FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Mercer Superannuation (Australia) Limited [2024] FCA 850

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: | 2 AUGUST 2024 |

THE COURT DECLARES THAT:

1. The defendant (Mercer) contravened s 12DF(1) of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth) (ASIC Act) by engaging in conduct, as described in subparagraphs 1(a) to 1(d) below, in trade or commerce that was liable to mislead the public as to the nature and characteristics of financial services that it provided through seven different “Sustainable Plus” investment options (Sustainable Plus Options) offered in the Mercer Super Trust:

(a) Mercer made representations that its Sustainable Plus Options excluded, and would continue to exclude, investments in companies involved in, or deriving profit from:

(i) the production or sale of alcohol;

(ii) gambling; and

(iii) the extraction or sale of carbon intensive fossil fuels,

(b) those representations were made in following periods and in the following ways:

(i) in the first period from 12 November 2021 to 25 January 2022, by statements made in a video (Video Statement) included on Mercer’s website, and on Vimeo and YouTube;

(ii) in the second period from 25 January 2022 to 4 April 2022, by:

A. statements made on a web page on Mercer’s website headed “Mercer Super Trust’s investment options” (First Website Statement);

B. statements made on a web page on Mercer’s website headed “Sustainable Investing”; and

C. continuing to make the Video Statement on Vimeo and YouTube;

(iii) in the third period from 4 April 2022 to 22 July 2022, by:

A. including the First Website Statement on Mercer’s website;

B. statements made on a web page on Mercer’s website headed “Sustainable and ethical super”; and

C. continuing to make the Video Statement on Vimeo and YouTube and posting it again on Mercer’s website; and

(iv) in the fourth period from 22 July 2022 to 1 March 2023, by:

A. including the First Website Statement on Mercer’s website;

B. statements made on a web page on Mercer’s website headed “Sustainable and ethical super”; and

C. up to 2 September 2022, continuing to make the Video Statement on Vimeo and YouTube,

(c) at the time each representation was made, it was liable to mislead the public as to the nature and characteristics of the Sustainable Plus Options because six of those seven options actually included investments as follows:

(i) the “Mercer Sustainable Plus Australian Shares” and “Mercer Sustainable Plus Shares” options each held investments in two companies involved in, or deriving profit from, the extraction or sale of carbon intensive fossil fuels;

(ii) the “Mercer Sustainable Plus High Growth” option held investments in up to:

A. 15 companies involved in, or deriving profit from, the extraction or sale of carbon intensive fossil fuels;

B. 15 companies involved in the production or sale of alcohol; and

C. 19 companies involved in gambling;

(iii) the “Mercer Sustainable Plus Growth” option held investments in up to:

A. 13 companies involved in, or deriving profit from, the extraction or sale of carbon intensive fossil fuels;

B. 14 companies involved in the production or sale of alcohol; and

C. 14 companies involved in gambling;

(iv) the “Mercer Sustainable Plus Moderate Growth” option held investments in up to:

A. 15 companies involved in, or deriving profit from, the extraction or sale of carbon intensive fossil fuels;

B. 15 companies involved in the production or sale of alcohol; and

C. 18 companies involved in gambling; and

(v) the “Mercer Sustainable Plus Conservative Growth” option held investments in up to:

A. 13 companies involved in, or deriving profit from, the extraction or sale of carbon intensive fossil fuels;

B. 14 companies involved in the production or sale of alcohol; and

C. 14 companies involved in gambling,

(d) at the time each representation was made, it was also liable to mislead the public as to the future nature and characteristics of the Sustainable Plus Options because Mercer did not have reasonable grounds to make the representation in circumstances where:

(i) at all relevant times, Mercer’s investment policies permitted each of the Sustainable Plus Options to invest in companies involved in, or deriving profit from:

A. the production or sale of alcohol;

B. gambling; and

C. the extraction or sale of carbon intensive fossil fuels;

(ii) throughout first, second, third and fourth periods the Sustainable Plus Options were in fact investing in companies as described in subparagraph 1(c) above.

2. By reason of the conduct and circumstances set out in paragraph 1 above, Mercer contravened s 12DB(1)(a) of the ASIC Act in making each of the representations because, in each case, the representation:

(a) was made in trade and commerce in connection with the promotion and supply of financial services; and

(b) was false and misleading as to:

(i) the standard, quality, value and grade of the Sustainable Plus Options as it existed at the time of the representation; and

(ii) the future, and ongoing, standard, quality, value and grade of the Sustainable Plus Options.

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Within 30 days of receipt of a penalty notice, Mercer pay to the Commonwealth a pecuniary penalty of $11,300,000 in respect of Mercer’s conduct declared to be contraventions of ss 12DF(1) and 12DB(1)(a) of the ASIC Act.

2. Within 14 days, Mercer publish or cause to be published a notice in the form of Annexure A to this order (the Notice) on the “Sustainable investing with Mercer Super” webpage located at https://www.mercersuper.com.au/sustainable-investing-with-mercer-super/ (Sustainable Investing Webpage) of Mercer’s website located at https://www.mercersuper.com.au/ (the Website) such that:

(a) the Notice shall be viewable by clicking a “click-though” banner located on the Sustainable Investing Webpage of the Website;

(b) the “click-through” banner is to be:

(i) located in the top half of the Sustainable Investing Webpage; and

(ii) not obscured, blocked or interfered with by any operation of the Sustainable Investing Webpage or Website;

(c) the “click-through” banner shall contain the words “False and Misleading Statements by Mercer about Sustainable Investing – Notice ordered by the Federal Court of Australia” in at least size 14, bold, black and sans-serif font centred on a white background;

(d) the “click-through” banner is to operate in the form of a one-click hyperlink to the Notice;

(e) the Notice shall occupy the entire Sustainable Investing Webpage that is accessed via the “click-though” banner;

(f) the Notice shall be in size 14, bold, black and sans-serif font that is on a white background and in a black bordered box;

(g) the Notice is to remain on the Sustainable Investing Webpage for a period of 6 months;

(h) the Sustainable Investing Webpage and Website are to be maintained or otherwise kept active for the period during which the Notice is required to remain on the Sustainable Investing Webpage; and

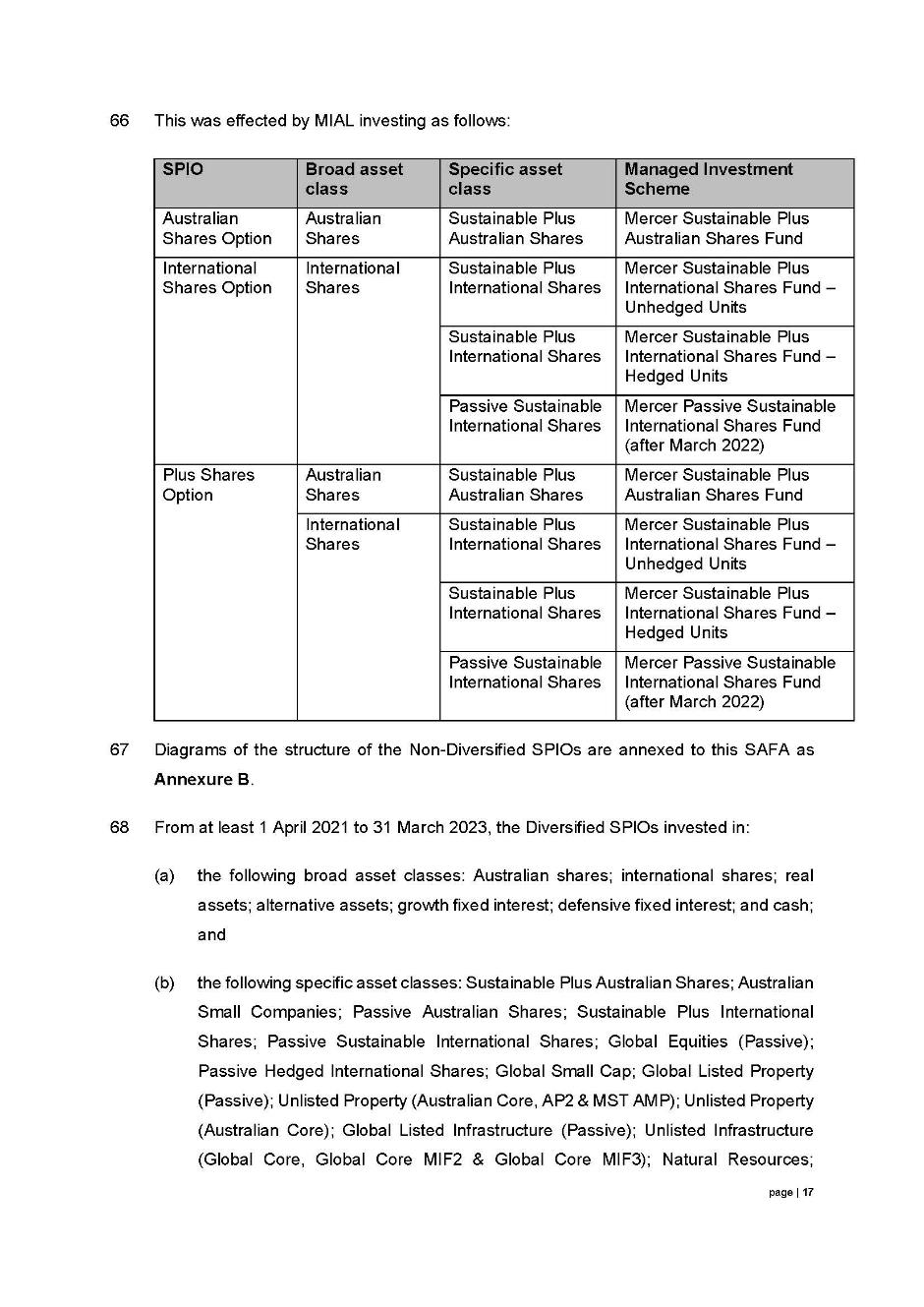

(i) the Website shall not have in place any mechanism which would preclude search engines from indexing the pages or scanning the pages for links to follow.

3. Within 30 days of receipt of an invoice with payment details, Mercer pay ASIC’s costs of and incidental to the proceeding, and the expenses of the investigation into Mercer under s 91 of the ASIC Act, in the agreed sum of $200,000.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ANNEXURE A – ADVERSE PUBLICITY NOTICE

HORAN J:

INTRODUCTION

1 By an amended originating application and accompanying amended concise statement filed on 13 September 2023, the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) alleged that Mercer Superannuation (Australia) Limited (Mercer), a superannuation trustee, made false or misleading representations in contravention of s 12DB(1)(a) of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth) (ASIC Act) and engaged in conduct that was liable to mislead the public in relation to financial services in contravention of s 12DF(1) of the ASIC Act.

2 The contraventions, which Mercer admits, arise from representations made by Mercer on its website and in a video published online during four different periods from 12 November 2021 to 1 March 2023 that its “Sustainable Plus” investment options excluded, and would continue to exclude, investments in companies involved in or deriving profit from the production or sale of alcohol, gambling, and the extraction or sale of carbon intensive fossil fuels. The representations were false and misleading because six of those seven investment options actually included investments in such companies, and Mercer’s investment policies actually permitted such investments.

3 Conduct of this kind is known as “greenwashing”, which broadly speaking involves making false or misleading environmental or sustainability claims in order to make a company or its business appear more environmentally friendly, sustainable or ethical, particularly in order to induce consumers to purchase its products or services or to invest in the company. Greenwashing has a particular manifestation in relation to financial products, including superannuation and life products. As O’Callaghan J recently said in Australian Securities and Investments Commission v LGSS Pty Ltd [2024] FCA 587 at [1]:

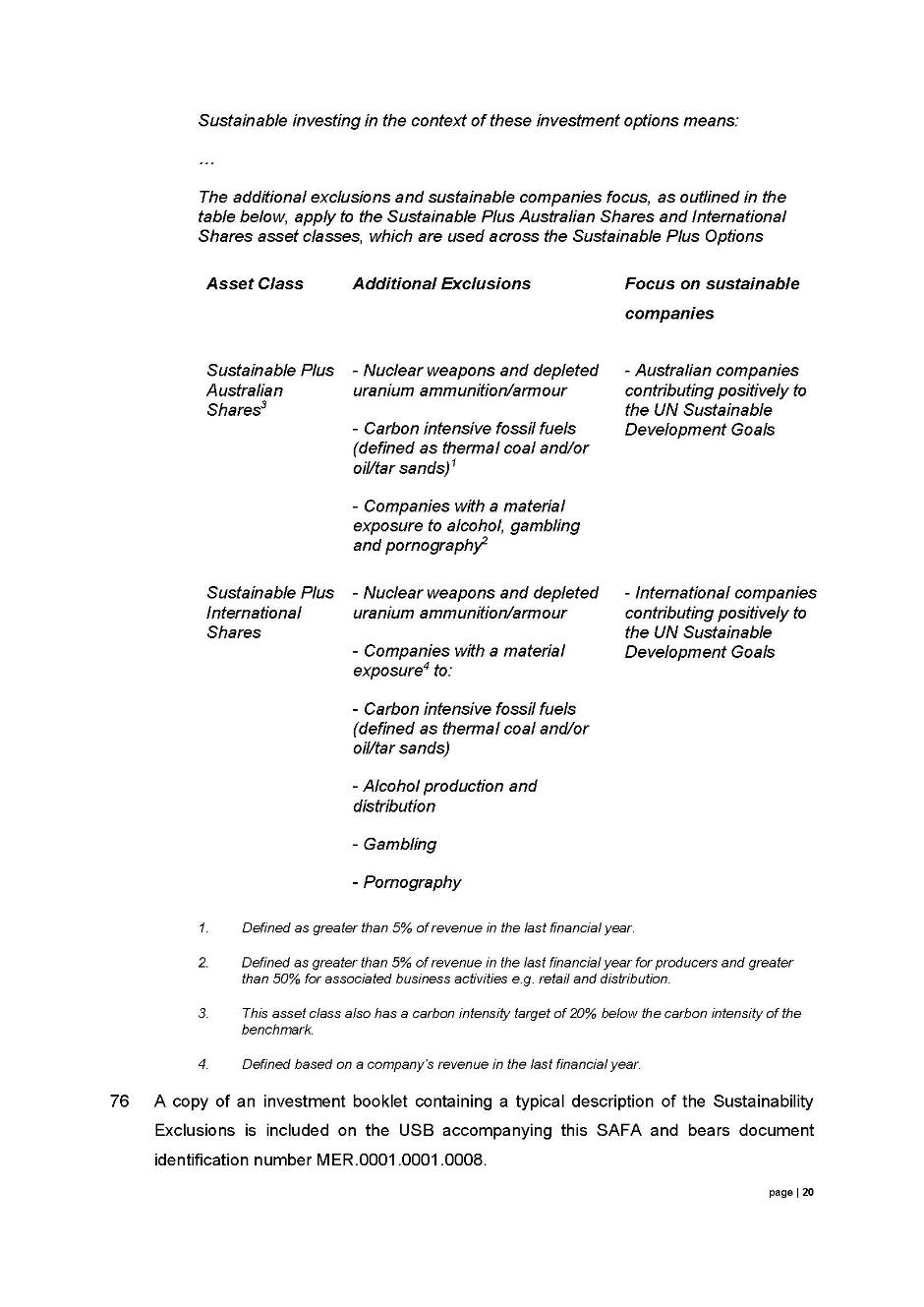

[i]n the realm of financial product investments, “greenwashing” is a term that:

… pertains to the misleading and deceptive disclosures employed by financial institutions to entice environmentally conscious investors into purchasing their financial products that, in reality, fall short of meeting the expected Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) or green credentials. These ESG credentials encompass environmental compliance and measures to protect the environment, reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and manage natural resources; social compliance, which evaluates how a company treats its stakeholders; and governance compliance, focusing on appropriate governance practices such as executive transparency and accountability.

See Das C, Pearce P and Henson T, “What’s Green and Ethical about Greenwashing in the Promotion of Financial Products” [2023] NZLJ 400 at 401.

4 As the parties accept, greenwashing practices have the potential to reduce consumer confidence in environmental, social and corporate governance (ESG) claims, which undermines the efforts of businesses that are pursuing ESG goals accurately and fairly. In addition to harming consumers by depriving them of information relevant to making choices in accordance with environmental, social and ethical values or objectives, false or misleading ESG claims may confer unfair competitive advantages on companies in marketing their financial products and services. To quote from an information sheet published by ASIC in June 2022 (Information Sheet 271: How to avoid greenwashing when offering or promoting sustainability-related products):

Greenwashing distorts relevant information that a current or prospective investor might require in order to make informed investment decisions. It can erode investor confidence in the market for sustainability-related products and poses a threat to a fair and efficient financial system.

5 Greenwashing has been identified as a key regulatory and enforcement priority by regulators, including ASIC and the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission. The Senate Standing Committee on Environment and Communications is currently conducting an inquiry into greenwashing, with its report due by 20 November 2024. This increased recognition of greenwashing practices by companies and their impact on consumers is relevant to the consideration of general deterrence to which the Court is required to have regard in determining the appropriateness of any proposed pecuniary penalty and other relief in relation to contraventions of the relevant provisions of the ASIC Act or analogous legislation.

6 ASIC and Mercer have agreed to resolve the present proceeding, and jointly seek declarations of contravention together with pecuniary penalties, adverse publicity orders and costs orders under ss 12GBA(1), 12GBB(1), and 12GLB(1) of the ASIC Act and s 21 of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (FCA Act). In particular, Mercer has admitted that it contravened ss 12DB(1)(a) and 12DF(1) of the ASIC Act by making representations that were false or misleading and were liable to mislead the public in relation to financial services, namely, by falsely representing that certain superannuation investment options offered by it excluded investments in companies involved in or deriving profit from the production or sale of alcohol, gambling and carbon intensive fossil fuels.

7 The parties have filed:

(a) a statement of agreed facts and admissions under s 191 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) dated 19 September 2023 (SAFA); and

(b) joint submissions on liability and relief dated 24 November 2023.

8 For the following reasons, I make declarations in the terms sought by the parties, an order that Mercer pay a pecuniary penalty of $11.3 million, and an adverse publicity order requiring Mercer to publish a notice to be displayed on the sustainable investments page of its website for a period of six months that describes the admitted conduct giving rise to the contraventions.

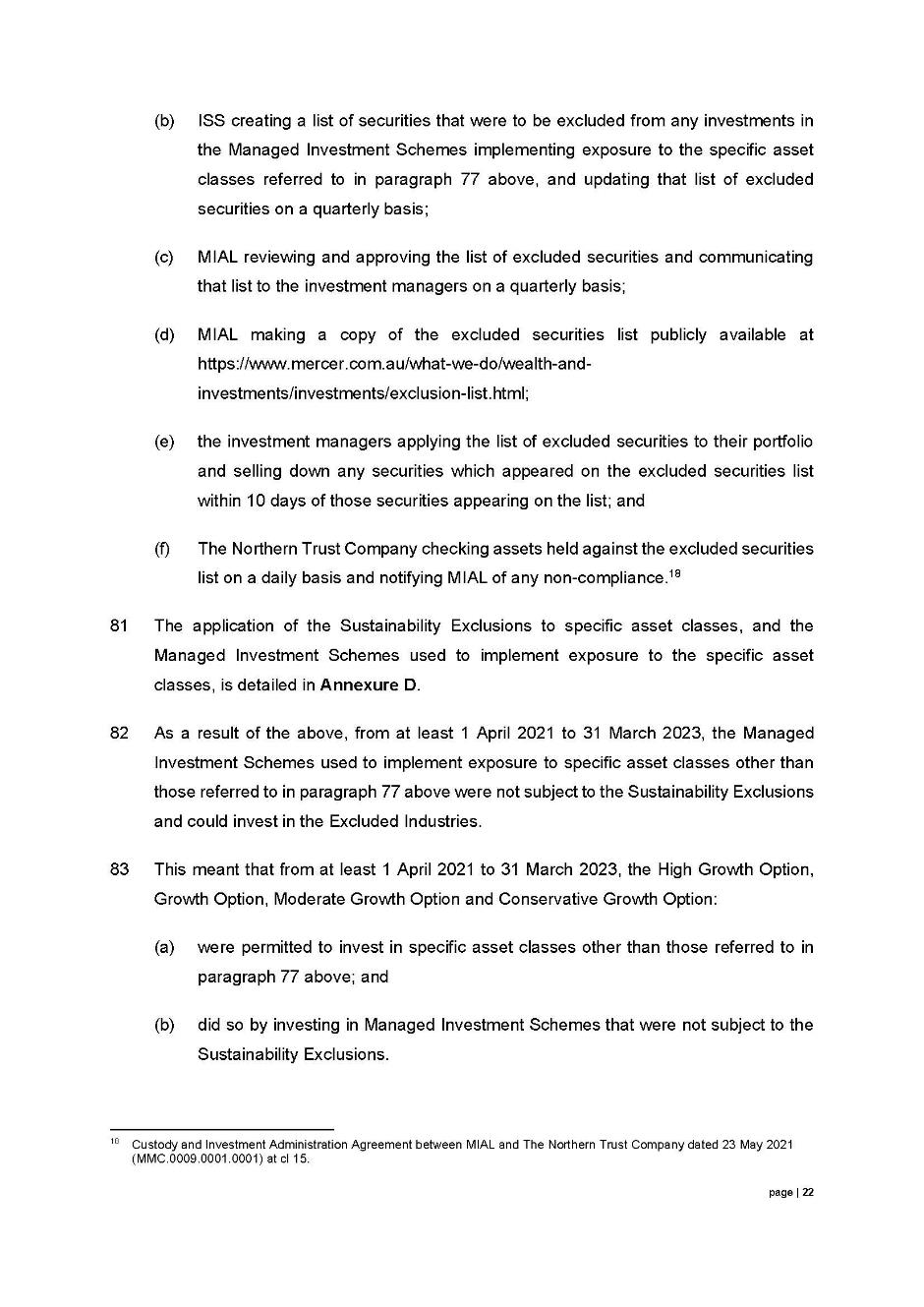

THE ADMITTED CONTRAVENTIONS

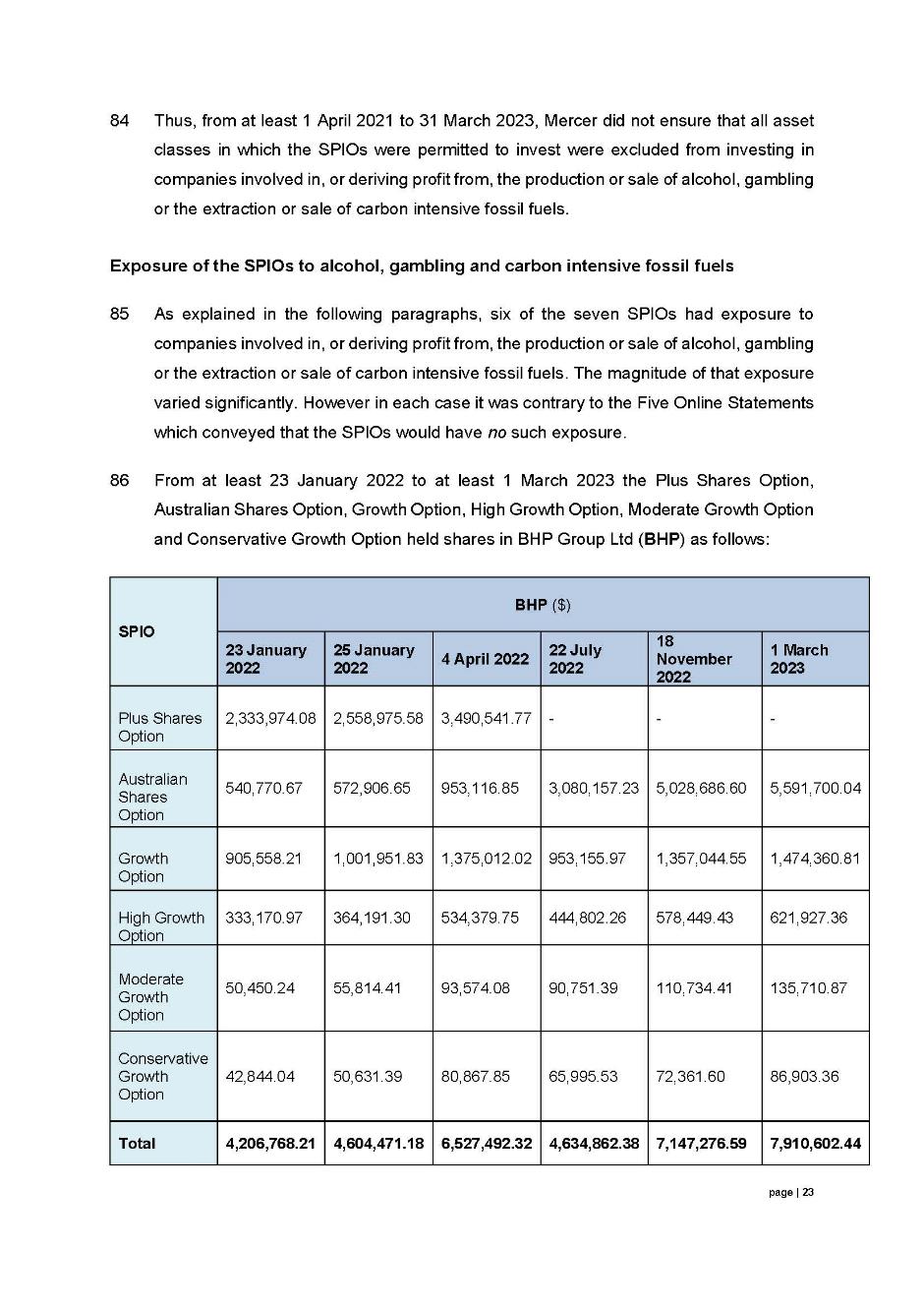

9 The SAFA sets out the detailed facts agreed to by the parties, including the admissions made by Mercer, for the purposes of the current proceeding. To assist in understanding the admitted contraventions and the relief that is jointly sought by the parties, the SAFA (excluding its annexures) is attached to these reasons as Annexure A.

10 Given the parties’ agreement to the facts underlying the contraventions, and the effect of s 191 of the Evidence Act in relation to those agreed facts, the fact-finding role of the Court in the present proceeding is limited. In Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Commonwealth Bank of Australia [2020] FCA 790 at [12], Beach J observed that, as a consequence of facts having been agreed under s 191 of the Evidence Act, he had “not been required to determine any factual question on its merits” and was able to proceed on the premise that the relevant facts were not in issue between parties. Justice Beach continued:

To so invoke s 191 provides a sufficient factual foundation to support my exercise of power to impose a penalty and to make the required declarations without any necessity to receive evidence let alone independently adjudicate on whether those facts exist. Accordingly, all that I need to be satisfied of is whether the agreed facts on their face provide a sufficient foundation for the declarations and orders sought. The text of s 191(2)(a) makes this plain.

See also Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Mercer Financial Advice (Australia) Pty Ltd [2023] FCA 1453 at [58] (McEvoy J).

11 It is convenient to set out in these reasons a summary of key aspects of the agreed facts.

Mercer and the Mercer Super Trust

12 Mercer is a subsidiary of Mercer (Australia) Pty Ltd, which is itself a subsidiary of Marsh Mercer Holdings (Australia) Ltd. The ultimate parent company of Mercer is Marsh & McLennan Companies Inc, a publicly listed company in the United States of America.

13 At all relevant times, Mercer held an Australian Financial Services Licence (AFSL), which authorised it to provide financial product advice, deal in a financial product in relation to superannuation and life products, and provide a superannuation trustee service to retail and wholesale clients. In particular, Mercer was the trustee of the Mercer Super Trust in respect of which it held a Registrable Superannuation Entity Licence.

14 The Mercer Super Trust is a large superannuation fund that holds significant net assets for its members’ benefit. During the relevant period, the Mercer Super Trust had almost 300,000 member accounts with net assets of approximately $29.8 billion as at 30 June 2021 and $27.5 billion as at 30 June 2022. Following a merger with BT Super in April 2023, the Mercer Super Trust had approximately 850,000 members with total assets under management to the value of approximately $65 billion.

15 Mercer admits that it provided a superannuation trustee service within the meaning of s 12BA(1) and a financial service pursuant to s 12BAB(1)(ea) of the ASIC Act, and that a beneficial interest in the Mercer Super Trust was a financial product within the meaning of s 12BAA(7)(f) and therefore a financial service within the meaning of s 12BAB(1AA) of the ASIC Act.

16 Mercer was responsible for the overall strategy and governance of the products and investment options available in the Mercer Super Trust. To assist in running the Trust, Mercer appointed service providers, including entities within the broader Mercer group in Australia as well as external service providers. Each of those service providers was an agent of Mercer, who admits that their conduct is taken to have been engaged in by Mercer for the purposes of s 12GH of the ASIC Act. Mercer also admits that the conduct of its employees, officers and agents was engaged in within the scope of their authority, and that such conduct is taken to have been engaged in by Mercer with the knowledge and state of mind of those persons.

17 During the relevant period, members in the Mercer Super Trust were in either the Allocated Pension Division, which provided retirement income products to members who were retired or transitioning to retirement; the Corporate Superannuation Division, which provided superannuation services to employees of employers who participated in employer sponsored superannuation plans; or the Retail Division, which provided superannuation services to members of the public.

18 There were 141 different investment options offered to members, each of which had particular investment strategies. These included a “Ready made” investment option with a mix of asset classes and investment management styles; “Select-your-own” investment options by which an investor could blend different investment options; the “Mercer Direct” option by which an investor could select their own direct investments from a portfolio of shares, term deposits or exchange traded funds; and the default “Mercer SmartPath” investment option in which the member’s assets would be invested in a mix of asset classes based on his or her age.

19 For each investment option, Mercer set strategic asset allocations that identified the asset class or classes in which the option was permitted to invest and the percentage of funds (typically a range) to be invested in each asset class. Mercer Investments (Australia) Limited (MIAL) was appointed as an “implementation consultant”, and was responsible for giving effect to the strategic asset allocations by investing assets in various managed investment schemes, the majority of which were managed by MIAL.

20 During the relevant period, the Mercer Super Trust offered a category of investment options known as the “Sustainable Plus” investment options (Sustainable Plus Options). The Sustainable Plus Options, which were only available to members through the “Select-your-own” investment option, included:

(a) the Mercer Sustainable Plus Australian Shares Option;

(b) the Mercer Sustainable Plus International Shares Option;

(c) until 1 June 2022, the Mercer Sustainable Plus Shares Option;

(d) the Mercer Sustainable Plus High Growth Option;

(e) the Mercer Sustainable Plus Growth Option;

(f) the Mercer Sustainable Plus Moderate Growth Option; and

(g) the Mercer Sustainable Plus Conservative Growth Option.

The investment options in (a) to (c) above were classified by Mercer as “non-diversified”, and the investment options in (d) to (f) above were classified as “diversified”.

21 The process by which investments were selected for the Sustainable Plus Options involved the approval by the board of Mercer of a strategic asset allocation for the broad asset classes for each option, after considering advice from MIAL. These allocations were then implemented through specific asset classes. The implementation and ongoing management of the asset allocations was delegated by Mercer to the Chief Investment Officer of MIAL, who was responsible for overseeing the investment of funds in managed investment schemes by third party investment managers.

The Representations

22 During the relevant period, Mercer had a website accessible to the public (the Website), the design and content of which was managed by Mercer Outsourcing (Australia) Pty Ltd (MOAPL) pursuant to an agreement with Mercer. The typical process by which information relating to sustainable investing was published on the Website involved the preparation of an initial draft by members of MOAPL’s digital and marketing team. The initial draft was provided to MIAL’s sustainable investment team for technical subject matter expertise input and then to Mercer’s legal and compliance teams for comments and “sign-off”, following which the final approved content was posted on the Website by MOAPL.

The Video Statement

23 From 12 November 2021 to 25 January 2022, a video was accessible on the Website with the title “Responsible and Sustainable Investing with Mercer” and a subtitle that relevantly stated “… our Head of Sustainable Investments and … our Sustainable Investment Manager unpack our sustainable investment approach in this video” (the Video).

24 The Video was 3 minutes and 18 seconds long, and relevantly included the following statement in relation to the Sustainable Plus Options (the Video Statement):

“Hello my name is … and I lead the responsible investment team in Australia and New Zealand. At Mercer, sustainability is embedded in every option we manage so if you’re concerned about climate change human rights or diversity we’re considering that in the way we invest your money. But for potential members who want to go further, we also offer seven Sustainable Plus options you can choose from. For potential members that are deeply committed to sustainability, I encourage you to consider the Sustainable Plus options. Our Sustainable Plus options go further than the other options in their commitment to sustainable investment. First they exclude investments in certain sectors deemed not to be sustainable. These options will not invest in alcohol, gambling and carbon intensive fossil fuels like thermal coal. In addition they go further in investing in solutions to sustainability challenges like renewable energy water management and waste reduction.

Hi I’m …, Sustainable Investment Manager at Mercer. We believe climate change is both an investment risk as well as an investment opportunity. So when constructing portfolios, we seek to minimize the climate risk and maximize the climate opportunity. So for instance, we think about ‘what is the impact of climate change on my investment returns’ as well as ‘how do our members investments in turn impact climate change’.

Mercer is deeply committed to the fight against climate change and to using our influence as an investor to drive towards a low carbon economy. Within the Mercer Super Trust, we’ve set a goal to be net zero absolute carbon emissions by 2050 in keeping with the goals of the Paris Agreement. So what does that mean? Well, it means we’ll be reducing our carbon emissions as far as possible within our investment portfolios. It also means we’ll be looking to invest in solutions to climate change where these are expected to deliver a strong investment return. This will look like investments in renewable energy, sustainable transport, waste management and other environmental services. And lastly we’re engaged in conversations with companies and policy makers about how we can reduce emissions across the economy and deliver a more sustainable retirement for Mercer super members.

At Mercer, we challenged the assumption that focusing on sustainable investment could negatively impact my investment rates. In fact, we believe that strong investment returns can be enjoyed without compromising your sustainability values.”

(Emphasis added.)

25 The following message was displayed as text at the end of the Video:

Prior to acting on any information contained in this document, you need to take in to account your own financial circumstances, consider the Product Disclosure Statement for any product you are considering and seek financial advice from a licensed, or appropriately authorised financial adviser if you are unsure of what action to take.

26 It may be observed that the critical statements made in the Video about the exclusion of investments in alcohol, gambling and carbon intensive fossil fuels were made in absolute terms, that is, without any qualifications as to the materiality of any exposure to those sectors “deemed not to be sustainable”.

27 The Video remained on the Website until 25 January 2022, after which it was removed when the Website changed its URL web address. The Video was again posted on the Website on 4 April 2022 at the new URL web address. It remained on the Website until it was removed on 22 July 2022. In addition to the Website, Mercer published the Video on Vimeo and YouTube, where it was accessible from 12 November 2021 to 2 September 2022.

The Website Statements

28 During the relevant period, the following statements were made on the Website in relation to the Sustainable Plus Options.

(a) The First Website Statement was made from 25 January 2022 to 1 March 2023:

‘Select-Your-Own’ investment options

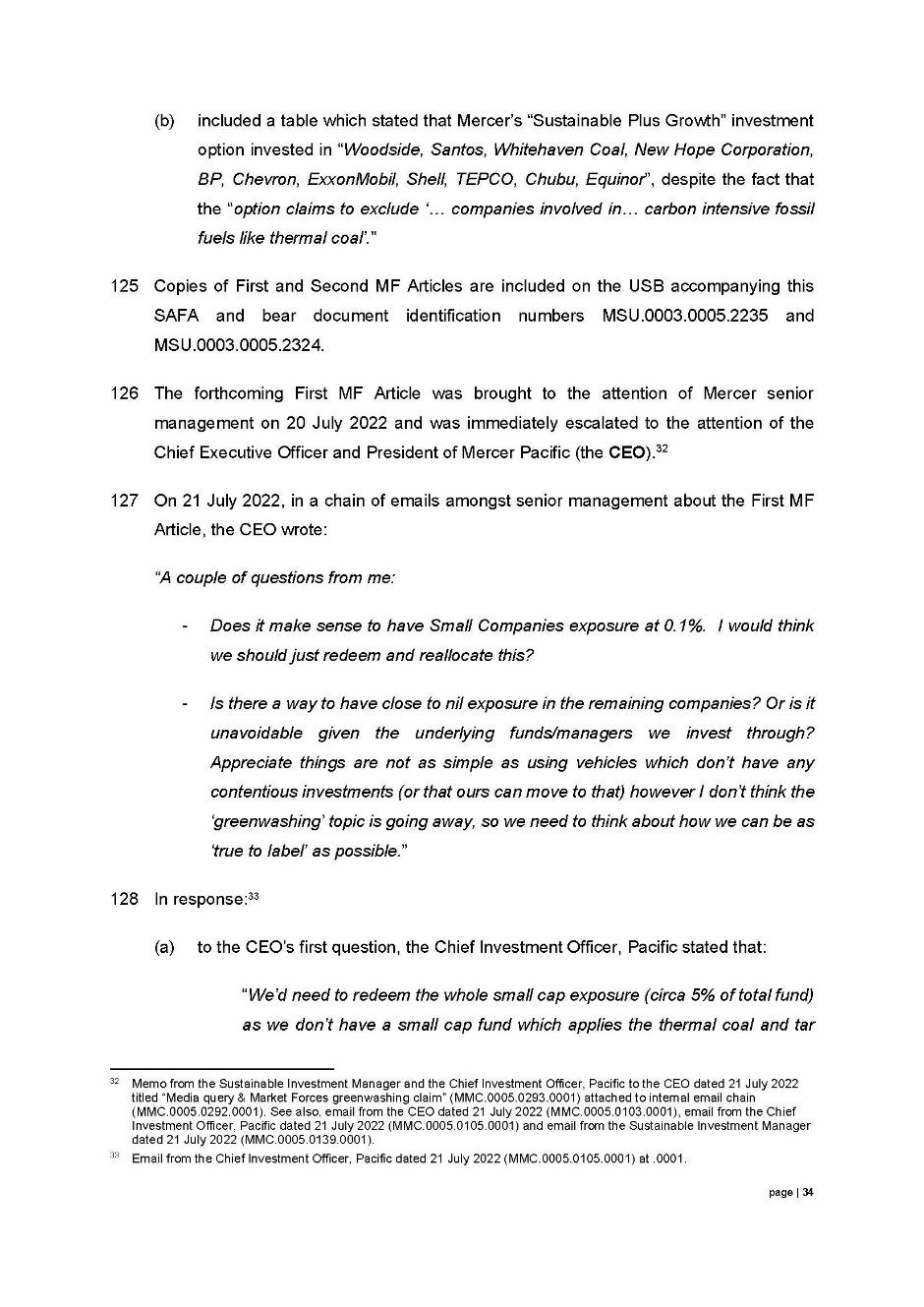

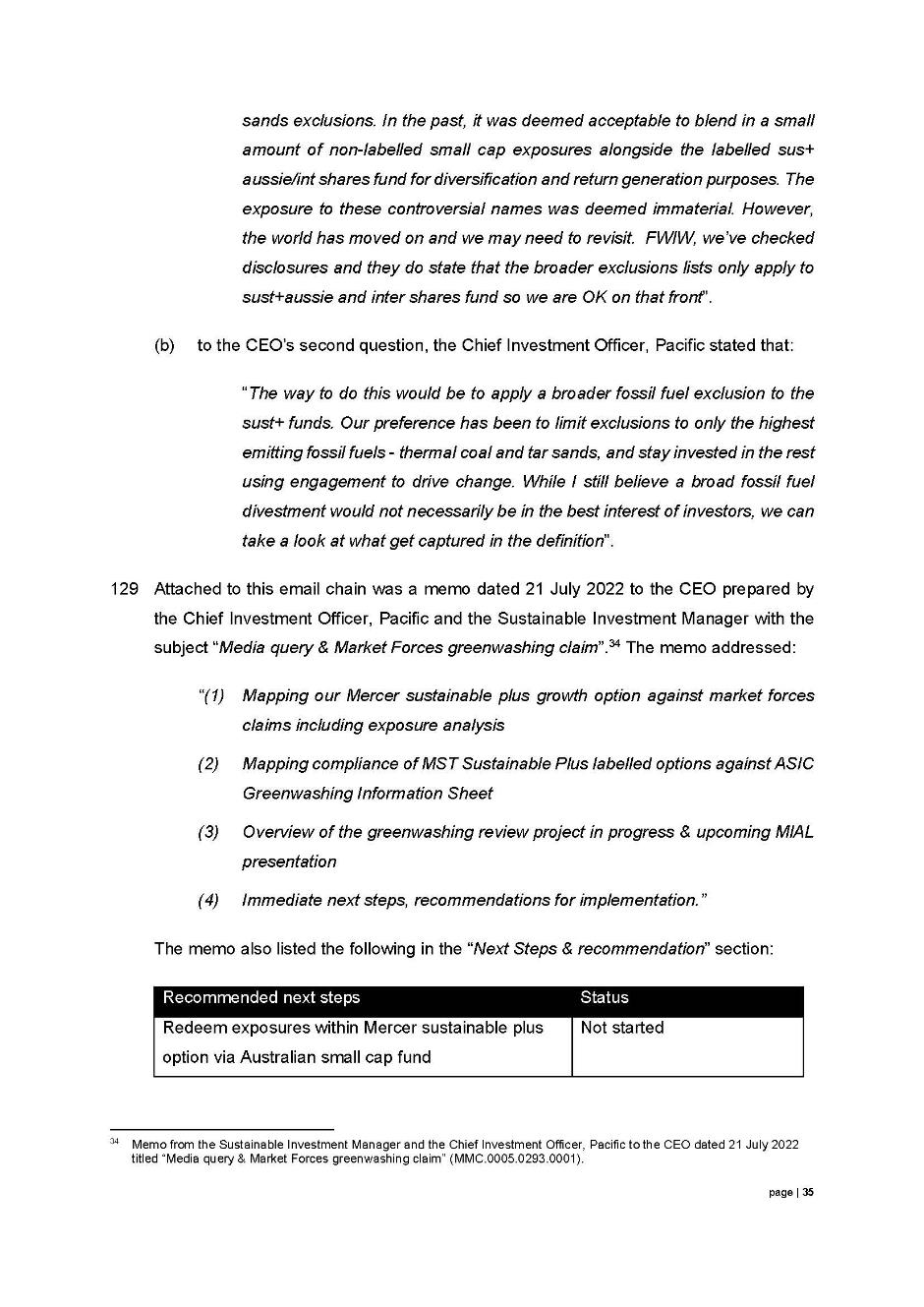

…

In addition to this, we also offer a number of Sustainable Plus investment options. These are investment options that have a higher proportion of sustainability-themed assets and exclude companies involved in alcohol production, carbon intensive fossil fuels, gambling and pornography. The list of exclusions will vary for each option.

The following disclaimer appeared at the bottom of the webpage on which the First Website Statement was made:

Please consider the Product Disclosure Statement, Product Guide, Insurance Guide, and Financial Services Guide before making a decision about the product, or seek professional advice from a licensed, or appropriately authorised financial adviser if you are unsure of what action to take.

(b) The Second Website Statement was made from 25 January 2022 to 4 April 2022:

Take it to the next level with our Sustainable Plus options

You may want to invest according to an even wider set of ethical criteria.

In that case, there are seven Sustainable Plus investment options you can choose from.

These options have a higher proportion of sustainability-themed assets and exclude companies involved in alcohol production, carbon intensive fossil fuels, gambling and pornography. The list of exclusions varies for each investment option.

(c) The Third Website Statement was made from 4 April 2022 to 22 July 2022:

Match your ethos further with our Sustainable Plus options

Although all our investment options are invested sustainably, we offer Sustainable Plus investment options, which go beyond the standard approach to sustainable investing.

They are invested according to a wider set of ethical criteria and have a greater exposure to sustainability-themed investments. They have a broader exclusion approach, for example, excluding companies involved in production of alcohol, carbon intensive fossil fuels like thermal coal, gambling and adult entertainment. The list of companies excluded varies for each investment option.

29 Again, each of these statements suggested that the investment options excluded companies involved in (relevantly) alcohol, gambling and carbon intensive fossil fuels. While there was no elaboration of the criteria by which a company would be regarded as “involved” in the relevant sectors, the statements did not contain any qualification to suggest that the investment options might include companies with only a minor exposure to the excluded industries. Nor was there any suggestion that an investment option might hold a minor investment in any excluded company.

30 The First, Second and Third Website Statements were also made in the context of other statements accessible on the Website during the relevant period that emphasised sustainability and the Mercer Super Trust’s ESG credentials, such as:

[From 10 March 2022 to 4 April 2022]

As a Mercer Super member you can rest assured your money is invested sustainability, working to create a world you want to live in.

We invest your super responsibly by applying Environmental, Social and Governance principles to each investment decision we make. …

We do this, not just because it’s the right thing to do, but because we believe companies that take ESG issues seriously are more likely to enjoy strong, sustainable financial returns over time.

[From 4 April 2022 to 27 July 2023]

Sustainable and ethical super

We invest your money sustainably to help maximise your returns, make a positive impact and be part of a brighter, more sustainable future.

Being ethical and sustainably can mean different things to different people, so it’s essential to understand what, they mean in practice and why they are important when it comes to matching a super fund with your investment objectives and your ethical values and beliefs.

…

We take a holistic, sustainable approach to your investments

At Mercer Super, we believe that taking a holistic approach to investing is paramount, so we consider the environmental, social, corporate governance (ESG) and ethical factors, alongside financial performance when making investment decisions, to help deliver you stronger returns.

31 On 20 July 2022, Mercer was notified of an article that was about to be published by “Market Forces”, an environmental advocacy project, regarding the exposure of the Sustainable Plus Options to companies in the fossil fuel industry. Mercer was notified that the article would claim that, as at 31 December 2021, 7.45% of the equities portfolio in the “Sustainable Plus Growth option” was “in climate wreckers, namely Woodside, Santos, Whitehaven Coal, New Hope Corporation, BP, Chevron, ExxonMobil, Shell, TEPCO, Chubu and Quinor”.

32 On or around 21 July 2022, Market Forces published two articles which identified potential greenwashing by Mercer in respect of investments using the “Sustainable Plus Growth” option (the Market Forces articles).

(a) The first of these articles was titled “Super funds ‘sustainable’ options invest in fossil fuel expansion”, and contained the following statement:

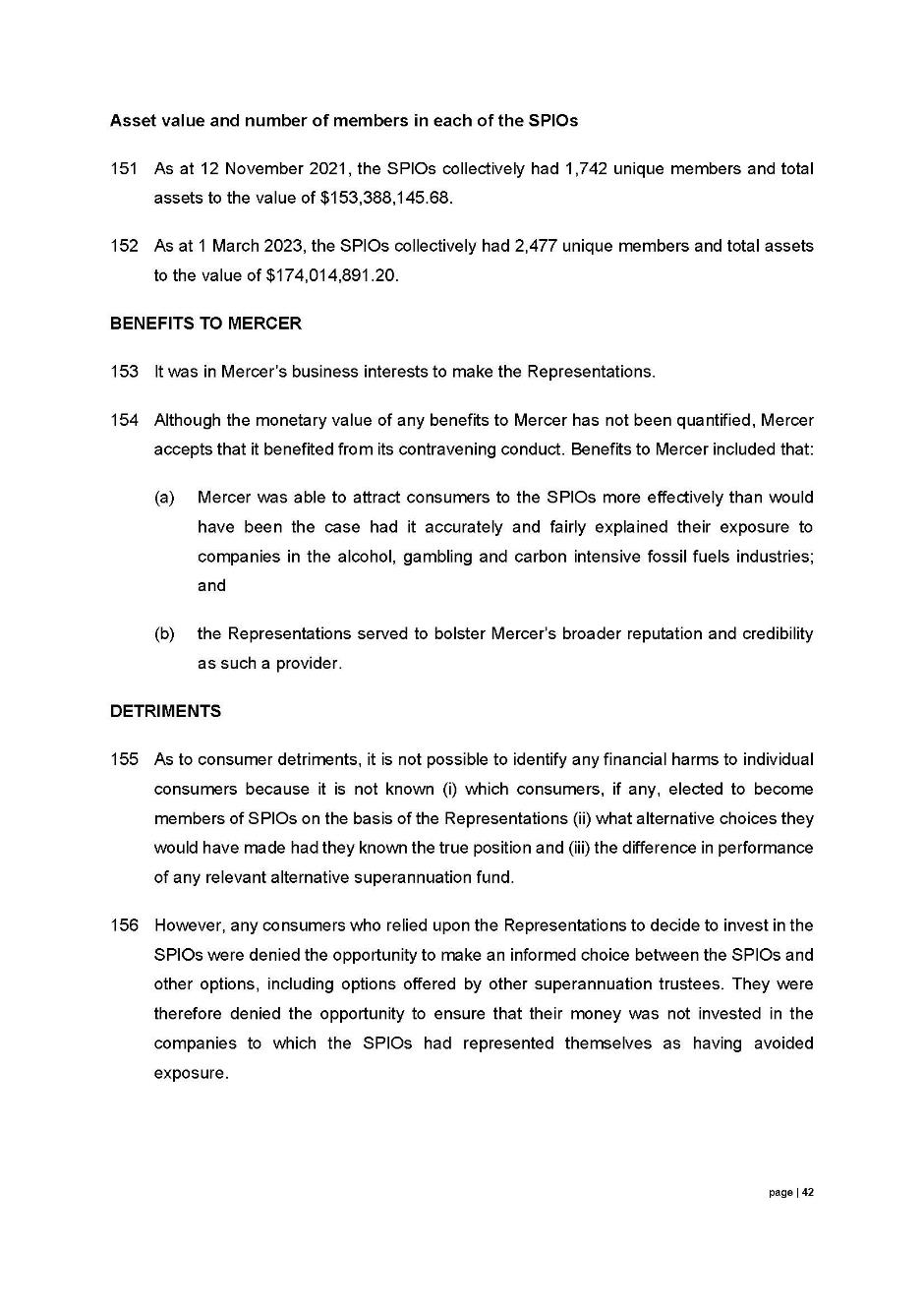

Super fund Mercer, for example, claims its ‘Sustainable Plus’ options exclude thermal coal companies, yet the ‘Sustainable Plus Growth’ option is invested in Whitehaven Coal and New Hope Corporation, among several other companies expanding the scale of the climate wrecking thermal coal industry.

In fact, 7.45% of Mercer Sustainable Plus Growth’s listed equities investments are in companies that appear on the Climate Wreckers Index due to their fossil fuel expansion plans. This is higher than the average of default options Market Forces recently analysed (6.26%).

(b) The second article was titled “Is your super fund’s ‘sustainable’ option invested in companies expanding the fossil fuel industry?”, and contained the following statement:

Mercer, for example, claims its ‘Sustainable Plus’ options exclude thermal coal companies, yet the ‘Sustainable Plus Growth’ option is invested in Whitehaven Coal and New Hope Corporation, among several other companies expanding the scale of the climate wrecking thermal coal industry.

The second article also included a table showing that the “Sustainable Plus Growth” option was invested in a number of named companies (Woodside, Santos, Whitehaven Coal, New Hope Corporation, BP, Chevron, ExxonMobil, Shell, TEPCO, Chubu and Equinor) despite claims to exclude companies involved in carbon intensive fossil fuels like thermal coal.

33 On 21 July 2022, following the publication of the Market Forces articles, Mercer took steps to remove the words “carbon intensive fossil fuels like thermal coal” from the Third Website Statement, leaving the balance of the statement unamended. The Amended Third Website Statement was made from 22 July 2022 to 1 March 2023.

34 Mercer admits that, on each occasion that a person viewed the Video Statement, the First Website Statement, the Second Website Statement, the Third Website Statement or the Amended Third Website Statement (the Five Online Statements), Mercer made a representation that the Sustainable Plus Options excluded, and would continue to exclude, investments in companies involved in, or deriving profit from, the production or sale of alcohol, gambling, and (except in the case of the Amended Third Website Statement) the extraction or sale of carbon intensive fossil fuels (the Representations). Mercer also admits that the disclaimers made at the end of the Video and at the bottom of the webpage on which the First Website Statement appeared did not relevantly qualify the Five Online Statements and the Representations, in part because they were not prominent and also because the Product Disclosure Statements (PDS) and other guides referred to did not contain anything that detracted from the representations made about excluded investments.

35 The Representations were made in four successive periods between 12 November 2021 to 1 March 2023, which are defined by reference to different permutations of the Five Online Statements that were made during each such period on the Website and, in respect of the Video Statement, on Vimeo and YouTube.

36 Mercer admits that its decision-making process in relation to the making of the Five Online Statements was inadequate. Among other things, Mercer’s delegations and approvals policy did not prescribe a process for approving website communications other than updates to Mercer’s PDS, and Mercer had no formal process to mandate or monitor the use of its “Marketing Checklist” (which set out a list of questions to ensure that information was accurate and complete and that there were “reasonable grounds” for making all representations) or its “Legal & Compliance Checklist” (which comprised a table to be completed and sent to the legal and compliance teams when seeking approval for marketing communications). In particular, Mercer has not located any Marketing Checklist or Legal & Compliance Checklist prepared in respect of any of the Five Online Statements. While the Video and draft template website pages containing the First Website Statement, the Second Website Statement and the Third Website Statement were reviewed in stages by various persons, including by persons employed as legal counsel and in risk and compliance roles, no concerns were identified about those statements.

The Representations were false, misleading or deceptive

37 Contrary to the Representations made through the Five Online Statements, the Sustainable Plus Options did not exclude all investments in companies involved in alcohol, gambling or carbon intensive fossil fuels.

38 Investment in such companies was not excluded by any general exclusions. During the relevant period, Mercer had general exclusions which were described in investment booklets for the Mercer Super Trust as excluding investments in tobacco companies, “controversial weapons”, and (since 20 April 2022) the divestment and exclusion of Russian securities. However, the general exclusions did not exclude investments in companies involved in alcohol, gambling or carbon intensive fossil fuels.

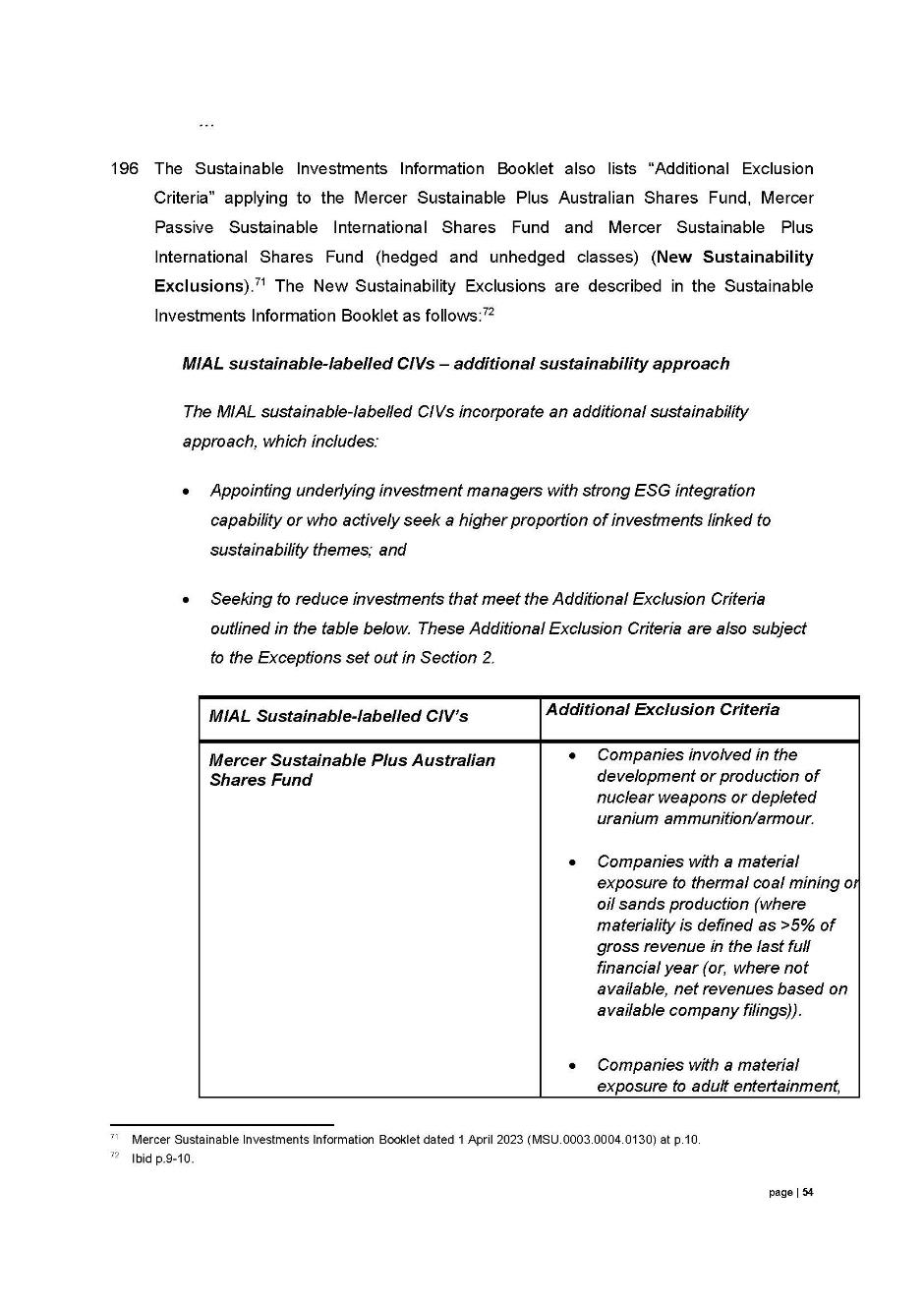

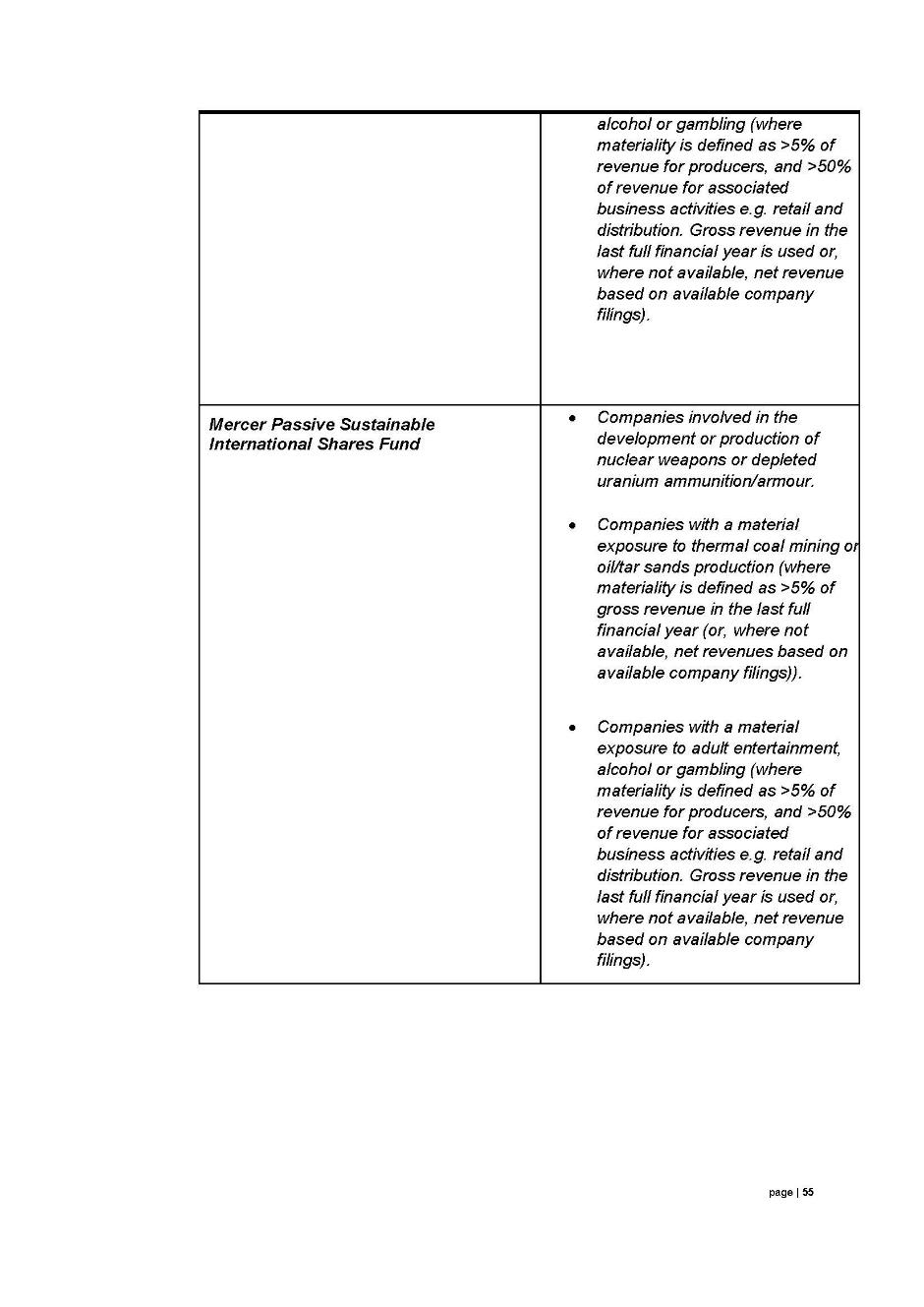

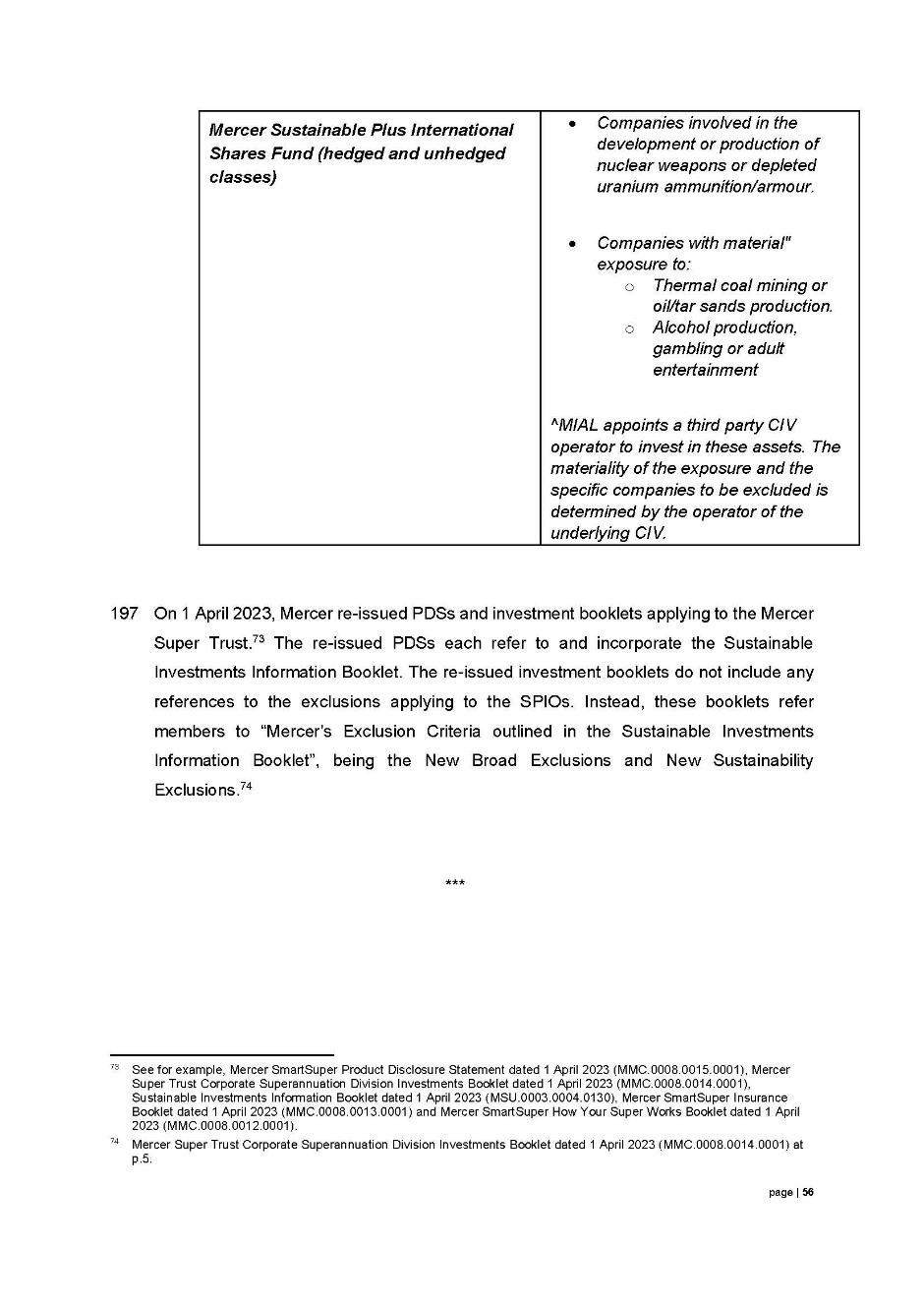

39 For some of the specific asset classes in the Sustainable Plus Options, Mercer applied additional sustainability exclusions in relation to nuclear weapons, carbon intensive fossil fuels, alcohol production and distribution, gambling and pornography. Some of those specific exclusions were expressed by reference to a materiality threshold based on the relevant company’s revenue in the last financial year, thereby expressly permitting investments in companies with a limited exposure to the excluded industries.

40 As the parties jointly submitted, the sustainability exclusions “were defined in such a way that, even for those specific asset classes, some limited investment was expressly permitted in companies with exposure to alcohol production and distribution, gambling and carbon intensive fossil fuels below certain materiality thresholds”.

41 Further, the diversified Sustainable Plus Options (namely, the High Growth Option, Growth Option, Moderate Growth Option and Conservative Growth Option) were permitted to invest in specific asset classes through managed investment schemes that were not subject to the sustainability exclusions.

42 Accordingly, Mercer admits that, during the relevant period, it did not ensure that all asset classes in which the Sustainable Plus Options were permitted to invest were excluded from investing in companies involved in, or deriving profit from, the production or sale of alcohol, gambling or the extraction or sale of carbon intensive fossil fuels.

43 Further, six of the seven Sustainable Plus Options offered by Mercer in fact had some exposure during the relevant period to companies involved in, or deriving profit from, the production or sale of alcohol, gambling, or the extraction or sale of carbon intensive fossil fuels. There was considerable variation in the magnitude of that exposure.

44 From at least 23 January 2022 to at least 1 March 2023 the Plus Shares Option, Australian Shares Option, Growth Option, High Growth Option, Moderate Growth Option and Conservative Growth Option held shares in BHP Group Ltd and Origin Energy Limited. At all relevant times, both BHP and Origin were companies involved in, or deriving profit from, the extraction or sale of carbon intensive fossil fuels. (BHP did not exceed the materiality threshold under Mercer’s relevant exclusions of 5% of revenue from thermal coal until September 2022, as the result of a sharp increase in the price of thermal coal, following which the Board of Mercer granted a temporary approval or exclusion exception in respect of the continued holding of BHP in the Sustainable Plus Australian Shares Fund for a period of up to 12 months.)

45 In addition, the Growth Option, High Growth Option, Moderate Growth Option and Conservative Growth Option collectively also held investments during the relevant period in 13 other companies involved in, or deriving profit from, the extraction or sale of carbon intensive fossil fuels, 15 companies involved in the production or sale of alcohol, and 19 companies involved in gambling. The amount of the investment held in those companies was in many cases relatively small, in the scale of tens or hundreds of dollars.

46 Mercer published PDS applying to the Mercer Super Trust, which referred to and incorporated the investment booklets that contained the general exclusions and the additional sustainability exclusions. The PDS relevantly stated that the investment booklets were accessible on the Website, and contained information about the extent to which ESG considerations were taken into account for the investment options (under the heading in the investment booklets titled “Sustainable Investment and ESG Considerations”). However, none of the webpages that contained the Five Online Statements contained a link to the investment booklets. Rather, it was necessary to navigate from the webpages containing the Five Online Statements to a separate webpage that contained links to the investment booklets. Further, the statements made in the PDS and the investment booklets did not relevantly qualify any of the Five Online Statements or the Representations.

47 At relevant times, Mercer had a “Sustainable Investment Policy”, which applied to all investment options in the Mercer Super Trust, except for the Mercer Direct investment option. As agreed in the SAFA, the Sustainable Investment Policy “outlines Mercer’s approach to environmental, social and governance integration, sustainability themes, climate change, active ownership, and screening”. The Sustainable Investment Policy was available on the Website and included the following statement in relation to the screening and monitoring of investment portfolios and the application of the sustainability exclusions:

Mercer also offers a number of Sustainable or Sustainable Plus funds and investment options to which additional exclusions apply. These additional exclusions are designed to align with the expectations of investors in those funds. Examples include excluding companies involved in adult entertainment, alcohol, the most carbon intensive fossil fuels, and gambling.

48 The Sustainable Investment Policy stated that MIAL relied on a third-party research provider in determining the individual companies to be excluded, noting that it may not be able to “dictate” the exclusions in all cases and would “make best endeavours to implement the exclusions and … notify the investment manager of any approved exclusions and the specific definitions for those exclusions”. The Policy stated that, in selecting investment managers, MIAL would consider the ability of a manager to implement the exclusions, and that “[c]ompliance with the exclusions will be encouraged but cannot be guaranteed”. The Policy stated that “[i]f a [collective investment vehicle (CIV)] is known to have material exposure to an excluded product, activity or industry, and the manager is unable or unwilling to divest these exposures, the CIV will be terminated in an orderly manner”.

49 The parties agree that statements made in the Sustainable Investment Policy did not relevantly qualify any of the Five Online Statements or the Representations.

50 In these circumstances, Mercer admits that each of the Representations was made in trade or commerce in connection with the promotion and supply of financial services, and was false and misleading as to the standard, quality, value or grade of the Sustainable Plus Options, in contravention of s 12DB(1) of the ASIC Act. Each of the Representations falsely conveyed that the Sustainable Plus Options did not include any investments in companies involved in, or deriving profit from, the production or sale of alcohol, gambling or the extraction or sale of carbon intensive fossil fuels. Each of the Representations conveyed that the Sustainable Plus Options would not in the future include any such investments, even though Mercer did not have reasonable grounds to make such a representation.

51 Further, Mercer admits that it contravened s 12DF(1) of the ASIC Act by engaging in conduct in trade or commerce that was liable to mislead the public as to the nature and characteristics of financial services, because the Sustainable Plus Options actually included investments in companies involved in, or deriving profit from, the production or sale of alcohol, gambling and the extraction or sale of carbon intensive fossil fuels, and because it did not have reasonable grounds to make the Representations.

RELIEF

52 The parties jointly seek orders in respect of the admitted contraventions comprising declarations of contravention of ss 12DB(1)(a) and 12DF(1) of the ASIC Act, pecuniary penalties of $11.3 million, and an adverse publicity order requiring Mercer to publish a notice in an agreed form in relation to the contraventions and the relief ordered by the Court.

Statutory framework

53 At present, there is no specific statutory regime in relation to the regulation of greenwashing practices, including in relation to financial products or services. Rather, regulators such as ASIC rely on prohibitions in relation to misleading or deceptive conduct and false or misleading representations, such as those contained in Subdiv D of Div 2 of Pt 2 of the ASIC Act or Pt 7.10 of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth).

54 Sections 12DB(1)(a) and 12DF(1) of the ASIC Act provide:

12DB False or misleading representations

(1) A person must not, in trade or commerce, in connection with the supply or possible supply of financial services, or in connection with the promotion by any means of the supply or use of financial services:

(a) make a false or misleading representation that services are of a particular standard, quality, value or grade; or

...

Note: Failure to comply with this subsection is an offence (see section 12GB).

…

12DF Certain misleading conduct in relation to financial services

(1) A person must not, in trade or commerce, engage in conduct that is liable to mislead the public as to the nature, the characteristics, the suitability for their purpose or the quantity of any financial services.

Note: Failure to comply with this subsection is an offence (see section 12GB).

55 Each of ss 12DB(1) and 12DF(1) is a civil penalty provision, which enlivens the Court’s power to order the payment of a pecuniary penalty upon the making of a declaration of contravention: see ss 12GBA(6)(b) and 12GBB.

56 In Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Vanguard Investments Australia Ltd [2024] FCA 308 at [21], O’Bryan J stated:

The prohibitions against making false or misleading representations in s 12DB and against conduct that is liable to mislead the public in s 12DF of the ASIC Act are part of a suite of legislative prohibitions of misleading conduct in trade or commerce which originated in the Australian Consumer Law (through its statutory predecessor, Part V of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth)) and are now also contained in the ASIC Act and the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) ... The central conception of misleading conduct, which lies at the heart of each of the prohibitions, has been interpreted in a consistent manner across the various prohibitions.

57 The principles applicable to such prohibitions were recently summarised by the High Court in Self Care IP Holdings v Allergan Australia [2023] HCA 8; 97 ALJR 388 at [80]-[84] (Kiefel CJ, Gageler, Gordon, Edelman and Gleeson JJ), and have been applied by this Court in the context of the prohibitions under ss 12DB(1)(a) and 12DF(1) of the ASIC Act: see e.g. Vanguard Investments at [21] (O’Bryan J); LGSS at [25]-[29] (O’Callaghan J). Adapting those principles to the relevant prohibitions and the facts of the present case:

(a) The first step is to identify with precision the contravening “conduct” – that is, the relevant representation that was made in relation to the standard, quality, value or grade of any financial services or as to the nature, characteristics, suitability for purpose or quantity of any financial services that is said to contravene ss 12DB(1)(a) or 12DF(1).

(b) The second step is to consider whether the identified conduct or representation was engaged in or made in trade or commerce.

(c) The third step is to consider what meaning was conveyed by the conduct or representation to its intended audience.

(d) The fourth step is to determine, in the light of that meaning, whether the representation was false or misleading in the requisite sense for the purposes of s 12DB(1)(a) or whether the conduct was liable to mislead the public in the requisite sense for the purposes of s 12DF(1).

58 The third and fourth steps require an objective characterisation of the conduct or representation viewed as a whole and its notional effects, judged by reference to its immediate and broader context, on the state of mind of the relevant person or class of persons. Where the conduct was directed to the public – as is expressly contemplated by s 12DF(1) – those steps “must be undertaken by reference to the effect or likely effect of the conduct on the ordinary and reasonable members of the relevant class of persons”, so as to avoid assessing the effect or likely effect by reference to the very ignorant or the very knowledgeable, or those credited with habitual caution or with exceptional carelessness, or by considering the assumptions of persons which are extreme or fanciful: Self Care at [82]-[83].

59 As Wigney, O’Bryan and Jackson JJ stated in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd (2020) 278 FCR 450 at [22], “[t]he central question is whether the impugned conduct, viewed as a whole, has a sufficient tendency to lead a person exposed to the conduct into error (that is, to form an erroneous assumption or conclusion about some fact or matter)”. See also Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd (2013) 250 CLR 640 at [39] (French CJ, Crennan, Bell and Keane JJ); Campbell v Backoffice Investments Pty Ltd (2009) 238 CLR 304 at [24]-[25] (French CJ).

60 In the present case, the conduct of Mercer involved making the Representations to members of the public, or a section thereof, by publishing the Five Online Statements on the Website and, in respect of the Video Statement, on Vimeo and YouTube. The statements that the Sustainable Plus Options excluded all investments in companies involved in alcohol, gambling and carbon intensive fossil fuels during the relevant period were factually incorrect and, in so far as they related to future matters concerning excluded investments, Mercer did not have reasonable grounds for making such representations. There was a real possibility that the Representations would lead the persons to whom they were made into error.

61 The nature and extent of the admitted contraventions of ss 12DB(1) and 12DF(1) by Mercer are considered further below.

Declaratory relief

62 ASIC seeks declarations under s 12GBA of the ASIC Act and s 21 of the FCA Act as to the admitted contraventions. Mercer does not oppose the making of declarations in the form proposed by ASIC.

63 Section 12GBA of the ASIC Act empowers the Court to make a declaration of contravention of a civil penalty provision:

12GBA Declaration of contravention of civil penalty provision

Application for declaration of contravention

(1) ASIC may apply to a Court for a declaration that a person has contravened a civil penalty provision.

(2) ASIC must make the application within 6 years of the alleged contravention.

Declaration of contravention

(3) The Court must make the declaration if it is satisfied that the person has contravened the provision.

(4) The declaration must specify the following:

(a) the Court that made the declaration;

(b) the civil penalty provision that was contravened;

(c) the person who contravened the provision;

(d) the conduct that constituted the contravention.

Declaration of contravention conclusive evidence

(5) The declaration is conclusive evidence of the matters referred to in subsection (4).

64 In addition, s 21(1) of the FCA Act provides:

21 Declarations of right

(1) The Court may, in civil proceedings in relation to a matter in which it has original jurisdiction, make binding declarations of right, whether or not any consequential relief is or could be claimed.

The power to grant declaratory relief pursuant to s 21 of FCA Act “is a very wide one” and the Court is “limited only by its discretion”: Seven Network Ltd v News Ltd (2009) 182 FCR 160 at [1016] (Dowsett and Lander JJ), citing Forster v Jododex Australia Pty Ltd (1972) 127 CLR 421 at 435 (Gibbs J).

65 Before making a declaration, the Court must be satisfied that: (i) there is a real question and not a hypothetical or theoretical one; (ii) the applicant has a real interest in raising the question; and (iii) there is a proper contradictor: Forster at 437-438 (Gibbs J); Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Coles Supermarkets Australia Pty Ltd [2014] FCA 1405 at [76] (Gordon J).

66 In the present case, the agreed facts give rise to a real question as to the contravention by Mercer of ss 12DB(1)(a) and 12DF(1) of the ASIC Act. ASIC has a real interest in raising that question, and Mercer is a proper contradictor notwithstanding that it has chosen not to oppose the grant of declaratory and other relief: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v MSY Technology Pty Ltd (2012) 201 FCR 378 at [14], [30], [34] (Greenwood, Logan and Yates JJ).

67 The exercise of the power to make a declaration under s 21 of the FCA Act is discretionary. On an application by ASIC for a declaration under s 12GBA of the ASIC Act that a person has contravened a civil penalty provision, however, the Court is required by s 12GBA(3) to make a declaration if it is satisfied that the person has contravened a civil penalty provision.

68 Section 12GBA(4) requires the declaration to specify certain matters, including “the conduct that constituted the contravention”, and s 12GBA(5) provides that the declaration becomes conclusive evidence of those matters. In this context, the declaration should “describe the contravening conduct with reasonable specificity” and should “indicate the gist of the findings that identify the contravention”: Mayfair Wealth Partners Pty Ltd v Australian Securities and Investments Commission (2022) 295 FCR 106 at [183] (Jagot, O’Bryan and Cheeseman JJ). The declaration must be “informative as to the basis on which the Court declares that a contravention has occurred” and “should contain appropriate and adequate particulars of how and why the impugned conduct is a contravention of the Act”: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v EnergyAustralia Pty Ltd [2015] FCA 274 at [83] (Gordon J). The declaration should concisely and accurately reflect the impugned conduct: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Danoz Direct Pty Ltd [2003] FCA 881; 60 IPR 296 per Dowsett J at [260].

69 The declarations proposed by ASIC, and agreed to by Mercer, succinctly identify the principal elements of the admitted contraventions by reference to the Representations made by Mercer in each of the four periods between 12 November 2021 and 1 March 2023 in relation to excluded investments for the Sustainable Plus Options, and the basis on which those Representations were false or misleading and liable to mislead the public, contrary to ss 12DB(1)(a) and 12DF(1) of the ASIC Act.

70 Based on the facts set out in the SAFA, I am satisfied that Mercer contravened ss 12DB(1)(a) and 12DF(1) of the ASIC Act on the occasions and in the manner set out in the proposed declarations. In my view, the proposed declarations are in a form that accurately reflects the nature of the contravening conduct by Mercer, and they provide appropriate and adequate particulars of how and why that conduct is a contravention of those civil penalty provisions.

71 Accordingly, I consider that it is appropriate to make the declarations of contravention under s 12GBA of the ASIC Act.

Pecuniary penalties

72 Section 12GBB provides that, on an application made by ASIC, the Court may make a pecuniary penalty order, namely, an order that a person in respect of whom a declaration of contravention has been made under s 12GBA should pay a pecuniary penalty to the Commonwealth, of an amount that the Court considers is appropriate. In determining the pecuniary penalty, the Court is required by s 12GBB(5) to take into account all relevant matters, including:

(a) the nature and extent of the contravention; and

(b) the nature and extent of any loss or damage suffered because of the contravention; and

(c) the circumstances in which the contravention took place; and

(d) whether the person has previously been found by a court (including a court in a foreign country) to have engaged in any similar conduct; and

(e) in the case of a contravention by the trustee of a registrable superannuation entity—the impact that the penalty under consideration would have on the beneficiaries of the entity.

73 The maximum pecuniary penalty applicable to the contravention of a civil penalty provision by a body corporate is the greatest of: (a) 50,000 penalty units; or (b) three times the amount of the benefit derived and detriment avoided because of the contravention; or (c) 10% of the annual turnover of the body corporate for the 12‑month period ending at the end of the month in which the body corporate contravened, or began to contravene, the civil penalty provision, up to a maximum of 2.5 million penalty units: ss 12GBC, 12GBCA(2). For such purposes, the benefit derived and detriment avoided because of a contravention of a civil penalty provision is the sum of the total value of all benefits obtained by, and all detriments avoided by, one or more persons that are reasonably attributable to the contravention: s 12GBCE.

74 At the times relevant to this proceeding, the value of a penalty unit as fixed by s 4AA of the Crimes Act 1914 (Cth) was $222 for contraventions that occurred on or after 1 July 2020 and before 31 December 2022, and $275 for contraventions that occurred on or after 1 January 2022 and before 30 June 2023.

75 The parties jointly submit that, in respect of its admitted contraventions of ss 12DB(1)(a) and 12DF(1), Mercer should be ordered to pay pecuniary penalties amounting to a total of $11.3 million, comprising:

(a) an aggregate penalty of $1 million in respect of the contraventions arising from the making of representations by the Video Statement during the first period from 12 November 2021 to 25 January 2022 (the first course of conduct);

(b) an aggregate penalty of $2 million in respect of the arising from the making of representations by the Video Statement, the First Website Statement and the Second Website Statement during the second period from 25 January 2022 to 4 April 2022 (the second course of conduct);

(c) an aggregate penalty of $3.3 million in respect of the contraventions arising from the making of representations by the Video Statement, the First Website Statement and the Third Website Statement during the third period from 4 April 2022 to 22 July 2022 (the third course of conduct); and

(d) an aggregate penalty of $5 million in respect of the contraventions arising from the making of representations by the Video Statement, the First Website Statement and the Amended Third Website Statement during the fourth period from 22 July 2022 to 1 March 2023 (the fourth course of conduct).

Applicable principles

Fixing an appropriate penalty

76 The principal purpose of a civil penalty is to protect and promote the public interest in compliance with the law by deterring further contraventions of a like kind by the contravenor and by others: Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Pattinson (2022) 274 CLR 450 at [9]-[10], [15]-[19], [42], [48] (Kiefel CJ, Gageler, Keane, Gordon, Steward and Gleeson JJ), [105] (Edelman J); see also Commonwealth of Australia v Director, Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate (2015) 258 CLR 482 (FWBII) at [55] (French CJ, Kiefel, Bell, Nettle and Gordon JJ). That is, the purpose of pecuniary penalties is deterrence, both specific and general, rather than punishment or retribution. The imposition of a pecuniary penalty involves a financial disincentive which encourages compliance with the law “by ensuring that contraventions are viewed by the contravenor and others an economically irrational choice”: Pattinson at [66]. The penalty puts “a price on contravention that is sufficiently high to deter repetition by the contravenor and by others who might be tempted to contravene”: Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Westpac Banking Corporation [2019] FCA 2147 at [255] (Wigney J).

77 A civil penalty therefore “must be fixed with a view to ensuring that the penalty is not such as to be regarded by [the] offender or others as an acceptable cost of doing business”: Pattinson at [17], referring to Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd (2013) 250 CLR 640 at [66] and Singtel Optus Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2012] FCAFC 20; 287 ALR 249 at [62]; see also Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union (2018) 262 CLR 157 at 195 [116] (Keane, Nettle and Gordon JJ). Nevertheless, an appropriate penalty is one “that strikes a reasonable balance between oppressive severity and the need for deterrence in respect of the particular case”: Pattinson at [40]-[41], [46]; cf. at [110] (Edelman J).

78 In Trade Practices Commission v CSR Ltd [1990] FCA 521; [1991] ATPR ¶41-076, French J (as his Honour then was) set out a list of relevant factors which inform the assessment of a pecuniary penalty of appropriate deterrent value, including:

1. The nature and extent of the contravening conduct.

2. The amount of loss or damage caused.

3. The circumstances in which the conduct took place.

4. The size of the contravening company.

5. The degree of power it has, as evidenced by its market share and ease of entry into the market.

6. The deliberateness of the contravention and the period over which it extended.

7. Whether the contravention arose out of the conduct of senior management or at a lower level.

8. Whether the company has a corporate culture conducive to compliance with the Act, as evidenced by educational programs and disciplinary or other corrective measures in response to an acknowledged contravention.

9. Whether the company has shown a disposition to co-operate with the authorities responsible for the enforcement of the Act in relation to the contravention.

The first three factors identified by French J are prescribed as relevant considerations by s 12GBB(5) of the ASIC Act, together with the person’s compliance history and the impact of the penalty on the beneficiaries of any registrable superannuation entity.

79 These relevant factors have been accepted and augmented in subsequent cases: see TPG Internet Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2012) 210 FCR 277 at [140]-[141] (Jacobson, Bennett and Gilmour JJ); Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Westpac Banking Corporation (No 3) [2018] FCA 1701; 131 ACSR 585 at [49] (Beach J)). The factors “may conveniently be categorised according to whether they relate to the objective nature and seriousness of the offending conduct, or concern the particular circumstances of the defendant in question”: Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union (2017) 254 FCR 68 at [102]-[104] (Dowsett, Greenwood and Wigney JJ).

80 Factors that relate to the objective nature and seriousness of the contravening conduct include:

(a) the extent to which the contravention was the result of deliberate, covert or reckless conduct, as opposed to negligence or carelessness;

(b) whether the contravention comprised isolated conduct, or was systematic or occurred over a period of time;

(c) if the contravenor is a corporation, the seniority of the officers responsible for the contravention;

(d) the existence, within the corporation, of compliance systems and whether there was a culture of compliance at the corporation; and

(e) the impact or consequences of the contravention on the market or innocent third parties; and the extent of any profit or benefit derived as a result of the contravention.

81 Factors that concern the particular circumstances of a corporate contravenor include:

(a) the size and financial position of the company;

(b) whether the company has been found to have engaged in similar conduct in the past;

(c) whether the company has improved or modified its compliance systems since the contravention;

(d) whether the company (through its senior officers) has demonstrated contrition and remorse;

(e) whether the company had disgorged any profit or benefit received as a result of the contravention, or made reparation;

(f) whether the company has cooperated with and assisted the relevant regulatory authority in the investigation and prosecution of the contravention; and

(g) whether the company has suffered any extra-curial punishment or detriment arising from the finding that it had contravened the law.

82 It has been recognised that such lists of relevant factors do not constitute a rigid catalogue or legal checklist: see e.g. Pattinson at [18]-[19], [47], [54]. The task involved in fixing an appropriate penalty has been described as “a difficult and complex process of multi-factorial decision-making”, and likened to the “instinctive synthesis” involved in criminal sentencing, adopting an “integrated and holistic approach, requiring the balancing of all relevant factors into a final result”: see Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Reckitt Benckiser (Australia) Pty Ltd [2016] FCAFC 181; 340 ALR 25 at [44] (Jagot, Yates and Bromwich JJ). As Lee J observed in Australian Securities and Investments Commission v AMP Financial Planning Pty Ltd (No 2) [2020] FCA 69; 377 ALR 55 at [159], “the process of quantifying pecuniary penalties is an inexact science, not subject to rigidity in approach but guided by well-accepted factors”.

83 The maximum penalty prescribed by the Parliament for a contravention of a civil penalty provision can be taken into account, together with all other relevant factors, as a “yardstick” when determining an appropriate penalty: Pattinson at [52]-[53]. There should be a reasonable relationship between the theoretical maximum and the final penalty imposed, by reference to both the circumstances of the contravenor and the circumstances of the contravening conduct in so far as those circumstances bear upon the extent of the need for deterrence in the penalty to be imposed: Pattinson at [55]. However, the maximum penalty is not reserved only for the most serious examples of misconduct, and there may be cases in which the imposition of a penalty at or close to the prescribed maximum is appropriate on the basis that it is no more than what might be considered to be reasonably necessary to deter future contraventions: Pattinson at [10], [49]-[50].

84 In a case such as the present, where it is accepted that there were a large number of separate contraventions of the relevant provisions, the theoretical maximum penalty in respect of all of the contraventions can be difficult to ascertain with any precision and may in any event be less meaningful in fixing the amount of an appropriate penalty for the contravening conduct: see Reckitt Benckiser at [3], [157] (Jagot, Yates and Bromwich JJ). The statutory maximum penalty for a single contravention does not provide an upper limit on the penalty that may be imposed in such circumstances, even allowing for the operation of the principles discussed below relating to course of conduct and totality. But it may be an “arid exercise … to engage in a mere arithmetical calculation multiplying the maximum penalty by the number of contraventions to get a theoretical maximum for all offending even if one could theoretically quantify that latter number”: Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Commonwealth Bank of Australia [2020] FCA 790 at [65] (Beach J).

85 This does not preclude the Court from having regard to the prescribed maximum as a guide or a reference point in relation to whether the penalty imposed in respect of the contraventions, or in respect of each relevant course of conduct, bears a reasonable relationship to the maximum for a single contravention: see e.g. Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Birubi Art Pty Ltd (in liq) (No 3) [2019] FCA 996; 374 ALR 776 at [71]-[72] (Perry J), referring to Australian Energy Regulator v Snowy Hydro Limited (No 2) [2015] FCA 58 at [119] (Beach J). Thus, it may nevertheless be “instructive to take account of the theoretical maximums so that consideration can be given to the egregiousness of the conduct in question”: Australian Securities and Investments Commission v AGM Markets Pty Ltd (in liquidation) (No 4) [2020] FCA 1499; 148 ACSR 511 at [40] (Beach J).

86 The determination of an appropriate penalty for multiple contraventions also requires consideration of two related principles – the “course of conduct” principle and the “totality” principle: see Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Yazaki Corporation (2018) 262 FCR 243 at [226]-[237] (Allsop CJ, Middleton and Robertson JJ); Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Employsure Pty Ltd [2023] FCAFC 5; 407 ALR 302 at [51]-[53] (Rares, Stewart and Abraham JJ); Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Hillside (Australia New Media) Pty Ltd trading as Bet365 (No 2) [2016] FCA 698 at [21]-[25] (Beach J).

87 In relation to the former, where there is an interrelationship between the factual and legal elements of two or more contraventions, it may be appropriate to group those multiple contraventions together as a single course of conduct so as to avoid double “punishment” in respect of the overlapping acts or omissions that comprise the contraventions (albeit recognising that the principal purpose of imposing pecuniary penalties is deterrence rather than punishment): see Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union v Cahill [2010] FCAFC 39; 269 ALR 1 at [39], [41] (Middleton and Gordon JJ); Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Insurance Australia Limited, in the matter of Insurance Australia Limited [2023] FCA 724 at [41] (Abraham J); Pattinson at [96] (Edelman J).

88 The course of conduct principle requires a fact-specific inquiry to identify conduct that is properly characterised as involving the “same criminality”, or as arising out of the same course of conduct or the one transaction: Cahill at [39]; Yazaki Corporation at [234]. However, the principle remains no more than an analytical tool that can assist in the determination of an appropriate penalty, and does not operate to limit the penalty to the statutory maximum in respect of each course of conduct: Yazaki Corporation at [226]-[227]; Pattinson at [45]. As Beach J stated in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Murray Goulburn Co-Operative Co Limited [2018] FCA 1964 at [29]:

… to apply such an approach is not to downplay the wrongdoing. This does not convert the many separate contraventions into only one contravention, and nor does it constrain the available maximum penalty let alone necessarily constrain it to the maximum penalty for one contravention. And notwithstanding a grouping into a course(s) of conduct, one must ensure that any penalty imposed is of appropriate deterrent value, whether specific or general.

89 Similarly, the Full Court (Middleton, Beach and Moshinsky JJ) observed in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Cement Australia Pty Ltd (2017) 258 FCR 312 at [424]:

Putting expressions of caution to one side, the course of conduct principle is commonly employed and is a useful “tool” in the determination of appropriate civil penalties: Cahill at [41]. As we have already indicated, the principal object of the penalties imposed by s 76 of the Act is that of specific and general deterrence. With this in mind, in a civil penalty context, the course of conduct principle can be conceived of as a recognition by the courts that the deterrent effect in respect of a civil penalty (at both a specific and general level) is measured by reference to the nature of the conduct for which it is imposed. It is therefore of paramount importance to identify whether multiple contraventions constitute a single course of conduct or separate instances of conduct, so as to ensure that an appropriate deterrent effect is achieved by the imposition of the penalty or penalties in respect of that particular conduct.

90 The totality principle operates as a “final check” to ensure that the penalties to be imposed, considered as a whole, are just and appropriate and do not exceed what is proper having regard to the totality of the contravening conduct: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Australian Safeway Stores Pty Ltd (1997) 77 FCR 238 at [53] (Goldberg J); Hillside at [22].

Agreed penalties

91 In the present case, the parties have filed joint submissions on liability and relief in which they have agreed to proposed orders including the imposition of pecuniary penalties of $11.3 million in total.

92 In FWBII, the High Court held that it is permissible in a civil penalty proceeding for a court to receive and, if appropriate, accept an agreed submission as to the amount of a pecuniary penalty. In such proceedings, the specialist regulator that has the statutory function of securing compliance with the provisions of a regulatory regime, the purpose of which is the protection or advancement of particular aspects of the public interest, must choose the enforcement mechanism which it considers to be the most conductive to securing such compliance, balancing the competing considerations of compensation, prevention and deterrence: FWBII at [24]. The regulator purses the chosen option “as a civil litigant in civil proceedings”, which among other things involve “an adversarial contest in which the issues and scope of possible relief are largely framed and limited as the parties may choose”, and in which “there is generally very considerable scope for the parties to agree on the facts and upon consequences” including the appropriate remedy: FWBII at [24], [53], [57]; see also at [78] (Gageler J), [103], [105]-[106] (Keane J).

93 In that context, French CJ, Kiefel, Bell, Nettle and Gordon JJ accepted in FWBII (at [46]) that:

… there is an important public policy involved in promoting predictability of outcome in civil penalty proceedings and that the practice of receiving and, if appropriate, accepting agreed penalty submissions increases the predictability of outcome for regulators and wrongdoers. As was recognised in [Trade Practices Commission v Allied Mills Industries Pty Ltd [No 5] (1981) 60 FLR 38; 37 ALR 256] and authoritatively determined in [NW Frozen Foods Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (1996) 71 FCR 285], such predictability of outcome encourages corporations to acknowledge contraventions, which, in turn, assists in avoiding lengthy and complex litigation and thus tends to free the courts to deal with other matters and to free investigating officers to turn to other areas of investigation that await their attention.

94 To similar effect, Keane J considered (at [109]) that:

… the willingness of the [Australian Building and Construction] Commissioner to accept a particular sum by way of civil penalty in discharge of the Commissioner’s claim against the defendant can be expected to reflect a considered estimation that, given the hazards and expense of litigation, satisfaction of the Commissioner’s claim against the defendant on such terms is apt to advance the public interest in the enforcement of the regulatory regime more effectively and efficiently than the continued prosecution of the claim.

95 It is ultimately a matter for the Court to determine whether an agreed penalty is appropriate. However, given the public policy interests that are advanced by agreed penalty submissions and the fact that fixing the quantum of a civil penalty is not an exact science, it is open to the Court to accept an agreed penalty as being within the appropriate range notwithstanding that it might otherwise have selected a different amount: see FWBII at [47], [57]. That is not to say that the Court’s function is limited to a determination whether or not the agreed penalty is within the permissible range. Nevertheless, as French CJ, Kiefel, Bell, Nettle and Gordon JJ stated in FWBII (at [58]):

Subject to the court being sufficiently persuaded of the accuracy of the parties’ agreement as to facts and consequences, and that the penalty which the parties propose is an appropriate remedy in the circumstances thus revealed, it is consistent with principle and … highly desirable in practice for the court to accept the parties’ proposal and therefore impose the proposed penalty.

(Emphasis in original.)

96 In FWBII at [60], the plurality noted that a further reason for a court to act upon a joint submission as to penalties is that the specialist regulator will fashion such a submission with an overall view to achieving the statutory objectives and “with one eye to considerations beyond the case in hand”, and “will be in a position to offer informed submissions as to the effects of contravention on the industry and the level of penalty necessary to achieve compliance”.

97 The above principles in relation to agreed civil penalties were subsequently summarised in Volkswagen Aktiengesellschaft v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2021) 284 FCR 24 at [124]-[131] (Wigney, Beach and O’Bryan JJ), from which the following key points emerge.

(a) The agreement of the parties does not bind the Court, which must be persuaded that the penalty proposed by the parties is appropriate.

(b) If the Court is persuaded of the accuracy of the parties’ agreement as to facts and consequences, and that the agreed penalty jointly proposed is an appropriate remedy in all the circumstances, it is highly desirable in practice for the Court to accept the parties’ proposal and therefore impose the proposed penalty. This promotes predictability of outcome, which encourages corporations to acknowledge contraventions and in turn assists in avoiding lengthy and complex litigation. However, this is only one relevant consideration, and is subject to the overriding statutory directive that the Court must impose a penalty that it determines to be appropriate.

(c) There is no single appropriate penalty. Rather, there is a permissible range of penalties within which no particular figure can necessarily be said to be more appropriate than another. The permissible range is determined by all the relevant facts and circumstances, and a jointly proposed penalty may be considered to be an appropriate penalty if it falls within that permissible range. It does not follow, however, that the Court’s task is limited to determining whether the jointly proposed penalty falls within the permissible range, nor that the Court is bound to start with the proposed penalty and limit itself to considering whether that penalty is within the permissible range.