FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Macquarie Bank Limited [2024] FCA 416

ORDERS

AUSTRALIAN SECURITIES AND INVESTMENTS COMMISSION Plaintiff | ||

AND: | MACQUARIE BANK LIMITED ACN 008 583 542 Defendant | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT DECLARES THAT:

1. Macquarie Bank Limited (Macquarie) contravened s 912A(l)(a) of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) between l May 2016 and 12 March 2019, by failing to do all things necessary to ensure that the financial services covered by its financial services licence were provided efficiently, honestly and fairly, as a result of Macquarie not implementing effective controls to prevent or detect transactions conducted by third parties through Macquarie’s bulk transacting system that were outside the scope of the authority conferred on them that only permitted them to withdraw their fees from their clients’ Cash Management Accounts, such as the fraudulent transactions made by Mr Ross Hopkins.

2. Macquarie contravened s 912A(l)(a) and (5A) of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) between 13 March 2019 and 15 January 2020, by failing to do all things necessary to ensure that the financial services covered by the financial services licence were provided efficiently, honestly and fairly, as a result of Macquarie not implementing effective controls to prevent or detect transactions conducted by third parties through Macquarie’s bulk transacting system that were outside the scope of the authority conferred on them that only permitted them to withdraw their fees from their clients’ Cash Management Accounts, such as the fraudulent transactions made by Mr Ross Hopkins.

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Pursuant to s 1317G of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth), Macquarie pay to the Commonwealth of Australia within 28 days a pecuniary penalty in the amount of $10,000,000.00 in respect of Macquarie's contravention s 912A(l)(a) and (5A) of the Corporations Act referred to in declaration 2 above.

2. Macquarie pay the plaintiff’s costs of the proceeding as agreed or assessed within 28 days of such agreement or assessment.

3. The proceeding otherwise be dismissed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

(Revised from transcript)

WIGNEY J:

1 Macquarie Bank Limited is a large and well-known financial institution that, among other things, holds a financial services licence and provides financial services to its many customers. The Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) commenced this proceeding against Macquarie alleging that it failed to do all things necessary to ensure that certain specified financial services covered by its financial services licence were provided efficiently, honestly, and fairly, and thereby contravened s 912A(1)(a) of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth). ASIC claimed, in short summary, that between 1 May 2016 and 15 January 2020, Macquarie failed to implement effective controls to prevent or detect fraudulent withdrawals by third parties from cash management accounts held by some of its clients. The account holders had given certain financial intermediaries, including financial advisers, stockbrokers, and accountants, limited authority to withdraw their fees from their cash management accounts via a bulk transacting system provided by Macquarie, but the absence of any effective controls in respect of that system permitted the intermediaries to conduct fraudulent withdrawals which were outside the scope of their authority. ASIC sought declarations of contravention by Macquarie and an order that Macquarie pay a pecuniary penalty in respect of its contravention.

2 While Macquarie initially defended the proceeding and opposed the declarations and orders sought by ASIC, it now admits that it contravened s 912A(1)(a) of the Corporations Act. It also consents to both the making of the declarations of contravention sought by ASIC and the making of an order that it pay the Commonwealth a pecuniary penalty in the amount of $10,000,000.

3 While Macquarie consents to the making of those declarations and orders, it is nevertheless necessary for the Court to consider and determine whether the declarations and orders are appropriate and should be made.

STATUTORY CONTEXT

4 The following references to provisions of the Corporations Act are to the text of those provisions at the time or times relevant to Macquarie’s contravening conduct.

5 Section 912A(1)(a) of the Corporations Act provides:

(1) A financial services licensee must:

(a) do all things necessary to ensure that the financial services covered by the licence are provided efficiently, honestly and fairly …

6 A person provides ‘financial services’ if they (relevantly) deal in a financial product: ss 766A(1) and 766C of the Corporations Act.

7 Section 912A(1)(a) was amended by the Treasury Laws Amendment (Strengthening Corporate and Financial Sector Penalties) Act 2019 (Cth) (the Amending Act). Schedule 1, item 76 of the Amending Act inserted s 912A(5A), which had the effect of rendering s 912A(1)(a) a civil penalty provision.

8 Section 912A(5A) provides as follows:

(5A) A person contravenes this subsection if the person contravenes paragraph (1)(a), (aa), (ca), (d), (e), (f), (g), (h) or (j).

Note: This subsection is a civil penalty provision (see section 1317E).

9 The Amending Act also inserted s 1657 of the Corporations Act which provides:

Subject to this Part, the amendments made by Schedule 1 to the [A]mending Act apply in relation to the contravention of a civil penalty provision if the conduct constituting the contravention of the provision occurs wholly on or after the commencement day.

10 The commencement day of Schedule 1 of the Amending Act, which inserted s 912A(5A), was 13 March 2019. As will be seen, that date is significant. It explains why ASIC has sought separate declarations concerning Macquarie’s conduct prior to 13 March 2019 and after that date. It is also important to note that the pecuniary penalty sought by ASIC only relates to Macquarie’s conduct after 13 March 2019.

11 There is no dispute that Macquarie was a financial services licensee. It was a financial services licensee because it held an Australian financial services license: see the definition of financial services licensee in s 761A of the Corporations Act.

12 There is also no dispute Macquarie’s conduct which is the subject of this proceeding occurred in the context of it providing financial services covered by that licence. That is because the relevant cash management accounts that Macquarie offered or provided to its customers were financial products within the meaning of s 764A(1)(i) of the Corporations Act, and by dealing with those accounts (see s 766C(1) of the Corporations Act), Macquarie provided financial services within the meaning of ss 766A(1)(b) of the Corporations Act. As there was no dispute about those matters, it is unnecessary to set out the somewhat labyrinthine provisions of the Corporations Act that deal with them.

13 Subsection 1317E(1) provides that if a Court is satisfied that a person has contravened a civil penalty provision, it must make a declaration of contravention. Subsection 1317E(3) (in the form it was in during the relevant period) identifies provisions in the Corporations Act which are civil penalty provisions. Subsection 912A(5A) is identified as a civil penalty provision.

14 Subsection 1317G(1) of the Corporations Act provides that if the Court has made a declaration of contravention of a civil penalty provision pursuant to s 1317E, it ‘may’ order the person to pay to the Commonwealth a pecuniary penalty. The pecuniary penalty must not exceed the pecuniary penalty applicable to the contravention: s 1317G(2).

15 Subsection s 1317G(4) of the Corporations Act provides that the pecuniary penalty applicable to the contravention of a civil penalty provision by a body corporate is the greatest of:

(a) 50,000 penalty units;

(b) if the Court can determine the benefit derived and detriment avoided because of the contravention – that amount multiplied by 3; and

(c) either:

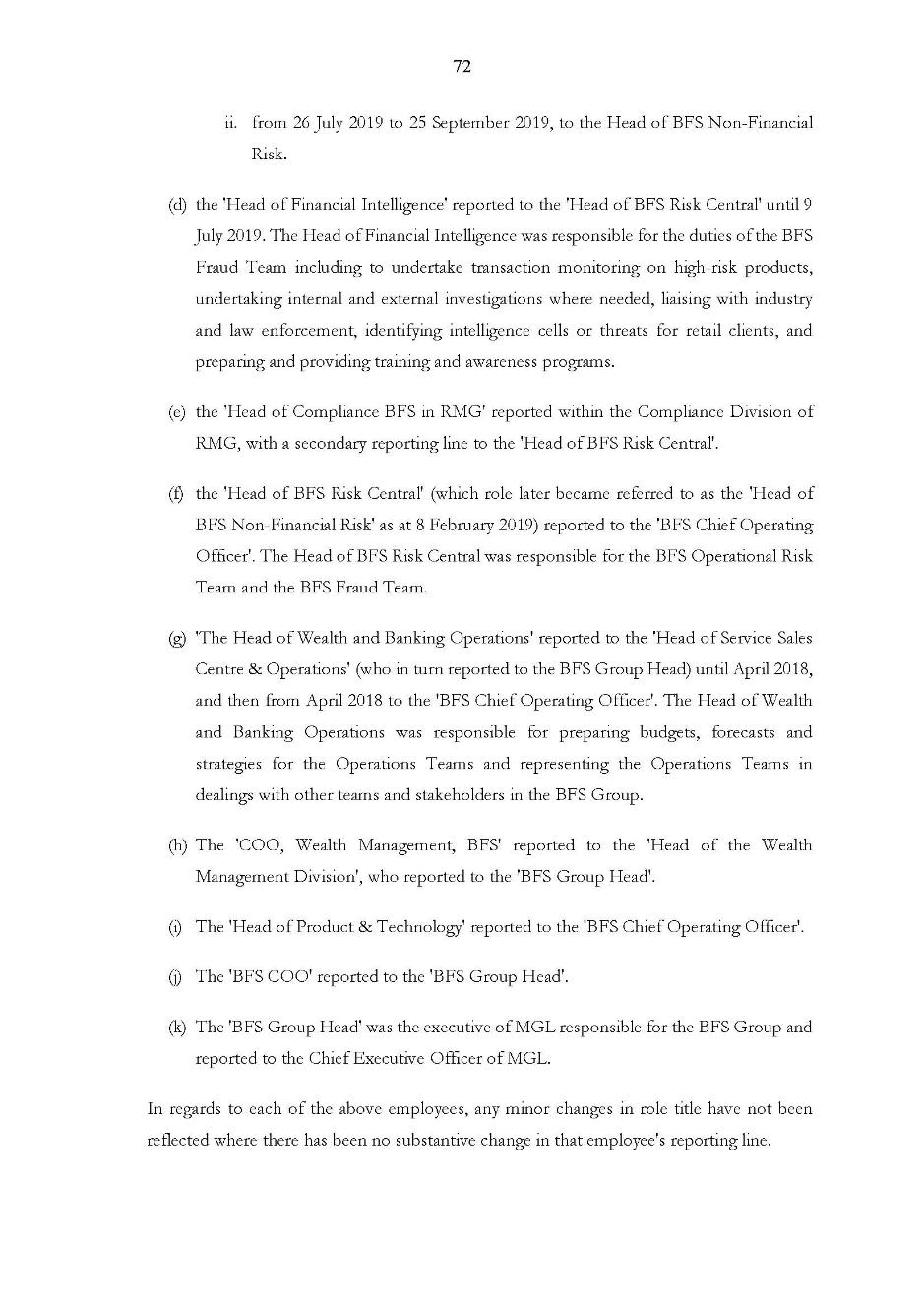

(i) 10% of the annual turnover of the body corporate for the 12-month period ending at the end of the month in which the body corporate contravened, or began to contravene, the civil penalty provision; or

(ii) if the amount worked out under subparagraph (i) is greater than the amount equal to 2.5 million penalty units – 2.5 million penalty units.

16 It is common ground that the pecuniary penalty applicable to the contravention by Macquarie is the penalty calculated pursuant to s 1317G(4)(c)(ii) because the figure representing 10% of the annual turnover of Macquarie during the relevant 12-month period is greater than $525,000,000, being 2.5 million penalty units (at the time of the contravention in question the value of a penalty unit was $210), and there was no suggestion that the Court could determine any benefit derived by reason of the contravention in accordance with s 1317G(4)(b).

17 The maximum penalty for the relevant contravention by Macquarie is accordingly $525,000,000.

18 Section 1317G(6) of the Corporations Act provides that, in determining the pecuniary penalty, the Court must take into account “all relevant matters”, including: the nature and extent of the contravention; the nature and extent of any loss or damage suffered because of the contravention; the circumstances in which the contravention took place; and whether the person has previously been found by a court to have engaged in any similar conduct. The relevant matters identified in s 1317G(6) are plainly not exhaustive.

MACQUARIE’S CONTRAVENING CONDUCT

19 The parties jointly relied upon a Statement of Agreed Facts and Admissions. A copy of that document (not including Confidential Annexure A, and redacted in accordance with a suppression order made by the Court) is attached to this judgment at Annexure A. There is no basis for the Court to believe or conclude that the agreed facts are inaccurate or incomplete in any material respect. Indeed, they identify the contravening conduct in very clear and painstaking detail.

20 It is unnecessary to rehearse the facts in any detail in this judgment. Following is a short summary of the salient facts. The facts relate to the period 1 May 2016 to 15 January 2020 unless otherwise indicated. That period is generally referred to as the relevant period.

21 Macquarie was an authorised deposit-taking institution for the purposes of the Banking Act 1959 (Cth) and held an Australian Financial Services Licence (AFSL).

22 Macquarie offered its customers a deposit account product called a Cash Management Account (CMA).

23 CMAs were deposit-taking facilities made available by Macquarie in the course of its banking business. As such, they were ‘financial product[s]’ within the meaning of s 764A(1)(i) of the Corporations Act. In issuing CMAs, Macquarie dealt with financial products and provided financial services within the meaning of ss 766A(1)(b) and 766C(1) of the Corporations Act. Those financial services were covered by the terms of Macquarie’s AFSL.

24 CMAs allowed for various transfers to be made to or from the account, including: the transfer of funds to term deposit accounts; the transfer of funds to purchase shares; the transfer of funds to invest in managed funds; the transfer of funds for the payment of fees to third party intermediaries; the receipt of investment returns such as dividends and interest. Macquarie’s CMA customers could grant third party financial intermediaries, such as financial advisers, authority to withdraw funds from their CMAs. There were different levels of authorities, ranging from a general authority which effectively permitted any transaction, to a limited authority which only permitted the payment of a third party’s fees.

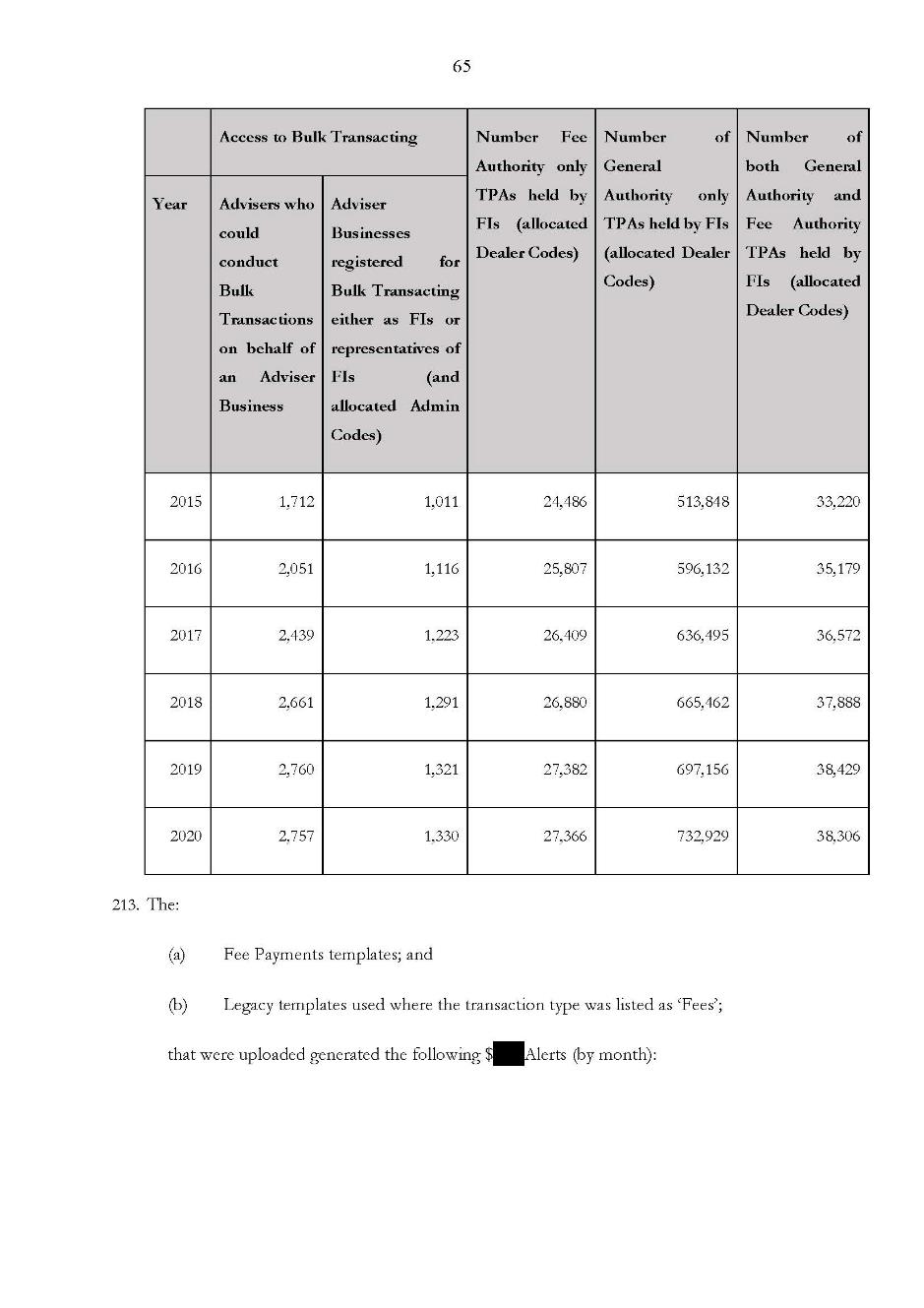

25 Macquarie made available a ‘bulk transacting’ system or facility for effecting transactions on CMAs. That facility or system enabled third parties who had been granted an authority by account holders to, among other things, effect multiple withdrawals from multiple CMAs at once. To access that facility, a third party was required to register with Macquarie, distribute Macquarie products, and obtain access to an online facility operated by Macquarie. The third party was also required to complete and upload a template or data file. One such template was a fee payments template, which was the applicable template where the transaction type was the payment of fees and the CMA holder had granted a fee authority.

26 Bulk transactions involving the payment of fees using the bulk transaction system or facility involved inherent risks for customers, particularly risks associated with fraudulent or otherwise unauthorised transactions by third party intermediaries who had been granted authorities by the account holder.

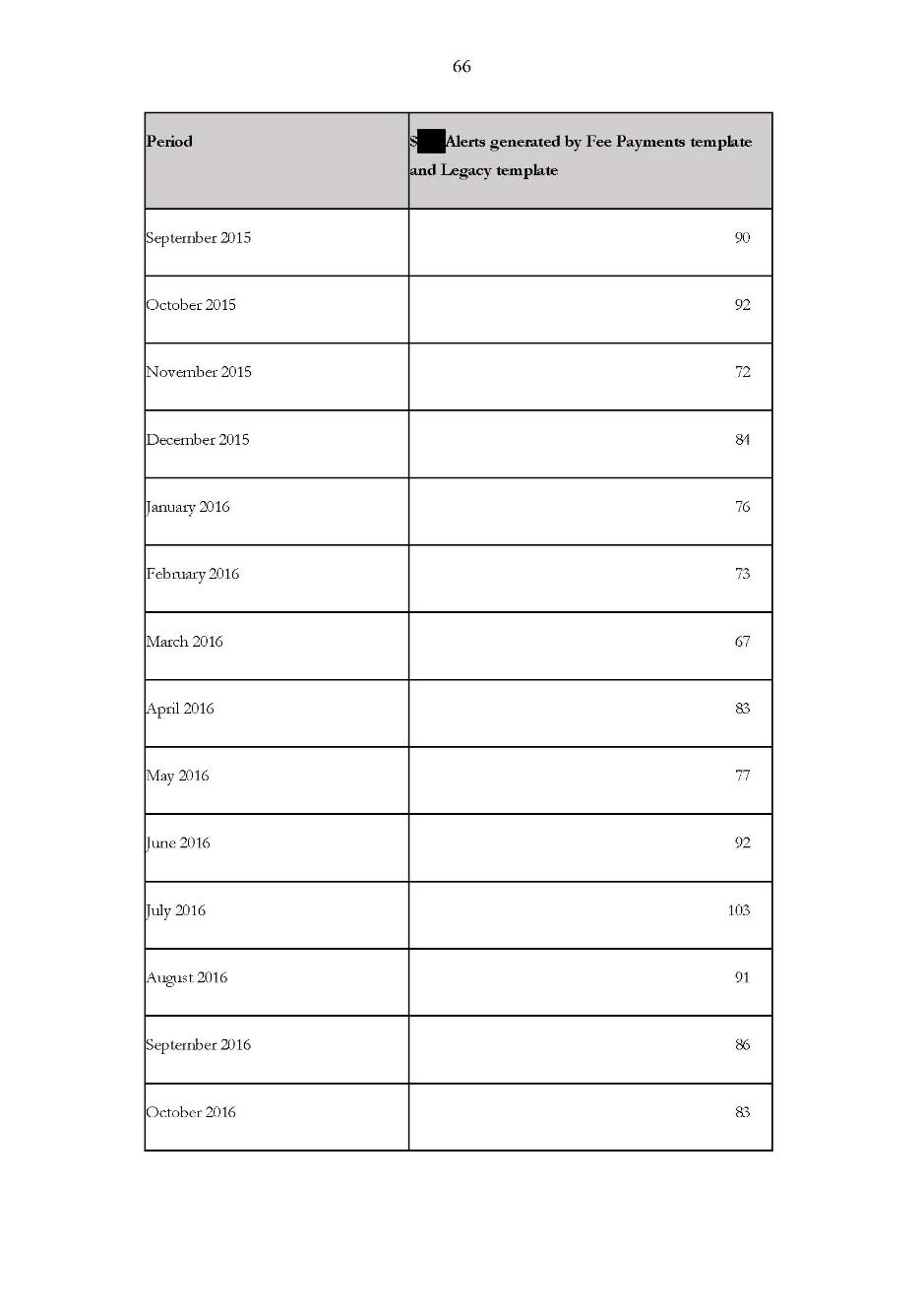

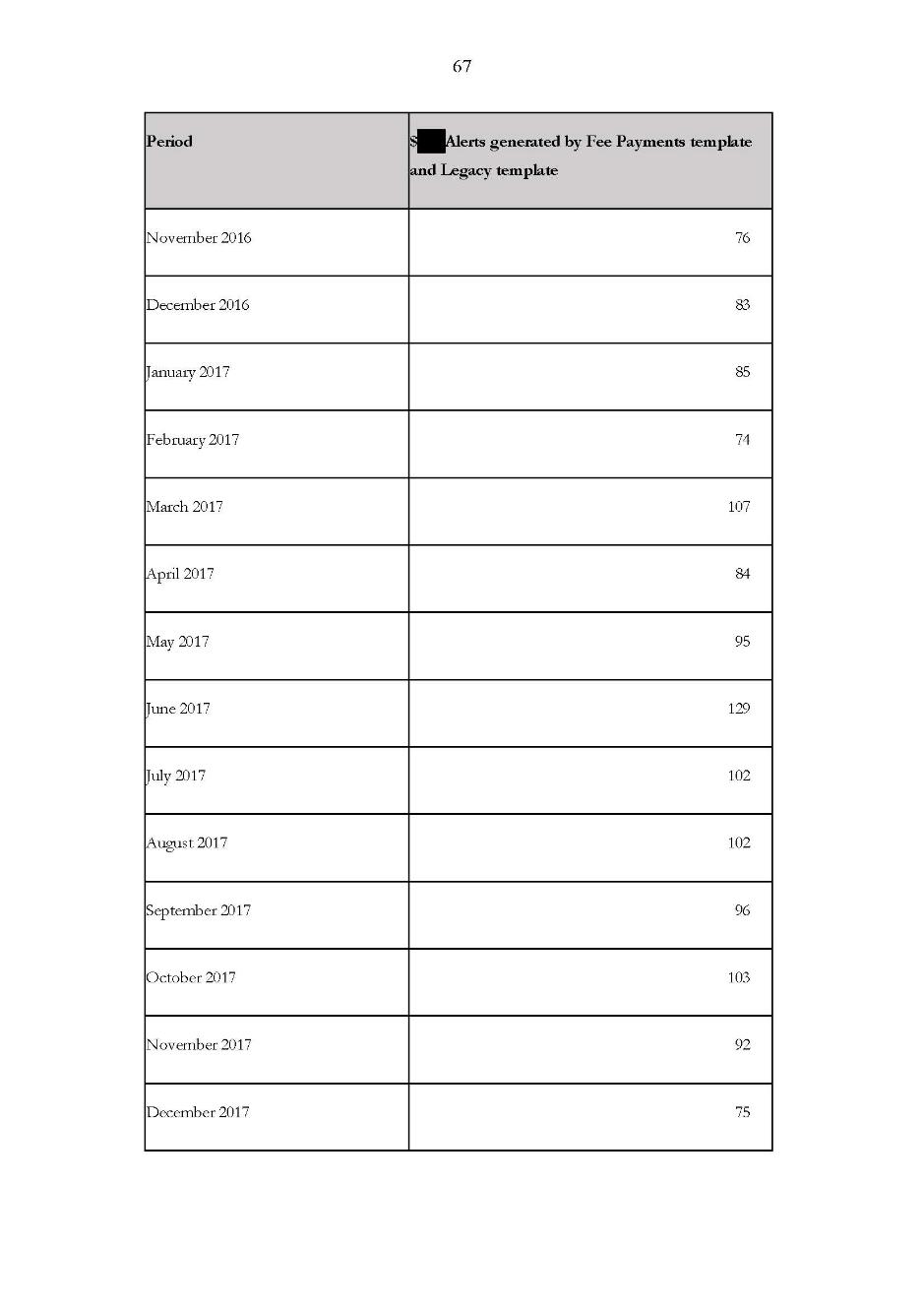

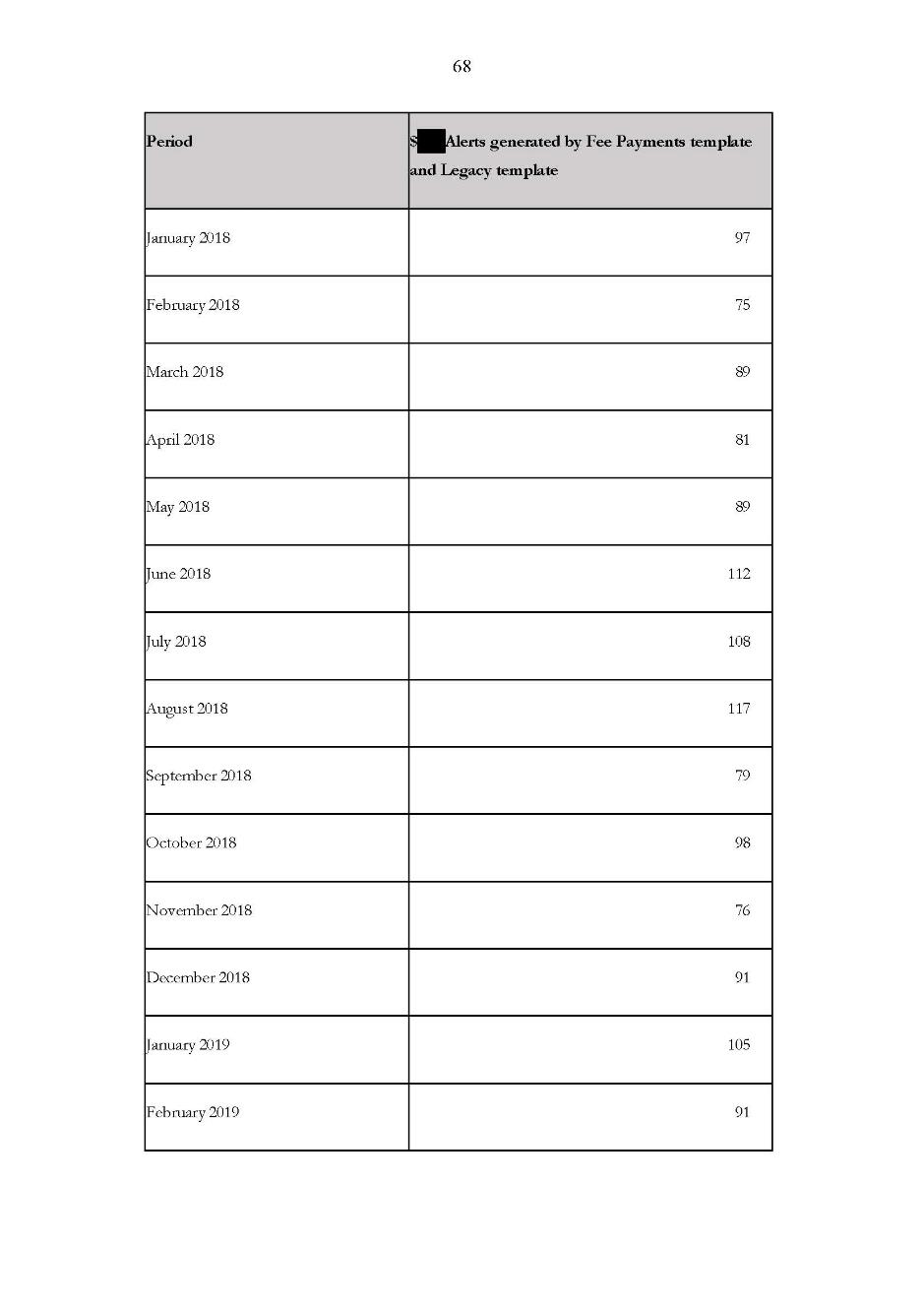

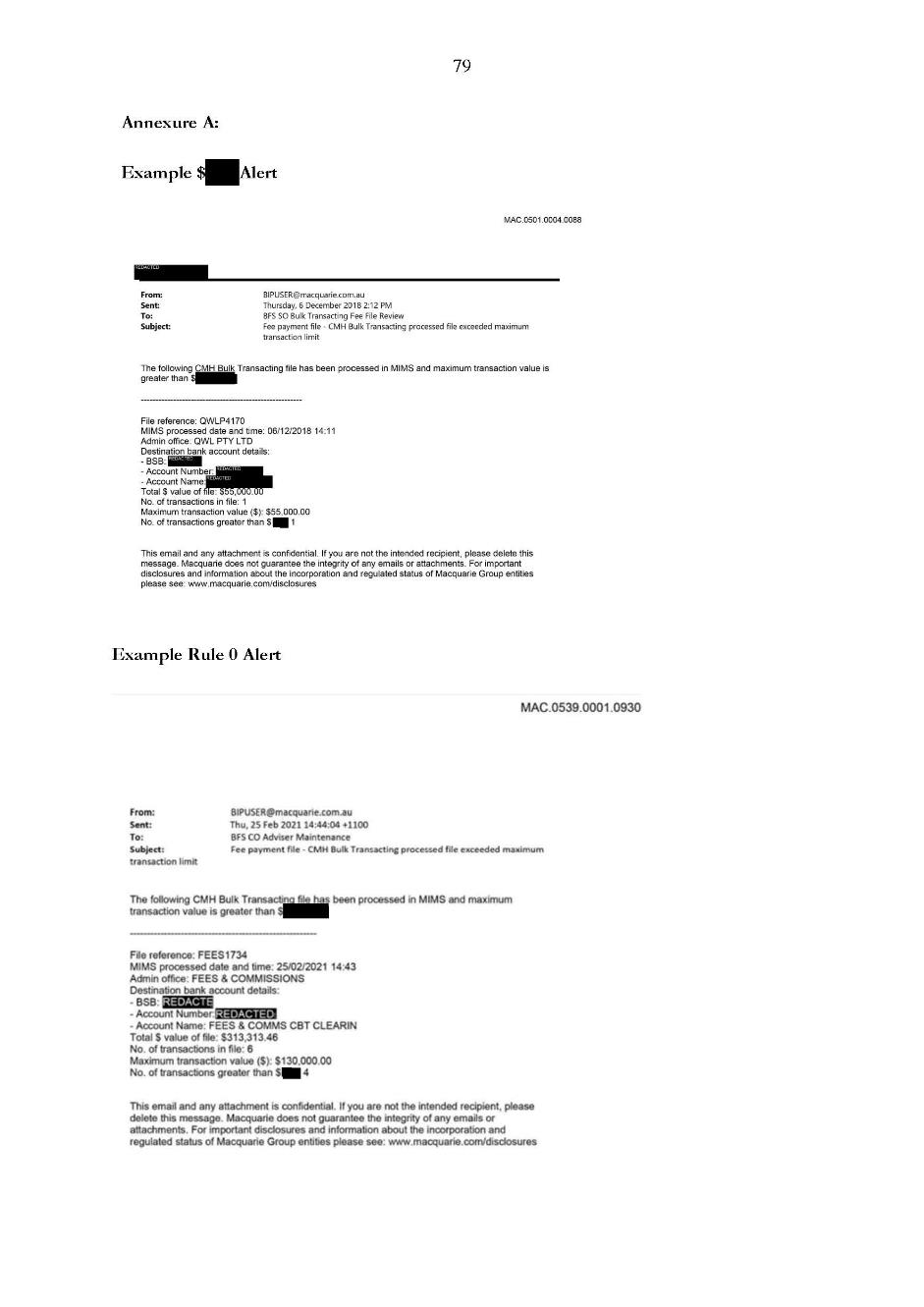

27 Macquarie put in place some systems or controls to mitigate the risk of fraudulent transactions by third parties acting beyond the scope of their fee authorities. For example, by early 2014, bulk transactions involving fees generated an email alert if they contained one or more transactions for an amount which exceeded a certain specified amount (the alerts). There was, however, no written practice or procedure in place to review or monitor the alerts. As a result, the alerts had little or no effect in mitigating the risk of fraudulent transactions.

28 Between about mid-2012 and mid-2016, certain Macquarie employees became aware that some financial intermediaries had misused their fees authorities by conducting bulk transactions ostensibly in respect of fees, but for purposes other than the payment of fees. A number of those instances of misuse involved a financial adviser named Mr Ross Hopkins, though he was not the only third party involved in such wrongdoing. Some steps were taken to deal with that issue. Those steps, however, were obviously inadequate and ineffective.

29 From about mid-2016, various Macquarie employees prepared papers and presentations, and undertook reviews, in which they identified the clear risk that bulk transacting, including bulk transacting involving fees, could be used by third parties to effect fraudulent or unauthorised transactions on CMAs held by Macquarie clients. It is unnecessary to spell out in detail the content of those papers, presentations, and reviews, or what they uncovered and recommended could or should be done. The details are contained in the Statement of Agreed Facts and Admissions. Suffice it to say that, despite what was uncovered or discovered during those processes concerning fraudulent transactions and the ongoing risks inherent in bulk transacting without further controls, Macquarie failed to implement effective controls to prevent or detect bulk transactions involving fees that were outside the scope of the limited fee authority conferred on third parties until January 2020.

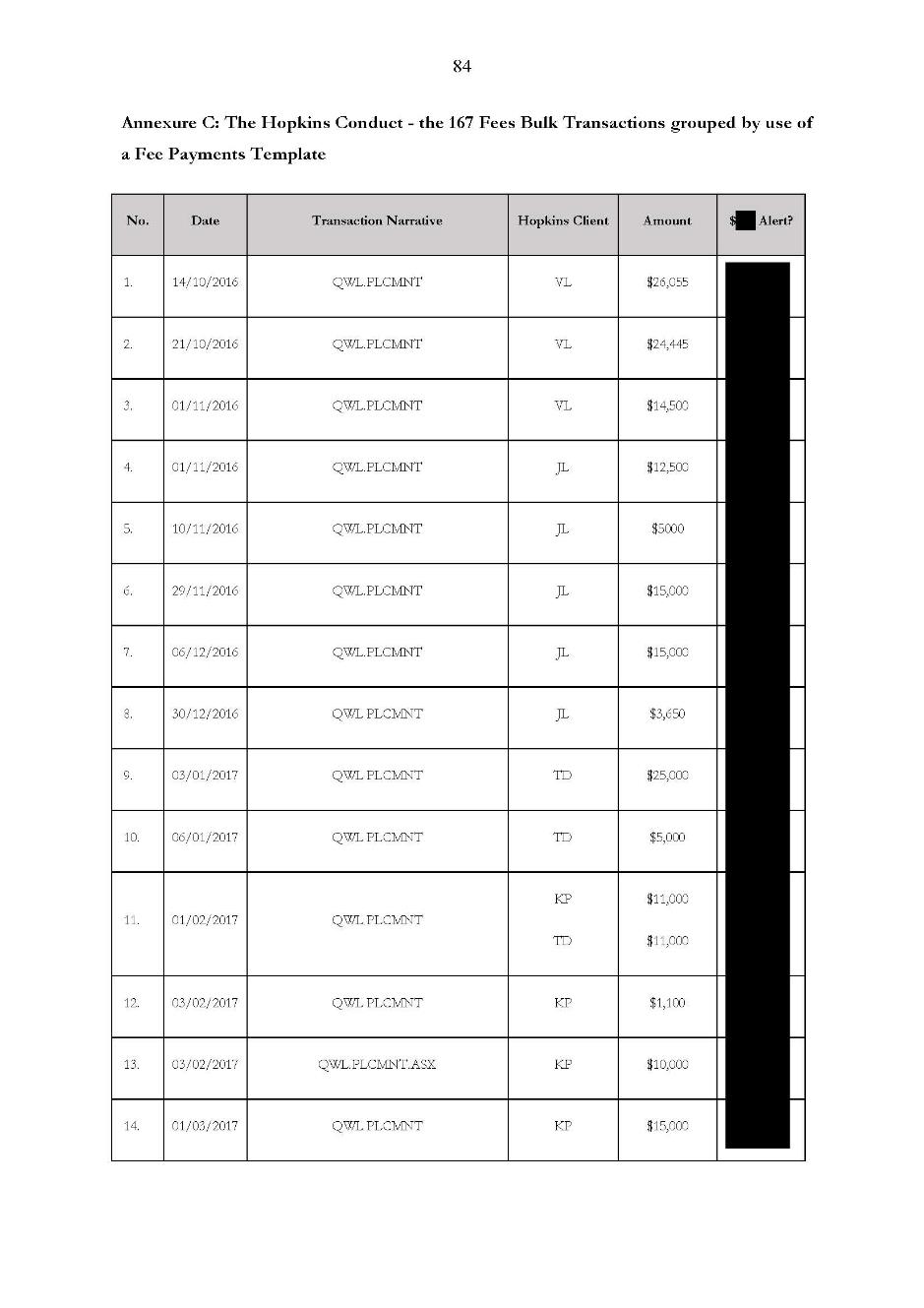

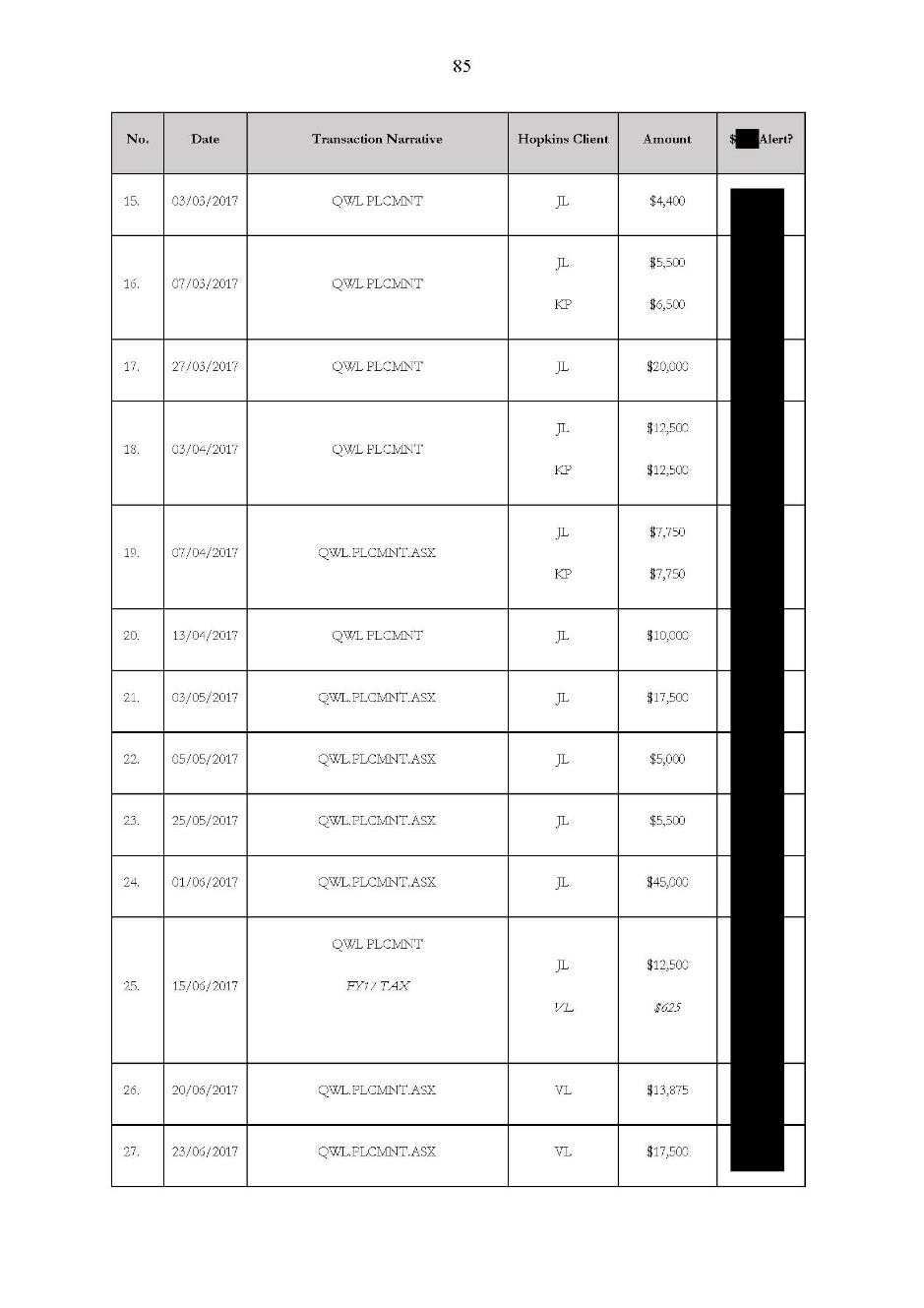

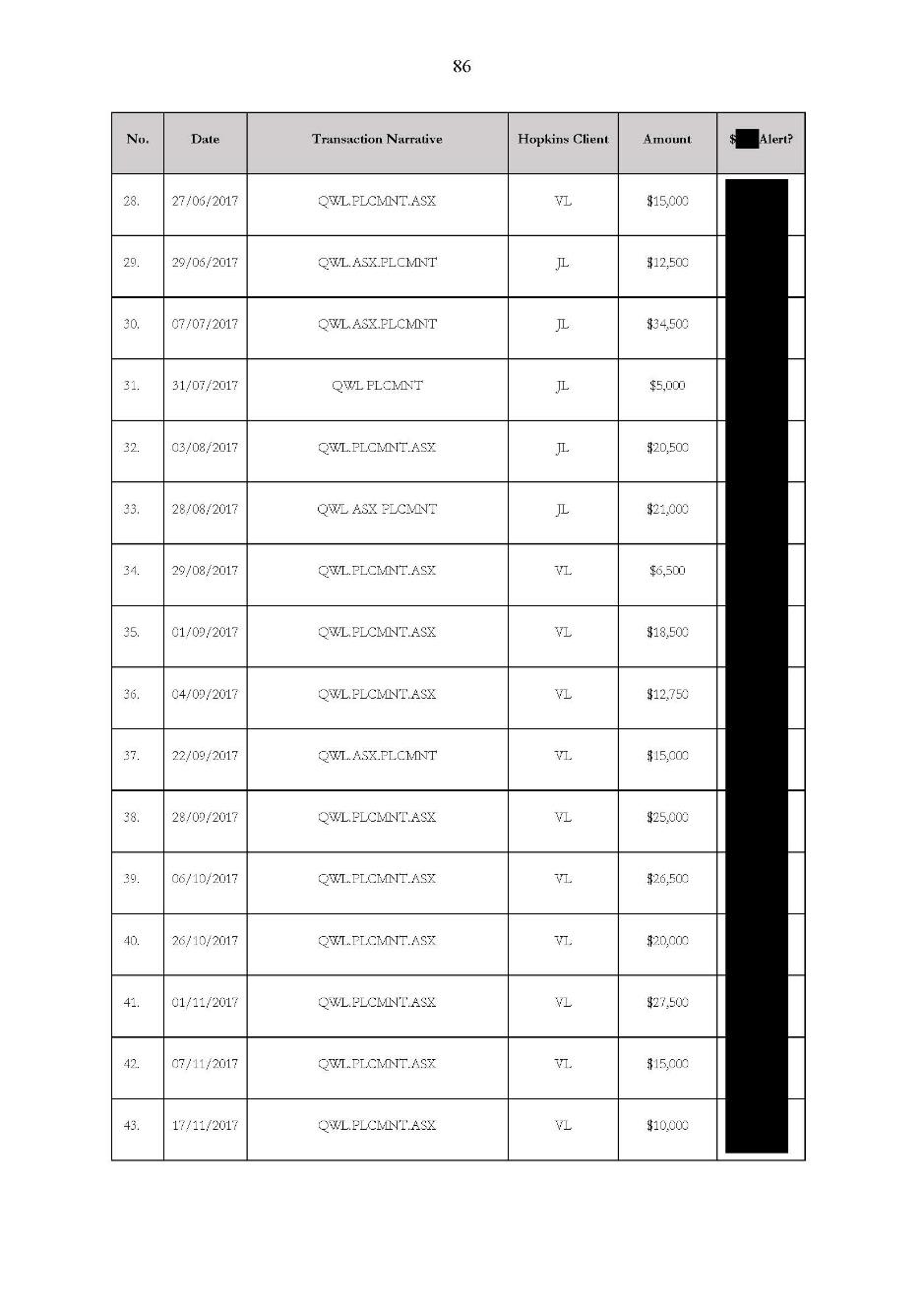

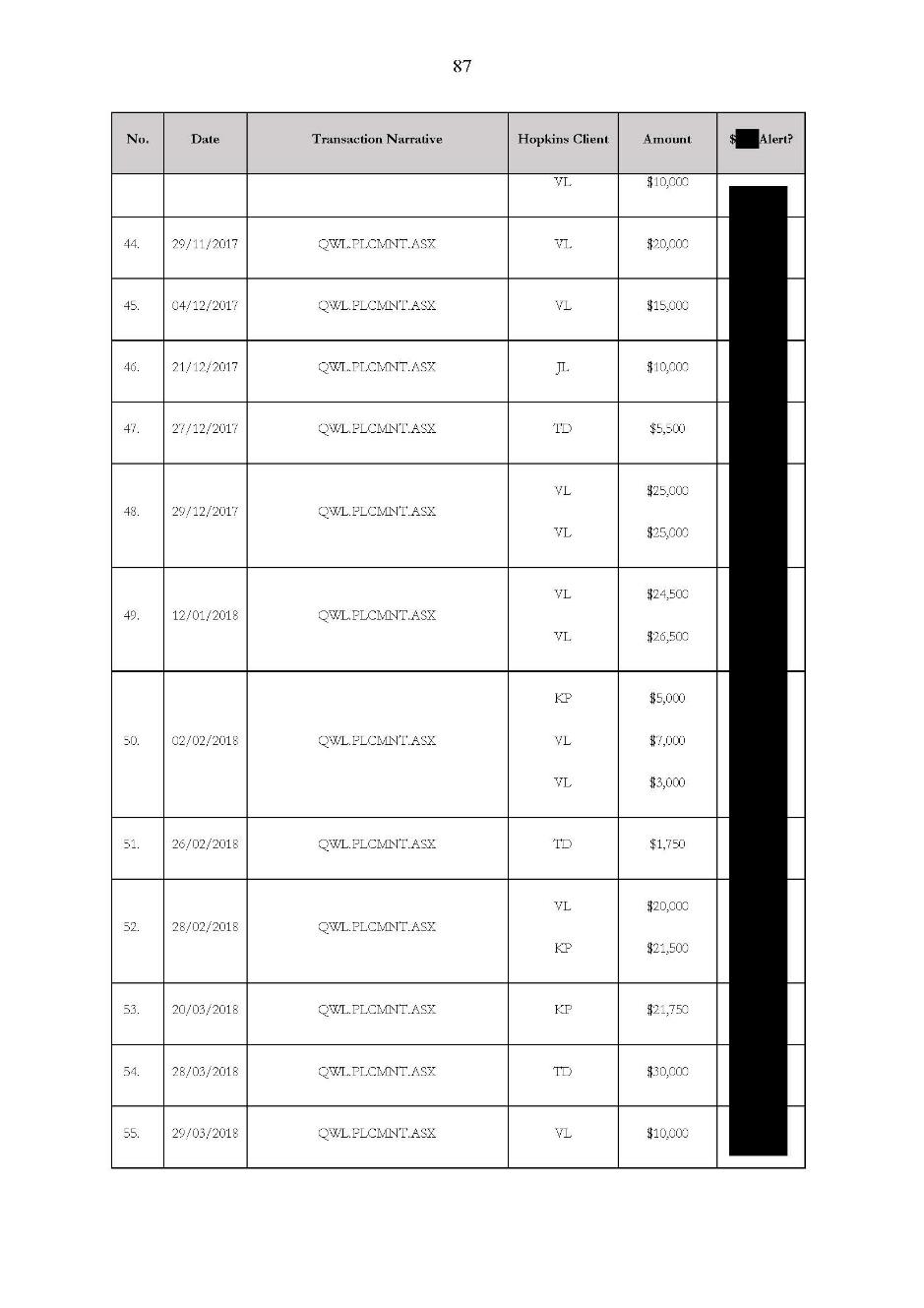

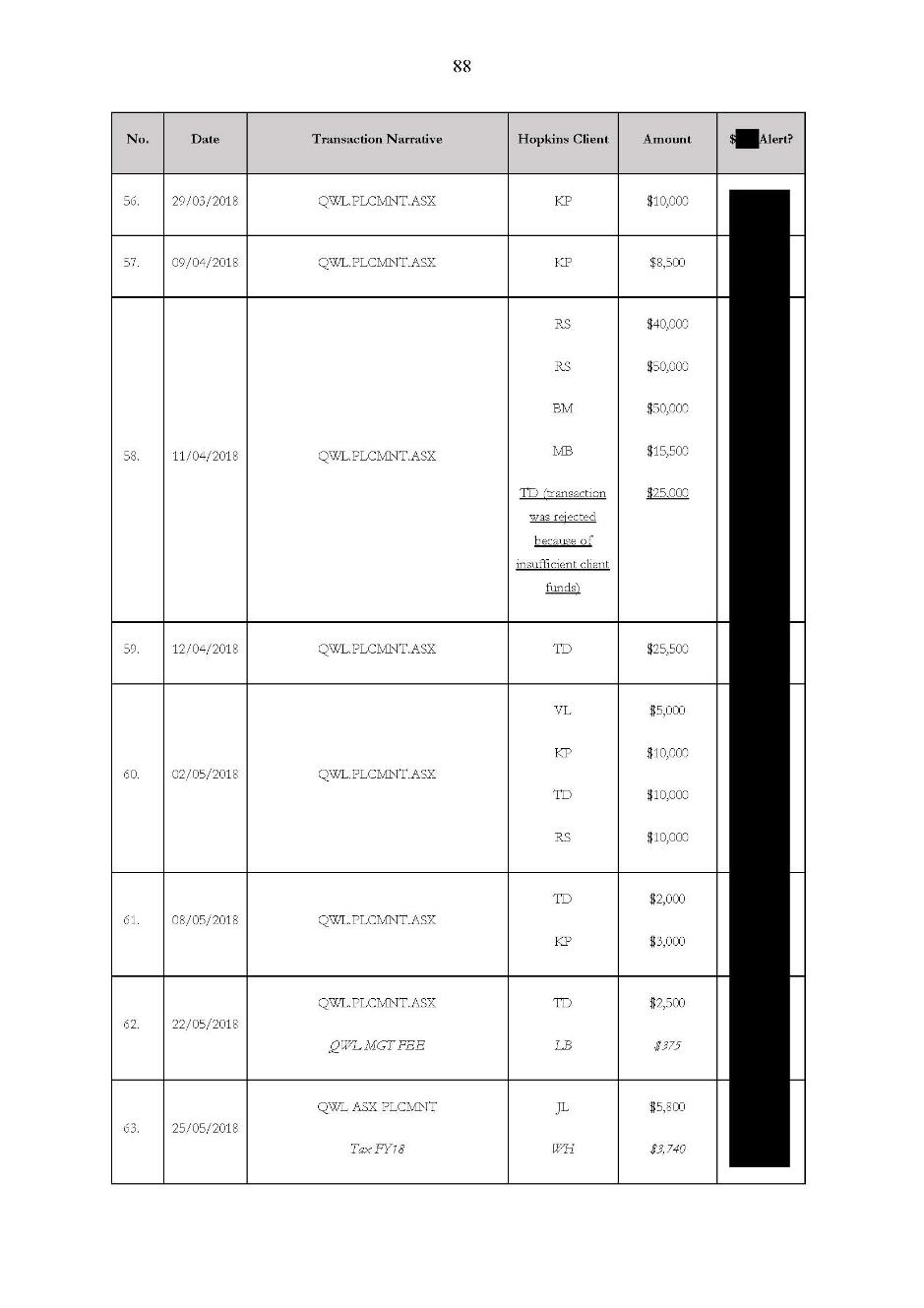

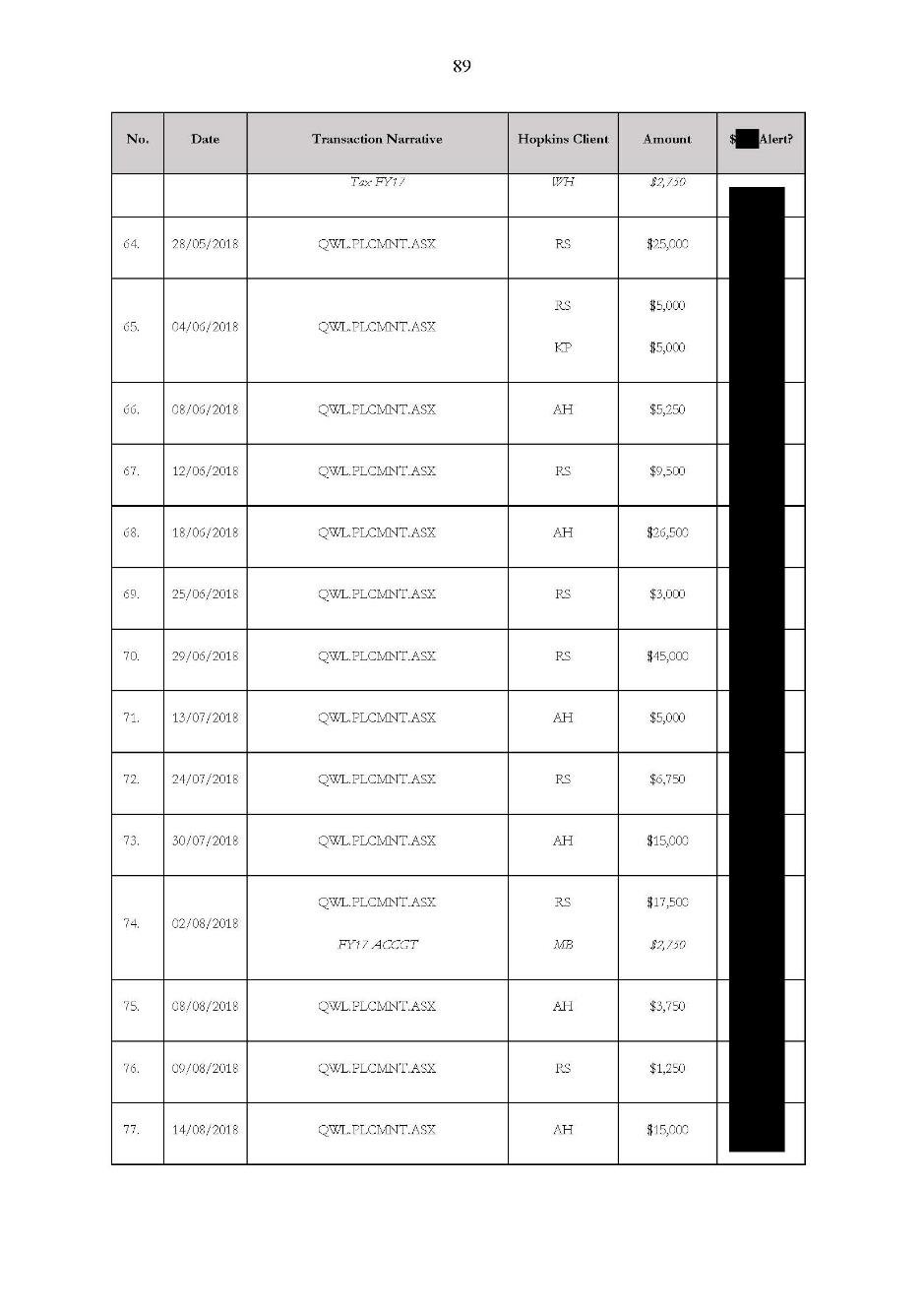

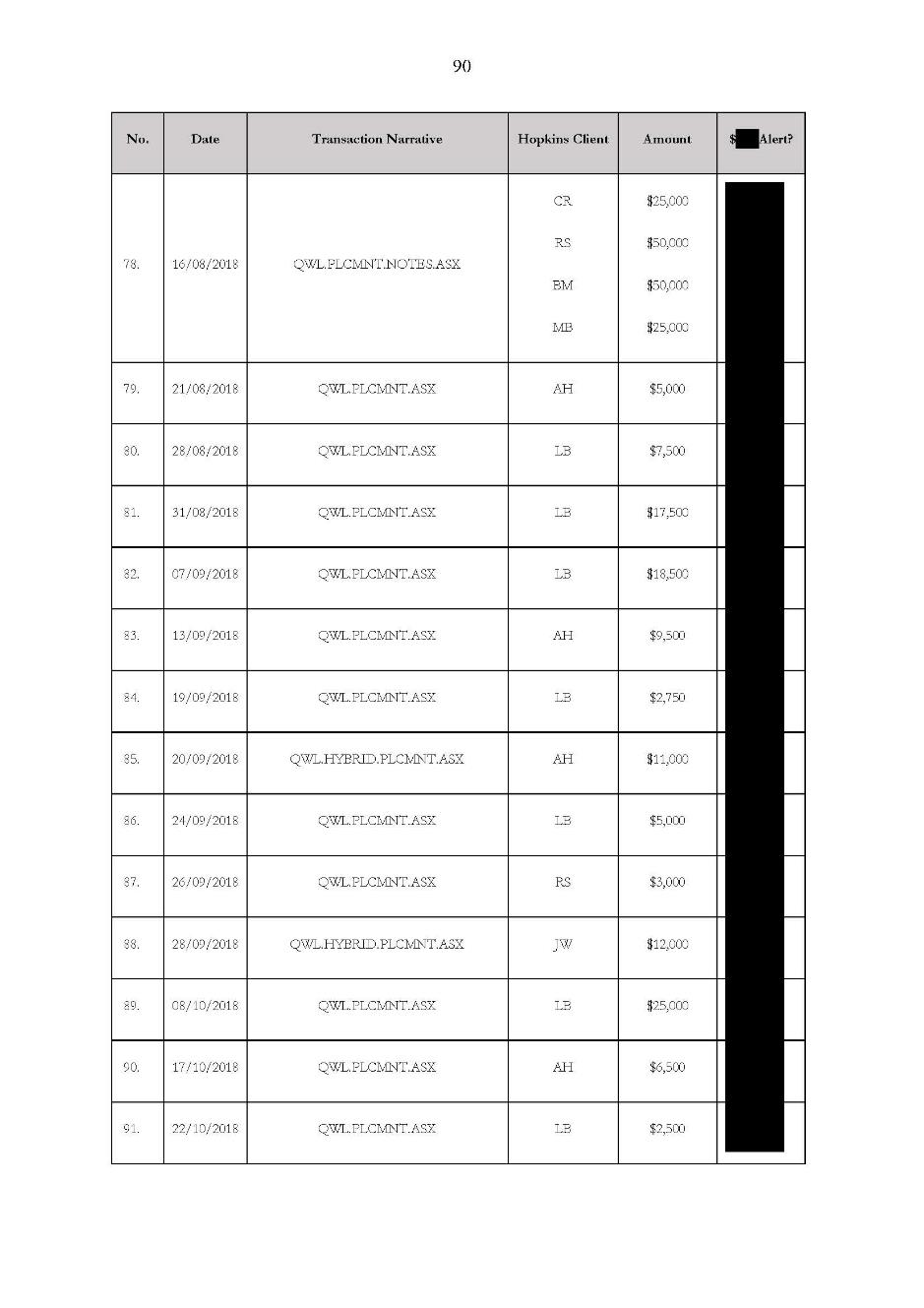

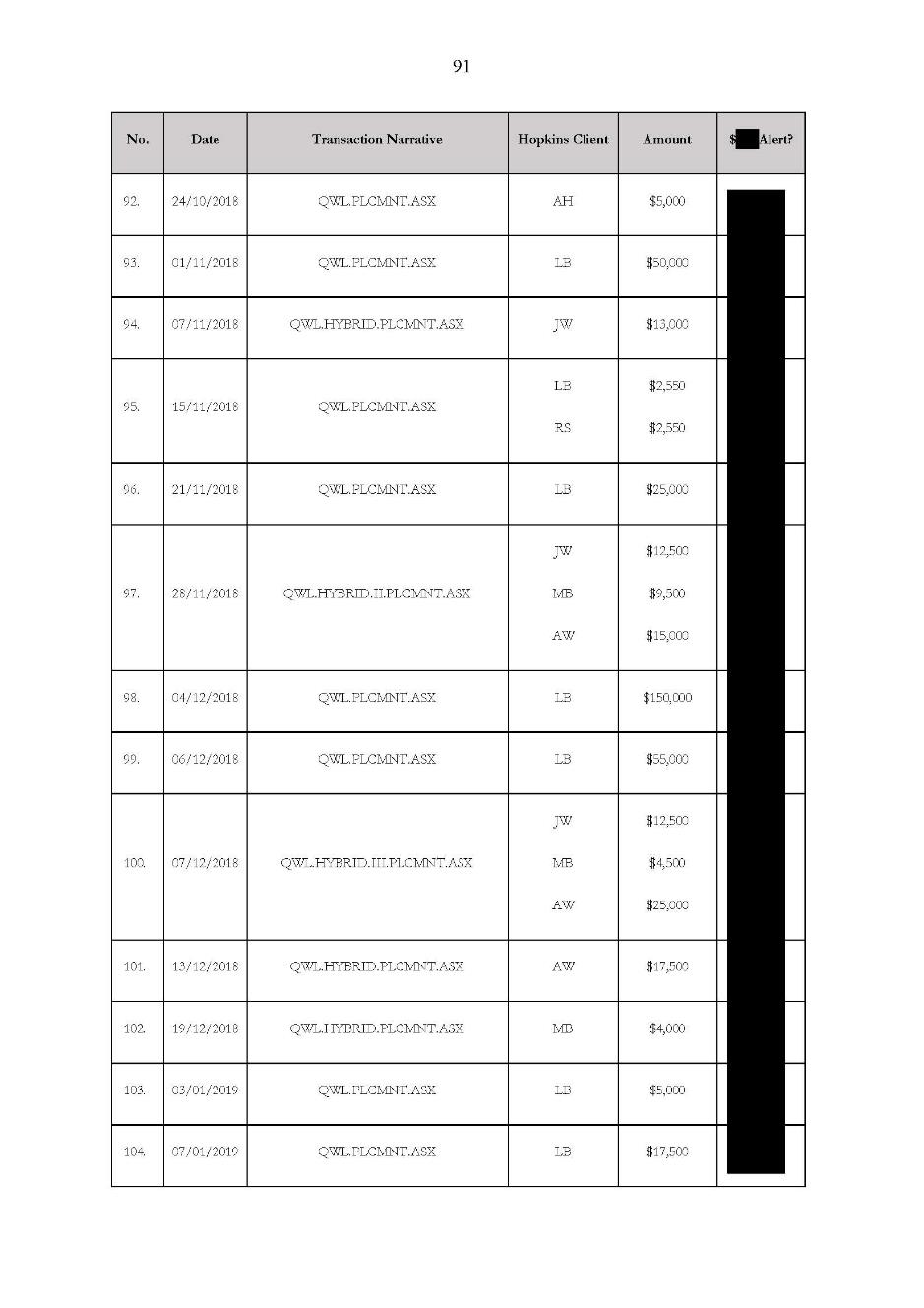

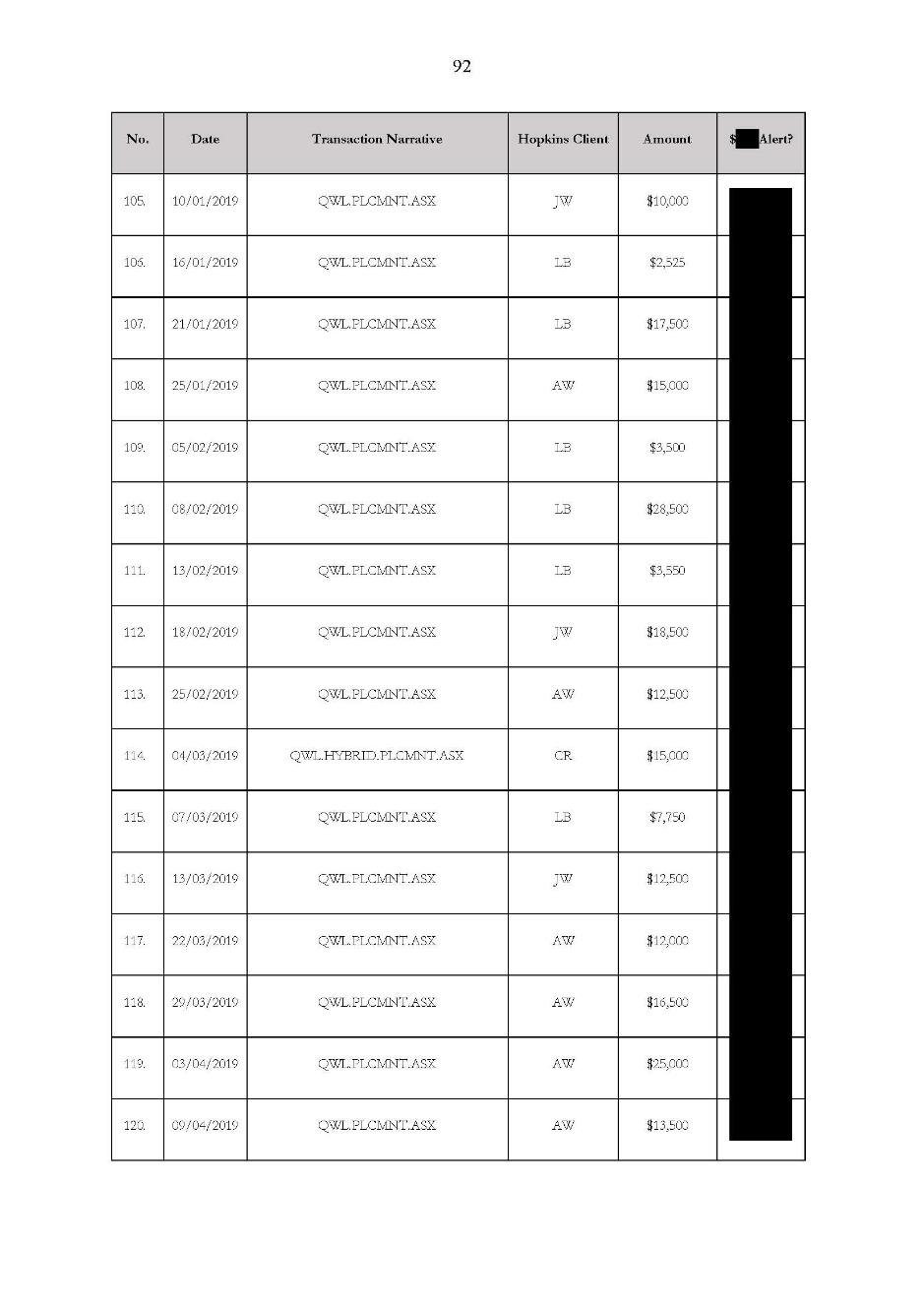

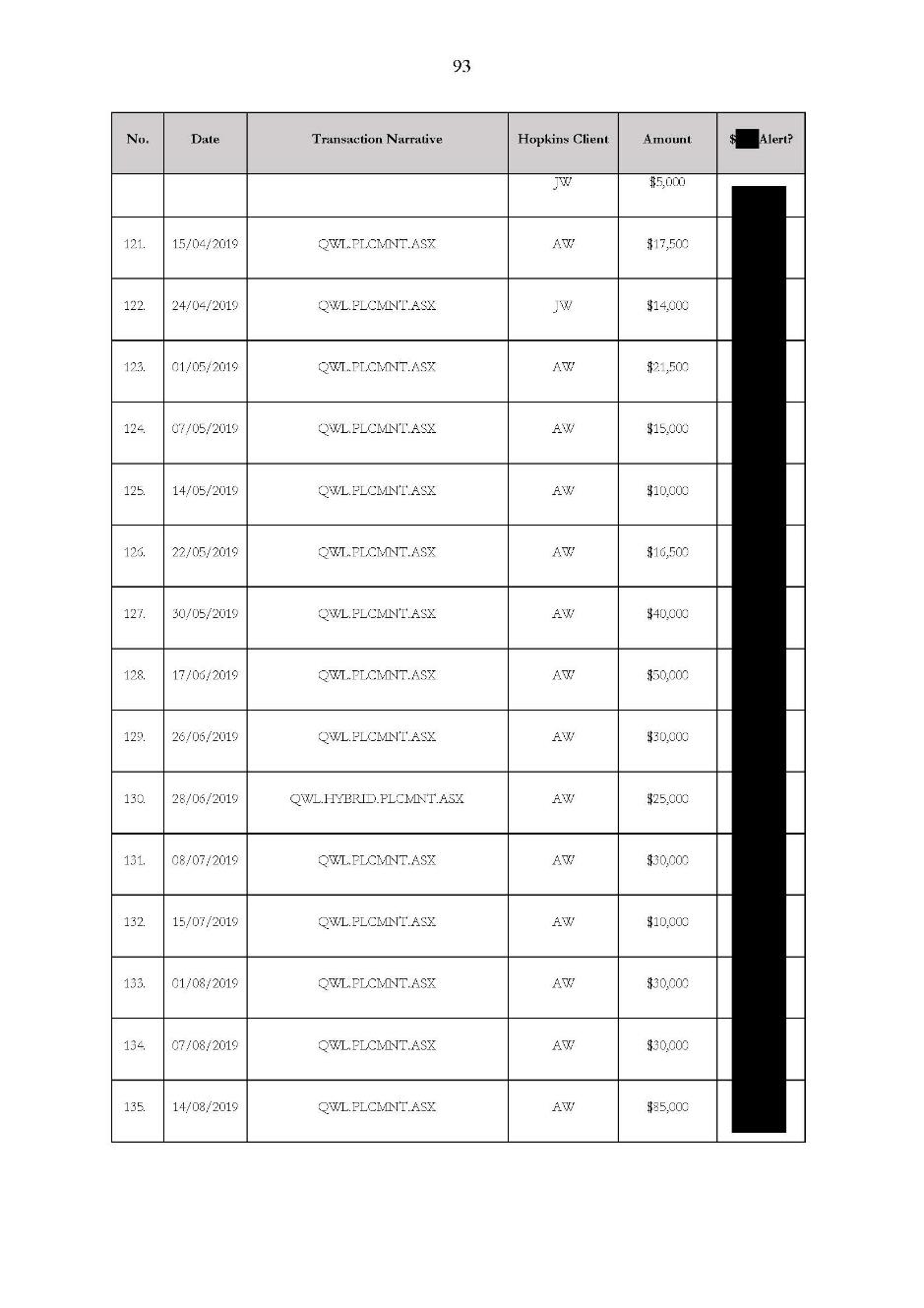

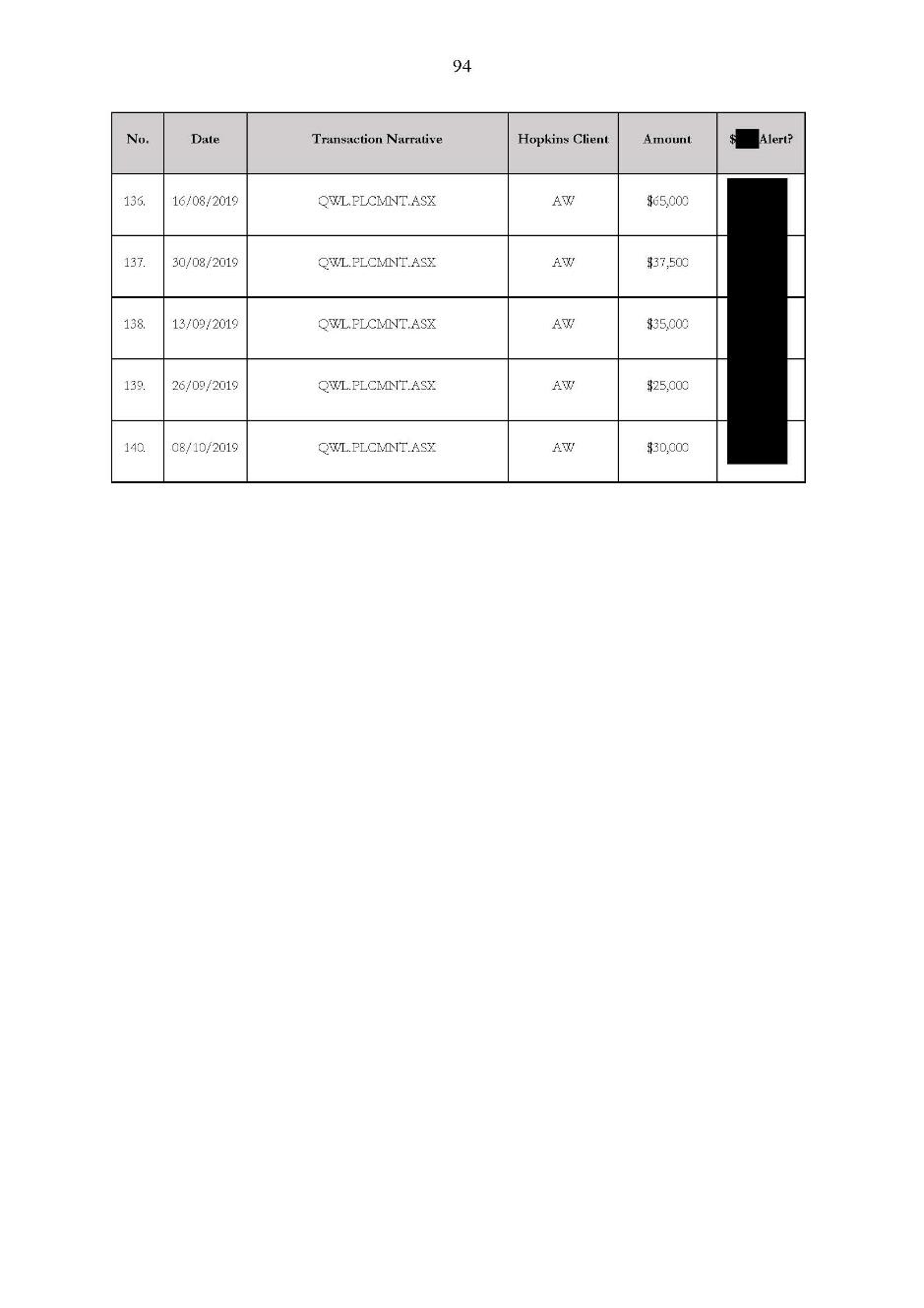

30 The upshot of Macquarie’s failures in that regard was that it did not detect 167 fraudulent transactions, totalling almost $3,000,000 that were effected by Mr Hopkins in the period October 2016 to October 2019 utilising Macquarie’s bulk transaction system or facility in respect of 14 CMAs held by 13 of his clients. Those transactions included 97 transactions that gave rise to alerts, though as explained earlier, those alerts were not systematically reviewed.

31 Macquarie’s failures in that regard were effectively remedied in January 2020 when it implemented a real-time alert system which alerted CMA holders of transactions initiated by persons to whom they had granted authorities, including fee authorities. In May 2020, Macquarie also implemented a fraud monitoring program for bulk transacting. A review conducted in late 2020 or early 2021 did not identify any further instances of fraudulent transactions involving bulk transactions concerning fees.

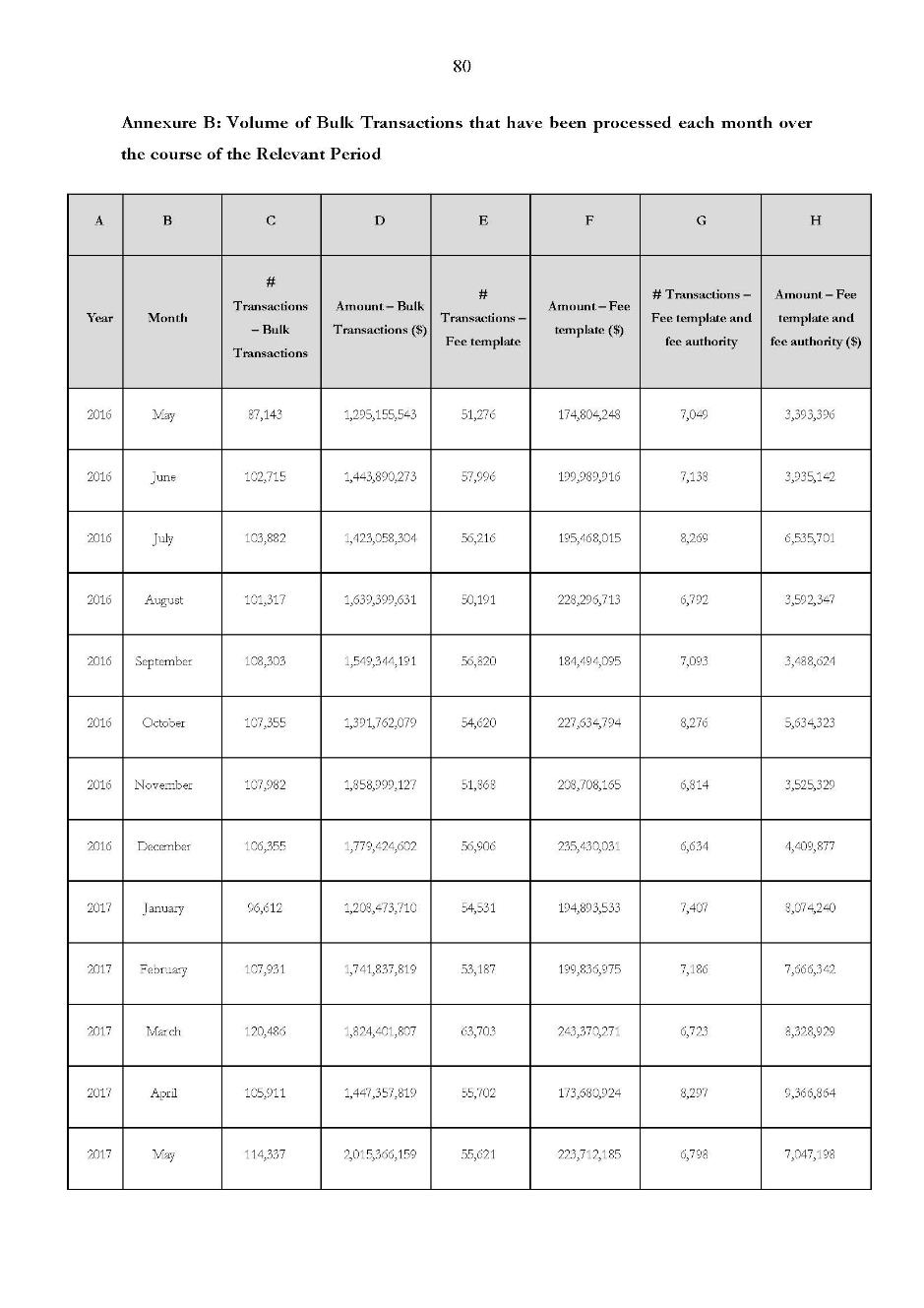

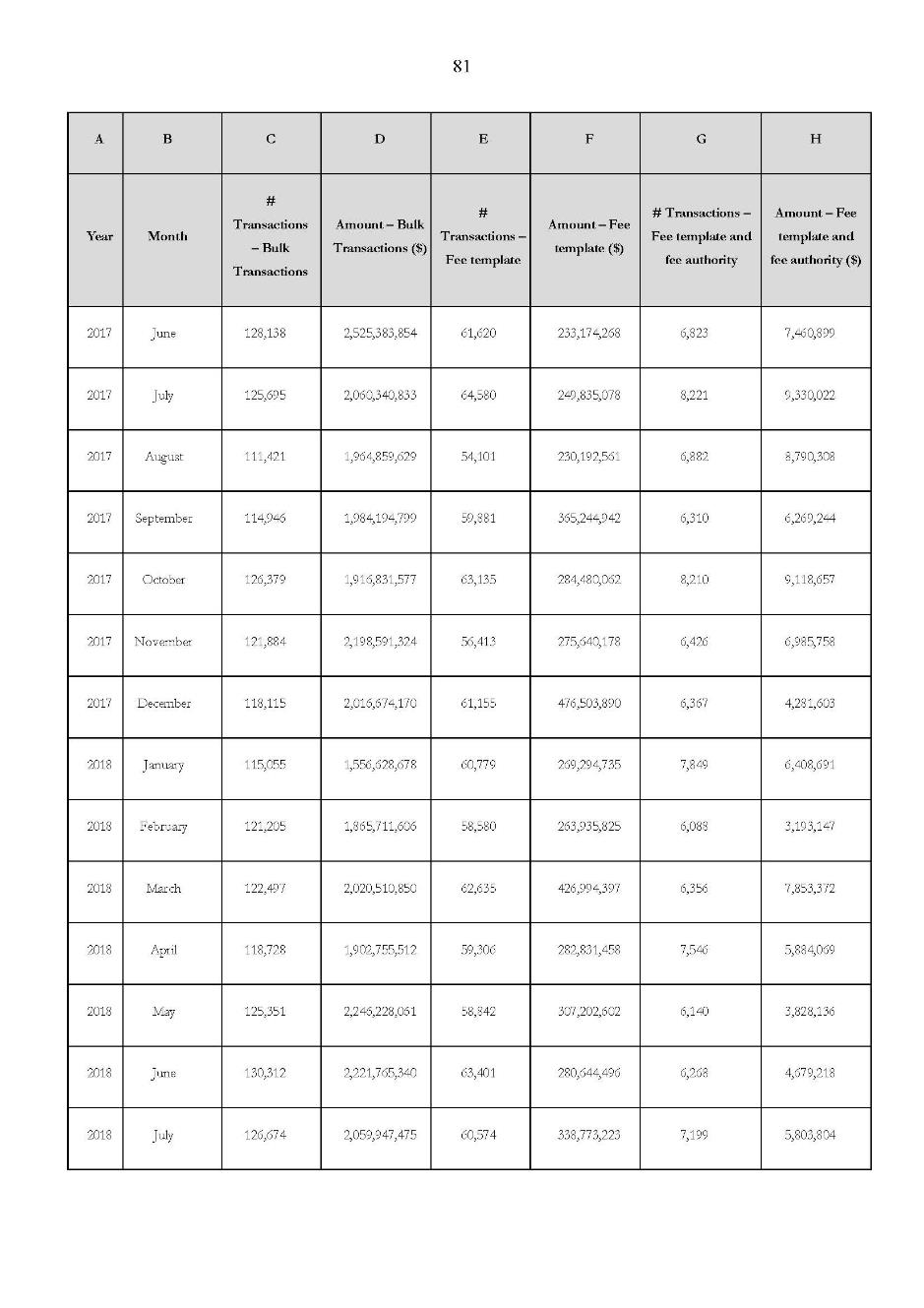

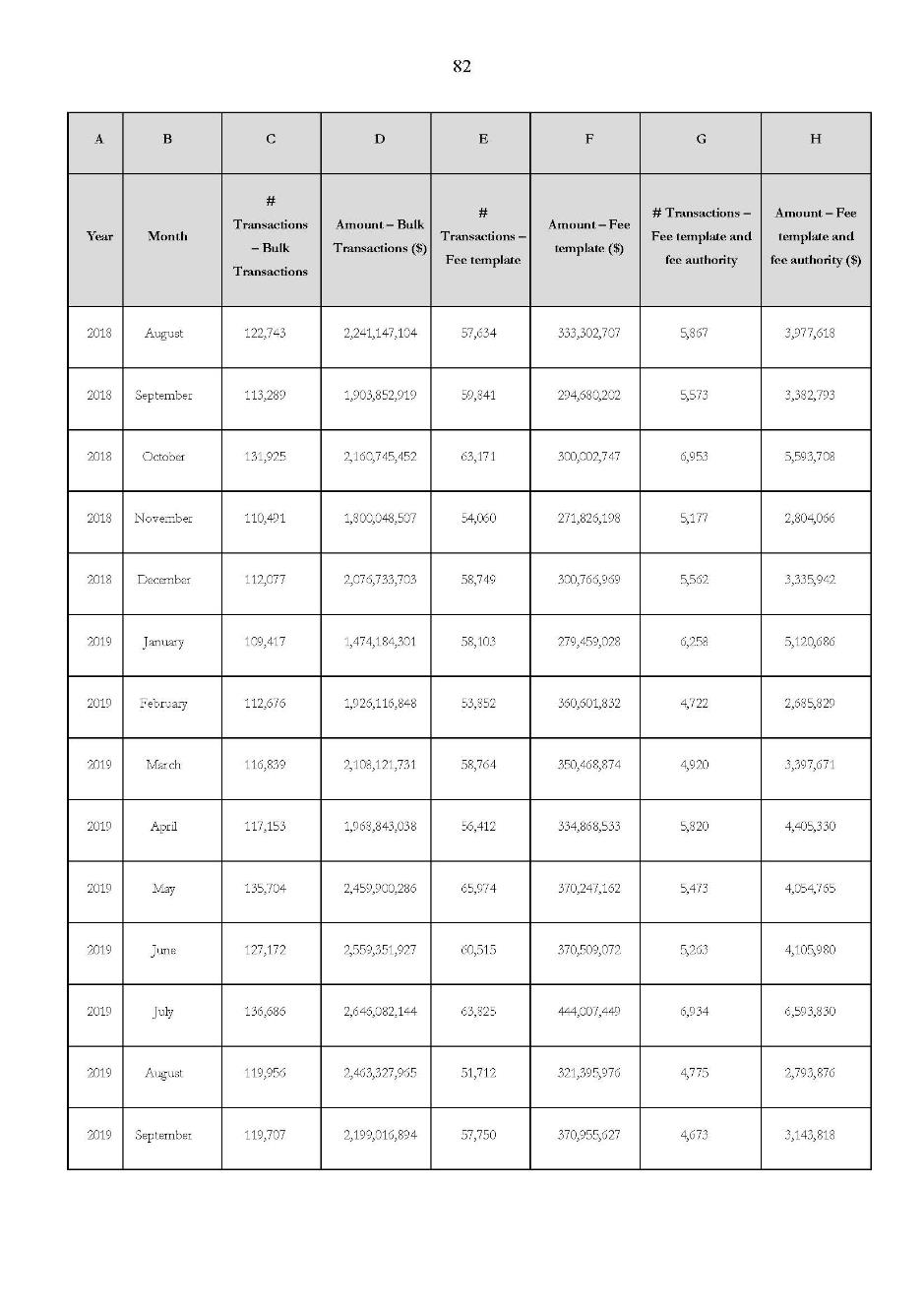

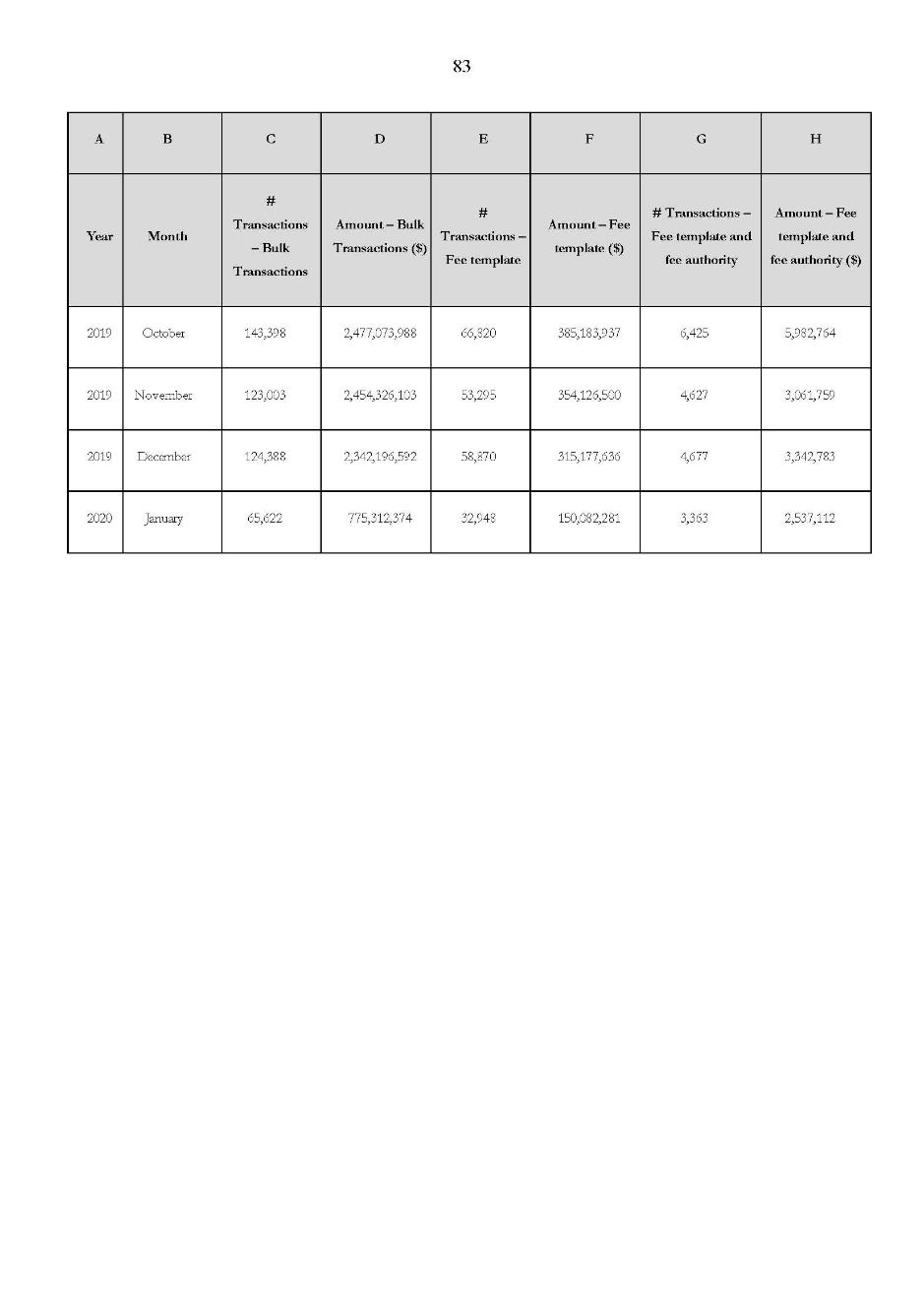

32 Some additional facts should be highlighted to provide appropriate context. As at August 2017, over half a million customers held a Macquarie CMA and over $26 billion was under management or on deposit in respect of CMA products. CMA customers mostly had external financial advisers and were long term customers of Macquarie. The monthly volume of transactions using the fee payments template during the relevant period ranged from about $174 million to about $477 million.

33 Macquarie admitted that between 1 May 2016 and 12 March 2019, it failed to do all things necessary to ensure that the financial services covered by its financial services licence were provided efficiently, honestly, and fairly, as a result of it not implementing effective controls to prevent or detect transactions conducted by third parties through its bulk transacting system that were outside the scope of the authority conferred on them that only permitted them to withdraw their fees from their clients’ CMAs, such as the fraudulent transactions made by Mr Hopkins.

34 Macquarie similarly admitted that between 13 March 2019 and 15 January 2020, it failed to do all things necessary to ensure that the financial services covered by its financial services licence were provided efficiently, honestly, and fairly, as a result of it not implementing effective controls to prevent or detect transactions conducted by third parties through its bulk transacting system that were outside the scope of the authority conferred on them that only permitted them to withdraw their fees from their clients’ CMAs, such as the fraudulent transactions made by Mr Hopkins.

35 The reason for the separate admissions by Macquarie and ASIC’s application for separate declarations in respect of those two periods was explained earlier.

ADDITIONAL FACTS RELEVANT TO PENALTY

36 The Statement of Agreed Facts and Admissions also includes the following facts which were said to be relevant to the assessment of the appropriate pecuniary penalty.

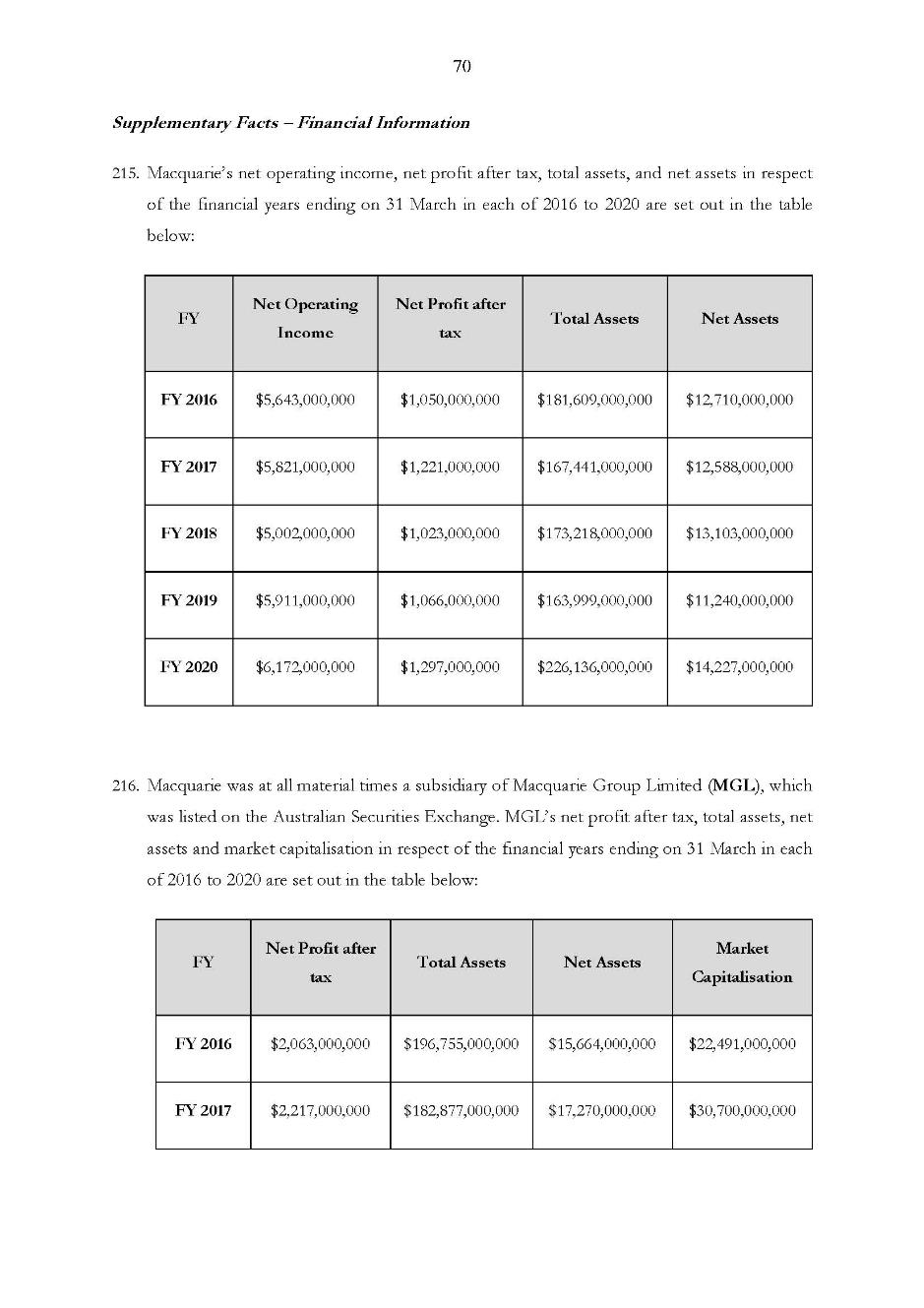

37 Macquarie was, and is, a very large and profitable company. For the 2016 to 2020 financial years, Macquarie’s net operating income ranged between about $5 billion and about $6.2 billion, its net profit after tax ranged between about $1 billion and $1.3 billion, its total assets ranged between about $164 billion and $226 billion and its net assets ranged between $11.2 billion and $14.2 billion.

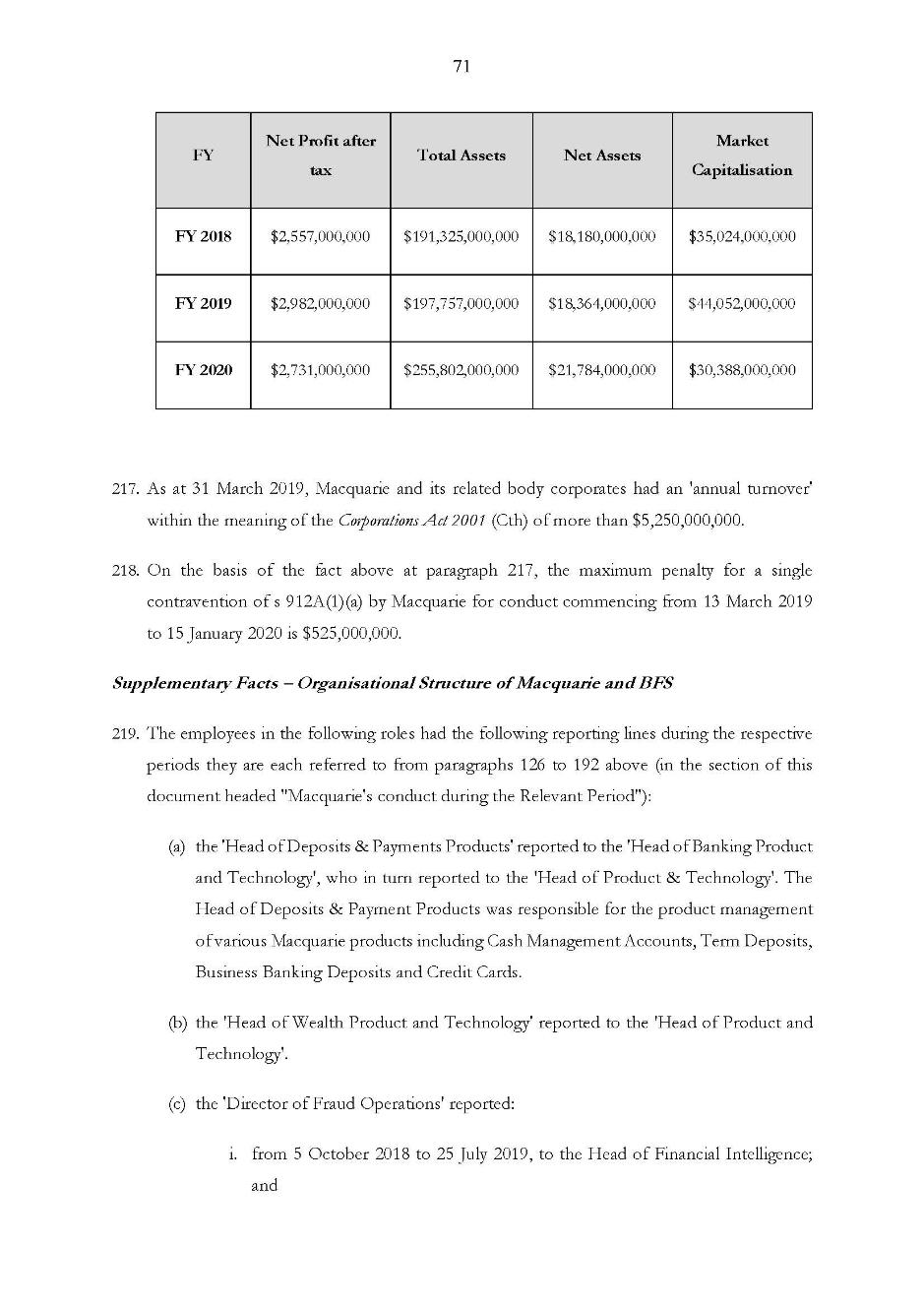

38 Macquarie was, and is, a subsidiary of Macquarie Group Limited, a public company listed on the Australian Stock Exchange. For the 2016 to 2020 financial years, Macquarie Group’s market capitalisation ranged between $22.5 billion and $44 billion.

39 As at 31 March 2019, Macquarie and its related bodies corporate had an 'annual turnover' within the meaning of the Corporations Act of more than $5,250,000,000. That fact is particularly relevant as it provides the basis for the calculation of the maximum pecuniary penalty for Macquarie’s contravention of s 912A(1)(a) referrable to the period from 13 March 2019 to 15 January 2020.

40 The Statement of Agreed Facts and Admissions contains details of the seniority and reporting lines of the Macquarie employees who were aware that Macquarie’s monitoring and control of bulk transacting concerning fees during the relevant period was deficient. It suffices for present purposes to note that those employees were quite senior. They reported up two or three reporting lines to the chief executive officer of Macquarie Group. There was, however, no evidence to suggest that Macquarie’s directors at the time were aware of the facts giving rise to the contravention.

41 Macquarie has not previously been found by any court to have contravened s 912A of the Corporations Act, and no court has previously made any declaration that Macquarie has contravened a civil penalty provision under the Corporations Act or made any order that Macquarie pay a penalty in respect of such a contravention.

42 On 23 August 2016, the Supreme Court of New South Wales found that Macquarie Investment Management Limited had contravened ss 601FC(1)(b) and 601FC(5) of the Corporations Act. At that time, Macquarie Investment Management was a subsidiary of both Macquarie Group and Macquarie.

43 ASIC commenced its investigation into Macquarie regarding its CMAs and the conduct of Mr Hopkins on about 22 September 2020. The investigation concluded when ASIC commenced this proceeding in April 2022. During the investigation, Macquarie engaged openly and transparently with ASIC, engaged in voluntary meetings with ASIC, and provided information about the availability and structure of data that could be provided to ASIC in respect of the investigation.

44 Since the commencement of this proceeding, Macquarie: agreed to a statement of agreed facts for use in the proceeding if it proceeded to a contested hearing; responded promptly to requests by ASIC for clarification and the production of documents in connection to this proceeding; and attended a mediation and ultimately admitted liability in this proceeding. Macquarie also participated in the process resulting in the Agreed Statement of Facts and Admissions and joint written submissions.

RELEVANT PRINCIPLES

45 The principles which are relevant to determine the issues before the Court were not in issue and need only be addressed in short terms.

Section 912A(1)(a) of the Corporations Act

46 The standard created by the words “efficiently, honestly and fairly” in s 912A(1)(a) of the Corporations Act has been considered in a number of cases, including: Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Camelot Derivatives Pty Ltd (in liq) (2012) 88 ACSR 206; [2012] FCA 414 at [69]-[70]; Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Cassimatis (No 8) (2016) 336 ALR 209; [2016] FCA 1023 at [674]; Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Avestra Asset Management Ltd (in liq) (2017) 348 ALR 525; [2017] FCA 497 at [191]; Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Westpac Securities Administration Ltd (2019) 373 ALR 455; [2019] FCAFC 187; Australian Securities and Investments Commission v National Australia Bank Limited (2022) 164 ACSR 358; [2022] FCA 1324; and Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Commonwealth Bank of Australia [2022] FCA 1422.

47 Different views have been expressed as to whether “efficiently, honestly and fairly” comprises a single compendious standard or imposes three concurrent obligations. It is unnecessary to decide that issue in this case. Macquarie has admitted that it failed to meet the standard in any event. It is also somewhat difficult to see how or why it would make any practical difference if there was a single compendious standard, as opposed to three concurrent standards or obligations. It is also doubtful that there is any real utility in exploring in the abstract the meaning of what are otherwise ordinary words, the meaning of which is generally well understood. Nevertheless, the following useful principles emerge from some of the authorities.

48 First, the standard of honesty is to be considered having regard to commercial norms and morality, as opposed to the broader societal norms that generally inform the meaning of the standard of honesty in the criminal law. A licensee may fail to meet the standard of honesty even though its conduct could not be said to be criminally dishonest.

49 Second, a licensee may breach or fail to comply with the obligation created by s 912A(1)(a) even if it has not breached any separate legal duty or obligation under the Corporations Act or otherwise.

50 Third, the standard, or standards, imposed by s 912A(1)(a) do not require absolute perfection by the licensee in providing financial services.

51 Fourth, the use of the word “ensure” tends to indicate that compliance with the obligation created by s 912A(1)(a) involves or requires a degree of forward looking and may require the licensee to take steps to prevent future lapses or failures.

Declarations of contraventions

52 As noted earlier, s 1317E(1) provides that if a Court is satisfied that a person has contravened a civil penalty provision, it must make a declaration of contravention. It is nevertheless useful to briefly consider the general principles that apply in respect of the making of declarations.

53 The Court has a wide discretionary power to make declarations under s 21 of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth).

54 Before making a declaration, even by consent, the Court must be satisfied that: first, the proceeding involves a real controversy, as opposed to hypothetical or theoretical question; second, that the applicant has a real interest in raising the controversy or question; and third that there is a proper contradictor: Forster v Jododex Australia Pty Ltd (1972) 127 CLR 421 at 437-438; [1972] HCA 61.

55 The fact that a respondent who has a real interest in opposing the declaration nevertheless consents to the making of the declaration does not mean that there is no contradictor: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v MSY Technology Pty Ltd (2012) 201 FCR 378; [2012] FCAFC 56 at [30]-[33].

56 Where the declaration concerns a contravention of a civil penalty provision, the Court must be satisfied that the respondent contravened that provision, even if the respondent consents to the making of the declaration. The material that provides the basis for the Court’s satisfaction can be a statement of agreed facts and admissions: Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Rich (2004) ACSR 500; [2004] NSWSC 836 at [15].

57 Declarations relating to contraventions of legislative provisions are likely to be appropriate where they serve to record the Court’s disapproval of the contravening conduct, vindicate a regulator’s claim that the respondent contravened the provisions, assist a regulator to carry out its duties, and deter other persons from contravening the provisions: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union (2007) ATPR 42-140; [2006] FCA 1730 at [6] (and the cases cited therein).

58 The Court must be satisfied that a proposed declaration of contravention identifies the conduct that constituted the contravention or the gist of the findings that amounted to the contravention: Rural Press Limited v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2003) 216 CLR 53; [2003] HCA 75 at [89].

Agreed penalties

59 The principles that the Court must apply in considering whether to impose an agreed pecuniary penalty jointly proposed by the parties were explained in Commonwealth v Director, Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate (2015) 258 CLR 482; [2015] HCA 46 (Agreed Penalties Case).

60 In short summary, the Court must consider and determine whether the agreed penalty is within the range of possible penalties that the Court could reasonably impose in all the circumstances. If the agreed penalty is within that range, the public policy of promoting the predictability of outcomes in civil penalty proceedings makes it highly desirable for the Court to accept the parties’ joint proposal and impose the agreed penalty. The court is nevertheless not bound by the parties’ agreement in respect of the size of the penalty.

Pecuniary penalties generally

61 In considering and determining whether the agreed penalty falls within the range of appropriate penalties in the circumstances, it is necessary to have regard to the applicable principles concerning the fixing of pecuniary penalties. Those principles are also settled. They were recently considered in Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Pattinson (2022) 274 CLR 450; [2022] HCA 13.

62 In short summary, the purpose of imposing a civil penalty is to promote the public interest in compliance with the relevant Act by the deterrence of further contraventions of a like kind. The Court must, in effect, attempt to put a price on contravention that is sufficiently high to deter repetition by the contravener and by others who might be tempted to contravene. The penalty must not be one which would be regarded by the contravener or others as an acceptable cost of doing business. The penalty must not, however, be greater than is necessary to achieve the object of deterrence. An appropriate penalty is said to be one that strikes an appropriate balance between oppressive severity and the need for deterrence in the particular case.

63 In determining the size of the penalty which would serve the objective of deterrence, the Court must have regard to both the circumstances of the contravener and the circumstances of the contravention.

64 Without intending to be exhaustive, the factors concerning the circumstances of the contravener which are generally relevant when determining the size of the penalty which would serve the objective of deterrence, where the contravener is a corporation, include: the size and financial position of the corporation; whether the corporation has a corporate culture conducive to compliance with the relevant Act; whether the contravener has engaged in similar conduct in the past; and whether the contravener has demonstrated contrition and co-operated with the relevant authorities.

65 Likewise, without intending to be exhaustive, the factors concerning the circumstances of the contravention which are generally relevant to determining the size of the penalty which would serve the objective of deterrence include: whether the contravening conduct was systematic, deliberate or covert; the period over which the contravening conduct occurred; whether the contravention arose out of the conduct of senior management; whether the contravener profited from the contravention and if so the extent of that profit; and whether the contravention caused any loss or injury.

66 It should be emphasised that both the factors relating to the circumstances of the contravener, and those relating to the circumstances of the contravention, are only relevant to the extent that they bear on the question of the size of the penalty that is necessary to achieve the objective of deterrence. The purpose of imposing a pecuniary penalty does not include retribution or punishment. The pecuniary penalty need not be proportionate to the nature and circumstances of the contravention, at least in the sense that the principle of proportionality is understood in the criminal law.

67 The maximum penalty is also a relevant consideration in determining the size of the penalty, though it does not constrain the exercise of the discretion beyond requiring some reasonable relationship between the theoretical maximum and the final penalty imposed. The maximum penalty would generally only be appropriate in the case of a contravention which warranted the strongest deterrence.

DECLARATION OF CONTRAVENTION BY MACQUARIE

68 As has already been noted, Macquarie admitted that its conduct between 1 May 2016 and 15 January 2020 in failing to implement effective controls to prevent or detect conduct by third parties through its bulk transacting system that were outside the scope of the authority conferred on them in respect of fees contravened s 912A(1)(a) of the Corporations Act. I am also satisfied, having regard to the principles referred to earlier, that the agreed facts establish that Macquarie contravened s 912A(1)(a) of the Corporations Act during the relevant period.

69 While there was, in effect, a single contravention arising from the conduct throughout the relevant period, as explained earlier, ASIC sought two declarations because the amendments to the Corporations Act only made s 912A(1)(a) a civil penalty provision on, and from, 13 March 2019.

70 In light of Macquarie’s admissions, it is unnecessary to provide detailed reasons for finding that the agreed facts establish Macquarie’s contravention. It suffices to refer to the following key points that emerge from the agreed facts.

71 First, by allowing and facilitating its CMA customers to authorise third parties to deduct their fees from their CMA, and then enabling the third parties to utilise the bulk transacting system or facility, Macquarie effectively exposed their customers to the risk that the third parties might conduct fraudulent transactions outside the terms of their authorities.

72 Second, Macquarie was no doubt aware of that risk during the relevant period. Specifically, it was aware that third parties who had been granted authorities in respect of their fees might misuse those authorities when using the bulk transacting system or facility. Indeed, it was aware that third party intermediaries, including Mr Hopkins, had so misused their authorities.

73 Third, in those circumstances, in order to ensure that it provided its financial services efficiently, honestly, and fairly, it was incumbent on Macquarie to have, or to put in place, effective controls to prevent or detect transactions conducted by third parties which were outside the scope of their limited authorities. While Macquarie put in place some controls, such as the alerts, those controls were plainly deficient or inadequate. In the case of the alerts, they were not systematically reviewed.

74 Fourth, there were no effective or insurmountable barriers which prevented or excused Macquarie from putting effective controls in place. Nor was Macquarie’s conduct adequately explained or its failures absolved by factors such as the high volume of bulk transactions.

75 As for the making of the declarations sought by ASIC, I am satisfied that the proceeding involves a real controversy, that ASIC had, and has, a real interest in raising the controversy, and that Macquarie was an appropriate and effective contradictor in all the circumstances. I am also satisfied that the declarations are appropriate as they serve to record the Court’s disapproval of Macquarie’s contravening conduct, vindicate ASIC’s claim that Macquarie contravened the provisions, and will operate to deter other persons from contravening s 912A(1)(a) in a similar or comparable way. Needless to say, I am also satisfied that Macquarie contravened s 912A(1)(a) in the manner referred to in the declarations.

76 As for the form of the declarations, I am satisfied that the agreed terms of the declarations are appropriate. They adequately identify the conduct that constituted the contravention.

77 In all the circumstances, it is appropriate for the Court to make the declarations sought by ASIC and agreed to by Macquarie.

THE PECUNIARY PENALTY TO BE PAID BY MACQUARIE

78 I am persuaded that the agreed penalty of $10,000,000 is an appropriate penalty in all the circumstances, in the sense that I consider that is within the range of possible penalties that the Court could reasonably impose in all the circumstances of the case. I do not suggest that I would necessarily have imposed that precise penalty had I not been confronted with the parties’ agreement and joint submissions, though that is essentially beside the point. I am nevertheless satisfied that it is appropriate to make the agreed penalty order for the purposes identified in the Agreed Penalties Case.

79 The main factors relevant to the assessment of an appropriate penalty in this case may be summarised as follows.

80 First, there could be little doubt that the contravention in respect of which the pecuniary penalty is to be imposed was a serious contravention of s 912A(1)(a) of the Corporations Act. It occurred over a 10-month period, though it must, to an extent, be considered in the context of the earlier contravening conduct, being the conduct which occurred before 13 March 2019. The contravention involved quite senior employees of Macquarie, being those employees who had become aware of the inadequacies and deficiencies of the controls that Macquarie had in place and who, it may be inferred, failed to take, or cause others to take, the necessary and appropriate steps to ensure that the inadequacies and deficiencies were appropriately addressed. As a result of the contravening conduct, Macquarie’s CMA clients who had granted fee authorities to third parties were at risk of fraudulent activity on their accounts. The contravening conduct in fact resulted in losses to CMA clients as a result of Mr Hopkins’s conduct totalling at least $2,938,750, $701,500 of which occurred on or after 13 March 2019.

81 Second, there are nevertheless some features of the contravening conduct that moderate the seriousness of the contraventions. The contravening conduct was not in any relevant sense deliberate or even reckless. Rather, the contravention was the product of a degree of neglect, laxity or inaction on the part of certain employees of Macquarie. The deficiencies and inadequacy of the existing controls in respect of bulk transacting was known to, and recognised by, Macquarie, as was the risk to CMA clients who had granted fee authorities, but not enough was done to address the inadequacies and deficiencies, or eliminate the risks to CMA clients. Macquarie received no direct financial benefit from the contravening conduct, though it could perhaps be said that it avoided, or at least deferred, the cost that was most likely involved in remedying the inadequate controls.

82 Third, the seriousness of the offending conduct does not itself necessarily compel or require the imposition of a very large penalty. As discussed earlier, the purpose for which a pecuniary penalty is imposed is to deter, not to punish. There is no retributive purpose in imposing a pecuniary penalty. Nor is it necessary for the penalty to be proportionate to the seriousness of the offence in the same way that, for example, a criminal sanction must “fit the crime”. The features of the contravening conduct that render it a serious contravention are only relevant in assessing the size of the penalty if they suggest that, in light of those features, a larger penalty is required to achieve the purpose of deterrence, both specific and general. In this case, despite the seriousness of the contravening conduct, the fact that the contravention was not deliberate or reckless, let alone contumelious, would tend to suggest that an especially large penalty is not required to achieve specific deterrence.

83 Fourth, there are some factors relating to Macquarie’s circumstances that also bear directly on the size of the penalty that is necessary to appropriately secure specific deterrence. Macquarie has not previously been found to have been involved in any contraventions of civil penalty provisions in the Corporations Act or been found to have engaged in any conduct similar to the contravening conduct involved in this matter. It is certainly not a recidivist or recalcitrant contravener. While there is no evidence of any clear or direct expression of contrition or remorse on Macquarie’s behalf, nevertheless some degree of contrition can be inferred from the fact that Macquarie ultimately admitted its contravention. It also cooperated, to an extent, with ASIC’s investigation and displayed a willingness to facilitate the course of justice by making admissions and joining in the Agreed Statement of Facts and Admissions and joint submissions.

84 Fifth, Macquarie is a very large and very profitable corporation. If, as has been said to be the case, the court must fix a penalty which puts a price on the contravention that is sufficiently high to deter repetition, the size and financial capacity of Macquarie would tend to suggest that anything other than a very large penalty would have little or no deterrent effect in respect of Macquarie itself. A penalty that might be seen as very being large and as having a significant deterrent effect by many corporations would be likely to be considered to be piffling to Macquarie having regard to its size and financial resources. That said, it would plainly be wrong to impose a very large penalty on Macquarie in respect of this contravention simply because it is a large and profitable corporation.

85 Sixth, in fixing an appropriate penalty in the case of a contravention like the one the subject of this case, the Court must not lose sight of the importance of general deterrence. The reality is that many financial services licensees are, like Macquarie, large and profitable corporations. If the Court imposes penalties for contraventions of s 912A(1)(a) of the Corporations Act, or similar provisions, which are likely to be seen by financial services licensees generally as being modest or insignificant, they will have little effect in deterring others from engaging in similar conduct.

86 Seventh, while it is necessary to have some regard to the very large maximum penalty for Macquarie’s contravention, the maximum penalty is only one of many relevant considerations. In this case, it is of quite limited relevance. A penalty approaching the maximum penalty in this case would only be appropriate if the circumstances of Macquarie’s contravening conduct, and the circumstances pertaining to Macquarie itself, suggested that the strongest possible deterrence was warranted. I do not consider that the circumstances of this case are such that anything like the strongest possible deterrence is warranted.

87 Eighth, it is relevant, and of some significance, that ASIC has agreed that $10,000,000 is an appropriate penalty in all the circumstances. As a specialist regulator, ASIC may be taken to have some insight and expertise in assessing the level of penalty that might appropriately secure deterrence, both specific and general, in the circumstances of the case: Agreed Penalties Case at [60]-[61]. That said, the joint submissions must be assessed on their merits, and the Court must be wary of the possibility that the agreed penalty may be the product of the regulator having been too pragmatic in reaching the settlement: Agreed Penalties Case at [61], [110]; Volkswagen Aktiengesellschaft v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2021) 284 FCR 24; [2021] FCAFC 49 at [129]. There is, however, nothing to suggest that ASIC took an overly pragmatic approach in this matter when it reached an agreement with Macquarie in respect of the size of the pecuniary penalty.

88 Ninth, the Court’s attention has been drawn to the penalties that have been imposed in some other cases involving contraventions of s 912A(1)(a) of the Corporations Act, in particular: Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Westpac Banking Corporation (Omnibus) (2022) 407 ALR 1; [2022] FCA 515; Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Mercer Financial Advice (Australia) Pty Ltd [2023] FCA 1453; Australian Securities and Investments Commission v RI Advice Group Pty Ltd (2022) 160 ACSR 204; [2022] FCA 496. The parties correctly conceded, however, that those cases are of limited assistance when it comes to the fixing of the appropriate penalty in this case. It is consistency in the application of the relevant legal principles that is important, not consistency in numerical outcome: McDonald v Australian Building and Construction Commissioner (2011) 202 IR 467; [2011] FCAFC 29 at [23]-[25], referring to Hili v The Queen (2010) 242 CLR 520; [2010] HCA 45 at [48]. Each case must be considered having regard to its own unique facts and circumstances. The outcome in other cases is of even less assistance where the penalties imposed in them were agreed penalties. That is because the most that could be said in those circumstances is that the penalties imposed by the Court were within the range of penalties that the Court could reasonably impose in the circumstances of those cases.

89 Nevertheless, nothing in the previous cases involving the imposition of penalties for contraventions of s 912A(1)(a) of the Corporations Act would suggest that the agreed penalty in this case is outside the range of penalties that the Court could reasonably impose.

90 In all the circumstances, I accept that a pecuniary penalty of $10,000,000 is an appropriate penalty in the sense that it is likely to serve the objective of deterrence and cannot be said to be greater than is necessary to achieve that objective.

DISPOSITION

91 The Court will make the declarations sought by ASIC and agreed by Macquarie in respect of Macquarie’s contraventions of s 912A(1)(a) of the Corporations Act.

92 Macquarie will be ordered to pay a pecuniary penalty of $10,000,000 in respect of its contravention of s 912A(1)(a) of the Corporations Act that occurred on and after 13 March 2019.

93 The parties also agreed that Macquarie should be ordered to pay ASIC’s costs of the proceeding as agreed or assessed.

94 Finally, the parties applied for a suppression order in respect of a document annexed to the Agreed Statement of Facts and Admissions (Confidential Annexure A), as well as some parts of the Statement of Agreed Facts and Admissions that, like Confidential Annexure A, reveal the content of fraud monitoring rules that Macquarie put in place after the relevant period. I am satisfied that a suppression order should be made in respect of that document on the basis that it is necessary to prevent prejudice to the proper administration of justice. Plainly the content of any fraud monitoring rules put in place by Macquarie should remain confidential, otherwise unscrupulous persons could endeavour to work out ways to circumvent those rules. The precise terms of the suppression order have not yet been settled. That order will accordingly be made at a later date.

I certify that the preceding ninety-four (94) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice Wigney. |

Associate:

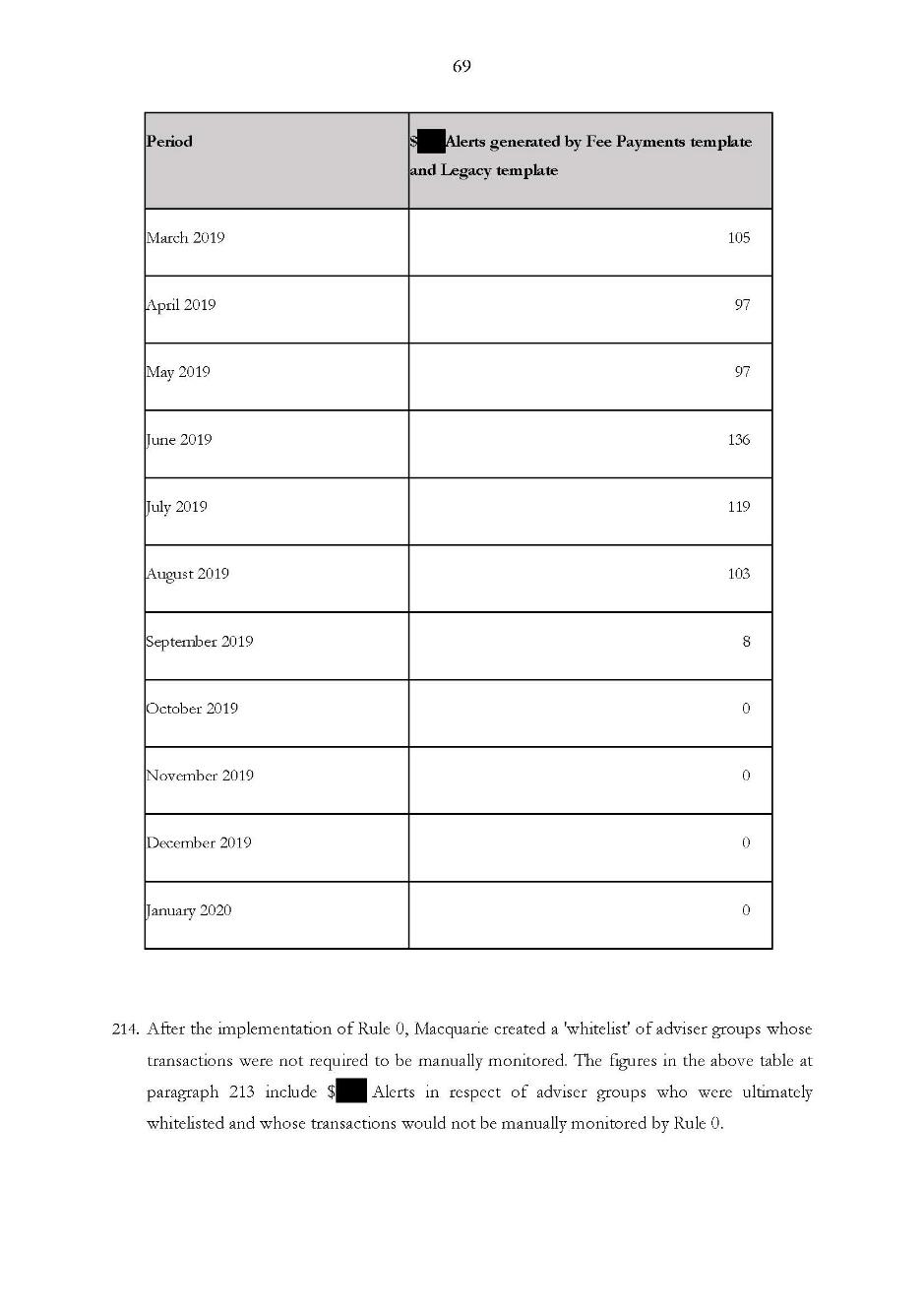

ANNEXURE A – STATEMENT OF AGREED FACTS AND ADMISSIONS