FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Energy Regulator v AGL Retail Energy Limited [2024] FCA 969

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties are to confer and prepare short minutes of order which reflect these reasons, and which contain directions as to the further conduct of this proceeding, and provide these to the associate to Downes J by 4.00 pm on 30 August 2024.

2. If the parties are unable to agree on a form of order as referred to in Order 1, each party prepare their own version of a draft order and provide this to the associate to Downes J by 4.00 pm on 6 September 2024.

3. The proceeding be listed for a case management hearing at 9.30 am on 10 September 2024.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

[1] | |

[12] | |

[12] | |

[16] | |

[23] | |

[34] | |

[34] | |

[36] | |

[42] | |

[47] | |

[60] | |

[69] | |

[69] | |

[72] | |

[84] | |

[85] | |

6.2 Consideration of meaning of “overcharged” and “overcharging” | [90] |

[90] | |

[97] | |

[101] | |

[121] | |

[126] | |

[128] | |

[132] | |

[134] | |

[136] | |

[140] | |

[150] | |

[162] | |

[163] | |

[164] | |

[169] |

DOWNES J:

1 Centrepay is a voluntary direct deduction facility operated by Services Australia. It allows a recipient of welfare payments to authorise the deduction of amounts from their welfare payments (a deduction) to pay the customer’s bills from a business approved by Services Australia to use Centrepay (Approved Business). The deduction is paid directly by Services Australia to the Approved Business in order to pay the customer’s bills for goods or services provided by the Approved Business to the Customer.

2 At all times between at least 23 December 2016 and 2 November 2021 (the relevant period), the four respondents – AGL Retail Energy Limited, AGL Sales Pty Ltd, AGL South Australia Pty Ltd and Powerdirect Pty Ltd (the AGL Entities or AGL) – were Approved Businesses.

3 The use of Centrepay by an Approved Business is governed by:

(1) the Centrepay Policy and Terms (Centrepay Policy) (the document is styled “Centrepay Policy and Terms”, and contains two distinct sections comprising the Policy and then the Terms respectively);

(2) the Procedural Guide for Businesses (Procedural Guide);

(3) the Centrepay Business Application;

(4) the Centrepay Deduction Authority; and

(5) the approval letter issued by Services Australia providing its approval for an Approved Business to use Centrepay, including any additional conditions imposed by Services Australia;

(together, the Centrepay Framework).

4 It is common ground for the purposes of this proceeding that each of the AGL Entities had an agreement to use Centrepay which was governed by the terms of the Centrepay Policy, Procedural Guide and an additional condition imposed by Services Australia on its approval to use Centrepay (the AGL Centrepay Agreement).

5 In this proceeding, the Australian Energy Regulator (AER) alleges that the AGL obtained and retained deductions from 483 recipients of Centrelink benefits via Services Australia’s Centrepay service after these customers ceased to obtain electricity or gas from AGL in circumstances where those customers did not owe money to AGL (Affected Customers).

6 By reason of this conduct, the AER alleges that AGL “overcharged” the Affected Customers for electricity or gas within the meaning of rule 31 of the National Energy Retail Rules (Version 30) (Retail Rules) and therefore contravened rules 31(1), 31(2) and 31(3), each of which is a civil penalty provision.

7 As rule 31 is a civil penalty provision, I am required to reach a “state of satisfaction or actual persuasion, on the balance of probabilities, while taking into account the seriousness of the allegations and the consequences which will follow if the contraventions are established”, being a standard which is set out in s 140(2) of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) and which is the statutory expression of the principle in Briginshaw v Briginshaw (1938) 60 CLR 336: see Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Daly (Liability Hearing) [2023] FCA 290 at [37] (Cheeseman J).

8 The AER also alleges that AGL contravened s 273 of the National Energy Retail Law (Retail Law) (which is contained in the Schedule to the National Energy Retail Law (South Australia) Act 2011 (SA)) by failing to establish policies, systems and procedures to enable them to efficiently and effectively monitor their compliance with the Retail Rules.

9 Pursuant to an order of this Court made on 13 September 2023, the trial was held in relation to the issue of liability only.

10 For the reasons that follow, I am satisfied to the required standard that the alleged contraventions have been established.

11 I will direct the parties to confer and provide orders which reflect these reasons, and which address directions relating to the further conduct of this proceeding. Each party should have leave to appeal and, to the extent necessary, leave to cross-appeal.

2. EVIDENCE RELIED ON BY THE PARTIES

2.1 Evidence relied upon by the AER

12 By way of lay evidence, the AER relied upon the following affidavits:

(1) Mr Andrew Vogt, Director of the Program Compliance and Confirmation Team at Services Australia, affirmed two affidavits on behalf of Services Australia dated 7 February 2024 and 3 May 2024.

(2) Mr Matthew Irvine, Lead Data Analyst in the Strategic Data Analysis Unit of the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission, affirmed an affidavit dated 7 February 2024.

(3) Ms Helen Joyce, solicitor at Baker McKenzie, affirmed an affidavit dated 3 May 2024.

13 None of the AER’s witnesses was required for cross-examination.

14 By way of expert evidence, the AER tendered the expert report of Ms Siobhan Hennessy dated 19 February 2024 (Hennessy Report). Ms Hennessy is a chartered accountant and partner in McGrathNicol’s Forensic and Advisory practice and specialises in forensic accounting and the provision of expert evidence.

15 The AER also relied on further documentary evidence, a description of which is set out in the parties’ consolidated tender list.

2.2 Evidence relied upon by AGL

16 Mr Eugenio Fragapane, Head of Connections and Billing at AGL Energy Limited (the parent company of each of the AGL Entities), affirmed an affidavit dated 11 April 2024 and was cross-examined on the second day of trial.

17 Mr Steven Horbury, Head of Credit and Affordability at AGL Energy Limited, swore an affidavit dated 11 April 2024 and was cross-examined on the second day of trial.

18 Ms Suriyanti Susarla, Operational Change Manager at AGL Energy Limited, affirmed an affidavit dated 10 April 2024 and was cross-examined on the second day of trial.

19 Ms Kim Nguyen, Payment Transformation Lead at AGL Energy Limited, affirmed an affidavit dated 11 April 2024 and was cross-examined on the second day of trial.

20 Mr Abhishek Das, SAP FI-CA Consultant at Tata Consultancy Services, affirmed an affidavit dated 10 April 2024 and was cross-examined on the third day of trial.

21 Ms Angela Gregory, Group Counsel in the Competition Regulation and Strategy team at AGL Energy Limited, affirmed an affidavit dated 12 April 2024. Ms Gregory was not required for cross-examination.

22 AGL relied on further documentary evidence, a description of which is set out in the parties’ consolidated tender list.

3. THE CONDUCT OF THE AGL ENTITIES

23 The conduct of the AGL Entities which is the subject of this proceeding, and which is common ground, is as follows.

24 First, a customer entered into a contract (identified in Column A of Schedules 1 and 2 to the Further Amended Statement of Claim or FASOC) with one of the AGL Entities (the Relevant AGL Entity). The Relevant AGL Entity which entered into the contract with the particular customer is identified in Column B of the schedules by reference to an identifying code. Each of the customers were recipients of welfare payments through Services Australia and are described below as the Affected Customers.

25 Second, the Relevant AGL Entity supplied the Affected Customers with electricity or gas and issued bills to the Affected Customers (AGL Bills).

26 Third, before the end of the contract between the Relevant AGL Entity, each of the Affected Customers had authorised deductions to be made through the Centrepay service in favour of the Relevant AGL Entity to pay AGL Bills.

27 Fourth, on the date identified in Column D of Schedules 1 and 2 to the FASOC, the Affected Customers ceased to obtain energy from the Relevant AGL Entity in respect of that account. As a consequence, their account was either closed or became inactive. This is referred to as the Account Cessation Date. The Relevant AGL Entity issued a final bill.

28 Fifth, after the Account Cessation Date and before the next scheduled payment for the deduction, neither the Relevant AGL Entity nor the customer had cancelled the deductions through Services Australia. The AGL Entities were required to do this by the terms of the AGL Centrepay Agreement.

