Federal Court of Australia

Kirk as trustee of the Property of Smith (a Bankrupt) v Smith [2024] FCA 240

ORDERS

DARRYL EDWARD KIRK, THE TRUSTEE OF THE PROPERTY OF RICHARD JOHN SMITH, A BANKRUPT Applicant | ||

AND: | First Respondent THE OFFICIAL RECEIVER Second Respondent | |

IN THE CROSS-CLAIM | |

BETWEEN: | GLENYS SUSANNE SMITH Cross-claimant RICHARD JOHN SMITH (A BANKRUPT) Second Cross-claimant |

AND: | THE OFFICIAL RECEIVER First Cross-respondent DARRYL EDWARD KIRK, THE TRUSTEE OF THE PROPERTY OF RICHARD JOHN SMITH, A BANKRUPT Second Cross-respondent COLONIAL FIRST STATE INVESTMENTS LIMITED Third Cross-respondent |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties liaise and endeavour to agree on draft dispositive orders giving effect to the findings in this judgment referable to the Originating Application filed on 15 April 2021, the Amended Statement of Claim filed on 15 October 2021, and the Statement of Cross-Claim filed on 23 November 2021 (Draft Agreed Orders).

2. Draft Agreed Orders be provided to the Chambers of Justice Collier by 4.00pm on 5 April 2024.

3. In the event that the parties cannot reach agreement in respect of Draft Agreed Orders, the matter be listed for case management before Justice Collier at 9.30am on 10 April 2024.

4. Costs be reserved.

5. There be liberty to apply.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

COLLIER J:

1 The proceeding currently before the Court constitutes three related proceedings arising from the bankruptcy of Mr Richard John Smith, and declarations sought by his Trustee in Bankruptcy (Trustee), Mr Darryl Edward Kirk, referable to alleged transfers of property by Mr Smith to his wife Mrs Glenys Smith which were, in turn, allegedly void as against the Trustee. As originally commenced, the proceedings in the Federal Court were as follows:

(1) QUD117/2021, commenced by the filing of an originating application on 15 April 2021 by Mr Kirk. The first respondent is Mrs Smith. The second respondent is the Official Receiver.

(2) QUD217/2021, commenced by the filing of an application on 5 July 2021 by Mr Smith and Mrs Smith. In that application Mr Smith and Mrs Smith sought orders against the Official Receiver, Mr Kirk and Colonial First State Investments Ltd ABN 92 002 348 352 (Colonial First State), including an order under s 139ZS of the Bankruptcy Act 1966 (Cth) (Bankruptcy Act) that a notice issued to Colonial First State on 22 April 2021 under s 139ZQ of the Bankruptcy Act be set aside. Interim relief was also sought in that application.

(3) QUD251/2021, commenced by the filing of an application on 29 July 2021 by Mr Smith and Mrs Smith. In that application Mr Smith and Mrs Smith sought orders against the Official Receiver and Mr Kirk that a notice issued to Mrs Smith on 1 June 2021 under s 139ZQ of the Bankruptcy Act be set aside.

2 On 30 September 2021 Derrington J made consent orders as follows:

1. Pursuant to rule 30.11 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth), this proceeding (Federal Court of Australia Proceeding number QUD 117/2021) (the Trustee Proceeding) be consolidated with Federal Court of Australia Proceeding number QUD 251/2021 (the Property Notice Proceeding) and Federal Court of Australia Proceeding number QUD 217/2021 (the Superannuation Notice Proceeding), and the consolidated proceeding be known as Kirk, as trustee of the estate of Smith v Smith & Ors and identified as proceeding QUD 117/2021 (the Consolidated Proceeding).

3 It is convenient to first deal with the primary claim before the Court, being the proceedings originally commenced by Mr Kirk against Mrs Smith and the Official Receiver in QUD117/2021. I shall return to the cross-claims and their proper disposition later in this judgment.

Background Facts

4 There is some dispute between the parties as to relevant background facts. The following facts however appear to be agreed.

5 At material times, Mr Smith and Mrs Smith were the registered proprietors (as joint tenants) of two properties in south-east Queensland.

6 The first property was located at 1205/157 Old Burleigh Road, Broadbeach, Queensland, and more particularly described as Lot 59 on BUP 4263, Local Government: Gold Coast, Title Reference 16147152 (Broadbeach Property). Mr and Mrs Smith were the registered proprietors between 10 March 2005 and 31 March 2016.

7 The second property was located at 23 Murphys Creek Road, Blue Mountain Heights, Queensland, and more particularly described as Lot 11 on RP121698, Local Government: Toowoomba, Title Reference 50600754 (Blue Mountain Heights Property). Mr and Mrs Smith were the registered proprietors between 29 January 2006 and 20 April 2016.

8 Each property was, at a particular time, the subject of a mortgage to the Commonwealth Bank of Australia.

9 At material times Mr Smith was the sole director of Faloda Pty Ltd ACN 009 956 772 (Faloda). Faloda was the corporate trustee of the R.D. Smith Trust (the Trust). Mr Smith’s parents had established the Trust by way of Trust Deed dated 1 April 1976 (the Trust Deed). Mr Smith’s mother, Mrs Ruth Smith, was the appointor, and had power to replace and/or appoint trustees. Mr Smith and Mrs Smith were included in the class of beneficiaries of the Trust.

10 The Smith family operated businesses under a partnership known as TFD Joinery Works (TFD). The TFD partnership was operated by companies controlled by the Smith family, namely Nu-Al Pty Ltd, Ruron Pty Ltd, Toowoomba Joinery Pty Ltd and RD Smith Pty Ltd. TFD conducted two manufacturing operations, one which produced aluminium windows and doors, and another which produced residential and commercial cabinetry and joinery.

11 The land and factory on which TFD operated its business was owned by Faloda in its capacity as trustee of the Trust, namely premises at 123 North Street, Toowoomba, Queensland and more particularly described as Lots 11 and 12 RP 17275, Local Government: Toowoomba, Title Reference 15150210 (North Street Property).

12 At material times, TFD had a business loan and an overdraft facility with the Commonwealth Bank (TFD Facility). On or around 17 December 2014, the limit of the overdraft facility was varied to $1.3 million. It appears that the TFD Facility was guaranteed by both Faloda and Mr Smith. Mr Smith’s guarantee in respect of the TFD Facility was limited to $1.3 million.

13 In 2015 TFD’s financial position deteriorated. On 14 August 2015 the Commonwealth Bank wrote the following letter to the directors of TFD:

Dear Mr Smith

…

We refer to the telephone discussion on 7 August 2015.

As discussed the Bank has the following concerns relating to the 2015 Company financial performance:

• The substantial loss of over $974,000 incurred for the year ended 30 June 2015. This had followed a loss of $585,695 incurred in the 2014 financial year.

• The significant ATO arrears position.

• The deterioration in the aged receivables position with over 25% of accounts over 90 days.

• The business is possibly trading insolvent.

Due to the above concerns, the Bank is not prepared to continue our banking relationship. Accordingly the Bank requests that the company's total indebtedness including all Hire Purchase Contracts and Equipment Loans be fully repaid by 15 November 2015 or as a minimum, an unconditional contract of sale of the factory to be provided to the Bank with settlement to be no greater than 60 days thereafter.

Should the total debt not be repaid or an unconditional sale of the factory not be achieved by 15 November 2015, then:

• The Overdraft limit will be cancelled. Please note the Overdraft Account is an on-demand facility which limit can be cancelled at any time at the Bank's discretion.

• Formal Letters of Demand will be issued requesting that the company's total indebtedness be repaid. These demands may be a precursor to the Bank acting pursuant to securities held to recover all monies owing. Note: this could lead to the appointment of an Agent for the Mortgagee to take possession and arrange the sale of company assets.

• The interest rate on all variable interest rate loan facilities will be increased to the Bank's Overdraft Index Rate plus a margin of 4.5% pa variable (this rate is currently 13.98% pa variable).

…

14 On 8 September 2015, pursuant to Part 5.3A of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth), administrators were appointed to the companies comprising TFD. On 29 September 2015, the Commonwealth Bank made a formal demand for payment from Mr Smith under his personal guarantee of TFD’s debts, in the amount of $1,253,172.58.

15 Creditors of TFD subsequently lodged caveats under the Land Title Act 1994 (Qld) over properties owned by Mr and Mrs Smith, in particular:

(1) Nation Glass Pty Ltd lodged a caveat over both the Broadbeach Property and the Blue Mountain Heights Property on 11 September 2015;

(2) Lincoln Sentry Group Pty Ltd lodged a caveat over both the Broadbeach Property and the Blue Mountain Heights Property on 30 October 2015; and

(3) Borg Manufacturing Pty Ltd lodged a caveat over the Blue Mountain Heights Property on 4 November 2015.

16 On 1 December 2015 Faloda entered into a contract of sale to sell the North Street Property for $1.7 million. The sale was completed on 23 December 2015, and after discharging the Commonwealth Bank’s mortgage and other costs of sale, Faloda received nett proceeds of sale of $600,446.30, which were paid into the trust account of lawyers Wonderley & Hall.

17 On or about 2 December 2015 Mr Smith executed a Deed of Covenant with the Commonwealth Bank, by which the Commonwealth Bank agreed to forbear from enforcing its rights under the TFD Facility in consideration of Faloda agreeing to pay the full outstanding amount to the Commonwealth Bank from the proceeds of the North Street Property.

18 Around this time Mr and Mrs Smith attended various meetings with Mr Jeffrey Thomson and Mr Craig Thomson of Wonderley & Hall. Transcribed contemporaneous file notes of Mr Jeffrey Thomson were tendered at the hearing as an exhibit, and Mr Jeffrey Thomson gave evidence at the hearing. From the material before the Court it appears that Mr and Mrs Smith sought advice referable to future protection of their asset position, including the creation of a new trust over which Mr Smith would have total control.

19 It is not in dispute that on 28 January 2016 Faloda paid the Commonwealth Bank the sum of $506,543.29 to secure the transfer to Faloda of the Commonwealth Bank’s mortgages over the Broadbeach Property and the Blue Mountain Heights Property (Faloda Refinance). The transfer of the mortgages from the Commonwealth Bank to Faloda was registered on 16 February 2016.

20 The Broadbeach Property was sold for $430,000.00 on 23 March 2016. The following day the real estate agent engaged to sell the property transferred to Mrs Smith monies paid by way of the deposit in the amount of $30,100.00. Of the remaining proceeds of sale, $194,386.33 was paid to Mrs Smith, and an equivalent amount (less one cent) was paid into the trust account of Wonderley & Hall held in the name of Faloda.

21 The Blue Mountain Heights Property was sold on 20 April 2016 for $765,000.00. Of these proceeds of sale, $430,644,74 was transferred to Mrs Smith. The balance of $313,121.97 was paid to the trust account of Wonderley & Hall, again in the name of Faloda.

22 It is convenient to cumulatively refer to the sale of the Broadbeach Property, the sale of the Blue Mountain Heights Property, and the subsequent disposition of sale proceeds as the Property Transactions.

23 On 22 April 2016 Faloda and Mrs Smith executed a loan agreement, whereby Faloda, in its capacity as Trustee of the Trust, loaned the amount of $250,000.00 to Mrs Smith (Loan Agreement). On 26 April 2016 the amount of $250,000.00 was paid to Mrs Smith out of the funds held in the trust account of Wonderley & Hall in the name of Faloda.

24 On 17 May 2016 Mrs Smith was registered as the sole proprietor of real property located at 1402/2865 Gold Coast Highway, Surfers Paradise, Queensland, more particularly described as Lot 80 on SP 161863, Local Government: Gold Coast, Title Reference 50483118 (Surfers Paradise Property). Mrs Smith acquired that property for the sum of $785,000.00.

25 Some time in the first half of September 2016, Mr Smith deposited the sum of $247,639.88 into a superannuation account in his name (Account 0045) with Colonial First State.

26 On 1 December 2016 Mr Smith deposited an amount of $383,549.44 into another superannuation account in his name with Colonial First State (Account 5820).

27 On 19 December 2016 Mrs Smith applied for a superannuation account with Colonial First State (Mrs Smith’s Superannuation Account 3306).

28 On 21 December 2016 Mr Smith caused the amount of $244,651.71 to be transferred from Account 0045 to a bank account in his name (Mr Smith’s Heritage Account).

29 Further on 21 December 2016, Mr Smith caused the amount of $84,000.00 to be transferred from Account 5820 to a bank account in Mrs Smith’s name (Mrs Smith’s Heritage Account).

30 On 23 December 2016, Mr Smith paid, from the money in Mr Smith’s Heritage Account, the amount of $244,651.71 into Mrs Smith’s Superannuation Account 3306 (First Superannuation Transfer).

31 On 23 December 2016, the amount of $80,348.29 was transferred from Mrs Smith’s Heritage Account into Mrs Smith’s Superannuation Account 3306 (Second Superannuation Transfer).

32 It is not in dispute that Mr Smith committed an act of bankruptcy within the meaning of s 40 of the Bankruptcy Act on 17 October 2018 when he failed to comply with the requirements of a bankruptcy notice issued by a creditor on 14 September 2018.

33 On 27 March 2019 a sequestration order was made by the Federal Circuit Court of Australia (as the Court then was) in respect of Mr Smith, and the applicant was appointed as Trustee of Mr Smith’s estate.

34 On 16 August 2021, the Court ordered that the balance of funds in Mrs Smith’s superannuation account be paid into the Court and that Colonial First State be taken to have discharged any debt in relation to these proceedings.

PLEADINGS

Amended Statement of Claim

35 The applicant filed an Amended Statement of Claim on 15 October 2021. The relief sought by the applicant in the Amended Statement of Claim was as follows:

1. A declaration that each Transfer, as that term is defined in the Statement of Claim filed with this originating application, is void against the Applicant pursuant to s 120 or alternatively s 121 of the Bankruptcy Act 1966 (Cth) (Act).

2. A declaration that the First Respondent received the property located at 1402/2865 Gold Coast Highway, Surfers Paradise, Queensland, more particularly described as Lot 80 on SP 161863, Local Government: Gold Coast, Title Reference 50483118 (the Surfers Paradise Property) as a result of a transaction that is void against the Applicant.

4. A declaration that the Surfers Paradise Property is charged with the payment to the Applicant of 74%, or alternatively half the value of the Surfers Paradise Property or, in the further alternative, such other amount or proportion as is found to be equitable.

5. An order for the sale of the Surfers Paradise Property to enforce the charge.

6. In the alternative to paragraphs 4 and 5 above, an order requiring the First Respondent to take all necessary steps and do all necessary things to enable half or, alternatively, such other proportion as is found to be equitable, of her right, title and interest in the Surfers Paradise Property to be transferred to the Applicant.

6A. A declaration that each of the First and Second Superannuation Transfers, as those terms are defined in the Statement of Claim, are void against the Applicant pursuant to s 120 or alternatively 121 or alternatively 128B of the Act.

6B. An order requiring the money paid into Court in this proceeding pursuant to the Court’s order dated 30 September 2021, plus any accretions, be paid to the Applicant.

6C. In the alternative to the relief sought in paragraphs 2, 3, 5 and 6 above:

(a) restitution of the value of each of the Transfers, the First Superannuation Transfer, and the Second Superannuation Transfer, less any amount which may be paid pursuant to the claim for relief in paragraph 6B above; alternatively

(b) an order pursuant to s 30 of the Act requiring the Respondent to pay the Applicant an amount representing the value of each of the Transfers, the First Superannuation Transfer, and the Second Superannuation Transfer, less any amount which may be paid pursuant to the claim for relief in paragraph 6B above.

7. Interest on any sum found to be payable pursuant to section 51A of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth).

8. Such further or other relief as the Court finds to be equitable or appropriate.

9. Costs.

(tracked changes omitted)

36 In summary, in the Amended Statement of Claim filed 15 October 2021, the applicant pleaded:

From the money Mrs Smith received from the sale of the Broadbeach Property, the Blue Mountain Heights Property, and the monies received in accordance with the Loan Agreement, Mrs Smith paid the balance of $734,265.65 at the settlement of the Surfers Paradise Property.

The main purpose of Mr Smith in engaging in transactions referable to those properties and the various superannuation funds into which monies were paid, was:

• to prevent his interest in the Broadbeach Property, the Blue Mountain Heights Property and the cash withdrawn from his superannuation from becoming divisible among his creditors; or

• to hinder or delay the process of making property available for division among the transferor’s creditors.

(Relevant Purpose)

The Loan Agreement was a sham transaction, in that:

• the payment by Faloda to Mrs Smith of the amount of $250,000.00 was recorded in the financial statements of the Trust for the year ended 30 June 2016 as a distribution to Mr Smith, which was the true character of that payment;

• There was no record in the financial statements of the Trust for the year ended 30 June 2016 of a loan to Mrs Smith from Faloda;

• neither Faloda nor Mrs Smith ever intended that Mrs Smith repay the sum of $250,000.00 to Faloda;

• the Loan Agreement was entered into for the purposes of defeating creditors of Mr Smith, and to redirect his entitlement from the Trust to Mrs Smith; and

• the Loan Agreement was part of a scheme designed to keep Mr Smith’s equity in the Broadbeach Property and the Blue Mountain Heights Property beyond the reach of his creditors, and to permit Mrs Smith to buy a property in her name.

The material effects of the Property Transactions were to transfer:

• Mr Smith’s interests as joint tenant in the Broadbeach Property and the Blue Mountain Heights Property to Mrs Smith; or alternatively

• Mr Smith’s share of the net proceeds of sale in the Broadbeach Property and the Blue Mountain Heights Property to Mrs Smith.

37 In respect of the transfers by Mr Smith of his interest in, or alternatively his share of the nett sale proceeds, of each of the Broadbeach Property and the Blue Mountain Heights Property, to Mrs Smith, and s 120 of the Bankruptcy Act:

each transfer was a transfer of property by a person who later became bankrupt;

each transfer took place in the period beginning 5 years before the commencement of the bankruptcy and ending on the date of bankruptcy;

Mrs Smith gave no consideration for any transfer to her; and

each transfer was void against the trustee in bankruptcy.

38 In respect of the transfers by Mr Smith of his interest in, or alternatively his share of the nett sale proceeds, of each of the Broadbeach Property and the Blue Mountain Heights Property, to Mrs Smith, and s 121 of the Bankruptcy Act:

each transfer was a transfer of property by a person who later became bankrupt;

but for the Property Transactions:

• Mr Smith’s interests as joint tenant in the Broadbeach Property and the Blue Mountain Heights Property; or alternatively

• Mr Smith’s half share in the nett proceeds of sale (after paying out the Commonwealth Bank Mortgages),

would probably have been divisible property available to his creditors.

Mr Smith’s main purpose in making each transfer was the Relevant Purpose;

alternatively, Mr Smith’s main purpose in making each transfer was taken to be the Relevant Purpose because it could reasonably be inferred that in late 2015 he was, or was about to become, insolvent;

each transfer was void against the trustee in bankruptcy.

39 But for the loan agreement, the sum of $250,000.00 distributed by Faloda as trustee of the Trust to Mr Smith would probably have been divisible property available to his creditors;

40 Alternatively, s 121A of the Bankruptcy Act applied to the sequence of events from the transfer to Faloda through to the loan from Faloda to Mrs Smith.

41 In respect of the First Superannuation Transfer and the Second Superannuation Transfer, for the purposes of s 120 of the Bankruptcy Act:

the First Superannuation Transfer and the Second Superannuation Transfer were transfers of property by a person who later became bankrupt;

the First Superannuation Transfer and the Second Superannuation Transfer took place in the period beginning 5 years before the commencement of Mr Smith’s bankruptcy and ending on the date of his bankruptcy;

Mrs Smith gave no consideration for either the First Superannuation Transfer or the Second Superannuation Transfer; and

The First Superannuation Transfer and the Second Superannuation Transfer were both void against the trustee in bankruptcy.

42 In respect of the First Superannuation Transfer and the Second Superannuation Transfer, for the purposes of s 121 of the Bankruptcy Act:

each of the First Superannuation Transfer and the Second Superannuation Transfer were a transfer of property by a person who later became bankrupt;

but for the First Superannuation Transfer and the Second Superannuation Transfer:

• the sum of $244,651.71 in the Bankrupt’s Heritage Account; and

• the sum of $80,348.29 in Mrs Smith’s Heritage Account,

would probably have been divisible property available to Mr Smith’s creditors.

Mr Smith’s main purpose in making each of the First Superannuation Transfer and the Second Superannuation Transfer was the Relevant Purpose;

alternatively, Mr Smith’s main purpose in making each of the First Superannuation Transfer and the Second Superannuation Transfer was taken to be the Relevant Purpose, because it could be reasonably inferred that in late 2015 Mr Smith was, or was about to become, insolvent; and his financial position had not materially improved by late 2016; and

the First Superannuation Transfer and the Second Superannuation Transfer were void against Mr Smith’s trustee in bankruptcy.

43 The Trustee pleaded that, for the purposes of s 128B of the Bankruptcy Act, each of the First Superannuation Transfer and the Second Superannuation Transfer were made by way of contribution to an eligible superannuation plan and, but for those transfers, the sum of $244,651.71 in the Bankrupt’s Heritage Account and the sum of $80,348.29 in Mrs Smith’s Heritage Account would probably have been property available to Mr Smith’s creditors. Further, Mr Smith’s main purpose in making each of the superannuation transfers was the Relevant Purpose, or his main purpose could be taken to be the Relevant Purpose because in late 2015 Mr Smith was, or was about to become, insolvent and his financial position had not materially improved by late 2016.

Defence

44 On 23 November 2021 the first respondent, Mrs Smith, filed a Defence.

45 I note that, while the Defence pleaded that Mr Smith was not motivated by the Relevant Purpose in engaging in the Property Transactions, the First Superannuation Transfer, and the Second Superannuation Transfer, at the hearing Counsel for Mrs Smith accepted that there was an intention of Mr Smith to defeat creditors.

46 Mrs Smith pleaded that Mr Smith was not a party to, and could not be said to have been involved in, the Property Transactions, or where he was involved, Mr Smith did not have an interest in those assets, or the transactions did not relate to property that would not have been available for division among Mr Smith’s creditors.

47 Mrs Smith denied that the Loan Agreement was a sham transaction because:

the character of the payment by Faloda to Mrs Smith was not a distribution to Mr Smith as he was not entitled to receive a distribution;

the parties entered into the Loan Agreement with the intention that it be legally effective between them as an arms-length and legitimate loan;

from 28 July 2019 it was not possible for Mrs Smith to make repayment of monies owing under the Loan Agreement because Faloda was deregistered as a company and ceased to be a trustee of the Trust, and the only person with power to appoint a new trustee was Mr Smith’s elderly mother Ruth who was 97 years old at the time and in a nursing home;

Mr Smith and Mrs Smith had discussed an interest-free loan being made by Faloda to Mrs Smith to permit her to buy the Surfers Paradise Property; and

the Loan Agreement was designed to permit Mrs Smith to buy a property in her name, this purpose was permitted pursuant to the terms of the Trust Deed, and was consistent with the longstanding operations of the Trust.

48 Mrs Smith had made additional equity contributions in respect of the Broadbeach Property as follows:

a. on or about 19 May 2015, First Respondent caused $90,000.00 to be transferred from her Heritage Bank 'Online Saver' bank account described as 'S26' to a TFD Facility 'Overdraft Cheque Account' (Facility Contribution);

b. on or around 15 June 2015, the First Respondent caused $178,351.77 to be withdrawn from her "One Path" personal superannuation fund and deposited into a Heritage Bank account held in the name of the First Respondent and the Bankrupt with the account number '6981917S24' (Superannuation Transfer A);

c. the Balance Sheet for TFD dated 28 October 2015 recorded a liability to 'Sue Smith' in the amount of $100,000.00, which was:

i. a reference Superannuation Transfer A; and

ii. understated the actual amount of the amount thereby paid by the First Respondent to TFD;

d. the monies comprising Facility Contribution and Superannuation Transfer A were subsequently used by TFD to pay wages and other expenses on behalf of TFD;

e. shortly before the sale of the Broadbeach Property, the First Respondent arranged and made payment of certain necessary costs in relation to the sale of the Broadbeach Property, including advertising and real estate agent's fees, the value of which was at least $2,000.00 (Broadbeach Advertising Contribution);

Particulars of Broadbeach Advertising Contribution

The Broadbeach Advertising Contribution included a payment of approximately $2,000.00 which the First Respondent paid to the real estate agency 'The Professionals Broadbeach' in respect of the Broadbeach Property.

f. between 8 September 2015 and 23 March 2016, the First Respondent also made non-financial contributions to the Broadbeach Property;

Particulars of non-financial contributions

The First Respondent's non-financial contributions to the Broadbeach Property included:

I. undertaking and procuring maintenance and cleaning work in preparation for the sale of the Broadbeach Property; and

II. liaising with real estate agents and advertisers in order to procure the sale of the Broadbeach Property.

g. between 8 September 2015 and 20 April 2016, the First Respondent arranged and paid for tradespeople to attend the Blue Mountain Heights Property in order to undertake repairs with the view of increasing the value of that property, the value of which was at least $40,000.00 (Blue Mountain Heights Renovation Contribution);

Particulars of Blue Mountain Heights Renovation Contribution

The Blue Mountain Heights Renovation Contribution included:

I. Town and Country floor polishing, which cost approximately $4,500.00;

II. the purchase of a ride-on mower, which cost approximately $5,000.00;

III. substantial landscaping and garden maintenance work, which cost around $10,000.00;

IV. the engagement of arborists in order to care for and preserve an historically significant fig tree located at the property;

V. the purchase of a large number of truckloads of soil for terracing the rear of the property;

VI. the installation of sprinkler systems;

VII. replacing the carpeting within the house itself;

VIII. refurbishing of the external entrance, veranda and timber ceilings; and

IX. other general repairs and refurbishments such as revarnishing of wooden surfaces, rendering and decking.

h. between 8 September 2015 and 20 April 2016, the First Respondent arranged and made payment of certain necessary costs in relation to the sale of the Blue Mountain Heights Property, including advertising and real estate agency costs, the value of which was at least $10,000.00 (Blue Mountain Heights Advertising Contribution); and

Particulars of Blue Mountain Heights Advertising Contribution

The Blue Mountain Heights Advertising Contribution included:

I. approximately $6,500.00 which the First Respondent paid to real estate agency 'Peter Snow & Co'; and

II. approximately $3,500.00 which was paid to the real estate agency 'Colliers' and their related entity, 'Diversified Properties'.

i. between 8 September 2015 and 20 April 2016, the First Respondent made nonfinancial contributions to the Blue Mountain Heights Property.

Particulars of non-financial contributions

The First Respondent's non-financial contributions to the Blue Mountain Heights Property included:

I. undertaking and procuring maintenance and cleaning work in preparation for the sale of the Blue Mountain Heights Property; and

II. liaising with real estate agents and advertisers in order to procure the sale of the Blue Mountain Heights Property.

(paragraph 14a to 14i. of Defence)

49 In relation to the Property Transactions and the disposition of the relevant proceeds of sale:

only four transfers of real property were alleged in the Amended Statement of Claim – namely the sale of the North Street Property, the Broadbeach Property and the Blue Mountain Heights Property, and the purchase of the Surfers Paradise Property – however the Loan Agreement had no connection to any of those transactions;

Mrs Smith never received Mr Smith’s interest in either the Broadbeach Property or the Blue Mountain Heights Property;

although Mr Smith’s share of nett proceeds of the sale of the Broadbeach Property and the Blue Mountain Heights Property was transferred to Mrs Smith, she received those monies in circumstances where she was lawfully entitled to do so;

in relation to the Broadbeach Property, Mrs Smith had made Additional Equity Contributions as identified at paragraphs 14a to 14i of the Defence.

Mrs Smith pleaded the following in relation to the proceeds of sale of the Broadbeach Property:

a. the sum of $194,386.33 which was paid into the Trust Account was paid in reduction of the secured debt of $506,543.29 which the First Respondent and the Bankrupt owed to Faloda pursuant to the Faloda Refinance (First Faloda Refinance Payment);

b. as a result the First Faloda Refinance Payment being made, the total secured debt which was owed to Faloda under the Faloda Refinance was reduced to $312,156.62;

c. the sum of $194,386.32 which was paid to the First Respondent at settlement (Broadbeach Settlement Payment) constituted part of the nett proceeds from the sale of the Broadbeach Property (after deducting the Broadbeach Settlement Adjustments and the First Faloda Refinance Payment) (Broadbeach Nett Proceeds);

d. the contributions which are pleaded at paragraph 14.a to 14.i of this Defence (Additional Equity Contributions) made it fair and equitable for the First Respondent to receive the entirety of the Broadbeach Settlement Payment, rather than one half of it (as would otherwise be the case in view of the fact that the First Respondent and the Bankrupt held the Broadbeach Property in equal shares);

e. upon the Bankrupt becoming bankrupt on or about 27 March 2019:

i. the substratum of the joint relationship or endeavour between the Bankrupt and the First Respondent was removed; and

ii. that occurred without any blame which is attributable to the First Respondent; and

f. in the premises of the matters pleaded at paragraphs c to e above:

i. it would be unconscionable to deny the First Respondent recourse to the proceeds of the sale of the Residential Properties in order to recover the Additional Equity Contributions; and

ii. the First Respondent:

1. was entitled to a constructive trust over the Bankrupt's interest in the Broadbeach Property; and

2. was entitled to recover the Additional Equity Contribution from the Bankrupt's interest in the Broadbeach Nett Proceeds; and

g. further or alternatively in the premises of the matters pleaded at paragraphs c to e above, to the extent to which the Bankrupt had any entitlement to receive part of the Broadbeach Nett Proceeds for himself, those proceeds:

i. were paid into the First Respondent's bank account in her capacity as the Bankrupt's carer;

ii. were used by the First Respondent to pay the day-to-day expenses of the Bankrupt between 24 March 2016 and 27 March 2019; and

iii. were not used to fund the purchase of the Surfers Paradise Property.

(paragraph 15 of the Defence)

In relation to the payment of the deposit of $30,100.00 forming part of the proceeds of sale of the Broadbeach Property, Mrs Smith was entitled to receive that money because she was entitled to recover the Additional Equity Contributions, and was entitled to:

• a constructive trust over Mr Smith’s interest in the Broadbeach Property; and

• recover the Additional Equity Contribution from Mr Smith’s interest in that deposit.

Alternatively, Mrs Smith was entitled to recover part of that deposit because those proceeds:

• were paid into Mrs Smith’s bank account in her capacity as Mr Smith’s carer;

• were used by Mrs Smith to pay the day-to-day expenses of Mr Smith between 24 March 2016 and 27 March 2019; and

• were not used to fund the purchase of the Surfers Paradise Property.

Similar constructive trust arguments were pleaded by Mrs Smith in relation to the sum of $430,644.74 which was paid to Mrs Smith at settlement of the Blue Mountain Heights Property.

The Loan Agreement arose following a conversation between Mr Smith and Mrs Smith in April 2022, whereby Faloda would make an interest free loan to Mrs Smith to fund the purchase of the Surfers Paradise Property. The purpose of the loan was:

• to make use of funds which Faloda held;

• to provide financial assistance to Mrs Smith, in accordance with the terms of the Trust Deed, to purchase the Surfers Paradise Property; and

• to continue Faloda's practice of providing loans to beneficiaries and their related persons and entities.

It was incorrect to aver that Mr Smith was entitled to receive a distribution from the Trust in the amount of $284,130.00 because, since on or around 23 December 2015, he had owed a nett amount to Faloda of $313,659.73. This was because although prima facie Mr Smith was entitled to receive a distribution of $284,130.00 from the Trust, Faloda was entitled to recover from Mr Smith the amount of $597,789.72 which was 50% of the amount paid by Faloda to the Commonwealth Bank to purchase the mortgages and discharge the guarantees of Faloda and Mr Smith to the Commonwealth Bank.

50 In relation to the deposits of monies by Mr Smith into his superannuation accounts (Account 0045 and Account 5820), those deposits were made by Mr Smith as consolidation of his personal superannuation holdings, and following advice that it would be worthwhile for him to establish two accounts with Colonial First State (namely a regular fund and a pension fund). It followed that Mr Smith transferred the total amount of $631,189.32 into Account 0045 and Account 5820. If those funds had not been transferred to those accounts, they would have remained in his previous superannuation accounts, and been exempt from being divisible amounts available to Mr Smith’s creditors pursuant to s 116(2)(d) of the Bankruptcy Act.

51 In relation to the superannuation transactions, Mrs Smith further pleaded that, for the purposes of the applicant’s claim pursuant to s 128B of the Bankruptcy Act, the superannuation transactions were not separate, but formed part of the one transaction. Mrs Smith further pleaded in relation to the superannuation transactions that the provisions of s 128B had not been met in respect of conduct of Mr Smith or Mrs Smith.

52 To the extent that the first respondent’s pleadings concerned ss 120 and 121 of the Bankruptcy Act and the superannuation transactions, it was unnecessary for me to have regard to that aspect of the Defence given that the Trustee ultimately did not press a case based on those sections in relation to the superannuation transactions.

53 In respect of the Loan Agreement, the sale of the North Street Property and the disposition of its proceeds, the Faloda Refinance, and the purchase of the Surfers Paradise Property, Mrs Smith pleaded that those transfers did not include a transfer of property by Mr Smith or by any person who later become bankrupt for the purposes of s 120 of the Bankruptcy Act.

54 Further, in relation to the sale of the Broadbeach Property, the sale of the Blue Mountain Heights Property, the disposition of the proceeds of those sales to Mrs Smith, and the subsequent purchase of the Surfer Paradise Property, Mrs Smith pleaded those transfers:

were transfers to transferees who were not related entities of Mr Smith for the purpose of s 120 of the Bankruptcy Act;

took place more than two years before the commencement of Mr Smith’s bankruptcy;

occurred at times when Mr Smith was solvent; and

were not transfers to which s 120(1) of the Bankruptcy Act applies.

Reply

55 Materially, the applicant pleaded the following in Reply:

It was the intention of Faloda that Mr Smith would not be obliged to pay any contribution to Faloda in the event the Commonwealth Bank called on Faloda’s guarantee or Faloda’s mortgage to the Commonwealth Bank;

Faloda and Mr Smith were not equal co-sureties, but rather Faloda was the primary surety and Mr Smith a subsidiary surety, such that it would be inequitable to permit Faloda to claim contribution from Mr Smith;

By the time Faloda and Mr Smith entered into the Deed of Covenant with the Commonwealth Bank, Mr Smith had commenced upon a course of conduct designed to defeat or delay his creditors, of which the discharge of TFD’s Commonwealth Bank facility was the first step;

Any right of Faloda against Mr Smith as a result of their relationship as co-guarantors was not in the nature of a debt, but an equitable right of contribution, and it would be inequitable to permit Faloda to claim a right of contribution from Mr Smith; and

Even if the payments to Mrs Smith and Faloda of the proceeds of sale of the Broadbeach property and the Blue Mountain Heights Property gave rise to a right of Mr Smith to make a claim against Mrs Smith in equity, such a right would only result in Mrs Smith being an unsecured creditor of Mr Smith and, to the extent that such a right was capable of giving rise to the remedy of a constructive trust, that constructive trust would be a remedial constructive trust which could only arise by an order of the Court.

Cross-Claim of First Respondent

56 On 23 November 2021 Mrs Smith and Mr Smith filed a notice of a cross claim which sought:

1. An order under section 139ZS of Bankruptcy Act 1966 (Cth) that the notice issued to Colonial First State Investments Limited on 22 April 2021 under section 139ZQ of the Bankruptcy Act 1966 (Cth) (First 139ZQ Notice) be set aside.

2. An order pursuant to section 139ZS of Bankruptcy Act 1966 (Cth) that the notice issued to Glenys Susanne Smith on 1 June 2021 under section 139ZQ of the Bankruptcy Act 1966 (Cth) (Second 139ZQ Notice) be set aside.

3. Costs.

4. Any further or other order that this Honourable Court considers appropriate.

57 On the first day of the hearing, Mr Russell for the Trustee submitted as follows:

MR RUSSELL: I will commence to open the applicant’s case. Your Honour will have seen, from the written outline, that this is a consolidated proceeding of what was originally three proceedings. The first is the one in which my client is the applicant, and that is, in substance, a claim for various relief under what can broadly be termed the voidable transactions provisions of the Bankruptcy Act. The transactions which underly those claims were also the subject of notices given by the official receiver under section 139ZQ. Those proceedings – the other two proceedings are 217 and 251 of – I should say QUD 257 and 217 of – 251 and 217, I’m sorry, your Honour, of 2021, in which Mrs Smith applied to set aside those 25 notices.

Those applications have now been subsumed by the cross-claim filed in this proceeding. Your Honour will have seen, from my learned friend’s written opening, the submission that the cases largely mirror each other, in that if my client fails to establish its primary claim, it follows the notice should be set aside. There’s another point made - - -

HER HONOUR: Do you agree with that, Mr Russell?

MR RUSSELL: I think that must be true, your Honour. So that it’s not quite, as I understand my friend’s submission – it doesn’t work entirely the other way, for two reasons. One is that, as I understand it, there’s an additional point not dissimilar, it seems, to the decision your Honour handed down a week or so ago, in relation to the quality of the notice. But that may transpire to be academic, because it’s difficult to imagine a scenario where my client succeeds in establishing its voidable transaction claim, but the notice is insufficient, so that the notice is set aside, but nevertheless, the transaction is held to be voidable.

So it really does seem that the substance of success, on my client’s case, is what’s going to determine the ultimate outcome in the proceeding, and it’s for that reason that I’ve opened the case, and the parties have proceeded throughout and will conduct the trial throughout as though my client is the plaintiff.

HER HONOUR: Good. Thank you.

(Emphasis added)

(Transcript of hearing pp 4-5)

58 There was no demur to this submission by Mrs Smith.

59 Plainly, the success or otherwise of the cross-claim is tied to the result of the substantive claim of the Trustee. It is logical to deal first with the substantive claim, before turning to the cross-claim.

Submissions in the substantive claim

Applicant’s submissions

60 In summary the case of the Trustee was as follows.

61 The relevant transfers of property identified were void pursuant to Part IV, Div 3 of the Bankruptcy Act because:

Mrs Smith gave no consideration for the property she received and, as a consequence, s 120 of the Bankruptcy Act applied;

Mr Smith’s main intention in entering into the transactions was to prevent those assets from becoming divisible among his creditors or to hinder or delay the process of making property available for division among his creditors. That intention was established by evidence, and also because it could reasonably be inferred from all the circumstances that, at the time of the transfer, Mr Smith was, or was about to become, insolvent;

each of the superannuation transfers are also void because of s 128B of the Bankruptcy Act.

62 It was admitted on the pleadings that Mrs Smith paid the purchase price for the Surfers Paradise Property from the proceeds of sale of the Broadbeach Property and the Blue Mountain Heights Property, and the $250,000 she received under the Loan Agreement. The terms of the loan would be repayable within 7 days of written demand. No interest was payable, and no security was provided.

63 Mr Smith and Mrs Smith had been warned or told numerous times by their lawyer, Mr Jeffrey Thomson, that moving money outside of Faloda could be traced by creditors.

64 Faloda paid the Commonwealth Bank the total sum of $506,543.29.40. The characterisation of that payment was in dispute, but there could be no real doubt that it was paid in consideration of the transfer from the Commonwealth Bank to Faloda of the mortgages over the Broadbeach Property and the Blue Mountain Heights Property.

65 Mr Smith’s and Mrs Smith’s affidavit evidence should not be accepted, save for so much of it as was supported by objective documentary evidence or amounted to an admission against interest. Their version of events was totally inconsistent with the contemporaneous documentary record, and Mr Jeffrey Thomson’s file notes.

66 The insuperable obstacle for Mrs Smith’s case was that, beyond the transaction documents themselves, there was no documentary evidence which supported her version of events. For example, Mr Smith and Mrs Smith’s alleged “Faloda Mortgage Agreement” was entirely inconsistent with the origin and very clear purposes recorded in Mr Jeffrey Thomson’s file note. There was no independent consideration of Faloda purchasing the residential mortgages – it was a device developed by the solicitors in order to sell the residential properties through the caveats.

67 Mr Smith was not a credible witness in that:

He blamed his poor memory on the medication he was taking, however his memory appeared to improve during cross-examination. Despite that, Mr Smith claimed to have a good recollection of the transactions the subject of this proceeding. When it suited him, Mr Smith relied on his medications as explaining his conduct or lack of memory, but then quickly retreated from accepting that his memory was poor as a consequence.

The Court should not accept the proposition that Mr Smith’s memory has inexplicably improved in a way that bolstered critical parts of Mrs Smith’s defence of the Trustee’s claim.

In terms of demeanour, Mr Smith was an unimpressive witness. He frequently gave evasive answers or refused to accept obviously correct propositions. He was often argumentative.

Mr Smith’s cross-examination also revealed the reason why many of his and Mrs Smith’s financial records were not produced in this trial, namely Mr Smith had destroyed them. He did so at a time when his solicitors had given him many warnings about the prospect of a challenge to the transactions of the very kind now advanced by the Trustee. His willingness to do so reflects very poorly on his credibility.

68 In respect of evidence of Mrs Smith:

Mrs Smith presented as a witness who was, for the most part, attempting to give honest evidence. Nonetheless, her evidence still suffered from real credibility issues, and also presented as unreliable when closely scrutinised.

Mrs Smith’s evidence frequently demonstrated a lack of sophistication or understanding about the transactions or involvement in her and Mr Smith’s financial affairs.

Mrs Smith admitted she had signed her affidavit without reading the entirety of the document.

During the course of cross-examination of Mrs Smith:

• Mrs Smith did not recall any conversation with Mr Smith about how to allocate their respective shares of the proceeds of sale of the Broadbeach Property and the Blue Mountain Heights Property;

• Mrs Smith accepted that the amount of $194,386.32 paid to Wonderley & Hall’s trust account from the proceeds of the sale of the Broadbeach Property represented Mr Smith’s share of the property (and not any joint payment to Faloda on account of the supposed Faloda Refinance);

• Mrs Smith accepted that, on the advice of Mr Thomson, she and Mr Smith made an agreement that Mr Smith’s share of the residential properties would be used to repay the mortgage, and her share would be used to buy a new property;

• Mrs Smith accepted that she did not recall any conversation with Mr Smith prior to signing the Loan Agreement, and that she signed the Loan Agreement merely because Mr Smith and Mr Thomson told her to; and

• Mrs Smith accepted that the Loan Agreement was simply a way for her to get money out of the Trust to enable her to purchase the Surfers Paradise Property.

Mrs Smith’s oral evidence bore significant inconsistencies with her affidavit.

69 There was ample evidence to support the inference that in late 2015 and in 2016, Mr Smith was about to become insolvent from the collapse of TFD.

70 The position in respect of the Loan Agreement was as follows:

Mr Smith transferred his entitlement to receive payment from Faloda on account of the outstanding distribution of $284,129.00.

The Loan Agreement was a sham, in that:

• Mrs Smith effectively conceded as much under cross-examination;

• Mr Smith’s conduct was not consistent with a genuine intention for Mrs Smith to repay the loan;

• Objective documentary evidence did not support the existence of a real loan; and

• Mr Smith’s explanations for the state of accounts were nonsensical and should not be accepted.

The evidence established that Mr Smith was warned about making a distribution to himself because of the potential impact on his plan to deceive his creditors about his financial position.

Consistently with the overall asset protection strategy, the amount of the loan was fixed by reference to the purchase price of a new property for Mrs Smith, rather than the funds which Faloda had on hand.

71 The position in relation to superannuation transactions was as follows:

Mr Smith and Mrs Smith’s explanation for the First Superannuation Transfer and the Second Superannuation Transfer should be rejected.

These transfers occurred in circumstances in which Mr Smith and Mrs Smith had, by the middle of 2016, successfully achieved their goal of protecting their major assets from Mr Smith’s creditors by converting them into property held only in Mrs Smith’s name.

That property would have been available to Mr Smith’s creditors.

72 Most of the amount the subject of the alleged constructive trust in respect of proceeds of sale of the Broadbeach Property and the Blue Mountain Heights Property, was not owed by Mr Smith to Mrs Smith:

Of the $320,351.77 claimed as forming part of Mrs Smith’s “Equity Entitlement”, $268,351.77 was owed by TFD and not Mr Smith. An additional $3,981.80 of the advertising costs was owed by Faloda.

Of the $52,000.00 claimed as being direct contributions to the properties, there was objective evidence for only two payments totalling $4,290 (the $3,981.80 having been applied to the North Street Property). Equity intervenes in these circumstances only where it positively appears that it would be unconscionable for one party to retain the benefit of the other’s contributions to the property in circumstances where they were not intended to enjoy it.

In any event, in the absence of an intention, express or implied, or some type of estoppel, a constructive trust based on unequal contributions to a failed joint endeavour is purely remedial in nature. It does not come into existence until the Court declares it to.

Mrs Smith had notice of the claims of other creditors by reason of her knowledge of the caveats, and of her involvement in the conferences with Wonderley & Hall in which those claims were discussed. That knowledge and her participation in Mr Smith’s scheme to defeat his creditors made it unlikely that equity would intervene to assist her.

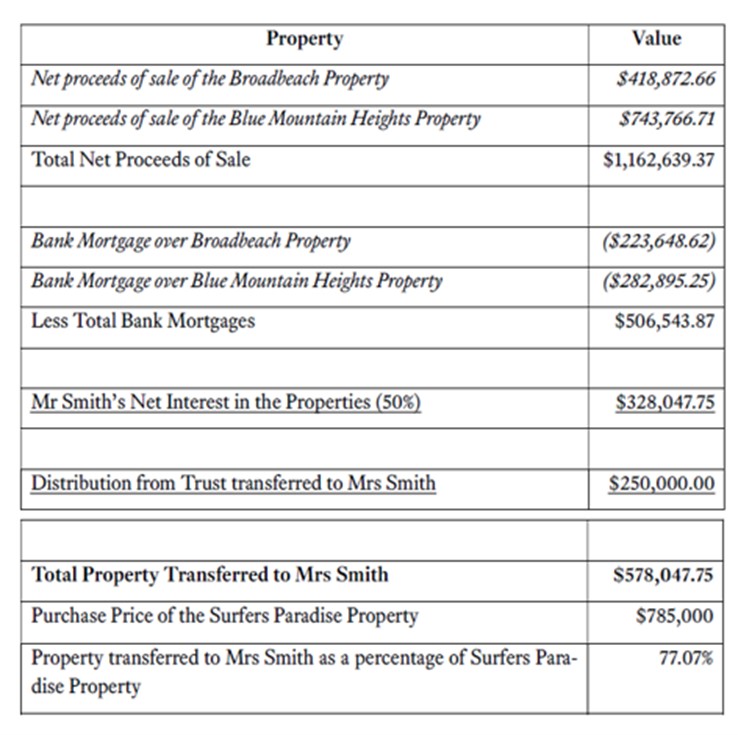

73 The applicant submitted that 77.07% of the value of Surfers Paradise Property should be transferred to the Trustee for relief, on the basis of the following table:

(Extract from Trustee’s closing submissions)

74 Ultimately the Trustee submitted that the transactions underlying his claim were not in serious dispute. Mrs Smith did not press her challenge to the issue of Mr Smith’s intention in engaging in relevant transactions, and further accepted that, to the extent she received more than what constituted her beneficial interest in the sale proceeds from the two properties, she received a transfer of property for which she gave no consideration. It followed that, in the submission of the Trustee, the real issue for determination was whether the property the subject of the transfers would probably have become part of Mr Smith’s estate in bankruptcy or would probably have been available to creditors if the property had not been transferred.

First Respondent’s Submissions

75 The first respondent submitted that, insofar as proceeds of sale of the Broadbeach Property and the Blue Mountain Heights Property were transferred to Mrs Smith, the question was whether Mrs Smith had an equitable interest that exhausted the sale proceeds of the properties, because of costs incurred by her in preparing the properties, being advertising and renovation costs, and in respect of the substantial contributions made by her out of her own funds for the purposes of maintaining her husband’s business. If she did:

there was no “transfer” of property from Mr Smith to enliven s 120 of the Bankruptcy Act; and

section 121 of the Bankruptcy Act was not enlivened because none of the property alleged to have been transferred would have been divisible among Mr Smith’s creditors.

76 In relation to the Loan Agreement, Mrs Smith submitted that it was not a sham, and accordingly there was no transfer of property by Mr Smith for the purposes of the Bankruptcy Act, nor a transfer of property that was divisible among his creditors. There was simply a transfer of property by Faloda, to which Mr Smith had no entitlement, and for which Mrs Smith gave market value, being a promise to repay the same sum of money. Even if the Loan Agreement was found to be a sham, there was no evidentiary basis for the assertion that the payment to Mrs Smith was a distribution to Mr Smith that was assigned to Mrs Smith, as opposed to nothing more than an unauthorised distribution of trust property by Faloda.

77 The First Superannuation Transfer and the Second Superannuation Transfer were only challengeable under s 128B of the Bankruptcy Act. Further, the payments made came from money originally sourced in superannuation accounts held by Mr Smith, which was not divisible among his creditors.

78 On 19 May 2015 Mrs Smith transferred the amount of $90,000 from a Heritage bank account in her name (described as “S26”) to the TFD Facility Overdraft Cheque Account.

79 On 15 June 2015, Mrs Smith also transferred $178,351.77 from a superannuation account in her name, held with OnePath superannuation, to a Heritage Bank account held jointly in the name of Mr Smith and Mrs Smith that was used to pay expenses of TFD.

80 No evidence adduced by the Trustee contradicted this.

81 In relation to whether Mrs Smith paid the amount of $12,000.00 or $8,271.50 for advertising costs of the properties and approximately $40,000.00 to renovate the properties:

from the Bank statement it was clear that at least $8,271.50 was used in respect of preparing the properties for sale; and

Mrs Smith’s evidence that she paid approximately $40,000 on account of the renovations, and a further $3,700 in relation to the sale of the properties should be accepted.

82 The Court should accept that Mrs Smith made contributions of $52,000 in preparing the Broadbeach Property and the Blue Mountain Heights Property for sale.

83 Mrs Smith relied on the following principles in relation to whether she had a beneficial interest in the Broadbeach Property and the Blue Mountain Heights Property in excess of 50%:

Equity will restore the parties to a joint endeavour which fails when contributions have been made, in circumstances where it is not intended that the other party enjoy them should endeavour fail.

A constructive trust following the failure of a joint endeavour is imposed by equity without regard to the actual presumed intention of the parties.

The right of a party to be restored in equity is one that will ordinarily be supported by a constructive trust.

A trustee in bankruptcy stands in the shoes of the bankrupt, and accordingly takes the property subject to all the liabilities and equities that affect it in the bankrupt’s hands. Consequently, equity will intervene where it would be unconscionable for the legal owner of property to deny the beneficial ownership of another person.

It is not necessary for a relationship to end for the substratum of a joint endeavour to fail.

It is not necessary for equity’s intervention that the contributions made to the joint endeavour have been made directly to the acquisition or improvement of the relevant property.

A transfer of the proceeds of sale held legally by a bankrupt representing the transferee’s equitable interest in a property will not constitute a transfer of property to the transferee.

84 These principles were applicable to the present case as follows:

Mrs Smith could establish that she had a beneficial interest in the Broadbeach Property and the Blue Mountain Heights Property exceeding 50%, and was entitled to the proceeds representing that interest.

Mr Smith’s insolvency brought the joint endeavour in respect of the Broadbeach Property and the Blue Mountain Heights Property to an end.

Improvements to the properties by Mrs Smith were plainly not intended to be for the benefit of Mr Smith.

Mrs Smith made two payments totalling $268,351.77 out of her own money to support TFD.

Even though she would have had a claim in the liquidation of TFD for the sums advanced to support the business, Mrs Smith’s contributions were nonetheless contributions to the acquisition, maintenance or improvement of the Broadbeach Property and the Blue Mountain Heights Property, because the payments reduced Mr Smith’s potential liability in respect of the guarantees given by him to the Commonwealth Bank, which were secured by mortgages over those properties.

The consequences of the payments created a sufficient nexus between them and the maintenance of the relevant properties to entitle Mrs Smith to be repaid the equity from the proceeds of sale before any division of the remaining equity.

85 Mrs Smith claimed that, out of the proceeds of sale (being $655,131.06), she was entitled to:

50% of the balance of the proceeds (being $327,565.53);

repayment of her contributions of $52,000; and

a further $268,351.77, referable to the payments she made which:

• supported Mr Smith’s business; and

• as a consequence, maintained the properties and prevented any risk of foreclosure by the Commonwealth Bank, while they were prepared for sale.

86 Accordingly, Mrs Smith submitted that:

Payments to her did not constitute a transfer of property to her—it was property to which she was already beneficially entitled.

As that exhausted the whole of the sale proceeds, the claim against her in reliance on s 120 for the recovery of what was said to be Mr Smith’s interest in the Broadbeach Property and the Blue Mountain Heights Property should be dismissed.

If the claim under s 120 fails because there was no transfer of property, it follows that the claim under s 121 must also fail.

87 In relation to the Loan Agreement, the bare facts relating to that transaction were not in dispute, including that, on 22 April 2016, Mr Smith (on behalf of Faloda) and Mrs Smith executed the Loan Agreement by which Faloda agreed to loan Mrs Smith the sum of $250,000.

88 In respect of the allegation that the Loan Agreement was a sham:

The Loan Agreement was made only after consultation with Mr Jeffrey Thompson, the Smiths’ solicitor. It did not appear that Mr Thompson had any reason to think that the transaction was not genuine, as it reflected the instructions which Mr Smith had been given. The Loan Agreement was drawn up and signed by Faloda and Mrs Smith.

Mr Smith and Mrs Smith in their evidence understood that the loan had to be repaid.

It was necessary that the Trustee show that both Faloda and Mrs Smith intended the Loan Agreement to be a false document.

There was no direct evidence of Mrs Smith’s intention, and there was no evidence from which an inference adverse to Mrs Smith could be drawn. The evidence on which the Trustee relied was that Faloda had been deregistered and its books did not include the loan. Had Faloda made a written demand for repayment of the loan, Mrs Smith would have no good legal defence to a claim by Faloda.

Mrs Smith did not cause Faloda to be deregistered. The fact that Faloda was deregistered cannot, therefore, be relied upon to draw inference about her state of mind.

Although the Trust accounts appeared to show a distribution to Mr Smith, rather than a loan to Mrs Smith, there was no suggestion that Mrs Smith prepared those accounts or agreed that they reflected the true position.

The Trust accounts which were put to Mr Smith were not particularly reliable.

89 The rejection of the Trustee’s case that the Loan Agreement was a sham necessitates the rejection of his claim that the $250,000 paid under it was void either under s 120 or 121.

90 There was no transfer of property from Mr Smith to Mrs Smith that was voidable. There was instead a transfer of Faloda’s money to Mrs Smith, and the money held in this Trust was for the various discretionary beneficiaries of the Trust.

91 Factually, that assertion could not be squared with the true position, which was that Mr Smith owed a substantial sum of money to Faloda which far exceeded any distribution entitlements that he had as a beneficiary of the Trust (or could have had). If the Loan Agreement was not intended to take effect according to its terms, then the transfer of money to Mrs Smith was still not a transfer from Mr Smith, it was simply an unauthorised payment of trust money by Faloda which was only recoverable at the suit of Faloda.

CONSIDERATION

92 The evidence before the Court in this case reveals a complex history of transactions, over several years, involving property of Mr Smith, of his businesses, and of Mrs Smith, at a time when Mr Smith and businesses which he controlled were facing serious financial difficulties. The evidence further reveals that Mr Smith was concerned about the prospect of himself and Mrs Smith, in their retirement years, facing insolvency. An asset Mrs Smith ultimately acquired is the Surfers Paradise Property.

93 The Trustee has relied on ss 120, 121 and 128B of the Bankruptcy Act. Sections 120 and 121 are of relevance in relation to that aspect of the Trustee’s claim concerning the proceeds of sale of the Broadbeach Property and the Blue Mountain Heights Property. Section 128B is relevant insofar as concerns the Trustee’s claims regarding monies the subject of the First Superannuation Transfer and the Second Superannuation Transfer.

94 To the extent material for the purposes of the present case, those sections are as follows:

120 Undervalued transactions

Transfers that are void against trustee

(1) A transfer of property by a person who later becomes a bankrupt (the transferor) to another person (the transferee) is void against the trustee in the transferor's bankruptcy if:

(a) the transfer took place in the period beginning 5 years before the commencement of the bankruptcy and ending on the date of the bankruptcy; and

(b) the transferee gave no consideration for the transfer or gave consideration of less value than the market value of the property.

Note: For the application of this section where consideration is given to a third party rather than the transferor, see section 121A.

Exemptions

(2) Subsection (1) does not apply to:

(a) a payment of tax payable under a law of the Commonwealth or of a State or Territory; or

(b) a transfer to meet all or part of a liability under a maintenance agreement or a maintenance order; or

(c) a transfer of property under a debt agreement; or

(d) a transfer of property if the transfer is of a kind described in the regulations.

(3) Despite subsection (1), a transfer is not void against the trustee if:

(a) in the case of a transfer to a related entity of the transferor:

(i) the transfer took place more than 4 years before the commencement of the bankruptcy; and

(ii) the transferee proves that, at the time of the transfer, the transferor was solvent; or

(b) in any other case:

(i) the transfer took place more than 2 years before the commencement of the bankruptcy; and

(ii) the transferee proves that, at the time of the transfer, the transferor was solvent.

…

(6) This section does not affect the rights of a person who acquired property from the transferee in good faith and by giving consideration that was at least as valuable as the market value of the property.

Meaning of transfer of property and market value

(7) For the purposes of this section:

(a) transfer of property includes a payment of money; and

(b) a person who does something that results in another person becoming the owner of property that did not previously exist is taken to have transferred the property to the other person; and

(c) the market value of property transferred is its market value at the time of the transfer.

121 Transfers to defeat creditors

Transfers that are void

(1) A transfer of property by a person who later becomes a bankrupt (the transferor) to another person (the transferee) is void against the trustee in the transferor's bankruptcy if:

(a) the property would probably have become part of the transferor's estate or would probably have been available to creditors if the property had not been transferred; and

(b) the transferor's main purpose in making the transfer was:

(i) to prevent the transferred property from becoming divisible among the transferor's creditors; or

(ii) to hinder or delay the process of making property available for division among the transferor's creditors.

…

(8) This section does not affect the rights of a person who acquired property from the transferee in good faith and for at least the market value of the property.

Meaning of transfer of property and market value

(9) For the purposes of this section:

(a) transfer of property includes a payment of money; and

(b) a person who does something that results in another person becoming the owner of property that did not previously exist is taken to have transferred the property to the other person; and

(c) the market value of property transferred is its market value at the time of the transfer.

128B Superannuation contributions made to defeat creditors--contributor is a person who later becomes a bankrupt

Transfers that are void

(1) A transfer of property by a person who later becomes a bankrupt (the transferor) to another person (the transferee) is void against the trustee in the transferor's bankruptcy if:

(a) the transfer is made by way of a contribution to an eligible superannuation plan; and

(b) the property would probably have become part of the transferor's estate or would probably have been available to creditors if the property had not been transferred; and

(c) the transferor's main purpose in making the transfer was:

(i) to prevent the transferred property from becoming divisible among the transferor's creditors; or

(ii) to hinder or delay the process of making property available for division among the transferor's creditors; and

(d) the transfer occurs on or after 28 July 2006.

…

Protection of successors in title

(6) This section does not affect the rights of a person who acquired property from the transferee in good faith and for at least the market value of the property.

Meaning of transfer of property and market value

(7) For the purposes of this section:

(a) transfer of property includes a payment of money; and

(b) a person who does something that results in another person becoming the owner of property that did not previously exist is taken to have transferred the property to the other person; and

(c) the market value of property transferred is its market value at the time of the transfer.

95 During closing submissions at the hearing, Counsel for Mrs Smith submitted as follows:

MR DERRINGTON: I will not press a submission that it cannot be established – or, sorry, that it cannot be reasonably inferred from the circumstances at the time of the transfers that Mr Smith was or was about to become insolvent. So your Honour can take from that concession that the question of subjective intention is not something that I’m going to argue about either and that - - -

HER HONOUR: Is not what?

MR DERRINGTON: Is not something I’m going to argue about and that for the purposes of section 121 your Honour can presume that there was an intention to defeat creditors because provided that one can reasonably infer circumstances of insolvency, the Act requires that assumption to be made.

HER HONOUR: Right.

MR DERRINGTON: So the case that is advanced by my side is limited really then in respect of each of the transactions to the propositions that either the property that was transferred was not property of Mrs Smith’s or that the property that was transferred would not have been divisible amongst Mr Smith’s creditors or formed part of his estate. That’s really the ambit of the ballpark that I’m dealing with.

(transcript p 129 ll 6-25)

96 Further, I note that only s 128B of the Bankruptcy Act is in issue between the parties in respect of the First Superannuation Transfer and the Second Superannuation Transfer. That this is the case was clarified during closing submissions, as follows:

MR DERRINGTON: So for the purposes of the transfers, to the extent that there is a challenge to them under section 121 of the Act, the fight is over subparagraph (a).

HER HONOUR: Yes.

MR DERRINGTON: And for the purposes of 128(b) which deals with the superannuation transfers the fight is over the subparagraph (b). The second thing I can tell you is that I understand from my learned friend that the claims in respect of superannuation and the recovery of the money that was transferred into Mrs Smith’s superannuation account were challenged under each of 120, 121 and 128B. I understand my friend will concede that he can only succeed under 128(b) and so I no longer – I have intended to but I won’t need to take your Honour through the proper construction of 120 and 121 because there’s no long a claim being pressed on that basis.

(transcript p 130 ll 6-21)

MR RUSSELL: Finally, your Honour, can I turn to the – the superannuation transactions. Not to clarify, but just to confirm and perhaps state more precisely the concession in relation to this, about sections 120 and 121. My friends put it fairly – just so that your Honour has it – some of the submissions that were made commencing at paragraph 176 of my friend’s submission, argue that the trustee cannot have recourse both to section 128B and section 120 and 121, to a lesser extent, of the Act. My friend provides some analysis of the proper interpretation to be given to the Act in the passages that follow. We accept those – we accept the arguments and the interpretation of the Act there offered, and therefore accept that to succeed on the superannuation transactions, section 128B is the only avenue available to the applicant.

The point really turns on the proper construction of section 128B of the Act…

(transcript p 157 l 41 – p 158 l 6)

97 Having regard to the submissions of the parties and the background facts, it appears that the fundamental question for the Court to consider is whether the monies which were ultimately used by Mrs Smith to purchase the Surfers Paradise Property were monies which constituted property that would have become part of Mr Smith’s estate, or would probably have been available to his creditors.

Contended Entitlement of Mrs Smith to Increased Proportion of Proceeds of Sale of the Broadbeach Property and Blue Mountain Heights Property

98 Mrs Smith conceded that she received more than 50% of the proceeds of sale of the Broadbeach Property and the Blue Mountain Heights Property. Mrs Smith contended however that she was entitled to do so because:

she was entitled to be repaid the costs incurred in preparing those properties for sale, being advertising and renovation costs; and

she had made two substantial contributions out of her own funds for the purposes of maintaining her husband’s business, which reduced the debts which Mr Smith owed which were secured against the properties and likely forestalled any action being taken by the Commonwealth Bank in respect of the Broadbeach Property and the Blue Mountain Heights Property (which equity required Mr Smith to account for in the distribution of proceeds).

99 It followed, in Mrs Smith’s submission, that as a result she had an equitable entitlement to more than 50% of the proceeds of sale, and, to the extent that her receipt of the sale proceeds reflected a greater beneficial interest in the properties, Mrs Smith was not receiving a transfer of property from Mr Smith so as to enliven s 120 or 121 of the Bankruptcy Act.

100 For completeness I further note that, although s 116(1)(a) of the Bankruptcy Act provides (inter alia) that all property that belonged to, or was vested in, a bankrupt at the commencement of the bankruptcy, is property divisible amongst the creditors of the bankrupt, s 116(2)(a) provides that s 116(1) does not extend to property held by the bankrupt in trust for another person.

101 Mrs Smith submitted that relevant contributions by her were as follows:

on about 19 May 2015, Mrs Smith caused a payment of $90,000 to be transferred from her Heritage Bank “Online Saver” bank account described as “S26” to a TFD Facility Overdraft Cheque Account;

on about 15 June 2015, Mrs Smith caused $178,351.77 to be withdrawn from her “One Path” personal superannuation fund and deposited into a Heritage Bank account held in her and her husband’s joint names, which was then used by Mr Smith to pay expenses of TFD, including wages;

at least $8,271.50, and then a further $3,700.00, were paid from Mrs Smith’s personal funds to preparing the properties for sale, being payments identified in her bank statements; and

Mrs Smith paid approximately $40,000.00 (from money inherited by her from her mother) on account of renovations of the properties.

102 In her affidavit dated 29 July 2021, Mrs Smith gave evidence of both payments of $90,000.00 and $178,351.77 (Exhibits GSS-02 and GSS-03). That these payments were made did not appear to be disputed by the Trustee.

103 As also submitted by Mrs Smith, the Trustee’s cross-examination of Mr Smith was conducted on the basis that the payments of $90,000.00 and $178,351.77 were made by Mrs Smith.

104 Further, Mrs Smith deposed that she likely paid approximately $12,000.00 in advertising costs relating to the sale of the Broadbeach Property and the Blue Mountain Heights Property, with that estimate comprising:

approximately $2,000.00 paid to the real estate agency “The Professionals Broadbeach” in respect of the Broadbeach Property;

approximately $6,500.00 paid to real estate agency “Peter Snow & Co” in respect of the sale of the Blue Mountain Heights Property; and

approximately $3,500.00 paid to the real estate agency “Colliers” and their related entity, “Diversified Properties”, in respect of the sale of the Blue Mountain Heights Property.

105 Despite estimating advertising costs of $12,000.00, Mrs Smith in her affidavit was only able to provide evidence of three payments. Those payments totalled $8,271.50, were made between 16 September 2015 and 17 November 2015, and were in the amounts of $3,981.50, $1,750 and $2,540 respectively. These payments were each made from a bank account in Mrs Smith’s name to Diversified Properties, a related entity of Colliers who provided advertising services. During cross-examination, Mrs Smith accepted that these 3 transactions were the only transactions she was able to identify referable to advertising costs.

106 The closing submissions of the first respondent further appear to accept that payments totalling $8,271.50 were established. The Trustee does not appear to dispute that Mrs Smith paid $8,271.50 to Diversified Properties in respect of advertising costs, however submitted that the third payment of $3,981.50 was paid by Mrs Smith on behalf of Faloda to advertise the North Street Property. During cross-examination, Mrs Smith could not recall to which property each payment was referable.

107 In the same affidavit Mrs Smith gave evidence that she had paid approximately $40,000.00 in respect of renovations of the Blue Mountain Heights property, including:

Town and Country floor polishing, in the amount of approximately $4,500.00;

the purchase of a ride-on mower, in the amount of approximately $5,000.00;

substantial landscaping and garden maintenance work, in the amount of approximately $10,000.00;

the engagement of arborists in order to care for and preserve an historically significant fig tree located at the property;

the purchase of a large number of truckloads of soil for terracing the rear of the property;

the installation of sprinkler systems;

replacing the carpeting within the house itself;

refurbishing of the external entrance, veranda and timber ceilings; and

other general repairs and refurbishments such as revarnishing of wooden surfaces, rendering and decking.

108 Mrs Smith further deposed that she did not keep any record or receipts of any of these renovation costs and that some of the renovations were “cash jobs”. During cross-examination, Mrs Smith further gave evidence that she did not keep records of the amounts spent on renovations.