FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Vald Pty Ltd v KangaTech Pty Ltd (No 5) [2024] FCA 333

Table of Corrections | |

In paragraph 367, in the first sentence, the word “however” has been removed and replaced with “in any event” | |

ORDERS

VALD PTY LTD (ACN 603 446 171) Applicant | ||

AND: | KANGATECH PTY LTD (ACN 609 070 340) Respondent | |

AND BETWEEN: | KANGATECH PTY LTD (ACN 609 070 340) Cross-Claimant | |

AND: | VALD PTY LTD (ACN 603 446 171) Cross-Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties are to confer and provide to the chambers of Downes J an agreed form of order giving effect to the reasons for judgment and proposed directions as to the further conduct of this proceeding by 12.00 pm AEST on 12 April 2024.

2. If the parties are unable to agree upon a form of order and proposed directions, the parties shall each provide their proposed draft of same to the chambers of Downes J by 12.00 pm AEST on 16 April 2024 accompanied by any written submissions not exceeding three (3) pages.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

[1] | |

[14] | |

[14] | |

[17] | |

[21] | |

[22] | |

[25] | |

[25] | |

[31] | |

[52] | |

[73] | |

[78] | |

[80] | |

[81] | |

5.2 Whether claims require assessment of strength in reliable and accurate way | [84] |

[93] | |

[143] | |

[144] | |

[147] | |

[160] | |

[162] | |

[162] | |

[163] | |

[164] | |

[179] | |

[186] | |

[188] | |

[188] | |

[197] | |

[199] | |

[200] | |

[219] | |

[231] | |

[232] | |

[232] | |

[255] | |

[261] | |

[264] | |

[282] | |

[282] | |

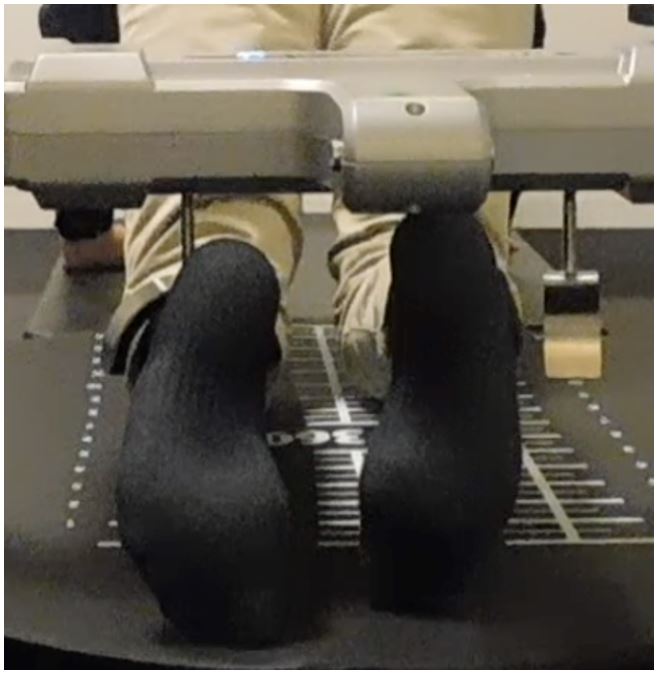

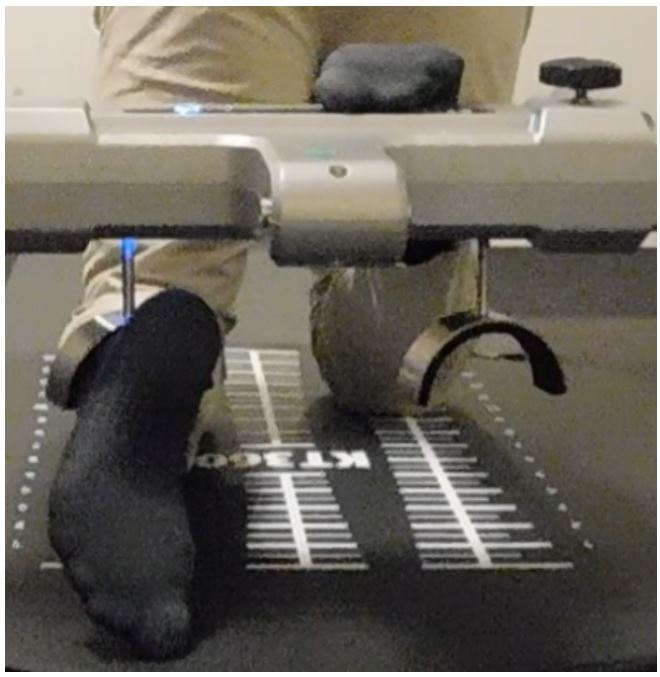

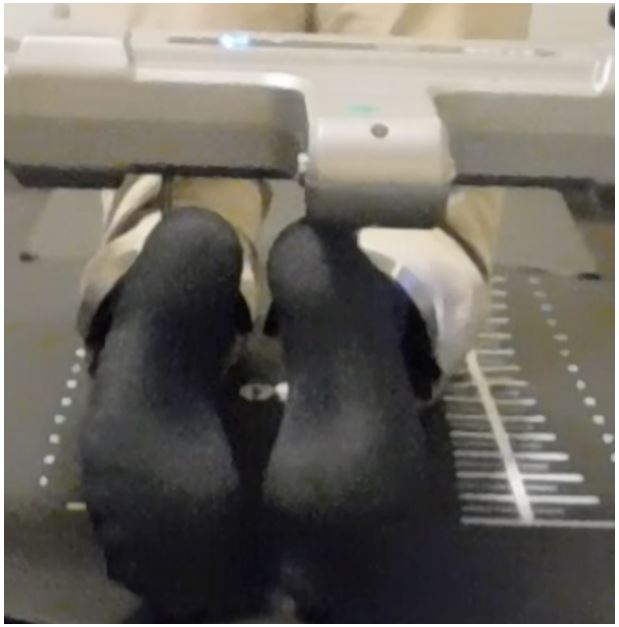

7.5.2 The demonstrations of the Other Nordics on Post-SM KT360 | [288] |

[309] | |

[316] | |

[327] | |

[334] | |

7.6 Whether exploitation of claims by sale of Post-First SM KT360 | [336] |

[343] | |

[347] | |

[362] | |

7.8 Whether KangaTech has authorised infringement of the claims | [371] |

[374] |

DOWNES J:

1 The applicant and cross-respondent (Vald) is the registered proprietor of Australian Standard Patent No. 2012388708 entitled “Apparatus and method for knee flexor assessment” (Patent).

2 The Patent claims a priority date of 3 September 2012 (the priority date).

3 In general terms, the Patent concerns an apparatus for use in assessing the strength of a knee flexor muscle of a person and, in one example, for assessing hamstring strength while the person performs an eccentric knee flexor contraction. In passing, I observe that the first “e” in “eccentric” in this context is pronounced with a long vowel sound, like “email”.

4 The respondent and cross-claimant (KangaTech) carries on the business of developing and commercialising testing devices to assist athletic performance and the prevention of physical injuries. KangaTech admits that it has made, sold and supplied, and offered to make, sell and supply (among other acts) in Australia the following devices:

(1) before approximately November 2018, the KangaTech Product (also called the KT Product);

(2) since approximately December 2018, the KT360 (also called the KangaTech360). The software code of the KT360 was modified in December 2019 and again in July 2022.

5 Vald alleges that, by its conduct, KangaTech has infringed claims 1–4, 6–14 and 16–20 of the Patent. Vald does not press its allegations of infringement of claims 5 or 15 of the Patent.

6 KangaTech accepts that, if any of claims 1–3, 6–14 and 18–20 are found to be valid, then KangaTech’s exploitation of the KangaTech Product infringed such claims. For the following reasons, claims 4, 16 and 17 were also infringed.

7 KangaTech also did not challenge the infringement case in relation to the KT360 prior to the software modifications being made to that device.

8 However, KangaTech did challenge the infringement case in relation to the versions of the KT360 following the software modifications. For the reasons which follow, that challenge was successful.

9 KangaTech otherwise denies infringement for reasons which include that the claims of the Patent are invalid for lack of support (s 40(3) of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth)), lack of sufficiency (s 40(2)(a) of the Patents Act) and want of inventive step. However, it did not press these claims if I adopted a particular construction of claim 1 of the Patent (which, for the following reasons, I have done).

10 By its cross-claim, it seeks orders which include an order revoking the claims of the Patent pursuant to s 138 of the Patents Act. That cross-claim should therefore be dismissed.

11 The present hearing concerns liability only, liability and quantum having been separated by an order of Greenwood J made on 21 August 2019. While Vald seeks additional damages, it is common ground that Vald’s entitlement to, and the quantum of, any additional damages is to be determined as part of any quantum phase of the proceeding.

12 I will order the parties to confer with a view to drafting a form of order giving effect to my findings and draft directions in relation to the further conduct of this proceeding. Subject to hearing from the parties, my preference is that any costs orders await the outcome of the further hearing.

13 Additionally, the parties should have leave to appeal and, if necessary, leave to cross-appeal.

2. WITNESSES CALLED BY THE PARTIES

14 Dr Tania Pizzari is a physiotherapist and academic and the expert witness called by Vald in this proceeding. Dr Pizzari holds a Bachelor of Physiotherapy and a Doctorate of Philosophy in the field of physiotherapy. Since 1997, she has worked as a physiotherapy clinician in hospitals, rehabilitation centres and private practice. Since 2000, Dr Pizzari has worked as a lecturer and researcher within the La Trobe University School of Allied Health. Her research focus includes the prevention and treatment of sport-related soft tissue injuries, including hamstring injuries. Since 2014, Dr Pizzari has been an Adjunct Senior Research Fellow at the Australian Centre for Research into Injury in Sports and its Prevention and has managed the Australian Football League (AFL) soft tissue registry which receives, collates and researches data provided by AFL clubs on all hamstring injuries that occur in players. Dr Pizzari is widely published and is regularly invited to present her research at national and international sports medicine and physiotherapy conferences. Dr Pizzari’s evidence was contained in three affidavits which were filed on 4 February 2021, 2 June 2022 and 6 July 2023. Dr Pizzari gave oral evidence together with the expert called by KangaTech (Dr Lovell) during a concurrent session on the second and third day of trial.

15 Ms Grace Gunn, solicitor, affirmed an affidavit dated 30 June 2023 and was cross-examined on the first day of trial.

16 Ms Ashleigh Sams, solicitor, swore an affidavit dated 4 February 2021 and was not required for cross-examination.

2.2 Witnesses called by KangaTech

17 Mr Carl Dilena is a non-executive Director and Chairman of the Board of KangaTech. He is qualified as a Chartered Accountant and holds a Bachelor of Economics and a Master of Business Administration. Mr Dilena affirmed one affidavit in this proceeding dated 17 July 2023 (with an unsigned version filed on 7 December 2021). Mr Dilena was cross-examined on the first day of trial.

18 Mr David Scerri is the Chief Technical Officer of Biarri Optimisation Pty Ltd, a company which develops bespoke commercial mathematics software for businesses. Mr Scerri holds a Bachelor of Science (majoring in computer science) from Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology University. From November 2015 until July 2020, he was the Chief Technical Officer of KangaTech. Mr Scerri affirmed one affidavit in this proceeding dated 18 July 2023 (with an unsigned version filed on 7 December 2021). Mr Scerri was cross-examined on the second day of trial.

19 Dr Steven Saunders is a science and medicine consultant, clinician and researcher. He holds a Bachelor of Applied Science, Physiotherapy from Sydney University and a PhD from the University of Queensland. He is also a founder and director of KangaTech. Dr Saunders affirmed three affidavits in this proceeding dated 19 July 2023 (with unsigned versions being filed on 7 December 2021, 8 July 2022 and 3 July 2023). Dr Saunders was not required for cross-examination.

20 Dr Ric Lovell, a sports scientist and academic, is the expert called by KangaTech in this proceeding. Dr Lovell holds a Bachelor of Sports Studies and a Masters of Sport Science from Teesside University in Middlesbrough, United Kingdom, and a Doctorate in Sport and Exercise Science from the University of Hull, United Kingdom. Dr Lovell worked as a sports physiologist at the University of Hull from 2006 to 2011. Since 2011, he has worked as a Senior Lecturer and, since 2019, has been an Associate Professor in Sport and Exercise Science at the University of Western Sydney. Dr Lovell’s primary research focus is optimal preparation and athletic development strategies for soccer players, including injury prevention and monitoring training and match loads. Dr Lovell has worked with various sports organisations in roles that include measuring and recording athletes’ lower limb muscle strength to assist their preparation, development and injury prevention. Dr Lovell’s evidence was contained in two affidavits which were filed on 7 January 2022 and 8 July 2022. Dr Lovell, together with Dr Pizzari, gave oral evidence during the concurrent session on the second and third day of trial.

21 A joint expert report was prepared with the helpful assistance of a judicial registrar of this Court. The report followed a conclave attended by the expert witnesses, Dr Pizzari (for Vald) and Dr Lovell (for KangaTech). The report is dated 5 June 2023 and was filed on 29 June 2023 (JER).

2.4 Observations about the experts

22 The primary role of the independent experts was to assist the Court in understanding the technical background to, and the purpose of, the invention. In this regard, for the reasons given below and elsewhere in the judgment, the evidence of Dr Lovell has generally been preferred to the evidence of Dr Pizzari, where their evidence is in conflict.

23 Dr Lovell gave careful and considered answers to questions asked of him during the hearing, appeared to be attempting to assist the Court and, by his answers and general demeanour, did not appear to be favouring any party or outcome in the dispute.

24 By contrast, Dr Pizzari did, on occasion, appear to be seeking to assist Vald when answering questions asked of her during the concurrent session, which affected my perception of her independence. This was particularly evident when Dr Pizzari gave oral evidence about key disputed terms in the claims. During that evidence, Dr Pizzari appeared determined to ignore the plain meaning of parts of the specification which was inconsistent with her preferred construction of the claims. This occurred when Dr Pizzari gave oral evidence concerning her understanding of the consistory clauses and even extended to Dr Pizzari giving evidence that claim 18 – which refers to “securing the lower legs of the subject, using the respective securing members” – also encompasses only one leg being secured (which was inconsistent with her own affidavit evidence but which was evidence which was favourable to Vald’s case).

25 The Patent claims an earliest priority date of 3 September 2012, being the date on which the application was filed under the terms of the Patent Cooperation Treaty: s 30 of the Patents Act; reg 3.5AA(a) of the Patents Regulations 1991 (Cth). That application was filed by the Queensland University of Technology (QUT) and entered the national phase of processing on 25 February 2015.

26 The Commissioner of Patents issued a direction to QUT to request an examination of the Patent on 5 October 2016. In compliance with that direction, QUT requested an expedited examination of the Patent on 22 November 2016. Relevantly, because the examination was requested after the commencement of the Intellectual Property Laws Amendment (Raising the Bar) Act 2012 (Cth), the Patent is subject to the Patents Act as amended by that Act: s 2 and Sch 1 item 55.

27 On 2 November 2017, IP Australia accepted an application by QUT to amend the Patent. Those amendments will become relevant later in these reasons.

28 The Patent was granted on 8 March 2018.

29 Relevantly, by a licence agreement dated 16 December 2014, QUT had earlier granted QUTBluebox Pty Ltd an exclusive licence to exploit the Patent.

30 On 11 November 2019, QUT and QUTBluebox Pty Ltd entered a deed of assignment with Vald, by which they assigned to Vald all of their property, rights, title and interest in and to the Patent, including all rights of action. As such, on 15 November 2019, Vald became the registered proprietor of the Patent.

3.2 Nordic curl or Nordic Hamstring Exercise

31 The primary muscle group that flexes (bends) the knee is the hamstring muscle group. The hamstrings are made up of the semimembranosus, the semitendinosus and the bicep femoris. Other muscles that contribute to knee flexion include the gracilis, the gastrocnemius and the sartorius. These muscles are referred to at [0074] of the specification of the Patent as the knee flexor muscles.

32 During an eccentric contraction, the muscle lengthens as the resistance becomes greater than the force which the muscle is producing whereas during a concentric contraction, the tension in the muscle increases to meet the resistance then remains stable as the muscle shortens. During an isometric contraction, the muscle does not change length during a contraction.

33 A Nordic curl or Nordic Hamstring Exercise (NHE) is an exercise thought to contribute to a reduction in hamstring injury (or HSI). According to Dr Lovell’s evidence in his first affidavit:

…This is primarily because it is an exercise which builds strength in the hamstrings through an eccentric contraction – that is, as the hamstrings are lengthening while they are under significant tension…

In its modern form, the NHE is performed [as follows]. That is, the athlete kneels on a padded surface of some sort – facing away from either a person (who will restrain her/his ankles) or, if being performed without assistance, with the athlete placing their ankles under an immovable restraint which may or may not be attached to the pad on which the subject kneels (for example, gymnasium wall-bars, a loaded barbell, sit-up apparatus, or common resistance training equipment). At the start, the torso is vertical, and the athlete then slowly leans forward from the knees, lowering their torso in a controlled manner. The pivot point is the knees rather than the hips. While doing this, athlete’s ankles/lower legs are restrained from moving upwards – either by another person or a firm restraint against which their ankles are pressing.

The motion forward in the NHE is done in a slow and controlled manner as the aim of the exercise is to benefit from the eccentric contraction of the hamstrings. This eccentric contraction controls (slows) the gradual lengthening of the hamstrings while they are under tension resisting the forward motion of the torso. Most people – unless they are elite athletes – are unable to control the movement of their torso much beyond 30 degrees (from a vertical position) and accordingly, they will need to catch their upper body with their hands at the end of the exercise.

The building of strength using the NHE, as a training exercise not only strengthens the hamstrings but, because that strengthening is performed while the muscle is under tension and is also increasing in length – the NHE is also thought to assist in preventing HSI. The NHE can also assist an athlete to regain strength (and confidence) after suffering a hamstring injury as they prepare to return to their athletic discipline.

In order to determine whether these benefits are achieved and to assist athletes to reach their potential and, wherever possible to evaluate the risk of injury, sports scientists and those working in the field of training elite athletes, seek to accurately measure the forces generated by muscles in performing various knee flexion/extension actions.

(Emphasis original.)

34 When a subject’s knee flexor muscle force is measured during a Nordic curl, inferences can be drawn as to injuries, recovery rates and improvements from, for example, muscle strengthening activities.

35 Typically, the Nordic curl is performed using the knee flexor muscles in both legs (also called a bilateral Nordic curl). In such a situation, both legs are secured (such as by holding both ankles). However, the Nordic curl may also be performed using one leg (also called a unilateral Nordic curl). In performing a unilateral Nordic curl, the intention is for the subject (as best as they can) to hold their body up during descent using the hamstring muscles in one leg. The leg not in use is called the contralateral leg and must not be secured. If the contralateral leg is secured, the exercise being performed is no longer a unilateral Nordic curl but a bilateral Nordic curl.

36 In his first affidavit, Dr Lovell expressed concerns about asking an athlete to perform a one-legged NHE on the basis that it would be encouraging the performance of an activity that may lead to an HSI. He further stated:

In my opinion there would only be a small proportion of highly elite athletes who might be capable of performing such an exercise without unacceptable risk. It is not something I would ask an athlete to do, nor would I prescribe a unilateral NHE as part of an exercise program.

37 In his second affidavit, Dr Lovell stated that:

In my experience, even most elite athletes are unable to perform what I would describe as a controlled lengthening of the knee flexor unless both his or her legs are restrained or their body weight is, at least partly, supported in some manner – for example with resistance bands…

(Emphasis original.)

38 During the concurrent evidence session, Dr Lovell stated that:

I would say that it’s a relatively limited group of people that were familiar and advocating this kind of exercise [as at 3 September 2012], in my opinion. I would also state that performing unilateral in the way that you mention can certainly have some benefits but only, in my opinion, having read this information, only in the context of having some form of support to perform that unilateral exercise. So I agree that the unilateral exercise is important. Personally I wouldn’t do it without some additional support to stop rotation of the body during the exercise and also to make sure that we don’t exacerbate risk to the client.

(Emphasis added.)

39 This was consistent with the evidence of Dr Lovell in the JER that:

I consider unilateral (single leg) Nordic Curls to be of limited value unless performed with adequate support for both the contralateral leg and the torso to provide the necessary time under tension to either a) stimulate musculotendon unit adaptations or b) assess the eccentric hamstring muscle strength of a single limb with adequate measurement precision... Having been introduced to the concept, I agree that by using external support structures …, time under tension can be increased and the exercise can be useful in increasing unilateral eccentric strength. I maintain that without such support, assessment of unilateral hamstring strength via single leg Nordic curls is confounded by the stability requirements of the contralateral limb, and the speed of descent.

40 By contrast, Dr Pizzari did not think it was necessary to have support to reduce risk when performing a unilateral Nordic.

41 However, Dr Pizzari’s evidence concerning the topic of unilateral Nordic curls was difficult to follow and, in some respects, confusing and inconsistent. By her second affidavit, she stated that:

In my view, a single leg Nordic curl was (before the Relevant Date) and is an appropriate exercise for various athletes or subjects who have been specifically focused on building up hamstring strength through prior exercises.

42 During the concurrent evidence session, Dr Pizzari agreed that the NHE was not commonplace amongst elite sportspeople, indicated that she prescribed it for “younger athletes” and volunteered that “Most people don’t do Nordics if they’re not athletic”. Dr Pizzari also gave this evidence:

MR FITZPATRICK: And how did those patients perform the unilateral Nordic hamstring exercise?

DR PIZZARI: So within the clinic we had the gym bars, so the railings that are set up, stuck to the wall. And so they would hook their ankle heel under those gym bars or – and perform the Nordic in that way.

MR FITZPATRICK: So they perform these exercises in your – in the setting of your practice?

DR PIZZARI: Correct. And then they were encouraged to find a way to do that at home. So some people would do it just under their bed railings, for example, and some people may have had assistance by someone else holding their leg, which is reasonably common practice way of doing Nordic as well.

MR FITZPATRICK: Yes. And these exercises, when they were conducted in your practice, were supervised by you.

DR PIZZARI: Not always. They were – certainly initially when we – they were prescribed, but then if they came to the practice and were doing a gym sort of program that was part of it, then certainly they could be doing that independently.

MR FITZPATRICK: And did any of the patients performing this exercise measure the muscle force generated by the exercise?

DR PIZZARI: No.

(Emphasis added.)

43 Dr Pizzari also gave evidence at trial that she did not think that an eccentric contraction necessarily has to be controlled: T159/1–5. She later repeated this evidence, saying that:

An eccentric contraction, to be called eccentric, doesn’t have to be controlled, but I think a Nordic hamstring exercise, to the best that the person can perform it, should try and minimise that fall….

(Emphasis added.)

44 However, in Dr Pizzari’s first affidavit, in the context of discussing her interpretation of the Patent, she stated that:

An eccentric knee flexor contraction involves the controlled lengthening of the knee flexor as the subject lengthens his or her leg from a kneeling position, specifically a “Nordic contraction”.

(Emphasis added.)

45 This inconsistency between her affidavit and oral evidence raises a real doubt as to precisely what type of exercise Dr Pizzari was asking her patients to perform as at the priority date, and about her understanding of the unilateral Nordic curl (both as at the priority date and in the context of her evidence concerning her understanding of the claims). Further and in any event, Dr Pizzari did not obtain force measurements from the performance of this exercise by her patients.

46 This raises a real question about whether the performance of a unilateral or one-legged Nordic curl for the purposes of obtaining a reliable force measurement (and how that would be done) was common general knowledge as at the priority date.

47 As Vald submits, the common general knowledge is that which is “known and accepted without question by the bulk” of those in the art: see Idenix Pharmaceuticals LLC v Gilead Sciences Pty Ltd (2017) 134 IPR 1; [2017] FCAFC 196 at [192] (Nicholas, Beach and Burley JJ). Further, as Vald also submits, the fact that witnesses knew something at the priority date does not establish that it was common general knowledge. Conversely, that an expert was not aware of certain information “may be evidence, possibly powerful evidence depending on the circumstances”, that the information was not common general knowledge: Boehringer Ingelheim Animal Health USA Inc v Elanco New Zealand (2021) 164 IPR 17; [2021] FCA 1457 at [180] (Besanko J).

48 In this case, there is such powerful evidence, being that of Dr Lovell, an experienced sports scientist who has worked in the United Kingdom and Australia, and who has consulted for or worked with (for example) the English Premier League, Football Australia and the AFL before the priority date. His evidence is that he has never asked someone to perform an NHE, or observed an NHE being performed, with only one lower leg of the subject being restrained – whether using an apparatus said to fall within this Patent or any other apparatus – either in clinical practice or in training or strength assessments. I accept this evidence. One would have expected Dr Lovell to have been taught about, seen or himself asked someone to perform a unilateral Nordic curl at some stage between 2002 (when he obtained his first degree) and the priority date in 2012, a decade later, if such an exercise was common general knowledge as at the priority date.

49 Vald submits that nothing turns on whether unilateral Nordic curls were common general knowledge as at the priority date; however, I disagree. It is relevant to both construction of the specification as well as invalidity.

50 For these reasons, I find that the performance of a unilateral or one-legged Nordic curl for the purposes of obtaining a reliable force measurement, and the manner in which such an exercise would be done, are matters which were not common general knowledge as at the priority date.

51 My concerns about Dr Pizzari’s evidence also causes me to prefer the evidence of Dr Lovell (which is set out above) on the topic of unilateral Nordic curls generally. For that reason, I find that there is a real risk of an HSI if a person attempts to use the hamstring muscles in one leg only to stop their body from falling forward in a kneeling position (that is, if they attempt to perform a unilateral Nordic curl). The use of a support will reduce the risk, will stop rotation of the body and, if the exercise is being done for strengthening purposes, a support will assist in providing control so as to enable the gradual lengthening of the hamstrings while they are under tension.

52 The invention is entitled “Apparatus and method for knee flexor assessment”.

53 At [0001], the “Background of the Invention” is stated as follows:

The present invention relates to an apparatus for use in assessing the strength of at least one knee flexor muscle of a subject, and in one example, for assessing at least the hamstring strength in at least one leg of the subject while the subject performs an eccentric knee flexor contraction.

54 In the section entitled “Description of the Prior Art” at [0003] and [0004], the specification refers to the prevalence of HSIs in amateur and elite participants in a number of sports, and the high rate of reoccurrence after an initial HSI, with the period of recovery increasing following subsequent HSIs. It observes that numerous investigations have been conducted into the factors that influence a subject’s susceptibility to HSI, as well as circumstances which aid a subject’s recovery and decrease instances of reoccurrence. It refers to a study concerning the correlation between hamstring strength and the incidence of HSIs and then refers to another patent (WO-03/094732) as providing an example apparatus for performing eccentric exercises including a padded board and ankle straps.

55 The specification then details various limitations with existing devices for quantitatively assessing knee flexor muscle strength, such as the current “gold standard” laboratory based isokinetic dynamometer. At [0005], the specification explains that during assessment on an isokinetic dynamometer:

[A] subject is seated, or prone, with an ankle secured to a rotatable arm such that the torque applied by the leg upon rotating the arm is sensed, while the maximum velocity of rotation is constrained by the dynamometer. Isokinetic dynamometers are, however, expensive, require experienced operators, have limited portability, and require significant time to assess each leg of a subject independently... Thus they are largely used for research purposes and only occasionally by elite athletes or sporting teams to assess players at a higher risk of HSI, or to monitor rehabilitation progress. Furthermore, there is a perception among some sporting support personnel that isokinetic dynamometry itself poses an injury risk.

56 After identifying other disclosures and devices, the specification then explains at [0012]:

It will be appreciated that the abovementioned disclosures suffer from a number of disadvantages including a substantial size or weight which impedes portability, and, significant assessment times that preclude mass screenings, for example, of entire sporting teams. Furthermore, previous methods and apparatus have failed to provide simultaneous assessment of hamstring strength in both legs, independently, during a bilateral exercise, or a combined assessment of hamstring strength in both legs during a bilateral exercise. Additionally existing techniques have questionable reliability and repeatability of measurements of between limb strength imbalances.

57 In clause [0013], the specification states that the invention seeks to ameliorate “one or more” of the problems associated with the prior art.

58 Under the heading “Summary of the Present Invention”, the specification goes on to describe the invention in what are termed three “broad forms” or consistory clauses. Each of these broad forms describes an apparatus in which both legs of the subject are secured or constrained by the securing members.

59 In relation to the first broad form, which is addressed at [0014] to [0039], the following is stated:

[0014] In a first broad form the present invention seeks to provide an apparatus for use in assessing strength of at least one knee flexor muscle of a subject, the apparatus including:

a) a support;

b) two securing members, each securing member securing a respective lower leg of the subject in a position that in use is substantially fixed relative to the support; and,

c) at least one sensor, which in use senses a force indicative of the strength of the at least one knee flexor muscle in at least one leg of the subject while the subject performs an eccentric contraction of the at least one knee flexor muscle.

[0015] Typically the at least one sensor is coupled to at least one of the two securing members, and wherein the sensor senses a force exerted at an [sic] lower leg of the subject.

[0016] Typically the at least one sensor includes two sensors, each sensor being coupled to a respective securing member to thereby sense the force indicative of the strength of the at least one knee flexor muscle in each leg of the subject.

[0017] Typically in use the sensors sense the force indicative of the strength of the at least one knee flexor muscle in each leg of the subject simultaneously.

[0018] Typically in use the sensors sense the force indicative of the strength of the at least one knee flexor muscle in each leg of the subject at different times.

…

[0038] Typically the sensor senses a force indicative of the hamstring strength in at least one leg of the subject while the subject performs a Nordic hamstring exercise.

[0039] Typically the at least one knee flexor muscle includes at least a hamstring muscle.

(Emphasis added.)

60 The second broad form describes the same apparatus for assessing the muscle strength of a subject and is not confined to the measurement of knee flexor muscle strength. It is addressed at [0040] in these terms:

In a second broad form the present invention seeks to provide an apparatus for use in assessing muscle strength of a subject, the apparatus including:

a) a support;

b) two securing members, each securing member constraining movement of a respective lower leg of the subject relative to the support; and,

c) at least one sensor, which in use senses a force indicative of the muscle strength while the subject performs an exercise of the muscle, the exercise exerting at least some force on the sensor.

(Emphasis added.)

61 The third broad form describes a method for assessing hamstring strength of a subject using the apparatus. It is addressed at [0041] to [0047]. This part of the specification includes the following:

[0041] In a third broad form the present invention seeks to provide a method of assessing hamstring strength of a subject using an apparatus including a support, two securing members, and at least one sensor, the method including:

a) securing two lower legs of a subject using the respective securing members, at a position that is in use substantially fixed relative to the support;

b) sensing a force indicative of the strength of the at least one knee flexor muscle in at least one leg of the subject using the sensor while the subject performs an eccentric contraction of at least a hamstring.

[0042] Typically at least one sensor includes two sensors, each sensor being coupled to a respective securing member, and wherein the method includes sensing the force indicative of the strength of the at least one knee flexor muscle in each leg of the subject.

[0043] Typically the method includes sensing the force indicative of the strength of the at least one knee flexor muscle in each leg of the subject simultaneously.

[0044] Typically the method includes sensing the force indicative of the hamstring strength in at least one leg of the subject while the subject performs a Nordic hamstring exercise.

(Emphasis added.)

62 The specification then contains a “Brief Description of the Drawings”, being examples of the invention. Those drawings will be addressed in these reasons where relevant. However, it suffices to observe that the drawings portray various examples of the apparatus, including examples of the apparatus in use by a subject performing a bilateral NHE. There is no drawing of a subject performing a unilateral NHE on any example of the apparatus.

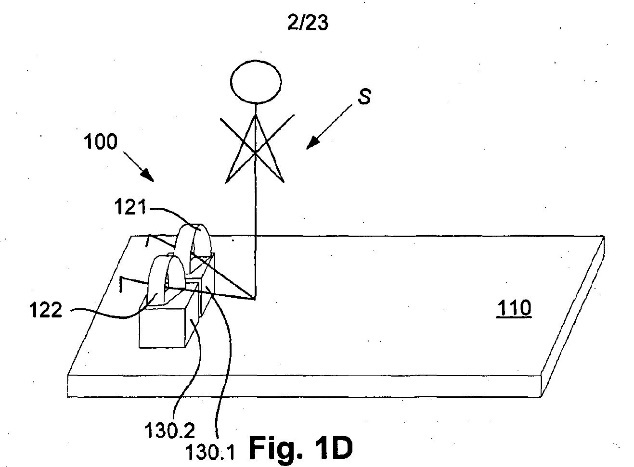

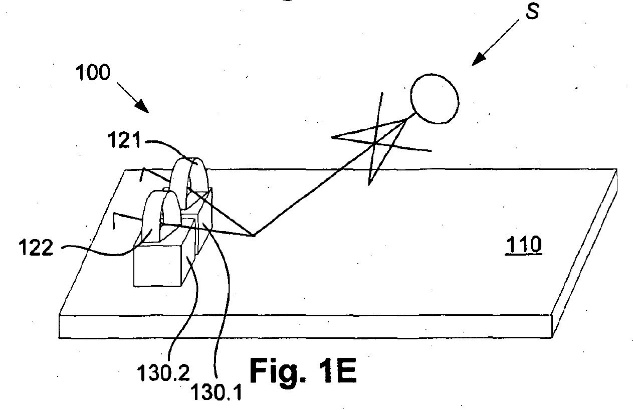

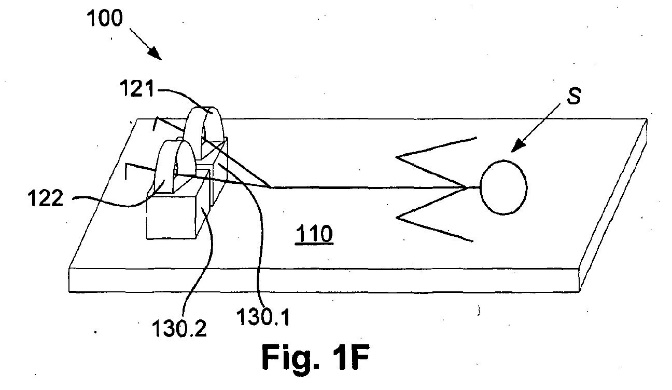

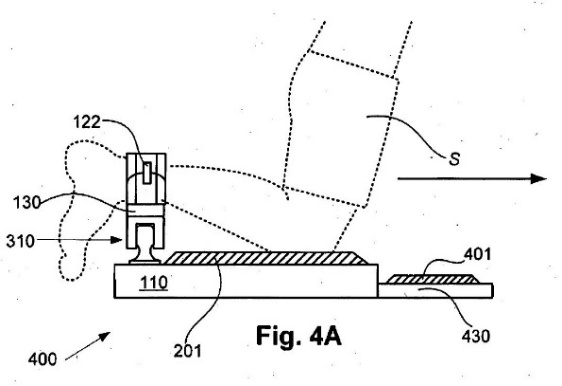

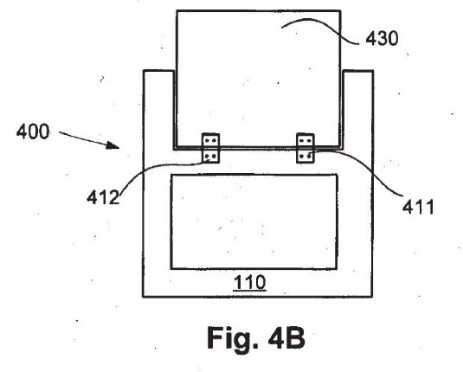

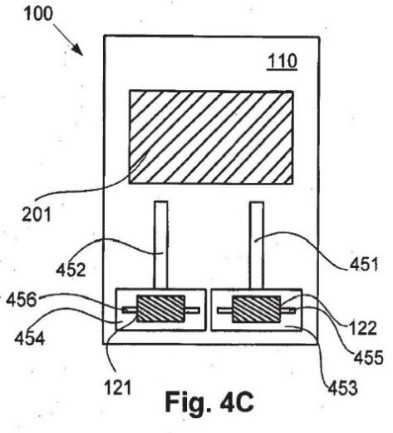

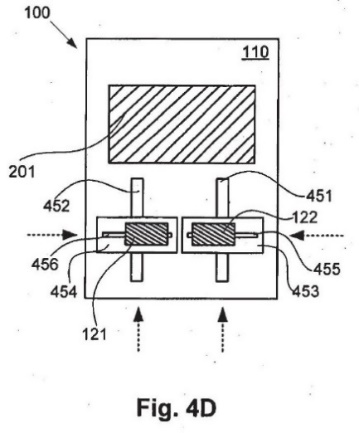

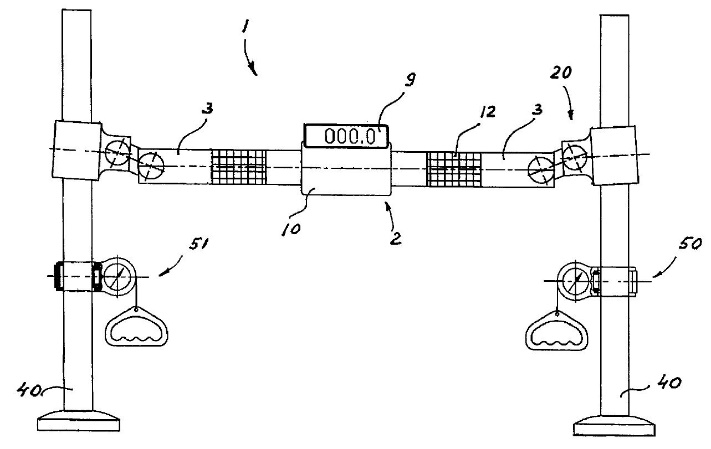

63 Figures 1D to 1F are schematic drawings of a first example of a subject performing an eccentric contraction of at least a knee flexor using the apparatus: [0050]. They depict a subject performing a bilateral NHE (with both legs secured in the securing members) as follows:

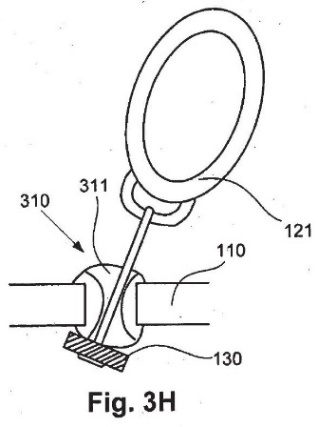

64 The various drawings are referred to throughout the section of the specification entitled “Detailed Description of the Preferred Embodiments”. The following is stated in relation to Figures 1A to 1F:

[0072] In this example, the apparatus 100 includes a support 110, and two securing members 121, 122, that in use secure a respective lower leg of the subject S in a position that is substantially fixed relative to the support 110.

[0073] The apparatus 100 further includes two sensors 130.1, 130.2 that, in use, sense a force indicative of the strength of at least one knee flexor muscle in one or both legs of the subject S while the subject S performs an eccentric contraction of the at least one knee flexor muscle.

[0074] It should be noted that the knee flexor muscles typically include the three major hamstring muscles, semitendinosus, semimembranosus and biceps femoris, as well as the minor knee flexors, sartorius, gastrocnemius, and gracilis. For ease, the following description will refer primarily to measuring the strength of the hamstring. However, it will be appreciated that the techniques can apply to measuring any one or more of the knee flexor muscles and that reference to the hamstring is not intended to be limiting.

[0075] Figures 1D to 1F show a subject S performing an eccentric contraction of at least a hamstring using the apparatus 100. In this respect, Figure 1D shows the subject S in an initial kneeling position prior to commencing the contraction, in which the subject’s lower legs are secured using the respective securing members 121, 122 in a position that in use is substantially fixed relative to the support. The subject S subsequently proceeds to lower their upper body toward the support 110 in a controlled manner, while substantially maintaining alignment of the upper legs or thighs and torso, as shown in Figure 1E. Figure 1F shows a final position, with the subject S laying substantially prone on the support 110. It will be appreciated that the abovementioned eccentric contraction is typically called the ‘Nordic hamstring exercise’, ‘Nordic curl’, or the like.

[0076] Accordingly, the above-described arrangement provides apparatus 100 for use in assessing hamstring strength of a subject S, in which the force exerted at the lower leg of the subject S while they perform an eccentric contraction of at least the hamstring is indicative of hamstring strength. In this regard, the apparatus 100 can be utilised to monitor hamstring strength, including any changes in hamstring strength over time, for example, to detect injury precursors such as temporal strength differences, imbalances between legs at rest (i.e. not fatigued) or in response to fatigue, to monitor rehabilitation progress, to monitor progress during strength training, or to benchmark against a population. Additionally or alternatively, the apparatus 100 can also be used in order to strengthen the hamstring, for example, by performing repetitions of an eccentric contraction of the hamstring using the apparatus 100, such as shown in Figures 1D to 1F.

…

[0079] It will also be appreciated that the apparatus 100 including two sensors 130.1, 130.2 allows the assessment of the hamstring strength of both hamstrings of a subject S, at the same time. Accordingly the sensors 130.1, 130.2 may sense the force indicative of at least the hamstring strength in each leg of the subject S simultaneously. In this regard, the assessment may be performed in significantly less time than existing methods, for example isokinetic dynamometry, which is limited to assessing hamstrings of opposing legs at different times. The apparatus also appears to provide enhanced sensitivity and reliability for the assessment of between limb strength imbalances compared to existing techniques. This reduces the time required to assess a subject S, which allows the assessment of hamstring strength to become accessible to entire sporting teams as part of regular health and fitness assessments. In this example, two sensors 130.1, 130.2 are shown, however this is not essential and any number of sensors, including a single sensor may be used for monitoring force in one leg, or alternatively a single sensor may be used to monitor the combined hamstring strength of both legs.

[0080] In this example, an eccentric contraction of at least the hamstring of a subject S is shown in Figures 1D to 1F, however it will be appreciated that any suitable exercise which includes an eccentric contraction of the hamstring may be performed. For example, the subject’s hip may be positioned differently, such that the eccentric contraction is performed with the subject's hip and trunk flexed forward. However, this is not essential, and although in this example, the apparatus 100 is for use during an eccentric contraction of at least the hamstring of a subject S, it will be appreciated that the apparatus 100 may be used to measure other muscles or muscles groups while performing other types of muscle contractions. For example, the apparatus 100 may be used to assess any suitable muscle or muscle group, such as the knee flexor, hip flexor, knee extensor, quadriceps, or the like. In this regard, the assessment may be made during an eccentric, isometric, or concentric contraction, or the like, of the respective muscle or muscle group.

65 At [0083], it is stated that a number of further features will now be described.

66 The section of the specification following this statement includes [0085], which was the focal point of the expert evidence of Dr Pizzari in support of Vald’s posited construction of claim 1:

Furthermore, the assessment of hamstring strength may occur during a unilateral or bilateral contraction/s of the hamstring/s. For example, during a bilateral contraction, two sensors 130.1, 130.2 may be used to sense the force in each leg of the subject simultaneously or at different times, or alternatively a single sensor 130.1, 130.2 may be used to sense the force in either or both legs. During a unilateral contraction, the apparatus may include one sensor 130.1, 130.2 which is interchangeable between the lower legs of the subject, by repositioning the sensor 130.1, 130.2 and/or the securing members 121, 122 and/or the subject S relative to the support 110, such that the hamstring strength in both legs can be assessed sequentially. However, this feature is not essential.

67 The specification addresses the support from [0088] to [0095] (which is relevant to one of the issues of construction).

68 For example, at [0091], it is stated that the support 110 may include any suitable shape, including oval, circular, polygonal, square, rectangular, ergonomic, or the like. Furthermore, the support 110 may be composed of any suitable material in order to withstand the weight of at least part of the subject S, such as timber, medium density fibreboard (MDF), plastic, fibreglass, carbon fibre reinforced polymer (CFRP), aluminium, or the like.

69 At [0093], it is stated that:

It will also be appreciated that whilst a single unitary support is shown, this is for ease of illustration only and that in practice the support could be formed from multiple support members, which may or may not be interconnected. In one example, the support could include two parallel support members, each of which is for coupling to a respective securing member.

70 The specification addresses IT aspects of the apparatus and methods of assessment from [0145] to [0169].

71 The specification then describes the various experiments that were performed to demonstrate the effectiveness of the invention as arranged in Figures 1A to 1C. These experiments are addressed in further detail below.

72 Finally, the specification stated at [0192] that:

Persons skilled in the art will appreciate that numerous variations and modifications will become apparent. All such variations and modifications which become apparent to persons skilled in the art, should be considered to fall within the spirit and scope that the invention broadly appearing before described. Thus, for example, it will be appreciated that features from different examples above may be used interchangeably where appropriate.

73 The Patent has two independent claims. Independent claim 1 provides (with the integers identified for convenience):

1.1 An apparatus for use in assessing strength of at least one knee flexor muscle of a subject, the apparatus including:

1.2 two securing members;

1.3 each securing member being configured to secure a respective lower leg of the subject in a position that, in use, is substantially fixed relative to a support when the subject lowers the subject’s upper body from a kneeling position to perform an eccentric contraction of the at least one knee flexor muscle of the subject; and

1.4 at least one sensor coupled to at least one of the securing members;

1.5 to sense a force applied to the at least one securing member by the subject’s knee flexor muscle acting in eccentric contraction while the subject lowers the subject’s upper body, the force being indicative of the strength of the at least one knee flexor muscle acting in eccentric contraction.

74 Independent claim 18 provides (with the integers identified for convenience):

18.1 A method of assessing strength of at least one knee flexor muscle of a subject using an apparatus including:

18.2 two securing members; and

18.3 at least one sensor coupled to at least one of the two securing members;

18.4 the method including securing the lower legs of the subject, using the respective securing members, in a position that is substantially fixed relative to the support when the subject lowers the subject’s upper body from a kneeling position to perform an eccentric contraction; and

18.5 sensing, with the, or each, sensor a force applied to at least one of the securing members by the at least one knee flexor muscle acting in eccentric contraction while the subject lowers the subject’s upper body from the kneeling position to perform an eccentric contraction of the at least one knee flexor muscle while the subject’s lower legs are secured to the respective securing members, which force is indicative of the strength of the at least one knee flexor muscle.

75 The claims which are dependent on claim 1 are as follows:

(1) Claim 2: The apparatus according to claim 1, wherein the at least one sensor is coupled to the at least one of the two securing members;

(2) Claim 3: The apparatus according to claim 1 or 2, wherein the at least one sensor includes two sensors, each sensor being coupled to a respective securing member to sense the force indicative of the strength of the at least one knee flexor muscle in each leg of the subject;

(3) Claim 4: The apparatus according to any one of the preceding claims, wherein the securing members are movably mounted to the support;

(4) Claim 5: The apparatus according to any one of the preceding claims, wherein the securing members include any one of a strap, a cuff and a tie;

(5) Claim 6: The apparatus according to any one of the preceding claims, which includes at least one knee support that, in use, supports at least one knee of the subject;

(6) Claim 7: The apparatus according to any one of the preceding claims, wherein the sensors are configured to sense the force indicative of the strength of the at least one knee flexor muscle in each leg of the subject simultaneously;

(7) Claim 8: The apparatus according to any one of claims 1 to 6, wherein the sensors are configured to sense the force indicative of the strength of the at least one knee flexor muscle in each leg of the subject at different times;

(8) Claim 9: The apparatus according to any one of the preceding claims, wherein the apparatus includes an electronic processing device for monitoring signals from the at least one sensor and generating, at least in part using the signals, an indicator indicative of a strength of the at least one knee flexor muscle of the subject;

(9) Claim 10: The apparatus according to claim 9, wherein the indicator is indicative of at least one of an instantaneous force, a rate of force development, an average force, a peak force, an impulse, work, an instantaneous torque, a rate of torque development, an average torque, changes in force over time, changes in torque over time, and a peak torque;

(10) Claim 11: The apparatus according to claim 9 or 10, wherein the electronic processing device is configured to compare the signals, at least in part, and reference data, and to generate the indicator in accordance with the results of the comparison;

(11) Claim 12: The apparatus according to claim 11, wherein the reference data includes at least one of a tolerance determined from a normal population, a predetermined range, a predetermined reference, a previously generated indicator and an indicator generated for another leg;

(12) Claim 13: The apparatus according to claim 11 or 12, wherein the indicator is indicative of the signals, at least in part, and the reference data, and a difference between the signals, at least in part, and the reference data;

(13) Claim 14: The apparatus according to any one of claims 9 to 13, wherein the apparatus includes an output for presenting at least the indicator to the user;

(14) Claim 15: The apparatus according to any one of the preceding claims, wherein the apparatus includes an input, thereby allowing a user to input data;

(15) Claim 16: The apparatus according to any one of the preceding claims, wherein the support is elongated and wherein the securing members are provided at a first end of the support and a second end of the support is configured to support a weight of the subject;

(16) Claim 17: The apparatus according to any one of the preceding claims, wherein the sensor includes any one of a load cell, a force plate, a piezoresistive force sensor, a strain gauge and a hydraulic pressure gauge, the sensor being configured to sense any one of compression and tension.

76 Claim 19 is dependent on claim 18. It states:

The method according to claim 18, which includes monitoring signals from the at least one sensor and generating, at least in part using the signals, an indicator indicative of the strength of the at least one knee flexor muscle.

77 Claim 20 is also dependent on claim 18. It states:

The method according to claim 19, the method including comparing the signals, at least in part, and reference data, and generating the indicator in accordance with the results of the comparison.

78 The person skilled in the art is the hypothetical person to whom the patent specification is addressed and who, generally speaking, works in the art or science with which the invention is connected: see, e.g., Root Quality Pty Ltd v Root Control Technologies Pty Ltd (2000) 49 IPR 225; [2000] FCA 980 at [70]–[71] (Finkelstein J). It is not a reference to a specific person but is a legal construct or notional person who may have an interest in using the products or methods of the invention, making the products of the invention, or making products used to carry out the methods of the invention either alone or in collaboration with others having such an interest: Aristocrat Technologies Australia Pty Ltd v Konami Australia Pty Ltd (2015) 114 IPR 28; [2015] FCA 735 at [26] (Nicholas J); Hanwha Solutions Corporation v REC Solar Pte Ltd [2023] FCA 1017 at [86] (Burley J).

79 Based on the subject matter of the Patent, the person skilled in the art has skills (at least) in sports medicine, being a person with knowledge of and familiarity with exercise and training apparatus (for example, as a physiotherapist or sports scientist). There was no dispute in this case that both experts had such expertise.

80 The focus of the construction debate concerned claim 1 of the Patent. To the extent that there was a dispute concerning other claims (namely 4 and 16), that debate will be addressed as part of the reasons relating to infringement.

81 The principles of claim construction are not relevantly in dispute and are conveniently set out in Jupiters Ltd v Neurizon Pty Ltd (2005) 65 IPR 86; [2005] FCAFC 90 at [67] (Hill, Finn and Gyles JJ) as follows:

(i) the proper construction of a specification is a matter of law: Décor Corporation Pty Ltd v Dart Industries Inc (1988) 13 IPR 385 at 400;

(ii) a patent specification should be given a purposive, not a purely literal, construction: Flexible Steel Lacing Company v Beltreco Ltd (2000) 49 IPR 331; [2000] FCA 890 at [81] (Flexible Steel Lacing); and it is not to be read in the abstract but is to be construed in the light of the common general knowledge and the art before the priority date: Kimberley-Clark Australia Pty Ltd v Arico Trading International Pty Ltd (2001) 207 CLR 1; 177 ALR 460; 50 IPR 513; [2001] HCA 8 at [24];

(iii) the words used in a specification are to be given the meaning which the normal person skilled in the art would attach to them, having regard to his or her own general knowledge and to what is disclosed in the body of the specification: Décor Corporation Pty Ltd at 391;

(iv) while the claims are to be construed in the context of the specification as a whole, it is not legitimate to narrow or expand the boundaries of monopoly as fixed by the words of a claim by adding to those words glosses drawn from other parts of the specification, although terms in the claim which are unclear may be defined by reference to the body of the specification: Kimberley-Clark v Arico at [15]; Welch Perrin & Co Pty Ltd v Worrel (1961) 106 CLR 588 at 610; Interlego AG v Toltoys Pty Ltd (1973) 130 CLR 461 at 478; the body of a specification cannot be used to change a clear claim for one subject matter into a claim for another and different subject matter: Electric & Musical Industries Ltd v Lissen Ltd [1938] 4 All ER 221 at 224–5; (1938) 56 RPC 23 at 39;

(v) experts can give evidence on the meaning which those skilled in the art would give to technical or scientific terms and phrases and on unusual or special meanings to be given by skilled addressees to words which might otherwise bear their ordinary meaning: Sartas No 1 Pty Ltd v Koukourou & Partners Pty Ltd (1994) 30 IPR 479 at 485–6 (Sartas No 1 Pty Ltd); the Court is to place itself in the position of some person acquainted with the surrounding circumstances as to the state of the art and manufacture at the time (Kimberley-Clark v Arico at [24]); and

(vi) it is for the Court, not for any witness however expert, to construe the specification; Sartas No 1 Pty Ltd at 485–6.

82 As point (iv) in the summary in Jupiters makes clear, the claims are to be read in the context of the specification as a whole. However, balanced against that is the requirement that the body of a specification cannot be used to change a clear claim for one subject matter into a claim for another different subject matter. Put another way, the correct approach to construction is to read the document in its context, including the claims: see Fresenius Medical Care Australia Pty Ltd v Gambro Pty Ltd (2005) 67 IPR 230; [2005] FCAFC 220 at [44], [94] (Wilcox, Branson and Bennett JJ).

83 It is for the Court to determine the meaning of the language of the claims, aided by the evidence of experts to assist in understanding unfamiliar terms and the technical context of the subject matter. Expert opinion does not supplant the judicial role: see Airco Fasteners Pty Ltd v Illinois Tool Works Inc (2023) 170 IPR 225; [2023] FCAFC 7 at [59] (Rares, Moshinsky and Burley JJ).

5.2 Whether claims require assessment of strength in reliable and accurate way

84 The first issue concerns whether the claims require the assessment of the strength of a knee flexor muscle in a reliable and accurate way to provide clinically relevant information (KangaTech’s characterisation of the issue) or whether the claims require perfect or even near perfect accuracy or reliability in assessing such strength (Vald’s characterisation of the issue). However, the latter characterisation overstates KangaTech’s position on this issue.

85 By its opening submissions on infringement, KangaTech did not refer to perfection, instead submitting that:

…the disclosure of the invention, including the apparatus, is always conditioned by reference to its use in effectively and reliably assessing the strength of at least one knee flexor muscle by the user performing an NHE.

86 Although complaint was made by Vald that this construction issue was not raised by KangaTech through its pleadings, it was opened by KangaTech both orally (for example, at T44/10–45) and in writing as set out above, and without objection by Vald. As addressed in more detail below, the experts addressed issues relating to reliability and accuracy, including in the JER. Further, Vald sought a finding that the force measurement from unilateral Nordic curls is sufficiently reliable. Finally, Vald addressed this construction issue in its closing submissions, both orally in and writing. Specifically, by reference to its characterisation of the issue above, Vald submits that:

(1) The claims do not specifically refer to reliability or accuracy, let alone quantitative thresholds thereof. See also e.g., Lovell T301.19-37 and cf T69.17-20.

(2) Neither the claim nor the specification requires any specific duration of descent. See also e.g., Lovell T300.39-301.19.

(3) The Patent is aimed at something that is “a bit more functional” than an ISD; i.e., “easier to test multiple athletes, but not quite as controlled”: Lovell T293.46-3.

87 Although the claims do not refer to reliability or accuracy expressly, integer 1.1 describes the apparatus as one “for use in assessing strength of at least one knee flexor muscle of a subject”. Integer 1.5 describes a force being sensed which is “indicative of the strength” of at least one knee flexor muscle acting in eccentric contraction.

88 Similarly, integer 18.1 describes the method as one of “assessing strength of at least one knee flexor muscle of a subject using an apparatus”. Integer 18.5 describes a force being sensed which is “indicative of the strength” of at least one knee flexor muscle acting in eccentric contraction.

89 The Patent discloses that the result which is achieved by the assessments of strength conducted by the disclosed apparatus and method are accurate and reliable in that:

(1) the apparatus overcomes disadvantages of existing techniques which were known as at the priority date, which are said to have “questionable reliability and repeatability of measurements of between limb strength imbalances” and the apparatus “appears to provide enhanced sensitivity and reliability for the assessment of between limb strength imbalances compared to existing techniques”: [0012], [0079];

(2) the apparatus “displays acceptable levels of test-retest reliability when measuring peak or average peak knee flexor force during a bilateral NHE”: [0179];

(3) the apparatus displays acceptable reliability for “the measurement of between limb strength differences” when the NHE was “completed bilaterally, and peak force was average across six contractions”: [0179];

(4) “a bilateral NHE performed with multiple repetitions across a number of sets to determine average eccentric peak knee flexor force produces optimal reliability”: [0179];

(5) “the apparatus 100 is capable of effectively assessing the hamstring strength of a subject S, and in particular displays acceptable levels of test-retest reliability and correlation with gold standard, i.e. isokinetic dynamometry, assessments”: [0189].

90 In circumstances where the person skilled in the art has skills in sports medicine, the purposive, common-sense construction of the claims is that they describe an apparatus (claim 1 and its dependent claims) and a method (claim 18 and its dependent claims) which can be used to assess strength of at least one knee flexor muscle of a subject in a reliable and accurate way in order to provide clinically relevant information.

91 In other words, in construing the claims in the context of the specification as a whole (as addressed above), a person skilled in the art would understand the reference to an apparatus for use in assessing strength of at least one knee flexor muscle of a subject in integer 1.1, or to a method of assessing strength of at least one knee flexor muscle of a subject using an apparatus in integer 18.1, as only being capable of achieving that result if that assessment is a reliable and accurate one.

92 Dr Lovell’s commentary around what the claims and the specification do, or do not, contain (as highlighted in Vald’s closing submissions) does not detract from this conclusion.

5.3 Whether claim 1 requires both legs to be secured

93 A central issue in this case is whether claim 1 requires that both legs be secured in the securing members (KangaTech’s construction) or whether claim 1 requires that either one or both legs be so secured (Vald’s construction).

94 Claim 1 refers to two securing members, each securing member being configured to secure a respective lower leg of the subject in a position that, in use, is substantially fixed relative to a support when the subject lowers the subject’s upper body from a kneeling position to perform an eccentric contraction of the at least one knee flexor muscle of the subject (integers 1.2 and 1.3).

95 In support of its construction, Vald submits, and I accept, that the word “configured” in claim 1 is not a word which has a technical meaning and nor is it a word to which the specification ascribes a special meaning. The ordinary meaning of the word “configured” means “designed or adapted to form a desired configuration”.

96 Vald also contrasts the words of claim 1 to that of claim 18, which is a method claim and which it submits requires a performative action, that is, “securing the lower legs of the subject, using the respective securing members” (emphasis added).

97 Finally, Vald cites s 116 of the Patents Act and observes that the reference to “securing” was contained in the original version of claim 1 but that this was amended as follows (with the mark up showing the amendments):

two securing members, each securing member securing being configured to secure a respective lower leg of the subject in a position that, in use, is substantially fixed relative to the support when the subject lowers the subject’s upper body from a kneeling position to perform an eccentric contraction of the at least one knee flexor muscle of the subject.

98 However, notwithstanding these matters, the proper construction of claim 1, when read in the context of the specification as a whole (rather than selected parts of it), is that both legs must be secured in the securing members.

99 That is for the following reasons.

100 The “Background of the Invention” describes the invention as being an apparatus for use in assessing the strength of at least one knee flexor muscle of a subject. The reference to at least one knee flexor muscle being tested, even if that muscle is only tested in one but not both legs, does not have the consequence that only one leg is secured for the purpose of testing that knee flexor muscle. That is made plain by, for example, [0038] and [0039] of the specification.

101 The “Background of the Invention” then states to the effect that, in one example, the invention relates to an apparatus for use in assessing at least the hamstring strength in at least one leg of the subject while the subject performs an eccentric knee flexor contraction. While the superficial impression of these words is that only one leg is secured (the hamstring strength of which is being tested), it will be seen that the Patent contemplates the testing of only one leg using one sensor, with the other leg being secured but not tested.

102 As observed above, the specification refers to existing devices, including the “gold standard” isokinetic dynamometer, which device assesses the strength in each leg independently (one leg at a time), with the specification stating that this requires “significant time”: [0005].

103 At [0012], the specification reiterates that a disadvantage of existing devices is “significant assessment times” and further states that, “previous methods and apparatus have failed to provide simultaneous assessment of hamstring strength in both legs, independently, during a bilateral exercise, or a combined assessment of hamstring strength in both legs during a bilateral exercise” (emphasis added). No mention is made of deficiencies in existing devices by reference to unilateral exercises.

104 Further, taking into account the emphasis in [0005] and [0012] upon the undue length of assessment times where each leg is tested one at a time (particularly through use of the isokinetic dynamometer), the solution which is proffered by the Patent is an apparatus which permits the hamstring strength in both legs to be tested at the same time, either independently or on a combined basis, thereby reducing the assessment time. If the apparatus was one which tested the hamstring strength of one leg at a time (which would be the case if only one leg was secured), this would not reduce the assessment time, and would not be regarded as overcoming the perceived disadvantage of existing devices.

105 In the “Summary of the Present Invention”, the specification reveals that the invention seeks to ameliorate “one or more” of the abovementioned problems. It goes on to describe the invention in three broad forms at [0014], [0040] and [0041]. Each of these broad forms or consistory clauses contains wording which indicates that both legs are secured by the securing members, namely:

(1) “two securing members, each securing member securing a respective lower leg of the subject…”: [0014];

(2) “two securing members, each securing member constraining movement of a respective lower leg of the subject…”: [0040];

(3) “securing two lower legs of a subject using the respective securing members…”: [0041].

106 There is nothing in the part of the specification described as the “Summary of the Present Invention” which contemplates that only one leg is secured by a securing member. If this was contemplated, one would expect to see at least some reference to it here.

107 Each of the consistory clauses also refers to the apparatus having “at least one sensor” which is then described as, in effect, sensing a force indicative of the strength of at least one knee flexor muscle in at least one leg. However, the reference to and use of only one sensor does not mean that only one leg is secured; it simply means that a knee flexor muscle of one of the two secured legs is being assessed by that one sensor when the bilateral Nordic curl is performed using the apparatus.

108 This construction is supported by [0015] (for example), where reference is made to at least one sensor being coupled to at least one of the two securing members. It is also supported by the words used in the consistory clauses such as [0014] which provides:

at least one sensor, which in use senses a force indicative of the strength of the at least one knee flexor muscle in at least one leg of the subject while the subject performs an eccentric contraction of the at least one knee flexor muscle.

109 Further support for this construction is found at (for example) [0044] which provides that: “Typically the method includes sensing the force indicative of the hamstring strength in at least one leg of the subject while the subject performs a Nordic hamstring exercise”. This paragraph is connected with the third broad form which is in turn the consistory clause of claim 18 (the method claim) which Vald accepts requires both legs to be secured. Yet [0044] refers to sensing the force indicative of the hamstring strength in at least one leg of the subject. Although only one leg is referred to in [0044] as being tested, both legs are secured using the method described in [0041].

110 An example of the invention is then described with reference to the drawings. Figures 1D, 1E and 1F are shown above. At [0050], these drawings are described as schematic drawings of a first example of a subject performing an eccentric contraction of at least a knee flexor using the apparatus.

111 The Detailed Description of the Preferred Embodiments provides an example of the apparatus by reference to Figures 1A to 1F.

112 As already identified above, the specification then states:

[0072] In this example, the apparatus 100 includes a support 110, and two securing members 121, 122, that in use secure a respective lower leg of the subject S in a position that is substantially fixed relative to the support 110.

[0073] The apparatus 100 further includes two sensors 130.1, 130.2 that, in use, sense a force indicative of the strength of at least one knee flexor muscle in one or both legs of the subject S while the subject S performs an eccentric contraction of the at least one knee flexor muscle.

113 Pausing there, although the words refer to an eccentric contraction of the at least one knee flexor muscle, the description refers to an example shown in drawings which depict the apparatus being used with both legs secured by the securing members.

114 At [0075], it is stated that:

Figures 1D to 1F show a subject S performing an eccentric contraction of at least a hamstring using the apparatus 100. In this respect, Figure 1D shows the subject S in an initial kneeling position prior to commencing the contraction, in which the subject's lower legs are secured using the respective securing members 121, 122 in a position that in use is substantially fixed relative to the support. The subject S subsequently proceeds to lower their upper body toward the support 110 in a controlled manner, while substantially maintaining alignment of the upper legs or thighs and torso, as shown in Figure 1E. Figure 1F shows a final position, with the subject S laying substantially prone on the support 110. It will be appreciated that the abovementioned eccentric contraction is typically called the 'Nordic hamstring exercise', 'Nordic curl', or the like.

(Emphasis added.)

115 There is no drawing which depicts, and nor does the specification identify, how the subject S lowers their upper body toward the support 110 in a controlled manner, while substantially maintaining alignment of the upper legs or thighs and torso, if only one leg is secured in a securing member.

116 At [0076], it is stated that:

Accordingly, the above-described arrangement provides apparatus 100 for use in assessing hamstring strength of a subject S, in which the force exerted at the lower leg of the subject S while they perform an eccentric contraction of at least the hamstring is indicative of hamstring strength. …

117 Again, the advantage of the apparatus over the existing methods is emphasised at [0079] by reference to the fact that each leg may be tested at the same time, as follows:

It will also be appreciated that the apparatus 100 including two sensors 130.1, 130.2 allows the assessment of the hamstring strength of both hamstrings of a subject S, at the same time. Accordingly the sensors 130.1, 130.2 may sense the force indicative of at least the hamstring strength in each leg of the subject S simultaneously. In this regard, the assessment may be performed in significantly less time than existing methods, for example isokinetic dynamometry, which is limited to assessing hamstrings of opposing legs at different times. …

118 At [0083], it is stated that a number of further features will now be described. At [0084] and [0085], the following is then stated:

[0084] In another example, each sensor 130.1, 130.2 is coupled to a respective securing member 121, 122 that secures the ankles of a subject S relative to the support 110 and accordingly the force sensed at the ankles is indicative of hamstring strength. However, this feature is not essential and it will be appreciated that the sensors 130.1, 130.2 may sense a force exerted at any part of the lower leg, for example under the knees of the subject S.

[0085] Furthermore, the assessment of hamstring strength may occur during a unilateral or bilateral contraction/s of the hamstring/s. For example, during a bilateral contraction, two sensors 130.1, 130.2 may be used to sense the force in each leg of the subject simultaneously or at different times, or alternatively a single sensor 130.1, 130.2 may be used to sense the force in either or both legs. During a unilateral contraction, the apparatus may include one sensor 130.1, 130.2 which is interchangeable between the lower legs of the subject, by repositioning the sensor 130.1, 130.2 and/or the securing members 121, 122 and/or the subject S relative to the support 110, such that the hamstring strength in both legs can be assessed sequentially. However, this feature is not essential.

(Emphasis added.)

119 Dr Pizzari’s evidence (both affidavit and oral evidence) concerning the construction of the Patent (which favoured Vald) was centred upon [0085] of the specification in particular.

120 In reliance upon Dr Pizzari’s evidence, Vald points to the emphasised words in [0085] to contend that claim 1 should not be construed as requiring both legs to be secured by the securing members on the basis that a person skilled in the art as at the priority date would know that, in order to perform a unilateral contraction of the hamstring, one leg must be unsecured.

121 However, I do not accept this submission having regard to my finding as to the common general knowledge as at the priority date.

122 My view as to the proper construction of claim 1 aligns with that of Dr Lovell, whose evidence I prefer to that of Dr Pizzari for the reasons already stated. Dr Lovell gave the following evidence in his first affidavit (which evidence I accept):

111. In my opinion, none of the claims of the Patent encompass a subject performing an NHE with only one lower leg secured. While there are references to testing ‘at least one knee flexor’, I read this as meaning the force generated by only a single leg may be measured but that both the subject’s lower legs are both secured in their respective securing members.

112. My understanding of the apparatus described and claimed in the Patent is that it encompasses:

• an apparatus where the subject has both their legs secured (i.e., fixed relative to the support (platform);

• An NHE is performed to cause an eccentric contraction of at least one hamstring (knee flexor) – that eccentric contraction being necessary to resist the subject’s upper body falling forward; and

• The force which the subject leaning forward – and the resultant eccentric contraction generates – being measured in one or both legs – via a sensor (or sensors) connected to the securing member(s).

…

114. While there is no specific reference to the contralateral leg (being the leg for which force is not being measured) being secured, in my opinion that leg must also be secured for stability purposes.

115. In my opinion, the stability required to perform an NHE in a way which would produce any useful form of measurement in one leg, would require that the other ‘contralateral’ lower limb – being the leg for which no force measurement was being taken – was supported and/or restrained or otherwise stabilised by some form of support, platform or restraint.

…

121. While, at paragraph 173, the Patent refers to the performance of “unilateral contractions” and NHEs being performed “unilaterally”, it is unclear to me whether this is referring to unilateral measurements (i.e. measuring the force exerted in one leg whilst the other leg remains secured) or that it contemplates a one-legged Nordic curl being performed. To the extent that it is the latter, the Patent does not explain how this is done and the drawings do not depict this activity. Accordingly, while the Patent refers to both bilateral and unilateral NHE’s, it does not explain how a unilateral NHE is performed and measured in any meaningful way.

122. …Furthermore, any force results obtained in carrying out [a one-legged NHE] would, in my view be of very limited value.

(Emphasis original.)

123 An additional reason in support of my construction rests upon my finding that claim 1 requires the apparatus to assess strength in a reliable and accurate way to provide clinically relevant information. That is because, based upon Dr Lovell’s evidence as follows (which evidence I accept), such an assessment is not achieved when a unilateral NHE is performed on the apparatus disclosed in claim 1. Dr Lovell explained in his first affidavit that:

[P]erforming an NHE in the way outlined above, with one leg restrained and the other stabilised, supported or held in a different manner, would compromise the accuracy of the assessment as the contralateral limb (i.e., the limb not restrained in the same way) would inevitably be absorbing a proportion of the force generated in performing an NHE but that force would not be measured in any way.

124 Returning then to the Patent itself, there are many strong indicators within it that Vald’s construction is not the correct one. Some of these have already been addressed above. Others will now be considered.

125 Use of the apparatus with only one leg secured by a securing member is not depicted in any of the drawings, and [0085] does not state in express terms that only one ankle or one leg of the subject is secured (unlike other paragraphs in the specification which refer expressly to the ankles or legs of the subject being secured, such as [0075], [0081] and [0084]). Nor does the specification (whether through any drawing or otherwise) describe where the unsecured leg is to be placed (for example) or, as already observed, how the subject S lowers their upper body toward the support 110 in a controlled manner, while substantially maintaining alignment of the upper legs or thighs and torso, if only one leg is secured in a securing member.

126 The specification is detailed in its description of the different means of using the apparatus with both legs secured, including by reference to numerous drawings, but is silent as to how this is to be achieved with only one leg secured. These matters tell against a construction of claim 1 which does not require both legs to be secured. If it was a simple matter of informing the person skilled in the art to perform a bilateral Nordic curl on the apparatus and leaving it to them to understand how to undertake that process, these details and drawings would not be required. Having regard to the evidence of Dr Lovell, a unilateral Nordic curl is more difficult for a person to perform, and there are impediments to obtaining a reliable force measurement from such an exercise without the use of a support. This makes it more, not less, likely that there would be an explanation in the specification about the manner of performing a strength assessment on the apparatus with only one leg secured if claim 1 encompassed that.

127 This is especially as one of the advantages which the Patent holds the apparatus out as having is better reliability and repeatability of measurements of between limb strength imbalances. It is to the issue of reliability that I now turn.

128 At [0012] of the specification, after addressing existing methods and devices for testing hamstring strength, the specification identifies that existing techniques have questionable reliability and repeatability of measurements of between limb strength imbalances.

129 In the Detailed Description of the Preferred Embodiments at [0079], it is stated that the apparatus also appears to provide enhanced sensitivity and reliability for the assessment of between limb strength imbalances compared to existing techniques.

130 At [0170], it is stated that, “A number of experiments were performed in order to demonstrate the effectiveness of the abovementioned apparatus 100…”.

131 The section which follows is entitled “Reliability and Validity Experiments” and appears at [0171]–[0182] of the specification.