Federal Court of Australia

Davis v Military Rehabilitation and Compensation Commission [2024] FCA 736

ORDERS

Applicant | ||

AND: | MILITARY REHABILITATION AND COMPENSATION COMMISSION Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: | 9 JULY 2024 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Pursuant to s 31A(2) of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) and r 26.01(1)(a) of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth), judgment be entered in favour of the respondent for the whole of the proceeding.

2. The applicant pay the respondent’s costs of the interlocutory application filed on 29 April 2024, and the proceeding.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

SARAH C DERRINGTON J

INTRODUCTION

1 By its interlocutory application filed on 29 April 2024, the Military Rehabilitation and Compensation Commission seeks an order, pursuant to s 31A(2) of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (FCA Act) and/or r 26.01(1)(a) of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) for summary judgment in its favour, in relation to the judicial review proceeding commenced by Mr Andrew Davis by an originating application filed on 13 June 2023.

2 In the latter proceeding, Mr Davis seeks review of a decision of the Commission dated 15 May 2023 (the May 2023 Decision) under Ch 4 of the Military Rehabilitation and Compensation Act 2004 (Cth) (MRCA), concerning his entitlement to incapacity compensation payments. Mr Davis is currently receiving weekly payments pursuant to the provisions of the MRCA in the amount of $1,403.70 gross. He will continue to receive payments (in an amount subject to change) until 18 August 2047.

3 In a “Claim for Incapacity for Service/Work” dated 11 May 2023, Mr Davis had claimed that casual wages earned by him through the Department of Home Affairs (DHA), prior to him commencing his full-time position with Fire & Safety Industries (F&SI), ought be considered in the calculation of the civilian component of his ‘Normal Earnings’, notwithstanding that there was no period either before or after the date that he was discharged from the Australian Defence Force (ADF) in which he simultaneously derived earnings from both the DHA and F&SI.

4 On 17 May 2023, a delegate on behalf of the Department of Veteran Affairs (DVA) communicated to Mr Davis by email that his “Claim for Incapacity for Service/Work” had been denied and attached the May 2023 Decision. Mr Davis asserted that, in the making of the May 2023 Decision, he was denied procedural fairness, procedural requirements were not followed, the decision involved an error of law, and it accounted for an irrelevant consideration.

5 Except for Mr Davis’ assertion that the May 2023 Decision involved an error of law, his complaints rise no higher than ones as to findings of fact that were solely within the province of the decision-maker and, although susceptible to merits review, are not the proper subject of an application for judicial review.

6 In support of its application for summary judgment, the Commission relied on two affidavits of Ms Lindsay Cooper (Senior Lawyer – AGS) dated 19 April 2024 (the First Cooper Affidavit) and 29 April 2024 (the Second Cooper Affidavit), written submissions filed on 29 April 2024 and reply submissions filed on 13 May 2024. Two further affidavits of Ms Cooper dated 13 May 2024 and 16 May 2024) (the Fourth Cooper Affidavit) were subsequently filed by the Commission.

7 Mr Davis relied on written submissions filed on 7 May 2024 and three affidavits to oppose the application, one by Mr Davis dated 7 May 2024, and two by Mr Matthew Jensen dated 7 May 2024 and 14 May 2024. Mr Jensen describes himself as a “Representative Advocate for Veterans”. His affidavits were read, but as they contained matters of opinion and comment, I have treated them as submissions made on behalf of Mr Davis. They are of no probative value. I also note that both parties, by their written submissions, made arguments about the appropriateness of Mr Davis’ complaint in respect of the May 2023 Decision being heard on a merits review. Those matters are not relevant to the current application, and I have no regard to them.

8 For the reasons that follow, I am satisfied that Mr Davis has no reasonable prospects of succeeding on his application for judicial review. It is, therefore, appropriate to grant summary judgment in favour of the Commission.

BACKGROUND

Entitlement to incapacity payments

9 Mr Davis served during peacetime as a part-time Reservist in the ADF. He claims the period of his service was from 28 November 2011 until 19 February 2019. Although nothing turns on it in the current proceeding, documents filed by the Commission refer to his service commencing from 23 November 2017: First Cooper Affidavit LJC-4. In the course of his service, Mr Davis was injured and medically discharged from the ADF. It is not disputed that, as a result of his injuries, Mr Davis was, and remains, entitled to compensation from the Commonwealth for incapacity for work: MRCA ss 118(1) and 319(1). It is also apparent that his injuries are accepted by the Commission to amount to a total permanent incapacity.

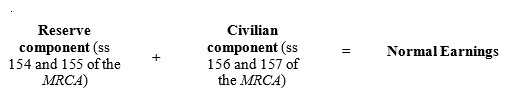

10 The amount of Mr Davis’ incapacity payments is determined according to his Normal Earnings (NE). In the role of a part-time Reservist, engaged in civilian work, his NE were calculated, for a weekly period, according to the formula set out at s 153(1) of the MRCA, reproduced below:

11 The relevant history of Mr Davis’ entitlement to incapacity payments can be stated shortly. On 4 February 2019, by his initial “Claim for Incapacity for Service/Work” received on 7 December 2018, the Commission determined the civilian component of Mr Davis’ NE according to his casual employment with the DHA, which was calculated to be $749.38 gross per week. Mr Davis last received earnings for hours worked at the DHA on 24 January 2019.

12 Mr Davis subsequently applied for review of the 4 February 2019 decision, which had incorrectly determined his discharge date as 22 January 2019, rather than 19 February 2019. By a decision of 9 April 2020, the 4 February 2019 decision was set aside, and Mr Davis’ entitlement to incapacity payments was recalculated. The civilian component of Mr Davis’ NE was determined based on his payslips from F&SI, calculated as $1,442.31 gross per week. Mr Davis had begun working at F&SI on 28 January 2019, with an annual income of $75,000.

13 Having sought a further review of the decisions of 4 February 2019 and 9 April 2020, a decision dated 29 May 2020 set aside both prior decisions, due to “a higher history of reserve days”. Mr Davis’ entitlement was, again, recalculated, and the civilian component of his NE was, again, determined according to his F&SI earnings. Following the 29 May 2020 decision, on 10 June 2020, Mr Davis withdrew his appeal to the Veterans’ Review Board (VRB), on the basis that,

[t]he DVA have issued a new determination letter under S347 MRCA dated 29/05/2020 and I am satisfied with this written decision and how my incapacity payments are being calculated.

14 For reasons that are unexplained, some three years later, Mr Davis apparently became aware that wages from his past casual employment with the DHA were not (but, allegedly, should have been) accounted for in the civilian component of his NE. On 1 May 2023, he emailed the General Enquiries email address of the DVA, advising that “the Delegate calculating [his] discharge pay (Military and Civilian) did not offer the opportunity to calculate [his] ‘casual’ work” and that this “[had] therefore impacted calculations moving forward”. Mr Davis asked for the “correct form to be completed” to rectify the alleged miscalculation of his entitlement.

15 On 11 May 2023, Mr Davis submitted the relevant “Claim for Incapacity for Service/Work” to the DVA, seeking that his NE be recalculated to account for his DHA wages. He also provided payslips from the DHA that represented a 12 week period of employment from 1 November 2018 to 20 February 2019, and a breakdown of wages paid during that period. That breakdown, however, showed that Mr Davis had not worked any hours for the DHA after 30 December 2018, nor received any earnings from 25 January 2019 to 19 February 2019. Relevantly, Mr Davis calculated the total of his additional earnings from the DHA to be $4,961.71, which he divided by 12 weeks, the quotient of which (being $212.41) he claims represents his weekly earnings from DHA to be accounted for in the calculation of the civilian component of his NE.

16 On 17 May 2023, a delegate from the DVA informed Mr Davis by letter dated 15 May 2023 that, pursuant to s 131 of the MRCA, his “Claim for Incapacity for Service/Work” had been denied, on the basis that “the current rate of [his] incapacity payment taking into account [his] civilian component of Normal Earnings is correct”. Relevantly, that letter also stated:

The Veteran Review Board re-assessed your entitlement from the commencement of your incapacity payments and determined that it would be more beneficial to calculate the civilian component of your normal weekly earnings based on Fire & Safety Industries. This resulted in a weekly civilian earnings calculation of $1,442.31 gross per week.

Your employment with the Department of Home Affairs and Fire & Safety Industries are viewed as two separate employment periods and do not overlap. As a result the Veteran Review Board have used the more financially beneficial employment period being your full time employment with Fire & Safety Industries.

…

I have determined the current rate of your incapacity payment continues to be $1,403.70 pre-tax per week for the period from 11 May 2023 to 18 August 2047 …

…

If you would like us to review this decision

You can ask for a review within 12 months of receiving this letter. Please set out your response in writing and email to [xxxx]@dva.gov.au or post to GPO Box [XXX], Brisbane QLD 4001. You can go to www.dva.gov.au/appeals for details.

(Emphasis added.)

17 The reference to the “Veteran Review Board” in the first sentence of the letter as set out above is an error. Mr Davis had applied to the VRB for a review of the decisions dated 4 February 2019 and 9 April 2020. As is apparent from the 29 May 2020 decision referred to at [13] above, a Review Officer decided to set aside the decisions before Mr Davis’ application reached the VRB for determination. Mr Davis was then invited to either seek a review of the Review Officer’s decision by the VRB, or to withdraw his application. On 10 June 2020, as has already been mentioned, he took the latter course.

18 In response to the delegate’s email of 17 May 2023, Mr Davis responded on the same day, asserting that, in substance, the decision to deny the claim did not properly account for ss 157(1) and (2) of the MRCA:

Good morning

Had you contacted me prior in accordance with DVA’s Natural Justice Consideration and Prior Warning of Adverse Decisions policy I could have further explained the situation with regard to Home Affairs.

The periods did over lap.

My earnings in January were impacted by a workplace fall (as per the documents provided). I took the last two weeks of January off to have a break, and during the first two weeks at Fire and Safety Industries I was required to travel away from Brisbane.

MRCA s157(1) being applied to the scenario I actually earned $631.87 on 7 February 2019. Which should provide compensation of $315.93 per week.

MRCA s157(2) allows the Commission to utilise another period it considers reasonable if the two weeks prior to discharge would not fairly represent the daily rate. Hence I provided a broad “range” of weeks to fairly represent that some weeks were higher and lower, and given this was casual employment on top of another full time job the ongoing involvement decreased. Therefore I submit the 12 week average figure of $212.41 per week fairly represents the amount paid before ceasing to be a member of the Defence Force.

This earnings should definitely be included in the ongoing … calculations.

(Emphasis added. Errors in original.)

19 On 22 May 2023, a Claims Support Officer from the DVA advised Mr Davis by email that his email was “currently in [the] delegates’ inbox for … review”. On 26 May 2023, the delegate responded to Mr Davis’ email of 17 May 2023, stating, relevantly:

In relation to the matter concerning the calculations of your Normal Earning, the Veteran Review Board has previously re-assessed your entitlement and any further reviews needs to be undertaken through the Appeals process for external review.

Please set out your reasons in writing and email … or post … You can go to www.dva.gov.au/app=alS for details.

(Emphasis added. Errors in original.)

20 On the same day, Mr Davis responded by stating that “[t]he matter of Home Affairs [had] never been raised until now, as no one told [him] at the time it was eligible to be assessed”.

21 On 5 June 2023, the delegate again advised Mr Davis that any further reviews had to be undertaken externally, and that, alternatively, he “may be able to appeal with” the Administrative Appeals Tribunal (AAT) (emphasis added).

Summary of procedural history

22 On 7 June 2023, Mr Davis commenced this proceeding.

23 On 23 June 2023 and 3 October 2023 respectively, Mr Davis requested that the Commission “review what has occurred and act according to law” and advise whether it “will reconsider this matter according to law”: First Cooper Affidavit [7.1]. The Commission, through its legal representatives, Australian Government Solicitor (AGS), responded substantively on 13 October 2023, advising Mr Davis, inter alia, that, as a consequence of his request for a further review, it had begun progressing the VRB merits review process: First Cooper Affidavit [8].

24 On 13 October 2023, Mr Davis informed AGS that he would request that the Court “expedite the matter …”: First Cooper Affidavit [10].

25 By letter dated 9 November 2023, AGS advised Mr Davis, inter alia, that “the appropriate recourse for review of the 15 May 2023 decision was the VRB review pursuant to s 352 of the [MRCA] and the further merits review in the Administrative Appeals Tribunal subsequently available” under s 354(1) of the MRCA: First Cooper Affidavit [11.2]. Mr Davis was also advised that, if he discontinued his application for judicial review, the Commission would bear its own costs in respect of that application: First Cooper Affidavit [11.3]. Mr Davis asserted that, by email dated 15 November 2023, he had “not requested [the] matter be transferred to the VRB”: First Cooper Affidavit [15].

26 On 15 April 2024, Ms Cooper again sent a letter to Mr Davis, advising of, inter alia, the availability of merits review: First Cooper Affidavit [20]. That letter also drew Mr Davis’ attention to the observations of Meagher J in Davis v Military Rehabilitation and Compensation Commission [2024] FCA 322 (Davis per Meagher J), involving the same parties as in this proceeding, where Her Honour, at [99], observed:

It is … disappointing that, notwithstanding Logan J drawing the applicant’s attention to other means by which grievances might be resolved, namely by way of application to the VRB and then, if necessary, the AAT, the applicant felt obliged to bring a further application in this Court. … [T]he applicant has had numerous claims for tolls paid over the last four years. The evidence does not support that the only way he can [seek the relief sought] is by bringing an application to the Court, which begs consideration of the important public interest in the appropriate use of judicial resources.

(Emphasis added.)

27 At the case management hearing on 23 April 2024, Mr Davis insisted that his alternative review options were “not mandatory under section 10 [of the Administrative Decisions (Judicial Review) Act 1977 (Cth) (ADJR Act)]”. Having been warned about the obligations of litigants under ss 37M and 37N of the FCA Act, Mr Davis submitted that the “case has got significant public interest” and that “if … the respondent is interpreting the legislation in an incorrect manner, … that judicial interpretation can only be rectified by this forum”, being the Federal Court of Australia.

SUMMARY JUDGMENT

28 This Court may grant summary judgment pursuant to s 31A of the FCA Act, which relevantly provides:

31A Summary judgment

…

(2) The Court may give judgment for one party against another in relation to the whole or any part of a proceeding if:

(a) the first party is defending the proceeding or that part of the proceeding; and

(b) the Court is satisfied that the other party has no reasonable prospect of successfully prosecuting the proceeding or that part of the proceeding.

…

(3) For the purposes of this section, a defence or a proceeding or part of a proceeding need not be:

(a) hopeless; or

(b) bound to fail;

for it to have no reasonable prospect of success.

29 Section 31A is supplemented by r 26.01 of the Rules, by which a party may apply for summary judgment. That rule provides, relevantly:

26.01 Summary judgment

(1) A party may apply to the Court for an order that judgment be given against another party because:

(a) the applicant has no reasonable prospect of successfully prosecuting the proceeding or part of the proceeding …

…

30 The principles governing summary judgment are well established and it is not necessary that they be restated: Spencer v Commonwealth [2010] HCA 28; 241 CLR 118 at [56]-[60] per Hayne, Crennan, Kiefel and Bell JJ; see Leach v Burston [2022] FCA 87 at [36] per Halley J; Prior v South West Aboriginal Land and Sea Council Aboriginal Corporation [2020] FCA 808 at [29] per McKerracher J.

31 It is, however, important to reiterate that the power to dismiss an action summarily is not to be exercised lightly: Spencer at [24] and [60]; Burrows v The Ship ‘Merlion’ [2024] FCA 220 at [72]. Nonetheless, as I said in The ‘Merlion’ at [72], merely because complexity exists in the underlying issues, courts should not shy away from granting summary judgment where, after considering the facts and law of the present case, the outcome of the disputation is apparent: ThoughtWare Australia Pty Limited v IonMy Pty Ltd [2023] FCA 906 at [53]. If it is clear that the outcome of a proceeding will not be altered by the holding of a trial, it is apposite to the proper administration of justice to require the parties to be put to the effort and expense of conducting a full hearing: ThoughtWare at [53]; Theseus Exploration NL v Foyster (1972) 126 CLR 507; FCA Act ss 37M and 37N. As I also stated in The ‘Merlion’ at [73]:

As the assessment of the prospects of success under s 31A necessitates the making of a value judgment in the absence of a “full and complete matrix of fact and argument thereon”, the judge hearing the summary judgment application has discretion: Kowalski v MMAL Staff Superannuation Fund Pty Ltd (2009) 178 FCR 401; [2009] FCAFC 117 at [28]. Therefore, when determining whether there is a reasonable prospect of success, much will depend on the case at hand, and “no hard and fast rule can be laid down as to when summary judgment is available”: Polar Aviation Pty Ltd v Civil Aviation Safety Authority (No 4) (2011) 203 FCR 293 at [17].

THE GROUNDS OF REVIEW

32 In his originating application, Mr Davis identified three grounds on which he challenged the May 2023 Decision and which he asserted had sufficient prospects of success to defend the Commission’s application for summary judgment. Those grounds were articulated as:

1. A breach of the rules of natural justice occurred in connection with the making of the decision.

2. Procedures that required by the law to be observed in connection with the making of the decision were not observed.

3. The decision involved an error of law.

33 At the case management hearing on 23 April 2024, at which Mr Davis was self-represented, particulars of those grounds were sought by the Commission. In an effort not to delay the hearing of the matter, the particulars of those grounds were discerned from discussion with Mr Davis during that hearing. As to the first ground, Mr Davis contended that the relevant denial of procedural fairness was the failure of the Commission to inform him of its likely decision prior to making the May 2023 Decision. As to the second ground, Mr Davis contended that the Commission “had not considered s 157(1) and s 157(2) of the MRCA”. Mr Davis, however, did not articulate what procedure was required by s 157(1) or s 157(2). Nonetheless, this is, in effect, a complaint that an error of law was made. As to the third ground, Mr Davis contended that the Commission had misconstrued s 157 of the MRCA “as being subject to one of the s 157 example periods”.

34 By the time of the hearing on 17 May 2024, Mr Davis was represented by a solicitor who, in a somewhat unorthodox manner, was assisted at the Bar table by Mr Jensen. Mr Jensen rose at various times throughout the hearing to correct or elaborate on matters articulated by Mr Davis’ solicitor.

35 The grounds of review were framed in the following way. First, Mr Davis relied on s 5(1)(a) of the ADJR Act to contend that the Commission’s delegate was obliged (and failed) to accord him procedural fairness. Secondly, he relied on s 5(1)(b) to contend that the delegate failed to adhere to the requirements of s 157 of the MRCA. Thirdly, he relied on s 5(1)(f) to contend that the Commission “misconstrued the approach to [their] determination as being subject to one of the s 157 example periods”.

36 At the hearing, I granted Mr Davis leave to rely on an additional ground in opposing the application, which is with respect to s 5(1)(e). As such, his fourth ground is that the delegate took into account an irrelevant consideration (s 5(2)(a)), being that the “Veteran Review Board made a decision”, where Mr Davis alleged that no such decision was made. It was agreed, however, that the reference to the “Veterans Review Board” in the May 2023 Decision was an error of fact.

Ground 3 – Construction of s 157

37 It is convenient to deal with Ground 3 first. In oral submissions, Mr Davis’ solicitor accepted that if Ground 3 had no prospects of success, the other Grounds of review fell away. The gravamen of Ground 3 is that the delegate had, in contravention of s 5(1)(f) of the ADJR Act, committed an error of law by “misconstruing” the approach to determining NE under s 157 “as being subject to [the example period under subsection (1)]” rather than a different example period under subsection (2). His submission, in short, is that “S157(1) may work as an example period of incapacitated service personnel who were full-time employed by a single employer but it does not work for reservists who may have multiple sources of income from several employers or businesses or self employment” (errors in original). As a result of what is alleged to be an erroneous reading of the section by the delegate, Mr Davis contended the delegate’s decision to discount his DHA earnings in calculating the civilian component of his NE means that his current rate of incapacity payments do not properly reflect his civilian earnings.

38 Mr Davis submitted that “[t]he legislative regime requires the comprehensive determination of ‘normal earnings’ prior to reliance on s 157(1), as the determination of ‘normal earnings’ may necessitate as fair and reasonable the enlivening of the requirement to exercise the discretion in [s 157(2)] and choose a different example period” (emphasis added).

39 I have summarised the relevant underpinnings of Mr Davis’ construction of s 157 below, which were explained in the following terms:

• The “statutory purpose of ss156 and 157 MRCA is to provide compensation for incapacity for work for former members who were reservists by establishing the totality of their sources of income and then determining the appropriate example period” (errors in original).

• Section 157 “requires the [Commission] to determine the best example period to reflect the entirety of [a person’s] normal earnings …”. While “S157 defines the example period for the purposes of the calculation pursuant to the s156 formula”, the use of that example period in s 157(1) “is only fair when the applicant has identified only one source of uncontested continuously engaged civilian employment” (errors in original).

• Section 157(2), therefore, “may enliven the need for a different example period because [Mr Davis’] ‘normal earnings’ are derived from more than one source” and at “varying times and rates” (errors in original). The enlivening of the discretion in s 157(2) is “obtained by an investigation … into the civilian employment of the person, and whether that investigation shows a true indication of the ‘normal’ civilian employment”.

40 Contingent on the acceptance of this construction is Mr Davis’ contention that the delegate “did not correctly understand their task in calculating the quantum of the civilian component of [Mr Davis’] normal earnings in the context of s 156 and s157” and – flowing from that apparent misunderstanding by the delegate – she “made an error of law by concluding that the ‘normal earnings’ … were only the [F&SI] … earnings” and “[viewing] the … [DHA] employment as a separate employment period” (errors in original).

Principles of construction

41 The principles of statutory construction are well settled and need only be shortly summarised. The paramount consideration in any exercise of statutory construction is that a court must give effect to what Parliament has enacted. A provision must be construed as a whole, and consistently with the language and purpose of all provisions of the relevant statute: see Project Blue Sky Inc v Australian Broadcasting Authority [1998] HCA 28; 194 CLR 355 at [69] per McHugh, Gummow, Kirby and Hayne JJ; SZATL v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection [2017] HCA 34; 262 CLR 362 at [14] per Kiefel CJ, Nettle and Gordon JJ; Mondelez Australia Pty Ltd v Automotive, Food, Metals, Engineering, Printing and Kindreds Industries Union [2020] HCA 29; 271 CLR 495 at [13] per Kiefel CJ, Nettle and Gordon JJ.

42 In construing a provision, the Court must begin with the text of the statute. Other indicia of meaning include the relevant context (which includes relevant statutory provisions), the general purpose and policy of a provision, and the fairness and consistency of its operation: see Mondelez at [13]; The Queen v A2 [2019] HCA 35; 93 ALJR 1106 at [33] per Kiefel CJ and Keane J, with Nettle and Gordon JJ agreeing generally at [14]; Certain Lloyd’s Underwriters v Cross [2012] HCA 56; 248 CLR 378 at [24] per French CJ and Hayne J, applying Project Blue Sky at [69]; see Taylor v Public Service Board (NSW) [1976] HCA 36; 137 CLR 208 at 213 per Barwick CJ.

43 In CIC Insurance Ltd v Bankstown Football Club Ltd [1997] HCA 2; 187 CLR 384 at 408 per Brennan CJ, Dawson, Toohey and Gummow JJ, the High Court set out what is referred to as the modern approach to statutory interpretation:

[T]he modern approach to statutory interpretation (a) insists that the context be considered in the first instance, not merely at some later stage when ambiguity might be thought to arise, and (b) uses ‘context’ in its widest sense to include such things as the existing state of the law and the mischief which, by legitimate means such as those just mentioned, one may discern the statute was intended to remedy.

(Emphasis added.)

44 The exercise of statutory construction is assisted by reference to extrinsic materials, as to relevant context: Minister for Immigration and Multicultural and Indigenous Affairs v Nystrom [2006] HCA 50; 228 CLR 566 at [98] per Heydon and Crennan JJ, with Gleeson CJ agreeing. Section 15AB of the Acts Interpretation Act 1901 (Cth) states, relevantly, as follows:

Use of extrinsic materials in the interpretation of an Act

(1) Subject to subsection (3), in the interpretation of a provision of an Act, if any material not forming part of the Act is capable of assisting in the ascertainment of the meaning of the provision, consideration may be given to that material:

(a) to confirm that the meaning of the provision is the ordinary meaning conveyed by the text of the provision taking into account its context in the Act and the purpose or object underlying the Act; or

(b) to determine the meaning of the provision when:

(i) the provision is ambiguous or obscure; or

(ii) the ordinary meaning conveyed by the text of the provision taking into account its context in the Act and the purpose or object underlying the Act leads to a result that is manifestly absurd or is unreasonable.

The relevant legislation

45 It is useful to state shortly the key sections of the MRCA that create the legislative framework for calculating the relevant incapacity payments.

46 The Commission is established by the MRCA: s 361. Section 362 states, relevantly:

362 Functions

(1) The functions of the Commission are as follows:

(a) to make determinations under this Act relating to:

(i) acceptance of liability; and

(ii) the payment or provision of compensation; and

(iii) the provision of services for treatment and rehabilitation;

…

47 Pt 4, Ch 4 of the MRCA governs the payment of compensation to former members who are incapacitated. For the purpose of the MRCA, compensation is defined as compensation under the MRCA, and former member is defined as a person who has ceased to be any of a member of the Defence Force, a cadet, a person to whom s 7A applies, or a declared member: s 5.

48 Under s 118 of the MRCA, the Commonwealth is liable to pay compensation to a person who satisfies certain conditions set out under subsection (1):

(a) the person is a former member; and

(b) the Commission has accepted liability for a service injury or disease of the person; and

(c) the service injury or disease results in the person’s incapacity for work for the week; and

(d) a claim for compensation in respect of the person has been made under s 319.

49 Where a person to whom the Commonwealth is liable to pay compensation has not chosen to receive a Special Rate Disability Pension under Pt 6, the amount of compensation payable to that person is calculated under Division 2: s 118(2)(b). Under Division 2, s 125(1) designates that, generally, the amount of compensation for former members is determined under Subdivision C, where no Commonwealth superannuation benefit is received, and which relevantly includes a claim for a former member pursuant to s 319: ss 118 and 319(1)(d). Subdivision C provides for the calculation of compensation for: maximum rate weeks (s 129); the week whose hours exceed 45 times the normal weekly hours (s 130); and after 45 weeks (s 131). The amount worked out under any of ss 129, 130 and 131 is by the relevant mathematical formula under each section.

50 Notwithstanding whether an amount of compensation is calculated under ss 129, 130 or 131, each of the formula requires consideration of NE as a mandatory variable: s 118(2)(b). In the case of Mr Davis as an incapacitated person, for the reasons set above, s 153(1) sets out that his NE is to be worked out by the formula reproduced above at [10].

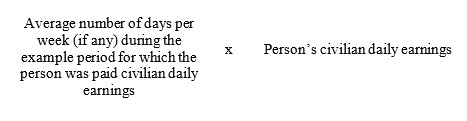

51 Section 156(1) sets out the formula for working out the civilian component of NE for the period of a week:

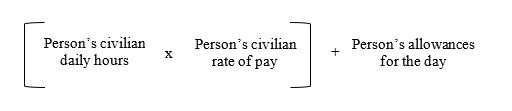

52 Civilian daily earnings are calculated by the formula set out in s 156(2):

53 Section 156(4) states that example period has the meaning given by s 157. Section 157 states:

Definition of example period for the civilian component of normal earnings

(1) For the purposes of this section 156 and the definition of civilian days in section 158, the example period for an incapacitated person is the latest period of 2 weeks:

(a) during which the person was continuously engaged in civilian work; and

(b) ending before the person last ceased to be a member of the Defence Force.

(2) However, the Commission may determine as the example period:

(a) a different 2 week period that it considers reasonable; or

(b) a period of a different length that it considers reasonable.

if the civilian daily earnings for the example period under subsection (1) would not fairly represent the daily rate at which the person was being paid for his or her civilian work before last ceasing to be a member of the Defence Force.

(Emphasis added.)

Section 157

54 The nature of the disagreement between the parties’ competing constructions of s 157 can be confined to determining the nature of the delegate’s exercise of discretion pursuant to s 157(2).

55 Subsection (1) prescribes the example period for the purpose of the section “is the latest period of 2 weeks … during which the person was continuously engaged in civilian work” and “ending before the person last ceased to be a member of the Defence Force”. As the Commission submitted, the text of s 157(1) is highly prescriptive.

56 Subsection (2), however, confers discretion on the Commission to determine a different period to be the example period. That discretion is subject to two limitations on the text of s 157:

(a) Any different period or a period of different length under subsection (2)(a) or (b) (respectively) must be considered reasonable by the Commission (ss 157(2)(a) and (b)); and

(b) The period prescribed in subsection (1) would not fairly represent the daily rate at which the person was being paid for their civilian work before last ceasing to be a member of the ADF.

57 A plain reading of s 157 reveals that the exercise of discretion under s 157(2) is enlivened when the 2 week example period as prescribed by s 157(1) would not fairly represent the daily rate at which the person was paid for civilian work. Any different example period or an example period of a different length must also be considered reasonable by the Commission.

58 The context of s 157 supports such a textual construction. It is tolerably clear that s 157(1) has the purpose of providing certainty and fairness to a highly structured means of calculating the civilian component of NE across a set short period (ie, the latest period of 2 weeks during which the person continuously engaged in civilian work before discharge). Section 157(2) then provides a mechanism whereby unfair outcomes that may arise from applying s 157(1) can be averted, but only where the Commission’s discretion under s 157(2) is enlivened. Read contextually, the purpose of s 157(2) is to provide the Commission with a discretion to set an example period where such a period more fairly represents the daily rate in a particular case, through specified means the Commission considers to be reasonable.

59 The meaning of s 157 can also be gleaned from other provisions of the MRCA. Section 157 finds equivalence in: s 99 in relation to incapacitated part-time Reservists; s 113 in relation to incapacitated part-time Reservists who were previously continuous full-time Reservists; s 148 in relation to former continuous full-time Reservists; and s 172 in relation to incapacitated former part-time Reservists who were previously continuous full-time Reservists. The example periods in each are the “latest period of 2 weeks” before the relevant triggering event. In this way, the civilian component of NE for all Reservists, however their service was rendered, is treated in the same way.

60 The justification for the degree to which the discretion under s 157 is constrained can be gleaned from the Explanatory Memorandum to the Military Rehabilitation and Compensation Bill 2004 (EM), which explained:

Clause 157 – Definition of example period for the civilian component of normal earnings

To establish the average amount an incapacitated Reservist usually earned in civilian employment, the Commission will look at an example period of two weeks. In most cases this will be the last two week period before the person ceased to be a member of the ADF, during which the person was continuously employed in civilian work.

If however, that last period is not truly indicative of the normal civilian employment of the person, then the Commission may look at a different two-week period or a different length of period it considers reasonable. This clause allows for consideration in cases where the person’s circumstances changed immediately before discharge from the ADF. For example, the person may have been unable to work due to unusual circumstances in the two weeks immediately before the discharge from the ADF, thus making that period an unsuitable indication of the person’s normal work or salary pattern.

(Emphasis added.)

61 Indeed, the textual construction at which I have arrived is fortified by the EM. It makes pellucid that the circumstances required for the exercise of discretion under s 157(2) are that the period under subsection (1) “is not truly indicative of the normal civilian employment of the person”. It is at that point the Commission “may look at a different … period … it considers reasonable” (emphasis added). That discretion is directed by the clause to “cases where the person’s circumstances changed immediately before discharge” from the ADF, owing to “unusual circumstances” that render the example period under s 157(1) an “unsuitable indication of the person’s normal work or salary pattern”.

62 However, it is not right, as Mr Davis submitted, that “the determination of ‘normal earnings’ may necessitate as fair and reasonable the enlivening of the requirement to exercise the discretion in s157(2) [to] choose a different example period” (emphasis added). The conferral of discretion on the delegate by s 157 cannot be taken as a requirement to exercise it. It is upon that difference in construction that Mr Davis’ interpretation cannot be accepted. Rather, reading the subsections together, and as a logical corollary of the limitations in s 157, the purpose of the discretion under subsection (2) is to provide a means by which unfair outcomes arising from use of the example period under subsection (1) can be avoided. The purpose of subsection (1), absent an unfair outcome, is to provide a standard period by which the relevant civilian earnings are calculated. Of course, none of that is to say that a decision under s 157 “which lacks an evident and intelligible justification” could not be found to be legally unreasonable: Minister for Immigration and Citizenship v Li [2013] HCA 18; 249 CLR 332 at [76].

Did the delegate err in law in the construction of s 157?

63 A considered reading of the May 2023 Decision identifies no error of law in the delegate’s approach to s 157. She was, at the time of making the May 2023 Decision, informed of the relevant information: Second Cooper Affidavit [5]. Relevantly, the delegate stated in the May 2023 Decision that:

• she had received the new Claim for Incapacity for Service/Work form on 11 May 2023;

• she had reassessed Mr Davis’ entitlement;

• she had noted that his entitlement was initially based on his normal weekly earnings with the DHA but that the re-assessment had determined it would be more beneficial to calculate the civilian component of his NE based on his F&SI earnings;

• she had identified that Mr Davis’ employment with DHA and F&SI were viewed as two separate employments and do not overlap;

• she had found that, as a result, the more financially beneficial employment period, being [his] full-time employment, was used; and

• Mr Davis could ask for a review within 12 months of receiving the letter.

64 In this respect, the reassessment arrived at by the delegate, confirming Mr Davis’ current rate of entitlement based on his full-time employment with F&SI, is consistent with the information Mr Davis provided with his Claim for Incapacity for Service/Work form on 11 May 2023. Indeed, from that information, there is no evidence that Mr Davis ever earned wages through his casual position with the DHA whilst also earning wages working in a full-time capacity at F&SI. His reliance on cl 117 of the EM does not assist, and critically, his submission that the delegate erred in calculating his entitlement cannot be accepted.

65 Mr Davis’ legal representative sought to adduce evidence from the Bar table of a contract between Mr Davis and the Australian Border Force (DHA) in relation to his casual employment. That contract was not exhibited to any of the affidavits filed on Mr Davis’ behalf, nor does it appear to have been before the delegate, but I accepted that such a contract existed.

66 However, even if I accept that Mr Davis’ contractual periods of employment with each employer overlapped, the reality before the delegate was a mere hypothetical possibility of Mr Davis being able to combine his full-time position at F&SI with his additional casual employment at the DHA. Not only did he not do that in the latest period of 2 weeks, during which he was continuously employed with F&SI, ending before his discharge date of 19 February 2019, but he never did so – nor was that fact contested. On each occasion when Mr Davis requested a review, he had the opportunity to provide whatever evidence of his employment that he wished to provide. None of the DHA payslips provided by Mr Davis to the delegate, nor his 12 week breakdown of his DHA earnings, evidenced any earnings after the pay period ending 23 January 2019 (albeit for work completed on 30 December 2018), nor was it suggested by Mr Davis that any evidence of additional earnings existed. The delegate, therefore, had nothing before her by which she could substantiate Mr Davis’ claim.

67 It follows that the delegate cannot be said to have made an error of law as a result of failing to choose a different example period which would have had no semblance with the reality of Mr Davis’ pre-discharge employment. In these circumstances, there was nothing “unfair” or unreasonable about the delegate’s use of the example period that would have compelled her to determine a different example period as contemplated by s 157(2). Rather, the delegate’s reassessment, confirming the more financially beneficial employment period for calculating the civilian component of Mr Davis’ NE, is consistent with the Commonwealth’s commitment to the beneficial interpretation of the MRCA as expressed in s 7(1) of the Australian Veterans’ Recognition (Putting Veterans and Their Families First) Act 2019 (Cth). It must be observed, however, that s 7 does not create or give rise to any rights (whether substantive or procedural) or obligations that are legally enforceable in judicial or other proceedings (s 10(1)), nor does a failure to comply with s 7 affect the validity, or provide a ground for review, of any decision (s 10(2)).

68 Even if Mr Davis could have established any such unfairness, that would be a matter to challenge by way of merits review, a course that Mr Davis has declined to pursue on several occasions. It is not an error of law.

69 Ground 3 has no reasonable prospects of success.

Ground 1 – Was there a breach of natural justice (s 5(1)(a))?

70 Articulating the requirements of procedural fairness in any given context can be somewhat elusive. In SZRMQ v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection [2013] FCAFC 142; 219 FCR 212, the then Chief Justice put it this way, at [7]:

Fairness is normative, evaluative, context specific and relative. As such, its assessment is somewhat imprecise in articulation and open to debate. Nevertheless, subject to any clear contrary statutory intention, fairness is an inhering requirement of the exercise of state power: Jarratt v Commissioner of Police for NSW [2005] HCA 50; 224 CLR 44 at 56-57 [26]; and SZRUI at [5].

71 In the absence of a clear legislative intention to the contrary, the delegate was obliged to accord Mr Davis procedural fairness: Minister for Immigration and Border Protection v WZARH [2015] HCA 40; 256 CLR 326. The question is “what is required in order to ensure that the decision is made fairly in the circumstances having regard to the legal framework within which the decision is to be made”: WZARH at [30] per Kiefel CJ, Bell and Keane JJ (emphasis added).

72 Mr Davis could not point to any construction of s 157 that required the delegate to provide prior notice to a claimant, such as Mr Davis, that an adverse decision was proposed to be made. It is also not apparent that the delegate did not afford him procedural fairness. His reference to “DVA’s Natural Justice Consideration and Prior Warning of Adverse Decisions policy” does not assist in any submission to the contrary. While, at Ch 3, that policy notes “[i]t is … policy to give clients who are to receive an adverse decision … advance warning of that likely outcome”, such advance notice is not only “generally not necessary”, but the policy stipulates only that “thought should be given” about whether such notice is “appropriate”. Further, as was addressed in Davis per Meagher J at [54]-[55], the policy relied upon by Mr Davis is inapplicable to the MRCA.

73 In any event, if no error of law was made by the delegate in construing s 157, then even if Mr Davis had been notified that the delegate proposed to make an “adverse decision”, such notification would not be material. Mr Davis has no reasonable prospects of establishing any breach of natural justice on the part of the delegate.

74 Ground 1 has no reasonable prospects of success.

Ground 2 – Did the delegate fail to adhere to the requirements of s 157 (s 5(1)(b))?

75 Similarly, Mr Davis cannot establish that there is any procedure required by s 157 that was not followed by the delegate. He alleged that the delegate was “required to be fully appraised of all the claimed civilian income” and determine his “normal earnings” before deciding whether an example period applied under s 157(1) or s 157(2). As has been explained in respect of Ground 3, even if there were such a procedural requirement, the difficulty for Mr Davis is that he has not pointed to any evidence which suggests the delegate was not fully appraised of Mr Davis’ two earnings streams. In fact, they were both expressly referred to in the May 2023 Decision.

76 Ground 2 has no reasonable prospects of success.

Ground 4 – An irrelevant consideration (s 5(1)(e))?

77 As has already been explained above, and as was accepted by Mr Davis’ solicitor at the hearing, the reference to the “Veteran Review Board” in the May 2023 Decision is an error of fact. Mr Davis has not demonstrated that the delegate’s misidentification of the correct decision-maker was in any way material to the May 2023 Decision.

78 Ground 4 has no reasonable prospects of success.

DISPOSITION

79 I cannot be satisfied that any ground on which Mr Davis relies in his originating application demonstrates that he has any reasonable prospects of success in prosecuting this proceeding. It is appropriate that the Commission’s application for summary judgment be granted.

80 Mr Davis has, for the second time, used the resources of a superior court in circumstances where he had every opportunity to have the decision about which he complains reviewed by the VRB and the AAT. His insistence on pursuing his application for judicial review in the face of the more appropriate alternatives was inconsistent with his obligations under ss 37M and 37N of the FCA Act. The Commission has not, however, sought anything more than a standard costs order. Consequently, Mr Davis will be ordered to pay the Commission’s costs on the standard basis only.

I certify that the preceding eighty (80) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice Sarah C Derrington. |

Associate:

Dated: 9 July 2024