FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Soong v Gleeson (Trustee), in the matter of Soong [2024] FCA 289

ORDERS

Applicant | ||

AND: | BRUCE GLEESON AS TRUSTEE OF THE PROPERTY OF DESLEY SOONG, A DISCHARGED BANKRUPT Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The application for leave to appeal filed on 22 September 2023 is dismissed.

2. The applicant is to pay the respondent’s costs.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

MARKOVIC J:

1 This is an application for leave to appeal and, if leave is granted, an appeal brought by Desley Soong, a discharged bankrupt, from orders made by the Federal Circuit and Family Court of Australia (Div 2) on 8 September 2023. The respondent to the application is Bruce Gleeson in his capacity as trustee of Ms Soong’s property (Trustee). Relevantly, the primary judge was asked to determine as a separate question whether a notice dated 3 June 2021 issued by the Trustee purportedly pursuant to s 129AA(4) of the Bankruptcy Act 1966 (Cth) (Extension Notice) was valid (Separate Question). The primary judge answered the Separate Question in the affirmative: see Gleeson (Trustee), in the matter of Soong v Soong [2023] FedCFAmC2G 819 (J).

BACKGROUND

2 The Separate Question arose against the following background.

3 On 15 May 2012 the Trustee was appointed the trustee in bankruptcy of Ms Soong’s estate pursuant to a sequestration order made by the Federal Circuit Court: J [2].

4 Pursuant to s 54(1) of the Bankruptcy Act Ms Soong was required, within 14 days from the day on which she was notified of her bankruptcy, to make out and file with the Official Receiver a statement of her affairs and provide a copy of that statement to the Trustee. It was common ground before the primary judge that Ms Soong did so on 18 June 2012: J [3].

5 In her statement of affairs, at [28], Ms Soong disclosed that: in 1973 she had contributed approximately $23,000 towards the purchase of a property at Concord (Concord Property); that the estimated value of the Concord Property as at 18 June 2012 was $2 million; and that the Concord Property secured debts in the amount of $3,026,764: J [4].

6 Pursuant to s 149(4) of the Bankruptcy Act Ms Soong was discharged from bankruptcy “at the end of the period of three years from the date on which [she] filed … her statement of affairs”. There was a dispute about whether s 149(4) of the Bankruptcy Act operated to discharge Ms Soong from her bankruptcy on 18 or 19 June 2015: J [5]. The primary judge observed that the validity of the Extension Notice turned on the determination of that question.

7 On 3 June 2021 the Trustee served the Extension Notice on Ms Soong which was relevantly in the following terms (at J [8]):

I refer to my appointment as Trustee of the above Bankrupt Estate on 15 May 2012 and your subsequent discharge on 19 June 2015.

I note that you are one of the registered owners of the property located at … Concord NSW 2137 being the land contained in folio identifier … (“the Property”) together with Jim Soong (“Mr Soong”) as joint tenants. The Property was disclosed in your Statement of Affairs dated 14 June 2012 and filed with the Official Receiver on 18 June 2012.

I confirm you were discharged at law from your bankruptcy on 19 June 2015 but notwithstanding your discharge from bankruptcy, the Property remains vested in me until 19 June 2021 pursuant to s129AA(3)(a) of the Bankruptcy Act unless I give written notice to you stating that a later revesting time applies to particular property.

In accordance with s129AA(4) of the Bankruptcy Act I hereby give notice to you that a later revesting time will apply in respect of the Property. I have made a decision to extend the revesting time for the Property for three (3) years from 19 June 2021. Accordingly, the revesting time in respect of the Property is 19 June 2024. This means your interest in the Property will remain vested in me until 19 June 2024 notwithstanding your discharge from bankruptcy.

Should you have any queries, please do not hesitate to contact … of this office on telephone number … or via email…

8 On 24 November 2022 the Trustee commenced a proceeding in the Federal Circuit Court against Ms Soong and three other respondents, including as second respondent, Jim Soong, and as fourth respondent, Banfirn Pty Ltd, seeking relief under s 121 of the Bankruptcy Act and s 37A of the Conveyancing Act 1919 (NSW) in relation to a transaction purportedly effected by a deed of agreement made on 17 January 2011 between Ms Soong, Mr Soong, and Banfirn: J [9].

9 On 8 May 2023 Mr Soong and Banfirn filed a cross claim in the Federal Circuit Court proceeding against the Trustee as cross respondent: J [10]. They sought three declarations including:

1. A declaration that the purported extension notice issued by the Cross-Respondent on or about 3 June 2021 extending the revesting time under section 129AA(4) of the Bankruptcy Act 1966 (Cth) (Act) to 19 June 2024 (Purported Extension Notice) is invalid.

2. A declaration that the Cross-Respondent does not have any right, interest or title in the [Concord Property].

10 On 28 June 2023 the primary judge ordered that the Court determine as a separate question the validity of the Extension Notice issued by the Trustee: J [11].

11 On 28 August 2023 the primary judge heard argument on the Separate Question and on 8 September 2023 his Honour made orders, answering “yes” to the Separate Question. That is, his Honour found that the Extension Notice is valid.

STATUTORY FRAMEWORK

12 Before proceeding further, it is convenient to set out the relevant statutory framework.

13 Section 149 of the Bankruptcy Act concerns discharge from bankruptcy. At the relevant time s 149(4) provided:

If the bankrupt becomes a bankrupt after the commencement of section 27 of the Bankruptcy Amendment Act 1991, the bankrupt is discharged at the end of the period of 3 years from the date on which the bankrupt filed his or her statement of affairs.

I pause to note that s 149 of the Bankruptcy Act has since been amended but that the section as amended does not apply to Ms Soong: see s 27 of the Bankruptcy Amendment Act 1991 (Cth).

14 Section 129AA, titled “Time limit for realising property”, relevantly provides:

(1) This section applies only to:

(a) property (other than cash) that was disclosed in the bankrupt’s statement of affairs; and

(b) after‑acquired property (other than cash) that the bankrupt discloses in writing to the trustee within 14 days after the bankrupt becomes aware that the property devolved on, or was acquired by, the bankrupt.

In this subsection, cash includes amounts standing to the credit of a bank account or similar account.

(2) If any such property is still vested in the trustee immediately before the revesting time, then it becomes vested in the bankrupt at the revesting time by force of this section.

(3) Initially, the revesting time for property is:

(a) for property disclosed in the statement of affairs—the beginning of the day that is the sixth anniversary of the day on which the bankrupt is discharged from the bankruptcy; and

…

(4) If the trustee, before the current revesting time, gives the bankrupt a written notice (an extension notice) stating that a later revesting time applies to particular property, then that later time becomes the revesting time for that property.

…

(6) The time specified in an extension notice must be either:

(a) a specified time that is not more than 3 years after the current revesting time; or

(b) a time that is reckoned by reference to a specified event (for example, the death of a life tenant), but is not more than 3 years after the happening of that event.

…

15 Also relevant to the reasoning of the primary judge and a resolution of the application before me is the Acts Interpretation Act 1900 (Cth) which applies to all Acts, subject to a contrary intention: see s 2(2).

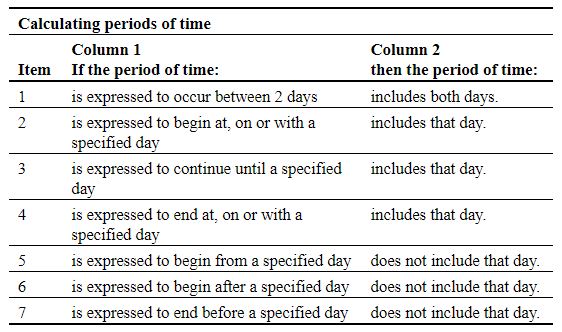

16 Section 36(1) of the Acts Interpretation Act headed “Calculating time” provides:

A period of time referred to in an Act that is of a kind mentioned in column 1 of an item in the following table is to be calculated according to the rule mentioned in column 2 of that item:

Example 1: If a claim may be made between 1 September and 30 November, a claim may be made on both 1 September and 30 November.

Example 2: If a permission begins on the first day of a financial year, the permission is in force on that day.

Example 3: If a licence continues until 31 March, the licence is valid up to and including 31 March.

Example 4: If a person’s right to make submissions ends on the last day of a financial year, the person may make submissions on that day.

Example 5: If a variation of an agreement is expressed to operate from 30 June, the variation starts to operate on 1 July.

Example 6: If a decision is made on 2 August and a person has 28 days after the day the decision is made to seek a review of the decision, the 28‑day period begins on 3 August.

Example 7: If a person must give a notice to another person at any time during the period of 7 days before the day a proceeding starts and the proceeding starts on 8 May, the notice may be given at any time during the 7‑day period starting on 1 May and ending on 7 May.

REASONS OF THE PRIMARY JUDGE

17 After setting out how the Separate Question arose, the primary judge recorded the parties’ respective contentions and noted (at J [18]) that they raised a question of construction, namely whether when calculating the period of three years provided for by s 149(4) of the Bankruptcy Act there is to be included or excluded the day on which a bankrupt files his or her statement of affairs.

18 His Honour observed that the question of construction was to be determined first by considering whether, assuming there is no contrary intention, s 36(1) of the Acts Interpretation Act applies to s 149(4) of the Bankruptcy Act by operation of s 2(1) of the Acts Interpretation Act; and secondly, assuming s 36(1) of the Acts Interpretation Act does apply, whether s 149(4) of the Bankruptcy Act, construed in context, manifests a “contrary intention” within the meaning of s 2(2) of the Acts Interpretation Act.

19 In relation to the construction of s 149(4) of the Bankruptcy Act, the primary judge concluded that it is the type of provision that item 5 of s 36(1) of the Acts Interpretation Act specifies. His Honour reasoned (at J [20]) that:

(1) subs 149(4) provides for a period of time that begins “from a specified day” being “the date on which the bankrupt filed his or her statement of affairs”;

(2) if s 36(1) of the Acts Interpretation Act applies, the calculation of the period of three years specified in s 149(4) of the Bankruptcy Act would not include 18 June 2012, being the day on which Ms Soong filed her statement of affairs; and

(3) it follows that 19 June 2012 would be the day from which the period of three years is to be calculated and 19 June 2015 would be the corresponding date three years after 19 June 2012, being the date on which the period of three years would end.

20 On the question of contrary intention, the primary judge recorded Ms Soong’s (and the other respondents’ to the proceeding in the court below) contention that “there is no basis for applying the Acts Interpretation Act to interpret s 129 or s 129AA of the Bankruptcy Act” because the definitions in the Bankruptcy Act are sufficiently specific and the language of the Bankruptcy Act may have constituted a contrary intention. The primary judge set out the details of the submissions relied on in support of that contention. Given the matters addressed by the primary judge in considering that contention, including by reference to the submissions relied on by Ms Soong (and the other respondents in the court below) in support of it, I assume that the reference to s 129 of the Bankruptcy Act was a typographical error and that his Honour intended to refer to s 149(4).

21 At J [25] the primary judge concluded that the submissions relied on did not satisfy him that s 149(4) of the Bankruptcy Act, construed in context, manifests a contrary intention that item 5 to s 36(1) of the Acts Interpretation Act does not apply to that section. His Honour then referred to two additional related matters which were not referred to by the parties but which his Honour considered may be relevant to the question of whether s 149(4) of the Bankruptcy Act manifests a contrary intention.

22 The first concerned the history of provisions such as s 36(1) of the Acts Interpretation Act and the second was that the Bankruptcy Act has used different words to describe a period of years commencing from a particular day or from an event that occurs on a particular day, that includes that day when computing the relevant period. As to the latter, the primary judge found that to be the case with s 129AA(3)(a) of the Bankruptcy Act which “describes a six year period by reference to the ‘sixth anniversary of the day on which the bankrupt is discharged from bankruptcy’”. His Honour observed that “[t]his description requires that there be included in the six year period the day of the event (the discharge of bankruptcy) by reference to which the sixth year anniversary is to be computed”. His Honour concluded that if Parliament had intended that the three year period in s 149(4) of the Bankruptcy Act was to be calculated by including the date on which the bankrupt filed his or her statement of affairs, it would have used words other than “from the date” to manifest its intention: J [29].

23 At J [30] the primary judge concluded that:

On the proper construction of s 149(4) of the Bankruptcy Act, the period of three years provided for in s 149(4) is to be calculated by not including the date on which the bankrupt filed his or her statement of affairs. Thus, the date on which Ms Soong filed her statement of affairs, namely, 18 June 2012, is not to be included in determining the period of three years provided for by s 149(4). That means that:

(a) Ms Soong was discharged from her bankruptcy on 19 June 2015;

(b) s 129AA(3)(a) of the Bankruptcy Act operated to specify 19 June 2021 as the current revesting time of Ms Soong's interest in the [Concord Property];

(c) 19 June 2024 is the latest time the Trustee could have specified in an extension notice issued under s 129AA(4);

(d) by extending in the Extension Notice the revesting time of Ms Soong's interest in the [Concord Property] to 19 June 2024, the Trustee specified a time in the Extension Notice that is not more than three years after the current revesting time of 19 June 2021; and

(e) the Extension Notice is valid.

THE APPLICATION FOR LEAVE TO APPEAL

24 Ms Soong’s application for leave to appeal was accompanied by a draft notice of appeal (draft NOA) which raises 11 proposed grounds of appeal, although senior counsel appearing for Ms Soong, Dr Birch SC, indicated that the critical grounds were [2], [3], [4] and [9] of the draft NOA by which Ms Soong alleges that:

2. The Trial Judge should have found that the time upon which the Appellant was discharged from bankruptcy was at the end of the period of 3 years from the date on which the Appellant filed her statement of affairs, the statement of affairs being filed on 18 June 2012, thus discharge occurred on 18 June 2015.

3. The Trial Judge erred in failing to correctly construe section 129AA(3)(a) of the Act by not finding that the initial revesting time for property disclosed in the Appellant's statement of affairs was the beginning of the day that is the sixth anniversary of the day on which the Appellant was discharged from bankruptcy.

4. The Trial Judge should have found that the sixth anniversary of the day on which the Appellant was discharged from bankruptcy was the beginning of 18 June 2021.

…

9. The Trial Judge erred in his finding that the Extension Notice was valid.

Dr Birch SC informed the Court that the remaining grounds were repetitious of the grounds identified and set out above. Accordingly, I do not intend to set them out.

25 In support of the application for leave to appeal, Ms Soong read two affidavits sworn by her solicitor Sean O’Donnell on 21 September 2023 and 22 September 2023 respectively.

26 Ms Soong contends that leave to appeal should be granted because:

(1) success on appeal could result in the dismissal of the whole of the proceeding in the court below;

(2) the proposed grounds of appeal demonstrate sufficient doubt in the judgment below to warrant the granting of leave;

(3) there is no factual dispute. The hearing at first instance took less than half a day and the hearing on appeal will take less time;

(4) the appeal is limited to questions of law;

(5) the argument on appeal will take little time more than arguments concerning whether leave to appeal should be granted;

(6) the decision at first instance was clearly erroneous; and

(7) she would suffer significant prejudice if the proceeding in the court below continued without her appeal being permitted.

27 On the one hand, the Trustee contends that leave to appeal may not be required because, while the answer given by the primary judge to the Separate Question did not conclude the entirety of the proceeding, it did determine the parties’ rights vis-à-vis the question of whether Ms Soong’s property continues to be vested in the Trustee and the entirety of the relief sought on the cross-claim in the court below. On the other hand, if leave to appeal is required, the Trustee contends that is should not be granted because the proposed grounds lack merit.

28 In my view the orders made disposing of the Separate Question were not final in that they did not finally dispose of the proceeding in the court below and only determined the parties’ rights to the extent that Ms Soong (and the other respondents below who do not seek leave to appeal) sought relief on the cross-claim in relation to the validity of the Extension Notice on an interim basis. That is, although the Separate Question may have disposed of the cross-claim, as Ms Soong conceded, she will have an appeal as of right at the conclusion of the proceeding in the court below including in relation to the Separate Question. Thus, Ms Soong does require leave to appeal.

29 Leave to appeal will be granted where, in all the circumstances, the decision is attended with sufficient doubt to warrant it being reconsidered on appeal and where substantial injustice would result if leave were refused, supposing the decision to be wrong: see Decor Corporation Pty Ltd v Dart Industries Inc (1991) 33 FCR 397 at 398.

30 For the reasons that follow, I am not satisfied that the primary judge’s decision is attended by sufficient doubt to warrant its reconsideration on appeal. That being said, it is apparent that Ms Soong would suffer injustice if leave was refused (supposing the decision to be wrong). That is because she would be left to defend the proceeding in the court below, incurring unnecessary costs and wasting resources. However, in the circumstances of this case, that prejudice does not outweigh the view I have formed in relation to merit. It follows that leave to appeal should be refused.

The proposed grounds of appeal

31 As set out above Ms Soong focussed on proposed grounds 1 to 4 and 9 of the draft NOA.

Proposed grounds 1 and 2

32 Proposed grounds 1 and 2 concern the date of discharge of bankruptcy pursuant to s 149(4) of the Bankruptcy Act (see [24] above).

33 Ms Soong submits that the primary judge erred at [20] when his Honour found that “19 June 2012 would be the day from which the period of 3 years is to be calculated, and 19 June 2015 would be the corresponding date three years after 19 June 2012 on which the period of 3 years would end”.

34 It was not in dispute that for the purposes of calculating the period in s 149(4) the date on which the bankrupt lodges his or her statement of affairs, in this case 18 June 2012, is excluded: see s 36 of the Acts Interpretation Act. However, the parties disagree on the way in which the calculation should thereafter be carried out.

35 Ms Soong relies on the decision in Prowse v McIntyre (1961) 111 CLR 264 at 271 and 274 and submits that, although the decision in Prowse was referred to by the primary judge, his Honour only referred to that decision in a limited way. Ms Soong does not dispute that the three year period for the purpose of identifying the date of discharge from bankruptcy commences after the filing of her statement of affairs, starting on and including 19 June 2012, but submits that the three year period will end at the moment before midnight on 18 June 2015.

36 Ms Soong contends that under the common law and in accordance with s 36 of the Acts Interpretation Act fractions of a day are not usually counted and therefore 18 June 2012 is not included in the three year period. Ms Soong further contends that s 149(4) refers to the period of time, i.e. exactly three years, to arrive at a precise point in time for an event to occur, i.e. the time of discharge from bankruptcy, and that at the end of 18 June 2015 does not mean the beginning of 19 June 2015.

37 Ms Soong submits that the end of the three year period does not include the beginning or any part of the following day. Accordingly, the end of the three year period does not include any part of 19 June 2015 and, as a consequence, the date of automatic discharge of her bankruptcy was on 18 June 2015, albeit at the end of 18 June 2015, and certainly not on 19 June 2015.

38 The Trustee’s written submissions refer in a number of places to s 149(2) of the Bankruptcy Act. However, given his oral submissions and the proposed grounds of appeal, I have proceeded on the basis that the references to s 149(2) are an error and that the Trustee intended to refer in each case to s 149(4) of the Bankruptcy Act.

39 On that basis the Trustee submits that the calculation of the period in s 149(4) can be approached in two ways but both illustrate that a full three year period, commencing on 19 June 2012 and ending with the whole of the day on 18 June 2015, must expire prior to discharge occurring:

(1) reference can be made to item 4 of s 36(1) of the Acts Interpretation Act which dictates that the three year period in s 149(4) of the Bankruptcy Act must include the day on which the period ends, namely 18 June 2015; or

(2) reference can be made to item 6 of s 36(1) of the Acts Interpretation Act. Insofar as discharge from bankruptcy can be seen as a period of time that commences after the period of bankruptcy, that period does not include the day which is the last day of the three year period, namely 18 June 2015 and thus the discharge occurs no earlier than 19 June 2015.

40 As set out above, Ms Soong relies on Prowse. That case concerned a claim for damages made out of time. The appellant, Mr Prowse, was born on 28 November 1930. The question before the High Court was when Mr Prowse reached the age of 21, which at the time was the age from which a person had capacity to sue, limited only by the expiration of the applicable limitation period, in that case six years. In answering that question at 270-1 Dixon CJ said:

The next question is, when did the plaintiff become of full age so that time began to run and the ultimate running out of the six calendar years could be determined? Now the first thing to observe is that at whatever hour of the day or night a man is born the whole of that day is reckoned for the purpose of calculating his age: … It follows that throughout the day of 27th November 1951 (i.e. from the midnight separating 26th from 27th November) the appellant Charles John Prowse was of full age. Inasmuch as s. 7 of the Limitation Act, 1623 gave him six more years exactly, that is six years of full capacity, within which he must sue, it was necessary that his summons in this case must issue on or before 26th November 1957. As it was issued on 27th November 1957 it was out of time.

41 To like effect at 271-2 McTiernan J found that:

The appellant's birthday being 28th November 1930 he completed twenty-one years of life on 28th November 1951 but, of course, it is not possible to say at what time by the clock on that day he did so. A day is not in law divisible and a person is deemed in law for the purpose of computing his age to have lived through the whole of the first day of his life. He would thus have been deemed to have attained full age with the expiration of the day preceding the twenty-first anniversary of his birth were it not for an ancient though artificial rule treating him as of full age throughout the whole of the day preceding that anniversary. As I understand the rule of law applicable to the matter a person is deemed to have become of full age coincidentally with the passing of midnight. In this case that point of time was when the date changed from 26th November 1951 to 27th November 1951. Then his status of infancy ceased and consequently at the earliest point of time included in the day indicated on the calendar by 27th November 1951 the appellant was sui juris. It follows that in computing time for the period of the statute the whole of 27th November 1951 must be included. The result is that the appellant issued the writ six years and a day after coming to full age; the writ was issued on 27th November 1957. The appeal should be dismissed.

42 At 274-5 Kitto J concluded that:

Accordingly, as it seems to me, the proposition to be accepted as positive law is that full age is attained as the day before the twenty-first birthday begins. If so, the whole of the day is after the coming to or being of full age - just as the whole of a piece of land with a western boundary is east of that boundary. In my opinion the correct view in the present case is that the disability of infancy fell from the appellant at the midnight which was at once the end of 26th November and the beginning of 27th November 1951, and that consequently the whole of 27th November 1951 was after the appellant's coming to or being of full age and must be counted in calculating the statutory six years.

43 In separate reasons Windeyer J came to the same conclusion.

44 The decision in Prowse has been applied on numerous occasions. For example, in State of New South Wales v Nikua (Final) [2021] NSWSC 1240, when referring to the date of expiration of an interim supervision order (ISO), Dhanji J said at [7]:

At the hearing, I was informed the ISO would expire on 2 October 2021. The most recent extension of the order was made on 27 August. That order renewed the ISO for a period of 28 days from midnight on 3 September. Midnight, is commonly (though not necessarily correctly) referred to as 12am. It divides one day from the next, and is, as a point without dimension, not part of either day (see Prowse v McIntyre (1961) 111 CLR 264 at 274, 278). In 24 hour time the point in time could be expressed as 24:00 on one day or as 0:00 on the next. But, the usual reference to 12am as midnight and 12pm as noon is more consistent with midnight being the first moment of the new day. A period of one day commencing from midnight on 3 September, on this basis, is all of 3 September up until the moment before 12 am on 4 September (cf. Interpretation Act 1987 (NSW), s 36(1); Acts Interpretation Act 1901 (Cth), s 36(1)). On this basis, I calculate a 28-day period from midnight on 3 September as concluding at the last moment of 30 September.

45 In State of New South Wales v Bou-Antoun [2022] NSWSC 513 Dhanji J considered whether to impose an ISO. At [84] his Honour relevantly said:

An ISO should be imposed. The conditions I regard as appropriate in all the circumstances of this case, based on the above reasons, are those set out in the Schedule to this judgment. It is not appropriate to order that the ISO commence from “midnight on 1 May 2022” as sought in the summons: see State of New South Wales v Nikua (Final) [2021] NSWSC 1240 at [7]. The defendant’s sentence expires on 1 May 2022. He remains subject to the sentence for the entirety of 1 May. I apprehend what is sought is an order that commences at the conclusion of 1 May. The conclusion of 1 May is the commencement of 2 May. An order that commences on 2 May is temporally contiguous with the expiry of the defendant’s sentence on 1 May. It is therefore sufficient to impose the order such that it commences on 2 May 2022.

46 Having regard to the terms of s 149(4) of the Bankruptcy Act, in my view Ms Soong was discharged from her bankruptcy on 19 June 2015. That is for the following reasons:

(1) as the parties accept, when calculating the three year period from the date on which Ms Soong filed her statement of affairs, the date of filing, 18 June 2012, is not included: see s 36(1) and item 5 of s 36(1) the Acts Interpretation Act;

(2) excluding the remaining hours of the date of filing of the statement of affairs and thus commencing the calculation from 19 June 2012, the period of three calendar years (with 365 days in each year), ends on 18 June 2015;

(3) the bankrupt, Ms Soong, was discharged from bankruptcy at the end of that period. That is at the end of 18 June 2015; and

(4) it follows that Ms Soong was a bankrupt for the whole of 18 June 2015 and her discharge became effective at the first moment on 19 June 2015.

47 Contrary to Ms Soong’s submission, she was not discharged at the first moment of 18 June 2015. She was discharged at the end or conclusion of 18 June 2015 which was the very first moment of 19 June 2015. That is because although the period of three years ended on 18 June 2015, s 149(4) of the Bankruptcy Act provides that the bankrupt is discharged at the end of the period of three years. The end of the period must be the end of the day that is calculated to be three years from the date of filing of the statement of affairs by the bankrupt. That is, the bankruptcy continues for the whole of that day and the bankrupt is discharged at the end of that day i.e. at midnight, which is also the commencement of the following day. In Ms Soong’s case that was 19 June 2015.

48 That is the same conclusion that the primary judge reached, albeit, it seems, by a different reasoning process, and is the date shown as Ms Soong’s date of discharge from bankruptcy on the search of the National Personal Insolvency Index extracted on 16 May 2022 that was in evidence before me.

49 Thus, proposed grounds 1 and 2 of the draft NOA are not made out.

Proposed grounds 3 and 4

50 Proposed grounds 3 and 4 of the draft NOA concern the application of s 129AA(3)(a) of the Bankruptcy Act. Ms Soong contends that the primary judge erroneously found that s 129AA(3)(a) of the Bankruptcy Act operated to specify 19 June 2021 as “the current revesting time of Ms Soong’s interest in the [Concord] Property”.

51 Ms Soong submits that it appears that the primary judge’s analysis of s 129AA is based partially on the view that there was no contrary intention manifested for the purposes of s 2(2) of the Acts Interpretation Act that item 5 of s 36(1) of that Act does not apply to it. Ms Soong contends that his Honour’s conclusion was erroneous because of the presence of the words “beginning of the day that [is] the sixth anniversary on which the bankrupt was discharged from bankruptcy”.

52 Ms Soong submits that, in addition, the primary judges’ reasoning and finding at J [29] is incorrect because his Honour placed no weight on the presence of the words “beginning of the day” and “sixth anniversary” in interpreting s 129AA(3)(a) of the Bankruptcy Act. She contends that those words inform the interpretation of the section and cannot be disregarded.

53 Ms Soong submits the primary judge erred in failing to correctly construe s 129AA(3)(a) of the Bankruptcy Act by not finding that the initial revesting time for property disclosed in Ms Soong’s statement of affairs was the beginning of the day that is the sixth anniversary of the day on which she was discharged from bankruptcy.

54 The Trustee submits that for the purposes of s 129AA(3)(a) of the Bankruptcy Act the starting point is to identify “the day on which the bankrupt is discharged” and for Ms Soong that date was 19 June 2015. He contends that consequently the “sixth anniversary” of the date must have been 19 June 2021. The Trustee observed that save for the fact that Ms Soong starts counting the six year period from the earlier and wrong date of 18 June 2021, she accepts that if the date of discharge was 19 June 2015 then the sixth anniversary must have been 19 June 2021.

55 As Ms Soong accepts, she filed her statement of affairs on 18 June 2012, three years after the filing of the statement of affairs commenced at the beginning of 19 June 2012 and she was discharged from bankruptcy at the end of 18 June 2015. However, as set out above, the end of 18 June 2015, midnight, is also the beginning of 19 June 2015. As the discharge took effect from the end of that three year period, it was operative and Ms Soong was discharged from the first moment of 19 June 2015.

56 The time prescribed for the purposes of s 129AA(3)(a) of the Bankruptcy Act is the beginning of the day that is the sixth anniversary of the day on which Ms Soong was discharged. That is, the initial revesting time for the Concord Property was the beginning (the very first moment) of 19 March 2021. That was the conclusion to which the primary judge came.

57 It follows that proposed grounds 3 and 4 cannot succeed.

Proposed ground 9

58 Proposed ground 9 concerns the Extension Notice (as do proposed grounds 5 to 11 inclusive). Ms Soong contends that the primary judge erred in finding that the Extension Notice was valid.

59 Section 129AA(6)(a) provides that the time specified in an extension notice must, relevantly, be a specified time that is not more than three years after the current revesting time.

60 At the time the Extension Notice was served, the current revesting time was 19 June 2021. The Extension Notice specified an extended revesting time of 19 June 2024 for Ms Soong’s interest in the Concord Property, which is not more than three years after what was, at the time of service of the Extension Notice, the “current revesting time”.

61 As the primary judge found to be the case, the Extension Notice is valid. Proposed ground 9 (and the associated grounds 5 to 11 inclusive) cannot succeed.

CONCLUSION

62 For these reasons Ms Soong’s application for leave to appeal should be dismissed. As she has been unsuccessful Ms Soong should pay the Trustee’s costs of the application for leave to appeal.

63 I will make orders accordingly.

I certify that the preceding sixty-three (63) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice Markovic. |

Associate: