Federal Court of Australia

Parkin v Boral Limited (Loss of Privilege Issue) [2024] FCA 1039

ORDERS

Applicant | ||

AND: | BORAL LIMITED (ACN 008 421 762) Respondent | |

NSD 935 of 2020 | ||

| ||

BETWEEN: | MARTINI FAMILY INVESTMENTS PTY LTD ACN 606 000 944 ATF MARTINI FAMILY INVESTMENTS SUPER FUND Applicant | |

AND: | BORAL LIMITED (ACN 008 421 762) Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: | 9 SEPTEMBER 2024 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The hearing be adjourned part-heard to 12:45pm on 11 September 2024 for the hearing of any applications concerning the timing of the resumption of the evidence of Mr Michael Kane and the balance of the hearing, and as to the costs of (and related to) the voir dire.

AND THE COURT RULES THAT:

2. Exhibit A1 on the voir dire be admitted as evidence in the trial and be given the same exhibit marking in the trial.

3. The applicants be permitted to adduce evidence in cross-examination of Mr Kane of representations, being representations made by persons within Ernst & Young LLP (EY), received or communicated to Mr Kane prior to 8:49am on 25 January 2020, being communications recording or referring to findings by EY about the controls that existed in the Windows business (subject to further rulings relating to any objections to individual questions).

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

LEE J:

A INTRODUCTION AND THE SCOPE OF THE VOIR DIRE

1 Eight hearing days have passed of an initial trial of a securities class action in which two representative applicants, Mr Parkin and Martini Family Investments Pty Ltd (applicants) seek damages and statutory compensation for losses allegedly suffered on the value of shares in Boral Limited (Boral) said to arise because of Boral’s failure to comply with its market disclosure obligations. The alleged failure centred on the consequences of Boral’s discovery in November 2019 of financial irregularities in one of its US subsidiaries, known as its Windows business.

2 Leaving aside expert evidence, the case of the applicants is entirely documentary and, consistently with a practice that has grown up in large class actions, and with the agreement of the parties, the documentary tender was deferred until the end of the oral evidence and was proposed to take place immediately prior to final submissions. The perceived benefit was to avoid either receiving the vast and wholly unmanageable bulk of documents in the court book into evidence or experiencing delay by the tender of documents individually during the trial. It was thought this would save time and achieve some discipline (in that the documentary evidentiary record would be limited to records sufficiently material to have been referred to by the parties in evidence or which were proposed to be referred to in final submissions).

3 Such a course perforce requires informality in the closing of cases and in identifying whether evidence is being adduced by the moving parties in chief or in reply. It can also, in some cases, serve to obscure issues of evidentiary and persuasive onus. But the upside is sufficiently obvious that except for a case where there is a chance a no-case submission will be made, this course has become common in large commercial cases (although I would not impose it absent the consensus of all parties).

4 Hence following openings which (again, departing from the old common law norms but consistently with modern commercial practice) I received from both sides consecutively, we are into Boral’s case.

5 The cross-examination of Mr Michael Kane is underway. Mr Kane was the Chief Executive Officer (CEO) and Managing Director of Boral at all material times and was responsible for matters including managing Boral’s affairs and implementing its strategy and policy initiatives; and was also an executive director of the board of Boral (Boral Board) and a member of the Executive Committee. It is uncontroversial he was an officer of Boral within the meaning of s 9 of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (Corporations Act).

6 An issue has now arisen about the scope of questions that may be asked of Mr Kane and, relatedly, as to an alleged loss of client legal privilege. More particularly, the applicants seek to ask questions relating to representations made by Mr Kane recorded in a document (BOR.603.030.0772–0074), being a chain of emails between Mr Kane, Mr David Mariner (then CEO of Boral North America (BNA)), Mr Dominic Millgate (then Company Secretary of Boral) and Mr Ernest McLean (then Vice President and General Counsel of BNA) (Ex A1) – for convenience, a copy of Ex A1 is annexed to these reasons. More particularly, the applicants seek an order in the following terms:

An advance ruling that upon the tender of BOR.603.030.0772 [that is, the tender of Ex A1 at the trial] the applicants are permitted to adduce evidence in cross-examination of Mr Mike Kane of communications or the contents of documents recording or referring to findings by Ernst & Young about the controls that existed in the respondent’s Windows business.

7 As can be seen, the proposed order sought initially by the applicants is described as an “advance ruling”. In some cases, of course, trial preparation may be assisted by an evidentiary ruling in advance of the trial. The enactment of s 192A of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) (EA) gave effect to recommendations by, among others, the Australian Law Reform Commission, to permit a court, if it thought fit, to give an advance ruling on an evidentiary issue. But that is not what we are dealing with now – I am dealing with an objection to evidence during a final hearing. The determination of the question as to whether the evidence discussed below should be admitted (whether in the exercise of a discretion or not), depends upon the Court finding various facts and gives rise to preliminary questions. These questions can be resolved on a voir dire: see s 189 EA.

8 The applicants also wish to tender Ex A1 in the trial. This tender is the subject of an objection, and both parties consent to this admissibility dispute being determined now. As I explained in BrisConnections Finance Pty Ltd and Others v Arup Pty Ltd [2017] FCA 1268; (2017) 252 FCR 450 (at 469 [73]), even though Ex A1 is now in evidence on the voir dire, it will be necessary for it to be tendered in the trial if reference is later to be made to it in determining the substantive facts in issue. I am conscious the view has been expressed that evidence given on the voir dire in a civil case heard by a judge alone may be taken into account on the issues arising at the trial itself (see R v Amo [1963] P & NGLR 22 (per Mann CJ); Ex parte Whitelock; Re Mackenzie [1971] 2 NSWLR 534 (at 540 per Meares J); Casley-Smith v F S Evans & Sons Pty Ltd (No 2) (1988) 49 SASR 332 (at 335 per Olsson J)). But I doubt those cases are correct and, at best, the position is not settled (see the Full Court’s observations in Brown v Commissioner of Taxation [2002] FCA 318; (2002) 119 FCR 269 (at 291–292 [92] per Sackville and Finn JJ); Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Rich [2004] NSWSC 1062; (2004) 213 ALR 338 (at 341–345 [23]–[49] per Austin J)). Relevantly, I have made it plain that unless tendered in the trial, I will not have regard to any evidence adduced in this adjectival hearing.

B BACKGROUND TO THE CASE

9 To understand how these issues have arisen, it is useful initially to outline the substantive case briefly.

10 On 8 May 2017, Boral completed the acquisition of a business known as Headwaters Incorporated (Headwaters), a building products and construction materials business in the United States for approximately US$2.6 billion. Prior to the acquisition, and put simply, Headwaters had acquired businesses which focussed on the design and manufacture of windows and doors (Windows). Windows therefore formed part of Headwaters, which Boral acquired. Headwaters was subsequently incorporated into BNA.

11 The applicants allege that up until an announcement made on 5 December 2019, Boral repeatedly assured the market that Headwaters was being successfully integrated into BNA. Boral published financial accounts, and gave forward earnings guidance, on that basis. It is said that the systems and controls in place at Windows were, however, inadequate (as was its integration with the wider BNA business). Those alleged inadequacies from around March 2018 resulted in Boral’s earnings being overstated. It is alleged Boral’s financial accounts were impacted and, because the erroneous accounts were the basis for Boral’s forward earnings guidance, the irregularities at Windows resulting from its inadequate systems and controls and flawed integration also impacted the guidance Boral had given to the market. The true position, it is alleged, was that the Windows business would only deliver low single digit margins, and Boral’s FY19 EBITDA would be significantly less than the 20% improvement on FY18 which had guided the market.

12 The applicants contend that inadequate systems and controls in the Windows business were not matters which ought to have surprised Boral; nor was the fact that those inadequacies led to substantial misreporting. Boral’s internal audits flagged the deficient control environment soon after the Headwaters acquisition, but the issues identified (including specific issues as to inventory systems and reporting) were never resolved. The applicants say that Boral’s senior management, including Mr Kane, Mr Mariner, Ms Ros Ng (Boral Chief Financial Officer (CFO)), and Mr Oren Post (BNA CFO) knew or ought to have become aware of these matters from at least 30 August 2017. Of these persons, only Mr Kane is being called to give evidence and, for reasons not yet clear to me, Boral denies all the others were “officers”.

13 On 5 December 2019, Boral announced that it had identified financial irregularities in Windows, which were still the subject of investigation, but which it estimated would result in a US$20–30 million impact on its reported earnings (December announcement). The applicants submit that the market was surprised by the December announcement and had concerns surrounding the financial implications of the financial irregularities and its wider implications on Boral’s oversight of BNA and its integration of Headwaters. The applicants further contend the market reacted negatively to the news, with Boral’s share price falling approximately 8.5% in total over the following two days.

14 Importantly for present purposes, earlier the previous month, on 11 November 2019, Ernst & Young LLP (EY) had been engaged by Boral’s US lawyers, Alston & Bird LLP (A&B), to assist A&B advise Boral in relation to allegations of misconduct in the Windows business (Ex B1 (at 17–25)). EY’s scope of work included performing forensic accounting activities and interviewing parties (Ex B1 (at 26–33)).

15 Although not formally placed in evidence on the voir dire, Boral does not dispute (and has noted in submissions) that the December announcement stated “a privileged and confidential investigation is being conducted by lawyers retained by Boral, who have also engaged forensic accountants to assist the investigation” and the following day, Boral convened a call with investors, in which Mr Kane stated that he understood “we’re in the midst of a detailed investigation that is being led by an outside law firm and forensic accountants”.

16 On 10 February 2020, Boral confirmed the precise impact of the financial irregularities (February announcement), namely that pre-tax earnings were overstated by a total of US$24.4 million between March 2018 and October 2019, and that the financial misreporting issues were limited to Windows. Of this, US$22.6 million impacted Boral’s FY18 and FY19 historical reported Group EBITDA.

17 Although the applicants initially pressed a claim up until the February announcement, they no longer allege that Boral engaged in contravening conduct after the December announcement. As a result, the applicants contend that the market was trading on an uninformed basis prior to the market’s impounding of the “true position” following the December announcement, and that Boral’s share price was inflated artificially by the conduct of Boral in connexion with public announcements it had made, contrary to various statutory norms.

C EXHIBIT A1 AND THE PRIVILEGE ISSUE

18 During the cross-examination of Mr Kane by leading counsel for the applicants, Mr Edwards KC, the following exchange occurred (for clarity, it should be noted that MFI-13 later became Ex A1) (T470.23–472.29):

MR EDWARDS: Mr Kane, your mindset at the time was that EY had already told you that the internal controls at window were adequate; correct?

MR WITHERS: I object. I object. I object. That calls for disclosure of privileged communication. He is saying “You have already been told by EY that the internal controls were inadequate.” That’s calling for disclosure of what EY had said about the internal controls.

HIS HONOUR: I’m sorry, Mr Kane, I’m going to have to ask you to go out. I’m sorry, Mr Kane, again?---Okay.

Witness leaves court 11:56 a.m.

HIS HONOUR: Mr Withers, isn’t there a document where this man says he was told by Ernst & Young that the controls were bad? What’s the point of the objection?

MR WITHERS: Well that’s not the way we read it. But also, if we look at the question by itself, it is:

EY had already told you that the controls were bad.

That is calling for a disclosure of what EY had communicated with this company. That’s what it is and that’s a privileged communication. That’s my objection.

HIS HONOUR: Well, I think I’m – can someone give me a hard copy of that document you referred to before, Mr Edwards, so I can – it seems to me it is a much easier way of doing this by reference to the document but, in any event - - -

MR EDWARDS: I withdraw that question and I will do that your Honour.

HIS HONOUR: …you withdrawn the question so I don’t need disallow it. If I could have the document for any further objection, it might be easier for me to rule. I will mark the document I’m referring to for the purposes of the transcript as MFI 13.

MFI #13 DOCUMENT

HIS HONOUR: Being relevantly an email from a witness, Mr Kane, to Mr Millgate of Boral of 25 January 2020 at 9.30 am. Just let me read that whole email before Mr Kane comes in to make sure that I haven’t – because I only read it on the screen. Is it worth you indicating, before Mr Kane is brought in, what is the question you [intend to] ask so we don’t have to send him out again if there’s a – I will see if it is objected [to]. If it [is] objected to, then I will perhaps deal with it then. If it’s not objected to, then we will have him in just to see if it is objected to. Then perhaps I can indicate the course I propose [to] take. I’m conscious of what Mr Withers said about the horse not bolting and [causing] some unfairness to the respondent in that regard.

MR EDWARDS: Well, I already, in a sense, identified the question earlier on. The ultimate question is what does he mean when he says “Controls were as bad as EY suggests.”

HIS HONOUR: All right. Do you [object] to question what did he mean, by the representation contained in the last two sentences of that email? How would that be objectionable? He is entitled to be asked what he meant by representation contained in an email he sent, surely.

MR WITHERS: Yes. But if the answer is going to be “Well, I was referring to the content of the E&Y report”, then we have a waiver by the witness of the contents or a disclosure of what’s in that privileged communication.

HIS HONOUR: Why would it be – the waiver has to occur by the client, not the witness.

MR WITHERS: No - - -

HIS HONOUR: The holder of – the holder of the privilege. He doesn’t hold privilege. He is no longer an employee at Boral. I presume he is not authorised to make waiver and you can strike out any privileged communication if you have instructions to do so to the extent it is properly privileged. But the witness – the witness is someone who is not the client. The witness is entitled to be asked what he meant by [a] representation in an email. If there is, through giving the answer, a disclosure of communication, then you can ask that that be struck out. You could even stop him in the event that he is seeking – he is disclosing something and the apprehension that he is about to go into something which is privileged and I will have to make a ruling on it. But the question that Mr Edwards has articulated does not seem to me to be in any way other than entirely licit.

MR WITHERS: Well, we could cut through this. Because my learned friend is going to try to make the argument to your Honour that these words on this page, these six or seven words have the effect of waiving the contents of the EY report so we could just get to that argument.

HIS HONOUR: I think you are a step ahead. There has been no allegation made yet, as I understand it, that I have been asked to rule upon by waiver of [the] EY report. You say the representation is ambiguous or there may be other – there may be a way he can answer it which, on no view of it, could be said to disclose a privileged communication which, of course, does not belong to him. It belongs to your client.

MR WITHERS: I mean, I will just have to try to stop him if he starts to talk about the content of the report or ask your Honour to do it.

HIS HONOUR: Okay. And, if that’s the case and then there is an argument about – if there is an argument about waiver … can I say to you the waiver exists by reason of action of your client, not by anything this witness does.

MR WITHERS: No, I understand that. I understand that.

D THE SUMMARY CONTENTION OF THE APPLICANTS

19 As noted above, the applicants have attempted to tender Ex A1 at the trial. Boral objects on the ground of relevance. For reasons I will explain, this relevance objection is untenable. Boral also contends Ex A1 should be the subject of discretionary exclusion under s 135 EA on the basis that its probative value is substantially outweighed by the danger that the evidence might cause or result in undue waste of time, but this objection should also be rejected.

20 Although Ex A1 will be admitted in the trial, the argument that initiated this collateral dispute is the issue as to whether the applicants are permitted to adduce evidence in cross-examination of Mr Kane of representations, made by persons within EY, received or communicated to Mr Kane, being communications recording or referring to findings by EY about the controls that existed in the Windows business. The relevant representations of EY are those received or communicated to Mr Kane prior to 8:49am on 25 January 2020 (being when he sent his email, which is a part of Ex AI). For reasons I will explain, I have described the proposed evidence in a slightly different way than as proposed by the applicants in Order 1 (see [6] above) and will describe my formulation of the scope of the proposed cross-examination as the Proposed Kane Evidence.

21 The argument of the applicants proceeds in the following way.

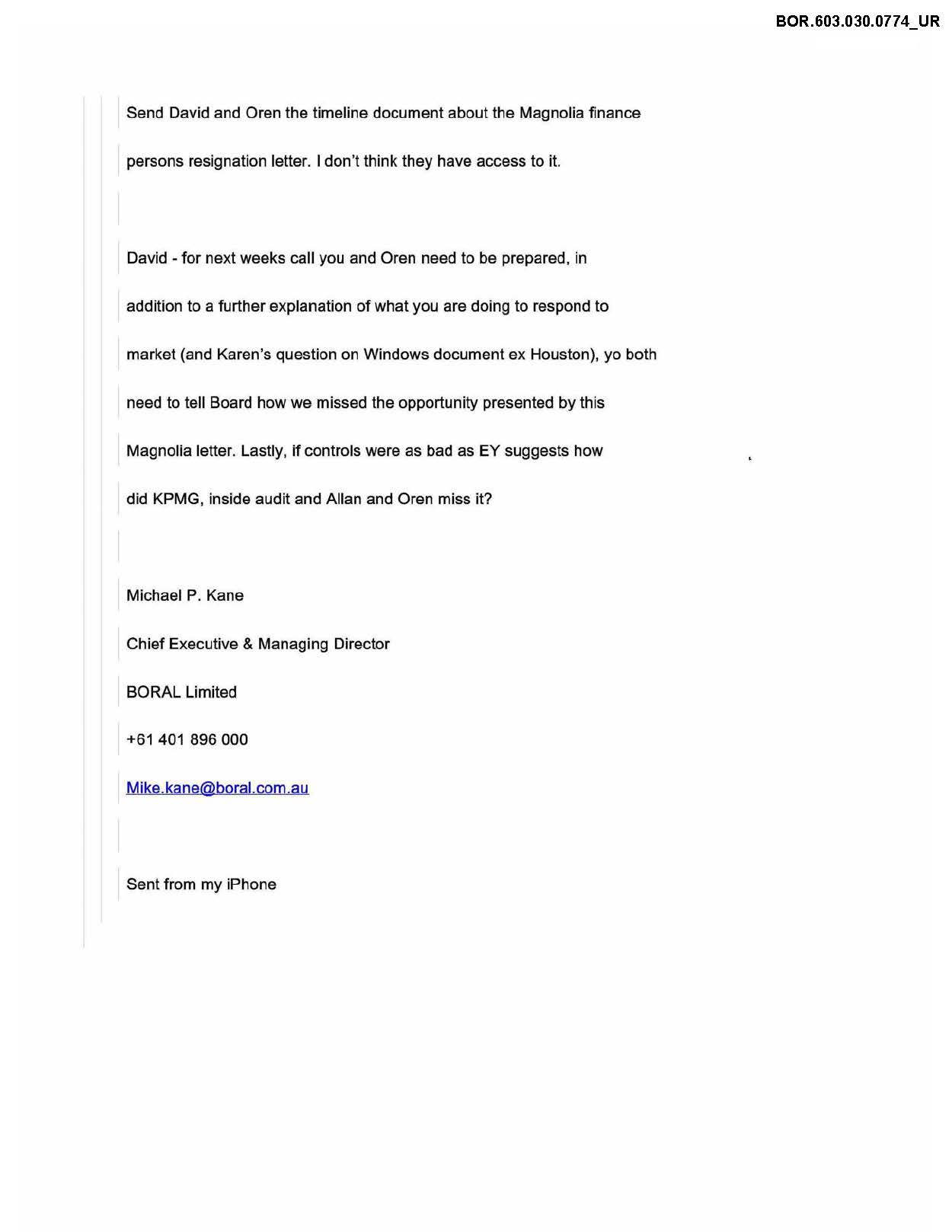

22 As can be seen from the annexure, Ex A1 contains an email from Mr Kane, sent on 25 January 2020, containing the paragraph:

David [Mariner (Boral North America’s CEO)] – for next weeks [sic] call you and Oren [Post (Boral North America’s CFO)] need to be prepared, in addition to a further explanation of what you are doing to respond to market (and Karen’s question on Windows document ex Houston), yo [sic] both need to tell [sic] Board how we missed the opportunity presented by this Magnolia letter. Lastly, if controls were as bad as EY suggests how did KPMG, inside audit and Allan and Oren miss it?

(Emphasis added).

23 The bolded section of the above quotation (relevant communication) indicates that part of the document that had been redacted prior to trial by Boral based on legal professional privilege in the circumstances described in detail below. It appears the claim for privilege was initially asserted by Boral because the relevant communication was contained in an internal Boral document, which was said to have reproduced or otherwise revealed other communications, which were protected because those other communications were made for the dominant purpose of Boral obtaining legal advice from A&B or to conduct, or aid in the conduct, of litigation: see Parkin v Boral Limited (Privilege Argument) [2022] FCA 1467 (at [8] per Rares J); DSE (Holdings) PTY Ltd v Intertan Inc [2003] FCA 1191; (2003) 135 FCR 151 (at 168 [53] per Allsop J).

24 That is, the relevant communication was protected by what is commonly known as common law advice privilege and/or litigation privilege and, given legal professional privilege is a rule of substantive law which may be called in aid by a person to resist the giving of information or the production of documents, the document containing the relevant communication was required to be discovered, but was not required to be produced by Boral for inspection by the applicants on discovery.

25 Despite this, in the circumstances set out below, it is said Boral “waived legal professional privilege over” the relevant communication when:

(1) Boral discovered an unredacted copy of Ex A1 and did not assert privilege within a reasonable time thereafter; or

(2) when an unredacted copy of Ex A1 was tendered into evidence at an interlocutory hearing and Boral did not object or assert privilege within a reasonable time thereafter; or

(3) when Boral agreed to provide the applicants with an unredacted copy of Ex A1 on 20 August 2024 rather than contesting the applicants’ request that the Court rule on the validity of Boral’s disputed privilege claim over that document.

26 It is then said the Proposed Kane Evidence, that is, evidence adduced on cross-examination of Mr Kane as to communications or contents of documents recording or referring to the findings made by EY about the controls that existed in the Windows business is reasonably necessary to enable a proper understanding of the relevant communication contained in Ex A1.

27 Hence, as counsel has made explicit, by the Proposed Kane Evidence, the applicants propose to adduce evidence from Mr Kane concerning the representations made by EY from which Mr Kane drew the conclusion, expressed in the relevant communication, that EY characterised controls as being “bad”. This is in circumstances where, when Mr Kane made the relevant communication: (1) the investigation undertaken by A&B and EY had been “substantially completed”; (2) Mr Kane, as a member of the Boral Board, had received advice in relation to that investigation in December 2019; and (3) where Mr Kane has given evidence that the question of financial irregularities at Windows were “front of mind” for him, and that he had read the A&B advice thoroughly as soon as he received it (T469.5–7; T469.21–26).

28 The applicants contend that the adduction of the Proposed Kane Evidence ought to be permitted because, given the relevant provisions of the EA do not prevent the applicants adducing evidence of the relevant communication at trial, the applicants are now not prevented from adducing evidence of other privileged communications (being those made by EY received by or communicated to Mr Kane), if those other communications are reasonably necessary to enable a proper understanding of the relevant communication.

29 After some toing and froing, it emerged that Boral has several cascading arguments as to why the applicants should be prevented from adducing the Proposed Kane Evidence, but before identifying and then considering those arguments, it is worth turning immediately to s 126 of the EA, being the section upon which the applicants rely to enable them to adopt their proposed course.

E THE PRINCIPLED APPROACH TO SECTION 126

30 Those practising prior to 1995 will recall that when first enacted, there was some controversy as to the extent to which the statutory provisions in the EA relating to privileges modified or displaced the common law of Australia. It is unnecessary to go into the history, but the controversy assumed some importance in relation to the topics of legal professional privilege and waiver. Why this is worth mentioning is that despite some initial uncertainty, it was quickly resolved that in Federal Courts it is common law principles of legal professional privilege that apply at pre-hearing stages, which includes producing documents on discovery or under a subpoena: see Esso Australia Resources Limited v Commissioner of Taxation of the Commonwealth of Australia [1999] HCA 67; (1999) 201 CLR 49 (at 59–63 per Gleeson CJ, Gaudron and Gummow JJ).

31 But we are now, of course, at trial, and concerned with not with production but with the adduction of evidence, and it is hence necessary to have regard to Pt 3.10, Div 1 of the EA, which deals with “Client legal privilege”.

32 After dealing with definitions (s 117); legal advice privilege (s 118); litigation privilege (s 119); and privilege and unrepresented parties (s 120), the Division deals with the loss of client legal privilege in certain circumstances being: generally (s 121); consent and related matters (s 122); associated defendants in criminal proceedings (s 123); joint clients (s 124) and misconduct (s 125).

33 Then s 126 appears, which, leaving aside notes, is in the following terms:

126 Loss of client legal privilege: related communication and documents

If, because of the application of ss 121, 122, 123, 124 or 125, this Division does not prevent the adducing of evidence of a communication or the contents of a document, those sections do not prevent the adducing of evidence of another communication or document if it is reasonably necessary to enable a proper understanding of the communication or document.

34 The effect of s 126 is clear: where there is a loss of client legal privilege of an otherwise privileged communication (under any of the sections to which s 126 refers), the loss of client legal privilege extends to such associated communications or documents as are reasonably necessary to enable a proper understanding of the communication or document in respect of which client legal privilege was initially lost.

35 This was described in submissions from time to time as “waiver” or “statutory waiver”, which is understandable, but it is important that not distract from the fact that we are presently dealing with a statutory conception of loss of privilege. In Towney v Minister for Land and Water Conservation (NSW) (1997) 76 FCR 401, Sackville J explained (at 413) that s 126 could not be read as simply incorporating, unchanged, the common law and it cannot be safely assumed that s 126 “is intended to embody the common law test of waiver of legal client privilege”.

36 It is useful to approach the issue of an asserted loss of client legal privilege under s 126 in the following two steps.

37 First, identifying whether client legal privilege has been lost in a communication or document (first communication) because of the application of one or more of ss 121–125 of the EA: see Sugden v Sugden [2007] NSWCA 312; (2007) 70 NSWLR 301 (at 319 [91] per McDougall J, Mason P and Ipp JA agreeing). In this case, of course, this first communication is the relevant communication.

38 Secondly, if so, one then looks at the first communication (over which client legal privilege has been lost) and asks whether, to understand it properly, it is reasonably necessary to know what is in another communication or document (second communication): see ML Ubase Holdings Co Ltd v Trigem Computer Inc [2007] NSWSC 859; (2007) 69 NSWLR 577 (at 593 [45]–[46] per Brereton J). In undertaking this objective analysis, one does so while bearing in mind that:

(1) the concept of “understanding” in s 126 is an objective standard, and hence the Court has to determine for itself whether the standard has been satisfied in the particular circumstances of the case;

(2) the words “proper” and “understand” in s 126 are to be given their dictionary meanings of “complete or thorough” and “apprehend clearly the character of” respectively (Sugden (at 304 [1] per Mason P; 304 [2] per Ipp JA; 320 [96] per McDougall J);

(3) it is not necessary that the second communication be referred to in the first communication (or vice versa); what matters is whether the second communication assists in reaching a proper understanding of the first communication (Matthews v SPI Electricity Pty Ltd [2013] VSC 33 (at [42] per Derham AsJ); Mullett v Nixon (Subpoena Application) [2016] VSC 129 (at [87] per J Forrest J)); and

(4) the test is concerned with the comprehensibility of the first communication: if it can be completely or thoroughly understood without more, then access to the second communication is not reasonably necessary: see ML Ubase Holdings (at 593 [45] per Brereton J).

39 In this case, of course, the second communication is any representation by EY from which Mr Kane drew the conclusion, expressed in the relevant communication, that EY characterised controls as being “bad”.

F BORAL’S SIX CONTENTIONS

40 By the end of oral argument (T593–4), Boral accepted its contentions in opposition to the rulings sought by the applicants could be summarised into the following six propositions.

41 First, the relevant communication was never privileged such that there is no room for the operation of either common law principles of waiver of legal professional privilege or the operation of Pt 3.10, Div 1 of the EA (such that s 126 is not engaged) (No Privilege Contention).

42 Secondly, if the relevant communication is privileged, the Proposed Kane Evidence is not relevant, within the meaning of ss 55 and 56 of the EA, such that the proposed question ought to be disallowed on that basis; Boral also asserts that Ex A1 is not relevant (No Relevance Contention).

43 Thirdly, even if Ex A1 is relevant to a fact in issue, the Court ought, by reference to its general discretion, exclude it under s 135 of the EA, because its probative value is substantially outweighed by the danger that the evidence might cause or result in an undue waste of time (Discretionary Exclusion Contention).

44 Fourthly, even if the document containing the relevant communication was formerly privileged and is now admissible, s 126 of the EA is not engaged because the Proposed Kane Evidence is “not reasonably necessary” to understand the relevant communication (Not Reasonably Necessary Contention).

45 Fifthly, even if all of the above four contentions are rejected, it would amount to an abuse of process for the applicants now to seek to adduce the Proposed Kane Evidence in circumstances where there has already been a contested privilege hearing that has been determined and the applicants knew: (a) from the moment Ex A1 was adduced into evidence (before Rares J) that the relevant communication was in the public domain and hence no longer a confidential communication that could not be privileged; and (b) the applicants knew or ought to have known that when the solicitors for Boral made a later assertion of inadvertent waiver of the relevant communication, that assertion had no substance, and that the applicants unreasonably delayed the assertion of any entitlement to inspect the relevant communication, contrary to the case management imperatives of Pt VB of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (FCA Act) (Abuse of Process Contention).

46 Sixthly, to the extent that the applicants maintain an argument that production by Boral of the relevant communication at 2:15pm on 20 August 2024 amounted to voluntary waiver of a privileged communication, they are estopped from doing so because the decision to produce was made on the basis of the applicants’ submission made on 19 August 2024 that the document was not privileged and the applicants should be estopped from departing from this prior representation made in the course of litigation and upon which Boral relied (Estoppel Contention).

47 Before moving on, it is convenient to deal immediately with the sixth of these contentions. The point of departure for this submission is that there was a loss of privilege during the trial on 20 August 2024. Although this assertion as to “waiver” was initially embraced by the applicants, on proper examination, such a contention is unsustainable. On the assumption that the relevant communication was privileged, for reasons that will be explained below, it is beyond argument that any loss of privilege occurred much earlier: this was when Ex A1 was received into evidence at an interlocutory hearing and hence entered the public domain. Despite the vast bulk of evidence and the submissions directed to this distracting estoppel point, it is based upon this false premise (and, although it does not matter, a further false premise that Boral had any ”choice” about handing over a document for inspection over which privilege was lost).

48 I will deal with the balance of the contentions below, but before doing so, it is useful to set out a chronology of relevant events.

G RELEVANT CHRONOLOGY

49 To understand how this dispute has crystallised and the nature of some of Boral’s contentions, it is necessary to bear in mind the happening of the following events:

(1) On 9 August 2021, orders were made requiring Boral to make standard discovery pursuant to r 20.14 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) (FCR), in two tranches (12 November 2021 and 16 December 2021) with “a list of documents verified in accordance with FCR 20.17” by 17 January 2022.

(2) On 14 December 2021, an order was made extending the time for Boral to provide a verified list of documents to 28 February 2022; this order was not complied with according to its terms but, by March 2022, Boral had given discovery of approximately 90,000 documents in four tranches.

(3) On 17 December 2021, as part of that process of discovery, Boral produced a copy of Ex A1 (that is, a version of the document annexed to these reasons, which did not redact the relevant communication).

(4) On 22 March 2022, Freehills wrote to Maurice Blackburn enclosing Boral’s list of documents, relevantly claiming privilege over an extract from the minutes of a meeting of the Boral Board on 24 January 2020 when the Board was presented with the A&B preliminary report (January Board Minutes) and the reports to the Boral Board from A&B dated 1 December 2021, 18 December 2019 and 21 January 2020 (A&B Reports).

(5) On 29 April 2022, orders were made programming a timetable for the resolution of a privilege dispute.

(6) On 1 June 2022, Maurice Blackburn wrote to Freehills enclosing a list of Contested Documents, including the January Board Minutes and the A&B Reports.

(7) On 21 October 2022, the applicants filed written submissions in support of the challenge to various sample documents, which included submissions that privilege over the A&B Reports had been waived by reason of the publication of the December Announcement and the February Announcement and served an affidavit by the applicants’ solicitor, Mr Schimmel, which affidavit contained evidence of the relevant communication.

(8) On 9, 10 and 14 November 2022 the privilege dispute was heard by Rares J and Ex A1 (that is, a copy of the business record containing the relevant communication) was tendered as part of a joint tender bundle (see T99.39–43); the Schimmel affidavit, containing the relevant communication, was read; and, at the conclusion of the hearing, Rares J rejected the applicants’ contentions as to common law waiver ruling that: “[Boral]’s claim of legal professional privilege in respect of the three [A&B Reports] be upheld”. No other rulings were made.

(9) On 24 November 2022, the applicants served a draft tender list, which included Ex A1.

(10) On 3 March 2023, an important letter was sent by Freehills to Maurice Blackburn (Privilege Assertion Letter) in which it was contended:

(a) Freehills had undertaken “a re-review of privilege claims in light of his Honour’s rulings and the parties’ discussions with respect to the 25 sample documents”;

(b) that as “a consequence of the re-review, [Freehills] have become aware that certain documents containing privileged material were inadvertently produced to [Maurice Blackburn] in the course of [Boral]’s discovery”;

(c) that one of the “11 documents which contain privileged material and which were inadvertently not redacted at the time [Boral] gave discovery” was Ex A1 and a replacement version of the document with a redaction (being the relevant communication) was provided; and

(d) that “[Boral] asserts claims for privilege over the redacted portions of the documents listed in Schedule 1 [including the relevant communication] and confirms that the disclosure of the privileged material was inadvertent”.

(11) On 27 June 2023, Maurice Blackburn responded (MB Response Letter) to the Privilege Assertion Letter and:

(a) confirmed that Maurice Blackburn “have taken all necessary steps pursuant to clause 17 of the Protocol for the Electronic Exchange of Discoverable Documents in relation to the documents which you advised were inadvertently produced to us”, including Ex A1;

(b) noted, in relation to Ex A1, that:

(a) Since it was produced on 17 December 2021, the original unredacted version of the document was inspected and discussed on several occasions between solicitors as well as between counsel and solicitors for the applicants, including in relation to the preparation of their amended pleadings;

(b) The document was cited in the applicants’ written submissions dated 21 October 2022 in respect of their challenge to Boral’s privilege claims;

(c) The document was then tendered by the applicants, without objection, on 9 November 2022 at the hearing before Justice Rares, and was also included in the Application Book, a copy of which is on the court file, and the document itself is therefore on the public record; and

(d) The document was included in the applicants’ draft tender list served on your client on 24 November 2022.

4. In light of the above and in particular the uses that had already been made of the document before we received your letter on 3 March 2023 and the fact that the document was tendered in open court, we invite your client to reconsider its privilege claim in relation to the now redacted parts of BOR.603.030.0772 (as well as the same parts of BOR.603.030.0751 and BOR.603.030.0753 which are variants of the same email chain).

5. As an interim measure we have replaced all previous copies of these documents with the revised versions that were provided. However our clients reserve their position pending your response to this letter.

6. We look forward to hearing from you once your client has had the opportunity to consider the issues raised in this letter.

(Emphasis added).

(12) On and from 27 June 2023, until the commencement of the initial trial, Boral: (a) did not respond to the invitation to reconsider the privilege claim in relation to the relevant communication made in the MB Response Letter; and (b) continued to maintain privilege in the relevant communication as an incident of its continuing discovery obligations. Nor, despite reserving the applicants’ rights in the MB Response Letter and receiving no substantive response from Freehills, the applicants did not press the waiver issue it had implicitly raised.

(13) On 19 August 2024 (the day before Mr Kane commenced his evidence), the applicants served a further affidavit of Mr Schimmel and submissions relating to privilege issues, including as to the relevant communication, and sought to have that privilege challenge determined before Mr Kane gave evidence (a course opposed by Boral).

(14) The submissions filed by the applicants on that day noted (correctly as I explain below):

5. There has been a clear waiver of privilege and the facts are far removed from Expense Reduction Analysts Group Pty Ltd v Armstrong Strategic Management and marketing Pty Ltd (2013) 250 CLR 303… It does not matter that unredacted copies of [Ex A1] were replaced on the e-discovery platform. The waiver occurred when the document became public by reason of being tendered openly in Court documents. It is far too late to ‘claw back’ privilege after that.

(Emphasis added).

(15) On the same day, senior counsel for Boral sent an email to senior counsel for the applicants stating:

For the 2 documents you’re after - the unredacted page BOR.003.001.0135 and [the relevant communication] - we would be prepared to let you have them if you agree not to make any argument that such agreement from our client constitutes any form of waiver in relation to privilege generally or otherwise try to use them to challenge the privilege claims. This would also mean not seeking to adduce from Mike Kane evidence about the EY investigation based on what’s in the second document.

(Emphasis added).

(16) No such agreement was reached, but on 20 August 2024 at 10:49am, Freehills sent an email to Mr Schimmel making various complaints about “privilege issues” being raised and noting:

The agitating of these privilege issues mid-hearing is an unfair distraction for Boral, and there is prejudice occasioned by requiring Boral to deal with this in the midst of defending a final hearing. Nevertheless, in an attempt to resolve these issues without causing further disruption to the hearing, and consistently with the overarching purpose, Boral is prepared to make the following proposal to resolve the issues being raised:… it will produce [Ex A1] with the redaction on page 0774 [that is, the redaction of the relevant communication] removed;… Boral reserves all of its rights.

(17) The next day, 21 August 2024, the applicants asserted that the provision of Ex A1 had itself constituted the waiver (incorrectly, and inconsistently with the position asserted in the submissions of 19 August 2024); in any event, orders were then made to facilitate resolution of the dispute that had arisen and deferring the cross-examination of Mr Kane.

H NO PRIVILEGE CONTENTION

50 Neither side has been entirely consistent in their arguments, but given the Privilege Assertion Letter, and the assertion of privilege in the relevant communication until well into the trial, Boral’s submission the relevant communication was never privileged, made for the first time during argument on the voir dire, could be fairly described as demonstrating considerable forensic chutzpah. But despite inconsistency and any perceived opportunism, speaking generally, determining whether privilege exists is an objective exercise (following any findings based upon subjective evidence as to dominant purpose), and this new contention must be considered on its terms.

H.1 Boral’s Submissions

51 Boral’s submissions on this aspect of the case melded together arguments about what occurred before Rares J, waiver, and related topics, but when they got to the point of this contention, Boral asserted that:

Boral was right to discover the [relevant communication] in unredacted form during discovery in 2019 (at that time, the applicants maintained an allegation that Boral had breached its continuous disclosure obligations up until 10 February 2020 (2FASOC [1(a)], [54], [55], [58], [144], [146], [147], [149], [151], [152], [164], [166]) and therefore the alleged knowledge of Mr Kane in January 2020 was in issue), and was right not to seek to “clawback” the [relevant communication] when it formed part of Mr Schimmel’s affidavit before Rares J. Mr Schimmel correctly concluded the document was not privileged when he received it which is why he did not ask Boral whether the [relevant communication] had been produced by mistake (which he would have been required to do had he thought it may be privileged). The applicants, represented by Mr McHugh SC (as his Honour then was) and Mr Roche were also correct in making the evident forensic decision not to argue that the [relevant communication] led to a common law waiver before Rares J.

52 This is said to be the case because:

The words “if controls were as bad as EY suggests” are expressed at such a high level of generality, conclusion and opacity that they do not even disclose the “bottom-line” of any legal advice with respect to which EY assisted (or the work of EY), let alone the substance of any such advice or work. Mr Kane asking a direct report to consider work previously performed by KPMG and internal staff, in the event that controls were as suggested by EY, is not inconsistent with maintaining privilege over EY’s work. It is also relevant that Mr Kane’s comments are not even about the legal advice from Alston & Bird itself – at their highest, they are comments at a high level of generality relating to an alleged input into a legal advice. They are for that reason another step removed from a disclosure about the substance of legal advice.

H.2 Conclusion on the No Privilege Contention

53 The starting (and finishing) point, is that contrary to the submissions of Boral, the relevant communication amounts to Mr Kane, in an email with other Boral executives, representing the effect or substance (or a characterisation of the findings) of other privileged documents or communications made by EY, that Mr Kane had received or which had been communicated to him by 25 January 2020 (T469.9–25).

54 It is evident from the relevant communication itself that Mr Kane is cognisant of representations made by EY, that is, what EY “suggests”. This is reinforced by other evidence that reveals Mr Kane was privy to both written and oral communications either recording or discussing EY’s work including the meeting of the Boral Board of 5 December 2019 at which the first A&B’s Report was presented and of 24 January 2020 which was attended by EY personnel.

55 As the applicants point out (and as is trite), a communication will generally be privileged if it discloses the substance of another privileged document or communication: Turner v Bayer Australia Ltd (Privilege Ruling) [2023] VSC 104; (2023) 70 VR 290 (at 327–328 [137] per Matthews AsJ); Fenwick v Wambo Coal Pty Ltd (No 2) [2011] NSWSC 353 (at [30] per White J). A communication discloses the substance of a privileged document or communication if it “supports an inference of fact as to the content of the confidential communication or document, which has a definite and reasonable foundation”: Re Southland Coal Pty Ltd (Receivers & Managers Appointed) (In Liquidation) [2006] NSWSC 899; (2006) 203 FLR 1 (at [14(e)] per Austin J).

56 Counsel for Boral’s submissions that Boral’s solicitors were “right” to do something they later solemnly contended in the Privilege Assertion Letter was inadvertent and Boral’s further submissions which speculate about later forensic decisions of Mr Schimmel, or the applicants’ former leading counsel, are beside the point. We are faced with a question, the answer to which is binary: the relevant communication was either privileged or it was not privileged.

57 There is an insufficient basis in the evidence for me to conclude that litigation privilege existed but given the purpose of EY’s representations to A&B was for the dominant purpose of those lawyers advising Boral (a matter which is common ground), the “bottom line” of other (and privileged) communications is revealed. Boral’s submission that what was said by Mr Kane in the relevant communication is “opaque” might be correct (to the extent that it does not expose the full picture), but a broad summation of the effect or substance of what EY represented to A&B is, on the evidence before me on the voir dire, disclosed.

58 The implicit notion that a second document which contains the gist or effect of a confidential communication or document would not be privileged because it did not disclose the pathway or reasoning process by which that conclusion was reached in the first confidential communication cannot be accepted as a matter of logic or as a correct statement of the law. The numerous authorities that have developed in the different context of waiver make it plain that the protection of the effect or substance of a confidential communication is privileged. Indeed, this is the whole reason why, if one discloses the effect or substance of a privileged communication, it can lead to a waiver of legal professional privilege at common law or a loss of client legal privilege under the EA (see s 122(2) and (3)(a)) and, for example, Ampolex Ltd v Perpetual Trustee Co (Canberra) Ltd (1996) 40 NSWLR 12 (at 18–19 per Rolfe J); Bennett v Chief Executive Officer of the Australian Customs Service [2004] FCAFC 237; (2004) 140 FCR 101 (at 105 [13] per Tamberlin J, 119 [65] per Gyles J); Rio Tinto v Commissioner of Taxation [2005] FCA 1336; (2005) 224 ALR 229 (at 312–316 [49]–[62] per Sundberg J)).

59 The relevant communication was privileged. It follows there is no need to consider the applicants’ submission that Boral is now estopped from denying the relevant communication was privileged.

I NO RELEVANCE CONTENTION

I.1 Boral’s Submissions

60 Boral makes four points.

61 First, it is said it is irrelevant to know what Mr Kane understood EY had said about Boral’s controls in their ex post facto investigation.

62 Secondly, to the extent the applicants rely upon Mr Kane’s recollections of factual opinions expressed by EY to A&B and received or communicated to him, the Court could not treat those recollections as evidence of the truth of the opinions expressed, unless the applicants can show an exception to the opinion rule. It is said the applicants have sought to establish their case with respect to the inadequacy of Boral’s systems through the expert evidence of Ms Shamai of Grant Thornton, and Boral has responded with the expert evidence of Ms McKern of McGrath Nicol and that this “is the proper manner to adduce expert opinion evidence about systems and controls – not through the admission of Ex A1 and through cross-examining a former employee on his recollections of the opinions of a third party whose qualifications are unknown, who was engaged after the fact and who is not giving evidence”.

63 Thirdly, the relevant communication was made on 25 January 2020 in circumstances where the period of alleged inflation ended on 5 December 2019 and to the extent EY made any “findings” they would be with respect to a hindsight analysis almost two months after the alleged period of inflation and would suffer from the problems of relying upon hindsight material as explained by Jagot J in Australian Prudential Regulation Authority v Kelaher [2019] FCA 1521; (2019) 138 ACSR 459.

64 Fourthly, the lack of relevance of EY’s work is said to be reflected in the fact the applicants have not identified with any specificity any fact in issue to which Ex A1 or the proposed cross-examination might be relevant save as to Mr Kane’s knowledge, but the applicants have provided detailed particulars of Mr Kane’s knowledge which contain no reference to Ex A1 or hindsight work by EY as at January 2020.

I.2 Conclusion on the No Relevance Contention

65 This contention is without merit.

66 Returning to basic principles, the admissibility of evidence is subject to the rules contained in Chapter 3 of the EA. Relevantly, s 56 contains the primary rule of admissibility, that is: (1) except as otherwise provided by the EA, “evidence that is relevant in a proceeding is admissible in the proceeding”; and that (2) evidence that is not relevant is not admissible. Section 55 then provides that evidence that is relevant in a proceeding is evidence that, if it were accepted, could rationally affect (directly or indirectly) the assessment of the probability of the existence of a fact in issue in the proceeding and that evidence is not taken to be irrelevant only because it relates only to the credibility of a witness, the admissibility of other evidence, or a failure to adduce evidence. Needless to say, the party who seeks to adduce a written representation into evidence bears the onus of identifying the representation, proving the provenance and authenticity of the document containing the representation (if put in issue), and satisfying the Court that it is relevant.

67 As Gleeson CJ usefully explained in HML v The Queen [2008] HCA 16; (2008) 235 CLR 334 (at 352 [6]):

Information may be relevant, and therefore potentially admissible as evidence, where it bears upon assessment of the probability of the existence of a fact in issue by assisting in the evaluation of other evidence. It may explain a statement or an event that would otherwise appear curious or unlikely. It may cut down, or reinforce, the plausibility of something that a witness has said. It may provide a context helpful, or even necessary, for an understanding of a narrative.

68 “Context evidence”, as referred to by Gleeson CJ, is evidence which may help the tribunal of fact assess and evaluate other evidence in the case in a true and realistic context, and may, for example, be used to explain the conduct or state of mind of a person: see Hollingsworth v The Queen [2021] VSCA 354; (2021) 294 A Crim R 179 (at 204 [104] per Niall and Kennedy JJA, Macaulay AJA)

69 I not only have the pleadings to assist in identifying the facts in issue, but also an agreed document identifying the issues of fact and law I must decide. That statement of issues includes the following:

Boral and Windows’ systems and controls

2. What were Windows’ systems and controls, and Boral’s systems and controls insofar as they related to Windows, during 21 November 2016 to 10 February 2020?

3. During the Relevant Period:

(a) Was the lack of automatic integration between the inventory systems and the accounting systems unreasonable and inadequate? If so, at what point in time?

(b) Were certain manual controls in place regarding the inventory systems and the accounting systems unreasonable and inadequate? If so, at what point in time?

(c) Were certain controls in place relating to journal entries in the accounting systems used within the Windows business unreasonable and inadequate? If so, at what point in time?

(d) Were the “accountability mechanisms” in relation to Windows, relating to shared services, formal policies and procedures, and fraud reporting, unreasonable and inadequate? If so, at what point in time?

4. If the systems were unreasonable or inadequate, what were the potential consequences (if any) of Boral (including Windows) maintaining systems and controls of the kind that it did during the Relevant Period as at the dates identified in answer to question 3?

70 Apart from the termination date of the relevant period, matters have not been refined by the way the case has been opened. In particular, Boral has not taken the step of confining its case (as it might have done) and running the trial on the basis that it admits that information as to inadequate systems and controls existed (and it was information of which officers ought to have been aware), but that the applicants case simply goes nowhere because this information (as to a minor part of the business of Boral) was not material. During the oral opening of Boral, which seemed to be heavily focussed on materiality, I thought this development may be occurring, but was soon corrected. As Mr Withers explained in his opening when I enquired of Boral’s case theory (T226.4–227.15):

HIS HONOUR: So you’re not saying there were adequate – are you saying there were adequate controls in place during all of this period?

MR WITHERS: I most certainly am. My expert says there were adequate - - -

HIS HONOUR: Leave aside what your expert says. I’m just trying to understand what the case theory is. The – and I know this is joined on the pleading. I’m just trying to work out really what the substance of the case is…. I’m not suggesting this is a well-informed decision but I will just give you an indication. Look, at the end of the day, people recognise there was a stuff-up, but the stuff-up didn’t really matter very much and, again, it – there was a real question as to whether the – how quickly the stuff-up should have been identified and should have been escalated by people who would be aware of it. That’s really the answer to this claim.

But you’re – putting it bluntly, your case goes beyond that to say, “Well, notwithstanding what they said at the time when this was all revealed, and the admissions that have been made in that regard, there wasn’t a stuff-up. It is all tickety boo.”

MR WITHERS: No. There was a stuff-up insofar as two people colluded and manipulated - - -

HIS HONOUR: No. There were things that happened which ought not to have happened but all the systems and controls were in place at the time. That could reasonably have been placed – reasonably be in place at the time. No one can be perfect, no control is perfect, and this is something which was never going to be detected, even with adequate controls, etcetera. I understood that case was pleaded. But how does that sit happily with what your people said at the time, you know, when we get to the end of the relevant period of the mea culpas?

MR WITHERS: What they said at the time in the – some of the materials you were shown this afternoon was there were two people who engaged in collusion

HIS HONOUR: No. They went further than that.

MR WITHERS: Well, one has to be a bit careful about using after the event analysis from people who aren’t actually necessarily qualified to express an opinion on whether a control was inadequate or not.

HIS HONOUR: No. I understand that. That’s why I say – I’m not suggesting for a moment whether or not that’s a good argument or a bad argument. I was just giving you an indication of where I thought the real core of this dispute was in this case.

MR WITHERS: Yes.

HIS HONOUR:… – and I don’t know enough about the underlying facts to express an informed view. But I had thought that there was sort of a corporate recognition that there had been a failure. It’s just that it was not – it was an explicable failure on one level because of, you know, the nature of these businesses and the very small – the very small component of the business that was affected and, in any event, who cares because it wasn’t particularly material.

MR WITHERS: Well, that’s a very good summary, with respect, what your Honour just said about what the real issue is in the case but I’m still having to meet a case that said you had unreasonable and inadequate systems in place and you should have disclosed that from 30 August 2017.

HIS HONOUR: No. I understand.

71 Hence it is clear that the present facts in issue include whether Windows had inadequate systems and controls, and whether those within Boral (including Messrs Kane, Mariner and Post) ought to have been aware of those inadequate systems and controls and whether there had been financial manipulation and misreporting within Windows.

Ex A1

72 There is no issue as to the authenticity of Ex A1, being the document containing the relevant communication and other representations, and there is no ground of objection to the document being received into evidence as part of the applicants’ case in chief other than as to a want of relevance.

73 Boral places great emphasis upon the fact that the relevant communication was made on 25 January 2020 and the contravening conduct is alleged to have ceased on 5 December 2019. But this cannot mean the relevant communication (and other representations within Ex A1) are not relevant within the meaning of ss 55 and 56 of the EA.

74 It is beyond serious disputation that Mr Kane reviewed and considered some representations from EY during the period of contravening conduct, including immediately before Boral made the December Announcement to the ASX (T462.12–13, 467.7–469.22). To repeat, A&B had engaged EY on 11 November 2019 to investigate financial irregularities that had occurred within the Windows business. Mr Kane’s contemporaneous state of mind as to whether “controls were as bad as EY suggests” and his understanding of what was known, or ought to be known, as to financial manipulation and misreporting within Windows at any time prior to, and contemporaneously with, the December Announcement is plainly relevant. Similarly, given the evidence he has now given on oath at trial in support of Boral’s case as to the adequacy of the controls that were put in place, his apparently contemporaneous understanding of EY’s characterisation of the controls, which then led Mr Kane to query whether Boral’s auditor, KPMG, its internal audit team and others within Boral should have picked up the difficulty could rationally affect (directly or indirectly) the assessment of the cogency of his evidence at trial that he believed (and believes) that sufficient controls were in place. In this way it may bear upon the plausibility of what Mr Kane has said about his state of mind as to the adequacy of controls and, at the very least, given the receipt and consideration of the representations of EY, may provide some relevant context.

75 Further, as the applicants submit, the representations within Ex A1 from Mr Kane to Mr Mariner referring to the “Magnolia letter” (which is evidently a reference to Mr Tinkey’s letter of resignation in which he alleges that there had been financial manipulation and misreporting within Windows by Mr Phillips adjusting the books) as a “missed opportunity” is relevant to an issue in the proceeding.

76 The above deals sufficiently with Boral’s four points but for completeness it can be further observed that:

(1) although there is expert evidence about systems and controls, this does not mean other evidence, which could bear upon or be used to challenge evidence given as to the contemporaneous understanding of an officer of Boral, is irrelevant, and to dismiss Mr Kane’s understanding of what was said by EY as being “hindsight material” is incomplete given the nature of the representations contained in Ex A1 as explained above and, in any event, is not determinative of the question of relevance;

(2) there is no point going to procedural fairness in the tender of Ex A1; the present issue is not one of pleading or particulars but of the relevance of representations in Ex A1 to a fact in issue;

(3) the narrow approach taken by Boral as to relevance is well illustrated by its submission (T578.31–37) that Ex A1 is irrelevant “[b]ecause it is hard to imagine a scenario where your Honour says ‘I find that controls are bad because EY found the controls are bad’. Very hard to imagine that”. But contrary to the notion implicit in this submission, the truth of the relevant communication does not need to be accepted (or even be considered to be of real weight) for it to be relevant and its weight and its assessment, in the light of all other evidence, is an entirely different matter; and

(4) the conclusion as to relevance is hardly surprising given that it ought not be forgotten that Boral itself discovered the document that has become Ex A1 because it formed the view, conscientiously and on the basis of advice given to it during the course of preparing a list of documents pursuant to an order of the Court, that Ex A1 was a document that is “directly relevant to the issues raised by the pleadings” (see r 20.14(1)(a)).

Proposed Kane Evidence

77 As I noted during oral submissions, attempting to rule on the relevance of what might be described as a “line of questioning” before specific questions have been asked is fraught with difficulty. To the extent the Proposed Kane Evidence can be anticipated, I deal with it (in the context of the Abuse of Process Contention at Section L below).

J DISCRETIONARY EXCLUSION DISCRETION

J.1 Boral’s Submissions

78 If otherwise relevant and admissible, Boral submits Ex A1 should be excluded in the exercise of discretion because its probative value is substantially outweighed by the danger that the evidence might cause or result in undue waste of time: see s 135(c) EA.

79 Boral accepts the discretion under s 135 is to be applied on a case-by-case basis, and a great deal is left to the discretion of the trial judge, but submits that the overarching principle is one which tells against admitting the evidence or undertaking a burdensome enquiry “from which there might be no substantial countervailing benefit in assisting the resolution of the primary issues”: D F Lyons Pty Limited v Commonwealth Bank of Australia [1991] FCA 86; (1991) 28 FCR 597 (at 607 per Gummow J); Koninklijke Philips Electronics NV v Remington Products Australia Pty Ltd [2000] FCA 876; (2000) 100 FCR 90 (at 106–107 [21] per Burchett J). Admitting evidence which would require the Court to lengthen a protracted trial by introducing a further factual contest on what is a collateral factual issue will attract the exercise of the discretion.

80 Boral’s position is that if Ex A1 is relevant, any probative value must be very limited. It points to the evidence adduced on the voir dire from Mr Betts as to the steps that would be taken if Ex A1 were admitted into evidence, including considering whether: (1) Boral obtains any further lay evidence including from persons employed by EY or A&B involved in preparing relevant reports; and (2) any further documents, including any EY reports, would need to be provided to the systems experts, who have already prepared a joint report. It is said considering and, if thought appropriate, actioning these steps would cause delay and increased costs.

81 As to the fact the trial has now been adjourned, Boral asserts that a party must conduct its case consistent with the overarching purpose obligations in Pt VB of the FCA Act and “cannot raise a collateral issue, resulting in the trial being adjourned… and then be rewarded with an entitlement to advance a collateral issue and require the respondent to respond to it because the trial has been adjourned”.

J.2 Conclusion on the Discretionary Exclusion Contention

82 As I noted in Lehrmann v Network Ten Pty Limited (Expert Evidence) [2023] FCA 1577 (at [33]–[34]), s 135 requires the probative value of the proposed evidence to be weighed against the dangers listed in the provision. The starting point is to form an assessment as to probative value and then, in the weighing exercise, it must be borne in mind that the dangers are required to substantially outweigh the probative value of the evidence for it to be excluded: see Stephen Odgers, Uniform Evidence Law (18th ed, Lawbook Co, 2023) (at 1314–1328). Boral submits that the Court does not have to determine that the probative value is substantially outweighed by the fact that it will lead to an undue waste of time, just that there is a danger that this may be so.

83 In doing so, it relies upon a decision of Bellew J in Welsh v Carnival Plc trading as Carnival Australia (No 4) [2016] NSWSC 1296 (at [21]) which cited Sackville J’s observations in Seven Network Ltd v News Ltd (No 8) [2005] FCA 1348; (2005) 224 ALR 317 (at 321 [16]). When one looks at Seven Network Ltd v News Ltd (No 8), it ought to be noted that Sackville J’s observations were in the context of a different discretion (s 136 limitation on use) and were as follows:

The Court has power under s 136 of the Evidence Act to limit the use of evidence if there is a danger that a particular use of evidence might be unfairly prejudicial to a party. The Court does not have to be satisfied that a particular use of evidence will be unfairly prejudicial. The section speaks of a danger involved that such a use of evidence might be unfairly prejudicial: Guide Dog Owners’ & Friends’ Association Inc v Guide Dog Association of New South Wales and ACT (1998) 154 ALR 527, at 532, per Sackville J. The fact that the Court’s power is enlivened does not mean that a direction must be made under s 136. The section confers a discretion on the Court which must be exercised judicially, having regard to the circumstances of the particular case.

(Emphasis in original).

84 But in Welsh v Carnival Plc and in a series of cases (R v Rogerson; R v McNamara (No 45) [2016] NSWSC 452 (at [36]), R v Medich (No 8) [2016] NSWSC 1713 (at [42] in the context of s 137 EA), Capar v SPG Investments Pty Limited t/a Lidcombe Power Centre (No 2) [2017] NSWSC 1372 (at [25]); R v Ronald Edward Medich (No. 30) [2018] NSWSC 206 (at [68], again a s 137 case); and R v We (No 13) [2020] NSWSC 225 (at [23]), Bellew J has cited Sackville J’s observations as being applicable to discretions other than s 136, including the discretion with which we are presently concerned.

85 Put in terms of s 135 and the argument advanced by Boral, I must take the following steps.

86 First, I must assess the probative value of the evidence with the term “probative value” defined in the Dictionary to the EA in the following terms:

Probative value of evidence means the extent to which the evidence could rationally affect the assessment of the probability of the existence of a fact in issue.

87 Secondly, assess the danger that the evidence might cause or result in an undue waste of time.

88 Thirdly, undertake the balancing exercise to determine whether the probative value of the evidence is substantially outweighed by such danger. If I am satisfied that it is, the evidence may be excluded.

89 Although not referred to in submissions by the parties, in Herron v HarperCollins Publishers Australia Pty Ltd [2022] FCAFC 68; (2022) 292 FCR 336 (at 426–427 [390]–[391]), I also explained (in observations with which Rares and Wigney JJ agreed), the general discretion needs to be exercised in accordance with s 192 of the EA which provides:

192 Leave, permission or direction may be given on terms

(1) If, because of this Act, a court may give any leave, permission or direction, the leave, permission or direction may be given on such terms as the court thinks fit.

(2) Without limiting the matters that the court may take into account in deciding whether to give the leave, permission or direction, it is to take into account:

(a) the extent to which to do so would be likely to add unduly to, or to shorten, the length of the hearing; and

(b) the extent to which to do so would be unfair to a party or to a witness; and

(c) the importance of the evidence in relation to which the leave, permission or direction is sought; and

(d) the nature of the proceeding; and

(e) the power (if any) of the court to adjourn the hearing or to make another order or to give a direction in relation to the evidence.

(Emphasis added).

90 It is well accepted that the terms “leave, permission or direction” in s 192 carry a broad meaning and encompass an order or direction to admit or exclude evidence: see Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Rich [2006] NSWSC 643; (2006) 201 FLR 207 (at 210 [9] per Austin J); Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Citigroup Global Markets Australia Pty Ltd (No 2) [2007] FCA 121; (2007) 157 FCR 310 (at 311–312 [7]–[8] per Jacobson J). Further, the use of the term “is to take into account” dictate that these considerations in s 192(2) are mandatory to the extent they are applicable.

91 Given the terms of the written submissions of Boral, it became clear discretionary exclusion was sought only in relation to Ex A1 and I do not need to consider whether s 135 was being called in aid in some form of anticipatory way to disallow the Proposed Kane Evidence (on the basis that, if given, the likely answers would properly be the subject of discretionary exclusion). This is understandable as any such argument would be premature.

92 Dealing first with probative value, we know whether Windows had adequate systems and controls is in issue; we also know there is an issue as to whether officers of Boral, including Mr Kane, were aware, within the meaning of ASX Listing r 19.12, of any inadequate systems and controls. Ex A1 is the only vaguely contemporaneous document recording the effect or substance of EY representations to A&B following their apparently detailed investigation into the financial irregularities and manipulation that had occurred within Windows. Mr Kane’s relevant communication will no doubt be relied upon, together with other evidence, to suggest that the controls were bad in a way which ought to have been obvious to Boral’s officers and to undermine Mr Kane’s evidence to the contrary.

93 One only has to consider the evidence in chief given by Mr Kane, supportive of Boral’s case as to the adequacy of controls, and the questions that could be legitimately asked of Mr Kane as to his relevant communication contained in the document (discussed below at [119]–[121]) to ascertain that Ex A1 is a far from insignificant document (which is no doubt why Boral considered it was “directly relevant” at the time it was discovered and why the hearing has been derailed in arguing about whether it, and related evidence, should be able to be adduced into evidence).

94 Having reached a view as to the significance of its probative value, I next need to assess the danger that the admission of Ex A1 in the trial might cause or result in an undue waste of time. This relevantly requires an assessment “of the time that would [or, I interpolate, might] be unduly wasted by the evidence”: Cadbury Schweppes Pty Ltd v Darrell Lea Chocolate Shops Pty Ltd [2007] FCAFC 70; (2007) 159 FCR 397 (at 414 [76] per Black CJ, Emmett and Middleton JJ) (emphasis in original).

95 We are here dealing with the tender of one, not lengthy document, in the context of what is certain to be a large documentary tender. Although as a practical matter the admission of Ex A1 will or might lead to subsequent steps being undertaken, strictly speaking, cross examination going to the previous representations made by Mr Kane (including the relevant communication) could occur without the tender of Ex A1. Notwithstanding this, to approach the assessment generously from the point of view of Boral, I will take into account the likely Proposed Kane Evidence and that, as Mr Betts has indicated, this cross examination may cause Boral to consider further lay evidence including from persons employed by EY or A&B and that any further documents, including any EY reports which might be required to be produced, would need to be provided to the systems experts.

96 The trial has already been required to be adjourned, for reasons discussed below. I accept there will be costs associated with making any enquiries as to additional lay witnesses (if that is a course that ultimately commends itself to Boral) and costs occasioned by calling such witnesses – if that was ever to occur. I accept it might be necessary to show additional material to the experts and there might also be costs involved in this process (although consistently with the approach I have thus far taken as to opinion evidence, any process of procuring any further opinions from experts, if requested by either party, will be controlled by the Court so as to minimise costs and maximise security as to the integrity of the evidence).

97 Given the vicissitudes of this case have already required an adjournment, any further incremental delay caused by the reception into evidence of Ex A1 is likely to be minor, but I accept there will be some additional delay and additional cost. Steps can be taken to minimise any delay by Boral doing its best to assess now whether, in reality, it is likely that further lay evidence would be called once the Proposed Kane Evidence is adduced and making preliminary enquiries and for both parties to reserve time now for the experts to confer again, prior to the joint evidence session, if it becomes necessary for them to do so.

98 Finally, in the light of the above (and the matters referred to in s 192 EA to the extent relevant), I am required to undertake the balancing exercise to determine whether the probative value of the evidence is substantially outweighed by the danger identified by Boral and found to exist.

99 I have done so, and it is not a close-run thing.

100 Such costs and delays that might be occasioned do not outweigh (let alone substantially outweigh) the probative value of the evidence, particularly when one has regard to the overall costs involved and the relative extent of any additional costs, the nature of the proceeding (including that any determination of common issues may affect non-parties (see s 192(2)(d)), the fact that any additional costs may form part of a costs order in relation to any consequences flowing from the admission of the evidence (s 192(2)(e)); and, most importantly, the possible significance of the evidence (that is, the significance as to the adequacy of controls that remains in issue).

101 As to Boral’s reliance on the overarching purpose obligations in Part VB of the FCA Act, even on the assumption it was a relevant consideration for the exercise of this EA statutory discretion (which is not self-evident), as I will explain below, the biblical injunction in Matthew 7:3 springs to mind, and Boral’s infirm maintenance of a claim for privilege in the relevant communication means it has its own significant responsibility for the trial being derailed.

102 Given that representations made in Ex A1, including the relevant communication is relevant, and the document containing the representations is not the subject of discretionary exclusion, it should be admitted and, to avoid confusion, it will bear that exhibit marking in the trial.

K NOT REASONABLY NECESSARY CONTENTION

K.1 Boral’s Submissions

103 The next plank in Boral’s argument is that even if the relevant communication was formerly privileged and that the privilege has been lost, s 126 does not apply to the Proposed Kane Evidence because it is not reasonably necessary to enable a proper understanding of the relevant communication. After making further complaint about delay and referring to the principled approach to s 126 explained above, Boral contends that the relevant communication:

[C]an be perfectly understood on its own. It is Mr Kane informing Mr Mariner that he needs to be ready to explain why “KPMG, inside audit and Allan and Oren” missed control issues at Windows, “if” work by EY at a particular point in time was correct as to controls. Mr Kane is putting a hypothetical question to Mr Mariner to be prepared for a question.