FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Auto & General Insurance Company Limited [2024] FCA 272

ORDERS

AUSTRALIAN SECURITIES AND INVESTMENTS COMMISSION Plaintiff | ||

AND: | AUTO & GENERAL INSURANCE COMPANY LIMITED (ACN 111 586 353) Defendant | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The originating process be dismissed.

2. The plaintiff pay the defendant’s costs.

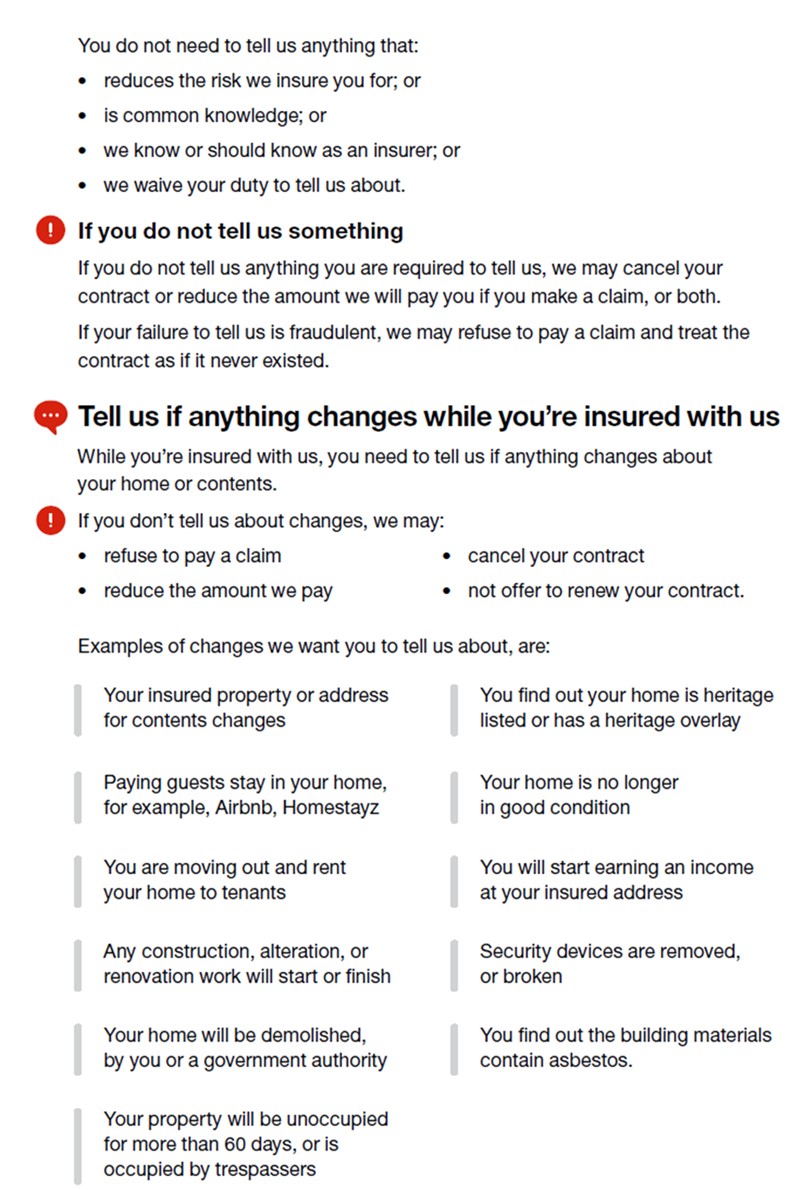

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

JACKMAN J

Introduction

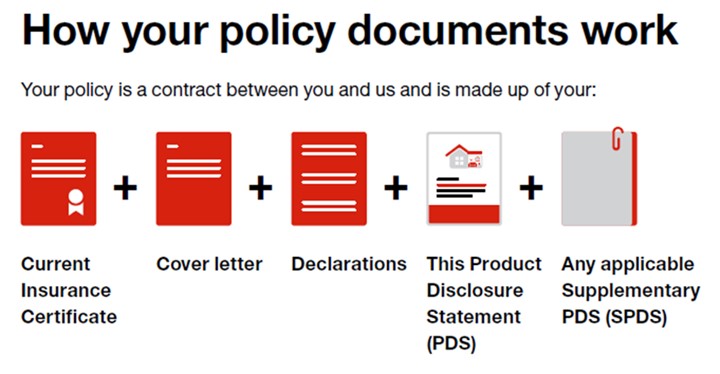

1 These proceedings concern contracts for home or contents insurance, or both, entered into by the defendant between 5 April 2021 and 4 May 2023 (the Relevant Period), which contained certain notification obligations on the part of the insureds which operated after the contracts were entered into and during the period of cover. Each of the contracts of insurance comprised a Product Disclosure Statement (PDS) dated 1 March 2021, a cover letter, an insurance certificate, declarations and applicable supplementary PDSs. The PDSs were issued under various brands (such as Budget Direct, ING and Virgin Insurance) but were otherwise in substantially identical terms. Consumers could elect to take insurance cover over their home or their contents or both on the terms stipulated in the PDSs and supplementary PDSs. The cover also included legal liability cover. The contracts were renewable on an annual basis. The defendant admits that between 5 April 2021 and 21 March 2023, the defendant entered into, including by renewal, approximately 1,377,900 contracts of insurance which contained the relevant obligations for notification.

2 The following are the PDSs dated 1 March 2021 which are in issue in the proceedings:

(a) Auto & General Your Home and Contents Insurance Policy (issued under the following brands: 1st for Women, Best Buy, Ozicare, Retirease, and Maxxia);

(b) Budget Direct Your Home and Contents Insurance Policy;

(c) Australia Post Your Home and Contents Insurance Policy;

(d) ING Home and Contents Insurance Policy;

(e) Catch Insurance Your Home and Contents Insurance Policy; and

(f) Qantas Home and Contents Insurance.

Various supplementary PDSs were issued on 14 May 2021, 31 August 2021, 14 July 2022 and 4 May 2023.

3 The plaintiff (ASIC) claims that the obligation for notification stipulated in the PDSs is unfair within the meaning of ss 12BF(1)(a) and 12BG(1) of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth) (ASIC Act). The commencement date for the period of the claim, being 5 April 2021, was the date when the Financial Sector Reform (Hayne Royal Commission Response — Protecting Consumers (2019 Measures)) Act 2020 (Cth) (Amending Act) became effective, amending s 15 of the Insurance Contracts Act 1984 (Cth) (ICA) to render contracts of insurance subject to relief relating to the effect of s 12BF of the ASIC Act, and inserting a note into s 12BF of the ASIC Act to the effect that s 12BF “applies to Insurance Contracts Act insurance contracts in addition to the Insurance Contracts Act 1984”.

Salient Aspects of the PDSs

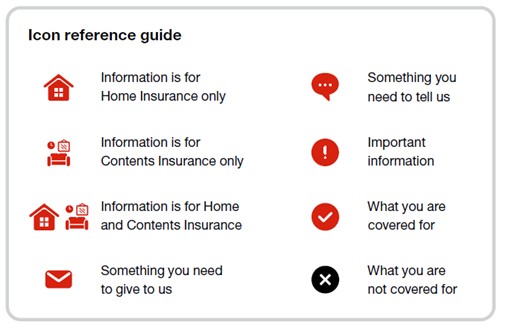

4 The images and page numbers set out below are taken from the PDS entitled “Auto & General Your Home and Contents Insurance Policy”, and substantially the same material appears in each of the PDSs. The PDS stated as part of the “Overview” (p 3) that: “We’ve written this document in plain language to help you understand your insurance cover and how to make a claim.” It was also said that icons were included representing the key cover to make it easier to read the document, and an icon reference guide as follows was set out (p 4):

5 Under the heading “How we work together for an easy claims process” (p 5), various steps were set out, the last of them being as follows:

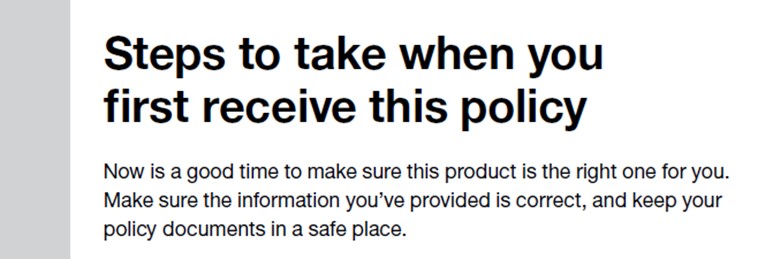

6 Several pages later the following appeared (pp 8–9):

…

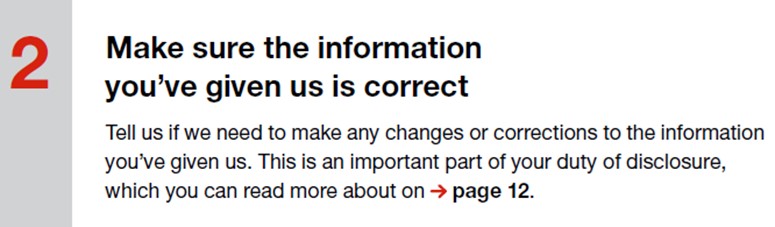

7 Section 2 of the PDS dealt with the agreement between the defendant and its insureds, and began with the following (p 11):

I note that the cover letter stated, after referring to the need to check the insurance certificate and declarations:

It’s an important part of your duty not to make a representation (as per the Product Disclosure Statement) to let us know if any details are incorrect or need to be updated.

…

Please review all pages of your insurance policy documents carefully. In particular, you need to check all the details in the Insurance Certificate and Declarations. It’s an important part of your duty not to make a misrepresentation to tell us if any details are incorrect or need updating.

I also note that the declarations commenced with the words:

“This is the information we have on our records, based on the questions we asked and the answers you gave us. Please check that the answers you provided still apply and contact us if anything has changed. This is an important part of your duty not to make a misrepresentation”.

8 On the following two pages of the PDS (pp 12 and 13), the following appeared:

9 I refer to the last portion of that section beginning with the sub-heading “Tell us if anything changes while you’re insured with us” as the Notification Clause. The Notification Clause is the focus of ASIC’s claim. It was amended from 4 May 2023.

10 Supplementary PDSs were issued on 14 July 2022 to remove “Your duty of disclosure” and replace it with “Your duty not to make a misrepresentation”, consistently with amendments to the ICA in relation to consumer insurance contracts embodied in ss 20A and 20B. The Supplementary PDSs included the following under the heading “Your duty to us”:

You have a legal duty under the Insurance Contracts Act to take reasonable care not to make a misrepresentation to us. This duty first arises when you enter into an insurance contract with us. Before we agree to renew, extend, vary or reinstate your policy, we may remind you of your previous answers to our questions. Your duty extends to telling us whether any of this information has changed.

11 In Section 5 of the PDS, the topic of policy renewals was dealt with under the heading “Renewing the policy”, and that section of the PDS contained the following (p 67):

Processes Relating to Applications for Insurance

12 Evidence concerning the processes involved in the Relevant Period for the application by customers for the defendant’s home and contents insurance products was given in two affidavits by Ms Jenner, an underwriting manager for the defendant. Certain aspects of that evidence were clarified in correspondence between ASIC and the solicitors for the defendant on 20 and 23 February 2024, which was agreed to be admitted without limitation.

13 A customer could initiate the application process by obtaining a price quote for, and purchasing, home and contents insurance from the defendant in one of three ways: (i) via the website of Budget Direct or the website of one of the defendant’s other brand partners; (ii) via the website of an insurance “aggregator”, which is an intermediary providing price comparisons of insurance offerings from different insurers (such as the aggregator known as “Compare the Market”); or (iii) via telephone, by calling the Budget Direct call centre, the call centre of one of the defendant’s other brand partners or the call centre of an aggregator, and speaking with a consultant to start an application. A customer could also complete an application using a combination of the above three methods, for example by starting an application online but then completing it over the phone, or vice versa. Whichever method was deployed, the customer was advised of their duty of disclosure and of the duty to take reasonable care not to make a misrepresentation, and the potential consequences of not complying with those obligations.

14 Under each method of application, potential customers were asked a series of questions about the customer and their home and contents. In relation to an online application through the website of Budget Direct or one of the defendant’s other brand partners, the customer was required to answer questions concerning the following:

(a) the customer’s address, being the address, including the postcode, of the property to be insured;

(b) the property type;

(c) whether the property was part of a body corporate or a strata title complex;

(d) the year in which the home was built;

(e) whether the home was heritage listed or subject to a National Trust classification. For online sales, if the customer indicated that the building was built before 1940, the customer was then asked whether the property was heritage listed or subject to a National Trust classification. That question was followed by the words: “Select ‘yes’ if the property is included on a local, state or national list that provides legal protection for items of heritage value or is subject to a heritage overlay”. There were then two possible answers, “Yes” or “No”, and the customer had to select one of those options. For call centre sales, if the customer selected an option indicating that the building was built before 1945 (noting that the relevant date range option was 1940–1945), the customer was then asked whether the home has a heritage, heritage overlay, or National Trust listing. I note that it would appear that the defendant was operating on the assumption that a building which was built in or after 1940 would not be heritage listed or subject to a National Trust classification, and there is no evidence before me which indicates that the assumption was wrong or unreasonable;

(f) the construction material of the home’s exterior walls and roof. In this regard, the potential customer was first asked: “What is the main building material of the exterior walls?” That question was followed by the words:

If different building materials have been used on the home’s exterior, please select the primary type of material that surrounds the main living area of the home. If any Asbestos exists in the walls, please select Asbestos. If your walls are rendered, please choose the material underneath the render.

They were then shown ten possible answers and the customer had to select one of those options. The ten possible answers included asbestos, and the customer was told to choose this if “any Asbestos exists in the walls e.g. Fibrolite, Hardiflex, Imitation brick cladding, Villaboard”. The customer was then asked: “What is the main construction material for the roof?” followed by the words:

If different construction materials have been used on the home’s roof, please select the primary type of material that covers the main living areas of the home. If any Asbestos is present in the roof, please select Asbestos.

They were then shown eight possible answers and the customer had to select one of them, which included “Asbestos e.g. Super Six, Fibrolite and corrugated cement sheeting”. Customers who contacted the call centre were also given the specific instruction that if any Asbestos exists in the walls or roof, then the customer was told to select the asbestos option, but those who contacted aggregators were not given that precise instruction (noting that aggregators sought to standardise their questions across all insurers as a fundamental aspect of their service was to provide price comparisons of insurance offers from different insurers to customers);

(g) the nature of the occupancy, and in this regard the customer was asked “How is the property occupied?” and had to select one of seven options, namely (a) “Owner occupied”, (b) “Owner – yet to occupy”, (c) “Rented to tenants – landlord”, (d) “Renting as a tenant”, (e) “Owner – to be rental investment”, (f) “Holiday home – not rented”, and (g) “Holiday home – may be rented. Rented out for payment as holiday accommodation e.g. Airbnb, Stayz and holiday rentals etc”. Similar questions were asked by aggregators and call centre personnel;

(h) the type of cover the customer wanted to purchase;

(i) the month and year in which the customer moved into the property;

(j) the name of any mortgagee or home lender for the property;

(k) the customer’s estimate of the total cost to rebuild the home at today’s prices;

(l) the security of the home, in which regard the potential customer was asked whether the home was fitted with a security alarm and, if so, was asked whether the alarm had an internal siren, external siren, external strobe light or active back to base monitoring;

(m) the customer’s estimate of the total cost to replace the home’s contents at today’s prices;

(n) whether the property was used as business premises. In this regard, the potential customer was asked “Is any part of the property used as a business premises, or for buying, selling or storing business products or equipment?” The screen then displayed the words: “Business activity is defined as any registered business, or any activity that derives an income. This does not include working remotely from a home office.” Customers who contacted aggregators were not given that definition of “business activity”. If the potential customer said “yes”, they were asked to select which type of business it was (eg surgery, childcare, bed and breakfast), and provide further information such as the number of rooms used in conjunction with the business, and the number of non-household members who worked in the business. Childcare centres attracted additional questions about the number of children and whether the business was registered;

(o) the customer’s date of birth;

(p) the customer’s claims and loss history; and

(q) whether any person living in the home was retired.

15 After obtaining a quotation, if a customer wished to continue to purchase the insurance online, further questions were asked of them which related to:

(a) whether the home was under an immediate threat of damage by severe storms, bushfires, grassfires or floods;

(b) whether the home was structurally sound. In this regard the potential customer was asked: “Is the home in good condition?” That was followed by the words:

This means your home, property and contents do not have any faults or defects that might cause:

a. loss or damage to your home/property and contents,

b. loss or damage to property of others or,

c. injury to people.

This includes but is not limited to:

- No leaks, holes, damage, rust or wood rot in the roof, gutters, windows, floors, fences or other parts of your home.

- A sound and solid structure with no damage to foundations, walls, steps, flooring, ceilings, gates and fences.

- No damage from or infestation of termites, ants, vermin, or other creatures,

- No broken or boarded-up windows.

The customer then had to select “Yes” or “No”, and if the customer selected “No”, the customer was given the following statement:

You have told us that the home, property or contents is not in good condition. We are unable to offer you insurance.

(c) whether the customer shared the home with anyone other than the customer’s family and the number of those persons;

(d) the occupancy of the home. In this regard the potential customer was asked “Is the home currently unoccupied?” followed by the words: “You need to let us know if the home becomes unoccupied for more than 60 consecutive days during the term of the policy.” The potential customer had to select “Yes” or “No”, and they were then asked: “On what date will the home be unoccupied?” followed by a text box requiring the day, month and year to be input;

(e) the security of the home’s exterior doors and windows;

(f) whether the home is under construction, undergoing renovation, alteration, extension or being demolished. If the customer selected “Yes”, the customer was then asked: “What type of work is being conducted?” If the customer selected demolition, the screen stated: “You have told us that the home is being demolished. We are unable to offer you insurance.” The customer was otherwise asked: “Are any of the external walls or areas of the roof being removed?”; “Is the home being raised, stumps removed or replaced or being built underneath?”; “When is the building work expected to be completed?”; and “What is the value of the work being completed?”;

(g) whether the customer had held insurance for the home in the previous seven days;

(h) the customer’s claims and loss history;

(i) whether the customer or a member of their household had other insurance cancelled or an insurance claim refused in the previous five years; and

(j) whether the customer or a member of their household had ever been convicted of a criminal offence.

16 The same process and questions set out above were asked of a customer who applied for home and contents insurance via an aggregator’s website or via a call centre, subject to the exceptions and qualifications to which I have referred above.

17 As is apparent from the text of the Notification Clause which I have extracted above, that portion of the PDSs provided 11 examples of changes which the defendant said it wanted insureds to tell it about. Each of the 11 examples set out in the Notification Clause relates to questions seeking information concerning the relevant property to be insured which were asked of customers applying for insurance. Not all customers were asked exactly the same questions, nor were all the questions framed in exactly the same way, irrespective of the method used by the potential customer to make an application for insurance. I have indicated above the particular differences in relation to the questions concerning heritage listing and the presence of asbestos. However, those differences do not detract from the proposition that each of the 11 examples in the Notification Clause did relate to questions which were asked generally of customers applying for insurance, and to the information which either was or may have been provided in answer to those questions, depending on the circumstances of each customer.

18 Answers to the questions to which I have referred above provided the defendant with information about the customer and their home and contents which the defendant then used in its underwriting and pricing algorithms to make an underwriting decision whether to offer insurance to that potential customer and, if so, on what terms. Those questions were framed with reference to the defendant’s Underwriting Policy and Underwriting Guidelines.

19 The Underwriting Policy sets out how the defendant manages the risks arising from its underwriting function across its main areas of business. The defendant says that its commercial objective is to offer customers competitive premiums and dependable insurance and the Underwriting Policy sets out how the defendant seeks to balance price competitiveness with product quality, service reputation and security by outlining the components of the underwriting framework. Those components included the underwriting processes used by the defendant which are largely automated and controlled by proprietary software (known as “DISC”), the scope of cover the defendant may offer customers, the unacceptable risks the defendant will not accept, the risk assessment criteria for underwriting decisions, and various operational matters (including indemnity limits, the authority limits for members of the underwriting team, and the process for reviewing the policy).

20 The Underwriting Guidelines also set out, for the defendant’s home and contents insurance products, the acceptable and unacceptable risks to the business. Section 2 sets out the “underwriting rules” as to “unacceptable risks” and “risks to be referred to underwriting”. Section 3 describes the rationale behind the guidelines and explains why the defendant does not accept certain types of risks and treats certain matters as posing a greater risk. As Ms Jenner explains, the pricing of the defendant’s insurance is heavily dependent on the actuarial assessment of certain kinds of risks, and risks outside those which the defendant would normally accept have the potential to change materially the likelihood and size of the claims, and as such, the level of premium that would be charged to customers within the relevant pool.

21 In relation to the 11 examples set out in the Notification Clause, each of those examples corresponds to a matter described in the Underwriting Guidelines as posing either an unacceptable risk or a greater risk.

22 If a customer wished to renew an existing policy during the Relevant Period, they were advised before renewal (on their insurance renewal documents, on screen during the renewal process online, or over the phone by the consultant) that they needed to confirm if any changes or corrections needed to be made to insurance details already provided to the defendant before renewal in accordance with their duty of disclosure or their obligation to take reasonable care not to make a misrepresentation. A customer could update their details any time online or by calling the call centre of Budget Direct or the call centre of one of the defendant’s other brand partners.

The Claims Assessment Processes

23 The defendant’s claims management processes are the subject of evidence given by Ms Hartley, the defendant’s General Manager, Home Claims Operations. Ms Hartley outlines the four phases of the claims handling process, being: (i) claims lodgement and processing; (ii) underwriting assessment and policy decision; (iii) claims review of the underwriting policy decision; and (iv) communication and execution of the claims decision.

24 As to claims lodgement and processing, a claim could be lodged online or over the phone. When lodged by phone, the customer was asked questions by the claims consultant aimed at confirming if the policy information provided by the customer at the time of the entry into the policy was still accurate. If there were changes, then the consultant asked further questions about those changes, after a disclosure statement was read out to the customer. When a claim was lodged online, the customer was asked to confirm that the policy information provided by the customer at the time the insurance was taken out or renewed was still accurate. If the answer was no, then the customer was provided a free text field to input information about the nature of the changes. The information obtained during a phone call or through the online claims platform was recorded by the claims consultant into DISC, the defendant’s claims management platform.

25 Once the relevant information about the claim was added to the claim file in DISC, if a change relevant to the defendant’s underwriting criteria was identified, the policy was then referred to the defendant’s underwriting team to make a “policy decision” as to whether the policy was “acceptable” or “unacceptable”, that decision usually being made within 24 to 48 hours of claim lodgement. A policy was “acceptable” if no changes to the policy were necessary and the claim could progress, or, alternatively, the claim could progress but some changes were necessary, for example the application of a fixed excess (in addition to the standard excess) to the policy or the payment of an additional premium. If a policy was “unacceptable”, the underwriter could then decide either that: (i) notwithstanding that the policy was unacceptable and had to be cancelled (typically in 14 days or not until the next renewal date), the claim could progress, for example if the defendant discovered that the customer’s roof contained asbestos materials but that information did not impact the claim and it was reasonable that the customer was not aware of the asbestos at policy inception or renewal; or (ii) the policy should be cancelled from inception, or from the date when the relevant change to the customer’s property occurred and, given that there was no valid policy in place at the time of the claim, there was no claim cover available to the customer, so the claim could not progress.

26 All “unacceptable” policy decisions made by the underwriting team were subject to a three-line review by (a) the claims team (being the claims consultant), (b) the claims team leader (who conducted a “reasonable care assessment”), and finally (c) the claims manager, who conducted a final review.

27 A “reasonable care assessment” involved assessing the circumstances surrounding the customer’s failure to notify the defendant of the relevant matters at policy inception or renewal, and which were only discovered during the processing of the claim. The defendant assessed whether the customer used reasonable care when the “misrepresentation” was made, and the level of seriousness of the “misrepresentation”. The assessment was conducted in accordance with an internal guidance note.

28 If the policy was “acceptable”, the outcome of the reasonable care assessment typically informed whether the defendant sought to recover an additional premium from the customer in connection with the claim, given the change in coverage circumstances since policy inception. If the defendant determined that the customer took reasonable care, then the additional premium was waived; if not, the additional premium was applied, and the defendant sought to have the customer pay it. If the policy was assessed to be “unacceptable”, then the outcome of the reasonable care assessment typically informed whether the claims team agreed and upheld the underwriting team’s decision, or whether that decision was reassessed.

29 After the claims decision was made, that decision was communicated to the customer by the claims consultant. If the claim progressed, the claims consultant administered the claim outcome, for example by arranging payment to the customer or organising a service provider to repair the damage to the property. If the claim was not accepted, the claims consultant issued a letter to the customer confirming the claim had been denied and explaining the reasons why that decision had been made, and providing information about the customer complaint process and customer’s rights to participate in an external dispute resolution scheme run by the Australian Financial Complaints Authority.

30 The evidence shows that eight claims were made in the period from 5 April 2021 to 15 September 2022 which resulted in the defendant relying on the Notification Clause to cancel the customer’s policy. Of those eight claims, the defendant refused to cover six of them, but paid the claims for the other two. Since 15 September 2022, the defendant has not cancelled any policies or refused or reduced any claims brought by customers for a failure to tell the defendant about a change to their home or contents in reliance on the Notification Clause.

Relevant Legislative Provisions

ASIC Act

31 Section 12BF(1) of the ASIC Act provides as follows:

A term of a consumer contract or small business contract is void if:

(a) the term is unfair; and

(b) the contract is a standard form contract; and

(c) the contract is:

(i) a financial product; or

(ii) a contract for the supply, or possible supply, of services that are financial services.

There is no dispute concerning whether the disputed term in the present case was part of a “consumer contract”. Further, the defendant accepts that paras (b) and (c) of subs 12BF(1) are satisfied in the present case. The dispute concerns what the term is, and whether the term is unfair within the meaning of para (a). As I have indicated above, the Amending Act inserted a note at the end of s 12BF to the effect that the section applies to “Insurance Contracts Act insurance contracts in addition to the Insurance Contracts Act 1984”.

32 The meaning of “unfair” is dealt with in s 12BG, which provides as follows:

(1) A term of a contract referred to in subsection 12BF(1) is unfair if:

(a) it would cause a significant imbalance in the parties’ rights and obligations arising under the contract; and

(b) it is not reasonably necessary in order to protect the legitimate interests of the party who would be advantaged by the term; and

(c) it would cause detriment (whether financial or otherwise) to a party if it were to be applied or relied on.

(2) In determining whether a term of a contract is unfair under subsection (1), a court may take into account such matters as it thinks relevant, but must take into account the following:

(b) the extent to which the term is transparent;

(c) the contract as a whole.

(3) A term is transparent if the term is:

(a) expressed in reasonably plain language; and

(b) legible; and

(c) presented clearly; and

(d) readily available to any party affected by the term.

(4) For the purposes of paragraph (1)(b), a term of a contract is presumed not to be reasonably necessary in order to protect the legitimate interests of the party who would be advantaged by the term, unless that party proves otherwise.

ICA

33 It is common ground between the parties that the contracts of insurance in the present case are governed by the ICA. Part II of the ICA deals with the duty of utmost good faith. Section 12 provides as follows:

The effect of this Part is not limited or restricted in any way by any other law, including the subsequent provisions of this Act, but this Part does not have the effect of imposing on an insured, in relation to the disclosure of a matter to the insurer, a duty other than:

(a) in relation to a consumer insurance contract or proposed consumer insurance contract – the duty to take reasonable care not to make a misrepresentation; or

(b) in relation to any other contract of insurance or proposed contract of insurance – the duty of disclosure.

Section 12 also contains a note to the effect that Part II operates in addition to the unfair contract terms provisions of the ASIC Act.

34 Section 13(1) provides as follows:

A contract of insurance is a contract based on the utmost good faith and there is implied in such a contract a provision requiring each party to it to act towards the other party, in respect of any matter arising under or in relation to it, with the utmost good faith.

35 Section 14 provides as follows:

(1) If reliance by a party to a contract of insurance on a provision of the contract would be to fail to act with the utmost good faith, the party may not rely on the provision.

(2) Subsection (1) does not limit the operation of section 13.

(3) In deciding whether reliance by an insurer on a provision of the contract of insurance would be to fail to act with the utmost good faith, the court shall have regard to any notification of the provision that was given to the insured, whether a notification of a kind mentioned in section 37 or otherwise.

Section 37 provides that an insurer may not rely on a provision included in a contract of insurance of a kind that is not usually included in contracts of insurance that provide similar insurance cover unless, before the contract was entered into, the insurer clearly informed the insurer in writing of the effect of the provision.

36 Section 54 provides as follows:

(1) Subject to this section, where the effect of a contract of insurance would, but for this section, be that the insurer may refuse to pay a claim, either in whole or in part, by reason of some act of the insured or of some other person, being an act that occurred after the contract was entered into but not being an act in respect of which subsection (2) applies, the insurer may not refuse to pay the claim by reason only of that act but the insurer’s liability in respect to the claim is reduced by the amount that fairly represents the extent to which the insurer’s interests were prejudiced as a result of that act.

(2) Subject to the succeeding provisions of this section, where the act could reasonably be regarded as being capable of causing or contributing to a loss in respect of which insurance cover is provided by the contract, the insurer may refuse to pay the claim.

(3) Where the insured proves that no part of the loss that gave rise to the claim was caused by the act, the insurer may not refuse to pay the claim by reason only of the act.

(4) Where the insured proves that some part of the loss that gave rise to the claim was not caused by the act, the insurer may not refuse to pay the claim, so far as it concerns that part of the loss, by reason only of the act.

(5) Where:

(a) the act was necessary to protect the safety of a person or to preserve property; or

(b) it was not reasonably possible for the insured or other person not to do the act;

the insurer may not refuse to pay the claim by reason only of the act.

(6) A reference in this section to an act includes a reference to:

(a) an omission; and

(b) an act or omission that has the effect of altering the state or condition of the subject-matter of the contract or of allowing the state or condition of that subject-matter to alter.

37 Section 55 provides as follows:

The provisions of this Division with respect to an act or omission are exclusive of any right that the insurer has otherwise than under this Act in respect of the act or omission.

Construction of the Notification Clause

Principles of Construction

38 The principles of construction of commercial contracts were summarised by French CJ, Nettle and Gordon JJ in Mount Bruce Mining Pty Ltd v Wright Prospecting Pty Ltd [2015] HCA 37; (2015) 256 CLR 104 relevantly as follows:

(a) the rights and liabilities of parties under a provision of a contract are determined objectively, by reference to its text, context (the entire text of the contract as well as any contract, document or statutory provision referred to in the text of the contract) and purpose: at [46];

(b) in determining the meaning of the terms of a commercial contract, it is necessary to ask what a reasonable businessperson would have understood those terms to mean, and that inquiry will require consideration of the language used by the parties in the contract, the circumstances addressed by the contract and the commercial purpose or objects to be secured by the contract: at [47]; and

(c) unless a contrary intention is indicated in the contract, a court is entitled to approach the task of giving a commercial contract an interpretation on the assumption that the parties intended to produce a commercial result, or put another way, a commercial contract should be construed so as to avoid it making commercial nonsense or working commercial inconvenience: at [51].

39 The principles concerning the construction of commercial contracts apply to contracts of insurance: Todd v Alterra at Lloyd’s Limited [2016] FCAFC 15; (2016) 239 FCR 12 at [42] (Allsop CJ and Gleeson J). As Allsop CJ and Gleeson J said in that case at [38], a contract of insurance has the object or purpose of sharing the risk of, or spreading loss from, a contingency. The defendant submits, and I accept, that that object or purpose necessarily involves identifying the risks that the insurer has agreed to cover, and those which it has declined. Further, in construing an insurance policy, preference is to be given to a construction supplying a congruent operation to the various components of the whole: Wilkie v Gordian Runoff Ltd [2005] HCA 17; (2005) 221 CLR 522 at [16] (Gleeson CJ, McHugh, Gummow and Kirby JJ).

40 The issues of construction relating to the Notification Clause concern two principal matters. First, there is a question as to which matters fall within the obligation of the insured consumer to notify the defendant. Second, there is an issue concerning the extent of the defendant’s rights which arise upon breach of the duty to notify.

Content of the Duty of the Insured to Notify

41 The literal meaning of the word “anything” in the expressions “Tell us if anything changes while you’re insured with us” and “While you’re insured with us, you need to tell us if anything changes about your home or contents” should readily be rejected. Although the Concise Statement filed by ASIC appeared to place reliance on the literal meaning of “anything” (in paras 12(a) and 13(a)), ASIC accepted in its written and oral submissions that such a literal reading leads to absurdity. That concession was well made. The contents of an insured’s home change whenever groceries are brought home from an everyday shopping outing, and again when they are consumed in preparing and eating meals. Every time a book or an item of clothing is purchased, or received as a gift, the contents of the home again will change. No rational person would think that the Notification Clause was intended to compel the insured to notify the defendant of such routine and everyday changes.

42 The defendant submits that the Notification Clause, on its proper construction, requires the insured to notify the defendant if, during the term of the policy, there is any change to the information about the insured’s home or contents that the insured disclosed to the defendant prior to entry into the contract. The defendant draws attention to the textual support for that construction in the PDS and other contractual documents as a whole. I have extracted the relevant portions of the PDS and other contractual documents above. In the section of the PDS headed “How we work together for an easy claims process” (p 5), the word “changes” is clearly used with reference to information that the insured has already given the defendant about a claim or their living situation. In the section headed “Steps to take when you first receive this policy” (pp 8–9), step 2 expressly requires the insured to tell the defendant if the insured needs to make any “changes or corrections to the information you’ve given us”. The arrow at the end of step 2 pointing to p 12 directs the reader to the very section of the PDS in which the duty of disclosure and the Notification Clause appear. When one goes to p 12 of the PDS, dealing with the duty of disclosure, there are several references to the information provided pursuant to the duty of disclosure, together with the statement that when the insured renews their insurance with the defendant: “we may give you a copy of anything you have previously told us and ask you to tell us if it has changed. If we do this, you must tell us about any change or tell us that there is no change.” That is followed by the statement that if the insured does not tell the defendant about a change to something which the insured has previously told the defendant, the defendant is entitled to act as if the insured has told it that there is no change.

43 The Notification Clause uses the word “changes” five times. There is no reason to think that these are changes of any different kind from those referred to on pp 8, 9 or 12 with respect to the insured’s obligation of disclosure. Read in the context of the earlier pages of the PDS, the ordinary and natural meaning of the word “changes” when used in the Notification Clause is that it refers to changes to information which the insured has previously given the defendant. The only indication in the text which identifies any other kind of “change” requiring disclosure is a change to claim details which have already been provided, in discussing the particular topic of the claims process on p 5.

44 Further, the passage concerning renewal of the policy on p 67 of the PDS requires the insured to tell the defendant if any “information in our offer of renewal is incorrect”. The reference to “information” in that passage is plainly a reference to information which the insured has given the defendant previously.

45 The language used in the PDS is consistent with the language which appears in the cover letter and declarations, which both form part of the relevant contract of insurance. I have quoted above the two passages from the cover letter which require the insured to check all the details in the insurance certificate and declarations and to tell the defendant if any details are incorrect or need updating. I have also quoted above the opening sentences of the declarations referring to the information which the defendant has on its records based on the questions which it asked and the answers which the insured gave, and requiring the insured to check that the answers provided still apply and contact the defendant if “anything has changed”. Those statements reinforce the conclusion that the requirement in the Notification Clause to notify the defendant “if anything changes” concerns the information already provided by the insured to the defendant.

46 In my view, there is nothing in the purpose or the object of the transaction which would point away from that construction. As I have indicated above, the purpose or object of a contract of insurance is to share the risk arising from a contingency, and fundamental to the parties’ bargain is the identification of the risks which the insurer agrees to bear in return for a premium on an informed basis. The defendant submits, and I accept, that the process of asking detailed questions and obtaining specific answers from potential insureds is the means by which the parties to these contracts achieve that object at policy inception, and the Notification Clause is directed to achieving the same object once the policy is on foot. The contract was entered into necessarily on the basis of information provided by the insured, and it is consistent with the purpose of the contract that the insurer would require the insured to disclose any changes to that information in order to preserve the balance of risk and reward inherent in the bargain.

47 ASIC submits that there are four difficulties with this construction. First, ASIC argues that it is not what the words used in the Notification Clause actually say and involves substantial supplementation of those words. However, once one rejects the literal construction in light of the absurdity of reading the word “changes” as meaning literally “any change”, then the word “changes” must be construed as having a more limited meaning. That requires the addition of words to the text. The best guide to identifying that more limited meaning is to look at the text of the contract as a whole, and to identify textual indications as to what was intended by the word “changes”. Those other references provide powerful textual support for the defendant’s construction.

48 Second, ASIC submits that an express formulation of the very kind contended for by the defendant is contained in various other places in the PDS, referring to pp 8, 9, 12 and 67. However, they are the references that provide the clear textual support for the defendant’s construction, rather than detracting from it. As the defendant submits, and I accept, ASIC’s argument turns commonsense on its head.

49 Third, ASIC contends that when one looks at the ten particular instances of insurance certificates and declarations which are contained in the evidence, while many of the examples of changes set out in the Notification Clause correspond to matters stated in those insurance certificates and declarations, others do not. There are two flaws in that argument. The first is that the evidence provides an indicative sample of only ten sets of such documents, relating to ten particular insureds, whereas it is common ground that there were more than 1.3 million such contracts entered into. Second, it does not appear that all the information provided by the insureds (including negative answers to questions about such matters as asbestos) was recorded in the declarations. As such, it was apparent that the declarations were not an exhaustive record of the information disclosed. As I have concluded above in the analysis of the defendant’s application processes, each of the 11 examples in the Notification Clause related to questions which were asked generally of customers applying for insurance, although not all customers were asked exactly the same questions, and the information which they provided would depend on their particular circumstances.

50 Fourth, ASIC contends that if the Notification Clause only required the insured consumer to notify the defendant of changes to information already provided, it would have been possible to give an exhaustive list of the circumstances requiring notification, rather than an open-ended list of examples. However, an exhaustive statement of all the information potentially provided by any of the insureds would have amounted to a very lengthy and wearisome recitation which few (if any) insureds would bother to read. A concise list of illustrative examples strikes me as a practical and realistic way of conveying useful information to the reader.

51 In my view, the construction contended for by the defendant is clearly correct. In saying that, I am approaching the matter as a question for judicial determination. Whether an ordinary consumer would reach the same conclusion and with the same level of conviction is a different question, which I will deal with later in these reasons when I turn to the issue of “transparency”.

52 For completeness, I will deal with three alternative constructions propounded by ASIC.

53 ASIC submits that it is an equally probable, if not more probable, construction of the Notification Clause that it obliges the insured to notify the defendant of those changes to the home or contents which are relevant to the conditions of cover under the policy. ASIC submits that each of the “examples” of changes given in the Notification Clause (with the exception of the heritage example) is directly related to terms found elsewhere in the PDS. ASIC submits that this construction involves less supplementation of the express words of the Notification Clause than does the construction propounded by the defendant, and is more consistent with the adoption of open-ended examples of changes which the insured is to notify. However, ASIC’s submissions do not identify any textual indication linking the subject-matter of those other aspects of the PDS to an ongoing duty to notify, except for the requirement to notify the defendant if the insured’s home will be unoccupied for more than 60 days (p 14). Although the language used at the end of p 12 of the PDS does tell the customer that they have a duty to tell the defendant anything which they know, or could reasonably be expected to know, that may affect the defendant's decision to insure them and on what terms, that appears in the context of variation, extension or reinstatement of the insurance and expressly states that the insured’s duty changes in that context. By way of contrast, the Notification Clause is concerned with the insured’s more limited duty to notify “changes” occurring in the ordinary course of the term of the policy. Further, ASIC accepts that this alternative construction would require the consumer to recall the terms of a contract of insurance that is over 70 pages long, and to assess which changes to their house or contents were of relevance to those terms (written submissions in reply at [64(b)]), which strikes me as unrealistic and working commercial inconvenience.

54 Another alternative construction propounded by ASIC is that the Notification Clause requires the insured only to notify changes which are material or which materially increase the risk insured or which materially alter the nature of the insured risk. However, ASIC does not identify any textual support for that construction except to submit that it accommodates each of the 11 examples given in the Notification Clause. The only reference in the surrounding context of the PDS to a duty of disclosure that does not involve answers to the insurer’s questions is the passage at the foot of p 12 concerning variation, extension or reinstatement, which is different from the situation which the Notification Clause is addressing. Further, such a construction would require the consumer to form an evaluative judgment, continuously throughout the term of the policy, about matters which might be relevant to the insurer’s risk. By contrast, the construction propounded by the defendant is directed to the process by which the insurer gathers information, framed by the insurer with reference to its own assessment of risk, by asking the insured specific questions before the contract is entered into.

55 The third of ASIC’s alternative constructions is that it only obliges the insured to notify the defendant of changes to the home and contents of the kinds set out in the examples provided. I do not regard that alternative as a tenable construction at all. The examples are no more than illustrative examples, and are clearly intended to be inclusive. No reasonable person could read the examples as intended to be exhaustive or as requiring notification only of changes that are ejusdem generis with the 11 specific examples. In its written submission in reply, ASIC propounds a variation on this construction whereby the changes requiring notification were “at the level of significance of the examples given”. I regard that construction as unworkable in circumstances where the insureds have no means of knowing the significance which the defendant attaches in its Underwriting Policy and Underwriting Guidelines to matters other than those which are given by way of the 11 examples.

The Defendant’s Rights upon Breach

56 The Notification Clause states that if the insured does not tell the defendant about changes then the insurer “may” refuse to pay a claim, reduce the amount we pay, cancel the contract, or not offer to renew the contract. The word “may” indicates that the defendant has a discretionary right or power to do one or more of those four things.

57 The effect of the Notification Clause in this respect, however, must also take into account the implied provision under s 13 of the ICA, relevantly requiring the insurer to act towards the insured in respect of any matter arising under or in relation to the contract of insurance with the utmost good faith. That implied requirement is paramount to the other provisions of the contract because, as s 14(1) of the ICA states, if reliance by a party to a contract of insurance of a provision of the contract would be to fail to act with the utmost good faith, the party may not rely on the provision.

58 In Allianz Australia Insurance Ltd v Delor Vue Apartments CTS 39788 [2022] HCA 38; (2022) 97 ALJR 1 at [92], Kiefel CJ, Edelman, Steward and Gleeson JJ identified two aspects of the duty of utmost good faith in s 13(1), namely:

(i) it is a principle upon which a contract of insurance is “based” and thus assists in the recognition of particular implied duties; and (ii) it is an implied condition on existing rights, powers and duties, governing the manner in which each contracting party must act towards the other party “in respect of any matter arising under or in relation to” the contract of insurance.

59 In relation to the second aspect of the duty of utmost good faith, their Honours said that this aspect of the duty requires each party to have regard to more than its own interests when exercising its rights and powers under the contract of insurance, although this condition upon the exercise of rights and powers and the performance of obligations is not fiduciary: [95]. The duty does not require a party to an insurance contract to exercise rights or powers or to perform obligations only in the interests of the other party, but nor is the condition limited to honest performance: [95]. Their Honours stated that it has therefore been said that rights and powers must be exercised, and duties must be performed, “consistently with commercial standards of decency and fairness”, as distinct from standards of decency and fairness more generally, citing the passage in the judgment of Gleeson CJ and Crennan J in CGU Insurance Ltd v AMP Financial Planning Pty Ltd [2007] HCA 36; (2007) 235 CLR 1 at [15]. Their Honours stated further that the obligation to act decently and with fairness is a condition on how existing rights, powers and duties are to be exercised or performed in the commercial world: [97].

60 It follows that the duty of utmost good faith operates, as a paramount provision implied in the contract of insurance, to limit what the defendant can do under the Notification Clause in response to an insured’s failure to notify the defendant of the relevant changes. That much is common ground between the parties. There remains a difference between the parties as to the extent to which the duty of utmost good faith restricts the defendant from exercising its rights in accordance with the Notification Clause. The defendant submits that the effect of the duty of utmost good faith is that it had the right to refuse to pay a claim in whole or in part or to cancel a policy if and to the extent that it would be reasonable for the defendant to do so. In the course of oral submissions, the defendant’s submissions were cast in terms of a standard of reasonableness “having regard to commercial standards of decency and fairness” (T84.22–24). ASIC disputes that the relevant standard is one of “reasonableness”.

61 The notion of reasonableness no doubt has a role to play in assessing whether a party has acted with the utmost good faith towards the other, as Emmett J recognised in AMP Financial Planning Pty Ltd v CGU Insurance Ltd [2005] FCAFC 185; (2005) 146 FCR 447 at [89]. However, the standard which the High Court adopted in Allianz was not one of reasonableness as such. Rather, the High Court said at [96] that the effect of the duty of utmost good faith was that rights and powers must be exercised, and duties must be performed, consistently with commercial standards of decency and fairness. Accordingly, the limitation on the ability of the defendant to exercise the rights or powers upon breach which are set out in the Notification Clause should be expressed in terms that those rights or powers must be exercised consistently with commercial standards of decency and fairness. ASIC accepts that the rights referred to in the Notification Clause can only be exercised in a manner which is commercially decent and fair (T45.43–46.04; 46.30–34). I will address later in these reasons the relationship between that limitation and s 54 of the ICA.

Conclusion on the proper construction of the Notification Clause

62 Accordingly, upon the proper construction of the Notification Clause, the contracts of insurance in the present case contained a term that:

(a) the insured must notify the defendant if, during the term of the policy, there was any change to the information about the insured’s home or contents that the insured had disclosed to the defendant prior to entry into the contract; and

(b) if the insured failed to notify the defendant of such changes, the defendant had the right to refuse to pay a claim, reduce the amount it paid, cancel the contract or not offer to renew the contract if and to the extent that it would be consistent with commercial standards of decency and fairness for the defendant to do so.

63 To the extent that it may be relevant to the issue of “transparency”, which I deal with below, I do not regard this question of construction as finely balanced. On the contrary, I regard the construction of the Notification Clause which I have adopted to be the proper construction by a very substantial and comfortable margin.

The meaning of “unfair”

64 Section 12BG(1) sets out three criteria to be applied to the relevant term of the contract. If all three of those criteria are satisfied, then the term is “unfair” without any further evaluative judgment or exercise of discretion. The language of ss 12BF and 12BG is substantially identical to ss 23 and 24 of the Australian Consumer Law (the ACL), being Sch 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth). Accordingly, decisions concerning ss 23 and 24 of the ACL are directly relevant and applicable to ss 12BF and 12BG of the ASIC Act.

65 In dealing with the issues which arise concerning the construction and application of s 12BG, I propose to follow the order which was adopted by the High Court in Karpik v Carnival plc [2023] HCA 39; (2023) 98 ALJR 45 at [29]–[32] and also at [51]–[60]; that is, to take each of the three elements in s 12BG(1) in turn, and then deal with the issue of transparency under s 12BG(2)(b) and s 12BG(3). It is to be observed that the extent to which the term is transparent is not one of the three criteria set out in s 12BG(1), but is a matter which the court must take into account pursuant to s 12BG(2)(b). I also note that s 12BG(2)(c) provides that the court must take into account the contract as a whole, which I have done so far in these reasons in relation to identifying the relevant term on its proper construction, and which I continue to do in what follows.

66 Three general comments concerning s 12BG(1) may be made at the outset. First, the reference to “a term of a contract” in the opening words of s 12BG(1) means in general the term on its proper construction; that is, the meaning-content of the term: see Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Smart Corporation Pty Ltd [2021] FCA 347; (2021) 153 ACSR 347 at [71] (Jackson J). That is made clear by the reference in s 12BG(1)(a) to “the parties’ rights and obligations arising under the contract”, which means their legal rights and obligations as properly and definitively construed. Similarly, one can only determine whether a term “would cause a significant imbalance” (para (a)), whether it is “reasonably necessary” (para (b)) or whether it “would cause detriment” (para (c)), if one knows what the term actually means on its proper construction. Subsection 12BG(1) does not ask whether the three criteria are satisfied by a construction which may be arguable, but ultimately found to be erroneous. While I accept that the reference to “a term of a contract” includes the language actually used in expressing the term, subs 12BG(1) is concerned principally with the meaning of those words on their proper construction. The term in question is not merely the words actually used, nor is it those words taken in isolation from the contract as a whole. By contrast, s 12BG(3) is focused on the manner of expression and presentation of the term, although as I explain later in these reasons, s 12BG(3) does encompass questions of ambiguity and lack of clarity in meaning from the perspective of consumers. It is common ground between the parties that the notion of a “term” as used in ss 12BF and 12BG includes not just the written language but also its meaning content (T30.09–18; 35.27–30).

67 Second, both parties proceeded on the basis that s 12BG(1) is concerned with an assessment of the relevant term in the context of the legal environment in which the term operates, comprising both statutory and non-statutory law (T120.16–27). Accordingly, I will apply the criteria in s 12BG(1) in the context of the legal environment applicable to contracts of insurance, which necessarily includes the ICA. I will deal below with the way in which ss 13–14 and 54–5 of the ICA affect the analysis of the term in question in these proceedings. However, it is worth noting at this point the long title of the ICA which in my view is an appropriate description of its subject-matter, namely:

An Act to reform and modernise the law relating to certain contracts of insurance so that a fair balance is struck between the interests of insurers, insureds and other members of the public and so that the provisions included in such contracts, and the practices of insurers in relation to such contracts, operate fairly, and for related purposes.

68 Nonetheless, ASIC submits that a premise of the Amending Act, which rendered contracts of insurance governed by the ICA subject to ss 12BF and 12BG of the ASIC Act, must have been that the unfair contracts terms regime in the ASIC Act would have work to do in respect of consumer insurance contracts. In other words, ASIC submits that the criteria in s 12BG(1) of the ASIC Act may be satisfied, and a term may be found to be unfair, notwithstanding the ameliorative operation of the ICA. ASIC draws attention to a paper published by the Commonwealth Department of Treasury in June 2018 entitled “Extending Unfair Contract Terms Protections to Insurance Contracts”, which noted that one of the objectives of the then-proposed model was to “increase incentives for insurers to improve the clarity and transparency of contract terms, and remove potentially unfair terms from their contracts” (p 2). The defendant draws attention to the discussion in that paper of terms that may be considered unfair, and the proposal that examples specific to insurance contracts be added to the list set out in s 12BH of the ASIC Act, suggesting (at p 18) that the following kinds of terms be added to that list of examples:

• terms that permit the insurer to pay a claim based on the cost of repair or replacement that may be achieved by the insurer, but could not be reasonably achieved by the policyholder;

• terms which make the insured’s ability to make a claim conditional on the conduct of a third-party over which the insured has no control; and

• terms in a contract that is linked to another contract (for example, a credit contract) which limit the insured’s ability to obtain a premium rebate on cancellation of the linked contract.

69 ASIC also draws attention to the Replacement Explanatory Memorandum, Financial Sector Reform (Hayne Royal Commission Response – Protecting Consumers (2019 Measures)) Bill (Cth) (Replacement Explanatory Memorandum), which preceded the Amending Act and indicated an intention that the unfair contract terms regime should operate “independently” of the duty of utmost good faith under the ICA and contemplated that “some scenarios may give rise to relief under both sets of provisions” (para 1.49).

70 Third, although there is no express provision to this effect, it is the time of entry into the contract that is the relevant time of assessment of the criteria set out in s 12BG(1): Karpik v Carnival plc at [52]; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Ashley & Martin Pty Ltd [2019] FCA 1436 at [168] (Banks-Smith J).

Significant imbalance in rights and obligations

71 The following principles have been stated in the authorities dealing with s 12BG(1)(a) of the ASIC Act and s 24(1)(a) of the ACL (noting that where I refer below to Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v CLA Trading Pty Ltd [2016] FCA 377 at [54], it should be borne in mind that that passage in the judgment of Gilmour J was quoted with approval in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Servcorp Ltd [2018] FCA 1044 at [15] (Markovic J) and in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Smart Corporation Pty Ltd [2021] FCA 347; (2021) 153 ACSR 347 at [65] (Jackson J)):

(a) significant imbalance relates to the substantive unfairness of the contract: ACCC v CLA Trading at [54(b)];

(b) significant imbalance requires consideration of the relevant term, together with the parties’ other rights and obligations arising under the contract: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Chrisco Hampers Australia Ltd [2015] FCA 1204 at [51]; (2015) 239 FCR 33 at [51] (Edelman J); Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Ashley & Martin Pty Ltd [2019] FCA 1436 at [45] (Banks-Smith J);

(c) the word “significant” means “significant in magnitude”, or “sufficiently large to be important”, “being a meaning not too distant from substantial”: ACCC v CLA Trading Pty Ltd at [54(e)];

(d) a significant imbalance exists if the term is so weighted in favour of one party as to tilt the party’s rights and obligations significantly in its favour, and this may be by granting to that party a beneficial option or discretion or power: ACCC v Chrisco Hampers Australia Ltd at [47]–[49]; ACCC v CLA Trading Pty Ltd at [54(d)];

(e) a term is less likely to give rise to a significant imbalance if there is a meaningful relationship between the term and the protection of a party, and that relationship is reasonably foreseeable at the time of contracting: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v JJ Richards & Sons Pty Ltd [2017] FCA 1224 at [31] (Moshinsky J);

(f) a useful factor in the analysis is the effect that the contract would have on the parties with the term included, and the effect it would have without it: ACCC v CLA Trading Pty Ltd at [54(c)];

(g) another relevant factor is whether the contract gives one party a right without imposing on that party a corresponding duty or without giving any substantial corresponding right to the counterparty: ACCC v Chrisco Hampers Australia Ltd at [53].

72 Putting to one side for the moment ASIC’s submissions concerning transparency, which as I have said I will deal with in the order adopted by the High Court in Karpik, ASIC makes three main submissions concerning the issue of significant imbalance in the parties’ rights and obligations. First, ASIC submits that in the absence of the Notification Clause, the insured consumer would be under no obligation to notify the defendant, following entry into the contract of insurance, of changes to the insured property or of matters increasing the insured risk. ASIC refers to the statement of principle by Rogers J that it “has been held by courts of the highest authority that the duty to disclose material facts … comes to an end once the contract of insurance is entered into”: NSW Medical Defence Union Ltd v Transport Industries Insurance Co Ltd (1985) 4 NSWLR 107 at 108E. I note that the same principle is reflected in the reasons of Isaacs ACJ (with whom Gavan Duffy J agreed) in The Western Australian Insurance Company Limited v Dayton (1924) 35 CLR 355 at 379, with reference to the seminal case on the duty of utmost good faith of Carter v Boehm (1766) 97 ER 1162 (Lord Mansfield). ASIC thus submits that the Notification Clause subjects the insured consumer to an obligation to which they otherwise would not be subject.

73 I do not regard the fact that the Notification Clause created rights and obligations which do not exist at common law absent a contractual term as creating a significant imbalance in the parties’ rights and obligations arising under the contract. The comparison between the effect that the contract has on the parties with the term included, and the effect that it has without it, is no more than a factor in the overall analysis. The real question is whether the newly created rights and obligations have caused a significant imbalance.

74 As the defendant submits, the Court must take into account “the contract as a whole” (s 12BG(2)(c)), which includes its subject matter. The term is aimed at furnishing the defendant with relevant information about the risks which it is covering. There is, in my view, a meaningful relationship between the notification obligation on the part of the insured and the protection of the defendant’s interests as insurer that was foreseeable at the time of contracting. Although ASIC submitted that the common law position represents the risk that the insurer “ordinarily” assumes (T50.18–26), there is no evidence as to the statistical frequency of insurers in Australia of home and contents policies inserting a contractual provision for continuing notification in their contracts. However, an internal document dated 29 August 2022 produced by the defendant to ASIC indicated that 8 out of the 10 competitors of the defendant whose policy language was analysed did include such a term (Court Book tabs 54 and 54.1).

75 Second, ASIC submits that the contract contains no corresponding rights which relate to the impugned obligation in favour of the insured customer. ASIC submits that the insured has no right to a reduction in premium if it notifies the defendant of changes to the home or contents which reduce the risk insured. However, again the Notification Clause must be viewed in the context of the contract as a whole. As the defendant submits, the term does confer reciprocal rights on the insured in the context of the contract as a whole, as the insured’s obligation to provide information about “changes” is a promise which the insured makes in exchange for the defendant’s ongoing provision of cover. It is not necessary for the Notification Clause to spell out the consequences for either an increase or partial refund of premium in order for the Notification Clause to avoid causing any significant imbalance.

76 Further, the fact that the obligation to notify is a unilateral obligation by the insured, rather than a bilateral obligation owed reciprocally by both parties, is simply a reflection of the nature of the contract. As the defendant submits, and I accept, whether a term causes any “imbalance” depends on how it deals with the inherent subject matter of the contract, not the subject matter itself.

77 Third, ASIC submits that breach of the Notification Clause confers broad discretionary rights upon the defendant, including to deny claims in their entirety. ASIC submits that this issue raises a novel question as to the interaction of the unfair contract terms provisions of the ASIC Act and the effect of s 54 of the ICA, and how s 54 is to be taken into account in determining whether the criteria in s 12BG(1) of the ASIC Act are satisfied. ASIC submits that before one can determine whether s 54 has any application to a given contract of insurance, one must first ask what the effect of the contract of insurance would be in a hypothetical counterfactual world where s 54 does not exist; that is, the effect of the contract “but for this section” (to adopt the language towards the beginning of s 54). ASIC submits that in order to answer that question, one must consider the operation of any other legislative provisions that might alter the effect of the contract of insurance. ASIC submits that if, but for the existence of s 54 of the ICA, s 12BF of the ASIC Act would render void the term which allowed the insurer to refuse to pay a claim, then s 54 is never engaged, and the contract does not have the effect stipulated in s 54 because, but for s 54, s 12BF would render the term void and thus s 54 has no work to do. If, on the other hand, s 12BF does not render the term void in a given case, then ASIC submits that s 54 applies in accordance with its terms to the benefit of the consumer where the contract would have the stipulated effect.

78 ASIC then submits that, if the operation of s 54 of the ICA is not to be taken into account in considering the application of s 12BF of the ASIC Act, then the Notification Clause confers on the defendant a broad contractual discretion to refuse claims and cancel policies even where the insured’s breach has not caused the insured loss or otherwise prejudiced the defendant in any way. The Notification Clause would, in ASIC’s submission, give rise to the very sort of imbalance that s 54 was enacted to redress, namely that the term may impose heavy loss upon an insured, even though an insurer has suffered little or no loss as a result of the insured’s breach (with reference to the Australian Law Reform Commission’s Report No 20 (1982) on Insurance Contracts, which led to the enactment of the ICA).

79 ASIC also submits in the alternative that, even if the operation of s 54 of the ICA is to be taken into account in considering the application of s 12BF of the ASIC Act, then the Notification Clause is nevertheless productive of significant imbalance in the parties’ rights and obligations, because in ASIC’s submission the Notification Clause makes no reference to, and gives no explanation of, the effect of ss 54 and 55 of the ICA. Accordingly, ASIC submits, a non-expert consumer is likely to think mistakenly that the defendant’s rights under the Notification Clause may be enforced in accordance with their terms and that the defendant has an unqualified discretion to refuse to pay a consumer’s claim in full, whereas s 54(1) reduces the insurer’s liability to the amount that fairly represents the extent to which the insurer’s interests were prejudiced. I will consider this particular submission later in relation to the issue of transparency.

80 In my view, there are two fundamental difficulties with this third line of argument by ASIC. The first is that, as I have stated above, on the proper construction of the Notification Clause, the defendant’s rights which arise upon a breach of that term are qualified by the implied requirement under s 13 of the ICA that the defendant must exercise its rights and powers with the utmost good faith. It is common ground that, when assessing the three criteria of unfairness in s 12BG(1), the Court must take into account the context of the overall legal environment (including statutory provisions like s 13) in which the terms of the contract operate. Section 13 makes the duty of utmost good faith an implied provision of the contract, and s 12BG(2)(c) requires the court to take into account the contract as a whole. It is therefore necessary to consider the effect of s 13 of the ICA when determining whether a clause has created a significant imbalance for the purposes of s 12BG(1). ASIC’s concession in this respect was arguably in tension with its earlier reliance on the Replacement Explanatory Memorandum, which as noted above indicated an intention that the unfair contract terms regime should operate “independently” of the duty of utmost good faith under the ICA (as reflected in the note to s 12 of the ICA) and contemplated that “some scenarios may give rise to relief under both sets of provisions”. If the criteria in s 12BG(1) take into account the duty of utmost good faith under s 13, it is not easy to see how “some scenarios may give rise to relief under both sets of provisions”. I need not consider that issue further in light of the case advanced by ASIC, which was that the unfair contract terms regime takes into account the context of the overall legal environment without qualification.

81 In s 13, the requirement that insurers act with the utmost good faith means that they must act consistently with commercial decency and fairness. Commercial decency and fairness require that the defendant not exercise its rights in a way which is opportunistic, such as by seizing upon a breach by the insured which has not caused the defendant any loss, or by refusing to pay a claim or reducing the amount of a claim beyond the extent to which the defendant would be prejudiced by the breach. The ability of an insurer to rely upon a breach of warranty to refuse an insured’s claim even if the breach did not cause or contribute to the relevant loss or prejudice the interests of the insurer in some other way (such as increasing the risk) is what led to the recommendation and enactment of ss 54 and 55 of the ICA (see the Australian Law Reform Commission’s Report No 20 (1982) on Insurance Contracts at [219]–[220]). This feature of the common law was described, with appropriate restraint, by Lord Templeman as “one of the less attractive features of English insurance law”: Forsikringsaktieselkapet Vesta v Butcher [1989] AC 852 at 893–4.

82 Now that the duty of utmost good faith has been given statutory recognition in ss 13 and 14 of the ICA, and undoubtedly applies beyond the formation of the contract of insurance to the way in which the contract is performed by the insurer, the question arises as to what the standards of commercial decency and fairness would require of the defendant when considering whether to refuse to pay or reduce the amount of a claim by the insured by reason of a breach of the Notification Clause. In my view, commercial decency and fairness would prevent the defendant from any opportunistic reliance on the Notification Clause. It would be contrary to commercial standards of decency and fairness for the defendant to exercise the rights referred to in the Notification Clause to the prejudice of an insured unless and to the extent that the insured’s failure to notify a change in information had prejudiced the defendant’s interests. Further, as the defendant submits, and I accept, in exercising its powers, the defendant must carry out its assessment of such prejudice in a bona fide way. In other words, the substantive effect of s 54 of the ICA is consistent with the Notification Clause on its proper construction. Accordingly, it is not necessary to consider how the analysis required by s 12BG(1) relates to s 54 per se.

83 ASIC submits that that conclusion has the effect of rendering s 54 largely redundant given the work done by s 13 (T116.45–46). However, that argument overlooks the fact that it was not until CGU Insurance Ltd v AMP Financial Planning Pty Ltd [2007] HCA 36; (2007) 235 CLR 1 at [15] (Gleeson CJ and Crennan J), [129]-[131] (Kirby J) and [257] (Callinan and Heydon JJ) that the High Court clearly stated that absence of good faith is not limited to dishonesty. Even since that decision, the rule of law is enhanced by s 54 expressly setting out how the insurer’s rights are limited in this situation in order to give clear and predictable guidance to insurers and insureds, irrespective of whether a court would reach the same destination after travelling through the pearly fog of a principle as vaguely expressed as the duty of utmost good faith.