FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Roebuck v Shopping Centres Australasia Property Group Re Limited [2024] FCA 503

ORDERS

Applicant | ||

AND: | SHOPPING CENTRES AUSTRALASIA PROPERTY GROUP RE LIMITED (ACN 158 809 851) Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Upon the statement of agreed facts annexed to the orders of 28 June 2023, the separate questions arising in the proceedings be answered as follows:

(1) The Real Estate Industry Award 2020 covered the applicant’s employment with the respondent, pursuant to s 48 of the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth).

(2) The guarantee of annual earnings, annexed to the employment agreement between the respondent and the applicant dated 4 December 2020, complied with s 330(1)(b) and Part 2-9, Division 3 of the Act, and the Award did not apply to the applicant’s employment with the respondent pursuant to s 47 of the Act.

2. By 4.30pm (AWST) on 29 May 2024 the parties are to file an agreed minute or competing minutes of proposed orders addressing the future conduct of the proceedings.

3. The matter be listed on a date to be fixed for further or other orders in the proceedings.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

FEUTRILL J:

Introduction

1 Mr Roebuck, the applicant, was an employee of Shopping Centres Australasia Property Group RE Limited, the respondent. Mr Roebuck’s employment was terminated on 29 July 2021 when his role was made redundant. Mr Roebuck alleges that the Real Estate Industry Award 2020 (as a modern award) covered and applied to him (as employee) and SCA Property Group (as employer). Mr Roebuck alleges that SCA Property Group contravened the Award and made misrepresentations in connection with Mr Roebuck’s redundancy contrary to s 45 and s 345 of the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth). SCA Property Group contends that Mr Roebuck was not covered by the Award within the meaning of s 48(1) of the Act because, having regard to the duties of his position, the Award was not expressed to cover an employee engaged in work of that nature. SCA Property Group also contends that, even if Mr Roebuck was covered by the Award, the Award did not apply to him, within the meaning of s 47 of the Act because, at the time his employment was terminated, he was a high income employee, within the meaning of s 329 of the Act.

2 As a consequence of SCA Property Group’s contentions, the parties agreed and the Court made orders for the following questions to heard separately from all other questions in the proceedings and for those questions to be determined on the basis of a statement of agreed facts.

(1) Did the Award cover Mr Roebuck’s employment with SCA Property Group, pursuant to s 48 of the Act?

(2) If the answer to question (1) is in the affirmative, did the guarantee of annual earnings, annexed to the employment agreement between SCA Property Group and Mr Roebuck dated 4 December 2020, comply with s 330(1)(b) and Pt 2-9, Div 3 of the Act, and if so, did the Award apply to Mr Roebuck’s employment with SCA Property Group pursuant to s 47 of the Act?

3 Resolution of the first separate question turns on the proper construction of the provisions of the Award that describe the classifications for employees of employers engaged in the real estate industry and whether the nature of the work described in the duty statement for Mr Roebuck’s position fell within the meaning of at least one of those classifications. In essence, SCA Property Group contends that the duties of Mr Roebuck describe a position that is far more senior than any classification of employee described in the Award and, therefore, Mr Roebuck was not covered by the Award.

4 Resolution of the second separate question turns on questions of statutory interpretation and the proper construction of Mr Roebuck’s written contract of employment. The point of statutory interpretation is whether the criterion of a ‘guarantee of annual earnings’ in s 330(1)(b) of the Act that an employer give ‘an undertaking in writing to pay the employee an amount of earnings in relation to the performance of work during a period of 12 months or more’ requires there to be a ‘guaranteed period’, within the meaning of s 331 of the Act, for a ‘fixed’ period with a specified or identifiable end date. SCA Property Group contends that such a fixed period is not a requirement. Further, that an undertaking of the kind described in s 330(1)(b) may be evergreen or rolling so as to renew for annual periods of 12 months throughout an employment of an indefinite period. Mr Roebuck contends that there is a requirement for a fixed period and that evergreen or rolling undertakings are not permitted such that, in effect, a guarantee of annual earnings must be renegotiated or given again at the end of each guarantee period. The point of contractual construction is whether the contract of employment contains an undertaking to pay an amount of earnings in relation to the performance of work during a period of 12 months with or without a specific or identifiable end date and, in any event, whether it provides for an evergreen or rolling series of annual undertakings for the duration of Mr Roebuck’s employment.

5 For the reasons given below, the undertaking SCA Property Group gave to Mr Roebuck as a term of his written contract of employment was an undertaking of the kind described in s 330(1)(b). On the proper construction of the contract of employment it was a promise or an undertaking to pay Mr Roebuck $219,178 for each year of his employment commencing on 1 January 2021. At the time of termination of his employment, the guarantee period was identifiable and ended on 31 December 2021. Therefore, on the agreed facts and otherwise uncontentious matters, Mr Roebuck was a high income employee of SCA Property Group on 29 July 2021. Accordingly, even if Mr Roebuck was covered by it, the Award did not apply to him.

6 In light of the conclusions I have reached regarding separate question 2, it is not strictly necessary to answer separate question 1. Nonetheless, I have addressed that question as it was fully argued and it should be answered in the event that I am wrong with regard to separate question 2. With respect to separate question 1, I have concluded, for the reasons that follow, that Mr Roebuck was engaged in a classification of employment that was covered by the Award.

7 I will hear the parties on what, if any, orders should be made as a consequence of the determination of the separate questions.

Legislative framework

8 Section 3 provides that the object of the Act is to provide a balanced framework for cooperative and productive workplace relations that promotes national economic prosperity and social inclusion of all Australians by, amongst other things:

(a) providing workplace relations laws that are fair to working Australians, flexible for businesses, promote productivity and economic prosperity and take into account Australia’s international labour obligations; and

(b) ensuring a guaranteed safety net of fair, relevant and enforceable minimum terms and conditions through the National Employment Standards, modern awards and national minimum wage orders; and

(c) ensuring that the guaranteed safety net of fair, relevant and enforceable minimum wages and conditions can no longer be undermined by the making of statutory individual employment agreements of any kind given that such agreements can never be part of a fair workplace relations system.

9 Chapter 2 of the Act contains provisions relating to the National Employment Standards, modern awards, enterprise agreements and workplace determinations. The main terms and conditions of employment of an employee that are provided for under the Act are set out in the National Employment Standards [Pt 2-2], a modern award [Pt 2-3], an enterprise agreement [Pt 2-4], or a workplace determination [Pt 2-5] that applies to an employee: s 43 of the Act.

10 A person must not contravene a term of a modern award: s 45. A person will not contravene a modern award unless the award applies to that person: s 46(1). A modern award does not give a person an entitlement unless the award applies to that person: s 46(2). A contravention of a modern award may result in the imposition of a civil penalty: ss 45, 539(1) and 539(2) item 2.

11 A modern award applies to an employee or employer if:

(a) the award covers the employee or employer; and

(b) the award is in operation; and

(c) no other provision of the Act provides, or has the effect, that the award does not apply to the employee or employer.

However, a modern award does not apply to an employee (or employer in relation to that employee) at a time when the employee is a high income employee: s 47(1) and s 47(2). A modern award covers an employee or employer if the award is expressed to cover the employee or employer unless the award has ceased to operate: s 48(1) and s 48(4).

12 Part 2-9 deals with other terms and conditions of employment. Part 2-9 Div 3 contains provisions concerning guarantees of annual earnings which define or describe the meaning of high income employee for the purposes of the Act. At the time relevant for these proceedings, a full-time employee was a ‘high income employee’ of an employer if, at that time, the employee had a guarantee of annual earnings for the guaranteed period and the annual rate of the guarantee of annual earnings exceeded the high income threshold: s 12 (dictionary) and s 329. The terms ‘guarantee of annual earnings’, ‘annual rate’ and ‘guarantee period’ are defined or described in ss 329(1), 329(3), 331 and 333. The ‘high income threshold’ is the amount prescribed, or worked out in the manner prescribed, by the regulations: s 333(1). Regulation 2.13(3) of the Fair Work Regulations 2009 (Cth) prescribes a formula for calculating the high income threshold by reference to the current average weekly ordinary time earnings published by the Australian Statistician and the threshold for the previous year. As at 29 July 2021, the date relevant in these proceedings, the prescribed amount in accordance with the formula was $158,500.

13 It follows that a modern award does not apply to an employee otherwise covered by that award if that employee is a high income employee. As a consequence, none of the terms and conditions of employment contained in the modern award apply to the employee and the employee is, in effect, taken out of the operation of Pt 2-3 of the Act. The employer will not contravene the modern award for failing to adhere to its terms with respect to the high income employee. However, the statutory quid pro quo for non-application of the terms and conditions of the award is that the employer must comply with the guarantee during any period during which the employee is a high income employee and is covered by a modern award that is in operation: s 328(1). Civil penalties may result from a failure to so comply: s 328(1) and s 539(2) item 10.

Agreed facts

14 The separate questions are to be answered upon agreed facts to the following effect.

(1) Mr Roebuck is a natural person.

(2) SCA Property Group is, and at all times material to this action was:

(a) a duly incorporated company and parent company of the SCA Property Group of companies in Australia; and

(b) on 25 November 2022, SCA Property Group changed its name to Region RE Limited as Responsible Entity of Region Retail Trust and Region Management Trust.

(3) Shopping Centres Australasia Property Operations Pty Ltd provided a letter of offer of employment to Mr Roebuck dated 3 October 2018, which was signed (on behalf or by both parties) on 17 October 2018 and an employment contract between SCA Property Operations and Mr Roebuck was dated and signed on 26 October 2018.

(4) By written agreement dated 4 December 2020 (contract of employment), the employment of Mr Roebuck was transferred to SCA Property Group.

(5) Mr Roebuck was employed by SCA Property Group as a Regional Leasing Manager (WA) under the contract of employment. A document entitled ‘SCHEDULE 1 – Duties Statement’ was annexed to the contract of employment (duty statement).

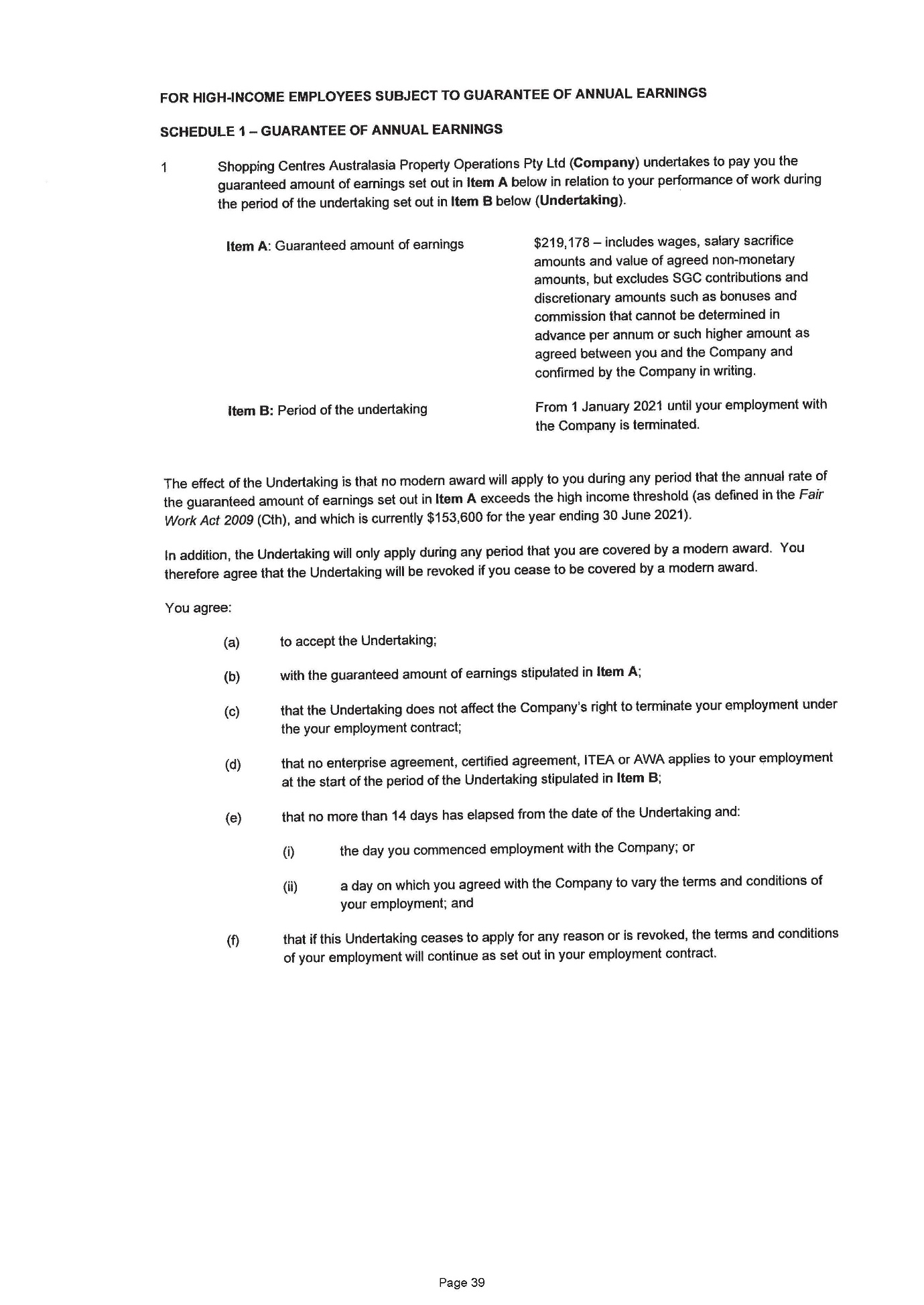

(6) A document entitled ‘SCHEDULE 1 – GUARANTEE OF ANNUAL EARNINGS’ was annexed to the contract of employment (guarantee). The guarantee contained terms that stated, in effect, that:

(a) SCA Property Group undertook to pay Mr Roebuck the guaranteed amount of earnings set out at Item A in relation to Mr Roebuck’s performance of work during the period of the undertaking set out in Item B;

(b) Item A stated that the guaranteed amount of earnings was a base salary of $219,178;

(c) Item B stated that the period of the undertaking was from 1 January 2021 until Mr Roebuck’s employment with SCA Property Group was terminated; and

(d) the effect of the undertaking was that no modern award would apply to Mr Roebuck during any period that the annual rate of the guaranteed amount of earnings set out in Item A exceeds the high income threshold (as defined in the Act), which was $153,600 for the year ending 30 June 2021).

(7) On 29 July 2021, Mr Roebuck’s role was made redundant and his employment with SCA Property Group was terminated with immediate effect. Mr Roebuck was informed of his redundancy and dismissal:

(a) in a Microsoft Teams meeting by Ms Leigh Dunn (Head of Leasing of SCA Property Group) and Ms Helen Voss (Head of Human Resources of SCA Property Group); and

(b) via a notice of redundancy letter dated 29 July 2021.

15 In addition to the statement of agreed facts, a court book comprising the letter offer dated 3 October 2018, the employment agreement dated 26 October 2018, the contract of employment of 4 December 2020 (together with the guarantee and duty statement), the notice of redundancy dated 29 July 2021 and the Award was tendered and received in evidence, by consent, on the hearing of the separate questions.

Is Mr Roebuck a high income employee?

16 It is convenient to start with a consideration of the principal issue underlying separate question 2 because, if Mr Roebuck was a high income employee of SCA Property Group at the time his employment was terminated, then even if he was covered by the Award at that time, the Award would not apply to him. Therefore, if separate question 2 is answered affirmatively as to the compliance of the guarantee with s 330(1)(b) and negatively as to the applicability of the Award to Mr Roebuck’s employment, it is not necessary to determine separate question 1.

Relevant terms of the contract of employment

17 The contract of employment is comprised of a letter of offer dated 1 December 2020 and accepted by execution by Mr Roebuck on 4 December 2020, a terms sheet, the guarantee and the duty statement. The letter of agreement contained the following relevant provisions.

1. Commencement and Term

1.1 Your employment commenced on 16 October 2018 (Commencement Date).

…

2. Position and Location

2.1 You will be employed on a Full Time basis in the position of Regional Leasing Manager (WA) (Position) or such other position determined by the Company from time-to-time. If your position with the Company changes for any reason, then the terms of this letter will continue to apply unless varied by the parties in writing.

2.2 You will initially be based at 208 Barker Road, Subiaco, WA although you may be required to work at other locations from time-to-time.

…

4. Remuneration

4.1 Your Remuneration is $240,000.00 gross per annum.

4.2 Your Remuneration presently consists of the following components:

Base Salary | $219,178.00 |

Superannuation (compulsory contributions as required by relevant superannuation legislation) | $20,822,00 |

Remuneration | $240,000.00 |

Base Salary

4.3 The Company will pay the Base Salary component of your Remuneration in equal monthly instalments by way of electronic funds transfer to a bank account or bank accounts nominated by you. The Company may change both the pay period and the date of payment.

…

5. Incentive Plans

5.1 In addition to your Remuneration, you may be eligible to participate in a short term incentive plan known as the "SCA Property Group Incentive Plan". Any payment is at the absolute discretion of the Company. The Company may rescind, change or replace the terms of the incentive plan including retrospectively.

6. Guarantee of Annual Earning

6.1 You agree to accept the Company's undertaking contained in Schedule 1 to this Agreement, being a Guarantee of Annual Earnings (Guarantee). You therefore acknowledge and agree that whilst the Guarantee is in operation, any applicable modern award which may otherwise apply to your employment will not apply to your employment. Should the Guarantee cease to apply to your employment for any reason, your terms and conditions of employment will continue to be as set out in this agreement.

18 The guarantee was in the following terms.

Applicable provisions of the Fair Work Act

19 The following provisions of Pt 2-9 Div 3 are relevant:

328 Employer obligations in relation to guarantee of annual earnings

Employer must comply with guarantee

(1) An employer that has given a guarantee of annual earnings to an employee must (subject to any reductions arising from circumstances in which the employer is required or entitled to reduce the employee’s earnings) comply with the guarantee during any period during which the employee:

(a) is a high income employee of the employer; and

(b) is covered by a modern award that is in operation.

Note 1: Examples of circumstances in which the employer is required or entitled to reduce the employee’s earnings are unpaid leave or absence, and periods of industrial action (see Division 9 of Part 3 3).

Note 2: This subsection is a civil remedy provision (see Part 4 1).

Employer must comply with guarantee for period before termination

(2) If:

(a) the employment of a high income employee is terminated before the end of the guaranteed period; and

(b) either or both of the following apply:

(i) the employer terminates the employment;

(ii) the employee becomes a transferring employee in relation to a transfer of business from the employer to a new employer, and the guarantee of annual earnings has effect under subsection 316(2) as if it had been given to the employee by the new employer; and

(c) the employee is covered by a modern award that is in operation at the time of the termination;

the employer must pay earnings to the employee in relation to the part of the guaranteed period before the termination at the annual rate of the guarantee of annual earnings.

Note: This subsection is a civil remedy provision (see Part 4 1).

Employer must give notice of consequences

(3) Before or at the time of giving a guarantee of annual earnings to an employee covered by a modern award that is in operation, an employer must notify the employee in writing that a modern award will not apply to the employee during any period during which the annual rate of the guarantee of annual earnings exceeds the high income threshold.

Note: This subsection is a civil remedy provision (see Part 4 1).

329 High income employee

(1) A full-time employee is a high income employee of an employer at a time if:

(a) the employee has a guarantee of annual earnings for the guaranteed period; and

(b) the time occurs during the period; and

(c) the annual rate of the guarantee of annual earnings exceeds the high income threshold at that time.

…

330 Guarantee of annual earnings and annual rate of guarantee

(1) An undertaking given by an employer to an employee is a guarantee of annual earnings if:

(a) the employee is covered by a modern award that is in operation; and

(b) the undertaking is an undertaking in writing to pay the employee an amount of earnings in relation to the performance of work during a period of 12 months or more; and

(c) the employee agrees to accept the undertaking, and agrees with the amount of the earnings; and

(d) the undertaking and the employee’s agreement are given before the start of the period, and within 14 days after:

(i) the day the employee is employed; or

(ii) a day on which the employer and employee agree to vary the terms and conditions of the employee’s employment; and

(e) an enterprise agreement does not apply to the employee’s employment at the start of the period.

(2) However, if:

(a) an employee is employed for a period shorter than 12 months; or

(b) an employee will perform duties of a particular kind for a period shorter than 12 months;

the undertaking may be given for that shorter period.

(3) The annual rate of the guarantee of annual earnings is the annual rate of the earnings covered by the undertaking.

331 Guaranteed period

The guaranteed period for a guarantee of annual earnings is the period that:

(a) starts at the start of the period of the undertaking that is the guarantee of annual earnings; and

(b) ends at the earliest of the following:

(i) the end of that period;

(ii) an enterprise agreement starting to apply to the employment of the employee;

(iii) the employer revoking the guarantee of annual earnings with the employee’s agreement.

Summary of the parties’ submissions

20 The question of whether Mr Roebuck was a high income employee of SCA Property Group turns on whether the contract of employment contains ‘a guarantee of annual earnings for the guaranteed period’ within the meaning of s 329(1)(a). It is not in issue that, if all other criteria are satisfied, that annual earnings of an amount of $219,217 exceed the high income threshold for the purposes of s 329(1)(c). Nor is it in issue that all criteria for ‘a guarantee of annual earning’ except the criterion in s 330(1)(a), which is the subject of separate question 1, and the criterion in s 330(1)(b), whether the guarantee in the contract of employment was ‘undertaking in writing to pay [Mr Roebuck] an amount of earnings in relation to the performance of work during a period of 12 months or more’, were satisfied. Also in issue is whether the guarantee in the employment contract was for a ‘guaranteed period’ within the meaning of s 331 and, thus, ‘the guaranteed period’ referred to in s 329(1)(a).

21 Relying on the reasoning of Wigney J in Association of Professional Engineers, Scientists and Managers Australia v Peabody Energy Australia Coal Pty Ltd [2022] FCA 945; (2022) 318 IR 113 (at [52]), Mr Roebuck submits that a guarantee of annual earnings requires an undertaking to pay an amount of earnings for a fixed or determinate and readily identifiable period. The reference in s 331 to the ‘end of that period’ means that the undertaking in question must specify the end date, or have an identifiable end date. Further, by operation of s 330(1)(b) the specified or identifiable end date must be a date at least 12 months after the start date of the undertaking.

22 SCA Property Group submits, in effect, that on the proper construction of the contract of employment and the guarantee it meets the criteria in s 330(1)(b) and s 331 of the Act based on the ordinary meaning of the text of those provisions. Further, to the extent that Peabody Energy is authority for the proposition that s 330(1)(b) requires a specified or identifiable end date, SCA Property Group submits Peabody Energy is plainly wrong and should not be followed because that interpretation introduced an additional and unnecessary requirement that is not to be found in the text of the Act. Alternatively, Peabody Energy is distinguishable because the purported undertaking under consideration in that case was a standard clause in an employment agreement to the effect that the employee would be paid a salary expressed as an annual amount during the period of employment. Accordingly, Peabody Energy should be confined to its facts and not applied to the circumstances of this case. Last, SCA Property Group submits that, in any event, the guarantee in Mr Roebuck’s contract of employment contained an identifiable end date and, therefore, falls within the interpretation favoured in Peabody Energy.

23 The last of SCA Property Group’s submissions is founded on a construction of the guarantee in the contract of employment by which the undertaking is, in effect, evergreen or rolling such that there are a series of guarantee periods of 12 months for each year of Mr Roebuck’s employment starting on 1 January and ending on 31 December of that year of employment. In each year SCA Property Group undertakes to pay Mr Roebuck $219,217 for work during that 12-month period. Therefore, in any given year of Mr Roebuck’s employment there is an identifiable end date for the guarantee period; namely, 31 December of that year of employment.

24 Mr Roebuck submits that an evergreen or rolling undertaking to pay an amount in each year that automatically renews year on year is not permitted under Pt 2-9 Div 3 of the Act. He submits that an undertaking in such terms is contrary to the purpose of the Act, which is to extend the entitlements of modern awards to employees in industries covered by the awards, except in limited circumstances. In substance, he submits the limited circumstances should be strictly applied and that renewal of any guarantee of annual earnings must take place at the end of the guarantee period for that guarantee. That is, the criteria of Pt 2-9 Div 3 must be re-applied for each guarantee period including the notice in s 328(3) and agreement in s 330(1)(c).

Is an evergreen or rolling undertaking capable of meeting the requirements of s 330(1)(b)?

25 While the analysis of the meaning of a provision in a statute or legislative instrument starts and finishes with the text, the text must be considered in context and having regard to the legislative purpose: Commissioner of Taxation v Consolidated Media Holdings Ltd [2012] HCA 55; (2012) 250 CLR 503 at [39] (French CJ, Hayne, Crennan, Bell and Gageler JJ). Where different interpretations are open, the interpretation that would best achieve the purpose or object of the Act is to be preferred to each other interpretation: Acts Interpretation Act 1901 (Cth), s 15AA. To that end, material not forming part of the Act that is capable of assisting in the ascertainment of the meaning of the provision to be considered may be taken into account, either to confirm the ordinary meaning of the provision or to determine the meaning in cases where meaning is ambiguous, obscure, absurd or unreasonable: Interpretation Act, s 15AB.

26 In CIC Insurance Ltd v Bankstown Football Club Ltd [1997] HCA 2; (1997) 187 CLR 384 at 408 (Brennan CJ, Dawson, Toohey and Gummow JJ) summarised the ‘modern approach to statutory interpretation’ as follows:

[T]he modern approach to statutory interpretation (a) insists that the context be considered in the first instance, not merely at some later stage when ambiguity might be thought to arise, and (b) uses "context" in its widest sense to include such things as the existing state of the law and the mischief which, by legitimate means such as those just mentioned, one may discern the statute was intended to remedy. Instances of general words in a statute being so constrained by their context are numerous. In particular, as McHugh JA pointed out in Isherwood v Butler Pollnow Pty Ltd [(1986) 6 NSWLR 363 at 388], if the apparently plain words of a provision are read in the light of the mischief which the statute was designed to overcome and of the objects of the legislation, they may wear a very different appearance. Further, inconvenience or improbability of result may assist the court in preferring to the literal meaning an alternative construction which, by the steps identified above, is reasonably open and more closely conforms to the legislative intent.

27 In Peabody Energy the relevant employment agreement contained no ‘undertaking’ and was merely an agreement to pay the employees a specified salary for an indefinite period or until the agreement was varied or terminated. The employees had not accepted any ‘undertaking’ for the purposes of s 330(1)(c). Further, before or at the time of giving the purported ‘guarantee of annual earnings’ the employer had not given the employees notice that a modern award would not apply as required by s 328(3) of the Act.

28 In that context, Wigney J observed:

47 It may be accepted that, under the terms of the contracts of employment of each of the relevant employees, Peabody agreed to pay, and the employees agreed to accept, a specified “Base Annualised Salary”, to be paid in equal monthly instalments, in return for the employees performing work. Peabody’s agreement to pay the employees an annualised salary could, at least in a general sense, perhaps be said to constitute an undertaking of sorts by Peabody to pay the employees the specified amount of earnings in relation to the performance of work. However, upon closer consideration of the terms of ss 328-331 of the Fair Work Act, and the terms of the contracts of employment between Peabody and the relevant employees, it cannot be accepted that any such undertakings by Peabody were capable of constituting “guarantee[s] of annual earnings” within the meaning of s 330 of the Fair Work Act. Nor can it be concluded that the employees relevantly accepted any such undertakings, as opposed to agreeing to the amount of the earnings Peabody had agreed to pay.

29 In keeping with the applicable principles of statutory interpretation, Wigney J then made the following observations with respect to the purpose of Pt 2-9 Div 3 of the Act:

48 Looking first at the relevant provisions, it would be erroneous to read and construe the terms of s 330 of the [Act] in isolation. Rather, s 330 must be read in the context of the entire scheme in Div 3 of Pt 2-9 of the [Act], which allows an employer to offer, and an employee to accept, a guarantee by the employer that the employee will earn more than a certain amount for a period of time, with the result that a modern award that would otherwise apply to the employee no longer applies. Importantly, the scheme includes protections to ensure that the guarantee is identifiable, enforceable and voluntarily accepted by the employee with knowledge that the result will be that the modern award will no longer apply to them. When read as a whole, it is readily apparent that a guarantee of annual earnings involves something more than a mere contractual promise to pay an employee a specified salary.

49 Subsection 328(1) provides that an employer who has given a guarantee of annual earnings to an employee must comply with that guarantee while the employee is a high income employee and covered by a modern award. Subsection 328(2) similarly provides that, in the case of a high income employee who has been terminated, the employer must in effect comply with the guarantee by paying the employee earnings at the annual rate for the period prior to termination. Importantly, ss 328(1) and (2) are civil remedy provisions, with the result that the guarantee is enforceable pursuant to the provisions in Pt 4-1 of the Fair Work Act. An employer found to be in contravention of either of the provisions is liable to pay a potentially substantial pecuniary penalty. It is difficult to accept that the intended operation of s 328 was such that an employer who breaches a contractual term requiring the employer to pay an employee a specified salary which happens to exceed the high income threshold would be liable to pay a pecuniary penalty for breaching that term. Given that ss 328(1) and (2) are civil remedy provisions, one would expect that a guarantee of annual earnings would be readily identifiable as such and therefore would involve or require something more than a mere agreement between an employer and an employee in respect of earnings.

50 The requirement imposed by s 328(3) is also an important element of the statutory scheme. It requires an employer, before or at the time of giving a guarantee of annual earnings, to notify the employee who is covered by a modern award of the consequences of the guarantee — the consequences being that the modern award that would otherwise apply to the employee will not apply. The obvious purpose of this provision is to ensure that an employee who accepts an undertaking given by an employer to pay an amount of earnings above the high income threshold only does so knowingly and voluntarily. Subsection 328(3) is also a civil remedy provision. It is difficult to imagine that it was intended that an employer who merely entered into a contract to pay an employee a salary which happened to be higher than the high income threshold could be liable to pay a pecuniary penalty for failing to notify the employee in accordance with s 328(3). One would again expect, in the circumstances, that the giving of a guarantee of annual earnings would be something that was readily recognisable and involve something more than a mere offer by an employer to pay a particular salary.

51 It should perhaps be noted, in the context of s 328(3) of the Fair Work Act, that Peabody submitted that an employer’s failure to comply with s 328(3) would not invalidate a guarantee of annual earnings given by an employer. It is unnecessary to decide that issue. APESMA did not contend that any guarantees of annual earnings given by Peabody were invalidated by Peabody’s contravention of s 328(3). APESMA’s case was, in effect, that no guarantees of annual earnings had been given in accordance with s 330, and therefore no question in relation to the effect of any contravention of s 328(3) arose. In any event, there is much to be said for the proposition that the statutory scheme in Pt 2-9 evinces a legislative purpose to invalidate any guarantee of annual earnings given or entered into in circumstances where the employer had failed to comply with s 328(3) of the Fair Work Act: cf Project Blue Sky Inc v Australian Broadcasting Authority (1998) 194 CLR 355 at [93] (McHugh, Gummow, Kirby and Hayne JJ). As has already been noted, s 328(3) provides an important protection for employees and is plainly intended to ensure that employees are made aware that if they accept an undertaking given by an employer pursuant to s 330(1)(b), a modern award will not apply to them throughout any period during which their income exceeds the high income threshold. It involves no great leap to conclude that the legislative purpose was to vitiate or nullify any acceptance of an undertaking given in the absence of compliance with s 328(3) of the Fair Work Act.

(Emphasis added.)

30 The reasons of Wigney J (at [52]) must be read in the context of the facts and terms of the contracts of employment under consideration in that case and the observations about the legislative purpose of Pt 2-9 Div 3 of the Act. In particular, the view expressed that the ‘guarantee period’ must have a specified or identifiable end date. Likewise, the statement of Wigney J (at [58]) to the effect that the employment contracts under consideration in that case contained no fixed period, capable of constituting a ‘guarantee period’ as defined in s 331.

31 I agree, with respect, with the summary of the legislative purpose of Pt 2-9 Div 3 of Wigney J in Peabody Energy at [48]-[51] and his view that ‘guarantee period’, as defined in s 331 of the Act, requires, at least, an identifiable ‘period’. That means that both the start and end of the ‘period’ must be capable of identification at ‘the time’ for the purposes of s 329(1)(b); namely, at the time relevant to determining whether an employee is a high income employee. The ‘guarantee period’ clearly relates to the period of the employer’s undertaking referred to in s 330(1)(b) ‘12 months or more’, but in the case of fixed term contracts for periods less than 12 months, an undertaking and, therefore a guarantee period, may be less than 12 months: s 330(2).

32 However, there is nothing in the legislative purpose of Pt 2-9 Div 3 or the purpose of the Act set out in s 3 to suggest that an employer cannot give multiple or serial undertakings to pay an amount of earnings in relation to the performance of work during multiple periods of 12 months. An interpretation of Pt 2-9 Div 3 that permits employers to give and employees to accept evergreen or rolling guarantees of annual earnings that exceed the high income threshold is consistent with object of the Act to provide ‘a balanced framework for cooperative and productive workplace relations’ by ‘providing workplace relations laws that are fair to working Australians, are flexible for businesses and promote productivity and economic growth’.

33 Part 2-9 Div 3 facilitates the object of the Act by making provision for employees to lose entitlements under a modern award in exchange for a guarantee to be paid an amount of earnings in an identifiable period at an annual rate that exceeds the high income threshold provided that the employee agrees to that exchange with notice of the consequence so agreeing. The protections contained within Pt 2-9 Div 3 are directed to ensuring that ‘the guarantee is identifiable, enforceable and voluntarily accepted by the employee with knowledge that the result will be that the modern award will no longer apply to them’. In that context, a guarantee of annual earnings ‘involves something more than a mere contractual promise to pay an employee a specified salary’: Peabody Energy at [48].

34 Further, there is nothing in the Explanatory Memorandum to the Fair Work Bill 2008 (Cth) to suggest that s 330(1)(b) should not be given its natural and ordinary meaning. In the case of multiple or serial undertakings, each undertaking for each separate period is capable of meeting the description of ‘an undertaking in writing to pay the employee an amount of earnings in relation to the performance of work during a period of 12 months’ on the plain meaning of the text of that provision. Moreover, provided that the amount in each guarantee period exceeds the high income threshold, notice is given in accordance with s 328(3) and s 330(1)(d) and the employee agrees to accept each undertaking in accordance with s 329(1)(c), the protective requirements and purpose of Pt 2-9 Div 3 are met.

35 It follows that Pt 2-9 Div 3 permits and does not preclude an employer giving multiple or serial undertakings each of which is separately ‘a guarantee of annual earnings for the guarantee period’ of that undertaking. Pt 2-9 Div 3 also permits and does not preclude an employer giving such undertakings in a form by which one follows the other for the duration of the employee’s employment. That is, the undertaking is ‘evergreen’ or ‘rolling’. I do not accept Mr Roebuck’s submission to the effect that to give an undertaking that meets the requirements of Pt 2-9 Div 3 it is necessary for the employer to give a new undertaking at the end of each guarantee period and for the employee to agree to that undertaking at that time.

Was an undertaking given to pay an amount of earnings during a period of 12 months?

36 Where, as here, the parties have comprehensively committed the terms of their relationship to a written contract the validity of which is not in dispute, the terms of the employment agreement are to be found within the written contract. In this respect, the principles governing the interpretation of a contract of employment are no different from those that govern the interpretation of contracts generally: Construction, Forestry, Maritime, Mining and Energy Union v Personnel Contracting Pty Ltd [2022] HCA 1; (2022) 275 CLR 165 at [40]-[62] (Kiefel CJ, Keane and Edelman JJ). See, also, Robinson v BMF Pty Ltd (in liq) (No 2) [2022] FCA 1191 at [182]-[186].

37 The relevant principles of contractual interpretation may be summarised as follows.

(1) The contract must be given an objective construction, by giving proper effect to the text, context, subject matter and purpose of its provisions: e.g. Pacific Carriers Ltd v BNP Paribas [2004] HCA 35; (2004) 218 CLR 451 at [22]; Toll (FGCT) Pty Ltd v Alphapharm Pty Ltd [2004] HCA 52; (2004) 219 CLR 165 at [40]; Mount Bruce Mining Pty Ltd v Wright Prospecting Pty Ltd [2015] HCA 37; (2015) 256 CLR 104 at [46]-[52].

(2) The approach to be adopted in construing the contract is the ‘objective approach’ so that the ‘meaning of the terms of a commercial contract is to be determined by what a reasonable business person would have understood those terms to mean’. Also, ‘[a] commercial contract is to be construed so as to avoid it making commercial nonsense or working commercial inconvenience’ (omitting footnotes): Electricity Generation Corporation t/as Verve Energy v Woodside Energy Ltd [2014] HCA 7; (2014) 251 CLR 640 at [35].

(3) The contract has to be construed in context, considering its terms as a whole, giving consistent meaning to all of its terms, and avoiding any apparent inconsistency: Australian Broadcasting Commission v Australasian Performing Right Association Ltd [1973] HCA 36; (1973) 129 CLR 99 at 109 (Gibbs J, in dissent, but not on the applicable principle). Put another way, preference is to be given to a construction that gives ‘a congruent operation to the various components of the whole’: Wilkie v Gordian Runoff Ltd [2005] HCA 17; (2005) 221 CLR 522 at [16].

(4) In the case of a contract of employment, the context includes that the employment relationship, in Australia, operates within a legal framework defined by statute and by common law principles, informing the construction and content of the contract of employment: Commonwealth Bank of Australia v Barker [2014] HCA 32; (2014) 253 CLR 169 at [1] (French CJ, Bell and Keane JJ); Personnel Contracting at [40] (Kiefel CJ, Keane and Edelman JJ).

(5) Words may be supplied, omitted or corrected in a written contract, as a matter of contractual interpretation, where it is clearly necessary in order to avoid absurdity or inconsistency: Fitzgerald v Masters [1956] HCA 53; (1956) 95 CLR 420 at 426-427, 437.

38 The construction of the guarantee must be reasonable and commercial. The literal meaning of the text is that SCA Property Group undertakes to pay Mr Roebuck $219,178 in relation to his performance of work during the period beginning 1 January 2021 until his employment is terminated. However, the literal text must be read having regard to the purpose or object of the transaction in the context of the agreement as a whole. When those matters are taken into consideration, it is evident that the effect of the guarantee is that SCA Property Group undertakes to pay Mr Roebuck $219,178 per year for each year of his employment from 1 January 2021 until his employment is terminated.

39 The parties manifestly intended that SCA Property Group’s undertaking would operate as guarantee of annual earnings from the purpose of Pt 2-9 Div 3 of the Act. Clause 6.1 of the contract of employment provides that Mr Roebuck accepts SCA Property Group’s undertaking contained in Sch 1 and it is described as a ‘Guarantee of Annual Earnings’. Mr Roebuck acknowledges and agrees that while the guarantee is in operation any applicable modern award will not apply to his employment. That is consistent with the criterion of a guarantee of annual earnings contained in s 330(1)(c) of the Act. The guarantee contains a notice in writing to the effect that a modern award will not apply to Mr Roebuck during any period during which the annual rate of the amount set out in Item A exceeds the high income threshold. That notice is consistent with SCA Property Group’s obligation under s 328(3) of the Act. The guarantee provides that the undertaking will only apply during any period that Mr Roebuck is covered by a modern award. That is consistent with the criterion for a guarantee of annual earnings contained in s 330(1)(a) of the Act.

40 Although the first paragraph of the guarantee refers to an undertaking to pay ‘the guaranteed amount of earnings set out in Item A [$219,178] … during the period of the undertaking set out in Item B [1 January 2021 until Mr Roebuck’s employment is terminated]’, the paragraph under Item A and Item B provides that ‘no modern award will apply to [Mr Roebuck] during any period that annual rate of the guaranteed amount of earnings set out in Item A [$219,178] exceeds the high income threshold (as defined in the [Act], and which is currently $153,600 for the year ending 30 June 2021)’ (emphasis added). Therefore, the sum set out in Item A ($219,178) while described as ‘the guaranteed amount of earnings’ is equated with ‘the annual rate of the guaranteed amount’. The concept of ‘annual rate’ is described in s 330(3) of the Act as the ‘annual rate of the guarantee of annual earnings is the annual rate of the earnings covered by the undertaking’. In context, where the expression ‘guaranteed amount of earnings’ is used in the guarantee it means ‘guaranteed amount of [annual] earnings’.

41 That construction is consistent with other provisions of the contract of employment. Clause 4.1 provides that Mr Roebuck’s remuneration is $240,000 gross per annum. Clause 4.2 and cl 4.3 provide that the gross sum includes a base salary component of $219,178 to be paid in equal monthly instalments. Therefore, the reference to ‘guaranteed amount of earnings’ in the guarantee is evidently a reference to a guarantee to pay the base salary amount of $219,178 per annum.

42 Given the clear intention of the parties that the guarantee would operate as a guarantee of annual earnings and that the sum of $219,178 referred to in the guarantee was an annual amount of earnings, a construction of the guarantee that gives effect to the parties’ evident intention is to be preferred to one that would render the guarantee ineffective or redundant. It is also important to keep in mind that SCA Property Group was obliged to comply with the guarantee during any period during which Mr Roebuck was a high income employee and covered by a modern award that was in operation. The guarantee reflects an exchange of entitlements under a modern award for a guarantee of high annual earnings that the Act mandates, in effect, as fair as between employer and employees. I see no reason not to give effect to the intention of the parties and the legislature. Thus, having regard to the purpose of the guarantee and its text read in the context of the contract of employment as a whole, reasonable parties would understand that the effect of the guarantee is that SCA Property Group undertakes to pay Mr Roebuck $219,178 per year for each year of his employment from 1 January 2021 until his employment is terminated.

Separate question 2: disposition

43 On the proper construction of the guarantee, it contained ‘an undertaking in writing to pay [Mr Roebuck] an amount of earnings [$219,178] in relation to the performance of work during a period of 12 months [per year]’ within the meaning of s 330(1)(b) of the Act. At the time of termination of Mr Roebuck’s employment on 29 July 2021, the ‘guarantee period’ was identifiable and was the period that started on 1 January 2021 and ended on 31 December 2021. That is, SCA Property Group had guaranteed to pay Mr Roebuck $219,178 in that period, subject to earlier termination of his employment in accordance with the provisions of the contract of employment. As Mr Roebuck’s employment was terminated by SCA Property Group before the end of the relevant identifiable guarantee period, s 328(2) of the Act applied and Mr Roebuck was entitled to be paid earnings in relation to the part of the guarantee period before termination at the annual rate of the guaranteed amount of annual earnings.

44 If Mr Roebuck’s employment had not been terminated within the first guarantee period, the undertaking would have renewed and applied to a further guarantee period between 1 January 2022 and 31 December 2022. That process of renewal would have continued indefinitely until the termination of Mr Roebuck’s employment or a variation in the terms of the contract of employment. In whichever year Mr Roebuck’s employment was terminated, the guarantee period, for the purposes of s 331, would be identifiable and start on 1 January and end on 31 December of that year of Mr Roebuck’s employment.

45 It follows that the answer to separate question 2 is that the guarantee of annual earnings, annexed to the employment agreement between SCA Property Group and Mr Roebuck dated 4 December 2020, complied with s 330(1)(b) and Pt 2-9 Div 3 of the Act. Further, the Award did not apply to Mr Roebuck’s employment with SCA Property Group pursuant to s 47 of the Act.

Was Mr Roebuck covered by the Award?

46 In light of the answer to separate question 2, it is not necessary to answer separate question 1. However, given that the matter was fully argued and in the event the answer to separate question 2 is wrong, set out below are the reasons why I have concluded that Mr Roebuck was covered by the Award.

Relevant provisions of the Award

47 As already mentioned, s 48(1) of the Act provides that a modern award covers an employee or employer if the award is expressed to cover the employee or employer. Clause 4.1 of the Award provides that it ‘covers employers in Australia engaged in the real estate industry in respect to their employees engaged in classifications in clause 14 – Minimum rates to the exclusion of any other modern award’. Clause 4.2 provides that the real estate industry means the provisions of services associated with sales, acquisitions, leasing and/or management of residential, commercial, retail, industrial, recreational, hotel, retirement and any other leasehold or real property and/or businesses. It is not in issue that SCA Property Group is engaged in the real estate industry and, therefore, the Award covers SCA Property Group. Thus, the question is whether Mr Roebuck was engaged in one of the classifications in cl 14 of the Award.

48 Clause 12.1 provides that Sch A – Classification Structure and Definitions to the Award contains a definition for each classification in cl 14.1. Clause 12.2 provides that at the time of engagement the employer must advise the employee in writing of their classification and also at any time when there is a change to an employee’s classification.

49 Clause 14.1 contains minimum rates for ordinary hours worked by an employee. These are set out in a table that identifies five classifications: (1) Real Estate Employee Level 1 (Associate Level) – first 12 months of employment at this level; (2) Real Estate Employee Level 1 (Associate Level) – after first 12 months of employment at this level; (3) Real Estate Employee Level 2 (Representative Level); (4) Real Estate Employee Level 3 (Supervisory Level); and (5) Real Estate Employee Level 4 (In-Charge Level). Clause 14.3 provides that the minimum weekly rate in cl 14.1 is not payable to an employee engaged on a commission-only basis pursuant to cl 16.7. Clause 14.4 deals with junior employees who are entitled to a percentage of the minimum rates based on their age starting at 60% for under 19 years and ending at 100% at 21 years. A junior employee must not be employed on a commission-only basis. The classifications are described in more detail in Sch A – Classification Structure and Definitions of the Award. Each classification is described by reference to a general description of duties and responsibilities, indicative job titles and indicative tasks.

50 Clause 16 deals with commissions and bonus or incentive payments. Clause 16.7(a) permits the employer to enter into a commission-only employment arrangement with employees engaged in property sales or commercial, industrial or retail leasing as a Real Estate Employee Level 2 or higher. Clause 16.7(b) provides that the objective of commission-only employment arrangements is to provide a mechanism by which a salesperson who meets the requirements set out in cl 16.7(c) should achieve remuneration of 125% or more of the annualised minimum wage that an employee working at the same property sales level under the Award would be entitled to be paid. One of the criteria in cl 16.7(c) is that employees can establish that they have achieved the Minimum Income Threshold Amount described in cl 16.7(d). Clause 16.7(e) provides that cl 10 (part-time employees), cl 11 (casual employees), cl 14 (minimum rates), cl 16.1 (payment by wages with commission, bonus or incentive payments), cll 17.1-17.8 allowances, cl 19.1 and cl 19.2 (overtime) and cl 20.6 (annual leave loading) do not apply to commission-only employees. Broadly, many entitlements under the Award do not apply to high income employees on commission-only arrangements by which they are expected to earn in excess of 125% of the minimum rates. Clause 16.7(f) provides that the minimum commission-only rate is 31.5% of the employer’s gross commission.

51 Relevantly, Sch A of the Award provides:

A.2 Real Estate Employee Level 2 (Representative level)

A.2.1 Employees at this level have been classified as Level 2 by the employer. An employee at this level may perform any of the duties of a Real Estate Employee Level 1 (Associate Level) but will also have responsibility for the listing and/or selling of real property or businesses, for helping clients to buy real property or businesses or for managing rental or strata/community title properties or for sourcing and/or securing new property managements (including strata title managements).

A.2.2 Indicative job titles of a Real Estate Employee Level 2 (Representative Level) include:

• Property Sales Representative or Real Estate Salesperson;

• Buyer’s Agent;

• Property Management Representative or Property Manager;

• Business Development Manager;

• Strata/Community Title Management Representative or Strata Title Manager.

A.2.3 Indicative tasks

[A list of 22 indicative tasks is then set out.]

A.3 Real Estate Employee Level 3 (Supervisory level)

A.3.1 A principal requirement of an employee at this level is the supervision of employee(s) classified as Real Estate Employee Level 2 (Representative Level). An employee at this level may perform any of the duties of a Real Estate Employee Level 2 (Representative Level) but will also have responsibility for the allocation of duties, co-ordinating work flow, checking progress, quality of work and resolving problems of an employee(s) at a lower level.

A.3.2 Indicative job titles of a Real Estate Employee Level 3 (Supervisory Level) include:

• Property Sales Manager or Property Sales Supervisor;

• Property Management Supervisor;

• Strata/Community Title Management Supervisor.

A.3.3 Indicative tasks

[A list of 10 indicative tasks is then set out.]

A.4 Real Estate Employee Level 4 (In-Charge-Level)

A.4.1 Employees at this level have been classified as Level 4 by the employer. An employee at this level may perform any of the duties of a Real Estate Employee Level 3 (Supervisory Level). The employee at this level will hold applicable qualification(s) under real estate law and have been appointed by the employer to be responsible for ensuring the business complies with its statutory obligations under real estate law.

A.4.2 Indicative job titles of a Real Estate Employee Level 4 include:

• Licensee-In-Charge;

• Agency Manager.

A.4.3 Indicative tasks

Indicative tasks at this level may include:

(a) overall supervision and management of the office;

(b) planning and managing business finances for the organisation;

(c) ensuring that the office complies with all of its statutory obligations imposed under relevant real estate law;

(d) facilitating change and innovation.

Duty statement

52 The duty statement in the contract of employment with SCA Property Group is as follows:

SCHEDULE 1 – Duties Statement

JOB DESCRIPTION

Position Title | Regional Leasing Manager | Reports to | Head of Leasing |

Department | Leasing | Approved |

POSITION SUMMARY

The role of the Regional Leasing Manager is to maximise the rental income of the property by securing lease renewal to ensure maximum value and return for the organisation. This role will driving ongoing growth of the SCA Property Group Portfolio identifying the ideal retail mix, conducting feasibility/ benchmarking studies, securing new site leases and lease renewals, negotiating and documenting commercial terms that ensure viable businesses, and delivery of tenancies in an efficient and cost effective manner, whilst ensuring effective communication and management of all parties involved in such dealings. The Regional Leasing Manager is also responsible for managing financial budgets and performance targets are met/exceeded each year and that the values of the organisation are upheld in any interactions with all internal and external stakeholders. This role will also have supervisory responsibility of Leasing Executives |

KEY WORKING RELATIONSHIPS

INTERNAL | EXTERNAL |

Chief Operating Officer | Retailers |

Head of Leasing | External Leasing Operatives |

National Leasing Manager | Centre Managers |

Asset Manager | |

Finance | |

Legal |

KEY RESULT AREAS (KRAs)

[The duty statement sets out four KRAs: Lease Renewals; New Sites; Internal & External Relationships; and General Areas of Responsibility and lists of Main Activities associated with each KRA.]

COMPETENCY PROFILE

[The duty statement sets out a list of Competencies with associated Qualifications and a list of Knowledge with associated Experience.]

Authority for the role |

• Leasing Executive is not authorised to sign/execute acceptance letters, heads of agreements, tenancy proposals etc without the written approval of SCA Property Group Senior Management |

ACCEPTANCE OF POSITION DESCRIPTION

[The duty statement ends with a declaration of acceptance and Mr Roebuck’s signature.]

Summary of the parties’ submissions

53 Mr Roebuck submits that his role as Regional Leasing Manger was to undertake tasks that are typical of a property manager, responsible for the day-to-day tasks associated with the leasing of real property. The duty statement does not describe a senior management position, nor a position with any decision-making authority. Mr Roebuck draws on an earlier award and changes to the manner in which classifications are described between the earlier award and the Award to aid the construction of the Award. He also draws on the manner in which his duties were described under his contract of employment with SCA Property Operations to aid in determining the nature of the work he was to perform under the later contract of employment with SCA Property Group. Mr Roebuck submits, based on the duty statements in each contract of employment, that the nature of his work fell within the classification Real Estate Employee Level 2 (Representative level) or Real Estate Employee Level 3 (Supervisory level) of the Award.

54 Although Mr Roebuck was not advised by SCA Property Group at the time of his engagement of his classification in accordance with cl 12.2 of the Award, Mr Roebuck submits that this is not material. He submits that the relevant question is not how or whether SCA Property Group classified him, but whether as a matter of the proper construction of the Award his duties fell within a classification in the Award.

55 Mr Roebuck submits, by way of comparison between the duty statement in each contract of employment and the description of the indicative tasks in the Award, the position summary closely aligns with the description of the Real Estate Employee Level 2 (Representative level) and Real Estate Employee Level 3 (Supervisory level) and many of the key result areas (KRAs) referred to in the duty statement correspond with the indicative tasks described in Sch A of the Award. That comparison, in so far as it relates to the duty statement in the contract of employment with SCA Property Group, is reflected in the schedule to these reasons.

56 SCA Property Group submits that only the description of Mr Roebuck’s role in the duty statement of his contract of employment with SCA Property Group is relevant. It submits that the relevant duty statement indicates that Mr Roebuck was appointed to a position that was more senior than the classification Real Estate Employee Level 4 (In-Charge Level) which is the highest classification in the Award.

57 SCA Property Group submits it had not classified Mr Roebuck as Level 4 and that fact, in and of itself, is determinative. Further, Mr Roebuck’s position title ‘Regional Leasing Manager (WA)’ is indicative of a role far more senior than ‘Licensee-In-Charge’ or ‘Agency Manager’. The list of indicative tasks in the Award for Level 4 with repeated references to ‘office’ suggest a narrow or limited scope of responsibility limited to a particular location or office. The KRA activities described in the duty statement also indicate that Mr Roebuck’s role carried a wider scope of authority, greater complexity and more responsibility than the Level 4 Award classification.

58 SCA Property Group emphasises that the duty statement included activities such as:

(a) negotiating all commercial terms for each lease renewal;

(b) conducting all relevant site visits, market analysis etc. for all leasing deals and sites;

(c) establishing and maintaining effective partnerships with retailers; and

(d) attending and (or) conducting retailer portfolio reviews etc.

59 SCA Property Group also relies on the position summary and its references to responsibility for ‘securing new site leases and lease renewals’, ‘driving ongoing growth of the SCA Property Group’ and upholding ‘the values of the organisation … in any interactions with all internal and external stakeholders’. SCA Property Group submits that these are indications that Mr Roebuck was to be the external face of the business and that his level of seniority was well beyond that described by Level 4 of the Award. Additionally, the level of Mr Roebuck’s remuneration is so out of proportion with the minimum rates in the Award as to indicate a role of far greater seniority than Level 4 of the Award. Also, the terms of the employment contract included participation in a short term incentive plan which is indicative of a role in senior management.

60 In substance, SCA Property Group submits that Mr Roebuck was employed as ‘Regional Leasing Manager (WA)’ and that, having regard to the duty statement, the principal purpose of that role was management of a part of SCA Property Group’s business that involved leasing real properties it owned in Western Australia. While there were aspects of the classification Real Estate Employee Level 4 (In-Charge Level) that involve management functions, these are confined or limited to a location or office of a real estate business. Therefore, the principal purpose of that classification is management of an office and other employees in that office, not a State or region.

Consideration

61 There are two related questions to determine whether Mr Roebuck’s employment fell within the coverage of the Award. First, what is the proper construction of the Award? In particular, what is the meaning and effect of the classifications described in cl 14 and Sch A of the Award. Second, on the proper construction of the contract of employment, do the duties of Mr Roebuck fall within the scope of at least one of the classifications in the Award?

62 The principles applicable to interpretation of the contract of employment have been addressed earlier in these reasons. However, these principles do not apply to the interpretation of a modern award.

63 A modern award is a legislative instrument and, as such, is interpreted in accordance with the provisions of the Interpretation Act: City of Wanneroo v Australian Municipal, Administrative, Clerical and Services Union [2006] FCA 813; (2006) 153 IR 426 at [51]-[57] (French J). Accordingly, the general principles of statutory interpretation referred to earlier in these reasons apply equally to the Award and the ordinary meaning of the text must be considered in context and having regard to the legislative purpose. In the case of a modern award, the industrial context and purpose as well as the commercial and legislative context forms part of the relevant interpretive context and purpose: see, generally, Swissport Australia Pty Ltd v Australian Municipal Administrative Clerical and Services Union (No 3) [2019] FCA 37; (2019) 284 IR 97 at [52] (Rangiah J) and the authorities there cited. Having regard to the relevant context and purpose, a narrow or pedantic approach to construction of a modern award is not appropriate, but ‘[a] court is not free to give effect to some anteriorly derived notion of what is fair or just regardless of what has been written in the award’: Communications, Electrical, Electronic, Energy, Information, Postal, Plumbing and Allied Services Union of Australia v Excelior Pty Ltd [2013] FCA 638 at [30] (Katzmann J), citing Kucks v CSR Limited [1996] IRCA 141; (1996) 66 IR 182 at 184; Ansett Australia Limited (subject to Deed of Company Arrangement) v Australian Licenced Aircraft Engineers' Association [2003] FCAFC 209 at [8]; City of Wanneroo at [57]; and Australian Communication Exchange Ltd v Deputy Commissioner of Taxation [2003] HCA 55; (2003) 77 ALJR 1806 at [115] (Hayne J).

64 Having regard to these principles, I do not accept SCA Property Group’s submission to the effect that the absence of SCA Property Group advising Mr Roebuck of his classification or otherwise classifying him is determinative. That interpretation would give the Award and the description of the classification a narrow and pedantic construction of the kind eschewed by the authorities. Clause 12.2 places a positive obligation on an employer to advise employees in writing of their classification. Failure to do so would be a contravention of a term of the Award for the purposes of s 45 of the Act. Therefore, the reference to classification ‘as Level 4 by the employer’ in Sch A.4.1 of the Award and similar expressions in each of Sch A.1.1., Sch A.2.1 and Sch A.3.1 presupposes the employer’s compliance with cl 12.2 of the Award. It is not a requirement of the classification that the employer has, in fact, complied with cl 12.2. Therefore, I accept Mr Roebuck’s submission to the effect that the real question is whether the tasks that the employee performs meet the functional requirements of the classification.

65 White J in Bis Industries Limited v Construction, Forestry, Maritime, Mining and Energy Union [2021] FCA 1374 at [269] and Flick J in NSW Trains v Australian Rail, Tram and Bus Industry Union [2021] FCA 883; (2021) 174 ALD 521 at [120] implicitly accepted that, for the purposes of classification, it is necessary to ascertain whether the ‘principal purpose’ for which the employee was employed falls within the classification. In this respect, the Full Bench of the Industrial Relations Commission made the following observations concerning classification in Carpenter v Corona Manufacturing Pty Ltd (2002) 122 IR 387 at [8]-[9].

8 At the time of the termination of his employment, the appellant was employed by the respondent as National Sales Manager. The agreement under which he was employed stated that the “function and responsibilities of the employee will involve sales and management duties throughout Australia”. The appellant’s job description identified his duties in a way that, in our view, can only be described as principally managerial in nature. The Commissioner found that the tasks for which the appellant was employed were those set out in the job description. We agree. Whilst the appellant may, on occasion, have performed tasks that might fall under the headings of “soliciting orders”, “obtaining sales leads” or “promoting sales”, such tasks formed a minor part of the work he was required to perform.

9 In our view, in determining whether or not a particular award applies to identified employment, more is required than a mere quantitative assessment of the time spent in carrying out various duties. An examination must be made of the nature of the work and the circumstances in which the employee is employed to do the work with a view to ascertaining the principal purpose for which the employee is employed. In this case, such an examination demonstrates that the principal purpose for which the appellant was employed was that of a manager. As such, he was not “employed in the process, trade, business or occupation of . . . soliciting orders, obtaining sales leads or appointments or otherwise promoting sales for articles, wares, materials” and was not, therefore, covered by the award.

(Footnotes omitted.)

66 While it may be accepted that the relevant enquiry is whether the ‘principal purpose’ for which Mr Roebuck was employed falls within a classification in Sch A of the Award, as the cited extract from the Full Bench’s reasons in Carpenter makes clear, the purpose is ascertained from an examination of the ‘nature of the work and the circumstances in which the employee is employed to do the work’. Here, the parties rely only on the statement of agreed facts and the documents tendered in the court book. There is no evidence of precisely what work Mr Roebuck performed from which any quantitative assessment of the time spent on the various tasks could be made. Likewise, there is no evidence, beyond that which can be inferred from the text of the employment contract, of the circumstance in which Mr Roebuck was employed. Moreover, there is no evidence from which to ascertain context or a broader understanding of the nature of the work Mr Roebuck performed that corresponds with the various activities described in the duty statements.

67 As to the applicable duty statement, in these circumstances, I accept SCA Property Group’s submission that the only relevant duty statement is that attached to the contract of employment with SCA Property Group. That is the only description of the nature of Mr Roebuck’s work at the time he was employed that is in evidence. Therefore, in the circumstances of this case, the nature of Mr Roebuck’s work and whether he was engaged in one of the classifications described in the Award must be determined by reference to that duty statement and the proper construction of the written terms of that contract of employment.

68 In keeping with the general principles of award interpretation, in the context of interpreting classification criteria in a modern award, Bromwich J said in Putland v Royans Wagga Pty Limited [2017] FCA 910 at [301]:

… An award classification should not be read so strictly to require each and every criterion to apply in order that the classification apply. [By reference to the text of the classifications in the Clerks Award] it will suffice if enough of the features apply to represent fairly the “characteristic and typical duties/skills”, with the characteristics being the “primary guide” as they “indicate the level of basic knowledge, comprehension of issues, problems and procedures required and the level of supervision or accountability of the position”. The “key issue” is the level of “competency and skill” required to be exercised in the work performed, not the duties performed per se. A perfect fit is not required.

(Emphasis original.)

69 These observations of Bromwich J in Putland apply, with all necessary modifications, to the description of the duties and responsibilities, indicative job titles and indicative tasks set out in Sch A of the Award. Further, the observations are not inconsistent with an approach that requires an examination of the ‘nature of the work and the circumstances in which the employee is employed to do the work’ to ascertain if the ‘principal purpose’ of the employee’s employment falls within a classification in a modern award. The question is whether enough of the features of the duties of Mr Roebuck’s position, as described in the duty statement, apply to represent fairly the duties and responsibilities of at least one of the classifications in Sch A of the Award. Consideration of that question naturally forms part of an examination of the ‘nature of the work’ for the purposes of ascertaining the principal purpose of the employment. Thus, there need not be precise correspondence in the duties and responsibilities described in the duty statement and the description of the classification in the Award for the nature of the work and principal purpose of the employment to meet the classification in the Award. However, if significant or substantive duties and responsibilities described in the duty statement fall outside the duties and responsibilities of any classification described in the Award, that may indicate that the principal purpose of the position is not within any classification in the Award.

70 In the context of an examination of the nature of Mr Roebuck’s work derived from the duty statement, SCA Property Group’s reliance and emphasis on the job description and position summary has limitations. As Flick J observed in NSW Trains (at [120]) a focus on an employee’s position description ‘is susceptible of leading to too narrow an inquiry as to what [an employer] may ask of its [employees] pursuant to … contracts of employment’.

71 In this case, the duty statement, as a whole, describes a diverse range of activities. These are identified as ‘Key Result Areas’ suggesting that all the activities under that heading are core components of the nature of the work Mr Roebuck was to perform. Certain activities are managerial in character, but many, if not most, are functional and, broadly, fall within the indicative tasks of a real estate employee engaged in leasing work described in the classifications for Level 2 and Level 3 in Sch A of the Award. Moreover, Mr Roebuck’s managerial responsibility for SCA Property Group’s leasing business in Western Australia was quite limited in that he had no authority to execute any relevant agreements relating to leases without approval of ‘senior management’.

72 Overall, the descriptions of the activities in the duty statement are indicative of supervision and management of internal leasing executives (which I take to mean other employees of SCA Property Group engaged in leasing activities) and external leasing teams (which I take to mean independent real estate agents engaged by SCA Property Group) as well as directly performing leasing functions. Management of SCA Property Group’s business is largely limited to ensuring that budgets (which I take to mean budgets set by others) are met and reporting performance against budget to senior management.

73 I accept that the description of the position summary and activities in the duty statement do not fall neatly within the description of the indicative tasks for the classification Level 4 in the Award. However, Mr Roebuck does not contend that he was engaged in that classification. He puts his case on the footing that he was engaged in the classification for Level 2 or Level 3 having regard to indicative tasks for those classifications compared to the activities of his position described in the duty statement. Therefore, it is not critical, on Mr Roebuck’s case, whether or not the principal purpose of his employment meets the classification for Level 4.

74 Typically, real estate agents are appointed as agents of a third-party principal and are paid a commission for facilitating a successful transaction relating to real estate on behalf of the principal. It is evident that the Award is largely focussed on employers which conduct real estate agency businesses of that character and their employees. In the case of SCA Property Group, I infer from the provisions of the contract of employment that it employed real estate agents directly (internal agents) rather than as independent contractors to facilitate real estate transactions on its behalf. I also infer that it engaged independent real estate agent businesses (external agents) from time to time. Mr Roebuck’s duties and responsibilities included supervision of ‘Leasing Executives’ and having key working relationships with ‘External Leasing Operatives’. Given that SCA Property Group was not engaged in business as a real estate agent, but employed persons to perform the functions of real estate agents, it is inevitable that there will be a degree of mismatch and lack of cohesion in the application of the provisions of the Award to SCA Property Group, as employer, and its employees engaged in real estate agent functions. However, whether a person is engaged directly as employee of the principal or indirectly as employee of independent real estate agent business, that person performs the functions of a real estate agent for the principal (e.g., landlord). The real estate industry functions of the person in each case are essentially the same which is to facilitate a real estate transaction between the principal and a third-party. In this regard, the observations of Bromwich J in Putland are apposite and the Award should be given a purposive construction in its application such that the classifications extend to employees engaged in work of substantially the same nature irrespective of whether or not the employers covered by the Award are engaged in business as real estate agents or engaged in business that includes buying and selling or leasing real estate on their own account.

75 Having regard to the nature of SCA Property Group’s business, Mr Roebuck’s position title ‘Regional Leasing Manger (WA)’ is similar to the indicative job titles for the Level 4 classification for a real estate agent business which include: ‘Licensee-In-Charge; and ‘Agency Manager’. All titles suggest a significant role in supervision and management of an office or part of the employer’s business, a role in planning and managing business finances for the organisation, and a role ensuring that the office or part of the employer’s business complies with applicable statutory obligations relating to the real estate industry. While not confined to a particular location or office, the supervisory and management activities described in the duty statement are of a broadly similar nature.