FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Ross on behalf of the Cape York United #1 Claim Group v State of Queensland (No 24) (Olkola determination) [2024] FCA 740

Table of Corrections | |

In paragraph [15](r), the year “2023” has been replaced with “2024”. | |

30 October 2024 | In paragraph [89], a closed bracket “)” has been added after “(s 66(2)”. |

30 October 2024 | In paragraph [122], “the” has been added before “State submits”. |

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: | 10 July 2024 |

BEING SATISFIED that an order in the terms set out below is within the power of the Court, and it appearing appropriate to the Court to do so, pursuant to s 87A of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth);

THE COURT NOTES THAT:

A. The Applicant agrees that the areas listed in Part 1 of Schedule 5 are areas where native title has been wholly extinguished.

B. Part 2 of Schedule 5 excludes that part of Lot 1 on WR2 that falls within the External Boundary (Lot 1) and Lot 4 on KA835480 that falls within the External Boundary (Lot 4) from this Determination on the basis that Lot 1 and Lot 4 are subject to tenures which may be affected by outcome of the separate question hearing heard in Bernard Richard Charlie & Ors on behalf of the North Eastern Peninsula Sea Claim Group and State of Queensland & Ors (QUD115/2017) (the NEP claim) relating to special leases granted pursuant to ss 203(a) and (b) of the Land Act 1962 (Qld).

C. The parties intend to seek a determination on the papers for Lot 1 and Lot 4 following the delivery of judgment in the NEP claim, and the parties reaching agreement on how the outcome applies to Lot 1 and Lot 4.

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. There be a determination of native title in the terms proposed in these orders, despite any actual or arguable defect in the authorisation of the applicant to seek and agree to a consent determination pursuant to s 87A of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth).

BY CONSENT THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Pursuant to s 199C(1A) of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth), the Registrar is not to remove the following Indigenous Land Use Agreements from the Register of Indigenous Land Use Agreements, at least to the extent the Indigenous Land Use Agreements fall within the External Boundary:

a. Olkola Land Transfer ILUA (QI2014/085);

b. Thingalkal (Mary Valley) ILUA (QI2014/071);

c. Peninsula Developmental Road ILUA (QI2016/049); and

d. Kalinga Mulkay ILUA (QI2010/036).

2. There be a determination of native title in the terms set out below (the Determination).

3. Each party to the proceedings is to bear its own costs.

BY CONSENT THE COURT DETERMINES THAT:

DEFINITIONS AND INTERPRETATION

4. In this Determination, unless the contrary intention appears:

“Animal” has the meaning given in the Nature Conservation Act 1992 (Qld); “External Boundary” means the area described in Schedule 3; |

“land” has the same meaning as in the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth); |

“Laws of the State and the Commonwealth” means the common law and the laws of the State of Queensland and the Commonwealth of Australia, and includes legislation, regulations, statutory instruments, local planning instruments and local laws; “Local Government Area” has the meaning given in the Local Government Act 2009 (Qld); “Native Title Determination Application” means the Cape York United #1 native title claim filed on 11 December 2014 in QUD 673 of 2014; |

“Natural Resources” means:

|

“Plant” has the meaning given in the Nature Conservation Act 1992 (Qld); “Register of Indigenous Land Use Agreements” has the meaning as in the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth); “Reserve” means a reserve dedicated, or taken to be a reserve, under the Land Act 1994 (Qld); “Spouse” has the meaning given in the Acts Interpretation Act 1954 (Qld); “Water” means:

“waters” has the same meaning as in the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth). Other words and expressions used in this Determination have the same meanings as they have in Part 15 of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth). |

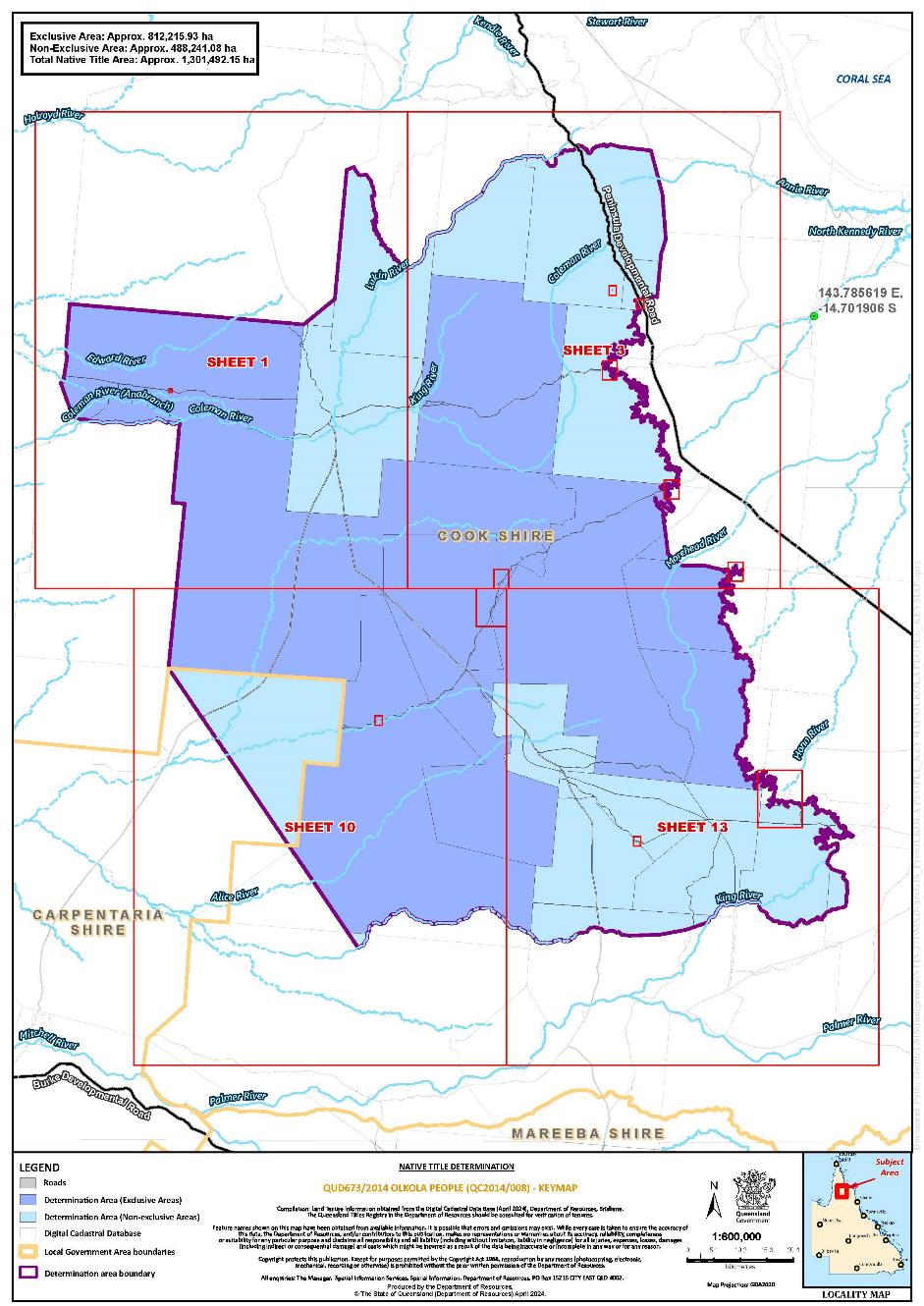

5. The determination area is the land and waters described in Schedule 4 and depicted in the map attached to Schedule 6 to the extent those areas are within the External Boundary and not otherwise excluded by the terms of Schedule 5 (the Determination Area). To the extent of any inconsistency between the written description and the Determination Area map, the written description prevails.

6. Native title exists in the Determination Area.

7. The native title is held by the Olkola People described in Schedule 1 (the Native Title Holders).

8. Subject to orders 10, 11, and 12 below, the nature and extent of the native title rights and interests in relation to the land and waters described in Part 1 of Schedule 4 are:

(a) other than in relation to Water, the right to possession, occupation, use and enjoyment of the area to the exclusion of all others; and

(b) in relation to Water, the non-exclusive right to take the Water of the area for personal, domestic and non-commercial communal purposes.

9. Subject to orders 10, 11, and 12 below, the nature and extent of the native title rights and interests in relation to the land and waters Part 2 of Schedule 4 are the non-exclusive rights to:

(a) access, be present on, move about on and travel over the area;

(b) live and camp on the area and for those purposes to erect shelters and other structures thereon;

(c) hunt, fish and gather on the land and waters of the area;

(d) take the Natural Resources from the land and waters of the area;

(e) take the Water of the area for personal, domestic and non-commercial communal purposes;

(f) be buried and to bury Native Title Holders within the area;

(g) maintain places of importance and areas of significance to the Native Title Holders under their traditional laws and customs on the area and protect those places and areas from harm;

(h) teach on the area the physical and spiritual attributes of the area and the traditional laws and customs of the Native Title Holders to other Native Title Holders or persons otherwise entitled to access the area;

(i) hold meetings on the area;

(j) conduct ceremonies on the area;

(k) light fires on the area for cultural, spiritual or domestic purposes including cooking, but not for the purpose of hunting or clearing vegetation; and

(l) be accompanied on to the area by those persons who, though not Native Title Holders, are:

(i) Spouses of Native Title Holders;

(ii) people who are members of the immediate family of a Spouse of a Native Title Holder; or

(iii) people reasonably required by the Native Title Holders under traditional law and custom for the performance of ceremonies or cultural activities on the area.

10. The native title rights and interests are subject to and exercisable in accordance with:

(a) the Laws of the State and the Commonwealth; and

(b) the traditional laws acknowledged and traditional customs observed by the Native Title Holders.

11. The native title rights and interests referred to in orders 8(b) and 9 do not confer possession, occupation, use or enjoyment to the exclusion of all others.

12. There are no native title rights in or in relation to minerals as defined by the Mineral Resources Act 1989 (Qld) and petroleum as defined by the Petroleum Act 1923 (Qld) and the Petroleum and Gas (Production and Safety) Act 2004 (Qld).

13. The nature and extent of any other interests in relation to the Determination Area (or respective parts thereof) are set out in Schedule 2 (the Other Interests).

14. The relationship between the native title rights and interests described in orders 8 and 9 and the Other Interests described in Schedule 2 is that:

(a) the Other Interests continue to have effect, and the rights conferred by or held under the Other Interests may be exercised notwithstanding the existence of the native title rights and interests;

(b) to the extent the Other Interests are inconsistent with the continued existence, enjoyment or exercise of the native title rights and interests in relation to the land and waters of the Determination Area, the native title rights and interests continue to exist in their entirety but the native title rights and interests have no effect in relation to the Other Interests to the extent of the inconsistency for so long as the Other Interests exist; and

(c) the Other Interests and any activity that is required or permitted by or under, and done in accordance with, the Other Interests, or any activity that is associated with or incidental to such an activity, prevail over the native title rights and interests and any exercise of the native title rights and interests.

THE COURT DETERMINES THAT:

15. The native title is held in trust.

16. The Ut-Alkar Aboriginal Corporation (ICN: 10231), incorporated under the Corporations (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander) Act 2006 (Cth), is to:

(a) be the prescribed body corporate for the purpose of ss 56(2)(b) and 56(3) of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth); and

(b) perform the functions mentioned in s 57(1) of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) after becoming a registered native title body corporate.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

LIST OF SCHEDULES

Schedule 1 – Native Title Holders viii

Schedule 2 – Other Interests in the Determination Area x

Schedule 3 – External Boundary xv

Schedule 4 – Description of Determination Area xix

Schedule 5 – Areas Not Forming Part of the Determination Area xxiv

Schedule 6 – Determination Area Map xxvi

Schedule 1 – Native Title Holders

1. The Native Title Holders are the Olkola People. The Olkola People are those Aboriginal persons who are descended by birth, or adoption in accordance with the traditional laws acknowledged and the traditional customs observed by the Olkola People, from one or more of the following apical ancestors:

(a) Willie Johnson (aka Jack Johnson);

(b) Parry (father of Linda Long and grandfather of Albert Upton);

(c) Charlie (spouse of Topsy/Bessie);

(d) Old Man Barney Dockerty;

(e) Mosquito Upton;

(f) Long Jim Coleman;

(g) Johnson Upton;

(h) Charlie Gunnawarra;

(i) Jimmy Long (aka Brasso/Basil);

(j) Polly (spouse of Mustard);

(k) Mustard;

(l) Nellie Musgrave;

(m) Bally (father of Lucy Long);

(n) Old Man Bally (Oto aka Possum Bally);

(o) Bally Upton;

(p) Ngoingum;

(q) Therese Upton aka Awundayi;

(r) Old Man Boxer;

(s) Mary Callaghan (spouse of Jack McIvor);

(t) Jack Spratt;

(u) Old Man Saturday (aka Jimmy Thompson);

(v) Frank Yam;

(w) Charlie Sugarbag and Charlie Crocodile (siblings);

(x) Willie Long aka Willie Bandfoot/Bamford (spouse of Jinny Long);

(y) Sandy (spouse of Nellie/Lily);

(z) Georgina Lee Cheu Snr;

(aa) Paddy Cook;

(bb) George Dockerty (spouse of Rosie);

(cc) Rosie (spouse of George Dockerty);

(dd) Charlie (father of Linda Bob);

(ee) Nellie (mother of Linda Bob); or

(ff) Old Lady Molly Long (aka Molly Barney).

Schedule 2 – Other Interests in the Determination Area

The nature and extent of the other interests in relation to the Determination Area are the following as they exist as at the date of the Determination:

1. The rights and interests of the parties under the following agreements registered on the Register of Indigenous Land Use Agreements:

(a) Olkola Land Transfer ILUA (QI2014/085);

(b) PNG Gas Pipeline ILUA (QI2006/043);

(c) Peninsula Developmental Road ILUA (QI2016/049);

(d) Thingalkal (Mary Valley) ILUA (QI2014/071); and

(e) Kalinga Mulkay ILUA (QI2010/036).

2. The rights and interests of Olkola Aboriginal Corporation:

(a) as trustee in fee simple of Lot 20 on SP241432, Lot 21 on SP241432, Lot 7 on SP241432, Lot 16 on SP262570, Lot 6 on SP262570, Lot 10 on SP261207, and Lot 36 on SP215745 pursuant to deeds of grant under the Aboriginal Land Act 1991 (Qld), to the extent those parcels fall within the External Boundary; and

(b) under the Land Act 1994 (Qld) as the holder of rolling term lease (PH 34/3875) for pastoral purposes (also known as Glen Garland) over Lot 3875 on SP141968.

3. The rights and interests of Telstra Corporation Limited (ACN 051 775 556), Amplitel Pty Ltd as trustee of the Towers Business Operating Trust (ABN 75 357 171 746) and any of their successors in title:

(a) as the owner(s) or operator(s) of telecommunications facilities within the Determination Area;

(b) created pursuant to the Post and Telegraph Act 1901 (Cth), the Telecommunications Act 1975 (Cth), the Australian Telecommunications Corporation Act 1989 (Cth), the Telecommunications Act 1991 (Cth) and the Telecommunications Act 1997 (Cth), including rights:

(i) to inspect land;

(ii) to install, occupy and operate telecommunication facilities; and

(iii) to alter, remove, replace, maintain, repair and ensure the proper functioning of their telecommunications facilities;

(c) for their employees, agents or contractors to access their telecommunication facilities in and in the vicinity of the Determination Area in the performance of their duties; and

(d) under any lease, licence, access agreement, permit or easement relating to their telecommunications facilities in the Determination Area.

4. The rights and interests of Evan Frank Ryan, Paul Bradley Ryan and Scott Evan Ryan under the Land Act 1962 (Qld) as the holders of rolling term lease (PH 14/2593) for pastoral purposes (also known as Koolburra) over that part of Lot 2 on SP280073 that falls within the External Boundary.

5. The rights and interests of Colin Innes and Margaret Anne Innes under the Land Act 1962 (Qld) as the holders of rolling term lease (0/241013) for grazing purposes over that part of Lot 46 on SP235313 excluding an area formerly described as Lot 1 on KG2 and that falls within the External Boundary.

6. The rights and interests of Rodney Glen Raymond under the Land Act 1962 (Qld) as the holder of rolling term lease (0/241014) for grazing purposes over Lot 47 on SP235313 excluding an area formerly described as Lot 1 on KG2.

7. The rights and interests of Thomas Donald Shephard and Susan Shephard under the Land Act 1962 (Qld) as the holders of rolling term lease (PH 14/4365) for pastoral purposes over that part of Lot 4365 on SP182310 that falls within the External Boundary.

8. The rights and interests of the Corporation of the Kowanyama Aboriginal Community Council under the Land Act 1962 (Qld) as the holder of rolling term lease (PH 34/5545) for pastoral purposes over that part of Lot 12 on CTH804427 that falls within the External Boundary.

9. The rights and interests of Cook Shire Council and Carpentaria Shire Council:

(a) under their local government jurisdiction and functions under the Local Government Act 2009 (Qld), under the Stock Route Management Act 2002 (Qld) and under any other legislation, for that part of the Determination Area within the area declared to be their Local Government Area:

(i) lessor(s) under any leases which were validly entered into before the date on which these orders are made and whether separately particularised in these orders or not;

(ii) grantor(s) of any licences or other rights and interests which were validly granted before the date on which these orders were made and whether separately particularised in these orders or not;

(iii) party to an agreement with a third party which relates to land or waters in the Determination Area;

(iv) holder(s) of any estate or any other interest in land, including as trustee of any Reserves, under access agreements and easements that exist in the Determination Area;

(c) as the owner(s) and operator(s) of infrastructure, structures, earthworks, access works and any other facilities and other improvements located in the Determination Area validly constructed or established on or before the date on which these orders are made, including but not limited to any:

(i) undedicated but constructed roads except for those not operated by the councils;

(ii) water pipelines and water supply infrastructure;

(iii) drainage facilities;

(iv) watering point facilities;

(v) recreational facilities;

(vi) transport facilities;

(vii) gravel pits operated by the councils;

(viii) cemetery and cemetery related facilities; and

(ix) community facilities;

(d) to enter the land for the purposes described in paragraphs 9(a), (b) and (c) above by their employees, agents or contractors to:

(i) exercise any of the rights and interests referred to in this paragraph 9 and paragraph 10 below;

(ii) use, operate, inspect, maintain, replace, restore and repair the infrastructure, facilities and other improvements referred to in paragraph 9(c) above; and

(iii) undertake operational activities in their capacity as a local government such as feral animal control, erosion control, waste management and fire management.

10. The rights and interests of the State of Queensland, Cook Shire Council and Carpentaria Shire Council to access, use, operate, maintain and control the dedicated roads in the Determination Area and the rights and interests of the public to use and access the roads.

11. The rights and interests of the State of Queensland in Reserves, the rights and interests of the trustees of those Reserves and the rights and interests of the persons entitled to access and use those Reserves for the respective purpose for which they are reserved.

12. The rights and interests of the State of Queensland or any other person existing by reason of the force and operation of the laws of the State of Queensland, including those existing by reason of the following legislation or any regulation, statutory instrument, declaration, plan, authority, permit, lease or licence made, granted, issued or entered into under that legislation:

(a) the Aboriginal Land Act 1991 (Qld);

(b) the Fisheries Act 1994 (Qld);

(c) the Land Act 1994 (Qld);

(d) the Nature Conservation Act 1992 (Qld);

(e) the Forestry Act 1959 (Qld);

(f) the Water Act 2000 (Qld);

(g) the Petroleum Act 1923 (Qld) or Petroleum and Gas (Production and Safety) Act 2004 (Qld);

(h) the Mineral Resources Act 1989 (Qld);

(j) the Transport Infrastructure Act 1994 (Qld); and

13. The rights and interests of members of the public arising under the common law, including but not limited to the following:

(a) any subsisting public right to fish; and

(b) the public right to navigate.

14. So far as confirmed pursuant to s 212(2) of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) and s 18 of the Native Title (Queensland) Act 1993 (Qld) as at the date of this Determination, any existing rights of the public to access and enjoy the following places in the Determination Area:

(a) waterways;

(b) beds and banks or foreshores of waterways;

(c) stock routes; and

(d) areas that were public places at the end of 31 December 1993.

15. Any other rights and interests:

(a) held by the State of Queensland or Commonwealth of Australia; or

(b) existing by reason of the force and operation of the Laws of the State and the Commonwealth.

Schedule 3 – External Boundary

The area of land and waters:

Commencing at the intersection of the eastern boundary of Lot 3384 on SP182311 and the centreline of Red Blanket Creek at Latitude 14.668541° South; then generally westerly along the centreline of Red Blanket Creek until the intersection with the 110m contour line; then generally southerly along that contour line until a point at Longitude 143.525512° East, Latitude 15.05757° South; then south easterly to another point on the 110m contour line at Longitude 143.626601° East, Latitude 15.140918° South, passing through the following coordinate points:

Longitude ° East | Latitude ° South |

143.528784 | 15.079739 |

143.532651 | 15.113349 |

143.556445 | 15.133277 |

143.596599 | 15.133872 |

then generally southerly along that contour line until Longitude 143.621675° East, Latitude 15.232089° South; then south easterly until the intersection with the 190m contour line at Longitude 143.632479° East, Latitude 15.235537° South; then generally southerly and south easterly along that contour line until the intersection with the north western boundary of Lot 5218 on PH1103 (commonly known as Fairlight Station) at Longitude 143.825079° East; then south westerly along the boundary of that lot until a north western corner at approximate Longitude 143.815228° East; then south westerly until a point on the Great Dividing Range at Latitude 15.64833° South; then generally southerly along the Great Dividing Range until Latitude 15.729880° South, then westerly until the headwaters of a tributary of King River at Longitude 143.816676° East, Latitude 15.729642° South; then generally south westerly and westerly along the southern bank of that tributary and the southern bank of King River until Longitude 143.600917° East; then westerly until the headwaters of an unnamed tributary of Ten Mile Creek at Longitude 143.451733° East, Latitude 15.773102° South, passing through the following coordinate points:

Longitude ° East | Latitude ° South |

143.563427 | 15.765022 |

143.518970 | 15.773265 |

143.465233 | 15.775191 |

then generally westerly along the southern bank of that tributary, Ten Mile Creek, and Maddigans Creek until the junction of Maddigans Creek and Lorraine Creek, then north westerly until the south eastern corner of Lot 473 on SP206203 (Harkness), also being a corner point of Kowanyama People Part B Native Title Determination (QCD2012/016); then clockwise following the boundaries of that determination and Native Title Determinations Strathgordon Mob (QCD2007/001), Wik and Wik Way Native Title Determination No. 3 (QCD2004/003), Wik and Wik Way Native Title Determination No. 4 (QCD2012/010), Ayapathu People (QCD2022/007) and Lama Lama People (QCD2022/008) until the point of commencement, also described as:

then northerly, westerly, and northerly along the eastern boundaries of Lot 473 on SP206203 (Harkness); until the intersection with the southern bank of the Coleman River, also being the northern boundary of that lot; then westerly along that river bank and lot boundary until Longitude 142.534155° East; then north westerly until a point on the northern bank of the Coleman River, also a southern boundary of Lot 10 on SP261207 (Olkola Aboriginal Corporation), at Longitude 142.532419° East; then generally westerly, northerly and easterly along the boundaries of that lot until the intersection with the north western corner of Lot 5 on KA835479 (Strathaven Station); then north easterly until a point on the western boundary of Lot 3874 on SP273462 (Astrea Station) at Latitude 14.671650° South; then northerly and south easterly along the boundaries of Astrea Station until Latitude 14.492031° South; then south westerly a short distance until the intersection with the headwaters of an unnamed tributary of Fish Creek in the vicinity of Camp Oven Lagoon at Longitude 143.023356° East, Latitude 14.492834° South; then generally southerly along the centreline of that tributary, generally south easterly along the centreline of Fish Creek and generally north easterly along the centreline of the Lukin River until Longitude 143.321382 East; then southerly, easterly, and northerly to again intersect the centreline of Lukin River at Longitude 143.336990° East, passing around Mount Ryan through the following coordinate points:

Longitude ° East | Latitude ° South |

143.325716 | 14.438504 |

143.328741 | 14.441065 |

143.333025 | 14.441119 |

143.336452 | 14.440160 |

143.337841 | 14.437100 |

143.338238 | 14.432602 |

then easterly along the centrelines of the Lukin River, Duckholes Creek and an unnamed tributary of Duckholes Creek until the headwaters of that tributary at Longitude 143.433544° East, Latitude 14.403611° South; then south easterly to a point on the Great Dividing Range just north of Mount Walsh at Longitude 143.449180° East, Latitude 14.407860° South; then easterly until the intersection of an unnamed road (also known as the Old Telegraph Line) and Annie River at Latitude 14.414312° South (a place known as 25 Mile or Hot Water Story); then southerly along the centreline of that road to its intersection with the eastern boundary of Lot 3384 on SP182311 at Latitude 14.667379° South; then easterly and southerly along the eastern boundary of that lot until the point of commencement.

Data Reference and source

Cadastral data sourced from Department of Resources, Queensland (published 07/08/2023).

Watercourse Lines sourced from Department of Resources, Queensland (published 05/10/2022).

Mountain Ranges, Beaches and Sea Passages sourced from Department of Resources, Queensland (27/07/2023).

Local Government Areas sourced from Department of Resources, Queensland (published 23/11/2023).

Native Title Determinations and Representative Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Body boundaries sourced from the Commonwealth of Australia, National Native Title Tribunal (published 03/08/2023).

Reference datum

Geographical coordinates are referenced to the Geocentric Datum of Australia 1994 (GDA94), in decimal degrees.

Use of Coordinates

Where coordinates are used within the description to represent cadastral or topographical boundaries or the intersection with such, they are intended as a guide only. As an outcome to the custodians of cadastral and topographic data continuously recalculating the geographic position of their data based on improved survey and data maintenance procedures, it is not possible to accurately define such a position other than by detailed ground survey.

Schedule 4 – Description of Determination Area

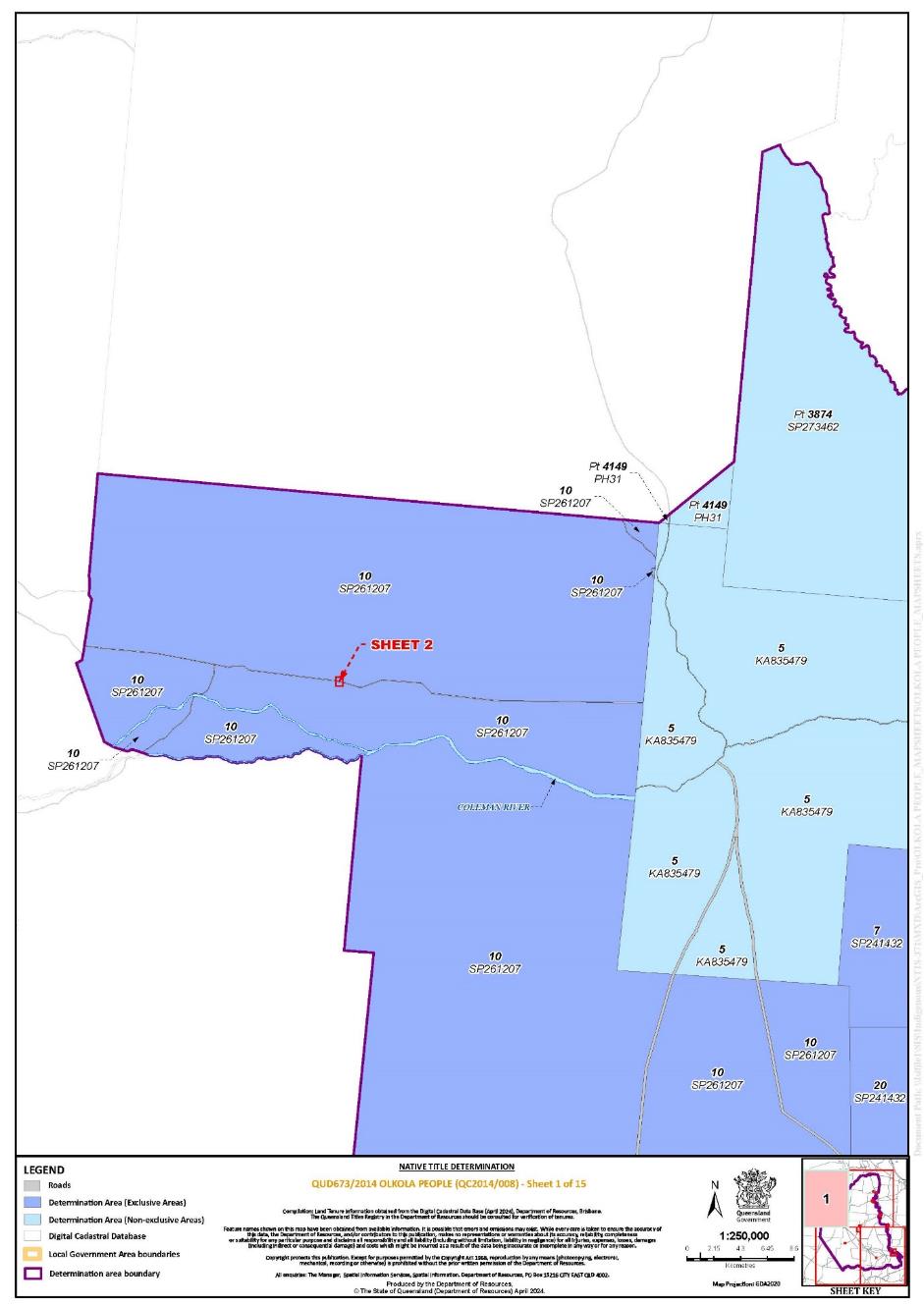

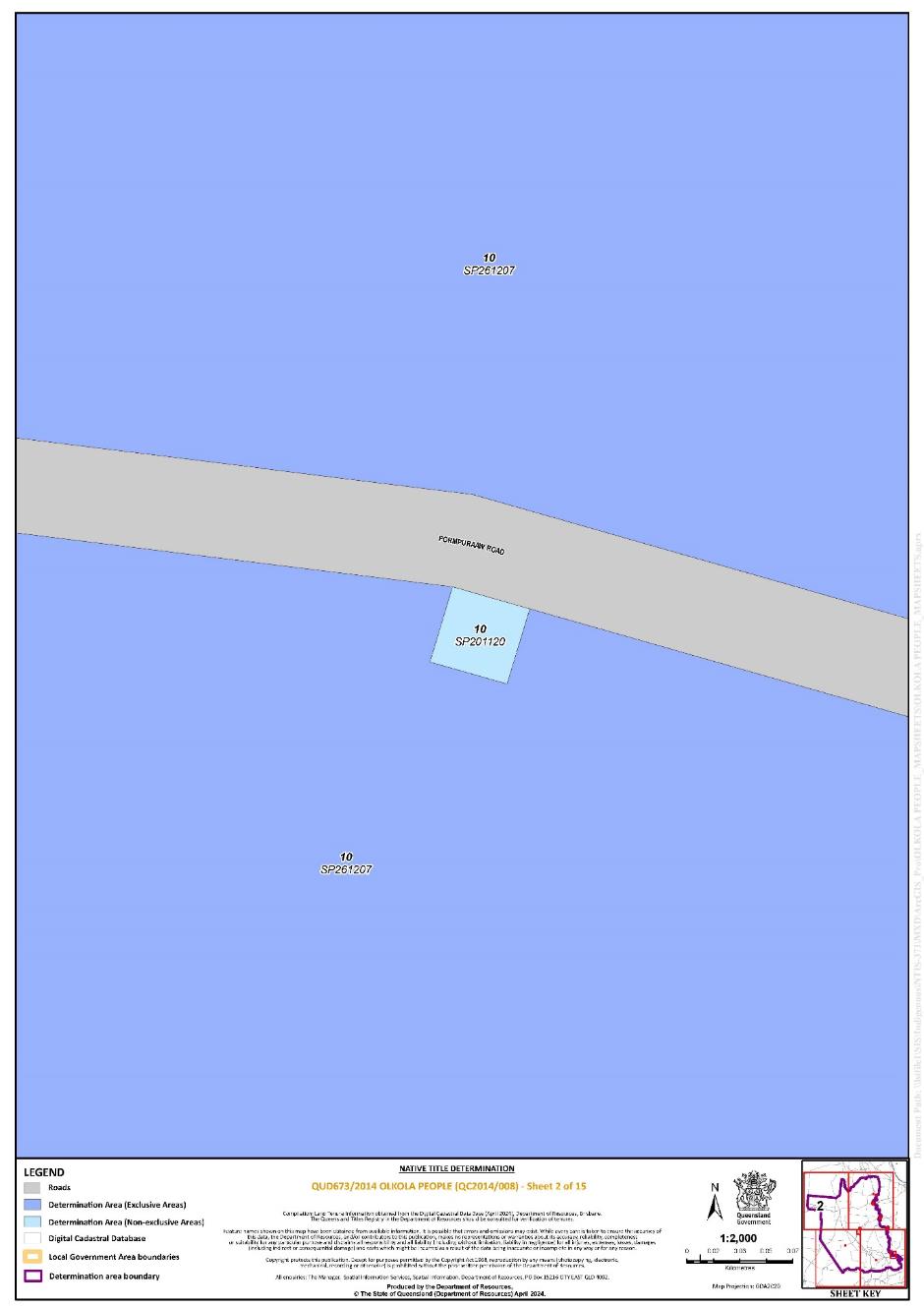

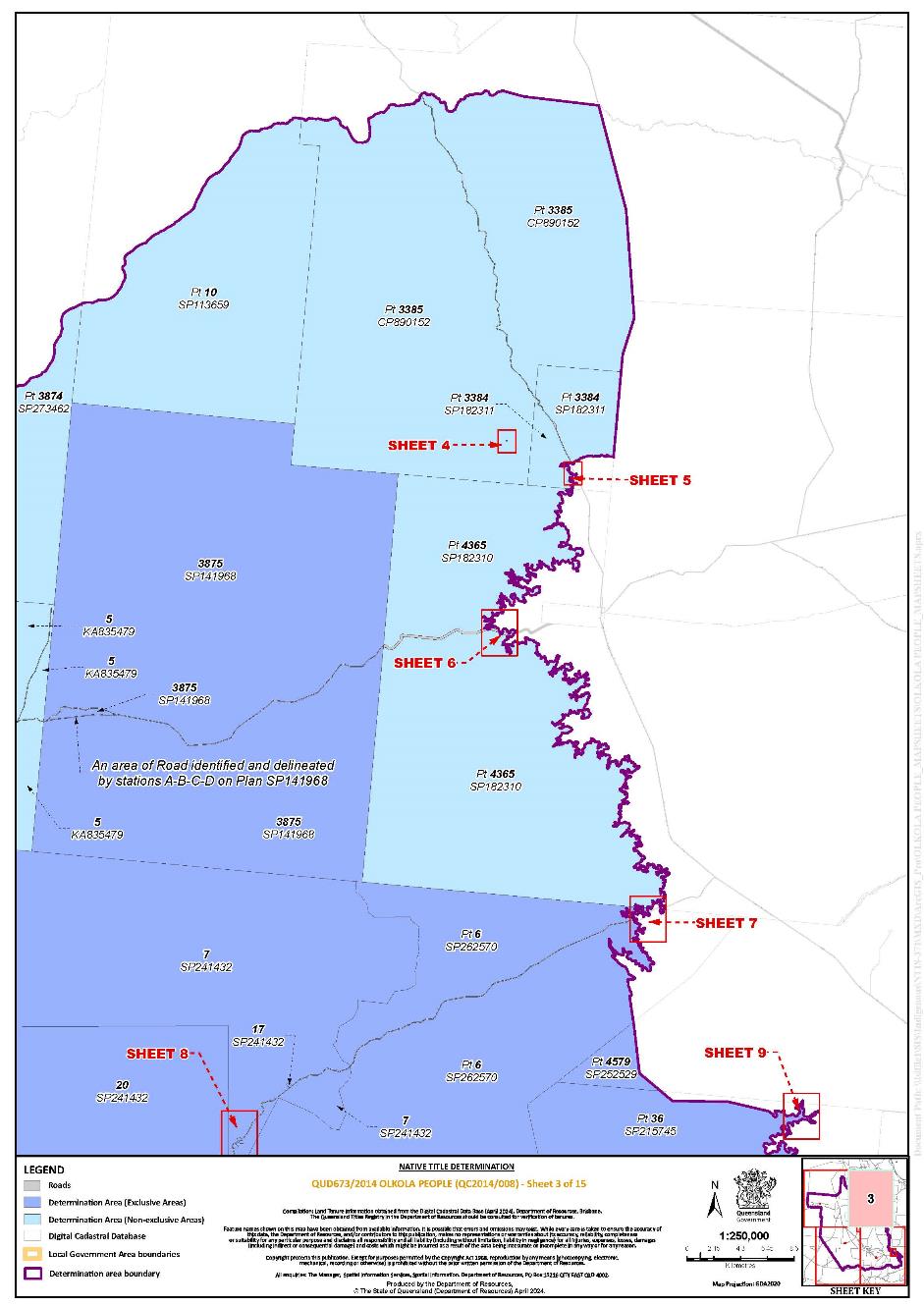

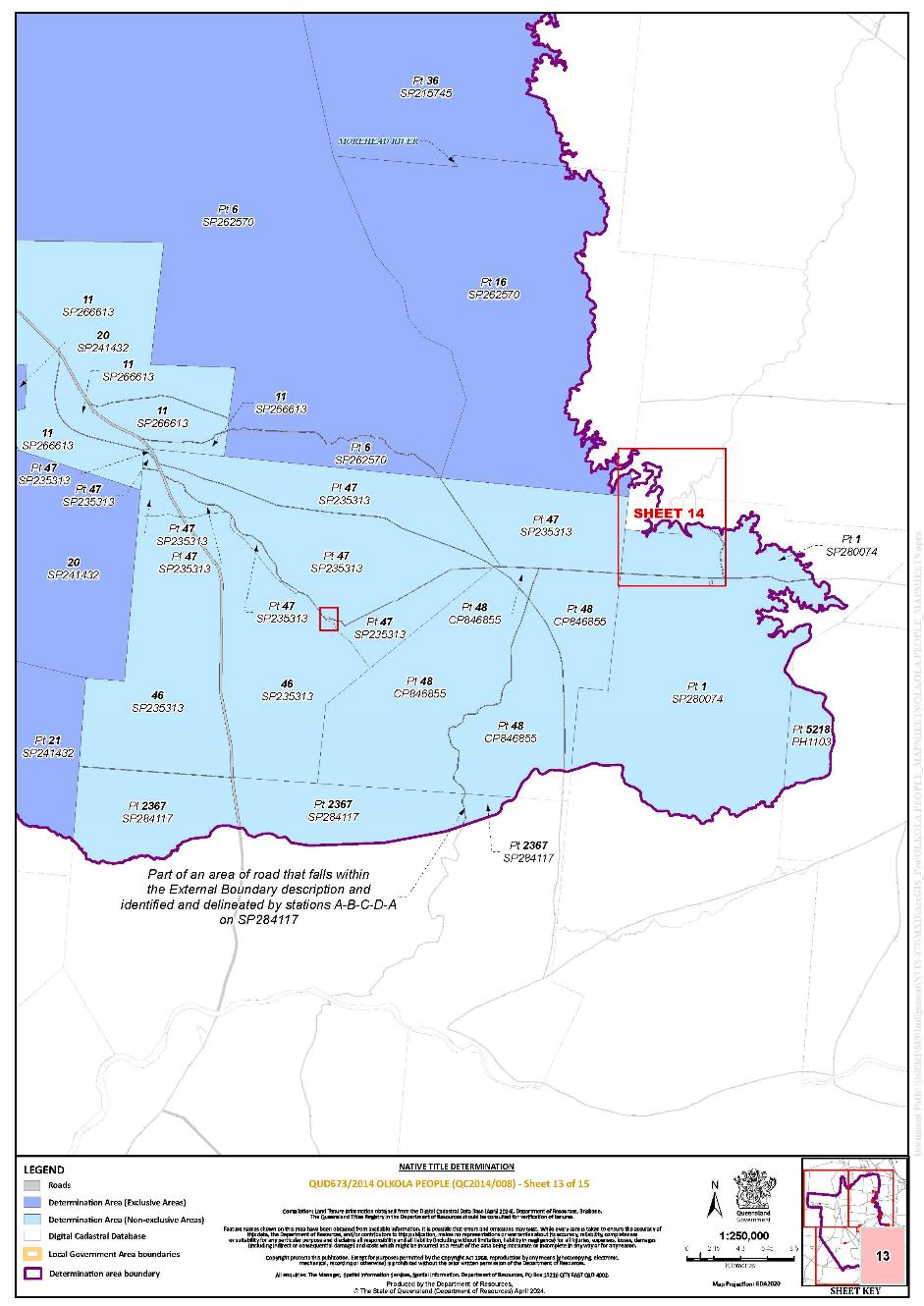

The Determination Area comprises all of the land and waters described by lots on plan, or relevant parts thereof, and any rivers, streams, creeks or lakes described in the first column of the tables in the Parts immediately below, and depicted in the Determination Area map in Schedule 6, to the extent those areas are within the External Boundary and not otherwise excluded by the terms of Schedule 5.

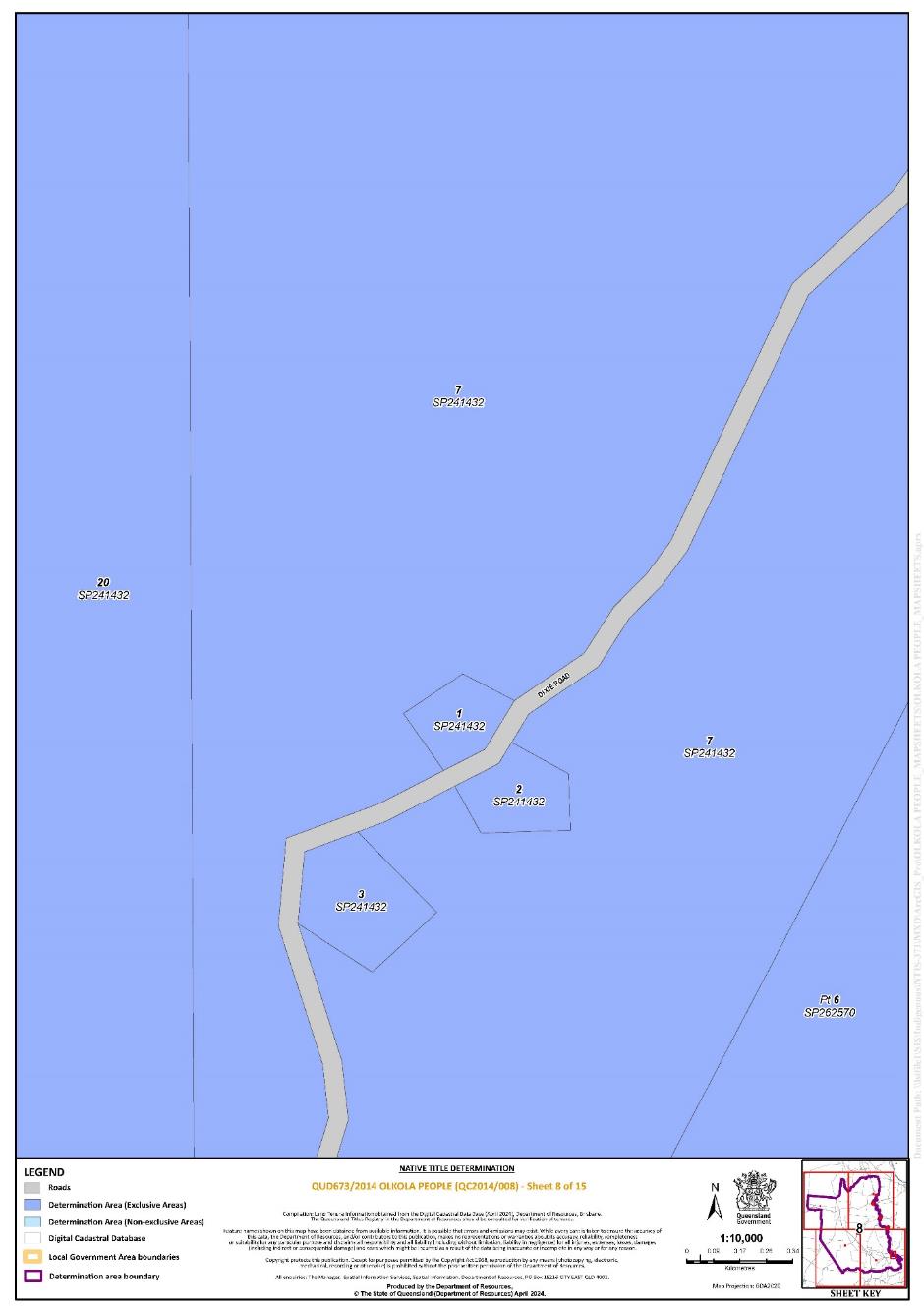

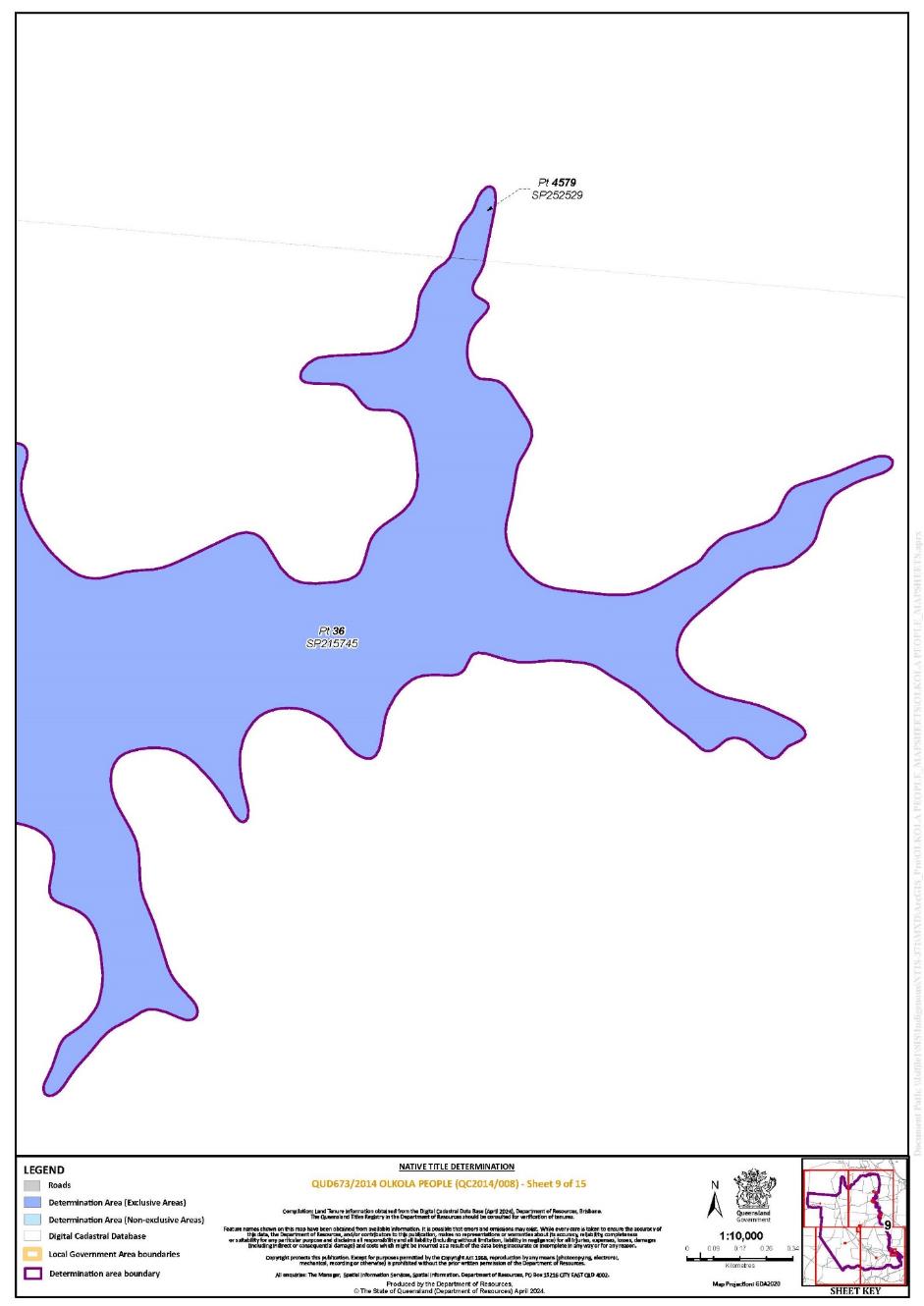

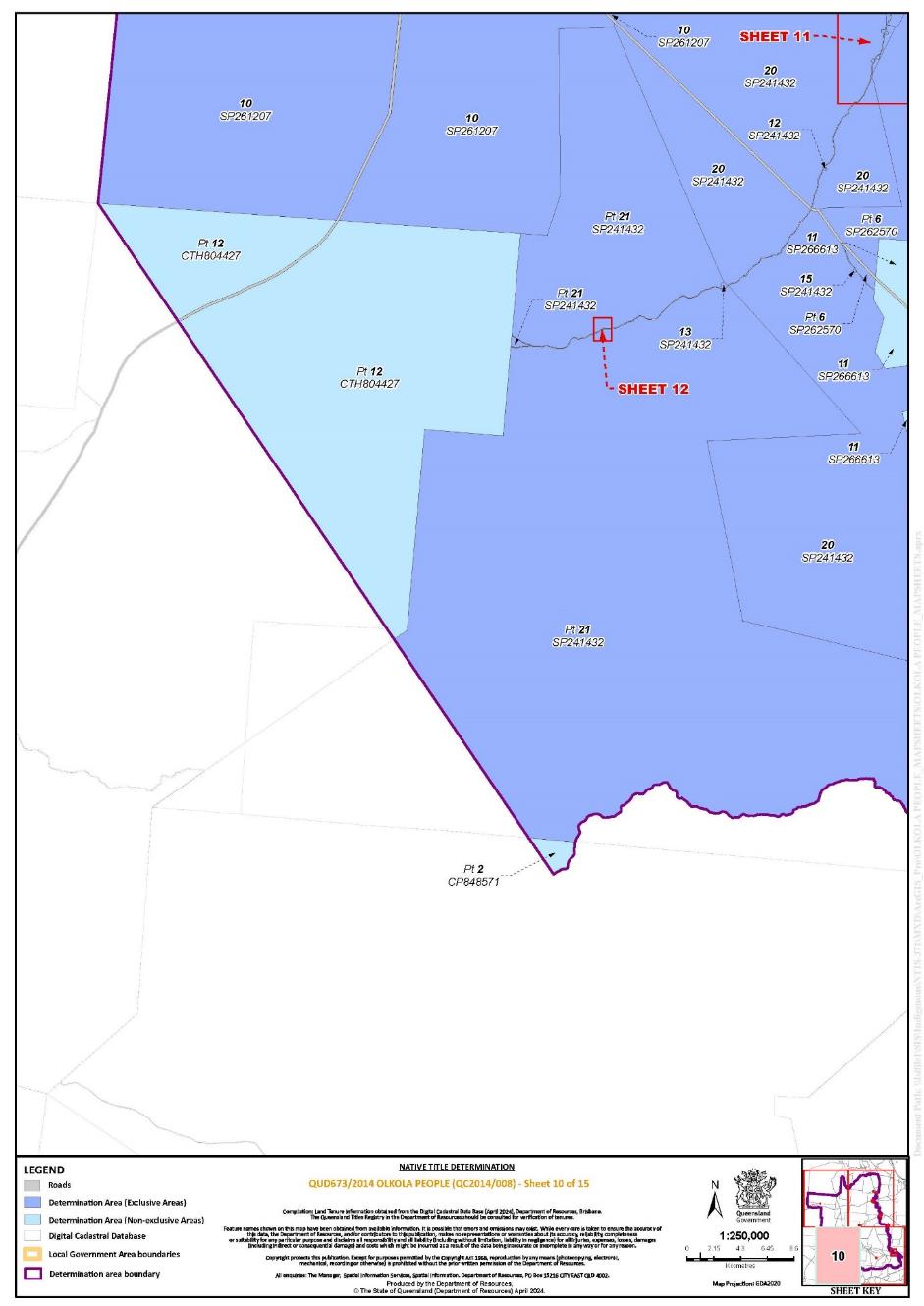

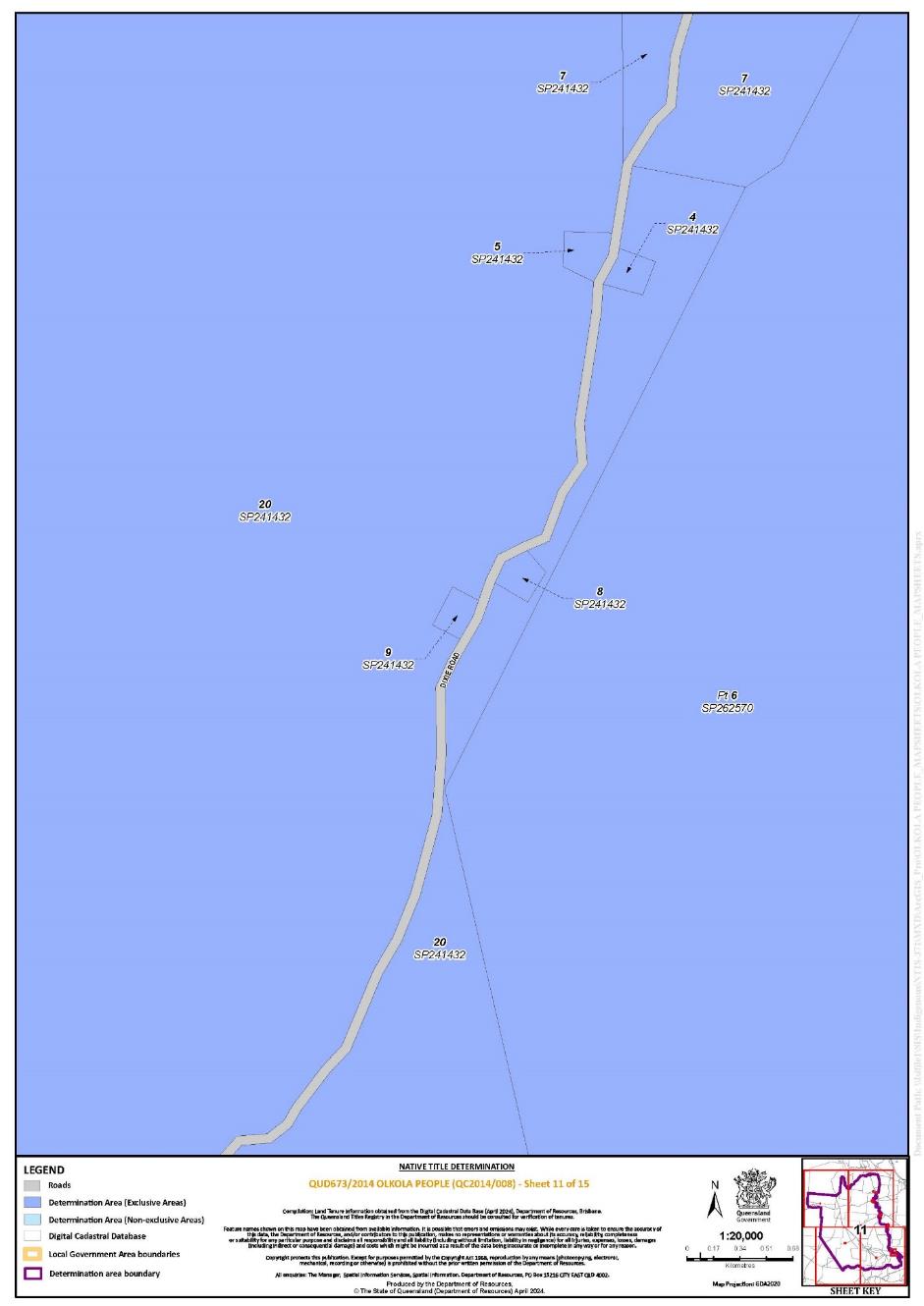

All of the land and waters described in the following table and depicted in dark blue on the Determination Area map contained in Schedule 6:

Area description (at the time of the Determination) | Determination Area map sheet reference | Note |

Lot 3875 on SP141968 | Sheet 3 | * |

An area of road identified and delineated by stations A-B-C-D on SP141968 | Sheet 3 | * |

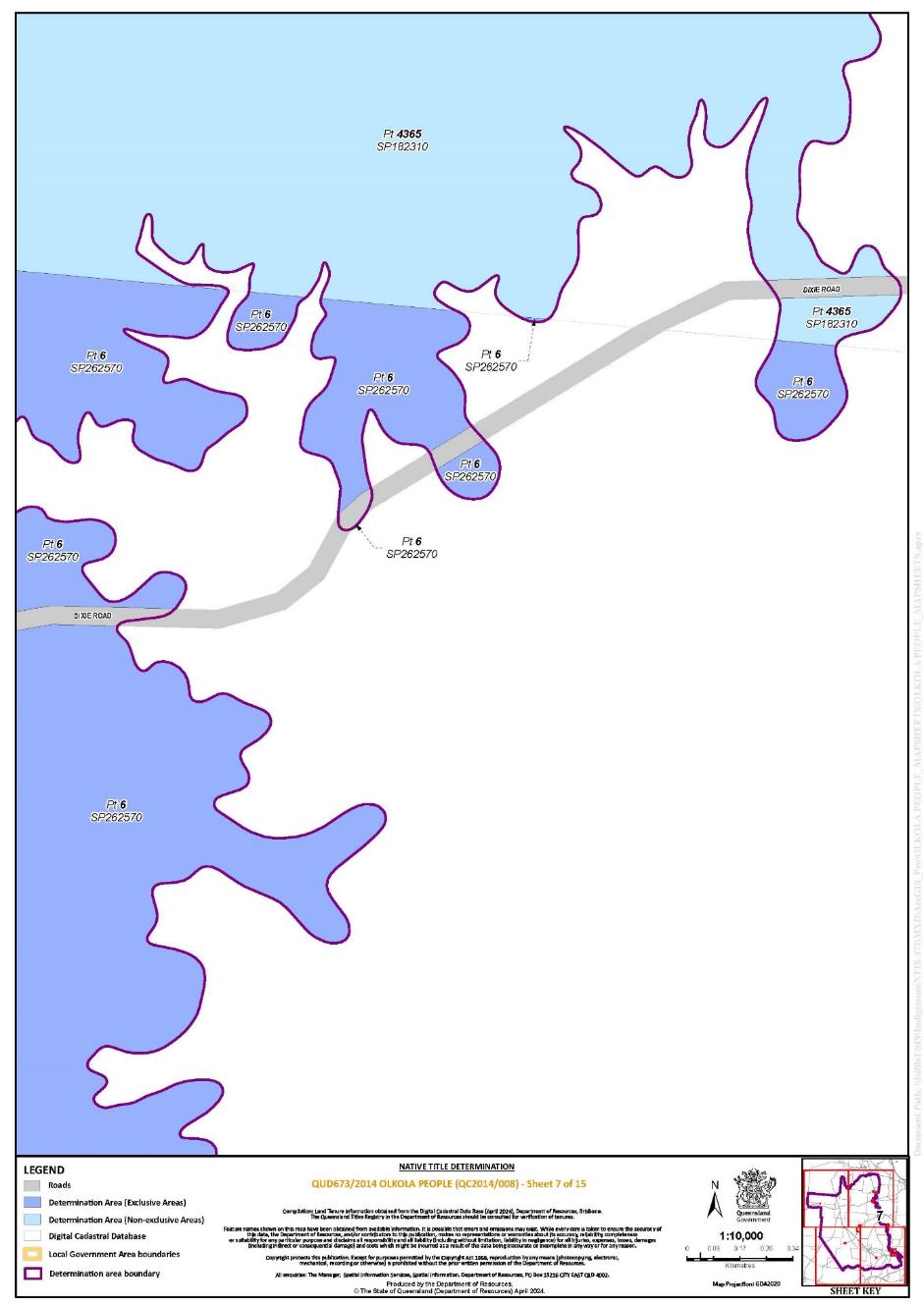

That part of Lot 6 on SP262570 that falls within the External Boundary | Sheets 3, 7, 8, 10, 11 and 13 | * |

That part of Lot 4579 on SP252529 that falls within the External Boundary | Sheets 3 and 9 | * |

That part of Lot 36 on SP215745 that falls within the External Boundary | Sheets 3, 9 and 13 | * |

That part of Lot 16 on SP262570 that falls within the External Boundary | Sheets 13 and 14 | * |

Lot 7 on SP241432 | Sheets 1, 3, 8 and 11 | * |

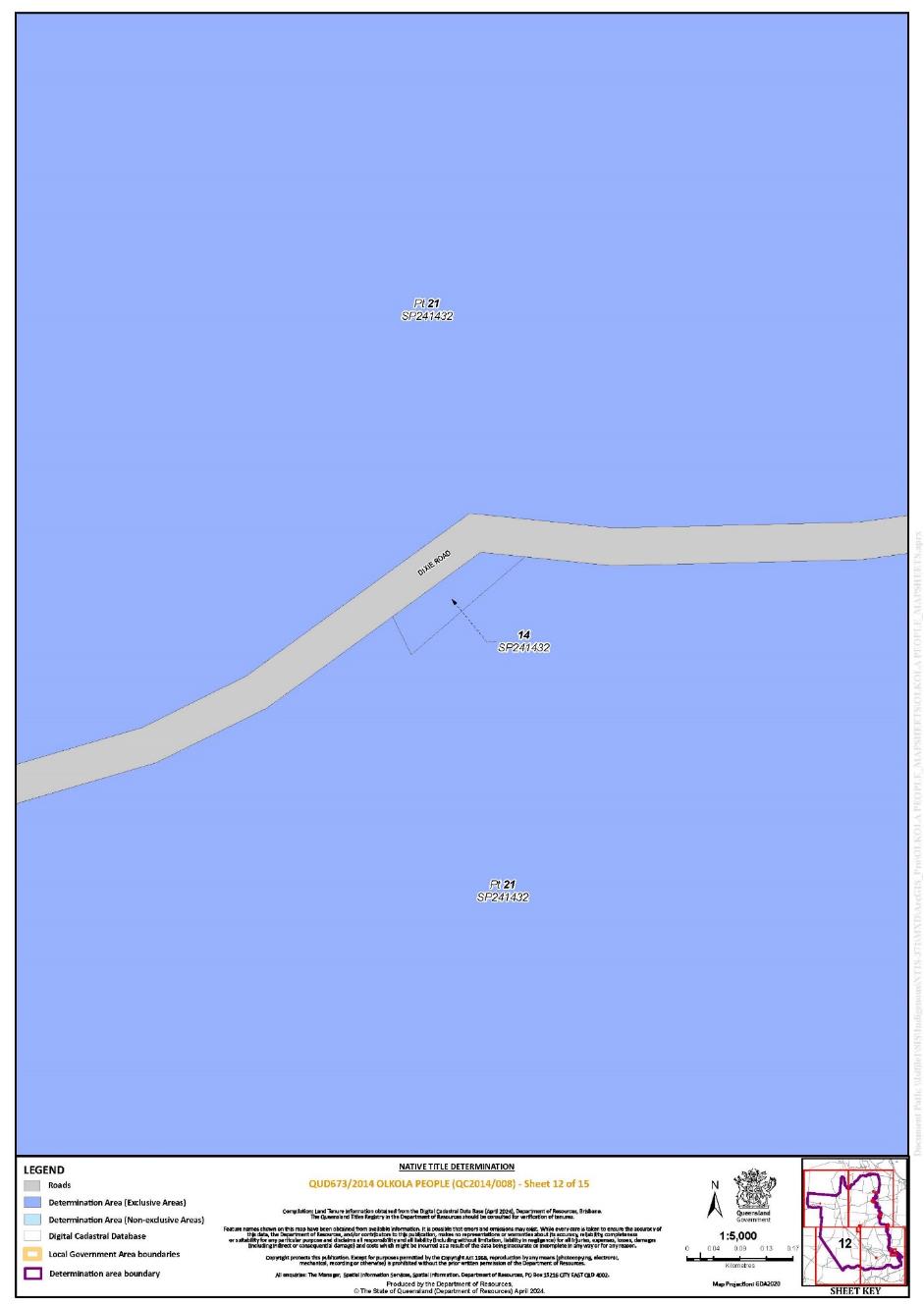

That part of Lot 21 on SP241432 that falls within the External Boundary | Sheets 10, 12 and 13 | * |

Lot 1 on SP241432 | Sheet 8 | * |

Lot 2 on SP241432 | Sheet 8 | * |

Lot 3 on SP241432 | Sheet 8 | * |

Lot 4 on SP241432 | Sheet 11 | * |

Lot 5 on SP241432 | Sheet 11 | * |

Lot 8 on SP241432 | Sheet 11 | * |

Lot 9 on SP241432 | Sheet 11 | * |

Lot 12 on SP241432 | Sheet 10 | * |

Lot 13 on SP241432 | Sheet 10 | * |

Lot 14 on SP241432 | Sheet 12 | * |

Lot 15 on SP241432 | Sheet 10 | * |

Lot 17 on SP241432 | Sheet 3 | * |

Lot 20 on SP241432 | Sheets 1, 3, 8, 10, 11 and 13 | * |

Lot 10 on SP261207 | Sheets 1, 2 and 10 | * |

* denotes areas to which s 47A of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) applies.

All of the land and waters described in the following table and depicted in light blue on the Determination Area map contained in Schedule 6:

Area description (at the time of the Determination) | Determination Area map sheet reference |

Lot 1 on CP884629 | Sheet 4 |

That part of Lot 3385 on CP890152 that falls within the External Boundary | Sheets 3 and 4 |

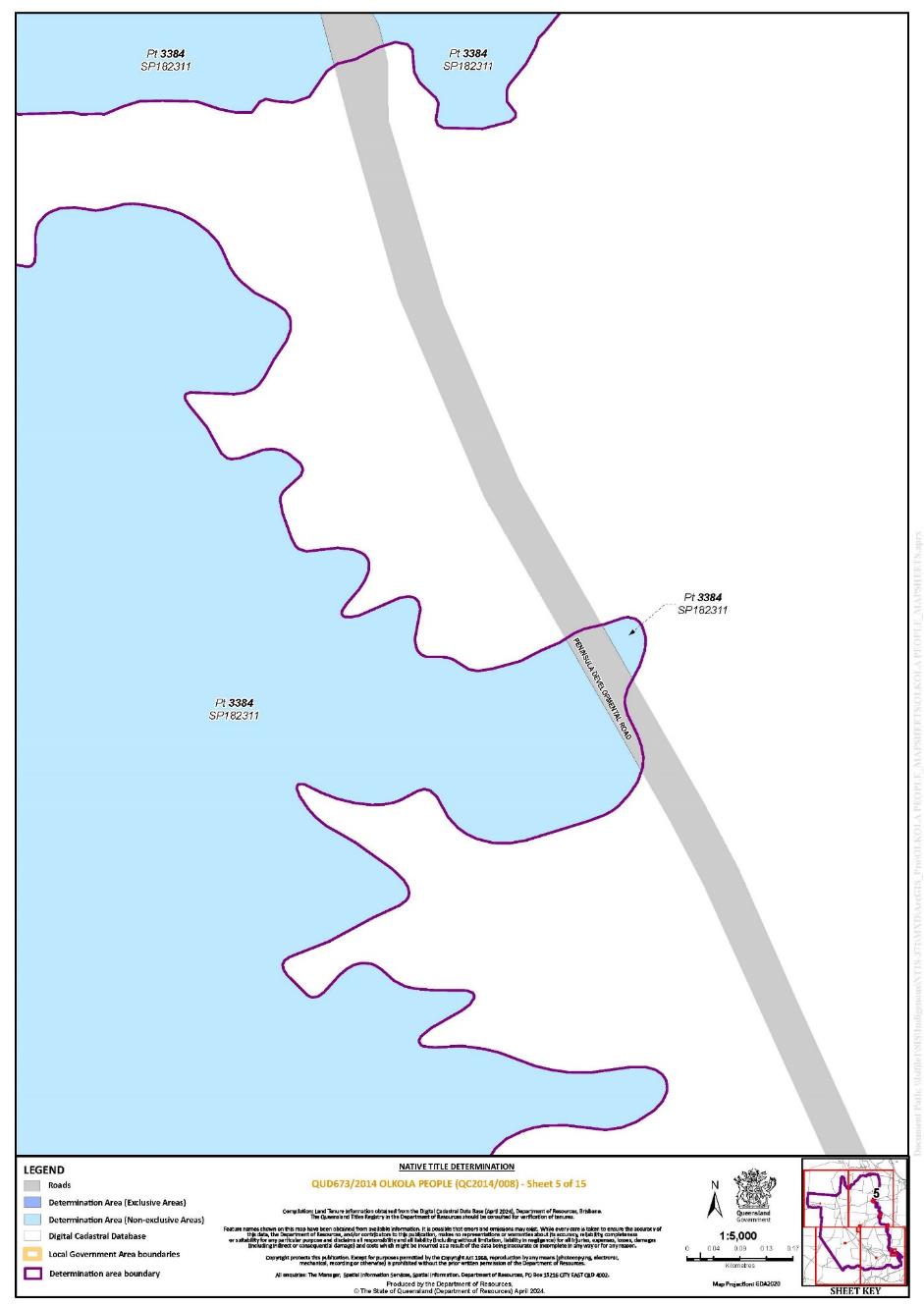

That part of Lot 3384 on SP182311 that falls within the External Boundary | Sheets 3 and 5 |

That part of Lot 10 on SP113659 that falls within the External Boundary | Sheet 3 |

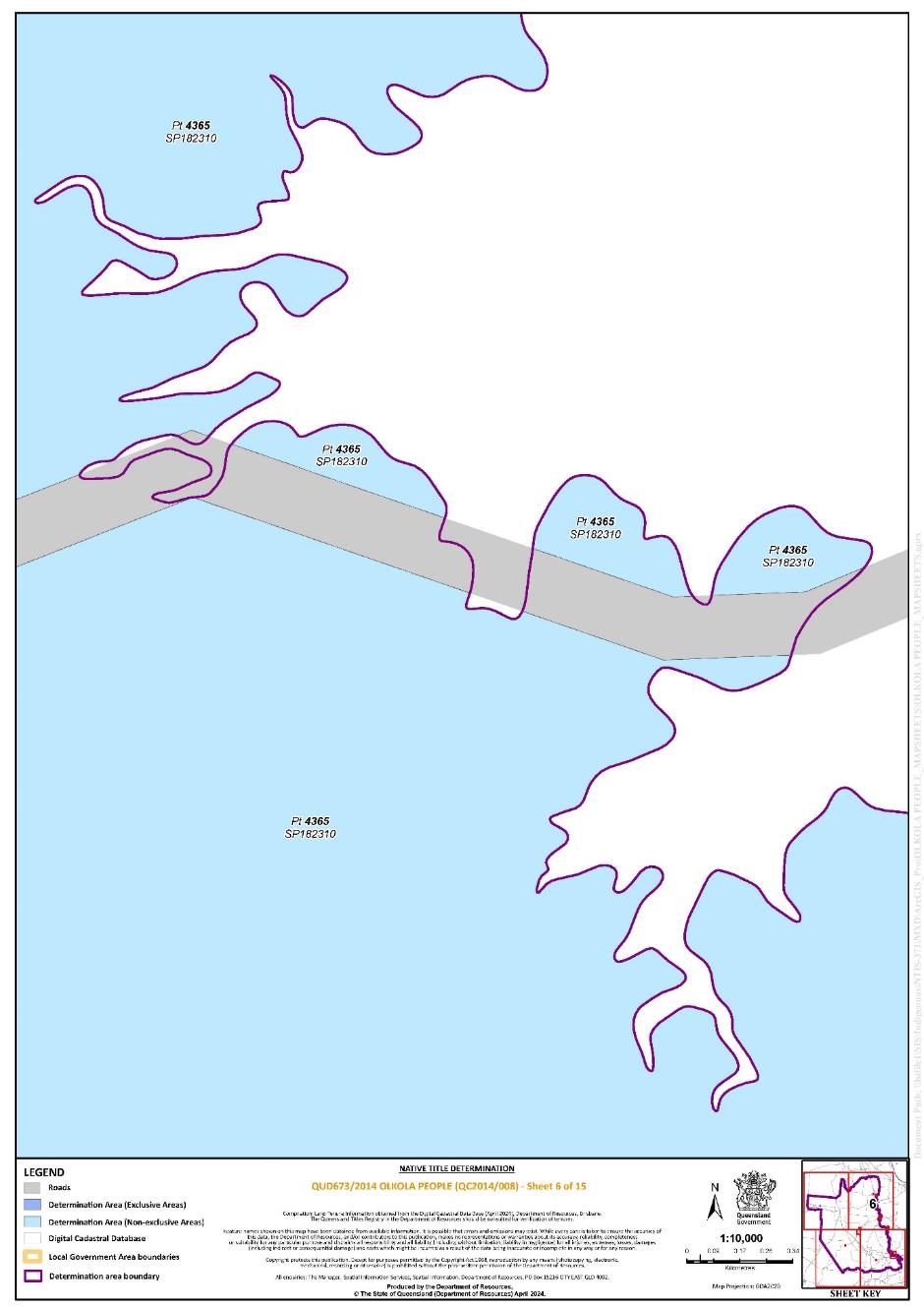

That part of Lot 4365 on SP182310 that falls within the External Boundary | Sheets 3, 6 and 7 |

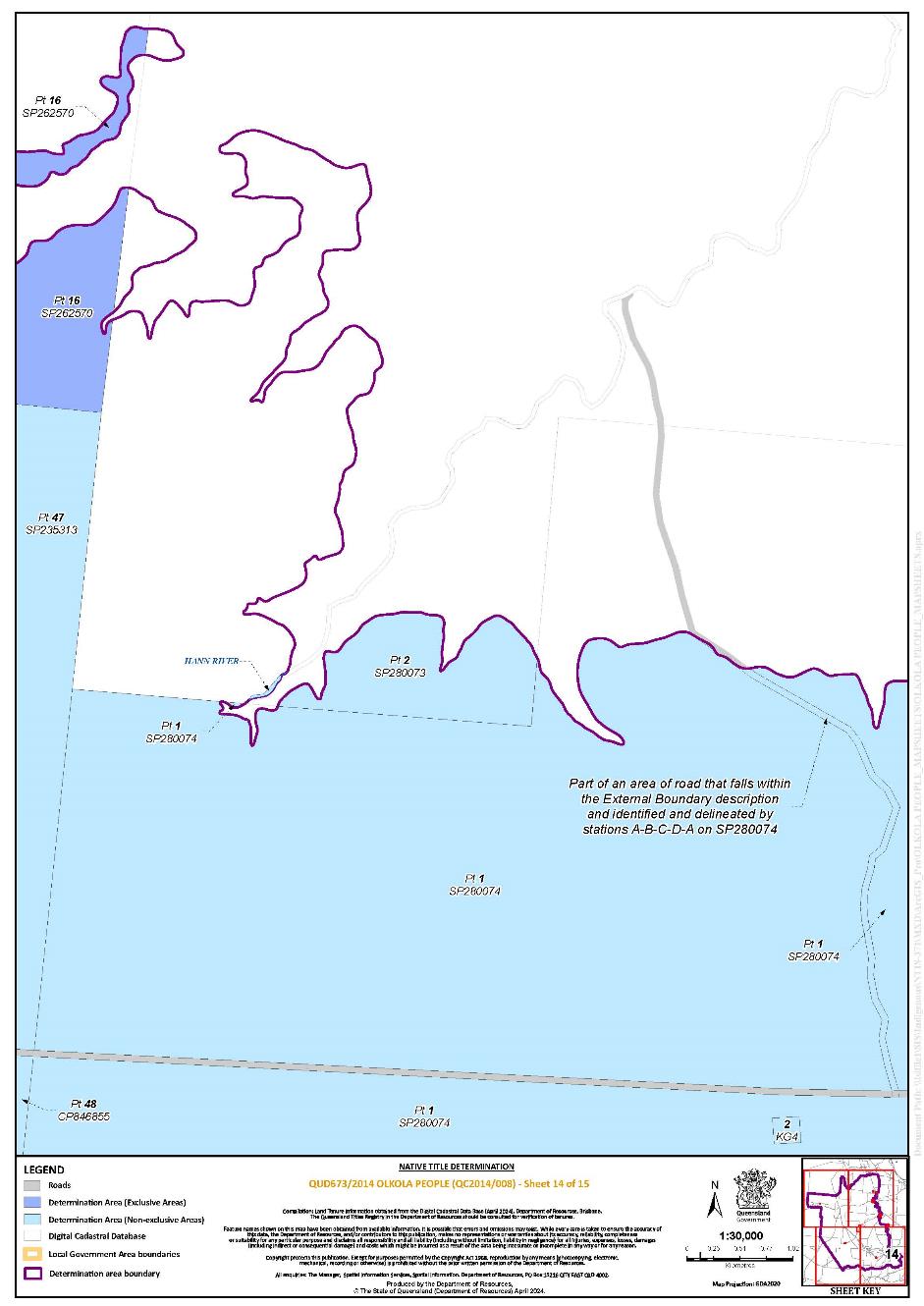

That part of Lot 2 on SP280073 that falls within the External Boundary | Sheet 14 |

That part of Lot 1 on SP280074 that falls within the External Boundary | Sheets 13 and 14 |

That part of an area of road that falls within the External Boundary and is identified and delineated by stations A-B-C-D-A on SP280074 | Sheet 14 |

Lot 2 on KG4 | Sheet 14 |

That part of Lot 2367 on SP284117 that falls within the External Boundary | Sheet 13 |

That part of an area of road that falls within the External Boundary and is identified and delineated by stations A-B-C-D-A on SP284117 | Sheet 13 |

That part of Lot 48 on CP846855 that falls within the External Boundary | Sheets 13 and 14 |

Lot 11 on SP266613 | Sheets 10 and 13 |

That part of Lot 3874 on SP273462 that falls within the External Boundary | Sheets 1 and 3 |

Lot 5 on KA835479 | Sheets 1 and 3 |

That part of Lot 4149 on PH31 that falls within the External Boundary | Sheet 1 |

That part of Lot 12 on CTH804427 that falls within the External Boundary | Sheet 10 |

That part of Lot 2 on CP848571 that falls within the External Boundary | Sheet 10 |

Lot 10 on SP201120 | Sheet 2 |

That part of Lot 5218 on PH1103 that falls within the External Boundary | Sheet 13 |

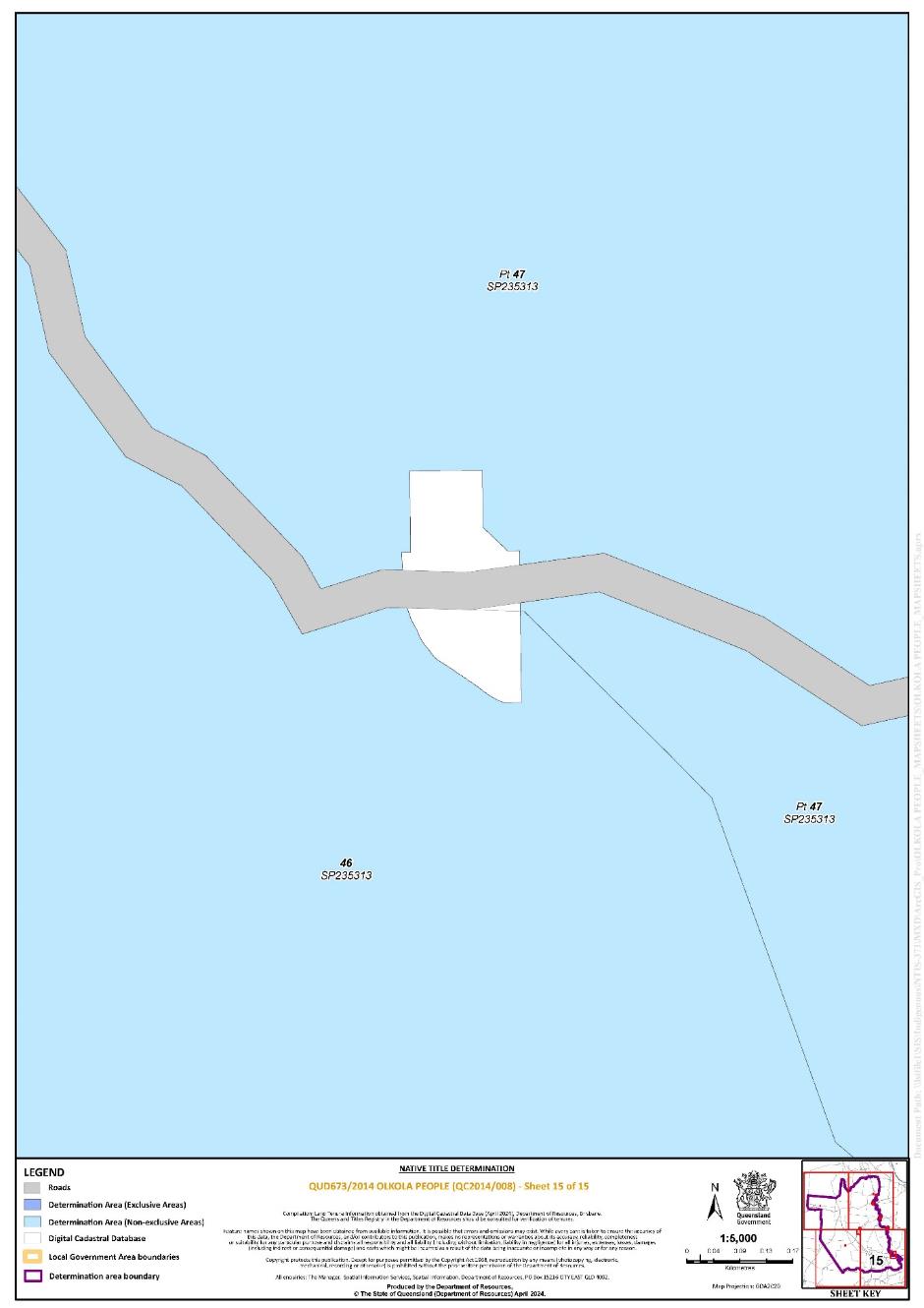

That part of Lot 47 on SP235313 excluding an area formerly described as Lot 1 on KG2 | Sheets 13, 14 and 15 |

Lot 46 on SP235313 | Sheets 13 and 15 |

Save for any waters forming part of a lot on plan, all rivers, creeks, streams and lakes within the External Boundary described in Schedule 3, including but not limited to: Ten Mile Creek; King River; Middle Spring; Brumby Creek; Pinnacle Creek; Granite Creek; Maddigans Creek; Jerry Dodds Creek; Alice River; One Mile Creek; Dickies Creek; Waterbag Creek; Eight Mile Creek; Spring Creek; Ethel Creek; Potallah Creek; O’Lane Creek; Emily Creek; Plane Creek; Morehead River; Water Branch Creek; Sugarloaf Creek; Dixie Creek; Emu Creek; Coleman River; Lucy Creek; Lindalong Creek; Dinah Creek; Alec Creek; Newirie Creek; Barwon Creek; Lightning Creek; Bamboo Creek; Batter Creek; Lukin River; Edward River; and Crosbie Creek. | |

Schedule 5 – Areas Not Forming Part of the Determination Area

The following areas of land and waters are excluded from the Determination Area as described in Part 1 of Schedule 4 and Part 2 of Schedule 4.

Part 1 – Areas excluded on the basis of extinguishment

1. Those land and waters within the External Boundary in relation to which one or more Previous Exclusive Possession Acts, within the meaning of s 23B of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) was done and was attributable to either the Commonwealth or the State, and to which none of ss 47, 47A or 47B of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) applied, as they could not be claimed in accordance with s 61A of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth).

2. Specifically, and to avoid any doubt, the land and waters described in paragraph (1) above includes:

(a) the Previous Exclusive Possession Acts described in ss 23B(2) and 23B(3) of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) to which s 20 of the Native Title (Queensland) Act 1993 (Qld) applies, and to which none of ss 47, 47A or 47B of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) applied, including but not limited to that part of Lot 47 on SP235313 subject to an area formerly described as Lot 1 on KG2.

(b) the land and waters on which any public work, as defined in s 253 of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth), is or was constructed, established or situated, and to which ss 23B(7) and 23C(2) of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) and to which s 21 of the Native Title (Queensland) Act 1993 (Qld), applies, together with any adjacent land or waters in accordance with s 251D of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth).

3. Those land and waters within the External Boundary that were excluded from the Native Title Determination Application on the basis that, at the time of the Native Title Determination Application, they were an area where native title rights and interests had been wholly extinguished, and to which none of ss 47, 47A or 47B of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) applied, including, but not limited to:

(a) any area where there had been an unqualified grant of estate in fee simple which wholly extinguished native title rights and interests; and

(b) any area over which there was an existing dedicated public road which wholly extinguished native title rights and interests.

Part 2 – Other excluded areas

1. Those land and waters described as that part of Lot 1 on WR2 and Lot 4 on KA835480 that fall within the External Boundary.

Schedule 6 – Determination Area Map

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

MORTIMER CJ:

INTRODUCTION

1 The parties have sought a determination of native title under s 87A of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth), with associated orders, recognising the native title of the Olkola People. This determination is being made on the same day as a determination recognising the native title of the Kunjen Olkol People, and the day before a determination recognising the native title of the Kowanyama People. Concurrently with these determinations, the Court also makes determinations recognising the jointly held native title of these groups over certain lands and waters, as well as a determination recognising the native title of the Southern Kaantju people over a parcel excluded from their previous determination, and a determination recognising the native title of the Kowanyama People over further independent parcels. Those determinations are being made on the papers.

2 This is the sixth group of determinations made in the Cape York United #1 proceeding, with the first having been made in November 2021.

3 Together, these determinations resolve parts of the Cape York United #1 claim, within geographic regions that have been described by the parties and in the Court’s case management timetables as the ‘Corrigan and Taylor 2 (Sefton Oriners) Timetable Area’, or simply the ‘Corrigan Report Area’, because those areas were the subject of reports by expert anthropologists Dr Brendan Corrigan and Dr John Taylor. This country is generally located in the central Cape York Peninsula area. As well as being neighbours, and sharing some country as some of the shared determinations being made in this round of determinations recognise, there are many kinship and traditional connections, including language and story connections, between the Olkola, Kunjen Olkol and Kowanyama Peoples.

4 The Olkola People’s traditional country lies to the north of the Kunjen Olkol People, and is agreed to encompass parts of the upper reaches of the Lukin and Coleman Rivers.

5 Like many other determinations in this proceeding, there are large areas in which exclusive native title is being recognised: for the Olkola People, approximately 812,216 hectares, being almost two-thirds of the determination area.

6 The Olkola People are a language-affiliated group comprised of many groups or family lines.

7 The material filed in support of the determination in favour of the Olkola People reveals the traditional connection of the Olkola People to the determination area, and the importance of that connection being passed down to future generations.

8 Mr Michael Ross, a senior Olkola man and the lead applicant in the entire Cape York United #1 claim proceeding, explains in his witness statement the importance of learning about, and being able to speak for, country:

The people who have the right to speak for country are from the families for the area and are the senior people with knowledge. I am one of the senior people that speaks for Kurrimbila country. But I am not the only one. Other family members also have a say depending on what the issue is, such as the Yam, Ross, Boxer, and Friday families. They all from our grandmother, Nanna Lily - from Brasso, that the line we come down. But you can’t speak for country just because you are from a family. You have to be introduced to country, taken into and learn about country. We have to sing out to the spirit to let them know who we are. You can’t just rock up and because you are a traditional owner you can do what you want. No we have protocols. I or other senior traditional owners have to take them there, warm them and put water on them. Tell the spirits that this one has been gone from country for a long time and he come back to learn and to visit and don’t hurt him. We sing to our spirit to let them know who they are.

9 The Court’s orders represent the long overdue recognition by Australian law of the land and waters of the Olkola People. The Court’s orders will assist the preservation and protection of Olkola country, as the Olkola People have done for thousands of years, so that their knowledge and law can continue to be passed down to future generations.

10 For the reasons set out below, the Court is satisfied it is appropriate to make the orders sought, and that it is within the power of the Court to do so.

THE MATERIAL BEFORE THE COURT

11 The applications for consent determinations were supported by two sets of submissions filed by the applicant on 3 June 2024: one in relation to seven of the determinations, and another relating to the Southern Kaantju #2 determination. The State also filed submissions on 7 June 2024. The Court has been greatly assisted by the parties’ submissions, and the material provided.

12 The applicant relied on a number of affidavits dealing with matters relevant to the determinations. First, an affidavit of Ms Kirstin Donlevy Malyon affirmed on 3 June 2024 (2024 Malyon affidavit). Second, an affidavit of Mr Parkinson Wirrick affirmed on 31 May 2024. Third, paragraphs [5] to [30] of an affidavit filed earlier in this proceeding by Ms Malyon on 27 October 2021 regarding the re-authorisation process undertaken by the applicant in the period from April to September 2021 (2021 Malyon affidavit). The State relied on an affidavit of Ms Carrie Tobler affirmed on 5 June 2024.

13 Ms Malyon is the Principal Legal Officer at the Cape York Land Council, and has had carriage of the Cape York United #1 claim. In the 2024 Malyon affidavit, she deposes to the process undertaken for determining appropriate group and boundary descriptions for each determination, and describes the way in which the Olkola People’s s 87A agreement was approved, including pre-authorisation and authorisation meetings.

14 Ms Malyon deposes to how the Ut-Alkar Aboriginal Corporation (ICN 10231) was nominated as the prescribed body corporate (PBC) for the Olkola People determination. She annexes to her affidavit the consent to the nomination of the Ut-Alkar Aboriginal Corporation (ICN 10231) to act as the PBC for the determination area. This PBC nomination was the subject of a challenge, which I discuss later in these reasons.

15 In relation to the Olkola People determination, the applicant relies on the following material to demonstrate there is a credible basis for connection, and to establish what material had been available to the State for the purposes of the s 87A agreement:

(a) expert report by Dr Corrigan dated 30 October 2017 and filed 31 October 2017;

(b) expert report by Ms Kate Waters dated 5 March 2018 and filed 6 March 2018;

(c) expert report by Dr Anthony Redmond dated 26 April 2023 and filed 31 May 2024;

(d) supplementary expert report by Ms Waters dated 26 April 2023 and filed 31 May 2024;

(e) supplementary expert report by Ms Waters dated 23 October 2023 and filed 31 May 2024;

(f) statement of Mr Mike Ross dated 10 June 2020 and filed 31 May 2024;

(g) apical report of Ms Waters dated 23 October 2023 regarding Jimmy Long (aka Brasso/Basil) filed 31 May 2024;

(h) apical report of Ms Waters dated 23 October 2023 regarding Old Lady Molly Long (aka Molly Barney) filed 31 May 2024;

(i) apical report of Ms Waters dated 23 October 2023 regarding Parry (father of Linda Long) filed on 31 May 2024;

(j) apical report of Ms Waters dated 23 October 2023 regarding Willie Long (aka Bamford) filed 31 May 2024;

(k) apical report of Ms Waters dated 24 October 2023 regarding Charlie (father of Linda Bob) filed 31 May 2024;

(l) apical report of Ms Waters dated 24 October 2023 regarding Nellie (mother of Linda Bob) filed 31 May 2024;

(m) apical report of Ms Waters dated 24 October 2023 regarding Paddy Cook filed 31 May 2024;

(n) apical report of Ms Waters dated 10 November 2023 regarding Charlie (spouse of Topsy/Bessie) filed 31 May 2024;

(o) apical report of Ms Waters dated 9 November 2023 regarding Charlie Sugarbag and Charlie Crocodile (siblings) and Mo Billy filed 31 May 2024;

(p) apical report of Ms Waters date 9 November 2023 regarding Georgina Lee Cheu Snr filed 31 May 2024;

(q) apical report of Ms Waters dated 12 November 2023 regarding Dick Callaghan, Topsy Callaghan and Mary Callaghan (spouse of Jack McIvor) filed 31 May 2024;

(r) apical report of Ms Waters dated 10 November 2023 regarding Frank Yam filed 31 May 2024.

16 It is apparent from the dates of some of this material that a careful and iterative process has been undertaken by the applicant, addressing any concerns of the State, explaining how debates with the neighbours of the Olkola People have been resolved, and ensuring that there was adequate material to support, in particular, the boundary and group descriptions proposed for this determination.

PROCEDURAL HISTORY

17 The Cape York United #1 claim was filed in this Court in December 2014. It covers various types of tenure, including pastoral leases, protected areas, reserves and areas of unallocated State land. It is the largest native title claim currently before the Court, and covers most of the undetermined parts of Cape York.

18 The complex procedural history and nature of the Cape York United #1 claim is summarised in the Court’s reasons for the Kuuku Ya’u and Uutaalnganu (Night Island) determinations made in November 2021: Ross on behalf of the Cape York United #1 Claim Group v State of Queensland (No 2) (Kuuku Ya’u determination) [2021] FCA 1464 at [3], [12]-[19], [30]-[37]; Ross on behalf of the Cape York United #1 Claim Group v State of Queensland (No 3) (Uutaalnganu (Night Island) determination) [2021] FCA 1465 at [3], [13]-[20], [28]-[35]. In addition to those determinations, there have been 16 further consent determinations made in this proceeding prior to this round of determinations, the most recent of which being the four determinations made in November 2023. The Court’s reasons in each of those determinations also note the complex and individualised process leading to each determination within the overall Cape York United #1 claim.

AUTHORISATION

The Olkola People section 87A agreement

19 Like the previous and completed s 87A processes in this proceeding, the process undertaken by the CYLC with the Olkola People native title group was methodical. Prior to the proposed authorisation of the s 87A agreement, there were two decision-making processes which needed to involve landholding groups: the process to settle boundaries between the Olkola People and their neighbours; and the process to settle group composition, by identification of apical ancestors.

20 The Boundary Identification Negotiation and Mediation or ‘BINM’ process was adopted by the applicant, through the CYLC, in April 2020 to deal with the reality existing within the Cape York United #1 claim area that distinctly identifiable groups hold interests in that area: see Kuuku Ya’u determination at [18], [25]-[26] and Uutaalnganu determination at [19], [23]-[24]. The BINM process was employed for the Olkola, Kowanyama People and Kunjen Olkol native title groups’ claims. This is what Ms Malyon describes in the 2024 Malyon affidavit at [57]-[74].

21 Putative boundary descriptions for the Olkola, Kowanyama People and Kunjen Olkol native title groups were developed from desktop research by the CYLC and Dr Redmond. They were provided to the State on 12 May 2023 on a ‘without prejudice’ basis. The boundary descriptions were prepared in consultation with anthropologists engaged by CYLC in relation to neighbouring areas.

22 Fieldwork and desktop research about boundaries was carried out between 2020 and 2022, noting that much of this had to occur under challenging conditions imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic and consequent restrictions. Following the provision of the putative boundary descriptions to the State in May 2023, the CYLC facilitated consultations with the Olkola, Kowanyama People and Kunjen Olkol native title groups. This commenced in July 2023 after approximately three years of consultation, research and reporting by Dr Redmond, following on from work done by Dr Corrigan. However, in his report, Dr Redmond states that his report is based on anthropological research in this area conducted since 2012.

23 For the Olkola, Kowanyama People and Kunjen Olkol native title groups, this consultation involved engaging Dr Redmond for a total of 11 days from July to December 2022 to consult with relevant families, elders and other key persons in the Cape York Region. It also involved engaging Mr Ray Wood, Dr Kevin Mayo, Dr Natalie Kwok and Mr Mark Winters as consultant anthropologists for neighbouring groups to discuss common boundaries, including those between the Thaypan, Possum and Western Yalanji native title groups, and the Lama Lama and Ayapathu native title groups.

24 The consultations helped identify who should attend meetings on behalf of the groups and their neighbours, and helped ensure that those people could attend those meetings. The consultations also helped inform the proposed descriptions for the groups.

25 The CYLC held ‘preliminary meetings’ between May 2023 and October 2023 with each of the Olkola, Kowanyama People and Kunjen Olkol native title groups to discuss boundaries, provide further information about the BINM process, and to receive instructions. The first tranche of the preliminary meetings were open to all members of the respective native title groups. The second tranche of the preliminary meetings were open to those representatives specifically nominated by their respective native title groups at the first tranche of meetings. Copies of the applicable notices were sent to all members of each of the native title groups on the CYLC contact database by post and email (where email addresses were available), and were notified on the CYLC website, CYLC Facebook page and community noticeboards.

26 The CYLC facilitated a number of ‘boundary meetings’ between neighbouring native title groups where instructions were taken as to final descriptions of common boundaries. These took place between April 2021 and October 2023. A CYLC lawyer and anthropologist were present at each boundary meeting. Each of the relevant consultant anthropologists were present for most meetings.

27 At the introductory session for the boundary meetings, each consultant anthropologist provided an overview of the available anthropological materials. The anthropologists supported and facilitated the participation of appropriate group representatives, providing advice and feedback to them about previous anthropological research, communicating their understanding of the research materials, assisting in the translation of maps (including the identification of any particular locations, landmarks or cultural sites), and helping to identify family affiliations to particular areas of country through recollection of genealogical data. Group representatives also had access to the CYLC’s genealogical records (subject to confidentiality), private break-out spaces, a series of maps and the State’s response to the putative boundary descriptions. At the end of the meetings, agreement as to boundaries by consensus was sought, and if there was agreement, it was recorded in written resolutions.

28 The Olkola, Kowanyama People and Kunjen Olkol native title groups met with their neighbours over a period of around two and a half years:

(a) Ayapathu, Lama Lama, Kuku Thaypan and Olkola native title groups: 20–21 April 2021;

(b) Thaypan, Possum, Kuku Warra, Olkola and Western Yalanji native title groups: 16 November 2022;

(c) Olkola and Kunjen Olkol native title groups: 10 October 2023;

(d) Kunjen Olkol and Kowanyama People native title groups: 11 October 2023; and

(e) Kunjen Olkol and Western Yalanji native title groups: 12 October 2023.

29 Members of the Olkola native title group attended these meetings, and agreement was reached as to boundaries.

30 Group descriptions for the Olkola, Kowanyama People and Kunjen Olkol native title groups were considered at various meetings during the fieldwork phase. In conjunction with the BINM process, the applicant provided to the State a number of reports relating to apical ancestors identified through the BINM who were to be included or excluded from the proposed group descriptions. This included 12 ancestor reports relating to the Olkola People. These reports are referred to at [15] above.

31 The s 87A agreements were settled and authorised after the BINM process, and the group description process, were complete. The Olkola People authorisation meeting was conducted on 29 February 2024. At that meeting, the group considered the terms of the Olkola s 87A agreement, and voted to direct the applicant to enter into that agreement.

32 What occurred at the Olkola authorisation meeting, and in the preparation leading to it, was the subject of two interlocutory applications filed in this proceeding on 8 April 2024, one by Olkola woman Ms Deborah Symonds, and one by the Olkola Aboriginal Corporation (OAC). Mr Ross is the director and chairperson of OAC and provided the principal affidavit in support of OAC’s application. In summary, those interlocutory applications challenged the decision made at the Olkola authorisation meeting to nominate the Ut-Alkar Aboriginal Corporation to be the PBC for the proposed Olkola determination, instead of OAC, and sought to deal with the consequences of OAC not being nominated as the PBC.

33 By orders and reasons delivered on 21 May 2024, the Court dismissed the interlocutory application by Ms Symonds challenging the decision at the Olkola authorisation meeting.

34 However, after the hearing of the interlocutory application by OAC, the active parties agreed on orders joining OAC as a respondent to these proceedings for the limited purpose of seeking to include an ‘Other Interests’ clause in the relevant determinations which would recognise the considerable interests held by OAC in the Olkola determination area. Mr Ross had set those interests out in his affidavit.

35 The Court’s orders and reasons can be found at Ross on behalf of the Cape York United #1 Claim Group v State of Queensland (No 23) [2024] FCA 533.

36 The applications by Ms Symonds and Mr Ross were clearly seriously considered, capably prepared and capably argued. The applicant and the State eventually recognised the force of the joinder application by agreeing to it. While the Court did not uphold the challenge to the decisions made at the Olkola authorisation meeting about the nomination of Ut-Alkar Aboriginal Corporation as the Olkola PBC, the Court did make some observations which pointed out some of the difficulties that arise where there is a genuine and serious debate within a native title holding group about matters such as the nomination of a PBC: see [95]-[102] of the Court’s reasons.

37 As I explained in the Kuuku Ya’u determination, finality is an important value in the Australian legal system, and that is especially so where property rights are concerned, because they are enforceable against the world. Native title rights are a particular kind of property rights. While seriously considered and arguable challenges such as those brought by Ms Symonds can certainly be made, if the challenges do not succeed, then the consequence is that the Court has upheld the validity of the process undertaken, and it is appropriate for that decision to be respected. It may not be easy for people to move on from such decisions by the Court, but it is important to try, so that the native title holding community can work together to make the most of the rights that are being recognised in this determination.

The authorisation of the Cape York United #1 applicant

38 The applicant’s authority to enter into the Olkola People s 87A agreement stems from the re-authorisation process undertaken between April and September 2021, in respect of the claim as a whole. Ms Malyon describes this process in the 2021 Malyon affidavit, and the Court described and endorsed it in Kuuku Ya’u determination at [30]-[37] and Uutaalnganu determination at [28]-[35]. In those determinations, I agreed with the State’s submission that the weight of authority supports the view that the Native Title Act affords flexibility to shape the content of an ultimate determination of native title, provided there is compliance with s 94A and s 225 of the Act. For that reason, I agreed with the State’s submission that the re-authorisation process for the applicant was lawful, and compliant with the Native Title Act. The applicant’s submissions also supported this approach, unsurprisingly. No objections were made by any other parties to the determinations.

39 Nevertheless, in Kuuku Ya’u determination at [38]-[50] and Uutaalnganu determination at [36]-[48], I explained why I considered it also appropriate to make orders under s 84D(4) of the Native Title Act to deal with any uncertainty arising from differences between the claim group description in the original Cape York United #1 application and those in the proposed s 87A determinations at a more local level, in light of the change in the way the claim was proceeding and the re-authorisation process.

40 Those orders were made under s 84D(4) out of an abundance of caution and to avoid any doubt about the validity of the s 87A determinations. At [50] in Kuuku Ya’u determination and [48] in Uutaalnganu determination, I said:

It is plainly in the interests of the administration of justice to do so, in circumstances where the overall Cape York United #1 claim is gargantuan, and has already consumed seven years’ worth of resources, mostly sourced from public funds. Substantial, dedicated and methodical efforts have been made to comply with the requirements of the Native Title Act in each step along the way to these first two determinations. Despite significant factual and legal challenges, the two key parties have navigated a consensual path to the recognition of native title for the Kuuku Ya’u and Uutaalnganu (Night Island) groups. All other respondents have been consulted and given opportunities to participate in the process as it has progressed. They have been included in steps in the complex timetables. All consent to the Kuuku Ya’u and Uutaalnganu (Night Island) determinations. If ever there was a situation in the Court’s native title jurisdiction where a favourable exercise of discretion by the Court is appropriate to ensure resolution of a claim to which all parties agree, this is that situation.

41 Similar orders are sought in each of the eight determinations being made in July 2024. The State agrees with this proposal. I adopt the above reasons in each of the eight determinations now made. For the reasons given in the extract above, I continue to consider such orders are appropriate.

THE CONNECTION OF THE OLKOLA NATIVE TITLE GROUP TO THE DETERMINATION AREA

42 Both Dr Corrigan and Dr Redmond presented a detailed analysis of the connection of the Olkola People, and other groups they were briefed to report on, to country in this Central West Cape York region. Their reports were informed by detailed consideration of historical, anthropological and archival records, as well as field research and interviews with members of the various native title holding groups over a long period of time.

43 As well as the material in each of these reports that comes directly from Olkola People, some of whom have passed away, the applicant also relied on a witness statement and annexures provided by Mr Ross, which contains a wealth of material, some of which I describe and extract below.

44 The applicant submits that, together, the connection material establishes a credible basis for the proposition that the Olkola, Kowanyama People and Kunjen Olkol native title groups have maintained their connection to their respective determination areas, under their respective traditional laws and customs since prior to sovereignty. The State supports that submission, and in making each of the determinations in favour of these groups, I have accepted those submissions.

45 Opinion evidence supporting the Olkola, Kowanyama People and Kunjen Olkol group descriptions, and the identification of apical ancestors, is found throughout the reports prepared by Ms Waters. Ms Waters’ work concentrates on the correct identification of apical ancestors, and is, like her other work for other determinations in this proceeding, meticulous. The State accepts this material, and there is no objection from the other parties to the present determinations.

46 The material from Olkola People themselves, whether recorded in anthropological reports or provided separately as Mr Ross’ witness statement was, described the lived experiences that ultimately provide the foundation for this determination. As I noted in the 2021 determinations, it is the group members who “live and understand their law and custom, and how it connects them to their country”: Kuuku Ya’u determination at [68]; Uutaalnganu determination at [59]. It is they who understand their family and kinship connections, who are the right elders to speak for various parts of their country, and who can explain the stories that go with certain parts of country.

47 In his witness statement, which repays careful reading, Mr Ross explains how he takes his mother’s line, and that she was named Kurrimbila (which means Grasshopper in Olkola) after the Kurrimbila story. He describes her as “a very senior Kurrimbila woman”, who passed away in 2014, and was between 96 and 98 years old. Mr Ross poignantly relates the stories of his mother’s forced removal from her family, of the 12 children she bore and of some of the traditional birth practices she engaged in.

48 Mr Ross explains that he has worked and travelled in many areas of Cape York, both as a ringer when he was younger and in his role as chairperson of the CYLC from 2005-2010. As he says, “[t]he best way to be on country was to get a job on country”, and this is how he learnt “a lot about country and the old people’s laws. The old people would tell me yarns”. While he has knowledge of a lot of country, including Yalanji country through some family connections, he explains he does not speak for that country, as he has not learnt from the old people. Mr Ross speaks for Kurrimbila country, as one of the senior people with knowledge.

49 In his statement, Mr Ross describes in detail the nature and extent of the rights in country. He explains how the right to speak for and make decisions about country operates (at [136]):

Our law says that the mob from the land speaks for that land. For example, for Oriners Station [T7], you have to talk to the Yam, Boxer, and Ross families. You talk to the oldest one in the family. If there is an issue, the mobs or families will send their people to make the decisions. We call a meeting and the families talk. If the decision is big decision, like a mine, then we need a big mob. That is what I have been told by the old fellas, like old Jerry Coleman.

50 Mr Ross explains how Sorry Business goes on his country (at [149]-[150]):

When one of the close family pass away you grow your beard. We have been told that from day one. You keep the beard until the family put a date on it. It could be a year. It’s called Sorry Business. All the deceased person’s gear is put it away until the day the family say. The person’s traditional country is also closed. People should not go to that country. If they do, they can get sick. Then on a day the family have a ceremony. That is the day you cut your beard and the family are invited to come in to take something as a memory of the person, like a pen or a knife. The rest of it, whatever is not gone, if the family don’t want it then you burn it. That day is also the day that the family will also say to open up the person’s traditional country again.

During the time the country is shut down, no traditional owner will access that country. While the country is shut down, the name of the deceased is not used. When the country is reopened, the belongings of the deceased are warmed up, smoked and their name can once again be used.

51 Mr Ross sets out the nature of some of the rights to access and use country (at [157], [159] and [181]):

In my country I can take what I want but I must still respect what I take and don’t take too much; that is the law. If you don’t follow the law, the spirit - our ancestors - and the country, the country get wild and you can get sick or your family can get sick.

…

If a person has connection through his mother or his father that doesn’t mean that he can go anywhere in that country because you still have to ask permission of the families for that area. It doesn’t matter how much connection you have. If I want to go flat rock fishing, I ask the families from the area. That is the law.

…

The big grasshopper Kurrimbila country is lancewood country which make the best shaft or handle for a spear. The lancewood is a very important tree to us and it is used for spear handles and woomera. When we take a tree, we have to talk language to it and ask permission to cut. You have to ask permission to cut it, you can’t just go and cut it down. You have to ask the land by singing out to the spirits that you are going to take handle for spear. You can get sick in that country if you don’t ask the land. We can only take one, only what we need. We can’t knock those trees down, and neither can anyone else. We don’t go hunting in that lancewood area in Olkola National Park as that place needs to be left alone. That is my grandmother’s Story there; I still sing out and ask for a handle before I take one.

52 It is clear from his statement that Mr Ross profoundly feels the duty to protect Olkola country, and to pass on knowledge of country to the younger generation. As he explains (at [187]-[189]):

I have walked all over my country and the neighbouring country. I have hunted and fished and learned the old ways and the Stories from the old people. The Stories are very important to us.

…

The Stories taught to us speak about how the land was created and why we have birds and animals. I know the Stories like, for example, where the Brolga and Emu fought, how the Kingfisher got his colour, and the Rainbow Serpent Story. I tell those Stories to younger generations when I take them out on country so that they can tell their kids. Olkola country is still very alive and powerful with those old Stories.

I go out there and look at country to check on things. Country has a strong way of drawing you back. It is like it is calling you home. I have a passion for my country; I can’t get enough of it. I take my boys and show them this place and that place. The more time I am out on my country, the happier I am. It is my job to teach them in a way that they understand and respect and so they develop the same passion for Olkola country as I have. Your heart is there and it becomes part of your body and spirit. That is the true traditional owner.

PROPER PARTIES TO THE PROCEEDING

53 It is necessary to address this issue first because of a submission made in this proceeding by the State of Queensland, and second because of uncertainty generated nationally by the decision in Arnaboldi v State of Queensland [2023] FCA 788. It is desirable for me to express my own opinion on this issue.

54 At a case management hearing before me on 1 March 2024 in this proceeding, the applicant and State proposed the following order, amongst others:

11. Everything done in the name of the State of Queensland in this proceeding from and including 3 February 2015 (the date on which the State of Queensland filed a Notice of Address for Service) to the date of this order, including filing and otherwise sending of documents in the name of the State of Queensland, is deemed to have been done by the State Minister for the State of Queensland under the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) on the date they were done.

12. Leave be granted for the State of Queensland to cease to be a party to this proceeding pursuant to s 84(7) of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth).

55 I infer, based on oral submissions on behalf of the State of Queensland, that these proposed orders were sought following the decision in Arnaboldi. The proposed orders extracted at [54] were not made by the Court on the basis that, at that stage, I was not persuaded that there was something irregular or inappropriate in the State of Queensland being a respondent in this proceeding.

56 The decision in Arnaboldi was handed down on 14 July 2023. Since then, approximately 19 consent determinations of native title have been made by the Federal Court, including four determinations of native title by consent in this proceeding. In each of these determinations, the Court was satisfied that it was appropriate to make a determination pursuant to ss 87 or 87A of the Native Title Act. Only one of those consent determinations has canvassed Arnaboldi. So far as I have been able to ascertain, no other State party in native title proceedings has sought orders in the nature of those sought by the State of Queensland in respect of a determination under ss 87 or 87A of the Native Title Act.

57 In a recent determination by consent in the Northern Territory pursuant to s 87 of the Native Title Act, Halley J considered the reasons in Arnaboldi: see Madrill on behalf of the members of the Amapete, Apwetyerlaneme, Atnweale and Warrtharre Landholding Groups v Northern Territory of Australia [2024] FCA 529. From [32]-[36] of Madrill, his Honour said:

The parties drew to the Court’s attention an apparent divergence of authority regarding the identification of the parties to a native title determination given the recent decision of this Court in Arnaboldi v State of Queensland [2023] FCA 788 (SC Derrington J). In Arnaboldi, the Court was asked to resolve a non-claimant native title determination application under s 86G of the Act. The parties submit that the decision of this Court in Arnaboldi ought not to be followed.

Section 86 enables the resolution of unopposed applications without a hearing, if each respondent party notifies the Court in writing that the proposed orders are not opposed. Justice SC Derrington considered that the language of s 84(4) required the State Minister to be a party, rather than the State qua State. Her Honour concluded that given the relevant State Minister was not also a party, the State Minister had not consented in writing pursuant to s 86G(2) of the Act and the Court was not able to conclude the application was “unopposed”.

It is reasonably arguable that the reasoning in Arnaboldi could also apply to s 87(1)(aa) of the Act, which requires that all parties to the proceeding are parties to the agreement as to the terms of a proposed order. As acknowledged by SC Derrington J in Arnaboldi at [10], however, any requirement that the State Minister, rather than the State, is a necessary party to a consent determination is inconsistent with “numerous” existing authorities. Any departure from those authorities would have profound consequences for the validity of previous consent determinations of native title.

For present purposes, it is not necessary to reach any concluded view on this issue. The Territory Minister in this case specifically endorsed the solicitor for the Northern Territory as the legal representative of the Respondent to consent to the Agreement. There was no evidence of any such endorsement or involvement of the relevant Minister in Arnaboldi. Moreover, the principles governing consent determinations pursuant to s 87 of the Act were considered in the decision of the Full Court in McLennan on behalf of the Jangga People #3 v State of Queensland [2023] FCAFC 191 at [27]-[32] (Perry, SC Derrington and Colvin JJ). The consent determination in Jangga was founded on the consent of the State of Queensland, not the State Minister. For present purposes, it is significant that although Jangga was determined after Arnaboldi, neither party in Jangga appears to have raised any concern about the Court’s power to make the consent determination in the absence of any consent from the State Minister and the Full Court made no reference to Arnaboldi in their reasons for judgment or expressed any concern that the State Minister was not a party to the agreement giving rise to the consent determination.

Further as submitted by the Applicant and Respondent, I am satisfied that the progress of this matter including the steps taken by the respondent in the proceeding, are sufficient to constitute implied notice to the Court that it is the intention of the Northern Territory and the Territory Minister that the Territory qua Territory seeks to be a respondent to these proceedings and to carry out the Northern Territory’s role in the capacity of parens patriae.

58 I respectfully agree with the observations of Halley J.

59 However, in these reasons, I consider it is appropriate to express a more concluded view, to attempt to place the role of s 84 of the Native Title Act in what I consider to be its correct context, thus avoiding the potentially highly disruptive consequences for the Court’s native title jurisprudence, and determinations, that may result from an overly narrow reading of s 84 and like provisions, and from the obiter statements in Arnaboldi.

60 Section 84 of the Native Title Act relevantly provides:

Coverage of section

(1) This section applies to proceedings in relation to applications to which section 61 applies.

Applicant

(2) The applicant is a party to the proceedings.

…

State or Territory Ministers

(4) If any of the area covered by the application is within the jurisdictional limits of a State or Territory, the State Minister or Territory Minister for the State or Territory is a party to the proceedings unless the Minister gives the Federal Court written notice, within the period specified in the notice under section 66, that the Minister does not want to be a party.

…

61 In my opinion, the correct meaning of s 84(1) is that the section is engaged where there is an application under s 61. In other words, s 84 is directed at parties other than a s 61 applicant.

62 The definitional provision in s 253 relevantly provides:

State Minister, in relation to a State, means:

(a) if there is no nomination under paragraph (b)—the Premier of the State; or

(b) a Minister of the Crown of the State nominated in writing given to the Commonwealth Minister by the Premier for the purposes of this definition.

63 And:

Territory Minister, in relation to a Territory, means:

(a) if there is no nomination under paragraph (b)—the Chief Minister of the Territory; or

(b) a Minister of the Territory nominated in writing given to the Commonwealth Minister by the Chief Minister for the purposes of this definition.

Commonwealth Minister means the Minister applicable, in relation to the provision in which the expression is used, under section 19 of the Acts Interpretation Act 1901.

65 There is no doubt that in each claim for a determination of native title, and in each claim for compensation for any loss, diminution, impairment or other effect of an act on native title rights and interests, government parties are necessary and appropriate parties. That is because of their own landholdings and proprietary interests across Australian land and waters, and also because of their representative role in respect of the communities they govern, communities which include First Nations Peoples, but include all people residing in each State and Territory, many of whom might also hold proprietary interests in land and waters, but many who will not and yet comprise the communities with a public interest in the recognition or non-recognition of native title according to law. In Farrer v Western Australia [2019] FCA 655; 369 ALR 324 at [42], I said:

Thus, the State’s responsibility is to satisfy itself there is a sufficient basis for concluding that the proposed determination is capable of meeting the requirements of s 225 of the Native Title Act. The way in which the State satisfies itself of that matter may vary considerably from case to case. No minimum requirements of proof can or should be set out. If the State embarks on such a course, and ultimately accepts it is appropriate to recognise the existence of native title in the determination area, then the Court is entitled to proceed on the basis the State has made a reasonable and rational assessment of the material to which it has been given access.

66 In Lovett on behalf of the Gunditjmara People v State of Victoria [2007] FCA 474, North J stated, in relation to the role of the State in the context of the requirements of s 87 of the Native Title Act, at [36] to [37]:

The focus of the section is on the making of an agreement by the parties. This reflects the importance placed by the Act on mediation as the primary means of resolving native title applications. Indeed, Parliament has established the National Native Title Tribunal with the function of conducting mediations in such cases. The Act is designed to encourage parties to take responsibility for resolving proceedings without the need for litigation. Section 87 must be construed in this context. The power must be exercised flexibly and with regard to the purpose for which the section is designed.

In this context, when the Court is examining the appropriateness of an agreement, it is not required to examine whether the agreement is grounded on a factual basis which would satisfy the Court at a hearing of the application. The primary consideration of the Court is to determine whether there is an agreement and whether it was freely entered into on an informed basis: Nangkiriny v State of Western Australia (2002) 117 FCR 6; [2002] FCA 660, Ward v State of Western Australia [2006] FCA 1848. Insofar as this latter consideration applies to a State party, it will require the Court to be satisfied that the State party has taken steps to satisfy itself that there is a credible basis for an application: Munn v Queensland (2001) 115 FCR 109; [2001] FCA 1229. There is a question as to how far a State party is required to investigate in order to satisfy itself of a credible basis for an application. One reason for the often inordinate time taken to resolve some of these cases is the overly demanding nature of the investigation conducted by State parties. The scope of these investigations demanded by some States is reflected in the complex connection guidelines published by some States.

67 The joint submissions of the applicant and the Northern Territory in Madrill are on the Court record. The matter has been finalised and therefore, generally, submissions then become publicly available. Accordingly, I see no difficulty in referring to them. Relevantly, the parties made the following submission:

The special role, and indeed obligation, of the State or Territory in carefully scrutinising claims for native title is recognised by the Act. It does not advance the objects of the Act to treat the consent of the Territory qua Territory as somehow less effective to convey the Territory’s approval of the proposed determination than the consent of a Territory Minister who has had no independent role in the proceedings.

(Footnotes omitted.)

68 See also Malone on behalf of the Western Kangoulu People v State of Queensland [2021] FCAFC 176; 287 FCR 240 at [207]-[208]. These observations have force in the context of the proper construction and operation of s 84(4), and like provisions in the Native Title Act.

69 In its provisions, the legislative scheme of the Native Title Act recognises the various roles of government, generally of the polity itself: see ss 24BD(2), 24CD(5), 24DE(3) and see generally Part 2, Division 3, Subdivision P.

70 An examination of the legislative scheme of the Native Title Act confirms that it cannot have been Parliament’s intention in s 84(4), nor other similar provisions, to constrain or restrict the States and the Territories, nor indeed the Commonwealth itself (by references to “Commonwealth Minister”), in how they choose to be represented and participate as a necessary party in Native Title Act proceedings.

71 In neither s 3 (objects of the Native Title Act) nor in s 4 (overview of the Native Title Act) does the scheme indicate any express or implied intention to restrict or constrain the way that a government party can choose to be represented in a native title claim, whether as an applicant (in a non-claimant application) or as a respondent. Nor is any express or implied intention discernible in the Preamble. Rather, the government entities referred to in the Preamble are referred to in the following way:

Governments should, where appropriate, facilitate negotiation on a regional basis between the parties concerned in relation to:

(a) claims to land, or aspirations in relation to land, by Aboriginal peoples and Torres Strait Islanders; and

(b) proposals for the use of such land for economic purposes.

72 Section 5 provides: