Federal Court of Australia

Societe Civile et Agricole du Vieux Chateau Certan v Kreglinger (Australia) Pty Ltd [2024] FCA 248

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: | 15 march 2024 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Within 14 days of the date of this order, the applicant file and serve minutes of proposed orders to give effect to these reasons and short written submissions limited to 3 pages dealing with such orders and any costs question.

2. Within 7 days of the receipt of such minutes and submissions, the respondents file and serve minutes of proposed orders and responding submissions limited to 3 pages.

3. Costs reserved.

4. Liberty to apply.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

BEACH J:

1 This dispute concerns a conflict between wine producers where it is essentially said that a Tasmanian wine producer has wrongly represented and passed off its product as being affiliated or associated with a French wine producer.

2 The applicant, Societe Civile et Agricole du Vieux Château Certan (VCC), is the owner of the Bordeaux wine estate, Vieux Château Certan. For present purposes, VCC produces two types of expensive French red wine involving various up-market grape types.

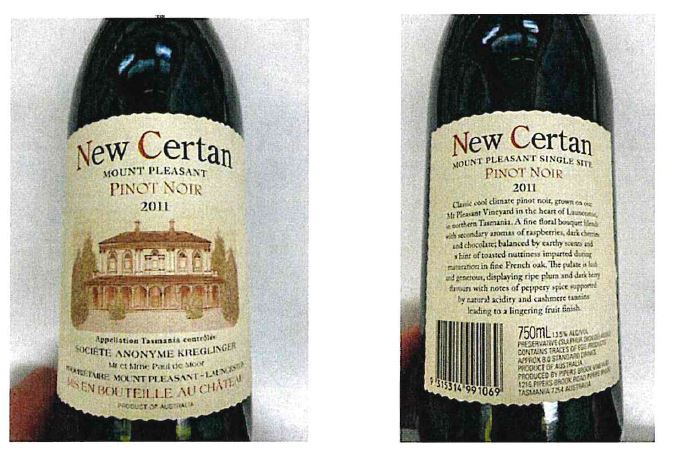

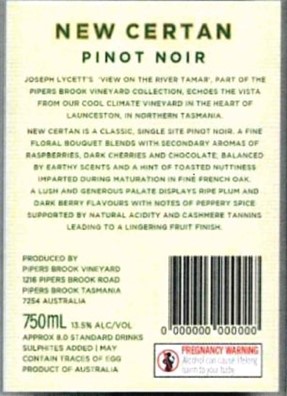

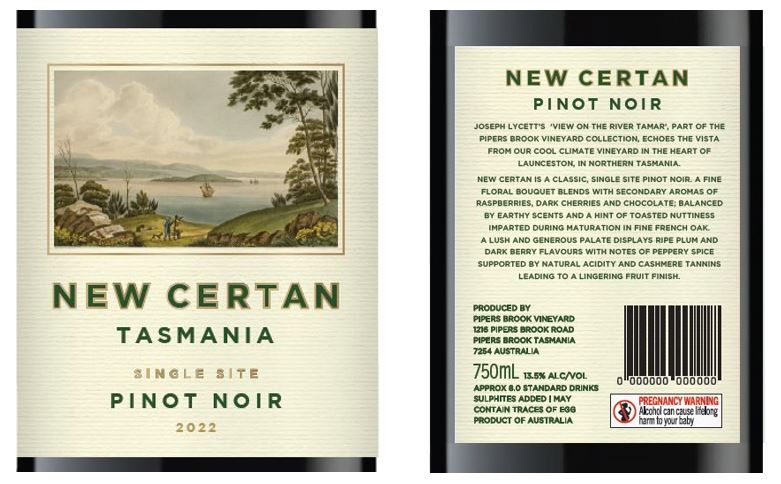

3 The first and third respondents produce wine in Tasmania. They have promoted and sold a wine known as New Certan, which is a much cheaper pinot noir as compared with the expensive French wine produced by VCC.

4 The first respondent, Kreglinger (Australia) Pty Ltd (Kreglinger), was registered as a company in Australia on 30 October 1914 and is a sister company of Kreglinger Europe NV.

5 The third respondent, Pipers Brook Vineyard Pty Ltd (PBV), was established in August 1973. It was originally called Tamar Valley Wine Estate Pty Ltd. In 2001, Kreglinger acquired majority ownership of PBV. The vineyards of PBV are located in Tasmania, covering two hundred hectares of low-lying land. PBV owns nine vineyards and manages the Mount Pleasant estate under contract with Mr Paul de Moor, the second respondent, who owns the land. PBV produces and sells wines under or by reference to various names.

6 Mr de Moor was appointed a director of Kreglinger on 1 December 1995 and was appointed the CEO of Kreglinger in 1998. Mr de Moor also became a director of PBV on 21 December 2001 and was appointed its CEO on 1 December 2018.

7 VCC has brought claims against the respondents alleging contraventions of ss 18 and 29(1)(g) and (h) of the Australian Consumer Law (Schedule 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth)) (ACL) and for the tort of passing off. It has also sought the cancellation of Kreglinger’s registered New Certan trade mark. The essential elements of VCC’s case include the following aspects.

8 First, VCC says that it has the necessary reputation to support its claim in passing off and to provide the factual foundation for its claim under the ACL. It is said that VCC’s reputation is long-standing, and existed long before the commencement of the respondents’ activities in relation to the New Certan wine. It is said that the reputation covers both the name Vieux Château Certan and the presentation of the wine sold under that name. I should say now that the question of the reputation of VCC and its wines in Australia was the subject of considerable contest before me at trial.

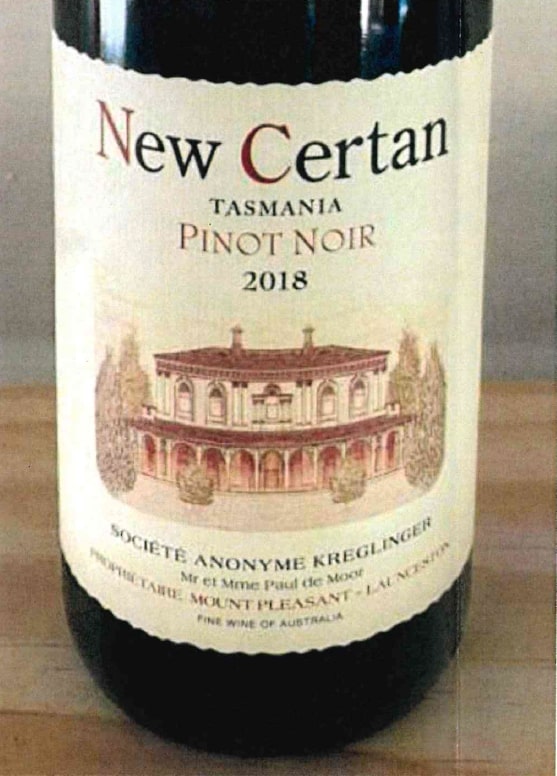

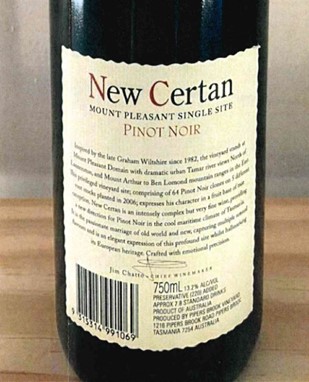

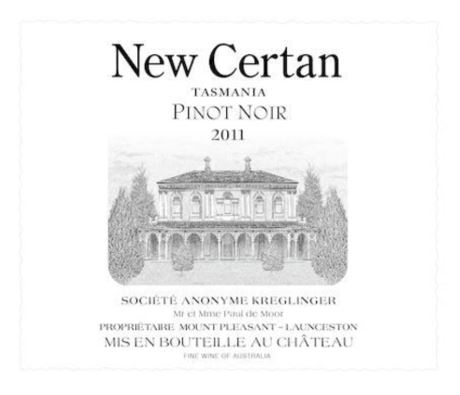

9 Second, it is said that when Mr de Moor set about developing the label for the first vintage of the New Certan wine, which was the 2011 vintage released in 2013, he did so by providing an example of VCC’s wine to the respondents’ designer, Ms Annette Harcus, with instructions to use it as inspiration. Now it is apparent that Mr de Moor was involved in the creation of the overall bottle presentation of the 2011 and 2016 vintages of the New Certan wine. He approved the final presentation and sale of the 2011, 2016 and subsequent vintages of the New Certan wine. There was little contest before me as to the accuracy of such matters.

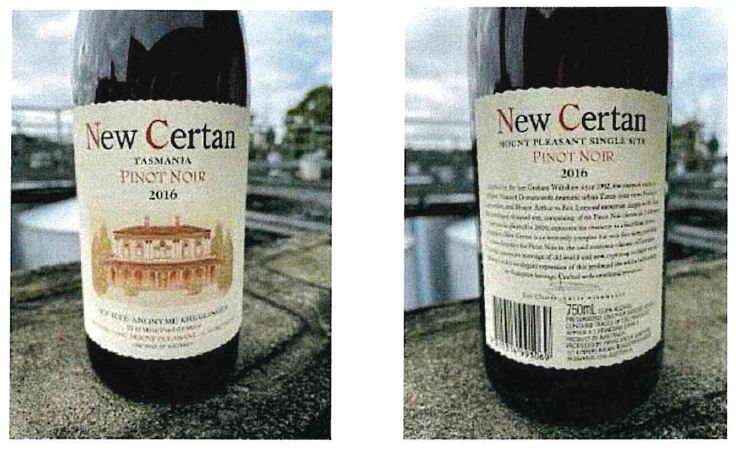

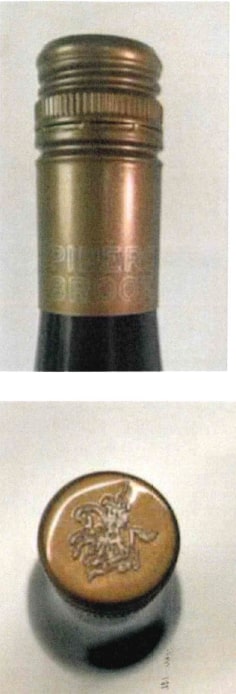

10 Third, VCC says that as a result of Mr de Moor’s involvement in the design of the overall presentation of the 2011, 2016 and subsequent vintages, there is a high degree of visual similarity between the presentation used to date by the respondents for the New Certan wine and the presentation of VCC’s wine. This includes the use of the name Certan, the use of a pink cap and accent colour in the New Certan name, the use of a stately home, the French text, the fluted edge profile and the aged appearance of the label, and more generally the overall look and feel of the wine presentation. It is said that the similarity is so strong because the presentation of the New Certan wine has been copied from the presentation of VCC’s wine. In large part I have accepted VCC’s case on these aspects. But of course these propositions do not address the proposed new branding of the New Certan wine that in my view substantially removes many of these similarities.

11 Fourth, it is said that the respondents have promoted the New Certan wine by expressly referring to VCC and a family connection to it. In doing so, it is said that the respondents have availed themselves of the fame and reputation of VCC and its wines for their own commercial benefit. I will return to these matters later. But it is not in issue that there is no arrangement or authorisation in place between VCC and the respondents in relation to the New Certan wine.

12 Fifth, VCC says that the effect of the respondents’ conduct is such that Australian consumers of fine wine and members of the fine wine trade have been led to erroneously believe that the New Certan wine was in some way connected with or approved by VCC. This has been a substantial area of contest before me and I will discuss this later.

13 Sixth, VCC says that the impression created by the respondents’ conduct to date has been misleading and false in that it has been suggested that the New Certan wine was in a commercial way associated with VCC or its products. It is said that there is no commercial connection between VCC and the respondents, and VCC has not approved or authorised the respondents’ conduct in connection with the New Certan wine. In summary, I would largely agree with VCC in relation to the respondents’ past conduct.

14 Seventh, it is said that Mr de Moor has been the driving force behind the New Certan wine. It is said that the evidence establishes that it has been a highly personal project to him. It is said that his conduct is such that he has gone beyond his role as an officer and employee of Kreglinger and PBV and has been knowingly involved in the relevant sense. Generally speaking I have agreed with VCC on this aspect of the case.

15 Now for the reasons that follow, I have largely accepted VCC’s case as to the respondents’ past conduct.

16 But the present proposal by Kreglinger and PBV to adjust the presentation of the New Certan wine for future vintages and not to sell current stock in my view addresses any problems previously created by the respondents’ conduct and will avoid any future infringing conduct.

17 There is one further matter. Kreglinger is the registered proprietor of Australian trade mark no. 815277 for the words New Certan in class 33 filed on 25 November 1999; class 33 concerns alcoholic beverages including wines. The registration of that trade mark was unopposed. But as part of its case, VCC now seeks its cancellation. But I have rejected this aspect of its case.

18 For convenience I have divided my discussion into the following sections:

(a) Some relevant background ([20] to [86]);

(b) The witnesses ([87] to [123]);

(c) The presentation, sale and promotion of VCC’s wines ([124] to [156]);

(d) Evidence of reputation or consumer awareness ([157] to [214]);

(e) The previous design and packaging of the New Certan wine ([215] to [263]);

(f) The significant resemblance between the New Certan wine and VCC’s wine ([264] to [318]);

(g) The new branding for New Certan ([319] to [353]);

(h) VCC’s claims under the ACL and in passing off ([354] to [543]);

(i) VCC’s claim against Mr de Moor – accessorial liability ([544] to [551]);

(j) Cancellation of Kreglinger’s registered trade mark for New Certan ([552] to [601]);

(k) Conclusion ([602] to [608]).

19 Let me begin with some further relevant background.

Some relevant background

20 Let me begin by saying something further about the parties.

Parties

21 The VCC vineyard estate is located in Pomerol in the Bordeaux region of France, and lies to the east of the Dordogne River. It is part of the wine making region of Bordeaux that is referred to as the Right Bank.

22 The VCC estate was originally granted by royal decree to a Scottish family – the de Mays – in the late sixteenth century. The name in its current form, “Vieux Château Certan”, has existed in local records in Pomerol since 1745. It is one of several vineyards established in the original “Sertan” estate, which also include Château Certan de May and, until about 20 years ago, Château Certan-Giraud. “Certan” is recorded as the name of a place in the French equivalent of the Titles Office.

23 The modern history of VCC began in 1924 when Georges and Josephine Thienpont purchased the VCC wine estate. Georges Thienpont was working in the Thienpont family wine merchant business in Belgium at that time and travelled to Bordeaux to source wines. Georges Thienpont produced his first vintage of wine from the estate in 1924, and the wine was given the same name as the wine estate, Vieux Château Certan. In order to be precise I will from hereon refer to this particular product as the VCC Wine. The VCC Wine has been produced since that time, and is made from a mix of Merlot, Cabernet Franc and Cabernet Sauvignon grapes.

24 Further, in 1946, Georges Thienpont purchased an adjacent parcel of land known as Clos de la Gravette, which was amalgamated into the VCC wine estate.

25 The management of the VCC estate was passed from Georges Thienpont to his sons, Léon and George Thienpont, and in 1985 to Léon’s son and the current manager, Mr Alexandre Thienpont, who gave evidence before me. Mr Thienpont and his immediate family have lived on the VCC estate since 1965.

26 Now VCC itself was incorporated in 1957. It is operated by way of a management committee, the membership of which is determined by the shareholders of VCC. It is convenient to note here that Mr de Moor is not and has never been a member of the management committee of VCC or an employee of VCC.

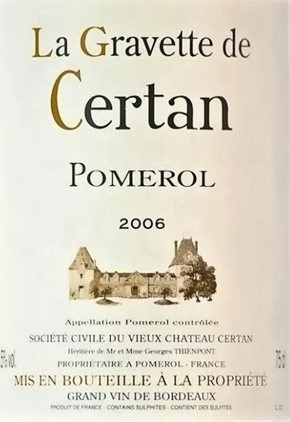

27 In 1985, Mr Thienpont introduced a second wine for VCC, which was the La Gravette de Certan. In order to be precise I will describe this as the Gravette Wine. The Gravette Wine is also made from Merlot, Cabernet Franc and Cabernet Sauvignon grapes.

28 The VCC Wine and the Gravette Wine are each the subject of limited annual production. Each year VCC produces between 30,000 to 50,000 bottles of VCC Wine and approximately 10,000 to 20,000 bottles of Gravette Wine.

29 But sales of VCC’s wines in Australia have been very limited. The only evidence before me of sales of the VCC Wine shows that a few thousand bottles of the VCC Wine were sold over the past 25 years. Further, the only evidence of sales of the Gravette Wine shows that around eleven bottles were sold in the period 2012 to 2020.

30 The VCC Wine retails for between approximately $600 and $800 per bottle. To the extent the Gravette Wine has been sold in Australia, the most recent sale on the evidence is one bottle for $109 in 2020.

31 Let me now say something further about Mr de Moor. Mr de Moor is the great-grandson of Mr Georges Thienpont, the Belgian wine merchant who was responsible for acquiring the VCC estate in 1924. Mr de Moor is the grandson of Mr Georges Thienpont’s only daughter, Mrs Marie-Louise Thienpont. Mrs Thienpont was the eldest child of Mr Georges Thienpont, and she chaired VCC’s annual general meetings following his death in 1962 until she died in 1995. Mr de Moor’s mother, Mrs Marie-Louise Heymans, is the eldest child of Mrs Thienpont. She chaired VCC’s annual general meetings from her mother’s death in 1995 until about 2016. Mr de Moor is a shareholder of VCC, which shares he received from his mother in 2010.

32 Now Mr de Moor claims a strong and authentic familial connection with VCC and members of the Thienpont family. And of course it cannot be disputed that Mr de Moor is a member of the Thienpont family.

33 So, to the extent that it is or has been represented by Mr de Moor or others that he has a familial connection with VCC, that would be correct. He does have such a connection. But statements about a familial connection do not represent or imply a commercial association or connection between Kreglinger and PBV on the one hand and VCC on the other hand or the parties’ respective products.

34 Let me now deal with some general matters concerning the Australian wine industry and French imports. In that context I need to begin with some statistics.

Australian wine and French wine – some statistics

35 Wine Australia is an Australian government statutory corporation funded primarily by industry levies, government contributions, voluntary contributions made by industry members, and costs recovered from regulatory activities undertaken by Wine Australia.

36 Wine Australia is empowered to coordinate and fund research and development for grapes and wine, facilitate the dissemination, adoption and commercialisation of the results of such research, control the export of wine from Australia and promote the sale and consumption of wine, both in Australia and overseas.

37 Wine Australia collects data relating to both the Australian and international wine markets including in relation to wine consumers, as well as the Australian wine sector including in relation to wine producers. Such data includes data regarding imports and exports of wine, as well as grape production and pricing, sales and supply and demand generally.

38 Wine Australia also analyses customs data made available by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), subscribes to third party data sources on the Australian and global wine market, such as IRI MarketEdge, the International Wine and Spirit Record (IWSR) and Statista, and purchases published reports from other organisations. Wine Australia provides analysis based on this data to Australian wine makers and grape growers, Australian wine exporters and other persons and entities.

39 Let me begin by saying something about the value of imported and domestic wine in Australia.

40 In evidence were screen captures of Wine Australia’s “Market Explorer” interactive online tool. The screen captures showed data displayed in response to the drop down menu question “Which markets consume the most imported wine?”. This data was made available by IWSR to Wine Australia in its capacity as a subscriber. The screen captures record the following.

41 In 2020, imported wines accounted for 31.4% of the Australian wine market by value, which equates to around US $1.907 billion. The remaining 68.6% of the market comprised domestic wines. Of the 31.4% market share that was imported, the majority of those wines originate from France (37.6% by value) and New Zealand (40.1%).

42 In 2021, imported wines accounted for 34.3% of the Australian wine market by value, which equates to around US $2.054 billion. The remaining 65.7% of the market comprised domestic wines. Of the 34.3% market share that was imported, the majority of those wines originate from France (39.7% by value) and New Zealand (37.7%). Italy supplied the third majority of imported stock (14.8%), followed by Spain (2.4%) and the USA (1.1%).

43 Let me say something about the on and off-premise consumption in Australia and France.

44 In evidence were screen captures of Wine Australia's "Market Explorer" interactive online tool concerning on-premise and off-premise consumption of wine, in both Australia and France. The screen captures showed data displayed in response to the drop down menu question "What is the share of on vs off-premise in each market?". This data was made available by IWSR. The data for this question is calculated by reference to the volume of 9 litre cases sold, which equates to twelve 750ml bottles.

45 It was recorded that in 2020, of the 58.2 million 9L cases of wine purchased for consumption in Australia, 8.9% was consumed on-premise, for example, in restaurants, bars, and other hospitality venues, and 91.1% was purchased for consumption off-premise, such as purchased at bottle shops or from online retailers. It was recorded that in 2020, of the 243.4 million 9L cases of wine purchased for consumption in France, 19.5% was consumed on-premise and 80.5% was purchased for consumption off-premise.

46 It was recorded that in 2021, of the 54.8 million 9L cases of wine purchased for consumption in Australia, 10.9% was consumed on-premise and 89.1% was purchased for consumption off-premise. It was also recorded that in 2021, of the 236.9 million 9L cases of wine purchased for consumption in France, 20.6% was consumed on-premise and 79.4% was purchased for consumption off-premise.

47 Let me say something about the importation of French wines into Australia by region.

48 Evidence was given that it is not possible to statistically determine the percentage of wine imported into Australia per region of France. However, the ABS customs data available to Wine Australia demonstrates that in 2021 approximately 23 million litres of wine were imported from France into Australia. Based on the information set out in the following tables, it is estimated that wine from the Bordeaux region accounts for approximately 3% to 4% of French wine imported into Australia.

49 Table 1 relates to customs data made available by the ABS to Wine Australia and shows that red table wine accounted for 29% of the volume of French wine imported into Australia in 2021. The ABS-supplied customs data does not specify the region of France of the imported wine, only that it was imported from France.

Table 1: Share of wine import volume from France in 2021 by colour/wine style (source: ABS-supplied customs data)

Wine style/colour | Share |

Red table wine | 29% |

White table wine | 14% |

Sparkling | 42% |

Other | 15% |

50 Table 2 relates to data collected by IRI MarketEdge, but it does not capture every individual wine sale made in off-premise retail channels. However, it was the most reliable data source available to Wine Australia in respect of off-premise retail channels. The data in Table 2 concerns off-premise retail sales of French wine in Australia, for example, wine sold in bottle-shops or online, for consumption elsewhere, for the year 2021. This data is broken down by region.

Table 2: Share of French wine off-premise retail sales volume in Australia by region in 2021 (source: IRI MarketEdge)

Region | Share of French wine sales | Percentage red wine products | Estimated share of red wine sales |

Champagne | 55% | 0% | 0% |

Languedoc-Roussillon | 13% | 29% | 39% |

Loire Valley | 8% | 4% | 4% |

Provence | 8% | 0% | 0% |

Rhone | 4% | 30% | 13% |

Unknown | 3% | 5% | 2% |

Burgundy | 3% | 7% | 2% |

Other Region | 3% | 90% | 25% |

South West | 1% | 18% | 2% |

Bordeaux | 1% | 97% | 10% |

Alsace | 1% | 0% | 0% |

Beaujolais | 0% | 100% | 3% |

Cahors | 0% | 100% | 0% |

51 Table 2 shows that wines from the Bordeaux region accounted for 1% of total off-premise retail sales of all French wine of all varieties in Australia in 2021. Of this percentage, 97% was red wine. It shows that wines from the Bordeaux region accounted for 10% of total off-premise retail sales of French red wine in Australia in 2021.

52 Table 3 relates to data collected by consulting group Wine Business Solutions and published in its Wine On-Premise Australia 2022 report. The data shows a breakdown by region of France's wine listings in the on-premise channel, for example, restaurants, hotels, clubs and wine bars, for consumption on-site.

Table 3: Share of France’s wine listings in the on-premise channel by region (source: Wine Business Solutions)

Region | Share of listings 2022 |

Champagne | 27% |

Loire Valley | 14% |

Rhone | 11% |

Burgundy | 10% |

Bordeaux | 8% |

Alsace | 7% |

Provence | 6% |

Chablis | 6% |

Beaujolais | 5% |

Languedoc-Roussillon | 4% |

Other Regions | 2% |

53 Table 3 shows that wines from the Bordeaux region accounted for approximately 8% of the on-premise listings for French wines. The data was collected from a study which quantified the number of wines listed by region in France, on a sample of wine lists at a variety of on-premise venues.

54 In relation to the data in Tables 2 and 3 above, Bordeaux wines have a higher proportion of listings on wine lists and menus compared to Bordeaux's proportion of off-premise retail sales. However, the number of listings does not necessarily correlate with the volume of wine sold.

55 Let me now say something about the trends in the volume and value of French wines imported into Australia over the last 20 to 30 years.

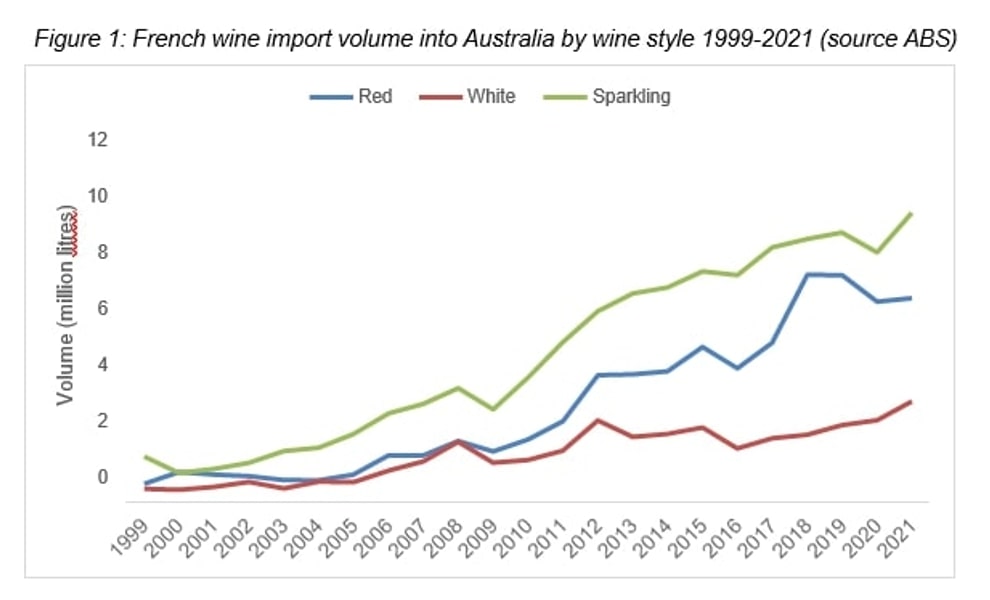

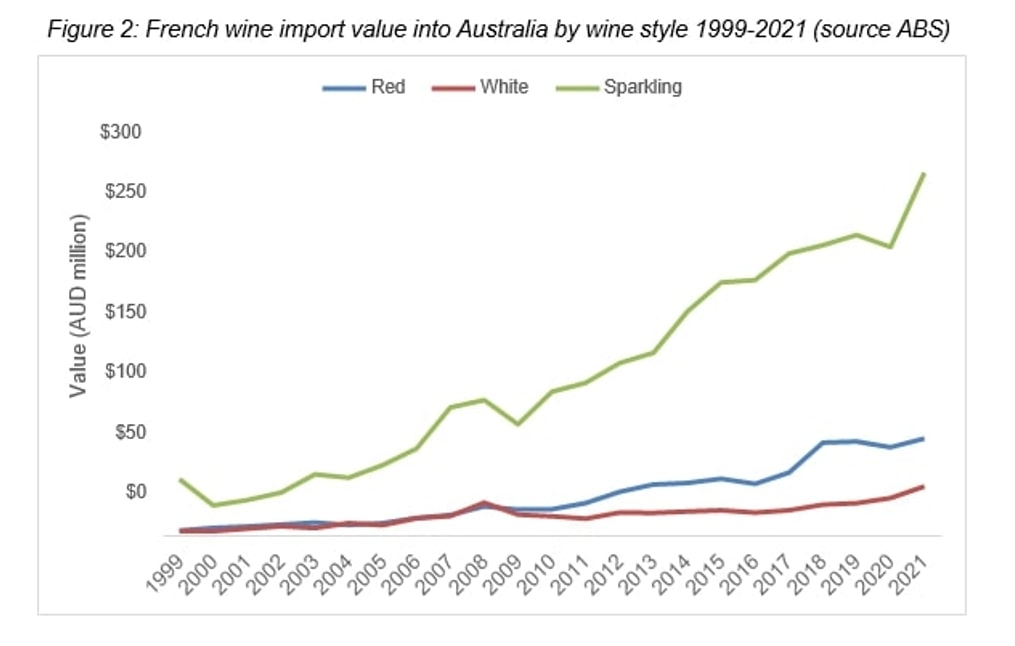

56 Based on customs data made available by the ABS to Wine Australia as depicted in Figures 1 and 2 below, imports of French wine across all types into Australia have increased significantly in the last 20 years with respect to both volume and value.

57 In relation to ABS-supplied customs data, value is calculated by the "customs value", which is the transaction value actually paid or payable by the importer to the supplier. This is a measure of wholesale value, rather than retail value.

58 Figures 1 and 2 show that between 2000 and 2021, imports of French wine into Australia increased by 745% in volume and 1094% by value, and imports of French red wine specifically increased by 586% in volume and 1120% by value. Over this period, French red wine has consistently accounted for approximately 30% of imports by volume, and 17% by value.

Red wine varieties grown in Australia

59 In Australia, shiraz is by far the most dominant red wine variety sold, followed by cabernet sauvignon and grenache. Pinot noir entered the market in the early 1980s, however, it represents a small proportion of the market by reference to sales volume. The total area of pinot noir vines planted in Australia is very small when compared to the other three varieties mentioned.

60 In evidence was Wine Australia's varietal snapshot which is based on data from the National Vintage Survey 2022 conducted by Wine Australia. It was recorded that the area of pinot noir vines in Australia was 4,948 hectares out of 135,133 hectares for all varieties, comprising 3.7% of the total area planted and 5.7% of the total area of all red varieties planted. Further, 44,271 tonnes of pinot noir grapes were crushed of a total of 1,734,260 tonnes for all varieties in Australia, comprising 2.6% of the total crush and 4.6% of the total crush of all red varieties. Further, ten percent of pinot noir crush was from Tasmania. Further, Tasmania has produced an estimated average winegrape crush of around 12,000 tonnes per year over the 6 years from 2017 to 2022, which equates to approximately 8 to 9 million litres of wine. This accounts for less than 1% of Australia's total wine production.

61 The typical Australian wine drinker to the extent there is such a consumer does not purchase or drink very much pinot noir.

62 Cheap pinot noir is typically priced at around $25 per bottle, whereas a good quality pinot noir is typically priced at between $40 to $65 per bottle or potentially higher. I note that New Certan wine has sold in the range of $75 to $95 per bottle. In contrast, the majority of all wine sold in Australia is priced at below $25 per bottle.

63 Let me turn more generally to the pricing of Australian wine.

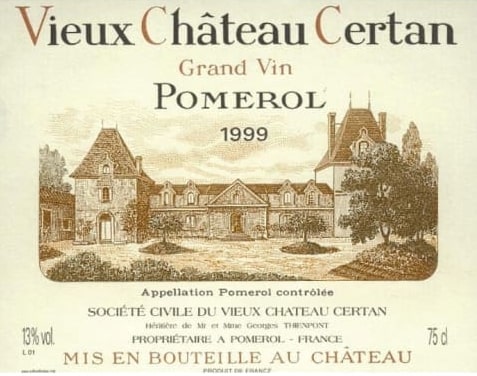

Prices of Australian wine

64 It is important to appreciate that wine is comparatively expensive in Australia, when compared to average prices in Europe. There is no international formalised set of definitions concerning market segments and prices of wine.

65 The pricing of expensive wine in Australia has shifted significantly. For example, around five years ago, Australian wine drinkers would not typically purchase a bottle of Australian wine for $150. However, presently, $150 is not an uncommon price for a "super premium" wine.

66 The price of iconic wines such as Penfolds Grange has increased dramatically over the years. In 1984 the then current vintage of Penfolds Grange was selling at a retail price of between around $50 to $70 a bottle. The 2018 Penfold Grange is currently $1,000 per bottle. Producers of such exclusive iconic wines have generally increased their price per bottle by around $50 each year. As an example, Henschke, a small family owned wine producer, followed this practice with their Hill of Grace wine. The increased price of wines such as Grange and Hill of Grace has the effect of creating room in the market for wines priced beneath that level.

67 The increase in the price of "premium" wines, that is, a wine sold for $25 or above, is due in part to the increased willingness of consumers, particularly Chinese consumers, to pay high prices for premium Australian wine. This practice has driven up the price of many premium wines.

Consumers purchasing premium and non-premium wines

68 Now Mr Jeremy Oliver, one of the respondents’ expert witnesses and whose evidence I have accepted on some topics, described the typical consumer of non-premium wines to the extent there is such a typical consumer.

69 He took the price point of less than $25 as describing a non-premium wine. A consumer purchasing a wine under $25 is someone who likes wine, but is not obsessed by it. For example, if you are buying three bottles per week, this would equate to spending around $75 a week on wine, which is, for many people, a large amount of money for a discretionary purchase. This type of consumer may buy a $50 bottle of wine for a gift or special occasion, but not very often.

70 Mr Oliver described the typical consumer of wines at a price point of $70 to $100 to the extent there is such a typical consumer. He considered that the purchaser of a $70 to $100 bottle of wine is likely to be either someone that has a cellar or collection, or a consumer who wants to buy a nice gift or otherwise has significant disposable income. Such consumers are generally better informed about wine than consumers of wine priced at $25 or less. To understand and justify spending $70 to $100 on a bottle of wine, such a consumer might have one or more characteristics such as being wealthier, being better educated about wine, being a subscriber to a wine publication or website, using wine apps such as Vino and Decanter to value and gain information about wine, being a member of a wine club or a wine group, or visiting wineries and showing off their knowledge of wine.

71 These types of people would regard themselves as being engaged with their purchase. That is, the purchase of wine at this price point will likely involve careful consideration of the wine being offered for sale, its characteristics, the “story” behind the vineyard, and critical reviews of that wine. Such matters will aid in justifying spending $70 to $100, when such consumers could otherwise purchase something drinkable at $25.

72 In relation to a consumer purchasing a $500 bottle of wine, these consumers would be a small subset of consumers purchasing a $70 to $100 bottle of wine in the sense that they would not exclusively buy $500 bottles; their everyday drinking wines will likely cost less than $500. However, that does not suggest that a typical consumer of $70 to $100 wine is likely to buy a $500 bottle of wine, but that the “$500 consumer” will also typically be prepared to spend less than this amount on wine. There are very few consumers who have both the disposable income and the interest to be spending $500 on a bottle of wine in the first place.

73 The above attributes would also apply to consumers at the $500 price point. Consumers of $500 bottles of wine are likely to purchase such a wine to be cellared for later consumption. Mr Oliver expected these consumers to be aware that by the time they take possession of the wine, it will be at least four to five years old, and might typically need another decade or more of cellaring before the optimum time to drink the wine arrives. These people will almost invariably have a very detailed knowledge about wines and be acutely aware of the wine that they are buying. These people will also often be looking to make a statement by purchasing and later serving such wine, for example, they might have a collection of Mouton Rothschild or vintages of Haut-Brion.

74 I will return to the question of consumer classes later.

What do Australians know about Bordeaux and Bordeaux wines?

75 The average Australian wine consumer, that is, someone who typically purchases wine at $25 or less per bottle, would have minimal awareness and understanding of Bordeaux, its regions and estates. Amongst the average Australian consumer, only a small proportion are likely to have heard of some of the more famous brands from the Medoc region in Bordeaux, such as Lafite and Latour, and maybe Haut-Brion from Graves. Such consumers might be aware of the elite and therefore expensive châteaux but even if so are unlikely to be able to name many châteaux below that elite level.

76 Mr Oliver commented on the knowledge that Australian consumers typically buying wine for around $70 to $100 per bottle would have of Pomerol in Bordeaux, and further VCC.

77 Only a tiny percentage of Australian wine consumers would have heard of the Bordeaux sub-regions, less would be aware that there is a Right Bank area and a Left Bank area, less again would be aware of Pomerol, and less again would be aware of VCC. Serious wine collectors and people who buy Bordeaux wine every year will be aware of Pomerol.

78 Mr Oliver commented on the type of consumer who would purchase a bottle of wine from Pomerol at a price point of $500, and whether any cross-over might exist between this person and a consumer interested in buying a $75 to $95 Tasmanian pinot noir. In his view, which I accept, the likelihood of such a consumer "crossing over" is small, at best. The people interested in buying Bordeaux and Burgundy are often quite different people. If you are spending $500 buying a wine from Pomerol, you are a rare customer. People who collect wines from Pomerol and Right Bank châteaux are typically deeply engaged with Pomerol and its wine, which is what drives up the prices of Right Bank wines. People who are buying such Bordeaux wines at $500 will almost invariably have carefully selected cellars. That said, such a person may also be an enthusiast of pinot noir, and might be prepared to buy an expensive pinot noir, of which Tasmanian pinot noir represents only a tiny fraction of the market.

79 The evidence also establishes that a typical customer of a $500 Pomerol wine would generally obtain a personal allocation from a retailer or distributor importing these wines into Australia, known as a "negociant". Accordingly, they are likely to have connections with and be aware of who is importing the wines.

80 The negociant and customer relationship is a very personalised one, in the sense that these consumers are not required to wait until the wines arrive in Australia to be sold at full price, but they often buy en primeur. The en primeur system is the traditional means by which trade and customers are able to buy wines from Bordeaux châteaux with a payment prior to delivery, but set at a lower price than later sales of the same wine. Additionally, these buyers would have typically read reviews of the vintage they are purchasing. This is because they are more engaged with the purchase decision, are seriously committed to it, and will often have favourite châteaux. For example, there are some Australian purchasers who buy wine in large volume and also have cellars in France or London used to initially store that wine before importing it to Australia.

81 Dealing with the reverse position, Mr Oliver commented on the type of consumer who would purchase a $75 to $95 Tasmanian pinot noir and the cross-over to the extent that it exists between this person and a person buying a $500 bottle of Pomerol wine.

82 Based on his experience and knowledge of the Australian wine market, he considered Tasmanian pinot noir to be somewhat niche. Production of Tasmanian pinot noir is minuscule in the context of Australia's national wine production. However, it is currently the subject of significant favourable media coverage. Tasmanian pinot noir does not have a substantial international reputation, but does have a local reputation within Australia. In his experience, a large proportion of Tasmanian pinot noir is drunk and sold within Tasmania or by people travelling through Tasmania.

83 In his experience, any cross-over between consumers purchasing $75 to $95 Tasmanian pinot noir and $500 Pomerol wine would be small at best. Based on his experience and knowledge of Australian consumers and their buying habits, and the market segments for Australian wine, he considered that if someone is spending $75 to $95 on a Tasmanian pinot noir, they are committed to pinot noir and in particular Tasmanian pinot noir. Accordingly, it would be unlikely for such a consumer to spend $500 per bottle on Bordeaux wine.

84 Further, Mr Oliver observed that consumers typically have specific preferences which narrow their interest to particular wine styles and varietals. Tasmanian pinot noir is typically light to medium body in structure and of medium flavour intensity, whereas the premium wines from the right bank in Bordeaux deliver significant depth of flavour and structure. In his opinion, they could hardly be more different.

85 Further, in his experience a Tasmanian pinot noir drinker would be more expected to gravitate to and be far more interested in Burgundy and Rhone wine, unless they are an individual who likes and purchases every style of wine, which is rare.

86 I accept his evidence on such matters.

The witnesses

87 Let me say something more at this point concerning the witnesses.

VCC’s witnesses

88 As I have said, Mr Thienpont is the manager of VCC. He gave evidence about the history of the VCC wine estate, the history of VCC, the way in which VCC’s wines have been labelled over time, the sale and promotion of the VCC wines, VCC’s discovery and reaction to the New Certan wine and the absence of any commercial connection between VCC and the respondents. Mr Thienpont was cross-examined very briefly, but the substance of his evidence was not challenged.

89 Mr Huon Hooke is a professional wine writer and critic with more than 40 years’ experience in the Australian wine industry. He gave expert evidence about the characteristics of Australian wine consumers, the Bordeaux region and the Pomerol sub-region and the extent of their reputation in Australia, the involvement of French wine producers in Australian wine businesses, the reputation of the VCC wine estate and its wines in Australia, the presentation of VCC’s wines and his experience of the New Certan wine. Mr Hooke was cross-examined briefly.

90 Ms Jane Faulkner is a professional wine writer and critic with more than 20 years’ experience in the Australian wine industry. She gave expert evidence about the reputation of the VCC wine estate and its wines in Australia, the presentation of VCC’s wines and her experience of the New Certan wine. Ms Faulkner was cross-examined briefly. Ms Faulkner was a straight-forward witness. She gave short and sharp answers to the questions asked.

91 Mr Daniel Airoldi is a wine importer and distributor with more than a decade’s experience in the Australian wine industry and a particular interest in Bordeaux wines. He gave evidence about how Bordeaux wines are typically sold, the reputation of the VCC wine estate and its wines in Australia, and his experience of the New Certan wine. Mr Airoldi was cross-examined.

92 Mr Andrew Caillard MW is a Master of Wine, which is a prestigious international wine qualification. His particular areas of expertise are the wines of Bordeaux and the Australian wine auction market. He gave expert evidence about how Bordeaux wines are typically sold, the reputation of the VCC wine estate and its wines in Australia, the presentation of VCC’s wines and his reaction to the New Certan wine. Mr Caillard was cross-examined.

93 Mr Timothy Evans is the National Business Manager of Imported Wines at Negociants Australia, an Australian wine distributor; the business is operated by Samuel Smith & Son Pty Ltd. He gave evidence about the promotion and sale of Bordeaux wines in Australia, including the VCC Wine, but was not cross-examined.

94 Mr Philip Rich is a wine professional with more than 35 years’ experience in the Australian wine industry, involving wine writing, wine judging and the importing and retailing of wine. He gave evidence about the reputation of the VCC wine estate and its wines in Australia, but was not cross-examined.

95 Mr John Myers is a director of Dunkeld Pastoral Co. Pty Ltd, which operates the Royal Mail Hotel at Dunkeld. He gave evidence about the availability and promotion of the VCC Wine at the Royal Mail Hotel, but was not cross-examined.

96 Ms Caroline Ryan is the solicitor for VCC who gave evidence in relation to publications available in Australia which refer to the VCC wine estate and its wines and publications referring to the New Certan wine. She was not cross-examined.

97 Let me at this point say something more about VCC’s witnesses.

98 To support its claimed reputation in, or consumer recognition of, the VCC features and the word “Certan”, VCC relied upon these various wine professionals. But none of these witnesses is representative of the ordinary and reasonable consumer. Each of them is an expert in wine, with a high degree of interest in, and level of knowledge of, French wines, including wines from the Bordeaux region. In fact, each of them has spent time in the Pomerol area, and many of them have visited and dealt directly with VCC in their professional capacity. Contrastingly, none of them are marketing or branding experts.

99 VCC suggests that this is a rare case in which the trade is involved and were or were likely to be misled. But the probative evidence about the nature or extent of that class was thin.

100 VCC’s only attempt to identify the trade was to lead evidence from experts with a high degree of knowledge of and an interest in Bordeaux wines, many of whom have esoteric and idiosyncratic personal experiences.

101 In particular and as I have indicated, Ms Faulkner is a wine writer who has travelled to leading wine regions, including in the sub-region of Pomerol, since the late 1990s for her professional development which Ms Faulkner said are an important part of learning about these regions, the vineyards, the producers and their wines. She has read extensively on the Bordeaux region and its wines, including the VCC wines. She has written on wines and wine producers from the Bordeaux region, including the VCC wine. She attended the 2011 dinner at Jacques Reymond that I will discuss later.

102 Mr Hooke studied the Bordeaux wine region of France as part of an Associate Diploma in Wine Marketing and Production in 1980 and 1981. He now teaches about the Bordeaux region in masterclasses on wine. He has travelled extensively in connection with his work in the wine industry, including spending six months during 1985 visiting wine regions, including Bordeaux. He has written about French wines, including wines from Bordeaux, since 1983. He has published a number of reviews on the VCC wine.

103 As I have said, Mr Caillard is a Master of Wine. He has over 42 years of experience, which commenced with four months working in the Bordeaux region. He has read extensively about wine regions and wine producers. In 1989, he established and managed the Sydney office of Langton’s Fine Wines, a specialist fine wine auction house. From 2003 onwards, Mr Caillard regularly travelled to Bordeaux to source wines for Langton’s, including from VCC. He has visited the VCC estate on many occasions.

104 Mr Rich is a wine professional who has been involved in sourcing and selling a range of French wines, including from Bordeaux, from at least 1996 when he founded Prince Wine Store. He taught an introductory French wine course, which focused on Bordeaux, Burgundy, Champagne and Rhône. He attended Bordeaux en primeur week in 2011, which included tasting the VCC wine.

105 As I have said, Mr Airoldi is a wine professional who has a particular interest in Bordeaux wines. He is originally from Pessac, an outer suburb of Bordeaux, and would cycle around Pomerol from time to time and pass the VCC wine estate when he was growing up. He has experience in the French wine industry, in which context he was involved in the 2010 Bordeaux en primeur campaign. He has completed wine qualifications, which included studying Bordeaux wines. He is completing his Master of Wine studies. From 2012, he has travelled to Bordeaux each year for en primeur week and to visit négociants and Châteaux contacts. He has taught subjects on Bordeaux wines.

106 Mr Evans has worked in the wine industry since 1993. He has been the National Business Manager of Imported Wines at Negociants Australia since 2007. He travelled to Bordeaux including Pomerol in 1996 whilst in France working a vintage in another wine region, and in the last 22 years, has attended or hosted dozens of Bordeaux wine-tasting events.

107 And as I have said, Mr Myers is a director of the company which owns and operates The Royal Mail Hotel in Dunkeld, Victoria, a food and wine destination venue. In that role, he oversees a collection of more than 30,000 bottles of approximately 3,700 wines, which collection was started in the early 1970s by his father who apparently had an interest in French wine. According to Mr Myers, his father began purchasing and importing VCC wine in the mid-1980s. Mr Myers has travelled to Pomerol as recently as 2017, at which time he was given a tour of the VCC by Mr Thienpont.

108 Now each of these witnesses is very knowledgeable and is not representative of the ordinary and reasonable consumer of a $75 to $95 bottle of Tasmanian pinot noir. They are similarly not representative of the ordinary and reasonable member of the wine trade. I agree with the respondents that in assessing these witnesses’ evidence on the question of whether the ordinary and reasonable person would have knowledge of wines from the Pomerol region generally, let alone knowledge of VCC or its wines specifically, and more particularly of the VCC features or the name Certan and any particular association between those features and VCC, caution must be exercised.

109 Let me say something about the respondents’ witnesses.

The respondents’ witnesses

110 Mr Craig Devlin is a director of both Kreglinger and PBV. He gave evidence about the management of Kreglinger and PBV and the sale of the New Certan wine. Mr Devlin was cross-examined.

111 Mr Oliver is a wine author and critic. As I have indicated, he gave evidence about the Australian wine market and consumers, the Bordeaux and Burgundy wine regions, naming and labelling practices for Bordeaux wines, the VCC wine estate and its reputation in Australia and the New Certan wine and his reaction to it. Mr Oliver was cross-examined, and occasionally was a little testy. To the extent that there is a conflict between the evidence of VCC’s experts, namely Mr Hooke, Ms Faulkner and Mr Caillard, and the evidence of Mr Oliver, on some topics I have preferred the evidence of Mr Oliver.

112 Mr de Moor is a director and the CEO of both Kreglinger and PBV. He gave evidence about the operations of Kreglinger and PBV, his family history, his shareholding in VCC, his understanding of the name Certan, his knowledge of VCC and its wines, and the development, promotion, labelling and sale of the New Certan wine. Mr de Moor was cross-examined. Some aspects of Mr de Moor’s evidence were not reliable.

113 Ms Annette Harcus is the creative director of Harcus Design who gave evidence about the process of designing the packaging of the 2011 and 2016 vintages of the New Certan wine. She was not cross-examined.

114 Ms Sandra Hathaway is a senior analyst at Wine Australia who gave evidence about a range of wine industry statistics. She was not cross-examined. I have referred to some of these statistics earlier.

115 Mr Jonathan Kelp is the solicitor for the respondents who gave evidence in relation inter-alia to the third party use in Australia of the name Certan, and the use of pink or similarly coloured capsules on wine bottles and materials. He also gave evidence concerning textbooks and other materials referencing the name Certan or pink or similarly coloured capsules, but he was not cross-examined.

116 Ms Rebecca Pereira is also one of the solicitors for the respondents who gave evidence about a visit to a Dan Murphy’s retail store in leafy upper middle-class Malvern East, Victoria and some wines that she observed during that visit. She was not cross-examined.

117 Ms Julia Kingwill is also one of the solicitors for the respondents. She gave evidence about visits to various retail wine stores in middle-class South Melbourne, Victoria and some wines that she observed during those visits. She was not cross-examined.

Other matters

118 Let me refer to some other matters that it is convenient to deal with at this point.

119 First, during the trial VCC introduced a new foundation for its alleged misrepresentations, namely, the promotion of the New Certan wine on the basis of Mr de Moor being related to the Thienpont family of VCC and having a connection with the VCC wine estate. But that allegation relied upon various articles, all of which were published from July 2018 onwards and being after the relevant date.

120 Second, VCC also tendered copies of communications between employees of Kreglinger and representatives of Dan Murphy’s, Coles and Winestate Magazine from November 2020 onwards in relation to the New Certan wine, but those communications also occurred after the relevant date.

121 Third, although VCC has relied on various documents as evidence of how the respondents promoted the New Certan wine to members of the wine trade, it does not allege that the publication of those articles or the sending of those communications themselves contravenes the ACL.

122 Fourth, during the trial there was an inordinately high level of evidence that was given from the Bar table. Perhaps this is explicable given the nature of the subject matter and the fact that counsel for the parties were drawn from the fashionable and expensive end of the Commercial Bar. Further, it seemed to be suggested that judicial notice could be taken as to the characteristics of some of the products and where they could be purchased and consumed. Unsurprisingly I declined that invitation.

123 Fifth, as far as the smorgasbord of expert evidence was concerned, much of it was nebulous and subjective. I have had to plate this together, taking bits and pieces from different witnesses for different purposes.

The presentation, sale and promotion of VCC’s wines

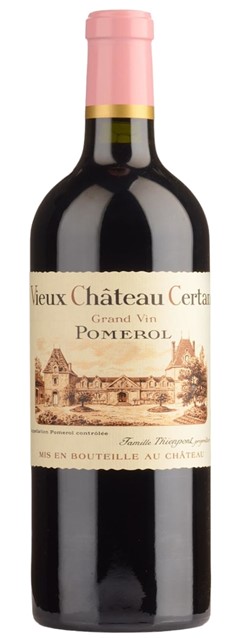

124 Although there have been some changes over time, the presentation of both the VCC Wine and the Gravette Wine have been largely consistent for decades. The presentation of VCC’s wines includes the following distinctive features.

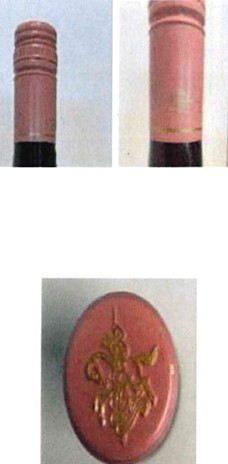

125 First, there is a pink capsule, with gold decoration around the base and on the top of the capsule.

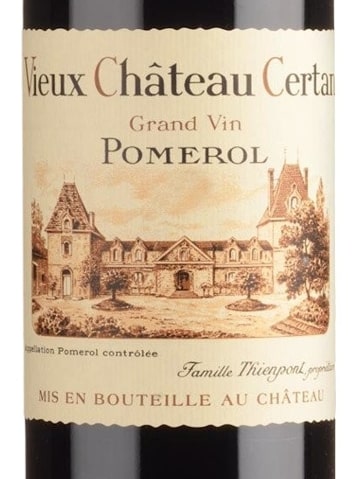

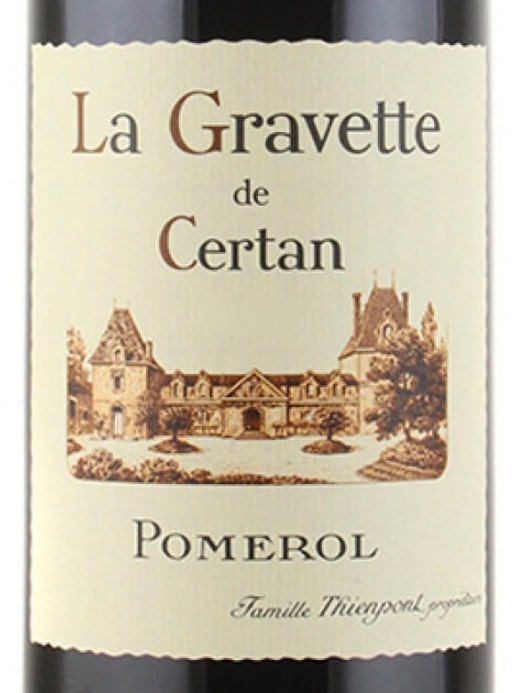

126 Second, there is a label featuring the name Certan, as a prominent part of the names Vieux Château Certan and La Gravette De Certan. Further, the label uses a pink font for the first letters of the name of the wine (Vieux Château Certan and La Gravette de Certan). Further, as to the label, in the case of the VCC Wine, the name Vieux Château Certan means “Old Chateau Certan” or “Old Certan Estate”, the words Grand Vin mean “great wine”, and Mis En Bouteille Au Château mean “bottled at the estate”, in pink font. Further, there is a centrally located image of a stately house known as the Vieux Château Certan, which is located on the wine estate owned by VCC. Further, there is a fluted edge profile.

127 These VCC features are in many respects distinctive and unusual.

128 The pink capsule appears as follows:

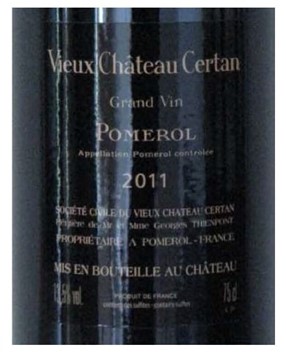

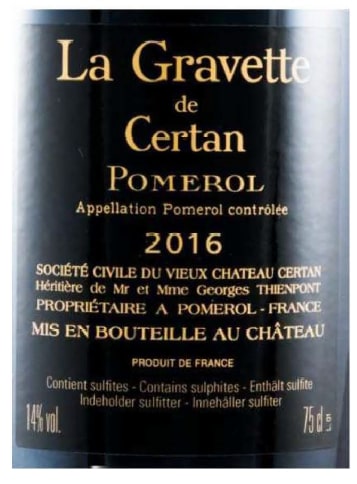

129 Earlier vintages of the VCC Wine and Gravette Wine were sold with the front labels depicted below:

130 Earlier vintages of the VCC Wine and Gravette Wine were sold with the rear labels depicted below:

131 Recent vintages of the VCC Wine and Gravette Wine are sold with the front label depicted below, with the year for the relevant vintage added to the centre of the label:

132 The overall presentation of both wines is as follows, with the year for the relevant vintage added to the centre of the label:

133 Mr Hooke gave evidence, which I accept, that the visual presentation of VCC's wines was distinctive and unusual. He said that the pink capsule used on the VCC Wine and Gravette Wine were distinctive and unusual. He also said that the labels of both the VCC Wine and Gravette Wine have other features that were distinctive and unusual, namely the fluted edging of the label and the use of pink font for the capitalised letters of the wine name. He said that taken together, the pink capsule, the fluted label and the pink font which features on the label were unusual and distinctive. I accept such evidence and observations.

134 Mr Caillard gave evidence that with respect to VCC, the name Vieux Château Certan appears prominently on the label, together with an image of the Château at the estate. The label itself has an aged appearance, which to him reflects the history of the wines. To him, these elements of the VCC wine labels convey a sense of history, place and prestige. He said that VCC is also distinguished by the use of the pink capsule. He regarded this capsule colour as unusual for Bordeaux wines, and when he saw VCC wines amongst other Bordeaux wines, they stood out to him for this reason. The pink capsule has become part of the narrative of the VCC wines as it has a widely reported historical story attached to it. I accept his evidence on these aspects.

135 Mr Caillard also agreed that the name of the wine, Vieux Château Certan or La Gravette de Certan, is important. However, he also considered that the overall visual appearance of the wine label and the pink capsule is how he would visually identify the bottle itself at first instance. To him, the label presentation of the VCC Wine and the Gravette Wine is unique for Bordeaux, and successfully conveys the product narrative and sense of history, place and prestige of VCC. The name of the wine is prominent, with pink font used as the first capitalised letter of each word in the name ‘Vieux Château Certan’ and 'La Gravette de Certan'. This same pink colour is used for the words Grand Vin and Mis En Bouteille Au Château. Further, the wine labels feature a reference to the Thienpont family. Further, he said that the pink capsule of the VCC wines is a significant and distinguishing feature of the estate's product presentation. Again, there is no basis not to accept his evidence on such matters.

136 Mr Rich also said that to his mind, VCC bottles are memorable, particularly when compared to other Bordeaux wines. He regarded the pink and gold wine capsule as eye catching when on a wine shelf in a retail store or on a tasting table with other Bordeaux wines. He also considered the serrated edge of the label to be unusual, as is the dusky pink font used to accent the first letter of the name of the wine.

137 Now Mr Oliver maintained that in respect of the VCC Wine, the most important aspect of its presentation was its name, rather than the distinctive aspects of its appearance. But Mr Oliver’s approach did not give proper weight to the importance of the overall presentation of the VCC Wine for both consumers and the trade. Further, the body of evidence before me amply supports the conclusion that the overall presentation of VCC’s wines is distinctive, notwithstanding that it shares some individual features in common with other wines.

138 Further, the name Certan has some association with VCC and its wines, but also other producers who use the name Certan. But VCC has no monopoly in that word, and any reputation that it may have does not derive wholly or substantially from that word. I will return to this later.

139 Let me now turn to how the VCC sells its wines.

140 VCC sells its wines through a structured market known as La Place de Bordeaux, which is widely used by the premium wine estates of Bordeaux. Within that market, courtiers are retained by wine estates to negotiate the sale of wines to négociants, which are wine brokers who on-sell the wines to distributors around the world.

141 The wines are primarily sold en primeur, meaning that they are purchased prior to being bottled and delivered some months later. Again, this is common amongst the premium wine estates of Bordeaux. The en primeur campaign is conducted annually. Over the course of several weeks from March to May, VCC typically hosts about 1,000 wine writers, journalists, negociants and wine merchants for tastings of the forthcoming wines. The outcome of those tastings informs the price that can be commanded for the vintage in question.

142 VCC retains a small number of courtiers for each vintage and its wines are typically sold through those courtiers to about 45 different négociants. This ensures that VCC’s wines have the best opportunity to be as widely distributed as possible. The négociants then on-sell the wine to their customers, some of whom are also wine professionals who in turn sell the wine to their customer networks. As part of La Place de Bordeaux, VCC’s wines are also sold through two separate wine negociant businesses that are operated by other members of the Thienpont family, namely Thienpont Wine in Etikhove, Belgium, and the Bordeaux based Wings.

143 VCC itself also engages in a range of promotional activities, including conducting promotional tours and tastings both as part of the en primeur campaign and otherwise, giving interviews to the wine media and conducting promotional events including in Australia. Many internationally renowned wine writers and critics have posted on social media or published articles on the internet about their visits to the VCC wine estate.

144 Further, the VCC wine estate and its wines have been referred to extensively in wine books and wine magazines including Wine Spectator, World of Fine Wine, The Wine Advocate and Gourmet Traveller Wine. These have been published internationally and in Australia. VCC and its wines have also featured in articles published in the Australian media. The extracts set out below from wine books are examples of how VCC has been described to international and Australian audiences over recent decades:

145 In Bordeaux by David Peppercorn (1982) it was said:

Vieux Château Certan

One of the few growths of Pomerol to boast a fine château. The oldest part is seventeenth-century and the whole building is very pleasing, with its two squat towers of differing ages and proportions at either end. It is beautifully kept by the Thienpont brothers, Belgian wine merchants whose father bought the property in 1924. Originally, it had belonged to the Demay family, who sold it in 1850 to Charles Bousquit.

This has always been regarded as one of the top growths of Pomerol, and in recent years its reputation has spread to England and the USA, while the excellence of the wines has been equalled by their consistency …

146 In Grand Vins – The Finest Château of Bordeaux and Their Wines by Clive Coates (1995) it was said:

Vieux Château Certan, it is said, dates back to the early sixteenth century, when it was a manor house and the centre of quite a large estate dominating a little plateau, about 35 metres above sea level, two or three kilometres north-east of the old port of Libourne. If this is so, it is probably the oldest property in the area. It is certainly one of the largest in a commune where few properties produce more than a few dozen tonneaux. And it is also one of the best. After Pétrus itself, Vieux Château Certan can compete, if it so wishes, with L'Evangile, La Conseillante, Lafleur and Trotanoy for the title of number two in the commune of Pomerol.

…

One curious detail is the capsule, which, unlike most clarets is not wine red or black, but shocking pink, with a gold band. This was Georges Thienpont's idea, in order to make the wine easy to pick out. The wine is matured for between 20 and 22 months and not filtered before bottling. The second wine is called La Gravette de Certan.

…

Vieux Château Certan has been producing excellent wines for decades. There were splendid bottles in the 1920s, a superlative 1947, a fine 1952 and 1959, and a notable 1964. Since Alexandre Thienpont has been in charge the intensity of the wine has, if anything, increased even more ...

147 In Pomerol by Neal Martin (2012) it was said:

In recent years, a succession of fêted vintages has firmly installed Vieux Château Certan in the top echelon of Pomerol wine, with a loyal, devoted fan base that buys the wine year in and year out. It's not just a wine they are purchasing, but a bottle of history.

Vineyard

I regard Vieux Château Certan as the epicentre of Pomerol, perhaps due to its historical significance and its name, or maybe because it seems to stand like a sentry at an important junction on the plateau ...

…

After fining with egg whites, the wine is bottled with its distinctive pink capsule chosen by Georges Thienpont to make it stand out from the crowd ...

148 In relation to the documentary evidence tendered concerning third party publications, I admitted much of that material subject to a limitation under s 136 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) such that third party statements contained in these publications were admitted not to prove the truth of the fact asserted or the opinion expressed, but rather as evidence of the fact that such views were held and expressed at the time of the relevant publication(s).

149 The VCC Wine has been to a limited extent sold in Australia since at least the 1980s, including through a major Australian wine distributor, Negociants Australia, and through auction houses such as Langton's.

150 In relation to the VCC Wine, the records of Negociants Australia date back to the sale of the 1995 vintage, which wines were delivered to customers in Australia in 1998. Those records show that the VCC Wine has been sold by Negociants Australia since that time.

151 Moreover, it has also been promoted and sold through prominent retailers such as The Prince Wine Store in Melbourne, through tasting events and restaurants.

152 PBV itself has promoted and offered for sale the VCC Wine, along with the wine of Château Le Pin in Australia. Kreglinger has been promoting the VCC Wine since at least 2011. It appears that Kreglinger obtained these wines from its Belgian parent company.

153 On 21 February 2011, Kreglinger invited guests to attend an Armadale Cellars dinner at Jacques Reymond in Melbourne which featured vintages of the VCC Wine with vintages of the Château Le Pin wine. The Kreglinger invitation included images of both the VCC Wine and Le Pin wine labels, and stated “[b]oth estates are recognised as two of Bordeaux’s most prestigious producers. Their wines are highly sought after collector’s items, held in high regard world-wide, and rarely available within Australia”.

154 The VCC Wine and the Château Le Pin wine were also featured in trade brochures issued by PBV in 2016, 2017 and 2019. Those trade brochures contain images of the full bottle presentation of the VCC Wine and the following description of VCC and the VCC Wine: “[t]he Vieux Château Certan estate is located in the heart of the Pomerol plateau. Fermented in oak vats and aged in new French oak barrels, Vieux Château Certan is regularly ranked by the world’s press and international tasting panels among the very top wines. With its brilliant dark garnet colour, outstandingly rich red fruit aromas, elegant, silky structure and beautiful balance, it displays inimitable style and finesse”.

155 Further, the 2017 and 2019 versions of these trade brochures promoted both the VCC Wine and New Certan wine in the same document. But I do not accept VCC’s assertion that this in and of itself suggests a commercial link between the New Certan wine and VCC and/or the VCC Wine.

156 Let me now turn more directly to the question of some of the evidence led concerning reputation.

Evidence of reputation or consumer awareness

157 The wine industry experts who gave evidence on behalf of VCC gave evidence as to the nature and extent of the reputation of VCC and its wines in Australia.

158 Mr Hooke gave evidence that in his experience both VCC and the VCC Wine were known to Australian wine professionals and some consumers, and in particular those with an interest in very high quality French wines, from at least the 1980s. Further, he said that the reputation of VCC and its wines in Australia has increased over time and he also said that VCC and its wines had a significant reputation amongst Australian wine professionals and consumers, and in particular those with an interest in high quality French wines, both before and after 25 November 1999. And this was particularly applicable to wine consumers and professionals who have an interest in Bordeaux, such as the consumers and professionals who have attended his Bordeaux masterclasses and tasting events and those who read wine publications. Now I do not accept that there was a sufficient reputation as at 1999, but I do accept that there was one as at 2013.

159 Ms Faulkner gave evidence that in her experience in the wine industry, VCC is an internationally renowned wine estate in Pomerol. It has produced a famous red wine of the same name, the VCC Wine, for nearly a century, and since the mid-1980s has produced the Gravette Wine.

160 Further, Mr Caillard stated that based on his 42 years of experience in the wine industry, and in particular, his many years of experience selling Bordeaux wines at auction, he believed that VCC is regarded as one of the great producers of the Pomerol appellation by many wine writers, critics and consumers of fine wines. To him, it is an ultra-fine wine which has had for many decades now a very special reputation with wine professionals and consumers of Bordeaux wine, both in Australia and internationally. In his experience, the VCC Wine is a highly regarded, ultra-fine Bordeaux wine which is produced in very small quantities. The rarity and special reputation of its wines is reflected in the prices at which the wines are offered for sale. As such, he would not expect many Australian wine consumers to have bought or tasted the VCC Wine or the Gravette Wine. However, he did believe that many Australian wine consumers who have an interest in fine wines would know of and be interested in these two wines, without necessarily having the means or access to experience or purchase bottles. In his experience, this is quite common in the fine wine industry, where many consumers attend wine tasting events and read wine columns and books, but cannot necessarily purchase or experience the ultra-fine wines or visit the wine estates firsthand.

161 Mr Caillard also said that serious wine collectors and people who buy Bordeaux wine every year will be aware of the Pomerol sub-region of Bordeaux. However, he did not agree that, even amongst this cohort, recognition of VCC or its wines will be limited. He believed that those with an interest in Bordeaux wines who purchase vintages year on year would be aware of both the Pomerol sub-region and its most famous producers, which in his view included VCC. In his experience of working at Rushton and with Langton's, these consumers who purchase Bordeaux wines annually are likely to know of VCC, and are, in many cases, likely to have had the opportunity to purchase and taste its two wines.

162 Mr Oliver appeared to suggest that the reputation of VCC and its wines was less significant in Australia than the views of Mr Hooke, Ms Faulkner and Mr Caillard would indicate. However, he agreed that VCC is a well-known, respected château. He described it as prestigious. He also agreed that because of its cost, it is likely to be an aspirational product. However, he sought to confine this favourable reputation to a very small cohort of consumers who are highly engaged with Bordeaux wines.

163 Now VCC pleads that it has developed a valuable and distinctive reputation and substantial goodwill among wine consumers and the wine trade in Australia in relation to the VCC Wine and the Gravette Wine, the name Certan only, and the combination of the VCC features. But VCC has abandoned its claim concerning the name Certan only. It opened its case on the basis that it did not claim that its reputation accrues in relation to the name Certan simpliciter. It accepted that it kept company with the rest of the words and markings on the label and more generally the VCC features.

164 Let me elaborate further on some themes relevant to the question of reputation in Australia. And at the outset, let me again say that I am not satisfied that VCC had the requisite reputation as at 1999, but that it had it by 2013.

The level of sales

165 I agree with the respondents that the scarcity of the VCC wines is reflected in the evidence of sales. When taken at its highest, the evidence shows that VCC has sold only a few thousand bottles of the VCC Wine in Australia since 1989, and the evidence shows that only around 190 bottles of the Gravette Wine have been imported into Australia during that period.

166 When measured against the Australian wine market, the volume of products sold is very small. These sales of the VCC Wine are likely to represent around 0.01% of Bordeaux red wine, and less than 0.002% of French red wine, sold in Australia since 1989.

167 Sales of Bordeaux wine comprised approximately 10% of off-premise retail French red wine sales in 2021. In that year, imports of French red wine totalled approximately 6.8 million litres. Assuming imports roughly approximate sales, this equates to approximately 680,000 litres or approximately 907,000 bottles of 750ml wine. At approximately 100 bottles of VCC sold per year, this equates to approximately 0.011% in 2021.

168 Imports of French red wine totalled approximately 4.2 million litres in 2013, 5.3 million litres in 2017 and 6.8 million litres in 2021. Taking the lowest of those values in 2013, this equates to approximately 5.6 million 750ml bottles of French red wine. At approximately 100 bottles of VCC per year, this represents less than 0.002%.

Promotional or marketing activities

169 The evidence establishes that VCC does not engage in promotional or marketing activities in Australia or directed to Australian consumers.

170 VCC appears to accept this, but it relies upon the promotion of its products by Australian resellers or distributors, such as Negociants Australia and Airoldi Fine Wines, at auction houses such as Langton’s, and at prominent retailers such as Prince Wine Store.

171 Negociants Australia has offered the VCC Wine for sale as part of its portfolio of Bordeaux wines since at least 1996. But there is no evidence of promotion of the VCC Wine by Negociants Australia in any relevant sense. The VCC Wine is one product in a long list of products which was available for purchase; more than 200 products are listed in each of the 2009 and 2020 lists. And the product itself is not depicted in the Negociants Australia lists.

172 Airoldi Fine Wines has offered the VCC Wine for sale as part of its portfolio of Bordeaux wines since 2012. Again, the VCC Wine is one product in a list of many other wines. The product itself is not depicted. Whilst Mr Airoldi gave evidence that he has hosted hundreds of educational activities such as wine dinners, tastings and masterclasses around Australia, he identified only two relating to the VCC Wine. In the first of those tastings in March 2016, the VCC Wine was featured as one of 30 wines on that evening. In the second in September 2018, the VCC Wine was one of 50 wines. And whilst Mr Airoldi gave evidence of conducting annual tours to Bordeaux, the only evidence of visiting the VCC estate relates to a small group of between 8 to 10 Australian customers in October 2017. On a similar tour in 2019, Mr Airoldi did not visit the Pomerol region, let alone the VCC estate, apparently for no specific reasons. VCC similarly did not feature on the brochure for the 2021 tour.

173 Now Langton’s commenced its own Bordeaux en primeur campaign in 2004, and in that context sourced and imported wines from Bordeaux including the VCC Wine. It sold the VCC Wine at auction prior to that time from about 1989. The evidence includes a copy of the Langton’s Vintage Price Guide published in 1991, which exemplifies how the VCC Wine was promoted at that time. In short, a few vintages of the VCC Wine are located amongst hundreds of listings in the “Red Bordeaux” section of a 200+ page book. Château Certan de May and Château Certan-Giraud also appear in the guide. The VCC Wine is now available via the Langton’s website. I must say that the evidence of sales via Langton’s was underwhelming.

174 Further, Prince Wine Store secured VCC’s wines from time to time and offered them for sale to customers in Australia. This included as part of en primeur campaigns run by Prince Wine Store for its customers. In those campaigns, the VCC Wine appeared amongst a long list of Bordeaux wines, with no particular prominence and no images of the product. Mr Rich gave evidence that the VCC Wine was featured with other exclusive Pomerol wines such as Petrus and Château Lafleur on occasion at tastings and educational events, but he did not identify any specific events or suggest that this was a regular occurrence. His evidence also suggests that such events would typically feature between 20 to 30 Bordeaux wines. There is no evidence indicating the volume of sales of the VCC Wine via Prince Wine Store.

175 The other example of promotional activity is a VCC and Le Pin dinner at Jacques Reymond in February 2011. This event was hosted by Kreglinger, as it coincided with a visit to Australia by Jacques Thienpont and his wife to attend an event for Mr de Moor’s 50th birthday. It was a one-off event which took place several years before the 2011 vintage of the New Certan wine was released onto the market.

176 Moreover, save for generalised assertions by Mr Rich, there is no evidence of any specific promotional events involving the VCC Wine in Australia prior to 1999.

The relevance of the wine press?

177 VCC says that both itself and its wines have been promoted in Australia to Australian audiences extensively through what the parties referred to before me as the wine press.

178 Mr Hooke’s evidence is that he and his team taste and review over 10,000 wines submitted by wine producers each year from around the world and that his website, The Real Review, now hosts his 50,000 tasting notes which he has published during the course of his career. Mr Hooke explained that, by around 2018, he was publishing about 5,000 wine reviews each year, roughly 100 wines per week. For a simple, straightforward wine he could sum it up very quickly, but for very complex wines, especially an aged red, he would come back several times over four or five minutes.

179 In 1983, Mr Hooke started writing a weekly wine column in the Australian Financial Review, and since then he has written and published thousands of articles, columns and other pieces about wine in various publications, including the Australian Financial Review, the Sydney Sun-Herald, Sydney Morning Herald and Decanter magazine. He has also been the Australian correspondent for the Oxford Wine Companion and World Atlas of Wine. His published articles have included many about wines from Bordeaux. Despite this, putting aside tasting notes, there is only one article in evidence written by Mr Hooke which refers to VCC.

180 Ms Faulkner’s evidence is that she similarly tastes and reviews about eight thousand wines a year, being both international and local. Despite that evidence, Ms Faulkner did not encounter the New Certan wine until she was asked to review the 2018 vintage in January 2020.

181 Between 2009 and 2014, Ms Faulkner wrote around 250 weekly columns and 60 feature articles for The Age and The Sydney Morning Herald, only two of which (on 27 November 2007 and 8 March 2011) mentioned VCC at all. Neither of those two articles depicted VCC product labels. She also wrote feature articles for numerous other publications including Gourmet Traveller Wine magazine for around 10 years, Wine-Searcher, Halliday Magazine from 2016, Wine Companion from 2016, Meiningers Wine Business International, Le Pan and Falstaff, but did not suggest in her evidence that any article in any of those publications made any mention of VCC.

182 Mr Oliver’s website has reviewed or referred to many thousands of wines since its inception. The VCC Wine is not mentioned on the website. At the time he reviewed the New Certan wine, Mr Oliver was receiving upwards of 10,000 bottles in a year and tasting about 4,000 a year or 150 wines in a day.

183 Mr Oliver has written articles about wine in Australian newspapers and magazines since the mid-1980s, including The Age and The Sunday Age, Winestate, Wine and Spirit Buying Guide, The Australian Way (Qantas’ travel magazine), Gourmet Traveller Wine Magazine, Business Review Weekly, The Bulletin, Marie-Claire, and the Herald Sun. He produced a subscription newsletter between 1996 and 2003 and has also written hundreds of articles regarding Australian wine for overseas publications since around 1986. Mr Oliver has not written any articles or reviews in relation to the VCC wines.

184 Now there is no evidence indicating the number of consumers, if any, who have, in fact, read any reviews or tasting notes about the VCC wines. The presence of reviews of the VCC wines amongst the many thousands of reviews published every year does not establish consumer recognition of the VCC wines, let alone a reputation in the VCC features or the word “Certan” such that they distinctively indicate VCC or its products. Even if it is assumed that consumers of wines, or at least fine wines, take an interest in the wines they are consuming or purchasing, that would not rise any higher than the evidence of actual sales, which evidence is very limited.

185 The same can be said about articles in the wine press. Whilst the volume of material is not as extensive as wine reviews or tasting notes, the wine press is similarly flooded with articles. But in that context there is little evidence of publications about VCC or its wines in Australia.

186 Further, there is no evidence that any of those articles were actually read by any actual or potential purchaser of the New Certan wine.

187 Further, as at 1999, there is only one potential article in evidence. The article contains only a brief reference to Mr Thienpont and the VCC estate and does not include any images of the VCC Wine. The article, written by Julia Mann and titled ‘Earliest Bordeaux Harvest since 1893’, was apparently published in The Wine Spectator magazine in 1997 according to Mr Thienpont, but he does not give evidence of this publication. Mr Thienpont’s evidence refers only to the article as published on The Wine Spectator website, accessed in around 2021 or 2022. The version of the article includes an advertisement for a “2022 Grand Tour”, so cannot have been accessed materially earlier than 2021.

188 In the period from 1999 to 2013, there is evidence of no more than 25 wine industry articles referring to VCC, from anywhere worldwide. And of those articles, the following points may be made.

189 First, only one includes an image of the VCC Wine, and even in that case it is limited to the label alone not the full bottle presentation.

190 Second, 15 were published in a single specialist wine publication, The Wine Spectator.

191 Third, the remaining articles were published in print or online at jancisrobinson.com, which is an online wine publication that has a limited audience, The Age (in Ms Faulkner’s Cellar Door column), The Sydney Morning Herald, The World of Fine Wine (an English magazine dedicated to wine), and Australian Gourmet Traveller.

192 Fourth, with the exception of The Sydney Morning Herald and The Age, these publications are specifically directed to consumers with an interest in fine wine, and not necessarily the ordinary reasonable consumer of the New Certan wine.

193 Fifth, as to the specialist publications, there is no evidence from any Australian who reads any of them, setting aside the wine industry specialists who have given evidence in this case. To the extent the wine industry specialists speculate about where such readership might exist, it would consist of very engaged or deeply committed consumers, which are likely to be a small number of people.

194 Sixth, as to mainstream media publications, the probability of even the deeply committed ordinary reasonable consumer reading every one of Mr Hooke’s and Ms Faulkner’s articles to stumble upon one that mentions VCC is remote.

195 Further, in the period from 2013 to May 2021, there is evidence of no more than 25 wine industry articles referring to VCC, none of which include an image of the packaging. Of these articles, seven were published in The Wine Spectator. With the exception of one article in The Tasmanian Times, the remaining publications are directed to consumers with an interest in fine wine: Gourmet Traveller Wine, the UK based website jancisrobinson.com, The Wine Advocate, The World of Fine Wine, Langton’s, and Winetitles Media.

The extent of social media?

196 Now VCC relies upon social media as a source of consumer knowledge or reputation, but as at the earliest relevant date, 1999, there was no social media evidence.