FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Mylan Australia Holding Pty Ltd v Commissioner of Taxation (No 2) [2024] FCA 253

ORDERS

VID 526 of 2022 | ||

MYLAN AUSTRALIA HOLDING PTY LTD Applicant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: | 20 MARCH 2024 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. By 27 March 2024, the parties provide draft orders to chambers giving effect to these reasons.

2. If the parties disagree as to the appropriate outcome as to costs, each party must file and serve any submissions on costs (limited to four pages) by 27 March 2024, with any responsive submissions (limited to two pages) by 29 March 2024.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

BUTTON J:

1 The Applicant, Mylan Australia Holding Pty Ltd (MAHPL), brought two proceedings against the Respondent, the Commissioner of Taxation (the Commissioner) under Pt IVC of the Taxation Administration Act 1953 (Cth) (the TAA). By determinations issued under s 177F of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1936 (Cth) (the ITAA36), the Commissioner disallowed MAHPL’s deductions for interest expenses under an intercompany promissory note referred to as PN A2, and consequential carry forward losses. PN A2 had flexible terms, permitting interest to be capitalised and allowing the prepayment of principal without penalty. The deductions for interest claimed by MAHPL also reflected the fixed interest rate that was determined (exactly when was in dispute) to apply to PN A2.

2 The Commissioner issued amended assessments for the income years ending 31 December 2009 to 31 December 2020.

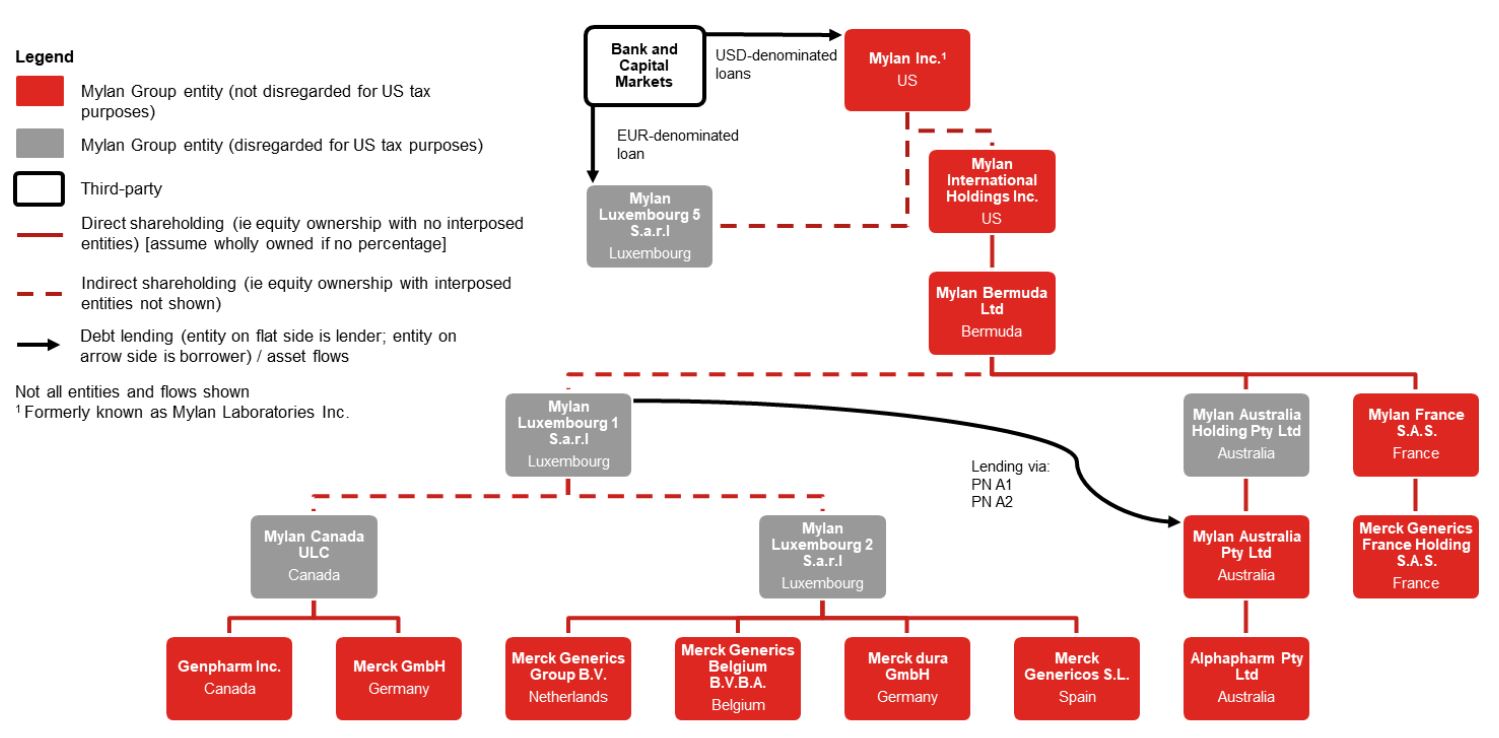

3 MAHPL is the head company of a tax consolidated group, which includes Mylan Australia Pty Ltd (MAPL). MAHPL is the immediate parent company of MAPL. The ultimate holding company of MAPL and MAHPL is Mylan Inc (formerly known as Mylan Laboratories Inc) (Mylan). Mylan is the head of the Mylan group of companies.

4 MAPL acquired all of the shares in Alphapharm Pty Ltd (Alphapharm) in October 2007. Alphapharm was one of the operating subsidiaries of Merck KgaA (Merck) which, together with its related entities, carried on a global generics pharmaceutical business (Merck Generics). Merck Generics was acquired by members of the Mylan group in October 2007. The acquisition was a USD 7 billion transaction. The proceedings concern the application of Pt IVA of the ITAA36 to the funding arrangements associated with MAPL’s acquisition of the shares in Alphapharm. In short, MAPL was funded with a mix of interest-bearing debt and equity at a 3:1 ratio. The debt component was constituted by PN A2, issued by MAPL to Mylan Luxembourg 1 S.a.r.l. (Lux 1). As its name suggests, Lux 1 was a Luxembourg company.

5 In applying Pt IVA, the Commissioner identified a wider scheme (also referred to as the primary scheme), and a narrower scheme (also referred to as the secondary and tertiary schemes — the secondary and tertiary schemes being identical).

6 The Commissioner considered that the entry into the wider scheme (which included the incorporation of the local Australian holding company structure (MAPL and MAHPL)) generated a tax benefit, being all the interest deductions on PN A2 (and a subsequent note, entered into in 2014, referred to as PN A4). This was on the basis of the Commissioner’s view that, had the wider scheme not been pursued, the shares in Alphapharm would not have been separately acquired through a local Australian holding company structure. Rather, Alphapharm would have remained a subsidiary of the Netherlands company, Merck Generics Group B.V. (MGGBV) and would have become part of the Mylan group with the acquisition of MGGBV. In this scenario (described as the primary counterfactual), MAPL would not have acquired the shares in Alphapharm and would not have incurred interest expenses under PN A2.

7 At the objection stage, the Commissioner identified the narrower scheme, and developed two alternate counterfactuals (being the secondary counterfactual and the tertiary counterfactual). The narrower scheme does not include the establishment of the Australian holding company structure with MAHPL as the head entity. According to the counterfactuals the Commissioner developed in respect of the narrower scheme, MAPL and MAHPL would still have been incorporated and MAPL would still have acquired the shares in Alphapharm but, on the secondary counterfactual, MAPL would have borrowed a lesser sum (ie it would have had a lower gearing ratio) and would have borrowed under the same facility that Mylan and another group company in fact borrowed to fund the Merck Generics acquisition (ie MAPL would have taken on external debt at a floating rate). The tertiary counterfactual was the same, save that it posited the lender being Mylan or another US subsidiary of Mylan.

8 Although entry into PN A4 formed part of the wider and narrower schemes, the Commissioner did not take issue with the terms on which PN A4 was issued. Rather, his case was that, on the primary counterfactual MAPL would not have incurred any debt, therefore there would have been nothing to refinance and PN A4 would not have come into existence. How PN A4 featured in the secondary and tertiary counterfactuals was not clear. I can only assume that, by parity of reasoning, the deductions obtained as a result of the interest incurred under PN A4 was only contended to form part of the tax benefit to the extent that, on either of those counterfactuals, a different (and lesser) amount would have been refinanced by PN A4, with lower associated deductions for interest.

9 Initially, the Commissioner also defended his amended assessments on transfer pricing grounds, but dropped that part of his case before trial. Accordingly, the matter went to trial only on the Pt IVA issue (and some minor issues whose outcome rested on the determination of the Pt IVA case).

10 The conclusions I have reached on the principal issues are as follows:

(a) MAHPL did not obtain a tax benefit in connection with the primary scheme that may be calculated by reference to the primary counterfactual;

(b) had none of the schemes been entered into or carried out, the most reliable — and a sufficiently reliable — prediction of what would have occurred is what I have termed the “preferred counterfactual”;

(c) the principal integers of the preferred counterfactual are as follows:

(i) MAPL would have borrowed the equivalent of AUD 785,329,802.60 on 7 year terms under the SCA (specifically the term applying to Tranche B), at a floating rate consistent with the rates specified in the SCA;

(ii) MAPL would otherwise have been equity funded to the extent necessary to fund the initial purchase of Alphapharm and to stay within the thin capitalisation safe harbour ratio from time to time;

(iii) Mylan would have guaranteed MAPL’s borrowing under the SCA;

(iv) Mylan would not have charged MAPL a guarantee fee;

(v) interest on the borrowing would not have been capitalised;

(vi) MAPL would have been required to pay down the principal on a schedule consistent with that specified in the SCA and would have made voluntary repayments to reduce its debt as necessary to stay within the thin capitalisation safe harbour, from time to time;

(vii) MAPL would not have taken out hedges to fix some or all of its interest rate expense;

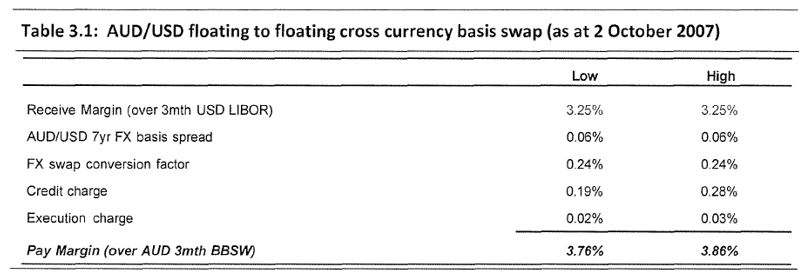

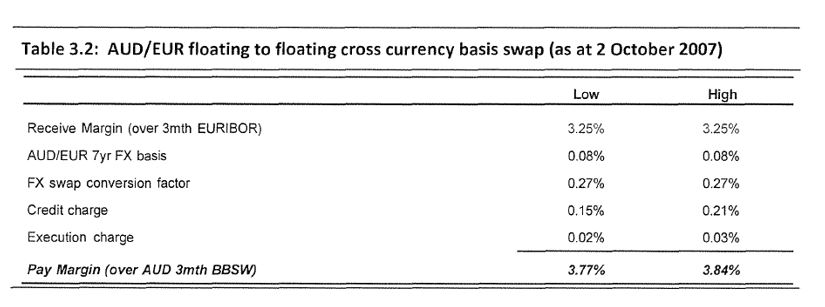

(viii) MAPL would have taken out cross-currency swaps into AUD at an annual cost of 3.81% per annum over AUD 3 month BBSW; and

(ix) if MAPL’s cashflow was insufficient to meet its interest or principal repayment obligations, Mylan would have had another group company loan MAPL the funds necessary to avoid it defaulting on its obligations, resulting in MAPL owing those funds to that related company lender by way of an intercompany loan, accruing interest at an arm’s length rate;

(d) MAHPL did (subject to matters of calculation) obtain a tax benefit in connection with the schemes, being the difference between the deductions for interest obtained in fact, and the deductions for interest that would be expected to be allowed on the preferred counterfactual; and

(e) MAHPL has discharged its onus in relation to the dominant purpose enquiry specified by s 177D of the ITAA36 and so has established that the assessments issued to it were excessive.

11 The parties tendered a substantial number of documents at trial. Following the conclusion of the trial, the parties marked up versions of the indexes to the Court Book and the Supplementary Court Book, striking out documents that were not referred to at trial (and were therefore not treated as having been tendered). The parties also prepared a Second Supplementary Court Book, all of which was referred to at trial (such that there was no need to prepare a marked up index of that court book).

12 There was limited lay evidence. MAHPL read the following affidavits of lay witnesses:

(a) an affidavit of Paul Campbell dated 4 August 2022;

(b) an affidavit of Thomas Salus dated 23 August 2023; and

(c) a further affidavit of Thomas Salus dated 20 October 2023.

13 Mr Campbell is the Senior Vice President, Controller and Chief Accounting Officer at Viatris Inc, the present ultimate parent of MAHPL. In 2007, Mr Campbell was Mylan’s Vice President Corporate Accounting and Reporting, Business Development, Strategic Development. His responsibilities were mainly focused on accounting, finance business development activities, purchase accounting for acquisitions and preparation of consolidated financial statements. Mr Campbell gave some very limited evidence concerning the acquisition of the Merck Generics business. He deposed to Mylan having completed the acquisition in accordance with version 17 of a “step plan” prepared by Mylan’s advisors.

14 Mr Salus is the Assistant Secretary of Viatris Inc, and the Deputy Global General Counsel of Mylan. Mr Salus’s August 2023 affidavit set out the names of individuals employed in various roles and when they were last employed by any member of the Mylan group. This evidence was to the effect that, the CFO, two treasurers, the Vice President Tax, the Director – International Tax and various others, had all left the employ of members of the Mylan group years prior to the present litigation.

15 Mr Salus’s October 2023 affidavit is addressed in more detail below. It produced documents that relate to when the interest rate on PN A2 was fixed and when intercompany accruals reflecting the fixed rate, were effected.

16 Mr Campbell and Mr Salus were not cross examined. MAHPL also relied on an affidavit of its solicitor Daniel James Slater dated 2 May 2023 (sworn in connection with a pre-trial discovery application) in relation to some points concerning what documentation had been produced to the Commissioner, and when such documentation was produced.

17 The parties also relied on reports of experts.

18 The Commissioner and MAHPL each called an expert on US tax law. The Commissioner relied on an expert report of Harry David Rosenbloom dated 28 November 2022, an attorney engaged in private practice and a visiting professor of law at New York University School of Law. MAHPL relied on two reports of Kevin Glenn dated 2 August 2022 and 10 April 2023. Mr Glenn is a practising attorney at law and a partner of DLA Piper LLP (US). Prof Rosenbloom and Mr Glenn prepared a joint expert report, which was also tendered at trial, dated 16 June 2023.

19 Mr Glenn and Prof Rosenbloom both gave evidence and were cross-examined.

20 MAHPL also called evidence from two further experts: Terence Stack, and Mozammel Ali. Mr Ali is a financial markets expert, and is the Managing Director of Theorem Consulting PtyLtd, a firm specialising in advising on mergers and acquisitions, acquisition financing, capital raisings and capital structuring. Mr Ali prepared two reports: dated 10 August 2022, and 9 April 2023. Mr Stack is an expert in corporate treasury functions, including in relation to capital structuring, capital allocation, debt and equity market transactions, financial market risk management, liquidity management and related matters. Mr Stack prepared two reports: dated 5 August 2022 and 8 April 2023.

21 The Commissioner called expert evidence from Gregory Johnson. Mr Johnson is a capital markets expert and is the Managing Director of Global Capital Advisors LLC. He prepared a report dated 12 February 2023.

22 Mr Stack, Mr Ali and Mr Johnson prepared a joint expert report, which was tendered at trial, dated 18 July 2023.

23 Mr Stack and Mr Ali also participated in the preparation of a further joint expert report, dated 18 July 2023, along with David Bernard. Mr Bernard had been retained by the Commissioner, and had prepared a report. However, the Commissioner determined not to rely on his evidence at trial. Nevertheless, and as the joint expert report involving Mr Bernard contained material on which MAHPL wished to rely even though Mr Bernard was not being called, a redacted version of that report was tendered at trial.

24 Mr Stack, Mr Ali and Mr Johnson all gave evidence at trial and were cross-examined.

25 All of the experts were amply qualified to give opinion evidence on the topics covered by their reports.

26 The parties jointly put forward, as the version of Pt IVA of the ITAA36 according to which the issues arising are to be determined, the version operative from 1 October 2007 to 31 December 2007. Relevant extracts were provided by the joint book of authorities.

27 This proceeding falls to be determined under the “old” Pt IVA regime, being the provisions in place prior to the amendments introduced by the Tax Laws Amendment (Countering Tax Avoidance and Multinational Profit Shifting) Act 2013 (Cth).

28 Section 177F provided for the making of determinations to disallow tax benefits. Section 177F(1)(b) provided as follows in the applicable version of Pt IVA:

(1) Where a tax benefit has been obtained, or would but for this section be obtained, by a taxpayer in connection with a scheme to which this Part applies, the Commissioner may:

...

(b) in the case of a tax benefit that is referable to a deduction or a part of a deduction being allowable to the taxpayer in relation to a year of income—determine that the whole or a part of the deduction or of the part of the deduction, as the case may be, shall not be allowable to the taxpayer in relation to that year of income;

29 As may be seen, the key concepts are the existence of a “tax benefit” obtained in connection with a “scheme” to which Pt IVA applies.

30 The term “scheme” was broadly defined by s 177A(1) and (3), as follows:

scheme means:

(a) any agreement, arrangement, understanding, promise or undertaking, whether express or implied and whether or not enforceable, or intended to be enforceable, by legal proceedings; and

(b) any scheme, plan, proposal, action, course of action or course of conduct.

...

(3) The reference in the definition of scheme in subsection (1) to a scheme, plan, proposal, action, course of action or course of conduct shall be read as including a reference to a unilateral scheme, plan, proposal, action, course of action or course of conduct, as the case may be.

31 Section 177C governs determination of whether a taxpayer has obtained a “tax benefit in connection with a scheme”, and the amount of the tax benefit. Sections 177C(1)(b) and (d) provided as follows in relation to deductions:

(1) Subject to this section, a reference in this Part to the obtaining by a taxpayer of a tax benefit in connection with a scheme shall be read as a reference to:

...

(b) a deduction being allowable to the taxpayer in relation to a year of income where the whole or a part of that deduction would not have been allowable, or might reasonably be expected not to have been allowable, to the taxpayer in relation to that year of income if the scheme had not been entered into or carried out;

...

and, for the purposes of this Part, the amount of the tax benefit shall be taken to be:

...

(d) in a case to which paragraph (b) applies—the amount of the whole of the deduction or of the part of the deduction, as the case may be, referred to in that paragraph;

32 Section 177D provided for Pt IVA to apply only to some schemes. Relevantly, it provided that Pt IVA applies only to schemes entered into with the requisite purpose (objectively determined):

This Part applies to any scheme that has been or is entered into after 27 May 1981, and to any scheme that has been or is carried out or commenced to be carried out after that date (other than a scheme that was entered into on or before that date), whether the scheme has been or is entered into or carried out in Australia or outside Australia or partly in Australia and partly outside Australia, where:

(a) a taxpayer (in this section referred to as the relevant taxpayer) has obtained, or would but for section 177F obtain, a tax benefit in connection with the scheme; and

(b) having regard to:

(i) the manner in which the scheme was entered into or carried out;

(ii) the form and substance of the scheme;

(iii) the time at which the scheme was entered into and the length of the period during which the scheme was carried out;

(iv) the result in relation to the operation of this Act that, but for this Part, would be achieved by the scheme;

(v) any change in the financial position of the relevant taxpayer that has resulted, will result, or may reasonably be expected to result, from the scheme;

(vi) any change in the financial position of any person who has, or has had, any connection (whether of a business, family or other nature) with the relevant taxpayer, being a change that has resulted, will result or may reasonably be expected to result, from the scheme;

(vii) any other consequence for the relevant taxpayer, or for any person referred to in subparagraph (vi), of the scheme having been entered into or carried out; and

(viii) the nature of any connection (whether of a business, family or other nature) between the relevant taxpayer and any person referred to in subparagraph (vi);

it would be concluded that the person, or one of the persons, who entered into or carried out the scheme or any part of the scheme did so for the purpose of enabling the relevant taxpayer to obtain a tax benefit in connection with the scheme or of enabling the relevant taxpayer and another taxpayer or other taxpayers each to obtain a tax benefit in connection with the scheme (whether or not that person who entered into or carried out the scheme or any part of the scheme is the relevant taxpayer or is the other taxpayer or one of the other taxpayers).

(Emphasis added.)

33 The concept of the “purpose” behind entry into the scheme was elaborated upon by s 177A(5), which provided that:

A reference in this Part to a scheme or a part of a scheme being entered into or carried out by a person for a particular purpose shall be read as including a reference to the scheme or the part of the scheme being entered into or carried out by the person for 2 or more purposes of which that particular purpose is the dominant purpose.

34 While some very limited lay evidence was given by affidavit, the factual dimensions of the case were entirely documentary. In its opening submissions, MAHPL set out an account of the facts by reference to the documents. Its account was, very substantially, couched in neutral terms; the account of the facts was not used as an opportunity for advocacy. In his opening submissions, the Commissioner addressed the factual background in one paragraph:

The Commissioner apprehends MAHPL’s statement of material facts at AS1 [12]-[58], [65]-[107] to be broadly accurate. The weight to be given to any particular fact, and the inferences that may be drawn from such facts, are likely to turn on the evidence given at trial and will therefore be addressed by the Commissioner in closing.

35 In view of the Commissioner’s acceptance that MAHPL’s account of the facts was “broadly accurate”, in the course of opening submissions, I requested that the Commissioner detail any respect in which he contended the narrative was inaccurate. I also requested, noting the paragraphs carved out of the Commissioner’s concession, that the Commissioner “be a bit more granular about what it is about those paragraphs that [he did not] accept”. The Commissioner then sent a letter to MAHPL dated 18 October 2023, a copy of which was provided to the Court. The letter stated, in respect of wide ranges of paragraphs in MAHPL’s written opening submissions, that the Commissioner “put [MAHPL] to proof”. This entirely unhelpful response was staunchly defended by counsel for the Commissioner on the basis that the taxpayer has the onus of proof and had chosen not to call lay evidence. Ultimately, on 19 October 2023, a somewhat more helpful document was provided by the Commissioner, which set out the basis for the Commissioner’s “non-admission” (as it was characterised in the Commissioner’s letter) of certain facts.

36 I will not dwell on this episode further, save to observe that the taxpayer’s onus in Pt IVC appeals does not absolve the Commissioner of his obligations under s 37N of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) to conduct the proceeding in a way that is consistent with the overarching purpose. The overarching purpose includes the resolution of disputes as quickly, inexpensively and efficiently as possible, and the efficient use of the judicial and administrative resources of the Court (s 37M). I would not have thought that asking a litigant to identify with some specificity the respects in which it does not accept, or wishes to supplement, the document-based factual summary of his opponent is straining at the edges of the obligation of a litigant to conduct the proceeding in a way that is consistent with the overarching purpose.

37 Somewhat surprisingly, in view of the contents of its written opening and the interactions referred to above, the Commissioner’s closing submissions contained an annexure — which ran to more than 30 pages and whose delivery had not been foreshadowed — setting out the facts.

38 Nevertheless, the Commissioner’s factual narrative did not differ significantly from the factual narrative presented by MAHPL in opening. The main factual matters on which the parties differed concerned: whether or not Mylan had settled on an acquisition structure when it initially signed the SPA; whether or not Mylan intended that 100% of free cash flow would be repatriated; and when the interest rate on PN A2 was in fact fixed and retroactively applied.

39 Given the very limited compass of the divergence in views of the facts and the documentary source of the factual narratives, what follows is an account of the facts that, in part, reproduces and expands upon the parties’ accounts of the facts. MAHPL’s account in opening constitutes the base, but significant additional facts that were included by the Commissioner in his account in closing, but omitted from MAHPL’s account, have been incorporated. Most of the additional facts addressed in the Commissioner’s factual summary, but not in MAHPL’s summary in opening, concern what the Commissioner characterised as the “debt pushdown” (viz, the creation of intercompany debt at the MAPL level). In their respective narratives, the parties highlighted different aspects of some documents. In the setting out the factual summary below, I have had regard to those differences of emphasis or construction. I have also had regard to, and included, factual matters canvassed in oral submissions, as well as additional factual matters that I considered ought to be addressed. I have also had regard to the Commissioner’s comments (in his letter of 19 October 2023) regarding MAHPL’s account of the facts in opening.

40 I have addressed the more significant factual controversies in the course of my reasons on “tax benefit” and “dominant purpose”, and have addressed more minor factual controversies in the context of the narrative that follows.

41 The factual narrative below is arranged chronologically, within topics.

42 As noted above, MAHPL is the head company of a tax consolidated group formed under Part 3-90 of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1997 (Cth). The other members of the group are MAPL, which became a member when the group was formed with effect from 17 September 2007, and Alphapharm, which became a member at the time it was acquired by MAPL on 2 October 2007.

43 At all material times, Mylan was a publicly held company incorporated under the laws of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, US, which was listed on the New York Stock Exchange or NASDAQ and a resident of the US for tax purposes. Through the Mylan group, it carried on a business which principally included the development, licensing, manufacturing, marketing and distribution of generic pharmaceutical products, as well as the supply of active pharmaceutical ingredients around the world.

44 Prior to 2006, the Mylan group’s operations and sales were primarily in the US domestic market. In 2006, it expanded its global operations by acquiring a controlling interest in Matrix Laboratories Limited (Matrix), a publicly traded Indian company which was one of the world’s leading suppliers of active pharmaceutical ingredients.

45 In the financial year ended 31 March 2007, the Mylan group’s principal markets were the US, India and Europe. It derived a total of USD 1,611,819 in revenues. In the same year, Mylan’s total debt was USD 1,776,362 and total shareholders’ equity was USD 1,648,860.

46 As at the close of market on Friday 28 September 2007, Mylan had a market capitalisation of approximately USD 3.97 billion.

47 At all material times, Merck was a global chemical and pharmaceutical company headquartered in Germany.

48 Prior to 2 October 2007, Merck Generics carried on the world’s third largest generics pharmaceutical business which, in 2006, generated revenues in excess of EUR 1.8 billion. Merck Generics had a number of indirectly held subsidiaries around the world, including in the US, France, Australia and Canada, which were its four largest markets, accounting for approximately 68% of Merck Generics’ sales and about 84% of profit, excluding R&D.

49 Alphapharm was Merck’s indirectly held subsidiary in Australia. Alphapharm’s immediate parent was MGGBV.

50 In 2007, Alphapharm was the leading generic pharmaceuticals company in Australia.

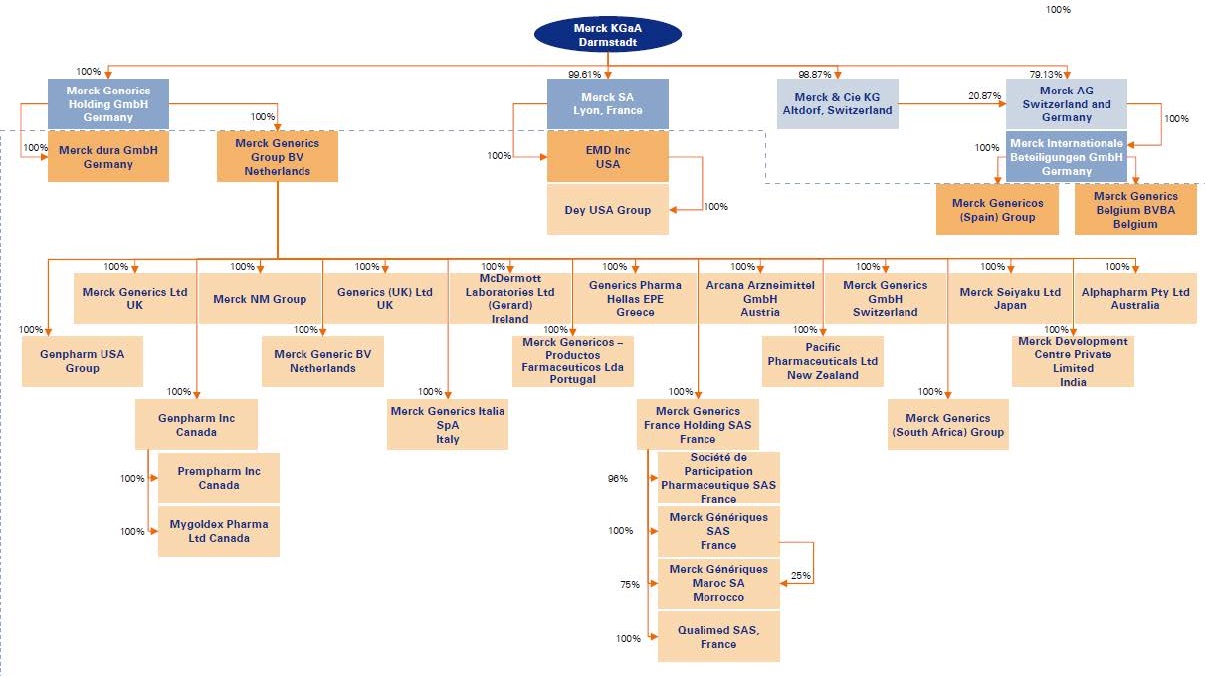

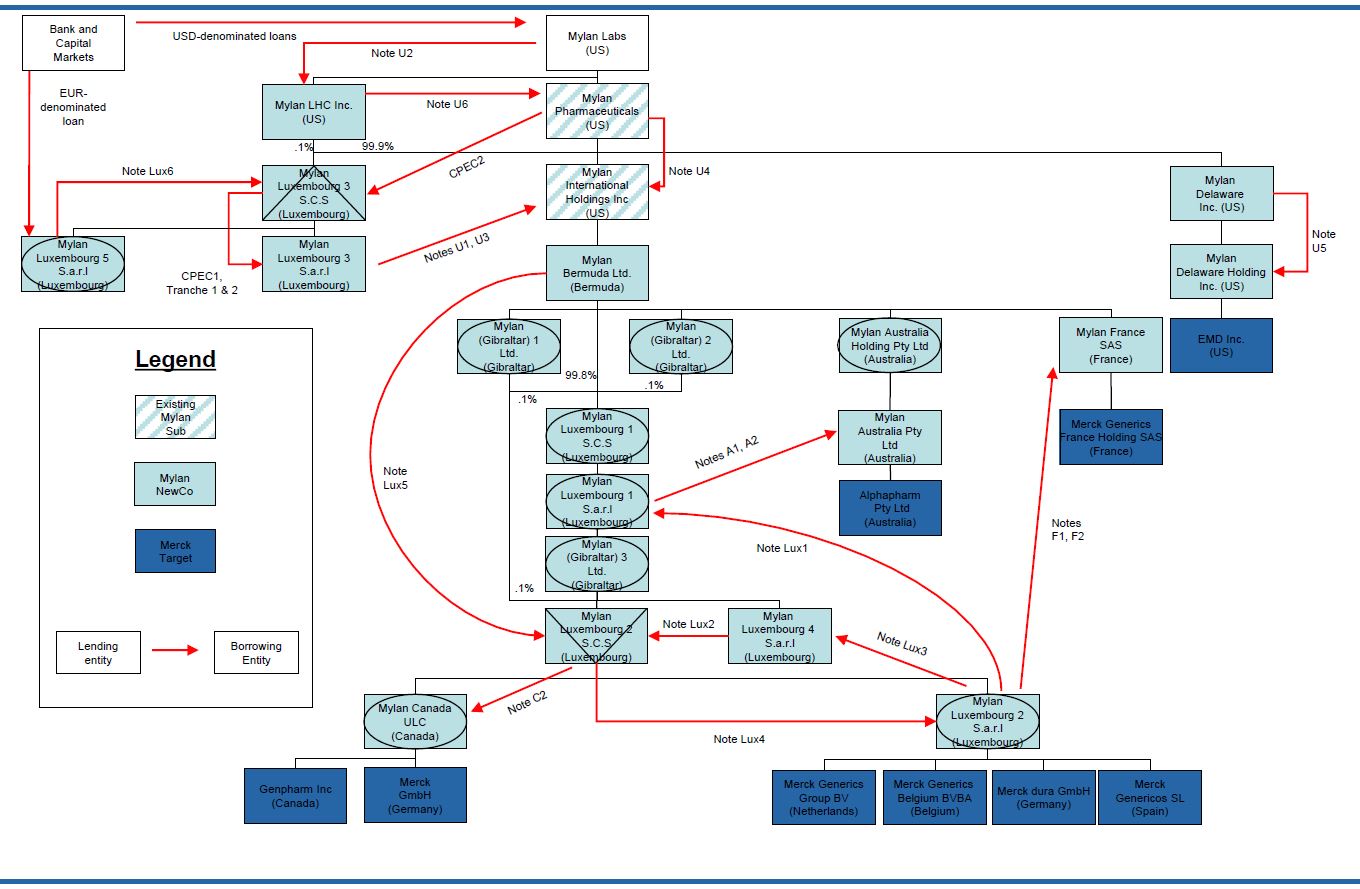

51 The structure of Merck Generics in early 2007 is depicted in the following diagram:

52 On or about 6 March 2007, Mylan received a letter from Bear, Stearns & Co Inc on behalf of Merck. The letter stated that Merck was exploring the potential sale of its generics pharmaceuticals business (being Merck Generics). It also enclosed a Confidential Information Memorandum, and invited Mylan to provide a preliminary, non-binding indication of interest in acquiring Merck Generics (the Acquisition). The Acquisition was code-named “Project Genius”, with Merck given the code name “Mastermind”.

53 From about March 2007, for the purposes of preparing its indicative offer (and subsequently its bid) for the Acquisition, Mylan engaged, among others:

(a) Merrill Lynch as its primary financial advisor;

(b) Cravath Swaine & Moore LLP (Cravath) as its external counsel; and

(c) Deloitte & Touche LLP (Deloitte) as its accounting and tax advisor.

54 On 12 March 2007, the Mylan Board of Directors (Mylan Board) met and resolved to submit a preliminary non-binding indication of interest for the Acquisition with a proposed purchase price of EUR 4.2 to 4.7 billion. Mylan submitted an indicative offer for the Acquisition on the same day. Mylan was subsequently invited to participate in a “second round” process for the Acquisition, with a final bid to be submitted by 30 April 2007.

55 In March, April and May 2007, Merrill Lynch provided Mylan with modelling, analysis and structuring alternatives for the Acquisition. The modelling included scenarios involving both wholly debt and partial debt/partial equity funding for the Acquisition. Mylan also received due diligence materials and analysis.

56 On 30 April 2007, the Mylan Board met and resolved (inter alia) to approve the submission of an updated non-binding proposal for the Acquisition, attaching revised drafts of a “Share Purchase Agreement”, “Transitional Services Agreement” and “Brand License Agreement”, as well as a copy of a “commitment letter” for the financing of the Acquisition received by Mylan from a syndicate of lenders (Merrill Lynch, Citibank and Goldman Sachs) (referred to in more detail below). Mylan submitted its updated proposal on the same day, proposing a base purchase price in the range of EUR 4.4 to 4.75 billion.

57 The marked-up draft Share Purchase Agreement and Transitional Services Agreement attached to Mylan’s updated proposal included the following notation:

Note to Sellers: Purchaser’s acquisition structure to be further discussed with Sellers. We understand based upon our discussions during due diligence process that Mastermind [Merck] is willing to discuss and accommodate an optimal acquisition structure for Purchaser.

58 The marked-up draft Brand Licence Agreement attached to the proposal similarly included the notation: “Note to Sellers: “Purchaser’s acquisition structure to be further discussed with Sellers”.

59 On or about 3 May 2007, Mylan was invited to participate in the final stage of the Merck Generics sale process.

60 On 6 May 2007, Christian Brause from Cravath sent an email to representatives from Mylan with the subject “Genius/Structuring”. It stated, inter alia:

As you know, the negotiations on Monday and Tuesday will move very fast. Thus, we will have no time to come up with a fully agreed upon acquisition structure. We therefore intend to built [sic] into the SPA some flexibility to rearrange the acquisition structure between signing and closing. We intend to do that by incorporating a new section that would essentially look like the one set forth at the end of this email

61 The end of the email set out a new proposed clause which ultimately became the basis for clause 3.1.5 of the Share Purchase Agreement. It stated:

Structure of Transaction. At the election of Purchaser’s Guarantor, (i) any one or more Affiliates of Purchaser’s Guarantor may be substituted for Purchaser in the transaction and (ii) Purchaser or any such substituted purchaser may directly acquire the Interests in any Subsidiary … In any such event, the parties will cooperate in good faith to effectuate any such substitution any/or change in the acquisition structure

62 On 8 May 2007, the Mylan Board met and resolved that it approved the submission of the updated, non-binding proposal for the acquisition of Merck Generics for EUR 4.9 billion.

63 On 12 May 2007, the Mylan Board again met and resolved (inter alia) that it approved the execution and delivery of the Share Purchase Agreement and all of the transactions contemplated thereby. The Mylan Board also approved and authorised the financing described in the lenders’ Commitment Letter accompanying the Share Purchase Agreement (referred to in more detail below).

64 Also on 12 May 2007, Mylan, Merck Generics Holding GmbH, Merck S.A., Merck Internationale Beteiligung GmbH and Merck KgaA executed the Share Purchase Agreement (SPA), which provided for the Acquisition by Mylan of all of the shares in Merck dura GmbH, MGGBV, EMD Inc, Merck Generics Belgium B.V.B.A and Merck Genericos S.L. for a cash purchase price of EUR 4.9 billion (subject to certain adjustments) (being approximately USD 6.7 billion).

65 Mylan issued a press release on 12 May 2007 which stated (inter alia, emphasis added):

Mylan Laboratories Inc. (NYSE: MYL) and Merck KGaA today announced the signing of a definitive agreement under which Mylan will acquire Merck’s generics business (‘Merck Generics’) for EUR 4.9 billion ($6.7 billion) in an all-cash transaction. The combination of Mylan and Merck Generics will create a vertically and horizontally integrated generics and specialty pharmaceuticals leader with a diversified revenue base and a global footprint. On a pro forma basis, for calendar 2006, the combined company would have had revenues of approximately $4.2 billion, EBITDA of approximately $1.0 billion and approximately 10,000 employees, immediately making it among the top tier of global generic companies, with a significant presence in all of the top five global generics markets.

…

Under terms of the transaction, which have been unanimously approved by Mylan’s Board of Directors, Mylan will acquire 100% of the shares of the various businesses comprising Merck Generics for a cash consideration of EUR 4.9 billion ($6.7 billion). Mylan has secured fully committed debt financing from Merrill Lynch, Citigroup and Goldman Sachs.

The transaction is anticipated to be dilutive to full-year cash EPS in year one, breakeven in year two, and significantly accretive thereafter based on management’s internal projections. The company is committed to reducing its leverage in the near term through the issuance of $1.5 billion to $2.0 billion of equity and equity-linked securities. The combined company will generate substantial free cash flow that will further enable it to rapidly reduce acquisition-related debt. Reflecting its more leveraged capital structure and focus on growth, Mylan is suspending the dividend on its common stock.

66 While it was bound to proceed with the Acquisition pursuant to the SPA as signed, at the time that the SPA was executed, Mylan had not settled upon its preferred structure for the acquisition of the Merck Generics business. The terms of the SPA included provisions which allowed Mylan to put forward a finalised transaction structure, with provision also being made for indemnification of the Merck Generics side for any increase in its tax costs arising from such changes.

67 Clause 3.1.5 of the SPA provided as follows:

Structure of Transaction. At the election of Purchaser [Mylan], (i) any one or more Affiliates of Purchasers may be substituted for Purchaser in the transaction and (ii) Purchaser or any such substituted purchaser or purchasers may directly acquire Interests in any Subsidiary … The parties will cooperate in good faith to effectuate any such substitution and/or change in the acquisition structure, including executing any necessary or advisable amendments to this Agreement in order to reflect the foregoing. Purchaser will agree to an appropriate full indemnification arrangement with Sellers and Sellers’ Affiliates to the extent such change in acquisition structure increases the tax costs to Sellers and Sellers’ Affiliates above the amount of costs that would have been incurred in connection with the sales and transfers set forth in this Section 3.1 as of the Signing Date.

68 Clause 21.5 (headed “Assignment and Designation of Transferors”) relevantly provided that Mylan:

may designate any of its direct or indirect, wholly owned subsidiaries as a transferee of the Shares and Purchaser may assign its rights under this Agreement by way of security in connection with the Financing.

69 Notwithstanding the terms of the SPA that provided for changes to the stated acquisition structure, the Commissioner sought to emphasise that the original SPA was an agreement which Mylan was obliged to perform. The Commissioner contended that the fact Mylan entered into the original SPA prevented MAHPL from arguing that it would not have acquired Alphapharm in a way analogous to that which was provided for under the agreement. While I perceive the Commissioner’s point to be one concerning the implications of this matter for the primary counterfactual (as distinct from a factual contest), to the extent he disputed the fact, I find that Mylan had not settled on a final acquisition structure when it signed the SPA. This matter is further addressed in relation to the primary counterfactual below.

70 During May and June 2007, Mylan’s advisors presented it with various potential structures for the acquisition of Merck Generics. They contemplated (inter alia) that:

(a) various US and non-US entities would be created, including indirect Australian, French, and Canadian subsidiaries of Mylan – MAPL, Mylan France SAS (Mylan France) and Mylan Canada NSULC (Mylan Canada), respectively; and

(b) MAPL, Mylan France and Mylan Canada would acquire the shares in local MGGBV subsidiaries, financed by a mixture of equity (common stock) and debt.

71 One of the slide decks prepared by Mylan’s advisors was a Deloitte slide deck dated 27 April 2007 titled “Project Genius – Tax Overview”. That report assumed a total acquisition price of USD 7 billion, of which USD 1 billion was to be allocated to the Australian component of the Merck Generics business. In relation to the entities to be acquired in Australia, Canada and Japan, Deloitte’s report contemplated that:

(a) the Australian entity would borrow from a “US/UK third party financial institution” the AUD equivalent of USD 750 million and otherwise be capitalised by USD 250 million equity, reflecting a debt capitalisation proportion of 75%;

(b) the Canadian entity would borrow from a “Canadian branch of a US/UK third party financial institution” the CAD equivalent of USD 437.5 million and otherwise be capitalised by USD 62.5 million equity, reflecting a debt capitalisation proportion of 87.5%; and

(c) the Japanese entity would borrow from a “Japanese branch of a US/UK third party financial institution” the JPY equivalent of USD 437.5 million and otherwise be capitalised by USD 62.5 million equity, also reflecting a debt capitalisation proportion of 87.5%.

72 On the same day (27 April 2007) there was also an email from Mr Todd Izzo (Deloitte) to Mr Jeffrey Mensch (Deloitte). In that email, Mr Izzo stated that he “would like to limit the foreign loans to Japan, Australia and Canada if possible”, to which Mr Mensch responded, “Australia is 3:1 safe harbour”, and quoted the following extract from “IBFD” (which is apparently a service provider in relation to cross-border tax affairs):

From 1 July 2001, new thin capitalization measures (the “safe harbour” test) contained in Div. 820 of the ITAA97 apply a debt-to-equity ratio of 3:1 to all debt of an entity and not just related foreign party debt. For financial entities the debt-to-equity ratio is 20:1. Nevertheless, if the safe harbour test is failed, debt deductions will not be denied if the entity is able to demonstrate that the debt amount is at arm’s length (i.e. an independent party would be able to raise the same amount of debt under the same terms and conditions). Further, Australian entities with overseas investments may avoid the application of the thin capitalization provisions by satisfying the worldwide gearing test, which requires that the average value of their Australian assets be at least 90% of their worldwide assets.

73 Mr Izzo responded “fine” and also said as follows:

Also, let’s not do a debt push down to Ge [apparently Germany]. Too much hassle. So, in sum, one bank, loaning to Japan and Canada through branches and directly to Austr[a]lia and Lux.

74 As further addressed below, MAHPL did not dispute that the thin capitalisation rules in each relevant jurisdiction influenced the amounts of debt being contemplated for acquisitions in a number of jurisdictions, but disputed that adopting structures that stayed within thin capitalisation limits could be characterised as tending to suggest a desire to maximise tax deductions.

75 On 1 May 2007, Deloitte issued a slide deck to Mylan entitled “Project Genius – Tax Overview”, which was labelled as “Draft: For Discussion Purposes Only (Subject to Review by Non-U.S. Tax Professionals)”. The slide deck contemplated (inter alia) that:

(a) Mylan and a newly established Luxembourg S.a.r.l. would borrow funds from third party lenders;

(b) various US and non-US entities would be created, including MAPL, Mylan France and Mylan Canada;

(c) MAPL would acquire the shares in Merck’s Australian subsidiary, Alphapharm, from MGGBV, financed as follows:

(i) a US subsidiary of Mylan “contributing the Australian dollar equivalent of US$250,000,000 in exchange for common stock” in MAPL; and

(ii) MAPL borrowing “the Australian dollar equivalent of US$750,000,000 from a US/UK third party financial institution … secured by a guarantee from Mylan US and all Mylan’s non-US assets”; and

(d) each of Mylan France and Mylan Canada would also acquire the shares in a local Merck subsidiary, financed with a mixture of equity (common stock) and external debt.

76 MAHPL relied on the fact that the subsequent slide decks prepared by Deloitte dated 11 May 2007, 30 May 2007 and 4 June 2007 also contemplated the formation of MAPL, Mylan France and Mylan Canada, each of which was to acquire the shares in a local Merck subsidiary using a mixture of equity and debt. MAHPL relied on the debt component of MAPL’s financing having been expressed in each slide deck as:

the Australian dollar equivalent of US$750,000,000 … from a US/UK third party financial institution … secured by a guarantee from Mylan US and all Mylan’s non-US assets.

77 The Commissioner sought to focus the Court’s attention to other aspects of these slide decks, which he contended demonstrate Mylan’s tax structuring objectives. In respect of the 11 May 2007 presentation, the Commissioner observed that the presentation continued to contemplate that the Australian acquisition entity would obtain external debt funding, while the source of funding for the Canadian and Japanese acquisition entities had been varied to include internal borrowing.

78 The Commissioner pointed to the following statements in the 30 May 2007 revised slide deck as illustrating the influence of thin capitalisation rules in Australia, France and Canada on the planned capitalisation of each of the Australian, French and Canadian entities:

The debt:equity ratio of Mylan France is 1.5:1, which is in line with the new French thin capitalization rules.

…

Related party debt push-down may have adverse Australian tax consequences; therefore, Genius Pty. Ltd. should be acquired before Lux Holdco’s acquisition of Genius BV.

…

Interest Deductions – Australia’s thin capitalization rules are based on accounting book values rather than issued capital (total debt cannot exceed 75% of the Australian asset values).

…

Since Mylan Canada is funded with intercompany debt, the Canadian thin capitalization rules come into play, which limits the debt:equity ratio to 2:1. Therefore, assuming a $500m total price for Genius Canada, the debt:equity ratio should be $333m of debt at $167m of equity.

79 In relation to the 4 June 2007 Deloitte slide deck, the Commissioner drew attention to the “Alternative A” structure, which assumed third party lenders loaning funds into each of Mylan Australia, Mylan Japan and Mylan Canada, and the relationship between the gearing ratios derived in relation to the posited quantum borrowed, and the thin capitalisation limits in those jurisdictions.

80 On 12 June 2007, Deloitte circulated a further slide deck dated 11 June 2007 entitled “Project Genius – ‘Simple’ Alternative” (marked as a draft for discussion purposes). MAHPL contended that this slide deck contemplated a structure under which (inter alia) MAPL would acquire the shares in Alphapharm using USD 250 million in equity and USD 750 million in debt in the form of a note from “Lux Holdco” (Mylan Luxembourg Sarl), rather than external financing from a third party lender. The Commissioner disputed this description and drew attention to step 18. The Commissioner stated that that step showed that, under the structure being contemplated, only the Australian Merck entity was to be acquired separately (and for cash consideration) whereas the Canadian and Japanese Merck (and other) entities were to be acquired indirectly. Step 18 of the slide deck stated:

Mylan Australia acquires 100% of the outstanding shares of Genius Pty. Ltd. from Genius Genericos Group BV (“Genius BV”) in exchange for the Australian dollar equivalent of US $1,000,000,000 in cash.

81 On 10 July 2007, Mr Joseph Vitullo (PwC US) sent an email to Mr Tony Carroll (PwC Australia) regarding PwC US having been engaged by Mylan. Mr Vitullo sought Mr Carroll’s assistance in relation to a “debt pushdown into Australia related to the acquisition of the Merck generics business”. That email included the following:

Steve White (ITS partner) and I (ITS director) have been engaged by Mylan to assist them in the structuring of a debt pushdown into Australia related to the acquisition of the Merck generics business. We would like to have a conversation with you this week to discuss alternative means by which we can accomplish this goal.

82 On 13 July 2007, Mr David Kennedy (Vice President of Corporate Taxation, Mylan) signed a “Statement of Work” (SOW) between Mylan and its subsidiaries and PwC. The purpose of the SOW was stated as follows:

This SOW covers services in connection with the acquisition and integration of Merck’s Generics Business (“MGB”). Examples of the types of services covered by this SOW include evaluation of the tax implications and possible tax planning strategies at the federal, state and international level, associated with the acquisition and integration of MGB.

83 The SOW also described the nature of the services to be provided by PwC, which were grouped in three categories – namely, “Analyze”, “Develop” and “Implement”. The description of the services to be provided did not refer to the repatriation of foreign income or Mylan’s stated de-leveraging plans (the absence of which was a matter to which the Commissioner called attention).

84 Following Mylan’s engagement of PwC to provide tax advice in relation to the Acquisition, PwC’s personnel undertook a range of activities, recorded in email correspondence and other documents, in furtherance of its retainer.

85 On 14 July 2007, Mr Vitullo sent an email to various PwC personnel attaching “a projection by country of Merck’s operating profits from 2007 through 2010”. The email stated that “[t]his should help in assessing each country’s interest capacity”. The attachment to that email included hand-written notations that highlighted Alphapharm, among other entities. As is discussed below, MAHPL and the Commissioner put diametrically opposed constructions on this document. The Commissioner said it showed an analysis directed at working out how much interest had to be charged to eliminate taxable income, whereas MAHPL contended it showed that there was (contrary to the Commissioner’s submission) analysis of MAPL’s capacity to service debt.

86 On or around 18 July 2007, Mylan prepared a document titled “Weekly Update – Finance: 6 – Tax Plan & Compliance – Week of 071607”. In a section with the heading “Issues/Risks/Key Decisions”, that document included the following:

• Conclude which alternative acquisition structure is optimal from a tax perspective

• Assess taxable income capacity, on a country-by-country basis, to absorb acquisition finance interest expense

• Assess optimal levels of local country debt giving consideration to income capacity, debt:equity restrictions, income tax rate arbitrage, and fair values

87 On 19 July 2007, Mr Carroll sent an email to Mr Vitullo attaching a slide deck prepared by PwC entitled “Mylan Laboratories Structure Alternatives” (marked as “Draft Report”). In the email, Mr Carroll stated that:

I have suggested limiting the borrowing level to the same proportion of the total borrowing to the total purchase price. We could always stretch this further within the safe harbour rules in Australia but we need to be comfortable from an anti avoidance perspective that we can justify a greater amount form a commercial perspective.

88 The slide deck set out five alternative structures for the acquisition of Alphapharm in Australia. Structure 1 contemplated external borrowing by an Australian subsidiary of Mylan to fund the Acquisition. Structure 1 included a note that:

It is recommended that the level of borrowing be limited to the worldwide debt funding proportion for this acquisition. Where there is any increase above this level, the Australian anti-avoidance provisions would need to be considered.

89 Structures 2, 4 and 5 contemplated “internal” debt funding into Australia. Structure 3 contemplated an external borrowing by a partnership that would be treated as part of the Australian tax consolidated group.

90 Also on 19 July 2007, Mr Vitullo responded to Mr Carroll’s email stating that:

we have agreed with Mylan that on 8/3 we will deliver a comprehensive holding company structure along with proposed debt pushdown structure for Australia, France, Canada, and Japan. We will incorporate each separate country’s debt pushdown strategy into this presentation.

91 Also on 19 July 2007, Mr Carroll sent an email to Mr Vitullo stating:

As you will see from my note I did not want to push the debt to the limit unless we have strong commercial reasons for doing so.

92 Also on 19 July 2007, Mr Steve White (PwC US) sent an email to Mr Carroll stating that:

Mylan has asked if we would give them the names of law firms that we have worked with on similar debt pushdowns/financings in that they would hope that this would help expedite the implementation of any strategy that we develop.

93 On 1 August 2007, Mr Vitullo sent an email to his PwC colleagues, attaching a PowerPoint file titled “Merck Acq Structures”. In his email, Mr Vitullo commented on the Canada, Australia and France acquisitions (among other things) (emphasis in original):

October 1 Structure – This represents the proposed minimum structure required to be in place at the date of the closing of the Merck transaction. The following are specific country questions with respect to this structure.

Canada

Would it be possible to simply put in place a loan/equity from Bermuda 1 to a newly formed ULC which would be used to acquire the Canadian target entity? We would then after Oct 1 drop the note down into the structure and form the Canadian holding partnership structure which ultimately generates the tax savings element of the structure.

Australia

Would it be possible to simply put in place a required loan/equity from the 80/20 company to Aus Holdco to acquire the target entity? We would then after Oct 1 drop the note down into the structure and form the Australian high/low tax structure which ultimately generates the tax savings element of the structure.

…

1) France – we contemplate establishing internal debt levels of 1.5:1. Are we correct that as long as Mylan maintains this relationship, there should not be a thin-cap exposure?

2) All Countries – Please indicate if there is any principal repayment requirements for the internal debt that we are putting into place. In other words, is a demand loan that Mylan keeps in place for a significant period of time acceptable, is there a requirement that principal payments are made over the life of the loan or at a point in time.

94 On 2 August 2007, Mr Garth Drinkwater (PwC Australia) sent an email (“on behalf of Tony Carroll”) to Mr Vitullo which, among other things, stated that:

Interest payments by Aust Hold should be deductible for Australian income tax purposes (subject to thin capitalisation provisions – broadly 75% of Australian assets less non-debt liabilities).

…

There are no requirements for principle [sic] payments to be made over the life of the loan (i.e. principle [sic] can be repaid at the end of the loan term). However, interest would need to capitalised (if not paid). Interest withholding tax would continue to be payable as the interest accrues.

…

We note that if interest is capitalised to the loan balance, rather than being paid, it may put pressure on the Australian group’s thin capitalisation position where there is no corresponding increase in the book value of the assets (e.g. via increases in retained profits or asset revaluations).

95 On 3 August 2007, PwC prepared a slide deck titled “Merck Tax Integration August 2007”. Under the heading “Tax Integration Goals/Objectives”. MAHPL accepted on the transcript that this document was received by Mylan even though the covering email was not in evidence. The slides included the following statements:

(1) Allow for redeployment of foreign excess cash via tax efficient Treasury Centre

(2) Foreign tax reduction

A. Use of debt-pushdown to effect immediate ETR reduction

B. Consider utilizing a tax-efficient Principal in developing the new centralized supply chain management structure.

…

(2) Foreign tax reduction

A. Use of debt-pushdown to effect immediate ETR reduction

- Tax efficient internal debt utilized in Australia, France, Canada and Japan. Approximately $40M-$50M of annual tax savings over the first five years (resulting in immediate ETR benefits) may be realized by Mylan

96 On 10 August 2007, Mr Drinkwater sent an email to Mr Vitullo with the subject “Mylan acquisition – Stamp duty comments”. That email provided comments in relation to a “Direct Acquisition”, “Indirect Acquisition” and an “Alternative” structure.

97 Regarding the “Direct Acquisition”, Mr Drinkwater stated that a liability would arise for “New South Wales share transfer duty at 0.6% on the greater of market value or consideration paid”.

98 Regarding the “Indirect Acquisition”, being an “indirect acquisition of Alphapharm by acquiring a foreign holding company further up the chain”, Mr Drinkwater stated that no liability for share transfer duty would arise “provided the foreign company does not have a share register in Australia or a registered office in South Australia”. Mr Drinkwater also stated that “[i]f an indirect acquisition occurs, it would not be possible to push debt into Australia until Alphapharm is later moved under the Australian holding company”.

99 Mr Drinkwater commented on the “Alternative” structure as follows:

Merck Generics Group BV could incorporate a new Australian holding company in Victoria (“Newco”) and transfer Alphapharm under the Newco prior to Mylan’s acquisition of the three global Merck companies. This transfer should be eligibile [sic] for the New South Wales corporate reconstruction exemption (subject to land rich issues etc as noted above). In addition, the debt pushdown would be effective on acquisition by Mylan (and therefore we would not need to wait one year before the debt pushdown could be effected).

Newco and Alphapharm could be transferred and incorporated into your preferred structure one year later.

Of course, this requires the co-operation of Merck and for Merck Generics Group BV to apply for the corporate reconstruction exemption. That said, this is not an unusual transaction here in Australia.

100 On 23 August 2007, Mr Drinkwater sent an email to Mr Vitullo. Among other things, that email confirmed that “we should be able to get a step up in the accounting values of the Australian Group” and then commented that “this was important for Australia’s thin capitalisation rules”.

101 On 1 September 2007, Mr Vitullo sent an email to Messrs Carroll and Drinkwater with the subject “Time of Transactions”. That email included the following (underlining in original):

We have been reviewing all of the Oct 1 steps and researching some of the US tax issues associated with the transactions which achieve the purchase of Merck targets in France and Australia prior to the acquisition of Merck BV. Some of the US tax, legal, and govenmental [sic] approval issues are particularly troublesome and we are now wondering if we may want to reconsider the timing of the debt pushdowns into France and Australia.

Accordingly, we would like you to provide us, in a return email, confirmation of our understanding that it would be possible to push debt into your respective countries after Mylan acquires Merck BV. We anticipate that the internal debt pushdowns would occur within days or weeks of Oct. 1.

102 On 4 September 2007, Mr Carroll sent an email to Mr Vitullo with the subject “Acquisition structures”. That email included the following:

Further to our discussions this morning, I confirm that if the purchaser of Alphapharm is a wholly owned subsidiary of New Australian Hold Co, there are no adverse consequences from an Australian perspective. Your need for this from a US perspective also assists me in any arguments I might have regarding why we set up a two tiered structure and formed a tax consolidated group, prior to acquiring the Alphapharm company, from an Australian thin capitalisation perspective, so I welcome that addition.

In relation to the alternative acquisitions [sic] structures, I would confirm that my preferred option, would be to establish New Australian Hold Co and its wholly owned subsidiary, underneath the proposed Bermuda structure and debt fund either, Australian Hold Co or Australian Interposed Co, to fund the acquisition. Under this arrangement an agreement would be entered into with BV prior to your acquisition of BV but conditional on Mylan’s acquisition of BV.

In my view from an income tax perspective, I believe there are considerably stronger arguments in relation to the debt push down, under this alternative than the one set out below.

The alternate structure would involve the establishment of Australian Hold Co and Australian Interposed Co by BV and then an acquisition from BV after Mylan has acquired BV. In my view this proposal substantially increases the risk that interest deductions may be denied under the debt push down arrangements.

The stamp duty corporate reconstruction exemptions is on the basis of an internal reorganisation and whilst the technicalities of the relief are available it is not really intended that there would be a change in ownership of BV and bearing in mind that the NSW government, to whom this duty would be payable, is as I understand it, one of Alphapharm’s largest customers, I am not sure you necessarily want to push the letter of the law to this extent, bearing in mind the commercial relationships between Alphapharm and the NSW government from whom you are obtaining the concession. Further from an income tax perspective, the debt pushdown is on the basis this is a third party acquisition. There is a clear conflict between the reasons for obtaining the stamp duty relief and the reasons for undertaking the debt push down transaction. The Australian Revenue are very wary of internal reorganisations that achieve a debt push down.

As originally discussed in one of our earlier conference calls, I believe the avoidance of the AU$6 million in stamp duty whilst potentially available, does increase the risks both from a tax perspective, in respect of the debt pushdown and secondly has a potential commercial outcome which could be adverse. I would strongly advise adopting the original proposal and pay the stamp duty.

As mentioned from a thin capitalisation perspective, the establishment of a two company structure in Australia is our preferred route in any event.

103 On 10 September 2007, Mr Drinkwater responded to an email from Mr Vitullo concerning the timing of the transfer of legal title of Alphapharm. Mr Drinkwater’s email stated as follows:

Following on from your email below, I understand that the legal transfer of Alphapharm will be effected minutes before the legal transfer of Merck Generics Group BV (despite issues around the timing of cash transfers). This should not give rise to an Australian income tax problem and the debt pushdown should still be effective in Australia.

104 Also on 10 September 2007, Mr Drinkwater sent an email to Mr Vitullo which included comments regarding “timing of steps”, “foreign exchange gains/losses” and “incorporation of companies”. Among other things, that email noted that it would be necessary to undertake “a thin capitalisation calculation to ensure that the transfer of Note A1 to the Australia 1 would provide sufficient equity value from a thin capitalisation perspective”. This document was objected to when the Commissioner sought to tender it. The Commissioner did not press the tender at that time. However, the Commissioner’s annexure detailing facts annexed to his closing submissions did refer to this document and the document was not struck through in the marked up index to the court book, prepared by the parties. Accordingly, I have treated it as in evidence, notwithstanding the initial objection and withdrawal of the initial tender.

105 On 11 September 2007, Mr Drinkwater responded to an email from Mr Vitullo, by which Mr Vitullo sought comments on “copies of the draft intercompany notes to effectuate the transfers”. Mr Drinkwater’s email included comments regarding “transfer pricing”, “thin capitalisation” and “legal review”. Among other things, that email included the following:

I have spoken to my transfer pricing colleagues regarding the terms of the Al and A2 PNotes. An interest rate 400 basis points above the 1 month AUD LIBOR rate may be on the high side of what is acceptable to the Australian Taxation Office.

…

we would recommend that a benchmarking exercise be carried out for the A2 and Lux8 PNotes to determine an appropriate interest rate. A benchmarking exercise would take approx 4 weeks to determine an appropriate rate and another approx 4 weeks to pull the documentation together as supporting evidence for the interest rate. As part of this exercise we could incorporate terms that would justify a higher interest rate (e.g. duration of the loan, fixed rate, early repayment at discretion of the borrower and subordinating the loan to any external borrowing).

…

I understand that the thin capitalisation position of the Australian Group (including Alphapharm) will be determined post-acquisition. On this basis, we will need flexibility as to the amount of the A2 or Lux8 PNotes coming into Australia. As such, we recommend that the A2 and Lux8 PNotes contain a clause which enables them to be partly paid down if required.

106 On 12 September 2007, there was a meeting of the Mylan Board. The minutes of that Board meeting record that: “the primary purpose of the meeting was to update the Board with regard to the upcoming closing of the Merck Generics acquisition and related matters”; there was discussion of “the status of the financing”; and certain Merrill Lynch personnel “gave an overview of the debt capital markets including the impact of supply and demand imbalances with respect to newly issued debt”. The Commissioner observed that the minutes indicate that no representative of PwC was present at the meeting and emphasised the absence of any record of consideration of the proposed debt push-down structure and its relationship with the debt-servicing capacity of Mylan’s subsidiaries, or the Merck Generics entities that were to be acquired.

107 On 13 September 2007, PwC Australia sent a note to PwC US titled “Mylan – Australian acquisition of Alphapharm – List of tax issues considered”. That note addressed a number of issues under the headings “US considerations”, “Australian income tax” and “Australian stamp duty”. Among other things, under the bullet point which reads “Deductibility of interest”, PwC Australia referred to “[t]hin capitalisation”, “[t]iming of recapitalisation of the Australian group” and “[t]iming of acquisition of Alphapharm compared to acquisition of Merck Generics Group BV”.

108 On 20 September 2007, Mr Drinkwater sent an email to Mr Vitullo which included the following comments with respect to the topic of the “timing of legal transfer”:

It would be preferable from an Australian perspective for a sale and purchase agreement to be drafted in relation to the transfer of Alphapharm and signed before the sale and purchase agreement to transfer Merck Generics Group BV is signed. The actual transfer of Alphapharm would be conditional on the transfer of Merck Generics Group BV.

If the agreement is structured this way the debt pushdown would be effective in Australia. If it is not possible for the agreements to be drafted in this way, we expect that the debt pushdown would still be effective (given that it would occur contemporaneously with the acquisition of Merck Generics Group BV) but at a marginally higher risk of being challenged by the Australian Taxation Office.

109 Also on 20 September 2007, Mr Drinkwater sent an email to Mr Vitullo stating that he had received confirmation that the transfer agreement for Alphapharm would be signed before the transfer agreement for MGGBV. Mr Drinkwater then stated:

Further, the transfer will be effected before the transfer of Merck Generics Group BV will be effected. As such, the debt pushdown would be effective in Australia.

110 Also on 20 September 2007, Mr Drinkwater responded to an email from Mr Vitullo by which Mr Vitullo requested comments on “revised drafts of the notes”. Mr Drinkwater stated as follows:

The terms of the Promissory Notes seem fine, although l would add one clause to PNote A2 to allow it to be partially repaid if needed (any partial repayment would need to be funded by an equity injection). This is to provide flexibility from a thin capitalisation perspective. Whilst broadly the thin capitalisation rules work on a ratio of 75% debt to Australian assets, there are adjustments which could impact this. We would not be in a position to accurately forecast the actual allowable debt level until the valuation is complete.

111 On 26 September 2007, there was a further meeting of the Mylan Board. The minutes of the Board meeting indicate that Merrill Lynch representatives and Cravath representatives were present, and PwC representatives were not present. The Commissioner noted that, while management addressed the board on a number of matters concerning the Acquisition, there is no record that the Board was addressed on the debt push-down structure. I do not regard that as a matter of real significance; there is no reason why the Board would, or ought, not have left the detail such as internal financial structuring to management, without requiring a presentation on the topic.

112 On 28 September 2007, Mr Vitullo sent an email to (among others) Messrs Carroll and Drinkwater (both of PwC) with the subject “Final Version of Oct 1 & and latest ver of Post-Acq Slide Decks”. In that email (which was an internal, PwC communication), Mr Vitullo said that “[t]he client has asked that we keep the momentum going with regard to the implementation of the post-closing steps as it is critical for Mylan to attaining the intended tax benefits”. The email does not make reference to Mylan. Indicating that implementation of the post-closing steps was critical to attaining any non-tax benefits.

113 The Commissioner relied on the above emails in support of his contention that the debt push-down structure was developed by PwC independent of any non-tax (eg, corporate finance or debt capital markets) discipline.

114 On 1 October 2007, the SPA was amended (Amended SPA). The amendments provided for (inter alia):

(a) the designation of Genius GmbH, Alphapharm and Merck Generics France Holding SAS as “Additional Target Companies”;

(b) the designation of MGGBV as an “Additional Seller”;

(c) the designation of Mylan Delaware Holding Inc, MAPL, Mylan Canada, Mylan France and Mylan Luxembourg 2 S.a.r.l. (Lux 2) as “Additional Purchasers”; and

(d) a Closing Date for the transactions of 2 October 2007 (Frankfurt time).

115 Section 4 of the Amended SPA provided for the sale and transfer of Additional Target Companies prior to the Closing Date. These actions included the sale of Alphapharm, Mylan Canada and Mylan France in exchange for promissory notes.

116 Amendments made to the SPA are addressed further below.

117 Beginning in about April 2007, Mylan’s advisors exchanged with counsel for a syndicate of external lenders drafts of a “Commitment Letter” (including Term Sheets) under which the lenders agreed to provide finance for Mylan’s acquisition of Merck Generics, and refinancing of its existing indebtedness, through a series of Senior Credit Facilities and an Interim Loan.

118 A draft Term Sheet for the Senior Credit Facilities labelled “CS&M Draft—4/24/07” contemplated “[s]enior secured credit facilities… in an aggregate principal amount of up to $4,250.0 million” and contained the following definition of “Borrower” (emphasis in original):

With respect to the US First Lien Term Loan Facility and the First Lien Revolving Facility, Mylan Laboratories Inc. (“US Borrower”). With respect to the Euro First Lien Term Loan, [ ] (the “Euro Borrower” and, together with the US Borrower, the “Borrowers”). [To be discussed: additional foreign borrowers]

119 A subsequent draft of the Term Sheet for the Senior Credit Facilities dated 26 April 2007 retained the notation in bold, above.

120 In a draft Term Sheet for the Senior Credit Facilities labelled “CS&M 4/27/07”, the definition of “Borrower” was as follows (emphasis in original):

With respect to the US Term Loan Facility and the Revolving Facility, Mylan Laboratories Inc. (“US Borrower”). With respect to the Euro Term Loan, [ ] a European subsidiary of the US Borrower to be mutually agreed (the “Euro Borrower” and, together with the US Borrower, the “Borrowers”). [To be discussed: If requested by the US Borrower, one or more additional foreign borrowers may be added on terms and conditions to be agreed between the US Borrower and the Lead Arrangers.]

121 On 30 April 2007, the lenders issued a final Credit Facilities Commitment Letter to Mylan. The Term Sheet for the Senior Credit Facilities contemplated “[s]enior secured credit facilities … in an aggregate principal amount of up to $4,850.0 million” and defined “Borrower” as follows (emphasis in original):

With respect to the US Term Loan Facility and the Revolving Facility, Mylan Laboratories Inc. (“US Borrower”). With respect to the Euro Term Loan, a European subsidiary of the US Borrower to be mutually agreed (the “Euro Borrower” and, together with the US Borrower, the “Borrowers”). If requested by the US Borrower, one or more additional borrowers (including non-U.S. borrowers) may be added on terms and conditions to be mutually agreed between the US Borrower and the Lead Arrangers.

122 On 11 May 2007 and 18 June 2007, the lenders issued a further Credit Facilities Commitment Letter and an Amended and Restated Credit Facilities Commitment Letter, respectively, to Mylan. In each case, the definition of “Borrower” in the Term Sheet for the Senior Credit Facilities remained the same. Under the Amended and Restated Credit Facilities Commitment Letter, the lenders committed to provide the following Senior Credit Facilities:

(a) Euro Term Loan: EUR equivalent of USD 1.6 billion, maturing seven years after the closing date;

(b) US Tranche A Term Loan: USD 500 million, maturing six years after the closing date;

(c) US Tranche B Term Loan: USD 2 billion, maturing seven years after the closing date; and

(d) Revolving Facility: USD 750 million, maturing six years after the closing date.

123 On or about 20 June 2007, representatives from Mylan gave a presentation to the lenders. MAHPL contended that that the presentation included financial projections for Mylan (based on modelling undertaken by Merrill Lynch) that were consistent with the use of 100% of free cash flow across the Group (adjusted for certain specified changes in Mylan’s cash balance, and other than free cash flow referable to Matrix) to repay debt.

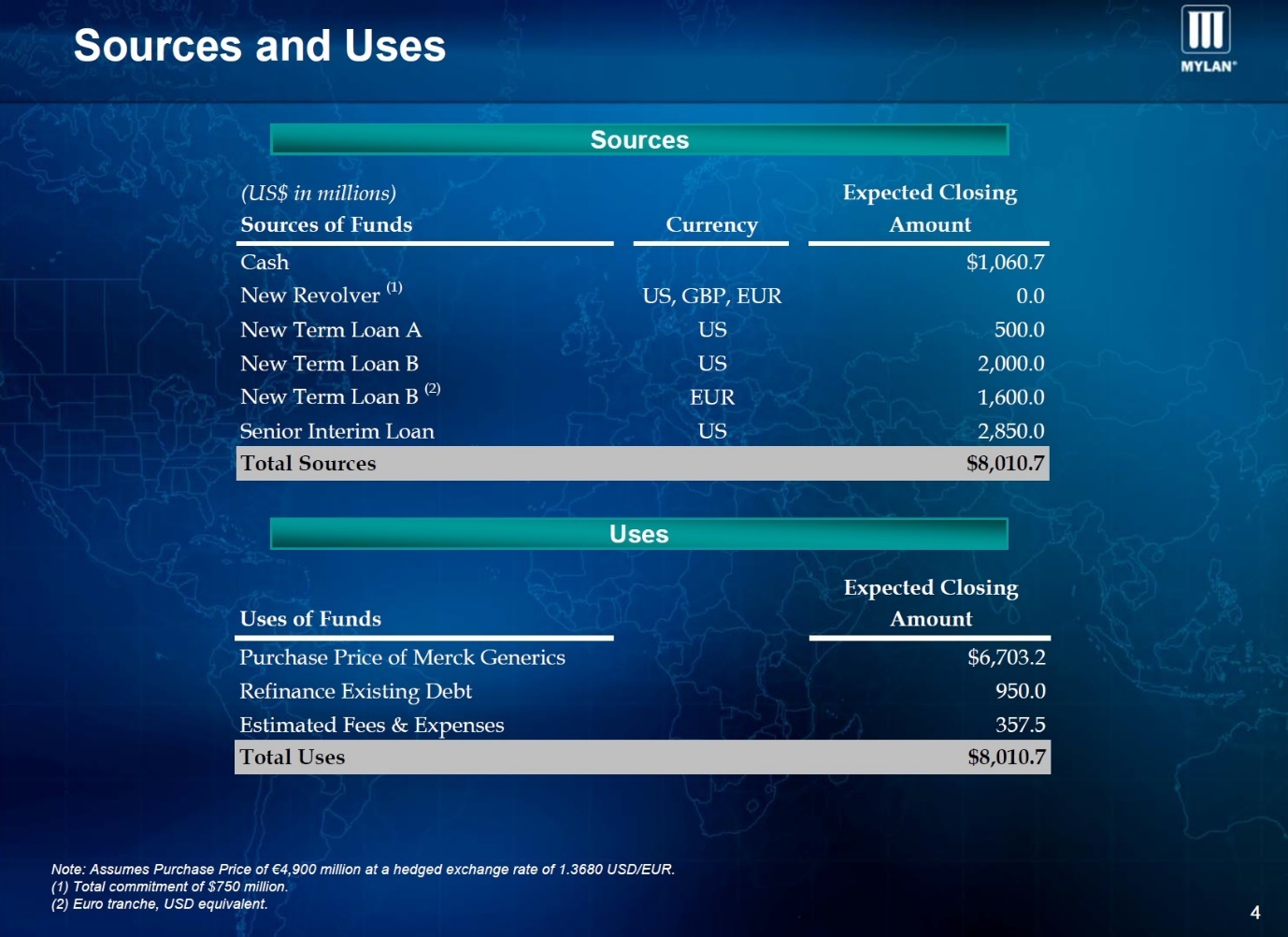

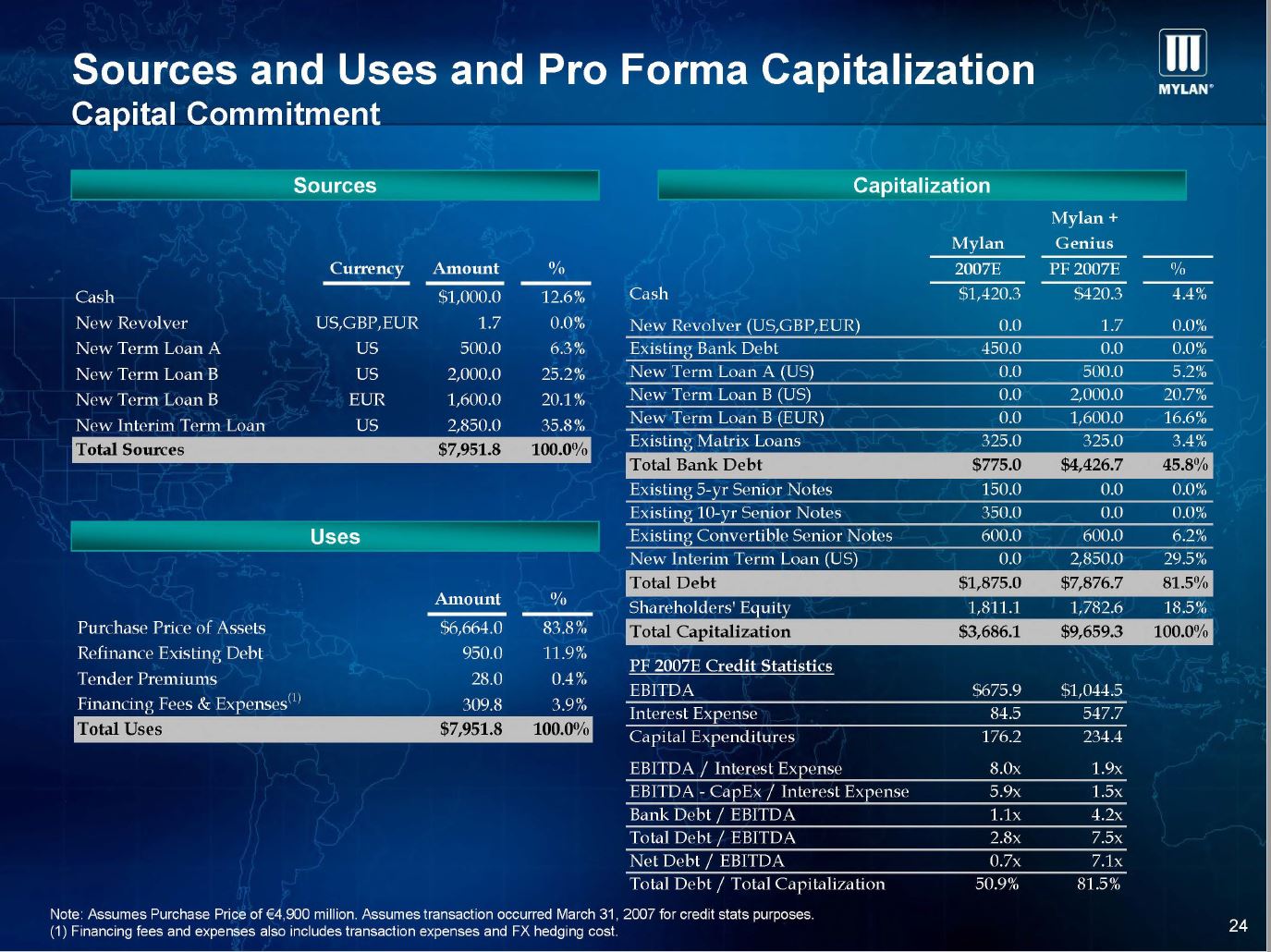

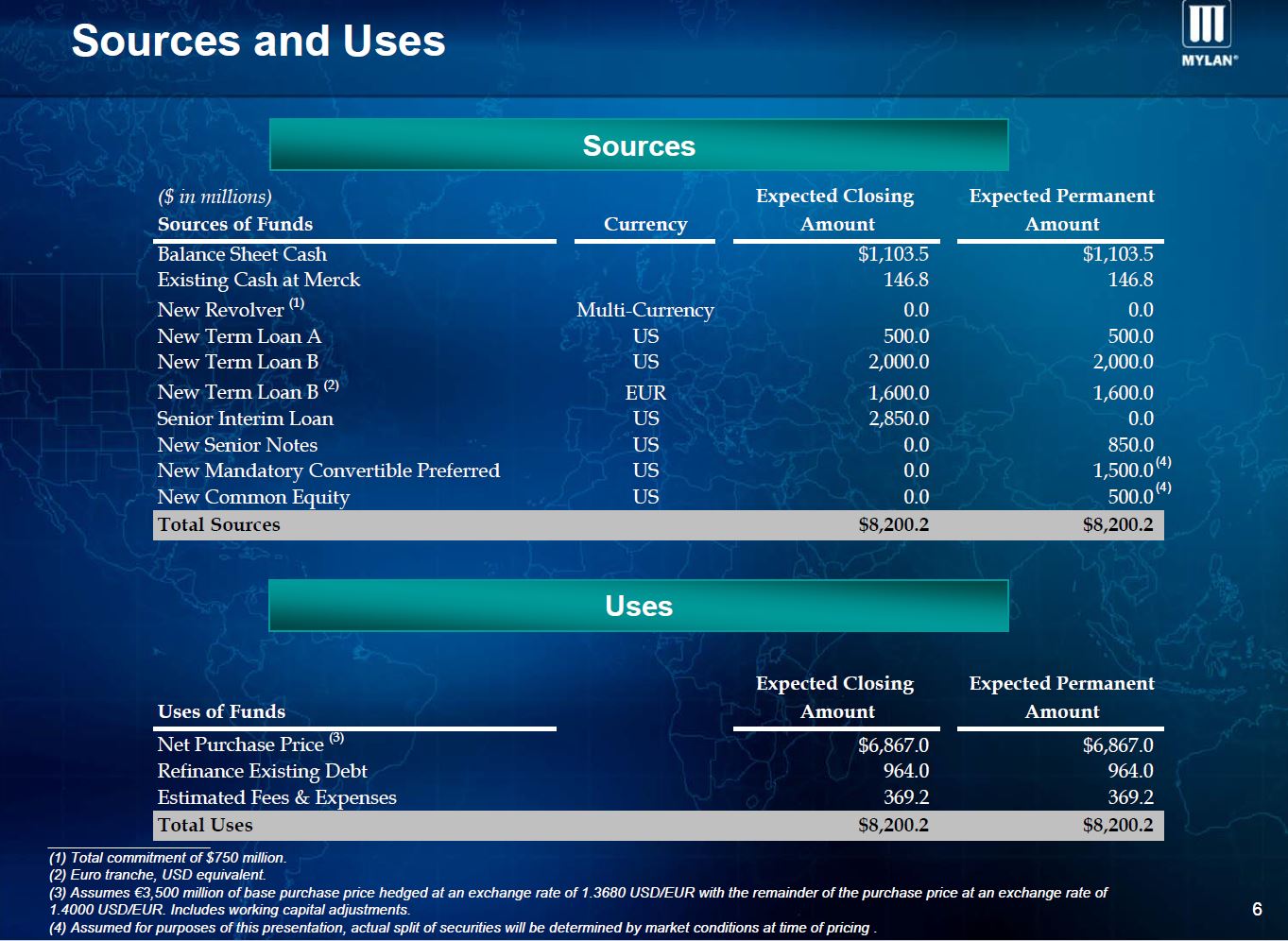

124 The sources and uses of funds was presented in the following form:

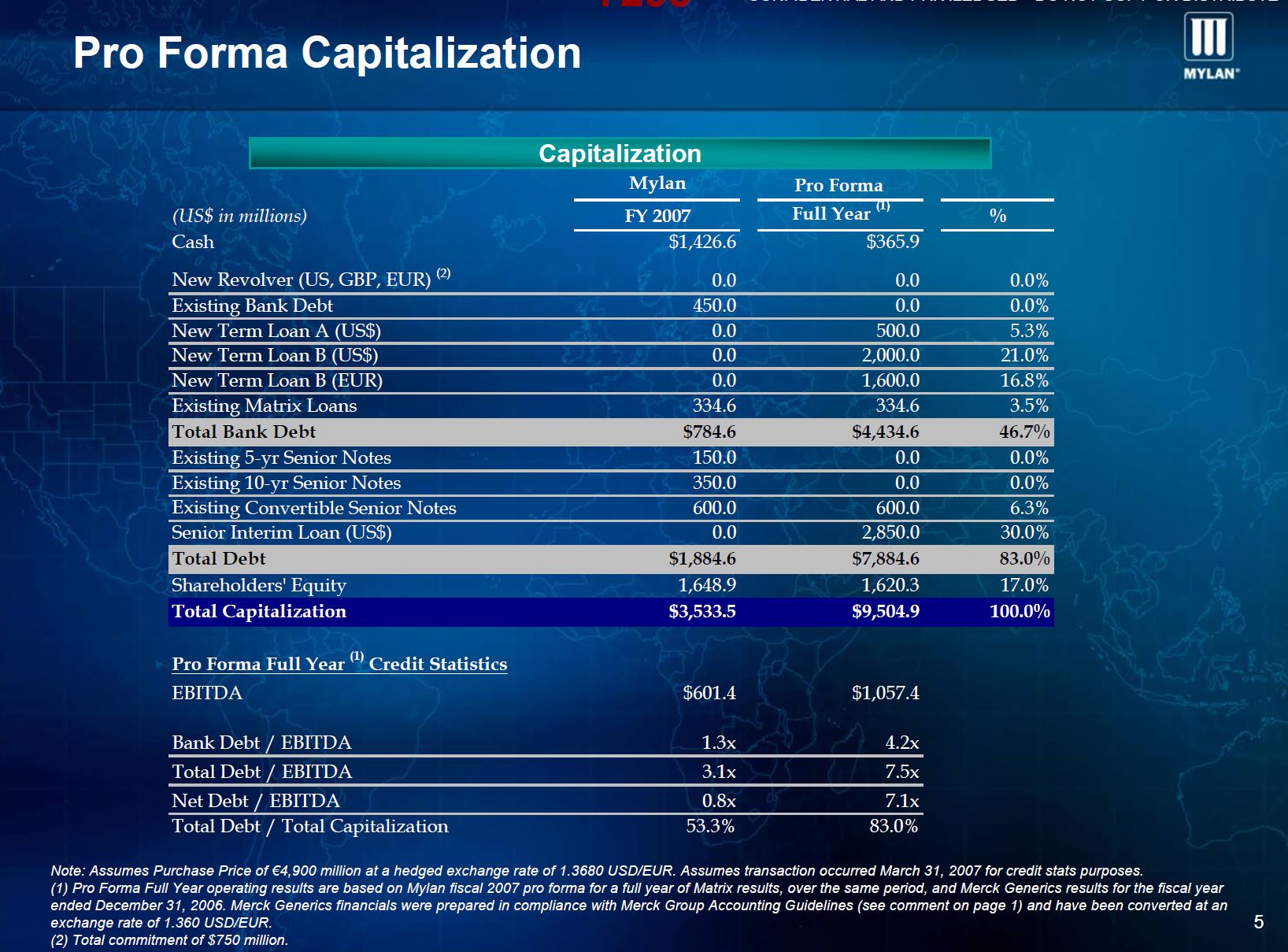

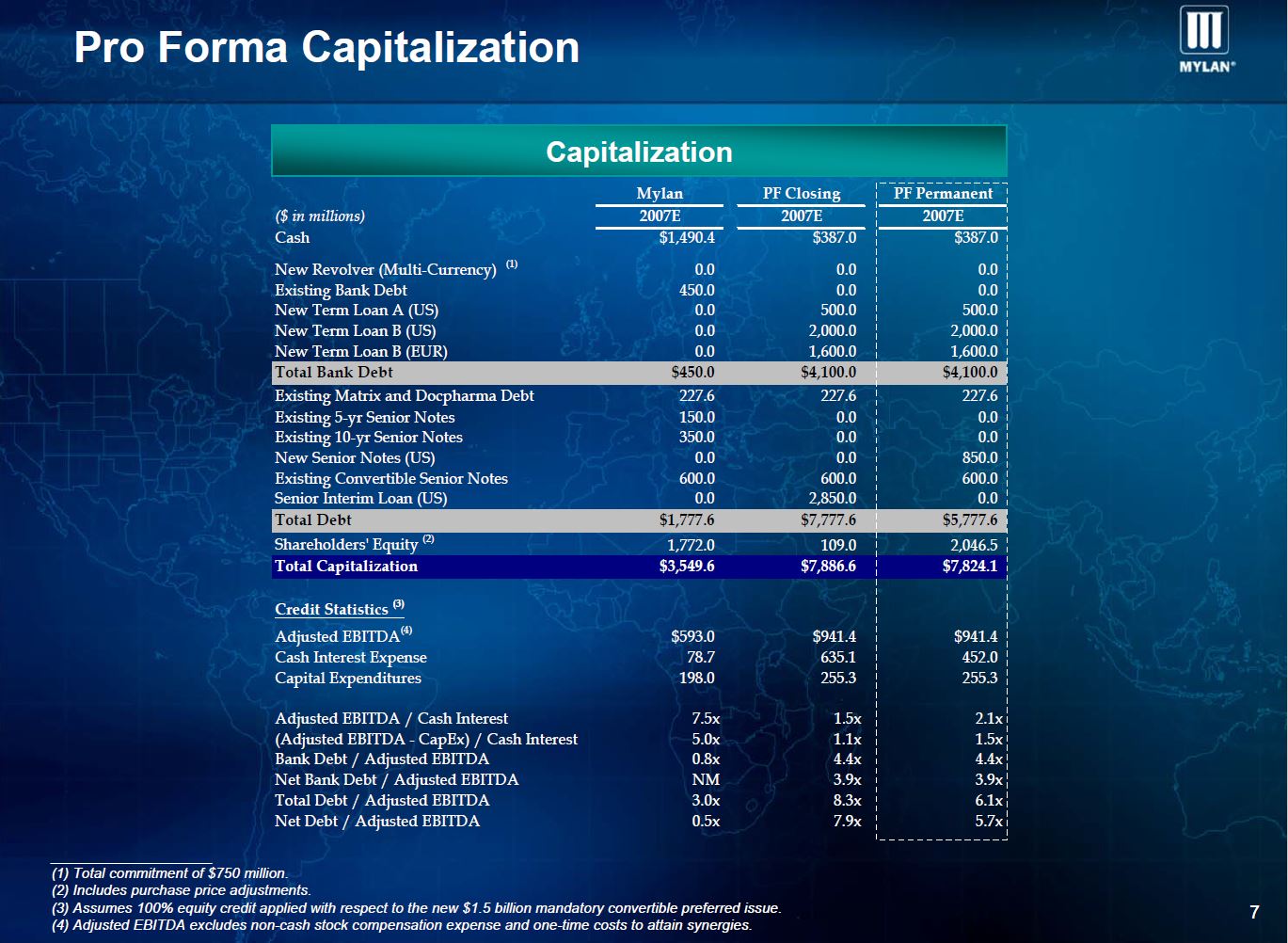

125 The presentation also included a slide depicting “pro forma capitalization” after the Acquisition (but before the anticipated capital raising and repayment of the USD 2.85 billion interim loan). That chart was as follows and showed a debt to equity ratio of 83% debt and 17% equity:

126 The presentation referred to Mylan intending to reduce leverage in the near term through the issuance of a mix of USD 1.5 to 2.0 billion of common stock and mandatory convertible notes. It also referred to dividends being suspended.

127 One of the “modelling assumptions” identified in the presentation was that there would be a “100% cash flow sweep with the exception of Matrix cash flow which is assumed to remain at Matrix subsidiaries”.

128 The Commissioner disputed MAHPL’s characterisation of this presentation to the lenders. The Commissioner did not accept that the projections for Mylan should be interpreted as evidence of an intention to use 100% free cash flow to repay debt, nor that reference to a “100% free cash flow sweep” should be interpreted as a warranty or representation that all free cash flow across the group would be used to repay debt. Rather, the Commissioner contended that the assumption was intended to be “point in time” such that any 100% cash flow sweep was to be confined to 2007.

129 This dispute about what was conveyed to the lenders is addressed below. As set out there, the Commissioner’s construction of the presentations is incorrect.

130 In or about July 2007, Deloitte prepared a memorandum headed “Summary of Third Party Borrowing Considerations”. The memorandum stated (inter alia) that:

(a) “direct borrowings” by “newly established Mylan entities in Australia, Canada and Japan … in their local currency from third party lenders or local branches of third party lenders” may offer “multiple tax benefits for Mylan relative to Mylan financing these entities through related party loans”; and

(b) in Australia, if Mylan used intercompany/related party loans to finance the acquisition of Alphapharm, Merck’s Australian subsidiary (rather than “direct borrowing” from a third party lender), interest payments would be subject to a 10% Australian withholding tax resulting in approximately USD 4,500,000 of withholding tax (which Mylan “may or may not” be able to credit for US foreign tax credit purposes).

131 The Commissioner directed attention to the three tax considerations identified and addressed by Deloitte in respect of the Australian direct borrowing option, namely, Australia’s corporate tax rate, Australia’s thin capitalisation limits, and Australian withholding tax on interest. The Commissioner highlighted Deloitte’s focus on the general interest withholding tax rate, being 10%, and certain exemptions from interest withholding tax arising under the AUS-US DTA (that is, the Convention for the Avoidance of Double Taxation and the Prevention of Fiscal Evasion with respect to Taxes on Income, US–Australia, signed 6 August 1982 (entered into force 31 October 1983)) and s 128F of the ITAA36.

132 Between 27 September 2007 and 2 October 2007, Mylan executed:

(a) a Senior Credit Agreement (SCA) with a syndicate of lenders comprising Lasalle Bank, National Association, The Bank of Tokyo-Mitsubishi UFJ, Ltd., New York Branch, Merrill Lynch, Pierce, Fenner & Smith Incorporated, Citibank, N.A. and JPMorgan Chase Bank, National Association. Under the SCA, the lenders provided the following loans to Mylan and Mylan Luxembourg 5 S.a.r.l. (Lux 5) (which was a disregarded entity for US purposes) to finance the Acquisition and refinance Mylan’s existing indebtedness:

(i) US Trance A Term Loan to Mylan: USD 500 million, maturing on 2 October 2013;

(ii) US Tranche B Term Loan to Mylan: USD 2 billion, maturing on 2 October 2014;

(iii) Euro Term Loan to Lux 5: EUR 1,130,703,095.33, maturing on 2 October 2014; and

(iv) Revolving Facility to Mylan or Lux 5: USD 750 million, maturing on 2 October 2013;

(b) “Term Borrowing Requests” under the SCA between Mylan, Lux 5 and the lenders, requesting the following from the lenders on 2 October 2007:

(i) the Euro equivalent of USD 1.6 billion under the Euro Term Loan;

(ii) USD 500 million under the US Tranche A Term Loan; and

(iii) USD 2 billion under the US Tranche B Term Loan;

(c) an “Irrevocable Funding Indemnity Agreement” in relation to the Eurocurrency loans;

(d) an “Interim Loan Borrowing Request” under a (then) draft Interim Loan Agreement between Mylan and the lenders, requesting a loan of USD 2.85 billion; and

(e) an “Irrevocable Funding Indemnity Agreement” in relation to the (then) draft Interim Loan Agreement.

133 On 2 October 2007, Mylan entered into an Interim Loan Agreement with Merrill Lynch and other lenders for a principal amount of USD 2.85 billion.

134 As addressed further below, funds borrowed under the SCA and Interim Loan Agreement were on-lent to other Mylan group entities to fund the acquisition of MGGBV and other Merck companies.

135 On or about 20 December 2007, the SCA was amended and restated with effect from 28 December 2007. The amended and restated SCA added a number of financial institutions to the syndicate of lenders, split the Euro Term Loan into two tranches and converted a portion of US Tranche A Term Loans to US Tranche B Term Loans. The outstanding amounts and maturity dates under each of the loans became as follows:

(a) US Tranche A Term Loan to Mylan: USD 312.5 million, maturing on 20 October 2013;

(b) US Tranche B Term Loan to Mylan: USD 2.556 billion, maturing on 2 October 2014;

(c) Euro Tranche A Term Loan: EUR 350,414,947.37, maturing on 20 October 2013;

(d) Euro Tranche B Term Loan: EUR 525 million, maturing on 2 October 2014; and

(e) Revolving Facility: USD 300 million, maturing on 2 October 2014.

136 The US Tranche A Term Loan and the US Tranche B Term Loan bore interest at LIBOR plus 3.25% or at a base rate (defined to be equal to the greater of (a) prime rate and (b) the Federal Funds Effective rate plus one half of one percent) plus 2.25%. The Euro Term Loans bore an interest rate of the Euro Interbank Offered rate (EURIBO) plus 3.25%. Borrowings under the Revolving Facility bore interest at LIBOR (or EURIBO) plus 2.75%. The interest rates could vary based on a calculation of the borrowers’ consolidated leverage ratio.

Credit ratings and engagement with ratings agencies

137 As at February 2007, Mylan had a credit rating of BBB- (Standard & Poor’s Ratings Services (S&P)) and Ba1 (Moody’s Investors Service (Moody’s)).

138 On or about 14 May 2007, following the announcement of the Acquisition, S&P downgraded Mylan’s corporate credit rating to BB+.