FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Fitzgerald, in the matter of Tempo Holidays Pty Ltd (in liq) v Tully [2024] FCA 391

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The proceeding is dismissed.

2. Any application for costs is to be made in writing, with supporting submissions not exceeding 3 pages, within 14 days of the publication of these reasons and any such application if made is to be responded to within 14 days thereafter limited to a submission not exceeding 3 pages.

3. Subject to any further order of the Court, the question of costs will be determined on the papers.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

MCELWAINE J:

1 Tempo Holidays Pty Ltd (in liquidation) was part of the international corporate travel Group known as Cox & Kings which traced its origins to 1758 when Richard Cox was appointed as a military agent. In more recent times, the ultimate holding company for the worldwide Group was Cox & Kings Ltd, a company registered in and listed on the National Stock Exchange of India. It was considered as the longest established travel brand in the world. Cox & Kings became insolvent and, with effect from 22 October 2019, subject to external administration pursuant to the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016 (India). The trademarks and intellectual property were subsequently sold.

2 Tempo was incorporated on 8 December 1989. It carried on business as a wholesaler of travel agency services. Cox & Kings acquired the shares in Tempo in November 2008. Mr Ajay Ajit Peter Kerkar was the CEO of Cox & Kings, based in the United Kingdom. He is also the brother-in-law of Mr Patrick Tully. In late 2008, Mr Kerkar approached Mr Tully and requested that he accept appointment as a director of Tempo. Mr Tully agreed and was appointed as a director on 7 November 2008, which office he held until 19 August 2019, when he resigned. Mr Kerkar was also appointed as a director of Tempo on 7 November 2008. He did not resign prior to its liquidation. Between 7 November 2008 and 18 May 2012, Mr Khalid Mahmood Malik was also a director of Tempo. For present purposes it is significant that Mr Tully was the only Australian based director of Tempo during the period of the events relevant to this proceeding.

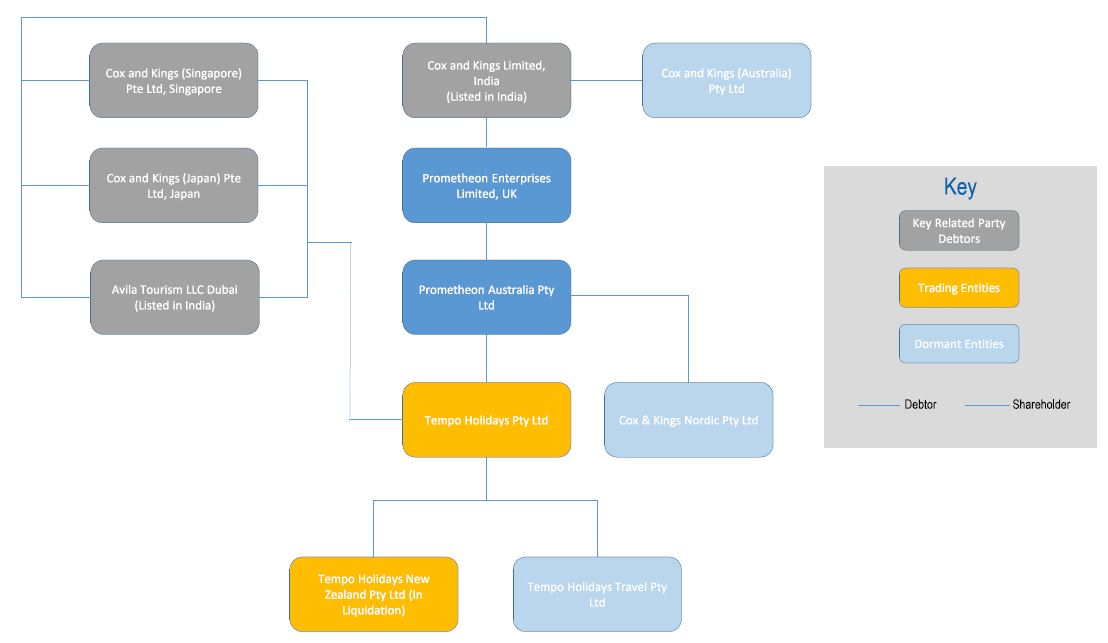

3 The Group corporate structure was:

4 It will be noticed that Tempo was a direct subsidiary of Prometheon Australia Pty Ltd (Prometheon AU) of which Mr Tully was also a director between 5 October 2015 and 19 August 2019. Mr Kerkar was a director of Prometheon AU for a brief period in October 2015. Another key player in this proceeding, Mr Sudarshan Madan was also a director of Prometheon AU between 8 October 2015 and 1 July 2019. Mr Madan, a resident of Melbourne, was the CFO of Tempo.

5 Mr Laurence Andrew Fitzgerald was appointed as voluntary administrator of Tempo on 20 September 2019, and subsequently as liquidator on 28 October 2019. Mr Fitzgerald as the first plaintiff and Tempo as the second, initially (on 10 December 2021), commenced this proceeding only against Mr Tully for compensation for breach of Mr Tully’s duties as a director and for his liability for debts incurred during the period of Tempo’s insolvency. Later, on 5 April 2022, Berkley Insurance Company, (which is a registered foreign company) was joined as the second defendant. Tempo was named as one of the companies, and was therefore an insured, pursuant to a Management Liability Insurance Policy for the period from 4 pm on 31 March 2019 to 4 pm on 31 March 2020. The Policy definition of Insured Person included any director of Tempo. In these reasons I follow the nomenclature of the Policy that capital letters are employed for terms defined in the Policy.

6 Broadly, Mr Fitzgerald formulated two claims against Mr Tully. One, that he breached his statutory and fiduciary duties as a director by failing to monitor the inter-group transfer of funds by Tempo pursuant to an informal debtor/creditor arrangement, known as the Global Treasury Arrangement (GTA). Amounts totalling $5,862,429, in five instalments, were paid to Group companies between 16 April and 19 June 2019 (I note that all figures in this judgment are in Australian Dollars unless indicated otherwise). The debt was unsecured and became unrecoverable. If, as alleged, Mr Tully had monitored the GTA, the plaintiffs contend that he failed to take steps to prevent the first and each subsequent payment. Had he done so Tempo would not have suffered damage equivalent to the amounts paid. I refer to this as the breach of director’s duty claim.

7 The other, that he is liable for the consequences of insolvent trading by Tempo from 31 March 2019, for third party creditor debts of $26,069,536.90 and for failing to take steps to prevent Tempo from incurring each liability pursuant to s 588M of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth). I refer to this as the insolvent trading claim.

8 Berkley declined to indemnify Mr Tully for the breach of director’s duty claim, which Mr Fitzgerald did not accept, which explains its joinder on application of the plaintiffs to claim declaratory relief to the effect that Berkley is liable to indemnify Mr Tully pursuant to the Policy: cf CGU Insurance Limited v Blakeley [2016] HCA 2; 259 CLR 339. It is not in issue that Berkley has no obligation to indemnify Mr Tully for the insolvent trading claim.

9 Shortly prior to commencement of the trial, the plaintiffs settled the proceeding against Mr Tully in the terms of a Settlement Deed dated 11 December 2023. Mr Tully consented to judgment in the amount of $5,862,429 on the breach of director’s duty claim and in the amount of $24,223,940.89 on the insolvent trading claim, each inclusive of interest and costs. Judgment was accordingly entered on 21 December 2023, following approval of the settlement pursuant to s 477(2B) of the Corporations Act. The effect of the Settlement Deed is that, despite Mr Tully’s liability pursuant to the judgment, in consideration of the payment of $500,000 (Security Sum) by instalments, the plaintiffs agree to enforce the judgment first against any proceeds recovered pursuant to the Policy, and once exhausted only against the Security Sum.

10 In consequence of the settlement reached with Mr Tully, the plaintiffs contend that Berkley is liable to indemnify Mr Tully for the full amount of the breach of director’s duty claim on two bases. First, that the settlement is a reasonable compromise of the claim, for which Mr Tully is entitled to be indemnified: Unity Insurance Brokers Pty Ltd v Rocco Pezzano Pty Ltd [1998] HCA 38; 192 CLR 603.

11 Second, in any event by proving the breach of director’s duty claim for which Berkley is liable to indemnify Mr Tully as a Claim for a Wrongful Act within the indemnity at cl 1.1 of the Policy: Enterprise Oil Ltd v Strand Insurance Co Ltd [2006] 1 Lloyd’s Rep 500 at [167]-[173] (Aikens J).

12 The pleadings raised multiple issues for determination, roving across a court book of almost 6,000 pages, mostly peripheral to the real questions for determination. By way of example, hundreds of pages are consumed by invoices and travel confirmations. None of this material was directly referred to: it was unnecessary to do so because of the synthesised analyses in the accounting expert reports. Fortunately, by the point of closing addresses, counsel agreed a list of 14 issues for determination and very considerably culled the relevant documents in the form of the joint tender list. It is very frequently the case that this Court receives excessively lengthy electronic court books, packed with every conceivable document that has been generated by or exchanged between the parties to a dispute, rapidly compiled and indexed at the click of a mouse. Proper attention to the overarching purpose at ss 37M and 37N of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth), at the time of preparation of the court book for trial, should have resulted in a work of much less volume and thus greater utility from the outset. Solicitors by training and experience are well skilled to sift and evaluate material to isolate the documents that are centrally relevant to the real issues in dispute. Adherence to the core goal of efficiency as required by the overarching purpose is readily achieved by reference to the design philosophy usually attributed to the notable German architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe: Less is More.

13 There are in my view three determinative issues in this case: (1) whether a claim was made within the Policy period; (2) if so, have the plaintiffs established a claim for loss within the meaning of the Policy, of which there are two sub-parts: was the settlement reached with Mr Tully reasonable or, if not, whether in any event, have the plaintiffs proven the breach of director’s duty claim; and (3) if so, has Berkley succeeded in proving breach of the duty of disclosure at s 21 of the Insurance Contracts Act 1984 (Cth) (IC Act) with the result that it is entitled to reduce its liability to nil.

14 For the reasons that follow, I have concluded that the plaintiffs succeed on issue (1) but fail on issue (2) with the consequence that the proceeding must be dismissed. Although that conclusion makes it unnecessary to decide issue (3), it is one that occupied considerable time in the evidence and submissions, and it is desirable that I determine it as well. I find that there was a breach of the duty of disclosure and that Berkley would otherwise have been entitled to reduce its liability to nil.

15 The parties agreed certain facts and all relevant documents. There are areas of factual dispute largely concerning whether Mr Tully breached his director’s duties, what facts were known to Tempo to engage the duty of disclosure and whether Berkley would not have written the Policy if certain information had been disclosed. There is also a large dispute about the date when Tempo became insolvent about which I have the benefit of expert evidence from Mr Fitzgerald and Mr Damien Beven together with their joint expert report. My findings comprise a mixture of agreed and determined facts based on resolving conflicts in the evidence. Where I refer to evidence without critical analysis, I find according to it.

THE COX & KINGS GROUP

16 As noted, Cox & Kings was the ultimate holding company of the Group. It was a very substantial corporation. In the annual report for 2017-2018 (the reporting period for each financial year was to 31 March) it reported total transactions to a value of USD2.3 billion, more than 6,000 employees and an enterprise value of approximately USD1.2 billion. Net revenue, expressed in lakhs increased from INR41,872 in 2014 to INR73,370 in 2018. A lakh is a unit of measurement in the Indian system of numbering equal to 100,000. Thus, for the purposes of comparison, as Mr Fitzgerald explained, a rough conversion rate is $2,000 for INR1 lakh, which results in a net revenue figure for the 2018 year of approximately $146 million.

17 The group accounts were audited. In the 2018 year (as expressed in lakhs), the consolidated group profit before tax was INR69,138, non-current assets were INR487,330, net debt was INR234,369, long term debt was INR228,584, short-term debt was INR162,110 and net assets INR10,76,994. Separately, the holding company reported revenue of INR274,193 and profit before tax of INR28,001. The audit report dated 28 May 2018 certifies that having completed the audit task, the auditor was satisfied that he had a reasonable basis to conclude that Cox & Kings had during the audit period, prima facie complied with a number of statutory provisions relevant to the conduct of the business and had in place “proper Board-processes and compliance mechanisms”.

18 Staying with the 2018 annual report, the Group chair was Mr ABM Good, who was first appointed to the board in 1971. He has substantial experience in corporate management. There were five other directors, including Mr Kerkar for whom this summary was provided:

Mr. Peter Kerkar has been intimately involved in the growth of the C & K Group and was responsible for its transformation from a business travel and shipping and forwarding agency to one of the leading leisure players in the industry. He is the driving force behind the Company’s initiatives in the geographies in which it operates today. He is based in the UK and is responsible for the Company’s overall leadership, strategy, global centralised buying and international growth. In this role, he has been actively involved in the identification of new opportunities. Under his leadership, the Company is now positioned as the premier travel company in India as well as a brand leader in the premium market segment in the UK, US and Japan. He is a graduate in Arts (B.A.) with distinction in Economics and Anthropology from Stanford University, US.

19 Within the directors’ report to the shareholders, signed by Mr Good on 28 May 2018, the following statements are made, amongst many others:

There have been no material changes and commitments affecting the financial position of the Company between the end of the financial year and the date of this report. There has been no change in the nature of the business of the Company.

…

In FY 2017–18, we focused on growth and managed to grow all our businesses faster than in FY 2016–2017 in constant currency terms. This is testament to our resilience which is achieved by being dynamic and adaptive to changes. Brexit continued to pose a challenge to our UK operations while India business saw receivables increase due to the confusion emanating from the implementation of Goods and Services Tax (GST).

In this backdrop, Cox & Kings’ consolidated net revenues grew by 9.9% yoy in FY 2017–18 more than double the growth of 4.4% in FY 2016–17 as nearly all businesses kept up the momentum.

…

Credit analysis & Research Ltd (CARE), the Rating Agency, has reaffirmed and enhanced the Commercial Paper issue carved out of sanctioned working capital limit of the company… The Rating has been reaffirmed as CARE A1+ (A One Plus). Instruments with this rating indicate very strong capacity for timely payment of financial obligations and carry lowest credit risk.

[The directors state that]:

(a) In the preparation of the annual accounts, the applicable accounting standards had been followed along with proper explanation relating to material departures;

(b) The directors had selected such accounting policies and applied them consistently and made judgments and estimates that are reasonable and prudent so as to give a true and fair view of the state of affairs of the Company at the end of the financial year and of the profit and loss of the Company for that period;

(c) The directors had taken proper and sufficient care for the maintenance of adequate accounting records in accordance with the provisions of [Companies Act 2013 (India)] for safeguarding the assets of the Company and for preventing and detecting fraud and other irregularities;

(d) The directors had prepared the annual accounts on a going concern basis; and

(e) The directors, had laid down internal financial controls to be followed by the Company and that such internal financial controls are adequate and were operating effectively.

(f) The directors had devised proper systems to ensure compliance with the provisions of all applicable laws and that such systems were adequate and operating effectively.

…

The Company has in place Internal Financial Control system, commensurate with size & complexity of its operations to ensure proper recording of financial and operational information & compliance of various internal controls & other regulatory & statutory compliances. During the year under review, no material or serious observation has been received from the Internal Auditors of the Company for inefficiency or inadequacy of such controls.

20 The consolidated Group accounts for 2019 were tangentially adduced into evidence as an attachment to email correspondence from Mr Anil Khandelwal of 9 July 2019. Those accounts are incomplete. They comprise accounts for Cox and Kings as a standalone entity (revenue, expenses, profit, and a balance sheet) and a consolidated balance sheet only for the Group. These accounts were not addressed in submissions and there are some material differences between amounts in those accounts and the summary of the Group accounts that Mr Fitzgerald sets out in his expert report. No questions were asked about the differences. Mr Fitzgerald’s report was admitted into evidence without objection. Having not received assistance about the missing Group revenue accounts, I proceed by reference to the summary of Mr Fitzgerald. Expressed in lakhs revenue was INR578,598, expenses INR543,580, net profit INR35,018, current assets INR654,939, non-current assets INR272,402, total assets INR 927,341, total liabilities INR454,117 and net equity INR473,224.

21 In the concurrent expert evidence given by Mr Fitzgerald and Mr Beven, each accepted that the Group accounts for 2018 and 2019 presented a “healthy financial position” (balance sheet and financial performance) which plainly was the case for any person concerned to understand the Group financial position in those years.

22 As I have noted, Cox & Kings was placed into external administration on 22 October 2019. There is in evidence a statement of unaudited standalone financial accounts for the company to 31 March 2020 which records (in lakhs) total revenue of INR78,756, total expenses of INR174,478, exceptional items (INR939,880) a loss of (INR1,035,602) and negative equity of (INR729,312). Further, cash on hand declined to INR2,666, current assets declined to INR29,547 and current liabilities (borrowings) increased from INR170,440 in 2019 to INR553,216 in 2020.

23 The cause of the financial collapse of the Cox & Kings Group was not specifically addressed in evidence. Insight, however, may be gleaned from the following. On 19 July 2019, an officer of the Ministry of Corporate Affairs of India sent correspondence to Cox & Kings. Default in the payment of certain fees was noted and, upon the author’s examination of filed financial statements and “and other relevant documents”, 22 questions were put to the company. Information was required about secured and unsecured loans, trade debtors and creditors, details of the largest 20 lenders, with particulars of the loans payable on the terms of each loan, together with an explanation of why the “company’s cash flow from operations continues to remain negative”. The author required the correspondence to be treated “as most urgent” and that the response was required to be verified by affidavit.

24 If there was a response, it is not in evidence. However, on 12 August 2019, Cox & Kings advised the National Stock Exchange of India that 70% of its lenders had signed an inter-creditor agreement with the State Bank of India, the effect of which was to obtain a “standstill for 180 days” to enable the company to implement a resolution plan acceptable to its lenders. The substance of that arrangement is set out in a minute of meeting held between Cox & Kings and its lenders on 20 August 2019. The purpose of the “standstill” was to “assist the company in its monetisation/equity raise plan in the next 180 days” to enable it to pay its debts and “transact as normal”. A lender, Stellite Finance Ltd was clearly not a party to that arrangement because on 21 August 2019, it issued a notice of default to one of the Group companies and demanded repayment of its debt in full.

25 Another lender, Rattan India Finance Pvt Ltd commenced a proceeding against Cox & Kings in the National Company Law Tribunal at Mumbai based on default in the repayment of loan agreements entered into in May and June 2019. The Tribunal upheld the complaint and made orders for initiation of the corporate insolvency resolution process under the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016 (India).

The GTA

26 Whilst the Group operated as a viable entity, each member utilised an informal arrangement known as the GTA. The parties agree the following facts about it:

(1) Companies within the Group, including Tempo, paid funds to Cox & Kings (Singapore) or other entities in the Group from time to time at the request of Cox & Kings;

(2) there was no monetary limit on the funds paid by Tempo to Cox & Kings (Singapore);

(3) the funds paid by Tempo to Cox & Kings (Singapore) or other entities in the Group, net of the funds paid by Cox & Kings (Singapore) or other entities in the Group back to Tempo, were accounted for as a receivable in the accounts of Tempo;

(4) there was no documentation providing a contractual right of repayment of the funds paid under the GTA;

(5) the funds paid under the GTA were unsecured; and

(6) if Tempo needed funds to be repaid from the GTA it would request a repayment from Cox & Kings.

27 Dr Bigos KC for the plaintiffs does not contend impropriety in the fact that Tempo participated in the GTA. It is common ground that arrangements of that type are implemented in global businesses for the purpose of regulating cash flow within groups. In the global travel industry, there is a high and low season. For Tempo in the Southern hemisphere the high season in each year was March to September (corresponding with the warmer months in the Northern hemisphere) and the low season ran from October to February.

28 Mr Tully gave uncontradicted evidence, which I accept, that Tempo participated in the GTA to alleviate seasonal cash flow pressure, which is an inherent risk in the travel industry. The arrangement was beneficial to Tempo on many occasions and provided Mr Tully with comfort in the knowledge that Tempo would always be able to access funds from the GTA in order to address short-term difficulties with cash flow. Mr Madan as CFO was responsible for managing the finances of Tempo and with it, participation in the GTA. The GTA was in place well before Mr Tully accepted appointment as a director of Tempo. He stated that although he was not directly involved in the management of seasonal cash flows, nonetheless it made sense to him for Tempo to participate in the GTA.

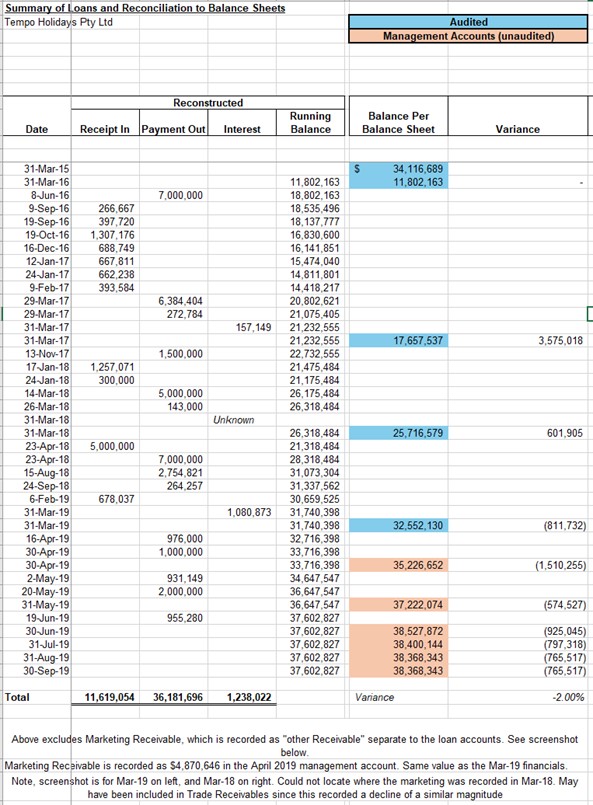

29 Each of Mr Fitzgerald and Mr Beven accepted that arrangements of this type were orthodox within global businesses, particularly those engaged in the travel industry. They differed in their views as to when Tempo could no longer rely upon receiving funds pursuant to the GTA. Mr Beven undertook a forensic analysis of the available historic accounts of Tempo and produced a spreadsheet, which in evidence was referred to as his aide memoire. It records the ebb and flow of cash as:

30 What this discloses is that substantial receivables were owing to Tempo throughout the period from March 2015 and, despite the receipt of substantial monies sometimes in amounts up to $7 million, the total indebtedness grew substantially over time. The benefits received were substantially outweighed by the amounts paid. Despite that fact, the plaintiffs do not contend that Tempo should have ceased participation in the GTA before April 2019. On their case until 31 March 2019, there remained a prospect that the total debt, then exceeding $32 million, would at least be reduced by the receipt of further payments. That contention is expressed succinctly in the plaintiffs’ written outline of closing submissions at [135] as follows:

Tully’s breaches of duties were to allow substantial payments to be made under the Global Treasury Arrangement without monitoring or considering recoverability, in circumstances where there was some doubt as to the recoverability of the loans (for the first 4 payments), and the 5th payment was irrecoverable (because C&K India had gone into a standstill so it was unable to repay Tempo Holidays). The breaches occurred between 16 April and 19 June 2019. They did not occur earlier, because at earlier points in time when payments were made under the Global Treasury Arrangement (the most recent previous payment was in September 2018), there was no doubt as to the recoverability of the loans.

(Footnote omitted.)

31 I return to this contention in more detail in these reasons as it is fundamental to the plaintiffs’ case.

32 The difference in the opinions of Mr Fitzgerald and Mr Beven were drawn into sharp focus in their joint expert report. Mr Fitzgerald’s evidence is that:

[T]he operation of the [GTA] is not an uncommon process in large multinational groups. The Company’s audited reports as at 31 March 2018 and 31 March 2019 disclose a healthy financial position of the Company and the Group. The Loan Accounts, although increasing during this period, did not affect the trading and performance of the Company. Mr Fitzgerald agrees that the future solvency of the Company was reliant on repayment of the Loan Accounts, however in Mr Fitzgerald’s opinion the Company was able to rely on the [GTA] until 7 June 2019.

33 The reference to 7 June 2019 is to the agreed fact that Cox & Kings signed an inter-creditor agreement with 70% of its lenders on that day. However, when one looks more carefully at the documentary evidence what becomes clear is that 7 June 2019 is the day on which Cox & Kings issued a circular with the heading: “Prudential Framework for Resolution of Stressed Assets” which stated to the effect that an inter-creditor agreement was intended to be entered into with 75% by value, or 60% by number, of its lenders. The primary lender, the State Bank of India, did not resolve to enter into that agreement until 15 July 2019. These facts are recorded in the decision of the Tribunal published on 22 October 2019 at paragraph [11]. The inter-creditor agreement is not in evidence. If that difference had been noticed earlier, it may well have been material to the expert opinions of Mr Fitzgerald and Mr Beven, each of whom was instructed to proceed by reference to the date of 7 June 2019. However, as this matter was not explored at the trial, I consider that I should proceed by reference to the erroneous date that is recorded in the statement of agreed facts.

34 In contrast, the evidence of Mr Beven in the joint expert report is:

[T]here was mounting reason to suspect the loan accounts were not recoverable from May 2018. Mr Beven considers that escalating levels of debt to related parties over multiple periods with little or no repayments is an indicator that a business has poor cash management, lack of strategic direction and inadequate collection protocols. Mr Beven understands that the purpose of the [GTA] was to alleviate seasonal cash flow pressures. However, requests for funding during the Company’s low season in 2018 went answered, and as a result, it is Mr Beven’s opinion the [GTA] was not working how it was intended and the Company did not enjoy the benefits of being a member of this arrangement. In Mr Beven’s view, as the recoverability of the related party loans grew uncertain from May 2018, it is likely that the Company became insolvent around this time.

35 Later in these reasons I return to the insolvency question in detail. What emerges from this evidence, and the contention that Mr Tully did not breach his director’s duties before 31 March 2019, is that the plaintiffs have not established an evidentiary basis to support several of their pleaded contentions that Mr Tully breached his duties as a director relating to the GTA by:

(1) allowing Tempo to participate in the GTA;

(2) allowing Tempo to make payments to group companies under the GTA without contractual documentation providing full repayment and on an unsecured basis; and

(3) failing to prevent Tempo from making payments to group companies under the GTA, without contractual documentation providing full repayment, and on an unsecured basis.

36 In the preceding paragraph the first proposition is common ground between the experts. On the second and third, the plaintiffs’ submissions and Mr Fitzgerald’s evidence dates the failures at some time between 31 March and 16 April 2019. On Mr Beven’s evidence the date is from May 2018. This exposes a difficulty with the plaintiffs’ pleaded case in that these allegations are not tied to a point in time. As such, they cannot be reconciled with the evidence and for that reason accepted.

37 Additionally and to the contrary, on this evidence I find that there was nothing unusual, improper or inappropriate in permitting Tempo to participate in the GTA. The arrangement was of benefit to Tempo, its participation was a necessary incident of being a member of the Group, and there was no requirement for the terms of the arrangement to be documented or for security to be provided in relation to advances. Indeed, the latter contention of the plaintiffs fails to grapple with the obvious question of mutual security as between Tempo and each Group company, or perhaps more specifically Cox & Kings (Singapore) for all inter-company advances. What is plain is that Cox & Kings determined the terms and operational requirements of the GTA, and the plaintiffs have failed to lead any evidence to the effect that Mr Tully, as one of the directors of Tempo as a Group subsidiary was able to decide that Tempo would not participate in the GTA or only do so on terms other than those determined by Cox & Kings from time to time.

The financial position of Tempo

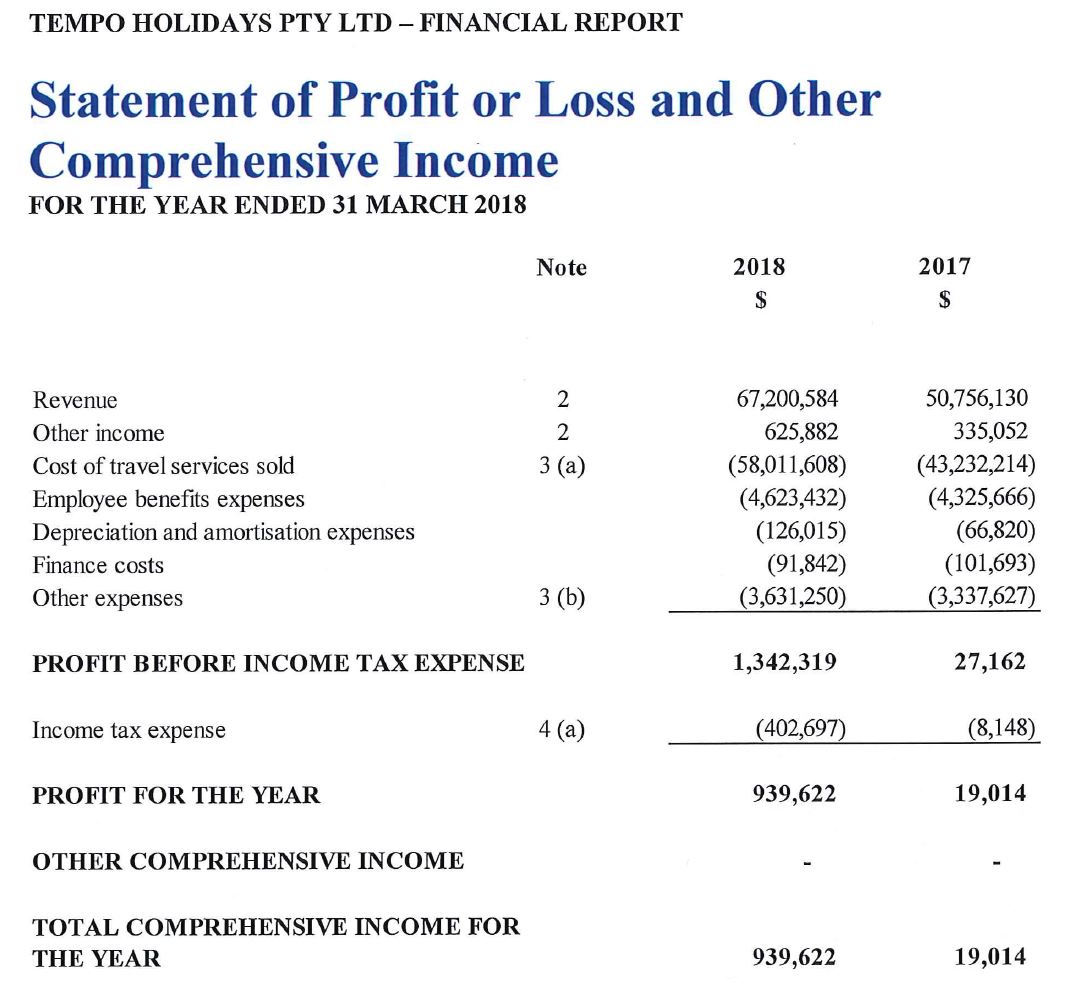

38 As a director, Mr Tully was responsible for reviewing and approving the annual externally audited accounts of Tempo. The audit firm was RSM Australia Partners. The auditor in 2018 and 2019 was Mr P Sexton. At trial considerable attention was paid to the accounts to 31 March 2018 which Mr Tully signed on 17 May 2018. As is customary, the accounts provide a comparison with the results for the 2017 year.

39 The profit and loss statement provides:

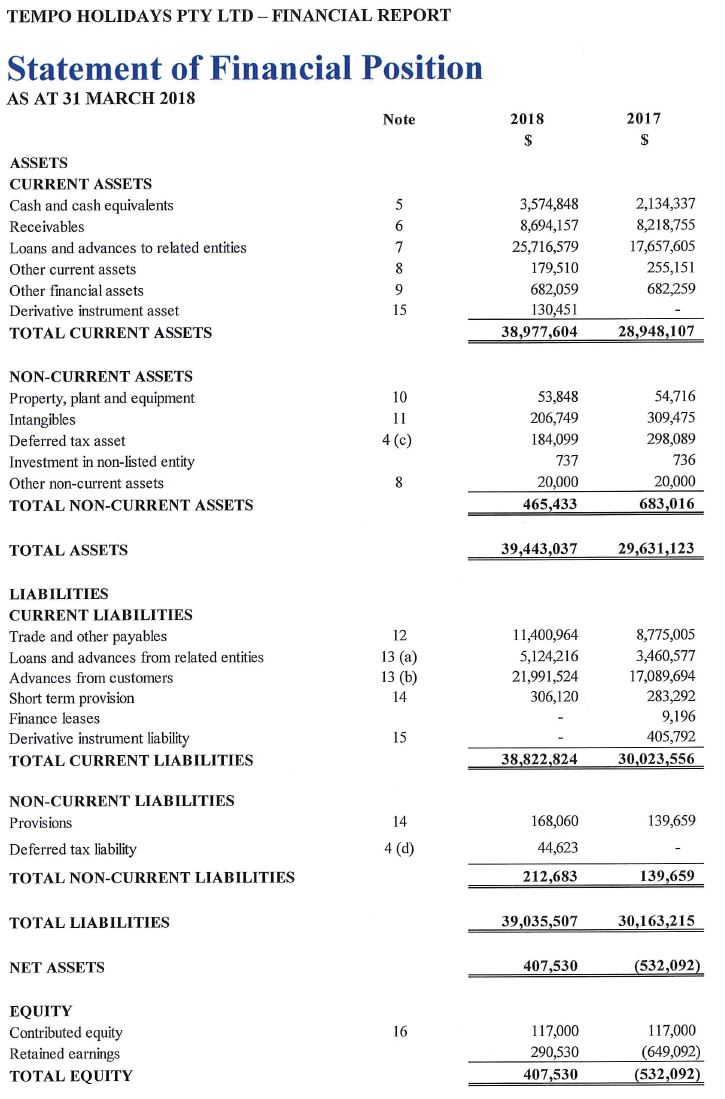

40 Note (2) records the most substantial source of revenue is the sale of travel services in the amount of $66,298,617 for the 2018 year, an increase from $50,454,779 in the 2017 year. The statement of financial position provides:

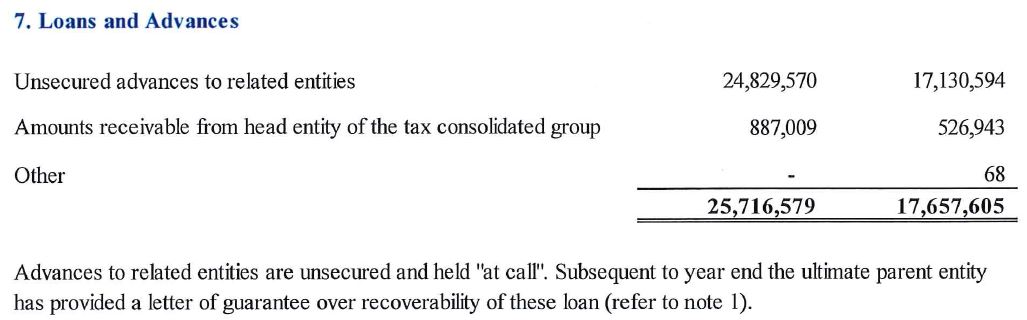

41 Several of the notes require elaboration. Note (5) records cash at bank in the amount of $3,521,625, an increase from $1,419,885 in the 2017 year. Note (6) is concerned with trade receivables, including advances to suppliers. The total of $8,694,157 includes a marketing contribution receivable from Prometheon Enterprise Ltd, UK (Prometheon UK) in the amount of $4,840,183. Note (7) provides:

42 The cross reference to note (1) includes subparagraph (e) which provides:

Trade receivables are carried at amounts due, less provision for impairment of receivables. Receivables from related parties are recognised and carried at the nominal amount due.

Collectability of trade receivables is reviewed on an ongoing basis. Debts which are known to be uncollectable are written off. A provision for impairment of receivables is established when there is objective evidence that the company will not be able to collect all amounts due according to the original terms of receivables.

43 Note (12) states that the amount of $11,400,964 comprised trade creditor amounts of $10,196,897, an increase from $7,855,314 in the 2017 year and the balance being accrued employee entitlements and sundry amounts payable, including accrued expenses. Note (13)(a) simply states that the $5,116,024 is an unsecured advance from related entities, an increase from the previous year of $3,460,577.

44 In signing the audited accounts Mr Tully declared, on behalf of the directors, their joint opinion that the accounts complied with relevant accounting standards and “give a true and fair view of the company’s financial position as at 31 March 2017 [sic] and of its performance for the year ended on that date in accordance with the accounting policies described in Note 1 to the financial statements” and that “there are reasonable grounds to believe that the company will be able to pay its debts as and when they become due and payable”. No point was taken at the trial about the obvious error in the date in the statement made by Mr Tully.

45 Relatedly, Mr Sexton in his audit report dated 17 May 2018, recorded his independence, the fact of the audit, his opinion that the accounts give a true and fair view of the financial position on 31 March 2018, and comply with the relevant Australian accounting standards. Amongst other things, Mr Sexton stated:

The directors of the Company are responsible for the preparation of the financial report that gives a true and fair view and have determined that the basis of preparation described in Note 1 to the financial report is appropriate to meet the requirements of the Corporations Act 2001 and is appropriate to meet the needs of the members. The directors’ responsibility also includes such internal control as the directors determine is necessary to enable the preparation of the financial report that gives a true and fair view and is free from material misstatement, whether due to fraud or error.

In preparing the financial report, the directors are responsible for assessing the ability of the Company to continue as a going concern, disclosing, as applicable, matters related to going concern and using the going concern basis of accounting unless the directors either intend to liquidate the Company or to cease operations, or have no realistic alternative but to do so.

…

Our objectives are to obtain reasonable assurance about whether the financial report as a whole is free from material misstatement, whether due to fraud or error, and to issue an auditor's report that includes our opinion. Reasonable assurance is a high level of assurance, but is not a guarantee that an audit conducted in accordance with the Australian Auditing Standards will always detect a material misstatement when it exists. Misstatements can arise from fraud or error and are considered material if, individually or in the aggregate, they could reasonably be expected to influence the economic decisions of users taken on the basis of this financial report.

46 A matter of significance in this proceeding is that the plaintiffs do not contend that there was a material error or omission in the 2018 accounts of Tempo. To 31 March 2019, their case is that there remained a realistic prospect that the accumulated debt of almost $32 million would be repaid and the GTA would continue to function.

47 Mr Tully did not give direct evidence as to how he came to make the declarations in support of the 2018 accounts in his affidavit made on 10 February 2023, although he does for the corresponding declarations in the 2019 accounts. In his oral evidence he was questioned in general terms about his investigations, if any, which caused him to be satisfied that it was appropriate to approve the 2018 figures. He said that it was not his responsibility to engage or deal with the auditors, as this was attended to by Mr Madan. He confirmed that he read the financial accounts before signing the declaration. He confirmed his understanding that the trading position had significantly improved, in terms of net profit, from the 2017 financial year. He understood that the assets of Tempo included as a receivable amount payable to it pursuant to the GTA. He was aware that Cox & Kings had provided an assurance to the auditors in the form of a letter of support for its subsidiaries, which he considered to be a form of guarantee. Overall, he relied upon the audited accounts as being accurate and he did not make independent enquiries as to the information contained therein.

48 By 2019, there is indirect evidence that the auditor was concerned about the recoverability of the inter-company advances made by Tempo pursuant to the GTA and other related amounts receivable. Mr Madan sent an email to head office on 26 March 2019, stating that he had met earlier in the day with the audit signing partner who had raised the following issues, and on which Mr Madan sought clarification (the solecisms are not corrected):

1. Marketing contribution of USD 3.710 mill outstanding since 2013 -14. We cant show it any more in receivables. It needs to be either moved to related party with a separate interest-bearing loan arrangement and a classification as “non-current assets” OR to write off. The write off will attract the deemed dividend provisioning and taxation thereof. Please let us know how you want to proceed on this?

2. Goodwill: we need to have a policy to write-off of goodwill is treating the same for perpetuity is not acceptable principle.

3. Intercompany funding: they are uncomfortable on the situation as the receivable from related parties has grown in a big way with one sided movement with no return in sight and questioning the recoverability of the same. Looking for justification and HO stand on the same.

4. Revenue split: till now we are showing gross revenue is a single line item. Going forward need to show revenue split on some criteria and need guidance from HO on “basis to split”.

5. Time lines for getting final go ahead on the figures AND signed financials. Not clear on dates as UK office is asking for 15th April, UK auditor is asking for mid-May.

49 Two responses are relevant to this proceeding. On 26 March 2019, Mr Khandelwal from Cox & Kings responded. He questioned whether the marketing contribution could be written off and sought clarification as to the quantum of the intercompany loans at 2018 when compared with 2019. Mr Madan promptly responded that writing off the marketing contribution (again without corrections):

[I]s not possible as it will bring [Tempo] in negative net worth, making It as insolvent entity resulting in all sort of legal and compliance. In couple of years’ time, it may be possible if Tempo makes sufficient profit and accumulate reserve. Hence the option is to move the same and the related entities section and create loan documentation and charge interest on the same.

50 In response to the question about the inter-company loans, Mr Madan went no further than providing advice as to the figures.

51 On 24 April 2019, Prometheon UK sent correspondence to the auditor concerning the marketing contribution and stated:

We hereby confirm that an amount of USD 3,710,000 is payable to Tempo Holidays Pty Ltd Australia on account of Share of Supplier Overrides and Other Support Contributions pertains to financial year 2013 -14.

We further confirm that we are OK to classify this amount as “Non-current Other Receivables” which is/will be adjusted against the various services CNK UK and/or CNK India will provide to Tempo Holidays in the past as well as going forward.

52 Despite the cryptic nature of that correspondence, it must have satisfied this query raised by the auditor because the marketing contribution is disclosed as “other receivable” in the amount of $4,890,646 from Prometheon UK at note (8) to the audited accounts for the 2019 year.

53 As to the amount receivable by Tempo pursuant to the GTA, Prometheon UK, in separate correspondence to the auditor dated 11 April 2019, stated:

This letter’s purpose is to confirm that Cox & Kings Limited (an Indian public company) will continue to provide ongoing financial support to its subsidiaries listed below (in so far, they trade with one another):

…

Cox & Kings Limited will ensure that there is a provision of funds sufficient to meet the working capital requirements for a period of not less than twelve (12) months from the date the directors approve the financial report of Cox & Kings (Australia) Pty Ltd., Prometheon Australia Pty Ltd & controlled entities consolidated financial statements and the date from which each individual company’s domestic financial statements are adopted.

We also confirm that should any company within the wholly owned group of Cox & Kings Limited not be able to meet the inter-entity trading loans or payable commitments with another wholly owned subsidiary, we will provide sufficient resources to fund the financial commitment on that subsidiary’s behalf or arrange alternative settlement means so not to financially disadvantage the said entity to the detriment of all other creditors of the Group subsidiaries listed above.

54 The list of subsidiaries included Tempo. Thereafter, the audited accounts of Tempo for the 2019 year, which Mr Tully signed on 24 June 2019, recorded the quantum of the inter-company indebtedness as a current asset and with the qualification at note (7) in the same terms as that note to the accounts for 2018. Similar letters of comfort had been provided to the auditors on 26 April 2016, 18 April 2017 and 5 April 2018.

55 Mr Tully did give direct evidence in his affidavit as to the steps that he took in satisfying himself that it was appropriate to make the declarations contained in the 2019 accounts. He was aware that the auditors had been paid $40,000 for their services and assumed that the audit had been thorough and comprehensive and undertaken in accordance with appropriate professional standards. He noted the opinion of the auditors, to the effect that the accounts disclosed a true and fair view of the financial position of Tempo as at 31 March 2019. He noted that total revenue was approximately $75 million, an increase of approximately $8 million from the previous financial year. In his view this was the largest amount of revenue ever recorded in the trading history of Tempo, for the period that he had been a director. He noted that Tempo had traded profitably and had derived a net operating profit after tax of $3,110,742. Similarly, he noted that this was the largest profit ever recorded by Tempo during his tenure as a director. He specifically noted that this was the second consecutive year of profitable trading by Tempo, that it had net assets of $3,518,272 and had significant cash reserves exceeding $4 million.

56 Mr Tully formed the view that the growth in revenue and profits was consistent with the information provided to him by Mr Madan in the weekly sales reports and his general opinion that the travel industry was experiencing significant growth.

57 Mr Tully was aware that there was a significant loan to related entities exceeding $32 million. He was also aware that the loans were guaranteed by the parent company, were at call and were unsecured. These matters did not concern him. Why is revealed in this statement:

I had assumed that Tempo’s auditors had been in contact directly with the related entities and/or the auditors of the related entities in respect to these loans and would have made notes on the audited financial accounts 2019 if there were any increased risks or difficulties had arisen in accessing these funds should they be required by Tempo.

In the absence of any such notes or advices from any other person I did not see any reason to make any enquiries or investigations in addition to what had already been undertaken by the auditors. In any event I did not have the skills or expertise to conduct such investigations or access to the relevant information of the related entities.

I had been a director of Tempo for over a decade at the time I signed the 2019 audited financial accounts and I had become aware that the amount of loans between related entities would always fluctuate. It was my understanding that the whole function of the [GTA] was to alleviate seasonal cash flow pressures inherent in the travel industry by sharing funds amongst members of the Cox & Kings Group which were subject to different high and low seasons due to their different geographic locations. The [GTA] had been a benefit to Tempo on many occasions and it was comforting for me to know that Tempo would always have access to the benefits of the [GTA] in the future.

58 This affidavit was tendered in evidence by Berkley. The plaintiffs separately tendered a transcript of the public examination of Mr Tully conducted on 4 March 2021 pursuant to s 596A of the Corporations Act. Mr Tully stated that he was not aware at the time of the query raised by the auditors in March 2019 about recoverability of the inter-company loans. Specifically, Mr Madan did not draw the relevant correspondence to his attention and the auditors did not otherwise make it known to him. Otherwise, Mr Tully did not give evidence during his examination inconsistent with his affidavit.

59 In oral evidence before me, concerning the 2019 financial accounts, Mr Tully reconfirmed that when he made the declarations he believed that Tempo would be able to pay its debts as and when they became due and payable, that no concerns about financial viability had been raised with him by Mr Madan or Mr Kerkar and that he was not otherwise then aware of any information contrary to the financial position as stated in the accounts. When asked specifically about the GTA and his state of mind in June 2019, he confirmed that he had “no reason to doubt” that the loans would be repaid.

60 Mr Tully presented as a straightforward, honest and therefore credible witness. His evidence does not conflict with any contemporaneous documents. I have no reason to doubt the accuracy of his evidence.

The GTA payments in issue

61 Mr Beven’s aide memoire records five transfers by Tempo pursuant to the GTA between 16 April and 19 June 2019 amounting to $5,862,429. They are central to this proceeding. To recap, the amounts transferred to Cox & Kings were $976,000 on 16 April, $1 million on 30 April, $2 million on 20 May and $955,280 on 19 June 2019. An amount of $931,149 was transferred to the Group company Avilia Tourism on 2 May 2019.

62 Mr Tully’s evidence is that he was not made aware of requests for the payments at the time and was not consulted as to whether the payments should be made. It was Mr Madan who was responsible. That evidence is confirmed in a contemporaneous document, being Mr Tully’s letter of resignation as a director of Tempo and Prometheon AU dated 19 August 2019 wherein, after submitting his “immediate resignation” he continued:

It has been brought to my notice that there have been several payments made towards our own group companies from our advances received and I was not previously aware of this. Having become aware I wish to resign with immediate effect.

63 In his public examination, Mr Tully was questioned as to whether his acquisition of knowledge of these payments prompted his resignation. He denied that it was the only reason, stating that there were others. When permitted to expand on that answer he said:

…there were many reasons: the parent company was clearly in trouble, the situation in Australia was difficult and I had absolutely no control over it. So I was very stressed by the situation. I had personal – you know, it was causing me a great deal of personal distress. I didn’t know you had to write a list of reasons in a resignation letter.

64 Mr Madan was not called as a witness. He was also publicly examined on 4 March 2021, but no transcript of that examination was tendered in evidence. There is however a good deal of documentary evidence (and the agreed facts) which explains the circumstances in which requests were made for payments and the transfers were effected by him accordingly. The transfers must be understood in the context of requests made by Mr Madan for funds from Cox & Kings, commencing in mid-2018. In what follows, I largely reproduce (save for the emails of 27 March 2019) paragraphs from the statement of agreed facts, with minor edits.

On 29 August 2018, [Mr Madan] emailed Abhishek Goenka and [Mr Khandelwal] of [Cox & Kings] and stated:

As you are aware that we are moving into our lean season for inflow, it is necessary to have funds back.

Can you please return below funds, if not possible in one trench (sic), may be in two/three trenches (sic) on regular monthly intervals:

USD 5,330,750 remitted in April 18

2. USD 2,000,000 remitted on 15 August.

On 9 October 2018, Madan emailed Goenka and Khandelwal and stated:

As you are aware that, we are already in our lean season inflow is not large enough to manage the situation satisfactorily.

The net position on related entity outflow is now standing at around +$23million impacting our commitments to suppliers.

We have on average 2 mil per month payable to our GSA partner “Hurtigruten” this month and next two months. Amounts due to other suppliers also piling up.

I am sure you are working on arranging the same, but we can’t wait any longer and need some ASAP. I am not asking for all, but please give us back the funds remitted this year (US$7.5 mill), in two/three monthly instalments starting this week.

At about 1.18 pm on 29 October 2018, Madan sent a WhatsApp message to Khandelwal that read, “Sir, funds please”.

At about 7.31 pm on 29 October 2018, Khandelwal sent a WhatsApp message to Madan that read, “Can I call you later?”

At about 7.31 pm on 29 October 2018, Madan sent a WhatsApp message to Khandelwal that read, “ Yes sir any time. I need 2.5 million urgently. I don’t want to default on my corporate cc card also with 800k outstanding”.

On 1 November 2018, Madan emailed Khandelwal and stated:

In continuation with my earlier communication on our fund position, not sure what the plan/situation is, but today one of our suppliers credit card facilities and put us on immediate credit card payment failing which they will cancel all bookings we have with them. Secondly, I mentioned other day about not having enough funds to pay to HURTIGRUTEN’s due of 1 million plus GBP and credit card dues along with other long overdue Foreign a d [sic] payment including overrides to agency chains and marketing spend.

I somehow managed to paying HURTIGRUTEN’s above overdue but not in a position to stop Tempo defaulting on credit card liabilities of $780+ k and other 2 mil + long overdue liabilities.

Per our last telecom, I am supposed to get funds last week or latest by last Monday, which gone without any news of funds.

Request you to please arrange urgently to reach Tempo by Monday (5th Nov) morning.

On 20 November 2018, Madan emailed Khandelwal and stated:

Not sure if my earlier emails on the subject reached you or not as haven’t got any reply / response on these, nor on my calls.

Writing again as the long overdues are growing day by day and reached at $6 million mark which includes 2 million of Hurtigruten, 850k to Amex card and around 400k to local suppliers and retail distribution networks commission.

I tried my best even on personal level and stopped the default last months credit card dues but am not in a position to do it more.

On 14 December 2018, Madan emailed Khandelwal and stated:

I understand the current issues and am aware that you are trying your best to manage the situation, but please be aware of the coming festive season, wherein everyone needs funds.

Having two/three months overdues with suppliers, support services here are becoming major issue and are now not manageable.

Request you to please arrange whatever funds you can manage ASAP to pay at least in parts to all these creditors before Christmas.

On 18 December 2018, Madan emailed Khandelwal and stated:

I am sure, you are trying your best to arrange the funds, but now we are a situation [sic], where suppliers with large long overdues can’t be managed any longer. Festive season makes things worse as every one wants full amount.

Looking at around AUD 1.5 mill on top urgent basis.

On 16 January 2019, Kashmira Commissariat, Tempo Holidays’ chief executive officer, emailed Khandelwal and stated:

This is to inform you that currently our AUS & NZ unit is facing immense cash flow problem which in turn is affecting our payments to our suppliers. We are no longer in the position to stall our suppliers any further which in turn affecting our credibility in the marker.

Request you to please remove some time from your busy schedule and please help to resolve this problem …

On 6 February 2019, Tempo Holidays received USD 485,000 [AUD678,037] under the Global Treasury Arrangement from Prometheon. These were the only funds received from Tempo Holidays in the period from 29 August 2018 to the Appointment Date.

At about 2.28 pm, on 12 February 2019 Madan sent a WhatsApp message to Khandelwal that read, “Sir, I am sure you must be trying your best to manage this, but we are now in extreme position as the supplier started changing customers and also stopping confirming new business as the delays are too much. Can something be done urgently, say, this week with 100% surety. Thanks. Sudarshan”.

At about 2.28 pm on 12 February 2019 Khandelwal sent a WhatsApp message to Madan that read, “How much is required bare … minimum”.

At about 2.28 pm, on 12 February 2019 Madan sent a WhatsApp message to Khandelwal that read in part, “… what max can you manage?”

At about 2.28 pm on 12 February 2019 Khandelwal sent a WhatsApp message to Madan that read, “Let me come back by 12 noon India time. All I can tell you is I am trying my level best”.

At about 11.10 pm, on 12 February 2019 Madan sent a WhatsApp message to Khandelwal that read in part, “Sir, any possibility?”

At about 11.10 pm, on 12 February 2019 Khandelwal sent a WhatsApp message to Madan that read in part, “Trying Sudarshan. Still no success”.

65 There is one email from Mr Madan that belies the clear inference from this correspondence that Tempo was experiencing financial difficulty from at least 9 October 2018. On 27 March 2019, Mr Madan emailed Mr Malik and Mr Kashimina at Cox & Kings and stated:

SBI Account:

I am not sure what do you mean here by willing to oblige. They agreed to look into our request for financing, subject to complete documentation including guarantees from ultimate holding company.

I can’t say that these are the reasons, but one has to follow the procedure and fulfil the documentation requirement as defined by SBI, and we are working on.

It is an Indian bank, and South Asian psyche is still prevalent. They need all documents (to my surprise, even the application form and supported originals) to be by attested by a competent authority, which is the major issue.

Having two directors in different locations, getting the basic original documents signed takes its own time.

Secondly I have to start the process again as functional Board doesn’t want “Ryan Bennett” as an authorised signatory for the bank, requiring the re-initiation of basic account opening documents.

We are doing our best to get the base documents ready for account opening.

Per my discussion with SBI Sydney, “for security arrangements, SBI Sydney is in contact with their counter part in SBI India, who in turn will contact CnK India”.

Cash Position:

The current period being a peak travel season, currently we are in a safe position when it comes to cash and supplier payments and working toward clearing all the outstanding supplier dues (barring related entities). This position will remain comfortable for another 4 / 5 months till the lean season for travel and high season for booking start.

Hurtigruten has also been paid on time this month and will continue to pay on time in coming couple of months

66 The reference to SBI is to the state Bank of India and Hurtigruten was a substantial customer to whom Tempo was indebted in an amount exceeding GBP1 million, according to an email of 1 November 2018. Mr Malik responded that day:

I have been dealing with SBI and other Indian banks for a long time and I know how they operate. However, they do not take so long when it comes to opening accounts. Changing a bank mandate (change Ryan as authorised signatory...) does not take over 2 weeks to open an account. Can you please let us have a detailed note on what needs to be done with regards to a) opening the bank account and b) arrange a facility. Have you sent them a proposal? If so let us have the details.

As far as “willing to oblige” statement is concerned, reading the emails below and my conversations with SBIUK, they have shown interest and are keen to start a relationship with Cox & Kings. Australia. All such matters are always subject to them getting comfort, which I am sure they will. As stated above what has been presented to them.

As far as cash-flows are concerned, please send us your cash-flow projections for the next 6 to 8 months. We may be ok for now but we need to look ahead and ensure that the facility is in place well before the low season starts.

Please ensure that you have this as top priority and KEEP US POSTED on a regular basis instead of us chasing you for an update.

67 The evidence does not disclose if Mr Madan provided the requested cash flow projections. The next series of emails concerned the queries raised by the auditor as notified by Mr Madan on 26 March 2019 and the letter of financial support from Prometheon UK of 11 April 2019.

68 Returning to payment requests pursuant to the GTA as set out in the statement of agreed facts:

On 15 April 2019, [Mr Malik] emailed Mr Madan and stated, “Further to our conversation, can you please transfer US$600k to Cox & Kings, India. Peter has asked if you could check and see if you can transfer any amount above the $600k. Kindly note that there will be delay in remitting funds back to Australia”.

On 29 April 2019, Sagar Deshpande of [Cox & Kings] emailed Mr Madan and stated, “As discussed with Anil Sir, please transfer funds to India. Please remit in INR. Please ensure its Value Date tomorrow.” Mr Kerkar sent a follow up email on 30 April 2019 which stated, “Sudarshan please remit urgently”.

On 1 May 2019, Mr Kerkar emailed Mr Madan and stated, “Please send all available funds to india (sic) urgently discuss the amount with Anil now.”

On 17 May 2019, Mr Khandelwal emailed Mr Madan and stated, “Further to our telecon, kindly transfer 2 Million AUD for a very important funds requirement. Sagar will send you the bank account details vide a separate email. I will organise to refund the funds back to Australia early June.”

Later, on 17 May 2019, Mr Madan emailed Mr Khandelwal and stated, “I can manage around AUD1.5 mil.” Mr Khandelwal replied, “Can you help with more? Monday is very very important and the last bit of the rollover that needs to be managed before we get fresh funding next week.”

69 It will be recalled that Cox & Kings publicly announced on 7 June 2019, that it intended to enter into an inter-creditor agreement with its primary lenders. It did and quickly thereafter it substantially defaulted, which leads to the next issue.

The Demise of Tempo

70 An understanding of the reasons for the financial collapse of Tempo begins with a decision of the directors to guarantee a group liability under a facility agreement with Yes Bank Ltd. A minute of meeting dated 18 June 2018, attended by Mr Kerkar and Mr Tully, records a decision that Tempo agreed to be one of the guarantors to a facility agreement in the amount of USD187,000,000 between Prometheon UK (and other group members) and Yes Bank. The minutes contain a note that the directors considered the transaction to be in the best interests of and for the benefit of Tempo as a subsidiary of the principal borrower. On the same day, Mr Tully and Mr Madan as the directors of Prometheon AU signed a resolution in its capacity as the shareholder of Tempo, approving of the decision to provide a guarantee. The accession instrument was also signed by Mr Kerkar and Mr Tully on 18 June 2018.

71 Despite what is recorded in these documents, Mr Tully, when publicly examined, did not recall the transaction, did not understand that Yes Bank was an Indian banking institution and did not know what was meant by accession to the transaction. He did, however, recollect receiving correspondence from Yes Bank dated 27 September 2019 which demanded payment of USD187 million. That demand followed default by Prometheon UK in its obligations under the facility agreement at some time prior to 12 July 2019, which is the date of the first letter of demand from Yes Bank to Prometheon UK. On 2 August 2019, Yes Bank made a separate demand upon Tempo as guarantor of the facility for USD187 million. That letter of demand states that Prometheon UK failed to make a payment of USD7,042,788.17 that was due on 17 June 2019.

72 Earlier, on 3 July 2019, the Australian Federation of Travel Agents (AFTA) suspended Tempo’s accreditation. Tempo responded to that decision by letter of 26 July 2019, and provided a short analysis of its financial position which disclosed a shortfall between cash at bank of $3,904,647 and net customer advances of $19,577,866. As explained by Mr Fitzgerald in the joint expert report, customer advances represent un-earned revenue and amounts paid by customers to Tempo for advance tour bookings. The funds were not treated as held on trust in the accounts. When a customer completes a booked tour, the unearned revenue is allocated to actual revenue. At the same time a liability is created to the tour supplier, which is reflected in the trade creditors ledger. Mr Beven did not disagree with how Tempo treated these funds, but in his opinion they ought to have been regarded as advances classified as due and payable as a debt, because ultimately the funds represent the amount payable to suppliers, less amounts paid in advance on behalf of prepaid customers or an amount refundable to customers in the event of cancelled bookings. For present purposes, that difference in opinion as to how the funds should have been treated does not affect the fact that Tempo disclosed a shortfall to AFTA as at 26 July 2019.

73 AFTA was not satisfied with Tempo’s response. On 29 July 2019, it gave notice of termination of a Sales Agency Agreement with effect from 31 August 2019. Relevant to these events is the evidence of Mr Tully as set out in his affidavit. He became aware in late July 2019, from media reports, that AFTA had suspended Tempo’s accreditation. He had a conversation with Mr Madan, who explained that the suspension did not have anything to do with a default by Tempo in that it was “trading strongly” and the default related to one of the subsidiary companies in the Group. Mr Madan assured Mr Tully that he was dealing with the issue and Mr Tully did not take further action to address it.

74 Separately, American Express with effect from 3 July 2019, advised Tempo that it had suspended payments pending a review into the financial capacity of Tempo. The suspension resulted in $789,000 in customer payments made using the American Express credit system being withheld. The suspension was due to Cox & Kings’ default.

75 On 2 July 2019, Mr Kerkar sent email correspondence to Mr Madan, amongst others, stating that:

The working capital situation at Cox & Kings stretched in the last few months and was further impacted due to its inability to replace the short-term loans with long-term loans/regular working capital lines.

The Company is taking all required measures to resolve the temporary cash flow mismatch.

For the benefit of all its stakeholders, the Company asserts that C&K has robust operating businesses. It has a thriving and highly valuable Hybrid hotels business in Meininger. It has a niche business in Leisure International. C&K is also an emerging player in the visa processing services business. Each of these businesses carry high intrinsic value.

To make it clear all our foreign operations are ring-fenced with their own cash flows and businesses and are able to trade independently.

76 Mr Tully was not a recipient to that email. On 3 July 2019, Maridza Riccioni, described as the marketing manager for the Australian operation, sent an email to Mr Bruce Piper, from the trade publication Travel Daily. It was sent in response to several emails from Mr Piper in which he foreshadowed publishing an article referencing the financial position of the Cox & Kings global business. The Riccioni email attached a statement from Cox & Kings “regarding recent press” under the heading “Defaults triggered by temporary mis-match in liquidity and the measures being taken to addressed [sic] the situation” which provided (without corrections):

The working capital situation at Cox & Kings stretched in the last few months and was further impacted due to its inability to replace the short term loans with long term loans / regular working capital lines.

None of the foreign operations has any impact of this situations and are able to trade independently.

The Company is taking all required measures to resolve the temporary cash flow mismatch. It is evaluating each business and identifying ways to improve operational performance. The Company is focusing on cash flow generation from each business and working at the highest priority to free working capital.

The company will also be approaching its lenders to work out some time bound program to meet this emergency.

For the benefit of all its stakeholders, the Company asserts that C&K has robust operating businesses. It has a thriving and highly valuable Hybrid hotels business in Meininger. It has a niche business in Leisure International. C&K is also an emerging player in the visa processing services business. Each of these businesses carries high intrinsic value.

In the circumstances above, the company requests the co-operation and understanding of all its stakeholders, including employees, franchisees, shareholders, lenders, vendors and other partners, as we work tirelessly to restore the unblemished value in the legacy brand.

77 Mr Piper responded on 3 July 2019 stating: “[n]o problem, we’ll put this in tomorrow”, expressed concerns about the financial capacity of the Australian business and sought clarification as to whether client funds were held in a trust account. If there was a response to those queries, it is not in evidence.

78 There was considerable correspondence between Tempo and its suppliers in July 2019, concerning late payment of accounts or questioning the financial viability of Tempo. As an example, Iceland Travel sought urgent attention to an overdue payment on 8 July 2019 in the amount of EUR327,426.64. The amount was not paid.

79 An internal management cash flow for Tempo prepared on 8 July 2019, projected receipts and payments from July 2019 to March 2020. It forecast a deficit commencing in the amount of $6,119,485 in September 2019, increasing to $14,140,305 in March 2020. A note to the projections provides (again without corrections):

The cash flow is prepared based on the current confirmed business volume. Media reports about CNK India, IATA, ATAS & AFTA news has already started impacting the business and the actual future inflow on confirm business may not flow as projected.

Secondly the new business will also be impacted heavily and may not bring any cash going forward.

It is now very important that, The board of directors should take the stock with an urgency and arrange returning the funds back to Tempo to enable us to manage the operation without any interuption and further damage to the business

80 There were staff resignations in July 2019, in particular Mr Darren Wakefield resigned his position as Tempo’s Inside Sales, Reservations and Retail Manager. A reason that he recorded is that Tempo had been blocked from issuing tickets for air travel, which had caused significant stress within the office. Despite Tempo’s deteriorating financial position, on 8 August 2019, it granted a general security deed in favour of Stellite Finance Ltd, to secure monies borrowed by Prometheon UK. Shortly thereafter, on 21 August 2019, Stellite Finance issued a notice of default to Prometheon UK. Of this arrangement, Mr Tully stated in his affidavit that in late July 2019 he was requested to sign the security deeds, which he understood were required to secure the obligations of Prometheon UK. He discussed the proposal with Mr Madan, who told him that Mr Kerkar was responsible for it and was assured that he would not incur personal liability thereunder. When asked in the course of his public examination whether he considered the granting of this security interest to be the “right thing to do for the business”, he answered: “I don’t know the answer to that, I’m afraid.” He was pressed further as to whether he considered the granting of the interest to be an important matter for Tempo and answered: “I suppose it depends on the assets”. He was not further pressed on that issue. This transaction was not explored in Mr Tully’s oral evidence before me.

81 As I have noted, Mr Tully provided his letter of resignation to Mr Madan on 19 August 2019. In his affidavit he described the circumstances which led to that decision. He considered suspension of the ATAS accreditation and the fact of granting the Stellite security as troubling events, but not sufficiently alarming to trigger his decision. He believed, in consequence of what he had been told by Mr Madan, and his confidence in the management ability of Mr Kerkar, that the liquidity problems were caused by other Group members and steps were being taken to address the issue. In late July 2019, he was still of the opinion that Tempo was a successful and profitable business.

82 Mr Tully travelled to India in August 2019, for business and personal reasons. Whilst there he noticed several media reports concerning the distressed financial position of Cox & Kings. This caused him to telephone Mr Kerkar on 19 August 2019, which conversation he recalls as follows:

Me: “Peter I am in Delhi visiting my father. There are stories in the local press about Cox & Kings being under a lot of financial pressure and employees not being paid and I am very concerned.”

Peter: “Yes I know we still have some liquidity issues but we will get them resolved.”

Me: “It seems to me the problems are more than just normal liquidity problems and you are urgently selling assets to pay off debts and stay afloat and not paying salaries. I was totally unaware things were so bad over here and I concerned [sic] about the funds owed to Tempo.”

Peter: “We are facing problems and I am also currently trying to get my head around what has happened. There have been major changes to the banking system in India which is not help the situation. However these problems are temporary and will be resolved.”

Me: “I am no longer comfortable with the situation and I think the best option is for me to immediately resign.”

Peter: “Ok I understand and agree it will be best for you to resign. Can you please inform Sudarshan.”

83 The effect of the resignation of Mr Tully is that Mr Kerkar became the sole non-resident director of Tempo from 19 August 2019. Mr Tully also resigned from Prometheon AU with effect from 19 August 2019. Mr Madan had earlier resigned from Prometheon AU with effect from 1 July 2019, which left it without a director.

84 On 18 September 2019, Mr Madan emailed Mr Kerkar, amongst others, requesting advice as to the status of the Australian operations. Amongst other things he stated:

…As mentioned on multiple times, we are practically trading insolvent as we are continuously telling to trade, our customers & our suppliers that, we have no impact on us due to Cox & Kings situation and for us business is as usual based on communications, information and updates, we are getting from Board and yourself since July 3rd 2019, which the Board surely knows was/is not the case as they are well aware of the whole cashflow and funding situation.

…

Staffs are practically crying in front of me since morning as they can’t cope with the constant barrage of calls from agents asking for real situation…

Please decide the fate of this operation by today before close of business our time. It is already late, but every passing hour making things worst.

85 Mr Kerkar responded to the effect that he would “immediately look for a safe harbour situation”, but if not found by 30 September 2019 would declare voluntary administration. On 20 September 2019, Mr Fitzgerald and his business partner Mr Michael Humphris were appointed as joint and several administrators of Tempo.

86 On 17 October 2019, Mr Fitzgerald provided the second report of the administrators to Tempo’s creditors. In Pt 5 of the report, Mr Fitzgerald stated that in his opinion:

[T]he primary reason for the Company’s difficulties are attributable to the drain on its cash resources through Cox & Kings Group and its inability to recover loans receivable from related entities within the Group, which had increased by c$17.26m in the 18 months prior to our appointment. That is, the Company’s financial resources had been applied to its parent and related companies of some c$17m over the past 18 months. The Company was unable to meet its own financial obligations as a result.

ISSUE 1: A CLAIM IS MADE ON MR TULLY

87 It will be recalled that the Policy period commenced at 4 pm on 31 March 2019 and expired at 4 pm on 31 March 2020. At 2.49 pm on 31 March 2020, Mr Fitzgerald sent email correspondence to Mr Tully in the form of a Demand for payment in the sum of $5,297,133 for breach of director’s duties and/or insolvent trading. Berkley denies this Demand amounted to a Claim within the meaning of the director and officer liability indemnity at cl 1.1 of the Policy. The Policy adopts the familiar format in that indemnity is provided on a claims made and notified basis. Although Mr Tully did not notify Berkley of the demand until 1 April 2020, Berkley makes no complaint about that.

88 Clause 1.1 of the Policy provides:

We shall pay to or on behalf of any Insured Person Loss arising from any Claim for a Wrongful Act which is first made against the Insured Person during the Period of Insurance and notified to Us in accordance with the terms of this Policy, except when and to the extent that the Company has indemnified the Insured Person.

89 It is not in issue that Tempo is a Company as defined in the Policy, that Mr Tully as a former director is an Insured Person and that each of Mr Tully and Tempo are within the Policy definition of an Insured. What is in issue is whether the Demand was a Claim which corresponds with the claims subsequently made against Mr Tully in this proceeding. The Policy defines Claim for the purpose of cover for any Insured Person exhaustively at cl 3.5. Relevant to this proceeding is subparagraph (i) where Claim means:

[A] written demand by a third party against an Insured Person for compensation, damages or for non-monetary relief.

90 In short, Berkley’s argument is that properly construed the demand was confined to loss caused by insolvent trading, which is not the loss claimed to have been suffered by reason of the breach of director’s duty claim relating to the GTA payments made between April and June 2019. To understand that submission, I set out the Demand in full (omitting formal parts):

I refer to my appointment as Joint and Several Liquidator of the Company.

Background

I have undertaken investigations into the pre appointment affairs of the Company, and advise the following:

• The Company was part of a corporate group which included entities including but not limited to Cox & Kings Limited (“CKL”), Prometheon Enterprises Limited (“PEL”) and Cox & Kings Singapore Pty Ltd (“CKLS”).

• The Balance Sheet of the Company as at 20 September 2019 showed significant related party debtors the major amounts owing were CKLS at c$25.1m, PEL at c$5m and CKL at $4.9m.

• As part of this group, the Company had access to a Global Treasury Function (“Treasury Function”). The Treasury Function, as you are aware, acted as a means of which, subject to seasonal cashflow pressures, allowed the Company to access financial support from other entities within the group, as well as provide funding and support to the group.

• The final amount the Company received from the Treasury Function was on 4 February 2019 of c$607k.

• Historically the Company had provided funds to the Treasury Function however was able to sources [sic] funds from time to time to meet its ongoing requirements.

• The final amount advanced by the Company to the Treasury Function was on 20 June 2019 of $955,280.

• On 26 June 2019, CKL defaulted on a commercial paper worth approximately AUD$31m and between this date and 15 July 2019, defaulted on 3 other financer obligations. I have been advised by the Company's former CFO that it was at this date (26 June 2019) that he became aware no further funds would be received from the Treasury Function.

• By 26 June 2019 CKL and its subsidiaries were not in a position to provide any financial assistance to the Company due to the defaults suffered in Europe and India, with an announcement on the Bombay Stock Exchange dated 1 July 2019 disclosing the revision of CKL credit ratings as a result.

• The Company’s revenue and cash flow had a traditional seasonal fluctuation, with comparatively low receipts from customers in the period 1 June to 30 September. It was during this time that related party assistance through the Treasury Function was most required.

• The Company continued to trade until 19 September 2019, where the Company’s sole remaining Director Mr Kerkar addressed the Company’s employees via teleconference and confirmed the Company had insufficient funds to continue trading and subsequently, on 20 September 2019, I was appointed as Voluntary Administrator of the Company.

Breach of Director's Duties

The Corporations Act 2001 (“the Act”) imposes specific duties on officers of companies (i.e. directors). Pursuant to the Act, you were at all times subject to obligations and duties, including, but not limited to:

• A duty to exercise your powers and discharge your duties with a degree of care and diligence; and

• A duty to exercise your powers and discharge your duties:

• In good faith; and

• For a proper purpose.

The default by CKL on 26 June irretrievably affected the financial capacity of the Company to continue. Thereafter the situation continued to deteriorate. Once CKL defaulted on 26 June 2019 the financial affairs of the Group were permanently disaffected. As a consequence the Company, which was reliant both on a balance sheet and cashflow basis on the loans it had extended to related parties, was not able to continue that reliance and was not financially viable thereafter.

Between 26 June 2019 and 20 September 2019, the following events confirm the Company’s financial concerns during this period:

• On 3 July 2019, American Express (AMEX) commenced withholding certain customer payments from the Company, with approximately $789k being withheld from this date (further straining the Company’s cashflow).