FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Fair Work Ombudsman v Foot & Thai Massage Pty Ltd (in liquidation) (No 8) [2024] FCA 483

ORDERS

Applicant | ||

AND: | FOOT & THAI MASSAGE PTY LTD (ACN 147 134 272) (IN LIQUIDATION) First Respondent COLIN KENNETH ELVIN Second Respondent JUN MILLARD PUERTO Third Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT DECLARES THAT:

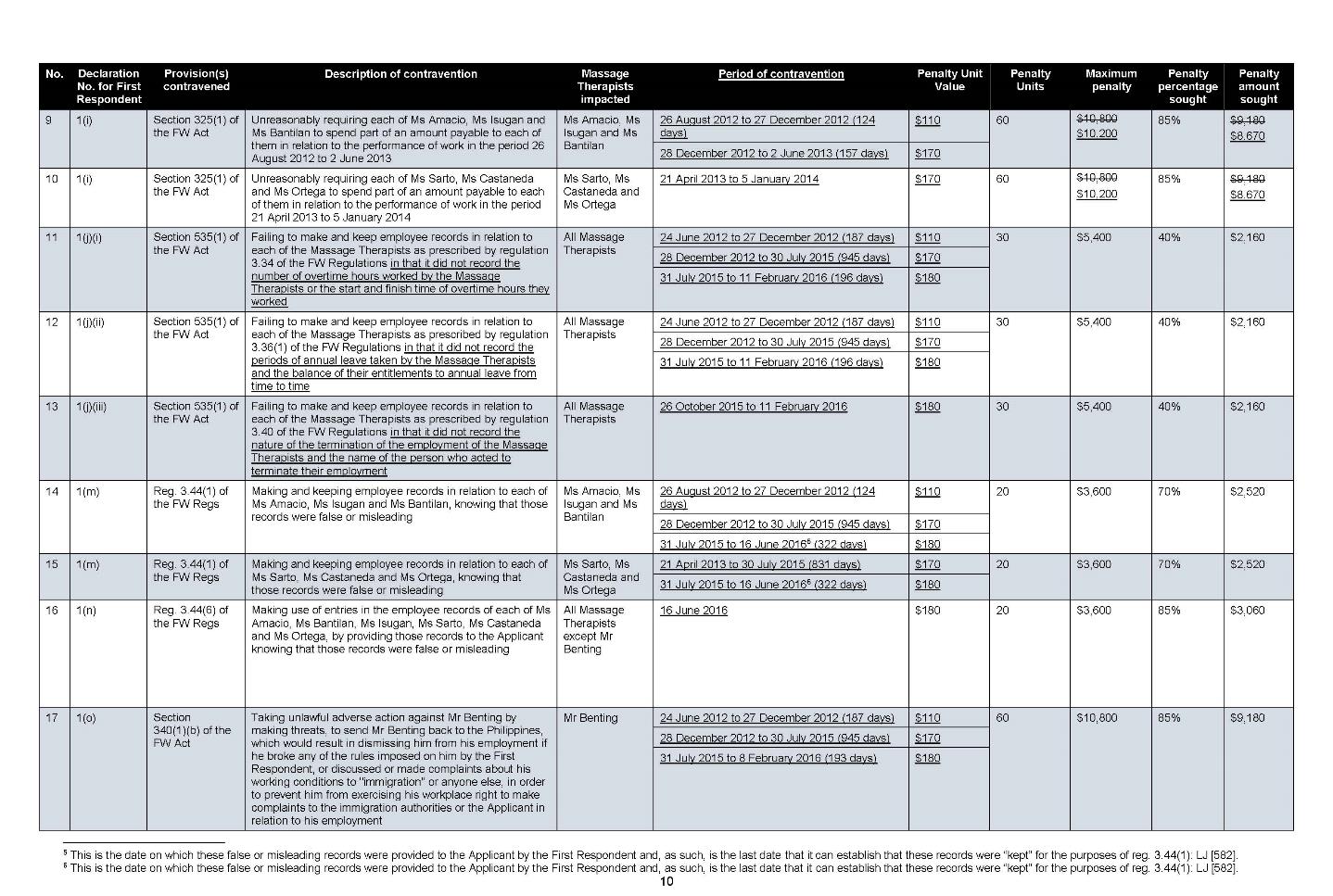

1. During various periods from 24 June 2012 until 16 June 2016 inclusive, the first respondent contravened:

(a) s 45 of the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) (FW Act) by failing to pay each of Irene Amacio (Ms Amacio), Crisanta Bantilan (Ms Bantilan), Ruben Benting (Mr Benting), Delo Be Isugan (Ms Isugan), Janice Castaneda (Ms Castaneda), Mayet Ortega (Ms Ortega), and Cyrene Sarto (Ms Sarto) (collectively, the Massage Therapists) the minimum hourly rates of pay, as Health Professional Level 1 employees (HP Level 1), in accordance with cl 15.2 of, and cl A.2.5 of Schedule A to, the Health Professionals and Support Services Award 2010 (Health Award);

(b) s 45 of the FW Act by failing to pay each of the Massage Therapists public holiday rates, as HP Level 1 employees, in accordance with cl 32.2 of, and cl A.7.3 of Schedule A to, the Health Award;

(c) s 45 of the FW Act by failing to pay each of the Massage Therapists overtime rates for overtime work performed between Monday and Saturday as HP Level 1 employees, in accordance with cl 28.1(a) of the Health Award;

(d) s 45 of the FW Act by failing to pay each of the Massage Therapists overtime rates for overtime work performed on Sundays, as HP Level 1 employees, in accordance with cl 28.1(b) of the Health Award;

(e) s 44(1) of the FW Act by requesting or requiring each of the Massage Therapists to work more than 38 hours a week when it was unreasonable to do so, in contravention of s 62(1) of the FW Act;

(f) s 44(1) of the FW Act by failing to pay each of the Massage Therapists their respective accrued untaken annual leave entitlements on termination, in accordance with s 90(2) of the FW Act;

(g) s 44(1) of the FW Act by failing to give the Fair Work Information Statement to each of the Massage Therapists as it was obliged to do under s 125(1) of the FW Act;

(h) s 323(1) of the FW Act by failing to pay each of the Massage Therapists in full in that it made deductions from their wages when it was not authorised to do so;

(i) s 325(1) of the FW Act by unreasonably directing each of Ms Amacio, Ms Bantilan, Ms Isugan, Ms Castaneda, Ms Ortega and Ms Sarto to refund part of their wages to the first respondent;

(j) s 535(1) of the FW Act by failing to make and keep employee records in relation to each of the Massage Therapists, as prescribed by:

(i) reg 3.34 of the Fair Work Regulations 2009 (Cth) (FW Regulations) in that it did not record the number of overtime hours worked by the Massage Therapists or the start and finish times of overtime hours they worked;

(ii) reg 3.36(1) of the FW Regulations in that it did not record the periods of annual leave taken by the Massage Therapists and the balance of their entitlements to annual leave from time to time; and

(iii) reg 3.40 of the FW Regulations in that its records did not document the manner in which the employment of the Massage Therapists was terminated;

(k) s 536(1) of the FW Act by failing to give pay slips to each of the Massage Therapists within one working day of payment for work performed by them in that, except for three or four pay slips it provided in 2015, it did not give them any pay slips after about 31 March 2014;

(l) s 536(2) of the FW Act by failing to ensure that the pay slips it provided to each of the Massage Therapists included the information prescribed by reg 3.46(2) of the FW Regulations;

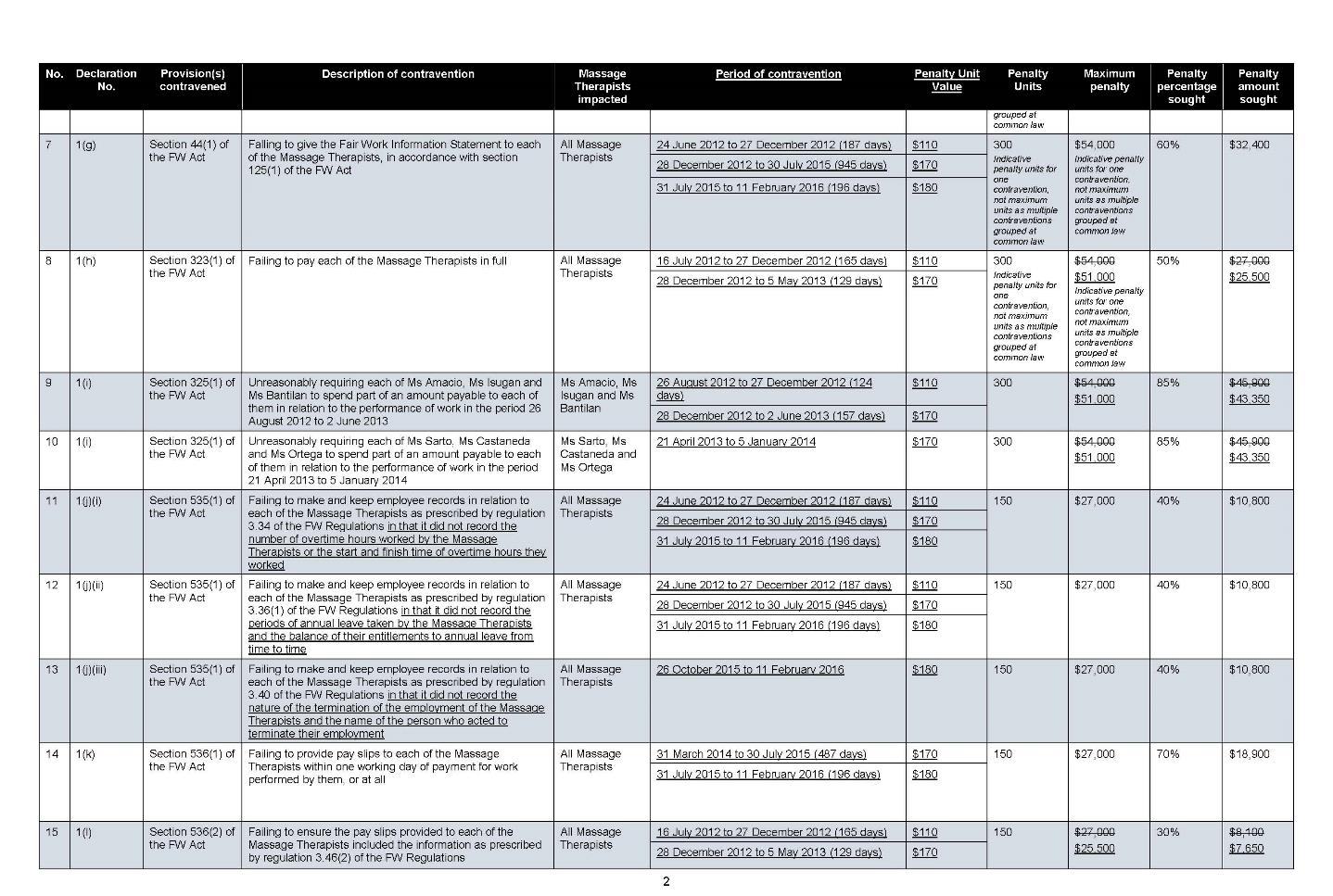

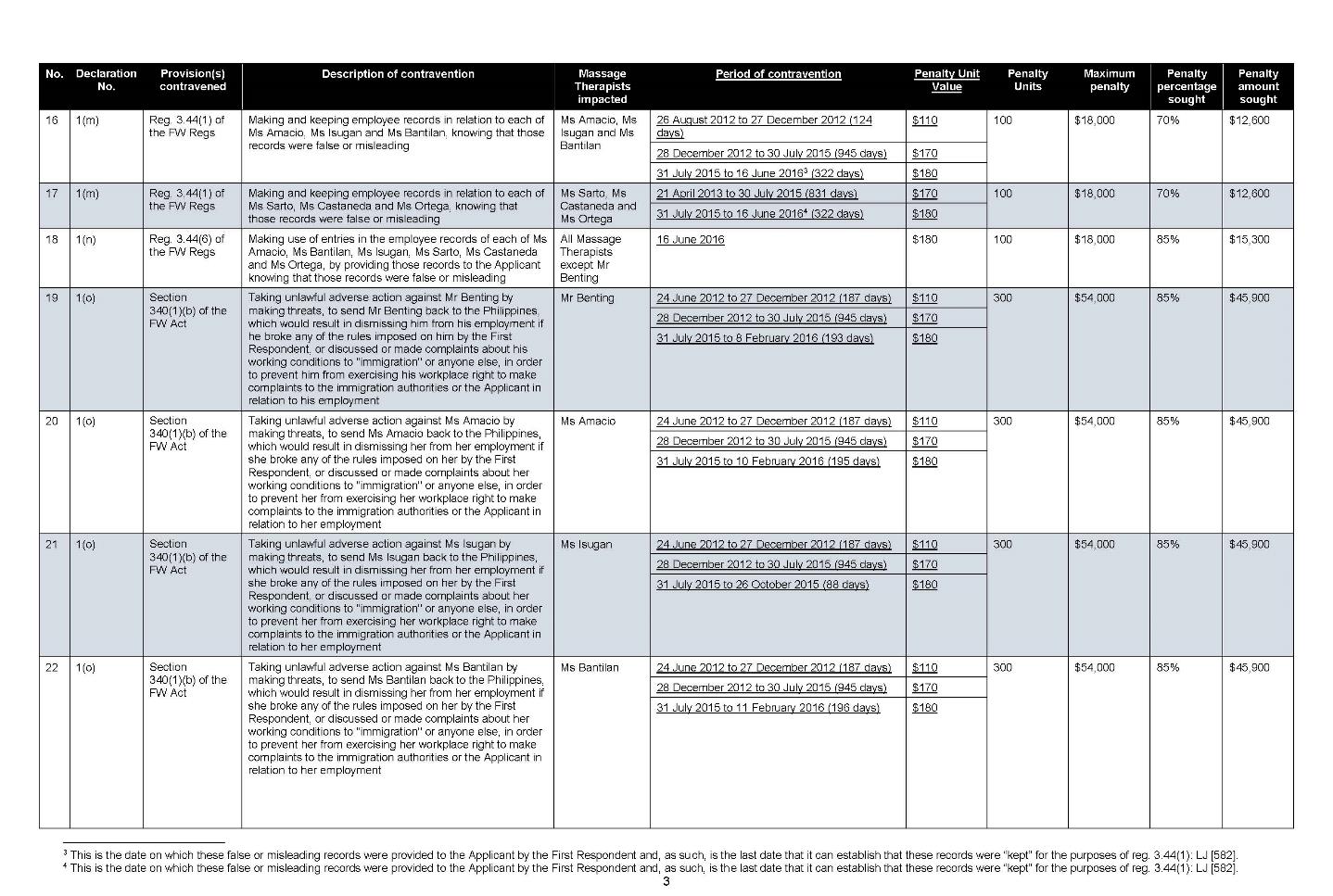

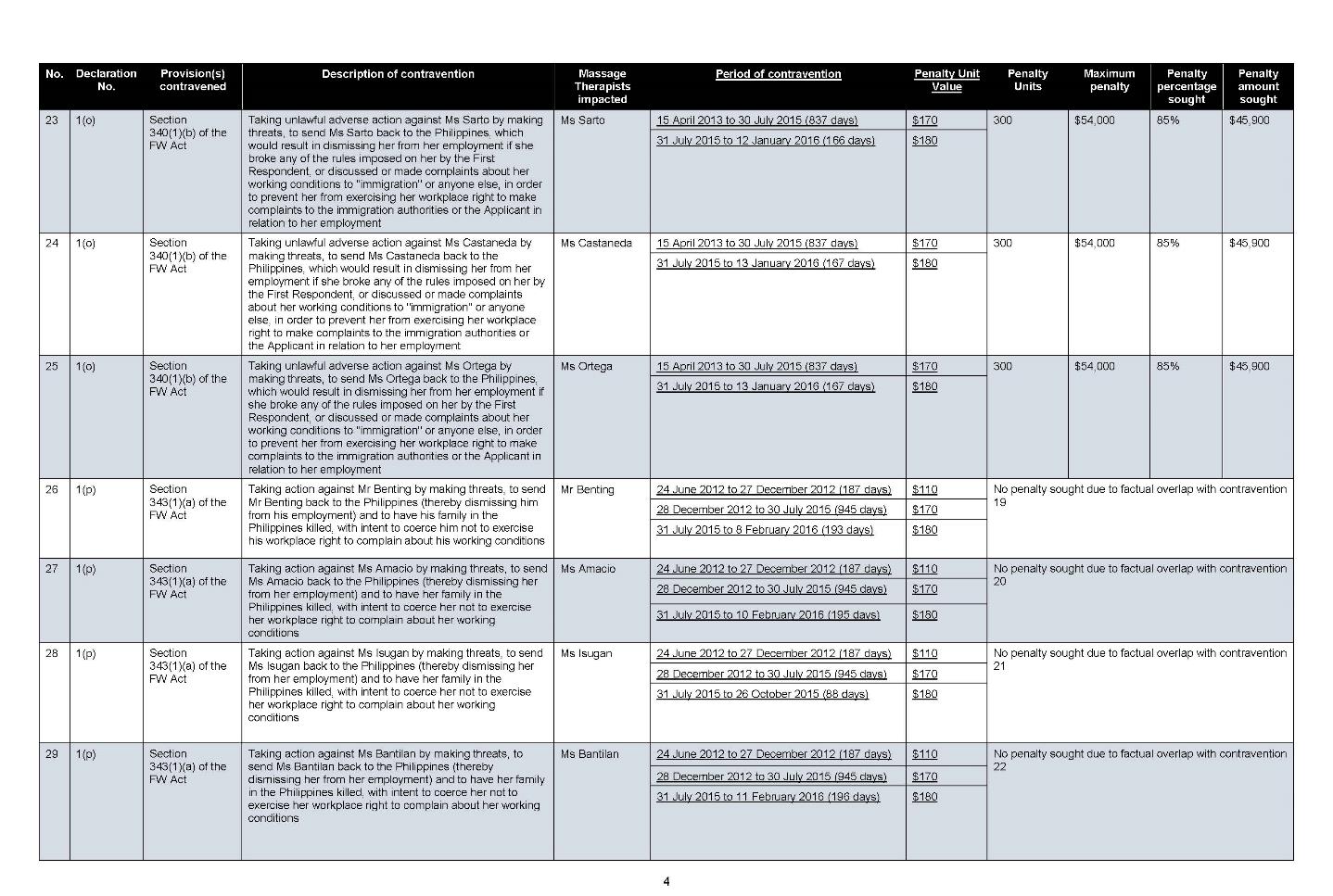

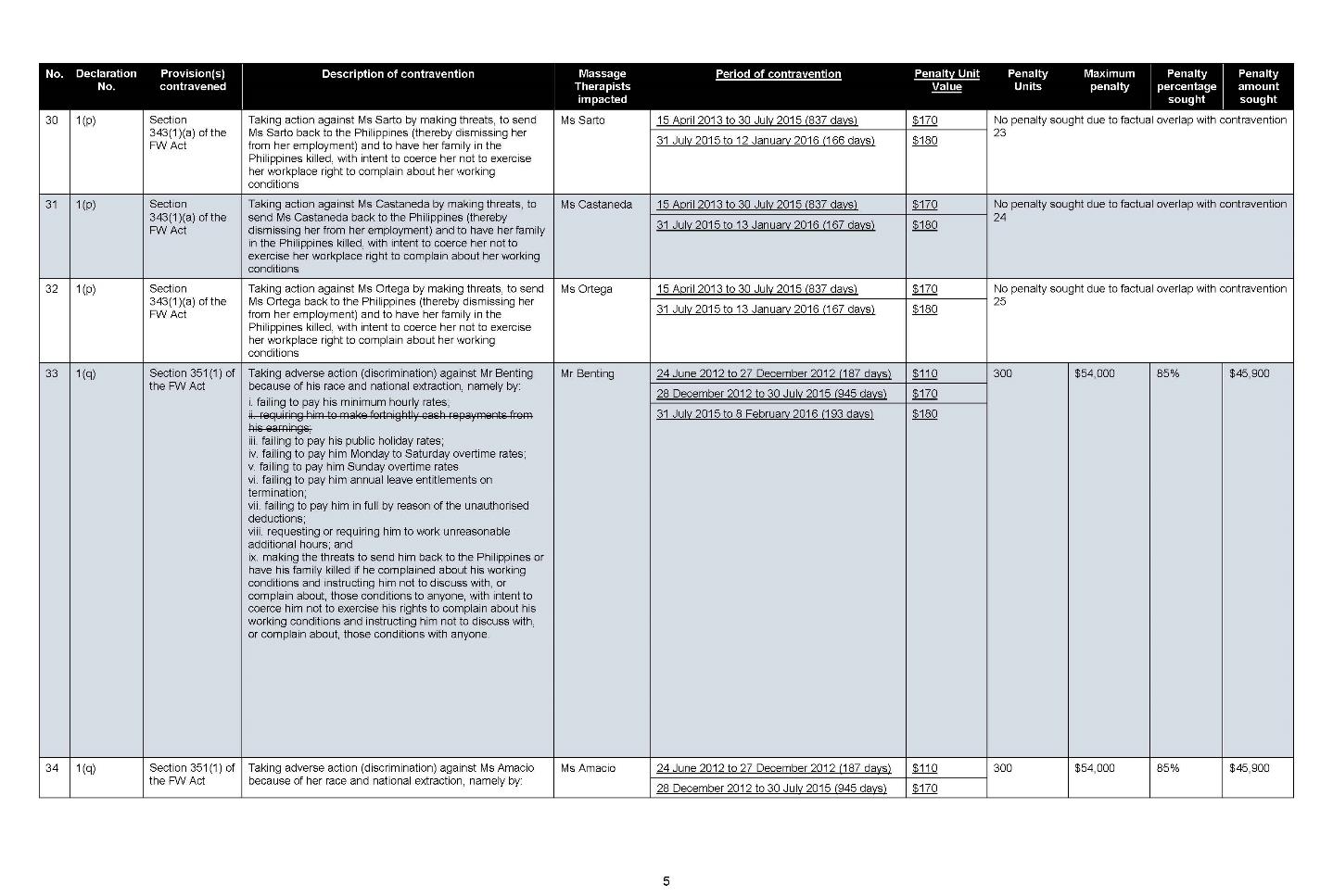

(m) reg 3.44(1) of the FW Regulations by making and keeping employee records in relation to each of Ms Amacio, Ms Bantilan, Ms Isugan, Ms Castaneda, Ms Ortega and Ms Sarto, knowing that those records were false or misleading in that they did not refer to the amounts they were directed to refund from their wages;

(n) reg 3.44(6) of the FW Regulations by making use of entries in the employee records of each of Ms Amacio, Ms Bantilan, Ms Isugan, Ms Castaneda, Ms Ortega and Ms Sarto in that it provided those records to the applicant knowing that they were false or misleading;

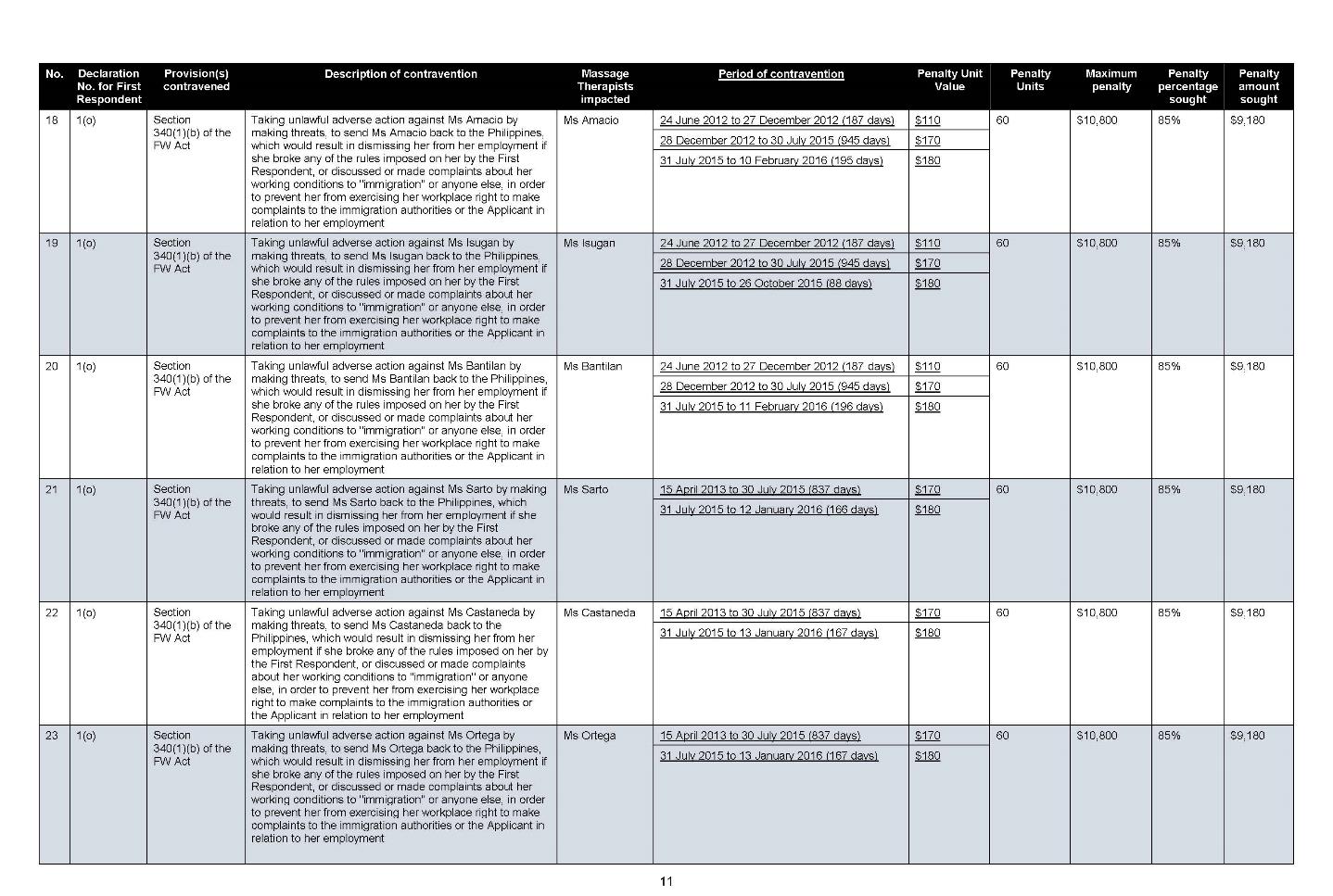

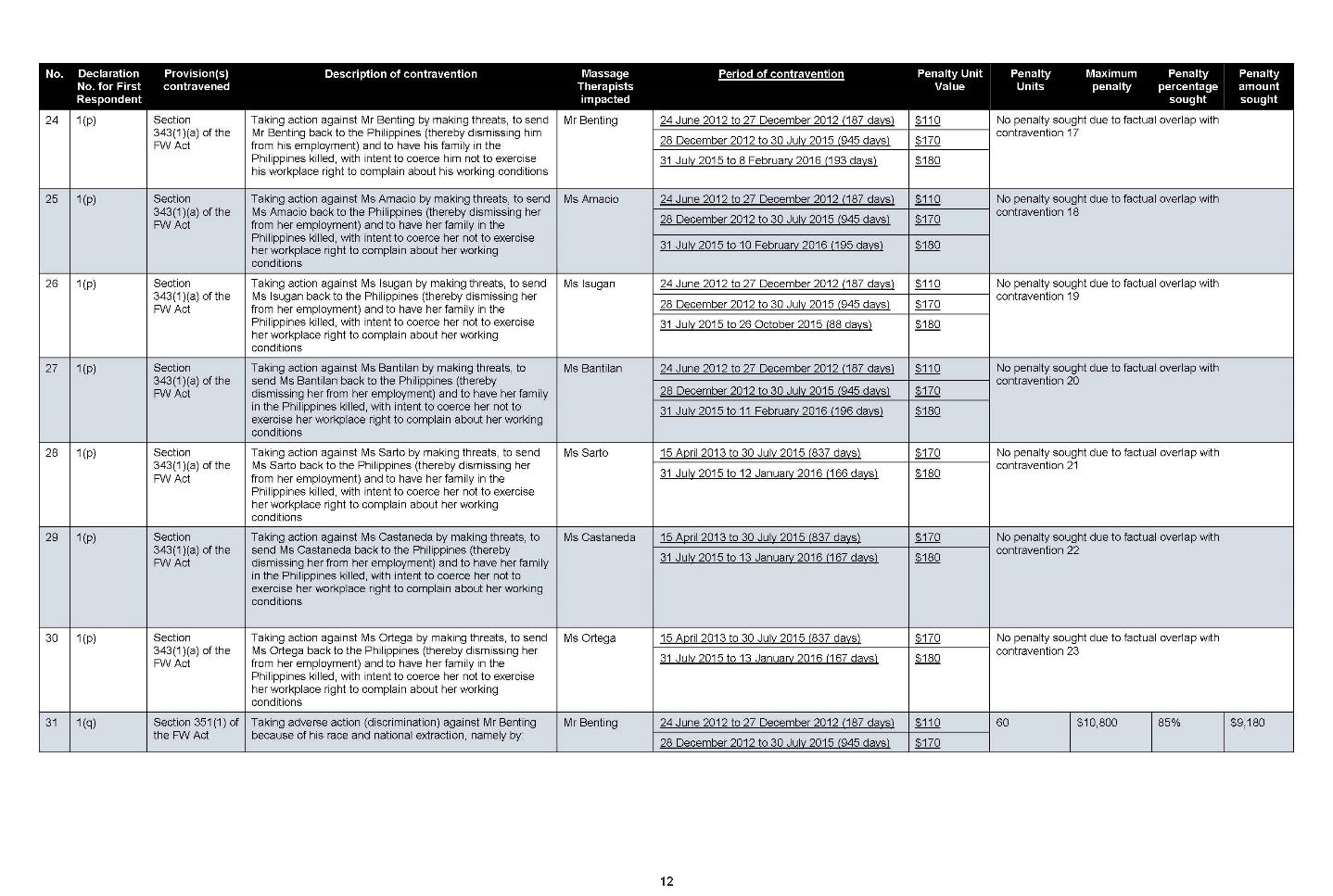

(o) s 340(1)(b) of the FW Act by taking adverse action against each of the Massage Therapists by making threats to send them back to the Philippines in order to prevent them from exercising their workplace rights to make complaints in relation to their employment to the immigration authorities or the applicant;

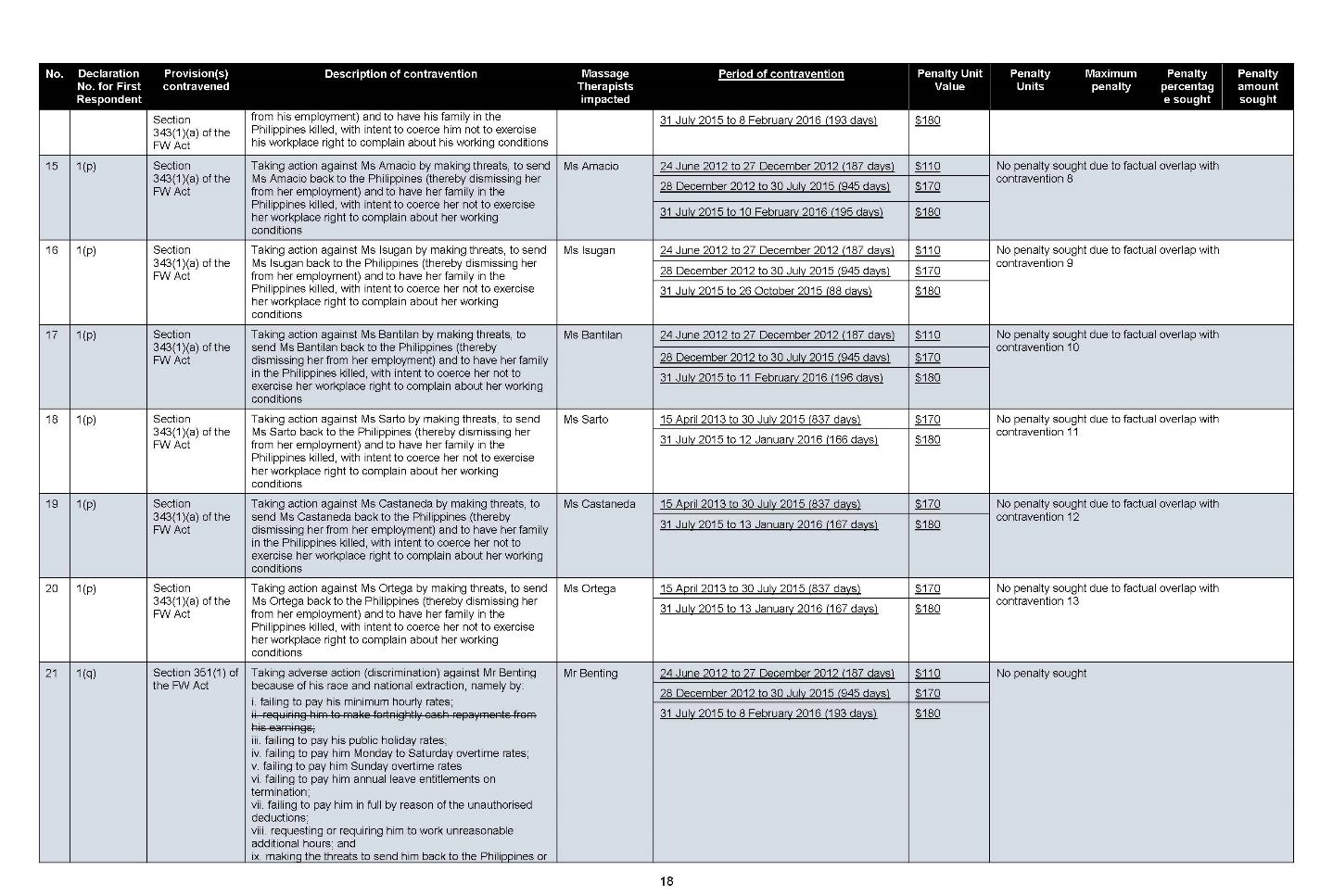

(p) s 343(1)(a) of the FW Act by threatening to send each of the Massage Therapists back to the Philippines and to have their families in the Philippines killed with intent to coerce them not to exercise their workplace rights to complain about their working conditions to the immigration authorities or the applicant; and

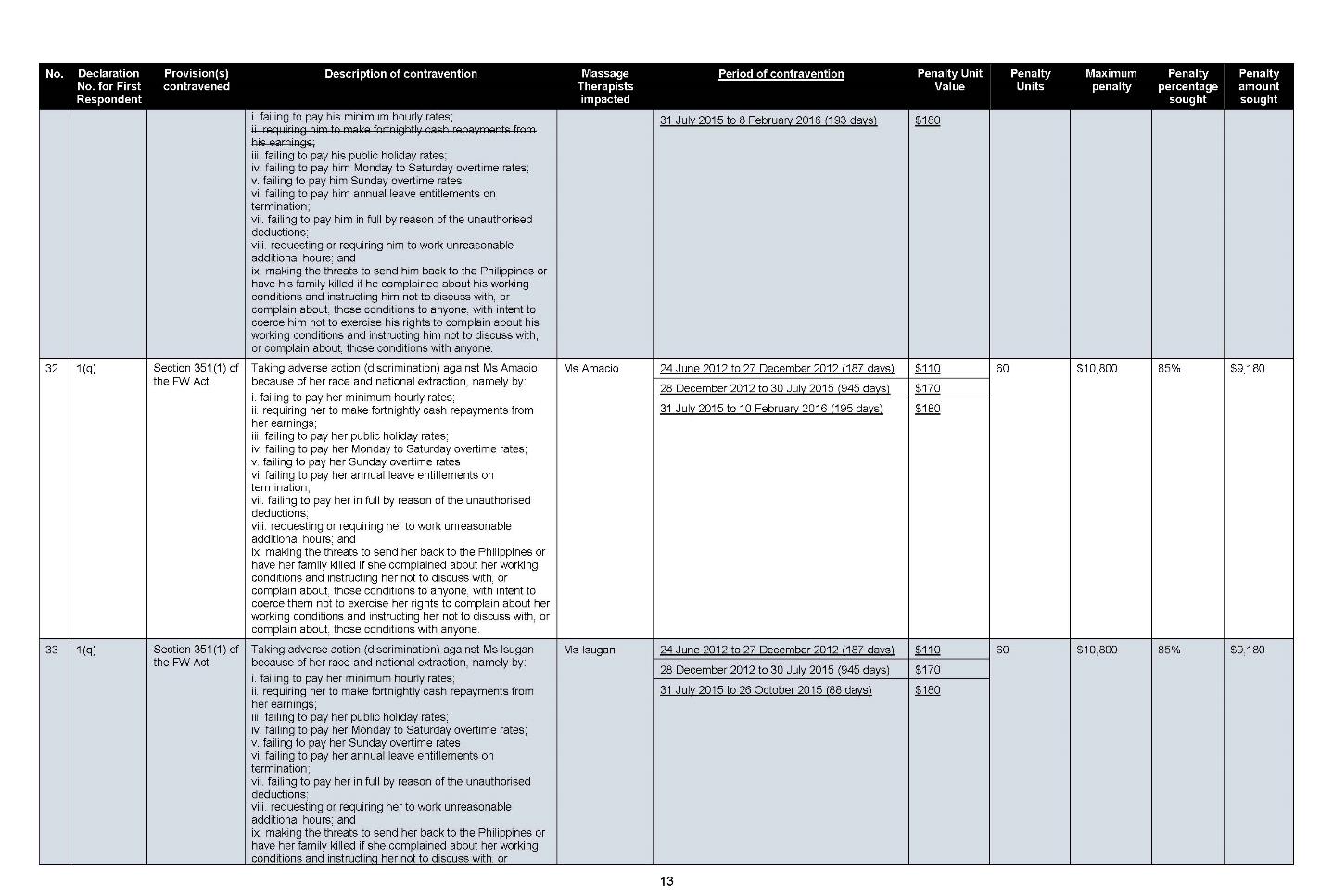

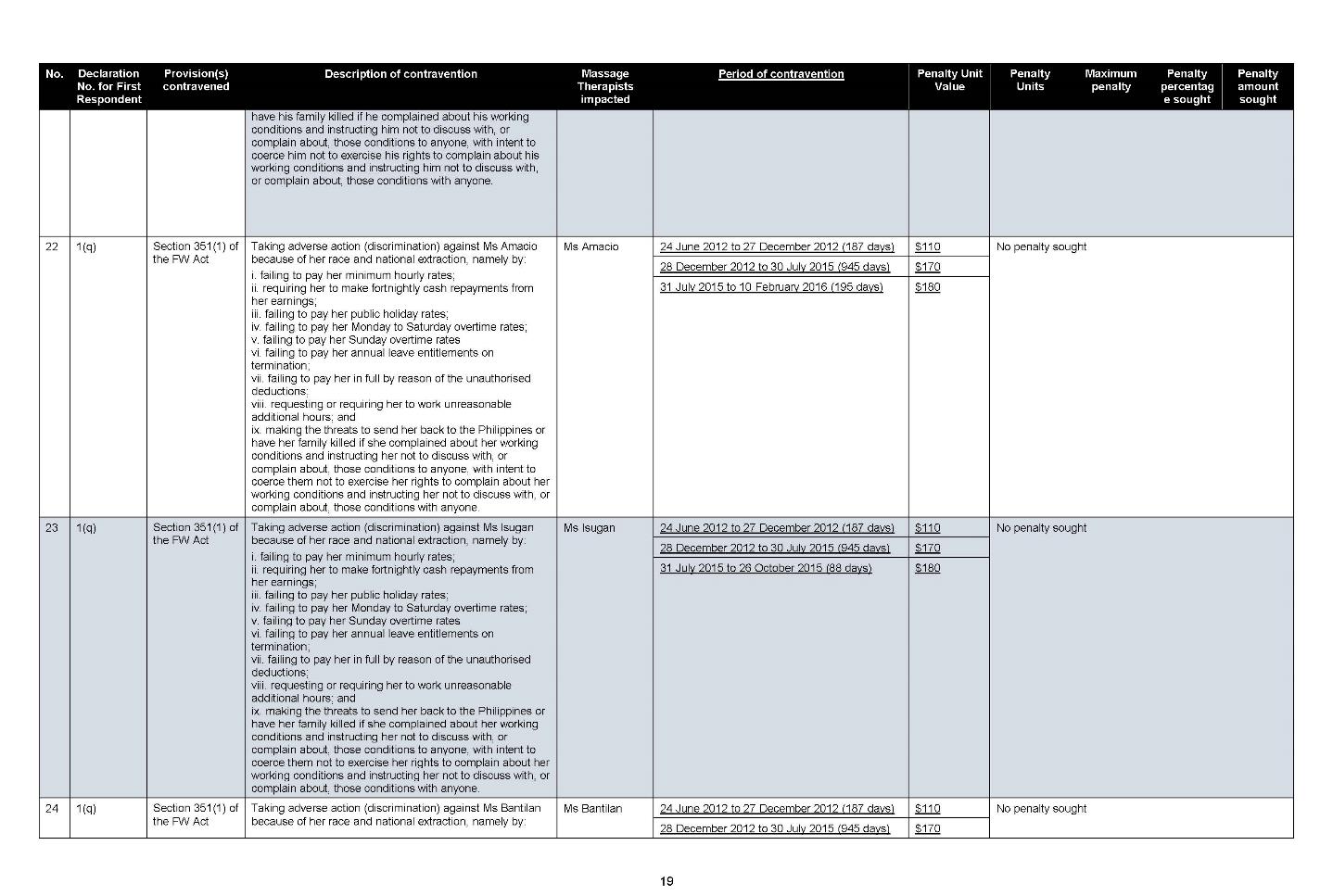

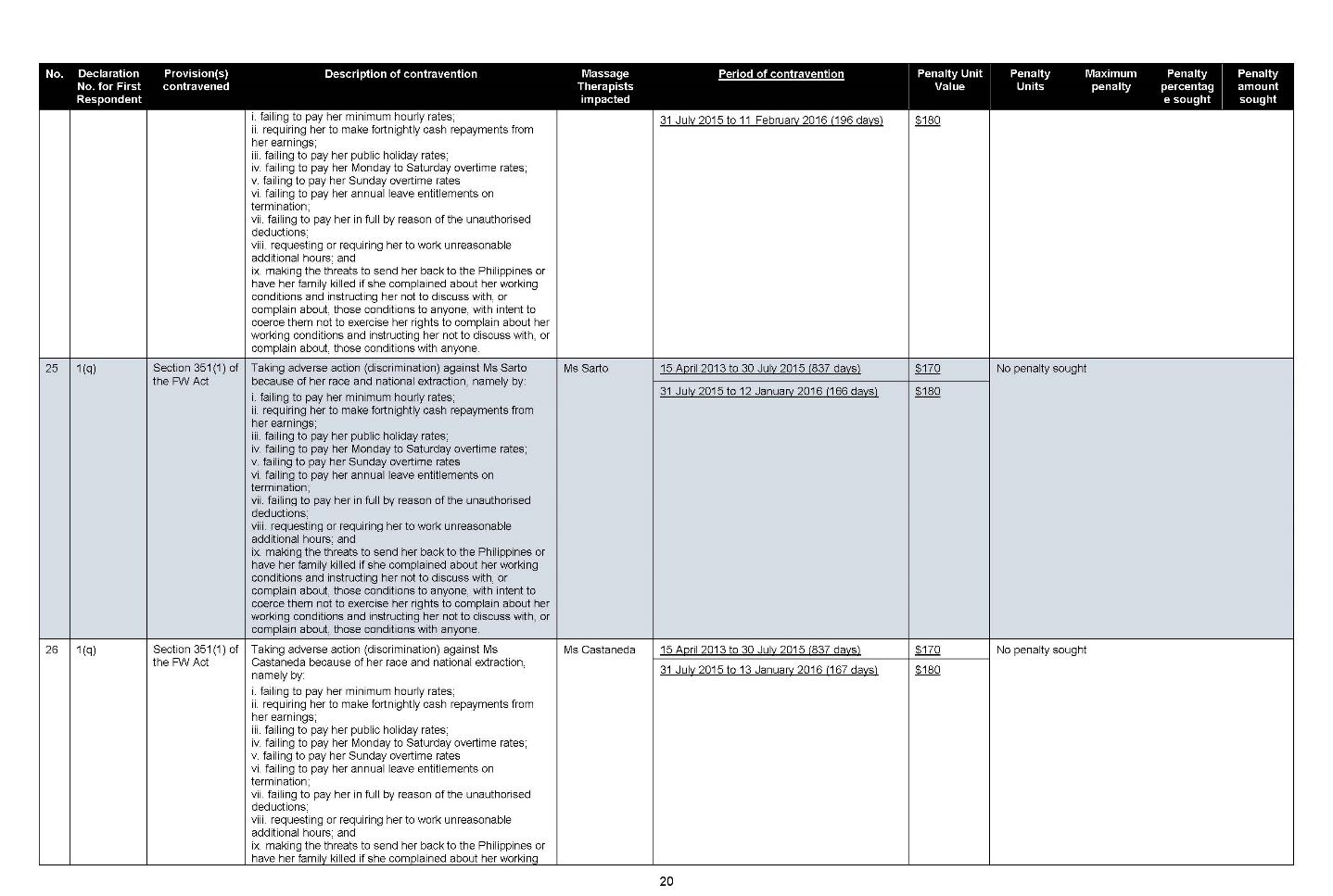

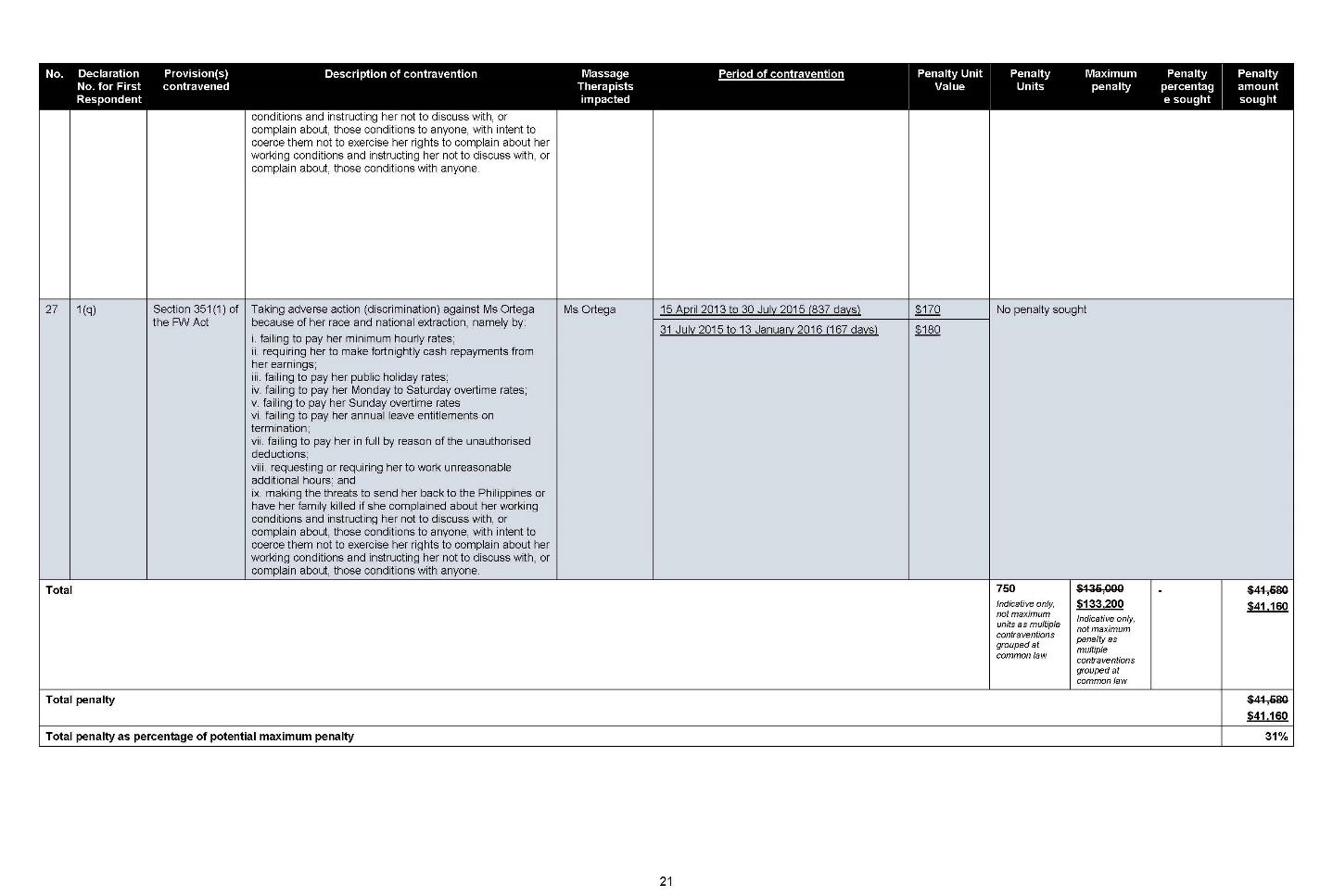

(q) s 351(1) of the FW Act by taking adverse action against each of the Massage Therapists because of their race and national extraction in that it:

(i) failed to pay them minimum hourly rates;

(ii) required them to make fortnightly cash repayments from their earnings;

(iii) failed to pay them public holiday rates;

(iv) failed to pay them Monday to Saturday overtime rates;

(v) failed to pay them Sunday overtime rates;

(vi) failed to pay their annual leave entitlements on termination;

(vii) failed to pay them in full by reason of unauthorised deductions;

(viii) requested or required them to work unreasonable additional hours; and

(ix) made threats to send them back to the Philippines or have their families killed if they complained about their working conditions and instructed them not to discuss with, or complain about, those conditions to, anyone.

2. The second respondent was knowingly concerned and therefore involved in each of the contraventions by the first respondent set out at paras 1(a) to 1(j) and 1(m) to 1(q) above.

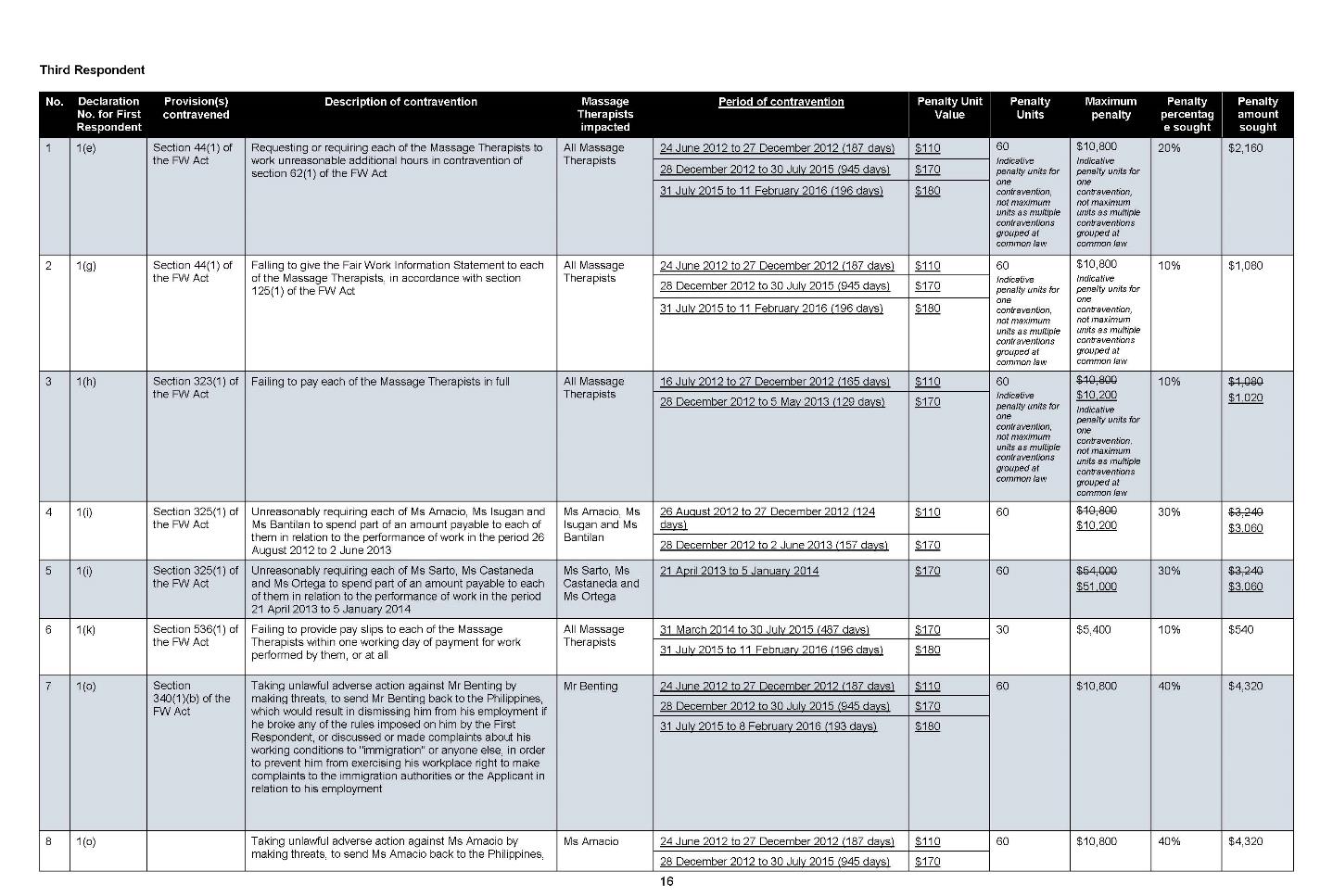

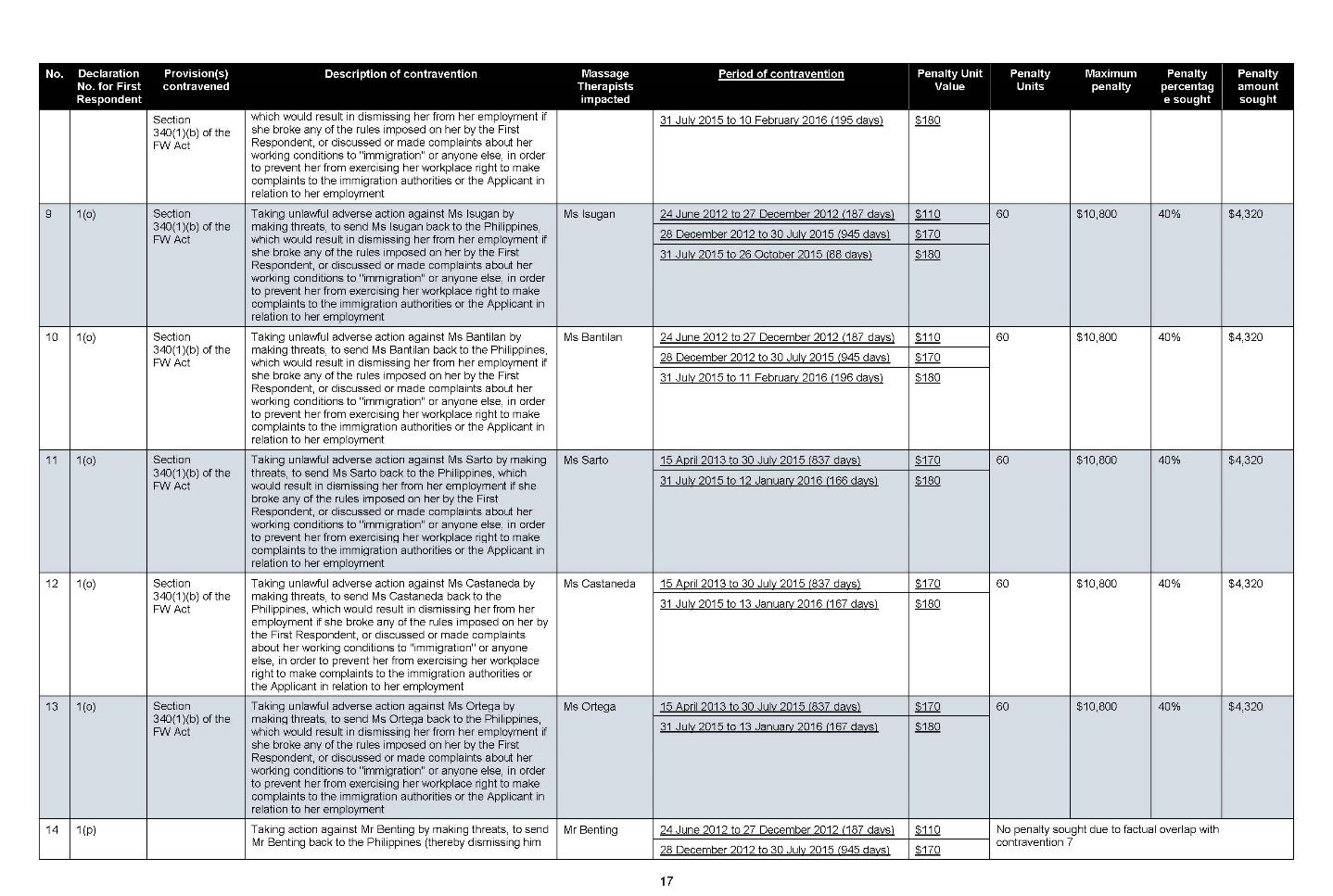

3. The third respondent was knowingly concerned and therefore involved in the contraventions by the first respondent set out at paras 1(e), 1(g) to 1(i), 1(k) and 1(o) to 1(q) above.

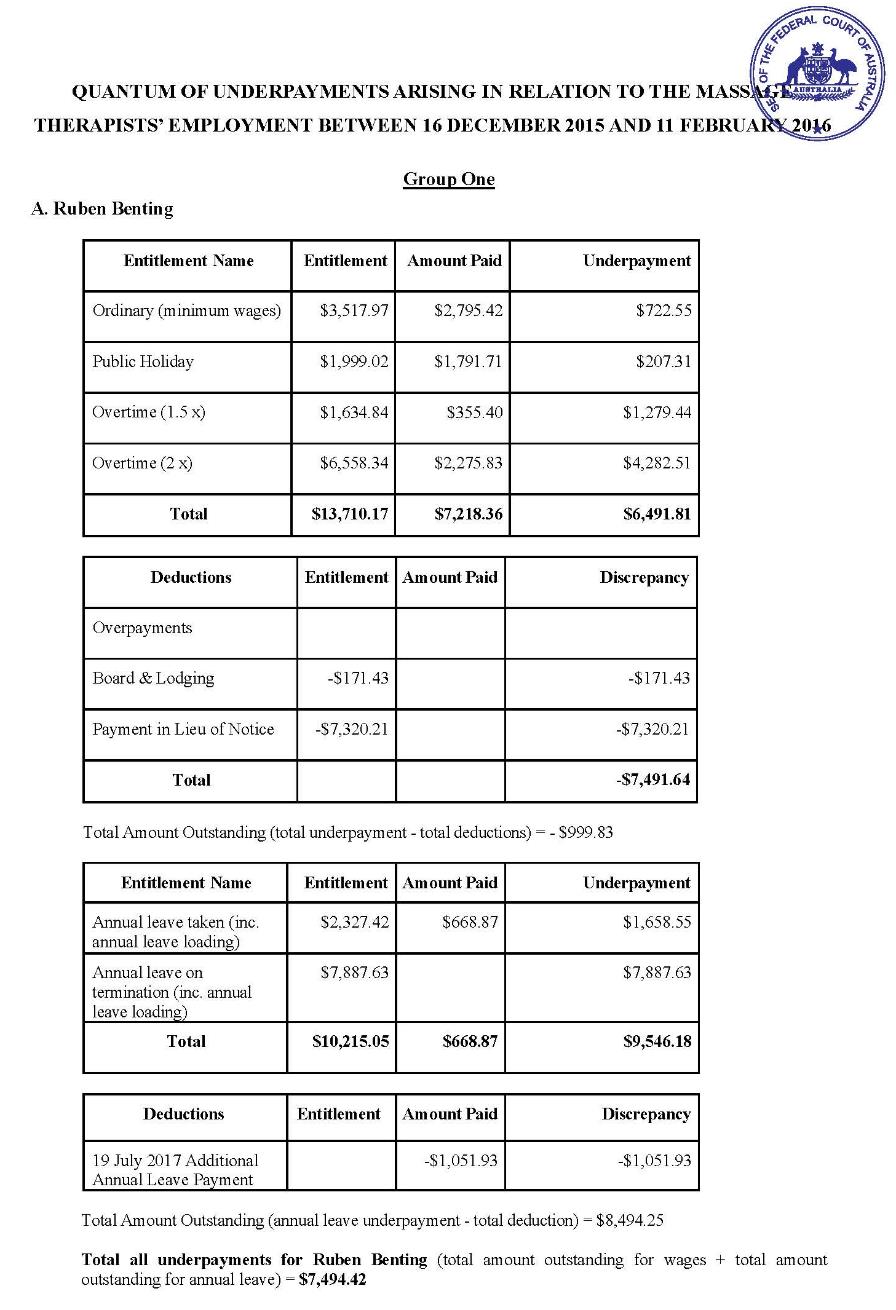

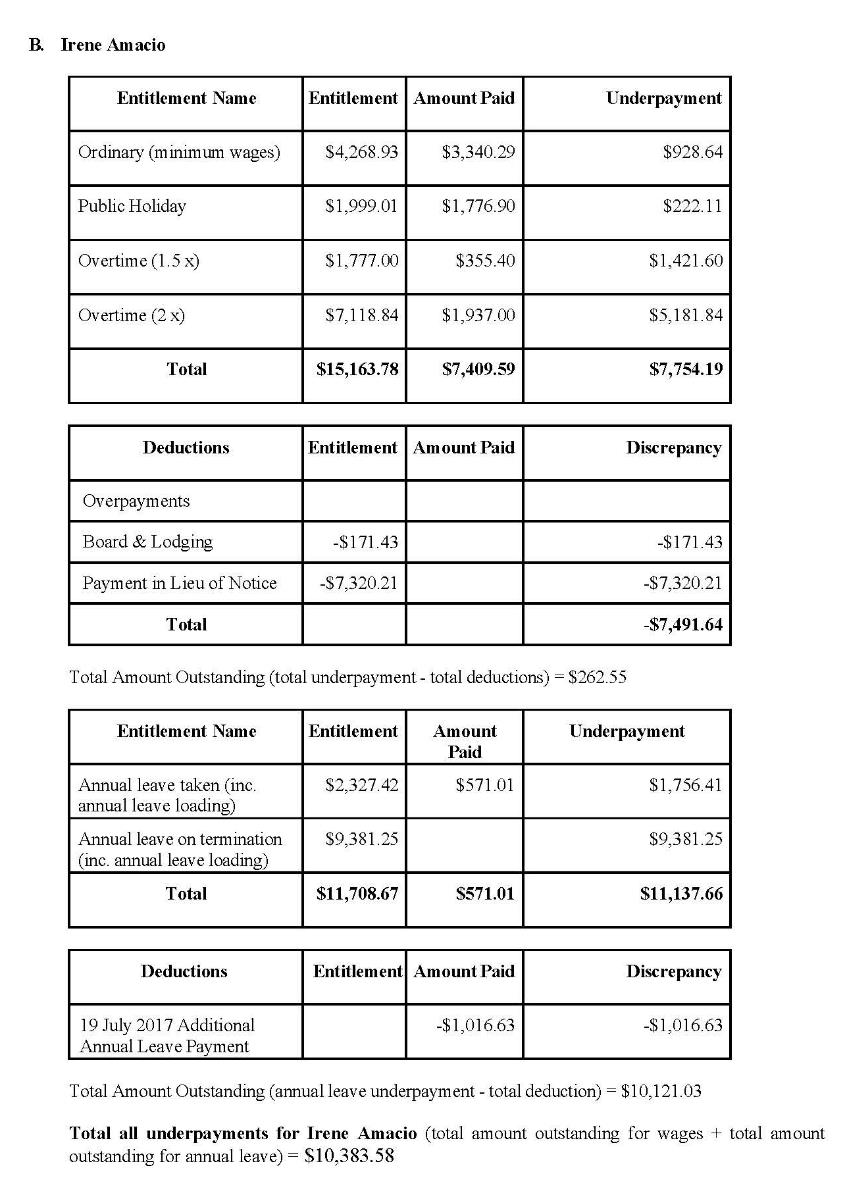

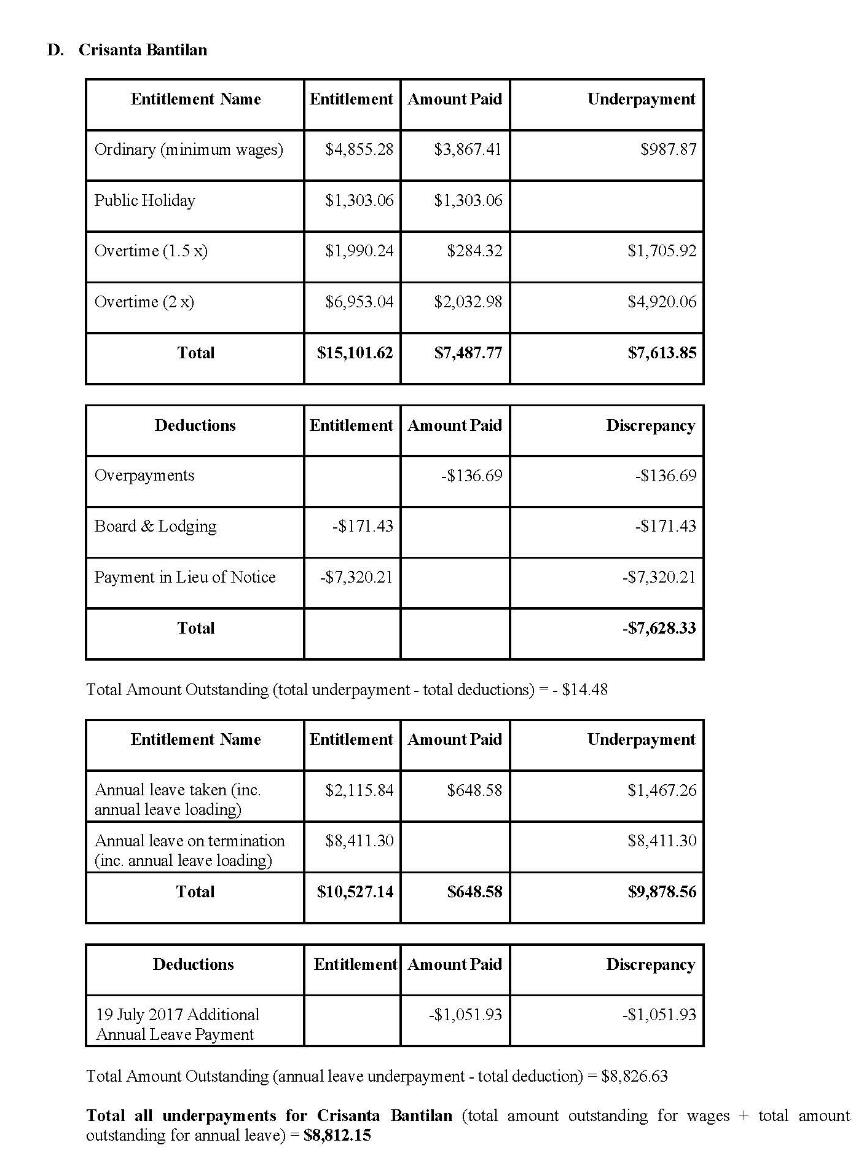

4. After credit is given for the amounts paid by Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu on or about 19 July 2017, the first respondent underpaid the Massage Therapists by the following amounts (the underpayments):

(a) Ms Amacio by $159,799.21;

(b) Ms Bantilan by $152,200.47;

(c) Mr Benting by $140,307.06;

(d) Ms Isugan by $149,331.13;

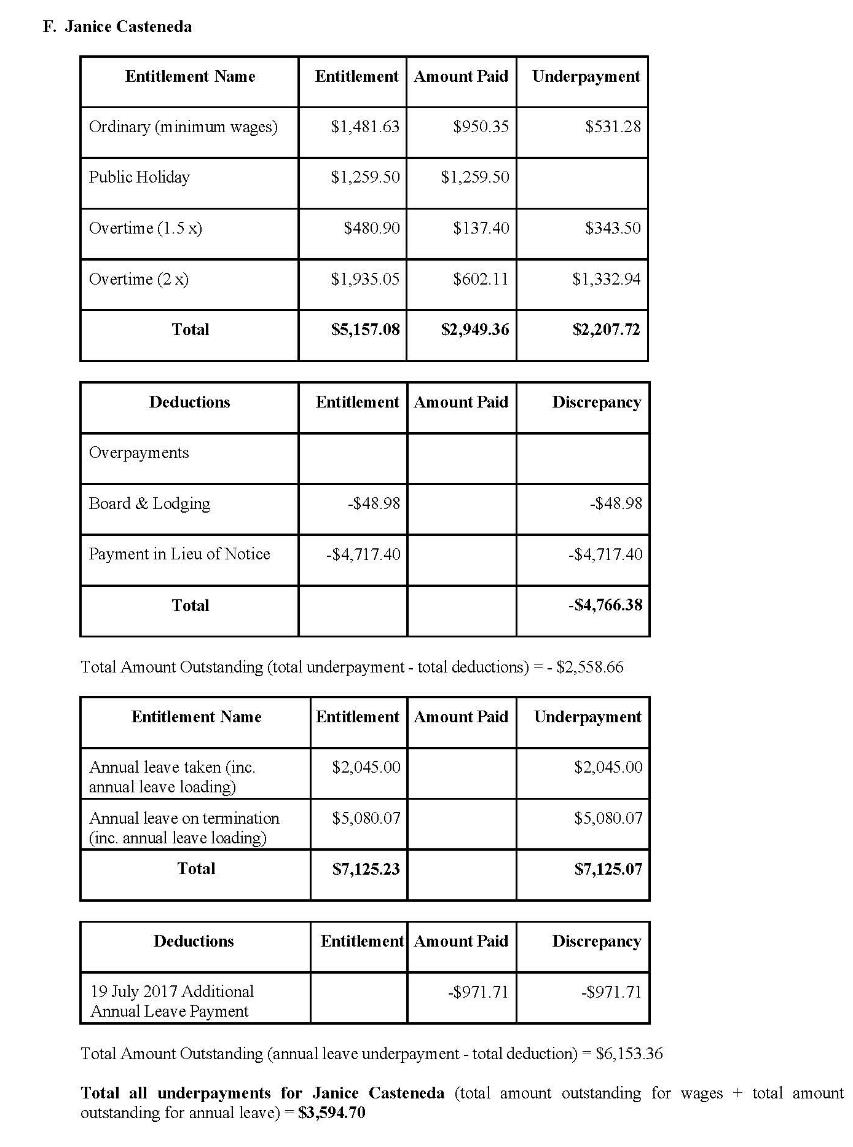

(e) Ms Castaneda by $120,055.56;

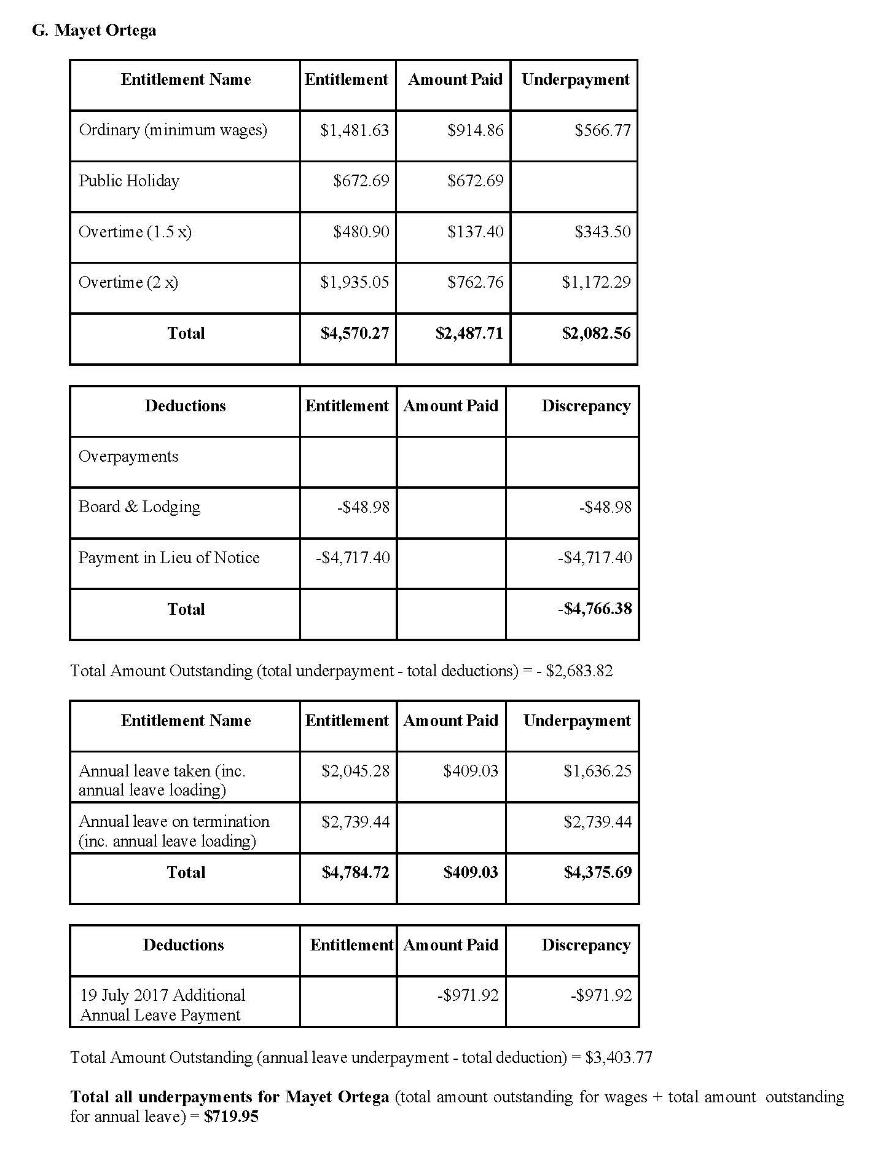

(f) Ms Ortega by $123,783.29; and

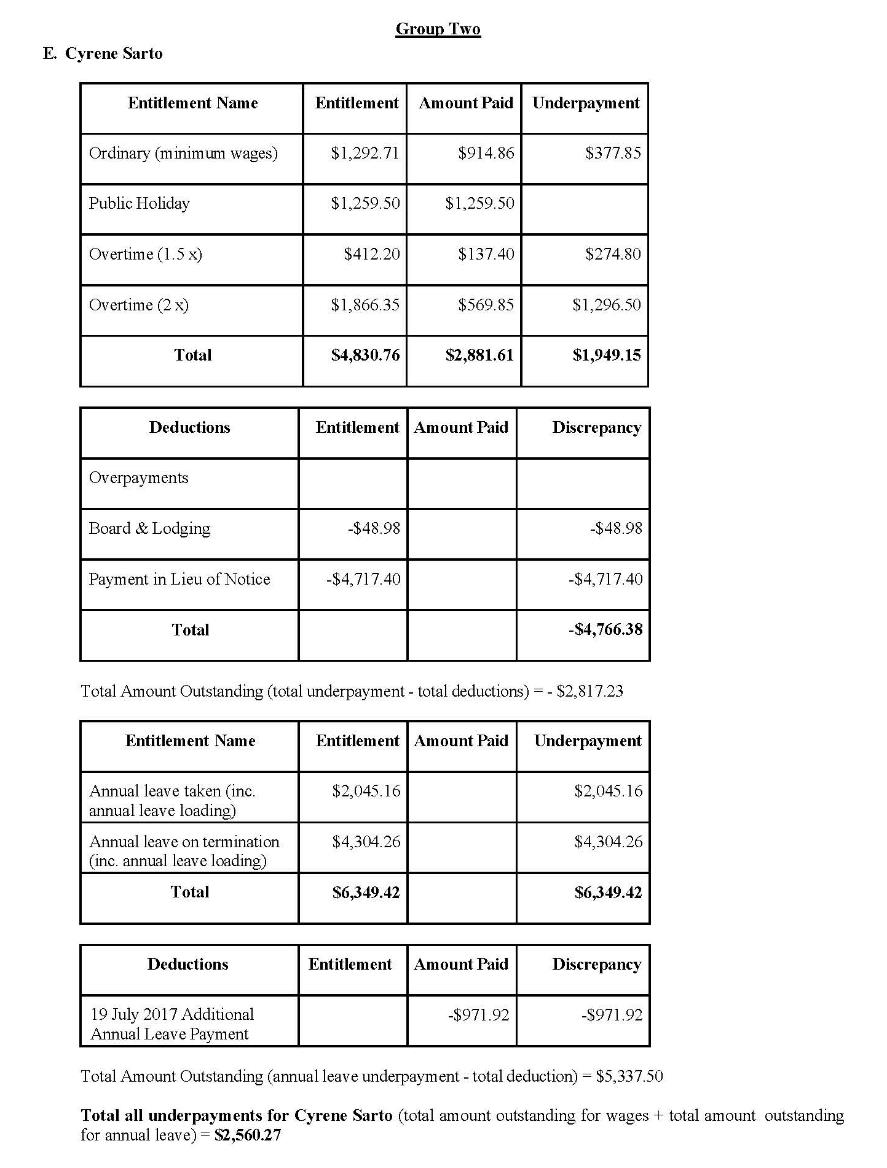

(g) Ms Sarto by $125,615.99.

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Pursuant to s 545 of the FW Act, within 28 days the first and second respondents pay the applicant the following amounts as compensation for the contraventions:

(a) $971,092.27, being the total of the above underpayments;

(b) $30,000 for the non-economic loss suffered by Ms Amacio, Ms Bantilan, Mr Benting and Ms Isugan; and

(c) $25,000 for the non-economic loss suffered by Ms Castaneda, Ms Ortega and Ms Sarto.

2. The first and second respondents pay interest from 16 February 2016 on:

(a) the underpayments at the rates prescribed by Practice Note GPN–INT; and

(b) 90% of the sums payable for non-economic loss.

3. Within 28 days of receipt of any of the amounts mentioned in orders 1 and 2, the applicant pay the amounts to the Massage Therapists or, in the event that the applicant cannot locate one or more of the Massage Therapists or for any reason payment cannot be made to one or more of them, pay any such amount to the Commonwealth of Australia.

4. Pursuant to s 546 of the FW Act, within 28 days:

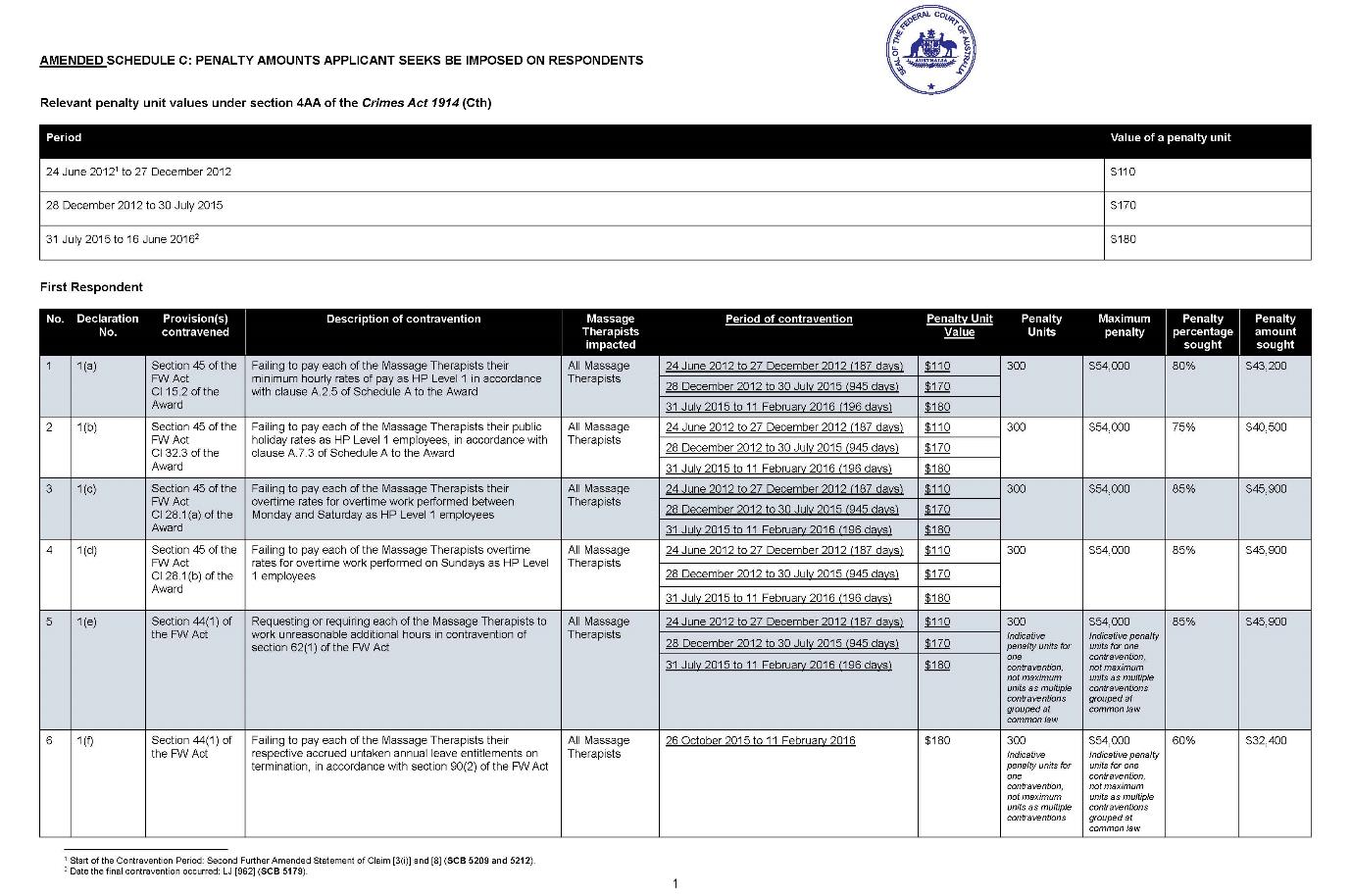

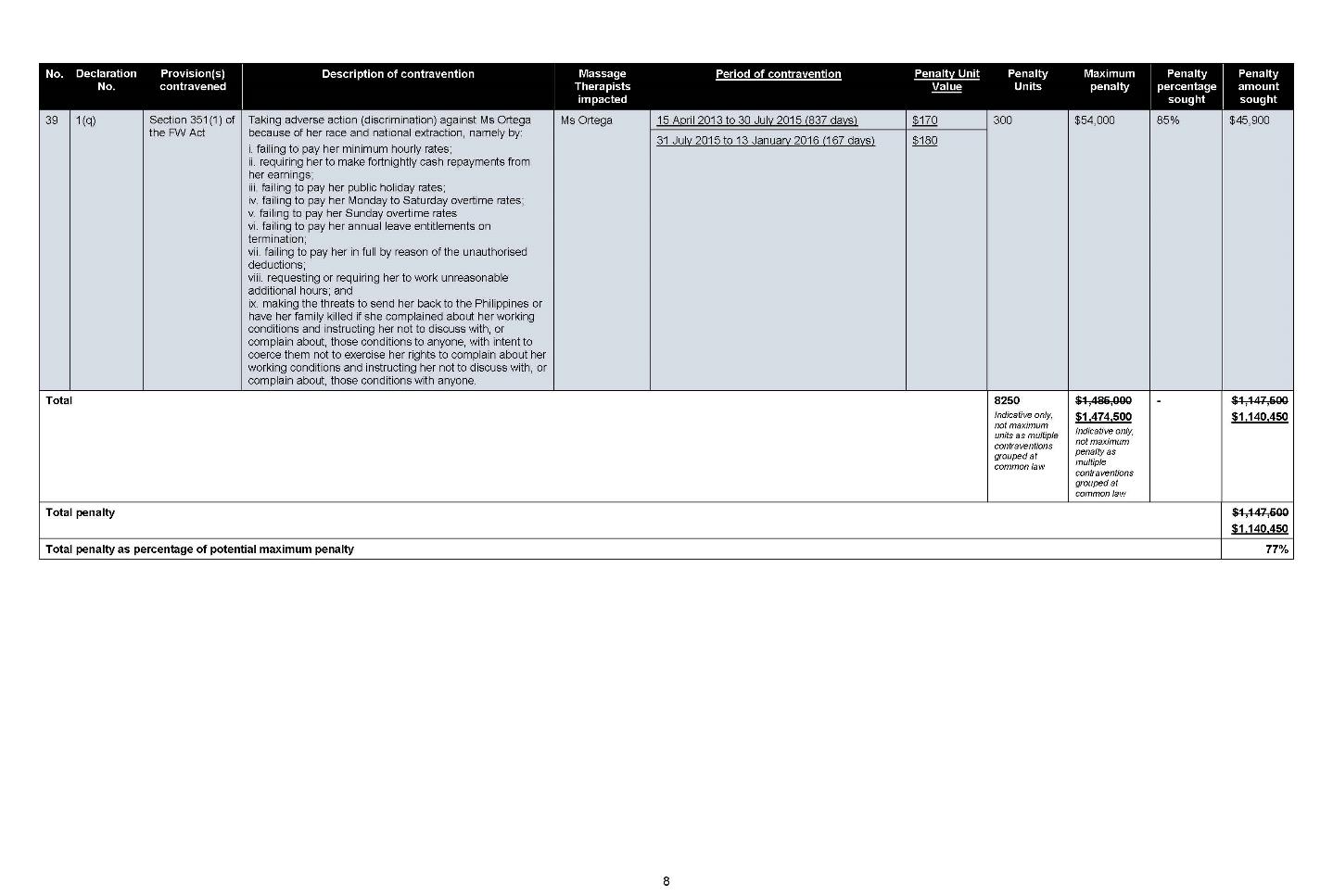

(a) the first respondent pay pecuniary penalties for the contraventions the subject of declaration 1 in the sum of $778,100;

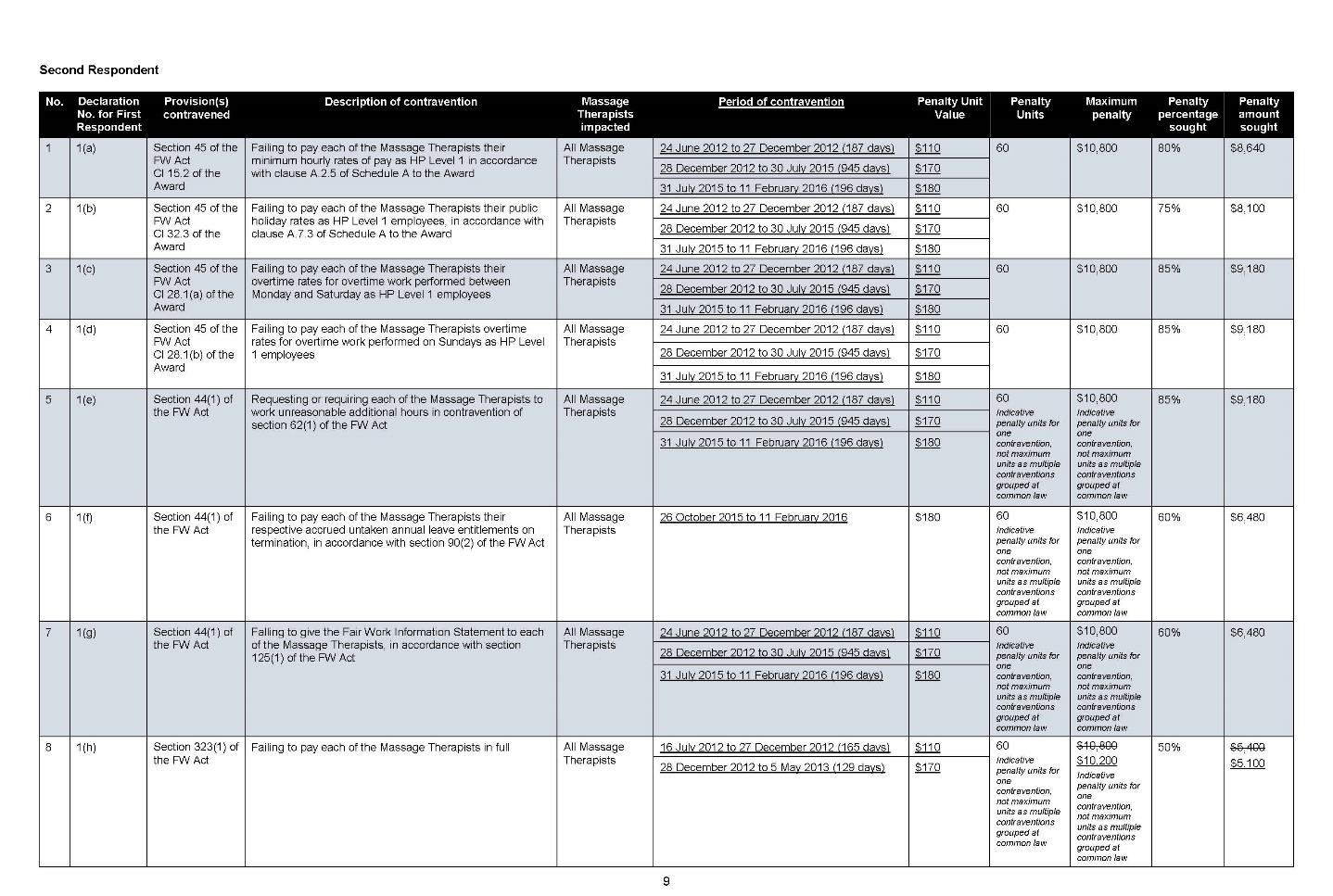

(b) the second respondent pay pecuniary penalties for the contraventions the subject of declaration 2 in the total sum of $150,140;

(c) the third respondent pay pecuniary penalties for the contraventions the subject of declaration 3 in the total sum of $38,650.

5. Pursuant to s 546(3)(a) of the FW Act the penalties be paid to the Commonwealth.

6. In the event that some or all of the compensation (including interest) is not paid to the Massage Therapists in accordance with the orders for payment, the applicant may remit to the Massage Therapists, in her discretion, all the penalties or a portion of them.

7. The applicant not seek to enforce against the first respondent the orders for compensation or pecuniary penalties without first obtaining the leave of the Court.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

KATZMANN J:

INTRODUCTION

1 This proceeding is concerned with multiple contraventions of the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) (FW Act) and Fair Work Regulations 2009 (Cth) (FW Regulations) over a period of almost four years affecting seven employees of the first respondent, Foot & Thai Massage Pty Ltd (FTM). All questions relating to liability were heard separately. Judgment on liability was published on 14 October 2021: Fair Work Ombudsman v Foot & Thai Massage Pty Ltd (in liquidation) (No 4) [2021] FCA 1242 (liability judgment or LJ). Because of issues relating to the calculation of the underpayments of the employees’ entitlements, I appointed a referee to determine the extent of the entitlements. The second respondent, Colin Elvin, objected to the adoption of the referee’s report but I dismissed his objections and adopted the report: Fair Work Ombudsman v Foot & Thai Massage Pty Ltd (in liquidation) (No 6) [2023] FCA 1116 (Foot & Thai (No 6)). This judgment is concerned with the question of relief and should be read with the liability judgment.

2 In addition to declarations to reflect my findings, the Fair Work Ombudsman seeks orders for the payment of compensation to the affected employees and pecuniary penalties for breaches of the civil remedy provisions of the FW Act.

3 There was a considerable delay between the publication of the liability judgment and the hearing on relief occasioned by the inability of the parties to agree on the value of the underpayments of wages and other entitlements to reflect the findings in the liability judgment, the consequential referral to a referee of the determination of the amount of underpayments, delay in the receipt of the referee’s report, and the lengthy period of time afforded the parties to make submissions on the adoption of the report and then on the questions relating to relief.

4 FTM was the owner and operator of a therapeutic massage business in Canberra, which traded under the name “foot&thai”. The seven employees covered by the liability judgment were recruited from the Philippines and employed by FTM as massage therapists. Four of them (Irene Amacio, Crisanta Bantilan, Ruben Benting and Delo Be Isugan) were employed from 24 June 2012 (the first group). Ms Isugan was employed until 26 October 2015, Mr Benting until 8 February 2016, Ms Amacio until 10 February 2016, and Ms Bantilan until 11 February 2016. The remaining three (Janice Castaneda (formerly Mapute), Mayet Ortega and Cyrene Sarto) started on 15 April 2013 (the second group). Ms Sarto finished on 12 January 2016, Ms Ortega and Ms Castaneda the following day. From now on, I will refer to them, as I did in the liability judgment, as the Massage Therapists.

5 At all relevant times Mr Elvin was the sole director of FTM and its only executive officer. He hired the Massage Therapists, set their wages and conditions, and managed the business of FTM. The third respondent, Jun Millard Puerto, was an employee of FTM, who was responsible for supervising the Massage Therapists. Mr Puerto elected not to file any evidence, cross-examine any witness, or make any submissions despite being present in court for the duration of the hearing. I found that Mr Elvin was knowingly concerned and therefore involved in the vast majority of the contraventions by FTM and that Mr Puerto was knowingly concerned and therefore involved in many of them.

THE EVIDENCE

6 The Ombudsman relied on two affidavits affirmed by Luke Russell Thomas on 8 June 2023 (affidavit in chief) and 31 August 2023 (reply affidavit). Mr Thomas is a Fair Work Inspector and currently an Assistant Director of Enforcement Team 3 within the Office of the Fair Work Ombudsman. He was involved in the Ombudsman’s investigation which culminated in the initiation of this proceeding, had the primary carriage of the investigation at certain times, and at other times supervised the investigation. I will refer to this evidence as and where it is relevant.

7 Mr Elvin filed an affidavit affirmed on 10 August 2023. Most of the affidavit is irrelevant and/or inadmissible for other reasons. In substance it consisted of submissions and complaints about the liability judgment and the referee’s report. It also repeated Mr Elvin’s attacks on the credibility of the Ombudsman’s witnesses, which I found wholly unpersuasive, and criticised the Ombudsman’s conduct in the prosecution of the case.

8 In only one respect does it contain potentially relevant information. That information consists of Mr Elvin’s statements that he is unemployed, has “no money”, was left with a $200,000 debt to his bank following the sale of the FTM business, and is indebted to his parents “for a substantial amount of money”. I accept that such matters could be relevant to the question of penalty in that, if I were satisfied of their truth, I might take them into account in determining the amount necessary to deter him from committing further contraventions. But no evidence was adduced to support these bald statements and having regard to the adverse opinion I formed of Mr Elvin’s credit, (see LJ [206]–[217]), I cannot give them any weight.

9 Annexed to Mr Elvin’s affidavit were applications for personal protection orders filed in the Magistrates Court of the Australian Capital Territory exactly a week after the publication of the liability judgment and an excerpt from a transcript of the consequential proceedings in August 2022 of Mr Elvin’s evidence and the magistrate’s decision declining to make the orders. He stated that he was providing this material “to demonstrate that there is a real likelihood the Federal Court has been misled”.

THE RESPONDENTS’ POSITION

Mr Elvin’s submissions

10 Mr Elvin’s submissions ran to 23 pages. Like his evidence, they were largely irrelevant. They consisted of complaints about the calculations of the underpayments, grievances he bears about the Ombudsman’s decision not to seek any relief in relation to one matter about which Mr Benting gave evidence and the Ombudsman’s claim of legal professional privilege over certain documents. All these matters were dealt with in the liability judgment, Foot & Thai (No 6) or, in the case of the last matter, were resolved against him by Raper J in Fair Work Ombudsman v Foot & Thai Massage Pty Ltd (in liquidation) (No 5) [2023] FCA 1098.

11 Mr Elvin also complained about the findings I made in the liability judgment and of bad faith on the part of the Ombudsman. He attached to his submissions a copy of a notice to admit facts and the authenticity of certain documents together with correspondence referred to in the notice. He claimed that he had repeatedly raised concerns with the Ombudsman which were never satisfactorily dealt with.

12 None of this material bears on the issues falling for determination at this point and none of it establishes impropriety by the Ombudsman. As I explained to Mr Elvin at the hearing, the remaining questions are to be decided on the facts as found. I reject his invitation to the Court to revisit the findings and dismiss the proceeding in its entirety. Nothing he said and nothing contained in the material annexed to his affidavit would justify such an extraordinary step.

13 Nevertheless, I propose to address a number of Mr Elvin’s submissions.

14 First, Mr Elvin submitted that the Ombudsman did not disclose to the Court or the respondents for two and a half years that no claim was being made in relation to “Mr Benting’s alleged cashbacks”. That claim is false. Moreover, Mr Elvin knew it to be false. As I noted in the liability judgment at [532], in every iteration of her pleading the Ombudsman did not include an allegation that FTM had required Mr Benting to pay back money from his wages, limiting her claim to the six female Massage Therapists, despite the evidence given by Mr Benting which was to the same effect. He filed a defence to the Ombudsman’s pleading and must be taken to have read it. Even if it escaped his attention at the time, he certainly knew by the time of the closing argument that the Ombudsman’s “cashback” claims did not cover Mr Benting when I sought clarification from counsel about it and, at the latest, when I published the liability judgment. I made the same point in response to a similar complaint in Foot & Thai (No 6) at [56].

15 Second, Mr Elvin submitted that in their calculations neither Ronnie Wong of the Ombudsman’s Office nor the referee took into account the voluntary administration of FTM. That, too, is false. At footnotes 1 and 3 to her submissions to the referee, the Ombudsman accepted that the payments to the Massage Therapists by the administrators during the voluntary administration had to be taken into account, and in the calculations she submitted to the referee she reduced the total underpayments by those amounts. In determining the “total amounts outstanding”, the referee deducted the “amounts paid” from the gross value of the entitlements. The referee made it clear that those deductions reflected the amounts paid to the Massage Therapists by the administrators (at [49] and [53]).

16 Third, Mr Elvin took issue with the statement I made at LJ [787] that “[a]t all relevant times it was he who controlled what the company did”. He submitted that he had no control of FTM after 15 December 2015 when administrators were appointed. Rather, he contended, the administrators were in fact and law in control of what the company did from 15 December 2015 to 11 April 2016. I accept that what I said at LJ [787] was an overstatement in that the administrators were in control of the company in that period. A more accurate statement would have been that Mr Elvin was in complete control of the company for all but 16 weeks of the four-year contravention period. It is not true, however, that Mr Elvin had no control over the company during that 16-week period. On 4 January 2016 Mr Elvin entered into an agreement with the company and the administrators, called an “operating licence”, under which he would “operate and manage” the FTM business on certain terms. The licence was in place on and from 4 January 2016 until 4 April 2016.

17 Clause 2.6 of the licence agreement required, amongst other things, that Mr Elvin, as the licensee, “at [his] own cost and risk and without limitation, conduct and manage the Business:

(i) in the ordinary course;

(ii) in a professional, diligent, businesslike and efficient manner to high standard expected of a business operator and manager of business such as the Business;

(iii) by employing its own employees;

…”

“Business” was defined in cl 1.1 to mean “the massage services and other businesses operated by [FTM] but exclud[ing] all cash in hand, cash at bank; debtors, goodwill and work in progress”.

18 Fourth, Mr Elvin submitted that the deed of company arrangement (DOCA) prevented the Court from ordering penalties. This submission impugns my finding to the contrary (at LJ [937]-[948]).

19 The only relevant submission Mr Elvin made was that the Ombudsman’s proposed penalties were excessive. It was an unhelpful submission in that it was based on a misrepresentation about the extent of the contraventions covered by the Ombudsman’s claim. Mr Elvin contended that the Ombudsman’s proposed orders “appear essentially to cover threatening to send the massage therapists back to the Philippines and making them pay cash backs that according to the [Ombudsman] totalled $91,200.00 for which the [Ombudsman] seeks to have FTM repay that amount and impose on FTM penalties amounting to $958,500.00”. That is simply a fallacy.

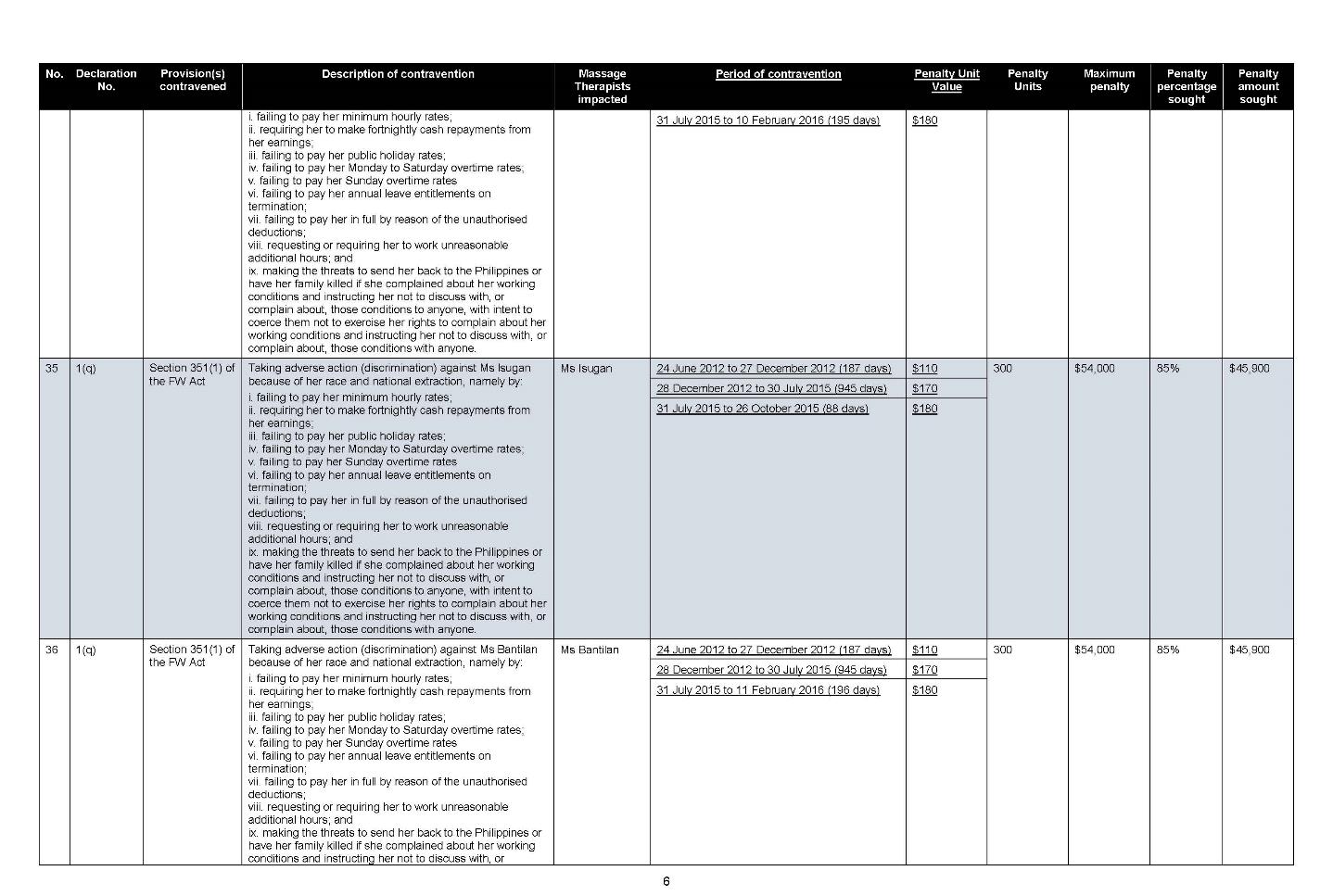

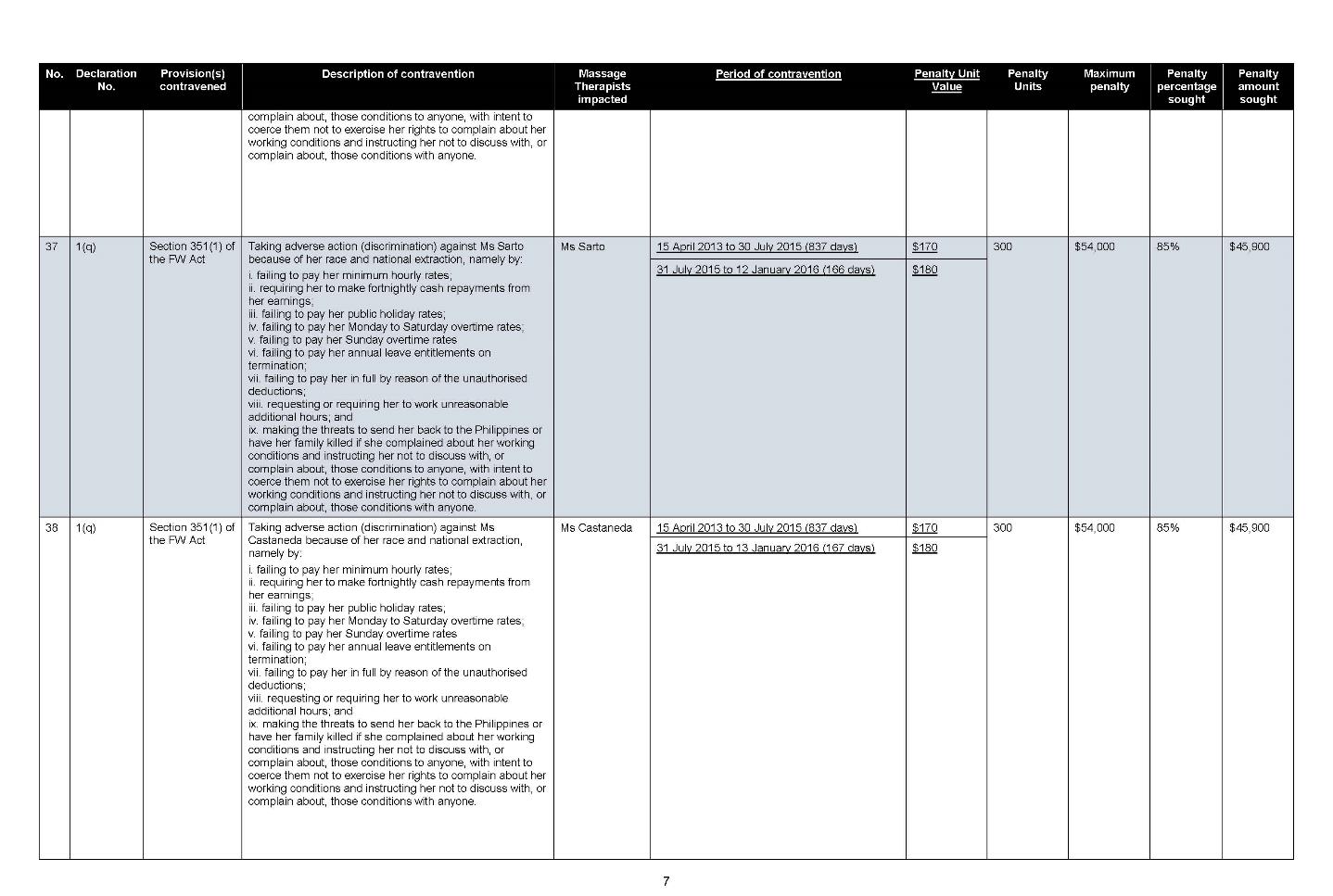

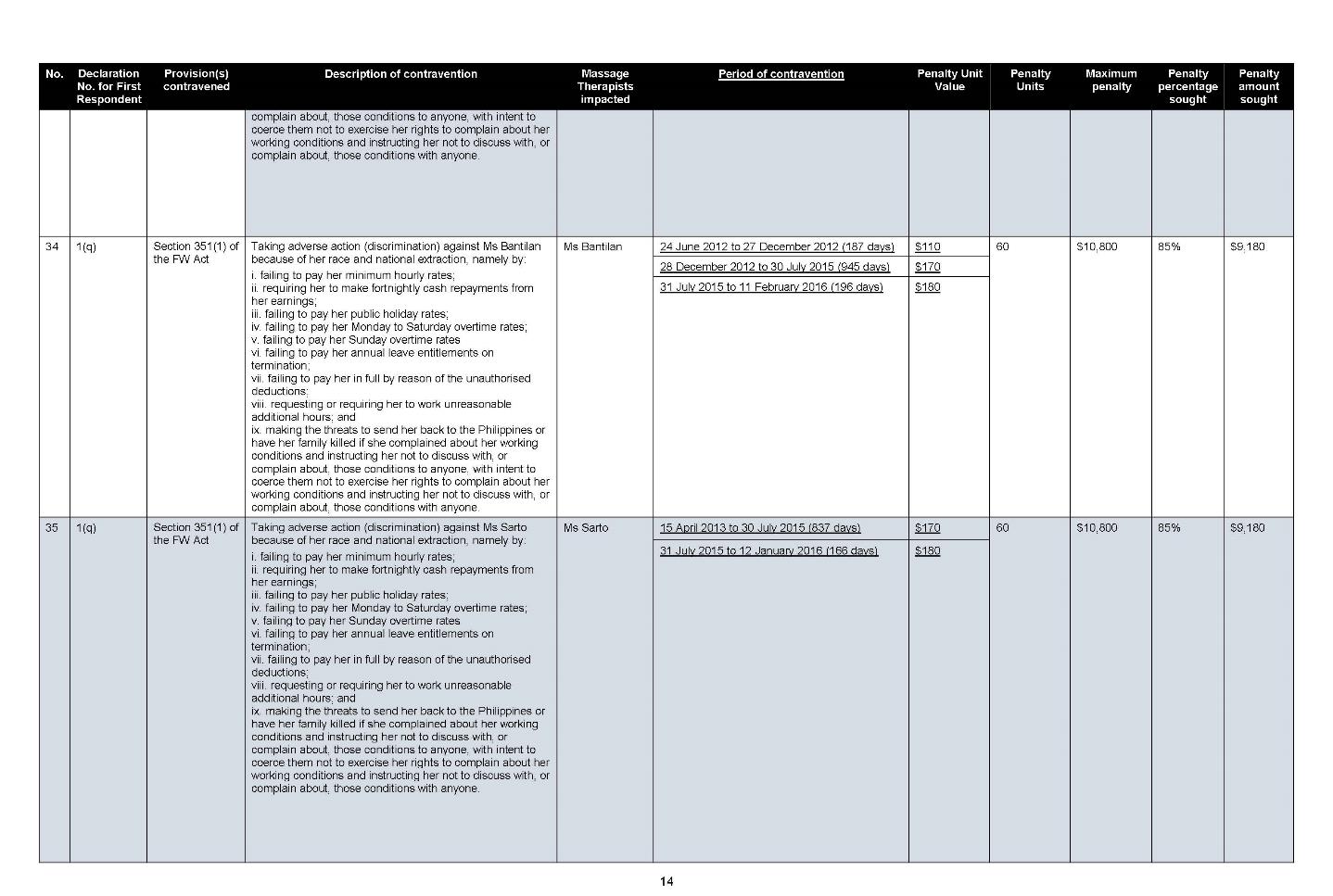

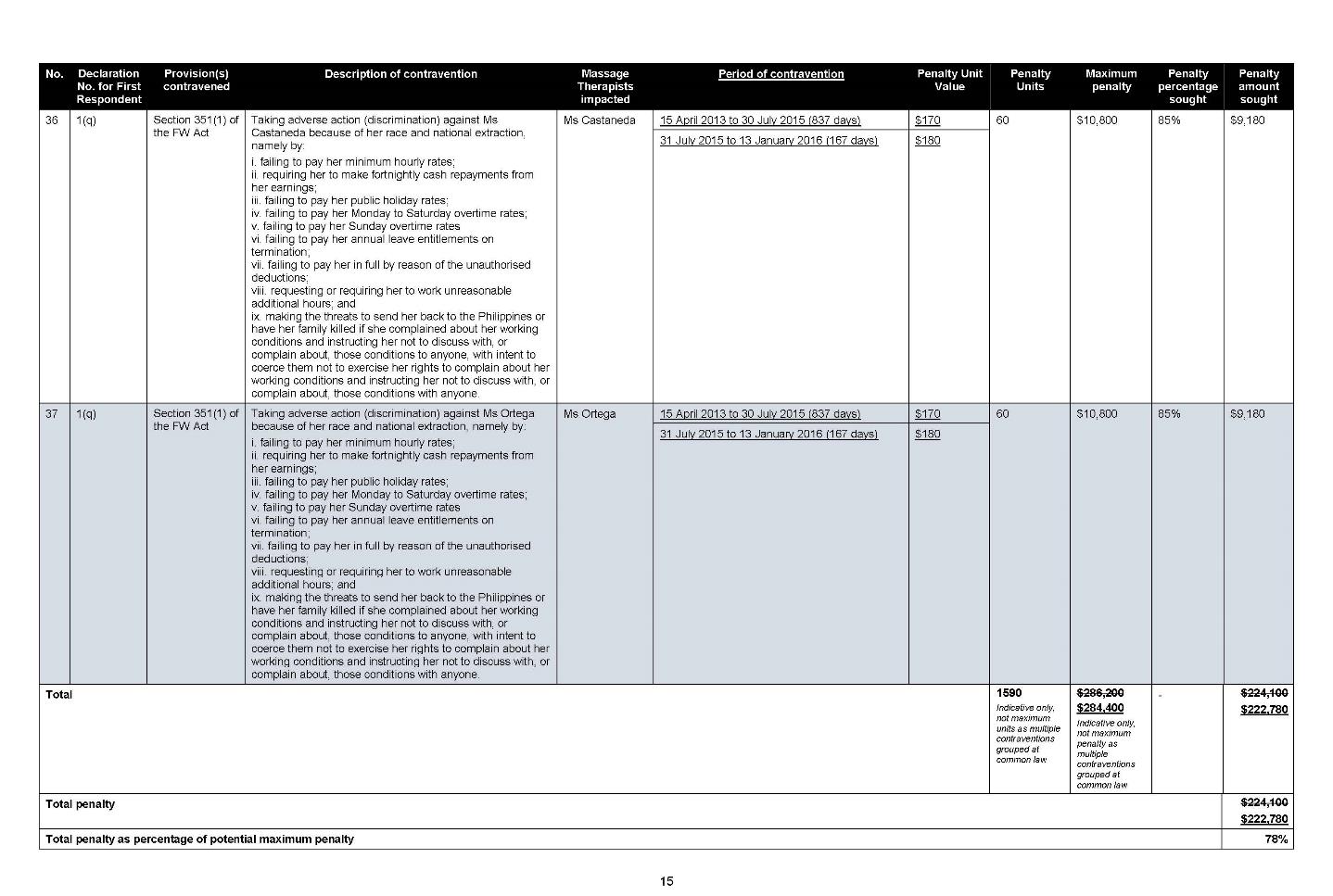

20 Mr Elvin did not engage with the Ombudsman’s submissions on compensation or penalties except in two respects. One was to challenge the Ombudsman’s characterisation of the Massage Therapists as “vulnerable” employees. I address that matter later in these reasons. The other was to respond to certain entries in the Ombudsman’s table of proposed penalties which included an allegation that Mr Benting was required to make fortnightly cash repayments from his earnings as part of the description of the s 351 contraventions as they affected him. These entries contained an obvious error, no doubt occasioned by the use of the cut and paste word-processing function and a lapse in proof-reading. The Ombudsman acknowledged the error and corrected it in an amended table.

21 For completion, I note Mr Elvin’s contention in correspondence with the Ombudsman annexed to his submissions that I made a finding (at LJ [339(3)(a)) that Mr Benting was required to pay back $800 a fortnight from his wages in the period from 26 August 2012 to 2 June 2013. That contention is false. The reference is to my summary of the issues. It should not have been made. It is abundantly clear from my reasons that I did not make that finding (see esp. LJ [532] and [564]).

Mr Puerto

22 Since Mr Puerto did not file any evidence or submissions and offered no explanation for his silence, I infer that there was nothing he could say that would assist his case.

DECLARATORY RELIEF

23 I found that FTM contravened the FW Act in the following respects:

(1) by failing to pay the Massage Therapists minimum hourly rates, public holiday penalty rates, Monday to Saturday overtime rates, and Sunday overtime rates prescribed by the Health Professionals and Support Services Award 2010 (Health Award) (contraventions of s 45);

(2) by requiring the Massage Therapists to work unreasonable hours over and above 38 hours a week, contrary to s 62(1) (contraventions of s 44);

(3) by not paying each of the Massage Therapists the amounts that would have been payable to them with respect to the periods of untaken annual leave they had at the end of their employment, contrary to s 90(2) (contraventions of s 44);

(4) by failing to give each of the Massage Therapists the Fair Work Information Statement as required by s 125 (contraventions of s 44);

(5) by unreasonably requiring Ms Amacio, Ms Bantilan, Ms Isugan, Ms Castaneda, Ms Ortega, and Ms Sarto to spend $800 per fortnight of their wages on its business by directing them to refund that amount during the so-called cashback periods, contrary to s 325(1) (contraventions of s 44);

(6) by deducting amounts from the wages of the Massage Therapists described in the records as “staff loans” when the deductions were not authorised by any of the exceptions in s 324(1), contrary to s 323(1) (contraventions of s 44);

(7) by failing to make and keep records of:

(a) the number of overtime hours worked by each of the Massage Therapists or the start and finish times of their overtime hours as prescribed by reg 3.34 of the FW Regulations;

(b) the periods of annual leave they took and the balance of their entitlements to annual leave from time to time as prescribed by reg 3.36(1); and

(c) setting out the nature of the termination of their employment as prescribed by reg 3.40 (all contraventions of s 535(1));

(8) by making and keeping pay records that, to its knowledge, were false or misleading as to the net amounts paid to Ms Amacio, Ms Bantilan, Ms Isugan, Ms Castaneda, Ms Ortega and Ms Sarto because they did not record or reflect the amounts they were required to return in cash from their salaries during the so-called cashback periods (contraventions of reg 3.44(1));

(9) by producing to FWI Hurrell on 16 June 2016, in response to a notice to produce issued by the Ombudsman, records which to its knowledge were false as they did not record the cashback amounts (a contravention of reg 3.44(6));

(10) by not giving the Massage Therapists pay slips after about 31 March 2014 (contraventions of s 536(1));

(11) by failing to record the details prescribed by reg 3.46(2) in the pay slips which it did give the Massage Therapists (contraventions of s 536(2));

(12) by taking adverse action against the Massage Therapists and by threatening to send the Massage Therapists back to the Philippines if they broke any of FTM’s “rules”, complained about their working conditions or reported FTM to “immigration”, and to have their families killed if they did (contraventions of s 340(1) and 343(1)); and

(13) by injuring them in their employment in various respects for reasons which included their race and national extraction (contraventions of s 351(1)).

24 I found that Mr Elvin was knowingly concerned and therefore involved in all but the pay slip contraventions and Mr Puerto in the contraventions of s 44 with respect to the requirement to work unreasonable hours and the failure to provide Fair Work Information Statements: ss 323(1); 325(1); 340(1); 343(1); s 351(1) (to a limited extent only); and s 536(1). The effect of those findings is that Mr Elvin and Mr Puerto are taken to have contravened those provisions.

25 The Ombudsman seeks declarations to reflect those findings and there is no good reason why I should not make them. The Court has jurisdiction to make binding declarations as of right under s 21 of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) and nothing in the FW Act limits the exercise of that power. The conditions which must generally be satisfied before the discretion will be exercised (see Forster v Jododex Australia Pty Ltd (1972) 127 CLR 421 at 437–8 per Gibbs J) are satisfied here. Moreover, it is appropriate to mark the Court’s disapproval of the respondents’ conduct in this way: Fair Work Ombudsman v South Jin Pty Ltd (No 2) [2016] FCA 832 at [7] (White J). I will therefore grant the Ombudsman declaratory relief.

COMPENSATION

The power

26 Section 545(1) of the FW Act provides that the Court may make any order it considers appropriate if it is satisfied that a person has contravened a civil remedy provision including an order for compensation for loss suffered because of a contravention.

27 The power conferred by s 545(1) is a broad one, “constrained only by limitations that are strictly required by the language and purpose of the section”: Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union (2018) 262 CLR 157 at [103] (Keane, Nettle and Gordon JJ, Gageler J agreeing at [51]).

28 There is no doubt that the power is wide enough to capture both economic and non-economic loss. Nor is there any doubt that the Court may order both the principal and the accessories to pay compensation: see, for example, Veeraragoo v Goldbreak Holdings Pty Ltd (No 2) [2018] FCA 1448 at [42]–[52] (Colvin J) and the cases cited there and Fair Work Ombudsman v IE Enterprises Pty Ltd [2020] FCA 848 at [24] (Anderson J).

29 The Ombudsman submitted that “[i]t would frustrate the legislative intent … not to make orders compensating the Massage Therapists for the significant loss[es] they have suffered as a result of the underpayment of their entitlements”.

The claim

30 The Ombudsman seeks an order that FTM and Mr Elvin “jointly and severally” pay her the total amount of the underpayments (less the amounts paid by the administrators) for payment out to the Massage Therapists as compensation and, if they cannot be located, to the Commonwealth. The claim is based on the findings in the liability judgment and the conclusions of the referee whose report I adopted in Foot & Thai (No 6).

31 The total amount of the underpayments, after taking into account the amounts paid to the Massage Therapists by the administrators of FTM, is $971,092.27, made up as follows:

(1) Ms Amacio: $159,799.21;

(2) Ms Bantilan: $152,200.47;

(3) Mr Benting: $140,307.06;

(4) Ms Isugan: $149,331.13;

(5) Ms Castaneda: $120,055.56;

(6) Ms Ortega: $123,783.29; and

(7) Ms Sarto: $125,615.99.

32 Obviously enough, having regard to the terms of s 545(2)(b), the Ombudsman must prove that the loss has been incurred “because of the contravention[s]”. As in any civil proceeding, the standard of proof is the balance of probabilities. In the present case the causal connection is readily established, as the amounts in the penultimate paragraph were calculated by comparing what each of the Massage Therapists was entitled to receive under the relevant provisions of the Health Award with the amounts they did receive.

33 In addition, the Ombudsman seeks compensation for non-economic loss caused by the contraventions of s 340(1) (adverse action for exercising workplace rights), s 343 (coercion) and s 351 (discrimination based on race and national extraction). Once again, notwithstanding the involvement of all the respondents in the contraventions giving rise to these claims, the orders are only sought against FTM and Mr Elvin.

Compensation for the underpayments

34 In the liability judgment I found that FTM contravened s 45 of the FW Act by failing to pay the Massage Therapists minimum hourly rates, public holiday penalty rates, Monday to Saturday overtime rates and Sunday overtime rates in breach of various clauses of the Health Award. I also found that FTM contravened s 325(1) of the Act by unreasonably requiring six of the Massage Therapists to spend $800 per fortnight of their wages on its business by directing each of them to refund that amount during periods in which the fortunes of the business were suffering (the so-called cashback periods). And I found that FTM contravened s 323(1) of the Act by deducting certain amounts from the wages of the Massage Therapists, described in the company’s records as “staff loans” when the deductions were not permitted by any of the authorised exceptions in s 324(1). Collectively, these were the underpayments claims.

35 In its defence FTM pleaded that it could not be subjected to “any order for underpayment” because it was a party to a deed of company arrangement, which extinguished any claims by, or debts to, the relevant employees who were also parties to the DOCA and paid in accordance with its terms. I did not uphold that defence (at LJ [886]–[925]).

36 Nevertheless, I was concerned that there might be public interest considerations which could conceivably militate against the making of an order for compensation in relation to the underpayments. For this reason, I caused a request to be made of the President of the NSW Bar Association for the appointment of amicus curiae to make submissions on the question. Mr Assaf SC and Mr Rose of counsel (the amici) kindly accepted the appointment. They filed an outline of submissions and appeared to support their arguments. I am most grateful to them for their assistance.

The submissions of amici curiae

37 The amici accepted that I was correct to hold, for the reasons I gave in the liability judgment, that the DOCA only bound creditors in respect of claims arising on or before 15 December 2015 (at LJ [868]), being the date of the appointment of the administrators, and that the Ombudsman was not a creditor at that time (at LJ [925]). But the amici submitted that I was incorrect to find that the DOCA did not extinguish any claims or debts of the Massage Therapists. They contended that s 545 of the FW Act was “not intended to provide a mechanism for the shortfall from any DOCA”. In particular, they argued that it was not the intention of Parliament that s 545B be deployed “to effectively seek to resurrect claims — including employee claims — which have effectively … been compromised by the DOCA”. In summary, the amici submitted that the following “public interest and discretionary considerations” militate against the making of the proposed compensation orders.

38 First, notwithstanding the scope of the question and their express disavowal of any contention that the liability judgment should be corrected, the amici submitted that contrary to the conclusion reached at [928] of the liability judgment the effect of the prescribed provisions, set out in Schedule 8A to the Corporations Regulations 2001 (Cth) (which are taken to have been included in the DOCA by virtue of s 444A(5) of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth)), is that the underlying debts and claims of the employees that existed against FTM as at the day the administration began have been satisfied in full and completely discharged, such that they have consequently been extinguished. The amici correctly observed (and the Ombudsman acknowledged) that my attention had not previously been drawn to the prescribed provisions.

39 Second, the compensation orders sought by the Ombudsman are (or are arguably) contrary to the policy and purpose of Pt 5.3A of the Corporations Act. That is because, by seeking those orders, the Ombudsman effectively seeks to resurrect the Historical Employee Claims as defined in the DOCA when those claims were captured, fully satisfied and completely discharged by the DOCA; the Massage Therapists engaged with the deed administration process by submitting formal proofs of debt, having those claims adjudicated upon, and receiving dividends of distribution in respect of those claims.

40 Third, assuming the Court were to find that the proposed compensation orders are not contrary to the policy and purpose of Pt 5.3A, in the proper exercise of its discretion the Court would have to be satisfied of the quantum of proposed compensation orders in light of the tension between the contemporaneous statutory records of the administrators of the DOCA and the Ombudsman’s evidence on quantum.

41 Fourth, no sufficient evidence appears to have been adduced to establish the utility of the proposed orders.

42 In oral argument, however, the amici accepted that the Court could make an order for compensation in the event of fraud or misleading or deceptive conduct. They pointed to s 445D(1) of the Corporations Act, which gives the Court the power to make an order terminating a deed of company arrangement in certain circumstances, and s 445G, which allows the Court to declare a deed, or a provision of it, void.

43 The circumstances covered by s 445D(1) include where the Court is satisfied that:

(a) information about the company’s business, property, affairs or financial circumstances that:

(i) was false or misleading; and

(ii) can reasonably be expected to have been material to creditors of the company in deciding whether to vote in favour of the resolution that the company execute the deed;

was given to the administrator of the company or to such creditors;

…

(f) the deed or a provision of it is, an act or omission done or made under the deed was, or an act or omission proposed to be so done or made would be:

(i) oppressive or unfairly prejudicial to, or unfairly discriminatory against, one or more such creditors; … or

(g) the deed should be terminated for some other reason.

44 With respect to the circumstances in s 445D(1), a “material factor” is something which was relevant to, and did affect or might have affected, the outcome of the vote: Bidald Consulting Pty Ltd v Miles Special Builders Pty Ltd [2005] NSWC 1235; 226 ALR 510 at [165] (Campbell J). The test of materiality under both ss 445D and 445G is an objective one; it does not matter whether anyone was actually misled: Bidald at [147]; [166]. See also Commissioner of Taxation v Comcorp Australia Ltd and Others (1996) 70 FCR 356 at 385 (Carr J, Lockhart J agreeing at 358). Whether the information is false or misleading is to be judged on the basis of information available at the time of the hearing: Bidald at [147].

45 The amici submitted that, while no application was made to the Court for such an order, if any of the circumstances in which such an order could be obtained could be established, then that would be relevant to the exercise of the Court’s discretion to order compensation for claims otherwise caught by cll 5 and 6 of Schedule 8A to the Corporations Regulations. In particular, they acknowledged that their submissions were “predicated on the basis that the requirements of Pt 5.3A were complied with, including, implicitly, the requirements to not mislead creditors – to not mislead the administrator, by way of example”. Put another way, they said that the benefits that accrue to a company under Pt 5.3A are “predicated on an assumption that … there has been honest and fair dealing”. They accepted that the provision by the company of false or misleading information either to the creditors or the administrators would be “a relevant discretionary factor” to take into account in determining whether to make a compensation order under s 545 of the FW Act.

Consideration

46 The third submission can be disposed of straight away. I am satisfied of the quantum of the proposed compensation orders for the reasons I gave in the liability judgment and Foot & Thai (No 6).

47 I will now address the other submissions. Before doing so, however, I would make the following preliminary observations.

48 As I said in the liability judgment at [866], s 444D(1) of the Corporations Act provides that a deed of company arrangement binds all creditors of the company, “so far as concerns claims [against it] arising on or before the day specified in the deed under paragraph 444A(4)(i)”. The “day specified in the deed under s 444A(4)(i)” is “the day (not later than the day when the administration began) on or before which claims must have arisen if they are to be admissible under the deed”. The administration of the company begins when an administrator is appointed (s 435C). In the present case that was 15 December 2015. As the amici recognised, any underpayments after that date are not covered by the DOCA and there is no impediment to the making of an order under s 545 for compensation for those underpayments.

49 That means that, even if the amici are correct, not all the underpayments would be extinguished by the DOCA. Some $33,565.07 of the total sum related to debts incurred after 15 December 2015. A list of those underpayments is annexed to these reasons and marked “Annexure B”.

50 Further, as I said in the liability judgment at [952], regardless of whether the DOCA operates in the way the respondents contended a deed of company arrangement only binds creditors in relation to claims against the subject company; it does not bind third parties: Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc. v City of Swan (2010) 240 CLR 509 at [52]–[55]. In other words, contrary to Mr Elvin’s submissions, it does not and cannot prevent the Court from making orders that he pay compensation.

51 Moreover, contrary to Mr Elvin’s submissions, the DOCA has no effect on the Court’s power to make declarations with respect to the underpayments or its power to impose pecuniary penalties on the respondents.

The policy and purpose of Pt 5.3A of the Corporations Act

52 I accept the submissions of the amici as to the policy and purpose of Pt 5.3A of the Corporations Act.

53 The policy and purpose of Pt 5.3A are apparent from s 435A. It provides that:

The object of this Part is to provide for the business, property and affairs of an insolvent company to be administered in a way that:

(a) maximises the chances of the company, or as much as possible of its business, continuing in existence; or

(b) if it is not possible for the company or its business to continue in existence—results in a better return for the company’s creditors and members than would result from an immediate winding up of the company.

54 I also accept that a construction of the provisions of Pt 5.3A that will best achieve the object of the Part is to be preferred to any other interpretation: Acts Interpretation Act 1901 (Cth), s 15AA.

55 The mechanism by which these objects are to be achieved is through a deed of company arrangement: Commonwealth of Australia v Rocklea Spinning Mills Pty Ltd (2005) 145 FCR 220 at [26] (Finkelstein J). In Rocklea Spinning Mills at [30] Finkelstein J observed that where the object of the deed is to preserve the company’s business, the legislation does not assume that the creditors will be paid in full. Rather, Pt 5.3A assumes that it might often be necessary to extinguish certain claims “by compositional bar”. His Honour also observed that in the circumstances Pt 5.3A makes no assumption that the creditors will be treated equally or that they will be given the same priority as in a winding up. As he explained, that is because “the equal treatment of creditors or the maintenance of priorities when there is not enough money for everyone can easily thwart the attempt to revive an ailing company”.

56 It is implicit in the statutory scheme in Pt 5.3A, as the amici put it, that a “key policy objective” is to give an insolvent company a “fresh start”: see, for example, Australian Gypsum Industries Pty Ltd v Dalesun Holdings Pty Ltd (2015) 297 FLR 1; WASCA 95; 106 ACSR 79 at [218] (Newnes and Murphy JJA).

57 The Ombudsman did not quarrel with this. Rather, she submitted that, like most statutory provisions, Pt 5.3A does not have “a singular purpose”. She contended that it seeks to balance competing considerations which are reflected in the detail of the legislative scheme. She argued that one of those considerations is the “high public policy” underlying s 556 of the Corporations Act of protecting employees in the aftermath of an insolvency (see, for example, Re Killarnee Civil & Concrete Contractors Pty Ltd (in Liq); Jones (Liquidator) v Matrix Partners Pty Ltd (2018) 260 FCR 310 at [112] (Allsop CJ), which is “carried through” in s 444DA. She claimed the same public policy considerations are embodied in those sections of the FW Act providing for a guaranteed enforceable safety net. She contended that these provisions are “complementary” and “do not conflict” with Pt 5.3A of the Corporations Act.

58 Whether or not the Ombudsman is right, the objects of Pt 5.3A can only be relevant to the interpretation of the provisions of that Part of the Corporations Act. They have no, or at least no direct, bearing on the interpretation of provisions in the FW Act.

The prescribed provisions

59 Section 444A(5) of the Corporations Act provides that “the instrument [setting out the terms of a deed of company arrangement] is taken to include the prescribed provisions, except so far as it provides otherwise”. The amici submitted the DOCA did not provide otherwise. The Ombudsman contended that it did.

60 Regulation 5.3A.06 provides that for s 444A(5), the prescribed provisions are those set out in Sch 8A.

61 Schedule 8A relevantly provides:

5 Discharge of debts

The creditors must accept their entitlements under this deed in full satisfaction and complete discharge of all debts or claims which they have or claim to have against the company as at the day when the administration began and each of them will, if called upon to do so, execute and deliver to the company such forms of release of any such claim is the administrator requires.

6 Claims extinguished

If the administrator has paid to the creditors their full entitlements under this deed, all debts or claims, present or future, actual or contingent, due or which may become due by the company as a result of anything done or omitted by or on behalf of the company before the day when the administration began and each claim against the company as a result of anything done or omitted by or on behalf of the company before the day when the administration began is extinguished.

62 Once an obligation such as a debt is satisfied or discharged, it is necessarily extinguished: Federal Commissioner of Taxation v Orica Ltd (1998) 194 CLR 500 at [114] (Gummow J).

63 I reject the Ombudsman’s contention that the reference in cl 6 to the creditors’ “full entitlements under [the] deed” is a reference to “full amounts owing to them” by the company, irrespective of whether those amounts exceed the amounts in the proofs of debt they submitted. The reason she proffered — that s 553(1) of the Corporations Act provides that all debts payable by, and all claims against, the company are admissible to proof against the company if the circumstances giving rise to them occurred before the relevant date — is no reason at all.

64 Recital C to the DOCA states that the deed “binds all of the Creditors of the Company pursuant to s 444D of the Act …”. Section 444D provides that a deed of company arrangement binds all creditors of the company, so far as concerns claims arising on or before the day specified in the deed …”. While the Ombudsman was not a creditor, each of the Massage Therapists was.

65 Having regard to the terms of s 444A(5), I accept that I was wrong to conclude (at LJ [928]) that the DOCA did not purport to extinguish claims or debts without considering the effect of the prescribed provisions. Provided that “the creditor concerned is bound by the deed”, it is clear from the combined effect of s 444H, s 444A(5), reg 5.3A and Sch 8A that the DOCA will have extinguished them unless it provides otherwise.

66 The first question, then, is whether the DOCA provided otherwise.

Did the DOCA provide otherwise?

67 The DOCA does not contain a provision to the effect of either cl 5 or cl 6 of Sch 8A. But as Rees J observed in a similar situation, the absence of a provision in a deed of company arrangement is not providing otherwise; it is not providing at all: In the matter of Oneoz Pty Ltd (subject to Deed of Company Arrangement) [2019] NSWSC 1247 at [18].

68 Clause 17.1 of the DOCA, however, relevantly provides that, “for the purposes only of administering this Deed” (my emphasis), the prescribed provisions are taken to be included in it “where they are not expressly referred to, pursuant to section 444A of the Act, including but not limited to” certain powers which, as the amici submitted, are identical to those contained in cl 2 of Sch 8A.

69 The amici submitted that the clause was “not a paragon of drafting clarity” and conceded that it was arguable that the purpose of the words in the chapeau to the clause (italicised in the preceding paragraph of these reasons, hereafter referred to as the italicised words) was to limit the incorporation of the prescribed provisions to those provisions relating to the powers of the administrator. Nevertheless, for the following reasons they argued that this construction should be rejected.

70 First, while it is necessary to focus on the terms of the DOCA to determine its proper construction, the DOCA must be construed contextually and that context includes first and foremost the legislative context, as a deed of company arrangement is an instrument which “derives its operative force from statute”: City of Swan v Lehman Brothers Australia Limited (2009) 179 FCR 243 at [7] (Stone J) (Rares J agreeing at [125]). See also Matheson Property Group Pty Ltd (Trustee) v Virgin Australia Holdings Limited [2022] FCA 1243; 165 ACSR 550 at [25] (Lee J). Consequently, “it is to be interpreted as a statute”, rather than a contract.

71 Second, whether a particular provision is within the scope of a deed of company arrangement made under Pt 5.3A is a matter of statutory construction: City of Swan at [9] (Stone J) (Rares J agreeing at [125]). That means that the object and purpose of Pt 5.3A must be taken into account: Ibid.

72 Third, to read the italicised words in such a way as to limit the incorporation of the prescribed provisions only to those provisions relating to the powers of the administrator would not be contrary to the object and purpose of Pt 5.3A.

73 The Ombudsman submitted that the words “except so far as [the deed] provides otherwise” directs attention to whether there is a provision about a particular subject-matter which differs in terms from those contained in the prescribed provisions. She submitted that this can be achieved either expressly, by providing that a prescribed provision is excluded or omitted, or implicitly, by the DOCA making provision on a relevant subject-matter in terms which are different from, or inconsistent with, the prescribed provision.

74 The Ombudsman also argued that, properly construed, cl 17 of the DOCA only incorporates those clauses in the prescribed provisions which confer powers on the deed administrator and cll 5 and 6 do not confer any powers on the administrator. Further, she contended that the DOCA “expressly and exhaustively” addresses the topic of the administration of employee claims in cll 10–12. These clauses are set out at LJ [872]–[878].

75 I accept these submissions. While the words in the DOCA must be read in their statutory context, the construction urged by the amici would have the Court ignore altogether the italicised words in the chapeau. Yet if the DOCA is to be construed like a statute, as the amici argued, the principles in Project Blue Sky Inc v Australian Broadcasting Authority (1998) 194 CLR 355 apply. And that means that the Court “must strive to give meaning to every word of the provision”, since it is “a known rule in the interpretation of [s]tatutes that such a sense is to be made upon the whole as that no clause, sentence, or word shall prove superfluous, void, or insignificant, if by any other construction they may all be made useful and pertinent”: Project Blue Sky at [71] (McHugh, Gummow, Kirby and Hayne JJ).

76 I do not accept the amici’s submission that to read the italised words in cl 17.1 of the DOCA, so as to limit the incorporation of the prescribed provisions only to those provisions relating to the powers of the administrator, would be contrary to the object and purpose of Pt 5.3A. While regard may be had to an objects clause to resolve uncertainty or ambiguity, an objects clause does not control clear statutory language: Minister for Urban Affairs and Planning v Rosemount Estates Pty Ltd (1996) 91 LGERA 31 at 78 (Cole JA); Lynn v New South Wales (2016) 91 NSWLR 636 at [54] (Beazley P, Gleeson JA agreeing at [147]). There is nothing uncertain or ambiguous about the meaning of s 444A(5). Section 444A(5) clearly enables the parties to a deed of company arrangement to choose whether to incorporate the prescribed provisions. The italicised words are words of limitation. Their evident purpose was to incorporate the prescribed provisions only for the purposes of administering the DOCA and thus to the extent to which they relate to those purposes.

Are the proposed compensation orders contrary to the policy and purpose of Pt 5.3A?

77 The amici submitted that the proposed compensation orders are “arguably contrary to the policy and purpose of Part 5.3A” and that, in applying for those orders, “the Ombudsman effectively seeks to resurrect the Historical Employee claims as defined in the DOCA”, when:

(a) the claims were “captured and fully satisfied and completely discharged by the DOCA”;

(b) “the relevant statutory framework … has been properly engaged and invoked”; and

(c) Parliament could not have intended by the enactment of s 545 of the FW Act “to provide a mechanism permitting the Court to effectively undermine the objectives of Part 5.3A by subjecting a company, having the benefit of a deed of company arrangement, [to] new debts in the form of compensation orders – the quantum of which is directly referable to, and ascertainable by, the claims of employees whose debts have been captured by any relevant deed of company arrangement”.

78 The amici accepted that the Ombudsman did not bring the proceedings on behalf of the Massage Therapists but pursuant to her statutory power to enforce the legislation (LJ [889]). Nevertheless, they argued that “in substance” the orders for compensation she sought against FTM undermine the proper operation of Pt 5.3A.

79 In relation to the first matter, the amici submitted first, that the claims of the Massage Therapists that existed as at 15 December 2015 were captured by the DOCA and were “[s]atisfied, discharged and subsequently extinguished by virtue of the operation of [cl] 5 of the Prescribed Provisions”; second and alternatively, they were extinguished by virtue of the operation of cl 6 of the prescribed provisions; third, they were barred by virtue of the operation of cl 12 of the DOCA; and fourth, they were statute-barred by operation of s 544 of the FW Act.

80 As I am persuaded that the DOCA excludes cll 5 and 6 of the prescribed provisions, I do not accept the first two propositions.

81 In relation to the third, I held at LJ [928] that cl 12 operates as a covenant on the part of the creditors not to sue FTM to enforce their claims or recover their debts. I accept that that is a relevant consideration in determining whether to make the compensation orders and I will take it into account.

82 I reject the fourth proposition.

83 Section 544 of the FW Act relevantly provides that a person may apply for an order in relation to a contravention of a civil remedy provision or a safety net contractual entitlement only if the application is made within six years after the day on which the contravention occurred. Section 545(5) provides that a court must not make an order under this section in relation to an underpayment that relates to a period that is more than six years before the commencement of the proceedings concerned.

84 These proceedings were commenced on 22 June 2018. No contravention occurred more than six years before that date. The contravention period began on 24 June 2012, within six years of the filing of the originating application.

85 With respect to the second matter, as the amici submitted, the Massage Therapists did engage with the deed administration process. They each submitted formal proofs of debt and were present at the meeting of creditors held on 18 March 2016 when the creditors resolved to execute the DOCA. All were paid “dividends” pursuant to the DOCA. Consequently, it may be inferred that the administrators adjudicated the value of their entitlements. Contrary to the amici’s submission, however, s 554A(3) did not give them a right to appeal the administrators’ adjudication. That right is only given to persons aggrieved by an evaluation of debts or claims of uncertain value. As the Ombudsman submitted, the value of the underpayments was not uncertain.

86 Further, while they accepted the money paid to them by the administrators, there is no evidence that any of the Massage Therapists executed a form of release as contemplated by cl 5 of Sch 8A of the Corporations Regulations.

87 In addition, the Ombudsman contended that, despite cl 10.2 of the DOCA, the Massage Therapists only received 8.9% of their “annual leave entitlement claims”, by which I gather she meant their annual leave entitlements. For this reason, she contended that any putative bar in cl 10.2 to proceedings to recover their annual leave entitlements is ineffective. I agree.

88 The figure of 8.9% comes from the End of Administration Return, which is a statutory report, filed by the deed administrators on 17 October 2017. It is part of exhibit LRT–C to FWI Thomas’s reply affidavit. There, the administrators recorded the following payments:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

89 It was common ground that the second item related to annual leave. The reason for the shortfall in the annual leave payments is not apparent.

90 Clause 10.2 of the DOCA provides:

The Company will honour annual leave Claims of every Current Employee, and to that extent Current Employees will not be able to prove for annual leave entitlements under this Deed and will be barred from instituting or continuing any legal action, or other proceedings, or from otherwise maintaining an entitlement to a Claim to recover those annual leave entitlements as against the Deed Fund.

91 “Claims” is defined in cl 1.1 of the DOCA (unless the contrary intention appears) as:

all and any existing, or contingent claims, including Historical Employee Claims, and or causes of action, debts, or liability of whatever nature which exist as at the Appointment Date.

92 “Historical Employee Claims” is defined in the same clause, again subject to an apparent contrary intention, as:

all current or contingent claims by current or former employees of the Company arising out of or in connection with the employees’ employment relationship with the Company, including, but not limited to, outstanding employee entitlements, superannuation claims, unpaid overtime and unfair dismissal claims.

93 The effect of cl 10.2, read with the definition of Claims in cl 1.1, is that FTM undertook to pay all current employees, including the Massage Therapists, the full extent of their annual leave entitlements and only then would the Massage Therapists be precluded from recovering anything more in annual leave entitlements.

94 Payments were made under the DOCA by the administrators to each of the Massage Therapists on or about 19 July 2017. Those amounts are set out at LJ [879]. They represent a very small fraction of the amounts they claimed, let alone the amounts they were owed. The amounts paid with respect to annual leave, for example, in contrast to the amounts I found they were owed were: $1,016.63 to Ms Amacio (instead of $10,121.03); $1,051.93 to Ms Bantilan (instead of $8,826.63); $1,051.93 to Mr Benting (instead of $8,494.25); $988.18 to Ms Isugan (instead of $9,180.94); $971.71 to Ms Castaneda (instead of $6,153.36); $971.92 Ms Ortega (instead of $3,403.77); and $971.92 to Ms Sarto (instead of $5,377.50).

95 The contrast between the amounts paid in wages by the administrators and the amounts they were actually owed is even starker: for example, the administrators paid Ms Amacio $22,870.73 in wages when the actual amount she was underpaid in minimum wages, public holidays and overtime penalty rates was $149,678.18. In other words, she recovered less than 15% of what she was owed.

96 I now turn to the third matter.

97 The Court’s powers under s 545 of the FW Act are extremely broad. Insofar as they are relevant, they provide (omitting headings and notes):

(1) The Federal Court … may make any order the court considers appropriate if the court is satisfied that a person has contravened, or proposes to contravene, a civil remedy provision.

(2) Without limiting subsection (1), orders the Federal Court … may make include the following:

(a) an order granting an injunction, or interim injunction, to prevent, stop or remedy the effects of a contravention;

(b) an order awarding compensation for loss that a person has suffered because of the contravention;

(c) an order for reinstatement of a person.

…

(4) A court may make an order under this section:

(a) on its own initiative, during proceedings before the court; or

(b) on application.

…

98 It is reasonable to infer that the power in s 545 is unconfined except to the extent of any limitations imposed, expressly or impliedly, by the subject matter, scope, and purpose of the FW Act: Minister for Aboriginal Affairs v Peko-Wallsend Ltd (1986) 162 CLR 24 at 40 (Mason J, Gibbs CJ agreeing at 30, Brennan J at 56, Deane J at 70 and Dawson J at 71).

99 The amici submitted that, by enacting the FW Act, Parliament must be taken to have been aware of Chapter 5 of the Corporations Act and not to have intended in any way to have modified its impact on employees of corporations, citing the familiar passage in the judgment of Gaudron J in Saraswati v The Queen (1991) 172 CLR 1 at 17:

It is a basic rule of construction that, in the absence of express words, an earlier statutory provision is not repealed, altered or derogated from by a later provision unless an intention to that effect is necessarily to be implied. There must be very strong grounds to support that implication, for there is a general presumption that the legislature intended that both provisions should operate and that, to the extent that they would otherwise overlap, one should be read as subject to the other …

100 The amici also submitted that, in enacting s 545 of the FW Act, Parliament assumed the relevant employer was not subject to any form of external administration because other sections of the Act (ss 119(1), 226(2), 226A(1) and 226(3)) expressly deal with circumstances where an employer is insolvent or bankrupt. Further, they referred to the enactment of the Fair Entitlements Guarantee Act 2012 (Cth) (FEG Act), which they said was “part of the statutory framework” implemented by Parliament “in respect of unpaid wages and entitlements for employees of insolvent companies”.

101 I will deal with the second submission first.

102 I do not accept this submission. At the time FTM was under administration, ss 226(2), 226A(1) and 226(3) had not been enacted. At that time s 226 had no subsections. Sections 226(2), 226(3) and 226A(1) were not introduced until 2022. And s 119(1) does not support the submission. It provides, relevantly, that an employee is entitled to be paid redundancy pay by the employer if the employee’s employment is terminated because of the insolvency or bankruptcy of the employer. If anything, it supports the Ombudsman’s position.

103 The FEG Act establishes a scheme for the provision of limited financial assistance for certain types of “employee entitlements” on the insolvency of an employee’s employer. But it is a scheme of “last resort”, in that no requirement to make an advance arises unless there is no other available source of funds: Secretary, Attorney-General’s Department v Warren (2022) 292 FCR 498 at [8] (Rares, Thawley and Anderson JJ). Moreover, entitlements under that scheme were not accessible to the Massage Therapists because they were migrants on subclass 457 visas and the scheme did not extend to them: FEG Act, s 10(1)(g).

104 Nevertheless, I accept the amici’s submission that Parliament should be taken to have been aware of Chapter 5 of the Corporations Act and did not intend to modify its impact on employees of corporations.

105 While Saraswati was concerned with provisions of the same Act, the authorities her Honour went on to cite, in passages to which I was not taken, were not.

106 One of those authorities was Seward v The “Vera Cruz” (1889) 10 App Cas 59 at 68 in which the Earl of Selborne LC stated:

Now if anything be certain it is this, that where there are general words in a later Act capable of reasonable and sensible application without extending them to subjects specially dealt with by earlier legislation, you are not to hold that earlier and special legislation indirectly repealed, altered, or derogated from merely by force of such general words, without any indication of a particular intention to do so.

107 Another was Bank Officials’ Association (South Australian Branch) v the Savings Bank of South Australia (1923) 32 CLR 276 in which Seward was relied upon. In that case the High Court held that the Industrial Code 1920 (SA), which empowered the Industrial Court of South Australia to fix wages and conditions of employment, was a general enactment and did not repeal provisions in the Savings Bank Act 1875 (SA) which enabled the trustees of the bank with the approval of the Governor to lawfully fix a maximum salary for a given position.

108 These cases are applications of the maxim generalia specialibus non derogant, that is, a general provision does not derogate from a special one. As explained in Bennion on Statutory Interpretation (6th edition, LexisNexis, 2013), §88 p 281:

Where the literal meaning of a general enactment covers a situation for which specific provision is made by another enactment contained in an earlier Act, it is presumed that the situation was intended to continue to be dealt with by the specific provision rather than the later general one. Accordingly the earlier specific provision is not treated as impliedly repealed.

109 In the present context, s 545 of the FW Act is a general provision which applies to any person who the Court finds has contravened or proposes to contravene a civil remedy provision of that Act. In contrast, the provisions in Pt 5.3A of the Corporations Act are specific provisions dealing with companies that enter into deeds of company arrangement. Accordingly, the latter will not be impliedly repealed by the former.

110 It does not necessarily follow, however, that in an appropriate case the Court is precluded from making an order under s 545 of the FW Act against a company which has entered into a deed of company arrangement requiring it to pay compensation to the Ombudsman for underpaying employees who were creditors bound by the deed and therefore unable to sue the company themselves. After all, Pt 5.3A of the Corporations Act includes ss 445D and 445G, which give the Court the power to terminate a deed of company arrangement or declare the deed or a provision of it void. In other words, the object of Pt 5.3A, as described in s 435A, is not to be achieved at all costs. The legislature contemplated that there are circumstances in which a court ought or might not give effect to it.

Is it appropriate to order that FTM pay compensation in the circumstances of this case?

111 In exercising its discretion to order compensation under s 545 of the FW Act, the Ombudsman submitted that the Court should have regard to the following considerations:

(1) the fact that FTM created and kept false or misleading employee records and did not have adequate records, which meant that the deed administrator proceeded to determine employee entitlements based on incomplete, limited, or incorrect information;

(2) more likely than not the Massage Therapists did not know the full extent of their legal rights and entitlements including the amount of the underpayments and therefore lacked the capacity to lodge a proof of debt or commence legal proceedings in a proper and timely manner for adjudication by the deed administrator;

(3) the deed administrator did not “extensively investigate and properly determine” their legal entitlements;

(4) the DOCA only provided for a short period in which to lodge proofs of debt and for the deed administrator to adjudicate claims when it took the Ombudsman a much longer period to investigate those entitlements; and

(5) Mr Elvin may be held liable for compensation as an accessory to FTM’s contraventions and is not bound by the DOCA.

112 As to the first matter, it is highly likely that the administrators were misled. While there is no evidence to explain the reasons for the administrators’ calculations, as the amici submitted the Court may infer that they analysed and relied on the books and records of the company. Mr Elvin did not suggest otherwise. Indeed, he informed the Court that he provided everything to the administrators. Quite apart from the deficiencies in the books and records disclosed in the present proceedings, the liquidator reported to creditors in 2019 that the books and records of the company were inadequate and did not meet the requirements of s 286 of the Corporations Act with respect to the keeping of financial records. In the same report the liquidator identified possible breaches of other sections of the Act, including duties of directors and officers to exercise care and diligence (s 180) and to act in good faith (s 181).

113 Having regard to the state of the company’s records, the administrators were not in a position to assess the true value of the Massage Therapists’ entitlements. Among other things, the leave and pay records relating to the Massage Therapists for the duration of the contravention period, which were produced to the Ombudsman in response to a notice to produce and admitted into evidence in the liability hearing, purported to identify the gross and net wages paid to them and deductions (other than for income tax) made from the gross wages (LJ [576]–[577]). Yet, contrary to the requirements of the FW Regulations, FTM did not produce any record of the number of overtime hours they worked or the start and finish times of those hours, the periods of annual leave they took and the balance of their annual leave entitlements, or the nature of the termination of their employment (LJ [578]–[580]). Further, the pay records were false or misleading as to the net amounts the Massage Therapists received during the periods covered by the contraventions of s 325(1) of the FW Act because they did not record the moneys they were required to repay in cash (LJ [581]).

114 It can reasonably be expected that false or misleading information in FTM’s records given to the creditors and/or the administrators would have been material to the creditors in deciding whether to vote in favour of execution of the DOCA.

115 As to the second matter, I have no doubt that the Massage Therapists were unaware of the full extent of their entitlements as of 15 December 2015 or, for that matter, at any time before the Ombudsman’s investigation concluded in 2018. That is apparent when their proofs of debt, which were exhibited to FWI Thomas’s reply affidavit, are compared with the actual shortfall in their entitlements. Ms Amacio only claimed that she had “unpaid overtime” debts totalling $70,000. Ms Bantilan said she was only owed annual leave in the amount of $10,199. Each of Mr Benting, Ms Castaneda, Ms Ortega, and Ms Sarto claimed to be owed unpaid wages and leave entitlements of “at least $40,000” together with an unspecified amount of unpaid superannuation contributions. Yet, the actual amounts they were underpaid, as recorded by the referee were as follows: Ms Amacio – $159,799.21; Mr Benting – $140,307.06; Ms Bantilan – $152,200.47; Ms Castaneda – $120,055.56; Ms Ortega – $123,783.29 and Ms Sarto – $125,615.99.

116 Other documents exhibited to FWI Thomas’s reply affidavit, however, show that Ms Isugan received assistance from Legal Aid ACT in order to complete her proof of debt. Her claim was more detailed and extensive, although still less than the full extent of her entitlements. In a letter to the administrators written by her lawyer, dated 14 January 2016, she claimed to be entitled to in excess of $100,000 including $3,262.50 representing three weeks’ pay in lieu of notice as a result of her summary dismissal from FTM’s employment; unpaid overtime totalling $88,619.44; unpaid annual leave entitlements totalling $11,434.93; and unpaid superannuation entitlements of $2,153.95. The same day she lodged a formal proof of debt in the amount of $118,520 to which she attached the letter from her Legal Aid lawyer. On 16 February 2016 Ms Isugan submitted a second formal proof of debt, also accompanied by a letter from her lawyer, this time for unpaid wages and an amount of $13,200 referable to the amounts of money she said she was required to return in cash to FTM. Then, on an unknown date, Ms Isugan lodged yet a third formal proof of debt, this time for outstanding annual leave payments in the sum of $9,071. In the result, her formal proof of debt claims totalled $140,791.

117 Ms Isugan’s unpaid entitlements were higher, however, than the amounts claimed, although not by much – at $149,331.13.

118 Mr Elvin intimated that all the Massage Therapists were represented by the law firm, Ashurst, but there was no evidence to support that claim.

119 The minutes of the meeting held on 26 February 2016 disclose that four of the eight employees in attendance, seven of whom were the Massage Therapists, were “represented by” a lawyer, Claire Bradbury (who I gather is or was a solicitor with Ashurst) and, although they then voted against the motion to execute the DOCA, at the subsequent meeting on 18 March 2016, when they were also present as was Ms Bradbury, the motion was carried unanimously.

120 Even so, no matter how skilled and informed the lawyers may have been they did not have the powers given by Parliament to the Ombudsman to investigate the extent of the underpayments and they would not have had access to all the relevant documents.

121 As for the third matter, I do not know the extent to which the deed administrator investigated the underpayments. The only evidence on the subject appears in the remuneration report dated 21 January 2016, annexed to FWI Thomas’s affidavit filed on 25 November 2020 but that affidavit was never read. The amounts paid to the Massage Therapists, however, were substantially less than their claims and considerably less than the amounts to which they were entitled.

122 As to the fourth matter, it is true that the Ombudsman took a long time to investigate the extent of the underpayments and that she was likely to be much better informed than the deed administrators. At the time the dividends were paid to the Massage Therapists, the Ombudsman’s investigation was still in progress. Mr Elvin complained that the Ombudsman could have taken action before or during the DOCA. But the first complaint to the Ombudsman was not lodged until the day the administrators were appointed; the Ombudsman’s investigation did not start until 28 April 2016; the deed was wholly effectuated by 17 October 2017; and the Ombudsman’s investigation did not conclude until the third week of May 2018.

123 As to the fifth matter, Mr Elvin was bound by the DOCA. However, as I have said already, the DOCA does not preclude the Court from ordering him to pay compensation. Even so, the fact that an order can be made against Mr Elvin is not a factor that weighs in favour of exercising the discretion to make an order against FTM.

124 It seems to me that the fact that the Massage Therapists are not covered by the FEG Act is a factor weighing in favour of the making of a compensation order against FTM.

125 The final matter that needs to be addressed is the question of utility.

126 The evidence does not indicate that FTM will be able to pay compensation at least to the extent of the underpayments.

127 The Ombudsman acknowledged that the utility (quaere futility) of making compensation orders and the inability of FTM to comply with them “may have some limited relevance” but is not determinative. She claimed that “this may be inferred” from the fact that the Court granted leave to proceed against the company in liquidation. I accept that the inability of FTM to comply with an order that it pay compensation is not determinative but the fact that leave was granted to proceed against FTM after it went into liquidation had little to do with the capacity of the company to comply with an order for compensation: Fair Work Ombudsman v Foot & Thai Massage Pty Ltd (in liq) [2019] FCA 1601.

128 The Ombudsman submitted that refraining to make a compensation order in such circumstances might “directly undermine the protective purposes of the FW Act” as it “may encourage employers to engage in a deliberate and systematic pattern of conduct of underpayment” and avoid liability by claiming that, as at the date of the liability hearing, the employer did not have the means to rectify the underpayments. She submitted that, even if an employer is unable to pay the amounts ordered in compensation at the time the order is made, they may be able to do so in the future. In any event, she argued, the making of a compensation order would allow her to use the enforcement processes of the Court “to interrogate more deeply and extensively the financial position of the alleged impecunious respondent, whose financial circumstances may be opaque or misrepresented at trial …”.

129 The Ombudsman noted that in the statutory report provided to creditors in November 2019 the liquidator had identified some potentially material or significant voidable related party transactions and some uncommercial transactions that may be void as against a liquidator which required investigation. The Ombudsman also pointed to the fact that the company was still in liquidation and the most recent administration return recorded that investigations were ongoing.

130 I accept these submissions. I am not satisfied that it would be futile to order FTM to pay compensation.

Conclusion

131 Taking all relevant matters into account, and notwithstanding the terms of cll 11 and 12 of the DOCA, I am persuaded that it is appropriate to order FTM to pay compensation.

132 Even if I am wrong to conclude that the DOCA is not an insuperable barrier to the making of a compensation order referable to debts and claims covered by it, it cannot operate as a barrier to the Court making an order for compensation for FTM’s underpayments after 15 December 2015, which total $33,565.07.

Compensation for non-economic loss

133 Although a broader claim was made in the originating application, the claim to compensation for non-economic loss as advanced in final submissions is confined to “the emotional harm and distress and the loss of enjoyment of life” allegedly caused by the various threats made to the Massage Therapists throughout their employment.

134 I addressed these matters at [607]–[673] of the liability judgment. It was apparent from the evidence that all the Massage Therapists had been threatened by Mr Elvin and that they remained, years later, in fear of him. Their distress was palpable. At [204] of the liability judgment I observed that:

A number of them broke down in cross-examination when recounting some of their experiences working for FTM and Mr Elvin’s behaviour, in particular. Ms Isugan sobbed as she recounted the threats of harm to her family. Mr Benting wept as he recalled the anger displayed by Mr Elvin the night he threatened to harm family members of staff who reported the “real situation”. Ms Castaneda broke down several times. She sobbed as she gave evidence about Mr Elvin’s criticisms of her performance and his threats to send her home if she did not improve. She was in tears as she told the Court about his angry outbursts and her fear of him. Ms Amacio fought back tears as she recalled Mr Puerto conveying Mr Elvin’s threats of reprisals.

135 At [663] I said: