Federal Court of Australia

Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Retail Employees Superannuation Pty Ltd [2024] FCA 1081

File number: | VID 94 of 2021 |

Judgment of: | BEACH J |

Date of judgment: | 18 September 2024 |

Catchwords: | SUPERANNUATION — industry superannuation fund — rollover requests by members — Division 6.5 of the Superannuation Industry (Supervision) Regulations 1994 (Cth) — sections 10, 19 and 42 of Superannuation Industry (Supervision) Act 1993 (Cth) — representations to members concerning rollover entitlements — limitation or restriction on members’ ability to transfer their superannuation balance to other funds — misleading or deceptive conduct — sections 12DA and 12DB of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth) — section 1041H of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) — whether conduct or representations “in trade or commerce” — construction of superannuation trust deed and the SIS Regulations — meaning of “member’s interest in the fund” — contingent equitable interest — mere expectancy |

Legislation: | Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth) ss 12BA, 12BAA, 12BAB, 12CB, 12DA, 12DB Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) ss 601RAC, 764A, 766A, 766C, 1041H Corporations Legislation Amendment (Financial Services Modernisation) Act 2009 (Cth) Superannuation Guarantee (Administration) Act 1992 (Cth) ss 19, 32C Superannuation Industry (Supervision) Act 1993 (Cth) ss 3, 10, 19, 30, 31, 34, 42, Superannuation Industry (Supervision) Regulations 1994 (Cth) Div 6.5 Explanatory Memorandum, Corporations Legislation Amendment (Financial Services Modernisation) Bill 2009 Explanatory Statement, Superannuation Industry (Supervision) Amendment Regulations 2003 (No 5), Statutory Rules 2003 No 251 Explanatory Statement, Select Legislative Instrument 2005 No 142 |

Cases cited: | Australian Securities and Investments Commission v TAL Life Ltd (No 2) (2021) 150 ACSR 224 Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Westpac Banking Corporation (No 2) (2018) 127 ACSR 110; (2018) 266 FCR 147 Commissioner of Taxation v Everett (1980) 143 CLR 440 Concrete Constructions (NSW) Pty Limited v Nelson (1990) 169 CLR 594 Glorie v W A Chip & Pulp Co Pty Ltd (1981) 39 ALR 67 Horwood v Millar’s Timber and Trading Company, Limited [1917] 1 KB 305 Kowalski v Mitsubishi Motors Australia Ltd Staff Superannuation Fund Pty Ltd (2007) 242 ALR 370 Monroe Topple & Associates Pty Ltd v Institute of Chartered Accountants in Australia (2002) 122 FCR 110 National Australia Bank Ltd v Norman (2009) 180 FCR 243 Norman v Federal Commissioner of Taxation (1963) 109 CLR 9 Pallette Shoes Proprietary Limited (in Liquidation) v Krohn (1937) 58 CLR 1 Shepherd v Commissioner of Taxation (1965) 113 CLR 385 Tobacco Institute of Australia Limited v Australian Federation of Consumer Organisations Inc (1992) 38 FCR 1 Village Building Company Ltd v Canberra International Airport Pty Ltd (2004) 139 FCR 330 Williams v Pisano (2015) 90 NSWLR 342 |

Division: | General Division |

Registry: | Victoria |

National Practice Area: | Commercial and Corporations |

Sub-area: | Regulator and Consumer Protection |

Number of paragraphs: | |

Date of hearing: | 1 and 2 November, 18 December 2023 |

Mr M Wise KC, Ms E A Bennett SC and Mr A Ounapuu | |

Solicitor for the Plaintiff: | Australian Securities and Investments Commission |

Counsel for the Defendant: | Mr C M Caleo KC and Mr P G Liondas SC |

Solicitor for the Defendant: | Allens |

ORDERS

AUSTRALIAN SECURITIES AND INVESTMENTS COMMISSION Plaintiff | ||

AND: | RETAIL EMPLOYEES SUPERANNUATION PTY LTD (ACN 001 987 739) Defendant | |

DATE OF ORDER: | 18 SEPTEMBER 2024 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The proceeding be dismissed.

2. Subject to order 3, the plaintiff pay 80% of the defendant’s costs of and incidental to the proceeding to be taxed in default of agreement.

3. If either party within 7 days of the date hereof notifies the Court that they wish to contend for a different costs order than that provided for in order 2, then order 2 will not operate.

4. If any such notification contemplated by order 3 is given, the Court will then make directions for the resolution of any costs questions.

5. Liberty to apply.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

BEACH J

1 Retail Employees Superannuation Pty Ltd (REST) is the trustee of the Retail Employees Superannuation Trust (the Trust), which is an industry superannuation fund covering workers in the retail and hospitality sectors.

2 The present proceeding brought by the Australian Securities and Investments Commission concerns REST’s former practices in response to rollover requests received from members for whom a major employer was required to make contributions to REST’s superannuation fund (the fund) under a workplace determination or enterprise bargaining agreement; from time to time I will refer to such a member as a determination member.

3 Rollover requests are and have been governed by Div 6.5 of the Superannuation Industry (Supervision) Regulations 1994 (Cth) made under the Superannuation Industry (Supervision) Act 1993 (Cth).

4 ASIC alleges that REST’s rollover practices between 2 March 2015 and 2 May 2018 (the relevant period) had the effect of limiting or restricting determination members’ ability to transfer their superannuation balance to other funds.

5 In that context, it is alleged by ASIC that REST made various categories of representations to more than 31,000 determination members, each of which was false or misleading or deceptive, in the scenario where members sought to transfer the whole of their superannuation balance to another fund. It is said that such conduct contravened s 12DA(1) and/or s 12DB(1)(i) of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth) and/or s 1041H of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth).

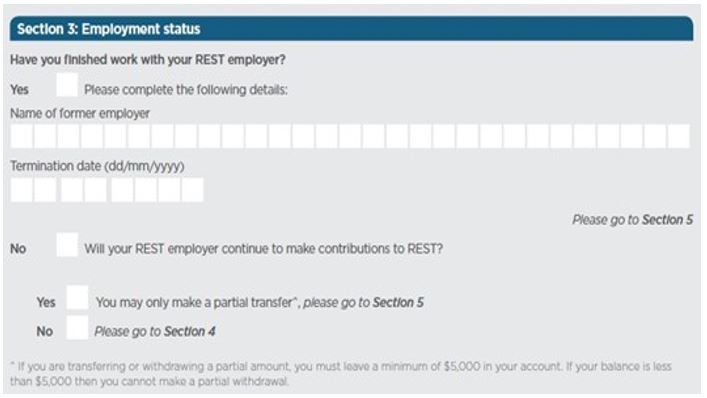

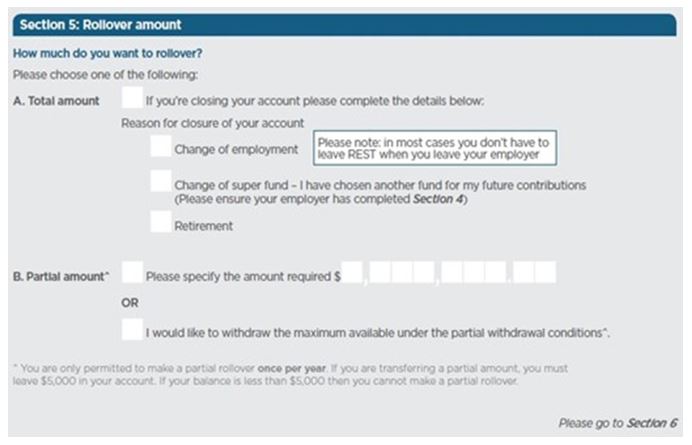

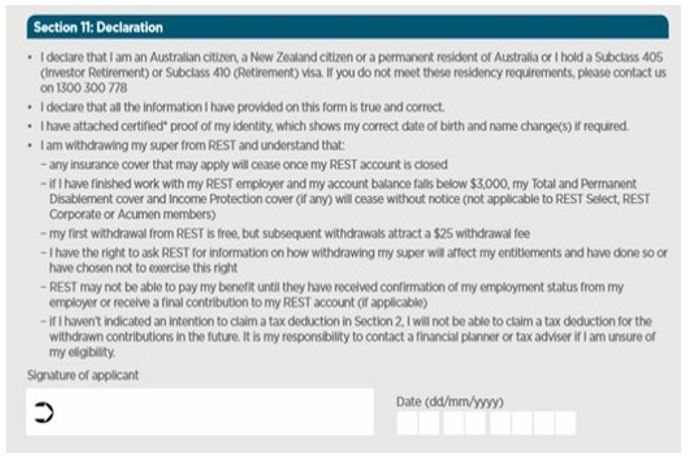

6 First, it is said that REST represented that if a member remained employed by a REST employer and the REST employer was to continue to make contributions to the fund, then the member could only partially transfer their superannuation balance out of the fund (the partial transfer representation).

7 Second, it is said that REST represented that if a member continued to be employed by a REST employer, then they were required to maintain a minimum amount of $5,000 in their REST account (the $5,000 representation).

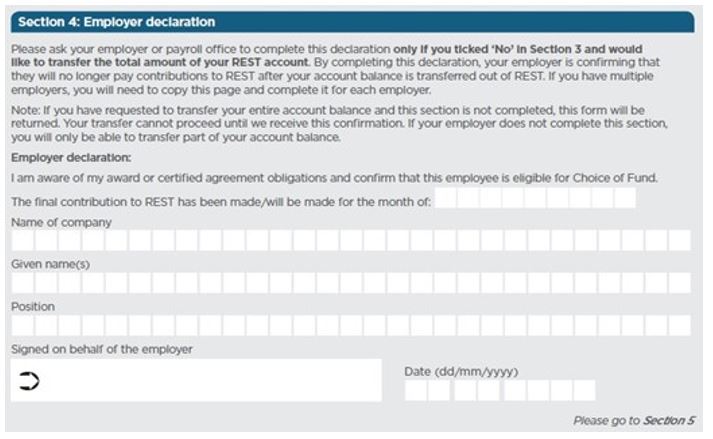

8 Third, it is said that REST represented that members were required to obtain a declaration from their employer that the member had choice of fund rights and of the date upon which the REST employer ceased making contributions to the fund, as a pre-requisite to effecting the transfer, and that a failure to provide that declaration meant that the transfer request could be refused by REST (the declaration requirement representation).

9 Fourth, it is said that REST represented that a request could only be processed where a member obtained a separation certificate from their employer or provided a date of termination (the certificate requirement representation).

10 One or more of these representations were said to be made to determination members in circumstances which I will set out in detail later. It is said by ASIC that such representations were representations of fact as distinct from statements of opinion or representations of law. And it is said that such representations were false or misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive.

11 More generally, ASIC says that in the relevant period, and as a consequence of REST’s practices, REST prevented its members from transferring out their funds where the member was a determination member of the fund who continued to be employed by the same employer. And it did this by treating any whole of balance transfer request as a partial transfer request, by imposing a minimum balance amount of $5,000 and by requesting information beyond that permitted by the SIS Regulations. It is said that REST was wrong to treat determination members as incapable of transferring the entirety of their funds from REST to a superannuation provider of their choice.

12 Now REST has resisted ASIC’s case on various grounds. Let me briefly summarise them.

13 First, it is said that because all determination members had an expectation of receiving further contributions, REST was justified in treating any transfer request as a partial transfer request. And as a corollary of this, it says that its practice complied with the requirements of Div 6.5 of the SIS Regulations.

14 Second, it is said that the representations alleged by ASIC were not made by reason of the statements on which ASIC relies.

15 Third, REST says that if the representations were made and had the character alleged by ASIC, then having regard to the proper construction of Div 6.5 of the SIS Regulations at the time, the representations were not false, misleading or deceptive.

16 Fourth, it is said that the representations, if made, were not representations as to the fact of the operation of Div 6.5 of the SIS Regulations, but were either statements of REST’s practices as a matter of fact or, to the extent that the representations were statements as to what was required by Div 6.5, the statements were no more than representing REST’s opinion of the law, which opinion was honestly and reasonably held.

17 And on that latter point as to whether REST’s opinion was reasonably held, REST has relied upon its dealings with the Australian Prudential Regulatory Authority in the period 2007 to 2009, and external legal advice received in the period 9 September 2005 to 13 April 2018 to justify the reasonableness of the opinion held. I should say that before me there was no serious issue as to the fact of REST holding the relevant opinion or that it was honestly held.

18 Fifth, REST says that the claims under ss 12DA(1) and 12DB(1)(i) fail because the representations relied on were not relevantly made “in trade or commerce”. I should say now that I have rejected REST’s case on that legal point.

19 Sixth, it is said that the representations were not relevantly in relation to financial services or in connection with the supply of financial services, as required by s 12DA(1) and s 12DB(1)(i). I have also rejected REST’s argument on that point.

20 Seventh, it was originally said by REST that the representations did not concern the existence, exclusion or effect of a “right” within the meaning of s 12DB(1)(i). But during submissions, Mr Christopher Caleo KC for REST abandoned the point. REST does not now contend that the representations, if made, did not concern the existence, exclusion or effect of a right within the meaning of s 12DB(1)(i). If I accept that the representations were made, then they did concern the existence, exclusion or effect of a right, being a determination member’s right to transfer the whole of their superannuation balance to another fund.

21 Let me briefly say something about the evidence.

22 ASIC contends that the representations were made in REST’s standard forms provided to determination members whenever they requested a balance transfer. ASIC also contends that the representations were made in telephone calls and written correspondence. ASIC relies upon the affidavits of former members of REST, being person A, person B, person C, person D and person E. It also relies upon the affidavits of an ASIC investigator and an ASIC data analyst. There was no cross-examination of any of these witnesses.

23 REST relied upon the affidavit of Mr Joseph de Bruyn, a director of REST during the relevant period. Ms Elizabeth Bennett SC for ASIC cross-examined Mr de Bruyn, and I will identify some of the highlights of this later.

24 The parties have also tendered voluminous documentary material and a further amended statement of agreed facts.

25 More generally, the parties have also agreed on the terms of an amended grouping document, which groups the many instances of oral and written representations in the schedules to the statement of claim. The effect of this agreement is that for the majority of representations, I need only make relevant findings about exemplar instances of representations.

26 In summary and for the reasons that follow, I have rejected ASIC’s case.

27 In terms of my detailed reasons, it is convenient to divide the relevant topics into the following sections:

(a) Some relevant background — [29] to [103].

(b) The SIS Act and the SIS Regulations — [104] to [124].

(c) The question of a “member’s interest in the fund” — [125] to [264].

(d) Legal principles concerning ASIC’s claims — [265] to [284].

(e) Was the relevant conduct “in trade or commerce”? — [285] to [321].

(f) Were the representations “in relation to” or “in connection with” financial services? — [322] to [369].

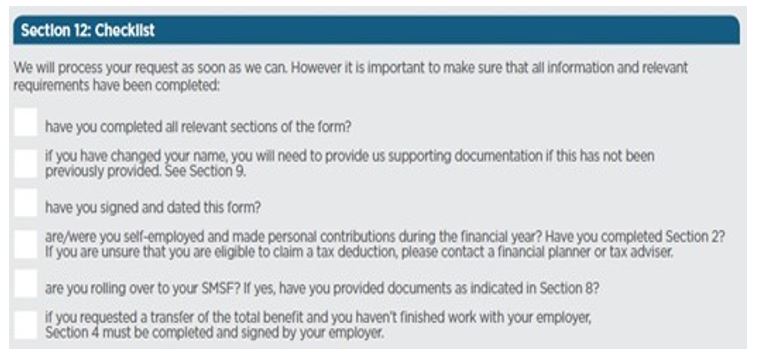

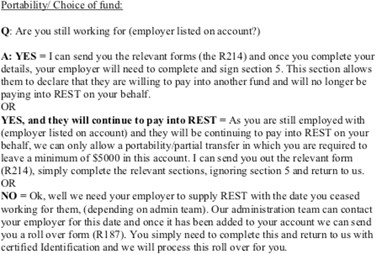

(g) Benefit payment rollover forms — [370] to [397].

(h) Exemplar determination member instances — [398] to [447].

(i) The partial transfer representation — [448] to [481].

(j) The $5,000 representation — [482] to [530].

(k) The declaration requirement representation — [531] to [575].

(l) The certificate requirement representation — [576] to [628].

(m) The question of characterisation — [629] to [667].

(n) Was REST’s opinion reasonably held? — [668] to [810].

(o) ASIC’s case concerning REST’s opinion — [811] to [938].

(p) Were the representations false or misleading or deceptive? — [939] to [950].

(q) Conclusions — [951] to [953].

28 Let me begin by setting out some of the relevant background.

29 REST is amongst the largest superannuation funds in Australia by membership, and is a profit-to-member fund. It is required to operate subject to the relevant provisions of the SIS Act and the relevant provisions of the SIS Regulations, as in force at the relevant time. I will elaborate on some aspects of this later.

30 During the relevant period, REST held net assets available for member benefits on behalf of members of the Trust as follows:

Year | Net assets |

Financial year ended 30 June 2015 | $37b |

Financial year ended 30 June 2016 | $40b |

Financial year ended 30 June 2017 | $46b |

Financial year ended 30 June 2018 | $52b |

31 During the relevant period, REST’s membership was as follows:

Year | Members |

Financial year ended 30 June 2015 | Approximately 2m |

Financial year ended 30 June 2016 | Approximately 1.9m |

Financial year ended 30 June 2017 | Approximately 1.9m |

Financial year ended 30 June 2018 | Approximately 1.95m |

32 The Trust administered by REST is a complying superannuation fund for the purposes of s 42 of the SIS Act. Moreover, pursuant to s 52(2)(a) of the SIS Act, the governing rules of REST are taken to contain a covenant that REST will act honestly in all matters concerning the entity.

33 The Trust and REST’s obligations thereunder are governed by a trust deed.

REST membership

34 The rules of management, which are set out within the trust deed, detail the rules of the Trust. The rules in operation during the relevant period were set out in the trust deed amendment no. 39 (2013 rules) and the trust deed no. 41 (2016 rules).

35 Under the 2013 rules and the 2016 rules, the following people were eligible to become a member of the Trust. First, an employee, who was eligible to become an employer-sponsored member, and where a contribution was validly made in accordance with the rules. Second, a person, on receipt by REST of an amount transferred to the Trust in respect of the successor fund member from another superannuation fund. Third, a person, if the person was not eligible to become an employer-sponsored member, and applied in writing in such form as REST determined.

36 REST accepted contributions or other payments to the Trust in respect of members. Moreover, a member could hold one or more classes of beneficial interest in the Trust at any one time.

37 Now during the relevant period, REST permitted members to direct it to invest their superannuation balance in accordance with an investment option or investment options.

38 Further, REST was required under the 2013 rules and the 2016 rules to ensure that each member was notified in writing of, inter-alia, their right and the right of their dependents to receive benefits from the associated Plan, the conditions relating to those benefits and the method of determining those benefits, and such other matters as required by the SIS Act and, where applicable, the Corporations Act, and regulations made under those Acts.

39 Until 11 May 2018, REST had in place rules which recorded practices and operational requirements to be applied by Australian Administration Services Pty Limited (AAS), the administrator appointed by REST to administer the Trust, in performing administration services on behalf of REST and maintaining the register of members and their benefits.

REST’s rules and insurance

40 During the relevant period, new and returning members of REST were automatically provided with a default basic cover insurance package, which included death, total and permanent disablement and long-term income protection cover.

41 Unless the member notified REST to cancel their insurance, the insurance fees would be automatically deducted from their account. If a member’s account balance was insufficient to cover the cost, their cover would cease.

42 Relevantly, the 2013 rules and the 2016 rules contained the following provisions.

43 Rule 2.13 of the 2013 rules and rule 2.19 of the 2016 rules provided that:

(a) A Member’s membership of the Plan ceases on the last to occur of the following;

(i) when the Trustee has paid the benefits including any amount payable under any insurance cover to which the Trustee believes that the Member is entitled: and

(ii) on any insurance cover as specified in the applicable insurance policy or in writing by the Trustee ceasing.

44 Rule 5A.2(c) of the 2013 rules provided that:

The benefit of any insurance cover shall cease in accordance with the terms set out in the insurance policy or if rule 5A.3 [of the Rules of Management] applies, then the benefit of the insurance cover will cease in terms of rule 5A.3.

45 Similarly, rule 5.1(c) of the 2016 rules provided that:

The benefit of any insurance cover shall cease in accordance with the terms set out in the insurance policy or, if rule 5.2 applies, then the benefit of the insurance cover will cease in terms of rule 5.2.

46 Rule 5A.3 of the 2013 rules and rule 5.2 of the 2016 rules provided that insurance cover would cease in the following scenarios:

(a) in accordance with the terms contained in the policy of insurance with the Insurer and set out in the Member Information attached to the Member Application;

(b) on written notice to the Trustee given by the Member;

…

(e) if the amount standing to the credit of a Member’s Member Account is insufficient to pay the costs attributable to that Member of providing that cover.

47 Rule 5.3 of the 2016 rules detailed where insurance cover applying to a member may change.

48 In addition, REST’s rules during the relevant period provided further detail as to the cessation and top-up of insurance cover.

49 Rule 10.2.9 of the rules defined an insufficient amount to pay the premium. A member’s cover would cease on the earliest of circumstances including:

…

When a REST Corporate or REST Super member has an insufficient account balance to cover the premiums, the member will be given an opportunity to top up their account balance within 28 days (+ 7days to allow for postage). If no top-up is received, the member will lose their insurance cover from the last Friday in the month in which the balance becomes insufficient to cover that month’s premium;

When the member cancels cover;

The date the member leaves REST Super;

A member’s date of death;

For a member on continued cover, TPD and IP cease once the member’s account balance falls below $3,000 (only for REST Super);

Death cover will continue while the account remains above $1,200. Once their account balance drops below $1,200, all cover will cease without notice (only for REST Super).

…

Where an employed member’s account balance is insufficient to cover insurance costs, the Administrator will write to the member to advise that cover has ceased and offer the member an opportunity to top up their account within 28 days (+7 days to allow for postage) of the account going negative…

REST’s member superannuation transfer processes

50 Now superannuation contributions are made by members directly or by employers to REST on behalf of members.

51 From at least October 2000, where a member sought to transfer their superannuation balance from the Trust, in circumstances where REST’s records indicated that the member was employed by an employer which was required to make mandatory contributions into the Trust on behalf of a member under a workplace determination or an enterprise agreement, which as I say I will from time to time refer to as a determination member, REST required a minimum balance to be retained in that member’s account (minimum transfer balance) unless satisfied that the employer would not be making further mandatory contributions into the Trust.

52 The minimum transfer balance was $1,000 from at least October 2000 to January 2003 and $1,200 from January 2003 to May 2005.

53 But on 26 May 2005 the board of directors of REST resolved to increase the minimum transfer balance from $1,200 to $5,000.

54 A REST board paper for the board meeting on 26 May 2005 stated that:

The SIS Regulations allow a trustee to refuse an application for transfer where the fund has received an employer contribution in the last 6 months.

Where this is not the case, and a member wishes to rollover or transfer, the legislation allows the fund to impose a minimum of $5,000 to remain in the fund unless the member rolls over or transfers their entire benefit.

…

Over $3.2 million was transferred out of REST. If a minimum of $5,000 was imposed, approximately $700,000 would have been retained, more than was retained with the $1,200 limit. 51 transfers would not have been processed at all.

55 Now in September 2005, REST’s rules provided for various matters, some of which it is necessary to set out.

56 In rule 6.3.2 it was provided:

Where a request for a partial transfer is received and the transfer would result in the member’s account balance falling below $5,000, the transfer request will be refused and the administrator will write to the member to advise the member. A partial transfer applies where:

…

(b) if the member requests a transfer of their full account balance, where the employer has a contribution obligation, via legislation, industrial agreement or deed of application, to continue to make ongoing contributions to REST.

57 In rule 6.3.4 it was provided:

Where a request for a transfer of the whole account balance, or it is unclear whether the member wishes to make a full or partial transfer, is received for a member for whom no termination date is received, the administrator will contact the member’s employer to:

• confirm the member’s termination date (if applicable); or

• confirm whether or not the employer will be continuing to make contributions to REST on behalf of the member.

The administrator may accept the advice of the employer via telephone in this instance providing a file note is made on the member’s record.

58 In rule 6.3.5 it was provided:

Where the member has left employment, the administrator will send the member a Portability Notice. Unless a response is received from the member (either verbally or in writing) within 10 business days from the date of REST’s letter, the administrator will action the transfer request and close the member’s account.

59 In rule 6.3.6 it was provided:

Where the member’s employer advises that the member is still employed but that no further contributions will be made to REST, the administrator send [sic] to the Member for signature and return a Portability Acknowledgement containing an acknowledgement that the member understands the benefit entitlements for which the member will no longer be entitled upon closure of the account.

Upon receipt of a signed Portability Acknowledgement, the administrator will transfer the amount in terms of the request and close the member’s account.

60 In rule 6.3.7 it was provided:

Where the member’s account balance is above $5,000 and his or her employer advises that further contributions will be made to REST, the administrator will advise the REST Client Service Manager of the individual member’s request to transfer out.

61 In rule 6.3.8 it was provided:

Where the member’s account balance is below $1,200 ($5,000 from 1 January 2006) and his or her employer advises that further contributions will be made to REST, the transfer request will be refused and the administrator will write to the member and transferring fund to advise of the refusal.

62 In rule 6.3.9 it was provided:

The REST Client Service Manager is responsible for providing a report to the administrator on the reasons for transfer in respect of those transferring members employed by employers who:

(a) have more than 9 employees in REST; and

(b) are not on the automatic approval list. Or

(c) a transfer request is made and ongoing contributions are expected as per 6.3.7.

63 In rule 6.3.10 it was provided:

The administrator is responsible for finalising the transfer out within 5 days of all documentation being received provided that Trustee approval has been provided.

64 Now on 10 March 2006, REST amended rule 6.0 of its rules to define an “individual partial transfer” to be:

Where a transfer request is made and either the member:

• … the member’s employer confirms that contributions will continue to be made to REST (as such, the member will have a continuing interest in the fund); or

• the Trustee is aware of an industrial instrument that requires contributions to continue to be made to REST (ie a continuing interest).

Where a partial transfer is requested, REST requires that the member leave a minimum balance of $5,000 in his or her account after the transfer is processed.

65 From February 2009, REST’s benefit transfer form stated that:

You can only transfer your entire account balance out of REST if your current employer will no longer be making super contributions into your account. If you select to transfer your entire account balance, your employer must complete section 5 [the employer declaration section] of this form, unless you have been promoted and are transferring into a corporate fund or your award has changed.

66 In August 2013, REST amended its rules to provide in rule 6.4.3.1 as follows:

The Administrator must notify REST Operations of any member who is part of a major REST employer. REST will provide a database of enterprise agreements as negotiated by the SDA and / or REST’s employers to REST Operations. Where a rollover to an APRA regulated super fund request is received from a member who is subject to an enterprise agreement specified in the database, the Administrator will notify REST Operations (Askops@Rest.com.au). The transfer out will not be actioned by the administrator without approval from REST Operations.

67 Let me at this point summarise some other matters.

68 The trust deed, and the rules which appeared at the end of the trust deed and formed part of the trust deed (clause 1.2), provided for the following matters.

69 First, it provided for the commencement of membership, which occurred only when REST received a contribution or transfer from another fund (rule 2.4.1 of the 2013 rules and rule 2.10 of the 2016 rules).

70 Second, it provided for the maintenance of member accounts, which recorded only dollar amounts (rule 4.1).

71 Third, it provided for the cessation of membership, which generally occurred when REST had paid out the benefits (including any amount under an insurance policy) to which REST believed the member was entitled and any insurance cover had ceased (rule 2.13 of the 2013 rules and rule 2.19 of the 2016 rules).

72 Fourth, it provided for transfers or rollovers out of the fund (clause 18 of the trust deed).

73 Further, in respect of transfers out, the trust deed provided that (clause 18.3(b) of the trust deed):

Upon the transfer to another fund of the whole of the amount standing to the credit of a Member’s Member Account, that Member will cease to be a Member and the Trustee shall be thereupon released and discharged from all liability whatsoever to or in respect of that Member.

74 Now ASIC says that, properly construed, the trust deed makes clear the following.

75 First, a person can only be a member if they have an amount in actual dollars standing to their credit in their member account.

76 Second, if, for any reason, a member’s account balance reduces to nil, they will cease to be a member.

77 Third, if a member requests a whole balance transfer, being a transfer of the entire dollar amount standing to their credit in their member account, then upon that transfer they will cease to be a member.

78 On that construction, ASIC says that there can be no concept of a person remaining a member because they might receive further contributions at some future time from their employer. Further, ASIC says that the trust deed explicitly excludes the possibility that a person’s possible future receipt of such contributions might constitute a present “interest in the fund”.

79 I will return to these propositions shortly. But it is convenient to deal with another matter at this point.

Obligation on employers

80 Clause 19 of the original trust deed dated 2 December 1987 required employers to complete and deliver a deed of adoption to participate in “the Plan”, that is, the trust of which REST is the trustee, and be bound by the trust deed.

81 On 13 December 1988, REST amended the trust deed to include the following clauses:

13. ADMISSION OF EMPLOYERS

13.1 Application

An Employer which desires to participate in the Plan shall apply to the Trustee for admission to the Plan in or to the effect of the form set out in Appendix “A” to this Deed or in any other form acceptable to the Trustee generally or in particular.

13.2 Acceptance or Rejection

The Trustee may, after obtaining such advice as is necessary, accept or reject any such Application by an Employer.

13.3 Effect of Application

The Application by the Employer for admission to the Plan shall, on being accepted as referred to in Clause 13.2 and until amended as hereinafter provided:-

(i) set out in the terms and conditions under which the Employees of the Employer are admitted to the Plan, the contributions by and in respect of those Employees and the benefits to be provided: and

(ii) be binding on the Employer and each of the Employees of the Employer who become a Member of the Plan.

82 At this time, the trust deed was also amended to include an “Application Form to become a Participating Employer of the R.E.S.T Superannuation Plan” at Appendix A. This form contained the following clause:

The Participating Employer agrees to be bound by the terms and conditions of the Trust Deed

83 On 20 December 2012, REST deleted the existing clauses of the trust deed and inserted inter-alia new clauses and rules. Clauses 13 and 17.1 were inserted as follows and applied throughout the relevant period:

13.1 Application

An employer which desires to participate in the Plan may apply to the Trustee for admission to the Plan in or to the effect of the form set out in Appendix “A” to this Deed or in any other form acceptable to the Trustee generally or in particular.

13.2 Acceptance or Rejection

The Trustee may, after obtaining such advice as is necessary, accept or reject any such Application by an employer.

13.3 Effect of Application

The Application by the employer for admission to the Plan shall, on being accepted as referred to in clause 13.2 and until amended as hereinafter provided:

(a) set out the terms and conditions under which the employees of the Employer are admitted to the Plan and the contributions by and in respect of those Employees;

(b) be binding on the employer and each of the Employees of the employer who become a Member of the Plan; and

(c) operate as an amendment to the Plan.

…

17.1 Withdrawal of Employer

(a) An Employer may not terminate its contributions in respect of a Member employed by it unless it applies in writing to the Trustee giving reasons for the request to terminate its contributions and the Trustee gives its approval to the request;

…

(d) Permission to terminate contributions in terms of paragraph (a) will not be granted where to do so would to the Trustee’s knowledge breach any legislation or Industrial Agreement;

(e) An Employer’s liability to cease paying contributions to the Plan will end on the earlier of the date specified in the Trustee’s written approval or if no date is specified the date of the Trustee’s written approval;

(f) An Employer will remain liable to pay to the Trustee all contributions due before the date the Employer’s liability to cease paying contributions to the Plan took effect.

…

84 Further, clause 18 provided the following:

18. TRANSFERS TO OR FROM OTHER PLANS

18.1 If a Member becomes a member of another Complying Fund and the trustee of that other fund permits then, subject to clause 18.3(a) hereof, the Trustee shall, unless the Trustee decides otherwise, at the request of the Member transfer all or part of the amount standing to the credit of that Member’s Member Account to that other Complying Fund.

…

18.3

…

(b) Upon the transfer to another fund of the whole of the amount standing to the credit of a Member’s Member Account, that Member will cease to be a Member and the Trustee shall be thereupon released and discharged from all liability whatsoever to or in respect of that Member.

(c) Upon the transfer to another fund of a portion of the amount standing to the credit of the Member’s Member Account, the Trustee shall thereupon be discharged from all liability whatsoever in respect of the portion so transferred and may thereafter reduce or otherwise adjust any benefit to be provided for in respect of that Member under this Deed to such extent as it in its discretion considers to be appropriate having regard to the amount transferred.

…

85 Appendix A was re-inserted with a note that “This form is no longer in use”.

86 The employer guides in operation from April 2010 to February 2011 and from February 2011 to July 2013 contained a copy of the employer application. This application stated:

We hereby agree to:

(a) be bound by the terms and conditions of the trust deed and rules of REST (dated 2 December 1987) as amended from time to time

(b) pay contributions:

(i) monthly, or

(ii) as required to reduce our superannuation guarantee obligation to nil and to meet our other legal obligations.

(Cross out whichever is not applicable. If neither i or ii have been crossed out, i applies)

(c) inform the Trustee of a terminating employee, or an employee for whom we will be ceasing to make contributions, within 30 days of the event.

87 The employer guides in the relevant period stated:

It’s important you let us know when your staff leave or join your company. It will help us ensure payments are correctly allocated, made on time and that members will not become ‘separated’ from their super. You’ll also have up to date records which will help us provide you with meaningful and correct information.

…

We have an obligation to take reasonable steps to ensure contributions for members are paid on time. If you fail to make contributions, we will send you a reminder. If we still do not receive outstanding contributions, we will ask our arrears collection agency to look into the matter.

88 Now for a number of major REST employers, REST received participating employer applications.

89 So for example, in early 1989, REST received participating employer application forms from Woolworths (Q.L.D.) Limited in respect of Queensland employees, Woolworths Limited in respect of New South Wales employees, Woolworths Limited and Australian Safeway Stores Pty Limited in respect of Victorian employees, Woolworths (S.A.) Limited in respect of South Australian employees, and Woolworths Limited in respect of Western Australian employees.

90 In addition, Bunnings Building Supplies joined REST as a REST employer on 3 August 1993 and REST received an application on 23 August 1993. Officeworks joined REST on 26 April 1994 and REST received an application on 8 June 1994.

91 Let me by way of background say something more about REST’s practice during the relevant period.

REST’s practice during the relevant period

92 Now as I have already indicated, from at least October 2000, where a member sought to transfer their superannuation balance from the Trust, in circumstances where REST’s records indicated that the member was employed by an employer which was required to make mandatory contributions into the Trust on behalf of a member under a workplace determination or an enterprise agreement, REST required a minimum transfer balance to be retained in that member’s account unless satisfied that the employer would not be making further mandatory contributions into the Trust.

93 Now practically speaking, during the relevant period when REST received a rollover request from a determination member for the whole of their withdrawal benefit, its practice was as follows.

94 If REST had not received notification from the employer that the member’s employment had been terminated, REST would ask the determination member for a statement from their employer (or former employer) to confirm whether or not the determination member’s employment had been terminated and, if it had not, whether the employer was otherwise not required to make any further contributions to the fund under the determination for the member.

95 Where the employer notified REST that the determination member’s employment had terminated, or that the employer otherwise would not be making any further contributions for the member under a determination, REST would proceed to rollover the member’s account balance in accordance with the member’s rollover request.

96 Where the employer notified REST that the determination member’s employment had not terminated and the employer’s obligation to make contributions to the fund for the member under a determination continued, REST did not permit the member to rollover all of their account balance. REST required the member to retain in the fund the minimum transfer balance which, during the relevant period, was $5,000.

97 But REST would process the transfer without confirmation of whether the determination member’s employment had been terminated if, prior to the request, 12 months had passed since the last contribution for a determination member.

98 Now it is convenient to deal with one other matter at this point.

99 Section 19 of the Superannuation Guarantee (Administration) Act 1992 (Cth) in essence makes an employer liable to a superannuation guarantee charge if mandatory employer contributions are not made in accordance with the “choice of fund” requirements.

100 The “choice of fund” requirements under that Act were satisfied if the employer contributed to a fund specified in an award or determination (s 32C(6)). Accordingly, if the employer was contributing in accordance with an award or determination, the employer was not required to offer choice of fund to the employees for whom such contributions were made.

101 Now there were “portability” provisions in the SIS Act and the SIS Regulations, which enabled members to rollover some or all of their superannuation to another fund and provided that trustees could decline a rollover request in certain circumstances.

102 Moreover, in general terms whilst members had the ability subject to certain qualifications to request a rollover of their superannuation withdrawal benefit, members’ employers were obliged, in certain cases, to continue making contributions to the fund specified in an award or determination.

103 So, the practical outcome that prevailed during the relevant period was that a member could seek to rollover from the fund but the prospect existed where future employer contributions could continue to be paid into the fund.

The SIS Act and the SIS Regulations

104 The main object of the SIS Act is to “make provision for the prudent management of certain superannuation funds … and for their supervision by APRA, ASIC and the Commissioner of Taxation” (s 3(1)).

105 A “superannuation fund” is defined in the SIS Act to include an indefinitely continuing fund (s 10(1)). A superannuation fund may be a “regulated superannuation fund” if, relevantly, it has a corporate trustee and it gives a notice to the Commissioner of Taxation electing that the SIS Act is to apply in relation to the fund (s 19(2), (3)(a) and (4)). Such a regulated superannuation fund is then a “superannuation entity” and a “registrable superannuation entity” (s 10(1)). It may also, from year to year, be a “complying superannuation fund” (s 42)).

106 The fund operated by REST at all material times has been a complying superannuation fund and therefore a regulated superannuation fund.

107 Part 3 of the SIS Act establishes a system of operating standards that apply to, inter-alia, regulated superannuation funds (s 30). Pursuant to s 31(1), the standards themselves are found in the SIS Regulations. Pursuant to s 31(2)(i), the standards may provide for “the portability of benefits arising directly or indirectly from amounts contributed to funds”.

108 Part 6 of the SIS Regulations is headed “Payment standards” and sets out operating standards in relation to a number of matters. Relevantly for this proceeding, Div 6.5 deals with the rollover and transfer of superannuation benefits in regulated superannuation funds.

109 Div 6.5 of the SIS Regulations is entitled “[c]ompulsory rollover and transfer of superannuation benefits in regulated superannuation funds and approved deposit funds”. Div 6.5 was amended in 2013 and again in 2014. It is the version of the SIS Regulations in force following those amendments that applied during the relevant period.

110 Regulation 6.33(1) of the SIS Regulations allows a member of a regulated superannuation fund (the transferring fund) to request, in writing, that the whole or a part of the “member’s withdrawal benefit” in the transferring fund be rolled over or transferred to, among other entities, a regulated superannuation fund.

111 The term “withdrawal benefit” was defined to mean the total amount of benefits that would be payable if the member voluntarily ceased to be a member (reg 1.03(1)).

112 If a fund received a request to transfer a member’s “withdrawal benefit” to another fund, the request was required to be complied with (reg 6.34(2)), subject to two matters. First, the necessary information had to be provided (regs 6.34(1)(b) and (c)). Second, it was required that none of the circumstances justifying refusal applied (reg 6.35).

113 Moreover, the requirement under reg 6.34 was subject to regs 6.35 and 6.38.

114 Now pursuant to reg 6.34(1)(b), if the request was to transfer the whole of the member’s withdrawal benefit, the information that was required was that specified as mandatory in the relevant form. If the receiving fund was not a self-managed superannuation fund, schedule 2A was to be used. But in any other case, schedule 2B was to be used.

115 Pursuant to reg 6.34(1)(c), if the request was to transfer part of the member’s withdrawal benefit, the information that was required was that which would be required by the form. So, if the receiving fund was not a self-managed superannuation fund, what was required was the information set out in schedule 2A and any other information that was reasonably required to give effect to the rollover or transfer. If the receiving fund was a self-managed superannuation fund, what was required was the information set out in schedule 2B and any other information that was reasonably required to give effect to the rollover or transfer.

116 The forms in schedules 2A and 2B required members to provide the following information. Personal details being title, name, date of birth, tax file number, sex/gender, phone number, current and previous residential addresses were required. Transferring fund details being the fund name, fund phone number, membership or account number, ABN and Unique Superannuation Identifier were required. Receiving fund details were also required. In this context, schedule 2A required fund name, fund phone number, membership or account number, ABN and USI and schedule 2B required SMSF name, fund phone number, ABN, SMSF bank details and certified copies of proof of identity documents.

117 Now reg 6.35 relevantly provided as follows:

6.35 When a trustee may refuse to roll over or transfer an amount

(1) A trustee may refuse to roll over or transfer an amount under regulation 6.34 if:

…

(b) the amount to be rolled over or transferred is part only of the member’s interest in the fund, and the effect of rolling over or transferring the amount would be that the member’s interest in the fund from which the amount is to be rolled over or transferred would be less than $5,000; or

(c) the trustee has, under regulation 6.34, rolled over or transferred an amount of the member’s interest within 12 months before the request is received; …

…

(2) If a trustee refuses to roll over or transfer an amount under subregulation (1), the trustee must tell the member of the refusal in writing.

118 A fund was entitled to refuse a request for a transfer if, inter-alia, the amount to be rolled over or transferred is part only of the “member’s interest in the fund”, and the effect of rolling over or transferring the amount would be that the “member’s interest in the fund” from which the amount is to be rolled over or transferred would be less than $5,000 (reg 6.35(1)(b)).

119 Now it is to be noted that rather than using the defined term “withdrawal benefit”, reg 6.35(1)(b) used the term “member’s interest in the fund”, which is not defined.

120 As can be seen, under regs 6.34 and 6.35, a trustee must rollover a “withdrawal benefit” except that a trustee may refuse to rollover or transfer “an amount” if “the amount … is part only of the member’s interest in the fund” and the rollover would cause the member’s interest in the fund to be less than $5,000.

121 In these provisions, the SIS Regulations thereby utilise two (different) concepts: first, a member’s “withdrawal benefit” from the fund; and, secondly, a member’s “interest in the fund”.

122 A member’s withdrawal benefit is defined in reg 1.03(1) of the SIS Regulations as follows:

withdrawal benefit, in relation to a member of a superannuation entity, means the total amount of the benefits that would be payable to:

(a) the member; and

(b) the trustee of another superannuation entity or an EPSSS in respect of the member; and

(c) an RSA in respect of the member; and

(d) another person or entity because of a payment split in respect of the member’s interest in the superannuation entity;

if the member voluntarily ceased to be a member.

123 The word “interest”, and the phrase “interest in the fund”, are not defined.

124 Before dealing with the conduct elements of ASIC’s case against REST, it is necessary to deal with a point of construction and the lawfulness of REST’s practices which have significance for the causes of action alleged concerning the falsity or misleading nature of any representations made to determination members and also the question of whether REST had reasonable grounds for the expression of any opinion if indeed any representation made to a determination member could be characterised as a statement of REST’s opinion.

The question of a “member’s interest in the fund”

125 Let me begin with ASIC’s arguments concerning the meaning of the phrase “member’s interest in the fund”.

126 ASIC says that reg 6.35(1)(b) appears in Div 6.5, and that the focus of the division, together with the meaning of the defined term “withdrawal benefit”, is upon the amount in dollars that may be transferred. ASIC says that there are no provisions of Div 6.5 that suggest that a member might transfer non-monetary benefits. It is said that reg 6.35(1)(b) invites a comparison between the “member’s interest in the fund” and the fixed amount of $5,000.

127 It is therefore said that a “member’s interest in the fund” must be a monetary concept capable of being quantified in dollar terms.

128 Accordingly, ASIC says that a “member’s interest in the fund” does not include the expectation of future contributions from the member’s employer.

129 It says that the context in which superannuation portability was introduced, and the mischief to be addressed by the introduction of Div 6.5, was the immobility of retirement savings despite an increasingly mobile workforce.

130 It says that it should be assumed that the legislature was cognisant of the fact that in some industry awards and determinations, contributions by employers to a particular fund would be mandatory.

131 It says that were it the case that a “member’s interest in the fund” could include the right to receive future contributions, and putting to one side the difficulty in valuing that entitlement, Div 6.5 would have no operation whenever a determination member who continued in their employment with a REST employer requested a transfer. It says that the effect of that construction would be that such members would have their superannuation locked in to REST and would be denied the portability that was the object of the Division. It says that there is no indication that the legislature intended that outcome.

132 ASIC says that the extraneous material suggests the opposite.

133 The explanatory statement that accompanied the introduction of reg 6.35 stated, inter-alia, relevantly (Explanatory Statement, Superannuation Industry (Supervision) Amendment Regulations 2003 (No 5), Statutory Rules 2003 No 251, at p 4):

New Regulation 6.35 – When a trustee may refuse to roll over or transfer an amount

The trustee may refuse to roll over or transfer an amount if the fund or retirement savings account (RSA) to which the member has requested the transfer or rollover will not accept the amount.

The trustee may refuse to roll over or transfer an amount if the amount is only part of the member’s benefit and the roll over or transfer would result in the member’s residual interest in the fund being less than $5,000. This will allow funds to require a minimum balance to remain in the fund (provided the minimum balance is less than $5,000) in the case of part transfers. However, a member would still be able to move their entire balance (a full transfer) if they so desired.

The trustee may refuse a request to roll over or transfer an amount if the trustee has rolled over or transferred an amount of the member’s interest under Regulation 6.34 in the past 12 months. This will allow funds to develop rules so that regular contributions to a fund are not required to be transferred or rolled over every time they are made (e.g. every fortnight) avoiding the high administrative costs that may otherwise arise. Funds will still be able to allow more regular transfers or rollovers if they so wish.

If the trustee makes a refusal on the grounds above, they must inform the member in writing.

134 And in an explanatory statement that accompanied a further set of amendments in 2005, it was stated that: “[t]he Government considers that individuals should have the right to determine who manages their superannuation and should be free to move their benefits when they choose without unnecessary restrictions.” (Explanatory Statement, Select Legislative Instrument 2005 No 142, at p 1).

135 Moreover, and in any event, ASIC says that a right to receive future contributions is not trust property but a mere expectancy (Commissioner of Taxation v Everett (1980) 143 CLR 440 at 450 to 451). It says that the correct characterisation turns on whether the right to receive future superannuation contributions is uncertain or not; see Norman v Federal Commissioner of Taxation (1963) 109 CLR 9.

136 Further, it is said that this concept assumes importance when one considers the nature of the employment that many REST members undertake. They are often casual workers. It is said that future contributions being made on their behalf assumes that they will receive or be allocated further shifts by their employer, turn up to work and earn income for those shifts, and further, in the relevant period, earn sufficient income to exceed the minimum threshold for a superannuation contribution. But ASIC says that none of those conditions are certain to occur.

137 Accordingly, ASIC says that the right to receive such superannuation contributions as may be made if those uncertain conditions do occur in the future cannot form trust property, nor can it answer the statutory descriptor of “a member’s interest in the fund”.

138 But ASIC says that the contribution enforcement right is merely a future, rather than a present, chose in action and so does not have the proprietary character such as to form part of a “member’s interest in the fund”. And it is incapable of valuation in monetary terms.

139 Further, ASIC says that members of REST were employed by their employer. Most were casual or part time. There is no reason to believe that any of them could not resign their employment at any time on limited notice. Whether they chose to do so was outside the control of the employer and REST.

140 As such, ASIC says that any attempted assignment of their salary to be earned in the future would fail before the shift was actually worked because it was no more than a right which might thereafter come into existence and so could not be effectually assigned in equity without consideration.

141 In Everett, Barwick CJ, Stephen, Mason and Wilson JJ said (at 450 and 451):

It is, of course, well established that an equitable assignment of, or a contract to assign, future property or a mere expectancy for valuable consideration will operate to transfer the beneficial interest to the purchaser immediately upon the property being acquired, but not before. …

… For present purposes the point to be made is that an equitable assignment of present property for value, carrying with it a right to income generated in the future, takes effect at once whereas a like assignment of mere future income, dissociated from the proprietary interest with which it is ordinarily associated, takes effect when the entitlement to that income crystallizes or when it is received, and not before.

(citations omitted)

142 ASIC says that following a whole of balance transfer, it may be that a REST member might earn wages in the future that could give rise to an obligation on the employer to remit superannuation contributions to REST.

143 But ASIC says that the possibility that they may earn those wages was a mere expectancy, and the entitlement to those future wages is not a present chose in action capable of assignment. Any attempted assignment would take effect in equity as a contract binding on the assignor only after the wages were actually earned.

144 Moreover, ASIC says that the contribution enforcement right which permits REST to enforce against the employer the payment of contributions in respect of a member can be in no better position. It is not a present chose in action. There is no present obligation on the employer to remit contributions. The existence of the contribution enforcement right as a chose in action is subject to a triple possibility.

145 First, that the member will be given shifts by their employer.

146 Second, that they will work those shifts and thus may acquire the right to receive a superannuation contribution from their employer.

147 Third, that they will earn the requisite minimum amount so as to give rise to a definite obligation on their employer to make superannuation contributions in the relevant period (usually, $450 per month).

148 ASIC says that only upon the happening of all three events does the member have a present entitlement to superannuation. If the right that then exists is not paid by the employer, only then can the contribution enforcement right be classified as a present chose in action. Any legal action commenced by REST against an employer prior to these events occurring would necessarily fail, there being no present obligation on the employer to remit superannuation contributions. This is an unequivocal indicator that there is no present chose in action.

149 ASIC says that because the possibility of earning future wages is not a present chose in action, the enforcement of a future obligation to remit superannuation contributions which is wholly dependent upon the uncertain event of those wages being earned similarly cannot constitute a present chose in action.

150 ASIC says that it follows that the contribution enforcement right is not a present chose in action, and cannot form part of the “member’s interest in the fund” for the purposes of reg 6.35(1)(b).

151 Let me turn to another thread to ASIC’s position.

152 ASIC says that support for its position is found in the contractual obligation on the employer to remit contributions. It is said that the relevant contractual obligation presupposes that a deduction has been made from the employee’s salary that has already been earned and which must be remitted to REST.

153 In order to appreciate ASIC’s arguments, further reference needs to be made to the trust deed.

The trust deed

154 Clause 13 deals with the admission of employers. An employer must apply to REST using a form approved by REST. Once accepted, the terms of the employer application are binding upon the employer and each employee who becomes a member of the fund. By acceptance of their application, each employer agrees to be bound by the terms of the trust deed.

155 Clauses 10.1 and 10.3 of the trust deed are then relevant. They provided as follows:

10.1 Payments to Trustee

Each Employer shall pay by the due date to the Trustee or as directed by it:

(a) all contributions (if any) deducted from the Salary of each Member in accordance with the Rules; and

(b) out of the Employer’s own money (subject as provided below) the Employer’s contributions in accordance with the Rules.

…

10.3 Due date

(a) For the purposes of this clause 10, “due date” for contribution is the date specified in the Employer Application or the date agreed to between the Trustee and the Employer and otherwise twenty-eight days after the end of each quarter in which the Salary the subject of contributions to the Plan was paid to the Member.

(b) Interest is payable by the Employer on contributions which remain unpaid after the due date at the same rate charged by the Commonwealth Bank of Australia to its clients in respect of overdrafts of less than $100,000 together with any costs reasonably incurred by or on behalf of the Trustee in collecting these contributions. However, nothing in this Deed or the Rules shall impose an obligation on the Trustee to take any action to recover unpaid contributions or interest from an Employer where in the opinion of the Trustee it would be uneconomical to do so.

156 ASIC says that clause 10.1(a) makes clear, by use of the past tense “deducted” and by reference to the meaning of the defined term “Salary”, that the employer’s obligation arises only after an employee has earned salary from which contributions have been deducted. The definition of “Salary” is:

… the ordinary earnings received, whether weekly or monthly or fortnightly for services rendered by the Member to the Employer or at which the Member is employed by the Employer but excludes any overtime or special or ex-gratia grant or allowance for residence, travelling or otherwise.

157 It is said that in terms, no such obligation exists before the happening of those events.

158 ASIC says that although clause 10.1 of the trust deed, which applies to “Members” (as defined), contains an obligation upon employers to pay by the due date to REST “all contributions (if any) deducted from the Salary of each Member in accordance with the Rules”, that inchoate obligation, in and of itself, is not a chose in action.

159 ASIC says that the chose in action that might arise is premised upon a triple possibility, being a right arises only if the worker is given shifts, they work those shifts and acquire the right to a superannuation contribution, and the employee earns the requisite minimum amount to give rise to the obligation to contribute superannuation. Once the worker accrues the right to superannuation, and if the employer fails to make payment as required, then, and only then, does REST have an actionable right to enforce payment. ASIC says that until then, the potential chose in action is inchoate. In National Australia Bank Ltd v Norman (2009) 180 FCR 243 it was said by Graham J at [53]:

A credit in a bank account is not a chose in possession. Rather it is an inchoate chose in action (inchoate because of the need to make demand before there is a cause of action that can be sued on).

160 Now ASIC says that the evidence is that REST’s members were quite often employed in part-time or casual roles. There could therefore be no certainty, simply by virtue of their continued employment, that a member would receive a further superannuation contribution.

161 Further, ASIC says that when REST received a full transfer request from a determination member, it did not inquire whether they had worked any shifts in the last period, whether the threshold had been met and/or whether there were any unpaid superannuation contributions. Rather, it used the fact that the member was a determination member and perhaps that they were still employed with a REST employer as a proxy for those inquiries, and proceeded to deny them the ability to make a full rollover.

162 Further, ASIC says that the introduction by REST of the concept of a “non-Member beneficiary” does not advance REST’s argument. Such a concept is difficult to reconcile with the terms of the trust deed, and in any event, cannot arise until after the triple possibility just discussed has been satisfied.

163 Further, ASIC says that clause 18.3(b) of the trust deed, which I have already set out, is also relevant. Again, for convenience, it provided:

Upon the transfer to another fund of the whole of the amount standing to the credit of a Member’s Member Account, that Member will cease to be a Member and the Trustee shall be thereupon released and discharged from all liability whatsoever to or in respect of that Member.

164 ASIC says that clause 18.3(b) makes clear that if, following a transfer to another fund, a member’s account balance reduces to nil, then they cease to be a member of the fund.

165 Now ASIC says that the terms of the trust deed fasten upon the “amount standing to the credit” of the account, that is, the amount of actual dollars, to determine whether the person remains a member of the fund. “Cessation of membership” (rule 2.19) when read in combination with clause 18.3(b) provides that upon the transfer to another fund of the “whole of the amount standing to the credit” of the account, the member ceases to be a member, and REST is thereupon discharged from all liability whatsoever.

166 Now ASIC says that the significance of clause 18.3(b) is twofold.

167 First, properly construed, the trust deed does not contemplate and thereby excludes the possibility of a contribution enforcement right constituting an interest in the fund. Such an interest cannot be trust property.

168 Second, even if such a right could form an interest in the fund, the trust deed provides the mechanism whereby upon a full transfer out of the dollar amount standing to the credit of a member’s account, REST would be released from any and all obligations in respect of that right.

169 ASIC says that both of those matters support the conclusion that the contribution enforcement right does not constitute an ongoing or subsisting “interest in the fund”.

170 Let me address another point that ASIC has made.

171 ASIC says that in order to determine whether the member’s interest in the fund left after the transfer out of the requested amount would be more or less than $5,000, reg 6.35(1)(b) requires that the member’s interest in the fund be capable of valuation in money terms. Under reg 6.35(1)(b), this valuation must be done when the relevant officer or employee of the trustee is determining whether to grant or refuse the transfer request.

172 Now what is to be valued is the “member’s interest in the fund”.

173 ASIC says that upon REST’s case, the only thing beyond the amount standing to the credit of the member’s account is the alleged chose in action being the contribution enforcement right. But ASIC says that the exercise of valuing that alleged right, and before there is yet any accrued obligation to pay contributions in respect of that particular member, would require the valuation of some future opportunity.

174 ASIC says that this is a difficult exercise requiring a series of assumptions to be made and then quantified. It says that it is unlikely that the draftsperson contemplated that exercise. ASIC says that this is a strong textual indication that when using the expression “member’s interest in the fund” the draftsperson was not directing themselves to the contractual right to enforce contributions against the employer.

175 ASIC also says that there is no evidence that REST ever carried out any valuation of the contribution enforcement right in working out whether the “member’s interest in the fund”, after transfer out, was worth more or less than $5,000.

176 ASIC says that it is clear enough that the only matter REST considered or would have considered was whether more or less than $5,000 would be left in the member’s account.

177 Therefore, so ASIC says, to the extent that REST says that a “member’s interest in the fund” included the value of the contribution enforcement right, REST never applied a process mandated by reg 6.35(1)(b) that accorded with that proposition.

178 But in dealing with the point of construction and principle that I am now addressing, ASIC’s argument here has descended into little more than a jury point.

179 Let me return to the text of reg 6.35(1)(b).

The statutory text – “member’s interest in the fund”

180 ASIC says that the draftsperson’s use of the expression “member’s interest in the fund” rather than “member’s withdrawal benefit” does not necessarily signify that some interest different to the amount standing to the credit of the member’s account was contemplated by reg 6.35(1)(b).

181 ASIC says that regs 6.33 and 6.34 deal with a conceptual matter that has not yet crystallised. They contemplate the subject of the request for rollover as the total amount that would be payable if the member voluntarily ceased to be a member (see reg 1.03). ASIC says that at this point in the description of the rollover process, the draftsperson is describing the subject matter of the rollover request by reference to a category. That is the member’s withdrawal benefit as defined.

182 ASIC says that reg 6.33 sets out that the request may be made to roll over the whole or part of the member’s withdrawal benefit meaning the amount that would be payable if the member voluntarily ceased to be a member.

183 ASIC says that reg 6.34(1)(a) then sets out the application of that regulation. It deals with two separate steps.

184 Reg 6.34(1)(b) deals with a request to transfer or roll over the whole of the member’s withdrawal benefit where certain mandatory information is provided. Reg 6.34(1)(c) deals with a request to transfer or roll over part of the member’s withdrawal benefit where certain other information is provided. ASIC says that the draftsperson is dealing with categories of transfer requests.

185 Reg 6.34(2) then provides that where those earlier conditions are satisfied, the trustee must transfer or roll over “the amount” in accordance with the request unless reg 6.35 or reg 6.38 applies.

186 At this point, ASIC says that the draftsperson has shifted focus to dealing with a particular request that has satisfied the requirements for the categories described. The focus is therefore shifted so as to require the dollar amount requested to be transferred.

187 Reg 6.35 then focuses on when a trustee may refuse to make a transfer or to roll over as requested.

188 Accordingly, ASIC says that once the process being described in the SIS Regulations has reached the stage that the trustee is obliged to effect the transfer (reg 6.34(2)), the language shifts to deal with the particular transfer concerned with the request, and in that context, the draftsperson then speaks of the particular dollar sum to be transferred.

189 Further, ASIC says that where the trustee of a trust is obliged to pay a sum of money for the benefit of or, in the case of a superannuation fund, at the direction of a beneficiary, it is a natural use of language to describe the particular beneficiary’s rights as an “interest in the fund”.

190 Hence, so ASIC says, the language shifts to focus on whether the “amount” to be transferred is the whole or part only of the member’s “interest in the fund”.

191 ASIC says that the change in language is a product of the different stage in the rollover process under consideration from the hypothetical benefit (regs 6.33 and 6.34 (1)(b) and (c)) to the actual dollar amount that the trustee is obliged to transfer (regs 6.34(2) and 6.35(1)(a) and (b)).

192 ASIC says that it should also be noted that throughout reg 6.35, reference is made to amounts of money only. Further, even when considering the last words of reg 6.35(1)(b) being “member’s interest in the fund”, the regulation requires this “interest” to be reduced to a sum in dollars so as to determine whether it is more or less than $5,000.

193 Accordingly, ASIC says that the change in language does not signify that something beyond the balance in the member’s account is contemplated.

194 Further, the word “interest” is used as part of the composite expression “interest in the fund”. The use of the words “in the fund” means a regulated superannuation fund. Accordingly, so ASIC says, the statute thereby imports the technical legal concepts applicable to regulated superannuation funds to the concept of an “interest”, which travel beyond any dictionary meaning or use of that word in other legal contexts.

195 ASIC says that the most powerful indicator of the meaning of the expression “interest in the fund” is the immediate context in which it is used. It says that the words of the same provision invoke the need to determine whether that interest “would be less than $5 000”. ASIC says that the interest must therefore be monetary or capable of valuation in money terms.

196 ASIC makes one final point. Before the words “interest in the fund”, the word “member’s” is used. So, the word “member’s” is singular. Further, it is used possessively in respect of the “interest in the fund”. That excludes from the possible meaning a broader interest that belongs to all members or, if not all, some larger group of members of the fund collectively, but not individually. ASIC says that it also requires that the identified interest must, at the time under consideration, be a thing which belongs to the member.

Analysis

197 Now I would reject ASIC’s position on the construction and application of Div 6.5 of the SIS Regulations.

198 It is a well-established presumption or principle of interpretation of a statutory provision including sub-ordinate legislation that where a legislature could have used the same word but chose a different word or phrase, the intention was to change the meaning.

199 The context in which the different phrases, being “withdrawal benefit” and “interest in the fund”, are used supports the operation of this presumption or principle in the present case.

200 The different terms are used in the same Division of the SIS Regulations, and indeed in adjacent provisions.

201 There is no textual or other reason why the words “withdrawal benefit” could not have been used in reg 6.35, instead of “interest in the fund”, if the same meaning was intended. For example, reg 6.35 could have been drafted to read: “(b) the amount to be rolled over or transferred is part only of the member’s withdrawal benefit interest in the fund”.

202 It is evident that Part 6 of the SIS Regulations is carefully drafted. As REST points out, it can be noted that the specific defined term, “withdrawal benefit”, is used 34 times in Part 6 of the SIS Regulations, and 25 times in Div 6.5, which specifically deals with the rollover and transfer of withdrawal benefits. Given the repeated use of the defined term “withdrawal benefit” throughout, it seems to me that the drafter was referring to a different concept when using the different and broader word “interest”.

203 There is a distinction between a member’s withdrawal benefit in a fund, and the broader interests that a member has in the fund. A member’s interest in a fund is broader than the member’s current account balance or withdrawal benefit.

204 Now for members who are not determination members, a full rollover or transfer of the member’s withdrawal benefit would terminate their interest in the fund. But the position is different for a determination member.

205 First, under their existing award or determination and under the trust deed, a determination member’s employer has an ongoing obligation to make contributions to the fund for the employee for so long as the member is an employee. Those participating employers (REST employers) agreed to be bound by the terms and conditions of the trust deed and to pay contributions on behalf of employees to REST on a monthly basis or as required to reduce their superannuation guarantee obligation in respect of the employee to nil.

206 In particular, clause 10 of the trust deed required employers to pay to REST all contributions. Further, clause 13.3(b) of the trust deed provided that the application by the employer for admission to the Plan would be binding on the employer and each of the employees, and operate as an amendment to the Plan.

207 Second, I agree with REST that this obligation is more than a mere possibility of future employer contributions. It is a right to those contributions for so long as the member is an employee of the REST employer. REST’s right to receive contributions is held for the benefit of the member. And as a consequence, if the employer of a determination member did not make a required contribution to the fund, REST could on behalf of that member enforce the employer’s obligation to contribute to the fund and would be required to do so. And that this may occur was not merely hypothetical. If, on a failure of an employer to meet its obligations, REST did not take action against the employer, the determination member, as a beneficiary of the Trust, could enforce its interest in the Trust and compel performance by suing the employer and joining REST as defendant.

208 Accordingly, where a determination member requests to rollover or transfer the whole of their withdrawal benefit, the amount to be rolled over or transferred is part only of the member’s interest in the fund.

209 Now in its ordinary meaning, the word “interest” is a word of wide import. And in the present case the “interest” referred to is different and broader than the member’s withdrawal benefit. As such, where the member’s employer was subject to an obligation to make ongoing contributions to the fund for the member, the exception in reg 6.35(1)(b) applied and provided REST with a discretion.

210 And as I have said, the context in which the different phrases, being “withdrawal benefit” and “interest in the fund”, are used supports the proposition that different words would normally be given a different meaning. Further, that conclusion is consistent with the principle of statutory interpretation that meaning be ascertained by examining the language used in the statutory instrument as a whole.

211 The phrase “interest in the fund” in reg 6.35(1)(b) is undefined. It is to be interpreted in accordance with its ordinary and natural meaning, consistent with the purpose of Div 6.5. Nothing in reg 6.35 or Div 6.5 operates to rebut this presumption.

212 Now ASIC contends that the reference in reg 6.35(1)(b) to a member’s interest in the fund being less than $5,000 provides a textual indicator that the term “interest” is limited to the balance of a member’s account with REST. But this fails to recognise that “interest” has a well-accepted meaning that was used in reg 6.35 instead of the narrower concept of “withdrawal benefit”. I will return to this in a moment.

213 Further, the indirect textual indication that ASIC points to must be weighed against the more direct textual indication evident from the change of the words used in the SIS Regulations from “withdrawal benefit” to “member’s interest in the fund”.

214 Further, reg 6.35(1)(b) and REST’s practice did not require a precise valuation of the member’s interest, but just that it be ascertained whether it is less than $5,000.