FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Deputy Commissioner of Taxation v Defined Properties Investment Pty Ltd (in liquidation) [2024] FCA 562

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The defendant’s interlocutory application filed on 8 December 2023 (the review application) be dismissed.

2. The orders made on 23 November 2023 be confirmed.

3. Louie Nehme be made a respondent party to the review application.

4. Louie Nehme pay the plaintiff’s costs of and incidental to the review application on an indemnity basis.

5. Louie Nehme pay Joanne Monica Keating’s costs (as liquidator of the defendant) of and incidental to the review application on an indemnity basis.

6. The questions of whether it is appropriate to award the costs referred to in Orders 4 and 5 on a lump sum basis and, if so, the amount of those costs, be referred to a Registrar of the Court, acting as a referee pursuant to s 54A of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth), for inquiry and report.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

YATES J:

INTRODUCTION

1 On 17 November 2023, a Registrar of the Court made an order that the defendant, Defined Properties Investment Pty Ltd (DPI), be wound up in insolvency under the provisions of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (the Corporations Act).

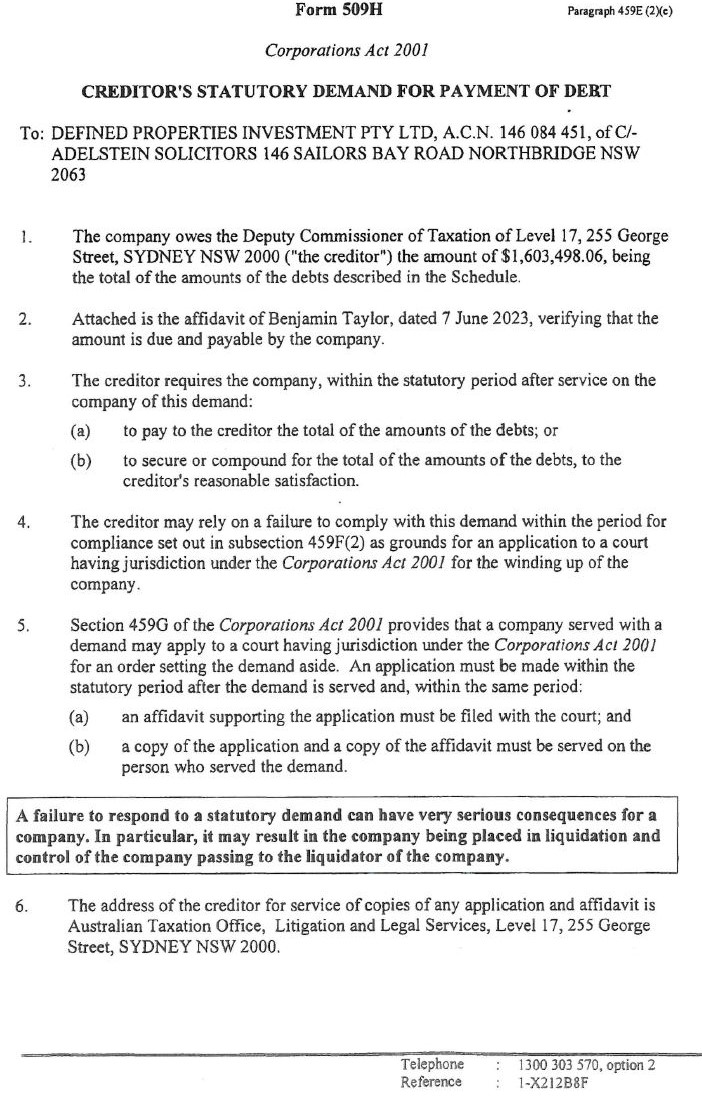

2 The winding up order was sought on an application under s 459A and s 459P of the Corporations Act. The application was based on DPI’s failure to comply with a statutory demand which was served by the plaintiff, the Deputy Commissioner of Taxation (the Deputy Commissioner), under s 459E of the Corporations Act on 7 June 2023 (the statutory demand or demand). The time for compliance expired on 28 June 2023.

