FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Fair Work Ombudsman v Doll House Training Pty Ltd (No 2) [2024] FCA 811

ORDERS

Applicant | ||

AND: | DOLL HOUSE TRAINING PTY LTD (ACN 634 366 411) Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: | 24 JULY 2024 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The respondent pay pecuniary penalties totalling $197,000 within 28 days.

2. The pecuniary penalties referred to in order 1 be paid to the Consolidated Revenue Fund of the Commonwealth.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

[1] | |

[4] | |

C. A PRELIMINARY QUESTION: THE STATUS OF THE WORKERS AFTER ABOUT 7 OCTOBER 2020 | [53] |

[77] | |

[78] | |

[83] | |

[89] | |

[92] | |

[96] | |

[97] | |

[100] | |

[105] | |

E.3.1 The nature and extent of the contravening conduct and the circumstances in which it took place | [111] |

[119] | |

[120] | |

E.3.4 Whether the contraventions arose out of conduct of senior management or at a lower level | [121] |

E.3.5 The culture of Doll House | [124] |

[127] | |

[130] | |

[131] | |

[133] |

GOODMAN J

1 Between 27 August 2020 and 28 October 2020, Ms Rachel Murray, Ms Jasmine David and Ms Diana Wickett (Workers) performed work for the respondent (Doll House) in the business which Doll House operated under the name Doll House Training Club. The activities of that business included generating research into robotics, coding and artificial intelligence and their application to the health and wellness industry.

2 The applicant (Ombudsman) contends that Doll House contravened the following provisions of the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth):

(1) s 323(1), by failing to pay each of the Workers amounts payable in relation to the performance of work in full, at least monthly;

(2) s 357, by representing to each of the Workers that the contracts of employment under which they were or would be employed were contracts for services under which the Workers performed or would perform work as an independent contractor;

(3) s 358, by dismissing, or alternatively threatening to dismiss, each of the Workers from their employment to engage them as independent contractors to perform the same, or substantially the same, work under a contract for services; and

(4) s 712(3), by failing to comply with a notice to produce records or documents.

3 The Ombudsman seeks declarations of contraventions of the above-mentioned sections and orders that Doll House pay pecuniary penalties pursuant to s 546(1) of the Act in respect of those contraventions.

4 Set out below are my findings as to the salient facts (together with some admissions as to the legal consequences of those facts). Many of these findings are based upon the admissions made by Doll House in its defence to the Ombudsman’s (then) statement of claim. The remaining findings are based upon the unchallenged evidence of: (1) the Workers; and (2) employees of the Ombudsman, namely Ms Anna Arnold, a Senior Fair Work Inspector and Ms Kate Davies, a lawyer.

5 Doll House was at all material times: (1) a “constitutional corporation” within the meaning of s 12 of the Act; (2) a “national system employer” within the meaning of s 14 of the Act; and (3) as a result required to comply with the Act in respect of its employees.

6 Ms Heidi Meuwissen (also known as Ms Heidi Vieria-Vanjek) was at all relevant times the sole director, secretary and sole shareholder of Doll House, as well as its chief executive officer. She was its operating mind, responsible for overseeing the direction of Doll House’s business; directing representatives of Doll House to hire employees or engage independent contractors (as the case may be); setting the duties, hours, classification, and the pay of employees of Doll House; and providing pay slips when required. In the period from on or around 5 November 2020 until 1 March 2021, Ms Meuwissen was responsible for responding to representatives of the Ombudsman regarding an investigation into alleged contraventions of the Act by Doll House.

7 Ms Michelle Saidi was the operations manager of Doll House at all relevant times until around mid-November 2020. She was responsible for the day-to-day management of Doll House’s business, including supervising its employees, and allocating and reviewing work on behalf of Ms Meuwissen; engaging with external agencies regarding the recruitment of employees to perform work for Doll House; and corresponding with employees of Doll House about terms and conditions of engagement, on behalf of Ms Meuwissen.

8 Mr Jeysun Colak was at all relevant times the executive assistant to Ms Meuwissen, responsible for providing administrative and other assistance to Doll House’s business, including corresponding with employees or independent contractors of Doll House (as the case may be) about terms and conditions of their engagement, on behalf of Ms Meuwissen.

9 By dint of s 793 of the Act, the conduct engaged in by, and knowledge of, Ms Meuwissen, Ms Saidi and Mr Colak is taken to be conduct engaged in by, and with the knowledge of, Doll House to the extent that the conduct was engaged in on behalf of Doll House and was within the scope of actual or apparent authority of those individuals. There is no dispute that the conduct of Ms Meuwissen, Ms Saidi and Mr Colak which is described below was within the scope of their respective actual or apparent authority.

10 Each of the Workers had disabilities and was found by Doll House through Ability Options Ltd, a disability employment services provider that specialises in finding work for persons with disabilities.

11 On or around 6 August 2020, Ms Saidi was in communication with Ms Kate Javor, employer accounts manager of Ability Options. Ms Saidi informed Ms Javor that Doll House wished to engage Ms David and Ms Wickett to work for Doll House for 12 hours per week and expected their working days to be on Thursday and Friday of each week. There was also a discussion concerning the wage subsidy that Doll House might receive, during which Ms Javor informed Ms Saidi by email:

Just had confirmation that if they are not an employee under your ABN the wage subsidy cannot be paid as she would be classified as “ Self Employed”. Wage subsidies can only be paid under the employers ABN from the Government terms and conditions.

Let me know what you come up with and if I can offer any further assistance on this please let me know

12 On the same day, Ms Javor or another representative of Ability Options, communicated Doll House’s offers of employment to Ms Wickett and Ms David, which they accepted.

13 In or around mid-August 2020, Ms Meuwissen offered Ms Murray employment with Doll House, which she accepted.

14 On 17 August 2020, Ms Saidi informed Ms Javor that the Workers would be engaged as employees and Doll House would be claiming a wage subsidy for employing persons with disabilities.

15 On 27 August 2020, Ms David and Ms Wickett each commenced working for Doll House. They continued to do so until 28 October 2020.

16 On 3 September 2020, Ms Murray commenced working for Doll House. She continued to do so until 26 October 2020.

17 The terms of the engagement of the Workers by Doll House included that the Workers:

(1) were required to work on Thursday and Friday of each week, from 10am until 4pm, for a total of 12 hours per week;

(2) would be hired as employees and paid by Doll House monthly in arrears; and

(3) were covered by the Miscellaneous Award 2020, with the applicable wage on commencement of $19.84 per hour.

18 Throughout the periods 27 August 2020 to 28 October 2020 for Ms Wickett and Ms David; and 3 September 2020 to 26 October 2020 for Ms Murray (Relevant Periods): (1) representatives of Doll House provided the Workers with various work tasks by email to be completed each week; and (2) the Workers performed duties including: (a) reading and summarising websites on required topics, generally relating to mental and physical health and the interplay between certain technologies (including robotics, artificial intelligence and coding) and the fitness and wellness industry; (b) creating powerpoint presentations and research memoranda on those topics, which were to be returned to Doll House; (c) attending Zoom calls regarding the allocation of tasks, work progress and the development of Doll House as a business; (d) occasionally attending robotics classes with a developer paid for and arranged by Doll House; and (e) practising coding and robotics programming on open-source websites.

19 From the beginning of the Relevant Periods until on or around 8 October 2020, each of the Workers worked 12 hours per week for Doll House.

20 On and from 7 October 2020, Doll House notified the Workers that they: (1) would be “converted” to independent contractors, with the terms of their engagement with Doll House to be set out in a contract for services; and (2) were each required to provide to Doll House an Australian Business Number (ABN) in order to be paid for their work for Doll House. In particular:

(1) on 7 October 2020, Mr Colak contacted Ms David by telephone and told her that: (a) Doll House was not going ahead with Ability Options; (b) she would need an ABN; (c) she would be an independent contractor; (d) her hours were changing and the new hours would be from 10am until 2pm; (e) her hourly rate would be $25 per hour; and (f) she would need to submit invoices to be paid;

(2) on or about 7 October 2020, Ms Saidi called Ms Wickett and told her that “you are being converted from an employee to an independent contractor;

(3) later on 7 October 2020, Mr Colak sent an email to Ms Wickett in the following terms (as written):

Thank you for your time today over the phone.

As discussed please see attached your Independent Contractor Agreement. Please check the details then sign and return to me. Once we have signed them off, I will send you a copy back with both signatures.

Just to recap our call,

- I will be your first point of contact moving forward. Please feel free to contact me via text phone or email.

- Moving forward, you will be contracted by Doll House as an Independent Contractor

- Your new hours of work will be 10AM to 2PM on Thursdays and Fridays.Total of 8 Hours per week.

- Your new pay rate will be $25 as per attached contract.

- Any super entitlements will be paid by 28th October.

- Ability options will still be available to you should you require any assistance.

Please let me know if you have any questions or concerns.

I look forward to our meeting on Zoom tomorrow ... ;

(4) on 8 October 2020, Ms Saidi sent an email to the Workers which included:

Also, there have been some exciting changes to your role which Jeysun discussed with you all yesterday. Those changes will start from today ... ; and

(5) on 8 October 2020, Ms Saidi and Mr Colak held a Zoom meeting with the Workers and others working for Doll House to advise them that they were going to become independent contractors, and that among other things: (a) they would need an ABN; (b) they would be responsible for their own taxation affairs; (c) their hours would change to 10am and 2pm (still on Thursdays and Fridays); (d) their hourly rates would increase to $25 per hour; and (e) they would be sent a contract for signature and return to Doll House.

21 From 7 October 2020 until the end of the Relevant Periods:

(1) Doll House continued to require the Workers to complete the same, or substantially the same, tasks as had previously been required;

(2) the Workers performed those duties and provided completed tasks to representatives of Doll House on Friday of each week, following the provision of detailed instructions by email;

(3) the Workers were to be paid on an hourly basis rather than for the completion of a set task;

(4) the Workers were not subject to deductions for defective or inferior work; and

(5) in performing work for Doll House, the Workers did not generate goodwill on their own behalf, or promote their services to other parties.

22 On 13 October 2020, Mr Colak of Doll House sent an email to each of the Workers in the following form:

Please find attached your new contract as discussed. Please have this signed and returned by Monday 19th of October 5PM.

Please also find attached a template invoice which you can use to fill in and send back to us each month.

Let me know if you have any questions.

23 The “new contract” sent to each of the Workers was titled “Independent Contractor Agreement” (ICA). Each was in identical terms (save as to the name of the proposed “independent contractor”) as follows:

This contract serves as a binding agreement between Doll House Training Club (ABN 634 366 411) and Independent Contractor [name] on agreement

Start date: 08/10/2020 Agreed finish date: Ongoing

Both parties agree to the following as listed below. Please READ and initial all statements below:

The Independent Contractor (IC)

Services:

1) understands that they will need to assist all managers to successfully complete their roles to ensure smooth running and operations of the business. Complete one-week practical instructional video tasks with following week research. You will come on as research assistants and under a technology traineeship.

2) attend all zoom sessions required and any one on ones required with team leader. Submit all works by end of day or week.

3) is always expected to uphold and represent the company values while uplifting the Doll House Training Club Team and work to their best for overall business success.

4) understands hours as follows: 8 hours per week remotely to commence immediately.

Relationship:

5) will follow IC relationship and strictly not an employer-employee relationship therefore IC pays their own benefits and does not receive benefits from Doll House Training Club as IC is self-employed and is in charge of the specifics of their work. This is a fully sub contracted role.

6) understands that all information is confidential and the sole property of Doll House Training Club business use and cannot be accessed for personal use.

7) is always expected to present themselves in a positive and professional manner

Pay:

8) understands that they will only receive compensation for actual working hours and are responsible for submitting an accurate invoice in a timely manner to ensure compensation and pay is paid on time. Invoices are due at the end of every month.

9) Pay is at $25 per hour for 8 hours per week.

Property:

10) understands that all research, information, and ideas collated by yourself during paid business hours, belongs to Doll House Training Club and becomes this business's intellectual property and cannot be challenged.

By signing below, you agree to the above conditions set forth by Doll House Training Club. Any violation of this contract may result in immediate termination without warning.

...

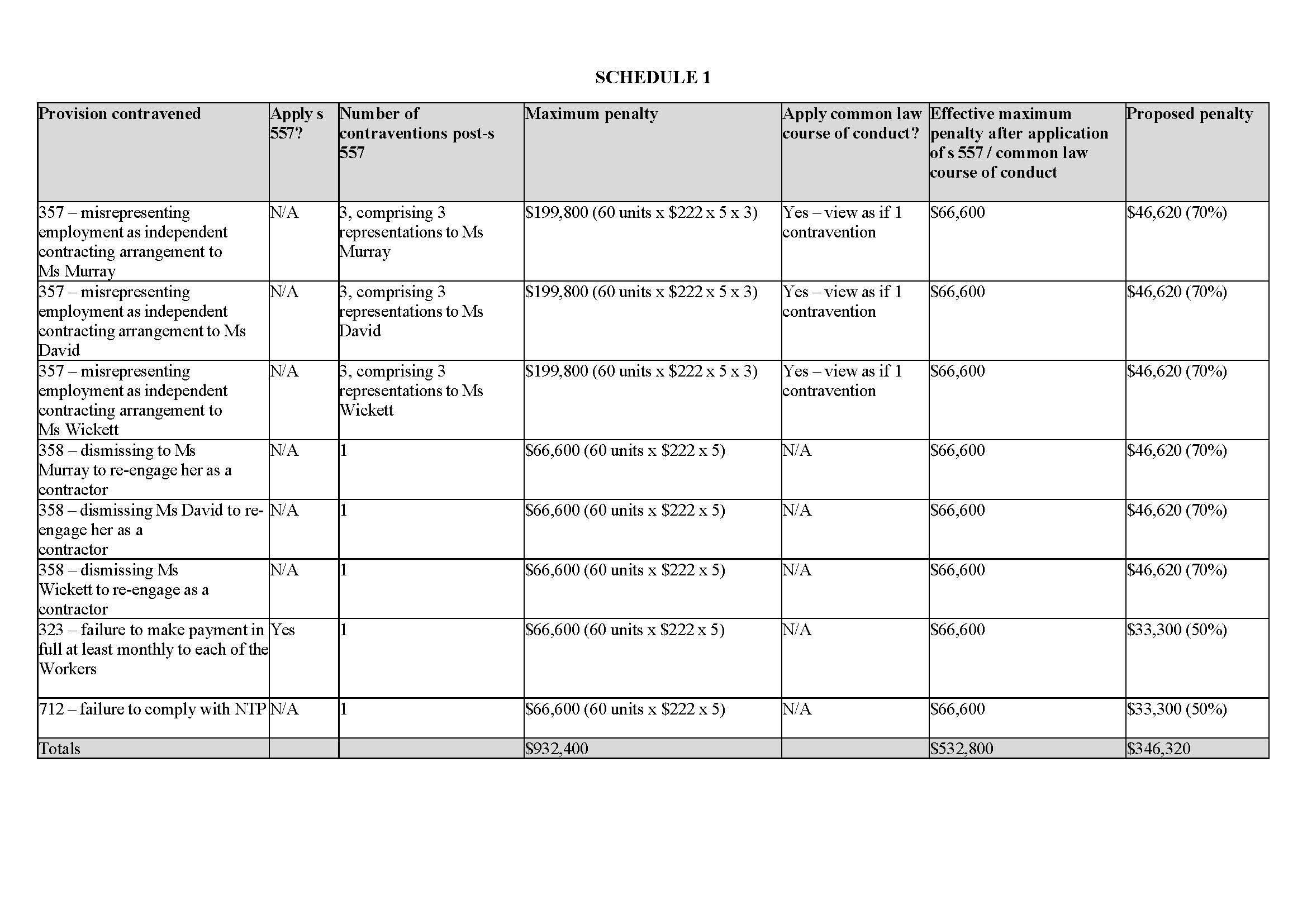

(as written; emphasis in original)

24 Doll House admitted that each ICA: (1) stipulated a start date of 8 October 2020; (2) provided, inter alia, that the Workers were to: (a) work eight hours per week remotely, to commence immediately; (b) provide accurate invoices at the end of every month to ensure compensation; and (c) be paid $25 per hour; (3) stated that the Workers were independent contractors; and (4) stated that the Workers were “strictly not an employer-employee relationship” and the Workers will therefore “pay their own benefits” and will be “in charge of the specifics of their work”.

25 On 13 October 2020, Ms David signed the ICA. Ms David did not understand why she was given the ICA, or what an independent contractor was, and she was too afraid to ask to change the rate. After receiving the ICA, she spoke with one of the other workers and asked her what it meant. That worker explained to Ms David that the ICA was a contract and that the workers would be going into partnership with Doll House. Ms David needed the job and believed – based on her discussions with Mr Colak and Ms Saidi on 7 and 8 October 2020 – that she needed to sign the ICA in order to keep her job.

26 On 15 October 2020, Ms Saidi sent an email to the Workers which included:

You would have all received our contracts as well as a sample invoice you can use, sent by Jeysun earlier this week. Just a friendly reminder, please have a read through, initial and sign back by Monday 19th October. If you have any questions around these, feel free to reach out ...

All other material such as ABN links and support will be followed through by the end of this week by Jeysun.

27 On or about 16 October 2020, Ms Murray signed the ICA and returned it to Mr Colak. She did so because she formed the impression from the 8 October email and the 8 October Zoom meeting (see 20(4) and (5) above) that she was required to sign it in order to continue to work for, and be paid by, Doll House.

28 Ms Wickett received the ICA but did not sign it because she had not been paid for her work to that point, and a representative of Ability Options had counselled her against signing it.

29 Between 23 and 28 October 2020, the Ombudsman received requests for assistance from the Workers concerning the ICAs and the fact that they had not been paid for the work they had performed since the commencement of the Relevant Periods (i.e. 27 August and 3 September 2020).

30 On 26 October 2020, Mr Colak notified Ms Murray that her “services/employment” were terminated.

31 On 28 October 2020, Mr Colak notified Ms Wickett and Ms David, in identical correspondence, that their “services/employment” were terminated “effective immediately”.

32 During the Relevant Periods, which ended on 26 and 28 October 2020, Doll House made no payments to any of the Workers.

33 On 2 November 2020, the requests for assistance were assigned to Ms Arnold on behalf of the Ombudsman for investigation.

34 On 5 November 2020, Ms Arnold wrote to Ms Meuwissen in the following terms:

I tried to call you today and left a voice message

The Fair Work Ombudsman (FWO) has received requests for assistance from Rachel Murray, Diana Whickett (sic) and Jasmine David (the Workers). The FWO is responsible for enforcing compliance with Commonwealth workplace laws. I have attached a fact sheet for your reference

The Workers have alleged:

• They have not been paid for time worked; and

• They have been incorrectly engaged as independent contractors when they were in fact employees

The requests for assistance are currently at the first phase of the investigation, which involves gathering evidence in order to form a view regarding whether or not the matters are within the scope of the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth)

I would like to discuss these matters with you please contact me on the details below at your earliest convenience

Thank you for your assistance

(emphasis added)

35 On the same day, Ms Arnold called Mr Colak who asked Ms Arnold to call him the following day, to which she agreed; and Ms Arnold sent Mr Colak an email confirming their conversation.

36 On 6 November 2020, Ms Arnold spoke to Ms Saidi and Mr Colak about the requests for assistance.

37 On 9 November 2020, Doll House paid $2,193.43 to Ms David and $1,571.66 to Ms Murray. On that day, Ms Meuwissen sent an email to Ms Arnold in the following terms (as written, with Ms Meuwissen’s email address deleted):

Thankyou again for your email. Ive just finished depositing the following:

1. Payment for September and oactober (everything owing) to Rachel Murray and Diana Wickett. I have tried to deposit Jasmines pay however the account number provided has a extra digit so i have emailed her to obtain the correct and we will immediately deposit once we have this

2. I have paid them as told to them a additional 0.5% per day that there pay was late. This was to apply from the 15th October onwards and for the amount of September waited on, however i applied it to everything owing too date for the 15 business days i calculated.

3. I have there super ready at 9.5% i have it deposited four our accountant to dispuruse in the next 2 business days (i have read the November 28 deadline) as i cannot directly deposit this super as ive tried to tonight

4. I have calculated all payments including super based off everyone being employee the entire time (please note there hourly rate was substantially increased however i have still paid super upon this. They also received over 3 days fully paid work whe4re no work was completed nor asked to complete due to our own error with delayed payment. I also provided the employees the option to cease work immediately and still be paid.

5. The period of reference regarding contractors, no actual work was completed. Some tasks were provided however as i had been paying to have training programs built for them the lessons were not ready. Sourced work was given as independent tasks with the reduced hours, as mentioned though i have ensured i have paid them inclusive of this period under employees.

6. I have ensured everyone has been paid within 1 full business day of the funds held up reaching my account, i have to date - applied 0.5% penalty paid onto each business day paid late, offered full pay for zero work completed and also given complete work periods off for full pay which i have now paid, paid super on this above period, inclusive of uncorked period paid with super, saucer paid at 9.5% to be deposited by our accountant by Friday cob with receipts provided at your request,

If you have any further questions please let me know, I'm the best one to speak with regarding this and ill do my very best to help the situation,

We will individually contact Rachel, Diana (and Jasmin to also obtain the correct account number today), and i can send over the super contribution details by Friday close of business if that is ok on your end as mentioned i will send off to our accountant today,

If its also ok to reply to:

... as i use that email for work related matters to ensure i see emails,

38 On 11 November 2020, Doll House paid $1,500.00 to Ms Wickett.

39 On 17 November 2020, Doll House $731.46 to Ms Wickett, $38.03 to Ms David and $386.01 to Ms Murray.

40 The Ombudsman accepts that by reason of the payments made on 9, 11 and 17 November 2020, the Workers have been paid for the work that they undertook for Doll House.

41 On 23 December 2020, and pursuant to s 712 of the Act, Ms Arnold, who as noted above was a Fair Work Inspector, issued the notice to Doll House. The notice was served on Doll House on the same day and required Doll House to produce the documents specified in it by 5 pm on 20 January 2021. An email sent by Ms Arnold to Ms Meuwissen that day provided a copy of the notice and notified the date for compliance.

42 On 18 January 2021, Ms Meuwissen wrote to Ms Arnold:

I apologise for the delay in my response and appreciate your patience. I am currently on leave until the 3rd of February 2021.

I will be able to provide a response when I return.

43 Ms Arnold responded on the same day:

Thank you for your email. The Notice to Produce is due on 20 January 2021. The Notice cannot be extended, if the business is unable to comply with the Notice it must set out in writing the reasons why. The Fair Work Ombudsman will then decide if there is a reasonable excuse for failing to comply with the Notice. I note your advice you are currently on leave, in our view this is not a reasonable excuse as the Notice was served on 23 December 2020. We believe we have already given the business sufficient time to comply with the Notice (in addition to previous voluntary requests for information)

If you have any questions or concerns regarding the above please contact me on the details below

(emphasis in original)

44 On 20 January 2021, the time set for compliance with the notice passed. Doll House did not comply with the notice.

45 On 21 January 2021, Ms Arnold sent a letter by express post to Doll House and by email to Ms Meuwissen stating that Doll House had failed to comply with the notice and requesting that any reasonable excuse be provided within seven days. No response to that letter was received.

46 On 31 May 2021, the Ombudsman commenced this proceeding by filing its originating application and statement of claim.

47 On 18 September 2021, Doll House filed a defence to the statement of claim. At that time, Doll House was represented by Mr Nathaniel Delaney of ACLG Lawyers. On 1 March 2022, Mr Delaney filed a Notice of ceasing to act which indicated that he had ceased to act for Doll House because his retainer had been terminated.

48 Subsequently, Ms Meuwissen sought, on behalf of Doll House, dispensation from the operation of r 4.01(2) of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) – which provides that corporations must not proceed in the Court other than by a lawyer – so that she could represent Doll House. On 24 May 2022, I dismissed that application; and allowed an application by the Ombudsman to amend the statement of claim in light of the decisions of the High Court of Australia in Construction, Forestry, Maritime, Mining and Energy Union v Personnel Contracting Pty Ltd [2022] HCA 1; (2022) 275 CLR 165 and ZG Operations Australia Pty Ltd v Jamsek [2022] HCA 2; (2022) 275 CLR 254: see Fair Work Ombudsman v Doll House Training Pty Ltd [2022] FCA 604.

49 On 25 May 2022, the Ombudsman filed an amended statement of claim.

50 On 18 October 2022, Ms Georgina Mullighan of Leeder Law filed a Notice of acting – appointment of lawyer. Ms Mullighan represented Doll House until 18 April 2023, when she filed a Notice of ceasing to act. No lawyer has subsequently appeared on behalf of Doll House and no application has been made for Doll House to be represented by a non-lawyer since Ms Mullighan ceased to act for it.

51 No defence to the amended statement of claim has been filed.

52 Since the commencement of the proceeding there has been ample correspondence from Ms Meuwissen to the Ombudsman, including:

(1) an email dated 17 March 2022 attaching a letter of the same date setting out a number of complaints against the Ombudsman and threatening to commence a proceeding against the Ombudsman unless the current proceeding was discontinued;

(2) an email dated 5 July 2022 stating, amongst other things:

4. Myself, Heidi Meuwissen will be filing detailed complaints (16 offences) listed in prior communication from The Ombudsman and The Agency, inclusive of during the investigation phase of these allegations from The Ombudsman. Heidi Meuwissen has already spoken with the Human Rights commission and has been advised this is the next step then proceeding into investigation;

...

7. All admissions will be seek to be removed by Dollhouse training on the grounds of no consent given to prior lawyers withe evidence backing this, and furthermore new evidence of the not for profit organisation now being available for Dollhouse training which impacted its ability to provide defence prior.

8. Dollhouse firmly denies all allegations of The Ombudsman

9. Upon completion of proceedings, Dollhouse holds intent to file malicious prosecution charges against The Ombudsman.

(as written; emphasis in original);

(3) an email dated 25 August 2022 stating, following the service of evidence filed by the Ombudsman in this proceeding, “I note receipt of the unsealed copies. I also note large transcripts of lies under oath”;

(4) an email dated 8 June 2023:

I refer to the below and correspond the following litigation which will be filed into the Supreme Court from myself Heidi Vieira-Vanjek against The Fairwork Ombudsman.

• malicious prosecution

• discrimination age & gender

• defamation

• bullying, harassment & coercion by the ombudsman during investigation and continued

• coercion interfering with investigation facts

• perjury

• lying under oath - relied upon interviews

Damages being filed: $2,400,000 lost in time period of litigation financial losses, $2,850,000 health, defamation, and lost franchising opportunity and ability during the litigation, $13,800,000 as a direct result of the ombudsman actions losses over the upcoming 5 years, liquidated companies, $4,000,000 damaged credit score, amongst other items.

Total litigation damages to proceed without further notice: $23,050,000 ; and

(5) an email dated 13 June 2023 which included:

Dollhouse will be seeking to either strike out or look into summary judgement against The Ombudsman claims on the grounds that there is no evidence … I also take this opportunity to without further notice advice The Ombudsman my personal claim against The Ombudsman will now be issued to relevant legal practitioners, governing bodies including ASIC, and media where appropriate for equality to be heard.

C. A PRELIMINARY QUESTION: THE STATUS OF THE WORKERS AFTER ABOUT 7 OCTOBER 2020

53 Against that background, I turn to consider the claims made by the Ombudsman against Doll House.

54 Doll House has admitted the contraventions alleged against it, save to the extent it has put in issue, with respect to the alleged contraventions of ss 323(1) and 357, whether the Workers were employees of Doll House after about 7 October 2020, when they were notified that they would be “converted” to independent contractors; and the correlative question of whether Doll House remained as an employer of the Workers.

55 After the maze of definitional sections in the Act has been navigated, the questions for determination are revealed as being whether: (1) each Worker was an “employee’ of Doll House; and (2) Doll House was their “employer”, by reference to the ordinary meaning of those words.

56 Following the decisions of the High Court of Australia in Personnel Contracting and Jamsek the task in answering these questions – regardless of the form of the contract between the parties – is to ascertain and characterise the contractual rights of the parties: see, e.g., EFEX Group Pty Ltd v Bennett [2024] FCAFC 35 at [3] to [10] (Katzmann and Bromwich JJ); Secretary, Attorney-General’s Department v O’Dwyer [2022] FCA 1183; (2022) 177 ALD 113 at 122 to 123 ([29] to [33]) (Goodman J); Chiodo v Silk Contract Logistics [2023] FCA 1047 at [7] to [9] (Kennett J); and Rizk v Basseal [2024] FCA 647 at [39] to [40] (Shariff J).

57 The starting point is to ascertain the terms of any post-7 October 2020 contracts between Doll House and the Workers. In this regard, it is important to note that Ms Murray and Ms David signed an ICA, but Ms Wickett did not.

58 I will consider first the position of Ms Murray and Ms David.

59 The terms of the contracts between Doll House and each of Ms Murray and Ms David included the terms of the ICA which they each signed. I note that the Ombudsman does not contend that the ICAs were sham agreements (indeed, express reliance is placed upon parts of them); or that the ICAs were varied, waived or the subject of an estoppel: cf Personnel Contracting at 186 [43].

60 The Ombudsman alleges, relevantly, that:

(1) there were post-7 October 2020 contracts between Doll House and each of Ms Murray and Ms David which contained both written and oral terms;

(2) the written terms included that:

(a) Ms Murray and Ms David must assist all managers to successfully complete their roles to ensure smooth running and operations of the business by completing one-week practical instructional video tasks and in the following week undertake research (cl 1 of the ICA);

(b) Ms Murray and Ms David would be appointed to perform work as research assistants and under a technology traineeship (cl 1 of the ICA);

(c) Ms Murray and Ms David must attend all Zoom sessions required by Doll House and any one on one meetings required by Doll House with their team leader (cl 2 of the ICA);

(d) Ms Murray and Ms David must submit all works undertaken by end of day or week (cl 2 of the ICA);

(e) Ms Murray and Ms David must always uphold and represent Doll House’s values while uplifting the “Doll House Training Club Team” and work to their best for overall business success (cl 3 of the ICA);

(f) Ms Murray and Ms David must always present themselves in a positive and professional manner (cl 7 of the ICA);

(g) all research, information, and ideas collated by Ms Murray and Ms David in the course of performing work under the ICA is the intellectual property of Doll House and cannot be challenged (cl 10 of the ICA);

(h) any violation of the ICA may result in immediate termination of the engagements of Ms Murray and Ms David without warning (cl 10 of the ICA);

(3) the oral terms included that:

(a) Ms Murray and Ms David received compensation for actual working hours;

(b) Ms Murray and Ms David were to perform the duties as set out at [18] above on Thursdays and Fridays from 10am until 2pm; and

(c) Ms Murray and Ms David were to provide their services personally and not delegate or subcontract the work provided to them by Doll House without the consent of Doll House.

61 This form of pleading of the terms of the post-7 October 2020 contracts was set out for the first time in the amended statement of claim. It was not traversed by any defence to that pleading and the Ombudsman has conducted the case on the basis that there is an implied joinder on this part of the case by dint of r 16.57 of the Rules.

62 I accept that the entry by Ms Murray and Ms David into an ICA with Doll House establishes that: (1) there was a post-7 October 2020 contract between Doll House and each of Ms Murray and Ms David; and (2) that contract contained, inter alia, the written terms described above (as well as the other terms in the ICA that have not been pleaded).

63 I have reservations as to whether the post-7 October 2020 contracts between Doll House and each of Ms Murray and Ms David also included the oral terms described above. However, it is unnecessary to undertake the requisite analysis to finally determine this question because, first, as the analysis below will demonstrate, the written terms construed alone establish that the post-7 October 2020 contracts between Doll House and each of Ms Murray and Ms David were contracts of employment; secondly, the contended additional oral terms are all terms which, if they were found to exist, would only support such a construction. It follows that the existence or otherwise of the alleged oral terms does not bear upon the result.

64 On the assumption that the post-7 October 2020 contracts between Doll House and each of Ms Murray and Ms David comprise at least the written terms in the ICAs, I turn now to consider whether those contracts are properly characterised as contracts of employment or contracts for services.

65 The rights and obligations created by the contract are central to the proper characterisation of the contract. Examples collected by Wigney J in JMC Pty Ltd v Federal Commissioner of Taxation [2022] FCA 750 at [21] are contractual rights and obligations that deal with “the mode of remuneration, the provision and maintenance of equipment, the obligation to work, the hours of work, the provision for holidays, the deduction of income tax, the delegation of work and the right to exercise direction and control”.

66 In this context, two considerations that often feature prominently in the characterisation exercise are:

(1) the extent to which the putative employer has the right to control how, where and when the putative employee performs the work; and

(2) the extent to which the putative employee can be seen to work in their own business, as distinct from the business of the putative employer,

(see JMC at [23] to [26] and the authorities there cited; EFEX at [13]).

67 In EFEX, Katzmann and Bromwich JJ observed at [12] to [14]:

12 The central question that remains, under an unwritten contract as in a written contract, is whether or not a person is an employee. As was observed in Personnel Contracting at [39] per Kiefel CJ, Keane and Edelman JJ (see also [113] per Gageler and Gleeson JJ), while the dichotomy between a person’s own business and the putative employer’s business may not be perfect so as to be of universal application, because not all independent contractors are entrepreneurs, that approach is still useful. That is because it focuses attention on whether the putative employee’s work as contracted to be performed was so subordinate to the putative employer’s business as not to be part of an independent enterprise. It also avoids the danger of an impressionistic and subjective judgement, or ticking off a checklist, running counter to objective contractual analysis.

13 Once the contours of the legal relationship are identified, its characterisation as one of employment or not often hinges on two considerations identified in Personnel Contracting, in particular by Kiefel CJ, Keane and Edelman JJ at [36]-[39], each of which may involve questions of degree, namely:

(a) the extent to which the putative employer has the right to control how, when and where the putative employee performs the work; and

(b) the extent to which the putative employee can be seen to be working in their own business as distinct from the putative employer’s business.

14 However, as a cautionary note, in some circumstances the proper analysis may be more nuanced than that. As Gordon J pointed out in Personnel Contracting at [181]-[183] (Steward J agreeing), asking whether a person is working for their own business may not always be a “suitable inquiry for modern working relationships”, given that it may not take much for even a low skilled person to be carrying on their own business. Analysis based on this dichotomy may distract from the relevant underlying analysis of the totality of the relationship created by the contract. It may also direct attention to non-contractual considerations, which are not relevant unless forming part of the contract itself. The better question may be to ask whether, by the terms of the contract, the person is contracted to work in the business or enterprise of the purported employer, so as to maintain the correct focus. That is, if the contract does not lead to the conclusion that the person was working in the business of the asserted employer, then the person will not be an employee. This approach has some traction in this case.

(emphasis added)

68 Having considered the rights and obligations created by the post-7 October 2020 contracts between Doll House and each of Ms Murray and Ms David, I have come to the conclusion that those contracts were contracts of employment for the following reasons.

69 First, those rights and obligations suggest that Ms Murray and Ms David were contracted to work for Doll House’s business rather than any business of their own. In particular:

(1) their services included assisting managers within Doll House so as to ensure the smooth running of Doll House’s business (cl 1 of the ICA);

(2) they were to “come on as research assistants and under a technology traineeship” (cl 1 of the ICA);

(3) they were to uphold and represent the values of Doll House, uplift the Doll House team and strive for the overall success of the Doll House business (cl 3 of the ICA); and

(4) cl 6 of the ICA provided that “all information” was the sole property of Doll House and could not be accessed by the counterparty for their personal use. Clause 10 of the ICA provided that “all research, information, and ideas collated by” the counterparty “during paid business hours” was intellectual property belonging to Doll House. These clauses suggest that Ms Murray and Ms David were required to provide services within Doll House’s business, rather than to that business as an independent contractor. An independent contractor might usually be expected to enjoy ownership and any intellectual property rights arising from their own work product.

70 Secondly, the rights and obligations created by the ICA also suggest a degree of control by Doll House over the manner in which Ms Murray and Ms David were to perform their work. In particular, they were required to: (1) complete “one-week practical instructional video tasks with following week research” (cl 1); (2) attend all Zoom sessions required (cl 2); (3) attend “any one on ones required with team leader” (cl 2); and (4) submit all work by the end of the day or week (cl 2).

71 Thirdly, they were to be paid per hour, rather than by reference to a particular outcome (cl 9).

72 Finally, whilst there are parts of the ICAs which are capable of suggesting that Ms Murray and Ms David were independent contractors, I do not consider these to be of any significant weight. In particular:

(1) I have had regard to the descriptors used for the Workers – “independent contractor” and “IC” – within the ICA, and to cl 5 of the ICA but I place little weight upon the use of these descriptors or upon cl 5 because:

(a) as Wigney J explained in JMC at [26] and [164], by reference to Personnel Contracting, a “label” which the parties may have chosen to describe their relationship is not determinative of the nature of the relationship and will rarely assist the Court in characterising the relationship by reference to the contractual rights and duties of the parties; and such a label is not determinative of, or even relevant to, that characterisation because the determination of the character of a relationship between two parties constituted by the rights and obligations by which they are to be bound is a matter for the Court;

(b) the expression in cl 5 that the “independent contractors” are “in charge of the specifics of their work. This is a fully sub-contracted role” is contradicted by other features of the ICA, and in particular those described at [69] to [71] above; and

(2) I have also had regard to the requirement that Ms Murray and Ms David submit invoices for work undertaken (cl 8). Whilst this is more consistent with Ms Murray and Ms David being independent contractors than employees, when considered in the context of the contract as a whole, I am satisfied that the post-7 October 2020 contracts between Doll House and each of Ms Murray and Ms David were contracts of employment.

73 I turn now to consider the position of Ms Wickett. The Ombudsman’s case proceeds upon the basis that Ms Wickett was a party to an ICA. However, as noted above, the evidence establishes that Ms Wickett refused to sign the ICA that was presented to her. It follows that she was not a party to an ICA, that she expressly rejected the terms of the ICA, and thus that the ICA was not a source from which the terms of any post-7 October 2020 contract between Doll House and Ms Wickett might be ascertained.

74 The question of whether there was any such contract is further complicated by the fact that it is common ground between the Ombudsman and Doll House that the contract of employment between Doll House and Ms Wickett which had existed was terminated between 7 and 16 October 2020.

75 However as Ms Wickett, following that termination, continued to perform the same duties for Doll House as she had prior to the termination, I infer that a further agreement came into existence after the termination, but on the same, or relevantly identical, terms as the contract which had existed between them prior to its termination. As it is common ground that the earlier contract was a contract of employment, it follows that the latter contract was also; and that Ms Wickett was employed by Doll House throughout her Relevant Period.

76 Thus, each of the Workers was an employee of Doll House and Doll House was the employer of each of the Workers throughout the Relevant Periods.

77 I turn now to consider the alleged contraventions of ss 323(1), 357, 358 and 712(3) of the Act.

78 Section 323 provided in so far as is presently relevant:

323 Method and frequency of payment

(1) An employer must pay an employee amounts payable to the employee in relation to the performance of work:

(a) in full ...; and

(b) in money ...; and

(c) at least monthly.

79 The Ombudsman has alleged that:

(1) Doll House was required to pay its employees amounts payable in relation to the performance of work in full at least monthly;

(2) throughout the Relevant Periods the Workers were entitled to payments in relation to the performance of work;

(3) Doll House failed to pay each of the Workers amounts payable in relation to the performance of work in full at least monthly; and

(4) thus, Doll House contravened s 323(1).

80 Doll House admitted these allegations for the period up to 8 October 2020, but otherwise denied them, on the basis that (it pleaded) on and from 8 October 2020, Doll House and each of the Workers were in a relationship of principal and independent contractor.

81 For the reasons set out at Part C of these reasons for judgment, I am satisfied that each of the Workers was an employee of Doll House throughout their respective Relevant Periods.

82 It follows that Doll House contravened s 323(1) with respect to each of the Workers for the entirety of the Relevant Periods.

357 Misrepresenting employment as independent contracting arrangement

(1) A person (the employer) that employs, or proposes to employ, an individual must not represent to the individual that the contract of employment under which the individual is, or would be, employed by the employer is a contract for services under which the individual performs, or would perform, work as an independent contractor.

(2) Subsection (1) does not apply if the employer proves that, when the representation was made, the employer:

(a) did not know; and

(b) did not know was not reckless as to whether;

the contract was a contract of employment rather than a contract for services.

84 The essence of the Ombudsman’s case concerning s 357 is that:

(1) throughout the Relevant Periods the Workers were each employees of Doll House;

(2) Doll House made representations to the Workers that the contracts under which they were, or would be employed by Doll House, were contracts for services under which they performed or would perform work as independent contractors, by:

(a) on 7 October 2020, notifying the Workers that they would be converted to independent contractors (see [20] above);

(b) from around 7 October 2020, telling the Workers to provide their ABNs as a requirement to be remunerated for their work in the Business (see [20] above); and

(c) on 13 October 2020, providing the ICA to each of the Workers, which:

(i) stated that the Workers were independent contractors;

(ii) stated that the Workers were “strictly not an employer-employee relationship” and the Workers will therefore “pay their own benefits” and will be “in charge of the specifics of their work”;

(iii) required the Workers to submit invoices to Doll House to be remunerated for their work for Doll House (see [23] above); and

(3) thus, Doll House contravened s 357.

85 Doll House: (1) admitted that it employed the Workers until 7 October 2020, but denied that it employed the Workers from 8 October 2020; and (2) admitted making the representations.

86 For the reasons set out at Part C of these reasons for judgment, I am satisfied that each of the Workers was an employee of Doll House during their respective Relevant Periods.

87 It also follows that Doll House contravened s 357 by making each of the representations to each of the Workers.

88 Doll House pleaded the defence in s 357(2). However, in circumstances where Doll House did not adduce any evidence in support of that defence, it need not be considered further.

89 Section 358 provided:

358 Dismissing to engage as independent contractor

An employer must not dismiss, or threaten to dismiss, an individual who:

(a) is an employee of the employer; and

(b) performs particular work for the employer;

in order to engage the individual as an independent contractor to perform the same, or substantially the same, work under a contract for services.

90 The Ombudsman alleged and Doll House admitted that:

(1) on or around 7 October 2020, by providing an ICA to each of the Workers, and informing the Workers that their roles had changed, Doll House represented that the Workers were required to convert to an independent contractor arrangement;

(2) in the period from on or around 7 October 2020 to 16 October 2020, by reason of the matters described at [20(5)] and (1) above, the employment of each of the Workers with Doll House was terminated on Doll House’s initiative;

(3) following the conduct of Doll House described in (1) above, the Workers performed the same, or substantially the same, work as they were performing prior to that conduct;

(4) Doll House’s dismissal of each of its Workers was in order to engage them as independent contractors to perform the same, or substantially the same, work under a contract for services; and

(5) by reason of the above matters, Doll House contravened s 358.

91 It follows that the alleged contraventions of s 358 have been established.

712 Power to require persons to produce records or documents

(1) An inspector may require a person, by notice, to produce a record or document to the inspector.

(2) The notice must:

(a) be in writing; and

(b) be served on the person; and

(c) require the person to produce the record or document at a specified place within a specified period of at least 14 days.

The notice may be served by sending the notice to the person’s fax number.

(3) A person who is served with a notice to produce must not fail to comply with the notice.

(4) Subsection (3) does not apply if the person has a reasonable excuse.

93 The Ombudsman has alleged and Doll House has admitted that:

(1) on 23 December 2020, Ms Arnold, being an inspector, issued the notice, pursuant to s 712, to Doll House;

(2) the notice was, and stated that it was, issued by an inspector under s 712 and for the purpose of determining whether the Act, was being or had been complied with;

(3) the notice was served on Doll House on the same day;

(4) the notice required production of the documents specified therein by 5 pm on 20 January 2021 in person at an address in the Sydney Central Business District, by post to an address in Adelaide or by email to Ms Arnold;

(5) Doll House failed to provide any of the specified documents on or before 5 pm on 20 January 2021; and

(6) Doll House’s failure to comply with the notice was a contravention of s 712(3).

94 I note for completeness, that there is no suggestion that Doll House had a reasonable excuse within the meaning of s 712(4).

95 It follows that the alleged contravention of s 712(3) has been established.

96 I turn now to consider the penalties that should be imposed with respect to the above contraventions.

97 Sections 323(1), 357(1), 358 and 712(3) are identified in s 539 of the Act as civil remedy provisions. For each of these sections, column 4 of the table in s 539(2) identifies a maximum penalty of 60 penalty units. I note with respect to s 323(1) that if the contraventions are “serious contraventions” within the meaning of s 557A, then the maximum penalties are 600 penalty units. However, there is no contention in this proceeding that the contraventions of s 323(1) were “serious contraventions” as defined.

98 Section 546 of the Act provides for the imposition of pecuniary penalties for contraventions of civil remedy provisions. It provides in so far as is presently relevant:

546 Pecuniary penalty orders

(1) The Federal Court … may, on application, order a person to pay a pecuniary penalty that the court considers is appropriate if the court is satisfied that the person has contravened a civil remedy provision.

Determining amount of pecuniary penalty

(2) The pecuniary penalty must not be more than:

…

(b) if the person is a body corporate—5 times the maximum number of penalty units referred to in the relevant item in column 4 of the table in subsection 539(2).

Payment of penalty

(3) The court may order that the pecuniary penalty, or a part of the penalty, be paid to:

(a) the Commonwealth; or

…

99 Also relevant are:

(1) s 556 of the Act which provides:

556 Civil double jeopardy

If a person is ordered to pay a pecuniary penalty under a civil remedy provision in relation to particular conduct, the person is not liable to be ordered to pay a pecuniary penalty under some other provision of a law of the Commonwealth in relation to that conduct.

(2) s 557 of the Act which provides, in so far as is presently relevant:

557 Course of conduct

(1) For the purposes of this Part, 2 or more contraventions of a civil remedy provision referred to in subsection (2) are, subject to subsection (3), taken to constitute a single contravention if:

(a) the contraventions are committed by the same person; and

(b) the contraventions arose out of a course of conduct by the person.

(2) The civil remedy provisions are the following:

...

(g) subsection 323(1) (which deals with methods and frequency of payment);

...

100 The approach to be taken in deciding what penalty is appropriate was explained by the High Court of Australia in Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Pattinson [2022] HCA 13; (2022) 274 CLR 450. In Pattinson, the plurality (Kiefel CJ, Gageler, Keane, Gordon, Steward and Gleeson JJ) explained that civil penalties, in contrast to punishments imposed by the criminal justice system, are imposed primarily, if not solely, for the purpose of deterrence (specific and general): Pattinson at 457 ([9] to [10]) and 459 to 460 ([15] to [17]). The penalty must be sufficiently high that it is not considered to be an acceptable cost of doing business, but should not exceed what is necessary to achieve the object of deterrence: Pattinson at 457 [10], 460 [17] and 475 [66].

101 A penalty is not to be fixed by reference to its proportionality to the seriousness of the contravening conduct, because that reflects an objective of retribution that is not an objective of a civil penalty regime. Rather, the Court is required to ensure that the penalty imposed is “proportionate” in the sense that it strikes a reasonable balance between deterrence and oppressive severity in the particular case: Pattinson at 457 [10], 467 to 469 ([40] to [43]) and 470 [46].

102 The maximum penalty is but one “yardstick that ordinarily must be applied” among other factors: Pattinson at 472 [54].

103 In determining what is reasonably necessary to achieve specific and general deterrence, relevant considerations may include those set out in Pattinson at 460 [18], being those identified by French J in Trade Practices Commission v CSR Ltd [1990] FCA 762; [1991] ATPR¶ 41-076 at 52,152 to 52,153. See also Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Employsure Pty Ltd [2023] FCAFC 5; (2023) 407 ALR 302 at 314 [50] (Rares, Stewart and Abraham JJ). Those factors concern both the character of the contravention and the character of the contravenor: Pattinson at 460 to 461 [19]. However, such factors are not to be regarded as a rigid catalogue or checklist: Pattinson at 460 to 461 ([19]). The Court’s discretion with respect to penalties is broad but is to be exercised judicially, that is fairly and reasonably having regard to the subject matter, scope and purpose of the Act: Pattinson at 467 [40]. The task is to determine the appropriate penalty in the particular case: Pattinson at 461 [19].

104 The concepts of totality, parity and course of conduct may also be useful analytical tools in assessing what may be considered reasonably necessary to deter further contraventions: Pattinson at 469 [45].

105 At the invitation of the Ombudsman, I will approach the task of considering the appropriate penalties broadly by reference to the approach described by Bromwich J in Fair Work Ombudsman v NSH North Pty Ltd (t/as New Shanghai Charlestown) [2017] FCA 1301; (2017) 275 IR 148 at 163 to 164 [36], an approach which has been followed subsequently: see, e.g., Fair Work Ombudsman v IE Enterprises Pty Ltd [2021] FCA 60 at [11] (Anderson J); Basi v Namitha Nakul Pty Ltd (No 2) [2023] FCA 671 (Halley J); Shergill v Singh (No 2) [2024] FCA 261 (Raper J); and Willis Brothers Installations (Qld) Pty Ltd v Ruttley [2023] FCA 1147 at [35] (Meagher J).

106 I start by considering the groups of contraventions in respect of which penalties are to be imposed. In this regard, I accept the following submissions made by the Ombudsman:

(1) the failures by Doll House to pay each of the Workers in full at least monthly in contravention of s 323(1) formed part of the same course of conduct, being a repetition of the same omission over a short period of time, arising from what may be inferred to be the same process or decision by Doll House. Thus, it is appropriate to apply s 557 and to treat Doll House’s omissions in this regard as a single contravention of s 323(1); and

(2) the three representations in contravention of s 357 were made to each of the Workers at around the same time. Thus, the three contraventions for each Worker overlap, with the practical effect that the Court should assess the appropriate penalty as if there were a single contravention with respect to each Worker pursuant to the course of conduct principle at common law. There is no scope for the operation of the course of conduct principle with respect to the other contraventions.

107 I have considered s 556 and am satisfied that it has no application in the present circumstances.

108 In my view, the contraventions in respect of which penalties are to be imposed are as follows:

(1) one contravention of s 323(1) by reason of the failure to pay the Workers in full at least monthly;

(2) three contraventions of s 357 by reason of the several misrepresentations made to each of the Workers;

(3) three contraventions of s 358 by reason of the dismissal of each of the Workers in order to re-engage them as contractors; and

(4) one contravention of s 712(3) for failing to comply with the notice.

109 Each of these contraventions has a maximum penalty of $66,600 (60 penalty units x $222 per unit x 5 (by dint of Doll House being a corporation)). The penalties sought by the Ombudsman are set out in the table which is Schedule 1 to these reasons for judgment.

110 The factors which are pertinent to the determination of appropriate penalties in the present case are as follows.

E.3.1 The nature and extent of the contravening conduct and the circumstances in which it took place

111 The contraventions of ss 357 and 358 involve conduct that is capable of inducing employees to believe that they are independent contractors and therefore do not have access to a wide range of statutory entitlements and basic protections to which they are entitled: see Fair Work Ombudsman v Quest South Perth Holdings Pty Ltd (No 4) [2017] FCA 580 at [50], [57] and [59] (Gilmour J). As French CJ, Kiefel, Bell, Gageler and Nettle JJ explained in Fair Work Ombudsman v Quest South Perth Holdings Pty Ltd [2015] HCA 45; (2015) 256 CLR 137 at 144 [16], the purpose of s 357 is:

... to protect an individual who is in truth an employee from being misled by his or her employer about his or her employment status. It is the status of an employee which attracts the existence of workplace rights.

112 As counsel for the Ombudsman submitted, such contraventions may have the effect of concealing from employees the true nature of legal relationship and the full extent of their entitlements under the Act, which may be expected to result in those contraventions and any consequential failures to pay the employees’ entitlements under the Act being more difficult to detect and enforce. Thus, the need for specific and general deterrence of contraventions of ss 357 and 358 is obvious.

113 The contravention of s 712(3) hindered the Ombudsman in the investigation of suspected contraventions of the Act. This is, for obvious reasons, a matter in respect of which there is a need for general deterrence in particular.

114 The contraventions all took place over a relatively short period: (1) August to November 2020 for s 323(1); (2) early to mid-October 2020 for ss 357 and 358; and (3) on 21 January 2021 for s 712(3).

115 The contraventions of ss 323(1), 357 and 358 involved conduct directed at persons with disabilities, who had been looking for work, and who were to receive an amount equivalent to the minimum wage.

116 There was also a clear power imbalance between Doll House and at least Ms Murray and Ms David who each felt that they had no alternative but to sign the ICA.

117 There is no evidence before the Court that Doll House benefitted financially from the contraventions of ss 357, 358 and 712(3). For example, the evidence does not allow a conclusion to be drawn as to how Doll House’s position under the employment contract (which involved payment of $19.84 per hour for 12 hours per week, plus superannuation and perhaps the receipt of a wage subsidy) compared to its position under the ICAs (which involved payment of $25 per hour for eight hours per week but not superannuation; and no receipt of a wage subsidy).

118 Whilst there was as immediate financial benefit to Doll House from the contravention of s 323(1) because it did not pay the wages that were due, the unpaid amounts were paid by mid-November and apparently included a “0.5% penalty paid onto each business day paid late ...” (see [37] above).

E.3.2 The loss and damage caused

119 The financial consequences of the contraventions for the Workers were, on one view, relatively small and occurred over a relatively short period of time. In particular, the contravention of s 323(1) meant that the Workers were not paid a total of $6,420.59 until mid-November 2020 for work they undertook from late August through to late October 2020. Although the amounts involved are relatively small, it must be borne in mind that, as noted above, the Workers were persons with disabilities, who had been searching for work and who were owed payments equivalent to the minimum wage. Ms David’s evidence included that the non-payment caused her financial and other stress and that, as a result, she needed to borrow money from a short-term lender.

E.3.3 The size and financial position of Doll House

120 No direct evidence was adduced concerning the size of Doll House or its financial position. However, a search of the records of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission database revealed that it remained a registered company. The admissions made by Doll House indicate that it was of sufficient size to employ an operations manager and an executive assistant to the chief executive officer. Further, the ICAs refer to “all managers” (cl 1) and “team leader” (cl 2).

E.3.4 Whether the contraventions arose out of conduct of senior management or at a lower level

121 As to the contravention of s 323(1), it is not apparent from the evidence who was responsible for the payment of wages.

122 As to the contraventions of ss 357 and 358, it is apparent that Ms Saidi, Doll House’s operations manager and Mr Colak, the executive assistant to Ms Meuwissen (Doll House’s chief executive officer) were directly involved (see [20], [22], [23] and [25] above). I infer from the matters set out at [6] and [7] above that Ms Meuwissen was aware of the plan to “convert” the Workers from employees to independent contractors. It is difficult to envisage that such a plan would have occurred without her approval.

123 As to the contravention of s 712(3), the notice was sent directly to Ms Meuwissen on 23 December 2020 ([41] above) and her awareness of it is clear from her 18 January 2021 email ([42] above).

E.3.5 The culture of Doll House

124 No evidence has been adduced of internal communications or policies evidencing Doll House’s culture, as to compliance or otherwise.

125 However, the evidence establishes that Doll House did not take seriously the notice or the requirement to answer it within the time specified therein. This is seen in Ms Meuwissen’s nonchalant response to the notice in her 18 January 2021 email ([42] above).

126 It is also noteworthy that the payments of wages which were made ultimately in November 2020, happened after Doll House became aware of the Workers’ requests for assistance to the Ombudsman and Ms Arnold had raised the Workers’ complaints with Doll House (see [29] to [40] above).

E.3.6 Co-operation and contrition

127 The evidence concerning Doll House’s disregard of requirements of the notice is also evidence of a lack of co-operation, particularly in circumstances where the documents sought were directly relevant to the other contraventions.

128 There is some evidence of co-operation in the admissions made by Doll House in its defence. Against this, however, is the subsequent correspondence from Ms Meuwissen to the Ombudsman in which she foreshadowed that Doll House would seek to withdraw its admissions, fully defend the proceeding, and repeatedly threatened to bring a proceeding against the Ombudsman with respect to the Ombudsman’s prosecution of the current proceeding (see [52] above).

129 There is no evidence of any contrition on the part of Doll House. The foreshadowing of an application to withdraw admissions and of the commencement of a proceeding against the Ombudsman suggests that there has been no acceptance on the part of Doll House that it has done anything contrary to the law. Thus, the need for specific deterrence is not reduced by reason of contrition.

E.4 Conclusion as to penalties

130 Taking all of the above matters into account, the appropriate penalties are:

(1) the contravention of s 323(1) by reason of the failure to pay the Workers in full at least monthly: $30,000;

(2) the three contraventions of s 357 by reason of the misrepresentations made to the Workers: $66,000 in total;

(3) the three contraventions of s 358 by reason of the dismissal of each of the Workers in order to re-engage them as contractors: $66,000 in total; and

(4) the contravention of s 712(3) for failing to comply with the notice: $35,000.

131 I have considered whether the penalties are appropriate and proportionate to Doll House’s conduct viewed as a whole. Having done so, I am satisfied that no adjustment is required.

132 Thus, the total penalty to be imposed is $197,000.

133 I am not inclined to grant declaratory relief. I do not regard such relief as serving any purpose, particularly in circumstances where declarations are unlikely to advance the object of deterrence beyond that which will be achieved by the imposition of the pecuniary penalty and the publication of these reasons for judgment. In this regard, see, e.g., Fair Work Ombudsman v Construction, Forestry and Maritime Employees Union (The Beams Lift Case) (No 2) [2024] FCA 779 at [32] to [34] (Snaden J).

134 An order imposing penalties totalling $197,000 should be made.

I certify that the preceding one hundred and thirty four (134) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice Goodman. |

Associate: