Federal Court of Australia

Tax Practitioners Board v Van Dyke [2024] FCA 899

ORDERS

NSD 786 of 2023 | ||

Applicant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

TO: JAYDEN VAN DYKE

Take notice that, pURsuant to rule 41.06 of the federal court rules 2011 (cth):

You are liable to imprisonment, sequestration of property or other punishment for contempt if you:

(a) refuse or neglect to do the things that this order requires you to do; or

(b) do the things that this order requires you to obtain from doing, or you otherwise disobey this order.

THE COURT Declares THAT:

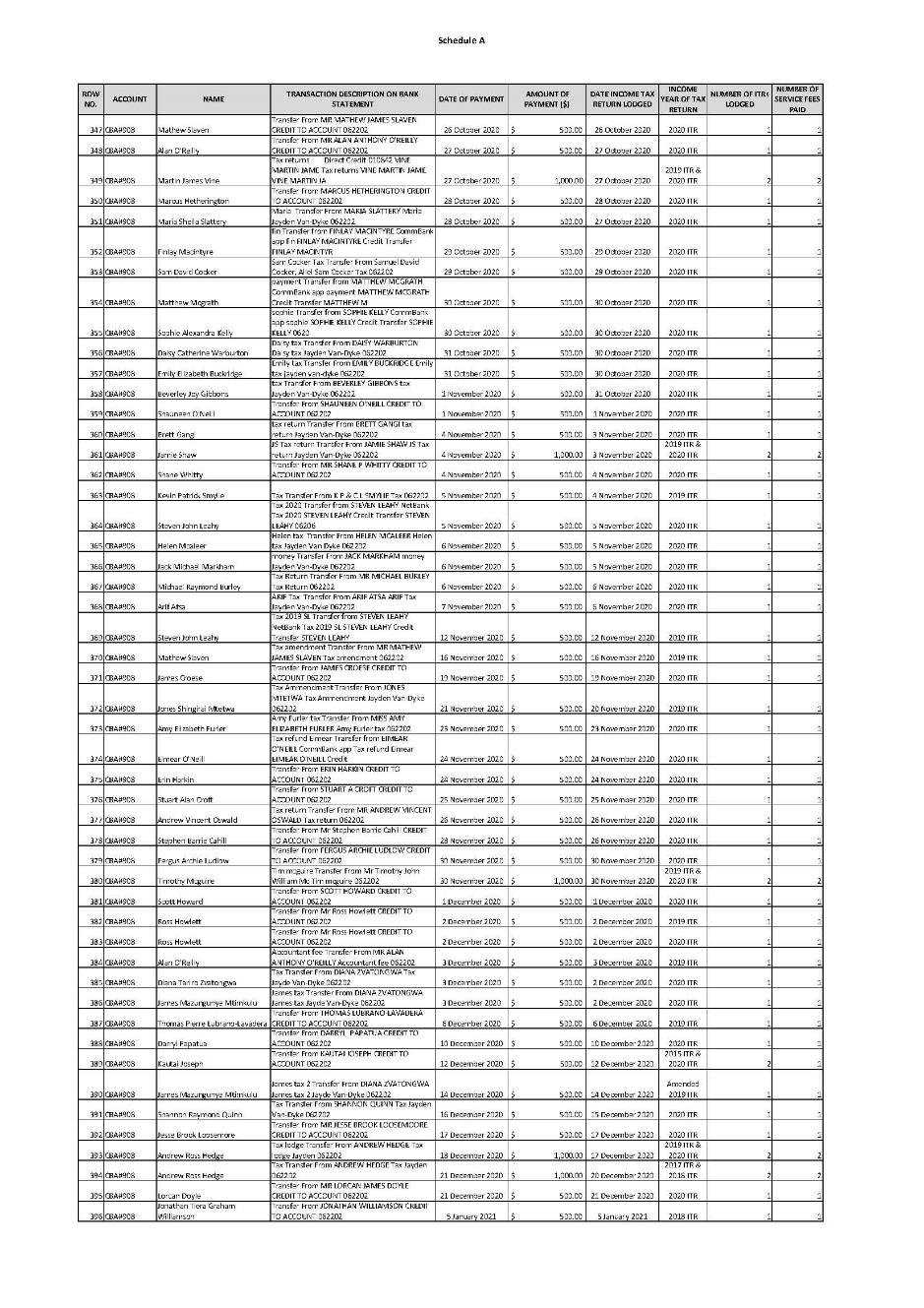

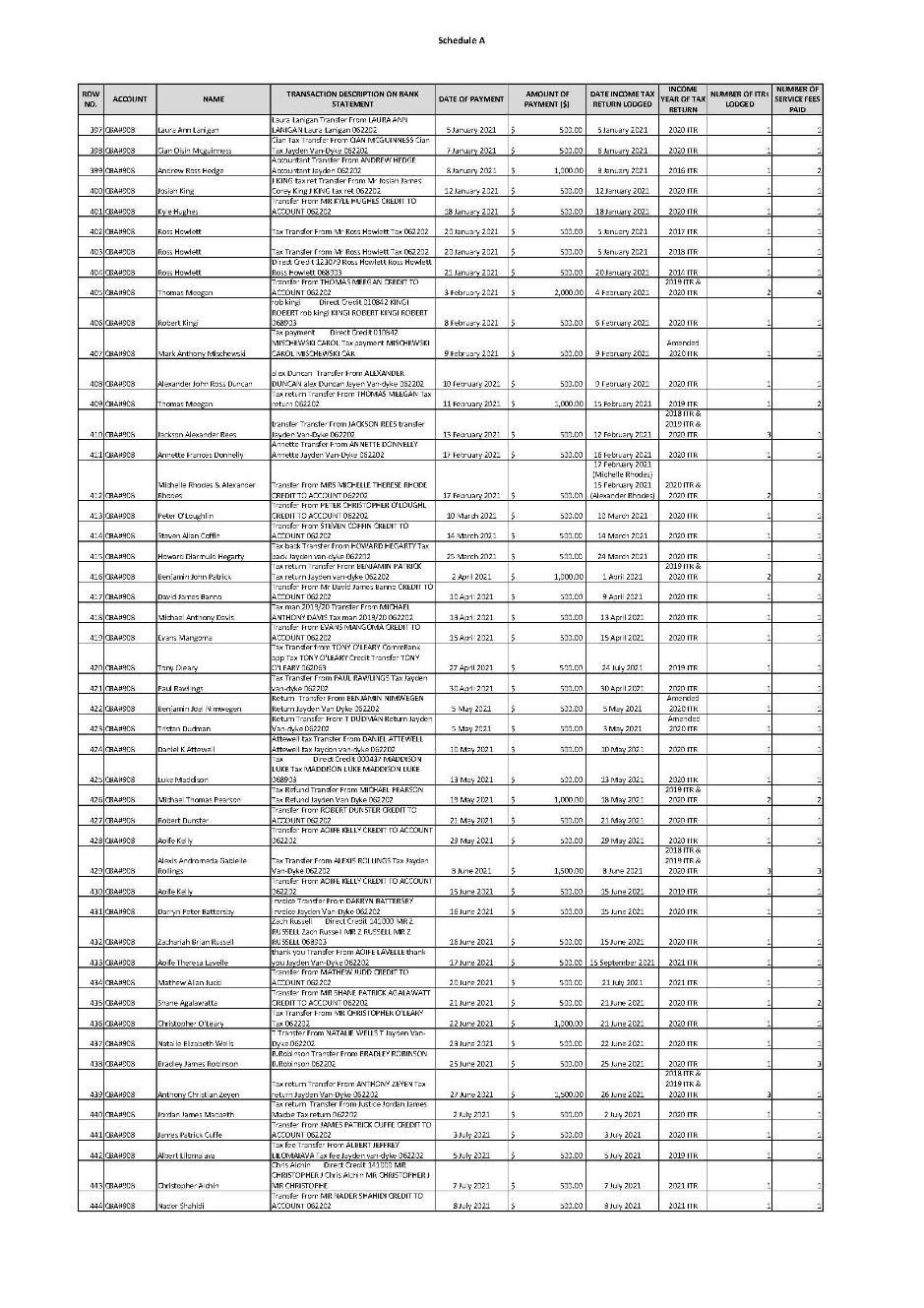

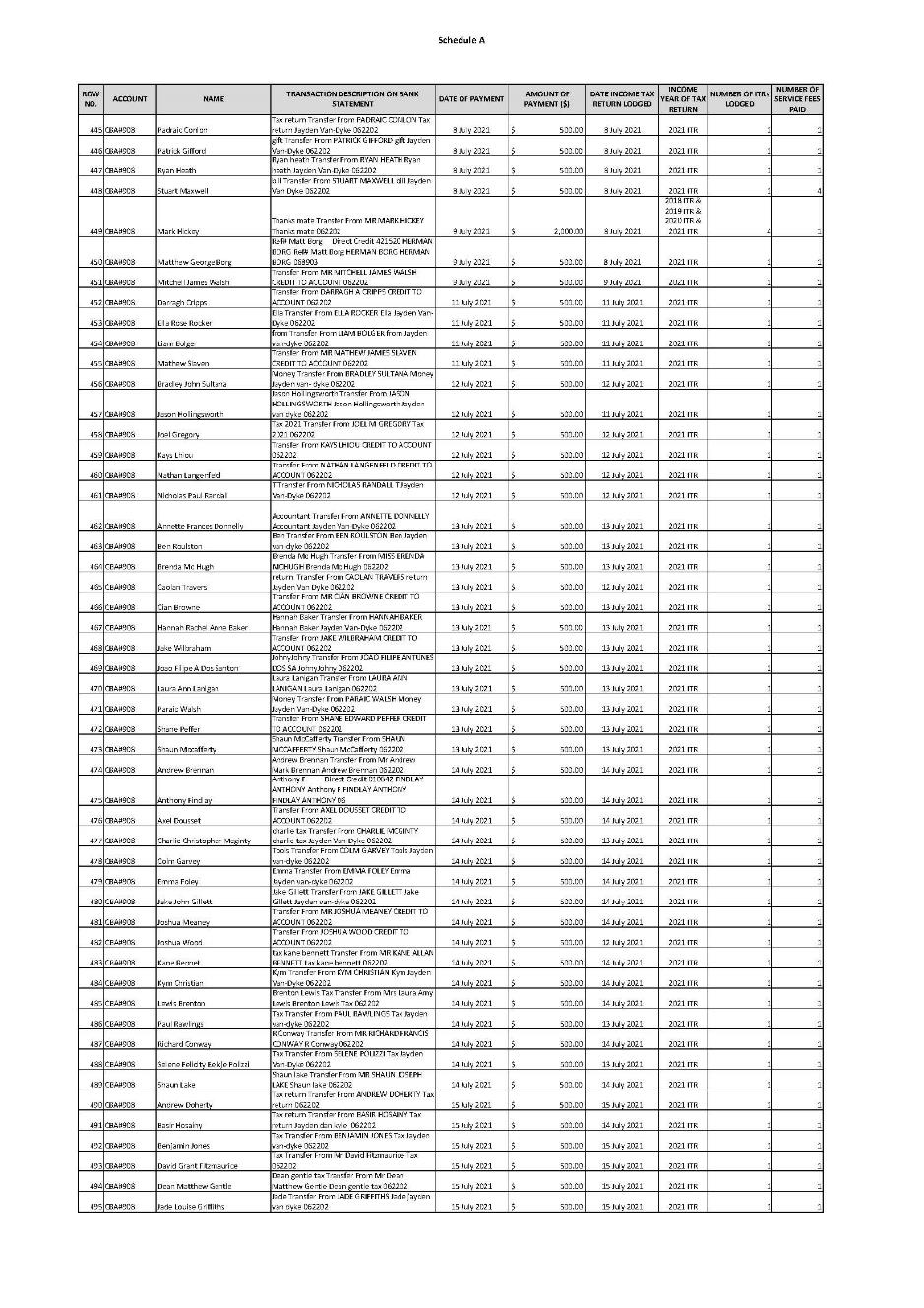

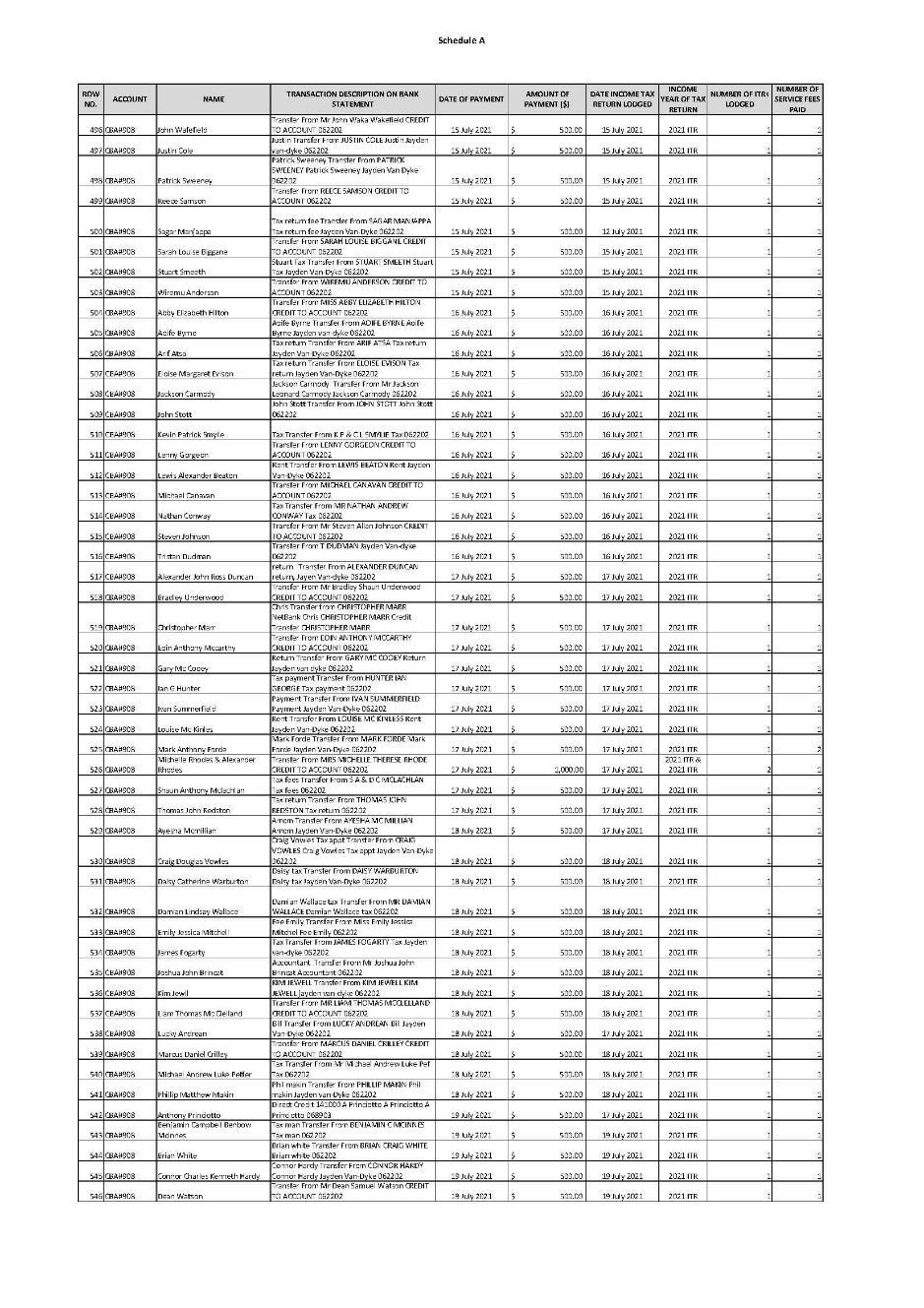

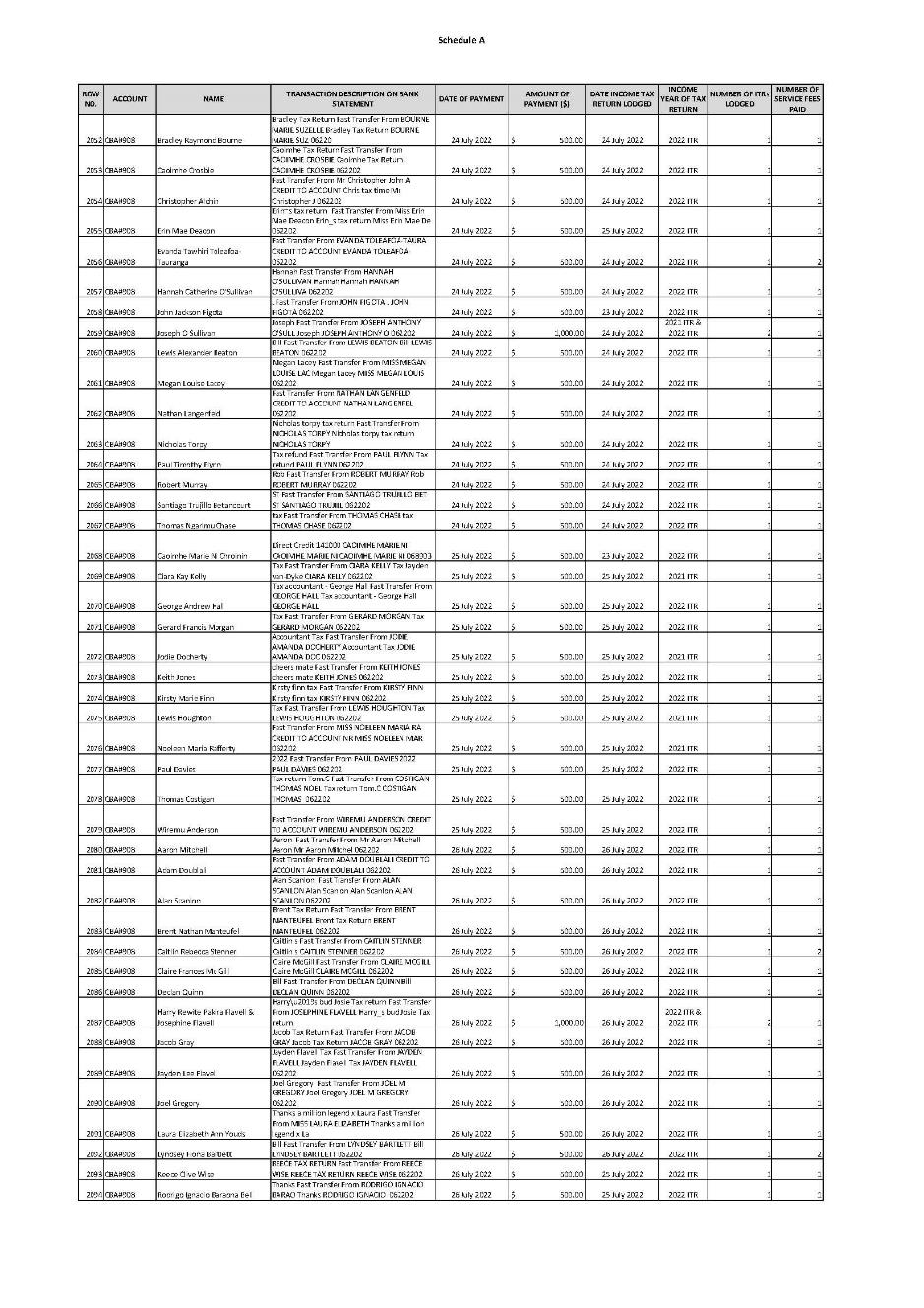

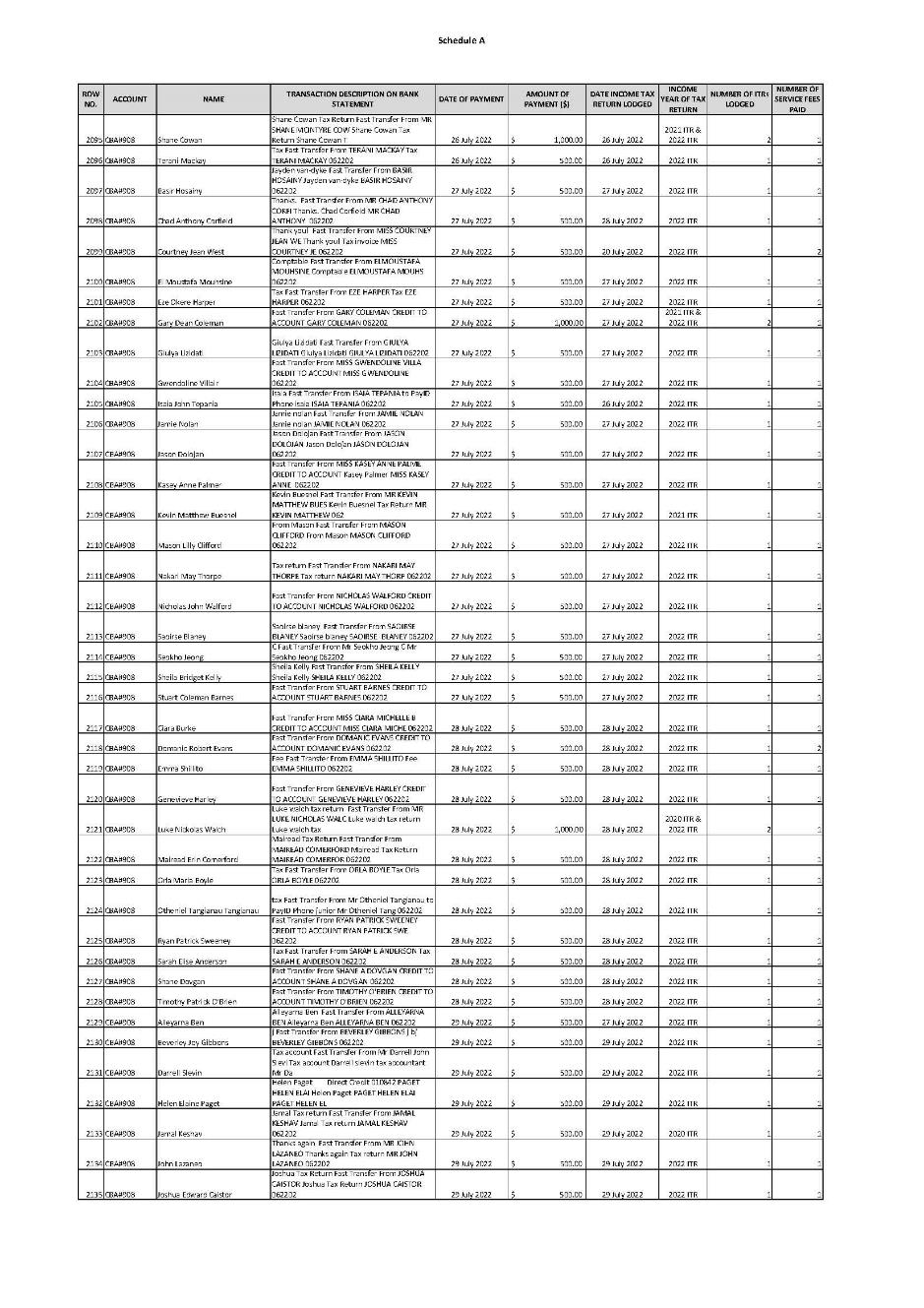

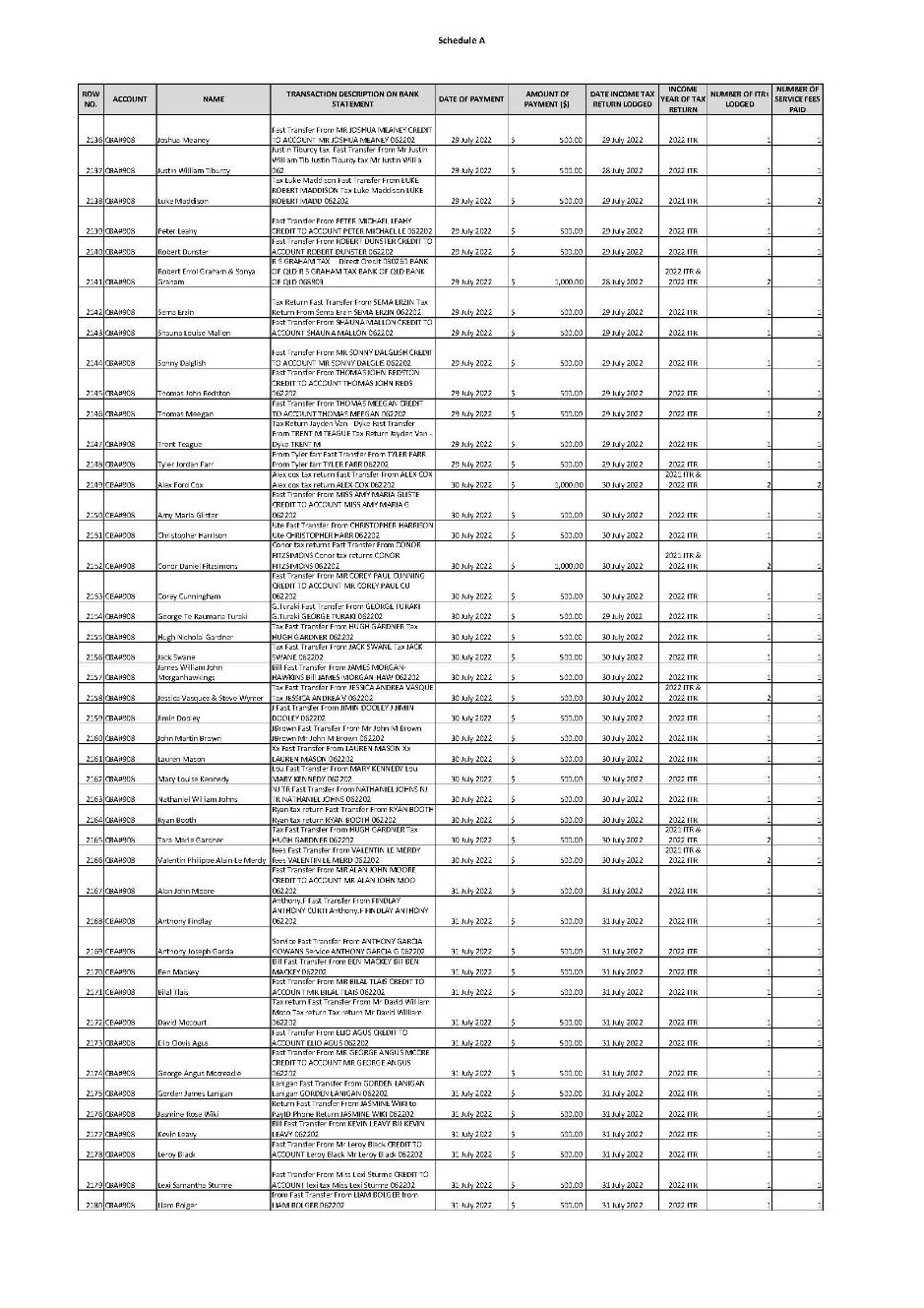

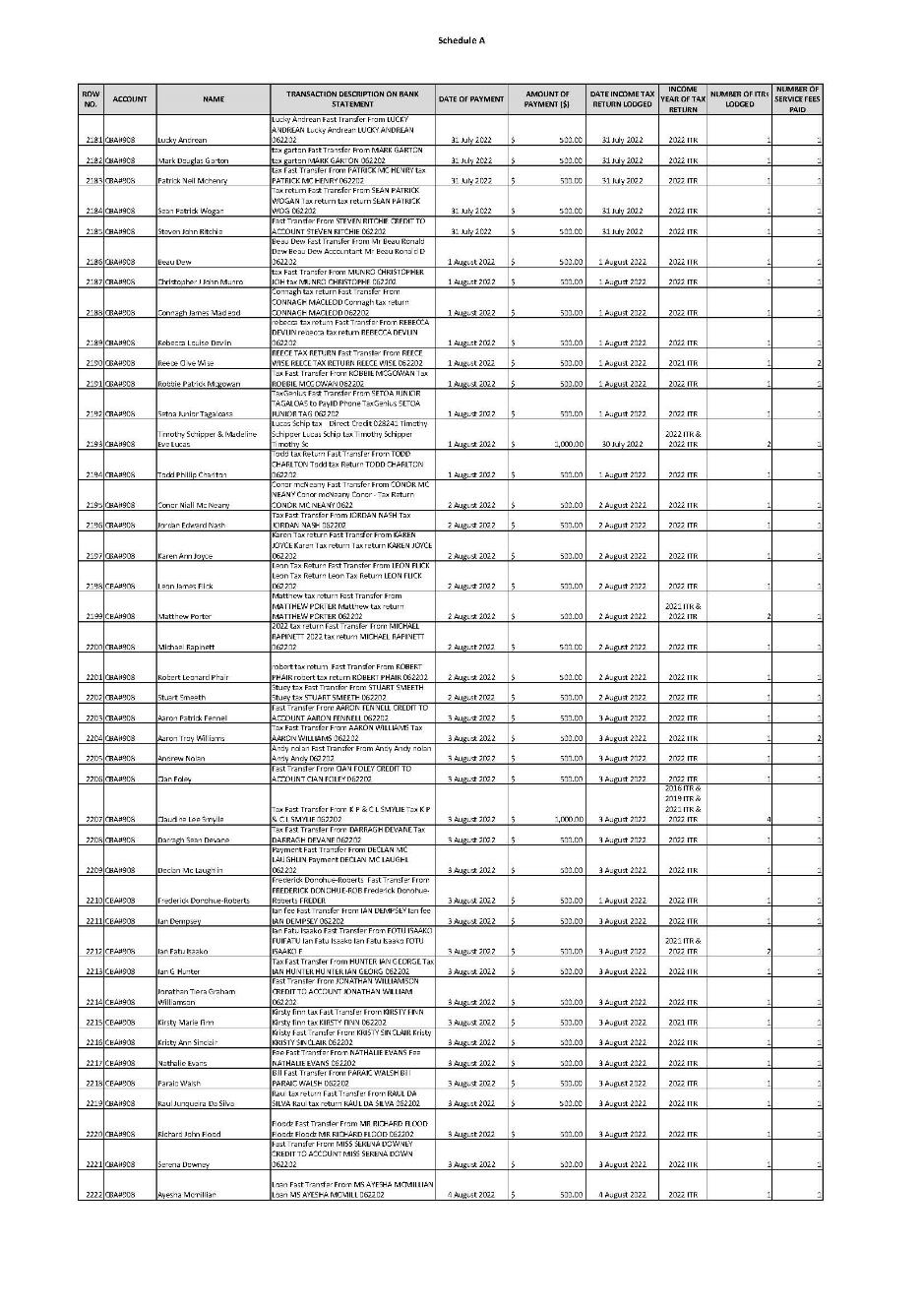

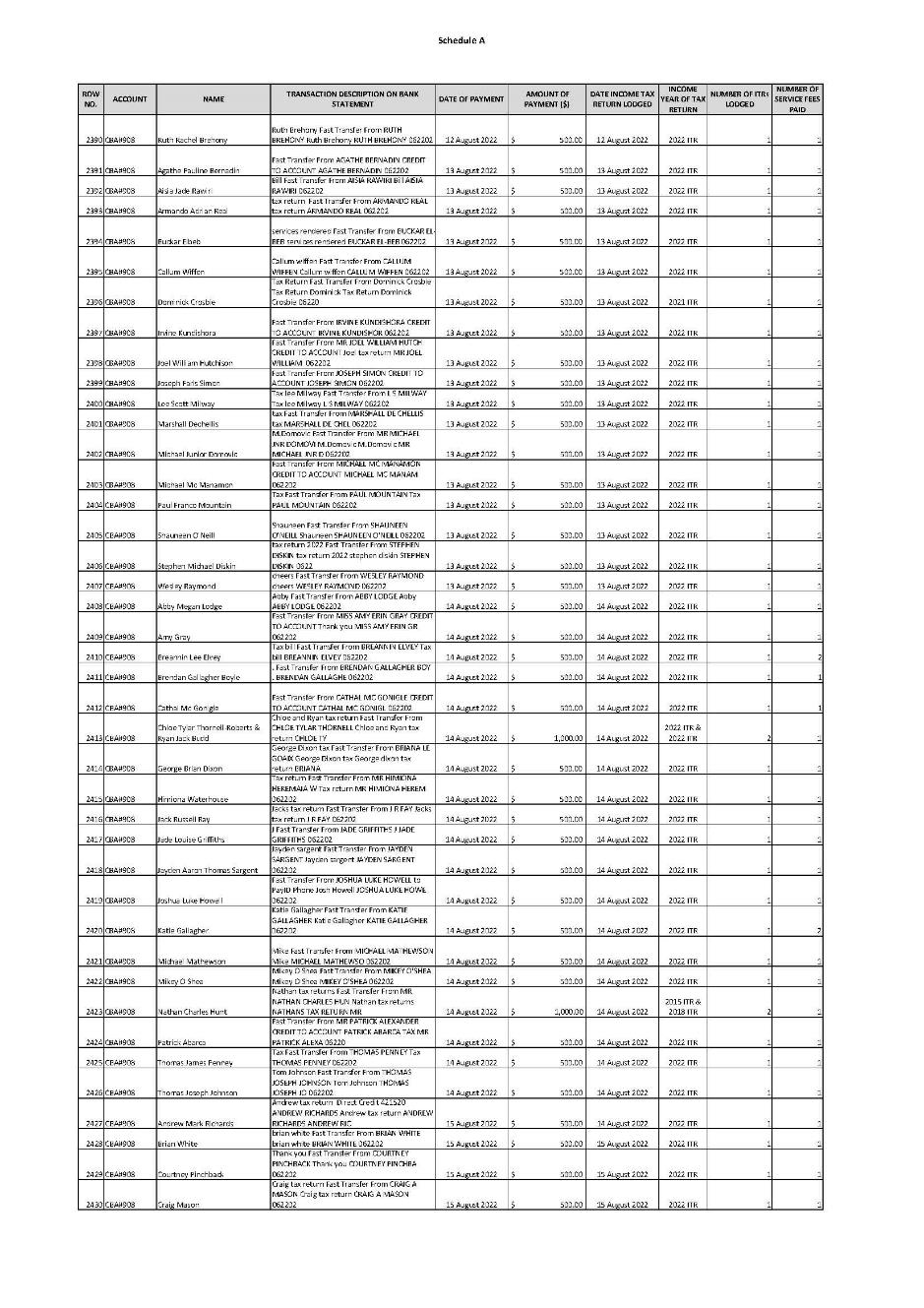

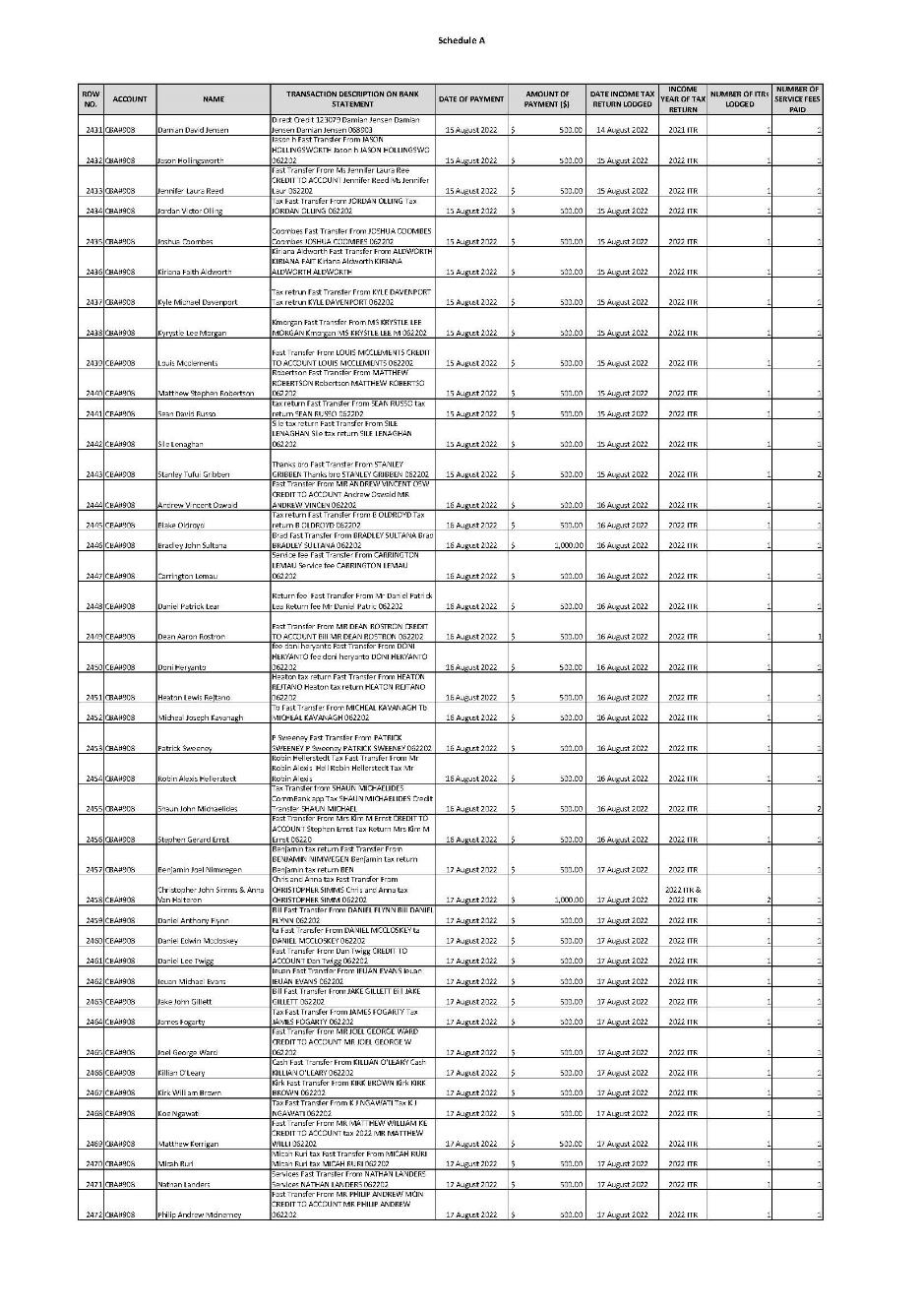

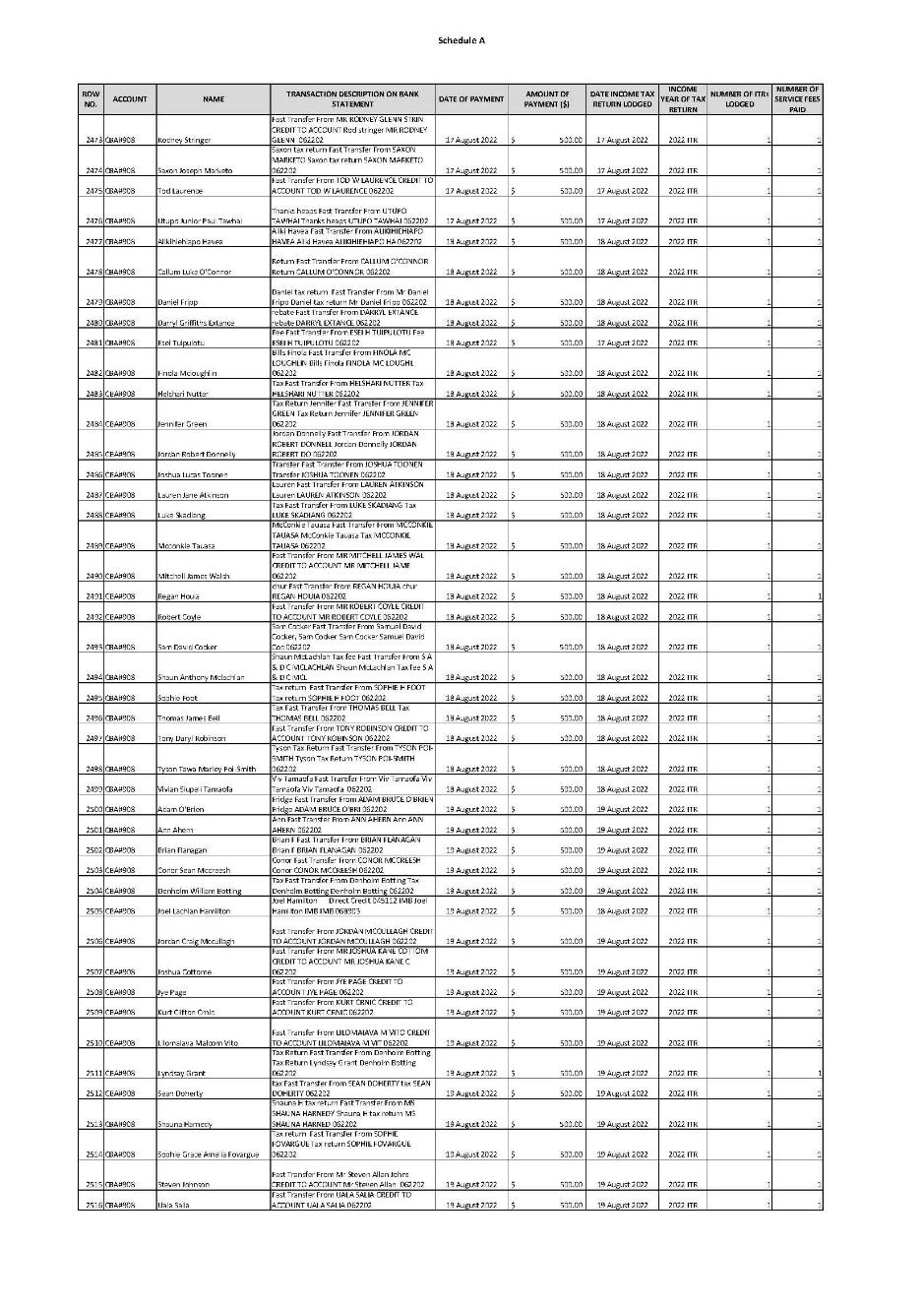

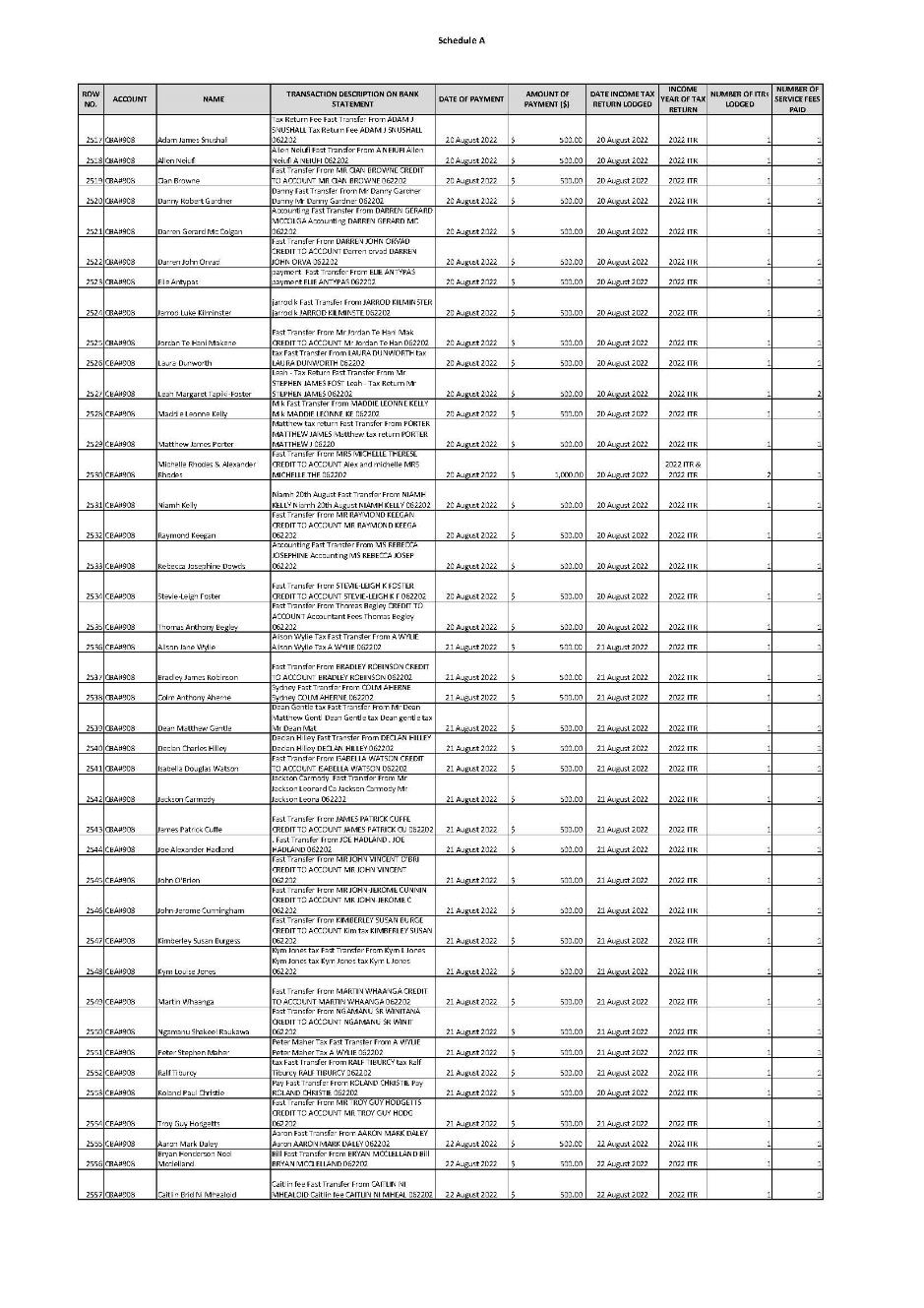

1. On each occasion specified in Schedule A of the Amended Statement of Agreed Facts dated 1 July 2024 filed in this proceeding and annexed hereto, the respondent contravened s 50-5(1) of the Tax Agent Services Act 2009 (Cth) (Act) by preparing and lodging income tax returns for taxpayers, being the provision of a tax agent service, for a fee or other reward, whilst not a registered tax agent within the meaning of the Act.

The court orders that:

1. Pursuant to s 50-35(2) of the Act, the respondent pay a pecuniary penalty totalling $1,800,000 in respect of 3,359 separate contraventions of s 50-5(1) of the Act.

2. The respondent pay the pecuniary penalty referred to in paragraph 2 above, to the Commissioner of Taxation of the Commonwealth of Australia on behalf of the Commonwealth of Australia.

3. Pursuant to s 70-5(1) of the Act, the respondent be permanently restrained from providing tax agent services (as defined in the Act) for a fee or other reward, whilst not a registered tax agent within the meaning of the Act.

4. The respondent pay the costs of the applicant on a party and party basis, to be agreed or assessed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ABRAHAM J

1 The applicant, the Tax Practitioners Board (the Board), seeks pecuniary penalties, a declaration, and injunction against Mr Van Dyke on the grounds he performed tax agent services without being registered under the Tax Agent Services Act 2009 (Cth) (TASA). Mr Van Dyke admits to 3,359 contraventions of s 50-5(1) of the TASA by preparing and lodging 3,359 income tax returns for taxpayers, for a fee or other reward, whilst not a registered tax agent within the meaning of that Act. He generally charged $500 for the preparation and lodgement of each income tax return.

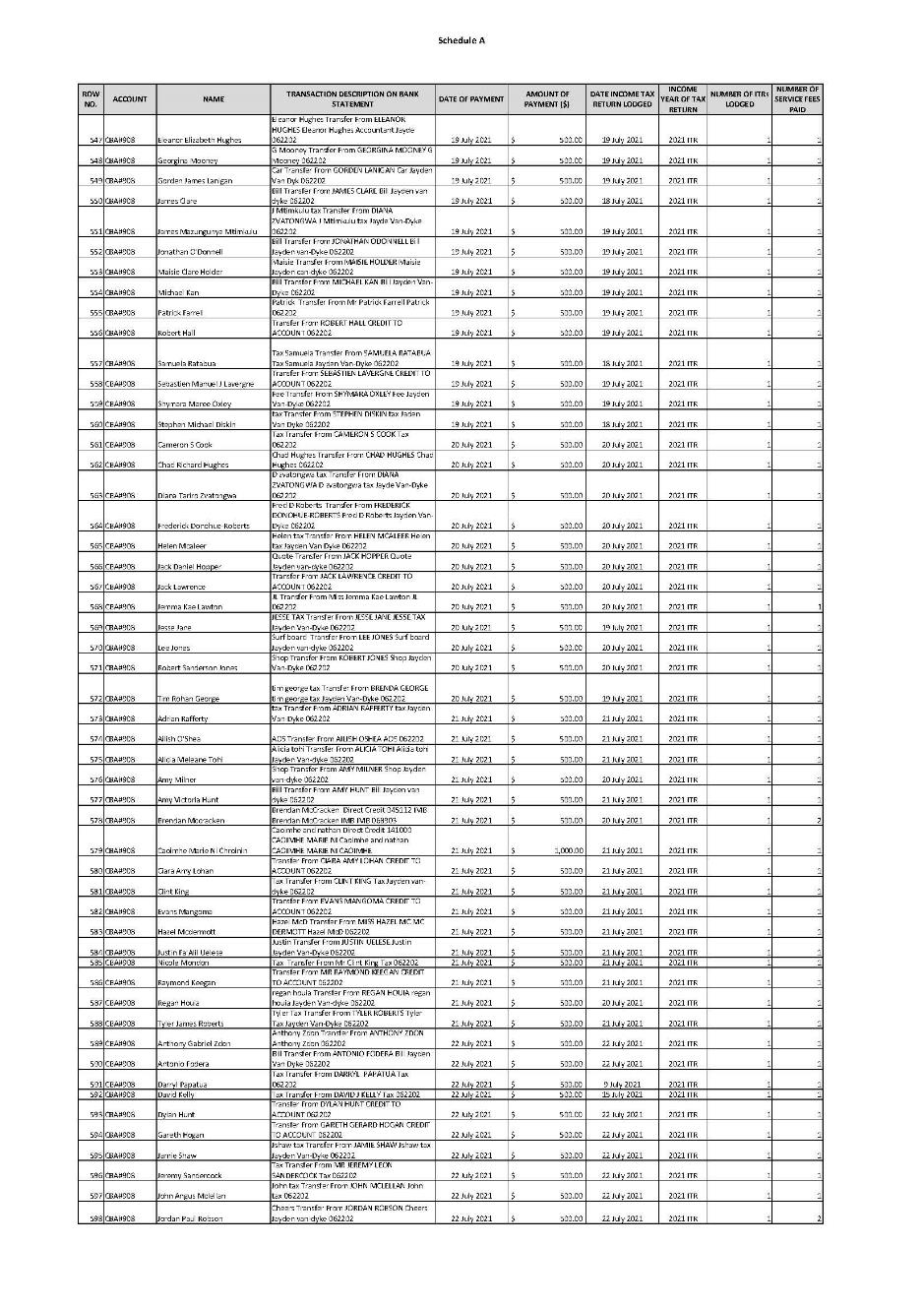

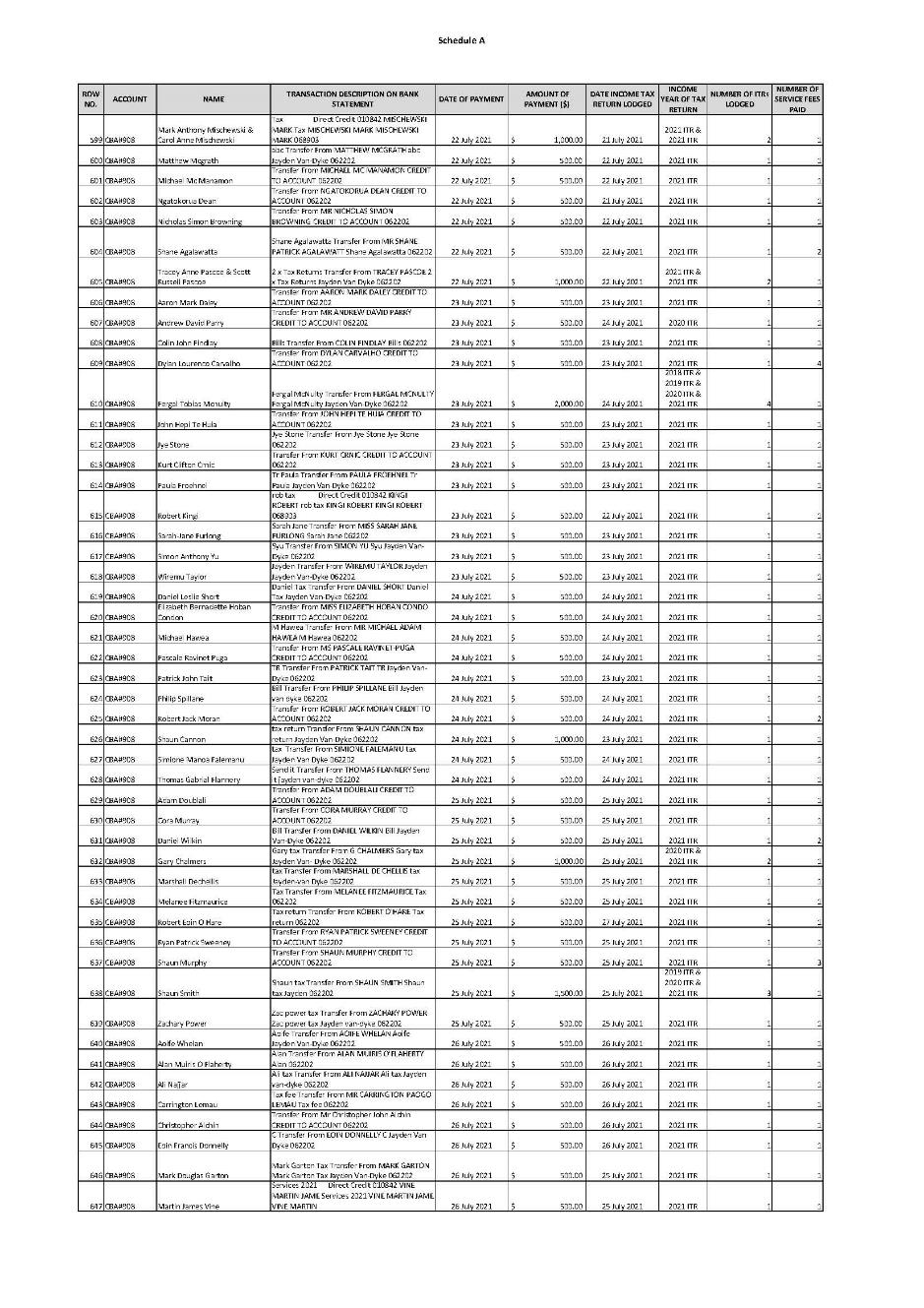

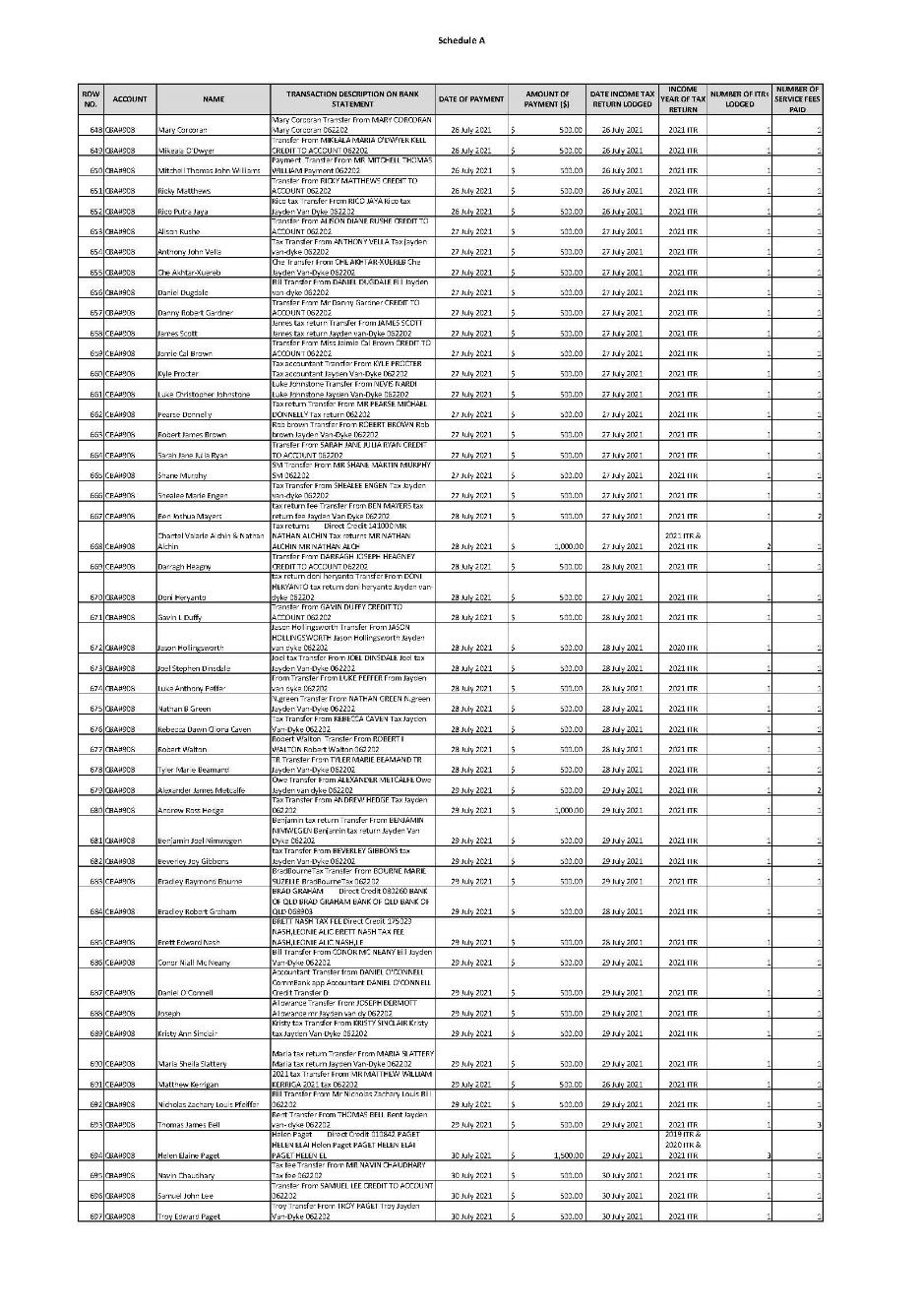

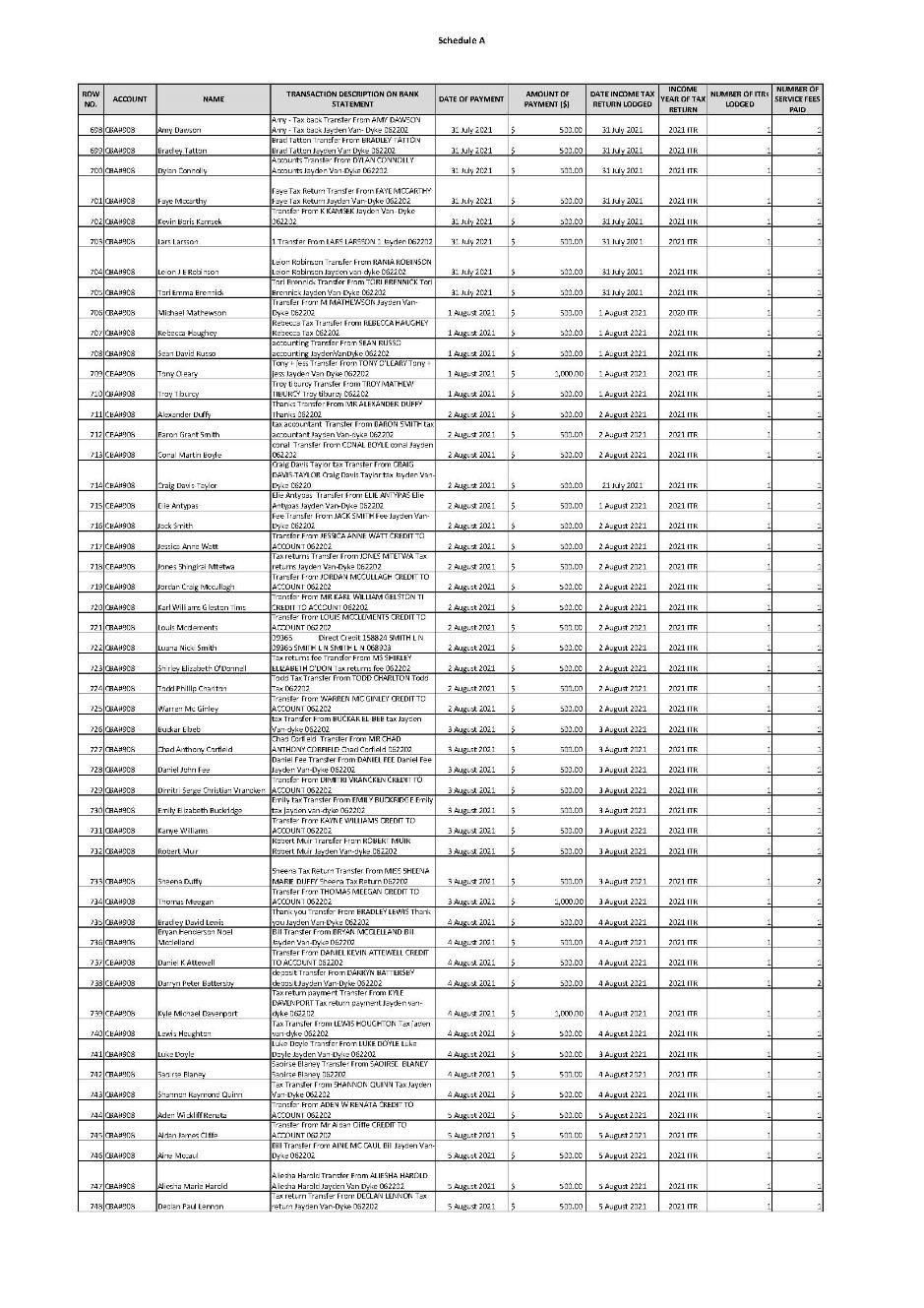

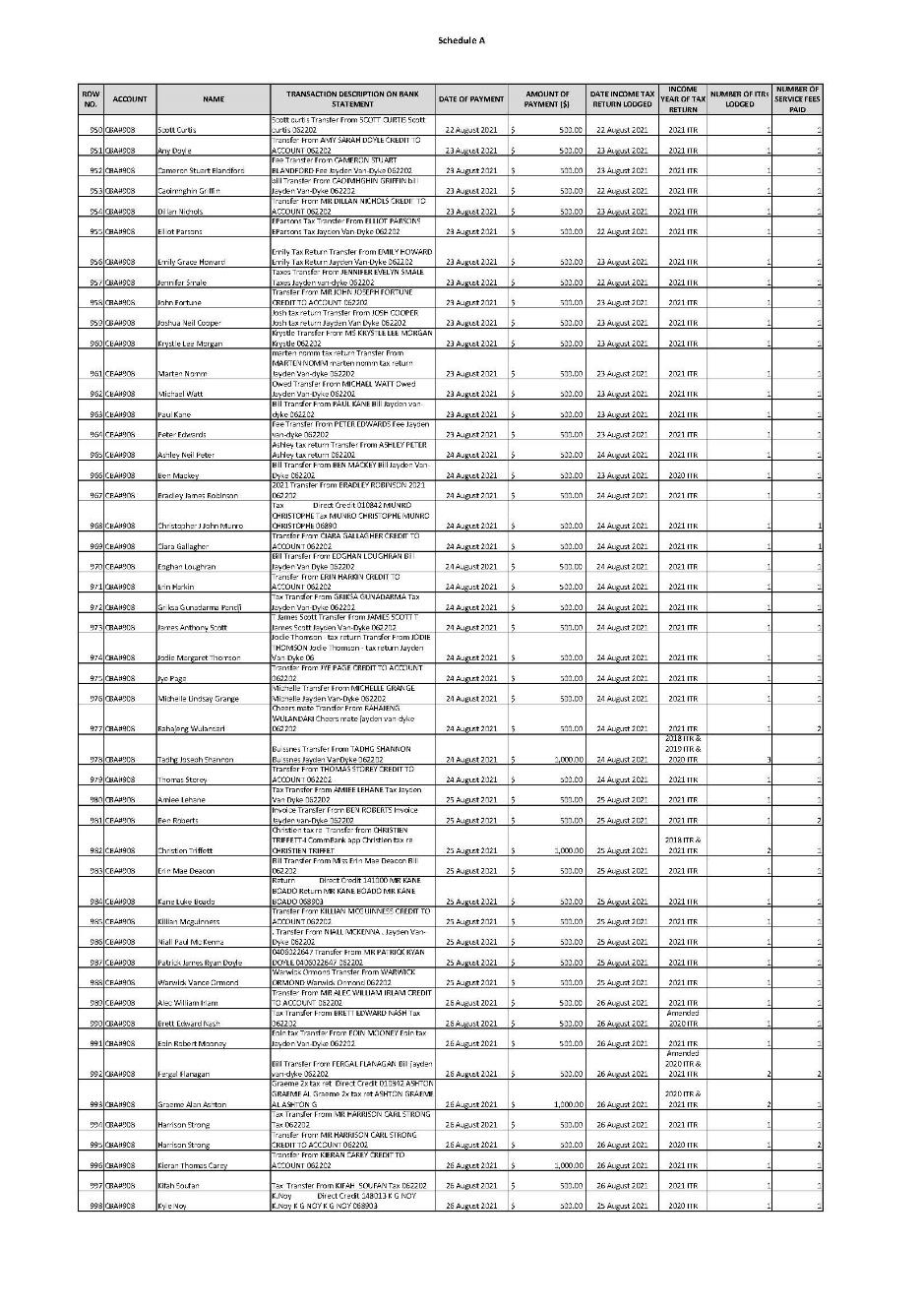

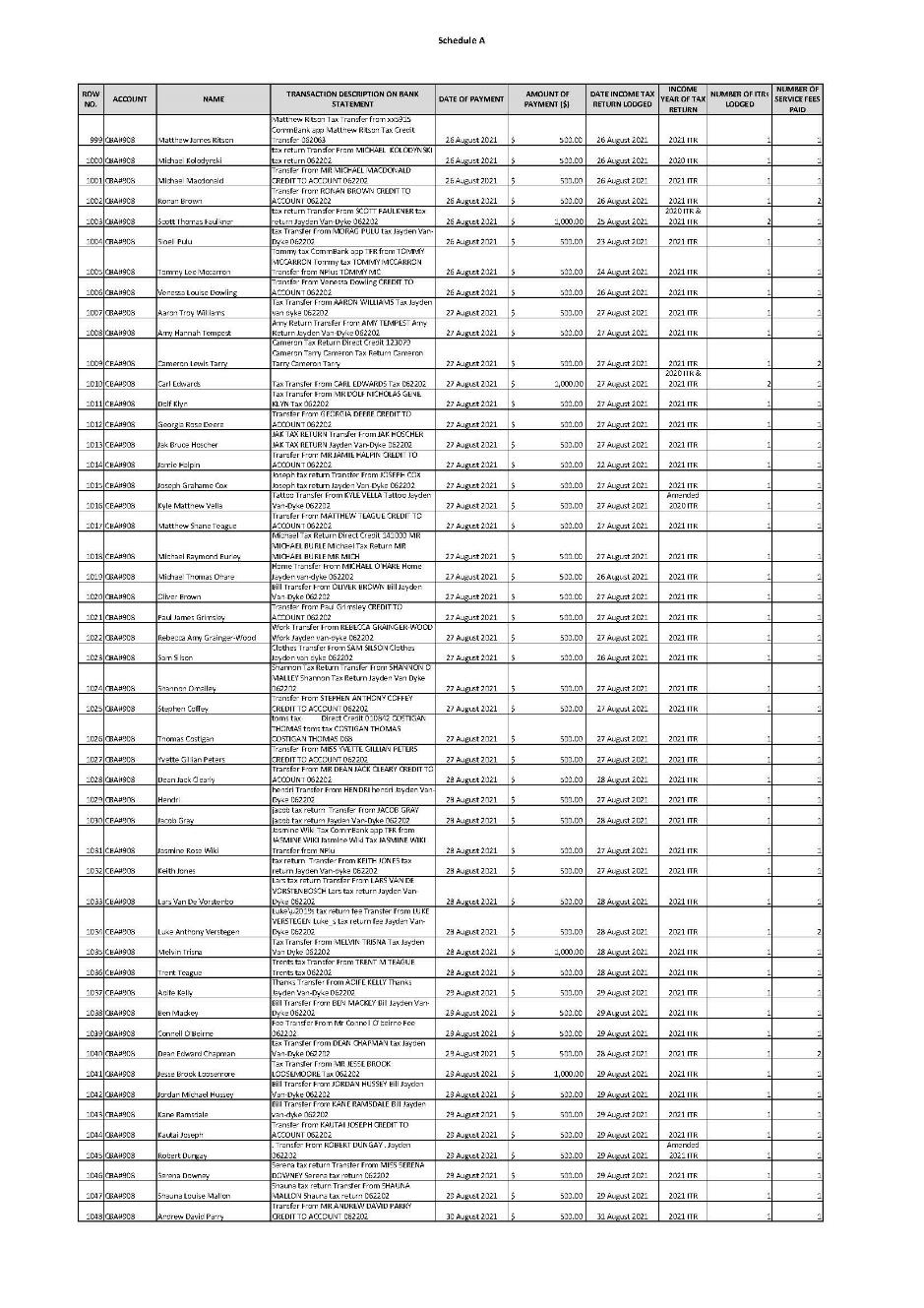

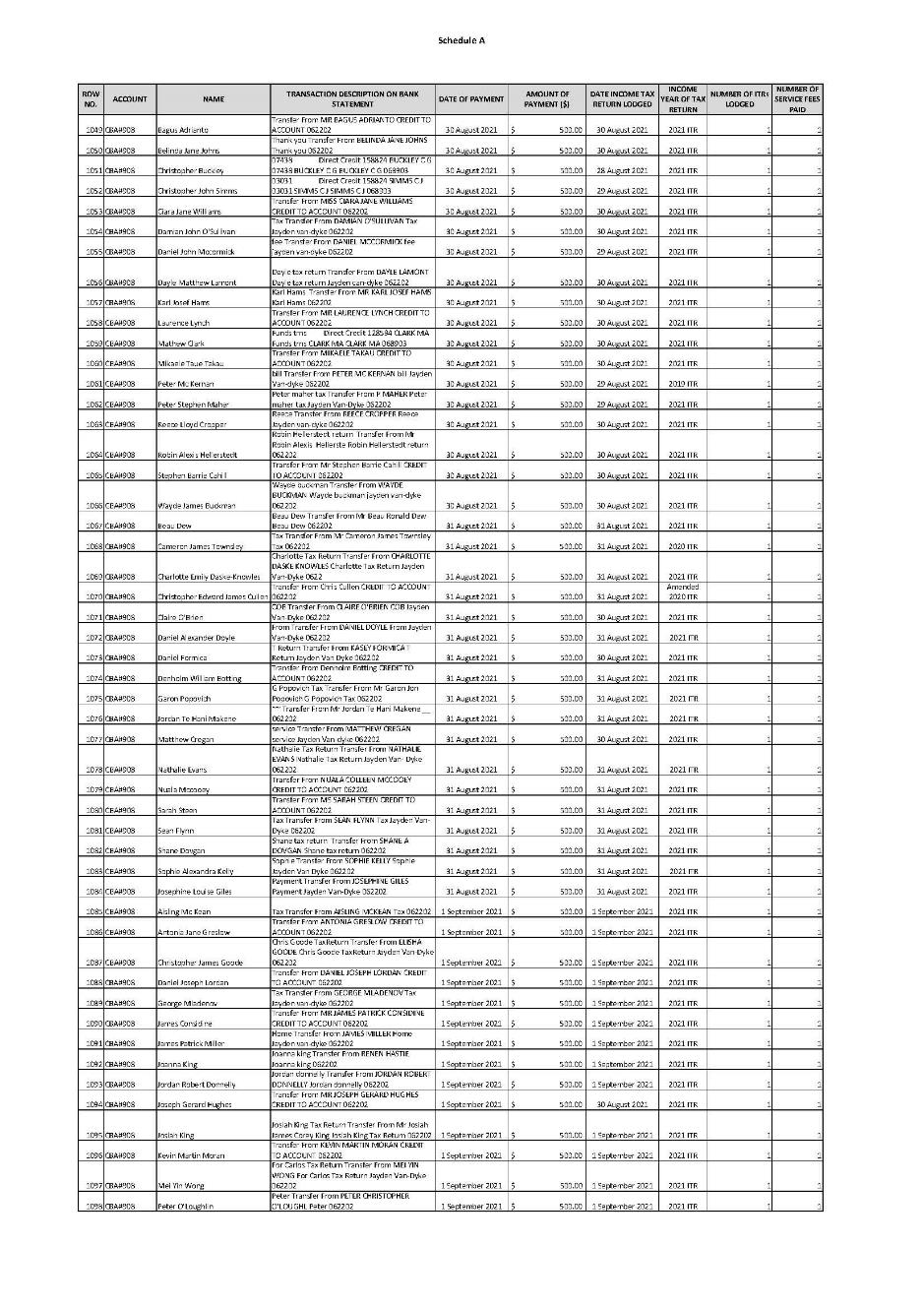

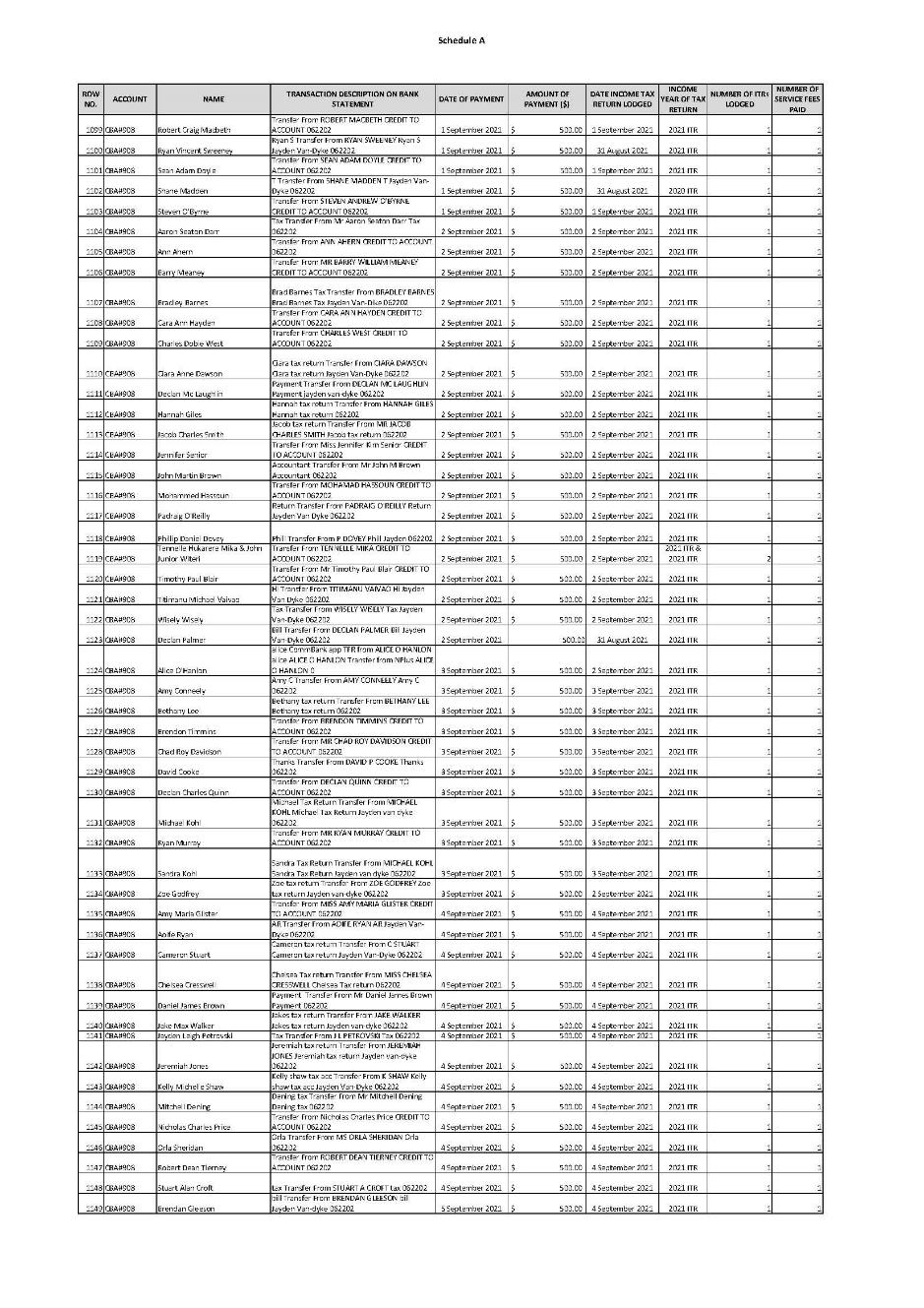

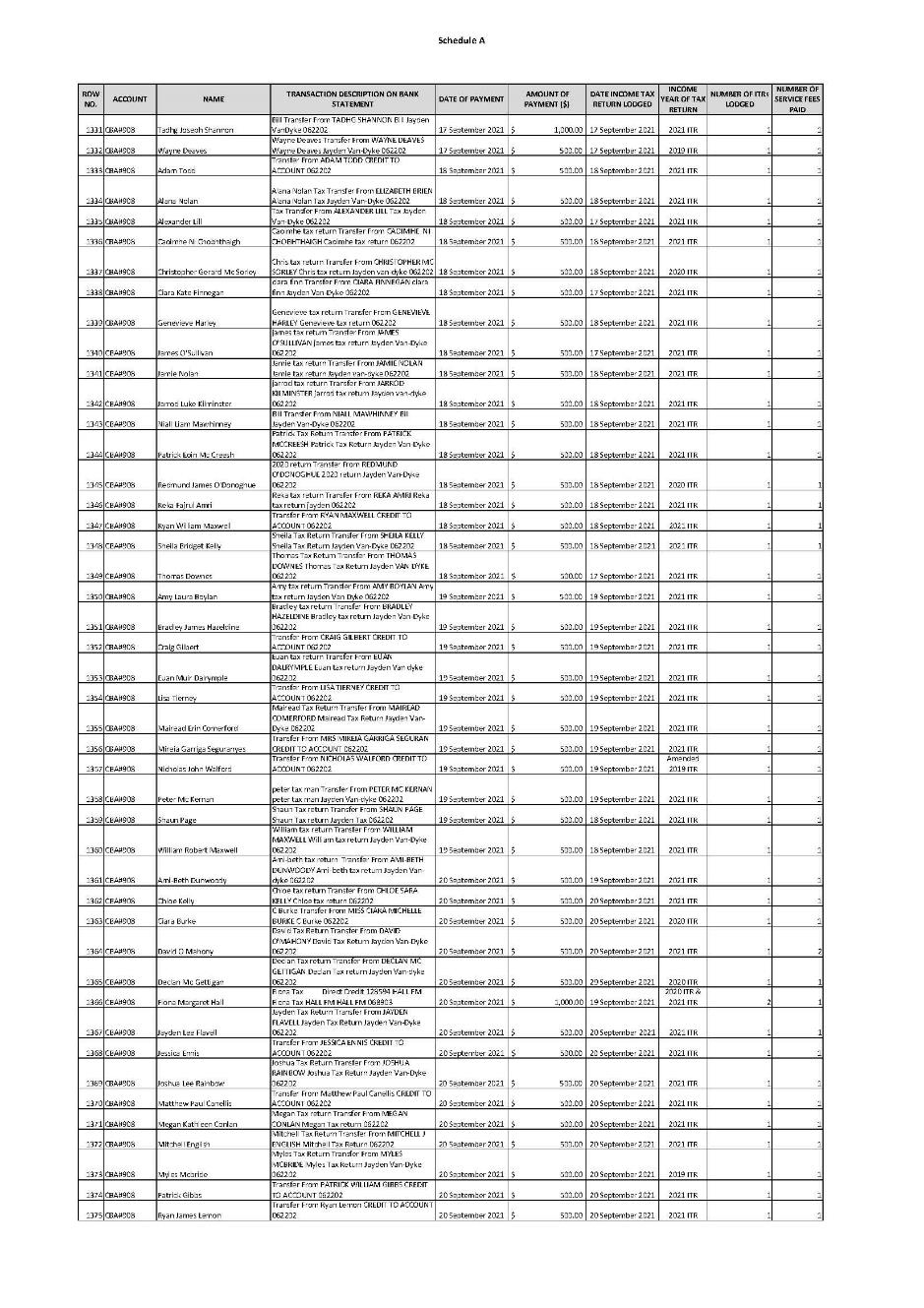

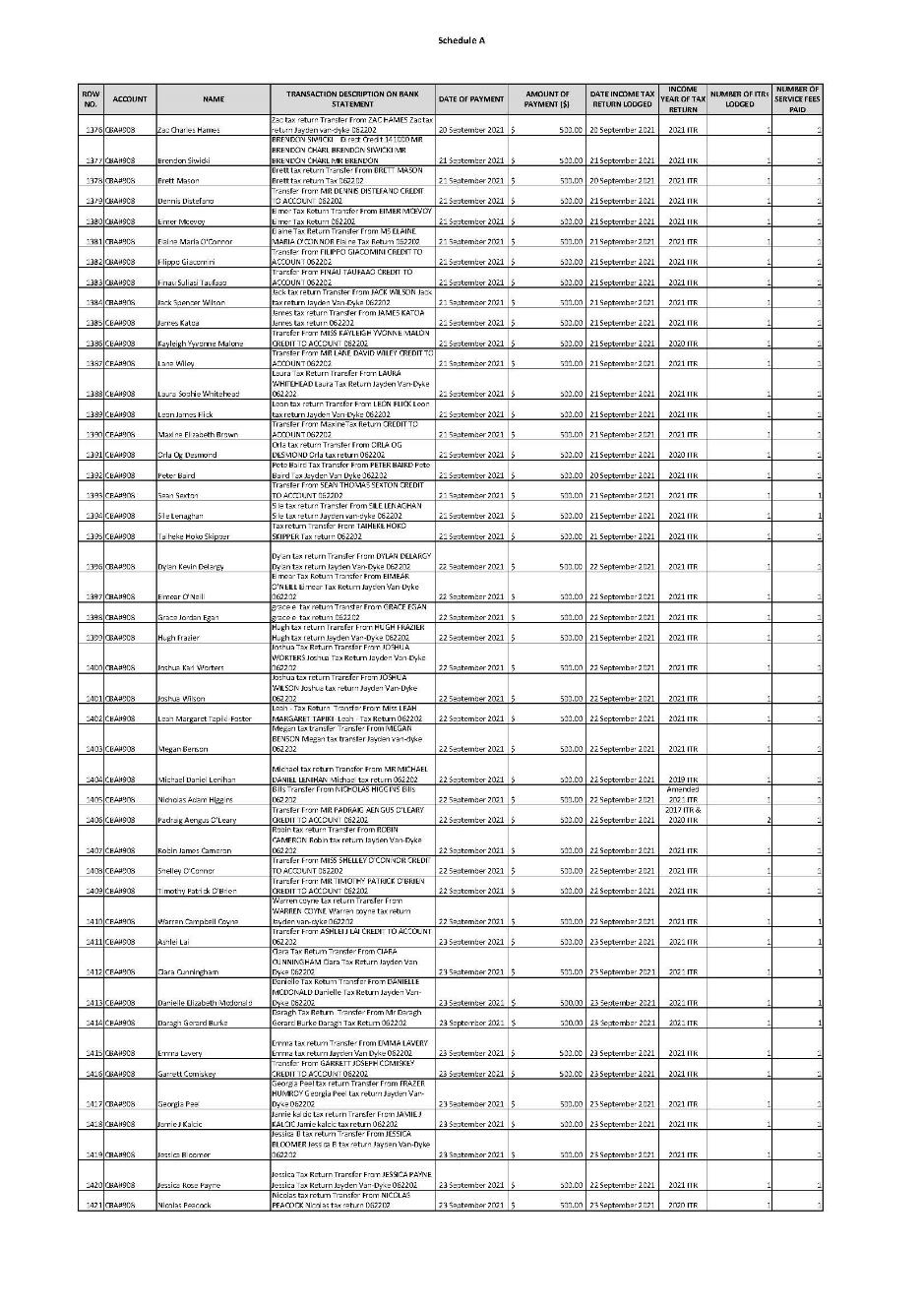

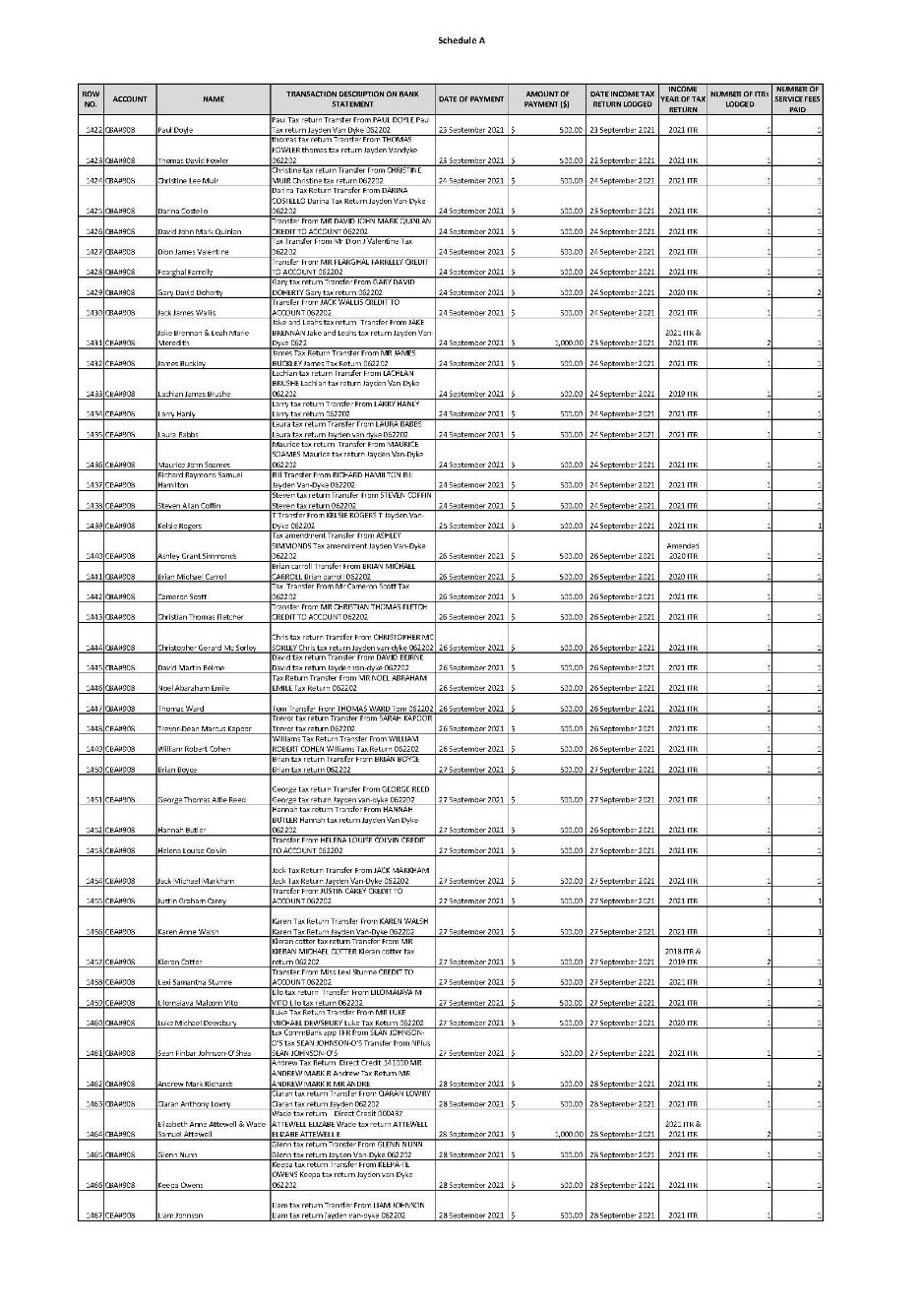

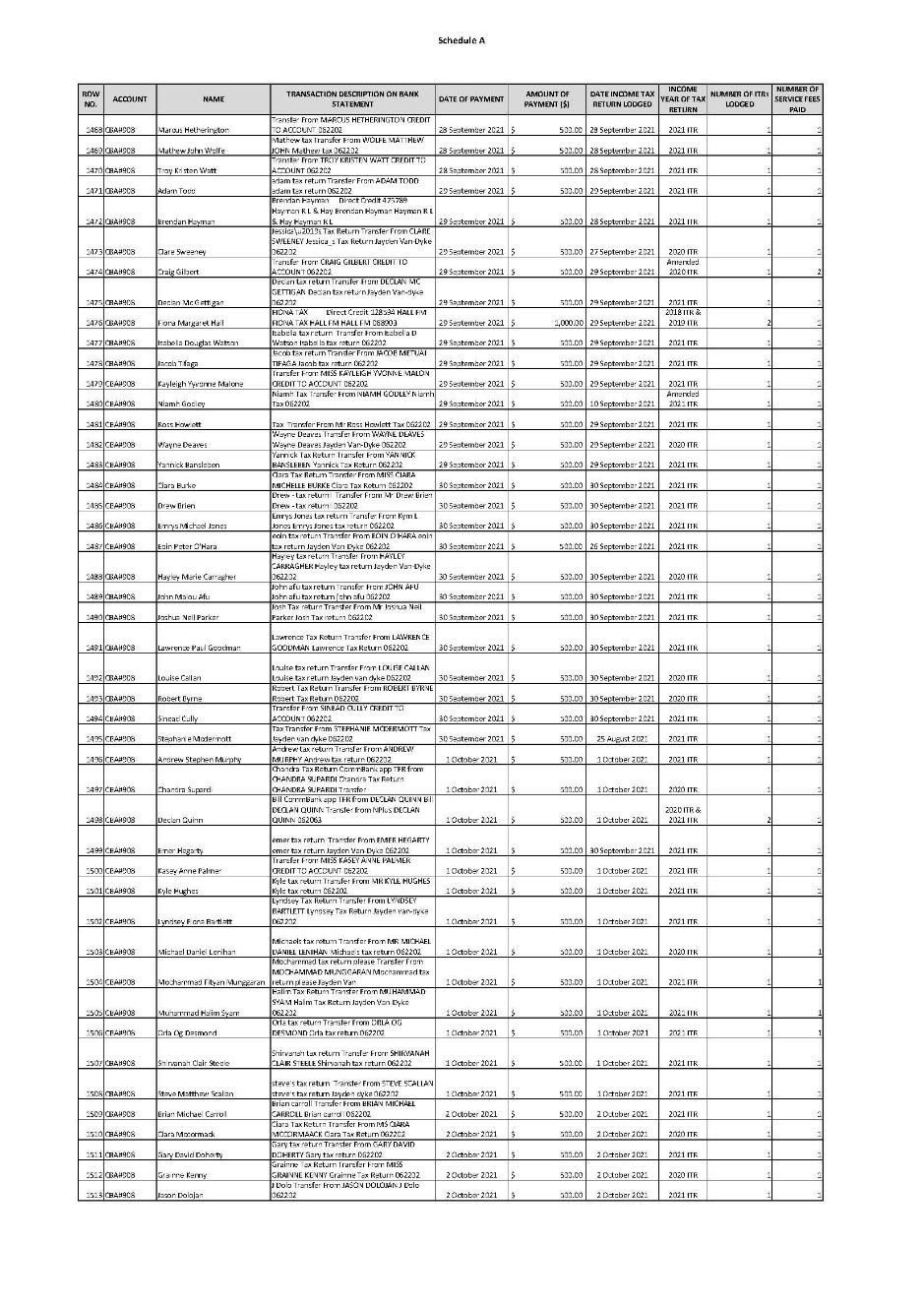

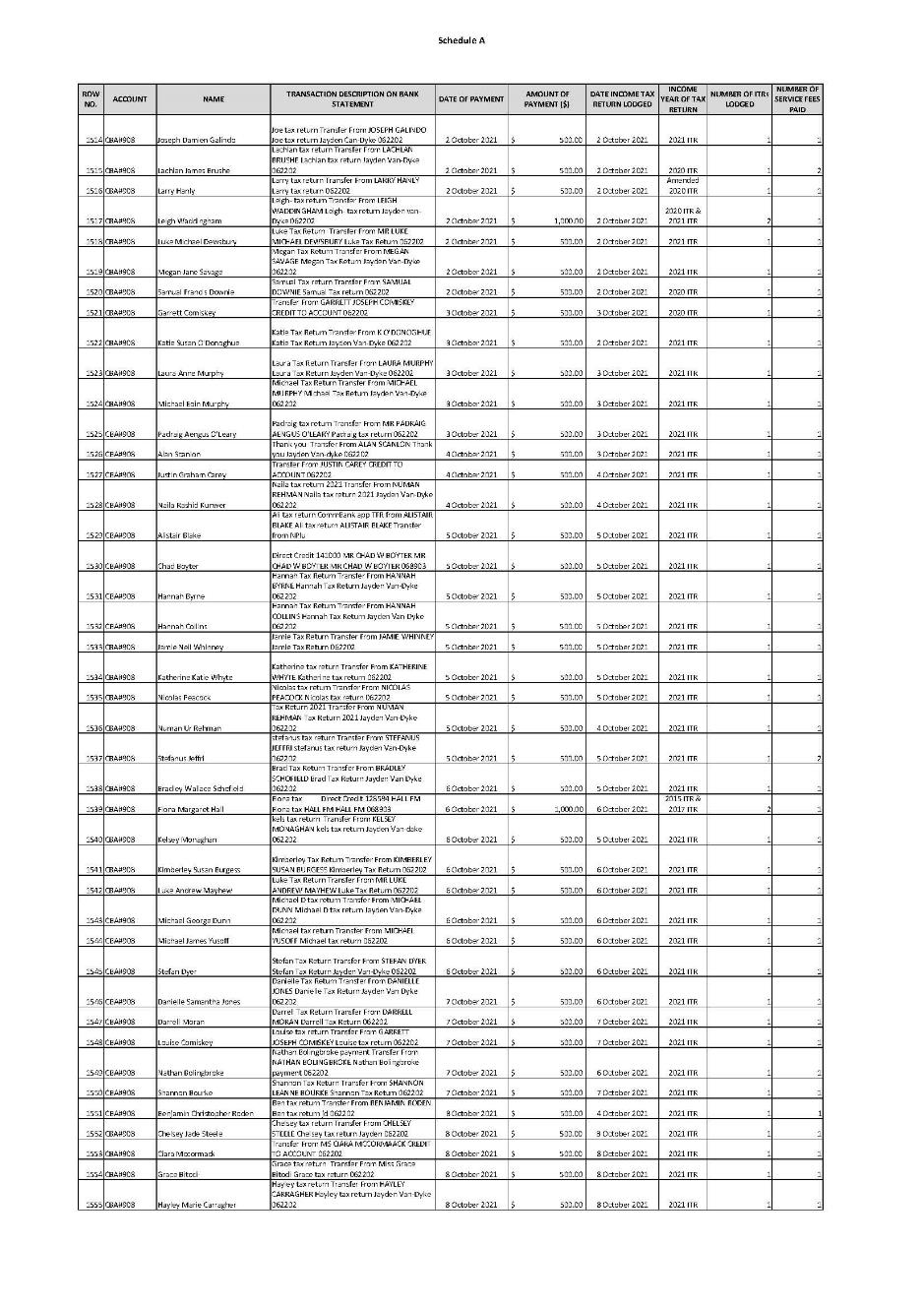

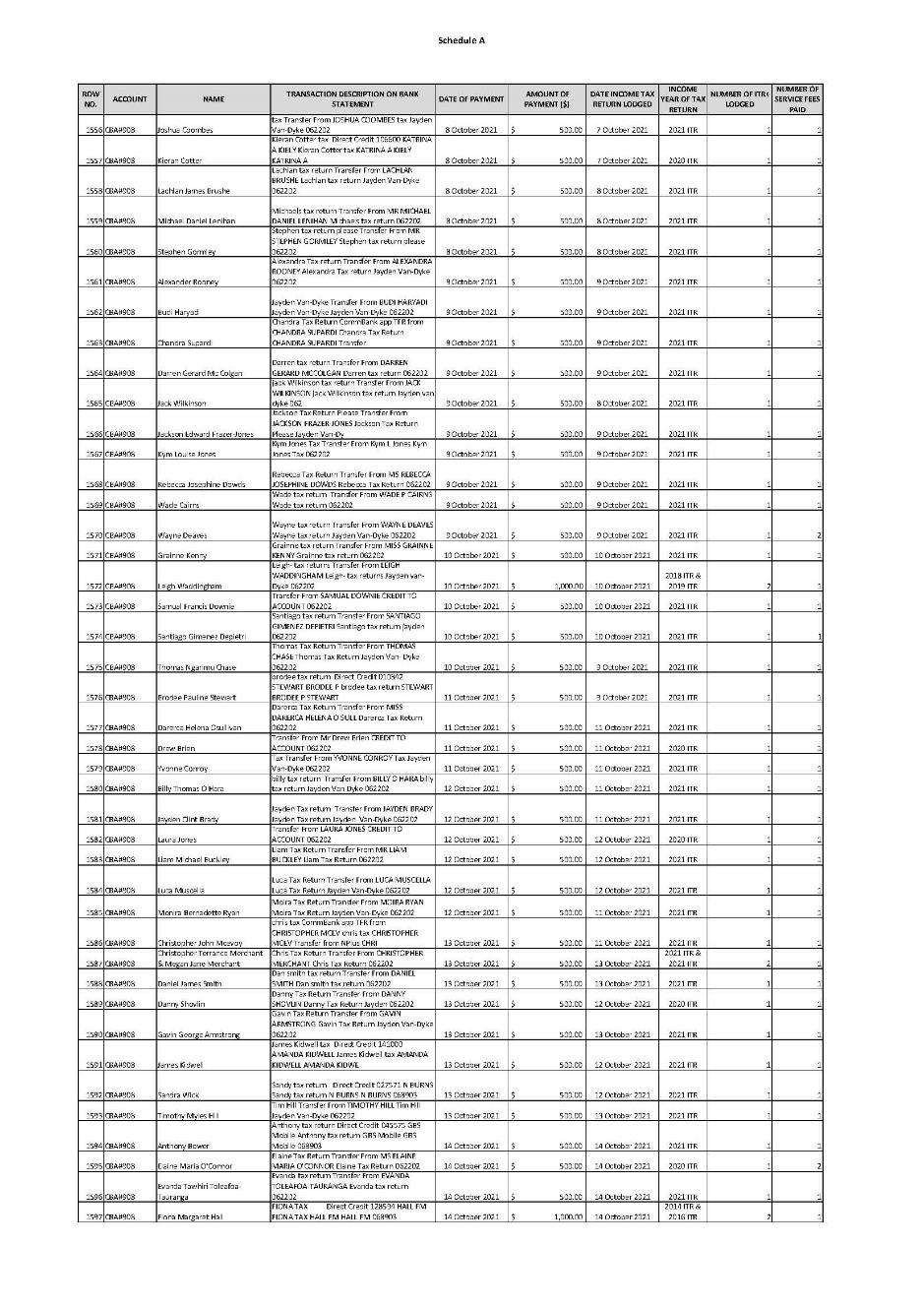

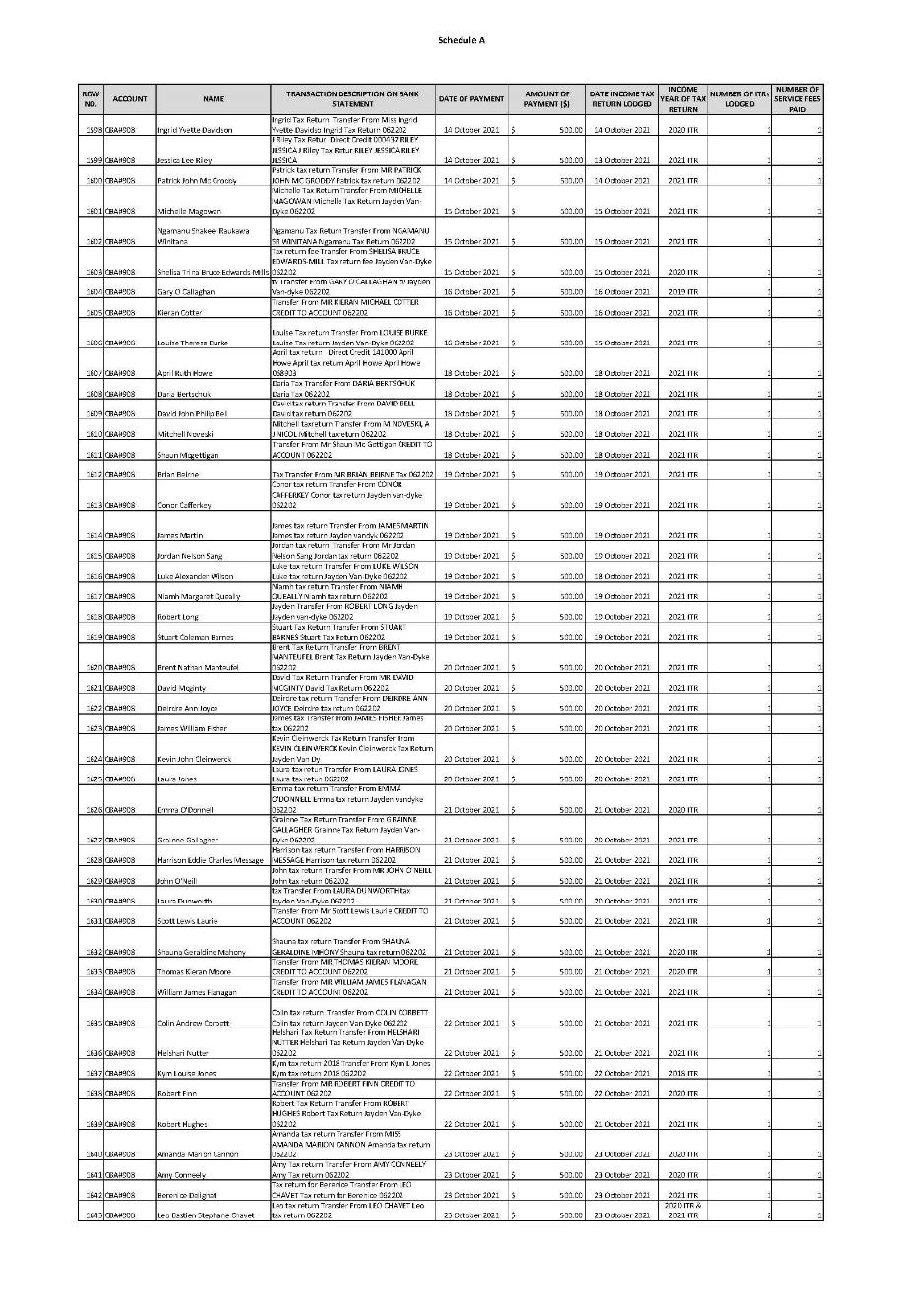

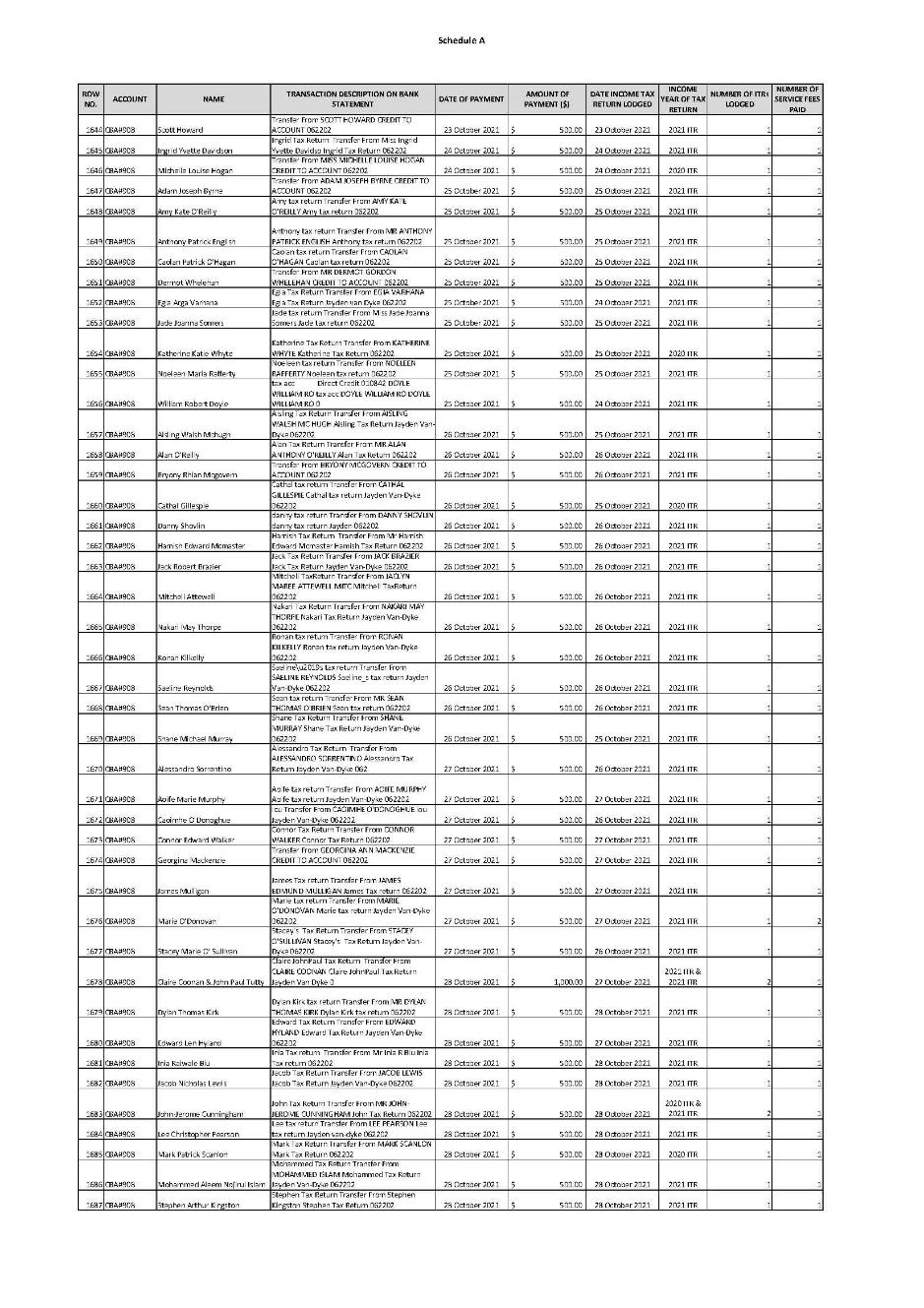

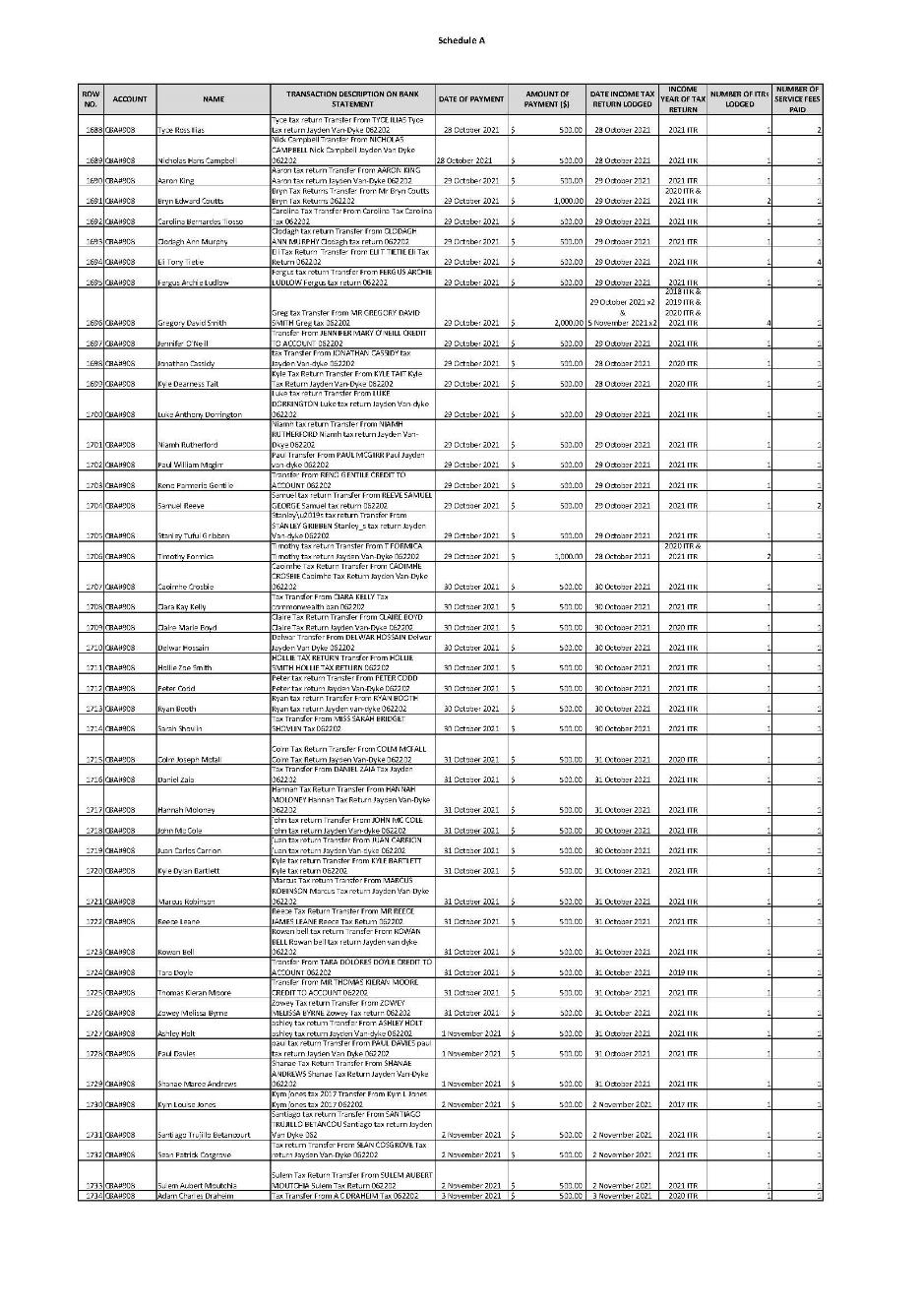

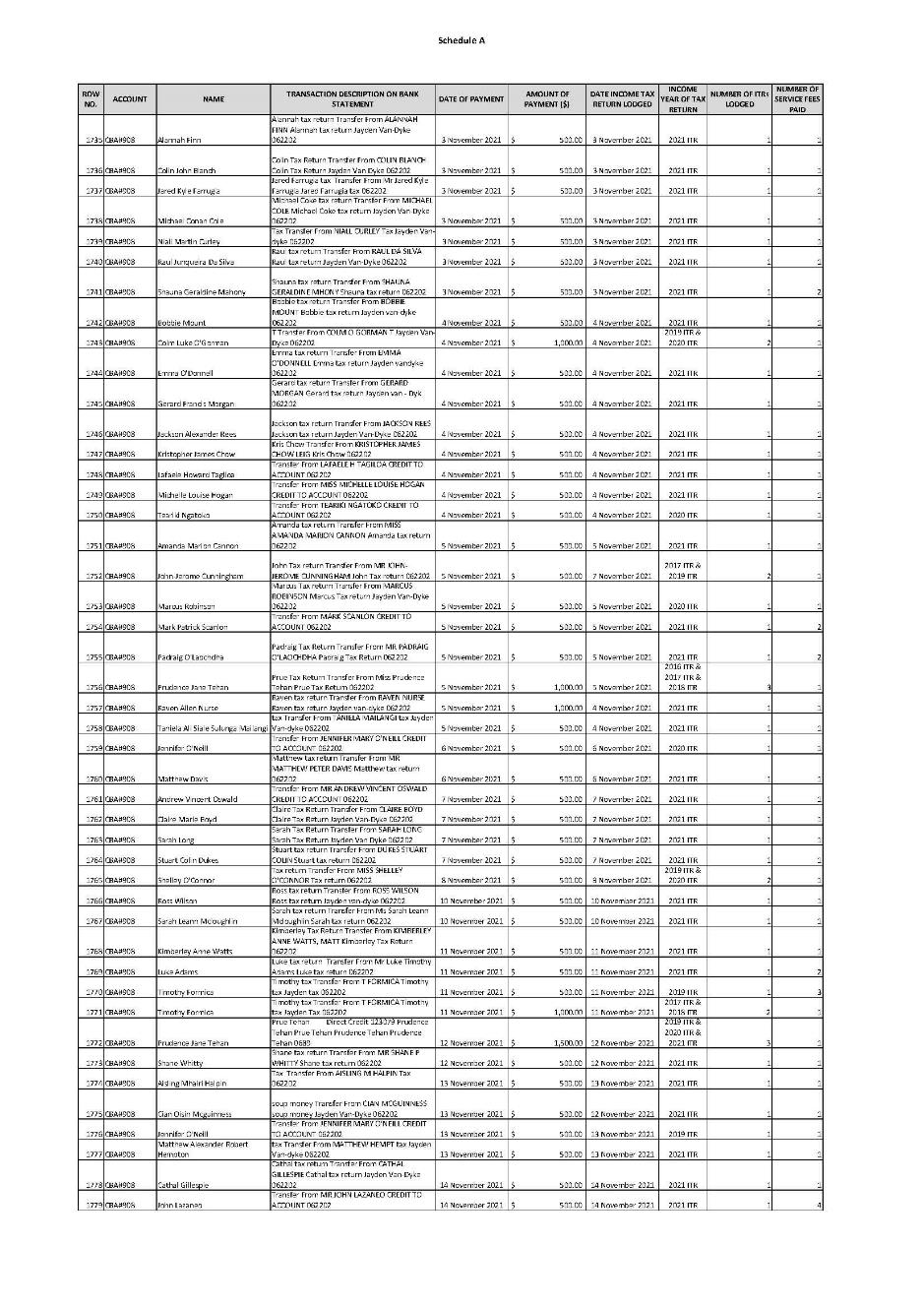

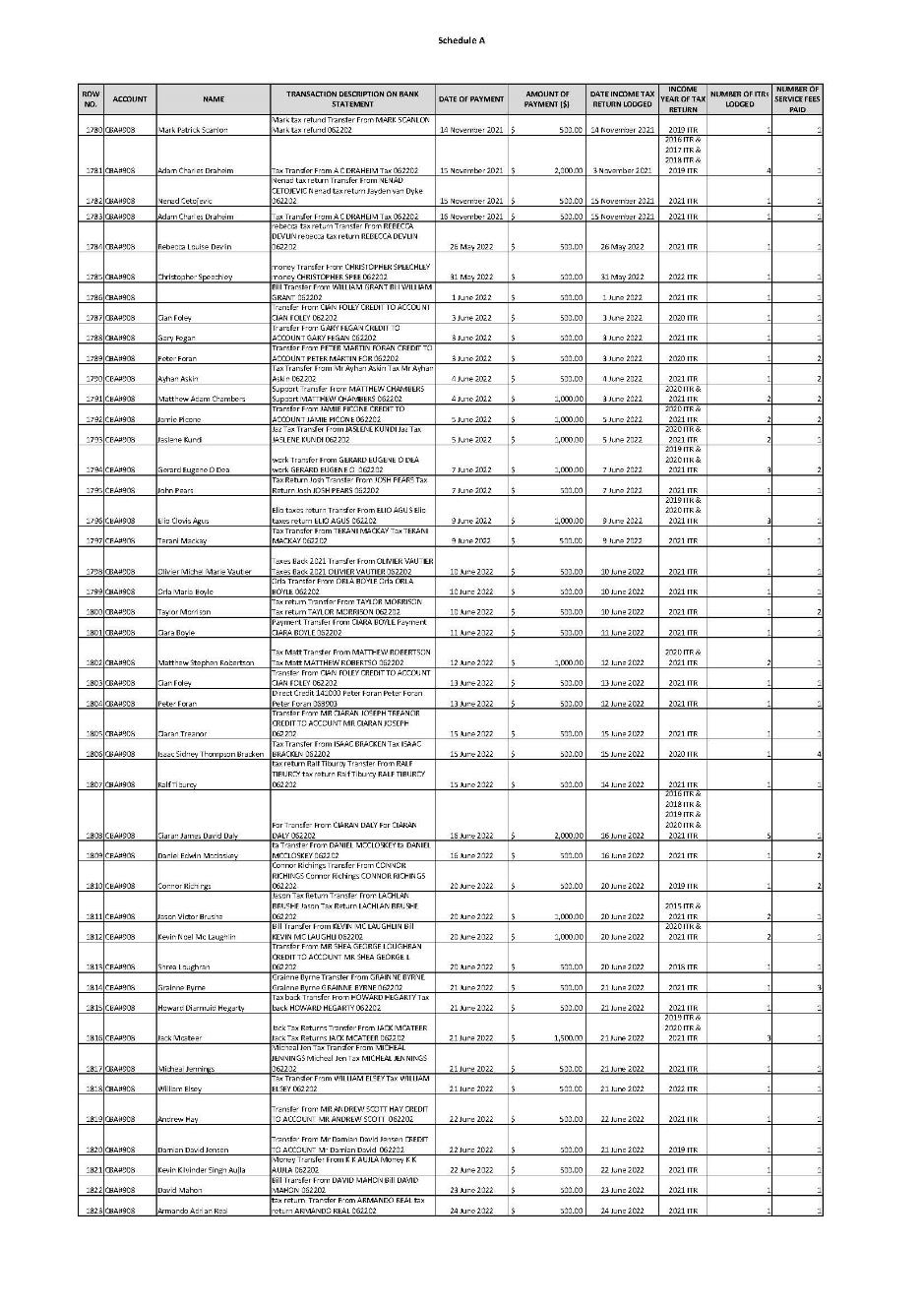

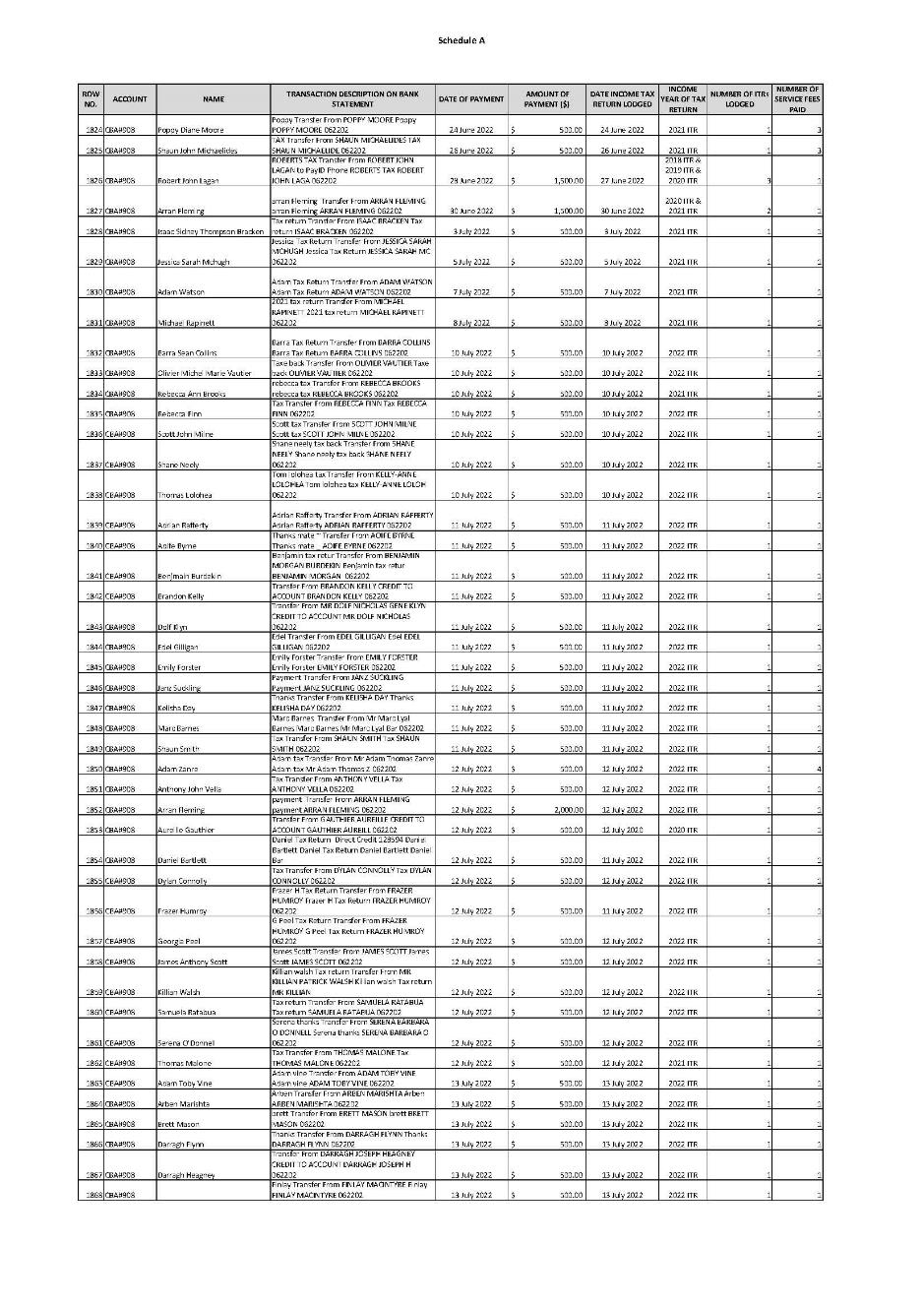

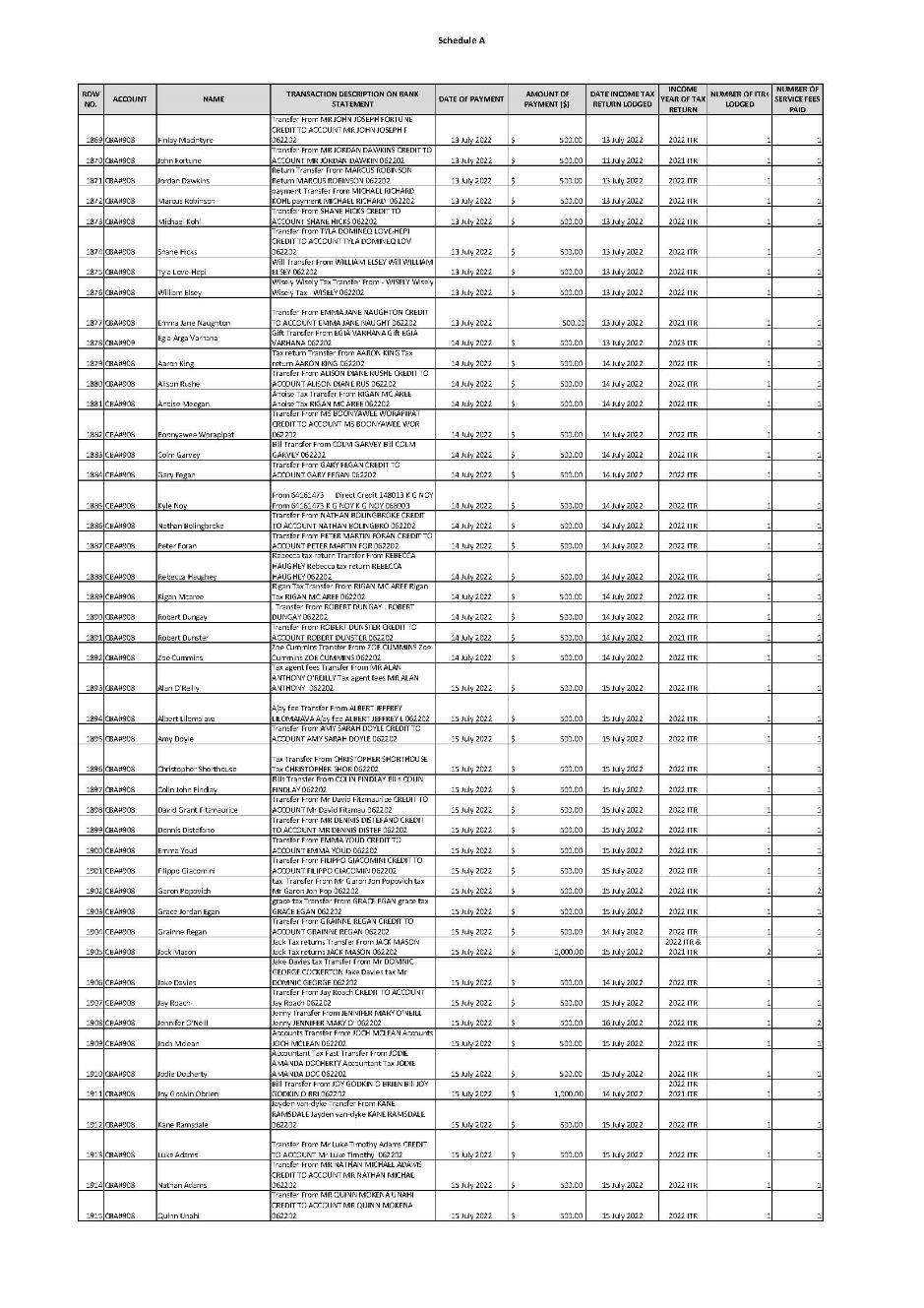

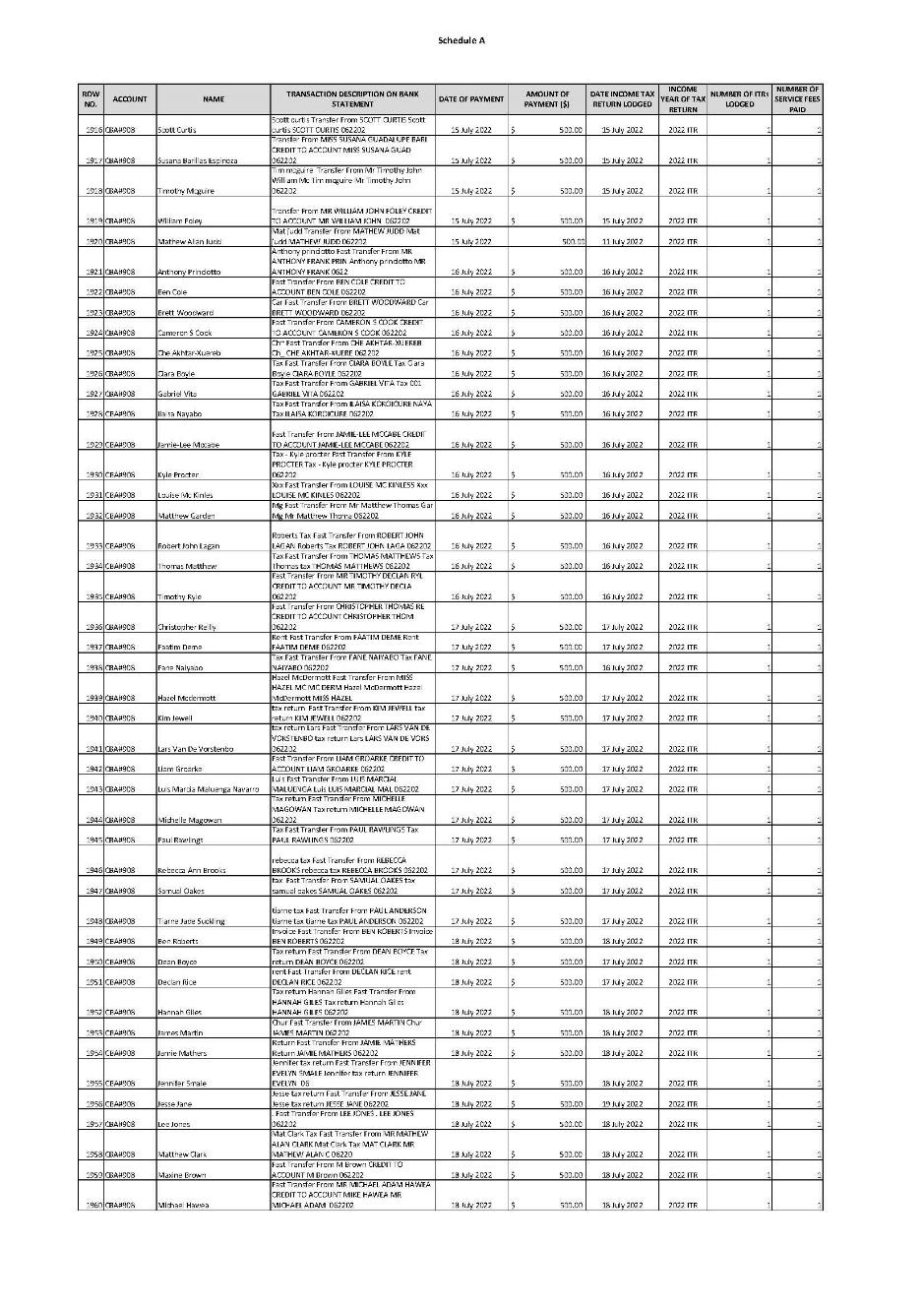

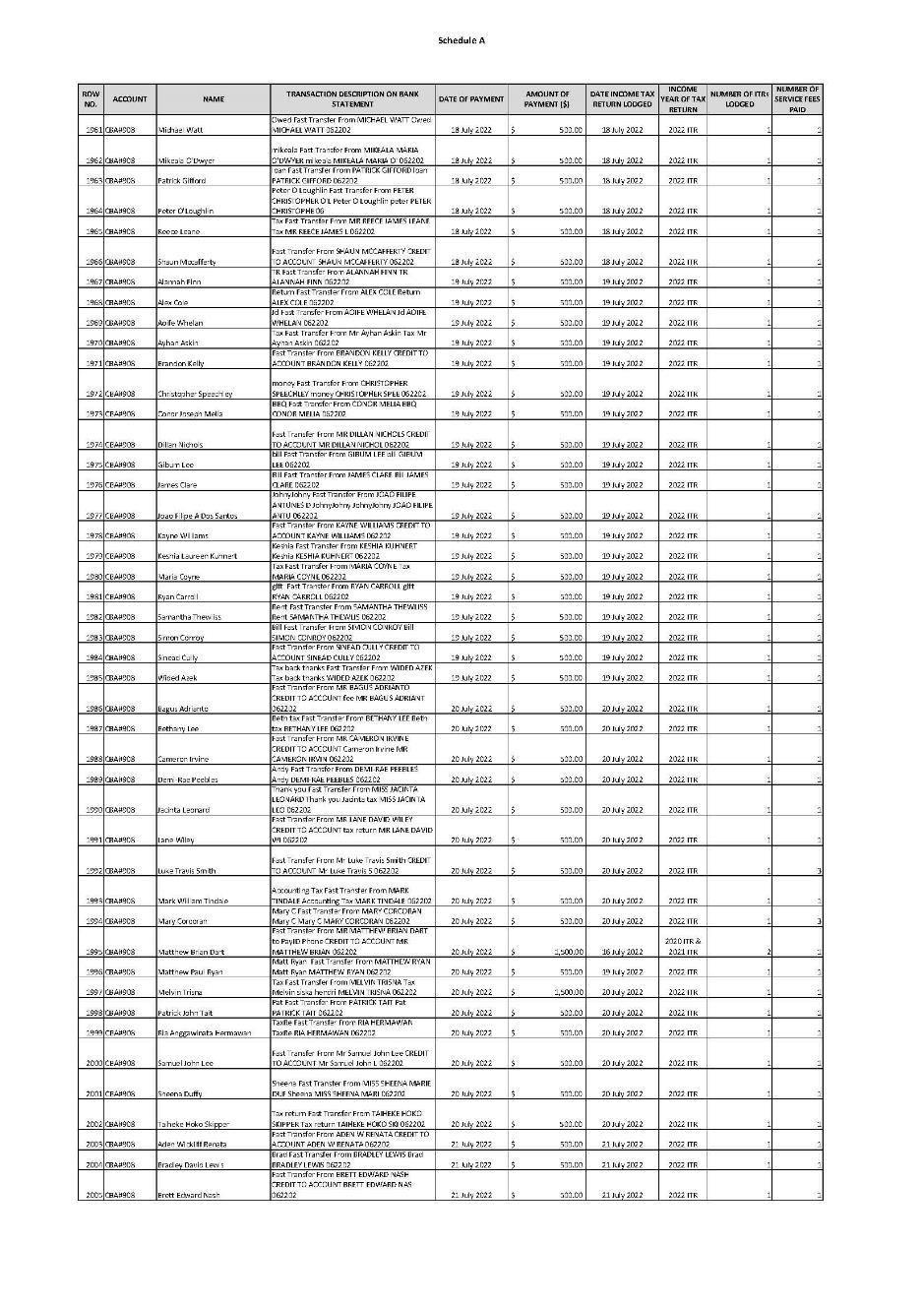

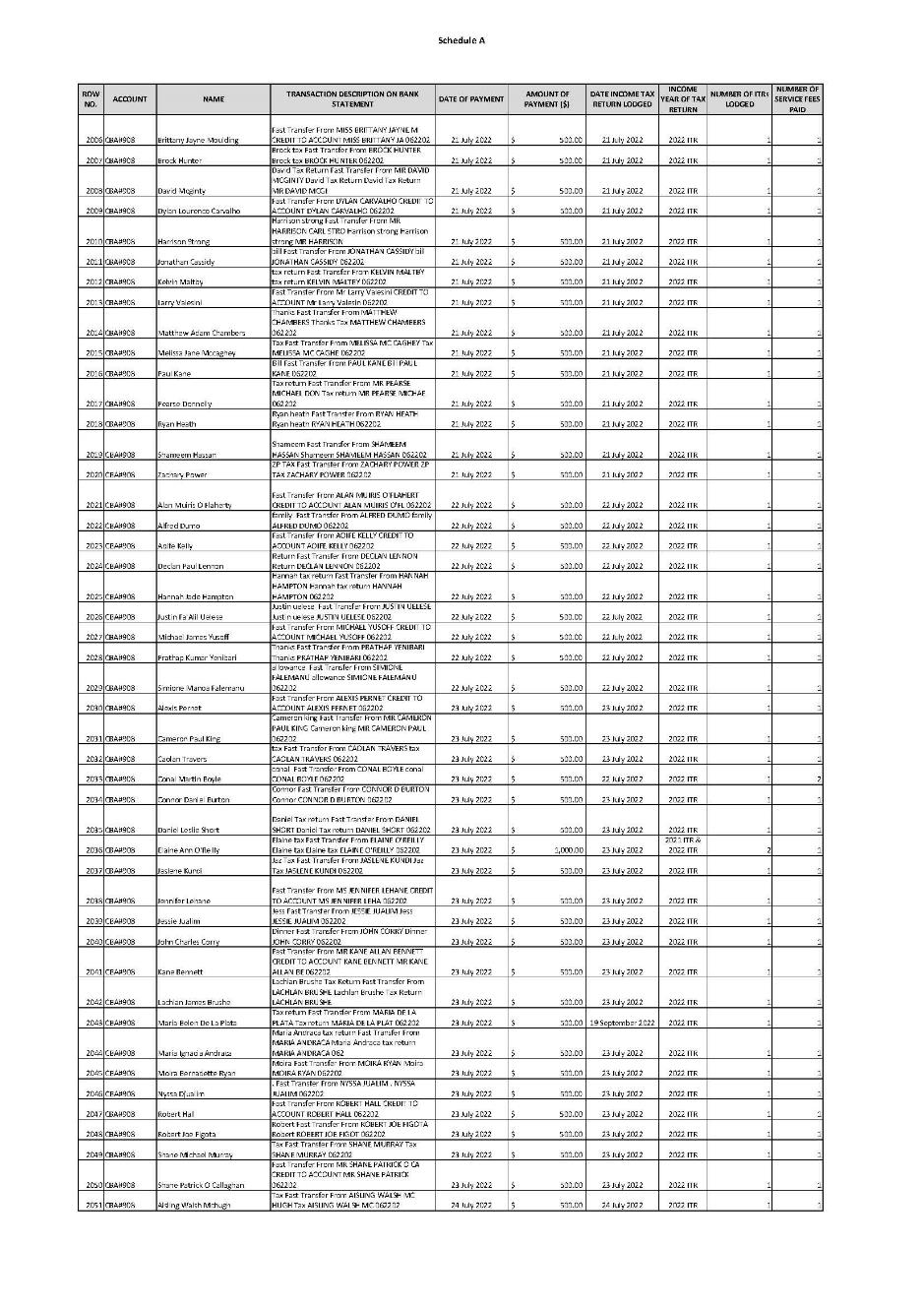

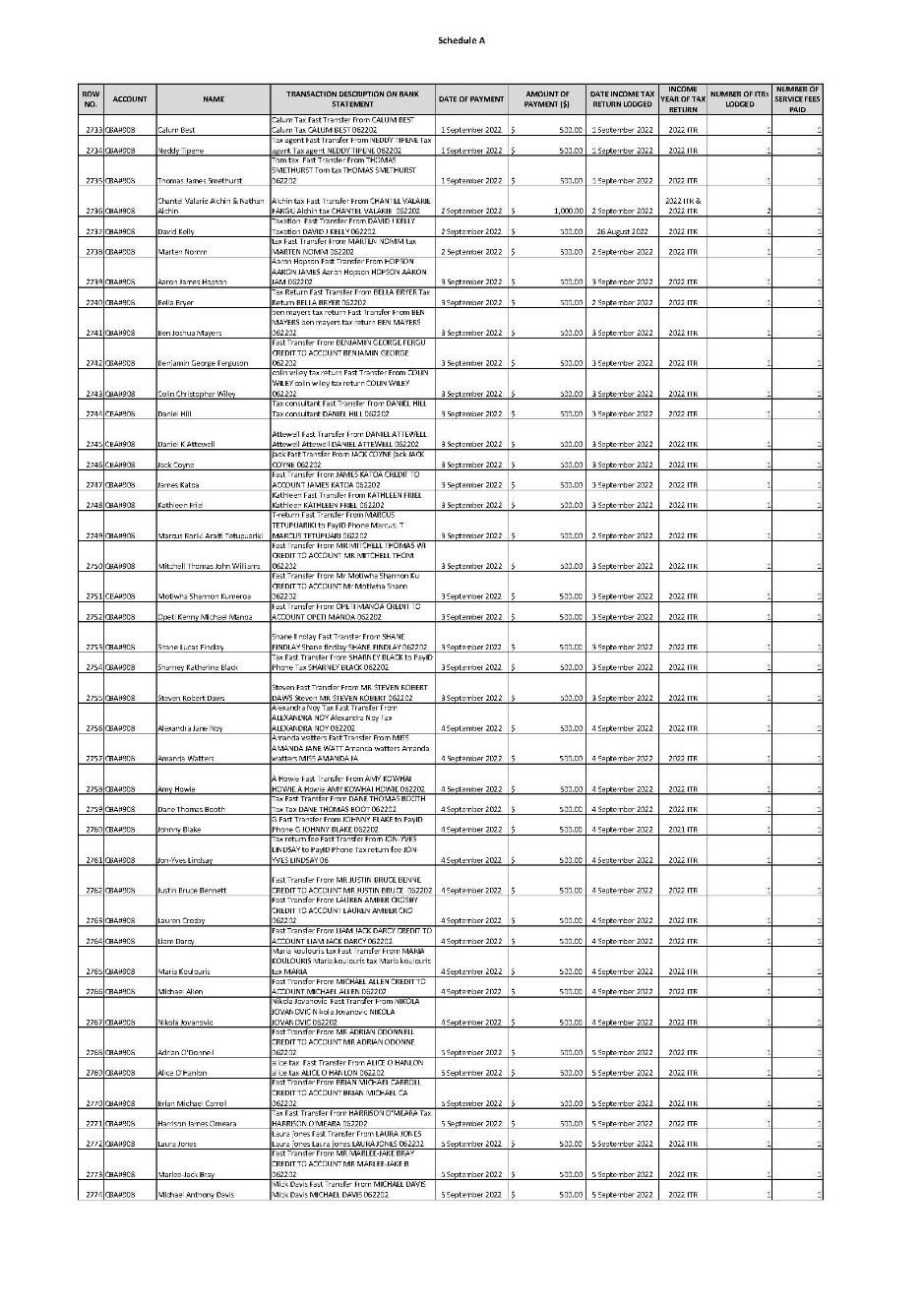

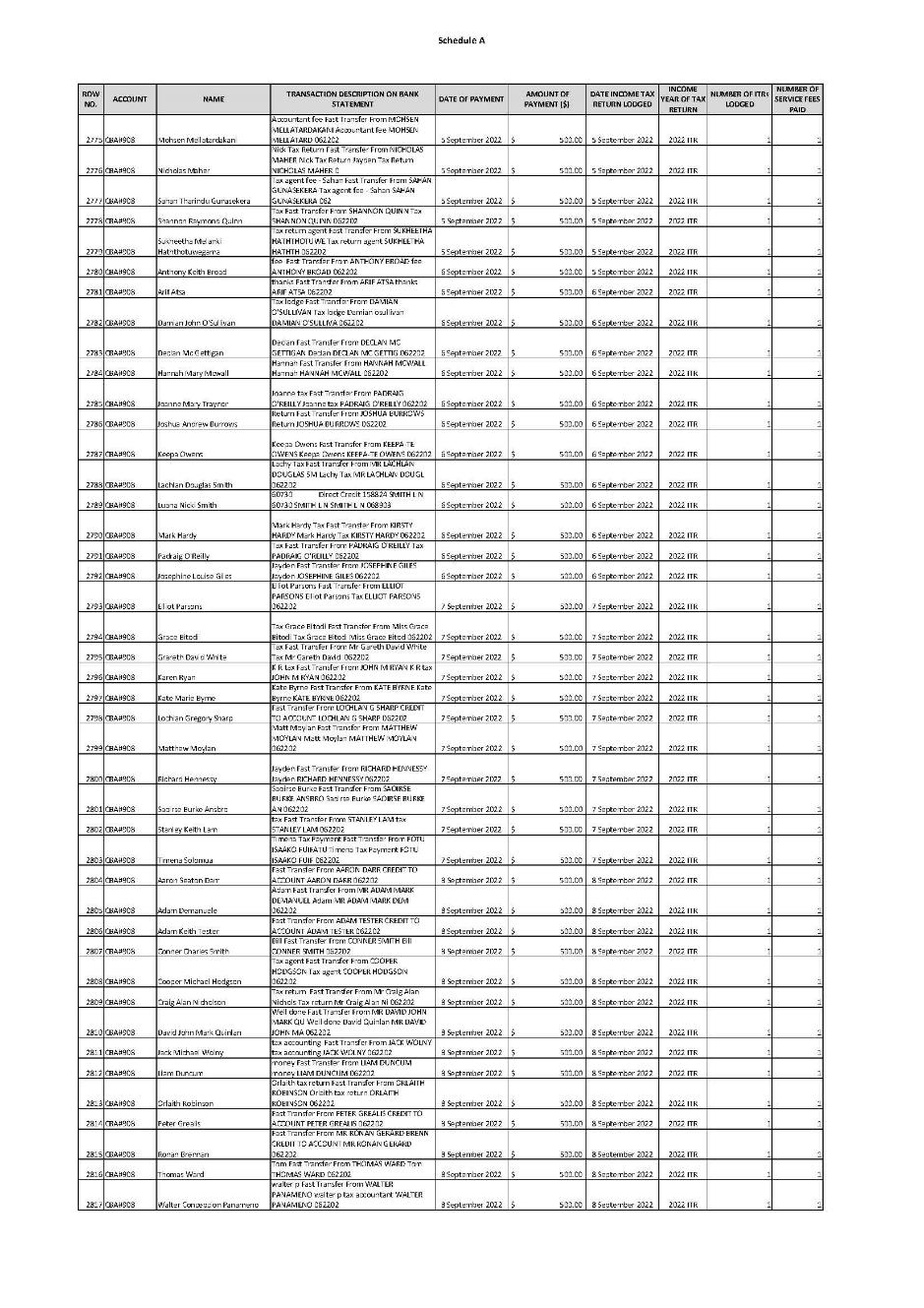

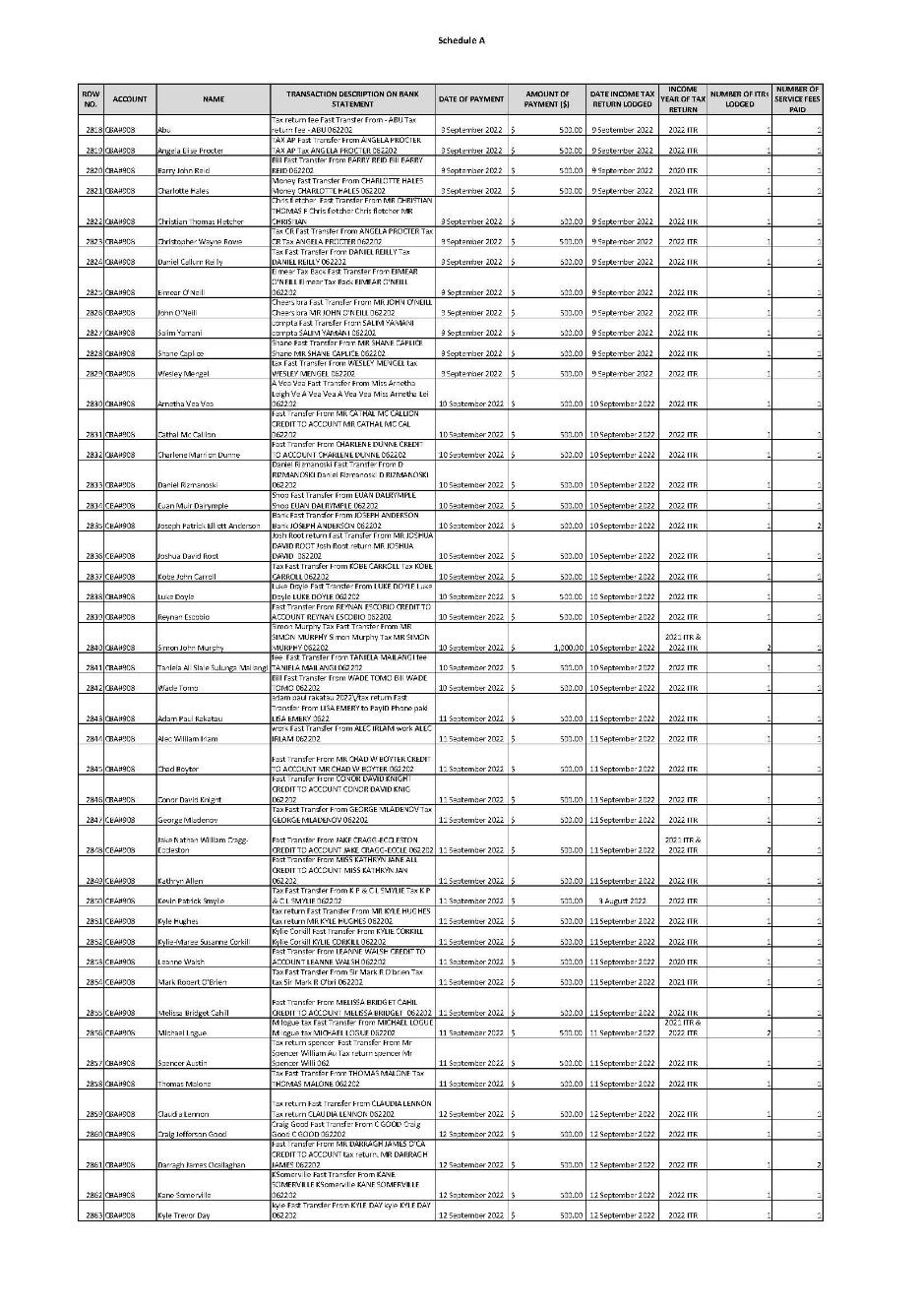

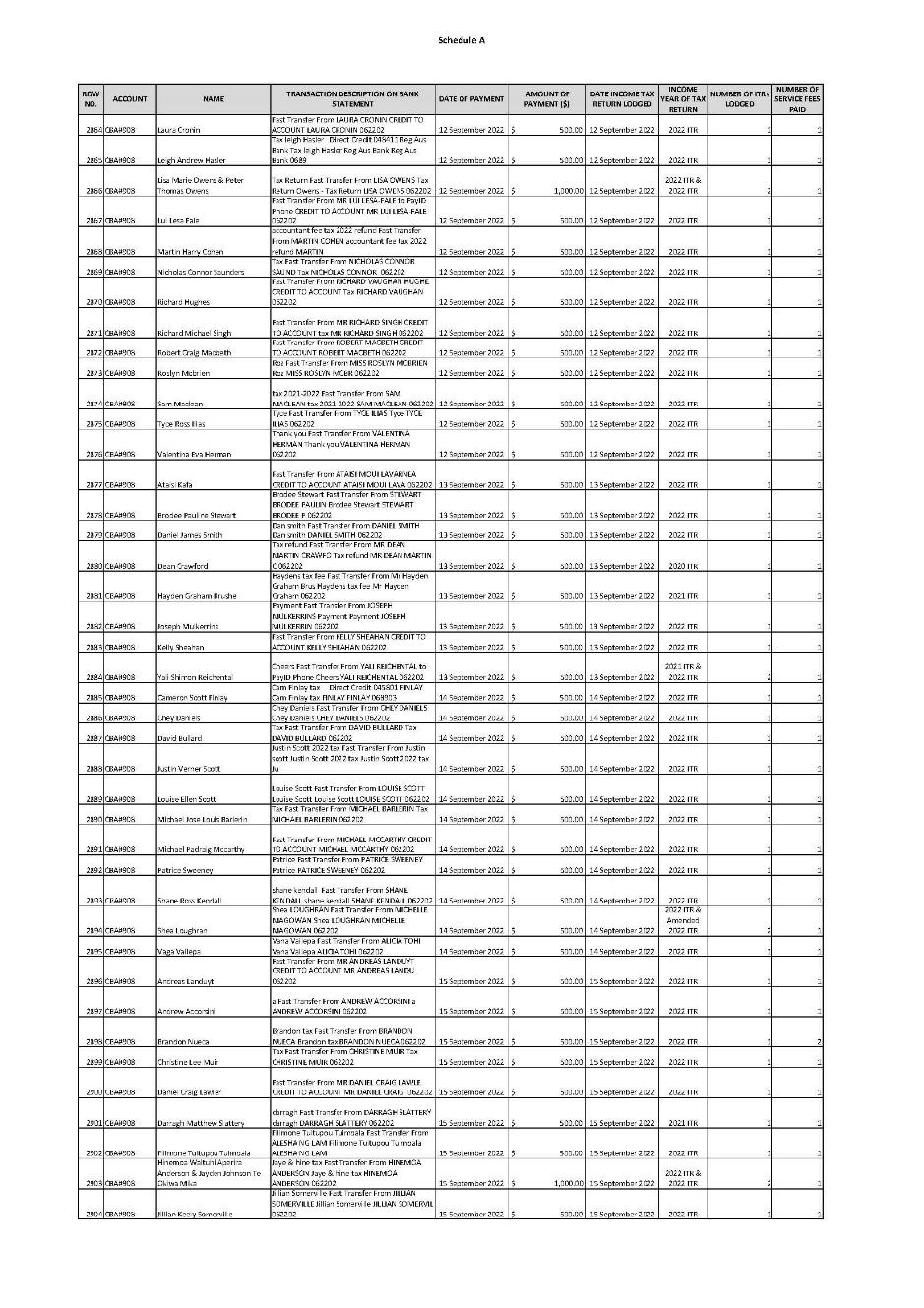

2 For the reasons below, I impose a penalty of $1,800,000. I make the declaration and grant the injunction in the terms sought.

Legislative scheme

3 The object of the TASA is to “ensure that tax agent services are provided to the community in accordance with appropriate standards of professional and ethical conduct”: s 2-5(1).

4 The Board is established by s 60-5 of the TASA. Its functions are set out in s 60-15 of the TASA, which includes administering the system of registration for registered tax agents and investigating conduct in breach of the TASA.

5 Part 5 of the TASA is headed “Civil Penalties”, and contains various prohibitions on conduct which if contravened, can lead to the imposition of civil penalties by a relevant court. Section 50-5 of the TASA is one such provision: the civil penalty for a contravention of that provision by an individual is 250 penalty units (currently $78,250). The Board may apply to this Court for an order that a person pay a pecuniary penalty to the Commonwealth, which order may be issued if the Court is satisfied that the person has contravened a “civil penalty provision”, which includes s 50-5: ss 50-35(1)-(2) of the TASA. On application of the Board, the Court may grant an injunction “restraining [a person] from engaging in the conduct” if satisfied that the person has engaged in conduct that would constitute a contravention of a civil penalty provision: s 70-5(1)(a).

6 The Court is to assess this on the civil standard of proof according to the rules of procedure and evidence applicable to civil proceedings: ss 298-80(b) and 298-85 of Schedule 1 of the Taxation Administration Act 1953 (Cth).

Evidence relied on

7 This matter proceeded by way of an agreed statement of facts, which is recited immediately below.

8 The respondent read an affidavit in his own name, affirmed 9 June 2024, and was cross-examined. I return to this below.

9 In addition, the respondent tendered exhibits, most relevantly, a statement of financial affairs dated 6 May 2024 which he was required to provide to his trustee in bankruptcy.

Facts

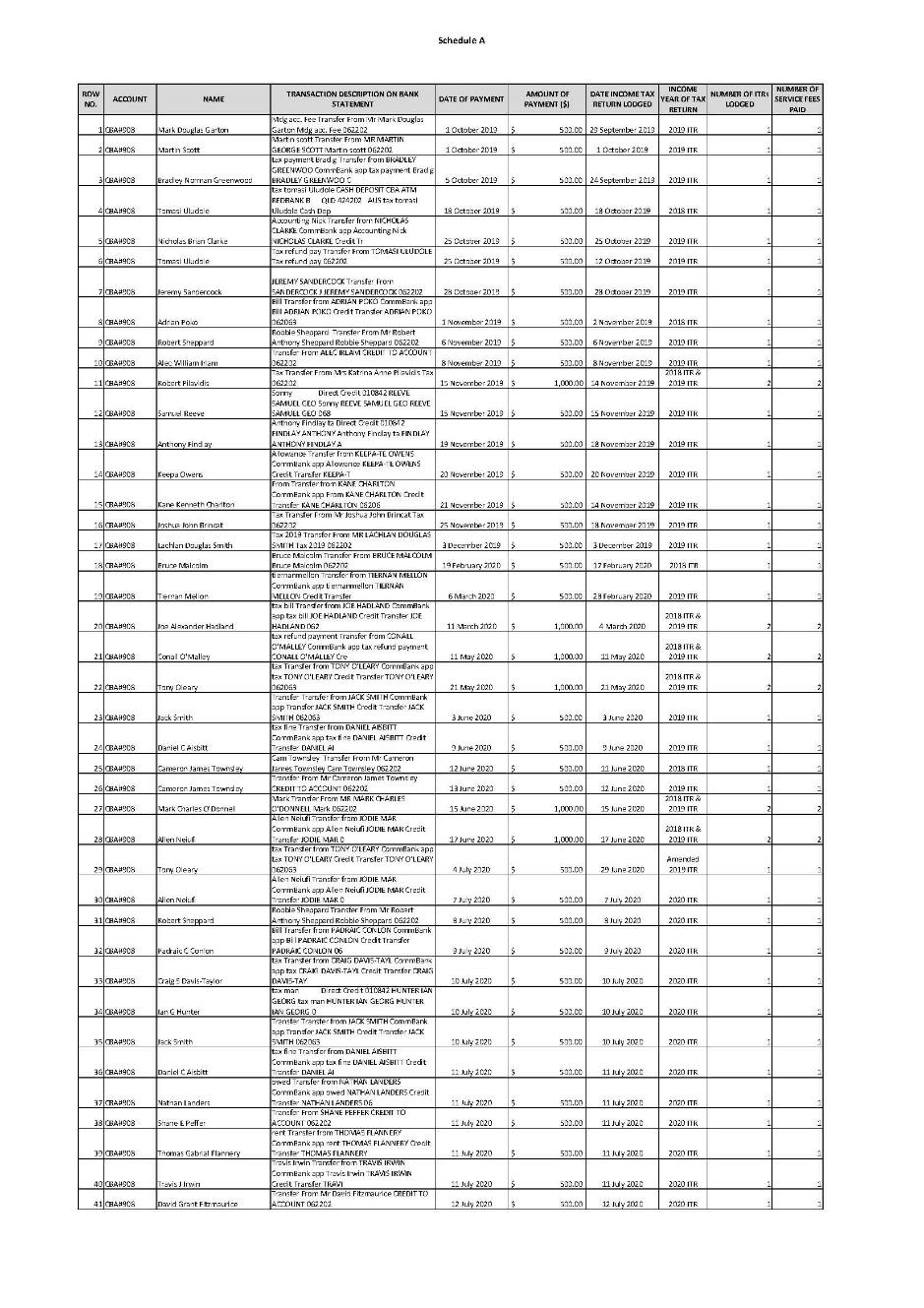

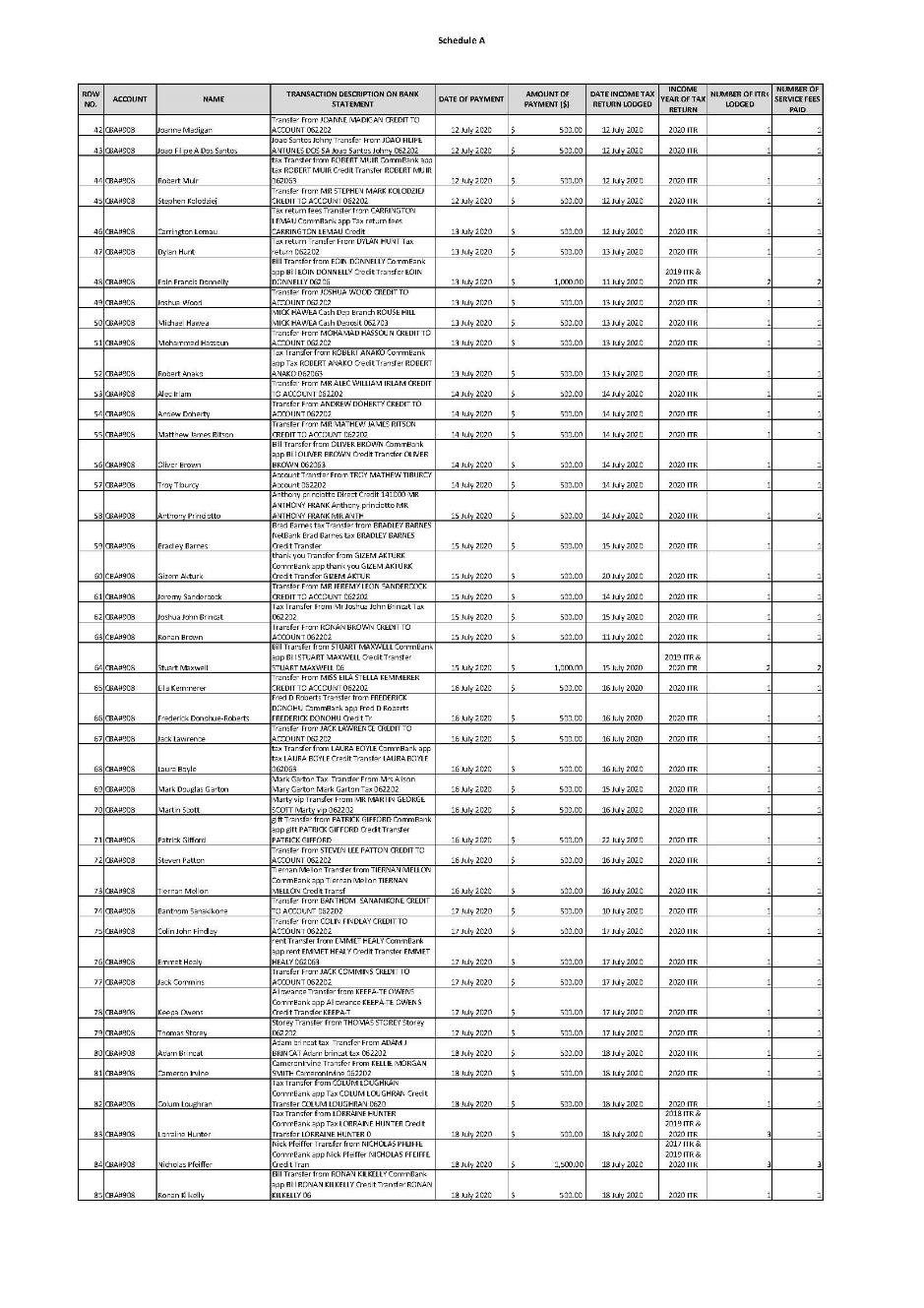

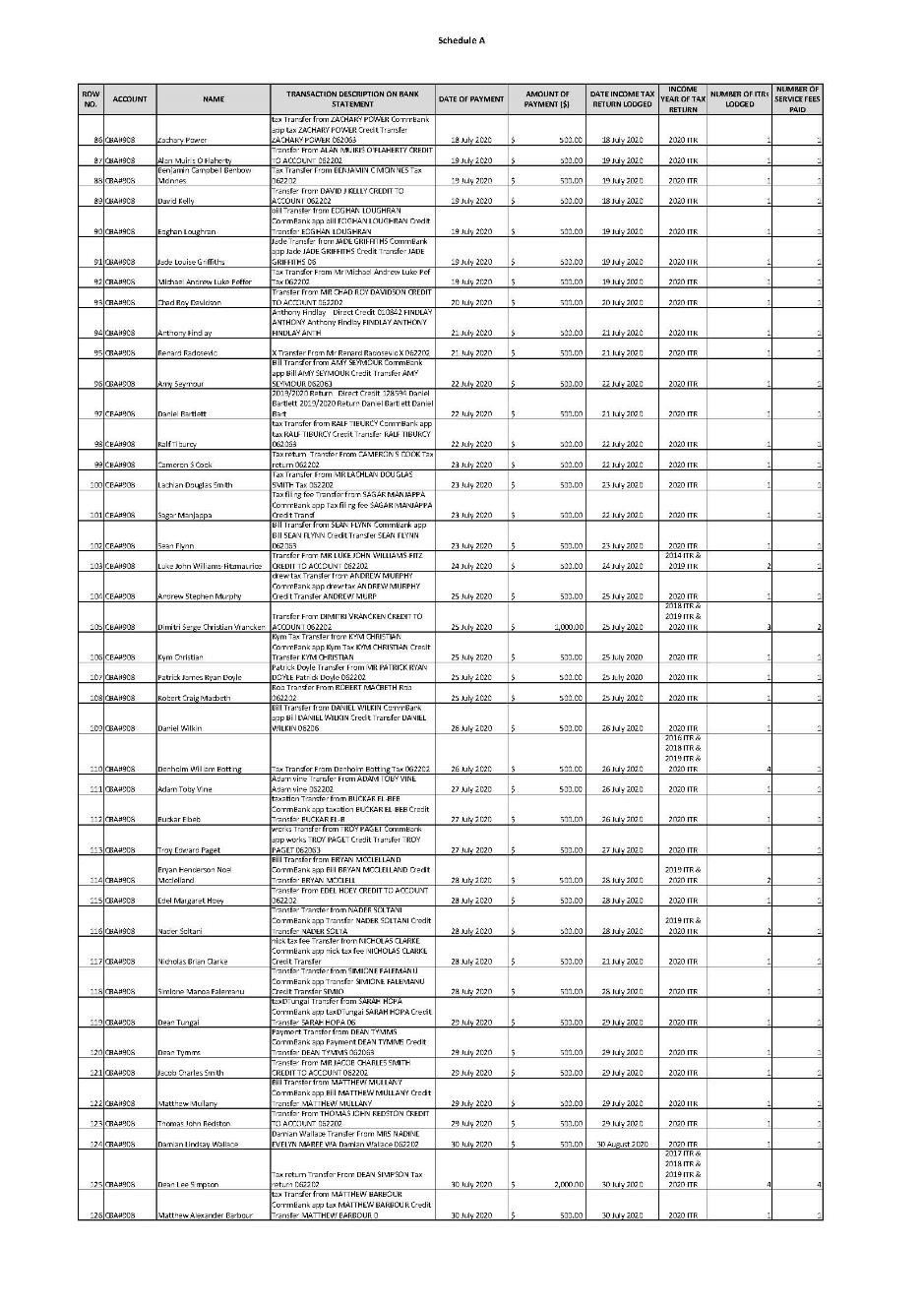

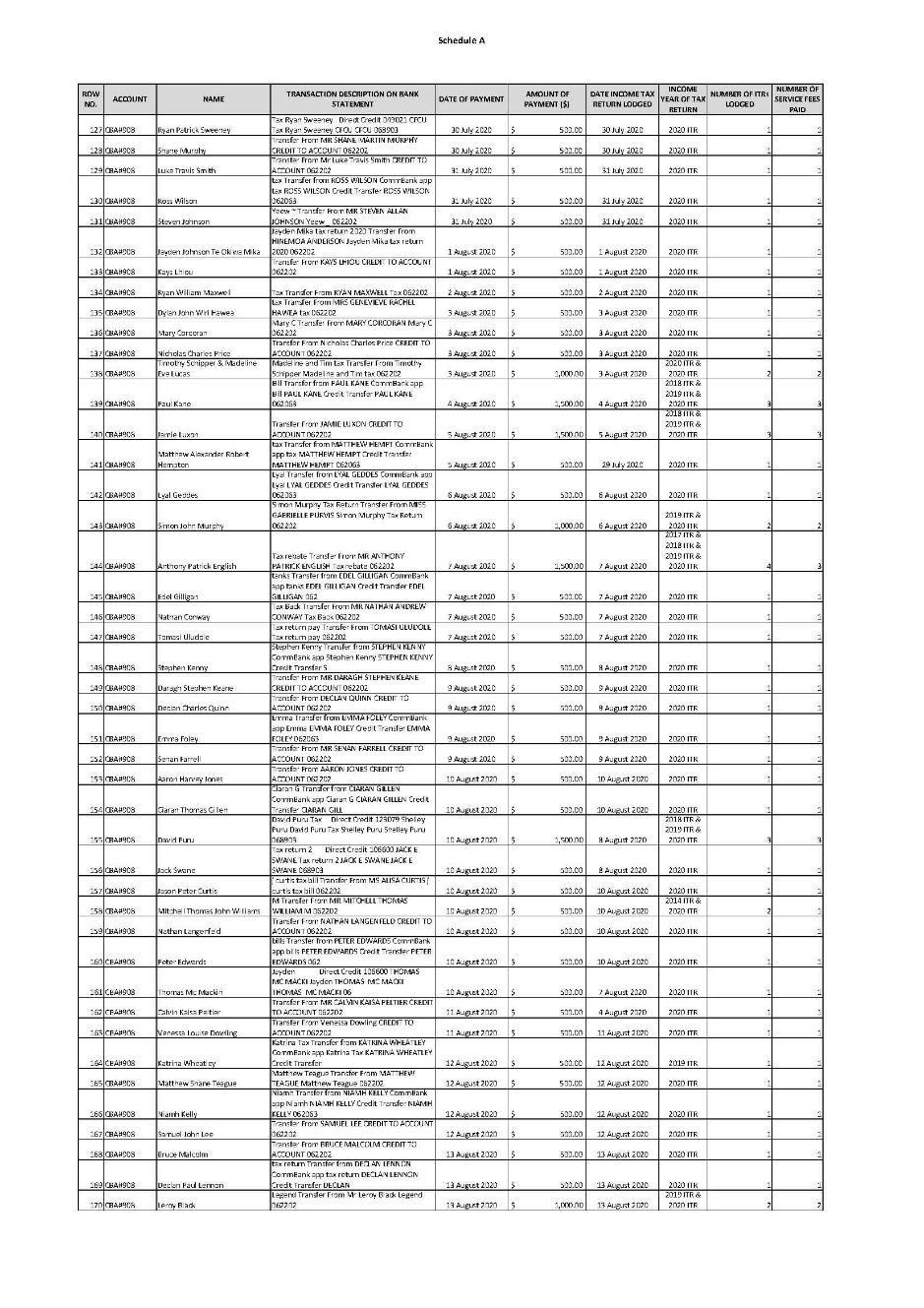

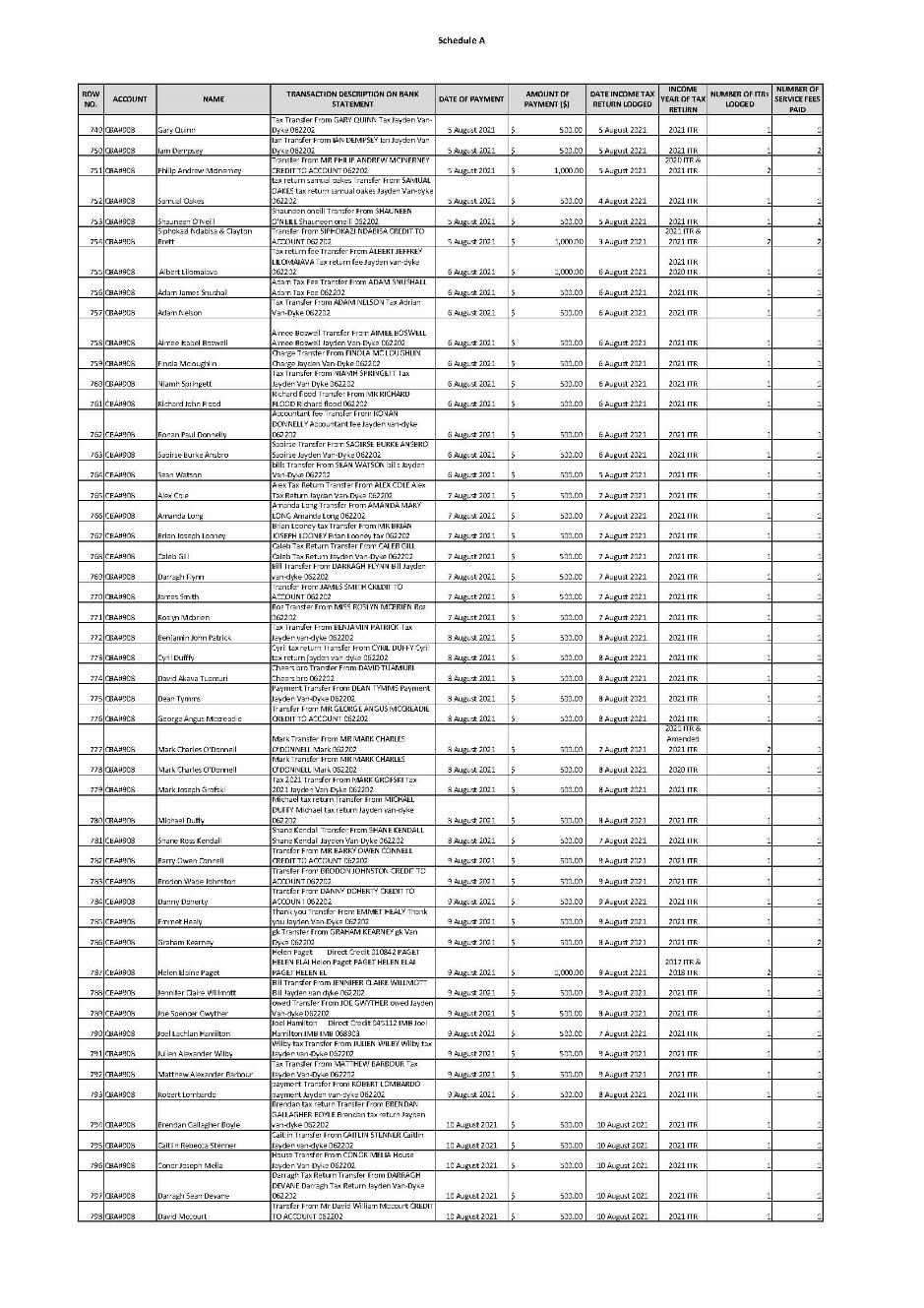

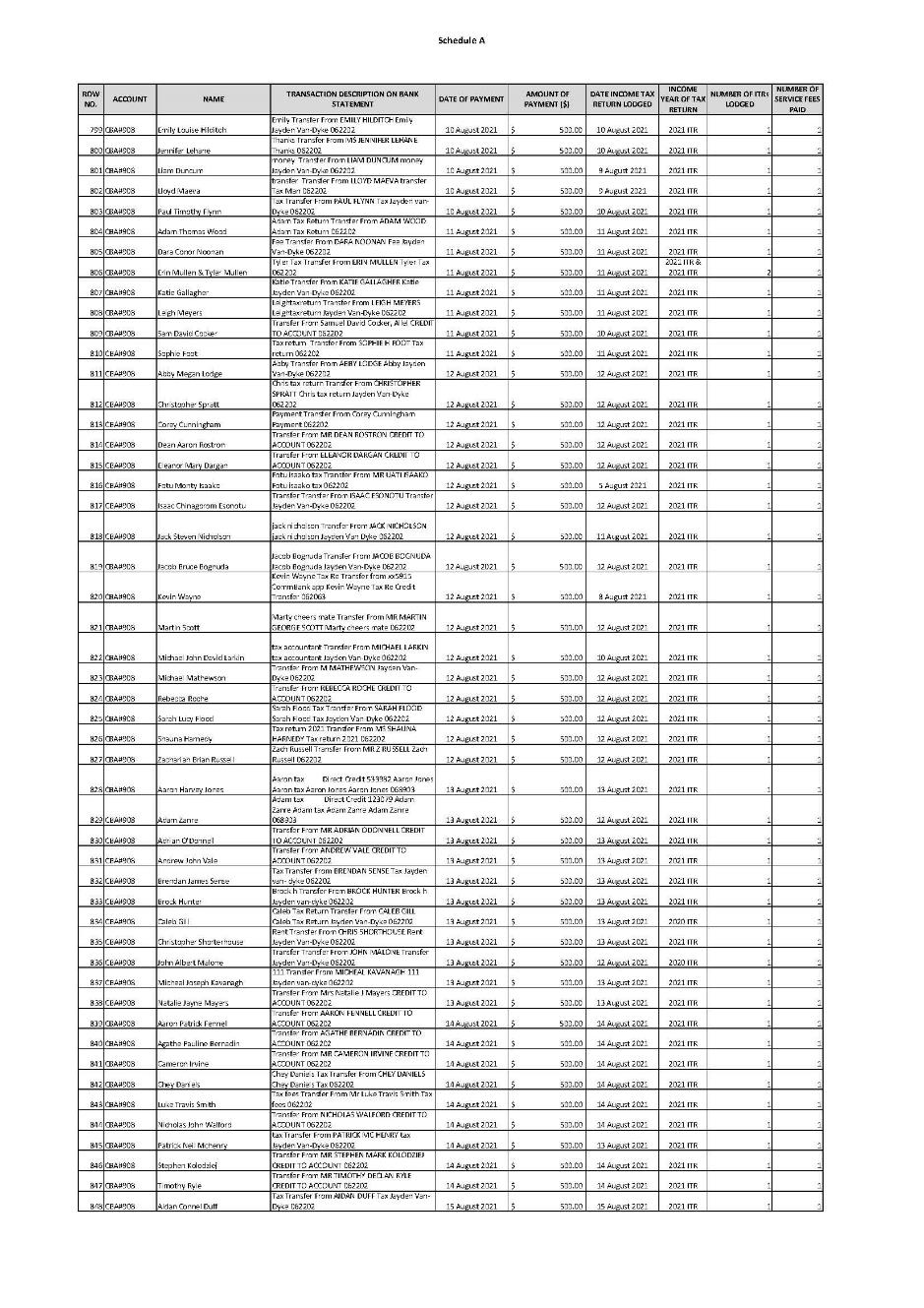

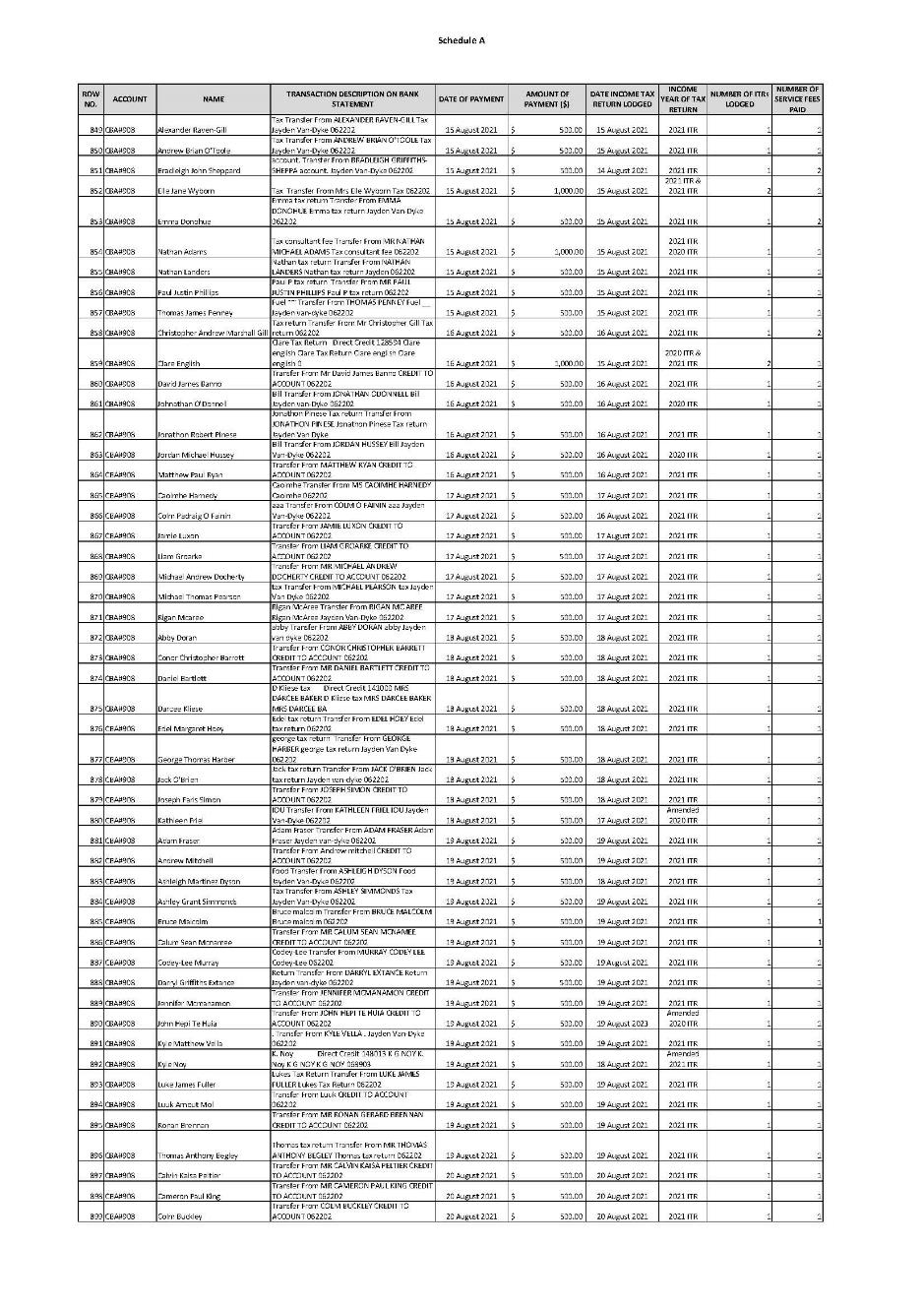

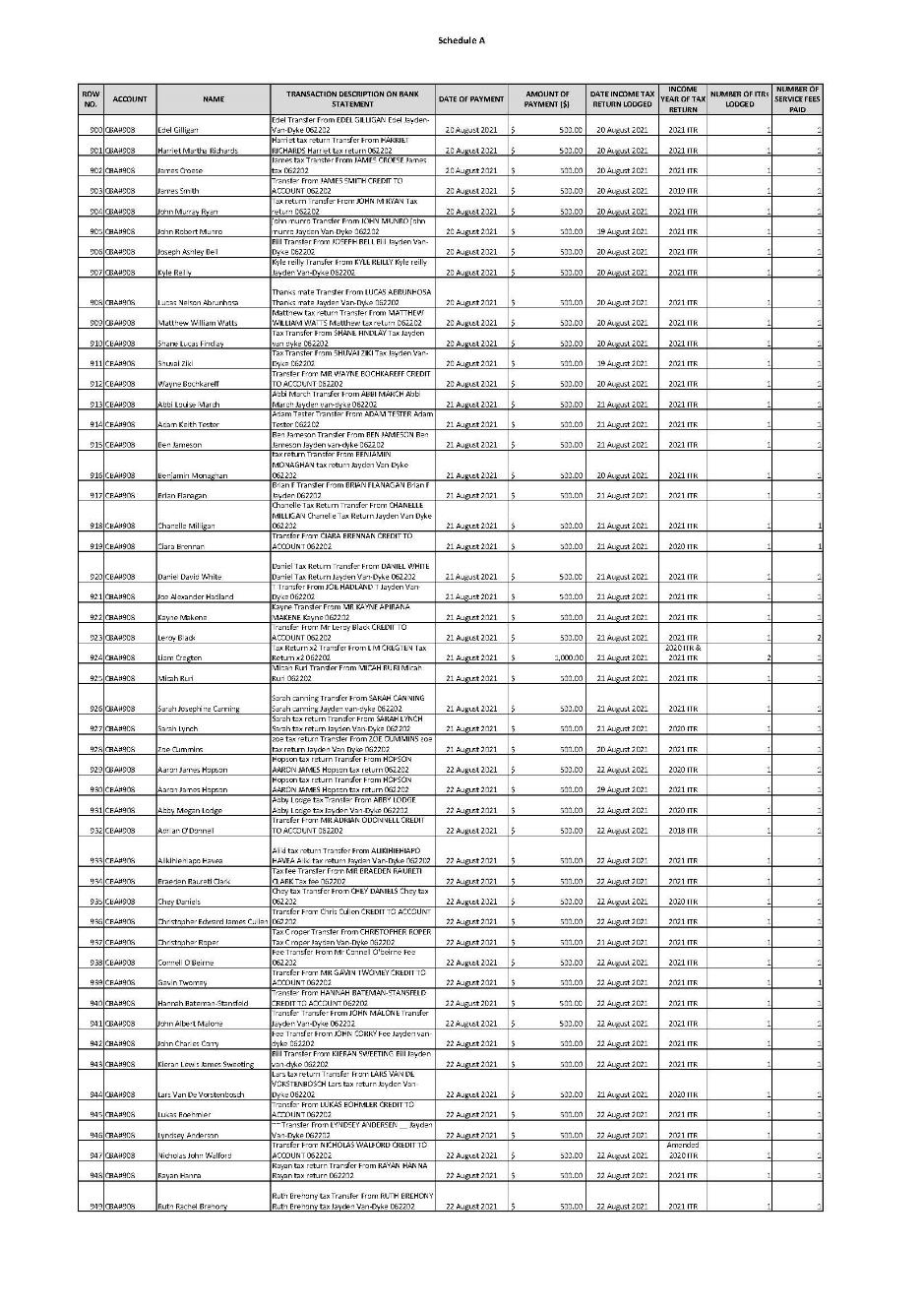

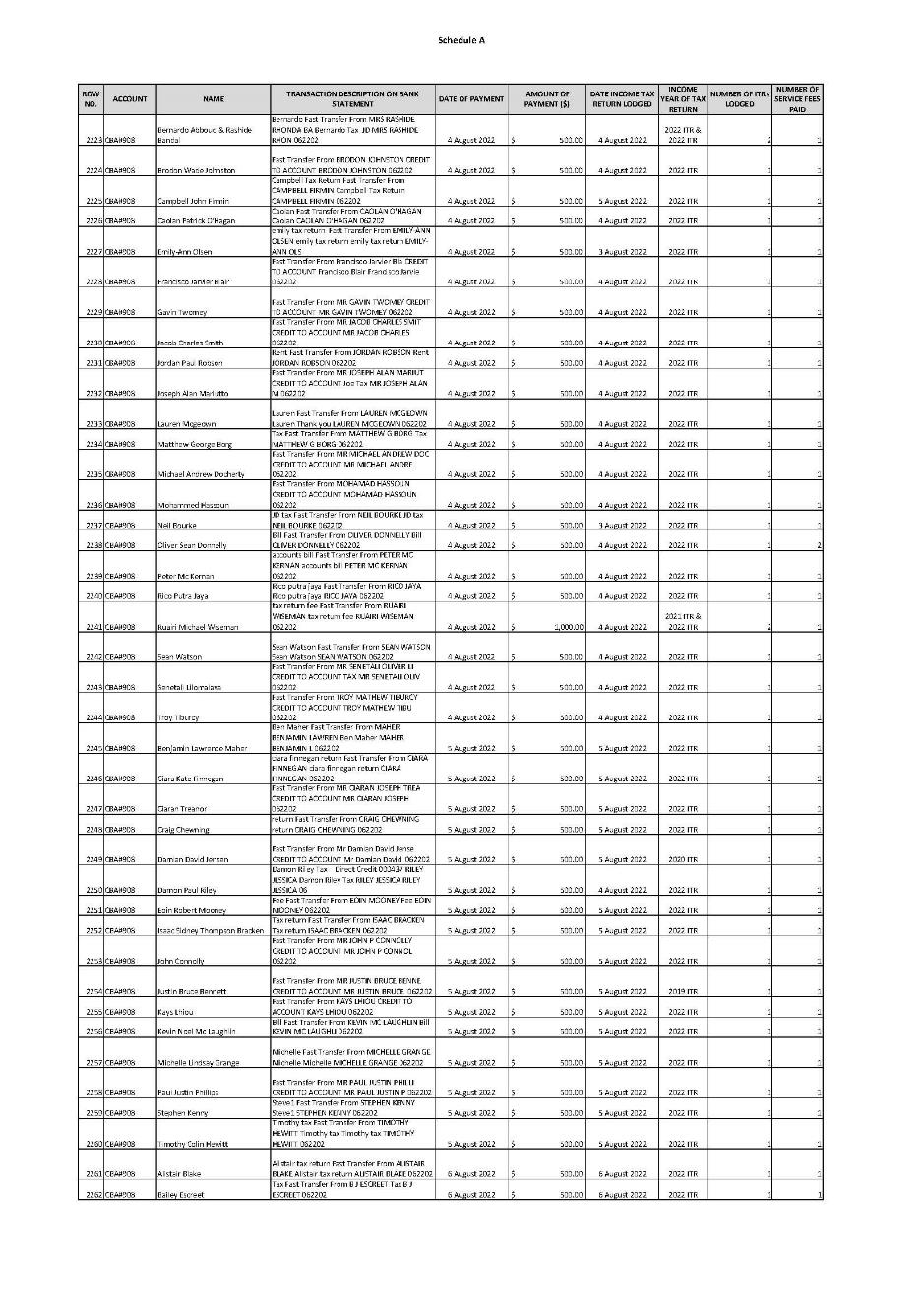

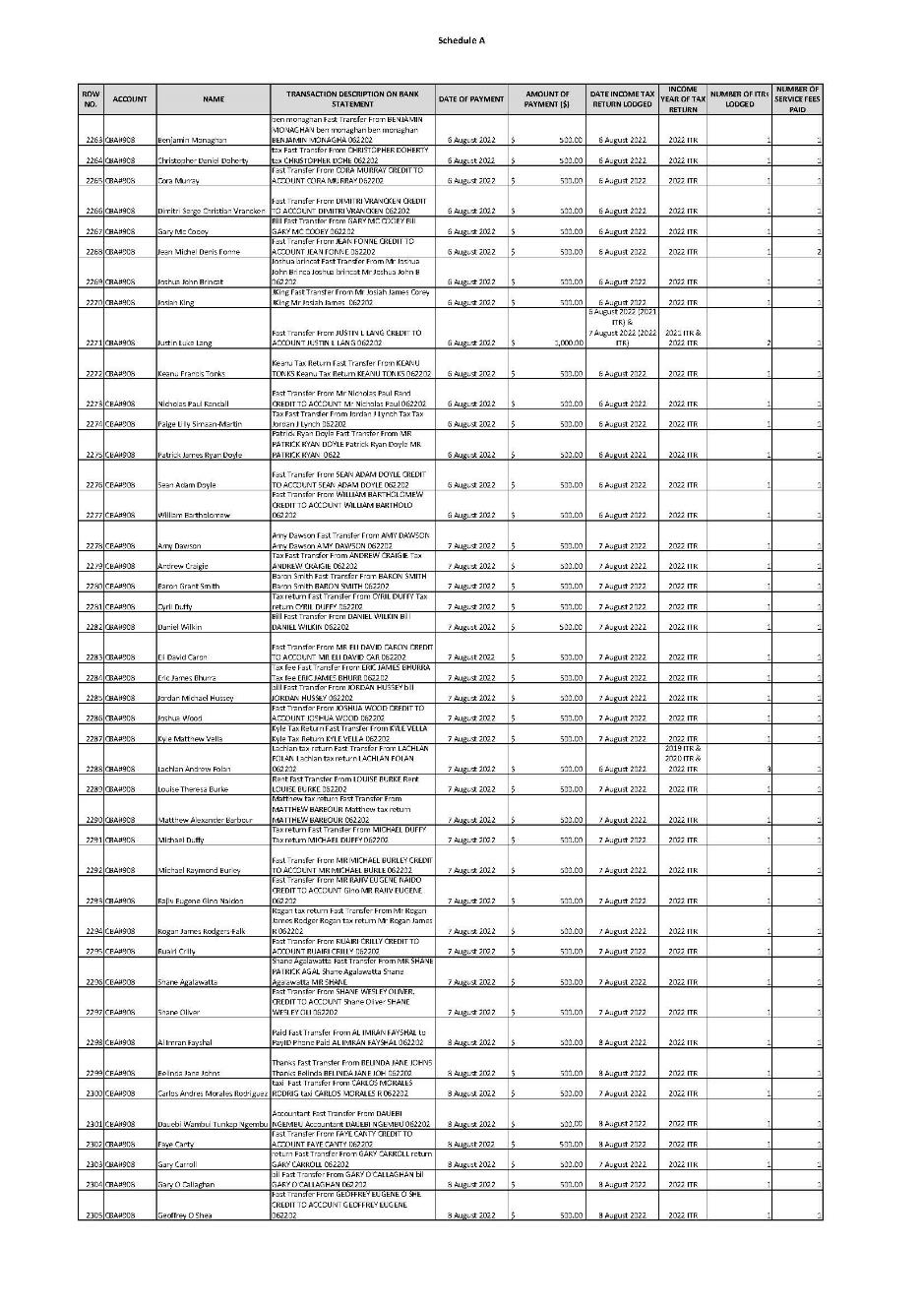

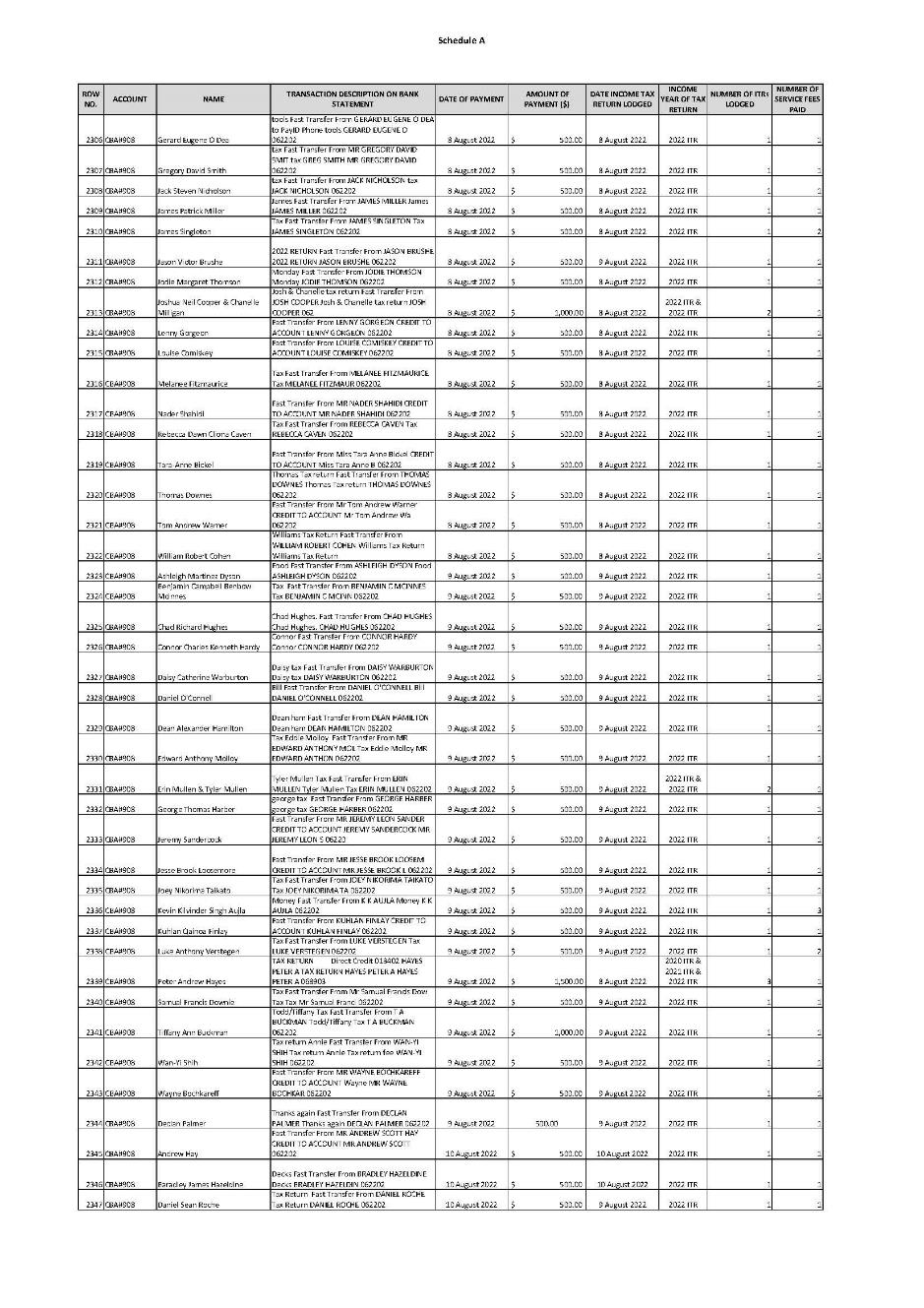

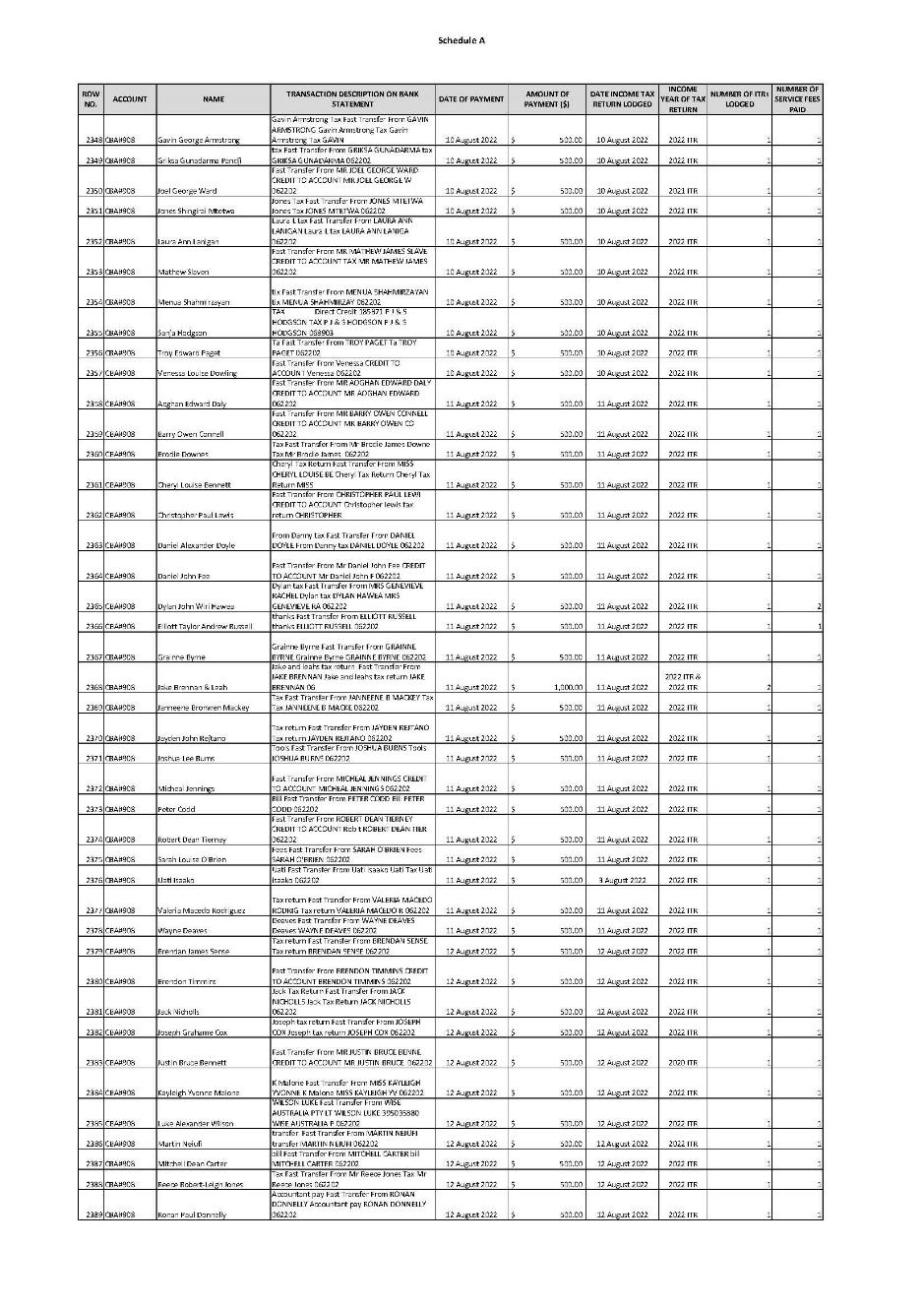

10 As referred to above Mr Van Dyke admits to 3,359 contraventions of s 50-5(1) of the TASA by preparing and lodging 3,359 income tax returns for taxpayers, for a fee or other reward, whilst not a registered tax agent within the meaning of that Act. The following recites the Amended Statement of Agreed Facts, with aspects redacted containing personal details.

11 Mr Van Dyke is not, and has never been, a registered tax agent with the Board within the meaning of the TASA.

12 Mr Van Dyke has never lodged an application with the Board for registration as a tax agent.

Communications between Mr Van Dyke and the Board prior to the filing of the proceedings

13 On or around 15 September 2022, the Board sent an email enclosing a cease-and-desist letter to Mr Van Dyke advising that:

The TPB is aware that you are engaging in conduct prohibited by the TASA, and is particularly concerned that:

1. you are charging or receiving a fee or other reward for providing tax agent or BAS agent (tax practitioner) services when you are not a registered tax practitioner and you are not working under the supervision and control of a registered tax practitioner:

a) assisting taxpayers with the preparation and lodgement of their income tax return/s.

b) assisting taxpayers with the preparation and lodgement of their BAS.

2. you are representing yourself as a registered tax practitioner when that representation is untrue.

…

What you must do to avoid legal action

You must immediately stop any conduct, including representing yourself as a registered tax practitioner referred to above. As you are providing tax practitioner services, you must also cease such activity whilst you remain unregistered.

We expect written confirmation of the above by 29 September 2022. Alternatively, you must provide reasons as to why you think your conduct is not a breach of the TASA. Failure to do so will lead to this matter being escalated for further action.

This may include the [Board] commencing Federal Court proceedings for injunctions and/or penalty orders against you. (Original emphasis.)

14 On or around 21 September 2022, Mr Van Dyke's legal representative emailed the Board confirming that:

1. Mr Van Dyke has received your correspondence dated 15 September 2022.

2. Mr Van Dyke understands the contents of the said correspondence, particularly the contention in relation to assisting taxpayers with preparation and lodgement of BAS and income tax returns.

3. Mr Van Dyke takes seriously the matters raised in the said correspondence.

Details of the respondent’s businesses

15 From 1 July 2014 (to least the date of the agreed facts) Mr Van Dyke had an active registered Australian Business Number (ABN) identified as 23 468 846 337.

16 From 9 June 2020 to 4 July 2023, Mr Van Dyke's registered business names associated with the ABN were:

(a) '24/7 TAX TO YOU'; and

(b) 'JVD ACCOUNTANTS'.

17 Mr Van Dyke communicated with taxpayers through a number of phone numbers or email addresses that he owned or controlled, including:

(a) XXXXXXXXX@hotmail.com; and

(b) +61 XXX XXX XXX / 04XX XXX XXX.

Providing tax agent services for fees while unregistered

18 Between about 29 September 2019 and 11 July 2023, Mr Van Dyke provided services at the request of individual taxpayers or other taxpayers who had some connection or association with the taxpayer for whom those services were provided (Related Taxpayer), in relation to the preparation and lodgement of original and amended income tax returns (Relevant ITR Services).

19 Each of the Relevant ITR Services that Mr Van Dyke provided consisted of Mr Van Dyke taking some or all of the following steps:

(a) requesting and/or receiving information from the taxpayer or Related Taxpayer;

(b) determining for the taxpayer or Related Taxpayer what their assessable income was and any deductions and offsets;

(c) inputting information in relation to the taxpayer or Related Taxpayer's assessable income and any deductions and offsets into an income tax return form;

(d) requesting and receiving the relevant taxpayers' MyGov login details from the taxpayer or Related Taxpayer; and

(e) causing the relevant income tax return form to be lodged with the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) by logging into the relevant taxpayers' MyGov account with the permission of the taxpayer or Related Taxpayer and lodging the income tax return form.

20 In respect of each of the Relevant ITR Services, Mr Van Dyke generally charged or received a monetary payment of $500 in consideration for providing each of the Relevant ITR Services (Fee). Where Mr Van Dyke performed more than one Relevant ITR Service for a taxpayer and/or a Related Taxpayer, he received a payment of a multiple of $500 in respect of the number of ITR Services provided.

21 Namely, in consideration for the ITR Services provided, the taxpayer or Related Taxpayer made payment to Mr Van Dyke by transferring the Fee to a bank account in the name or control of Mr Van Dyke, including:

(a) St George Account with a Bank, State and Branch (BSB) and account number of 112-879 XXXXXXX179 (#179 Bank Account); and

(b) Commonwealth Bank of Australia Account with a BSB and account number of 062-202 XXXXX908 (#908 Bank Account).

22 Between about 29 September 2019 and 11 July 2023, Mr Van Dyke provided a total of 3,359 Relevant ITR Services on approximately 3,131 occasions for a total consideration of $1,658,000 as set out in Schedule A to this Amended Statement of Agreed Facts, annexed hereto.

23 On 14 October 2022, the #908 Bank Account was disabled.

24 At all material times, Mr Van Dyke knew that individuals and other entities who intended to lawfully provide a 'tax agent service' within the meaning of the TASA for a fee or other reward were required to be registered as a tax agent with the Board.

25 At all material times, Mr Van Dyke was aware he was not a registered tax agent pursuant to the TASA.

Representations about tax agent services

26 Mr Van Dyke held himself out to be a registered tax agent to taxpayers that he provided the Relevant ITR Services to, as well as to a broader audience. For example, on 29 June 2022, the following text message exchange occurred with a person who subsequently made an anonymous complaint to the Board about Mr Van Dyke:

Complainant: Hey Jayden, Are you still doing tax?

…

Mr Van Dyke: Yes I am

Complainant: Ok. Do you have a business name?

Mr Van Dyke: All online over messages and a phone call.

Over 2000 clients never advertised.

…

Complainant: Are you a registered accountant? I had an accountant in the past, they never asked for my mygov log on details ...

Mr Van Dyke: Offcourse [sic] I am and yes I do have a business name and yes my office is in Sydney.

…

Mr Van Dyke: 22 years tax agent.

Mr Van Dyke’s income tax returns

27 On 19 January 2023, Mr Van Dyke lodged his income tax return for the 2019 income year. He listed his main occupation as a Radio Traffic Controller and his payer as Traffic Logistics Pty Limited (ABN 70 123 127 337). Mr Van Dyke also declared income from another employer K&D Traffic Management (ABN 43 123 149 539). He also reported $482 of gross interest.

28 On 19 January 2023, Mr Van Dyke lodged his income tax return for the 2020 income year. His main occupation was listed as Radio Traffic Controller and his employer was listed as Lack Group Traffic Pty Ltd (ABN 64 628 562 505). Mr Van Dyke also reported income from K & D Traffic Management Pty Ltd. He also reported $106 of gross interest.

29 On 26 November 2021, Mr Van Dyke lodged an income tax return for the 2021 income year. Mr Van Dyke's occupation was listed as Radio Traffic Controller and his employer was listed as Lack Group Traffic Pty Ltd. Mr Van Dyke also reported assessable income from Services Australia trading as Centrelink as "Dad And Partner Pay" (ABN 29 468 422 437). He also reported $48 of gross interest.

30 On 19 January 2023, Mr Van Dyke lodged his income tax return for the 2022 income year. He reported income from Australian Government Allowances and $40 of gross interest. No other income was reported.

31 For the 2019, 2020, 2021 and 2022 income years, Mr Van Dyke:

(a) declared in his income tax returns that his taxable income was as set out in Column 2 the table below (at [34]); and

(b) did not declare any income for his activities related to the preparation and lodgement of income tax returns.

Audit findings of Mr Van Dyke

32 Between 9 February 2023 and 21 June 2023, the ATO performed an audit of Mr Van Dyke's income tax returns for the financial years ended 30 June 2019, 30 June 2020, 30 June 2021 and 30 June 2022.

33 Following the audit, Mr Van Dyke's taxable income was adjusted by way of Amended Assessment on the basis of undeclared income for Mr Van Dyke's activities related to the preparation and lodgement of income tax returns as set out in Column 3 below.

34 For the 2019, 2020, 2021 and 2022 income years, Mr Van Dyke had a total tax shortfall amount of $1,326,974.59 as set out in Column 4 below.

Column 1: Income year | Column 2: Pre-audit taxable income | Column 3: Post-audit taxable income | Column 4: Tax shortfall |

2019 | $115,223 | $330,374 | $106,417.39 |

2020 | $127,650 | $399,264 | $127,863.90 |

2021 | $31,731 | $1,199,646 | $531,753.00 |

2022 | $6,210 | $1,255,956 | $560,940.30 |

Total | $280,814 | $3185,240 | $1,326,974.59 |

35 On 21 June 2023, total administrative penalties in the amount of $785,542.90 were imposed for the 2019, 2020, 2021 and 2022, income years on the basis of determinations by the ATO that Mr Van Dyke made statements which he knew to be false or misleading because he incorrectly stated his taxable income.

Legal principles

36 The primary purpose of any civil penalty regime is to ensure compliance with the statutory regime by deterring future contraventions: Commonwealth of Australia v Director, Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate [2015] HCA 46; (2015) 258 CLR 482 (Agreed Penalties Case (HC)) at [24]. The principal object of an order is deterrence: specific deterrence of the contravener and, by his or her example, general deterrence of other would-be contraveners: Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union [2018] HCA 3; (2018) 262 CLR 157 at [116]. Civil pecuniary penalties are “primarily if not wholly protective in promoting the public interest in compliance [with the statute]”: Agreed Penalties Case (HC) at [55] and see also [59] and [110]. This point was emphasised more recently in Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Pattinson [2022] HCA 13; (2022) 274 CLR 450 (Pattinson) at [15]-[16], [43], and [45].

37 That process involves an intuitive or instinctive synthesis of the relevant factors: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Coles Supermarkets Australia Pty Ltd [2015] FCA 330; (2015) 327 ALR 540 at [6]; TPG Internet Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2012] FCAFC 190; (2012) 210 FCR 277 at [145]. That is the method by which the judge identifies all the factors that are relevant to the penalty and, after weighing all of those factors, reaches a conclusion that a particular penalty is the one that should be imposed: Markarian v The Queen [2005] HCA 25; (2005) 228 CLR 357 (Markarian) at [37]: and see Viagogo AG v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2022] FCAFC 87 (Viagogo) at [129]-[133], [148]-[151].

38 The assessment of penalty of appropriate deterrent value will have regard to a number of factors including, relevantly given the contraventions: (1) the nature and extent of the contravening conduct; (2) the amount of loss or damage caused; (3) the circumstances in which the conduct took place; (4) the deliberateness of the contravention and the period over which it extended; and (5) whether there has been a willingness to cooperate with the authorities responsible for the enforcement of the relevant Act in relation to contravention: Pattinson at [18]. These are not a rigid list of factors to be ticked off: Pattinson at [19], and are not exhaustive, but rather are to inform a multifactorial consideration that leads to a result arrived at by a process of “instinctive synthesis” addressing the relevant considerations: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Reckitt Benckiser (Australia) Pty Ltd [2016] FCAFC 181; (2016) 340 ALR 25 (Reckitt Benckiser) at [44].

39 The circumstances of both the contravention and the contravenor are relevant to the assessment.

40 An issue in this case is the relevance of the respondent’s financial circumstances. The applicant referred to Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v High Adventure Pty Ltd [2005] FCAFC 247 at [11]:

Moreover, as deterrence (especially general deterrence) is the primary purpose lying behind the penalty regime, there inevitably will be cases where the penalty that must be imposed will be higher, perhaps even considerably higher, than the penalty that would otherwise be imposed on a particular offender if one were to have regard only to the circumstances of that offender. In some cases the penalty may be so high that the offender will become insolvent. That possibility must not prevent the Court from doing its duty for otherwise the important object of general deterrence will be undermined.

41 That passage has repeatedly been referred to and applied: see for example, Viagogo at [167]; Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Select AFSL Pty Ltd (No 3) [2023] FCA 723 at [120]; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Dimmeys Stores Pty Ltd [2011] FCA 372 at [54]; Tax Practitioners Board v Ordiales [2022] FCA 1612 (Ordiales) at [29].

42 However, in Tax Practitioners Board v Caolboy [2020] FCA 1559 (Caolboy) at [50], Wheelahan J observed:

The position is different in relation to natural persons. The burden of a liability to pay a civil penalty may be inescapable. This has a human element to it, because the liability of an individual to pay a civil penalty that has no real prospect of being discharged may be crushing: cf, Tax Practitioners Board v Su [2014] FCA 731 at [25] (Jagot J); Tax Practitioners Board v Dedic [2014] FCA 511; 98 ATR 373 at [8] (Davies J). Thus, the deterrent quality of a penalty is to be balanced against the consideration that it should not be so high as to be oppressive, and that if deterrence is the object, the penalty should not be greater than what is required to achieve that object: NW Frozen Foods Pty Ltd v Australian Competition & Consumer Commission (1996) 71 FCR 285 at 293 (Burchett and Kiefel JJ), cited in Pattinson v Australian Building and Construction Commissioner at [100] and [102] (Allsop CJ, White and Wigney JJ, Besanko and Bromwich JJ at [226] agreeing).

43 There is some merit in that observation. The penalty should be proportionate, in the sense of setting a reasonable balance between deterrence and oppressive severity: Pattinson at [41], approving Reckitt Benckiser at [152]; Tax Practitioners Board v Van Stroe (No 2) [2023] FCA 1533 (Van Stroe (No 2)) at [24].

44 Regard is also had to the maximum penalty. In this respect, in Markarian, the majority observed at [31] that attention to maximum penalties will almost always be required because the legislature has legislated for them; they invite comparison between the worst possible case and the case before the court at the time; and because they do provide, taken and balanced with all of the other relevant factors, a yardstick: and see Reckitt Benckiser at [155]-[156], and Pattinson at [53].

45 I note that there is no dispute that the total maximum penalties available in this case amount to $186,823,000.

46 It is recognised that, ordinarily, separate contraventions arising from separate acts should attract separate penalties. However, where separate acts give rise to separate contraventions that are inextricably interrelated, they may be regarded as a “course of conduct” for penalty purposes: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Yazaki Corporation [2018] FCAFC 73; (2018) 262 FCR 243 (Yazaki) at [234]. This avoids double punishment for those parts of the legally distinct contraventions that involve overlap in wrongdoing: see, for example, Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union v Cahill [2010] FCAFC 39; (2010) 269 ALR 1 (Cahill) at [39] and [41]. Whether the contraventions should be treated as a single course of conduct is fact specific having regard to all the circumstances of the case: see also Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Employsure Pty Ltd [2023] FCAFC 5; (2023) 407 ALR 302 (Employsure) at [51]. However, the use of the principle does not convert the maximum penalty for one contravention into the maximum penalty for the course of conduct as a whole: Reckitt Benckiser at [141]; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Employsure Pty Ltd (No 2) [2021] FCA 1488 at [79].

47 That course of conduct concept is separate from the principle of totality which requires the Court to make a “final check” of the penalties to be imposed on a wrongdoer, considered as a whole, to ensure that the total penalty does not exceed what is proper for the entire contravening conduct: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Australian Safeway Stores Pty Ltd [1997] FCA 450; (1997) 145 ALR 36 at 53, citing Mill v The Queen [1988] HCA 70; (1988) 166 CLR 59; Employsure at [52].

48 It will be necessary to return to these principles below.

Consideration

49 Given the purpose behind requiring registration of a tax agent, even a brief recitation of the respondent’s conduct reflects its seriousness.

50 Mr Van Dyke’s conduct involved 3,359 contraventions of s 50-5(1) of TASA by preparing and lodging 3,359 tax returns for taxpayers, for a fee, while not registered as a tax agent. As acknowledged by the parties, taking this number at face value, this case represents the largest number of contraventions against s 50-5(1) of the TASA for which the Board has commenced proceedings. This conduct, which was deliberate, and undertaken for financial gain, occurred over nearly four years. It was a business conducted by Mr Van Dyke, from which he obtained a significant financial gain, being $1,658,000.

51 Mr Van Dyke held himself out as a registered tax agent, knowing of the requirement for registration. The contraventions occurred in knowing defiance of the law. In doing so, he exposed many taxpayers to a scenario whereby tax agent services were being provided without the protections offered by a person who is registered under the TASA and subject to regulation by the Board.

52 Despite Mr Van Dyke receiving from the Board a cease-and-desist letter (dated 15 September 2022), he continued to engage in the conduct for many months thereafter. This was in the face of the respondent acknowledging to the Board on 21 September 2022 that he understood the contents of the correspondence and took the matters raised “seriously”.

53 Mr Van Dyke concealed the income that he earned from the conduct from the ATO by not disclosing it.

54 The serious nature of the respondent’s conduct is self-evident.

55 That said, I do not agree with the applicant’s characterisation that the respondent’s activities were “sophisticated”. Although it can readily be accepted that the respondent conducted a business, there was no sophistication to it. In that regard, I accept the respondent’s submission. However, therein lies the problem. The fact that this conduct can so easily be undertaken, and on a large scale, generating significant financial reward, starkly highlights the importance of deterrence.

56 Moreover, the respondent’s submission that his clients had not been deprived of the opportunity to choose a tax agent who was subject to regulation by the Board because the clients approached him, entirely misses the point. Those clients approached him in circumstances where the respondent held himself out to be a tax agent. In doing so, he provided services to many taxpayers without the protections offered by a person registered under the TASA.

57 The respondent, while accepting the serious nature of the conduct, submitted it occurred at the time when he was gambling heavily. He gave evidence that he became addicted to gambling at a young age, which had a significant impact on his mental health, personal life, and family.

58 In many respects, the respondent’s evidence in cross-examination was unsatisfactory. He sought to minimise his conduct, giving explanations which downplayed the circumstances in which he committed the contraventions. The respondent’s counsel sought to advance this as a positive attribute, being evidence that Mr Van Dyke appreciates the seriousness of the position he is in. I do not accept that submission. The answers reflected the respondent’s willingness to minimise the serious of his conduct, which in turn impacts on the issue of specific deterrence.

59 The respondent submitted that although his conduct continued beyond the receipt of the cease-and-desist letter, within a short period following its receipt, the conduct sharply decreased. He submitted that therefore the letter did in fact have a significant deterrent effect. I note that there were a further 159 contraventions after Mr Van Dyke’s legal representatives emailed the Board confirming receipt of the letter on 21 September 2022. Indeed, the period from 21 September 2022 until 1 January 2023 the contraventions continued relatively unabated. It was thereafter, that the frequency and volume of contraventions appeared to lessen. That said, the conduct continued until 11 July 2023, as later confirmed by the parties. The fact of any contraventions after the cease-and-desist letter aggravates the wrongdoing, although it would have been more so if there had been no change in conduct.

60 The respondent submitted that he has sought assistance for his gambling and mental health issues during moments of significant crisis and has done so more recently with some apparent degree of success. During this time, he experienced significant changes in his career and profession and recently obtained more stable employment. The respondent is currently employed as an accountant. It was submitted that the respondent apologised and gave an undertaking not to undertake such conduct again, which has been in effect for almost 12 months (without breach).

61 The respondent submitted that it is open for the Court to find that his own more recent steps to address his mental health and gambling addiction have also had a positive impact on reducing the likelihood of any further contraventions. Although the respondent’s own evidence referred to these matters, no medical evidence was provided in support. There is no evidence of any link with gambling, although there is some evidence he gambled (he had a TAB membership gold status). Mr Van Dyke’s affidavit dated 9 June 2024 did not depose to having ceased gambling, but rather to have “almost completely ceased gambling”. Despite that, in cross-examination he gave evidence that he did not gamble in June 2024. Although the respondent’s counsel submitted that his affidavit was ambiguous on this point and it was cleared up in cross-examination, I do not accept that submission. There is no ambiguity in the affidavit. Rather, given the importance of the issue, one can assume the words were carefully chosen. In cross-examination, he gave evidence inconsistent with that. I note also that the respondent’s evidence was that he had several sessions with a clinical psychologist in relation to gambling during the period between June 2023 and September 2023, and completed three sessions of financial counselling, but stopped them last year before commencing his current employment. His evidence was that he had ceased gambling and did not need counselling. That approach is problematic in relation to an addiction, which on his case, has caused this offending. I note that Mr Van Dyke said he had some mental health issues for which he obtained assistance, but again, there is no evidence of any counselling for those issues. Nor is there any evidence in support of his assertion that his efforts in that regard are ongoing.

62 The respondent was declared bankrupt on 16 April 2024. In this regard, it is noted that any penalties imposed would not be provable in the respondent’s bankruptcy (see Bankruptcy Act 1966 (Cth), ss 82(3) and 153(1)).

63 The respondent submitted that the Court should tread with caution when considering the submission by the Board that he actively took steps to conceal the income he earned from this conduct, as a factor in assessing the appropriate penalty. He submitted this is because administrative penalties have already been levied in respect of the respondent’s non-reporting of his income. It was further submitted that to consider such a matter in fixing the penalties in these proceedings at an amount higher than might otherwise be determined, would extend beyond consideration of the principles of deterrence, and amount to a form of dual sanction given the administrative penalties already imposed. That submission is misconceived. That the respondent concealed his income from the ATO is not an aggravating aspect of the contravening conduct, but rather a matter of fact (among others) as to the circumstances of the contravening. It reflects the respondent’s knowledge that he was not permitted to undertake the conduct.

64 The respondent also submitted that the existence of the administrative penalties is relevant in assessing the level of deterrence required in the present case, given the deterrent effect of the administrative penalties already levied, referring to Tax Practitioners Board v Hacker (No 3) [2020] FCA 1814 (Hacker (No 3)) at [67] – [75]. He submitted that it might be a form of double punishment. As the Board correctly submitted, the administrative penalties relate to different conduct (failure to declare income in income tax returns). Hacker (No 3) does not support the respondent’s submission. That said, I am mindful that Mr Van Dyke has been required to pay over $2 million dollars in unpaid taxes (relating to income obtained from these contraventions) and administrative penalty.

65 The respondent submitted that his conduct falls within the description of a course of conduct, relying on Caolboy at [64]-[65], also referring to Ordiales at [30]-[31], Tax Practitioners Board v Williams [2023] FCA 63 (Williams) at [78]-[79], and Van Stroe (No 2) at [29].

66 It is important to recall that the rationale for the course of conduct principle is that it avoids double punishment for those parts of the legally distinct contraventions that involve overlap in wrongdoing: Employsure at [81]; Cahill at [39]; Yazaki at [234]. Each case turns on its facts. It is important to address the basis on which it is said there is an overlap.

67 Although the respondent was conducting a business, the conduct the subject of the contraventions involves, with limited exception, the preparation and lodgement of separate tax returns, on separate dates to separate clients for separate fees. The limited exception are 228 contraventions, which the applicant submitted could be grouped together as 178 courses of conduct on the basis that on some occasions, the respondent prepared and lodged tax returns for taxpayers and their spouses at the same time; or prepared and lodged tax returns for taxpayers for multiple years at the same time and received a single payment in return for those multiple services. However, although a single payment was received, it was generally for a greater amount which in most cases reflected a multiple of $500 for each tax return lodged. That said, the filing of the tax returns in relation to each of those circumstances is arguably a separate contravention. The remaining 3,131 contraventions fit the description above, being the preparation and lodgement of separate tax returns, on separate dates for separate clients, for separate fees.

68 Different approaches have been taken to multiple contraventions of the TASA. For example, in Ordiales, Van Stroe (No 2) and Williams, the conduct was referred to as an ongoing course of conduct, while in Hacker (No 3), that submission was rejected. In Van Stroe (No 2) and Williams, the Courts imposed a single penalty, as opposed to specifying a penalty per contravention and then considering the totality principle. The respondent submitted in this case, even if I concluded that it was a course of conduct, the individual contraventions needed to be considered.

69 The respondent primarily submitted that the factual overlap between the contraventions is (if the Court accepted the applicant’s submission), that the conduct was part of a sophisticated business. As explained above, I do not accept the descriptor of sophistication. That a person engaged in the conduct regularly such that it could be described as a business, does not necessarily alter that characterisation into one of sophistication. That said, in this case, the applicant submitted that the fact that the contraventions were part of a business operation “designed to make a profit through its activities”, was significant in assessing their seriousness. On that basis, I accept there is a factual overlap in the contraventions such that they can be characterised as a course of conduct.

70 The applicant referred to other cases where a penalty has been imposed for contraventions of this provision. The use of such cases is well established: see for example, Hili v The Queen [2010] HCA 45; (2010) 242 CLR 520 at [18], [54]-[55]. The cases here are of limited assistance. As referred to above, the parties acknowledged that this case involves vastly more contraventions than has previously been considered (as compared to 636 contraventions in Ordiales, which involved the next in number). It follows that applying the correct principles to the facts will necessarily give rise to a far greater penalty than previously imposed. The respondent accepted as much.

71 The applicant submitted the penalty should be $1,000 to $1,500 for each contravention (amounting to approximately $3,300,000 to $5,000,000). Those figures per contravention are, except for one case, substantially greater than penalties previously imposed. The exception is Williams, where a total penalty imposed resulted in each individual contravention amounting to about $1,095. That was a case where a single penalty of $80,000 was imposed, but where the applicant extrapolated a penalty per contravention from that total figure. The same approach was adopted in relation to other cases where a total penalty had been imposed. Although the figure mathematically represents the amount a person was penalised per contravention in a particular case, the use of such a figure in future cases as an appropriate penalty range has its limitations. Extrapolating a figure in that manner may well fail to recognise the nature of the course of conduct, the circumstances of the individual case, and considerations of totality and oppression which were considered in imposing the total penalty.

72 I recognise that in the present case, Mr Van Dyke charged a greater fee for his services than in the previous cases referred to and obtained greater financial gain. That said, the amount of the penalty sought seems rather arbitrary. The amounts sought for each contravention must reflect that the applicant has placed significant weight on the number of contraventions, and the fact that the contraventions were part of a business operation. This confirms that the contraventions should be considered as a course of conduct. Care must be taken to avoid double punishment.

73 The respondent accepted that the principles of general and specific deterrence would suggest that in considering an appropriate penalty, the Court would ordinarily consider a penalty for each contravention with a starting range above the sum he had received for any contravening conduct. However, the respondent submitted that given his position as an undischarged bankrupt, the imposition of the administrative penalties already levied, the respondent’s cooperation, and the extensive course of conduct, the range which was submitted by the applicant of $1,000 to $1,500 would be so high as to be oppressive. The respondent contended that a starting point above $500 in respect of each contravention, but then subject to the consideration of totality, allowing for the course of conduct, and recognising the particular sting of any penalty given his status as an undischarged bankrupt, would provide more than sufficient deterrence to the respondent personally, and to any other person who became aware of the consequences to the respondent for his conduct that might have otherwise entertained such a course. The respondent submitted it would be open to the Court to consider a total amount that may not exceed the sum said to have been received in respect of the contraventions.

74 The respondent submitted that the amount of any pecuniary penalty is likely to be significant, and any significant penalty payable during the pendency of Mr Van Dyke’s bankruptcy will likely have a crushing effect upon him, and his family. It was submitted that the ability to enforce such a penalty during this period is similarly limited given that essentially all of Mr Van Dyke’s assets and income above the statutory amount permitted under the Bankruptcy Act have vested, or will vest in his trustee. The respondent submitted that although the consideration of an instalment order would not be relevant to the question of the fixing of an appropriate penalty, the making of an instalment order may enable the Court to ensure a closer supervision on Mr Van Dyke’s compliance with the penalty imposed (both prior to and following his discharge from bankruptcy), and increase the prospect of payment of the penalty including following Mr Van Dyke’s discharge from bankruptcy. In the alternative, the respondent submitted that the making of an order expressly granting leave to Mr Van Dyke to apply for the variation of the time to pay the penalty imposed, and/or for the making of payments by instalment would enable Mr Van Dyke to consider an appropriate regime, and to supply further evidence in respect of his ability to comply with such a regime, in a subsequent application, if appropriate, to a registrar of this Court (as with Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Yellow Page Marketing BV (No 2) [2011] FCA 352; (2011) 195 FCR 1). The Board submitted that an instalment order should not be made within the terms of the Court’s order, as there are other options which are more capable of tailoring to unknown future circumstances, and there is limited utility.

75 Recently, in Williams, Charlesworth J at [12] observed:

The importance of s 50-5 hardly needs stating. The prohibition against persons providing tax agent services for fee or reward without being registered as a tax agent is the lynch pin in the regime. It is the requirement to hold a license (in the form of registration) that subjects those who provide taxation services to standards of behaviour contained in the Code and enforceable by the Board. That requirement ensures that defined tax services are only provided by persons who are fit and proper to provide them. The conditions of fitness and propriety require not only that the registrant holds the necessary knowledge and qualifications, but also possesses personal characteristics that are not inimical to the statutory purpose. Conduct that contravenes s 50-5(1) is conduct that undermines the efficacy of the whole of the regime.

76 Strong penalties are required to deter others: Hacker (No 3) at [59]. There is a real temptation for unethical and unprofessional people to provide unregistered tax agent services for financial benefit. As reflected by this case, significant profits can be made. The penalties must be imposed at a level which will signal that such conduct will not pay: Hacker (No 3) at [59], recognising though that it must be limited to what is appropriate for the contraventions committed (applying the principles in relation to the imposition of a penalty).

77 I accept the respondent’s cooperation with the authorities. He has admitted the contraventions which have, amongst other things, facilitated the course of justice. I also accept the respondent is remorseful, although that is tempered by the fact that in cross-examination, he sought to downplay the seriousness of his conduct. In some respects, given his attempts to justify his conduct (e.g. that he was only helping people he knew who were asking for help and that he was merely engaging in a hobby), Mr Van Dyke’s remorse relates to the fact that he now has to face consequences, which have and will continue to impact him and his family. I recognise that the respondent has undertaken some steps to address the issues he said gave rise to this conduct, although the evidence is limited. In his affidavit, the respondent deposed intending to continue to do so. However, as noted above, the evidence was he had ceased counselling in relation to his gambling. Issues of specific deterrence have a clear role to play in any penalty imposed.

78 That said, this was deliberate, repeated, and sustained conduct, which continued (seemingly unabated initially, but later to a lesser degree), even after being warned of legal action in the cease-and-desist letter.

79 To serve the purpose of deterrence, the penalties must be more than the profit made by the respondent. To do otherwise, would undermine the deterrent effect of the penalty, and consequently, the purpose of the TASA and the integrity of the tax system: see for example, Van Stroe (No 2) at [41]. In Van Stroe (No 2), Banks-Smith J observed at [46] that the starting point is that any penalty must exceed the profit in an amount sufficient to have specific and general deterrent value. It needs to be sufficient to dissuade others from seeking to provide such services for benefit and without complying with the regulatory regime, including the requirement of registration: Van Stroe (No 2) at [41]. As explained above, this case illustrates that this conduct can so easily be undertaken, and on a large scale, generating significant financial reward. On the respondent’s submission, a total penalty less than the financial amount gained would still be ruinous to him. He submitted a lesser amount would nonetheless provide the relevant deterrence once the circumstances of the respondent were appreciated. The respondent’s bankruptcy is because of the respondent’s conduct, given his debt to the ATO. I note however, the debt relates to his tax liability in relation to income generated by these contraventions and the associated administrative penalty for failing to declare that income. While his financial circumstances are relevant, the penalty must be sufficient to act as a proper deterrent. A total penalty less than the financial gain, in this case, would not have the necessary sting.

80 It is timely to recall the need for there to be a reasonable balance between deterrence and oppressive severity, in any penalty imposed: Pattinson at [41].

81 As the respondent correctly accepted, the penalty will be significant. Given my conclusion that these contraventions are a course of conduct, a total penalty can be imposed to reflect that conduct: see for example, Van Stroe (No 2) at [48]. It is appropriate to adopt that approach in this case. I have regard to the principle of totality. Taking into account all relevant matters, I assess the appropriate penalty to be $1,800,000. Given the circumstances, that is the minimum that could be imposed, to satisfy the necessary deterrent sting.

82 I do not consider that there is utility in making any instalment order, as there is no information before the Court by which this could be properly assessed. No submission was advanced as to an appropriate instalment order. As the Board correctly submitted, there are other options, including a mechanism whereby a Court (or registrar thereof) can be approached to make such an order in the event of enforcement, and importantly the ability for Mr Van Dyke to negotiate a plan for payment with the Commissioner of Taxation. Those options can be tailored to the unknown future.

83 The applicant seeks declaratory relief in terms it identified. The respondent does not oppose a declaration being made in those terms.

84 The power to grant declaratory relief pursuant to s 21 of Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) "is a very wide one" and the court is "limited only by its discretion": Seven Network Ltd v News Ltd [2009] FCAFC 166; (2009) 182 FCR 160 at [1016], citing Forster v Jododex Australia Pty Ltd [1972] HCA 61; (1972) 127 CLR 421 (Forster) at 435. Three requirements need to be satisfied before making declarations: (1) the question must be a real and not a hypothetical or theoretical one; (2) the applicant must have a real interest in raising it; and (3) there must be a proper contradictor: Forster at 437-438. That a party has chosen not to oppose a grant of particular declaratory relief is not an impediment to such relief being granted by the Court: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v MSY Technology Pty Ltd [2012] FCAFC 56; (2012) 201 FCR 378 at [14], [30]-[33]. Other factors relevant to the exercise of the discretion include: (a) whether the declaration will have any utility; (b) whether the proceeding involves a matter of public interest; and (c) whether the circumstances call for the marking of the Court’s disapproval of the contravening conduct: Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Pegasus Leveraged Options Group Pty Ltd [2002] NSWSC 310; (2002) 41 ACSR 561 at 571; Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Monarch FX Group Pty Ltd, Re Monarch FX Group Pty Ltd [2014] FCA 1387; (2014) 103 ACSR 453 at [63]; Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Stone Assets Management Pty Ltd [2012] FCA 630; (2012) 205 FCR 120 at [42].

85 Given the circumstances of this case, I am satisfied that the declaratory relief in the terms sought is appropriate. The declaration within the annexure to the applicant’s submissions provides sufficient particulars. The issue is not hypothetical: it relates to the characterisation of conduct that affects a large number of persons identified as having paid money to the respondent for his services: Tax Practitioners Board v Van Stroe [2022] FCA 482 at [60].

86 I also make the injunction in the terms sought, which is by consent.

Conclusion

87 For the reasons above, I impose a civil penalty of $1,800,000, and the declaration and injunction are made in the terms sought. The respondent is to pay the costs of the applicant.

I certify that the preceding eighty-seven (87) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice Abraham. |

Associate:

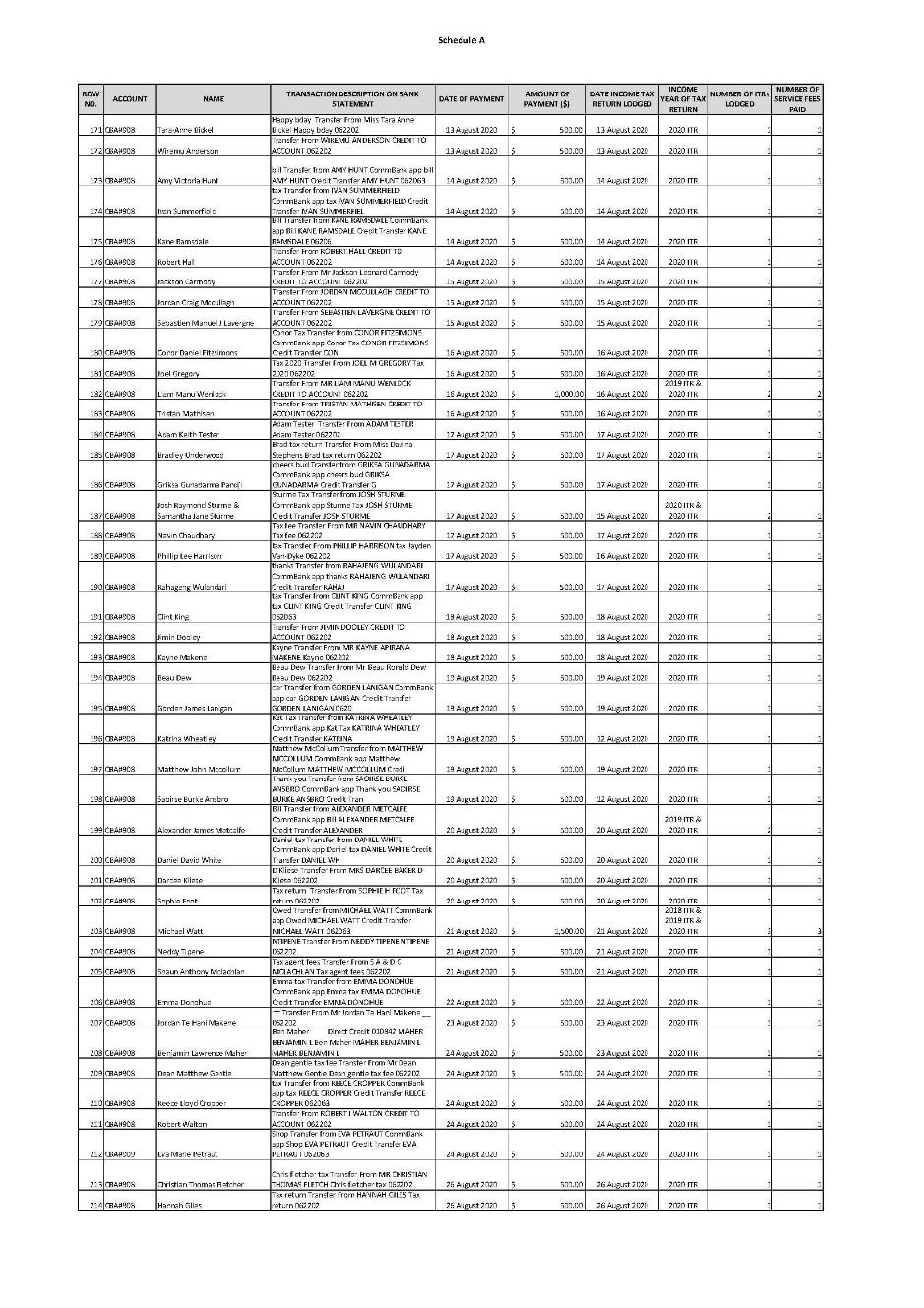

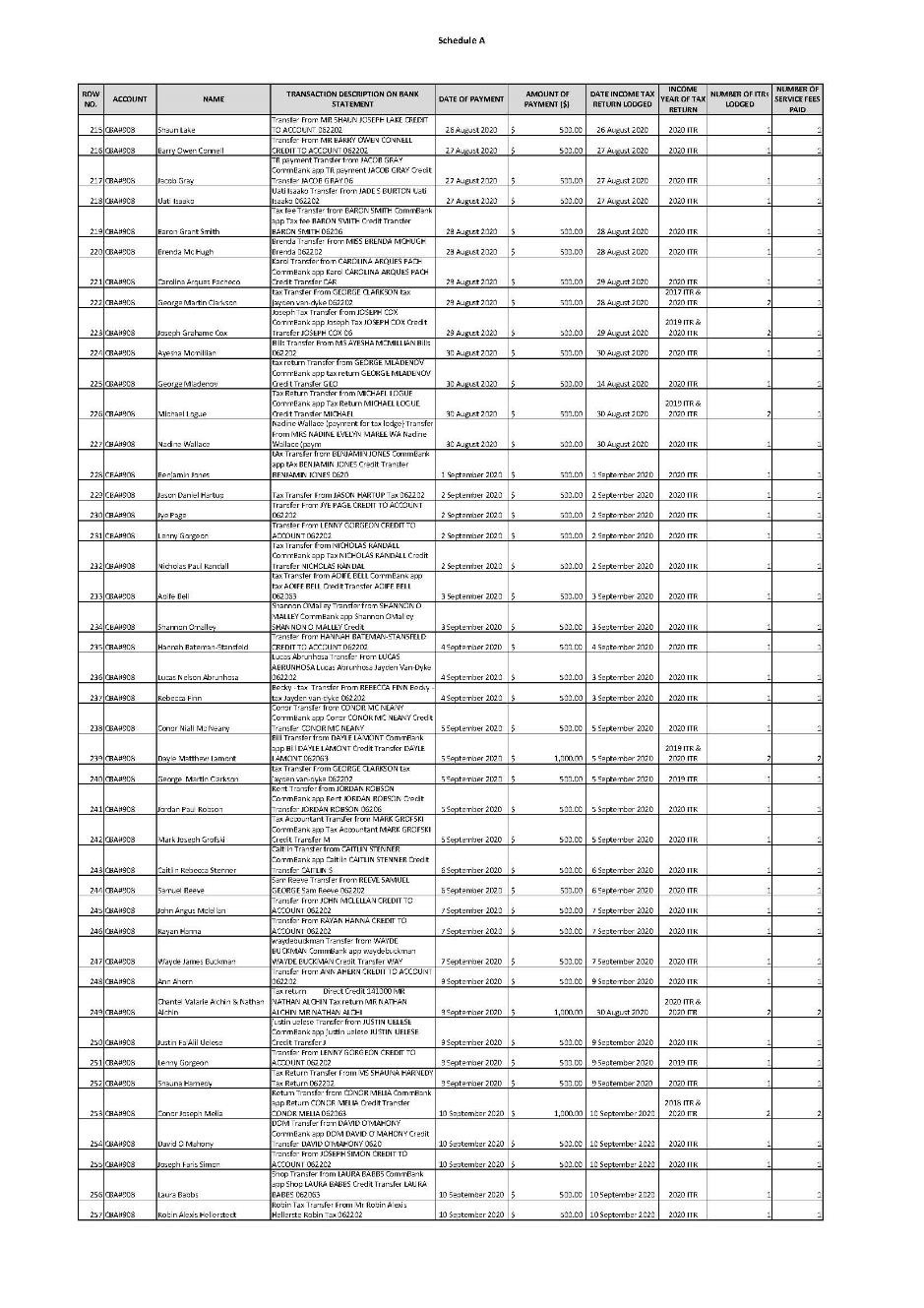

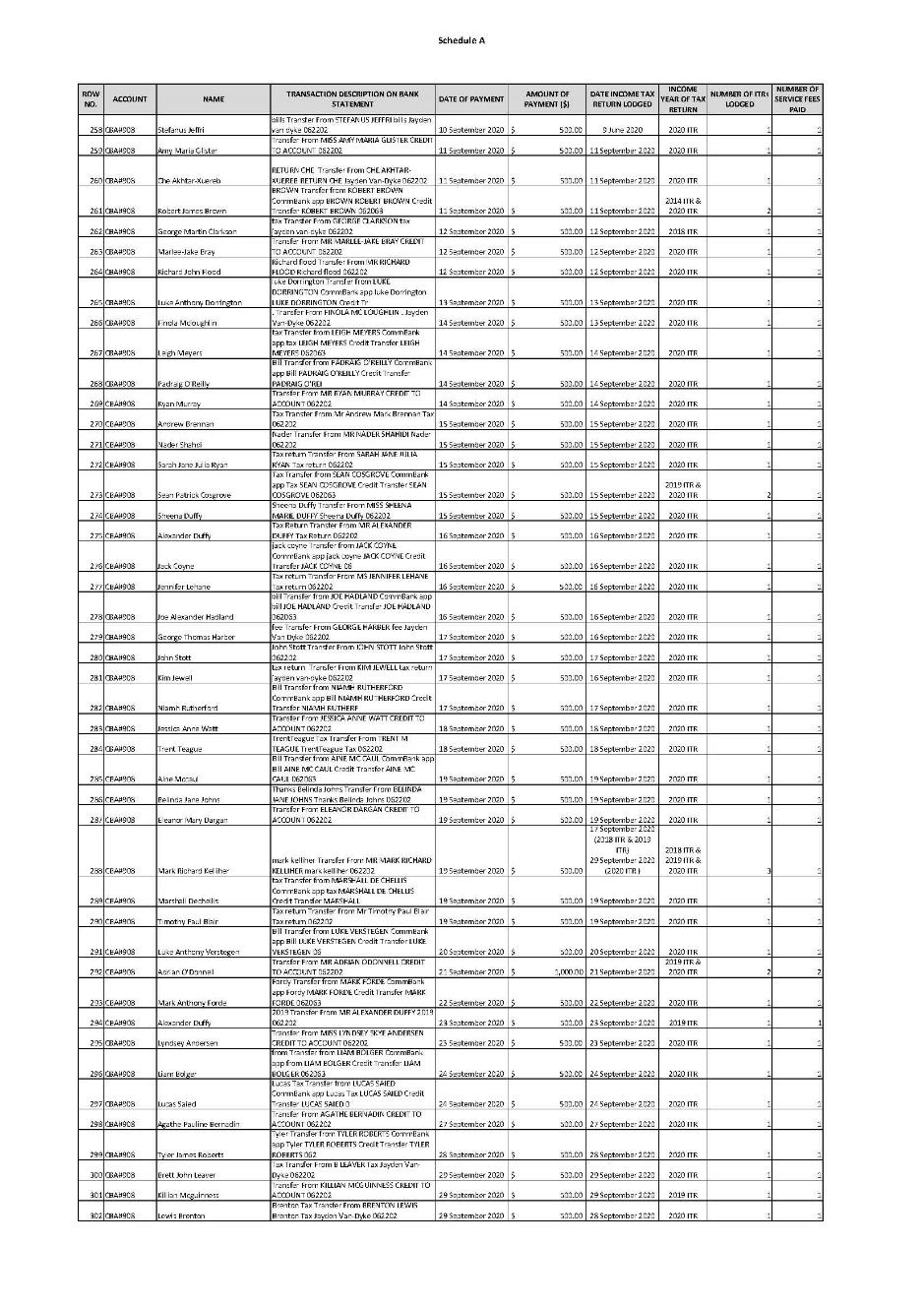

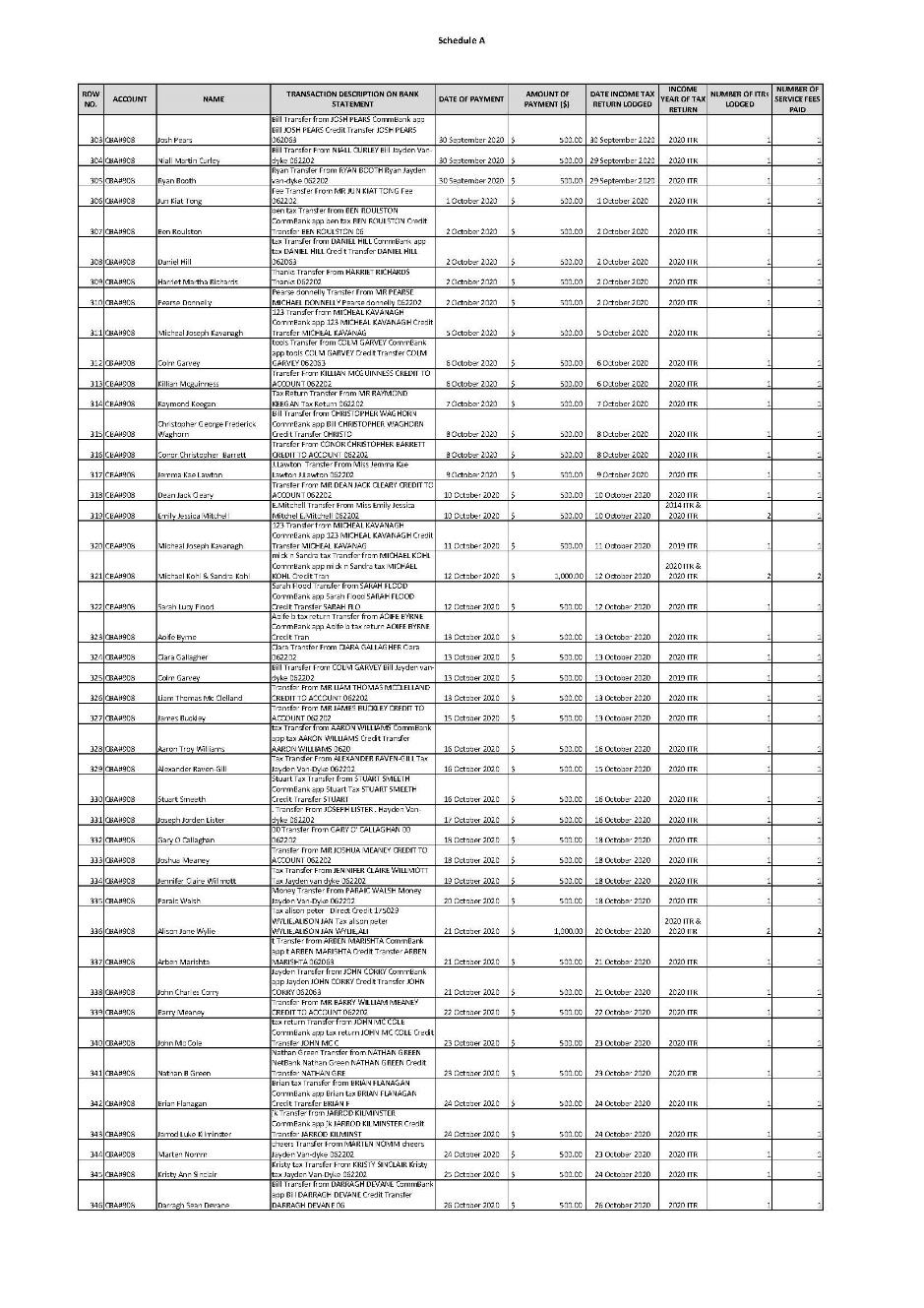

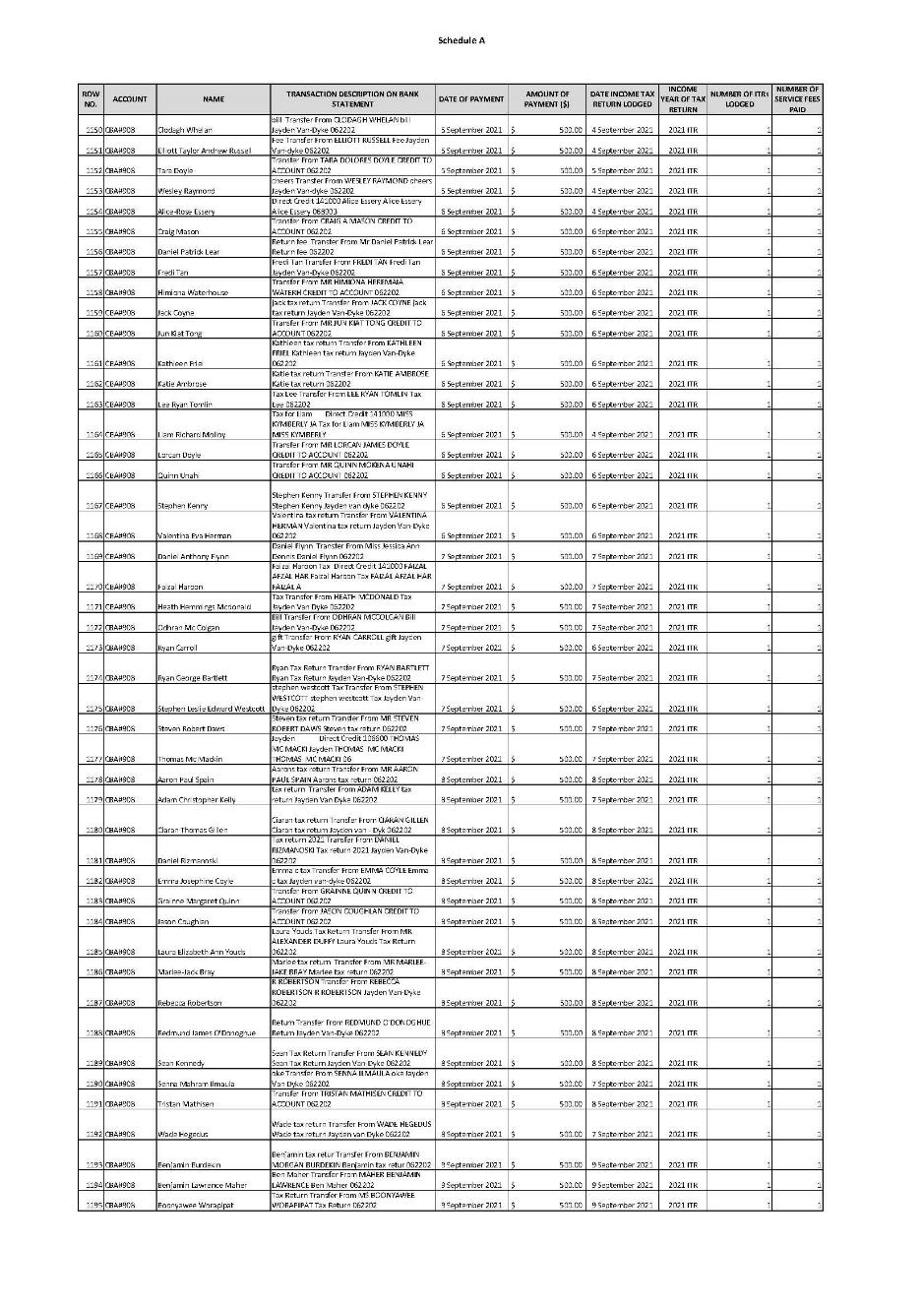

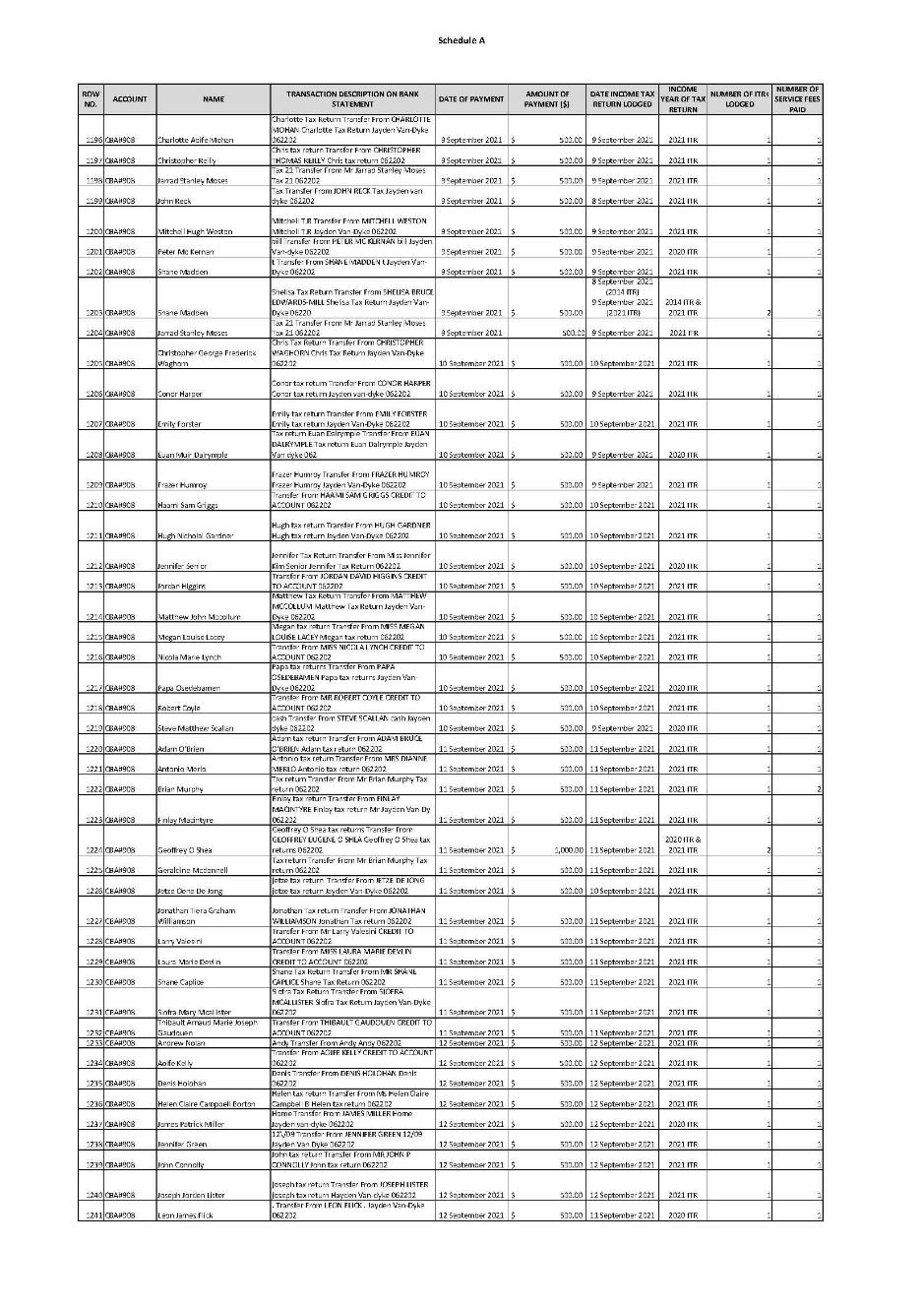

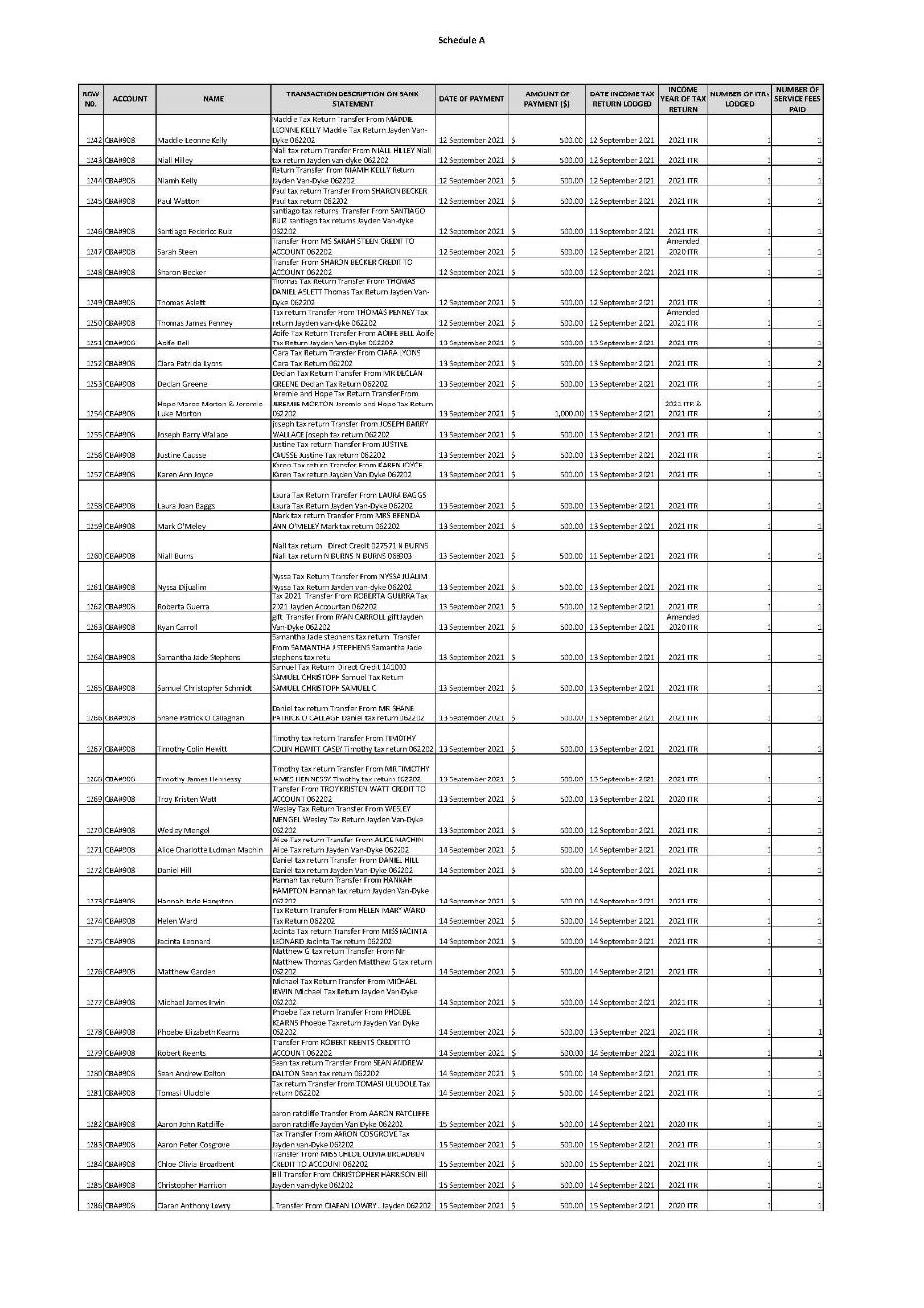

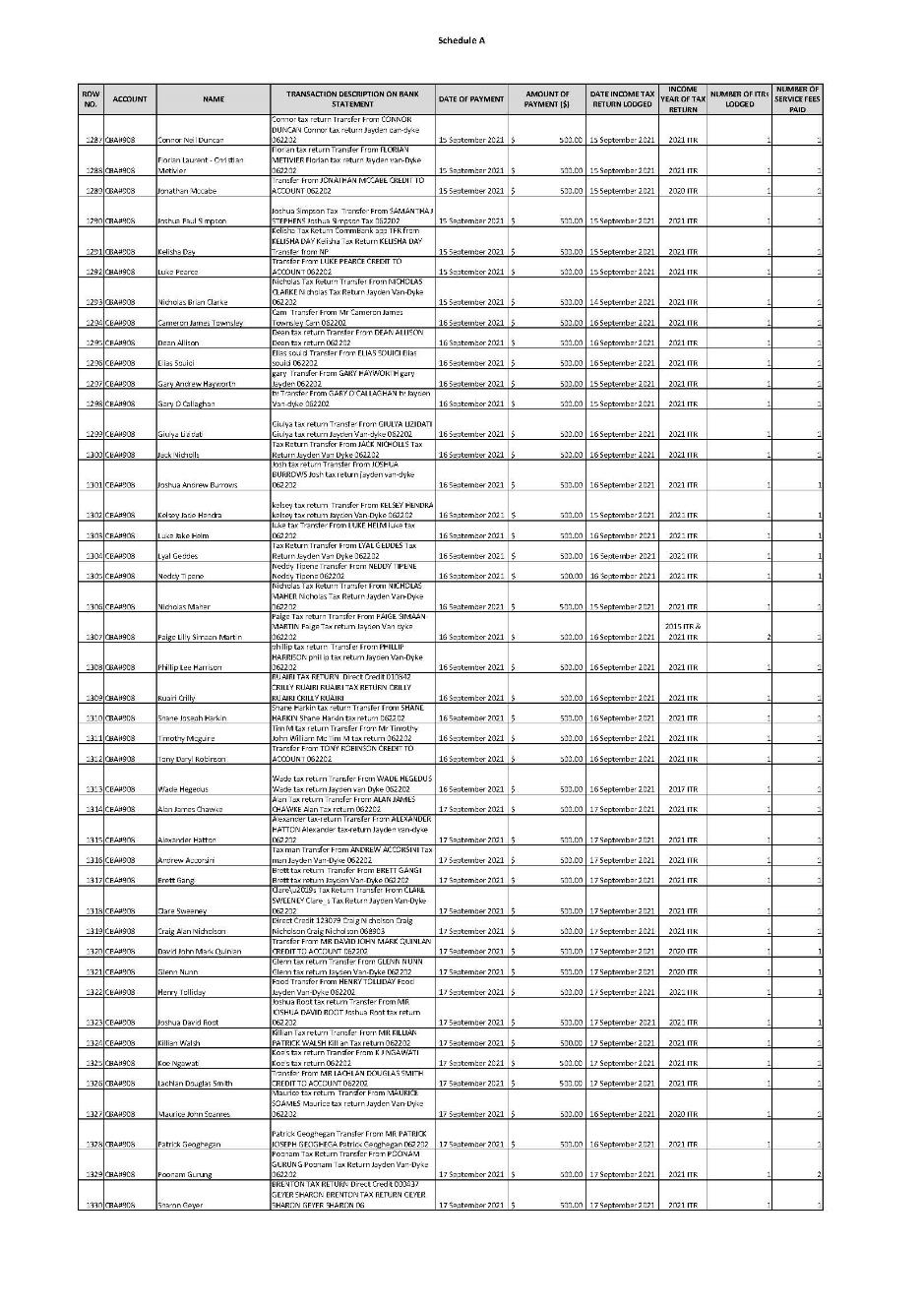

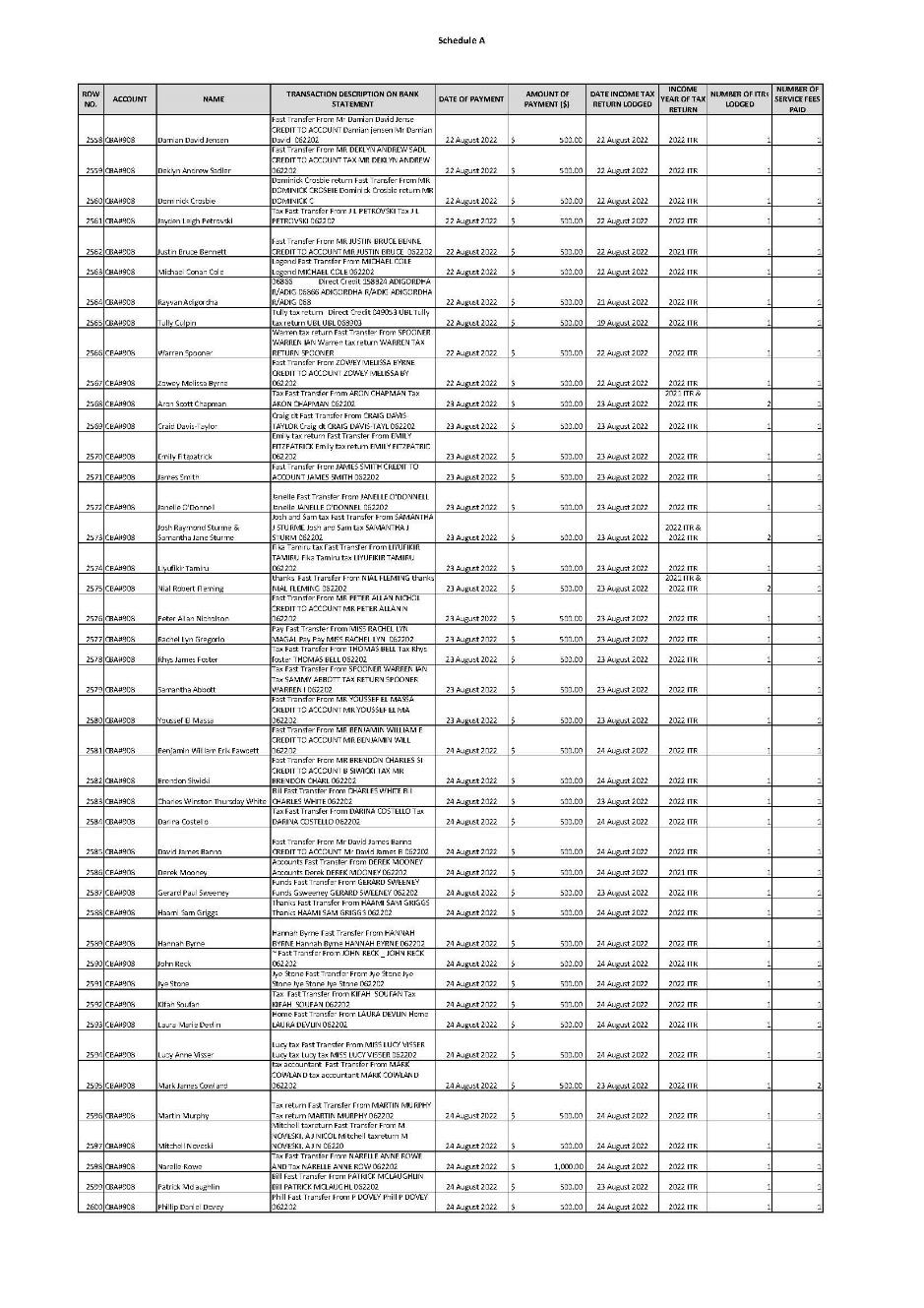

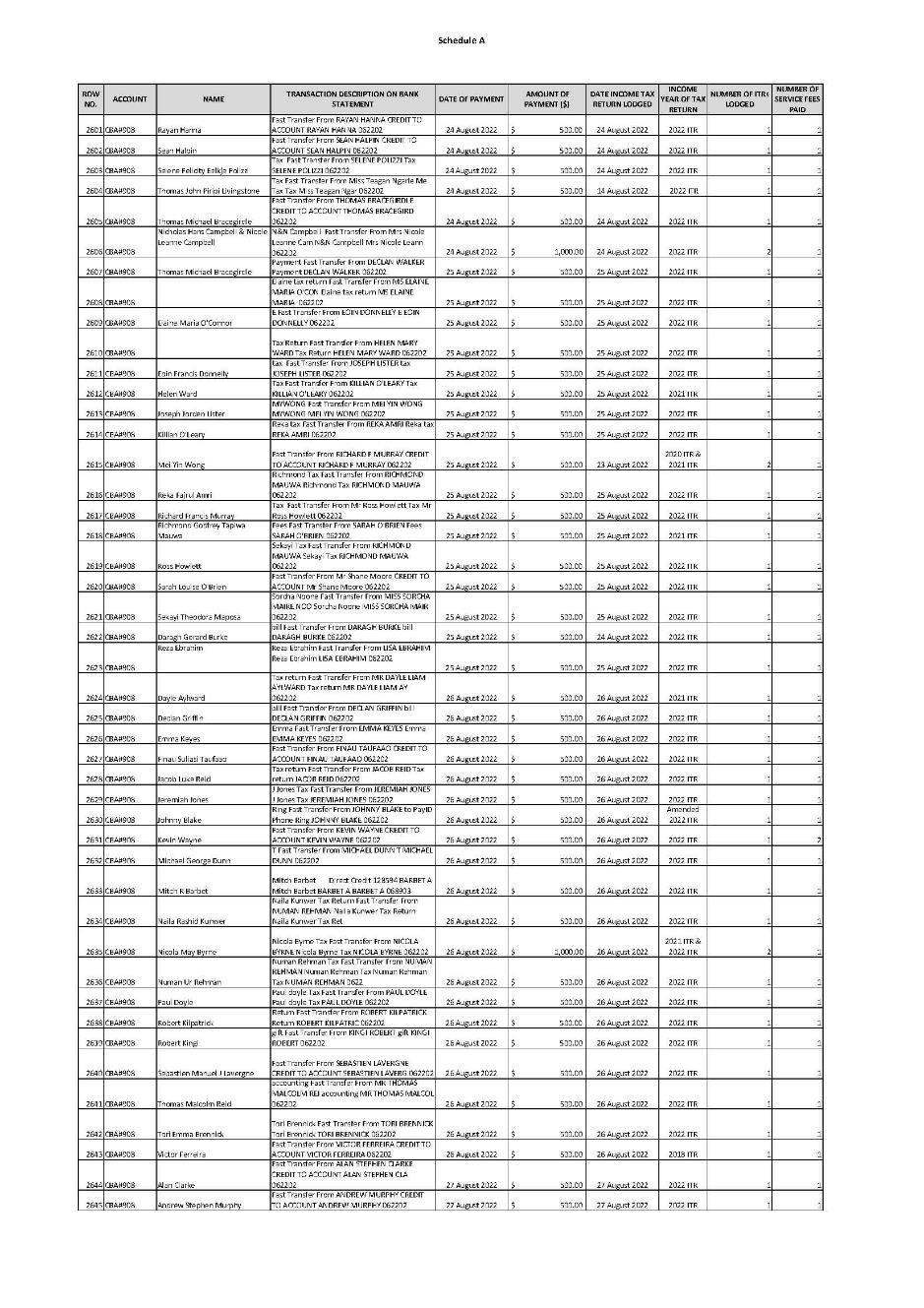

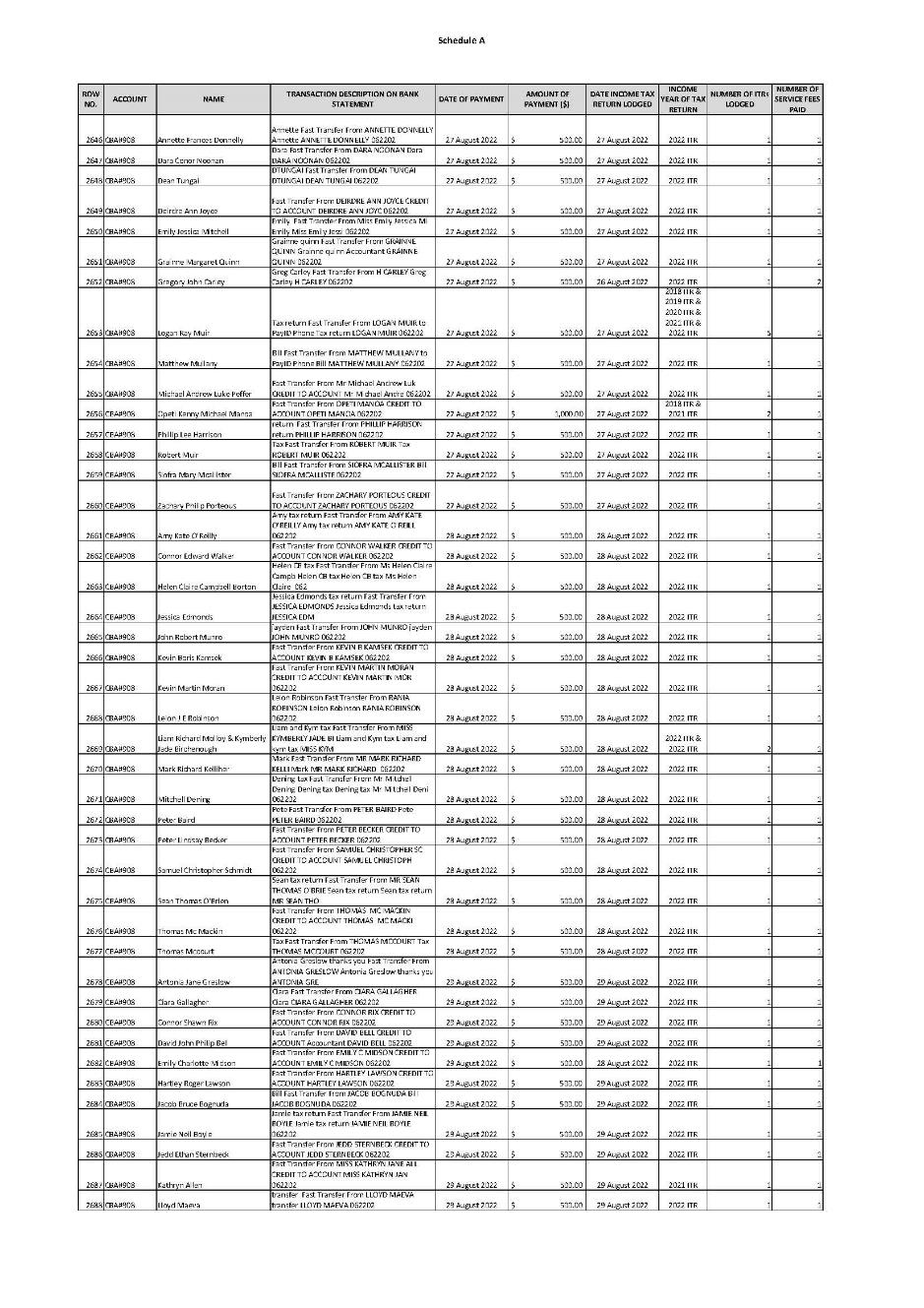

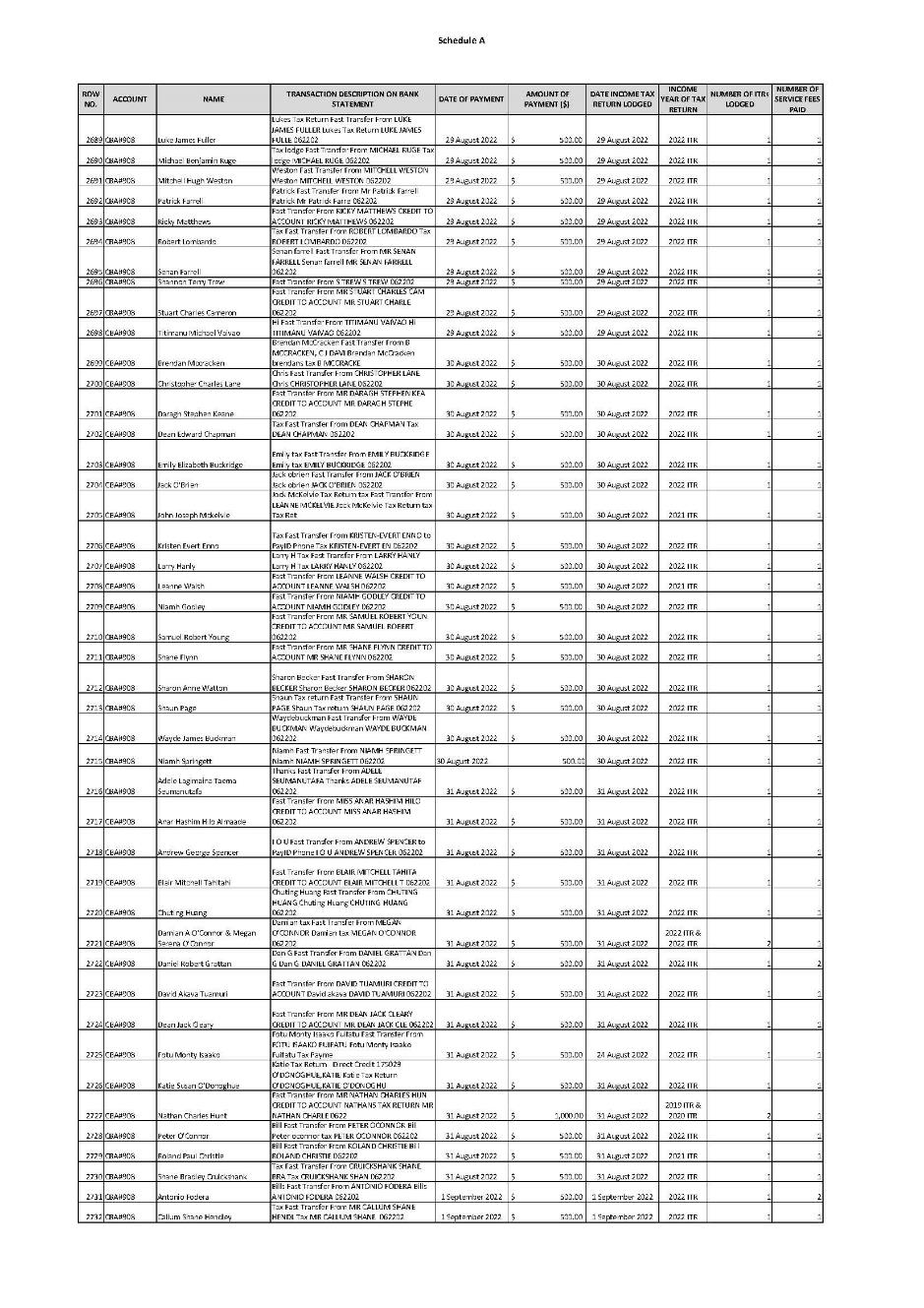

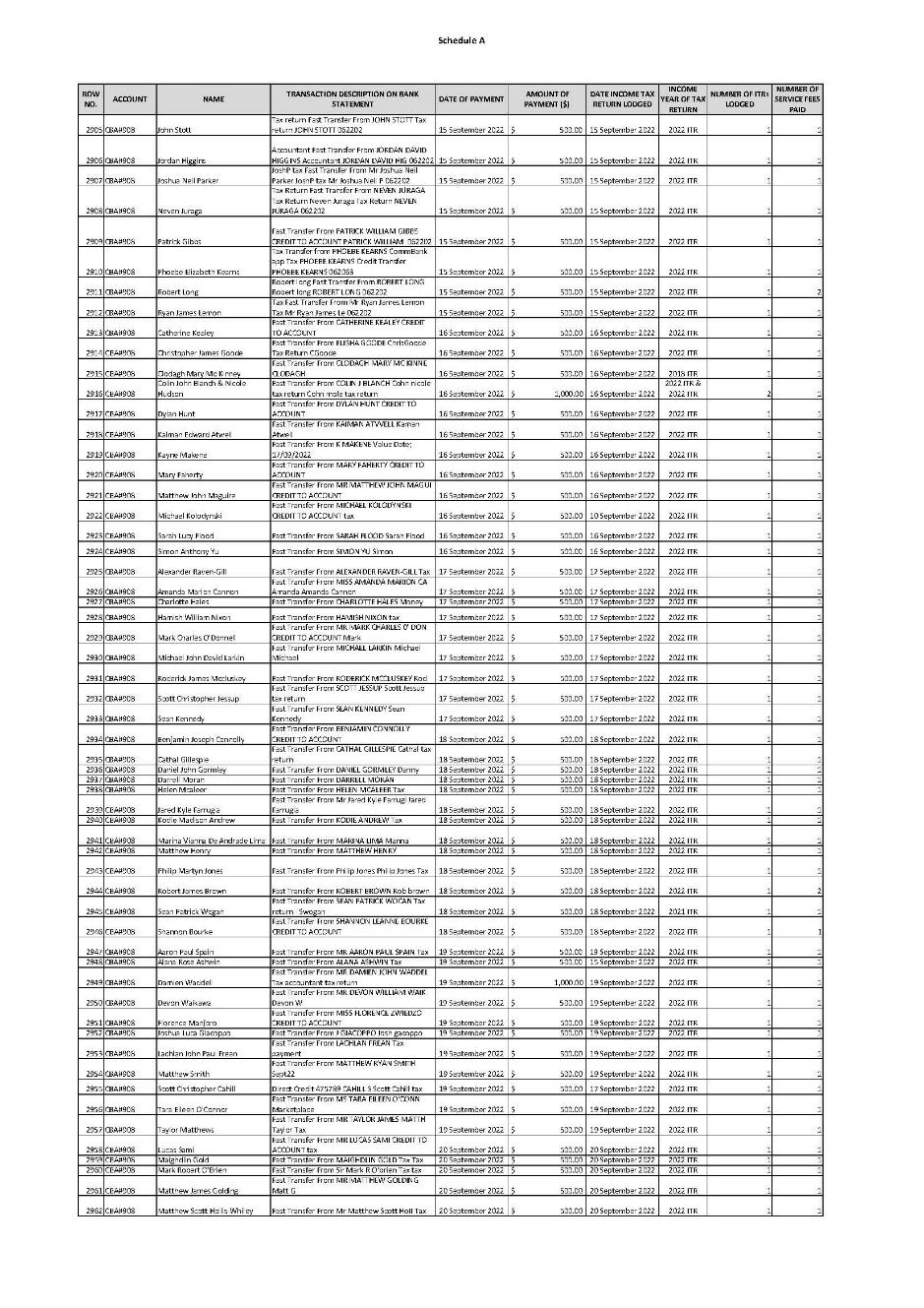

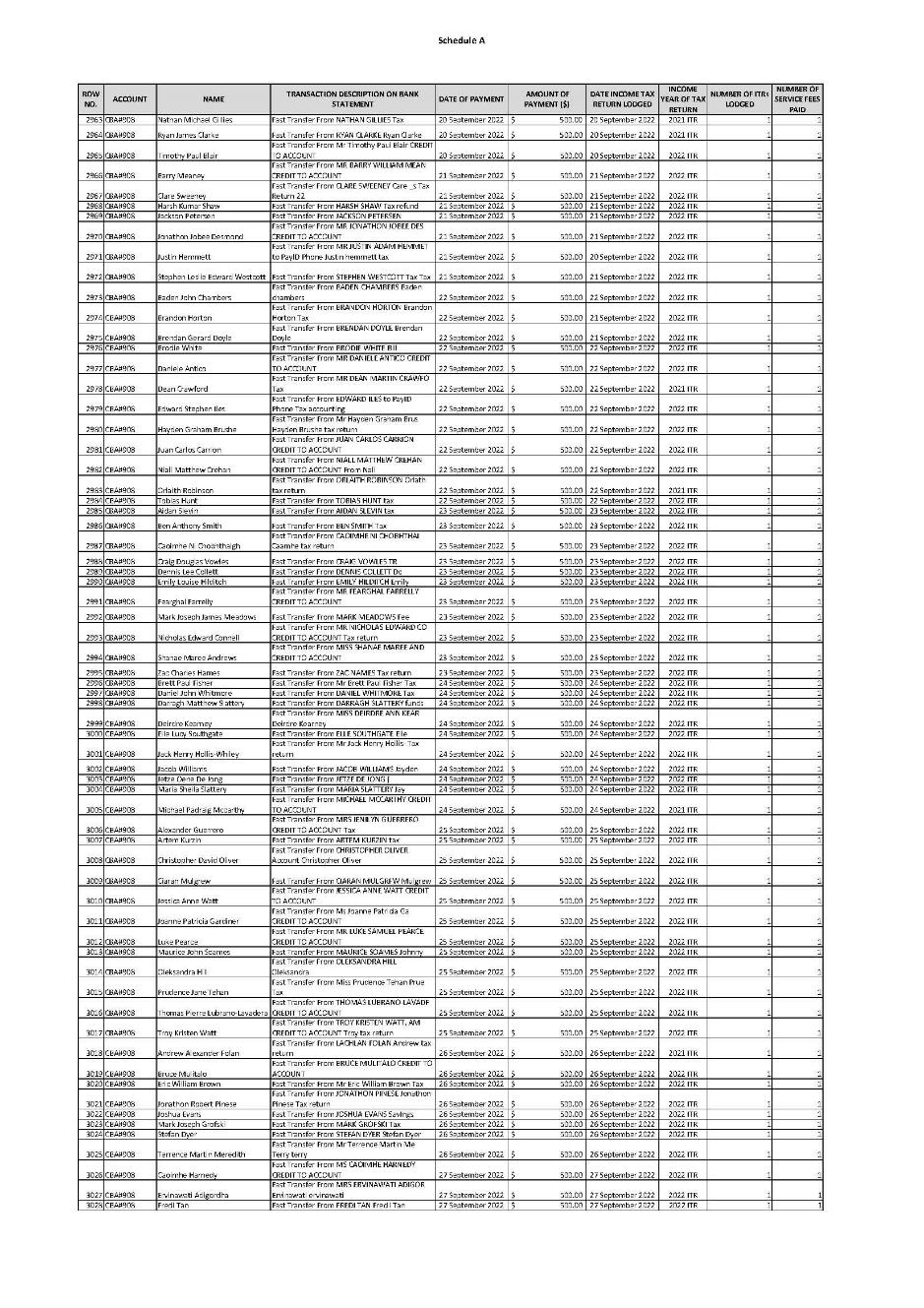

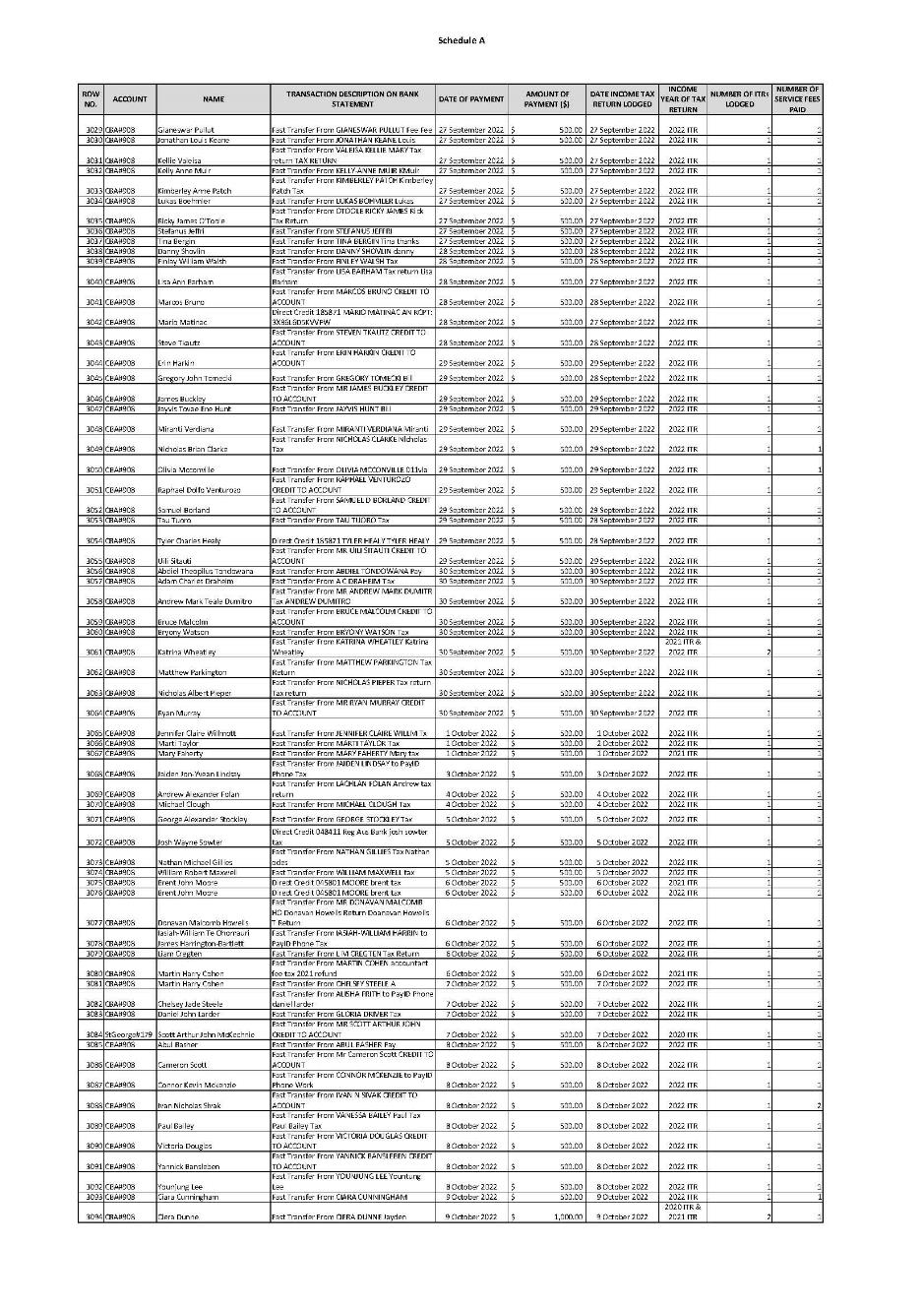

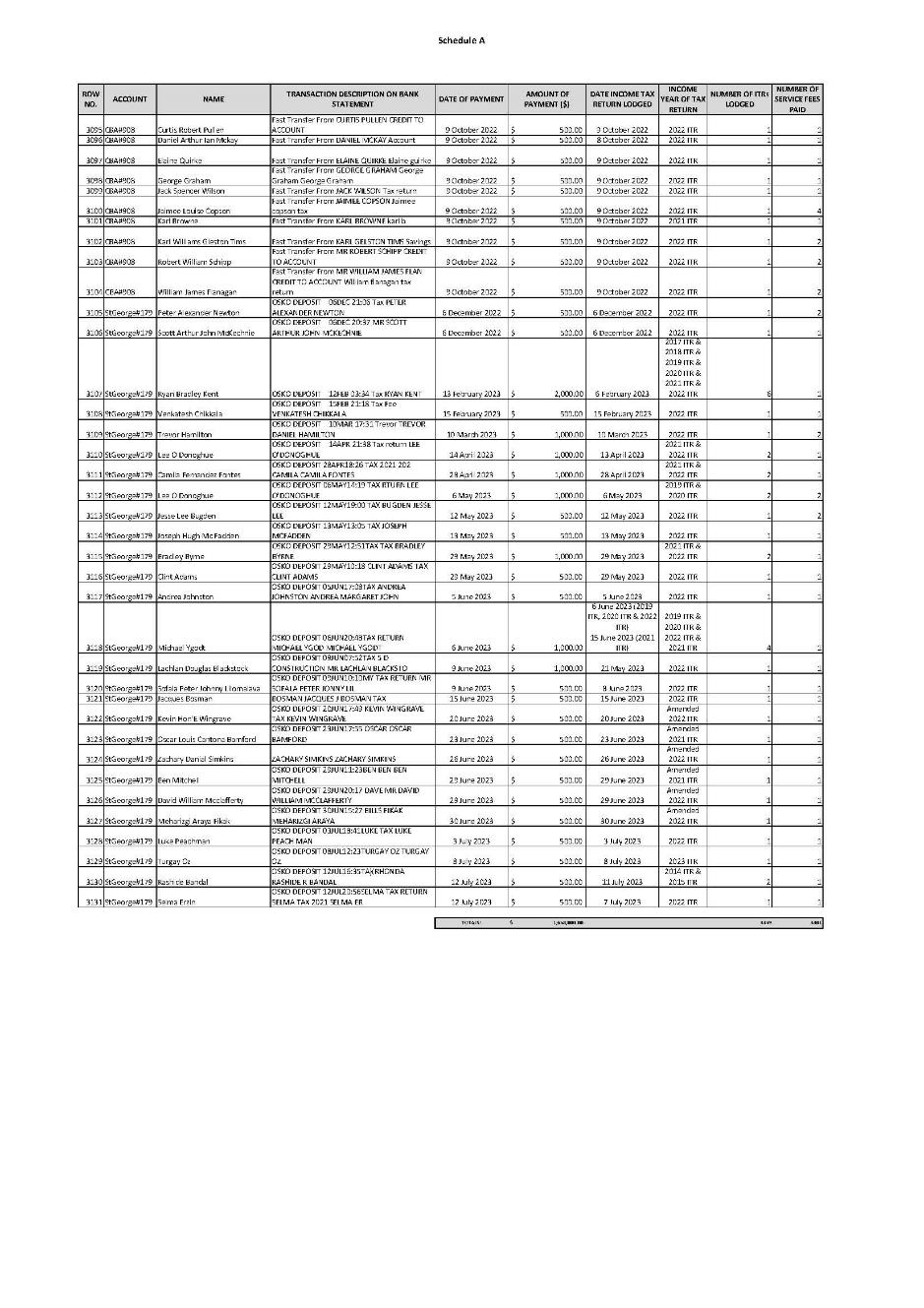

Schedule A