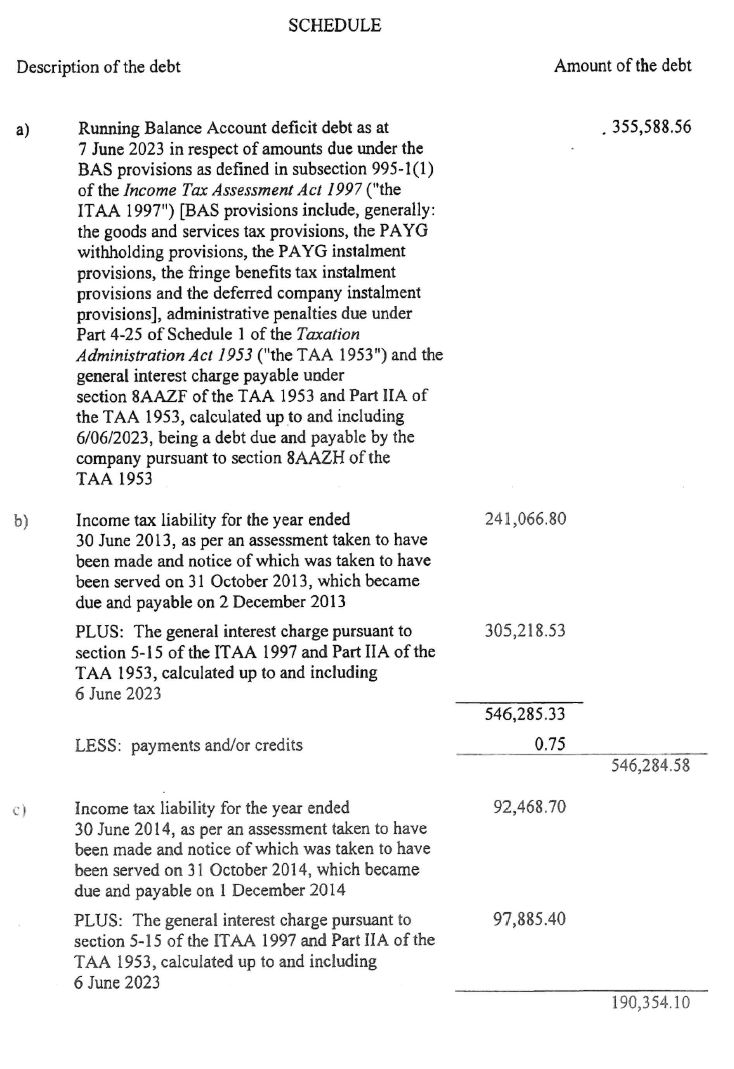

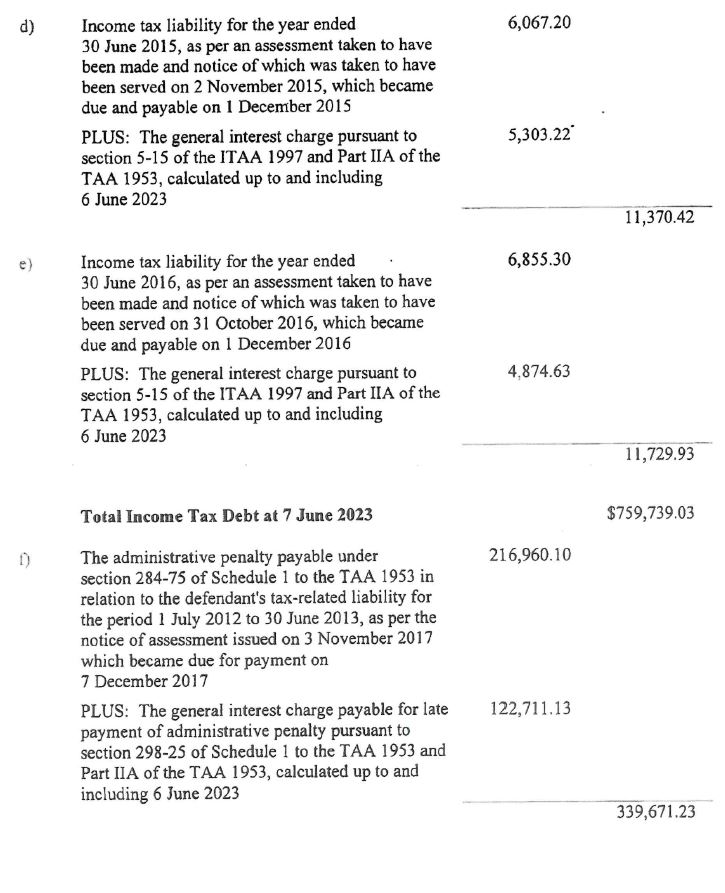

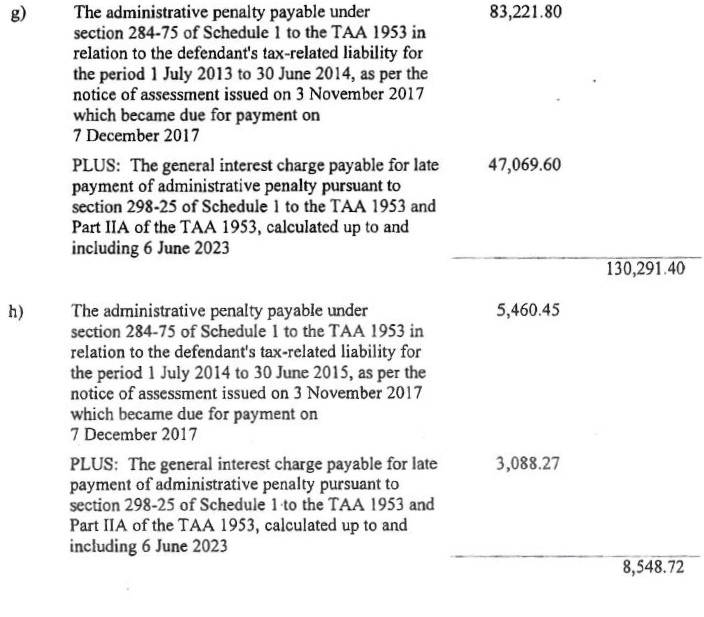

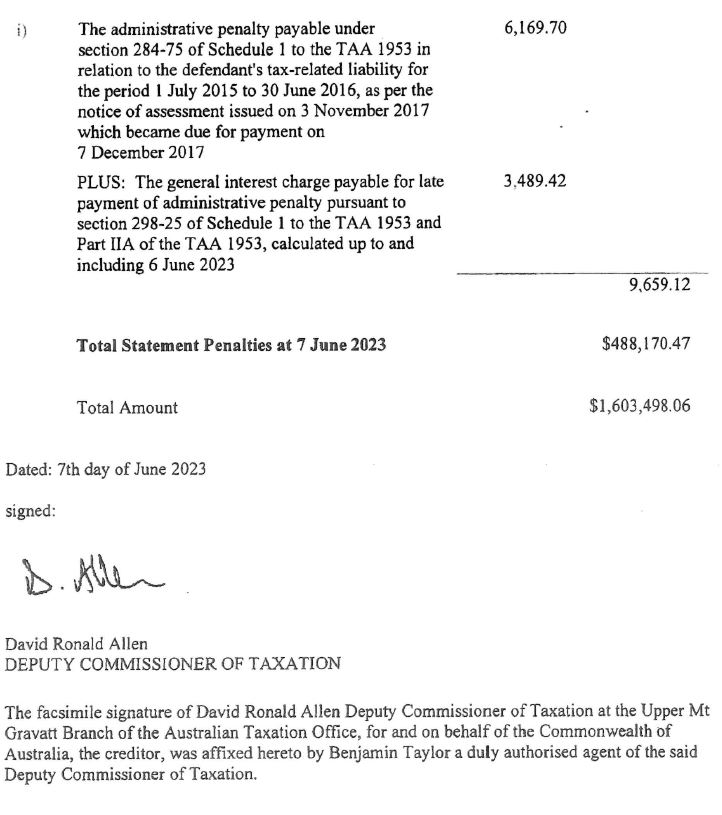

3 The statutory demand is reproduced in the Schedule to these reasons. The demand was for the sum of $1,603,498.06 in respect of a tax debt due to the Commissioner of Taxation (the Commissioner). This debt is recoverable by the Deputy Commissioner pursuant to the Taxation Administration Act 1953 (Cth) (the TAA).

4 The consequence of DPI’s failure to comply with the statutory demand was that, for the purposes of the winding up application, DPI was presumed to be insolvent: s 459C(2)(a) of the Corporations Act. This presumption operates except so far as the contrary is proved for the purposes of the winding up application: s 459C(3).

5 On 8 December 2023, DPI filed an interlocutory application under r 17.01 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) (Federal Court Rules) seeking a review of the Registrar’s decision and an order that the Court rehear the winding up application:

… after [DPI] has been given an opportunity to submit evidence as to solvency and why, in the circumstances, it would be unjust to wind up [DPI].

6 On 21 December 2023, Markovic J made an order that DPI file and serve a notice of its grounds of opposition to the making of a winding up order, any evidence on which it sought to rely, and its written submissions, by 4.00 pm on 19 January 2024. Her Honour also made an order that the respondents to the application (being the Deputy Commissioner, the appointed liquidator (Joanne Monica Keating), and the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC)) file and serve any evidence on which they sought to rely, and their respective written submissions, by 4.00 pm on 7 February 2024. Her Honour noted that these steps would make the matter ready for hearing. The matter was then docketed to me. On 22 January 2024, I set the matter down for hearing on 26 February 2024.

7 DPI did not comply with the orders made on 21 December 2023. By the time of the appointed hearing it had not filed a notice of grounds of opposition, the evidence on which it sought to rely (other than an earlier filed affidavit by its solicitor, Geoffrey John Adelstein, which was sworn on 8 December 2023), or submissions in support of its application.

8 The Deputy Commissioner did comply with those orders by filing an affidavit sworn by Joshua Varakumar on 6 February 2024 and written submissions. The Deputy Commissioner had previously filed the affidavits that were read in support of the making of the winding up order. Ms Keating filed an affidavit, sworn 16 February 2024, reporting on her work to date and expressing her view as to DPI’s solvency. On 23 February 2024, ASIC filed a submitting notice under r 12.01(1) of the Federal Court Rules.

9 Despite its non-compliance with the orders made on 21 December 2023, DPI sought leave, at the hearing listed on 26 February 2024, to agitate a ground of opposition based on an alleged defect in the statutory demand. I will refer to this as the defective notice ground although, as will become apparent, this ground has a number of aspects. DPI did not give notice of this ground of opposition to the respondents.

10 After hearing briefly from Mr Adelstein, who appeared on behalf of DPI, I made an order that DPI file and serve, by 4.00 pm on 1 March 2024, grounds of opposition limited to the defective notice ground, and the consequences of the alleged defect, and submissions in support. As events transpired, DPI’s submissions were not filed until 5 March 2024 and its notice of opposition was not filed until 7 March 2024. No objection was taken to this further non-compliance.

11 On 26 February 2024, I also made an order permitting the Deputy Commissioner to file and serve any evidence and submissions in response to the defective notice ground by 4.00 pm on 15 March 2024 (the time was subsequently extended without opposition). I then relisted the matter for hearing on 22 March 2024.

12 The principles on which the Court proceeds in such a review were summarised by Lander J in Callegher v Australian Securities and Investments Commission [2007] FCA 482; 239 ALR 749 at [46]:

46 The hearing before me is a hearing de novo: Mazukov v University of Tasmania [2004] FCAFC 159; Pattison v Hadjimouratis (2006) 155 FCR 226. The right to review arises because the Registrar has exercised the judicial power of the Commonwealth and, as such, is subject to the supervision of the Court. The Registrar’s orders are reviewable by hearing de novo: Harris v Caladine (1991) 172 CLR 84 per Dawson J at 124. A hearing de novo contemplates a complete rehearing. The moving party before the Registrar has the responsibility of satisfying the Court that the orders should have been made. The parties may adduce further evidence before the Court and the rehearing is determined on the evidence put before the Court which may include the evidence put before the Registrar. The judge determines the rehearing without being fettered by the decision of the Registrar: Southern Motors Pty Ltd v Australian Guarantee Corporation Ltd [1980] VR 187. ...

13 For the reasons which follow, I am of the view that DPI’s interlocutory application should be dismissed and that the orders made on 17 November 2023 should be confirmed.

THE NOTICE OF OPPOSITION

14 The grounds of DPI’s notice of opposition are expressed in these terms:

1 It is submitted that the Plaintiff’s Statutory Notice of Demand dated 7th June 2023 is defective such that the presumption of insolvency is displaced and it would cause substantial injustice to proceed with a winding up order.

2 The Court’s discretion under S459J of [the] Corporations Act should be exercised to set aside the Statutory Demand.

3 Alternatively, in the circumstances of this matter, the Court will make a finding that the Plaintiff has failed to make out grounds for the winding up order to be made, on the basis that the Court cannot be satisfied that a tax liability is presently due and payable, or alternatively enforceable and recoverable.

4 The failure by the Plaintiff to properly particularise a series of non-judgement debts and to rely on a running balance leads to uncertainty as to whether the BAS tax liability is presently due and payable as the tax liability is incapable of being calculated and verified.

5 The failure by the Plaintiff to explain how the tax liability for income tax in the years 2013-2016 is derived when it has been determined on a ‘taken to have been made’ basis similarly leads to an inability to determine that a tax liability is presently due and payable.

6 The failure by the Plaintiff to explain how the penalty claim attached to income tax in the years 2013-2016 is derived when it has been determined on a ‘taken to have been made’ basis similarly leads to an inability to determine that a tax liability is presently due and payable.

7 The failure by the Plaintiff to explain how the general interest charge is derived when there is no means of calculation provided as to how the figure is determined leads to an inability to determine that a tax liability is presently due and payable.

15 It is apparent that, by Grounds 1 and 2, DPI contends that the statutory demand should be set aside under s 459J of the Corporations Act because it is defective. By Grounds 3 to 7, DPI contends that the Deputy Commissioner has not established that the debts claimed in the statutory notice are presently due and payable and that, for that reason, a winding up order should not be made.

16 In its submissions, DPI advanced another ground—namely, that the affidavit verifying the debt claimed in the statutory demand does not comply with s 459E(3) of the Corporations Act.

RELEVANT PROVISIONS

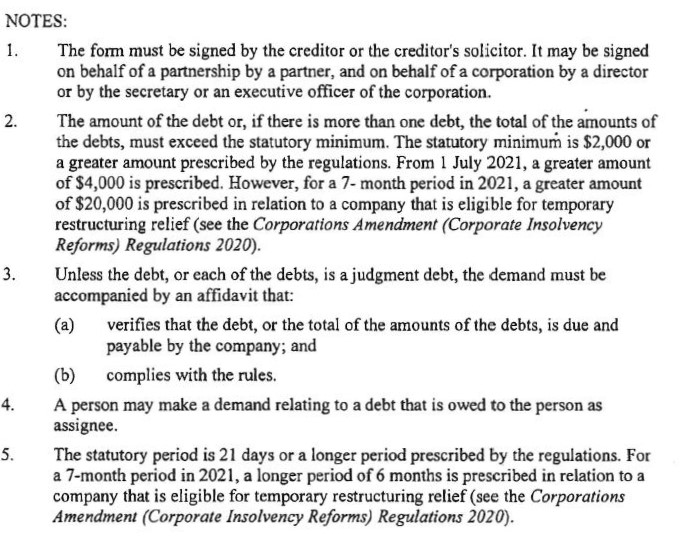

17 Section 459E of the Corporations Act provides:

(1) A person may serve on a company a demand relating to:

(a) a single debt that the company owes to the person, that is due and payable and whose amount is at least the statutory minimum; or

(b) 2 or more debts that the company owes to the person, that are due and payable and whose amounts total at least the statutory minimum.

(2) The demand:

(a) if it relates to a single debt--must specify the debt and its amount; and

(b) if it relates to 2 or more debts--must specify the total of the amounts of the debts; and

(c) must require the company to pay the amount of the debt, or the total of the amounts of the debts, or to secure or compound for that amount or total to the creditor's reasonable satisfaction, within the statutory period after the demand is served on the company; and

(d) must be in writing; and

(e) must be in the prescribed form (if any); and

(f) must be signed by or on behalf of the creditor.

(3) Unless the debt, or each of the debts, is a judgment debt, the demand must be accompanied by an affidavit that:

(a) verifies that the debt, or the total of the amounts of the debts, is due and payable by the company; and

(b) complies with the rules of court.

(4) A person may make a demand under this section relating to a debt even if the debt is owed to the person as assignee.

(5) A demand under this section may relate to a liability under any of the following provisions of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1936:

(aa) former section 220AAE, 220AAM or 220AAR;

(a) former section 221F (except subsection 221F(12)), former section 221G (except subsection 221G(4A)) or former section 221P;

(b) former subsection 221YHDC(2);

(c) former subsection 221YHZD(1) or (1A);

(d) former subsection 221YN(1);

(e) section 222AHA;

and any of the provisions of Subdivision 16 - B in Schedule 1 to the Taxation Administration Act 1953, even if the liability arose before 1 January 1991.

(6) Subsection (5) is to avoid doubt and is not intended to limit the generality of a reference in this Act to a debt.

18 Section 459J provides:

(1) On an application under section 459G, the Court may by order set aside the demand if it is satisfied that:

(a) because of a defect in the demand, substantial injustice will be caused unless the demand is set aside; or

(b) there is some other reason why the demand should be set aside.

(2) Except as provided in subsection (1), the Court must not set aside a statutory demand merely because of a defect.

19 As will be apparent, s 459J only operates in respect of an application under s 459G of the Corporations Act, which provides:

(1) A company may apply to the Court for an order setting aside a statutory demand served on the company.

(2) An application may only be made within the statutory period after the demand is so served.

(3) An application is made in accordance with this section only if, within that period:

(a) an affidavit supporting the application is filed with the Court; and

(b) a copy of the application, and a copy of the supporting affidavit, are served on the person who served the demand on the company.

20 As I have noted, the statutory period for compliance with the statutory demand expired on 28 June 2023. By dint of s 459G(2), an application under s 459G(1) can no longer be made. Therefore, Grounds 1 and 2 of DPI’s notice of opposition are not available to it.

21 For completeness, I note that s 459Q provides:

If an application for a company to be wound up in insolvency relies on a failure by the company to comply with a statutory demand, the application:

(a) must set out particulars of service of the demand on the company and of the failure to comply with the demand; and

(b) must have attached to it:

(i) a copy of the demand; and

(ii) if the demand has been varied by an order under subsection 459H(4)--a copy of the order; and

(c) unless the debt, or each of the debts, to which the demand relates is a judgment debt--must be accompanied by an affidavit that:

(i) verifies that the debt, or the total of the amounts of the debts, is due and payable by the company; and

(ii) complies with the rules of court.

22 This step has been complied with in the present case.

23 Finally, s 459S of the Corporations Act provides:

(1) In so far as an application for a company to be wound up in insolvency relies on a failure by the company to comply with a statutory demand, the company may not, without the leave of the Court, oppose the application on a ground:

(a) that the company relied on for the purposes of an application by it for the demand to be set aside; or

(b) that the company could have so relied on, but did not so rely on (whether it made such an application or not).

(2) The Court is not to grant leave under subsection (1) unless it is satisfied that the ground is material to proving that the company is solvent.

DPI’S SUBMISSIONS

24 DPI contends that the particulars given in the statutory demand are “inadequate to enable [it] to identify the actual core amounts claimed as due”.

25 As to the Running Balance Account deficit in respect of amounts due under the BAS provisions of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1997 (Cth) (the ITAA97), DPI submits that the opening balance amount is not identified or explained; nor is it explained how the debt has “compounded” to reach the total of $355,588.56. DPI submits:

… What is lacking is the break up calculation to enable [DPI] to check and determine how this amount is calculated and whether the running account balance is correct. There is no means of checking the calculations, which operates unfairly against [DPI].

26 As to the income tax liabilities for 30 June 2013 to 30 June 2016 years on assessments “taken to have been made” and in respect of notices “taken to have been served”, DPI submits that, by failing to explain in the statutory demand how each tax liability has been “made” in the notices in fact served, it does not know how the claimed tax liability has been derived and whether that liability is presently due or enforceable or recoverable. DPI submits that this causes “manifest unfairness”.

27 As to the administrative penalties due under the TAA, DPI submits that these claimed amounts “suffer the same difficulty” as the claimed income tax liabilities. Additionally, DPI submits that it is required to “speculate on how the penalty was calculated and on what primary amount the penalty was imposed”.

28 As to general interest calculated up to and including 6 June 2023, DPI submits that no attempt has been made to provide a means for it to calculate the charge. It argues that there is “no indication of the prime debt, the interest rate applicable or the period for calculation”. DPI argues that it is a “mystery calculation”.

29 As to compliance with s 459E(3) of the Corporations Act, DPI submits that an affidavit accompanying a statutory demand must verify each and every debt, not just the total debt that is claimed to be due. According to DPI, to read the provision otherwise would permit a creditor to include an “invalid” claim as part of an overall amount that is claimed to be due, which would be “manifestly unfair”.

30 In this regard DPI submits that, in the present case, the affidavit needed to “verify each of the debts claimed as being due and owing”. The affidavit also had to provide a “sufficient description” of each debt, including how each debt was derived and calculated so that it was “clearly on notice of the basis upon which [the Deputy Commissioner] claims the aggregate debt and each component debt is due and owing”.

31 Relying on Rees J’s observation in In the matter of Essential Media and Entertainment Pty Limited [2020] NSWSC 990 at [96] that a debt is due and payable when it is “ascertainable, immediately payable and presently recoverable or enforceable by action” (see also Re Elgar Heights Pty Ltd [1985] VR 657; 9 ACLR 846 (Elgar) at 671 (Ormiston J)), DPI submits that, on the face of the statutory demand, each debt is not ascertainable because the basis for calculation of each debt is “elliptical and opaque” and that “(i)t is not possible to derive the core debt due, nor how that core debt and the compounding of each amount to achieve the current liability has been derived”.

32 DPI makes the following further submissions.

33 First, it submits that, even if the existence of a debt is not in dispute, a debtor can dispute that the debt is due and payable: In the matter of MK Group Phoenix Pty Ltd [2014] NSWSC 1467. DPI contends that issuing a statutory demand for a debt that is not due and payable would be an abuse of the statutory demand procedure, entitling it to rely on s 459J(1)(b) of the Corporations Act. It is not clear to me how that principle has application in the present case, in light of DPI’s earlier submissions which appear to contest the existence of the debt that is claimed in the statutory demand. In any event, as I have already observed, s 459J is not available to DPI.

34 Secondly, DPI submits that the present case is analogous to the bill for legal services in Elgar which was found to be non-compliant with s 81 of the Supreme Court Act 1958 (Vic) such that the amount claimed in the statutory demand in that case was not “due” at the time the demand was served.

35 Thirdly, DPI submits that, even though, imprudently, it did nothing to challenge the statutory demand in the present case, it still had the right to challenge the demand on the basis that the debt was not due, that the debt was not ascertainable, and that the demand was defective because “it failed to establish each debt claimed, and on an aggregate basis”.

ANALYSIS

Introduction

36 Leaving aside DPI’s grounds of opposition based on s 459J of the Corporations Act (which, as I have said, are not available to it), the remaining grounds of its notice of opposition (Grounds 3 to 7) are all grounds on which it could have relied to set aside the statutory demand. That being so, the effect of s 459S(1)(b) of the Corporations Act is that DPI cannot rely on these grounds to oppose the winding up application unless it has the leave of the Court to do so. But, importantly, leave is not to be granted unless the Court is satisfied that the grounds are material to proving that DPI is solvent: s 459S(2).

37 It is important to understand that a favourable exercise of the Court’s discretion under s 459S would not lead to the setting aside of the statutory demand in question or remove the presumption of insolvency that has already arisen through DPI’s failure to comply with it: Chief Commissioner of Stamp Duties v Paliflex Pty Ltd [1999] NSWSC 15; 149 FLR 179 (Paliflex) at [48]; Braams Group Pty Ltd v MIRIC [2002] NSWCA 417; 44 ACSR 124 at [36].

38 In Paliflex, Austin J (at [49]) identified the following considerations as relevant to the grant of leave under s 459S(1):

(a) a preliminary consideration of the company’s basis for disputing the debt which is the subject of the demand;

(b) an examination of the reasons why the issue of indebtedness was not raised by the company in an application to set aside the demand, and the reasonableness of the company’s conduct at that time; and

(c) an investigation into whether the dispute about the debt is material to proving that the company is solvent.

The basis for disputing the debts

39 DPI’s submissions concerning whether the debts claimed in the statutory demand are due and payable cannot be accepted. Indeed, its submissions are without merit, as I will explain.

40 First, as to DPI’s submissions on the Running Balance Account deficit debt, s 8AAZC(1) of the TAA provides for the establishment of one or more systems of accounts for primary tax debts. Each such account is known as a Running Balance Account (RBA): s 8AAZC(2). For this purpose (and subject to one exception which is not relevant for present purposes), a “primary tax debt” is any amount due to the Commonwealth directly under a taxation law, including an amount that is not yet payable: s 8AAZA. RBAs can be established on any basis that the Commissioner determines, including for different types of primary tax debts: s 8AAZC(4).

41 A “RBA deficit debt” means a balance in an RBA in favour of the Commissioner based on: (a) primary tax debts that have been allocated to the RBA and that are currently payable; and (b) payments made in respect of current or anticipated primary tax debts of the entity, and credits to which the entity is entitled under a taxation law, that have been allocated to the RBA: s 8AAZA.

42 If there is an RBA deficit debt at the end of a day, then general interest charge (GIC) is payable by the tax debtor on that RBA deficit debt for that day and the balance of the RBA is altered in the Commissioner’s favour by the amount of the GIC payable: s 8AAZF.

43 If there is an RBA deficit debt on an RBA at the end of a day, the tax debtor is liable to pay to the Commonwealth the amount of the debt, which is due and payable at the end of that day: s 8AAZH(1). It is evident from the terms of s 8AAZH that an RBA deficit debt is a single debt. I accept the Deputy Commissioner’s submission that, when claiming an RBA deficit debt, there is no requirement that the statutory demand set out the primary tax debts or GIC making up the RBA deficit debt.

44 It follows that DPI’s submissions concerning the particulars given with respect to the RBA deficit debt in the statutory demand cannot be accepted.

45 The Commissioner may at any time prepare a statement for an RBA, containing such particulars as the Commissioner determines: s 8AAZG. The production of an RBA statement is prima facie evidence that the RBA was duly kept and that the amounts and particulars in the statement are correct: s 8AAZI.

46 In the present case, the Deputy Commissioner has produced an RBA statement. That statement shows that, as at 7 June 2023, the closing balance of the RBA deficit debt was $355,588.56. The statement also shows that, as at 18 March 2024, the closing balance of the RBA deficit debt was $373,335.04. Further, the Deputy Commissioner has provided a certificate under s 350-10(3) in Schedule 1 of the TAA that, from 18 March 2024, DPI has a RBA deficit debt for that amount.

47 Secondly, as to the income tax liabilities and associated GIC referred to in the statutory demand, s 167 of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1936 (Cth) (ITAA36) provides for the making of default assessments where: (a) there is default in furnishing a return; (b) the Commissioner is not satisfied with a return that has been furnished; or (c) the Commissioner has reason to believe that any person who has not furnished a return has derived taxable income. An assessment includes the amount of a person’s taxable income, the tax payable on that income, and the person’s total tax offset refund: ITAA36 s 166. The character of this assessment—as the Commissioner’s official act or operation of ascertainment— was explained in R v Deputy Federal Commissioner of Taxation (SA); Ex parte Hooper [1926] HCA 3; 37 CLR 368 at 373.

48 Under s 174(1) of the ITAA36, the Commissioner is to serve written notice of the assessment on the person liable to pay the tax. As explained in Batagol v Federal Commissioner of Taxation [1963] HCA 51; 109 CLR 243 at 251 – 252, service of a notice of assessment is the levying of the tax. Once the Commissioner serves the notice, the tax becomes due and payable: ITAA97 s 5-5(2).

49 In the present case, notices of assessment were issued to DPI for the years ended 30 June 2013, 30 June 2014, 30 June 2015, and 30 June 2016. The notices of assessment are in evidence. Each notice of assessment was served on DPI on or about the date of issue of that assessment. DPI failed to pay the amount due under each assessment by the due date. Under s 5-15 of the ITAA97, GIC accrues on unpaid income tax liabilities.

50 Section 350-10(1), Item 2 of Sch 1 of the TAA provides that a notice of assessment under a taxation law is conclusive evidence that the assessment was properly made and, except in proceedings under Part IVC of the TAA on a review or an appeal relating to the assessment, the amounts and particulars of the assessment are correct.

51 Further, the evidence before me includes a certificate issued under s 350-10(3) of Sch 1 of the TAA to the effect that an assessment has been made, or is taken to have been made, in relation to income tax for each year referred to above and that notices of assessment for each of those years was, or is taken to have been, served on DPI under a taxation law. The certificate states that DPI has a tax-related liability for each liability referred to in the certificate and to GIC on the unpaid amount of each liability. The certificate also states that, from 18 March 2024, an amount of $797,655.69 was payable by DPI to the Commissioner in respect of tax-related liabilities referred to in the certificate, inclusive of associated GIC.

52 Thirdly, as to administrative penalties and associated GIC, s 298-30(1) of Sch 1 of the TAA provides that the Commissioner must make an assessment of the amount of administrative penalties, including where a person fails to provide a document as required. The Commissioner is required to give written notice of an entity’s liability to pay the penalty and of the reasons why the liability arises: s 298-10 of Sch 1 of the TAA. An administrative penalty becomes due on the date specified in the notice, which must be at least 14 days after the notice is given: s 298-15. GIC accrues on an unpaid administrative penalty from the date on which the penalty is due and payable: s 298-25.

53 In the present case, notices of assessment of penalty were given to DPI. The notices of assessment are in evidence. DPI failed to pay the amount of each administrative penalty. By reason of that failure, DPI also became liable to pay GIC pursuant to s 298-25.

54 The evidence before me includes a certificate issued under s 350-10(3) of Sch 1 of the TAA to the effect that an assessment has been made, or is taken to have been made, in relation to the administrative penalties imposed on DPI to the years ended 30 June 2013, 30 June 2014, 30 June 2015, and 30 June 2016, and that notices of assessment of the administrative penalty for each of those years were, or are taken to have been, served on DPI under a taxation law. The certificate states that DPI has a tax-related liability for each liability referred to in the certificate and for GIC on the unpaid amount of each liability. The certificate also states that, from 18 March 2024, an amount of $512,533.77 was payable by DPI under a taxation law to the Commissioner in respect of the tax-related liabilities referred to in the certificate, inclusive of associated GIC.

The reasons why indebtedness was not raised in an application to set aside the demand

55 In his affidavit of 8 December 2023, Mr Adelstein deposed that he was aware of the statutory demand. He said that, on receipt of the notice, he forwarded a copy to a former director of DPI, George Dimitriou, with the request that Mr Dimitriou “make” the current director of DPI, Louie Nehme, “aware” of the demand.

56 Mr Adelstein explained that Mr Nehme was appointed as DPI’s director in late August 2019 just prior to Mr Dimitriou, DPI’s former director, being made bankrupt. Mr Adelstein said that, although he takes his “formal” instructions from Mr Nehme, he liaises with Mr Dimitriou “to obtain all necessary information, and to obtain access to relevant documentary records …”.

57 Mr Adelstein said that he had since become aware that the email address he used for this communication to Mr Dimitriou was not currently used by Mr Dimitriou. He said that he did not receive any instructions to file an application under s 459G of the Corporations Act. He conjectured that this was “no doubt because Mr Dimitriou was unaware of the service of the demand and did not hence forward on to Mr Nehme”.

58 There is, however, no satisfactory evidence of: (a) the email address that Mr Adelstein used; (b) the fact that this email address was not used by Mr Dimitriou at the time that Mr Adelstein says that he sent the communication referred to above; (c) the fact that Mr Dimitriou did not receive the statutory demand and Mr Adelstein’s request; or (d) the fact that Mr Nehme was not “aware” of the statutory demand and Mr Adelstein’s request.

59 I am bound to say that I also find it curious that, on such an important matter, Mr Adelstein did not directly communicate with Mr Nehme, on whose instructions he said he acted, or follow up Mr Nehme (either directly or through Mr Dimitriou) in the absence of receiving any communication from him in respect of the demand.

60 In all the circumstances, I am not persuaded that DPI has provided a satisfactory explanation for why, if it did dispute the debt claimed in the statutory demand, it did not move to set aside the demand in a timely manner.

Is the debt material to proving that DPI is solvent?

61 At the date of the hearing on 22 March 2024, Mr Nehme had not provided Ms Keating, in her capacity as liquidator, with a Report on Company Activities and Property. Further, DPI has not adduced evidence of its financial circumstances. On the present evidence, I am unable to determine whether the debt claimed in the statutory demand is material to proving that DPI is solvent.

62 As I have noted, s 459S(2) of the Corporations Act provides that the leave required by s 459S(1) must not be granted unless the Court is satisfied that the ground relied on is material to proving that the company in question is solvent. I have not reached that state of satisfaction.

Conclusion on Grounds 3 to 7 of the notice of opposition

63 I have found that DPI’s submissions concerning whether the debts claimed in the statutory demand are due and payable (Grounds 3 to 7 of its notice of opposition) are without merit and cannot be accepted. Further, I am not persuaded that DPI has provided a satisfactory explanation for why, in respect of those grounds, it did not move to set aside the demand in a timely manner. Critically, due to the absence of evidence, I am not satisfied that the grounds now relied on are material to proving that DPI is solvent.

64 Accordingly, the discretion in s 459S of the Corporations Act should not, and cannot, be exercised in DPI’s favour in respect of those grounds. Leave to rely on Grounds 3 to 7 in DPI’s notice of opposition is, therefore, refused. In any event, for the reasons I have given, those grounds could not possibly succeed even if they could be raised now.

Compliance with s 459E?

65 DPI’s contentions in relation to the Deputy Commissioner’s compliance with s 459E of the Corporations Act stand in a similar position. This additional ground of opposition is also one that DPI could have relied on in an application to set aside the statutory demand. Therefore, by dint of s 459S, it cannot rely on this ground now without the Court’s leave.

66 Leave should not be granted. The ground is without merit. Section 459E(3) does not require the affidavit that accompanies a statutory demand to conform to the requirements that DPI alleges. Further, DPI has not provided a satisfactory explanation for why, if it did regard the statutory demand to be defective because of the form of the accompanying affidavit, it did not move to set aside the demand, on that basis, in a timely manner. Thirdly, as this ground cannot be material to proving that DPI is solvent, leave to rely on it cannot be granted in any event.

SHOULD A WINDING UP ORDER BE MADE?

67 There is no dispute that the statutory formalities for obtaining a winding up order against DPI have been complied with. For the avoidance of doubt, I should make clear that, had DPI raised, in respect of the Deputy Commissioner’s compliance with s 459Q of the Corporations Act, the same objection it had made in relation to the Deputy Commissioner’s compliance with s 459E, I would have rejected that contention on the basis that s 459Q does not require the affidavit to which that provision refers to conform to the requirements to which DPI has referred.

68 Although Mr Adelstein’s affidavit referred to DPI’s intention to adduce evidence to establish its solvency, no such evidence has been adduced. Mr Adelstein’s affidavit referred, in somewhat vague terms, to DPI’s claimed entitlement to certain sums of money, but those entitlements have not been proved. In any event, at the hearing on 26 February 2024, DPI abandoned any claim that it is solvent.

69 I am not satisfied that DPI is solvent. What is more, Ms Keating has expressed the provisional view that it is likely that DPI has been trading insolvently from as early as 2012.

70 In addition, Ms Keating has deposed that, in her view, the directors of DPI have failed to maintain books and records pertaining to the affairs of DPI as required under s 286 of the Corporations Act.

71 Since the issue of the statutory demand, further interest has accrued on the tax debt and various credits have been applied. The evidence before me is that, as at 11 January 2024, DPI is indebted to the Deputy Commissioner of Taxation for the sum of $1,683,524.50.

72 DPI advanced a further submission that the winding up order should not be made on discretionary grounds. The gist of this submission is that DPI has prospective opportunities to recover funds in existing litigation (being the entitlements referred to in Mr Adelstein’s affidavit). However, these opportunities require “input” from DPI’s former director, Mr Dimitriou. According to DPI, these funds, if received, might be available to the Deputy Commissioner “following discussions” but this would require the winding up application against DPI to be dismissed with costs against the Deputy Commissioner. The Deputy Commissioner would also be required to pay the liquidator’s reasonable costs. DPI submitted that if it is wound up, Mr Dimitriou’s “assistance” would be “unlikely”.

73 I am not persuaded that these submissions provide any basis for, let alone justify, an exercise of discretion not to make a winding up order, particularly as the Deputy Commissioner continues to press that DPI be wound up.

74 The orders made by the Registrar on 17 November 2023 should be affirmed and DPI’s interlocutory application should be dismissed.

COSTS

Introduction

75 On 23 February 2024, Ms Keating filed an interlocutory application seeking an order that Mr Nehme pay her costs and disbursements of and incidental to this proceeding as a lump sum calculated on an indemnity basis or, alternatively, on an “ordinary basis” as agreed or assessed. The date of filing was the last business day before the hearing fixed for 26 February 2024. As at 23 February 2024, Mr Nehme was not a party to the proceeding and had not been served with the interlocutory application, although Mr Adelstein received a copy of it just after 5.00 pm on that day.

76 It appears that, on the morning of 26 February 2024, before the hearing on that day, the Deputy Commissioner informed Mr Adelstein that he, too, was seeking a costs order against Mr Nehme for a lump sum calculated on an indemnity basis.

77 Given that: (a) the question of costs could not be determined until after the review of the Registrar’s decision; and (b) the hearing of the review of the Registrar’s decision was to be adjourned in any event because DPI wished to rely on the defective notice ground, the hearing on the question of costs also had to be adjourned. However, had it not been necessary to adjourn the hearing of the review application, it would still have been necessary to adjourn the hearing on the question of costs because of the late notice given by Ms Keating and the Deputy Commissioner, of their respective applications for a personal costs order against Mr Nehme.

78 According to ASIC’s records: (a) DPI’s registered office is recorded as c/- Adelstein Solicitors 146 Sailors Bay Road Northbridge NSW 2063; (b) its principal place of business is recorded as 146 Sailors Bay Road Northbridge NSW 2063 (the Sailors Bay Road address); (c) Mr Nehme’s address is also recorded as the Sailors Bay Road address; and (d) Mr Nehme is DPI’s sole director and secretary.

79 Since her appointment as liquidator, Ms Keating, and her staff, have attempted to contact Mr Nehme, including by personal attendance at the Sailors Bay Road address and through emails and phone calls to Mr Adelstein. Until recently, those attempts have been unsuccessful. However, in his affidavit of 8 December 2023, Mr Adelstein deposed that, in relation to DPI, he acts on “formal instructions” given to him by Mr Nehme. He also deposed that he made his affidavit based on his own knowledge and on information provided to him by Mr Nehme.

80 I infer from these statements that Mr Nehme instructed Mr Adelstein to file the interlocutory application seeking the review of the Registrar’s decision. I also infer that Mr Nehme instructed Mr Adelstein, at least “formally”, that the basis of DPI’s review application was that: (a) in all the circumstances, a winding up order should not be made against DPI for discretionary reasons (presumably those to which I have referred above); and (b) DPI is solvent and would adduce evidence of its solvency.

81 On 19 December 2023, Ms Keating’s solicitors sent a letter to Mr Adelstein referring to the case management hearing that was then to take place before Markovic J on 21 December 2023: see [6] above. In that letter, Ms Keating’s solicitors raised the question of the costs of the review application and whether Mr Nehme was prepared to give an undertaking in respect of (amongst other things) legal costs, given that the liquidation was unfunded and that, as DPI had joined Ms Keating as a party to the review application, she was incurring such costs in respect of that application (in addition to the costs and disbursements she was incurring in the liquidation).

82 Later, on 19 December 2023, Mr Adelstein sent an email to the solicitors for Ms Keating and to the solicitors for the Deputy Commissioner proposing various orders to be made at the case management hearing. In that email, Mr Adelstein foreshadowed Mr Nehme’s preparedness to give an undertaking that he would personally meet any costs ordered against DPI in favour of Ms Keating and, or in the alternative, the Deputy Commissioner. As events transpired, it was not necessary for Mr Nehme to give that undertaking.

83 On 23 January 2024, Ms Keating’s solicitors sent an email to Mr Adelstein noting DPI’s non-compliance with the orders made by Markovic J on 21 December 2023 and informing Mr Adelstein that Ms Keating was continuing to incur legal costs in relation to the review application. The email concluded:

We reserve our client’s rights in relation to seeking costs of the proceedings against the director of the Applicant Company, Mr Nehme.

84 On 5 February 2024, having not received a response to the email of 23 January 2024 and an earlier communication addressed to Mr Nehme on 19 December 2023 in respect of the liquidation, Ms Keating’s solicitors sent a further email to Mr Adelstein noting DPI’s continuing non-compliance with the orders made on 21 December 2023. Once again, the email drew attention to the fact that Ms Keating was incurring legal costs in respect of that application. The reservation, quoted above, was repeated.

Ms Keating’s submissions on costs

85 Ms Keating submits that a personal costs order against Mr Nehme in respect of the review application is warranted. Ms Keating submits that Mr Nehme is DPI’s sole director who gave instructions on behalf of DPI to file and prosecute the review application. Ms Keating submits that Mr Nehme has played an active role in the review application which was initially advanced, but not prosecuted, on the basis that DPI was solvent.

86 Ms Keating submits that, at an earlier stage, Mr Nehme was prepared to give an undertaking to meet, personally, any costs that would be awarded against DPI in favour of Mr Keating and the Deputy Commissioner. Ms Keating submits that Mr Nehme has been on notice for some time, and reminded, that she would seek a costs order against him personally.

87 Ms Keating submits that, in the circumstances, a lump sum costs order should be made against Mr Nehme on an indemnity basis.

The Deputy Commissioner’s submissions on costs

88 The Deputy Commissioner’s submissions on costs are to the same effect as Ms Keating’s submissions.

89 The Deputy Commissioner submits that Mr Nehme was the controlling mind of DPI in bringing and prosecuting the review application, who offered to provide an undertaking to personally meet any costs ordered against DPI in respect of that application.

90 The Deputy Commissioner submits that DPI brought the review application on the basis that it was solvent. However, no steps were taken by it to advance that case. DPI did not comply with the orders made on 21 December 2023. Then, at the hearing on 26 February 2024, DPI sought to raise an entirely new case about defects in the statutory demand. The Deputy Commissioner submits that this change of position appears to have been “a tactic to delay the winding up of [DPI] where [DPI] was unable to put forward any evidence to [establish] solvency”. The Deputy Commissioner submits that DPI’s “failure to file any material ahead of the hearing on 26 February 2024 and attempt to raise the new ground at the very last available moment is an apparent attempt to further frustrate the legal process”.

91 The Deputy Commissioner submits that DPI’s failure to put on any evidence to support its contention that it was solvent, and then abandoning that claim and raising new grounds of opposition at the hearing on 26 February 2024, demonstrates that the review application was brought for the collateral purpose of delaying the winding up process. This, the Deputy Commissioner submits, constitutes misconduct that has caused the other parties to the review application, and the Court, to suffer “loss of time”.

92 The Deputy Commissioner submits that DPI had a “wilful disregard” for the fact that it knew that it was not solvent and could not obtain evidence to prove its solvency. The Deputy Commissioner submits, further, that the new grounds of opposition advanced by DPI were advanced “in wilful disregard to the clearly established law in respect of statutory debts owed to the Deputy Commissioner of Taxation as set out in the relevant legislation and trite case law”.

93 The Deputy Commissioner submits that the Court should “utilise its discretion to make a costs order against a non-party”—Mr Nehme— because: (a) Mr Nehme was DPI’s controlling mind and “the person who effectively brought” the review application; (b) DPI is in liquidation with limited means to satisfy an adverse costs order; and (c) the review application was brought for the collateral purpose of delaying the winding up.

94 The Deputy Commission submits:

… [DPI], upon instructions by Mr Nehme, has been taking consistent steps to frustrate the winding up process by bringing its various, baseless claims. By virtue of these claims, [the Deputy Commissioner] has unnecessarily incurred the costs associated with [the review application] on two separate occasions.

… the current circumstances justify the Court enlivening its discretion to make an indemnity costs [order] against Mr Nehme for costs thrown away by virtue of the unjustifiable and unwarranted conduct of [DPI].

DPI’s and Mr Nehme’s submissions on costs

95 DPI and Mr Nehme submit that lump sum costs orders are “not regularly given”—the implication being that this is not an appropriate case for a lump sum costs order.

96 As to indemnity costs, DPI and Mr Nehme advance the proposition articulated in Hamod v State of New South Wales [2002] FCAFC 97; 188 ALR 659 at [20] that indemnity costs are not designed to punish a party but:

… serve the purpose of compensating a party fully for costs incurred, as a normal costs order could not be expected to do, when the Court takes the view that it was unreasonable for the party against whom the order is made to have subjected the innocent party to the expenditure of costs.

97 They submit that the issue, here, is whether DPI or Mr Nehme acted “in an unreasonable or improper manner so as to enliven a special or unusual feature about these proceedings”.

98 In this regard, DPI and Mr Nehme call in aid the examples given by Sheppard J in Colgate Palmolive Company v Cussons Pty Ltd [1993] FCA 801; 46 FCR 225 at [24] as to the circumstances when the discretion to award indemnity costs has been exercised. These examples include: (a) particular misconduct that causes loss of time to the Court and to other parties; (b) where proceedings were commenced or continued for some ulterior motive or in wilful disregard of known facts or clearly established law; and (c) where a case has been unduly prolonged by groundless contentions.

99 In their written submissions, DPI and Mr Nehme submit that no such circumstances are advanced here. This submission, however, was formulated before the Deputy Commissioner filed his written submissions on costs. As matters now stand, the Deputy Commissioner (and Ms Keating in support) do raise these circumstances as applying to the present case.

100 As to whether a costs order should be made against Mr Nehme, DPI and Mr Nehme submit that such an order should not be made simply because Mr Nehme provided instructions and information to Mr Adelstein. They submit that:

… there is nothing exceptional or unusual as to how the application for review came before the Court, nothing to suggest any ulterior motive and nothing to support unreasonableness or impropriety to warrant a costs sanction against a non-party.

101 In this connection, DPI and Mr Nehme also submit that there is nothing improper in a party re-assessing the strength of its case on a particular issue and deciding, on advice, not to persevere with that issue. As Mr Adelstein put the matter in oral submissions:

… if I had sought to continue to argue solvency in circumstances where the evidence clearly does not permit such an application to be maintained, then such criticism might warrant some special order as to costs. No attempt was made in regards to further pressing what was an unmeritorious argument.

102 Mr Adelstein attempted to qualify his description of “an unmeritorious argument”, by stating that his affidavit showed that DPI had the prospect of recovering “some monies”.

103 DPI and Mr Nehme submit that the defective notice ground raised at the hearing on 26 February 2024 was not unarguable because the Court permitted DPI to advance it and made procedural orders to enable it to be fully argued at a later time. They submit that the defective notice ground was “a genuinely advanced argument in good faith”.

104 DPI and Mr Nehme also submit that Mr Nehme’s previous offer to provide an undertaking to meet costs is without consequence, particularly when the full circumstances attending that offer are understood. They submit that this offer was made at a time when it was suggested that DPI did not have standing to bring the review application. They say that separate proceedings, which would be commenced by Mr Nehme, were in contemplation. According to them, that was the circumstance in which the offer to providing a personal undertaking was made. However, at the case management hearing before Markovic J on 21 December 2023, it became clear that DPI did have standing to bring the review application. DPI and Mr Nehme contend that, as a consequence, no undertaking to meet costs was sought from Mr Nehme and no undertaking was proffered.

Analysis and conclusion

105 At the hearing on 22 March 2024, I informed the parties that I would determine whether: (a) a costs order should be made in favour of Ms Keating and the Deputy Commissioner; (b) if so, whether costs should be awarded against Mr Nehm personally; and (c) whether costs should be awarded on an indemnity basis. I informed the parties that, after making those determinations, I would refer the questions of whether it was appropriate to award costs on a lump sum basis and, if so, the amount of those costs, to a Registrar of the Court, acting as a referee pursuant to s 54A of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (the Federal Court Act), for inquiry and report.

106 I do not accept DPI’s and Mr Nehme’s submission that lump sum costs “are not regularly given”. The Court seeks to adopt, and encourages parties to utilise, sophisticated costs orders and procedures, including lump sum costs orders: see para 3.3 of the Court’s Practice Note on Costs (GPN – Costs). As GPN – Costs makes clear, the taxation of costs should be “the exception”.

107 Section 43 of the Federal Court Act confers a broad, discretionary power to award costs. This power must be exercised judicially and in accordance with “the general principles pertaining to the law of costs”: Knight v F.P. Special Assets Limited [1992] HCA 28; 174 CLR 178 (Knight) at 192.

108 It is not in dispute that the power under s 43 extends to making costs orders against non-parties: Knight at 192; Dunghutti Elders Council (Aboriginal Corporation) RNTBC v Registrar of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Corporations (No 4) [2012] FCAFC 50; 200 FCR 154 at [73]; Hardingham v RP Data Pty Limited (Third Party Costs) [2023] FCA 480 (Hardingham) at [19] approved in Court House Capital Pty Ltd v RP Data Pty Limited [2023] FCAFC 192 at [13].

109 In Hardingham, Thawley J (at [21]) considered the proposition that costs orders against non-parties are only awarded in exceptional circumstances. His Honour said that this proposition, and similar statements, are no more than an observation that costs usually (i.e., in the ordinary run of cases) fall on the parties to litigation:

… It is, accordingly, not particularly helpful to state that a third party costs order is rare and exceptional. When there is a sufficient connection between the litigation and a third party, and the circumstances are such that the making of a costs order is fair in all the circumstances, the making of a third party costs order is normal…

110 In Knight, Mason CJ and Deane J (at 192 – 193; Gaudron J agreeing at 205) said that it is appropriate to recognise a general category of case in which an order for costs should be made against a non-party if the interests of justice require that the order be made—namely, where: (a) the party to the litigation is insolvent or a “man of straw”; (b) the non-party has played an active part in the conduct of the litigation; and (c) the non-party, or some person on whose behalf he or she is acting or by whom he or she has been appointed, has an interest in the subject of the litigation.

111 This general category of case can encompass the actions of a sole director who is the controlling mind of a company which is a party to the litigation: Vanguard 2017 Pty Limited, in the matter of Modena Properties Pty Limited v Modena Properties Pty Limited (No 2) [2018] FCA 1461 at [46] – [48]; Hooke v Bux Global Limited (No 8) [2019] FCA 671 at [19] – [21]; Taylor v Pace Developments Ltd [1999] BCC 406 at 409.

112 Section 43(3)(g) of the Federal Court Act recognises, explicitly, that the Court has power to award costs on an indemnity basis against a party. It cannot be doubted that the Court’s broad, discretionary power to award costs extends to making an award of indemnity costs against a non-party, where it is appropriate to do so.

113 I am satisfied that the Deputy Commissioner and Ms Keating are each entitled to an award of costs in their favour. The review application was initiated by DPI in which they (and ASIC) were joined by DPI as parties. DPI has failed in the review application. Costs should follow that event.

114 Plainly, the Deputy Commissioner had a role to play in defending the winding up order it had obtained. I am satisfied that it was also appropriate for Ms Keating to play an active role in the review application by filing affidavit evidence and making submissions given that, at all times up to 26 February 2024, the review application was advanced, principally, on the basis that DPI was solvent. Ms Keating provided assistance to the Court in expressing her opinion on that question based on the facts known to her as a result of her (then) investigation into DPI’s financial circumstances and affairs.

115 I am satisfied that Mr Nehme should be ordered to pay the Deputy Commissioner’s and Ms Keating’s respective costs of and incidental to the review application on an indemnity basis.

116 Mr Nehme is the sole director of DPI. He is the person who, on the evidence, provides “formal instructions” on DPI’s behalf. I am satisfied that he provided “formal instructions” to commence the review application on the basis that DPI was solvent and that there was a basis to contend, on discretionary grounds, that a winding up order should not be made against it.

117 In providing those instructions, I am satisfied that Mr Nehme was either acting in his own right as a director or at the behest of Mr Dimitriou, whose role in respect of DPI appears to be a far more intimate and influential one than the simple liaison portrayed in Mr Adelstein’s affidavit.

118 In this connection, the following passage in Mr Adelstein’s affidavit is revealing. It concerns the circumstances in which Mr Adelstein, knowing that winding up proceedings against DPI were on foot, came to learn, through a telephone conversation initiated by Mr Dimitriou, that a winding up order had actually been made:

13. Mr Dimitriou: “Why didn't you attend today to oppose the wind up? I have just been advised by an acquaintance that the company was wound up today.”

Mr Adelstein: “I didn't have it in my diary. I had not been instructed to attend. I haven't sent a retainer. I don't believe I was instructed to act.”

Mr Dimitriou: “Of course you were. You act for Defined in all its matters. Why would this be different?”

Mr Adelstein: “I only act when I am instructed. In the other matters I have received formal instructions from Mr Nehme. That didn't happen here.”

Mr Dimitriou: “The company is solvent. The Court would be likely to exercise its discretion against a wind up in those circumstances. We will need to apply to review the decision. Can you do that? I understand it happened in Melbourne. The proceedings were filed in NSW, We are in NSW, the Liquidator is in NSW, the ATO’s lawyers are in Queensland and yet I believe the matter was heard by video link in Melbourne. Go figure.”

Mr Adelstein: “Very well. When I receive formal instructions, I will look into the possibility of a review.”

119 This evidence, taken with the fact that Mr Adelstein’s communications to Mr Nehme (as revealed in his affidavit) appear to be through, and only through, Mr Dimitriou, strongly suggests that Mr Dimitriou himself is the real source of instructions on behalf of DPI. I infer that, in relation to DPI’s affairs, it is Mr Dimitriou who instructs Mr Nehme who “formally instructs” Mr Adelstein.

120 I am satisfied that there was no proper basis for advancing the position in the review application that DPI was solvent or that there was a sound discretionary reason for not making a winding up order against it.

121 As to the question of solvency, DPI ignored the Court’s orders of 21 December 2023 to file a notice of opposition, affidavit evidence, and supporting submissions. I am satisfied that, unbeknown to the Deputy Commissioner and Ms Keating, there never was any prospect, at that time, that DPI would be able to support the review application on the basis that it was solvent. This fact was either known by Mr Nehme and Mr Dimitriou, or ought reasonably to have been known by them.

122 As I have noted, in oral submissions Mr Adelstein referred to the contention that DPI was solvent as an “unmeritorious argument”. That is an apt description. Mr Adelstein attempted to qualify his submission by contending that his affidavit showed that DPI had the prospect of recovering “some monies”. I reject that qualification. As I have noted, Mr Adelstein’s affidavit referred, in somewhat vague terms, to DPI’s claimed entitlement to certain sums of money. That evidence could not realistically support the proposition that DPI was solvent (if, in fact, the evidence was truly directed to that question). Indeed, Mr Adelstein’s affidavit appears to acknowledge that fact by its repeated references to DPI’s intention to file affidavit evidence demonstrating its solvency.

123 What is more, DPI made no attempt to inform the Deputy Commissioner or Ms Keating that it was not intending to prosecute the review application on the basis that it was solvent. Rather, it induced, and allowed, the Deputy Commissioner and Ms Keating to prepare for the hearing on 26 February 2024 (including by filing affidavit evidence and, in the case of the Deputy Commissioner, written submissions), and incur further costs, on a completely false basis. It was only at the hearing on 26 February 2024 that DPI abandoned any pretence that it was solvent.

124 Further, I am satisfied that, as at 21 December 2023, there was no sound discretionary reason not to make a winding up order against DPI. The contention that there was such a reason is an illusion. I am satisfied that this fact was also known by Mr Nehme and Mr Dimitriou at that time, or ought reasonably to have been known by them. As became apparent in DPI’s written and oral submissions at the hearing on 22 March 2024, DPI was, in fact, advancing nothing more than a bargaining chip to reach a settlement. The bargaining chip was that Mr Dimitriou would consider paying some money to the Deputy Commissioner on DPI’s behalf if the Deputy Commissioner would consent to the winding up application being dismissed and submit to a costs order in relation to DPI’s costs and Ms Keating’s costs.

125 As to the attempt to advance the defective notice ground as a viable ground of opposition, I accept that I permitted DPI to advance that ground. However, I did so only because, at the time that it was first raised, both the Court and the respondents were taken by surprise. I was not prepared to consider the merits of the defective notice ground “on the run” without informed assistance from the Deputy Commissioner, which could not realistically be given at that time. As I also appreciated at the time, that assistance required evidence, which was, in fact, subsequently provided by the Deputy Commissioner, at further cost. DPI and Mr Nehme cannot take comfort from the fact that I permitted DPI to advance the new ground.

126 I am satisfied that the review application was not commenced on a proper basis. Ultimately, it was not prosecuted, on a viable basis. As I have found, the defective notice ground is without merit.

127 Further, DPI’s conduct of the review application has been unsatisfactory throughout, and unreasonable. The Deputy Commissioner and Ms Keating should not have been put to the cost and inconvenience of the application, particularly at the hands of an insolvent applicant against whom they have no practical recourse. It is just and appropriate that they be indemnified for their legal costs by Mr Nehme who, I am satisfied, was the person who provided “formal instructions” to Mr Adelstein to commence the review application and to conduct it on behalf of DPI in the way it was conducted, knowing since at least January 2024 that a personal costs order would be sought against him (at least by Ms Keating).

128 Further, I am satisfied that the review application was brought in an attempt to delay the winding up. There does not appear to be any other rationale for taking that action. I can only conclude that Mr Nehme (or, if acting at the behest of Mr Dimitriou, Mr Dimitriou) had an interest in achieving that outcome that was at least equal to DPI’s interest. I can think of no other reason why the review application would have been commenced.

129 For completeness, I should record that I have not reached these findings or conclusions on the basis that, at an earlier stage of the proceeding, Mr Nehme offered to provide an undertaking as to costs. Having said that, I should make clear that I do not accept DPI’s and Mr Nehme’s submission as to the circumstances in which that offer was made. It is clear from the correspondence that the undertaking was offered to meet any order that might be made against DPI to pay costs. The correspondence in which the offer was made makes no mention of a proceeding to be commenced by Mr Nehme as a director. Moreover, it would be odd to offer an undertaking to pay an adverse costs order when the party against whom that order would be made is the person offering the undertaking.

DISPOSITION

130 Orders will be made accordingly.

I certify that the preceding one hundred and thirty (130) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice Yates. |

Associate:

SCHEDULE