Federal Court of Australia

Elanco Australasia Pty Ltd v Abbey Laboratories Pty Ltd [2024] FCA 640

ORDERS

Appellant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties confer and supply to the chambers of Justice Burley by 4pm on 20 June 2024 draft short minutes of order giving effect to these reasons and in so far as is necessary, a proposed timetable for further steps to be taken in the proceedings.

2. Insofar as the parties are unable to agree to the terms of the draft short minutes of order referred to in order 1, the areas of disagreement should be indicated in mark-up.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

[1] | |

[10] | |

[12] | |

[23] | |

[33] | |

[42] | |

[42] | |

[63] | |

[64] | |

[69] | |

[69] | |

[77] | |

[86] | |

[86] | |

[90] | |

[101] | |

[102] | |

[103] | |

[110] | |

[121] | |

6.3.5 The general approach to developing thiacloprid dosages in a pour-on | [122] |

[129] | |

[137] | |

[137] | |

[144] | |

[155] | |

[168] | |

[169] | |

[173] | |

[184] | |

[213] |

BURLEY J:

1 This is an appeal from two decisions of a delegate of the Commissioner of Patents who allowed an opposition to the grant of patent application No 2014280848 entitled “Ectoparasitic treatment method and composition”. The priority date of the patent application is 12 June 2013. The patent application relates to methods of treating biting lice on sheep and goats using the insecticide thiacloprid.

2 The applicant for the patent was initially Bayer Australia Ltd, which subsequently assigned it to Elanco Australasia Pty Ltd, the present appellant. The respondent is Abbey Laboratories Pty Ltd.

3 Abbey filed a notice of opposition under s 59 of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) on 9 August 2018. It advanced its opposition to grant on the grounds of: lack of clear enough and complete enough disclosure; lack of support; lack of clarity; lack of novelty; lack of inventive step; and secret use. The delegate in her first decision allowed the opposition on the basis that: claims 1 – 10 lacked support pursuant to s 40(3) of the Patents Act; claims 1 and 4 – 11 lacked novelty in the light of the prior publication of a document entitled “Trade Advice Notice on thiacloprid in the Product Piranha Dip for Sheep, APVMA product number 63766”; and, claims 1 – 3, 6 and 7 lacked an inventive step in light of the Trade Advice Notice and the common general knowledge in the art; Abbey Laboratories Pty Ltd v Bayer Australia Ltd [2020] APO 25 at [236].

4 Elanco then amended the patent application. A second opposition hearing was then conducted at which Abbey argued that the amendments did not serve to overcome the ground of lack of inventive step in the light of the common general knowledge and the Trade Advice Notice. In her second decision, the delegate again allowed the opposition and refused the application; Abbey Laboratories Pty Ltd v Elanco Australasia Pty Ltd [2021] APO 30.

5 In its Amended Notice of Appeal, Elanco contends that the delegate erred in concluding in the first decision that claims 1 – 3, 6 and 7 of the original claims lacked an inventive step and that she erred by concluding in the second decision that claims 1 – 10 of the patent application as amended lacked an inventive step.

6 Despite the appeal being brought by Elanco, the effective moving party is Abbey. That is because the present proceeding is in the original jurisdiction of this Court and involves a hearing de novo on the grounds and evidence before the Court. As the opponent to the grant, Abbey bears the onus in relation to each ground of opposition raised. Section 60(3A) of the Patents Act provides that the Commissioner of Patents may refuse an application if satisfied, on the balance of probabilities, that a ground of opposition exists. That is the standard by which the present proceeding is to be judged.

7 Abbey filed a statement of several grounds upon which it contended that the patent application should not proceed to grant. As a result of admirable co-operation between the parties, they agreed that the sole issue now between them is whether or not the amended claims of the patent application involve an inventive step in accordance with s 7(3) of the Patents Act, in the light of the common general knowledge and the content of the Trade Advice Notice. They also agree that this can be determined by examination of claim 1 on the basis that none of the other claims will serve to confer an inventive step if claim 1 does not. The parties provided a statement of agreed common general knowledge as at the priority date.

8 Examination of the patent request and complete specification was requested on 6 December 2016. As a result, all questions of validity are to be determined under the Patents Act as amended by the Intellectual Property Laws Amendment (Raising the Bar) Act 2012 (Cth).

9 For the reasons set out below I have found that the appeal must be dismissed.

10 Abbey relies on the evidence of Chhaya Mahashabde, pharmaceutical formulator and Kim Agnew, a veterinarian. Elanco relies on the evidence of Guiseppe (Joe) Pippia, an analytical chemist who provides consultancy services to the animal and human pharmaceutical industries and Edward Whittem, a veterinary pharmacologist.

11 I consider that each of the experts was qualified to give evidence of assistance in understanding the patent application and consideration of the issues. Where questions or weight arise, I refer to these more specifically below.

12 Ms Mahashabe graduated from the University of Mumbai with a Bachelor of Pharmacy in 1988 and completed a Master of Pharmaceutical Sciences from the same university in 1990. From 1991 to 1997, she was a research and development executive at Lupin Laboratories Ltd, a generic pharmaceutical company. From 1997 until 1999, she was responsible for product development, including the identification of natural active ingredients, establishing safety and efficacy profiles of new ingredients for incorporation into wound and skin care products, at Johnson & Johnson, India. From 1999 until 2002, she was a research scientist at the Regional Technology Centre at Colgate Palmolive, India where she was responsible for conducting formulation development and stability studies in relation to personal care products. In 2002, she immigrated to New Zealand where, from April 2002 until March 2010, she held various roles, including in new formulation development at Nutralife Health & Fitness (now Vitaco Health Limited), a nutraceuticals company. From April 2010 until July 2013, Ms Mahashabde was a formulation chemist at Virbac Australia Pty Ltd, where she was responsible for formulation development and evaluation of various products for sheep, cattle and horses.

13 In July 2013, she was promoted to Head of Pharma Formulation and became responsible for the formulation development of all vet pharma projects at Virbac Australia. In September 2021, she was appointed to her current role as Head of Formulation and Analytical Chemistry in which she is responsible for formulation development of new formulations and reformulation of existing products, and managing a team, including a formulation scientist and analytical chemist.

14 Ms Mahashabde was instructed to provide her evidence in several stages. She was first provided with the agreed common general knowledge and then explained, as at June 2013, how she would keep up with developments in the methods for controlling lice in an animal such as sheep or goats, the products known to her for use in controlling ectoparasites on an animal and the steps she would take to develop a pour-on formulation for the treatment of ectoparasites on a sheep or goat. Included in the agreed common general knowledge that Ms Mahashabde was provided was the agreed dipping calculation to which I refer at [39] below.

15 In her second affidavit, Ms Mahashabde was asked to assume that she had been asked, as at the priority date, to develop a formulation for controlling lice on an animal such as sheep and goats and provided with the Trade Advice Notice. She was then asked to explain the types of formulations containing thiacloprid she would consider developing for controlling lice on such animals, if there were any formulations she would consider taking to the development stage, and whether any different steps would need to be taken to ensure persistent control of the lice (for at least two weeks). The annexures to her second affidavit include a letter of instruction by Bird & Bird, solicitors and a copy of the Trade Advice Notice.

16 In her third affidavit, she was asked to provide her comments on the patent application. In her fourth affidavit, she provided comments on certain matters raised in Mr Pippia’s affidavit.

17 Mr Pippia obtained a Bachelor of Applied Science from the Queensland University of Technology in 1991 and a Master of Science and Technology from the University of New South Wales in 2004. From 1991 to 2000 he was a senior analytical chemist in the Queensland Department of Primary Industries where he was responsible for various analytical techniques, including trace residue analysis of veterinary drugs and pesticides, such as gas chromatography, high performance liquid chromatography and liquid chromatography mass spectrometry.

18 From 2000 until 2004, he was a senior chemist at Virbac Australia, where he worked in a product development team. His role was to provide analytical expertise to formulation development and product registration activities.

19 From 2004 until 2011, he was a technical manager at Troy Laboratories (Australia) Pty Ltd, a manufacturer of animal health products. In that role, he managed product development, product quality, regulatory affairs and quality control laboratories. He and his team developed tablets and topical formulations for the treatment and prevention of ecto- and endo-parasites and various other topical, oral and parenteral liquids and suspensions.

20 Since 2012, Mr Pippia has provided consultancy services to the animal and human pharmaceutical industries as Managing Director of Pia Pharma. This role includes the provision of analytical services, formulation development, product development, good manufacturing practice consulting and regulatory consulting.

21 Mr Pippia was provided sequentially with each of Ms Mahashabde’s first, second and third affidavits and provided his comments on each in turn.

22 Ms Mahashabde and Mr Pippia joined in the preparation of a joint expert report (formulation JER) and gave evidence concurrently, during which they were cross-examined. I found that both presented as witnesses who used their best endeavours to assist the Court.

23 Dr Agnew obtained a Bachelor of Science in Clinical Biochemistry from Massey University in New Zealand in 1980 and a Bachelor of Veterinary Science from the same university in 1987. From 1987 until 1995, he practised as a vet specialising in dairy cattle, pigs and sheep.

24 In 1995, he became the Veterinary Technical Manager for Elanco Animal Health New Zealand where he was responsible for product development and registration of veterinary products. In the late 1990s, he was a member of a team tasked with the development of a pour-on, dip and aerosol formulation containing spinosad (a parasiticide) as its active ingredient, for the control of sheep lice and flies. He recalls that Elanco’s dip formulation was the first spinosad product that was commercially available, followed by its aerosol and pour-on products. He was responsible for conducting clinical studies and preparing regulatory submissions for those products.

25 In 2006, Dr Agnew moved to Australia and became the Research and Regulatory Manager for Elanco Animal Health Australia where he led a team that applied for and managed the registration of spinosad products. In 2009, he became Elanco’s Innovations Business Unit Manager which involved, amongst other things, leading the regulatory team responsible for compliance maintenance of product registrations, conducting studies to support line extensions and new product development and managing product development work.

26 From 2011 until 2013, Dr Agnew was the Emerging Markets Regional Regulatory, Research and Product Development Manager, where he led teams responsible for: compliance maintenance of all new product registrations and submissions; conducting studies to support line extensions and new product development; and working on product development projects. From 2013 until 2015, he was the Associate Director ANZ R&D Hub and was responsible for leading the initiation of a regional research and development hub with a team comprising clinical, regulatory and scientific technical expertise, developing team strategy and leading due diligence assessment of new technologies including novel sources of parasiticide actives.

27 From 2015 until 2020, he was the R&D Leader for Australia and New Zealand at Merial/Boehringer-Ingelheim.

28 Since 2020, Dr Agnew has been a Director of KAP Consulting Pty Ltd, APAC Managing Partner at Paul Dick and Associates and Principal Investigator at PharmAust Monepantel in the treatment of canine lymphoma.

29 Dr Agnew was asked to provide his evidence in several stages. In his first affidavit he was asked to explain his knowledge as at the priority date of products and methods of administration used for controlling ectoparasites on an animal and the qualifications and roles of a team tasked with developing a formulation for administration by pour-on, dip or backlining of an ectoparasiticide for use on a sheep or a goat. He stated that as at the priority date, knowledge of an active with a known method of administration would be useful in developing a composition with the same active but designed for a different form of administration. In his second affidavit, Dr Agnew was provided with a copy of the patent application and also the Trade Advice Notice and asked to provide his comments on the range or amount of active ingredient used in the formulation in the claims and comment on the relationship between that range and the amount of active identified in the Trade Advice Notice. In his third affidavit Dr Agnew responded to the affidavit of Professor Whittem.

30 Professor Whittem has since 2021 been a Professor at James Cook University in Townsville and Dean of the College of Public Health, Medical and Veterinary Sciences. He obtained a Bachelor of Veterinary Science from the University of Melbourne in 1980 and a Doctor of Philosophy in Veterinary Pharmacology from the University of Georgia, in the United States, in 1991. He also holds a Residency Certificate in Veterinary Clinical Toxicology from the University of Georgia and a Fellowship in Therapeutics and Chemotherapy from the Australian and New Zealand College of Veterinary Scientists. Professor Whittem held various academic positions from 1991 until 2000. From 2000 to 2001, he was a Research Program Manager – Discovery at Schering-Plough Animal Health. From 2001 to 2008, he was employed by Jurox Pty Ltd as Head of Research and Development and a member of the Jurox senior executive team. In that role, he supervised the development and registration of various new veterinary products including for sheep and cattle. Between 2008 and 2021, he held various roles at the University of Melbourne in the Faculty of Veterinary and Agricultural Sciences and on the Academic Board. From 2019 to 2022, he was President of the Veterinary Practitioners Registration Board of Victoria.

31 Professor Whittem gave evidence in the course of the opposition proceedings before the delegate and in the present proceedings annexed three declarations that he had provided then. He responded sequentially to the affidavits of Dr Agnew.

32 Dr Agnew and Professor Whittem collaborated in the production of a joint expert report (veterinarian JER) and gave oral evidence concurrently, during which they were each cross-examined. I found that both presented as witnesses who used their best endeavours to assist the Court.

3. AGREED COMMON GENERAL KNOWLEDGE POSITION STATEMENT

33 The following is a summary of the agreed common general knowledge as at 12 June 2013.

34 The most prevalent species of lice to affect sheep in Australia is biting louse, Bovicola ovis. A range of chemical parasiticides were available for the treatment and prevention of sheep lice, such as insect growth regulators, spinosyns and macrocyclic lactones. Neonicotinoids is a class of insecticides that were known.

35 External application methods to administer pharmaceutically effective amounts of compositions to an animal such as sheep and goats included:

(a) dipping, such as by plunge, shower or cage dip;

(b) jetting; and

(c) topical administration, where the medicament is applied to only part of the outside of an animal, such as backlining. Treatment by backlining is recommended to be used within a day (or at most a week) of shearing and involves small volumes of product being applied along the backs of the animal from head to rump.

36 Administration of a lower concentration of active ingredient was generally known to be desirable, including to reduce cost and reduce residue on an animal, provided the active remains efficacious at a lower concentration.

37 In administering chemical parasiticides to an animal, such as a sheep or goat, by dipping or spraying, it is essential that the fleece be thoroughly wetted, regardless of the method being used.

38 When administration is via a dip:

(a) for stripping actives, the concentration of active decreases during use, and the dip liquid must be reinforced (addition of product) and topped up (combined product and water) to keep the dip at an effective level and strength as monitored during the treatment of the animals;

(b) for non-stripping actives, the concentration remaining in the dip liquid stays constant and the dipping liquid is topped up to maintain the desired volume of liquid as monitored during the treatment of the animals.

39 For dipping, the amount of an active ingredient that is applied to a sheep in mg/kg body weight can be calculated knowing the volume (mg/L) administered and the weight of the animal. For example, at 48ppm, assuming between 2L and 6L of formulation is “take-off”, this equates to an application of:

Sheep weight (kg) | Active applied (mg/kg) |

20 | 4.8 – 14.4 |

30 | 3.2 – 9.6 |

40 | 2.4 – 7.2 |

50 | 1.92 – 5.76 |

60 | 1.6 – 4.8 |

I refer to this paragraph below as the agreed dipping calculation.

40 As Ms Mahashabde explained, a sheep retains a volume of dip from a bath when it is treated with a dip product. This can be used to estimate the amount of active with which the sheep is treated by reference to the “take off” from the dip. In the agreed dipping calculation, the assumed take off is between 2L and 6L of formulation for which the application amounts may be determined as set out in the table.

41 Dosage determination studies, dosage confirmation and field trials are conducted to determine the appropriate dosage range in which a compound for treating lice on sheep is efficacious, including for determining the appropriate dosage range to provide persistent control.

42 The patent application is entitled “Ectoparasitic treatment method and composition”.

43 The field of the invention relates to an ectoparasitic treatment method and composition particularly relating to the treatment of biting lice on sheep.

44 The description of the “Background Art” identifies that ectoparasites on animals are of significant concern and that a particular problem for farmers in Australia is parasite infestation on sheep. It identifies that lice and blowflies are the two most significant external parasite problems that affect sheep and that lice are generally species specific. The most prevalent and significant type of sheep lice is the biting louse, Bovicola (formerly Damalinia) ovis.

45 The background refers to the harm caused by sheep lice to the wool industry and to sheep, noting that the control of lice requires effective chemical treatment of an entire flock and subsequent biosecurity measures to prevent re-infestation. It also refers to the impacts on animal welfare and production due to sheep lice and notes that although most lice are observed in the fleece, away from the skin surface, they are quite mobile and are likely to feed on substrates other than just the loose debris present at that location. Lice are noted to be transmitted between sheep via direct contact.

46 The specification continues (page 3 lines 5 – 8):

External administration of ectoparasiticides to sheep is usually most effective when applied immediately after shearing (off-shears). In particular, treatment by backlining either by pour-on or spray on is recommended to be applied within 24 hours of shearing, although within 7 days may be suitable for some products.

(Emphasis added)

47 The amended claims focus entirely on backlining (or “pour-on”), which is distinguished from other methods of administration.

48 The specification identifies the advantages of using smaller quantities of parasiticides (page 3 lines 20 – 27):

The administration of any chemical parasiticide will to some degree result in residue on the animal. If a smaller quantity of parasiticide can be used, the resultant residues may also be lower. For high volume applications such as dipping or jetting, residues in the environment may also be reduced by using lower concentrations of suitable actives. However, the actives must maintain efficacy at lower concentration to be suitable. The use of lower quantities of actives is also desirable to lower cost and/or potentially decrease safety issues. Lower residues are desired in that they may provide shorter withhold times, avoid export limitations, and increase market acceptability.

49 The specification then lists common types of parasiticides, the last of which is the neonicotinoid, imidacloprid. The claims in suit concern the use of a different neonicotinoid, which is thiacloprid. It says (page 3 line 29 – page 4 line 30):

In Australia the common types of externally administered chemical parasiticides suitable for the treatment and/or prevention of sheep lice include insect growth regulators (IGRs), such as triflumuron; spinosyns, such as spinosad; macrocyclic lactones, such as ivermectin; magnesium fluorosilicate; organophosphates; synthetic pyrethroids; and the neonicotinoid imidacloprid.

IGRs do not affect adult lice, resulting in a delay of up to 14 weeks for the developing stages to be killed and for the adult lice to die off. There have also been reports of emerging resistance to IGRs in Australia.

Spinosyns have low toxicity and provide rapid knock-down, but have a short duration of action.

Macrocyclic lactones also provide rapid knock-down, but are required to be administered in relatively large quantities to be effective.

Organophosphates are under increased scrutiny in regard to safety. In Australia the use of diazinon, the most commonly used organophosphate for control of sheep lice, has been discontinued since May 2007.

Synthetic pyrethroids can take 6-8 weeks to kill lice, which may lead to further spreading of lice across a flock. Significant resistance has also occurred with synthetic pyrethroids, being reported since the 1980s. The resistance has progressed to the extent that the use of synthetic pyrethroids in many locations may no longer be effective in the control of sheep lice.

In Australia, imidacloprid is the active ingredient in the parasiticide product Avenge™, sold by Bayer Australia Ltd, for the control of lice on sheep. Avenge™ contains imidacloprid at a concentration of 3.5% w/v, and is applied as a backline treatment. When used for lice control on sheep, Avenge™ provides up to four weeks of persistent activity when applied within 24 hours following shearing, which can prevent reinfestation by lice.

50 The specification identifies an objective of the invention as follows (page 5 lines 2 – 8):

There is a clear need for alternative methods for controlling ectoparasites such as sheep lice. Ideally such methods would use an active with high potency against lice to allow for relatively low quantities and concentrations of actives during use, be suitable for both off-shears (short wool) and long wool treatments, and have high persistency.

It is an object of the present invention to address on or more of the foregoing problems and/or to at least provide the public with a useful choice.

51 The “Disclosure of the Invention” then provides (emphasis added) (page 6 lines 1 – 7):

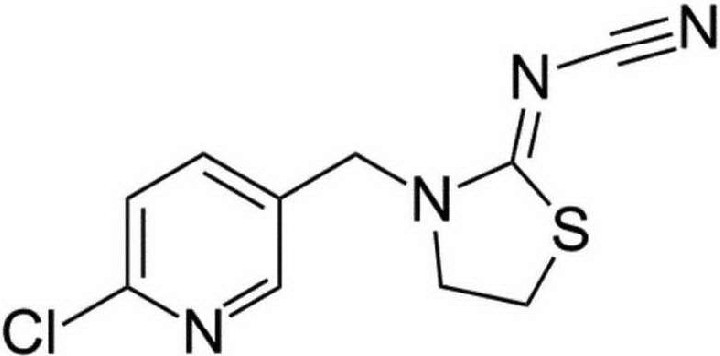

The invention is based in part on the surprising discovery that thiacloprid has high potency and suitability for the control of lice, when applied externally to an animal, thiacloprid is as shown in the chemical formula:

Thiacloprid: [3-[(6-Chloro-3-pyridinyl)methyl]-2-thiazolidinylidene] cyanamide is an insecticide of the neonicotinoid class.

52 The specification then provides a list of 28 items to which the invention is said to relate. The first three of these may be said to comprise the broadest statements of the invention (page 6 lines 10 – 15):

1 A method of controlling lice on an animal, characterised by the step of administering externally a pharmaceutically effective amount of thiacloprid.

2 The method of item 1, characterised by the step of topically administering a composition containing from 0.0001% to 3.5% w/v of thiacloprid.

3 The method of item 1 or 2, wherein the amount of thiacloprid administered to the animal is from 1 to 45 mg/kg by weight of the animal.

53 The invention is then described by 10 consistory paragraphs which match the language of the claims.

54 Under the heading “Modes for Carrying out the Invention” the specification states that the use of the invention will be particularly described in relation to the control of biting lice on sheep. A series of aspects of the invention are set out at pages 9 to 12 before the specification sets out a series of preferred methods of administration. Most of the aspects concern methods that were included within the scope of the claims of the patent application before they were narrowed by the amendments after opposition. Those included treatment by dipping and spraying.

55 The first preferred method is dipping, a “traditional form” of which is said to be plunge dipping, where sheep are mustered through a deep trough containing the treatment liquid and the liquid is allowed to penetrate into the fleece. An alternative identified is “shower dipping” where the sheep are sprayed with the treatment liquid. The second preferred method, “jetting” is then described.

56 More relevantly, the specification describes “backlining”, a further preferred method, as follows (page 13 line 26 – page 14 line 2):

Backlining

The backlining technique, otherwise referred to as pour-on or spray-on, is the application of a relatively small amount of liquid to back of an animal. The liquid may be applied as a spray or a stream or jet of liquid, using manual applicators or power assisted applicators. The volume, concentration viscosity and other properties of the treatment liquid may vary depending on the requirements. Typically a pour-on is administered in two or more bands along either side of the spine of the sheep.

57 The specification then says that the inventors have surprisingly discovered that thiacloprid has unexpectedly high efficacy in the control of lice on sheep. It says that one particular advantage provided by the invention is the long persistency following administration, for example, “when thiacloprid is administered as a plunge-dip and/or pour-on, four weeks of persistency has been measured” (page 14 lines 8 – 9). It continues (page 14 line 11 – page 15 line 2):

There is limited understanding in the prior art of the usefulness of thiacloprid in controlling parasites on animals.

The superior potency of thiacloprid compared to imidacloprid in the control of lice on sheep is a surprising result. The dose of imidacloprid recommended for the product AVENGE™ for the control of lice on sheep is around 49 mg/kg of the body weight of the sheep. By comparison, thiacloprid has been demonstrated as effective when used as a pour-on treatment at a dose as low as 5 mg/kg thiacloprid.

In one embodiment, the present invention provides a method of controlling lice on sheep, characterised by the step of administering externally thiacloprid in an amount of from 5 to 40 mg/kg by weight of the treated animal, wherein the thiacloprid is administered by localised topical application to the back of the animal. In one embodiment, the thiacloprid is administered as a pour-on. In one embodiment, the thiacloprid is administered as one or more bands along either side of the spine of the animal.

In one embodiment of the invention, the high potency of thiacloprid is utilised by the provision of a 1% w/v composition of thiacloprid for use as a backline treatment for lice control on sheep. By comparison, the backline imidacloprid formulation Avenge™, uses the substantially higher concentration of 3.5% w/v.

58 The specification identifies how it is said that the invention achieves the earlier stated objectives (page 15 lines 4 – 8):

This significantly higher potency allows for lower concentrations and/or quantities of thiacloprid to be used compared to similar parasiticides such as imidacloprid. It can be seen that the present invention has a number of advantages over the prior art, including lower residues both on the animal and the environment, lower costs for manufacture, ease of manufacture, and a lower chance of lice developing resistance.

59 Under the heading “Examples”, the specification provides that table 1 is a formulation example of the present invention, noting that the formulation provided may be used, in particular, as a concentrate that is diluted with water for use in dipping. Typically, it says, this would be diluted to around 48 ppm for such use. The detail is then set out (page 15 lines 15 – 30).:

Table 1: Formulation of thiacloprid concentrate

Formulation 1 | ||

Ingredients | Proportion | |

Thiacloprid | 48% | Active |

Polysorbate 80 | 10-15% | Surfactant |

Plasdone K25 | 2.0-5.0% | Dispersing |

Xanthan gum | 0.1- 0.3% | Thickening |

Wacker silica | 0.5- 1.5 | Thickening / dispersing |

Methyl paraben | 0.2 | Preservative |

Propyl paraben | 0.04 | Preservative |

Defoamer RD | 0-0.1 | Anti foam |

Propylene glycol | 10- 20% | Anti-freeze |

Deionised water | Qs to 100% | |

60 Table 2 is an example composition of the invention with particular suitability for use in a backlining treatment, such as a pour-on (page 16 lines 1 – 5):

Table 2: Formulation of thiacloprid pour-on

Formulation 2 | ||

Ingredients | Proportion | |

Thiacloprid | 1.0% | Active |

DMA (Dimethyl acetamide) | 40% | Solvent |

BHT | 0.2% | Antioxidant |

Dipropylene glycol methyl ether | Qs to 100% | Co-solvent |

61 The specification then sets out 11 ‘trial examples’. Examples 1 – 3 concern jetting. Examples 4 – 7 and 9 concern plunge dipping. Example 8 concerns in vitro assessment by means of an adult louse bioassay.

62 Example 10 concerns backlining and is of immediate relevance for present purposes as it is the only example that concerns backlining, which is the subject of the claims. It provides (page 18 lines 9 – 19):

Trial Example 10

A study was performed using 10 g/L thiacloprid pour-on formulation, on four groups of sheep at different dose rates including a negative control group, as summarised in table 3. The results of the study demonstrated that thiacloprid 10 g/L pour-on effectively controlled a natural infestation of sheep lice when applied at a dose level as low as 0.5 ml per kg bodyweight (approximately 200 mg thiacloprid per square metre of sheep body surface area). At each assessment time, including 22 weeks after treatment, there was an absence of live lice on all three groups.

Table 3: Trial of 1% w/v thiacloprid pour-on

Group | Treatment | Volume administered | Nominal Dose level | Number of Sheep | Assessment times |

1 | Thiacloprid 10 g/L Pour-On | 1.5 ml/kg | 600 mg/m2 | 8 | Pre-shearing, 4, 8, 12 and 22 weeks post treatment |

2 | Thiacloprid 10 g/L Pour-On | 1.0 ml/kg | 400 mg/m2 | 7 | |

3 | Thiacloprid 10 g/L Pour-On | 0.5 ml/kg | 200 mg/m2 | 8 | |

4 | Negative controls | Nil | Nil | 7 |

63 The claims are as follows:

1. A method of controlling lice on an animal, characterised by the step of administering by backlining a pharmaceutically effective amount of thiacloprid, wherein the amount of thiacloprid administered to the animal is from 10 to 30 mg/kg by weight of the animal, wherein the thiacloprid is administered in a composition containing 0.5%-2% w/v of thiacloprid, and wherein the animal is a sheep or a goat.

2. The method of claim 1, wherein the composition contains 1% w/v of thiacloprid.

3. The method of claim 1 or 2, wherein the amount of thiacloprid administered to the animal is from 10 to 15 mg/kg by weight of the animal.

4. A method of providing persistent control of lice on an animal, characterised by the step of administering by backlining a pharmaceutically effective amount of thiacloprid, wherein the amount of thiacloprid administered to the animal is from 10 to 30 mg/kg by weight of the animal, wherein the thiacloprid is administered in a composition containing 0.5%-2% w/v of thiacloprid, and wherein the animal is a sheep or a goat.

5. The method of claim 4, wherein persistent control is provided for at least two weeks following administration.

6. Use of thiacloprid in the manufacture of a composition for controlling lice on an animal, wherein the amount of thiacloprid administered to the animal is from 10 to 30 mg/kg by weight of the animal, wherein the composition is administered by backlining to the animal, wherein the composition contains 0.5%-2% w/v of thiacloprid, and wherein the animal is a sheep or a goat.

7. The method of any one of claims 1 to 5, or the use of claim 6, wherein the animal is a sheep.

8. A method of controlling lice on an animal, characterised by the step of topically administering a pharmaceutically effective amount of thiacloprid, wherein the amount of thiacloprid administered to the animal is from 10 to 30 mg/kg by weight of the animal, wherein the thiacloprid is administered in a composition containing 0.5%-2% w/v of thiacloprid, and wherein the animal is a sheep or a goat.

9. A method of providing persistent control of lice on an animal, characterised by the step of topically administering a pharmaceutically effective amount of thiacloprid, wherein the amount of thiacloprid administered to the animal is from 10 to 30 mg/kg by weight of the animal, wherein the thiacloprid is administered in a composition containing 0.5%-2% w/v of thiacloprid, and wherein the animal is a sheep or a goat.

10. Use of thiacloprid in the manufacture of a composition for controlling lice on an animal, wherein the amount of thiacloprid administered to the animal is from 10 to 30 mg/kg by weight of the animal, wherein the composition is administered topically to the animal, wherein the composition contains 0.5%-2% w/v of thiacloprid, and wherein the animal is a sheep or a goat.

4.3 The person skilled in the art

64 There is no dispute that the person skilled in the art in respect of the claimed invention would be a skilled team including: a formulation chemist; an analytical chemist; a clinical veterinarian or animal scientist; and a statistician. I accept that each of these people will have a high degree of skill.

65 The veterinarian experts agreed that their role would be to conduct studies concerning food safety, efficacy and animal safety required for registration in Australia, and that their expertise is useful to have in the team early in the conception of a product. The role of the statistician would be to ensure the correct design of studies and then process the data obtained.

66 Ms Mahashabde gave evidence that the formulation chemist decides the concentration of the formulation for the initial dose determination studies or the proof of concept studies and then has input in how much needs to go onto the animal, in consultation with the other members of the team. Mr Pippia considered that the formulation chemist does not determine the dose and it is the wider team that determines the dose and runs a dose determination study.

67 I accept that the formulator, in consultation with the other members of the team and most relevantly the clinical veterinarian, would propose starting doses for the determination of dose amounts. That accords with the fact that it is the formulator who would need to take into account the means of administration of the active ingredient to the animal in question. After the range is determined, the formulator would proceed to formulate the product.

68 Ultimately, in my view the contribution of the analytical chemist and statistician relates to implementing and checking data based on tests conceived and directed by the clinical veterinarian or animal scientist and the formulation chemist. Accordingly, it is the evidence of the veterinarian and formulation chemists that is of most relevance to the inventive step enquiry; Wellcome Foundation Ltd v VR Laboratories (Aust) Pty Ltd [1981] HCA 12; (1981) 148 CLR 262 at 281.

5. INVENTIVE STEP – THE SUBMISSIONS

5.1 The case advanced by Abbey

69 Abbey advances its lack of inventive step case on the basis of the state of the common general knowledge when considered together with the Trade Advice Notice, a document that is accepted by the parties to contain information that falls within s 7(3)(a) of the Patents Act.

70 Abbey submits that proof of concept studies formed an early part of dose determination and that they were of a routine nature as at the priority date, with the process of dose determination being well-defined and varying little between companies and product types.

71 Abbey submits that a range of known chemical parasiticides, including pour-on formulations, were available for the treatment and prevention of sheep lice before the priority date, that the veterinarian experts agreed that the amount of active ingredient used in each was set out on the product label and that information on those labels formed part of the common general knowledge. The AVENGE product was a known and successful product used in a pour-on and was considered by the formulation experts to be a useful reference product in developing a pour-on composition for thiacloprid. Abbey submits that the contents of the AVENGE product label fall within the common general knowledge and indicate that a 60mL volume of AVENGE applied to a 50kg sheep equates to a dose of imidacloprid of about 42 mg/kg. Imidacloprid and thiacloprid are both in the neonicotinoid class of insecticides. They have the same parent compound (the differences are in the side chains and the addition of one sulphur in thiacloprid) and their chemical structures formed part of the common general knowledge. They would have been considered as a matter of course and were readily available on resources such as PubChem.

72 Abbey contends, and the formulation experts agreed, that three basic propositions as to the development would form part of the common general knowledge. First, in determining the required amount of active for a pour-on product, it is ideal to keep the volume of dose that goes on the animal as constant as possible. Secondly, 60mL is an appropriate volume for a pour-on product. Thirdly, if one uses a fixed volume such as 60mL and a desired mg/kg has been set, then the calculation of the weight to volume concentration necessarily follows from those parameters.

73 Abbey submits that developing a pour-on product when there is an existing dipping product for the same active was known to have taken place for three of the six available dip products in the market. In such development, the administration of a lower concentration of active is generally known to be desirable, including to reduce cost and reduce residue on the animal. In estimating the amount of active to be used for a pour-on formulation when there is an existing dip or spray product, allowance must be made for the different method of application as set out in the agreed dipping calculation.

74 Abbey relies on the content of the Trade Advice Notice as providing the basis for the skilled team to move forward with a process of development. Abbey submits that in view of the Trade Advice Notice and the common general knowledge, arriving at the invention claimed before the priority date would have involved the following:

(a) Selecting the pour-on administration method for thiacloprid;

(b) Identifying a dosage or dosage range based on mg/kg;

(c) Identifying a concentration range in w/v %.

75 Abbey submits that the skilled team would have taken steps very close to those described in Example 10 of the patent application. It submits that one approach to the obviousness enquiry is whether “the hypothetical addressee faced with the same problem would have taken as a matter of routine whatever steps might have led from the prior art to the invention, whether they be the steps of the inventor or not”, citing Wellcome Foundation at 287. It submits in the alternative that the reformulated Cripps question, as set out in Aktiebolaget Hässle v Alphapharm Pty Limited [2002] HCA 59; (2002) 212 CLR 411 (AB Hässle) at [52] – [53], might be considered. Abbey would pose the reformulated Cripps question in the present case as “whether the person skilled in the art would have been directly led as a matter of course to try dosages within the claimed dosage range/concentration in the expectation that this might well produce a better or useful alternative to the existing sheep lice treatments or some other useful result”.

76 Abbey submits that the evidence supports the contention that the person skilled in the art would have had the requisite expectation of success.

77 Elanco disputes the case advanced by Abbey on several levels. It challenges the contention that the common general knowledge includes: thiacloprid and its chemical structure; the solvents used in AVENGE; and product labels used on other products in the market.

78 Elanco submits that the Trade Advice Notice does not teach the use of thiacloprid for use in a composition for a pour-on product nor the amounts to be administered or concentrations in any such product. Although the Trade Advice Notice provides a potential candidate for investigation, it is only the first step in a series of stages in the developmental process. Early stages also include determining the solubility and chemical structure of thiacloprid. Neither Ms Mahashabde nor Dr Agnew considered those matters in their affidavit evidence. Both are critical to the development pathway. Elanco submits that Professor Whittem gave evidence of the importance of chemical structure and the differences between imidacloprid and thiacloprid which meant that the person skilled in the art could not assume from information about imidacloprid that thiacloprid would work in a similar way. This meant that there could be no real expectation of success in the developmental pathway proposed by Abbey.

79 Elanco submits that the claimed dose and concentration ranges are narrow and although the evidence shows that the hypothetical team could have developed a pour-on formulation using thiacloprid, the skilled team could have no expectation of success in setting out to formulate thiacloprid as a pour-on product, citing, amongst other authorities, Apotex Pty Ltd v ICOS Corporation (No 3) [2018] FCA 1204; (2018) 135 IPR 13 at [354] – [358] (Besanko J).

80 Elanco submits that the approach taken by Abbey to the starting dosage of an hypothetical development process involves assumptions as to the amount of take-off in dipping, converting information from the Trade Advice Notice to devise a starting dosage for hypothetical testing of a pour-on formulation and then continuing on an assumption that every step of the theoretical development process identified would be successful. However, the evidence undermined the correctness of that assumption.

81 Elanco submits that Abbey’s case is essentially that, given the disclosure in the Trade Advice Notice of the use of thiacloprid in a plunge dipping formulation, provided that sufficient dose determination studies were undertaken, the skilled team would eventually arrive at a formulation and dose for a pour-on product containing thiacloprid in the concentration and dosage ranges claimed. However, it is apparent that as a “starting point” the dose that is proposed is a dose that would be tested in a preliminary dose determination study.

82 Elanco submits that Ms Mahashabde’s evidence is flawed for several reasons:

(a) First, her process of determining the solubility of thiacloprid in known solvents used in pour-on formulations, which is said to be a crucial step, relies on documents which Elanco contends did not form part of the common general knowledge as at the priority date.

(b) Secondly, her approach to calculating a starting point for a dose of thiacloprid in a pour-on formulation is based on impermissible assumptions. Ms Mahashabde estimates the dose required in a dipping formulation by reference to the amount of thiacloprid administered in the dip disclosed in the Trade Advice Notice. Her calculation involves what Elanco submits is an impermissible assumption as to the amount of take-off (being the amount that remains on a sheep after it is dipped). Ms Mahashabde arrives at an estimate of 4.8mg/kg and then converts that estimated dipping dose into a potential dose for a pour-on formulation in an impermissible manner. Despite acknowledging that it is not technically possible to correlate the dose of a dip formulation to a pour-on formulation, she doubles the dipping dose to arrive at a starting dose for a pour-on, on the basis that pour-on formulations are more concentrated and the safety information in the Trade Advice Notice discloses that residue studies were carried out at the double dose amount.

(c) Thirdly, she calculates the concentration of her hypothetical formulation based on the volume used for the AVENGE product (being 60mL for a 50kg sheep). This again has difficulties, given that AVENGE uses the separate active ingredient imidacloprid and the AVENGE product label was not part of the common general knowledge as at the priority date. Elanco notes that concentration will be heavily dependent on the solubility of thiacloprid, and that Ms Mahashabde’s evidence concerning the ultimate concentration of a formulation of a pour-on product involves assumptions as to the degree of solubility of that active, in comparison to imidacloprid.

83 In relation to the evidence of Dr Agnew, Elanco notes that he made no attempt to calculate the dose of thiacloprid but gives evidence in relation to two alternative pathways to a starting point. The first is to calculate a minimum effective dose for thiacloprid in a pour-on. This is not an approach that Professor Whittem would take (though the experts agreed this was for commercial reasons). Elanco criticises the approach taken by Abbey to this evidence, because: (a) it is based on the proposition that first, a “routine” minimum effective dose study would be conducted; (b) it would yield the same results as Trial Example 10 in the patent application; and (c) by this means, the dosage amounts and concentrations claimed were obvious.

84 The second is to calculate an effective dose by reference to the AVENGE product label, which Elanco submits was not common general knowledge. In any event, Abbey contends that this approach would not be adopted because of the structural differences between imidacloprid and thiacloprid but in any event, the dosing range for AVENGE is around 38 to 79 mg/kg, depending on the weight of the sheep, with the average dose being around 49 mg/kg. That is significantly higher than the range of 10 to 30 mg/kg claimed in the patent application.

85 Elanco submits that none of the hypothetical pathways proposed by Abbey would have the chance of success that the authorities require, emphasising the decision of Besanko J in ICOS Corporation at [338] – [356], and the authorities cited therein.

86 It is necessary first to consider the question of inventive step by reference to the steps that Abbey contends the hypothetical skilled worker – here a team – would have taken from the common general knowledge, with the addition of the Trade Advice Notice, to the invention claimed.

87 The invention as claimed is a method of controlling lice on sheep or goats by administering by backlining a pharmaceutically effective amount of thiacloprid where the amount administered is in a dose of 10 to 30 mg/kg by weight of the animal and the concentration of thiacloprid in the composition is 0.5% to 2.0% w/v.

88 Elanco accepts that the claims are concerned with thiacloprid used in a particular dosage and concentration range. It also accepts that no aspect of the inventive step lies in the mechanics of the formulation. That concession is properly made. The disclosure of the invention identifies no aspect of the formulation of any composition. The disclosure is of an invention of alternative methods for controlling ectoparasites to achieve high potency and high persistency by any means of external administration of thiacloprid. The “surprising discovery” identified in the section of the specification entitled “Disclosure of the Invention” is not of any particular type of formulation but of the finding that thiacloprid has high potency and is suitable for the control of lice when applied externally to an animal. The broadest statements of the invention, quoted at [52] above, concern the step of administering a pharmaceutically effective amount of thiacloprid externally. That invention is then narrowed to the topical administration of a composition containing “0.0001% to 3.5% w/v of thiacloprid”. The examples and preferred embodiments of the invention disclosed in the specification traverse administration by backlining, dip treatment or jetting treatment.

89 The delegate found in the first decision that the problem addressed by the specification is the need for alternative methods for controlling lice using actives of high potency and high persistency that allow for the use of relatively low quantities of actives for short and long wool treatments. In my respectful view, that summary accords with the disclosure of the specification. The claims, however, have been narrowed (after they were found by the delegate to be too broad and lacking an inventive step) such that the characterisation of the invention must be considered in light of their final form. Here, as I have noted, they are for a dose of thiacloprid in a particular mg/kg range with a concentration in a particular range. The invention does not concern formulation, but the identification of dosage amounts for use in the method of backlining, which is referred to in the evidence as a “pour-on formulation”.

90 By s 7(2) of the Patents Act an hypothetical person skilled in the art, notionally possessed with the common general knowledge as it existed before the priority date, must find the invention to be obvious, whether or not the common general knowledge is supplemented by prior art information within s 7(3): AstraZeneca AB v Apotex Pty Ltd [2015] HCA 30; (2015) 257 CLR 356 (AstraZeneca (HC)) at [18] (per French CJ).

91 The law concerning the requirement for an inventive step reflects the balance of policy considerations in patent law of encouraging and rewarding inventors without impeding advances and improvements by skilled, non-inventive persons: Lockwood Security Products Pty Ltd v Doric Products Pty Ltd (No 2) [2007] HCA 21; (2007) 235 CLR 173 (Lockwood No 2) at [48] (Gummow, Hayne, Callinan, Heydon and Crennan JJ). The cases over the years have made a number of statements as to what is required to answer the jury question of whether or not an invention is obvious. It is a question of fact. The question is not what is obvious to a court but depends on analysis of the invention as claimed having regard to the state of the common general knowledge, any information relied upon for the purpose of s 7(3), and the approach taken to it by the person skilled in the art: Lockwood No 2 at [51].

92 As a basic premise, the question is always “is the step taken over the prior art an ‘obvious step’ or an ‘inventive step’?”. This is often an issue borne out by the evidence of the experts: Lockwood No 2 at [52]. Whilst the question remains one for the courts to determine, the courts do so by reference to the available evidence, including that of persons who might be representative of the skilled person in the art: AstraZeneca (HC) at [70] (Kiefel J, as the former Chief Justice then was).

93 Various formulations of the question have been set out in the cases. In R D Werner & Co Inc v Bailey Aluminium Products Pty Ltd [1989] FCA 57; (1989) 25 FCR 565 at 574, Lockhart J said that there must be “some difficulty overcome, some barrier crossed”.

94 A “scintilla of invention” is sufficient to support the validity of a patent: AB Hässle at [48] (per Gleeson CJ, Gaudron, Gummow and Hayne JJ), although as I have noted previously, this proposition may be seen to be somewhat circular, because the requirement of the qualitative assessment remains that the scintilla so identified must be inventive.

95 In Allsop Inc v Bintang Ltd [1989] FCA 428; (1989) 15 IPR 686 at 701 the Full Court (Bowen CJ, Beaumont and Burchett JJ) noted that for the invention to be inventive, it must be “beyond the skill of the calling”.

96 In AstraZeneca (HC), French CJ noted at [15] that relevant content was given to the word “obvious” by Aickin J in Wellcome Foundation at 286, where Aickin J posed the test:

whether the hypothetical addressee faced with the same problem would have taken as a matter of routine whatever steps might have led from the prior art to the invention, whether they be the steps of the inventor or not.

97 At [15], French CJ (with whom Gageler and Keane JJ and Nettle J agreed) explained:

The idea of steps taken “as a matter of routine” did not, as was pointed out in AB Hässle, include “a course of action which was complex and detailed, as well as laborious, with a good deal of trial and error, with dead ends and the retracing of steps”. The question posed in AB Hässle was whether, in relation to a particular patent, putative experiments, leading from the relevant prior art base to the invention as claimed, are part of the inventive step claimed or are “of a routine character” to be tried “as a matter of course”. That way of approaching the matter was said to have an affinity with the question posed by Graham J in Olin Mathieson Chemical Corporation v Biorex Laboratories Ltd. The question, stripped of references specific to the case before Graham J, can be framed as follows:

“Would the notional research group at the relevant date, in all the circumstances, which include a knowledge of all the relevant prior art and of the facts of the nature and success of [the existing compound], directly be led as a matter of course to try [the claimed inventive step] in the expectation that it might well produce a useful alternative to or better drug than [the existing compound]?”

That question does not import, as a criterion of obviousness, that the inventive step claimed would be perceived by the hypothetical addressee as “worth a try” or “obvious to try”. As was said in AB Hässle, the adoption of a criterion of validity expressed in those terms begs the question presented by the statute.

(Citations committed and square brackets in original)

98 The approach proposed by Graham J in Olin Mathieson Chemical Corporation v Biorex Laboratories Ltd [1970] 1 WLUK 202; [1970] RPC 157 to which French CJ refers is often referred to as the “modified Cripps question”. The application of the modified Cripps question was the subject of consideration in Generic Health Pty Ltd v Bayer Pharma Aktiengesellschaft [2014] FCAFC 73; (2014) 222 FCR 336, where the Full Court said at [71] (Besanko, Middleton and Nicholas JJ):

We do not think that the plurality in [AB Hässle] were saying that the reformulated Cripps question was the test to be applied in every case. Rather, it is a formulation of the test which will be of assistance in cases, particularly those of a similar nature to [AB Hässle]. The plurality did not reject as an alternative expression of the test the question whether experiments were of a routine character to be tried as a matter of course (The Wellcome Foundation Limited v VR Laboratories (Aust) Proprietary Limited (1981) 148 CLR 262, at 280-281, 286, per Aickin J). We do not think there is a divide here in terms of whether an expectation of success is relevant between a test which refers to routine steps to be tried as a matter of course and the reformulated Cripps question. It is difficult to think of a case where an expectation that an experiment might well succeed is not implicit in the characterisation of steps as routine and to be tried as a matter of course. On the other hand, we think a test formulated in terms of worthwhile to try was firmly rejected by the High Court in [AB Hässle] (see also [Pfizer Overseas Pharmaceuticals v Eli Lilly and Co (2005) 225 ALR 416], at 476, [287], per French and Lindgren JJ). The fact (if it be the fact) that the position in the United States may have shifted does not affect the binding nature of what the plurality said in [AB Hässle].

(Emphasis added)

99 In Nichia Corporation v Arrow Electronics Australia Pty Ltd [2019] FCAFC 2; (2019) 175 IPR 187, the Full Court (Jagot J, with Besanko and Nicholas JJ agreeing) picked up on the emphasised passage above in concluding that, in finding that there were “a number of unknowns” and that the patentee “did not know” that a combination would produce a satisfactory result within the claim, the primary judge strayed from “the test of steps taken in an expectation that they might well produce the invention or a useful result towards a test of an expectation of knowing that steps will produce a useful result based on predictive capacity” (at [88] – [89]). The relevant test is merely expecting that the steps may well work, rather than knowing that steps will or would or even may well work (at [99]).

100 In relation to having multiple avenues to try, in Nichia the Full Court adopted as orthodox the statement of Laddie J in Brugger v Medic-Aid Ltd [1996] 6 WLUK 122; [1996] RPC 635 at 661:

…if a particular route is an obvious one to take or try, it is not rendered any less obvious from a technical point of view merely because there are a number, and perhaps a large number, of other obvious routes as well. If a number of obvious routes exist it is more or less inevitable that a skilled worker will try some before others. The order in which he chooses to try them may depend on factors such as the ease and speed with which they can be tried, the availability of testing equipment, the costs involved and the commercial interests of his employer. There is no rule of law or logic which says that only the option which is likely to be tried first or second is to be treated as obvious for the purpose of patent legislation.

6.3 Findings of common general knowledge

101 I have in section 3 above identified aspects of the agreed common general knowledge. Set out below are my findings in respect of other aspects of the common general knowledge relied upon by Abbey in support of its obviousness case.

6.3.1 Backlining is a preferred method

102 Backlining with small volumes of product being applied to the back of the sheep was the most preferred form of administration for treatment of ectoparasites on animals at the priority date because it was an easier and more efficient method of administration and was in many ways more convenient than dips.

103 During development, the investigation of a dose or dosage range of an active ingredient sufficient to kill a target parasite was routinely undertaken by conducting dose studies, which were a standard part of product development. This would involve the team selecting several bench scale formulations to take into proof of concept studies, where efficacy and animal safety data could be obtained.

104 Proof of concept studies involve in-vivo studies which are conducted at (sheep) pen scale typically involving multiple groups of 3 – 6 sheep, each with one of the selected formulations.

105 In the veterinarian JER, the experts agree that proof of concept studies are typically conducted on more than one test formulation that may not be the final one for commercialisation. Proof of concept studies use a wider dose range than would be used in the dose determination studies, with an aim that the dose range cover both effective and ineffective doses. There is a dispute between the parties as to the focus of proof of concept studies, and in particular whether they are used to identify an estimated minimum dose rate, which I address in section 6.5.4.1 below.

106 After proof of concept studies, dose determination studies would typically be conducted using more animals (30 – 100 sheep) for one or two of the most preferred test formulations to investigate a tighter dosage band (i.e. narrower range) than assessed in the proof of concept studies.

107 The size, number and design of dose determination studies varied between companies, but in general terms the studies were designed to identify the necessary dose for a formulation of the active ingredient. In the veterinarian JER, the experts agreed that the results of the proof of concept studies and dose determination studies can sometimes be unexpected and accordingly such studies are necessary in new formulation development.

108 The World Association for the Advancement of Veterinary Parasitology publishes guidelines (WAAVP Guidelines) for evaluating the efficacy of ectoparasiticides against, amongst other things, biting lice. The veterinary experts agreed that these were well known in the field and give advice as to how to conduct dose determination studies. They contain advice that for a dose determination study, four groups of animals adequately infested with the target parasite are administered with either a negative control, 0.5, 1 and 2 times the anticipated effective dose. This approach was known to both veterinarian experts without referring to the WAAVP Guidelines and I find it to form part of the common general knowledge. The experts further agreed that generally the proof of concept studies used a larger range of doses than used in the subsequent dose determination studies.

109 The final stage of investigation is the conduct of dose confirmation studies, which involve larger groups of sheep to assess the efficacy of the doses chosen. No party suggested that these are relevant to the question of inventive step.

110 One matter in dispute was whether the information contained in the product labels of commercially available parasiticides formed part of the common general knowledge.

111 Abbey submits, and the veterinarian experts agree, that a range of chemical parasiticides were available for the treatment and prevention of sheep lice before the priority date, as listed in the first affidavit of Dr Agnew and that the amount of active ingredient in each of the commercially available products was set out in the product label. It submits that the labels for the known parasiticides formed part of the common general knowledge as a resource routinely identified and referred to by those in the field.

112 Abbey relies on the following evidence to support its submission, which I accept.

113 First, that the product labels of commercial products as identified by Dr Agnew in his evidence were regarded in the field as standard reference tools which were accessed by veterinarians where necessary. Secondly, labels were generally available for access on the website of the Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority (APMVA). Thirdly, product labels were consulted as a matter of course, and in preference to being retained knowledge. As Professor Whittem said in his oral evidence, he does not teach his students to learn dosages by heart, but that they should “always look at the label”. Mr Pippia gave evidence that he would consult labels as part of his technical resources for product analysis.

114 Against this background, the question arises as to whether or not the information contained in the product labels formed part of the common general knowledge in June 2013. The evidence of Dr Agnew, with which Professor Whittem agreed, is that some 17 listed products used in controlling ectoparasites, and their methods of administration were known to them before the priority date. Included in that list is the AVENGE product which has as its active ingredient imidacloprid. The amount of active used for the various means of administration (which included pour-on, dipping, jetting and dressings) was included on the product label. The label generally also provided a guideline or recommended dosage based on the size of the animal, which for dips provided an initial charge and, depending on whether the active is striping or non-stripping, a replenishment plus topping up or topping up amount.

115 For the reasons that follow, I accept that the product label for AVENGE formed part of the common general knowledge.

116 The notion of common general knowledge involves the use of that which is known or used by those in the relevant trade and which forms the background knowledge and experience which is available to all in the trade; Minnesota Mining and Manufacturing Company v Beiersdorf (Australia) Limited [1980] HCA 9; (1980) 144 CLR 253 at 292 (Aickin J). Information that is merely ascertainable by a routine literature search is not of itself to be regarded as common general knowledge; AB Hässle at [31], [57] (Gleeson CJ, Gaudron, Gummow and Hayne JJ). It would be wrong to consider a document part of the common general knowledge simply because skilled persons could readily locate and assimilate its contents because that would leave open for inclusion contestable portions of journals and articles that would not satisfy the description of common general knowledge; British Acoustic Films Ltd v Nettlefold Productions Ltd [1935] 1 WLUK 2; (1936) 53 RPC 221 at 250 per Luxmoore J:

In my judgment it is not sufficient to prove common general knowledge that a particular disclosure is made in an article, or series of articles, in a scientific journal, no matter how wide the circulation of that journal may be, in the absence of any evidence that the disclosure is accepted generally by those who are engaged in the art to which the disclosure relates. A piece of particular knowledge as disclosed in a scientific paper does not become common general knowledge merely because it is widely read, and still less because it is widely circulated. Such a piece of knowledge only becomes general knowledge when it is generally known and accepted without question by the bulk of those who are engaged in the particular art; in other words, when it becomes part of their common stock of knowledge relating to the art.

(Emphasis added)

117 In an often-cited passage in ICI Chemicals & Polymers Ltd v Lubrizol Corporation Inc [1999] FCA 345; (1999) 45 IPR 577 at [111] – [112], Emmett J said:

The notion of common general knowledge involves the use of that which is known or used by those who are in the relevant field or area. It forms the background knowledge and experience which is available to all in that field in considering the making of new products or making of improvements in old products. It must be treated as being used by an individual as a general body of knowledge …

The common general knowledge is the technical background to the hypothetical skilled worker in the relevant art. It is not limited to material which might be memorized and retained at the front of the skilled worker’s mind but also includes material in the field in which he is working which he knows exists and to which he would refer as a matter of course. It might, for example, include:

• standard texts and handbooks;

• standard English dictionaries;

• technical dictionaries relevant to the field;

• magazines and other publications specific to the field.

118 Jagot J observed in Gilead Sciences Pty Ltd v Idenix Pharmaceuticals LLC [2016] FCA 169; (2016) 117 IPR 252 at [216] (affirmed in Idenix Pharmaceuticals LLC v Gilead Sciences Pty Ltd [2017] FCAFC 196; (2017) 134 IPR (Nicholas, Beach and Burley JJ)):

…Justice Emmett [in ICI Chemicals] is not suggesting anything more than that the common general knowledge might include information in articles (etc) if the skilled addressee knows the article (etc) exists and would refer to it as a matter of course. In other words, what his Honour is allowing for is that the skilled addressee does not have to have instant recall of every matter for it to be common general knowledge. If the skilled addressee knows that certain information exists in an article (etc) and would refer to that document as a matter of course to refresh his or her memory about the details of that which the skilled addressee already knows in broad outline then those details might themselves form part of the common general knowledge. Justice Emmett is not suggesting that merely because the skilled addressee could locate a document and, having located it, could read and assimilate its contents, the document and its contents would form part of the common general knowledge. This would be inconsistent with Minnesota Mining, in particular, that the common general knowledge is the background knowledge and experience which is available to all in the trade. For the possibility which Emmett J recognised in ICI Chemicals to arise there would have to be evidence that the particular document was known and would be referred to as a matter of course by those in the field.

(Emphasis added)

119 In each case, determination of whether identified information falls within the common general knowledge will be a matter of weight and evaluation according to these principles.

120 I am satisfied, on the basis of the evidence that I have summarised above, that those skilled in the art knew of the existence of the AVENGE label, knew of the type of information that was available on it and would refer as a matter of course to that label to provide them with information about the products in question.

6.3.4 Chemical structure of thiacloprid

121 Abbey submits that the chemical structure of thiacloprid formed part of the common general knowledge. There is no doubt that imidacloprid was a known active ingredient (in AVENGE) and that it, as well as thiacloprid, were both part of the neonicotinoid class of insecticides. Abbey contends that the chemical structures of both formed part of the common general knowledge because they were readily accessible on resources such as PubChem. However, I am not satisfied that this level of knowledge is sufficient for Abbey to discharge the burden on it to established that the chemical structures fall within the range of information that the skilled addressee knows to exist and would refer to as a matter of course to refresh their memory of that which they already know in broad outline (to paraphrase Gilead).

6.3.5 The general approach to developing thiacloprid dosages in a pour-on

122 Abbey relies on several aspects concerning the development of a pour-on product as forming part of the common general knowledge which I consider below.

123 It is not in dispute that the administration of a lower concentration of active ingredient is generally desirable, provided that the active ingredient maintains its efficacy at that concentration. As Ms Mahashabde and Mr Pippia agreed, in developing a product, the aim is to use the least amount of active ingredient as possible.

124 The formulation experts agreed, and I accept that in determining the required amount of active for a pour-on product, it is ideal to keep the volume of the treatment that goes on the animal as constant as possible.

125 Abbey contends that when calculating the amount of active for a new composition, the skilled team typically considers a 50kg sheep as a target. As the amount of active ingredient is calculated in terms of mg/kg, the selection of a particular weight is of no particular significance and to some extent arbitrary. The evidence indicates that an assumed 50kg animal is regarded by those in the field to be a convenient approach.

126 Abbey submits that if there is a fixed volume chosen and the desired mg/kg is determined (a matter of significant contest between the parties), the calculation of the weight to volume percentage concentration of the active ingredient follows as a matter of arithmetic. This follows as a matter of logic and was agreed between Mr Pippia and Ms Mahashabde.

127 I have referred in section 3 to the agreed dipping calculation, which I repeat for convenience:

For dipping, the amount of an active ingredient that is applied to a sheep in mg/kg body weight can be calculated knowing the volume (mg/l) administered and the weight of the animal. For example, at 48ppm, assuming between 2L and 6L of formulation is “take-off”, this equates to an application of:

Sheep weight (kg) | Active applied (mg/kg) |

20 | 4.8 – 14.4 |

30 | 3.2 – 9.6 |

40 | 2.4 – 7.2 |

50 | 1.92 – 5.76 |

60 | 1.6 – 4.8 |

128 I accept the evidence of Ms Mahashabde that dipping compositions are more diluted than pour-on treatments, which are more concentrated. As she says in the formulation JER, pour-on products are applied by backlining the animal and the active ingredient in the formulation has to migrate over the body of the animal to reach the lice at an effective concentration, hence they are required to be more concentrated than dips, which cover the entire body of the animal and allow the active ingredient to come in direct contact with the lice. This accords with the evidence of prior art formulations given by Mr Pippia, where he observes that the concentration of the active ingredient for a dip is a fraction of the concentration of the active ingredient in a pour-on.

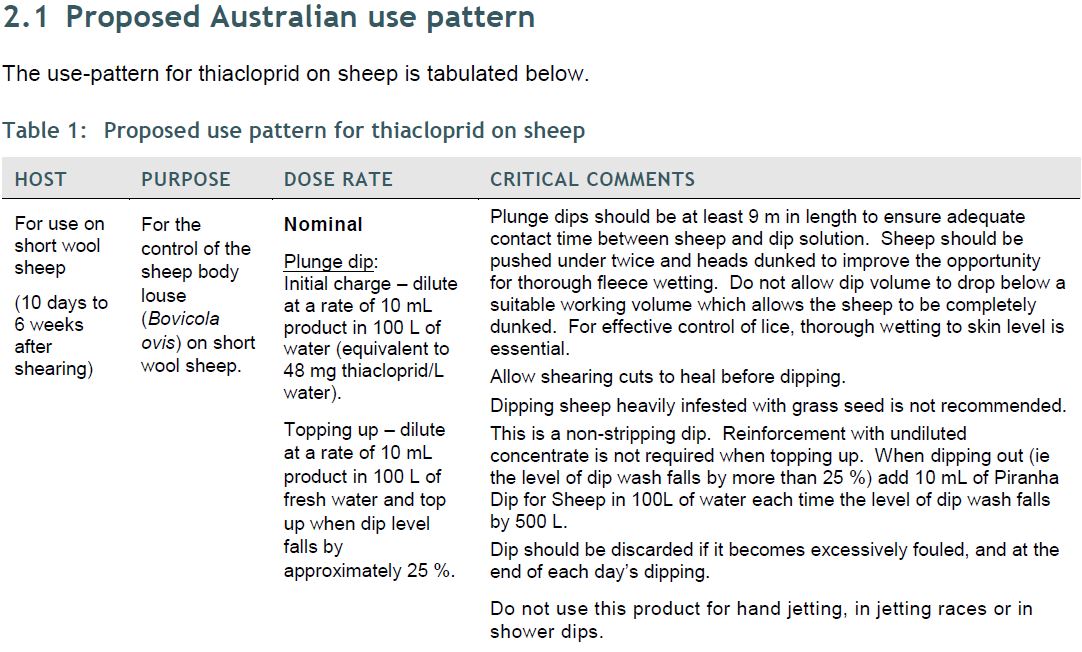

129 The Trade Advice Notice was published in February 2013. There is no dispute that it forms part of the prior art base for the purposes of s 7(3) of the Patents Act.

130 The Trade Advice Notice is entitled “Trade Advice Notice on thiacloprid in the Product Piranha Dip for Sheep, APVMA product number 63766” and relates to an application by Bayer Australia Ltd (Animal Health) for the registration of a new product called “Piranha Dip for Sheep”, containing an approved active constituent thiacloprid (480 g/L).

131 Under the heading “About this document” it provides:

… the Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority (APVMA) is considering an application to vary the use of an existing registered agricultural or veterinary chemical. It provides a summary of the APVMA’s residue and trade assessment.

132 The “Introduction” provides:

The [APVMA] has before it an application from Bayer Australia Limited (Animal Health), for the registration of a new product, Piranha Dip for Sheep, which contains the approved active constituent thiacloprid (480 g/L). The new product is a plunge dip that is intended for the control of the sheep body louse (Bovicola ovis) on short wool sheep.

To date, there are no products containing thiacloprid that are registered for use on food-producing animal species. However, there are two thiacloprid-based products registered for agricultural uses in Australia.

The existing Australian maximum residue limits (MRLs) for thiacloprid in animal commodities were established to cover the occurrence of residues as a result of animals consuming feedstuffs containing thiacloprid residues. Therefore, the current application does not involve the establishment of Australian MRLs for thiacloprid in edible sheep tissues.

However, the application does require the setting of meat and milk withholding periods (WHPs), establishment of an export slaughter interval (ESI), and approval of the proposed product label.

133 In section 2, entitled “Residues in Livestock”, the Trade Advice Notice includes the following:

134 Under the sub-heading 2.2, “Current Australian MRLs and residues definition”, entries for thiacloprid in the MRL (Maximum Residue Limits) standard are listed. Relevantly, the Trade Advice Notice provides, in relation to “residue definition/marker residue”, that it was concluded that the current residues definition/marker residue of parent thiacloprid “remains appropriate and is consistent with the use of the [Joint FOA/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA)]-approach to assessing residues of veterinary drugs”.

135 In relation to “Application rate (dip strength) and dipping process”, the Trade Advice Notice says:

Most of the residues trials were conducted at elevated rates (1.5 to 2x the label rate), and different dipping processes were used in each trial. The variability of the dipping processes seen in the residues trials is likely to reflect the variability of on-farm practices. Further, there is a broad range of factors that impact on the residues profiles of treated sheep. Therefore, in this instance, it was not considered appropriate to correct the residues data for dip strength (to the 1x rate). Analysis of the residues data, without correction for dose rate, reflects the “worst case” residues scenario.