FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Electoral Commissioner v McQuestin [2024] FCA 287

ORDERS

Applicant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT DECLARES THAT:

1. On 12 May 2022, the respondent contravened s 321D(5) of the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 (Cth) (Electoral Act) by failing to ensure that the following particulars as required by item 2 of the table in s 321D(5) of the Electoral Act:

(a) the registered name of the Liberal Party of Australia (Victoria Division);

(b) the relevant town or city of the entity, being Melbourne; and

(c) the name of the respondent, as the natural person responsible for giving effect to the authorisation,

(together, authorisation particulars), as notified in an electoral advertisement that was published in the Geelong Advertiser on 14 May 2022, were:

(d) reasonably prominent;

(e) legible at a distance at which the advertisement was intended to be read; and

(f) in a text that contrasted with the background on which the text appeared,

as required by ss 11(3)(a), (b) and (d) of the Commonwealth Electoral (Authorisation of Voter Communication) Determination 2021 (Cth) (Authorisation Determination) and s 321D(7) of the Electoral Act.

2. On 18 May 2022, the respondent contravened s 321D(5) of the Electoral Act by failing to ensure that the authorisation particulars, as notified in an electoral advertisement that was published in the Geelong Advertiser on 19 May 2022,were:

(a) reasonably prominent;

(b) legible at a distance at which the communication was intended to be read; and

(c) in a text that contrasted with the background on which the text appeared,

as required by ss 11(3)(a), (b) and (d) of the Authorisation Determination and s 321D(7) of the Electoral Act.

3. On 19 May 2022, the respondent contravened s 321D(5) of the Electoral Act by failing to ensure that the authorisation particulars, as notified in an electoral advertisement that was published in the Geelong Advertiser on 20 and 21 May 2022, were:

(a) reasonably prominent;

(b) legible at a distance at which the communication was intended to be read; and

(c) in a text that contrasted with the background on which the text appeared,

as required by ss 11(3)(a), (b) and (d) of the Authorisation Determination and s 321D(7) of the Electoral Act.

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

4. The respondent pay to the Commonwealth of Australia the following pecuniary penalties:

(a) a penalty of $10,000 in respect of the contravention of s 321D(5) of the Electoral Act referred to in paragraph 1 above;

(b) a penalty of $15,000 in respect of the contravention of s 321D(5) of the Electoral Act referred to in paragraph 2 above; and

(c) a penalty of $15,000 in respect of the contravention of s 321D(5) of the Electoral Act referred to in paragraph 3 above,

being an aggregate penalty of $40,000.

5. Subject to paragraph 6, the respondent pay the applicant’s costs of the proceeding.

6. Within 14 days of the date of this order, either party may apply to vary the order in paragraph 5 by filing and serving a submission of no more than 2 pages and, if required, any evidence in support.

7. If a party files and serves a submission pursuant to paragraph 6, within a further 14 days the other party may file and serve a submission in response of no more than 2 pages and, if required, any evidence in support.

8. Any application to vary the order in paragraph 5 will be determined on the papers.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

O’BRYAN J

Introduction

1 This proceeding concerns three electoral advertisements authorised by the Victorian Division of the Liberal Party of Australia for publication in the Geelong Advertiser newspaper on 14, 19, 20 and 21 May 2022 (the contravening advertisements). The 2022 federal election was held on Saturday 21 May 2022. Hence, the contravening advertisements were published in the days leading up to, and on the day of, the 2022 federal election.

2 The conduct of federal elections is regulated by the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 (Cth) (Electoral Act). Part XXA of the Electoral Act relates to the authorisation of “electoral matter” which is matter communicated or intended to be communicated for the dominant purpose of influencing the way electors vote in a federal election. Within that Part, s 321D stipulates that, in certain circumstances, electoral advertisements must contain specified “particulars” which comprise a statement of the person or entity who approved the content of the advertisement. Where the person or entity who approved the advertisement is a registered political party, the required particulars are the name of the party, the town or city in which it is located, and the name of the individual responsible for giving effect to the authorisation (that is, the individual who approved the advertisement on behalf of the political party). Relevantly, the particulars must be reasonably prominent, be legible at a distance at which the advertisement is intended to be read and be in a text that contrasts with the background on which the text appears.

3 By an originating application dated 15 February 2023, the Electoral Commissioner seeks relief against Charles McQuestin, alleging that he contravened s 321D(5) by failing to ensure that the contravening advertisements appearing in physical copies of the Geelong Advertiser complied with the requirements of that section. At the time of the advertisements, Mr McQuestin was the State Director of the Victorian Division of the Liberal Party and the person responsible for authorising the contravening advertisements. As discussed below, in circumstances where the Victorian Division of the Liberal Party is an unincorporated body, the Electoral Act attributes liability to Mr McQuestin as an officer of the Liberal Party acting in his actual authority.

4 There is no dispute between the parties as to the relevant facts and circumstances and Mr McQuestin admits that, with respect to each of the contravening advertisements, he contravened s 321D(5) of the Electoral Act by failing to ensure that those advertisements notified the relevant particulars in the form required.

5 The parties are agreed that it is appropriate for the Court to make declarations concerning the admitted contraventions of the Electoral Act. The parties are in dispute with respect to the imposition of pecuniary penalties. The Electoral Commissioner seeks a penalty within the range of $100,000 to $150,000. Mr McQuestin contended that, in the circumstances of this case, a pecuniary penalty should not be imposed. With respect to the amount of the pecuniary penalty sought by the Electoral Commissioner, the parties are in dispute as to the number of contraventions of the Electoral Act that have occurred. The Electoral Commissioner contended that a contravention occurred on each occasion that a physical copy of the newspaper containing a contravening advertisement was published and distributed, which equates to tens of thousands of contraventions. Mr McQuestin contended that a contravention occurred on each occasion that he authorised the publication of a contravening advertisement, which occurred either three or four times.

6 For the reasons set out below, I will make declarations that Mr McQuestin contravened s 321D(5) of the Electoral Act on three occasions, and order that he pay a total pecuniary penalty of $40,000.

Relevant Statutory Provisions

Legislative requirements for electoral matter

7 Part XXA of the Electoral Act is titled “Authorisation of electoral matter”. The objects are set out in s 321C, as follows:

321C Objects of this Part

(1) The objects of this Part are to promote free and informed voting at elections by enhancing the following:

(a) the transparency of the electoral system, by allowing voters to know who is communicating electoral matter;

(b) the accountability of those persons participating in public debate relating to electoral matter, by making those persons responsible for their communications;

(c) the traceability of communications of electoral matter, by ensuring that obligations imposed by this Part in relation to those communications can be enforced;

(d) the integrity of the electoral system, by ensuring that only those with a legitimate connection to Australia are able to influence Australian elections.

(2) This Part aims to achieve these objects by doing the following:

(a) requiring the particulars of the person who authorised the communication of electoral matter to be notified if:

(i) the matter is an electoral advertisement, all or part of whose distribution or production is paid for; or

(ii) the matter forms part of a specified printed communication; or

(iii) the matter is communicated by, or on behalf of, a disclosure entity;

(b) ensuring that the particulars are clearly identifiable, irrespective of how the matter is communicated;

(c) restricting the communication of electoral matter authorised by foreign campaigners.

(3) This Part is not intended to detract from:

(a) the ability of Australians to communicate electoral matters to voters; and

(b) voters’ ability to communicate with each other on electoral matters.

8 This proceeding concerns s 321D, which relevantly provides as follows:

321D Authorisation of certain electoral matter

(1) This section applies in relation to electoral matter that is communicated to a person if:

(a) all of the following apply:

(i) the matter is an electoral advertisement;

(ii) all or part of the distribution or production of the advertisement was paid for;

(iii) the content of the advertisement was approved by a person (the notifying entity) (whether or not that person is a person who paid for the distribution or production of the advertisement); …

…

Notifying particulars

(5) the notifying entity must ensure that the particulars set out in the following table, and any other particulars determined under subsection (7) for the purposes of this subsection, are notified in accordance with any requirements determined under that subsection.

Required particulars | ||

Item | If … | the following particulars are required … |

… | ||

2 | the communication is any other communication authorised by a disclosure entity that is not a natural person | (a) the particulars of the name of the entity required by subsection (5A); (b) the relevant town or city of the entity; (c) the name of the natural person responsible for giving effect to the authorisation |

Note 1: This provision is a civil penalty provision which is enforceable under the Regulatory Powers Act (see section 384A of this Act).

Note 2: A person may contravene this subsection if the person fails to ensure that particulars are notified or if the particulars notified are incorrect.

Note 3: For the application of this provision to a notifying entity that is not a legal person, see subsection (6).

Civil penalty: 120 penalty units.

(5A) For the purposes of items 1 and 2 of the table in subsection (5), the required particulars of the name of the entity are:

(a) if the entity is a registered political party—the name of the party (the registered name) that is entered in the Register of Political Parties …

…

Application of civil penalty to entities that are not legal persons

(6) For the purposes of this Act and the Regulatory Powers Act, a contravention of subsection (5) that would otherwise have been committed by a notifying entity that is not a legal person is taken to have been committed by each member, agent or officer (however described) of the entity who, acting in his or her actual or apparent authority, engaged in the conduct or made the omission constituting the contravention.

Legislative instrument

(7) The Electoral Commissioner may, by legislative instrument, determine:

…

(b) requirements or particulars for the purposes of any one or more of the following:

(i) subsection (5) of this section;

…

9 Item 2 of the table to s 321D(5) refers to a “communication authorised by a disclosure entity that is not a natural person”. The expression “disclosure entity” is defined in s 321B to include a registered political party. The word “authorise” is defined in s 321B as follows:

a person authorises the communication of electoral matter if:

(a) if the content of the matter is approved before the matter is communicated—the person approves the content of the matter;

(b) otherwise—the person communicates the matter.

10 On 30 June 2021 and pursuant to s 321D(7) of the Electoral Act, the Electoral Commissioner made the Commonwealth Electoral (Authorisation of Voter Communication) Determination 2021 (Cth) (Authorisation Determination). Section 11 sets out requirements relating to notifying particulars for printed communications, for the purposes of s 321D(5) of the Electoral Act, relevantly as follows:

11 Requirements relating to notifying particulars for printed communications

(1) This section applies if the communication is a printed communication.

Where the particulars must be notified

(2) The particulars must be notified:

(a) if the communication is published in a journal—at the end of the communication (except in relation to the name of the printer who printed the communication and the address of that printer which may be notified at the end of the communication or elsewhere in the journal); or

(b) in any other case—at the end of the communication.

Formatting and placement of particulars

(3) The particulars must:

(a) be reasonably prominent; and

(b) be legible at a distance at which the communication is intended to be read; and

(c) not be placed over complex pictorial or multicoloured backgrounds; and

(d) be in a text that contrasts with the background on which the text appears; and

(e) be printed in a way that cannot be removed or erased under normal conditions or use; and

(f) be printed in a way that the particulars will not fade, run or rub off.

Imposition of civil penalties for contraventions of s 321D

11 Part 4 of the Regulatory Powers (Standard Provisions) Act 2014 (Cth) (Regulatory Powers Act) creates a framework for the use of civil penalties to enforce civil penalty provisions. The Part operates if a civil penalty provision is made enforceable under the Part.

12 Section 384A of the Electoral Act is headed “Application of Regulatory Powers Act”. It relevantly provides that each civil penalty provision of the Electoral Act is enforceable under Part 4 of the Regulatory Powers Act and that the Electoral Commissioner is an authorised applicant for the purposes of Part 4 of the Regulatory Powers Act. As can be seen above, the note to s 321D(5) of the Electoral Act stipulates that it is a civil penalty provision which is enforceable under the Regulatory Powers Act. Also, s 321D(6) states that, for the purposes of the Electoral Act and the Regulatory Powers Act, a contravention of subsection (5) that would otherwise have been committed by a notifying entity that is not a legal person is taken to have been committed by each member, agent or officer (however described) of the entity who, acting in his or her actual or apparent authority, engaged in the conduct or made the omission constituting the contravention. In this proceeding, it is common ground that the Liberal Party is an unincorporated body (and is therefore not a legal person) and that Mr McQuestin was the officer of the Liberal Party who authorised the communication of the contravening advertisements.

13 Division 2 of Part 4 of the Regulatory Powers Act empowers an “authorised applicant” (here, the Electoral Commissioner) to seek the imposition of a pecuniary penalty in respect of a contravention of a civil penalty provision. Section 82 relevantly provides as follows:

82 Civil penalty orders

Application for order

(1) An authorised applicant may apply to a relevant court for an order that a person, who is alleged to have contravened a civil penalty provision, pay the Commonwealth a pecuniary penalty.

(2) The authorised applicant must make the application within 6 years of the alleged contravention.

Court may order person to pay pecuniary penalty

(3) If the relevant court is satisfied that the person has contravened the civil penalty provision, the court may order the person to pay to the Commonwealth such pecuniary penalty for the contravention as the court determines to be appropriate.

Note: Subsection (5) sets out the maximum penalty that the court may order the person to pay.

(4) An order under subsection (3) is a civil penalty order.

Determining pecuniary penalty

(5) The pecuniary penalty must not be more than:

(a) if the person is a body corporate—5 times the pecuniary penalty specified for the civil penalty provision; and

(b) otherwise—the pecuniary penalty specified for the civil penalty provision.

(6) In determining the pecuniary penalty, the court must take into account all relevant matters, including:

(a) the nature and extent of the contravention; and

(b) the nature and extent of any loss or damage suffered because of the contravention; and

(c) the circumstances in which the contravention took place; and

(d) whether the person has previously been found by a court (including a court in a foreign country) to have engaged in any similar conduct.

85 Multiple contraventions

(1) A relevant court may make a single civil penalty order against a person for multiple contraventions of a civil penalty provision if proceedings for the contraventions are founded on the same facts, or if the contraventions form, or are part of, a series of contraventions of the same or a similar character.

Note: For continuing contraventions of civil penalty provisions, see section 93.

(2) However, the penalty must not exceed the sum of the maximum penalties that could be ordered if a separate penalty were ordered for each of the contraventions.

14 The combined effect of s 321D(5) of the Electoral Act and s 82(5) of the Regulatory Powers Act is that the maximum penalty for a contravention of s 321D(5) by an individual is 120 penalty units. At the time of the alleged contraventions, the value of one penalty unit was $222, equating to a maximum penalty of $26,640 per contravention.

Factual findings

15 The evidence adduced at the hearing comprised the following:

(a) an affidavit of Phoebe Annabelle Port, a lawyer at the Australian Government Solicitor, affirmed 6 July 2023;

(b) an affidavit of Abigail Caitlin Cooper, a lawyer at the Australian Government Solicitor, affirmed 31 July 2023;

(c) a joint statement of agreed facts dated 20 December 2023;

(d) a bundle of documents referred to in the SOAF; and

(e) a copy of a document titled “News Corp Australia Print Specifications”, produced on subpoena by News Corp Australia.

Statement of agreed facts

16 The parties reached an agreement for the purposes of s 191 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) with respect to most of the relevant facts and circumstances. It is convenient to reproduce the statement of agreed facts in full:

A. PARTIES AND BACKGROUND

1. The applicant is the Electoral Commissioner (Commissioner) of the Australian Electoral Commission (AEC).

2. The respondent is Charles David McQuestin. Between 18 November 2019 and 31 January 2023, Mr McQuestin was the State Director of the Victorian Division of the Liberal Party of Australia (Liberal Party Vic). From 12 February 2021 to 27 February 2023 he was also the Registered Officer of the Liberal Party Vic.

3. The Liberal Party Vic was, at all material times:

a. A political party registered under Part XI of the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 (Cth) (Act); and

b. A disclosure entity within the meaning of s 321B of the Act; and

c. The notifying entity for the purpose of s 321D(5) of the Act.

4. Writs were issued for the 2022 federal election on 11 April 2022 and election day was on 21 May 2022.

5. During the 2022 federal election campaign the Liberal Party Vic authorised electoral advertisements to be published throughout metropolitan and regional Victoria on various media formats including (but not limited to):

5.1. Print media;

5.2. Radio;

5.3. Television;

5.4. Corflutes;

5.5. Online;

5.6. Leaflets and how to vote cards; and

5.7. Social media.

6. For the 1 July 2021 to 30 June 2022 financial year, the Liberal Party Vic declared the following in its annual return provided to the AEC in accordance with Part XX of the Act (document 41, Applicant’s List of Documents):

a. total receipts: $21,094,525

b. total payments: $24,381,933.

B. THE ADVERTISEMENTS

Geelong Advertiser

7. The Geelong Advertiser is a Victorian newspaper, published by The Herald & Weekly Times Pty Ltd, which forms part of News Corp Australia.

8. The Geelong Advertiser is published in a daily edition, with each edition being published in two mediums:

a. A hardcopy print edition; and

b. A digital print edition (which is a digital duplicate of the hardcopy print edition).

9. In the lead up to the 2022 federal election, the Liberal Party Vic placed advertisements in the Geelong Advertiser, including in editions published on 14, 19, 20 and 21 May 2022.

10. The Commissioner sues upon a total of three different forms of advertisements which were published on those four dates.

11. The Geelong Advertiser is distributed for retail sale at supermarkets, convenience stores and petrol stations in the City of Geelong, along the surf coast as far as Port Fairy and in some western suburbs of the City of Melbourne. It is also delivered to subscribers at their homes and to hotels.

12. The Geelong Advertiser has a website which publishes the digital edition of its daily newspaper.

13. The distribution of hardcopy print editions of the Geelong Advertiser on the relevant dates was as follows (documents 42 and 43, Applicant’s List of Documents):

a. on 14 May 2022, 15,634 copies of the Geelong Advertiser were distributed for retail sale, 5,607 were delivered to subscribers and 266 were delivered to hotels;

b. on 19 May 2022, 7,006 copies of the Geelong Advertiser were distributed for retail sale, 3,858 were delivered to subscribers and 269 were delivered to hotels;

c. on 20 May 2022, 6,341 copies of the Geelong Advertiser were distributed for retail sale, 3,853 were delivered to subscribers and 273 were delivered to hotels; and

d. on 21 May 2022, 15,774 copies of the Geelong Advertiser were distributed for retail sale, 5,583 were delivered to subscribers and 266 were delivered to hotels.

Contravening Advertisements

14. The three advertisements were each electoral advertisements, being electoral matter, paid for by the Liberal Party Vic, the content of which was approved by Mr McQuestin on behalf of the Liberal Party Vic for the purpose of s 321D(1)(a) of the Act.

15. The three advertisements were each provided to the Geelong Advertiser by uploading a digital version of the advertisement onto an online “AdDrop” system which coordinates advertisements for the Geelong Advertiser.

16. Item 2 of s 321D(5) of the Act applied to the advertisements and required the Liberal Party Vic to ensure that the particulars in the table in that subsection and the particulars determined under s 321D(7) were notified in accordance with the requirements determined under s 321D(7). Those particulars were the name of the registered political party (in accordance with s 321D(5A)), the name of the town or city of the entity and the name of the natural person responsible for giving effect to the authorisation, being Mr McQuestin (authorisation particulars).

17. Pursuant to s 321D(7) and s 11(3) of Commonwealth Electoral (Authorisation of Voter Communication) Determination 2021 (Cth) (Authorisation Determination), the authorisation particulars were required to be, relevantly, reasonably prominent, legible at a distance at which the communication was intended to be read, and in text that contrasts with the background on which the text appears.

(a) First Asher Advertisement

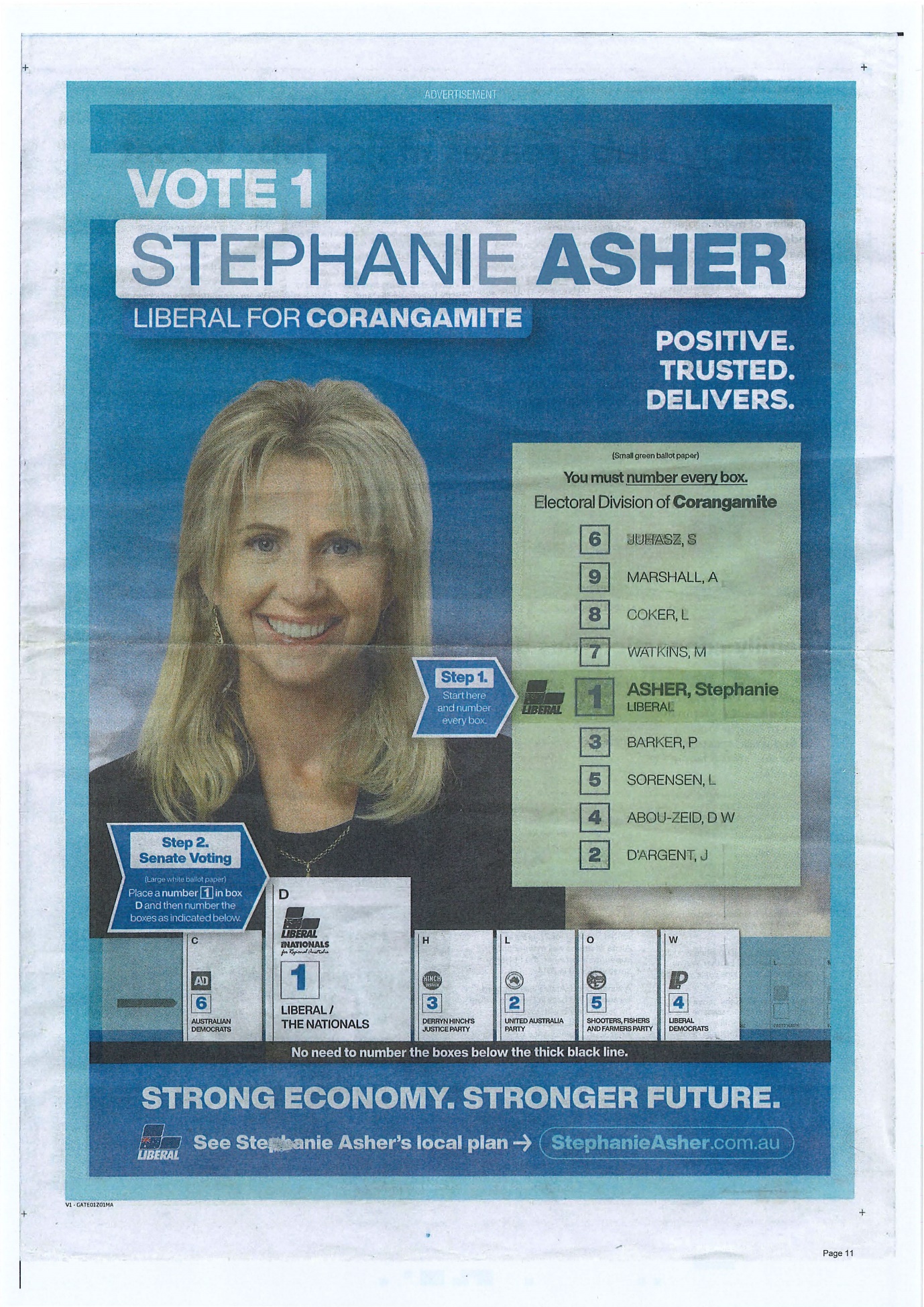

18. On 14 May 2022, the Geelong Advertiser published an advertisement, provided by the Liberal Party Vic on 12 May 2022, which supported Stephanie Asher, the Liberal Party Vic’s candidate in the electoral division of Corangamite (First Asher Advertisement).

19. The advertisement was submitted to the Geelong Advertiser by providing a digital version (document 7, Applicant’s List of Documents).

20. The authorisation particulars were not legible at a distance at which the communication was intended to be read on the First Asher Advertisement published in the hardcopy print edition of the Geelong Advertiser dated 14 May 2022 (document 8A, Applicant’s List of Documents, page 16).

21. The Liberal Party Vic failed to ensure that the particulars in the hardcopy print edition of the First Asher Advertisement were legible at a distance at which the communication was intended to be read.

22. Mr McQuestin, acting in his actual or apparent authority as an officer of the Liberal Party Vic, engaged in the conduct or made the omission which constituted the failure referred to in the paragraph above.

(b) Anti-Coker Advertisement

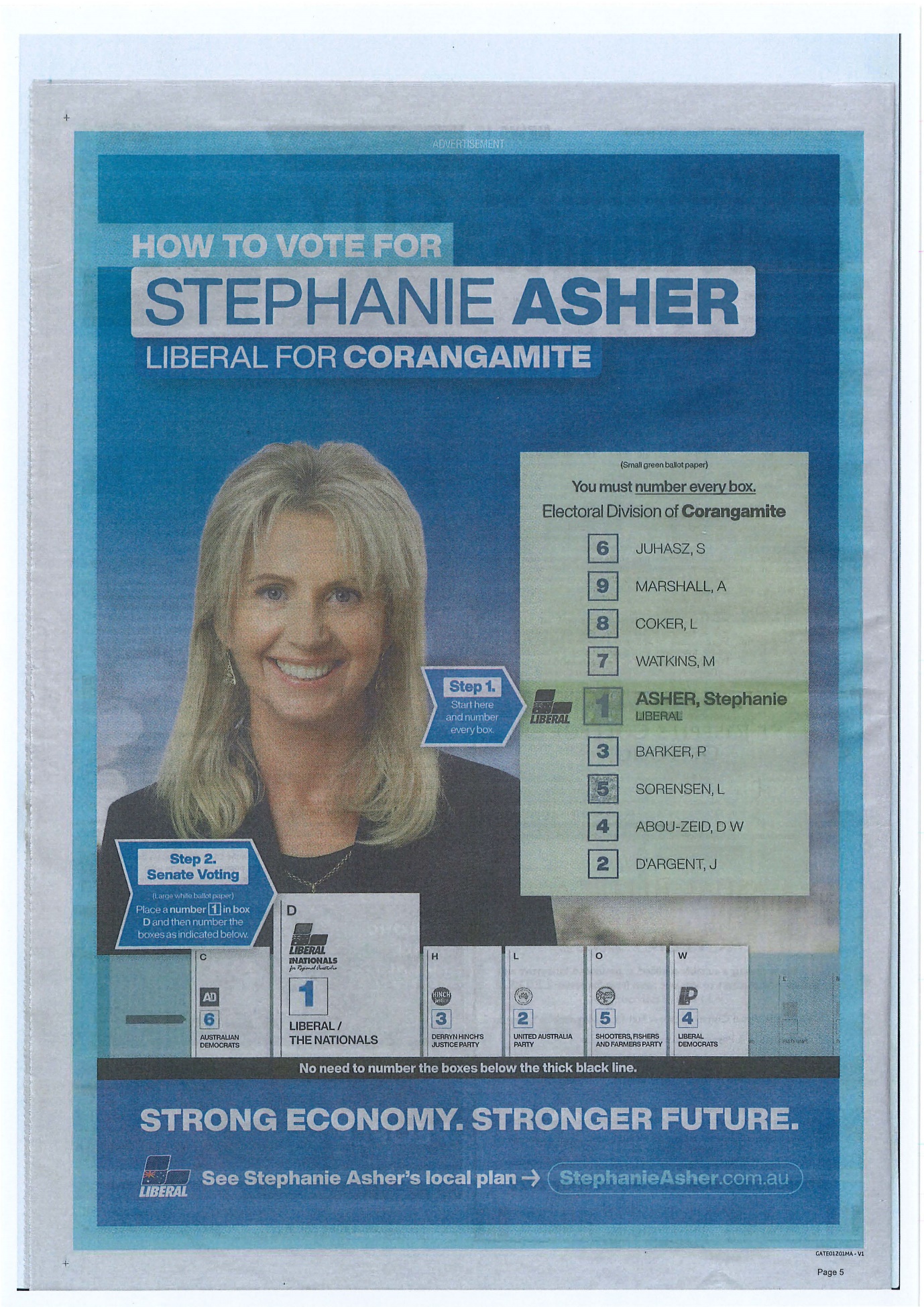

23. On 19 May 2022, the Geelong Advertiser published an advertisement, provided by the Liberal Party Vic on 18 May 2022, which opposed Libby Coker, the Australian Labor Party candidate and sitting member in the electoral division of Corangamite (Anti-Coker Advertisement).

24. The advertisement was submitted to the Geelong Advertiser by providing a digital version (document 21 in the Applicant’s List of Documents).

25. Mr McQuestin approved the content of the Anti-Coker Advertisement by responding to a message he received on Whatsapp on 18 May 2022 (document 13 in the Applicant’s List of Documents).

26. The authorisation particulars were not legible at a distance at which the communication was intended to be read on the Anti-Coker Advertisement published in the hardcopy print edition of the Geelong Advertiser dated 19 May 2022 (document 22A in the Applicant’s List of Documents, page 22).

27. The Liberal Party Vic failed to ensure that the particulars in the hardcopy print edition of the Anti-Coker Advertisement were legible at a distance at which the communication was intended to be read.

28. Mr McQuestin, acting in his actual or apparent authority as an officer of the Liberal Party Vic, engaged in the conduct or made the omission which constituted the failure referred to in the paragraph above.

(c) Second Asher Advertisement

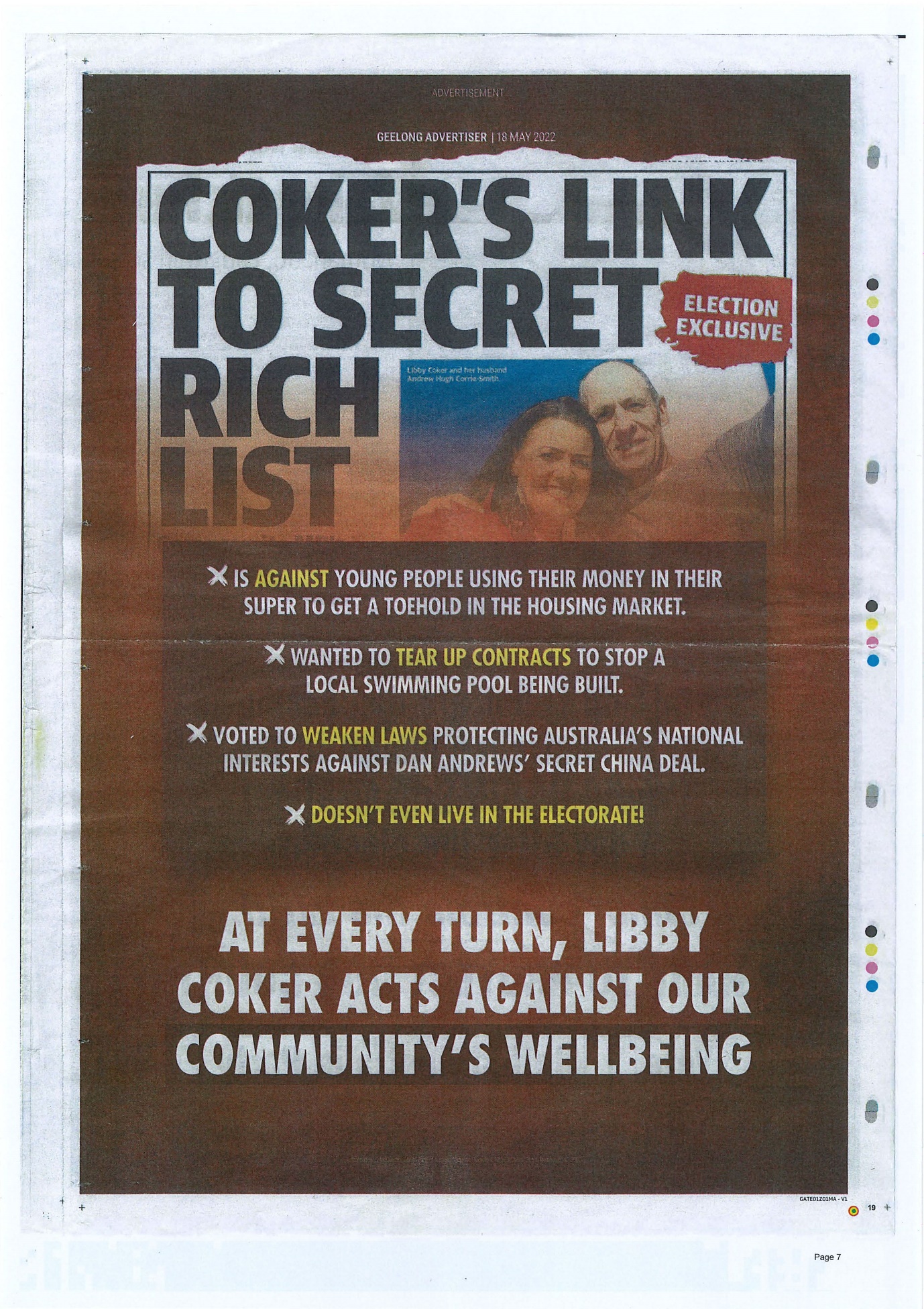

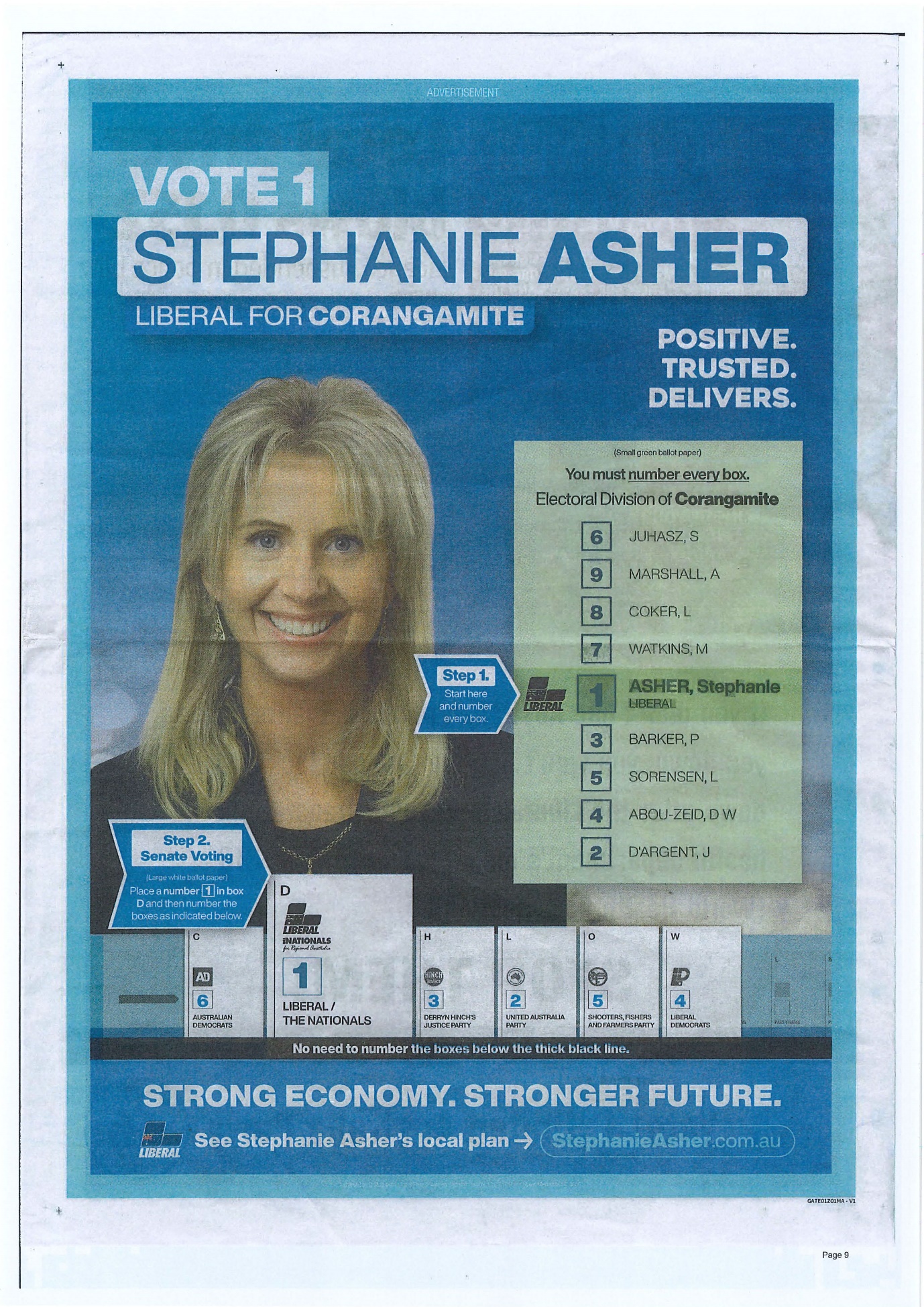

29. On 20 and 21 May 2022, the Geelong Advertiser published a further advertisement, provided by the Liberal Party Vic on 19 May 2022, in support of Ms Asher (Second Asher Advertisement).

30. The advertisement was submitted to the Geelong Advertiser by providing a digital version (document 25 in the Applicant’s List of Documents).

31. The authorisation particulars were not legible at a distance at which the communication was intended to be read on the Second Asher Advertisement published in:

31.1. the hardcopy print edition of the Geelong Advertiser dated 20 May 2022 (document 26A in the Applicant’s List of Documents, page 20); and

31.2. the hardcopy print edition of the Geelong Advertiser dated 21 May 2022 (document 30A in the Applicant’s List of Documents, page 19).

32. The Liberal Party Vic failed to ensure that the particulars in the hardcopy print editions on 20 and 21 May 2022 of the Second Asher Advertisement were legible at a distance at which the communication was intended to be read.

33. Mr McQuestin, acting in his actual or apparent authority as an officer of the Liberal Party Vic, engaged in the conduct or made the omission which constituted the failure referred to in the paragraph above.

Complaints Received by the AEC

34. The AEC did not receive any complaints specific to the First Asher Advertisement.

35. Between 19 and 20 May 2022, the AEC received three complaints specific to the Anti-Coker Advertisement (documents 44, 45 and 46 in the Applicant’s List of Documents).

36. On 12 June 2022, the AEC received one complaint specific to the Second Asher Advertisement (document 47 in the Applicant’s List of Documents).

37. Neither the Respondent nor the Liberal Party Vic was copied into any of the four complaints received by the AEC. Further, prior to the close of the polls for the federal election, the AEC did not forward or otherwise notify the Respondent or the Liberal Party Vic of any complaints in respect of the First Asher Advertisement, the Anti-Coker Advertisement, or the Second Asher Advertisement.

Communication with the Liberal Party Vic regarding the contravening advertisements

38. On 7 July 2022, the AEC served a notice under s 321F of the Act on Brad Stansfield of Font PR (Mr Stansfield was engaged by the Liberal Party Vic during the 2022 federal election campaign), requiring information in relation to electoral advertisements provided to the Geelong Advertiser in May 2022. A response to that notice was given by the Liberal Party Vic on 19 July 2022.

39. There was further correspondence regarding the notice between the AEC and the Director, Legal & Compliance of the Liberal Party Vic from 22 July – 2 August 2022.

40. The AEC did not otherwise communicate directly with Mr McQuestin or the Liberal Party Vic in respect of any issue with any of the three advertisements prior to the commencement of proceedings in February 2023.

C. MATTERS RELEVANT TO PENALTY

41. The Liberal Party Vic is not a legal person. A contravention of s 321D(5) that would otherwise have been committed by the Liberal Party Vic is taken to have been committed by Mr McQuestin being the officer of the entity who, acting in his actual or apparent authority, engaged in the conduct or made the omission constituting the contravention pursuant to s 321D(6) of the Act.

42. The Liberal Party Vic is a major political party that regularly engages in electoral campaigns and will likely participate in electoral campaigns in the future.

43. The amount charged by the Geelong Advertiser and paid by the Liberal Party Vic for publication of the four advertisements was $14,783.49 (documents 33 and 34 in the Applicant’s List of Documents).

44. During the 2022 federal election campaign, Mr McQuestin was aware of his obligations under the Act, including with respect to the authorisation of advertisements.

17 Copies of the First Asher Advertisement, Second Asher Advertisement and Anti-Coker Advertisement are set out in the Schedule to these reasons.

Phoebe Port

18 Ms Port’s affidavit includes as annexures scanned copies of the following:

(a) the First Asher Advertisement as it appeared in the Geelong Advertiser on 14 May 2022;

(b) the Anti-Coker Advertisement as it appeared in the Geelong Advertiser on 19 May 2022;

(c) the Second Asher Advertisement as it appeared in the Geelong Advertiser on 20 May 2022; and

(d) the Second Asher Advertisement as it appeared in the Geelong Advertiser on 21 May 2022.

(together, the contravening advertisements).

19 The relevant particulars on the contravening advertisements are in an extremely small font and nearly illegible. The particulars were not reasonably prominent, legible at a distance at which the communication was intended to be read or in a text that contrasted with the background on which the text appeared, as was required by ss 11(3)(a), (b) and (d) of the Authorisation Determination and thus s 321D(5) of the Electoral Act. Mr McQuestin does not dispute that conclusion.

Abigail Cooper

20 Ms Cooper’s affidavit includes as annexures scanned copies of various other, compliant, electoral advertisements appearing in the Geelong Advertiser on the same dates as the contravening advertisements.

Declaratory relief

21 The parties agree to the Court making declarations of contraventions in the following form:

1. On 14 May 2022 the Respondent contravened s 321D(5) of the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 (Cth) by not ensuring that the required particulars were notified on an advertisement published in the Geelong Advertiser promoting the Liberal Party of Australia candidate in the electoral division of Corangamite.

2. On 19 May 2022 the Respondent contravened s 321D(5) of the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 (Cth) by not ensuring that the required particulars were notified on an advertisement published in the Geelong Advertiser opposing the sitting member for Corangamite.

3. The Respondent contravened s 321D(5) of the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 (Cth) by not ensuring that the required particulars were notified on an advertisement published in the Geelong Advertiser on 20 and 21 May 2022 promoting the Liberal Party of Australia candidate in the electoral division of Corangamite.

22 As observed by the Full Court (Dowsett, Greenwood and Wigney JJ) in Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union (2017) 254 FCR 68 at [90], the fact that the parties have agreed that a declaration of contravention should be made does not relieve the Court of the obligation to satisfy itself that the making of the declaration is appropriate. However, the Full Court also stated (at [93]):

Declarations relating to contraventions of legislative provisions are likely to be appropriate where they serve to record the Court’s disapproval of the contravening conduct, vindicate the regulator’s claim that the respondent contravened the provisions, assist the regulator to carry out its duties, and deter other persons from contravening the provisions: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union [2006] FCA 1730; (2007) ATPR 42-140 at [6], and the cases there cited; Rural Press Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2003) 216 CLR 53 at [95].

23 I am satisfied that the Electoral Commissioner, as an authorised applicant for the purposes of the Regulatory Powers Act (under s 384A(2)(a) of the Electoral Act) and the person who made the Authorisation Determination, has a real interest in seeking declaratory relief. Declaratory relief serves to record the Court’s disapproval of the contravening conduct, vindicate the Electoral Commissioner’s claim that Mr McQuestin contravened the relevant statutory provisions and deters other persons from contravening those provisions. As the person declared to have contravened the law, Mr McQuestin has an interest in opposing the relief, notwithstanding his admissions and agreement: IMF (Australia) Ltd v Sons of Gwalia Ltd [2004] FCA 1390; (2004) 211 ALR 231 at [47] (French J); Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v MSY Technology Pty Ltd (2012) 201 FCR 378 at [30] (Greenwood, Logan and Yates JJ).

24 The Court is not bound by the form of the declarations proposed by the parties and must determine for itself whether the form is appropriate. As the High Court stated in Rural Press Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2003) 216 CLR 53 at [89] (Gummow, Hayne and Heydon JJ), a declaration that a person has contravened a statutory prohibition should indicate the gist of the findings that identify the contravention. Declarations must be “informative as to the basis on which the Court declares that a contravention has occurred” and “should contain appropriate and adequate particulars of how and why the impugned conduct is a contravention of the Act”: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v EnergyAustralia Pty Ltd [2015] FCA 274 at [83] (Gordon J). The declaration should accurately reflect the contravening conduct in a concise way: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Danoz Direct Pty Ltd [2003] FCA 881; (2003) 60 IPR 296 at [260] (Dowsett J).

25 I consider that the form of declarations proposed by the parties is not appropriate, primarily because it does not articulate any detail as to the lack of compliance with item 2 of the table in s 321D(5) of the Electoral Act or the requirements in s 11(3) of the Authorisation Determination. A more informative form of declarations is required to accurately reflect the contravening conduct. Declarations in a more descriptive form will be made.

Pecuniary penalty

Overview of the issues

26 The Electoral Commissioner seeks an aggregate pecuniary penalty in respect of the admitted contraventions of s 321D(5) of the Electoral Act by Mr McQuestin in the range of $100,000 to $150,000.

27 Although Mr McQuestin is personally liable for any pecuniary penalty imposed in this proceeding, he has disclosed to the Court that any penalty that is imposed upon him will be paid by the Liberal Party. That circumstance, which was properly disclosed by Mr McQuestin, is relevant to the quantum of penalty that may be required to be imposed in this case to achieve the principal goal of ensuring compliance with the requirements of the Electoral Act.

28 Mr McQuestin submitted that a pecuniary penalty is unnecessary in the circumstances of this case. He submitted that the making of declarations of contravention by the Court will have a significant adverse reputational impact and will be sufficient to deter future contraventions. Alternatively, Mr McQuestin submitted that a penalty of no more than $20,000 is appropriate.

29 I am not persuaded that declarations alone are sufficient to serve the objective of deterrence. As discussed below, the evidence indicates that the Liberal Party, under Mr McQuestin’s supervision, failed to have in place effective procedures to ensure compliance with s 321D(5) of the Electoral Act on every occasion that an electoral advertisement was authorised. That indicates a degree of carelessness with respect to compliance. In my view, it is necessary to impose a pecuniary penalty to deter such carelessness in the future.

30 The parties disagree as to the number of contraventions of s 321D(5) of the Electoral Act that occurred, and consequently the maximum penalty that may be imposed by the Court in respect of the contraventions. The Electoral Commissioner submitted that Mr McQuestin contravened s 321D(5) each time the contravening advertisements were communicated (that is, each time a physical copy of the Geelong Advertiser containing a contravening advertisement was read). The parties agree that the total distribution of the contravening advertisements in the Geelong Advertiser was over 64,000 copies, although the Electoral Commissioner submitted that it is not possible to identify the precise number of contraventions because more than one person may have viewed each distributed copy. Mr McQuestin submitted that a contravention occurred at the time he approved each contravening advertisement for publication, being the time at which he failed to ensure the inclusion of the requisite particulars. On that basis, Mr McQuestin submitted he contravened s 321D(5) on three occasions.

31 For the reasons discussed below, I accept Mr McQuestin’s submissions with respect to the number of contraventions that occurred in the present case. However, even if that conclusion were wrong, it would not alter my overall assessment of the penalty that ought to be imposed in this case. Applying the course of conduct and totality principles, I would have imposed the same penalty even if, as the Electoral Commissioner submitted, a contravention occurred on each occasion that a contravening advertisement was viewed.

General principles concerning the assessment of penalty

32 The legal principles that have been developed with respect to the imposition of civil penalties under Commonwealth statutes such as the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth), the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth) and the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) have general application to all similar Commonwealth statutory schemes including Part 4 of the Regulatory Powers Act. The principles are well known. In this case, it is only necessary to refer to three matters.

33 First, the primary objective of civil penalties is deterrence, both specific and general. The Court aims to fix a penalty that is sufficient, but no more than is necessary, to deter future contraventions of the relevant prohibition by the respondent and by others.

34 Second, where there is an interrelationship between the factual and legal matters of two or more contraventions, the Court will consider whether it is appropriate to group them together as a single course of conduct such that a “concurrent” or single penalty should be imposed for the contraventions. The purpose is to avoid double punishment in respect of what is effectively the same conduct.

35 Third, in determining the appropriate penalty for a large number of contraventions, the Court will seek to ensure that the cumulative total of the penalty is just and appropriate having regard to the contravening conduct as a whole.

36 Section 82(6) of the Regulatory Powers Act stipulates that, in determining the pecuniary penalty, the Court must take into account all relevant matters, including:

(a) the nature and extent of the contravention;

(b) the nature and extent of any loss or damage suffered because of the contravention;

(c) the circumstances in which the contravention took place; and

(d) whether the person has previously been found by a court (including a court in a foreign country) to have engaged in any similar conduct.

37 The following additional factors have been widely recognised in the cases as being relevant to the assessment of civil pecuniary penalties:

(a) the extent of any profit or benefit derived as a result of the contravention;

(b) the size and financial position of the contravening company; and

(c) whether the contravenor has shown a disposition to cooperate with the authorities responsible for the enforcement of the statute in relation to the contravention.

38 Differences in the facts and circumstances which underlie different cases mean there is usually little to be gained by comparing the penalties imposed in other cases where the facts differ. However, this does not mean that penalties imposed in other cases are never relevant. Comparable decisions may give the Court some broad guidance: Flight Centre Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (No 2) (2018) 260 FCR 68 at [69] (Allsop CJ, Davies and Wigney JJ).

The number of contraventions and the maximum penalty

39 By s 86(3) of the Regulatory Powers Act, the Court is empowered to impose a pecuniary penalty “for the contravention”. The penalty that may be imposed for each contravention cannot exceed the maximum specified by s 86(5) which, in this case, is $26,640 per contravention. It is therefore necessary to identify with precision the conduct that constitutes the contravention being penalised, both to assess the nature and seriousness of the contravening conduct and to determine the maximum penalty that is applicable to the contravening conduct.

The parties’ submissions

40 As noted earlier, the Electoral Commissioner submitted that Mr McQuestin contravened s 321D(5) each time the contravening advertisements were communicated (each time a physical copy of the Geelong Advertiser containing a contravening advertisement was read). The submission focusses upon s 321D(1) of the Act which states that the section “applies in relation to electoral matter that is communicated to a person”. The Electoral Commissioner argued that Parliament has applied s 321D only to “electoral matter” which is “communicated to a person” and approved by or communicated by or on behalf of a “notifying entity”. Parliament is concerned not with “electoral matter” per se, nor even a general “communication” of such matter; it is concerned with the concrete event of an actual communication of electoral matter to someone (“a person”) by someone (“a notifying entity”, or someone acting on its behalf). The Electoral Commissioner argued that, in this way, the statutory text makes clear that a contravention of s 321D(5) occurs in respect of each non-compliant “communication to a person”. That is, it operates by reference to the recipients of the communication.

41 The Electoral Commissioner submitted that its preferred construction of the section is consistent with the approach taken by the Court in respect of the statutory prohibitions against misleading and deceptive conduct. In such cases, the Court has concluded that a separate contravention of the prohibition occurs on each occasion that a person reads a misleading advertisement or statement: see for example Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Hillside (Australia New Media) Pty Ltd trading as Bet365 (No 2) [2016] FCA 698 at [16]-[17] (Beach J); Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Reckitt Benckiser (Australia) Pty Ltd [2016] FCAFC 181; (2016) 340 ALR 24 at [141] and [145] (Jagot, Yates and Bromwich JJ); Australian Securities and Investments Commission v La Trobe Financial Asset Management Ltd [2021] FCA 1417; (2021) 158 ACSR 363 at [81] (O’Bryan J).

42 Mr McQuestin submitted that s 321D(5) places upon the notifying entity (or the natural person acting with its authority) an obligation to “ensure” (that is, to make certain) that electoral matter that is communicated to a person or persons contains the required particulars. The provision is contravened where the notifying entity (or the natural person acting with its authority) fails to so ensure. Mr McQuestin argued that, while a necessary element of the contravention of s 321D(5) is that “electoral matter is communicated to a person” (as per s 321D(1)), the contravention arises by reason of the notifying entity (or the natural person acting with its authority) failing to ensure that the electoral matter contains the required particulars. Section 321D(5) is not framed as a prohibition of the communication of electoral matter which fails to contain the required particulars.

43 In that regard, Mr McQuestin relied on the recent decision of Rangiah J in Electoral Commissioner of the Australian Electoral Commission v Laming (No 2) [2023] FCA 917 (Laming). In that case, Andrew Laming, a candidate in the 2019 federal election, was found to have contravened s 321D(5) of the Electoral Act by communicating electoral matter through three posts on Facebook without ensuring that the necessary particulars were notified as required. The evidence demonstrated that the three contravening posts were viewed by at least 28 people. Justice Rangiah found that Mr Laming contravened s 321D(5) on three occasions, with the contravention occurring when the electoral matter was “posted” on Facebook. His Honour reasoned (at [231]) that:

… The substance of a contravention of s 321D(5) is the action of communicating electoral matter to one or more persons without ensuring that the required particulars are notified in the determined way. If there is a single act which results in communication of non-complying electoral matter to more than one person, it does not follow that there is more than one contravention. In my opinion, only a single contravention results from a single act.

44 Mr McQuestin referred to the well-established principle that, as a matter of judicial comity, a judge of this Court should follow the earlier decision of another judge of the Court unless of the view that it is “plainly” or “clearly” wrong: BHP Billiton Iron Ore Pty Ltd v National Competition Council (2007) 162 FCR 234 at [88] (Greenwood J). Mr McQuestin also referred to the observations of French J in Nezovic v Minister for Immigration and Multicultural and Indigenous Affairs (2003) 133 FCR 190 at [52] that: “where questions of law and in particular statutory construction are concerned, the view that a judge who has taken one view of the law or a statute is ‘clearly wrong’ is not likely to be adopted having regarded to the choices that so often confront the courts particularly in the area of statutory construction”.

45 The Electoral Commissioner has appealed the decision in Laming. The appeal has been heard and the Full Court has reserved its decision. I have considered whether to defer judgment in the present case pending the decision by the Full Court. I have concluded that judgment should not be deferred for the reason that my assessment of the appropriate penalty in the circumstances of this case would be the same whether I accepted the submissions of the Electoral Commissioner or Mr McQuestin on the issue of the number of contraventions. In those circumstances, it is desirable that this proceeding is finalised and the parties receive judgment.

Consideration

46 For the following reasons, I respectfully agree with the conclusion reached by Rangiah J in Laming, although I would express my reasons in different terms.

47 In identifying a contravention of a statutory provision in a given case, close attention must be given to the terms of the statutory prescription, including whether it is expressed as a positive obligation or a negative prohibition. Although the subject matter addressed by s 321D is relatively simple, the section is framed in an exceptionally complex manner. The complex drafting obscures, to some extent, the identification of the statutory prescription.

48 It can be accepted, as the Electoral Commissioner submitted, that s 321D is concerned with electoral matter that is communicated to one or more persons. Subsection 321D(1) stipulates that the section “applies in relation to electoral matter that is communicated to a person” in the circumstances described in one of paragraphs (a), (b) or (c) of the subsection. Thus, the section has no application to electoral matter that is not communicated to any person. It is important to observe, however, that s 321D(1) does not define the relevant statutory prescription. It merely defines an element of the prescription. It defines the electoral matter to which the statutory prescription attaches.

49 The statutory prescription imposed by s 321D is stated in subsection (5). It is helpful to reproduce that subsection:

The notifying entity must ensure that the particulars set out in the following table, and any other particulars determined under subsection (7) for the purposes of this subsection, are notified in accordance with any requirements determined under that subsection.

50 It can be seen that subsection (5) imposes a positive obligation on the notifying entity to ensure that the specified particulars are notified in accordance with the requirements specified in the legislative instrument made by the Electoral Commissioner under subsection (7). It follows that a person will contravene subsection (5) if the person fails to ensure that the specified particulars are notified in accordance with the specified requirements.

51 It can be accepted that the obligation imposed by subsection (5) applies to all electoral matter that is communicated to a person in the circumstances described in one of paragraphs (a), (b) or (c) of subsection (1). It can also be accepted that the object of Part XXA of the Electoral Act is relevantly to promote free and informed voting at elections by enhancing the transparency of the electoral system “by allowing voters to know who is communicating electoral matter” and “by making those persons responsible for their communications”: see ss 321C(1)(a) and (b). The importance of such transparency and accountability has been well-understood for more than a century: see for example Smith v Oldham (1912) 15 CLR 355 at 358-89 (Griffith CJ). Undoubtedly, the object of s 321D is to bring about the result that all electoral matter that is communicated to persons in the circumstances described in subsection (1) contains the required particulars. However, identifying that object of s 321D does not provide a final answer to the question: what is the statutory obligation imposed by s 321D(5) and what is the conduct that constitutes a contravention of that obligation?

52 In that regard, the analogy that the Electoral Commissioner seeks to draw with the statutory prohibitions of misleading or deceptive conduct is inapt. Those prohibitions are framed in different terms to s 321D(5). The conduct that is the subject of the prohibitions are acts or omissions which can be characterised as misleading or deceptive. The prohibitions apply to each misleading communication and the person responsible for making each such communication contravene the prohibitions in respect of each communication.

53 In contrast, a contravention of s 321D(5) occurs where a notifying entity fails, by act or omission, to ensure that a communication (relevantly, of an electoral advertisement) contains the required particulars. The acts or omissions that constitute a failure, and therefore the number of contraventions, will depend on the facts in a given case. A relevant question in identifying the acts or omissions that constitute a failure is: what should have been done to comply with s 321D(5)?

54 In the present case, the Electoral Commissioner alleged that Mr McQuestin contravened s 321D(5) because he did not ensure that the relevant particulars on the contravening advertisements, the content of which he approved on behalf of the Liberal Party, were reasonably prominent, legible at a distance at which they were intended to be read and in a text that contrasted with the background on which the text appeared, as required by s 11(3) of the Authorisation Determination. The agreed facts are that the contravening advertisements were provided to the Geelong Advertiser by uploading a digital version into that publication’s online “AdDrop” system. It was at that point of upload that the relevant failure by Mr McQuestin was complete. The relevant failure was not ensuring that the particulars were reasonably prominent, legible at a distance at which the advertisement was intended to be read and in a text that contrasted with the background on which the text appeared. Although there was no direct evidence on the issue, I infer that, once an advertisement is uploaded to AdDrop, a person has no other opportunity to alter the advertisement to ensure compliance with s 321D(5). In this case, the act or omission that constituted the relevant contravention of s 321D(5) occurred at the time of upload because that was the final point at which a notifying entity could ensure the inclusion of the relevant particulars.

55 The agreed facts are that:

(a) the Liberal Party uploaded the First Asher Advertisement via AdDrop on 12 May 2022, and the advertisement was published in the Geelong Advertiser on 14 May 2022;

(b) the Liberal Party uploaded the Anti-Coker Advertisement via AdDrop on 18 May 2022 and the advertisement was published in the Geelong Advertiser on 19 May 2022; and

(c) the Liberal Party uploaded the Second Asher Advertisement via AdDrop on 19 May 2022 and the advertisement was published in the Geelong Advertiser on 20 and 21 May 2022.

56 In my view, Mr McQuestin contravened s 321D(5) on three occasions by failing to ensure that the required particulars were included on the uploaded advertisements in a form that complied with s 11 of the Authorisation Determination. I note for completeness that I do not accept an alternative submission advanced by the Electoral Commissioner that Mr McQuestin contravened s 321D(5) twice in respect of the Second Asher Advertisement because the advertisement was published in two editions of the Geelong Advertiser on 20 and 21 May 2022. The relevant conduct involved a single advertisement that was approved on a single occasion (by being uploaded via AdDrop on 19 May 2022). In my view, the contravening conduct involved a single failure to ensure that the required particulars were notified on that advertisement, notwithstanding that the advertisement was then published on two consecutive days. My assessment of that contravention would have been different if two different advertisements had been uploaded.

57 As noted earlier, the maximum penalty for each contravention of s 321D(5) by Mr McQuestin is $26,640 per contravention.

The facts and circumstances relevant to the assessment of penalty

Nature and extent of the contraventions

58 With respect to the nature and circumstances of the contraventions, I generally accept the following submissions advanced by Mr McQuestin. First, the contraventions were isolated incidents across an extensive electoral advertisement programme. Second, the contraventions were limited, having occurred on three occasions over a period of only one week. Third, there is no evidence that the contraventions were deliberate. Fourth, there is no evidence that any problems with the notification of the required particulars were brought to Mr McQuestin’s attention, or that he was aware of such issues during the period of the contraventions. Fifth, the contravening advertisements contained deficient particulars, not the absence of particulars. It was not a case where no steps were taken to comply with s 321D(5) of the Electoral Act.

Nature and extent of any loss or damage suffered because of the contravention

59 A mandatory factor to be considered is the nature and extent of any loss or damage suffered as a result of the contravening conduct (see s 82(6)(b) of the Regulatory Powers Act). It is likely that the phrase “loss or damage” takes its common law meaning, being compensable loss or damage. As such, the factor has no immediate application to contraventions of s 321D(5) of the Electoral Act. Nevertheless, s 82(6) of the Regulatory Powers Act requires the Court to have regard to all relevant matters. Having regard to the objects of Part XXA as stated in s 321C, a relevant factor is the likely damage to the electoral process by the contravening conduct. As Rangiah J observed in Laming (at [244]):

Section 321D(5) fulfils an important public role in strengthening Australia’s system of representative democracy by requiring those communicating electoral matter to identify themselves. This allows voters to critically assess the credibility of information when forming political judgments and electing their representatives.

60 Two factors are relevant to note in this context.

61 First, although it is not possible to identify the total readership of the relevant editions of the Geelong Advertiser in which the contravening advertisements were published, the agreed total distribution was over 64,000 copies. I can infer from that figure that the contravening advertisements were likely seen by tens of thousands of voters. That is a significant matter.

62 Second, the failure to include legible particulars in the Anti-Coker Advertisement was a serious failure because that advertisement did not otherwise identify the person or political party on whose behalf the advertisement was placed. That can be contrasted with the First and Second Asher Advertisements which were identifiable as Liberal Party advertisements (by the inclusion of the Liberal Party logo, the prominence of the word “Liberal”, the blue background and the recommendation to place “1” in the Liberal Party box on the graphic of the ballot paper). It follows that the contraventions in respect of the Asher Advertisements were less serious in comparison to the Anti-Coker Advertisement.

Circumstances in which the contraventions took place

63 Mr McQuestin did not adduce any evidence to explain why and how the contraventions occurred. In particular, there was no evidence about any processes or procedures applied by the Liberal Party to ensure compliance with the requirements of the Electoral Act.

64 Mr McQuestin’s submissions suggested that the busy nature of the final days of a federal election campaign, which involves preparing, approving and submitting electoral advertisements throughout Victoria, means the content of those advertisements was “approved on an ongoing basis, and sometimes by way of text message on mobile telephones”. I can readily accept that the final days of a federal election campaign may be busy. However, the need to protect free and informed voting is not diminished as election day approaches. Indeed, the contrary is true: transparency and accountability become more crucial the closer in time one gets to an election.

65 It is open for me to find, and I do find, that whatever processes or procedures the Liberal Party had in place to ensure compliance with the requirements of the Electoral Act, they were not sufficiently robust or systematic to prevent the contraventions that occurred. There is therefore a need to ensure that the processes are strengthened.

History of similar conduct

66 Mr McQuestin has not previously been found by a court to have engaged in any similar conduct.

Benefit derived as a result of the contravention

67 There was no evidence of whether the contravening advertisements persuaded voters to give greater preference to the Liberal Party candidate (or lesser preference to the Labor Party candidate). Such evidence would be difficult to obtain. The Liberal Party candidate for Corangamite did not succeed at the election.

Size of the contravenor

68 As the majority observed in Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Pattinson (2022) 274 CLR 450 at [60] (Kiefel CJ, Gageler, Keane, Gordon, Steward and Gleeson JJ), all other things being equal, a greater financial incentive will be necessary to persuade a well-resourced contravenor to abide by the law than will be necessary to persuade a poorly resourced contravenor.

69 Although these proceedings have been brought against Mr McQuestin, it is relevant to keep in mind that the statutory prescription in s 321D(5) is directed to the “notifying entity” which is the person who approved the electoral advertisement. In this case, the notifying entity was the Liberal Party. In the present case, the Liberal Party would have been liable for the contravention of s 321D(5) but for the fact that it is not an incorporated body and therefore it is not a legal person. In those circumstances, s 321D(6) attributes liability to each member, agent or officer of the Liberal Party who, acting in his or her actual or apparent authority, engaged in the conduct or made the omission constituting the contravention. Liability has been attributed to Mr McQuestin in that manner.

70 Having regard to the manner in which ss 321D(5) and (6) are framed, the objective of deterrence can be seen to be directed to both Mr McQuestin, as the officer of the Liberal Party who engaged in the conduct or made the omissions constituting the contraventions, as well as the Liberal Party which would otherwise have been liable for the contravention. The assessment of penalty should take into account those matters, including particularly the person or entity that will ultimately pay the penalty. If the penalty is to be borne personally by the relevant officer to whom liability is attributed, a lower penalty would ordinarily be imposed than would be the case if the penalty is to be borne by the political party concerned.

71 As noted earlier, Mr McQuestin informed the Court that the Liberal Party will pay any penalty on behalf of Mr McQuestin. It is therefore appropriate to take into account the Liberal Party’s financial circumstances. The evidence, however, was limited. The evidence was confined to the “Political Party Disclosure Return – Financial Year 2021-22” furnished by the Victorian Division of the Liberal Party to the Australian Electoral Commission under s 314B of the Electoral Act. That document showed that the Victorian Division of the Liberal Party’s total receipts for that financial year were approximately $21.1 million, its total payments were approximately $24.4 million, and its total debts were approximately $6.6 million. Mr McQuestin emphasised the loss incurred in that financial year and submitted that the Court should not infer from that document that “there was some embarrassment of riches” in the Liberal Party.

72 Although the evidence on this issue was limited, the income and expenses of the Victorian Division of the Liberal Party in the 2022 financial year were significant. I have borne those amounts in mind in assessing the appropriate penalty to be imposed.

Cooperation

73 Ultimately, Mr McQuestin made extensive admissions in this proceeding which avoided the need for a contested hearing, other than on the question of liability. Although the proceeding took longer than it should have to reach that point, I consider that the penalty should take account of Mr McQuestin’s cooperation.

Conclusion on penalty

74 Mr McQuestin contravened s 321D(5) on three occasions by failing to ensure that the required particulars were included on the contravening advertisements in a form that complied with s 11 of the Authorisation Determination. The maximum penalty for each contravention of s 321D(5) is $26,640.

75 Taking into account all of the considerations referred to above, I consider that the following penalties should be imposed in respect of the contraventions:

(a) $10,000 in respect of the First Asher Advertisement;

(b) $15,000 in respect of the Anti-Coker Advertisement; and

(c) $15,000 in respect of the Second Asher Advertisement.

76 The admitted contraventions undermined the important objective of allowing voters to know who is communicating electoral matter and accordingly protecting Australia’s system of representative democracy. In my view, penalties of that magnitude are required to ensure that the Victorian Division of the Liberal Party, as a major participant in Australia’s political process and government, takes greater care to comply with its obligations under Part XXA of the Electoral Act. A higher penalty is warranted in respect of the Anti-Coker Advertisement because, as discussed above, that advertisement did not otherwise identify the person or political party on whose behalf the advertisement was placed. It therefore had greater potential to cause harm to the democratic process. A higher penalty is also warranted in respect of the Second Asher Advertisement because it was published in two editions of the Geelong Advertiser on two different days, resulting in a larger volume of communications.

77 As stated earlier, if my conclusion with respect to the number of contraventions of s 321D(5) committed by Mr McQuestin were to be incorrect, and if a contravention occurred on each occasion that a contravening advertisement was communicated in a copy of the Geelong Advertiser, I would impose the same penalties applying the course of conduct and totality principles. In my view, Mr McQuestin’s principal culpability arose at the time that the contravening advertisements were approved. The number of publications of the advertisements by the Geelong Advertiser is a relevant factor to be taken into account, but is properly seen as being part of a single course of conduct. Whether the number of publications is taken into account as constituting a series of related contraventions (comprising a single course of conduct), or whether it is taken into account as a matter relevant to the nature or effect of a single contravention, in the circumstances of the present case I would impose the aggregate penalties referred to above. Further, applying the totality principle, I consider that an overall aggregate penalty of $40,000 is appropriate in this case.

Conclusion

78 In conclusion, I will make declarations of contravention as discussed earlier and order that Mr McQuestin pay an aggregate pecuniary penalty of $40,000.

79 In the ordinary course, costs should follow the event and I will make an order to that effect. However, I will also provide the parties with an opportunity to seek a variation to the costs order by filing a short submission and any evidence in support.

I certify that the preceding seventy-nine (79) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice O’Bryan. |

Associate:

FIRST ASHER ADVERTISEMENT – 14 MAY 2022

ANTI-COKER ADVERTISEMENT – 19 MAY 2022

SECOND ASHER ADVERTISEMENT – 20 MAY 2022

SECOND ASHER ADVERTISEMENT – 21 MAY 2022