Neurim Pharmaceuticals (1991) Ltd v Generic Partners Pty Ltd (No 5) [2024] FCA 360

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. By 4.00pm 26 April 2024 the parties provide proposed short minutes of order to the Associate to Nicholas J in accordance with his Honour’s reasons published today.

2. By 4.00pm 26 April 2024 the parties provide to the Associate to Nicholas J written notice of the scope of any disagreement between them in relation those parts of the short minutes of order referred to in order 1 that are not agreed.

3. The proceeding stand over to 9.30am on 2 May 2024 for the making of further orders.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

[1] | |

[9] | |

[9] | |

[12] | |

[13] | |

[14] | |

[30] | |

[31] | |

[37] | |

[40] | |

[41] | |

[42] | |

[50] | |

[68] | |

[69] | |

[70] | |

[70] | |

[76] | |

[118] | |

[147] | |

[147] | |

[158] | |

[166] | |

[195] | |

[207] | |

[222] | |

[225] | |

[227] | |

[259] | |

[290] | |

[298] | |

[304] | |

[310] | |

[313] | |

[384] | |

[464] | |

[469] | |

[474] |

NICHOLAS J:

1 This is a proceeding brought by the applicant (“Neurim”) against the first respondent (“Generic Partners”) and the second respondent (“Apotex”) for infringement of claims 1-7 of Australian Patent 2002326114 (“the Patent”) entitled “Method for treating primary insomnia”. The Patent was based on a PCT application filed on 12 August 2002 (“the PCT application”) and claims priority from a patent application filed in Israel on 14 August 2001 (“priority date”). The Patent was granted on 5 July 2007 and expired on 12 August 2022.

2 Neurim applied to amend claims 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 8 and 9 and related consistory statements so as to bring those statements into alignment with the proposed amended claims. The amendments were allowed by this Court on 19 February 2019 see: Neurim Pharmaceuticals (1991) Ltd v Generic Partners Pty Ltd (No 2) (2019) 139 IPR 424.

3 The patent has nine claims, including, independent claims 1 and 8, each of which is a Swiss-style claim, and independent claims 4 and 9, each of which is for a method of treatment. Claims 1-9 (as amended) are in these terms:

1. Use of melatonin in the manufacture of a medicament for treating a patient suffering from primary insomnia characterized by non-restorative sleep and improving the restorative quality of sleep in said patient, wherein said medicament comprises also at least one pharmaceutically acceptable diluent, preservative, antioxidant, solubilizer, emulsifier, adjuvant or carrier, said medicament is a prolonged release formulation in unit dosage form and said melatonin is present in said medicament in an effective amount within the range of 0.025 to 10 mg.

2. Use according to claim 1, wherein the medicament comprises at least one of the following features:

(i) it is adapted for oral, rectal, parenteral, transbuccal, intrapulmonary (e.g. by inhalation) or transdermal administration;

(ii) it is in a depot form which will release the melatonin slowly in the body, over a preselected time period.

3. Use according to claim 2, wherein said prolonged release formulation includes an acrylic resin.

4. Method for treating a patient suffering from primary insomnia characterized by non-restorative sleep and improving the restorative quality of sleep in said patient, which comprises administering an effective amount within the range of 0.025 to 10 mg of melatonin to said patient, wherein said melatonin is administered in the form of a medicament, said medicament is a prolonged release formulation in unit dosage form, and said melatonin is the only therapeutically active agent administered according to said method.

5. Method according to claim 4, wherein the medicament comprises also at least one pharmaceutically acceptable diluent, preservative, antioxidant, solubilizer, emulsifier, adjuvant or carrier.

6. Method according to claim 5, wherein the medicament comprises at least one of the following features:

(i) it is adapted for oral, rectal, parenteral, transbuccal, intrapulmonary (e.g. inhalation) or transdermal administration;

(ii) it is in a depot form which will release said at least one compound slowly in the body, over a preselected time period.

7. Method according to claim 6, wherein said prolonged release formulation includes an acrylic resin.

8. Use of melatonin in the manufacture of a medicament for treating a patient suffering from primary insomnia characterized by non-restorative sleep and improving the restorative quality of sleep in said patient, substantially as herein described with reference to any one of the examples but excluding comparative examples.

9. Method for treating a patient suffering from primary insomnia characterized by non-restorative sleep and improving the restorative quality of sleep in said patient, substantially as herein described with reference to any one of the examples but excluding comparative examples.

4 Neurim’s commercial embodiment of the medicament described in (inter alia) claim 1 is registered on the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods (“ARTG”) under the product name “CIRCADIN melatonin 2 mg prolonged release tablet blister pack” (“Circadin”). It is registered in respect of “Monotherapy for the short term treatment of primary insomnia characterized by poor quality of sleep in patients who are aged 55 or over”.

5 On or around 3 April 2017, Generic Partners registered products containing 2 mg of the pharmaceutical compound melatonin in prolonged release form on the ARTG (“Generic Partners Products”). The Generic Partners Products, including “MELOTIN MR melatonin 2 mg modified release tablet blister pack” (“Melotin”), were registered for the same indication as Neurim’s product, Circadin.

6 On or around 17 July 2018, Generic Partners transferred sponsorship of some of the Generic Partners Products to Apotex (“Apotex Products”). Generic Partners remains the sponsor of Melotin, which it has supplied to Apotex from 12 March 2020. Apotex admits that from 22 April 2020, it has undertaken, and continues to undertake, marketing activities in respect of Melotin as the Australian distributor of the product. Apotex further admits that from around 28 April 2020, it has supplied Melotin with instructions for its indicated use, and authorises medical practitioners to prescribe Melotin for its indicated use.

7 The respondents have filed cross-claims seeking declarations of invalidity and orders for revocation of the Patent. The validity issues are to be determined by reference to the provisions of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) (“the Act”) in the form it took prior to its amendment by the Intellectual Property Laws Amendment (Raising the Bar) Act 2012 (Cth) and, as explained later in these reasons, in the form s 7 of the Act took as at 12 August 2002. The grounds of invalidity relied on include that the invention as claimed lacks novelty and does not involve an inventive step. The respondents also contend that the complete specification does not fully describe the invention as required by s 40(2)(a) of the Act and that the claims are not fairly based or clear as required by s 40(3) of the Act.

8 The parties agreed on a statement of issues to which I have had regard, though I have chosen not to frame my reasons for judgment around it.

9 The field of the invention is described in the Patent as follows at page 1, lines 4-9:

The present invention relates to a method for treating primary insomnia (as defined by DSM-IV or nonorganic insomnia as defined by ICD-10) when characterized by non-restorative sleep, to the use of melatonin or certain other compounds in the manufacture of a medicament for this purpose, and to a medicament comprising a combination of compounds, for use in improving both the quality and quantity of sleep, in primary insomnia.

10 “DSM-IV” refers to the fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders which was first published in 1994 by the American Psychiatric Association. It is a diagnostic system used to diagnose patients suffering from mental disorders. A revised edition, DSM-IV-TR, was published in 2000 and was current at the priority date. However, the diagnostic criteria for primary insomnia are identical in DSM-IV and DSM-IV-TR and minor differences in the description of the primary insomnia between those versions of texts would not result in any change in how a person skilled in the art would understand the Patent.

11 “ICD-10” refers to the tenth edition of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems which was published in 1992, and which was current at the priority date. It is a diagnostic system published by the World Health Organization (“WHO”).

12 The background to the invention is set out as follows at page 1, line 15 to page 3, line 24:

Sleep disorders, which are complex, are widespread, especially in Western industrial countries, in which it is estimated that about one third of the adult population reports at least occasional difficulties with sleeping, while at least half of the sleep-disordered population have had sleep complaints for years. In US 5,776,969 (James), which discloses a method of treating various sleep disorders, by therapy with a specified combination of chemical compounds, there is discussed and defined inter alia, primary insomnia, which may or may not be characterized by non-restorative sleep.

The definition of primary insomnia in the fourth revision of the [DSM-IV] (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) states: “The predominant complaint is difficulty initiating or maintaining sleep, or non-restorative sleep, for at least one month. The sleep disturbance (or associated daytime fatigue) causes clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational or other important areas of functioning.” Furthermore, according to the definition, non-restorative sleep alone is sufficient to establish the diagnosis of primary insomnia, providing it results in impaired daytime functioning.

The tenth revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) (World Health Organisation, 1991) describes nonorganic insomnia as “a condition of unsatisfactory quantity and/or quality of sleep.” It goes on to state that “there are people who suffer immensely from the poor quality of their sleep, while sleep in quantity is judged subjectively and/or objectively as within the normal limits.”

The diagnostic guidelines from ICD-10 state that the essential clinical features for a definitive diagnosis of primary insomnia are as follows: a) the complaint is either of difficulty falling asleep or maintaining sleep, or of poor quality sleep; b) the sleep disturbance has occurred at least three times per week for at least one month; c) there is preoccupation with the sleeplessness and excessive concern over its consequences at night and during the day; d) the unsatisfactory quantity and/or quality of sleep either causes marked distress or interferes with social and occupational functioning. Thus, there is repeated emphasis in ICD-10 on the equal importance of quality of sleep and quantity of sleep in the diagnosis of insomnia. The invention thus relates to primary insomnia (DSM-IV) or nonorganic insomnia (ICD-10).

Because, in normal humans, the natural hormone melatonin has an increased nocturnal concentration in the blood (according to a particular profile, see e.g. US 5,498,423 (Zisapel)), compared with its daytime concentration, and because also a lack of nocturnal melatonin appears to correlate with the existence of sleep disorders, especially although not exclusively in the elderly, the possibility of administering exogenous melatonin to ameliorate sleep disorders has been investigated and is the subject of many scientific papers.

Thus, for example, in James, S.P., et al. (Neuropsychopharmacology 1990, 3:19-23), melatonin (1 and 5 mg) and placebo were given at 10:45 pm for one night each to 10 polysomnographically pre-screened insomniacs with a mean age of 33.4 years. These patients (who may not necessarily have had non-restorative sleep related insomnia) had quantitative sleep deficits that were demonstrable by PSG. Administration of melatonin did not alter sleep latency, sleep efficiency, total sleep time, or wake after sleep onset. The patients reported improved sleep quality, though they were not more rested in the morning and believed that their total sleep time had been shorter when on melatonin.

In Ellis, C.M., et al. (J. Sleep Res., 1996, 5: 61-65), where melatonin (5 mg) was given at 8:00 pm for 1 week to patients with psychophysiological insomnia, there was no reported change in sleep quantity or quality; 8 patients out of 15 were unable to distinguish the period of active melatonin treatment.

In Hughes, R.J., et al. (Sleep 1998, 21: 52-68), immediate release and controlled release formulations of melatonin (0.5 and 5 mg) were given 30 min before sleep and additionally, an immediate release preparation of 0.5 mg melatonin was given halfway through the night to polysomnographically prescreened elderly patients with sleep maintenance insomnia. They found that both melatonin preparations reduced sleep latency but did not alter wake time after sleep onset (an important variable in sleep maintenance insomnia) or total sleep time. No melatonin-induced changes in reported sleep quality or daytime measure of mood and alertness were found.

MacFarlane J.G., et al. (Biol Psychiatry 1991, 30(4): 371-6) have reported that melatonin (75 mg per os), administered at 10 PM daily to 13 insomniac patients for 14 consecutive days gave a significant increase in the subjective assessment of total sleep time and daytime alertness, whereas 7/13 patients reported no significant effect on subjective feelings of well-being.

Thus, there appears to be little or no evidence from published articles, that administration of exogenous melatonin (or other melatonergic agents, melatonin agonists or melatonin antagonists), in the dosages contemplated by the present invention, would be likely to improve the restorative quality of sleep in subjects affected by primary insomnia characterized by non-restorative sleep.

However, in contrast with the results of the above published papers, the present inventors have surprisingly found that melatonin (and other melatonergic agents, melatonin agonists or melatonin antagonists) in fact improves the restorative quality of sleep in subjects suffering from primary insomnia. Suitable melatonin agonists and antagonists for use in the present invention include (but are not restricted to) such compounds described in US Patents Nos. US 5,151,446; US 5,318,994; US 5,385,944; US 5,403,851; and International Patent Specification No. WO 97/00069.

13 The Summary of the Invention includes two consistory statements (at p 4 line 23-p 4a line 5 in the marked-up copy of the Patent), the first of which uses the same language of claim 1, and the second of which uses the same language as claim 4:

In a first aspect, the present invention provides use of melatonin in the manufacture of a medicament for treating a patient suffering from primary insomnia characterized by non-restorative sleep and improving the restorative quality of sleep in said patient, wherein said medicament comprises also at least one pharmaceutically acceptable diluent, preservative, antioxidant, solubilizer, emulsifier, adjuvant or carrier, said medicament is a prolonged release formulation in unit dosage form, and said melatonin is present in said medicament in an effective amount within the range of 0.025 to 10 mg.

In a second aspect, the present invention provides method for treating a patient suffering from primary insomnia characterized by non-restorative sleep and improving the restorative quality of sleep in said patient, which comprises administering an effective amount within the range of 0.025 to 10 mg of melatonin to said patient, wherein said melatonin is administered in the form of a medicament, said medicament is a prolonged release formulation in unit dosage form, and said melatonin is the only therapeutically active agent administered according to said method.

14 The Patent states that the invention will be illustrated by examples (“Examples”). Five Examples are provided.

15 Example 1 involved a randomised double-blind trial of 40 elderly primary insomnia patients treated with either a 2 mg prolonged-release melatonin formulation, or placebo. Melatonin (or placebo) was administered every evening for three weeks.

16 On the last two days of treatment, full-night polysomnographic recordings were used to measure quantitative aspects of sleep, and on each morning following sleep recording in the laboratory, a battery of psychomotor tests was administered to assess daytime vigilance. In addition, sleep diaries were used daily to record patient assessments of their perceived quality of sleep for the previous night.

17 In the results section, it is reported that sleep induction (as measured by sleep onset latency, duration of wake prior to sleep onset and percentage of time spent asleep prior to sleep onset) significantly improved with melatonin compared with placebo. Sleep maintenance variables (number of awakenings, duration of wake after sleep onset, sleep efficiency, total sleep time) did not improve.

18 The study conclusions were:

These results show beneficial effects of melatonin on sleep initiation, similar to effects of hypnotic drugs. The hypnotic effects of melatonin were in line with reports in the literature showing that melatonin promotes sleep in humans without altering normal sleep architecture. In contrast to this apparently hypnotic effect, psychomotor skills were significantly higher in the melatonin compared to placebo-treated group: significant treatment effects for the Critical Flicker fusion test and total reaction time under melatonin vs. placebo were observed at the end of treatment.

These results thus show for the first time the association of hypnotic effect (shortening of sleep latency) by melatonin with enhanced daytime vigilance in primary insomnia patients suggesting that the restorative value of sleep has increased in these patients. With hypnotic drugs shortening of sleep latency and improved quality of sleep is associated with impaired psychomotor skills in the morning or at best no significant deterioration. No hypnotic drug has ever been shown to increase daytime vigilance. Surprisingly, in their diaries, patients did not evaluate the ease of getting to sleep as being better with melatonin compared to placebo. In fact, the patients judged their quality of sleep to be improved with melatonin but not placebo treatment. The restorative value of sleep may thus be associated with a perceived improvement in quality of sleep.

(Emphasis added)

19 It is apparent that this trial was assessing both quantitative aspects of the patients’ sleep (such as sleep latency) and daytime vigilance, and the quality of sleep based on the patients’ subjective reports. The patients’ subjective reports indicated that the quality of sleep of the patients given melatonin improved, compared to the control arm. It is apparent that the phrase “restorative value of sleep” (which is not used in the claims) is referring to the objective measurements of patients’ sleep latency and daytime vigilance rather than the patients’ subjective assessment of their sleep quality. The final sentence in the passage quoted above is pointing to an association between improvements in the restorative value of sleep and improvements in perceived quality of sleep (i.e., a subjective measurement).

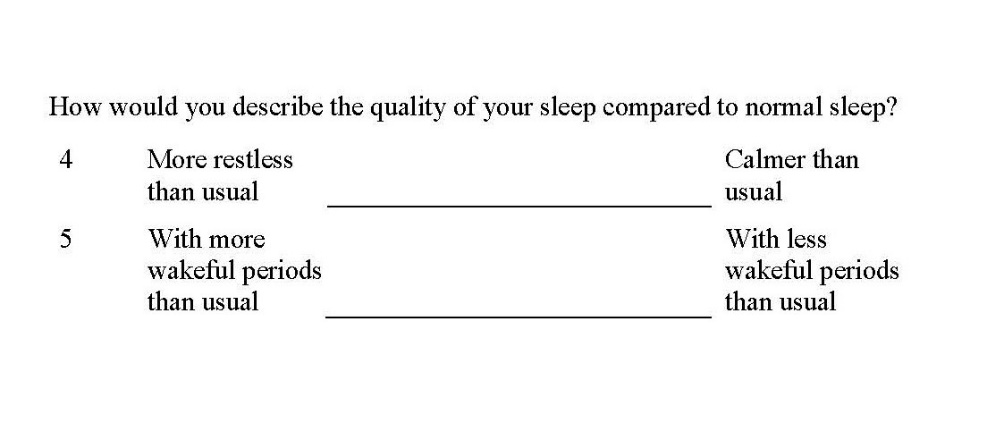

20 Example 2 involved another randomised, double-blind trial in which 170 elderly patients suffering from primary insomnia were treated with either melatonin or placebo, to study the effects of a prolonged release melatonin formulation on subjectively assessed sleep quality and daytime vigilance. The subjects were treated for two weeks with a placebo to establish baseline characteristics, and then for three weeks with prolonged release melatonin (2 mg per night) or placebo. On the last three days of the baseline and treatment periods, patients were asked in the morning to indicate:

(a) the quality of their sleep (when compared to their usual, non-medicated sleep) by marking on a visual analogue scale with the end points “more restless than usual” and “more restful than usual”; and

(b) their feeling in the morning by responding to the question “how do you feel now?” using a visual analogue scale with the end points “tired” and “alert”.

21 It was found that both quality of sleep and daytime alertness improved significantly with melatonin, compared to the placebo, showing a link between improved restful sleep and less fatigue in the morning. It was concluded that the results showed that melatonin enhanced the restorative value of sleep in the primary insomnia patients.

22 Example 3 was also a randomised, double-blind trial of 131 insomnia patients aged between 20 and 80 years whose sleep quality and feeling at daytime was subjectively assessed. The subjects were treated for one week with a placebo to establish baseline characteristics, and then for three weeks with prolonged release melatonin (2 mg per night) or placebo. On the last three days of the baseline and treatment periods, patients were asked to assess the quality of their sleep the previous night and their feeling at daytime as described in Example 2.

23 In the results section, it is reported that: “[i]n the 55 years and older patients, there was an improvement of quality of sleep and daytime alertness… Surprisingly, it was found that in patients <55 years of age there was a significant worsening of the quality of sleep and daytime alertness compared to placebo.”

24 The results are set out in Table 2. Row 4 of Table 2 records that there was a mean improvement (-1.6mm) in perceived quality of sleep after treatment with melatonin (relative to perceived quality of sleep prior to melatonin treatment) in patients under the age of 55, but that the mean improvement was much greater with placebo (-13.7 mm) in this treatment group.

25 The conclusion drawn was that the results of the trial clearly indicate that melatonin was effective in primary insomnia related to non-restorative sleep, but could be detrimental to insomnia related to other causes (e.g., a sleep deficit due to an inability to initiate sleep). The Patent states:

The elderly are more likely to have maintenance and non-restorative sleep problems … Younger people typically have sleep onset problems and their main problem may be due to sleep deficit not non-restorative sleep. These results (Table 2) clearly indicate that melatonin was effective in primary insomnia related to non-restorative sleep, but can be detrimental to insomnia related to other aetiologies (e.g. sleep deficit due to inability to initiate sleep).

(Citation omitted)

26 The suggestion is that the mean improvement in perceived quality of sleep was less significant in the younger patients because few of them would be expected to suffer from non-restorative sleep (as opposed to, for example, primary insomnia characterised by difficulty initiating sleep). Thus, the Patent seeks to attribute the difference between the mean response in the two age groups to the elderly being more likely to have complaints of sleep maintenance and non-restorative sleep, whereas younger people are more likely to have a complaint of difficulty initiating sleep.

27 Example 4 was a randomised, double-blind, cross-over study which assessed psychomotor skills and driving performance in 16 healthy elderly volunteers given a tablet of placebo in the evening to establish baseline, and then a tablet or melatonin, zolpidem or placebo in a random order in the evening with one week with no treatment between treatments. A battery of psychomotor tasks, driving performance and wake EEG during a driving test were studied in the subjects at pre-selected intervals after administration of the tablet.

28 Example 4 involved healthy volunteers, not primary insomnia patients, and did not subjectively assess the quality of sleep of those healthy volunteers. The results found that there were several acute impairments seen with zolpidem compared to the placebo, while no cognitive effect of melatonin (adverse or otherwise) was identified. It was concluded that improvement in quality of sleep reported by patients (as is the case with zolpidem) does not necessarily indicate enhanced restorative sleep, since it is not associated with improved daytime vigilance. Further, the example was found to demonstrate that melatonin did not improve vigilance in non-insomnia patients.

29 Example 5 describes the method by which the formulation used in Examples 1-4 was prepared.

30 I have previously set out claims 1-9 of the Patent. The Swiss-style claims (claims 1-3), the method of treatment claims (claims 4-7) and the omnibus claims (claims 8-9) are concerned with the treatment of “a patient suffering from primary insomnia characterised by non-restorative sleep and improving the restorative quality of sleep in said patient”. A proper understanding of each of the claims requires consideration of the meaning of the following terms as used in the claims:

primary insomnia;

non-restorative sleep;

primary insomnia characterised by non-restorative sleep;

restorative quality of sleep; and

improving the restorative quality of sleep.

31 DSM-IV is incorporated in the Patent by reference.

32 Section 307.42 of DSM-IV is entitled “Primary Insomnia”. It is a nosology that was widely used by psychiatrists practicing in Australia at the priority date.

33 DSM-IV relevantly states at pages 553-557:

Primary Sleep Disorders

Dyssomnias

Dyssomnias are primary disorders of initiating or maintaining sleep or of excessive sleepiness and are characterized by a disturbance in the amount, quality, or timing of sleep. This section includes Primary Insomnia, Primary Hypersomnia, Narcolepsy, Breathing-Related Sleep Disorder, Circadian Rhythm Sleep Disorder, and Dyssomnia Not Otherwise Specified.

307.42 Primary Insomnia

Diagnostic Features

The essential feature of Primary Insomnia is a complaint of difficulty initiating or maintaining sleep or of nonrestorative sleep that lasts for at least 1 month (Criterion A) and causes clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning (Criterion B). The disturbance in sleep does not occur exclusively during the course of another sleep disorder (Criterion C) or mental disorder (Criterion D) and is not due to the direct physiological effects of a substance or a general medical condition (Criterion E).

Individuals with Primary Insomnia most often report a combination of difficulty falling asleep and intermittent wakefulness during sleep. Less commonly, these individuals may complain only of nonrestorative sleep, that is, feeling that their sleep was restless, light, or of poor quality. Primary Insomnia is often associated with increased physiological or psychological arousal at nighttime in combination with negative conditioning for sleep. A marked preoccupation with and distress due to the inability to sleep may contribute to the development of a vicious cycle: the more the individual strives to sleep, the more frustrated and distressed the individual becomes and the less he or she is able to sleep. Lying in a bed in which the individual has frequently spent sleepless nights may cause frustration and conditioned arousal. Conversely, the individual may fall asleep more easily when not trying to do so (e.g., while watching television, reading, or riding in a car). Some individuals with increased arousal and negative conditioning report that they sleep better away from their own bedrooms and their usual routines. Chronic insomnia may lead to decreased feelings of well-being during the day (e.g., deterioration of mood and motivation; decreased attention, energy, and concentration; and an increase in fatigue and malaise). Although individuals often have the subjective complaint of daytime fatigue, polysomnographic studies usually do not demonstrate an increase in physiological signs of sleepiness.

Associated Features and Disorders

Associated descriptive features and mental disorders. Many individuals with Primary Insomnia have a history of “light” or easily disturbed sleep prior to the development of more persistent sleep problems. Other associated factors may include anxious overconcern with general health and increased sensitivity to the daytime effects of mild sleep loss. Symptoms of anxiety or depression that do not meet criteria for a specific mental disorder may be present. Interpersonal, social, and occupational problems may develop as a result of overconcern with sleep, increased daytime irritability, and poor concentration. Problems with inattention and concentration may also lead to accidents. Individuals with Primary Insomnia may have a history of mental disorders, particularly Mood Disorders and Anxiety Disorders. Conversely, the chronic sleep disturbance that characterizes Primary Insomnia constitutes a risk factor for (or perhaps an early symptom of) subsequent Mood Disorders and Anxiety Disorders. Individuals with Primary Insomnia sometimes use medications inappropriately: hypnotics or alcohol to help with nighttime sleep, anxiolytics to combat tension or anxiety, and caffeine or other stimulants to combat excessive fatigue. In some cases, this type of substance use may progress to Substance Abuse or Substance Dependence.

Associated laboratory findings. Polysomnography may demonstrate poor sleep continuity (e.g., increased sleep latency, increased intermittent wakefulness, and decreased sleep efficiency), increased stage 1 sleep, decreased stages 3 and 4 sleep, increased muscle tension, or increased amounts of EEG alpha activity during sleep. These features must be interpreted within the context of age-appropriate norms. Some individuals may report better sleep in the laboratory than at home, suggesting a conditioned basis for sleep complaints. Other psychophysiological tests may also show high arousal (e.g., increased muscle tension or excessive physiological reactivity to stress). Individuals with Primary Insomnia may also have elevated scores on self-report psychological or personality inventories (e.g., on profiles indicating chronic, mild depression and anxiety; an "internalizing" style of conflict resolution; and a somatic focus).

Associated physical examination findings and general medical conditions. Individuals with Primary Insomnia may appear fatigued or haggard, but show no other characteristic abnormalities on physical examination. There may be an increased incidence of stress-related psychophysiological problems (e.g., tension headache, increased muscle tension, gastric distress).

Specific Age and Gender Features

Survey data consistently demonstrate that complaints of insomnia are more prevalent with increasing age and among women. Young adults more often complain of difficulty falling asleep, whereas midlife and elderly adults are more likely to have difficulty with maintaining sleep and early morning awakening. Paradoxically, despite the greater prevalence of insomnia complaints among elderly women, polysomnographic studies generally indicate better preservation of sleep continuity and slow-wave sleep in elderly females than in elderly males. The reason for this discrepancy between self-report and laboratory data is not known.

Prevalence

The true prevalence rate of Primary Insomnia in the general population is unknown.

Population surveys indicate a 1-year prevalence of insomnia complaints of 30%-40% in adults (although the percentage of those whose sleep disturbance would meet criteria for Primary Insomnia has not been studied). In clinics specializing in sleep disorders, approximately 15%-25% of individuals with chronic insomnia are diagnosed with Primary Insomnia.

Course

The factors that precipitate Primary Insomnia may differ from those that perpetuate it. Most cases have a fairly sudden onset at a time of psychological, social, or medical stress. Primary Insomnia often persists long after the original causative factors resolve, due to the development of heightened arousal and negative conditioning. For example, a person with a painful injury who spends a great deal of time in bed and has difficulty sleeping may then develop negative associations for sleep. Negative associations, increased arousal, and conditioned awakenings may then persist beyond the convalescent period, leading to Primary Insomnia. A similar scenario may develop in association with insomnia that occurs in the context of an acute psychological stress or a mental disorder. For instance, insomnia that occurs during an episode of Major Depressive Disorder can become a focus of attention with consequent negative conditioning, and insomnia may persist long after resolution of the depressive episode. In some cases, Primary Insomnia may develop gradually without a clear stressor.

Primary Insomnia typically begins in young adulthood or middle age and is rare in childhood or adolescence. In exceptional cases, the insomnia can be documented back to childhood. The course of Primary Insomnia is variable. It may be limited to a period of several months, particularly if precipitated by a psychosocial or medical stressor that later resolves. The more typical course consists of an initial phase of progressive worsening over weeks to months, followed by a chronic phase of stable sleep difficulty that may last for many years. Some individuals experience an episodic course, with periods of better or worse sleep occurring in response to life events such as vacations or stress.

Familial Pattern

The predisposition toward light and disrupted sleep has a familial association. Formal genetic and/or family studies have not been conducted.

Differential Diagnosis

“Normal” sleep duration varies considerably in the general population. Some individuals who require little sleep (“short sleepers”) may be concerned about their sleep duration. Short sleepers are distinguished from those with Primary Insomnia by their lack of difficulty falling asleep and by the absence of characteristic symptoms of Primary Insomnia (e.g., intermittent wakefulness, fatigue, concentration problems, or irritability).

Daytime sleepiness, which is a characteristic feature of Primary Hypersomnia, can also occur in Primary Insomnia, but is not as severe in Primary Insomnia. When daytime sleepiness is judged to be due to insomnia, an additional diagnosis of Primary Hypersomnia is not given.

Jet Lag and Shift Work Types of Circadian Rhythm Sleep Disorder are distinguished from Primary Insomnia by the history of recent transmeridian travel or shift work. Individuals with the Delayed Sleep Phase Type of Circadian Rhythm Sleep Disorder report sleep-onset insomnia only when they try to sleep at socially normal times, but they do not report difficulty falling asleep or staying asleep when they sleep at their preferred times.

Narcolepsy may cause insomnia complaints, particularly in older adults. However, Narcolepsy rarely involves a major complaint of insomnia and is distinguished from Primary Insomnia by symptoms of prominent daytime sleepiness, cataplexy, sleep paralysis, and sleep-related hallucinations.

A Breathing-Related Sleep Disorder, particularly central sleep apnea, may involve a complaint of chronic insomnia and daytime impairment. A careful history may reveal periodic pauses in breathing during sleep or crescendo-decrescendo breathing (Cheyne-Stokes respiration). A history of central nervous system injury or disease may further suggest a Breathing-Related Sleep Disorder. Polysomnography can confirm the presence of apneic events. Most individuals with Breathing-Related Sleep Disorder have obstructive apnea that can be distinguished from Primary Insomnia by a history of loud snoring, breathing pauses during sleep, and excessive daytime sleepiness.

Parasomnias are characterized by a complaint of unusual behavior or events during sleep that sometimes may lead to intermittent awakenings. However, it is these behavioral events that dominate the clinical picture in a Parasomnia rather than the insomnia.

Primary Insomnia must be distinguished from mental disorders that include insomnia as an essential or associated feature (e.g., Major Depressive Disorder, Generalized Anxiety Disorder, Schizophrenia). The diagnosis of Primary Insomnia is not given if insomnia occurs exclusively during the course of another mental disorder. A thorough investigation for the presence of other mental disorders is essential before considering the diagnosis of Primary Insomnia. A diagnosis of Primary Insomnia can be made in the presence of another current or past mental disorder if the mental disorder is judged to not account for the insomnia or if the insomnia and the mental disorder have an independent course. In contrast, when insomnia occurs as a manifestation of, and exclusively during the course of, another mental disorder (e.g., a Mood, Anxiety, Somatoform, or Psychotic Disorder), the diagnosis of Insomnia Related to Another Mental Disorder may be more appropriate. This diagnosis should only be considered when the insomnia is the predominant complaint and is sufficiently severe to warrant independent clinical attention; otherwise, no separate diagnosis is necessary.

Primary insomnia must be distinguished from Sleep Disorder Due to a General Medical Condition, Insomnia Type. The diagnosis should be Sleep Disorder Due to a General Medical Condition when the insomnia is judged to be the direct physiological consequence of a specific general medical condition (e.g., pheochromocytoma, hyperthyroidism) (see p. 597). This determination is based on history, laboratory findings, or physical examination. Substance-Induced Sleep Disorder, Insomnia Type, is distinguished from Primary Insomnia by the fact that a substance (i.e., a drug of abuse, a medication, or exposure to a toxin) is judged to be etiologically related to the insomnia (see p. 601). For example, insomnia occurring only in the context of heavy coffee consumption would be diagnosed as Caffeine-Induced Sleep Disorder, Insomnia Type, With Onset During Intoxication.

Relationship to International

Classification of Sleep Disorders

Primary Insomnia subsumes a number of insomnia diagnoses in the International Classification of Sleep Disorders (ICSD), including Psychophysiological Insomnia, Sleep State Misperception, Idiopathic Insomnia, and some cases of Inadequate Sleep Hygiene. Psychophysiological Insomnia most closely resembles Primary Insomnia, particularly in terms of arousal and conditioning factors. Sleep State Misperception is a condition characterized by complaints of insomnia with a marked discrepancy between subjective and objective estimates of sleep. Idiopathic Insomnia includes those cases with onset in childhood and a lifelong course, presumably due to an abnormality in the neurological control of the sleep-wake system. Inadequate Sleep Hygiene refers to insomnia resulting from behavioral [sic] practices that increase arousal or disrupt sleep organization (e.g., working late into the night, taking excessive daytime naps, or keeping irregular sleep hours).

• Diagnostic criteria for 307.42 Primary Insomnia

|

34 Appendix C of DSM-IV is entitled “Glossary of Technical Terms” and includes the following definition of “insomnia”:

A subjective complaint of difficulty falling or staying asleep or poor sleep quality. Types of insomnia include

initial insomnia Difficulty in falling asleep.

middle insomnia Awakening in the middle of the night followed by eventually falling back to sleep, but with difficulty.

terminal insomnia Awakening before one’s usual waking time and being unable to return to sleep.

35 Appendix H of DSM-IV is entitled “DSM-IV Classification With ICD-10 Codes”. The introduction states:

As of the publication of this manual (in early 1994), the official coding system in use in the United States is the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM). At some point within the next several years, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services will require for reporting purposes in the United States the use of codes from the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10). To facilitate this transition process, the preparation of DSM-IV has been closely coordinated with the preparation of Chapter V, “Mental and Behavioural Disorders,” of ICD-10 (developed by the World Health Organization). Consultations between the American Psychiatric Association and the World Health Organization have resulted in DSM-IV codes and terms that are fully compatible with the codes and terms in the tabular index of ICD-10. Presented below is the DSM-IV Classification with the ICD-10 codes.

36 “Primary Insomnia” is listed in the appendix with a reference to ICD-10 code F51.0 and a cross-reference to page 553 of DSM-IV which is extracted above.

37 ICD-10 is incorporated in the Patent by reference.

38 Section F51 of ICD-10 is entitled “Nonorganic Sleep Disorders” and relevantly states:

This group of disorders includes:

(a) dyssomnias: primarily psychogenic conditions in which the predominant disturbance is in the amount, quality, or timing of sleep due to emotional causes, i.e. insomnia, hypersomnia, and disorder of sleep — wake schedule; and

(b) parasomnias: abnormal episodic events occurring during sleep; in childhood these are related mainly to the child’s development, while in adulthood they are predominantly psychogenic, i.e. sleepwalking, sleep terrors, and nightmares.

This section includes only those sleep disorders in which emotional causes are considered to be a primary factor. Sleep disorders of organic origin such as Kleine — Levin syndrome are coded in Chapter VI of ICD-10. Nonpsychogenic disorders including narcolepsy and cataplexy and disorders of the sleep — wake schedule are also listed in Chapter VI, as are sleep apnoea and episodic movement disorders which include nocturnal myoclonus. Finally, enuresis is listed with other emotional and behavioural disorders with onset specific to childhood and adolescence, while primary nocturnal enuresis, which is considered to be due to a maturational delay of bladder control during sleep, is listed in Chapter XVIII of ICD-10 among the symptoms involving the urinary system.

In many cases, a disturbance of sleep is one of the symptoms of another disorder, either mental or physical. Even when a specific sleep disorder appears to be clinically independent, a number of associated psychiatric and/or physical factors may contribute to its occurrence. Whether a sleep disorder in a given individual is an independent condition or simply one of the features of another disorder (classified elsewhere in Chapter V or in other chapters of ICD-10) should be determined on the basis of its clinical presentation and course, as well as of therapeutic considerations and priorities at the time of the consultation. In any event, whenever the disturbance of sleep is among the predominant complaints, a sleep disorder should be diagnosed. Generally, however, it is preferable to list the diagnosis of the specific sleep disorder along with as many other pertinent diagnoses as are necessary to describe adequately the psychopathology and/or pathophysiology involved in a given case.

…

F51.0 Nonorganic insomnia

Insomnia is a condition of unsatisfactory quantity and/or quality of sleep, which persists for a considerable period of time. The actual degree of deviation from what is generally considered as a normal amount of sleep should not be the primary consideration in the diagnosis of insomnia, because some individuals (the so-called short sleepers) obtain a minimal amount of sleep and yet do not consider themselves as insomniacs. Conversely, there are people who suffer immensely from the poor quality of their sleep, while sleep quantity is judged subjectively and/or objectively as within normal limits.

Among insomniacs, difficulty falling asleep is the most prevalent complaint, followed by difficulty staying asleep and early final wakening. Usually, however, patients report a combination of these complaints. Typically, insomnia develops at a time of increased lifestress and tends to be more prevalent among women, older individuals and psychologically disturbed and socioeconomically disadvantaged people. When insomnia is repeatedly experienced, it can lead to an increased fear of sleeplessness and a preoccupation with its consequences. This creates a vicious circle which tends to perpetuate the individual’s problem.

Individuals with insomnia describe themselves as feeling tense, anxious, worried, or depressed at bedtime, and as though their thoughts are racing. They frequently ruminate over getting enough sleep, personal problems, health status, and even death. Often they attempt to cope with their tension by taking medication or alcohol. In the morning, they frequently report feeling physically and mentally tired; during the day, they characteristically feel depressed, worried, tense, irritable, and preoccupied with themselves.

Children are often said to have difficulty sleeping when in reality the problem is a difficulty in the management of bedtime routines (rather than of sleep per se); bedtime difficulties should not be coded here, but in Chapter XXI of ICD-10 (Z62.0, inadequate parental supervision and control).

Diagnostic guidelines

The following are essential clinical features for a definite diagnosis:

(a) the complaint is either of difficulty falling asleep or maintaining sleep, or of poor quality of sleep;

(b) the sleep disturbance has occurred at least three times per week for at least 1 month;

(c) there is preoccupation with the sleeplessness and excessive concern over its consequences at night and during the day;

(d) the unsatisfactory quantity and/or quality of sleep either causes marked distress or interferes with ordinary activities in daily living.

Whenever unsatisfactory quantity and/or quality of sleep is the patient’s only complaint, the disorder should be coded here. The presence of other psychiatric symptoms such as depression, anxiety or obsessions does not invalidate the diagnosis of insomnia, provided that insomnia is the primary complaint or the chronicity and severity of insomnia cause the patient to perceive it as the primary disorder. Other coexisting disorders should be coded if they are sufficiently marked and persistent to justify treatment in their own right. It should be noted that most chronic insomniacs are usually preoccupied with their sleep disturbance and deny the existence of any emotional problems. Thus, careful clinical assessment is necessary before ruling out a psychological basis for the complaint.

Insomnia is a common symptom of other mental disorders, such as affective, neurotic, organic, and eating disorders, substance use, and schizophrenia, and of other sleep disorders such as nightmares. Insomnia may also be associated with physical disorders in which there is pain and discomfort or with taking certain medications. If insomnia occurs only as one of the multiple symptoms of a mental disorder or a physical condition, i.e. does not dominate the clinical picture, the diagnosis should be limited to that of the underlying mental or physical disorder. Moreover, the diagnosis of another sleep disorder, such as nightmare, disorder of the sleep wake schedule, sleep apnoea and nocturnal myoclonus, should be made only when these disorders lead to a reduction in the quantity or quality of sleep. However, in all of the above instances, if insomnia is one of the major complaints and is perceived as a condition in itself, the present code should be added after that of the principal diagnosis.

The present code does not apply to so-called “transient insomnia”. Transient disturbances of sleep are a normal part of everyday life. Thus, a few nights of sleeplessness related to a psychosocial stressor would not be coded here, but could be considered as part of an acute stress reaction (F43.0) or adjustment disorder (F43.2) if accompanied by other clinically significant features.

(Some citations omitted)

39 ICD-10 also includes a diagnostic criteria for “F51 Nonorganic sleep disorders” and relevantly states:

F51 Nonorganic sleep disorders

Note: A more comprehensive classification of sleep disorders is available (International classification of sleep disorders) but it should be noted that this is organized differently from ICD-10.

For some research purposes, where particularly homogeneous groups of sleep disorders are required, four or more events occurring within a 1-year period may be considered as a criterion for use of categories F51.3, F51.4, and F51.5.

F51.0 Nonorganic insomnia

A. The individual complains of difficulty falling asleep, difficulty maintaining sleep, or non-refreshing sleep.

B. The sleep disturbance occurs at least three times a week for at least 1 month.

C. The sleep disturbance results in marked personal distress or interference with personal functioning in daily living.

D. There is no known causative organic factor, such as a neurological or other medical condition, psychoactive substance use disorder, or a medication.

(Footnote omitted)

40 The International Classification of Sleep Disorders (“ICSD”) is discussed in DSM-IV at pages 556-557 (in the extract set out above) but is not itself incorporated in the Patent by reference.

41 There were eight principal witnesses, all of whom made affidavits. All except for Associate Professor Rawlin and Mr Anthony Jennings gave oral evidence and were cross-examined.

42 Dr Behi made two affidavits dated 21 August 2019 and 4 February 2020. He is a psychiatrist specialising in child, youth and family psychiatry who has 18 years of experience in the field of psychiatry. He holds a Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery and a Postgraduate Diploma in Psychological Medicine from the University of Wales College of Medicine. He is a Member of the Royal College of Psychiatry in the United Kingdom and a Fellow of the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists (“RANZCP”).

43 Over the course of his career, he has diagnosed and treated numerous patients with non-respiratory sleep complaints including insomnia in patients of all ages. He is familiar with a range of medications that are available in Australia for the treatment of sleep complaints (both as a sole and primary complaint, or accompanying other disorders), and has many years of experience in prescribing for patients in Australia medications and treatment regimes for non-respiratory sleep complaints such as insomnia.

44 Dr Krapivensky made two affidavits dated 22 August 2019 and 31 January 2020. She is a psychiatrist who has 30 years of research and clinical experience in mental health, including non-respiratory sleep disorders such as insomnia. She holds a Bachelor of Medicine and Surgery and a PhD in Psychological Medicine in psychoendocrinology from Monash University. She has held various roles in clinical psychiatry at Alfred Hospital, Montclair Hospital, Southern Health group of hospitals, Cedar Court Private Hospital, St Vincent’s Hospital and Melbourne MediBrain Centre and MediSleep.

45 She is the founder of the Melbourne MediBrain Centre, which is a private hospital providing specialised assessment and treatment programmes addressing non-respiratory sleep disorders, including insomnia in psychiatric patients. She is also the Medical Director of MediSleep, the sleep unit she established at the Melbourne MediBrain Centre. Throughout her career, she has diagnosed and treated a significant proportion of her patients for non-respiratory sleep disorders including insomnia, and this has been the focus of her practice since 2009. She is very familiar with the range of medications that have been available in Australia for the treatment of non-respiratory sleep disorders, including insomnia, and has prescribed these medications for the treatment of such disorders throughout her career.

46 Professor Roth made two affidavits dated 5 December 2019 (“Roth 1”) and 30 January 2020 (“Roth 2”). He is a professor of sleep medicine and has approximately 50 years of clinical and research experience in sleep medicine, a speciality or subspecialty devoted to the diagnosis and therapy of sleep disturbances and disorders. He holds a Masters and a Doctorate in Psychology from the University of Cincinnati, Ohio and a Bachelor of Arts degree in Psychology from the City University of New York, Hunter College.

47 Professor Roth is the founder and Director of the Henry Ford Sleep Disorders Centre, a Professor of Internal Medicine and Psychiatry at the Wayne State University, a Clinical Professor in the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Michigan School of Medicine, and a Consulting Professor and Advisor for the Division of Public Mental Health and Public Sciences for Stanford Medicine. He estimated that 65-80% of his work in sleep medicine involved the diagnosis and management of insomnia with the main focus of his research being related to the different phenotypes of insomnia, the pathophysiology of insomnia, and the different approaches to the pharmacological management of insomnia.

48 Professor Roth has held various clinical and research roles at Howard University, the University of Cincinnati, the Sleep Research Laboratory at Veterans Administration Hospital in Cincinnati, Xavier University, the Sleep Disorders Center at Cincinnati General Hospital, and the University of Michigan School of Medicine. He has also served as President of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, the Sleep Research Society and the National Sleep Foundation. He has authored approximately 270 articles and approximately 130 book chapters relating to insomnia, its diagnosis and its treatment and is the former Editor-in-Chief of the primary journal in the field of sleep, Sleep. He is the former Chairman of the WHO’s worldwide project on sleep and health.

49 As his qualifications are in psychology, Professor Roth does not have prescribing rights, but in his clinical practice and teaching roles he supervises fellows (in psychiatry and other disciplines) who do have prescribing rights.

50 Professor Wheatley made four affidavits dated 23 August 2019 (“Wheatley 1”), 21 November 2019 (“Wheatley 2”), 29 January 2020 (“Wheatley 3”) and 12 March 2020 (“Wheatley 4”). Wheatley 4 was prepared and affirmed approximately four weeks after the Joint Expert Reports which I refer to below. He is a Professor of Respiratory and Sleep Medicine at the University of Sydney and at Westmead Hospital in Sydney. He holds a Bachelor of Medicine with First Class Honours from the University of Sydney and a PhD in respiratory physiology, and has been admitted to the Fellowship of the Royal Australasian College of Physicians (“FRACP”).

51 Professor Wheatley currently holds several positions at Westmead Hospital including Director of the Department of Respiratory Medicine where he is responsible for the delivery of respiratory and sleep medicine services. He also is a Senior Staff Specialist Physician in the Department of Respiratory Medicine, as part of which he is appointed as a senior clinician in respiratory and sleep disorders to manage patients requiring admission to hospital with complex respiratory and sleep disorders, as well as managing outpatients with complex medical problems requiring specialist medical consultation. He is also responsible for running an outpatient clinic twice a week for patients with sleep disorders. He is the Founder and Director of the Sleep Laboratory at Westmead Hospital where he is responsible for overall management of the laboratory services with the assistance of the Sleep Services Manager, and the provision, scoring and interpretation of all sleep tests undertaken by the laboratory, as well as supervision of all teaching and research functions of the laboratory. He is also the Founder and Director of the Respiratory Failure and Sleep Disorders Service at Westmead Hospital, which undertakes clinical management of all patients with respiratory sleep disorders including obstructive sleep apnoea, central sleep apnoea and nocturnal respiratory failure.

52 Professor Wheatley is also a Director in the Department of Respiratory and Sleep Medicine at the Western Sydney Local Health District (formerly Sydney West Area Health Service), where he is the senior clinical leader for all respiratory and sleep clinical services for the local area health service comprising Westmead, Blacktown, Mount Druitt and Auburn Hospitals. The service manages patients with both acute and chronic respiratory and sleep disorders.

53 Professor Wheatley has also simultaneously held clinical academic positions in the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Sydney including as a Clinical Senior Lecturer, Clinical Associate Professor and Clinical Professor. He has taught both undergraduate and postgraduate medical students in the fields of respiratory medicine and sleep medicine. He was also involved in the development of the post-graduate FRACP training program in sleep medicine and the FRACP curriculum in Australia for sleep medicine training of respiratory physicians in the mid-1990s.

54 Professor Wheatley has also conducted research programs in both sleep and respiratory disorders and has been involved as the principal investigator of a number of research clinical trials at Westmead Hospital including in the fields of chronic insomnia and primary insomnia. Several of the clinical trials involved the assessment of new pharmaceutical agents in the treatment of chronic and primary insomnia. He has also researched and authored around 100 peer reviewed journal articles and book chapters on respiratory and sleep medicine and he has held a number of research grants for research in the field of respiratory and sleep medicine.

55 Professor Glozier made three affidavits dated 22 November 2019 (“Glozier 1”), 31 January 2020 (“Glozier 2”) and 13 March 2020 (“Glozier 3”). Glozier 3 was prepared and sworn approximately four weeks after the Joint Expert Reports. He is a Professor of Psychological Medicine at the Brain and Mind Centre and Clinical School at the University of Sydney, and is a Senior Staff Specialist in Psychiatry for the Sydney Local Health District. He has more than 20 years’ experience in psychiatry. He holds a Bachelor of Medicine and a Bachelor of Arts majoring in physiology from Oxford University, and a Bachelor of Medicine and a Bachelor of Surgery from London University, and is a member of the Royal College of Psychiatrists in the United Kingdom. He also holds a Masters in Health Policy from the London School of Economics and was awarded a PhD from London University. He is currently a Fellow of the RANZCP.

56 Professor Glozier is also a part-time Senior Staff Specialist Psychiatrist with the Sydney South West Area Health Service where he established Australia’s first sleep treatment program for public psychiatric inpatients. Since 2009 he has held academic positions at the University of Sydney as an Associate Professor and Professor and has been extensively involved in teaching medical students all aspects of psychiatry. He has also taught the Masters course on sleep medicine which is aimed at specialists and advanced trainees with a high level of prior knowledge of sleep disorders. He also has experience in conducting psychiatric clinical trials of novel medicines and behavioural and digital treatments predominantly in patients with depression, sleep and cognitive disorders. He was, or is currently, the chief investigator of three trials relating to insomnia and has undertaken significant and extensive research into insomnia and sleep disorders.

57 Professor Glozier is a member of the editorial boards for the Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry and Sleep Health and reviews academic papers for several journals including Lancet Psychiatry, Sleep, Medical Journal of Australia, British Journal of Psychiatry and Sleep Research. He has delivered insomnia and sleep health focused plenary lectures, symposia, and has been a panel member at numerous conferences including at World Sleep, American Professional Sleep Society, World Association of Psychiatry, European Sleep Research Society and Australasian Sleep Association.

58 For a period of five years, Professor Glozier ran twice-yearly courses in psychiatric diagnostic classification methods for European psychiatrists in the UK, and overseas psychiatrists in Singapore, Ethiopia, Ukraine and Sri Lanka. He was a member of a Specialist Advisory Group for the review undertaken by the Australian National Prescribing Service on insomnia treatments resulting in published insomnia treatment guidelines.

59 Before the priority date Professor Glozier worked as a Senior House Officer and Specialist Psychiatry Registrar for the Bethlem and Maudsley National Health Service (“NHS”) Trust and as a Specialist Psychiatry Registrar in Australia for the Central Sydney Area Health Service. He was also a UK Project Manager for the Classification and Assessment Division of the WHO, where he worked with Australian psychiatrists and directors of the Australian Health Classification Centres at the Institute of Health and Welfare. From 1999 to 2003, he completed a clinical training fellowship and gained a qualification in Advanced Psychiatry Training in Consultation Liaison Psychiatry. After the priority date, he also worked as a Consultant Liaison and Occupational Psychiatrist with the Kings College Hospital and London Ambulance Service NHS Trusts in London.

Associate Professor Morton Rawlin

60 Associate Professor Rawlin made two affidavits dated 22 November 2019 and 15 October 2020. He is a General Practitioner at the Macedon Medical Centre, an Associate Professor of General Practice at the University of Sydney, and the Medical Director of the Royal Flying Doctor Service (Victoria). He has more than 30 years’ experience in general medical practice. He holds a Bachelor of Medicine and a Master’s Degree of Medical Science (Clinical Epidemiology) from the University of Newcastle. He is a Fellow of the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners, the Australian College of Rural and Remote Medicine, the Mental Health Association and Advanced Rural General Practice RACGP.

61 Before the priority date he worked as a Medical Registrar doing specialist physician training at Blacktown Hospital and Hornsby Hospital and held the role of Acting Director of the Emergency Department at Mt Druitt Hospital. His career in general practice commenced in 1988 when he founded a rural general practice. Between 1998 and 2001 he was involved in a successful trial of Standards for General Practice, and he worked as a Senior Lecturer in Rural General Practice at the University of Melbourne and was a Member of the Assessment Committee of the Faculty of Medicine. Between 2000 and 2001, he worked as the Director of Medical Services at Dianella Community Health and achieved full Australian General Practice Accreditation Limited accreditation of the practice. He then began his current role as a General Practitioner at Macedon Medical Centre in 2000.

62 Between 2000 and 2001 he was also State Education Manager of Victoria for General Practice Education Australia where he managed the education of all general practitioner registrars for Victoria, and between March 2002 and April 2003 he was National Education Manager, Fellowship also for General Practice Education Australia, where he managed the education of all general practice registrars across Australia. He was also involved in the RACGP training program as both an educator and an assessor over many years and played an active role in the RACGP in various leadership capacities including as a Board Member, Vice Chair, Vice President and Chair. He has also undertaken research in the following areas: accreditation in general practice; integration in teaching medicine; promotion of rural practice in undergraduate education; standards and training of general practitioner teachers; and dermatology and mental health in general practice.

63 Mr Anthony Jennings made one affidavit dated 28 August 2019. Mr Jennings is a principal partner at an independent research firm, Intellectual Technology Services Pty Ltd, which specialises in conducting searches of commercial patent and scientific literature databases. He was retained by the respondents’ solicitors to conduct both literature and patent searches relevant to the respondents’ inventive step case.

64 Mr Manuel made one affidavit dated 15 October 2020. He is a registered pharmacist and a 50% shareholder and Director of Elements Health Care Pty Ltd, trading as Amcal+ Tuart Hill, Western Australia. He is also a 50% equity partner of Amcal+ Express Max Burswood, an Amcal pharmacy in Burswood, Western Australia. He holds a Bachelor of Pharmacy from the Western Australian Institute of Technology, now known as Curtin University. In 1985 he became a registered pharmacist and a member of the Pharmaceutical Society of Australia. He has been practicing as a proprietor pharmacist since 1989 and since 1999 has been a partner in Amcal+ Express Max Burswood.

65 In his role as a pharmacist, he has a special interest in opiate dependency treatments, aged care medication management services, compounding and healthcare innovation and technology. He has provided pharmacy advice and dispensing services to the many and varied populations within the community for a wide range of conditions, including insomnia, for over 25 years. He estimated that during this period he has personally dispensed over 1 million medicine prescriptions.

66 He is a member of the Opioid Pharmacotherapy Recruitment and Advisory Committee and a committee member of the Western Australian branch of the Pharmacy Guild of Australia (the national peak body that represents community pharmacy proprietors and provides member services).

67 Mr Manuel’s evidence was principally directed to the decision of the Secretary of the Department of Health to “down schedule” melatonin dosages of 2 mg or less from Schedule 4 to Schedule 3 with effect from 1 June 2021 and his understanding of the therapeutic indication for Circadin. He described the words “characterised by poor quality sleep” as a “blunt instrument” and “broad term” encompassing a wide range of difficulties with sleep. Ultimately, Mr Manuel’s evidence received very little attention in the parties’ submissions. I do not regard his evidence as of any real assistance in resolving the issues to be determined in this proceeding. To be clear, that is not in any sense a reflection on the quality of Mr Manuel’s evidence (none of which was challenged) or his extensive qualifications and experience as a pharmacist.

General Comment on Expert Evidence

68 As to the witnesses’ evidence more generally, I have approached the written evidence of the witnesses, but particularly that of Dr Krapivensky, Dr Behi and Professor Roth, with caution. Regrettably, parts of Dr Krapivensky’s, Dr Behi’s and Professor Roth’s written evidence were overstated, needlessly tendentious and argumentative and, in that respect, not what the Court expects to see from witnesses presenting themselves as independent experts. Parts of their written evidence commenting on the evidence of Professor Wheatley were also quite disrespectful and dismissive in tone. That said, all three witnesses were the subject of detailed and probing questioning in the oral evidence which I generally found more helpful than their written evidence even though it was at times (particularly in the case of Dr Behi) verbose and non-responsive. Professor Wheatley and Professor Glozier were both impressive witnesses who, in my opinion, did their best to assist the Court.

69 There were two expert conclaves held prior to the hearing and two concurrent sessions of expert evidence at the hearing. The first expert conclave included Dr Behi, Dr Krapivensky, Professor Roth, Professor Glozier and Professor Wheatley who together prepared a Joint Expert Report dated 12 February 2020 (“JER 1”). The second expert conclave included Professor Roth, Professor Glozier and Professor Wheatley who together prepared a Joint Expert Report dated 13 February 2020 (“JER 2”). Associate Professor Rawlin and Mr Manuel did not participate in the joint expert conclaves or contribute to the Joint Expert Reports.

THE NOTIONAL SKILLED ADDRESSEE

70 The notional skilled addressee is a legal construct and a tool of analysis framed by reference to the available evidence. This will include the patent specification and, typically, evidence of persons with knowledge and experience in the field of the invention.

71 The notional skilled addressee is a person who is likely to have a practical interest in the subject matter of the invention: Catnic Components Ltd v Hill & Smith Ltd [1982] RPC 183 at 242 per Lord Diplock. A person may have a practical interest in an invention at a number of levels. He or she may have an interest in using the products or methods of the invention, making the products of the invention, or making products used to carry out the methods of the invention either alone or in collaboration with others having such an interest: Apotex Pty Ltd v Warner-Lambert Company LLC (No 2) (2016) 122 IPR 17 at [27]. Broadly speaking, the skilled addressee will be a person who also has knowledge and experience in the field of the invention and who will bring to the reading of the relevant document the background knowledge and experience available to those working in that field.

72 It is through the eyes of the notional skilled addressee that the Patent must be construed. As French CJ observed in AstraZeneca AB v Apotex Pty Ltd (2015) 257 CLR 356 (“AstraZeneca HCA”) at [23]:

… The notional person is not an avatar for expert witnesses whose testimony is accepted by the court. It is a pale shadow of a real person – a tool of analysis which guides the court in determining, by reference to expert and other evidence, whether an invention as claimed does not involve an inventive step.

73 Neurim submitted that it was not sufficient that a person with a practical interest in the subject matter of the invention be a person skilled in the relevant art unless they also had practical knowledge and experience in the field of the invention. On this view, the notional skilled addressee is someone not only with a practical interest in the subject matter of the invention but also the relevant background knowledge and experience shared by those working in the field of the invention.

74 I accept Neurim’s submission which is consistent with authority. As Middleton J observed in Ranbaxy Laboratories Ltd v AstraZeneca AB (2013) 101 IPR 11 at [93] (“Ranbaxy Laboratories”), “[t]he first step in identifying the membership of the skilled team is to identify the field of knowledge to which the invention relates”. This is not a case in which either party suggested that the notional skilled addressee would consist of a notional team. However, I accept that it is necessary to identify the field of knowledge to which the invention relates and then identify the notional skilled addressee by reference to that body of knowledge. That approach is consistent with the High Court’s observation in Kimberly-Clark Australia Pty Ltd v Arico Trading International Pty Ltd (2001) 207 CLR 1 (“Kimberly Clark”) at [24] (per Gleeson CJ, McHugh, Gummow, Hayne and Callinan JJ) that in construing the complete specification, the Court is to place itself “in the position of some person acquainted with the surrounding circumstances as to the state of [the] art and manufacture at the time”. In Meat & Livestock Australia Ltd v Cargill, Inc (2018) 129 IPR 278 Beach J observed at [219]:

… A patent specification is addressed to those having a practical interest in the subject matter of the invention; such persons are those with practical knowledge and experience of the kind of work in which the invention is intended to be used.

(Emphasis added)

75 It is common ground between the parties that Dr Behi, Dr Krapivensky, and Professor Glozier are skilled addressees with a practical interest in and knowledge of the field of primary insomnia and the diagnosis and treatment of that condition. There is a significant debate between the parties as to whether Professor Wheatley and Professor Roth are properly regarded as skilled addressees. I will return to this question shortly, and merely note at this stage that Neurim contends that the notional skilled addressee is a clinician with expertise in primary insomnia and the diagnostic guidelines used in the diagnosis of primary insomnia, including, as at the priority date, DSM-IV and ICD-10. Neurim contends that Professor Wheatley is not representative of the notional skilled addressee because the focus of his clinical and research work is on the diagnosis and treatment of insomnia due to respiratory sleep disorders in patients that do not have primary insomnia. The respondents contended that Professor Roth is a psychologist who is not a prescriber of pharmacological treatments who is not representative of the notional skilled addressee. They also said that he was “over-qualified”.

76 The experts who participated in JER 1 were asked to express their views as to the identity of the person skilled in the art at the priority date. The experts agreed that the person skilled in the field of primary insomnia and likely to have a practical interest in the subject matter of the Patent would have knowledge and experience in taking a history of sleep disturbances and identifying causes and associations of such disturbances in the course of making a diagnosis of primary insomnia. They also agreed the person would have experience, knowledge or a research interest in the psychopharmacology of sleep and its disorders, and an ability to understand the diagnosis of primary insomnia specifically in relation to DSM-IV. Relevantly, the experts agreed that primary insomnia in the patent is a reference to that term as it appears in DSM-IV.

77 The experts did not agree, however, on the role of other classification systems, and specifically the extent to which ICSD was translatable to the diagnosis of primary insomnia in the context of the Patent. The main area of disagreement consequently was whether a person familiar with ICSD but not DSM-IV would be a person skilled in the art. Dr Behi stated that where a person did not recognise or understand the concept of non-restorative sleep in the context of DSM-IV, such a person could not be skilled in the art because the Patent specifically requires an understanding of that term to make a diagnosis. Dr Krapivensky and Professor Roth were of largely the same view, and each pointed out that while different nosologies were “translatable”, that translation would require familiarity with DSM-IV in the first place. Dr Krapivensky also considered that such a translation would be highly subjective.

78 Professor Glozier held the view that a person who understood the relevant diagnoses in ICSD that are subsumed by a diagnosis of primary insomnia in DSM-IV would be a person skilled in the art, and pointed to the fact that DSM-IV specifically refers to ICSD and enables the translation between the two nosologies. Professor Wheatley held the same view, and asserted that a sleep physician who embodied the characteristics agreed upon by the group would be able to fully understand the diagnosis of primary insomnia in DSM-IV and would be a person skilled in the art.

Criticism of Professor Wheatley

79 Professor Wheatley was heavily criticised in Neurim’s submissions in relation to various corrections and qualifications he made to views expressed by him in JER 1. It will be necessary to refer to some of the differences between those views and the contents of his supplementary affidavit where relevant. Insofar as the identity of the person skilled in the art is concerned, Professor Wheatley did not purport to correct or qualify any of the information contained in response to Q1 of JER 1. However, in his affidavit evidence, he did make a number of statements which Neurim submitted showed that Professor Wheatley was “plainly not appropriately qualified to give evidence as the notional skilled addressee”. There were three statements in Professor Wheatley’s affidavit evidence that Neurim focused on in support of that submission:

(a) while Professor Wheatley was aware of DSM-IV and ICD-10, he did not refer to them in his clinical practice for the diagnosis and management of sleep disorders;

(b) non-restorative sleep is not a technical term Professor Wheatley was familiar with or a concept he used in diagnosing patients; and

(c) Professor Wheatley did not know what non-restorative sleep was from either the Patent or his own background knowledge.

80 Neurim submitted that a clinician who does not use DSM-IV or ICD-10, and who does not understand terms that are used in those nosologies, cannot give admissible evidence about a patent that defines the invention by reference to those terms and, in those circumstances, Professor Wheatley’s evidence should be “wholly disregarded”. Neurim submitted that, alternatively, if his evidence was to be admitted, it should be given no weight. It was also submitted that the circumstances in which his supplementary affidavit came to be filed demonstrated that he did not have the necessary expertise and that he was “out of his depth in the task he was asked to perform”.