29 Sixth, after the Account Cessation Date, the AGL Entities continued to receive payments for AGL Bills pursuant to the deduction which was in place for each one of the Affected Customers, and processed these payments even though the Affected Customers were no longer being supplied energy and after the Affected Customers had fully paid all AGL Bills issued for energy supplied under their contract with the Relevant AGL Entity.

30 Seventh, on the assumption that the AER’s construction of “overcharging” in rule 31 is accepted, it is common ground that the AGL Entities became aware of the overcharging within the meaning of rule 31(1). The dispute concerns when the AGL Entities became so aware (Awareness Date), and the different positions of the parties is shown in Schedules 1 and 2 to the FASOC.

31 In relation to Schedule 1, the Awareness Date is the date on which the AER alleges that AGL became aware of the overcharging. It is the date on which AGL attributed an amount of money referable to a deduction to a customer’s account after the Account Cessation Date where the customer did not owe any money for the electricity or gas they had consumed and following receipt by AGL of a deduction payment report from Services Australia.

32 A deduction payment report is a report which is designed to be read by a computer system and which is made available by Services Australia to the Approved Business. It is addressed in more detail below.

33 In relation to Schedule 2, the Awareness Date is the date which the AGL Entities admit that they became aware that each particular Affected Customer had been the subject of what the AER alleges constituted “overcharging” (but which the AGL Entities do not admit constitutes “overcharging” within the meaning of rule 31).

4.1 Relevant terms of AGL Centrepay Agreement

34 The AGL Centrepay Agreement, in broad terms, allowed the AGL Entities to use Centrepay in accordance with the terms of that agreement so as to offer Centrepay as a payment option to customers of the AGL Entities. Deductions were obtained through Centrepay from customers on account of electricity or gas supplied by the AGL Entities to those customers. The AGL Centrepay Agreement also required the AGL Entities to register their relevant employees as individual users to access Centrepay online services through the Centrelink Business Online Service (CBOS). CBOS is the secure online service provided by Services Australia by which Approved Businesses manage their Centrepay activities, including creating and cancelling deductions.

35 The relevant terms of the AGL Centrepay Agreement are as follows:

(1) Deduction Attribution Term: the AGL Entities were required to credit a customer’s account with the AGL Entity with the amount of any deduction as notified to the AGL Entity in Services Australia’s deduction and payment reconciliation reports, or as otherwise notified to the AGL Entity by Services Australia;

(2) Valid Deduction Term: the AGL Entities could only claim a deduction from Centrepay where a valid consent and instruction from the customer was in place and had not been withdrawn;

(3) Cancellation Term: the AGL Entities were required to cancel a deduction within three business days if the customer did not continue to receive the electricity or gas in relation to which the deduction had been established. The AGL Entities were not required to obtain the consent of a customer to cancel an existing deduction;

(4) No Arrears Term: the AGL Entities were required not to use Centrepay to collect payments from a customer who was no longer an ongoing customer, and not to collect arrears from a customer who was not an ongoing customer;

(5) Proper Process Term: the AGL Entities were required to take reasonable care and later, to have processes, to avoid them receiving any amounts deducted from a welfare payment that were more than the amount they should have received consistently with the Centrepay Policy;

(6) Adequate Systems Warranty: from 10 December 2018, the AGL Entities represented and warranted that they had adequate arrangements, processes, documentation and systems in place to support their agreements with customers and participation in Centrepay in accordance with the Centrepay Policy.

4.2 Setting up and cancelling deductions

36 In order to use Centrepay, a business must register for CBOS. Once approved to use CBOS, the business itself is identified by a Customer Reference Number (CRN), and then individual users for that business (Business Users) are provided with a unique User ID and password and assigned to particular business CRNs.

37 The AGL Entities have been registered users of CBOS since at least 6 February 2015. The AGL Entities had numerous Business Users assigned to their CBOS accounts during the relevant period.

38 Once registered, Business Users of CBOS can access both the Deduction and Payment Application (DAPA) and the Deduction Bulk Upload Service (DBUS) through CBOS.

39 DAPA is an online service specific to Centrepay which is accessible through CBOS. In summary, DAPA allows a Business User to see the name and payment amount in relation to each customer in respect of whom a payment has been sent to the relevant Approved Business on a given day, and to add, vary or cancel deductions in relation to particular customers.

40 DBUS is also an online service specific to Centrepay which is accessible through CBOS. In summary, DBUS enables an Approved Business to add, vary or cancel Centrepay deductions for their customers in bulk. That is, compared to DAPA, which allows an Approved Business to change deductions one at a time, DBUS enables this to be done for multiple customers at one time.

41 The evidence demonstrated that the AGL Entities did in fact use DAPA and DBUS to create, vary and cancel deductions. In particular, between 23 December 2016 and 14 October 2021, the AGL Entities created 5,617 new Centrepay deductions, changed 6,402 Centrepay deductions, and sent instructions to cease 1,794 deductions.

42 FileX is a file exchange system which is provided by Services Australia as a legacy system for certain businesses, including AGL. FileX is used by Services Australia to deliver deduction payment reports to Approved Businesses who were registered to use that system before 2015.

43 Deduction payment reports contain the following information in relation to each Centrepay deduction relevant to the Approved Business: (a) the relevant customer’s name; (b) the relevant customer’s reference number or CRN; (c) the account reference number associated with the Approved Business (if this has been provided by the Approved Business to Services Australia); (d) the date of the Centrepay deduction; (e) the date of payment to the Approved Business, being the date that the payment was sent to the Business; (f) the deduction amount from the relevant customer’s welfare payment, being the amount that has been deducted from the customer’s payment and paid to the Business; and (g) the service type for the deduction amount, being the identifier for the service that the Business offers for which the payment was deducted.

44 The purpose of a deduction payment report is to allow the AGL Entities to reconcile the payments which are made into their bank accounts by Services Australia with the individual customer details to which those payments relate, so that they can process and allocate each deduction to the relevant customer.

45 A deduction payment report becomes available for download on each business day that a Centrepay deduction is paid by Services Australia to one of the AGL Entities.

46 A deduction payment report downloaded through FileX is not in a form which is readable by a human person; rather it is designed to be processed by a computer system.

47 The AGL Entities adduced evidence from Mr Das, an “SAP FI-CA Consultant” who is engaged by AGL Retail Energy Limited. Mr Das deposed that the AGL Entities “developed a script in-house which it runs each day within SAP”. SAP is a reference to AGL’s ICT or information and communication technology system. The script “pulls” the deduction payment report from Services Australia directly into AGL’s “SAP information system user interface”. Mr Das gave evidence that AGL’s SAP information system “enables the data in the [deduction payment reports] to be allocated against customer accounts without human involvement or interaction”.

48 In around 2006, AGL designed and implemented a batch processing program within SAP to automatically process “incoming payment files” from third party payment agencies, including Australia Post, Westpac, Centrelink, mercantile agents, ePayplus and Paypal. The batch processing program involves: (1) reading the file from the application server; (2) validating the file; (3) reformatting the payment file; (4) outputting the reformatted file to the application server; (5) performing reconciliation between the reformatted file and the source file; and (6) archiving the source file. There was a batch processing program specific to Centrelink within SAP.

49 At around 7:00pm each evening, the AGL-developed script accessed the Services Australia FileX website to download deduction payment reports. From about 7:45pm to 8:00pm, the Centrelink batch processing program began to process the deduction payment reports. By around 9:00pm, the SAP subledger system was updated with information from the deduction payment reports from Services Australia.

50 It is the responsibility of the SAP FI-CA team within AGL to ensure that: (a) deduction payment reports are received, (b) the Centrelink batch processing program is being run, and (c) the payments are posted successfully to particular accounts in accordance with the design documentation for the batch processing program.

51 The evidence of Mr Fragapane, who was responsible for the Credit and Payments Function from April 2016 to June 2018, was that it was the responsibility of employees of the AGL Entities within the payments team to determine how the SAP system, including the batch processing program, should function to manage billing and payments, which determination was communicated to the information technology teams to implement. All changes to the batch processing program were signed off by AGL employees within the payments team. The system was intentionally designed such that whenever AGL receives a payment, the processing program identifies the customer account to which it relates and records it against that customer’s account. The process is applied to all accounts that AGL has, whether they are active or inactive and final-billed. The system was designed in this way so that AGL could collect debts if a person had money owing, and it was designed to apply payments from customers to accounts even if the account was in credit.

52 That is, the Centrelink batch processing program was designed such that it would post payments to customer accounts that were inactive and in credit or with a zero balance.

53 In May 2016, the batch processing program was updated to include a new “Credit Balance Transfer” process. The purpose of the update to the SAP system was to automate the manual monthly process which had been in place to “identify credits on inactive contracts” and transfer them to other eligible active contracts.

54 The Credit Balance Transfer process was a custom functionality in SAP designed to identify the attributes of the account to which a payment was to be allocated, identify whether the account was active or inactive and in debt or in credit, and allocate payments according to priority rules. It was applied to the Centrelink batch payment process.

55 The evidence demonstrates that this system identified whether the contract account number in the deduction payment report was for a customer account which had been inactive for more than 60 days, had been final billed, had a zero or credit balance and was a residential customer account.

56 It was then designed to allocate amounts to a different destination contract, according to particular criteria. The criteria required that the account be for the same customer, that there were no payment locks or posting locks on the account, that the account was for energy and the account was for a residential customer. Where multiple accounts satisfied those criteria, money was allocated according to particular priorities: first to inactive accounts with debt, then to active accounts with debt, and then to active accounts in credit. If there was no eligible destination contract, the money would be allocated to the “source contract” (described in the interface design as “Step 60”). That is the source contract which had been identified as being for an inactive account, which had been finally billed, had a zero or credit balance and was for a residential customer.

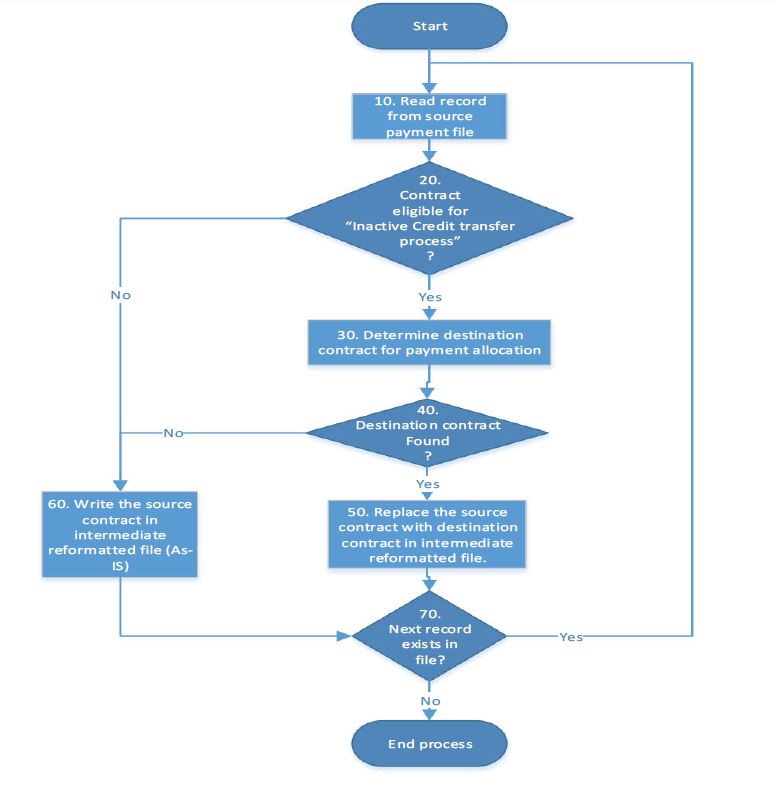

57 The processing flowchart is depicted below:

58 This process was run in respect of each deduction payment report, and it was run before the SAP system processed the payment file and allocated amounts to customer accounts in the SAP subledger system.

59 It follows that from May 2016 onwards, the Centrelink batch processing program was designed to, and did, identify whether the account to which a Centrelink deduction would be allocated was active or inactive, and in credit or debt. If there was no other account identified for credit balance transfer, the amount would continue to be attributed to an inactive account in credit (the source contract).

60 On 14 June 2013, Services Australia wrote to AGL Sales Pty Ltd to advise that Services Australia had become aware that AGL Sales Pty Ltd had been obtaining deductions through Centrepay in circumstances where customers had ceased to be a current customer or use any services provided by it, and had failed to advise Services Australia of that, or that AGL Sales Pty Ltd had become aware that it had received overpayments. Services Australia informed AGL Sales Pty Ltd that it considered that this conduct amounted to “a serious non-compliance … which must be remedied by AGL Sales Pty Ltd and addressed to ensure that similar non-compliances do not occur in the future”.

61 As the AGL Entities’ evidence is that the respondents all “share the internal resources of the AGL group (including people, data, processes and technology) including in relation to connections, billing and payments”, I infer that information provided on behalf of one respondent to Services Australia was known to all respondents. AGL conceded as much. Further, the “Procurement Relationship Manager” (Mr Frederick Olsen) of AGL Energy Limited responded to Services Australia on 25 October 2013 which letter stated, amongst other things, that:

We can now advise AGL has completed a review of its Centrepay related processes within its business and has made a number of changes that will enable AGL, going forward, to meet the above requirements that have been stipulated to AGL by Centrelink [being the requirements outlined in the 14 June 2013 letter].

62 In July 2013, Mr Andrew Harman (the Payments Manager) had created a “Deduction Cancellation Process Proposal” which stated that AGL “currently have a number of Accounts where the customer has moved-out, but Centrepay deductions have remained in place, accruing credit on the account” and that AGL had a “contractual obligation with Centrelink to notify them to cancel a deduction when a customer no longer uses AGL services, and we are not currently meeting this requirement”. Mr Harman proposed a solution “Phase 1”, which he described as a “short-term manual reporting solution” which would extract customers who meet “reporting criteria”, which included that the customer account was inactive, had been issued a final bill, and had a zero or credit balance.

63 That manual reporting solution was implemented in the payments team from at least 2 August 2013 until around 15 January 2016.

64 Mr Harman proposed a solution “Phase 2a” which constituted an “automated reporting solution” to replace the manual solution. The interface design of the batch processing program demonstrates that this automated reporting solution was created, described as “Initiative Iceberg”, in November 2013, by which “Centrelink payment files will not removed [sic] from the input directory after payment interface process. These files will be processed by the Centrepay program which will be scheduled after payment interface program to update Z table”. A “Z table” is a custom table in SAP. The batch processing program was updated in 2013 so that the report downloaded each day by AGL that recorded any changes to its customer’s Centrepay deduction status (including where AGL created, varied or cancelled a deduction on behalf of a customer) had the relevant data extracted from it and included in the SAP Z table. Through this modification, from 2013, AGL had a record in SAP of whether a customer had an active Centrepay deduction, and when that deduction was created, varied or cancelled.

65 Between 2013 and 2016, AGL (through Mr Harman’s manual process) created monthly extracts of data which met validation criteria and identified inactive customers who had ongoing Centrepay deductions from their welfare payments. Also prior to 2016, AGL had a manual “monthly” process to identify credits on inactive accounts and transfer those credits to other eligible accounts. In January 2016, the manual reporting process created by Mr Harman ceased. No explanation was offered by the AGL Entities as to why the manual reporting process ceased in January 2016.

66 In response to a notice which required AGL to produce “all written AGL policies, systems, procedures or reference guides” in use which described the “policies, procedures and systems of AGL that were current” in relation to (inter alia) how AGL identifies and records when a Centrepay Customer closes their AGL account or ceases using its services”, AGL produced versions of an internal document described as the Payment Enquiries Reference Guide. The first version of this document is dated July 2016 and it states that “Accounts Receivable monitor inactive accounts on a regular basis, and any customer who continues to make CentrePay payments to an inactive account once their final consumption invoice is cleared will have their CentrePay arrangements cancelled by AGL”.

67 The Payment Enquiries Reference Guide was updated in July 2018 and July 2019 to reflect the processes and procedures that the payments team was following at that point in time. Each iteration of the Payment Enquiries Reference Guide continued to state that it was part of the processes of the payments team to monitor inactive accounts and that AGL would cancel their Centrepay arrangements with that customer once those accounts went into credit (i.e. when the final consumption invoice was cleared).

68 In October 2019, Ms Nguyen identified that there were customers in the Centrepay payment channel with high credit balances. She reported this to Mr Horbury by email on 1 October 2019. During 2019 – 2020, the payments team (including Ms Nguyen) was involved in a credit remediation program which focused only on the identification and remediation of accounts with high credit balances. Under cross-examination, Ms Nguyen accepted that the program did not address high credit balances of customers in the Centrepay payment channel until mid-2020.

5.1 The National Energy Retail Rules

69 Rules 31(1)–(3) of the Retail Rules, as applicable in New South Wales, Queensland and South Australia during the relevant period, are in the following terms:

31 Overcharging (SRC and MRC)

(1) Where a small customer has been overcharged by an amount equal to or above the overcharge threshold, the retailer must inform the customer accordingly within 10 business days after the retailer becomes aware of the overcharging.

Note

This subrule is classified as a tier 2 civil penalty provision under the National Energy Retail Regulations. (See clause 6 and Schedule 1 of the National Energy Retail Regulations.)

(2) If the amount overcharged is equal to or above the overcharge threshold, the retailer must:

(a) repay that amount as reasonably directed by the small customer; or

(b) if there is no such reasonable direction, credit that amount to the next bill; or

(c) if there is no such reasonable direction and the small customer has ceased to obtain customer retail services from the retailer, use its best endeavours to refund that amount within 10 business days.

Note

Money not claimed is to be dealt with by the retailer in accordance with the relevant unclaimed money legislation.

Note

This subrule is classified as a tier 2 civil penalty provision under the National Energy Retail Regulations. (See clause 6 and Schedule 1 of the National Energy Retail Regulations.)

(3) If the amount overcharged is less than the overcharge threshold, the retailer must:

(a) credit that amount to the next bill; or

(b) if the small customer has ceased to obtain customer retail services from the retailer, use its best endeavours to refund that amount within 10 business days.

Note

This subrule is classified as a tier 2 civil penalty provision under the National Energy Retail Regulations. (See clause 6 and Schedule 1 of the National Energy Retail Regulations.)

(4) No interest is payable on an amount overcharged.

(5) If the small customer was overcharged as a result of the customer’s unlawful act or omission, the retailer is only required to repay, credit or refund the customer the amount the customer was overcharged in the 12 months before the error was discovered.

(6) The overcharge threshold is $50 or such other amount as the AER determines under subrule (7).

70 The term “retailer” is defined in s 2 of the Retail Law to mean “a person who is the holder of a retailer authorisation”. The term “retailer authorisation” is defined to mean a “retailer authorisation issued under Part 5”. There is no dispute that each of the AGL Entities was a “retailer” within the meaning of s 2 of the Retail Law throughout the relevant period.

71 Neither the phrase “becomes aware”, nor the terms “overcharged” or “overcharging” are defined in the Retail Rules or the Retail Law. It was the meaning to be given to these terms which was the primary battleground at the liability trial.

5.2 General rules of interpretation

72 The note at the commencement of rule 3 of the Retail Rules provides that “[w]ords and expressions used in these Rules have the same meaning as they have, from time to time, in the Law or relevant provisions of the Law, except so far as the contrary intention appears in these Rules”. The term “the Law” is defined in rule 3 of the Retail Rules to mean the Retail Law.

73 Section 8 of the Retail Law is entitled “Interpretation generally” and provides in s 8(1) that, “Schedule 2 to the NGL applies to this Law, the National Regulations and the Rules and any other statutory instrument made under this Law in the same way as it applies to the NGL and the regulations, rules and any other statutory instruments made under the NGL”. The term NGL is defined in s 2 of the Retail Law to mean “the National Gas Law set out in the Schedule to the National Gas (South Australia) Act 2008 of South Australia”. Schedule 2 to the NGL is titled “Miscellaneous provisions relating to interpretation”.

74 Section 13 of the Retail Law states that its objective is to “promote efficient investment in, and efficient operation and use of, energy services for the long term interests of consumers of energy with respect to … price, quality, safety, reliability and security of supply of energy” (the national energy retail objective).

75 Relevantly for present purposes, Sch 2 to the NGL contains the following principles of interpretation to be applied in determining the proper construction of rule 31.

76 First, cl 4 of Sch 2 to the NGL provides that “[a] heading to a section or subsection of this Law does not form part of this Law” (subcl (3)), “[a] note at the foot of a provision of this Law does not form part of this Law” (subcl (4)) and “[a]n example (being an example at the foot of a provision of this Law under the heading ‘Example’ or ‘Examples’) does not form part of this Law” (subcl (5)). However, “[t]he heading to a Chapter, Part, Division or Subdivision into which this Law is divided is part of this Law” (subcl (1)) and “a Schedule to this Law is part of this Law” (subcl (2)).

77 Second, cl 7 of Sch 2 to the NGL is entitled “Interpretation best achieving Law’s purpose”, and provides:

(1) In the interpretation of a provision of this Law, the interpretation that will best achieve the purpose or object of this Law is to be preferred to any other interpretation.

(2) Subclause (1) applies whether or not the purpose is expressly stated in this Law.

78 Third, cl 3 of Sch 2 to the NGL is entitled “Changes of drafting practice not to affect meaning” and provides that “Differences of language between provisions of this Law or the Rules may be explicable by reference to changes of legislative drafting practice and do not necessarily imply a difference of meaning”.

79 Fourth, cl 8(3) of Sch 2 to the NGL provides that, in the interpretation of a provision of the Rules, consideration may be given to “Law extrinsic material” or “Rule extrinsic material” capable of assisting in the interpretation:

(1) if the provision is ambiguous or obscure, to provide an interpretation of it; or

(2) if the ordinary meaning of the provision leads to a result that is manifestly absurd or unreasonable, to provide an interpretation that avoids such a result; or

(3) in any other case, to confirm the interpretation conveyed by the ordinary meaning of the provision. “Ordinary meaning” means the ordinary meaning conveyed by a provision having regard to its context in this Law and to the purpose of this Law: see cl 8(1).

80 “Law extrinsic material” is defined in cl 8(1) of Sch 2 as “relevant material not forming part of this Law,” which provision then sets out several examples.

81 “Rule extrinsic material” is defined in cl 8(1) of Sch 2 as:

(a) a draft Rule determination; or

(b) a final Rule determination; or

(c) any document (however described)—

(i) relied on by the AEMC in making a draft Rule determination or final Rule determination; or

(ii) adopted by the AEMC in making a draft Rule determination or final Rule determination.

82 Fifth, cl 8(4) of Sch 2 to the NGL provides that, in determining whether consideration should be given to Law extrinsic material or Rule extrinsic material, and in determining the weight to be given to Law extrinsic material or Rule extrinsic material, regard is to be had to:

(1) the desirability of a provision being interpreted as having its ordinary meaning; and

(2) the undesirability of prolonging proceedings without compensating advantage; and

(3) other relevant matters.

83 Finally, the interpretation statutes of each of the relevant jurisdictions do not apply to the Retail Law or Retail Rules: National Energy Retail Law (South Australia) Act 2011 (SA) s 2(2); National Energy Retail Law (Adoption) Act 2012 (NSW) s 7; National Energy Retail Law (Queensland) Act 2014 (Qld) s 7.

6. WERE THE AFFECTED CUSTOMERS “OVERCHARGED”?

84 The first question is whether the Affected Customers were “overcharged” within the meaning of rule 31.

6.1 Contentions by the parties

85 The AER submits that, on its proper construction, a customer “has been overcharged” within the meaning of rule 31(1), and there is an “amount overcharged” for the purposes of rules 31(2) and 31(3), where a retailer has received and processed a payment of an amount of money from a customer that exceeds the amount that the retailer is in fact entitled to charge under any contract which it has with the customer for the electricity or gas it has supplied. The AER therefore contends that a customer may be “overcharged” where:

(1) a retailer has received a payment for a bill that exceeds what the retailer was entitled to receive for the electricity or gas to which the bill relates;

(2) a retailer receives regular payments or payments for a bill either in advance or in arrears (and whether through a direct debit arrangement, Centrepay or otherwise) and those regular payments ultimately exceed the amount that the retailer is entitled or becomes entitled to charge for electricity or gas supplied to the customer (for example, if payments made for a bill in advance ultimately exceed the amount of the bill when it is issued); and

(3) a retailer receives a payment from a customer who has ceased to obtain electricity or gas that exceeds what the retailer is entitled to receive under the customer’s contract for the electricity or gas consumed by it (i.e. that exceeds the final bill).

86 That is, the AER submits that the determination of whether a customer “has been overcharged” necessarily involves looking at what the retailer is entitled to charge compared to what the retailer has received from the customer, but it is not limited, either in its terms or by implication, only to excess amounts that arise from the payment of an erroneously generated or miscalculated bill. It submits that one looks at the economic substance of the relationship between the retailer and the customer, and whether the retailer has received and is in possession of a sum of money that belongs to the customer.

87 By contrast, AGL submits that “overcharging” within the meaning of rule 31 will only occur where:

(1) first, an energy retailer makes a demand or request for payment, in particular by issuing a bill for services provided to the customer, of an amount greater than the amount which the customer owes the retailer for those services (i.e., over the amount owed); and

(2) second, the customer makes a payment in response to that demand or request.

88 AGL submits that the AER’s contention that “overcharging” can occur without any request for payment faces insurmountable difficulties and overlooks the foundational interpretative principles applicable to rule 31. It submits that the AER’s construction:

(1) is inconsistent with the ordinary meanings of “overcharged” and “overcharging”;

(2) is not supported by the statutory context;

(3) is inconsistent with the national energy retail objective;

(4) is unnecessary and would result in inefficient duplication; and

(5) would lead to manifestly absurd or unreasonable results, such as categorising any mistaken payment by a customer, without any action or involvement by the retailer, as conduct amounting to a breach of a tier 2 civil penalty provision by the retailer.

89 In response, the AER submits that, if an assertion of an entitlement is required for “overcharging” to occur, then a customer “has been overcharged” within the meaning of rule 31(1), and there is an “amount overcharged” for the purposes of rules 31(2) and 31(3), where a retailer asserts an entitlement to the payment of an amount of money from a customer (which assertion is not confined to the issue of a bill but can be by conduct) and the retailer has received and processed a payment of an amount of money from a customer that exceeds the amount that the retailer is in fact entitled to charge the customer under any contract which it has with that customer. On this basis, the AER submits that the conduct of the AGL Entities plainly does assert entitlement to funds: that in each case the AGL Entity has failed to cancel a deduction as required under its agreement with Services Australia and then received, processed and kept the deductions that exceeded their entitlements as payments for electricity or gas and allocated to the customer’s account accordingly. It submits that AGL has thereby communicated to Services Australia (and to customers by not returning the funds to them) that it continued to be entitled to receive those deductions, in circumstances when it was plainly not.

6.2 Consideration of meaning of “overcharged” and “overcharging”

Dictionary meaning of “overcharged” and “overcharging”

90 In determining the proper interpretation of terms used in statutes or legislative instruments, it can sometimes assist to have regard to authoritative dictionaries to identify the range of possible meanings that a word may have. However, doing so requires caution as a dictionary is not a substitute for interpretation by the Court and because dictionary definitions specify a range of meanings, rather than the particular meaning of the word in its context having regard to the statutory purpose or object.

91 With that caution in mind, both parties rely upon the dictionary definition of “overcharge” in the Macquarie Dictionary (online) as follows:

- verb (t) 1. to charge (a person) too high a price.

2. to charge (an amount) in excess of what is due.

…

- verb (i) 5. to make an excessive charge; charge too much for something.

- noun

6. a charge in excess of a just price.

92 The AER also submits that the Oxford English Dictionary (online) defines the verb (relevantly) as “to charge (a person) a sum that exceeds the proper or agreed price” (meaning 3(a)) or “to charge (an amount or sum) over and above the proper or agreed price” (meaning 3(b)). Similarly, the noun is defined in the Oxford English Dictionary as “a monetary charge in excess of the proper or agreed amount; the amount by which the sum charged exceeds the proper amount” (meaning 2).

93 AGL also relies upon the definition of “charge” in the Macquarie Dictionary (online) as follows:

- verb (t) 1. to put a load or burden on or in.

…

12. to hold liable for payment; enter a debit against.

13. to list or record as a debt or obligation; enter as a debit.

…

15. to impose or ask as a price.

…

- noun …

29. expense or cost: improvements made at a tenant’s own charge.

30. a sum or price charged: a charge of $2 for admission.

31. a pecuniary burden, encumbrance, tax, or lien; cost; expense; liability to pay.

32. an entry in an account of something due.

94 It can therefore be seen that aspects of these definitions support each side’s construction, but it cannot be said that these dictionary definitions are conclusive as to the central issue. Further, it goes too far to say that the AER’s preferred construction is inconsistent with the ordinary meanings of “overcharged” and “overcharging”. For example, one dictionary meaning of “charge” is expense or cost. If a former customer has not utilised any gas or electricity and owes no money to AGL for any previous usage by them and an amount is deducted from that person’s welfare payments and retained by AGL, it is open to find by reference to this definition that this is the imposition of an expense or cost on that person (“charge”) which exceeds what is due (“overcharge”).

95 Further, while the past tense usage of “overcharged” in the first sentence of rule 31(1) indicates that something has been done, or has occurred, it does not follow from the dictionary definitions that the thing which has occurred in the past can only be the issue of a bill or other demand for payment in excess of what is due, being words which do not appear in the rule. The receipt of a deduction of an amount from a person’s welfare payment and retention of it is also a past event.

96 For these reasons, the dictionary definitions are of limited assistance in resolving the debate.

Ordinary meaning of “overcharged” and “overcharging”

97 Leaving aside dictionary definitions, the ordinary meaning of being “overcharged” is typically a situation in which one party asserts an entitlement to be paid more than they are entitled to be paid (whether that entitlement arises pursuant to contract or something else) and the other party responds by paying more than they should. The assertion can be contained in a bill or other document which seeks payment but it can also be an oral assertion (such as over the telephone or shop counter) or by conduct (such as failing to correct a customer who misreads the price tag on an item in a shop and accepting the money tendered by the customer based on that misunderstanding).

98 As to this, AGL submits that the AER’s construction is not consistent with the ordinary meaning of “overcharged” on the basis that it extends to an overcharge which occurs as a result of an omission or error by the customer, submitting that “[h]ow could a customer paying too much by way of the customer’s own error … constitute an ‘overcharge’?”.

99 However, the answer to that question is supplied by the language of the rule itself, which provides in rule 31(5) “[i]f the small customer was overcharged as a result of the customer’s unlawful act or omission, the retailer is only required to repay, credit or refund the customer the amount the customer was overcharged in the 12 months before the error was discovered”. As rule 31 applies to amounts overcharged as a result of a customer’s unlawful act or omission (which are treated differently by rule 31(5)), rule 31(1) must also apply to a customer’s lawful act or omission by necessary implication.

100 This supports a construction that the meaning of “overcharged” and “overcharging” in rule 31(1) is directed to the payment of an amount in excess of what is due, including by the customer’s own mistake, irrespective of whether that payment is preceded by a demand or request by the retailer.

101 Rule 31 is in Part 2, Div 4 of the Retail Rules which is headed: “Customer retail contracts—billing” and AGL relies on the fact that the heading to a Division is part of this Law: Sch 2 to the NGL, cl 4. It submits that the inclusion of rule 31 in a Division concerned with billing provides a strong statutory indication that rule 31 is concerned with billing such that it follows that rule 31 is concerned with a situation where a customer has received a bill from a retailer which includes an incorrect charge which, in turn, gives rise to an overpayment. In this regard, AGL also relies upon the fact that Part 3 of Sch 3 to the Retail Rules, which schedule sets out the Savings and Transitional Rules, is headed “Billing-related transitional rules”. This part contains, at rule 5, the transitional rule relating to rule 31 of the Retail Rules.

