Federal Court of Australia

Save Our Strathbogie Forest Inc v Secretary to the Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action [2024] FCA 317

ORDERS

SAVE OUR STRATHBOGIE FOREST INC Applicant | ||

AND: | SECRETARY TO THE DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY, ENVIRONMENT AND CLIMATE ACTION Respondent | |

ATTORNEY-GENERAL OF THE STATE OF VICTORIA Intervener | ||

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The applicant’s originating application dated 14 June 2023 be dismissed.

2. Within 14 days of these orders, the parties file and serve any submissions on the question of costs of no more than five (5) pages in length.

3. Subject to further order, the question of costs be determined on the papers.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

HORAN J:

Introduction

1 At some time during autumn this year, as part of the Victorian Government’s bushfire risk management program, the Secretary to the Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action (DEECA) intends to conduct planned fuel management burns in four defined areas within the Strathbogie State Forest, which is located approximately 120 kilometres north-east of Melbourne, Victoria.

2 The applicant contends that the planned burns involve a controlled action under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cth) (the EPBC Act) on the basis that they are likely to have a significant impact on the Southern Greater Glider, which is a listed threatened species included in the endangered category under the EPBC Act. Accordingly, the applicant contends that, in the absence of an applicable exemption, the action of the Secretary in carrying out the planned burns requires the approval of the Commonwealth Minister for the Environment (Commonwealth Minister) under Pt 9 of the EPBC Act. As no such approval has been given, the applicant seeks an injunction to prevent the Secretary from carrying out the planned burns without such an approval contrary to s 18(3) of the EPBC Act.

3 There is no dispute that the Strathbogie State Forest, and in particular the four planned burn areas, include habitat suitable for the Southern Greater Glider and that some gliders are likely to be present in the planned burn areas.

4 The ultimate question raised by this proceeding is whether the planned burns can proceed without being required to obtain the approval of the Commonwealth Minister under Pt 9 of the EPBC Act. That in turn raises three main issues.

(a) whether it is likely that the planned burns will have a significant impact on the Southern Greater Glider as a listed threatened species included in the endangered category within the meaning of s 18(3) of the EPBC Act;

(b) if so, whether s 43B of the EPBC Act operates to provide the Secretary with an exemption from the requirement to obtain an approval under Pt 9, on the basis that the planned burns amount to a lawful continuation of a use of land that was occurring immediately before the commencement of the EPBC Act on 16 July 2000; and

(c) whether the application of s 18(3) of the EPBC Act to the functions and activities of the Secretary under s 62(2) of the Forests Act 1958 (Vic), or to the conduct of these four planned burns, offends the Constitutional principle recognised in the High Court’s decision in Melbourne Corporation v The Commonwealth (1947) 74 CLR 31, and is to that extent invalid.

5 Each of the parties adduced a significant amount of evidence directed to the manner in which the fire might behave if and when the planned burns are carried out, and the possible effects of the fire on Southern Greater Gliders present in the burn area and their habitat. The Secretary also adduced evidence addressing the broader context of the State’s bushfire risk management, including in particular the risk to lives and property, and the history of planned fuel reduction burns as one of the measures designed or intended to mitigate such risks.

6 There was a consensus between the parties that, in resolving the issues in dispute in this proceeding, this Court is not required to consider policy issues bearing upon whether or not the planned burns should be carried out, nor to attempt any balancing of the environmental values protected by the EPBC Act against the objectives of planned burning as a measure to address bushfire risk. The applicant submits that those issues are matters that are properly considered by the Commonwealth Minister in deciding whether or not to grant approval to the proposed action under the EPBC Act. The Secretary submits that no such approval is required.

7 In particular, neither the applicant nor the Secretary have invited the Court to consider or make any findings as to the effectiveness of planned burns as a bushfire risk management tool. There has been a long history of investigative commissions which have addressed many aspects of those matters, which lie well outside the scope of this proceeding: see e.g. 2009 Victorian Bushfires Royal Commission Final Report (2010), Fire Preparation, Response and Recovery: Land Management Vol II, Ch 7. The evidence and submissions in this proceeding focused on the impact of the planned burns on protected matters under the EPBC Act. The applicant’s case is concerned with the direct and indirect effects of the proposed planned burns on gliders in the Strathbogie State Forest, but it is no part of that case that the planned burns might have an effect of increasing the risk or severity of bushfires in the future. Conversely, the Secretary does not contend that any risk to the Southern Greater Glider arising from the conduct of the planned burns can or should be offset against a reduction in the risk to gliders in the Strathbogie State Forest from future bushfires as the result of the planned burns. While the Attorney-General of Victoria (Attorney-General), who intervened under s 78A of the Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth) in relation to the Melbourne Corporation issue, places some reliance on the objectives of planned burns in the context of the performance by the Secretary of the statutory duty under s 62(2) of the Forests Act to carry out proper and sufficient work on certain public land for the prevention and suppression of fire, as well as the broader public function or duty of the State to protect lives and property in Victoria, that submission does not turn on any factual contentions concerning the efficacy of planned burns in that context, which for present purposes may largely be assumed.

8 At the request of the parties, the trial of this matter was listed on an expedited basis and was heard over two weeks commencing on 29 January 2024.

9 For the reasons set out below, I have concluded that s 18(3) of the EPBC Act validly applies to the Secretary in the conduct of works for the prevention of fire, including planned fuel reduction burns. However, on the evidence before the Court, I am not satisfied that the four planned burns that the Secretary proposes to carry out in the Strathbogie State Forest will have, or are likely to have, a significant impact on the population of Southern Greater Gliders in the Strathbogie State Forest or on the species as a whole within the meaning of s 18(3).

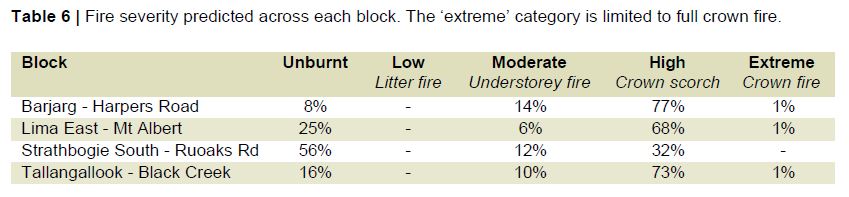

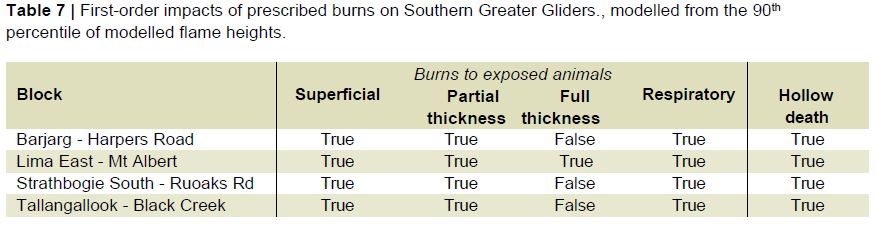

10 In summary, I have found that the planned burns will be conducted in accordance with the prescriptions and objectives set out in their Delivery Plans, and will generally result in low intensity fire with limited impacts on the canopy in most of the planned burn areas. While there is a real chance the planned burns may kill or injure some individual gliders that are present in areas where the fire burns with higher severity, so as to result in a high degree of canopy scorch, such areas (if any) will constitute a relatively minor proportion (less than 2.5%) of the planned burn areas, and an even smaller proportion of the Strathbogie State Forest as a whole. There is also a real chance that the collapse of hollow-bearing trees during or following the planned burns may kill or injure any individual gliders that are sheltering in such trees when they collapse, but the evidence does not establish that such losses are likely to be common or widespread. More generally, there is a real chance that the planned burns will cause some reduction in the abundance of hollow-bearing trees in the planned burn areas, but the evidence does not establish that this is likely to lead to any significant reduction in the abundance of gliders in the planned burn areas, nor in the Strathbogie State Forest.

11 In the circumstances, any impacts of the planned burns on individual gliders in the areas affected by fire are not likely to have a significant impact on the population of Southern Greater Gliders in the Strathbogie State Forest, or on the species, for the purposes of s 18(3) of the EPBC Act.

12 Otherwise, I have found that the four planned burns cannot be characterised as a lawful continuation of a use of land that was occurring immediately before the commencement of the EPBC Act, and accordingly the exception in s 43B of the EPBC Act is not attracted. Further, in relation to the Melbourne Corporation principle, I do not accept that the application of s 18(3) of the EPBC Act to the conduct by the Secretary of works for the planned prevention of fire in State forests, or to the conduct of these four planned burns, curtails or impairs either the capacity of the State to function as a government or the exercise by the State of its constitutional powers. As a consequence, the Secretary is generally required to comply with Pt 3 of the EPBC Act when conducting any planned burn that has or will have, or is likely to have, a significant impact on any matters of national environmental significance within the meaning of that Part.

13 It follows that the applicant’s application for an injunction under s 475 of the EPBC Act in relation to the proposed conduct of the four planned burns must be dismissed.

Background factual matters

The planned burns

14 Planned burning involves the deliberate introduction of fire into the landscape in order to manage fuel and bushfire hazard and damage potential: see generally s 4 of the Code of Practice for Bushfire Management on Public Land 2012 (amended 2022) (the Code). It has been defined as “the controlled application of fire under specified environmental conditions to a predetermined area and at the time, intensity, and rate of spread required to attain planned resource management objectives”: Australian Fire Authorities Council, Bushfire Glossary (January 2012) (Australian Bushfire Glossary), p 24. The term “planned burning” is sometimes used interchangeably with terminology such as “prescribed burning” or “fuel reduction burning”. It is different from “backburning”, which refers to a fire suppression technique sometimes used when actively fighting bushfires.

15 As a part of the Victorian fuel management program to reduce bushfire risk in the Hume region, the Secretary proposes to conduct planned burns in four areas within the Strathbogie State Forest:

(a) Lima East – Mt Albert (Lima East);

(b) Barjarg / Harpers Road (Barjarg);

(c) Strathbogie South / Ruoaks Road (Ruoaks Road); and

(d) Tallangallook – Black Creek Track (Tallangallook).

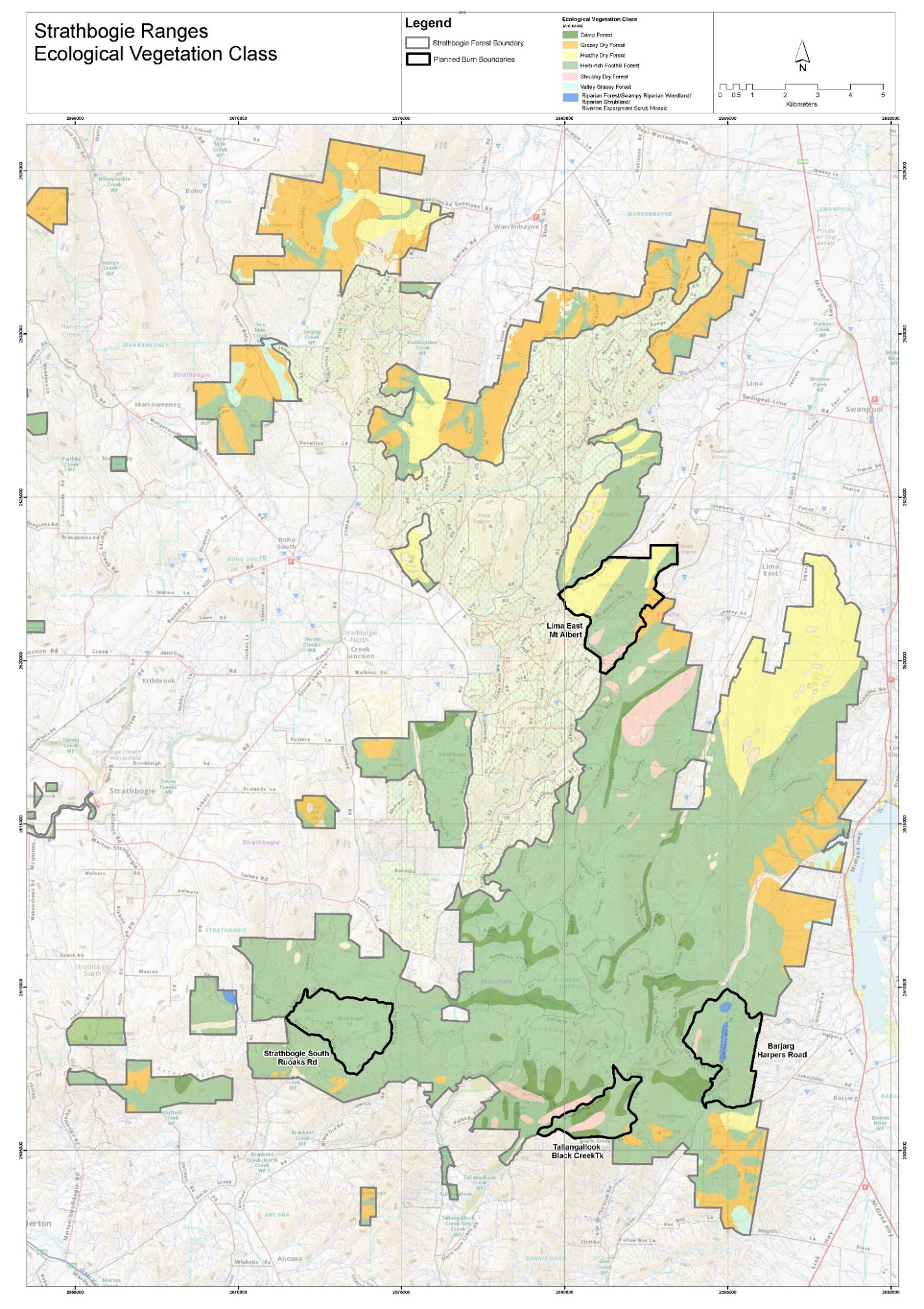

16 I consider the evidence in relation to the planning and delivery of these four planned burns in more detail below. In order to give a general picture of the location of the planned burn areas in the context of the Strathbogie State Forest, the following map depicts the area of each of the planned burns (outlined in black) within the boundaries of the Forest, showing the distribution of ecological vegetation classes derived from the DEECA’s spatial data (predominantly herb-rich foothill forest, with some damp forest, grassy dry forest, healthy dry forest, shrubby dry forest, valley grassy forest and riparian forest).

The Strathbogie Ranges and the Strathbogie State Forest

17 The Strathbogie Ranges are situated approximately 120 kilometres north-east of Melbourne. As summarised in a report by Dr Charles Meredith, an expert witness called by the applicant, drawing on a publication by the Victorian Environmental Assessment Council (Assessment of the values of the Strathbogie Ranges Immediate Protection Area (March 2022)):

The Strathbogie Ranges cover an area of about 240,000 hectares north of the Great Dividing Range situated between the Goulburn River to the west, the Broken River to the east and the Hume Highway to the north (VEAC 2022). The Strathbogie Ranges are mostly within the Highlands - Northern Fall bioregion. The Ranges are effectively a promontory of granite extending northwest from the main part of the Great Dividing Range. Over much of the Ranges, the granite forms a relatively flat-topped ‘tableland’ between about 500 and 900 metres above sea level. This elevation draws rain from prevailing weather systems coming from the west and northeast, with less run off on the gentle topography of the tableland than on more dissected ranges in this part of Victoria (VEAC 2022).

The Crown land within the Strathbogie Ranges falls into several land-use designations. The largest in area of these is State forest and the second largest is land leased for pine plantations. Small areas of other land-use designations include a reference area, several historic areas and an education area. By far the bulk of the native vegetation in the Ranges occurs in the State forest.

18 The Strathbogie State Forest comprises an area of approximately 23,000 hectares within the Strathbogie Ranges. State forests are Crown lands that are reserved or dedicated under the Forests Act and are managed by DEECA for a number of different uses, including timber production, recreation and the conservation of flora and fauna. State forests are distinct from parks and conservation reserves managed by Parks Victoria, committees of management or local government: see generally DEECA, Overview of Victoria’s Forest Management System, December 2019, pp 7-8.

The Southern Greater Glider

19 The Greater Glider is a large gliding possum, which has a head and body length of 35-46 cm with a long, furry, non-prehensile tail measuring 45-60 cm, and an adult weight range from 900-1,700 grams. There are currently two recognised species: Petauroides minor (Greater Glider (northern)) found in north-eastern Queensland, and Petauroides volans (Greater Glider (southern and central)) found in south-eastern Australia. This proceeding is concerned with the latter species, which is generally referred to in Victoria as the Southern Greater Glider. I will adopt that terminology in these reasons for judgment, so as to distinguish the Southern Greater Glider from the Greater Glider (northern). I note in passing that the latter species is now separately listed under the EPBC Act and is the subject of a separate conservation advice.

20 The Southern Greater Glider is a listed threatened species included in the endangered category under the EPBC Act (with effect from 5 July 2022), and is included in the Threatened List with a category of threat of endangered under the Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act 1988 (Vic) (FFG Act). Under the applicable statutory definitions, this means that the species is one that is “facing a very high risk of extinction in the wild in the near future”, but which is not critically endangered (i.e. facing an extremely high risk of extinction in the wild in the immediate future): see s 179(4) of the EPBC Act, s 3(1) of the FFG Act.

Conservation Advice under the EPBC Act

21 The EPBC Act requires an approved conservation advice to be prepared for each listed threatened species: s 266B(1). An approved conservation advice must contain a statement setting out the grounds on which the species is eligible to be included in the category in which it is listed and the main factors that are the cause of it being so eligible: s 266B(2)(a). It must also set out information about what could appropriately be done to stop the decline of, or support the recovery of, the species: s 266B(2)(b)(i).

22 Conservation advices under the EPBC Act are provided to the Commonwealth Minister by the Threatened Species Scientific Committee established under s 502 of the EPBC Act, whose expert members are appointed by the Commonwealth Minister. The functions of the Scientific Committee include advising the Minister on approved conservation advice and the amendment and updating of the lists established under Pt 13 of the EPBC Act (including the lists of threatened species for which ss 178 and 179 provide): s 503. A conservation advice must be approved in writing by the Commonwealth Minister, following consultation with the Scientific Committee, before its publication on the internet: s 266B(2)-(7).

23 In Friends of Leadbeater’s Possum Inc v VicForests (No 4) [2020] FCA 704; 244 LGERA 92 at [25]-[26], Mortimer J (as her Honour then was) described such conservation advices as “the mandatory and foundational documents describing each threatened species, its characteristics and habitat, and the threats posed to it”, and as containing “the formal recognition, for the purposes of the EPBC Act, of why the listed threatened species has been determined to need protection and what measures need to be taken to ensure its conservation and recovery”.

24 In the present case, the applicant places considerable reliance on the approved conservation advice published under the EPBC Act for the Southern Greater Glider: Conservation Advice for Petauroides volans (greater glider (southern and central)) (as in effect from 5 July 2022) (the Conservation Advice). Although counsel for the Secretary accepted that the Conservation Advice is an “authoritative document”, they submitted that it should not be “used as a proxy or surrogate for expert evidence in the case”. While that may be so, the Conservation Advice is nevertheless itself in evidence and was referred to and relied on by several expert witnesses.

25 There does not appear to be any dispute about the correctness of the contents of the Conservation Advice in so far as it has any bearing on the issues for determination in this case (although counsel for the Secretary noted that the contents of the Conservation Advice had not been specifically pleaded). I note that Mortimer J, in her fact-finding in Friends of Leadbeater’s Possum, considered that it was appropriate to place “significant weight” on the conservation advice for each of the species addressed in that case (which included an earlier iteration of the Conservation Advice for the Greater Glider, prior to the elevation of the Southern Greater Glider from the vulnerable category to the endangered category). As an instrument that has been approved by the Commonwealth Minister and published under the EPBC Act, the Conservation Advice is especially relevant to any assessment of whether an action will have or is likely to have a significant impact on a listed threatened species for the purposes of 18(3) of the EPBC Act. In the absence of any directly conflicting evidence or specific disagreement, I will proceed on the basis that the Conservation Advice is a reliable and accurate source of general information about the Southern Greater Glider, including its taxonomy, biology and ecology, distribution, and threats to its survival.

Conservation status

26 The Greater Glider was previously listed in the vulnerable category of the threatened species list under the EPBC Act effective from 5 May 2016. With effect from 5 July 2022, the Southern Greater Glider was recognised as a separate species and was listed in the endangered category following an assessment by the Scientific Committee against the applicable listing criteria, based on an observed, estimated, inferred, projected or suspected population reduction, the causes of which may not have ceased, may not be understood, or may not be reversible. The Conservation Advice states that “[t]he main factors that make the species eligible for listing in the Endangered category are an overall rate of population decline exceeding 50 percent over a 21-year (three generation) period, including population reduction and habitat destruction following the 2019–20 bushfires”. The supporting evidence on which the Scientific Committee relied is set out in its listing assessment, which is included as an attachment to the Conservation Advice. It may be noted that the Scientific Committee assessed the species as ineligible for listing as vulnerable, endangered or critically endangered under other criteria dealing with geographic distribution, total population size and number of mature individuals. As population viability analysis had not been undertaken for the full species, there was insufficient data to determine the eligibility of the species for listing in any category under the criterion dealing with the probability of extinction in the wild.

Distribution

27 The Conservation Advice describes the Southern Greater Glider as the largest gliding possum in eastern Australia. It has a broad distribution “from around Proserpine in Qld, south through NSW and the ACT, to Wombat State Forest in central Vic”. Its area of occupancy has decreased substantially since European settlement, mostly due to land clearing, and is continuing to decline due to further clearing, fragmentation impacts, edge effects, bushfire, climate change and some forestry activities.

28 In relation to important populations and sub-populations, the Conservation Advice states:

Given its Endangered status, all populations of the greater glider (southern and central) are important for the conservation of the species across its range. Due to the species’ low fecundity and limited dispersal capabilities, areas where the species has become locally extinct are not readily recolonised. Coastal populations may be important for maintaining genetic diversity, as they are geographically distinct from inland populations (DoEE 2016b).

29 The Strathbogie State Forest supports a high density of the Southern Greater Glider, with the total population across the Strathbogie Ranges having been estimated to be approximately 69,000: see generally J L Nelson et al, “Estimating the density of the Greater Glider in the Strathbogie Ranges, North East Victoria” (2018), Arthur Rylah Institute for Technical Environmental Research: Technical Report Series No. 293 (Nelson 2018). Referring to a comparison of survey data collected between 1983 and 2017, the Conservation Advice notes that the population of Southern Greater Gliders in the Strathbogie State Forest appears not to have declined over a 34-year period to the same extent as has been observed elsewhere in Victoria, and that surveys “found relatively high densities of gliders”.

Habitat

30 The Southern Greater Glider is an arboreal nocturnal marsupial, predominantly solitary and largely restricted to eucalypt forests and woodlands of eastern Australia. It is typically found in highest abundance in taller, montane, moist eucalypt forests on fertile soils, with relatively old trees and abundant hollows. Gliders have an estimated longevity of 15 years, and females give birth to a single young from March to June.

31 During the day, the Southern Greater Glider shelters in tree hollows, with a particular preference for large hollows in large, old trees. While both live and standing dead trees are used for denning, the species prefers to use live hollow-bearing trees when adequate numbers are available. Most hollow-bearing trees used for denning by arboreal and scansorial mammals are at least 100 years of age. However, the size and age at which suitable hollows develop depends on tree species and climate. Multiple dens are used by each individual glider, typically within a relatively small home range (1 to 4 hectares). Densities of gliders vary significantly across the glider’s range, and average densities have been found to range from 0.6 to 2.8 individuals per hectare in Victoria.

32 The availability of tree hollows is identified in the Conservation Advice as a key limiting resource and the probability of the occurrence of the species is positively correlated with the availability of tree hollows. The Conservation Advice notes that “[l]arge hollow-bearing trees are in rapid decline in some landscapes primarily due to timber production practices and bushfires that prevent trees growing to an age when they might produce hollows”, and that this is a concern for recovery of the species. In addition, the abundance of hollow-bearing trees may be an overestimate of the actual number that are suitable for occupation by wildlife, as only one in every three to five hollow-bearing trees within montane ash forests is occupied by arboreal marsupials. The Conservation Advice states that “[a] decline or loss of hollow-bearing trees reduces the numbers of greater gliders in the landscape”.

33 The Conservation Advice states that the Southern Greater Glider is sensitive to bushfire and is slow to recover following major fires. Thus, “[o]ver the longer term, repeated disturbance such as intense or too-frequent fires degrades greater glider habitat by changing the composition, structure and nutrient profile of forests”, including the destruction of live and dead hollow-bearing trees, particularly in young forests. While unburnt areas provide critical refuges for gliders in regions heavily impacted by fires, Southern Greater Gliders have limited dispersal capabilities and are slow to recover and recolonise burnt sites following fire.

34 The Southern Greater Glider’s diet mostly comprises eucalypt leaves supplemented by buds and flowers. It feeds from a restricted range of eucalypt species, including Narrow-Leaved Peppermint (Eucalyptus radiata) in Victoria. The tree species favoured by Southern Greater Gliders varies regionally. It favours forests with a diversity of eucalypt species, due to seasonal variation in growth and nutrient content of its preferred tree species. Approximately 85 percent of the Southern Greater Glider’s water requirements are provided by consumed leaves.

35 The Conservation Advice describes habitat critical to the survival of the Southern Greater Glider as follows:

Habitat critical to survival for the greater glider (southern and central) may be broadly defined as (noting that geographic areas containing habitat critical to survival needs to be defined by forest type on a regional basis):

• large contiguous areas of eucalypt forest, which contain mature hollow-bearing trees and a diverse range of the species’ preferred food species in a particular region; and

• smaller or fragmented habitat patches connected to larger patches of habitat, that can facilitate dispersal of the species and/or that enable recolonization; and

• cool microclimate forest/woodland areas (e.g. protected gullies, sheltered high elevation areas, coastal lowland areas, southern slopes); and

• areas identified as refuges under future climate changes [sic] scenarios; and

• short-term or long-term post-fire refuges (i.e. unburnt habitat within or adjacent to recently burnt landscapes) that allow the species to persist, recover and recolonise burnt areas.

Habitat meeting any one of the criteria above is considered habitat critical to the survival of greater glider (southern and central), irrespective of the current abundance or density of greater gliders or the perceived quality of the site. Forest areas currently unoccupied by the greater glider (southern and central) may still represent habitat critical to survival, if the recruitment of hollow-bearing trees as the forest ages could allow the species to colonise these areas and ensure persistence of a subpopulation.

Threats

36 The Conservation Advice identifies the key threats to the Southern Greater Glider as frequent and intense bushfires, inappropriate prescribed burning, climate change, land clearing and timber harvesting – noting that “[t]here are synergies between these threats, and their combined impact needs to be considered in the recovery of the species”.

37 The threat arising from “inappropriate fire regimes” is addressed as encompassing both extensive severe bushfires and high frequency fires. Dealing with the former, the Conservation Advice states: “Substantial population losses or declines have been documented in and after high severity bushfires … Losses can occur as a result of direct mortality due to lethal heating or suffocation from smoke, or indirect mortality due to the loss of key habitat features and resources”. As to “high frequency fires”, the Conservation Advice notes that “[f]requent fire can decrease the availability of hollow-bearing trees in the landscape, and change the floristic composition and nutritional profile of glider habitat”. In that context, the Conservation Advice specifically addresses planned burning:

Too intense or frequent planned burning may contribute to population losses or declines in the southern part of the greater glider’s range. Bluff (2016) reported that hollow-bearing trees (HBTs) affected by fire during planned burns were 28 times more likely to collapse than HBTs that were not burnt. Parnaby et al. (2010) found that following low intensity prescription burns in the Pilliga forests (NSW), mean collapse rates for burnt HBTs were 14-26%. This was consistent with the collapse rate of 25.6% found by Bluff (2016). A survey following a planned burn at Tallarook Range in the Central Highlands (Vic) in 2021 found that a large number of potential greater glider habitat trees were burnt, with “many destroyed” (N. Stimson 2021, pers. Comm. 26 June).

There is increased pressure from some parts of the community to undertake more hazard reduction burning, follow[ing] the severe bushfires of 2019-20.

38 It may be observed that the language used in the Conservation Advice here specifically refers to planned burning that is “[t]oo intense or frequent”, rather than necessarily treating all planned burning as a threat to the Southern Greater Glider.

39 The Conservation Advice also refers to physical disturbances associated with firefighting operations, including the construction of roads and control lines, earthworks, tree removal and backburning. In relation to planned burning, the Conservation Advice relevantly notes:

In Vic, loss of HBTs due to mechanical site preparation works associated with prescribed burning (which primarily occurs in foothill forests close to settled areas) may reduce suitable habitat for the greater glider (southern and central). Trees that are assessed as potentially hazardous (if they were to catch fire) are routinely removed from the perimeter of planned burns on public land in Vic. They are also removed from bushfire control lines during and after bushfire suppression activities (DELWP n.d). Although not all hazardous trees are hollow bearing, many are, or are likely to be trees that form hollows more quickly (J Nelson 2021. pers comm 16 April).

40 The conservation and recovery actions contemplated in the Conservation Advice relevantly include the following:

• Re-assess and revise current prescriptions used for prescribed burning to ensure that the frequency and severity of fires in greater glider habitat are minimised, in order to mitigate the risk of further population declines and loss of hollow-bearing trees. Measures to reduce risk from future bushfires should be strategic, incorporate adaptive management, and include a risk assessment that considers trade-offs between fire control efficiency and environmental damage.

• Implement and enforce measures to reduce direct mortality and loss of hollow-bearing trees during site preparation and execution of prescribed burns, including rake hoeing around the base of trees.

• Ensure that eucalypt forests and the impacts of disturbance (including fire) are managed to prevent them transitioning to less nutritious, hotter, and/or more fire-prone plant communities, and to ensure that food tree species preferred by the greater glider (southern and central) continue to be the dominant canopy trees.

• Protect and maintain sufficient areas of suitable habitat, including denning and foraging resources and habitat connectivity, to sustain viable subpopulations throughout the species’ range.

41 The Conservation Advice also addresses survey and monitoring priorities both in relation to Southern Greater Gliders and hollow-bearing trees, as well as information and research priorities including “the development of guidelines for fire management by assessing the impacts of fire management and different fire regimes (including frequency and intensity) on habitat, subpopulation size and hollow availability”.

Action Statement under the FFG Act

42 As mentioned above, the Southern Greater Glider is also classified as endangered under the FFG Act. Section 19 of the FFG Act relevantly requires the Secretary to prepare an action statement for any listed taxon of fauna as soon as possible after that taxon is listed, having regard to any management advice given by the Scientific Advisory Committee and any other relevant nature conservation, social and economic matters. The action statement must set out what has been done to conserve and manage that taxon and what is intended to be done, and may include information on what needs to be done: s 19(2).

43 An action statement for the Southern Greater Glider was published in 2019: Greater Glider (Petauroides volans subsp. volans): Action Statement No 267 – Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act 1988 (Action Statement). At the time the Action Statement was issued, the Southern Greater Glider was listed in the category of vulnerable (facing a high risk of extinction in the wild in the medium-term future) before its elevation in June 2023 to the category of endangered (facing a very high risk of extinction in the wild in the near future).

44 The contents of the Action Statement are consistent with the Conservation Advice. It states that Southern Greater Gliders are “forest dependent and prefer older tree age classes in moist forest types” and that they are “obligate users of hollow-bearing trees for shelter and nesting, with each family group using multiple den trees within its home range”. The Action Statement continues: “Greater Glider density varies proportionally to the availability of hollow-bearing trees and do not persist in areas of forest where such trees are absent”, and notes that “Lindenmayer et al. (1990) found the abundance of Greater Gliders in the Victorian Central Highlands was positively correlated with forest age and the density of hollow-bearing trees”.

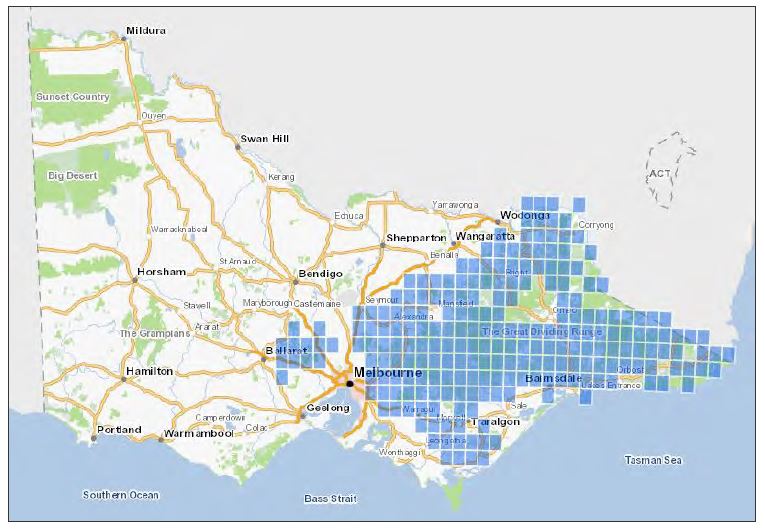

45 The Action Statement contains the following map showing the distribution of the Southern Greater Glider in Victoria:

46 Under the heading “Threats”, the Action Statement states:

The key threats to the Greater Glider can be summarised in terms of elevated mortality, habitat degradation and the risks associated with small, fragmented populations, including genetic decline. Factors contributing to elevated mortality and the loss of hollow-bearing trees include bushfire, planned burning, drought, timber harvesting and hyper-predation (SAC 2017). There is some evidence to indicate that climate change in the form of more extreme droughts and higher temperatures might result in a reduction in quality or availability of food. Increased morbidity or mortality might also be associated with heat stress. As populations decline and become more isolated, they are more prone to the effects of small population size and potentially genetic decline. This may result from habitat fragmentation due to land management practices or contraction of suitable habitat due to climate change. Fragmentation and isolation impact on the ability of Greater Gliders to recolonise suitable habitat and reduce genetic exchange between sub-populations.

47 In relation to “social and economic issues”, under the sub-heading “Bushfire Risk”, the Action Statement provides:

Fuel management practices across Victoria’s public and private lands aim to reduce the impact of bushfires to communities at risk and provide for the regeneration or preservation of forest assets including ecological and cultural values. This includes undertaking fuel management by planned burning, slashing and mulching. Forest Fire Management Victoria (FFMVic) further reduces risk on public land through early detection and rapid suppression of bushfires. Other works such as upgrading fire towers, building new bridges and improving roads make suppression more achievable and safer, helping to reduce the impact on community and the environment. These activities can require the removal of hazardous trees to ensure that staff can undertake bushfire management work safely. While these activities may have an impact on Greater Glider populations and their habitat, the protection of life and property is an overriding priority of the Victorian Government. Recognising that hazardous trees may also be important habitat for arboreal mammals, wherever possible FFMVic undertakes values checking before undertaking on-ground works to mitigate impacts to habitat.

48 Under the sub-heading “Animal Welfare”, the Action Statement notes:

The management of public land, including timber harvesting and bushfire prevention and suppression, has the potential to result in injury and death to many animals each year. As a large and readily observable mammal, the impact of these activities on the Greater Glider arouses concern.

49 The Action Statement addresses existing conservation measures, including in relation to “fire management”. In that regard, the Action Statement provides:

The primary objectives of DELWP’s fuel management program is to minimise the impact of major bushfires on human life and other values – including the environment, as well as maintaining or improving the resilience of natural ecosystems. DELWP’s fuel management processes are designed to consider forest values and how they can be protected through strategic planning and the way we operationally deliver any fuel management activities. Planning and delivery of this work is guided by expert knowledge and advice to ensure forests are managed for a diverse range of ecological, cultural and built values.

The Greater Glider is recognised as a threatened species in DELWP’s processes of strategic and operational bushfire management planning. In strategic bushfire management planning, DELWP will take account of Greater Glider habitat and colonies when designating different fire management zones in the landscape.

Operational planning includes additional checks of values that may be impacted by fuel management activities. Nominated burns are tested against known data surveys which encompass a range of information, to determine if they overlap habitat areas and ranges of vulnerable species. If a potential impact is flagged, biodiversity experts within DELWP recommend options to minimise impact. Examples of mitigation measures include:

• clearing fine fuels from around hollow-bearing habitat trees with rake hoes to ensure they do not burn;

• burning at a lower intensity;

• burning during particular seasons;

• undertaking mechanical treatment rather than planned burning; and

• avoiding using heavy machinery or chemicals in certain areas.

50 The Action Statement notes that research was being carried out by the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (DELWP) (a predecessor of DEECA) to investigate “the impact of fuel management on Greater Glider as part of its monitoring, evaluation and reporting program for bushfire risk management while loss of hollow-bearing trees resulting from planned burning has been assessed for sites in East Gippsland (Bluff 2016)”. The “intended management actions” listed in the Action Statement include:

Determine the most appropriate fire management practices to ensure viable populations of Greater Glider and their habitat (including key features such as hollows in large old trees). This includes developing feasible, cost-effective measures to mitigate any significant impacts of planned burning on Greater Glider populations and their habitat. Incorporate these measures into strategic, tactical and operational fire management plans.

Fire management

General comments

51 The Secretary led a great deal of evidence in relation to Victoria’s approach to fire management, including the framework and context in which fire management activities are conducted. While much of this evidence was uncontroversial and unchallenged, it has limited direct relevance to most of the critical factual issues for determination in the proceeding.

52 As mentioned above, the case does not raise questions about the content of the broader fire management regime in Victoria or the efficacy of planned burning within that regime, nor any challenge to the public policy in relation to the mitigation of bushfire risks (whether to lives, property or environmental values). Those matters do not have a direct bearing on the question whether or not the conduct of the planned burns as proposed in the Strathbogie State Forest will have or is likely to have a significant impact on the Southern Greater Glider. Apart from that question, the defence under s 43B of the EPBC Act requires some consideration of the evidence in relation to the history of planned burns in the Strathbogie State Forest, including the planned burn areas, and the Melbourne Corporation issue requires some consideration of the purposes or objects of fuel reduction burns as works for the “prevention or suppression of fire”.

53 The evidence about the framework of policies and procedures governing fire management in Victoria was given by Mr Chris Hardman, who is the Chief Fire Officer (CFO), Forest and Fire Operations Division, DEECA and Mr Shaun Lawlor, Regional Manager, Forest and Fire Operations for the Hume Region of Forest Fire Management Victoria (FFMVic). In the circumstances, it is necessary to refer to this evidence in order to provide background and context to the questions to be determined in the proceeding.

54 I will deal separately with the evidence of Mr Lawlor and Mr Hardman in relation to the actual conduct of planned burns, including the measures that are taken to keep fire under control and ensure that it does not behave in an unplanned manner, and their predictions or expectations based on their experience as to the likely fire behaviour in the proposed planned burns. In so far as the latter involved opinion evidence, its admissibility was not challenged, and it may be taken as having been accepted that their evidence in that regard was based on their specialised knowledge from training, study or experience: see Evidence Act 1995 (Cth), s 79.

55 As CFO, Mr Hardman leads DEECA’s fire management operations under the Forests Act and is responsible for fire prevention, preparedness and response operations on behalf of the Secretary. As set out in further detail below, the Secretary is responsible under the Forests Act (and its predecessor legislation) for managing the risk of bushfire in State forests, national parks and other protected land in Victoria: see, currently, Forests Act, s 62(2). The CFO also represents DEECA in Victorian and national emergency management arrangements.

56 As the Regional Manager, Forest and Fire Operations for the Hume Region, Mr Lawlor is responsible for the tactical and operational planning and delivery of regional forest fire programs, including bushfire response, planned burning, and other forest management in the Hume Region.

Fire management in Victoria

57 Victoria has a particularly high bushfire risk when compared to other parts of the world and other parts of Australia due to its landscape, vegetation types and weather patterns. This risk is increasing as a result of climate change. Victoria has hot dry summers with very little rain. In summer, Victoria is generally subject to hot, dry northerly wind conditions, followed by south-westerly wind changes. When a bushfire ignites, it is common for a northerly wind to push a narrow bushfire from north to south and, when the wind changes to a south-westerly direction, the bushfire will move from west to east and have a broad and dangerous front.

58 Victoria has experienced an increase in scale of bushfires in the last 20 years, as evidenced by the increased number of megafires in the State. A megafire is a fire which burns over one million hectares. There have been three megafires in the last 20 years, being the 2003 Eastern Victorian alpine bushfires, the 2006-2007 Great Divide Complex bushfires in eastern Victoria, and the 2019-2020 bushfires in East Gippsland and other locations (known as the Black Summer bushfires). By comparison, in the 152 years leading up to 2003, Victoria experienced two recorded megafires (Black Thursday in 1851 and Black Friday in 1938-1939).

59 Victoria has a risk-based approach to bushfire management, which seeks to reduce impacts from bushfire including on people, property, the economy and the environment. This risk-based approach ultimately recognises that the protection of human life is the highest priority.

60 DEECA delivers programs to manage bushfire risk through FFMVic, which was established in 2013 and is responsible for all forest fire management activities in Victoria. FFMVic is led by DEECA, but also draws on capability from Parks Victoria, VicForests and Melbourne Water. FFMVic works with the Country Fire Authority (CFA) and Fire Rescue Victoria to deliver fire management services in Victoria.

61 Fuel management activities in Victoria are undertaken in accordance with the Code, which is a Code of Practice made by the Victorian Minister for Environment under Pt 5 of the Conservation Forests and Lands Act 1987 (Vic). The Code sets the objectives for bushfire management on public land across Victoria, and provides a risk analysis framework that assists DEECA to achieve those objectives. The Code does not prescribe the operational detail for the achievement of bushfire management outcomes and objectives. The operational detail is specified in bushfire management manuals and guidelines, which must be publicly available and consistent with the Code.

62 For administrative purposes in relation to the delivery of fire management services, Victoria is divided into six regions: Barwon South West, Grampians, Loddon Mallee, Gippsland, Hume and Port Phillip. The Strathbogie State Forest is located within the Hume region. There are four districts within the Hume region: Upper Murray, Ovens, Goulburn and Murrindindi. The Strathbogie State Forest is located within the Goulburn district.

63 Each of the six regions in Victoria has its own Bushfire Management Strategy, which describes the bushfire risk for that region, taking account of its unique environment and landscape. The Bushfire Management Strategies identify actions that can be taken to protect communities, infrastructure and the environment from the threat of bushfire, and provide the direction and options for fuel management across a region and for each district.

64 Fuel management is a key strategy for reducing the risk of bushfire in Victoria. While there are several layers to how the Bushfire Management Strategies are implemented on the ground, the objective is to reduce bushfire fuels and fuel hazard, particularly the leaves, bark, twigs and shrubs that cause the greatest risk of a bushfire spreading. Fuel management includes planned burning, mechanical treatment activities (such as mowing, slashing and mulching), and non-burn treatment activities such as spraying.

65 Victoria’s fuel management program includes “residual risk targets” which are set by the CFO and implemented across the regions and districts. A residual risk target is the percentage of bushfire risk remaining after fuel in forests has been reduced, either through fuel management activities or as a result of bushfires, and before any fire suppression activities are undertaken. Bushfire risk is the risk of destruction of property from bushfire, which is also used in this context as a proxy for risk to human life. The State-wide residual risk target is 70%. The residual risk target for each region and district varies depending on factors including vegetation, topography, and the population and assets in the area. The target for the Hume region is 69%, and for the Goulburn district is 75%.

66 The specific activities that comprise a region’s fuel management program are listed in a “Joint Fuel Management Program” for that region, which is created and implemented jointly between FFMVic and the CFA. A Joint Fuel Management Program sets out a rolling three-year program of planned fuel management activities, including planned burns. The Joint Fuel Management Program for the Hume Region refers to the regional residual risk target of 69% and notes that, without any fuel management, the projected residual risk will increase to 73%. Through the conduct of the activities programmed in the Joint Fuel Management Program, the region works towards managing local bushfire risk by identifying planned burns and other works that will meet regional and State-wide targets.

67 Fire Management Zones are “areas of public land where fire is used for specific asset, fuel and overall forest and park management objectives”: see the Code at [122]. There are four different classes of Fire Management Zone: Asset Protection Zones, Bushfire Moderation Zones, Landscape Management Zones and Planned Burning Exclusion Zones.

68 As will be discussed further below, the four planned burns that are the subject of this proceeding are within an area that is zoned as a Bushfire Moderation Zone. According to the Code (at [128]), a Bushfire Moderation Zone “aims to reduce the speed and intensity of bushfires”, and “complements the [Asset Protection Zone] in that the use of planned burning … is designed to protect nearby assets, particularly from ember spotting during a bushfire”. The Code continues (at [129]):

Where practicable, the [Bushfire Moderation Zone] will aim to achieve ecological outcomes by seeking to manage for ecologically desirable fire regimes, provided bushfire protection objectives can still be met. This may include using other fuel management methods.

69 This can be compared to the Landscape Management Zone, within which planned burning is used for three broad aims, namely:

• bushfire protection outcomes by reducing the overall fuel and bushfire hazard in the landscape

• ecological resilience through appropriate fire regimes

• management of the land for particular values including forest regeneration and protection of water catchments at a landscape level.

70 The key principles of the fuel management strategy for the Hume Region, as set out in its Bushfire Management Strategy, include to “focus fuel management activities within Asset Protection Zone and Bushfire Moderation Zone, where fuel hazards are reduced to an acceptable level whilst protecting ecological assets where possible, and to select fuel management regimes that meet the target reduction in risk to life and property, reduce risk of large fires to other important values (such as water catchments) and minimise the negative impact on ecosystem resilience”. Fuel management activities in the Landscape Management Zone are undertaken “where there is a clear bushfire risk reduction objective or ecological outcome”, otherwise such activities are minimised within the Landscape Management Zone to reduce negative impacts on ecosystem resilience. Another key principle is to “avoid fuel management within high value ecological areas (HVEAs), particularly within [the Landscape Management Zone]”.

71 The use of Fuel Management Zones is illustrated in the document published by DEECA titled “Hume Bushfire Management Strategy 2020: Bushfire Risk Engagement Areas” (2020) at p 43 using an example of zoning in areas around Jamieson. Among other things, this includes the placement of Landscape Management Zone “in areas further from communities, where fuel management can reduce overall fuel and bushfire hazard in the landscape”, and where “[m]aintaining ecosystem resilience is equally important, and we apply fire regimes that protect ecosystem values (for example, old-growth vegetation that provides critical habitat for Greater Glider and Powerful Owl)”.

Fuel management burning in Victoria

72 Section 4 of the Code addresses planned burning in the following terms:

111. Planned burning is the deliberate introduction of fire into the landscape to:

• modify fuel hazard, bushfire hazard and damage potential

• contribute to ecological objectives

• contribute to regeneration following timber harvesting activities.

112. Planned burning is the most effective technique for managing fuel hazard over large areas. Other localised treatments include ploughing, mulching, herbicide application, chain rolling, grazing, mowing and slashing.

113. Planned burning assists bushfire suppression actions by reducing the intensity and severity of bushfires.

73 Consistently with the primary objectives for bushfire management on public land, the Code identifies the “outcomes” of fuel management including planned burning as “[r]educed impact of major bushfires on human life, communities, essential and community infrastructure, industries, the economy and the environment”, and states that “[h]uman life will be afforded priority over all other considerations”.

74 Prior to 2016, planned burning on public land in Victoria was administered to meet annual hectare-based bushfire fuel management targets, consistent with the recommendations of various Commissions of Inquiry and Royal Commissions. However, since 2016, Victoria has employed a risk reduction target (also referred to as a residual risk target), as noted above. The State-wide target of 70% “means that bushfire fuels have been reduced to the point where impacts to life and property are reduced by about a third of the maximum risk”: DEECA, “Safer together: A new approach to reducing the risk of bushfire in Victoria” (2015). The regional residual risk targets and the delivery of the regional Bushfire Management Strategies are aggregated to assess the State-wide target of 70%.

75 In this context, the Secretary measures bushfire risk by using a model called Phoenix RapidFire to simulate a set of bushfires across the landscape using real time information about weather, topography, vegetation, fire characteristics (such as flame height, ember density, spotting distance, convection column strength and intensity), in order to show how the fire will spread and behave under specified conditions, and thereby predict bushfire behaviour both with fuel reduction and without fuel reduction. In broad terms, the Secretary models how fires would behave on a “worst case” scenario (assuming weather conditions such as those prevailing on Black Saturday and fuel at its maximum risk level), and then runs modified risk scenarios seeking to reduce the number of houses or “address points” that are lost down to the applicable residual risk target. In this way, the Secretary can determine the risk reduction value of a particular planned burn or burns. The results of this modelling are used to predict how different fuel management activities will affect bushfire risk across landscapes, so as to inform fuel management priorities and determine strategies for reducing bushfire risk.

Federal and State legislative frameworks

EPBC Act

76 The EPBC Act commenced operation on 16 July 2000. The objects of the Act are set out in s 3(1) and relevantly include:

(a) to provide for the protection of the environment, especially those aspects of the environment that are matters of national environmental significance; and

…

(c) to promote the conservation of biodiversity; and

(ca) to provide for the protection and conservation of heritage; …

...

77 Section 3(2) of the EPBC Act provides that, in order to achieve those objects, the EPBC Act, inter alia:

(a) recognises an appropriate role for the Commonwealth in relation to the environment by focussing Commonwealth involvement on matters of national environmental significance and on Commonwealth actions and Commonwealth areas; and

...

(d) adopts an efficient and timely Commonwealth environmental assessment and approval process that will ensure activities that are likely to have significant impacts on the environment are properly assessed; and

(e) enhances Australia’s capacity to ensure the conservation of its biodiversity by including provisions to:

(i) protect native species (and in particular prevent the extinction, and promote the recovery, of threatened species) and ensure the conservation of migratory species; …

...

78 The EPBC Act binds the Crown in each of its capacities: s 4.

79 Chapter 2 of the EPBC Act is headed: “Protecting the environment”. The simplified outline of the Chapter set out in s 11 states that it “provides a basis for the [Commonwealth] Minister to decide whether an action that has, will have or is likely to have a significant impact on certain aspects of the environment should proceed”, and that “[i]t does so by prohibiting a person from taking an action without the Minister having given approval or decided that approval is not needed”.

80 Division 1 of Pt 3 of Ch 2 of the EPBC Act contains requirements for environmental approvals by imposing conditional prohibitions on the taking of actions that have or will have, or are likely to have, a significant impact on various “matters of national environmental significance”: see the heading to Div 1; and the object set out in s 3(1)(a). While the term “matters of national environmental significance” is undefined, it is clear from the context and structure of the Division and from references elsewhere in the Act that it refers to the matters with which the Subdivisions contained in Div 1 are concerned, namely: World Heritage properties; National Heritage places; Ramsar wetlands; listed threatened species and ecological communities; listed migratory species; nuclear actions; actions in or affecting Commonwealth marine areas; actions in or affecting the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park; certain actions involving unconventional gas development or large coal mining development impacting on water resources; and actions prescribed by the regulations. Each Subdivision contains its own civil penalty provisions and offence provisions in respect of a contravention of the prohibitions, together with exceptions including where an approval has been given under Pt 9 of the EPBC Act in relation to the taking of the action.

81 Relevantly to the present case, Subdiv C of Div 1 deals with listed threatened species and ecological communities. Section 18 prohibits a person from taking an action that has or will have, or is likely to have, a significant impact on a listed threatened species that is included in the extinct in the wild, critically endangered, endangered or vulnerable categories, and imposes civil penalties for contravention by an individual or a body corporate. Section 18A creates corresponding criminal offences.

82 The central provision for the purposes of this case is s 18(3) of the EPBC Act, which provides:

Endangered species

(3) A person must not take an action that:

(a) has or will have a significant impact on a listed threatened species included in the endangered category; or

(b) is likely to have a significant impact on a listed threatened species included in the endangered category.

Civil penalty:

(a) for an individual—5,000 penalty units;

(b) for a body corporate—50,000 penalty units

83 Section 18A(2) relevantly provides that a person commits an offence if the person takes an action that is “likely to have a significant impact” on a listed threatened species (other than one included in the extinct category or a conservation dependent species), which is punishable on conviction by imprisonment for a term not more than 7 years, a fine not more than 420 penalty units (or up to 5 times that amount for a body corporate), or both. For such purposes, the element whether the species is a listed threatened species is subject to strict liability: s 18A(2A).

84 Section 19 provides a range of exceptions or defences to the civil penalty and offence provisions, namely: if an approval is in operation under Pt 9; if Pt 4 lets the person take the action without such an approval; if there is in force a decision of the Minister under Div 2 of Pt 7 that the relevant subsection of ss 18 or 18A is not a “controlling provision” for the action; and if the action is one whose authorisation is subject to a special environmental assessment process as described in s 160(2).

85 The term “action” is relevantly defined to include “an activity or series of activities”: s 523(1)(d). It may be noted that a decision by a government body, including a State or an agency of a State, to grant a governmental authorisation for another person to take an action is not itself an action: s 524(2). While a decision to grant a governmental authorisation is removed from the operation of the EPBC Act, the subsequent physical acts or activities pursuant to the authorisation or by way of implementation of the decision can be actions within the meaning of s 523: see Secretary, Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment v Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre Inc (2016) 244 FCR 21 at [77]-[79] (Allsop CJ, Griffiths and Moshinsky JJ). The present case is concerned with the actions proposed to be taken by the State of Victoria or its agencies in conducting the planned burns, rather than the grant of any governmental authorisation. Neither the applicant nor the Secretary or the Attorney-General suggested that s 524(2) had any relevance to the present case.

86 The term “impact” is relevantly defined under s 527E as follows:

527E Meaning of impact

(1) For the purposes of this Act, an event or circumstance is an impact of an action taken by a person if:

(a) the event or circumstance is a direct consequence of the action; or

(b) for an event or circumstance that is an indirect consequence of the action—subject to subsection (2), the action is a substantial cause of that event or circumstance.

(2) For the purposes of paragraph (1)(b), if:

(a) a person (the primary person) takes an action (the primary action); and

(b) as a consequence of the primary action, another person (the secondary person) takes another action (the secondary action); and

(c) the secondary action is not taken at the direction or request of the primary person; and

(d) an event or circumstance is a consequence of the secondary action;

then that event or circumstance is an impact of the primary action only if:

(e) the primary action facilitates, to a major extent, the secondary action; and

(f) the secondary action is:

(i) within the contemplation of the primary person; or

(ii) a reasonably foreseeable consequence of the primary action; and

(g) the event or circumstance is:

(i) within the contemplation of the primary person; or

(ii) a reasonably foreseeable consequence of the secondary action.

(Emphasis in original)

87 The term “listed threatened species” is defined in s 528 to mean a native species included in the list referred to in s 178, which requires the Minister by legislative instrument to establish a list of threatened species divided into the following categories:

(a) extinct;

(b) extinct in the wild;

(c) critically endangered;

(d) endangered;

(e) vulnerable;

(f) conservation dependent.

88 Section 179 of the EPBC Act addresses when a native species is eligible to be included in each of the categories listed in s 178(1). As noted above, the Southern Greater Glider has been included on the list of threatened species in the endangered category from 5 July 2023, having previously been included in the vulnerable category. Those categories are dealt with by s 179(4) and (5), which provide:

(4) A native species is eligible to be included in the endangered category at a particular time if, at that time:

(a) it is not critically endangered; and

(b) it is facing a very high risk of extinction in the wild in the near future, as determined in accordance with the prescribed criteria.

(5) A native species is eligible to be included in the vulnerable category at a particular time if, at that time:

(a) it is not critically endangered or endangered; and

(b) it is facing a high risk of extinction in the wild in the medium-term future, as determined in accordance with the prescribed criteria.

(Emphasis in original)

89 Part 4 of the EPBC Act deals with cases in which environmental approvals are not needed, which generally provides an exception to the prohibitions contained in Div 1 of Pt 3. These include actions covered by Ministerial declarations in relation to the accreditation of management arrangements or authorisation processes either under State or Territory laws pursuant to bilateral agreements between the Commonwealth and the State or Territory, or under Commonwealth laws; Ministerial declarations in relation to bioregional plans; conservation agreements; forestry operations undertaken in accordance with a Regional Forest Agreement; actions in accordance with zoning plans in the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park; and actions with prior authorisation. The only provision contained in Pt 4 which has any potential relevance to the facts of the present case is s 43B (under Div 6 – Actions with prior authorisation), which deals with the lawful continuation of uses of land, sea or seabed that were occurring immediately before the commencement of the EPBC Act. The Secretary relies on s 43B as providing an exemption from the requirements of s 18(3) in relation to the conduct of planned burning in the Strathbogie State Forest.

90 Part 9 of the EPBC Act is contained in Ch 4, which sets out processes for environmental assessments and approvals by the Commonwealth Minister. These processes generally involve three stages: deciding whether approval is needed and identifying the applicable “controlling provisions” (Pt 7); assessing the relevant impacts of the action (Pt 8); and deciding whether or not to approve the action, and on what conditions (Pt 9).

91 The environmental assessment and approval process contained in Ch 4 of the EPBC Act is generally enlivened by a referral to the Commonwealth Minister by the proponent (generally the person proposing to take the action, or a party to a contract or agreement under which the action is proposed to be taken) or by a State or an agency of a State that is aware of the proposed action. The Commonwealth Minister also has a power to request a proponent to refer the proposal: s 70. A proposed action is a “controlled action” if the taking of the action by the person without approval under Pt 9 would be prohibited by a provision of Pt 3, which is referred to as a “controlling provision” for the action: see s 67. A proponent may refer the proposed action to the Commonwealth Minister for a decision whether or not the action is a controlled action even if the proponent does not think that the action is a controlled action: s 68(2). Thus, the referral mechanism can potentially be used as a way to obtain a decision by the Commonwealth Minister that the action is not a controlled action.

92 Once a proposed action is referred to the Commonwealth Minister, s 75(1) provides that the Minister must decide whether the action the subject of the referral is a controlled action and which provisions of Pt 3 (if any) are controlling provisions for the action. In so deciding, the Commonwealth Minister must consider all adverse impacts (if any) the action has or will have, or is likely to have, on the matter protected by each provision of Pt 3: s 75(2)(a). The Commonwealth Minister must not consider any beneficial impacts the action has or will have, or is likely to have, on the protected matters: s 75(2)(b). It is an offence for a proponent to take the action while a decision is pending on whether or not it is a controlled action: s 74AA.

93 The “relevant impacts” of a controlled action must be assessed in accordance with Pt 8 of Ch 4, which prescribes a range of different assessment approaches. The relevant impacts are the impacts that the action has or will have, or is likely to have, on the matter protected by each provision of Pt 3 that the Commonwealth Minister has decided is a controlling provision for the action.

94 After the controlled action has been assessed, the Commonwealth Minister must decide whether or not to approve the taking of the action for the purposes of each controlling provision: ss 130(1), 133. The Commonwealth Minister can attach conditions to the approval of the controlled action if he or she is satisfied that the conditions are necessary or convenient for protecting, or repairing or mitigating damage to, a matter protected by a relevant controlling provision: s 134. In deciding whether or not to approve the taking of an action, and what conditions to attach to an approval, the Commonwealth Minister must consider certain mandatory considerations set out in s 136(1) and (2), including matters relevant to the controlling provision or provisions, and “economic and social matters”. The Commonwealth Minister may have regard to whether the proponent is a suitable person to be granted an approach, having regard to the person’s environmental history: s 134(4). In relation to decisions about threatened species, the Commonwealth Minister must not act inconsistently with Australia’s obligations under specified international conventions, or with a recovery plan or a threat abatement plan: s 139(1). If the Commonwealth Minister is considering whether to approve a proposed action for the purposes of a subsection of s 18 that has or will have, or is likely to have, a significant impact on a particular listed threatened species, the Commonwealth Minister must have regard to any approved conservation advice for the species or community: s 139(2). Otherwise, the Commonwealth Minister must not consider any matters that he or she is not required or permitted by Div 1 of Pt 9 to consider: s 134(5).

95 It must be emphasised that the present case does not directly concern any aspect of the assessment and approval processes set out in Ch 4 of the EPBC Act. Rather, the applicant’s contention is that the Secretary is required to follow those processes by obtaining approval from the Commonwealth Minister under Pt 9 before carrying out the proposed planned burns, in order to avoid a contravention of s 18(3) of the EPBC Act. In the absence of any such approval, the applicant seeks injunctive relief under s 475 of the EPBC Act to restrain what it contends is a threatened contravention of the EPBC Act. Section 475 is in the following terms:

475 Injunctions for contravention of the Act

Applications for injunctions

(1) If a person has engaged, engages or proposes to engage in conduct consisting of an act or omission that constitutes an offence or other contravention of this Act or the regulations:

(a) the Minister; or

(b) an interested person (other than an unincorporated organisation); or

(c) a person acting on behalf of an unincorporated organisation that is an interested person;

may apply to the Federal Court for an injunction.

Prohibitory injunctions

(2) If a person has engaged, is engaging or is proposing to engage in conduct constituting an offence or other contravention of this Act or the regulations, the Court may grant an injunction restraining the person from engaging in the conduct.

...

Meaning of interested person—organisations

(7) For the purposes of an application for an injunction relating to conduct or proposed conduct, an organisation (whether incorporated or not) is an interested person if it is incorporated (or was otherwise established) in Australia or an external Territory and one or more of the following conditions are met:

(a) the organisation’s interests have been, are or would be affected by the conduct or proposed conduct;

(b) if the application relates to conduct—at any time during the 2 years immediately before the conduct:

(i) the organisation’s objects or purposes included the protection or conservation of, or research into, the environment; and

(ii) the organisation engaged in a series of activities related to the protection or conservation of, or research into, the environment;

(c) if the application relates to proposed conduct—at any time during the 2 years immediately before the making of the application:

(i) the organisation’s objects or purposes included the protection or conservation of, or research into, the environment; and

(ii) the organisation engaged in a series of activities related to the protection or conservation of, or research into, the environment.

(Emphasis in original)

96 The jurisdiction of this Court to grant an injunction under s 475 of the EPBC Act is separate from the administrative processes established under Pts 7, 8 and 9 of the EPBC Act. As summarised above, the latter involves the referral of a proposed action to the Commonwealth Minister, who must then consider and determine whether the action is a controlled action and, if so, what the controlling provisions are. Such a determination will require the Commonwealth Minister to make factual findings as to whether the proposed action has or will have, or is likely to have, a significant impact on a protected matter, such as a listed threatened species within the meaning of s 18 of the EPBC Act. When determined administratively in that context, such findings will not involve matters of jurisdictional fact which constitute objective pre-conditions on the powers conferred on the Commonwealth Minister by the EPBC Act: see e.g. Anvil Hill Project Watch Association Inc v Minister for Environment and Water Resources (2008) 166 FCR 54 at 60 (Tamberlin, Finn and Mansfield JJ). Accordingly, while a decision made by the Commonwealth Minister that an action is (or is not) a controlled action is amenable to judicial review, the Court in any such judicial review proceedings would not be required itself to make findings of fact on the evidence as to whether or not the action is a controlled action under any of the provisions of Pt 3 of Ch 2 of the EPBC Act, that is, whether the action would be prohibited by the relevant provision in the absence of an approval under Pt 9.

97 In contrast, an application to this Court for an injunction under s 475 of the EPBC Act raises a justiciable issue whether a person “has engaged, is engaging or is proposing to engage in conduct constituting an offence or other contravention of this Act or the regulations”. While the grant of any injunctive relief remains subject to discretionary considerations, it is clear that the Court is required to determine on the evidence before it whether the past, current or future conduct of the person contravenes a provision of the EPBC Act. Relevantly to the present case, this includes the question whether the action that the Secretary proposes to take in conducting the planned burns in the Strathbogie State Forest has or will have, or is likely to have, a significant impact on the Southern Greater Glider as a listed threatened species in the endangered category within the meaning of ss 18(3) and 18A of the EPBC Act. On an application for a prohibitory injunction under s 475(2), this is essentially a question of fact: see e.g. Friends of Leadbeater’s Possum at [1292], [1342] ff; see also Booth v Bosworth (2001) 114 FCR 39 (Branson J); Minister for Environment and Heritage v Greentree (No 2) (2004) 138 FCR 198 at [192] (Sackville J); Australian Brumby Alliance Inc v Parks Victoria Inc (2020) 277 FCR 559.

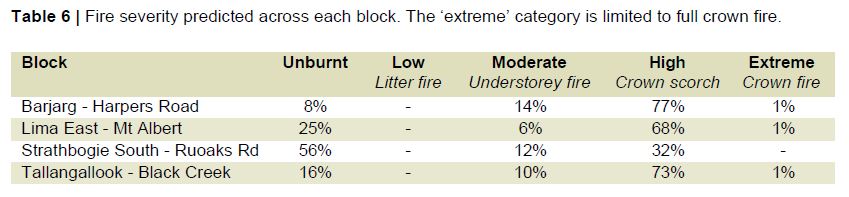

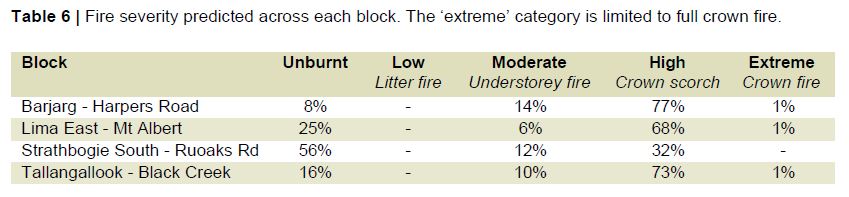

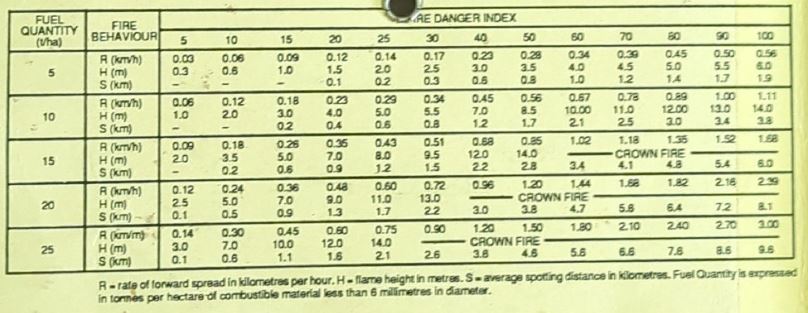

98 For present purposes, it is unnecessary to explore fully the relationship between, on the one hand, the administrative processes of environmental assessment and approval by the Commonwealth Minister and, on the other hand, the enforcement provisions under the EPBC Act, including the jurisdiction to grant injunctions in respect of contraventions of the Act. At least in circumstances where a person threatens to engage in, or to continue to engage in, conduct that contravenes the EPBC Act, this Court may be required to determine the factual and legal questions as to whether that conduct constitutes an action that, in the absence of an approval under Pt 9 or some other statutory exception or defence, would contravene an applicable statutory prohibition under Pt 3 of the EPBC Act. The fact that the Commonwealth Minister may be able to determine similar questions in the context of a referral or an environmental assessment and approval under Ch 4 of the EPBC Act, including whether a proposed action is a controlled action in respect of one or more provisions in Pt 3 for which approval is required, does not detract from or qualify the Court’s task in hearing and determining an application for an injunction under s 475 of the EPBC Act. Section 67A contains a prohibition on taking a controlled action without an approval under Pt 9, with a note indicating that a person can be restrained from contravening that section by an injunction under s 475. A “controlled action” is defined for such purposes by s 67 in terms that are not expressly confined to an action that the Commonwealth Minister has decided is a controlled action under s 75. In any event, even if s 67A were to be read as referring to actions that the Commonwealth Minister has decided are controlled actions, the jurisdiction conferred by s 475 is capable of being enlivened in appropriate circumstances by a threatened contravention of a prohibition in Pt 3, such as ss 18 or 18A of the EPBC Act.