Federal Court of Australia

Commissioner of the NDIS Quality and Safeguards Commission v LiveBetter Services Ltd [2024] FCA 374

ORDERS

NSD 282 of 2023 | ||

COMMISSIONER OF THE NDIS QUALITY AND SAFEGUARDS COMMISSION Applicant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT DECLARES THAT:

1. On 15 occasions, LiveBetter contravened s 73J of the National Disability Insurance Scheme Act 2013 (Cth) by failing to comply with the standard which specified that risks to Ms Lucas be identified and managed, as imposed by cl 10 of Sch 1 Pt 3 to the National Disability Insurance Scheme (Provider Registration and Practice Standards) Rules 2018 (Cth), by reason of its failure to:

(a) conduct a formal risk assessment of Ms Lucas’ residence prior to providing bathing supports;

(b) formally train each of the seven Relevant Support Workers in proper bathing technique; and

(c) formally assess the competency of each of the seven Relevant Support Workers in proper bathing technique.

2. In providing bathing support to Ms Lucas on 2 February 2022, LiveBetter contravened s 73J of the NDIS Act, by failing to provide Ms Lucas, as required by cl 21 of Sch 1 Pt 4 to the Practice Standards, with access to competent and appropriate supports to meet her needs.

3. In providing bathing support to Ms Lucas on 2 February 2022, LiveBetter contravened s 73V of the Act, by failing to provide to Ms Lucas, as required by ss 5(3) and 6(c) of the National Disability Insurance Scheme (Code of Conduct) Rules 2018 (Cth), supports and services in a safe and competent manner, with care and skill.

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Pursuant to s 82(3) of the Regulatory Powers (Standard Provisions) Act 2014 (Cth), read with s 73ZK of the NDIS Act, LiveBetter pay to the Commonwealth a pecuniary penalty in the amount of $1,800,000 for the contraventions of ss 73J and 73V of the NDIS Act which are the subject of the three declarations above.

2. LiveBetter pay the Commissioner’s costs as agreed or taxed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

RAPER J:

Introduction

1 The National Disability Insurance Scheme was set up to transform the services provided by the Australian government to persons with disability. The objects of the National Disability Insurance Scheme Act 2013 (Cth) include promoting the provision of high quality and innovative support to enable persons with disability to maximise their independent lifestyles and full inclusion in the community and protecting and preventing people with disability from experiencing harm arising from poor quality or unsafe supports or services: ss 3(1)(g), 3(1)(ga). The circumstances of this tragic case bring into stark relief the respondent, LiveBetter’s fundamental failures to provide Ms Kyah Lucas with quality supports and services and to protect her.

2 On 2 February 2022, Ms Lucas sustained burns to 35 to 40% of her body while receiving bathing support services from LiveBetter. Tragically, five days after sustaining the burns Ms Lucas died at Concord Repatriation General Hospital. The medical records refer to her death as being caused by burns.

3 The applicant, the Commissioner’s functions are prescribed by ss 181C–181H of the NDIS Act. Among those functions are enumerated ‘core’ functions, which include:

(a) upholding the rights and promoting the health, safety and wellbeing of persons with disability in receipt of support or services under the NDIS (s 181E(a));

(b) securing compliance with the NDIS Act through effective compliance and enforcement arrangements (s 181E(d)); and

(c) promoting progressively higher standards of supports and services to people with disability by NDIS providers (s 181E(e)).

4 By originating application and concise statement filed on 30 March 2023 the Commissioner commenced the proceeding against LiveBetter. The Commissioner sought:

(a) declarations that LiveBetter contravened ss 73J and 73V of the NDIS Act; and

(b) the imposition of pecuniary penalties pursuant to s 82(3) of the Regulatory Powers (Standard Provisions) Act 2014 (Cth) read together with s 73ZK of the NDIS Act.

5 LiveBetter is a charity and not-for-profit organisation registered by the Australian Charities and Not-for-Profits Commission.

6 LiveBetter has been a registered NDIS provider since around 1 July 2018. For the 2021 and 2022 financial years their principal activity was providing support services to the elderly and persons with a disability in regional New South Wales, Queensland and Victoria.

7 LiveBetter accepts that:

(1) it failed to conduct a formal risk assessment of Ms Lucas’ residence prior to providing bathing supports in breach of cl 10 of Sch 1 Pt 3 to the National Disability Insurance Scheme (Provider Registration and Practice Standards) Rules 2018 (Cth) and s 73J of the NDIS Act;

(2) it failed to ensure access to responsive, timely, competent and appropriate supports to meet Ms Lucas’ needs, desired outcomes, and goals on 2 February 2022 in breach of cl 21 of Sch 1 Pt 4 to the Practice Standards and therefore s 73J of the NDIS Act;

(3) it failed to provide Ms Lucas with bathing supports in a safe and competent manner, with care and skill on 2 February 2022 in breach of s 6(c) of the National Disability Insurance Scheme (Code of Conduct) Rules 2018 (Cth) and therefore s 73V of the NDIS Act;

(4) it failed to formally train seven support workers in the proper bathing technique in breach of cl 10 of Sch 1 Pt 3 to the Practice Standards and s 73J of the NDIS Act; and

(5) it failed to formally assess the competency of seven support workers in the proper bathing technique in breach of cl 10 of Sch 1 Pt 3 to the Practice Standards and s 73J of the NDIS Act.

8 The Commissioner seeks declaratory relief and civil penalty orders as contained in his amended originating application, filed in Court, with leave.

9 The parties attended mediation on 2 August 2023 which resulted in LiveBetter admitting liability before the service or filing of evidence. The mediation also resulted in the parties producing a Statement of Agreed Facts to the Court for the purposes of s 191 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth). The SOAF is extracted in its entirety at Annexure A to these reasons.

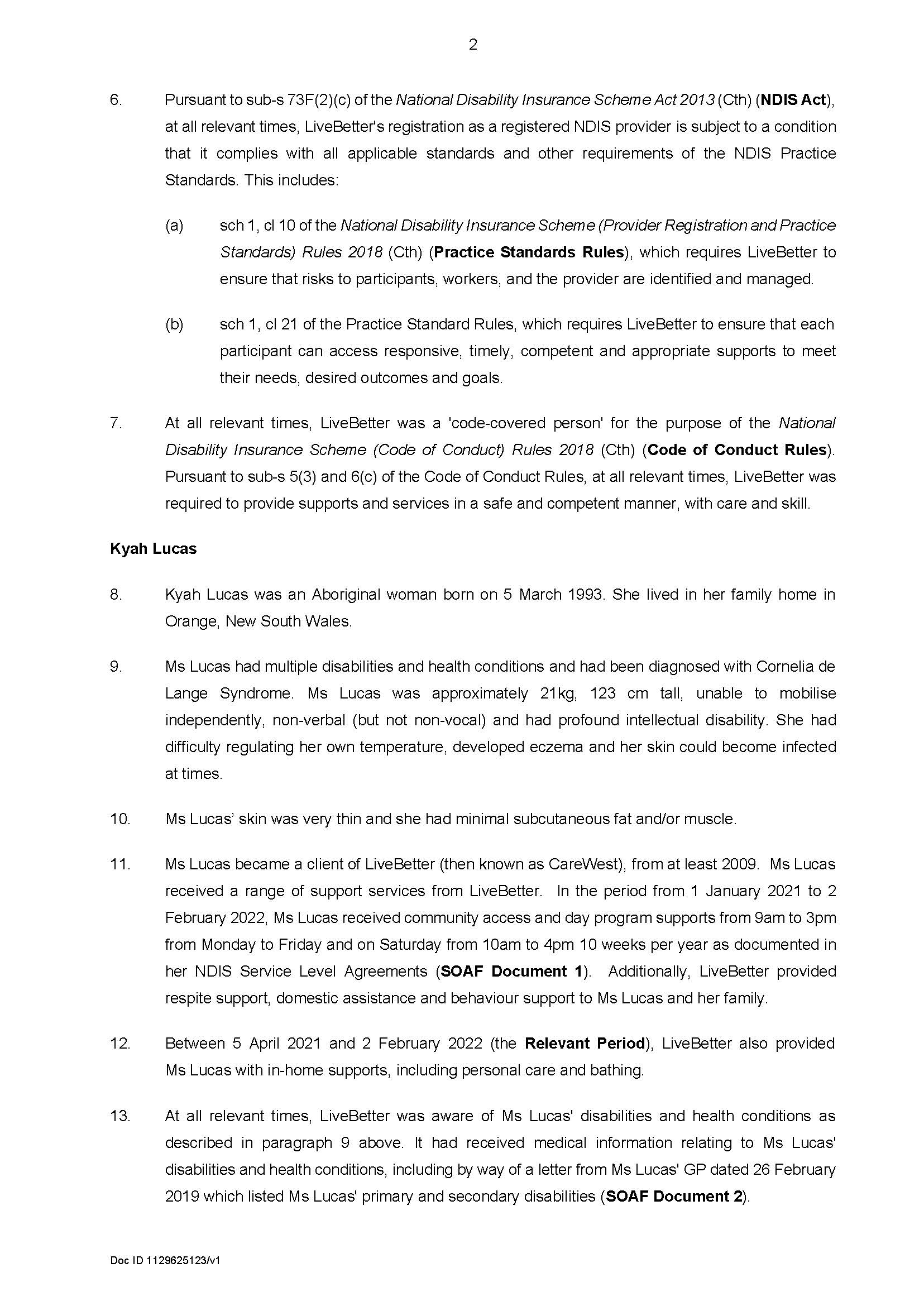

10 The parties helpfully provided the Court with a joint list of the agreed 17 contraventions, with reference to the relevant parts of the SOAF, which is set out as follows:

No. | Contravention description | Section of NDIS Act | NDIS Practice Standards or Code | Supporting SOAF paragraph(s) |

1. | Failure by LiveBetter to conduct formal risk assessment of Kyah Lucas’ residence prior to providing bathing supports | Section 73J | NDIS Practice Standards cl 10 | 12 – 14, 17 – 18, 28(a) |

2. | Failure to ensure access to responsive, timely, competent and appropriate supports to meet Ms Lucas’s needs, desired outcomes and goals on 2 February 2022 | Section 73J | NDIS Practice Standards cl 21 | 29 – 32, 33(a) |

3. | Failure to provide bathing supports in a safe and competent manner, with care and skill on 2 February 2022 | Section 73V | NDIS Code s 6(c) | 29 – 32, 33(b) |

4. | Failure to formally train Sandra Kennedy in proper bathing technique | Section 73J | NDIS Practice Standards cl 10 | 15, 20 – 23, 26, 28(b) |

5. | Failure to formally assess the competency of Sandra Kennedy in proper bathing technique | Section 73J | NDIS Practice Standards cl 10 | 15, 27, 28(c) |

6. | Failure to formally train Jasmin Morris in proper bathing technique | Section 73J | NDIS Practice Standards cl 10 | 15, 20 – 23, 26, 28(b) |

7. | Failure to formally assess the competency of Jasmin Morris in proper bathing technique | Section 73J | NDIS Practice Standards cl 10 | 15, 27, 28(c) |

8. | Failure to formally train Madison Riley in proper bathing technique | Section 73J | NDIS Practice Standards cl 10 | 15, 20 – 23, 26, 28(b) |

9. | Failure to formally assess the competency of Madison Riley in proper bathing technique | Section 73J | NDIS Practice Standards cl 10 | 15, 27, 28(c) |

10. | Failure to formally train Kyah Priest in proper bathing technique | Section 73J | NDIS Practice Standards cl 10 | 15, 20 – 23, 26, 28(b) |

11. | Failure to formally assess the competency of Kyah Priest in proper bathing technique | Section 73J | NDIS Practice Standards cl 10 | 15, 27, 28(c) |

12. | Failure to formally train Zoe Urquhart in proper bathing technique | Section 73J | NDIS Practice Standards cl 10 | 15, 20 – 23, 26, 28(b) |

13. | Failure to formally assess the competency of Zoe Urquhart in proper bathing technique | Section 73J | NDIS Practice Standards cl 10 | 15, 27, 28(c) |

14. | Failure to formally train Stacey Powe in proper bathing technique | Section 73J | NDIS Practice Standards cl 10 | 15, 20 – 23, 26, 28(b) |

15. | Failure to formally assess the competency of Stacey Powe in proper bathing technique | Section 73J | NDIS Practice Standards cl 10 | 15, 27, 28(c) |

16. | Failure to formally train Madeline Ewin in proper bathing technique | Section 73J | NDIS Practice Standards cl 10 | 15, 20 – 23, 26, 28(b) |

17. | Failure to formally assess the competency of Madeline Ewin in proper bathing technique | Section 73J | NDIS Practice Standards cl 10 | 15, 27, 28(c) |

11 In addition, the parties provided an additional supplementary statement of agreed facts, after the hearing, providing further documentary evidence regarding the additional training and competency assessments which have now been adopted by LiveBetter. The supplementary statement is attached at Annexure B.

12 Accordingly, the two issues requiring determination are whether the Court is satisfied that liability has been established and it is appropriate to make the declaratory orders sought and secondly, the appropriate penalties in the circumstances.

13 For the following reasons, I am satisfied that liability has been established, and it is appropriate to make the declaratory orders sought and impose a pecuniary penalty in the sum of $1,800,000 on LiveBetter.

The relevant facts giving rise to the contraventions

14 It is worthwhile briefly describing the factual context as agreed between the parties.

Relevant obligations as a registered provider under the NDIS Scheme

15 As a registered NDIS provider, LiveBetter is subject to the condition that it complies with all applicable standards and other requirements as imposed by s 73F of the NDIS Act, including relevantly:

(a) cl 10 of Sch 1 of Pt 3 to the Practice Standards, which requires providers to ensure risks to participants are identified and managed;

(b) cl 21 of Sch 1 Pt 4 to the Practice Standards, which requires ensuring each participant can access competent and appropriate support to meet their needs; and

(c) s 6(1)(c) of the Code of Conduct, requiring support and services to be provided in a safe and competent manner with care and skill.

16 With respect to the latter, it was undisputed that LiveBetter is a ‘code-covered person’ for the purpose of the Code of Conduct: ss 5(2) and 5(3).

Ms Kyah Lucas

17 Ms Lucas was a young (28-year-old) Indigenous Australian woman who, at the time of sustaining the fatal burns, resided with her family at their home in Orange, New South Wales.

18 Ms Lucas had Cornelia de Lange Syndrome and other disabilities and health conditions which LiveBetter were aware of at relevant times. She was small in stature, unable to independently mobilise herself, and non-verbal (but could be vocal). Ms Lucas also suffered from profound intellectual disability. Ms Lucas’ disabilities and health conditions meant that she had difficulty regulating her temperature, eczema, minimal subcutaneous fat and muscle, and her skin become infected from time to time.

19 Ms Lucas had been LiveBetter’s client since at least 2009. From that time until her death LiveBetter had provided her with a range of support services. Over the last twelve months of Ms Lucas’ life LiveBetter had provided services which included: community access and day program support between 9:00 am to 3:00 pm Monday through Friday and 10:00 am to 4:00 pm on Saturday for a period of 10 weeks, respite support and domestic assistance.

20 Between 5 April 2021 and 2 February 2022, which the parties agree to be the relevant period, LiveBetter also provided Ms Lucas with personal care and bathing support.

21 Throughout the relevant period LiveBetter was aware of Ms Lucas’ disabilities and conditions. An “Interim Behaviour Support Plan” they created that was dated November 2021 included the following statements:

(a) …‘Kyah has been diagnosed with Cornelia de Lang syndrome (CdLS). Kyah’s CdLS has contributed to her being unable to independently mobilise, having no verbal communication, and a range of other health concerns.’

(b) …‘Kyah is quite small in stature with a height of 123 cms. She is unable to mobilise independently and uses a tilt in space stroller (attendant propelled)…’

(c) …‘Kyah also has difficulties regulating her own temperature. She tends to get hot or cold easily and is unable to seek support to raise or lower her temperature. It is, therefore, important that those supporting Kyah monitor her temperature and take steps to make her feel comfortable’.

(d) …‘Kyah has been diagnosed … as having a profound intellectual disability.’

(e) …‘Kyah also has no real understanding of the impact of risks, hazards, or unplanned events on her life. While Kyah does demonstrate when she is distressed through her vocalisations and motor agitation, she would struggle to seek assistance without those supporting her being attuned to her needs and providing constant supervision’.

(Emphasis added)

Bathing Support Services Provided to Ms Lucas

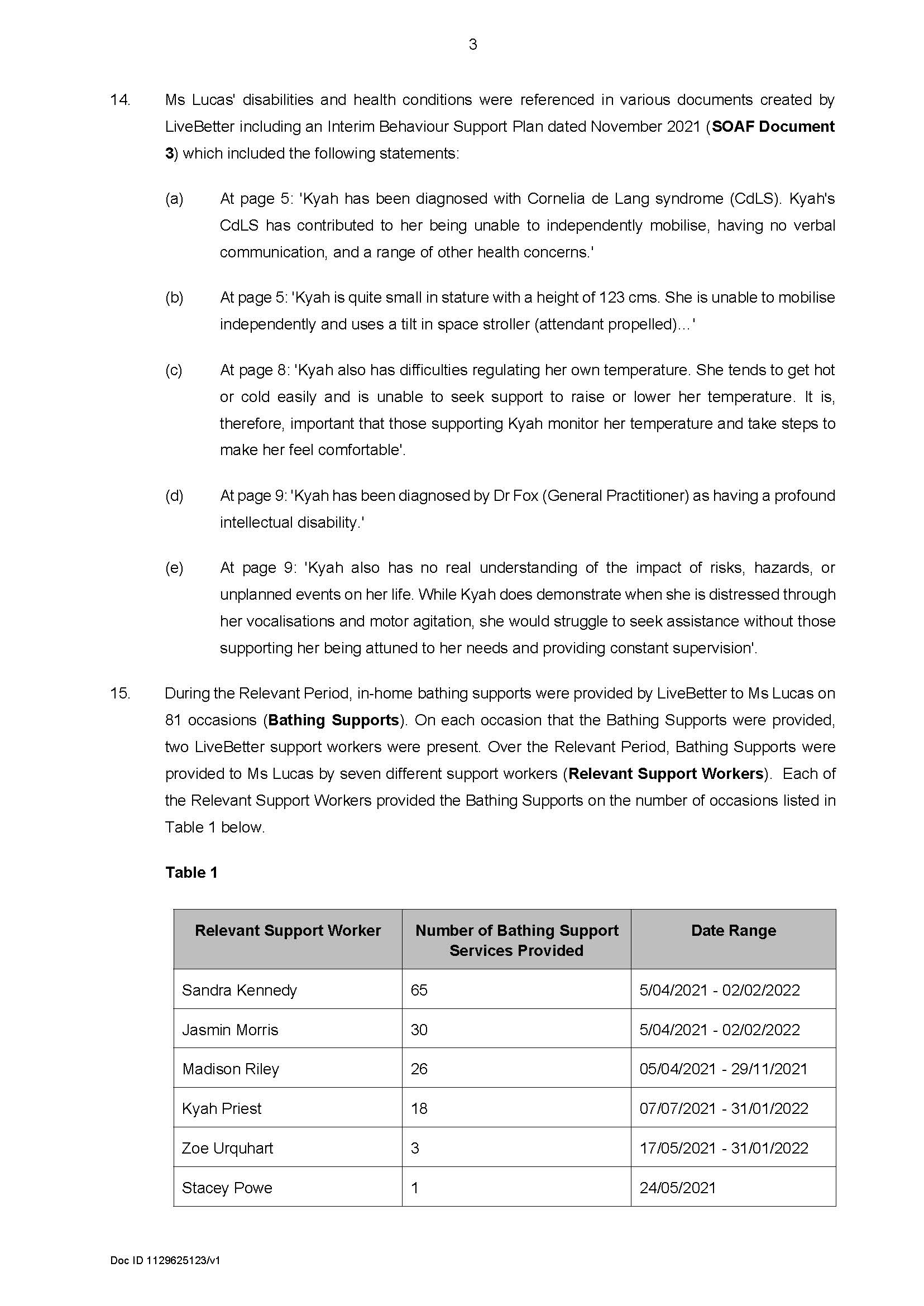

22 LiveBetter provided bathing support to Ms Lucas on 81 occasions throughout the relevant period. On each occasion two workers were present.

23 Where any person receives bathing support services there exists a risk that the recipient of the service may be burned.

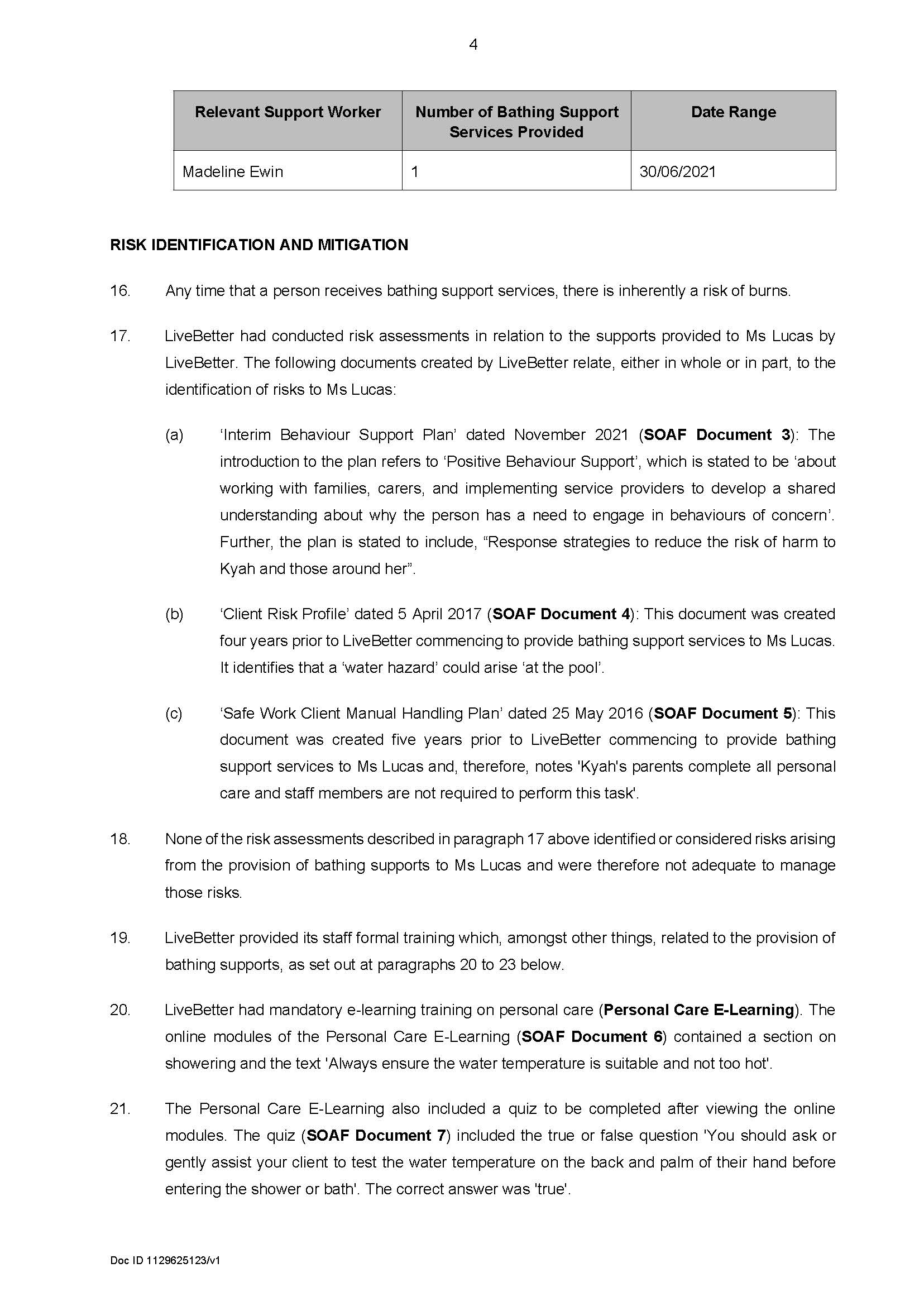

24 LiveBetter performed certain risk assessments of the support services they provided to Ms Lucas. Included among the evidence were three documents which relate to identifying risks to Ms Lucas:

(a) a “Safe Work Client Manual Handling Plan” dated 25 May 2016;

(b) a “Client Risk Profile” dated 5 April 2017; and

(c) an “Interim Behaviour Support Plan” dated November 2021 (Risk Assessments).

25 LiveBetter’s Risk Assessments failed to identify the real risk that Ms Lucas may be burned. That failure rendered the Risk Assessments inadequate in managing the risk.

Statutory scheme

26 The NDIS statutory scheme is unique. As observed by the Full Court in National Disability Insurance Agency v WRMF [2020] FCAFC 79; 276 FCR 415 at [138], the NDIS Act embeds an approach to the support of persons with disability that did not previously exist. It incorporates into its structure a number of values which are integral to the scheme.

27 Its objects include promoting the provision of high quality and innovative supports that enable people with disability to maximise independent lifestyles and full inclusion in the community: s 3(1)(g); and to protect and prevent people with disability from experiencing harm arising from poor quality or unsafe supports or services provided under the NDIS: s 3(1)(ga).

28 These objects are to be achieved, amongst other things, by establishing a national regulatory framework for persons and entities who provide supports and services to people with disability, including certain supports and services provided outside the NDIS.

29 The Commissioner’s primary functions, prescribed in s 181E(a), include upholding the rights of, and promoting the health, safety and wellbeing of, people with disability receiving supports or services, including those received under the NDIS. In addition, the Commissioner’s functions include securing compliance with the NDIS Act through effective compliance and enforcement arrangements, including through the monitoring and investigative functions conferred by Div 8 of Pt 3A of Ch 4: s 181E(d).

30 Section 73F(1) of the NDIS Act provides that the registration of a person as a registered NDIS provider is subject to certain conditions specified in s 73F(2), together with any conditions imposed by the Commissioner under s 73G or determined by the rules under s 73H.

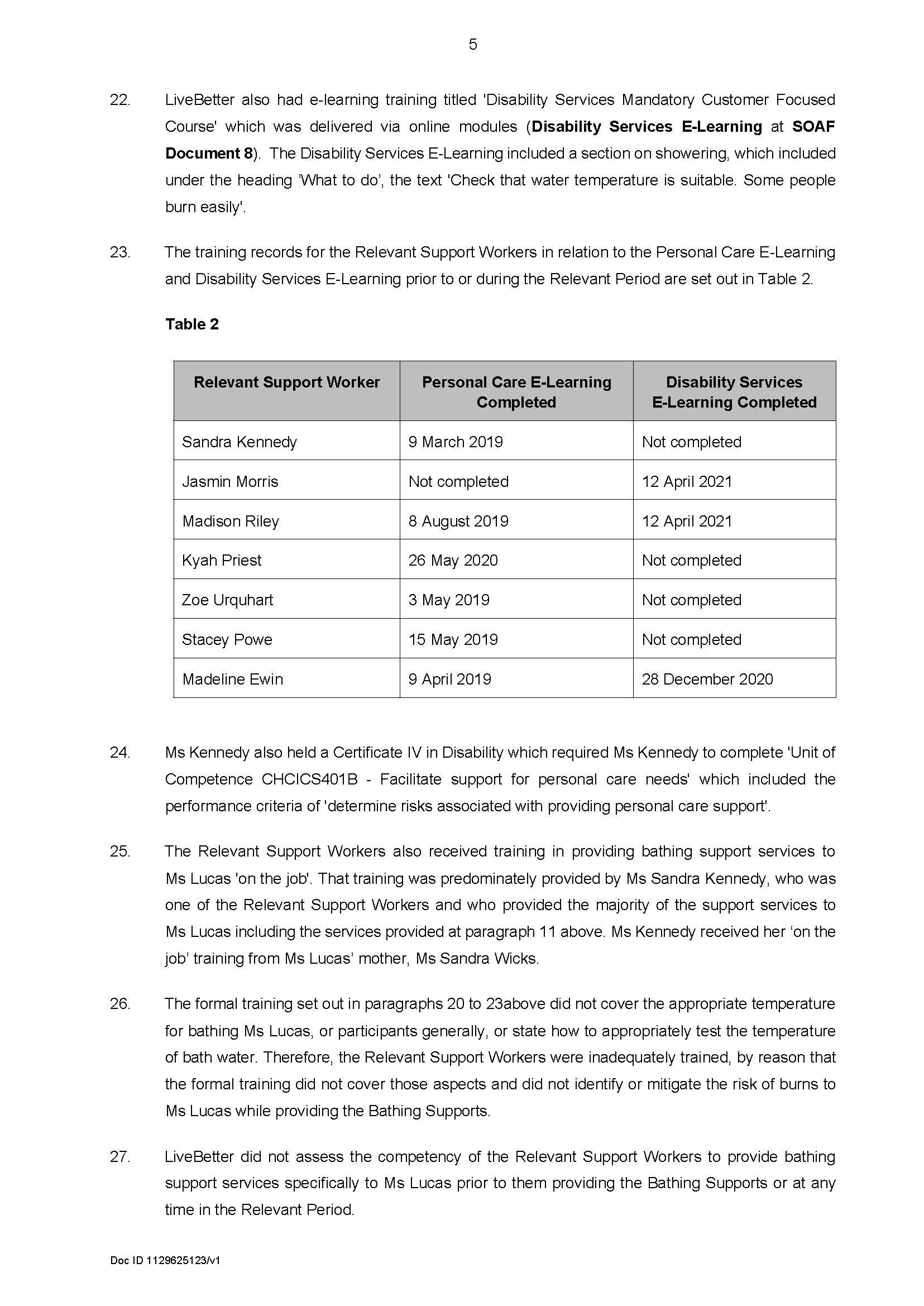

31 Relevantly, s 73F(2) provides that the registration of a person as a registered NDIS provider is subject to:

(a) a condition that the person comply with all applicable requirements of the Code of Conduct: s 73F(2)(b); and

(b) a condition that the person comply with all applicable standards and other requirements of the Practice Standards: s 73F(2)(c).

32 Section 73J of the NDIS Act provides that a person contravenes that section if they are a registered NDIS provider and breach a condition to which the registration of the person is subject. Section 73T(1) provides that the NDIS rules may make provision for or in relation to standards concerning the quality of supports or services to be provided by registered NDIS providers. Rules made for the purposes of s 73T(1) are known as the “NDIS Practice Standards”: s 73T(2). A failure by a registered provider to comply with the NDIS Practice Standards will constitute a contravention of s 73J.

33 Section 73V(1) of the NDIS Act provides that the rules may make provision for or in relation to a code of conduct that applies to either or both NDIS providers and persons employed or otherwise engaged by NDIS providers. Rules made for the purposes of s 73V(1) are described as the “NDIS Code of Conduct”: s 73V(2). A person contravenes s 73V if the person is subject to a requirement under the Code of Conduct and fails to comply with the requirement: s 73V(3).

Declarations

34 The Commissioner seeks a number of declarations be made. As observed by Abraham J in Commissioner of the NDIS Quality and Safeguards Commission v Australian Foundation for Disability [2023] FCA 629, the power to grant declaratory relief, under s 21 of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) is a broad, discretionary one, for which there are a number of considerations at [39]:

39 The power to grant declaratory relief pursuant to s 21 of Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) “is a very wide one” and the court is “limited only by its discretion”: Seven Network Ltd v News Ltd [2009] FCAFC 166; (2009) 182 FCR 160 at [1016], citing Forster v Jododex Australia Pty Ltd [1972] HCA 61; (1972) 127 CLR 421 (Forster) at 435. Three requirements need to be satisfied before making declarations: (1) the question must be a real and not a hypothetical or theoretical one; (2) the applicant must have a real interest in raising it; and (3) there must be a proper contradictor: Foster at 437-438. That a party has chosen not to oppose a grant of particular declaratory relief is not an impediment to such relief being granted by the Court: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v MSY Technology Pty Ltd [2012] FCAFC 56; (2012) 201 FCR 378 at [14], [30]-[33]. Other factors relevant to the exercise of the discretion include: (a) whether the declaration will have any utility; (b) whether the proceeding involves a matter of public interest; and (c) whether the circumstances call for the marking of the Court’s disapproval of the contravening conduct: ASIC v Pegasus Leveraged Options Group Pty Ltd [2002] NSWSC 310; (2002) 41 ACSR 561 at 571; Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Monarch FX Group Pty Ltd, in the matter of Monarch FX Group Pty Ltd [2014] FCA 1387; (2014) 103 ACSR 453 at [63]; Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Stone Assets Management Pty Ltd [2012] FCA 630; (2012) 205 FCR 120 at [42].

35 LiveBetter submits that the declaratory relief sought by the Commissioner is appropriate.

36 The circumstances of this case call for declaratory relief. The determination of whether contraventions occurred in the agreed circumstances is not hypothetical or theoretical. As observed above, the Commissioner has a statutory obligation to uphold the rights of, and promote the health, safety and wellbeing of, people with disability as well as to ensure compliance. The Commissioner and the general public have an interest in it being raised. Effective compliance includes preventive measures, in part facilitated by the transparent pursuit of compliance through Court proceedings. This includes ensuring that current and potential contraveners understand the circumstances giving rise to the contravention(s) and the consequences for such contravening conduct. Accordingly, declaratory relief aids compliance. The tragic circumstances of this case speak loudly in favour of the Court, as strongly as possible, marking its disapproval of the contravening conduct.

Penalty

37 The Court’s power to order LiveBetter pay a pecuniary penalty to the Commonwealth arising from its admitted contraventions of the NDIS Act stems from, and is governed by, Pt 4 of the RP Act: see s 73ZK of the NDIS Act. Relevantly, ss 82 to 87 of the RP Act prescribe the power to award a penalty (s 82) including matters the Court must take into account (s 82(6)), its enforcement (s 83), when to fix only one pecuniary penalty where the relevant conduct constitutes a contravention of two or more civil penalty provisions (s 84) and the making of a single penalty where the contraventions are founded on the same facts, or if the contraventions form, or are part of, a series of contraventions of the same or a similar character (s 85). The relevant provisions are as follows:

82 Civil penalty orders

Application for order

(1) An authorised applicant may apply to a relevant court for an order that a person, who is alleged to have contravened a civil penalty provision, pay the Commonwealth a pecuniary penalty.

(2) The authorised applicant must make the application within 6 years of the alleged contravention.

Court may order person to pay pecuniary penalty

(3) If the relevant court is satisfied that the person has contravened the civil penalty provision, the court may order the person to pay to the Commonwealth such pecuniary penalty for the contravention as the court determines to be appropriate.

Note: Subsection (5) sets out the maximum penalty that the court may order the person to pay.

(4) An order under subsection (3) is a civil penalty order.

Determining pecuniary penalty

(5) The pecuniary penalty must not be more than:

(a) if the person is a body corporate—5 times the pecuniary penalty specified for the civil penalty provision; and

(b) otherwise—the pecuniary penalty specified for the civil penalty provision.

(6) In determining the pecuniary penalty, the court must take into account all relevant matters, including:

(a) the nature and extent of the contravention; and

(b) the nature and extent of any loss or damage suffered because of the contravention; and

(c) the circumstances in which the contravention took place; and

(d) whether the person has previously been found by a court (including a court in a foreign country) to have engaged in any similar conduct.

83 Civil enforcement of penalty

(1) A pecuniary penalty is a debt payable to the Commonwealth.

(2) The Commonwealth may enforce a civil penalty order as if it were an order made in civil proceedings against the person to recover a debt due by the person. The debt arising from the order is taken to be a judgement debt.

84 Conduct contravening more than one civil penalty provision

(1) If conduct constitutes a contravention of 2 or more civil penalty provisions, proceedings may be instituted under this Part against a person in relation to the contravention of any one or more of those provisions.

(2) However, the person is not liable to more than one pecuniary penalty under this Part in relation to the same conduct.

85 Multiple contraventions

(1) A relevant court may make a single civil penalty order against a person for multiple contraventions of a civil penalty provision if proceedings for the contraventions are founded on the same facts, or if the contraventions form, or are part of, a series of contraventions of the same or a similar character.

Note: For continuing contraventions of civil penalty provisions, see section 93.

(2) However, the penalty must not exceed the sum of the maximum penalties that could be ordered if a separate penalty were ordered for each of the contraventions.

38 The Court’s task in imposing a civil penalty under s 82 has been described in a pithy, succinct way by Abraham J, which I adopt, in Australian Foundation for Disability at [45]:

45 The nature of the court’s task in imposing a civil penalty under s 82 of the RPA, is to impose such pecuniary penalty as the court determines to be appropriate, having regard to all relevant matters, including those set out in s 82(6) of the RPA. That process involves an intuitive or instinctive synthesis of all of the relevant factors: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Coles Supermarkets Australia Pty Limited [2015] FCA 330; (2015) 327 ALR 540 at [6]; TPG Internet Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2012] FCAFC 190; (2012) 210 FCR 277 at [145]. Instinctive synthesis is the method by which the judge identifies all the factors that are relevant to the penalty and, after weighing all of those factors, reaches a conclusion that a particular penalty is the one that should be imposed: Markarian v The Queen [2005] HCA 25; (2005) 228 CLR 357 at [37]: and see viagogo AG v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2022] FCAFC 87; at [129]-[133], [148]-[151]. Section 82(6) sets out the factors required to be taken into consideration. In Balasubramaniyan at [93], the Court recognised that those factors are not exhaustive of what may be relevant, and the factors identified in other civil penalty contexts may also be relevant (recognising presently that there is overlap with the s 82(6) factors). The factors identified additionally include matters such as: the seriousness of the conduct; the size of the contravening company; the deliberateness of the contravention and the period over which it extended; whether further contraventions are likely; whether the contravention arose out of conduct of senior management; whether the contravenor has a corporate culture conducive to compliance as evidenced by educational programs and disciplinary or other corrective measures in response to an acknowledged contravention; and whether there has been co-operation with the authorities, including in the context of the proceedings.

39 Whilst s 82(6) requires that certain factors be taken into account, they are not exhaustive, and the Court is required to give consideration to all the relevant circumstances. Particular regard is to be given to the maximum penalty (which in this case is $277,500). This yardstick assists in determining where on the spectrum the contravening conduct sits and whilst a spectral analysis does not necessarily lead to a penalty being at the top or bottom of the range, ordinarily there “must be some reasonable relationship between the theoretical maximum and the final penalty imposed”: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Reckitt Benckiser (Australia) Pty Ltd [2016] FCAFC 181; 340 ALR 25 at [156]; Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Pattinson [2022] HCA 13; 274 CLR 450 at [53].

40 After considering the appropriate penalties to be awarded for each contravention, the Court’s task does not end with an arithmetic tally. Rather, a final overall consideration is given the sum of the penalties determined, described as the application of the totality principle, to determine whether the total penalty is appropriate for all of the contraventions: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Australian Safeway Stores Pty (1997) 145 ALR 36 at 53.

41 Relevantly, given in this case the parties have reached an agreement as to the appropriate penalty, the High Court has described it as being unexceptional that a Court could accept an agreed submission. In this context, the Court must be “sufficiently persuaded of the accuracy of the parties’ agreement as to facts and consequences, and that the penalty which the parties propose is an appropriate remedy in the circumstances thus revealed”: Commonwealth v Director, Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate (Agreed Penalties Case) [2015] HCA 46; 258 CLR 482 at [46] (French CJ, Kiefel, Bell, Nettle and Gordon JJ).

Consideration

42 The Commissioner, being an authorised applicant, seeks a civil penalty order under s 82 of the RP Act. Sections 73J and 73V are civil penalty provisions enforceable under the RP Act: s 73ZK NDIS Act. In accordance with ss 85 and 84(2) of the RP Act, the Commissioner seeks a single civil penalty order of $1,800,000 with respect to the 17 contraventions set out at [10] above.

43 Whilst the single civil penalty sought was agreed between the parties following mediation, I am not bound to accept it. However, I accept the holding in the Agreed Penalties Case, as to the public interest in bringing litigation to an end, that it is “highly desirable in practice” for the Court to do so when “sufficiently persuaded of the accuracy of the parties’ agreement as to facts and consequences, and that the penalty which the parties propose is an appropriate remedy in the circumstances”: Agreed Penalties Case at [46].

44 The primary purpose of any civil penalty regime is to ensure compliance with the statutory regime by deterring future contraventions by both specifically LiveBetter, in this case, and generally by other would be contraveners: Pattinson at [10], [15]–[16] and [25] (Kiefel CJ, Gageler, Keane, Gordon, Steward and Gleeson JJ).

45 By statutory command, the nature of the Court’s task in imposing a civil penalty under s 82 of the RP Act is to impose “such pecuniary penalty as the court determines to be appropriate, having regard to all relevant matters, including those set out in s 82(6) of the RPA”. The task involves an “intuitive or instinctive synthesis of all of the relevant factors”: Australian Foundation for Disability at [45] and cases cited therein.

46 It is my view that each of the claimed contraventions has been established based on the agreed facts.

47 As outlined above, there was no issue between the parties as to the identification of the number of contraventions (17) and as to the operation of ss 84 and 85 of the RP Act. The Commissioner only seeks one penalty be imposed for contraventions two and three, identified at [10] above, of ss 73J and 73V concerning breaches of cl 21 of Sch 1 Pt 4 to the Practice Standards and s 6(c) of the Code of Conduct respectively. I accept that by operation of s 84(2) of the RP Act, LiveBetter can only be liable for one penalty given the contraventions are in relation to the same conduct.

48 Furthermore, I am of the view that there was one contravention for each of the failures to provide formal training and to formally assess with respect to each of the seven support workers. Accordingly, as submitted by LiveBetter, it failed to comply with cl 10 of Sch 1 Pt 3 to the Practice Standards in contravention of s 73J of the NDIS Act on 14 occasions (seven occasions concerning the failure to formally train each of the support workers and seven occasions to formally assess each of them).

49 The Commissioner submitted the contravening conduct resulted in death, which is of the utmost seriousness. He submitted that the agreed penalty of $1,800,000 gives effect to the primary objects of general and specific deterrence given LiveBetter’s contraventions were repeated, serious and had foreseeable and potentially serious consequences, as demonstrated by the terrible consequences of the breaches. Furthermore, he submitted that the breaches occurred in the circumstance that LiveBetter assumed the responsibilities inherent in a socially very important Commonwealth scheme for provision of critical services to the most vulnerable members of the community, and their families. Additionally, general deterrence requires a civil penalty of the magnitude of the agreed penalty. Providers need to understand the importance of compliance with the various requirements of the statutory scheme.

50 I will now address each of the relevant factors.

51 It is worthwhile, before addressing each of the relevant factors, in the assessment of the appropriate penalties, to recall the different proposed penalties for each contravention as agreed between the parties.

52 The parties agree that the penalties for the failures that occurred on 2 February 2022 ought to attract close to the maximum penalty payable under ss 73J and 73V of the NDIS Act: 84.7% of the maximum penalty (being $235,000) with respect to the failure by LiveBetter to conduct a formal risk assessment of Ms Lucas’ residence prior to providing bathing supports in breach of cl 10 of Sch 1 Pt 3 to the Practice Standards; and 99.8% of the maximum penalty (being $277,000) with respect to the failures to ensure access to responsive, timely, competent and appropriate supports to meet Ms Lucas’ needs, desired outcomes and goals on in breach of cl 21 of Sch 1 Pt 4 to Practice Standards and its failure to provide bathing supports in a safe and competent manner, with care and skill in breach of s 6(c) of the Code of Conduct.

53 With respect to remaining contraventions relating to the failure to train and formally assess the competency of the relevant support workers, $92,000 per each of the 14 contraventions is sought, totalling $1,288,000.

The nature and extent of the contraventions

54 The contraventions were objectively extremely serious. LiveBetter’s failures were antithetical to stated object of the statutory scheme, to protect and prevent Ms Lucas from harm arising from unsafe supports and services provided under the Scheme.

55 LiveBetter accepts that, whilst providing in-home bathing supports to Ms Lucas on 81 occasions during the relevant period, at no time did LiveBetter:

(a) identify the risks to Ms Lucas in the provision of the bathing supports;

(b) conduct formal training of each of the Relevant Support Workers to safely provide bathing supports to Ms Lucas such that their training was inadequate; or

(c) assess the competency of each of the Relevant Support Workers to safely provide bathing supports to Ms Lucas such that LiveBetter’s assessment was inadequate.

Nature and extent of the loss and damage

56 The specific harm suffered by Ms Lucas was of the most acute kind, so too can it be said of the harm to Ms Lucas’ family: s 82(6)(b). There are no words to properly express the degree of the harm suffered. LiveBetter accepts that the nature and extent of the contraventions causing loss are serious as they ultimately resulted in the death of Ms Lucas: s 86(6)(a).

57 Furthermore, as agreed by the parties, the parties agree as to the magnitude of the general harm: The absence of adequate training for and assessment of the competency by LiveBetter of the relevant support workers in the provision of in-home bathing supports had the potential to manifest in serious consequences for any one of its clients and in the case of Ms Lucas, was fatal. The failure to identify and manage readily apparent risks in the provision of bathing supports was a significant, foreseeable risk for which LiveBetter accepts responsibility.

Circumstances in which the contraventions took place

58 It is of significance, that Ms Lucas’ mother placed her child in LiveBetter’s care and her family were entitled to expect that LiveBetter would be capable of delivering bath supports safely. Ms Lucas was particularly vulnerable to burns because of her disabilities and unable to verbally express discomfort. LiveBetter accepts that bathing supports involve an inherent risk of burns.

59 In this context, it is worthwhile recalling that there is an acceptance that the parties have agreed that almost the maximum penalties ought to be imposed with respect to the contravening conduct which occurred on 2 February 2022 and the failure to conduct a formal risk assessment. This is appropriate given the clear causal connection between these failures and what occurred on that day.

60 A different approach has been taken by the parties with respect to the failures regarding training and competency assessments. There is an acceptance as to the general seriousness of these failures, but the following matters have bearing on the appropriate penalties to be attributed to these contraventions and ultimately to the application of the totality principle, which I will address later.

61 It is relevant that during the relevant period, on 80 occasions, prior to 2 February 2022, LiveBetter provided in-home bathing supports to Ms Lucas without incident. It is of relevance, that regarding the training and competency assessment failures that it is not a case of complete failure but rather the adequacy of what was done. The evidence reveals that LiveBetter provided some formal training to support workers on testing water temperature in baths and showers. While LiveBetter accepts that such training was inadequate in the provision of services to Ms Lucas, it was not the case that no training was provided at all.

62 The formal training was supplemented by 'on the job' training. Some attempts were made to check the bathing temperature on 2 February 2022. On that day, one of the two support workers responsible for bathing Ms Lucas ran the hot water tap in the bath then added cold water for approximately 1–2 minutes. She then scooped her bare hand in the bath water, closer to the tap than the side of the bath, to check the temperature. She considered the temperature to be fine and did not observe steam coming off of the water. Whilst of course, the testing was completely inadequate, it was not the case that the support worker did not test the water temperature at all. It is agreed that LiveBetter's contraventions were not deliberate.

The contravener’s circumstances

63 It is relevant, from the perspective of both general and specific deterrence to consider the nature of LiveBetter’s enterprise. LiveBetter, is the largest provider of disability services in regional New South Wales – namely Far West New South Wales and Western New South Wales. LiveBetter also provides additional services of community transport, in-home out of hospital care, and Carer Gateway services.

64 As at June 2023, LiveBetter's unencumbered funds report shows $1,359,647 of unencumbered funds, comprising of:

(a) cash and cash equivalents of $62,077,367;

(b) liabilities of $40,733,109; and

(c) internally restricted funds constituted of:

(i) $11,795,925 of accumulated depreciation;

(ii) $1,092,508 of vehicle replacement reserve;

(iii) $2,496,178 business process improvement reserve;

(iv) $4,600,000 internal cash reserve requirement.

65 In the financial year ended 30 June 2023, LiveBetter’s audited financial report discloses that it reported:

(a) an operating loss of $5,366,889;

(b) total revenue and other income of $116,822,810;

(c) total expenditure of $122,189,699;

(d) net assets of $49,602,390.

66 LiveBetter submitted, without challenge, that its total expenditure typically exceeds its total revenue and income and its cash reserves are used to meet its liabilities. As at June 2023, LiveBetter only had $1,359,647 in unencumbered funds.

Mitigatory factors

67 In the following mitigatory factors are relevant to the assessment of the penalties.

68 After Ms Lucas’ untimely death, a representative from LiveBetter’s executive team and Board spoke with Ms Lucas’ mother and father on a number of occasions, apologising for the incident and offering additional support. LiveBetter continues to provide support services to Ms Lucas’ family.

69 In addition, at hearing, LiveBetter publicly apologised to Ms Lucas’ mother and father for its role in the tragedy, accepting that its employees were at Ms Lucas’ home, on 2 February 2022 to care for Ms Lucas and LiveBetter accepts, that through its failures, it contributed to Ms Lucas’ tragic death.

70 LiveBetter has co-operated, in a real sense, both at the investigative and curial stages of this matter. The NDIS Quality and Safeguards Commission commenced an investigation into Ms Lucas' death. LiveBetter cooperated with the investigation by complying with notices, in a timely way, which compelled the provision of information and the production of documents issued by officers of the NDIS Commission and by responding to requests for information made by officers of the NDIS Commission.

71 The Commissioner commenced the proceeding by filing an originating application and concise statement on 30 March 2023. LiveBetter filed a concise statement in response on 16 June 2023 making admissions to some allegations. The parties then attended mediation on 2 August 2023, the immediate consequence of which was a settlement of the proceeding. The admissions made by LiveBetter both in its pleading and as part of the settlement were at an early stage of the proceeding before the service or filing of any evidence.

72 In addition, LiveBetter has co-operated with other relevant governmental agencies and has produced materials relating to the incident to:

(a) the NSW Police on 8 February 2022;

(b) the Health Care Complaints Commission on 22 and 28 June 2022; and

(c) the NSW Coroner on 24 April 2023.

Prior contravention history

73 It is accepted that LiveBetter has no prior contravention history.

Remediation efforts

74 Since the incident, LiveBetter has restructured its services to ensure that all in-home supports are grouped together to ensure consistent policies, procedures and standard of care.

75 LiveBetter has also implemented formal training, policies and procedures regarding safe bathing over the period of April to August 2022 including:

(a) Taking the Temperature of Bathing Water Instruction – document reference INS-CLI-0004;

(b) Supported Bathing Policy – document reference POL-CLI-0009; and

(c) Safe Bathing of Customers Procedure – document reference PRO-CLI-0011.

76 These attempts at remediation go to the rectification of the inadequacy of training.

77 In addition, the parties filed supplementary documentation and a supplementary SOAF regarding what LiveBetter has done to better manage the risks to participant safety (as required under cl 10 of the Practice Standards) by ensuring in addition to the adequacy of training, its complement, the adequacy of the assessment of support workers’ competency is performed: see Annexure B to these reasons. I am satisfied that LiveBetter has addressed this issue. Since late 2022, LiveBetter has implemented a mandatory formal assessment in relation to proper bathing techniques, by both additional training, and the requirement of a quiz which includes specific questioning regarding the correct water temperature of the bath or shower being up to a maximum of 40 degrees Celsius. In addition, staff are required to complete a work sheet recording the water temperature of the bath or shower every time that caring service is provided. That sheet reinforces what is contained in the Quality Support Visit Checklist, the New Staff in Home Support Checklist and the Home Safety Assessment Checklist regarding the testing of the water temperature by thermometer. All support workers are required to complete this training when they commence employment and again annually. As at 27 March 2024, 95% of LiveBetter’s staff had completed the portion of the mandatory training which includes bathing safely considerations and detailed instructions regarding the testing of bath water temperature.

Further considerations

78 It is appropriate in the circumstances that the near maximum be awarded for the first three contraventions (noting that the second and third must be grouped by operation of s 84(2) of the RP Act). These obligations are in a sense, as couched by both the Practice Standards and the Code of Conduct, strict obligations.

79 As to the remaining fourteen contraventions, I accept that it is appropriate that the corresponding penalty fixed for each of these training and competency contraventions is lower than the first three contraventions. This is because these breaches are of a different kind: these training and competency contraventions concern the adequacy, not complete absence, of training and assessment.

80 Furthermore, whilst there is a difference between a contravention arising from training and a contravention relating to competency assessment, the individualisation of these contraventions must be taken into account; they are closely related and achieve common purposes. The consequences of both failures overlap. Whilst the absence of training and assessment may be culminative (missteps along the way), ultimately there is a causative acuteness with respect to the failures on 2 February 2022. To the extent that the failures included the failure to train and assess the competency of the two support workers who provided Ms Lucas with supports on 2 February 2022, I accept there is some overlap between the failures on that day (giving rise to the near maximum penalties) and these failures.

81 I accept, as the High Court observed, in the Agreed Penalties case, at [60], that a regulator in a civil penalty proceeding is not disinterested. Here, I have already adverted to the Commissioner’s statutory functions including promoting the appropriate standards and compliance. As a consequence, as observed by the High Court, it can be assumed in this case that the Commissioner has fashioned the penalty submissions (and the agreed amount) “with an overall view to achieving that objective and thus perhaps, if not probably, with one eye to considerations beyond the case at hand”. It may also be assumed, as the High Court essayed, that it can be expected that the regulator will be in a position to offer informed submissions as to the effects of contravention on the industry and the level of penalty necessary to achieve compliance.

82 It is my view that the application of the totality principle does not call for any reduction or increase in the penalty proposed by the parties.

Conclusion

83 For the reasons stated above, it is appropriate for the Court to grant the declaratory relief sought. In addition, it is appropriate for the Court to impose a pecuniary sum of $1,800,000 noting that by so awarding that penalty, almost the maximum penalty has been awarded with respect to the specific contraventions closely aligned with Ms Lucas’ tragic, untimely death.

I certify that the preceding eighty-three (83) numbered paragraph is a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice Raper. |

Associate:

Annexure A

Annexure B