FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Securities and Investments Commission v BPS Financial Pty Ltd [2024] FCA 457

ORDERS

AUSTRALIAN SECURITIES & INVESTMENTS COMMISSION Plaintiff | ||

AND: | BPS FINANCIAL PTY LTD (ACN 604 899 381) Defendant | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties are to confer and provide to the chambers of Downes J an agreed form of order giving effect to the reasons for judgment and proposed directions as to the further conduct of this proceeding by 4.00 pm AEST on 10 May 2024.

2. If the parties are unable to agree upon a form of order and proposed directions, the parties shall each provide their proposed draft of same to the chambers of Downes J by 4.00 pm AEST on 14 May 2024 accompanied by any written submissions not exceeding three (3) pages.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

[1] | |

[16] | |

[16] | |

[30] | |

[32] | |

[36] | |

[49] | |

[57] | |

[60] | |

[68] | |

[69] | |

[69] | |

[71] | |

2.3.3 Combined Financial Services Guide and Product Disclosure Statements | [78] |

[84] | |

[84] | |

[101] | |

[113] | |

[119] | |

[120] | |

[124] | |

[128] | |

[129] | |

[129] | |

3.5.2 Whether BPS is entitled to rely upon section 911A(2)(a) | [132] |

3.5.3 First Billzy AR Agreement and Second Billzy AR Agreement | [156] |

[173] | |

[176] | |

[176] | |

[180] | |

[190] | |

[196] | |

[205] | |

[206] | |

[206] | |

[219] | |

4.2.1 The representations conveyed by the impugned statements | [219] |

[229] | |

[229] | |

Section 12DB(1)(e): “approval, performance characteristics, uses or benefits” | [229] |

[232] | |

[247] | |

4.3 Characteristics of the hypothetical ordinary or reasonable member of audience | [255] |

[263] | |

[263] | |

[271] | |

[272] | |

[286] | |

[293] | |

[294] | |

[310] | |

[317] | |

[318] | |

[318] | |

[326] | |

[327] | |

[332] | |

If a representation as to a future matter, were there reasonable grounds? | [333] |

If a representation as to a present fact, was it false or misleading? | [350] |

[360] | |

[361] | |

[361] | |

[370] | |

[371] | |

[376] | |

4.6.3 Were the representations statements of fact or opinion? | [382] |

[387] | |

[397] | |

[398] | |

[407] | |

[408] |

DOWNES J:

1 In this proceeding, the plaintiff (ASIC) alleges that the defendant, BPS Financial Pty Ltd, unlawfully carried on a financial services business without holding an Australian Financial Services Licence (AFSL) and that, in the course of that business, it made false and misleading representations in connection with the supply or use of a financial product.

2 These allegations arise out of conduct engaged in by BPS when it developed and made available to the public a system for making non-cash payments using a digital currency or crypto-asset which it named Qoin.

3 There are two parts to ASIC’s claims brought in relation to BPS’s conduct.

4 The first part – the Unlicensed Conduct Case – consists of a claim that BPS contravened ss 911A(1) and 911A(5B) of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) by carrying on a financial services business within the meaning of Chapter 7 of the Corporations Act in issuing a financial product, and providing financial product advice in relation to that product, in circumstances where BPS did not hold an AFSL.

5 BPS claims that it was at all relevant times exempted from the requirement to hold an AFSL:

(1) in respect of its conduct of issuing a financial product:

(a) by s 911A(2)(a) of the Corporations Act, because it issued the product as a representative of the holder of an AFSL; and/or

(b) by s 911A(2)(b) of the Corporations Act, because it issued the financial product in the implementation of an intermediary arrangement as described in that section;

(2) in respect of its provision of financial product advice, by s 911A(2)(a) of the Corporations Act, because it provided that advice as a representative of the holder of an AFSL.

6 The satisfaction or otherwise of these exemptions was the primary battleground on which the parties fought the Unlicensed Conduct Case. ASIC accepted that it bore the legal burden of proving that they did not apply.

7 The second part – the Misleading Conduct Case – concerns ASIC’s claims that BPS contravened ss 12DA(1) and 12DB(1) of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth) (ASIC Act) by making certain statements on its website, and in a document that was published on that website.

8 ASIC alleges that the impugned statements gave rise to four false and misleading representations:

(1) The Trade Representation: that a person who purchases Qoin can be confident that, if and when they wished to do so, they would be able to exchange the Qoin that they held for fiat currency or other crypto-assets through independent exchanges, when no such exchanges existed;

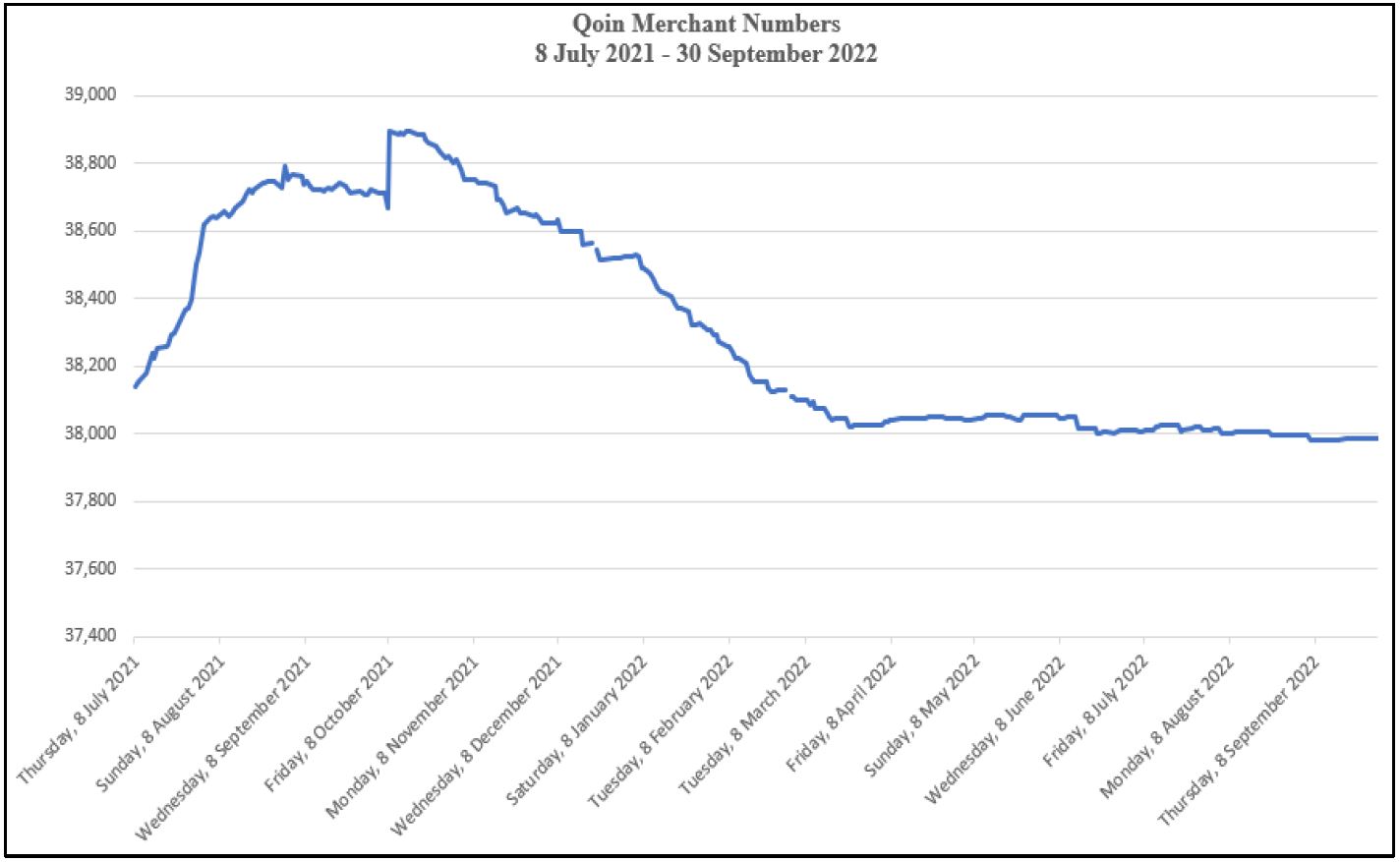

(2) The Merchant Growth Representation: that Qoin could be used to purchase goods and services from an increasing number of merchants, when that was not the case;

(3) The Approval / Registration Representation: that the Qoin NCP Product (defined below) had been officially approved and/or officially registered in the sense of having been granted some kind of official government imprimatur or having been included in some official register of financial products, when neither was the case; and

(4) The Compliance Representation: that the Qoin NCP Product (defined below) and/or BPS were each fully compliant with Australian financial services laws when, based on the Unlicensed Conduct Case, that was not so.

9 There was no serious dispute that BPS published the statements relied upon by ASIC. Rather, the real dispute in the Misleading Conduct Case concerns whether the statements conveyed the representations alleged and, if so, whether those representations were misleading.

10 Pursuant to an order dated 5 December 2022, the hearing proceeded on the issue of liability only, with a separate hearing to be held on any other questions.

11 Section 911A(5B) of the Corporations Act and s 12DB(1) of the ASIC Act are civil penalty provisions. Where I have reached conclusions concerning whether there has been a contravention of those provisions, I have reached a “state of satisfaction or actual persuasion, on the balance of probabilities, while taking into account the seriousness of the allegations and the consequences which will follow if the contraventions are established”; a standard which is set out in s 140(2) of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) and which is the statutory expression of the principle in Briginshaw v Briginshaw (1938) 60 CLR 336: see Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Daly [2023] FCA 290 at [37]–[38] (Cheeseman J).

12 For the reasons which follow, I have concluded that ASIC succeeded on its Unlicensed Conduct Case, other than in relation to the period during which BPS was an authorised representative of PNI Financial Services Pty Ltd, during which period BPS was exempt from the requirement to hold an AFSL by the operation of s 911A(2)(a) of the Corporations Act.

13 As to the Misleading Conduct Case, I have found that BPS contravened ss 12DA(1) and 12DB of the ASIC Act in relation to the Trade Representation, the Merchant Growth Representation and the Approval / Registration Representation, but that BPS did not contravene the ASIC Act in relation to the Compliance Representation, because the latter would have been understood as conveying an expression of opinion only.

14 I will direct the parties to confer and provide orders which reflect these reasons, and which address directions relating to the further conduct of this proceeding. Unless the parties can reach agreement about any proposed costs order, it is my present view that the determination of the appropriate costs order should await the next stage of this proceeding.

15 Additionally, the parties should have leave to appeal and, if necessary, leave to cross-appeal.

16 The business of the Bartercard Group, known as Bartercard, commenced in 1991. It operated as a business-to-business trading platform. Businesses which signed up as members could trade their goods and services with each other using a notional “currency” known as Trade Dollars.

17 In late 2018, two former long-term employees of the Bartercard Group, Mr Antonie Wiese and Mr Rajesh Pathak, acquired the Bartercard Group through their own corporate interests. By early to mid-2019, Mr Wiese, Mr Pathak and senior management of Bartercard discussed using blockchain technology to transition the Trade Dollar concept to a digital currency. The name applied to this intended new initiative in around August 2019 was the Qoin Project.

18 The Qoin Project, as proposed in 2019, was to implement some key changes from the existing Bartercard model. First, Qoin was to include consumers as members, as well as merchants. Second, transactions would be recorded on a distributed blockchain ledger instead of a centralised ledger. Third, no transaction fees were to be charged. Finally, the unit of exchange was to be labelled “Qoin” instead of “Trade Dollar”.

19 BPS is a member of the broader Bartercard Group and is the corporate vehicle through which the Qoin Project was established and implemented.

20 The proposed Qoin Project involved the provision of a “financial product” as defined in s 763A of the Corporations Act because it was a facility through which a person makes a non-cash payment (as defined in s 763D). By implementing the proposed Qoin Project, BPS therefore intended to carry on a financial services business in this jurisdiction and was required by s 911A(1) of the Corporations Act to hold an AFSL covering the provision of the financial services, or to bring itself within one or more of the exemptions to the requirements for BPS to hold an AFSL in s 911A(2). This is not controversial.

21 In November 2019, Mr Wiese and Mr Pathak decided to approach an existing non-cash payment facility AFSL holder to seek approval for BPS to be authorised under that other holder’s AFSL to implement the Qoin Project.

22 Mr Wiese received a list of existing non-cash payment AFSL holders on 20 November 2019. He became aware from this that Billzy Pty Ltd held an AFSL. Billzy was majority owned by a longstanding Bartercard member, Mr Steven Pantic. Mr Wiese and Mr Pathak approached Mr Pantic and told him that Bartercard had initiated the Qoin Project and required a non-cash payment facility AFSL.

23 Negotiations then ensued between Billzy and BPS. Those negotiations culminated in the execution of two documents between Billzy and BPS:

(1) a document entitled “Authorised Representative Agreement” dated 17 December 2019; and

(2) a document entitled “Intermediary Agreement” which was undated, but which the parties accept was executed on or about 17 December 2019.

24 In around October 2020, Mr Wiese was informed that Billzy had been approached for a commercial transaction with a possible consequence that Billzy may not be able to authorise BPS beyond an initial 12 month period. Mr Wiese was informed that PNI (who was also a responsible manager under Billzy’s AFSL) was also a non-cash payment facility AFSL holder, and that PNI had agreed to authorise BPS under its AFSL on materially the same commercial terms as had been agreed between BPS and Billzy.

25 BPS and PNI then entered into a document entitled “Authorised Representative Agreement” on 4 November 2020.

26 In 2021, Blockchain Investment Group Pty Ltd acquired a 65% interest in Billzy Holdings Pty Ltd, the holding company of Billzy. The arrangements with BPS then reverted back from PNI to Billzy.

27 On 1 September 2021, BPS and Billzy executed two agreements being:

(1) a document entitled “Authorised Representative Agreement”; and

(2) a document entitled “Intermediary Agreement”.

28 Each of the agreements referred to above are addressed in further detail below. There was no suggestion by ASIC that any of these agreements was a sham.

29 It is common ground that, at all material times, each of Billzy and PNI held AFSLs which covered the provision of financial services of the kind supplied by BPS, namely:

(1) general financial product advice in relation to non-cash payment products; and

(2) dealing in a financial product by:

(a) issuing, applying for, acquiring, varying, or disposing of non-cash payment products; and

(b) applying for, acquiring, varying, or disposing of non-cash payment products on behalf of another person to retail and wholesale clients.

30 Since January 2020, BPS has developed and made available to the public a system for making and receiving non-cash payments using Qoin (which for convenience I will describe as the Qoin Facility).

31 The Qoin Facility has a number of elements, which allow users to transact using Qoin. These elements were explained by Mr Andrew Atkinson, Chief Technology Officer of Bartercard Global Pty Ltd, who also provides information and communication technology services to BPS. His evidence was not contradicted or challenged, and I accept it.

32 The Qoin Wallet App is an application specifically designed for the Qoin system. The software is owned and operated by BPS. The Qoin Wallet App can be downloaded onto compatible Apple and Android devices from Google Play and the Apple App Store. It first became available for download by members of the public in January 2020.

33 When a person first downloads the Qoin Wallet App, they are asked to complete a sign-up process which requires them to verify their email address, mobile phone number, location/country and create a password. Once this process is completed, users are then directed to a “Before We Start” screen, which contains links to terms and conditions, including the Financial Services Guide and Product Disclosure Statement. Users must check a box which states that they agree to be bound by the above documents before they can move to the next page.

34 Once a person has completed the sign-up process for the Qoin Wallet App, they can go on to create a Qoin Wallet (discussed below), access the Q Shop (discussed below) and access other features such as merchant registration.

35 Even if a person has downloaded and signed up on the Qoin Wallet App, they cannot make any transactions using Qoin without first creating a Qoin Wallet. Downloading the Qoin Wallet App does not automatically initiate or access the Qoin Wallet feature.

36 The Qoin Wallet is a component of the Qoin Wallet App and is its own discrete software product, integrated with the broader application. It is a separate program called (or activated) by any part of the Qoin Wallet App which requires its functionality.

37 The Qoin Wallet was customised from a crypto-wallet product supplied by a company called AlphaWallet. Data for the Qoin Wallet is stored on a user’s device.

38 The Qoin Wallet uses an Application Programming Interface gateway to send requests to, and receive responses from, the Qoin Blockchain Nodes.

39 Once a user has completed the sign-up process described above, they will be directed to the homepage for the Qoin Wallet App, which contains four tabs at the bottom: “Browser”, “Wallet”, “Transactions” and “Settings”. If the user is new, then this homepage will also contain a link with the message, “Verification Required”.

40 To create a Qoin Wallet, the user must first click on the “Verification Required” message, which will direct them through a series of steps comprising the Qoin system’s “Know Your Customer” (KYC) process. The KYC process was not always a part of the Qoin Wallet App but was introduced as mandatory for Australian wallet holders in April 2022.

41 To complete the KYC process, a user must:

(1) enter some basic information about themselves;

(2) provide a picture of a valid Government photo ID;

(3) provide a live photo to match their Government photo ID; and

(4) provide their name, address, date of birth and card number;

which information is then validated.

42 Once a user has been verified by the KYC process, they will be able to create a Qoin Wallet.

43 This is done after about 30 seconds, at which time a create screen is presented which displays a button “Create a New Wallet”.

44 Once a user clicks on “Create a New Wallet”, the Qoin Wallet software generates a new public/private key pair.

45 The public key is the unique Qoin Wallet address, which becomes the identifier for the user’s newly created Qoin Wallet. It is, in effect, the equivalent of an account number and BSB for a traditional bank account. A person may provide their unique Qoin Wallet address to another user either by transcribing the string of letters and numbers comprising the public key, or by providing them with a QR code for scanning which contains that information.

46 The private key acts, in effect, as a secure digital password, stored on the user’s mobile device, which can be used to authorise (or “sign”) transactions using the Qoin Wallet.

47 The Qoin Wallet component of the Qoin Wallet App has the function of both viewing the balance of Qoin for a wallet address recorded on the blockchain, and the payment facility (the function to send and receive Qoin and for the transaction to be recorded). There is separate source code for each function.

48 Business operators can register as users and can accept Qoin in payment for goods and services (Qoin Merchants). In practice, there is no significant difference in the functionality of the Qoin Wallet App between a user who does not operate a business and Qoin Merchants because any user can list an item for sale. A prospective Qoin Merchant must provide an Australian Business Number, business turnover data, and additional “Know Your Business” information. However, the process of creating a Qoin Wallet is the same.

49 The Qoin Blockchain is a decentralised, distributed ledger that stores a record of all transactions using Qoin. Mr Atkinson gave evidence that one can think of the blockchain, in simple terms, as a sort of security-enhanced spreadsheet which contains constantly updated, computer-coded, transaction data.

50 A “node”, in this context, is a computer or device connected to other “nodes” in the Qoin Blockchain network, each of which hosts a copy of the entire Qoin Blockchain, validates transactions, and propagates them across the network (as well as occasionally performing other functions which are not relevant) (Qoin Blockchain Nodes).

51 There are a total of seven Qoin Blockchain Nodes, each owned by a different entity. For example, Node 1 is owned and operated by Blockchain Investments Pty Ltd and is located in Australia. Node 5 is owned and operated by Bartercard Services Pty Ltd and is located in Germany.

52 Transactions are recorded on the Qoin Blockchain in the form of “blocks”, with each block containing a series of verified transactions represented as computer-coded data. These blocks are linked together in a sequential manner, forming a chain – hence the term “blockchain”. Each block also contains a reference to the preceding block, ensuring the integrity and immutability of the entire transaction history on the Qoin Blockchain.

53 For any particular transaction using Qoin, transaction data is communicated to one of the Qoin Blockchain Nodes, which then broadcasts the transaction data to all nodes on the Qoin Blockchain. On a round-robin basis a Proposer Node is selected. The Proposer Node aggregates the transactions broadcasted to the network during a given period into a “block” and applies a cryptographic process to the block called “hashing”. The hash for a block is linked to the information in the block in such a way that any modification to the data within a block will result in a different hash. In this way, the hash serves as a digital fingerprint of the block’s data. Each block holds its own hash, as well as a reference to the hash of the previous block in the Qoin Blockchain, thus establishing the chain’s continuity.

54 After a block has been created and hashed, the Proposer Node broadcasts the block to all of the other Qoin Blockchain Nodes. These nodes then employ a consensus algorithm, specifically Istanbul Byzantine Fault Tolerance, to collectively validate the contents of the block and its position in the Qoin Blockchain. If a block is validated, each Qoin Blockchain Node will add it to the node’s copy of the Qoin Blockchain, thereby recording the transaction.

55 There is only ever one Qoin Blockchain, comprising the ledger which is replicated across the seven Qoin Blockchain Nodes. The creation of a new Qoin Wallet allows a user to access the Qoin Blockchain (in the sense of sending commands to the blockchain), but does not otherwise affect the Qoin Blockchain itself.

56 The completion of a transaction through the Qoin Wallet involves a series of steps, namely:

(1) Open the payment screen: Once a user has opened up the Qoin Wallet function within the Qoin Wallet App, the first step is to press the button marked “Send” on the landing page, to bring up the payment screen.

(2) Create the transaction: To create a transaction, a user fills out the necessary information in accordance with the prompts displayed on the payment screen, being the recipient’s Qoin Wallet address (the sender is automatically populated by the wallet), and the amount of Qoin to be “transferred”. The recipient’s Qoin Wallet address can be obtained through the proposed recipient either providing the string of numbers and letters that make up their public key, or by the scanning of the QR Code which is their public key.

(3) Sign the transaction using the private key: To validate the transaction, the private key, stored in a secure enclave on the user’s mobile device, is utilised. This private key is safeguarded by a biometric or PIN authentication system. The user selects “Send” and is prompted to confirm a transaction by clicking “Confirm” on the payment screen and providing the required biometric data or PIN. The secure enclave is then unlocked, and the private key is used internally by the wallet software to sign the transaction. This process creates a unique hash that identifies the transaction to the Qoin Blockchain Nodes as a verified transaction.

(4) Send the raw transaction information: Once signed, the transaction information is then sent to the Qoin Blockchain Nodes as a raw transaction.

(5) Verify the transaction: Once received by the Qoin Blockchain Nodes, the transaction data is broadcast and validated.

(6) Process the transaction: If the transaction is verified, it is then processed, and the state of the Qoin Blockchain is updated to reflect the “transfer” of Qoin from the sender to the recipient.

(7) Record the transaction: The transaction details, including the transaction hash and completion time, are recorded in the user’s Qoin Wallets for future reference, and the user’s Qoin balance is updated.

57 A smart contract is a computer program that runs on a blockchain node and automates the execution of predefined actions or agreements once certain conditions are met. It is essentially a self-executing contract with the terms of the agreement directly written into code, operating on the “if-then” logic principle.

58 The smart contract associated with the Qoin Blockchain (the Qoin Smart Contract) can be regarded as the “rule book” for the Qoin Blockchain and Qoin transactions. It is deployed on the nodes holding and processing the Qoin Blockchain and sets the rules for what transactions can be made, by whom and under what conditions. The Qoin Wallet interacts with the Qoin Blockchain and conducts transactions in compliance with these rules.

59 The Qoin Smart Contract is responsible for:

(1) establishing the basic building blocks of Qoin (i.e. that the currency is called “Qoin”, that it can be broken down to 18 decimal places and that there can only ever be a maximum of 10,000,000,000 Qoin);

(2) establishing the rules for validating transaction data, such as ensuring that the transaction involves two valid Qoin Wallet addresses, the “payer’s” Qoin balance is sufficient to effect the transaction and the correct public and private keys have been provided.

60 Qoin is the notional unit of exchange in transactions undertaken through the Qoin Wallet, and recorded on the Qoin Blockchain.

61 It is a unit of measurement, rather than a discrete thing. There is no distinct serial number or unique identifier that allows for identifying an individual Qoin. As a result, it is impossible to distinguish one Qoin from another or track their ownership individually.

62 As submitted by BPS, a user’s starting balance is 0 Qoin, and that will only increase if they acquire Qoin through transactions conducted using their Qoin Wallet (for example, transactions with other users, or by purchasing Qoin directly from BPS).

63 When a person “transacts” using Qoin, they do not actually “send” a Qoin to another person or “acquire” a Qoin from another person, even though those terms are sometimes used colloquially to explain a transaction that gives rise to a decrease or increase in a Qoin balance. Instead, the Qoin Wallet communicates with the Qoin Blockchain Nodes through the mechanisms described above to carry out a command that records a deduction of a certain amount of Qoin against the “payer’s” Qoin Wallet, and an addition of the same amount of Qoin against the “payee’s” Qoin Wallet on the Qoin Blockchain, and prompts the Qoin Wallet to decrease/increase the Qoin balances associated with each Qoin Wallet address by the amount.

64 A single “transaction” involves both the deduction of Qoin from the payer’s Qoin Wallet and the addition of Qoin to the payee’s Qoin Wallet. In this sense, a Qoin transaction does not involve the actual transfer of a thing, so much as an updating of the Qoin Blockchain to reflect a different balance in each Qoin Wallet. The blockchain entry serves as a record of the transaction, indicating the sender, recipient and amount of Qoin involved.

65 The subdivision of a Qoin into 18 decimal places means that a transaction can involve the “transfer” of as little as 0.000000000000000001 Qoin.

66 A user’s Qoin balance, at any one time, reflects the total combined product of all of the various transactions which have been undertaken using a particular Qoin Wallet, as recorded by additions and deductions on the Qoin Blockchain.

67 Within the Qoin Wallet, a user can opt to show their Qoin balance in Qoin, Australian dollars (AUD), US dollars (USD), New Zealand dollars (NZD), UK pounds (GBP), Singapore dollars (SGD) or South African Rand (ZAR).

68 The Q Shop is an online directory in which Qoin Merchants and other users can list their services or products for sale. The Q Shop feature does not allow users to engage in Qoin transactions and it can be accessed through the Qoin Wallet App regardless of whether the user has created a Qoin Wallet.

2.3 Description of Qoin Facility by BPS

69 In evidence are printouts of browser screenshots depicting the Qoin Website (the homepage of which is at https://qoin.world) at various points in time. The following are extracts from those screenshots, with the emphasis as it appears in the extracts:

(1) The organisation which you know as Qoin commenced operating in October 2019 as the Qoin Program which consists of:

(a) the Qoin token (“Qoin Token”) that is minted and issued by the Qoin Reserve;

(b) the Qoin blockchain (“Qoin Blockchain”);

(c) a wallet facility that enables a user to view the Qoin balance available to the user known as the “Qoin Wallet”;

(d) a related payment facility enabling a user to purchase goods and services from another user using Qoin on the Qoin Blockchain, referred to as the “Payment Facility” which:

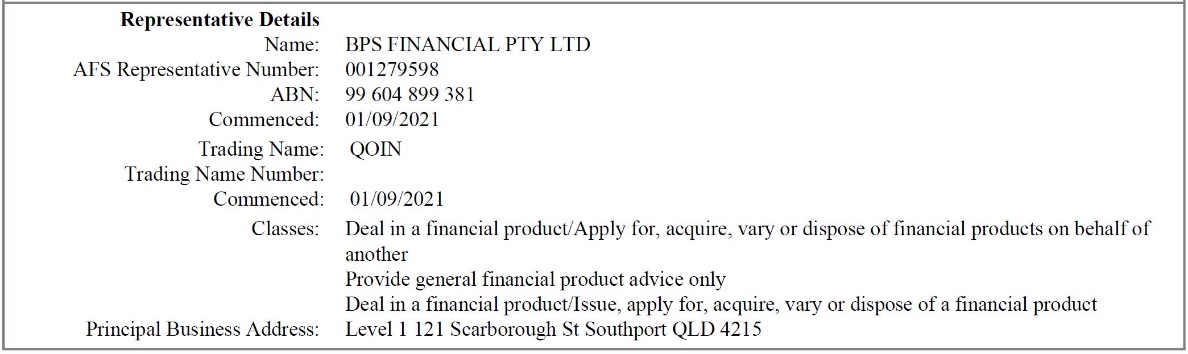

(i) is issued by BPS Financial Limited under an Authorised Representative Agreement with PNI Financial Services Pty Ltd under AFSL Number 408735, for the purposes of the Corporations Act 2001; and

(ii) in respect of which BPS is authorised to provide general financial product advice as Authorised Representative No. 001279598 of the AFSL held by PNI; and

(e) Block Trade Exchange known as BTX by which a user may trade Qoin for AUD fiat and reciprocally. BTX is registered as a digital currency exchange provider no. 100635628 with the Australian Transaction Reports and Analysis Centre (AUSTRAC).

(2) The world of commerce is ready to adopt a widely used reliable digital currency platform that enables shoppers or buyers to easily obtain global currency to spend at their favourite merchants in-store or online. Merchants on average have 25 to 35% capacity to engage new customers and are keen to accept global currency and reward these shoppers. Sellers continuously seek an edge on their competitors to attract new Buyers as their goods are no longer easily selling on existing marketplaces like eBay and Amazon.

Now is the time to create this new commercial digital currency built on a foundation of blockchain technology. The mission for Qoin is a commercial global currency platform that empowers millions of business owners, sellers and merchants to trade their Goods & Services with shoppers and buyers globally.

Qoin is made of three parts that will work together to create a more inclusive commerce system:

(a) It is built on a secure, scalable and reliable blockchain

(b) It is backed by the participating merchant's supply of goods & services in a growing merchant ecosystem designed to give it intrinsic value

(c) The Qoin Association, tasked with evolving and expanding the ecosystem, governs it.

The Qoin currency is built on the Qoin Blockchain, intended to address a global community of buyers and sellers of goods & services. The blockchain has been built on the world's safest, robust and scalable interoperable technologies. It has been designed for millions of users to hold and transfer Qoins and hence the blockchain and wallets will be hosted in one of the world's most secure environments.

(3) The Qoin Blockchain & Consensus Model

We have built this blockchain system on the leading Quorum platform and Byzantine Fault Tolerant (BFT) consensus protocol to ensure an optimum balance of speed, scale and security.

…

The objective of the Qoin Blockchain is to act as a reliable distributed ledger platform for payments and rewards services, including a new global currency, which can meet the daily transactional needs of millions of buyers and sellers. Thus, we have designed a blockchain based on these three requirements:

Fast transaction speeds, high transaction volumes, scalable for millions of accounts and a high capacity storage system

Fast transaction speeds, high transaction volumes, scalable for millions of accounts and a high capacity storage system

Highly secure, to ensure safety of funds, rewards and financial data

Highly secure, to ensure safety of funds, rewards and financial data

Governance friendly and interoperable with other tokens, chains and exchanges.

Governance friendly and interoperable with other tokens, chains and exchanges.

Qoin Blockchain is designed to holistically address these requirements and build on the learnings from existing projects and research.

…

The Quorum platform was designed and built over two years by the world’s leading bank, JP Morgan Chase & Co, and in partnership with Microsoft to power their JPM coin. Amazon Web Services will initially host Qoin Blockchain, providing the required security and firewall protocols.

(4) With over 30 years of success supporting small business’ [sic] globally through the Bartercard brand, Qoin realised the need for global commerce to adopt a widely used, reliable digital currency platform that enables consumers to spend with their favourite merchants instore or online.

(5) The Qoin model stands apart from other digital currencies in that the purchasing power of Qoin becomes more powerful as the merchant ecosystem grows. The more businesses that join the Qoin community, the more everyone benefits, providing a vital boost to local economies. Qoin is represented by the goods and services of participating businesses within the ecosystem.

With the number of validated merchants in Qoin growing regularly, the result is an ecosystem where digital currency works more favourably for business owners and creates a digital currency tailor-made to sustain cashflow and make the most of their downtime. Qoin enables them to do both while offering a payment method to their customers that is fast, secure, and virtually contactless.

70 The Qoin Website also made the following statements in relation to the Qoin Wallet:

(1) The Qoin Wallet is an Australian regulated product, registered under BPS Financial Limited ABN 99 604 899 381 as authorised representative No. 1279598 of PNI Financial Services Pty Ltd ABN 74 151 551 076 AFSL 408735.

(2) The Australian Qoin Wallet is a regulated non cash payments product approved as Authorised Representative number 1279598 of Australian Financial Services Licence (AFSL) number 408735.

(3) Users must only use the official Qoin wallet to access the blockchain and their transaction balance.

71 From on or around 30 January 2020, a document called the White Paper appeared on the Qoin Website entitled “Qoin – Official White Paper”. Many of the sections of the most recent version of the White Paper in evidence (accessible to the public on 28 March 2022) are in the same terms as the initial version of the White Paper. Any differences from the initial version in the extracts below are marked by underline and strikethrough, with the emphasis being as it appeared in the White Paper.

72 The first version of the White Paper stated in the foreword section:

The Qoin mission is to enable a global commercial digital currency that empowers millions of Sellers to trade their goods & services with Buyers around the world.

Most businesses have some spare capacity to accept new customers. We tokenise this spare capacity in the form of the Qoin digital currency. Participating merchants in the ecosystem accept Qoin from customers as payment for their goods and services.

This White Paper describes our plans and progress made towards opening the world’s largest private merchant trading ecosystem to the public on a distributed blockchain and smart contract platform. This new cryptocurrency, backed by participating merchant’s supply of goods and services, allows innovative ways for merchants to attract shoppers. Qoin is built on the latest Smartcoin, Tokenscript and Distributed Ledger Technology.

Simply put, Qoin is all about bringing together Buyers and Sellers through the tokenisation of the spare capacity in each business.

73 Section 2 of the same document included the following statements:

Now is the time to create this new commercial digital currency built on a foundation of blockchain technology. The mission for Qoin is a commercial global currency platform that empowers millions of business owners, sellers and merchants to trade their Goods & Services with shoppers and buyers globally. Qoin is made of three parts that will work together to create a more inclusive commerce system:

1. It is built on a secure, scalable and reliable blockchain

2. It is backed by real goods & services in a growing merchant ecosystem designed to give it intrinsic value

3. The Qoin Association, tasked with evolving and expanding the ecosystem, governs it.

The Qoin currency is built on the Qoin Blockchain, intended to address a global community of buyers and sellers of goods & services. The blockchain has been built on the world’s safest, robust and scalable interoperable technologies. It has been designed for millions of users to hold and transfer Qoins and hence the blockchain and wallets will be hosted in one of the world’s most secure environments. To read more see below the overview of the Qoin Blockchain or the Technical Information.

The unit of currency is named a Qoin. Qoins will be accepted with confidence backed by real goods and services in the participating merchant ecosystem, creating trust in its intrinsic value. The minting and distribution of Qoins will be administered by the Qoin Reserve with the objective of continuously expanding the merchant base and preserving the value of Qoin over time. To read more see below the Qoin Reserve.

…

To maintain the speed, scalability, stability and security required for transactions between buyers and sellers, the Association will in the future only grant access to credible independent validators to ensure a distributed and reliable blockchain. Unlike other blockchains that allow anybody, including bad actors, to operate validator nodes on their systems, Qoin Blockchain will be a Permissioned Distributed Blockchain.

(Emphasis original.)

74 In section 3, the following appeared:

The objective of the Qoin Blockchain is to act as a reliable distributed ledger platform for payments and rewards services, including a new global currency, which can meet the daily transactional needs of millions of buyers and sellers. Thus, we have designed a blockchain based on these three requirements:

• Fast transaction speeds, high transaction volumes, scalable for millions of accounts and a high-capacity storage system

• Highly secure, to ensure safety of funds, rewards and financial data

• Governance friendly and interoperable with other tokens, chains and exchanges

(Emphasis original.)

75 In section 4 of the White Paper, Qoin is described as having been “designed as a smart digital cryptocurrency that will be backed by real goods & services and complemented by a global sales initiative”. That section also states the following:

The Qoin Reserve will administer the expansion of the ecosystem through a global sales initiative, onboarding, and incentivisation of new merchants. This means that anyone who has purchased Qoins has a high degree of assurance they can utilise or spend their digital currency in the participating merchant ecosystem, or in the future trade their Qoins for fiat or cryptos with others through independent Exchanges.

As per Metcalfe’s law, the value of Qoins will be effectively linked to the size of the merchant ecosystem. This may cause fluctuations in the value of Qoins.

Access to the existing Bartercard Ecosystem of approximately 21,000 merchants and 40,000 cardholders across the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand and Thailand will form the nucleus as the kickstart of this project.

The blockchain only has one way to mint new Qoins for the Reserve:

• For the expansion of the merchant ecosystem and validation of all transactions, a fixed amount of Qoins equivalent to US$7,500 per merchant will be minted to fund the sales initiative, attract, sign up, incentivise and onboard new merchants and their customers, as well as maintain the technology and node network. This fixed amount will be reviewed annually by the Reserve to consider inflationary and global economic changes.

The maximum Qoins that can ever be minted by the Reserve is capped at 10 Billion in order to create the +US$1.0 Trillion merchant ecosystem.

An algorithm will value and adjust the Qoin price regularly based on:

• Number of merchants

• Average annual revenues of each merchant

• Average available capacity of each merchant

• Number of Qoins minted and in circulation.

76 In section 6 of the White Paper, it is stated that:

The Australian Qoin Wallet is a regulated non cash payments product approved as Authorised Representative number 1279598 of Australian Financial Services Licence (AFSL) number 494176. When the merchant ecosystem is expanded into the rest of the world, the Council will engage with country regulators and law firms to get the appropriate guidance.

77 In section 9 of the White Paper, the Qoin Wallet is described as “an Australian developed Mobile APP explicitly designed to connect to the Qoin Blockchain”. It then states: “The number one priority of the Qoin wallet is security. Both IOS and Android Qoin Wallet’s [sic] protect your private keys with a strong seed phrase backup and protection from the secure enclave within your mobile device”.

2.3.3 Combined Financial Services Guide and Product Disclosure Statements

78 BPS issued six combined Financial Services Guides and Product Disclosure Statements (combined FSG/PDS) during the period December 2019 to November 2021. The combined FSG/PDS which was available to the public on 31 August 2021 is a representative sample of these documents, although all six versions contain the same or similar statements as the following.

79 At the foot of the first page, the following is stated:

This Combined FSG and PDS provides information about the payment system provided by BPS Financial Ltd (Payment System) to assist you in making an informed decision about this product. The Payment System is an electronic Bill Paying Service.

(Emphasis original.)

80 On page 3, the following is stated:

The Financial Services Guide (FSG) is designed to help you decide whether to use any of the services we provide. The Product Disclosure Statement (PDS) contains information you require to make an informed decision about whether or not to register for and use our Payment System and services.

81 On page 6, the following is stated:

(1) under the heading “About this PDS”:

This PDS only applies to your Australian Qoin Wallet or if you otherwise use our services in Australia.

(2) under the heading “Remuneration and commissions”:

We may also enter into arrangements to jointly provide software solutions which are integrated with our financial products and services (for example, accounting software which is integrated with our Payment System).

(3) under the heading “Our Services”:

Our services allow you to securely and conveniently make payments to Merchants and other members of the Qoin membership community. To find out more, please visit www.qoin.world[.] When you register to use our Payment System, we will open a Qoin Account in your name. Our Payment System allows you to: [make, request and receive payments and withdraw money as set out at the top of page 7 of the document].

82 The combined FSG/PDS available on 31 August 2021 uses the term Payment System extensively in parts 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9. It also uses the term “Qoin Wallet” (such as, for example, on page 8 under the headings “Security” and “Payment Failure”).

83 Its glossary also contains these definitions:

(1) “Qoin Wallet or Q Wallet” means a cryptocurrency wallet developed by BPS that connects to the Q Chain, stores a user’s cryptocurrency (such as Qoin) and allows a user to make cryptocurrency transactions.

(2) “Q Chain” means the Qoin Blockchain.

3.1 Overview of the parties’ contentions

84 Section 911A(1) of the Corporations Act provides that, subject to certain exemptions, “a person who carries on a financial services business in this jurisdiction must hold an Australian financial services licence covering the provision of the financial services”. Section 911A(5B) has the effect of rendering a contravention of s 911A(1) a contravention of a civil penalty provision.

85 The term “financial services business” was defined in s 761A (until 20 October 2023) as a business of providing “financial services” within the meaning of Part 7.1, Division 4 of the Corporations Act.

86 Sections 766A(1)(a) and (b) relevantly provide that a person provides a financial service if they:

(a) provide financial product advice within the meaning of s 766B; or

(b) deal in a financial product within the meaning of s 766C (including by issuing a financial product: s 766C(1)(b)).

87 Both of these limbs of “financial services” relate to the provision of certain services with respect to dealing in a “financial product”.

88 In the circumstances of this case, the parties agree that there was a financial product through which a person makes non-cash payments. ASIC’s primary case is that the Qoin Facility was a financial product, specifically a non-cash payment product. BPS does not dispute that the Qoin Facility (which it calls the “Qoin Project”) included such a financial product, but contends that the financial product was the Qoin Wallet, which was merely a component of the overall Qoin Facility. ASIC adopts this contention in the alternative.

89 The term Qoin NCP Product was used by both parties to describe the financial product which BPS issued, according to their respective cases. I will also adopt that term.

90 ASIC alleges that BPS has carried on a financial services business by dealing in a financial product, and/or by providing financial product advice, the relevant financial product being, in both cases, the Qoin NCP Product.

91 ASIC also alleges that BPS has breached the requirement in s 911A(1) of the Corporations Act that a person who carries on a financial services business in this jurisdiction must hold an AFSL covering the provision of the financial services.

92 BPS admits that, since January 2020, it has:

(1) carried on a business in the ordinary course of which it has issued a financial product, being the Qoin NCP Product (that is, on its case, the Qoin Wallet);

(2) provided financial product advice in relation to the Qoin NCP Product;

and that it has not at any time held an AFSL.

93 BPS does not dispute that:

(1) the Qoin NCP Product is a financial product which is a non-cash payment facility, which it issued;

(2) it provided general financial product advice in relation to the Qoin NCP Product;

(3) an offer was made in respect of the non-cash payment facility by the publication of the combined FSG/PDS;

(4) the issuing of the Qoin NCP Product constitutes dealing in a financial product (within the meaning of Chapter 7 of the Corporations Act) and constitutes the provision of financial services;

(5) the giving of general financial product advice constitutes providing financial product advice (within the meaning of Chapter 7 of the Corporations Act) and constitutes the provision of financial services.

94 However, BPS claims that it was at all relevant times exempt from the requirement to hold an AFSL:

(1) in respect of its business of issuing a financial product:

(a) by s 911A(2)(a) of the Corporations Act, because it issued the Qoin NCP Product as a representative of the holder of an AFSL; and/or

(b) by s 911A(2)(b) of the Corporations Act, because it issued the Qoin NCP Product in the implementation of an intermediary arrangement as described in that section;

(2) in respect of its provision of financial product advice, by s 911A(2)(a) of the Corporations Act because it provided that advice as a representative of the holder of an AFSL.

95 BPS relies upon its arrangements with two AFSL holders, Billzy and PNI, as bringing its conduct within the exemptions provided for by ss 911A(2)(a) and (b) of the Corporations Act.

96 These arrangements comprised:

(1) between 18 December 2019 and 4 November 2020, the First Billzy Arrangement, comprising the First Billzy Authorised Representative Agreement (First Billzy AR Agreement) and the First Billzy Intermediary Agreement;

(2) between 5 November 2020 and 30 August 2021, the PNI Arrangement, as recorded in the PNI Authorised Representative Agreement (PNI AR Agreement); and

(3) from 1 September 2021 to the present, the Second Billzy Arrangement, comprising the Second Billzy Authorised Representative Agreement (Second Billzy AR Agreement) and the Second Billzy Intermediary Agreement.

97 In its closing submissions, BPS described the periods of time during which the First and Second Billzy Arrangements were in place as the Billzy Periods, and I will adopt the same terminology. It also described the period during which the PNI Arrangement was in place as the PNI Period.

98 BPS summarised its case in its closing submissions as follows and by reference to its Further Amended Defence:

(1) BPS’s position with respect to the Billzy Periods is that it:

(a) provided general financial product advice in relation to the Qoin Wallet as an authorised representative of Billzy, pursuant to the Billzy AR Agreements; and

(b) issued Qoin Wallets pursuant to an arrangement between it and Billzy, recorded in the Billzy Intermediary Agreements, under which:

(i) BPS, in its capacity as authorised representative of Billzy, made offers to people to arrange for the issue of Qoin Wallets pursuant to the Billzy AR Agreements; and

(ii) BPS, in its own capacity as product provider, issued Qoin Wallets in accordance with such offers, if they were accepted.

(2) In so doing:

(a) BPS’s conduct in providing general financial product advice about, and making offers to people to arrange for the issue of, Qoin Wallets fell within the exemption under s 911A(2)(a); and

(b) BPS’s conduct in issuing Qoin Wallets fell within the exemption under s 911A(2)(b).

(3) BPS’s position is the same with respect to the PNI Period in that, during this period, it:

(a) provided general financial product advice in relation to the Qoin Wallet as an authorised representative of PNI, pursuant to the PNI AR Agreement; and

(b) issued Qoin Wallets pursuant to an arrangement between it and PNI under which:

(i) BPS, in its capacity as authorised representative of PNI, made offers to people to arrange for the issue of Qoin Wallets pursuant to the PNI AR Agreement; and

(ii) BPS, in its own capacity as product provider, issued Qoin Wallets in accordance with such offers, if they were accepted.

99 In response, ASIC contends that:

(1) BPS is not exempt from the requirement to hold an AFSL under s 911A(2)(a) of the Corporations Act because it did not provide its financial services, or financial product advice, “as representative for” Billzy or PNI;

(2) BPS is not exempt from the requirement to hold an AFSL under s 911A(2)(b) of the Corporations Act because:

(a) it did not “make offers to arrange for the issue” of the Qoin NCP Product;

(b) even if BPS did make offers to arrange the issue of Qoin NCP Product, it did not do so as a representative of Billzy or PNI; and

(c) the exemption has no application if the issuer and the authorised representative are the same person.

100 Before turning to consider the arguments raised by the parties, the following preliminary issues must be determined, namely:

(1) What was the financial product issued by BPS?

(2) What was the financial product advice given by BPS?

(3) What were the precise arrangements between BPS and either Billzy or PNI?

3.2 Identification of the financial product

101 It is common ground that the Qoin NCP Product falls within the third limb of the definition of “financial product” in s 763A(1) of the Corporations Act, being “a facility through which, or through the acquisition of which, a person…. (c) makes non-cash payments” within the meaning of s 763D (i.e. a non-cash payment facility).

102 As to the meaning of “non-cash payment”, s 763D(1) provides:

a person makes non-cash payments if they make payments, or cause payments to be made, otherwise than by the physical delivery of Australian or foreign currency in the form of notes and/or coins.

(Emphasis original.)

103 As to what constitutes a “facility”, the definition of that term in s 762C provides:

facility includes:

(a) intangible property; or

(b) an arrangement or a term of an arrangement (including a term that is implied by law or that is required by law to be included); or

(c) a combination of intangible property and an arrangement or term of an arrangement.

(Emphasis original.)

104 Pursuant to s 762B of the Corporations Act, if a financial product is a component of a facility that also has other components, Chapter 7 of the Corporations Act applies only in relation to the facility to the extent it consists of the component that is the financial product.

105 By its Amended Statement of Claim, ASIC pleads that the Qoin Facility (which it ultimately pleads is the financial product) is comprised of:

(1) Qoin Tokens (later defined as a digital token);

(2) a distributed digital ledger implemented by blockchain technology (which it defined as the Qoin Ledger but is plainly a reference to the Qoin Blockchain);

(3) a wallet facility;

(4) a means of acquiring Qoin Tokens, including from BPS or an entity associated with BPS;

(5) a means whereby business operators who hold Qoin Wallets can register as participating merchants (that is, the Qoin Merchants) in the Qoin Facility.

106 ASIC submits that these elements of the Qoin Facility “constitute a single scheme which has been implemented by BPS for a substantial purpose of enabling consumers who choose to participate in it to make payments for goods and services otherwise than by the physical delivery of cash”. It submits that, upon reading the Qoin Website, White Paper, and combined FSG/PDS as a whole, the product which is offered is the Qoin Facility as a whole of which the Qoin Wallet is but a component. Drawing on the aspect of the definition of “facility” which includes the word “arrangement”, ASIC submits that it is not the mechanism of payment that is a facility, but rather the arrangement under which a (non-cash) payment may be made. ASIC draws an analogy with a loyalty scheme and submits that ways of obtaining points and arrangements for how those points can be used are required in addition to a ledger to record them.

107 However, for the following reasons, the Qoin NCP Product is not the Qoin Facility as pleaded by ASIC.

108 First, that a financial product’s functionality requires integration with another product, facility, or thing does not necessarily mean that the other product, facility, or thing forms part of the financial product. For example, in this case, each Qoin Wallet is built on top of the Qoin Blockchain, of which there is only one and which exists separately to each Qoin Wallet. While the ability to make non-cash payments using a Qoin Wallet depends upon the existence of the Qoin Blockchain, it does not follow that the Qoin Blockchain is itself a financial product, or that it forms part of the financial product.

109 Second, the system by means of which a facility operates is not itself a financial product capable of being “issued” or “acquired” such that “dealing” in it may occur as contemplated by ss 766A(1)(b) and 766C of the Corporations Act. For this reason, the identification of the financial product should focus upon the point at which a person performs one of the functions identified in s 763A(1) of the Corporations Act (i.e. make a financial investment, manage a financial risk, or make non-cash payments) with the question then being asked: what is the direct mechanism or thing which is allowing the person to perform this function?

110 Applying that test, the relevant “financial product” in this case is the arrangement between BPS and each user which allows the user to make non-cash payments upon the issue of the Qoin Wallet. Contrary to ASIC’s submissions, the Qoin Blockchain, a means of acquiring Qoin and a means whereby business operators who hold Qoin Wallets can register as Qoin Merchants are not components of, and are not themselves, the mechanism which allows the user to make the non-cash payment. One cannot “deal” in these aspects of the system, which may be contrasted against the ability to issue Qoin Wallets.

111 This conclusion is supported by the examples given of the actions that constitute making non-cash payments as identified in s 763D of the Corporations Act, one of which is “making payments by means of a facility for a direct debit of a deposit account”. In terms of defining a financial product in s 763D, there is no distinction between direct debits of a deposit account whether drawn from a deposit account by a merchant account facilitated by the same financial institution, and a merchant account facilitated by another, separate financial institution. The financial product is no more than the direct debit facility; the systems with which it is integrated, and in relation to which it functions, are separate. To include those systems, which include aspects controlled by third party financial institutions, cannot be intended when one has regard to the statutory purpose of Chapter 7. As submitted by BPS, because other systems, or aspects of them, are required for non-cash payments to be made does not mean those systems are encapsulated in the financial product. The same approach applies when considering the Qoin Wallet and the associated components of the Qoin Facility.

112 For these reasons, the Qoin NCP Product (and the financial product within the meaning of s 763A of the Corporations Act) is the Qoin Wallet alone.

3.3 Identification of the financial product advice

113 Section 766B(1) of the Corporations Act defines financial product advice as a recommendation or a statement of opinion, or a report of either of those things, that:

(a) is intended to influence a person or persons in making a decision in relation to a particular financial product or class of financial products, or an interest in a particular financial product or class of financial products; or

(b) could reasonably be regarded as being intended to have such an influence.

114 By the Amended Statement of Claim, ASIC pleads 17 statements published by BPS which ASIC alleges were opinions or recommendations intended, or which could reasonably be regarded as intended, to influence a person in making a decision in relation to the Qoin NCP Product, and were therefore financial product advice.

115 Save for some minor differences as to the dates, BPS admits in its Further Amended Defence that these statements were made and that they were statements of opinion “insofar as it is alleged that the Qoin NCP Product was the Qoin Wallet”. As to the dates of publication of statements in the combined FSG/PDS on which the parties disagreed on the pleadings, the evidence established that the dates pressed by ASIC in its closing submissions are the correct ones, and BPS did not submit otherwise.

116 Further, by its closing submissions, BPS submits that:

(1) there is no dispute that “BPS provided general financial product advice in relation to the non-cash payment facility”;

(2) there is no dispute that “since January 2020, BPS has provided financial services by providing financial product advice, within the meaning of Chapter 7 of the Corporations Act”;

(3) BPS “provided general financial product advice in relation to the Qoin Wallet as an authorised representative of Billzy, pursuant to the Billzy AR Agreements”;

(4) BPS “provided general financial product advice in relation to the Qoin Wallet as an authorised representative of PNI, pursuant to the PNI AR Agreement”.

117 Under cross-examination, Mr Wiese was taken to each of the statements pleaded by ASIC and accepted that they were “intended to influence persons reading the website … white paper or the financial services guides or the product disclosure statements … to make a decision to participate in the Qoin program”.

118 Given the admissions made in the Further Amended Defence, the concessions made in BPS’s closing submissions and the evidence of Mr Wiese (which I accept), I am satisfied that the statements pleaded by ASIC in the Amended Statement of Claim were statements of opinion that constitute financial product advice within the meaning of s 766B(1) of the Corporations Act. That is, they were statements of opinion that were intended to influence a person or persons in making a decision in relation to a particular financial product, namely the Qoin NCP Product.

3.4 The arrangements with Billzy and PNI

119 As the First and Second Billzy Arrangements concerned agreements in essentially identical terms, the issues raised by them will be dealt with together.

3.4.1 The First Billzy Arrangement

120 On or around 17 December 2019, Billzy and BPS entered the First Billzy AR Agreement and the First Billzy Intermediary Agreement.

121 The First Billzy AR Agreement relevantly provided:

(1) Billzy Pty Ltd was the “Licensee” and BPS (being the person listed in item 3 Schedule 1 of the Agreement) was the “Company”;

(2) by Recital B: “The Company has requested the Licensee appoint it as its Authorised Representative and to authorise it to provide the Specified Financial Services to enable it to promote and distribute the Product”.

(3) by clause 1.1(a):

The Licensee appoints the Company as an Authorised Representative to provide the Specified Financial Services. This appointment is an authorisation for the purposes of section 916A(1) of the Corporations Act.

(4) by clause 12.1, “Authorised Representative” “has the same meaning as it has in Section 916A(1) of the Corporations Act”.

(5) by clause 1.1(b):

Notwithstanding any other provision of this Agreement, the Company is strictly prohibited from providing Financial Services that are not Specified Financial Services.

(6) by clause 12.1, that “Financial Services” “has the meaning given by Section 766A of the Corporations Act”.

(7) by clause 12.1 and Schedule 1, Item 7, “Specified Financial Services” means:

(a) General Advice on non-cash payment facilities issued by the Licensee, limited to the Product.

(b) Dealing in non-cash payment facilities issued by the Licensee, limited to the Product.

(8) by clause 12.1 and Schedule 1, Item 8, “Product” means:

Qoin or the Qoin Wallet is [a] digital ewallet which allows users to purchase goods and or services from merchants who use and accept the Qoin as a form of payment, which is a non-cash payment product.

(9) by clause 12.1, that “Deal” and “Dealing”:

… has the meaning given by Section 766C(1)(a) of the Corporations Act and is limited to arranging for a Client to apply for, acquire or dispose of a Financial Product.

(10) by clause 12.1, “Financial Product” “has the meaning given by Division 3 of Part 7.1 of the Corporations Act”.

122 The First Billzy AR Agreement also imposed various obligations upon BPS in relation to the manner in which it provided financial services under the agreements. These included obligations on the part of BPS:

(1) under clause 3.1(d)(i), not to do any act or thing, or omit from doing any act or thing, which might detrimentally affect the reputation of Billzy, its directors, employees, or other authorised representatives;

(2) under clause 3.1(e), to provide Billzy all information and documents reasonably requested concerning the financial services provided under the agreement;

(3) under clause 3.1(g), not to issue any advertising, promotional or marketing material or public statements of any kind with respect to the provision of financial services without the prior written consent of Billzy;

(4) under clause 3.1(i), to permit Billzy to monitor and supervise the provision of financial services by BPS;

(5) under clause 3.5, to immediately notify Billzy upon becoming aware of certain matters, such as of any complaint from a client regarding the provision of financial services;

(6) under clause 3.6, to allow all complaints to be handled and managed by Billzy, unless Billzy otherwise agrees; and

(7) under clause 3.2(f), to clearly disclose the capacity in which it provided financial services, and Billzy’s name, contact details, and AFSL number, in all documents associated with the provision of financial services under the agreement.

123 The First Billzy Intermediary Agreement, in turn, relevantly provided:

(1) as to the parties, Billzy was the “Licensee” and BPS was the “Issuer”;

(2) by Recital A:

The Licensee holds an AFS licence which authorises it to arrange the issue of non-cash payment products to both retail and wholesale clients.

(3) by Recital B:

The Issuer appoints the Licensee (and its authorised representatives) as an Intermediary to arrange the issue of the Product, which is a non-cash payment product, pursuant to the PDS. The Licensee accepts this appointment in accordance with the terms of this Agreement.

(4) by clause 1.1, the term “Intermediary” means the role and service provided by the Licensee to the Issuer pursuant to section 911A(2)(b) of the Corporations Act;

(5) by clause 1.1, the term “Product” means the “Qoin Wallet, being a non-cash payment product”;

(6) by clause 2.1:

The Issuer appoints the Licensee (and its authorised representatives) as the Intermediary to arrange the issue of the Product pursuant to the PDS prepared in accordance with this Agreement. The Licensee accepts the appointment on the terms and conditions set out in this Agreement.

(7) by clause 3.1(e):

The Licensee and its authorised representatives are authorised to make offers to people to arrange for the issue of the Product in accordance with the terms of the PDS.

(8) by clause 1.1, the term “Applicant” means “a person that applies to acquire the Product” and the term “Application” means “an application to acquire the Product and includes all supporting documents, such as identification documents”;

(9) by clause 3.2(d):

The Licensee will do the following in respect of each Application:

(i) Review the application form;

(ii) Review the Applicant’s Identity;

(iii) Advise the Issuer if the Application can be accepted.

(10) by clause 3.3(a):

The Issuer is only permitted to accept Applications approved by the Licensee.

(11) by clause 4.2(d):

In performing its obligations under this Agreement, the Issuer must do the following:

…

(d) Issue the Product in accordance with clause 3 and any reasonable direction of the Licensee.

124 On or around 5 November 2020, PNI and BPS entered into the PNI AR Agreement.

125 The terms of the PNI AR Agreement relevantly provided:

(1) as to the parties, PNI was the “Licensee” and BPS was the “Company”;

(2) by Recital B:

The Company has requested the Licensee appoint it as its Authorised Representative and to authorise it to provide the Specified Financial Services to enable it to promote and distribute the Product.

(3) by clause 2.1(a):

The Licensee appoints the Company as an Authorised Representative to:

(i) provide Financial Services. This appointment is an authorisation for the purposes of section 916A(1) of the Corporations Act; and

(ii) arrange the issue of the Product pursuant to section 911A(2)(b) of the Corporations Act.

(4) by clause 1.1, the term “Authorised Representative” “has the same meaning as it has in Section 916A(1) of the Corporations Act”;

(5) by clause 1.1, the term “Financial Services” “has the meaning given to that term in the Corporations Act”;

(6) by clause 1.1, the term “Product” means “the Qoin Wallet, a non-cash payment product”;

(7) by clause 1.1, the term “Qoin” means “the Company’s digital currency on a blockchain network”;

(8) by clause 1.1, the term “Qoin Wallet” means “the Company’s online platform that stores private and public keys and interacts with various blockchain to enable Clients to send and receive digital currency (such as Qoin) and monitor their digital currency balance”;

(9) by clause 1.1 and Schedule 1, the term “Specified Financial Services” comprises:

(a) providing general financial product advice;

(b) dealing in a financial product by issuing, varying or disposing of a financial product; and

(c) dealing in a financial product by applying for, acquiring, varying or disposing of a financial product on behalf of another person,

in respect of “deposit and payment products, limited to… non-cash payment products”;

(10) by clause 2.1(b), the Company is strictly prohibited “from providing Financial Services that [are] not permitted under the Licensee’s AFSL”;

(11) by clause 2.2(a)(iii), the Company acknowledges that the Licensee is not authorising the issue of any digital currency, including Qoin;

(12) by clause 2.2(b), the Company (relevantly) confirms the terms of the AFSL are sufficient to enable the Company to promote and operate the Product;

(13) by clause 6.1(e), “[t]he Company, in its capacity as an Authorised Representative of the Licensee, is authorised to make offers to people to arrange for the issue of the Product in accordance with the terms of the PDS and this Agreement”;

(14) by clause 4.2(b), “[w]hen providing Financial Services under this Agreement”, the Company must “[o]nly provide the Specified Financial Services in connection with the promotion, issue and operation of the Product”;

(15) by clause 14.2:

This Agreement embodies the entire agreement between the parties with respect to the subject matter of this Agreement and supersedes and extinguishes all prior agreements and understandings between the parties with respect to the matters covered by this Agreement.

126 Clauses 4.1 to 4.5 of the PNI AR Agreement imposed various obligations upon BPS in relation to the manner in which it provided financial services under the agreement, similar to those imposed upon it under the First Billzy AR Agreement.

127 Unlike the First Billzy Arrangement, the PNI Arrangement was documented in a single document, rather than two. However, it is common ground that this was not intended by the parties to constitute a change to the way BPS’s arrangement with the AFSL holder operated (as opposed to a change in the way in which the arrangement was documented). Notwithstanding this, the definition of “Specified Financial Services” in the PNI AR Agreement differed from the definition of “dealing” in the First Billzy AR Agreement which, for reasons explained below, is significant.

3.4.3 The Second Billzy Arrangement

128 On or around 1 September 2021, Billzy and BPS entered into the Second Billzy AR Agreement and the Second Billzy Intermediary Agreement, which are in essentially identical terms to the First Billzy AR and Intermediary Agreements.

3.5 BPS’s claim for exemption under section 911A(2)(a)

129 Section 911A(2)(a) of the Corporations Act provides that a person is exempt from the requirement to hold an AFSL for a financial service they provide if:

(a) the person provides the service as representative of a second person who carries on a financial services business and who:

(i) holds an Australian financial services licence that covers the provision of the service; or

(ii) is exempt under this subsection from the requirement to hold an Australian financial services licence that covers the provision of the service.

130 There is no suggestion in this case that the agreements relied upon by BPS did not have legal effect insofar as they governed the relationships between the parties, or that the parties did not genuinely believe themselves to be acting in accordance with those agreements and the requirements of the Corporations Act.

131 Further, ASIC admits that each of the First Billzy AR Agreement, the PNI AR Agreement, and the Second Billzy AR Agreement had the effect of appointing BPS as the authorised representative of Billzy/PNI within the meaning of ss 761A and 916A of the Corporations Act. It is also common ground that the Billzy AR and PNI AR Agreements are valid written notices pursuant to s 916A(1) of the Corporations Act.

3.5.2 Whether BPS is entitled to rely upon section 911A(2)(a)

132 ASIC’s fundamental challenge to the three arrangements entered into by BPS is its contention that, to be an authorised representative of an AFSL holder, the authorisation must be on the basis that the financial services will be, and are, provided on behalf of the AFSL holder as its agent and that, as BPS was the issuer of the Qoin NCP Product, and the provider of the advice in relation to that product, BPS was not an authorised representative of Billzy/PNI because those financial services were not provided as the agent of Billzy/PNI.

133 Section 911A(2)(a) requires that BPS has provided the financial services “as representative of” Billzy/PNI. The term “representative” was defined in s 910A (as it was until 2023) as meaning an authorised representative of the licensee or (inter alia) any other person acting on behalf of the licensee. That definition now appears in s 9 of the Corporations Act.

134 An “authorised representative” was defined in s 761A (as it was until 2023; the same definition now appears in s 9) in the following terms:

authorised representative of a financial services licensee means a person authorised in accordance with section 916A or 916B to provide a financial service or financial services on behalf of the licensee.

(Emphasis added; original emphasis removed.)

135 Section 916A(1), which is the relevant provision in this case, provides:

A financial services licensee may give a person (the authorised representative) a written notice authorising the person, for the purposes of [Chapter 7], to provide a specified financial service or financial services on behalf of the licensee.

(Emphasis added; original emphasis removed.)

136 By reference to these provisions, and the use of the phrase “on behalf of” within them, ASIC submits that the statutory defining feature of the concept of “representative” and “authorised representative” is acting on behalf of the principal and that “on behalf of” means “as representative of” or “for” the relevant persons, in this case Billzy or PNI. The definition of “on behalf of” in s 9 of the Corporations Act states “on behalf of includes on the instructions of” (emphasis removed), which does not assist with resolving its meaning in this context.

137 ASIC submits that its interpretation is consistent with the High Court’s approach in R v Toohey; Ex parte Attorney-General (NT) (1980) 145 CLR 374. In that case, the High Court was required to consider the meaning of the phrase “on behalf of” in the context of the phrase “an area of land… held by, or on behalf of, Aboriginals” in s 50 of the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 (Cth).

138 The plurality observed at page 386:

The phrase “on behalf of” is, as Latham CJ observed in R v Portus; Ex parte Federated Clerks Union of Australia (1949) 79 CLR 428 at 435, “not an expression of strict legal meaning”, it bears no single and constant significance. Instead it may be used in conjunction with a wide range of relationships, all however in some way concerned with the standing of one person as auxiliary to or representative of another person or thing.

In what is perhaps its least specific use, “on behalf of” may be applied to someone who does no more than express support for persons or for a cause, as with one who speaks on behalf of the poor or on behalf of tolerance. It may be used when speaking of an agency relationship, but also of some quite ephemeral relationships, such as that which exists between a party to litigation and the witness he calls, a witness “on behalf of” the defence… Context will always determine to which of the many possible relationships the phrase “on behalf of” is in a particular case being applied; “the context and subject matter” … will be determinative.

139 ASIC also relies upon NMFM Property Pty Ltd v Citibank Ltd (No 10) (2000) 107 FCR 270; [2000] FCA 1558. In that case, Lindgren J considered the meaning of “on behalf of” in s 84(2) of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth). Before reaching a conclusion about this issue, his Honour referred to earlier decisions concerning the interpretation of this phrase at [1240] and [1242]:

In R v Portus; Ex parte Federated Clerks Union of Australia (1949) 79 CLR 428 at 435, Latham CJ observed that the phrase “‘on behalf of’ is not an expression which has a strict legal meaning”. In R v Toohey; Ex parte Attorney-General (NT) (1980) 145 CLR 374, in a joint judgment Stephen, Mason, Murphy and Aickin JJ said of the expression (at 386):

“…it bears no single and constant significance. Instead it may be used in conjunction with a wide range of relationships, all however in some way concerned with the standing of one person as auxiliary to or representative of another person or thing.”

The expression was considered more recently by Kirby P in the New South Wales Court of Appeal in Citizens Airport Environment Association Inc v Maritime Services Board (1993) 30 NSWLR 207, esp at 221-223, but as his Honour recognised, since the meaning of the expression is influenced so much by the statutory context in which it appears, authorities relating to a different statutory context afford little guidance.

…

In Walplan Ptd Ltd v Wallace [(1985) 8 FCR 27] Lockhart J (with whom Sweeney and Neaves JJ agreed) stated (at 37):

“The phrase ‘on behalf of’ is not one with a strict legal meaning and it is used in a wide range of relationships. The words are not used in any definitive sense capable of general application to all circumstances which may arise and to which the subsection has application. This must depend upon the circumstances of the particular case, but some statements as to the meaning and operation of the subsection may be made. In the context of s 84(2) the phrase suggests some involvement by the person concerned with the activities of the company. The words convey a meaning similar to the phrase ‘in the course of the body corporate’s affairs or activities’… Section 84(2) refers to conduct by directors and agents of a body corporate as well as its servants. Also, the second limb of the subsection extends the corporation’s responsibility to the conduct of other persons who act at the behest of a director, agent or servant of the corporation. Hence the phrase ‘on behalf of’ casts a much wider net than conduct by servants in the course of their employment, although it includes it.”

140 Lindgren J then concluded at [1244] that: