FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

FanFirm Pty Limited v Fanatics, LLC [2024] FCA 764

ORDERS

NSD 963 of 2022 | ||

Applicant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

AND BETWEEN: | Cross-Claimant | |

AND: | Cross-Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT DECLARES THAT:

1. The respondent/cross-claimant has infringed the applicant/cross-respondent’s registered word mark (Australian Registered Trade Mark Number 1232983) (FanFirm Word Mark) in contravention of s 120(1) and (2) of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) by using the FANATICS word marks (Australian Registered Trade Mark Numbers 1288633 and 1905681) and FANATICS Flag Mark (Australian Registered Trade Mark Number 1894688) (together, Infringing Marks) in relation to the following goods (Infringing Goods):

(a) clothing;

(b) headgear;

(c) sportswear;

(d) sports bags;

(e) scarves;

(f) water bottles;

(g) towels; and

(h) blankets.

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

Injunction

2. The respondent whether by itself, its directors, employees, servants, agents, related bodies corporate, or others, be permanently restrained from using the FanFirm Word Mark or any signs that are substantially identical with or deceptively similar to the FanFirm Word Mark, including the Infringing Marks, in relation to the goods and services in respect of which the FanFirm Word Mark is registered, without the permission, authority or licence of the applicant.

Rectification

3. The Register of Trade Marks be rectified by removing the Infringing Marks (Australian Registered Trade Mark Number 1288633, 1894688 and 1905681) in respect of the services in class 35 in which they are registered.

4. The Register be rectified by removing the respondent’s SPORTS FANATICS mark (Australian Registered Trade Mark Number 1680976) from the Register.

5. The Register be rectified by removing the applicant’s FanFirm Word Mark (Australian Registered Trade Mark Number 1232983) and device mark (Australian Registered Trade Mark Number 1232984) in respect of:

(a) The goods in classes 9, 16 and 32 in respect of which they are registered; and

(b) The services in class 38 in respect of which they are registered.

Other

6. The applicant’s claim is otherwise dismissed.

7. The respondent’s cross-claim is dismissed.

Costs

8. Subject to paragraph 9 below, the respondent pay the applicant’s costs of the whole proceeding, including the cross-claim.

9. If either party seeks a variation of the costs orders in paragraph 8 above, it may, within 14 days, file and serve a written submission (of no more than two pages). The issue of costs will be determined on the papers.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

[1] | |

[16] | |

[21] | |

[21] | |

[22] | |

[23] | |

[23] | |

[37] | |

[65] | |

[81] | |

[83] | |

[100] | |

[106] | |

[111] | |

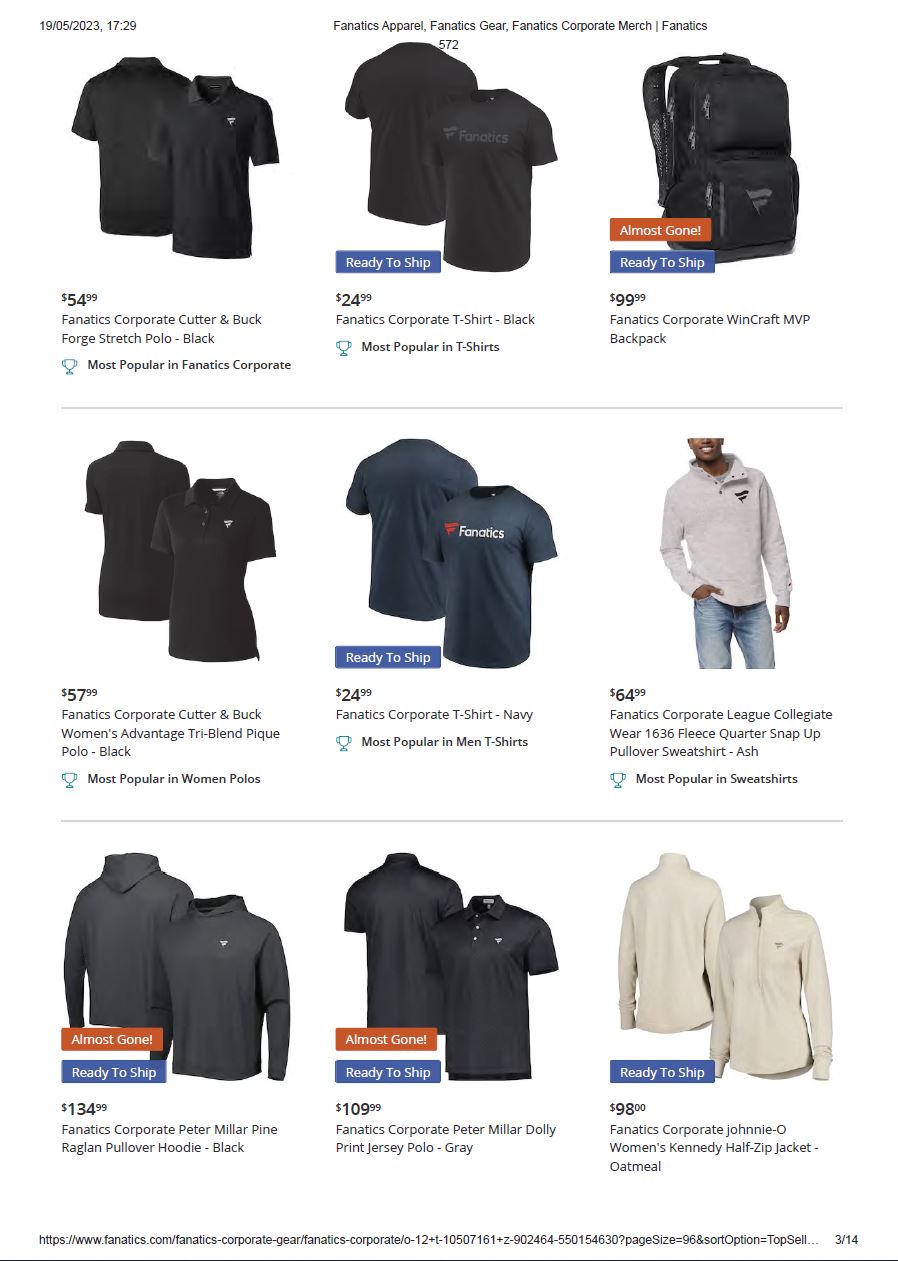

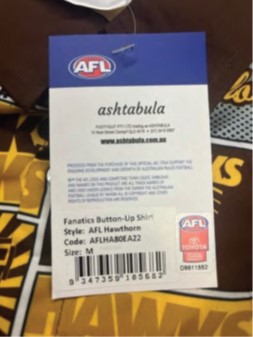

4.2.3 The respondent’s third party partner e-commerce business | [117] |

[120] | |

[122] | |

[123] | |

4.2.7 The respondent’s presence in Australia intensifies in 2020 | [124] |

[133] | |

[143] | |

[160] | |

[164] | |

[168] | |

[175] | |

[180] | |

[223] | |

[224] | |

6.5 Deceptive similarity – FANATICS MVP and FANATICS LIVE Marks | [238] |

6.6 Section 120(2) – goods and services of the same description | [242] |

[251] | |

[252] | |

[254] | |

[257] | |

[273] | |

[275] | |

[277] | |

[302] | |

7.3 Respondent would obtain registration if it applied – ss 122(1)(f) and (fa) | [315] |

[325] | |

[334] | |

[338] | |

[346] | |

[348] | |

[352] | |

[361] | |

[366] | |

[370] | |

[375] | |

[377] | |

[383] | |

[385] | |

[390] | |

[392] | |

[398] | |

[402] | |

[406] | |

[416] | |

[418] | |

[418] | |

[424] | |

[427] | |

[427] | |

[431] | |

[440] | |

[444] | |

[445] | |

[461] | |

[480] | |

[480] | |

[491] | |

[493] |

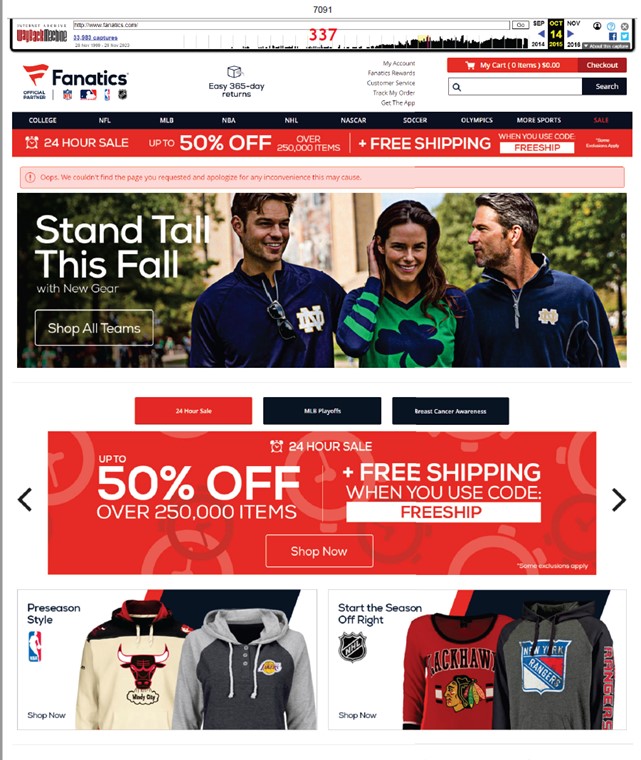

ROFE J:

1 At its core, this is a dispute about the trade mark “Fanatics” and its use in Australia with respect to clothing and online sales of clothing (including third party licensed sports merchandise).

2 The applicant, FanFirm Pty Limited, is an Australian company, the business of which has been run by Mr Warren Livingstone since its inception in 1997. The applicant began as a travelling cheer squad for the Australian Davis Cup tennis team and expanded into offering travel, tours and merchandise for (primarily) international sporting events.

3 The respondent, Fanatics, LLC, is a United States corporation based in Florida that operates an online retail store for sports merchandise.

4 The respondent maintains that both parties coexisted in Australia for over two decades until the applicant changed its business in mid-2020 to 2021 to promote and sell licensed sports merchandise, which it says is the genesis of the current dispute.

5 The applicant maintains that the Australian based activities of the respondent were minimal at best until about 2020 when it entered into agreements with the retailer Rebel Sport, the Australian Football League (AFL) and some AFL clubs to sell branded apparel.

6 The applicant is the owner of the following Australian Trade Mark Registrations:

(a) 1232983 for the word “FANATICS” in classes 9, 16, 24, 25, 32, 38 and 39 and having a priority date of 2 April 2008 (FanFirm Word Mark); and

(b) 1232984 for the word “FANATICS” and device in classes 9, 16, 24, 25, 32, 38 and 39 and having a priority date of 2 April 2008, using the following device (FanFirm Device Mark or Logo):

(together, the FanFirm Marks).

7 The applicant says it first used the FanFirm Word Mark in Australia in 1997 and has continuously used it since then.

8 The respondent is the owner of the following Australian Trade Mark Registrations:

(a) 1288632 for the words “FOOTBALL FANATICS” in class 35 and having a priority date of 10 September 2008 (632 TM);

(b) 1288633 for the word “FANATICS” in classes 35 and 42 and having a priority date of 10 September 2008 (633 TM);

(c) 1680976 for the words “SPORT FANATICS” in class 35 and having a priority date of 18 May 2010 (976 TM);

(d) 1905681 for the word “FANATICS” in classes 35 and 42 and having a priority date of 9 January 2018 (681 TM); and

(e) 1894688 for the word “Fanatics” and device (flag device) as shown below, in classes 35 and 42 and having a priority date of 15 November 2017 (688 TM or FANATICS Flag Mark):

.

.

9 The respondent’s marks primarily at issue in this dispute are the 633 TM and 681 TM (FANATICS Word Marks) and the FANATICS Flag Mark (688 TM) which together I will call the “FANATICS Marks”.

10 To avoid confusion, I will use upper case letters when referring to the respondent’s marks and lower-case letters when referring to the applicant’s marks.

11 Both parties have alleged that the other party has:

(a) infringed its registered marks under s 120 of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth);

(b) contravened s 18(1) and s 29(1)(g) and (h) of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL) as contained in Sch 2 of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth); and

(c) engaged in the tort of passing off.

12 Both parties seek cancellation of some of the other’s marks under s 88 of the Act. There is no dispute that each party is a person aggrieved for the purposes of its s 88 challenge.

13 Both parties also largely rely upon the same defences to trade mark infringement. Most of the issues in this case can be resolved by determining which party first used the “Fanatics” trade mark in Australia with respect to the relevant goods and services, and assessing the nature of each party’s reputation and when that reputation can be established in Australia.

14 This hearing was on the issue of liability only.

15 By way of summary, and for the reasons that follow, I am satisfied that:

(a) The applicant has established that the FANATICS Marks infringe the applicant’s FanFirm Word Mark in relation to certain goods (class 25), and that none of the defences raised by the respondent are successful;

(b) I should exercise my discretion to cancel the respondent’s registrations of the FANATICS Word Marks and FANATICS Flag Mark in class 35 (online retail services) pursuant to s 88(2)(a) and one or other grounds of cancellation;

(c) The FANATICS Word Marks and FANATICS Flag Mark registered in class 42 should not be cancelled;

(d) The respondent’s SPORTS FANATICS Mark should be removed from the Register pursuant to s 88 and s 59 of the Act and for non-use under s 94(4)(a) and (b);

(e) The applicant has not infringed the respondent’s registered trade marks because it can successfully rely on several defences to infringement;

(f) The registration of the FanFirm Marks in classes 9, 16, 32 and 38 should be removed for non-use under s 92(4); and

(g) Neither party has contravened the ACL or engaged in passing off.

16 The applicant read affidavits from the following lay witnesses:

(a) Mr Warren David Livingstone, who made four affidavits dated 28 April 2023, 17 October 2023, 12 December 2023 and 8 March 2024. Mr Livingstone is the Managing Director, sole director and secretary of the applicant.

