LTD Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Pursuant to s 42Y(2) of the Therapeutic Goods Act 1989 (Cth), within 28 days of the making of this Order, the Respondent pay to the Commonwealth of Australia a civil penalty in the amount of $22,000,000.

2. Pursuant to s 43 of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth), within 28 days of the making of this Order, the Respondent pay the Applicant’s costs of, and incidental to, this proceeding, agreed in the amount of $1,000,000.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011

NEEDHAM J

1 These proceedings relate to the supply of therapeutic goods for use in humans that were not entered on the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods (ARTG) by Medtronic Australasia Pty Ltd (Medtronic or the respondent).

2 The proceeding was commenced by Originating Application filed by the Secretary, Department of Health (Secretary or the applicant) on 31 August 2021, which sought, inter alia, declarations to the effect that the respondent had contravened s 19D(1) of the Therapeutic Goods Act 1989 (Cth) (the Act), an order for pecuniary penalties pursuant to s 42Y(2) of the Act, and costs.

Procedural History

3 I set out below the procedural history in rather more detail than would usually be warranted, given the way in which these proceedings have been conducted on an agreed, rather than an adversarial basis, and the implications of that process on the findings I have made.

4 The proceedings were initially managed by Perram J, before being transferred into the docket of Goodman J on 12 November 2021. In the intervening period, the matter came before the Court for case management on several occasions, however it generally progressed by way of administratively made consent orders.

5 For the purposes of these reasons, it is unnecessary to traverse those orders in full. However, the orders of Goodman J made on 14 December 2023 relevantly provided a timetable for the filing of a Statement of Agreed Facts, submissions (both in chief and reply), any objections to evidence, a Court book, a list and consolidated bundle of authorities, and also listed the matter for hearing commencing on 9 September 2024 with an estimate of 5 days (timetabling orders).

6 The timetabling orders were varied once by consent orders made by Goodman J on 8 March 2024.

7 On 17 June 2024, the parties emailed the Chambers of Goodman J as below:

We refer to the orders made on 14 December 2023 (as varied on 8 March 2024) in the above proceedings (Orders). This is a joint communication from the parties, and the solicitors for the Respondent are copied to this email.

Order 2 of the Orders includes provision for the parties to file any Statement of Agreed Facts (SOAF) by 17 June 2024, and the Orders included various other procedural steps in advance of a penalty hearing listed in September 2024.

The parties wish to inform the Court that they have reached agreement in relation to a pecuniary penalty to be proposed to the Court in respect of the contraventions of the Therapeutic Goods Act 1989 (TG Act) which are admitted by the Respondent in these proceedings. The parties are now in the process of preparing a Statement of Agreed Facts and Admissions, and also anticipate preparing a joint submission to his Honour in relation to the proposed penalty.

The Orders, including Order 2, were made in a context where the parties were moving towards a contested penalty hearing. The situation has now developed, by reason of the parties’ agreement. The parties therefore jointly seek the attached proposed orders, vacating Orders 2 - 9 of the Orders.

The parties are currently in discussions as to how the matter could be timetabled from here, and propose to contact the Court as soon as possible on this topic. At this stage, the parties respectfully request that the penalty hearing remain listed for 9 - 13 September 2024 pending further communications with the Court.

We would be grateful if you could indicate whether his Honour is minded to make the attached proposed orders in Chambers.

8 In response, Goodman J made orders on 18 June 2024 vacating the balance of the timetabling orders, granted liberty to apply on 3 days’ notice, and reserved costs. Notably, the hearing dates were maintained.

9 On 10 July 2024, the proceedings were docketed to me. The next day, at my direction my Associate wrote to the parties informing them that the matter had been listed for case-management hearing on 13 August 2024, and requesting that they provide proposed short minutes of order, with any areas of disagreement indicated in mark-up, to Chambers by midday on 12 August 2024.

10 In response, on 17 July 2024 the parties sent the below email to Chambers:

Dear Associate

We refer to the parties’ joint communication to the Court on 17 June 2024. This is a joint communication from the parties. The solicitors for the respondent are copied to this email.

The parties have been in discussions about management of the matter in light of the agreement reached in relation to pecuniary penalty.

The parties attach proposed consent orders. If the course proposed by the parties is adopted, the parties consider that the matter can be resolved without further evidence (other than agreed facts), on agreed written submissions and in a one-day hearing.

There is one issue in particular which the parties wish to draw to her Honour’s attention. The issue is described below. The parties are content for the issue to be considered in chambers, but are also happy to appear before her Honour to address the matter orally should her Honour consider that appropriate.

The issue arises in the following way.

The Therapeutic Goods Act 1989 (Cth) (Act) relevantly distinguishes between “medical devices” (which are relevantly covered by Chapter 4 of the Act) and other therapeutic goods which are not “medical devices” (which are relevantly covered by Pt 3-2 : see s 15A). Unless a therapeutic good is exempt or subject to an approval or authority (which was not the case here), supply of a therapeutic good not entered on the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods (ARTG) is a contravention of the Act, whether the good is a device or not, but the specific provision which proscribes supply of devices not included in the ARTG differs from the specific provision which proscribes supply of other therapeutic goods: the former is addressed by s 41MIB(1), and the latter is addressed by s 19D(1). The question of whether a therapeutic good is or is not a device turns on, amongst other things, the operation of ss 41BD and 41BF of the Act.

This matter is about supply of the “INFUSE Bone Graft Kit” (Kit), and Medtronic has admitted that it supplied the Kit other than in accordance with the ARTG entry, and thus Medtronic contravened the Act. The Secretary has, to date, not taken a concluded position on whether or not the Kit was a “medical device” in the proceedings. The Originating Application sought relief on the hypothesis that the Kit was either not a device (prayer 1.1) or was a device (prayer 1.2).

It is the parties’ joint view that the classification of the Kit as a “device”, or not a “device”, is a matter which is not straightforward. The parties anticipate that, in order to resolve any question of whether the Kit was or was not a device, it would be necessary for expert evidence (and possibly lay evidence) to be procured, with a possible need for oral expert evidence and divergent submissions. The parties also anticipate that it might not be possible for this to occur while keeping the current hearing period.

The parties are, however, of the view that the disposition of this matter does not require the Court to resolve any question of whether the Kit was or was not a device. The Secretary does not (and will not) seek a declaration that there has been a contravention of the Act (or that there has been a contravention of a particular provision of the Act). Rather, the substantive relief sought by the Secretary is solely (and will solely be) in the nature of pecuniary penalties. It is the parties’ joint view that the quantum of any pecuniary penalties is not (and ought not be) affected by the classification of the Kit as a “device” or not a “device”. First, the parties note that the maximum penalty for a contravention of s 41MIB(1) or s 19D(1) is the same. Further, it is the parties’ joint view that the substance of the contravention was supply of the Kit other than in accordance with the ARTG entry, and the gravity and character of the contravention is not affected by whether or not the Kit was a “device”. It is thus the parties’ joint view that it will be open to the Court, and appropriate, for the Court to order pecuniary penalties without determining whether the Kit was or was not a “device”.

Given the potential additional cost and delay that would be involved if it were to become necessary to resolve the question of whether the Kit was or was not a “device”, the parties’ joint position is that it is unnecessary and undesirable for the Court to resolve that question, and they will not ask the Court to resolve it. The timetable proposed by the parties (which does not include a timetable for further evidence as to the character of the Kit or a timetable for potentially competing submissions, and which includes a one-day hearing in September) reflects a position which the parties consider is appropriate in the event that the Court does not proceed to make a determination on whether the Kit was or was not a “device”.

The parties thought it prudent to raise this issue with her Honour at this point as, if her Honour holds a different view to the parties’ joint view, then a different timetable to the one set out in the attached proposed orders is likely to be appropriate.

The parties also note that her Honour yesterday listed this matter for case management hearing on 13 August 2024. If her Honour is minded to make the attached orders in chambers, please let us know whether her Honour is also minded to vacate that hearing. If her Honour does wish to proceed with a case management hearing, we respectfully request an alternative date due to counsel availability. Counsel for the parties are available on any of 22 – 23, 26 or 28 August 2024 and the parties would be grateful if her Honour could list any case management hearing on one of these dates if convenient to the Court.

11 Upon considering the proposed consent orders in light of the above email, I directed my Chambers to reply as below:

The proposed Consent orders are noted. However, her Honour takes the preliminary view that each of ss 19D(1) and s 41MIB(1) of the Therapeutic Goods Act requires a finding that a contravention of that section has taken place, prior to the imposition of a civil penalty. That is so whether that finding of contravention is made by way of a contested hearing involving expert evidence, or by way of an agreed fact between the parties, or some course in between.

Accordingly, her Honour is minded to proceed with a case management hearing. Noting the availability below, her Honour has listed the matter for case management hearing on 23 August 2024 at 2:15 pm. A stamped copy of her Honour’s order is attached.

Please provide an outline of any written submissions (of no more than 5 pages) by Thursday 21 August 2024, along with any proposed orders either by consent or which are contended for by any party, failing consent.

12 The applicant and respondent each filed submissions as directed in advance of the 23 August case management hearing.

13 These submissions, which were expanded upon at hearing, proposed two possible ways forward for the matter, which can be described as the proposed position and the alternative position.

14 The proposed position, which had been outlined in the email extracted above at [10], sought that the Court proceed to make pecuniary penalties without a finding or forming a view on whether the INFUSE® Bone Graft Kit (the Kit) was a therapeutic good, or a medical device. The parties submitted that although there were no analogous cases in which this particular question has arisen, in principle the court could find that there was a contravention of either s 19D(1) or s 41MIB(1) without finding which of the two provisions has been contravened.

15 As indicated in the email extracted above at [11], I had formed the preliminary view that this was not the case, and that a finding as to the section contravened would have to be made. At the case management hearing, the parties were given an opportunity to speak to this preliminary view, with Counsel for the respondent taking up the task. In short, it was put to me that due to the way the Act was structured, specifically the use of the indefinite article “a” in s 42Y(2) of the Act extracted below, I could be able to be satisfied on the parties’ agreement that the respondent has contravened a civil penalty position, but it was not required of me to determine which one. Section 42Y(2) provides (emphasis added):

42Y Federal Court may order person to pay pecuniary penalty for contravening civil penalty provision

…

Court may order wrongdoer to pay pecuniary penalty

(2) If the Court is satisfied that the wrongdoer has contravened a civil penalty provision, the Court may order the wrongdoer to pay to the Commonwealth for each contravention the pecuniary penalty that the Court determines is appropriate (but not more than the maximum amount specified for the provision).

16 It seemed to me however that I was required to be satisfied of the actual section contravened, before a penalty could be imposed. The contravention itself, as well as its nature and the risk of harm arising from it, were matters to which I needed to have regard. This is clear from s 42Y(3) which provides (emphasis added):

Determining amount of pecuniary penalty

(3) In determining the pecuniary penalty, the Court must have regard to all relevant matters, including:

(a) the nature and extent of the contravention; and

(b) the nature and extent of any loss or damage suffered as a result of the contravention; and

(c) the circumstances in which the contravention took place; and

(d) whether the person has previously been found by the Court in proceedings under this Act to have engaged in any similar conduct.

17 Accordingly, despite the helpful submissions from the parties, both written and advanced from the Bar table, I concluded that the alternative position was both consistent with the legislation, and provided a more practical path forward. This would involve the matter proceeding upon a qualified expression of the position that would be taken as agreed solely for the purposes of these proceedings as to whether the contraventions were under s 19D or s 41MIB.

18 As such, I made the below orders on 23 August 2024 (August Orders):

(a) The parties file a joint statement of agreed facts and admissions by 6 September 2024.

(b) The parties file joint written submissions on relief by 6 September 2024.

(c) The parties serve a joint list of authorities for hearing by 9 September 2024.

(d) The parties have liberty to apply on 3 days’ notice.

19 I also noted that should the parties be unable to reach the requisite agreement, the matter would have to be relisted for a contested hearing.

THE JOINT STATEMENT OF AGREED FACTS AND ADMISSIONS

20 As required by the August Orders, the parties filed a Joint Statement of Agreed Facts and Admissions on 6 September 2024. I consider it appropriate to record these in full, with only necessary amendments, rather than needlessly rewording or summarising them. I also wish to express my appreciation to the parties for assisting the Court in an effective and efficient manner. The Joint Statement (referred to therein as SAFA) provides as follows.

Joint statement - Introduction

21 For the purposes of these proceedings: the Secretary and Medtronic agree that the statements of fact in this SAFA are “agreed facts” within the meaning of s 191 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth), and to the extent that any statements in this SAFA are statements as to law or mixed fact and law, they constitute formal admissions by Medtronic as to those matters; and the statements of fact, statements of law and statements of mixed fact and law are agreed and admitted by each party for the purpose of this proceeding only.

22 This proceeding is brought by the Secretary under s 42Y(1) of the Act. It concerns the supply by Medtronic of therapeutic goods for use in humans that were not entered on the ARTG.

23 Between 1 September 2015 and 31 January 2020 (the Relevant Period), Medtronic supplied 16,267 units of the Kit, to 109 hospitals.

24 Medtronic admits that each of those instances of supply was a supply of the Kit otherwise than as a supply of the Device and was therefore in contravention of the Act.

The Device and the Regulatory Scheme

25 The objects of the Act include to provide for the establishment and maintenance of a national system of controls relating to the quality, safety, efficacy and timely availability of therapeutic goods that are used in Australia, whether produced in Australia or elsewhere. The reference to the efficacy of therapeutic goods is a reference, if the goods are medical devices, to the performance of the device for its intended purpose.

26 The national system of controls established and maintained under the Act includes, among other things:

(a) an obligation on the Secretary to cause to be maintained the ARTG under s 9A of the Act, which functions as a list of the therapeutic goods which are permitted to be imported into, exported from, or supplied or manufactured in Australia;

(b) procedures by which therapeutic goods may be entered in the ARTG, with different procedures applying depending on the level of risk associated with particular goods;

(c) requirements which must be complied with by persons who have entered therapeutic goods in the ARTG, to assist in monitoring and providing ongoing assurance as to the quality, safety and efficacy of those goods;

(d) limited exemptions, approvals or authorities which may allow persons to deal with goods that are not entered in the ARTG in certain circumstances;

(e) and criminal offence and civil penalty provisions which prohibit the importation, exportation, manufacture or supply of a therapeutic good that is not entered in the ARTG, nor otherwise the subject of an exemption, approval or authority under the Act.

27 The Act is administered by the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA), being a part of the Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care (Department). The powers and functions of the Secretary and the Minister for Health and Aged Care under the Act are delegated to, and exercised or performed by, officers of the Department within the TGA.

28 From 5 August 2005, a therapeutic good of which the Kit formed one part, namely, the ‘Infuse Bone Graft/LT-Cage – Graft kit, spinal fusion’ (the Device), was included in the ARTG as ARTG Entry 121164. The sponsor of the registered good was Medtronic, and the manufacturer was identified as Medtronic Sofamor Danek USA Inc, a company based in Tennessee, USA.

29 The Device was included in the ARTG as a ‘medical device’ within the meaning of s 41BD of the Act. The entry on the ARTG identified it as a ‘Class III’ medical device within the meaning of Pt 3 of the Therapeutic Goods (Medical Devices) Regulations 2002 (Cth) (the Devices Regulations).

30 The Device comprised two separately packaged parts:

(a) a metallic spinal fusion cage (Cage), and

(b) the Kit, which contained: (1) a recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein (rhBMP-2) (Protein); (2) a vial of sterile water for injection; (3) an absorbable collagen sponge (Sponge); (4) empty syringes; and (5) corresponding needles.

31 At no time during the Relevant Period was the Kit alone entered on the ARTG. The Kit alone is a therapeutic good within the meaning in s 3 of the Act.

32 The parties have advanced different views as whether the Kit was or was not a “medical device” within the meaning of the Act. Solely for the purposes of these proceedings in order to enable the Court to resolve the matter on an agreed basis, the parties agree that the Court may proceed on the basis that the Kit was, during the Relevant Period, a “therapeutic good” (medicine). The parties agree that this does not reflect any broader agreed or admitted position as to whether the Kit is, or was during the Relevant Period, a medicine or medical device, nor any broader agreement or admitted position about the characterisation of the Kit that binds either party or otherwise affects the correct approach to any similar issue that might arise outside these proceedings.

33 Although, during the Relevant Period, there was significant clinical demand for the Kit by itself (including for use together with another cage), there was no real clinical demand for the Kit and Cage together.

34 As the Kit alone was not entered in the ARTG, its supply without the Cage was a contravention of s 19D of the Act, which prohibits, relevantly, the supply in Australia of therapeutic goods for use in humans, unless the goods are registered goods or listed goods, or are otherwise subject to a relevant exemption, approval or authority.

35 For the purposes of s 19D, there was no relevant exemption, approval or authority in force in the Relevant Period in respect of the Kit.

36 While the Act prohibited the supply of the Kit without the Cage by Medtronic, whether or not the Kit was supplied with or without the Cage the Act did not prohibit a health practitioner from using the Kit (without the Cage) in surgical procedures. The Secretary does not allege that health practitioners acted unlawfully by using the Kit in surgical procedures.

The nature of the Kit and the Cage

37 The human body produces numerous growth factors that regulate cell activity and help promote or suppress growth, cell type differentiation and various metabolic activities. A growth factor is a naturally occurring substance, such as a protein, capable of stimulating cell proliferation, wound healing and occasionally cellular differentiation. Growth factors are important for regulating a variety of cellular processes.

38 Bone morphogenetic protein-2 (BMP-2) is a growth factor produced by human cells and found in natural human tissue. When artificially produced in a laboratory or for commercial use, it is called “recombinant human BMP-2” or “rhBMP-2”. As set out in [30] above, the Kit is comprised of rhBMP-2 and various other components (the Sponge, sterile water, empty syringes and needles).

39 The Cage is a metal spinal fixation device and was intended to replace a diseased intervertebral disc by mechanically opening up the collapsed disc in the lower lumbar spine and rigidly fixing it in place by the circumferential screw grooves and ridges or “threads”.

40 The Kit and the Cage were physically able to be used in combination in some surgical procedures to treat degenerative disc disease in a skeletally mature spine. The Cage can physically only be inserted into a skeletally mature lumbar spine and only through an anterior approach at one level from L4 to S1. An anterior approach means that the surgical incision and exposure allows access through the abdomen and to the spine through a retroperitoneal approach. In addition, the Kit was physically capable of use with alternative spinal fixation devices, or without spinal fixation devices, to aid bone growth and spinal fusion in other parts of the spine (outside the lower lumbar spine).

41 Although the Cage is only capable of being used in the lower or sometimes mid-lumbar spine of an adult through an anterior approach from L4 to S1 due to its design, the Kit without the Cage is physically capable of being used through both an anterior and posterior approach to the spine to support fusion. For instance, the Kit can be used in a posterior or lateral approach to the spine, which would mean an incision and exposure of the spine through the back. From a simply physical and mechanical point of view, the rhBMP-2 solution in conjunction with the collagen sponge, is capable of being used in the skeleton outside of the spine in any person.

42 A medical device is required by Essential Principle 13.4 (set out in Schedule 1 to the Devices Regulations) to include instructions for use (IFU) provided by the manufacturer of the medical device to inform its user of the intended purpose, proper use and of any precautions to be taken in relation to the use of the medical device (including any contra-indications, warnings and restrictions). The IFU disseminated with the Device (after review by the TGA) was focused on the use of the Device according to its intended purpose. As a result, precautions to be taken in relation to use of the Device (including any contra-indications, warnings and restrictions) other than for its intended purpose were not fully documented in the IFU as reviewed by the TGA and supplied with the Kit.

43 For all medical devices included in the ARTG, the sponsor must specify the “intended purpose” of the device. When the TGA assesses a medical device for inclusion in the ARTG, it does so only with respect to the intended purpose proposed by the sponsor.

44 For all medicines entered in the ARTG, the sponsor must specify the “indication” of the medicine, being a statement made by the medicine’s sponsor describing the specific proposed therapeutic use of the medicine, that is, its claimed purpose or health benefit. Similar to a medical device, when a medicine is assessed for entry on the ARTG, it is assessed by reference to the proposed indication only and the TGA does not evaluate it in relation to potential off-label use (i.e., use outside the proposed indication).

45 The Secretary’s role includes ensuring that any therapeutic good supplied in Australia meets stringent requirements for safety, quality and efficacy. These quality, safety and efficacy criteria are intended to ensure that all therapeutic goods entered in the ARTG are safe and efficacious for the purposes for which they are to be used.

46 For registered medicines, the Secretary assesses the quality, safety and efficacy of the medicine by reference to a dossier submitted by the sponsor. As part of the evaluation process for medicines under Part 3-2, Division 2 of the Act, a sponsor is required to submit detailed information, including pharmacological and toxicological data; data from clinical trials relating to the proposed indications for the medicine (i.e., the particular condition that it is intended to treat, prevent or diagnose); and any reports of adverse reactions. A sponsor is required to provide evidence of the efficacy of the medicine for each proposed indication, including analysis of why and how the data supports each proposed indication; as well as clinical data pertinent to the efficacy of the medicine in its intended population, including analysis of the risks concerning efficacy and safety in specific sub-populations, e.g., children.

47 In order for the Secretary to decide to register a medicine on the ARTG, the data submitted by the sponsor must be sufficient to satisfactorily establish the safety and efficacy of the medicine for each proposed indication, including each of the patient populations that are included in the proposed indication. For example, the data must establish efficacy and safety for each area of the body and for each age group for which the medicine is indicated for use. The Secretary assesses the medicine for the proposed indication and does not evaluate it in relation to potential off-label use (i.e., outside the proposed indication).

48 The assessment process for medical devices depends upon the category of the device and its risk profile. Broadly speaking, the application process for a Class III medical device during the Relevant Period included applying for a conformity assessment certificate. In the application process, the TGA would examine whether the manufacturer of the device has appropriate procedures and processes in place to ensure compliance with the Essential Principles, as set out in Schedule 1 to the Devices Regulations, to the extent that they apply to the particular medical device.

49 Conformity assessment applications for medical devices are assessed by the Secretary to determine whether there is sufficient evidence to show that the device complies with the Essential Principles, set out in Schedule 1 of the Devices Regulations, to the extent that they apply to that device. The Essential Principles which most often apply to a medical device containing a medicine include:

(a) Essential Principle 1: Use of the medical device does not compromise health and safety;

(b) Essential Principle 2: Design and construction of the medical device conforms to safety principles;

(c) Essential Principle 3: The medical device is suitable for the intended purpose;

(d) Essential Principle 4: Long-term safety of the medical device;

(e) Essential Principle 5: Transport or storage does not adversely affect the medical device;

(f) Essential Principle 6: Benefits of the medical device outweigh any undesirable effects;

(g) Essential Principle 7: Chemical, physical and biological properties;

(h) Essential Principle 8: Infection and microbial contamination;

(i) Essential Principle 9: Construction and environmental properties;

(j) Essential Principle 13: Information to be provided with medical devices; and

(k) Essential Principle 14: Clinical evidence.

50 For a device that contains a medicine component, the TGA also undertakes specific assessments of pharmaceutical chemistry and toxicology. These same assessments would be undertaken for a medicine itself. As with a medicine, a medical device is only assessed for its intended purpose and not for off-label use.

51 If a conformity assessment certificate is issued following the above assessment, the applicant can apply for inclusion of the relevant medical device in the ARTG.

52 As a matter of practice, health practitioners may use medicines and medical devices outside of their approved indications or intended purposes, and exercise clinical judgment in the course of doing so.

The Secretary did not have an opportunity to apply relevant statutory procedures to the Kit alone

53 The intended purpose of the Device, as reflected in the entry on the ARTG, was for use in spinal fusion procedures in skeletally mature patients with degenerative disc disease (DDD) at one level from L4 to S1. The Cage was intended to hold the spine in the desired position; the Protein was the pharmacological active ingredient intended to promote bone growth; and the Sponge was an excipient ingredient intended to act as a carrier for the Protein and as a scaffold for new bone growth.

54 In the absence of Medtronic applying to the Secretary for registration or inclusion of the Kit alone on the ARTG, the Secretary did not have the opportunity to apply the statutory procedures in respect of the Kit which are intended to ensure risks associated with the Kit (including its quality, safety and efficacy as a stand-alone therapeutic good) were properly assessed and mitigated.

Risks Associated with Use of the Kit

55 Academic literature has referred to risks from use of the Kit. There are divergent opinions in the literature about what those risks are and the extent of those risks, as well as whether those risks can be mitigated and the mitigation techniques.

56 Some studies have suggested that there is an increased risk of cancer associated with the use of rhBMP-2 in higher concentrations in a posterior approach. Other possible risks identified in the literature include retrograde ejaculation, male sterility, difficulty urinating, wound infections and back and leg pain. These potential risks are reported as being different depending on a number of factors including which parts of the body and types of patients in which rhBMP-2 is used. Depending on the anatomical position rhBMP-2 is used in, some studies indicate its use without any cage may involve a risk of leakage of rhBMP-2 into soft tissue, which may result in swelling, inflammation and ectopic bone formation.

57 This literature is not accepted by all medical professionals and is disputed in some other studies. Some other studies have suggested that rhBMP-2 may not increase the risk of cancer or retrograde ejaculation. Further, some studies describing use of rhBMP-2 have suggested that smaller doses of rhBMP-2 and surgical techniques are used in spine fusion surgery which may optimise fusion rates and minimise the risk of complications, including risk of leakage, swelling, inflammation or ectopic bone formation noted above. Some studies and surgeons have suggested that the known risks associated with rhBMP-2 may be mitigated and that the appropriate use of rhBMP-2 is efficacious with an acceptable safety profile. Other studies suggest that use of the Kit may not improve surgical outcomes and may pose added risks to patients over other procedures. There is also some debate among some surgeons as to the extent that the risks associated with rhBMP-2 were prevented or materially mitigated by the use of the Cage in any event.

Background To and Nature of the Contraventions

Distribution of spinal products by Medtronic

58 Medtronic’s business in Australia is operated by various business units responsible for particular types of products. One business unit is the Spine and Biologics business unit (SBBU).

59 During and before the Relevant Period, the Device was primarily supplied to customers (hospitals and medical professionals) via a network of agents based in NSW, Victoria, Queensland, South Australia and Western Australia, each of which operated their own sales, warehouse and operations teams. Medtronic’s relationship with these agents was supervised by the head of the SBBU from time to time, and day-to-day contact with agents was managed by Medtronic’s Operations Manager within SBBU.

Manner of packaging and supply of the Kit by Medtronic

60 During the Relevant Period, Medtronic’s spine products (including the Device) were supplied through two models or channels:

(a) Consignment model: Medtronic or its agents would arrange for spine products to be available at hospital locations for use by surgeons when the products were required for surgical procedures. Once a product was used at the hospital, Medtronic would issue an invoice for the product and the product would be replenished at the hospital.

(b) Loan Set model: a loan set of spine products appropriate for a particular procedure would be requested by a surgeon or hospital. After a surgeon used some or all of the products in a loan set, the loan set would be returned to Medtronic or its agent, which would check which products were used and issue an invoice for the products that were used.

61 During the Relevant Period, the Kit and the Cage were packaged separately, for the following reasons:

(a) there were a number of different sizes of each of the Cage and the Kit. Use of the Device necessarily involved a clinician selecting the correct size Kit and the correct size Cage for the intended use;

(b) the Kit had temperature storage requirements that did not apply to the Cage; and

(c) the Kit had a shelf-life of two years, whereas the Cage had a shelf-life of 8 years.

62 Medtronic has internal product control systems used to monitor and control the supply of its products in Australia. The system in place from at least 2010 includes a module available in SAP referred to as the Global Trade Services (GTS) module. Each Medtronic product available for supply in Australia is recorded in the GTS module and assigned a “market licence” by reference to the relevant ARTG entry. The GTS modules and licences entered in GTS control the importing to and supply of products within Australia.

63 The Kit and the Cage were listed separately within GTS and each component had a “market licence” within the GTS module, enabling each component to be separately released from Medtronic’s warehouse to Spine and Biologics sites operated by Medtronic or its agents (i.e., the system allowed the Kit to be released without a Cage). There was no requirement in Medtronic’s GTS module referred to in the preceding paragraph that the Kit be released only with the Cage. Where an agent placed an order for products in the Medtronic system, Medtronic would release and ship the products from its warehouse to the agent’s premises, following which Medtronic's system did not monitor or record the supply of products from agents to hospitals – this was controlled by the agent.

64 When the Device was first included in the ARTG, an instruction was given by Medtronic to agents that the Kit and the Cage be delivered together. Medtronic has not been able to locate any document formalising this instruction prior to November 2009.

65 In around October or November 2009, concerns were raised within Medtronic that Spine agents were not supplying the Kit and Cage together as required by the ARTG entry. An internal email between a senior manager of SBBU and a director/board member of Medtronic referred to an “interim solution” for the “Infuse supply issue”, but also referred to the need to “move beyond the interim consignment solution to a 1 for 1 supply of a cage with each vial even if at a doctors choice cages may be returned to stock afterwards in some cases.”

66 In around October or November 2009, the SBBU Operations Manager developed a standard operating procedure (2009 SOP) dated 13 November 2009 which contained section 7.3 titled “Infuse Distribution Model” and includes the instructions, “Each loan set containing Infuse must be accompanied by LT Cage product” and “Every Infuse consignment site must include LT Cage implants and instruments on consignment”. Subsequent versions were developed in 2014, 2018 and 2019 which contained the same instructions.

67 In an email dated 19 November 2009, another senior manager within SBBU indicated that Cages would be delivered with each Kit “straight away” and that a “written plan” would be formally submitted by “tomorrow”. The senior manager instructed the SBBU Operations Manager to arrange for importation of sufficient Cages into Australia to ensure Cages could be supplied with the Kit and to prepare a procedure setting out the requirement that the Kit was to be supplied with the Cage.

68 If the Operations Manager followed his usual practice, hard copies of the 2009 SOP would have been sent to all agents by post; he would have arranged calls with agents to confirm the 2009 SOP had been received; and he would have confirmed that staff at agents’ sites had been made aware of the 2009 SOP and been directed to follow it. The Operations Manager believes he followed his usual practice in 2009 but has no specific recollection of this. A document which establishes what practice was actually adopted with respect to the 2009 SOP was the “written plan” referred to above, being a document entitled “2009 Action Plan”, which set out steps to be taken in relation to the Device. The steps included “Review of Medtronic Australasia legal advice regarding Infuse being supplied with LT Cage”; “Updated ISO 90001 Infuse Distribution document”; and “Agents notified”.

69 Medtronic has not been able to identify evidence that it trained or supervised the Spine agents in relation to the 2009 SOP or its subsequent iterations, nor the requirements of the ARTG entry. The SOPs were not followed by the agents or by SBBU operational team members. No practices were implemented which ensured compliance with the 2009 SOP by either Medtronic staff or its agents.

70 Those who were aware of the supply issue included members of Medtronic's senior management.

71 There is no evidence that the senior managers who were aware of the supply issue made further enquiries or undertook further checks between early 2010 and early 2020 regarding the implementation of a suitable operational plan to ensure the supply concerns had been addressed.

72 During the Relevant Period, Medtronic had a Quality team that from time to time conducted audits of SOPs used by the SBBU and has also conducted audits of the activities of Medtronic’s agents. The purpose of the audits of agents was to check that agents complied with procedures for storage, distribution and handling of Medtronic Spine products. However, the Quality team did not identify for inclusion, or include, the product-specific SOP for the Device within the scope of quality audits of Spine and Biologics sites. There were also no compliance reviews undertaken by Medtronic which included a review of supply conditions of Medtronic products and the associated ARTG entries during the Relevant Period with the result that no issue with respect to supply of the Kit or the Device was identified prior to January 2020 (discussed below). Medtronic's SBBU did not regularly interact with the Medtronic Regulatory and Quality teams, which may have resulted in a lack of awareness of the importance of regulatory compliance.

73 Further, during the Relevant Period, Medtronic’s policies and training in relation to 'unapproved' activities (for example, off-label promotion) did not include supply of unapproved products or components of products, or supply of products in contravention of ARTG conditions.

The Cage was withdrawn from supply in the Australian market in August 2018

74 The same SBBU Operations Manager who developed the 2009 SOP and the “2009 Action Plan” was responsible for updating the SOPs in 2014, 2018 and 2019.

75 In or around August 2018, the same SBBU Operations Manager was instructed to conduct a comprehensive review of Spine product inventory to identify any products which may be obsolete, as Medtronic’s parent company was seeking to reduce obsolete product inventory worldwide. The Operations Manager reviewed sales and inventory data against sales data to identify unused inventory and identified that there was little or no demand for over 170 Spine product types, including the Cage. While there were a small number of Cages in warehouses, there had been no sales in FY18 or FY19, indicating that the Cage was not being regularly requested or used by customers.

76 The Operations Manager then took steps to arrange withdrawal of the Cage from supply and sale by Medtronic. He did not turn his mind to the requirement to supply the Cage and the Kit together. Despite questions from agents regarding supplying the Cage with the Kit, the SBBU Operations Manager did not consider the requirement to supply the Kit with the Cage as he was focused on meeting the instructions from Medtronic US to reduce obsolete and slow moving inventory.

77 As a result, in August 2018 Medtronic withdrew the Cage from supply in Australia. Between at least August 2018 and January 2020 Medtronic did not supply any Cages in loan sets or on consignment.

78 The Medtronic Regulatory team was not informed or consulted in relation to the operational decision to withdraw the Cage in 2018 from supply in Australia. At the time that the Cage was withdrawn from supply, Medtronic did not turn its mind to lawful supply of the Kit in Australia without the Cage.

79 On 14 January 2020, Medtronic received a letter from the then-Department of Health in relation to the ARTG entry for the Device, the listing on the Prostheses List for the Kit and the Cage, and the use of the Kit and the Cage. The Prostheses List is a list of medical devices which private health insurers are required to fund, at a minimum payment amount, when used in medical procedures. The letter stated that “Private Health Insurers have raised concerns that the INFUSE Bone Graft is not being used in accordance with its regulatory approval which requires that the INFUSE Bone Graft should only be used with the corresponding LT Cage.”

80 On or around 23 January 2020, after the letter from the Department of Health, Medtronic became aware that it or its agents had been supplying Kits without Cages. On 24 January 2020, the Director, Quality and Regulatory Affairs for Medtronic, Australia and New Zealand, directed the Regulatory Operations team to block the GTS licence for the Kit with immediate effect, which meant that Kits could not be released from the Medtronic warehouse in Sydney without specific instruction. The Director, Quality and Regulatory Affairs also instructed the SBBU Operations Manager to take steps to ensure that Kits would not be released by Spine operations sites to customers.

81 On 24 January 2020, the Director, Quality and Regulatory Affairs, also telephoned the First Assistant Secretary in the Medical Devices and Product Quality Division of the TGA and informed them that Medtronic had identified that Kits had been supplied without Cages, and Medtronic had stopped the Kit from leaving its warehouse and instructed agents not to provide the Kit to customers. Subsequently, Medtronic communicated with the TGA on a number of occasions to keep the TGA updated on the supply issue and to discuss next steps.

82 Medtronic took steps to explore potential solutions to the supply issues, including whether it was possible to obtain sufficient quantities of Cages to supply with the Kits in Australia and whether, in the longer term, it was possible to obtain any different registrations or inclusions which would allow Medtronic to compliantly supply the Kit, including registration or inclusions of the Kit as a standalone medical device or medicine, or of the Kit with alternative cages. By around 6 March 2020, Medtronic concluded it was not feasible to resume compliant supply of the Device, including because the Cages were no longer being manufactured by Medtronic outside Australia, and it would take a significant amount of time to manufacture enough Cages to compliantly supply the Device. This was communicated to the TGA on or around 6 March 2020.

83 On or around 23 March 2020, Medtronic requested that the Secretary cancel the ARTG entry for the Device and ceased supplying the Kit in Australia, apart from via SAS applications where the TGA approved the supply of the Kit for use by a particular surgeon in relation to a particular patient.

Steps taken to address causes of the contraventions

84 Medtronic has taken considerable steps to seek to address the causes of the contraventions.

85 Medtronic has updated its processes to ensure regulatory controls are in place for “non-standard” products (being products that cannot be supplied in Australia in the form in which they are manufactured, requiring an extra step or steps to be taken by Medtronic locally before the products can be supplied in accordance with Australian-specific regulatory requirements).

86 Since March 2021, Medtronic’s “Product Approval SOP”, requires a Medtronic Regulatory Affairs specialist (RAS) to assess a product:

(a) Prior to adding a market license for the product in the GTS module of Medtronic’s internal database and allowing its release to market in Australia (Authorisation Assessment). The Authorisation Assessment requires the RAS to confirm that the Pre Submission Assessment and Post Approval Assessment (amongst others) have been completed, and if so, to authorise release of the product. The RAS must confirm that any special conditions or requirements applicable to TGA approval have been documented. The RAS must authorise product release in order for a market license to be applied to the product in the GTS module of Medtronic’s internal database by the Regulatory Operations Team.

(b) After TGA approval of an application for registration or inclusion (Post Approval Assessment). The Post Approval Assessment includes assessing whether there are special conditions or requirements applicable to the product ARTG entry, and what actions will be taken to address those conditions or requirements (e.g., where an approved product consists of multiple components which must be supplied together, such as the Device). The RAS is also required to consider whether the condition means the product needs to be documented as a “higher risk” or non-standard product, that is, a product that has specific requirements or conditions associated with the ARTG entry other than ARTG standard conditions; and

(e) Prior to applying to the TGA for approval and registration or inclusion (Pre Submission Assessment). The RAS is required to consider the indications for which Medtronic is proposing to seek approval from the TGA, the indications for which the product will be supplied, and whether any changes are required to the instructions for use or labelling based on the approved indication being sought.

87 Medtronic has implemented a new regulatory process in relation to “nonstandard”, “higher risk” products. In the course of the Product Assessments, the RAS must consider additional questions for these products including the actions needed to address the specific requirements or conditions associated with the ARTG entry. Where the RAS considers that a product has nonstandard requirements or conditions, those products are subject to periodic (twice yearly) reviews by the Quality and Regulatory Affairs team.

88 Medtronic has taken steps to ensure appropriate supervision and control of the activities of the Spine Operations Team, which has now been integrated within Medtronic’s broader Operations team and supply chain function, and reports to the Supply Chain team rather than the SBBU.

89 Medtronic has taken steps to improve communication between the Quality and Regulatory Affairs teams and Medtronic business units. This includes assigning specific Regulatory and Quality team members to different business units (now Operating Units), for which they attend business quarterly reviews and are regularly briefed upon current and upcoming products. The Quality and Regulatory Affairs team also closely coordinate with their respective operating units in relation to approval and registration or inclusion of new products (including by communicating with the marketing and/or product manager and providing them with a copy of the ARTG certificate).

90 Medtronic has implemented a new “Off-Label / Unregistered Product Promotion, Use, and Supply (ANZ) Policy” (Policy), which came into effect on 17 March 2021. Medtronic has also implemented training for Sales & Marketing Staff regarding the Policy. The training was implemented for all ANZ staff in 2021, 2022 and 2023. Training on the Policy is also provided to new employees of Medtronic.

91 Medtronic has conducted additional training on its quality management system (QMS) to ensure Medtronic personnel are aware of the importance of compliance with Medtronic’s QMS, policies, procedures and work instructions, and best practice for documenting business processes.

Whether Medtronic has been found by the Court in proceedings under the Act to have engaged in any similar conduct

92 Medtronic has not previously been found by the Court in proceedings under the Act to have engaged in any similar conduct.

93 Medtronic continues to supply a substantial number of medical devices in the Australian market and is currently the sponsor of over 1,900 kinds of medical devices included in the ARTG, of which over 500 are Class III medical devices.

94 Medtronic’s gross revenue each financial year during the period from FY21 to FY23 (noting Medtronic's financial years run 1 April – 31 May) was as follows:

(a) Financial Year 2021: $1,041,563,000

(b) Financial Year 2022: $1,007,178,000

(c) Financial Year 2023: $1,065,471,000

95 Medtronic incurs substantial costs in deriving its gross revenue. After accounting for expenses, Medtronic’s profit (after income tax expense attributable to Medtronic) in the period from FY21 to FY23 was as follows:

(a) Financial Year 2021: $55,298,000

(b) Financial Year 2022: $24,685,000

(c) Financial Year 2023: $49,111,000

Profit derived from the contraventions

96 Medtronic generated a total of $77,187,176 in gross revenue from the 16,267 contravening supplies of the Kit. The gross revenue generated by the contravening supplies in each financial year during the Relevant Period was as follows:

(a) Financial Year 2016: $7,406,000

(b) Financial Year 2017: $16,756,800

(c) Financial Year 2018: $17,090,272

(d) Financial Year 2019: $19,187,884

(e) Financial Year 2020: $16,746,220

97 After accounting for costs (including the costs of goods sold, operating product costs and intercompany transfer pricing), the net revenue from the contravening supplies of the Kit is estimated to be $8,982,474 (excluding GST).

98 Medtronic has cooperated with the Secretary in the course of his investigation, including by admitting the contraventions at an early stage.

99 Medtronic has, through its Director of Quality and Regulatory Affairs, apologised for the contraventions in the following terms:

‘[T]he Supply Contravention is a significant and serious matter. Medtronic has devoted significant resources to the remedial steps necessary to address the Supply Contravention, in circumstances where Medtronic considers the Supply Contravention to be a very serious and regrettable matter. Medtronic has great respect for the system of regulation of therapeutic goods in Australia, including the Therapeutic Goods Act 1989 and the activities of the Therapeutic Goods Administration. Medtronic apologises unreservedly for the Supply Contravention.’

CONSIDERATION OF PENALTY

100 Also on 6 September 2024, the parties filed a document entitled Joint Submissions on Penalty seeking to address, by way of a consent position, the matters that I should take into account in setting a penalty for the contraventions of the ARTG.

101 As noted above in paragraphs [34] and [35] above, the parties are agreed, for the purposes of imposition of penalty only, that the relevant provision contravened was s 19D(1) of the Act. That section provides:

19D Civil penalties relating to registration or listing etc. of imported, exported, manufactured and supplied therapeutic goods

Civil penalty relating to importing, exporting, manufacturing or supplying goods for use in humans

(1) A person contravenes this subsection if:

(a) the person does any of the following:

(i) imports into Australia therapeutic goods for use in humans;

(ii) exports from Australia therapeutic goods for use in humans;

(iii) manufactures in Australia therapeutic goods for use in humans;

(iv) supplies in Australia therapeutic goods for use in humans; and

(b) none of the following subparagraphs applies in relation to the goods:

(i) the goods are registered goods or listed goods in relation to the person;

(ii) the goods are exempt goods;

(iii) the goods are exempt under section 18A;

(iv) the goods are the subject of an approval or authority under section 19;

(v) the goods are the subject of an approval under section 19A.

Maximum civil penalty:

(a) for an individual—5,000 penalty units; and

(b) for a body corporate—50,000 penalty units.

102 “Therapeutic goods” is defined in s 3 of the Act as:

(a) that are represented in any way to be, or that are, whether because of the way in which the goods are presented or for any other reason, likely to be taken to be:

(i) for therapeutic use; or

(ii) for use as an ingredient or component in the manufacture of therapeutic goods; or

(iii) for use as a container or part of a container for goods of the kind referred to in subparagraph (i) or (ii); or

(b) included in a class of goods the sole or principal use of which is, or ordinarily is, a therapeutic use or a use of a kind referred to in subparagraph (a)(ii) or (iii); or

(ba) determined to be therapeutic goods under subsection 7AAA(1);

and includes biologicals, medical devices and goods declared to be therapeutic goods under an order in force under section 7, but does not include:

(c) goods declared not to be therapeutic goods under an order in force under section 7; or

(d) goods in respect of which such an order is in force, being an order that declares the goods not to be therapeutic goods when used, advertised, or presented for supply in the way specified in the order where the goods are used, advertised, or presented for supply in that way; or

(e) goods (other than goods declared to be therapeutic goods under an order in force under section 7 and goods determined to be therapeutic goods under subsection 7AAA(1)) for which there is a standard (within the meaning of subsection 4(1) of the Food Standards Australia New Zealand Act 1991); or

(f) goods (other than goods declared to be therapeutic goods under an order in force under section 7 and goods determined to be therapeutic goods under subsection 7AAA(1)) which, in Australia or New Zealand, have a tradition of use as foods for humans in the form in which they are presented; or

(g) goods covered by a determination under subsection 7AA(1) (excluded goods); or

(h) goods covered by a determination under subsection 7AA(2) (excluded goods), if the goods are used, advertised, or presented for supply in the way specified in the determination.

No declaration has been made under s 7 in relation to the Kit.

103 I reiterate that the issue of whether supply of the Kit, without it being entered on the ARTG without the Cage, was a breach of 19D or alternatively a breach of s 41MIB (which imposes a civil penalty, relevantly, for supplying a “medical device” within Australia and is in in similar terms to s 42Y in its application to medical devices rather than to therapeutic goods), was not argued before me and was not the subject of evidence.

104 However, taking into account the evidence in the form of the Joint Statement and the agreed position of the parties, I am prepared to accept that for the purposes of the imposition of a civil penalty, the Kit is a “therapeutic good” for the purposes of s 42Y of the Act.

105 As will be apparent from the degree of agreement in the procedural aspects of this case and the Joint Statement, the parties were also generally agreed (with some minor exceptions) on how I should apply the relevant principles to reach an appropriate pecuniary penalty in the circumstances of the contraventions of the Act.

106 The matters set out in the Joint Statement reproduced in paragraphs [28] to [33 ] above satisfy me that Medtronic contravened s 19D(1) of the Act by supplying 16,267 units of the Kit without the Cage. The consent of Medtronic to the Joint Statement should be treated as an admission of all facts necessary or appropriate to the granting of the relief sought; see Thomson Australian Holdings Pty Ltd v Trade Practices Commission (1981) 148 CLR 150 at [26] per Gibbs CJ, Stephen, Mason, and Wilson JJ.

107 The agreed penalty is, as will be discussed below, $22,000,000 plus costs. While this is in effect by consent, the imposition of a civil penalty order is not a “consent jurisdiction” and I need to be sufficiently persuaded of the appropriateness of the remedy in the context of the breaches and consequences of the breach (see Commonwealth v Director, Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate (2015) 258 CLR 482 at [58] per French CJ, Kiefel, Bell, Nettle and Gordon JJ).

108 The purpose of a civil penalty in a case such as this is the protection of the public interest, in ensuring compliance with a regulatory regime. In Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate, the Court said (at [24]):

In essence, civil penalty provisions are included as part of a statutory regime involving a specialist industry or activity regulator or a department or Minister of State of the Commonwealth (the regulator) with the statutory function of securing compliance with provisions of the regime that have the statutory purpose of protecting or advancing particular aspects of the public interest. Typically, the legislation provides for a range of enforcement mechanisms, including injunctions, compensation orders, disqualification orders and civil penalties, with or, as in the BCII Act, without criminal offences. That necessitates the regulator choosing the enforcement mechanism or mechanisms which the regulator considers to be most conducive to securing compliance with the regulatory regime. In turn, that requires the regulator to balance the competing considerations of compensation, prevention and deterrence. And, finally, it requires the regulator, having made those choices, to pursue the chosen option or options as a civil litigant in civil proceedings.

109 The assessment of a penalty in this case is made more complex, as pointed out in the Joint Submissions, by the fact that there is no one appropriate penalty prescribed by the legislation. The penalty prescribed by s 42Y is a maximum civil penalty. Were the maximum civil penalty of 50,000 penalty units per contravention to be applied, then the penalty would be:-

(a) $9,000,000 for each contravention between 1 September 2015 and 30 June 2017; and

(b) $10,500,000 for each contravention between 1 July 2017 and 31 January 2020.

110 Counsel for the Secretary and Medtronic agreed that were the notional maximum penalty to be imposed in respect of each of the 16,267 contraventions then the civil penalty would be, depending on the timing of the contraventions, around $162 billion. It is submitted, and I agree, that the maximum penalty is “effectively at large and … should be treated as but one of a number of relevant factors”.

111 The significance of the imposition of 50,000 penalty units per contravention is indicative of the seriousness with which Parliament regards contraventions of the Act. It should be noted that the same penalty provisions apply to breaches of the possible alternative, s 41MIB.

112 My attention was drawn to the proper approach to civil penalty orders as expressed by the plurality in Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate. There, it was emphasised that “important public policy [was] involved in promoting predictability of outcome in civil penalty proceedings” which “assists in avoiding lengthy and complex litigation and thus tends to free the courts to deal with other matters and to free investigating offers to turn to other areas of investigation that await their attention” (at [46]).

113 Here, as noted above, the matter was listed before me for five days. I was informed that were there to be a contested hearing on whether the Kit was a “therapeutic good” or a “medical device”, substantial and complex expert evidence would be required and the hearing as to the specific section which had been contravened, along with submissions as to appropriate penalties, would take most likely the five days and more. In the end, I had a constructive and helpful dialogue with Mr White SC and Ms Epstein for the Secretary, and Mr Free SC and Mr Hume for Medtronic, in relation to the sensible and pragmatic approach which was eventually taken in nominating, without definitively deciding, that the penalty was sought to be imposed for a breach of s 19D(1). The final hearing at which the Joint Submissions and Joint Statement were tendered lasted less than half an hour. Each of those documents is thoughtful and of significant assistance to me in preparing these reasons.

114 In my view the approach taken by the parties is consistent with the overarching purpose of s 37M(1) of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) to:

… facilitate the just resolution of disputes:

(a) according to law; and

(b) as quickly, inexpensively and efficiently as possible.

115 There are dangers, however, in being too grateful to the parties for the hard work they have put into the position they have jointly taken. In Volkswagen Aktiengesellschaft v ACC (2021) 284 FCR 24 at [127] per the Court (Wigney, Beach, and O’Brien JJ) at [129] the Court said:

… in considering whether the proposed agreed penalty is an appropriate penalty, the Court should generally recognise that the agreed penalty is most likely the result of compromise and pragmatism on the part of the regulator, and to reflect, amongst other things, the regulator’s considered estimation of the penalty necessary to achieve deterrence and the risks and expense of the litigation had it not been settled: Fair Work at [109]. The fact that the agreed penalty is likely to be the product of compromise and pragmatism also informs the Court’s task when faced with a proposed agreed penalty. The regulator’s submissions, or joint submissions, must be assessed on their merits, and the Court must be wary of the possibility that the agreed penalty may be the product of the regulator having been too pragmatic in reaching the settlement: Fair Work at [110].

116 Accordingly, the proper approach in synthesising the relevant factors is to assess the proposed figure against them, determine whether it falls within the permissible range, and, if no particular figure can be said to be more appropriate than another (see [127] of Volkswagen), accept it as appropriate. As noted by Gordon J in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Coles Supermarkets Australia Pty Ltd [2014] FCA 1405 at [72], once I am satisfied that orders are within power and appropriate, I should “exercise a degree of restraint when scrutinising the proposed settlement terms, particularly where both parties are legally represented and able to understand and evaluate the desirability of the settlement”.

117 One of the factors to be taken into account is that of deterrence. The purpose of a civil penalty is “protective in promoting the public interest in compliance” with the relevant law, so that the penalty should be fair but significant enough to protect the public from future contraventions – see Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Pattinson (2022) 274 CLR 450, [15], [71] (per Kiefel CJ, Gageler, Keane, Gordon, Steward and Gleeson JJ). It must also be sufficiently high enough that a cynical operator may not take it into account as the cost of doing business (see Pattinson at [17], ACCC v TPG Internet Pty Ltd (2013) 250 CLR 640, [66] per French CJ, Crennan, Bell and Keane JJ.

118 One purpose of the Act is, of course, protection of the public from harm from unregulated therapeutic goods (or medical devices). Its focus is public health. The contraventions leading to the imposition of the civil penalty here undermined the regulatory scheme comprising the ARTG. The contraventions were significant in number and, as noted in the Joint Statement, not free from risk (although there is no evidence of that risk coalescing into actual harm caused). A significant fine will have the benefit of general deterrence – that is, encouraging other importers or suppliers of items regulated by the Act to adhere to its terms.

119 Medtronic has apologised for its contraventions, and has taken steps to ensure that no further contraventions take place, as set out in the Joint Statement. It has not otherwise been found to have contravened the Act. There is no suggestion that the contraventions were deliberate. I have no reason to refute the contention that for all these reasons, there is limited importance to be placed on specific deterrence – that is, a penalty intended to deter Medtronic specifically from further contraventions.

120 I have dealt briefly above with the extent of the maximum possible penalty. The factors dealt with in the preceding paragraph are some of the factors which weigh against the maximum possible penalty being imposed; the maximum possible penalty is, indeed, a figure beyond which any reasonable Court might go in these circumstances. The maximum penalty is “but one yardstick that ordinarily must be applied”, and must be treated “as one of a number of relevant factors” in determining the appropriate penalty (see Pattinson at [54], citing Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Reckitt Benckiser (Australia) Pty Ltd (2016) 340 ALR 25 at 63).

121 In the Joint Submissions, I am urged to consider the following factors:

(a) the extent to which the contravention was the result of deliberate or reckless conduct by the corporation, as opposed to negligence or carelessness;

(b) the number of contraventions, the length of the period over which the contraventions occurred, and whether the contraventions comprised isolated conduct or were systematic;

(c) the seniority of officers responsible for the contravention;

(d) the capacity of the defendant to pay, but only in the sense that whilst the size of a corporation does not of itself justify a higher penalty than might otherwise be imposed, it may be relevant in determining the size of the pecuniary penalty that would operate as an effective specific deterrent;

(e) the existence within the corporation of compliance systems, including provisions for and evidence of education and internal enforcement of such systems;

(f) remedial and disciplinary steps taken after the contravention and directed to putting in place a compliance system or improving existing systems and disciplining officers responsible for the contravention;

(g) whether the directors of the corporation were aware of the relevant facts and, if not, what processes were in place at the time or put in place after the contravention to ensure their awareness of such facts in the future;

(h) any change in the composition of the board or senior managers since the contravention;

(i) the degree of the corporation’s cooperation with the regulator, including any admission of an actual or attempted contravention;

(j) the impact or consequences of the contravention on the market or innocent third parties;

(k) the extent of any profit or benefit derived as a result of the contravention; and

(l) whether the corporation has been found to have engaged in similar conduct in the past,

although these are not “a rigid catalogue of matters for attention” or any kind of checklist – see Pattison at [19].

122 These factors are reflected to some extent in the “checklist” that is contained in s 42Y(3), which is set out above in [16]. These are dealt with in the Joint Statement under the heading “Other Penalty Factors” at [84] ff above.

123 One factor relevant to the circumstances I need to take into consideration is the 2009 SOP which arose out of Medtronic becoming aware that the Kit was being supplied separately from the device, and in which it set out an instruction that the Cage accompany the Kit (see [66] above). It is clear that there were failings in the distribution or management of the 2009 SOP and its subsequent iterations. There is little evidence about how compliance was implemented after the concerns as to the supply arose, and it is in my view appropriate to draw inferences from the history provided in the Joint Statement that insufficient attention was paid to compliance, training, and systemic improvements to deal with any concerns as they arose, and thereafter. That situation has been ameliorated somewhat by the following:-

(a) Medtronic promptly ceasing to sell the Kits once the Department’s concerns were conveyed to it;

(b) Identification by Medtronic of Kits that had been supplied without Cages;

(c) Investigation of alternative solutions to the issue, for example, registration of the Kit as a standalone medical device or therapeutic good, or supply with Cages; and

(d) A request for cancellation of the ARTG entry for the Device and cessation of supply within Australia.

124 While these factors do demonstrate a prompt and thorough response, it remains the fact that the corrective actions were only taken after the Department brought the contraventions to the notice of Medtronic in 2020 (as set about above in [79] ff), rather than through proper compliance with Medtronic’s regulatory processes.

125 That lack of compliance after 2009 was compounded in 2018, when the Cage was withdrawn from supply in Australia, and the commercial decision to withdraw the Cage from supply and sale was not communicated to the Medtronic Quality or Medtronic Regulatory teams sufficiently, or at all. As a result, Medtronic did not properly engage with the question of whether the Kit was being sold separately from the Cage in contravention of the requirements of the Act.

126 Quite properly, both parties characterise the contraventions as occurring in a significant number (16,267) over a significant period of time (4.5 years). There is a question as to whether this was a “course of conduct”, or whether there was a continuing single contravention. This issue is one on which the parties do not agree; Medtronic contends that this was a course of conduct, because of the same essential facts (being the same therapeutic good, and the same unlawful supply), whereas the Department points to the independent nature of each separate transaction being a separate contravening supply. This is an evaluative question (see ACCC v Cement Australia Pty Ltd [2017] FCAFC 159; (2017) FCR 312 at [425] (Middleton, Beach and Moshinsky JJ) and requires me to look at the way in which the legal and factual elements are connected (see Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union v Cahill (2010) 269 ALR 1 at [40]-[41] per Middleton and Gordon JJ .

127 It seems to me that I should look at the contraventions is by way of the “fact-specific inquiry” referred to by Middleton and Gordon JJ in Cahill. Each separate sale of the Kit required a response to an order placed by a hospital, through an agent, and triggered a release of the Kit from Medtronic’s system and despatch to the particular agent (of whom there were several). I agree with the submissions of the Department that this suggests a string of separate contraventions. The impact of this finding is that instead of one (long-standing and significant) contravention by way of a course of conduct, there are 16,267 such contraventions.

128 As to the question of harm arising out of the contraventions, it is clear that the available academic literature refers to a risk of harm, however, there is nothing in the evidence before me that would indicate that any specific harm arose out of any contravention of the Act. There is, however, the harm done to the system of regulation of therapeutic goods in Australia, through the ongoing and numerous contraventions of the Act. This must be taken into account.

129 As can be seen from the summary of Medtronic’s financial position and income gained from the sale of the Kit, it received a total of $77,187,167 in gross revenue from the contraventions (and approximately $8,982,474 excluding GST by way of net sales).

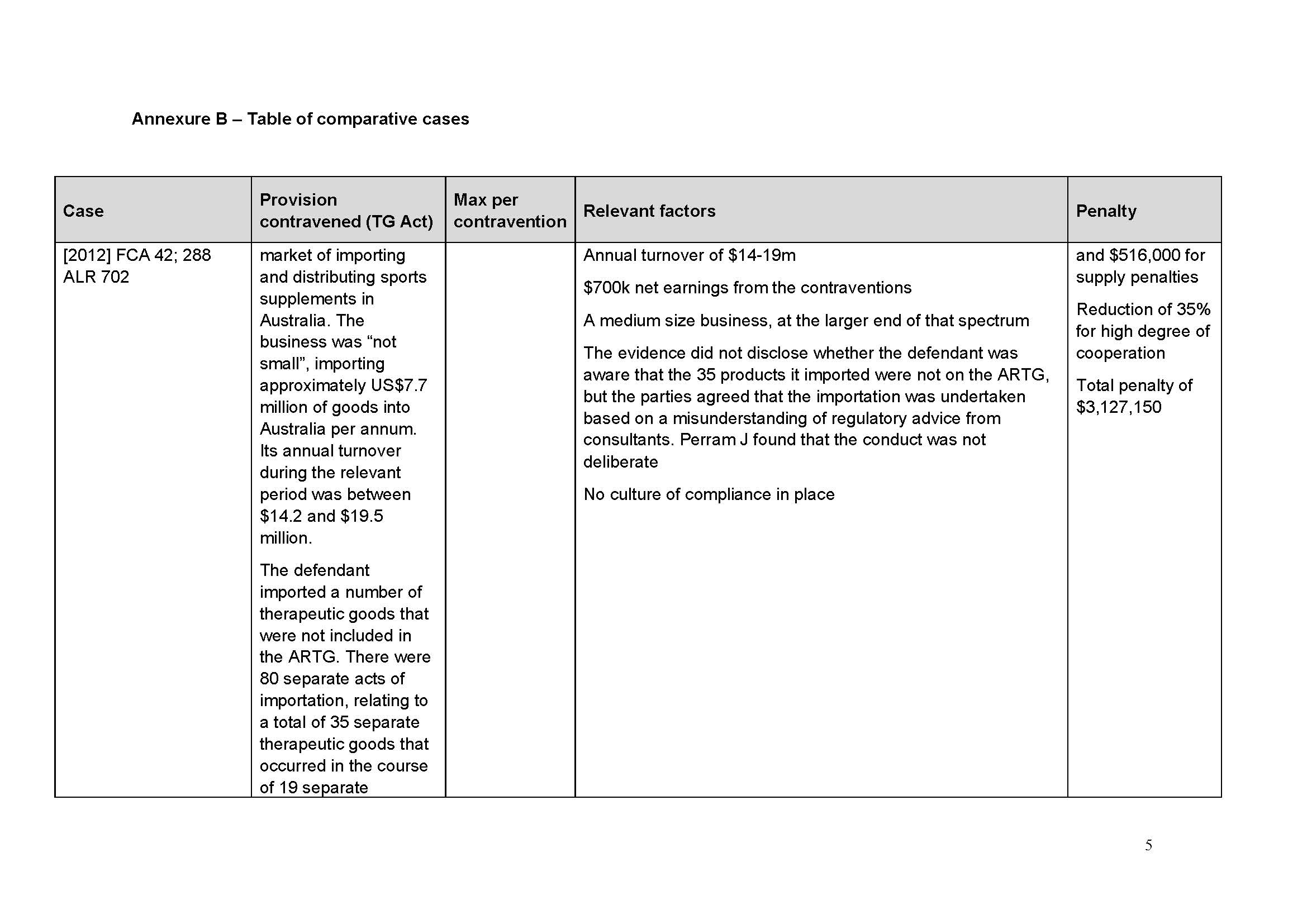

130 I am not confined to reference to the net profit in setting a penalty. In Secretary, Dept of Health and Ageing v Export Corporation (Australia) Pty Ltd [2012] FCA 42; 288 ALR 702, a case concerning multiple contraventions of s 19D(1) of the Act, Perram J imposed a penalty which “substantially exceed[ed] the net earnings” made by the contravener (at [83]). His Honour said this was a function of the size of the penalty prescribed by the Act, which “underscore[s] that non-compliance with this particular Act is likely to have disastrous consequences for the business involved. That is what Parliament has determined” (at [83]). See also viagogo AG v ACCC [2022] FCAFC 87 at [162] per the Court (Yates, Abraham and Cheeseman JJ).

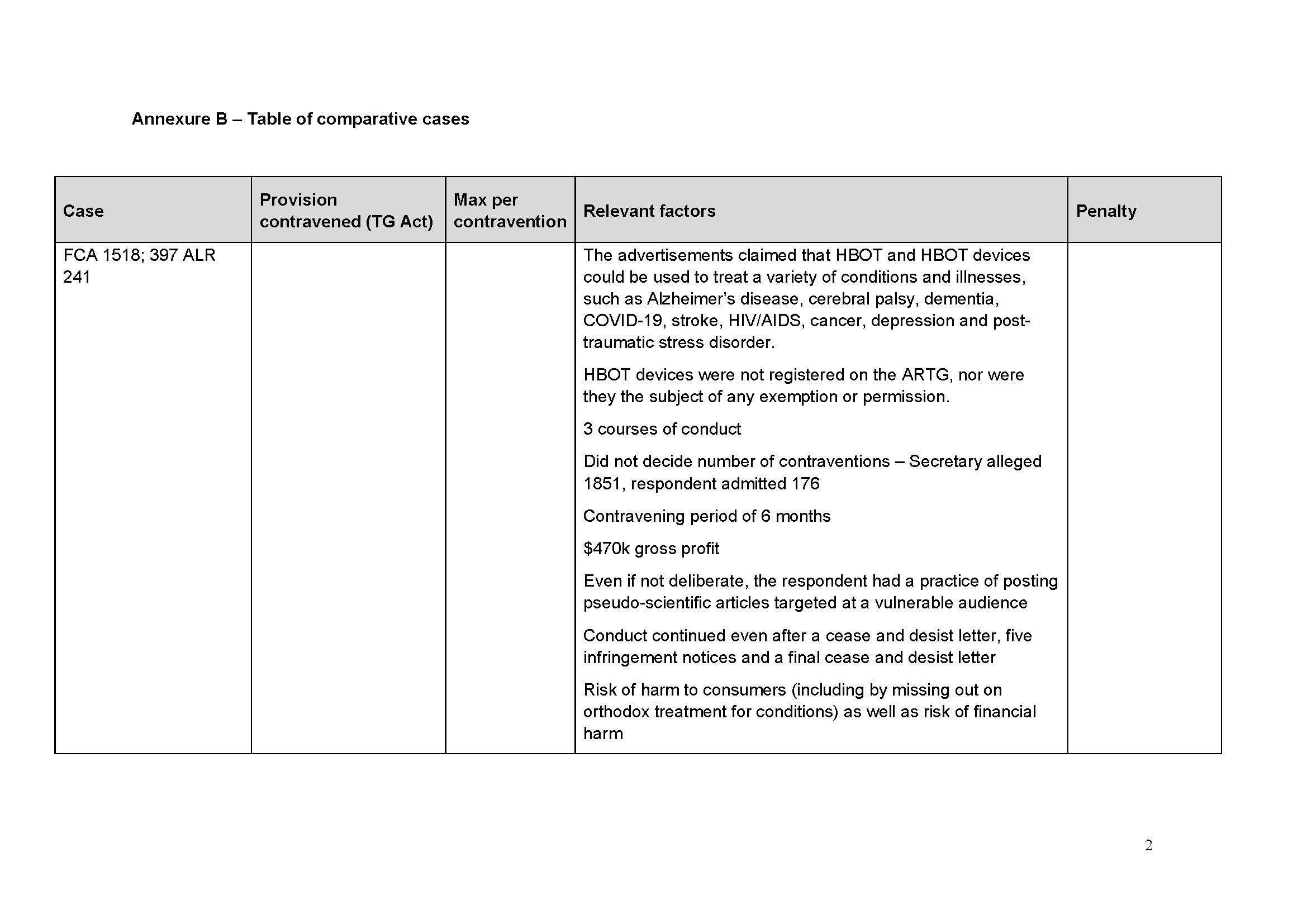

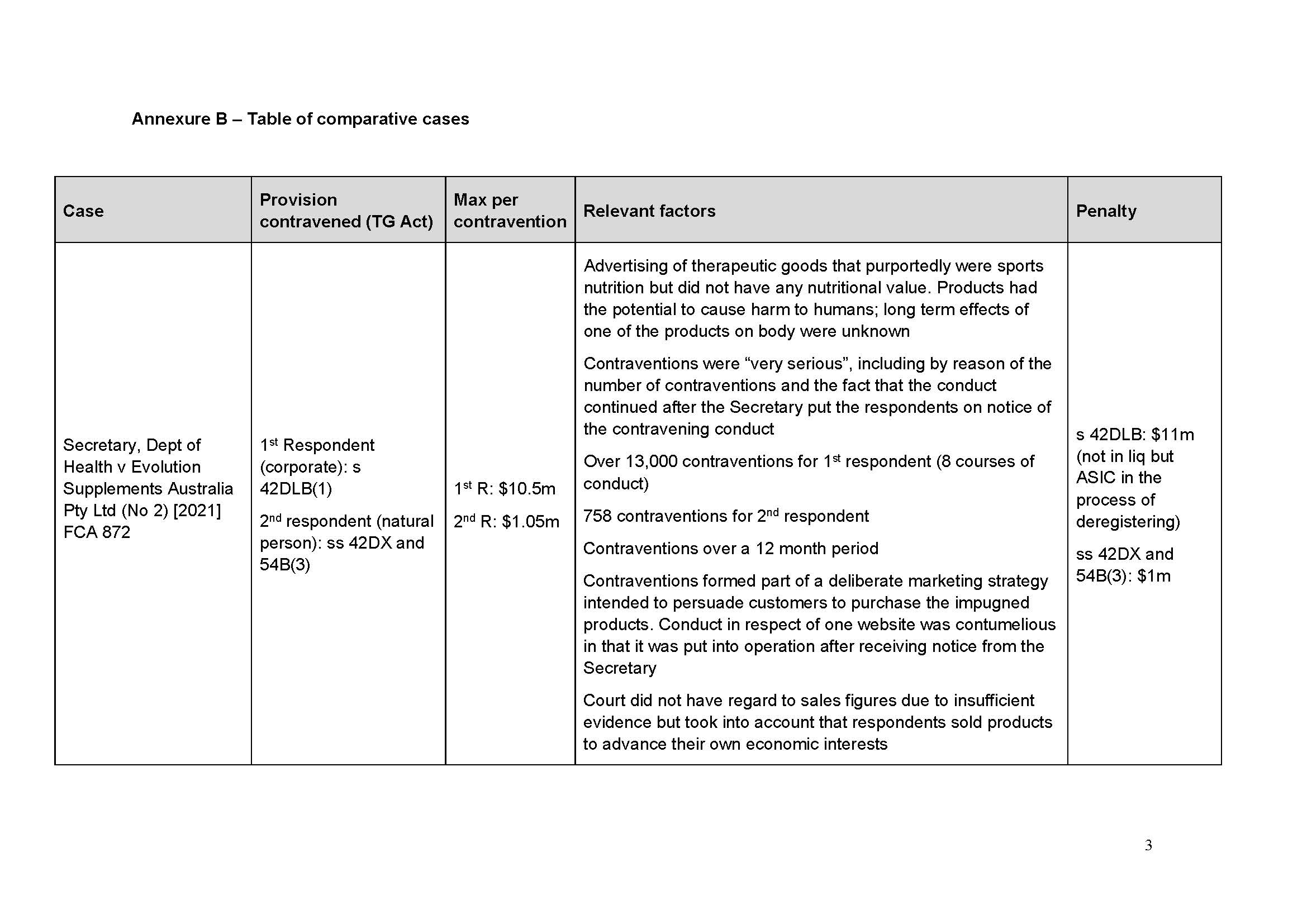

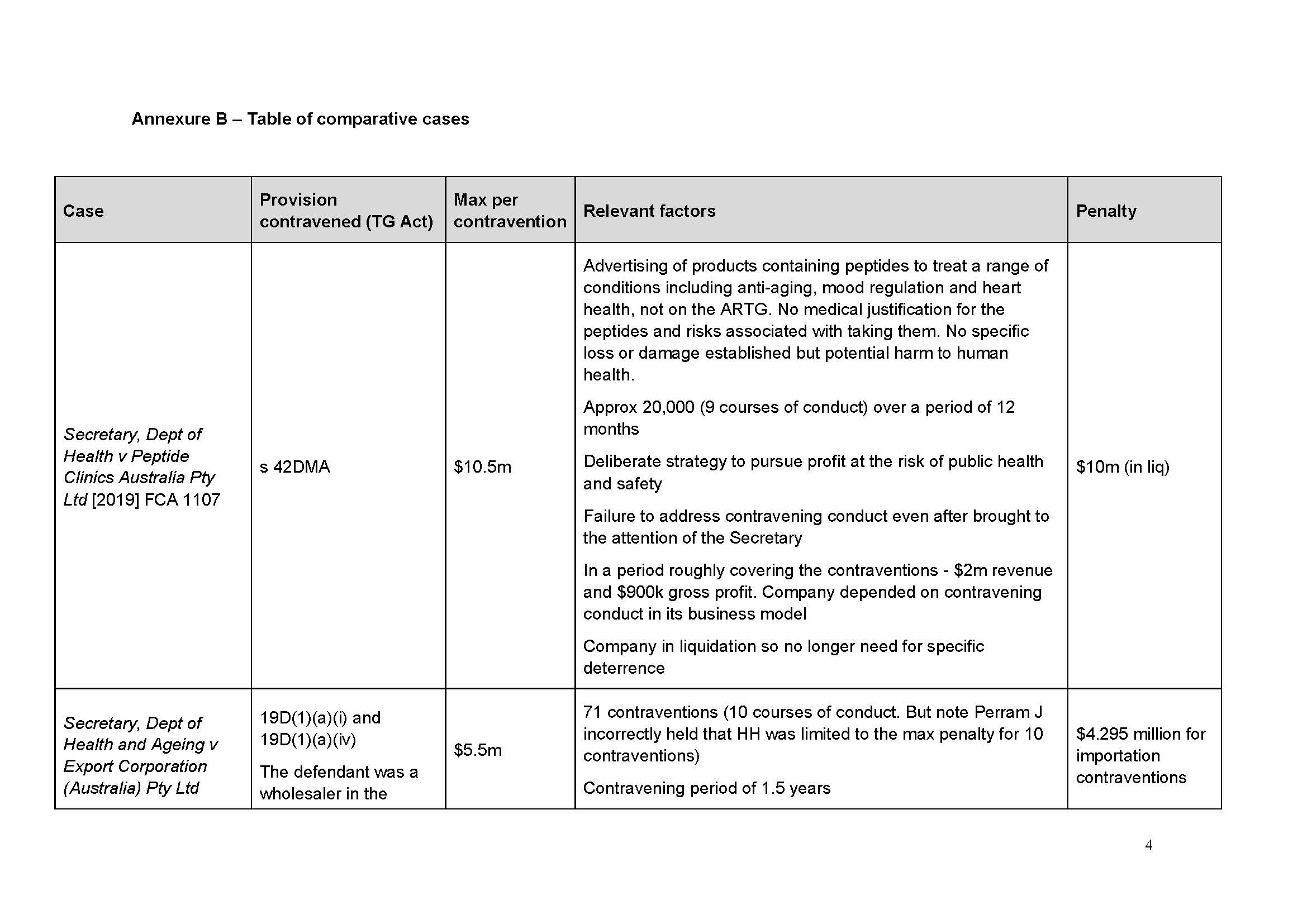

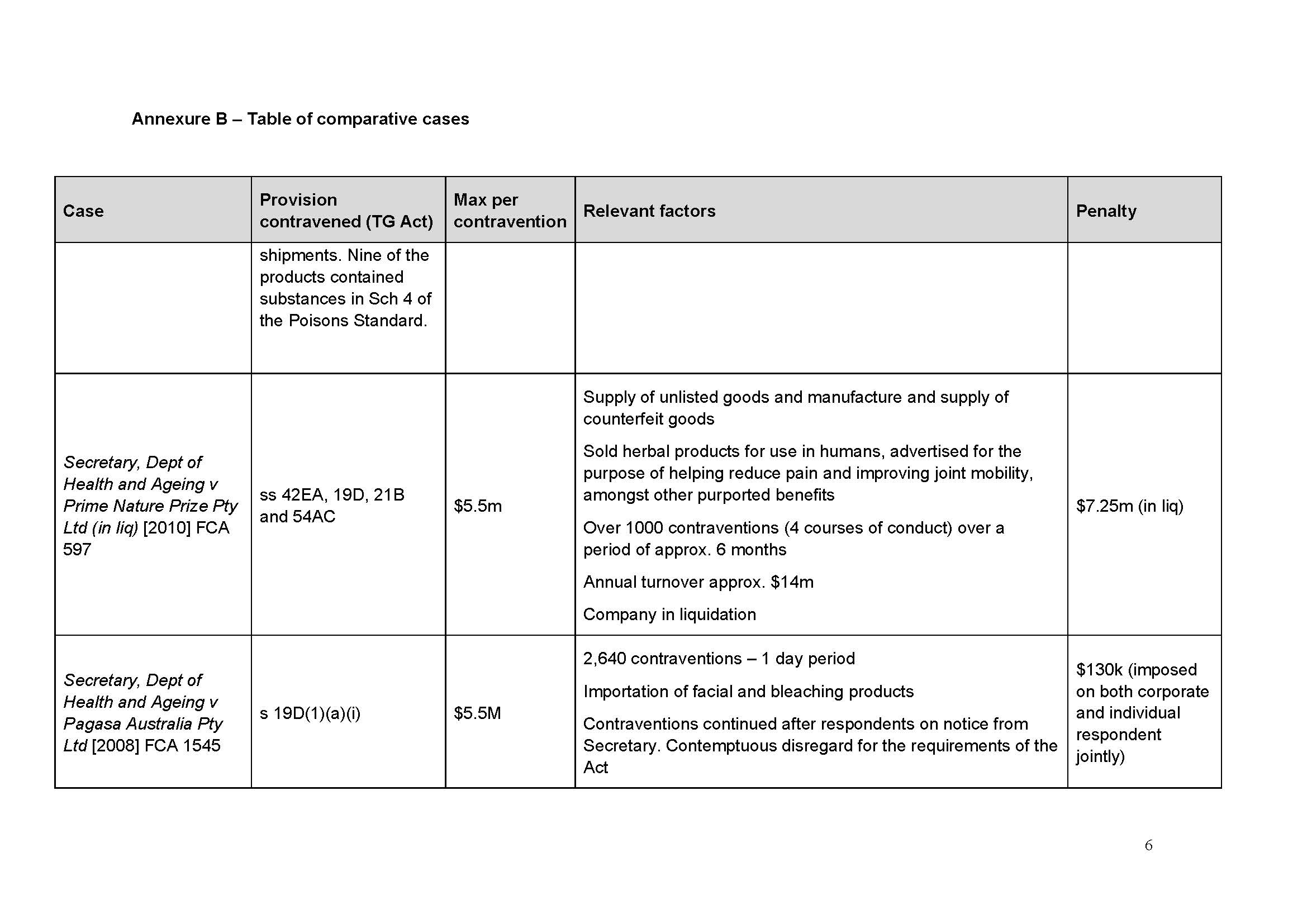

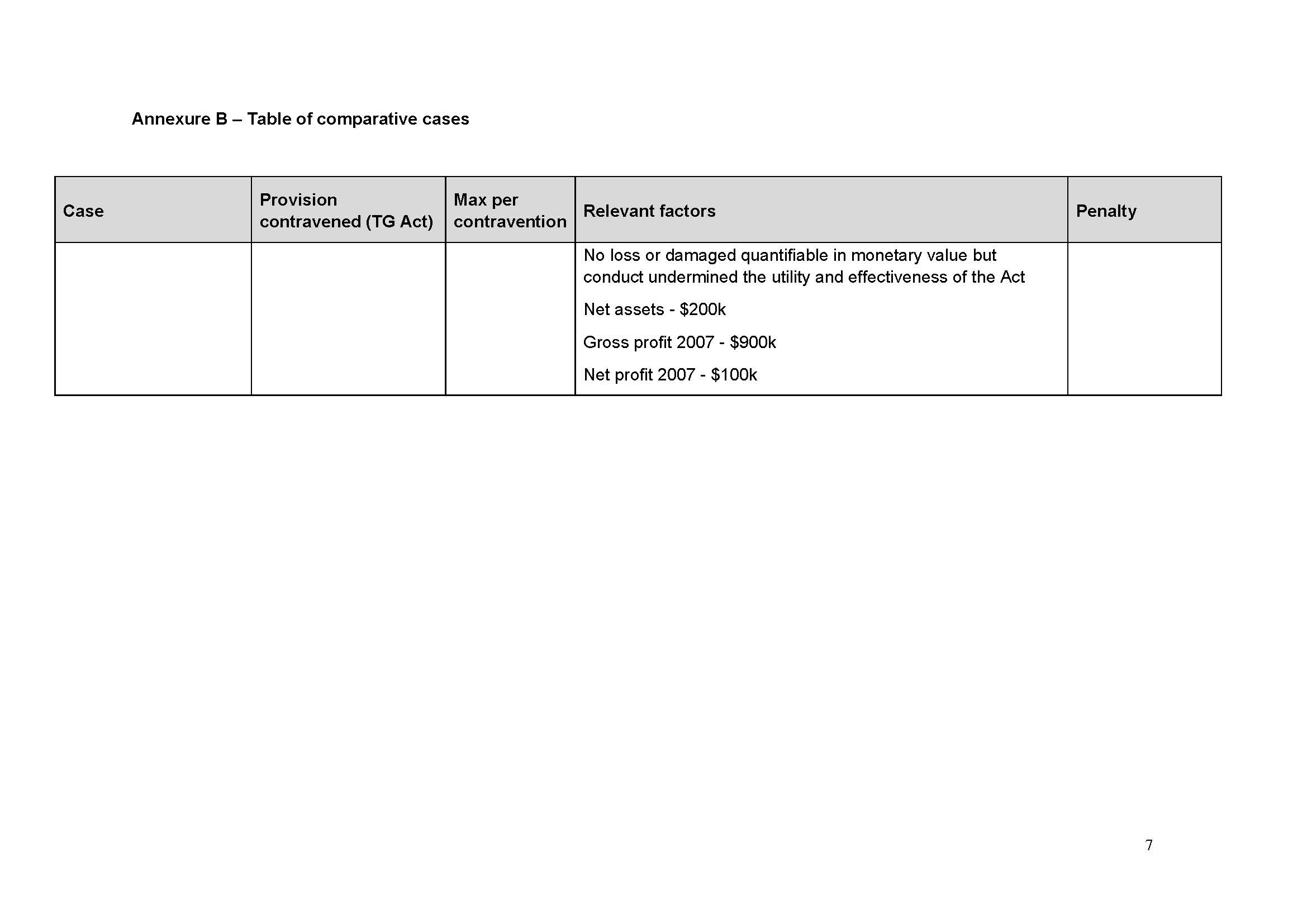

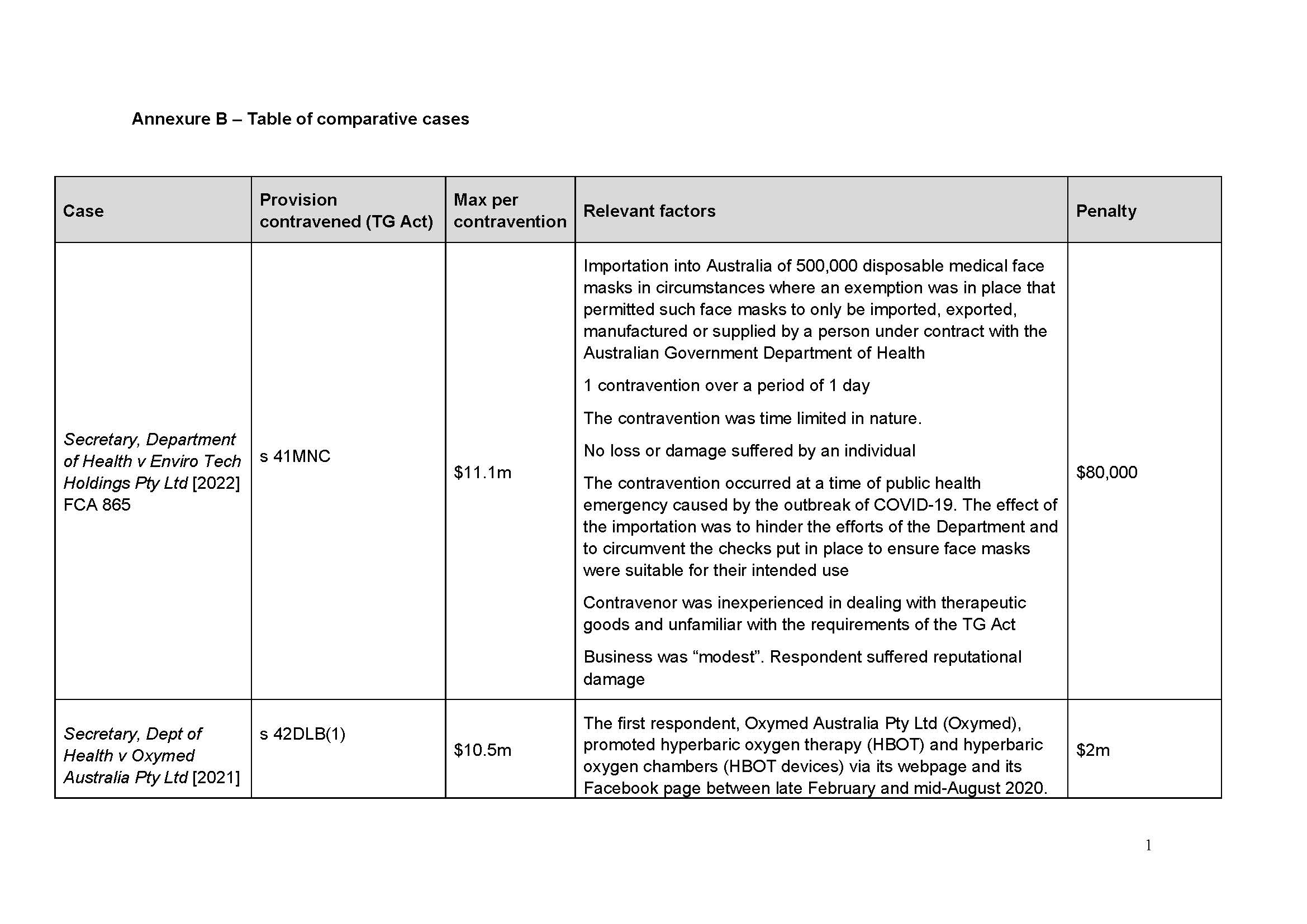

131 I have been supplied with a table of comparable cases (which is annexed to this judgment as Annexure A). None is a true comparator in the sense that there are such similar circumstances that they give me guidance as to penalty. I agree with the parties’ contention in the Joint Submissions that:

it is the consistent application of principle that is relevant to the assessment of penalty, rather than the range of penalties given in disparate circumstances that cannot be said to be analogous: Flight Centre Limited v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (No 2) [2018] FCAFC 53; 260 FCR 68 (Allsop CJ, Davies and Wigney JJ) at [63].

132 Having regard to the totality of the conduct, and the proposed penalty of $22 million as an agreed penalty, it seems to me that the penalty is a suitable one on the basis of both general and specific deterrence, as well as reflecting the significance of the extent of the contraventions and the failures of compliance and regulatory processes within Medtronic.

133 The parties, jointly, seek the following orders:

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Pursuant to s 42Y(2) of the Therapeutic Goods Act 1989 (Cth) (TG Act), [within 28 days] of the making of this Order, the Respondent pay to the Commonwealth of Australia a civil penalty in the amount of $22,000,000.

2. Pursuant to s 43 of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth), [within 28 days] of the making of this Order, the Respondent pay the Applicant’s costs of, and incidental to, this proceeding, agreed in the amount of $1,000,000.

134 For all the reasons above, I am prepared to make those orders.

I certify that the preceding one hundred and thirty four (134) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice Needham. |

Associate:

ANNEXURE A

ANNEXURE A