Federal Court of Australia

Fair Work Ombudsman v Sushi Bay Pty Ltd (in liq) (No 3) [2024] FCA 869

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: | 5 August 2024 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Pursuant to s 546(1) of the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth), for their respective contraventions:

(a) the First Respondent pay a penalty of $3.2 million;

(b) the Second Respondent pay a penalty of $5.8 million;

(c) the Third Respondent pay a penalty of $2.4 million;

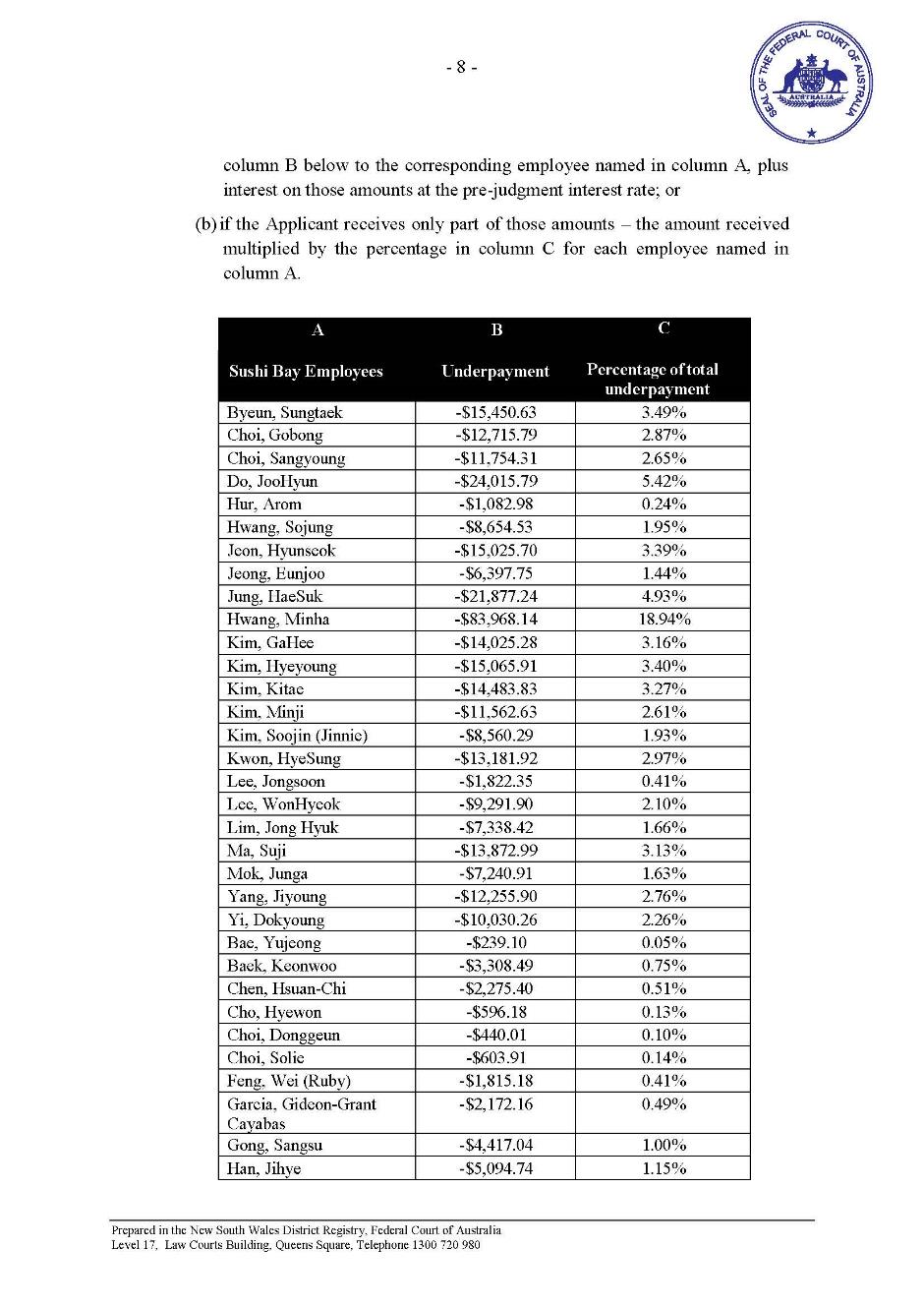

(d) the Fourth Respondent pay a penalty of $2.3 million; and

(e) the Fifth Respondent pay a penalty of $1.6 million.

2. Pursuant to s 546(3) of the Act:

(a) within 28 days, each of the First, Second, Third and Fourth Respondents pay the penalty imposed on it to the Consolidated Revenue Fund of the Commonwealth;

(b) within 28 days, the Fifth Respondent pay the penalty imposed on her to the Applicant;

(c) within 90 days of receipt of the Fifth Respondent’s payment, the Applicant distribute the money to the employees listed in column A of the table in order 9(b) of the orders made by the Court on 21 March 2024 (the Employees) in amounts proportionate to the amounts they were underpaid as set out in column C of that table; and

(d) in the event that any of the Employees cannot be located within 180 days of the receipt by the Ombudsman of the Fifth Respondent’s payment, the Applicant pay the balance into the Consolidated Revenue Fund of the Commonwealth.

3. The Applicant have liberty to apply on seven days’ notice in the event of non-compliance with any of the above orders.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

KATZMANN J:

1 This is yet another case of the exploitation of immigrant workers and a shameless but ultimately unsuccessful attempt to conceal it. It concerns the conduct of four corporations (the Entities) and their sole director and chief executive officer, Yi Jeong (known as Rebecca) Shin. The Entities, now in liquidation, were members of the Sushi Bay group of companies (Sushi Bay Group), a corporate group under the control of Ms Shin, which operated sushi restaurants in NSW, the ACT, and the Northern Territory.

2 Earlier this year I found that the respondents had contravened numerous civil remedy provisions of the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) (FW Act) and Fair Work Regulations 2009 (Cth) (FW Regulations): see Fair Work Ombudsman v Sushi Bay Pty Ltd (in liq) (No 2) [2024] FCA 76 (liability judgment or LJ). They included making and keeping records which they knew to be false or misleading; producing records to a Fair Work Inspector knowing that they were false or misleading; unreasonably requiring employees to return part of their wages to their employer; failing to pay minimum award rates, casual loadings, annual leave loadings, overtime rates, and Saturday, Sunday and public holiday penalty rates; and failing to pay annual leave entitlements on termination for accrued but untaken annual leave. Among the proven contraventions were contraventions committed on and after 15 September 2017 which were “serious contraventions” within the meaning of s 557A of the FW Act in that they were committed knowingly and as part of a systematic pattern of conduct.

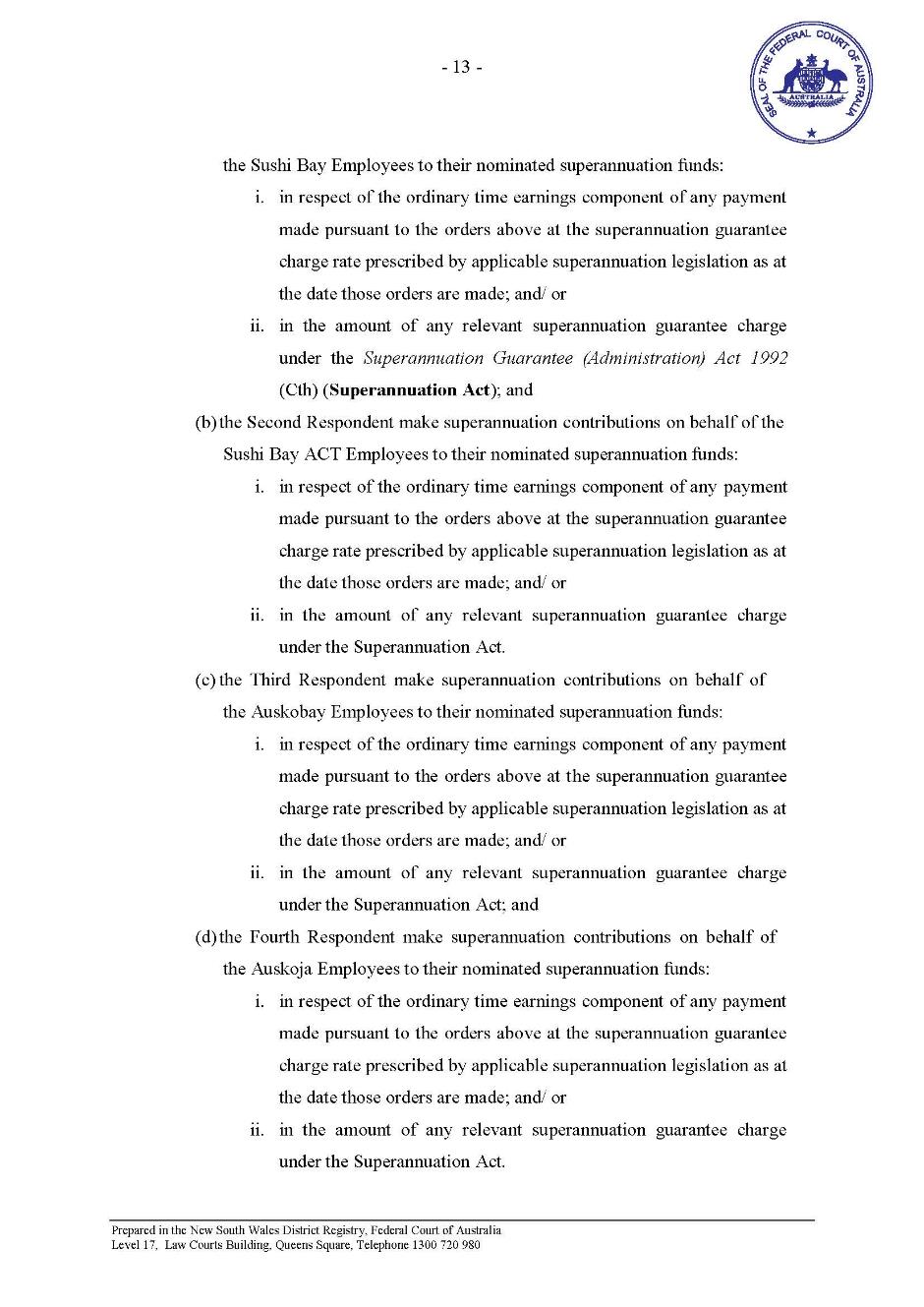

3 On 21 March 2024 I made declarations reflecting my findings. I also ordered each of the Entities to pay to the Ombudsman various sums representing the amounts their employees had been underpaid as a result of certain contraventions (with interest) for payment out to the employees as compensation and to make superannuation contributions on the ordinary time components of those underpayments. The Ombudsman notified the liquidator of the orders for rectification of the underpayments. The liquidator, who declined to take part in the proceeding, responded by saying that, as the Entities are in liquidation, “they cannot comply” and “the claims (sic) have been recorded on the listings of creditors”.

4 This judgment is concerned with the question of penalties. Familiarity with the liability judgment is assumed.

The legal framework and principles

5 If the Court is satisfied that a person has contravened a civil remedy provision, it may order the person to pay a pecuniary penalty that it considers “appropriate”: FW Act, s 546(1).

6 The maximum penalty for each contravention is defined by reference to “penalty units”, as defined by s 4AA of the Crimes Act 1914 (Cth): FW Act, s 12.

7 The contravention period ran from 29 February 2016 to 26 January 2020.

8 At the commencement of the contravention period the value of a penalty unit was $180. The amount was increased to $210, effective on and from 1 July 2017. In circumstances such as these, the higher figure applies for the entire contravention period but it is appropriate for the Court to have regard to the fact that a lower penalty unit value applied for part of the period: see Fair Work Ombudsman v DTF World Square Pty Ltd (in liq) (No 4) [2024] FCA 341 at [8]–[10] and the authorities referred to there.

9 The maximum penalty in the case of an individual is the maximum number of penalty units referred to in the relevant item in column 4 of the table in s 539(2) of the FW Act and five times that amount in the case of a body corporate: FW Act, s 546(2). The maximum number of penalty units for a serious contravention is 600. For all other contraventions, it is 60. The penalty units for the contraventions I found to have occurred in this case are set out in the table below, drawn from the Ombudsman’s submissions:

Contravention | Penalty unit | Multiplier | Total |

Section 44(1) of the FW Act | 60 | x 5 (body corporate) | 300 |

Section 45 of the FW Act | 60 | x 5 (body corporate) | 300 |

Serious contraventions - Section 45 of the FW Act | 600 | x 5 (body corporate) | 3000 |

Section 325(1) of the FW Act | 60 | x 5 (body corporate) | 300 |

Serious contraventions - Section 325(1) of the FW Act | 600 | x 5 (body corporate) | 3000 |

Section 535(1) of the FW Act (until 14 September 2017) | 30 | x 5 (body corporate) | 150 |

Section 535(1) of the FW Act (from 15 September 2017) | 60 | x 5 (body corporate) | 300 |

Section 535(4) of the FW Act | 60 | x 5 (body corporate) | 300 |

Serious contraventions - Section 535(4) of the FW Act | 600 | x 5 (body corporate) | 3000 |

Section 536(3) of the FW Act1 (from 15 September 2017) | 60 | x 5 (body corporate) | 300 |

Section 718A(1) of the FW Act1 (from 15 September 2017) | 60 | x 5 (body corporate) | 300 |

Contravention | Penalty units | Multiplier | Total |

Regulation 3.44(1) of the FW Regulations | 20 | x 5 (body corporate) | 100 |

Regulation 3.44(6) of the FW Regulations | 20 | x 5 (body corporate) | 100 |

10 The Court may order that the pecuniary penalty, or part of it, be paid to the Commonwealth, a particular organisation or a particular person: FW Act, s 546(3).

11 In determining the appropriate penalty in a particular case, the following principles must be applied. Unless otherwise indicated, they derive from the High Court’s judgment in Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Pattinson (2022) 274 CLR 450 (Kiefel CJ, Gageler, Keane, Gordon, Steward and Gleeson JJ) and the authorities referred to there.

12 First, unlike criminal sentences, civil penalties are imposed primarily, if not solely, to promote the public interest in compliance with the legislative requirements by the deterrence of further contraventions (Pattinson at [9]). Thus, a civil penalty must be fixed with a view to ensuring that it is not regarded by the contravener or others as an acceptable cost of doing business (Pattinson at [17]). As the plurality observed in Pattinson at [66]:

The theory of s 546 of the Act is that the financial disincentive involved in the imposition of a pecuniary penalty will encourage compliance with the law by ensuring that contraventions are viewed by the contravenor and others as an economically irrational choice.

In other words, the amount of the penalty must be sufficient to serve the objects of both specific and general deterrence. Regardless of whether specific deterrence is called for, it is important to send a message that contraventions are serious matters and are unacceptable: Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union (The Queensland Infrastructure Case) (2017) 254 FCR 68 at [98] (Dowsett, Greenwood and Wigney JJ).

13 Second, there must be a “reasonable relationship between the theoretical maximum and the final penalty imposed”: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Reckitt Benckiser (Australia) Pty Ltd [2016] FCAFC 181; 340 ALR 25 (Jagot, Yates and Bromwich JJ) at [156], quoted in Pattinson at [10]. That relationship is established where the maximum penalty does not exceed what is reasonably necessary to achieve the purpose of deterrence: Pattinson at [10].

14 Third, a civil penalty should be fixed at a level that strikes a reasonable balance between deterrence and oppressive severity (Pattinson at [41]). In Pattinson at [41] their Honours approved the following statements made by the Full Court of this Court in Reckitt Benckiser at [152]:

If it costs more to obey the law than to breach it, a failure to sanction contraventions adequately de facto punishes all who do the right thing. It is therefore important that those who do comply see that those who do not are dealt with appropriately. This is, in a sense, the other side of deterrence, being a dimension of the general deterrence equation. This is not to give licence to impose a disproportionate or oppressive penalty, which cannot be done, but rather to recognise that proportionality of penalty is measured in the wider context of the demands of effective deterrence and encouraging the corresponding virtue of voluntary compliance.

15 Fourth, in determining “a penalty of appropriate deterrent value”, a number of factors will be relevant, although there is “no rigid catalogue” or “legal checklist”: Pattinson at [18]–[19]. They include: the nature and extent of the contravening conduct and the circumstances in which it took place; the nature and extent of loss or damage; whether the conduct was deliberate; the period over which the conduct extended; whether senior management was involved; whether the contraventions are truly distinct or arose out of a single course of conduct; whether the contravener has previously engaged in similar conduct; the size of the contravening company; the existence and extent of any contrition and corrective action; whether the company has a corporate culture conducive to compliance; whether the contravener cooperated with enforcement authorities; and the need to ensure compliance with minimum standards by provision of an effective means for investigating and enforcing employee entitlements: see, for example, Trade Practices Commission v CSR Ltd [1991] ATPR ¶41-076 at 52,152–3 (French J); Kelly v Fitzpatrick [2007] FCA 1080; 166 IR 14 (Tracey J) at [14]. Some of these factors may weigh in favour of a heavy penalty, others may pull in the opposite direction. While the need for deterrence is often included in the list of relevant factors (for example in Kelly at [14]), it is clear from Pattinson at least that all the other factors, to the extent that they are relevant to the case at hand, must be seen through the prism of what is necessary to achieve deterrence.

16 Fifth, concepts familiar to criminal sentencing such as totality, parity and course of conduct principles may assist in determining the amount of a civil penalty that is reasonably necessary to achieve the statutory purpose: Pattinson at [45].

17 I discuss totality and the course of conduct principles later in these reasons. The parity principle was explained by French CJ, Crennan and Kiefel JJ in Green v The Queen (2011) 244 CLR 462 at [28]-[29] (footnotes omitted) as follows:

“Equal justice” embodies the norm expressed in the term “equality before the law” … It applies to the interpretation of statutes and thereby to the exercise of statutory powers. It requires, so far as the law permits, that like cases be treated alike. Equal justice according to law also requires, where the law permits, differential treatment of persons according to differences between them relevant to the scope, purpose and subject matter of the law. As Gaudron, Gummow and Hayne JJ said in Wong v The Queen:

“Equal justice requires identity of outcome in cases that are relevantly identical. It requires different outcomes in cases that are different in some relevant respect.”

(emphasis in original)

Consistency in the punishment of offences against the criminal law is “a reflection of the notion of equal justice” and “is a fundamental element in any rational and fair system of criminal justice”. It finds expression in the “parity principle” which requires that like offenders should be treated in a like manner. As with the norm of “equal justice”, which is its foundation, the parity principle allows for different sentences to be imposed upon like offenders to reflect different degrees of culpability and/or different circumstances.

…

The consistency required by the parity principle is focused on the particular case. It applies to the punishment of “co-offenders”, albeit the limits of that term have not been defined with precision.

18 Sixth, like the determination of a sentence in a criminal proceeding, the determination of a civil penalty is reached by a process of “instinctive synthesis” (see, for example, Reckitt Benckiser at [44]), that is to say, through an evaluative exercise, in which due account is taken of all the relevant factors, “not to be reached mechanically or by some illusory process of exactitude”: Flight Centre Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (No 2) (2018) 260 FCR 68 at [55] (Allsop CJ, Davies and Wigney JJ).

19 As the Ombudsman submitted, informed by these principles, the approach to determining the appropriate penalty or penalties is well-established. The following summary is drawn from the judgment of Bromwich J in Fair Work Ombudsman v NSH North Pty Ltd t/as New Shanghai Charlestown [2017] FCA 1301; 275 IR 148 at [36].

20 The first step is to identify the separate contraventions, with each contravention of each separate obligation in the FW Act being a separate contravention. Second, it is necessary to consider whether some of the contraventions constitute a single course of conduct within the meaning of s 557(1) of the Act. Third, it is necessary to consider whether there should be an adjustment to ensure that, where two or more contraventions overlap, a double penalty is not imposed. Only then, is a penalty to be fixed for each contravention and, if relevant, each group of contraventions. And finally, it is necessary to assess whether the overall penalty is an appropriate response to the contravening conduct.

21 The final step is commonly referred to as “the principle of totality” by which the Court is required to carry out a final check to ensure that the aggregate sum does not exceed that which is proper for the entire contravening conduct (Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Employsure Pty Ltd [2023] FCAFC 5; 407 ALR 302; 164 ACSR 103 at [52] per Rares, Stewart and Abraham JJ) or, put another way, to ensure that “a final, total or aggregate penalty is not unjust or out of proportion to the circumstances of the case”: Mornington Inn Pty Ltd v Jordan (2008) 168 FCR 383 at [42] (Stone and Buchanan JJ). A penalty will be appropriate if it serves the object of deterrence without being oppressive or, as Burchett and Kiefel JJ put it in NW Frozen Foods Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (1996) 71 FCR 285 at 293, “the penalty should not be greater than that which is necessary to achieve this object”.

The evidence

22 The Ombudsman read affidavits from Jessica Clare Alamyar, a senior lawyer in the Office of the Fair Work Ombudsman and Jacqualine Fay McArthur, a senior Fair Work Inspector (FWI), neither of whom were required for cross-examination. Ms Alamyar’s affidavit annexed the correspondence with the liquidator notifying him of the court orders and their effect and the liquidator’s response. FWI McArthur affirmed two affidavits. That evidence, which was extensive, included evidence elicited from various searches the inspector had carried out including personal name and company searches; land title and website searches; the liquidator’s reports to creditors; the Ombudsman’s recent reports and profiles of the café, restaurant, catering and takeaway food services industry; passages from the Ombudsman’s annual reports from 2017 to 2023; and extracts from various reports on the exploitation of migrant workers in Australia. FWI McArthur also deposed to the attempts she had made to contact affected employees with a view to determining whether they had received any payments from any of the Entities since the publication of the liability judgment.

23 Ms Shin read an affidavit she had affirmed, upon which she was cross-examined. The affidavit purports to have been prepared by Ms Shin, herself. In it, she stated that she “understand[s] English sufficiently well to be able to read and understand this affidavit” but was “not confident enough to speak about it without assistance”. She said nothing about her capacity to write English. Ms Shin deposed that she was born in South Korea in 1961 and first came to Australia in 1989. While the affidavit does not record her educational background, it does not read as if it was prepared by a non-lawyer, let alone one for whom English is not her first language. Rather, it reads as if it was prepared by a lawyer or at least a person with legal training. As the Ombudsman did not put to Ms Shin that the affidavit was not (or not entirely) her own work and Ms Shin did not suggest as much, I shall put my concerns to one side and proceed on the assumption that the contents of the affidavit were the result of her own unassisted endeavours: cf. Port Kembla Coal Terminal Ltd v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union (2016) 248 FCR 18 at [217] (Jessup J).

24 I will deal with the evidence as and when it arises for consideration.

25 Submissions were filed by the Ombudsman and Ms Shin. Ms Shin’s submissions were not signed, and their author was not identified. They were obviously prepared by a lawyer. Ms Brigden of counsel, who appeared for the Ombudsman, also addressed the Court orally. Ms Shin was given the opportunity to respond but she declined to take it.

26 The liquidator did not appear. Although he did not file a submitting appearance, he chose not to participate in any part of the hearing.

The contraventions

27 The contraventions are set out in the declarations which, for convenience, are included in Annexure A to these reasons. They involve:

(1) contraventions of s 45 of the FW Act by contravening various clauses of the Restaurant Industry Award 2010 (Award) by failing to pay minimum rates (cll 12.8, 12.10, 15.1, 20.1 and 20.3); failing to pay casual loadings (cl 13.1); failing to pay Saturday, Sunday and public holiday penalty rates (cl 34.1); failing to pay overtime rates (cl 33.2(a)–(c)); and failing to pay annual leave loading for periods of annual leave taken (cl 35.2(b));

(2) contraventions of s 44(1) of the FW Act by failing to pay annual leave entitlements contrary to s 90(1) of the Act;

(3) contraventions of s 325 of the FW Act by unreasonably requiring employees to pay part of their wages back to their employers;

(4) contraventions of s 535(4) of the FW Act by making and keeping certain records knowing that they were false or misleading;

(5) contraventions of s 536(3) by giving pay slips to employees knowing that they were false or misleading;

(6) s 718A of the FW Act by producing certain documents (payroll advices and pay slips) to a Fair Work Inspector, knowing them to be false or misleading;

(7) contraventions of reg 3.44(1) of the FW Regulations by failing to ensure that certain records they made or kept were not knowingly false or misleading; and

(8) contraventions of reg 3.44(6) of the FW Regulations by making use of entries in those records knowing the entries to be false or misleading.

The application of the course of conduct principle

28 Section 557 of the FW Act requires that multiple contraventions of certain civil remedy provisions are taken to constitute a single contravention in certain circumstances. It relevantly provides:

(1) For the purposes of this Part, 2 or more contraventions of civil remedy provision referred to in subsection (2) are, subject to subsection (3), taken to constitute a single contravention if:

(a) the contraventions are committed by the same person; and

(b) the contraventions arose out of a course of conduct by the person.

(2) The civil remedy provisions are the following:

(a) subsection 44 (which deals with contraventions of the National Employment Standards);

(b) section 45 (which deals with contraventions of modern awards);

…

(i) Subsection 325(1) (which deals with unreasonable requirements on employees to pay or spend amounts);

…

(n) subsections 535(1), (2) and (4) (which deal with employer obligations in relation to employee records);

(o) subsections 536(1), (2) and (3) (which deal with employer obligations in relation to pay slips);

…

(s) any other civil remedy provisions prescribed by the regulations.

(3) Subsection (1) does not apply to a contravention of a civil remedy provision that is committed by a person after a court has imposed a pecuniary penalty on the person for an earlier contravention of the provision.

29 Regulation 4.03A provides that, for the purpose of s 557(2)(s) of the Act, each civil remedy provision mentioned in items 4 to 19 of the table to reg 4.01A(2) is prescribed. Among those civil remedy provisions is reg 3.44(6) (at item 19) and, until 21 December 2017, reg 3.44(1) (at item 14).

30 The object and purpose of s 557 is to ensure that the contravener is not penalised twice for what is essentially the same wrongdoing: Rocky Holdings Pty Ltd v Fair Work Ombudsman (2014) 221 FCR 153 at [18] (North, Flick and Jagot JJ).

31 As the Full Court explained in Rocky Holdings, the effect of s 557(1) is that multiple contraventions of the same provision of the National Employment Standards (NES) and multiple contraventions of the same clause of a modern award are deemed to constitute a single contravention by a contravener where they arose out of a course of conduct committed by the contravener. The Ombudsman accepts that, with the exception of Sushi Bay ACT and Ms Shin in the case of certain contraventions of the Award, the respondents are entitled to the benefit of s 557(1) so that multiple contraventions of the same clause of the Award and the same section of the FW Act or FW Regulations occurring on multiple occasions in respect of multiple employees should be “grouped” together.

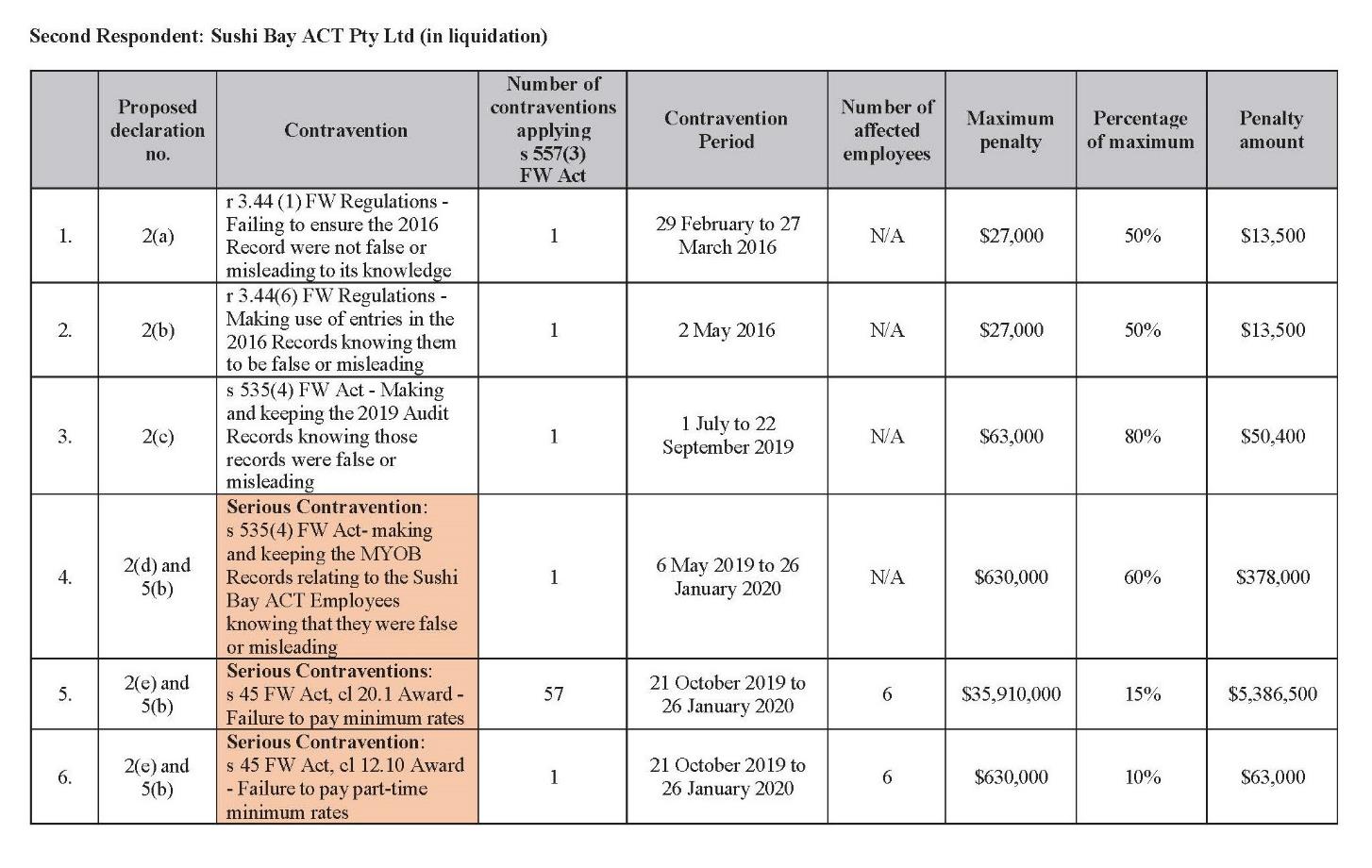

32 Sushi Bay ACT and Ms Shin are exceptions because some of the contraventions which I found they had committed occurred after the Federal Circuit Court of Australia (FCCA) imposed pecuniary penalties on them for contraventions of the same Award provisions. They are the following contraventions of s 45 committed after 28 June 2019: the conventions of cl 20.1 (failing to pay minimum rates); cl 20.3 (failing to pay junior minimum rates); cl 13.1 (failing to pay casual loadings); and cl 34.1 (failing to pay penalty rates for work on weekends and public holidays).

33 Ms Shin contended that she is in a different position from that of the Entities “as the Award did not bind her and s 45 did not compel her to abide by its terms”. She argued that “[a]s such, her liability as an accessory is linked to a single course of conduct, being her setting or approving rates of pay before the end of each financial year and having responsibility for the Payroll System that processed the pays”, notwithstanding that that conduct resulted in multiple contraventions by the other respondents, relying on Fair Work Ombudsman v PTES 928 Pty Ltd [2023] FCA 934 at [110]–[135] especially at [130]–[131] (Snaden J). She therefore submitted that each of the contraventions of s 325 should be “grouped together” as one contravention or grouped together for each financial year; the contraventions of s 45 should be grouped together as one contravention or grouped together for each financial year; and all the record-keeping contraventions should be grouped together.

34 In PTES 928 Snaden J held that Christine Ho, who was the sole director, secretary and shareholder of PTES 928 and its Chief Financial Officer, was involved in each of the company’s contraventions of the applicable award. Nevertheless, because the award posed obligations on the company and not her, his Honour held that the award did not bind her; her only obligation was to ensure that the company complied with its legal obligations, and her involvement in the company’s contraventions was properly to be regarded as a single course of conduct attracting the operation of s 557(1). At [130]-[132] his Honour said:

130 The position of Ms Ho thus differs to that of PES [PTES 928]. The Award imposed upon PES multiple obligations. For the purposes of s 45 of the FW Act, the contravention of its terms lay not in positive acts but in omissions: specifically and in each case, in the failure to make the payments that each individual requirement of the Award compelled. A failure to make one species of payment sufficed to constitute one omission; a failure to make another sufficed to constitute another; and so on. The conduct—that is to say, the omission—by which each of PES’s contraventions was constituted was, in each case, different. Hence, there are multiple, discrete contraventions of s 45 of the FW Act that attract multiple, discrete penalties.

131 The same cannot be said of Ms Ho. The Award did not bind Ms Ho and s 45 of the FW Act did not compel her to abide by its terms. There is only one (presently relevant) obligation that the amended statement of claim and the admissions made in response to it attach to her: namely, an obligation to “ensure that PES complied with its legal obligations under the FW Act”. Plainly, she failed (by omission) to discharge that obligation on multiple occasions; but each occasion involved the same conduct (that is, the same omission).

132 That understood, s 557(1) is applicable. Although she must be understood to have engaged (indeed, I have found that she did engage) in multiple contraventions of s 45—specifically, in each of the eight Accessorial Contraventions—they must, for the purposes of pt 4–1 of the FW Act (and, in particular, s 546), be “…taken to constitute a single contravention”.

35 The Ombudsman appealed from this aspect of his Honour’s judgment and the consequential orders against Ms Ho. The sole ground of appeal was that his Honour erred in concluding that s 557(1) operated in such a way as to treat her eight contraventions as a single contravention and to impose a single penalty.

36 The appeal was heard in May this year. Judgment is reserved. In her written submissions in the appeal, Ms Ho agreed that Snaden J was wrong and that the Ombudsman’s analysis (relying on Rocky Holdings and Fair Work Ombudsman v Lohr [2018] FCA 5; 158 ALD 457 per Bromwich J) was correct.

37 In my respectful opinion his Honour was plainly wrong in this respect. Once the Court has made a finding that a person was involved in a contravention of a civil remedy provision, the person is taken to have contravened that provision: FW Act, s 550. There is therefore no proper basis to distinguish the position of an accessory from that of a principal. Rocky Holdings applies equally to an accessory regardless of the nature of the accessory’s involvement.

38 Section 557 is not a code, however: see, for example, Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union (The Perth Airport Case) (2017) 249 FCR 458 at [88] (Dowsett and Rares JJ). As I said in Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Westpac Banking Corporation (The Consumer Credit Insurance Case) [2022] FCA 359; 158 ACSR 647 at [80], while “[i]t is neither appropriate nor permissible to treat multiple contraventions as one contravention for the purposes of determining the statutory limit” (see Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Yazaki Corporation (2018) 262 FCR 243 at [227] (Allsop CJ, Middleton and Robertson JJ), “in an appropriate case a single penalty may be imposed for multiple contraventions”. I continued:

One such case is where there is an interrelationship between the legal and factual elements of a number of contraventions, it is necessary to take care to ensure that the contravenor is not penalised twice for what amounts to the same wrongdoing. This principle, originally developed in the context of the sentencing discretion, is commonly known as the “course of conduct” or “one transaction” principle. See, for example, Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union v Cahill [2010] FCAFC 39; 269 ALR 1; 194 IR 461 (Cahill) at [39] (Middleton and Gordon JJ). The principle requires that in such a case consideration should be given to whether the contraventions arise out of the same course of conduct or the one transaction in order to determine whether it is appropriate that a “concurrent” or single penalty should be impose for the multiple contraventions: Yazaki at [234]. Even if the course of conduct principle is applicable, however, a judge is not obliged to apply the principle if the resulting penalty does not reflect the seriousness of the contraventions: Cahill at [39]; Yazaki at [235]. …

39 But the one transaction principle does not assist Ms Shin’s argument. As the Ombudsman submitted, there is no interrelationship between the legal and factual elements of the various contraventions Ms Shin argued should be grouped together as they are concerned with breaches of different legal obligations.

Double jeopardy

40 Section 556 provides:

Civil double jeopardy

If a person is ordered to pay a pecuniary penalty under a civil remedy provision in relation to particular conduct, the person is not liable to be ordered to pay a pecuniary penalty under some other provision of a law of the Commonwealth in relation to that conduct.

Note: A court may make other orders, such as an order for compensation, in relation to particular conduct even if the court has made a pecuniary penalty order in relation to that conduct (see subsection 546(5)).

41 In Construction, Forestry, Maritime, Mining and Energy Union v Australian Building and Construction Commissioner (2019) 272 FCR 290 at [14], the Full Court (Bromberg, Wheelahan and Snaden JJ) held that:

Commonly …, contravention of a civil remedy provision may be constituted by a range of conduct made up by a number of different acts or omissions. When a pecuniary penalty is imposed for a contravention, each of those acts or omissions involved in the contravention will be the subject of the pecuniary penalty if a pecuniary penalty is imposed. So much is recognised by the phrase “in relation to” in s 556. The purpose of that phrase is to make it clear that the provision is addressing “particular conduct” that is the subject of the penalty imposed, and not necessarily all of or the whole of the conduct for which the penalty was imposed. Where that particular conduct is the subject of a pecuniary penalty, s 556 requires that that particular conduct not be the subject of a further pecuniary penalty.

42 It was not suggested that s 556 had any role to play in the present case.

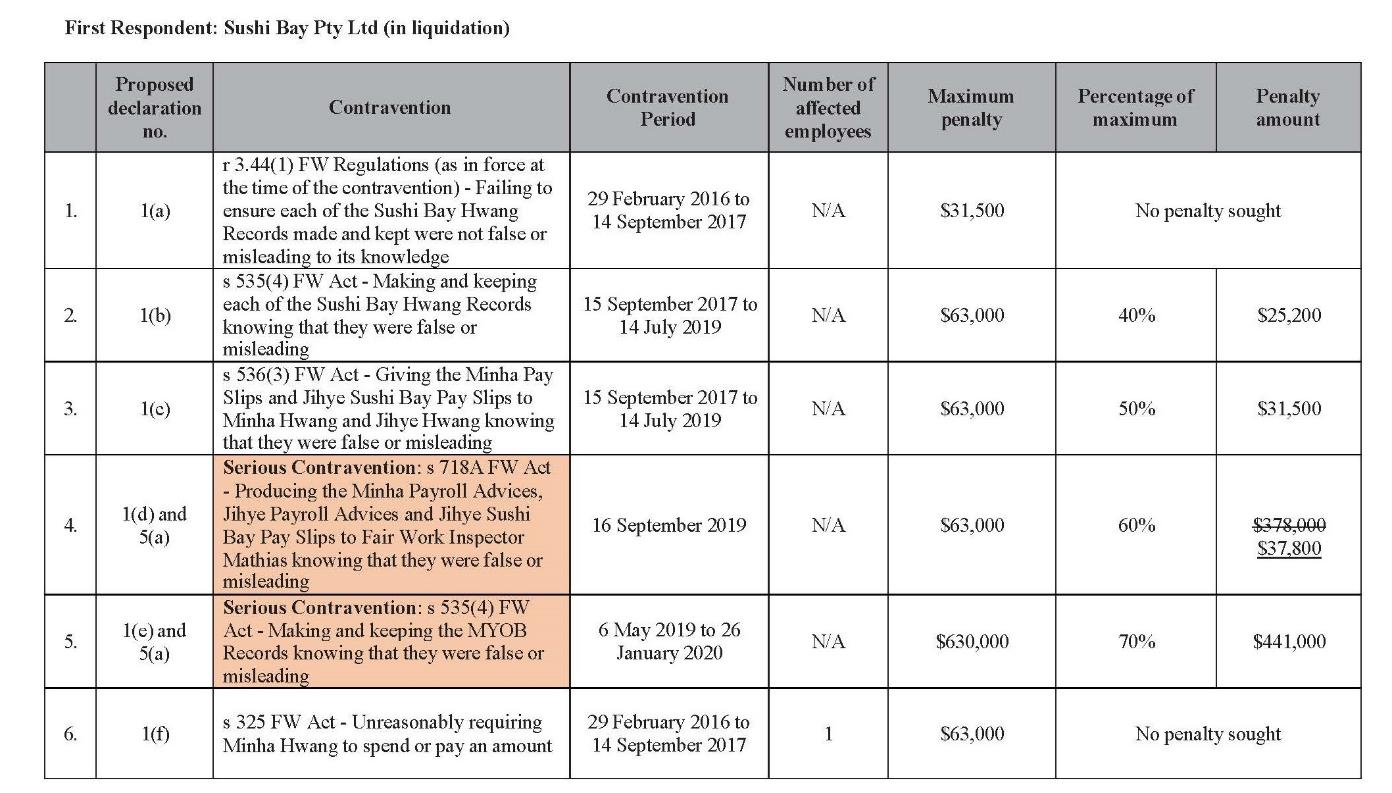

The nature, gravity and extent of the contravening conduct

43 The nature of the contraventions is evident from the declarations. The contravening conduct was serious. Nine of the 12 categories of underpayment contraventions were serious contraventions within the meaning of s 556A of the FW Act in that they were committed knowingly and the contravening conduct was part of a systematic pattern of conduct relating to one or more persons (LJ [353]; [361]-[362]). Other contraventions also met the statutory definition, including a number of the record-keeping contraventions and the contraventions of s 325. The conduct affected a total of 163 employees, representing about 73% of the Entities’ workforce, and occurred over a period of just under four years, although some of the contraventions were more confined. Of the 163 employees, 66 were employed by Sushi Bay (LJ [51]), 15 by Sushi Bay ACT (LJ [52]), 46 by Auskobay (LJ [53]) and 37 by Auskoja (LJ [55]).

44 With the exception of the contraventions relating to Minha and Jihye Hwang, which extended over the duration of the contravention period, Sushi Bay’s underpayment contraventions occurred over eight months, Sushi Bay ACT’s over a three month period, Auskobay’s occurred over three months, save for those relating to Mrs Hwang which spanned a six-month period, and Auskoja’s over eight months. The position of 24 of the 66 Sushi Bay employees (37%) was aggravated by the fact that they were also classified at a lower grade than the Award stipulated (LJ [182]-[248]). Three of the Auskobay employees and three of the Auskoja employees (7% and 8% respectively) were similarly affected.

45 The contraventions of s 325 affected 23 of the employees in the overall cohort, 20 from Sushi Bay (mostly over an eight-month period except for those affecting Mr Hwang which extended over a three-year period), and three from Auskoja over a six-month period.

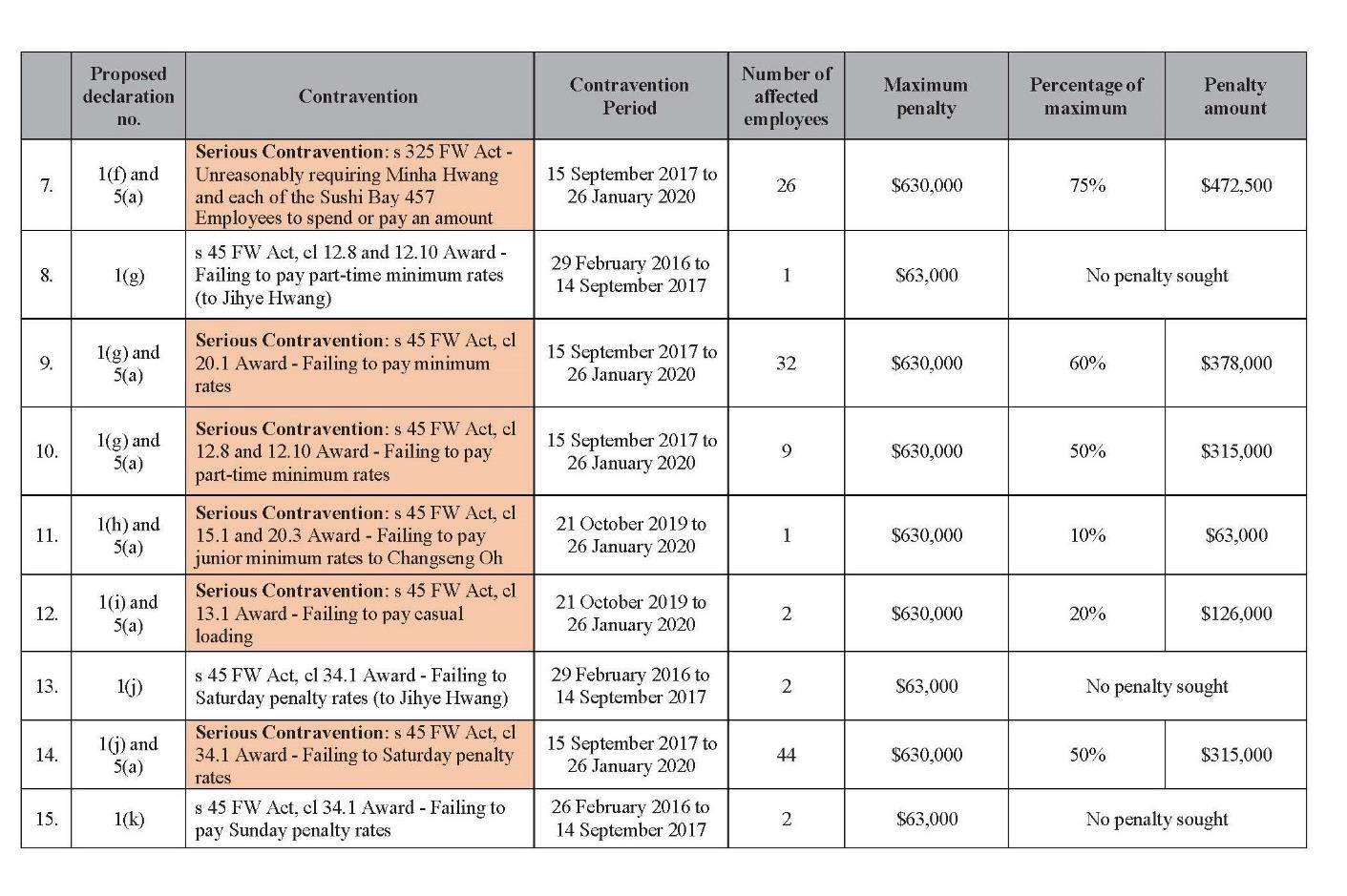

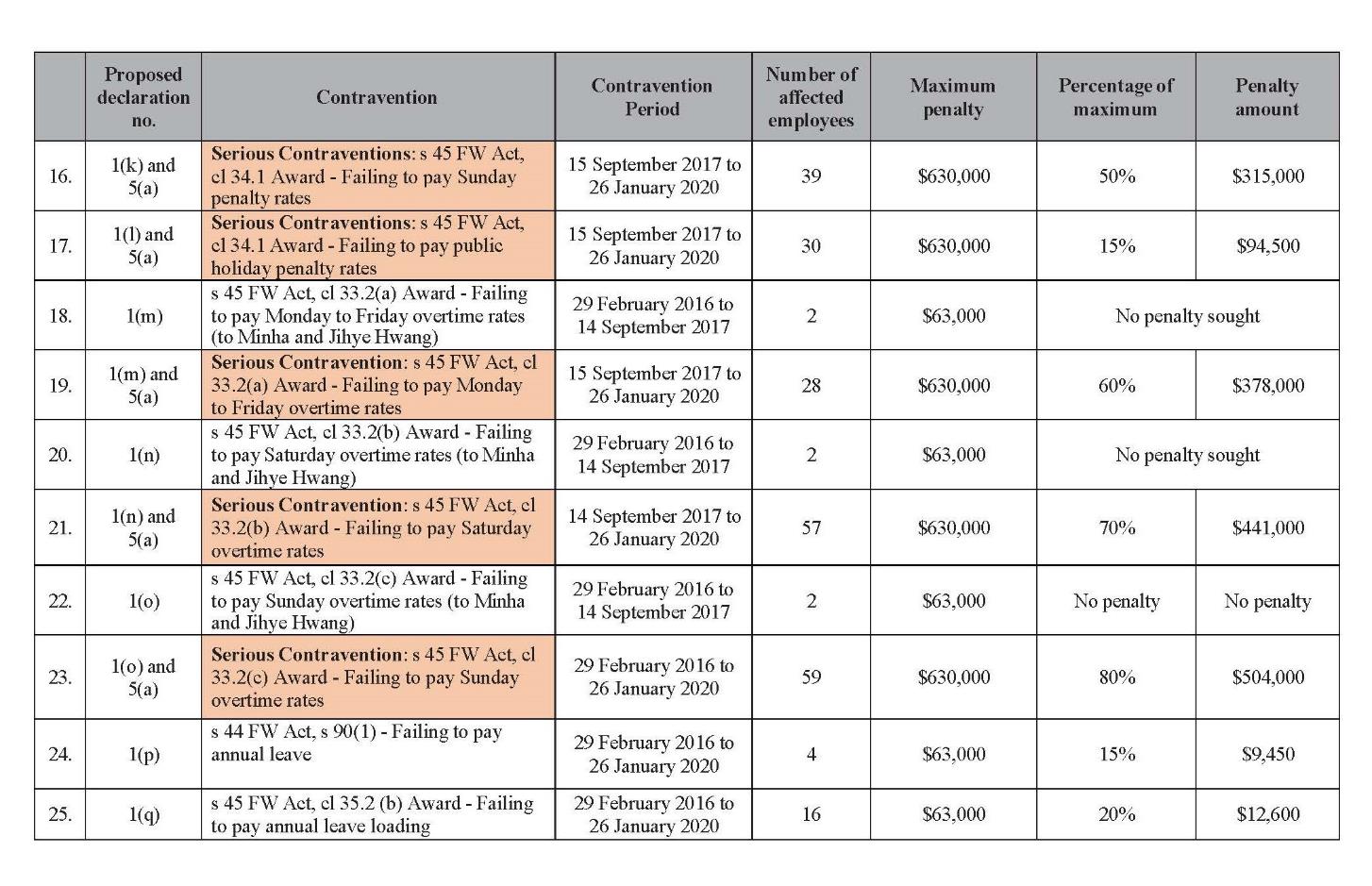

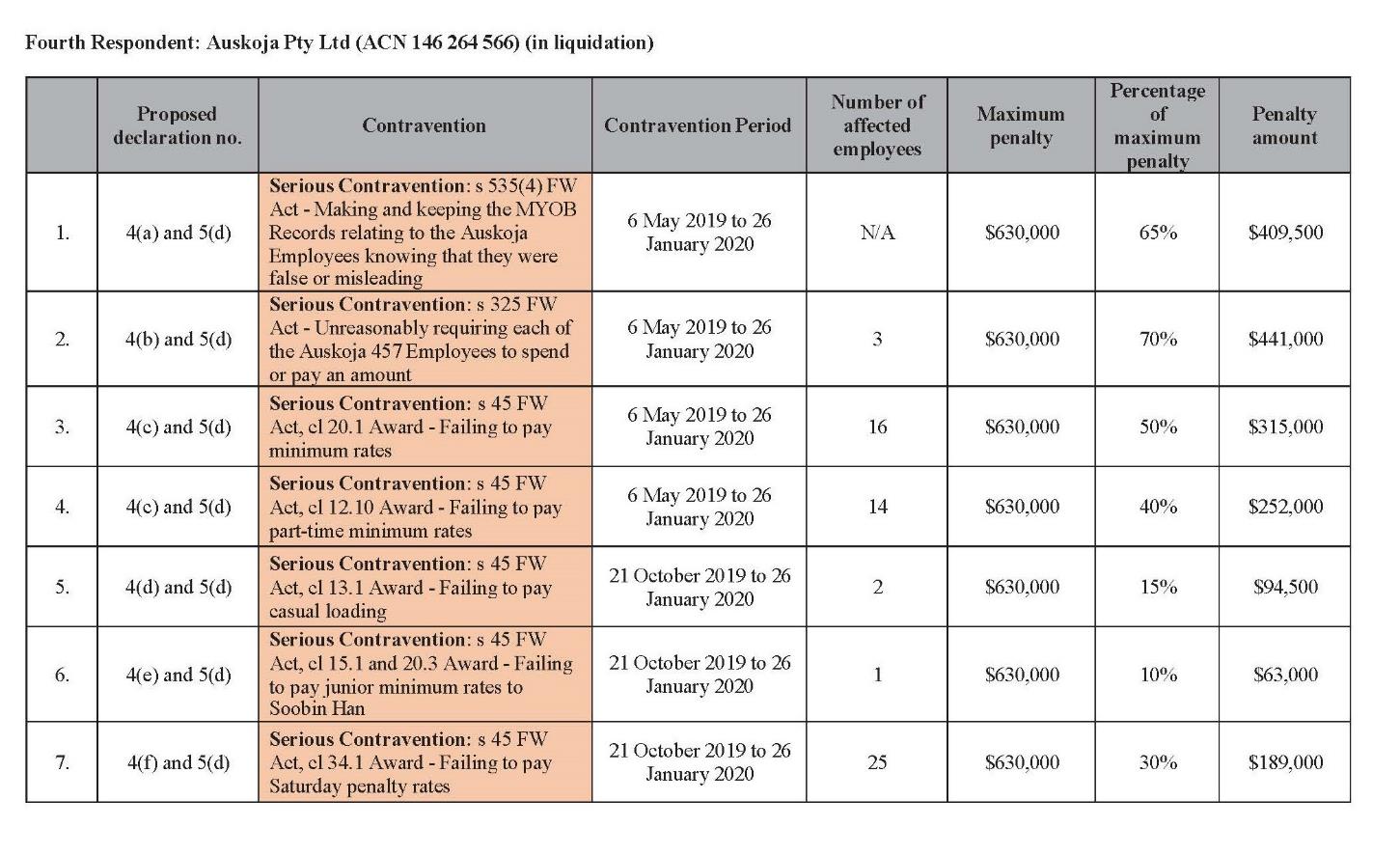

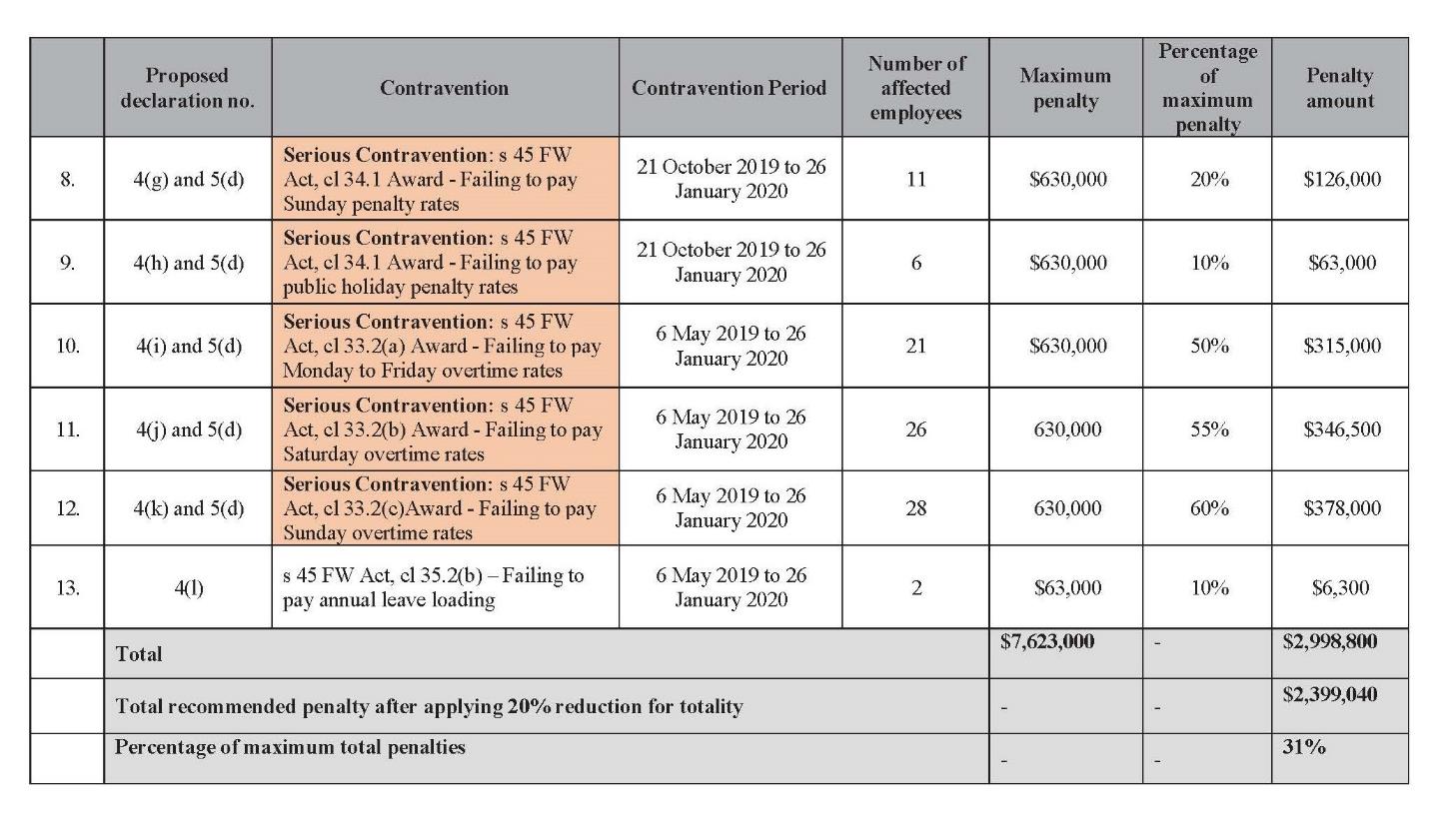

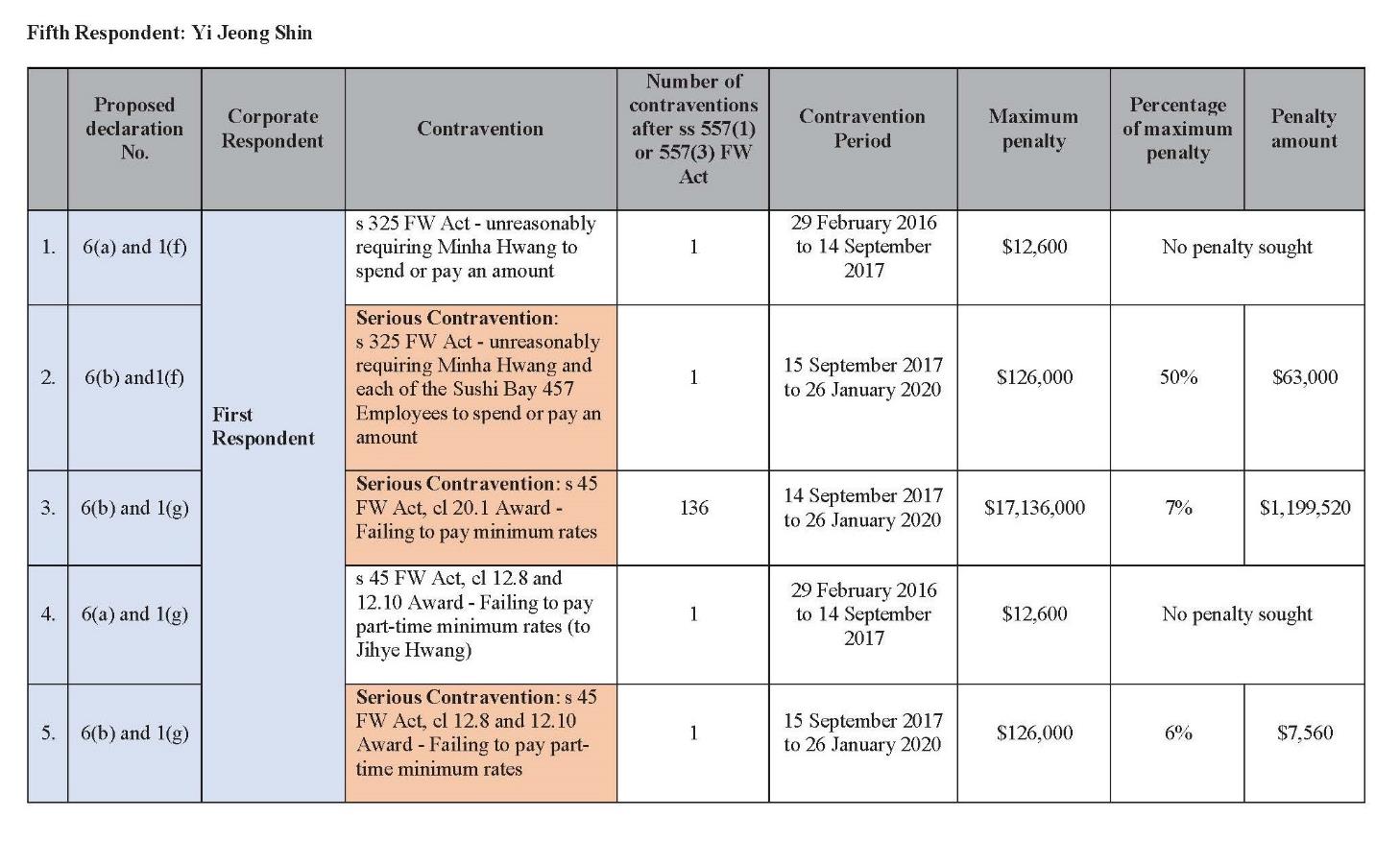

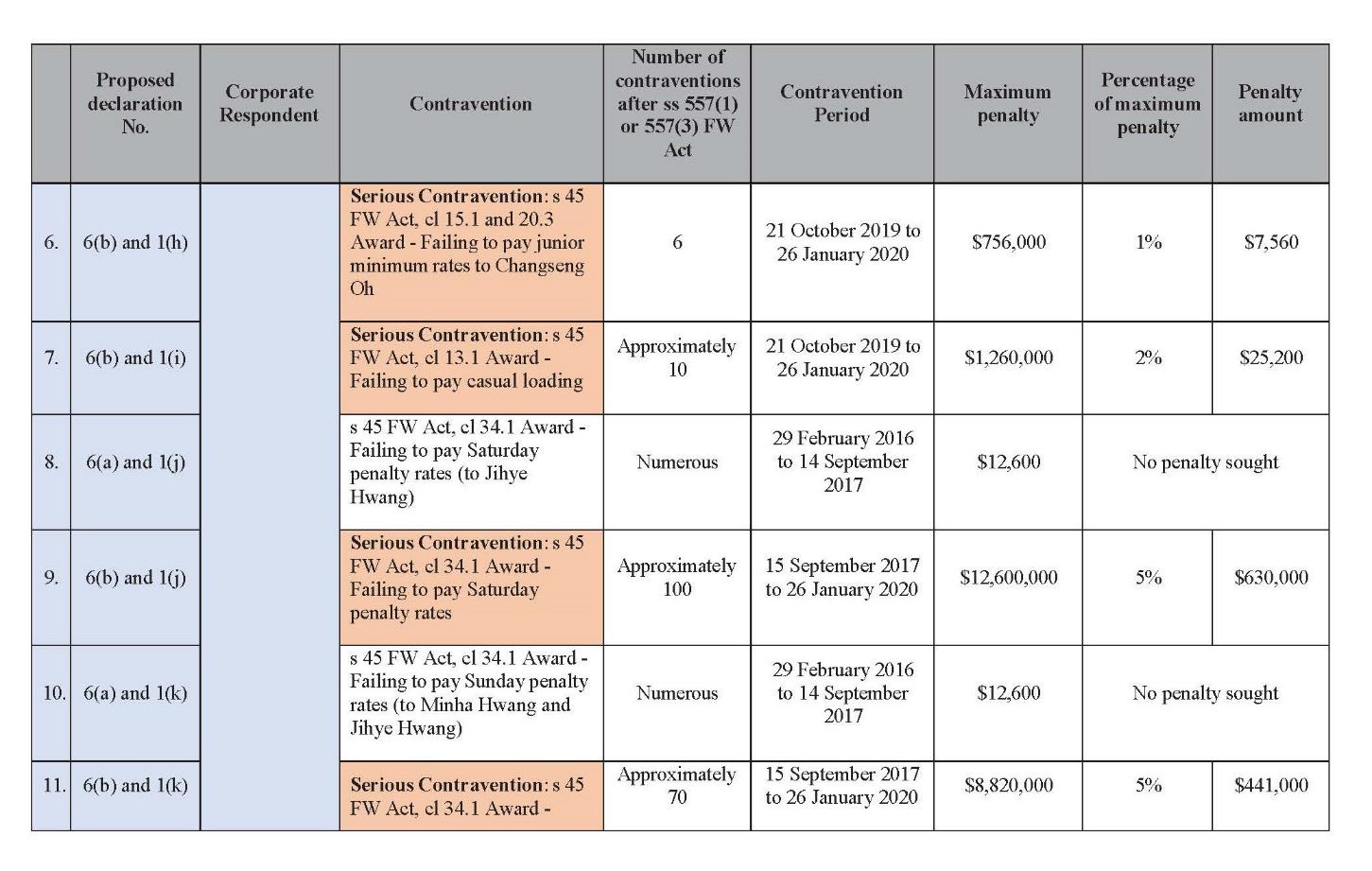

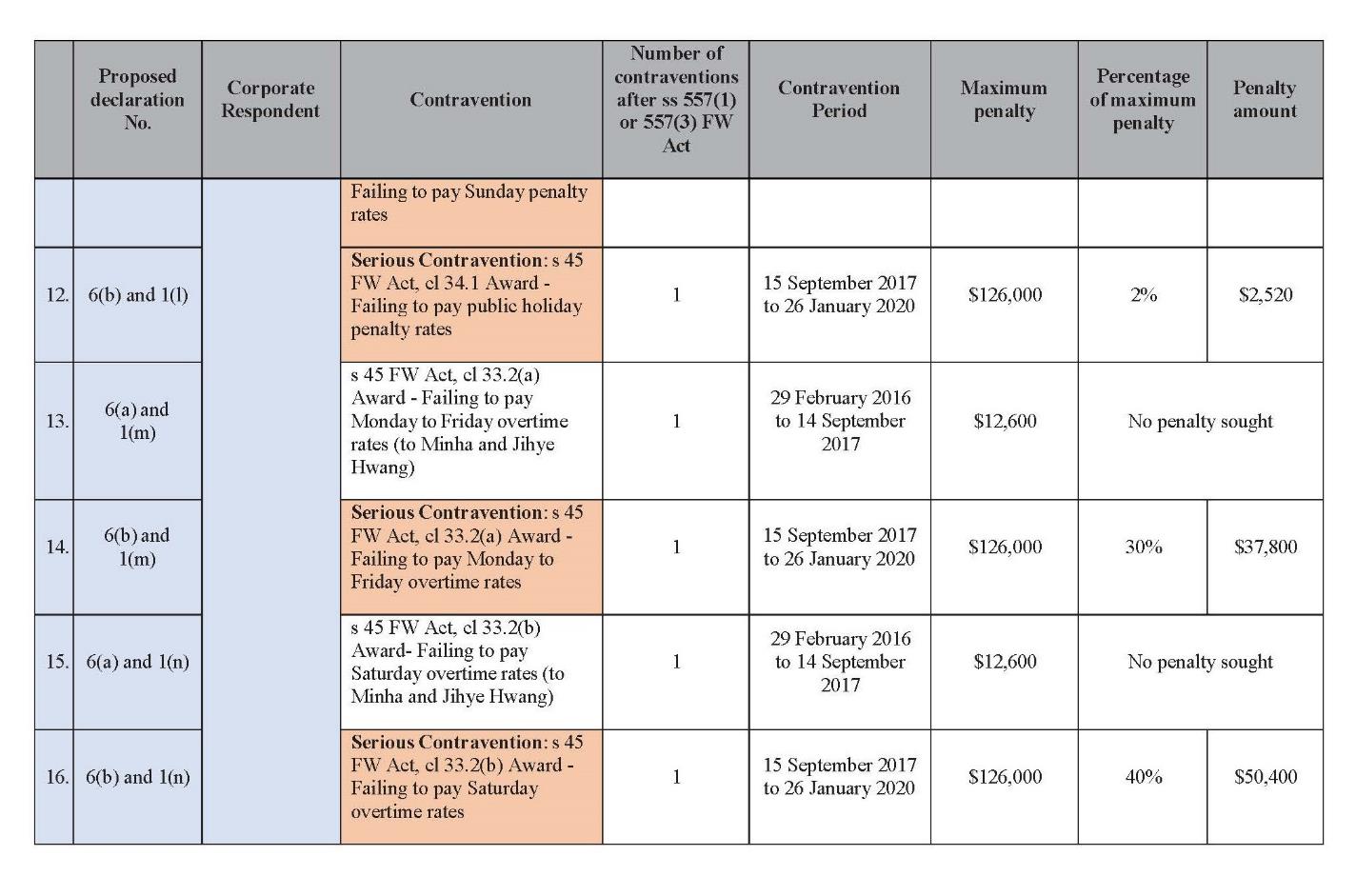

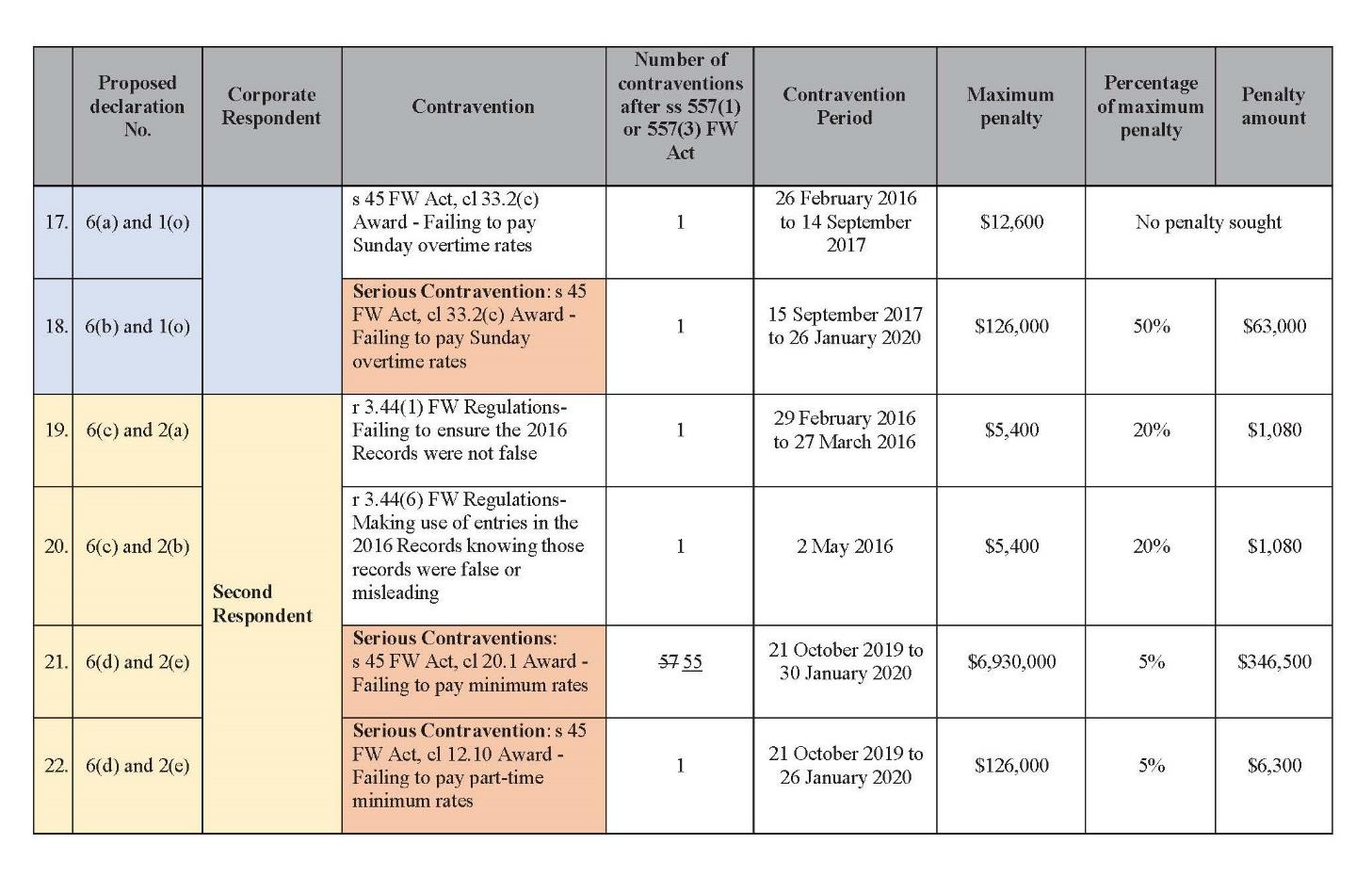

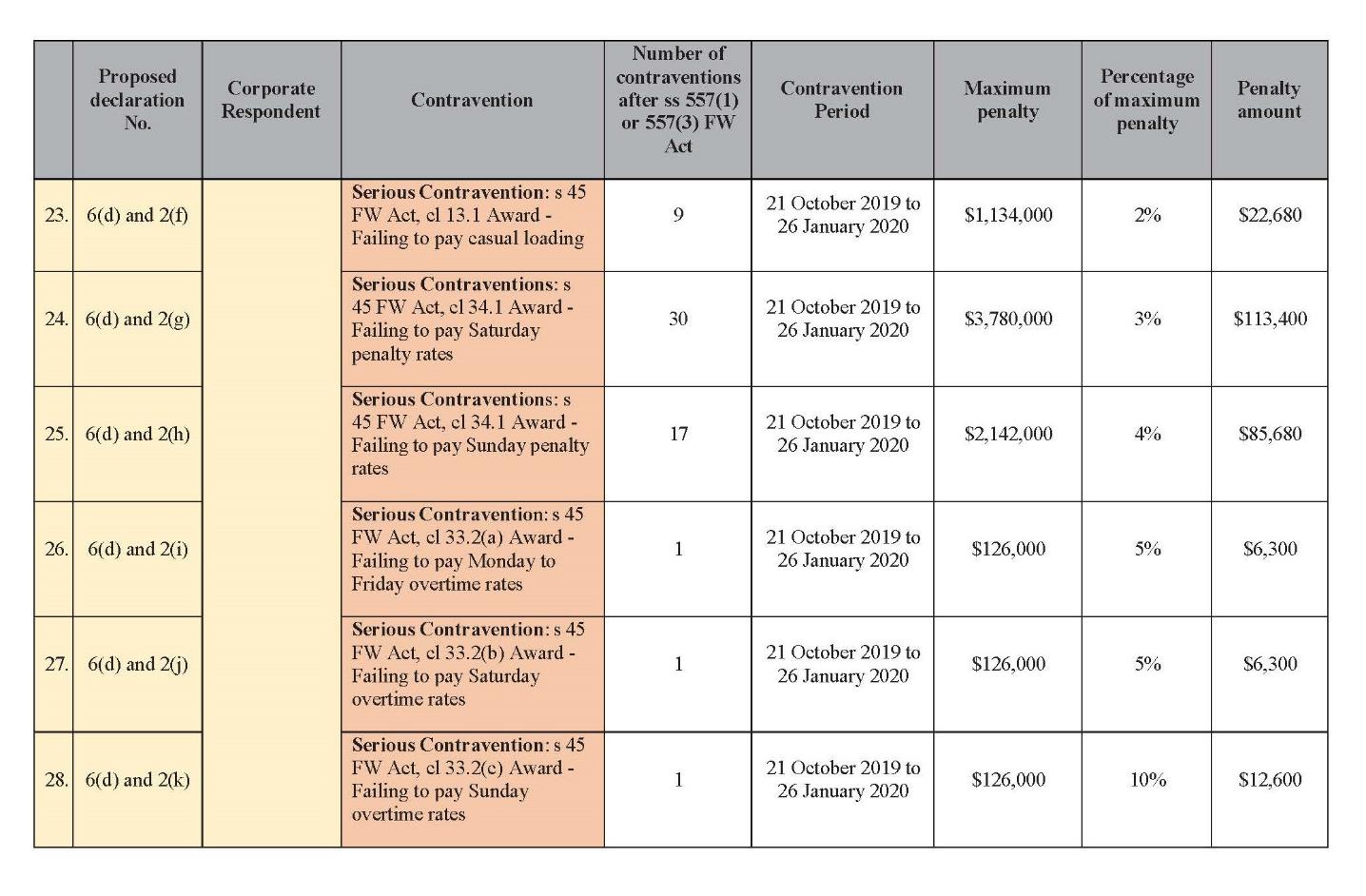

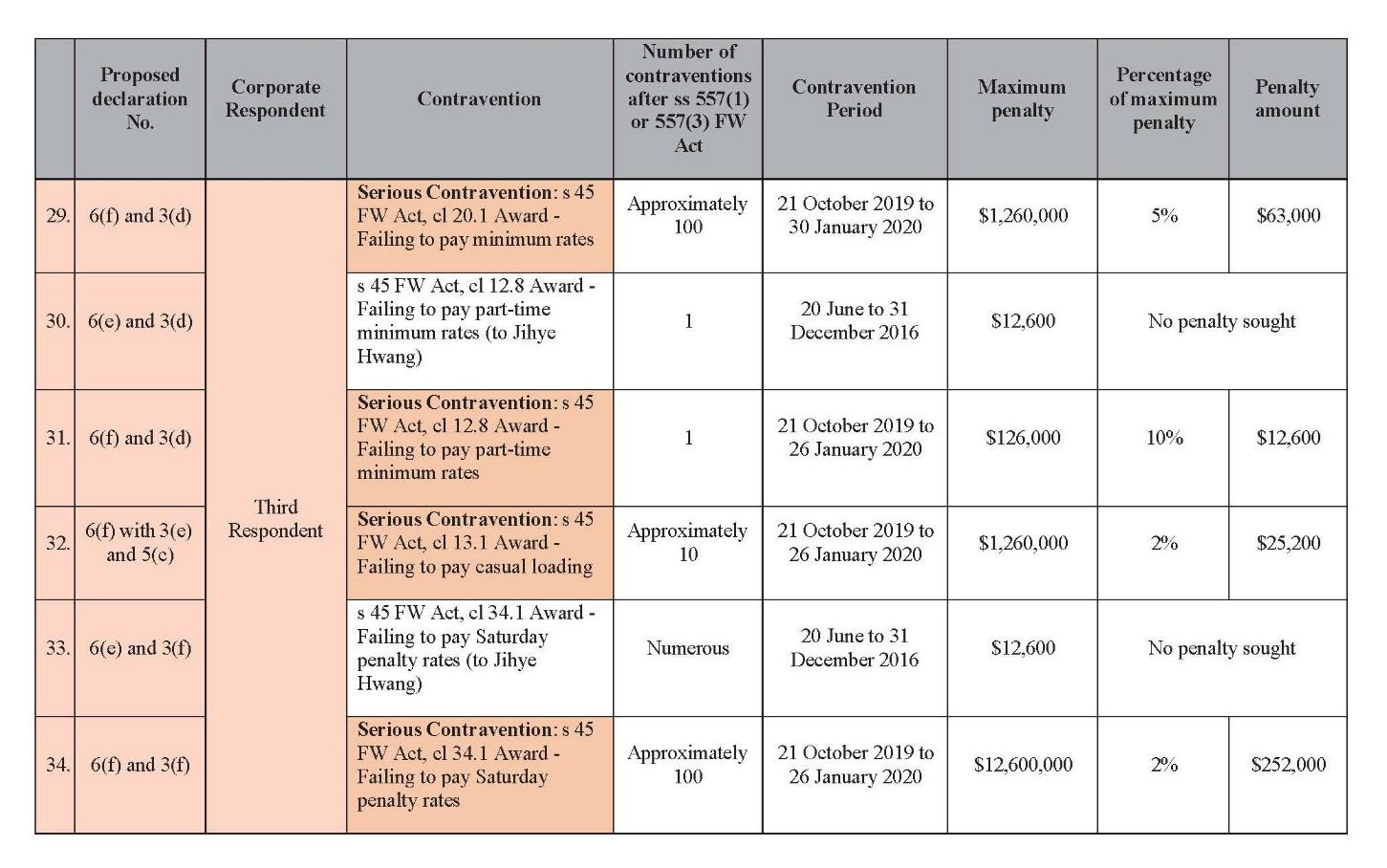

46 The number of employees affected by each underpayment contravention was identified in Annexure A to the Ombudsman’s submissions reproduced verbatim in Annexure B to these reasons. There appears to be a typographical error in item 7 of table 1 which records that 26 Sushi Bay employees were affected by the s 325 contraventions, whereas the Ombudsman claimed (and I found) that 20 employees were affected. In the absence of any submission to the contrary, I will proceed on the basis that the other numbers recorded in Annexure B are accurate. With respect to the contraventions in which the Ombudsman’s tables show “N/A” in the column headed “number of affected employees”, however, I cavil with the notion it conveys that employees were not affected by these contraventions. They are the record-keeping and pay slip contraventions and those relating to the production to a Fair Work Inspector of false or misleading documents. Contraventions of this kind affected all the employees, directly or indirectly, at least by hindering the detection of the underpayment contraventions.

47 As the Ombudsman submitted, the affected employees were highly vulnerable to exploitation. 85% of them were temporary visa-holders and a significant number (52% of the overall cohort) were under the age of 25 at least at the start of the contravention period (42% of the Sushi Bay employees, 53% of the Sushi Bay ACT employees, 63% of the Auskobay employees, and 54% of the Auskoja employees). In DTF World Square, which was a similar case, I observed at [37] that it is a notorious fact that foreign workers on temporary visas are particularly susceptible to exploitation and that underpayment was especially prevalent in food services. I referred there to the findings of the Migrant Workers’ Taskforce, chaired by Prof Allan Fels AO, reported in March 2019:

Migrant workers who are in Australia on a temporary basis may have poor knowledge of their workplace rights, are young and inexperienced, may have low English language proficiency and try to fit in with cultural norms and expectations of other people from their home countries. These factors combine to make them particularly vulnerable to unscrupulous practices at work.

Survey evidence suggests that many migrant workers are well aware that they are being paid less than they should be. Many factors may explain why they allow this situation to continue. The need to obtain and retain employment in a competitive labour market is one. People are often inclined to take what is available because they need the income or maybe feel that employment is necessary for them to achieve their ultimate goal of ongoing residency in Australia. Not knowing what to do about their underpayment or who to go to for help are other influences. Fears about the consequences of approaching government agencies are common among migrants from less democratic countries than our own. These fears will be more real in the unknown number of cases where there has not been full compliance with visa work restrictions. Also in an unknown number of cases, migrant workers may feel that they benefit from underpayment arrangements by not declaring their income to the Australian Taxation Office (ATO).

48 The Ombudsman continues to categorise the food services industry as “high risk”, with a high prevalence of low paid, young, poorly educated and migrant workers: Fair Work Ombudsman, Industry Priority Report, 2024. She considers that migrant workers and visa holders are one of the most vulnerable worker cohorts: Fair Work Ombudsman and Registered Organisations Commission Entity, Annual Report, 2018, p 17.

The circumstances in which the contravening conduct occurred

49 The circumstances in which the contraventions occurred are covered at length in the liability judgment. What follows is a summary of the findings.

50 The contraventions arose from the centralised payroll system which applied to all employees in the Sushi Bay Group (LJ [48]). Under this system, certain employees were paid pursuant to the Dual Rate Method (by which they were paid Award rates in respect of a set number of hours per fortnight and below Award flat cash rates in respect of additional hours worked) (LJ [90], [117]–[127]). Other employees, all of whom were on subclass 457 visas, sponsored by one or other Sushi Bay entity, were paid pursuant to the Deduction Method (by which, depending on the number of additional hours they worked beyond their contracted fortnightly hours, they were required to repay to their employer or, in some periods Ms Shin, part of their contractual gross fortnightly salaries) (LJ [91], [128]–[132]).

51 The purpose and the effect of both these methods was that the employees in question were paid below Award rates.

52 The distinction between “Award hours” and “cash hours” underpinning the Dual Rate Method was codified in a policy called “Calculation of Taxable Working Hours” (Working Hours Policy) and formed part of the “Operational Guidelines” for the Sushi Bay Group from 2013 (LJ [103]–[116]). They were stipulated for use in determining the ratio of taxable working hours and cash based working hours for holders of various visas, including student visas, working holiday visas, 457 or other long stay visas, and permanent resident visas. The Pay Guides, first published in 2015, provided a ready reckoner of the Award rates and the “Cash Rates”. The effect of the Guidelines was that Award rates were to be paid for ordinary hours on weekdays and the Cash Rates were to be paid for overtime and weekend work. The Pay Guides were regularly updated and the rates recorded in them approved by Ms Shin (LJ [115]–[116]).

53 As the Ombudsman submitted, the creation and maintenance of these documents shows that the overwhelming majority of the contraventions were committed deliberately and intentionally. The respondents’ conduct was both calculated and audacious. The liability judgment is replete with illustrations, such as the fact that the rates at which all employees of the Sushi Bay Group were to be paid were set out in the document entitled “Pay Guide – Restaurant Industry Award Rate & Sushi Bay Cash Rate”, which showed the applicable Award rates and the “Sushi Bay Cash Rates” alongside each other. An example of one of the Pay Guides, applicable from 1 July 2019 appears at LJ [112]. Among other things it reveals that the Award rate for a level 1 food and beverage attendant was $20.06 an hour on a weekday, $25.08 on a Saturday, and $30.09 on a Sunday and that the Cash Rate for work on any of these days was $15.00, that is to say, 75% of the rates prescribed in the Award for work on a weekday, 60% of the prescribed rate for work on a Saturday, and 50% of the prescribed rate for work on a Sunday. Slightly higher Cash Rates were to apply in Darwin. The payroll advices and pay slips created and kept by the Entities do not include below-Award payments made to any of the employees.

54 It was evident that the respondents knew that their conduct was unlawful. As I observed of the Dual Rate Method (at LJ [159]), it was obviously devised to avoid paying Award rates for all the work performed by the employees, while at the same time giving the appearance of compliance. No other rational inference is available. The same can be said of the Deduction Method.

55 Ms Shin, for example, responded to a notice to produce issued by a Fair Work Inspector in April 2016 requiring the production of “all records and documents during the period from 1 December 2015 to 31 March 2016 by purporting to produce, among other things “documents and records relating to the payment of wages” and “records of the working hours”. But the documents and records Ms Shin produced to the inspector were selective. They did not include any of the Pay Guides or Operational Guidelines. While payroll advices were produced, as I have already indicated they did not record payments for work performed on weekends or outside ordinary hours. An illustration appears at LJ [278]-[281]. In sum, Ms Shin (and therefore Sushi Bay ACT) produced false records to the inspector. Since they knew of the payroll system and had implemented it across all the Entities for years, their failure to produce the accurate records was a deliberate attempt to conceal the truth from the Ombudsman. Having succeeded in deceiving the Ombudsman in 2016, they continued with their nefarious practices until at least the end of the contravention period in 2020.

56 A particularly egregious example is discussed at LJ [287]–[296]. It is the subject of the contravention by Sushi Bay ACT of s 535(4) by making and keeping records, subsequently produced to the Ombudsman, knowing them to be false or misleading. They were records required to be made and given to the Ombudsman by order of the FCCA in June 2019. I will return to this matter shortly, but first, some context is necessary.

57 As I observed at [25] of the liability judgment, Sushi Bay had long been on the Ombudsman’s radar. The long history of the Ombudsman’s interactions with Ms Shin and the Sushi Bay Group is catalogued thereafter. They began on 24 July 2009 — some three weeks after the FW Act commenced — when the Ombudsman advised Sushi Bay, trading as Robina Sushi Bay, that it had been selected for an audit of its time and wage records. The company was found to have contravened the Workplace Relations Act 1996 (Cth), the predecessor of the FW Act, by underpaying hourly rates to three employees and directed to rectify the contraventions by taking certain action, including reviewing the weekly rates paid to all current and former staff and providing evidence of any “back payments”. In 2015 Ms Shin received a “letter of caution” in her capacity as director of Sushi Bay Qld, following an audit of its records which found that the company and each of the Entities had contravened numerous provisions of the FW Act by paying below Award rates (including by incorrectly classifying employees, paying below prescribed hourly rates, not paying penalty rates for working weekends or public holidays, and not paying annual leave loadings). They received what can fairly be described as a slap on the wrist. Each of the Entities and Sushi Bay Qld was penalised $2,550 and Sushi Bay Qld was required to “rectify the contraventions”. Ms Shin was sent a “letter of caution”, the express purpose of which was to encourage “voluntary compliance”, in which she was informed of the Ombudsman’s findings.

58 In early 2016 the Ombudsman started a “Fast Food and Restaurant Campaign” targeting employers in the ACT in the course of which she began investigating Sushi Bay ACT. That investigation culminated with the institution of the FCCA proceeding in November 2017. Apart from the orders for pecuniary penalties to which I referred above and the making of declarations as to the various contraventions, the Court ordered the company to undergo workplace relations compliance training and to arrange for the undertaking of an audit by a suitably qualified person. The terms of the declarations and orders are extracted in full at LJ [38].

59 In an affidavit Ms Shin affirmed in the FCCA proceeding in May 2018 she deposed:

I have also registered to attend a training course provided by ADP with two other managers from the management team in relation to leave entitlements. A copy of the paid tax invoice and flyer for this course is attached hereto and marked “Annexure F”.

Other corrective actions

A copy of the Restaurant Award and the Pay Guide issued by the FWO has been made available for review by the employees at Sushi Bay ACT. All employees of Sushi Bay ACT have been made aware of this and told that any queries about the contents of these documents can be directed to the Branch Manager and the management team.

I have engaged my lawyers to provide a seminar to the management team about the applicable employment laws, in particular, about the Restaurant Award and the NES. A copy of the power point slides prepared for the seminar is attached hereto and marked “Annexure G”.

I am also registered with the FWO's online learning centre. I have reviewed and shared learning materials made available by FWO with the management team.

Furthermore, I have completed the FWO's Workplace Basics Quiz online, which tested my knowledge about everyday workplace issues such as pay, leave, record keeping, and termination of employment. A copy of the certificate of completion is attached hereto and marked “Annexure H”.

60 I will have something to say about the training and other aspects of this affidavit later in these reasons. At this point, I am concerned with the audit.

61 I found that the records produced to the Ombudsman in purported compliance with the order of the FCCA (the 2019 Audit Records) were knowingly false or misleading because they recorded that the Audit Employees worked fewer hours that they in fact worked; that they did not work any overtime hours when they in fact worked overtime hours; and that they did not record the cash paid to the Audit Employees (LJ [296]).

62 Within months of the FCCA orders Sushi Bay and Auskobay also produced to a Fair Work Inspector payroll advices and pay slips in response to a notice to produce (the Hwang Records) which were false or misleading for the same reason (LJ [305]–[323]).

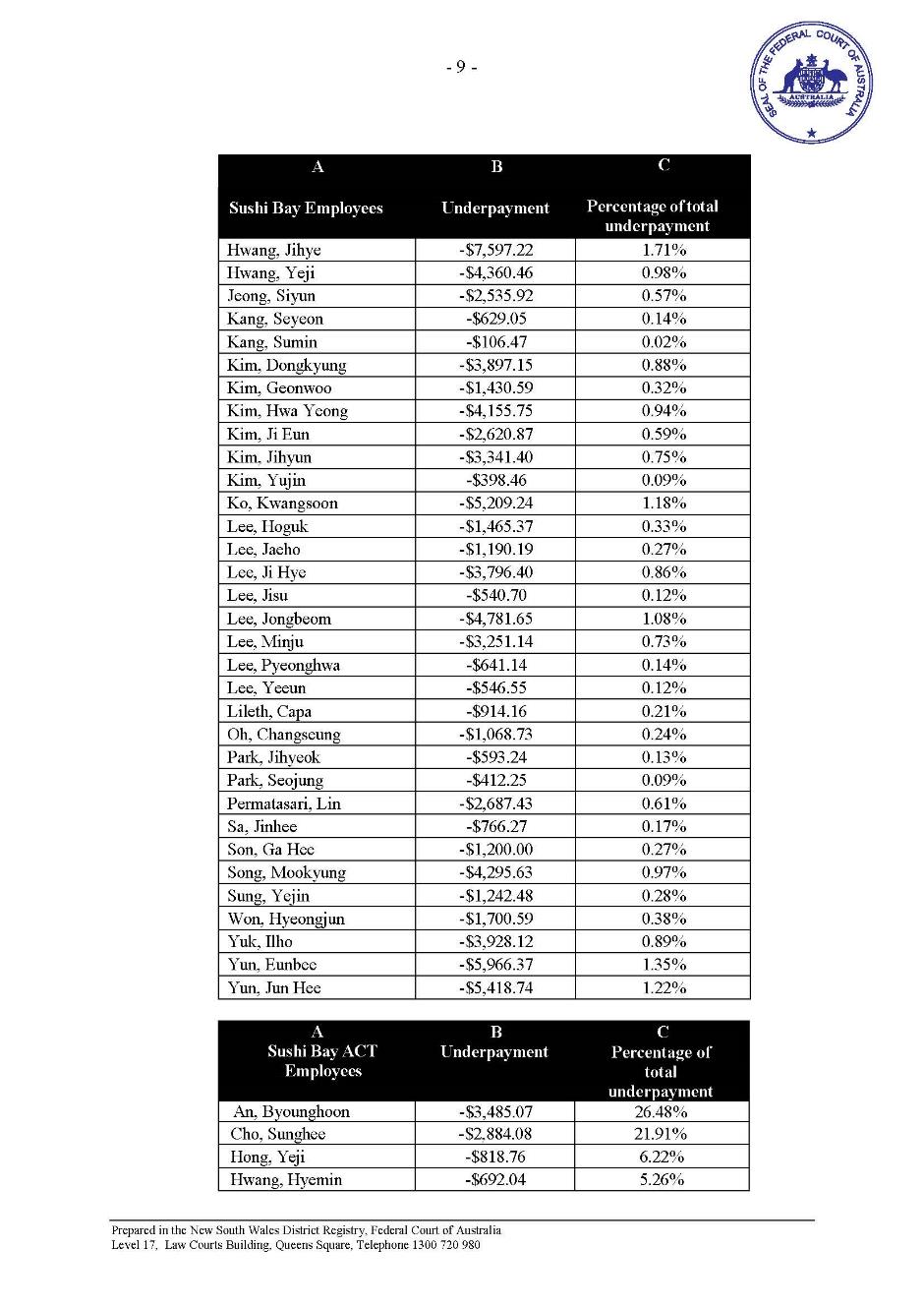

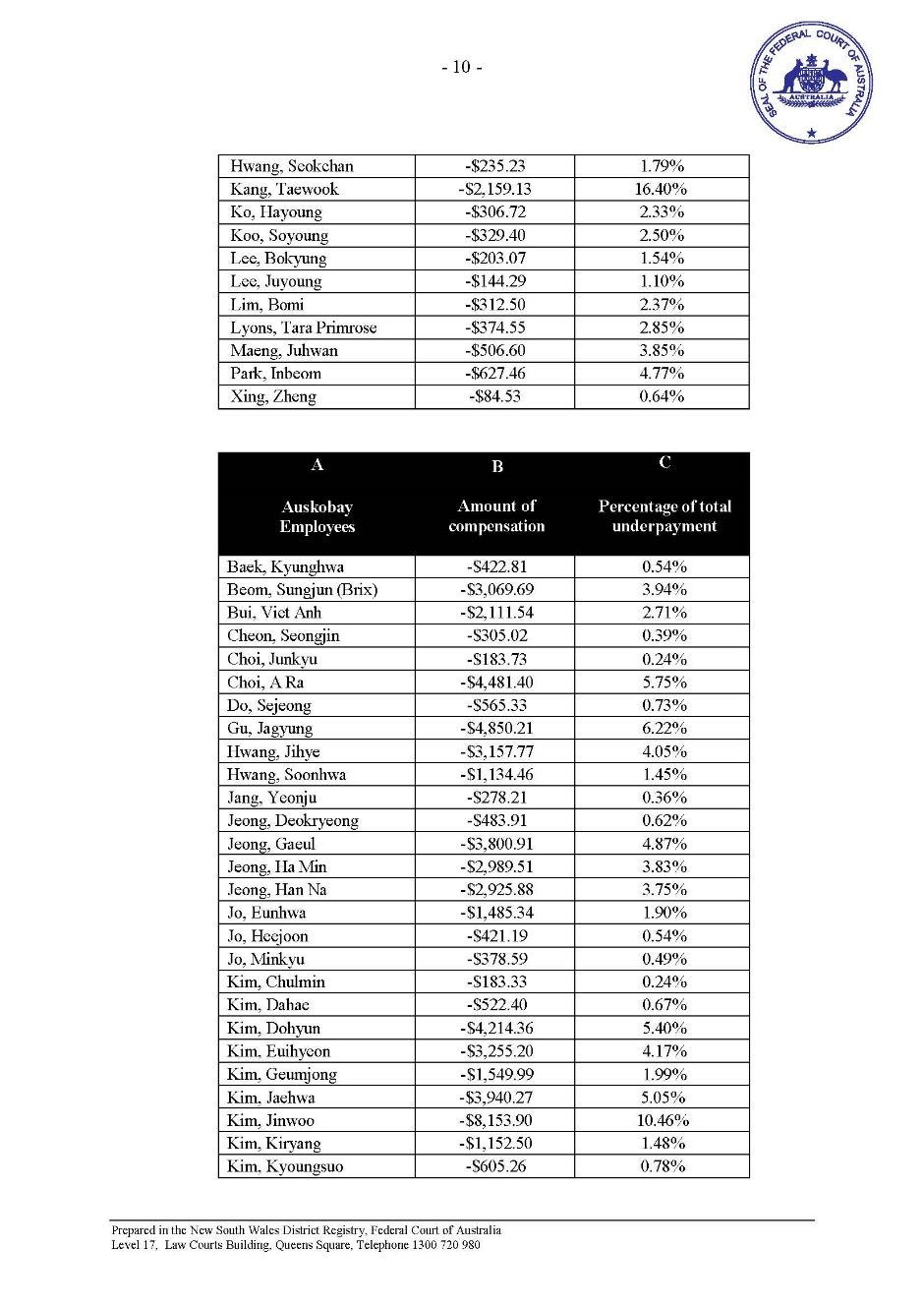

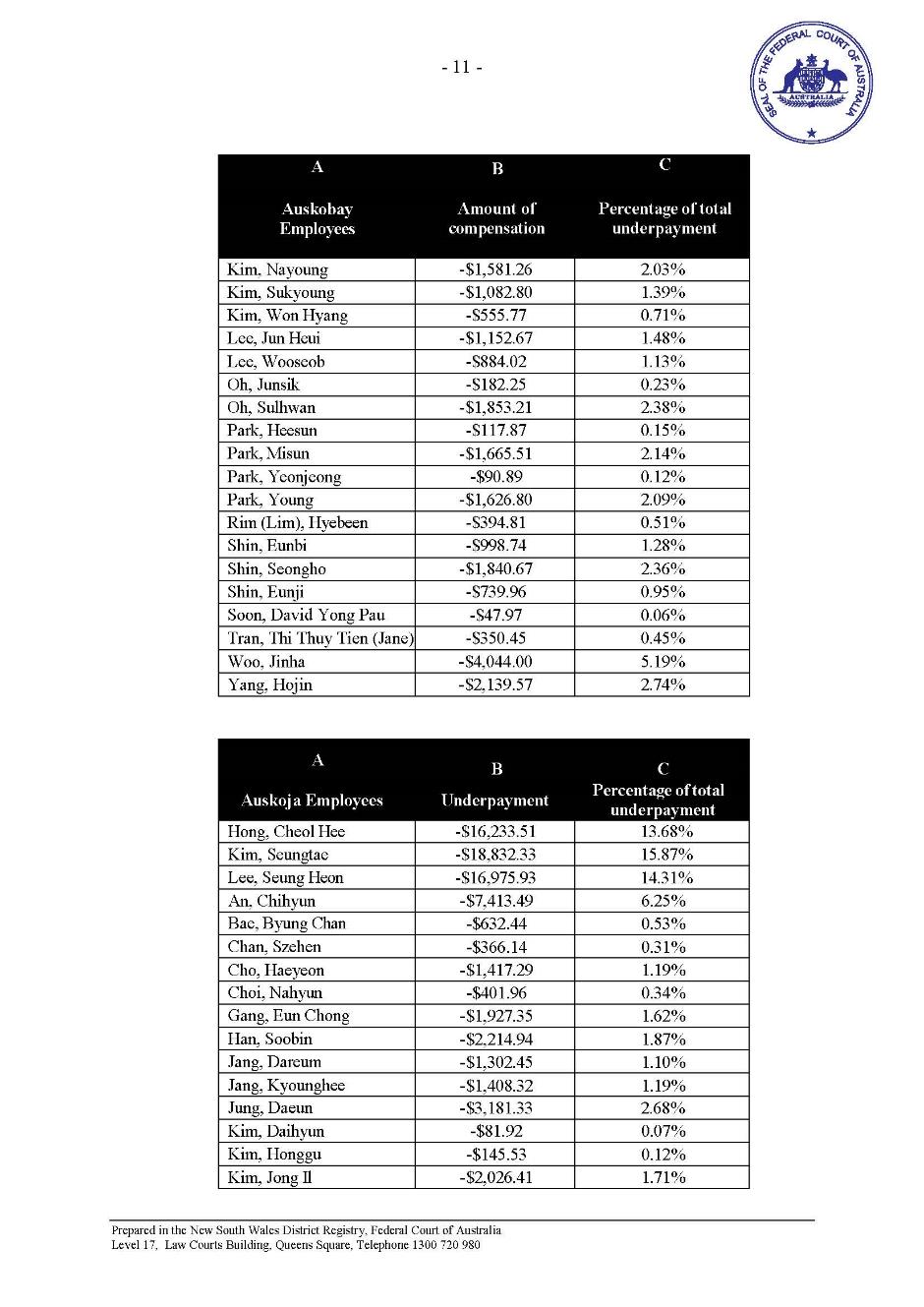

The loss or damage caused by the contravening conduct

63 In total, Sushi Bay underpaid the affected employees $443,327.39; Sushi Bay ACT $13,163.43; Auskobay $77,971.93; and Auskoja $118,667.22. The grand total of underpayments amounts to $653,129.97. Individual employees suffered losses ranging from $47.97 to $83,968.14, and which the Ombudsman submitted without contradiction ranged from between 1.09% to 73.85% of the amounts they should have been paid. In the main the losses are significant, if not substantial, for low-paid workers like the affected employees.

The size of the Entities

64 The Sushi Bay Group operated sushi restaurants in 16 locations across Australia, mostly in NSW (LJ [48]). The evidence indicates that through various companies it employed hundreds of people, but it does not disclose the size of the workforce of the individual Entities at the time of the contravening conduct or the profits they earned before they were placed in liquidation.

65 The most recent liquidator’s report to creditors discloses that none of Sushi Bay ACT, Auskobay or Auskoja has any assets and the estimated realisable value of Sushi Bay’s assets is $152,872; that Sushi Bay has liabilities of $3,714,687; Sushi Bay ACT’s liabilities are in the order of $225,000; and Auskobay and Auskoja each have liabilities in excess of $750,000. As the Ombudsman acknowledged, it is unlikely that the Entities will pay any penalties imposed upon them.

66 Size (that is to say the size of a company’s assets and income) matters when it comes to specific deterrence. It is relevant because, in the case of a large, prosperous company a very substantial penalty may be necessary to deter it from reoffending, so to speak, and a smaller penalty may be sufficient to deter a company of limited means and assets. As the Entities are in liquidation, the Ombudsman accepts that specific deterrence is not a relevant consideration in the calculation of penalties for their contraventions.

67 In Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Leahy Petroleum Pty Ltd (No 2) [2005] FCA 254; 215 ALR 281; (2005) ATPR ¶42-051 at [9], Merkel J observed that size may also be relevant to general deterrence “because other potential contraveners are likely to take notice of penalties imposed on companies of a similar size”. His Honour said that a company’s capacity to pay a penalty “is of less relevance to the object of general deterrence because that objective is not concerned with whether the penalties have been paid but with what penalty is necessary to deter others from engaging in contravening conduct of a like kind”. With respect, in view of the object of general deterrence, it is difficult to see how the size of a corporate contravener has anything to do with the need for general deterrence. Stone J observed in Secretary, Department of Health and Ageing v Prime Nature Prize Pty Ltd (in liq) [2010] FCA 597 at [22] that general deterrence is not defeated by the fact that the contravening company is in liquidation and unable to pay a penalty. I would go further. In my opinion, the need for general deterrence is neither defeated nor diminished by the fact that a contravener is unable to pay a penalty.

Ms Shin’s financial position

68 In her affidavit Ms Shin intimated that she was in a parlous financial position and had no capacity to pay a substantial penalty.

69 Under the heading “Personal Impact and Capacity to Pay”, she deposed to the following matters. She provided a personal guarantee on all the leases of the restaurants in the Sushi Bay Group, amounting to some $1.5 million, some of which have been called upon and she expects that the others will be called upon in due course. Since “mid-2022” the Australian Taxation Office has issued her with “a series of Director Penalty Notices” to the value of $1,664,620.80, “in respect of the tax liabilities of the Sushi Bay Group and other companies”. In August 2022 she and her husband sold their family home in Ryde for approximately $4.9 million and used the proceeds to discharge a number of debts in the sum of $3.4 million, “including a debt owed to National Australia Bank Ltd in respect of a consolidated loan for the business as guarantors”. She received $750,000 from that sale, being “50% of the value of the property which was used to discharge debts for the Sushi Bay Group and to operate the business”. The remaining 50% was provided to her husband to discharge his debts. She is a discretionary beneficiary under The Shin Family Trust, but since “approximately 2019” the trust has made no distributions to her. No documents were annexed or exhibited to the affidavit to corroborate or support these assertions.

70 Ms Shin submitted that specific deterrence was unnecessary in her case, as she “is likely to go bankrupt and therefore will not be able to be a director of a corporation”, and that the proceeds of the sale of her family home in August 2022 have been exhausted to discharge “a number of debts”.

71 Notwithstanding what she said in her affidavit, I do not accept Ms Shin’s submissions. Ms Shin has a history of dishonesty. Moreover, the evidence adduced by the Ombudsman in reply and the cross-examination disclosed that her affidavit did not contain a full and frank account of her financial situation. Without full disclosure of her assets, liabilities and income and a proper assessment of her capacity to pay her debts as and when they fall due, I cannot conclude that she is likely to “go bankrupt”: see Bankruptcy Act 1966 (Cth), s 5(2) and (3). A person is not insolvent merely for want of immediate access to cash to pay off debts: Lo Pilato v Kamy Saeedi Lawyers Pty Ltd (2017) 249 FCR 69 at [162]-[166] and the cases referred to there.

72 While Ms Shin’s evidence was that she received no distributions from the Family Trust after 2019, evidence adduced by the Ombudsman in reply shows that she continued to receive income from the trustee, Raphael Shin Enterprises Pty Ltd (RSE), for work performed as a director of the Family Trust in the 2021 and 2022 financial years. Her personal income tax return for the 2021 financial year represents that she received salary or wages of $124,702 for employment as “director – managing”. In the 2022 financial year, her personal income tax return represents that she received salary or wages of $54,033 from the trustee, also purportedly for work performed as managing director. In cross-examination, she accepted that she continued to receive income from RSE in those financial years, and testified that, despite ceasing to be a director of RSE in February 2020, the income was for services rendered (unhelpfully described as “helping my husband with what he was doing”). When it was put to her that it was misleading to have said in her affidavit that she received no distributions from the Family Trust after 2019, given that she had received other income from the trust since then, she responded, somewhat evasively: “I did receive money from the family trust [but] you can’t say they were distributions from the trust”.

73 More significantly, other evidence adduced by the Ombudsman shows that Ms Shin and her husband provided a loan of over $4 million to the Family Trust, which she failed to disclose in her affidavit, which has not been repaid, and which, as she reluctantly acknowledged, she can call on to be repaid in full at any time.

74 The evidence about the loan to the Family Trust emerged from documents produced on subpoena on 17 April 2024 (a week after Ms Shin’s affidavit was filed), annexed to FWI McArthur’s second affidavit filed in reply. They include the financial statements of the Family Trust. The financial statement for the 2018–19 financial year records that Ms Shin and her husband provided an unsecured loan to the Family Trust of $4,001,998 and the subsequent financial statements do not record any repayment, total or partial.

75 No evidence was adduced to indicate the purpose of the loan.

76 Ms Shin accepted in cross-examination that she and her husband made that loan to the Family Trust. The timing of the loan is suspicious, as is Ms Shin’s failure to disclose it. As the cross-examination did not explore the question of timing, I shall say nothing more about it. Ms Shin’s failure to disclose it reflects adversely on her credit. So, too, do many of her answers to counsel’s questions on that matter in cross-examination.

77 When Ms Shin was asked in cross-examination whether the loan had been repaid, she claimed that she could not remember. When it was put to her that she would remember whether a loan of $4 million had been repaid, Ms Shin replied that, “from memory”, it was not repaid in “one big lump sum” but that she thought it had been “repaid bit by bit”, then conceded that “that might not have been the accurate answer”. She was then taken to financial statements for the Shin Family Trust for the financial years ending in 2019, 2020, 2021, 2022 and 2023. As Ms Shin conceded in cross-examination, those financial statements show that, at least until the end of the 2023 financial year, the loan had not been repaid. When she was asked whether she had provided any other loans to the Family Trust, she professed not to remember.

78 Ms Shin’s evidence that she could not remember whether the loan had been repaid is implausible. Not only do the financial statements indicate otherwise, she did not point to any other evidence to indicate that any repayments have been made.. In the circumstances, I conclude that the loan has not been repaid.

79 Ms Shin’s personal taxable income in recent financial years has not been particularly high. As she conceded in cross-examination, however, Ms Shin she is able to call on the Family Trust to repay the $4 million.

80 Other documents obtained by FWI McArthur after Ms Shin’s affidavit was filed and which are also annexed to her affidavit in reply shows that the Family Trust is a discretionary trust, and that Ms Shin and her husband are the only beneficiaries. They also reveal that the Family Trust owns a number of assets, including real estate comprising at least five properties, four in New South Wales, one in Queensland, and seven motor vehicles, three of which are luxury vehicles. Title searches undertaken by the Ombudsman show that on 11 March 2024 all the properties were unencumbered.

81 According to the financial statements of the Family Trust for the financial year ending 30 June 2023, the total value of the five properties is $2,640,000. A report concerning RSE, lodged with the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) on 28 May 2021 by controllers appointed to one of those properties and two others not mentioned in the 2023 financial statement, shows that the $2,640,000 figure reflects the total amount RSE paid for the properties at the times of purchase (from 2003 to 2015). The controllers’ report, on the other hand, which was verified by Ms Shin’s husband, Raphael Shin, shows that the combined asset value of those properties in May 2021 was $26,850,000 — more than 10 times the amount recorded in the most recent financial statement. Even assuming the properties not mentioned in the 2003 financial statement were sold between May 2021 and June 2023, it is highly unlikely that the values recorded in the 2003 financial statement are correct. It is notorious that real estate values in Australia do not remain static.

82 FWI McArthur’s investigations also revealed that the purchaser of the family home was Ms Shin’s son, Sol. Despite the sale, Ms Shin’s affidavit records the address of the family home as her place of residence.

83 In her written submissions in chief, the Ombudsman argued that it was “significant” that on 31 August 2022 (six weeks after the pleadings closed and several months before the Entities went into liquidation), Ms Shin and her husband transferred ownership of the family home to their son for $4.9 million. Ms Shin, on the other hand, submitted that the transfer was irrelevant to the question of penalty, pointed out that the Ombudsman did not submit that the transfer was improper, and argued that there was no basis for the Ombudsman’s argument in any event because, as she said in her affidavit, the transfer was made to discharge a number of debts and the proceeds of the sale have been exhausted. These matters were not explored in cross-examination and the Ombudsman said nothing more about the matter either in writing or orally.

84 As I said in DTF World Square at [94], “a relatively small penalty might operate as a deterrent for a person of modest means who has not previously offended, so to speak”. But I am far from satisfied that Ms Shin is a person of modest means or that she lacks the capacity to pay a substantial penalty, such as one in the order of that which the Ombudsman seeks. What is more, Ms Shin has form. She is not a first offender.

The involvement of senior management

85 In the liability judgment I found that a number of senior managers, from the top down, were involved in the contraventions. In addition to Ms Shin, they were Phillip Kim (who gave evidence for the Ombudsman), the Human Resources and Management Team Manager; Daniel Oh, the Chief Operational Officer (at least until July 2017); Sol Shin, the Chief Operational Officer who replaced him; and Joseph Lee, the Chief Administrative Officer.

86 Ms Shin submitted that the Ombudsman elected not to bring proceedings against any of the other senior managers, who were also involved in the contraventions, and that the Court should be mindful, when imposing a penalty on her, to take into account their involvement and the fact that the contraventions were not solely referable to her conduct.

87 There are a number of difficulties with this submission.

88 First, as the Ombudsman submitted, the relative culpability with other individuals who were not sued is irrelevant to the question of the penalty to be imposed on Ms Shin.

89 Second, it is unlikely that the contraventions would have occurred but for her authorisation of the processes which generated them.

90 Third, as the Ombudsman put it, Ms Shin was a key actor in bringing about the contraventions. The extent of her involvement is discussed at length in the liability judgment at [391]-[416]. In particular, I found at [395] that:

Ms Shin was the only person who had final authority to make decisions about the operations, policies, and practices that were applied across the Sushi Bay Group. She had ultimate responsibility for all wage and expense-related decisions. This included setting employees’ rates of pay and the operation of the payroll system on the basis of the Dual Rate Method and the Deduction Method. In particular, Ms Shin approved the policy of applying the “pay back condition” in respect of the 457 Employees. She was the only one with authority to sign documents to be sent to the Department of Immigration. Important decisions regarding wages, vacancies, contracts, and pay rates had to be discussed with Ms Shin. For example, before the end of each financial year, Mr Kim sought Ms Shin’s approval to update the pay rates, specifically the “taxable” and “cash” components of employees’ wages. The 2017 Operational Guidelines expressly required CEO approval in reviewing wages and bonus payments. Ms Shin approved the Pay Guides which prescribed the different rates to be paid for Award laid down in the Operational Guidelines that was used by the corporate respondents to calculate the amounts paid to employees for different hours work. Ms Shin had the final say on the contents of the Operational Guidelines, Hours and Cash Hours respectively. Ms Shin also approved the Working Hours Policy laid down in the Operational Guidelines that was used by the corporate respondents to calculate the amounts paid to employees for different hours work. Ms Shin had the final say on the contents of the Operational Guidelines.

91 In her affidavit Ms Shin deposed that, due to her “many business commitments”, she relied heavily on the management team, including, specifically, Phillip Kim to ensure that there was compliance with the relevant industrial laws.

92 I cannot accept this evidence. While the evidence did not establish that she devised the Dual Rate Method and the Deduction Method or did so single-handedly, it did establish that she endorsed them and required their implementation. She did not rely on Mr Kim to ensure compliance with the law. She relied on him to avoid compliance and to conceal non-compliance. And she did so throughout the contravention period. In cross-examination she admitted that compliance with industrial laws could not be achieved where employees were being paid less than Award rates.

93 In cross-examination it was put to Ms Shin that she intended that the employees the subject of this proceeding would not be paid at Award rates for all the hours they worked. Her initial response was evasive:

I think you can draw your conclusion based on all the evidence or documents that I submitted for these proceedings, and you can have your conclusion.

94 When she was directed to answer the question, she replied:

I can’t say that I didn’t have an intention to pay them properly.

95 Ms Shin claimed she only learned her employees were not being paid Award rates during or following (it is not clear) the Ombudsman’s investigation of Sushi Bay ACT and intimated that she then told her management team “so that they can change their practice”. She claimed she took steps to educate and correct managers on workplace laws to make sure that contraventions did not occur again.

96 I reject both contentions. I reject the first because Ms Shin knew of the Working Hours Policy, which codified the distinction between Award and Cash Hours, and which was in operation with her approval throughout the contravention period. In cross-examination she accepted that she knew that the relevant employees were being paid “cash rates” and that the cash rates were below the Award rates. As to the second, in her May 2018 affidavit filed in the FCCA in the earlier proceeding, Ms Shin deposed that she had used her best endeavours to rectify all contraventions identified by the Ombudsman. Yet she admitted in cross-examination that at the time she affirmed that affidavit she knew that Sushi Bay ACT and the three other Entities were underpaying employees and that other contraventions were occurring. When it was put to her that she did not take steps to educate and correct managers on workplace laws to make sure that contraventions did not occur again, she replied:

I talked to them many times, and I educated them. However, but I think that drove a wedge between me, myself, and my management team, because I was the attitude of just make changes quickly. But the management team, considering what was happening industry-wise, if they made sudden changes they thought it would be difficult to find employees.

97 The first sentence is so vague as to be of no probative value. The rest of the answer is barely intelligible and on the face of things, irrational.

98 When it was put to her that, as the CEO and sole director of the Entities at the time of the contraventions, if she wanted employees to be paid Award rates she could have done that, she gave the following contradictory response:

Yes … but I was – I was not capable of doing so.

99 I asked Ms Shin what steps she took to educate her managers. Her reply was non-responsive:

There was education centre at the Fair Work Ombudsman office where they educate these things about award, which was requested by Fair Work Ombudsman’s office.

100 When pressed to answer the question, she replied that at the request of the Ombudsman’s office she and her management team attended an education session there. What, if anything, she said to her management team about changing the practices remains a mystery. In view of her non-responsive answers, the lack of detail and other problems with the responsive answers, and the continued application of the Dual Rate Method and the Deduction Method after the May 2018 affidavit was affirmed, I conclude that she did not give her management team any instructions to change their ways, let alone take appropriate steps to ensure compliance with the law. I am fortified in reaching this conclusion by Ms Shin’s unexplained failure to adduce evidence from any of the managers, not even her son, and I infer that nothing any of them could have said would have assisted her case: Jones v Dunkel (1959) 101 CLR 298 at 308 (Kitto J), 312 (Menzies J) and 320–321 (Windeyer J); Kuhl v Zurich Financial Services Australia Ltd (2011) 243 CLR 361 at [64] (Heydon, Crennan and Bell JJ).

The corporate culture

101 The corporate culture in the Entities was far from conducive to compliance. It was calculated to achieve non-compliance.

Cooperation with the Ombudsman

102 Ms Shin submitted that she cooperated with the Ombudsman by responding from time to time to correspondence and notices (by which I presume she means notices to produce); entering into an agreed statement of facts in this proceeding and the FCCA proceeding; engaging with the Ombudsman during this proceeding; informing the Ombudsman that she did not intend to appear at the liability hearing; and by the admissions made by the Entities in their defences.

103 I was not impressed by this submission. Cooperation was minimal.

104 I reject the proposition that responding to statutory notices is evidence of cooperation. As the Ombudsman submitted, she was legally obliged to do so. In any event, the foundation for the contraventions of reg 3.44(6) was Ms Shin’s use of entries in employee records produced in response to such notices which she knew to be false or misleading: LJ [272]–[273]; [282]-[284]; [398]-[401]. That conduct had the potential to interfere with the investigation. It is the antithesis of cooperation.

105 Neither is failing to appear at the liability hearing evidence of cooperation. The Ombudsman was still required to prove her case against both her and the Entities. And while Ms Shin did enter into a statement of agreed facts, she made few admissions about her involvement in the Entities’ contraventions (see LJ [391]).

106 Entering into a statement of agreed facts in the FCCA proceeding is irrelevant for present purposes.

107 As FWI McArthur’s evidence discloses, when Ms Shin was invited to cooperate with the Ombudsman by participating in voluntary interviews in 2019 and 2020, she declined to do so. While she was within her rights to decline to participate in an interview, that is evidence of non-cooperation. Its effect was to cause the Ombudsman to expend resources which might otherwise have been deployed elsewhere.

108 Had Ms Shin been truly cooperative, she would have participated in interviews as requested, made admissions on behalf of the Entities before they went into liquidation, and admitted to her own involvement at the earliest opportunity.

The extent of any contrition and corrective action

109 There is no evidence to suggest that any corrective action was taken. The employees remain unpaid.

110 Ms Shin claimed to be contrite. She deposed:

I am extremely embarrassed that I have allowed this situation to arise and to continue following the 2019 proceedings. Although I did not have control of the entire process, I accept as the director that I have ultimate responsibility for what occurred. However, at no stage was it intended that workers would be worse off, from a net position than if paid under the Award. The Sushi Bay Group was always short of qualified employees and therefore had to ensure the workers were paid an amount that made it attractive for them to work in the Sushi Bay Group.

I wish to express that I am truly sorry for my involvement in the contraventions by the First to Fourth Respondent. I am no longer in contact with any of the former employees. However, if the FWO locates any of the former employees I respectfully ask that the FWO please pass on this expression of my regret to those employees.

111 A bare apology, however, that is an apology unaccompanied by a genuine acceptance of responsibility, is not contrition.

112 In the affidavit she filed in the FCCA proceeding, Ms Shin also claimed to be contrite. She offered an “unreserved apology” on behalf of Sushi Bay ACT and “on a personal level” for what had occurred and informed the FCCA that she was “in the process of writing” a letter of apology to each employee who was underpaid. Yet her conduct at that time makes a mockery of her claim. At the time she professed to be contrite, to her knowledge all the Entities were underpaying employees and at least until January 2020 continued to do so. If Ms Shin were truly contrite, she would have admitted liability and caused the Entities to do likewise before they were placed in liquidation. If she were truly contrite, she would have taken steps to compensate the employees.

113 While Ms Shin repeatedly assured the Court that she accepted “full responsibility” for the contraventions found to have occurred in this proceeding, her attempts to shift or share blame with managers are inconsistent with an acceptance of full responsibility. I do not accept her evidence that she did not intend that workers would not be worse off than if they had been paid in accordance with the Award. I struggle to see how she reconciles the need to ensure that workers were paid an amount that made it attractive for them to work for a company in the Sushi Bay Group with a strategy of paying below Award wages. Moreover, she does not appear to recognise the vice in making and keeping pay slips and payroll advices, which did not record the actual working hours, rates of pay, gross and net amounts paid, or the fact that some payments had been made in cash, and producing them to a Fair Work Inspector without disclosing the true position.

The claim

114 The Ombudsman accepted that a totality discount was required in each case and, despite the need for both general and specific deterrence in Ms Shin’s case, a substantial discount.

115 The Ombudsman seeks penalties in the following amounts:

(1) $3,167,640 in respect of Sushi Bay;

(2) $5,787,180 in respect of Sushi Bay ACT;

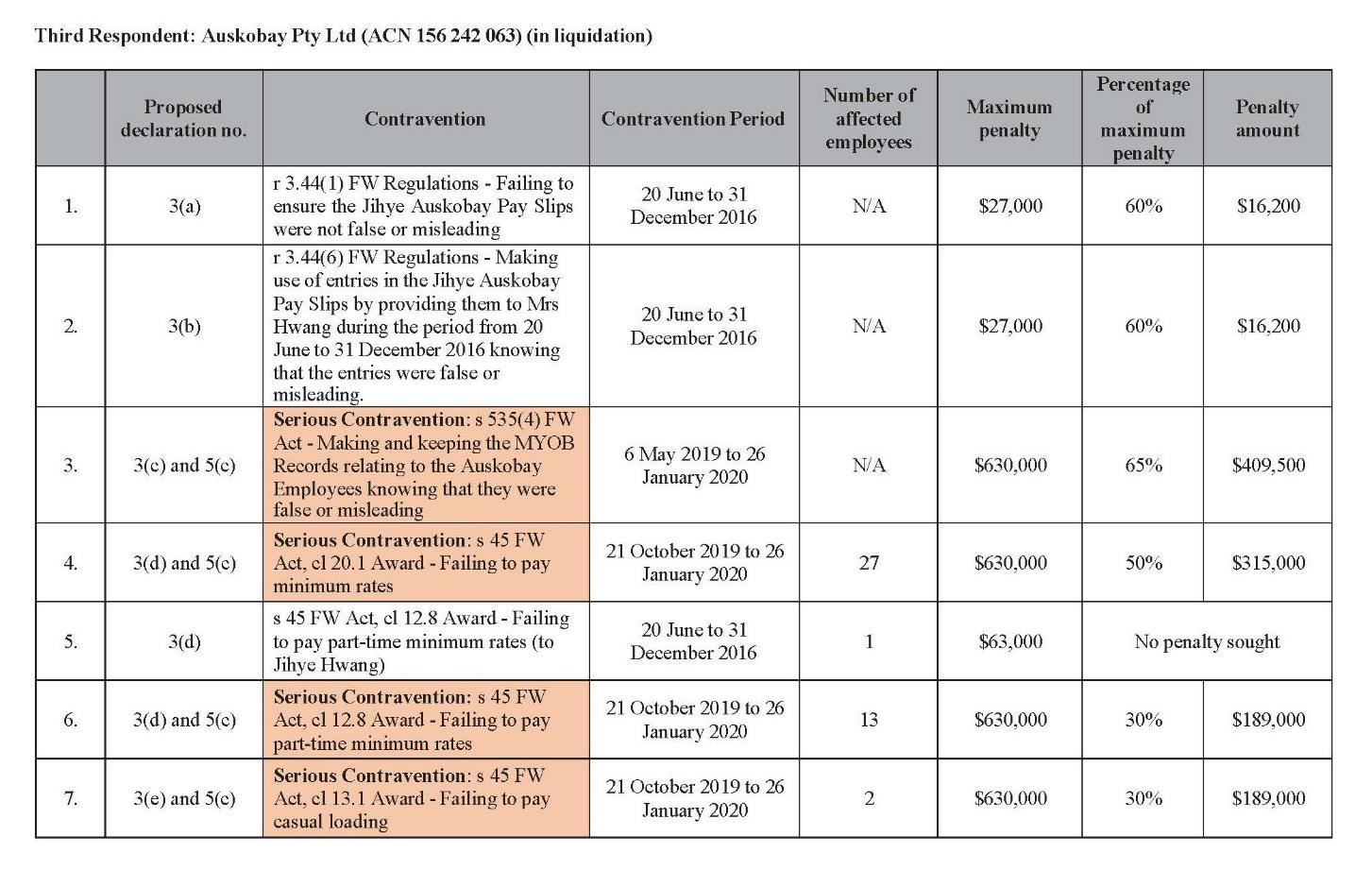

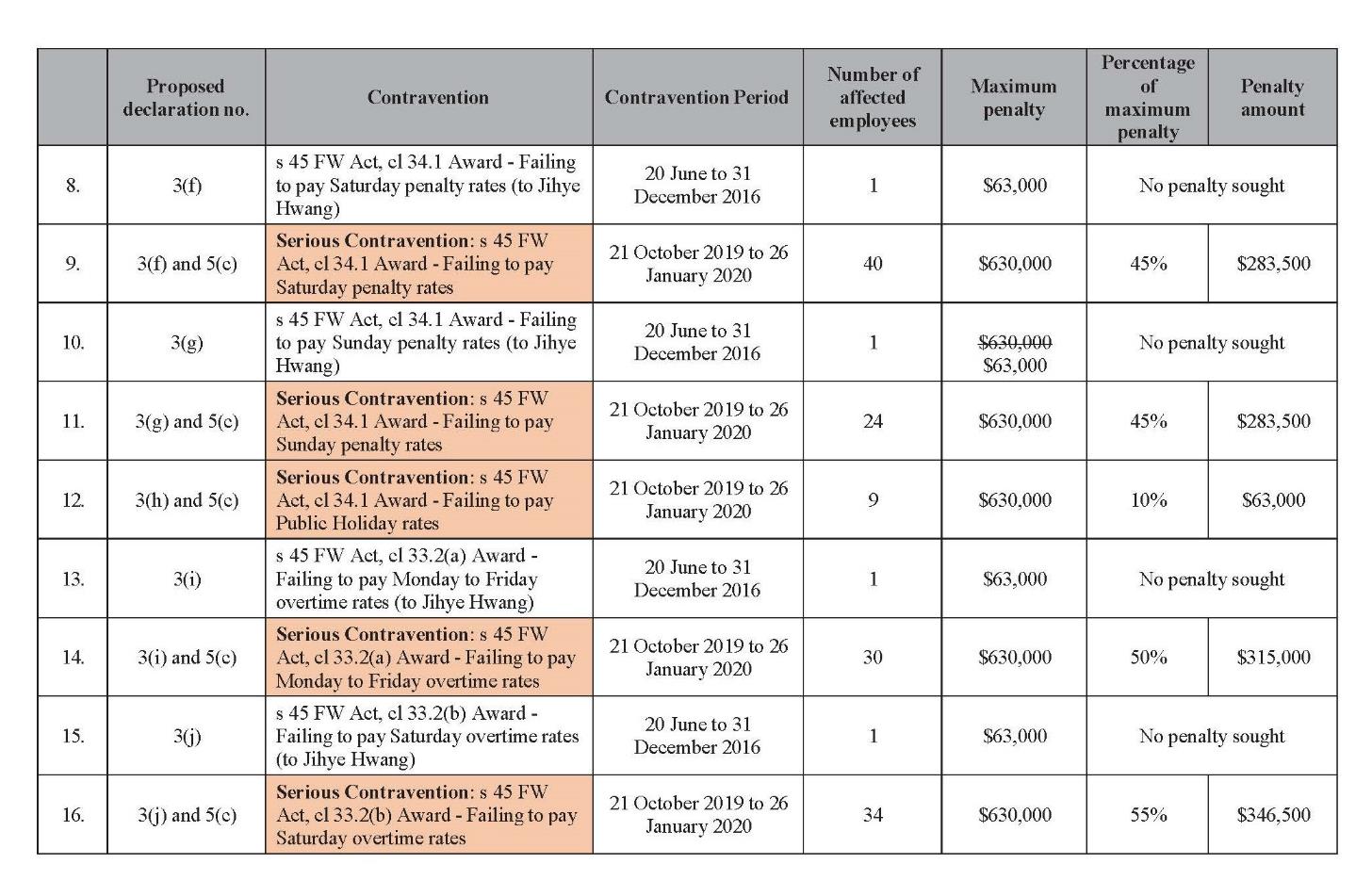

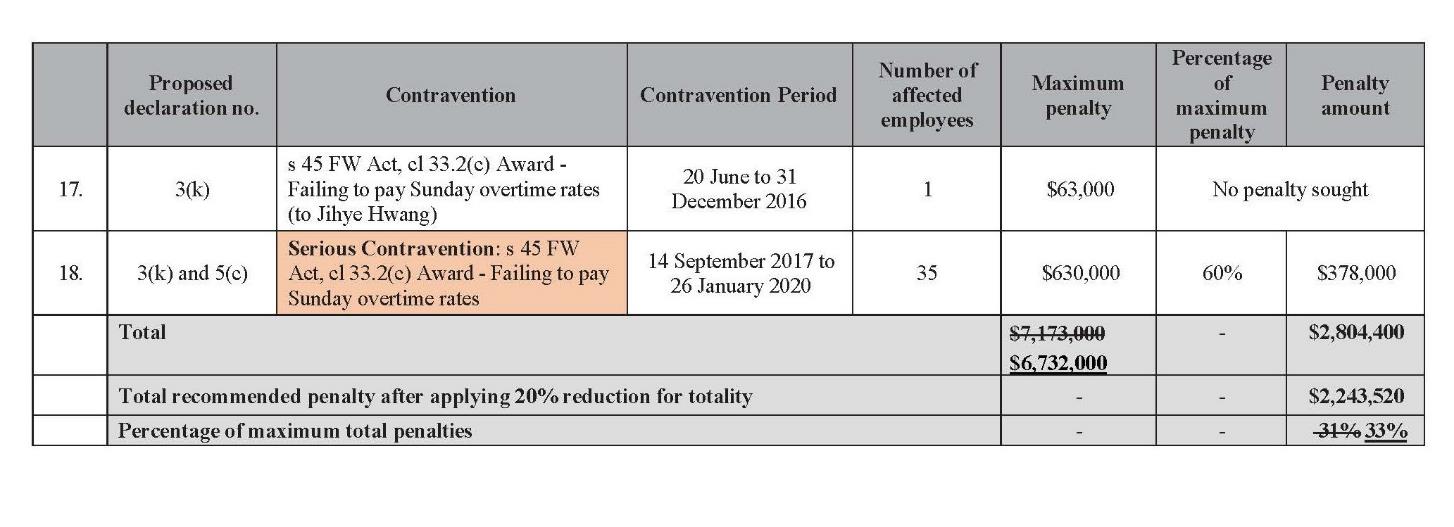

(3) $2,243,520 in respect of Auskobay;

(4) $2,399,040 in respect of Auskoja; and

(5) $1,571,598 in respect of Ms Shin.

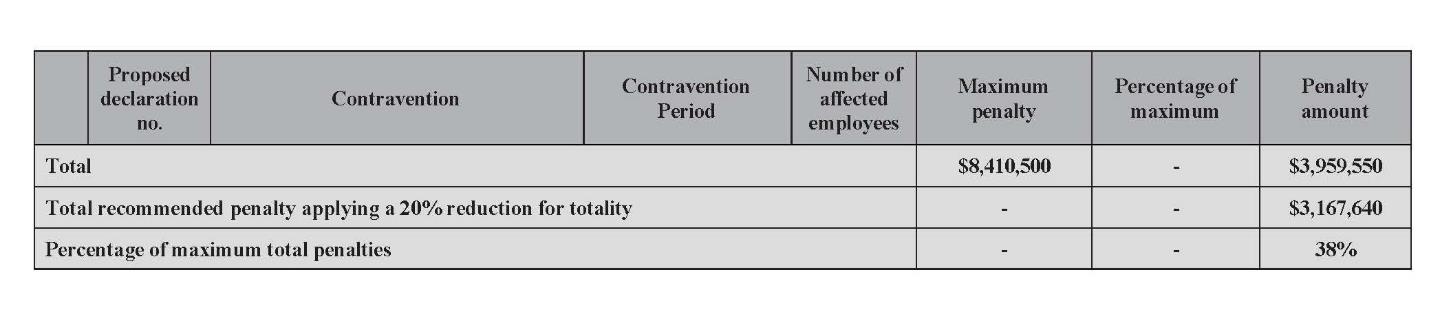

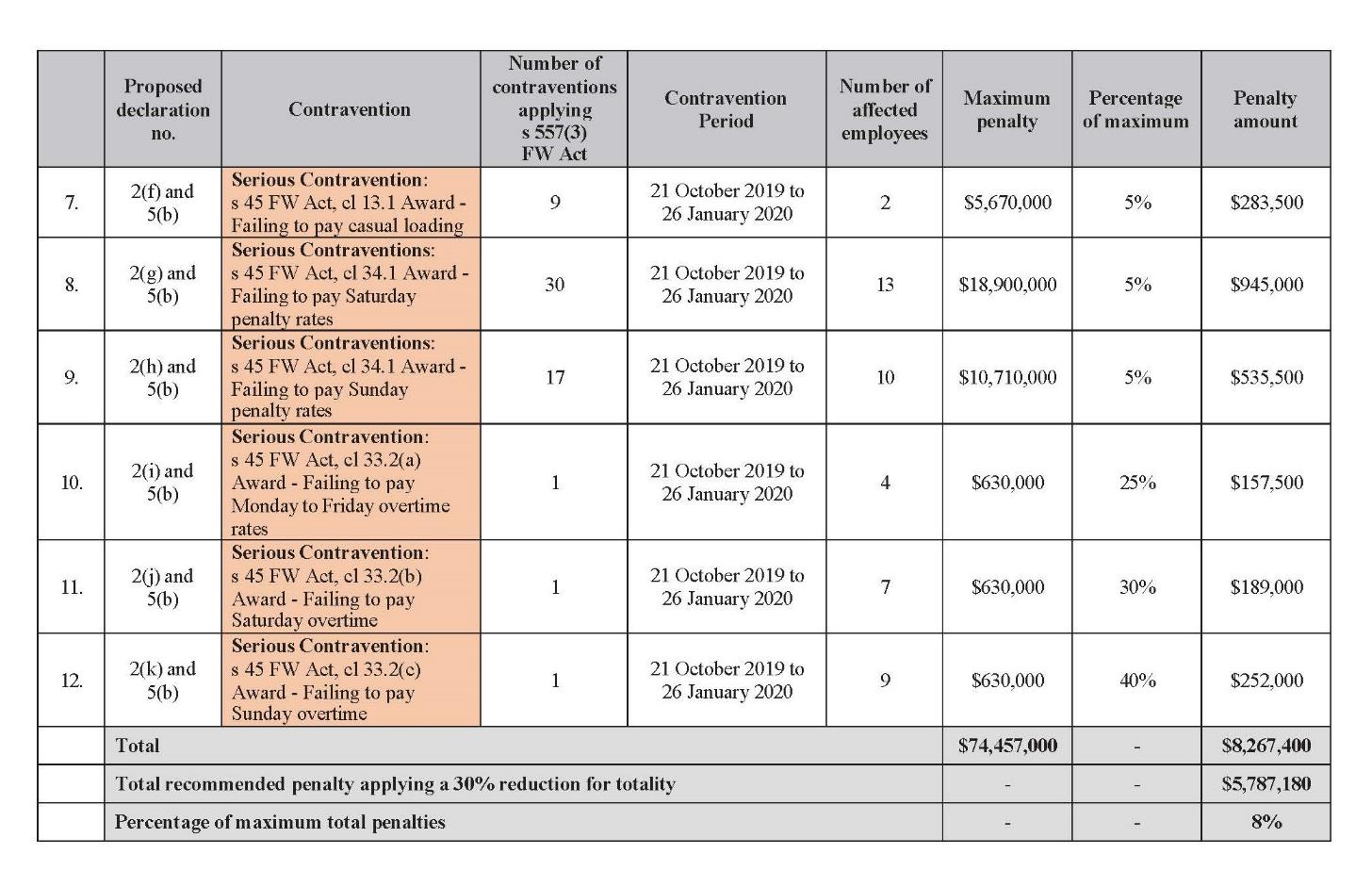

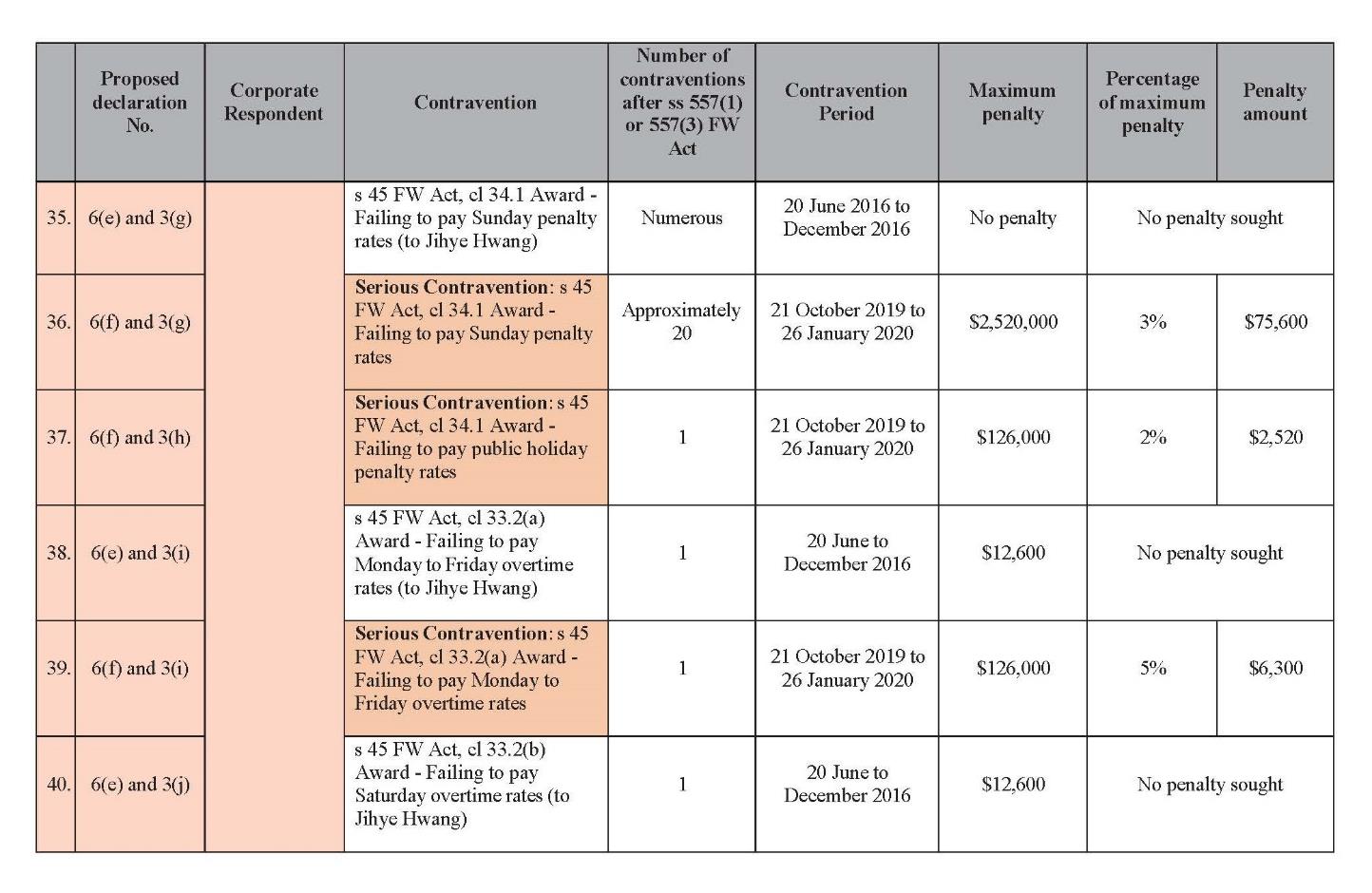

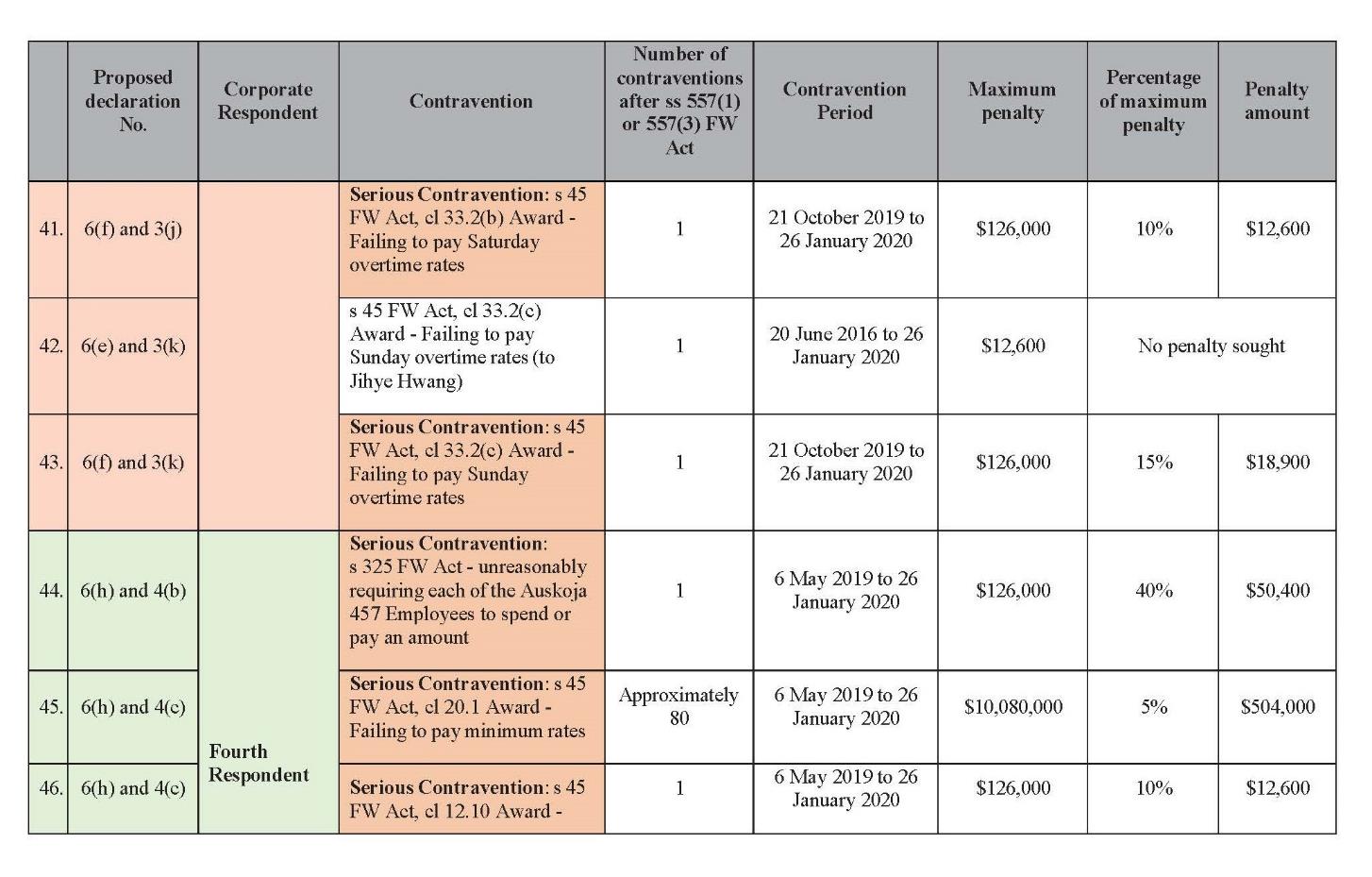

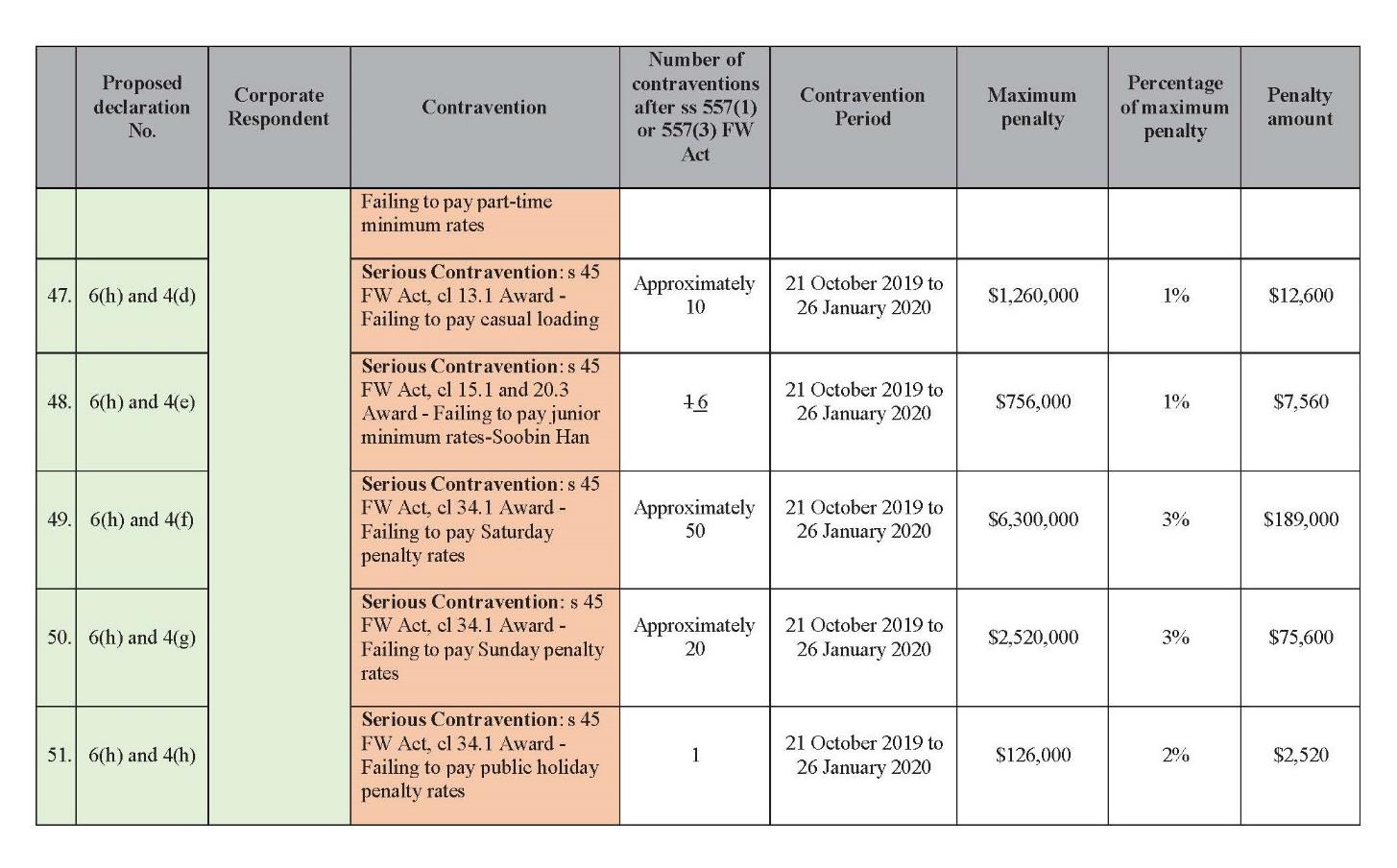

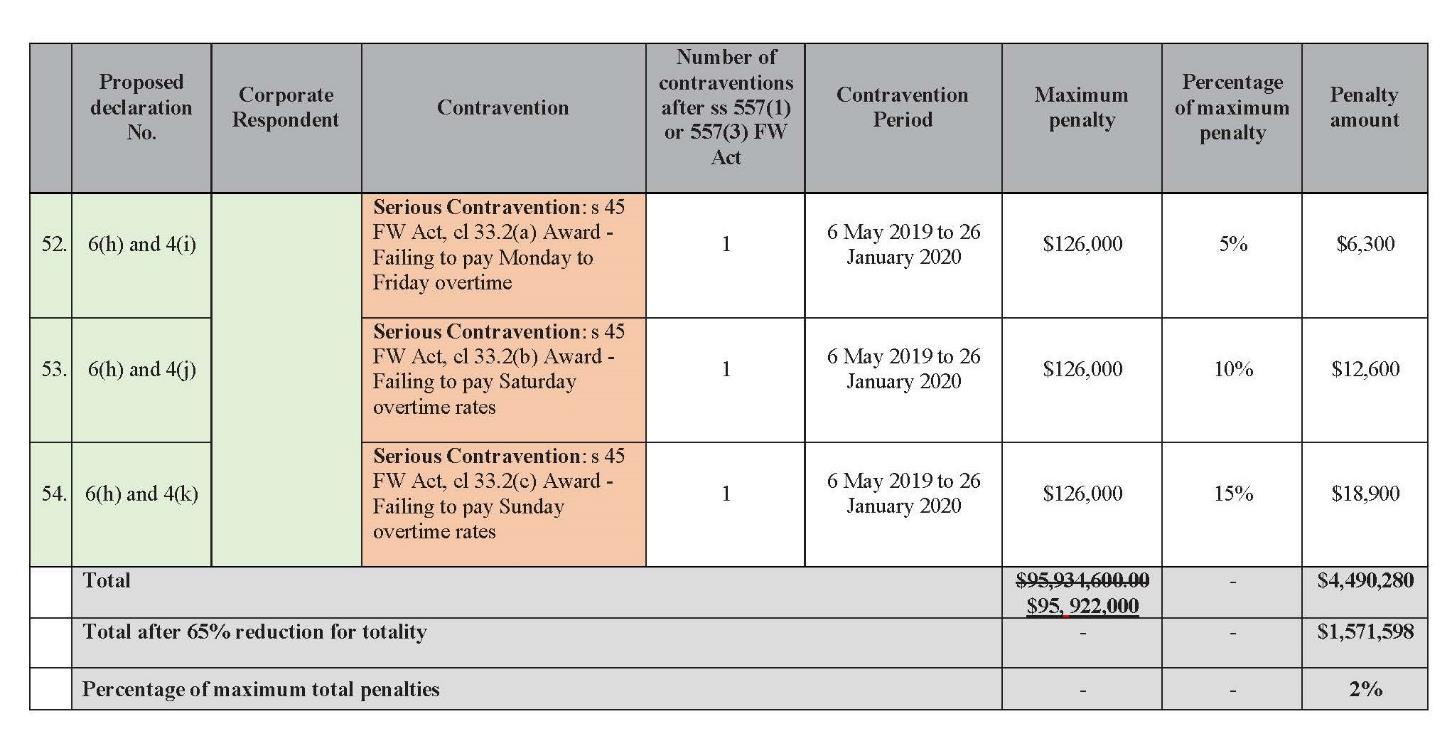

116 The foundations for these claims appears in a table annexed to the Ombudsman’s submissions. That table is reproduced in Annexure B to this judgment. A summary appears in the table below. It shows, by reference to each respondent, the total theoretical maximum, the total amount sought by the Ombudsman, the percentage adjustment for totality which the Ombudsman contended was appropriate, the total penalty sought after the adjustment, and the percentage of the penalty sought as a percentage of the theoretical maximum:

Respondent | Maximum | Total sought before adjustment | Percentage adjustment | Total sought after adjustment | Penalty sought as percentage of maximum |

Sushi Bay | $8,410,500 | $3,959,550 | 20% | $3,167,640 | 38% |

Sushi Bay ACT | $74,457,000 | $8,267,400 | 30% | $5,787,180 | 8% |

Auskobay | $6,732,000 | $2,804,400 | 20% | $2,243,520 | 33% |

Auskoja | $7,623,000 | $2,998,800 | 20% | $2,399,040 | 31% |

Ms Shin | $95,922,000 | $4,490,280 | 65% | $1,571,598 | 2% |

117 The maximum available penalties for the contraventions committed by Sushi Bay ACT and Ms Shin are far greater than the maximum available penalties for the contraventions committed by the other respondents. That is because some of the contraventions I found they committed were contraventions of the same Award provisions the subject of penalties imposed by the FCCA in 2019: see FW Act, s 557(3).

118 During the penalty hearing, Ms Brigden, counsel for the Ombudsman, explained that the percentage sought in relation to each contravention was informed by the objective seriousness of the contravention, having regard to all the relevant circumstances, including the period over which the contravention occurred and, where relevant, the number of employees affected. She offered the following as examples of the Ombudsman’s general approach.

119 Ms Brigden submitted that a penalty of 70% of the maximum penalty was appropriate for Sushi Bay’s serious contravention of s 535(4) with respect to making and keeping the MYOB Records knowing they were false or misleading (item 5 of the first table in Annexure B), as that contravention was “very extensive across all four entities” and there were “over 2,800 pages of records”. She submitted that the penalty sought (75% of the maximum) was appropriate for Sushi Bay’s contraventions of s 325 (item 7) because those contraventions were particularly serious as they were “targeted at visa employees” and were imposed merely for that reason. She submitted that a penalty of 60% of the maximum was appropriate for Sushi Bay’s serious contraventions of s 45 by failing to pay minimum rates as required by cl 20.1 of the Award (item 9) as the contravention affected 32 employees and occurred over two years. She submitted that a penalty of 50% of the maximum was appropriate for Sushi Bay’s failure to pay part-time minimum rates (item 10), although only nine employees were affected, because the contravention occurred over a lengthy period of time. In contrast, she pointed out that the Ombudsman seeks a lower penalty (10% of the maximum) in respect of Sushi Bay’s serious contravention of s 45 by failing to pay junior minimum rates in accordance with cll 15.1 and 20.3 of the Award as the contravention concerned only one employee over a period of just over three months (item 11).

120 In circumstances in which the Entities have not complied with the order of the Court that they pay to the Ombudsman the sum total of the underpayments (for payment out by the Ombudsman to the relevant employees), the Ombudsman seeks an order pursuant to s 546(3) of the FW Act that the pecuniary penalty imposed on Ms Shin be paid to the Ombudsman for payment out to the employees in amounts proportionate to the outstanding underpayments and, to the extent that any of them cannot be found within 180 days of payment to the Ombudsman, the balance be paid into the Consolidated Revenue Fund of the Commonwealth.

Conclusions

121 The nature and gravity of the contravening conduct, the circumstances in which and the period of time over which it occurred, the number and nature of the affected employees, the involvement of senior management, and the absence of any extenuating circumstances all point to the need, as the Ombudsman put it, to send a strong signal to employers in the industry that conduct of this kind is unacceptable and will not be tolerated. By continuing their contravening conduct after Sushi Bay ACT had been caught out, the Entities (through Ms Shin) and Ms Shin took a calculated risk. They must have determined that the payment of penalties was an acceptable cost of doing business. The penalties must be sufficiently high to disabuse them of that notion and make it crystal clear to Ms Shin and other people and companies who employ staff that contraventions of the kind the respondents committed are both unacceptable and economically irrational.

122 I reject Ms Shin’s contention that there is no need for specific deterrence in her case. Not all the companies in the Sushi Bay Group are in liquidation. She is still a director and manager of the Korean Daily Hanho Pty Ltd and complaints made to the Ombudsman by employees or former employees of that company indicate that she may have been underpaying employees there too. Moreover, unless action is taken by the corporate regulator, she may establish another company or set up another business in which she employs staff.