Federal Court of Australia

Societe Civile et Agricole du Vieux Chateau Certan v Kreglinger (Australia) Pty Ltd (No 2) [2024] FCA 755

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT NOTES THAT:

A. In these orders:

“Kreglinger” means the first respondent.

“New Branded New Certan Wine” means the product which Kreglinger and Pipers Brook intend to promote, offer for sale and sell under or by reference to the name “NEW CERTAN” as depicted in Annexure B.

“Old Chateau Certan Text” means the following text:

The label features the Mount Pleasant family homestead which was built in 1865 on the vineyard’s estate property, in Launceston. The name and the colour are inspired by old Chateau Certan, founded by family in Europe and the wine is produced in small quantities from the single Mount Pleasant vineyard around the house, that is 3.3 hectares in size, producing on average 200 cases per vintage.

“Paul de Moor” means the second respondent.

“Pipers Brook” means the third respondent.

“Prior Branded New Certan Wine” means the product presented, promoted, offered for sale and sold by Kreglinger and Pipers Brook under or by reference to the combination of features depicted in Annexure A, being the 2011, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019 and 2021 vintages of New Certan.

B. With effect from the release of the 2022 vintage, Kreglinger and Pipers Brook propose to present the New Branded New Certan Wine in accordance with the bottle presentation set out in Annexure B.

C. In accordance with the undertaking set out in the Court’s reasons for judgment dated 15 March 2024 at [516], images depicting the Prior Branded New Certan Wine have been removed from the Halliday Wine Companion website owned and operated by HGX Pty Ltd ACN 612 186 946 published online at www.winecompanion.com.au.

D. Upon Kreglinger and Pipers Brook by their counsel undertaking to the Court that with effect from 14 August 2023, they will not advertise, offer for sale, or sell any of the stock on hand of the Prior Branded New Certan Wine.

THE COURT DECLARES THAT:

1. By their promotion and sale of the Prior Branded New Certan Wine in Australia with the bottle presentation set out in Annexure A, Kreglinger and Pipers Brook have each represented that:

(a) the Prior Branded New Certan Wine has the approval of VCC;

(b) Kreglinger has an affiliation with VCC;

(c) Pipers Brook has an affiliation with VCC;

(d) in circumstances where no such approval or affiliation exists and have thereby:

(i) engaged in misleading or deceptive conduct, or conduct which is likely to mislead or deceive, and have thereby contravened s 18 of the Australian Consumer Law; and

(ii) (made false or misleading representations in contravention of ss 29(1)(g) and (h) of the Australian Consumer Law.

2. Paul de Moor has:

(a) aided, abetted or procured Kreglinger and Pipers Brook to engage in the conduct and contraventions referred to in paragraph 1;

(b) been directly or indirectly knowingly concerned in or a party to the conduct and contraventions of Kreglinger and Pipers Brook referred to in paragraph 1.

AND THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

3. Kreglinger and Pipers Brook, whether by themselves, their officers, employees, agents or otherwise howsoever, be restrained from bottling or otherwise supplying or distributing any Prior Branded New Certan Wine.

4. Kreglinger and Pipers Brook, whether by themselves, their officers, employees, agents or otherwise howsoever, be restrained from using the Old Chateau Certan Text to promote or sell the New Branded New Certan Wine.

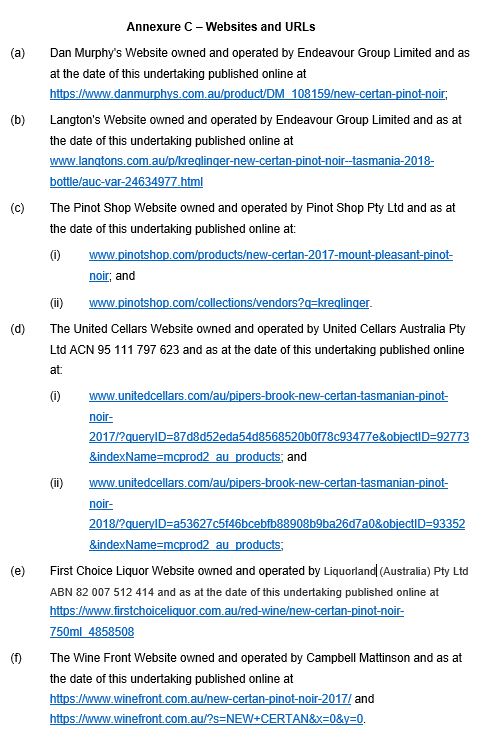

5. Kreglinger and Pipers Brook forthwith take all reasonable steps to procure the publishers of the websites referred to in Annexure C to remove the images of the Prior Branded New Certan Wine published at the listed URLs.

6. Paul de Moor, whether by himself, his employees or agents or otherwise howsoever, be restrained from:

(a) aiding, abetting or procuring Kreglinger and Pipers Brook to engage in;

(b) being directly or indirectly knowingly concerned in or a party to,

any conduct of Kreglinger or Pipers Brook that would contravene the undertaking set out above or the orders set out in paragraphs 3 and 4.

7. The further amended originating application otherwise be dismissed.

8. There be no order as to the costs of the proceeding.

9. There be liberty to apply concerning any stay of these orders pending any appeal (if filed) or for the return of any security for costs given by VCC in the event that no appeal is filed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

BEACH J:

1 On 15 March 2024, I delivered my principal reasons concerning the issues that had been the subject of the trial ([2024] FCA 248). It is now necessary to make final orders. For that purpose the parties have provided written submissions on the competing versions of their proposed orders which I have considered. These further reasons use the terms and expressions defined in my principal reasons.

2 There are three topics to address: (a) first, the question of declaratory relief; (b) second, the scope of any undertakings or injunctive relief in lieu; and (c) third, questions of the apportionment of costs and indemnity costs.

Are declarations appropriate?

3 VCC seeks declarations which encapsulate my findings that Kreglinger and Pipers Brook have contravened ss 18 and 29(1)(g) and (h) of the Australian Consumer Law and Mr de Moor has accessorial liability concerning those contraventions.

4 In my view the proposed declarations are appropriate. They concisely record the contravening conduct and the nature of the contraventions that I have found.

5 Now the respondents say that declaratory relief is unnecessary and inappropriate. They say that declarations are not an appropriate way of recording, in a summary form, conclusions reached by me in my principal reasons. It is said that declaratory relief would ordinarily be refused if it would produce no foreseeable consequences. In elaboration, the respondents make four points.

6 First, my principal reasons already set out in detail my findings with respect to the Prior Branded New Certan Wine.

7 Second, the principal reasons record the respondents’ undertaking to the Court not to advertise, offer for sale or sell any of the stock on hand of the Prior Branded New Certan Wine.

8 Third, it is said that considerations of deterrence do not arise given my findings that the Prior Branded New Certan Wine was a personal project for Mr de Moor, and was sold with no intention to mislead consumers.

9 Fourth, it is said that declaratory relief would not otherwise serve the public interest.

10 But in my view declaratory relief is appropriate. The respondents contested all of VCC’s allegations. Moreover, it was only during the course of the trial that an undertaking was proffered, and even then without admission of liability and with the respondents still contesting VCC’s case. VCC has for the most part made out its claim in relation to the Prior Branded New Certan Wine, and the declarations are an appropriate form of relief to resolve the controversy.

The respondents’ undertakings/additional injunctions

11 The form of undertaking proposed by the respondents appears in my principal reasons at [515] to [517] where I said:

Now as at the time of trial, 1,755 bottles of New Certan wine in the existing packaging up to the 2021 vintage remained in stock. This old stock has been withdrawn from sale. It has been withdrawn from the website and all promotional activity relating to that stock has ceased. The first and third respondents have agreed not to sell any of the old stock.

I note that the following undertaking has been proffered to the Court, which, subject to further discussions with counsel, I am prepared to accept:

UNDERTAKING

Definitions:

Halliday Wine Companion Website means the website owned and operated by HGX Pty Ltd ACN 612 186 946 and as at the date of this undertaking published online at www.winecompanion.com.au

Prior Branded New Certan Wine means the product presented, promoted, offered for sale and sold by the First and Third Respondents under or by reference to the combination of features defined as the New Certan Features in paragraph 17 of the Further Amended Statement of Claim dated 18 November 2022 (FASOC), being the 2011, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019 and 2021 vintages of New Certan.

New Branded New Certan Wine means the product which the First and Third Respondents intend to present, promote, offer for sale and sell under or by reference to the name "NEW CERTAN" but without the other New Certan Features, as depicted in paragraph 20B of the FASOC.

Undertaking:

1. Without admission, the First and Third Respondents undertake to the Court that:

(a) from 14 August 2023, they will not advertise, offer for sale or sell any of the stock on hand of the Prior Branded New Certan Wine;

(b) they will forthwith take all reasonable steps to procure the publisher of the Halliday Wine Companion Website to remove all images of the Prior Branded New Certan Wine from the Halliday Wine Companion Website, including those published at the following URLs:

i. www.winecompanion.com.au/wineries/tasmania/tasmania/pipers-brookvineyard/wines/red/pinot-noir/new-certan-pinot-noir/2019

ii. www.winecompanion.com.au/wineries/tasmania/tasmania/pipers-brookvineyard/wines/red/pinot-noir/new-certan-pinot-noir/2018

iii. www.winecompanion.com.au/wineries/tasmania/tasmania/pipers-brookvineyard/wines/red/pinot-noir/new-certan-pinot-noir/2017

iv. www.winecompanion.com.au/wineries/tasmania/tasmania/pipers-brookvineyard/wines/red/pinot-noir/new-certan-pinot-noir/2017/1

v. www.winecompanion.com.au/wineries/tasmania/tasmania/pipers-brookvineyard/wines/red/pinot-noir/new-certan-pinot-noir/2016

Other matters:

2. Without admission, the First and Third Respondents note that, if so required by the Court, they will abide by any requirement to apply a disclaimer to the label of the New Branded New Certan Wine.

3. The First and Third Respondents confirm that, as at 14 August 2023, the stock on hand referred to in paragraph 1 above comprises 1755 bottles.

The undertaking has been proffered in circumstances where there have been very few sales of the New Certan wine, the New Certan wine has not made any profits, there is no evidence of any damage to VCC, and the commercial value of the remaining old stock is insignificant. In my view the undertaking is adequate to deal with the question of stock and any known on-line material. VCC has expressed concern about “old” images remaining on the internet. This concern was over-stated but in any event is met by the undertaking or any necessary modification.

12 VCC seeks some modifications to the proposed undertaking as follows.

13 First, it says that the proposed undertaking identified the labels in dispute by cross-reference to the pleadings, but the various labels should be appended to the orders so that the orders can be read and understood independently. I agree.

14 Second, it is said that [1] of the proposed undertaking was said to be “without admission”, but that caveat is no longer appropriate in light of my findings. I also agree.

15 Third, it is said that [1] of the proposed undertaking was given on behalf of Kreglinger and Pipers Brook, but it should also be given by Mr de Moor, and extend to the conduct of the respondents by their officers, employees and agents. I also agree. I will, in the absence of agreement, make an order to this effect.

16 Fourth, it is said that [1(a)] of the proposed undertaking referred to advertising, offering for sale or selling the Prior Branded New Certan Wine, but the undertaking, alternatively an order, should extend to bottling and otherwise supplying or distributing. It is said that the addition of bottling ensures that no further stock will be brought into existence, and the addition of supplying or distributing ensures that existing stock is not given away or otherwise enters the market. I also agree.

17 Fifth, VCC seeks an undertaking, alternatively an order, with respect to any future use of the Old Chateau Certan Text. In my view this is justified by my findings. In the circumstances it is appropriate that there be a restraint to ensure that the relevant conduct is not repeated.

18 Finally, the proposed undertaking referred to seeking the removal of images in entries on the Halliday Wine Companion website. It appears that this has already occurred. Accordingly, I will note this in the order. In relation to other similar images on the pages of prominent retailers such as Dan Murphy’s and First Choice Liquor, I will make orders requiring the respondents to seek removal of such listings from the specified websites.

19 Now the respondents made various points in opposition. But in my opinion none of these points are of real substance.

20 The order sought in relation to the Old Chateau Certan Text is appropriate. VCC’s pleaded case related inter-alia to the promotion of the Prior Branded New Certan Wine by the respondents, and instances of such promotion were discovered by the respondents. VCC opened and closed its case in relation to the promotion of the Prior Branded New Certan Wine by reference to a selection of those materials. The Old Chateau Certan Text falls squarely within the case as pleaded and run by VCC. The respondents themselves considered the Old Chateau Certan Text to be an inappropriate promotion of the Prior Branded New Certan Wine. In my view in the circumstances a restraint is appropriate.

21 Now the respondents say that VCC seeks additional relief against them to take steps to remove images of the Prior Branded New Certan Wine from a further list of third-party websites, but none of which was sought at trial. The undertaking given to the Court related to the Halliday website and was given in light of concerns expressed by VCC’s senior counsel and witnesses about its pre-eminence as a source of information about Australian wines, and Ms Faulkner’s confusion from earlier Halliday reviews referring to a connection between the two wineries. Whilst VCC in closing relied on Ms Faulkner’s evidence to suggest that a similar problem arose regarding images on other review sites, VCC’s senior counsel acknowledged that attempts to purge online images were unlikely to be fruitful and did not suggest that the respondents’ undertaking was insufficient. Further, five of the seven websites now identified are not review sites, but retailers against whom VCC has not sought any relief. They are not restrained from selling any remaining stock of the Prior Branded New Certan Wine in their possession and are unlikely to continue publishing such images after that stock has been sold.

22 Further, it is said that insofar as VCC also seeks relief against Mr de Moor personally, that is unnecessary given that the findings against him are limited to his accessorial liability for the conduct of the other respondents.

23 Now in my view the order sought for the removal of images of the Prior Branded New Certan Wine from the websites identified is appropriate. The respondents themselves provided such images to the retailers. I found that the presentation of the Prior Branded New Certan Wine contravenes the ACL. It is an appropriate form of ancillary relief that the respondents be required to take steps to purge these images. Further, there is no relevant distinction between review sites and retailers concerning the promotion of wine.

24 Further, Mr de Moor has been found to have accessorial liability for the conduct in question. He had a personal involvement in that conduct. I agree with VCC that it is appropriate that Mr de Moor be restrained from engaging in such conduct in the future.

Costs apportionment / indemnity costs

25 Now VCC seeks orders apportioning costs which reflect that it has succeeded in obtaining relief to prevent the use of the branding for the Prior Branded New Certan Wine but it has failed to obtain relief in relation to the revised branding, which was first introduced into the case by the respondents in evidence in answer. VCC has also failed to obtain relief in relation to the cancellation of Kreglinger’s NEW CERTAN trade mark registration.

26 VCC seeks its costs concerning its case related to the Prior Branded New Certan Wine, but accepts that it should pay the respondents’ costs concerning the case related to the New Branded New Certan Wine and on the trade mark revocation question. VCC says that its proposed costs orders are appropriate for the following reasons.

27 First, it is said that they reflect the substantive outcome of the proceeding and the successes and failures of the parties. It is said that the orders do not separately address the costs of the passing off claim because there were no incremental costs associated with this claim. Further, VCC’s evidence and submissions in respect of the claims under the ACL and in passing off were overlapping.

28 Second, it is said that the majority of the written evidence in the case, and the majority of the oral evidence and submissions, concerned the current branding. VCC’s evidence in chief was directed only to the current branding, as the revised branding was only introduced by the respondents in evidence in answer. Subsequently, the revised branding was the subject of a modest body of evidence. Further, it is said that VCC’s claim for the cancellation of the trade mark registration was also “a very modest issue”.

29 Third, it is said that the respondents have at all times before and during the proceeding denied VCC’s reputation in the relevant product and features in Australia. Further, the respondents were on notice of VCC’s objections to the current branding from April 2014, and had given consideration to the legal risks associated with continuing the challenged conduct. Further, it is said that the undertaking to withdraw the current branding from the Australian market was first proposed by senior counsel for the respondents to Mr Devlin during evidence in chief.

30 But I reject VCC’s proposal that the respondents pay its costs related to the Prior Branded New Certan Wine on the basis that these are distinct from costs in respect of the New Branded New Certan Wine and the trade mark revocation claim. The proposal is artificial, and there is no bright line between the various costs categories.

31 One has to be cautious in engaging in the sort of exercise that VCC suggests concerning the apportionment of costs as between issues.

32 Of course in patent litigation this may be appropriate because of its nature concerning the distinction between invalidity questions and infringement questions, and yet further subsidiary distinctions between varying and separate invalidity grounds. Conceptual and forensic compartmentalisation readily manifests itself in such a complex context.

33 In BlueScope Steel Limited v Dongkuk Steel Mill Co. Ltd (No 3) [2020] FCA 113 I said at [15] to [19]:

In my view, there should be an appropriate discount on the costs to be awarded to Dongkuk to reflect the fact that Dongkuk’s challenge to the validity of the patents in suit succeeded only on the issue of failure to disclose the best method, and Dongkuk’s challenge on the other asserted grounds of invalidity, being novelty, inventive step, clarity, fair basis, sufficiency and false suggestion, was unsuccessful. Further, I note that in relation to the 258 Patent, only five dependent claims adding limitations relating to controlling thickness variation were found to be invalid. BlueScope succeeded in defending the validity of the substantive claims, including each of the key independent claims.

The Full Court in Les Laboratoires Servier v Apotex Pty Ltd (2016) 247 FCR 61 at [300] per Bennett, Besanko and Beach JJ recognised that in patent cases:

The practice has developed that where a party relies on grounds that are not established and where time has been expended and costs incurred as a consequence, that party, although it may ultimately be successful, might not recover all of its costs.

Servier involved an application for revocation of a patent on a number of grounds, but the best method ground was the only successful ground. An application to amend the patent in suit was refused. The Full Court determined that Apotex should recoup 40% of its costs of the revocation action and 75% of its costs of the amendment application.

It seems to me that given the plethora of issues that are usually raised in patent litigation, costs apportionment reflecting each party’s relative success and failure on the issues litigated should be the norm rather than the exception. Such an approach is firm but fair. Moreover, if parties know in advance that a judge is likely to take such an approach at the end of what is usually protracted and complex litigation, that prospect may have a salutary disciplinary effect on the use and allocation of the parties’ limited resources and judicial time. Of course, I accept that in this field I am not dealing with the usual problem of feral litigators. But it is to say that the judicious use of an economic tool such as costs apportionment is not out of place in the patent field where parties should be incentivised to run only their strong points, particularly once all the evidence is in.

As I have said, in the present case an apportionment is warranted. Of course the question of apportionment is a matter of discretion and generally does not lend itself to mathematical precision. …

34 In this respect, I endeavoured to keep faith with what was said in Les Laboratoires Servier v Apotex Pty Ltd (2016) 247 FCR 61 at [300] and [301] where Bennett, Besanko and Beach JJ said:

The practice has developed that where a party relies on grounds that are not established and where time has been expended and costs incurred as a consequence, that party, although it may ultimately be successful, might not recover all of its costs. This, in turn, may depend on whether evidence and argument can be separated. For example, evidence from the skilled worker in the art may be relevant to different grounds of revocation and to an understanding of the patent for the purposes of construction and disclosure. Further, the question of apportionment is a matter of discretion and generally does not lend itself to mathematical precision, by reference to time or to importance. In any event, as the primary judge recognised, it has not hitherto been the case that such a successful party which obtains an order for revocation of the patent is ordered to pay the patentee’s costs.

On the other hand, Courts have been increasingly concerned, generally, to use all proper means to encourage parties to consider carefully what matters they will put in issue in their litigation. This has led to decisions whereby the successful party does not recover all of its costs where it has been unsuccessful on a discrete issue or in what is decided to be an unmeritorious objection. While it is acknowledged that, ordinarily, costs follow the event, the wide discretion in awarding costs has led to circumstances where a successful party who has failed on certain issues may be ordered to pay the other party’s costs of them (as discussed in Hughes v Western Australian Cricket Association (Inc) [1986] ATPR 40-748 per Toohey J), although warnings have been stated that care should be taken in such a course and consideration be given to whether the issues on which the successful party failed are clearly dominant or separable (Waters v PC Henderson (Australia) Pty Ltd (1994) 254 ALR 328 at 330-331 per Mahoney JA) and to whether the issues involved different factual enquiries in the one proceeding or multiple causes of action, even if based on a common substratum of fact.

35 But in the present case I am dealing with a situation far removed from the patent context and much less suitable for costs apportionment of the type suggested by VCC.

36 Further, I reject the basis contended for by VCC for this approach, which is that the respondents should pay its costs in seeking to establish the relevant reputation, given that the respondents denied that reputation.

37 The foundation of VCC’s case was the assertion that it has and has had for many decades a substantial and valuable reputation in Australia in relation to its wines, the distinctive features of the presentation of its wines and the name CERTAN. Evidence as to reputation was relied on in respect of all of VCC’s claims. Now for the Prior Branded New Certan Wine it partially succeeded. But on the New Branded New Certan Wine it failed. Further, the trade mark revocation claim failed.

38 The revocation claim failed because VCC’s evidence did not establish the requisite reputation as at 1999. And the claim against the New Branded New Certan Wine failed because VCC’s evidence did not establish any reputation in CERTAN alone. Moreover, even as at 2013, I held that VCC had just established the requisite reputation to support its ACL claim, and that that reputation was only established amongst a narrow subset of consumers.

39 So, even in relation to establishing reputation, VCC’s case was only partially successful.

40 Further, VCC’s passing off claim failed, including in relation to the Prior Branded New Certan Wine, because I was not satisfied that it had or would suffer any damage.

41 Now VCC’s solicitors have endeavoured to calculate the proportion of the parties’ evidence and closing submissions that they say addressed the reputation of VCC and the VCC wines, the Prior Branded New Certan Wine, the New Branded New Certan Wine and the revocation claim. But the evidence on those matters overlapped significantly and VCC’s proposed distinction is problematic and impractical.

42 In my view, in all the circumstances it is more appropriate, subject to the indemnity costs question that I will come to in a moment, that I should make no order for costs in favour of any party. Each has had a substantial measure of success and allowing costs to lie where they have fallen is the most just and practical outcome.

43 Let me dispose of one other matter. The respondents have sought an indemnity costs order in their favour. The context for this is the following.

44 VCC rejected three settlement offers made by the respondents, each made as a Calderbank offer and also under rule 25.01(1) of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth). Those offers were made on 3 August 2022, 2 November 2022 and 7 March 2023. All three offers included a permanent injunction against all respondents regarding the Prior Branded New Certan Wine, plus payment of VCC’s legal costs. The third offer made on 7 March 2023 also added declarations, delivery up of stock of the Prior Branded New Certan Wine, and a further payment of $200,000 in respect of VCC’s claim for damages and exemplary damages. Let me elaborate.

45 By the time of the first offer, VCC had filed all its evidence in chief. The written offer explained that the offer would not restrain the respondents from using the name NEW CERTAN, on the basis that VCC did not “have any realistic prospect of establishing that the use by [the Respondents] of the name NEW CERTAN, in isolation from other elements of the branding of [the] New Certan wine, is [or would be] misleading or deceptive or constitute passing off.” It is said that VCC ought to have recognised that from its own evidence. Similarly, it is said that VCC’s own evidence showed that it had not suffered any loss or damage.

46 Consequently, by the time of the first offer, the respondents say that VCC ought reasonably to have understood that it was unlikely to achieve the additional relief it sought, being pecuniary relief, declarations and the revocation of the NEW CERTAN trade mark. It is said that VCC ought reasonably to have expected that it would not achieve a better outcome than it was offered.

47 Further, it is said that when it received the second offer, VCC had been put on notice of the visual appearance of the New Branded New Certan Wine which would be used with effect from the 2022 vintage. But it is said that not only did VCC reject the second offer, on 18 November 2022 it amended its pleadings to broaden its case to seek injunctions, damages and other relief against the New Branded New Certan Wine.

48 Further, when VCC received the third offer, all of the parties’ evidence had been filed and the trial had been fixed. And VCC had been on notice of the visual appearance of the New Branded New Certan Wine for more than five months.

49 Generally, it is said that each of the three offers would have given VCC at least substantially the same relief that it would ultimately obtain in the proceeding, but in addition, recovery of its costs and recovery of the security for costs it had provided.

50 It is said that VCC unreasonably rejected each offer. And it is said that VCC unreasonably persisted with its claims to seek damages for the Prior Branded New Certan Wine, to enjoin the New Branded New Certan Wine and to revoke the NEW CERTAN trade mark. It failed on all of those claims. It is said that VCC acted unreasonably in rejecting these offers.

51 But I agree with VCC that this is not an appropriate case to award indemnity costs based on the refusal of the respondents’ offers of compromise.

52 The fact that an offer of compromise was made which is more favourable than the outcome achieved does not automatically result in an award of indemnity costs. And it does not follow that any rejection of such an offer by VCC was unreasonable. In State Street Global Advisors Trust Company v Maurice Blackburn Pty Ltd (No 3) [2021] FCA 568, I said (at [38]):

Further and more generally, the fact that an offer of compromise is made which is more favourable than the final result does not automatically result in an award of indemnity costs. Further, it does not follow that even if an offer involved a genuine compromise, any rejection is unreasonable. The question of whether indemnity costs should flow from a rejected offer is whether, given the information then available to the offeree, it should have known that its case was likely to fail. The question of the unreasonableness of the rejection is to be analysed utilising the perspective at the time of the offer.

53 VCC’s claims were genuinely raised and reasonably litigated. And it was successful on most of its case concerning the Prior Branded New Certan Wine.

54 Further, the expert and trade witnesses who gave evidence for VCC substantially supported some of the claims made by VCC as to the nature of its reputation over time and the problems with the presentation of the New Branded New Certan Wine. And important aspects of the case turned on how I evaluated competing bodies of expert evidence. Moreover, the outcome of some issues could not be known in advance and it was not unreasonable for VCC to proceed with its case in those circumstances. Let me add some further detail.

55 It was not unreasonable for VCC to reject the 3 August 2022 offer. First, at that time VCC had filed a significant body of evidence which supported the reputation pleaded by VCC. The respondents were then yet to file evidence in answer. Second, the offer left unaddressed many matters.

56 Further, it was not unreasonable for VCC to reject the 2 November 2022 offer. The 2 November 2022 offer was received at a time when the New Branded New Certan Wine had been introduced into the proceeding in evidence in answer. When this offer was received, having been placed on notice of the proposed presentation, VCC sought the opinions of Mr Hooke, Mr Caillard and Ms Faulkner in relation to the New Branded New Certan Wine. As VCC rightly contends, each of those witnesses later gave opinions that the continued use of the name NEW CERTAN with respect to the New Branded New Certan Wine was problematic.

57 Further, it was not unreasonable for VCC to reject the 7 March 2023 offer for the reasons given in VCC’s solicitors’ letter of 24 June 2023, which included new evidence of confusion.

58 In my view, in summary, an indemnity costs order in favour of the respondents is not justified and in my discretion should be refused. If rule 25.14(2) applies, assuming that “proceeding” can include a claim, there has been no unreasonable failure to accept. If rule 25.14(1) applies, I would dispense with its effect or override it under rules 1.34 and 1.35 for similar reasons.

Conclusion

59 For the foregoing reasons I will not make a costs order in favour of any of the parties.

60 I will make the necessary declarations and orders to reflect these reasons.

61 Finally, it is premature to release at this stage the security for costs given by VCC given that an appeal may be filed against my principal orders including how I have disposed of the costs questions. I will review this matter in due course.

I certify that the preceding sixty-one (61) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice Beach. |

Associate: