FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Bloomex Pty Ltd [2024] FCA 243

ORDERS

AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION Applicant | ||

AND: | BLOOMEX PTY LTD (ACN 147 609 443) Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: | 15 MARCH 2024 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Within seven days of the date of these orders, the parties confer and submit a form of orders to give effect to the Court’s reasons for judgment.

2. Within seven days of the date of these orders, the parties file written submissions on the question of costs limited to five pages.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

INTRODUCTION

1 The Respondent, Bloomex Pty Ltd (Bloomex), is a large online floristry and gift retailer. The Applicant, the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC), commenced this proceeding in connection with material published on Bloomex’s website (Website) about advertised discounts, customer ratings and prices. Bloomex admits those representations were false or misleading and that, consequently, it contravened ss 18(1), 29(1)(a), (g) and (i) and 48(1) of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL) (as contained in Schedule 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (CCA)). The contraventions admitted by Bloomex, and the facts giving rise to those contraventions, are recorded in a Statement of Agreed Facts dated 7 August 2023 (SOAF).

2 In the light of Bloomex’s admissions, the ACCC and Bloomex have agreed on proposed final orders filed on 7 August 2023 (Joint Proposed Orders). The parties have filed joint submissions dated 7 August 2023, explaining why they consider the Proposed Orders to be appropriate (Joint Submissions).

3 The only outstanding matters are the quantum of penalties and orders as to costs (Contested Relief). The ACCC seeks an order for civil penalties totalling $1,500,000. Bloomex accepts that it is appropriate that it be ordered to pay a pecuniary penalty in respect of its admitted contravening conduct. Bloomex submits that an appropriate penalty in this matter would be not more than $350,000.

4 For the reasons given below:

(a) I consider it appropriate to make the Proposed Orders submitted jointly by the parties;

(b) I consider a penalty of $1,000,000 to be appropriate.

AGREED FACTS AND EVIDENCE

5 The evidence before the Court principally comprises the SOAF, two affidavits made by Mr Dimitri Lokhonia on 26 September 2023 (Affidavit) and 10 November 2023 (Second Affidavit), and the Court Book which was jointly tendered as Exhibit #AR1.

6 Mr Lokhonia is a director and founder of Bloomex. The Respondent objected to portions of the Affidavit, which were the subject of rulings during the hearing recorded in a document marked as MFI #1 on the Court file. The Lokhonia Affidavit was received into evidence, subject to my rulings as recorded in MFI #1.

7 Mr Lokhonia also gave oral evidence at the hearing, in which, amongst other things, he:

(a) stated that statements on the Bloomex website as to Bloomex’s business model were accurate;

(b) adopted as his own opinion an IBISWorld report, dated June 2023, which provided information about Bloomex’s competitors and the market in which Bloomex operated.

8 The below summary of the background facts is based on the SOAF and Mr Lokhonia’s oral and affidavit evidence. Mr Lokhonia’s apology and cross-examination at the hearing are separately addressed at [65]-[74] below.

Bloomex

9 It is agreed that Bloomex is an online floristry and gift retailer, conducting its business in Australia through the Website. Bloomex’s products available for purchase on the Website include floral bouquets, arrangements or wreaths, individual flowers, gift hampers and other items (Products). Bloomex promotes itself to its customers as offering Products at lower prices with customers receiving significant savings. Between 26 February 2019 and 25 March 2023, there were approximately 6.3 million visits to the Bloomex Website.

10 It is agreed that Bloomex is one of the largest florists in Australia. It has production facilities in New South Wales, Queensland, Victoria, South Australia and Western Australia. Bloomex customers may purchase, through the Website, the Products for delivery. Other entities associated with Bloomex also operate internationally in New Zealand and Canada. The Canadian entity delivers to both Canada and the United States. Bloomex has separate websites for customers in Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the United States.

11 Mr Lokhonia deposed that he founded the broader Bloomex business in Canada in 2005: Affidavit at [15]. Bloomex was established in Australia in 2011: Affidavit at [16]. Because of the success of the original business in Canada, Bloomex was mainly self-funded from the very beginning: Affidavit at [8].

12 It is agreed that the current directors of Bloomex are Ms Olga Slouguina, Mr Lokhonia (both appointed on 29 November 2010) and Ms Hai Binh Hoang (appointed on 2 December 2021).

13 Mr Lokhonia deposed that Bloomex is a large business by the standards of florists, but not in relation to retailers. He deposed that Bloomex has only one employee in Australia, a local director, and that Bloomex’s logistical operations in Australia are conducted by contractors: Affidavit at [36].

14 It is agreed that Bloomex’s Product orders, revenue, and gross profit in relation to its Australian business for the 2019, 2020, 2021 and 2022 calendar years are as set out below.

2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | |

Website orders | 67,329 | 132,409 | 184,755 | 165,115 |

Website revenue | $4,420,205.04 | $9,186,034.38 | $12,605,532.63 | $11,844,969.72 |

Total orders | 74,482 | 152,802 | 225,153 | 187,399 |

Total revenue – | $4,889,779.69 | $10,600,857.95 | $15,361,820.29 | $13,255,092.09 |

Total Gross Profit – | $1,520,065.05 | $3,263,133.68 | $3,153,514.53 | $2,736,560.64 |

15 It is agreed that Bloomex’s financial statements for the financial years 2019 to 2022 record the following sales, gross profit and net profit for its Australian business:

Sales (millions) | Gross Profits (millions) | Net Profits after Tax (Net Loss) | |

FY 2019 | $4.579m | $1.526m | $39,349 |

FY 2020 | $6.339m | $2.537m | $354,661 |

FY 2021 | $13.477m | $4.541m | $434,856 |

FY 2022 | $16.065m | $3.186m | ($1,803,657) |

16 Mr Lokhonia deposed that the loss recorded by Bloomex in 2022 was due to COVID-related issues, including supply chain issues arising from supply route disruption, management difficulties arising from travel restrictions, and labour shortages and labour disruptions due to lockdowns and the pandemic: Affidavit at [32].

17 Mr Lokhonia also deposed that, in the financial years 2019 to 2022, Bloomex did not pay any dividends to its shareholders and did not pay any remuneration to its directors, except for its local director, who was paid a salary: Second Affidavit at [11].

Bloomex’s model and competitors

18 Mr Lokhonia deposed that Bloomex has a direct-to-customer business model, which enables it to offer prices “at the lower end of the market” by buying directly from growers and suppliers, as opposed to buying products from wholesalers, which is a model used by some of Bloomex’s competitors: Affidavit at [11]-[12], [24], [26]. Mr Lokhonia deposed that Bloomex’s model has “significant supply chain efficiencies”: Affidavit at [26].

19 In his oral evidence, Mr Lokhonia adopted as his own opinion an IBISWorld report, dated June 2023, which provided commentary on the market in which Bloomex operates, including its competitors. The report relevantly stated that:

(a) there is “mounting competition from online-only retailers that enjoy lower overhead costs and can offer competitive pricing”;

(b) the “flower retailing industry is highly fragmented, with most business operating from only one location”, and that florists “are typically members of networks like Interflora, which offer small-scale retailers greater marketing power and help generate home delivery sales through advertising”;

(c) “Florists operate in a fragmented market with no dominant retailers controlling a significant share. Mergers and acquisitions have little impact on the competitive landscape thanks to a lack of retailer dominance”;

(d) “Households, wedding venues and funeral homes and corporate clients are the key markets for florists”;

(e) “Flower retailers have come up against mounting competition from online-only sites. With lower fixed and operating costs, online-only retailers don’t need to worry about shop fronts or customer service staff. The rapid uptake of online shopping has led consumers to buy anything and everything online, flowers included. Online flower retailers can offer consumers more competitive prices and a fast turnaround service”;

(f) “Florists can become members of international flower delivery agents like Interflora, Teleflora or Petals. As members, local florists can receive and fulfil interstate and international orders based on their proximity to the delivery address, generating additional revenue for the florist”;

(g) “Consumers and other end markets have loads of options when it comes to buying flowers. Supermarkets and grocery stores stock a range of cut flowers, basic floral arrangements and small potted plants. Consumers can choose to add other complementary products like chocolates and alcohol, meaning they can create a similar arrangement as florists. Convenience and street and roadside stalls are other viable choices for consumers looking to buy flowers. Buying from online retailers allows consumers to compare prices, read reviews and place orders at their convenience without waiting for stores to reopen”;

(h) “Purchase costs rose in the wake of the pandemic thanks to supply chain disruptions and logistical delays”.

Representations made by Bloomex

Discount Representations

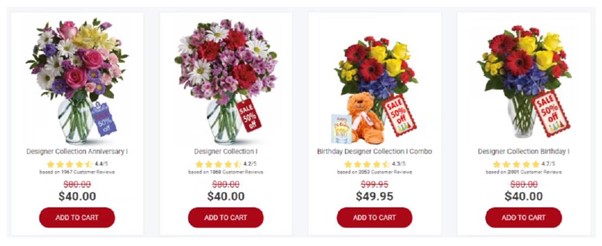

20 It is agreed that, between 26 February 2019 and 2 November 2022, almost all of the Products (approximately 730 Products), advertised for sale on the Website were accompanied by two prices: the price for purchase of the relevant Product (the Purchase Price); and a higher price than the Purchase Price displayed in strikethrough form which appeared on the Website (Strikethrough Price). The below example image capture of the Website, taken on 20 December 2021, shows the Purchase Price and Strikethrough Price:

21 It is agreed that, between 26 February 2019 and 28 March 2023, certain Products (approximately 70 Products) advertised for sale on the Website were also accompanied by the words “50% off” or “Half Price”.

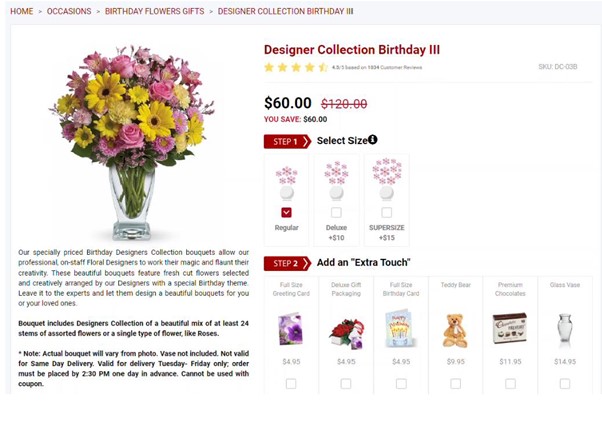

22 It is agreed that, between 20 December 2021 and 2 November 2022, when a potential customer clicked on the name or image of a Product, they were taken to a webpage with an image of the Product, a re-statement of the Strikethrough Price and Purchase Price, and underneath the words “You Save”, followed by an amount that was the difference (or the approximate difference) between the two prices (You Save Statement). The below example image capture of the Website, taken on 12 August 2022, shows the You Save Statement:

23 It is agreed that, by reason of the above conduct, Bloomex made express and implied representations, in trade or commerce, in connection with the supply or possible supply of goods and/or in connection with the promotion of the supply of goods to consumers on the Website that:

(a) the Purchase Price was a discounted price;

(b) the amount of the discount that a consumer purchasing the Product would receive was equivalent to the difference between the Strikethrough Price and the Purchase Price or 50% off the Strikethrough Price (if applicable);

(c) the Strikethrough Price was the price at which the Product was offered for sale by Bloomex to consumers before the discount was applied; and/or

(d) the Strikethrough Price was the price at which the Product was usually offered for sale to consumers absent any discounts (together, the Discount Representations).

24 It is agreed that, in fact:

(a) for almost all of the Products accompanied by a Strikethrough Price:

(i) Bloomex had never sold, nor had it offered for sale, the Products at the Strikethrough Price; and/or

(ii) the Strikethrough Price was higher than the price at which Bloomex ordinarily sold the Products, or offered the Products for sale;

(b) for almost all the Products accompanied by a “50% off” or “Half Price” statement (excluding “Bloomex’s Friday Only Roses Special”, when Bloomex’s roses were discounted to 50% of their usual price), Bloomex had never sold, nor offered for sale, the Products at a price that was twice the Purchase Price; and

(c) in light of these matters, a customer who bought any such Product would not have received savings in the amount of the difference between the Strikethrough Price and the Purchase Price or a 50% discount (if applicable).

25 It is agreed that, accordingly, the Discount Representations were false, misleading or deceptive.

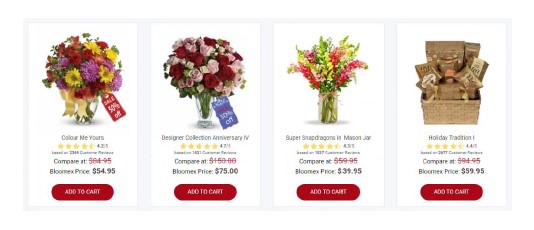

26 It is agreed that, between 3 November 2022 and about 12 March 2023, the Strikethrough Price for each of the Products was accompanied by the words “Compare At” and “Bloomex Price”, as depicted in the image capture of the Website, taken on 3 November 2022:

27 It is agreed that, from around 13 March 2023 until about 30 March 2023, Bloomex removed the Strikethrough Price from each Product on the Website.

28 It is agreed that, on or around 30 March 2023, Bloomex reinstated the Strikethrough Price for each of the Products and reinserted the words “Compare At” (but did not reinsert the phrase “Bloomex Price”) until about 25 April 2023.

29 It is agreed that, from 26 April 2023, Bloomex has not shown on the Website a Strikethrough Price for any of the Products. Bloomex progressively removed “50% off” or “Half Price” statements from the Website between 25 March 2023 and 27 April 2023.

30 Mr Lokhonia deposed that the original concept behind the Discount Representations was proposed to him by Bloomex’s then marketing director, Mark Campaugh: Affidavit at [38]-[39].

31 Mr Lokhonia further deposed that the original logic behind the Discount Representations was to show that Bloomex was cheaper than its competition. According to Mr Lokhonia, the theory was that when all prices were marked down from the usual market prices available elsewhere, and this was done all the time, customers would see that Bloomex was cheaper more generally, as a result of its business model: Affidavit at [42].

Star Rating Representations

32 It is agreed that, between 26 February 2019 and 17 March 2023, almost all of the Products (approximately 730 Products) advertised for sale on the Website were accompanied by what was described in the Statement of Agreed Facts as a Star Rating. The Star Rating comprised:

(a) a number out of five (such as “4.3/5”);

(b) an image of five stars; and

(c) a statement purporting to explain that the basis of the Star Rating was “Customer Reviews” (such as “based on 1653 Customer Reviews”).

33 It is agreed that examples of Star Ratings appear in the image captures set out at [20] and [26] above.

34 It is agreed that, by reason of this conduct, Bloomex made express and implied representations in trade or commerce, in connection with the supply or possible supply of goods and/or in connection with the promotion of the supply of goods to consumers on the Website that:

(a) Bloomex maintained a customer review system that was reasonably up to date, where other Bloomex customers gave or had given a rating out of five reflecting their degree of satisfaction with the Product purchased;

(b) the Star Rating was an average calculated by using all of the ratings that Bloomex had received from other customers in relation to the Product; and/or

(c) the Star Rating was a reliable indicator of the degree of customer satisfaction in the relevant Product (Star Rating Representations).

35 It is agreed that, in fact, the Star Ratings were not a reliable indicator of the degree of customer satisfaction for the relevant Product because:

(a) the Star Ratings on the Website had remained static since January 2015. They did not incorporate, or otherwise account for, customer ratings or reviews that Bloomex may have received after January 2015;

(b) the Star Ratings were based on data and reviews from Bloomex websites (www.bloomex.ca, www.bloomexusa.com, www.bloomex.com.au), including customer reviews for Products prepared and delivered outside Australia; and

(c) the Star Ratings included ratings provided by visitors to the abovementioned Bloomex websites, meaning that calculations accounted for Star Ratings from persons who may have never purchased any Products from Bloomex and who, therefore, may not have been Bloomex customers.

36 It is agreed that, accordingly, the Star Rating Representations were false, misleading or deceptive.

37 It is agreed that, on or around 3 November 2022, Bloomex added the following explanatory statement to the Product page for each of the Products in question:

Star Ratings as displayed were collected from visitors to Bloomex websites (Australia, Canada and USA) prior to 2015 and reflect visitor ratings of each product based on product composition and appearance.

38 It is agreed that the Product page could only be accessed by a user clicking on a Product icon from a list of Products.

39 Mr Lokhonia deposed that the explanation of the Star Ratings added to the Product page on 3 November 2022 represented an initial attempt to satisfy the concerns raised by the ACCC. He accepted that the additional information was insufficient, and the Star Ratings were still misleading: Affidavit at [64].

40 It is agreed that, on 17 March 2023, Bloomex removed the Star Ratings (and the explanatory statements on the Product pages) from the Website.

41 Mr Lokhonia deposed that the original concept behind the Star Ratings was proposed to him by Bloomex’s then marketing director, Mr Campaugh: Affidavit at [38]-[39].

Total Product Price Representations

42 It is agreed that, to purchase any Product on the Website, a customer is required to progress through several webpages before arriving at the “Express Checkout – Billing” webpage (the Checkout Page). At that point, a customer is required to enter their personal details to complete any purchase.

43 It is agreed that, between 10 August 2022 and 22 March 2023, for every Product on the Website, on each webpage prior to the customer entering their delivery postcode details on the Checkout Page, the Website displayed a purchase price for the Product.

44 It is agreed that, by reason of this conduct, Bloomex represented that the customer could purchase any particular Product for the displayed purchase price (Total Product Price Representations).

45 It is agreed that, in fact:

(a) the displayed purchase price was not the price of the Product. When a customer entered their delivery postcode and delivery date on the Checkout Page, the customer was then shown a surcharge that they would be required to pay if they continued with the transaction;

(b) the amount of the surcharge varied, but could have been an amount between $1.95 and $4.95 per order;

(c) the amount of the surcharge applied to each order, regardless of how many Products the customer was ordering; and

(d) the amount of the surcharge was not disclosed on the Website prior to the Checkout Page.

46 It is agreed that, accordingly, the Total Product Price Representations were:

(a) false, misleading or deceptive; and

(b) in respect to an amount that, if paid, would constitute a part of the consideration for the supply of the Product in circumstances where Bloomex did not also specify, in a prominent way and as a single figure, the single price for the Product.

47 It is agreed that, on the Checkout Page, the Website stated the following with respect to the surcharge:

(a) From on or about 10 August 2022, when the surcharge was first introduced, until about 13 March 2023, the Checkout Page featured an explanatory pop-up (when the cursor hovered over the surcharge item) which stated: “To maintain our ‘Best in Industry’ pricing we have been forced to apply a minimal surcharge to cover overhead cost increases due to rampant inflation.”

(b) From 13 March 2023, the surcharge was renamed “Fuel Surcharge” on the Checkout Page;

(c) From about 13 March 2023 until about 21 April 2023, the Checkout Page featured an explanatory pop-up (when the cursor hovered over the surcharge item) which stated: “We have introduced a surcharge of $3.95 to cover overhead cost increases due to inflation.”

(d) From about 21 April 2023 until about 5 May 2023, the Checkout Page featured an explanatory pop-up (when the cursor hovered over the fuel surcharge item) which stated: “The Fuel Surcharge is currently $3.95, so that Standard Delivery will be $18.90 and Same-Day Delivery will be $23.90, including the Fuel Surcharge.”

48 It is agreed that the Terms and Conditions Page of the Website stated the following with respect to the surcharge:

(a) Prior to 27 October 2022, neither the quantum nor the existence of the surcharge was disclosed on the Terms and Conditions Page of the Website;

(b) On or around 28 October 2022, a statement purporting to explain the surcharge appeared under the heading “Surcharge” on the Terms and Conditions Page of the Website. The statement read: “[i]n a continued effort to offer and maintain our ‘Best in Industry’ pricing we have been forced to introduce a $4.99 ‘Surcharge’.”

(c) On 23 March 2023, the explanation on the Terms and Conditions Page of the Website was amended to update the heading to “Fuel Surcharge” and state: “We have introduced a surcharge of $3.95 to cover overhead cost increases due to inflation.”

(d) On or around 30 March 2023, the explanation under the heading “Fuel Surcharge” on the Terms and Conditions Page of the Website was again amended to state: “The Fuel Surcharge is currently $3.95, so that Standard Delivery will be $18.90 and Same-Day Delivery will be $23.90, including the Fuel Surcharge.”

49 It is agreed that, between 10 August 2022 and 22 March 2023, Bloomex received $317,802 (including GST) from applying a surcharge to 90,197 orders made via the Website.

50 It is agreed that, from 5 May 2023, Bloomex has not added a separate surcharge to any of the Products sold via the Website, and the surcharge is no longer referred to on the Terms and Conditions Page.

“About Bloomex” webpage

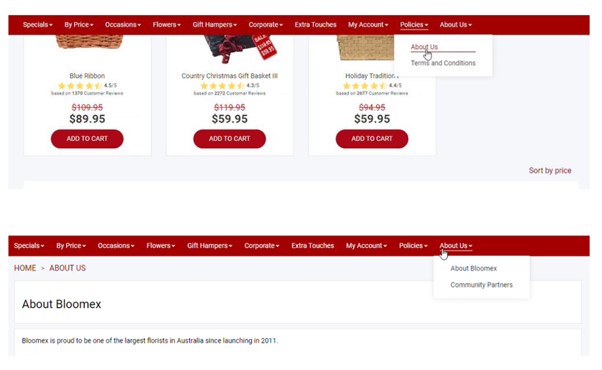

51 It is agreed that, at all material times, Bloomex had an “About Bloomex” webpage on the Website, that could be accessed:

(a) when a consumer clicked or hovered over the “Policies” weblink that appeared in the banner at the top of the Website and selected “About Us” from the drop-down list; or

(b) when a consumer clicked or hovered over the “About Us” weblink that appeared in the banner at the top of the Website and selected “About Bloomex” from the drop-down list

52 It is agreed that these drop-down lists are depicted in the below image capture of the Website, taken on 25 August 2022:

53 It is agreed that unless a consumer chose to click into the “Policies” or “About Us” weblinks at the top of the Website (and then click “About Bloomex” from the drop-down list), the information displayed on the “About Bloomex” webpage was not otherwise disclosed or brought to the attention of a consumer as part of the process to purchase a Product via the Website.

54 It is agreed that, between at least 26 February 2019 and 12 May 2022, the “About Bloomex”’ webpage displayed the following:

Firstly, the company buys products directly from growers and suppliers. This arrangement eliminates the wholesalers (middlemen) from the equation which greatly decreases costs and provides a much fresher product for you, the customer.

55 It is agreed that, from about 12 May 2022 until 30 March 2023, the “About Bloomex” webpage displayed the following:

Firstly, the company buys products directly from growers and suppliers which provides a much fresher product for you, the customer. This approach also eliminates the wholesalers (middlemen) from the equation which greatly decreases costs. Those savings are calculated and displayed on every product page in the form of comparative market pricing. The stricken out and “SALE” tag prices are based on Petals/Teleflora Suggested Retail Price or our competition, including local florists.

Bloomex’s price comparison schedule

56 During the hearing, the parties tendered an amended spreadsheet which, in respect of certain of Bloomex’s Products, purported to list relevant competing products from one of Bloomex’s competitors, with comparator prices for each product (price comparison schedule). In explaining the original version of the price comparison schedule, Mr Lokhonia deposed that the schedule demonstrated that Bloomex Products were significantly cheaper than competing products: Affidavit at [56]. The effect of his evidence was that, as reflected in the price comparison schedule, even though Bloomex should not have made the Discount Representations, the fact was that Bloomex did offer competitive prices compared to its competitors and could do so because of its supply chain efficiencies: Affidavit at [53], [56].

57 The parties, however, ultimately agreed that the price comparison schedule would be tendered subject to an order pursuant to s 136 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) limiting its use as an aide memoir showing solely the price differences between the Bloomex Product and the product asserted to be comparable product. The parties agreed that the price comparison schedule could not be used to prove that the products were comparable products or that the Bloomex Product was a discounted version of the asserted comparable product.

Benefits to Bloomex arising from contraventions of the ACL

58 Mr Lokhonia deposed that, in relation to the Discount Representations, the market for flowers and floristry products is not driven by discounts, but primarily by events, such as Christmas, Mother’s Day, Valentine’s Day, birthdays and other personal celebrations. He further deposed that it is easy to compare prices between online florists if a customer is minded to shop around: Affidavit at [82].

59 Mr Lokhonia further deposed, in his Affidavit at [83]:

In an attempt to measure the impact of the contraventions on Bloomex’s short-term sales, I have undertaken an analysis of its performance around Mother’s Day (the second Sunday in May – this year, Sunday 14 May 2023). For flower and gift retailers, Mother’s Day is one of the most critical days of the year, in terms of sales. If the misleading statements had unfairly inflated Bloomex’s sales while they were active on the Website on Mother’s Day the previous years, then I would expect that removing those statements from the Website prior to Mother’s Day in 2023 should mean that Bloomex’s sales would be less than expected. However, Bloomex’s sales on Mother’s Day 2023 actually increased, in comparison to the years when the misleading statements were active on the Website. The relevant figures are set out below:

Mothers Day Period | No of Orders | Gross Revenue | Avg Order Value |

May 8-15 2017 | 4,133 | $ 293,048 | $ 70.90 |

May 6-13 2019 | 4,944 | $ 351,866 | $ 71.17 |

May 7-14 2018 | 5,679 | $ 406,659 | $ 71.61 |

May 4-11 2020 | 8,022 | $ 593,563 | $ 73.99 |

May 3-10 2021 | 11,356 | $ 880,756 | $ 77.56 |

May 2-9 2022 | 13,445 | $ 1,030,361 | $ 76.64 |

May 8-15, 2023 | 16,646 | $ 1,355,380 | $ 81.42 |

60 In relation to the Total Product Price Representations, Mr Lokhonia deposed that, although Bloomex received about $317,802 in relation to the surcharge, it would not be correct to regard this amount as the benefit from Bloomex’s contraventions because Bloomex would have charged this additional amount in any event. Mr Lokhonia’s evidence, which was not challenged in cross-examination, was that the only benefit to Bloomex of charging the surcharge in the manner that it did was the possibility that some customers may have thought their orders were cheaper than they ultimately were and might have looked elsewhere if the total price (inclusive of the surcharge) had been disclosed earlier. Mr Lokhonia noted, however, that a customer still could have looked elsewhere after the surcharge was disclosed, as they were not bound to follow through with their orders at that time: Affidavit at [85].

Bloomex’s dealings with the ACCC

61 In his Affidavit, Mr Lokhonia deposed to Bloomex’s dealings with the ACCC prior to and during the proceeding. The relevant features of those dealings for the purposes of this proceeding are set out below:

(a) The ACCC first contacted Bloomex in relation to the issues the subject of this proceeding on 10 March 2022: Affidavit at [86].

(b) On 15 March 2022, Mr Lokhonia had a video call with the ACCC. At that time, the ACCC explained they were undertaking a review of the online florist industry’s compliance with the ACL, and that they would issue a request for information. Mr Lokhonia informed the ACCC that he would cooperate: Affidavit at [87].

(c) On 30 March 2022, Mr Lokhonia received a notice pursuant to s 155 of the CCA, requiring the production of certain documents (First Notice): Affidavit at [88]. The First Notice, which was addressed from the Chair of the ACCC, stated that the Chair had reason to believe that Bloomex “is capable of furnishing information and producing documents relating to matters that constitute or may constitute contraventions of sections 18, 29(1)(a), 29(1)(b) and 29(1)(i) of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL)”. The Notice went on to set out three matters that were said to “constitute or may constitute” contraventions of the ACL. Relevantly, those matters included that:

(i) Bloomex had engaged in conduct that was misleading or deceptive, or had made false or misleading representations, in making representations on the Website that Products were of a particular standard or quality, including through the use of “Customer Reviews and Star Ratings”, when the Products delivered were of a materially different standard or quality; and

(ii) Bloomex had engaged in conduct that was misleading or deceptive, or had made false or misleading representations, in making representations regarding discounts consumers would receive when purchasing Products on the Website.

(d) Mr Lokhonia deposed that it was not clear to him whether the above matters did constitute contraventions, or whether they “may constitute” contraventions, subject to the ACCC’s enquiries in the First Notice. He stated that he had understood that the ACCC was investigating the online florist industry more generally and had not necessarily formed any clear views about Bloomex: at [89]. He complied with the requirements of the First Notice: Affidavit at [91].

(e) On 3 June 2022, after receiving further correspondence from the ACCC, Mr Lokhonia sent a letter to the ACCC in which he stated that that he was “looking forward [to the ACCC’s] finding and recommendations as well to make sure we are fully compliant with [ACL] laws in Australia”: Affidavit at [95].

(f) On 6 September 2022, he had a video call with officers of the ACCC. The ACCC informed him that they wanted further clarification of certain issues but did not tell him they were intending to bring a proceeding alleging that Bloomex was breaching the ACL. The ACCC told him that they were satisfied with Bloomex’s level of cooperation and openness: Affidavit at [98].

(g) On 12 September 2022, Mr Lokhonia received a further notice pursuant to s 155 of the CCA, requiring the production of additional documents (Second Notice), with which he complied: Affidavit at [99], [101]. As with the First Notice, the Second Notice was addressed from the Chair of the ACCC and stated that the Chair had reason to believe that Bloomex “is capable of furnishing information and producing documents relating to matters that constitute or may constitute contraventions of sections 18, 29(1)(a), 29(1)(b) and 29(1)(i) of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL)”. The Notice went on to set out three matters that were said to “constitute or may constitute” contraventions of the ACL. The matters identified in the Second Notice relevantly included that:

(i) Bloomex’s use of the Star Ratings amounted to conduct contravening ss 18, 29(1)(a) and 29(1)(b) of the ACL; and

(ii) Bloomex’s representations concerning discounts applied to Products sold on the Website amounted to conduct contravening ss 18 and 29(1)(i) of the ACL.

(h) In relation to the Second Notice, Mr Lokhonia stated, in his Affidavit at [102]:

I did not take any legal advice at this time. I also took some comfort from the fact that most of the issues that were raised in the original notice had been abandoned, and by my video call on 6 September 2022. The ACCC did not warn me in that call that they considered that Bloomex was contravening the law, or that they were proposing to bring a proceeding. I thought they would have done so, if there was serious problem.

(i) Mr Lokhonia stated that the last communication he had with the ACCC prior to the ACCC commencing this proceeding was on 11 November 2022, in which he responded to a further letter from the ACCC which sought information about Bloomex. Mr Lokhonia relevantly deposed, in his Affidavit at [111], that:

During the ACCC’s investigation, if the ACCC had requested or directed that I make any specific amendments, or remove any specific material, then I would have done so (possibly subject to receiving my own legal advice, depending on the nature of the issues). I appreciate that the ACCC is not obliged to advise me on compliance, but while I did make some proactive changes to the Website, I also thought it was appropriate to wait for the ACCC to finish its process of assessment, and then make further changes (if necessary) based on its findings. If the ACCC had already formed a view that Bloomex was breaking the law, based on the matters it was aware of, I thought that it would come out and say that, in clear language, and tell us what we needed to stop doing.

(j) On 8 December 2022, the ACCC, by its lawyers, informed Mr Lokhonia that it had commenced this proceeding against Bloomex. Mr Lokhonia deposed that he was surprised that the ACCC did so without further communication with Bloomex: Affidavit at [113].

(k) On 12 December 2022, prior to having engaged a lawyer, Mr Lokhonia wrote to the ACCC’s lawyers, proposing a meeting in Melbourne “to find a solution which mutually and financially benefit your firm and ACCC”: Affidavit at [114].

(l) On 10 March 2023, Bloomex filed a Concise Statement in Response, by which it admitted to most of the contraventions alleged, and indicated certain amendments that it had made (or was making) to its Website: Affidavit at [122].

(m) Following a mediation on 4 May 2023, the parties submitted consent orders which provided for the filing of the SOAF, Joint Submissions and Joint Proposed Orders: Affidavit at [125].

(n) On 30 May 2023, Bloomex offered to accept an agreed penalty of $500,000 plus payment of the ACCC’s reasonable costs: Affidavit at [126].

Bloomex’s prior conduct

62 Mr Lokhonia’s Affidavit identified that New South Wales Fair Trading (NSWFT) had previously investigated Bloomex, and these investigations had resulted in NSWFT issuing three penalty infringement notices on 18 August 2022, and Bloomex providing two enforceable undertakings to NSWFT on 30 October 2017 and 30 April 2020: at [138], [145], [154]. The undertakings relevantly concerned false and misleading representations about goods and services, false and misleading representations that goods were of a particular standard, and wrongly accepting payment.

63 Mr Lokhonia deposed that Bloomex has not had similar issues in any other Australian states: Affidavit at [137].

Impact of civil penalty on Bloomex

64 Mr Lokhonia addressed the likely financial impact of the ACCC’s proposed penalty in the Affidavit at [131]-[133]. It is necessary to set out his evidence in this respect in full (subject to my rulings on admissibility in MFI #1):

On my present understanding, the ACCC has indicated that it will seek a penalty of around $1.25 - $1.5 million.

Despite experiencing heavy losses in FY2022, Bloomex has elected to continue trading in Australia and providing products to consumers. Where Bloomex’s entry to the market has substantially increased competition, any unduly large penalty risks threatening its continued viability. In light of the modest net profits after tax, and particularly the recent substantial net losses, the penalty proposed would have a major impact on Bloomex’s ability to conduct operating. In simple terms, if the penalty were so large as to make it unviable, Bloomex would have no incentive or financial ability to keep trading in Australia, as you could clearly see from our financial statements.

The most likely outcome is that Bloomex will cease to do business in Australia.

MR LOKHONIA’S ORAL EVIDENCE

65 Mr Lokhonia travelled from Canada to give his evidence in person at the hearing.

Apology

66 Mr Lokhonia delivered an oral apology to the Court, which reflected an apology contained in his Affidavit. He stated that it was never his intention to contravene the ACL, but accepted full responsibility for Bloomex’s contraventions. He stated he was proud of Bloomex, which he had developed into viability in Canada and Australia.

Cross-examination

67 Mr Lokhonia was subject to limited cross-examination by the ACCC on two topics.

68 First, Mr Lokhonia was asked about Bloomex’s New Zealand company, of which he is a director, and which sits within the larger Bloomex group. Mr Lokhonia was shown a printout of the homepage of Bloomex’s New Zealand website taken on 31 January 2024 (Exhibit #A1) (New Zealand Webpage Printout). The printout depicted images of 20 products – in each case, flower arrangements – available for purchase through the New Zealand website. Accompanying each image of a product was:

(1) a purchase price which was similar to the Purchase Price that appeared on the Website between 26 February 2019 and 2 November 2022;

(2) a star rating which was similar to the Star Ratings that appeared on the Website from 26 February 2019 and 17 March 2023 (albeit the star ratings appearing on the New Zealand Webpage Printout did not have a corresponding number out of five, or a statement purporting to explain the basis of the star rating).

69 Accompanying 19 of the 20 images of the products was also a higher price displayed in strikethrough form which was similar to the Strikethrough Price that appeared on the Website.

70 It was put to Mr Lokhonia that the strikethrough pricing that appeared on the New Zealand Webpage Printout performed the same job as the Strikethrough Price on the Australian Website. Mr Lokhonia disagreed, stating that any product with strikethrough pricing on the New Zealand website had been priced based on a pricing schedule, and had been sold in New Zealand for the price that had been struck though at some point. Mr Lokhonia explained that, after Bloomex had “trouble in Australia”, which I infer was a reference to the ACCC’s investigation into Bloomex’s representations on the Website, it implemented a system whereby each product was sold in accordance with a calendar for promotions.

71 Mr Lokhonia also explained that the star ratings on Bloomex’s New Zealand website were based on actual customer feedback.

72 Secondly, Mr Lokhonia was shown a printout from Coles’ website dated 31 January 2024, which recorded the price of a 750 mL bottle of “Hidden Gem Cabernet Merlot” at that date as $4.00 (Exhibit #A3). Mr Lokhonia was asked to compare this to an image capture from Bloomex’s Website for a “Classic Red Wine Basket”, which was taken on 27 October 2022 (Classic Red Wine Basket Image). The image accompanying this Product displayed a wine bottle, bearing the name “Hidden Gem Cabernet Merlot”, and a hamper with assorted “treats” in it. The Product was described as “[a] delectable hamper with a bottle of delicious red wine and gourmet treats. This basket includes one (1) bottle of Red Wine, and three (3) gourmet treats such as cheese straws, wine biscuits, and breadsticks”. The Strikethrough Price for this Product was displayed as $59.95. The Purchase Price for this Product was displayed as $39.95.

73 Mr Lokhonia was asked whether he accepted that the price of the bottle of wine depicted in the Classic Red Wine Basket Image was no more than $4. Mr Lokhonia accepted that, as Bloomex bought its wine directly from a wholesaler or manufacturer, it would generally buy wine for a price cheaper than the price for which Coles would sell it. However, Mr Lokhonia stated that he could not say what price Bloomex would have paid to purchase the wine depicted in the Classic Red Wine Basket Image because the price of wine varied over time.

Conclusion as to Mr Lokhonia’s evidence

74 Based on my observation of his evidence, Mr Lokhonia was a truthful and reliable witness. I accept that his apology was sincerely given. None of the cross-examination of Mr Lokhonia caused me to doubt his affidavit or oral evidence.

BLOOMEX’S FORMAL ADMISSIONS

75 In the SOAF, Bloomex admits that:

(a) by making the Discount Representations in trade or commerce, it:

(i) engaged in conduct that was misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive in contravention of s 18 of the ACL; and

(ii) in connection with the supply or possible supply of goods, or in connection with the promotion by any means of the supply of goods, made false or misleading representations with respect to the price of goods in contravention of s 29(1)(i) of the ACL;

(b) by making the Star Rating Representations in trade or commerce, it:

(i) engaged in conduct that was misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive in contravention of s 18 of the ACL; and

(ii) in connection with the supply or possible supply of goods, or in connection with the promotion by any means of the supply of goods, made false or misleading representations that goods were of a particular standard or quality, and/or had particular performance characteristics or uses or benefits and/or approval in contravention of ss 29(1)(a) and (g) of the ACL;

(c) by making the Total Product Price Representations in trade or commerce, it:

(i) engaged in conduct that was misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive in contravention of s 18 of the ACL;

(ii) in connection with the supply or possible supply of goods, or in connection with the promotion by any means of the supply of goods, made false or misleading representations with respect to the price of goods in contravention of s 29(1)(i) of the ACL; and

(iii) in connection with the supply or possible supply, or the promotion by any means of the supply, to another person of goods of a kind ordinarily acquired for personal, domestic or household use or consumption, made a representation with respect to an amount that, if paid, would constitute a part of the consideration for the supply of goods, without also specifying, in a prominent way and as a single figure, the single price for the goods in contravention of s 48(1) of the ACL.

JOINT PROPOSED ORDERS

Relief sought

76 In overview, the ACCC and Bloomex seek by way of partial relief:

(a) a declaration pursuant to s 21 of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) that in making the Discount Representations, Bloomex contravened ss 18 and 29(1)(i) of the ACL;

(b) a declaration pursuant to s 21 of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) that in making the Star Rating Representations, Bloomex contravened ss 18 and 29(1)(a) and (g) of the ACL;

(c) a declaration pursuant to s 21 of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) that in making the Total Product Price Representations, Bloomex contravened ss 18, 29(1)(i) and 48(1) of the ACL;

(d) an injunction restraining Bloomex from, in respect of the Products advertised for sale on the Website:

(i) specifying a Purchase Price for a Product on the Website that excludes further amounts payable (other than a charge that is payable in relation to delivery), without also prominently specifying as a single figure the price the total price of the Product including any additional amounts payable;

(ii) publishing Star Ratings for a Product on the Website, unless the Star Ratings relate to customer feedback in relation to purchases made via the Website and the Star Rating is kept updated by Bloomex to take into account recent feedback;

(iii) specifying a Strikethrough Price for a Product on the Website, unless the Product is usually or has recently been offered for sale by Bloomex, via the Website, at the Strikethrough Price; and

(iv) specifying a “50% off” or “Half Price” statement for a Product on the Website, unless the Product has recently been offered for sale by Bloomex, via the Website, at the non- discounted price.

(e) an order requiring Bloomex to undertake an Australian Consumer Law compliance and education program, to be maintained, continued and implemented for a period of three years.

Principles

Use of Statement of Agreed Facts

77 Pursuant to s 191(2)(a) of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth), no evidence is required to prove the existence of a fact in the SOAF. The effect of s 191 is to admit the agreed facts as evidence but it still remains for the Court to determine whether the facts are to be accepted as true and to determine what weight to attribute to that evidence: Australian Securities and Investments Commission v BHF Solutions Pty Ltd (2022) 293 FCR 330 at [24] (O’Bryan J). Section 191 only applies to agreed facts and the Court is not required to accept as evidence statements of argument and conclusion: BHF at [25].

Liability under s 18 of the ACL

78 Section 18 of the ACL provides that a person must not in trade or commerce engage in misleading or deceptive conduct, or conduct that is likely to mislead or deceive. The making of a representation may constitute “conduct” for the purposes of s 18 of the ACL.

79 Conduct is misleading or deceptive if it has a tendency to lead into error. That is to say there must be a sufficient causal link between the conduct and error on the part of persons exposed to it: ACCC v TPG Internet Pty Ltd (2013) 250 CLR 640 at [39] (French CJ, Crennan, Bell and Keane JJ). The question of whether conduct is misleading is anterior to the question of whether a person has suffered loss or damage. The characterisation of conduct as misleading or deceptive generally requires consideration of whether the impugned conduct viewed as a whole has a tendency to lead a person into error: TPG Internet at [49], citing Campbell v Backoffice Investments Pty Ltd (2009) 238 CLR 304 at [24]-[25] (French CJ).

80 Where the impugned conduct is directed to the public generally, the Court must consider the likely characteristics of the persons who comprise the relevant class of persons to whom the conduct is directed and consider the likely effect of the conduct on ordinary or reasonable members of the class, disregarding reactions that might be regarded as extreme or fanciful: Campomar Sociedad, Limitada v Nike International Ltd (2000) 202 CLR 45 at [101]-[105] (Gleeson CJ, Gaudron, McHugh, Gummow, Kirby, Hayne and Callinan JJ); Kraft Foods Group Brands LLC v Bega Cheese Ltd (2020) 377 ALR 387 at [236] (Foster, Moshinsky and O’Bryan JJ).

81 It is unnecessary to prove actual deception to establish a contravention of s 18 of the ACL: Google Inc v ACCC (2013) 249 CLR 435 at [8] (French CJ, Crennan and Kiefel JJ).

Liability under s 29 of the ACL

82 Section 29 of the ACL provides that a person must not, in trade or commerce, in connection with the supply or possible supply of goods or services or in connection with the promotion by any means of the supply or use of goods or services make a false or misleading representation:

(a) that goods are of a particular standard, quality, value, grade, composition, style or model (sub-s (1)(a));

(b) that the person has a sponsorship, approval, performance characteristics, accessories, uses or benefits (sub-s (1)(g));

(c) with respect to the price of goods or services (sub-s (1)(i)).

83 Although s 29 of the ACL uses the words “false or misleading”, it is not apparent that there is any meaningful difference between this expression and the expression “misleading or deceptive”: ACCC v Dukemaster Pty Ltd [2009] FCA 682 at [14] (Gordon J).

Liability under s 48 of the ACL

84 Section 48(1) provides that a person must not, in connection with the promotion or supply of goods or services of a kind ordinarily acquired for personal, domestic or household use or consumption, make a representation with respect to an amount that, if paid, would constitute a part of the consideration for the supply of the goods or services unless the person also specifies, in a prominent way and as a single figure, the single price for the goods or services.

85 In the context of s 48, the single price that must be displayed is the minimum quantifiable consideration for the particular goods or services. It must include all fees payable by the consumer as part of the transaction: viagogo AG v ACCC [2022] FCAFC 87 at [120] (Yates, Abraham and Cheeseman JJ). There is an exception if the charge is a delivery fee – that is, “a charge that is payable in relation to sending the goods from the supplier to the other person” – but this fee must then be specified: see section 48(2) and (3).

Declaratory relief

86 The Court has a wide discretionary power to make declarations under s 21 of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth). There are three requirements that must be satisfied before making a declaration. First, the question must be real and not hypothetical. Secondly, the ACCC must have a real interest in raising the question. Thirdly, there must be a real contradictor: Forster v Jododex Australia Pty Ltd (1972) 127 CLR 421 at 437-8 (Gibbs J) quoting Russian Commercial and Industrial Bank v British Bank for Foreign Trade Ltd [1921] 2 AC 438 at 448 (Lord Dunedin).

87 Declarations relating to contraventions of legislative provisions are likely to be appropriate where they serve to record the Court’s disapproval of the contravening conduct, vindicate the regulator’s claim that the respondent contravened the provisions, assist the regulator to carry out its duties, and deter other persons from contravening the provisions: Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union (2017) 254 FCR 68 at [93] (Dowsett, Greenwood and Wigney JJ).

88 Where a declaration is sought with the consent of the parties, the Court’s discretion is not supplanted, but nor will the court refuse to give effect to terms of settlement by refusing to make orders where they are within the court’s jurisdiction and are otherwise unobjectionable: ACCC v Coles Supermarkets Australia Pty Ltd [2014] FCA 1405 at [75] (Gordon J).

Injunctions

89 An injunction is a discretionary remedy: BMW Australia Ltd v ACCC (2004) 207 ALR 452 at [35] (Gray, Goldberg and Weinberg JJ). The Court has power to grant an injunction under s 232 of the ACL. Under s 232(1)(a), the Court may grant an injunction “in such terms as the Court considers appropriate” if it is satisfied that a person has engaged in conduct that constitutes a contravention of, inter alia, ss 18, 29, and 48 of the ACL.

90 The power of the Court to grant an injunction restraining a person from engaging in conduct may be exercised whether or not it appears that the person intends to engage again, or to continue to engage, in the contravening conduct: s 232(4) ACL. However, in these circumstances there must be a nexus between the conduct found to constitute the contravention and the injunction granted: Homart Pharmaceuticals Pty Ltd v Careline Australia Pty Ltd (2018) 264 FCR 422 at [134] (Murphy, Gleeson and Markovic JJ). Expressed another way, if injunctions are to be granted where there is no threatened or intended contravening conduct, the injunction ought to be limited precisely to preventing a repetition of the contravening conduct that has occurred. In the absence of threatened or intended conduct, there can be no justification for an injunction with broader scope, covering possible contraventions that the person subject to the injunction has neither committed before nor threatened or intended to commit in the future: ACCC v G.O. Drew Pty Ltd [2007] FCA 1246 at [40] (Gray J).

Compliance program

91 Section 246(2)(b) of the ACL empowers the Court to make an order for Bloomex to undertake a compliance and education program. In ACCC v Sontax Australia Pty Ltd [2011] FCA 1202 at [36], Gordon J stated that:

The purpose of a probation order is to ensure a company-wide awareness of responsibilities and obligations in relation to the contravening conduct. … There must be a nexus between the terms of the compliance program and the contravening conduct … The compliance program should set out the steps to be taken with sufficient clarity so that it is able to be performed. It should also be in the public interest that the respondent undertake the program

Consideration

Declaratory relief

92 I am satisfied, having considered the facts and admissions contained in the SOAF, that an appropriate evidentiary basis exists for the Court to make the declarations sought. I am satisfied that the other preconditions for declaratory relief, as identified in Forster, are established in this case. First, there is a real and not a hypothetical question in this case. The proposed declarations relate to conduct in contravention of the ACL and the matters in issue have been identified and particularised by the parties with precision. Secondly, the ACCC, as the Applicant, has a real interest in raising the question, as the ACCC is the regulator under the CCA and ACL. Finally, the respondent – Bloomex – is the proper contradictor as it is the subject of the proposed declarations and has an interest in opposing them.

93 Further, consistently with the authorities, I consider that the declaratory relief sought serves the public purpose of expressing the Court’s disapproval of Bloomex’s contravening conduct: CFMEU at [93].

94 I am therefore satisfied that it is appropriate to make the declarations sought jointly by the parties.

Injunctions

95 In the present case, the SOAF establishes that Bloomex has ceased making, on its Website, the Discount Representations, Star Rating Representations and Total Product Price Representations. This is no bar to making the proposed injunctions under the ACL, but I must be satisfied that there is a sufficient nexus between the injunctions sought and Bloomex’s contraventions of the ACL.

96 I am satisfied that such a nexus exists. The terms of the injunction proposed jointly by the parties are closely tied to Bloomex’s contravening conduct as identified in the SOAF. The injunctions sought are designed to deter any repetition of the same type of contravening conduct.

97 I am therefore satisfied that it is appropriate to order the injunctions sought jointly by the parties.

CONTESTED RELIEF

Scope of dispute

98 At the hearing of this proceeding, senior counsel for the ACCC informed the Court that the parties agree that each of the Discount Representations, Star Rating Representations and Total Product Price Representations constituted separate courses of conduct for penalty purposes: Mr Wallis KC, T 4.22-24. The ACCC contends that it would be appropriate to impose pecuniary penalties on Bloomex totalling $1.5 million. The ACCC submits that the appropriate penalties for each course of conduct are:

(a) $625,000 for the Discount Representations;

(b) $625,000 for the Star Rating Representations; and

(c) $250,000 for the Total Product Price Representations;

99 By contrast, Bloomex submits that a penalty of not more than $350,000 would be most appropriate in all of the circumstances. Bloomex has not, in its written or oral submissions, sought to quantify the appropriate penalty for each of the different courses of conduct.

Principles

The purpose of civil penalties

100 Pursuant to s 224(1)(a)(ii) of the ACL, if the Court is satisfied that a person has contravened a provision of Part 3-1 of the ACL (which includes s 29 and 48), the Court may order the person to pay such pecuniary penalty in respect of each act or omission by the person to which it applies, as the Court determines to be appropriate.

101 The proper approach to civil penalty remedies which are sought on an agreed basis is articulated in Commonwealth v Director, Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate (2015) 258 CLR 482. In Fair Work, a plurality of the High Court emphasised that the primary purpose of civil penalties is to secure deterrence. In contrast to criminal sentences, civil penalties are not concerned with retribution and rehabilitation but are “primarily if not wholly protective in promoting the public interest in compliance”: Fair Work at [55], [59] (French CJ, Kiefel, Bell, Nettle and Gordon JJ).

102 The High Court reiterated the primacy of deterrence in fixing an appropriate penalty in Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Pattinson (2022) 274 CLR 450. In that case, Kiefel CJ, Gageler, Keane, Gordon, Steward and Gleeson JJ stated (at [15]) that the object of imposing a civil penalty is to put a price on contravention that is sufficiently high to deter repetition by the contravener (specific deterrence) and by would-be contraveners (general deterrence). In this respect, in TPG, French CJ, Crennan, Bell and Keane JJ (at [64]) endorsed the proposition that, in fixing a penalty, the Court must make it clear to the contravener and to the market that the cost of courting a risk of contravention cannot be regarded as an acceptable cost of doing business.

103 In ACCC v Reckitt Benckiser (Australia) Pty Ltd (2016) 340 ALR 25 at [151], Jagot, Yates and Bromwich JJ explained that “the greater the risk of consumers being misled and the greater the prospect of gain to the contravener, the greater the sanction required, so as to make the risk/benefit equation less palatable to a potential wrongdoer and the deterrence sufficiently effective in achieving voluntary compliance”.

Multiple contraventions

104 In the case of multiple contraventions, the proper assessment of appropriate penalties requires attention to three issues.

105 First, s 224(4)(b) of the ACL provides that, where conduct constitutes a contravention of two or more provisions, the person is not liable for more than one penalty “in respect of the same conduct”. Such provisions apply to conduct which is truly “the same”, not merely similar, closely related or repeated, and can therefore be differentiated from the “course of conduct” principle (discussed below): ACCC v Yazaki Corporation (2018) 262 FCR 243 at [217]-[224] (Allsop CJ, Middleton and Robertson JJ); ACCC v Jetstar Airways Pty Ltd (No 2) [2017] FCA 205 at [13], [17] (Foster J).

106 Secondly, separate contraventions arising from separate acts should ordinarily attract separate penalties. However, a different principle may apply where separate acts, giving rise to separate contraventions, are nonetheless so inextricably interrelated that they may be grouped as a “course of conduct” for penalty purposes: Yazaki at [234].

107 Thirdly, where multiple separate penalties are to be imposed upon a particular wrongdoer, the totality principle necessitates the Court conducting a “final check” of the penalties to be imposed on a wrongdoer, considered as a whole to ensure that they are “just and appropriate”: ACCC v Safeway Stores Pty Ltd (1997) 75 FCR 238 at 52-3 (Goldberg J); ACCC v EnergyAustralia Pty Ltd (2014) 234 FCR 343 at [101], [102] (Middleton J).

The statutory maximum

108 In this matter, the default amount specified at s 224(3A)(a) of the ACL is the relevant maximum penalty per contravention. Prior to 10 November 2022, s 224(3A)(a) specified a penalty of $10 million; from 10 November 2022, the penalty specified is $50 million.

109 The maximum penalty identifies the scope of Parliament’s intended deterrent response to each subject contravention and is an important yardstick (noting that it is “but one yardstick” and is not to be applied “mechanically”): Pattinson at [53]-[54]. Courts must ensure that there is a “reasonable relationship” between the theoretical maximum for the conduct alleged and the penalty imposed. This will be achieved where the maximum penalty does not exceed what is reasonably necessary to achieve the purpose of s 224, namely specific and general deterrence of future contraventions of a like kind by the contravener and by others: Pattinson at [10]; ACCC v Dell Australia Pty Ltd (No 2) [2023] FCA 983 at [9] (Jackman J).

Relevant considerations

110 Section 224(2) of the ACL requires the Court to have regard to “all relevant matters” in determining an appropriate penalty for a contravention of the ACL, including:

(a) the nature and extent of the act or omission and of any loss or damage suffered;

(b) the circumstances in which the act or omission took place; and

(c) whether the person has previously been found to have engaged in similar conduct.

111 As explained by Edelman J in ACCC v Woolworths Ltd [2016] FCA 44 at [124], the reference to “the circumstances” in s 224(2) has long been taken to include reference to factors including:

(a) the size of the contravening company;

(b) the deliberateness of the contravention and the period over which it extended;

(c) whether the contravention arose out of the conduct of senior management of the contravener or at some lower level;

(d) whether the contravener has a corporate culture conducive to compliance, as evidenced by educational programmes and disciplinary or other corrective measures in response to an acknowledged contravention;

(e) whether the contravener has shown a disposition to co-operate with the authorities in relation to the contravention;

(f) whether the contravener has engaged in similar conduct in the past;

(g) the financial position of the contravener; and

(h) whether the contravening conduct was systematic, deliberate or covert.

112 His Honour further stated, at [126], that a consideration of deterrence also makes the following factors commonly relevant:

(a) the extent of contrition;

(b) whether the contravening company made a profit from the contraventions;

(c) the extent of the profit made by the contravening company; and

(d) whether the contravening company engaged in the conduct with an intention to profit from it.

113 The critical requirement is that all relevant matters are addressed, in substance and transparently: ACCC v SmileDirectClub LLC [2022] FCA 1343 at [36] (Anderson J).

114 The reasoning process in deriving a penalty figure having regard to the various relevant factors is described as an “instinctive synthesis”, as explained in a criminal sentencing context by Gleeson CJ, Gummow, Hayne and Callinan JJ in Markarian v The Queen (2005) 228 CLR 357 at [37], quoting Wong v The Queen (2001) 207 CLR 584 at [74]-[76]. In Reckitt at [44], the Full Court explained the process as follows (citations omitted):

The dominant common feature is that determining both a sentence and a civil penalty usually involves, and in this case did involve, a difficult and complex process of multi-factorial decision-making, where the result is arrived at by a process of “instinctive synthesis”, addressing many conflicting and contradictory considerations … This integrated and holistic approach, requiring the weighing up of all relevant factors into a final result, often makes the process of appellate review difficult, particularly for an appellant seeking to identify and establish error in the reasoning process and outcome, or sometimes the outcome alone.

ACCC Submissions

Overarching submission

115 The ACCC submits that Bloomex, as one of the largest florists in Australia, has a significant presence within the Australian florist industry. As a result, the ACCC contends that the penalties imposed must be significant if they are to achieve specific and general deterrence. This, in the ACCC’s submission, is consistent with the High Court’s approach in Pattinson. The ACCC submits that if an industry-leading corporation with the size and resources of Bloomex is permitted to be loose or careless in its compliance with ACL, this may be seen by other industry participants as a message that contraventions of the ACL will not be treated seriously, thereby undermining the underlying purposes of the ACL. The ACCC submits that undertaking a process of “instinctive synthesis” and weighing each of the relevant factors referred to above results in an appropriate pecuniary penalty of $1.5 million. The ACCC submits that weighing each of the relevant factors referred to above and making an allowance for a discount for cooperation on the part of Bloomex results in an appropriate penalty for each course of conduct as follows:

(a) Discount Representations: $625,000;

(b) Star Rating Representations: $625,000; and

(c) Total Product Price Representations: $250,000

116 The ACCC submits that these proposed pecuniary amounts are appropriately significant and reasonably reflect the differences between the conduct comprising each course of conduct.

117 The ACCC submits that the aggregate penalty amount is weighted in favour of the Discount Representations and Star Rating Representations because those representations likely involved a greater number of contraventions and were made in respect of nearly all of the products (approximately 730) on the Website for a period of approximately four years. During this time, almost 550,000 orders were placed and revenue in the order of $38 million was generated through Bloomex’s Website. A penalty of $625, 000 represents approximately 1.6 per cent of Bloomex’s relevant revenue. This amount, for the course of conduct arising from each of the Discount Representations and the Star Rating Representations, is appropriate in ASIC’s submission, as it reflects the scale of Bloomex’s operations and the potential benefits that Bloomex has received.

118 The ACCC submits that the Total Product Price Representations persisted for some seven months. They are distinct from the other two courses of conduct in that consumers were, eventually, made aware that they had been subjected to misleading representations as to the total price of a product. However, the ACCC submits that a substantial penalty is nevertheless warranted given the risk that consumers were enticed into the purchases because of the misrepresentation. The ACCC submits that a penalty of $250, 000 represents approximately three quarters of the revenue that Bloomex received from the surcharge. Although some of the 90,000 affected customers may have proceeded with their purchase had the total price been disclosed earlier, some would not have proceeded with the transaction. The ACCC submits that a penalty equivalent to approximately three quarters of the surcharge is appropriate and necessary to ensure that contraventions of this kind are not seen merely as the cost of doing business.

119 The ACCC contends that in all the circumstances, penalties in aggregate of $1.5 million are appropriate to achieve the purpose of specific and general deterrence, without being more than is necessary to achieve that object.

Submissions as to relevant factors

120 As to the application of the maximum penalty, the ACCC submits that Bloomex published the false, misleading or deceptive representations on the Website in some cases, for nearly four years. During that period, there were approximately 6.3 million visits to the Website. The ACCC submits that there have therefore been, theoretically, millions of possible contraventions of the ACL, and the maximum penalty for those contraventions was $10 million prior to 10 November 2022 and $50 million from 10 November 2022.

121 As to the nature and extent of Bloomex’s wrongdoing, the ACCC characterises Bloomex’s wrongdoing as follows:

(a) In relation to the Discount Representations, the wrongdoing comprised the Strikethrough Prices (which remained on the Website for nearly four years), the “Half Price” or “50% off” statements (which remained on the Website for over four years), and the “You save” statement (which remained on the Website for at least 10 months). The Discount Representations were to the effect that Bloomex’s prices were discounted from prices which had previously been, or were usually, used by Bloomex, and this was not true.

(b) In relation to the Star Rating Representations, the wrongdoing comprised untrue representations to the effect that the Star Ratings Bloomex published were up-to-date and were a reliable indicator of customer satisfaction with its Products. The Star Rating Representations were specifically addressed to online consumers and, given they comprised a part of Bloomex’s marketing strategy, were designed to influence them.

(c) In relation to the Total Product Price Representations, the wrongdoing comprised the failure to disclose the existence of a surcharge prior to a consumer entering their delivery postcode details on the final Checkout Page. The ACCC submits that the impropriety in Bloomex’s conduct arose from attracting consumers to a transaction which they might otherwise not have found appealing, and obtaining an advantage over competitors who were compliant with s 48 of the ACL: citing ACCC v AirAsia Berhad Company [2012] FCA 1413 at [31] (Tracey J).

122 The ACCC acknowledges that it cannot point to specific quantifiable loss or damage caused by Bloomex’s contraventions. However, the ACCC submits that the admitted contraventions deprived consumers of an opportunity to make purchasing decisions on a fully and properly informed basis. The ACCC also submits that Bloomex’s contraventions disadvantaged competing businesses that published accurate information about the discounts they were offering, the satisfaction of their customers, and the prices that they charged.

123 The ACCC also acknowledges that it is not possible to precisely quantify the value of benefits that Bloomex received as a result of the Discount Representations and the Star Rating Representations. The ACCC submits that, in assessing the extent of any benefit to Bloomex by this contravening conduct, the Court should have regard to the almost 550,000 orders placed and revenue of over $38 million generated through Bloomex’s Website during the period that it engaged in that conduct. The ACCC submits that Bloomex received a tangible benefit from the Total Product Price Representations, being the $317,802 (incl GST) generated as a result of applying a surcharge to 90,197 orders made via the Website.

124 As to the deliberateness of Bloomex’s conduct, the ACCC accepts that the evidence does not establish that Bloomex had any intention to deliberately mislead or deceive. Nonetheless, the ACCC submits that whether or not Bloomex set out to mislead or deceive, it is no accident that Bloomex made the Discount Representations, the Star Rating Representations and the Total Product Price Representations. This is because those representations formed part of a considered marketing strategy implemented by Bloomex, at a senior management level, in support of the sale of the Products via the Website.

125 The ACCC accepts that Bloomex’s admission of the contraventions, and the amendment of its Website, reflect a degree of cooperation and contrition. However, the ACCC submits that any discount applied on this account must also have regard to the fact that: Bloomex reintroduced strikethrough pricing on 30 March 2023 (only removing it on about 25 April 2023); Bloomex introduced the surcharge after becoming aware of the ACCC’s investigation; and Bloomex continued to make the Star Rating Representations, certain Discount Representations, and the Total Product Price Representations for an appreciable amount of time after the ACCC commenced proceedings against it.

126 The ACCC accepts that Bloomex has not previously been found to have engaged in any similar conduct by a court in proceedings under Ch 4 or Pt 5–2 of the ACL. Nonetheless, the ACCC refers to the NSWFT investigations set out at [62] above as evidence that Bloomex has a history of consumer law issues, which the ACCC submits heightens the need for specific deterrence in this case.

127 The ACCC submits that the Court should not be satisfied that Bloomex has a corporate culture conducive to compliance because Bloomex has failed to produce evidence that it has an effective ACL compliance program.

128 In relation to Bloomex’s size and financial position, the ACCC emphasises Bloomex’s prominent position in the Australian market, as well as its substantial revenue and growth, which the ACCC submits are key factors supporting the imposition of a higher penalty.

Bloomex’s Submissions

Overarching submission

129 Bloomex submits that in all the circumstances an appropriate penalty is $350,000 which it submits is sufficiently high to deter repetition by it and by others who might be tempted to contravene the Act. At the hearing of the proceeding, counsel for Bloomex explained that Bloomex did not strenuously oppose the Court determining penalties for each of the Discount Representations, Star Rating Representations and the Total Product Price Representations. However, Bloomex’s position was that individual penalties were not necessary given that the Discount Representations, Star Rating Representations and Total Product Price Representations each related to the advertisement of the same products during the same period of time: Mr Peckham, T 100.5-21.

Submissions as to relevant factors

130 As to the application of the maximum penalty, Bloomex submits that the principal object of imposing a civil penalty, is to “attempt to put a price on contravention that is sufficiently high to deter repetition by the contravener and by others who might be tempted to contravene” regardless of the available maximum: quoting NW Frozen Foods Pty Ltd v ACCC (1996) 71 FCR 285 at 293 (Burchett and Kiefel JJ), quoted in Pattinson at [40].

131 As to the nature and extent of its wrongdoing, Bloomex characterises its wrongdoing as follows:

(a) In relation to the Discount Representations, the wrongdoing was to falsely represent that nearly all of Bloomex’s Products were discounted when in fact the advertised low prices were available at all times.

(b) In relation to the Star Rating Representations, the wrongdoing was to present an unreliable picture of the customer feedback received for those products. This was in the sense that the Star Ratings had not been updated since 2015, were based on data that was not limited to Australia but included data from Canada and the USA, and where the ratings were from a product survey rather than directly from customer experience.

(c) In relation to the Surcharge, the wrongdoing was Bloomex’s failure to adequately disclose all the costs of an order before reaching the Check Out Page. Specifically, between 10 August 2022 and 22 March 2023, Bloomex imposed a surcharge on the cost of each order, reflecting fluctuations in delivery costs primarily relating to fuel, transportation, and labour.

132 Bloomex in its written submissions, filed 10 November 2023, produced an analysis of civil penalty cases, dealing primarily with misleading and deceptive conduct and the civil penalties imposed by courts. I do not find this analysis to be of utility. The authorities make clear that because individual cases have vastly different circumstances, the quantum of the penalty in one case cannot dictate the quantum of a penalty in a subsequent case: SingtelOptus Pty Ltd v ACCC (2012) 287 ALR 249 at [60] (Keane CJ, Finn and Gilmour JJ); Flight Centre Ltd v ACCC (No 2) (2018) 260 FCR 68 at [69] (Allsop CJ, Davies and Wigney JJ); Yazaki at [237]. I make no further reference to Bloomex’s analysis of these cases in these reasons.

133 Bloomex submits that the impact of its contraventions on consumers was minimal. This was because the products were flowers and similar gift items which were discretionary and perishable, with a limited financial impact. Bloomex submits that the contravening conduct did not impact on any significant financial or other decisions and would not have caused any financial hardship to consumers. Bloomex further submits that the online market for flowers is particularly transparent, in that consumers are easily able to compare prices between competing websites.

134 Bloomex submits that its contravening conduct had limited effect on its competitors. This was because it is relatively easy to compare Bloomex’s prices with those of its major competitors, each of which have websites that are similar in presentation to the Bloomex Website with prices available for comparison.

135 Bloomex submits that the ACCC has not established any material benefit to Bloomex and that, in fact, in the financial year 2022, Bloomex suffered a net loss of $1,803,657. Moreover, Bloomex submits that, on Mr Lokhonia’s affidavit evidence, Bloomex did not have a significant increase in sales coinciding with Bloomex’s contravening conduct, and in fact, Bloomex’s most significant increase in sales around Mother’s Day occurred after the contravening conduct ceased.

136 Bloomex submits that, while the alleged contraventions continued for some time, they were rectified within a reasonable time once the ACCC raised these matters with Bloomex and Bloomex became aware that its explanations did not resolve the issue in question. In this respect, Bloomex characterises the ACCC as having approached the proceeding with a view to gathering evidence and commencing the proceeding, rather than securing compliance from Bloomex.

137 As to the deliberateness of Bloomex’s conduct, Bloomex submits that it is significant that the ACCC does not allege, and the ACCC accepts that the evidence does not establish that Bloomex had any intention to deliberately mislead or deceive.