(b) Mr Alastair Rhys Cockerton, who made one affidavit dated 28 September 2023. Mr Cockerton is a solicitor at Sparke Helmore, the legal representative of the applicant.

(c) Ms Shannon Elizabeth Platt, who made two affidavits dated 28 September 2023 and 19 February 2024. Ms Platt is a partner at Sparke Helmore.

(d) Mr Fenton Coull, who made one affidavit dated 11 October 2023. Mr Coull is a former sports executive who had business dealings with the applicant and Mr Livingstone while employed at Tennis Australia.

(e) Mr Dean Woodbury, who made one affidavit dated 27 October 2023. Mr Woodbury is a barrister but previously worked with Mr Livingstone on a partnership with Flight Centre (discussed below) and attended a number of the applicant’s tours and events.

(f) Ms Vahini Naidoo, who made one affidavit dated 12 October 2023. Ms Naidoo is a solicitor at Sparke Helmore.

(g) Mr Christopher Butler, who made one affidavit dated 21 November 2023. Mr Butler is the Office Manager at Internet Archive who gave evidence about Wayback Machine data.

17 Only Mr Livingstone was cross-examined.

18 The respondent read affidavits from the following lay witnesses:

(a) Mr Brian C Swallow, who made one affidavit dated 13 December 2023. Mr Swallow is the Senior Vice President for Strategy and Business Development of the respondent.

(b) Mr Zohar Ravid, who made three affidavits dated 25 October 2023, 14 November 2023 and 21 December 2023. Mr Ravid joined the respondent in June 2018, and has held various roles since then. Since January 2022, Mr Ravid has been the Senior Vice President, Global Head of Corporate Development for the respondent. Mr Ravid gave evidence as to the corporate history of the respondent since the formation of FOOTBALL FANATICS in Florida in February 1995. Mr Ravid also gave evidence as to the respondent’s business since he joined in 2018.

(c) Ms Diana Liu, who made three affidavits dated 17 October 2023, 9 November 2023 and 4 December 2023. Ms Liu is a solicitor at King & Wood Mallesons, the legal representative of the respondent.

(d) Ms Sylvia Cui, who made one affidavit dated 6 March 2024. Ms Cui is a Staff Engineer, Commerce Science Global Brand Insight of the respondent.

(e) Mr Wade Tonkin, who made one affidavit dated 7 March 2024. Mr Tonkin is Director, Global Affiliate Marketing of the respondent.

(f) Mr Mustafa Abdelfatah, who made one affidavit dated 6 March 2024. Mr Abdelfatah is the Senior Analyst, Web Analytics – Site Experience of the respondent.

(g) Ms Erin Body, who made one affidavit dated 7 March 2024. Ms Body is the Senior Manager, Merchandise Insights and Reporting of the respondent.

(h) Mr Lee Goodall, who made one affidavit dated 7 March 2024. Mr Goodall is the Senior Director of Buying and Merchandising of Fanatics International.

(i) Ms Brittanie Boone Gracey, who made one affidavit dated 8 March 2024. Ms Gracey is the Senior Director, Merchandising Analytics of the respondent.

(j) Ms Gu Mi, who made one affidavit dated 8 March 2024. Ms Mi is the Senior Analyst, Strategy and Analytics of the respondent.

19 Only Mr Swallow and Mr Ravid were cross-examined.

20 Neither party called any expert witnesses.

21 The applicant’s FanFirm Marks are registered in the following classes:

(a) Class 9: motion picture films (recorded); for use in multimedia (not limited to recordings for television; world wide web and DVD).

(b) Class 16: Printed material used for advertising and promotional material (although not limited to); postcards, books, bumper stickers, calendars, posters, printed publications and printed matter and photographs; paper flags.

(c) Class 24: Banners; flags (not of paper), including textile flags; woven and non-woven textile fabrics; textile material; textiles made of linen, cotton, silk, satin, flannel, synthetic materials, velvet or wool; cloth.

(d) Class 25: Clothing, footwear and headgear, shirts, scarves, ties, socks, sportswear.

(e) Class 32: Mineral and aerated waters and beer.

(f) Class 38: Providing telecommunication services including content and entertainment; television broadcasts and Internet communication; press or information agencies (news).

(g) Class 39: Organisation of transport and travel facilities for tours; functions; sporting and entertainment events for people and products.

22 The respondents’ marks, other than FOOTBALL FANATICS and SPORTS FANATICS (which are only registered in class 35), are registered in the following classes:

(a) Class 35: Business marketing consulting services; customer service in the field of retail store services and on-line retail store services; on-line retail store services featuring sports related and sports team branded clothing and merchandise; order fulfillment services; product merchandising; retail store services featuring sports related and sports team branded clothing and merchandise.

(b) Class 42: Development of new technology for others in the field of retail store services for the purpose of creating and maintaining the look and feel of web sites for others, not in the field of web site hosting; computer services, namely, creating and maintaining the look and feel of web sites for others, not in the field of web site hosting services; computer services, namely designing and implementing the look and feel of web sites for others, not in the field of web site hosting services; computer services, namely, managing the look and feel of web sites for others, not in the field of web site hosting.

23 In 1997, Mr Livingstone attended the US Open tennis men’s singles final in New York. His enthusiastic support earnt him an invitation to attend a post-match celebration with the winner of the final, Pat Rafter. Also in attendance were John Newcombe and Tony Roche (the Australian Davis Cup team coach). At that meeting, Mr Livingstone proposed the idea of a travelling cheer squad for the Australian tennis squad. Part of the concept was that these people would wear clothing branded with the word or logo “Fanatics” while giving enthusiastic support for Australian sports teams and players, and would be given preferential seating at these sporting events.

24 A collaboration with Tennis Australia then commenced in about October 1997 and the name “The Fanatics” (later shortened to “Fanatics”) was chosen by Mr Livingstone.

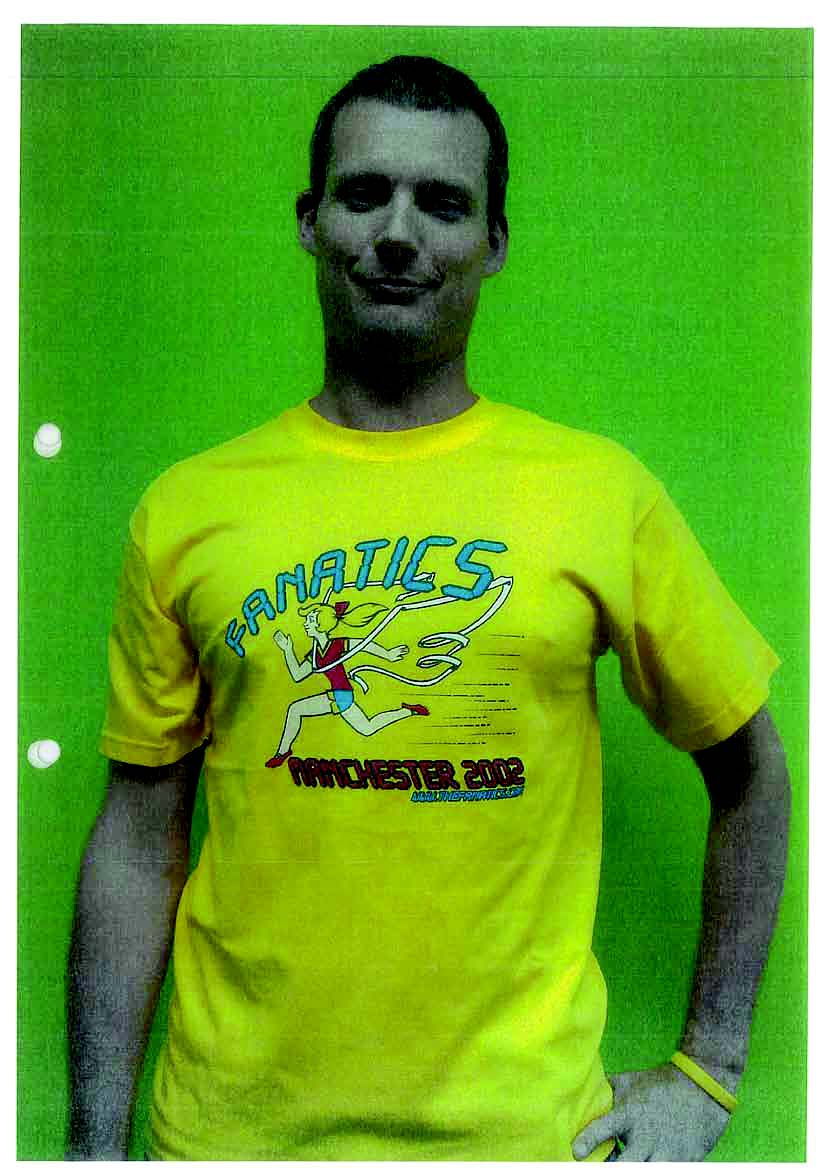

25 The first Fanatics tour took place in April 1998 to Mildura for the Davis Cup. Attendees wore “FanFirm branded” t-shirts and caps (ie, one or both of the FanFirm Marks were on the items, typically the FanFirm Logo).

26 Mr Coull had a longstanding association with the applicant’s business in his professional capacity, including as the General Manager of Operations and Events for Tennis Australia from 1998 to 2008. He gave evidence that the “Fanatics supporter group was so popular with the players that in or about 2003, [he] was asked by the Australian professional tennis players to allocate to the Fanatics supporter group preferential seating at each Davis Cup Tie”. Mr Coull also gave evidence of a tradition on the night after the Davis Cup Tie was completed where the players attended the post-match function wearing FanFirm branded T-shirts.

27 Mr Woodbury and Mr Livingstone gave evidence of various other tours and events organised by the applicant. Initially, the business focused on organising tour and event services for particular sporting events; first tennis, and subsequently other sports such as rugby, soccer, cricket and golf. In 2002, the applicant’s business expanded to providing organised tour and event services for a wide range of non-sport related events, such as Oktoberfest in Germany; Running of the Bulls in Pamplona, Spain; Anzac Day in Gallipoli, Turkey; St Patrick’s Day in Dublin, Ireland; and skiing trips to France and Japan. Many thousands of people have attended the applicant’s tours over the years.

28 In 2002, Mr Livingstone entered into a joint venture arrangement with Flight Centre, a travel agency business. As part of this arrangement, Flight Centre and Mr Livingstone sold tours and merchandise under the FanFirm Marks through various channels and websites. The joint venture came to an end in 2004. Mr Livingstone gave oral evidence that the reason the joint venture terminated was because it was “too focused on travel” and the applicant wanted to “do tours and merchandise and all those kind of things”.

29 In September 2004, Mr Livingstone incorporated the applicant. Upon incorporation, the applicant became responsible for, and continued to offer, all of the same goods, services and activities that Mr Livingstone had previously offered in his own right. From that time, Mr Livingstone has been the Managing Director of the applicant.

30 From the outset, Mr Livingstone and subsequently the applicant has maintained a database of its customers and subscribers (or as Mr Livingstone calls them “the Fanatics”). The customers in the database have purchased FanFirm branded merchandise from the applicant and/or purchased and participated in tours organised by the applicant. The majority of the people recorded in the database reside in Australia. The applicant uses the database to send newsletters to the customers, and inform them about new tours, FanFirm branded merchandise available for purchase and news of recent and upcoming Fanatics events. The applicant currently has around 160,000 members in its customer database.

31 Mr Livingstone also gave evidence that the applicant operated a loyalty and rewards program from its inception. Membership of the rewards program entitles a person to participate in the online communities which are operated at the website www.thefanatics.com and receive benefits including news of forthcoming sporting events and results of the Australian teams and sportspeople at the events. The Wayback Machine extracts set out at [44] and [46] below of the applicant’s website from 2007 and 2002, respectively, show a “member login” tab.

32 The applicant operates websites from three domain names:

(1) www.thefanatics.com – registered in 2000.

(2) www.fanatics.com.au – registered in 2003.

(3) thefanatics.com.au – registered in 2003.

33 It also operated a fourth domain name, www.sportingedge.com.au, until about 2000.

34 Mr Livingstone’s evidence was that www.thefanatics.com.au has always been redirected to www.thefanatics.com, save for a few discrete periods. As such, up until around 2020, the primary website of the applicant’s business was www.thefanatics.com.

35 The applicant contends that there have been, and continue to be, three distinct parts to the applicant’s business, each of which is promoted and provided under and by reference to the FanFirm Marks:

(a) “Tour Services” involving sports, festival and leisure tours conducted in Australia and in various countries around the world;

(b) “Sports-related Merchandise”, including clothing, sportswear, footwear and headgear. These have been, and continue to be, offered as a separate standalone offering, as well as in conjunction with the tour services referred to in (a); and

(c) “Sale Services”, involving selling the merchandise referred to in (b) on an online retail store.

36 The applicant rejects the respondent’s assertion that its business underwent a “dramatic change” in mid-2020. The applicant contends that it has been using its marks in relation to the same kinds of goods and in the same way, including on its website, since well before mid-2020, and there has been no change to its business or manner of using its marks after that date.

37 Mr Livingstone gave evidence that since 1998, the applicant (and Mr Livingstone before it) has sold clothing (including third party licensed merchandise) online via the website www.thefanatics.com. Since about 2000, the merchandise that was offered for sale and promoted via the website www.thefanatics.com.au (and www.fanatics.com.au from time to time) was offered and promoted to tour and event attendees. However, according to Mr Livingstone, it was not limited to those people.

38 Mr Coull gave evidence that in the early days, Mr Livingstone would sell surplus FanFirm branded merchandise in the lobby of the hotels where the Fanatics supporter group members were staying, and at the match venue.

39 The FanFirm Marks are registered in class 25 and the applicant submits that it has sold goods under those marks, including clothing, sportswear, footwear and headgear, since at least September 2004, and earlier via Mr Livingstone.

40 The applicant contends that it promotes, supplies and sells three categories of goods (including clothing, sportswear, footwear and headgear), by reference to the FanFirm Marks:

(a) FanFirm branded merchandise relating to a particular tour or event (such as a t-shirt relating to a particular Davis Cup tie or cricket tour). This category can be divided into:

(i) merchandise branded with the word “Fanatics” or the FanFirm Device Mark only; and

(ii) merchandise co-branded with a FanFirm mark and with indicia of the relevant sporting code – for example, a cricket shirt with the FanFirm Device Mark and the Cricket Australia logo;

(b) FanFirm branded merchandise used to promote the FanFirm business generally, rather than a particular tour or event. For example, a pair of FanFirm branded Dunlop Volley shoes were advertised as a “New product” on the applicant’s website in 2011;

(together, FanFirm branded merchandise)

(c) Official or third party licensed merchandise provided by way of a straight resale and not branded with either of the FanFirm Marks.

41 It is this last category of merchandise, and in particular its sale online by the applicant before 2020, that the respondent takes issue with. The respondent says that the applicant did not sell third party licensed merchandise prior to 2020 (or, if it did, any such sales were infrequent and negligible) and, therefore, the sale of such merchandise from mid-2020 signified a departure from the applicant’s ordinary activities.

4.1.1.1.1 Evidence of category (a) and (b) merchandise

42 There was evidence of the existence, promotion and supply of category (a) and (b) FanFirm branded clothing, sportswear, footwear and headgear going back to 1997. This included photographs of t-shirts (some dated on their face), newspaper articles showing the supporter group wearing the FanFirm branded merchandise and Wayback Machine extracts from 2002, 2003, 2004 and 2005 depicting people wearing FanFirm branded merchandise. Some of these examples are set out below.

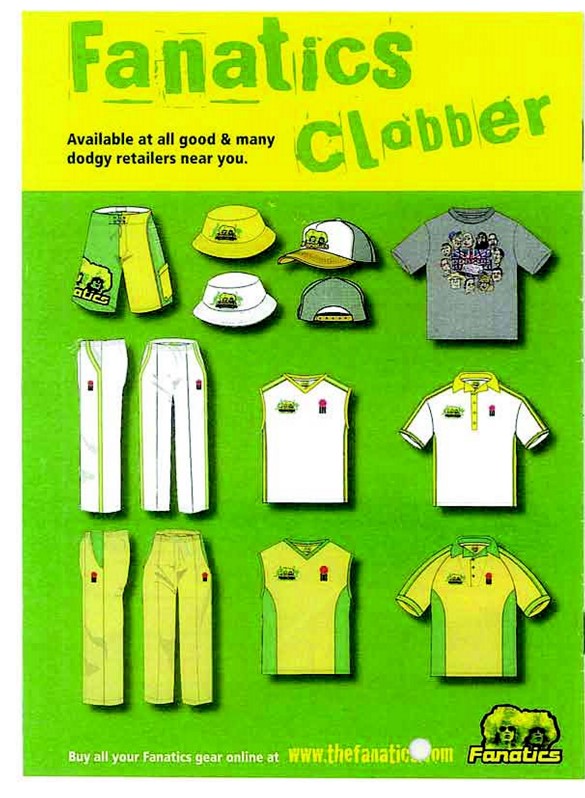

43 A further example of the use of the FanFirm Marks in relation to sportswear, footwear and headgear is a booklet created for the 2006/2007 Ashes cricket tour. The “Fanatics clobber” and gear pictured in the booklet was said to be available online at www.thefanatics.com. Set out below are the booklet and Wayback Machine extracts of the website (dated 23 November 2007) where the FanFirm branded merchandise promoted in the booklet could be purchased.

44 The Ashes 2006/2007 merchandise is third party licensed co-branded merchandise (category (a)(ii) at [40] above). The goods promoted in the booklet (second and third rows below) are co-branded with Cricket Australia logos and the FanFirm Device Mark. The items are also displayed for purchase on the website extract below.

45 There is no dispute that the applicant has promoted, supplied and sold FanFirm branded merchandise in relation to tours and to promote the business generally. The respondent accepts that the evidence shows that from around 2002, such goods were promoted via a “Merchandise” page on the website www.thefanatics.com.

46 For example, the Wayback Machine extract set out below from 24 May 2002 shows a “Merchandise” link on the left-hand side and, on the right-hand side, a photograph of John Newcome holding what Mr Livingstone described as “a shirt from ‘99”. When asked in cross-examination about the “tile” with “MERCHANDISE: Coming soon!” written underneath, Mr Livingstone explained that in the

early days we sold merchandise differently … there wasn’t an online shop per se. In the early days, you clicked on merchandise, you went to a page which had a couple of photos of merchandise and then people would call us, email us, send us a cheque and we would take the cheque and send the merchandise.

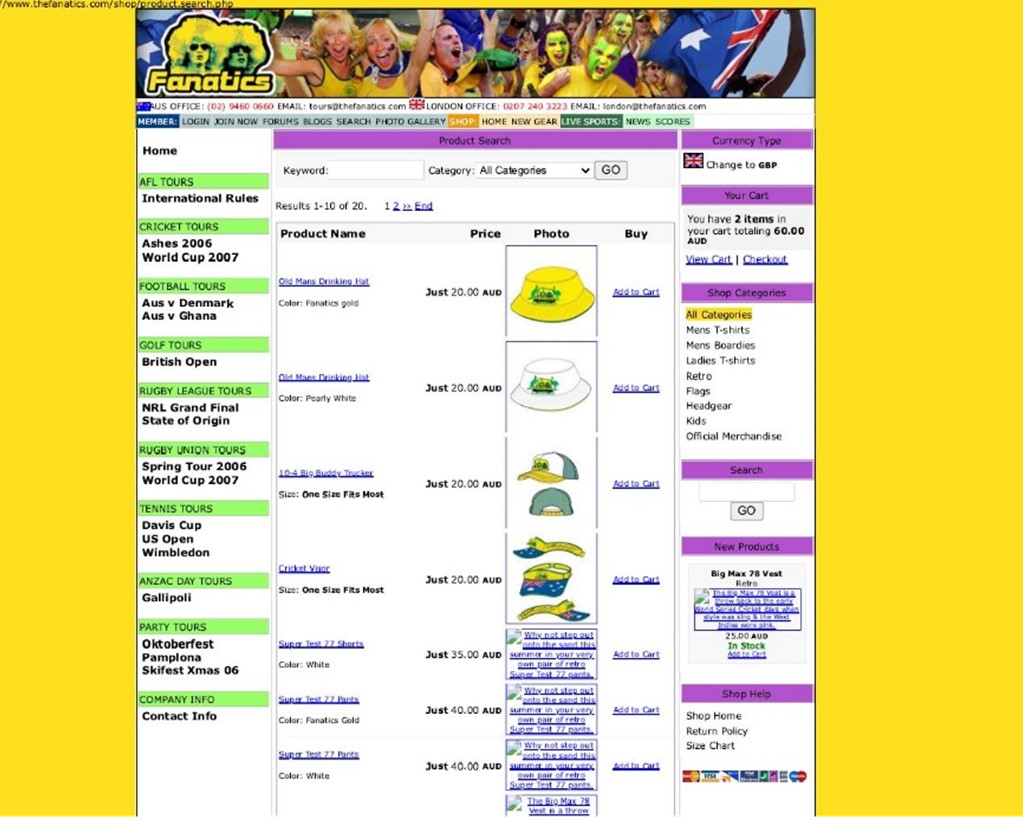

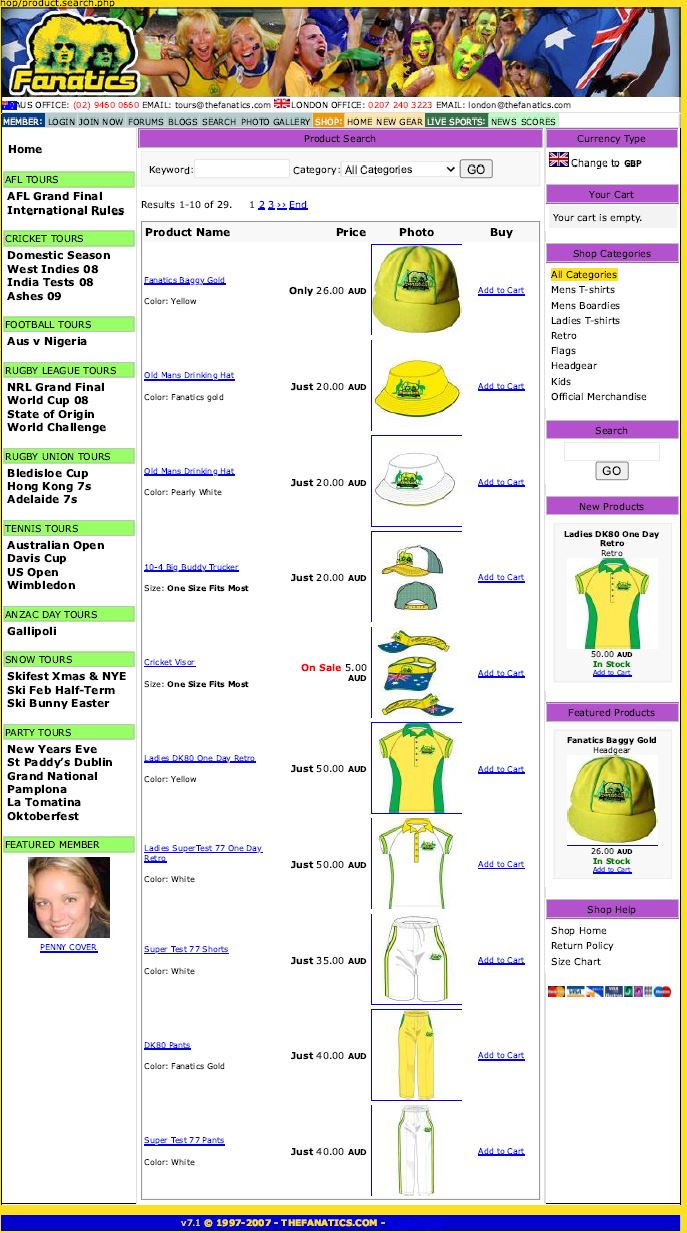

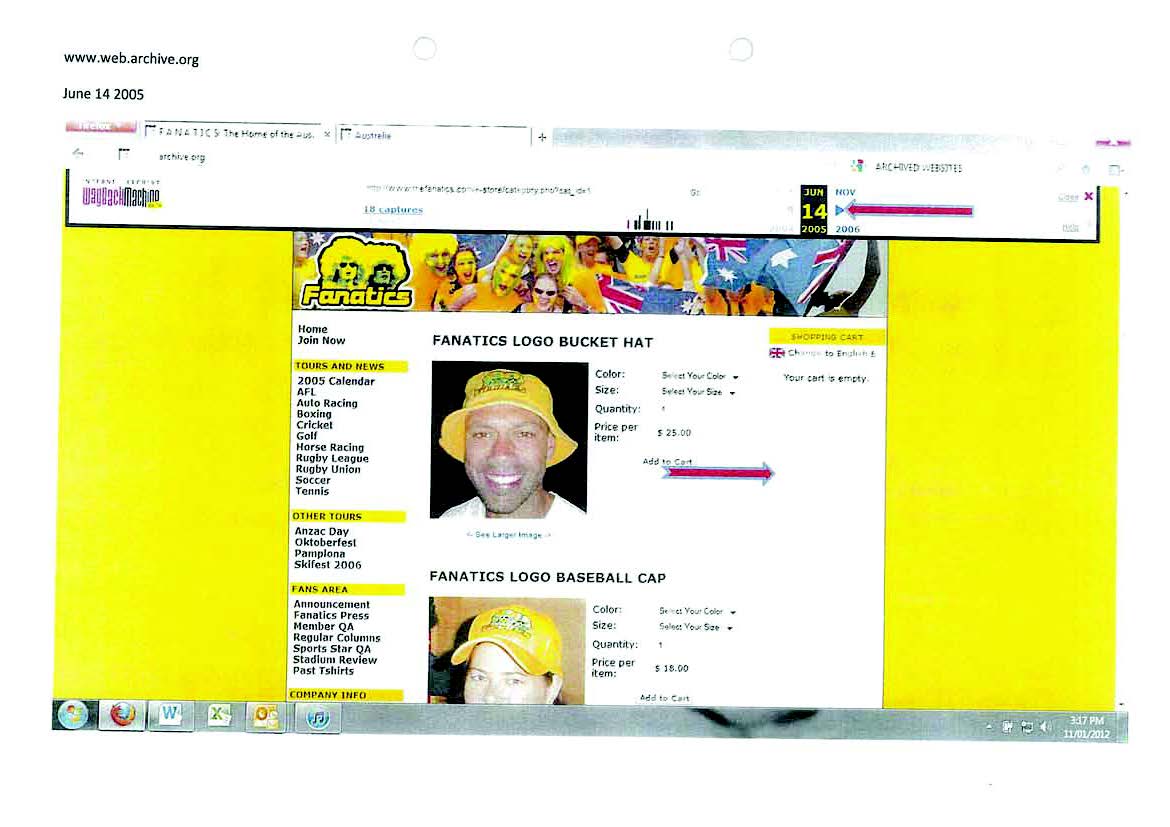

47 There was evidence that the applicant had, since 2002, sold merchandise on its website, including the Wayback Machine extract from 2007 displaying Ashes merchandise set out above and the Wayback Machine extract from 14 June 2005 set out below:

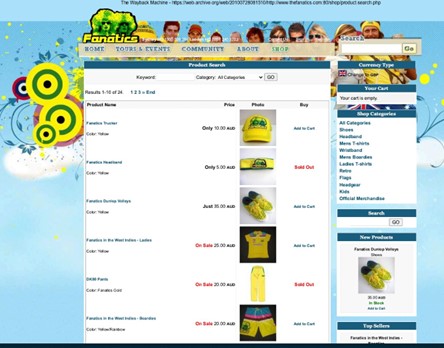

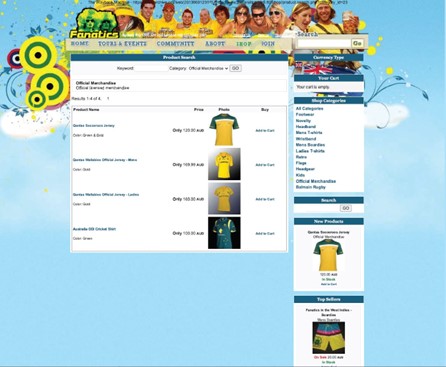

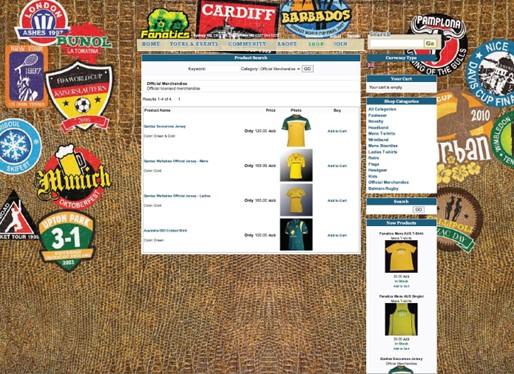

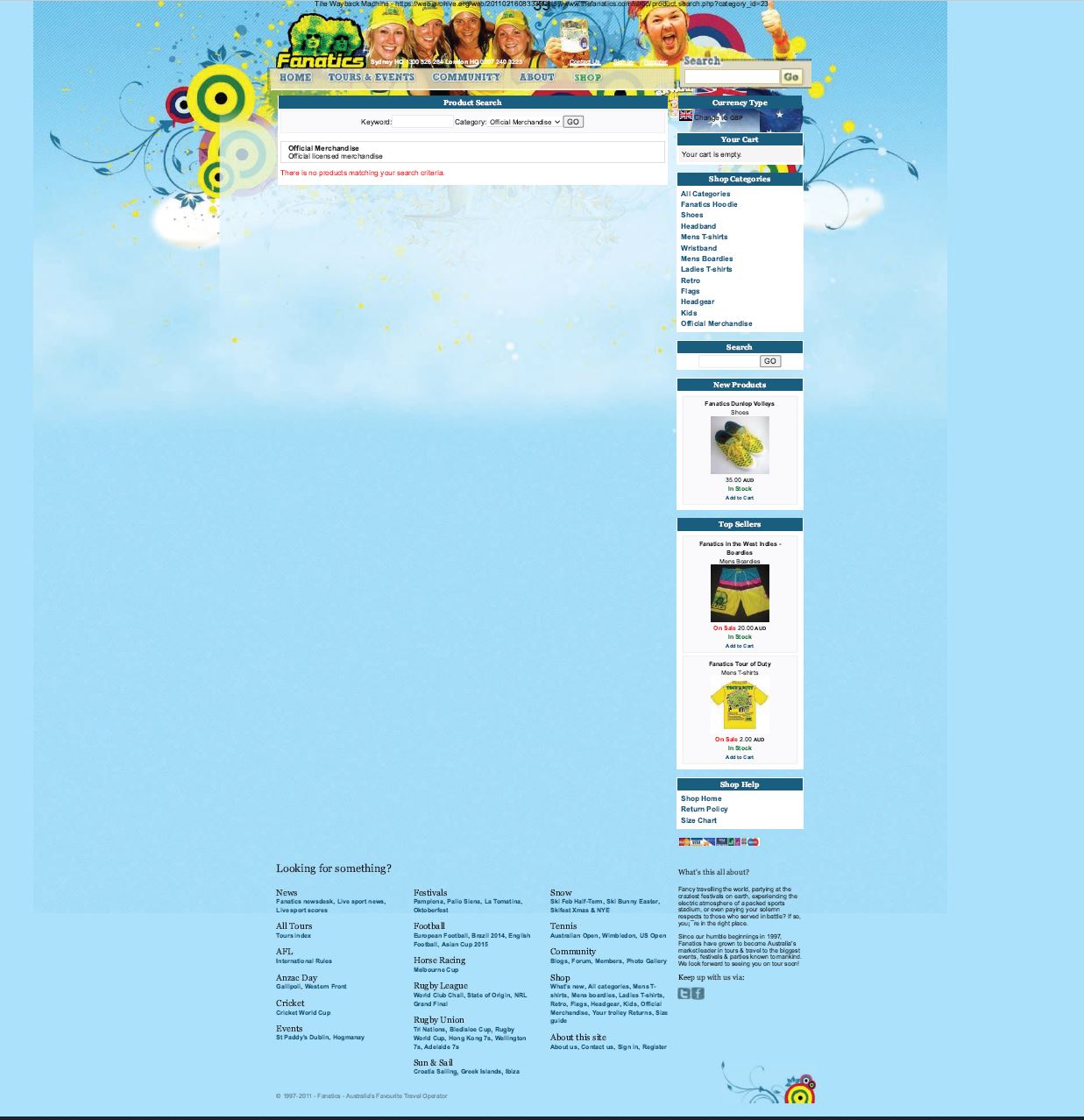

48 The applicant’s website in 2011 (displayed below) included a “SHOP” tab in the menu bar at the top of the page. There was a “Shop Help” in the vertical side bar, and the Shop section in the site map at the bottom of the page listed the following under “Shop”: “What’s new, All categories, Men’s T-shirts, Men’s boardies, Ladies T-shirts, Retro, Flags, Headgear, Kids, Official Merchandise, Your trolley Returns and Size guide”.

4.1.1.1.2 Evidence of category (c) merchandise

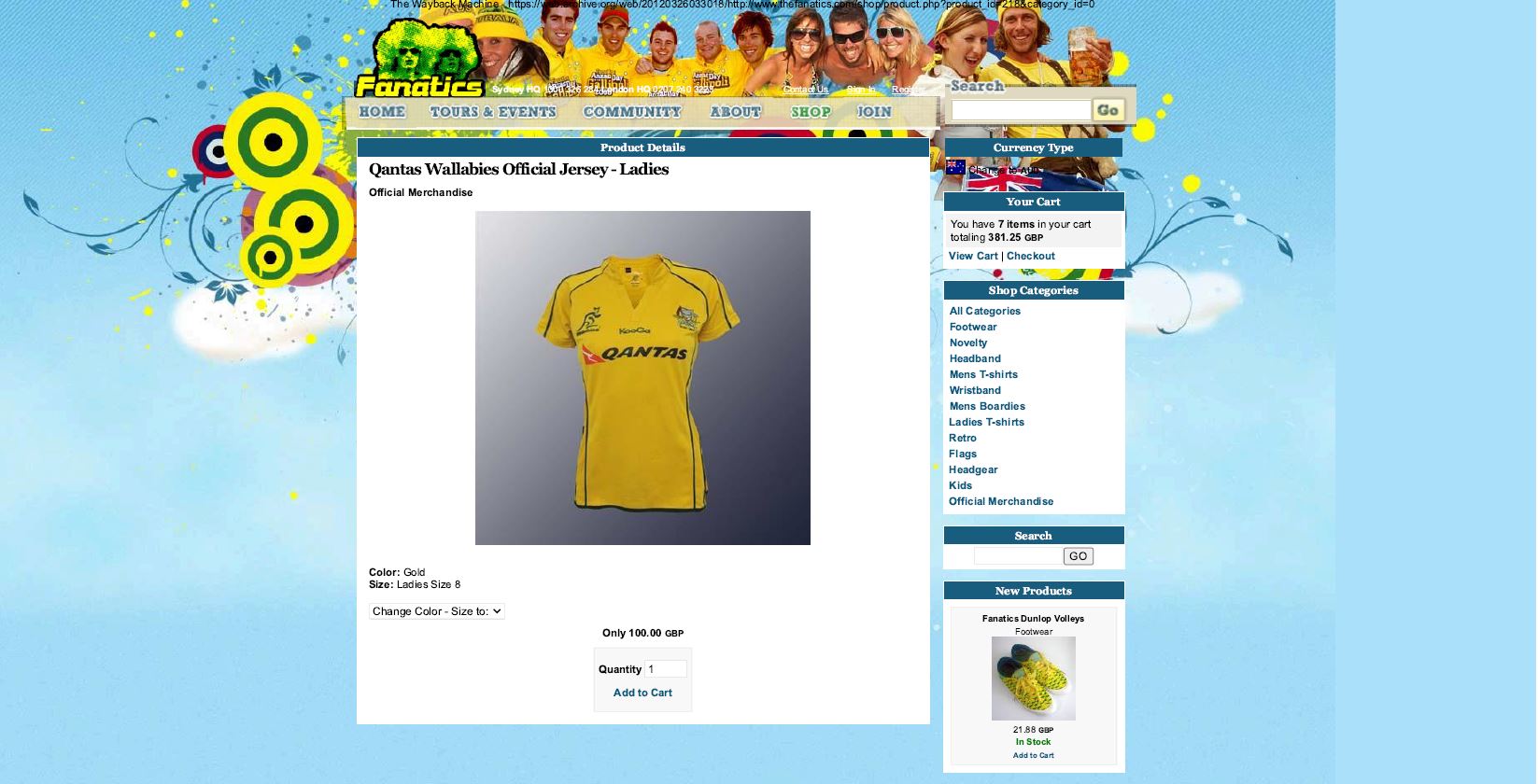

49 There is evidence that from at least January 2012, FanFirm sold via its website third party “straight resale” licensed merchandise, including Qantas Socceroos Jerseys, Qantas Wallabies Official Jerseys, and Australia ODI Cricket Shirts. Extracted below are Wayback Machine extracts of FanFirm’s website from 25 January 2012 showing third party licensed merchandise offered for sale:

50 These Wayback Machine extracts are the earliest documentary evidence of the applicant selling third party licensed merchandise.

51 Mr Livingstone gave evidence of some licensing arrangements and deals, including those concerning clothing, that the applicant and its predecessors have done with various sporting bodies and teams. This included Tennis Australia, the USA National Football League (NFL), Cricket Australia, USA National Hockey League (NHL), the Wallabies and Football Australia. Mr Livingstone gave evidence that in 1999 he produced 3,000 shirts co-branded with the NFL. The shirts had the NFL logo on the left-hand side and either the Denver Broncos or the Los Angeles Chargers logos on the right-side, and the FanFirm Device Mark on the back. 1,500 of these shirts were distributed to purchasers of tickets to the 1999 America Bowl in Australia. Mr Livingstone was cross-examined in relation to these arrangements. He agreed that FanFirm did not have any current affiliation with any of these sporting bodies or teams.

52 In his second affidavit, Mr Livingstone gave evidence that the applicant had, from around 2004, promoted for sale licensed merchandise from the NFL, National Basketball Association (NBA), NHL, English Premier League, FIFA, UEFA Champions League, Rugby Australia, Tennis Australia, Netball Australia, Soccer Australia, Cricket Australia, National Rugby League (NRL), National Basketball League (NBL), Olympics and the AFL. There were no examples in the applicant’s evidence of the applicant selling any third party licensed merchandise other than for Cricket Australia, Rugby Australia and Soccer Australia prior to 2021.

53 In cross-examination, Mr Livingstone gave evidence that the applicant sold third party licensed merchandise from as early as 2006 in relation to the 2006 Football World Cup in Germany (Germany World Cup). At that time, the applicant was involved in a partnership with Football Australia. Mr Livingstone explained that the applicant:

won a deal with Football Australia whereby [it] managed the sale of their tours and their tickets and their merchandise to the 2006 Football World Cup. [The applicant] produced about 20,000 units of merchandise for Football Australia – which we designed, which we produced – and [it] then sold them to Australians on tour or Australians picking up their tickets in Frankfurt, or people picking up just merchandise.

54 Mr Livingstone explained that this partnership came about because the applicant “had a lot of experience in … selling online merch”. He said that the applicant approached Football Australia as they had “more experience than any other person – any other company in Australia”. Mr Livingstone said that the Football Australia merchandise “all had a Football Australia logo on them. They had Fanatic swing tags. Some of them had Fanatics logos”. The 20,000 units of merchandise encompassed shirts, board shorts, visors, jerseys, thongs and outerwear.

55 Mr Livingstone gave evidence that the Germany World Cup merchandise was available on www.fanatics.com.au which was not redirected to www.thefanatics.com during 2005 and 2006. The domain name www.fanatics.com.au operated as a standalone website during this time where people could purchase merchandise, irrespective of whether they had already booked the tour to the Germany World Cup.

56 The respondent rightly notes that there is no documentary evidence to support Mr Livingstone’s account of the Football Australia partnership in 2005 and 2006, such as Wayback Machine extracts. As such, there is no evidence of what the website looked like during those periods, what the merchandise was or the manner in which it was made available. Nor is there any evidence of how many customers visited the website or invoices to show how many of these units were purchased.

57 Despite these criticisms, the respondent seems to accept Mr Livingstone’s description of the applicant selling third party licensed Football Australia merchandise in 2005 and 2006 via a standalone website. It was not put to Mr Livingstone that those sales did not take place. Nor did the respondent submit in closing that the Court should not give any weight to this evidence because it was not supported by documentary evidence and only raised for the first time in re-examination.

58 The extent of the respondent’s criticism was that Mr Livingstone’s evidence on this episode was “vague” and does “not advance FanFirm’s position in any way” because it merely describes a single, isolated incident of the applicant’s business.

59 However, the respondent criticises Mr Livingstone as a witness generally. The respondent claims that Mr Livingstone was argumentative in cross-examination, gave long answers unresponsive to questions, failed to make appropriate concessions, sought to pre-empt the direction of cross-examination and raised matters that had not be set out in his four affidavits. The respondent contends that Mr Livingstone’s evidence as a whole should therefore be treated with caution.

60 Mr Livingstone was, perhaps understandably, passionate in giving evidence about his business. I consider that he generally gave relevant and credible evidence. His evidence about the Football Australia partnership for the Germany World Cup in 2006 was very self-serving and unsupported by any contemporaneous document or raised in his affidavit. However, for the reasons explained below at [157]–[158], I do not consider that anything turns on when the applicant first sold third party, straight resale, licensed merchandise.

61 The respondent alleges that in about March 2021, the applicant made a “dramatic change” to its business, departing from its longstanding sporting and event tour organisation business by launching what the respondent calls the FanFirm “Retail Store”. The Retail Store is at the domain name www.thefanatics.com.au.

62 As noted above, www.thefanatics.com.au has always been redirected to www.thefanatics.com. In cross-examination, Mr Livingstone accepted that the re-direction came to an end by no later than some time in 2020 and now www.thefanatics.com and www.thefanatics.com.au are two separate, standalone websites.

63 The respondent contends that the Retail Store now promotes both licensed sports merchandise (ie “straight resale”) and a selection of FanFirm branded merchandise. The applicant continues to promote and sell its sporting tour and event services from the website at www.thefanatics.com.

64 The respondent says that the Retail Store is a significant departure from the applicant’s previous activities for two reasons. First, the applicant has transitioned away from being a business focused on tour and event services to operating a freestanding online retail store selling third party, straight resale, licensed merchandise. Second, the website’s colour theme and style are significantly different from the applicant’s website at www.thefanatics.com and its previous iterations since the early 2000’s. The respondent contends that these changes are the genesis of the current dispute and amount to misleading and deceptive conduct in contravention of s 18(1) of the ACL.

4.1.2 Alleged change in applicant’s website

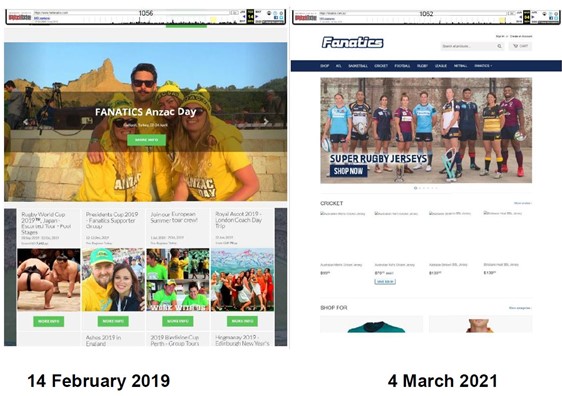

65 The respondent contends that the change in the presentation of the website located at www.fanatics.com.au is best illustrated when the following “before” and “after” screenshots from the Wayback Machine are compared:

66 The side-by-side comparison does, indeed, show a significant difference in appearance between the website at those two points in time.

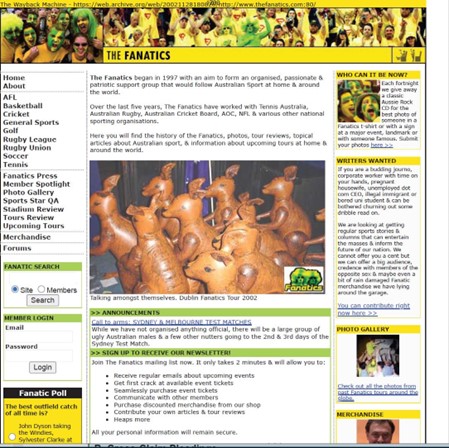

67 However, a review of the evidence as to the appearance of the applicant’s website over the years from its earliest days shows that the colour scheme and style of the applicant’s website has changed many times over the years, and the respondent has selected the examples that look the most different. Set out in the table below are a selection of Wayback Machine extracts from various webpages of www.thefanatics.com over the years. These are not an exhaustive list and are set out to illustrate how the website has changed overtime.

Year | Website |

2002 |

|

2006 |

|

2009 |

|

2010 |

|

2013 |

|

2014 |

|

2015 – 2017 |

|

2021–2022 |

|

68 The applicant’s website has recycled many of the different designs over time. For example, in May 2021, the website adopted the theme of the suitcase with stickers (in the 2014 row of the table) whereas in October 2021 it adopted the light blue theme (in the final row of the table).

69 It is evident from these examples that, contrary to the respondent’s contention, the Australian green and gold theme has not always been a consistent and prominent theme of the applicant’s website. The green and gold theme was prominent in the early years, but since 2009 the website has frequently adopted other designs, such as the light blue background or the suitcase design.

70 A key element that has been present in almost every iteration of the website and its various webpages over the years is the presence of the FanFirm Device Mark in the top left-hand corner.

71 The biggest change to the website is not in colour and design, but in the description of the applicant’s business, the focus of the business and the product offering.

72 The applicant has consistently described itself as a tour and event business on its website. For example, between at least 2002 and 2003, the website at www.thefanatics.com contained the following (or a very similar) description:

The Fanatics began in 1997 with an aim to form an organised, passionate & patriotic support group that would follow Australian Sport at home & around the world.

Over the last five years, The Fanatics have worked with Tennis Australia, Australian Rugby, Australian Cricket Board, AOC, NFL & various other national sporting organisations.

Here you will find the history of the fanatics, photos, tour reviews, topical articles about Australian sport, & information about upcoming tours at home & around the world.

73 The “About Us” page on www.thefanatics.com in September 2023 contained a broadly similar description:

Fanatics officially began in 1997 with the aim of forming an organised, passionate & patriotic support group that would follow Australian Sport at home & around the world.

These days over 115,000 members receive our newsletters & we’ve organised travel for over 130,000 punters since we started. We still run regular jaunts to a wide range of sports and party events around the world, while working closely with Rugby Australia, Cricket Australia, Football Australia, the NRL & ARL, Tennis Australia & various other international sporting organisations.

We now concentrate on two main things – firstly, organising events for passionate Australian sports fans to congregate at the biggest and best sporting events at home and overseas.

We also operate affordable travel options to the world’s biggest and craziest festivals and parties, sailing along the Croatian coast during the European summer, plus the annual Anzac Day commemorations at Gallipoli.

Fanatics are dedicated to ensuring we continue to offer the best range of tours and events anywhere in the world. So whether you want to join our supporter bays & tours to all the big sporting events in Aus, our massive tours to the World Cups and major international sporting events around the globe, our amazing range of annual party & festival events throughout Europe, or commemorating the Anzacs at Gallipoli, there is something for you!

We hope you enjoy our website & look forward to seeing you on tour soon!

74 The focus of the www.thefanatics.com website has consistently been tours and events. Merchandise has always been available for purchase and advertised on the homepage, but the primary offering is clearly tours and events.

75 In contrast, since at least 2021, the applicant has described itself on the Retail Store at www.fanatics.com.au as follows:

OFFICIAL LICENSED MERCHANDISE

Fanatics are a global leader in official sports merchandise & team apparel. Choose the latest jerseys, caps & other merchandise from the worlds [sic] leading sports teams & Fanatics supporter merchandise.

Fanatics Est. 1997

(Emphasis added.)

76 The Retail Store does not refer to tours and events promoted by the applicant or provide a link to www.thefanatics.com. However, the Retail Store does sell FanFirm branded merchandise.

77 Finally, prior to 2021, the applicant only sold third party licensed merchandise from Australian national sporting teams, such as the Socceroos, Matildas, Wallabies and Cricket Australia. There is no evidence that the applicant sold merchandise relating to domestic or international sporting leagues, such as the AFL, NRL, NFL, NBA or English Premier League. The Retail Store at www.thefanatics.com.au now offers merchandise in relation to all these sporting codes and seems to have done so since at least December 2020.

78 The applicant does not manufacture this third party, straight resale, licensed merchandise and Mr Livingstone said that the applicant does not have any agreement with any of these leagues in relation to the supply of such merchandise.

79 The respondent gave evidence of a “trap purchase” of an AFL Sydney Swans jersey from the Retail Store. The evidence showed that, to fulfil the order, the applicant purchased that jersey from Rebel Sport, marked it up and on-sold it.

80 The respondent contends that the applicant designed the Retail Store at some time in 2019 and launched it at some time in 2020, transitioning away from being a business focussed on sporting and event tour services to the operation of a freestanding online retail store selling the same types of goods as the respondent. However, the respondent did not put these allegations to Mr Livingstone directly.

4.1.3 Applicant’s social media

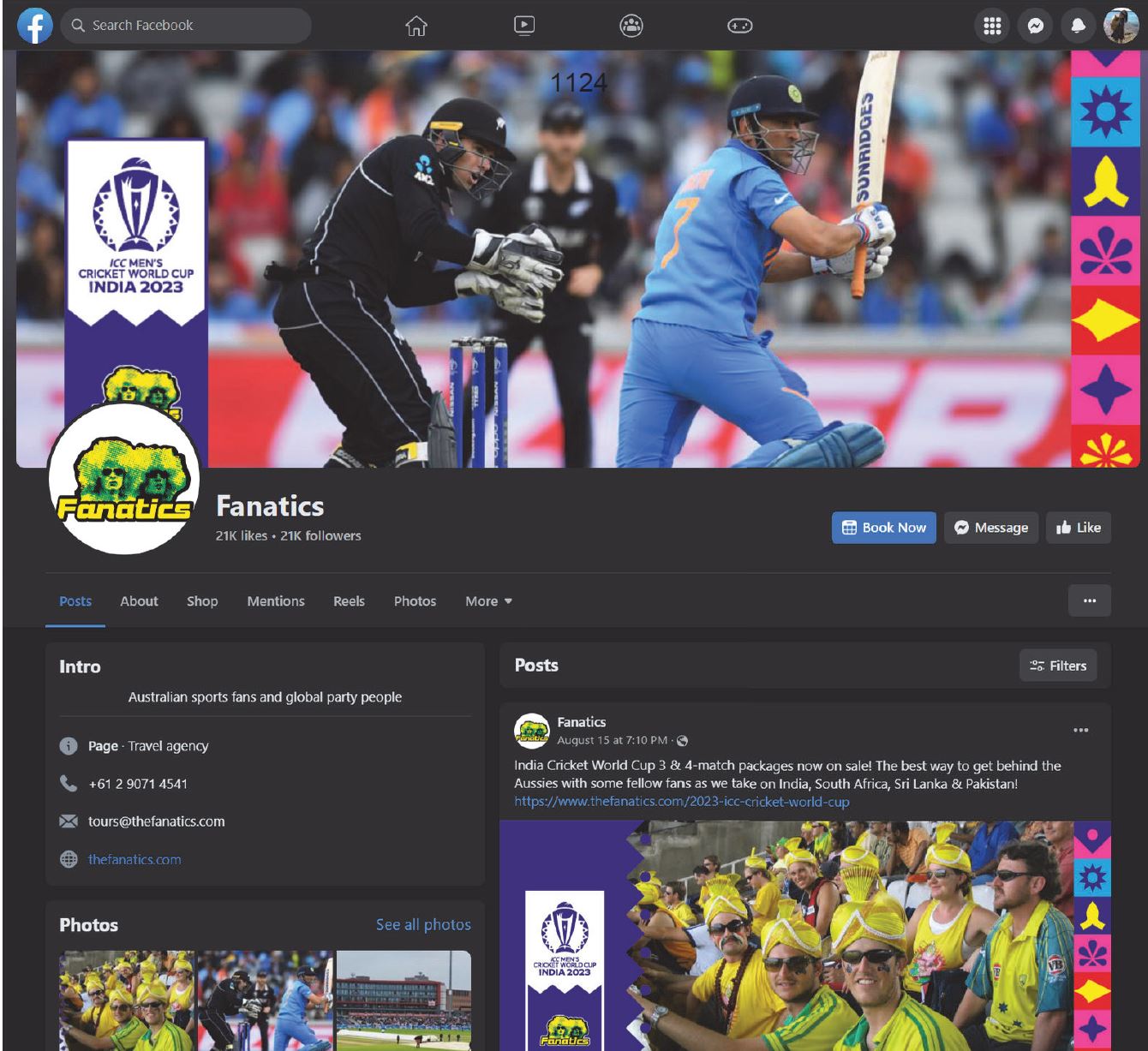

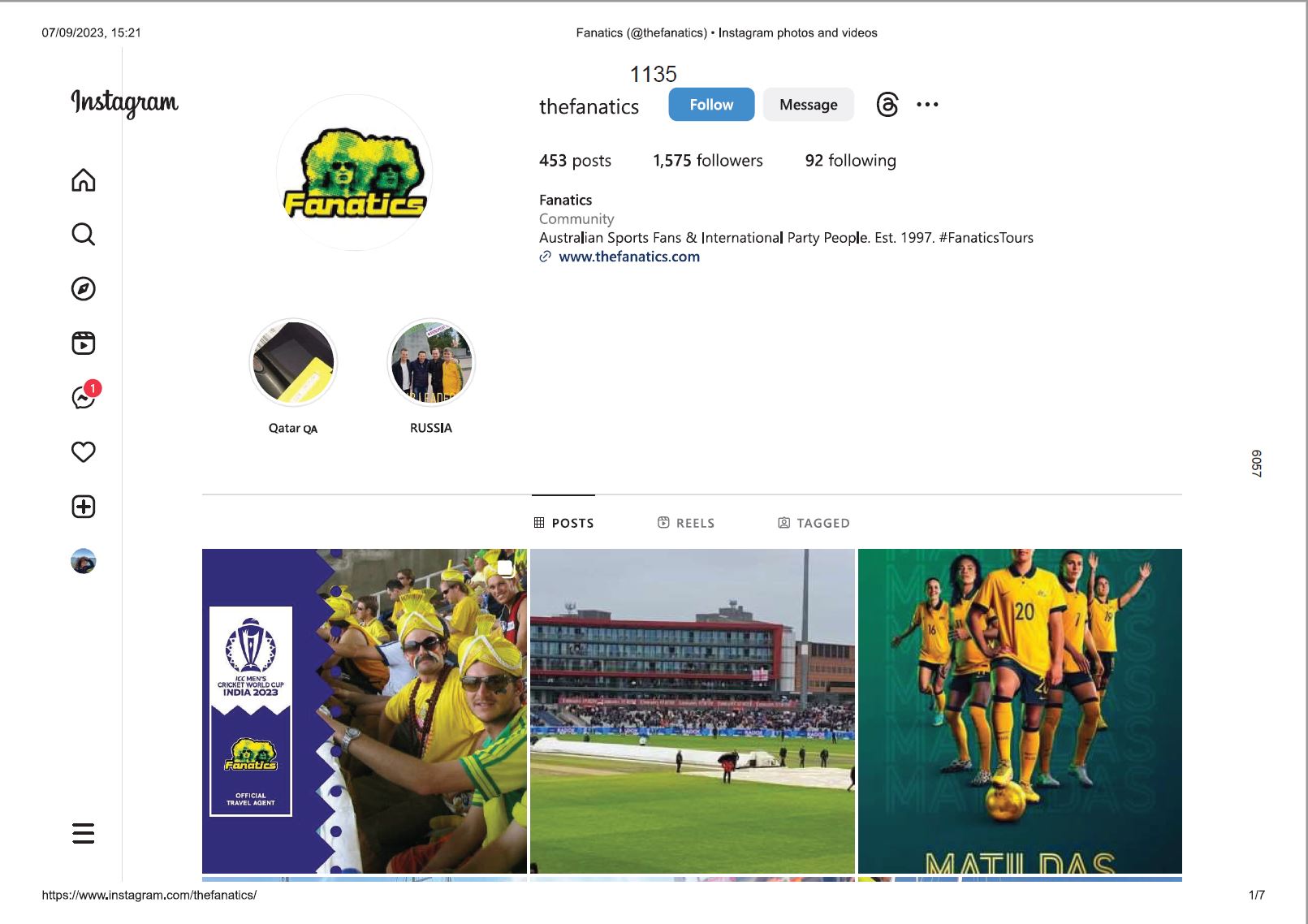

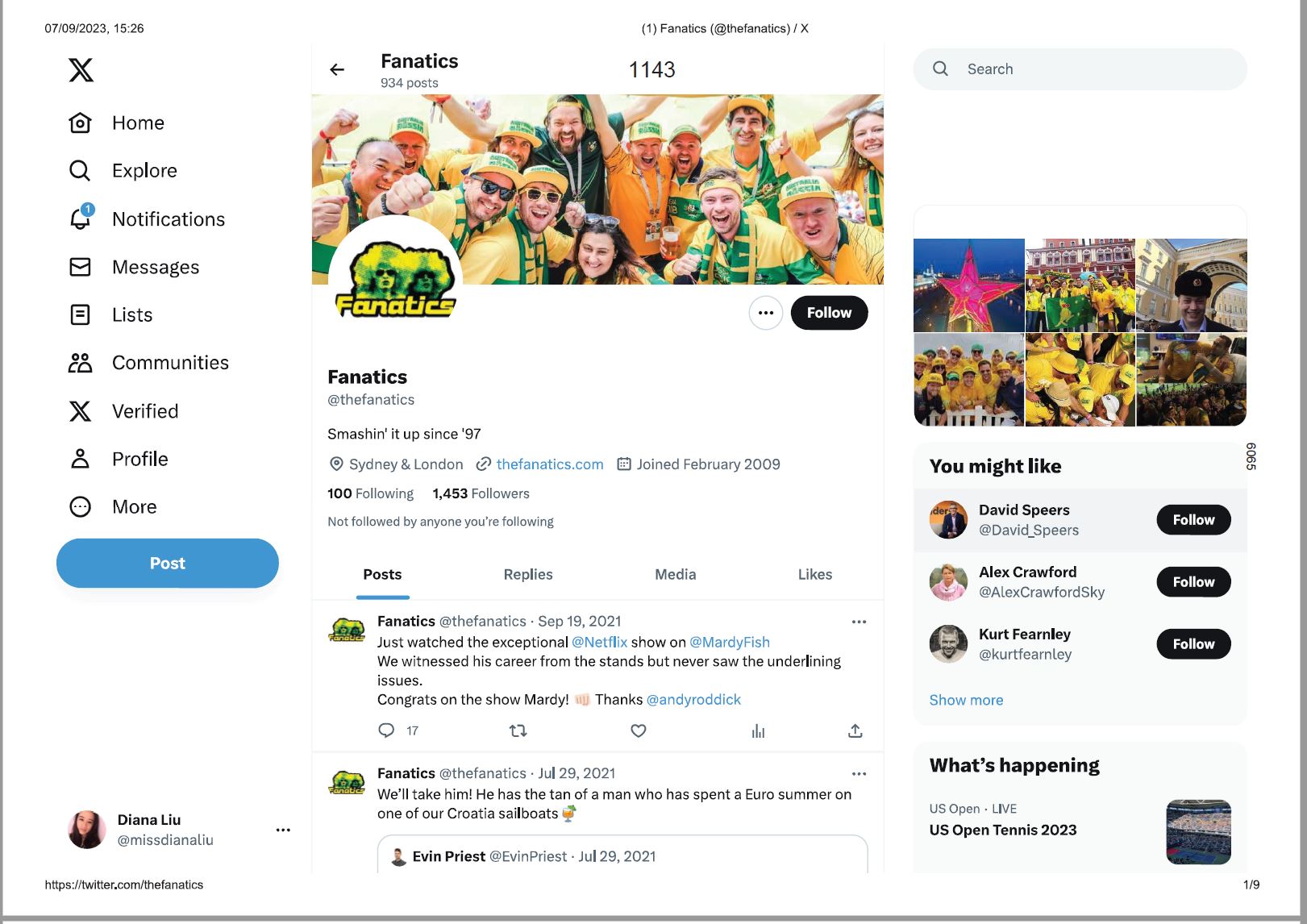

81 Mr Livingstone gave evidence of the applicant’s social media presence. The applicant has been active on Facebook since 2006, YouTube since 2008, X (Twitter) since 2009 and Instagram since 2018. The FanFirm Marks, particularly the Device Mark, are used on the applicant’s social media accounts, as illustrated by the examples below.

82 The applicant relies on its social media presence as further evidence of its significant reputation in the name Fanatics for tour services, sales services and merchandise.

83 The applicant contends that as at December 2010 (and indeed earlier), it had a valuable reputation in the word “Fanatics” with respect to sporting and other events tour services and sports merchandise, including clothing, headgear, sportswear, footwear.

84 The respondent does not dispute that the applicant has a reputation in Australia in the word “Fanatics” in connection with its business of promoting and providing sporting and event tour services. The respondent accepts that the applicant has promoted its sporting and event tour services business by reference to that name via its websites, newsletters to subscribers, and social media. Nor does the respondent deny that as part of its sporting and event tour services business, the applicant has supplied items of clothing and headgear to attendees of its tours and events.

85 However, the respondent rejects the proposition that the applicant has a reputation in relation to the promotion and sale of merchandise under the FanFirm Word Mark, including clothing, headgear, sportswear, and footwear, other than as an adjunct to its sporting and event tour service business.

86 The respondent contends that the promotion and sale of merchandise was an incident of, and on the evidence, a minor part of, the applicant’s tour and event services. According to the respondent, there is no basis to think that the promotion and sale of the merchandise in question would have occurred were the applicant not providing its tour and event services. The respondent says that consumers did not transact with the applicant on the basis that they were acquiring a retail service, but transacted with the applicant to obtain a tour or event service, and perhaps relatedly a piece of merchandise. The respondent submits that Mr Livingstone’s first trade mark application made in October 2002 supports its case as the registration was sought in class 39 for “[t]ravel services being services offered by travel agents in this class”.

87 The nature and extent of the applicant’s reputation in the word “Fanatics” is critical to several aspects of the case. First, both parties’ ACL cases. Second, both parties’ resort to s 60 and s 88(2)(c) of the Act in their attempt to cancel the other’s marks. Third, it is relevant to discretionary considerations.

88 Rather than extensive evidence of sales volumes and revenue to establish the existence of its reputation, the applicant relied on:

(a) the lengthy period of operation of its sporting and event tours business including the background matters set out above;

(b) evidence of the thousands of people who have attended its organised tours and events and attended those tours and events attired in FanFirm branded merchandise;

(c) widespread newspaper reports (including photos) of the activities of groups of Fanatics attending sporting matches and events whilst attired in FanFirm branded clothing; and

(d) the separate sale of FanFirm branded merchandise, including clothing, headgear, sportswear and footwear via its website.

89 The applicant also relied on evidence of its annual gross income for each year from 1997 to establish its reputation. Aside from 2020 and 2021 which were affected by the Covid-19 pandemic, the applicant’s gross annual income since 2002 has been substantial and, for the most part, increasing annually. The volume of sales are in the order to be expected from the “thousands” of people that have partaken of the applicant’s sporting tours and events over the years the applicant has been conducting its business.

90 The applicant also relied on its extensive customer database, which it said included around 160,000 contact details, as evidence of the large number of people in Australia aware of the applicant’s use of the word “Fanatics”.

91 Mr Coull gave evidence of large numbers of attendees at Davis Cup matches wearing clothing bearing the FanFirm Marks. He also gave evidence, noted above, that Australian professional tennis players requested that Fanatics supporter groups were given preferential seating.

92 For example, at the 2003 Davis Cup held in Australia, Lleyton Hewitt requested the match stadium seating allocation be organised so that the Fanatics supporter group (all of whom were wearing FanFirm branded t-shirts and hats) were given preferential seating, close to the court near where Mr Hewitt would receive balls from the ball kids when serving.

93 Mr Coull also gave evidence that around 1,000 to 1,300 Fanatics supporters attended each Davis Cup event with which he was associated.

94 Mr Woodbury, now a member of the New South Wales Bar Association, first attended a tour organised by the applicant to watch Australia v Zimbabwe in the first round of the Davis Cup hosted in Mildura in March 1998. He gave evidence of attending several FanFirm tours over the years where attendees wore FanFirm branded merchandise.

95 The applicant had relationships with sporting bodies such as Tennis Australia (1999–2017), Australian Rugby Union (2002–19) and Cricket Australia (2006) and famous Australian athletes such as Lleyton Hewitt. Thousands of people had been on the applicant’s tours and attended events. Those attending sporting events, such as the Davis Cup or cricket matches, sat together in highly visible groups wearing their FanFirm branded merchandise. Many more people had purchased FanFirm apparel.

96 The respondent criticises the applicant’s lack of evidence as to the volume or value of its sales of merchandise. The respondent notes that it was open to the applicant to adduce evidence of sales and submits that an inference should be drawn that such evidence would not have advanced the applicant’s case on reputation in relation to sports merchandise, including clothing, headgear and footwear.

97 At [86] of McCormick & Co Inc v McCormick (2000) 51 IPR 102, Kenny J observed that:

it is commonplace to infer reputation from a high volume of sales, together with substantial advertising expenditures and other promotions, without any direct evidence of consumer appreciation of the mark, as opposed to the product. This court has followed this approach as well, acknowledging that public awareness of and regard for a mark tends to correlate with appreciation of the products with which that mark is associated, as evidenced by sales volume, among other things.

(Citations omitted.)

98 Evidence of sales volume and revenue or advertising spend may be a common method from which to infer reputation, but they are not the only ways to establish the existence of reputation. The Full Court in Vivo International Corp Pty Ltd v Tivo Inc (2012) 99 IPR 1 at [57] (per Keane CJ, Dowsett J agreeing), in the context of s 60, endorsed the primary judge’s observation that a mark may acquire a reputation in Australia by the means of “direct preliminary marketing, direct advertising, indirect advertising, exposure in radio, film, newspapers and magazines or television”. The applicant’s evidence in support of its reputation included newspaper articles, Wayback Machine extracts from its website and evidence from Mr Coull and Mr Woodbury who had attended many of the applicant’s tours and events.

99 I consider that the applicant has established that as at December 2010, it had a reputation in the FanFirm Marks, including the word mark “FANATICS”, with respect to sports merchandise including at least clothing, headgear and footwear. This reputation was separate to, and not simply an adjunct of, the applicant’s sporting and events tour business.

100 The respondent is a US business that sells licensed sports merchandise across the globe, including clothing, accessories and memorabilia. Mr Ravid described the respondent’s business as a global online retailer of officially licensed sports merchandise and apparel via e-commerce stores.

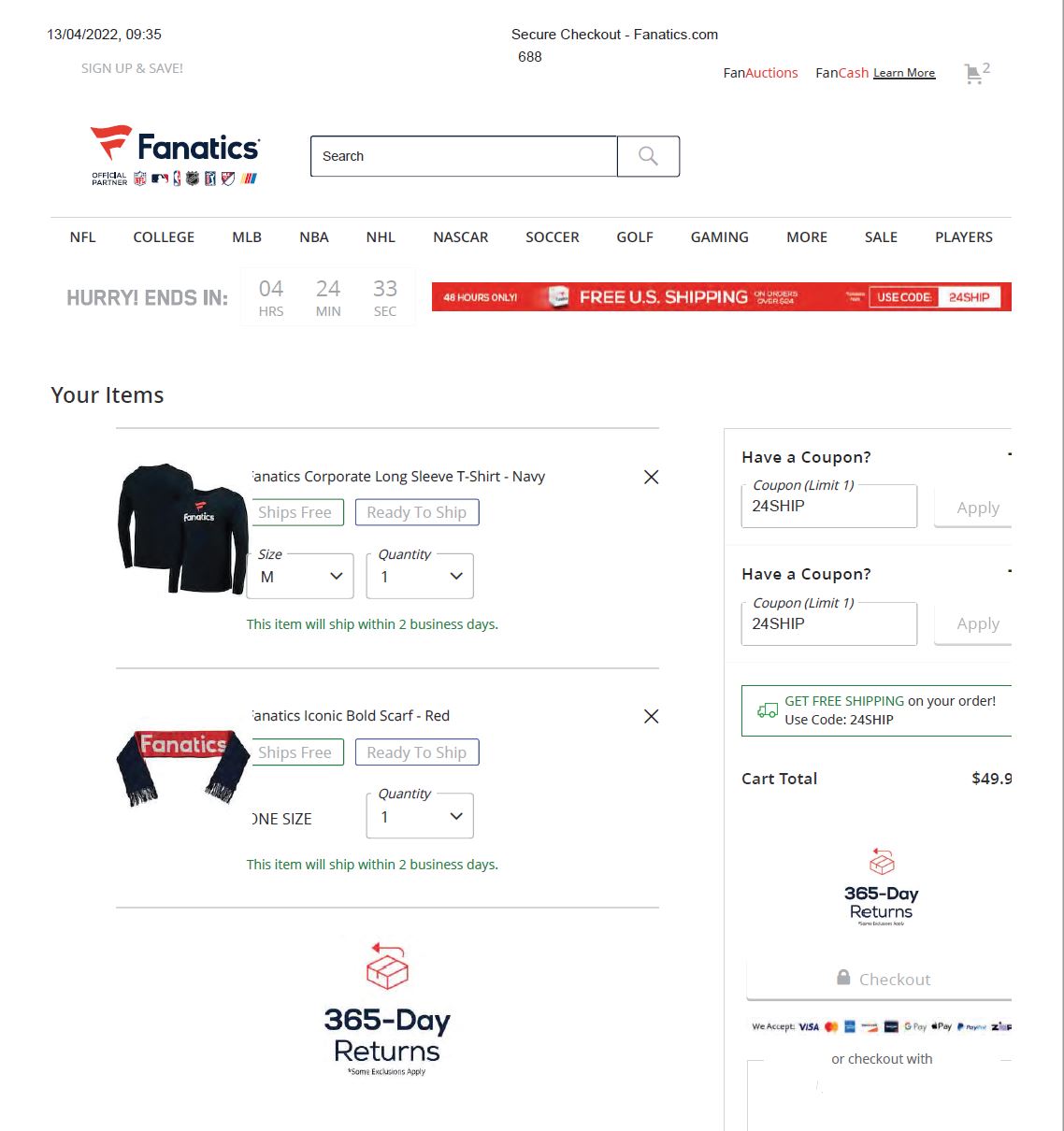

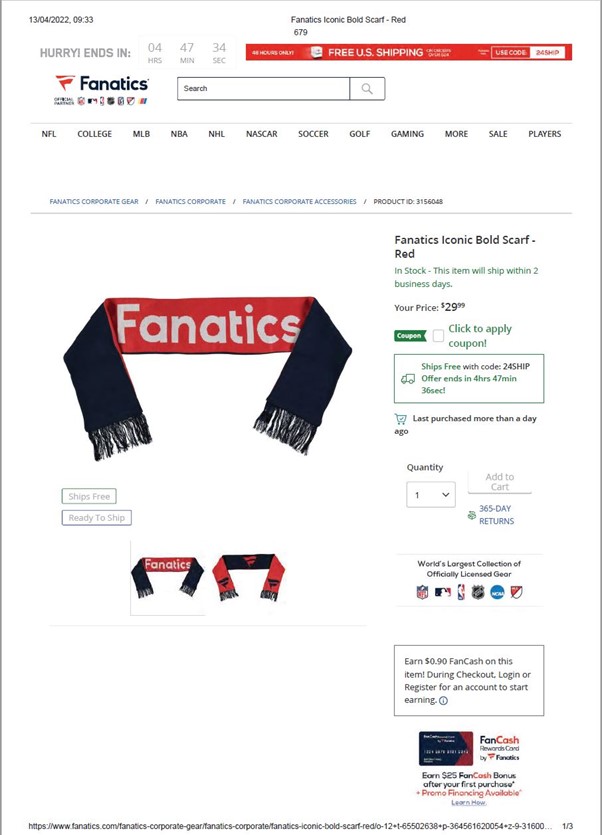

101 The merchandise sold by the respondent includes both straight resale third party licensed merchandise and what the respondent calls “FANATICS branded” goods. “FANATICS branded” goods are third party licensed merchandise which is manufactured by the respondent which typically bear FANATICS Marks, denoting that the goods are manufactured by the respondent. The respondent also sells “corporate merchandise” which has the FANATICS Flag Mark prominently on the clothing and is primarily sold to its employees (but is still available publicly).

102 The respondent has also conducted, from at least 2020, services which connect fans to athletes, such as FANATICS PRESENTS (which used to be called FANATICS LIVE), where fans are invited to meet athletes, both in person and online, and these events are filmed. I will refer to this service as FANATICS LIVE.

103 Mr Ravid’s evidence was that the respondent owns “many thousands of domains”, including:

(a) www.fanatics.com;

(b) www.footballfanatics.com;

(c) www.fanatics-intl.com (recently subsumed into www.fanatics.co.uk); and

(d) www.fanatics.co.uk.

104 According to Mr Ravid, since at least 2018, the respondent has offered for sale officially licensed sports merchandise and apparel including clothing (such as sweatshirts, t-shirts, jackets and jerseys), accessories (such as watches, hats, beanies, gloves, scarves and bags), and memorabilia (such as cups, pillows, rugs, mascots, flags and mugs) via its online stores, including at the domains at [103] above.

105 The company history of the respondent is not in dispute. The history involves a number of name changes, only some of which are relevant and worth noting.

On 27 January 1995, the respondent was formed as “Football Fanatics Inc”.

On 7 December 2010, the respondent changed its name to “Fanatics, Inc”.

On 20 December 2021, the respondent settled on its current corporate name “Fanatics, LLC”.

The respondent’s business currently operates internationally via a number of subsidiaries, including Fanatics UK Holdings Limited (UK), Fanatics (International) Limited (UK) and Fanatics Australia Pty Ltd (an Australian company, incorporated on 21 July 2022).

106 The respondent’s business was founded as “FOOTBALL FANATICS” by two brothers, Alan and Mitchell Trager, in February 1995 in Jacksonville, Florida. Originally, the business traded as a bricks-and-mortar store selling merchandise relating to the recently formed Jacksonville Jaguars NFL team.

107 The respondent’s business moved into online sales in around 1997 when it opened an online retail store at a collective marketplace located in Jacksonville. In 1998, the online store was moved to a website controlled by the respondent — www.footballfanatics.com. By 1999, a wide range of team apparel for local NFL and college sporting teams was being promoted and sold from this online store. These products were able to be shipped nationally and internationally.

108 Prior to 2010, the respondent’s corporate predecessors acquired a large number of different domain names to establish new e-commerce stores including the name FANATICS in combination with different sports and sporting terms or target audiences. Examples included www.fastballfanatics.com (2006), www.fastbreakfanatics.com (2007), www.faceofffanatics.com (2007), www.fightingfanatics.com (2008), www.surffanatics.com (2008), www.fanaticsoutlet.com (2008), www.kidfanatics.com (2009) and www.ladyfanatics.com (2009). The respondent also had separate branding for the e-commerce stores located at these domains. Mr Swallow gave evidence about the operation of a blog entitled “We are Fanatics” from around 2008, located at www.wearefanatics.com.

109 A key aspect of the respondent’s business is said to be the operation of online retail stores. The majority of this aspect of its business involves the promotion and sale of licensed sports merchandise, being goods that bear third party brands (mainly sporting clubs or leagues from the US or Europe) from its websites www.fanatics.com and www.fanatics-intl.com.

110 Mr Ravid’s evidence was that since at least 2018, the officially licensed merchandise and apparel has included North American sporting leagues and associations such as the NFL and NBA, and international sporting leagues and teams including English Premier League soccer and Formula 1 car racing.

4.2.2 Change of name from “FOOTBALL FANATICS” to “FANATICS”

111 Mr Swallow gave evidence that in about 2001 or 2002, the respondent began to see the word “football” in its online presence as a constraint on its ability to grow the business in relation to other sports, including baseball and basketball. Over the course of the next decade, the respondent focussed on expanding its business into other sports. To this end, in about 2004 or 2005, the respondent registered several sports-related domain names such those referred to above at [108]. It unsuccessfully tried to acquire the domain www.fanatics.com from a third party, but the price was prohibitive.

112 The respondent was eventually successful in acquiring the domain name www.fanatics.com on 9 November 2009. Between November 2009 and November 2011, visitors to the www.fanatics.com domain name were re-directed to the www.footballfanatics.com site. From mid-2010 to mid-2011, the logo that appeared in the website banner of the www.footballfanatics.com site varied, and included the following alternatives which prominently featured the word FANATICS:

.

.

113 However, from late November 2011 onwards, the www.fanatics.com domain hosted its own content and has been the primary domain used by the respondent ever since. As Mr Swallow explained, this transitional period of 2009 to 2011 involved the respondent’s business “weaning” itself off the www.footballfanatics.com domain name so that when the www.fanatics.com domain name became independently active, it would have sufficient commercial momentum.

114 In 2017, the respondent acquired www.fanatics-intl.com which also operates as a free-standing online retail store.

115 Mr Swallow gave evidence that in about 2010, the respondent began to consider re-branding its business. A range of possibilities were tested, including FANATICS, FANATICS CENTRAL, FANATICS WORLD and FANATICS BRAND. However, the business ultimately settled on FANATICS. The name of the brand was changed from FOOTBALL FANATICS to FANATICS on 7 December 2010.

116 The re-branding process eventually led to the respondent settling on the following logo:

.

.

4.2.3 The respondent’s third party partner e-commerce business

117 In addition to its own online sale of officially licensed sports merchandise and apparel described above, Mr Ravid’s evidence was that another aspect of the respondent’s business is the design, implementation, maintenance and management of third party partner e-commerce stores (Partner Stores) for the:

(a) major North American sporting leagues (such as the NFL’s www.nfl.shop.com);

(b) major North American sports media brands (including NBC Sports, CBS Sports and Fox Sports); and

(c) several international sporting leagues and teams (including the official sites of English Premier League teams Manchester United, Chelsea and Everton).

118 The respondent’s management of its Partner Stores covers the end-to-end customer experience, such as product manufacture, online sales, order fulfilment and customer service. Mr Ravid gave evidence as to the respondent’s investment in, and development of, technology to support the development and management of its Partner Stores and the end-to-end customer experience of those stores across all devices. One example given of the technology was the Fanatics Cloud Commerce Platform. Other examples provided by Mr Ravid of the services offered by the respondent included global payments methods, functionality to support auctions, personal product recommendations, “hyperspeed shipping”, search engine optimisation, comparison shopping engines and retargeting.

119 Prior to 2020, the respondent had no Australian third party partners or Australian Partner Stores.

120 Mr Ravid gave evidence about the respondent’s live events inviting fans to connect with athletes and obtain signed merchandise, that the respondent has hosted since 2018. As noted above, “FANATICS LIVE” has since been renamed “FANATIC PRESENTS” and rather than hosting live events, the business now relates to an online virtual marketplace for buying and selling collectables.

121 According to Mr Ravid, FANATICS LIVE events were marketed to customers of the respondent’s e-commerce stores who either purchased products from the store or signed up to the mailing list. Prior to 2020, the marketing of FANATICS LIVE was directed to customers with a billing or shipping address within the vicinity of the event (in most cases in North America). Since 2020, during the pandemic, FANATICS LIVE events were also offered virtually and attracted a more global audience.

4.2.5 FANATICS MVP (formerly FANATICS REWARDS)

122 According to Mr Swallow, the respondent has offered a rewards program since around 2004. Visitors to the respondent’s websites could elect to join the loyalty program to receive exclusive member only deals, special discounts, early access to sales and new collections and marketing emails which provided information about their favourite teams, details of new products and collections and sales.

4.2.6 The respondent’s sales figures 2010 – 2014

123 The respondent relied on confidential figures of sales into Australia as evidence of its reputation in Australia. These figures were not particularly helpful as the figures were not detailed or readily identifiable as sales made into Australia and the sales were not all in Australian Dollars. In any event, the volume of sales into Australia was not extensive.

4.2.7 The respondent’s presence in Australia intensifies in 2020

124 The respondent has sold products to Australia since 2000, initially under the FOOTBALL FANATICS brand. The confidential sales figures show that the volume of sales from www.fanatics.com to Australia slowly increased each year from 2014 to 2020 but has since dropped off. The volume of sales each year over that time has been meaningful but not overwhelming.

125 Mr Ravid accepted that prior to 2020, the respondent’s activity in Australia was limited to selling and shipping merchandise to persons present in Australia. His evidence was that since around 2020, the respondent has been pursuing Australian-based sporting leagues and teams offering its partner services, including the development of Partner Stores.

126 In 2020, Mr Ravid commenced discussions with the AFL and a select few AFL teams as potential Australian partners for Partner Stores. The respondent formed relationships with the AFL and the Essendon Football Club to sell licensed merchandise. The first Australian Partner Store for the Essendon Football Club was launched on 1 November 2023. The AFL and Essendon Partner Stores are currently managed by Fanatics Australia Pty Ltd.

127 A Wayback Machine extract from 7 November 2023 of the Essendon Partner Store showed the home page including a reference to Fanatics, Inc in the copyright notice in the footer and displaying in the top left corner the mark below:

.

.

128 In 2020, the respondent entered into a 10-year deal with the Australian retailer Rebel Sport to sell FANATICS branded apparel. A press release dated 24 August 2020 described the respondent as “the global leader in licensed sports merchandise” and said that the new deal would “provide sports fans across Australia with access to the most comprehensive range of licensed sports merchandise available anywhere in the country”. The release continued:

Fanatics and rebel are partnering to … offer Australian fans over 100,000 officially licensed products from some of the biggest sports leagues in the world, such as NFL, NBA, all major European Football Clubs, MLB and Formula 1.

The long-term deal, which will come into effect mid 2021, will see Fanatics enter its first significant partnership with an Australian retailer, as it becomes the exclusive supplier of all ‘non-Australia’ licensed team merchandise on the rebel website.

129 Mr Ravid accepted that these deals signified that the respondent had “intensified” its activities in Australia. Prior to 2020, the respondent did not have any official partnerships with Australian sporting codes or retail stores. I observe that the press release for the Rebel Sport deal does not mention licensed sports merchandise relating to Australian sporting codes, leagues or teams.

130 A Wayback Machine extract from the Rebel Sport website from January 2022 shows a page with the heading “THE ULTIMATE FANGEAR DESTINATION” which displays licensed sports apparel from overseas sporting leagues. On the webpage is displayed the following mark:

.

.

131 There is no evidence that prior to 2020 the respondent sold licensed merchandise for Australian national sporting teams or Australian sporting leagues such as the AFL. The respondent pointed to a Wayback Machine extract of its website from 15 January 2012 which promoted for sale a “Puma Australia Home Replica Jersey 10/11 – Red” as evidence that it sold Australian national team merchandise prior to 2020. That printout is exhibited below.

132 The product displayed is clearly a jersey for the Switzerland national team, with the Swiss flag emblazoned on the left breast. Whether the product has been incorrectly labelled on the website or the incorrect photo has been displayed is unclear and therefore this printout does not support the respondent’s claim.

133 The respondent contends that prior to the applicant launching the Retail Store in 2020, the two parties had engaged in “peaceful” co-existence for over twenty years. The applicant was operating tours and events, and the respondent was operating an online retail store. Therefore, they were operating in largely different commercial spheres.

134 The applicant rejects that characterisation of the parties’ relationship, pointing to several skirmishes in the Australian Trade Marks Office. The first dispute was in August 2010 when the respondent opposed the applicant’s trade mark applications for the FanFirm Marks in class 25. This occurred three months before the respondent changed its name from FOOTBALL FANATICS to FANATICS. The respondent withdrew those oppositions in June 2013.

135 Second, in 2013, the applicant opposed the respondent’s trade mark application for the 632 TM, FOOTBALL FANATICS. On 5 April 2017, the opposition decision was made in favour of the respondent. Third, in 2019, the applicant opposed the respondent’s trade mark application for the 688 TM, the FANATICS Flag Mark, but discontinued that process in August 2020. This proceeding commenced in November 2022.

136 The applicant says that the present dispute has arisen because the respondent intensified its activities in Australia in 2020 by developing relationships with AFL teams and a partnership with Rebel Sport.

137 I consider that, other than a few skirmishes in the Australian Trade Marks Office, the parties have largely coexisted until 2020. The respondent has since 2010, operated an online retail store selling licensed third-party team apparel for a wide variety of sports, initially focussing on US sporting leagues, such as the NFL and the NBA, and then expanding to every major sporting code around the world. The applicant operated a tour and events company which sold merchandise both directly related to those events and third-party licensed merchandise relating to Australian national sporting teams such as the Wallabies, Socceroos and Matildas.

138 I consider that the parties were operating in the same broad field. Both were targeting sports fans and their enthusiasm/love for their sport, and selling sports merchandise to fans over the internet. Prior to 2020, the applicant had a narrower focus on Australian customers and licensed sports apparel for Australian national sporting teams (save for the few discrete examples raised by Mr Livingstone in cross-examination in relation to the 1999 NFL America Bowl in Australia, a deal with the NHL in 2003 and the NBA in 2011). The respondent did not specifically target Australian customers, instead it sold sporting merchandise primarily relating to US sporting teams and codes and European football leagues and teams.

139 The respondent says it has no complaint against the applicant with respect to the applicant’s activities prior to 2020. The applicant, on the other hand, does now complain about the respondent’s conduct prior to 2020.

140 Although both parties operate in the broad same field, they largely managed to coexist at a commercial level until 2020 by, to put it colloquially, operating in slightly different lanes that largely did not overlap. The status quo changed in 2020 by both parties moving out of their lanes: the respondent through the Rebel Sport and AFL deals, and the applicant by launching its Retail Store.

141 Two further examples of the respondent moving out of its lane emerged during cross-examination. First, the respondent entered into a deal with Ticketmaster in 2018 whereby Ticketmaster customers are presented with FANATICS merchandise and consumers can purchase tickets through one of the respondent’s websites. Second, the respondent opened a bricks and mortar NBA store in Melbourne.

142 The respondent correctly notes that these two examples are irrelevant to the applicant’s claims of trade mark infringement, misleading or deceptive conduct and passing off because they were not pleaded. Further, no evidence was provided that the FANATICS Marks were used in relation to the NBA store or that Australian consumers could purchase tickets to events through the Ticketmaster partnership. I agree that, as these instances were not pleaded, they can play no greater role than providing a possible explanation for the applicant’s decision to commence the proceeding.

5. FIRST USE OF FANATICS IN AUSTRALIA

143 The issue of which party first used the word “Fanatics” as a mark and in respect of what goods and services in Australia is relevant to several issues in the proceeding. As such, it is convenient to deal with it here before considering each parties’ trade mark infringement claims.

144 The respondent changed its name to FANATICS from FOOTBALL FANATICS in December 2010. The respondent did not use FANATICS as a standalone brand or mark in Australia prior to that time. Mr Swallow gave evidence that until November 2011, when a person went to www.fanatics.com they were redirected to www.footballfanatics.com. On the basis of this evidence, senior counsel for the respondent essentially conceded in closing submissions that the respondent’s first use of the FANATICS Marks in Australia was in late 2010 or 2011. I discuss the respondent’s adoption of its name further below.

145 Accordingly, I am satisfied that the respondent first used the FANATICS Marks as trade marks in Australia in December 2010 at the earliest. As will be clear from my discussion below, nothing turns on whether the date selected for the respondent’s first use is 2010 or 2011.

146 The applicant contends that it first used the FanFirm Marks in relation to clothing (class 25) in around 1998 when its predecessor, Mr Livingstone, supplied t-shirts and caps to attendees of the Davis Cup event in Mildura which bore iterations of the FanFirm Marks. The respondent says that the applicant can only claim first use from the date of its incorporation on 30 September 2004 because it has not adduced any evidence that Mr Livingstone transferred title in the FanFirm Marks to the applicant. This disagreement is immaterial given that the respondent’s first use was no earlier than December 2010.

147 The applicant provided invoices from July 2006 for orders of Wallabies merchandise. This was the earliest evidence of the applicant’s actual orders or sales of merchandise. However, Wayback Machine extracts of the applicant’s website from as early as March 2004 show that customers could “browse the shop” for merchandise at that date.

148 Accordingly, I am satisfied that the applicant first used the FanFirm Marks in Australia in relation to clothing from at least September 2004.

149 The only real dispute is whether the applicant operated an online retail store for clothing before December 2010.

150 As noted at [45] above, the respondent accepts that the applicant (and before it, Mr Livingstone) sold clothing via a “merchandise” page on the website www.thefanatics.com from around 2002. The clothing sold on that page was limited to FanFirm branded merchandise relating to Australian sporting teams until 2012 (not third-party licensed merchandise). In 2012, it also sold third-party licensed merchandise for a select few Australian national sporting teams such as the Wallabies, Socceroos and Matildas.

151 This is sufficient to establish first use by the applicant in relation to the following class 35 services for which the respondent’s marks are registered:

(a) on-line retail store services featuring sports related and sports team branded clothing and merchandise;

(b) order fulfillment services; and

(c) product merchandising.

152 The respondent contends that the applicant has not used the FanFirm Marks in relation to clothing or online retail services because the relevant goods and services were only provided as an adjunct to the applicant’s core business of tour and event services. That contention cannot be sustained. I consider that the applicant’s sale of sports-related merchandise from its website was more than an incidental aspect of the provision of its sports and events tour services: MID Sydney Pty Ltd v Australian Tourism Co Ltd (1998) 42 IPR 561 at 566–7 (per Burchett, Sackville and Lehane JJ).

153 Customers could purchase clothing from the applicant’s website from 2002 whether or not they had purchased a ticket for one of the applicant’s tours or events. Although it may be assumed that most people who purchased clothing from the applicant’s website did so in relation to a tour or event, there is no necessary relationship between tours and events and merchandise, such as to characterise the use of the trade mark as use other than in relation to the sale of goods.

154 Markovic J in Taylor v Killer Queen, LLC (No 5) (2023) 172 IPR 1 found that the artist Katheryn Hudson (known by her stage name as Katy Perry) had used the mark “Katy Perry” as a trade mark in relation to clothing in Australia. That is despite the fact that the clothing was sold primarily in relation to Ms Hudson’s concerts. Her Honour observed at [595]:

The evidence before me establishes that the Katy Perry Mark has been used in connection with the advertising, offering for sale and sale of clothes in Australia in conjunction with Ms Hudson’s tours and the release of her albums as well as through websites and some retailers. In that regard I accept the respondents’ submission that the advertising, offering for sale, sale of clothes and the clothes themselves bearing the Katy Perry Mark have been closely tied to Ms Hudson’s role as a popular music artist in Australia. Indeed most of the clothes offered for sale and sold bear images of Ms Hudson or graphics that are related to her albums or individual songs. That is, there is a close connection between Ms Hudson and the use of the Katy Perry Mark on much of the merchandise offered for sale, including clothes and, to the extent I am found to be wrong, goods of the same description.

155 Markovic J’s findings on this issue were not challenged on appeal and I respectfully agree with her Honour. Using a trade mark on goods does not cease to be “use as a trade mark … in relation to goods” for the purposes of s 120(1) of the Act simply because the sale of the relevant goods is “closely tied” or an adjunct to some service offered by the applicant which is their primary or core business. In any event, I do not consider that the sale of merchandise on the applicant’s website to be merely an adjunct to its main business of providing tour and event services.

156 Accordingly, I am satisfied that the applicant first used the FanFirm Marks in relation to clothing (class 25) and online retail services (class 35) by September 2004 at the latest and therefore prior to the respondent’s first use of its FANATICS Marks in December 2010.

157 Much was made during the hearing of whether, and if so when, the applicant sold third party licensed merchandise. I do not consider that question is relevant to the question of first use in relation to class 35 services. The respondent’s marks in class 35 are limited to services for online retailing services in general and sports related and sports-team branded merchandise in particular. That describes what the applicant was selling on its website.

158 I consider that an online retail service selling goods is nothing more than the sale of goods via a website. The applicant’s website provided an online retail service from at least 2004 because customers could visit the website, select a product and then purchase that product. It therefore also provided order fulfillment services and product merchandising within the meaning of the respondent’s class 35 registration. The goods sold from the website from 2002 were sports related or Australian sports-team branded, such as the Davis Cup t-shirts and Australian Ashes merchandise extracted at [42] and [43] above.

159 However, I consider that the service of designing, setting up, managing and operating an online store for a third party, such as the respondent’s Partner Stores, is a different type of service (e-commerce creation services). This kind of service is covered by the respondent’s registrations in class 42. I consider that the respondent was the first to use FANATICS in relation to e-commerce creation services in Australia from around mid-2021, when it entered the Partner Store deals with the AFL and Essendon.

6. APPLICANT’S TRADE MARK CLAIMS

160 The applicant alleges that the respondent has contravened s 120(1) and (2) of the Act by advertising, promoting, offering for sale and selling in Australia a range of sports apparel and offering, advertising, promoting and providing both a loyalty and rewards services and a service where the respondent connects fans to athletes.

161 Section 120(1) and (2) of the Act provide:

120 When is a registered trade mark infringed?

(1) A person infringes a registered trade mark if the person uses as a trade mark a sign that is substantially identical with, or deceptively similar to, the trade mark in relation to goods or services in respect of which the trade mark is registered.

…

(2) A person infringes a registered trade mark if the person uses as a trade mark a sign that is substantially identical with, or deceptively similar to, the trade mark in relation to:

(a) goods of the same description as that of goods (registered goods) in respect of which the trade mark is registered; or

(b) services that are closely related to registered goods; or

(c) services of the same description as that of services (registered services) in respect of which the trade mark is registered; or

(d) goods that are closely related to registered services.

However, the person is not taken to have infringed the trade mark if the person establishes that using the sign as the person did is not likely to deceive or cause confusion.

162 Section 17 contains a definition of a trade mark in the following terms:

17 What is a trade mark?

A trade mark is a sign used, or intended to be used, to distinguish goods or services dealt with or provided in the course of trade by a person from goods or services so dealt with or provided by any other person.

163 Sign is defined in s 6 as follows:

sign includes the following or any combination of the following, namely, any letter, word, name, signature, numeral, device, brand, heading, label, ticket, aspect of packaging, shape, colour, sound or scent.

164 According to the High Court in Self Care IP Holdings Pty Ltd v Allergan Australia Pty Ltd (2023) 408 ALR 195 at [22] (per Kiefel CJ, Gageler, Gordon, Edelman and Gleeson JJ), there are two separate elements to establish trade mark infringement under s 120(1) of the Act:

(1) that the person has used as a trade mark a sign in relation to goods or services; and

(2) that the trade mark was substantially identical or deceptively similar to a trade mark registered in relation to those goods or services.

165 The principles in relation to (2) were not in dispute. I recently summarised those principles in Bed Bath ‘N’ Table Pty Ltd v Global Retail Brands Australia Pty Ltd [2023] FCA 1587 at [354]–[373].

166 The High Court discussed what constitutes use of a trade mark in Self Care at [23]–[25]: