FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Lehrmann v Network Ten Pty Limited (Trial Judgment) [2024] FCA 369

ORDERS

Applicant | ||

AND: | First Respondent LISA WILKINSON Second Respondent | |

LEE J | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Judgment for the respondents on the statement of claim.

2. The parties file submissions as to the costs order for which they contend, and any evidence they rely upon in relation to costs, on or by 22 April 2024.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

[1] | |

[14] | |

[15] | |

[15] | |

[20] | |

[24] | |

[27] | |

[30] | |

[35] | |

[38] | |

[41] | |

[47] | |

[47] | |

[52] | |

[58] | |

[59] | |

[63] | |

[67] | |

[70] | |

[76] | |

[90] | |

[90] | |

[96] | |

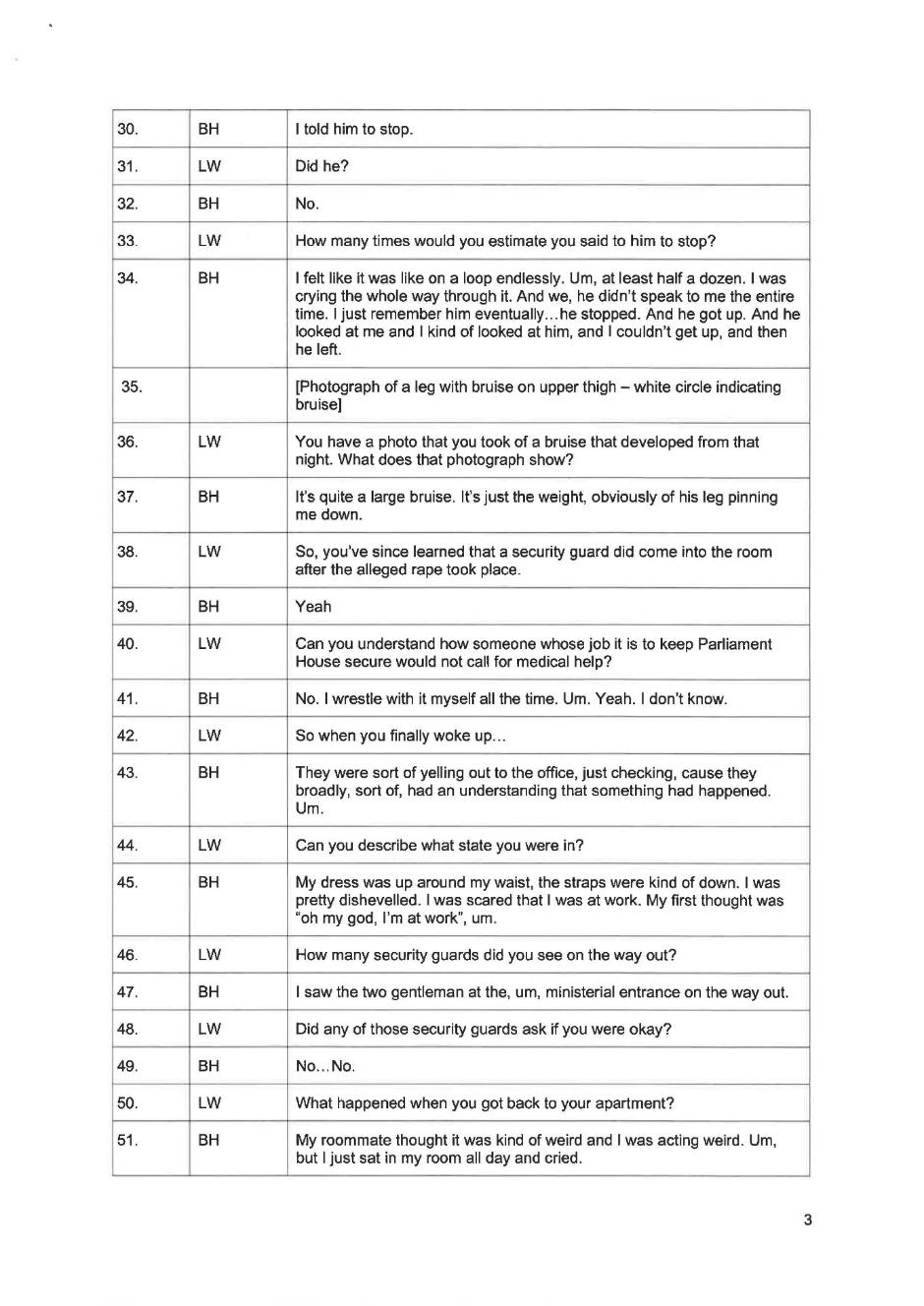

E.3 The Practical Difference Between the Civil and Criminal Standard | [105] |

[112] | |

[122] | |

E.6 The Court is Not Bound to Accept Either of the Parties’ Accounts | [126] |

[133] | |

[136] | |

[139] | |

[146] | |

[149] | |

[149] | |

II Miscellaneous Examples of False Statements during the Hearing | [154] |

[164] | |

[170] | |

[172] | |

[180] | |

[180] | |

[185] | |

[190] | |

[201] | |

[206] | |

[207] | |

[212] | |

[222] | |

[232] | |

[236] | |

[242] | |

[248] | |

[255] | |

[258] | |

[260] | |

[280] | |

[286] | |

[296] | |

[302] | |

[304] | |

[324] | |

[328] | |

[330] | |

[331] | |

[336] | |

[338] | |

[338] | |

[343] | |

III 2-3 March 2019: Drinks at the Kingston Hotel and Related Events | [345] |

[365] | |

[371] | |

[375] | |

[379] | |

[387] | |

[394] | |

[403] | |

[406] | |

[416] | |

G.2 A Snapshot in Time: Things We Know as to the Position as at 1:40am | [428] |

[443] | |

G.4 Whisky, and the Accounts of What Happened Inside the Ministerial Suite | [458] |

[459] | |

[464] | |

[465] | |

[473] | |

[489] | |

[501] | |

[502] | |

[511] | |

[525] | |

[548] | |

[551] | |

[561] | |

[561] | |

[562] | |

[562] | |

[575] | |

[588] | |

IV Further Observations as to Mr Lehrmann’s “Critical” Submission | [603] |

[613] | |

[620] | |

[622] | |

[630] | |

[630] | |

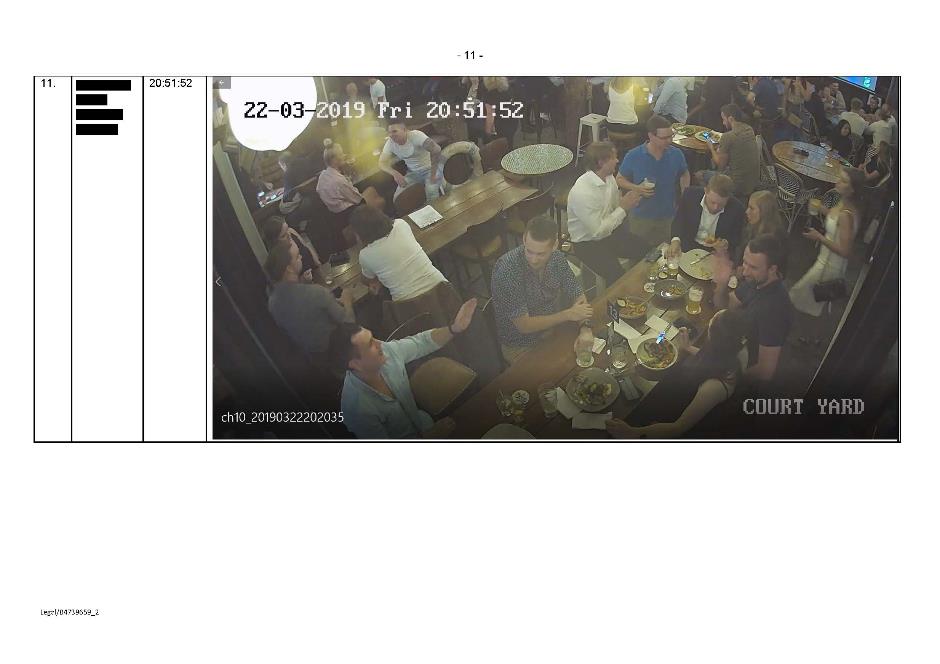

I.2 The Immediate Aftermath: Miscellaneous Matters Referred to in Submissions | [632] |

I.3 The Role of the AFP and the 2019 Decision of Ms Higgins not to Proceed | [656] |

[708] | |

[719] | |

[733] | |

[740] | |

[742] | |

[754] | |

[760] | |

[760] | |

[767] | |

[782] | |

I The First Interview, Weaponisation, Incomplete Data, and the Bruise Photograph | [789] |

[832] | |

[843] | |

[849] | |

[862] | |

[875] | |

[886] | |

[889] | |

[899] | |

[901] | |

[901] | |

[909] | |

[909] | |

[919] | |

K.3 Introduction and the General Approach of the Respondents | [922] |

[936] | |

[938] | |

[964] | |

[964] | |

[965] | |

[967] | |

[968] | |

[971] | |

[971] | |

[976] | |

M.3 Three Particular Issues as to Ordinary Compensatory Damages | [980] |

[981] | |

[989] | |

[998] | |

[1009] | |

[1023] | |

[1023] | |

[1026] | |

[1029] | |

[1032] | |

[1055] | |

[1056] | |

[1057] | |

[1063] | |

[1065] | |

[1069] | |

[1075] | |

[1077] | |

[1089] | |

[1091] | |

ANNEXURE A – TRANSCRIPT OF PROJECT PROGRAMME (EX 1) | |

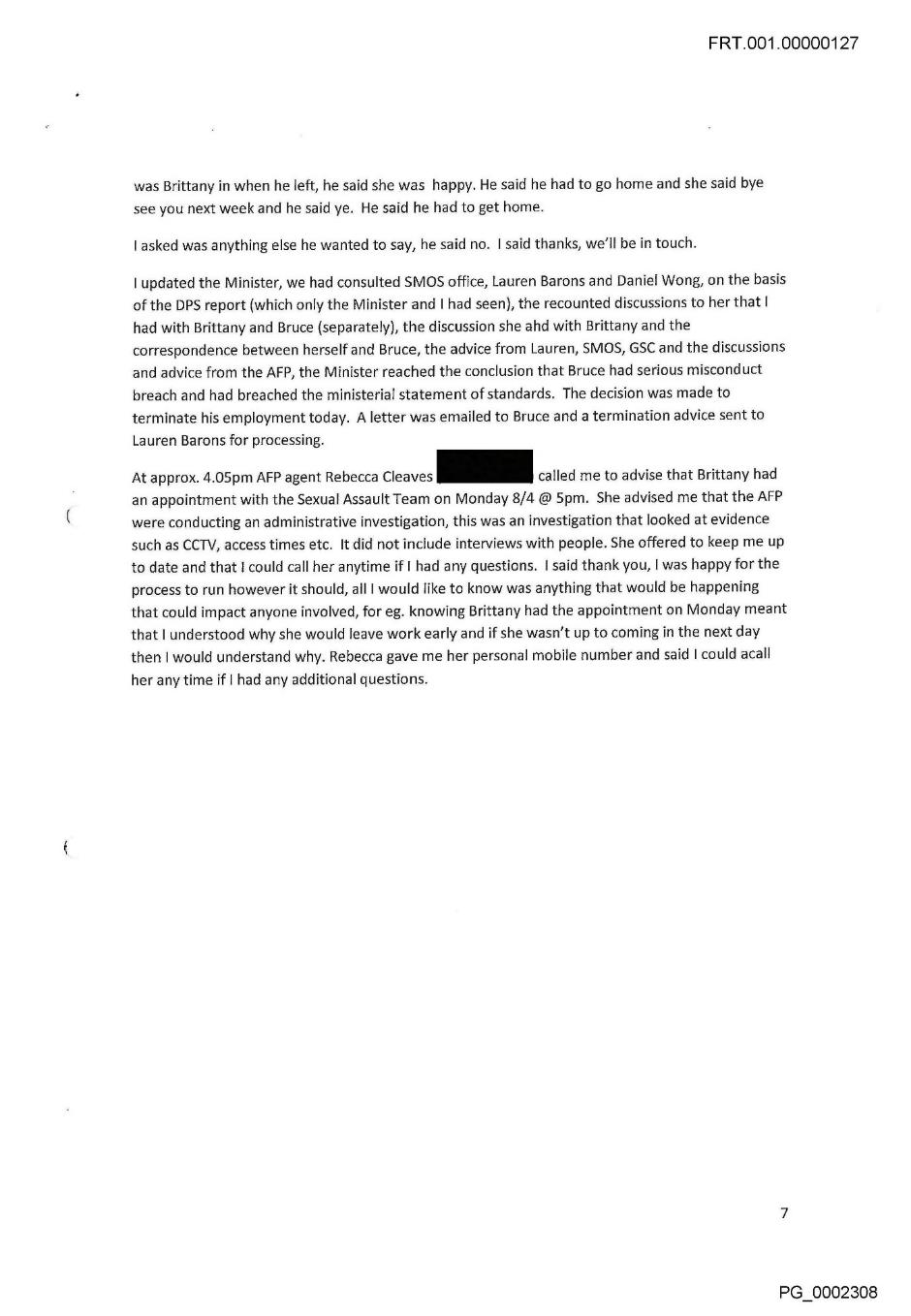

ANNEXURE B – NOTES OF MS FIONA BROWN (EX R87) | |

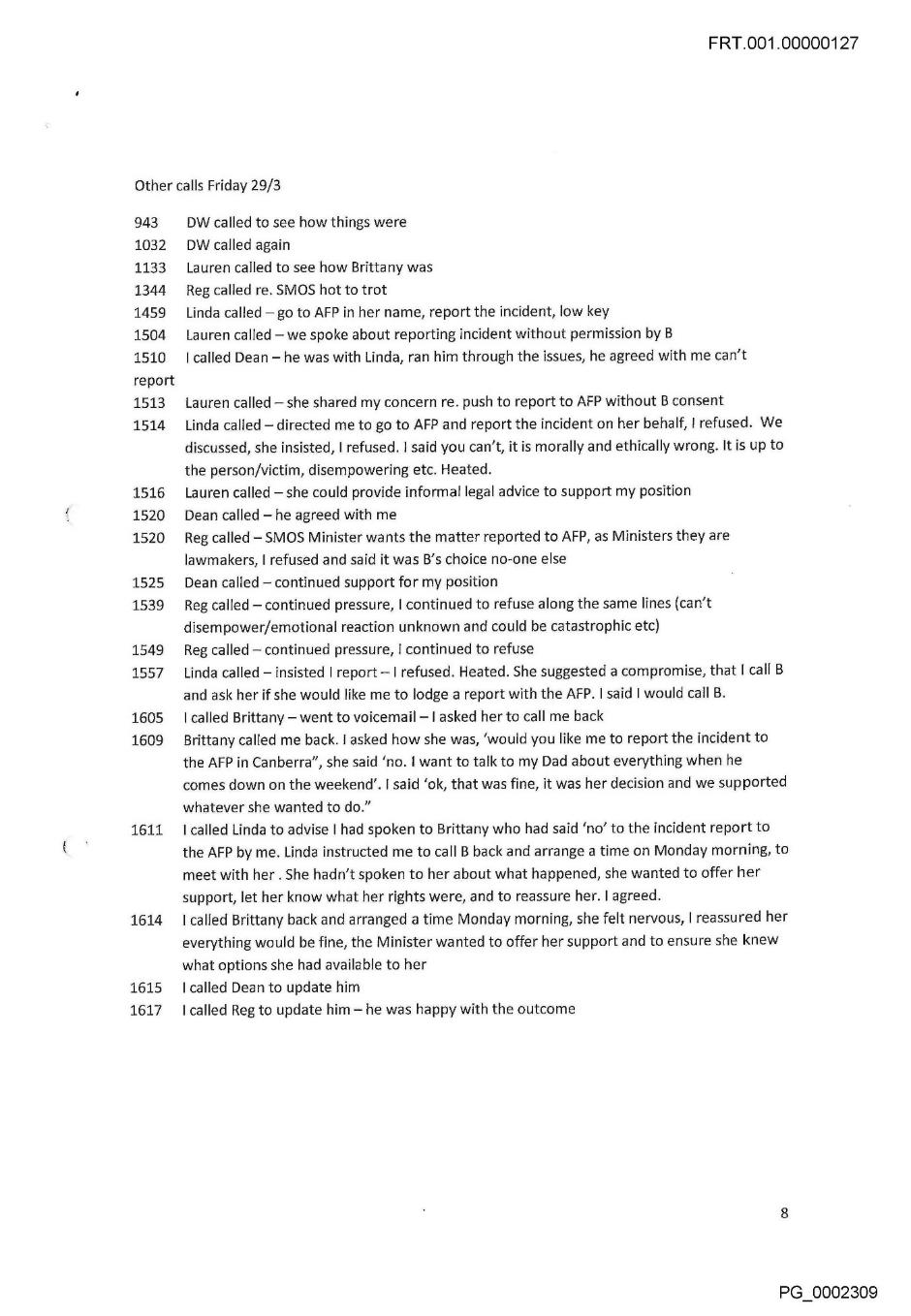

ANNEXURE C – MINISTERIAL SUITE FLOORPLAN (EX R1) | |

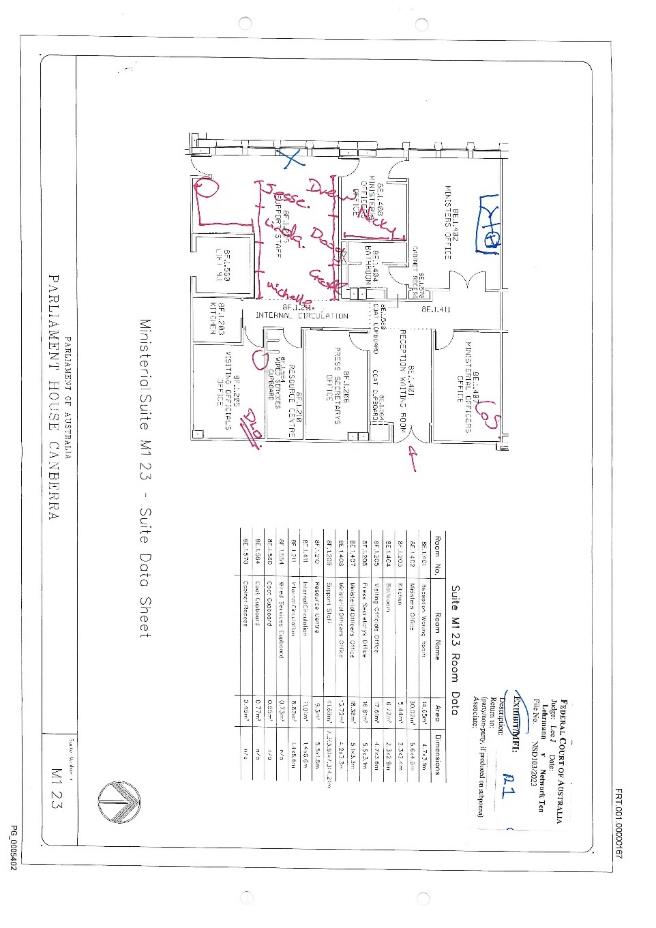

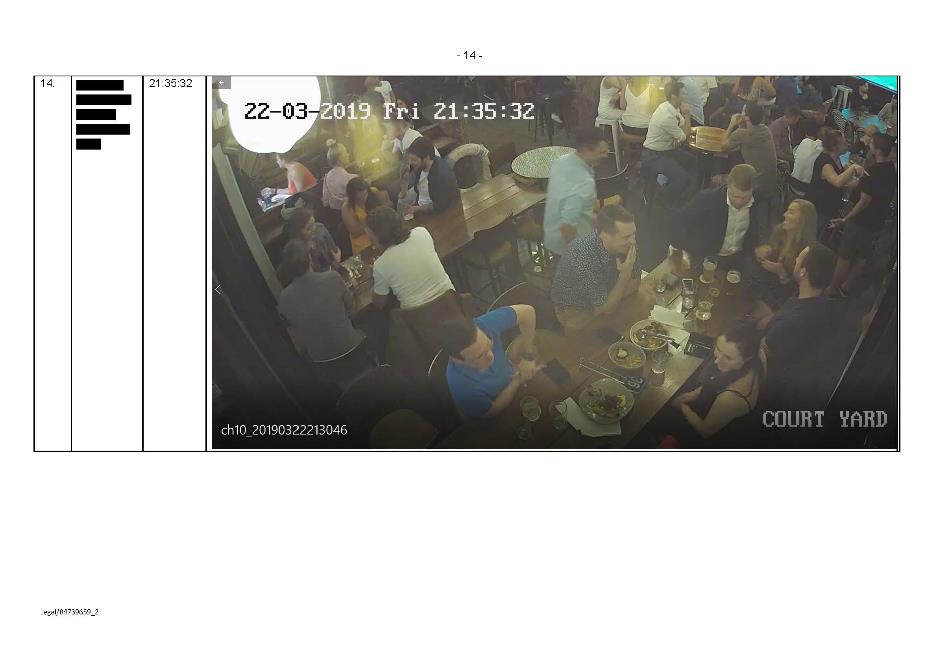

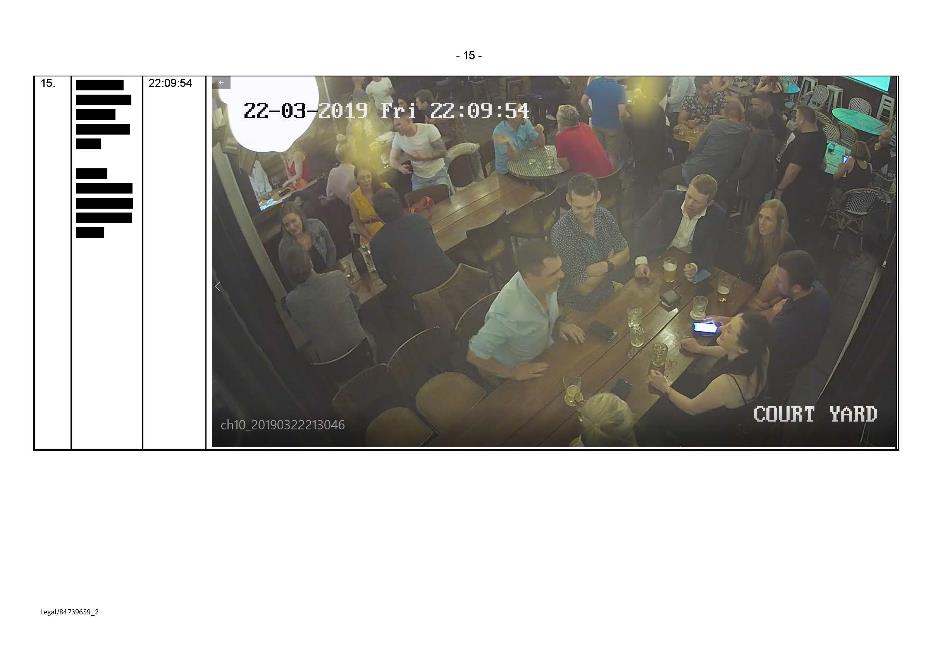

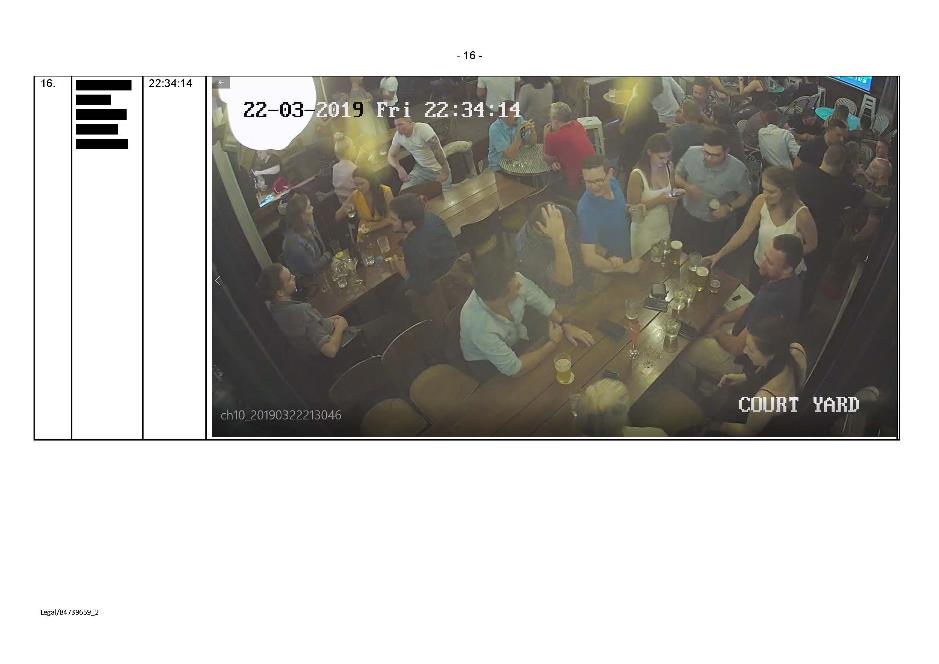

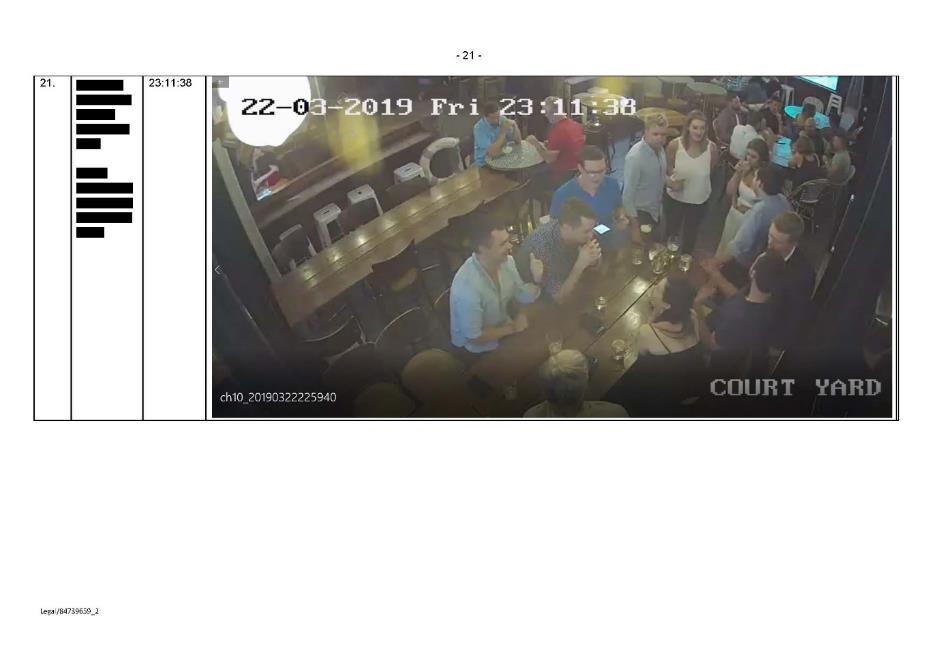

ANNEXURE D – CCTV IMAGES FROM THE DOCK (EX R17–R30) | |

LEE J:

1 Mr Bruce Lehrmann sues Network Ten Pty Limited (Network Ten) and Ms Lisa Wilkinson (together, the respondents) in defamation in relation to an episode of Network Ten’s The Project programme (Project programme).

2 It is a singular case: the underlying controversy has become a cause célèbre. Indeed, given its unexpected detours and the collateral damage it has occasioned, it might be more fitting to describe it as an omnishambles.

3 For some people, any unwelcome findings will be peremptorily dismissed. The reasoning process, including the drawing of fine distinctions based upon the subtleties of the evidence, will be of no interest. This reaction is inevitable given that several observers have a Rorschach test-like response to this controversy and fasten doggedly upon the “truth” as they perceive it. Their response is visceral because the “truth” is revealed and declaimed, rather than proven and explained. Some jump to predetermined conclusions because they are disposed to be sceptical about complaints of sexual assault and hold stereotyped beliefs about the expected behaviour of rape victims, described by social scientists as “rape myths”; others say they “believe all women”, surrendering their critical faculties by embracing and acting upon a slogan arising out of the #MeToo movement. Some have predetermined views as to the existence or otherwise of a conspiracy to suppress a rape for political purposes. For more than a few, this dispute has become a proxy for broader cultural and political conflicts.

4 This judgment is not written for people who have made up their mind before any evidence was adduced or are content to rest upon preconceived opinions. It is written to set out my factual findings comprehensively and explain my decision to the parties and to the open and fair-minded.

5 To achieve this end, from the start of this case, I have attempted to ensure as transparent a process as possible, conscious that a trial conducted in public, accessible to the public, and only upon evidence and submissions made fully available to the public, was the best security for confidence of the fair-minded in the impartiality and efficiency of the justice system.

6 An astute observer would have gleaned from the trial that this case is not as straightforward as some commentary might suggest. In part, this is because the primary defence hinges on the truth of an allegation of sexual assault behind closed doors. Only one man and one woman know the truth with certitude.

7 For an impartial outsider seeking to divine the truth (or, more accurately, ascertaining what most likely happened), two connected obstacles emerged.

8 The first is, at bottom, this is a credit case involving two people who are both, in different ways, unreliable historians.

9 Countless scholarly articles have been written seeking to explain the frailties of human memory and why it is that different people may remember the same event in different ways. People give unreliable evidence for various reasons and distinguishing between a false memory and a lie can often be difficult. Aspects of so-called “witness demeanour” or physiological signs of deceit are of little use unless the witness is cognitively aware of their deception. Recognising these realities, judges are reluctant to characterise a false representation as a lie unless another explanation is unavailable and it is necessary to do so to resolve a controversy. But as we will see, this is a case where credit findings are central and sometimes an explanation other than mendacity is not rationally available.

10 To remark that Mr Lehrmann was a poor witness is an exercise in understatement. As I will explain, his attachment to the truth was a tenuous one, informed not by faithfulness to his affirmation but by fashioning his responses in what he perceived to be his forensic interests. Ms Brittany Higgins, Mr Lehrmann’s accuser, was also an unsatisfactory witness who made some allegations that made her a heroine to one group of partisans, but when examined forensically, have undermined her general credibility to a disinterested fact-finder.

11 The second and related obstacle was the assertion that what went on between these two young and relatively immature staffers led to much more. By early 2021, allegations of wrongdoing had burgeoned far beyond sexual assault. It was said a sexual assault victim had been forced by malefactors to choose between her career and justice. The perceived need to expose misconduct (and the institutional factors that allowed it) meant the rape allegation was not pursued in the orthodox way through the criminal justice system, which provides for complainant anonymity.

12 As we will also see, when examined properly and without partiality, the cover-up allegation was objectively short on facts, but long on speculation and internal inconsistencies – trying to particularise it during the evidence was like trying to grab a column of smoke. But despite its logical and evidentiary flaws, Ms Higgins’ boyfriend selected and contacted two journalists and then Ms Higgins advanced her account to them, and through them, to others. From the first moment, the cover-up component was promoted and recognised as the most important part of the narrative. The various controversies traceable to its publication resulted in the legal challenge of determining what happened late one night in 2019 becoming much more difficult than would otherwise have been the case.

13 I will come to the legal issues, the principles that have guided fact-finding, some observations concerning the credit of various witnesses, and then my findings as to what relevantly went on. But before doing so, I will explain some uncontroversial matters and the issues in the case.

B THE PARTICIPANTS AND SOME BACKGROUND FACTS

14 Most of the important facts are contested. This section records some uncontroversial details as to the principal participants, the publications, and this and related proceedings.

15 Mr Lehrmann was born in 1995 in Texas. His father died in Mr Lehrmann’s infancy.

16 His mother, who was born in Australia, relocated to northern New South Wales with Mr Lehrmann and his younger sister. The family then moved to Toowoomba in Mr Lehrmann’s final years of primary school.

17 From a young age, Mr Lehrmann had a preternatural interest in politics. Upon leaving school, in 2014, he moved to Canberra to undertake study at the Australian National University. His first foray into politics came at the time he started university, as an electorate officer.

18 In March 2016, Mr Lehrmann commenced employment as an office manager with the then Commonwealth Attorney-General, before assuming a role as a health policy advisor to the then Assistant Minister for Health, in August 2017.

19 At the end of 2017, Mr Lehrmann commenced employment as a health policy advisor with the then Minister for Rural Health and Sport, a position he held until October 2018, when he became a policy advisor to the Hon Senator Linda Reynolds CSC, then Assistant Minister for Home Affairs.

20 Ms Higgins was born in Queensland in 1994. She grew up on the Gold Coast, completing her schooling there and later graduated from Griffith University. In 2017, she was employed as a staffer for Mr Samuel O’Connor MP, a member of the Queensland Parliament.

21 Ms Higgins moved to Canberra around September 2018 to commence work as an administrative assistant in the Ministerial office of the Hon Steven Ciobo MP. Around this time, she began a relationship with Mr Benjamin Dillaway, the media advisor to Mr Ciobo, which lasted until February or early March 2019. The pair remained close (and at times intimate) friends.

22 In early March 2019, Mr Ciobo announced his pending resignation and, shortly thereafter, Senator Reynolds received a commission to become the Minister for Defence Industry.

23 Ms Higgins was then successful in her application for a role as an administrative officer and junior media advisor in Senator Reynolds’ office.

24 Ms Wilkinson has been a journalist for over forty years. She has held a wide range of prominent roles. Her beginnings were in print journalism. Her first job was as an editorial assistant and cadet journalist at Dolly magazine. She held various roles at Dolly and Cleo magazines from 1978 to 1995, including rising to become editor-in-chief of both magazines from 1988 to 1995, and was editor-at-large of the Australian Women’s Weekly from 1999 to 2007.

25 Ms Wilkinson first turned to television in 1996. She rose to lounge-room prominence in the early 2000s, as co-host of The Morning Shift. Between 2004 and 2007, she was a news contributor and regular fill-in co-host of the Seven Network’s Sunrise and Weekend Sunrise programmes and, from 2007 to 2017, co-host of Today on the Nine Network.

26 In 2017, Ms Wilkinson became co-host of The Project and The Sunday Project, a role she held at the time of publication.

27 Mr Angus Llewellyn has been a producer for The Project since 2019. He is employed by 7PM Company Pty Ltd, which provides Network Ten with production services for The Project.

28 Mr Llewellyn is highly experienced and has held various producer roles in radio, including at the ABC, Radio 2UE, and television programmes, including the Seven Network’s Sunday Night; SBS’s Dateline and Insight; and the ABC’s Lateline.

29 Ms Wilkinson and Mr Llewellyn are both based in Sydney and have frequently worked together since about October 2019. They first met in about 2006 when Mr Llewellyn worked with Ms Wilkinson’s husband.

B.2 Publication of the Impugned Matters

30 On the morning of 15 February 2021, an article entitled “Young staffer Brittany Higgins says she was raped at Parliament House”, authored by Ms Samantha Maiden (Maiden article), was published on the news.com.au website.

31 Mr Lehrmann became aware of the Maiden article around the time it was published. I have set out the relevant chronology in Lehrmann v Network Ten Pty Limited (Limitation Extension) [2023] FCA 385 (limitation judgment) and do not propose to repeat it here.

32 It suffices to note that by 2pm that day, Mr Lehrmann had been informed that “government sources” were identifying him as the man accused of sexually assaulting Ms Higgins. His work supervisor, Mr Joshua Fett, informed Mr Lehrmann that Ms Rosie Lewis, a journalist at The Australian, had emailed Mr Fett to this effect.

33 That evening, Network Ten broadcast the Project programme, and republished it on the 10 Play website and The Project’s YouTube channel shortly thereafter. Mr Lehrmann watched the broadcast live from his then solicitor’s office.

34 It is common ground that the television broadcast attracted a national audience of over 725,000 people, from every state and territory. The publication on the 10 Play website had over 17,000 views, and the publication on YouTube had nearly 190,000 views.

35 On 17 August 2021, Mr Lehrmann was charged with one count of engaging in sexual intercourse with Ms Higgins without her consent, contrary to s 54(1) of the Crimes Act 1900 (ACT) (Crimes Act). On the same day, Mr Lehrmann was identified by “mainstream” media outlets as the person accused of the offence by Ms Higgins.

36 The trial was originally fixed to commence in the Supreme Court of the Australian Capital Territory on 27 June 2022, but was vacated by McCallum CJ six days earlier for reasons explained in R v Lehrmann (No 3) [2022] ACTSC 145; (2022) 299 A Crim R 276. The trial ultimately commenced before McCallum CJ and a jury of sixteen on 4 October 2022. A jury of twelve retired on 19 October 2022 and was discharged eight days later by reason of juror misconduct.

37 On 2 December 2022, the Director of Public Prosecutions, Mr Shane Drumgold SC, announced that he did not intend to proceed with the prosecution. The reason was said to be the ill-health of the complainant, Ms Higgins.

38 Mr Lehrmann brought this proceeding and a (now discontinued) proceeding against News Life Media and Ms Maiden (News Life proceeding) out of time, requiring him to seek an extension of the limitation period, which was granted for the reasons given in the limitation judgment.

39 He later commenced a proceeding within time against the ABC (ABC proceeding) in relation to the broadcast of an address given by Ms Higgins, alongside Ms Grace Tame, at the National Press Club in February 2022. The ABC proceeding travelled with this proceeding until the first day of the trial, when a settlement was formalised.

40 In December 2023, competing cross-claims were filed in this Court as between Ms Wilkinson and Network Ten in relation to an indemnity for legal costs (cross-claims). I directed that the cross-claims be heard separately, and they have been the subject of a judgment (Lehrmann v Network Ten Pty Limited (Cross-claims) [2024] FCA 102 (cross-claims judgment)). The only present relevance of the cross-claims is that each party agreed that evidence on the cross-claims be evidence in this proceeding.

41 Mr Lehrmann sues on three matters published on 15 February 2021, being the Project programme:

(1) broadcast on Network Ten;

(2) published on the 10 Play website; and

(3) published on The Project’s YouTube channel.

42 The substance of each matter is relevantly identical, and the transcript of the programme, being an aide memoire to Ex 1, is annexed to these reasons as Annexure A. I will refer to the impugned matters collectively as the Project programme.

43 Mr Lehrmann in the statement of claim (SOC) says the Project programme, in its natural and ordinary meaning, was defamatory of him and carried the following imputations:

SOC Reference | Imputation |

[4(a)]; [6(a)]; [8(a)] | [Mr Lehrmann] raped Brittany Higgins in Defence Minister Linda Reynolds’ office in 2019. |

[4(b)]; [6(b)]; [8(b)] | [Mr Lehrmann] continued to rape Brittany Higgins after she woke up mid-rape and was crying and telling him to stop at least half a dozen times. |

[4(c)]; [6(c)]; [8(c)] | [Mr Lehrmann], whilst raping Brittany Higgins, crushed his leg against her leg so forcefully as to cause a large bruise. |

[4(d)]; [6(d)]; [8(d)] | After [Mr Lehrmann] finished raping Brittany Higgins, he left her on a couch in a state of undress with her dress up around her waist. |

44 Network Ten and Ms Wilkinson deny the matters concerned Mr Lehrmann but, if they did, they admit the pleaded imputations were conveyed, and are defamatory of Mr Lehrmann: Network Ten’s defence (at [4(b)], [6(b)], [8(b)]); Ms Wilkinson’s defence (at [4.3], [4.4], [6.3], [6.4], [8.3], [8.4]).

45 Both respondents also say the pleaded imputations do not differ in substance from one another: Network Ten’s defence (at [4(c)], [6(c)], [8(c)]); Ms Wilkinson’s defence (at [4.5], [6.5], [8.5]). As Ms Wilkinson puts it, the pleaded imputations “contain gratuitous and irrelevant rhetorical flourish that adds nothing to the defamatory sting of rape”.

46 What was conveyed by the Project programme was not in issue, and I do not propose to rehearse the uncontroversial principles as to defamatory meaning. In short, the question of what was conveyed and whether it is defamatory depends upon what the ordinary reasonable viewer would understand, and it is common ground that if the Project programme identified Mr Lehrmann, the hypothetical referee would understand it conveyed the pleaded meanings, with the sting being an accusation of rape.

47 Identification is an essential element of defamation and Mr Lehrmann must establish the Project programme is “about” or “of and concerning” him: s 8 of the Defamation Act 2005 (NSW) (Defamation Act). That is, Mr Lehrmann must show that at least one person who viewed the Project programme reasonably understood the allegations concerned him: David Syme & Co v Canavan (1918) 25 CLR 234 (at 238 per Isaacs J).

48 Despite the pleadings, the contest in this case is not, however, whether at least one person identified Mr Lehrmann, so as to perfect the cause of action. Instead, what is really in dispute is the extent of identification: that is, the persons (or classes of persons) who reasonably identified Mr Lehrmann, which is relevant to damages and the defence of common law qualified privilege.

49 Mr Lehrmann contends he was reasonably identified by three classes of persons, being those:

(1) who either worked in Senator Reynolds’ office or had regular dealings with that office and, consequently, knew Mr Lehrmann: (a) was a “senior male advisor” to Senator Reynolds; (b) had previously worked for Senator Reynolds in the Home Affairs portfolio; (c) had attended a drinks event with Ms Higgins and other contacts and colleagues in Defence on the night of the alleged rape; (d) was called into a meeting with Ms Fiona Brown, Chief of Staff to Senator Reynolds, on the following Tuesday, after which he started packing up his belongings; and (e) by February 2021, had obtained a job in Sydney;

(2) who worked in Parliament, being federal politicians, assistants and staffers, journalists, and other persons, including family, friends and acquaintances of Mr Lehrmann; such that Mr Lehrmann’s identity must have been known generally to such persons through discussions and, provided they were not already aware, they would have soon discovered that he was the subject of the Project programme; and

(3) who were invited to speculate as to the identity of the person accused; such that a large, indeterminate number of viewers would have reasonably concluded, having read (or subsequently read) a series of social media posts and/or articles published online, that the programme identified Mr Lehrmann.

50 In establishing identification, Mr Lehrmann called Ms Kathleen Quinn, Ms Karly Abbott, and Mr David McDonald (identification witnesses). Additionally, Mr Lehrmann relies upon other witnesses who gave evidence that they identified Mr Lehrmann (either prior to airing or shortly thereafter).

51 I will return to this evidence below, but I will first expand upon the relevant principles.

52 The inquiry as to identification has two stages, which reflect the traditional and differing roles of judge and jury in a defamation case.

53 The first concerns whether, as a matter of law, the impugned publication is capable of identifying the applicant: that is, whether an ordinary sensible person could draw an inference that the publication referred to the applicant, with the Court’s function to determine the outer limits of the possible range of meanings: Corby v Allen & Unwin Pty Ltd [2014] NSWCA 227 (at [133] per McColl JA, with whom Bathurst CJ and Gleeson JA agreed). Indeed, “great caution” is mandated at this stage because the conclusion which necessarily underpins a finding that the matter is incapable of conveying the pleaded imputations is that no viewer could reasonably understand the publication to bear any meaning outside the range delimited by the judge: Corby (at [136] per McColl JA). It is an “exercise in generosity not parsimony”: Berezovsky v Forbes [2001] EWCA Civ 1251 (at [16] per Sedley LJ).

54 The second stage is for the trier of fact to decide whether the publication actually identified the applicant. As noted above, the fact-finder must determine whether, upon the evidence, persons with special knowledge of the applicant reasonably understood the publication to concern him: David Syme (at 238 per Isaacs J). However, identification does not require that readers or viewers already have the requisite knowledge at the time of the publication: Fairfax Media Publications Pty Ltd v Pedavoli [2015] NSWCA 237; (2015) 91 NSWLR 485 (at 503 [81] per Simpson JA, McColl JA agreeing).

55 Identification may be established by direct or indirect evidence. As Mason P observed in Channel Seven Sydney Pty Ltd v Parras [2002] NSWCA 202 (at [57]), an indirect way is where the applicant gives evidence of being contacted by people in circumstances showing that such contact was obviously a response to what they read in the publication (it was said of one member of the New South Wales Bar – now deceased – that it was remarkable how often his clients seemed to be importuned by strangers in the street commenting upon defamatory publications).

56 A variant of such evidence is “talk” or “tittle tattle” among readers or viewers indicative of identification. The Court must be satisfied that such evidence is capable of supporting the inference that the responses to the defamatory matter showed that the persons concerned reasonably understood it to refer to the applicant.

57 Whether the identification was correct is relevant to the question of reasonableness. As Bryson JA (with whom Mason P and Tobias JA agreed) observed in Gardener v Nationwide News Pty Ltd [2007] NSWCA 10 (at [47]), any purpose for establishing that identification was reasonable is well satisfied if it can be shown the identification was correct: see also Steele v Mirror Newspapers Ltd [1974] 2 NSWLR 348 (at 371–374 per Samuels JA).

58 As noted earlier, Mr Lehrmann adduced direct evidence from the identification witnesses, whose evidence I accept.

59 Ms Abbott met Mr Lehrmann around 2016 when he was employed in the Office of the Attorney-General. Since that time, she has “got to know [Mr Lehrmann] reasonably well” and considers him a friend (Abbott (at [6])).

60 Ms Abbott viewed the Project programme when broadcast and identified Mr Lehrmann because she knew he: (a) was an advisor to Senator Reynolds and, although he was not a “senior advisor”, he was senior to Ms Higgins; (b) had previously worked for Senator Reynolds in the Home Affairs portfolio; (c) was involved in “an incident involving Brittany” in the office which resulted in him being “fired” (information received from a conversation in July 2019 with a colleague, Mr Drew Burland); and (d) worked in Sydney.

61 Ms Abbott was aware of these matters, at least in part, because she had read the Maiden article and connected the allegations to Mr Lehrmann from the conversation with Mr Burland in July 2019 (T48.40–45; T45.20–21). She had a conversation with Mr Dillaway in which he said, concerning the Maiden article, “This is Bruce” (Abbott (at [12])).

62 Ms Abbott explained that following the broadcast, there were conversations and exchanges of text messages among political staffers and other participants in the Canberra rumour mill about identity (Abbott (at [11]); T47.19–48.1; T49.7). In the context of these conversations, Ms Abbott’s evidence is that she “[did not] believe that there was any other specific names mentioned to me, but just a ‘Do you know who this is?’ Or …” (T47.42–44).

63 Ms Quinn is Ms Abbott’s business partner.

64 Ms Quinn met Mr Lehrmann around 2016 and they interacted in work and social settings. She viewed the Project programme and identified Mr Lehrmann because he: (a) was an advisor to Senator Reynolds who was senior to Ms Higgins; (b) had previously worked with Senator Reynolds in the Home Affairs portfolio; and (c) ceased working for Senator Reynolds in about March 2019 and was working in Sydney for British American Tobacco (BAT) (Quinn (at [6])).

65 In cross-examination, Ms Quinn explained that prior to airing, she was aware of “a rumour that there had been a security incident in the office, and that was why Bruce had left” (T113.24–42). She discussed the Maiden article, and the fact that it was about Mr Lehrmann, with Ms Abbott prior to the broadcast (T114.34–116.5).

66 In the days following the broadcast, Ms Quinn noted the allegations were a “hot topic” of discussion among staffers (Abbott (at [8])). She recalled conversations with close to a dozen such people over a couple of days and recalled them saying that (T112.13–15):

Bruce was the person that had been identified in The Project broadcast and asking my opinion of his character and whether or not I had ever experienced anything untoward from him.

67 Mr McDonald is a close friend of Mr Lehrmann and his family. He watched the Project programme with his wife when it was aired, to whom he said: “this has to be about Bruce” (McDonald (at [7])).

68 Mr McDonald identified Mr Lehrmann from the programme because: (a) it stated that the former colleague was a male advisor to Senator Reynolds; (b) the person had previously worked for Senator Reynolds in the Home Affairs portfolio; and (c) the person had ceased working for Senator Reynolds in March 2019 and had moved to Sydney (McDonald (at [6]); T56.45–57.20). Mr McDonald promptly discussed the broadcast with his neighbour and said: “it looks like Bruce is in a bit of strife” (McDonald (at [9])).

69 Notwithstanding those identifying facts, in cross-examination, Mr McDonald conceded that he could not exclude the possibility that there were other men working for Senator Reynolds who fell within the description above (T57.40–44).

70 Mr Lehrmann also relies upon other testimony adduced from witnesses of broader significance and to whose evidence I will return, in detail, below. Insofar as they gave evidence relevant to identification, it was as follows.

71 Ms Nicole Hamer explained she watched the broadcast and knew, at that time, that the alleged perpetrator was Mr Lehrmann (T1064.5–1066.4). Prior to publication, she recalled unspecific discussions among people working in Parliament about the upcoming programme, during which Mr Lehrmann was named (T1065.41–45). Ms Hamer did not understand at the time that there was any other person to whom the allegations could relate, but accepted in re-examination that different names were mentioned (T1069.32–41).

72 Mr Austin Wenke gave evidence he read the Maiden article on the morning of the broadcast and watched some (but not all) of the Project programme (T1126.7–8). Following the publication of the Maiden article, Mr Wenke agreed there was “a bit of chatter within Parliament House [about the story]” (T1125.11–22). He concluded the allegations in the Maiden article concerned Mr Lehrmann and he did not recall thinking the allegations could have referred to anyone else (T1125.24–41). He agreed it was fair to characterise the identity of the alleged perpetrator referred to in the Maiden article as an “open secret” within Parliament House (T1126.14–22).

73 Major Nikita Irvine watched the Project programme. She gave evidence she received questions about it from colleagues in the military but did not want to discuss it (T1207.1–36). Major Irvine identified Mr Lehrmann because (as we will see) Ms Higgins had disclosed details of the incident to her in March 2019 (T1207.35–36) (Irvine (at [60]–[61])).

74 Mr Dillaway gave evidence he read the Maiden article. He knew the allegations concerned Mr Lehrmann because Ms Higgins had told him in March 2019 that Mr Lehrmann had sexually assaulted her (Dillaway (at [42]–[50])). He gave evidence “what was in that story was consistent with what she had told me previously” (T1276.11–25) and that he had a vague recollection of watching the Project programme (T1277.13).

75 Mr Lehrmann himself gave evidence of the actions of various acquaintances (with whom he had not remained in contact) following the broadcast (see, for example, Ex 8). In particular, he referred to a screenshot of a Facebook Messenger group chat (which had included Mr Lehrmann) which showed an image of an “EJECT” button, followed by several members leaving the group chat (Ex 11).

D.4 Identification Established

76 While there is necessarily some degree of overlap, given it is in issue, it is best not to elide the two stages of the relevant inquiry.

77 As to the first, it is plain as a pikestaff the Project programme was capable of identifying Mr Lehrmann. As noted earlier, there were several tell-tales, being (Ex 1, Annexure A):

(1) he was a “senior male advisor” to Senator Reynolds who had a “special bond” with her (lines 7–8), and was “a bit of a favourite [of the Senator]” (line 9);

(2) he “had been advising her in the home affairs portfolio prior to [working in the Defence Industry portfolio]” (line 10);

(3) he attended drinks with colleagues in Defence on 22 March 2019 (line 11);

(4) the following Tuesday morning, Ms Brown called the alleged perpetrator in for a meeting, following which he “immediately walked out of the office and started packing up his things” (lines 53–55); and

(5) the alleged perpetrator was, as at the date of broadcast, “working in Sydney … he’s got a good job” (line 157).

78 Even accounting for a certain degree of factual inaccuracy (for example, whether Mr Lehrmann was a “senior advisor”), the references above correspond to the particularised knowledge of the applicant possessed by the identification witnesses and other witnesses: see Plymouth Brethren (Exclusive Brethren) Christian Church v The Age Company Ltd [2018] NSWCA 95; (2018) 97 NSWLR 739 (at 756 [77] per McColl JA). In the light of that special knowledge, the ordinary reasonable viewer possessing that knowledge could understand that Mr Lehrmann was the subject of the allegations.

79 As to the second stage, I am amply satisfied that Mr Lehrmann was in fact identified.

80 First, Mr Lehrmann was reasonably identified by persons with special knowledge. Each of the identification witnesses identified Mr Lehrmann with knowledge they had acquired by working in Parliament, or by reason of being a friend or family acquaintance. It is immaterial whether they identified Mr Lehrmann from the Maiden article: what matters is the identification witnesses reasonably identified Mr Lehrmann from information contained in the programme. With the exception of Mr McDonald, who could not exclude the possibility he thought the programme may have referred to another person, it is significant for the purposes of assessing reasonableness that Ms Abbott and Ms Quinn were correct in their identification.

81 Secondly, it is important that several witnesses gave evidence of gossip and rumour both before and after the Project programme was broadcast. The fact that such “chitter chatter” took place is indicative of the kind of evidence referred to in Pedavoli whereby recipients of such information tend to make efforts to discover identity, thereby expanding the circle of people with the requisite knowledge.

82 This is sufficient to establish identification and perfect the cause of action, but given the need to focus on the extent of identification, it is necessary to say something more.

83 Reliance by Mr Lehrmann upon the third category, being other persons who may have identified Mr Lehrmann by reason of the Twitter/X “firehose” or “grapevine effect” presents difficulties: see Kumova v Davison (No 2) [2023] FCA 1 (at [319]). Unlike other cases where the “Twittersphere” trends with a name following a publication, as Mr Lehrmann conceded in cross-examination, his solicitors, despite their best efforts, could not locate any Tweets around the time of the broadcast which named Mr Lehrmann as the subject of the Project programme, save for a Tweet published by True Crime Weekly (Ex 7; T484.33–485.33) together with some articles on a website “Kangaroo Court of Australia” (Ex 4, 5 and 6).

84 All of this, including Mr Lehrmann’s evidence as to being contacted on social media following the broadcast, reflects very modest social media dissemination compared to other defamations provoking speculation as to identity.

85 It was less a firehose and more the splutter of an insecurely fastened sprinkler.

86 Before leaving the topic of identification, for completeness, it is worth dealing with a discrete point made by Ms Wilkinson.

87 In her written and oral closing submissions, Ms Wilkinson referred to a number of authorities concerning “small group identification” and, in particular, the decision of Hunt J in McCormick v John Fairfax & Sons Ltd (1989) 16 NSWLR 485 as authority for the proposition that in circumstances where there is a small group of persons referred to in an impugned publication, the matter is incapable of conveying an imputation of guilt unless it impugns every member of the class (at 488D–491D). In short, Ms Wilkinson submits this is relevant because Mr Lehrmann has not excluded the possibility that viewers reasonably identified him as one of a small group of persons who could have met the description of the alleged perpetrator, namely Mr Jesse Wotton, who worked for Senator Reynolds in March 2019.

88 I do not accept this submission, for the following reasons.

89 First, there were identifying facts which, for those armed with special knowledge, would have ruled Mr Wotton out as the alleged culprit; namely: (1) Mr Wotton did not leave Senator Reynolds’ office in March 2019; and (2) Mr Wotton was not working in Sydney in February 2021. Secondly, although not determinative of the question of identification by others, it is telling that when asked whether he was concerned that people might think he was the subject of Ms Higgins’ allegations, Mr Wotton gave evidence that he was not concerned because he was “quite confident in the fact that people [knew me well] … or were in a position to find out should they make their own inquiries” (T1092.32–37). Thirdly, prior to broadcast, Network Ten successfully took steps to guard against confusion with any other male who worked in Senator Reynolds’ office at the time. As Mr Llewellyn explained (Llewellyn (at [167(a)])):

We were very conscious that we did not want to inadvertently identify the wrong person as being the alleged perpetrator. We had to give sufficient detail to exclude other males who worked in Linda Reynolds’ office at the relevant time.

E APPROACH TO FACT-FINDING, ONUS, AND THE STANDARD OF PROOF

90 It is next appropriate to set out how I have directed myself as to fact-finding, the burden of proof, the standard of proof, and other more particular matters given the nature of the principal allegation.

91 Without introducing complications arising from the differing ways in which the phrase “burden of proof” has been used – and the differences between legal and evidential burdens (as to which see C R Williams, ‘Burdens and Standards in Civil Litigation’ (2003) 25(2) Sydney Law Review 165), I will use the expression burden or onus of proof as simply being the identification of which party has to demonstrate the case or an aspect of the case propounded, whereas the standard of proof is the applicable benchmark that the evidence adduced must meet to discharge that onus.

92 The question of who bears the onus in aspects of this case is straightforward. Mr Lehrmann had (and has successfully discharged) his onus in proving he has been defamed as alleged; the respondents now bear the onus of proof with respect to their defences. If those defences fail and Mr Lehrmann is entitled to damages, he will then be required to prove the compensatory damages he seeks.

93 What this means is that in order to make out the defence of substantial truth, the respondents need to discharge their onus of proving that Mr Lehrmann raped Ms Higgins. The nature of this aspect of the forensic contest brings with it considerations that are necessary to canvass in further detail.

94 I have discussed the relevant principles at length a number of times (see, for example, Transport Workers’ Union of Australia v Qantas Airways Limited [2021] FCA 873; (2021) 308 IR 244 (at 324–325 [284]–[288])). Notwithstanding this, it is worth referring to Besanko J’s recent survey of matters relevant to onus and proof in Roberts-Smith v Fairfax Media Publications Pty Ltd (No. 41) [2023] FCA 555. In Roberts-Smith, his Honour dealt with a number of matters relevant to: (a) the onus of proof in a justification or substantial truth case (at [93]–[94]); and (b) the standard of proof in a case where there is a serious allegation (at [95]–[110]). With respect, his Honour’s exposition in relation to these matters is comprehensive. I gratefully adopt the above-mentioned paragraphs.

95 At the risk of supererogation, I will, however, say something in my own words. I will also deal with the agreed facts relevant to Ms Higgins’ credit and some miscellaneous matters, which have informed my approach to the evidence.

E.2 Relevant Observations as to Standard of Proof

96 As to the standard of proof, the starting (and end) point is s 140 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) (EA), which relevantly provides:

Civil proceedings: standard of proof

(1) In a civil proceeding, the court must find the case of a party proved if it is satisfied that the case has been proved on the balance of probabilities.

(2) Without limiting the matters that the court may take into account in deciding whether it is so satisfied, it is to take into account:

(a) the nature of the cause of action or defence; and

(b) the nature of the subject-matter of the proceeding; and

(c) the gravity of the matters alleged.

97 The matters set out in subsection (2)(a), (b) and (c) are mandatory but not exhaustive considerations; other considerations may also be relevant, including the inherent likelihood of the occurrence of the fact alleged and the notion that all evidence is to be weighed according to the proof which it was in the power of one side to have produced, and the other to have contradicted: Blatch v Archer (1774) 1 Cowp 63 (at 65 per Lord Mansfield).

98 The concept used in subsection (1), being the “balance of probabilities”, is often misunderstood. It does not mean a simple estimate of probabilities; it requires a subjective belief in a state of facts on the part of the tribunal of fact. A party bearing the onus will not succeed unless the whole of the evidence establishes a “reasonable satisfaction” on the preponderance of probabilities such as to sustain the relevant issue: Axon v Axon (1937) 59 CLR 395 (at 403 per Dixon J). The “facts proved must form a reasonable basis for a definite conclusion affirmatively drawn of the truth of which the tribunal of fact may reasonably be satisfied”: Jones v Dunkel (1959) 101 CLR 298 (at 305 per Dixon CJ). Put another way, as Sir Owen Dixon explained in Briginshaw v Briginshaw (1938) 60 CLR 336 (at 361), when the law requires proof of any fact, the tribunal of fact must feel an actual persuasion of its occurrence or existence before it can be found.

99 Justice Hodgson put it differently, but to the same effect, by observing that when deciding facts, a civil tribunal of fact is dealing with two questions: “not just what are the probabilities on the limited material which the court has, but also whether that limited material is an appropriate basis on which to reach a reasonable decision”: see D H Hodgson, ‘The Scales of Justice: Probability and Proof in Legal Fact-finding’ (1995) 69 Australian Law Journal 731; Ho v Powell [2001] NSWCA 168; (2001) 51 NSWLR 572 (at 576 [14]–[16] per Hodgson JA, Beazley JA agreeing).

100 Whatever way it is put, a “[m]ere mechanical comparison of probabilities independent of a reasonable satisfaction will not justify a finding of fact”: NOM v DPP [2012] VSCA 198; (2012) 38 VR 618 (at 655 [124] per Redlich and Harper JJA and Curtain AJA); Brown v New South Wales Trustee and Guardian [2012] NSWCA 431; (2012) 10 ASTLR 164 (at 176 [51] per Campbell JA, Bergin CJ in Eq and Sackville AJA agreeing).

101 Although s 140 EA is now the starting point, the concepts it incorporates are neither new nor novel. Any fact-finding inquiry depends upon context. As Kiefel CJ, Gageler and Jagot JJ recently observed in GLJ v The Trustees of the Roman Catholic Church for the Diocese of Lismore [2023] HCA 32; (2023) 97 ALJR 857 (at 874–875 [57]), the statutory provision:

… reflects the position of the common law that the gravity of the fact sought to be proved is relevant to “the degree of persuasion of the mind according to the balance of probabilities”. By this approach, the common law, in accepting but one standard of proof in civil cases (the balance of probabilities), ensures that “the degree of satisfaction for which the civil standard of proof calls may vary according to the gravity of the fact to be proved”.

(Citations omitted)

102 As those acting for Mr Lehrmann correctly state, in Briginshaw, Dixon J (at 362) emphasised that reasonable satisfaction is not attained independently of the nature and the consequence of the fact to be proved, and his Honour referred to the seriousness of the allegation, the inherent unlikelihood of the alleged occurrence, or the gravity of the consequences flowing from the finding in question as matters which could all properly bear upon whether the court is reasonably satisfied or feels actual persuasion. The other members of the Court in Briginshaw also referred to the seriousness of the allegation sought to be proved as a matter relevant to whether or not the tribunal of fact could be satisfied of the fact alleged (at 347 per Latham CJ; 350 per Rich J; 353 per Starke J; and 372 per McTiernan J).

103 None of this is inconsistent with what I said in Kumova v Davison (No 2) (at [262]), where I noted “the focus on the gravity of the finding is linked to the notion that the Court takes into account the inherent unlikelihood of alleged misconduct”. They are linked in that both the inherent unlikelihood of the alleged occurrence and the gravity of the consequences each require consideration.

104 An allegation of rape ranks high in the calendar of criminal conduct, and, at the risk of repetition, the allegation needs to be approached with “much care and caution” and with “weight being given to the presumption of innocence and exactness of proof expected”: Briginshaw (at 347 per Latham CJ; 363 per Dixon J). Further, a finding of rape would, needless to say, be seriously damaging to Mr Lehrmann’s reputation and this consequence properly gives one pause before making it: Ashby v Slipper [2014] FCAFC 15; (2014) 219 FCR 322 (at 345–346 [68]–[69] per Mansfield and Gilmour JJ).

E.3 The Practical Difference Between the Civil and Criminal Standard

105 Although I will explain below why the allegations to be proved in making out the truth defence and the allegations to be made out by the Crown in the criminal proceeding are not identical, this is an example where the same essential wrongdoing is to be assessed by reference to both the criminal and the civil standard. Such cases are not common, and they bring into sharp focus cardinal aspects of our legal system.

106 Most first-year law students are introduced to the possibility of error of wrongful convictions and erroneous acquittals. They are (or at least were) made aware of what is often referred to as “Blackstone’s ratio”, being the fourth of five discussions of policy by Sir William Blackstone in his 1765 treatise Commentaries on the Laws of England, vol IV, ch 27 (Oxford University Press, 2016) (at 352) that “all presumptive evidence of felony should be admitted cautiously: for the law holds, that it is better that ten guilty persons escape, than that one innocent suffer”. I digress to note that this notion is ancient: the idea it is better to allow some guilty to escape rather than punish an innocent has Biblical origins (Genesis, 18:23–32) and later was the subject of discussion by Talmudic scholars (see Maimonides, The Commandments, Commandment No 290 (Charles B. Chavel, trans. 1967) (at 270)). Indeed, sixteen years before Blackstone, the concept had been expressed by Voltaire – albeit in a different ratio: “’tis much more prudence to acquit two persons, tho’ actually guilty, than to pass Sentence of Condemnation on one that is virtuous and innocent”: Voltaire, Zadig; or, The Book of Fate: An Oriental History (1749) (at 53).

107 In any event, this moral choice accommodating the possibility of error has been reflected in fundamental aspects of our criminal justice system, including the presumption of innocence and the logically connected requirement the burden of proof rests with the prosecution. It also finds reflection in the rigour of the criminal law standard of proof.

108 Hence, although it may be trite, it is worth stressing that in contrast to the present forensic contest, if this allegation of rape was to be determined at a criminal trial, it would not be open for the tribunal of fact to find the case proven unless it is satisfied that it has been proved beyond reasonable doubt: s 141(1) EA.

109 So even though it is necessary to bear in mind the mandatory s 140(2) EA factors and the cogency of the evidence necessary to establish rape on the balance of probabilities, and that the rape will not be proven unless I feel an actual persuasion of its occurrence, the difference between the criminal and civil standard of proof is substantive and can be decisive in dealing with the same underlying allegation.

110 Apart from anything else, this difference is evident from the necessity that in a criminal trial, the facts as established must be such as to exclude all reasonable hypotheses consistent with innocence.

111 By way of useful summary, as was emphasised by the High Court in Rejfek v McElroy (1965) 112 CLR 517 (at 521 per Barwick CJ, Kitto, Taylor, Menzies and Windeyer JJ):

[t]he difference between the criminal standard of proof and the civil standard of proof is no mere matter of words: it is a matter of critical substance. No matter how grave the fact which is to be found in a civil case, the mind has only to be reasonably satisfied and has not with respect to any matter in issue in such a proceeding to attain that degree of certainty which is indispensable to the support of a conviction upon a criminal charge.

E.4 Assessing the Credit of a Complainant of Sexual Assault

112 Another aspect of the context of this fact-finding exercise is that the determination of the justification defence involves, among other things, consideration of the credibility of evidence given by Ms Higgins, a person who alleges she is a victim of a sexual assault.

113 Prior to trial, Network Ten served purported expert evidence seeking to establish that aspects of Ms Higgins’ behaviour were not demonstrative of untruthfulness by reference to common or usual patterns of behaviour (as was anticipated would be asserted by Mr Lehrmann in cross-examination). This evidence was not proposed to be adduced by Network Ten in support of a submission that it was probable Ms Higgins was telling the truth, nor that her behaviour following the alleged rape rendered it more or less likely that the assault had occurred as alleged. Rather, the opinion evidence was said to support the proposition that any counterintuitive behaviour relied upon by Mr Lehrmann was of neutral significance.

114 It was a type of evidence discussed by Associate Professor Jacqueline Horan and Professor Jane Goodman-Delahunty in their article ‘Expert Evidence to Counteract Jury Misconceptions about Consent in Sexual Assault Cases: Failures and Lessons Learned’ (2020) 43(2) UNSW Law Journal 707. In that article (dealing with how so-called “rape myths” play a role in jury decision-making), the authors observed (at 710–11):

Legal authorities in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom and the United States of America accept that sexual assault myths and misconceptions have a potential to exert an undue influence on triers of fact when deliberating about a sexual assault case. To avoid this undesirable influence, courts rely on traditional processes to educate juries so that they can better assess the evidence in a sexual assault trial on a sound factual basis. The two primary mechanisms to counteract the undue influence of sexual assault myths are expert evidence and judicial directions.

Over the last decade, counterintuitive expert evidence has been permitted to educate the jury as to how complainants vary in their behaviour both during and following a sexual assault. Legal practitioners and academics have noted that this provision remains underused, despite the widely acknowledged need for this type of educative intervention.

115 Such opinions as to “counterintuitive evidence” have been admitted under s 108C(1) EA in criminal sexual assault trials in a number of cases, including: Hoyle v R [2018] ACTCA 42; (2018) 339 FLR 11 (at 46–48 [223]–[244] per Murrell CJ, Burns and North JJ); MA v R [2013] VSCA 20; (2013) 226 A Crim R 575 (at 586–587 [45]–[52] per Osborn JA; at 595 [95] per Redlich and Whelan JJA); R v Kirkham [2020] NSWDC 658 (at [41]–[42] per McLennan DCJ); Aziz (a pseudonym) v R [2022] NSWCCA 76; (2022) 297 A Crim R 345 (at 355–363 [49]–[92] per Simpson AJA, Lonergan J agreeing).

116 The evidence was objected to by Mr Lehrmann on a number of grounds, which are now unnecessary to detail. Prior to ruling on the objections, I raised with the parties my preliminary view that even if the evidence was admissible, it would be, at best, of marginal utility in circumstances where: (a) this was a judge-alone trial; and (b) that subject to submissions to the contrary, I considered it would be appropriate to direct myself as to the impact of alleged counterintuitive conduct in a manner consistent with some foundational propositions referred to in the proposed evidence which, it seemed to me, simply reflected the accumulated experience of the common law (seen in standard directions) or in ordinary human experience.

117 Sensibly, both parties agreed, and it became unnecessary to deal with admissibility or discretionary exclusion issues, as the following became common ground as agreed facts pursuant to s 191 EA (Agreed Facts dated 18 December 2023 (agreed facts)):

(1) trauma has a severe impact on memory by splintering and fragmenting memories; such that semantic or meaning elements become separated from emotion; and interfering with the timespan memories require to consolidate and become permanent;

(2) due to the potential for cuing of emotional responses to fragmented memories, memory can change, be subject to reconsolidation effects, and even when these effects are not marked initially, memories may remain labile for some time (thus changes in what the person reports as their memory of an event can be expected);

(3) lack of clarity and confused accounts can be expected until such time as the memory has consolidated;

(4) inconsistencies in reporting following a traumatic event are often observed and explicable through underlying theories of trauma and memory function;

(5) omissions can be understood as alterations in awareness due to high arousal at the time of the event that consolidate over time;

(6) inconsistency is often observed in reliable reports of sexual assault and is not ipso facto a measure of deception;

(7) in understanding the account of an alleged “survivor”, a person must consider how that account was elicited; this includes the skill and attitudes towards the person by the investigating officers; the time elapsed between the traumatic event and the formal interview; and the psychological/emotional state of the person being interviewed at the time of interview;

(8) the first forensic interview is potentially a trigger for intrusive thoughts that can lead to fragmentation of memory and dissociation; patterns of behaviour such as high confidence and clarity in the account are not helpful in determining whether the account is accurate;

(9) despite the belief that the emergence of inconsistencies across interviews is a sign of lying (people “can’t keep their story straight”), the literature on memory, impacts of trauma and the dynamic between interviewee and the interviewer must be considered; and

(10) multiple interviews are typically necessary to construct a clear narrative of events; however, the consequence of these multiple interviews may be patterns of inconsistency or omissions especially early in the interview process (which need to be carefully evaluated but are not in and of themselves necessarily indicative of deception or accuracy).

118 Consistently with the agreement of the parties, to the extent these propositions are relevant, I will bear them in mind in assessing the impact of any counterintuitive behaviour pointed to by Mr Lehrmann, after the alleged assault, on Ms Higgins’ credit.

119 In a similarly helpful and constructive way, the parties also agreed facts as to the impact of acute alcohol intoxication, in that it has:

(1) a significant and negative effect on memory as it can impair the memory for behaviour and motivation of all parties involved in a sexual act, including a sexually aggressive act; and

(2) been shown to impair judgment; impact negatively on executive function; and impair attention to environmental cues; it can lead to fragmentary memories that slowly recover and consolidate and from a forensic perspective, this process of fragmentation of memory with at times slow recovery may lead to apparent inconsistency and omissions between interviews.

120 Although not an agreed fact, there is a further matter worth mentioning about alcohol consumption that is uncontroversial. As was pointed out by Professor Julia Quilter, Professor Luke McNamara and Ms Melissa Porter in their article ‘The Nature and Purpose of Complainant Intoxication Evidence in Rape Trials: A Study of Australian Appellate Court Decisions’ (2022) 43(2) Adelaide Law Review 606, alcohol consumption is “strongly associated with sexual violence crimes, including rape” (at 607). A review of cases, however, suggests that complainant intoxication evidence has historically been more likely to impede, rather than support, the prosecution’s ability to prove non-consent, because it can be used to: suggest consent based on a “loss of inhibition” narrative; and/or challenge the credibility of the complainant as a witness and the reliability of their account.

121 But here, of course, the evidence adduced by Mr Lehrmann and the forensic choices he has made means he does not directly advance a “loss of inhibition” narrative and, significantly, any submission made as to the reliability of Ms Higgins as someone affected by alcohol is also relevant (if the evidence otherwise establishes sex took place) to the question of whether she was so affected by alcohol as to be incapable of consenting to sex.

E.5 The Importance of Contemporaneous Representations

122 In a complex commercial case, Webb v GetSwift Limited (No 5) [2019] FCA 1533, I noted the following about the process of fact-finding (at [17]–[18]):

[17] …what matters most in the determination of the issues in cases such as this is the analysis of such contemporaneous notes and documents as may exist and the probabilities that can be derived from these documents and any other objective facts. ...

[18] As Leggatt J said in Gestmin SGPS SA v Credit Suisse (UK) Limited [2013] EWHC 3560 (Comm) at [15]–[23], there are a number of difficulties with oral evidence based on recollection of events given the unreliability of human memory. Moreover, considerable interference with memory is also introduced in civil litigation by the procedure of preparing for trial… [T]he surest guide for deciding the case will be as identified by Leggatt J at [22]:

… the best approach for a judge to adopt in the trial of a commercial case is, in my view, to place little if any reliance at all on the witnesses’ recollections of what was said in meetings and conversations, and to base factual findings on inferences drawn from the documentary evidence and known or probable facts.

123 As the Full Court later observed in Liberty Mutual Insurance Company Australian Branch trading as Liberty Specialty Markets v Icon Co (NSW) Pty Ltd [2021] FCAFC 126; (2018) 396 ALR 193 (at 254 [239] per Allsop CJ, Besanko and Middleton JJ), this approach might be best seen as a helpful working hypothesis, rather than something to be enshrined in any rule. Although these observations were made in the context of fact-finding in commercial cases, this does not mean they are anything but apposite to the fact-finding task to be undertaken in this defamation proceeding.

124 Moreover, in this case, in addition to file notes, texts, social media messages and emails, hours of audio, video and closed-circuit television (CCTV) footage has been adduced into evidence. I have reviewed this contemporaneous material and, for my manifold sins, have listened or watched all the audio-visual records in evidence. I have trudged unyieldingly through this material because insofar as it casts light on the relevant issues, these contemporaneous records are a far surer guide as to what happened than ex post facto accounts or rationalisations, or unverifiable assertions as to what people “felt”.

125 The helpful working hypothesis of paying close regard to the contemporaneous documents and representations to disinterested third parties is of signal importance, especially where, as I will explain, I have misgivings as to the reliability of aspects of the accounts given by a number of important witnesses.

E.6 The Court is Not Bound to Accept Either of the Parties’ Accounts

126 As I will explain further below, the particularised allegation made by the respondents brings with it the requirement to prove:

(1) that, at the time and place alleged (that is, at Parliament House on 23 March 2019), Mr Lehrmann had sexual intercourse with Ms Higgins;

(2) without Ms Higgins’ consent; and

(3) knowing Ms Higgins did not consent.

127 It is notorious that in many rape trials, the forensic battleground is whether the Crown can prove beyond reasonable doubt the second element (non-consent element) and the third element (knowledge element). In recent times, law reformers have focused attention on whether it is appropriate that consent to sexual activity must be communicated by words or actions, such that there is a responsibility to take steps to find out whether the other person is consenting. This has spurred some recent legislative change: see, for example, the Crimes Legislation Amendment (Sexual Consent Reforms) Act 2021 (NSW).

128 It is beyond the scope of this judgment to discuss these changes, but as the Victorian Law Reform Commission recently put it in its report Improving the Justice System Response to Sexual Offences: Report (September 2021) (at [19.13]), some of the features of the criminal justice system:

make sexual offences more difficult to prove in court. By their nature, sexual offending often happens in private, without other witnesses. The accused does not have to give evidence because they have a right to silence. For rape, the need to prove there was no consent means that many cases will end up focusing on the complainant.

129 What is notable about this civil case, and the criminal case that preceded it, is that by reason of Mr Lehrmann’s forensic position to contest the establishment of the first element (that sexual intercourse occurred), he has not engaged directly (through challenging the Crown case at the criminal trial or by way of evidence before me) with the reality and appreciation of consent.

130 Specifically, Mr Lehrmann has advanced an account that he came back to the Ministerial Suite accompanied by Ms Higgins for them to then go their separate ways: not only was there no sex, but no intimacy of any kind.

131 Below I explain why this aspect of Mr Lehrmann’s evidence is stuff and nonsense, but for present purposes, this conclusion makes it necessary to point out that in general, disbelief of one witness’s account does not establish the contrary, or that a witness giving a contrary account must be believed: Kuligowski v Metrobus [2004] HCA 34; (2004) 220 CLR 363 (at 385–386 [60] per Gleeson CJ, McHugh, Gummow, Kirby, Hayne, Callinan and Heydon JJ).

132 Of course, if I am ultimately unable to make a finding one way or another as to what actually happened, it is open to decide the issue on the basis that the party who bears the burden of proof on this issue (that is, the respondents) have failed to discharge their burden: Rhesa Shipping Co SA v Edmunds [1985] 1 WLR 948 (at 955–956 per Lord Brandon, Lords Fraser, Diplock, Roskill and Templeman agreeing). Relatedly, and importantly, given my rejection of Mr Lehrmann’s account of what went on, it must be borne in mind that a civil onus of proof is not discharged by mere disbelief in opposing evidence (see, for example, in the context of a criminal onus, Liberato v R (1985) 159 CLR 507 (at 515 per Brennan J)).

E.7 Multiple Available Hypotheses and Onus

133 Related to the last point, it is also necessary to consider the existence and cogency of other hypotheses open on the evidence.

134 Recently, in Palmanova Pty Ltd v Commonwealth of Australia [2023] FCA 1391, Perram J, in an unusual circumstantial case (and with apologies to those, like me, who thought that algebra would not be involved in this case) observed (at [21]):

Where there are only two competing hypotheses that between them account for the universe of possibilities open on the evidence, a court’s satisfaction that one is more likely than the other will entail that the occurrence of the fact supported by the more likely hypothesis is proved on the civil standard. Whilst it is important not to approach the civil standard in an excessively arithmetical way in terms of numeric probabilities it can be useful to do so to illustrate some consequences in a circumstantial case where multiple hypotheses are in competition with each other. For example, where there are only two competing hypotheses and one is more probable than the other then it must follow that the more likely one is more likely than not. (More formally: if P(A)>P(B) then since P(A)+P(B)=1 then one may validly infer that P(A)>1/2.) But the logic of this breaks down where there are three or more competing hypotheses. If P(A)>P(B)>P(C) then the fact that P(A)+P(B)+P(C)=1 does not warrant the conclusion that P(A)>1/2 as will be seen if P(A)=45%, P(B)=30% and P(C)=25%. Thus the court will only be satisfied that a fact is established if the hypothesis supporting it is more likely than all of the others considered together (i.e. P(A)>(P(B)+P(C))). In particular, the mere fact that one of the hypotheses emerges as more likely than each of the others will not suffice, it must be more likely than all of them.

135 Of course, as his Honour recognised, nothing said in Palmanova is intended to depart from the realities that: (a) mechanical or arithmetic comparison of probabilities independent of belief will not justify a finding of fact; or (b) each competing hypothesis open on the evidence might range, possibly very significantly, in likelihood of occurrence. The important points made, however, are the need for care when there are a range of possibilities open, and the only way one reaches a state of reasonable satisfaction as to one being proven is to conclude its existence is more likely than all the other hypotheses available on the evidence.

E.8 False in One Thing does not mean False in Everything

136 Moreover, in assessing whether one has reached a state of reasonable satisfaction in making a finding of fact, it is jejune to proceed on the basis that rejecting part of an account of a witness of an event must mean one must reject all aspects of the account of the witness.

137 Consistently with ordinary human experience, some witnesses may misremember or lie about some things but tell the truth about others. Despite my concerns about the truthfulness of both Mr Lehrmann and Ms Higgins, it would be simplistic to proceed on the basis this means I must reject everything they say. As the Full Court (McKerracher, Robertson and Lee JJ) explained in CCL Secure Pty Ltd v Berry [2019] FCAFC 81 (at [94]):

It has been a long time since the maxim falsus in uno, falsus in omnibus (false in one thing, false in everything) was part of the common law, its broad applicability having been rejected long ago (including by no less a judge than Lord Ellenborough CJ in R v Teal (1809) 11 East 307; 103 ER 1022). It is trite that the tribunal of fact (be it a judge or jury), having seen and heard the witness, is to decide whether the evidence of the witness is worthy of acceptance and this may involve accepting or rejecting the whole of the evidence, or accepting some of the evidence and rejecting the rest: Cubillo v Commonwealth [2000] FCA 1084; (2000) 103 FCR 1 at 45-47 [118]-[123]; Flint v Lowe (1995) 22 MVR 1; and S v M (1984) 36 SASR 316. It is for this reason a jury is directed that they may accept some parts of a witness’s evidence, but not other parts: Dublin, Wicklow & Wexford Railway Co v Slattery (1878) 3 App Cas 1155. This reflects the accumulated wisdom and experience of the common law that witnesses may lie about some things and yet tell the truth about others, and the tribunal hearing the evidence is best placed to fix upon the truth. …

138 Another Full Court (Wigney, Wheelahan and Abraham JJ) in Kazal v Thunder Studios Inc (California) [2023] FCAFC 174 recently made the same point (at [272]) as follows:

… People sometimes tell lies when giving evidence. What is significant is not the mere fact of the untruthfulness, but its relevance to the issues in dispute. A finding that a witness has lied about a matter need not lead to the rejection of all of the evidence of that witness, but may affect the degree of satisfaction of the existence or otherwise of a fact in issue to which the witness’s evidence was directed. ...

E.9 Implied Admissions and “Consciousness of Guilt”

139 Given, as I will explain, the two principal witnesses in the justification case told lies during their evidence and in the making of out-of-court representations, the final matter to which I wish to draw attention is how these lies can be used in the fact-finding process.

140 Ms Higgins is not a party, and although any lies told by her will be central to my assessment of her creditworthiness (and hence reliability), the position of Mr Lehrmann, as a party and as someone who gave evidence contrary to the evidence adduced by the onus-bearing party, needs separate examination.

141 Recently, as part of the Full Court in Kim v Wang [2023] FCAFC 115; (2023) 411 ALR 402, I referred (at 428 [150]) to the decision of the High Court in Kuhl v Zurich Financial Services Australia Ltd [2011] HCA 11; (2010) 243 CLR 361 (at 384–385 [63]), where Heydon, Crennan and Bell JJ relevantly explained that when a party calls testimony known to be false, this conduct can amount to an implied admission or circumstantial evidence permitting an adverse inference, and I then (at 428–429 [151]) observed as follows:

Recently, in Roberts-Smith v Fairfax Media Publications Pty Limited (No 41) [2023] FCA 555, Besanko J addressed the circumstances in which lies can give rise to a finding of a consciousness of guilt or the making of an implied admission and described them as “complex and highly contentious” (at [197]). In summarising the authorities, his Honour observed (at [205]) that a court must “be cautious before treating a lie as an implied admission or evidence of a consciousness of guilt” and, among other things, should bear in mind there may be reasons for the telling of a lie apart from a realisation of guilt: Edwards v The Queen (1993) 178 CLR 193 (at 211 per Deane, Dawson and Gaudron JJ).

142 The concept derives from the criminal law and forms part of the more general principle that the Crown can rely upon an accused’s post-offence conduct as evidence of a consciousness of guilt: this could be a lie told in or out-of-court or by other conduct, including suborning witnesses or absconding to avoid arrest: McKey v R [2012] NSWCCA 1; (2012) 219 A Crim R 227 (at 233 [26] per Latham J, Hislop J and Whealy JA agreeing). A good example is seen in Pollard v R [2011] VSCA 95; (2011) 31 VR 416, where the evidence of the accused hiding a mobile phone was properly admitted as part of the Crown’s circumstantial case.

143 When it comes to “Edwards lies” as post-offence conduct, as is usefully explained by the Judicial College of Victoria in Pt 4.6 of its Victorian Criminal Charge Book (which deals with “Incriminating Conduct (Post Offence Lies and Conduct)”) (at [25]), at common law, untrue assertions and false denials are only capable of being used as an implied admission if the accused perceives that the truth is inconsistent with innocence and the jury was required to consider the following matters before using such lies as evidence of an implied admission:

(1) the lie was deliberate;

(2) the lie related to a material issue;

(3) the telling of the lie showed knowledge of the offence and was told because the truth would implicate the accused; and

(4) there was no other explanation for the telling of the lie consistent with innocence (see R v Edwards (1993) 178 CLR 193; R v Renzella [1997] 2 VR 88).

144 But there is a need for adaption of the principles explained in these criminal law authorities in a civil case. In the appeal in Australia’s longest running defamation case, Beazley, Giles and Santow JJA in Amalgamated Television Services Pty Ltd v Marsden [2002] NSWCA 419 comprehensively dealt with admissions by conduct (at [78]–[88]). In doing so, the Court of Appeal referred to the fourth of the matters noted above and observed the concept that no other rational inference may be drawn is a concept of the criminal law, necessitated by the standard of proof of beyond reasonable doubt. The Court of Appeal went on to explain that in a civil case, it is sufficient for “a lie to be accepted as an admission of guilt, if that is the more probable inference to be drawn” (at [88]). I respectfully agree that such an approach is not only appropriate, but necessary to accommodate the differing standard of proof.

145 How a lie can be used in assessing the reliability of the accounts given by Mr Lehrmann or Ms Higgins is straightforward. What I am presently concerned with is how an identified lie of Mr Lehrmann can and should be used to lend weight to the other evidence said to support the satisfaction of the onus of proof by the respondents. I will return below in Section H.2 to implied admissions and simply note for present purposes that the identification and use of “Edwards lies” should be approached with caution, including in the light of the warning in Briginshaw (reflected in s 140 EA) that reasonable satisfaction should not be produced by, among other things, indirect inferences.

F OBSERVATIONS AS TO THE CENTRAL WITNESSES

146 This section sets out my general assessment of the creditworthiness of the evidence given by a dozen (of a total of 33) witnesses who gave oral evidence. I will then turn to make specific factual findings. In the course of doing so, I will address the evidence of these and other witnesses in greater specificity where relevant.

147 In another defamation case (Russell v Australian Broadcasting Corporation (No 3) [2023] FCA 1223), I said (at [438]) that many experienced judges have expressed the caution that any criticisms of a witness, which go beyond the legitimate necessities of the occasion, should be avoided. Unnecessary credit findings should be eschewed. Part of this reticence reflects a body of research casting doubt on the ability of judges to make accurate credibility findings based on demeanour: see Fox v Percy [2003] HCA 22; (2003) 214 CLR 118 (at 129 [31] per Gleeson CJ, Gummow and Kirby JJ).

148 But like Russell, this is a case where several of the deficiencies were both patent and telling. Moreover, this is a case where credit, given the way it impacts upon the resolution of the determinative issues in the case, requires close and especially nuanced examination.

149 I will deal below in Section G.4 with the account given by Mr Lehrmann as to why he went back to the Ministerial Suite on the fateful night. I can make general observations as to his creditworthiness by reference to other aspects of his evidence.

150 Network Ten described Mr Lehrmann as “a fundamentally dishonest man, prepared to say or do anything he perceived to advance his interests” (T2215.5). Senior counsel for Ms Wilkinson described him as “an active and deliberate liar” and wondered aloud whether “Mr Lehrmann is just a compulsive liar” (T2316.43).

151 Hyperbolic submissions made about the lack of credit of a party witness are not uncommon. In a recent speech (“Seven Random Points About Judging”, National Judicial Orientation Program, 17 March 2024), Justice Beech-Jones made a similar point to that made in my introductory remarks: that is, a judge should be reticent about accepting such submissions “unless you really have to”.

152 But even taking this wisdom into account, this is one of those cases where expressing criticism is warranted. But one must not be simplistic. A falsehood told by a witness will be especially serious if the maker is under a legal obligation to tell the truth. But irrespective of legal obligation, there are gradations of the seriousness of untruths: an untruthful person may just be all mouth and trousers; or be recklessly indifferent to the truth or, by way of compulsion, finds it difficult to discern between what is true and untrue; or finally, and most culpably, may be someone who tells calculated, deliberate lies.

153 I do not think Mr Lehrmann is a compulsive liar, and some of the untruths he told during his evidence may sometimes have been due to carelessness and confusion, but I am satisfied that in important respects he told deliberate lies. I would not accept anything he said except where it amounted to an admission, accorded with the inherent probabilities, or was corroborated by a contemporaneous document or a witness whose evidence I accept.

II Miscellaneous Examples of False Statements during the Hearing

154 Instances of Mr Lehrmann’s false out-of-court statements or unsatisfactory evidence are legion, but the following important examples illustrate the point sufficiently.

155 First, there was the evidence denying that he found Ms Higgins alluring as at March 2019. As I will explain, from the start, Mr Lehrmann thought that Ms Higgins was attractive. This attraction informed a number of his later actions. Moreover, his denial of this fact was unwary as it contradicted what he had said on the Spotlight programme. When confronted by this inconsistency, his attempt to explain it away by suggesting the attraction he felt for Ms Higgins was “just like [the attraction] I can find [in] anybody else in this [court]room, irrespective of gender” (T351.8–11) was as disconcerting as it was unconvincing.