Federal Court of Australia

ToolGen Incorporated v Fisher (No 3) [2024] FCA 539

ORDERS

Appellant | ||

AND: | First Respondent ACN 004 552 363 PTY LTD Second Respondent | |

AND BETWEEN: | First Cross-Appellant ACN 004 552 363 PTY LTD Second Cross-Appellant | |

AND: | Cross-Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The appeal be dismissed.

2. The cross-appeal be allowed.

3. The decision of a Delegate of the Commissioner of Patents in relation to Australian Patent Application No. 2013335451 (“the Patent Application”) given on 18 September 2018 be set aside except insofar as it relates to the costs awarded to the first respondent (the opponent) by the Delegate.

4. The complete specification of the Patent Application be amended pursuant to section 105(1A) of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) by substituting for the existing claims the amended claims set out in the Annexure to these orders.

5. The Patent Application proceed to grant as amended in accordance with order 4.

6. The appellant pay the respondents’ costs incurred up to and including 16 November 2023 of and incidental to their consideration of the interlocutory application dated 1 September 2023.

7. The appellant serve a copy of these orders on the Commissioner of Patents within 7 days.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

Annexure

NICHOLAS J

Background

1 My reasons for judgment published on 14 July 2023 explain why each of the claims of Patent Application No. 2013335451 (“the patent application”) would, if granted, be invalid: see ToolGen Incorporated v Fisher (No 2) [2023] FCA 794. I will refer to those reasons for judgment as the “principal judgment” or “PJ”.

2 The appellant (“ToolGen”) has filed an interlocutory application seeking leave to amend the claims of the patent application pursuant to s 105(1A) of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) (“the Act”) by substituting for those claims the amended claims set out in Annexure A to these reasons for judgment (“the proposed amendments”). A markup comparing the claims in their current form to the claims in their amended form is also included as Annexure B. The affidavit evidence relied upon by ToolGen in support of the amendment application comprises three affidavits of its solicitor, Lisa Taliadoros of Jones Day, an affidavit of Debra Tulloch, a patent and trade marks attorney, and an affidavit of Jung Yeon Woo, in-house counsel and senior patent attorney for ToolGen.

3 The Commissioner of Patents (“the Commissioner”) was notified of the amendment application which was duly advertised. No party has raised any opposition to the proposed amendments. However, the Commissioner has provided a brief analysis in a letter dated 6 October 2023 (“the Commissioner’s letter”) which is in evidence.

4 On 16 November 2023, the respondents notified the Court that they did not oppose the proposed amendments. On 11 December 2023, after having been informed that the respondents did not oppose the proposed amendments, the Commissioner confirmed that he did not wish to be heard in relation to the amendment application.

Relevant Statutory Provisions

5 The Court is given power by s 105(1A) of the Act to direct the amendment of a complete specification in an appeal against a decision of the Commissioner in relation to a patent application. Section 105(4) provides that the Court “… is not to direct an amendment that is now allowable under section 102”. Section 102 of the Act relevantly provides:

102 What amendments are not allowable?

Amendment of complete specification not allowable if amended specification claims or discloses matter extending beyond that disclosed in certain documents

(1) An amendment of a complete specification is not allowable if, as a result of the amendment, the specification would claim or disclose matter that extends beyond that disclosed in the following documents taken together:

(a) the complete specification as filed;

(b) other prescribed documents (if any).

Certain amendments of complete specification are not allowable after relevant time

(2) An amendment of a complete specification is not allowable after the relevant time if, as a result of the amendment:

(a) a claim of the specification would not in substance fall within the scope of the claims of the specification before amendment; or

(b) the specification would not comply with subsection 40(2), (3) or (3A).

Meaning of relevant time

(2A) For the purposes of subsection (2), relevant time means:

(a) in relation to an amendment proposed to a complete specification relating to a standard patent—after the specification has been accepted; or

(b) in relation to an amendment proposed to a complete specification relating to an innovation patent—after the Commissioner has made a decision under paragraph 101E(1)(a) in respect of the patent.

…

Section does not apply in certain cases

(3) This section does not apply to an amendment for the purposes of:

(a) correcting a clerical error or an obvious mistake made in, or in relation to, a complete specification; or

(b) complying with paragraph 6(c) (about deposit requirements).

6 The amendment application was made after the specification was accepted by the Commissioner. Accordingly, if the proposed amendments are to be allowed then the complete specification must comply with ss 102(1) and 102(2) unless section 102(3) applies to the amendments.

The Commissioner’s Letter

7 The Commissioner’s letter states:

Claim 1 as proposed to be amended is based on claim 10 before amendment. Claim 1 as proposed to be amended specifies that component b) is an in vitro transcribed sgRNA. Claim 10 before amendment specifies that component b) is a “nucleic acid encoding a guide RNA”. That is, claim 10 is limited to a method in which the nucleic acid encodes the guide RNA and requires that the guide RNA be transcribed from nucleic acid in the eukaryotic cell (per [130] of the decision). Therefore, the scope of the claim as proposed to be amended has changed from (before amendment) a nucleic acid encoding the guide RNA - to (after amendment) the guide RNA itself. Therefore claim 1 as proposed to be amended prima facie falls outside the scope of the broadest method claim 10. While dependent claim 19 specified that component b) is an in vitro transcribed guide RNA, such that the proposed amendment is simply incorporating the feature of claim 19 into claim 10, the Court found that claim 19 “cannot be read sensibly with claim 10 on which it is dependent” and thereby lacks clarity ([145] of the decision). It therefore appears that claim 19 is of no meaningful scope (noting the decision at [422]: “if claim 19 (when read with claim 10) does not lack clarity and includes the use of in vitro transcribed guide RNA”) and that claim 1 as proposed to be amended falls outside the scope of claims prior to amendment leading to a potential non-compliance with s102(2)(a).

The Commissioner considers that the claims as proposed [to] be amended are otherwise allowable under section 102.

(Original emphasis)

8 It is apparent from the Commissioner’s letter that he considers that the proposed amended claim 1 would fall outside the scope of the claims prior to amendment because the requirement for an in vitro transcribed sgRNA in the proposed amended claim 1 is outside the scope of the claims. His argument is that claim 19 cannot expand the scope of claim 10 (which he correctly refers to as the broadest of the method claims) because (as found) claim 19 cannot be read sensibly with claim 10, and the proposed amendments may therefore not comply with s 102(2)(a). The Commissioner has raised no other issue in relation to the proposed amendments. In particular, the Commissioner does not suggest that the proposed amendments, if allowed, would result in the specification not complying with ss 40(2), (3) or (3A).

9 The Commissioner’s letter refers in particular to PJ [130], [145] and [422]. PJ [130], which is concerned with the proper construction of independent claim 10, relevantly states:

… Here, the language of claim 10 when read in the context of the Specification as a whole indicates that (for whatever reason) the claim has been limited to a method in which the nucleic acid encodes the guide RNA in the eukaryotic cell. In my opinion, this requires that the guide RNA be transcribed from nucleic acid in the eukaryotic cell.

10 As to the relationship between claims 10 and 19 (which is depended on claim 10), I found at PJ [145] that claim 19 lacks clarity because:

Claim 10 requires that the guide RNA be transcribed in the cell but claim 19 contemplates that the guide RNA will have been transcribed outside the cell. Claim 19 cannot be read sensibly with claim 10 on which it is dependent. In my opinion claim 19 lacks clarity.

11 PJ [422] is concerned with the novelty of claim 19 when read with claim 10 if (contrary to my finding) these claims when read together do not lack clarity. I do not think PJ [422] adds to what is said elsewhere in the primary judgment as to the difficulties involved in reading claims 10 and 19 together.

12 The point raised by the Commissioner is of significance because, as found in the primary judgment, a claim to a method utilising a guide RNA encoded in vivo is not disclosed in US Provisional Patent Application 61/717,324 with the consequence that claims 1-8 and 10-18 cannot take priority from that document and are invalid for lack of novelty: see PJ [417].

13 Other grounds of invalidity identified in the primary judgment are addressed by what are clearly narrowing amendments proposed by ToolGen limiting the amended claims to methods using a nucleic acid sequence encoding Cas9 derived from S. pyogenes (PJ [227], [363]) that recognises a NGG PAM sequence (PJ [364]-[365]) and a guide RNA truncated at the +48 position of the S. pyogenes tracrRNA (PJ [366]-[369]). The Commissioner’s letter raises no issue concerning these amendments which I am satisfied comply with the requirements of ss 102(1) and (2) of the Act.

The COMPOSITE Claim

14 Claim 10 when read with claim 19 (“the composite claim”) relevantly reads as follows:

… the CRISPR/Cas system comprises:

(a) a nucleic acid encoding a Cas9 polypeptide … and

(b) a nucleic acid encoding a guide RNA …

and wherein the Cas9 polypeptide and the guide RNA form a Cas9/RNA complex …

[Claim 10]

[and]

… wherein the nucleic acid encoding the guide RNA is in vitro transcribed RNA.

[Claim 19]

15 The words “nucleic acid encoding a guide RNA” in claim 10 were interpreted as referring to a nucleic acid that encodes the guide RNA inside the cell. As explained in PJ [145], this requires that the guide RNA be transcribed inside the cell (i.e. in vivo), while claim 19 contemplates that the guide RNA will be transcribed outside the cell (i.e. in vitro). It was this inconsistency that led to the finding that claim 19 lacked clarity.

Submissions

16 ToolGen submitted that the proposed amendments complied with s 102(2)(a) in that nothing falling within the scope of the amended claims would fall outside the scope of the claims before amendment. ToolGen submitted that if existing claim 10 and 19 are read together to form the composite claim, there is a lack of clarity as to whether the guide RNA is in vitro transcribed RNA or nucleic acid encodes the guide RNA in vivo. It submitted that both claim 10 and claim 19 are to a method using a system which includes a guide RNA and that the lack of clarity relates not to the presence of the guide RNA, but its provenance. ToolGen submitted:

Therefore, it is not correct to say, as the Commissioner suggests, that the scope of claim 19 will change from “a nucleic acid encoding the guide RNA – to … the guide RNA itself”, because the claim prior to amendment was not to a nucleic acid encoding the guide RNA – there was a lack of clarity as to that aspect of the claim. With due respect to the Commissioner, that is the effect of the [principal judgment] at [145].

17 ToolGen also submitted that claims 10 and 19 when read together contain an “obvious mistake” within the meaning of s 102(3)(a) with the consequence that s 102(2)(a) does not apply to the proposed amendments. It submitted that the instructed public would appreciate that, by having claim 19 seek to claim in vitro transcribed guide RNA (and in circumstances where the specification discloses the use of such as part of the invention), it was this which the patent applicant intended to claim instead of the guide RNA being transcribed from a nucleic acid in the eukaryotic cell. The instructed public would appreciate that the correction to that mistake would be to make an independent claim which has all of the features of claim 10, but without the inconsistent requirement that the guide RNA be transcribed from nucleic acid in the cell.

The Relevant Principles

18 Section 102(2)(a) requires the Court to ask whether any proposed amended claim would not in substance fall within the scope of the existing claims. This will usually involve asking whether the proposed amendment if allowed would make anything an infringement that was not an infringement before the amendment: Bristol-Myers Squibb Co v Apotex Pty Ltd (2010) 87 IPR 516 at [40], Fina Research SA v Halliburton Energy Services Inc (2003) 127 FCR 561 at [29]. If the answer is yes, subject to the operation of s 102(3), the amendment will not be allowable.

19 As mentioned, ToolGen says that the proposed amendment is to correct an “obvious mistake” in the complete specification within the meaning of s 103(a). What constitutes an obvious mistake was considered by Mr Blanco White QC in Patents for Inventions, 5th ed. Stevens & Sons, London, 1983. The learned author states at para 6-008:

For there to be an “obvious mistake” it must be apparent, on the face of specification when read by an instructed reader, not only that “something has gone wrong” but also what the mistake is and what is the correction needed. By “mistake” here is meant, it would seem, a failure to express the real intention of the writer of the specification. The correction does not cease to be “obvious” because there is more than one way of expressing it. But if extraneous evidence, beyond what is required to put the court in the position of an instructed reader, is needed to show the mistake, it is not an “obvious” one.

(Citations omitted)

20 In Holtite Ltd v Jost (Great Britain) Ltd [1979] RPC 81 Lord Diplock (with whom the remainder of the House of Lords agreed) when considering s 31(1) of the Patents Act 1949 (UK) (which relevantly provided “no amendment thereof shall be allowed, except for the purpose of correcting an obvious mistake”) said at 91:

The policy of the section is clear. A major purpose of a patent specification is to define the scope of the invention claimed (section 4(3)(c)), so as to give public notice of the limits of the monopoly claimed. An amendment, if allowed, is retrospective to the date of filing the complete specification. So, with one exception, an amendment which enlarged the limits of the scope of the invention claimed would make actionable, ex post facto, what at the time when it was done the doer had no reason to suppose amounted to an infringement of the patentee's rights. An amendment that would have this effect is what is forbidden by the section. The one exception is where the amendment is for the purpose of correcting an "obvious mistake"; but this exception is not in conflict with the policy disclosed by the remainder of the section, since if the mistake was obvious, it cannot have misled. In the context of correcting it, the natural meaning of the expression "obvious mistake" is that: what must be obvious is not simply that there has been some mistake but also what the mistake is and what is the correction needed. But the correction needed does not fail to be obvious merely because, as a matter of drafting, there is more than one way of expressing it without affecting its meaning. Furthermore, having regard to the function of the specification as a warning to the public of the limits of the monopoly claimed, the mistake must be apparent on the face of the specification itself to an instructed reader versed in the particular art to which the invention relates. If beyond such evidence of the relevant art as may be needed to equip the court with the knowledge that would be possessed by the instructed reader, some other evidence extraneous to the specification is required to show that there has been a mistake in expressing the real intention of the inventor, the mistake is not an "obvious mistake" within the meaning of the section. The words of the section are clear and simple without the need for judicial exegisis. I note, however, that this interpretation of the section conforms with that adopted by Graham, J. in General Tire and Rubber Company (Frost's) Patent [1972] R.P.C. 259 in which several of the previous cases are also referred to.

(Emphasis in the original)

21 The need for both the error itself and the necessary correction to be obvious to the instructed reader (which is merely another way of describing the person skilled in the art) is aimed at ensuring that relevant members of the public are not misled as to the scope of the monopoly.

22 The power to direct the amendment of a complete specification under s 105(1A) of the Act is discretionary: Meat & Livestock Australia Ltd v Cargill, Inc (No 2) (2019) 139 IPR 47 (“Cargill”) at [342]. The discretion is exercised by reference to guiding principles that seek to balance the right of the patent applicant to apply to amend claims and the public interest in ensuring that an amendment application is made promptly and for proper purposes, and that any amendment made does not confer on the patentee an unfair advantage: see in the context of the discretion under s 105(1) of the Act, Neurim Pharmaceuticals (1991) Ltd v Generic Partners Pty Ltd (No 2) (2019) 139 IPR 424 at [107].

23 In Cargill, Beach J referred to various cases concerned with the exercise of discretion under s 105(1) of the Act including Les Laboratoires Servier v Apotex Pty Ltd (2016) 247 FCR 61 in which the Full Court (Bennett, Besanko and Beach JJ) said at [242]:

While the power to amend should in appropriate circumstances be exercised in favour of the patentee, it bears mentioning that it will not always be possible to overcome a ground of revocation by an amendment. Accordingly, the ground of revocation sought to be overcome is also relevant to the way in which the discretion should be exercised. In the case of a failure to comply with the best method requirement, it would be necessary to take into account, in the exercise of the discretion, the reason for that obligation and the time at which it is meant to be fulfilled.

24 The Full Court went on at [243] to identify various considerations relevant to the exercise of the discretion as follows:

• The discretion exists for the benefit of the patentee.

• The onus to establish that amendment should be allowed is on the patentee.

• Generally, a permissible amendment (ie one which is permitted under the Act) will be allowed unless there are circumstances which would lead the court to refuse amendment.

• The patentee must make full disclosure of all relevant matters.

• The Court’s focus is on a patentee’s conduct, not the merit of an invention.

• Amendment should be sought promptly and where a patentee delays for an unreasonable period, the patentee has the onus of showing that it delayed on reasonable grounds, such as a belief, on reasonable grounds, that an amendment was not necessary.

• Unreasonable delay is a circumstance likely to lead to refusal of the amendment.

• In assessing delay, the time when the patentee was unaware and reasonably did not know of the need for amendment is not taken into account. The relevant delay is from when the patentee knows of the likely invalidity, or has its attention drawn to a defect in the patent, or is advised to strengthen the patent by amendment. That is, amendment will not be permitted in cases where a patentee knows or ought to know that amendment should be sought and fails to do so for a substantial period of time. Thus the reasonableness of the conduct of the patentee is a relevant consideration when assessing delay.

• Mere delay is not, of itself, sufficient to refuse to exercise the discretion to amend. The fact of delay is, however, relevant to whether the respondent or the general public have suffered detriment.

• If a patentee seeks to take unfair advantage of the unamended patent, knowing that it requires amendment, then refusal of the amendment is likely.

• The proportionality of the asserted culpability of the patentee as compared with the effect of loss of protection for the invention should be considered.

Consideration

25 I will first consider whether claim 19 when read with claim 10 is affected by an obvious mistake. Looking at the claims in their existing form, as found in the principal judgment, the person skilled in the art would understand claim 10 to describe a system in which the nucleic acid encoding the guide RNA provides the information used to produce the guide RNA in the cell (i.e. in vivo). They would further understand claim 19 to refer to a system in which the guide RNA is produced outside the cell (i.e. in vitro). They would therefore understand that there is a mistake in the composite claim because it uses language from claim 10 to describe a guide RNA produced in vivo and language from claim 19 to describe a guide RNA produced in vitro. The mistake would in my opinion be plainly apparent on the face of the specification when read by the person skilled in the art. I am satisfied that the composite claim is in this respect affected by an obvious error.

26 The next question is whether the required correction would also be obvious to the person skilled in the art. They would clearly understand from their reading of the specification that various embodiments of the system are described and that these include embodiments in which the guide RNA is created in vitro before introduction into the cell and embodiments in which nucleic acid encoding the guide RNA is introduced into the cell where the guide RNA is then transcribed. They would further understand that claim 10 is directed at embodiments in which the guide RNA is produced in vivo and that the composite claim is directed at embodiments in which the guide RNA is an in vitro transcribed RNA.

27 The relevant correction would be obvious to the person skilled in the art. It would involve re-writing the composite claim to eliminate the inconsistency in language between claim 10 and claim 19 so that, rather than referring to nucleic acid encoding a guide RNA, the composite claim instead refers to an in vitro transcribed guide RNA. In this way, claim 10 would continue to cover the use of a guide RNA produced in vivo and the composite claim would cover the use of a guide RNA produced in vitro.

28 In my opinion, proposed amended claim 1 corrects the obvious error in the composite claim in a manner that would be obvious to a person skilled in the art. In those circumstances, the question whether the relevant amendment complies with the requirements of s 102(2)(a) need not be decided.

29 With regard to discretion, there has not been any unreasonable delay in seeking to amend. It was not unreasonable for ToolGen to await judicial determination of the respondents’ opposition including as to the proper construction of claim 10 and the composite claim. The respondents do not suggest that they have suffered any detriment as a result of any delay in seeking the proposed amendments nor is there any reason to think that any other person has suffered any such detriment.

Costs

30 The respondents sought their costs of the interlocutory application. They relied on the decision of Burley J in Cytec Industries Inc. v Nalco Company [2019] FCA 1800 referred to by Jagot J in Novartis AG v Arrow Pharmaceuticals Pty Ltd [2020] FCA 139 at [18]. Both cases deal with circumstances where the patent applicant sought to amend the claims prior to the hearing of an appeal from a decision of the Commissioner. In both cases the amendments, if allowed, may have affected the scope of the appeals which were yet to be heard.

31 As I have mentioned, the respondents informed the Court on 16 November 2023 that they did not oppose the proposed amendments. Their position has not changed. In the circumstances I consider that the respondents should have their costs incurred up to and including 16 November 2023 of and incidental to their consideration of the interlocutory application filed 1 September 2023. However, I do not consider the respondents should be allowed any costs for attending the hearing on 10 May 2024, in circumstances where they had already communicated to ToolGen and the Court some months before that they would not oppose the amendments and where the appeal had already been heard.

Disposition

32 I will make the following orders disposing of the proceeding as a whole including the amendment application:

(1) The appeal be dismissed.

(2) The cross-appeal be allowed.

(3) The decision of a Delegate of the Commissioner of Patents in relation to Australian Patent Application No. 2013335451 (“the Patent Application”) given on 18 September 2018 be set aside except insofar as it relates to the costs awarded to the first respondent (the opponent) by the Delegate.

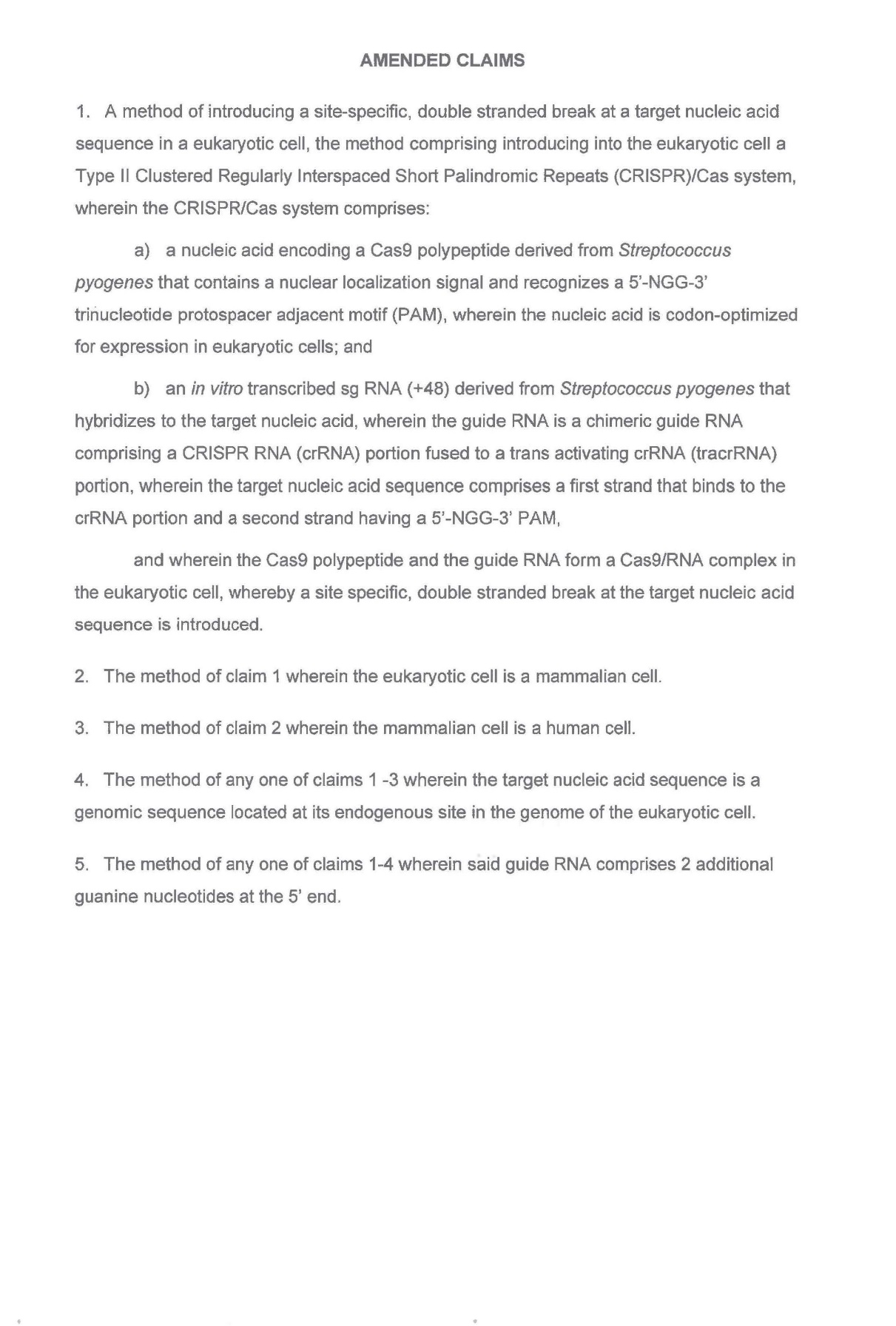

(4) The complete specification of the Patent Application be amended pursuant to section 105(1A) of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) by substituting for the existing claims the amended claims set out in Annexure A to these reasons.

(5) The Patent Application proceed to grant as amended in accordance with order 4.

(6) The appellant pay the respondents’ costs incurred up to and including 16 November 2023 of and incidental to their consideration of the interlocutory application dated 1 September 2023.

(7) The appellant serve a copy of these orders on the Commissioner of Patents within 7 days.

I note that costs of the proceeding in this Court up to and including 14 July 2023 were the subject of a consent order made by me on 6 September 2023. In the circumstances I do not propose to make any further order in relation to those costs.

I certify that the preceding thirty-two (32) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice Nicholas. |

Associate:

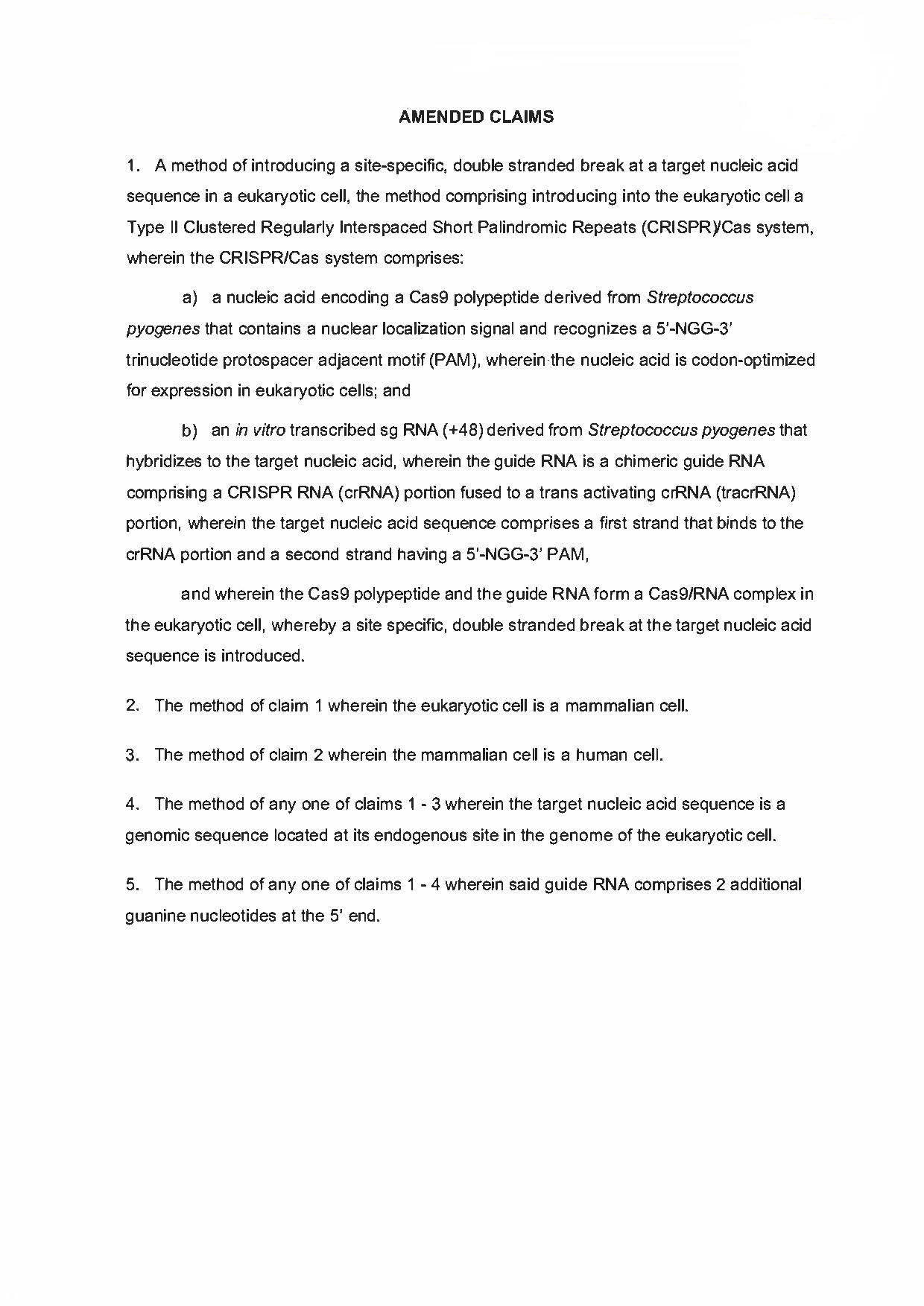

Annexure A

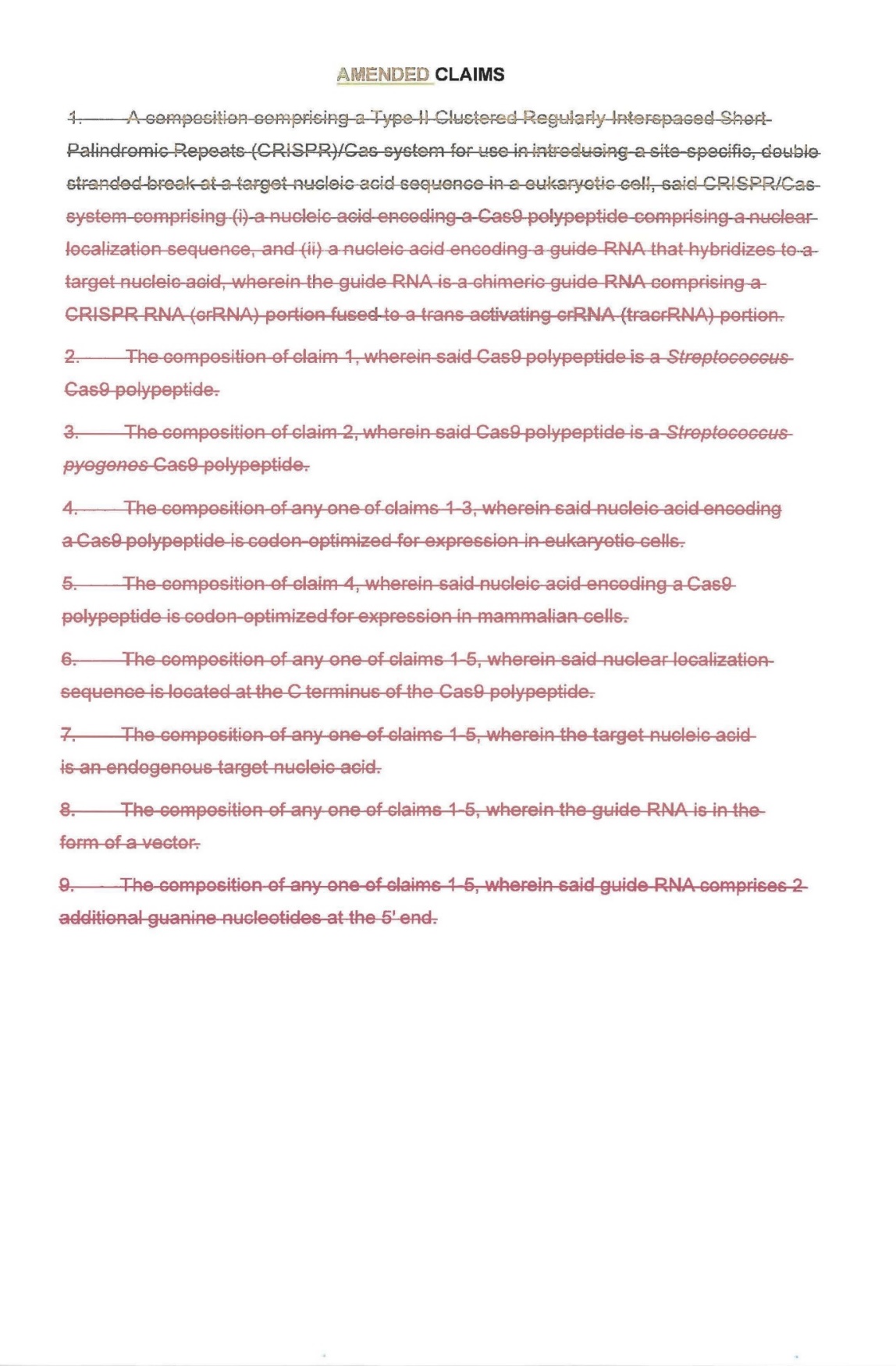

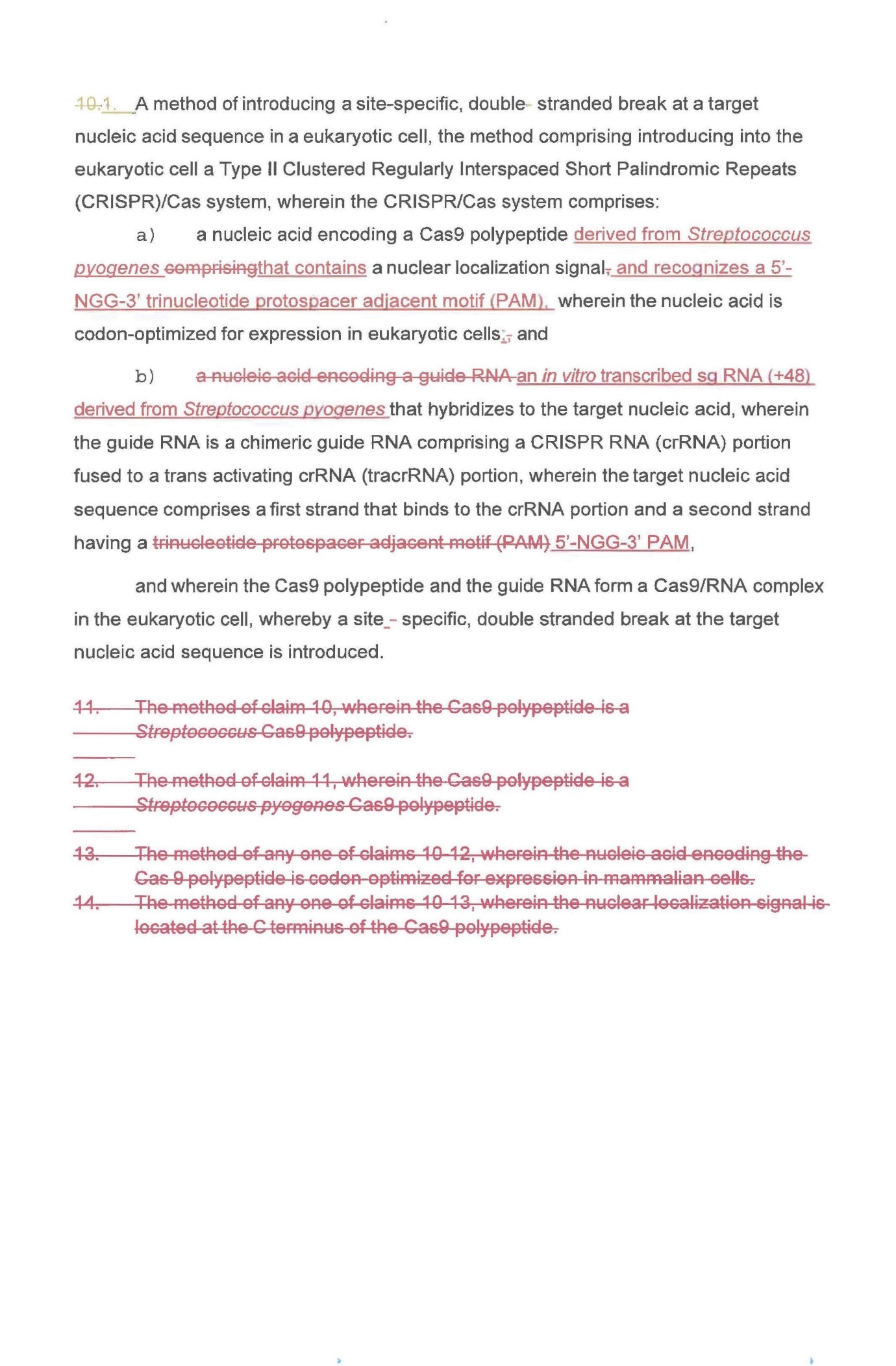

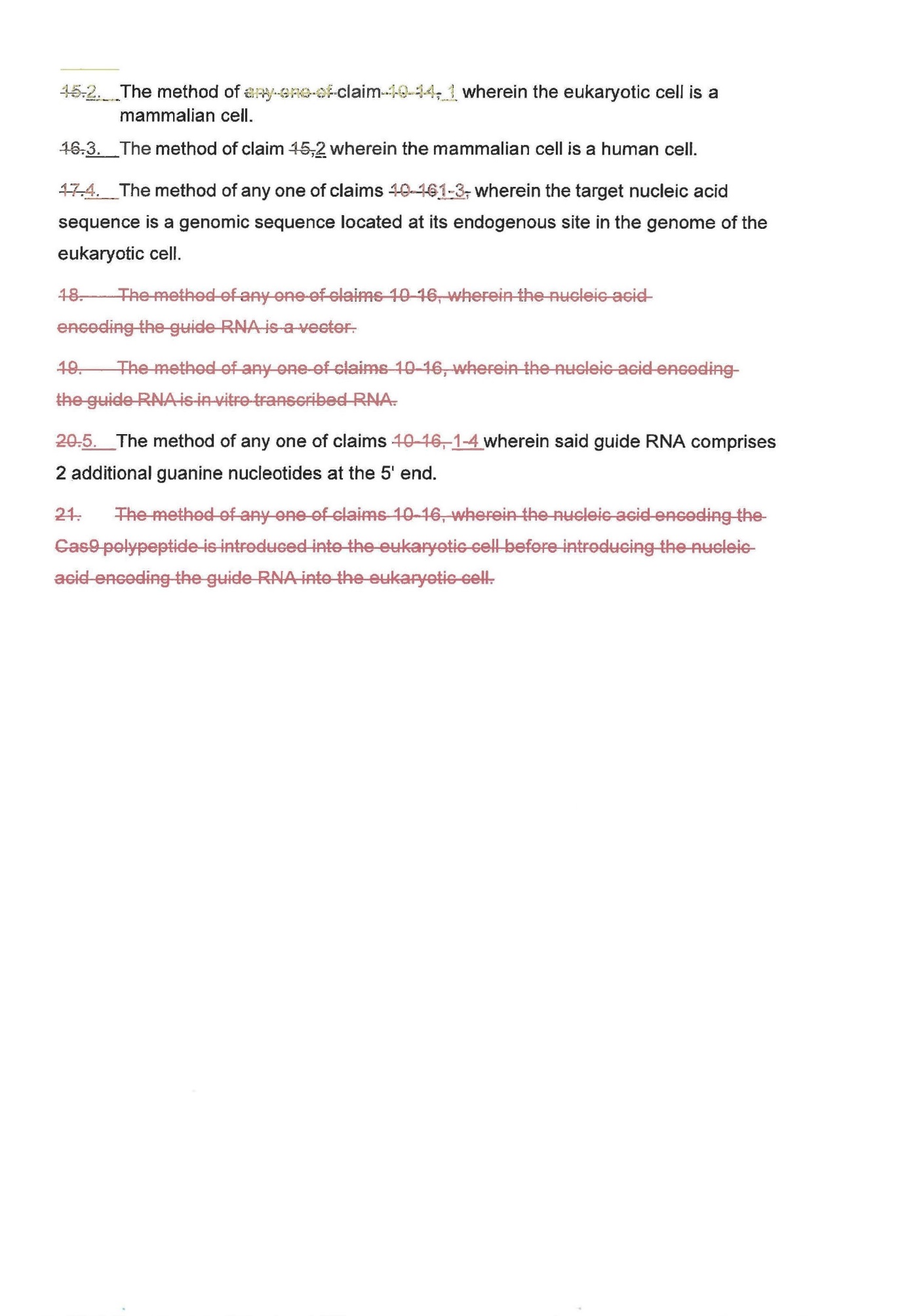

Annexure B