102 AGL also emphasises other rules in Div 4 which it contends are “singularly concerned” with billing such as rules 21(4) and 23 which, it submits, directly connect the concepts of “overcharging” and “billing”. However, that these rules refer to both bills and overcharging only serves to highlight that rule 31(1) does not contain the same connection between these concepts or refer to billing at all. This supports an interpretation that “overcharged” and “overcharging” within the meaning of rule 31(1) is not confined to a situation where a bill has been issued. Further, it is apparent from rule 32 (which deals with payment methods) and rule 33 (which deals with payment difficulties) that Div 4 is also concerned with the payment of bills.

103 Indeed, the starting point for construing the terms “overcharged” and “overcharging” in rule 31 is to recognise that these terms are used to describe a circumstance where a retailer has received payment of an amount of money that properly belongs to a customer. This can be seen from (for example) the direction in rule 31(2)(a) that, where “the amount overcharged” is equal to or above the overcharge threshold of $50 (rule 31(6)), the amount is to be repaid as reasonably directed by the customer. Thus, “the amount overcharged” is speaking of an amount received by the retailer which has been paid by the customer and which must be returned to the customer. The terms are therefore directed to the receipt of payments, not the issue of bills.

104 By reference to the overall scheme of Div 4, the way in which a retailer becomes entitled to receive money from a customer is through the issue of a bill. However, when one is considering money which is in the hands of a retailer that is more than what it is entitled to receive (that is, “the amount overcharged”), the comparison must be between what has been billed, what is entitled to be billed and what has been paid.

105 This conclusion is fortified through the other uses of the term “overcharging” in Div 4 which illustrate how “overcharging” can occur where a customer makes a payment for a bill that is based on an estimate of usage which results in the retailer having received an amount that exceeds (once actual usage is ascertained) that to which the retailer was entitled, namely:

(1) rule 21(4) which addresses what must happen if a retailer issues a bill based on estimated usage (permitted under rule 21(1)) and then subsequently issues a bill based on an actual meter reading or metering data. Subrule (a) requires the retailer to include “an adjustment on the later bill to take account of any overcharging of the customer that has occurred”. If the first (estimated) bill had not been paid, then no adjustment would be required. It is only if the first bill has been paid that the customer has been overcharged and an adjustment is required. This emphasises that the term “overcharging” is directed to the payment by a customer of more than the retailer is entitled to charge, and that “overcharging” occurs through payment, not billing.

(2) rule 23 which addresses bill smoothing arrangements. It allows bills to be issued for a 12-month period (if the customer gives explicit informed consent: subrule (2)) based on estimated usage (using either historical usage or a comparable customer), recalibrated in the seventh month. Rule 23(1)(d) provides that, at the end of the 12-month period, an actual meter is read or metering data is obtained “and any undercharging or overcharging is adjusted under rule 30 or 31”. Thus, if the customer has paid the retailer more during the 12-month period than the retailer was entitled to charge, the customer has been “overcharged”, and “the amount overcharged” must be repaid or credited as required by rule 31, depending on its quantum. Again, this illustrates that the term “overcharging” is directed to the payment by a customer of more than the retailer is entitled to charge, and that “overcharging” occurs through payment, not billing.

106 The following additional matters detract from AGL’s posited construction.

107 First, rule 31(1) refers to a circumstance where the customer “has been” overcharged. It is to be construed in context, which includes both rules 31(2) and 31(3). Those sub-rules make clear that the “overcharge” is a sum of money which has been received by the retailer, because those sub-rules assume that money is in the hands of the retailer because they impose an obligation to repay, refund or credit the money. That supports the conclusion that a customer has not been “overcharged” when a bill is issued for more than a retailer is entitled to charge; rather, a customer is “overcharged” when the retailer has received a payment that exceeds that which the retailer is entitled to receive from that customer. If the conduct was confined to assertions through billing in the manner contended by the AGL Entities, one would expect to see some reference to the issuing of a corrected bill in rule 31. However, there is no such reference, and the only reference to bills is to the crediting of the amount overcharged “to the next bill” in rules 31(2)(b) and 31(3)(a), reinforcing that the rule is directed to the return or reallocation of money obtained from a customer that exceeds what the retailer is entitled to charge the customer at that point in time.

108 Second, the term “overcharged” in rule 31(1) is used in the passive voice: “has been overcharged”, as compared to the active voice “the retailer has undercharged” in rule 30(1). This indicates that the intention of the drafter was to impose obligations on the retailer irrespective of whether there had been some active step by the retailer. The language used is deliberately wider and does not depend on the retailer being the cause of the overcharge. This is reinforced by rule 31(5), which explicitly acknowledges that a customer can be “overcharged” through their own unlawful act or omission and overcharging that occurs in that way can still be subject to rule 31. That is, “overcharging” can occur without an act or omission by a retailer.

109 To counter this, AGL submits that rule 5 in Part 3 of the Savings and Transitional Rules uses the following language to describe rule 31 of the Retail Rules: “[t]he provisions of the Rules requiring a retailer to reimburse amounts the retailer has overcharged a small customer (rule 31…)” (emphasis in submissions). It submits that this provides significant contextual support for a construction of the term “overcharged” in rule 31 as requiring a positive action by the retailer and supports the construction of “overcharged” that is consistent with that word being used as a verb in rule 31(1).

110 However, the chapeau of rule 5, which uses the language of “amounts the retailer has overcharged”, is used in a context where rule 5 is extending rule 31 to a particular form of overcharging which occurred before rule 31(1) commenced in the circumstances set out in rule 5(1)(a)–(b) (which is not this case). The identification of this confined set of circumstances described as “overcharging” for the purposes of the Savings and Transitional Rules does not overcome the differences in language between rule 30(1) and rule 31(1).

111 Third, AGL’s construction would leave a significant lacuna in the operation of the Retail Rules in that there would be no rule which addresses the situation where a person had ceased to be a customer of an AGL Entity and received their final bill, but whose welfare payments continued to be diverted to and retained by AGL. This would be an absurd outcome in circumstances where the Retail Rules are otherwise highly prescriptive and detailed as to retailers’ conduct vis-à-vis consumers, and in circumstances where it is the Retail Rules which provide for retailers to use Centrepay: see rules 32(2), 74.

112 That this would be an absurd outcome can be seen by reference to the following examples:

(1) rule 32(1) requires a retailer to accept payment inter alia by telephone. If a customer telephoned a retailer to pay a bill of $50, but through the error of the retailer, the amount of $500 was charged to the customer’s credit card during the telephone call and processed through the retailer’s system, then on the AER’s construction, the amount charged in error of $450 would fall to be dealt with under rule 31, because it would be a payment that exceeds that which the retailer is entitled to receive from, or charge, the customer. However, the AGL Entities would contend that the retailer had not overcharged the customer, because, while it had received an amount of $450 to which it was not entitled, it had only issued a bill for $50.

(2) rule 32(5) provides that a retailer must accept payments by a customer “for a bill in advance”. This allows a customer to make regular payments to a retailer in order to manage their expenses. If the payments made exceeded what was owed when a bill was issued, then on the AER’s construction there would be “an amount overcharged” which, if it was equal to or above the overcharge threshold, would require notification under rule 31(1) and then fall to be dealt with under rule 31(2). However, on the construction advanced by the AGL Entities, the retailer would not have to do anything about the excess, because no bill had been issued for that amount, and it would fall outside the scope of the Retail Rules.

(3) rule 72 allows for the establishment of payment plans for a “hardship customer” which allows the customer to pay for their energy consumption in advance or in arrears by instalment payments. If a customer on a payment plan was to pay in advance by instalment payments, and the sum of these instalments was to exceed that which was due when a bill was issued then, on the construction of the AGL Entities, this excess amount would not be an “overcharge” because no bill had been issued for that amount, and it would fall outside the scope of the Retail Rules.

113 Each of these provisions appear to contemplate a mismatch occurring (either by reasons of error or timing) between the amount that a customer has paid for electricity or gas and the amount that the retailer is entitled to charge for that electricity or gas. Yet none of them have their own provisions regarding how this excess is to be dealt with. Such an absurd outcome provides strong support for a conclusion that any such excess falls within the concept of an amount “overcharged” for the purposes of rule 31 and must be dealt with in accordance with its provisions which seek to ensure the funds are repaid, credited or returned to the customer as required by its terms.

114 AGL submits that there is no absurdity and no lacuna in the fact that the excess amounts are not addressed under rule 31 or any other part of the Retail Rules because it is addressed comprehensively by the Centrepay Framework, rather than the Retail Rules. AGL contends that the Centrepay Policy and the Procedural Guide impose detailed obligations on Approved Businesses with respect to an “Overpayment” and “Overpaid Deductions” and that the absence of any additional direct obligations on retailers in the Retail Law and the Retail Rules in respect of Centrepay indicates that the Centrepay Framework exclusively governs the obligations on retailers in respect of any overpayments of Centrepay deductions. AGL also relies upon “material differences” between the obligations owed under the Centrepay Framework, and the obligations imposed by rule 31 on the AER’s construction, in support of its construction of rule 31, on the basis that there would be “undesirable inconsistency” if rule 31 also applied to “overpayments”.

115 However, the Centrepay Framework is a contractual agreement between Services Australia and the AGL Entities, which could (one assumes) be amended. It is not a document that constitutes “Rule extrinsic material” pursuant to cl 8 of Sch 2 to the NGL, and it cannot, therefore, be extrinsic material that can be considered in determining the proper construction of rule 31. Further, it would subvert the proper analysis if I construed a legislative provision more narrowly in order to conform to a private contractual agreement applicable in a particular case, whether because of inconsistency or otherwise. Further, the earliest version of the Centrepay Policy in evidence is dated 1 July 2015. The Retail Rules commenced in South Australia on 1 February 2013, New South Wales on 1 July 2013, and Queensland on 1 July 2015. It is difficult in those circumstances to see how the Centrepay Framework can form part of the “context” in which the Retail Rules could be considered or that, because Centrepay is referred to in the Retail Rules, the Centrepay Framework has somehow been “incorporated” into the Retail Rules, as AGL submits. Finally, there is no evidence that the obligations imposed on AGL by the Centrepay Framework were considered by or known to the drafters of the Retail Rules.

116 Other arguments were advanced by AGL in favour of its construction of “overcharged” and “overcharging” in rule 31(1), to which I now turn.

117 AGL emphasises rule 30(3) (which provides, in the context of undercharging that “to avoid doubt, a reference in this rule to undercharging by a retailer includes a reference to a failure by the retailer to issue a bill”) and submits that this rule also supports its construction. However, rule 30(3) is an inclusive rule – that is, undercharging includes but is not confined to the situation where a retailer fails to issue a bill. Thus, the existence of rule 30(3) in the context of rule 30(1) which refers to where “a retailer has undercharged a small customer” does not take the resolution of the proper construction of rule 31(1) very far. That is especially because, as already observed, rule 31(1) does not use a similar phrase such as “where a retailer has overcharged” which indicates that rule 31(1) applies to a broader set of circumstances which extend beyond the overcharge being caused by the retailer. Further, rule 31(1) does not refer to overcharging in a bill, or that overcharging is confined to a situation where a customer has been issued with a bill which contains an excessive charge, which is then paid by the customer.

118 The term “overcharged” is used in rule 136 of the Retail Rules. Like rule 31, that rule is also entitled “Overcharging” but applies where a small customer with a prepayment meter market retail contract has been overcharged. It provides that where a customer has been overcharged as a result of “an act or omission of the retailer or distributor” or “without limitation, a fault in or incorrect operation of a prepayment meter system found following a check or test under rule 135”, a retailer must “(a) inform the customer of that overcharging within 10 business days of the retailer becoming aware of that overcharging; and (b) ask the customer for instructions as to whether the amount should be: (i) repaid to the small customer; or (ii) added to the balance of the prepayment meter system account”.

119 AGL submits that the explicit extension in rule 136 to where a small customer with a prepayment meter market retail contract has been overcharged as a result of “an act or omission of the retailer or distributor” is a statutory indicator that a bill must be issued by a retailer for an amount paid in relation to that bill to be considered an “overcharge” under rule 31. It submits that it is necessary in rule 136 to extend the concept of “overcharge” as something which occurs as a result of an act or omission of the retailer or distributor, because no bills are issued for prepayment meters. However, I do not accept this submission as it is plain that rule 136 is using the term “overcharge” in a narrower set of factual circumstances than rule 31 through the use of the causal limitation conveyed by “as a result of”. It does not include overcharging arising from a customer’s act or omission, lawful or otherwise (unlike rule 31(5)). Further, it provides a strong contextual indication that overcharging used in rule 31 is a broad concept, which encompasses a circumstance where a retailer has received and processed an amount from the customer as a payment of a bill that exceeds the retailer’s entitlement because of the retailer’s act or omission – here, a failure to cancel the deduction including after a final bill had been issued and satisfied.

120 For these reasons, I do not accept AGL’s submission that the AER’s construction is not supported by the statutory context.

National Energy Retail Objective

121 As the terms “overcharged” and “overcharging” are not defined in the Retail Rules or the Retail Law, they fall to be given an interpretation that will best achieve the specific purpose or object of the Retail Law: Sch 2 to the NGL, cl 7. This includes a consideration of the national energy retail objective.

122 AGL submits that its construction best achieves the national energy retail objective because it does not give rise to inefficiencies and inconveniences for customers, and correspondingly impractical administrative and regulatory burdens on retailers which would ultimately increase the price of their services for consumers.

123 However, the SAP system operated by AGL is already configured to identify circumstances where rule 31 applies on AGL’s construction. Notably, one of AGL’s witnesses, Mr Fragapane, gave evidence that, in the context of compliance with rule 31, “where AGL’s automated processes identify an overcharge [on AGL’s construction of the term], they will also automatically create and cause to be sent to the customer a letter advising them of the overcharge and their options”. There is no evidence to support a contention that the existing automated processes could not be modified to take the steps required by rule 31 under the AER’s construction.

124 It is therefore an overstatement for AGL to describe it as an impractical administrative and regulatory burden for retailers to comply with rule 31 if the AER’s construction of “overcharged” is accepted. Further, it would not be inconvenient for customers to be contacted in the manner prescribed by rule 31 so as to ensure that there were no payments which had been made by them which they did not intend to make, or which had been deducted through Centrepay (for example), being payments which they were not required to make to the retailer.

125 In my view, the construction advanced by the AER advances the national energy retail objective. That is because it is consistent with the efficient operation and use of energy services for the long-term interests of energy consumers with respect to price and quality of energy supply for retailers to efficiently operate their businesses so that any amounts that they receive from customers that exceed the “price” of the energy supplied are promptly given back or applied to the next bill, if any.

126 On its proper construction, a customer “has been overcharged” within the meaning of rule 31(1) of the Retail Rules, and there is an “amount overcharged” for the purposes of rules 31(2) and 31(3), where a retailer has received, processed and retained a payment of an amount of money from a customer that exceeds the amount that the retailer is in fact entitled to charge the customer under any contract which it has with that customer. The determination of whether a customer “has been overcharged” within rule 31(1) necessarily involves looking at what the retailer is entitled to charge compared to what the retailer has received from the customer, but it is not limited, either in its terms or by implication, only to excess amounts that arise from the payment of an erroneously generated or miscalculated bill. Rather, one looks at the economic substance of the relationship between the retailer and the customer, and whether the retailer has received and is in possession of a sum of money that belongs to the customer and which the retailer does not have any contractual entitlement to retain.

127 Having said that, I observe that it would suffice for the purposes of this case to construe rule 31(1) on the basis that a customer “has been overcharged” within the meaning of rule 31(1), and there is an “amount overcharged” for the purposes of rules 31(2) and 31(3), where a retailer asserts an entitlement to the payment of an amount of money from a customer (which assertion is not confined to the issue of a bill) and the retailer has received, processed and retained a payment of an amount of money from a customer that exceeds the amount that the retailer is in fact entitled to charge the customer under any contract which it has with that customer.

6.3 Application to facts of this case

128 The conduct of the AGL Entities which the AER alleges to have given rise to customers having been “overcharged” in this proceeding is comprised of the following:

(1) the customer has ceased to be a customer of the AGL Entities at all: that is, they no longer receive the supply of energy from an AGL Entity. The AGL Entities would not be issuing any further “bill’ to a customer in these circumstances claiming an entitlement to an amount for energy supplied (which happened to be greater than the amount to which they were entitled), as they had already issued a final bill for the account (in accordance with rule 35);

(2) the customer did not have any other active account with AGL;

(3) the customer did not owe any amount to the AGL Entity in respect of their closed account;

(4) the AGL Entities continued to receive deductions and processed and applied them as payments for energy supplied by them, even though all of the energy they had in fact supplied had already been paid for and they were no longer supplying energy to the customer.

129 Based on my construction of “overcharged” and “overcharging” in rule 31(1), the Affected Customers were “overcharged” because the AGL Entities received, processed and retained payments for amounts that exceeded the amount that they were entitled to charge the customers. AGL, through a deliberate design in its payment system methodology in its SAP system, treated each deduction as a payment for a bill, even when the final bill had been paid, and then rather than refunding that excess money to the Affected Customer at that point, AGL, through its payment methodology, applied the amount as a credit to a future bill, even when there was not going to be one. That is important because the effect of applying that amount to an account that has been final billed is to increase, as a matter of economic substance, the amount that the Affected Customer has paid to AGL for electricity or gas consumed during the life of the contract. The AGL Entities had no entitlement to receive and retain these amounts, and the Affected Customers were required to be notified and the amounts otherwise dealt with in accordance with rule 31.

130 If, contrary to my finding as to the proper construction of “overcharged” and “overcharging”, it is necessary for a retailer to assert an entitlement to the payment of an amount of money from a customer for the customer to be “overcharged”, the Affected Customers were “overcharged” within the meaning of rule 31(1) because:

(1) the failure by the AGL Entities to cancel the deductions as they were required to do when the customer closed their account was an omission that caused the “overcharges” to arise;

(2) the continued receipt and processing of the deductions as payments for energy when nothing was owed to the AGL Entities by the Affected Customers (to the knowledge of the AGL Entities, which, through senior management, had caused the SAP system to be designed so as to achieve this result) and therefore they had no ongoing entitlement to receive any money from the Affected Customers;

(3) the ongoing failure by the AGL Entities to (a) cancel the deductions after each new deduction was received and (b) cause the SAP system to be designed in a manner so that it took the steps identified in rule 31; and

(4) the holding on to these excess amounts for months or (in some cases) years before any attempt was made to return them to the Affected Customers, especially in the circumstances described in section 4.5 of these reasons,

was conduct that constituted an express or implied assertion of entitlement to the funds.

131 For these reasons, I am satisfied to the required standard that the relevant conduct by the AGL Entities resulted in the Affected Customers being “overcharged” within the meaning of rule 31(1).

7. AWARENESS OF THE AGL ENTITIES

132 The next question which arises is when AGL became aware of the overcharging in this case.

133 The question of when a retailer “becomes aware” within the meaning of those terms in rule 31(1) involves two sub-issues. The first is the meaning of “aware” in the context of rule 31(1). The second is how a retailer, which is a corporation and therefore an artificial person, can be deemed to have or be fixed with the “awareness” to which rule 31(1) refers.

134 In circumstances where rule 31(1) requires the retailer to take certain measures within 10 business days after it becomes aware of the overcharging, the meaning of “aware” is actual knowledge. This was common ground between the parties.

135 In the context of the allegations of “overcharges” in this proceeding, by way of the continued collection of money through deductions from Centrepay in circumstances where customers had ceased to obtain services from the AGL Entities and had no amounts owing to the AGL Entities, knowledge of the essential matters giving rise to the overcharges comprises actual knowledge of the following facts:

(1) receipt by the AGL Entity of a deduction in the form of a sum of money deposited into its bank account;

(2) that the deduction was attributable to the account of an individual identifiable customer of the AGL Entity; and

(3) that the relevant customer had:

(a) fully paid any amounts owing to the relevant AGL Entity with whom they had contracted for the supply of energy; and

(b) that the customer’s account with the AGL Entity was closed or inactive.

136 The determination of the question of when a retailer, which is a corporation, has actual awareness of the overcharging within the meaning of rule 31 is a question of construction, remembering that to determine what a corporation knows requires a process of attribution: QBE Underwriting Ltd v Southern Colliery Maintenance Pty Ltd (2018) 97 NSWLR 459; [2018] NSWCA 55 at [95] (Leeming JA, with whom Macfarlan and Payne JJA agreed).

137 The process of attribution relevant to a particular statutory provision must be fashioned having regard to the language of the provision and its content and policy. As observed by the Privy Council in Meridian Global Funds Management Asia Ltd v Securities Commission [1995] 2 AC 500 at 507:

One possibility is that the court may come to the conclusion that the rule was not intended to apply to companies at all; for example, a law which created an offence for which the only penalty was community service. Another possibility is that the court might interpret the law as meaning that it could apply to a company only on the basis of its primary rules of attribution, i.e. if the act giving rise to liability was specifically authorised by a resolution of the board or an unanimous agreement of the shareholders. But there will be many cases in which neither of these solutions is satisfactory; in which the court considers that the law was intended to apply to companies and that, although it excludes ordinary vicarious liability, insistence on the primary rules of attribution would in practice defeat that intention. In such a case, the court must fashion a special rule of attribution for the particular substantive rule. This is always a matter of interpretation: given that it was intended to apply to a company, how was it intended to apply? Whose act (or knowledge, or state of mind) was for this purpose intended to count as the act etc. of the company? One finds the answer to this question by applying the usual canons of interpretation, taking into account the language of the rule (if it is a statute) and its content and policy.

(Emphasis original.)

138 At page 511 of Meridian, the relevant question was described as “one of construction rather than metaphysics” and it was reiterated that:

It is a question of construction in each case as to whether the particular rule requires that the knowledge that an act has been done, or the state of mind with which it was done, should be attributed to the company.

139 Further, as Beach J explained in Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Westpac Banking Corporation (No 2) (2018) 266 FCR 147; [2018] FCA 751 at [1660]:

[T]he appropriate test is more one of the interpretation of the relevant rule of responsibility, liability or proscription to be applied to the corporate entity. One has to consider the context and purpose of that rule. If the relevant rule was intended to apply to a corporation, how was it intended to apply? Assuming that a particular state of mind of the corporation was required to be established by the rule, the question becomes: whose state of mind was for the purpose of the relevant rule of responsibility to count as the knowledge or state of mind of the corporation? (see Bilta (UK) Ltd (in liq) v Nazir (No 2) [2015] 2 WLR 1168 at [41] per Lord Mance). The question is one of the interpretation of the relevant rule taking into account its context and purpose.

7.3 Contentions by the parties

140 The AER advanced three bases to contend that AGL had actual knowledge.

141 The first is that AGL is fixed with the knowledge of its official records, which includes its accounting system.

142 The second is that the AGL Entities are fixed with knowledge of the outcome of their systems and processes in circumstances where those systems are designed to achieve a particular result and do in fact achieve that result.

143 The third arises if the AGL Entities can only be fixed with knowledge if an actual human person knows of the facts comprising the overcharges, in which case the AER submits that it is open to the Court to find that the relevant individuals had the requisite knowledge through the principles of wilful blindness.

144 Pursuant to s 286 of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth), a company must keep “written financial records” that correctly record and explain its transactions and financial position and performance, and retain them for seven years. Section 9 of the Corporations Act defines “financial records” to include (inter alia) invoices (i.e. bills), receipts and documents of prime entry.