FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Energy Regulator v Santos Direct Pty Ltd [2024] FCA 579

File number(s): | VID 862 of 2023 |

Judgment of: | NESKOVCIN J |

Date of judgment: | |

Catchwords: | CONSUMER LAW – application for declaration of contravention of the National Gas Rules (NGR) – failure to keep contemporaneous records in relation to renominations – where respondents admitted contravening the NGR –pecuniary penalties pursuant to s 44AAG(2) of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) – whether proposed penalties appropriate – order for implementation of an assurance program – contribution to costs |

Legislation: | Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) ss 4(1), 44AE, 44AAG(1)-(2)(a), (c)-(d) Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) s 191 Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) ss 21, 43 National Gas (New South Wales) Act 2008 (NSW) s 7 National Gas (Queensland) Act 2008 (Qld) s 7 National Gas (South Australia) Act 2008 (SA) s 7, Schedule National Gas (South Australia) Regulations (SA) National Gas (Victoria) Act 2008 (Vic) s 7 National Gas Law ss 2, 26, 91BRO, 234 National Gas Rules rr 593, 647, 648(4), 651(1)(c)-(e), 653(1), 655(3), 663, 664, 666(1)(a)-(d), 677, 678 |

Cases cited: | Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union [2017] FCAFC 113; 254 FCR 68 Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Pattinson [2022] HCA 13; 274 CLR 450 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Australian Safeway Stores Pty Ltd [1997] FCA 450; 75 FCR 238; 145 ALR 36 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v BlueScope Steel Limited (No 6) [2023] FCA 1029 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Coles Supermarkets [2014] FCA 1405 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Reckitt Benckiser (Australia) Pty Ltd [2016] FCAFC 181; 340 ALR 25 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd [2013] HCA 54; 250 CLR 640 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Uber B.V. [2022] FCA 1466 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Yazaki Corporation [2018] FCAFC 73; 262 FCR 243 Commonwealth v Director, Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate [2015] HCA 46; 258 CLR 482 Forster v Jododex Australia Pty Ltd [1972] HCA 61; 127 CLR 421 J McPhee & Son (Australia) Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2000] FCA 365; 172 ALR 532 Markarian v The Queen [2005] HCA 25; 228 CLR 357 Singtel Optus Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2012] FCAFC 20; 287 ALR 249 Trade Practices Commission v CSR Limited [1990] FCA 762; [1991] ATPR 41-076 Trade Practices Commission v TNT Australia Pty Ltd [1995] ATPR 41-375 Volkswagen Aktiengesellschaft v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2021] FCAFC 49; 284 FCR 24 |

Division: | General Division |

Registry: | Victoria |

National Practice Area: | Commercial and Corporations |

Sub-area: | Economic Regulator, Competition and Access |

Number of paragraphs: | |

Date of last submissions: | 18 April 2024 |

Date of hearing | Determined on the papers |

Solicitor for the Applicant: | DLA Piper |

Counsel for the Respondent: | J Arnott SC |

Solicitor for the Respondent: | Herbert Smith Freehills |

ORDERS

Applicant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT DECLARES THAT:

1. During the period between 1 March 2019 and 5 June 2021, the respondent, Santos Direct Pty Ltd, contravened rule 666(1) of the National Gas Rules (NGR) on 4,701 occasions by making 4,701 material renominations, for use on 717 gas days of a transportation service, without making a contemporaneous record in relation to the renomination which included all of the information required by subrules 666(1)(a) to (d) of the NGR.

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Pursuant to s 44AAG(2)(a) of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth), within 30 days from the date of this order, Santos pay to the Commonwealth of Australia a pecuniary penalty in the amount of $2,750,000 in respect of Santos’ contraventions of rule 666(1) of the NGR.

2. Pursuant to s 44AAG(2)(c) of the Competition and Consumer Act:

(a) within 30 days from the date of this order, Santos appoint a suitably qualified independent authority (Independent Reviewer) to be agreed between the Australian Energy Regulator (AER) and Santos, or failing agreement, as proposed by each of the parties and determined by the Court, to undertake an assurance program to ensure compliance with rule 666(1) of the NGR, which addresses the following matters:

(i) identification of the processes which Santos has in place to comply with rule 666(1);

(ii) an assessment of Santos’ processes and their robustness to ensure compliance with the rule 666(1);

(iii) an assessment of the operating effectiveness of Santos’ processes to comply with rule 666(1); and

(iv) any recommendations for any action to be taken by Santos having regard to the above assessments.

(b) Within 12 months from the date of this order, Santos provide to the AER:

(i) a written assurance certification report from the Independent Reviewer which describes how the steps described in subparagraphs 2(a)(i) to (iv) above have been completed and the outcome of the review; and

(ii) a written report signed by the Chief Commercial Officer (or equivalent) of Santos that states what steps Santos has taken in response to any action recommended by the Independent Reviewer and, if any recommendation has not been accepted, the reasons why.

3. There is liberty to apply in respect of the appointment of the Independent Reviewer.

4. Pursuant to s 43 of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth), within 30 days from the date of this order, Santos pay a contribution to the AER’s costs of and incidental to this proceeding, agreed in the amount of $100,000.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

NESKOVCIN J:

INTRODUCTION

1 The respondent, Santos Direct Pty Ltd, is a wholly owned subsidiary of Santos Limited, one of Australia’s largest domestic gas suppliers with interests in the production of natural gas and the operation of various plants, facilities and pipelines. Santos also acquires transportation services on gas pipelines pursuant to contracts for services it has with facility operators.

2 The Australian Energy Regulator (AER) is established by s 44AE of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth). On 19 October 2023, the AER filed an originating process and concise statement. The AER’s claims against Santos, which are set out in the concise statement, concern conduct related to the capacity auction established and operated by the Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO) under the National Gas Rules (NGR).

3 The parties agreed to a resolution of the proceeding, including a civil penalty. To that end, on 18 April 2024 the parties filed:

(a) Joint Submissions on relief; and

(b) a statement of agreed facts setting out the facts agreed between the parties pursuant to s 191 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) (SOAF).

4 The SOAF, which contains the facts agreed by the parties to establish the admitted contraventions, appears as a schedule to these reasons.

5 On the basis set out in the SOAF, Santos admits that during the period 1 March 2019 to 5 June 2021 (inclusive) (the Relevant Period) it contravened r 666(1) of the NGR on 4,701 occasions by making 4,701 material renominations, for use on 717 gas days of a transportation service, without making a contemporaneous record in relation to the renomination which included all of the information required by subrules 666(1)(a) to (d) of the NGR.

6 The parties provided an agreed minute of proposed orders (the Proposed Orders) which provided for:

(a) declarations to be made pursuant to s 44AAG(1) of the Competition and Consumer Act in relation to the admitted contraventions;

(b) an order for payment of a civil penalty by Santos in the amount of $2,750,000, pursuant to s 44AAG(2)(a) of the Competition and Consumer Act;

(c) the appointment of an Independent Reviewer to undertake an assurance program to ensure compliance with r 666(1) of the NGR and to provide information to the AER in connection with that assurance program, pursuant to s 44AAG(2)(c) and/or (d) of the Competition and Consumer Act; and

(d) payment by Santos of a contribution to the AER’s costs of and incidental to the proceeding in the amount of $100,000 pursuant to s 43 of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth).

7 For the reasons that follow, I consider there to be a proper basis for making the proposed declarations. I also consider the proposed civil penalty to be appropriate. In my view, the penalty reflects the circumstances of the contraventions and should operate as a deterrent against such conduct being engaged in by Santos or other participants in the gas markets in the future. I also consider it appropriate to make the other ancillary orders proposed by the parties.

BACKGROUND

8 This section summarises the facts that establish the admitted contraventions, which are more fully set out in the SOAF, and the legislative framework that applies to the capacity auction and renominations for transportation services under the NGR.

Legislative framework

9 The NGR are made under the National Gas Law (NGL) and have the force of law pursuant to s 26 of the NGL. The NGL is set out in the Schedule to the National Gas (South Australia) Act 2008 (SA). To the extent the conduct in question concerns pipelines located in New South Wales, Queensland, South Australia and Victoria, each state is a relevant jurisdiction and the NGL applies as law in each of these jurisdictions: s 7 of the National Gas (New South Wales) Act 2008 (NSW); s 7 of the National Gas (Queensland) Act 2008 (Qld); s 7 of the National Gas (South Australia) Act 2008 (SA); s 7 of the National Gas (Victoria) Act 2008 (Vic).

10 Unless otherwise stated, the various defined terms referred to below are to be found in s 2 of the NGL and rr 593, 647, 677 and 678 of the NGR.

Transportation facility user and transportation service providers

11 During the Relevant Period, Santos was a “transportation facility user” within the meaning of s 2 of the NGL, being a person who is a party to a contract with a “transportation service provider” under which the transportation service provider provides, or intends to provide, a “transportation service” to that person by means of a “transportation facility”.

12 The contracts Santos had with transportation service providers within the meaning of the NGL during the Relevant Period included contracts with:

(a) APT Pipelines Ltd (APT) relating to the Carpentaria Gas Pipeline (CGP);

(b) Jemena Eastern Gas Pipeline (1) Pty Ltd and Jemena Eastern Gas Pipeline (2) Pty Ltd relating to the Eastern Gas Pipeline (EGP);

(c) Epic Energy South Australia Pty Ltd relating to the Moomba to Adelaide Pipeline System (MAPS);

(d) APT and APA (SWQP) Pty Ltd relating to the Moomba Sydney Pipeline (MSP);

(e) APT and APA (SWQP) Pty Ltd relating to the South West Queensland Pipeline (SWQP) and the Roma to Brisbane Pipeline (RBP); and

(f) APA (SWQP) Pty Ltd relating to the SWQP.

13 Each of the CGP, EGP, MAPS, MSP, SWQP and RBP was, during the Relevant Period, a transportation facility within the meaning of the NGL. These transportation facilities each provided transportation services to Santos within the meaning of the NGL. Each of these transportation facilities was also an “auction facility” which was subject to the “capacity auction” (described in paragraphs 14 to 24 below).

The capacity auction

14 The “capacity auction” is an auction (established by AEMO under Part 25 of the NGL) for contracted but unnominated transportation capacity on a pipeline. It is conducted each “gas day” pursuant to a particular timetable, which is set out in Schedule 2 to the Capacity Transfer and Auction Procedures made under s 91BRO of the NGL. The timetable referred to below has been in effect since 1 October 2019. A different timetable applied prior to 1 October 2019.

15 The capacity auction conducted on gas day D-1 concerns the scheduling and use of gas transportation capacity on gas day D.

16 The standard gas day is a gas day starting at 6:00am.

17 By no later than 3:00pm on gas day D-1 (the “standard nomination cut-off time”), transportation facility users must make a “day-ahead nomination” - meaning a “nomination” given on a gas day about the intended use of a transportation service on the following gas day or any part of the following gas day.

18 By no later than 4:30pm on gas day D-1, “facility operators” must determine an “auction quantity limit” (AQL) for gas day D for each product component associated with each “auction product” on their pipelines and provide AQLs to AEMO: r 653(1) of the NGR. An auction product is the transportation capacity available for the use of an “auction service” on gas day D. Relevantly for present purposes, an auction service is a transportation service available on a pipeline. The amount of transportation capacity available through the capacity auction is determined by the AQLs.

19 The AQL for a product component is determined by reference to cl 19 of the Capacity Transfer and Auction Procedures, and in particular the formulae in cl 19.2. In brief, the AQL for a product component on gas day D is the lesser of:

(a) the difference (if any) between the physical capacity of the pipeline and the nominated capacity; and

(b) the difference (if any) between the capacity that is the subject of contracts for “firm services” and the capacity that is the subject of day-ahead nominations.

20 In this way, day-ahead nominations determine the amount of capacity that will be available through the capacity auction.

21 By no later than 5:00pm on each gas day D-1, auction participants submit bids for auction products.

22 By no later than 5:30pm on gas day D-1, AEMO auctions the available capacity. The auction determines both the auction clearing price and the allocation of auction products to successful bidders. The auction clearing price is the (one) price which all successful bidders for an auction product pay. If the total bid quantity is greater than the capacity available at the auction, then the clearing price is set by the lowest accepted bid. If the total bid quantity is less than the auction capacity available, the clearing price will be $0 per GJ.

23 By no later than 6:30pm on gas day D-1, facility operators must give effect to the auction results notified to it by AEMO: r 655(3) of the NGR.

24 By no later than 6:45pm on gas day D-1, a transportation facility user which has been allocated capacity at an auction must nominate the quantity of transportation capacity it wishes to use on gas day D (the “auction service nomination cut off time”).

Renominations

Firm services

25 After the standard nomination cut-off time on gas day D-1, a transportation facility user with a contract for “firm services” (as classified under r 648(4) of the NGR) may make a “renomination” - that is, a request to vary a day-ahead nomination for gas day D. If there is a renomination for use of a firm service, the scheduling of the renominated quantity, to the extent it does not result in the scheduled quantity exceeding the reserved capacity in relation to which the renomination is made, must be met:

(a) first, from auction capacity that was not allocated in the capacity auction;

(b) second, by curtailing “lower tier services” (as classified under r 648(4) of the NGR) to the extent the services are scheduled to use auction capacity; and

(c) third, by curtailing auction services: r 651(1)(c) of the NGR.

26 Therefore, a renomination that varies a day-ahead nomination to increase the capacity required for that firm service has the potential to curtail auction services as compared to before the (subsequent) renomination. Conversely, a renomination that varies a day-ahead nomination to decrease the capacity required for that firm service means that less auction capacity was made available to shippers at the time of the auction than is actually available after the (subsequent) renomination. Depending on the level of demand in any particular auction, having less auction capacity made available may mean that participants in the auction may pay more for the auction product than would otherwise have been the case if more auction capacity had been made available.

Auction services

27 After the auction service nomination cut off time of 6:45pm on gas day D-1, a transportation facility user that has been allocated capacity at the capacity auction may make a renomination for the use of an auction service. If an auction capacity holder makes a renomination, the scheduling of the renominated quantity, to the extent it does not result in the scheduled quantity exceeding the “auction MDQ” (meaning the quantity of auction product allocated in the capacity auction for the gas day) in relation to which the renomination is made, must be met:

(a) first, from auction capacity that was not allocated in the capacity auction for that gas day; and

(b) second, by curtailing lower tier services to the extent the services are scheduled to use auction capacity: r 651(1)(d) of the NGR.

28 If there is a capacity shortfall on a gas day, auction services must only be curtailed to meet any shortfall that remains after lower tier services have been curtailed to meet the capacity shortfall: r 651(1)(e) of the NGR.

29 Therefore, a renomination that varies a nomination for an auction service to increase the capacity required for that auction service has the potential to curtail lower tier services that the transportation service provider has scheduled. Conversely, a renomination that varies a nomination for an auction service to decrease the capacity required for that auction service means that less capacity for lower tier services is available to shippers after the (initial) auction service nomination cut-off time than is available after the (subsequent) renomination. If available capacity for lower tier services is constrained in this way, shippers taking up, or who would have sought to take up, lower tier services may be adversely affected, and transportation service providers may be prevented from selling capacity for lower tier services that they could otherwise have sold.

30 In addition, if a renomination varies a nomination for an auction service to decrease the capacity required for that auction service, this can have further effects in circumstances where an auction is constrained (that is, there is more demand in the auction than there is available capacity to be auctioned). These potential effects include auction participants paying more for auction services than they otherwise would have, or auction participants not being allocated some or all of the capacity sought by them in the auction.

Importance of the accuracy and reliability of nominations and renominations

31 Santos admits that during the Relevant Period it contravened r 666(1) of the NGR, which deals with renomination records for firm services and auction services. Before coming to r 666(1), it is necessary to make reference to rr 663 and 664 of the NGR which provide the broader context to the record keeping requirements in r 666(1) and emphasise the importance of compliance with those requirements and the AER’s role in compliance and enforcement more generally and, in turn, the proper operation of the day-ahead auction. It is important to observe that the AER does not allege that Santos has not complied with the requirements of r 663, nor does it contend that Santos’ conduct had any adverse market impact.

32 Rule 663 of the NGR provides:

663 Nominations and renominations must not be false or misleading

(1) A transportation facility user for an auction facility must not make a day-ahead nomination or a renomination that is false, misleading or likely to mislead.

Note

This subrule is classified as a tier 1 civil penalty provision under the National Gas (South Australia) Regulations. (See clause 6 and Schedule 3 of the National Gas (South Australia) Regulations.)

(2) For the purposes of subrule (1), the making of a day-ahead nomination or renomination is deemed to represent to transportation service providers, other transportation facility users and auction participants that the day-ahead nomination or renomination will not be changed, unless the person making the day-ahead nomination or renomination becomes aware of a change in the material conditions and circumstances upon which the day-ahead nomination or renomination is based.

Note

This subrule is classified as a tier 1 civil penalty provision under the National Gas (South Australia) Regulations. (See clause 6 and Schedule 3 of the National Gas (South Australia) Regulations.)

(3) Without limiting subrule (1), a day-ahead nomination or renomination is deemed to be false or misleading if, at the time of making the day-ahead nomination or renomination the transportation facility user:

(a) does not have a genuine intention to use the quantity of transportation capacity for which the day-ahead nomination or renomination is made; or

(b) does not have a genuine intention to use no more than the quantity of transportation capacity for which the day-ahead nomination or renomination is made; or

(c) does not have a reasonable basis to make the representations made by reason of subrule (2).

Note

This subrule is classified as a tier 1 civil penalty provision under the National Gas (South Australia) Regulations. (See clause 6 and Schedule 3 of the National Gas (South Australia) Regulations.)

(4) In any proceeding in which a contravention of subrule (1) is alleged, in determining whether a transportation facility user made a day-ahead nomination or renomination that was false, misleading or likely to mislead, a court must have regard to the need for accurate, reliable and timely information about the intended use of transportation capacity for the efficient conduct of the capacity auction and the efficient scheduling and use of transportation capacity for all transportation facility users.

(5) A transportation facility user may be taken to have contravened subrule (1) notwithstanding that, after all the evidence has been considered, the false or misleading character of the day-ahead nomination or renomination is ascertainable only by inference from:

(a) other nominations, including in a regulated gas market or under a gas sales agreement, made by the transportation facility user or in relation to which the transportation facility user had substantial control or influence;

(b) bids in a wholesale electricity market or wholesale gas market made by the transportation facility user or in relation to which the transportation facility user had substantial control or influence;

(c) other conduct (including any pattern of conduct), knowledge, belief or intention of the relevant transportation facility user;

(d) the conduct (including any pattern of conduct), knowledge, belief or intention of any other person;

(e) information published by AEMO or a transportation service provider or the relevant transportation facility user; or

(f) any other relevant circumstances.

33 Rule 664 of the NGR deals with the role of the AER and provides that the AER must monitor day-ahead nominations, renominations and activity in the capacity action “with a view to ensuring that transportation service providers, auction participants and transportation facility users comply with the market conduct and nomination rules”.

34 Rule 666 (1) to (3) of the NGR provides:

666 Renomination records for firm services and auction services

(1) A transportation facility user for an auction facility who makes a material renomination as defined in subrule (2) for use on a gas day of a transportation service must make a contemporaneous record in relation to the renomination, which must include a record of:

(a) the material conditions and circumstances giving rise to the renomination;

(b) the transportation facility user's reasons for making the renomination, which must be verifiable and specific;

(c) the time at which the event or other occurrence giving rise to the renomination occurred; and

(d) the time at which the transportation facility user first became aware of the relevant event or other occurrence.

Note

This subrule is classified as a tier 2 civil penalty provision under the National Gas (South Australia) Regulations. (See clause 6 and Schedule 3 of the National Gas (South Australia) Regulations.)

(2) For the purpose of subrule (1), a renomination of a transportation facility user is a material renomination in relation to a gas day and transportation service if:

(a) the renomination is for:

(i) a transportation service taken into account in the calculation of an auction quantity limit; or

(ii) an auction service; and

(b) the renomination, either alone or when taken together with other renominations of the transportation facility user for that transportation service for the gas day (whether before or after the renomination) results in a variation of more than 10% to:

(i) except in the case of an auction service, the last day-ahead nomination of the transportation facility user for that transportation service before the nomination cut-off time applicable to the transportation service; or

(ii) in the case of an auction service, the initial nomination for use of the auction service.

Note

This subrule is classified as a tier 2 civil penalty provision under the National Gas (South Australia) Regulations. (See clause 6 and Schedule 3 of the National Gas (South Australia) Regulations.)

(3) A record made under subrule (1) must be maintained for a period of 5 years after the gas day to which the record relates.

Santos’ record keeping in respect of renominations

35 From 1 March 2019 to 31 October 2020, Santos’ record keeping system in respect of renominations comprised a database which automatically recorded all renomination quantities and renomination times, the relevant gas day, auction facility and transportation service.

36 From 1 March 2019 to 31 October 2020, Santos made material renominations without making contemporaneous records that contained all of the information required by r 666(1) of the NGR. The total number of material renominations for which Santos did not make a contemporaneous record that contained all of the information required by r 666(1) was 4,399, for use on 598 gas days, comprising:

(a) CGP: 162, for use on 83 gas days;

(b) EGP: 610, for use on 271 gas days;

(c) MAPS: 202, for use on 106 gas days;

(d) MSP: 1,682, for use on 467 gas days;

(e) SWQP: 1,567, for use on 459 gas days; and

(f) RBP: 176, for use on 68 gas days.

37 From 1 November 2020, Santos had in place a new automated, contemporaneous system for record keeping in respect of renominations and to capture the information required under r 666(1) (the Contemporaneous Record Analysis and Keeping for the AER system, CRAKAER).

38 When it was rolled out on 1 November 2020, CRAKAER was incorrectly configured and did not collect information about some renominations until 8 June 2021. CRAKAER was inadequate for compliance with r 666(1) in the following three respects:

(a) From 1 November 2020 to 10 February 2021, CRAKAER captured only certain renominations in respect of firm services (and did not capture any renominations in respect of auction services). From 11 February 2021, CRAKAER also captured certain renominations in respect of auction services.

(b) From 1 November 2020 to 7 May 2021, in respect of those renominations that were captured by CRAKAER (namely, from 1 November 2020, certain renominations in respect of firm services only; from 11 February 2021, certain renominations in respect of both firm and auction services), not all of the categories of information required by r 666(1) of the NGR were captured. From 8 May 2021, this issue was rectified.

(c) From 1 November 2020 to 8 June 2021, in respect of those renominations that were captured by CRAKAER (namely, from 1 November 2020, certain renominations in respect of firm services only; from 11 February 2021, certain renominations in respect of both firm and auction services), only renominations made after 5:00pm AEST on gas day D-1 were captured. From 9 June 2021, Santos made further corrections to CRAKAER so that it captured all relevant nominations and this issue was rectified.

39 In consequence of the matters set out in paragraphs 37 and 38 above, during the period from 1 November 2020 to 5 June 2021, Santos made material renominations without making contemporaneous records that contained all of the information required by r 666(1) of the NGR. The total number of material renominations for which Santos did not make a contemporaneous record that contained all of the information required by r 666(1) during this period was 302, for use on 119 gas days, comprising:

(a) CGP: 9, for use on 4 gas days;

(b) EGP: 31, for use on 18 gas days;

(c) MAPS: 12, for use on 6 gas days;

(d) MSP: 72, for use on 50 gas days;

(e) SWQP: 173, for use on 84 gas days; and

(f) RBP: 5, for use on 4 gas days.

DECLARATORY RELIEF

40 This Court has a broad discretionary power to make declarations under s 21 of the Federal Court of Australia Act. The Court also has power under s 44AAG(1) of the Competition and Consumer Act to make an order, on application by the AER, declaring that a person is in breach of, relevantly, a State/Territory energy law. Pursuant to s 4(1) of the Competition and Consumer Act, the provisions of the NGL, including the NGR, are uniform energy laws.

41 The parties seek a declaration in the terms set out in the Proposed Orders.

42 As observed by the Full Court in Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union [2017] FCAFC 113; 254 FCR 68 at [90], the fact that the parties have agreed that a declaration of contravention should be made does not relieve the Court of the obligation to satisfy itself that the making of the declaration is appropriate. The Full Court also stated (at [93]):

Declarations relating to contraventions of legislative provisions are likely to be appropriate where they serve to record the Court’s disapproval of the contravening conduct, vindicate the regulator’s claim that the respondent contravened the provisions, assist the regulator to carry out its duties, and deter other persons from contravening the provisions: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union [2006] FCA 1730; [2007] ATPR 42-140 at [6], and the cases there cited; Rural Press Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2003] HCA 75; (2003) 216 CLR 53 at [95].

43 In Forster v Jododex Australia Pty Ltd [1972] HCA 61; 127 CLR 421, Gibbs J stated (at 437-438) that before making declarations three requirements should be satisfied:

(a) the question must be a real and not a hypothetical or theoretical one;

(b) the applicant must have a real interest in raising it; and

(c) there must be a proper contradictor.

44 I am satisfied the AER has a real interest in seeking declaratory relief in this proceeding. Declaratory relief serves to record the Court’s disapproval of the relevant conduct and to vindicate the AER’s claim that Santos contravened the NGR. Santos is a proper contradictor, notwithstanding that the parties have reached agreement on the SOAF, which provide a sufficient factual foundation for the making of the declaration.

45 The Court is not bound by the form of the declaration proposed by the parties and must determine for itself whether the form is appropriate. The parties submit, and I accept, that the Court has the power, and it is appropriate, to make the declaration in the form of the declaration in the Proposed Orders. The proposed declaration relates to conduct that contravenes the NGR and contains sufficient indication of how and why the relevant conduct is a contravention of the NGR.

CIVIL PENALTIES

The statutory power to impose a civil penalty

46 Pursuant to s 44AAG(2)(a) of the Competition and Consumer Act, the Court may impose a civil penalty on a person who is declared to be in breach of a civil penalty provision of, relevantly, a State/Territory energy law, which includes the NGR:

44AAG Federal Court may make certain orders

…

(2) If the order declares the person to be in breach of [a State/Territory energy law], the order may include one or more of the following:

(a) an order that the person pay a civil penalty determined in accordance with the law;

47 Section 234 of the NGL provides that every civil penalty ordered to be paid by a person declared to have breached a provision of, relevantly here, the NGR, must be determined having regard to all relevant matters, including:

(a) the nature and extent of the breach (s 234(a));

(b) the nature and extent of any loss or damage suffered as a result of the breach (s 234(b));

(c) the value of any benefit reasonably attributable to the breach that the person or, in the case of a body corporate, any related body corporate, has obtained, directly or indirectly (s 234(ba) (from 29 January 2021));

(d) the circumstances in which the breach took place (s 234(c));

(e) whether the person has engaged in any similar conduct and been found to have breached a provision of the NGL, the National Gas (South Australia) Regulations (SA) (Regulations) or the NGR in respect of that conduct (s 234(d)); and

(f) whether the service provider had in place a compliance program approved by the AER or required under the NGR, and if so, whether the service provider had been complying with that program (s 234(e)).

48 The relevant matters under s 234 of the NGL are non-exhaustive. In Trade Practices Commission v CSR Limited [1990] FCA 762; [1991] ATPR 41-076 (TPC v CSR) at 52,152-52,153, French J (as his Honour then was) listed a number of matters potentially relevant to the assessment of penalty under s 76 of the Competition and Consumer Act, some of which overlap with the mandatory considerations enumerated in s 234 of the NGL. These matters have been referred to on many occasions as the “French factors”. They are:

(a) the nature and extent of the contravening conduct;

(b) the amount of loss or damage caused;

(c) the circumstances in which the conduct took place;

(d) the size of the contravening company;

(e) the degree of power it has, as evidenced by its market share and ease of entry into the market;

(f) the deliberateness of the contravention and the period over which it extended;

(g) whether the contravention arose out of the conduct of senior management or at a lower level;

(h) whether the company has a corporate culture conducive to compliance with the Act as evidenced by educational programs and disciplinary or other corrective measures in response to an acknowledged contravention; and

(i) whether the company has shown a disposition to cooperate with the authorities responsible for the enforcement of the Act in relation to the contravention.

Where the parties have agreed a pecuniary penalty

49 The significance of the fact that the parties have agreed an amount for the pecuniary penalty was considered in Commonwealth v Director, Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate [2015] HCA 46; 258 CLR 482 (FWBII). The plurality (French CJ, Kiefel J (as her Honour then was), Bell, Nettle and Gordon JJ) referred to the existence of an “important public policy involved in promoting predictability of outcome in civil penalty proceedings and that the practice of receiving and, if appropriate, accepting agreed penalty submissions increases the predictability of outcome for regulators and wrongdoers” (at [46]).

50 The plurality said that the Court is not bound by the figure suggested by the parties. Their Honours said (at [48]):

... The court asks “whether their proposal can be accepted as fixing an appropriate amount” and for that purpose the court must satisfy itself that the submitted penalty is appropriate.

51 The plurality also said (at [58]):

... Subject to the court being sufficiently persuaded of the accuracy of the parties’ agreement as to facts and consequences, and that the penalty which the parties propose is an appropriate remedy in the circumstances thus revealed, it is consistent with principle and, for the reasons identified in [Trade Practices Commission v Allied Mills Industries Pty Ltd [No 5] (1981) 60 FLR 38], highly desirable in practice for the court to accept the parties’ proposal and therefore impose the proposed penalty.

52 The plurality also referred to the assistance the Court may obtain as to the appropriate penalty from the regulator which is, it is to be expected, in a position to offer “informed submissions as to the effects of contravention on the industry and the level of penalty necessary to achieve compliance” (at [60]).

Accepted principles

53 The principles in relation to the imposition of civil penalties are well established. They were summarised recently by O’Bryan J in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Uber B.V. [2022] FCA 1466 and Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v BlueScope Steel Limited (No 6) [2023] FCA 1029. I gratefully adopt his Honour’s summaries and repeat the principles relevant to this proceeding below.

54 First, the penalty to be imposed under s 44AAG(2) of the Competition and Consumer Act is a penalty that the Court considers to be appropriate.

55 Second, the principal object of imposing a civil penalty is deterrence; both the need to deter repetition of the contravening conduct by the contravener (specific deterrence) and to deter others who might be tempted to engage in similar contraventions (general deterrence): Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd [2013] HCA 54; 250 CLR 640 at [65] per French CJ, Crennan, Bell and Keane JJ; FWBII at [55] per French CJ, Kiefel J (as her Honour then was), Bell, Nettle and Gordon JJ and [110] per Keane J. The Court must seek to “put a price on contravention that is sufficiently high to deter repetition by the contravenor and by others who might be tempted to contravene” the relevant statute: Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Pattinson [2022] HCA 13; 274 CLR 450 at [15] per Kiefel CJ, Gageler J (as his Honour then was), Keane, Gordon, Steward and Gleeson JJ, citing TPC v CSR at [50] per French J (as his Honour then was). The penalty imposed should not be regarded by the contravenor or others as an acceptable cost of doing business: TPG at [66] per French CJ, Crennan, Bell and Keane JJ) citing Singtel Optus Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2012] FCAFC 20; 287 ALR 249 at [62]-[63]. A penalty should nonetheless be proportionate in the sense of striking “a reasonable balance between deterrence and oppressive severity” (Pattinson at [41], [46]-[47]). The question, therefore, is what is required to achieve deterrence in the specific circumstances of the case.

56 Third, the level of penalty required to achieve the objective of deterrence in a given case depends upon the facts and circumstances of the case. As set out in paragraph 47 above, s 234 of the NGL requires the Court to have regard to certain mandatory matters. Additional factors relevant to this case include the size and financial position of Santos, whether senior management were involved, the level of co-operation with the AER and Santos’ compliance culture.

57 The majority in Pattinson confirmed that regard may properly be had to the above factors as potentially relevant considerations in the assessment of penalty, while recognising that they are not a rigid catalogue of matters for attention nor a legal checklist (at [18] and [19]). In discussing those factors, the majority observed (at [46]-[47]), in the context of s 546 of the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth):

... It is important to recall that an “appropriate” penalty is one that strikes a reasonable balance between oppressive severity and the need for deterrence in respect of the particular case. A contravention may be a “one-off” result of inadvertence by the contravenor rather than the latest instance of the contravenor’s pursuit of a strategy of deliberate recalcitrance in order to have its way. There may also be cases, for example, where a contravention has occurred through ignorance of the law on the part of a union official, or where the official responsible for a deliberate breach has been disciplined by the union. In such cases, a modest penalty, if any, may reasonably be thought to be sufficient to provide effective deterrence against further contraventions.

The penalty that is appropriate to protect the public interest by deterring future contraventions of the Act may also be moderated by taking into account other factors of the kind adverted to by French J in CSR. For example, where those responsible for a contravention of the Act express genuine remorse for the contravention, it might be considered appropriate to impose only a moderate penalty because no more would be necessary to incentivise the contravenors to remain mindful of their remorse and their public expressions of that remorse to the court. Similarly, where the occasion in which a contravention occurred is unlikely to arise in the future because of changes in the membership of an industrial organisation, a modest penalty may be appropriate having regard to the reduced risk of future contraventions.

58 Fourth, in fixing a penalty, the Court should have regard to the maximum penalty prescribed by the legislature: see Markarian v The Queen [2005] HCA 25; 228 CLR 357. However, the statutory maximum penalty is “but one yardstick that ordinarily must be applied” and must be treated as “one of a number of relevant factors”: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Reckitt Benckiser (Australia) Pty Ltd [2016] FCAFC 181; 340 ALR 25 at [155]-[156]. In Pattinson, the majority rejected an approach whereby the Court seeks to grade contraventions on a “scale of increasing seriousness, with the maximum to be reserved exclusively for the worst category of contravening conduct” (at [49]). The majority explained (at [55]) that:

... the maximum penalty does not constrain the exercise of the discretion under s 546 (or its analogues in other Commonwealth legislation), beyond requiring “some reasonable relationship between the theoretical maximum and the final penalty imposed”. This relationship of “reasonableness” may be established by reference to the circumstances of the contravenor as well as by the circumstances of the conduct involved in the contravention. That is so because either set of circumstances may have a bearing upon the extent of the need for deterrence in the penalty to be imposed. And these categories of circumstances may overlap.

59 Fifth, in common with criminal sentencing, determining a civil penalty usually involves multi-factorial decision-making, identifying and balancing all the factors relevant to the contravention, and where the result is arrived at by a process of “instinctive synthesis” of the relevant factors: Reckitt Benckiser at [44].

Multiple contraventions

60 The parties submit that the multiple contraventions of r 666(1) by Santos can be viewed as arising from Santos not having in place a contemporaneous record keeping system that operated to ensure that each of the required categories of information listed in r 666(1) was captured in respect of the material renominations made by Santos during the Relevant Period.

61 In determining the appropriate penalty for a multiplicity of civil penalty contraventions, the Court may have regard to two common law principles that originate in criminal sentencing: the “course of conduct” principle and the “totality” principle: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Yazaki Corporation [2018] FCAFC 73; 262 FCR 243 at [226].

62 The course of conduct principle is a tool of analysis that does not convert the many separate contraventions into only one contravention. Nor does it constrain the available maximum penalty. In BlueScope Steel, O’Bryan J said at [31]:

Under the “course of conduct” principle, the Court considers whether the contravening acts or omissions arise out of the same course of conduct or the one transaction, to determine whether it is appropriate that a “concurrent” or single penalty should be imposed for the contraventions: Yazaki Corporation at [234]. The principle guards against the risk that the respondent is “doubly punished” in respect of multiple contravening acts or omissions that should be evaluated, for the purposes of assessing an appropriate penalty, as a lesser number of acts of wrongdoing: Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union v Cahill [2010] FCAFC 39; 269 ALR 1 at [39] per Middleton and Gordon JJ. However, as noted by the Full Court in Yazaki Corporation (at [227]), it is not appropriate or permissible to treat multiple contravening acts or omissions as just one contravention for the purposes of determining the maximum limit dictated by the relevant legislation. Accordingly, the maximum penalty for the course of conduct is not restricted to the maximum penalty for each contravening act or omission: Yazaki Corporation at [229]-[235].

63 The parties disagree as to whether Santos’ conduct should be characterised as four courses of conduct or two.

64 The AER submits that Santos’ conduct should be seen as four courses of conduct as follows:

(a) first, the conduct by which, prior to 1 November 2020, Santos’ record keeping system comprised a database which automatically recorded all renomination quantities and renomination times, the relevant gas day, auction facility and transportation service - this affected material renominations for which records were made between 1 March 2019 and 31 October 2020 (inclusive);

(b) second, the conduct by which, following the introduction of CRAKAER, that system had not been properly configured to capture renominations in respect of auction services - this affected material renominations for which records were made between 1 November 2020 and 10 February 2021 (inclusive);

(c) third, the conduct by which, following the introduction of CRAKAER, that system had not been properly configured to capture all of the categories of information required by r 666(1) - this affected material renominations for which records were made between 1 November 2020 and 7 May 2021 (inclusive);

(d) fourth, the conduct by which, following the introduction of CRAKAER, that system had not been properly configured to capture material renominations made between 3:00pm and 5:00pm AEST - this affected material renominations made between 1 November 2020 and 5 June 2021 (inclusive).

65 Santos submits that its conduct should be seen as two courses of conduct as follows:

(a) first, the conduct by which, prior to 1 November 2020, Santos’ record keeping system comprised a basic database which automatically recorded all renomination quantities and renomination times, the relevant gas day, auction facility and transportation service - this affected material renominations for which records were made between 1 March 2019 and 31 October 2020 (inclusive) – a total of 4,399 renominations, which is 93.6% of the total renominations affected;

(b) second, the conduct by which, following the introduction of CRAKAER, that system had not been properly configured to capture all material renominations and to capture all of the categories of information required by r 666(1) in relation to them - this affected material renominations for which records were made between 1 November 2020 and 5 June 2021 (inclusive) – a total of 302 renominations, which is 6.4% of the total renominations affected.

66 It is unnecessary to decide whether Santos’ conduct should be characterised as four or two courses of conduct. The parties submit, and I accept, that whether the Court regards Santos’ conduct as four courses of conduct, or two ought not affect the appropriate penalty in the present case. To take such an approach is not to downplay the seriousness of the wrongdoing.

67 The “totality” principle operates as a “final check” to ensure that the penalties to be imposed on a wrongdoer, considered as a whole, are just and appropriate and that the total penalty for related offences does not exceed what is proper for the entire contravening conduct in question: Trade Practices Commission v TNT Australia Pty Ltd [1995] ATPR 41-375; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Australian Safeway Stores Pty Ltd [1997] FCA 450; 75 FCR 238; 145 ALR 36 at 53 per Goldberg J; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Coles Supermarkets [2014] FCA 1405 at [132] per Gordon J.

Maximum penalty

68 The Relevant Period spans two civil penalty regimes:

(a) From the commencement of the Relevant Period (1 March 2019) to 28 January 2021 (inclusive), r 666(1) was prescribed as a civil penalty provision in respect of which the maximum penalty for a body corporate was $100,000 and $10,000 for every day during which the breach continued.

(b) From 29 January 2021 to the end of the Relevant Period (5 June 2021), r 666(1) was prescribed as a tier 2 civil penalty provision, in respect of which the civil penalty for a body corporate is an amount not exceeding $1,435,000 plus an amount not exceeding $71,800 for every day during which the breach continues.

69 The maximum penalty applies to each of the contraventions of Santos of r 666(1), notwithstanding the “course of conduct” principle.

70 The consequence of calculating the maximum penalty per contravention is, according to the parties, that the maximum theoretical penalty for Santos’ contraventions during the Relevant Periods would be in the order of $725 million, calculated as follows: for contraventions prior to 29 January 2021, $100,000 per contravention, being $100,000 x 4,510 = $451,000,000; for contraventions after 29 January 2021, $1,435,000 x 191 = $274,085,000.

71 However, it is established that, where a very large number of contraventions is involved, as is the case in this proceeding, the maximum penalty may rise to a number such that there is no meaningful maximum penalty: Reckitt Benckiser at [157], and the focus should be on the conduct and determining a penalty to match the conduct.

Consideration of the relevant matters

72 This section of the reasons considers the statutory matters required to be taken into account under s 234 of the NGL and the additional factors relevant to the Court’s consideration and assessment of the appropriate penalty to be imposed on Santos. The matters mentioned below are drawn substantially from the Joint Submissions.

Nature and extent of the breach – s234(a) of the NGL

73 The nature and extent of the offending conduct includes consideration of whether the offending conduct was systematic, deliberate or covert (see J McPhee & Son (Australia) Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2000] FCA 365; 172 ALR 532 at [158] and [163]) and the period over which it extended.

74 The contravening conduct involved 4,701 contraventions of r 666(1), which occurred on 717 gas days and spanned a period of just over 27 months. The failure to keep the required records occurred in connection with six gas pipelines.

75 The contraventions arose from Santos’ not having in place a contemporaneous record keeping system that operated to ensure that each of the required categories of information listed in r 666(1) was captured in respect of the material renominations made by Santos during the Relevant Period.

76 The contraventions were inadvertent and not deliberate.

77 Santos took steps in 2020 to develop CRAKAER, which was implemented from 1 November 2020. However, as mentioned in paragraph 38 above, CRAKAER was inadequate for compliance with r 666(1) in three respects, with these deficiencies addressed with effect from 11 February 2021, 8 May 2021 and 9 June 2021.

78 Compliant record keeping is an important part of ensuring the integrity of the capacity auction. It assists in protecting the proper function of the capacity auction by ensuring that proper records are kept of the reasons why renominations occur and allows the AER to review those reasons and take action if necessary. It thereby assists in promoting the effective and efficient operation of the capacity auction. The absence of compliant records may significantly hamper the ability of the AER to monitor day-ahead nomination and renomination activity in the capacity auction and investigate such conduct and, where appropriate, take enforcement action.

79 The systems Santos had in place were not sufficient to ensure that:

(a) at the time of the commencement of the day-ahead auction and the record keeping requirements, a record keeping system was established to facilitate Santos’ compliance with all of the requirements of r 666(1);

(b) in the development and initial implementation of CRAKAER, that the system was designed, and in fact operated, to facilitate compliance with all of the requirements of r 666(1); and

(c) during the period in which CRAKAER operated, that system was fit for purpose in ensuring compliance with the requirements of r 666(1).

80 Santos did not identify its initial non-compliance with r 666(1) until some months after the AER contacted Santos on 28 August 2020 requesting contemporaneous records in connection with a number of renominations made by Santos relating to gas days between 4 February and 12 June 2020.

Nature and extent of any loss or damage suffered as a result of the breach - s234(b) of the NGL

81 The parties agree that there was no actual loss or damage caused as a result of the admitted contraventions. However, this does not suggest that Santos’ contraventions were not of consequence. It is relevant to consider the potential loss or damage to have eventuated.

82 As mentioned above, a renomination that varies a day-ahead nomination to increase the capacity required for that firm service has the potential to curtail auction services as compared to before the (subsequent) renomination. Conversely, a renomination that varies a day-ahead nomination to decrease the capacity required for that firm service means that less auction capacity was made available to shippers at the time of the auction than is actually available after the (subsequent) renomination. Depending on the level of demand in any particular auction, having less auction capacity made available may mean that participants in the auction may pay more for the auction product than would otherwise have been the case if more auction capacity had been made available.

83 Furthermore, a renomination that varies a nomination for an auction service to increase the capacity required for that auction service has the potential to curtail lower tier services that the transportation service provider has scheduled. Conversely, a renomination that varies a nomination for an auction service to decrease the capacity required for that auction service means that less capacity for lower tier services is available to shippers after the (initial) auction service nomination cut-off time than is available after the (subsequent) renomination. If available capacity for lower tier services is constrained in this way, shippers taking up, or who would have sought to take up, lower tier services may be adversely affected, and transportation service providers may be prevented from selling capacity for lower tier services that they could otherwise have sold.

84 In addition, if a renomination varies a nomination for an auction service to decrease the capacity required for that auction service, this can have further effects in circumstances where an auction is constrained (that is, there is more demand in the auction than there is available capacity to be auctioned). These potential effects include auction participants paying more for auction services than they otherwise would have, or auction participants not being allocated some or all of the capacity sought by them in the auction.

85 The failure to comply with r 666(1), which has a substantive role in protecting the proper functioning of the capacity auction, heightens the need for deterrence in respect of this conduct.

The value of any benefit reasonably attributable to the breach obtained, directly or indirectly - s234(ba) of the NGL

86 The parties agree that Santos did not obtain any material benefit from the admitted contraventions.

The circumstances in which the breach took place - s234(c) of the NGL

87 The contraventions arose from a combination of inadequate internal compliance processes and practices and inadvertence. As previously mentioned, the contraventions occurred over a period of some 27 months. Some contemporaneous records of some material renominations were kept during this time, however, prior to 9 June 2021, Santos’ systems were not fit for purpose in ensuring that records were kept in respect of each of the categories set out in r 666(1) of the NGR.

Whether Santos has engaged in any similar conduct and been found to have breached a provision of the NGL, the Regulations or the NGR in respect of that conduct - s234(d) of the NGL

88 Santos has not previously been found by a court to be in breach of the NGR or the NGL for conduct of a similar nature.

Whether Santos had in place a compliance program approved by the AER or required under the NGR - s234(e) of the NGL

89 In relation to the mandatory consideration referred to in s 234(e) of the NGL, Santos was not required to, and did not, have an AER approved compliance program in place at the relevant time or now, nor was or is it required to have one in place under the NGR. As mentioned above, Santos has had a compliance framework in place since July 2021.

Size and financial position of the respondent (additional factors)

90 The contravener’s size and financial position is a relevant consideration in determining whether a civil penalty will achieve deterrence. The Full Court observed in Volkswagen Aktiengesellschaft v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2021] FCAFC 49; 284 FCR 24 at [154]:

The sum required to achieve that object [of deterrence] will generally be larger where the company has vast resources …. It follows that it may be appropriate to impose a higher penalty on a very large corporation than would be the case if the corporation was small and had limited resources, irrespective of the profit derived from the contravention.

91 In this case, the size and financial position of the Santos Group are relevant, both because:

(a) Santos Limited, a listed major Australian oil and gas exploration and production company and the parent of the Santos Group, bears some responsibility for the conduct of Santos, its wholly owned subsidiary, through its employment of the personnel who conduct activities for Santos; and

(b) the Santos Group’s financial position is relevant to Santos’ ability to meet a substantial civil penalty.

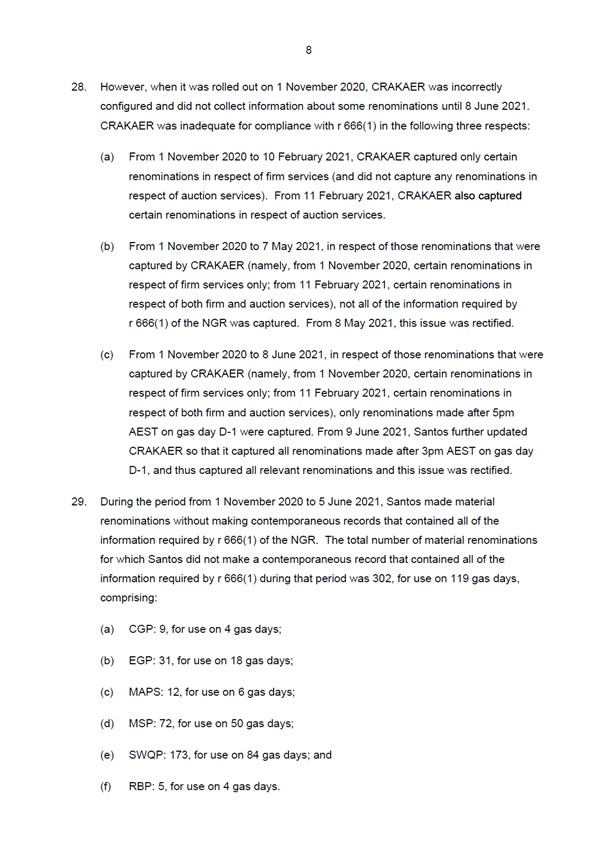

92 For the calendar financial years 2019-2022, the Santos Group reported the following results ($US million):

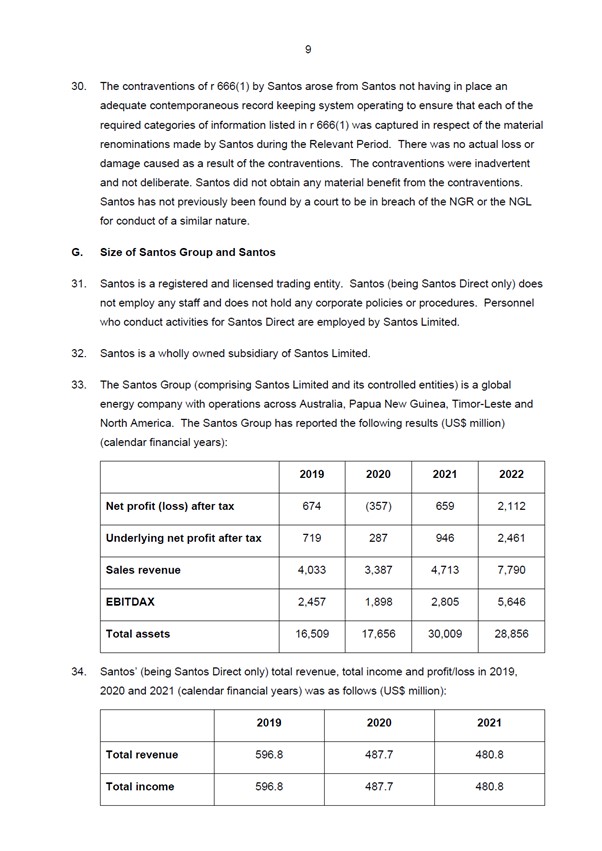

2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | |

Net profit (loss) after tax | 674 | (357) | 659 | 2,112 |

Underlying net profit after tax | 719 | 287 | 946 | 2,461 |

Sales revenue | 4,033 | 3,387 | 4,713 | 7,790 |

EBITDAX | 2,457 | 1,898 | 2,805 | 5,646 |

Total assets | 16,509 | 17,656 | 30,009 | 28,856 |

93 Santos’ (being Santos Direct only) total revenue, total income and profit/loss in 2019, 2020 and 2021 (calendar financial years) was as follows (US$ million):

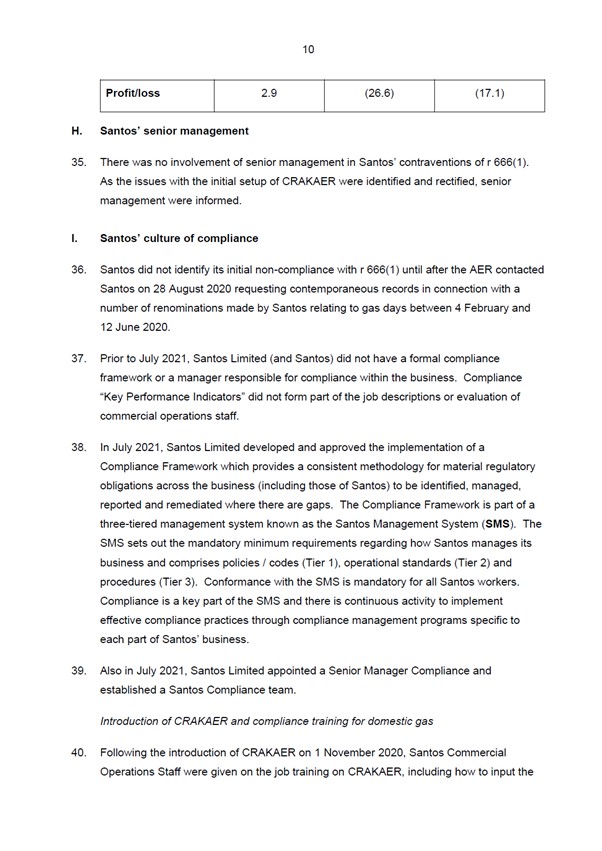

2019 | 2020 | 2021 | |

Total revenue | 596.8 | 487.7 | 480.8 |

Total income | 596.8 | 487.7 | 480.8 |

Profit/loss | 2.9 | (26.6) | (17.1) |

94 Having regard to the circumstances of Santos (including that Santos is a wholly owned subsidiary of Santos Limited and part of a large corporate group) and the circumstances of the contraventions, a substantial penalty of the quantum proposed is appropriate in this matter and Santos has the financial capacity to pay the proposed penalty.

Whether the conduct involved senior management (additional factor)

95 There was no involvement of senior management in the contravening conduct.

Level of cooperation with the AER (additional factor)

96 Santos has cooperated with the AER at all stages during its investigation and this proceeding. Santos admitted the contraventions alleged by the AER at an early stage in the proceeding and prior to the filing of any evidence or submissions.

Santos’ compliance culture (additional factor)

97 Santos did not identify its initial non-compliance with r 666(1) of the NGR until after the AER contacted Santos on 28 August 2020 requesting contemporaneous records in connection with a number of renominations made by Santos relating to gas days between 4 February 2020 and 12 June 2020.

98 Prior to July 2021, Santos Limited (and Santos) did not have a formal compliance framework or a manager responsible for compliance within the business. The SOAF outlines the steps Santos has taken to implement a compliance framework since July 2021, including appointing a Senior Manager Compliance and establishing a Santos Compliance team. The parties jointly seek orders relating to an assurance program to ensure compliance with r 666(1) of the NGR, which will assist to prevent a recurrence of the contraventions.

CONCLUSION

99 I am satisfied the proposed penalty of $2,750,000 is an appropriate penalty having regard to the matters required to be taken into account by s 234 of the NGL, the other relevant matters referred to above and to achieve the objectives of specific and general deterrence.

100 I will make an order that Santos pay a civil penalty in the amount of $2,750,000. I will make a declaration and the ancillary orders sought by the parties substantially in the form proposed by the parties in the Proposed Orders. I will also make an order in the terms sought in the Proposed Orders that Santos pay a contribution to the AER’s costs of and incidental to the proceeding in the amount of $100,000.

I certify that the preceding one hundred (100) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice Neskovcin. |

Associate:

SCHEDULE