FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Energy Regulator v Pelican Point Power Ltd (No 3) [2024] FCA 277

ORDERS

Applicant | ||

AND: | PELICAN POINT POWER LTD (ARBN 086 411 814) Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT DECLARES THAT:

1. By each of its four short term PASA submissions made between 6 February 2017 at 11:00 and 7 February 2017 at 11:25 identified below for each of the future trading intervals during the 8 February 2017 trading day identified below, the respondent contravened cl 3.7.3(e)(2) of the National Electricity Rules (NER) by submitting short term PASA availability values of 220 MW that did not represent its current intentions and best estimates as to the physical plant capability of the Pelican Point Power Station that could be made available on 24 hours’ notice which was 320 MW.

No | Date and Time of PASA Submission | Number of Time Intervals Affected |

1 | 6/2/2017 11:00 | 48 |

2 | 7/2/2017 9:56 | 48 |

3 | 7/2/2017 11:22 | 48 |

4 | 7/2/2017 11:25 | 48 |

2. The respondent contravened cl 3.13.2(h) of the NER by failing to notify the Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO) promptly on or after 3 February 2017 that the medium term PASA availability of the Pelican Point Power Station for 8 February 2017 which the respondent previously submitted to AEMO on 27 January 2017 had increased from 224 MW to 320 MW.

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

3. With respect to the contraventions identified in the aforesaid declarations, Pelican Point Power Ltd pay a civil penalty of $900,000.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

BESANKO J:

INTRODUCTION

1 The Australian Energy Regulator (AER) seeks declaratory orders under s 44AAG(1) of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (the CCA) to the effect that Pelican Point Power Ltd (PPPL) is in breach of a State energy law as defined in s 4 of the CCA. A State energy law includes the National Electricity Law (NEL) which has been enacted in South Australia as a Schedule to the National Electricity (South Australia) Act 1996 (SA) (s 6) and the National Electricity Rules (NER) which have the force of law by reason of s 9 of the NEL. The rules in the NER alleged by the AER to have been breached by PPPL are cll 3.7.3(e)(2), 3.7.2(d)(1) and 3.13.2(h) and each of those rules was designated a civil penalty provision at the relevant time (the NEL s 2AA; the National Electricity (South Australia) Regulations, reg 6(1) and Schedule 1). In addition to the declaratory orders, the AER seeks the imposition of civil penalties in relation to the breaches.

2 At an early stage of the proceedings, the Court made an order that liability for the alleged contraventions be heard separately from, and in advance of, the relief to be granted should the contraventions be established.

3 The trial as to liability for the alleged contraventions took place and I delivered reasons for my conclusions with respect to those matters (Australian Energy Regulator v Pelican Point Power Ltd [2023] FCA 1110 (PPPL No 1)).

4 The AER succeeded in establishing some of the allegations it made, but it did not establish all of them. It then asked the Court to make declarations reflecting the conclusions in PPPL No 1 or to make further findings before the hearing as to the civil penalties to be imposed. I declined to make declarations or make further findings at that stage because I took the view that having regard to the terms of the particular legislation, the declarations made by the Court and the civil penalties imposed must be included in the one order (Australian Energy Regulator v Pelican Point Power Ltd (No 2) [2023] FCA 1381 (PPPL No 2)).

5 The matter was then listed for hearing as to the declaratory orders to be made and the civil penalties to be imposed. By then, the AER had provided proposed declarations which differed in a number of respects from the declarations it advanced at the trial as to liability for the alleged contraventions.

6 The hearing proceeded and both sides called evidence. In the case of the AER, the further evidence it called related primarily to the loss and damage it alleges was caused by the contraventions. In the case of PPPL, the further evidence it called related to that matter and the compliance programs it had in place.

7 There was a substantial dispute between the parties about the declarations which should be made. This dispute was as to which declarations should be made and their terms. That matter was also relevant to the Court’s findings as to the number of contraventions which have been established. The number of contraventions determines the maximum penalties which is ordinarily a matter to be considered in fixing the appropriate civil penalties.

8 The dispute as to the declarations to be made involved not only a dispute about whether a particular declaration reflected the findings made in PPPL No 1, but also an objection that two of the declarations sought by the AER were outside the parameters of the case it advanced at the trial as to liability for the alleged contraventions.

9 The structure of these reasons is that I will deal first with the declarations which should be made. That will include the identification of the number of contraventions which have been established. I will then move to the factors relevant to the fixing of the appropriate civil penalty. Both parties have proceeded on the basis that a single course of conduct is involved and one civil penalty is appropriate.

THE DECLARATORY RELIEF SOUGHT BY THE AER

10 It is convenient to begin with a comparison of the declarations sought at the trial as to liability for the alleged contraventions and the declarations now sought by the AER following the findings in PPPL No 1. The declarations sought by the AER at the trial as to liability were described in the reasons in PPPL No 1 (at [2]–[4]) as follows:

… First, the AER seeks a declaration that in relation to each of its 27 short term PASA submissions submitted on or after 30 January 2017 for each trading interval during the 8 February 2017 trading day (but not including any trading interval that had concluded when the submission was made), PPPL contravened cl 3.7.3(e)(2) of the NER by failing to submit its short term PASA availability so as to reflect the true physical plant capability of the Pelican Point Power Station (Pelican Point PS) that could be made available on 24 hours’ notice and further, or in the alternative, by failing to submit its short term PASA availability to reflect its current intentions and best estimates as to the physical plant capability of the Pelican Point PS that could be made available on 24 hours’ notice …

Secondly, the AER seeks a declaration that in relation to PPPL’s medium term PASA submissions for the day 8 February 2017, PPPL contravened cl 3.7.2(d)(1) of the NER in relation to each of its 10 medium term PASA submissions made after 11 November 2016, by failing to submit medium term PASA availability so as to reflect the physical plant capability of the Pelican Point PS that could be made available on 24 hours’ notice after the gas turbine known as GT12 was brought from dry to wet storage on 11 November 2016.

Thirdly, the AER seeks further, or in the alternative to the second declaration, a declaration that PPPL contravened cl 3.13.2(h) of the NER by failing to notify AEMO promptly on or after 11 November 2016 of the increased medium term PASA availability of the Pelican Point PS after GT12 was brought from dry to wet storage on 11 November 2016. On the AER’s case, that contravention continued for a period of in the order of 86 days.

11 The declarations which the AER now seeks following the findings in PPPL No 1 are as follows:

1 By each of its 24 short term PASA submissions made after 3 February 2017 for each future or current trading interval during the 8 February 2017 trading day, the Respondent contravened cl 3.7.3(e)(2) of the National Electricity Rules (NER) by submitting short term PASA availability of values between 216 megawatts (MW) and 235 MW that did not represent its current intentions and best estimates as to the physical plant capability of the Pelican Point Power Station that could be made available on 24 hours’ notice, which was at least 320 MW.

2 The Respondent contravened cl 3.13.2(h) of the NER, by failing to notify the Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO) promptly on or after 3 February 2017:

(a) that the short term PASA availability of the Pelican Point Power Station for each trading interval on the 8 February 2017 trading day, which the Respondent previously submitted to AEMO on 2 February 2017 at 9:11 am, had increased from 220 MW to at least 320 MW; and

(b) that the medium term PASA availability of the Pelican Point Power Station for 8 February 2017, which the Respondent previously submitted to AEMO on 27 January 2017, had increased from 224 MW to at least 320 MW.27

12 There are three major changes in terms of the first declaration. In addition to the change to the number of ST PASA submissions identified (reduced from 27 to 24) and the change in date from 30 January 2017 to 3 February 2017, the conduct said to be the contravention or breach is cast in positive terms in that it has been changed from “failing to submit” to submitting ST PASA availability that “did not represent”, etc.

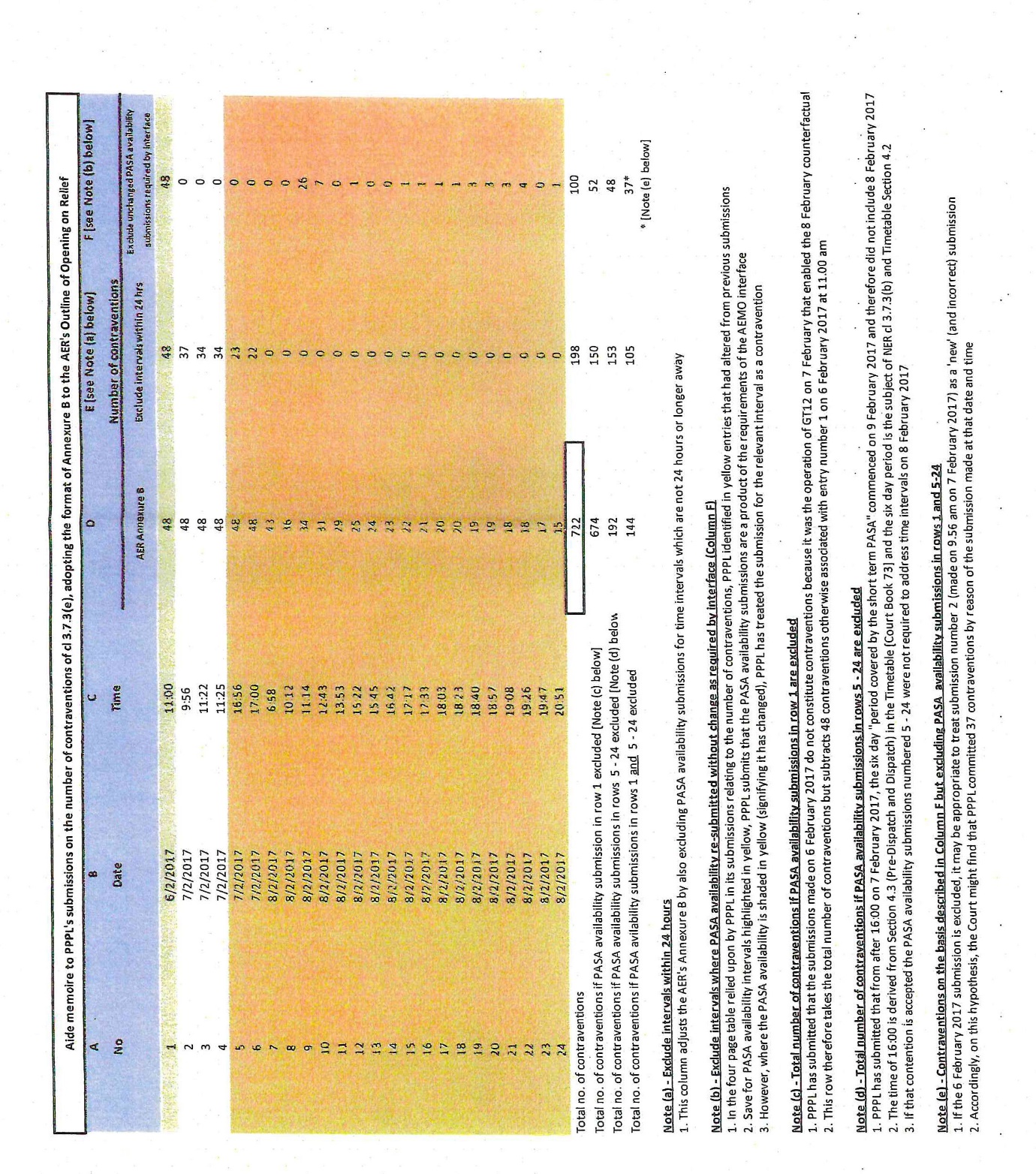

13 The AER’s case is that if the first declaration it now seeks is made, it means that PPPL has committed 722 contraventions of cl 3.7.3(e)(2) of the NER. There were 24 ST PASA submissions made after 3 February 2017 with the first being made on 6 February 2017 at 11:00 and the last being made on 8 February 2017 at 20:51. Each submission addressed PASA availability (in addition to other matters) for a trading interval of 30 minutes with 48 trading intervals across a day commencing at 4:00 am. The AER prepared a table showing the number of contraventions it alleges and it is as follows:

No | Date and Time of PASA Submission | No of TIs Affected |

1 | 6/2/2017 11:00 | 48 |

2 | 7/2/2017 9:56 | 48 |

3 | 7/2/2017 11:22 | 48 |

4 | 7/2/2017 11:25 | 48 |

5 | 7/2/2017 16:56 | 48 |

6 | 7/2/2017 17:00 | 48 |

7 | 8/2/2017 6:58 | 43 |

8 | 8/2/2017 10:12 | 36 |

9 | 8/2/2017 11:14 | 34 |

10 | 8/2/2017 12:43 | 31 |

11 | 8/2/2017 13:53 | 29 |

12 | 8/2/2017 15:22 | 25 |

13 | 8/2/2017 15.45 | 24 |

14 | 8/2/2017 16:42 | 23 |

15 | 8/2/2017 17:17 | 22 |

16 | 8/2/2017 17:33 | 21 |

17 | 8/2/2017 18:03 | 20 |

18 | 8/2/2017 18:23 | 20 |

19 | 8/2/2017 18:40 | 19 |

20 | 8/2/2017 18:57 | 19 |

21 | 8/2/2017 19:08 | 18 |

22 | 8/2/2017 19:26 | 18 |

23 | 8/2/2017 19:47 | 17 |

24 | 8/2/2017 20:51 | 15 |

722 |

14 The number of trading intervals progressively reduces after the commencement of the 8 February 2017 day because the AER accepts that there cannot be a contravention with respect to past trading intervals. For example, the number of alleged contraventions for the PASA submission made at 6:58 on 8 February 2017 is 43 because at the time of the submission, five 30-minute trading intervals had been completed.

15 Each contravention of the relevant Rules carries a maximum penalty of $100,000.

16 PPPL made a number of submissions challenging the terms of the first declaration, but did not submit that the subject matter of the declaration was not within the parameters of the case the AER advanced at trial as to liability. PPPL’s case is that the declaration does not accurately reflect the findings set out in PPPL No 1.

17 In the case of the other two declarations now sought by the AER, it relied on cl 3.13.2(h) which provides that a Scheduled Generator must notify the Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO) of, and AEMO must publish, any changes to submitted information within the times prescribed in the timetable. The timetable at the relevant time is set out below (at [69]). It contained a provision as to “Frequency” for ST PASA and MT PASA submissions as follows: “As frequently as changes occur”.

18 No equivalent of the declaration in para 2(a) was sought at the trial as to liability. In other words, there was no claim of a contravention of cl 3.13.2(h) in relation to ST PASA submissions. The declaration now sought in para 2(b) bears some similarity to the third declaration sought at the trial as to liability in that it refers to MT PASA submissions and the contravention of cl 3.13.2(h), but the particulars of the contravention are quite different and in that sense, no equivalent of the declaration in para 2(b) was advanced by the AER at the trial as to liability.

19 The AER’s case is that the declaration in para 2(a) involves PPPL having committed 48 contraventions of cl 3.13.2(h) in relation to ST PASA submissions and that the maximum penalty for each contravention is $150,000 being $100,000 for each of the 48 contraventions and a penalty of $10,000 per day for each day the contravention continued. The explanation for this allegation is as follows. The obligation breached by PPPL was an obligation to notify AEMO on 3 February 2017 of changes to submitted information with respect to 48 trading intervals on 8 February 2017 which were continuing breaches (s 66 of the NEL) which carried a maximum penalty, in the case of a body corporate, of $10,000 for each of the five days the breaches continued (see s 2 and the definition of “civil penalty”).

20 The AER’s case is that the declaration in para 2(b) involves PPPL having committed one contravention of cl 3.13.2(h) on 3 February 2017 in relation to MT PASA submissions which continued for five days resulting in a maximum penalty of $150,000.

21 PPPL contends that neither the declaration in para 2(a) or the declaration is para (b) should be made. Its submissions may be broadly summarised as follows: (1) the declaration is outside the parameters of the case which the AER advanced at the trial as to liability; (2) the declaration is not supported by the findings in PPPL No 1; and (3) the declaration characterises matters as contraventions which, on the proper construction of the NER, are not in fact contraventions.

22 On the AER’s case, the maximum penalty for PPPL’s contravening conduct is in the order of $80 million.

23 PPPL contends that only one declaration should be made and it is in the following terms:

By its short term PASA submissions for the 8 February 2017 trading day set out in Annexure A to these orders, the Respondent contravened cl 3.7.3(e)(2) of the National Electricity Rules by submitting short term PASA availability of less than 320 MW.

I will describe the annexure referred to in this proposed declaration later in these reasons.

THE REASONS IN PPPL NO 1

24 These reasons must be read with the reasons in PPPL No 1. It is necessary to highlight some of the findings and observations in PPPL No 1 in light of the issues which must now be resolved.

25 The important provisions of the NER are set out in the reasons in PPPL No 1 (at [11]–[27]) and need not be repeated. The following provisions are also relevant.

26 The precise terms of cl 3.7.3(h) at the relevant time were as follows:

AEMO must prepare and publish the following information for each trading interval (unless otherwise specified in subparagraphs (1) to (5)) in the period covered by the short term PASA in accordance with clause 3.13.4(c):

(1) forecasts of the most probable load (excluding the relevant aggregated MW allowance referred to in subparagraph (4B)) plus reserve requirement (as determined under clause 3.7.3(d)(2)), adjusted to make allowance for scheduled load, for each region;

(2) forecasts of load (excluding the relevant aggregated MW allowance referred to in subparagraph (4B)) for each region with 10% and 90% probability of exceedence;

27 Clause 3.7.3(b) provided as follows:

The short term PASA covers the period of six trading days starting from the end of the trading day covered by the most recently published pre-dispatch schedule with a trading interval resolution.

28 The term “pre-dispatch schedule” was defined as meaning a schedule prepared in accordance with cl 3.8.20(a) and that clause provided as follows:

(a) Each day, in accordance with the timetable, AEMO must prepare and publish a pre-dispatch schedule covering each trading interval of the period commencing from the next trading interval after the current trading interval up to and including the final trading interval of the last trading day for which all valid dispatch bids and dispatch offers have been received in accordance with the timetable and applied by the pre-dispatch process.

29 At the trial as to liability, the AER advanced two operating scenarios for the two generators (GT11 and GT12) as the basis of its case as to what the PASA availability at the Pelican Point PS was on 8 February 2017. They are described in PPPL No 1 as is their significance in terms of the issues in the case (at [68]–[72]). The MT PASA submissions and ST PASA submissions actually made by PPPL are also described or summarised in PPPL No 1 (at [65]–[67]).

30 The physical condition of GT12 was an issue at the trial as to liability. Mr Debasis Baksi was an employee of PPPL/ENGIE and he gave evidence relevant to this issue. Another matter which should be noted and is relevant to the performance of a generator is the minimum run-time of a generator. That means that certain circumstances relating to the operation of a generator may dictate (or strongly support) that if a generator is to be turned on, it must then be run for at least a certain period of time.

31 The evidence of Mr Baksi is summarised in PPPL No 1 (at [358]–[384]) as is the relevance of Mr Baksi’s evidence to PPPL’s case (at [374]):

374 PPPL relies on Mr Baksi’s evidence as to his concerns about the condition of GT12 because it had been run for almost 5,000 EOHs beyond the manufacturer’s specifications for a C-inspection of 24,000 EOH, it had cracks in the turbine blades and was overdue for a C-inspection and submitted that these concerns were plainly genuine and consistent with the underlying business records.

Mr Baksi also gave evidence which is now said to be significant about the minimum run-time of a gas turbine. The evidence is described in the reasons in PPPL No 1 as follows (at [375]):

375 Further, a hypothetical running time of four hours for GT12 on 8 February 2017 could only be postulated because of the coincidence of GT12 having been run for maintenance purposes on 7 February 2017. There is a need to draw a distinction between the period from which a gas turbine could ordinarily be returned to service and the minimum run-time of a gas turbine having regard to the date of its last operation. A gas turbine in wet storage may ordinarily be returned to service relatively quickly, that is to say, in approximately four hours or less. In terms of minimum run-time, a gas turbine which had been in wet storage, but not operated for approximately three weeks, would need a minimum run-time of at least eight hours. If the gas turbine had been operated more recently, then the minimum run-time would be less than eight hours.

32 I described further evidence of Mr Baksi about the minimum run-time of a generator as follows (at [380]):

380 Mr Baksi accepted that the minimum run-times he identified were not times prescribed by the manufacturer and that it was really a matter of what people on the spot determined having regard to site conditions. He also agreed that as to the minimum run-times, the management of PPPL could overrule the decision of the engineers. It is fair to say that in the course of his cross-examination on the letter from PPPL’s solicitors dated 31 January 2020, Mr Baksi quite reasonably agreed that the minimum run-times were not fixed in stone. He agreed that a run-time of less than eight hours might be possible sometimes when the other interests of PPPL “took precedence over preserving the design life of the CCGT”…

33 A number of earlier observations in the reasons in PPPL No 1 are also relevant and were as follows (at [68], [371], [372] and [373]):

68 The PASA submissions, whether they be medium term or short term, involve a forecast or prediction or prognostication, or to use one of the terms in the Rules, an estimate of physical plant capability available, or that can be made available, on 24 hours’ notice. After GT12 was brought out of dry storage, it was operated from time to time and, in fact, it was operated for a substantial period of time on 7 February 2017. It was operated in the alternative to GT11. They were not operated concurrently before 9 February 2017 when AEMO issued its direction under cl 4.8.9 of the NER.

…

371 GT12 was moved from dry storage to wet storage in November 2016 and was operated for 892 hours in November and December 2016 compared with GT11which was operated for 495 hours.

372 By mid-January 2017, GT12 had operated for approximately 29,000 EOH since its last C-inspection and PPPL had submitted a purchase order for the C-inspection of GT12 on 24 December 2016 which was subject to the successful completion of a gas tolling agreement which would provide a business case for PPPL to use GT12. Mr Baksi gave evidence that he was informed in or about the time GT12 was moved from dry storage to wet storage of the possibility of there being a C-inspection overhaul of GT12 in about April 2017.

373 In mid-January 2017, a decision was made by PPPL to operate GT11 as the primary gas turbine and GT12 as the secondary gas turbine. GT12 was not operated for a period of nearly three weeks between 18 January 2017 and 7 February 2017. It was run for approximately 16 hours on 7 February 2017 in order to maintain the appropriate water chemistry in the heat recovery steam generator. I note that in another part of his evidence, Mr Baksi said it was run for 14 hours, but I do not consider the difference to be material. The C-inspection and overall of GT12 was carried out in April 2017. It took 56 days and cost approximately $39.7 million AUD.

34 As to whether Mr Baksi was an honest witness, I made the following observations in PPPL No 1 (at [381]–[382]):

381 Mr Baksi was honest in giving his evidence. His focus was on the matter of most concern to him which was the condition of GT12 and whether there would be a backup turbine. The one matter where I had trouble accepting his evidence was his statement in para 38 of exhibit R7 that there was a medium to high risk of blade failure which would have catastrophic consequences (emphasis added). Having regard to the context of the observation and what he and PPPL did and did not do, I cannot think that this is correct, and I consider it likely, that he has confused the risk with the consequences should it materialise.

382 Mr Baksi said that he partially agreed with the suggestion that PPPL ran GT12 “harder” on 7 February 2017 than it did on 9 February 2017 and this leads back to a previous point that what made him nervous on 9 February 2017 was not the condition of GT12, but running the two together and the absence of a standby turbine.

35 In PPPL No 1, I identified what I said were the “three key issues” in determining whether the NER had been contravened as follows: (1) the availability of gas supply; (2) the availability of gas transport; and (3) the relevance (if any) of the physical plant capability of GT12 (at [496]). Those matters were to be assessed having regard to the 8 February counterfactual because I found that the other operating scenario advanced by the AER, being the basic 320 MW scenario, was unrealistic and inappropriate and that PPPL was not required to assess and determine its PASA submissions by reference to the basic 320 MW scenario (at [492]–[495]).

36 The availability of gas supply and gas transport was then addressed by reference to the amount of gas and gas transport needed to operate GT11 and GT12 in accordance with the 8 February counterfactual (as to gas supply see at [499] and [527]; as to gas transport see at [534], [617] and [653]). I found that the physical condition of GT12 was not a relevant matter pointing against the availability of GT12 on 8 February 2017 (at [670]).

37 I then turned to express my key conclusions. The key conclusion was that by the time Revision 1 of the Scheduled Quantities Report was issued on 3 February 2017 at 12:14 pm (at [631]), PPPL ought to have had a reasonable expectation of obtaining sufficient interruptible gas transport (and gas) to operate in accordance with the 8 February counterfactual. I said that subject to determining the number of contraventions, PPPL contravened cl 3.7.3(e)(2) after that date (at [680]). I had noted earlier in PPPL No 1 that there were disputes between the parties as to the number of contraventions, some of which were resolved and others which were not resolved (at [675]).

38 In my conclusion, I went on to say that PPPL did not contravene cl 3.7.2(d)(1) (MT PASA submissions) and it did not contravene cl 3.7.3(e)(2) prior to 3 February 2017 at 12:14 pm. I said that I would hear the parties on, inter alia, the effect of my conclusions on the AER’s case that PPPL contravened cl 3.13.2(h).

39 Returning briefly at this stage to the precise number of contraventions, the AER seemed to treat this issue as an issue to be determined at the penalty hearing should liability be established. The position of PPPL is less clear. It was critical in its closing written submissions of AER’s failure to be clear in its case as to the precise number of contraventions. In fairness to the AER, it did file an Amended Originating application which had the practical effect of limiting the number of contraventions. As noted in PPPL No 1 (at [675]), PPPL filed as an annexure to its closing written submissions, a helpful document addressing certain issues relating to the number of contraventions.

40 In the AER’s written outline of opening submissions at the trial as to liability, it contended that there were 10 contraventions of cl 3.7.2(d)(1) (MT PASA submissions), the first on 16 November 2016 and the last on 27 January 2017. There was one contravention of cl 3.13.2(h) which occurred on 11 November 2017 and that contravention continued for 89 days. There were 1,344 “discrete” contraventions of cl 3.7.3(e)(2) (ST PASA submissions) being 28 submissions each containing entries for 48 trading intervals.

The Declarations which will be made

41 It will assist in understanding the arguments and the reasons for their acceptance or rejection if I set out at this point the declarations which I consider should be made. They are as follows:

1. By each of its four short term PASA submissions made between 6 February 2017 at 11:00 and 7 February 2017 at 11:25 identified below for each of the future trading intervals during the 8 February 2017 trading day identified below, the respondent contravened cl 3.7.3(e)(2) of the National Electricity Rules (NER) by submitting short term PASA availability values of 220 MW that did not represent its current intentions and best estimates as to the physical plant capability of the Pelican Point Power Station that could be made available on 24 hours’ notice which was 320 MW.

No | Date and Time of PASA Submission | Number of Time Intervals Affected |

1 | 6/2/2017 11:00 | 48 |

2 | 7/2/2017 9:56 | 48 |

3 | 7/2/2017 11:22 | 48 |

4 | 7/2/2017 11:25 | 48 |

2. The respondent contravened cl 3.13.2(h) of the NER by failing to notify the Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO) promptly on or after 3 February 2017 that the medium term PASA availability of the Pelican Point Power Station for 8 February 2017 which the respondent previously submitted to AEMO on 27 January 2017 had increased from 224 MW to 320 MW.

The First Declaration (ST PASA submissions and contraventions of cl 3.7.3(e)(2) of the NER)

42 Annexure A to these reasons is a document prepared by PPPL which relates to the declaration it contends is appropriate in the sense that it identifies the period of contravening conduct and it shows the results of the various arguments it puts as to the number of contraventions.

43 Columns A, B and C in Annexure A identify the 24 ST PASA submissions and the date and time they were made by PPPL. Column D summarises the AER’s case as to the number of contraventions. Columns A, B, C and D contain the same information as the AER’s table which is set out above (at [13]).

44 Annexure A shows that the first ST PASA submission was made on 6 February 2017 at 11:00 and the AER contends that it gave rise to 48 contraventions. PPPL disputes this on the ground that it would not have been reasonably known to PPPL on 6 February 2017 that GT12 could have been run for approximately four hours on 8 February 2017. This is PPPL’s first argument.

45 PPPL’s second argument is that submissions 5 to 24 in the yellow box in Annexure A cannot constitute contraventions because, although they were made, they do not relate to the period covered by ST PASA submissions. This argument raises construction issues concerning certain rules in the NER.

46 PPPL’s third argument is reflected in the number of contraventions shown in Column E. It is that only those submissions made 24 hours or more before the relevant trading interval are capable of constituting contraventions. That follows, on PPPL’s argument, because of the reference in the definition of PASA availability of availability “on 24 hours’ notice”.

47 PPPL’s fourth argument is reflected in the number of contraventions shown in Column F. It is that it is only the ST PASA submissions that involve a change to PASA availability from that previously submitted that are capable of constituting contraventions. There are no contraventions, on PPPL’s argument, where there has been no change to information previously submitted. If this, and only this, argument succeeds, then there are 100 contraventions. If this argument and the first and second (or first and third) arguments succeed, then there are arguably no contraventions, although PPPL accepts that it may be appropriate to regard the second submission involving 37 contraventions as a “‘new’ (and incorrect) submission”.

48 I turn to consider each of these arguments.

(1) Whether the ST PASA submission made by PPPL at 11:00 on 6 February 2017 gives rise to contraventions (submission 1)

49 PPPL’s ST PASA submission at 11:00 on 6 February 2017 gave a value of 220 MW for PASA availability for each of the forty eight 30-minute trading intervals for 8 February 2017 from 4:00 am on that day to 3:30 am on the following day. PPPL submits that none of these entries is a contravention of cl 3.7.3(e)(2) because at the time the ST PASA submission was made, GT12 had not been operated for the 14 to 16 hour period on 7 February 2017 and, in the circumstances as they were on that day, it would not have been known that GT12 could be operated for a mere four hours on 8 February 2017. I summarised the steps in the argument in PPPL No 2 (at [28]).

50 I have set out above the findings, descriptions and observations made in PPPL No 1 concerning the operation of GT12 and the evidence Mr Baksi (at [30]–[34]).

51 It is necessary to provide some further explanation of aspects of Mr Baksi’s evidence at the trial as to liability.

52 Mr Baksi was cross-examined about two graphs, one showing the generation dispatched by PPPL on 8 February 2017 and the other showing the generation dispatched on 9 February 2017. Mr Baksi also gave evidence about the events at the Pelican Point PS on 9 February 2017, but it is not necessary to refer to the details.

53 The evidence shows that on 9 February 2017, GT12 was operated with a running time of four hours. As I have said, it seems from Mr Baksi’s cross-examination that the minimum run-time related to the heat recovery steam generator rather than the gas turbines. Mr Baksi considered that the water quality dropped dramatically once the three week limit was exceeded. He said the following:

It’s established outcome of running at site conditions as to what’s the best possible water chemistry maintained in a wet/cold condition of the heat recovery steam generator, for how long. …

54 It was put to Mr Baksi in cross-examination that under pressure from management, GT12 was operated for four hours on 9 February 2017, but his response to this was that GT12 had already operated for almost 14 hours on 7 February 2017 and this was more than eight hours. He said that the generator was ready to get started on that “count”. The start-up on 9 February 2017 was not dictated by the chemistry, but rather it was dictated by the condition of the blade. It was also dictated by the fact that GT12 was operated in tandem with GT11 and if something went wrong with GT12, there is no backup machine available.

55 Mr Baksi’s evidence was that he made a conscious decision in mid-January 2017 to revert to using GT11 as the primary turbine and keeping GT12 in wet storage as a backup. That was for the reasons discussed earlier in his cross-examination. On 7 February 2017 three weeks after that had been done, GT12 was brought into service and operated again. Mr Baksi said it was operated because it had already remained in cold conditions for three weeks. The previous operation of GT12 was on 8 January 2017 and, therefore, “it necessitated us to run it for at least eight hours on the 7th, which was the last day of the 21-day period before maintaining it for another three weeks”. Mr Baksi agreed that PPPL decided to run GT12 on 7 February 2017 “for maintaining water chemistry”.

56 The submissions of each party with respect to this particular argument were brief.

57 The AER contends that PPPL is inviting the Court to reopen a finding the Court made at [680] of PPPL No 1 to the effect that PPPL contravened cl 3.7.3(e)(2) after Revision 1 of the Scheduled Quantities Report was issued on 3 February 2017 at 12.14 pm and that is not warranted or permissible.

58 PPPL, on the other hand, contends that the Court’s finding at [375] of PPPL No 1 to the effect that a hypothetical running time of four hours for GT12 on 8 February 2017 could only be postulated because of the coincidence of GT12 having been run for maintenance purposes on 7 February 2017 and, therefore, prior to that time, PPPL could not have known that it was reasonably possible that GT12 could have been operated for four hours on 8 February 2017, means that it could not have contravened cl 3.7.3(e)(2) of the NER by a ST PASA submission made on 6 February 2017.

59 With respect to the AER’s submission, the finding in [680] of PPPL No 1 must be read in the context of the reasons as a whole. That paragraph was addressing the point in time at which PPPL ought to have had a reasonable expectation as to the availability of gas and gas transport (in the context of the 8 February counterfactual) and the latter in particular. I identified that point in time as the point at which Revision 1 of the Scheduled Quantities Report was issued and by reference to Annexures 2 and 3 to the reasons, that was on 3 February 2017 at 12:14 pm. The first ST PASA submission made by PPPL after that time and date was made at 11:00 on 6 February 2017. The finding I made ruled out a finding that the ST PASA submissions made prior to that time and date, for example, those made on 30 January 2017 and 2 February 2017, were contraventions of cl 3.7.3(e)(2). At the same time, there could only ever be a contravention of cl 3.7.3(e)(2) by the making of a ST PASA submission and that meant, on the facts, that the next possible contravention was on 6 February 2017. Read in context, the statement in [680] upon which the AER relies is not a finding that PPPL contravened cl 3.7.3(e)(2) immediately after 3 February 2017 at 12:14 pm.

60 At the same time, with respect to PPPL’s submission, the statement in [375] in PPPL No 1 is a description of the evidence given by Mr Baksi rather than a finding.

61 Mr Baksi was cross-examined by the AER about the evidence described in [375] in PPPL No 1. He gave evidence to the effect described in [380]. That evidence is set out above (at [31]).

62 The AER referred to the letter from PPPL’s solicitors, King & Wood Mallesons, dated 31 January 2020. Mr Baksi was asked about whether he agreed with various statements in that letter concerning the minimum run-time of a generator. He agreed with a number of the statements. He was asked whether he agreed with a statement to the following effect:

Further, a run time of less than 8 hours may be possible where the interests of PPPL in preserving the design life of the CCGT in accordance with its operating practice are subordinated by some other circumstance such as when AEMO issues a direction for PPPL to run a CCGT (provided that operation would be consistent with PPPL using its reasonable endeavours).

Mr Baksi was asked whether he agreed that the paragraph correctly reflected what happened from time to time in practice, that is, a run-time of less than eight hours might be possible when other interests of PPPL took precedence over preserving the design life of the CCGT. Mr Baksi said that he considered that this particular paragraph related to what PPPL did on 9 February 2017. He said that every other circumstance is driven by preserving the design life of the HRSG (heat recovery steam generator) which is dictated by water chemistry. He said the following:

If we have the water chemistry at the right level, then, yes, we can do it. And if it has run in the last 48 hours, yes, we can do it. So firstly, it doesn’t say that blankly, you can go ahead and start this CCGT even if your water chemistry is below par. It doesn’t say that.

63 The AER’s alternative argument to the argument that I should not reopen the finding at [380] in PPPL No 1 seemed to be that Mr Baksi had qualified his evidence about the minimum run-time of GT12 and that, in effect, there was no barrier to PPPL undertaking the 8 February counterfactual on 8 February 2017, regardless of the running of GT12 on 7 February 2017.

64 I reject PPPL’s first argument on the basis that it was not clearly advanced and adequately exposed prior to and at the trial.

65 I accept immediately that there is a reference to the minimum run-time of GT12 in the Joint List of Issues and Evidence, that Mr Baksi referred to the minimum run-time of GT12 and the operation of GT12 on 7 February 2017 in his first affidavit of 12 June 2020 at para 77 and it is mentioned in PPPL’s closing submissions, although it was not given a great deal of prominence (see paras 16.3, 43.2(a), 100 and 101).

66 The argument does not appear in the Amended Response to the Concise Statement, there is a somewhat passing reference to it in PPPL’s opening submissions (paras 61 and 293) and even there, the argument is that PPPL could not have anticipated that GT12 would be operated on 7 February 2017 “months in advance”. The argument does not appear in the note as to the number of contraventions attached to PPPL’s closing submissions. That the issue was not clearly advanced and adequately exposed can be shown by the following example. On one construction of Mr Baksi’s evidence, PPPL must have known sometime well prior to 7 February 2017 that the three week period was approaching and GT12 would be run before “maintaining it for another three weeks”, to use Mr Baksi’s words. For the argument to be rejected, PPPL did not need to know or have grounds to expect that GT12 would be operated on 7 February 2017 months in advance, or well in advance, of that date; it just needed to know or reasonably expect that circumstance the day before.

67 It follows that I would not exclude the contravention constituted by the ST PASA submission made at 11:00 on 6 February 2017.

(2) Whether the period covered by the ST PASA submissions included the ST PASA submissions after 16:00 on 7 February 2017 (i.e., submissions 5 to 24 inclusive)

68 The NER provide that ST PASA must be published at least daily by AEMO in accordance with the timetable and that ST PASA covers the period of six trading days starting from the end of the trading day covered by the most recently published pre-dispatched schedule with a trading interval resolution. Furthermore, the NER provide that AEMO may publish additional updated versions of the ST PASA in the event of changes which, in the judgment of AEMO, are materially significant (cll 3.7.3(a), (b) and (c)).

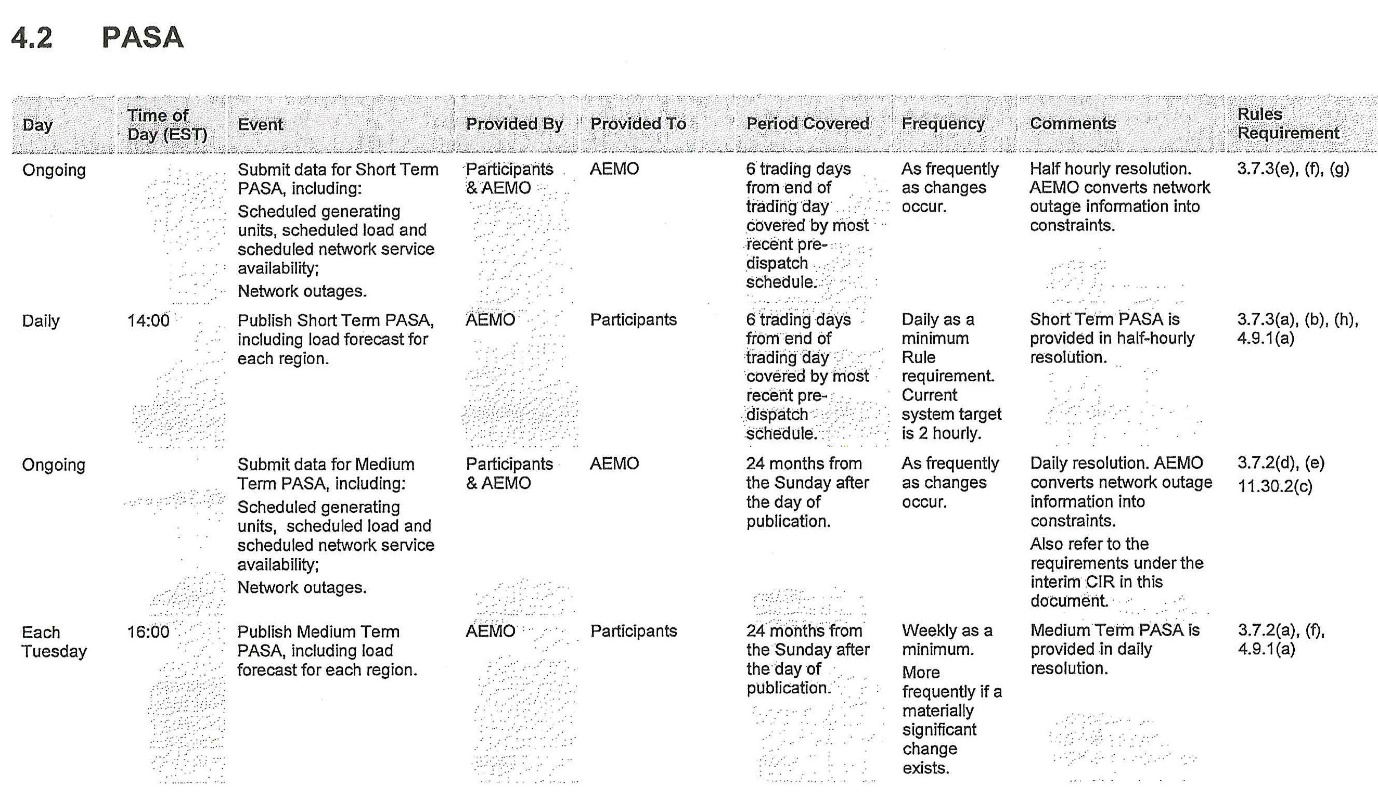

69 The section in the timetable at the relevant time in relation to both ST and MT PASA is as follows:

I refer to that part of the timetable which deals with ST PASA. The first row deals with the making of ST PASA submissions by participants and AEMO and the publication thereof by AEMO. The period covered is referred to as six trading days from end of trading day covered by most recent pre-dispatched schedule and that mirrors cl 3.7.3(b). The frequency is referred to as “As frequently as changes occur” and comments are made to the effect that the submission is in half-hourly resolution and that AEMO converts network outage information into constraints.

70 The row in the timetable which deals with the publication of ST PASA provides that it is to be done daily at 14:00. The first part of this reflects cl 3.7.3(a). Publication by AEMO is to participants and again, the period covered is referred to as six trading days from end of trading day covered by most recent pre-dispatched schedule (see cl 3.7.3(a)). As to frequency, the requirement is daily as a minimum Rule requirement and the current target system is said to be two hourly. The comments again refer to the fact that ST PASA is provided in half-hourly resolution.

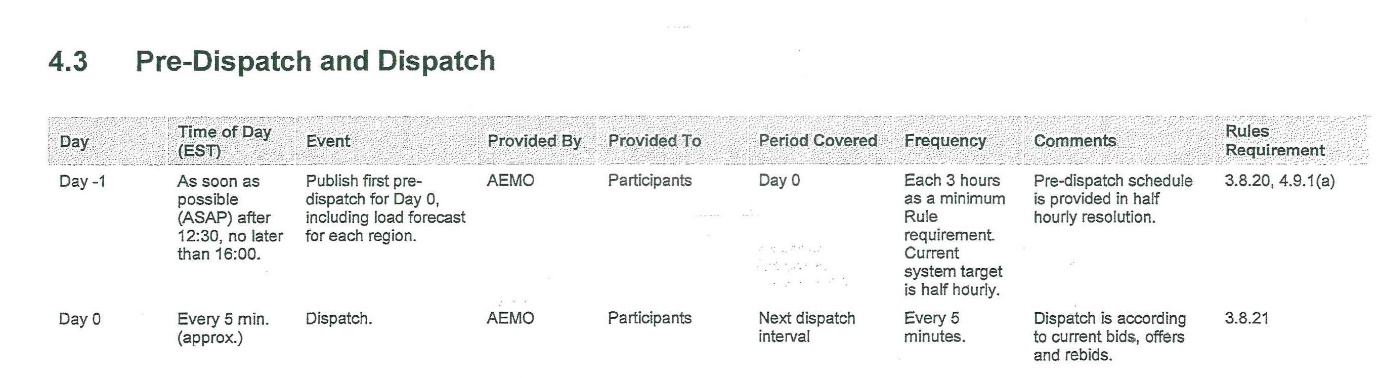

71 The topic of the pre-dispatch schedule is dealt with in cl 3.8.20 of the NER and it is addressed in two rows in Section 4.3 of the timetable. This section of the timetable is as follows:

Under the heading of “day”, there is reference to “Day-1” and the time of day (EST) being as soon as possible (ASAP) after 12:30, no later than 16:00. The event is identified as the publication of the first pre-dispatch for “Day 0” by AEMO to participants and the period covered is “Day 0”. The frequency is identified as being each three hours as a minimum Rule requirement and that the current system target was half-hourly. The comments refer to the fact that the pre-dispatch schedule was provided in half-hourly resolution.

Under the heading of “day”, there is reference to “Day-1” and the time of day (EST) being as soon as possible (ASAP) after 12:30, no later than 16:00. The event is identified as the publication of the first pre-dispatch for “Day 0” by AEMO to participants and the period covered is “Day 0”. The frequency is identified as being each three hours as a minimum Rule requirement and that the current system target was half-hourly. The comments refer to the fact that the pre-dispatch schedule was provided in half-hourly resolution.

72 PPPL submits that the effect of these rules is that even if, as was the case, PPPL’s ST PASA submissions after 16:00 on 7 February 2017 included PASA availability for the 48 trading intervals on 8 February 2017, those submissions were not required by the Rules and, in those circumstances, those submissions could not constitute contraventions. If this be correct, then the ST PASA submissions from submission 5 onwards do not give rise to contraventions. This factor alone would reduce the number of contraventions alleged by the AER from 722 to 192.

73 The short point is that having regard to the terms of the NER and the timetable, the period covered by a ST PASA submission made after 16:00 on 7 February 2017 would cover six trading days from the end of the 8 February 2017 trading day (emphasis added).

74 It was not in dispute that the six trading day period was a rolling period and that that meant that at various points in time the 8 February 2017 was the sixth day in the rolling period down to the first day in the rolling period. The AER’s principal contentions against this interpretation are that such an interpretation would not further the purpose of the Rules and that such an interpretation is inconsistent with the frequency requirement for ST PASA and the requirement in cl 3.13.2(h) that AEMO be notified of changes. PPPL’s response to the AER’s contentions is that this construction of the NER and the timetable is, for good or for ill, the clear effect of the language used.

75 I am presently considering cl 3.7.3(e)(2) of the NER which requires a Scheduled Generator to submit ST PASA inputs in accordance with the timetable. I am not presently considering cl 3.13.2(h) which requires a Scheduled Generator to notify AEMO of changes to submitted information. The purposive argument advanced by the AER may have more traction in an argument about the scope of cl 3.13.2(h), but I am not presently considering that rule. In my opinion, the words of the obligation which is the civil penalty provision are clear in that they are tied to the timetable which itself reflects earlier rules (i.e., cll 3.7.3(a) and (b)). The ST PASA submissions as referred to in the NER made after 16:00 on 7 February 2017 cover the period of six trading days commencing on 9 February 2017.

76 It follows that I would exclude from the number of contraventions, ST PASA submissions 5 to 24 inclusive.

(3) Whether submissions made within 24 hours of a relevant trading interval can constitute contraventions

77 PPPL submits that the phrase, “on 24 hours’ notice” as used in the definition of PASA availability means that a Scheduled Generator is not required to provide PASA availability with respect to a trading interval which is within 24 hours of a ST PASA submission. For the purposes of determining whether there is a contravention, a Scheduled Generator is only required to provide details of PASA availability in relation to a trading interval which is 24 hours or more from the time of the submission.

78 As can be seen from Column E of Annexure A, if this argument alone is successful, it reduces the number of contraventions from 722 to 198. There are no contraventions after submission 6. The argument, if successful, provides a basis independent of the second argument for concluding that there are no contraventions after submission 6. The argument, if successful, means that the number of contraventions is reduced from 192 (assuming the second argument is also successful) to 153 contraventions. To illustrate the argument by way of an example: the last trading interval for the 8 February 2017 gas day was the 30-minute period from 3:30 am to 4:00 am on 9 February 2017. The argument is that no ST PASA submission with respect to this period made after 3:30 am on 8 February 2017 is within the definition of PASA availability and therefore a contravention.

79 PPPL submits that the fact that PPPL actually made submissions with respect to trading intervals within 24 hours of the submission is beside the point. I note that not only did PPPL do that, but in its last submission made on 8 February 2017 at 20:51, it altered one of the PASA availability figures for the 34th trading interval. PPPL submits that it would be entirely artificial to ask a Scheduled Generator to make a prediction as to the physical plant capability it could make available on 24 hours’ notice with respect to a trading interval which was, in fact, only a couple of hours in advance of the time at which the estimation is made. Again, to illustrate the argument by way of an example: assume a Scheduled Generator is preparing a ST PASA submission at about 3:30 am for the first trading interval of the “next” day, that is, 4:00 am–4:30 am. It would be artificial to suggest that a Scheduled Generator is required to perform this exercise by considering what he or she knew approximately 24 hours earlier.

80 The AER submits that such complexities are avoided if “on 24 hours’ notice” is read to include within 24 hours.

81 I said in PPPL No 1 that the NER did not provide any indication that the postulated 24 hours’ notice was of any particular nature or given by any particular person (at [187]). Neither party suggested that that conclusion was incorrect.

82 The expression “on 24 hours’ notice” in the definition of PASA availability means that a generating unit that can be made available on say 30 hours’ notice is not PASA available for a trading interval say 24 hours from the time a submission is made.

83 As I understand PPPL’s submission, a generating unit which a Scheduled Generator discovered at the time of making a ST PASA could be made available on one hour’s notice, would not be PASA available for 23 hours (46 trading intervals) after the assumed notice was given. That seems an odd result, particularly as weather conditions, outages and other sources of supply and, therefore, generating capacity can change very rapidly (as this case illustrates) and accurate PASA availability is important. I would not reach the conclusion that PPPL’s construction is the correct one unless the words are intractable.

84 The definition of “PASA availability” was changed in 2010. The change was from “that can be made available within 24 hours” to “that can be made available … on 24 hours’ notice” (or at one point in the amendment process) “that can be made … given 24 hours’ notice”.

85 The correspondence between AEMO and the Australian Energy Market Commission (AEMC) and AEMC’s Rule Determination was put before the Court. PPPL relied on this correspondence and AEMC’s Rule Determination as supporting its construction. I reject that submission and consider that, if anything, the correspondence and AEMC’s Rule Determination supports the construction advanced by the AER.

86 It is not necessary to go through the correspondence and AEMC’s Rule Determination in detail. Three matters are important.

87 First, the amendment to the definition of PASA availability under consideration is not identified as a major change to the NER. It is identified as one of a collection of more minor changes designed to eliminate ambiguity.

88 Secondly, the mischief or ambiguity the change was designed to eliminate is stated in the material to be quite unrelated to the difference between the two constructions advanced in this case. First, it is said to be an ambiguity about “whether the 24-hour recall time applies to the period of time after or before the availability is required”. Secondly, the change was designed to avoid a situation where a participant interpreted the existing definition to mean that capability “that can be made available when, for example, only one hours’ notice is given, thereby excluding additional capability that could otherwise be made available given the full 24 hours’ notice”.

89 Thirdly, if the amendment had the effect for which PPPL contends, it is a significant change. One would expect to see in the material, a discussion of the nature of the change and the policy reasons for it. No such discussion is in the material.

90 In my opinion, the correspondence and AEMC’s Rule Determination does not support the construction advanced by PPPL.

91 In my opinion, the construction advanced by the AER can be accommodated within the words of the definition of PASA availability. It is both a sensible and practical construction and I reject PPPL’s submission to the contrary.

(4) Whether later ST PASA submissions made by PPPL which involved no change in ST PASA availability give rise to contraventions

92 PPPL submits that there can be no contravention where the Scheduled Generator made no change to PASA availability for a particular trading interval from the previous submission made by the Scheduled Generator. That is the case having regard to the terms of the rule said to have been contravened and the fact that AEMO’s computer system which requires an entry to be made for each trading interval, means that PPPL must make entries even if they involve no change to previously submitted information.

93 In Column F of Annexure A, PPPL has provided information as to the number of entries in relation to PASA availability which are different from previous entries. If one starts with the base figure of 48 entries on 6 February 2017 at 11:00, there are 52 entries thereafter (the first of which arises from the submission made on 8 February 2017 at 11:14) where PASA availability has been changed. The AER accepts that there were changes in relation to 52 entries. On this analysis, there would be 100 contraventions.

94 If the 48 entries on 6 February 2017 at 11:00 are excluded, then 52 entries are relevant. Each of the 52 entries falls after the fourth MT PASA submission. This means that if the second argument is accepted, then none of the submissions after the fourth submission are relevant. However, as I have said, PPPL appeared to accept that this did not mean that it had not committed any contraventions. It did so on the basis that if the ST PASA submission made on 6 February 2017 at 11:00 is excluded, then “it may be appropriate” to treat the second ST PASA submission made on 7 February 2017 at 9:56 as a “new” (and incorrect) submission. PPPL submitted that on this assumption the Court might find that it committed 37 contraventions by reason of the submission made at that date and time.

95 I do not accept that only changes to PASA availability can constitute contraventions. In my opinion, every time a PASA submission was made for whatever reason, it constituted a “statement” by the Scheduled Generator of its current intentions and best estimates as to (relevantly) PASA availability. The fact that there were no changes from a previous PASA submission is relevant to the penalty to be imposed.

Other matters

96 The AER submitted that the first declaration should refer to 3 February 2017 so as to reflect my finding in PPPL No 1 (at [680]). I have already referred to the significance of that finding. I do not accept the AER’s submission. The first contravention of the rule which is the subject of the declaration (i.e., cl 3.7.3(e)(2)) occurred on 6 February 2017 and that is the first date that should be referred to in the declaration.

97 The AER submitted that the reference to 320 MW should be a reference to “at least 320 MW”. It referred to passages in the transcript where it is clear that counsel for PPPL understood that the AER’s case was “at least 320 MW”. I reject the AER’s submission. I do not consider that notice is the issue. The AER set out to prove and did prove the 8 February 2017 counterfactual and that involved 320 MW. That is what should be included in the declaration (Rural Press Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2003] HCA 75; (2003) 216 CLR 53 at [89]–[90]). That PPPL’s submission is correct is neatly illustrated by the fact that there was no scope for it to make a ST PASA submission to AEMO involving an “at least” figure.

98 Finally, in view of my earlier conclusions, I do not need to consider whether there can be contraventions with respect to partially completed trading intervals. It seems unlikely that that is the case in view of the words in cl 3.7.3(e)(2) “for each trading interval”, but I do not need to decide the point.

Conclusions with respect to the First Declaration

99 It is for these reasons I consider the First Declaration should be in the terms set out above (at [41]). There were 192 contraventions of cl 3.7.3(e)(2) of the NER.

The Second Declaration (Para 2(a) cl 3.13.2(h) and ST PASA submissions)

100 The AER did not apply to amend its Originating application to include a claim for this declaration or file any evidence in support of such an application.

101 PPPL submits that the declaration sought by the AER in para 2(a) (see [11] above) is not within the case the AER advanced at trial. It is not identified in any of the documents prepared prior to and for the purposes of the trial. Further, or in the alternative, PPPL submits that the factual findings made in PPPL No 1 do not support the declaration. In other words, there is not a proper basis in the findings for the declaration.

102 The AER submits that the declaration fits “conformably” within the case it advanced at trial and it is based on the findings made in PPPL No 1.

103 The first point to note, and the first point raised by PPPL, is that a claim for declaratory relief for a contravention of cl 3.13.2(h) in relation to ST PASA submissions was not made in any form by the AER at trial.

104 There was no claim by the AER for a contravention of cl 3.13.2(h) in relation to ST PASA submissions in the Originating application, Concise Statement, Joint List of Issues and Evidence and AER’s Outline of Opening Submissions and Outline of Closing Submissions. That circumstance is to be considered in a context in which there were disputes between the parties before trial about the scope of their respective cases (PPPL No 1 at [7]). Having regard to those disputes, this is not a case where one would say that the parties were not insisting on strict adherence to the case as formulated in the documents they exchanged. They were insisting on precisely that. Furthermore, I consider that it should be inferred from the fact that the AER did advance a case of a contravention of cl 3.13.2(h) in relation to MT PASA that AER considered, but rejected, advancing a case of contravention of cl 3.13.2(h) in relation to ST PASA. As I have said, the AER has provided no explanation by way of affidavit as to the reasons it now seeks a declaration in terms of para 2(a). The circumstances do not suggest an explanation other than, in view of the findings in PPPL No 1, it now seeks to raise a claim it considered and could have raised from the outset. The AER raised this claim for the first time on 27 September 2023. The case was one in which events over the whole period from 11 November 2016 to 8 February 2017 were relevant, including those circumstances affecting gas supply and gas transport, and the possibility that the Court might find that there was a contravention at some point between those dates was clearly foreseeable. It is clear that the availability of gas and gas transport were said to be relevant issues from an early stage and that can be seen from questions in the notices served by the AER on PPPL under s 28 of the NEL dated 15 June 2018 and 8 March 2019 respectively.

105 PPPL submits that the AER’s argument that its case was that the circumstances which gave rise to the changes to submitted information were the transfer of GT12 from dry to wet storage on 11 November 2016 is correct, but it does not go anywhere because there was nothing at all which prevented the AER pleading in the alternative, a case of a contravention of cl 3.13.2(h) with respect to ST PASA submissions. In my opinion, PPPL’s submission is clearly correct.

106 PPPL submits that it is relevant that even now the AER does not bring forward an application to amend the Originating application and Concise Statement and an affidavit explaining why the matter was not alleged at the outset. As I understand it, the AER’s response is that it does not need to make an application to amend because the declaration is within the findings in PPPL No 1. I do not think that that is correct. An amendment might be hard to resist because of the findings made at the trial as to liability, but that does not mean that an application to amend does not need to be made. The declarations sought in a proceeding must be in the Originating application (Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) r 8.03).

107 PPPL submits that in terms of the prejudice, there is at least a question that evidence about how cl 3.13.2(h) interacts with cl 3.7.3(e)(2) as distinct from cl 3.7.2(d)(1) might have been relevant bearing in mind the frequency of ST PASA submissions. That is possible, but in the absence of any details from PPPL as to the nature of this evidence and its importance, I am not inclined to place much weight on this argument.

108 Irrespective of the procedural difficulties, PPPL also raised two matters which it said are relevant to whether the declaration should be made. The first matter is that there could not be a contravention of cl 3.13.2(h) before 7 February 2017 because prior to that date, GT12 could not have been operated in a way which met the 8 February counterfactual, in other words, it could not have been run for only four hours. I have dealt with this matter elsewhere and it is rejected. The second matter is that there is a real issue as to whether the declaration sought by the AER in para 2(a) is dealing with the same conduct as the declaration in para 1. Section 67 of the NEL is relevant in this respect. Subsection (1) provides that if the conduct of a person constitutes a breach of two or more civil penalty provisions, proceedings may be instituted against the person in relation to the breach of any one or more of those provisions. Subsection (2) provides that nevertheless, the person is not liable to more than one civil penalty in respect of the same conduct. Whether this section is restricted to the civil penalty imposed and does not speak to the making of declarations was not addressed. Furthermore, this argument raises a point of some complexity, not so much for the period from 3 February 2017 to a point on 6 February 2017, but for the period from a point on 6 February 2017 to 8 February 2017.

109 There are a number of cases which have discussed the function of Concise Statements, the obligation of an applicant to identify clearly the case it advances and the fact that the Court will not take a narrow and pedantic approach to a Concise Statement or, for that matter, a Concise Response. The parties referred, in particular, to the following authorities: Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Ltd [2019] FCA 1284; (2019) 139 ACSR 52; Allianz Australia Insurance Ltd v Delor Vue Apartments CTS 39788 [2021] FCAFC 121; (2021) 287 FCR 388 at [149] per McKerracher and Colvin JJ; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Meriton Property Services Pty Ltd (No 2) [2018] FCA 1125 at [56]–[66] and [89]–[90] per Moshinsky J (involving an issue as to the number of contraventions); Australian Securities and Investments Commission v National Australia Bank Ltd (No 2) [2023] FCA 1118 at [6]–[7], [12], [18], [35], [38], [39], [43]–[48], [52], [79], [84], [86] per Derrington J (also involving an issue as to the number of contraventions). I have considered all of those authorities.

110 The essence of the AER’s submission is that the matter should be analysed in terms of whether what it now seeks falls within the temporal boundaries of its case and the legal and conceptual boundaries of its case. The AER submits that the declaration in para 2(a) falls within these boundaries. There is certainly force in the submission that the declaration in para 2(a) is within the temporal boundaries of the case. It is less clear that the declaration in para 2(a) is within the legal and conceptual boundaries of the case. In this context, I note that one of the submissions made by the AER was that it was not pressing an allegation when, in fact, it could never have succeeded on that allegation which did not in reality seem to be part of its case (see AER’s written submissions on relief at [68(b)]). The fact is that the AER was claiming relief for contraventions of cl 3.7.3(e)(2) by the making of ST PASA submissions on particular days. In any event, the reference to legal and conceptual boundaries is only one way of looking at the matter.

111 In this case, there is no application to amend and whether or not such an application is necessary or not, there is no explanation for why the declaration is now sought in circumstances in which the declaration could have been sought in the alternative from the outset. Furthermore, it is open to the Court to infer that the AER considered, but rejected, seeking such a declaration at the outset. In the circumstances, I refuse to make the declaration sought in para 2(a).

The Third Declaration (Para 2(b) cl 3.13.2(h) and MT PASA submissions)

112 The declaration sought by the AER (see [11] above) in para 2(b) identifies a contravention of cl 3.13.2(h) and not cl 3.7.2(d)(1). The contravention is identified in the declaration as having taken place on and after 3 February 2017 which was the date, on the findings in PPPL No 1, PPPL ought to have had a reasonable expectation of obtaining sufficient interruptible gas transport (and gas) to operate in accordance with the 8 February counterfactual and the declaration identifies the increase in MT PASA availability. The declaration identifies the MT PASA submission immediately prior to 3 February 2017, that is, the MT PASA submission made on 27 January 2017 (see PPPL No 1 at [65]). The declaration in para 2(b) is similar to the third declaration sought at trial, except that it relates to a shorter period of time and does not rely on the event of GT12 being brought from dry storage and placed in wet storage on 11 November 2016 as the trigger for the obligation to notify AEMO of changes to submitted information.

113 Before turning to PPPL’s submissions, there are three further matters to note.

114 The first matter to note is further aspects of the timetable. PPPL’s ongoing obligation to submit data for MT PASA to AEMO is said to be “as frequently as changes occur”, the period “covered” is 24 months from the Sunday after the day of publication. AEMO’s related obligation is to publish MT PASA to the participants each Tuesday with a “Frequency” of weekly as a minimum and “[M]ore frequently if a materially significant change exists” and with a period “covered” of 24 months from the Sunday after the day of publication.

115 The second matter to note is how the AER advanced its case at trial concerning the alleged contravention of cl 3.13.2(h). The AER addressed the issue briefly in its written outline of opening submissions (see paras 167–168, 202–205 and 280–282).

116 In its closing written submissions, the AER submitted that there were three issues in the proceedings, one in relation to each rule alleged to have been contravened. In relation to cl 3.13.2(h), the issue was identified as being whether on and from 11 November 2016, the bringing of GT12 from dry storage into wet storage and into service resulted in a change of the MT PASA availability for 8 February 2017 and whether PPPL failed to notify AEMO of that change as soon as practicable.

117 The third matter to note concerns the mental element or standard of care which must be established in order to establish a contravention of cl 3.13.2(h). I addressed the mental element or standard of care required of Scheduled Generators in relation to each of the rules in PPPL No 1 (cl 3.7.2(d)(1) at [170]; cl 3.7.3(e)(2) at [189]; and cl 3.13.2(h) at [208]).

118 PPPL advanced four reasons in support of its submission that the declaration in para 2(b) should not be made.

119 First, PPPL submits that the declaration identifies a contravention of cl 3.13.2(h) which was not part of the AER’s case at trial. The event giving rise to the “changes” to submitted information as identified in the declaration in para 2(b) when read with PPPL No 1 was the availability of gas (at [532]) and gas transport (at [617] and [680]), whereas the event identified in the third declaration sought at trial was the transfer of GT12 from dry to wet storage on 11 November 2016.

120 I do not consider this point to be fatal to the AER’s claim for the declaration because the case was run on the basis that the availability of gas and gas transport were critical issues and those issues were to be considered at various points in time from 11 November 2016 onwards. As I have previously said, the evidence was not restricted to events on 11 November 2016.

121 Secondly, PPPL submits that there are insufficient findings in PPPL No 1 to support the conclusion that there has been a contravention of cl 3.13.2(h). There are two relevant differences between the requirements for ST PASA submissions on the one hand, and MT PASA submissions and cl 3.13.2(h) (when applied to MT PASA submissions) on the other, and they are the mental element or standard of care to be applied and the fact that, in the case of MT PASA submissions, the Scheduled Generator must estimate PASA availability taking into account “the ambient weather conditions forecast at the time of the 10% probability of exceedance peak load”, whereas that is not a matter referred to in the case of ST PASA submissions.

122 In my opinion, there are sufficient findings and conclusions in PPPL No 1 to draw a conclusion as to the first matter (at [208] and [680]). The standard of care for MT PASA submissions was identified in PPPL No 1 (at [170]) as was the standard for ST PASA submissions (at [187]–[189]). There are no findings, and nor I think was there any evidence, about ambient weather conditions and percentage probabilities of exceedance peak load. As to this matter, the AER submits, correctly in my view, that no issue was raised concerning the issue at the trial as to liability.

123 The third argument advanced by PPPL is a technical one. The obligation in cl 3.13.2(h) to notify AEMO of changes is designed to ensure that submitted information (which must be published by AEMO) is as accurate as possible. As I understand PPPL’s argument, it is that there is no contravention of cl 3.13.2(h) by PPPL where the information “covering” 8 February 2017 is accurate at the time it is provided by PPPL. The MT PASA submission made by PPPL on 27 January 2017 was accurate and would have been published by AEMO on 31 January 2017 and would have covered the period of 24 months from Sunday, 5 February 2017, including Wednesday, 8 February 2017. Had PPPL notified AEMO of a change of MT PASA availability on 3 February 2017 as the AER contends, the information would have been published by AEMO the following Tuesday, 7 February 2017, and covered the period from Sunday, 12 February 2017 onwards. In other words, the MT PASA information would not have covered 8 February 2017.

124 In my opinion, the AER’s response to this argument is correct. PPPL’s submission conflates the obligation in cl 3.7.2(d)(1) to make MT PASA submissions and the obligation in cl 3.13.2(h) to notify AEMO of changes to submitted information. The latter obligation arises when there are changes to submitted information.

125 Finally, PPPL submits that there can be no contravention of cl 3.13.2(h) before 7 February 2017 when GT12 was operated for a substantial period of time. It was only that circumstance, according to the evidence of Mr Baksi, that could give rise to a reasonable expectation that the 8 February counterfactual could be implemented on 8 February 2017. I have already addressed this argument and rejected it.

Conclusions with respect to the Second Declaration

126 It was for these reasons I consider the Second Declaration set out above (at [41]) should be made. There was one contravention of cl 3.13.2(h) on 3 February 2017 which continued for five days resulting in a maximum penalty of $150,000. For the same reasons I gave in relation to the First Declaration, the Second Declaration should refer to “320 MW” and not “at least 320 MW”.

CIVIL PENALTY

General Matters

127 Section 64 of the NEL provides that the Court must have regard to all relevant matters in determining the civil penalty to be paid by a person declared to be in breach of a provision of (inter alia) the Rules, including the following matters:

(a) the nature and extent of the breach; and

(b) the nature and extent of any loss or damage suffered as a result of the breach; and

(c) the circumstances in which the breach took place; and

(d) whether the person has engaged in any similar conduct and been found to be in breach of a provision of this Law, the Rules or the Regulations in respect of that conduct; and

(e) whether the service provider had in place a compliance program approved by the AER or required under the Rules, and if so, whether the service provider has been complying with that program.

128 The matters identified by French J (as his Honour then was) in Trade Practices Commission v CSR Limited [1990] FCA 521; (1991) ATPR 41-076 at [42] are also relevant. They correspond with, overlap or are additional to the matters identified in s 64 and are as follows:

1. The nature and extent of the contravening conduct.

2. The amount of loss or damage caused.

3. The circumstances in which the conduct took place.

4. The size of the contravening company.

5. The degree of power it has, as evidenced by its market share and ease of entry into the market.

6. The deliberateness of the contravention and the period over which it extended.

7. Whether the contravention arose out of the conduct of senior management or at a lower level.

8. Whether the company has a corporate culture conducive to compliance with the Act, as evidenced by educational programs and disciplinary or other corrective measures in response to an acknowledged contravention.

9. Whether the company has shown a disposition to co-operate with the authorities responsible for the enforcement of the Act in relation to the contravention.

The nature and circumstances of the contravening conduct

129 Under this heading, I address the matters identified in s 64(a) and (c) and the first and third of the matters identified by French J.

130 PPPL’s contravening conduct was in underestimating and failing to update its PASA availability and, in particular, the physical plant capability at the Pelican Point PS that could be made available on 24 hours’ notice. This was in a legislative or rule based context in which AEMO has the power to direct a Scheduled Generator to bring a generator online to avoid shortages which may lead to load shedding.

131 The summer of 2016/2017 was anticipated to be one in which South Australia would face significant energy security risks that it had not faced in previous summers. Mr Foulds was an ENGIE employee and between 2012 and January 2016, he was Origination Manager and Trading Manager based in Melbourne, and from January 2016 to August 2018, he was Head of Trading and Portfolio Management. His responsibilities in those two positions are identified in PPPL No 1 (at [296]–[297]). Mr Foulds said that there were two reasons South Australia faced significant energy security risks in the summer of 2016/2017 and they were as follows: (1) the Northern Power Station was closed as was the mothballed Playford B Power Station and this was South Australia’s first summer without the Northern Power Station providing 520 MW of coal-fired baseload power; and (2) the September 2016 Black System event when a number of wind farms reduced their power output by over 450 MW in a number of seconds causing the Heywood Interconnector to trip and isolating South Australia from the National Electricity Market. GT12 was brought from dry storage to wet storage so that it would be available to be used interchangeably with GT11. GT12 was a backup turbine and according to Mr Baksi was brought into wet storage to ensure market needs were met on very extreme days and that reliability of supply was assured to the extent possible.

132 It was not in dispute that GT12 was brought from dry to wet storage so that it would be a backup to GT11 and that the turbines would be used interchangeably from time to time. Furthermore, it was not in dispute that PPPL’s intention throughout was to operate one generator and provide one generator and provide 240 MW.

133 Mr Foulds did not turn his mind to changing PPPL’s PASA submissions at the time GT12 was taken from dry to wet storage (PPPL No 1 at [329] and [342]) and insofar as he did thereafter, the commercial intention to run only one turbine and a lack of firm gas supply beyond this led to the fact that the PASA availability did not exceed approximately 240 MW (PPPL No 1 at [344] and [357]).

134 It is not in dispute that PPPL’s non-disclosure of PASA availability after 12:14 pm on 3 February 2017 was not deliberate or intentional. In other words, it did not, with a proper understanding of its obligations, decide to proceed in the way in which it did. It misunderstood its obligations focusing on its current intentions and its arrangements with respect to gas supply and gas transport.

135 The AER submitted that this could not be a mitigating factor.

136 I do not consider that a great deal is to be gained by determining what might or might not constitute a mitigating factor in the case of these contraventions. The fact is that the contraventions were not deliberate or intentional and that is a matter to be taken into account.

137 PPPL asked the Court to take into account three matters.

138 First, had GT12 been left in dry storage, there would have been no contraventions and one of the reasons it was taken from dry storage to wet storage was to “maintain system security” (PPPL No 1 at [328]). That was a responsible approach by PPPL.

139 Secondly, with respect to the AER’s submission that the contraventions arose as a result of PPPL’s misunderstanding of the NER cannot be a mitigating factor, PPPL submits that, generally speaking, that would be correct. However, PPPL referred to the observation I made in PPPL No 1 (at [184]) that the NER dealing with PASA submissions are not a model of clear and precise drafting. More significant than that observation, is that a number of important aspects of the AER’s case taken to trial did not succeed. I do not propose to set out an exhaustive list as the matters are set out in PPPL No 1, but the following are examples:

(1) contrary to the AER’s case, the mere fact that GT12 was moved from dry to wet storage did not necessitate a change to PPPL’s PASA submissions;

(2) the AER’s case that PPPL contravened cl 3.7.2(d) of the NER failed;

(3) the AER’s case by reference to the 320 MW scenario, which its own expert described as “unrealistic”, failed; and

(4) it was necessary to read a requirement of reasonableness into cl 3.7.2(d) of the NER.

140 Thirdly, it is relevant that a number of the submissions made by PPPL were resubmissions without change which came about because the AER’s system was such that all fields must be completed when entering an updated ST PASA submission.

141 I consider that the first and third matters are relevant and I take them into account. I am unable to see how the aspects in respect of which the AER failed affects the penalty for contraventions it did establish.

Whether the contraventions arose out of the conduct of senior management or at a lower level