FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Aristocrat Technologies Australia Pty Limited v Commissioner of Patents (No 3) [2024] FCA 212

ORDERS

ARISTOCRAT TECHNOLOGIES AUSTRALIA PTY LIMITED (ACN 001 660 715) Applicant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties confer and supply to the Associate of Burley J by 15 March 2024 short minutes of order (marked up to indicate any areas of disagreement) giving effect to the reasons delivered on 8 March 2024, including a timetable for the filing and service of any submissions going to the question of costs.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

[1] | |

[13] | |

[14] | |

[31] | |

[54] | |

[55] | |

[55] | |

[70] | |

[78] | |

[78] | |

[92] | |

[102] | |

[102] | |

[103] | |

[130] | |

[131] | |

[138] | |

[143] | |

[150] |

BURLEY J:

1 This matter has been remitted for consideration of residual issues arising from a decision of the Full Court in Commissioner of Patents v Aristocrat Technologies Australia Pty Ltd [2021] FCAFC 202 (Full Court decision). At its heart is the issue of claims in a patent to an electronic gaming machine (EGM) functioning in a certain way to satisfy the requirement that they be a manner of manufacture within s 6 of the Statute of Monopolies (1623) (21 Jac 1, c 3) as required by s 18(1A)(a) of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth). Tied up with this is a broader question as to the approach to patent claims involving the use of a computer in its implementation.

2 The procedural history is tortuous but may be briefly summarised. A delegate of the Commissioner of Patents determined that the claims were not a manner of manufacture; Aristocrat Technologies Australia Pty Limited [2018] APO 45. The patent applicant, Aristocrat Technologies Australia Pty Limited appealed from that decision pursuant to s 101F(4) of the Patents Act and the decision of the delegate was reversed in Aristocrat Technologies Australia Pty Limited v Commissioner of Patents [2020] FCA 778 (Burley J) (first instance decision). A Full Court subsequently reversed that decision, with two judges (Middleton and Perram JJ, majority decision) giving one set of reasons for determining that the claims were not a manner of manufacture and one judge (Nicholas J, minority decision) providing separate reasons leading to the same conclusion; Full Court decision. The Full Court determined that the matter should be remitted to this Court for consideration of certain outstanding issues in light of its reasons.

3 Special leave to appeal to the High Court was granted, and the High Court considered the matter. Six justices heard the case with the unfortunate result that there was even division between them, three members of the Court deciding that the claims were not a manner of manufacture and that the appeal should be dismissed (Keifel CJ, Gageler and Keane JJ) (dismissing reasons) and three members deciding that they were and that the appeal should be allowed (Gordon, Edelman and Steward JJ) (allowing reasons); Aristocrat Technologies Australia Pty Ltd v Commissioner of Patents [2022] HCA 29 (High Court decision).

4 The consequence of the High Court’s three-all draw is that s 23(2)(a) of the Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth) applies, which provides:

(2) …when the Justices sitting as a Full Court are divided in opinion as to the decision to be given on any question, the question shall be decided according to the decision of the majority, if there is a majority; but if the Court is equally divided in opinion:

(a) in the case where… a decision of the Federal Court of Australia... is called in question by appeal or otherwise, the decision appealed from shall be affirmed…

5 Accordingly, the Full Court decision has been affirmed. This brings into play the remittal order made by the Full Court, which provides that the proceedings be remitted to the primary judge:

…for determination of any residual issues in light of the Full Court’s reasons including any issues which concern the position of claims other than claim 1 of Innovation Patent No 2016101967 (referred to at [8] of the reasons of the primary judge dated 5 June 2020) and the costs of the hearings before the primary judge.

6 In the first instance decision, I decided that claim 1 of innovation patent number 2016101967 entitled “A system and method for providing a feature game” (967 patent) was a manner of manufacture within s 18(1A)(a) of the Patents Act. Paragraph [8] of that decision records an agreement between the parties that if claim 1 of the 967 patent is for a manner of manufacture, then so too are the remaining claims in each of the patents in suit, thereby rendering it unnecessary to consider those other claims. On remitter, the parties agree that the residual issues identified concern whether the following claims (residual claims) are a manner of manufacture:

(a) claim 5 of the 967 patent (as dependent on claims 1, 3 and 4);

(b) clam 5 of innovation patent number 2017101629 (629 patent) (as dependent on claim 1); and

(c) claim 5 of innovation patent number 2017101097 (097 patent) (as dependent on claims 1, 3 and 4).

7 The parties agree that if none of the residual claims are found to be for an invention that is a manner of manufacture, then none of the claims of the 967 patent, 629 patent, 097 patent and a further related patent not the subject of separate submissions by the parties (innovation patent number 2017101098 (098 patent)) will satisfy the requirements of s 18(1A)(a) of the Patents Act.

8 The parties dispute the approach to be taken to the residual claims. Aristocrat contends that the Court should: (a) determine that the residual claims are for a manner of manufacture on the basis of the principles set out in the reasoning of the allowing reasons; and (b) make factual findings as to whether the claimed invention involves a “technical contribution” of the type, it contends, the dismissing reasons “observed to be missing”. The Commissioner submits that the Court should apply the reasoning of the Full Court decision to reach the conclusion, consistent with its finding in relation to claim 1 of the 967 patent, that none of the residual claims is for a manner of manufacture.

9 In broad terms the issues for determination concern: the operation of s 23(2)(a) of the Judiciary Act; the effect of the remittal order; the relevance, if any, of the High Court decision to the determination of the residual issues; and whether, in light of these matters, any of the residual claims are a manner of manufacture.

10 The parties advanced a number of arguments concerning the application of authorities which have considered the principles applicable to ss 18(1) and 18(1A) of the Patents Act. In particular, they refer to High Court decisions in National Research Development Corporation v Commissioner of Patents [1959] HCA 67; 102 CLR 252 (NRDC), Apotex Pty Ltd v Sanofi-Aventis Australia Pty Ltd [2013] HCA 50; (2013) 253 CLR 284 and D'Arcy v Myriad Genetics Inc [2015] HCA 35; (2015) 258 CLR 334 and decisions of the Full Court of the Federal Court in CCOM Pty Ltd v Jiejing Pty Ltd [1994] FCA 396; (1994) 51 FCR 260, Grant v Commissioner of Patents [2006] FCAFC120; (2006) 154 FCR 62, Research Affiliates LLC v Commissioner of Patents [2014] FCAFC 150; (2014) 227 FCR 378, Commissioner of Patents v RPL Central Pty Ltd [2015] FCAFC 177; (2015) 238 FCR 27, Encompass Corporation Pty Ltd v InfoTrack Pty Ltd [2019] FCAFC 161; (2019) 372 ALR 646, Commissioner of Patents v Rokt Pty Ltd [2020] FCAFC 86, (2020) 277 FCR 267 and Ariosa Diagnostics, Inc v Sequenom, Inc [2021] FCAFC 101; (2021) 391 ALR 473.

11 The version of the Patents Act applicable to the patents in suit is that which follows the commencement of the Intellectual Property Laws Amendment (Raising the Bar) Act 2012 (Cth).

12 For the reasons set out below I have concluded that in determining the residual issues in light of the Full Court’s reasoning, I am obliged to conclude that none of the residual claims is a manner of manufacture.

13 The priority date of the 967 patent, 629 patent and 097 patent (the patents) is 11 August 2014. Each derives from patent number 2015210489 filed on 10 August 2015 and each has materially the same specification, with different sets of claims. To assist in understanding the Full Court decision and High Court decision, I reproduce in this section parts of the first instance decision concerning the common general knowledge and the patent specification.

2.1 The agreed common general knowledge

14 For the purposes of the hearing at first instance, the parties prepared an agreed statement of the common general knowledge as at the priority date of the patents, the substance of which is set out in Section 3 of the first instance decision. For convenience, it is reproduced below.

Components and Features of an EGM

15 At August 2014, an EGM was a physical device that was available for sale to licenced venues such as casinos, hotels and clubs. EGMs typically consisted of:

(a) a central display area or screen that displays the game(s) to be played and other game-related information (for example, prizes won and available credits);

(b) relative to the central display area or screen, upper and/or lower display areas of screens that display various information about the game in the cabinet, including the name of the game, the supplier and other pertinent information;

(c) a random number generator;

(d) a game controller which controlled gameplay by executing software stored in memory;

(e) buttons for user interaction, either touch screen or physical buttons;

(f) a credit input mechanic, being either a cash note input or ticker reader;

(g) a coin out or ticket out mechanic;

(h) artwork featured above the display in digital form as well as artwork in hardcopy on the belly of the EGM; and

(i) speakers to play music, sound effects and announcements.

16 In 2014, although most EGMs comprised certain core physical or hardware components, such as those described above, including computer components, they were distinguished from each other by the way in which features were introduced to utilise the physical or hardware components to provide different products that would engage and entertain users in different ways.

Reels

17 At August 2014, an EGM commonly consisted of five reels of symbols being displayed, each of which spun vertically and stopped at random positions. The concept of the “reel” evolved from the old mechanical games where there was physically a reel carrying a fixed number of symbols displayed in an area showing three symbols on each reel at a time. The symbols were arranged on the reels in a fixed order. The player won or lost depending upon the appearance of predefined symbol combinations and/or particular types of symbols, such as scatters (which provide an award wherever they appear) or wilds (which substitute for other ordinary symbols).

18 Until the 1980s, EGMs used mechanical or electro-mechanical technologies. In these, the different symbols were usually printed in a specified order on strips fixed to the circumferential surface of the reels. An image of an example of reels of this type of mechanical and electro-mechanical reels is below:

19 The number of possible combinations of symbols in EGMs using mechanical or electro-mechanical technologies was limited by the size of the reels and the strips of symbols that fit them.

20 In the 1980s, EGMs started using electronics, including computers, electronic circuitry and electronic display screens such as video displays. In these, the different symbols appear on the electronic display in the same way as traditional spinning reels although they are in fact virtual reels or video reels. The number and distribution of the symbols on the virtual reel strips is part of the design of the game that is ultimately reflected in the game software.

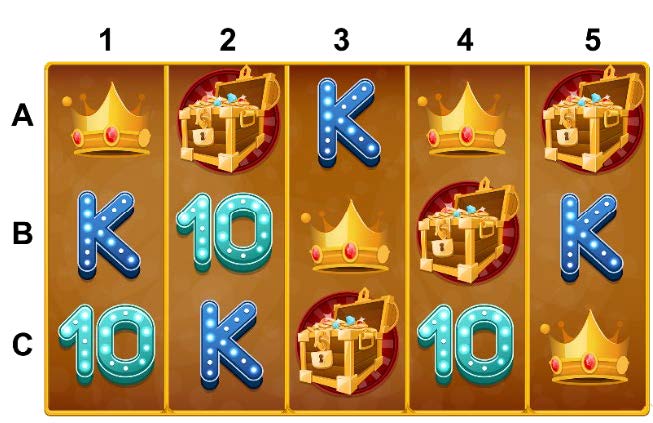

21 The five reels of symbols commonly found in EGMs in 2014 were generally arranged so that the symbols were displayed in a grid or matrix following the completion of a spin. In identifying the symbols in such a grid or matrix, each vertical line of symbols was a column referred to as a reel and each horizontal line of symbols was often referred to as a row. For example, in the following grid or matrix of symbols, the columns are reels numbered 1 to 5 and the rows are designated A to C:

22 The number of possible combinations of symbols in an EGM using virtual or video reels is in principle unlimited.

Win Lines on EGMs

23 EGMs function by a player inserting credits, in the form of money or some other form of payment, which allows for play to commence. A player is able to select the value of each bet he or she is prepared to make. A win is evaluated by having regard to the amount wagered and to occurrences of a winning symbol combination on predefined lines (also known as pay lines or win lines). A player can choose to place a wager to cover one or more win lines.

24 At August 2014, an EGM’s reel strips defined the set order in which symbols will appear on the various reels, based on the randomly selected stop location generated for each of the five individual reels. Each of the five reels was independent from the other reels, and the strips of symbols that appeared on one reel could be the same or different to the symbols that appeared on the other reels within that same game, depending upon the design of the reel strips. The specific number of given symbols (the “weighting” of symbols in comparison to other symbols on the reel) makes certain combinations more or less likely to be generated upon a random spin than other combinations.

25 The total number of symbols on a given reel is used to define its “reel strip order”, the order of symbols from stop position 0 (or stop position 1) to stop position (n), being defined by the game designer and comprising all symbols that may appear on the reel. Theoretically, there is no limit on the number of symbols on a reel, though in practice limits arise for ease of game design.

26 Therefore, at August 2014, a virtual reel strip had nominal stop positions. Each stop position corresponded to a symbol. The total number of symbols (i.e. stop positions) was the “reel strip order” from stop position 0 or 1 to stop position (n). The composition of symbols on each reel strip (i.e. what symbol is allocated to each stop position) was determined by the game designer.

27 At August 2014, a random number generator was used to determine the stop position for symbols on virtual reels. A stop position is independently determined for each of the five reel strips. The stop position of one reel strip did not affect the stop position of any other reel strip.

28 There were, at August 2014, numerous win lines that could be wagered, and the grid of symbols was used to determine whether appropriate winning combinations had been formed on these win lines. Winning combinations could also be formed if a certain symbol appeared anywhere in the grid (without reference to win lines). These are commonly called “scatter” symbols and were common in most EGMs at August 2014. EGMs often had different bonus triggering events or award payouts based on the quantity of scatter symbols of the same type. For example, three scatter symbols could pay 100 credits while four scatter symbols could pay 250 credits.

29 Since the introduction of gaming machines using electronics, different ways of stimulating player interest became common, especially through the use of free games, bonus games or secondary games in addition to the main or base game. A common way for players to qualify for these features was for them to be awarded when a specific symbol (including, for example, a scatter symbol) or a particular combination of symbols appeared in the main or base game when played. The use of scatter symbols was a typical means to trigger such features.

Regulatory standards

30 The gaming industry in Australia is (and was at August 2014) regulated by state-based authorities. There were, at August 2014, a set of national standards that apply to EGMs, the “Australia New Zealand Gaming Machine National Standard”. These regulated the minimum return to player. This is the theoretical proportion of money that must be returned to players over the entire lifecycle of a particular EGM

31 At the first instance hearing the parties agreed that the specification of the 967 patent is sufficiently similar to the specifications of the 629 patent and 097 patent to be used for the purpose of the analysis; first instance decision at [8]. In Section 4 of the first instance decision the specification of the 967 patent was summarised in the terms below.

32 The 967 patent is entitled “A system and method for providing a feature game”. The field of the invention is said to relate to a gaming system and a method of gaming. The “Background to the Invention” states (page 1 lines 12 – 17):

In existing gaming systems, feature games may be triggered for players in addition to the base game. A feature game gives players an additional opportunity to win prizes, or the opportunity to win larger prizes, than would otherwise be available in the base game. Feature games also offer altered game play to enhance player enjoyment.

A need exists for alternative gaming systems.

33 The “Summary of the Invention” contains a consistory clause in the same terms as independent claim 1 (reproduced in section 3.2 below) and dependent claims 2 – 5. There follows a brief description of figures 1 – 10B. Thereafter the “Detailed Description of a Preferred Embodiment of the Invention” commences with an overview (page 3 lines 17 – 30) by reference to a game structure as follows:

Referring to the drawings, there are shown example embodiments of gaming systems having components which are arranged to implement a base game, from which may be triggered a feature game. In these embodiments, symbols are selected from a set of symbols comprising a plurality of configurable symbols and non-configurable symbols. The gaming system incorporates a mechanism that enables the symbols to be configured. In one example, the gaming system is configured so that a feature game is triggered when six of the configurable symbols are selected for display. The invention is not limited to triggering a feature game only when six configurable symbols are selected, however. In other embodiments, any number of configurable symbols may trigger the feature game.

Furthermore, each of the configurable symbols comprises a variable portion which is indicative of the value of a prize. When the feature game is triggered, the player is guaranteed to win the accumulated value of the prizes indicated by the variable portions of the configurable symbols.

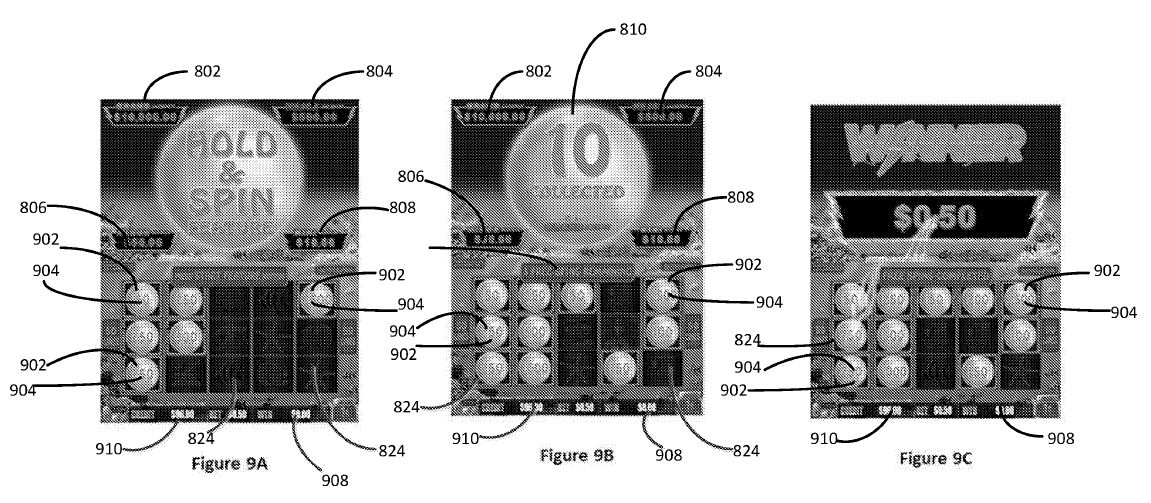

34 An embodiment of a “configurable symbol” is later described in more detail, by reference to figures 9A – C (set out below) as being a symbol that includes a common component and a variable component.

35 The common component in figures 9A – C is the pearl 902 and the variable component is the indicia 904 overlaying the pearl. In this example the indicia numerals on the pearls directly indicate the value of the prize, but in others they may indirectly do so, for example by referring to “major” or “minor”, or the prize may be represented by an icon such as a representation of a car.

36 After the overview, the specification identifies the “General construction of [the] gaming system”. In this part of the specification the EGM architecture is described. The specification says that gaming systems can take a number of different forms. One is a “standalone gaming machine” where all or most of the components required for implementing the game are present in a player operable EGM. In another form, a distributed architecture is provided where some of the components required are present in a player operable EGM and others are located remotely, such as by being networked to a gaming server.

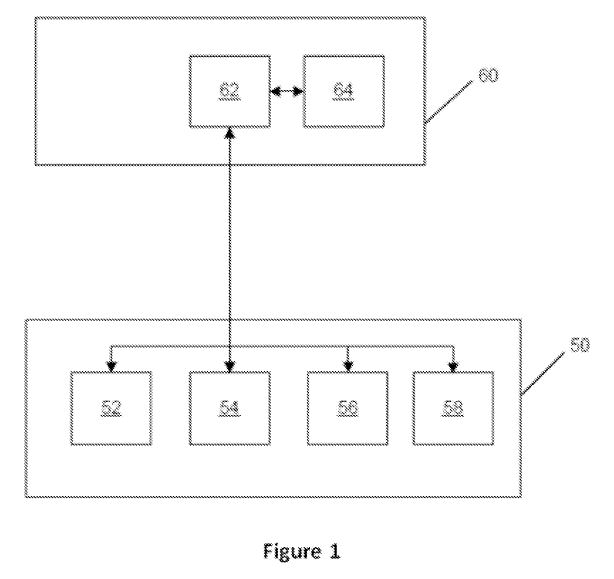

37 Figure 1 is a block diagram of the core components of a gaming system:

38 The specification at page 4 lines 15 – 24 says of these components:

Irrespective of the form, the gaming system 1 has several core components. At the broadest level, the core components are a player interface 50 and a game controller 60 as illustrated in Figure 1. The player interface is arranged to enable manual interaction between a player and the gaming system and for this purpose includes the input/output components required for the player to enter instructions to play the game and observe the game outcomes.

Components of the player interface may vary from embodiment to embodiment but will typically include a credit mechanism 52 to enable a player to input credits and receive payouts, one or more displays 54, a game play mechanism 56 including one or more input devices that enable a player to input game play instructions (e.g. to place a wager), and one or more speakers 58.

39 It may be seen that by having a credit input mechanism, a game play mechanism, speakers and displays, the EGM provides an interactive means of playing a game. That means is computerised having regard to the functions performed by the processor 62 and memory 64. The EGM is a device of a particular construction, known and recognised by those in the art. The specification describes the operation of the machine at page 4 lines 26 – 38 as follows:

The game controller 60 is in data communication with the player interface and typically includes a processor 62 that processes the game play instructions in accordance with game play rules and outputs game play outcomes to the display. Typically, the game play rules are stored as program code in a memory 64 but can also be hardwired. Herein the term “processor” is used to refer generically to any device that can process game play instructions in accordance with game play rules and may include: a microprocessor, microcontroller, programmable logic device or other computational device, a general purpose computer (e.g. a PC) or a server. That is a processor may be provided by any suitable logic circuitry for receiving inputs, processing item in accordance with instructions stored in memory and generating outputs (for example on the display). Such processors are sometimes also referred to as central processing units (CPUs). Most processors are general purpose units, however, it is also known[n] to provide a specific purpose processor using an application specific integrated circuit (ASIC) or a filed programmable gate array (FPGA).

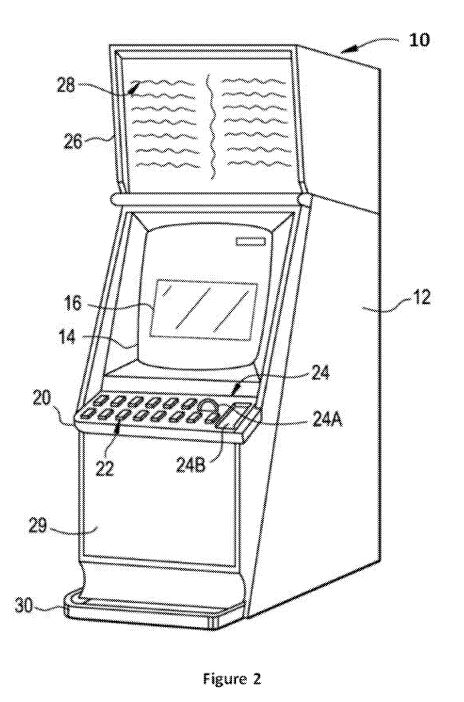

40 A gaming system in the form of a standalone EGM is depicted in Figure 2 as follows:

41 The relevant features are a console 12 having a display 14 on which are displayed representations of a game 16 in the form of a video display unit, liquid crystal display plasma screen or the like. The bank of buttons 22 enables a player to interact during gameplay. There is a credit input mechanism 24, and the top box 26 may carry artwork 28 with pay tables and details of bonus awards.

42 The operative components of a typical EGM are depicted in Figure 3 (not shown), and are described as including a game controller containing a processor mounted on a circuit board. Instructions and data to control operation of the processor are stored in a memory (volatile or non-volatile), which is in data communication with the processor. Hardware meters are included for the purposes of ensuring regulatory compliance and monitoring player credit. A random number generator module generates random numbers for use by the processor. The specification observes that persons skilled in the art “will appreciate that the reference to random numbers includes pseudo-random numbers”.

43 The game controller includes an input/output interface for communicating with peripheral devices including displays, a touch screen, credit input and output means and a printer. The EGM may include a communications interface such as a network card which may send status information, accounting information or other information to a bonus controller, central controller, server or database and receive data or commands from one or more of these.

44 At page 6 lines 6 – 17 the specification states:

In the example shown in Figure 3, a player interface 120 includes peripheral devices that communicate with the game controller 101 including one or more displays 106, a touch screen and/or buttons 107 (which provide a game play mechanism), a card and/or ticket reader 108, a printer 109, a bill acceptor and/or coin input mechanism 110 and a coin output mechanism 111. Additional hardware may be included as part of the gaming machine 100, or hardware may be omitted as required for the specific implementation. For example, while buttons or touch screens are typically used in gaming machines to allow a player to place a wager and initiate a play of a game any input device that enables the player to input game play instructions may be used. For example, in some gaming machines a mechanical handle is used to initiate a play of the game. Persons skilled in the art will also appreciate that a touch screen can be used to emulate other input devices, for example, a touch screen can display virtual buttons which a player can “press” by touching the screen where they are displayed.

45 Figure 4 (not shown) shows the main components of an exemplary memory containing RAM, EPROM and a mass storage device.

46 In one embodiment a server remote from the EGM implements part of the game and the EGM implements another part of the game, thereby the server and machine collectively providing a game controller. A database management server may manage storage of game programs and associated data for downloading or access by the gaming devices. This is referred to in the specification as a “thick client embodiment”.

47 In a “thin client embodiment” as described in the specification, the remote game server implements most or all of the game and the EGM essentially only provides the player interface.

48 The specification explains that other client/server architectures are possible and that further details are provided by reference to two other patents, which are incorporated by reference into the specification. The person skilled in the art “will appreciate that in accordance with known techniques, functionality at the server side of the network may be distributed over a plurality of different computers”.

49 The specification then provides further details of the gaming system by reference to its operation in the placing of a wager in order to play a game:

The player operates the game play mechanism 56 to specify a wager and hence the win entitlement which will be evaluated for this play of the game and initiates a play of the game. Persons skilled in the art will appreciate that a player’s win entitlement will vary from game to game dependent on player selections. In most spinning games, it is typical for the player’s entitlement to be affected by the amount they wager and selections they make (i.e. the nature of the wager).

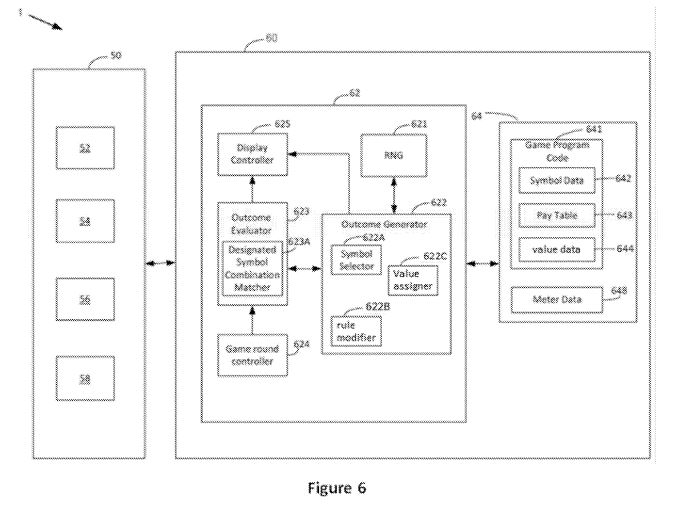

50 The specification states that in Figure 6 (below) the processor 62 of game controller 60 of gaming system 1 is shown implementing a number of modules based on game program code 641 stored in memory 64. It says that “persons skilled in the art will appreciate that various…modules could be implemented in some other way, for instance by a dedicated circuit”. In Figure 6 block 50 is the player interface:

51 Figure 7 provides a flow chart of a sequence of steps and decisions made during the course of a base game with a feature game that may be triggered. It is unnecessary to reproduce it here. Suffice to say that it, and the text that accompanies it, describe the steps whereby a base game is commenced using symbols that include configurable symbols. When a trigger event occurs, which may be when a certain number of configurable symbols appear on the display, a free feature game is initiated whereupon the configurable symbols are held in their display positions and the additional feature game is run. The feature game in operation may use symbols that include the configurable symbols and symbols from the base game, or different symbols. The feature game will play until it and any additional free games are played. Prizes are incremented throughout the play of both the base game and the feature game.

52 In summary, the embodiment describes the steps whereby the EGM:

(a) holds the configurable symbols that triggered the feature game, during the rounds of the feature game;

(b) awards the player with a predefined number of rounds of the feature game;

(c) selects, via the symbol selector, and displays symbols for the display positions that do not currently hold a configurable symbol;

(d) for any configurable symbols that are selected, holds them during further rounds of the feature game;

(e) for each round of the feature game, increases or decreases the number of rounds remaining in the feature game according to whether an additional configurable symbol is displayed in that round;

(f) checks, using the outcome evaluator (which, the evidence discloses, is software programmed to perform this function), whether the number of configurable symbols displayed has reached a predefined number to trigger a jackpot;

(g) pays the accumulated value of the individual prizes as indicated by the variable components of the collected configurable symbols.

53 The specification then describes some further alternatives and examples. The steps described in (a) – (g) are performed on the EGM by the use of a computer system that is programmed to interface with the hardware and firmware elements of the gaming machine. This is made explicit at the conclusion of the specification, which says (page 16 lines 9 – 15):

As indicated above, the method may be embodied in program code. The program code could be supplied in a number of ways, for example on a tangible computer readable storage medium, such as a disc or a memory device, e.g. EEPROM...or as a data signal...Further, different parts of the program code can be executed by different devices, for example in a client server relationship. Persons skilled in the art, will appreciate that program code provides a series of instructions executable by the processor.

54 Although claim 1 is not presently in issue, in order to understand the arguments advanced by the parties it is convenient to set it out in full in the form set out in the first instance decision, with added integers and emphasis:

(1) A gaming machine comprising:

(1.1) a display;

(1.2) a credit input mechanism operable to establish credits on the gaming machine, the credit input mechanism including at least one of a coin input chute, a bill collector, a card reader and a ticket reader;

(1.3) meters configured for monitoring credits established via the credit input mechanism and changes to the established credits due to play of the gaming machine, the meters including a credit meter to which credit input via the credit input mechanism is added and a win meter;

(1.4) a random number generator;

(1.5) a game play mechanism including a plurality of buttons configured for operation by a player to input a wager from the established credits and to initiate a play of a game; and

(1.6) a game controller comprising a processor and memory storing (i) game program code, and (ii) symbol data defining reels, and wherein the game controller is operable to assign prize values to configurable symbols as required during play of the game,

(1.7) the game controller executing the game program code stored in the memory and responsive to initiation of the play of the game with the game play mechanism to:

(1.8) select a plurality of symbols from a first set of reels defined by the symbol data using the random number generator;

(1.9) control the display to display the selected symbols in a plurality of columns of display positions during play of a base game;

(1.10) monitor play of the base game and trigger a feature game comprising free games in response to a trigger event occurring in play of the base game,

(1.11) conduct the free games on the display by, for each free game, (a) retaining configurable symbols on the display, (b) replacing non-configurable symbols by selecting, using the random number generator, symbols from a second set of reels defined by the symbol data for symbol positions not occupied by configurable symbols, and (c) controlling the display to display the symbols selected from the second set of reels, each of the second reels comprising a plurality of non-configurable symbols and a plurality of configurable symbols, and

(1.12) when the free games end, make an award of credits to the win meter or the credit meter based on a total of prize values assigned to collected configurable symbols.

55 The majority decision introduces the subject matter of the proceedings by identifying the issue as being whether claim 1 of the 967 patent is a manner of manufacture within the meaning of s 6 of the Statute of Monopolies, such that it is a patentable invention. It observes that patent law has long held that mere abstract ideas cannot, without more, be the subject of a patent and identifies that part of the Commissioner’s submissions on appeal turned on the extent to which the feature game is an abstract idea. In doing so, the majority described the parameters of the feature game as disclosed in claim 1 as follows:

10 The feature game is defined by integer 1.11. Its commencement is regulated by integer 1.10 which provides for the trigger event which enlivens it and its conclusion by integer 1.12 which explains what happens when it is over and how any relevant prize is to be calculated. Integer 1.10 may be seen as part of the feature game in integer 1.11 but it is ancillary in a sense and it is not suggested that it is in itself inventive. Integer 1.12 is inextricably linked into the feature game in integer 1.11 because it provides for a method by which the prize is calculated, an important part of any wagering-based game. Although the feature game itself is only provided for by integer 1.11 it is useful, so long as these distinctions are borne in mind, to consider the feature game to be constituted by integers 1.10-1.12.

It is therefore convenient to refer, consistent with the majority decision, to the matters defined in integers 1.10 1.12 as ‘the feature game’.

56 The majority decision, having noted earlier that it was not suggested that there is “anything inventive” about claim 1’s EGM except for its feature game, described the operation of the feature game as follows:

12 Returning to the feature game, each time a configurable symbol appears in the display grid at the end of the free game that particular symbol position on the relevant reel stops spinning for any remaining free games and the configurable symbol remains locked in place in any subsequent play of the feature game (i.e. if the player still has any free games left). When the player eventually runs out of free games in the feature game a prize is awarded related to the number of configurable symbols which have been locked in place (integer 1.12). In the preferred embodiment the prize is the sum of the assigned values on the pearls which have been frozen on the display grid but integer 1.12 is consistent with the prize being calculated in some other way.

13 At a theoretical level this description can be implemented in an infinite number of ways because a large number of rules are left wholly unspecified. For example, it is left up to the person implementing the feature game in integer 1.11 to determine the number of configurable symbols that can trigger a feature game and the number of ways that a configurable symbol can be configured. Integer 1.12 also leaves largely open the way in which the prize is calculated at the end of the feature game. So viewed integers 1.10-1.12 do not describe the rules of a single game but rather the defining attributes of a family of games with common attributes. Even so there are external constraints on the rules of any particular feature game falling within the general description in integers 1.11 and 1.12 which the parties agreed a person skilled in the art of constructing an EGM would know. In particular, the EGM must operate in accordance with the Australian/New Zealand Gaming Machine National Standard which regulates the minimum expected return paid out to players over the entire lifecycle of a particular EGM. Whilst this does not constrain the number of games potentially defined by integer 1.11 it does mean that each such game must behave in a particular probabilistic fashion, that is, in such a fashion as will not distort the EGM’s overall performance against the minimum expected return requirement.

57 The majority decision determined that regardless of whether characterised as a family of games with common attributes akin to the rules of a game or a method for increasing player interest in an EGM (and hence increasing revenue to the operator), integers 1.10 – 1.12 are nonetheless an abstract idea. However, the prohibition on patents being granted in respect of abstract ideas of this kind does not extend to inventions which physically embody an abstract idea by giving it some practical application. For example, in the case of a mechanical poker machine, the majority decision noted that the patent protects the invention, which is the poker machine and not the abstract idea consisting of the game which it plays. Insofar as integers 1.10 – 1.12 are concerned, they are not a claim for a particular computer program but instead for an abstract idea to be implemented by means of an unspecified computer program which is to be executed on the game controller referred to in integer 1.6. The majority decision considered that this form of implementation will not give rise to a patentable invention “unless the implementation itself can be seen as pertaining to the development of computer technology rather than to its utilisation”, citing RPL Central at [96] and [102]. It considered that because the integers do not purport to pertain to a development in computer technology and do no more than call for the utilisation of a computer by the person implementing the invention, it follows that the feature game defined by integers 1.10 – 1.12 would not be a patentable invention if they and the game controller in integer 1.6 were the only integers in claim 1. However, as the claim has other features, the majority decision at [18] then posed the question of whether other features in the claim mean that the invention so claimed comprises patentable subject matter?

58 The majority decision notes that the first instance decision posed two questions in considering whether the claimed invention amounted to a manner of manufacture; firstly, was claim 1 for a mere business scheme; and secondly, if it was a mere scheme implemented in a computer, did the invention lie in the manner in which it had been implemented in the computer?

59 The majority decision rejected this approach and proposed an alternate two-step analysis:

26 In cases such as the present we would therefore respectfully favour the posing of these two questions in lieu of those advanced by the primary judge:

(a) Is the invention claimed a computer-implemented invention?

(b) If so, can the invention claimed broadly be described as an advance in computer technology?

27 If the answer to (b) is no, the invention is not patentable subject matter. Of course if the answer to (a) is no, one must then consider the general principles of patentability.

60 The majority decision answered (a) in the affirmative for two reasons. First, because an EGM is a computer. Secondly, the invention claimed in claim 1 is an invention consisting of the feature game in integers 1.10-1.12 implemented on a particular kind of computer which is an EGM. Whilst a computer, in itself, may constitute patentable subject matter, because a computer is a physical invention, the majority decision considered that “it is clear that this is not the invention disclosed in claim 1 and to characterise it that way would be to disregard the feature game called for by integers 1.10 to 1.12” (at [30]). The invention disclosed by claim 1 differs from all other EGMs only by that feature game. As such, it was apparent that the invention disclosed by claim 1 is a computer implementation of the feature game in integers 1.10 – 1.12 where the computer in question is an EGM.

61 The majority decision then explained in some detail why it considered that the EGM is a computer ([32] – [49]) before returning to the question of whether claim 1 is for a computer-implemented invention. In relation to the latter, it said:

50 It follows that the EGM in Claim 1 is a computer. It does not follow automatically that Claim 1 is a computer-implemented invention. As we have said, there is no doubt in principle that a computer may constitute patentable subject matter although it is difficult to see that a claim for such a computer would not fail for want of novelty and inventiveness. But there is a distinction to be drawn between a claim for an invention which is a computer and a claim for an invention which is implemented on a computer. Both may take the form of what appears to be a claim for a computer. Indeed, that is precisely what has happened in this case.

51 Ascertaining which side of this line such an invention falls on turns on identifying the substance of the invention. In this case, are the 12 integers of Claim 1 to be characterised as a computer which is the EGM or are they to be characterised as a feature game implemented on the computer which is the EGM? It is this which is the question of substance. The form of the 12 integers does not allow one to choose between these two characterisations for they sustain both: an EGM with a feature game implemented on it does not cease to be an EGM.

62 The majority decision continued by noting that the only aspect of claim 1 which is said to be inventive is the feature game and what makes the invention different to all other kinds of EGM is that feature game. Accordingly, whilst it is correct to say that claim 1 is for an invention which is a computer, that description would be incomplete because it ignores the relevance of the feature game in integers 1.10 - 1.12. The majority decision reasoned (at [55]) that instead the correct characterisation of the invention claimed must account for the fact that the invention is something which includes not only the EGM (integers 1.1 – 1.9) but also requires the composition of computer code providing for the feature game on that EGM (integers 1.10 – 1.12). The invention cannot be solely the EGM itself (which it said had been found at first instance) but neither can it be solely the feature game. The characterisation must account for the way in which the feature game is integrated into the EGM by way of the game controller:

56 What is the relationship which emerges from the fact that the feature game in integers 1.10-1.12 is to be executed on the EGM? It is a relationship of implementation. What this purpose-specific but extremely common computer does is play the feature game. Consequently, the substance of the invention disclosed by Claim 1 is that feature game implemented on the computer which is an EGM. It is therefore a computer-implemented invention.

(Emphasis added)

63 After answering question (a) of the two-step analysis in the affirmative, the majority decision then turned to question (b) as follows:

57 As we have already observed, integers 1.10-1.12 embody an abstract idea which may be characterised both as a set of rules defining a family of games and as a business scheme for increasing player interest in an EGM. As such its implementation in the computer which is an EGM cannot constitute patentable subject matter unless it represents an advance in computer technology.

(Emphasis added)

64 In answering question (b), the majority decision noted that integers 1.10 – 1.12 leave it entirely up to the person designing the EGM to do the programming which gives effect to the family of games which those integers define. This, it concluded, compels the conclusion that claim 1 pertains only to the use of a computer and not to an advance in computer technology. The majority decision considered as irrelevant to the question, Aristocrat’s proposition that the invention improves player engagement or increases subjective satisfaction. The majority decision further rejected Aristocrat’s submission that changes in the reel structure (in claim 3 of the 967 patent, but not claim 1) and the idea of configurable symbols (in both) were to be seen as advances in computer technology. They ultimately considered that while those matters may be advances in gaming technology, they are not advances in computer technology.

65 The majority decision then considered Aristocrat Technologies Australia Pty Ltd v Konami Australia Pty Ltd [2015] FCA 735; (2015) 114 IPR 28 (Konami 1) (Nicholas J), a decision where the claims in suit also concerned an EGM. A validity challenge mounted in that case on the basis of a lack of manner of manufacture was rejected by the Court. In the first instance decision the claims in suit in Konami 1 were considered to be analogous to claim 1 of the 967 patent and the reasoning of Nicholas J was not plainly wrong, such that I was disposed to follow it. While the majority decision noted that the challenge to the patentability of the invention in Konami 1 was not put in the same way as that advanced before the Full Court, nonetheless, they accepted (at [79) that there is no conceptual distinction between the invention claimed in the 967 patent and that claimed in the patent the subject of Konami 1.

66 The majority, however, went on to note:

80 It may be that the trial judge in Konami worked on the assumption that because the apparatus disclosed by the patent was a new and useful gaming machine that it was not also a computer, however, this is by no means clear. In our respectful opinion, in any event, Konami is to be understood as a case in which the question of computer implementation was not addressed.

67 Given that the majority decision considered there to be no conceptual distinction between the invention claimed in the 967 patent and that claimed in Konami 1, it may be inferred that the majority would equally have concluded that it failed the two-step analysis. However, it did not address the point directly.

68 The majority decision went on to conclude at [94] that the invention claimed in claim 1 is not a patentable invention before briefly turning to address the notice of contention relied upon by Aristocrat, which is of some relevance to consideration of the remittal order.

69 The majority decision said:

95 …Broadly speaking, the notice of contention asserts that even if the primary judge was wrong to adopt his two step approach or wrong to conclude that Claim 1 was not a mere scheme, nonetheless the invention may be found to disclose patentable subject matter including because it is technical in nature and solves technical problems in, and involves technical and functional improvements to, the operation of EGMs.

96 Mr Shavin submitted that the matters addressed in the notice of contention should be remitted to the primary judge for two reasons: first, because his Honour – having concluded that Claim 1 was not for a mere scheme – did not embark on the alternative analysis and therefore the Full Court does not have the benefit of relevant factual findings; and, secondly, because much of the evidentiary material before the primary judge has not been reproduced in the appeal papers. If the position is as Mr Shavin described, then the notice of contention is procedurally misconceived because the Full Court is not in a position either to uphold it or not to uphold it. Consequently, if it is appropriate that there be a remitter, this has nothing to do with the merits of the notice of contention.

97 Nevertheless, in our view, it is appropriate that the matter be remitted to the primary judge to determine any residual issues in light of the Full Court’s reasons including any issues which concern the position of claims other than Claim 1 (identified at [8] of his Honour’s reasons).

70 The minority decision provides a summary of the cases where patent claims to mere discoveries, abstract ideas, information or schemes have been found not to be patentable. It first refers to Grant where it was held that a scheme for protecting assets from creditors was not patentable and then moves to each of Research Affiliates, Encompass and RPL Central, noting that each of these cases draw from the reasoning of the High Court in NRDC and the need to find an “artificial effect” resulting from the use of the method the subject of the relevant claims.

71 After further analysis, the minority decision observes that for the purpose of determining whether the invention produces the artificially created state of affairs referred to in NRDC and considered in Research Affiliates at [115] – [119], it will often be useful to ask whether the invention solves a technical problem or makes some other technical contribution to the field of the invention. The minority decision summarised the test to be considered as follows:

118 Mere business schemes, and abstract ideas or information, have never been regarded as sufficiently tangible in character to constitute patentable subject matter. Implementing the scheme, idea or information in a generic computer utilising its well-known and well-understood functionality does not change its fundamental character. But once a scheme is given practical effect and transformed into a new product or process which solves a technical problem, or makes some other technical contribution in the field of the invention, it may no longer be considered a mere scheme.

119 Ultimately, the question is whether what may have begun as a mere scheme, an abstract idea or mere information, has been transformed in some definite and tangible way so as to result in a product or method providing the required artificial effect. There must be some technical contribution either in the field of computer technology (eg. An improvement in processor, memory or display technology) or in some other field of technology to which the invention belongs. As the authorities to which I have referred to make clear, that transformation is unlikely to be achieved by taking an inherently unpatentable scheme and implementing it utilising generic computer technology for its well-known and well-understood functionality that does not involve any ingenuity in the way in which the computer is utilised.

120 It follows, for example, that a computer implemented scheme or idea (eg. An algorithm) for running a refrigerator in a more energy efficient way may be patentable even though the relevant technical contribution resides in the scheme or idea rather than in the workings of the computer with which the scheme or idea is implemented. If the result of the contribution of the refrigeration engineer who conceived the scheme or idea, and the computer engineer who implemented it using conventional (or generic) computing technology, is a more energy efficient refrigeration system, then the invention may well be patentable even though the technical contribution resides in the field of refrigeration technology rather than computer technology. Similarly, in the case of EGMs, patentable subject matter may be found to exist in the way in which a gaming system or machine functions even though a computer engineer may not consider that there has been any advance in the field of computer technology.

72 The minority decision disagreed with the majority decision in relation to Konami 1. It considered that there were findings made in that case, in the context of consideration of inventive step, to the effect that the invention claimed solved a number of well-known problems associated with progressive jackpots. Those findings were relevant to a manner of manufacture such that neither the problem nor the solution was abstract, and the solution could not be properly characterised as a mere scheme or rule of a game – “the invention provided a technical solution (using a random number generator) to a practical, real-world problem confronting gaming machine operators” (at [123]). In this regard, Konami 1 should, the minority decision considered, be understood as a case in which a gaming machine or gaming system that provided a technical solution to a practical problem in the field of gaming technology was proper subject matter of a patent.

73 In relation to the claim 1 of the 967 patent, the minority decision finds that the gaming machine defined by claim 1 includes five integers (integers 1.1 – 1.5) and at least part of integer 1.6 which were, at the priority date, common general knowledge features of EGMs. It finds that there is nothing new in an EGM that includes a game controller that executes game program code (integer 1.7) which enables play in the base game to trigger a feature game which will consist of a number of free games (integers 1.8 – 1.10). It also finds that at the priority date it was common for free games (or “free spins”) to be awarded based on a trigger event occurring in base game play.

74 The minority decision accepts that a “configurable symbol” as referred to in integers 1.6, 1.11 and 1.12 is a symbol that can be reconfigured during the course of play so as to change the prize value assigned to that symbol:

132 …The game controller assigns prize values to the configurable symbols as required during play. The configurable symbols which appear when the feature game is triggered and any additional configurable symbols collected during the playing of the feature game will represent the accumulated prize value which will be awarded when the feature game ends. In some embodiments described in the specification the configurable symbols will consist of a common component (eg. a pearl) and a variable overlaying component in the form of an indicia of prize value.

The Commissioner’s expert accepted that configurable symbols, of the kind referred to in the 967 patent, had not to have been used in EGMs before the priority date.

75 The minority decision does not adopt the two-step analysis of the majority decision. However, like the majority decision, it considered that the EGM described and claimed is either a computer or an apparatus that incorporates a computer and, regardless of which it is, the substance of the invention as described and claimed resides in the game program code which embodies a computer implemented scheme or set of rules for the playing of a game. Embodied in the game code are the instructions that determine the course of play for both the base game and the feature game and whether those instructions are expressed in machine readable form, or in some different language, they represent abstract information in the nature of a scheme or set of rules governing the playing of the game. The minority decision then posed the question of whether there is anything about the way in which the game code causes the EGM to operate which can be regarded “as having transformed” what might otherwise be regarded as purely abstract information encoded in memory into something possessing the required artificial effect. The minority decision answered that question as follows:

141 The specification does not identify any technological problem to which the patent purports to provide a solution. Nor did the expert evidence (insofar as it was made available to us) suggest that the invention described and claimed in the specification was directed to any technical problem in the field of gaming machines or gaming systems. Rather, as the specification makes clear, the purpose of the invention is to create a new game that includes a feature game giving players the opportunity to win prizes that could not be won in the base game. Ultimately, the purpose of the invention is to provide players with a different and more enjoyable playing experience. The invention is not directed to a technological problem residing either inside or outside the computer.

76 The minority decision then turns to whether the gaming machine described and claimed might be regarded as exhibiting “an unusual technical effect” due to the way in which the computer is utilised. It noted that the first instance decision did not involve any specific findings in relation to the use of configurable symbols and whether they were capable of amounting to a technological innovation, concluding:

142 ….The fact that a game is made more interesting to players is not in itself such an effect but there may well be ways in which the computer could be utilised that adds to the attractiveness of the game through the use of unconventional technical methods or techniques which might themselves give rise to patentable subject matter.

143 The extent to which the use of configurable symbols might amount to a technical contribution to the field of gaming technology was hardly touched on in oral argument in this Court. Mr Shavin QC informed us that he did not consider that all of the evidentiary material relevant to this question was before the Court and that the respondent’s preferred approach would be for the matter to be remitted to the primary judge for further confirmation. This would effectively leave the issues arising under the notice of contention (not the subject of findings by the primary judge) unresolved by the appeal. Mr Dimitriadis SC, who appeared for the applicant, submitted that while it was open to the Full Court to deal with the matters raised in the notice of contention, the Commissioner’s position was that this was a matter for the Full Court.

144 In my opinion the appropriate orders in this case require that leave to appeal be granted, the appeal be allowed and the primary judge’s orders be set aside. However, I would remit the proceeding to the primary judge pursuant to s 28(1)(c) of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) to consider whether claim 1 of the 967 patent, or any of the other claims in issue, is a manner of manufacture on the basis that it involves technical and functional improvements to EGMs through the use of configurable symbols of the kind more fully described in the specification. In the circumstances, I agree with the orders proposed by Middleton and Perram JJ.

77 It will be seen that, unlike the majority decision, the minority decision left room for a subsequent finding that the configurable symbols in claim 1 might amount to a technical contribution to the field of gaming technology. Such a finding was similarly left open in relation to what has now been termed the residual claims. Furthermore, despite expressing agreement with the terms of the orders proposed in the majority decision, it is apparent that the remitter contemplated in the minority decision was somewhat broader in scope and would involve a further factual inquiry.

78 The dismissing reasons summarise the agreed common general knowledge and claim 1 of the 967 patent. They provide a summary of the law relevant to the question of whether an invention amounts to a manner of manufacture, noting that the High Court determined in NRDC at 269, and affirmed in Myriad at [5] that the terminology of “manner of manufacture” taken from s 6 of the Statute of Monopolies is to be treated as a “concept for case-by-case development” applied in accordance with common law methodology. It is not to be confined to the use of any verbal formula in lieu of “manner of manufacture”, though various formulations have asked whether there is a “vendible product” or an “artificially created state of affairs” (at [23]).

79 The dismissing reasons refer to Grant at [30] – [32], International Business Machines Corporation v Commissioner of Patents [1991] FCA 811; (1991) 33 FCR 218 (IBM), CCOM at 295, RPL Central at [96] – [99]; Encompass at [88] noting :

25 Of course, a claimed invention which serves a "mechanical purpose that has useful results" is not unpatentable "merely because the purpose is in the carrying on of a branch of business". In relation to computers and computer-related technology, it has been held in decisions of the Federal Court that a claimed invention will be a proper subject of letters patent if it has some "concrete, tangible, physical, or observable effect", as distinct from "an abstract, intangible situation" or "a mere scheme, an abstract idea [or] mere intellectual information". It has been held that an artificial state of affairs may also be created if the invention can broadly be described as an "improvement in computer technology", where the computer is integral to the invention, rather than a mere tool in which the invention is performed. These propositions may be illustrated by reference to those decisions.

(Footnotes omitted)

80 The dismissing reasons then refer in further detail to each of these cases, and also to the decisions of the Full Court in Research Affiliates and Rokt.

81 After providing a summary of the first instance decision, the dismissing reasons then summarise the Full Court decision, observing that in the majority decision:

43 Their Honours asked two questions: is the invention claimed a computer-implemented invention; and if so, can the invention claimed broadly be described as an advance in computer technology? As it happened, their Honours answered the first question in the affirmative, finding that an EGM is a computer and the feature game identified in integers 1.10-1.12 is a computer-implemented invention. But their Honours' answer to the second question was "no". While their Honours said that some aspects of the 967 patent – being changes in the reel structure as identified in claim 3 and the idea of configurable symbols – may have been advances in gaming technology, they were not advances in computer technology. Fatal to the claim, in their Honours' view, was the circumstance that integers 1.10-1.12 left it entirely up to the person designing the EGM to do the programming which gave effect to the game or games defined by those integers.

(Footnotes omitted)

82 The dismissing reasons note that while the minority decision reached the same conclusion as the majority decision that the appeal be allowed, the minority decision was reached by asking a different question – namely whether the claimed invention produced an “artificially created state of affairs” which turned on whether the claimed invention “solves a technical problem or makes some other technical contribution to the field of the invention”. The dismissing reasons went on:

46 Nicholas J accepted that "[m]ere business schemes" and abstract ideas or information have never been regarded as sufficiently tangible in character to constitute patentable subject matter, but said that they may become something patentable if the abstract ideas or information are given "practical effect and transformed into a new product or process which solves a technical problem, or makes some other technical contribution in the field of the invention". His Honour rightly said that Konami should be understood as a case in which a gaming machine or gaming system that could be seen to provide a technical solution to a practical problem in the field of gaming was proper subject matter of a patent.

(Footnotes omitted)

83 In this regard, it might be observed that in endorsing the approach of the minority decision to Konami 1, the dismissing reasons implicitly rejected the contention that the decision in relation to the claims in Konami 1 were analogous to the present case, a position that had been adopted by the majority decision in the Full Court.

84 The dismissing reasons further noted that the minority decision expresses reservations as to whether the appeal to the Full Court could be finally determined, and would have remitted the proceeding to determine whether claim 1 of the 967 patent is a manner of manufacture “on the basis that it involves technical and functional improvements to EGMs through the use of configurable symbols of the kind more fully described in the specification” (at [49]).

85 Turning to the invention the subject of the 967 patent, the dismissing reasons note that in accordance with the approach in Myriad, it is necessary to characterise the claimed invention by reference to the terms of the specification having regard to the substance of the claim and in light of the common general knowledge. The dismissing reasons came to the following central conclusions as to the proper characterisation of Aristocrat’s claimed invention:

73 …In the absence of a claim to some variation of or adjustment to generic computer technology to give effect to, or accommodate the needs of, the new game, there is no reason to characterise the claimed invention as other than a claim for a new system or method of gaming: it is only in relation to the feature game that the invention is claimed to subsist. The title of the 967 patent and the field of invention described in the patent specification accurately characterise the invention claimed by Aristocrat. The claimed invention takes its character, as an invention, from those elements of the claim which are not common general knowledge. If that were not so, every EGM conforming to the generic physical and hardware components, including computer components, described in the claim would be patentable simply because it, like every other EGM, allowed a new game to be played. And the only thing differentiating each new claimed invention, as an invention, would be that unpatentable game.

74 Unlike CCOM, the present cannot be said to fall within a category of case in which, as an element of the invention, "there [is] a component that [is] physically affected or a change in state or information in a part of a machine".

75 All members of the Full Court were right to conclude that the subject matter of Aristocrat's claim is not patentable subject matter. It is common ground that the new game devised by Aristocrat, as an idea, is not itself patentable subject matter; and there is nothing in claim 1 that might lead to the conclusion that it has produced some adaptation or alteration of, or addition to, technology otherwise well-known in the common general knowledge.

76 Neither the primary judge nor the Full Court made any finding that any of the integers of claim 1 addressed the exigencies of the physical presentation of the operation of the game devised by Aristocrat. And it is not apparent from the terms of the specification of the 967 patent or claim 1 itself that there is a basis for such a finding. In the absence of such a finding, there is no basis for concluding that the claimed invention is patentable subject matter. It is no more than an unpatentable game operated by a wholly conventional computer, using technology which has not been adapted in any way to accommodate the exigencies of the game or in any other way.

(Footnotes omitted)

86 The dismissing reasons then criticise the two-step analysis proposed by the majority decision as unnecessarily complicating the analysis of the critical issue, which the dismissing reasons note is as to the characterisation of the invention by reference to the terms of the specification:

77 …It is not apparent in the present case that asking whether the claimed invention is an advance in computer technology as opposed to gaming technology, or indeed is any advance in technology at all, is either necessary or helpful in addressing that issue. As Nicholas J explained, the issue is not one of an "advance" in the sense of inventiveness or novelty. In conformity with the decision in N V Philips, the issue is whether the implementation of what is otherwise an unpatentable idea or plan or game involves some adaptation or alteration of, or addition to, technology otherwise well-known in the common general knowledge to accommodate the exigencies of the new idea or plan or game.

87 The dismissing reasons also considered that the suggestion in the majority decision that the claimed invention may be an advance in gaming technology but not an advance in computer technology was an “unnecessary flourish”:

78 …The flourish was unnecessary because there is no reason to conclude from the terms of claim 1 of the 967 patent that it was claiming an advance in gaming technology other than the use of a generic computer to play its new game. It was also neither necessary nor appropriate to speak of advances in gaming technology where one is concerned with a claimed invention that discloses no adaptation or alteration of, or addition to, apparatus well-known in common general knowledge in order to accommodate the exigencies of the new idea. As Nicholas J appreciated, a new idea implemented using old technology is simply not patentable subject matter. It may be noted here that the claim does not disclose any basis on which one might conclude otherwise. On that basis, there was no occasion for the Full Court to consider remitting the proceeding to the primary judge to enable findings to be made as to whether the claimed invention made any technical contribution to the common general knowledge of computerised gaming. Nicholas J had no sufficient reason to think that the remitter he proposed was necessary or appropriate.

(Footnote omitted)

88 In rejecting that the proceeding should be remitted, the dismissing reasons noted that a question arose in the course of argument as to the significance of the configurable symbols. However, because claim 1 of the 967 patent does not disclose that the configurable symbols somehow facilitate the implementation of the game by the EGM in any way different from a generic EGM there is nothing in the claim over and above an instruction to provide such symbols, an instruction which a person skilled in the art could be expected to act upon in light of the common general knowledge.

89 The dismissing reasons further rejected an argument advanced by Aristocrat that the matter should be remitted for determination of the issue whether the claimed invention involved a technical contribution, including in the field of gaming technology, on the basis that the essential question is to characterise the invention, an inquiry which is conducted by reference to the claim in light of the specification as a whole and the common general knowledge and not by reference to further evidence.

90 Aristocrat also sought leave to amend its notice of appeal to assert that the majority decision was in error in failing to remit the proceeding to the primary judge to consider whether claim 1 of the 967 patent is a manner of manufacture. To the extent that Aristocrat sought to embrace the reservations expressed in the minority decision as to the final disposition of the matter, the dismissing reasons state that that should not be entertained ([82]).

91 Having regard to the above, the material part of the dismissing reasons then concludes:

84 Claim 1 of the 967 patent does not disclose any technical contribution to either computer or gaming technology outside the common general knowledge. At best, the claimed invention contains a new game which may enhance player enjoyment; but that cannot be said to amount to a technical contribution or to solve a technical problem in the field of computer or gaming technology. In addition, special leave was granted in this matter on the footing that the appeal would resolve issues of legal principle that were ripe for determination. An appellant in such a case should not expect to be allowed to expand its appeal to extend the final resolution of the matter by remitting it for further litigation of issues of fact not adverted to when special leave was being sought.

(Footnote omitted)

92 The allowing reasons note the concession made by the Commissioner at trial that if the relevant claim involved a mechanical implementation "using cogs, physical reels and motors to create the gameplay" then there would have been no doubt that the relevant claim was a manner of manufacture and that in the 21st century, a law such as s 18(1A) of the Patents Act that is designed to encourage invention and innovation should not lead to a different conclusion where such physical mechanisms are replaced by complex software and hardware that generate digital images. In order to avoid this curious result, the Commissioner attempted to re-characterise claim 1 of the 967 patent as a mere scheme or abstract idea. However, such a characterisation could only be achieved by “filleting from the claim essential and interdependent integers providing for the implementation of the game on the EGM” (at [97]).

93 The allowing reasons cite Myriad and emphasise that the starting point is characterisation of the relevant claim which involves answering the fundamental question of “what is the subject matter of the claim?” and “what are the facts and matters which are relied upon to justify a conclusion that the claim contains an invention?”. This is a question of substance not mere form, requiring a consideration of all of the integers of the claim in light of the relevant facts and matters in the specification. The allowing reasons warn against an artificial characterisation at [103]. An artificially specific characterisation could confine any claim to a mere intellectual idea, which could deny an obvious manner of manufacture by ignoring the means of implementing the idea. Similarly, an artificially generalised characterisation could remove the element of novelty or inventiveness from any claim. This risk is particularly pronounced in the case of claims containing interdependent integers.

94 The allowing reasons go on to consider the low threshold requirement for “an alleged invention” that has emerged from the cases considering the chapeau to ss 18(1) and 18(1A) of the Patents Act by reference to the reasoning of the majority of the High Court in NV Philips Gloeilampenfabrieken v Mirabella International Pty Ltd [1995] HCA 15; (1995) 183 CLR 655 (Brennan, Deane, Toohey JJ) which required a minimal level of “newness” and “inventiveness” before something could be a patentable invention. The allowing reasons distinguish that requirement from the additional requirements contain in s 18 of the Patents Act, including the issue in the present case, which is whether the claim overcomes the separate requirement that the invention so claimed is a manner of manufacture within the meaning of s 6 of the Statute of Monopolies.

95 The allowing reasons note that numerous examples can be given where the proper characterisation of the claim is one that merely involves the use of a machine to manipulate an abstract idea rather than involving the implementation of the idea on a machine to produce an artificial state of affairs and a useful result, citing Grant, Research Affiliates, RPL Central, Encompass and Rokt and saying:

122 Although there was no artificial state of affairs created in any of these cases, and the results in all of these cases are plainly correct, some of the statements explaining the results in these and other cases must be read in the context of what was being decided. For instance, one expression of the characterisation question in some of the cases was whether the implementation of the scheme could be described as "an improvement in computer technology" [footnote: Rokt at [108], Repipe Pty Ltd v Commission of Patents (2021) 164 IPR 1 at [4]. Compare Encompass at [107] – [110]]. A better way of expressing the point in such cases, consistent with the ultimate single question of whether there is a manner of manufacture within s 6 of the Statute of Monopolies, would be to ask whether, properly characterised, the subject matter that is alleged to be patentable is: (i) an abstract idea which is manipulated on a computer; or (ii) an abstract idea which is implemented on a computer to produce an artificial state of affairs and a useful result. The artificial state of affairs and useful result may be a physical change in something, but it need not be. The artificial state of affairs may be an improvement in computer technology, but it need not be. It is enough that the artificial state of affairs and useful result are created by "the way in which the method is carried out in the computer"[footnote: RPL Central at [104]].

(Footnotes inserted)

96 The allowing reasons contrast these decisions with examples where there is an idea implemented on a computer to produce an artificial state of affairs and a useful result. One example is in CCOM (at [124]). Another is in IBM (at [126]). A further example which is drawn from a decision of the Patents Appeal Tribunal in the United Kingdom is in Burroughs Corporation (Perkins’) Application [1974] RPC 147 (at [125]).

97 The allowing reasons express the view that a characteristic of some of the Australian decisions in relation to the patentability of ideas implemented through the use of computers has been a focus on overseas authorities in which similar questions have arisen, where the statutory hinterland is different to that in Australia. In the United Kingdom the law as developed under the Patents Act 1977 (UK) following its entry into the Convention on the Grant of European Patents (1973) and in decisions of the European Patent Office Technical Board of Appeal, has led to a shift which has introduced as a requirement for an invention that there be a contribution having a “technical character” which is absent from Australian law ([128]). Similarly, §101 in Title 35 of the United States Code is expressed in very different terms from s 18 of the Patents Act ([129]).

98 The allowing reasons then consider claim 1 of the 967 patent: