FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Fair Work Ombudsman v DTF World Square Pty Ltd (in liq) (No 4) [2024] FCA 341

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Pursuant to s 546(1) of the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth):

(a) the first respondent pay pecuniary penalties in the sum of $1,997,100 for its contraventions of the Act;

(b) the second respondent pay pecuniary penalties in the sum of $1,896,300 for its contraventions of the Act;

(c) the fourth respondent pay a total of $92,232 in penalties for the contraventions by the first and second respondents in which she was involved;

(d) the fifth respondent pay a total of $105,084 in penalties for the contraventions by the first and second respondents in which she was involved.

2. Within 35 days, pursuant to s 546(3) of the Act, the first, second, fourth and fifth respondents respectively pay to the Consolidated Revenue Fund of the Commonwealth the penalties set out in orders 1(a)-(d).

3. The applicant have liberty to apply on 7 days’ notice in the event of non-compliance with any of the preceding orders.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

KATZMANN J:

1 In this proceeding the Fair Work Ombudsman alleged that DTF (World Square) Pty Ltd (DTF (WS)) and Selden Farlane Lachlan Investments Pty Ltd (Selden) (together the Employers), two members of the DTF group of companies, contravened several civil remedy provisions of the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) and the Fair Work Regulations 2009 (Cth). The proceeding relates to a particular cohort of employees who worked at restaurants in Sydney and Melbourne trading as “Din Tai Fung” over a four-year period from 6 July 2014 to 30 June 2018 (the contravention period). The Ombudsman further alleged that Hannah (aka Vera) Handoko, the General Manager of the DTF Group and DTF (WS), and Sinthiana (aka Sinthia) Parmenas, the HR Coordinator or Manager for the DTF Group, were involved in many of the Employers’ contraventions and are therefore taken to have committed those contraventions. Similar allegations were made against Dendy Harjanto, a director of both Employers, who was named as the third respondent, but the proceeding against him was discontinued after the Ombudsman was unable to serve him with the initiating process.

2 After the proceeding commenced the Employers went into administration and leave was granted to proceed against them in liquidation. After a hearing in which the liquidator did not participate but which Ms Handoko and Ms Parmenas defended, I found that all the Ombudsman’s allegations had been proved to the requisite standard: Fair Work Ombudsman v DTF World Square Pty Ltd (in liq) (No 3) [2023] FCA 201 (the liability judgment or LJ). Following the publication of judgment, I made declarations and consequential orders reflecting my findings. For convenience, those declarations and orders (including defined terms) are annexed to these reasons. Familiarity with the liability judgment is assumed. Reference in this judgment to the “FW Act” or “the Act” are references to the Fair Work Act and references to the Regulations are to the Fair Work Regulations. The defined terms used in the liability judgment are used in this judgment.

3 The effect of my conclusions is that the Employers, with the involvement of senior management including Ms Handoko and Ms Parmenas, deliberately deprived the Employees of their legislated entitlements and contrived to disguise their wrongdoing through the creation of a false set of records.

4 This judgment is concerned with the question of penalties.

The legal framework

5 If the Court is satisfied that a person has contravened a civil remedy provision, it may order the person to pay a pecuniary penalty that it considers “appropriate”: FW Act, s 546(1).

6 The maximum penalty in the case of an individual is the maximum number of penalty units referred to in the relevant item in column 4 of the table in s 539(2) and five times that amount in the case of a body corporate: FW Act, s 546(2). For a serious contravention the maximum number of penalty units is 600. For all other contraventions it is 60. It is common ground that the value of a penalty unit during the contravention period was:

(a) $170 from 6 July 2014 until 30 July 2015;

(b) $180 from 31 July 2015 until 30 June 2017; and

(c) $210 from 1 July 2017 until the end of the contravention period.

7 All the contraventions with the exception of some of those affecting Guoyong (aka Jet) Liu took place in the last period.

8 In Fair Work Ombudsman v Grouped Property Services Pty Ltd (No 2) [2017] FCA 557 at [394]–[401] I considered that, by parity of reasoning with the approach to sentencing, where contraventions spanned a period in which penalty units increased, the higher amount should apply but the Court can take into account the fact that for part of the period a lower amount applied. The position I took in that case has been followed in a number of cases including by Siopis J in Fair Work Ombudsman v Phua & Foo Pty Ltd [2018] FCA 137 at [31]; Barker J in Registered Organisations Commissioner v Australian Nursing and Midwifery Federation (No 2) [2018] FCA 2004 at [123]–[126]; Rares J in Ahmed v Al-Hussain Pty Ltd t/as The Cheesecake Shop (No 3) [2019] FCA 848 at [35]–[36]; and Snaden J in Fair Work Ombudsman v Australian Workers’ Union [2020] FCA 60 at [47]–[48].

9 In Basi v Namitha Nakul Pty Ltd (No 2) [2023] FCA 671 at [81] Halley J also agreed that this approach is appropriate. His Honour went on to say:

Any attempt to apply a proportionate allocation between two or more periods would likely provide an illusory level of precision. It would be dependent on the acceptance of a series of implicit assumptions as to the relative seriousness and extent of the conduct giving rise to the contravention in each period. Moreover, it might well be said that higher penalty units applicable at the conclusion of the conduct, provide the best measure of the legislative assessment of the penalties necessary to achieve specific and general deterrence given the continuation of the conduct into that period.

10 I respectfully agree.

11 The maximum penalty that may be imposed on each of the Employers is $630,000 for each of the serious contraventions and, with one exception, $63,000 for the other contraventions. There was no dispute that in the case of Ms Handoko and Ms Parmenas, with one exception, the maximum penalty for each contravention is $12,600. The exception concerns the record keeping contraventions relating to Mr Liu for the period 6 July 2014 to 4 November 2017. The maximum penalty for those contraventions is $21,000 for each of the Employers, and $4,200 for each of the other respondents. As it transpires, the exception is irrelevant, as the Ombudsman does not seek a penalty for the contraventions to which the lower maximum penalty would apply.

12 The Court may order that the penalty or part thereof be paid to the Commonwealth, a particular organisation or a particular person: FW Act, s 546(3).

13 Section 557 relevantly provides:

Course of conduct

(1) For the purposes of this Part, 2 or more contraventions of a civil remedy provision referred to in subsection (2) are, subject to subsection (3), taken to constitute a single contravention if:

(a) the contraventions are committed by the same person; and

(b) the contraventions arose out of a course of conduct by the person.

(2) The civil remedy provisions are the following:

(a) subsection 44(1) (which deals with contraventions of the National Employment Standards);

(b) section 45 (which deals with contraventions of modern awards);

…

(i) subsection 325(1) (which deals with unreasonable requirements on employees to spend or pay amounts);

…

(n) subsections 535(1), (2) and (4) (which deal with employer obligations in relation to employee records);

(o) subsections 536(1), (2) and (3) (which deal with employer obligations in relation to pay slips);

…

(s) any other civil remedy provisions prescribed by the regulations.

…

(3) Subsection (1) does not apply to a contravention of a civil remedy provision that is committed by a person after a court has imposed a pecuniary penalty on the person for an earlier contravention of the provision.

14 Even if s 557 does not require the Court to treat as a single contravention all the consequences of particular conduct, “it is open to the Court, in an appropriate case, to take into account, as a matter of discretion, the circumstance that the same acts or omissions have resulted in multiple contraventions”: QR Ltd v Communications, Electrical, Electronic, Energy, Information, Postal, Plumbing and Allied Services Union of Australia [2010] FCAFC 150; 204 IR 142 at [49] per Keane CJ and Marshall J.

The relevant principles

15 There was no dispute about the applicable principles. The Ombudsman referred to the summary in Basi at [24]-[32], which the active respondents accepted as accurate. It is sufficient for present purposes to make the following observations.

16 First, civil penalties, unlike criminal sentences, are imposed primarily, if not solely, for the purpose of deterrence and to promote the public interest in compliance. Consequently, the principal object of a civil penalty is to put a price on contravention that is sufficiently high to deter repetition by the wrongdoer and others who might be tempted to contravene. That may require the imposition of a total penalty which is out of all proportion to the nature and gravity of the contraventions: Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Pattinson (2022) 274 CLR 450. Any civil penalty “must be fixed with a view to ensuring that the penalty is not such as to be regarded by [the contravener] or others as an acceptable cost of doing business”: Singtel Optus Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2012] FCAFC 20; 287 ALR 249; [2012] ATPR ¶42–387 at [62] (Keane CJ, Finn and Gilmour JJ), approved in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd (2013) 250 CLR 640 at [66] (French CJ, Crennan, Bell and Keane JJ), cited in Pattinson at [17].

17 What is required is “some reasonable relationship between the theoretical maximum and the final penalty” and that is established where the penalty does not exceed that which is reasonably necessary to achieve the statutory purpose of deterring future contraventions of a like kind by the contravener and others: Pattinson at [10] quoting Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Reckitt Benckiser (Australia) Pty Ltd [2016] FCAFC 181; 340 ALR 25 at [156]. It makes no difference that the liability of the contravener is vicarious rather than direct or personal: Stuart v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union [2010] FCAFC 65; 185 FCR 308 (Besanko and Gordon JJ) at [52]–[57].

18 Second, an “appropriate” penalty is one which strikes a reasonable balance between oppressive severity and the need for deterrence: Pattinson at [41]. In cases of isolated contraventions caused by inadvertence or ignorance of the law a modest penalty might reasonably be thought sufficient to provide effective deterrence against future contraventions: Pattinson at [46]. The reasonableness of the relationship between the theoretical maximum and the final penalty imposed may be established having regard to the circumstances of the conduct involved in the contravention and the circumstances of the contravener (Pattinson at [55]). That is because either the circumstances of the contravening conduct or the circumstances of the contravener may bear upon the extent of the need for deterrence in the penalty.

19 Third, in assessing a penalty of appropriate deterrent value, a number of factors will generally be relevant. They relevantly include the nature and extent of the contravening conduct; the gravity of the wrongdoing; the nature and extent of the losses incurred as a result of the contraventions; the size of the corporation or business; the involvement of senior management; the need to ensure compliance with minimum standards by provision of an effective means for investigation and enforcement of employee entitlements; and questions of contrition and corrective action. See especially Trade Practices Commission v CSR Ltd [1990] FCA 521; [1991] ATPR ¶41-076 at [42]; 52,152–52,153 (French J); Kelly v Fitzpatrick [2007] FCA 1080, 166 IR 14 at [14] (Tracey J). As the plurality observed in Pattinson at [19], these sort of factors are not to be regarded as “a ‘rigid catalogue of matters for attention’ as if it were a legal checklist”; the Court is still required to determine the appropriate penalty or penalties in the circumstances of the case before it.

20 As the Ombudsman submitted, informed by these legal principles, the approach to the assessment of penalties is, as Bromwich J described in Fair Work Ombudsman v NSH North Pty Ltd trading as New Shanghai Charlestown [2017] FCA 1301; (2017) 69 AILR ¶102–890; 275 IR 148 at [36]. It involves:

(1) identifying the individual contraventions noting that each breach of a term of an award and each breach of an obligation is a separate contravention;

(2) considering whether each contravention should be penalised independently or whether “some degree of aggregation” is required arising out of a course of conduct;

(3) considering whether there should be further adjustment to ensure that, to the extent of any overlap, no double penalty is imposed, and that the penalty is appropriate;

(4) considering the appropriate penalty in respect of each final group of contraventions taken in isolation; and

(5) assessing whether the overall penalty is appropriate.

The last consideration is commonly referred to as “the principle of totality” by which a court is required to carry out a final check of the proposed penalties to ensure that the aggregate sum does not exceed that which is proper for the entire contravening conduct (Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Employsure Ltd [2023] FCAFC 5; 407 ALR 302; 164 ACSR 103 at [52] per Rares, Stewart and Abraham JJ).

21 As deterrence is the object, “the penalty should not be greater than that which is necessary to achieve this object; severity beyond that would be oppression”: NW Frozen Foods Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (1996) 71 FCR 285 at 293 (Burchett and Kiefel JJ).

The evidence

22 The Ombudsman adduced additional evidence from two Fair Work Inspectors, Luke Thomas, who supervised the investigation and from whom evidence was adduced in the liability hearing, and Fortina Colalancia; Guoyong Liu and Qiyin Lin, two former employees of DTF (WS) from whom evidence had also been adduced in the principal proceeding; and Amanda Staier, an officer in the Character and Cancellation Program Management Section of the Department of Home Affairs.

23 The only evidence proffered on behalf of the respondents consisted of an affidavit from the solicitor for Ms Handoko and Ms Parmenas, Donald Junn, which merely annexed correspondence from their tax agents and two notices of assessment from the Australian Taxation Office for the financial years 2017-18 and 2022-2023, and a number of documents. The documents consisted of a so-called “award compliance audit report” for DTF (WS); payslips issued by DTF (WS) for Ms Handoko and Ms Parmenas for a particular fortnight in November 2017 and a “DTF pay run summary” for the same period; a property search for Ms Handoko and two ASIC searches for Ms Parmenas. No affidavits were filed from either of the women and neither was called to give oral evidence.

Consideration

The nature and extent of the conduct etc.

24 I begin by addressing the nature and extent of the conduct, the circumstances in which it took place and related matters.

25 The conduct involved:

(1) contravening s 62 and therefore s 44 by requiring certain employees to work unreasonable hours;

(2) contravening the Restaurant Award and therefore s 45 by failing to pay:

(a) minimum award rates;

(b) Saturday or Sunday penalty rates;

(c) public holiday penalty rates;

(d) evening penalty rates;

(e) overtime rates;

(f) split shift allowances; and

(g) casual loadings;

(3) contravening s 535(4) and reg 3.44(1) by creating records they knew to be false or misleading, namely: false pay slips, timesheets, payroll journals and pay run summaries;

(4) contravening s 535(1) by failing to make and keep for seven years records containing:

(a) the information prescribed by reg 3.33, namely: records of the actual rate of remuneration paid to employees during each fortnight in which part of their wages was paid in cash and of the gross and net amounts actually paid to those employees; or

(b) the information prescribed by reg 3.34, namely: records of overtime hours for certain employees;

(5) contravening s 536(2) by failing to provide employees with pay slips which contained the information prescribed by the Regulations; and

(6) contravening s 536(3) by giving the employees pay slips which contained false and misleading information.

26 Each of the employees who DTF (WS) required to work in excess of 38 hours a week had to do so on multiple occasions, some of them every week. In the case of Mr Liu, the requirement was imposed for 93% of the weeks he worked over a period of nearly four years.

27 A number of the contraventions were “serious contraventions” within the meaning of s 557A of the Act. That is, they were knowing contraventions of civil remedy provisions which were part of a systematic pattern of conduct. I found that each of the Employers committed five such contraventions.

28 In upholding the Ombudsman’s allegations, I made the following observations at [246] of the liability judgment:

The contravening conduct was not isolated, ad hoc or inadvertent. Numerous concurrent contraventions were committed by both Employers, in Mr Liu’s case over a period of nearly four years and in the case of the other Employees over eight months and multiple pay periods. At least 17 employees were affected. All of these Employees are fairly characterised as vulnerable. They were migrant workers, a number of whom were on temporary visas.

29 Section 557A was one of a suite of provisions that came into effect on 15 September 2017 following the passage of the Fair Work Amendment (Protecting Vulnerable Workers) Act 2017 (Cth) and in the wake of several inquiries into the exploitation of vulnerable workers. As the Explanatory Memorandum to the Bill stated:

The Bill addresses increasing community concern about the exploitation of vulnerable workers (including migrant workers) by unscrupulous employers, and responds to a growing body of evidence that the laws need to be strengthened.

The exploitation of vulnerable workers has been examined in a range of reports, including the Senate Education and Employment References Committee’s report entitled A National Disgrace: The Exploitation of Temporary Work Visa Holders, March 2016; the Fair Work Ombudsman’s A Report of the Fair Work Ombudsman’s Inquiry into 7-Eleven, April 2016 and A Report on the Fair Work Ombudsman’s Inquiry into the labour procurement arrangements of the Baiada Group in New South Wales, June 2015; and the Productivity Commission’s Productivity Commission Inquiry Report: Workplace Relations Framework, No. 76, November 2015.

…

The Bill also addresses concerns that civil penalties under the Fair Work Act are currently too low to effectively deter unscrupulous employers who exploit vulnerable workers because the costs associated with being caught are seen as an acceptable cost of doing business. The Bill will increase relevant civil penalties to an appropriate level so the threat of being fined acts as an effective deterrent to potential wrongdoers.

30 It is apparent that the 2017 amendments were introduced to address the very kind of conduct that occurred in this case.

31 The bulk of the contraventions took place in the period 5 November 2017 to 30 June 2018, which was the period of the Ombudsman’s broader assessment. The exception related to Mr Liu, who lodged a complaint with the Office of the Fair Work Ombudsman in May 2018. In his case the contraventions covered a period of almost four years, from 6 July 2014 to 5 May 2018.

32 Ms Handoko and Ms Parmenas submitted that the contraventions relate to only a small proportion of the Employers’ employees. That is true. However, there is no reason to think that the contraventions were isolated or exceptional. In large part that is because the evidence was that the system of creating two sets of records — one reflecting the true picture, the other designed to conceal the truth — had been in operation since at least July 2016 and it was not restricted to the Employees.

The gravity of the wrongdoing

33 It goes without saying that the respondents’ conduct was extremely serious. This was not merely deliberate wrongdoing. It was deceitful and unscrupulous. It involved a calculated scheme to rob employees of their hard-earned wages and deceive the authorities, by which I mean at least the Ombudsman, the Department of Home Affairs and the Australian Taxation Office. It continued unabated after the passage of the 2017 amendments and while the Ombudsman’s investigation was under way.

34 The victims of the contraventions were particularly vulnerable to exploitation. The overwhelming majority of the Employees were young, migrant workers. All but one were under 30. Fifteen of the 17 (89%) were non-citizens on an assortment of temporary visas, including 457 and student visas.

35 In this respect it is likely that the Employees were representative of the broader DTF workforce. Documents before the Court, which DTF (WS) submitted to the Department of Immigration and Border Protection, show that as of 27 June 2017, 338 of its 382 employees (or 88.48%) were “foreign employees”, that is, non-citizens and that the vast majority of them were temporary visa holders. Two hundred and ninety-four (87%) were overseas students. The others included 22 temporary entrants, one on a working holiday. Similarly, as of 1 February 2018, of its 407 employees, 375 (92.13%) were foreign workers of whom 356 were overseas students and 19 were 457 visa holders.

36 Both Mr Liu and Ms Lin gave evidence which indicates that the Employers deliberately hired visa holders rather than Australian citizens or permanent residents in order to avoid their business practices coming to the attention of the authorities. Mr Liu said he was told by the manager of the Chatswood restaurant, Kitty Lee, that “[i]f we hire someone who is Australian citizen to work with us, maybe one day if this staff not happy with our payments, they might report us to Gov department”. In July 2017 Ms Lin received a text message from one of the staff in the HR Department, known as Nike, saying: “Boss doesn’t want to hire PR or citizen anymore so its getting hard to get someone”.

37 It is a notorious fact that foreign workers are particularly susceptible to exploitation. The Migrant Workers’ Taskforce, chaired by Prof Allan Fels AO, reported in March 2019:

Migrant workers who are in Australia on a temporary basis may have poor knowledge of their workplace rights, are young and inexperienced, may have low English language proficiency and try to fit in with cultural norms and expectations of other people from their home countries. These factors combine to make them particularly vulnerable to unscrupulous practices at work.

Survey evidence suggests that many migrant workers are well aware that they are being paid less than they should be. Many factors may explain why they allow this situation to continue. The need to obtain and retain employment in a competitive labour market is one. People are often inclined to take what is available because they need the income or maybe feel that employment is necessary for them to achieve their ultimate goal of ongoing residency in Australia. Not knowing what to do about their underpayment or who to go to for help are other influences. Fears about the consequences of approaching government agencies are common among migrants from less democratic countries than our own. These fears will be more real in the unknown number of cases where there has not been full compliance with visa work restrictions. Also in an unknown number of cases, migrant workers may feel that they benefit from underpayment arrangements by not declaring their income to the Australian Taxation Office (ATO).

38 The Taskforce also noted that a 2016 report on Wage Theft in Australia claimed that underpayment was especially prevalent in food services.

39 In her profile of cafes, restaurants, catering services and takeaway food (FRAC) for the period from July 2015 to June 2019, the Ombudsman categorised the “FRAC industry” as “high risk” with “a number of above-average proportions of risk cohorts, namely, high prevalence of low paid, young, low educated and migrant workers”.

The nature and extent of the losses sustained as a result of the contraventions

40 I now turn to the nature and extent of the losses sustained as a result of the contraventions.

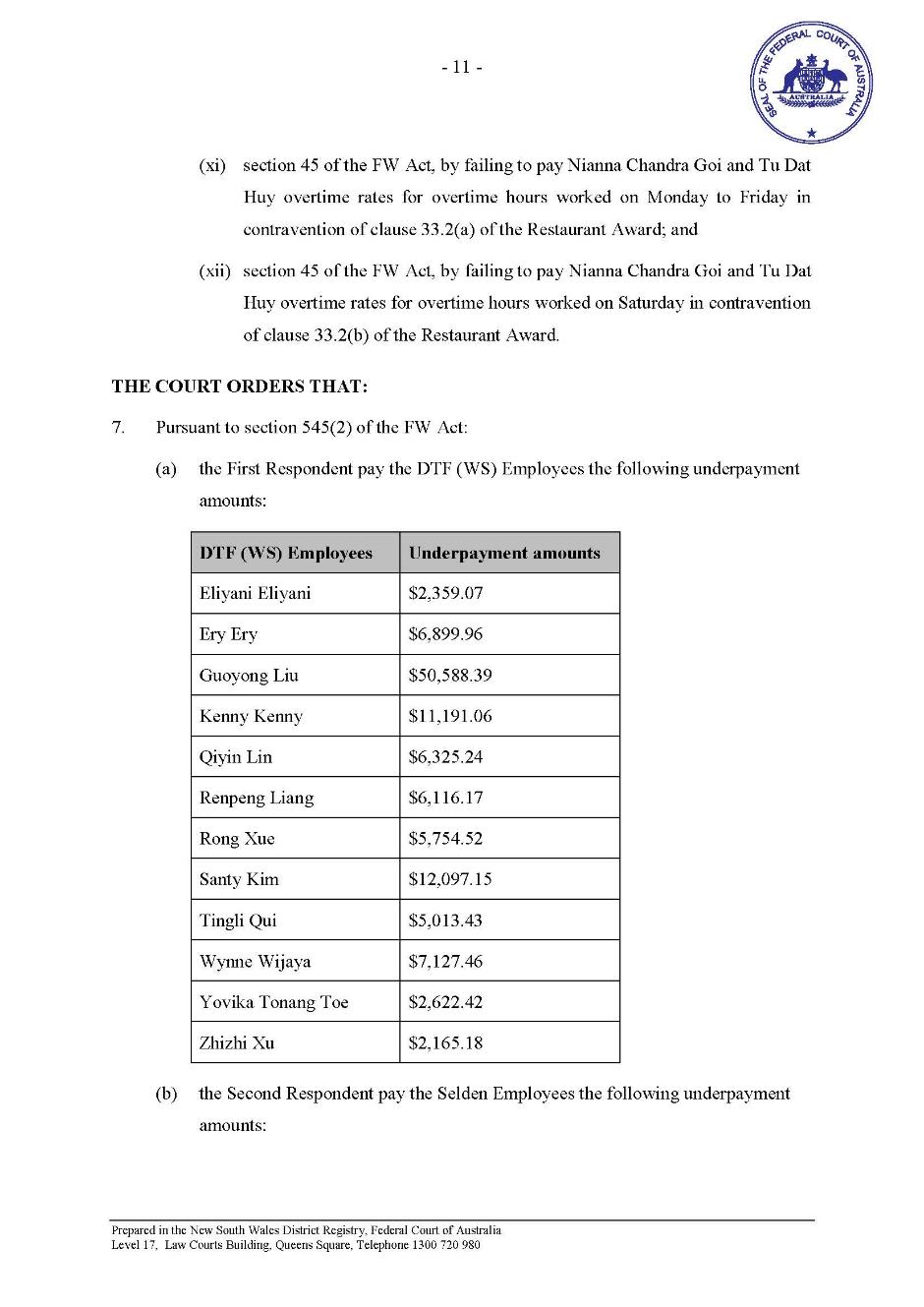

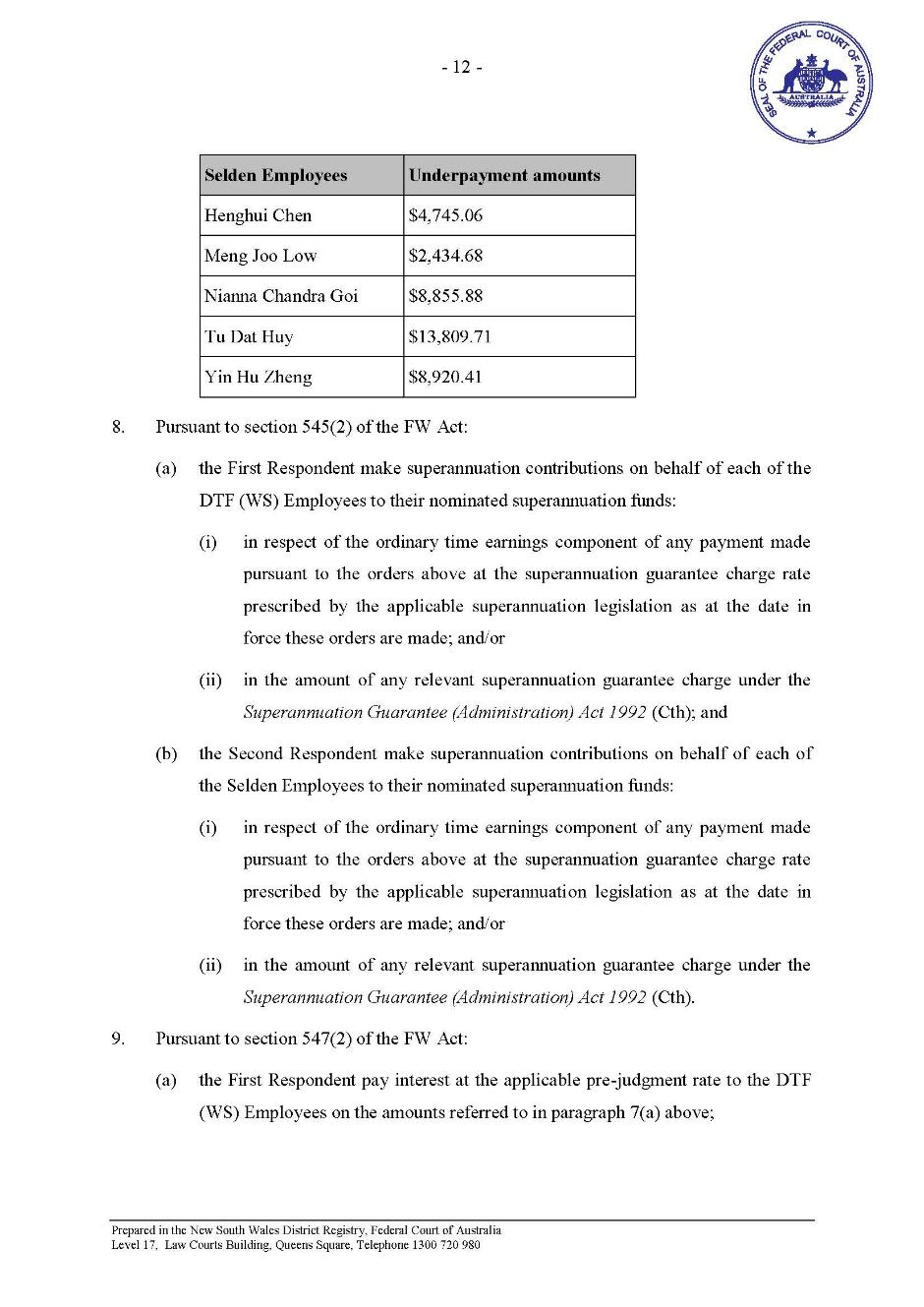

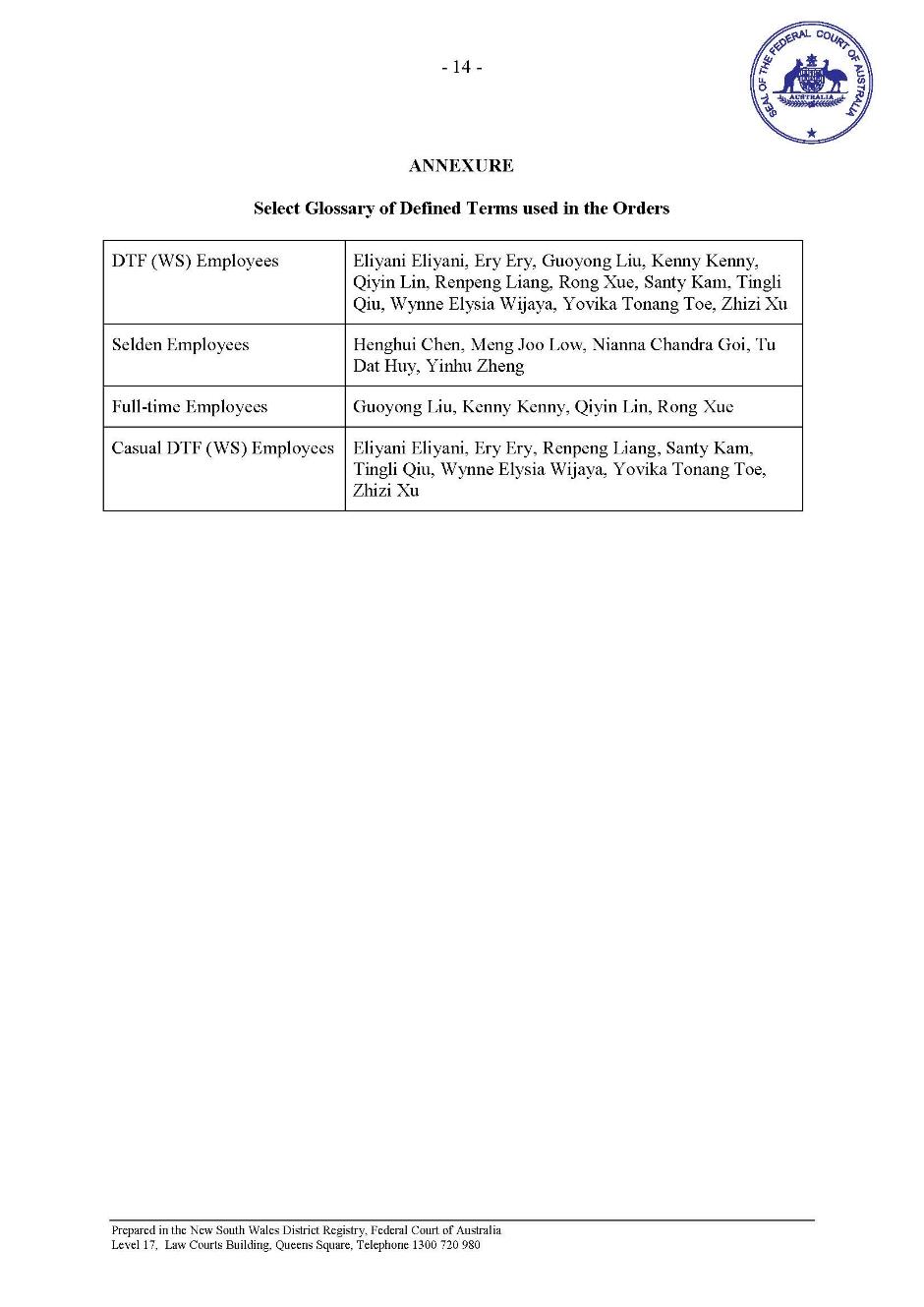

41 Employees were underpaid different amounts ranging from around $2,300 to over $50,000. The underpayments, or at least some of them, also had repercussions for their superannuation because they affected the amounts of superannuation contributions. I accept the Ombudsman’s contention that the amount of the underpayments, which were set out in a table in her submissions reproduced below, represent a substantial proportion of each of the Employees’ entitlements during the relevant periods (ranging from 12.17% to 36.03%) and are significant losses. The first 12 in the table were employees of DTF (WS), the remaining five were employees of Selden.

Employee | Entitlement | Amount paid | Underpayment | Underpayment as percentage of entitlement |

DTF (WS) Employees | ||||

Eliyani Eliyani | $9,643.07 | $7,284.00 | -$2,359.07 | 24.45% |

Ery Ery | $27,540.90 | $34,440.86 | -$6,899.96 | 25.05% |

Guoyong Liu | $268,786.38 | $218,197.99 | -$50,588.39 | 18.82% |

Kenny Kenny | $53,958.91 | $42,767.85 | -$11,191.06 | 20.74% |

Qiyn Lin | $41,209.44 | $34,884.20 | -$6,325.24 | 15.35% |

Renpeng Liang | $20,281.37 | $14,165.20 | -$6,116.17 | 30.16% |

Rong Xue | $47,291.40 | $41,536.88 | -$5,754.52 | 12.17% |

Santy Kam | $57,761.25 | $45,664.10 | -$12,097.15 | 20.94% |

Tingli Qui | $16,260.03 | $11,246.60 | -$5,013.43 | 30.83% |

Wynne Elysia Wijaya | $22,329.86 | $15,202.40 | -$7,127.46 | 31.92% |

Yovika Tonang Toe | $9,880.32 | $7,257.90 | -$2,622.42 | 26.54% |

Zhizi Xu | $7,884.68 | $5,679.50 | -$2,165.18 | 27.46% |

Selden Employees | ||||

Henghui Chen | $13,168.66 | $8,423.60 | -$4,745.06 | 36.03% |

Meng Joo Low | $7,926.78 | $5,492.10 | -$2,434.68 | 30.71% |

Nianna Chandra Goi | $36,246.68 | $27,390.80 | -$8,855.88 | 24.43% |

Tu Dat Huy | $39,958.21 | $26,148.50 | -$13,809.71 | 34.56% |

Yinhu Zheng | $25,839.61 | $16,919.20 | -$8,920.41 | 34.52% |

42 It does not appear that any steps have been taken to compensate the Employees for their losses. After the liability judgment was published, two Fair Work Inspectors contacted the Employees by email asking them to indicate whether they had received any money from their employer. They received responses from five who said that they had not. In addition, Mr Liu and Ms Lin deposed that they had not either.

43 Two of the Employees gave evidence about the impact on them of the long working hours which I found to be unreasonable. Mr Liu spoke of the mental and physical fatigue he experienced as a result of the six day weeks and long hours he was required to work and the effect that had on his family life. Ms Lin spoke of the toll these conditions had on her quality of life. She deposed that she was often exhausted and lacked both the time and the energy to see friends or enjoy “a personal life”. Ms Lin also deposed that the failure to pay her penalty or overtime rates meant that she could not travel to China to visit her family and see her parents as often as she would have liked.

44 Objections were taken to certain passages in their evidence on the basis that it was “in the nature of vague and generalised assertions”. I did (and do not) not think that the criticism was justified. The evidence was admissible and is entitled to some weight. In any case, Mr Liu gave similar evidence in his first affidavit which was read at the liability hearing. He deposed:

I found it hard and tiring to have to work such long hours for DTF. The restaurants where I worked were very busy, and there were often lots of customers waiting in line. This made it very busy in the kitchen. Because I was not meant to have more than one day off per week I was not able to spend time with my family and my young son. I was really struggling during this time and found it really stressful. I felt like I was selling myself for the job.

45 Objection was taken to that paragraph during the trial only on the basis of relevance and the objection was not pressed. Mr Fredericks of counsel, who appeared for Ms Handoko and Ms Parmenas, accepted it was relevant to the unreasonable hours contraventions and Mr Liu was not challenged in cross-examination about it. Ms Lin’s evidence about her inability to travel to China to visit her family as often as she would have liked is also relevant. It reveals some of the effects of the contravening conduct. While theirs was the only evidence of this kind, I would be very surprised if their experiences were unique.

The size of the Employers

46 Records provided to the Ombudsman by the Department of Home Affairs in 2018 show that in May 2014 Ms Handoko advised that DTF (WS) had a financial turnover of in excess of $15 million in the previous financial year and that on 1 February 2018 DTF (WS) had more than 400 employees, an annual turnover for the previous financial year of $7,251 million and a gross payroll of over $3.5 million. I was not taken to any evidence about Selden’s position.

47 A report to creditors from the liquidator of DTF (WS) discloses that that company was sold in February 2020 and had a net asset deficiency of nearly $121,000 and total liabilities of at least $144,187. Selden’s financial position was similar. In his report to creditors, Selden’s liquidator estimated that the realisable assets are just under $17,000 and its total liabilities of the same order as those of DTF (WS).

48 In considering the size of a civil penalty, however, “capacity to pay is of less relevance than the objective of general deterrence”: Jordan v Mornington Inn Pty Ltd [2007] FCA 1384; 60 AILR ¶100–744; 166 IR 33 at [99] (Heerey J); Mornington Inn Pty Ltd v Jordan (2008) 168 FCR 383 at [69] (Stone and Buchanan JJ).

The involvement of senior management

49 As the Ombudsman submitted, the contravening conduct was facilitated by the most senior levels of management. As Snaden J observed in Registered Organisations Commissioner v Australian Workers Union (No 2) [2020] FCA 1148 at [99], “[g]enerally speaking, corporate conduct that is engaged in contravention of a statutory injunction will be considered more egregious—and, therefore, more deserving of sterner penalty—if it is engaged in by or with the imprimatur of the corporation’s senior management”.

Dearth of cooperation

50 There is no evidence of cooperation with the authorities which might weigh in favour of any of the respondents.

The want of contrition or corrective action

51 None of the respondents have previously been found by a court to have contravened workplace laws. Ms Handoko and Ms Parmenas submitted that they are entitled to “credit” on account of their clean records (relying on Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Menon [2020] FCA 1418 at [76] per White J). I reject the submission.

52 In Menon at [76] White J said:

Generally, an absence of prior contraventions is seen as evidence of good character and therefore mitigatory: Ryan v The Queen [2001] HCA 21, (2001) 206 CLR 267 at [30]-[31] (McHugh J) and at [68] (Gummow J); R v Liddy (No 2) [2002] SASC 306, (2002) 84 SASR 231 at [23] but not if advantage was taken of the person’s good character to commit the instant offence. Counsel for the ABCC referred to Sayed v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union [2015] FCA 338 at [51] in which, in the particular circumstances of that case, the absence of prior contraventions of a like kind was not regarded as mitigatory. However, it is generally accepted that a previously blameless life may be evidence of good character, and therefore mitigatory. The individual respondents are entitled to credit on account of their clean records. I reject the submission.

53 With respect, I disagree.

54 I cannot see that prior good character has any role to play in the fixing of civil penalties unless it suggests that the prospect of future contraventions is unlikely. No such argument was mounted in the present case and there was no factual foundation for such an argument.

55 More importantly, neither Ms Handoko nor Ms Parmenas demonstrated any contrition and there is no evidence that any corrective action was taken at any time.

56 Ms Handoko and Ms Parmenas tendered a letter to the Ombudsman from Polczynski Robinson, the respondents’ former lawyers, dated 1 November 2019 and an attached report. In the letter the lawyers referred to a proposal the Employers had apparently made that they would engage an independent third-party expert to assist in ensuring that they complied with the Act “including the relevant awards and regulations”. They advised that the Employers had engaged Hospitality Legal Pty Limited to conduct a compliance audit “for the purpose of ensuring full compliance … going forward”. A copy of the report was enclosed.

57 In the report Hospitality Legal said that it had “reviewed documentation and/or relied on instructions provided by [DTF (WS)] in relation to the nature of its business operations, the work actually performed by employees and days and times that work was performed during the Audit Period”. The “contact person” was identified as Ms Handoko. I infer that she provided both the documentation and the instructions.

58 The audit related to DTF (WS) and covered a two-week period in September 2019.

59 Hospitality Legal identified “one matter of non-compliance” with the Restaurant Award relating to the calculation of the late night penalty rate and which resulted in an underpayment of $1.36 for one employee. It concluded that the payslips for each of the employees complied with the requirements in the Regulations.

60 The Ombudsman objected to the tender of the report. Mr Fredericks pressed the tender arguing that it showed that DTF (WS) took steps to address issues of compliance which included the provision of an audit report. On that basis I admitted the report.

61 In written submissions Ms Handoko and Ms Parmenas contended that the report showed that “DTF” was complying with its award obligations and, as the contact person, Ms Handoko was involved in the steps that DTF took to ensure its ongoing compliance with those obligations. In oral argument Mr Fredericks submitted that the report assisted his clients because it showed that “there was some endeavour to ensure compliance”.

62 The report does nothing of the sort and it is not entitled to any weight.

63 For a start, its author or authors are not identified and there is no evidence to indicate that they had the necessary expertise to conduct an audit. Second, the instructions provided to Hospitality Legal were not disclosed. Third, with the exception of a pay slip for a single employee, which was annexed to the report, the particular documents upon which it relied were not identified. Nor were they included with the report or otherwise provided to the Court. Fourth, the period of the audit was very short and covered only eight low level casual employees at one restaurant. Fifth, the report does not indicate how these particular employees were selected; in particular, whether a random selection process was deployed. Sixth, it is not apparent that Hospitality Legal was informed that DTF (WS) had a long-standing practice of creating and keeping two sets of records, a false set which represented that wages were paid in compliance with the Award and another which disclosed the real situation. For all I know, that practice continued at the time of the audit and Hospitality Legal was oblivious to it. In all likelihood, Hospitality Legal was oblivious to it. Otherwise, one would expect to see evidence that it had been informed about the practice and that it was satisfied that the practice had been abandoned. It is of no significance that the contravention period was over by the time of the period covered by the report. Absent evidence to indicate that the practice had ceased, the presumption of continuance applies. In other words, the Court may infer that the practice is continuing. See JD Heydon, Cross on Evidence, 13th ed, LexisNexis, [1125]. See also Stanoevski v The Council of the Law Society of New South Wales [2008] NSWCA 93 at [55]-[65] (Campbell JA, Hodgson JA and Handley AJA agreeing at [1] and [86]) for an application of the principle in a different, though broadly analogous, context.

The need for deterrence

64 The above-mentioned matters indicate the need for substantial penalties. This was not a case of mere carelessness or inadvertence. Rather, as the Ombudsman submitted, it was a case in which employees have been deprived of their statutory entitlements through the Employers’ deliberate contraventions in “contumelious disregard of the law”. Worse still, the contraventions of ss 535 and 536 and reg 3.44(1) were the product of a calculated effort by the respondents to conceal their wrongdoing.

65 Having regard to the position of the Employers as revealed by the liquidators’ reports, the Ombudsman did not submit there was a need for specific deterrence in their case. But general deterrence is another matter. The need for general deterrence is not defeated by the fact that the companies are in liquidation and are unable to pay penalties. Secretary, Department of Health and Ageing v Prime Nature Prize Pty Ltd (in liq) [2010] FCA 597 at [22] (Stone J). A penalty that is no greater than that which is necessary to achieve the object of general deterrence will not be oppressive: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Leahy Petroleum Pty Ltd (No 2) [2005] FCA 254, 215 ALR 281; ATPR ¶42–051 at [9] (Merkel J).

66 In Basi at [84] Halley J remarked that “[t]he introduction and operation of a dishonest scheme to deprive employees of their statutory entitlements may well demand much greater penalties to deter an employer and other employees from engaging in similar conduct than inadvertent failures to pay employees all of their statutory entitlements”. Frankly, it is difficult to conceive of any circumstances in which the introduction and operation of a dishonest scheme to deprive employees of their statutory entitlements to minimum wages or conditions would ever warrant anything but the imposition of substantial penalties. The penalties must be fixed at a figure which reflects the law’s disapproval of the contravening conduct and operate as a warning to others not to engage in conduct of that kind: Community and Public Sector Union v Telstra Corporation Ltd [2001] FCA 1364; 108 IR 228 at [9] (Finkelstein J).

67 I reject the submission put on behalf of Ms Handoko and Ms Parmenas that “there is no suggestion that [they] have engaged in any conduct which would require consideration of specific deterrence directed to them”. I found that they were involved in numerous contraventions by the Employers such that they are taken to have contravened the Act in multiple respects. There is no reason to suppose that there is no (or even a low) prospect that they might reoffend, so to speak. In the absence of an acknowledgment that they had any involvement in the contravening conduct, let alone any sign of contrition, one can have no confidence that, if given the opportunity, they would not behave in the future as they have done in the past.

68 Evidence adduced by the Ombudsman at the penalty hearing discloses that in 2020, while the Ombudsman’s investigations were still in progress, the DTF (WS) business was sold to another company, Austap 11 Pty Ltd, and the Selden business was sold to Pacific Gp Pty Ltd, both of which were registered on 25 November 2019. Amanda Staier, an officer in the Department of Home Affairs, indicated in her affidavit that Departmental records show that Austap trades as Din Tai Fung and operates restaurants under that name. She deposed that Austap is a Standard Business Sponsor for the purpose of sponsoring temporary skilled workers for visas and has sponsored nominated skilled workers for permanent resident visas.

69 The evidence also discloses that four employees of DTF (WS) were transferred to Austap, and that until 5 July 2020 (when she was replaced by Alinawaty Yiulianto, a former director of the Employers), Ms Handoko was a director of both Austap and Pacific. Ms Parmenas’s signature appears on two employees’ contracts as an authorised officer of Austap. Underneath her name the words “HR Department” appears, indicating that she continued to do the same kind of work as she was performing for DTF. I infer, based on the presumption of continuance and the absence of reliable evidence to the contrary, that Ms Parmenas still holds such a role. Although the evidence is that Ms Handoko ceased to be a director of the two companies in July 2020, there is no evidence to indicate that she has no continuing role in either business or is no longer involved in the restaurant industry or any other business which employs staff. If neither woman was in such a position one would expect she would have given evidence to that effect. The failure to adduce evidence from Ms Handoko and Ms Parmenas is unexplained. In these circumstances, I infer that they could say nothing in support of the submission that there is no need for specific deterrence for either of them: Jones v Dunkel (1959) 101 CLR 298.

Quantum

The Ombudsman’s position

70 The Ombudsman accepted that multiple contraventions of the same clause of the Restaurant Award or the same section of the FW Act should be treated as part of a single course of conduct. Accordingly, she proposed that, regardless of the number of employees with which each contravention is concerned, the contraventions of particular provisions which affect multiple employees be penalised as single contraventions. Thus, DTF (WS) should be taken to have committed 20 contraventions, Selden 13, Ms Handoko 25 and Ms Parmenas 30. Ms Handoko and Ms Parmenas did not take issue with this approach. Indeed, s 557(1) requires it.

71 With respect to DTF (WS) the Ombudsman submitted that the Court should impose:

(1) penalties representing 70% of the maximum for:

(a) the “serious contravention” of s 535(4) by making and keeping records in relation to the 12 DTF (WS) Employees which it knew to be false or misleading;

(b) the contraventions of s 44 by requesting or requiring four DTF (WS) Employees to work unreasonable additional hours contrary to s 62; and

(c) the contraventions of s 536(3) by providing all but one of the DTF (WS) Employees pay slips it knew were false or misleading;

(2) penalties representing 50% of the maximum for:

(a) each of the remaining four “serious contraventions” of s 45 relating to the failure to pay casual loadings, Saturday penalty rates; Sunday penalty rates; and public holiday penalty rates;

(b) the contraventions of s 535(1) for failing to make and keep for seven years records containing the information prescribed by reg 3.33 with respect to the 12 DTF (WS) Employees; and

(c) the contraventions of s 536(2) by failing to give the DTF (WS) Employees pay slips which included the information prescribed by reg 3.46;

(3) penalties representing 60% of the maximum for:

(a) the contraventions of s 45 by failing to pay eight DTF (WS) Employees overtime rates for overtime hours worked on weekdays in breach of cl 33.2(a) of the Restaurant Award.

(b) the contraventions of s 45 by failing to pay six DTF (WS) Employees overtime rates for overtime hours worked on Saturdays in breach of cl 33.2(b) of the Restaurant Award;

(4) penalties representing 40% of the maximum for:

(a) the contraventions of s 45 by failing to pay seven casual DTF (WS) Employees and Mr Liu the minimum rates prescribed by cl 20.1 of the Restaurant Award;

(b) the contraventions of s 45 by failing to pay the four full-time Employees a split shift allowance in breach of cl 24.2 of the Restaurant Award;

(5) penalties representing10% of the maximum for:

(a) the contraventions of s 535(1) for failing to make and keep for seven years records containing the information prescribed by reg 3.34 with respect to five DTF (WS) Employees; and

(b) the contraventions of s 45 by failing to pay four DTF (WS) Employees overtime rates for overtime hours worked on Sundays in breach of cl 24.2 of the Restaurant Award.

72 The Ombudsman sought no penalties for the contraventions of s 45 by the failure to pay Mr Liu Saturday, Sunday and public holiday penalty rates in breach of cl 34.1 of the Restaurant Award. Nor does she seek a penalty for the contravention of reg 3.44(1) by making and keeping records in relation to Mr Liu that DTF (WS) knew to be false or misleading.

73 With respect to Selden the Ombudsman submitted that the Court should impose:

(1) penalties representing 70% of the maximum for:

(a) the contraventions of s 536(3) by providing all but one of the Selden Employees with pay slips it knew to be false or misleading;

(b) the “serious contraventions” of s 535(4);

(2) penalties representing 50% of the maximum for:

(a) each of the remaining four “serious contraventions” of s 45 relating to the failure to pay casual loadings; Saturday penalty rates; Sunday penalty rates; and public holiday penalty rates;

(b) the contraventions of s 535(1) by failing to make and keep records in respect of five Selden Employees which contained the information prescribed by reg 3.33;

(3) penalties representing 40% of the maximum for:

(a) the contraventions of s 45 by failing to pay the Selden Employees the minimum rates of pay in breach of cl 20.1 of the Restaurant Award;

(b) the contraventions of s 45 by failing to pay two Selden Employees overtime rates for overtime hours worked on weekdays in breach of cl 33.2(a) of the Award; and

(c) the contraventions of s 45 of the FW Act by failing to pay the same two Selden Employees overtime rates for overtime hours worked on Saturdays in breach of cl 33.2(b) of the Award;

(4) penalties representing 10% of the maximum for:

(a) the contraventions of s 535(1) by failing to keep records containing the information prescribed by reg 3.34 with respect to one of the Selden Employees; and

(b) the contravention of s 45 by failing to provide all but one of the Selden Employees evening penalties in breach of cl 34.2(a)(1) of the Restaurant Award.

74 In the case of the two accessories, Ms Handoko and Ms Parmenas, penalties were sought in roughly the same proportions. No allegation was made against either of them that they committed a serious contravention within the meaning of s 557A. But I found that they were involved in some of the contraventions of provisions which fall within the definition of a “serious contravention” in that section. With respect to those contraventions, the Ombudsman sought penalties in excess of the proportions sought in relation to the Employers for contravening the same sections.

75 Thus, for the contraventions which each of Ms Handoko and Ms Parmenas are taken to have committed, the Ombudsman submitted that the Court should impose:

(1) penalties representing 70% of the maximum for:

(a) the contraventions of s 535(4) (making and keeping records known to be false or misleading); and

(b) the contraventions of s 536(3) (providing pay slips known to be false or misleading);

(2) penalties representing 50% of the maximum for:

(a) the contraventions of s 536(2) (failing to give pay slips which included the information prescribed by reg 3.46); and

(b) the contraventions of s 44 by requesting or requiring certain employees to work unreasonable additional hours in contravention of s 62;

(3) penalties corresponding to 65% of the maximum with respect to the contraventions of s 45 for the breaches of cl 13.1 of the Restaurant Award (failing to pay casual loadings);

(4) penalties representing 60% of the maximum for:

(a) the contraventions of s 45 for breaches of cl 33.2(a) (failing to pay overtime rates for overtime hours on weekdays) (in relation to DTF (WS));

(b) the contraventions of s 45 for breaches of cl 33.2(b) (failing to pay overtime rates for overtime hours worked on Saturdays) (in relation to DTF (WS));

(c) the contraventions of s 45 for the breaches of cl 34.1 (failing to pay Saturday penalty rates);

(d) the contraventions of s 45 for the breaches of cl 34.1 (failing to pay Sunday penalty rates); and

(e) the contraventions of s 45 for the breaches of cl. 34.1 (by failing to pay public holiday penalty rates);

(5) penalties representing 40% of the maximum for:

(a) the contraventions of s 45 for the breaches of cl 20.1 of the Restaurant Award (failing to pay minimum rates);

(b) the contraventions of s 45 for breaches of cl 24.2 (failing to pay split shift allowances);

(c) the contraventions of s 45 for breaches of cl 33.2(a) (by failing to overtime hours on weekdays) (in relation to Selden); and

(d) the contraventions of s 45 for breaches of cl 33.2(b) (failing to pay overtime rates and overtime hours worked on Saturdays) (in relation to Selden);

(6) penalties representing 10% of the maximum for:

(a) the contraventions of s 45 for breaches of cl 34.2(a)(i) of the Restaurant Award (failing to pay evening penalty rates); and

(b) the contraventions of s 45 for breaches of cl 33.2(c) (failing to pay overtime rates for overtime hours worked on Sundays) (in relation to DTF (WS) only).

76 The Ombudsman submitted that a 20% totality discount should be applied.

The submissions for Ms Handoko and Ms Parmenas

77 Mr Fredericks did not argue that they should be treated differently from each other. But he submitted that the penalties recommended by the Ombudsman were “excessive and disproportionate”. He argued that they failed to take into account several important factors, namely:

that neither Ms Handoko nor Ms Parmenas established the scheme that gave rise to the contraventions;

at all times they were subject to the direction of Mr Harjanto and others he did not name;

there were other participants in the scheme;

there is no apparent reason why Ms Handoko and Ms Parmenas should be treated as having the same level of culpability as the Employers;

Ms Handoko and Ms Parmenas were not highly paid employees, principals or shareholders of the Employers and there is no evidence that they stood to benefit from any of the contraventions; and

their financial positions are such that the penalties the Ombudsman seeks from them are “oppressive and crushing”.

Consideration

78 I accept the submission that Ms Handoko and Ms Parmenas were subject to the direction of Mr Harjanto. Ms Handoko was directly responsible to him and Ms Parmenas to Ms Handoko (LJ at [310]). The evidence indicated that nothing happened in the DTF business without his imprimatur (LJ [240]). However, there is no evidence about who established the scheme that gave rise to the contraventions. Nor can it be inferred that Ms Handoko or Ms Parmenas had nothing to do with its establishment or maintenance. Although Mr Harjanto had the final say, both Ms Handoko and Ms Parmenas were involved in setting the unlawful pay rates (LJ [293]). Moreover, I found that Ms Parmenas knew from the time she started working for the DTF Group or shortly thereafter that the pay slips, ADP and MYOB records were false or misleading (at LJ [278]–[280]). Not only was she implicated in the record keeping and pay slip contraventions but that she facilitated them, too (at LJ [280]). And I found that she condoned and participated in the creation of false and misleading records (at LJ [282]). As for Ms Handoko, there was no firm evidence about when she began working for the DTF Group and therefore no evidence that the scheme was in place when she started.

79 I concluded that Ms Handoko created or at least maintained the system of false or misleading record keeping (at LJ[313]):

Either Ms Parmenas was on a frolic of her own (with Mr Tandra) or she was acting in accordance with the directions of her supervisor, Ms Handoko. The former is unlikely. It was not suggested to Mr Tandra in cross-examination that he devised the system. Ms Parmenas reported directly to Ms Handoko and Ms Handoko directed her day to day activities and duties. Those activities included the supervision and operation of the payroll and record keeping system. In the absence of evidence to the contrary, I infer that this included the creation or at least maintenance of the system of false or misleading record keeping.

80 The fact that others were involved in the scheme is largely, if not entirely, irrelevant. It has nothing to do with the amount of the penalties necessary to deter either them or others from committing contraventions of a like kind.

81 Mr Fredericks urged the Court to impose lower penalties, not merely because he contended that there was no need for specific deterrence but also because the impact of the contraventions (by which he meant the losses suffered by the Employees) meant that the contraventions justified penalties in the middle of the range. He submitted that, spread across the 17 Employees, the average underpayment was under $10,000 and with one exception, at the time the proceedings were started, each of the “underpayment claims” was within the small claims jurisdiction provided for by the FW Act.

82 I have already rejected the submission about specific deterrence. I reject the submission about the impact of the contraventions, too. In the first place, by and large the penalties the Ombudsman is seeking against Ms Handoko and Ms Parmenas are in the middle of the range. Second, the figures the Ombudsman proposes take into account the extent of the underpayments. Third, as a proportion of their total wages, the losses the Employees incurred as a result of the contraventions were substantial.

83 In any case, there is no requirement that the amount of the penalties correspond to the extent of the underpayments. The extent of the losses is merely one relevant consideration. It is clear after Pattinson that a court may impose a civil penalty which is out of all proportion to the nature and gravity of the contravening conduct if it is appropriate to do so in order to serve the purpose of deterrence.

84 That said, if I were able to find that the contravening conduct was isolated or limited to the 17 Employees, I may well have accepted the submission that the proposed penalties are too high — even in the absence of contrition or corrective action. For the reasons given earlier, however, I am not. In short, it is apparent that the contraventions were merely illustrative of practices deployed across the two companies, if not the entire DTF Group, and all its employees.

85 Mr Fredericks submitted that the proposed penalties would be “oppressive and crushing” because neither of his clients has the means to pay the penalties and that it is likely that Ms Parmenas would have to sell her share of her home in order to pay a substantial penalty. He argued that in these circumstances a totality discount of not less than 40% was appropriate.

86 In the absence of any evidence from Ms Handoko or Ms Parmenas, this submission is at best speculative and I cannot accept it.

87 For a start, I am not satisfied that the evidence proffered about their earnings is reliable. The pay slips tendered on their behalf were in the form of the pay slips I found to be false or misleading in that they did not record the true number of hours worked by the Employees or cash payments made to them and were for pay periods during which wages were routinely paid both by electronic funds transfer and cash. The pay run summary merely reflects the amount in the pay slip and it was among the other documents I found to be false or misleading. And the assessment notices no doubt reflect the information in the pay slips.

88 Notably the pay slip for Ms Parmenas, the HR Coordinator or Manager, showed that in the period in question she was paid less than the amounts paid to Mr Liu and Ms Lin for a fortnightly period only about three months later. Her taxable income was recorded in the 2018 assessment notice as $49,580.

89 Ms Handoko was the General Manager of the DTF Group and DTF (WS). Yet, her pay slip discloses that she was paid at an hourly rate of $36.84, less than $7.00 more than Mr Liu. Her taxable income as recorded in her 2018 assessment notice was $70,665.

90 Mr Liu and Ms Lin were both cooks. I consider it highly unlikely that a member of the management team like Ms Parmenas would be paid less than a cook and that the General Manager would be paid at such a low rate. The inference that they were also paid partly in cash is inescapable.

91 The 2022 assessment notice for Ms Handoko shows that her taxable income was $7,037. The 2023 assessment notice for Ms Parmenas shows that her taxable income was $82. The property search conducted in relation to Ms Handoko shows that there were no verified title references to her name for real estate in NSW. The ASIC searches show that as of 25 August 2023 neither woman held any shares in any Australian companies.

92 I have no confidence, however, that this information provides a true or complete picture of their current financial circumstances.

93 In any event, as the Ombudsman submitted, the totality principle is not directed to the financial circumstances of the contravener. It is concerned with ensuring that the total penalty is “an appropriate response to the conduct which led to the [contraventions]”: Kelly v Fitzpatrick at [30].

94 I acknowledge that a relatively small penalty might operate as a deterrent for a person of modest means who has not previously offended, so to speak. But the evidence is insufficient to enable me to conclude that Ms Handoko or Ms Parmenas is such a person. It was open to them to disclose to the Court the full extent of their income, assets and liabilities or simply to confirm on oath or affirmation that they had no, or limited, resources available to them. It was also open to them to give evidence that they had learned from the experience of this proceeding. Yet they elected not to. In any event, the means of the individuals, like those of the Employers, are irrelevant to the question of general deterrence.

95 I accept the Ombudsman’s argument that, because there is a need for specific deterrence in the cases of Ms Handoko and Ms Parmenas and not for the Employers, there is no necessary correlation between the approach that should be taken to penalising each of them on the one hand and the Employers on the other.

Conclusions

96 Having regard to the various matters discussed above, I accept the Ombudsman’s submissions concerning the penalties that should be imposed upon the Employers for the various contraventions. I consider they are appropriate in all the circumstances in order to serve the legislative purpose. Given their seniority and the absence of any submission to the effect that they should be treated any differently from each other, with one qualification I also accept the Ombudsman’s submissions in relation to Ms Handoko and Ms Parmenas. The qualification relates to the Ombudsman’s submission on totality.

97 As I mentioned earlier, the maximum penalty for each of the serious contraventions committed by the Employers is $630,000 and, subject to the exception mentioned at [11] above, for the other contraventions $63,000, and $12,600 for the contraventions by each of Ms Handoko and Ms Parmenas. The percentages recorded after the figures represent the percentages of the maximum I consider appropriate, subject to the question of totality.

98 For DTF (WS):

(1) with respect to the serious contraventions:

(a) s 535(4) (by making and keeping records in relation to the DTF (WS) Employees for the purposes of s 535 that it knew to be false or misleading): $441,000 (70%);

(b) s 45 (by failing to pay the Casual DTF (WS) Employees casual loadings in contravention of cl 13.1 of the Restaurant Award): $315,000 (50%);

(c) s 45 (by failing to pay Eliyani Eliyani, Ery Ery, Renpeng Liang, Santy Kam, Tingli Qui, Wynne Elysia Wijaya and Zhizi Xu Saturday penalty rates in contravention of cl 34.1 of the Restaurant Award): $315,000 (50%);

(d) s 45 (by failing to pay Eliyani Eliyani, Ery Ery, Renpeng Liang, Santy Kam, Tingli Qiu, Wynne Elysia Wijaya and Zhizi Xu Sunday penalty rates in contravention of cl 34.1 of the Restaurant Award): $315,000 (50%); and

(e) s 45 (by failing to pay Ery Ery, Renpeng Liang, Santy Kam, Tingli Qiu, Wynne Elysia Wijaya, Yovika Tonang Toe and Zhizi Xu public holiday penalty rates in contravention of cl 34.1 of the Restaurant Award): $315,000 (50%).

(2) with respect to the other contraventions of s 45:

(a) by failing to pay Eliyani Eliyani, Ery Ery, Guoyong Liu, Renpeng Liang, Tingli Qiu, Wynne Elysia Wijaya, Yovika Tonang Toe and Zhizi Xu the minimum rates of pay required by the Restaurant Award in contravention of cl 20.1 of the Restaurant Award: $25,200 (40%);

(b) by failing to pay Ery Ery, Guoyong Liu, Kenny Kenny, Qiyin Lin, Renpeng Liang, Rong Xue, Santy Kam, Tingli Qiu, Wynne Elysia Wijaya and Zhizi Xu evening penalties in contravention of cl 34.2(a)(i) of the Restaurant Award: $6,300 (10%);

(c) by failing to pay Eliyani Eliyani, Ery Ery, Guoyong Liu, Kenny Kenny, Qiyin Lin, Rong Xue, Santy Kam and Wynne Elysia Wijaya overtime rates for overtime hours worked on Monday to Friday in contravention of cl 33.2(a) of the Restaurant Award: $37,800 (60%);

(d) by failing to pay Ery Ery, Guoyong Liu, Kenny Kenny, Qiyin Lin, Rong Xue and Santy Kam overtime rates for overtime hours worked on Saturday in contravention of cl 33.2(b) of the Restaurant Award: $37,800 (60%);

(e) by failing to pay Guoyong Liu, Kenny Kenny, Qiyin Lin and Santy Kam overtime rates for overtime hours worked on Sunday in contravention of cl 33.2(c) of the Restaurant Award: $6,300 (10%); and

(f) by failing to pay the Full-time Employees split shift allowances in contravention of cl 24.2 of the Restaurant Award: $25,200 (40%).

(3) with respect to the other contraventions of s 44 by requesting or requiring Guoyong Liu, Kenny Kenny, Rong Xue and Santy Kam to work unreasonable additional hours in contravention of s 62: $44,100 (70%).

(4) with respect to the contraventions of s 535(1):

(a) by failing to make and keep for seven years records in respect of the DTF (WS) Employees which contained the information prescribed by reg 3.33: $31,500 (50%); and

(b) by failing to make and keep for seven years records in respect of Eliyani Eliyani, Ery Ery, Guoyong Liu, Tingli Qiu and Wynne Elysia Wijaya which contained the information prescribed by reg 3.34: $6,300 (10%).

(5) With respect to the contraventions of s 536(2) by failing to give the DTF (WS) Employees pay slips which included the information prescribed by reg 3.46: $31,500 (50%).

(6) with respect to the contraventions of s 536(3) by providing all but one of the DTF (WS) Employees with pay slips which it knew were false or misleading (the exception not having been provided with any pay slips at all): $44,100 (70%).

99 As none are sought, I impose no penalties for the contraventions of s 45 by failing to pay Mr Liu Saturday, Sunday and public holiday penalty rates in contravention of cl 34.1 of the Restaurant Award or the contraventions of reg 3.44(1) that apply in his case.

100 The aggregate of these sums is $1,997,100.

101 For Seldon:

(1) with respect to the serious contraventions:

(a) s 535(4) (by making and keeping records in relation to the Selden Employees for the purposes of s 535 that it knew to be false or misleading): $441,000 (70%);

(b) s 45 (by failing to pay the Selden Employees casual loadings in contravention of cl 13.1 of the Restaurant Award): $315,000 (50%);

(c) s 45 (by failing to pay the Selden Employees Saturday penalty rates in contravention of clause 34.1 of the Restaurant Award): $315,000 (50%);

(d) s 45 (by failing to pay the Selden Employees Sunday penalty rates in contravention of cl 34.1 of the Restaurant Award): $315,000 (50%); and

(e) s 45 (by failing to pay the Selden Employees public holiday penalty rates in contravention of cl 34.1 of the Restaurant Award): $315,000 (50%).

(2) with respect to the other contraventions of s 45:

(a) by failing to pay the Selden Employees the minimum rates of pay required by the Restaurant Award in contravention of cl 20.1 of the Restaurant Award: $25,200 (40%);

(b) by failing to pay Henghui Chen, Nianna Chandra Goi, Tu Dat Huy and Yinhu Zheng evening penalties in contravention of cl 34.2(a)(i) of the Restaurant Award: $6,300 (10%);

(c) by failing to pay Nianna Chandra Goi and Tu Dat Huy overtime rates for overtime hours worked on Monday to Friday in contravention of cl 33.2(a) of the Restaurant Award: $25,200 (40%); and

(d) by failing to pay Nianna Chandra Goi and Tu Dat Huy overtime rates for overtime hours worked on Saturday in contravention of cl 33.2(b) of the Restaurant Award: $25,200 (40%).

(3) With respect to the contraventions of s 535(1):

(a) by failing to make and keep records in respect of the Selden Employees which contained the information prescribed by reg 3.33: $31,500 (50%); and

(b) by failing to make and keep records in respect of Tu Dat Huy which contained the information prescribed by reg 3.34: $6,300 (10%).

(4) With respect to the contraventions of s 536(2) by failing to give the Selden Employees pay slips which included the information prescribed by reg 3.46: $31,500 (50%).

(5) With respect to the contraventions of s 536(3) by providing all but one of the Selden Employees with pay slips which it knew were false or misleading: $44,100 (70%).

102 The aggregate of those sums is $1,896,300.

103 I intend to impose penalties on DTF (WS) and Selden in the amount of the aggregate sums. I am satisfied that neither of these sums exceeds that which is proper for the entire contravening conduct and is no greater than is necessary to operate as a deterrent to potential wrongdoers.

104 For Ms Handoko, in relation to DTF (WS):

(1) With respect to the contraventions of s 45:

(a) by failing to pay Eliyani Eliyani, Ery Ery, Guoyong Liu, Renpeng Liang, Tingli Qiu, Wynne Elysia Wijaya, Yovika Tonang Toe and Zhizi Xu the minimum rates of pay required by the Restaurant Award in contravention of cl 20.1 of the Restaurant Award: $5,040 (40%);

(b) by failing to pay the Casual DTF (WS) Employees casual loadings in contravention of cl 13.1 of the Restaurant Award: $8,190 (65%);

(c) by failing to pay Eliyani Eliyani, Ery Ery, Guoyong Liu, Renpeng Liang, Santy Kam, Tingli Qui, Wynne Elysia Wijaya and Zhizi Xu Saturday penalty rates in contravention of cl 34.1 of the Restaurant Award: $7,560 (60%);

(d) by failing to pay Eliyani Eliyani, Ery Ery, Guoyong Liu, Renpeng Liang, Santy Kam, Tingli Qiu, Wynne Elysia Wijaya and Zhizi Xu Sunday penalty rates in contravention of cl 34.1 of the Restaurant Award: $7,560 (60%);

(e) by failing to pay Ery Ery, Guoyong Liu, Renpeng Liang, Santy Kam, Tingli Qiu, Wynne Elysia Wijaya, Yovika Tonang Toe and Zhizi Xu public holiday penalty rates in contravention of cl 34.1 of the Restaurant Award: $7,560 (60%).

(f) by failing to pay Ery Ery, Guoyong Liu, Kenny Kenny, Qiyin Lin, Renpeng Liang, Rong Xue, Santy Kam, Tingli Qiu, Wynne Elysia Wijaya and Zhizi Xu evening penalties in contravention of cl 34.2(a)(i) of the Restaurant Award: $1,260 (10%);

(g) by failing to pay Eliyani Eliyani, Ery Ery, Guoyong Liu, Kenny Kenny, Qiyin Lin, Rong Xue, Santy Kam and Wynne Elysia Wijaya overtime rates for overtime hours worked on Monday to Friday in contravention of cl 33.2(a) of the Restaurant Award: $7,560 (60%);

(h) by failing to pay Ery Ery, Guoyong Liu, Kenny Kenny, Qiyin Lin, Rong Xue and Santy Kam overtime rates for overtime hours worked on Saturday in contravention of cl 33.2(b) of the Restaurant Award: $7,560 (70%);

(i) by failing to pay by failing to pay Guoyong Liu, Kenny Kenny, Qiyin Lin and Santy Kam overtime rates for overtime hours worked on Sunday in contravention of cl 33.2(c) of the Restaurant Award: $1,260 (10%); and

(j) by failing to pay the Full-time Employees split shift allowances in contravention of cl 24.2 of the Restaurant Award: $5,040 (40%).

(2) with respect to the contraventions of s 535(4) by making and keeping records in relation to the DTF (WS) Employees for the purposes of s 535 of the FW Act which were known to be false or misleading: $8,820 (70%);

(3) with respect to the contraventions of s 536(2) by failing to give the DTF (WS) Employees pay slips which included the information prescribed by reg 3.46: $6,300 (50%).

(4) with respect to the contraventions of s 536(3) by providing all but one of the DTF (WS) Employees with pay slips which it knew were false or misleading: $8,820 (70%).

105 I will impose no penalty for her involvement in the contraventions of reg 3.44(1).

106 For Ms Handoko, in relation to Selden:

(1) with respect to the contraventions of s 45:

(a) by failing to pay the Selden Employees the minimum rates of pay required by the Restaurant Award in contravention of cl 20.1 of the Restaurant Award: $5,040 (40%);

(b) by failing to pay the Selden Employees casual loadings in contravention of cl 13.1 of the Restaurant Award: $8,190 (65%);

(c) by failing to pay the Selden Employees Saturday penalty rates in contravention of cl 34.1 of the Restaurant Award: $7,560 (60%);

(d) by failing to pay the Selden Employees Sunday penalty rates in contravention of cl 34.1 of the Restaurant Award: $7,560 (60%);

(e) by failing to pay the Selden Employees public holiday penalty rates in contravention of cl 34.1 of the Restaurant Award: $7,560 (60%).

(f) by failing to pay Henghui Chen, Nianna Chandra Goi, Tu Dat Huy and Yinhu Zheng evening penalties in contravention of cl 34.2(a)(i) of the Restaurant Award: $1,260 (10%);

(g) by failing to pay Nianna Chandra Goi and Tu Dat Huy overtime rates for overtime hours worked on Monday to Friday in contravention of cl 33.2(a) of the Restaurant Award: $5,040 (40%);

(h) by failing to pay Nianna Chandra Goi and Tu Dat Huy overtime rates for overtime hours worked on Saturday in contravention of cl 33.2(b) of the Restaurant Award: $5,040 (40%);

(2) with respect to the contraventions of s 535(4) by making and keeping records in relation to the Selden Employees for the purposes of s 535 that it knew to be false or misleading: $8,820 (70%);

(3) with respect to the contraventions of s 536(2) by failing to give the Selden Employees pay slips which included the information prescribed by reg 3.46: $6,300 (50%).

(4) with respect to the contraventions of s 536(3) by providing all but one of the Selden Employees with pay slips which it knew were false or misleading: $8,820 (70%).

107 For Ms Parmenas, in relation to DTF (WS):

(1) with respect to the contraventions of s 45:

(a) by failing to pay Eliyani Eliyani, Ery Ery, Guoyong Liu, Renpeng Liang, Tingli Qiu, Wynne Elysia Wijaya, Yovika Tonang Toe and Zhizi Xu the minimum rates of pay required by the Restaurant Award in contravention of cl 20.1 of the Restaurant Award: $5,040 (40%);

(b) by failing to pay the Casual DTF (WS) Employees a casual loading in contravention of cl 13.1 of the Restaurant Award: $8,190 (65%);

(c) by failing to pay Eliyani Eliyani, Ery Ery, Guoyong Liu, Renpeng Liang, Santy Kam, Tingli Qui, Wynne Elysia Wijaya and Zhizi Xu Saturday penalty rates in contravention of cl 34.1 of the Restaurant Award: $7,560 (60%);

(d) by failing to pay Eliyani Eliyani, Ery Ery, Guoyong Liu, Renpeng Liang, Santy Kam, Tingli Qiu, Wynne Elysia Wijaya and Zhizi Xu Sunday penalty rates in contravention of cl 34.1 of the Restaurant Award: $7,560 (60%);

(e) by failing to pay Ery Ery, Guoyong Liu, Renpeng Liang, Santy Kam, Tingli Qiu, Wynne Elysia Wijaya, Yovika Tonang Toe and Zhizi Xu public holiday penalty rates in contravention of cl 34.1 of the Restaurant Award: $7,560 (60%).

(f) by failing to pay Ery Ery, Guoyong Liu, Kenny Kenny, Qiyin Lin, Renpeng Liang, Rong Xue, Santy Kam, Tingli Qiu, Wynne Elysia Wijaya and Zhizi Xu evening penalties in contravention of cl 34.2(a)(i) of the Restaurant Award: $1,260 (10%);

(g) by failing to pay Eliyani Eliyani, Ery Ery, Guoyong Liu, Kenny Kenny, Qiyin Lin, Rong Xue, Santy Kam and Wynne Elysia Wijaya overtime rates for overtime hours worked on Monday to Friday in contravention of cl 33.2(a) of the Restaurant Award: $7,560 (60%);

(h) by failing to pay Ery Ery, Guoyong Liu, Kenny Kenny, Qiyin Lin, Rong Xue and Santy Kam overtime rates for overtime hours worked on Saturday in contravention of cl 33.2(b) of the Restaurant Award: $7,560 (60%);

(i) by failing to pay Guoyong Liu, Kenny Kenny, Qiyin Lin and Santy Kam overtime rates for overtime hours worked on Sunday in contravention of cl 33.2(c) of the Restaurant Award: $1,260 (10%);

(j) by failing to pay the Full-time Employees split shift allowances in contravention of cl 24.2 of the Restaurant Award: $5,040 (40%);

(2) with respect to the contraventions of s 44, by requesting or requiring Guoyong Liu, Kenny Kenny and Rong Xue to work unreasonable additional hours in contravention of s 62: $6,300 (50%).

(3) with respect to the contraventions of s 535(4) by making and keeping records in relation to the DTF (WS) Employees for the purposes of s 535 that it knew to be false or misleading: $8,820 (70%);

(4) with respect to the contraventions of s 535(1):

(a) by failing to make and keep for seven years records in respect of the DTF (WS) Employees which contained the information prescribed by reg 3.33 of the FW Regulations: $6,300 (50%);

(b) by failing to make and keep for seven years records in respect of Eliyani Eliyani, Ery Ery, Guoyong Liu, Tingli Qiu and Wynne Elysia Wijaya which contained the information prescribed by reg 3.34: $1,260 (10%).

(5) with respect to the contraventions of s 536(2) by failing to give the DTF (WS) Employees pay slips which included the information prescribed by reg 3.46 of the FW Regulations: $6,300 (50%).

(6) with respect to the contraventions of s 536(3) by providing all but one of the DTF (WS) Employees with pay slips which it knew were false or misleading: $8,820 (70%).

108 I will impose no penalty for her involvement in the contraventions of reg 3.44(1) in relation to Guoyong Liu.

109 For Ms Parmenas, in relation to Selden:

(1) with respect to the contraventions of s 45:

(a) by failing to pay the Selden Employees the minimum rates of pay required by the Restaurant Award in contravention of cl 20.1 of the Restaurant Award: $5,040 (40%);

(b) by failing to pay the Selden Employees casual loadings in contravention of cl 13.1 of the Restaurant Award: $8,190 (65%);

(c) by failing to pay the Selden Employees Saturday penalty rates in contravention of cl 34.1 of the Restaurant Award: $7,560 (60%);

(d) by failing to pay the Selden Employees Sunday penalty rates in contravention of cl 34.1 of the Restaurant Award: $7,560 (60%);

(e) by failing to pay the Selden Employees public holiday penalty rates in contravention of cl 34.1 of the Restaurant Award: $7,560 (60%).

(f) by failing to pay Henghui Chen, Nianna Chandra Goi, Tu Dat Huy and Yinhu Zheng evening penalties in contravention of cl 34.2(a)(i) of the Restaurant Award: $1,260 (10%);

(g) by failing to pay Nianna Chandra Goi and Tu Dat Huy overtime rates for overtime hours worked on Monday to Friday in contravention of cl 33.2(a) of the Restaurant Award: $5,040 (40%);

(h) by failing to pay Nianna Chandra Goi and Tu Dat Huy overtime rates for overtime hours worked on Saturday in contravention of cl 33.2(b) of the Restaurant Award: $5,040 (40%);

(2) with respect to the contraventions s 535(4) by making and keeping records in relation to the Selden Employees for the purposes of s 535 that it knew to be false or misleading: $8,820 (70%);

(3) with respect to the contraventions of s 535(1):

(a) by failing to make, and keep records in respect of the Selden Employees which contained the information prescribed by reg 3.33 of the FW Regulations: $6,300 (50%);

(b) by failing to make, and keep records in respect of Tu Dat Huy which contained the information prescribed by reg 3.34: $1,260 (10%).

(4) with respect to the contraventions of s 536(2) by failing to give the Selden Employees pay slips which included the information prescribed by reg 3.46 of the FW Regulations: $6,300 (50%).

(5) with respect to the contraventions of s 536(3) by providing the Selden Employees (save for Meng Joo Low) with pay slips which it knew were false or misleading: $8,820 (70%).

110 For Ms Handoko, the aggregate amount of the penalties relating to her involvement in the DTF (WS) contraventions is $82,530 and in the Selden contraventions $71,190, totalling $153,720.

111 For Ms Parmenas, the aggregate sum relating to her involvement in the DTF (WS) contraventions is $96,390 and in the Selden contraventions $78,750, totalling $175,140.

112 As I mentioned earlier, the Ombudsman submitted that the total figures should be reduced by 20% having regard to the totality principle and Mr Fredericks argued for a reduction of no less than 40%.