FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Greiss v Seven Network (Operations) Limited (No 2) [2024] FCA 98

ORDERS

Applicant | ||

AND: | SEVEN NETWORK (OPERATIONS) LIMITED (ACN 052 845 262) First Respondent LEONIE RYAN Second Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. There be judgment for the applicant against the first respondent in the sum of $37,940.

2. Costs be reserved.

3. Within 28 days the applicant file and serve any evidence and/or submissions in relation to costs, not exceeding five pages.

4. Within 14 days thereafter the respondents file and serve any evidence and/or submissions in response, not exceeding five pages.

5. Within 7 days of receipt of the respondents’ submissions, the applicant file and serve submissions in reply.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

KATZMANN J:

INTRODUCTION

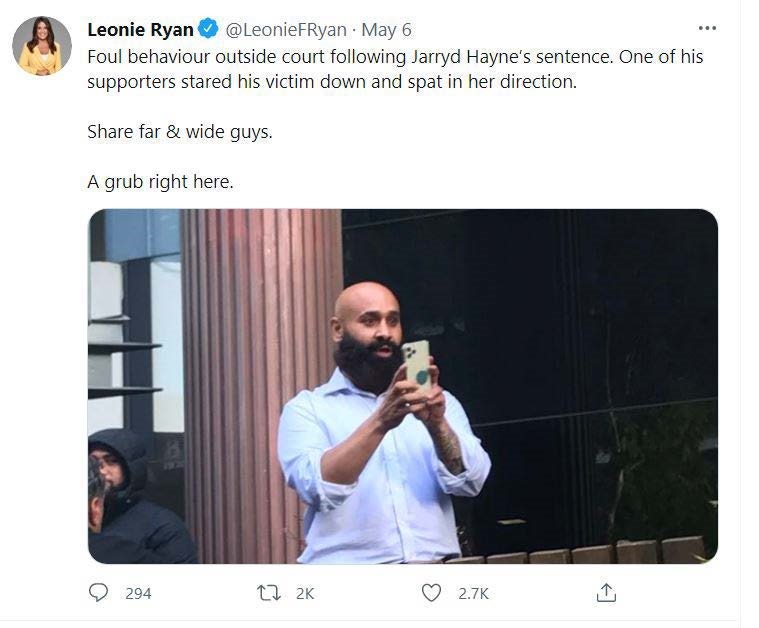

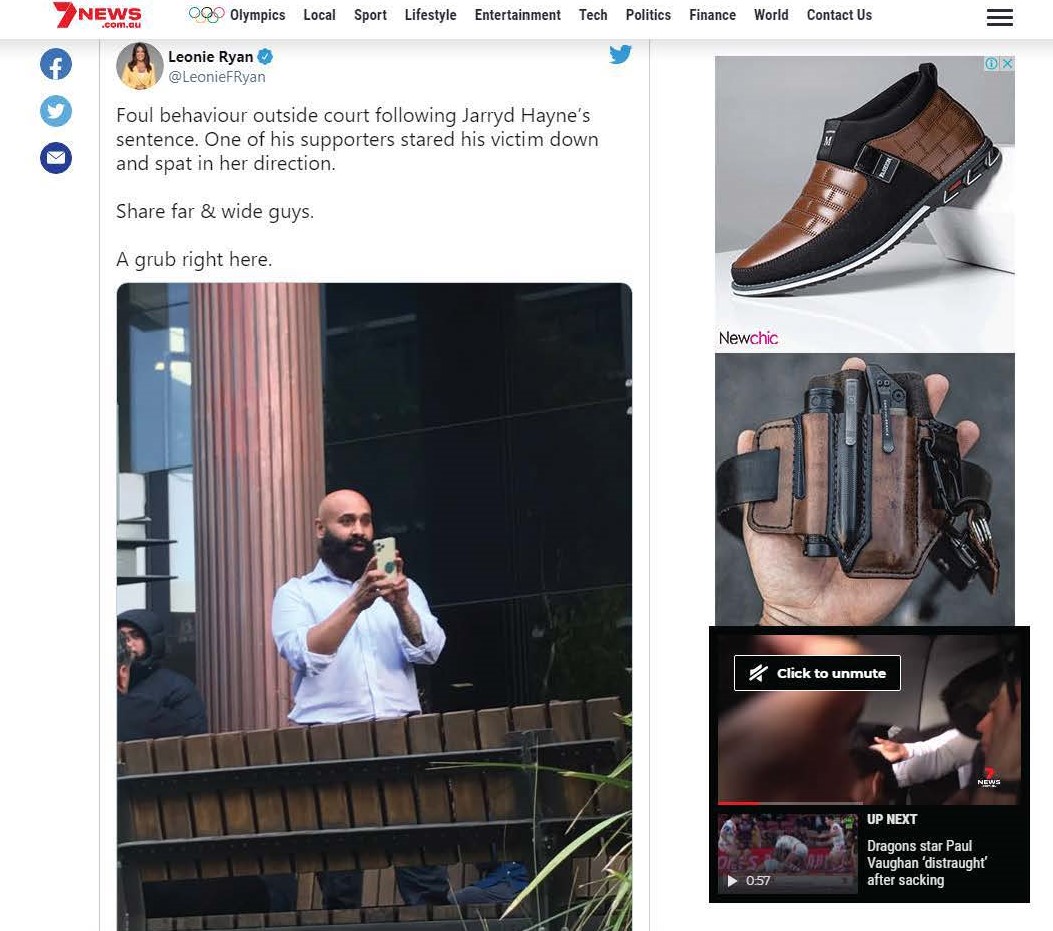

1 Mina Greiss alleges that he was defamed in an article appearing on the 7News website (the first matter complained of), a Facebook post on the 7News Facebook account (the second matter complained of) and a tweet posted by Leonie Ryan, a journalist employed by Seven Network (Operations) Ltd as a court reporter, on her personal Twitter account (the third matter complained of, hereafter generally referred to as “the Ryan tweet”). Copies of the three matters are annexed to these reasons. Each of them was published on 6 May 2021. Each of them contains a report of, and comment on, the conduct of Mr Greiss that day outside a courthouse in Newcastle.

2 The respondents admit publication and identification. They also admit that the pleaded imputations were conveyed. They contend, however, that they are not liable, relying on the defences of justification (truth) and honest opinion. In relation to the first and third matters complained of, they also plead the defence of contextual truth. In the event that they fail to establish any of these defences, they argue that no damages should be awarded anyway.

UNDISPUTED FACTS

3 The following facts were either agreed or not in dispute.

4 Seven is the distributor of the television programme, Seven News, and the operator and publisher of the content on the website www.7news.com.au (the 7news website) which is available for download throughout Australia. Seven is also the operator and publisher of content on the Facebook page “Channel 7” (the 7 Facebook account).

5 Ms Ryan is a journalist employed by Seven.

6 On 6 May 2021 Jarryd Hayne, a former star rugby league player, was sentenced at the District Court in Newcastle some six weeks after he had been convicted of two counts of sexual intercourse without consent.

7 Ms Ryan was one of a number of members of the media who attended the courthouse to report on the sentencing hearing. Mr Greiss attended with friends to support Mr Hayne. They were Daniel Petras, Alifeleti Sosefo Mateo and Henry Prince Iuta.

8 At about 3:40 pm, Mr Greiss and other supporters of Mr Hayne left the courthouse and stood together within a courtyard to the right of the entrance to the building.

9 About five minutes later, the victim emerged from the building, escorted by two sheriff’s officers, Andrew Girkin and Scott Weaver. She was part of a small group which also included detectives and the Crown prosecutor. For convenience, I will refer to this group as the victim’s group or the group. As the group left the building, they turned right and walked down a ramp which runs alongside the building to Hunter Street. When he noticed the group leaving, Mr Greiss rose from his seat outside the building and walked towards the ramp, positioning himself at the top of a small staircase which led to the ramp. He looked at the group and noticed that it included the victim.

10 At this time, the members of the media, including Ms Ryan, were standing on the footpath on Hunter Street, at the bottom of a wide set of stairs leading to the courthouse entrance.

11 A few minutes after the victim left the court precinct, Ms Ryan published the Ryan tweet. In the tweet, which was accompanied by a photograph of Ms Greiss, Ms Ryan wrote:

Foul behaviour outside court following Jarryd Hayne’s sentence. One of his supporters stared his victim down and spat in her direction.

Share far & wide guys.

A grub right here.

The photograph depicts Mr Greiss holding a mobile phone in front of him giving the impression that he is filming something.

12 The Ryan tweet was retweeted by Tiffiny Genders, a reporter for the Nine Network. A Twitter account apparently operated by Seven under the name “7News Sydney” replied to the Ryan tweet, proclaiming that:

The vile act aimed towards Hayne’s victim occurred just hours after she declared he had destroyed her life on the night of the 2018 NRL grand final.

13 Underneath a photograph of Mr Greiss, apparently cropped from the Ryan tweet, and one of Mr Hayne, the following statements were made:

Disgusting scenes as Jarryd Hayne supporter SPITS towards rape victim.

Chaos erupted outside court just moments after the disgraced ex-NRL star was sentenced to five years and nine months in prison.

14 Shortly after the victim’s group left the court precinct, Mr Hayne’s wife (Amellia Bonnici) left the court building. Various people attempted to shield her from press view as she moved towards and entered a waiting car.

15 Later that day, Seven published the first matter on the 7news website and the second matter on the 7 Facebook account.

16 The first matter was an article entitled:

Disgusting scenes outside court as Jarryd Hayne supporter SPITS towards rape victim.

17 The article embedded a copy of the Ryan tweet.

18 The second matter, the Facebook post, read:

Chaos erupted after disgraced NRL player Jarryd Hayne was handed a lengthy prison sentence.

19 A link to the article followed.

20 The post itself was accompanied by a large photograph of Mr Greiss, the same one that appeared in the Ryan tweet. Here, the photograph was captioned:

‘GRUB’ SPITS AT RAPE VICTIM OUTSIDE COURT

21 115,055 people viewed the first matter, 107,090 from IP addresses in Australia. Of the total page views of the first matter, 3,393 were accessed through Twitter.

22 66,701 people accessed the first matter through Facebook. A screenshot of the second matter taken the day it was removed shows that it had 371 “reactions”, 348 “comments” and 34 “shares”.

23 The third matter attracted 1,635 retweets, 371 “quote tweets” and 2,772 “likes”.

24 The second and third matters generated a considerable amount of comment on social media. Some 121 pages of comment were tendered in evidence, although a good deal of it was duplication.

25 Some of the commentary was critical of the sentence imposed on Mr Hayne, supportive of Mr Hayne and not in the least critical of the so-called “grub”. But most of it was negative and hostile to Mr Greiss, picking up the message in the Ryan tweet. Many commentators questioned why the spitter had not been charged because spitting at someone is an assault or because of the risk of transmission of COVID or both. Many called for him to be “locked up”. Mr Greiss was vilified, both in comments on Facebook posts and in messages sent to him directly via Facebook Messenger, as a “grub”, “an asshole”, “a low life”, “scum”, a “sick poor excuse as man”, “a woman hater”, “a filthy creature”, “a piece of shit”, “this disgusting specimen” and the like – and worse still. One commentator on Facebook asked whether it was “legal to flog this person?”.

26 Another wrote:

WTF, where did that swamp creature crawl from? Needs to go back on his medication. Gronk on the loose. Blatant misogynistic act by a man with the mental capacity of a toddler in a tantrum rage.

27 Yet another called for the “filthy grub” to be “locked up right beside his filthy grub mate”.

28 One man sent Mr Greiss a message via Facebook Messenger saying:

You are nothing but a piece of shit. Woodchipper material. Would love to get you in the ring you UnAustralian Cunt.

29 Some of the Facebook posts were more threatening, like this one:

Hey scum bucket. We know your name now. Won’t take long to find out where you live then we coming for ya[.]

30 Another post on Twitter in reply to the Ryan tweet referred to Mr Greiss as “a filthy pig” and a “scumbag” and called for somebody to “hunt the scumbag down”.

31 One commentator replying directly to the Ryan tweet wrote:

These people should not exist.

32 Many commentators mistakenly assumed from his appearance, particularly his long black bushy beard, that the spitter was a Muslim. One who did not was a woman who apparently recognised Mr Greiss. She addressed her remarks directly to him via a Facebook message:

Hi Mina! Thanks for being another who proves once again that christians are the biggest hypocrites on the planet! Hiding behind the bible, supporting convicted rapists, spitting at the victim ... what a disgusting, grubby, evil cult christianity is! Thank you for being a prime example of that cult - with examples such as yourself and your rapist friend, no wonder people are leaving said cult in droves!

33 The day after the matters were published, Mr Greiss was exposed by name in Twitter posts by several people, including as the “creep” who spat at the victim. The author of that particular post called on people never to hire or help him.

34 The same day the NSW police received information suggesting that a person, who I infer was the victim (the name is redacted in the police report), had been spat at and abused when leaving the court complex. The source of the information is not disclosed. The police also learned that “journalist’s [sic]” had been assaulted and spat at. Mr Greiss was identified as “being responsible for spiting [sic] onto the footpath as recorded upon commercial footage”.

35 During the evening Mr Greiss was interviewed by police. He admitted to spitting on the street but said the victim was “not around” when he spat. He agreed he was “revved up at the time” and that “emotion got the better of him”. Towards the end of the interview Mr Greiss said he had “phlegm”, asthma and bronchitis. When asked why he did not spit into a tissue or “somewhere more appropriate than the footpath”, he had no answer. On 11 May 2021 Mr Greiss was served with an infringement notice for offensive behaviour and fined.

36 After he was fined, Seven posted on Twitter:

A supporter of Jarryd Hayne has been fined for allegedly spitting outside court after the disgraced footballer was jailed for rape. Mina Greiss is accused of spitting as the victim left Newcastle Court last week.

37 When he received the infringement notice, Mr Greiss asked for a written account confirming that he did not spit at the victim. His request was declined.

38 On 4 June 2021 Mr Greiss’s solicitors served a concerns notice on Seven in relation to various publications including the first and second matters and on 28 June 2021 they served a concerns notice on Ms Ryan in relation to various tweets including the third matter.

39 Each of the matters was removed on or about 20 August 2021.

40 On 26 August 2021 Mr Greiss’s solicitors requested a copy of Seven’s video footage of the alleged spitting incident and on 18 February 2022 they informed Seven’s solicitors that they had obtained and viewed the CCTV footage from the Newcastle courthouse. On 8 July 2022 Mr Greiss’s solicitors produced a copy of the CCTV footage from the Newcastle courthouse to Seven’s solicitors.

THE IMPUTATIONS

41 Although there was initially a dispute about whether one of the pleaded imputations was conveyed, ultimately the respondents accepted that all the pleaded imputations were conveyed and were defamatory.

42 I therefore make the following findings.

43 The first matter conveyed the following imputations or imputations no different in substance, each of which is defamatory:

(1) Mr Greiss engaged in the vile act of staring down and spitting towards Mr Hayne’s rape victim;

(2) Mr Greiss stared down and spat in the direction of Mr Hayne’s rape victim;

(3) Mr Greiss is despicable, in that he stared down and spat in the direction of Mr Hayne’s rape victim; and

(4) Mr Greiss sought to harass and intimidate Mr Hayne’s rape victim by staring her down and spitting at her.

44 The second matter conveyed the following imputations or imputations no different in substance, each of which is defamatory:

(5) Mr Greiss spat at a rape victim outside court; and

(6) Mr Greiss is despicable, in that he spat at a rape victim outside court.

45 The third matter conveyed imputations (2), (3) and (4) or imputations no different in substance, each of which is defamatory.

THE RESPONDENTS’ AMENDMENT APPLICATION

46 In their defence the respondents originally pleaded justification and honest opinion. On 4 July 2022 I made case management orders which included provision for the exchange of witness statements, discovery and the fixing of the hearing dates.

47 On 3 February 2023, five weeks before the trial was due to start, the respondents filed an interlocutory application (the application) seeking leave to amend their defence. The application was supported by an affidavit of Justine Munsie, the respondents’ solicitor.

48 Mr Greiss opposed the application, relying on an affidavit sworn on 28 February 2023 by his solicitor, Margaret Antunes of Antunes Lawyers.

49 The application was listed for hearing on the first day of the trial. After hearing argument, I informed the parties that I would allow the application and give my reasons later. Counsel for Mr Greiss then indicated that reasons for that decision were not required “for the purpose of the trial”. At the time, I had the impression that reasons were not required at all. On reflection, however, I considered my impression may well have been wrong. Consequently I record the reasons below. As the amendments concerned multiple aspects of the respondents’ defence, it is convenient to set out my reasons for allowing them before turning to the substantive determination of this matter.

The relevant considerations

50 Rule 16.53 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) (Rules) requires that any party wishing to amend a pleading after pleadings have closed must apply for the leave of the Court. Rule 1.41 provides that, if a party makes an application, the Court may grant or refuse the order sought or make a different order. The Court’s discretion is at large, save that, like any power conferred by the Rules, it must be exercised in the way that best promotes the overarching purpose of the civil practice and procedure provisions of the relevant legislation, including the Rules, set out in s 37M(3) of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (FCA Act). That purpose is the just resolution of disputes according to law and as quickly, inexpensively and efficiently as possible: FCA Act, s 37M(1).

51 Various factors are relevant to the exercise of the power. The respondents relied on the uncontroversial summary contained in the judgment of Besanko J in Roberts-Smith v Fairfax Media Publications Pty Limited (No 5) [2020] FCA 1067, drawn from a number of authorities listed at [15] of that judgment. They are:

(1) the nature and importance of the amendments to the party applying for them;

(2) the extent of the delay and the costs associated with it;

(3) the explanation for the delay;

(4) the prejudice that might reasonably be assumed to follow from the amendment and that which is shown;

(5) the parties’ choices to date in the litigation and their consequences;

(6) the detriment to other litigants in the court if the amendments are allowed; and

(7) the potential loss of public confidence in the legal system which can arise where a court is seen to accede to applications made without adequate explanation or justification.

The proposed amendments

52 The respondents wished to amend their defence by:

(1) adding a defence of contextual truth under s 26 of the Defamation Act 2005 (NSW) (Defamation Act) to the first and third matters, including a new particular 8;

(2) amending particular 7 of their justification defence; and

(3) amending their particulars of mitigation to enable them to rely on the substantial truth of the contextual imputations in mitigation of damages in the event that their substantive defences were not made out.

The amendment to the particulars of the justification defence

53 It is convenient to deal first with this aspect of the amended defence.

54 Particular 7 initially read:

The Applicant faced the Walkway and stared at the Victim and spat towards her feet as she passed by him to exit the court precinct.

55 The respondents’ amendment sought to delete the words “towards her feet as” and insert “after” in substitution.

56 Mr Greiss submitted that, as amended, the particular was “hopelessly imprecise and … incapable of proving the substantial truth of any of the pleaded imputations because it does not address a material part of the sting”. He argued that “[t]here is no longer any particularised allegation that the spitting was directed towards the victim, and it is clear that it is no longer the respondents’ case that the spitting occurred in her presence, but merely an unspecified time after she had left”. In the result, he contended that the entire justification defence was no longer tenable and should be struck out. He claimed that the respondents’ case “now rises no higher than an allegation that Mr Greiss spat in an unspecified direction an unspecified amount of time after the victim left the area” and was incapable of proving the substantial truth of the pleaded imputations, let alone in the context in which they are conveyed by each publication.

57 In its proposed form the amendment was imprecise. But the reason for the amendment was apparent from the correspondence in which it was foreshadowed.

58 In Ms Munsie’s letter of 23 December 2022, in which she notified Mr Greiss’s lawyers of the respondents’ intentions to file the amended defence, the amendment was said to be necessary to remove part of an allegation following the preparation of a short supplementary statement of Ms Ryan served at the same time. In that statement Ms Ryan said that, having reviewed the footage discovered by Seven and the CCTV footage from the day of the incident, she “[does] not believe [Mr Greiss] spat in the direction of the victim’s feet” but rather believed that he “spat in her direction”. This is the point of the amendment.

59 In the circumstances, I decided that the justification defence should not be struck out. Instead, I granted the respondents leave to amend particular 7 so that it reflected what Ms Ryan said in her supplementary statement, namely that Mr Greiss spat in the victim’s direction as she passed by him, a course which Mr Greiss agreed disposed of his objection to the amendment.

60 Consequently, particular 7 now reads:

The Applicant faced the Walkway and stared at the Victim and spat in her direction as she passed by him to exit the court precinct.

The amendment to raise a contextual truth defence

61 The amendment proposed was a single contextual imputation with respect to each of the first and third matters in the following terms:

The Applicant behaved disgracefully outside of Court to the woman Jarryd Hayne had been sentenced for raping.

62 The respondents allege that the contextual imputation in each case is substantially true and, by reason of its substantial truth, publication of such of the pleaded imputations as may not be found to be substantially true did no further harm to Mr Greiss’s reputation.

63 Mr Greiss objected to the amendments on four bases:

(1) the contextual imputation does not arise;

(2) the particulars were not capable of proving the truth of the contextual imputations;

(3) the delay was not explained or at least not adequately explained; and

(4) he would be prejudiced by the amendment.

I deal with each of these objections below in the same order.

Does the contextual imputation arise?

64 As the respondents submitted, this was a trial issue. The real question on the application was whether the imputation was capable of being conveyed or, put another way, it was reasonably arguable that the contextual imputation arises.

65 Mr Greiss pointed out that s 26 of the Defamation Act (as it was before the amendments that commenced on 1 July 2021, which are inapplicable) required that a contextual imputation be carried “in addition to” the imputations pleaded by him. He submitted that any such imputation must be formulated so that facts, matters and circumstances that can be relied on to establish its truth bear a reasonable relationship to the contextual imputation itself and to the matters complained of. Otherwise, as Wigney J pointed out in Domican v Pan Macmillan Australia Pty Ltd [2019] FCA 1384 at [44], “the respondent can then rely on particulars of truth that may have nothing whatsoever to do with the published material”.

66 Mr Greiss submitted that the way his behaviour is said to have been disgraceful is that he stared down and spat towards the victim, but as the first and third matters do not refer to any other relevant conduct, the contextual imputations are not “in addition to” the pleaded imputations. As I explain below, a contextual imputation need only differ in substance from the pleaded imputation and I was persuaded that the contextual imputation the respondents wished to plead did differ in substance from the pleaded imputations. I considered it was at least reasonably arguable that the single act of spitting towards, or in the direction of, a rape victim was sufficiently serious to support the general meaning of disgraceful behaviour.

67 In any case, as the respondents submitted, the matters complained of were not bare recitations that Mr Greiss stared down and spat at the victim. The contextual imputation also arises from the headline of the first matter (“Disgusting scenes outside court …”) and from the description of Mr Greiss’s behaviour (staring the young woman down and spitting in her direction) in circumstances in which the publication also reported that her assailant had just been jailed for a “brutal sexual assault” and “the vile act aimed towards [her] occurred just hours after she declared [her assailant] had destroyed her life …”. In the third matter, the contextual imputation arises not merely from the reference to a supporter staring down the victim and spitting in her direction but from the words “foul behaviour”.

68 Mr Greiss also contended that “the vice of the proposed contextual imputations is that they seek to re-articulate the sting of the [f]irst and [t]hird matters at a high level of abstraction as the pretext for introducing evidence of a specific incident which is not mentioned anywhere in the [f]irst or [t]hird matter[ ] and which is remote from the conduct which is mentioned” (original emphasis). He argued that it involved a verbal exchange with a journalist, was not directed to the victim, and took place well after the victim is said to have left the court precinct. He claimed that this was the vice identified by Wigney J in Domican at [44] and in the authorities his Honour cited.

69 I reject this contention. The only new particular relied upon was that:

After the Victim had left the Court precinct the Applicant described her as an “escort” to a member of the media.

70 The proposed amendment did not reflect the vice identified by Wigney J in Domican. The facts, matters and circumstances upon which the respondents intended to rely in order to establish the truth of the contextual imputation were capable of bearing a reasonable relationship to the contextual imputation and would not have “nothing whatsoever” to do with it. The remark Mr Greiss is said to have made at the courthouse occurred after the victim’s assailant was convicted, within an hour after she left, and in an exchange which included references to the episode in which Mr Greiss was said to have spat towards, or in the direction of, the victim. Moreover, I considered it could indicate that Mr Greiss was contemptuous of the victim; that he felt she had no right to complain; and it arguably explained why he might have spat at or towards her (or in her direction), if indeed he did.

71 Nothing in Domican or the other authorities to which Wigney J referred in that case (in which contextual imputations were said to be so broad as to capture, as the respondents put it, “historical, disparate and wholly unconnected acts” of a plaintiff) suggests that the contextual imputations the respondents sought to plead were of that type: see Domican at [45]–[51].

Are the particulars capable of proving the truth of the contextual imputation?

72 Mr Greiss submitted that the “extremely limited particulars” do not support a contextual imputation of disgraceful behaviour “to” the victim because the reference to her as an escort was not made to her and, given the proposed amendment to particular 7 to the justification defence, there is now no allegation that Mr Greiss spat towards her or in her presence.

73 As a result of the respondents’ revised amendment to particular 7, this question also fell away. Particular 7 of the contextual truth defence is now in the same terms as the revised particular 7 to the justification defence. In their revised form, I was satisfied that the particulars were capable of proving the truth of the contextual imputation.

The extent of the delay

74 The originating application and statement of claim were filed on 21 April 2022 and sealed copies were served on the respondents’ solicitors by email on 26 April 2022, the day the documents were accepted for filing. The respondents filed their defence on 14 June 2022 and no reply was filed. Mr Greiss was notified of the proposed amendments by email six months later, on 23 December 2022. The email was sent to Ms Antunes and Andrew Kaine, an associate of her firm. Mr Kaine replied on 16 January 2023. He said that the firm’s office was closed from 22 December 2022 and the email did not come to their attention until 9 January 2023 when the office reopened. Ms Munsie wrote to Antunes on 2 February 2023 requesting their consent to an order she proposed to seek at the forthcoming case management hearing that leave be granted to the respondents to file their draft amended defence. Since that time the scope of the contextual truth defence had narrowed.

75 Ms Antunes’ affidavit disclosed that CCTV footage in the possession of Mr Greiss was served on the respondents’ solicitors on 8 July 2022 and Ms Ryan’s first statement was served on Antunes on 23 August 2022. A mediation took place on 18 October 2022.

Is the delay adequately explained? Is there the potential for the public to lose confidence in the legal system if the amendments are allowed?

76 These questions are related and can be considered together.

77 In my opinion the delay was not adequately explained.

78 As Mr Greiss pointed out, Ms Munsie did not expressly address the reason(s) for the delay in her affidavit. The rather opaque inference from her affidavit was that the amendments were proposed by senior counsel who was only briefed in late October 2022.

79 As Mr Greiss submitted, while Ms Munsie deposed that senior counsel was briefed on 26 October 2022 and a draft amended defence was served on 23 December 2022, she did not say that the defence was amended on the advice of senior counsel. The respondent’s written submissions on the application, however, which purported to be the work of both senior and junior counsel, recorded that “[a]s to the defence of contextual truth, senior counsel took the view that it ought to be pleaded” and, as to the change to particular 7 of the justification defence, “Ms Ryan took this view after further observing video footage”.

80 In these circumstances I accepted that the proposal to amend to plead contextual truth was made on the advice of senior counsel. That said, Ms Munsie did not say when she received the advice or how long it took to obtain instructions to make the application. If it was around the time senior counsel was briefed, then there was a two-month delay in notifying Mr Greiss which is unexplained. Moreover, the evidence upon which the respondents rely to plead the “escort” allegation was in their possession at all relevant times. It is contained in the Seven videos of which Ms Munsie was aware since before the proceeding commenced, as she referred to them in pre-litigation correspondence in August 2021. And no evidence was adduced to indicate when Ms Ryan first reviewed the footage or when she decided that her initial statement should be revised.

81 Nevertheless, for the following reasons I did not consider that there was any real risk of a loss of confidence in the legal system.

Would Mr Greiss be prejudiced if the amendments are allowed?

82 Mr Greiss did not suggest that he was unable to meet either the new contextual truth defence or the amendment to the justification defence. In particular, as the respondents observed, he did not suggest that if notice had been given at an earlier point in time he would have issued a subpoena, made some forensic decision or had lost some opportunity. Rather, he submitted that there was “general prejudice caused by the lateness of the amendment” and “specific prejudice because the contextual truth defence … [was] an attempt to introduce an exchange not referred to in the publications, so as to cause further harm and damage to Mr Greiss in the conduct of the trial”.

83 The “general prejudice” was not identified and no proper foundation was laid for the serious accusation of bad faith inherent in the allegation of “specific prejudice”.

84 While it was understandable that Mr Greiss would want to exclude from the trial evidence that he had referred to the victim as an escort, that is not relevant prejudice. Even if the respondents did not raise the making of the comment by way of a defence of contextual truth or in mitigation of damages, their counsel would be able to cross-examine on it and it would emerge in evidence in any event. It would be relevant to Mr Greiss’s state of mind and would arguably support the respondents’ version of events.

85 As no relevant prejudice was occasioned by the lateness of the amendments, I was of the opinion that little weight should attach to the inadequacy of the respondents’ explanation for the delay.

86 Of course, in some cases, the absence of an explanation (or an adequate explanation) for the delay in applying for an amendment will be significant. In Aon Risk Services Australia Ltd v Australian National University (2009) 239 CLR 175 at [103], the plurality (Gummow, Hayne, Crennan, Kiefel and Bell JJ) observed that “[g]enerally speaking, where a discretion is sought to be exercised in favour of one party, and to the disadvantage of another, an explanation will be called for” and in most cases in which delay has occurred the party responsible should explain it. In that case the absence of an adequate explanation was significant. The University had applied for an adjournment of a four-week trial on the third day of the trial in order to make substantial amendments to its statement of claim. Still, as the Full Court (Keane CJ, Gilmour and Logan JJ) observed in Cement Australia Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2010) 187 FCR 261 at [51]:

Aon Risk is not a one size fits all case. Whilst various factors are identified in the judgment as relevant to the exercise of discretion, the weight to be given to these factors, individually and in combination, and the outcome of that balancing process, may vary depending on the facts in the individual case. As the plurality in Aon Risk observed at [75], statements made in cases concerning amendment of pleadings are best understood by reference to the circumstances of those cases, even if they are stated in terms of general application.

87 The factors that persuaded the High Court in Aon that the applications for adjournment and amendment should not have been allowed were the timing of the application, the necessity to vacate or adjourn the trial dates, the inadequacy of the explanation, and the fact that new claims were intended to be raised which had not previously been agitated because of a deliberate tactical decision not to.

88 The circumstances of the present case were very different. I was not persuaded that the deficiencies in the respondents’ explanation were a sufficient reason to refuse their application. Where amendments to a pleading have arguable merit and there is no significant or appreciable prejudice, a court will rarely deny an application to amend a pleading. Nor is it to the point that some additional expense may be incurred in addressing the new defence. As Marshall, Rares and Flick JJ said in Dye v Commonwealth Securities Limited (No 2) [2010] FCAFC 118 at [81]:

A new factual allegation permitted by an amendment may involve putting the party against whom it is made to the expense of meeting it at trial. However, that will rarely, if ever, be a reason for refusing an amendment that enables a real issue to be heard and determined in the controversy between the parties provided that it can be done having regard to the overarching purpose in Pt VB of the Federal Court of Australia Act. The object of inexpensive determination of disputes does not require the Court to preclude a party ventilating a real dispute at all.

To what extent, if at all, would other litigants in the court be adversely affected if the amendments were allowed?

89 It was not suggested that leave should be refused because other litigants would be adversely affected if the amendments were to be allowed. Mr Greiss made no submissions on this question. In circumstances such as this, where no application was made or foreshadowed for the hearing dates to be vacated and the hearing would not be prolonged as a result of the amendments, no detriment to other litigants could arise.

Conclusion

90 Taking all relevant factors into consideration and weighing them in the balance, I was satisfied that the best way to promote the overarching purpose was to allow the respondents’ amendments and require the respondents to pay the costs of the application.

ISSUES

91 It follows that the remaining issues concern:

(1) whether the defences of justification, honest opinion and/or contextual truth have been made out; and

(2) if not:

(i) the extent to which any of the matters relied upon to prove justification, honest opinion and/or contextual truth mitigates damages;

(ii) whether Mr Greiss has made out a case for aggravated damages; and

(iii) the amount, if any, of damages that should be awarded.

THE JUSTIFICATION DEFENCE

The law

92 Section 25 of the Defamation Act provides that it is a defence to the publication of defamatory matter if the defendant proves that the defamatory imputations carried by the matter of which the plaintiff complains are substantially true. A defendant who raises such a defence must prove that each of the imputations and every material part of those imputations was substantially true at the time of publication: Channel Seven Sydney Pty Ltd v Mahommed [2010] NSWCA 335; 278 ALR 232 at [138] (McColl JA, with whom Spigelman CJ (at [1]), Beazley JA (at [2]), McClellan CJ at CL (at [283]) and Bergin CJ in Eq (at [284]) agreed). There is no defence of partial justification: Kumova v Davison (No 2) [2023] FCA 1 at [96] (Lee J). “Substantially true” is defined in s 4 of the Defamation Act to mean “true in substance or not materially different from the truth”. It is unnecessary for a defendant to prove that every part of an imputation is literally true; it is enough that its gravamen or “sting” of the imputation is true: Mahommed at [138].

93 In considering whether imputations that require an evaluative assessment of Mr Greiss’s conduct (such as the imputations that his conduct was “vile” or “despicable” or that he behaved “disgracefully”), it is necessary to consider whether ordinary decent people, that is, reasonable people of ordinary intelligence, experience and education, bringing to bear their general knowledge and experience of worldly affairs, would come to that conclusion: Harbour Radio Pty Ltd v Trad (2012) 247 CLR 31 at [54]–[56] (Gummow, Hayne and Bell JJ).

94 If the justification defence fails, however, evidence led in support of that defence may mitigate damages. Thus, if the respondents fail to prove that one imputation or a material part of an imputation is not substantially true but prove that another is, the substantial truth of the other may reduce the damages “perhaps almost to vanishing point”: Pamplin v Express Newspapers Ltd [1988] 1 WLR 116 at 120 (Neill LJ).

The scope of the factual dispute

95 Mr Greiss denied having any interest in the victim. He claimed not to have been looking at her, let alone staring her down, and in his evidence in chief he insisted he did not spit at all, let alone at the victim, until after the victim had left the court precinct.

96 I take it to be common ground that, if Mr Greiss is found to have acted in this way, that was a vile act, that it was despicable conduct and disgraceful behaviour, and that it was intimidating and harassing. Certainly there was no argument to the contrary. In any event, I have no doubt that ordinary decent people would so conclude.

What does the video footage show?

97 The CCTV footage shed some light on the events, although it has its limitations. One of those limitations is that there is no audio. Another is that that footage was taken from fixed cameras which do not apparently correspond to the perspectives of various witnesses at all material times. In particular, the evidence was insufficient to establish that the CCTV footage captured the line of sight of each of the respondents’ witnesses at any relevant time. In addition to the CCTV footage there was audiovisual evidence obtained from material produced on subpoena by three media organisations.

98 I have watched and listened to this material several times. I make the following findings based on what I saw and heard. The times given below reflect the time stamps on the CCTV footage. It was common ground, however, that the time stamps were inaccurate in that they were approximately 15 minutes behind the real time.

As the victim’s group leaves the courthouse

99 At 3:31:19 pm a sheriff's officer, who the parties agreed was Mr Girkin, emerged from the courthouse followed by the other members of the victim’s group. They immediately turned right and proceeded down a disability ramp, which runs along the front of the courthouse and then turns left towards Hunter Street. The ramp is wide enough for two people to walk alongside each other.

100 Mr Girkin led the group down the ramp, until he stopped at the bottom of the small staircase which connected the ramp to the mezzanine, while the rest of the group continued down the ramp. Behind Mr Girkin was a man in a suit. Walking behind that man were two women walking side-by-side. The woman closer to the wall of the courthouse was the victim. Behind the two women was the Crown Prosecutor followed by three women in single file. At the end of the group was Mr Weaver. At approximately 3:31:49 pm (around 30 seconds after Mr Girkin first exited the courthouse) the last member of the group (Mr Weaver) left the ramp and turned right down Hunter Street.

101 At the time this group emerged from the courthouse, Mr Greiss was sitting on a bench outside on the mezzanine level. The bench was approximately halfway between the entrance to the courthouse and the small staircase. Mr Greiss was facing away from the entrance. But at approximately 3:31:27 pm (that is eight seconds after Mr Girkin walked out of the courthouse) Mr Greiss looked over his left shoulder towards the group. At 3:31:29 pm Mr Greiss stood up from the bench and walked towards the stairs that connected the mezzanine and the ramp.

102 The following still depicts the scene as it would have appeared to anyone standing at the top of the ramp at 3:31:38 pm. Mr Greiss was looking towards, or in the direction of, the victim as she passed by with other members of the group. She did not look at him. Like all members of the group, she was looking ahead. Mr Girkin was standing at the bottom of the staircase but not obscuring Mr Greiss’s view of the victim.

103 At 3:31:39 pm Mr Greiss pointed in the direction of the victim. His mouth was moving. The woman walking next to the victim turned her head to look at Mr Greiss. I infer that he said something which attracted her attention.

104 Two seconds later, Mr Greiss pointed in the direction of the victim again and once more the woman to the left of the victim turned her head to look at him as the following still shows.

105 At 3:31:45 pm Mr Greiss turned his head slightly to face Hunter Street and spat into a garden bed:

106 The man in the blue shirt is Mr Petras. The man in the red shoes seated on the bench is Mr Iuta.

107 At this point the victim had almost reached the end of the ramp as the following still from the CCTV footage shows.

108 At 3:31:47 pm Mr Greiss pointed in the direction of the victim for a third time. At this juncture Mr Girkin started to walk up the stairs towards Mr Greiss. About a second later, three sheriff's officers standing outside the front of the courthouse moved towards Mr Greiss. Four seconds after that, the last member of the victim’s group disappeared from view.

109 The video footage taken by Channel 7 records the reactions of journalists. An unidentified man asked: “Are they intimidating her? That’s outrageous.” Three seconds later, Ms Genders said: “That’s disgusting. He just spat at them”. Three seconds after that, Ms Ryan said: “He was staring down the victim [inaudible] yeah”. These comments or comments to the same effect are picked up in a video taken by a Channel 10 camera operator. All but one of them is made within 36 seconds of the time the respondents allege Mr Greiss spat at or towards the victim or in her direction. In addition, both the Channel 7 and Channel 10 footage record Ms Ryan saying: “He was staring the victim down and then spat towards her”.

110 At 3:32:21 pm, after Mr Greiss and Mr Petras spoke to the sheriff’s officers, Mr Greiss spat for a second time into the garden bed near the main stairs outside the front of the courthouse. This second spit is difficult to discern on the CCTV footage but it is crystal clear on the Channel 10 footage. Following the second spit Mr Greiss returned to talk to the sheriff's officers.

After the victim’s group left

111 At 3:35:10 pm, footage obtained from Channel 10 reveals that Mr Greiss called out:

Did you put that she’s an escort? (gesticulating as though writing in the air) Did you put that in your…yeah, you’re journalists right?

Yeah, put that in your thing.

112 A woman in the media pack immediately responds but only her last word is audible. That is “spat”.

113 Two seconds later, Ms Ryan said: “Absolutely appalling behaviour”. Mr Greiss replied: “Yeah? Oh good, I’m happy with that.”

114 These exchanges were referred to in submissions as the first escort conversation.

115 At 3:35:40 pm, Mr Greiss, along with Mr Mateo, Mr Iuta and Mr Petras left the mezzanine via the stairs that lead down to the disability ramp.

116 A few minutes later, Ms Ryan tweeted the third matter complained of.

117 Approximately nine minutes later (and about 12 minutes after the respondents allege that Mr Greiss stared down the victim and spat at, towards, or in her direction) video footage obtained from Fairfax depicts Mr Greiss approaching Ms Ryan and other members of the media who were still milling around at the bottom of the stairs on Hunter Street outside the courthouse. At this point, the following exchange (the second escort conversation) took place:

Mr Greiss: You’re quick on Twitter.

Ms Ryan: What? Oh yeah, I’m good at tweeting.

Mr Greiss: [Inaudible] quick. Grub you reckon?

Ms Ryan: Yeah, you are.

Mr Greiss: Yeah, all good, yeah. I’m happy with that.

Ms Ryan: Ok.

Mr Greiss: I can, I can live with that.

Ms Ryan: If you want to be remembered by that, that’s fine.

Mr Greiss: I can deal-

Ms Ryan: And I just love that you’ve focused on another woman, haven’t you?

Mr Greiss: Yeah, absolutely. Yeah.

Ms Ryan: Yeah, yeah. Course.

Mr Greiss: Did you put that she’s an escort?

Ms Ryan: That’s indicative of the type of person that you are.

Mr Greiss: All good. Did youse put that an escort? None of your articles said es – nothing about her being an escort.

Ms Ryan: Didn’t come out in court, did it?

Mr Greiss: Oh, that’s what comes out in court, aye. Only what comes out in court.

Ms Ryan: No, yeah. We report on facts, mate.

Mr Greiss: Yeah

Ms Ryan: Yeah, we do, yeah.

Mr Greiss: Yeah, yeah? Good work. Good work.

Ms Ryan: Yeah.

Mr Greiss: Fuck out of here bro.

Female: She’s not an escort, that’s why.

(Emphasis added.)

118 About five minutes after this exchange, Mr Greiss (along with Mr Petras, Mr Mateo and Mr Iuta) walked away from Ms Ryan and the other members of the media and, at 3:50:16 pm on the CCTV footage, Mr Greiss spat for a third and final time, this time towards the journalists. The spit was immediately preceded by the following exchange (the third escort conversation), which was captured variously by Channel 9 and 10 video cameras and incorporated in a compilation video which was tendered without objection and became Exhibit 12:

Ms Ryan: Trying to intimidate another woman are you?

Mr Greiss: You’re not a woman.

Ms Ryan: Get out of my face.

Mr Greiss: You’re not a woman.

Ms Ryan: Get out of my face.

Mr Petras: Why you calling him a grub, why you calling him a grub on social media?

Mr Greiss: Yeah…[inaudible].

Ms Ryan: Uh, I called him a grub.

Mr Petras: Yeah, why you calling him a grub?

Ms Ryan: Because he spat towards the victim.

Mr Greiss: Yeah, I did spit.

Mr Petras: Yeah, he spat on an escort. He spat on an escort.

Mr Greiss: Don’t touch me, don’t touch me. Did you see what she’s fucking putting up?

Ms Ryan: Yeah, ok mate. Get out of my face.

Mr Petras: He should spit on you.

Male: Say that again.

Mr Petras: He should spit on you-

Mr Greiss: Yeah, exactly!

Mr Petras: Treat you like a dog like you are.

Mr Greiss: Fuck out of here.

Mr Petras: Look at the fucking dropouts from school. Look at the nerds.

Mr Greiss: Yeah, put that on your thing…still racks up, yeah? Hey, put that on there…

Mr Petras: Hey put that, put that on there she’s an escort. Put it on there, she’s an escort.

Mr Greiss: (spits) Here, another one for ya.

(Emphasis added.)

119 With the exception of the first remark by Mr Greiss (“You’re quick on Twitter”), which is plainly audible and which Mr Greiss accepted he made, the above account is taken from a transcript of the three conversations prepared by the respondents. While counsel for Mr Greiss disputed its accuracy, I have both watched and listened carefully to the footage. I consider that the transcript of these conversations that the respondents prepared is substantially correct, indeed almost word perfect. While the words uttered immediately after the final spit (at about 42 seconds into the compilation video) are not as loud as others, I am satisfied that Mr Greiss did say those words or words to precisely the same effect. Indeed, in cross-examination, immediately after Exhibit 12 had been played, Mr Greiss agreed:

MR RICHARDSON: Now, Mr Greiss, I want to suggest that at the last moment played there, you said, “Here’s another for you,” or, “There’s another one for you”?---Okay. I - - -

Do you agree with that?---Yes, I agree.

The evidence from the witnesses

120 Mr Greiss gave his account of what occurred. He also relied on evidence adduced from two friends and supporters of Mr Hayne, who were with him at the time the conduct the subject of the proceeding took place. They were Mr Mateo and Mr Iuta.

121 Ms Ryan was the first of the respondents’ witnesses to be called. Two other journalists were also called. They were Giselle Wakatama, a journalist with the Australian Broadcasting Corporation, and Ms Genders, a journalist with Channel 9.

122 What follows is a recitation of the salient parts of the evidence or its effect.

123 Although Mr Greiss was the first witness to be called in the proceeding, it is convenient to begin with the evidence of Ms Ryan and the other journalists who were called by the respondents since they bear the onus of proof on the justification defence.

Leonie Ryan

124 Ms Ryan sat in a designated media room where the proceedings concerning Mr Hayne were being livestreamed until the sentence was handed down when she left the courthouse and stood at the bottom of the stairs leading from Hunter Street to the front of the building with reporters from various media outlets. Her purpose was to try to obtain a reaction from Mr Hayne’s supporters outside court.

125 Ms Ryan saw a sheriff, followed by others including the victim, leave the courthouse and descend the ramp. She estimated that there were about half a dozen people in the group with the victim. At about the time they started to move, Ms Ryan noticed Mr Greiss stand up from his seat and “almost walk [in] the direction of where the alleged victim was walking” while “staring at her and mumbling”. In cross-examination she clarified that she did not hear him mumbling but saw his mouth moving. She maintained that she could see this movement from where she was standing because his face was “side on” rather than directed away from her. She denied that Mr Greiss’s large beard would have prevented her from being able to see him mumbling.

126 As the victim walked past, Mr Greiss “spat in her direction”. She saw his “head move back and go forward” and heard “a spitting sound”.

127 Mr Greiss appeared to be facing “the group of people that had just passed him” and she formed the impression that his behaviour was directed at the victim.

128 When asked what gave her that impression, Ms Ryan replied:

When he stood up, it coincided at the exact same moment she walked out of the doors. And she was on the inside, but almost third from the front. It just appeared that his – his – his eyeline was directed at her.

129 Ms Ryan stated that Mr Greiss was staring at the victim but that the victim did not notice him.

130 When put to her in cross-examination that she was too far away to hear any spitting sound, especially in light of her acceptance that she could not hear Mr Greiss mumbling, she stood her ground. She admitted, however, that she did not see Mr Greiss spit towards the victim’s feet, despite saying so in a witness statement she prepared about nine months earlier. In that respect she accepted that her recollection at that time was incorrect.

131 In cross-examination she said that “a second or two” after she saw Mr Greiss spit, she saw him point towards the group.

132 After being shown the footage from Channels 7 and 10 of the journalists’ reactions, Ms Ryan identified her voice and that of Ms Genders.

133 In cross-examination Ms Ryan recalled that she was standing on the footpath facing the court at the bottom-left of the main entry stairs when she saw Mr Greiss spit. She described (correctly) the victim’s position within the group. At the invitation of the cross-examiner, Ms Ryan marked her position at that time and the positions of other members of the media, the victim and Mr Greiss on a photograph of the courthouse (Exhibit R). She indicated that Ms Wakatama, Ms Genders and the Channel 7 and Channel 9 cameramen were standing with her. She placed Mr Greiss on the mezzanine level close to the small staircase and the victim on the lower part of the ramp near the position of the small staircase.

134 When challenged about the position of the victim at the moment of the spit, Ms Ryan said she was more focused on Mr Greiss so was not paying attention to the victim’s position. But she denied the proposition that at the time of the alleged spit the victim was about to step onto the footpath on Hunter Street.

135 Ms Ryan was unable to recall whether there was a sheriff’s officer near Mr Greiss at the time she claimed to have first seen him spit. But Ms Ryan testified that “within seconds” of seeing Mr Greiss spit, “a number of sheriffs” approached him.

136 Ms Ryan said she had two or three interactions with Mr Greiss after she saw him spit. She rejected the proposition put to her in cross-examination that his exchanges with her were not motivated by his animus towards the victim. She agreed that he first approached her about her tweet, saying words to the effect of “You’re very quick on Twitter” (see the second escort conversation). She denied the proposition that much of the exchange she had with him and Mr Petras related to content of her tweet. She also denied the proposition that Mr Greiss was “expressing to her his concern and upset” about the tweet. In this respect, the video footage of the escort conversations supports her denial.

Giselle Wakatama

137 Like Ms Ryan, Ms Wakatama sat in the media room during the sentencing hearing. After the sentence was handed down, she moved outside and waited on the pavement at the bottom of the main entry stairs.

138 She recalled seeing “a group gliding down the walkway” which she understood to consist of various officers and the victim. At this time she observed Mr Greiss stand up “quickly” and make his way to a “gap with stairs” that led to the disability ramp. When asked about what she observed about Mr Greiss at this point she said:

I just remember hands, and I remembered a lunge, like, sort of a – a motioning, a lunge towards that open area as they walked down. He had his mouth open. I didn’t see – I thought he was saying something or yelling something, but then there was just, as I said, this sort of motion and then, sort of, an ostrich-type move as he got to the end of the lunge.

139 At this time, Ms Wakatama remembered that the victim was “going past, down the walkway, past the open area where there are steps up to the mezzanine level from the rampway”.

140 At the moment she saw Mr Greiss lunge, she said he called the victim “an escort” and spat at her but in cross-examination it became clear that her evidence that he spat at her was based on what Ms Ryan or Ms Genders (or both) had said.

141 In cross-examination Ms Wakatama said that the mouth opening and hand movements occurred about 20 seconds before the lunge. She said she never saw or heard any spitting but did see Mr Greiss’s mouth open and saw him lunge, in an “ostrich-type” movement, while “facing across the walkway” when the victim passed. While it was put to Ms Wakamata that she could not have seen his mouth moving or moving to the extent she described, having regard to her position and his bushy beard, Ms Wakamata was unshakeable. She maintained that she could see “a profile of a mouth open and hands” and could see “his head move as [the victim] moved”.

142 Ms Wakatama said that Mr Greiss appeared to be facing the group and that, at the time, she formed the impression that his behaviour was directed at the victim. When asked what gave her that impression she stated that “his eyes seemed intent on focusing on her” and that, as she passed by the small staircase and proceeded down the ramp, his head “moved as she moved”. She also maintained that she could see the victim’s group “move in a wave” down the ramp, led by a sheriff’s officer. She rejected the proposition that Mr Greiss was standing at least two metres away from the victim. She said he was more like one and a half metres away.

143 In cross-examination Ms Wakatama also said that she believed that there were four or five people in the victim’s group, or at least that many “cocooned around her”, although she accepted that she could be mistaken. She recalled (correctly) that the victim was approximately two or three people back from the front of the group. She thought (incorrectly) that the victim was “more in the middle” and that there were people on either side of her. While she did not see the sheriff’s officer who was positioned at the bottom of the small staircase, having seen a video about a week earlier she accepted that he was there at the relevant time. When it was put to her that, because she could not see the sheriff’s officer at the bottom of the stairs, she did not know where the victim was, she accepted that she made “assumptions” about the position of the victim based on the speed at which the group was “gliding” down the ramp from one end to the other and noted that she was “looking at the whole scene”.

144 On a photograph that became Exhibit S, Ms Wakatama identified her position at the time of the first spit as near the bottom-left corner of the stairs leading to the courthouse from the footpath on Hunter Street. On being shown Exhibit A (a CCTV image of the foot of those stairs), which does not show any women standing in the bottom-left corner of the stairs, Ms Wakatama accepted that she may have been further to the right. She identified Mr Greiss’s position at the time she saw his mouth open. She placed the victim as “near the gap in the walkway”, meaning near the small staircase at the top of which Mr Greiss was standing. She said that at the time of the “lurching” or “lunging” motion, he had moved “slightly forward” and she placed the victim as past the “gap”. At the time Mr Greiss’s head moved to follow the victim, Ms Wakatama placed the victim towards the end of the ramp.

Tiffiny Genders

145 After Mr Hayne was sentenced, Ms Genders left the media room and stood outside the building to gauge the reaction of those present. As the group which included the victim left the building, she noticed another group of people standing on the mezzanine level just one level above her (Ms Genders). She saw one of the latter group, whom she identified as Mr Greiss, approach the victim’s group, and look down at the victim or the group as they walked down the ramp. She said Mr Greiss was “staring at the victim as she walked past” and indicated that he was standing as close as he could to the victim. She said she could hear him say something but could not make out the words. She had the impression from the fact that he was watching her, that his behaviour was directed at the victim. When asked what happened next, she replied: “He spat in her direction”. She testified that she saw the spittle. She said she was “in complete shock”. It was suggested to her in cross-examination that she had no idea where the victim was at the time she said she saw Mr Greiss spit, but she disagreed. She denied that she was mistaken about what she saw. She also denied that it was false to say that Mr Greiss spat at the victim. She rejected the proposition that, having regard to where she was standing, the positions of Mr Greiss, the victim’s group, all the other people surrounding her and the ambient noise, she could not possibly have given truthful evidence. She denied making assumptions and reconstructing events she did not actually see and hear. She accepted that, if her evidence was correct and Mr Greiss did spit in the direction of the victim, he was also spitting in the direction of the sheriff.

146 On a photograph of the courthouse that became Exhibit U, Ms Genders identified her position at the bottom-left corner of the main entry stairs at the time Mr Greiss spat. She placed Mr Greiss at the top of the small staircase. And she placed the victim in a position past the small staircase.

147 In cross-examination, Ms Genders testified that, “moments after the spitting incident”, she asked Mr Greiss whether he spat in the victim’s direction and he did not deny it.

148 Consistent with her recollection, footage taken by a Seven camera operator discloses that she called out: “That is disgusting. He just spat at them”.

149 Almost immediately after she saw Mr Greiss spit at the victim, sheriff’s officers approached Mr Greiss. She could not hear what they were saying.

150 At 3:50 pm that day (four minutes before Ms Ryan’s tweet), Ms Genders published a tweet in the following terms:

A repulsive Jarryd #Hayne supporter was just staring down the victim & spat as she walked past with police. @9NewsSyd

151 In cross-examination Ms Genders denied giving the evidence she did in order to try to justify her tweet.

152 After sending this tweet, Ms Genders became aware of the Ryan tweet and re-tweeted it.

153 In cross-examination Ms Genders recalled “maybe eight to 10 people” in the victim’s group and that the victim was “a couple of people” inside the group although she admitted that she could not remember the “exact formation” of the group. She described Mr Greiss’s conduct, including speaking, looking and spitting at the victim, as having occurred in “one fell swoop, in one fluid movement”.

154 It was suggested to Ms Genders that there was a difference between spitting at someone and spitting in their direction but Ms Genders disagreed.

155 That evening, on the 6 pm news bulletin, Channel 9’s story featured commentary from the newsreader, Georgie Gardner, and Ms Genders which was interspersed with statements recorded at the courthouse.

Georgie Gardner: There’s been outrage at the behaviour of Jarryd Hayne supporters who turned on his rape victim outside court. Tonight, police are considering charges, with concerns the ugly scenes will deter other women from speaking out about sexual assault.

Tiffiny Genders: Do you think it’s acceptable to spit at a woman? [directed to Mr Greiss]

Mina Greiss went to court to support Jarryd Hayne, but today, he became the story.

Mina Greiss: Get out of here, get of here [inaudible], shove that camera [inaudible] get out of here.

Tiffiny Genders: This was the 38-year-old moments after witnesses claim he tried to intimidate the rape victim. The father of one seen hurling abuse at the 28-year-old before spitting in her direction.

Tiffiny Genders: Others within in the group then unleashed on a female reporter.

Unnamed man [in all probability Daniel Petras]:

He should spit on you, treat you like a dog like you are.

…

156 In cross-examination Ms Genders admitted that she was the source for Ms Gardner’s opening remarks and maintained that her comments were accurate.

Mr Greiss

157 On 5 May 2021 Mr Greiss drove to Newcastle with Mr Petras, Mr Mateo and Mr Iuta in order to support Mr Hayne who was to be sentenced the following day. Mr Greiss had been friends with Mr Hayne for around 17 years at the time of his sentencing.

158 At around 9:30 am on 6 May 2021, the four men arrived at Newcastle courthouse. At around 3:00pm Mr Greiss heard that Mr Hayne had been sentenced. At this time he was in the foyer of the court. Soon afterwards he moved outside with his three friends and waited outside the entrance to the courthouse to make sure that Mr Hayne’s wife, Ms Bonnici, found her way safely to the car. He believed the dozen or so members of the media, who were gathered outside, were waiting for her. In cross-examination he accepted that he was not part of the group of people with umbrellas that assisted Ms Bonnici in leaving the court.

159 Mr Greiss denied spitting at the victim, spitting in her direction or staring her down.

160 Mr Greiss conceded in cross-examination that he was angry after learning the sentence because he felt the sentence was unjust. He said he believed that Mr Hayne was innocent and that the victim was not telling the truth. He denied blaming the victim for his friend’s plight.

161 Before Ms Bonnici emerged, Mr Greiss noticed other people leaving the court led by a sheriff’s officer. He then rose from his seat and walked towards the top of the stairs connecting the mezzanine and the ramp. In the group led by the sheriff’s officer he saw a man wearing a barrister’s robe and a woman whom he said he initially mistook for Ms Bonnici, but within a second or two he realised that it was the victim.

162 He denied that he moved to that position so that he could be nearer to the victim and that he looked at her as she passed by in an attempt to see her close up. He also denied that he wanted her to see him or that he intended to draw attention to himself.

163 While standing at the top of the stairs Mr Greiss pointed at the victim’s group twice, but denied pointing at the victim or anyone in particular. He accepted that he was speaking but claimed to be addressing the sheriff’s officer. He said that he asked the sheriff why they had not escorted Ms Bonnici out first and that the officer informed him that they were going to do so after they had “finished with the victim”.

164 Mr Greiss described his interactions as “harmless”. He said he asked the officer a “simple question” (“when are you taking the accused’s wife out?”). He denied calling the victim a liar or saying anything derogatory about her. He also denied that the victim would have been able to hear what he was saying, denied raising his voice and denied wanting to intimidate or harass the victim. He maintained that he was speaking in a quiet voice. Nonetheless, he accepted that his conduct might be intimidating and harassing but only if it were directed at her:

MR RICHARDSON: You would agree, wouldn’t you, that a man standing a few metres away from a sexual assault victim moments after a sentencing hearing who is pointing and speaking in a raised voice would likely be found by that woman to be intimidating?---If he was directing at her, yes. It would be.

And also, I suggest to you, likely to be found by that woman to be harassing?---Yes.

Mr Greiss, do you agree, in circumstances where a woman has been the victim in a sexual assault case and the man who assaulted her has just been sentenced and she is leaving a public courthouse, that she would likely be in a vulnerable state?---Of course.

You knew, didn’t you, that in those circumstances, a man pointing and speaking, would very probably make that woman feel intimidated, didn’t you?---Yes.

And also harassed, you agree?---Yes.

165 Mr Greiss accepted that at the time he was pointing he was angry. When it was put to him that there was no reason to be angry with the sheriff, he said that he “wasn’t angry at the sheriff” while also denying that he was angry with the victim.

166 Mr Greiss accepted that he turned to his left to face the street and moved his head in a sharp downward motion. The cross-examiner then put to him that that was the precise moment when he first spat. At first he claimed not to recall that, but then denied the possibility. When asked whether he could suggest any other explanation for the movement of his head, he said that he could not recall and did not know, but suggested he could have sneezed.

167 Mr Greiss denied that his head gesture was an expression of his disgust or contempt for the victim or a reaction to her having walked past him.

168 He accepted that four sheriff’s officers came straight to him after the sharp downward movement of his head, that one ascended the ramp and that a number of others approached from the main entrance.

169 He also accepted that he was angry at the time but he denied that the sheriff’s officers were critical of his behaviour moments before and that he was defending himself. He described the interaction as “simple” and “a normal conversation” that did not involve “harsh talking” or “confrontation”.

170 Although he initially denied the second spit, after being shown the relevant footage Mr Greiss accepted that he did spit following his conversation with the sheriff’s officers. He agreed that that was “a deliberate act”. He denied it was an expression of his anger.

171 After the victim left he and his friends walked down to Hunter Street.

172 While on the street, Mr Petras showed him Ms Ryan’s tweet. When asked how he felt on seeing it, he replied:

Well, I was shocked. I was shocked. I felt like – I felt – there was no words that I could say that – I felt embarrassed. Really embarrassed. And I felt let down. I felt that there’s nothing I could do or say to fix this, to even – It was just embarrassing. It was just so embarrassing, and there was nothing I could – that I could do to defend myself over – about it.

173 In cross-examination, Mr Greiss initially denied speaking twice to the journalists on two occasions before Ms Bonnici left, maintaining that there was only one conversation with Ms Ryan, and also denied speaking to Ms Ryan after Ms Bonnici had left the precinct. He later accepted that all three interactions occurred, although he denied speaking to the journalists during the first interaction.

174 In relation to the first escort conversation, Mr Greiss accepted that the video footage shows that he was filming the journalists. He claimed, however, not to remember calling the victim an escort or saying to the journalists “did you put that she’s an escort” and after hearing the recording he denied it.

175 In relation to the second escort conversation, Mr Greiss agreed that he approached Ms Ryan about her tweet. He accepted that there were many people within earshot, plenty of cameras around and many media representatives listening. Relevantly, he agreed that he said to her “grub, you reckon?” to which Ms Ryan said “yeah, you are” and that he then replied: “yeah, all good, yeah. I’m happy with that”. He also accepted that he asked her: “did you put that she’s an escort”. He claimed not to understand Ms Ryan’s remark that “I just love that you’re focussed on another woman …”, despite voicing his agreement with her at the time (“Yes, absolutely”), and denied that he had previously been focussed on the victim.

176 Mr Greiss testified that when he confronted Ms Ryan “it was basically about the whole tweet”, which he described as “all a lie”. While he accepted that he did not say to her that the tweet was a lie, he maintained that he confronted Ms Ryan about the whole content of the tweet. He agreed, however, that at no point in time did he ask Ms Ryan to take down the tweet.

177 Mr Greiss testified that he was speaking to journalists outside the courthouse because he was upset that “there [were] things that didn’t come out” in Mr Hayne’s trial and, although he could not “go into too much detail”, there were “things that the jury weren’t told”. In cross-examination he stated that he had discussed the allegations made against Mr Hayne with him. He agreed that his comments about the victim being an escort were meant to convey that she was a prostitute and “a person of little worth”. Incredibly, he denied wanting the media to report his comments in the following troubling exchange:

You wanted the media to write that about her, didn’t you?---No, it wasn’t – it wasn’t my business.

You felt that, if the media reported she was an escort, it would be good for your friend, the accused?---No, I just felt that it didn’t come out in court.

You felt it would mean it would be less likely she would be believed?---No, I felt like it would give my friend a better chance to defend himself in court.

You felt contempt for this woman, didn’t you, Mr Greiss?---I had no – I don’t know who she is. I have got nothing against her. Okay. Mr Richardson, I have got nothing against her. I don’t know her. Okay. I was angry because my friend was sent to jail. Okay, and the truth of the whole matter didn’t come out as it should have been. Okay, and now this is – this is why I didn’t want to talk in the first place. Okay. This is happening right now, that we should not be discussing this. Okay, but there are a lot of things, aspects, that did not come out in his sentencing that did come out now and that’s why he’s getting a retrial.

You didn’t even sit through the first and second trials, did you?---I know – I know about.

You didn’t sit through either the first or the second trial. You said that earlier, didn’t you?---No, I didn’t.

178 Despite denying that he wanted the media to write about the victim, Mr Greiss ultimately conceded that he urged the journalists to report that she was an escort. Although he claimed to have nothing against the victim, he said he wanted them to report she was an escort because he believed she falsely accused his friend of rape and was responsible for his imprisonment. He disavowed a belief that an escort could not be raped. He claimed his point was that he was “just angry that … a lot of things … didn’t come out in [the] trial”. He thought it would have made a difference to the outcome if the jury had been told she was an escort but was unable to explain why.

179 He admitted to spitting while walking down to the street (third spit) and accepted that it was an expression of his anger following his conversation with Ms Ryan. Although he initially denied saying “here’s another one for ya”, as I indicated above, after the video was replayed he accepted that he did say words to that effect, but claimed (disingenuously in my opinion) not to know what he meant by them or to what he was referring. Similarly, he flatly denied saying to Ms Ryan “You’re not a woman”, although at that point, too, the video had been played twice to him. I accept that the latter comment was difficult to hear in the courtroom. I, myself, could not then hear it. But that was not Mr Greiss’s evidence.

180 Mr Greiss accepted, however, that (in the third escort conversation) Mr Petras said that “he spat on an escort” and that he did not correct him. After multiple denials, he also accepted that he said “I did spit” after Ms Ryan had said “… he spat towards the victim”, but denied that in doing so he was agreeing with Ms Ryan. He also denied replying “Yeah, exactly” to Mr Petras’s statement that, “He should spit on you”.

181 Again, Mr Greiss accepted that during this confrontation with Ms Ryan there were many people within earshot, plenty of cameras around and he had an audience.

182 On the drive home Mr Greiss was shown publications by Channel Seven. His former partner called and told him “there was a lot of publications and comments”. When asked how he felt about “publications being put up about [him]”, he replied:

It was embarrassing. It was – it was an overwhelming feeling of let down and shame. Shame. Because it’s not the way we were brought up. It was something way beyond comprehension. Like, I couldn’t – I was never in that position in my life before. I’ve never been accused of something like this, or – I didn’t know how to feel. Later on I was just – I just felt let down. I just felt really let down.

183 The next day Mr Greiss saw the first matter complained of (the news article). His reaction to that was the same. He said he “felt shame”, “felt ashamed” and “embarrassed”.

184 He was “outraged” by the Facebook post (the second matter), “very angry” and “very upset”.

Mr Mateo

185 At the time the victim left the court, Mr Mateo was standing on the footpath on Hunter Street. He had walked down the small staircase onto the disability ramp and then the street to call his mother. He said that he was standing “probably directly down from where the waiting area was on the upper level of the courthouse” and, at the time the victim left, he “turned towards where she was coming from”. He could see Mr Greiss from where he was standing. He testified that he did not see Mr Greiss spit towards, or in the direction of, the victim’s group and could not hear what Mr Greiss was saying to the victim’s group as he was still on the phone.

186 In cross-examination, however, Mr Mateo said that he did observe Mr Greiss spit at the time the victim left. He testified:

As I was watching the victim leave, she was – well, like, the group that she was with almost turned the corner around the building, and he spat in – pretty much in my direction, into the garden bed.

187 When shown the CCTV footage he confirmed that this was at the time of the first spit, which Mr Greiss had denied:

And you see now, Mr Mateo, there’s a group of people leaving?---Yes.

And you see Mr Greiss has stood up and is moving to the top of the ramp there?---Yes.

Did you see Mr Greiss move his head then?---Yes.

Was that the moment that you believe that he spat?---Yes.

188 He agreed with the cross-examiner that he saw Mr Greiss turn to the left to face the street, then move his head and spit. At the time, he said, he believed he (Mr Mateo) was “facing where the victim was coming down”.

Mr Iuta

189 Mr Iuta’s evidence on this point was of little to no assistance.

190 In his evidence in chief, Mr Iuta testified that, when the victim’s group left the court building down the ramp he was sitting down facing the street with his back to the courthouse. Mr Greiss, he said, was on his right. At that time he did not see Mr Greiss spit in the direction of the victim or towards the victim. Nor did he see him talk to the victim.

191 In cross-examination Mr Iuta said that he did not see Mr Greiss spit at any time, although it is common ground that he spat at least once while on the mezzanine level and once on the footpath in front of the reporters. He did not say that he was watching Mr Greiss. All of that is unsurprising since his evidence indicates that he was not focussed on Mr Greiss. Indeed, it suggests that he was not paying any attention to Mr Greiss as he was preoccupied with thoughts of Mr Hayne.

Other evidence

192 Mr Greiss also relied on certain passages in two statements produced on subpoena. Those statements were made by Mr Weaver (the sheriff’s officer at the back of the victim’s group) and Mr Marsay (another sheriff’s officer who was presented at the courthouse that day).

193 The relevant representations from Mr Weaver were:

At the conclusion of the sentencing Acting Sergeant GIRKIN and I escorted the victim in the substantive matter away from the court without incident. There was no interaction with her and the HAYNE group.

After the (substantive) victim in the matter had safely left the area, I walked back towards the court entrance.

(Emphasis added).