Federal Court of Australia

Zonia Holdings Pty Ltd v Commonwealth Bank of Australia Limited (No 5) [2024] FCA 477

ORDERS

ZONIA HOLDINGS PTY LTD (ACN 008 565 286) Applicant | ||

AND: | COMMONWEALTH BANK OF AUSTRALIA LIMITED (ACN 123 123 124) Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. In the event that agreement can be reached on the form of the orders that should be made, and the answers to the common questions that should be given, in light of the reasons for judgment published as Zonia Holdings Pty Ltd v Commonwealth Bank of Australia Limited (No 5) [2024] FCA 477 (the reasons for judgment), the parties provide a draft of the orders and the answers, which they propose, to the Associate to Yates J on or before 4.00 pm on 24 May 2024.

2. In the event that agreement on the matters referred to in Order 1 cannot be reached, the parties inform the Associate to Yates J, on or before 4.00 pm on 24 May 2024, of the nature and extent of the disagreement between them, whereupon a case management hearing will be appointed to make further directions that are necessary to allow all outstanding matters in dispute to be determined.

3. Subject to further order, until 5.00 pm on 15 May 2024 the reasons for judgment be published only to the parties and their legal advisers and not be disclosed to any other person.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ORDERS

NSD 1158 of 2018 | ||

BETWEEN: | PHILIP ANTHONY BARON First Applicant JOANNE BARON Second Applicant | |

AND: | COMMONWEALTH BANK OF AUSTRALIA LIMITED (ACN 123 123 124) Respondent | |

order made by: | YATES J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 10 May 2024 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. In the event that agreement can be reached on the form of the orders that should be made, and the answers to the common questions that should be given, in light of the reasons for judgment published as Zonia Holdings Pty Ltd v Commonwealth Bank of Australia Limited (No 5) [2024] FCA 477 (the reasons for judgment), the parties provide a draft of the orders and the answers, which they propose, to the Associate to Yates J on or before 4.00 pm on 24 May 2024.

2. In the event that agreement on the matters referred to in Order 1 cannot be reached, the parties inform the Associate to Yates J, on or before 4.00 pm on 24 May 2024, of the nature and extent of the disagreement between them, whereupon a case management hearing will be appointed to make further directions that are necessary to allow all outstanding matters in dispute to be determined.

3. Subject to further order, until 5.00 pm on 15 May 2024 the reasons for judgment be published only to the parties and their legal advisers and not be disclosed to any other person.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

[1] | |

[9] | |

[14] | |

[16] | |

[37] | |

[45] | |

[49] | |

[49] | |

[52] | |

The Bank’s Joint Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorism Program Part A | [58] |

[61] | |

[67] | |

[71] | |

The Bank’s dealings with AUSTRAC immediately before the relevant period | [84] |

[91] | |

[97] | |

[105] | |

[118] | |

[144] | |

[162] | |

[162] | |

[165] | |

[170] | |

[174] | |

[196] | |

[202] | |

[205] | |

[209] | |

[222] | |

[222] | |

[224] | |

[228] | |

[250] | |

[270] | |

[270] | |

[273] | |

[286] | |

[290] | |

[290] | |

[299] | |

[302] | |

[309] | |

[314] | |

[323] | |

The Bank develops a communications strategy on a “worst case scenario” | [332] |

[333] | |

[333] | |

[337] | |

[349] | |

[352] | |

The market disclosure regime governing the Bank’s obligations of disclosure | [352] |

[365] | |

[370] | |

[370] | |

[371] | |

[372] | |

[373] | |

[374] | |

[375] | |

[376] | |

[377] | |

[378] | |

The June 2014 IDM ML/TF Risk Assessment Non-Compliance Information | [379] |

The August 2015 IDM ML/TF Risk Assessment Non-Compliance Information | [380] |

[381] | |

[382] | |

[392] | |

[392] | |

[399] | |

[434] | |

[478] | |

[489] | |

[502] | |

[514] | |

[532] | |

[554] | |

[566] | |

[568] | |

[568] | |

[577] | |

[596] | |

[607] | |

[618] | |

[631] | |

[632] | |

[632] | |

[634] | |

[639] | |

[650] | |

[650] | |

[652] | |

[665] | |

[666] | |

[679] | |

[687] | |

[710] | |

[710] | |

[712] | |

[720] | |

[725] | |

[727] | |

[728] | |

[730] | |

[738] | |

[756] | |

[777] | |

[813] | |

[836] | |

[836] | |

[842] | |

[845] | |

[856] | |

[874] | |

[889] | |

[901] | |

[901] | |

[903] | |

[904] | |

[907] | |

[915] | |

[922] | |

[923] | |

[942] | |

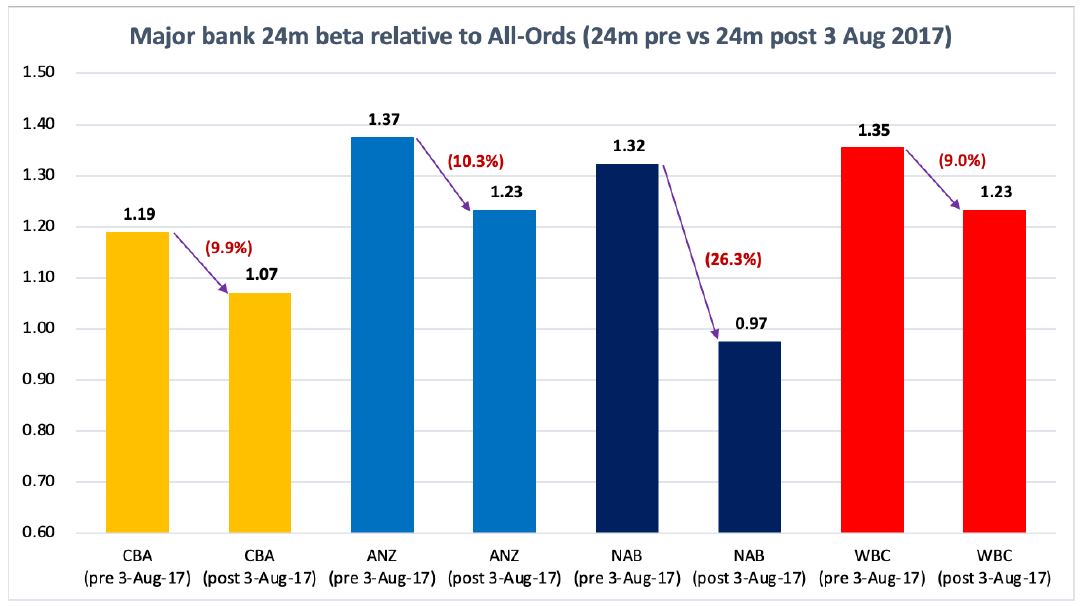

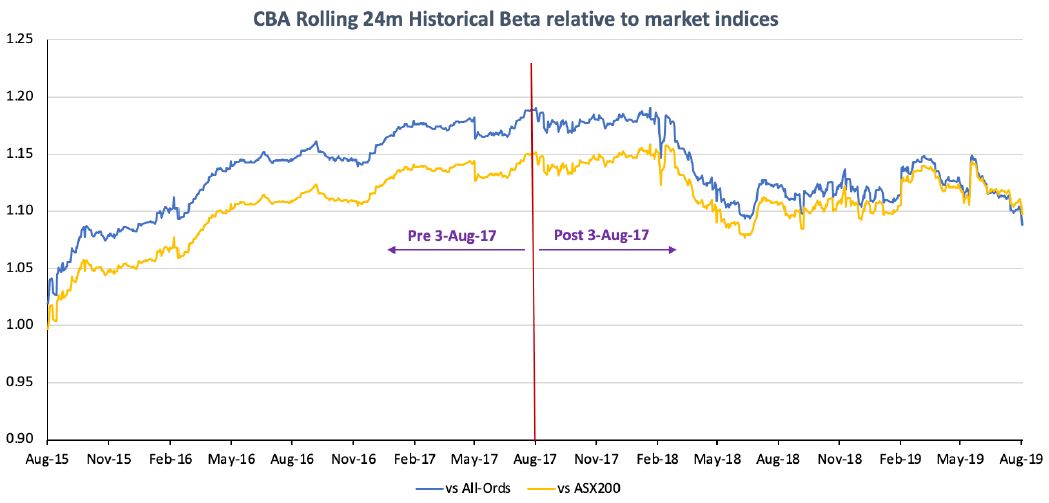

The significance of the market reaction to the 3 August 2017 announcement | [942] |

[953] | |

[953] | |

[957] | |

[973] | |

[979] | |

[985] | |

[992] | |

The materiality of the information of which the Bank was “aware” | [1021] |

[1030] | |

[1032] | |

[1032] | |

[1042] | |

[1054] | |

[1064] | |

[1064] | |

[1089] | |

[1097] | |

[1098] | |

[1098] | |

[1108] | |

[1119] | |

[1120] | |

[1120] | |

[1137] | |

[1165] | |

[1198] | |

[1198] | |

[1204] | |

[1207] | |

[1208] | |

[1209] | |

[1211] | |

[1212] | |

[1231] | |

[1235] | |

[1236] | |

[1238] | |

[1245] | |

[1246] | |

[1259] | |

[1264] | |

YATES J:

1 On 3 August 2017, the Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of the Australian Transaction Reports and Analysis Centre (AUSTRAC) commenced a proceeding against the respondent, Commonwealth Bank of Australia Limited (the Bank), for civil penalties and other relief (the civil penalty proceeding) because the Bank failed to comply with its obligations under the Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorism Financing Act 2006 (Cth) (the AML/CTF Act). As events transpired, the Bank made various admissions of contravention for the purposes of that proceeding. On 20 June 2018, the Court granted declarations in relation to the Bank’s contraventions and imposed a pecuniary penalty pursuant to s 175(1) of the AML/CTF Act in the sum of $700 million: Chief Executive Officer of the Australian Transaction Reports and Analysis Centre v Commonwealth Bank of Australia Limited [2018] FCA 930.

2 The present proceedings concern events and circumstances that gave rise, in part, to the civil penalty proceeding. They are, however, separate from the civil penalty proceeding and involve markedly different questions of legal liability.

3 The applicants allege that the Bank breached its obligations of continuous disclosure under Ch 6CA of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (the Corporations Act)—specifically, s 674(2)—because, in the period 16 June 2014 and 1.00 pm on 3 August 2017 (the relevant period), it had information relating to some of (what were later found to be) its contraventions of the AML/CTF Act which it did not disclose to the market operated by the Australian Securities Exchange (the ASX) on which its shares (CBA shares) were traded. This information, which the applicants plead in various forms, is conveniently categorised as the Late TTR Information, the Account Monitoring Failure Information, the IDM ML/TF Risk Assessment Non-Compliance Information, and the Potential Penalty Information. The applicants allege that the Bank was required by r 3.1 of the ASX Listing Rules to disclose this information. They allege, further, that, had this information (or a combination of it) been disclosed, it would have had a material effect on the market price of CBA shares.

4 Relatedly, the applicants allege that, throughout the relevant period, the Bank engaged in misleading or deceptive conduct on a continuous basis by publishing, and failing to correct or modify, various representations. These representations included representations to the effect that the Bank had in place effective policies, procedures, and systems to ensure its compliance with relevant regulatory requirements, and with its continuous disclosure obligations.

5 The applicants contend that these representations were misleading or deceptive because the Bank did not have effective policies, procedures, and systems in place to ensure compliance with the AML/CTF Act or to ensure compliance with its continuous disclosure obligations under Ch 6CA of the Corporations Act. The applicants allege that, by engaging in this conduct, the Bank contravened s 1041H(1) of the Corporations Act, s 12DA(1) of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth) (the ASIC Act) and, or alternatively, s 18(1) of Sch 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (the Australian Consumer Law).

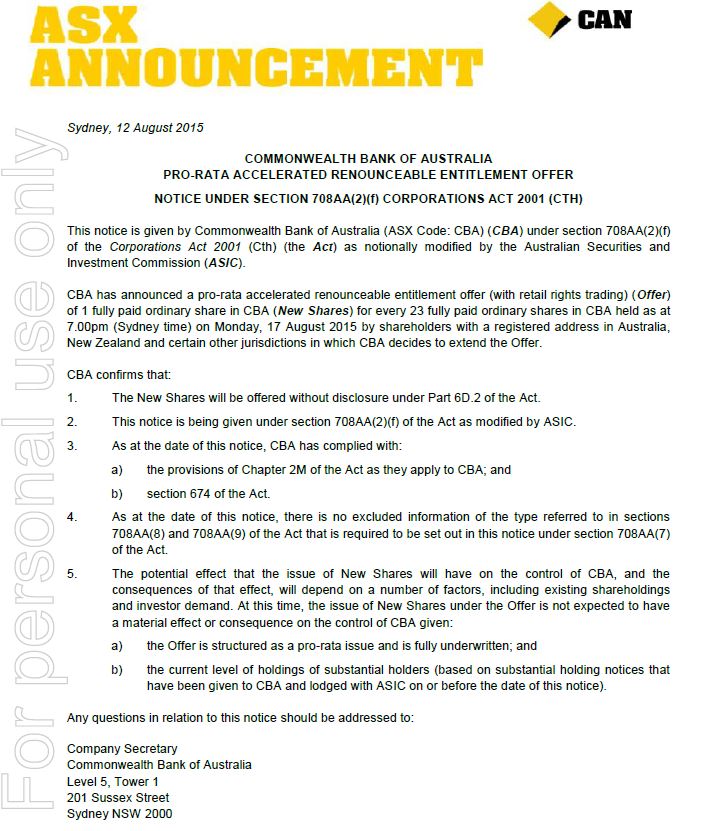

6 Further, the applicants allege that, in connection with a pro-rata renounceable entitlement offer of new CBA shares that was made to shareholders in September and October 2015 to raise $5 billion in capital (the 2015 Entitlement Offer), the Bank issued a cleansing notice that was defective within the meaning of s 708AA(11), and which was not corrected as required by s 708AA(10), of the Corporations Act.

7 The applicants allege that, because the Bank did not comply with its continuous disclosure obligations as it should have done, or because the Bank engaged in misleading or deceptive conduct, or because the Bank issued and did not correct an allegedly defective cleansing notice, CBA shares traded on the ASX at an artificially inflated price (i.e., at a price above the price that a properly informed market would have set). They contend that they acquired CBA shares in that inflated market and, as a consequence, paid too much for them. They seek to recover, by way of damages, the amount of that inflation or an amount referable to that inflation.

8 For the reasons that follow, I have concluded that the applicants’ case against the Bank fails at a number of levels.

9 There are two proceedings before the Court that have been commenced under Pt IVA of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth).

10 The first proceeding is Zonia Holdings Pty Ltd v Commonwealth Bank of Australia Limited: VID 1085 of 2017 (the Zonia proceeding). The second proceeding is Philip Anthony Baron and Joanne Baron v Commonwealth Bank of Australia Limited: NSD 1158 of 2018 (the Baron proceeding). The Zonia proceeding was commenced as an “open” class action. The Baron proceeding was commenced as a “closed” class action (whose Group Members are those who had signed a funding agreement with Therium Australia Limited at the commencement of that proceeding).

11 For some time, the two proceedings were case-managed together. After a significant period of conferral between the applicants in each proceeding, interlocutory applications were filed seeking orders that the two proceedings be consolidated. This proposal was abandoned before the interlocutory applications were heard. The interlocutory applications were then amended, with leave, to seek (what were called) Cooperative Case Management orders. These orders were made over the Bank’s opposition on 10 July 2019: Zonia Holdings Pty Ltd v Commonwealth Bank of Australia Limited (No 2) [2019] FCA 1061.

12 Amongst other things, the Cooperative Case Management orders provided for the filing of harmonised pleadings to ensure that the allegations against the Bank in each proceeding were substantially the same. The orders also provided that one set of counsel be briefed to represent the applicants and Group Members in each proceeding.

13 As a consequence, one case was presented against the Bank at the hearing. In these reasons, I have referred to this case as “the applicants’ case”. I have drawn distinctions between the applicants only when it has been necessary to do so. I have also referred to the final amended, but nevertheless harmonised, versions of the statements of claim filed by the applicants in their respective proceedings as, simply, “the statement of claim” and the defences filed by the Bank as “the defence”.

14 The applicants’ case was advanced through documentary tenders and expert evidence.

15 The Bank’s case was advanced through documentary tenders, lay evidence, and expert evidence responding to the applicants’ expert evidence.

16 As to the lay evidence, the Bank read affidavits by:

(a) Ian Mark Narev, who was the Managing Director and CEO of the Bank and its related corporate entities (together, the Group) from 1 December 2011 until 8 April 2018;

(b) Shirish Moreshwar Apte, who was, at relevant times, a non-executive director of the Bank and a member of the Risk Committee and the Audit Committee (both Board committees);

(c) Mark Andrew Worthington, who was, from July 2010 to 31 March 2019, the Executive General Manager of Group Audit and Assurance (Group Audit) for the Bank (i.e., the internal Group Auditor); and

(d) David Antony Keith Cohen, who was, at the time of hearing, the Bank’s Deputy CEO. From February 2012 to June 2016, he was the Group’s General Counsel and Group Executive (Group Corporate Affairs). From July 2016 to November 2018, he was the Group’s Chief Risk Officer (CRO).

17 These deponents were cross-examined.

18 The Bank also read affidavits by Gopal Jana, Justin Jun-Ting Lee, Leisa Nicole Zaharis, Craig Bruce Woodburn, Prathish Jose, and Nada Novakovic, all of whom, at the time of the hearing, were employees of the Bank, and affidavits from Bryony Kate Adams, a partner in Herbert Smith Freehills, the solicitors for the Bank. These deponents were not cross-examined.

19 The Bank expected to read an affidavit by Sir David Hartmann Higgins who was, at relevant times, a non-executive director of the Bank and a member of Board committees, including the Risk Committee (from April 2016 until his retirement from the Board on 31 December 2019) and the Audit Committee (from October 2014 until March 2016). However, following my refusal of the Bank’s application to permit him to give oral evidence by audio-visual link (Zonia Holdings Pty Ltd v Commonwealth Bank of Australia Limited (No 3) [2022] FCA 1323), Sir David’s affidavit was not read.

20 The applicants advance a number of submissions criticising the evidence given by Mr Narev, Mr Apte, Mr Worthington, and Mr Cohen.

21 The applicants contend that Mr Narev’s affidavit evidence provided “a selective account of events” that was “an elaborately crafted artifice”. In closing submissions, they compared various passages in Mr Narev’s affidavit with various passages in the transcript of his cross-examination in an endeavour to demonstrate what they saw to be inconsistencies in his evidence. The applicants went so far as to contend that Mr Narev’s affidavit was “never a true or accurate reflection of his recollection of events or state of mind during the Relevant Period”.

22 I do not accept these submissions. I do not consider the applicants’ criticisms to be warranted. I found Mr Narev to be a sound witness who, in cross-examination, was prepared to revisit his affidavit and accept various propositions put to him. Generally speaking, I do not think that any matters of substance arose in the course of Mr Narev’s cross-examination that revealed material inconsistencies with the matters to which he had deposed in his affidavit. On the whole, I accept Mr Narev’s evidence.

23 The applicants contend that Mr Apte “had no genuine recollection of, or was not involved in, significant events during the Relevant Period”. They contend that Mr Apte “did not appear to possess any memory of significant events immediately prior to or during the Relevant Period”. They contend, further, that the opinions expressed by Mr Apte in his affidavit were “nothing more than self-serving submissions constructed after the fact”.

24 I do not accept these submissions. Indeed, I think the applicants’ criticisms of Mr Apte’s evidence are unfair. I found Mr Apte to be a careful witness who attended to the detail of the questions put to him in cross-examination. I do not accept that he did not have, or did not appear to have, a memory of significant events during the time that he was a director of the Bank. I do not think that Mr Apte is to be criticised for making clear the limits of his memory of events that occurred a significant number of years before the hearing. Moreover, I do not consider it to be unusual that, as a non-executive director of the Bank, Mr Apte did not profess to have knowledge of some matters of detail that were put to him. On some occasions, Mr Apte made clear that he was not prepared to speculate on what his state of mind would have been on matters of which he had no actual knowledge. This, however, indicates the care with which Mr Apte attended to the questions put to him. On the whole, I accept Mr Apte’s evidence.

25 The applicants contend that Mr Worthington’s evidence had “little, if any, relevance to the issues in dispute in this proceeding” and that there were “inconsistencies between [his] affidavit and oral testimony”. The applicants contend that Mr Worthington was “a wholly unimpressive witness” whose evidence should be disregarded.

26 I do not accept these submissions. I do not accept that Mr Worthington was “a wholly unimpressive witness” and do not understand why his evidence should be characterised as such. Mr Worthington’s evidence was relevant and informative and, on the whole, I accept it.

27 The applicants contend that Mr Cohen’s affidavit was “a carefully constructed artifice that did not withstand scrutiny during cross-examination”. The applicants contend that because of “significant and numerous contradictions” revealed in Mr Cohen’s cross-examination and “his frequently convoluted accounts in the witness box”, the Court should not have “any confidence in the reliability or truthfulness of [his] evidence” which, according to the applicants, the Court should set aside save where Mr Cohen made admissions against the Bank’s interests.

28 I accept that there were some concerning aspects of Mr Cohen’s evidence. One such aspect was Mr Cohen’s account of when he first learned of the late TTR issue—a significant matter discussed in greater detail below. In his oral evidence in chief, Mr Cohen corrected the statement he had made in his affidavit (to the effect that he became aware of this issue in October 2015). Mr Cohen said that, in preparing to give his oral evidence, it had become apparent to him that he had received a copy of a 6 September 2015 email referring to this issue and that a verbal disclosure of the issue was also made by Mr Toevs at a meeting of the Bank’s Executive Committee on 17 September 2015 (Mr Cohen said that he had mistakenly thought that this disclosure had been made verbally by Mr Toevs at an Executive Committee meeting on 8 October 2015, but Mr Cohen later realised that Mr Toevs was not in attendance at that meeting).

29 In his oral evidence in chief, Mr Cohen said that he wanted to draw attention to these matters because his affidavit “might give the impression that the very first time I heard of the TTR issue was in October 2015”. In that assessment, Mr Cohen was correct. I think this is how his affidavit reads.

30 When cross-examined on the correction, Mr Cohen maintained that his affidavit evidence was still correct because, in October 2015, he became aware that, in August 2015, the Bank had (as he said in his affidavit) identified “an error which had resulted in more than 50,000 threshold transaction reports … not being submitted to AUSTRAC through [the Bank’s] intelligent deposit machines … within the required 10 day time frame …”. In other words, although he had recently come to accept that he had had earlier knowledge of the late TTR issue, Mr Cohen only learned of the number of late TTRs in October 2015 and, to this extent, his affidavit was correct.

31 Mr Cohen was cross-examined on the truthfulness of the last-mentioned explanation. In closing submissions, his explanation was at the forefront of the applicants’ contention that his evidence was unsatisfactory, and that his explanation had cast “doubt on both the accuracy of his recollections and his capacity to provide truthful evidence under oath”.

32 I am not persuaded that Mr Cohen was being untruthful in defending his affidavit evidence. However, on this matter, I think that Mr Cohen’s affidavit evidence was inadvertently incomplete on an important issue. Although Mr Cohen’s affidavit evidence on this topic was not critical to establishing the Bank’s awareness of the late TTR issue (because the Bank’s own evidence was that Mr Narev and Mr Comyn were aware of that issue by 6 September 2015 at the latest), it was important in relation to events concerning the 2015 Entitlement Offer—another significant matter discussed in greater detail below. Uncorrected, the effect of Mr Cohen’s affidavit was that, as Chairman of the due diligence committee appointed to oversee the 2015 Entitlement Offer, he did not know of the late TTR issue until after the final meeting of the committee on 17 September 2015 (the day before the shares under the offer were issued). Mr Cohen’s inadvertence on this matter leads me to treat his evidence with some care on other topics he addressed.

33 The applicants also criticise Mr Cohen for the lateness of his correction. However, ultimately, nothing turns on this. I do not think it fell to Mr Cohen to decide when the correction to his affidavit should have been communicated to the applicants’ legal representatives.

34 The applicants also submit that Mr Cohen’s explanation for his correction was “conflicting, incoherent and garbled”. I do not accept that submission. Mr Cohen’s explanation was clear.

35 The applicants also criticise Mr Cohen’s evidence that, as at 24 April 2017, the Bank’s Executive Committee did not have sufficient information to warrant disclosure to the market of AUSTRAC’s investigation into the Bank’s non-compliance with the AML/CTF Act. In his affidavit, Mr Cohen provided reasons for that view. The applicants submit that, in cross-examination, Mr Cohen contradicted the reasons he had given. I am not persuaded that Mr Cohen’s affidavit evidence was contradicted by his oral evidence in cross-examination. That said, the cross-examination did assist in putting Mr Cohen’s affidavit evidence, on that topic, in context.

36 There are some other aspects of Mr Cohen’s evidence on which I will comment in later paragraphs of these reasons. However, for present purposes it is sufficient for me to state that I do not accept that Mr Cohen’s affidavit was “a carefully constructed artifice” or that, in cross-examination, he made “significant and numerous contradictions” or “frequently convoluted accounts in the witness box”. Further, even though some aspects of Mr Cohen’s evidence were qualified in cross-examination, I do not accept that I should set aside his evidence as unreliable or untruthful. On the whole, I found him to be a satisfactory witness although, as I will later explain, I do not accept all his evidence.

The applicants’ submissions on inferences to be drawn

37 The applicants also contend that I should draw inferences that are adverse to the Bank’s interests because of its failure to call certain witnesses. As a general observation, it is not clear to me what these witnesses could have added to what is already apparent from the extensive documentary record that is before the Court.

38 For example, the applicants point to the fact that the Bank did not call certain employees who (they say) could have given evidence concerning the late TTR issue in relation to events in 2013. I deal with these events in later sections of these reasons. In my view, the documentary record is clear. As will become apparent, my interpretation of that record does not accord with the applicants’ interpretation. Therefore, I do not draw the inferences that the applicants say I should draw simply because the Bank did not call these employees to give evidence.

39 The applicants submit that I should draw certain inferences because the Bank did not call Mr Comyn as a witness (in the relevant period, Mr Comyn was the Group Executive for Retail Banking Services). However, the documentary record (as it relates to communications to and from Mr Comyn, or with which Mr Comyn was copied) is clear. The applicants do not suggest that the record is incomplete or contrived. The Bank does not suggest that Mr Comyn had an understanding of events that differs from the documentary record. There is, therefore, no reason why I should not take these communications at face value.

40 The applicants submit that I should infer that Mr Comyn was aware from October 2015 that “no … risk assessment had been completed since May 2012” in respect of the Bank’s Intelligent Deposit Machines (IDMs) (as to which see [60] and [97] – [104] below). I am not prepared to draw an inference that adds to the evidence in that way. Even so, I do not see how this submission advances the applicants’ case because, as I will later explain, it is not in doubt that the Bank knew in October 2015 that a separate risk assessment had not been carried out when IDMs were introduced in 2012.

41 The applicants also submit that I should infer that Mr Comyn was aware of the seriousness of certain matters communicated to him in emails of 23 June 2016 and 13 July 2016 in relation to a (first) notice given to the Bank under s 167 of the AML/CTF Act seeking the production of information and documents, and in an email dated 7 March 2017 relating to the outcome of a meeting between two employees of the Bank and AUSTRAC. Once again, the content of the emails is clear on the face of the documents themselves, and the Bank does not suggest that Mr Comyn had any view that differed from what the emails clearly say.

42 The applicants submit, further, that I should infer that Mr Comyn knew of, and was kept abreast of, an undertaking within the Bank called Project Concord and that Mr Comyn was concerned to manage reputational damage from the public disclosure of “AML issues” by AUSTRAC, “including by way of a penalty proceeding”. Once again, I am not prepared to make an inference that adds to the evidence in that way. In any event, the evidence establishes, independently, that officers of the Bank knew the details of Project Concord, which is discussed in more detail below.

43 The applicants submit that I should infer that, in light of a proceeding commenced by AUSTRAC against Tab Limited, Tabcorp Holdings Limited, and Tabcorp Wagering (Vic) Pty Ltd (collectively, Tabcorp) (the Tabcorp proceeding), certain officers of the Bank (who were not called as witnesses) were concerned that civil penalty proceedings might also be commenced against the Bank for its breaches of the AML/CTF Act. However, as I will come to explain, the evidence already makes it abundantly clear that the Bank knew of the Tabcorp proceeding and that it was possible that civil penalty proceedings could also be commenced against it. Equally, the evidence makes it clear that AUSTRAC had informed the Bank on a number of occasions prior to 3 August 2017 that, if enforcement action were to be taken against the Bank: (a) AUSTRAC had a number of options available to it; (b) that AUSTRAC had made no decision on the question of enforcement action (including what, if any, enforcement option it might take); and (c) that AUSTRAC would give notice to the Bank before taking any enforcement action.

44 The applicants submit that I should draw certain inferences because the Bank did not call Ms Livingstone, the Bank’s former Chair, as a witness. Again, I am not prepared to draw inferences that add to the evidence in the way that the applicants suggest. The documents on which they rely—a transcript of part of Ms Livingstone’s evidence to the Royal Commission into Misconduct in the Banking, Superannuation and Financial Services Industry (the Financial Services Royal Commission) and a copy of Ms Livingstone’s file note of a meeting with Mr Jevtovic on 30 January 2017, also discussed below—are in evidence and speak for themselves.

45 Expert evidence was given through the tender of expert reports (including joint reports) and orally in concurrent expert evidence sessions in which each of the participants was cross-examined.

46 The applicants called expert evidence from:

(a) Professor Raymond da Silva Rosa, who is a Professor of Finance at the University of Western Australia’s Business School. He is the Chair of the University’s Academic Board and Council, a member of the Senate of the University, and a past-President of the Accounting and Finance Association of Australia and New Zealand. He has expertise in studying investor behaviour. He has co-authored research on the impact of Australia’s continuous disclosure regime. He has also undertaken and published, in both academic and industry refereed journals, research on the appropriate way to measure investor reaction to corporate events, such as takeover announcements and the publication of substantial shareholder notices. He has lectured on Behavioural Finance (how psychology and economics explain investor behaviour).

(b) Mr Rowan Johnston, who has expertise in arranging, managing, underwriting, and advising on share issues and engaging with market participants via a corporate advisory role. From 1987 to 2002, Mr Johnston worked at Deutsche Bank AG in Sydney and Hong Kong in Corporate Finance and then Equity Capital Markets, including some five or six years as Joint Head or Head of Equity Capital Markets in Australia. From 2003 to 2014, Mr Johnston worked at Greenhill (formerly called Caliburn Partnership Pty Ltd) with a focus on advising on capital raisings and sell-downs. Mr Johnston was formerly a corporate lawyer.

(c) Professor Peter Easton, who is the Notre Dame Alumni Professor of Accountancy and Director of the Center of Accounting Research and Education at the Mendoza College of Business at the University of Notre Dame in the United States of America. Professor Easton has held a number of other academic positions in Australian and overseas universities. Over the past 40 years, his research has focused on the role of information in securities valuation and investors’ decision-making. He has published numerous articles in peer-reviewed academic journals and several textbooks on these subjects. He has also served as editor of a number of peer-reviewed journals. His teaching, as well as a large part of his consulting activities, has involved the detailed analysis of complex accounting and valuation issues, forecasting future financial statements, determining the feasibility of investment opportunities, and exploring the link between financial statements and the value and viability of the underlying entity.

(d) Mr Howard Elliot, who has expertise in the design and development of IT systems.

47 The Bank called expert evidence from:

(a) Dr Sanjay Unni, who is a former academic with more than 30 years’ experience. He has taught at the University of California, Berkeley, the University of Strathclyde, Glasgow, the University of Texas, and Southern Methodist University. He is the Managing Director of the Berkley Research Group. Dr Unni has expertise as a financial economist.

(b) Mr Mozammel Ali who is a former investment banker with more than 25 years’ experience in the financial services industry. He was a senior executive in the Corporate Finance division of Deutsche Bank AG, including in the Financial Institutions Group and the Capital Markets and Treasury Solutions team. He was also Head of Capital Solutions. Before then he was employed by Citibank advising on mergers and acquisitions, and capital raising transactions. Mr Ali has expertise in equity capital markets.

(c) Mr David Singer, who is a former investment banker with more than 25 years’ experience. Mr Singer was the Managing Director and Head of Sales Trading at UBS Securities Australia. In that employment, he was active in the market speaking to investors, trading shares (including CBA shares) and making assessments on a day-to-day basis as to the information that was material to investors’ decisions.

(d) Mr Shane Bell, who is a partner in McGrathNicol. Mr Bell is a technology and cybersecurity expert, and a certified computer examiner.

48 The parties advanced criticisms of the evidence given by the opposing experts. I do not propose to deal with these criticisms seriatim. It is sufficient for me to record that, contrary to some of the submissions that were advanced, I found each expert to be a satisfactory witness whose analysis and opinions provided assistance in elucidating the issues before the Court that were within his field of expertise. I discuss the expert evidence in some considerable detail in later sections of these reasons, including the extent to which I accept that evidence. The fact that I have not accepted a particular expert’s opinion is not intended to reflect, and should not be taken as reflecting, adversely on that witness’s competence.

49 The Bank is, and was at all times relevant to this proceeding, Australia’s largest bank. For the years ended 30 June 2014 to 30 June 2017 (a period covering, substantially, the relevant period), the Bank’s total annual income was between $22 billion and $26 billion; its profit was between $8.6 billion and $9.9 billion. It employed approximately 52,000 staff members.

50 The Bank operates (and, in the relevant period, operated) in a highly regulated market and processes a large volume of domestic and cross-border transactions. The Bank’s own estimate is that it has “visibility” of around 40% of all financial transactions in Australia. According to the Bank, one in two inbound cross-border commercial payments are destined to its account holders.

51 The Bank is required to monitor all these transactions under AML/CTF legislation, to which I will refer in more detail. For present purposes, it is sufficient to record that, as at May 2015, the Bank was monitoring approximately 7 million transactions per day with a value of $219 billion. At that time, peak volumes stood at 16 million transactions per day with a value of $570 billion. As at June 2016, the Bank was monitoring over 8 million transactions per day with a value of $300 billion. As at April 2017, the Bank was reporting approximately 3.1 million International Funds Transfer Instructions (IFTIs), 800,000 Threshold Transaction Reports (TTRs), and almost 9,000 Suspicious Matter Reports (SMRs) to AUSTRAC each year.

52 The Bank is, and was at all times relevant to this proceeding, licensed to carry on banking business in Australia and authorised to take deposits from customers as an Authorised Deposit-Taking Institution (ADI) under the Banking Act 1959 (Cth). It was subject to the AML/CTF Act and the Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorism Financing Rules Instrument 2007 (Cth) (the AML/CTF Rules).

53 The AML/CTF Act imposes obligations on ADIs which provide “designated services”. These services are defined in s 6 of the AML/CTF Act. A “designated service” includes opening an account or allowing a transaction to be conducted in relation to an account. A person who provides a “designated service” is a “reporting entity”: s 5.

54 Part 3 of the AML/CTF Act contains reporting obligations for reporting entities. Relevantly to this proceeding, one obligation is to report a “threshold transaction” (as defined in s 5) to the CEO of AUSTRAC (the AUSTRAC CEO): ss 43(2)–(3). A “threshold transaction” includes, for example, a transaction involving the transfer of physical currency, where the total amount of physical currency transferred is not less than $10,000. I will refer to these reports as “TTRs”, in accordance with what appears to be the commonly used acronym for these transactions. Section 43(2) is a civil penalty provision: s 43(4). The obligation to report threshold transactions features prominently in this case.

55 Section 81(1) of the AML/CTF Act provides that a reporting entity must not commence to provide a designated service to a customer if the reporting entity has not adopted and maintained an anti-money laundering and counter-terrorism financing program that applies to the reporting entity. Section 81(1) is a civil penalty provision: s 81(2). The program can be a standard AML/CTF program, a joint AML/CTF program, or a special AML/CTF program: s 83(1). The Bank adopted and maintained a joint anti-money laundering and counter-terrorism program. Such a program is divided into two parts—Part A (general) and Part B (customer identification): s 85(1).

56 The primary purpose of Part A is to identify, manage, and mitigate the risk that a reporting entity may reasonably face that the provision of designated services at or through its Australian operations might involve or facilitate money laundering or the financing of terrorism: s 85(2)(a). Section 82(1) provides that a reporting entity must comply with Part A of the program. Section 82(1) is a civil penalty provision: s 82(2). The Bank’s compliance with Part A of its program also features in this case.

57 The sole or primary purpose of Part B is to set out the applicable customer identification procedures for the purpose of the application of the Act to customers. Part B must comply with the requirements of the AML/CTF Rules: s 85(3).

The Bank’s Joint Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorism Program Part A

58 Part A of the Bank’s program provided that the program would be implemented and monitored in accordance with its Group Compliance Risk Management Framework and Group Operational Risk Management Framework.

59 In relation to risk identification and assessment, Part A provided that the Group must conduct an assessment of Money Laundering and Terrorism Financing (ML/TF) risks faced by members of the Group and maintain a current assessment, with changes in risk recognised and assessed. Each Business Unit or Designated Business Group (where the reporting entities in the Group were related to each other) was required to conduct an assessment, using the Group’s ML/TF Risk Assessment Methodology (or another appropriate and approved method), of the inherent ML/TF risk posed by (a) each new designated service prior to introducing it to the market; (b) each new method of designated service delivery prior to adopting it; and (c) each new or developing technology used for the provision of a designated service prior to adopting it. Further, periodic reviews were to be carried out at least every two years.

60 The applicants contend—and it is not disputed—that the “IDM channel” rolled out by the Bank in 2012 (see [97] – [104] below) fitted these descriptions: it was (at least) a “new method of designated service delivery” or a “new or developing technology used for the provision of a designated service”.

The Group Compliance Risk Management Framework

61 The Group Compliance Risk Management Framework (CRMF) was directed to the risk of legal and regulatory sanctions, material financial loss, or loss of reputation that the Group might incur as a result of its failure to comply with the requirements of relevant laws, industry and Group standards and policies, and codes of conduct. Compliance risk is also known as regulatory risk.

62 One of the Group CRMF principles concerned monitoring and measuring. The principle was expressed as:

Transparency around compliance incidents, control weaknesses and framework effectiveness will be maintained, including timely escalation and reporting.

63 In this regard, the framework also provided that:

Issues or incidents must be reported in accordance with the relevant incident and issue procedures.

64 It is appropriate to mention here that, in relation to monitoring and measurement, the Bank adopted a “Three Lines of Defence” model (the 3LoD model) under which the accountability for the management of risk fell primarily (the first line of defence) to business management to ensure effective compliance risk and incident management within their operations, with the second line of defence falling to (a) Business Units to establish and maintain an effective Business Unit CRMF and compliance control infrastructure, and to monitor compliance consistent with that framework; and (b) Group Compliance to monitor and report on compliance risk management across the Group, raising issues where necessary and reporting to senior management, the Risk Committee, and the Board. The third line of defence was Group Audit and External Audit to conduct independent audits of the implementation, condition, maintenance, and management of the Group CRMF.

65 On 3 November 2015, following the findings of the transaction monitoring program (TMP) review report, the 2013 audit report, and the 2015 audit report (discussed at [170] – [221] below), a briefing paper was prepared for Mr Narev which discussed “a range of potential options” in relation to improvements in the Bank’s 3LoD model from “tactical adjustments” to “major structural shifts”. It would seem that Mr Narev (and perhaps others) had arrived at the view that the Bank’s implementation of the then current 3LoD model was neither effective nor efficient and that this state of affairs was not acceptable. These issues led to Project Trifecta, which was a redesign of the Bank’s 3LoD model.

66 On 16 November 2015, Mr Toevs (who, at the time, was Group CRO) and Mr Dingley (who, at the time, was Chief Operational Risk Officer) presented a proposal to the Bank’s Executive Committee containing three options. The recommended option was a centralisation of specific functions (as opposed to full centralisation (Option 2) or a global model (Option 3)). In March 2016, Mr Toevs circulated a further proposal, which he described as “an iteration of an option presented in the original Trifecta strategy presentation last year” and which included a proposal to create a “Financial Crime Centre of Excellence”.

The Compliance Incident Management Group Policy

67 As part of the Group CRMF, the Bank adopted a Compliance Incident Management Group Policy. It was identified as a key component of the framework. The purpose of the policy was to establish principles in relation to identifying, assessing, and managing compliance issues, and outlining the requirements with respect to the regulatory reporting of compliance issues.

68 The policy identified a compliance issue as an actual, suspected, likely, or imminent contravention of an obligation of any applicable law, regulation, industry standard, industry code, or external business rule or guideline (such as the ASX Listing Rules). The policy identified a reportable breach as a compliance incident which had been assessed and had been determined as being reportable to a regulator.

69 Paragraph 5.1 of the policy principles provided:

5.1 BUs must develop and maintain up to date and approved procedures that are clear, well-understood and document the process for:

• Identifying compliance incidents or likely compliance incidents;

• Assessing all compliance incidents; including determining if they are reportable breaches;

• Reporting and escalating compliance Incidents, ensuring the relevant people including those responsible for compliance, are made aware of compliance incidents and reportability; and

• Rectifying and resolving compliance incidents.

70 RiskInSite was the Group’s integrated system which provided a common platform for managing operational risk and compliance risk across the Group. The policy provided that all compliance risk incidents were to be accurately recorded and maintained in RiskInSite, with the expectation that such incidents would be recorded within a maximum of five business days of discovery.

71 AUSTRAC has certain investigative powers. Under s 202(2) of the AML/CTF Act, the AUSTRAC CEO (or another person authorised by s 202(1)) can give a written notice to a person (who the AUSTRAC CEO or another authorised person believes, on reasonable grounds, is a reporting entity) requiring the person to give information or produce documents relevant to: (a) determining whether the person provides designated services at or through a permanent establishment in Australia; (b) ascertaining details relating to any permanent establishment in Australia at or through which the person provides designated services; and (c) ascertaining details relating to designated services provided by the person at or through a permanent establishment of the person in Australia. However, such a notice can only be given where, on reasonable belief, the notice is required to determine whether to take action under the AML/CTF Act or in relation to proceedings under that Act: s 202(3).

72 Under s 167 of the AML/CTF Act, the AUSTRAC CEO (or another authorised officer, as defined in s 5) can give written notice to certain persons, including a reporting entity, to give information or to produce documents where, on reasonable belief, the person has information or a document that is relevant to the operation of the AML/CTF Act, the Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorism Financing Regulations (Cth) (when in force) (the Regulations), or the AML/CTF Rules. In the present case, notices were given to the Bank under this provision, in the circumstances discussed below.

73 There are a number of avenues open to the AUSTRAC CEO where non-compliance with the AML/CTF Act, Regulations, or AML/CTF Rules has occurred.

74 First, no formal action need be taken. AUSTRAC may engage with the reporting entity on an informal basis to remedy the non-compliance.

75 Secondly, if there are reasonable grounds to think that there has been a contravention of an “infringement notice provision” (defined in s 184(1A)), the AUSTRAC CEO (or another authorised officer) can issue an infringement notice under s 184(1) requiring payment of a penalty.

76 Thirdly, the AUSTRAC CEO can give a remedial direction under s 191(2) of the AML/CTF Act if satisfied that a reporting entity has contravened, or is contravening, a civil penalty provision. The written direction requires the reporting entity to take specified action directed towards ensuring that the entity does not contravene the civil penalty provision, or is unlikely to contravene the civil penalty provision, in the future.

77 Fourthly, the AUSTRAC CEO can accept enforceable undertakings under s 197 of the AML/CTF Act to the effect that a person will take specified action or refrain from taking specified action in order to comply with the AML/CTF Act, Regulations, or AML/CTF Rules, or will take specified action directed towards ensuring that the person does not contravene, or is unlikely in the future to contravene, the AML/CTF Act, Regulations, or AML/CTF Rules. The breach of such an undertaking can result in proceedings being taken against the person for certain relief: see s 198.

78 Fifthly, if the AUSTRAC CEO has reasonable grounds to suspect that a reporting entity has contravened, is contravening, or is proposing to contravene the AML/CTF Act, Regulations, or AML/CTF Rules, a written notice can be given under s 162 of the AML/CTF Act requiring the reporting entity to appoint an external auditor to carry out an audit of, and report on, the reporting entity’s compliance with the AML/CTF Act, Regulations, or AML/CTF Rules.

79 Sixthly, the AUSTRAC CEO can commence proceedings under s 175 of the AML/CTF Act seeking a civil penalty order for the contravention of a civil penalty provision.

80 In its published Enforcement Strategy 2012 – 2014, AUSTRAC stated that it generally chooses to use a supervisory approach to secure reporting entity compliance before proceeding to “more formal enforcement activities”. AUSTRAC referred to its supervisory activities as having “three levels of intensity: (a) low intensity or “engagement” activities (such as by providing information and tools to enable reporting entities to comply with their obligations); (b) moderate intensity or “heightened” activities (such as behavioural assessments, desk reviews, and themed reviews directed at specific behaviours); and (c) high intensity or “escalated” activities (such as providing tailored on-site activities designed to have a direct impact on improving compliance outcomes).

81 AUSTRAC said:

While AUSTRAC prefers to engage and work cooperatively with reporting entities, where these activities do not result in improved compliance, matters are referred to AUSTRAC’s Enforcement team for consideration of enforcement action.

82 I observe that this statement implies that, certainly at that time, enforcement action would not necessarily ensue simply because a matter had been referred to AUSTRAC’s enforcement team. Moreover, enforcement action did not necessarily mean applying for a civil penalty order.

83 Before 3 August 2017, AUSTRAC had taken 33 enforcement actions. Only one was for a civil penalty order, namely the Tabcorp proceeding, which I discuss below. This action was taken in July 2015 with a civil penalty order for $45 million made by this Court on 16 March 2017. The rest of the enforcement actions involved remedial directions (four cases); the issuance of an infringement notice (four cases); the acceptance of enforceable undertakings (15 cases); and the appointment of an external auditor (nine cases).

The Bank’s dealings with AUSTRAC immediately before the relevant period

84 As at March 2012, the Bank’s dealings with AUSTRAC were managed through the Group’s AML/CTF Compliance Officer. In a briefing to the Bank’s Board on 13 March 2012, this relationship was described as “transparent and open” which had enabled the Bank and AUSTRAC “to work collaboratively through a number of AML/CTF issues”. The Bank and AUSTRAC met once a month to discuss improvements to the Bank’s AML/CTF Program, including quality assurance initiatives on transaction reporting, and progress on open audit items. AUSTRAC also audited the Bank annually.

85 On 16 July 2012, the Bank’s Risk Committee was informed that AUSTRAC had conducted its annual audit for 2012 of the Group’s AML/CTF Program and had verbally communicated that it had not identified any material issues with that program.

86 At a meeting on 28 June 2012, the Bank’s Group Head of AML/CTF and Sanctions, Mr Byrne was informed that AUSTRAC was looking to move to 18 month review periods for the Bank (whereas other banks would be getting three to four reviews per year).

87 AUSTRAC conducted a two-day onsite audit on 19 and 20 November 2013. A Senior Manager provided the Bank with a “high level debrief” during which the Bank was informed that AUSTRAC was “extremely pleased with the process, collaboration and availability of people and systems”. AUSTRAC had picked up some “minor errors” and “a few issues” but “nothing systemic” and “nothing serious”. It seems that AUSTRAC indicated that an initial draft of its report would be provided before Christmas 2013, with the Bank given a period of approximately one month to provide comments.

88 At what appears to have been a follow-up meeting on 19 February 2014, AUSTRAC explained that the language used in a letter accompanying its audit report may have come across in “somewhat a terse manner”. However, as understood by the Bank, AUSTRAC attributed this to the fact that “some institutions [had] not proved as collaborative as [the Bank] so AUSTRAC has ‘hardened’ its language in formal communications to all entities for consistency”.

89 These interactions support the proposition that, before the relevant period, the Bank enjoyed a collaborative, business-like relationship with AUSTRAC that appears to have been free of significant non-compliance issues.

90 Mr Narev gave evidence that, at a meeting with Mr Jevtovic (then the new AUSTRAC CEO) on 19 December 2014 (held in Mr Narev’s office), Mr Jevtovic told Mr Narev that there was a “strong relationship” between AUSTRAC and the Bank and that Mr Jevtovic had received “positive feedback” from his team about the Bank. According to Mr Narev, Mr Jevtovic told him that there had been some “minor issues” but these “had always been remedied quickly”.

The Bank’s IT environment, processes and procedures

91 It is appropriate at this stage to say something briefly about the Bank’s information technology (IT) environment.

92 At relevant times, the Bank operated an IT environment of scale and complexity, characterised by a large number of interconnected IT enterprise systems and a large number of internal IT and system support staff. Support was also provided by a large number of external service providers who provided services ranging from system development to day-to-day support.

93 Complex IT environments are prone to possible issues or errors during their life cycles. These issues or errors are driven by various factors. System interdependencies can be affected by upstream changes which can impact information flows and the downstream interpretation of data. Knowledge gaps can occur with system specific teams not having an holistic view of the enterprise architecture and structure. Issues and errors can arise from the requirement to support, update, or replace legacy systems. There may also be dependencies on external service providers, rather than internal staff members, to implement change appropriately.

94 As to complex systems within an IT environment, Mr Elliott and Mr Bell agreed that:

… a complex system within an IT environment … consists of a series of steps or events, perhaps with many inputs and outputs. Complex process steps often rely on previous steps to have completed in a specific order and with a specific result in order to determine the next step. Sometimes complex processes may have to deal with many external events, sometimes being introduced randomly.

95 I discuss in more detail below some of the Bank’s IT processes that are of particular relevance to this proceeding.

96 Mr Elliott and Mr Bell agreed that organisations such as the Bank, operating within a regulatory environment with compliance obligations, will often call upon numerous frameworks to help them achieve enterprise governance of IT. The Bank had various governance frameworks (broader than IT alone) to assist it in achieving its regulatory requirements and obligations. I have referred to some of them above (being those that are more relevant than others to the issues canvassed in this proceeding). As Mr Elliott and Mr Bell also recognised, the Bank’s approach to governance involved an internal audit and assurance capability. I will discuss the output of that capability in later sections of these reasons.

97 IDMs are a type of automated teller machine (ATM) with additional functionality. They are part of the Bank’s NetBank platform. IDMs allow customers to deposit cash or cheques into their accounts without the need to enter the branch itself. Cash deposits are automatically counted and credited instantly to the nominated recipient account. This means that these funds are then immediately available for transfer to other domestic or international accounts.

98 During the relevant period, the Bank’s IDMs could accept up to 200 notes per deposit (i.e., up to $20,000 per cash transaction). The Bank did not limit the number of IDM transactions a customer could make each day. A card was required to activate and make a deposit through an IDM. The card could be issued by any financial institution, but the funds could only be deposited to one of the Bank’s account holders.

99 The IDM channel favours anonymity and there is no mechanism to identify the person who activates the machine and performs the transaction. IDMs can also be used to structure transactions in which large cash amounts can be deposited in smaller quantities. IDMs present a high inherent ML/TF risk. When challenged with the proposition that IDMs present a higher risk profile than ATMs, Mr Narev said that the risk with IDMs was different to the risk with ATMs which was worthy of, or required, separate consideration.

100 The Bank began rolling out its fleet of IDMs in around May 2012. At the commencement of the relevant period (16 June 2014), the Bank had 245 active IDMs and 3,147 active ATMs. At the end of the relevant period (3 August 2017), the Bank had 904 active IDMs and 2,522 active ATMs.

101 Before rolling out the IDMs in May 2012, the Bank did not conduct a formal risk assessment in relation to the designated services provided through this channel. The Bank accepts this fact, and also that such an assessment was not made before July 2015. It accepts that, by not conducting the required risk assessment before rolling out the IDMs, it failed to comply with its AML/CTF Program. I will refer to this as the IDM ML/TF risk assessment non-compliance issue.

102 This is not to say, however, that the Bank did not have regard to AML/CTF risks in respect of IDMs at the time they were rolled out. In a business requirements document, the Bank considered the need to report threshold transactions to the AUSTRAC CEO and the means by which this would be done through IDMs. TTR reporting and transaction monitoring were considered to be mandatory requirements as part of the IDM roll out project, and TTR reporting functionality was built and linked to IDMs. IDM deposits were also linked to automated transaction monitoring rules that targeted certain practices.

103 The Bank also gave specific consideration as to whether to impose limits of less than $10,000 on the amount of cash deposits that could be made through IDMs, but decided against this on the basis that, by doing so, the Bank might encourage “structuring activity”.

104 The Bank completed its first formal risk assessment of IDMs on 14 July 2015. This assessment was carried out following inquiries from “law enforcement agencies”, not AUSTRAC. Following that assessment, the IDMs were rated as “high risk”. However, transaction monitoring was in place and, based on its performance as at 28 July 2015, was considered (by the Bank) to be “working well”. No further controls were envisaged as necessary at that time. A further risk assessment was carried out in July 2016.

105 As I have noted, a “threshold transaction” is a transaction with a cash component of not less than $10,000 in respect of which the Bank is required to submit a TTR to the AUSTRAC CEO.

106 During the relevant period, there were two main ways in which a threshold transaction could occur at the Bank. First, by cash deposit or cash withdrawal at one of the Bank’s branches through its “over-the-counter” system. Secondly, by cash deposit into an IDM.

107 Data with respect to a threshold transaction “flowed” from the relevant “input” through various systems within the Bank before a TTR was submitted to the AUSTRAC CEO. These “flows” involved real-time data flows (i.e., data which flowed almost instantaneously) and batch data flows (i.e., data which flowed periodically and which, typically, included data about batches of multiple transactions).

108 The Group Data Warehouse (GDW) was one of the systems within the Bank involved in the TTR process. It stored data relating to the Bank’s customers, their accounts, and their transactions. As its name suggests, it was the largest system within the Bank, storing current and historical data for millions of customers in relation to a range of products across the Bank.

109 The systems used in the TTR process connected with other systems across the Bank, such as the Bank’s financial crimes systems. These systems included the Financial Crime Platform (FCP) (described in more detail below at [144] – [154]) and Real Time Transaction Monitoring (RTTM). The FCP was used for functions such as sanctions screening, account monitoring, and fraud monitoring. RTTM monitored for fraud in real-time. Its functions included payment and card screening, such as to detect a fraudulent transaction on a customer’s credit card. Because of the sensitivity of their functions, access to these systems and their data was restricted to a limited number of the Bank’s personnel.

110 The TTR process did not involve data flowing directly to AUSTRAC. Rather, there were a number of intermediate systems which involved a combination of real-time and periodic batch data flows. This meant that there was not a single, uniform TTR process which applied to all transactions. There were separate TTR processes depending on the input used and the nature of the transaction. Further, not all transactions processed through an IDM or “over-the-counter” involved threshold transactions.

111 The Bank used transactional data, including about threshold transactions, for a multitude of purposes in addition to threshold transaction reporting, such as:

(a) crediting and debiting customer accounts to reflect the transaction;

(b) monitoring transactions for fraud and anti-money laundering (AML) purposes as part of the Bank conducting its own monitoring of transactions for suspicious matters; and

(c) customer reporting, customer support, and suggesting ways to improve customers’ financial well-being.

112 Therefore, many of the intermediate systems used as part of the Bank’s TTR processes also formed part of other processes within the Bank. This meant that common systems contained data which was unrelated to TTRs. In addition to TTR data flows, data from these common systems was exported to other intermediate systems across the Bank which were wholly unrelated to TTRs. Thus, there was a “web” of data flows. TTR processes were just one component of these flows.

113 Data was not stored in a uniform format in all systems. As data flowed downstream, it was filtered and re-formatted as necessary before being sent to the next system. As a result, whilst some irrelevant data flowed downstream, not all data compiled about a transaction at the input stage flowed downstream to the various intermediate systems involved in the Bank’s TTR processes. As data did not necessarily remain in the same format from system to system, comparing data at the start of the process with data at the end of the process was not a “one-for-one” comparison.

114 Further, the timing of data flows differed according to the type of transaction. Deposits were processed differently depending on whether they related to a debit account or a credit account. In the case of a debit account, the deposit was credited to the relevant account in real-time. In the case of a credit account, the deposit typically settled the following business day. There was, therefore, a lag between the time of the transaction and the time at which the data hit the GDW. This impacted the timing of submitting a TTR to AUSTRAC because the TTR was only generated once the deposit settled, which, in the case of a transaction on a credit account, could be days later (depending on when the transaction occurred and when the settlement occurred).

115 Deposits in IDMs involved other complexities, such as where cash was not removed from a component of the IDM within the “timeout period” (for example, when the deposited cash was held together by a clip or a rubber band). This led to a “failed” transaction in which the cash was directed to a “retract canister” within the IDM. When this happened, the cash “deposited” was not identified and counted for the purposes of the Bank’s automated systems. Such transactions were identified by a customer reporting the failed transaction in a Branch or by the staff within the Branch (in which the IDM was located) identifying the failed transaction from the IDM’s end of day balance. The process of identifying the failed transaction could be complicated because the retract canister could contain other cash. In order to process a failed transaction, Branch staff typically pay the relevant funds to the customer through an electronic funds transfer, which was not processed as an IDM transaction.

116 Of central importance to the present case is an issue concerning the late reporting to the AUSTRAC CEO of threshold transactions through IDMs. When the IDMs were introduced, the Bank’s processes relied on two transaction codes to generate TTRs (codes 5022 and 4013). However, in November 2012, the Bank introduced an additional transaction code (code 5000) for a sub-set of IDM transactions to clarify a deposit message that was visible to customers via the NetBank platform. The new transaction code fixed the message problem, but it was not factored into the downstream process by which threshold transactions were identified for reporting. In short, a “flag” in the system for TTR reporting was missing.

117 This problem was not discovered, and its implications brought home to officers of the Bank, until much later. It is certainly the case, however, that, much earlier in 2013, a potential problem, with an association with code 5000, was identified by the Bank’s staff, but regrettably not fully investigated and rectified. It is necessary to turn, now, to the circumstances in which this occurred.

118 On 29 August 2013, a Compliance Executive employed by the Bank in the AML Sanction section of Risk Management in Retail Banking Services (RBS), Mr Kalra, sent an email to employees responsible for the GDW seeking confirmation that TTRs were being lodged for cash deposits made through IDMs. The evidence does not suggest that this original inquiry was connected with transaction code 5000. Indeed, the applicants’ expert, Mr Elliott, made it clear that “this internal issue was not specifically related to transaction code 5000”.

119 On the same day, a Senior Technical Business Analyst, Mr Ashdown (who had done work on extracting TTRs from the GDW), responded to this inquiry by confirming that cash deposits through IDMs were included in TTRs. However, Mr Ashdown raised a concern about whether the cash component of “mixed deposits” (i.e., deposits involving cash and cheques), where the cash component was a threshold amount ($10,000 or more), was being reported. The reason for raising this appears to have been Mr Ashdown’s understanding that, during his involvement in working on the “TTR extract”, IDMs “couldn’t do mixed deposits”. He did not know “if the functionality was ever developed”.

120 This information prompted Mr Kalra to request that an investigation be conducted:

…

It has come to my attention that Threshold Transaction Reports (TTR) may not be getting lodged for mixed deposits (cash + cheque) made via the Intelligent Deposit Machines (aka IDA or IDM). [I’m assuming the IDM’s would sit under the D&T world.]

As per below email from the Group Data Warehouse (GDW) team, they have confirmed that if cash deposits of $10k or more are accompanied with a cheque deposit, no TTR is lodged for the cash component.

Regulatory requirement is that any transactions in physical currency of $10k or more are supposed to be lodged as a TTR to AUSTRAC. Therefore if what the GWD team is saying is correct, then there may have been some breaches.

Can I please request you to check this process and confirm?

…

121 Later, on 3 September 2013, Mr Kalra raised a further query—whether cash deposits in IDMs using an OFI (Other Financial Institution) card were being reported.

122 The context for each of Mr Kalra’s queries was an upcoming on-site audit by AUSTRAC.

123 A Service Manager in Retail & Business Banking Enterprise Services, Mr Wright, provided a response to Mr Kalra on 4 September 2013. In relation to the question whether there were “(a)ny cash deposits for which TTRs are not currently reported?”, Mr Wright responded:

Would appear yes based on this issue being raised.

124 Properly considered, this answer does not evidence Mr Wright’s knowledge, or indeed any other employee’s knowledge, that these cash transactions were not being reported. Indeed, it was not a substantive answer to Mr Kalra’s question. Self-evidently, Mr Wright’s answer was no more than the unhelpful comment that, because a query had been raised by Mr Kalra, it “appeared” that there were cash deposits for which TTRs were not being given.

125 It is clear that, at this time, two issues had been raised: whether (a) the cash component of a “mixed deposit” and whether (b) cash deposited using an OFI card (in each case, using an IDM to deposit a threshold amount), were being reported.

126 On about 12 September 2013, Mr Kalra escalated these matters to Ms Ishlove-Morris (the Executive Manager AML/CTF & Sanctions, Group Operational Risk & Compliance, Risk Management) and Mr Byrne. In doing so, he informed Ms Ishlove-Morris and Mr Byrne that “(t)he business is checking to confirm whether or not this is actually an issue or not”.

127 There are emails in evidence whose language can be interpreted as stating that, at this time, TTRs were not being provided when they should have been. However, when these emails are read in the context of accompanying emails, it is tolerably clear that Mr Kalra was raising a potential problem and escalating it to those who had an interest in knowing whether there was an actual problem, as Mr Kalra’s email to Ms Ishlove-Morris and Mr Byrne makes clear.

128 On 19 September 2013, Mr Kalra was informed by Mr Razdan, a Project Manager in Retail Banking Enterprise Services that, in fact, cash deposits using an OFI card were being reported.

129 Separately, on the same day, Mr Ashdown informed Mr Kalra that “the TTR report is reporting the Mixed Deposits”. In somewhat chastising language, Mr Kalra responded:

Mark – I thought you’d initially mentioned that for mixed deposits, TTR’s weren’t being generated even for the cash component and that’s why I escalated this issue to the business. Can you please double check again and confirm once and for all?

130 Later that day, Mr Ashdown replied:

I didn’t know whether they were being reported – that was the issue.

I can confirm they are being reported …

131 Having escalated the matter to Ms Ishlove-Morris and Mr Byrne, Mr Kalra then sent an email to Ms Ishlove-Morris on 19 September 2013, stating:

After email chains floating around the world, GDW team have come back and confirmed that TTR’s are being reported for all relevant cash deposits (whether mixed or individual) and there’s no issue.

So we don’t need to report anything to AUSTRAC.

132 Ms Ishlove-Morris then forwarded Mr Kalra’s email to Mr Byrne.

133 It is appropriate to record at this juncture that there is no evidence before the Court as to AUSTRAC’s on-site audit which Mr Kalra had mentioned in his emails. It is not disputed that, at this time, AUSTRAC had not detected any problems with the Bank’s TTR reporting in respect of cash deposits made through IDMs.

134 On 20 September 2013, employees of the Bank identified two OFI card cash deposits for investigation. One deposit was for $10,000; the other was for $10,500. Details of these transactions found their way to Mr Ashdown on 8 October 2013.

135 On 10 October 2013, Mr Ashdown advised that the two transactions had not been reported in TTRs. Mr Ashdown sought further information. Later that day, Mr Ashdown advised that the two transactions had been processed with transaction code 5000 and that “we only pick up Transaction types (cash and mixed deposits)”. In this regard, Mr Ashdown said that there were only two transactions to be considered—those under code 4013 for cheque and mixed deposits to savings accounts, cheque accounts and credit accounts, and those under code 5022 for cash deposits to savings accounts, cheque accounts, and credit accounts.

136 On 11 October 2013, Mr Ashdown was asked to “summarise … if there is an issue, and if there is – what exactly is it and who should be … the owner?”. On 14 October 2013, Mr Ashdown provided the following “summary”:

…

Kote sent me 2 transactions (cash deposits on OFI cards) to check if they had been picked up by TTR.

These transactions (with transaction code 5000) are not being identified as cash transactions by TTR and were not reported.

Kote reported that transaction code 5000 is not on the transaction range for IDA cash transactions. TTR is performing as expected.

However, these 2 transactions are the one identified by Kote as being cash transactions on OFI cards, which would indicate to me that there is possibly a problem.

My understanding of the actions are:

- Refresh Team Confirm whether the tran code on the transactions is correct and therefore the transaction is not a cash transaction.

- If not a cash transaction, Refresh Team need to provide new examples of cash transactions on the OFI cards for me to investigate.

- If it is a cash transaction, Refresh team need to look into why the transactions have the wrong code.

- If Tran code 5000 should be included as a cash deposit, then that’s a bigger issue. We’ll need to discuss how to resolve this,

…

137 It is apparent from this response that the possibilities exercising Mr Ashdown’s mind were that: (a) the two transactions were not, in fact, cash transactions; (b) if they were cash transactions, it was possible that the wrong transaction code had been used; and (c) if the transactions were cash transactions and the correct transaction code had been used and transaction code 5000 should have been on the transaction range for IDMs, then there was “a bigger issue”. However, Mr Ashdown’s advice was that “TTR is performing as expected”.

138 Further email correspondence shows that, as at 24 October 2013, the view was taken that “TTR is working as expected” and that “any potential issues with OFI transactions are at the source system level”. The matter appears to have been left with those who were responsible for advancing that matter at that level, but nothing happened.

139 With hindsight, the ramifications of that inaction can be readily appreciated. I accept the Bank’s submission, however, that, as at 24 October 2013, no-one in the Bank had identified that transactions which should have been flowing through to TTR reporting were not flowing through and being reported to AUSTRAC. While, initially, questions had been raised about TTR reporting in respect of “mixed deposits” and cash deposits using an OFI card, the Bank’s employees had determined that these transactions were being reported. While, later, two other OFI card transactions had been identified for investigation, it was queried whether the transactions had been correctly coded and whether they were even cash transactions. Although the possibility of a “bigger issue” had also been flagged, no further investigation was undertaken, and the facts were not known as to whether there was a “bigger issue”.

140 The evidence does not elaborate on why, at that time, further investigation of the two OFI card transactions was not undertaken. With hindsight, there should have been further investigation to elucidate whether there was a “bigger issue”. Had there been further investigation, it is likely that the general problem associated with cash deposits processed under code 5000 would have come to light. The applicants’ disclosure case, however, is concerned with the information that officers of the Bank had, or ought reasonably to have had. The employees with knowledge of the matters in 2013 that I have described, were many levels below “officer” level, and none had identified a general and significant problem with deposits processed through IDMs under transaction code 5000.

141 The next relevant event is that, on 11 August 2015 (some 22 months later), AUSTRAC asked the Bank to locate TTRs relating to “two ATM deposits” (these are not the two deposits considered in October 2013). The Bank could not locate these reports. It realised that they had not been made. On investigation, it was found that the deposits were processed under code 5000, but that code 5000 had not been linked to TTR reporting, as it should have been. It was then found that this resulted in the non-reporting of 51,637 threshold transactions from November 2012 to 18 August 2015. The number of affected transactions represented approximately 2.3% of the overall volume of TTRs provided by the Bank over the same period.

142 On 8 September 2015, the Bank notified AUSTRAC about the issue. By 24 September 2015, the outstanding TTRs had been lodged. In the meantime, the Bank continued to report threshold transactions identified by the two original codes.

143 I will refer to this as the late TTR issue. I provide further details in relation to this issue at [250] – [269] below.

The Bank’s Financial Crimes Platform

144 The FCP contained data about the Bank’s customers, accounts and transactions, which were sourced from different upstream systems. The platform was used by the Bank to undertake various functions, including:

(a) certain kinds of fraud detection, in particular internal fraud by the Bank’s employees, cheque fraud, and application fraud;

(b) automated politically exposed person and sanctions customer screening; and

(c) automated transaction monitoring for AML/CTF purposes

145 The platform was not used by the Bank to undertake “know your customer” (KYC) procedures, suspicious matter reporting, threshold transaction reporting, sanctions payment screening, or manual politically exposed person screening.

146 There were three main ways in which data entered the FCP. The first was from the GDW, discussed above. The second was from the Bank’s Operational Data Store which contained data from SAP (the Bank’s core banking platform) and the Payments Journal (which recorded payments processed by the Bank). The third was direct data flow (i.e., data not stored in, and then extracted from, an intermediate system such as the GDW).

147 As with the flow of data into the GDW, data flowing into the FCP needed to be “normalised”— in other words, reorganised and transformed into a standardised format that was compatible with the platform.