FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Native Extracts Pty Ltd v Plant Extracts Pty Ltd (No 2) [2024] FCA 106

Table of Corrections | |

In paragraph 27, in the first sentence, the words “(defined as Confidential Information)” have been added after the word “misused” | |

26 February 2024 | In paragraph 77, in the first sentence, the words “or the Trust” have been added after the words “Native Extracts” |

26 February 2024 | In paragraph 186, in the first sentence, the word “However,” has been removed and replaced with “That is because” |

26 February 2024 | In paragraph 198, in the second sentence, the word “per” has been removed and the words “Mitchelmore JJA and Griffiths AJA agreeing” have been replaced with “whom Mitchelmore JA and Griffiths AJA agreed” |

26 February 2024 | In paragraph 242, in the first sentence, the words “is then” have been replaced with “must then be” |

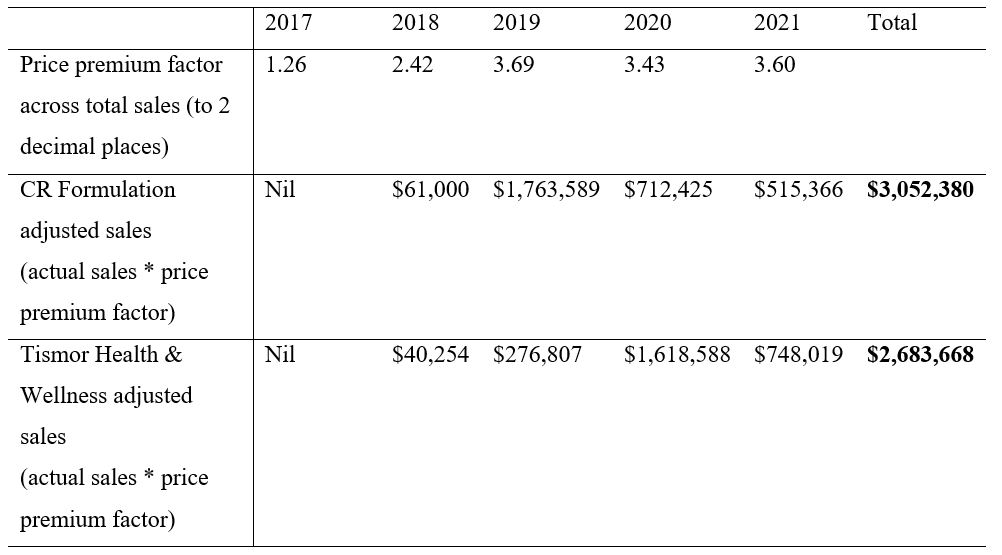

26 February 2024 | In paragraph 277, in the second sentence, the words “2.5 times more than” is replaced with “3.5 times” |

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: | 23 february 2024 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The claim against the Fifth Respondent be dismissed;

2. Pursuant to section 115(4) of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth), the First Respondent pay to the First Applicant the sum of $157,198 as additional damages;

3. The parties are to confer on the form of the remaining orders to be made to give effect to these reasons, including on the question of costs;

4. By 4.00 pm on 28 February 2024:

(a) if the parties can agree on the form of orders to be made, including, if agreement can be reached, on the question of costs, they are to provide to the Associate to Downes J draft orders to be made in chambers; or

(b) if the parties cannot agree on the form of orders to be made:

(i) each party is to provide to the Associate to Downes J their proposed draft orders marked up so as to show the areas of disagreement, including on the question of costs, along with any submissions limited to five pages, and also file and serve any affidavit relevant to the question of costs;

(ii) the proceeding be listed for case management hearing on 1 March 2024 at 10.15 am AEST to resolve the form of orders to be made.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

[1] | |

[25] | |

[33] | |

[33] | |

[36] | |

[39] | |

[39] | |

[65] | |

[66] | |

[73] | |

[77] | |

[78] | |

[82] | |

[82] | |

[90] | |

[95] | |

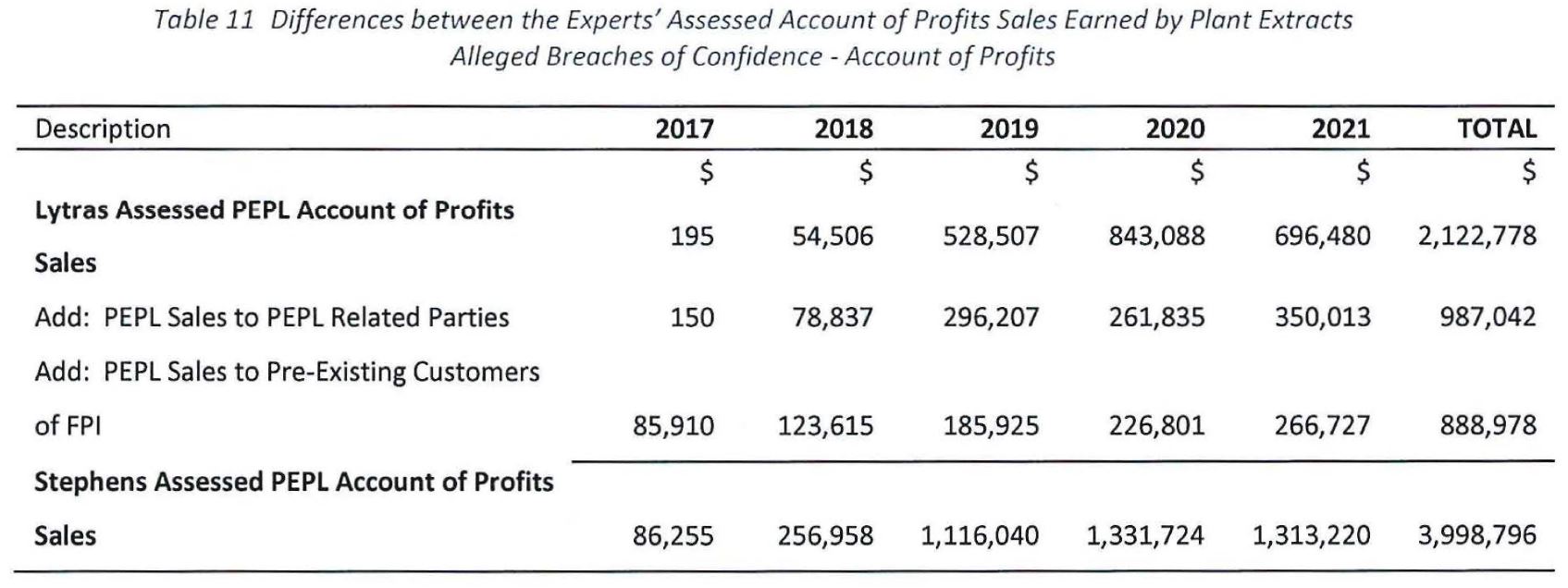

[101] | |

[102] | |

[107] | |

[108] | |

[108] | |

[119] | |

[119] | |

5.2.2 Knowing assistance of breach of equitable and fiduciary duties | [125] |

[132] | |

[132] | |

[180] | |

[194] | |

[197] | |

[197] | |

[202] | |

[202] | |

[204] | |

[208] | |

[220] | |

[226] | |

[230] | |

[232] | |

[232] | |

[239] | |

[243] | |

[262] | |

[263] | |

[277] | |

[288] | |

[295] | |

[296] | |

[298] | |

[307] | |

[309] | |

[311] | |

[315] | |

7.3.3 Conduct after infringement/being informed of infringement: s115(4)(b)(ib) | [321] |

7.3.4 Whether infringement involved conversion: s115(4)(b)(ii) | [327] |

[329] | |

[331] | |

[334] | |

[335] |

DOWNES J:

1 Ms Lisa Carroll and Mr Ross Macdougald, the second respondent, met in September 2011. They commenced living together in January 2012. They have six children between them. One of these children is Mr Jordan Macdougald (his son, not hers) who is the fifth respondent and was approximately 17 years old in January 2012. Other children include Mr Zac Carroll and Mr Cianan Joel (or CJ) Carroll (her sons, not his).

2 Mr Ross Macdougald was and remains a director of a company called FPI Oceania Pty Ltd, which is the fourth respondent. As at 2012, FPI was a wholesale distributor of essential oils, vegetable oils and ingredients used in products sold in the cosmetic and pharmaceutical industry. At this time, FPI sold a small number of botanical plant extracts supplied by Hughes & Co, which extracts had been manufactured by third parties. Mr Stephen Hughes was then a 51% shareholder and Mr Ross Macdougald was a 49% shareholder.

3 As a result of their personal relationship, Ms Carroll commenced to work for FPI on a part-time basis (two days a week) in a sales and marketing capacity. Initially, her role included reception duties, and she was also involved in various marketing activities, being an area in which she deposed to having some expertise.

4 During 2012, Ms Carroll and Mr Ross Macdougald had discussions about starting a new business which would manufacture and sell botanical plant extracts.

5 According to Ms Carroll’s unchallenged evidence, botanical plant extracts are derived directly from plants through a variety of extraction methods and “have been around for centuries”. She also deposed that extracts are used extensively in Australia and internationally, including (in 2012) in the beauty sector.

6 Before the first applicant, Native Extracts Pty Ltd, was incorporated, Mr Ross Macdougald told Ms Carroll about a type of extraction machine which he said he had learned about from his Italian oil supplier, Mr Andrea Parodi. More detail about this conversation appears below. Ms Carroll and Mr Ross Macdougald then travelled to Italy and received hands-on training on how to perform cold liquid extractions using the machine on dry eucalyptus leaves.

7 A 2 litre extraction machine was purchased by FPI and installed at its warehouse by Mr Zac Carroll, who was then a university student. In evidence is a manual for the machine, which relevantly states that the machine uses “an innovative solid-liquid extraction technique” and is designed to (inter alia) extract from officinal plants for the pharmaceutical, homeopathic, botanical and cosmetic sectors.

8 On 12 November 2012, Native Extracts was incorporated with Mr Ross Macdougald as the sole director. Native Extracts operated out of FPI’s warehouse, although the two companies had separate businesses. Ms Carroll became a director of Native Extracts on 22 April 2014.

9 Native Extracts was initially engaged in research and development, and it later commenced manufacturing and selling botanical plant extracts for use in products such as food, beverages, cosmetics and pharmaceuticals, using the 2 litre extraction machine referred to above as well as a 40 litre extraction machine acquired in late 2012. Native Extracts launched its first extracts for sale on 20 March 2013, and by her first affidavit, Ms Carroll explained the lengths to which she went at this time to inform customers about the cellular extraction methods being used by Native Extracts as a “clear point of differentiation” from its competitors.

10 On 3 July 2014, the Native Extracts Holding Trust came into existence, with Mr Ross Macdougald and Ms Carroll as its trustees. Certain transactions were entered into between Native Extracts and the Trust. The current trustee of the Trust is the second applicant.

11 Mr Jordan Macdougald was hired by his father in around October 2014 to work as a warehouse assistant for FPI. He gave evidence that he used one of the extraction machines on a limited number of occasions when Mr CJ Carroll was not present in the warehouse, but this was challenged by Mr CJ Carroll. In any event, Mr Jordan Macdougald’s involvement in the Native Extracts’ business was limited, even on his own evidence.

12 The third respondent, Phytoverse Pty Ltd, was incorporated by Mr Ross Macdougald on 15 December 2014, and it also operated a business out of the same warehouse.

13 Ms Carroll and Mr Ross Macdougald ended their personal relationship in about December 2015, and Mr Ross Macdougald agreed to leave the business of Native Extracts.

14 On 31 March 2016, Mr Ross Macdougald, Phytoverse and FPI entered a Deed of Settlement with (inter alia) Native Extracts and the Trust through its then trustees. Mr Jordan Macdougald witnessed his father’s signature on the deed, but he did not read it.

15 Relevantly, the Deed of Settlement contained a restraint of trade clause restraining Mr Ross Macdougald and any entities under his control from competing with the extract business conducted by Native Extracts, undertaking any work in the botanical extracts industry and contacting (inter alia) any current customers and growers of Native Extracts for a period of 12 months (the restraint period).

16 The Deed also contained a confidentiality clause restraining Mr Ross Macdougald, Phytoverse and FPI and “all employees, agents and contractors of Ross, Phytoverse and FPI” from disclosing to any third party “any knowledge, records or understanding of any information, processes, trade secrets, client records, or any other intellectual property used by” (inter alia) Native Extracts in the conduct of its business.

17 The first respondent, Plant Extracts Pty Ltd was incorporated on 8 July 2016. Mr Jordan Macdougald was appointed as one of its directors, along with a solicitor.

18 Like Native Extracts, Plant Extracts is in the business of manufacturing and selling botanical plant extracts, and it commenced operating that business shortly after its incorporation and within the restraint period. For that purpose, it used two extraction machines which had been acquired by Phytoverse in May 2016 and which were of the same kind as those used by Native Extracts. Both Mr Ross Macdougald and Mr Jordan Macdougald were involved in its business.

19 During the restraint period, Phytoverse provided a start-up working capital loan to Plant Extracts which totalled $58,518.04 by the end of that period.

20 Less than a month after the restraint period elapsed, the ownership and control of Plant Extracts was transferred to Mr Ross Macdougald.

21 The applicants commenced these proceedings in July 2020. At the trial held in October 2023, the respondents (other than Mr Jordan Macdougald) did not call any lay witnesses and amended their defence to admit many of the allegations made against them. After closing submissions on 12 October 2023, the respondents (other than Mr Jordan Macdougald) agreed to a form of order which was made on 19 October 2023: see Native Extracts Pty Ltd v Plant Extracts Pty Ltd [2023] FCA 1265 (Native Extracts (No 1)).

22 Despite those orders, the relief to be granted in respect of certain admitted breaches remains to be determined, and certain allegations concerning liability remain in dispute. All issues concerning Mr Jordan Macdougald remain live.

23 For convenience, the respondents (other than Mr Jordan Macdougald and Biologi Pty Ltd, the sixth respondent) will be referred to as the RM respondents.

24 The trial was held in open court.

25 Each of the claims raised in these proceedings (including those which have been admitted) were summarised by the applicants in their closing submissions. I have adopted that summary as follows:

(1) The applicants claim that Mr Ross Macdougald, Phytoverse and FPI breached the restraint of trade clause in the Deed of Settlement by assisting Plant Extracts to compete with Native Extracts, to undertake work in the extracts industry, to supply extracts and to contact Native Extracts’ growers and customers during the restraint period. They further allege that Plant Extracts was under the control of Mr Ross Macdougald during the restraint period and that, as a result, Native Extracts suffered loss and damage (the restraint of trade claims).

(2) The applicants claim that Mr Ross Macdougald and Phytoverse breached the confidentiality clause in the Deed of Settlement by disclosing information to Plant Extracts that was confidential to Native Extracts or the Trust. They submit that, by reason of those breaches, Mr Ross Macdougald also breached his statutory and equitable duties of confidence which arose by reason of his position as a director of Native Extracts and a trustee of the Trust, and that Plant Extracts, Phytoverse and Mr Jordan Macdougald breached their statutory and equitable duties by aiding and abetting, or by being knowingly concerned in, a party to, or knowingly involved in Mr Ross Macdougald’s breaches. They allege that, as a result, Native Extracts or the Trust suffered loss or damage and that Plant Extracts made unlawful profits (the breach of confidence claims).

(3) The applicants claim that Plant Extracts infringed Native Extracts’ copyright in scientific documents which Native Extracts commissioned from Southern Cross University. The applicants allege that Plant Extracts substantially reproduced and modified these scientific documents before sending them to customers and that, as a result, Native Extracts has suffered loss or damage and Plant Extracts has made unlawful profits. The applicants submit that the circumstances warrant an award of additional damages pursuant to s 115(4) of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) (the copyright infringements).

(4) The applicants claim that Plant Extracts and Biologi engaged in misleading or deceptive conduct contrary to ss 18 and 29 of the Australian Consumer Law, being Sch 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (ACL), and they seek declarations, injunctions and orders for corrective advertising. Damages are also sought by Native Extracts (the ACL contraventions).

26 By way of the Second Further Amended Defence (Defence) to the Second Further Amended Statement of Claim (SOC) tendered during closing submissions, the RM respondents and Biologi admit the bulk of the material facts concerning the restraint of trade claims, the copyright infringements and the ACL contraventions.

27 As for the breach of confidence claims, the applicants plead in the SOC that there were four categories of “confidential information” which had been (or were at risk of being) misused (defined as Confidential Information). Those categories are:

(1) the brand, model number and technical features of the extraction machine used by Native Extracts to manufacture its botanical plant extracts “in circumstances where that machine was not ordinarily used for the purpose of manufacturing botanical plant extracts” (which I will describe in these reasons as the pleaded information concerning the extraction machine);

(2) information concerning the methods, formulas and raw materials used by Native Extracts to manufacture its botanical plant extracts – namely Native Extracts’ Extract Log / Formula Book;

(3) information concerning the growers used by Native Extracts to manufacture its botanical plant extracts – namely Native Extracts’ Grower’s Matrix; and

(4) information concerning the customers and prospective customers to whom Native Extracts sold its botanical plant extracts – namely Native Extracts’ List of Suppliers and Customers.

28 By their Defence, the RM respondents and Biologi admit that:

(1) the Extract Log / Formula Book, Grower’s Matrix and the List of Suppliers and Customers are confidential information;

(2) Mr Ross Macdougald breached his contractual, statutory, fiduciary and equitable duties of confidence to Native Extracts and the Trust;

(3) Plant Extracts and Phytoverse were involved in Mr Ross Macdougald’s breach of his statutory duty of confidence to Native Extracts and assisted, with knowledge, in a dishonest and fraudulent design involving Mr Ross Macdougald’s breach of his fiduciary and equitable duties of confidence towards Native Extracts;

(4) Native Extracts has suffered loss and damage by reason of these matters, including the loss of sales of botanical plant extracts that Native Extracts would otherwise have made;

(5) Plant Extracts received profits which were unlawful.

29 At trial, Mr Jordan Macdougald did not challenge any of the matters referred to in the previous paragraph.

30 Because of the manner in which the respondents ran their respective cases, it is not necessary to decide whether Native Extracts or the Trust is the proper applicant for the purposes of the breach of confidence claims (noting that Native Extracts and the Trust advanced cases in the alternative). The respondents either admitted, or did not challenge at trial, the entitlement of Native Extracts to bring the breach of confidence claims, and so I will proceed on that basis.

31 However, all respondents dispute that the pleaded information concerning the extraction machine is confidential information, with the consequence that they deny the alleged breaches and contraventions, and alleged accessorial liability, insofar as those claims relate to the use of that information.

32 Other than the orders made on 19 October 2023, the balance of the relief sought by the applicants is opposed by the respondents. That relief as finally sought by the applicants was contained in a draft order which was handed up at the conclusion of the trial. Other than costs, no relief appears to be sought against Biologi in those draft orders.

33 The applicants relied upon the evidence of Ms Carroll and Mr CJ Carroll. Both prepared affidavit evidence and were cross-examined by the respondents.

34 Mr Jordan Macdougald filed two affidavits and was cross-examined by the applicants.

35 The RM respondents and Biologi did not lead any lay evidence at trial.

36 The applicants adduced the following expert evidence:

(1) the scientific report of Professor Melissa Fitzgerald dated 13 December 2021;

(2) the affidavit of Professor Fitzgerald affirmed 15 June 2022;

(3) the affidavit of Ms Rita Sellars affirmed 27 June 2022;

(4) the forensic accounting report of Mr David Stephens dated 24 June 2022; and

(5) the supplementary report of Mr Stephens dated 7 June 2023.

37 The RM respondents relied on a forensic accounting report prepared by Mr Elia Lytras dated 10 May 2023, which responded to the evidence contained in Mr Stephens’ first report.

38 On 14 September 2023, the forensic accounting experts, Mr Stephens and Mr Lytras, produced a joint expert report pursuant to Orders made by the Court (JER).

39 The applicants’ pleaded case is that the Confidential Information owned by Native Extracts includes the pleaded information concerning the extraction machine. The key facts relating to the extraction machine will now be addressed in more detail than appears above.

40 During 2012, Mr Ross Macdougald told Ms Carroll that “he had found out about a machine in Italy manufactured by Atlas Filtri, from his Italian oil supplier, Mr Parodi. Mr Parodi knew the engineer and patentee... The machine [was] designed to extract soluble substances in a liquid solid material from a product and suspend it in liquid. The process seemed to be established in Italy in the beverage sector, used to produce limoncello”. There is no suggestion that Mr Parodi supplied this information on a confidential basis, or that he has not informed others about this machine (either before or after 2012).

41 On 23 June 2012, Ms Carroll and Mr Ross Macdougald travelled to Italy, and on about 28 June 2012, they received training on how to operate the machine. Ms Carroll deposed that they received hands-on training on how to perform cold liquid extractions using the machine on dry eucalyptus leaves. There is no suggestion that the training was conducted on a confidential basis.

42 Neither Ms Carroll nor Mr Ross Macdougald had experience performing plant extraction processes prior to travelling to Italy, and after doing so, they “reached out to various sources for information, including [Mr] Hughes” in order to learn about botanical extracts. While information about certain extraction solvents and solvent ratios had been provided in their training, Mr Hughes later provided detailed suggestions on extraction mediums and preservatives to consider as well as general advice on the extraction process.

43 As to the extraction machine itself, Ms Carroll deposed that:

The [machine] is built and supplied by a manufacturer's representative in Italy, Atlas Filtri.

The solid (botanical plant matter) is placed in a filter bag, in a suitable container (the extractor) and is covered with extraction liquid. The patent indicates that this can be performed at a variety of temperatures including zero degrees Celsius.

Another way to describe the process utilised by the … machine would be a system using cold liquids within a closed system.

44 It is apparent from her evidence that Ms Carroll has read the patent of which the extraction machine appears to be an embodiment, and that it discloses information concerning extraction methods involving plants; however, the patent itself was not in evidence. Of course, a patent contains information which is in the public domain.

45 Ms Carroll deposed that, whilst undertaking the training in Italy in 2012, the pair was told by an unidentified person that the extraction machine was the first machine of its kind in Australia and had not been used to make botanical extracts. It must be observed that the conversation deposed to occurred around a decade prior to when Ms Carroll’s evidence was ultimately taken. Given the passage of time and the lack of detail concerning the source of the information, I find it difficult to accept this aspect of Ms Carroll’s evidence and accordingly, I place little weight on it.

46 Sometime after visiting the manufacturer, Ms Carroll and Mr Ross Macdougald determined to purchase a 2 litre model of the extraction machine. Ms Carroll deposed that the purchase was made through FPI for €6,000.

47 Ms Carroll deposed that Mr Hughes co-ordinated the purchase and delivery of the machine from the United Kingdom. As FPI funded the purchase and as he had this direct involvement, it may be inferred that Mr Hughes was aware of the brand, model and intended use of the extraction machine. However, there is no evidence or even a suggestion that Mr Hughes was asked or required to keep any information about the extraction machine confidential.

48 Ms Carroll deposed that, when the extraction machine arrived in Australia, Mr Zac Carroll installed and commissioned it at the premises of FPI at some time before 2 August 2012. There is no evidence that Mr Zac Carroll was asked or required to keep any information about the extraction machine confidential.

49 Ms Carroll annexed a manual for the extraction machine, which relevantly states that the machine uses “an innovative solid-liquid extraction technique” and is designed to:

• prepare fluid extracts, mother tinctures, glycerine preparations, oleolites

• extract from officinal plants for the pharmaceutical, homeopathic, botanical and cosmetic sectors

• extract from vegetable substances in the food, diet, zootechnical sectors

• produce fruit and herb spirit

• rehydrate dried vegetables quickly.

(Emphasis added.)

50 It then details the potential uses for the machine as follows:

Particularly suitable for research and analysis laboratories, industries, chemistry, universities, it can treat both dry and fresh materials such as: flowers, leaves, buds, fruit, roots, bark, stems, seeds, officinal plants, herbs and any other vegetable material.

51 After the extraction machine arrived, Ms Carroll and Mr Ross Macdougald started performing research and development at FPI’s warehouse using the machine.

52 Ms Carroll gave this evidence:

I did everything I could to keep the existence and identity of the [machine] confidential, including asking Steve Fawcett, Liam Hampson, my son Cianan Joel Carroll (CJ) and others in the warehouse not to talk about the machine.

53 This evidence is unsatisfactory in many respects. It is not explained by Ms Carroll when she spoke to those people and asked them “not to talk about the machine” (and for how long the machine had been in place when she did this), what position she held at the relevant time, who those “others in the warehouse” were, whether that request was made to others who commenced work at the warehouse at a later date, the substance of what she said to these people on each occasion and how they responded. Without this information, including as to the detail of the words that were used, it cannot be concluded that the circumstances were such as to impose an obligation of confidentiality on those people who were spoken to by Ms Carroll. For example, if the conversations occurred shortly after the extraction machines arrived, it is difficult to elevate a request by the part-time sales and marketing manager employed by FPI to a circumstance which imposes an obligation of confidentiality, especially as Ms Carroll does not appear to have been in any position of authority over the people in the warehouse and Native Extracts did not then exist.

54 Further, it is unclear what Ms Carroll means by doing everything she could, in circumstances where, according to her own evidence, it was not until an unidentified date in 2013, prior to a visit by an outside party to the warehouse, that Ms Carroll took steps to cover up the names of the machines so that the brand and model number could not be seen by those in the warehouse. As to this, Ms Carroll explained:

… I wanted to keep the brand, model number and technical specifications of the machine confidential, so that our competitors would not know that the machine was capable of manufacturing Extracts. At first, this was not a problem, because only Ross, Steve Fawcett, Liam Hampson and I were around the machine. However, in 2013, Chris Oliver from Blackmores visited Native Extracts’ warehouse, and Ross wanted to show Chris the machines. In order to keep our technology confidential, I arranged for all descriptive marks and plates on the 2L and 40L [extraction machines] to be covered up. … Those coverings still remain on the machines at the date of this affidavit.

55 Ms Carroll also gave evidence that a copy of the machine’s operating manual was kept “in or on CJ’s desk” in the warehouse. The copy of the manual in evidence contains multiple references to the machine’s brand, model number and technical specifications, including on the front cover. There is no evidence that there was any attempt to prevent the manual being seen by other employees or by visitors to the warehouse who might have walked past “CJ’s desk”. Indeed, Ms Carroll’s evidence suggests that the manual was seen in 2016 by at least one other employee, a graphic designer. There is no evidence that that employee was instructed to keep confidential any information obtained from the manual.

56 Ms Carroll also gave evidence that it was common for Native Extracts to ask potential partners to sign non-disclosure or confidentiality agreements. While the agreements in evidence define information broadly enough to cover plant and equipment, it does not alleviate my concerns as to the lack of confidentiality of the pleaded information concerning the extraction machine.

57 On 12 November 2012, Native Extracts was incorporated, which was approximately three months after the 2 litre extraction machine was installed at the warehouse. A 40 litre extraction machine was purchased at the end of 2012 and installed at the warehouse.

58 Mr Jordan Macdougald worked in the warehouse for FPI from October 2014, and he saw the extraction machines (although I accept that the machines would have had their brand and model number covered by this time). He gave evidence that he was trained on how to operate the machines, and he also gave evidence as to how to use them. Regardless of whether he used, or was trained on, the machines at this time, there is no evidence or even a suggestion by the applicants that he was instructed by anyone to keep any information about the machines confidential.

59 Ms Carroll and Mr Ross Macdougald had separated by the end of 2015, and they (along with other parties) entered the Deed of Settlement in March 2016.

60 Plant Extracts was incorporated on 8 July 2016. The evidence suggests that in May or June 2016, Phytoverse purchased a 2 litre and 40 litre model of the extraction machine, apparently on Plant Extracts’ behalf.

61 Mr Jordan Macdougald’s evidence was that, during August 2016, the extraction machines were delivered to the warehouse. He deposed that, once the extraction machines arrived, he and Mr Liam Hampson tested the machines and began making extracts. This evidence is consistent with the documentary evidence which shows that Plant Extracts began selling extracts in August 2016.

62 Ms Carroll also deposed that Ms Carla Prendin at Atlas Filtri has confirmed that, other than the machines sold to Native Extracts, Atlas Filtri has only supplied three other extraction machines in Australia, including two that were supplied in 2016. This means that at least one extraction machine has been acquired in Australia by a purchaser other than Native Extracts and Plant Extracts.

63 Ms Carroll also deposed that, to the best of her knowledge, prior to Native Extracts’ purchase of two machines, there were no machines like the extraction machine in Australia. However, the evidence did not establish that if other extraction machines had been purchased and shipped to Australia prior to 2012, Ms Carroll would have been aware of it. This evidence is therefore of no real assistance to the applicants.

64 During her oral evidence and while under cross-examination, Ms Carroll disclosed the brand name of the extraction machine in question.

4.2 Whether breach of equitable duty of confidentiality

65 The applicants accept that, to establish the alleged breaches of the equitable duty of confidence, they must establish that the pleaded information concerning the extraction machine is confidential information as that term is used in equity.

66 An equitable duty of confidence lies in the notion of an obligation of conscience arising from the circumstances in or through which the information was communicated or obtained: Moorgate Tobacco Co Ltd v Phillip Morris (No 2) (1984) 156 CLR 414 at page 438 (Deane J, with whom Gibbs CJ, Mason, Wilson and Dawson JJ agreed); see also Del Casale v Artedomus (Aust) Pty Ltd (2007) 73 IPR 326; [2007] NSWCA 172 at [101] (Campbell JA, McColl JA agreeing).

67 There are four elements that need to be satisfied to establish a claim for breach of confidence: Optus Networks Pty Ltd v Telstra Corporation Ltd (2010) 265 ALR 281; [2010] FCAFC 21 at [39] (Finn, Sundberg and Jacobson JJ); see generally IPC Global Pty Ltd v Pavetest Pty Ltd (2017) 122 IPR 445; [2017] FCA 82 at [189]–[196] (Moshinsky J).

68 First, the information in question must be identified with specificity.

69 Second, the information must have the necessary quality of confidence. This is a question of fact having regard to a range of factors. Such factors include the extent to which the information is known outside the business; the extent of measures taken to guard the secrecy of the information; the value of the information to the applicant and its competitors; the amount of effort or money expended by the applicant in developing the information; the ease or difficulty with which the information could be properly acquired or duplicated by others; and whether the usages and practices in the industry support the claim of confidentiality: see generally Del Casale at [40].

70 Whether the identified information has the necessary quality of confidence has sometimes been described as requiring the information to be relatively secret: see RLA Polymers Pty Ltd v Nexus Adhesives Pty Ltd (2011) 280 ALR 125; [2011] FCA 423 at [42] (Ryan J) adopting Finn J’s observations in Australian Medic-Care Co Ltd v Hamilton Pharmaceuticals Pty Ltd (2009) 261 ALR 501; [2009] FCA 1220 at [632]–[634]. It has also been said that, for information to have a necessary quality of confidence, it must not be something which is public property and public knowledge: Saltman Engineering Co Ltd v Campbell Engineering Co Ltd [1963] 65 RPC 203; [1963] 3 All ER 413 at page 415 (Lord Greene MR).

71 Third, the information must have been received by the respondent in circumstances importing an obligation of confidence. As Campbell JA said in Del Casale at [133] (with whom McColl JA agreed), the question is whether the information was imparted in circumstances where a reasonable person must have realised, on reasonable grounds, that he or she was not free to deal with the information as his or her own or must have realised that he or she could deal with the information only within certain limitations: see also IPC Global at [193].

72 Fourth, there must be an actual or threatened misuse of the information without the applicant’s consent.

73 The first and fourth elements are met in this case and require no further elaboration.

74 By the SOC, the applicants allege that the pleaded information concerning the extraction machine was of a confidential nature, that it was not in the public domain, and that it was the property of Native Extracts or, alternatively, the Trust.

75 However, for the following reasons and as to the second element, the pleaded information concerning the extraction machine did not constitute information which had the necessary quality of confidence and, contrary to the applicants’ pleaded case, it was in the public domain. Further, the pleaded information was not confidential to, and did not constitute trade secrets of, Native Extracts or the Trust such that either of them can claim any entitlement in equity to its protection. That is because, having regard to the facts above:

(1) information about the existence and brand of the extraction machine was the subject of unrestricted disclosures to Mr Ross Macdougald, Ms Carroll, Mr Hughes and Mr Zac Carroll, all prior to the incorporation of Native Extracts and the establishment of the Trust;

(2) information about the brand and technical features of the extraction machine was the subject of an unrestricted disclosure in Italy to Mr Ross Macdougald and Ms Carroll prior to the incorporation of Native Extracts and the establishment of the Trust, including the machine’s ability to perform extractions on eucalyptus leaves;

(3) information about the brand, model number and technical features of the extraction machine are contained in the manual, which was able to be viewed by any entrant to the warehouse when it was on “CJ’s desk”. In addition, there is no basis in the evidence to infer that a version of the manual is anything other than publicly available, or at least that one has been made available on an unrestricted basis to purchasers of the extraction machines. The manual identified that the machine is designed to (inter alia) “extract from officinal plants for the pharmaceutical, homeopathic, botanical and cosmetic sectors” which belies the notion that the machine is “not ordinarily used for the purpose of manufacturing botanical plant extracts”;

(4) information about the technical features of the extraction machine appears to be referred to in its associated patent, which is a public document which Ms Carroll was able to access and review, without any apparent restriction;

(5) having regard to the observations made above in relation to the relevant facts, the evidence was insufficient to demonstrate that information about the brand, model number and technical features of the extraction machine was kept confidential prior to and upon its arrival in Australia, and subsequently in the warehouse, let alone that it was confidential information owned by Native Extracts or the Trust. This is especially as the extraction machine arrived in the warehouse some months prior to the incorporation of Native Extracts;

(6) the evidence was insufficient to establish that all others in the botanical extracts industry (whether overseas or in Australia) were not aware of the extraction machine’s existence including its technical features and ability to manufacture botanical plant extracts, and that not one of them has used the same type of extraction machine for that purpose. This is especially as, even if no-one in the extracts industry was performing cellular extractions prior to Native Extracts doing so (and publicising that fact) in 2013, it does not follow that a competitor did not decide to copy Native Extracts in the interim and was not undertaking this form of extraction process in 2017 or later. This is particularly as Mr Ross Macdougald and Ms Carroll discovered the extraction machine through a contact, learned about its features from public sources and devised extraction processes using the machine. Neither of them appear to have any scientific qualifications, and there is no suggestion that a competitor in the same industry as Native Extracts could not also devise appropriate methods to use the extraction machine to manufacture plant extracts. Nor is there any reason that a competitor could not have discovered the existence of this specific brand and model of extraction machine and its ability to be used for that purpose.

76 As to the third element and having regard to the relevant facts, the evidence does not support a conclusion that the pleaded information concerning the extraction machine was received by Mr Ross Macdougald in circumstances importing an obligation of confidence to Native Extracts or the Trust. Mr Ross Macdougald was told about the extraction machine by a third party before Native Extracts and the Trust existed. There is nothing to suggest that he was prevented from sharing this information with anyone. He was then given further information about the extraction machine in Italy, and was trained to use it, and there was no restriction imposed on him concerning the information which he received or the content of his training (all occurring, again, before Native Extracts and the Trust came into existence). FPI purchased an extraction machine, it was installed at the warehouse and remained in situ for months before Native Extracts was incorporated. Ms Carroll did not depose to discussing with Mr Ross Macdougald that the pleaded information concerning the extraction machine be kept confidential by him.

77 For these reasons, the applicants have failed to establish that Mr Ross Macdougald owed an equitable duty of confidence to Native Extracts or the Trust in relation to the pleaded information concerning the extraction machine. It follows that Mr Ross Macdougald has not breached his equitable duty of confidence in this respect. The applicants also pleaded that Plant Extracts, FPI, Phytoverse and Mr Jordan Macdougald were bound by the same equitable duty of confidence in connection with the extraction machines; however, those claims were not pressed in closing submissions. Had they been pressed, they would have also failed on the basis that (at the least) the second element was not established by the evidence for the reasons given above.

4.3 Whether breach of fiduciary duty

78 The applicants allege that fiduciary duties were owed by Mr Ross Macdougald to each of Native Extracts and the beneficiaries of the Trust. In relation to the pleaded information concerning the extraction machine, this allegation was made on the basis that:

(1) he had obtained the information as a director, and therefore owed a duty not to disclose or use the information for profit without the fully informed consent of Native Extracts;

(2) as trustee of the Trust, he owed the beneficiaries of that trust a duty not to disclose or use any of the information he obtained while trustee for profit without the fully informed consent of the beneficiaries;

(3) the pleaded information concerning the extraction machine was Confidential Information (as defined) to which Mr Ross Macdougald had access to and possession of while he was a director of Native Extracts and trustee of the Trust.

79 However, having regard to the chronology of events established by the evidence (including the timing of the incorporation of Native Extracts and the establishment of the Trust), the applicants did not establish that Mr Ross Macdougald had obtained the pleaded information concerning the extraction machine in his capacity as director or trustee.

80 Further, and for the reasons already given, the pleaded information concerning the extraction machine was not “of a confidential nature and not in the public domain” as alleged by the applicants, with the consequence that it was not information which Mr Ross Macdougald knew or ought to have known was confidential to Native Extracts or trade secrets of Native Extracts and nor was it confidential information owned by Native Extracts such that it was capable of being assigned to the Trust as part of its intellectual property.

81 For these reasons, Mr Ross Macdougald did not breach his fiduciary duties to either Native Extracts or the beneficiaries of the Trust as alleged.

4.4 Whether breach of confidentiality clause

4.4.1 Key provisions of the Deed of Settlement

82 The recitals to the Deed of Settlement include the following statements:

A. Ross and Lisa were in a de facto relationship for the purposes of the Family Law Act 1975 (Cth).

B. During the course of the de facto relationship, Ross and Lisa incorporated the company known as Native Extracts of which:

a. Ross and Lisa are directors; and

b. Ross and Lisa are joint holders of sixty (60) shares in Native Extracts on trust for the Native Extracts Holding Trust.

C. The de facto relationship between Ross and Lisa ended during 2015.

D. Native Extracts sells extracts and native seed oil to various customers.

E. The Native Extracts Holding Trust owned all the intellectual property pertaining to botanical extraction processes including all formulas, research documentation and Southern Cross University analysis.

F. Phytoverse, a company controlled and owned by Ross, sells vegetable oils and other oils to customers.

G. Ross and Lisa are in a dispute about the future direction of Native Extracts and about its management generally.

H. On the terms set out in this Deed, the parties have agreed to a compromise of the dispute in relation to Native Extracts and all of their financial relationship.

83 Clause 3, which concerns the terms of settlement, provides:

3.1 Subject to Clause 3.3 and 3.4 of this Deed, within 2 business days of the date of this Deed:

3.1.1 Ross agrees to relinquish all rights he has (whether beneficially or otherwise) in Lisa’s Entities (including his role as a director, secretary[,] shareholder, appointer, trustee and/or beneficiary) and will transfer all of his right, title and interest in Lisa’s Entities and will sign all necessary transfers (or other documents as may be necessary) to convey the shares and control of Lisa’s Entities to Lisa. Ross further agrees that any descendant, spouse or other lineal or associated person of Ross shall be removed from any entitlement as beneficiary or otherwise that they may have in any of Lisa’s Entities.

…

3.3 In consideration for the transfer and control of Lisa’s Entities, Lisa and Native Extracts jointly and severally agree to pay, and are liable for, the following amounts to the following entities:

3.3.1 to Ross, the RM Loan within 2 business days of the date of this Deed;

3.3.2 to Phytoverse:

3.3.2.1 the Service Charge within 2 business days of the date of this Deed.

3.3.2.2 the Phytoverse Invoices within 2 business days of the date of this Deed;

3.3.2.3 the Phytoverse Management Fee to be paid as follows:

3.3.2.3.1 $60,500.00 (inclusive of GST) within 2 business days of the date of this Deed; and

3.3.2.3.2 $60,500.00 (inclusive of GST) within three (3) months from the date access is granted to the Premises.

84 “Lisa’s Entities” is defined in cl 1 of the Deed of Settlement as follows:

Lisa’s Entities: means:

• Native Extracts Pty Limited

• Onior Pty Ltd;

• Native Extracts Holding Trust;

• Australian Pharmacopoiea Pty Ltd;

• Wild Harvested Organics Pty Ltd; and

• Native Seed Oils Pty Ltd,

which, for the avoidance of doubt includes all plant & equipment, intellectual property and any other assets owned by each and all of the entities.

85 Clause 6 contains the restraint of trade, and provides:

6.1 Subject to clause 6.2, Ross, Phytoverse and FPI and any other entity under his control or that Ross may have an interest in as employee, shareholder or some other beneficial interest hereby agree that subject to payment of the sums set out in paragraph 3.3 of this Deed, that for a period of 12 months commencing on the date of this Deed that Ross, Phytoverse, FPI and any other entity that Ross is in control of be restrained from:

6.1.1 competing with Native Extracts’ current extract business;

6.1.2 undertaking any work in the botanical extract industry;

6.1.3 supplying water soluble botanical extracts;

6.1.4 providing Australian seed oils that will compete with Native Extracts native seed oil range;

6.1.5 undertaking work in the Australian native powder extracts industry; and

6.1.6 contacting any current Native Extracts Customers, Growers, Distributors, Partners or Investors.

6.2 Ross, Phytoverse, FPI or any entity controlled by Ross will be at liberty to trade, supply or sell Oils or other raw material (other than botanical extracts) to any customer (including new customers) and supply Oils or other raw material (other than botanical extracts) to customers that it has customarily supplied such Oils (or raw material) to even if the said customer is also a Native Extracts customer.

6.3 In consideration of the transfer of Ross’s interest in Lisa’s Entities, Native Extracts or any entity controlled by Lisa hereby undertake for a period of 12 months from the date of this Deed to not trade Oils with Natural Beauty Care Pty Ltd or otherwise compete against Phytoverse for the Natural Beauty Care Pty Ltd business in relation to Oil sales.

86 Clause 11, entitled “Confidentiality”, first addresses the confidentiality of the Deed of Settlement within cll 11.1–11.2 as follows:

11.1 Subject to Clause 11.2, the contents of this Deed and all books, documents and information made available to any party for the purposes of entering into this Deed or in the course of the performance of this Deed shall be kept confidential and shall not be disclosed to any other person without the written consent of the other parties, which consent is not to be unreasonably withheld.

11.2 Clause 11.1 shall not apply to any disclosure:-

l l.2.1 required by law;

11.2.2 required by any applicable stock exchange listing rules;

11.2.3 to solicitors, barristers, accountants or other professional advisers under a duty of confidentiality;

11.2.4 by a party to its bankers or other financial institutions, to the extent required for the purpose of raising funds or maintaining compliance with credit arrangements, if such banker of [sic] financial institution first gives a binding covenant to the other parties to maintain confidentiality, in form and substance satisfactory to the other parties;

l l.2.5 required by this Deed or necessary for or incidental to the performance of the obligations and duties contained in this Deed; and

11.2.6 of information in the public domain otherwise than due to a breach of Clause 11.1.

87 Clause 11.3 contains the confidentiality clause which is relied upon by the applicants. It states:

11.3 Ross, Phytoverse, FPI and all employees, agents and contractors of Ross, Phytoverse and FPI shall keep confidential and not disclose to any third party any knowledge, records or understanding of any information, processes, trade secrets, client records, or any other intellectual property used by Lisa’s Entities in the conduct of their businesses and Ross, Phytoverse and FPI will use their best endeavours to ensure compliance with this clause by any applicable person.

88 The “knowledge, records or understanding of any information, processes, trade secrets, client records, or any other intellectual property” which form the subject of the confidentiality clause are not defined in the Deed of Settlement.

89 There is no dispute that cl 11.3 of the Deed of Settlement imposes an obligation of confidence on Mr Ross Macdougald, Phytoverse and FPI. The dispute concerns whether that obligation extends to the pleaded information concerning the extraction machine.

4.4.2 Principles of construction

90 A convenient summary of the general principles of construction is to be found in Mount Bruce Mining Pty Limited v Wright Prospecting Pty Limited (2015) 256 CLR 104; [2015] HCA 37 where French CJ, Nettle and Gordon JJ said at [46]–[51]:

The rights and liabilities of parties under a provision of a contract are determined objectively, by reference to its text, context (the entire text of the contract as well as any contract, document or statutory provision referred to in the text of the contract) and purpose.

In determining the meaning of the terms of a commercial contract, it is necessary to ask what a reasonable businessperson would have understood those terms to mean. That inquiry will require consideration of the language used by the parties in the contract, the circumstances addressed by the contract and the commercial purpose or objects to be secured by the contract.

Ordinarily, this process of construction is possible by reference to the contract alone. Indeed, if an expression in a contract is unambiguous or susceptible of only one meaning, evidence of surrounding circumstances (events, circumstances and things external to the contract) cannot be adduced to contradict its plain meaning.

However, sometimes, recourse to events, circumstances and things external to the contract is necessary. It may be necessary in identifying the commercial purpose or objects of the contract where that task is facilitated by an understanding “of the genesis of the transaction, the background, the context [and] the market in which the parties are operating”. It may be necessary in determining the proper construction where there is a constructional choice…

Each of the events, circumstances and things external to the contract to which recourse may be had is objective. What may be referred to are events, circumstances and things external to the contract which are known to the parties or which assist in identifying the purpose or object of the transaction, which may include its history, background and context and the market in which the parties were operating. What is inadmissible is evidence of the parties’ statements and actions reflecting their actual intentions and expectations.

Other principles are relevant in the construction of commercial contracts. Unless a contrary intention is indicated in the contract, a court is entitled to approach the task of giving a commercial contract an interpretation on the assumption “that the parties ... intended to produce a commercial result”. Put another way, a commercial contract should be construed so as to avoid it “making commercial nonsense or working commercial inconvenience”.

(Footnotes omitted.)

91 In LCA Marrickville Pty Ltd v Swiss Re International SE (2022) 290 FCR 435; [2022] FCAFC 17, Derrington and Colvin JJ (with whom Moshinsky J agreed) observed at [57]–[58]:

It is often identified as “trite law” that the duty of a court when construing a document is to discover its meaning by considering it “as a whole”: Australian Broadcasting Commission v Australasian Performing Rights Association Ltd (1973) 129 CLR 99 at 109 per Gibbs J. The rationale is, as Gibbs J observed, that “the meaning of any one part of it may be revealed by other parts” and, as a corollary, “the words of every clause must if possible be construed so as to render them all harmonious one with another”. In Wilkie v Gordian Runoff Ltd (2005) 221 CLR 522 (Wilkie v Gordian Runoff), a majority of the High Court observed that in construing a policy of insurance, as with other instruments, “preference is given to a construction supplying a congruent operation to the various components of the whole”: at [16] citing Project Blue Sky Inc v Australian Broadcasting Authority (1998) 194 CLR 355 at [69]–[71]. Necessarily, the identification of that construction can only be achieved by ascertaining how a contract or policy might operate as affected by each of the competing interpretations. This “iterative process”, involving “checking each of the rival meanings against the other provisions of the document and investigating its commercial consequences”, “enables a court to assess whether either party’s preferred legal meaning gives rise to a result that is more or less internally consistent and avoids commercial absurdity”: HP Mercantile Pty Ltd v Hartnett [2016] NSWCA 342 at [134] quoting Re Sigma Finance Corp [2010] BCC 40 at [12].

In the interpretive process, the concept of reading a document as a whole involves more than merely acquiring an awareness of the surrounding and related provisions. It requires a substantive intellectual process of evaluating the degree of operative coherence and consistency between a proffered construction and the instrument’s other terms. ...

(Emphasis original.)

92 A contractual obligation may be imposed which requires a person to keep information confidential which extends beyond the subject matter which would otherwise be protected by an equitable duty of confidence: see Zomojo Pty Ltd v Hurd (No 2) (2012) 299 ALR 621; [2012] FCA 1458 at [179(1)] (Gordon J) and the cases cited therein. However, absent an express indication to the contrary, a contractual confidentiality provision will generally be construed as limited only to information which is confidential in character: Isaac v Dargan Financial Pty Ltd (2018) 98 NSWLR 343; [2018] NSWCA 163 at [137] (Gleeson JA, with whom Bathurst CJ and Beazley P agreed). In Maggbury Pty Limited v Hafele Australia Pty Limited (2001) 210 CLR 181; [2001] HCA 70, Gleeson CJ, Gummow and Hayne JJ said at [45]:

Ordinarily, the obligations relating to the use and disclosure of the information would be construed as limited to subject matter which retained the quality of confidentiality at the time of breach or threatened breach of those obligations. An expression of a contrary intent should [be] explicit…

93 Finally, as Lord Diplock said in Antaios Compania Naviera SA v Salen Rederierna AB [1985] AC 191 at 201:

… if detailed semantic and syntactical analysis of words in a commercial contract is going to lead to a conclusion that flouts business commonsense, it must be made to yield to business commonsense.

94 This passage was approved by the majority of the High Court in Maggbury at [43].

95 The applicants assert that the obligation under cl 11.3 attaches to any knowledge, information (and so on) used by Native Extracts or the Trust, such that establishing a breach of cl 11.3 is not dependent on the relevant information being properly characterised as confidential (i.e. the clause can cover subject matter which would not generally be considered as confidential in equity). The necessary consequence of this submission is that Mr Ross Macdougald (for example) would be prevented from ever utilising the extraction machines in the business of Plant Extracts.

96 However, for the following reasons, a reasonable businessperson would immediately reject such a construction as flawed or as a commercial nonsense.

97 First, adopting the applicants’ literal approach has the consequence that cl 11.3 would capture the disclosure of any knowledge or understanding of any information used by Lisa’s Entities in the conduct of their businesses, not just information which is confidential. So, for example, if Native Extracts used a commercially available accounting software program in its business, Mr Ross Macdougald would be prevented by cl 11.3 from disclosing his knowledge of the name of that software program or his understanding of how that program operates to any third party such as Plant Extracts. That would be so even if he had known of the existence of that program before Native Extracts was incorporated and the program had been and continues to be available for purchase by anyone. Such an extreme result cannot have been intended.

98 Second, the Deed of Settlement contains the restraint of trade clause. Construing the Deed as a whole and objectively, a reasonable person would consider that the intention of the parties was that Mr Ross Macdougald would be able to work in the botanical extracts industry and compete with Native Extracts after the expiration of the restraint period. In doing so, it must have been contemplated that he would be able to use commercially available products, such as the extraction machine, and publicly known methods for using that machine, if he resumed work in that industry after the restraint period ended. That is the result which it is assumed that the parties intended as otherwise it would lead to a commercial absurdity.

99 Third, the obligation imposed by cl 11.3 should be construed as limited to subject matter which retained the necessary quality of confidence at the time of breach or threatened breach. In this case and for the reasons given above, the pleaded information concerning the extraction machine has not ever had, let alone retained, the necessary quality of confidence.

100 There is a weak argument that the inclusion of the exceptions in cl 11.2 which apply to cl 11.1, but not cl 11.3, indicate that the parties turned their minds to excluding information in the public domain from the application of cl 11.1 (which is also a confidentiality clause) but not cl 11.3. It might then be said that the failure to have similar exceptions to the operation of cl 11.3 supports the broader construction of that clause. However, such an argument cannot be accepted when one considers the type of information which would be captured by the language used in cl 11.3, and the commercially untenable consequences which follow from such a construction. Further, the failure to include express exceptions to the operation of cl 11.3 is not an explicit expression of a contrary intent of the kind referred to in Maggbury at [45]. Rather, it bears the hallmarks of oversight.

101 For these reasons, the pleaded information concerning the extraction machine does not fall within cl 11.3 of the Deed of Settlement with the consequence that there has been no breach by Mr Ross Macdougald of that clause.

4.5 Whether breach of statutory duty of confidentiality

102 Finally, the applicants contend that, by his alleged disclosure to Plant Extracts of the pleaded information concerning the extraction machine, Mr Ross Macdougald breached his duty owed to Native Extracts pursuant to s 183(1) of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) by reason of his former position as a director of that company.

103 There is no dispute that Mr Ross Macdougald owes a continuing duty to Native Extracts under s 183(1). That section relevantly provides:

A person who obtains information because they are, or have been, a director or other officer or employee of a corporation must not improperly use the information to:

(a) gain an advantage for themselves or someone else; or

(b) cause detriment to the corporation.

Note 1: This duty continues after the person stops being an officer or employee of the corporation.

104 The applicants submit that the disclosure of the details of the extraction machine was a breach of s 183(1) as knowledge of the exact model of extraction machine to be purchased, and its usage in the botanical extracts industry, was obtained by Mr Ross Macdougald because of his position as a director of Native Extracts.

105 However, having regard to the chronology of events established by the evidence (including the timing of the incorporation of Native Extracts), the evidence did not establish that Mr Ross Macdougald had obtained the pleaded information concerning the extraction machine in his capacity as director.

106 For these reasons, Mr Ross Macdougald did not breach his duty under s 183(1) of the Corporations Act as alleged.

107 For these reasons, the breach of confidence claims, insofar as they relate to “the brand, model number and technical features of the machine used by [Native Extracts] to manufacture its botanical plant extracts in circumstances where that machine was not ordinarily used for the purpose of manufacturing botanical plant extracts”, must fail.

5. ACCESSORIAL LIABILITY OF MR JORDAN MACDOUGALD

108 The following is a summary of the key allegations in the case brought against Mr Jordan Macdougald as they appear in the SOC.

109 Shortly after the exit of Mr Ross Macdougald from Native Extracts, Mr Jordan Macdougald incorporated Plant Extracts and commenced the following conduct (which I will call the pleaded conduct):

(1) manufacturing and selling botanical plant extracts in competition with Native Extracts;

(2) undertaking research and development in the botanical plant extract industry;

(3) supplying water soluble botanical extracts;

(4) contacting Native Extracts’ growers to source raw materials to manufacture botanical plant extracts; and

(5) contacting Native Extracts’ customers to sell its botanical plant extracts.

110 From its incorporation and during the restraint period, Plant Extracts engaged Mr Ross Macdougald to assist in carrying out the pleaded conduct.

111 Further or alternatively to the above, prior to the incorporation of Plant Extracts, there was an understanding reached between Mr Ross Macdougald, Mr Jordan Macdougald and Mr Ashley Moore (a solicitor) that:

(1) during the restraint period, Mr Ross Macdougald would assist Plant Extracts and Mr Jordan Macdougald in carrying out the pleaded conduct;

(2) Mr Jordan Macdougald and Mr Moore would act in accordance with the wishes and instructions of Mr Ross Macdougald in carrying out the pleaded conduct; and

(3) after the restraint period ended, Mr Jordan Macdougald and Mr Moore would resign as directors of Plant Extracts and its holding company HGWIT Pty Ltd, transfer their shares in HGWIT Pty Ltd to Mr Ross Macdougald, and Mr Ross Macdougald would become the sole director of Plant Extracts and legal owner of all share capital issued in HGWIT Pty Ltd.

112 From its incorporation, Plant Extracts, Mr Jordan Macdougald and Mr Moore gave effect to that understanding. By reason of this, Mr Ross Macdougald acted as a de facto director and shadow director of Plant Extracts, and Plant Extracts was therefore under his control.

113 By reason of the above matters, Mr Ross Macdougald disclosed the Confidential Information to (inter alia) Plant Extracts and Mr Jordan Macdougald or alternatively there was disclosure of the Confidential Information to Mr Jordan Macdougald by Phytoverse and FPI.

114 By no later than August 2016, Plant Extracts had commenced using the Confidential Information in its business to (inter alia) manufacture, supply and sell botanical plant extracts.

115 The Confidential Information (as defined) in the SOC is, apart from the pleaded information concerning the extraction machine:

(1) the Extract Log / Formula Book;

(2) Grower’s Matrix;

(3) List of Suppliers and Customers.

116 In [50] of the SOC, it is pleaded that this occurred in circumstances where Mr Jordan Macdougald knew, or ought to have known, that:

(1) Mr Ross Macdougald had been a director of Native Extracts and a trustee of the Trust;

(2) Mr Ross Macdougald had recently executed the Deed of Settlement;

(3) the Confidential Information (as defined) was information confidential to, and trade secrets of, Native Extracts or the Trust;

(4) Mr Ross Macdougald obtained the Confidential Information while he was a director of Native Extracts and a trustee of the Trust; and

(5) Mr Ross Macdougald was not permitted to use information he obtained whilst he was a director of Native Extracts and a trustee of the Trust for his own benefit or for the benefit of Plant Extracts, Phytoverse, FPI or Mr Jordan Macdougald.

117 Based on these facts and by the SOC, the applicants allege that Mr Jordan Macdougald:

(1) has, for the purposes of ss 79 and 183(2) of the Corporations Act, aided or abetted Mr Ross Macdougald, or been directly or indirectly knowingly concerned in, or a party to, Mr Ross Macdougald’s breach of his Statutory Duty of Confidence;

(2) was bound by an Equitable Duty of Confidence not to use or disclose the Confidential Information without the consent of Native Extracts or the Trust. However, as already noted, this claim was not pressed during closing submissions;

(3) assisted, with knowledge, Mr Ross Macdougald in a dishonest and fraudulent design, involving the breach of his Equitable Duty of Confidence, his Fiduciary Duty (Confidence) and his Fiduciary Duty (Trustee).

118 It should be observed at the outset that, to the extent that these allegations are premised upon the contention that the pleaded information concerning the extraction machine is Confidential Information, those allegations fail for the reasons given above.

5.2.1 Involvement in a breach of the Corporations Act

119 Section 183(2) of the Corporations Act provides that a person who is “involved” in a contravention of s 183 will also contravene s 183.

120 The term “involved” is defined in s 79 of the Corporations Act, which provides that:

A person is involved in a contravention if, and only if, the person:

(a) has aided, abetted, counselled or procured the contravention; or

(b) has induced, whether by threats or promises or otherwise, the contravention; or

(c) has been in any way, by act or omission, directly or indirectly, knowingly concerned in, or party to, the contravention; or

(d) has conspired with others to effect the contravention.

121 Mr Jordan Macdougald cannot be found to have been “involved” in any of the breaches of the Corporations Act unless he intentionally participated in them: Re PFS Wholesale Mortgage Corporation Pty Ltd; Australian Securities and Investments Commission v PFS Business Development Group Pty Ltd (2006) 57 ACSR 553; [2006] VSC 192 at [390] (Hargrave J) citing Yorke v Lucas (1985) 158 CLR 661 (Mason ACJ, Wilson, Deane and Dawson JJ). That is, the applicants must establish that Mr Jordan Macdougald had actual knowledge at the time of the contraventions of each of the essential matters that go to make up the contraventions, although it was not necessary for him to know that the matters amounted to a contravention.

122 Although constructive knowledge is not sufficient, knowledge of matters giving rise to suspicion and the wilful failure to make appropriate inquiry when confronted with the obvious make it possible to infer knowledge of the relevant essential matters: see Re PFS Wholesale at [390]; Australian Securities and Investments Commission v ActiveSuper Pty Ltd (in liq) (2015) 235 FCR 181; [2015] FCA 342 at [400] (White J).

123 However, it is not sufficient for the purposes of s 79 that a person acquires knowledge of the essential matters which go to make up the contravention after it has occurred and, at that time, fails to take appropriate action even if the effect of that action is to conceal, ratify or knowingly derive benefit from the contravention: see Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Australian Investors Forum Pty Ltd (No 2) (2005) 53 ACSR 305; [2005] NSWSC 267 at [114]–[118] (Palmer J) approved in Digital Cinema Network Pty Ltd v Omnilab Media Pty Ltd (No 2) [2011] FCA 509 at [171] (Gordon J) (upheld on appeal in Omnilab Media Pty Ltd v Digital Cinema Network Pty Ltd (2011) 86 ACSR 674; [2011] FCAFC 166 (Jacobson, Rares and Besanko JJ)).

124 The elements of the contraventions of s 183 which the applicants must demonstrate that Mr Jordan Macdougald had knowledge of are that Mr Ross Macdougald:

(1) was, at the relevant time, a director of Native Extracts; and

(2) acquired the Confidential Information; and

(3) acquired the Confidential Information by virtue of his position as director; and

(4) made improper use of that information; and

(5) made that improper use in order to directly or indirectly gain an advantage; and

(6) gained that advantage either for himself or for some other person or persons; or

(7) alternatively, made that improper use to cause detriment to Native Extracts.

See Smart EV Solutions Pty Ltd v Guy [2023] FCA 1580 at [69] (Derrington J) citing Huang v Wang [2015] NSWSC 510 at [41] (Black J).

5.2.2 Knowing assistance of breach of equitable and fiduciary duties

125 The principles concerning liability for knowing assistance (otherwise referred to as the second limb of Barnes v Addy (1874) LR 9 Ch App 244) are well-established. In broad terms, the applicants must establish that:

(1) Mr Jordan Macdougald possessed the requisite degree of knowledge;

(2) Mr Ross Macdougald’s breaches of equitable and fiduciary duty were dishonest and fraudulent; and

(3) Mr Jordan Macdougald actually assisted Mr Ross Macdougald in the dishonest and fraudulent breaches. With this, it must be shown that he had the intention of furthering that dishonest and fraudulent breach – merely permitting or allowing the breach to occur may be insufficient.

See Digital Cinema Network at [172]–[177] (Gordon J).

126 As the High Court clarified in Farah Constructions Pty Limited v Say-Dee Pty Limited (2007) 230 CLR 89; [2007] HCA 22 at [171]–[178], the following four categories of knowledge are sufficient to establish liability for knowing assistance:

(1) actual knowledge;

(2) wilfully shutting one’s eyes to the obvious;

(3) wilfully and recklessly failing to make such inquiries as an honest and reasonable person would make; and

(4) knowledge of circumstances that would indicate the facts to an honest and reasonable person.

127 The applicants submit that the final three categories apply in the present case. In these reasons, these three categories will be described collectively as the requisite degree of knowledge.

128 The allegation that Mr Jordan Macdougald assisted his father in his dishonest and fraudulent breach ought to be assessed having regard to the principles in Briginshaw v Briginshaw (1938) 60 CLR 336.

129 As will be seen, aspects of the case advanced by the applicants in their closing submissions were not pleaded or opened. They ought to have been if it was to be contended by the applicants that there were facts and circumstances from which it ought to be inferred that Mr Jordan Macdougald had actual or the requisite degree of knowledge required to impose liability on him: see r 16.43 Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth). This is especially as Mr Jordan Macdougald represented himself at the trial.

130 In Say-Dee at [170], the High Court referred to an allegation that a person was liable as a knowing participant in a dishonest and fraudulent design as, “an allegation the seriousness of which means that it ought to have been pleaded and particularised, and the assessment required by Briginshaw v Briginshaw …kept in mind”.

131 In Briginshaw, Dixon J (as his Honour then was) said at pages 361–362:

Fortunately, however, at common law no third standard of persuasion was definitely developed. Except upon criminal issues to be proved by the prosecution, it is enough that the affirmative of an allegation is made out to the reasonable satisfaction of the tribunal. But reasonable satisfaction is not a state of mind that is attained or established independently of the nature and consequence of the fact or facts to be proved. The seriousness of an allegation made, the inherent unlikelihood of an occurrence of a given description, or the gravity of the consequences flowing from a particular finding are considerations which must affect the answer to the question whether the issue has been proved to the reasonable satisfaction of the tribunal. In such matters “reasonable satisfaction” should not be produced by inexact proofs, indefinite testimony, or indirect inferences.

5.3.1 Overarching submissions by applicants

132 The applicants submit that the following facts support an inference that “[Mr] Jordan Macdougald [was] involved in Ross Macdougald’s breach of his Statutory Duty of Confidence and knowingly assisted in a dishonest and fraudulent design involving Ross Macdougald’s breach of his Fiduciary Duty (Confidence), his Fiduciary Duty (Trustee) and/or his Equitable Duty of Confidence” (which are defined terms in the SOC) (the relevant inference).

133 The extraction machines: the first fact relied upon in the applicants’ submissions in support of the relevant inference is that Plant Extracts purchased and uses the exact same 2 litre and 40 litre extraction machines used by Native Extracts.

134 However, for the reasons already given, the pleaded information concerning the extraction machines is not Confidential Information within the meaning of the SOC and the mere fact of the purchase and use by Plant Extracts of the same machines in its business did not constitute a breach of any duty by Mr Ross Macdougald.

135 In any event, there was no evidence that Mr Jordan Macdougald had actual or the requisite degree of knowledge that information about the brand, model number and technical features of the extraction machines constituted information which was not in the public domain (as the applicants allege in the SOC) or that it was confidential information owned by Native Extracts or the Trust. Nor did the applicants establish that Mr Jordan Macdougald had actual or the requisite degree of knowledge that the extraction machines were not ordinarily used for the purpose of manufacturing botanical plant extracts, and that this information was confidential information.

136 To the contrary, under cross-examination, Mr Jordan Macdougald gave this evidence:

Now, we then come to paragraph 44 of your affidavit, where you’re referring to some extraction machines arriving. Now, you know, don’t you, that these machines were ordered and paid for by Phytoverse?---The – the two machines outlined in the – my affidavit?

Yes?---I didn’t at the time. I – I didn’t know at the time who actually paid for them.

But you know that now?---I do know that now. Yes.

[sic] and, again, that was something that – the choosing of those machines wasn’t something that you were involved in?---Well, it’s pretty logical to get the same machines that I had working knowledge of.

Pretty logical. So did you discuss that with your father?---No.

So the machines just turned up?---Essentially, yes.

And were you surprised that they were exactly the same as the ones that you had seen at Native Extracts and ---?---No.

---you say you has [sic] used before?---I – I – I – I wasn’t surprised. No.

You knew, didn’t you, that the reason that they were exactly the same was because the information about what machine to be using and what machine to be ordering was something that Ross had – your father had from his time at Native Extracts?---Well, I just knew you could just go buy the machines. There wasn’t a barrier to entry. It wasn’t – they were, like, an off-the-shelf kind of thing. If you had the contact, then you could buy them.

And you say you know – you knew all about that at the time?---Yes.

But it wasn’t you having any involvement in choosing these machines?---No. But I – yes, I did know that – know that at the time.

But you also knew too, didn’t you, that these were machines that others hadn’t been using for botanical extracts---?---I didn’t know ---

--- other than Native Extracts?---I didn’t know if anyone else was using them or not.

(Emphasis added.)

137 It was not put to Mr Jordan Macdougald that any aspect of this evidence was false. Nor was any evidence adduced by the applicants to contradict this evidence insofar as it relates to Mr Jordan Macdougald’s knowledge. Nor was any submission made by the applicants that this evidence given by Mr Jordan Macdougald should not be accepted and why that is so.

138 The applicants also submit that:

Given the measures taken by Native Extracts to protect the secrecy of the extraction machines, knowledge of the exact model of extraction machine to be purchased could only have been obtained by Ross Macdougald as a result of his position as a director of Native Extracts. There can be no doubt that an honest and reasonable person in Jordan Macdougald’s position would have known that to be the case.

139 However, the use of a commercially available extraction machine by Plant Extracts in a business engaged in manufacturing plant extracts is unremarkable. No suggestion was made by the applicants that Mr Jordan Macdougald knew about the measures taken by Native Extracts to protect the secrecy of the extraction machines, and there was no evidence to support a proposition that an honest and reasonable person in his position would have such knowledge, or why that was so. How then would Mr Jordan Macdougald or an honest and reasonable person in his position know that information as to the exact model of extraction machine to be purchased could only have been obtained by Mr Ross Macdougald as a result of his position as a director of Native Extracts? Other than submitting that there be “no doubt”, the applicants’ submissions do not answer this question.

140 This aspect of the applicants’ submissions is therefore rejected.

141 Absence of research and development: the second fact relied upon in the applicants’ closing submissions in support of the relevant inference is that Plant Extracts “created” its extracts and obtained customers and suppliers without any true initial research and development phase.

142 They submit that Plant Extracts immediately started making extracts after obtaining the extraction machines, selling those extracts to Native Extracts’ customers and purchasing raw materials from Native Extracts’ suppliers. A series of further facts are then listed in [120] of their closing submissions as follows:

(a) Jordan Macdougald pleads in [15(c)(ii)] of his Defence that no research or development in the botanical extract industry was undertaken and gives evidence that immediately after receiving and testing the extraction machines he and Mr Hampson started making extracts;

(b) the evidence set out [above] shows that Ross Macdougald, through Plant Extracts and under the guise of Jordan Macdougald, immediately engaged in a concerted effort to poach Native Extracts’ customers;