Federal Court of Australia

Australian Securities and Investments Commission v LGSS Pty Ltd [2024] FCA 587

ORDERS

AUSTRALIAN SECURITIES AND INVESTMENTS COMMISSION Plaintiff | ||

AND: | LGSS PTY LTD ACN 078 003 497 AS TRUSTEE FOR LOCAL GOVERNMENT SUPER ABN 28 901 371 321 Defendant | |

DATE OF ORDER: | 5 June 2024 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The proceeding be listed for further hearing on a date to be fixed.

2. The costs of the proceeding to date be reserved.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

O’CALLAGHAN J

Introduction

1 In the realm of financial product investments, “greenwashing” is a term that:

… pertains to the misleading and deceptive disclosures employed by financial institutions to entice environmentally conscious investors into purchasing their financial products that, in reality, fall short of meeting the expected Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) or green credentials. These ESG credentials encompass environmental compliance and measures to protect the environment, reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and manage natural resources; social compliance, which evaluates how a company treats its stakeholders; and governance compliance, focusing on appropriate governance practices such as executive transparency and accountability.

See Das C, Pearce P and Henson T, “What’s Green and Ethical about Greenwashing in the Promotion of Financial Products” [2023] NZLJ 400 at 401.

2 Some American authors have said that the origin of the term “greenwashing” can be traced to an unpublished 1986 essay by an environmentalist named Jay Westerveld, in which he is claimed to have:

described a hotel sign urging patrons to use fewer towels to reduce their environmental impact. Despite the hotel’s purported concern for the environment, Westerveld opined that the hotel’s true incentive for posting the sign was to save money by not having to launder as many towels. Based on the term “whitewashing” - using white paint to cover up dirt - environmental groups adopted the term “greenwashing” to signal misleading environmental claims.

(footnotes omitted)

See Peterson VJ, “Gray Areas in Green Claims: Why Greenwashing Regulation Needs an Overhaul” (2024) 35(1) Vill Env’t LJ 177 at 179. Professor Miriam A Cherry, however, suggests that the story described by Ms Peterson may be apocryphal. See Cherry MA, “The Law and Economics of Corporate Social Responsibility and Greenwashing” (2014) 14 UC Davis Bus LJ 281 at 284 (and footnote 5).

3 In this proceeding, commenced on 10 August 2023 by way of originating process and concise statement, the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) alleges that the defendant (LGSS) contravened s 12DB(1)(a) and s 12DF(1) of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth) (ASIC Act) by making false or misleading representations, and engaging in conduct liable to mislead the public in relation to investments made by the superannuation fund, of which LGSS is the trustee, now known as Active Super (also known as Local Government Super), during the relevant period, being from 1 February 2021 to 30 June 2023. ASIC alleges, in substance, that LGSS engaged in greenwashing by making false or misleading representations to members and potential members of the fund about their “green” or “ESG” credentials.

4 LGSS contended in its response to ASIC’s concise statement, in substance, that:

(a) none of the representations ASIC relied on was conveyed;

(b) the representations, if made, were not made “in trade or commerce”;

(c) it did not engage in conduct contrary to the representations, if made; and

(d) in any event, the representations, if made, were as to future matters and LGSS had a reasonable basis for making them; and

(e) the proceeding was without merit and should be dismissed.

5 On 24 August 2023, Yates J ordered that LGSS’s alleged liability for contravening ss 12DB(1)(a) and 12DF(1) of the ASIC Act and ASIC’s application for declarations in respect of those alleged contraventions be determined separately from, and prior to, all other claims for relief. The matter was subsequently reallocated to my docket.

6 At the hearing, Mr J Hewitt SC appeared with Ms J Buncle for ASIC. Mr HK Insall SC appeared with Ms AE Smith for LGSS.

7 ASIC read the affidavits of Vanessa Keir dated 13 November 2023, and of Liam Toohey dated 1 March 2024.

8 Ms Keir is a Senior Manager at ASIC responsible for the management and supervision of enforcement matters in investigation and litigation. Among other things, Ms Keir produced a number of documents obtained by ASIC during the investigation it carried out in 2023 in relation to suspected contraventions by LGSS of the ASIC Act.

9 Mr Toohey is employed by ASIC as an Investigator in Enforcement and Compliance. He also produced a number of documents upon which ASIC relied.

10 LGSS read the affidavits of Craig Anthony Turnbull dated 9 February 2024, Moya Yip dated 9 February 2024 and of Ken Pholsena dated 16 February 2024.

11 Mr Turnbull is the Chief Investment Officer of Active Super. He deposed, among other things, to the history and growth of Active Super, the content of various documents (annual reports and so on), the nature of the fund’s investments, Active Super’s corporate structure and governance, its investment structure, its “long standing commitment to responsible investing”, its responsible investment policies, its “investment restriction list”, certain investment agreements and its 2022 ban on investing in Russia.

12 Mr Pholsena is employed by Active Super as a Portfolio Manager. He deposed, among other things, to Active Super’s so-called “overlay process” and related short trading.

13 Ms Yip is employed by Active Super as the Head of Responsible Investment. She described various activities that she undertook “to ensure that Active Super’s portfolios maintained strong ESG credentials”, and restricting investments in Russia.

14 Mr Turnbull, Ms Yip and Mr Pholsena were cross-examined.

LGSS and Active Super

15 LGSS holds an Australian Financial Services Licence and is the trustee of Active Super.

16 Active Super was originally known as the Local Government Superannuation Scheme. It was established as a “profit-to-member” industry scheme under a trust deed dated 30 June 1997. It thus reinvests its profits for the benefit of its members.

17 By the time of the relevant period Active Super was an “open” fund — that is, any member of the public could invest their superannuation in Active Super, whether or not they were a local government employee. Further, local government employees had a choice as to whether they invested in LGSS, or another fund.

18 By the end of the relevant period, Active Super managed approximately $13.5 billion in superannuation assets for around 89,000 members.

19 Its investment portfolio was spread across various asset classes, including, relevantly: international equities (about 21% of assets held); Australian equities (about 40% of assets held); international unit trusts (about 10% of assets held); and Australian unit trusts (about 2% of assets held). During the relevant period, LGSS held units in, among other funds, Colonial First State Wholesale Small Companies Fund - Core ARSN 089 460 891 (CFS Fund), the Macquarie Emerging Markets Fund (Class I USD) (Macquarie Fund), the Wellington Emerging Markets Fund (Australia) ARSN 133 266 903 (Wellington Fund) and the SPDR S&P/ASX 200 Fund (ASX 200 Fund), which is an exchange traded fund that provides investment exposure to all of the companies comprising the ASX 200 index (together, the Investment Funds).

20 LGSS says that it is committed to “environmental, social and governance” (usually abbreviated as “ESG”) factors in its investment decision making, including pursuant to its “Sustainable and Responsible Investment Policy”, which is often abbreviated as “the SRI Policy”.

21 The concept of corporate “sustainability”, and investor focus on it, is accelerating globally. See generally Fisch JE, “Making Sustainability Disclosure Sustainable” (2019) 107(4) Geo LJ 923. As Professor Fisch said at 925–926:

The extent to which corporations should incorporate sustainability objectives into their operational decision making is highly contested, as is the relationship between societal impact and economic value. Indeed, the Department of Labor subsequently issued new guidelines for retirement plans cautioning that “[f]iduciaries must not too readily treat ESG factors as economically relevant to the particular investment choices at issue when making a decision.” At the same time, however, issuers are modifying their operations in response both to investor demands and to the claim that sustainable business practices lead to improved economic performance. Being able to assess an issuer’s sustainability practices is critical to evaluating the effect of sustainability practices on economic value. For investors and capital markets to consider the societal impact of a firm’s operations--and to determine the consequences of that impact--they must have access to adequate sustainability disclosure.

(footnotes omitted)

22 The idea behind sustainability is decision making “that incorporates social, political, and ethical concerns in addition to traditional financial performance” and “involves matters that can impact the long-term success of the company and the economy”. Ibid at 931.

The law

23 Section 12DB(1)(a) of the ASIC Act provides that “[a] person must not, in trade or commerce, in connection with the supply or possible supply of financial services, or in connection with the promotion by any means of the supply or use of financial services: (a) make a false or misleading representation that services are of a particular standard, quality, value or grade…”

24 Section 12DF(1) provides that “[a] person must not, in trade or commerce, engage in conduct that is liable to mislead the public as to the nature, the characteristics, the suitability for their purpose or the quantity of any financial services”.

25 Determining whether a person has engaged in misleading or deceptive conduct involves four steps: first, identifying with precision the “conduct” said to contravene the relevant provision; second, considering whether the identified conduct was conduct “in trade or commerce”; third, considering what meaning that conduct conveyed; and fourth, determining whether that conduct in light of that meaning was misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive. Compare Self Care IP Holdings Pty Ltd v Allergan Australia Pty Ltd (2023) 97 ALJR 388; [2023] HCA 8 at [80] (Kiefel CJ, Gageler, Gordon, Edelman and Gleeson JJ)); RB (Hygiene Home) Australia Pty Ltd v Henkel Australia Pty Ltd [2024] FCAFC 10 at [168] (Nicholas, Burley and Hespe JJ).

26 The third and fourth steps require the court to characterise, as an objective matter, the conduct viewed as a whole and its notional effects, judged by reference to its context, on the state of mind of the relevant person or class of person. That context includes the immediate context (including all the words in the document or other communication and the manner in which those words are conveyed, not just a word or phrase in isolation) and the broader context of the relevant surrounding facts and circumstances. See Self Care at [82].

27 Where the conduct was directed to the public or part of the public, the third and fourth steps must be undertaken by reference to the effect or likely effect of the conduct on the ordinary and reasonable members of the relevant class of persons. This avoids using the very ignorant or the very knowledgeable to assess the effect or likely effect; it also avoids using those credited with habitual caution or exceptional carelessness; it also avoids considering the assumptions of persons which are extreme or fanciful. Self Care at [83].

28 Further, conduct is, or is likely to be, misleading or deceptive if it has a tendency to lead into error. The threshold “likely to be” is satisfied where there is a real and not remote possibility that conduct will mislead or deceive.

29 Where the persons in question are not identified individuals to whom a particular misrepresentation has been made or from whom a relevant fact, circumstance or proposal was withheld, but are members of a class to which the conduct in question was directed in a general sense, the alleged conduct must be judged by its effect on ordinary or reasonable members of the class. In this case, ASIC contended, and LGSS did not say otherwise, that the relevant class to which the representations alleged were directed are consumers who are members or prospective members of the fund.

The representations alleged

The concise statement

30 ASIC alleged in its concise statement that LGSS made false or misleading representations and engaged in conduct liable to mislead the public contrary to ss 12DB(1)(a) and 12DF(1) of the ASIC Act as follows:

Active Super’s ESG marketing

…

8. During the relevant period, LGSS represented Active Super in the manner described in the preceding paragraph by the following means:

(a) statements on its website and on social media concerning the investments that Active Super seeks to eliminate because of the risks posed to the environment and the community;

(b) the publication on Active Super’s website of multiple versions of a Sustainable and Responsibility Investment Policy (SRI Policy) which purported to outline the responsible investment principles by which Active Super was managed;

(c) the publication on Active Super’s website of an annual Impact Report which purported to explain why “Active Super investments are making a difference” (the Impact Report);

(d) the publication of product disclosure statements (PDS); and

(e) public statements by a senior executive of LGSS on its behalf in relation to Active Super’s investments.

9. In relation to paragraph 8(e) above, Active Super’s chief executive officer at the time, Phil Stockwell, recently stated that Active Super sees its commitment to ethical and sustainable investment as being a critical part of its offering in a competitive superannuation market. Mr Stockwell also stated that Active Super was one of the first super funds in Australia to rule out investing in tobacco 20 years ago, and that Active Super specifically excludes any investments in gambling, tobacco, weapons manufacture and certain investments which are carbon intensive.

Active Super’s representations

10. During the relevant period, LGSS made each of the statements identified in Annexure A to this Concise Statement (Annexure A) in relation to the investments that would not be made or held by Active Super.

11. During the relevant period, by making the statements numbered 1, 2, 5, 6, 11, 18 and 19 in Annexure A, LGSS represented that Active Super would not make or hold investments in companies that derive more than 10% of their revenue from gambling (the Gambling Representations).

12. During the relevant period, by making the statements numbered 2 through 11, 18 and 19 in Annexure A, LGSS represented that Active Super would not make or hold investments in companies that derive any revenue from tobacco (the Tobacco Representations).

13. During the relevant period from May 2022, LGSS made statements in respect of the restrictions it placed on investments by Active Super in Russia from in or around May 2022. By making the statements numbered 12, 15, 16, 17 and 19 in Annexure A, LGSS represented that following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Active Super would divest its Russian investments and make or hold no further investments in Russia (the Russia Representations).

14. During the relevant period, by making the statements numbered 6, 13, 14 [which was not pressed], 18, 19 and 20 [also not pressed] in Annexure A, LGSS represented that Active Super would not make or hold investments in companies that derive any revenue from oil tar sands projects (the Oil Tar Sands Representations).

15. During the relevant period, by making the statements numbered 13, 14 [not pressed] and 20 in Annexure A, LGSS represented that Active Super would not make or hold investments in companies that derive one-third or more of their revenue from coal mining (the Coal Mining Representations).

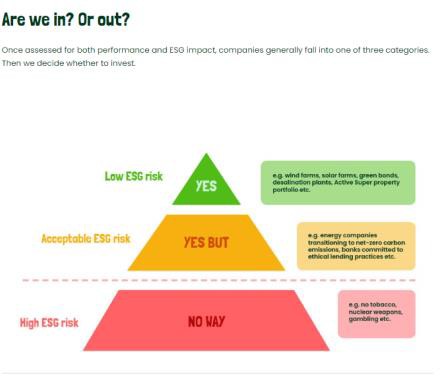

16. Each of the representations referred to in paragraphs 9, and 11 to 15 above were continuing representations.

Active Super’s investments

17. During the relevant period, LGSS made investments for Active Super that were contrary to the statements and representations referred to in paragraphs 9 to 15 above.

18. Specifically, and as identified in Annexure B to this Concise Statement (Annexure B), during the relevant period LGSS made or held (either directly or indirectly):

(a) investments contrary to each of the Gambling Representations, being investments in the companies identified in Table 1 of Annexure B each of which derived more than 10% of its revenue from gambling;

(b) investments contrary to each of the Tobacco Representations, being investments in the companies identified in Table 2 of Annexure B;

(c) investments contrary to each of the Russia Representations, being investments in the companies identified in Table 3 of Annexure B;

(d) investments contrary to each of the Oil Tar Sands Representations, being investments in the companies identified in Table 4 of Annexure B; and

(e) investments contrary to each of the Coal Mining Representations, being investments in the companies identified in Table 5 of Annexure B each of which derived one-third or more of its revenue from coal mining.

31 Annexure A to the concise statement was headed “Representations” and it is attached to these reasons.

32 Annexure B was headed “Active Super’s investments contrary to representations” and it is also attached to these reasons.

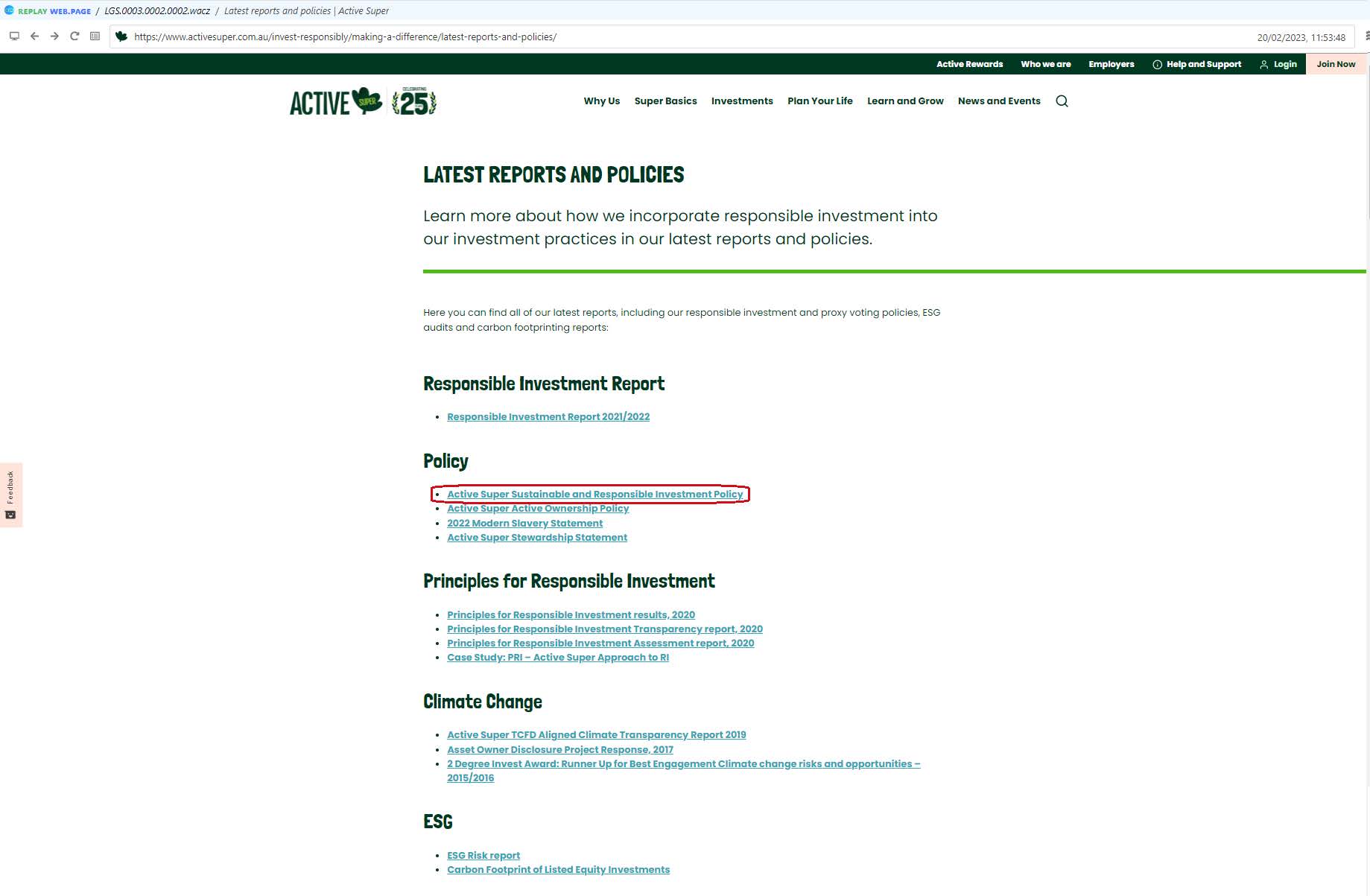

33 The matters relied on in Annexure A were, variously, published on Active Super’s website; in its SRI Policy, in Active Super reports and factsheets, on its social media platforms; and in an email sent from Active Super to existing members. The statements identified at item 11 in Annexure A were contained in an article published by Investment Magazine.

34 LGSS did not dispute that it made the express statements identified in Annexure A, except for the statements contained in item 11 (in which the then CEO is quoted as saying that Active Super ruled out investing in tobacco 20 years ago and also specifically excludes any investments in gambling and weapons manufacturers).

The case should have been pleaded

35 In order to make sense of ASIC’s allegations, it is regrettably necessary, not to say inconvenient, to have the concise statement in one hand, and Annexures A and B in the other.

36 Judges of this court have repeatedly pointed to the unsatisfactory nature of concise statements in cases of complexity, or where multiple representations are said to have been conveyed in myriad places. See, by way of example, Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Ltd [2023] FCA 1150 at [15]–[17] (Beach J); Australian Securities and Investments Commission v National Australia Bank Ltd (No 2) [2023] FCA 1118 at [30]–[39] (Derrington J); Invisalign Australia Pty Ltd v SmileDirectClub LLC [2024] FCAFC 46 at [38]–[39] (O’Callaghan, Halley and Button JJ) (where the Full Court observed that a “concise statement was a most unfortunate way of pleading a case about alleged false, misleading or deceptive representations said to arise from a large body and variety of promotional material”).

37 In Allianz Australia Insurance Ltd v Delor Vue Apartments CTS 39788 (2021) 287 FCR 388 at 416 [140] McKerracher and Colvin JJ reiterated that concise statements are not intended to be a substitute for conventional pleadings. They are instead intended “to enable the applicant to bring to the attention of the respondent and the Court the key issues and key facts at the heart of the dispute and the essential relief sought from the Court before any detailed pleadings.”

38 As their Honours went on to say at 416–417 [141]:

The concise statement is intended to facilitate the case management of the proceedings from an early stage. It enables the Court to consider whether it is appropriate for the application to proceed on the basis of the concise statement without pleadings, whether the efficient conduct and disposition of the application is better served by requiring pleadings or whether some other procedure might be followed to expose the issues, such as requiring a statement of issues, the provision of detailed particulars of particular aspects of the claim or the disclosure of certain categories of documents that are of key significance for the resolution of the dispute.

39 This proceeding is yet another example of a case where the efficient conduct and disposition of the application would have been better served by it being pleaded in the conventional fashion at an early stage.

40 Senior counsel for ASIC also pressed the tender of the following six documents, which were said to contain requests for particulars and responses thereto:

• Letter from ASIC to LGSS Pty Ltd requesting particulars dated 28 September 2023.

• Letter from LGSS Pty Ltd to ASIC providing particulars dated 12 October 2023.

• Letter from ASIC to LGSS Pty Ltd requesting further particulars dated 13 October 2023.

• Letter from LGSS Pty Ltd to ASIC providing further particulars dated 27 October 2023.

• Letter from LGSS Pty Ltd to ASIC requesting particulars of evidence dated 15 November 2023.

• Letter from ASIC to LGSS Pty Ltd providing particulars of evidence dated 23 November 2023.

• Schedule of particulars of Exhibit VCK-1 23 November 2023.

41 When he said that he sought to tender each of those documents — which run to over forty pages — the following exchange ensued between us:

MR HEWITT: And then what I was proposing to do is to tender, from the court book, part A, tabs 3 through 10, which are the requests for particulars and various responses. And then ---

HIS HONOUR: What bearing do they have on it?

MR HEWITT: Well, for example, I took your Honour to one of those letters this morning to indicate to your Honour what the metes and bounds of the disputed issues are, so they – that’s the bearing they have, is that there were some – effectively, some admissions made in the course of that correspondence about what’s in dispute.

HIS HONOUR: Well, this is the problem with concise statements, isn’t it, that – what are the metes and bounds of what’s pleaded?

MR HEWITT: Well, yes, I mean, that ---

HIS HONOUR: And then even using the word “pleaded” isn’t, strictly speaking, accurate, because they’re not meant to be pleadings …

MR HEWITT: Well, one of the things the authorities contemplate in terms of how the concise statement process can be made workable is by request for particulars, and so that’s one of the steps that was taken here, and the response that we received – I don’t think there’s any attempt to resile from the responses, in terms of it being a statement of what’s in dispute.

HIS HONOUR: All right. Well

MR HEWITT: So we do think that it would be relevant for your Honour to have that material. Whether it’s – you know, should be tendered, or if it just forms part of a – of, in effect, the body of material that is loosely defined as the pleadings – and that’s – but I think we would press for the tender.

HIS HONOUR: All right. Well, Mr Insall is not objecting, so over my own objection, it will go in. Yes.

42 None of the tendered documents listed in paragraph 40 was ever mentioned again – which does suggest a lack of focus by the parties on defining with precision the issues that truly divided them. Rather than resorting to the exchange of lengthy requests for particulars (and tendering at trial the requests and responses thereto), the parties should have jettisoned the “concise” approach, and adopted pleadings instead. I have no doubt that, had they done so, this proceeding would have been more efficiently heard and determined. As the correspondence about particulars and the lengthy annexures to these reasons demonstrate, in any event, there is nothing remotely concise about the concise statements.

In trade or commerce

43 LGSS submitted that no part of the conduct impugned by ASIC in its concise statement was “in trade or commerce” within the meaning of s 12DB or s 12DF of the ASIC Act.

44 Its submission in support of that proposition was as follows.

45 Active Super is a “profit-for-member” fund, established by a trust deed dated 30 June 1997 by the then Treasurer under s 127 of the Superannuation Administration Act 1996 (NSW), which authorised the Treasurer to approve the preparation of a trust deed for a superannuation scheme for the benefit of certain classes of state public sector employees. Section 127(5) required that “the trust deed must be consistent with the requirements of [the Superannuation Industry (Supervision) Act 1993 (Cth) (SIS Act)] for a regulated fund within the meaning of that Act”.

46 Pursuant to clause 1.2 of its constitution, LGSS was formed for the sole purpose of acting as the trustee of a regulated superannuation fund within the meaning of s 19 of the SIS Act and “has no commercial purpose”.

47 The constitution of LGSS contains limitations on the entitlements of the shareholders, including that the directors are prohibited from declaring or determining a dividend or applying any portion of the trustee’s capital or income to a shareholder (clause 21.1).

48 Before 1 January 2022, LGSS did not charge any fee for providing trustee services to the fund. Following the receipt of judicial advice pursuant to s 63 of the Trustee Act 1925 (NSW), LGSS amended its trust deed. In reliance on that amendment LGSS has determined to charge a fee of around $36,000 per month for acting as trustee, for the purpose of guarding against the risk of a future penalty for which LGSS could not be indemnified due to amendments to the SIS Act.

49 While LGSS provides a service to its members and recovers its costs of providing that service, any profits from its activities are reinvested for the benefit of its members. It follows, so it was submitted, that the relationship between LGSS and its members is not “intrinsically commercial” (citing Kowalski v MMAL Staff Superannuation Fund Pty Ltd (2007) 242 ALR 370; [2007] FCA 1069 at [52] (Finn J)), and statements made to those members about the nature of the investments made on their behalf could not therefore be “in the central conception” of trade or commerce.

50 It was further submitted that LGSS’s relationship with prospective members is not materially different, and that “it is difficult to see where commerce manifests in the relationship between the trustee and prospective beneficiaries. The only service that LGSS was offering was its services as a trustee for which it recovered its costs but was not otherwise rewarded. The offer and acceptance of those services is not trade or commerce”.

51 As a consequence, it was submitted, none of the statements that ASIC relied upon fulfills the statutory condition of being made “in trade or commerce”.

52 That submission cannot be accepted.

53 In my view, as ASIC submitted, nothing turns on the fact that the trustee is a not-for-profit company in circumstances where it is the trustee of a trust, which is a superannuation fund, and which is operating with a view to making profits for the members of the fund.

54 The size of the profit made is neither here nor there as a matter of principle, but it is worth noting that Active Super’s profits in the 2021 financial year were in the order of $220 million.

55 I reject the submission made by LGSS that merely because a trustee company is a not-for-profit company, that means, without more, that it is not operating in trade or commerce.

56 The profit earned (or not) by the trustee company is not the point. The function of the trustee company was to operate and manage the superannuation fund.

57 And part of that function was to engage in promotional activities in relation to or for the purpose of the supply of services to actual or potential customers of the fund.

58 LGSS submitted that most if not all of the statements itemised in Annexure A of the concise statement were not of a promotional nature.

59 But that is simply not so.

60 The whole thrust of the itemised statements in the context in which they appear is to promote the green and community credentials of the fund, by “eliminat[ing] investments that pose too great a risk to the environment and the community … [such as] Tobacco, Nuclear weapons, Oil tar sands [and] Gambling”. That is to say, the statements are directed towards encouraging existing members to remain and new members to join, and to share in the success of investing, directly or indirectly, in enterprises which promote ESG objectives.

61 By way of example, the 2020-2021 “Impact Report” said the following:

At Active Super we continually monitor the organisations we invest in to ensure they’re meeting our standards for financial performance and ESG impact. If they fall short, we engage in different ways to turn things around.

(emphasis added)

62 Further, the 2021-2022 “Responsible Investment Report” said the following:

In line with our [SRI Policy] (available on our website) all our investments are assessed for their ability to deliver strong financial returns, balanced against the [ESG] risk they pose to the world. So, as a member, you can take comfort knowing we’re focused on your financial future while also looking out for the future of the planet.

(Emphasis added).

63 How could it be otherwise? It would be passing strange – not to say a fundamental breach of its duty – for a trustee to pursue ESG objectives without proper and cautious regard to financial performance. As the United States Department of Labor is quoted as saying in the extract from Professor Fisch’s article at paragraph 21 above, “fiduciaries must not too readily treat ESG factors as economically relevant to the particular investment choices at issue when making a decision.”

64 LGSS relied on the following answers given by Mr Turnbull for the proposition that “the reason for [its] approach to responsible investing was not to make itself attractive to prospective members, but was rather the legacy of the values of certain … directors some years ago”:

Now, did you understand that Active Super’s approach to responsible investments was a means by which Active Super was trying to make itself more attractive to members?---I’m aware that that is definitely not how it started out. It – it was a value-based approach that was in place before I joined, and we just continued that and tried to do the best that we could.

But when you say – when you give evidence about how it started out, what’s your perception over – in recent years? Do you say that Active Super’s approach to responsible investing is something it does to make itself attractive to members?---I don’t agree with that.

And why don’t you – why do you say that?---We did it because it was the values of our directors that they didn’t want investments in certain areas.

65 I intend no disrespect to Mr Turnbull, but those answers — and the submission of LGSS founded on them — defy common sense and must be rejected, because: (i) responsible investment objectives of a trustee cannot possibly be met without proper regard to financial performance; and (ii) the various publications directed to members and new members were self-evidently intended to broaden the fund’s appeal to a wider membership base by promoting the fund as an attractive investment.

66 In my view, it is quite plain that each of the statements relied on in Annexure A to the concise statement were, and were intended, to promote LGSS’s supply of services to actual or potential members.

67 That includes the Investment Magazine article. LGSS submitted that the article “was directed towards those working in the industry rather than prospective members of LGSS” and that “so much is clear from the references to fund mergers and growth strategies and other industry jargon”. Quite how that fact, if it be one, was relevant to the issue was left unexplained.

68 Despite the assertion by LGSS to the contrary, the alleged conduct is obviously “in trade or commerce”. As Mason CJ, Deane, Dawson and Gaudron JJ said in Concrete Constructions (NSW) Pty Ltd v Nelson (1990) 169 CLR 594 at 602, “[i]t is well established that the words ‘trade and commerce’ … are not terms of art but are terms of common knowledge of the widest import”. And as their Honours went on to say at 604:

What the section is concerned with is the conduct of a corporation towards persons, be they consumers or not, with whom it (or those whose interests it represents or is seeking to promote) has or may have dealings in the course of those activities or transactions which, of their nature, bear a trading or commercial character. Such conduct includes, of course, promotional activities in relation to, or for the purposes of, the supply of goods or services to actual or potential consumers, be they identified persons or merely an unidentifiable section of the public.

(emphasis added)

69 LGSS sought to make much of Finn J’s reasons in Kowalski. But that was a case with facts far removed from this one. Mr Kowalski, who was self-represented, brought proceedings against MMAL Staff Superannuation Fund Pty Ltd claiming, among other things, that it had engaged in misleading and deceptive conduct in contravention of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth). His Honour held, at [50]–[53] and [55], that those claims should be dismissed as having no reasonable prospect of success, because his claims related to the fund’s failure, as a trustee, to discharge obligations owed to Mr Kowalski as a beneficiary of the fund, and that the fund’s impugned conduct was not in trade or commerce. As his Honour said at [52]:

[The] relationship [between the fund and its members] was not intrinsically a commercial relationship nor did the conduct complained of otherwise bear a trading or commercial character: compare Village Building Co Ltd v Canberra International Airport Pty Ltd (2004) 139 FCR 330 ; 210 ALR 114 ; [2004] FCAFC 240 at [52] . This is not to say that, in the management of the fund, [the trustee] may not have engaged in conduct that was in trade or commerce as, for example, in the making and management of the trust’s investments. The relevant conduct in question here related simply to [the fund’s] performance of the obligations it had to Mr Kowalski under the trust. That conduct, in the context of their relationship, was not an aspect of an activity or transaction that bore a trading or commercial character. It related simply to the provision by [the trustee] of such entitlements as Mr Kowalski had under the trust instruments by virtue of his membership of the fund to which he had had access in virtue of his employment …

70 The case has no bearing on the facts here, because the claims concerning misleading and deceptive conduct in it related solely to the fund’s performance of its obligations under the trust to Mr Kowalski. In any event, that passage from the reasons of Finn J stands for the very opposite of the proposition for which LGSS contended. As his Honour said, had the case been about allegations concerning “the making and management of the trust’s investments” (as is plainly the case in this proceeding) he would have considered that conduct to be in trade or commerce.

71 It follows that the submission by LGSS that none of the impugned conduct was in trade or commerce is not accepted.

72 I will now turn to the gambling representations alleged by ASIC.

Gambling representations

73 The first gambling statement was published on the Active Super website on 25 May 2021, was removed on 28 February 2023, and was in these terms: “Additionally, we will not invest in organisations that derive more than 10% of their revenue from armaments, gambling, old-growth logging and uranium mining …” (emphasis added).

74 The second gambling statement was published on the Active Super website on 25 May 2021, was removed on 1 March 2023, and was set out in this visual representation:

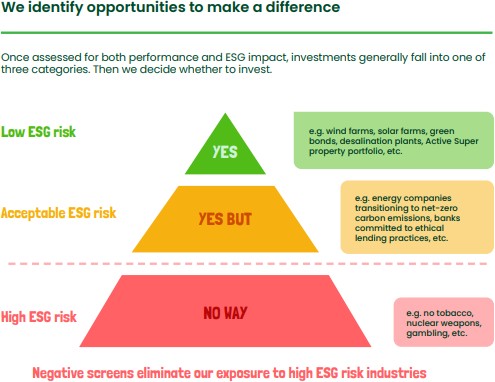

75 The third and fourth gambling statements were published by LGSS in Active Super’s 2021 Impact Report. The report included a similar visual representation to that above, and said that gambling investments fall into the “No way” category of investment and that Active Super’s negative screens will “eliminate” Active Super’s “exposure to high ESG risk industries”. The 2021 Impact Report was available to the public on Active Super’s website from 28 October 2021 to 1 March 2023.

76 The fifth gambling statement was comprised of words attributed by Investment Magazine to the then CEO of Active Super, Mr Phil Stockwell. Relevantly, he is reported as having said that Active Super “specifically excludes any investments in gambling”.

77 The sixth gambling statement was published in the Responsible Investment Report 2021-2022 on 20 December 2022. A relevantly identical statement, the seventh gambling statement, was made in several Product Disclosure Statements (PDS) published on 1 July 2022, as follows: “[w]e eliminate investments that pose too great a risk to the environment and the community, for example nuclear weapons, tobacco manufacturing, oil tar sands and gambling … ” (emphasis added).

78 ASIC contended that contrary to each of the above statements, during different times in the relevant period, LGSS made or held investments indirectly in seven gambling companies through the CFS Fund and the ASX 200 Fund that derived more than 10% of their revenue from gambling; and directly in two gambling companies (PointsBet Holdings Limited and Jumbo Interactive Limited) that derived more than 10% of their revenue from gambling, as follows:

No. | Company | Type of holding | First date held | Disposal date/Last date held |

1. | Skycity Entertainment Group Limited | Indirect (via the Colonial First State Wholesale Small Companies Fund) | 1 February 2021 | Held as at 31 May 2023 |

Indirect (via SPDR S&P/ASX 200 ETF) | 30 November 2016 | 21 March 2022 | ||

2. | PointsBet Holdings Limited | Indirect (via SPDR S&P/ASX 200 ETF) | 4 February 2021 | 19 September 2022 |

Direct | 30 November 2016 | 23 December 2021 | ||

3. | Jumbo Interactive Limited | Direct | 3 April 2019 | 6 June 2023 |

4. | Aristocrat Leisure Limited | Indirect (via SPDR S&P/ASX200 ETF) | 30 November 2016 | Held as at 23 May 2023 |

5. | The Lottery Corporation Limited | Indirect (via SPDR S&P/ASX200 ETF) | Added to the ASX200 24 May 2022 | Held as at 23 May 2023 |

6. | Tabcorp Holdings Limited | Indirect (via SPDR S&P/ASX200 ETF) | 30 Nov 2016 | Held as at 23 May 2023 |

7. | Crown Resorts Ltd | Indirect (via SPDR S&P/ASX200 ETF) | 30 Nov 2016 | 20 June 2022 |

8. | The Star Entertainment Group Ltd | Indirect (via SPDR S&P/ASX200 ETF)

| 30 Nov 2016 | Held as at 23 May 2023 |

Indirect (via the Colonial First State Wholesale Small Companies Fund) | 31 March 2023 | Held as at 31 May 2023 |

79 LGSS contended, on the other hand, that it did not make or hold investments in any companies that derived more than 10% of their revenue from gambling for the following reasons.

Are lotteries “gambling”?

80 In the case of Jumbo (in which it held shares directly), LGSS contended that it was not a company that derived more than 10% of its revenue from gambling. Rather, it said that Jumbo’s principal business was running lotteries, and that “[n]o reasonable person would understand the ‘gambling’ restriction to extend to companies that sold lottery tickets”, because the reasonable member or prospective member of Active Super would only “associate gambling-related social ills with pokie machines, casinos and online sports betting agencies, but not retailing lottery tickets”. The submission continued:

This is especially true for Jumbo, which provides its proprietary lottery software platform and lottery management expertise to charity and government lottery sectors, including Mater, Endeavour Foundation, Deaf Services, Gatherwell, St John and Paralympics Australia. Lottery ticket retailers include local newsagencies and most charities. It might be supposed that many people have had some experience in buying the odd lottery ticket. It is submitted that it would be a rare person indeed who associated gambling addictions with such activities, such that they would expect lottery ticket retailers to be excluded under the “gambling” restriction. The Court would not accept that an ordinary and reasonable member of the class would have harboured that view.

81 Jumbo operates the website www.ozlotteries.com and sells tickets in national draw lottery games to customers under an agreement with the licenced operator, The Lottery Corporation.

82 The Lottery Corporation is the owner of the “Lott” and “Keno” lotteries in Australia. Its total revenue for FY 2022 was approximately $104.3 million, of which $91.1 million was derived from “Lottery Retailing”. The 2021 figures were about $83.3 million and $75.08 million respectively. Its total revenue from operations for 2020 was about $71.17 million, of which about $64.28 million was derived from “Internet Lotteries Australia”.

83 The submission that the reasonable ordinary member or prospective member of Active Super would associate “gambling-related social ills” with pokie machines, casinos and online sports betting agencies, but not retailing lottery tickets, cannot be accepted.

84 No evidence was adduced in support of such a contention and how or why it was asserted that lotteries are not associated with gambling-related “social ills” (including gambling addictions) was never explained.

85 But in any event, the relevant question is not whether a reasonable member would associate lotteries with “social ills”. The relevant question is whether that reasonable member would consider “gambling” to include lotteries. In my view, an ordinary reasonable consumer who was a member or prospective member of the fund would reasonably understand the business of running lotteries to be a gambling business, because so much follows as a matter of ordinary English.

86 “Gambling” is defined in the Macquarie Dictionary as “to stake or risk money, or anything of value, on the outcome of something involving chance”; “to act on favourable hopes or assessment”; “to risk or venture”; or as a noun, “any matter or thing involving risk or uncertainty”.

87 It seems to me plain that “gambling” includes and would be understood by the ordinary reasonable consumer to include lottery tickets, because the purchase of such tickets satisfies each of those definitions.

The role of the Sustainable and Responsible Investment Policy

88 LGSS contended that the statements on which the gambling representations were based did not convey a representation that Active Super would not invest in investment funds which held shares in gambling companies.

89 LGSS said that the gambling representations should be understood in their relevant context, which, it was argued, included the terms of LGSS’s Sustainable and Responsible Investment Policy, which I will refer to either as “the SRI Policy” or “the policy”. It relevantly stated that LGSS “will not” derive 10% or more of its revenue from gambling, defined as companies “involved in the manufacture and/or production of gambling machines and services and/or ownership of outlets housing these machines.”

90 It will immediately be observed that there is a tension between that version of the anti-gambling policy, and what was said in the Impact Reports and on the website, which said nothing about the proscription on investing in gambling being limited to companies making, servicing, owning or housing “gambling machines” and, in almost all instances, made no reference to any 10% revenue threshold amount.

91 It is convenient first to deal with the role that LGSS contended is to be played by the policy in the context of the gambling representations. As will become apparent, the role played by the policy arises in respect of each of the other alleged representations.

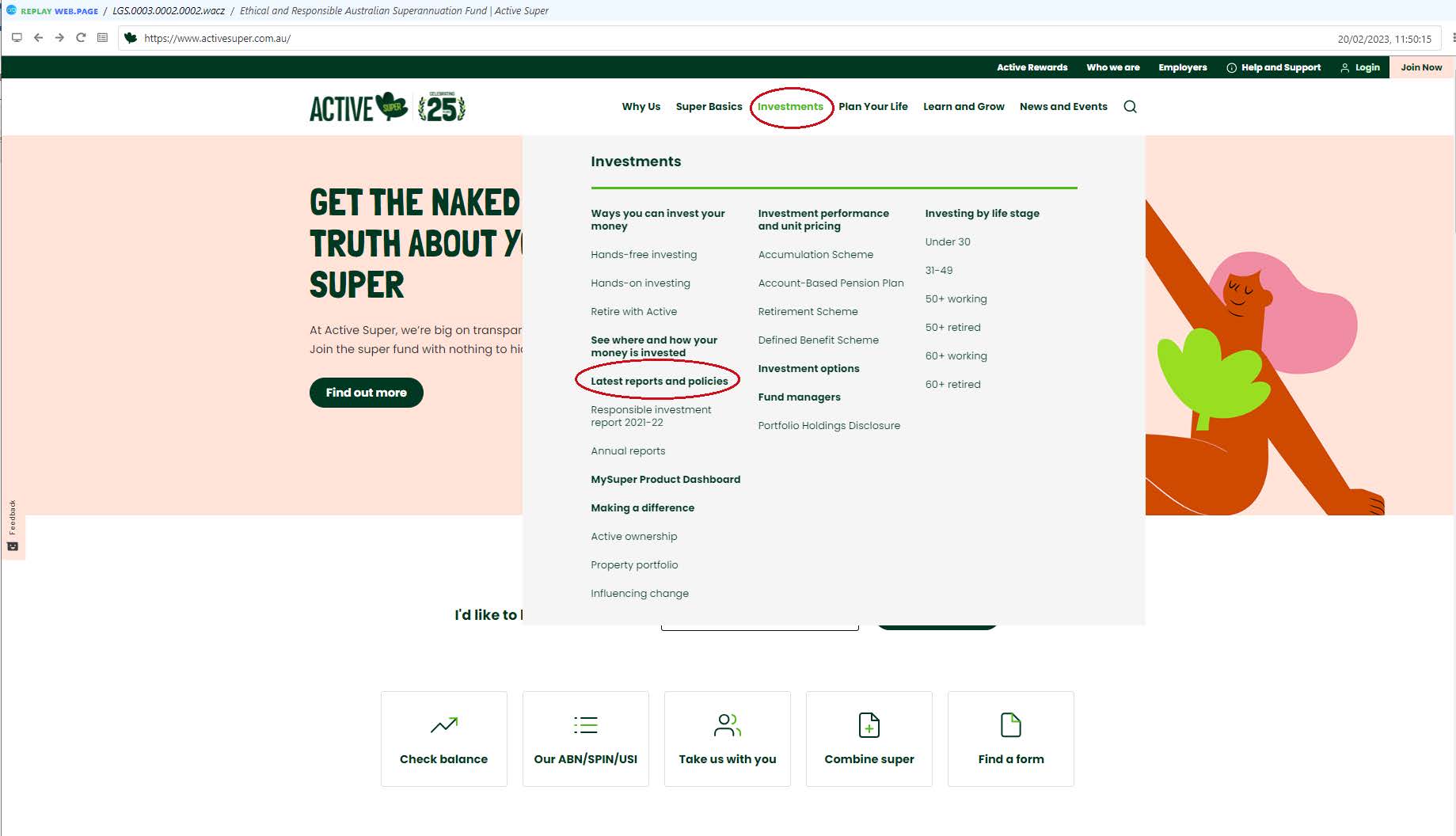

92 LGSS submitted that the policy appeared prominently on Active Super’s website under the “Investments” tab, which appeared at the top of every page of the website. It says that from wherever a viewer happened to be located on the website, “the SRI Policy was two clicks away”. It relied on a document marked during the hearing as exhibit MFI D6, which consisted of annotated screenshots of the website headed “25 March 2024 Web Archive Home Page ‘Investment’ Menu”. Those screenshots are attached to these reasons, marked as Annexure C. In the course of the hearing, LGSS also referred to a “web capture” of Active Super’s website as it existed at the relevant time, to demonstrate how a viewer may navigate the website to arrive at, and download, a PDF copy of the policy.

93 ASIC submitted that the policy was densely worded, and was not readily viewable without a lot of searching. LGSS disagreed, and maintained that the policy was accessible because it was expressly referred to in the Impact Report, the Responsible Investment Report, and the PDS. LGSS also said that “importantly” the policy did not “commit to perfect exclusion of restricted companies and identified relevant limitations to LGSS’s investment approach”.

94 It was further contended that “a reasonable fund member would not expect its trustee to be immediately aware of, and immediately divest holdings in, a company that tipped above a threshold such that it ought to become a restricted investment”.

95 In support of each of those propositions, LGSS pointed to the following language in the SRI Policy (version 7, dated December 2020) which, like the relevantly identical policies for other years, it said qualified the gambling representations relied on by ASIC:

1. Policy statement

a) Local Government Super (LGS) was established in 1997 as the fund for NSW local government employees. It is an open fund and provides responsible and sustainable investments for its members. LGSS Pty Limited, the Trustee of the Fund is solely responsible for the management and control of the Fund, ensuring LGS operates in accordance with the LGS Trust Deed and superannuation law.

b) This Sustainable and Responsible Investment Policy (‘Policy’) recognises that LGS is long term in nature and that the long term prosperity of the economy and the wellbeing of members depends on a healthy environment, social cohesion and good governance of LGS and the companies in which it invests. As a highly diversified investor, LGS has an interest in a large number of all major companies in Australia and internationally.

c) This Policy sets down the responsible investment principles by which LGS will be managed, and the requirements for all investments made by LGS. It covers the total investment portfolio, with specific policies for public and private equity investments and direct property. The Policy includes the list of collective engagement initiatives that LGS will participate in and the ESG risk assessment required of LGS’ asset consultants and investment managers.

…

3. Governance

a) This Policy provides a description of how the Trustee incorporates sustainability considerations and ESG risks as part of its fiduciary investment management obligations. It should be read in conjunction with the Guidelines, LGS Investment Policy Statement, Investment Governance Framework, Risk Management Framework and Due Diligence Policy.

b) The Policy is consistent with the long term investment objectives of LGS and its risk tolerance. LGS’ Investment Beliefs recognise ESG factors and sustainability as important considerations in driving both long term investments returns and reducing risk. These factors are likely to become more important in all investment decisions.

c) The following sections in this Policy outline how LGS implements responsible investment throughout its investment processes. It uses a combination of internal management, including specialist responsible investment personnel, along with the provision of outsourced responsible investment-related services. The Board, via its nominated subcommittees, has ultimate oversight of responsible investment activities.

…

9. Investment restrictions

a) The Trustee has determined that LGS will not make investments in companies that derive any revenues in the following areas of activity:

i) Controversial weapons: Companies involved in the manufacture and/or production of controversial weapons such as land mines, cluster bombs and nuclear weapons

ii) Tobacco: Companies involved in the manufacture and/or production of tobacco products

b) The Trustee has determined that the Fund will not make investments in companies that derive 10% or more of their revenues in the following areas of activity:

i) Armaments: Companies involved in the manufacture and/or production of armaments

ii) Gambling: Companies involved in the manufacture and/or production of gambling machines and services and/or ownership of outlets housing these machines

iii) Old growth logging: Companies involved in the logging of old growth forests

iv) Uranium Mining/Nuclear: companies involved in uranium mining and production of nuclear energy

(c) The Trustee has determined that the Fund will not make investments in companies that derive 33.3% (one-third) or more of their revenues in high carbon sensitive activities.

i) Companies assessed as being the most vulnerable from the sectors that are evaluated as being highly sensitive to the multiple investment risks associated with climate change. This list will include companies which derive their revenue or assets from coal mining, oil tar sands and coal fired electricity utilities. LGS will reference external research to determine which companies are high carbon sensitive.

…

10. SRI and High Carbon Overlays

(a) In situations where it is not possible to avoid indirect investment in restricted companies, for example because of index mandates or investments made through pooled trusts, LGS will aim to eliminate exposure to restricted companies by shorting the same number of securities via an overlay process.

96 LGSS contended that it negated its exposure to restricted investments through the “overlay” process referred to in clause 10 immediately above, which, it was said, was supposed to involve entering short positions for the same number of securities in instances where there was an unavoidable exposure to restricted companies. But it emerged during the hearing that the overlay policy, in the main, was not employed during the relevant period.

97 LGSS also relied on the October 2020 version of the SRI Policy which included the following information about LGSS’s policy of using an external ESG research provider to source the list of companies to be placed on the “Investment Restrictions List”:

7.2 Investment Restrictions List

(a) LGS will use an external ESG research provider to source the list of companies to be placed on the Investment Restrictions List. The excluded companies are sourced from the entire universe of indices used to benchmark LGS’ aggregate portfolio performance (ASX 300 companies for listed Australian equities and MSCI World ACWI for International equities).

(b) The data is sourced bi-annually from the external ESG research provider. LGS’ Responsible Investment and Investment teams produce the Investment Restrictions List highlighting companies excluded, exclusion criteria, stock identifiers and market capitalisation.

(c) The Head of Responsible Investment is responsible for updating and maintaining the Restrictions List. The Head of Responsible Investment will send the Restrictions List to Head of Investment Operations, who will send to the custodian for software coding.

(d) The Head of Responsible Investment will complete a letter with Restrictions List attachment for issuance to applicable LGS fund managers. This will be signed by two authorised signatories.

(e) Any changes and updates to the Investment Restrictions List are reported to the Committee as required.

98 The ESG research provider employed by LGSS to source the list of companies to be placed on the Investment Restrictions List and to prepare, update and maintain it, was a company called MSCI ESG Research (UK) Limited (MSCI).

99 Among other things, MSCI defined the parameters of the Investment Restrictions List according to its methodology. For example, for reasons that were not explained, it excluded “retailing lottery ticketsˮ or “[manufacturing] lottery ticket printing machinesˮ from the definition of “gambling”.

100 In summary, LGSS submitted that:

The Gambling Representation [as alleged by ASIC] was not conveyed by the Gambling Statements. Read in light of all the context, the Gambling Statements conveyed that:

(a) Active Super restricted investments in companies that derived more than 10% of their revenue from gambling;

(b) Active Super had processes utilising external research by MSCI to identify whether companies met this definition;

(c) if a company was found to derive more than 10% of their revenue from gambling, Active Super would consider whether to divest the holding (though it may not do so); and

(d) if Active Super considered it appropriate to divest the holding, it would do so within a reasonable period.

101 Aside from the SRI Policy, LGSS also contended that some of the individual gambling representations contained language that indicated that the Gambling Representation (as LGSS defined it in its concise response) was a “guiding principle”, rather than “a strictly applied rule”. LGSS pointed to an example of language immediately above the statements found in the Impact Reports (item 5 and 6 in Annexure A) that stated: “Any investments on our restricted list are considered on a case-by-case basis.ˮ Those words were said “[to] imply[] that investments may be held in restricted companies”.

PointsBet

102 In the case of its direct investment in PointsBet, LGSS relied on the following evidence about the role of MSCI.

103 PointsBet was first listed on the Australian Stock Exchange on 12 June 2019. LGSS first held its investment in it on 29 June 2020 (not 30 November 2016, as ASIC alleged), and disposed of the investment on 23 December 2021. It was omitted entirely from the 2020 MSCI Report. Why that was so was not explained.

104 PointsBet was included in the 2021 MSCI Report, where it was identified as deriving a maximum of 100% revenue from gambling.

105 Ms Yip deposed to the following.

106 On 26 July 2021, LGSS received a report from MSCI containing the ESG research and data.

107 By 26 August 2021, an analyst in the Responsible Investment Team had completed a review of the data (which it was said took three weeks) and identified PointsBet as a proposed addition to the Investment Restrictions List. Ms Yip and Mr Turnbull then prepared a Responsible Investment Report, which included the proposed additions to the Investment Restrictions List.

108 On 29 September 2021, the Responsible Investment Report was presented to the Investment Committee, and it approved the proposed amendments.

109 Letters were then provided to Active Super’s domestic and international equities investment managers providing the updated Investment Restrictions List, which included Pointsbet.

110 LGSS submitted that “the investment in PointsBet was not contrary to the Gambling Statements, as properly understood” and that “[c]onsistent with the SRI Policy”:

(a) LGSS maintained its Investment Restrictions List, reasonably relying on external data provided by a specialist ESG research provider;

(b) an external investment manager made an investment decision that was, at the time of investment, consistent with the Investment Restrictions List;

(c) LGSS identified that PointsBet ought to be a restricted company once MSCI provided data with respect to its activities; and

(d) LGSS followed its proper processes within a reasonable time to add PointsBet to the Investment Restrictions List and instruct its external investment manager to divest of the stock.

Consideration

111 I do not accept LGSS’s submissions about the role of the SRI Policy set out above.

112 First, no reasonable person would construe the gambling representations as mere “guiding principles”, because the critical language used in them (such as “not invest”, “No Way” and “eliminate”) was unequivocal.

113 In the case of the expression “No Way”, it must be read in the context of the pyramid set out at paragraph 74 above. In response to the questions “Are we in? Or out?”, it was there said that “wind farms, solar farms, green bonds, desalination plants, Active Super property portfolio, etc” are a low ESG risk and that “Yes”, Active Super invests in such projects. Next is the category “Yes, But” which is said to be an “[a]cceptable ESG risk”. Companies in that category were said to include “energy companies transitioning to net-zero carbon emissions, banks committed to ethical lending practices, etc”. And then it was said that there was “No way” that Active Super would invest in “high ESG risk” tobacco, nuclear weapons or gambling companies. The “Yes, But” category obviously admits of exceptions. The “No Way” category does not.

114 Secondly, in my view, the ordinary reasonable consumer is unlikely to have read any of the gambling representations as being the subject of potential qualification by LGSS’s “Sustainable and Responsible Investment Policy.”

115 I do not agree with the submission made by LGSS that the ordinary reasonable consumer, having read statements of the kind contained in the pyramid at paragraph 74 above, would nonetheless follow the menus from the homepage of the website to access, and then read through the detail of, the SRI Policy.

116 In my view, the emphatic statements made in the pyramid and elsewhere, and upon which ASIC relied, did not admit of the possibility that they were subject to any terms and conditions. There were, for example, no footnotes or asterisks appended to them, containing the sort of language that all consumers are familiar with, such as that the claims are subject to specific limitations contained in terms and conditions. Compare for example Invisalign Australia Pty Ltd v SmileDirectClub LLC [2023] FCA 395 at [792]–[795] (Anderson J), iNova Pharmaceuticals (Australia) Pty Ltd v Reckitt Benckiser (Australia) Pty Ltd [2018] FCA 1209 (Bromwich J); George Weston Foods Ltd v Goodman Fielder Ltd (2000) 49 IPR 553; [2000] FCA 1632 (Moore J); Astrazeneca Pty Ltd v GlaxoSmithKline Australia Pty Ltd [2006] ATPR 42-106; [2006] FCAFC 22 (Wilcox, Bennett and Graham JJ).

117 If such a consumer was told, as they were told, that there was “No way” that LGSS would invest in tobacco or gambling, he or she would not search around for some investment policy that might qualify such statements. Absent some indicator on the face it, such as a footnote or asterisk with some accompanying statement that the apparently unqualified language was, in fact, something that was subject to qualifications or limitations, they would have no reason to.

118 It is true that in certain limited examples relied upon by ASIC, the SRI Policy is referred to in terms. For example, the 2020-2021 Impact Report states that “[a]t Active Super, we’ve had a Responsible and Sustainable Investment Policy since 2009.” But the Policy is not hyperlinked, and neither those words (nor the surrounding context) give any indication that the references to the policy were intended to suggest to the consumer that it in some fashion or another qualified or modified what was being said elsewhere.

119 Thirdly, in my view, no ordinary reasonable consumer could possibly have understood the SRI Policy to convey that if a company was found to derive more than 10% of their revenue from gambling, Active Super “would consider whether to divest the holding” and “may not do so”; or that “if Active Super considered it appropriate to divest the holding, it would do so within a reasonable period”. Even if one were to read the gambling statements in light of the SRI Policy, the policy does not say that, nor does it remotely suggest it.

120 Fourthly, LGSS’s submission that “it did not commit to the perfect exclusion of restricted companies and identified relevant limitations to its investment approach” because the assertion in an Impact Report that “‘[a]ny investments on our restricted list are considered on a case-by-case basis’ necessarily implied that investments may be held in restricted companies” only has to be stated to be rejected.

121 Fifthly, I do not accept LGSS’s submission that the investment in PointsBet was not contrary to the gambling statements and was consistent with the SRI Policy because LGSS maintained its Investment Restrictions List, reasonably relied on external data provided by a specialist ESG research provider and “followed its proper processes within a reasonable time” to put it on the Investment Restrictions List and sell the stock. The argument boils down to saying that the ordinary reasonable consumer would, if they read it at all, read the terms of the SRI Policy as a whole to imply that all that LGSS promised to do was to use its best endeavours not to invest in gambling. That is, if I may say so, farfetched and no ordinary reasonable consumer would ever have imagined any such a thing.

Indirect ownership of shares

122 It is next necessary to deal with the issue of “indirect” ownership of shares by way of units held in the Investment Funds, which was also an issue raised by LGSS with respect to many of the alleged representations.

123 LGSS adduced evidence, and ASIC did not dispute, that the CFS Fund, the Wellington Fund and the ASX 200 Fund were unit trusts that have the following common features:

(a) although a unit holder has an interest in the assets of the fund as a whole, it does not have any interest in any particular fund asset; and

(b) no unit holder is entitled to interfere in the management of the fund.

124 LGSS also relied on the undisputed fact that each Investment Fund had its own investment strategy and was managed in accordance with that strategy by a third-party fund manager.

125 In view of these features, it was submitted:

an investment in an Investment Fund cannot be conflated with an investment in the underlying shares. It is simply not accurate to describe an investor in any of those Investment Funds as “holding” any shares that happen to form part of the Investment Fund’s assets under management from time to time.

The [r]epresentations (if made) would be understood to convey that LGSS would not invest in the companies deriving revenue from the proscribed industries or in Russia or in Russian entities, not that LGSS would not invest in Investment Funds.

126 LGSS contended that an ordinary and reasonable consumer “would undoubtedly draw a distinction between holding shares in a company and indirect exposures through a pooled fund” and that “[t]hey would appreciate that when LGSS makes statements about its investments, those statements are likely to be about matters LGSS can control (for example, its direct holdings in companies) and not about matters LGSS cannot control (for example, its indirect exposure to companies via a pooled fund managed by a third party manager)”.

127 ASIC submitted, on the other hand, that an ordinary and reasonable member of the relevant class would not draw a distinction between investment exposure to companies based on the manner in which the investment was held by the trustee and that there is nothing in any of the statements in Annexure A that refers to such a distinction.

128 ASIC pointed to the fact that not only did Active Super not draw any express distinction between “indirect” and “direct” investments or between investments in companies and investments in managed funds but, to the contrary, its annual reports asserted that “[a]ll investments are held directly by Active Super”.

129 As to LGSS’s submission that a member as a unit holder does not have any interest in any particular fund asset, and that no unit holder is entitled to interfere in the management of the fund, ASIC said that that was irrelevant in circumstances where LGSS accepted that it had an interest in the assets of the funds as a whole in relation to the managed funds in which it held units.

130 I am unable to accept LGSS’s contention that an ordinary and reasonable member of the relevant class would draw a distinction between holding shares in a company and indirect exposures through pooled funds. It seems to me that such a consumer would not draw that distinction, including in particular because there is nothing in the Impact Reports or on the LGSS website that suggests that the claims that there was, for example, “No way” Active Super would invest members funds in gambling, tobacco and so on, was to be read subject to a proviso that there was a way in which it would do exactly that, by investing indirectly, not directly. In my view, that distinction is one which no ordinary reasonable consumer would draw.

131 I should also deal with one other submission made by LGSS about the “overlay” process, which I refer to above. That process had no relevance to the CFS Fund, the Wellington Fund or the Macquarie Fund, because it was not used in relation them. But as to the seven investments in companies that ASIC alleged were contrary to the gambling representations (and the three coal mining investments dealt with below) which were held in the ASX 200 Fund, LGSS denied that it engaged in conduct contrary to the alleged representations “because it did not have a net exposure” to the fund, as a result of the application or adoption of the overlay process.

132 Mr Pholsena gave an explanation of the overlay process in that context in his evidence, which counsel summarised in LGSS’s final submissions as follows:

LGSS aimed to eliminate exposure to certain restricted companies through its overlay process. At [17] to [32] of his affidavit, Mr Pholsena gives a detailed explanation as to how that overlay process worked …

The implementation of the overlay process to off-set exposure to a restricted company required LGSS to borrow shares from UBS [Prime Brokerage] in the particular restricted company for a fee. LGSS then sold those shares. It used the money from the sale of the restricted shares to buy unrestricted investments. When LGSS came to return the restricted shares, it sold the unrestricted investments and used the money to purchase the restricted shares, so that they could be returned to UBS. That process had the effect of “cancelling out” LGSS’s exposure to the restricted company during the period LGSS had borrowed the restricted shares.

That process could be expensive. The costs associated with the overlay process included the cost of borrowing stocks to short or swap, broker fees, and the costs of meeting a short if it was called on. It was also necessary to manage liquidity to fund margin calls when they arose.

Rather than keep cash sitting in a bank account for the purpose of meeting those costs, LGSS was able to generate higher, safe returns by holding:

(a) a position in the ASX 200 Fund; and

(b) a corresponding short position in a number of futures contracts with a notional value approximately equal to the market value of the long positions.

The purpose of this strategy was to receive quarterly distributions from Standard & Poor’s while minimising exposure to the ASX 200 Fund.

133 Counsel for LGSS relied on this passage from the cross-examination of Mr Pholsena in support of that submission:

MR HEWITT: Could you just answer, if you can, the question that I asked. Do you agree or disagree with the proposition that Active Super retained investment exposure to the distribution return in respect of each company in the ASX 200 fund?

MR PHOLSENA: We also have this exposure in the short position with ASX, you know, buys future. So that index is also referencing the ASX 200. The underlying index also have accumulated distribution in there as well. So, you know, I’m might (sic) misleading, you know, to say that we did not, thinking about that distribution that have been factored into this by a future…

MR HEWITT: Mr Pholsena, it was no part of the purpose of the strategy that you describe in your affidavit to negate the investment exposure to the distributions from the ASX 200 fund, was it?

MR PHOLSENA: No. … but the future itself also accounted for dividend as well. (emphasis added).

134 It was submitted that, by his answers, “Mr Pholsena confirmed … that the value of the units in the ASX 200 Fund took into account any accumulated but unpaid distribution, and it was this value that LGSS sought to short by purchasing corresponding futures”. It was said that his “explanation was straightforward, and there is no reason it ought not be accepted.”

135 I do not agree.

136 First, I fail to understand how taking a financial position in the way Mr Pholsena explained it rectified or overcame an otherwise false or misleading assertion (for example) that there was “No way” LGSS would invest in gambling or tobacco stocks.

137 LGSS contended that the overlay process “cancelled out” LGSS’s exposure to gambling and tobacco companies because it:

(1) borrowed shares in gambling and tobacco companies;

(2) sold those shares;

(3) used the money from the sale to buy unrestricted investments;

(4) sold the unrestricted investments; and

(5) then used the money to purchase the restricted shares, so that

(6) the restricted shares could be returned to the person from whom Active Super borrowed the shares in the first place.

138 In my view, even if that explanation had been provided to ordinary and reasonable consumers of the relevant class (rather than the brief description of the overlay process contained in clause 10 of the SRI Policy set out at paragraph 95 above), they would have been left scratching their heads.

139 But secondly, and in any event, Mr Pholsena accepted in his cross-examination that the overlay process did not affect the distribution return (so the exposure to the restricted companies was not in fact off-set):

[MR HEWITT] Now I want to ask you, then, to come, please, over to page 3894. Do you see there the words “fund performance”? And then if you come, please, over to page 3896, do you see there the heading S&P ASX200 Fund, and then do you see a table that identifies the performance of the ASX200 fund over various different time periods? Have you had occasion, in your role with Active Super, to review the performance of the ASX200 fund over the last set of periods described there – five years, three years, one year and so on?---Yes. I don’t – I don’t directly – reviewing this index, but, you know, we have the ASX200 – that could have a return similar to this STW.

But this is the – when you say a return similar, this is a description of the STW fund; do you accept that?---Yes. Yes.

So, when you say you have a holding that’s a return similar, do you agree that this actually is describing the fund that is held by Active Super?---Yes.

And what I was asking you is whether you were generally, as part of your work, familiar with the return that that investment has earned over recent periods?---Yes.

Can I just ask you to look at the table. Do you see that there’s three – the first three labels for the rows in the table are Fund Distribution Return, Fund Growth Return and Fund Total Return; do you see that?---Yes.

And then there’s “as of” – “as of date 31 January 2024”; do you see that? That’s the second column?---Column? Yes

…

Would you agree with this? That what’s being recorded on this document is that the performance of this fund that was held by Active Super in that three-year period was a distribution return of 5.43 per cent per annum; do you agree?---In theory, yes.

I’m sorry, what?---In theory, yes.

When you say “in theory”, what do you mean by “in theory”?---Well, we don’t – we don’t know. It be changing. If you are assuming that you’re constantly holding this investment - - -

Yes?---But we do changes from time to time, so I can’t tell you whether or not it would be exactly that number or not.

So, what you’re saying is – you – I mean, this information is being presented on the basis that it relates to the position for someone who was holding the investment on an uninterrupted basis- - -?---Yes.

- - - over this period of time; is that what - - -?---Yes.

All right. In any event, there’s the distribution return, and then the second part is the growth return; do you see that?---Mmm.

And that growth return was 4.06 per cent. Do you see that?---Yes.

And then the total return, do you agree, is the aggregate of the distribution return and the growth return?---Yes. Total return. Yes.

So that’s 5.43 plus 4.06 is 9.49 per cent. You see that?---Mmm.

So do you agree that, over the last three-year period, the return from distributions in the ASX 200 fund has exceeded the growth return?---Yes.

Now, what you’ve said at paragraph 40 of your affidavit – can I just ask you to look at that, please, and just read paragraph 40 of your affidavit. You can put the document to the side, if you like, and then go back to your affidavit, please. What you say at paragraph 40 of your affidavit – do you see that paragraph?---Yes.

Is that:

The purpose of the strategy was to receive quarterly distributions from [Standard & Poors] while negating or minimising equity exposure to the fund.

Do you see that?---Yes.

So just coming back to the performance of the fund over the last three years, to translate what you’re saying in paragraph 40 to that three-year period. Is this right? That what your evidence is, is that the purpose of the strategy was to receive the fund distribution return which, over that last three-year period, was 5.43 per cent per annum. Correct?---Yes.

And to negate, or minimise the growth return. Correct?---Yes. That’s correct. Yes.

So you were – the purpose was to receive the distribution return, which was 5.43 per cent per annum over the last three years and to negate the growth return of 4.06 per cent over the last three years. Correct?---Yes.

And do you agree that, as a result of that approach, Active Super retained investment exposure to the distribution return in respect of each of the 200 companies in the ASX 200 index?---It’s debatable.

Well, I’m not really asking you to comment on whether it’s debatable or not. I’m just asking you to tell his Honour whether you agree or disagree with what I’m putting to you.

MR INSALL: I object, your Honour. He didn’t agree or disagree, and he said it’s debatable. It’s an answer to the question.

MR HEWITT: Could you just answer, if you can, the question that I asked. Do you agree or disagree with the proposition that Active Super retained investment exposure to the distribution return in respect of each company in the ASX 200 fund?---We also have this exposure in the short position with ASX, you know, buys future. So that index is also referencing the ASX 200. The underlying index also have accumulated distribution in there as well. So, you know, I’m – I’m might (sic) misleading, you know, to – to say that we did not, thinking about that distribution that have been factored into this by a future. So that’s why I say debatable here, because it’s just - - -

Have you finished your answer?---Yes.

Mr Pholsena, it was no part of the purpose of the strategy that you describe in your affidavit to negate the investment exposure to the distributions from the ASX 200 fund, was it?---No.

The purpose of the strategy was to negate the equity exposure to the ASX 200 fund, wasn’t it?---Yes, but the future itself also accounted for dividend as well.

So you receive additional dividends from the futures exposure?---It doesn’t, but the future itself also accounted for dividend in there.

But there were - - -?---So they have to be discount back to the present while – before that.

But there was no part of the purpose of the futures position to negative exposure to the distributions from the ASX 200 fund, was it?---Not directly.

And you agree that throughout the relevant period, Active Super retained exposure to the distributions from the ASX 200 fund?---We received distribution from STW, yes.

140 In my view, the gambling representations as alleged were conveyed and they were misleading and deceptive.

Tobacco representations

141 The statements made by LGSS during the relevant period regarding its investment in companies with exposure to the tobacco industry were as follows.

142 The first tobacco statements were published on the Active Super website on and from 25 May 2021, as follows:

(a) the visual representation headed “Are we in? Or out?” indicating tobacco as in the “No Way” category (see paragraph 74 above);

(b) a statement that Active Super stopped investing in tobacco over 20 years ago; and

(c) a statement that “[t]here are some industries in which we will not invest any money because we believe the harm they cause is not worth any potential profit we could gain. These companies include those that derive revenue from controversial weapons — such as land mines, cluster bombs and nuclear weapons — as well as tobacco”.

143 The second tobacco statements were published by LGSS in Active Super’s 2021 Impact Report, which stated that tobacco investments are in the “No way” category of investment and Active Super’s negative screens will “eliminate” Active Super’s “exposure” to it as a high ESG risk industry.

144 The third tobacco statement was made in the SRI policy, where under the heading “Investment Restrictions”, it was said that Active Super “will not make investments in companies that derive any revenues” where the companies are “involved in the manufacture and/or production of tobacco products”.